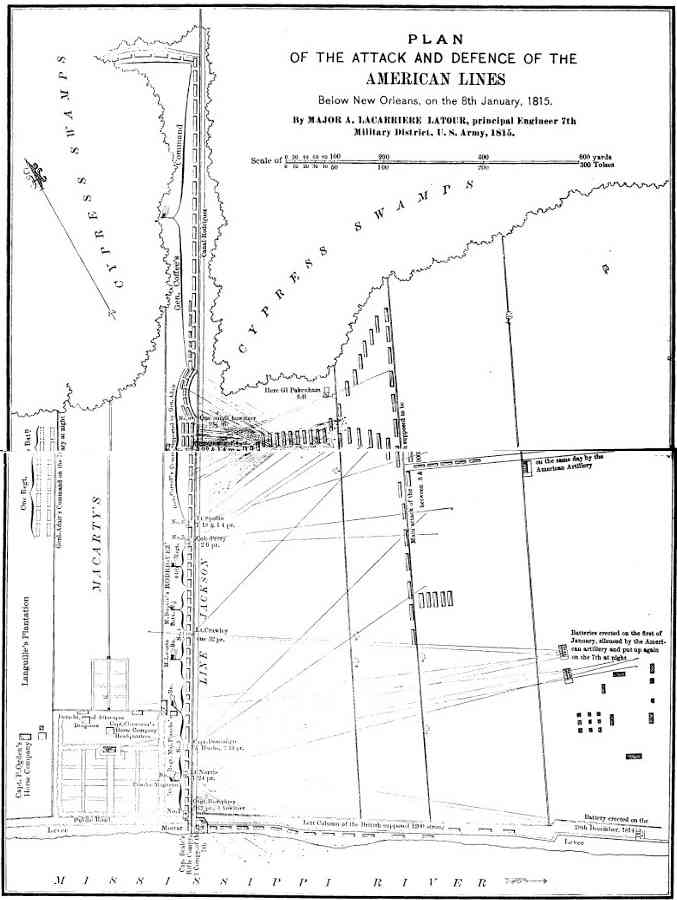

PLAN

OF THE

BATTLE OF CHIPPAWA

STRUTHERS & CO., ENGR’S, N. Y.

Title: History of the United States of America, Volume 8 (of 9)

During the second administration of James Madison

Author: Henry Adams

Release date: February 27, 2024 [eBook #73057]

Language: English

Original publication: New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1889

Credits: Richard Hulse,Karin Spence and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

THE

SECOND ADMINISTRATION

OF

JAMES MADISON

1813–1817

HISTORY OF THE UNITED STATES.

BY

HENRY ADAMS.

Vols. I. and II.—The First Administration of Jefferson. 1801–1805.

Vols. III. and IV.—The Second Administration of Jefferson. 1805–1809.

Vols V. and VI.—The First Administration of Madison. 1809–1813.

Vols. VII., VIII., and IX.—The Second Administration of Madison. 1813–1817. With an Index to the Entire Work.

By HENRY ADAMS

Vol. II.

NEW YORK

CHARLES SCRIBNER’S SONS

1891

Copyright, 1890

By Charles Scribner’s Sons.

University Press:

John Wilson and Son, Cambridge.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

|---|---|---|

| I. | Massachusetts Decides | 1 |

| II. | Chippawa and Lundy’s Lane | 24 |

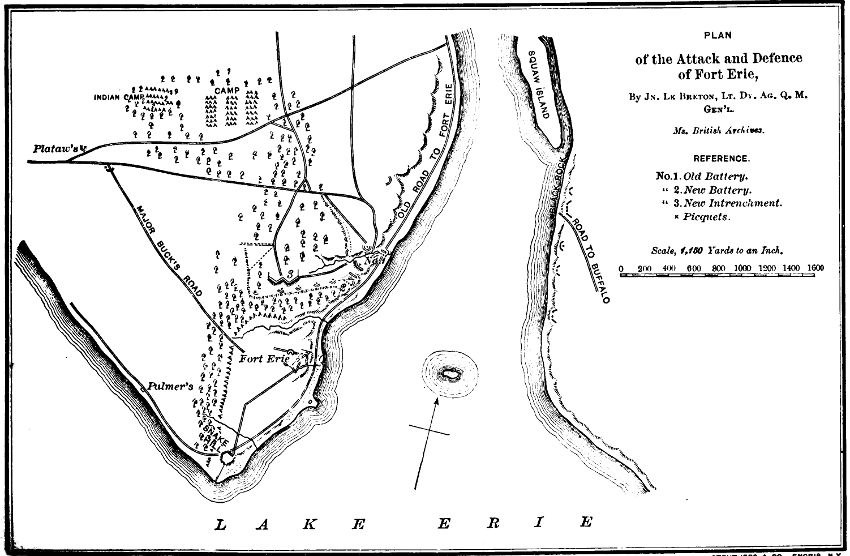

| III. | Fort Erie | 62 |

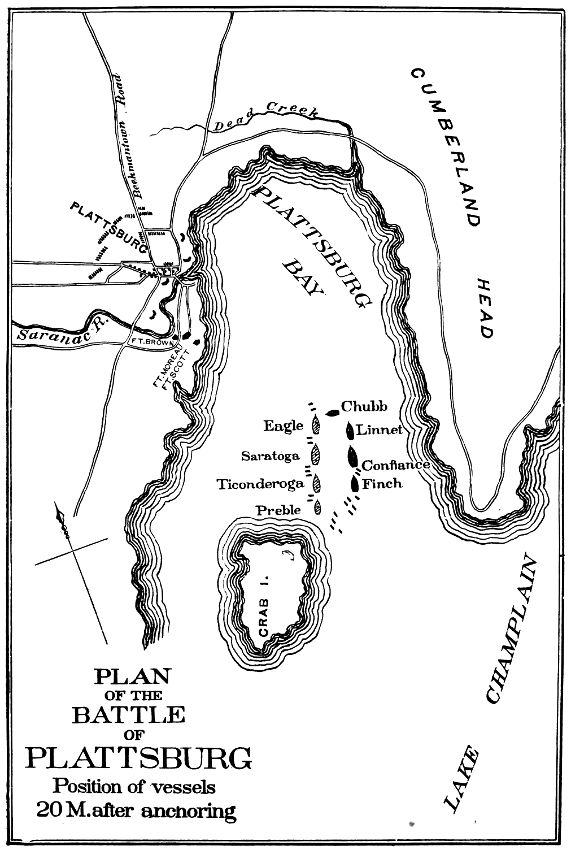

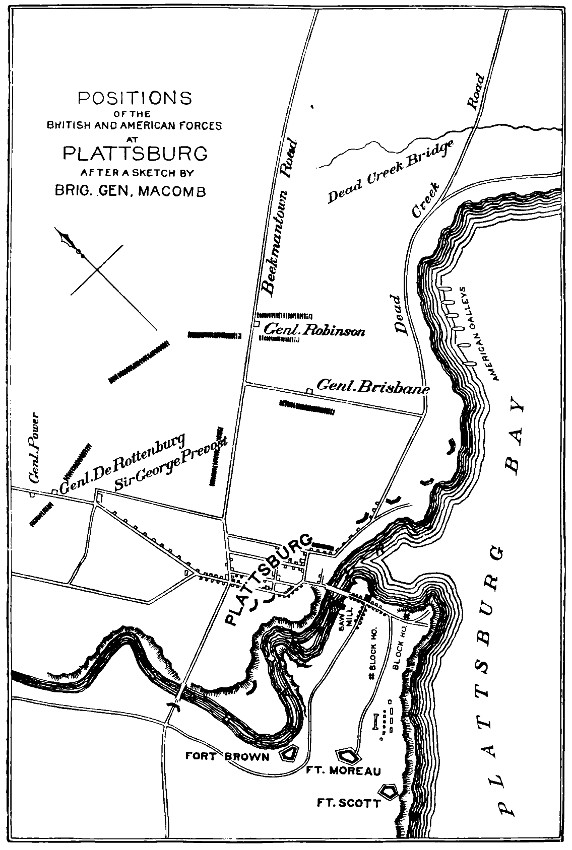

| IV. | Plattsburg | 91 |

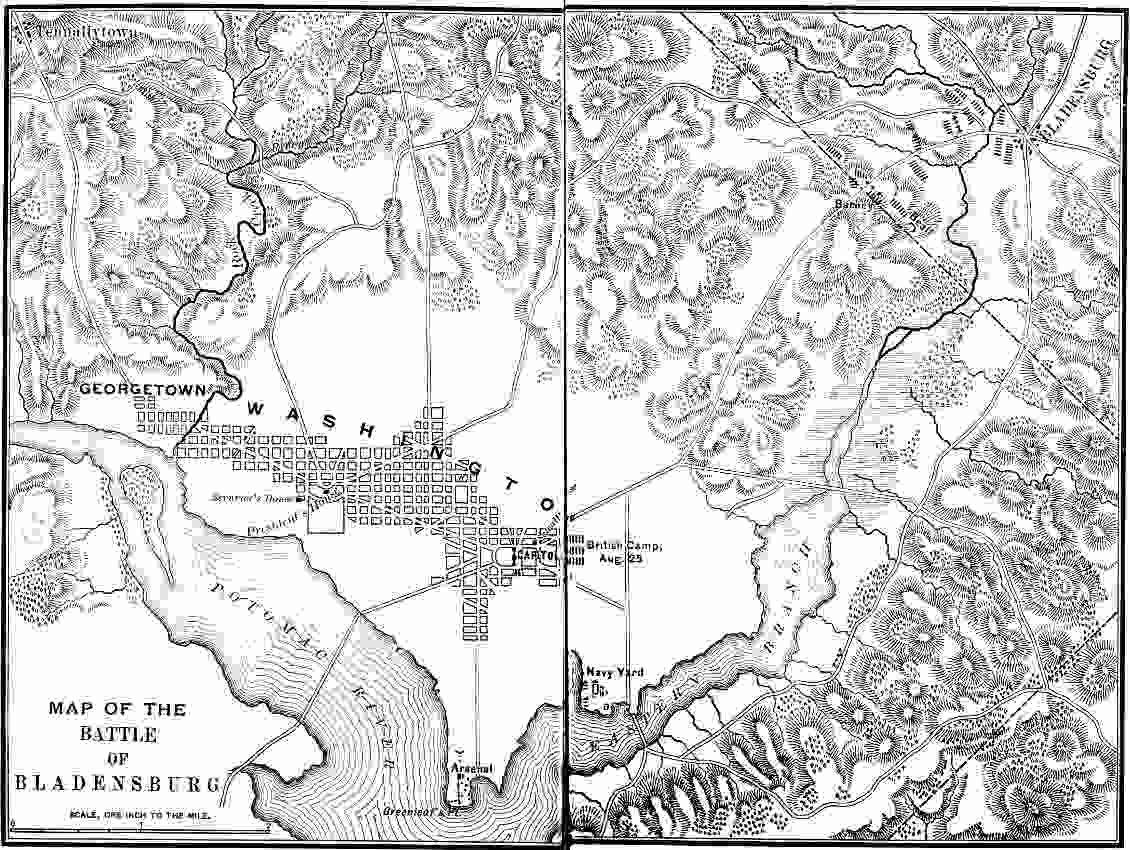

| V. | Bladensburg | 120 |

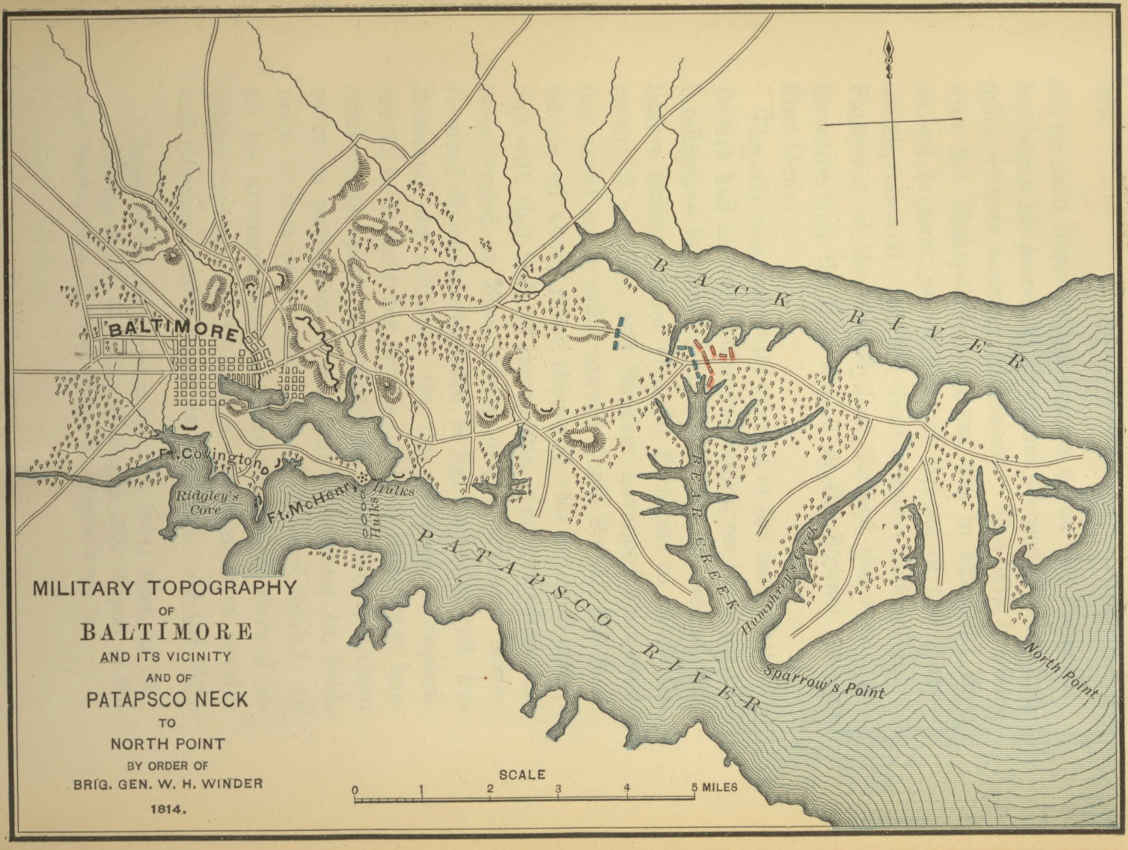

| VI. | Baltimore | 149 |

| VII. | Sloops-of-war and Privateers | 174 |

| VIII. | Exhaustion | 212 |

| IX. | Congress and Currency | 239 |

| X. | Congress and Army | 263 |

| XI. | The Hartford Convention | 287 |

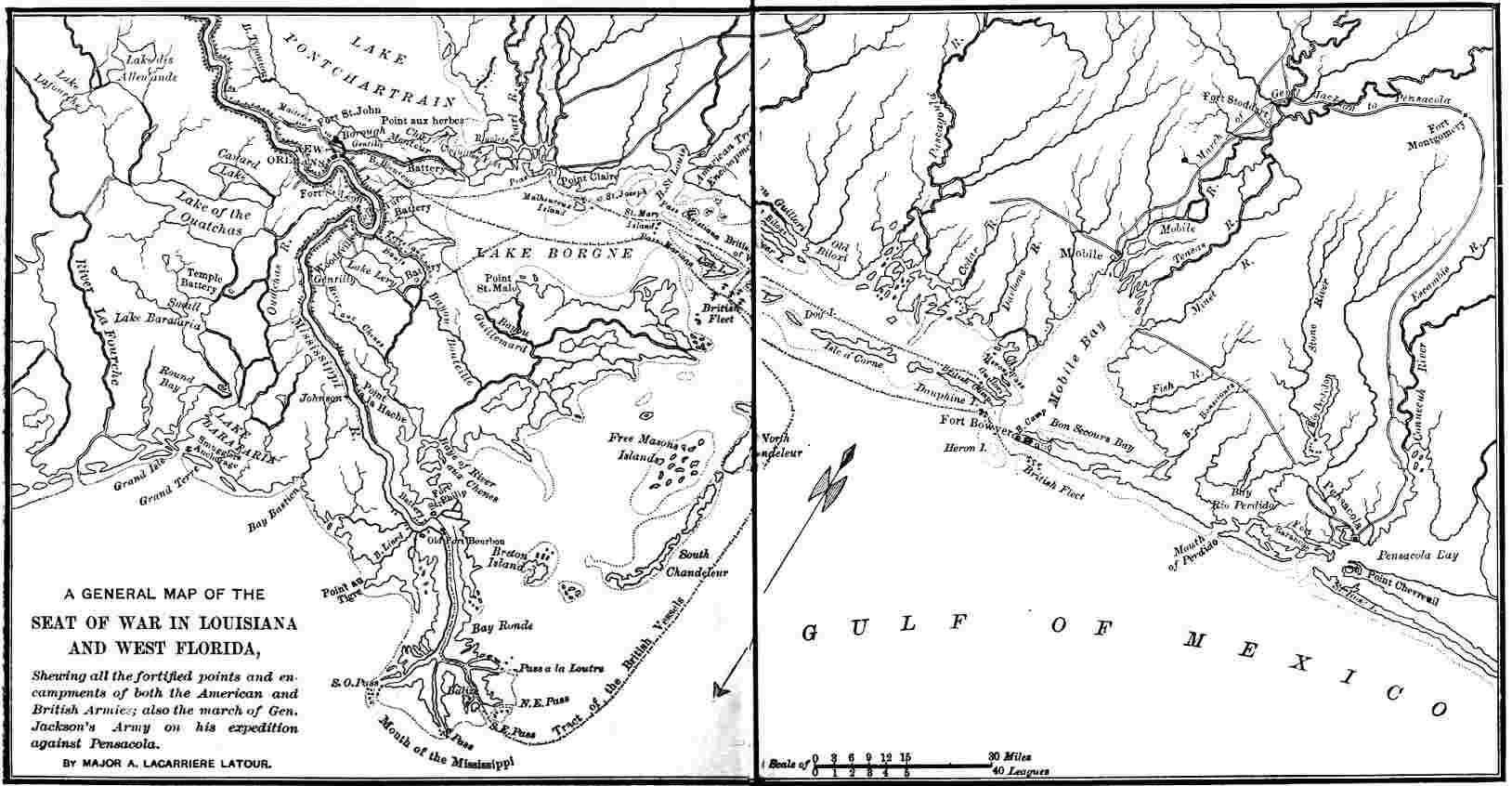

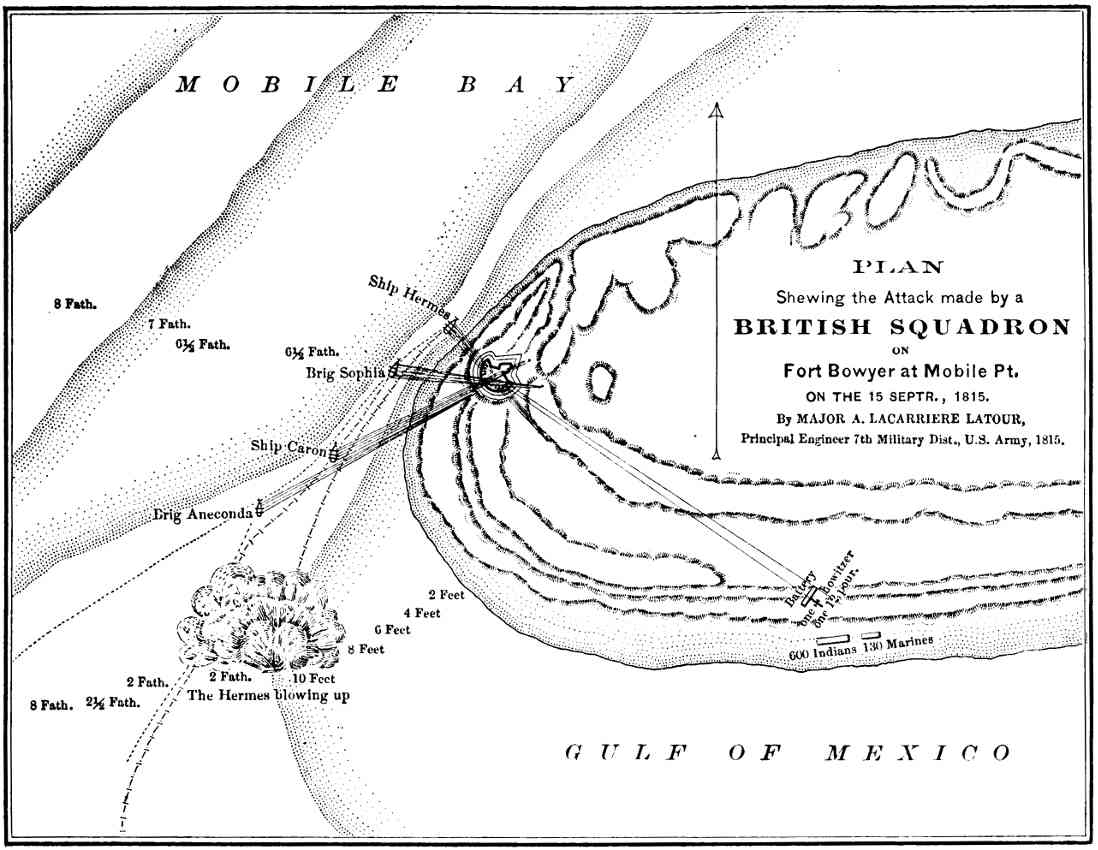

| XII. | New Orleans in Danger | 311 |

| XIII. | The Artillery Battle | 340 |

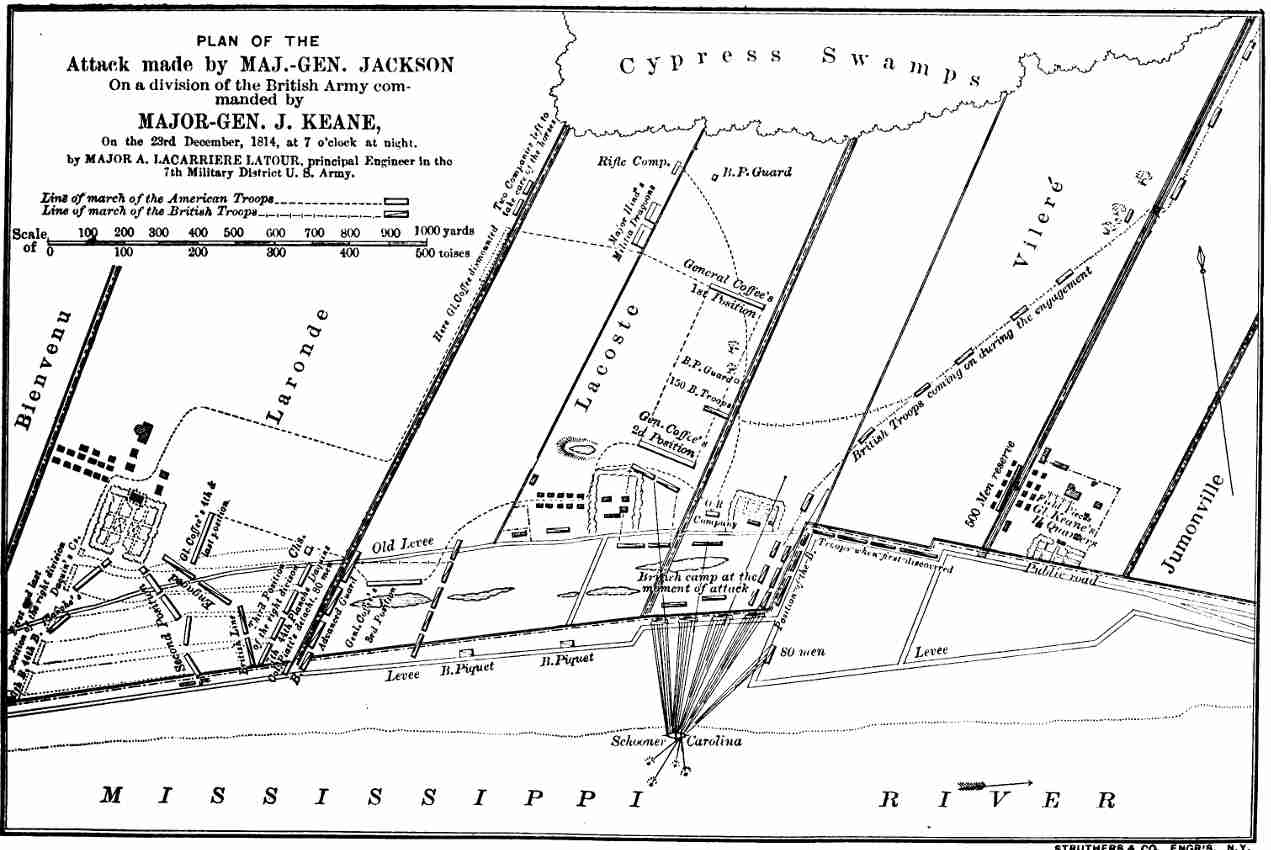

| XIV. | The Battle of New Orleans | 367 |

[1]

HISTORY OF THE UNITED STATES.

At the beginning of the year 1814, the attitude of New England pleased no one, and perhaps annoyed most the New England people themselves, who were conscious of showing neither dignity, power, courage, nor intelligence. Nearly one half the people of the five New England States supported the war, but were paralyzed by the other half, which opposed it. Of the peace party, one half wished to stop the war, but was paralyzed by the other half, which threatened to desert their leaders at the first overt act of treason. In this dead-lock every one was dissatisfied, but no one seemed disposed to yield.

Such a situation could not last. In times of revolution treason might be necessary, but inert perversity could at no time serve a useful purpose. Yet the Massachusetts Federalists professed only a wish to remain inert. Josiah Quincy, who fretted at restraints, and whose instincts obliged him to act as energetically as he talked, committed his party to[2] the broad assertion that “a moral and religious people” could not express admiration for heroism displayed in a cause they disapproved. They would defend Massachusetts only by waiting to be invaded; and if their safety depended on their possessing the outlet of Lake Champlain, they would refuse to seize it if in doing so they should be obliged to cross the Canadian line. With one accord Massachusetts Federalists reiterated that until their territory should be actually invaded, they would not take arms. After January 1, 1814, when news of the battle of Leipzig arrived, the dreaded invasion of New England became imminent; but the Federalists, officially and privately, insisted on their doctrine of self-defence.

“In the tumult of arms,” said Governor Strong in his speech to the legislature, January 12, 1814, “the passions of men are easily inflamed by artful misrepresentations; they are apt to lose sight of the origin of a contest, and to forget, either in the triumph of victory or the mortification of defeat, that the whole weight of guilt and wretchedness occasioned by war is chargeable upon that government which unreasonably begins the conflict, and upon those of its subjects who, voluntarily and without legal obligation, encourage and support it.”

The Massachusetts Senate echoed the sentiment in language more emphatic:—

“Beyond that submission which laws enacted agreeably to the Constitution make necessary, and that self-defence which the obligation to repel hostile invasions justifies, a people can give no encouragement to a war[3] of such a character without becoming partakers in its guilt, and rendering themselves obnoxious to those just retributions of Divine vengeance by which, sooner or later, the authors and abettors of such a war will be assuredly overtaken.”

The House of Representatives could see but one contingency that warranted Massachusetts in making voluntary exertion:—

“It is only after the failure of an attempt to negotiate, prosecuted with evidence of these dispositions on the part of our Administration, that any voluntary support of this unhappy war can be expected from our constituents.”

In thus tempting blows from both sides, Massachusetts could hardly fail to suffer more than by choosing either alternative. Had she declared independence, England might have protected and rewarded her. Had she imitated New York in declaring for the Union, probably the Union would not have allowed her to suffer in the end. The attempt to resist both belligerents forfeited the forbearance of both. The displeasure of Great Britain was shown by a new proclamation, dated April 25, 1814, including the ports of New England in the blockade; so that the whole coast of the Union, from New Brunswick to Texas, was declared to be closed to commerce by “a naval force adequate to maintain the said blockade in the most rigorous and effective manner.”[1]

[4]

However annoying the blockade might be, it was a trifling evil compared with other impending dangers from Great Britain. Invasion might be expected, and its object was notorious. England was known to regret the great concessions she had made in the definitive treaty of 1783. She wished especially to exclude the Americans from the fisheries, and to rectify the Canadian boundary by recovering a portion of Maine, then a part of Massachusetts. If Massachusetts by her neutral attitude should compel President Madison to make peace on British terms, Massachusetts must lose the fisheries and part of the District of Maine; nor was it likely that any American outside of New England would greatly regret her punishment.

The extreme Federalists felt that their position could not be maintained, and they made little concealment of their wish to commit the State in open resistance to the Union. They represented as yet only a minority of their party; but in conspiracies, men who knew what they wanted commonly ended by controlling the men who did not. Pickering was not popular; but he had the advantage of following a definite plan, familiar for ten years to the party leaders, and founded on the historical idea of a New England Confederation.[2] For Pickering, disunion offered no terrors. “On the contrary,” he wrote, July 4, 1813, “I believe an immediate separation[5] would be a real blessing to the ‘good old thirteen States,’ as John Randolph once called them.”[3] His views on this subject were expressed with more or less fidelity and with much elaboration in a pamphlet published in 1813 by his literary representative, John Lowell.[4] His policy was as little disguised as his theoretical opinions; and in the early part of the year 1814, under the pressure of the embargo, he thought that the time had come for pressing his plan for a fourth time on the consideration of his party. Without consulting his old associates of the Essex Junto, he stimulated action among the people and in the State legislature.

The first step was, as usual, to hold town-meetings and adopt addresses to the General Court. Some forty towns followed this course, and voted addresses against the embargo and the war. Their spirit was fairly represented by one of the most outspoken, adopted by a town-meeting at Amherst, over which Noah Webster presided Jan. 3, 1814.[5] The people voted—

“That the representatives of this town in the General Court are desired to use their influence to induce that honorable body to take the most vigorous and decisive measures compatible with the Constitution to put an end[6] to this hopeless war, and to restore to us the blessings of peace. What measures it will be proper to take, we pretend not to prescribe; but whatever measures they shall think it expedient to adopt, either separately or in conjunction with the neighboring States, they may rely upon our faithful support.”

The town of Newbury in Essex County made itself conspicuous by adopting, January 31, a memorial inviting bloodshed:—

“We remember the resistance of our fathers to oppressions which dwindle into insignificance when compared with those which we are called on to endure. The rights ‘which we have received from God we will never yield to man.’ We call on our State legislature to protect us in the enjoyment of those privileges to assert which our fathers died, and to defend which we profess ourselves ready to resist unto blood. We pray your honorable body to adopt measures immediately to secure to us especially our undoubted right of trade within our State. We are ourselves ready to aid you in securing it to us to the utmost of our power, ‘peaceably if we can, forcibly if we must;’ and we pledge to you the sacrifice of our lives and property in support of whatever measures the dignity and liberties of this free, sovereign, and independent State may seem to your wisdom to demand.”

The voters of Newbury were constituents of Pickering. Their address could not have reached him at Washington when a few days afterward he wrote to Samuel Putnam, an active member of the General Court, then in session, urging that the time for remonstrances[7] had passed, and the time for action had come:[6]—

“Declarations of this sort by Massachusetts, especially if concurred in by the other New England States, would settle the business at once. But though made now by Massachusetts alone, you surely may rely on the co-operation of New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Connecticut, and I doubt not of Vermont and New York. With the executives and legislatures of most, and the representatives of all of them, you can freely communicate. Ought there not to be a proposal of a convention of delegates from those six States?”

The project of a New England convention was well understood to violate the Constitution, and for that reason alone the cautious Federalists disliked and opposed it. Doubtless a mere violence done to the law did not necessarily imply a wish for disunion. The Constitution was violated more frequently by its friends than by its enemies, and often the extent of such violations measured the increasing strength of the Union. In such matters intent was everything; and the intent of the proposed New England convention was made evident by the reluctance with which the leaders slowly yielded to the popular demand.

The addresses of the towns to the General Court were regularly referred to a committee, which reported February 18,[7] in a spirit not altogether satisfactory to the advocates of action:—

[8]

“Whenever the national compact is violated and the citizens of this State are oppressed by cruel and unauthorized laws, the legislature is bound to interpose its power and wrest from the oppressor his victim. This is the spirit of our Union, and thus it has been explained by the very man who now sets at defiance all the principles of his early political life.... On the subject of a convention, the committee observe that they entertain no doubt of the right of the legislature to invite other States to a convention and to join it themselves for the great purposes of consulting for the general good, and of procuring Amendments to the Constitution whenever they find that the practical construction given to it by the rulers for the time being is contrary to its true spirit and injurious to their immediate constituents.... This was the mode proposed by Mr. Madison[8] in answer to objections made as to the tendency of the general government to usurp upon that of the States.”

The argumentum ad personam commonly proved only weakness. Madison’s authority on these points had always been rejected by the Federalists when in power; and even he had never asserted the right of States to combine in convention for resistance to measures of the national government, as the General Court was asked to do. So revolutionary was the step that the committee of both Houses shrank from it: “They have considered that there are reasons which render it inexpedient at the present moment to exercise this power.” They advised that the subject should not be immediately decided, but should[9] be referred to the representatives soon to be returned for the next General Court, who would “come from the people still more fully possessed of their views and wishes as to the all-important subject of obtaining by future compact, engrafted into the present Constitution, a permanent security against future abuses of power, and of seeking effectual redress for the grievances and oppressions now endured.”

To the people, therefore, the subject of a New England convention was expressly referred. The issue was well understood, and excluded all others in the coming April election. So serious was the emergency, and so vital to the Administration and the war was the defeat of a New England convention, that the Republicans put forward no party candidate, but declared their intention to vote for Samuel Dexter, a Federalist,—although Dexter, in a letter dated February 14, reiterated his old opinions hostile to the embargo, and professed to be no further a Republican than that he offered no indiscriminate opposition to the war. His Federalism was that of Rufus King and Bayard.

“What good is to be expected,” he asked,[9] “from creating division when engaged in war with a powerful nation that has not yet explicitly shown that she is willing to agree to reasonable terms of peace? Why make publications and speeches to prove that we are absolved from allegiance to the national government, and hint[10] that an attempt to divide the empire might be justified?... The ferocious contest that would be the effect of attempting to skulk from a participation of the burdens of war would not be the greatest calamity.”

Under such circumstances the load of the embargo became too heavy for the Massachusetts Republicans to carry. They tried in every manner to throw it off, as persistently as President Madison tried to hold it on. Their candidate, Dexter, argued strongly against the restrictive system in his letter consenting to stand. They drew a distinction between the restrictive system and the war; but even in regard to the war they required not active support, but only abstinence from active resistance. The Federalists used the embargo to stimulate resistance to the war, and advocated a New England convention under cover of the unpopularity of commercial restrictions.

With the pertinacity which was his most remarkable trait, Madison clung to the embargo all winter in face of overwhelming motives to withdraw it. A large majority in Congress disliked it. England having recovered her other markets could afford to conquer the American as she had conquered the European, and to wait a few months for her opportunity. The embargo bankrupted the Treasury, threatened to stop the operations of war, and was as certain as any ordinary antecedent of a consequent result to produce a New England convention. Yet the President maintained it until the news from Europe caused a panic in Congress.

[11]

The Massachusetts election took place in the first days of April, while Congress was engaged in repealing the embargo and the system of commercial restrictions. The result showed that Dexter might have carried the State and defeated the project of a New England convention, had the embargo been repealed a few weeks earlier. A very large vote, about one hundred and two thousand in aggregate, was cast. The Federalists, whose official vote in 1813 was 56,754, threw 56,374 votes; while the Republicans, who cast 42,789 votes in 1813, numbered 45,359 in 1814.

The reduction of the Federalist majority from fourteen thousand to eleven thousand was not the only reason for believing that Dexter might have carried Massachusetts but for the embargo. At the same time William Plumer, supported like Dexter by the Republicans, very nearly carried New Hampshire, and by gaining a majority of the executive council, precluded the possibility that New Hampshire as a State could take part in a New England convention. The President’s Message recommending a repeal of the embargo was sent to Congress March 31, and the Act of Repeal was signed April 14. Two weeks later, April 28, the New York election took place. To this election both parties anxiously looked. The Administration press admitted that all was lost if New York joined Massachusetts,[10] and the New England Federalists knew that a decisive defeat in New York would[12] leave them to act alone. The returns were watched with such anxiety as had seldom attended a New York election, although no general State officer was to be chosen.

In May, 1813, Governor Tompkins carried the State by a majority of only 3,506, and the Federalists in the House of Assembly numbered sixty, while the Republicans numbered fifty-two. The city of New York and the counties of Queens, Westchester, Dutchess, Columbia, Rensselaer, and Washington—the entire range of counties on the east shore of the Hudson—were then Federalist. The counties of Albany, Montgomery, Oneida, Otsego, Madison, and Ontario in the centre of the State were also Federalist. At the congressional election of 1812, twenty Federalists and six Republicans had been chosen. The May election of 1814 was for the State Assembly and for Congress. No opportunity was given for testing the general opinion of the State on a single issue, but no one could mistake what the general opinion was. City and State reversed their political character. The Republicans recovered possession of the Assembly with a large majority of seventy-four to thirty-eight, and the Congressional delegation numbered twenty-one Republicans and only six Federalists.

The result was supposed to be largely due to a dislike of the New England scheme and to a wish among New York Federalists that it should be stopped. The energy of the demonstration in New York marked[13] the beginning of an epoch in national character; yet the change came too late to save Massachusetts from falling for the first time into the hands of the extreme Federalists. The towns of Massachusetts chose as their representatives to the General Court a majority bent on taking decisive action against the war. Connecticut and Rhode Island were controlled by the same impulse, and the discouraged Republicans could interpose no further resistance. A New England convention could be prevented only by a treaty of peace.

The effect of the attitude of New England was felt throughout the Union, and, combined with the news from Europe, brought a general conviction that peace must be made. No man in the Union was more loyal to the war than Governor Shelby of Kentucky, but Shelby already admitted that peace had become necessary.

“I may in confidence confess to you,” wrote Shelby, April 8,[11] “that I lament over my country that she has in her very bosom a faction as relentless as the fire that is unquenchable, capable of thwarting her best interests, and whose poisonous breath is extending to every corner of the Union. There is but one way to cure the evil, and that is an awful and desperate one; and in the choice of evils we had better take the least. Were we unanimous I should feel it less humiliating to be conquered, as I verily believe that the Administration will be driven to peace on any terms by the opposition to the war.”

[14]

If Governor Shelby had reached this conclusion before he knew the result of the Massachusetts election, the great mass of citizens who had been from the first indifferent to the war felt that peace on any terms could no longer be postponed. Mere disunion was not the result chiefly to be feared. That disunion might follow a collapse of the national government was possible; but for the time, Massachusetts seemed rather disposed to sacrifice the rest of the Union for her own power than to insist on a separation. Had the Eastern States suffered from the hardships of war they might have demanded disunion in despair; but in truth New England was pleased at the contrast between her own prosperity and the sufferings of her neighbors. The blockade and the embargo brought wealth to her alone. The farming and manufacturing industries of New England never grew more rapidly than in the midst of war and commercial restrictions.[12] “Machinery for manufactures, etc., and the fruits of household industry increase beyond calculation,” said a writer in the “Connecticut Herald” in July, 1813. “Wheels roll, spindles whirl, shuttles fly. We shall export to other States many more productions of industry than ever were exported in any one former season.” Manufactures were supposed to amount in value to fifteen or twenty million dollars a year. The Federalists estimated the balance due by the Southern States to New England at six million dollars a[15] year.[13] The New England banks were believed to draw not less than half a million dollars every month from the South.

“We are far from rejoicing at this state of things,” wrote a Connecticut Federalist;[14] “and yet we cannot but acknowledge the hand of retributive justice in inflicting the calamities of war with so much more severity on that section of the Union which has so rashly and so unmercifully persisted in their determination to commence hostilities. The pressure of this balance is sensibly felt, and will continue to increase as long as the war continues.”

John Lowell declared[15] that “the banks are at their wits’ end to lend their capital, and money is such a drug ... that men against their consciences, their honor, their duty, their professions and promises, are willing to lend it secretly to support the very measures which are intended and calculated for their ruin.” To avoid the temptation of lending money to support Madison’s measures, many investors bought British government bills of exchange at twenty to twenty-two per cent discount. These bills were offered for sale in quantities at Boston; and perhaps the most legitimate reason for their presence there was that they were taken by New England contractors in payment for beef and flour furnished to the British commissariat in Canada.

[16]

While New England thus made profits from both sides, and knew not what to do with the specie that flowed into her banks, the rest of the country was already insolvent, and seemed bent on bankruptcy. In March, 1814, the legislature of Pennsylvania passed a bill for the creation of forty-one new banks. March 19 Governor Snyder vetoed it.[16]

“It is a fact well ascertained,” said Governor Snyder, “that immense sums of specie have been withdrawn from the banks in Pennsylvania and certain other States to pay balances for British goods which Eastern mercantile cupidity has smuggled into the United States. The demand for specie has in consequence been and is still so great that the banks in Philadelphia and in some other parts have stopped discounting any new paper. I ask a patriotic legislature, Is this an auspicious era to try so vast an experiment? Shall we indirectly aid our internal and external enemies to destroy our funds and embarrass the government by the creating of forty-one new banks which must have recourse for specie to that already much exhausted source? Is there at this time an intelligent man in Pennsylvania who believes that a bank-note of any description is the representative of specie?”

The Pennsylvania legislature instantly overrode Governor Snyder’s veto and chartered the new banks, which were, according to the governor, insolvent before they had legal existence. In ordinary times such follies punished and corrected themselves in regular course; but in 1814 the follies and illusions[17] of many years concentrated their mischiefs on the national government, which was already unequal to the burden of its own. The war was practically at an end as far as the government conducted it. The army could not show a regiment with ranks more than half full.[17] The first three months of the year produced less than six thousand recruits.[18] The government could defend the frontier only at three or four fortified points. On the ocean, government vessels were scarcely to be seen. The Treasury was as insolvent as the banks, and must soon cease even the pretence of meeting its obligations.

The Secretary of the Treasury, authorized by law to borrow twenty-five millions and needing forty, offered a loan for only ten millions shortly before Congress adjourned. In Boston the government brokers advertised that the names of subscribers should be kept secret,[19] while the Boston “Gazette” of April 14 declared that “any man who lends his money to the government at the present time will forfeit all claim to common honesty and common courtesy among all true friends to the country.” The offers, received May 2, amounted to thirteen millions, at rates varying from seventy-five to eighty-eight. Jacob Barker, a private banker of New York, offered five million dollars on his single account. The secretary[18] knew that Barker’s bid was not substantial, but he told the President that if it had been refused “we could not have obtained the ten millions without allowing terms much less favorable to the government.”[20] The terms were bad at best. The secretary obtained bids more or less substantial for about nine millions at eighty-eight, with the condition that if he should accept lower terms for any part of the sixteen millions still to be offered, the same terms should be conceded to Barker and his associates. The operation was equivalent to borrowing nine millions on an understanding that the terms should be fixed at the close of the campaign. Of this loan Boston offered two millions, and was allotted about, one million dollars.

The event proved that Campbell would have done better to accept all solid bids without regard to rate, for the government could have afforded to pay two dollars for one within a twelve-month, rather than stop payments; but Campbell was earnest to effect his loan at eighty-eight, and accordingly accepted only four million dollars besides Barker’s offer. With these four millions, with whatever part of five millions could be obtained from Barker, with interest-bearing Treasury notes limited to ten million dollars,[21] and with the receipts from taxes, the Treasury was to meet demands aggregating about forty millions[19] for the year; for the chance was small that another loan could succeed, no matter what rate should be offered.

For this desperate situation of the government New England was chiefly responsible. In pursuing their avowed object of putting an end to the war the Federalists obtained a degree of success surprising even to themselves, and explained only by general indifference toward the war and the government. No one could suppose that the New England Federalists, after seeing their object within their grasp, would desist from effecting it. They had good reason to think that between Madison’s obstinacy and their own, the national government must cease its functions,—that the States must resume their sovereign powers, provide for their own welfare, and enter into some other political compact; but they could not suppose that England would forego her advantages, or consent to any peace which should not involve the overthrow of Madison and his party.

In such conditions of society morbid excitement was natural. Many examples in all periods of history could be found to illustrate every stage of a mania so common. The excitement of the time was not confined to New England. A typical American man-of-the-world was Gouverneur Morris. Cool, easy-tempered, incredulous, with convictions chiefly practical, and illusions largely rhetorical, Morris delivered an oration on the overthrow of Napoleon to a New York audience, June 29, 1814.

[20]

“And thou too, Democracy! savage and wild!” began Morris’s peroration,—“thou who wouldst bring down the virtuous and wise to the level of folly and guilt! thou child of squinting envy and self-tormenting spleen! thou persecutor of the great and good!—see! though it blast thine eyeballs,—see the objects of thy deadly hate! See lawful princes surrounded by loyal subjects!... Let those who would know the idol of thy devotion seek him in the island of Elba!”

The idea that American democracy was savage and wild stood in flagrant contrast to the tameness of its behavior; but the belief was a part of conservative faith, and Gouverneur Morris was not ridiculed, even for bad taste, by the society to which he belonged, because he called by inappropriate epithets the form of society which most of his fellow-citizens preferred. In New England, where democracy was equally reviled, kings and emperors were not equally admired. The austere virtue of the Congregational Church viewed the subject in a severer light, and however extreme might be the difference of conviction between clergymen and democrats, it was not a subject for ridicule.

To men who believed that every calamity was a Divine judgment, politics and religion could not be made to accord. Practical politics, being commonly an affair of compromise and relative truth,—a human attempt to modify the severity of Nature’s processes,—could not expect sympathy from the absolute and abstract behests of religion. Least of all could war,[21] even in its most necessary form, be applauded or encouraged by any clergyman who followed the precepts of Christ. The War of 1812 was not even a necessary war. Only in a metaphysical or dishonest sense could any clergyman affirm that war was more necessary in 1812 than in any former year since the peace of 1783. Diplomacy had so confused its causes that no one could say for what object Americans had intended to fight,—still less, after the peace in Europe, for what object they continued their war. Assuming the conquest of Canada and of Indian Territory to be the motive most natural to the depraved instincts of human nature, the clergy saw every reason for expecting a judgment.

In general, the New England clergy did not publicly or violently press these ideas. The spirit of their class was grave and restrained rather than noisy. Yet a few eccentric or exceptional clergymen preached and published Fast-day sermons that threw discredit upon the whole Congregational Church. The chief offenders were two,—David Osgood, of the church at Medford, and Elijah Parish, a graduate of Dartmouth College, settled over the parish of Byfield in the town of Newbury, where political feeling was strong. Parish’s Fast-day sermon of April 7, 1814, immediately after the election which decided a New England convention, was probably the most extreme made from the pulpit:—

“Israel’s woes in Egypt terminated in giving them the fruits of their own labors. This was a powerful[22] motive for them to dissolve their connection with the Ancient Dominion. Though their fathers had found their union with Egypt pleasant and profitable, though they had been the most opulent section in Egypt, yet since the change of the administration their schemes had been reversed, their employments changed, their prosperity destroyed, their vexations increased beyond all sufferance. They were tortured to madness at seeing the fruit of their labors torn from them to support a profligate administration.... They became discouraged; they were perplexed. Moses and others exhorted them not to despair, and assured them that one mode of relief would prove effectual. Timid, trembling, alarmed, they hardly dared to make the experiment. Finally they dissolved the Union: they marched; the sea opened; Jordan stopped his current; Canaan received their triumphant banners; the trees of the field clapped their hands; the hills broke forth into songs of joy; they feasted on the fruits of their own labors. Such success awaits a resolute and pious people.”

Although Parish’s rhetoric was hardly in worse taste than that of Gouverneur Morris, such exhortations were not held in high esteem by the great body of the Congregational clergy, whose teachings were studiously free from irreverence or extravagance in the treatment of political subjects.[22] A poor and straitened but educated class, of whom not one in four obtained his living wholly from his salary, the New England ministers had long ceased to speak with the authority of their predecessors,[23] and were sustained even in their moderate protest against moral wrong rather by pride of class and sincerity of conviction than by sense of power. Some supported the war; many deprecated disunion; nearly all confined their opposition within the limits of non-resistance. They held that as the war was unnecessary and unjust, no one could give it voluntary aid without incurring the guilt of blood.

The attitude was clerical, and from that point of view commanded a degree of respect such as was yielded to the similar conscientiousness of the Friends; but it was fatal to government and ruinous to New England. Nothing but confusion could result from it if the war should continue, while the New England church was certain to be the first victim if peace should invigorate the Union.

[24]

After the close of the campaign on the St. Lawrence, in November, 1813, General Wilkinson’s army, numbering about eight thousand men, sick and well, went into winter-quarters at French Mills, on the Canada line, about eight miles south of the St. Lawrence. Wilkinson was unfit for service, and asked leave to remove to Albany, leaving Izard in command; but Armstrong was not yet ready to make the new arrangements, and Wilkinson remained with the army during the winter. His force seemed to stand in a good position for annoying the enemy and interrupting communications between Upper and Lower Canada; but it lay idle between November 13 and February 1, when, under orders from Armstrong, it was broken up.[23] Brigadier-General Brown, with two thousand men, was sent to Sackett’s Harbor. The rest of the army was ordered to fall back to Plattsburg,—a point believed most likely to attract the enemy’s notice in the spring.[24]

[25]

Wilkinson obeyed, and found himself, in March, at Plattsburg with about four thousand effectives. He was at enmity with superiors and subordinates alike; but the chief object of his antipathy was the Secretary of War. From Plattsburg, March 27, he wrote a private letter to Major-General Dearborn,[25] whose hostility to the secretary was also pronounced: “I know of his [Armstrong’s] secret underworkings, and have therefore, to take the bull by the horns, demanded an arrest and a court-martial.... Good God! I am astonished at the man’s audacity, when he must be sensible of the power I have over him.” Pending the reply to his request for a court-martial, Wilkinson determined to make a military effort. “My advanced post is at Champlain on this side. I move to-day; and the day after to-morrow, if the ice, snow, and frost should not disappear, we shall visit the Lacolle, and take possession of that place. This is imperiously enjoined to check the reinforcements he [Prevost] continues to send to the Upper Province.”[26]

The Lacolle was a small river, or creek, emptying into the Sorel four or five miles beyond the boundary. According to the monthly return of the troops commanded by Major-General de Rottenburg, the British forces stationed about Montreal numbered, Jan. 22, 1814, eight thousand rank-and-file present for duty. Of these, eight hundred and eighty-five[26] were at St. John’s; six hundred and ninety were at Isle aux Noix, with outposts at Lacadie and Lacolle of three hundred and thirty-two men.[27]

Wilkinson knew that the British outpost at the crossing of Lacolle Creek, numbering two hundred men all told,[28] was without support nearer than Isle aux Noix ten miles away; but it was stationed in a stone mill, with thick walls and a solid front. He took two twelve-pound field-guns to batter the mill, and crossing the boundary, March 30, with his four thousand men, advanced four or five miles to Lacolle Creek. The roads were obstructed and impassable, but his troops made their way in deep snow through the woods until they came within sight of the mill. The guns were then placed in position and opened fire; but Wilkinson was disconcerted to find that after two hours the mill was unharmed. He ventured neither to storm it nor flank it; and after losing more than two hundred men by the fire of the garrison, he ordered a retreat, and marched his army back to Champlain.

With this last example of his military capacity Wilkinson disappeared from the scene of active life, where he had performed so long and extraordinary a part. Orders arrived, dated March 24, relieving him from duty under the form of granting his request for a court of inquiry. Once more he passed the ordeal[27] of a severe investigation, and received the verdict of acquittal; but he never was again permitted to resume his command in the army.

The force Wilkinson had brought from Lake Ontario, though united with that which Wade Hampton had organized, was reduced by sickness, expiration of enlistments, and other modes of depletion to a mere handful when Major-General Izard arrived at Plattsburg on the first day of May. Izard’s experience formed a separate narrative, and made a part of the autumn campaign. During the early summer the war took a different and unexpected direction, following the steps of the new Major-General Brown; for wherever Brown went, fighting followed.

General Brown marched from French Mills, February 13, with two thousand men. February 28, Secretary Armstrong wrote him a letter suggesting an attack on Kingston, to be covered by a feint on Niagara.[29] Brown, on arriving at Sackett’s Harbor, consulted Chauncey, and allowed himself to be dissuaded from attacking Kingston. “By some extraordinary mental process,” Armstrong thought,[30] Brown and Chauncey “arrived at the same conclusion,—that the main action, an attack on Kingston, being impracticable, the ruse, intended merely to mask it, might do as well.” Brown immediately marched with two thousand men for Niagara.

When the secretary learned of this movement, although[28] it was contrary to his ideas of strategy, he wrote an encouraging letter to Brown, March 20:[31]

“You have mistaken my meaning.... If you hazard anything by this mistake, correct it promptly by returning to your post. If on the other hand you left the Harbor with a competent force for its defence, go on and prosper. Good consequences are sometimes the result of mistakes.”

The correspondence showed chiefly that neither the secretary nor the general had a distinct idea, and that Brown’s campaign, like Dearborn’s the year before, received its direction from Chauncey, whose repugnance to attacking Kingston was invincible.

Brown was shown his mistake by Gaines, before reaching Buffalo March 24, and leaving his troops, he hurried back to Sackett’s Harbor, “the most unhappy man alive.”[32] He resumed charge of such troops as remained at the Harbor, while Winfield Scott formed a camp of instruction at Buffalo, and, waiting for recruits who never came, personally drilled the officers of all grades. Scott’s energy threw into the little army a spirit and an organization strange to the service. Three months of instruction converted the raw troops into soldiers.

Meanwhile Brown could do nothing at Sackett’s Harbor. The British held control of the Lake, while Commodore Chauncey and the contractor Eckford were engaged in building a new ship which was to[29] be ready in July. The British nearly succeeded in preventing Chauncey from appearing on the Lake during the entire season, for no sooner did Sir James Yeo sail from Kingston in the spring than he attempted to destroy the American magazines. Owing to the remote situation of Sackett’s Harbor in the extreme northern corner of the State, all supplies and war material were brought first from the Hudson River to Oswego by way of the Mohawk River and Oneida Lake. About twelve miles above Oswego the American magazines were established, and there the stores were kept until they could be shipped on schooners, and forwarded fifty miles along the Lake-shore to Sackett’s Harbor,—always a hazardous operation in the face of an enemy’s fleet. The destruction of the magazines would have been fatal to Chauncey, and even the capture or destruction of the schooners with stores was no trifling addition to his difficulties.

Sir James Yeo left Kingston May 4, and appeared off Oswego the next day, bringing a large body of troops, numbering more than a thousand rank-and-file.[33] They found only about three hundred men to oppose them, and having landed May 6, they gained possession of the fort which protected the harbor of Oswego. The Americans made a resistance which caused a loss of seventy-two men killed and wounded to the British, among the rest Captain Mulcaster of the Royal Navy, an active officer, who was dangerously[30] wounded. The result was hardly worth the loss. Four schooners were captured or destroyed, and some twenty-four hundred barrels of flour, pork, and salt, but nothing of serious importance.[34] Yeo made no attempt to ascend the river, and retired to Kingston after destroying whatever property he could not take away.

Although the chief American depot escaped destruction, the disgrace and discouragement remained, that after two years of war the Americans, though enjoying every advantage, were weaker than ever on Lake Ontario, and could not defend even so important a point as Oswego from the attack of barely a thousand men. Their coastwise supply of stores to Sackett’s Harbor became a difficult and dangerous undertaking, to be performed mostly by night.[35] Chauncey remained practically blockaded in Sackett’s Harbor; and without his fleet in control of the Lake the army could do nothing effectual against Kingston.

In this helplessness, Armstrong was obliged to seek some other line on which the army could be employed against Upper Canada; and the idea occurred to him that although he had no fleet on Lake Ontario he had one on Lake Erie, which by a little ingenuity might enable the army to approach the heart of Upper Canada at the extreme western end of Lake Ontario. “Eight or even six thousand men,” Armstrong[31] wrote[36] to the President, April 30, “landed in the bay between Point Abino and Fort Erie, and operating either on the line of the Niagara, or more directly if a more direct route is found, against the British post at the head of Burlington Bay, cannot be resisted with effect without compelling the enemy so to weaken his more eastern posts as to bring them within reach of our means at Sackett’s Harbor and Plattsburg.”

Armstrong’s suggestion was made to the President April 30. Already time was short. The allies had entered Paris March 31; the citadel of Bayonne capitulated to Wellington April 28. In a confidential despatch dated June 3, Lord Bathurst notified the governor-general of Canada that ten thousand men had been ordered to be shipped immediately for Quebec.[37] July 5, Major-General Torrens at the Horse-guards informed Prevost that four brigades,—Brisbane’s, Kempt’s, Power’s, and Robinson’s; fourteen regiments of Wellington’s best troops,—had sailed from Bordeaux for Canada.[38] Prevost could afford in July to send westward every regular soldier in Lower Canada, sure of replacing them at Montreal by the month of August.

“A discrepancy in the opinions of the Cabinet,” according to Armstrong,[39] delayed adoption of a plan[32] till June, when a compromise scheme was accepted,[40] but not carried out.

“Two causes prevented its being acted upon in extenso,” Armstrong afterward explained,[41]—“the one, a total failure in getting together by militia calls and volunteer overtures a force deemed competent to a campaign of demonstration and manœuvre on the peninsula; the other, an apprehension that the fleet, which had been long inactive, would not yet be found in condition to sustain projects requiring from it a vigorous co-operation with the army.”

Brown might have been greatly strengthened at Niagara by drawing from Detroit the men that could be spared there; but the Cabinet obliged Armstrong to send the Detroit force—about nine hundred in number—against Mackinaw. Early in July the Mackinaw expedition, commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel Croghan, started from Detroit, and August 4 it was defeated and returned. Croghan’s expedition did not even arrive in time to prevent a British expedition from Mackinaw crossing Wisconsin and capturing, July 19, the distant American post at Prairie du Chien.[42]

Armstrong did not favor Croghan’s expedition, wishing to bring him and his two batteries to reinforce Brown, but yielded to the Secretary of the Navy,[33] who wished to capture Mackinaw,[43] and to the promises of Commodore Chauncey that on or before July 1 he would sail from Sackett’s Harbor, and command the Lake. In reliance on Chauncey, the Cabinet, except Monroe, decided that Major-General Brown should cross to the Canadian side, above the Falls of Niagara, and march, with Chauncey’s support, to Burlington Heights and to York.[44]

This decision was made June 7, and Armstrong wrote to Brown, June 10, describing the movement intended.[45] The Secretary of the Navy, he said, thought Chauncey could not be ready before July 15:

“To give, however, immediate occupation to your troops, and to prevent their blood from stagnating, why not take Fort Erie and its garrison, stated at three or four hundred men? Land between Point Abino and Erie in the night; assail the Fort by land and water; push forward a corps to seize the bridge at Chippawa; and be governed by circumstances in either stopping there or going farther. Boats may follow and feed you. If the enemy concentrates his whole force on this line, as I think he will, it will not exceed two thousand men.”

Brown had left Sackett’s Harbor, and was at Buffalo when these orders reached him. He took immediate measures to carry them out. Besides his regular[34] force, he called for volunteers to be commanded by Peter B. Porter; and he wrote to Chauncey, June 21,[46] an irritating letter, complaining of having received not a line from him, and giving a sort of challenge to the navy to meet the army before Fort George, by July 10. The letter showed that opinion in the army ran against the navy, and particularly against Chauncey, whom Brown evidently regarded as a sort of naval Wilkinson. In truth, Brown could depend neither upon Chauncey nor upon volunteers. The whole force he could collect was hardly enough to cross the river, and little exceeded the three thousand men on whose presence at once in the boats Alexander Smyth had insisted eighteen months before, in order to capture Fort Erie.

So famous did Brown’s little army become, that the details of its force and organization retained an interest equalled only by that which attached to the frigates and sloops-of-war. Although the existence of the regiments ceased with the peace, and their achievements were limited to a single campaign of three or four months, their fame would have insured them in any other service extraordinary honors and sedulous preservation of their identity. Two small brigades of regular troops, and one still smaller brigade of Pennsylvania volunteers, with a corps of artillery, composed the entire force. The first brigade was commanded by Brigadier-General Winfield Scott,[35] and its monthly return of June 30,1814, reported its organization and force as follows:[47]—

| Present for Duty. | Aggregate. | ||

| Non-com. Officers, rank-and-file. |

Officers. | Present and absent. |

|

| Ninth Regiment | 332 | 16 | 642 |

| Eleventh Regiment | 416 | 17 | 577 |

| Twenty-second Regiment | 217 | 12 | 287 |

| Twenty-fifth Regiment | 354 | 16 | 619 |

| General Staff | 4 | 4 | |

| Total | 1319 | 65 | 2129 |

The Ninth regiment came from Massachusetts, and in this campaign was usually commanded by its lieutenant-colonel, Thomas Aspinwall, or by Major Henry Leavenworth. The Eleventh was raised in Vermont, and was led by Major John McNeil. The Twenty-second was a Pennsylvania regiment, commanded by its colonel, Hugh Brady. The Twenty-fifth was enlisted in Connecticut, and identified by the name of T. S. Jesup, one of its majors. The whole brigade, officers and privates, numbered thirteen hundred and eighty-four men present for duty on the first day of July, 1814.

The Second, or Ripley’s, brigade was still smaller, and became even more famous. Eleazar Wheelock Ripley was born in New Hampshire, in the year 1782. He became a resident of Portland in Maine, and was sent as a representative to the State legislature at[36] Boston, where he was chosen speaker of the Massachusetts House of Representatives, Jan. 17, 1812, on the retirement of Joseph Story to become a Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. A few weeks afterward, March 12, 1812, Ripley took the commission of lieutenant-colonel of the Twenty-first regiment, to be enlisted in Massachusetts. A year afterward he became colonel of the same regiment, and took part in the battle of Chrystler’s Field. Secretary Armstrong made him a brigadier-general April 15, 1814, his commission bearing date about a month after that of Winfield Scott. Both the new brigadiers were sent to Niagara, where Scott formed a brigade from regiments trained by himself; and Ripley was given a brigade composed of his old regiment, the Twenty-first, with detachments from the Seventeenth and Nineteenth and Twenty-third. The strength of the brigade, July 1, 1814, was reported in the monthly return as follows:—

| Present for Duty. | Aggregate. | ||

| Non-com. Officers, rank-and-file. |

Officers. | Present and absent. |

|

| Twenty-first Regiment | 651 | 25 | 917 |

| Twenty-third Regiment | 341 | 8 | 496 |

| General staff | 2 | 2 | |

| Total | 992 | 35 | 1415 |

Ripley’s old regiment, the Twenty-first, was given to Colonel James Miller, who had served in the Tippecanoe campaign as major in the Fourth Infantry,[37] and had shared the misfortune of that regiment at Detroit. The other regiment composing the brigade—the Twenty-third—was raised in New York, and was usually commanded by one or another of its majors, McFarland or Brooke. Ripley’s brigade numbered one thousand and twenty-seven men present for duty, on the first day of July.

The artillery, under the command of Major Hindman, was composed of four companies.

| Present for Duty. | Aggregate. | |

| Towson’s Company | 89 | 101 |

| Biddle’s Company | 80 | 104 |

| Ritchie’s Company | 96 | 133 |

| Williams’s Company | 62 | 73 |

| Total | 327 | 413 |

The militia brigade was commanded by Peter B. Porter, and consisted of six hundred Pennsylvania volunteer militia, with about the same number of Indians, comprising nearly the whole military strength of the Six Nations.[48]

| Present for Duty. | Aggregate. | ||

| Non-com. Officers, rank-and-file. |

Officers. | Present and absent. |

|

| Artillery | 330 | 15 | 413 |

| Scott’s Brigade | 1312 | 65 | 2122 |

| Ripley’s Brigade | 992 | 36 | 1415 |

| Porter’s Brigade | 710 | 43 | 830 |

| Total | 3344 | 159 | 4780 |

[38]

Thus the whole of Brown’s army consisted of half-a-dozen skeleton regiments, and including every officer, as well as all Porter’s volunteers, numbered barely thirty-five hundred men present for duty. The aggregate, including sick and absent, did not reach five thousand.

The number of effectives varied slightly from week to week, as men joined or left their regiments; but the entire force never exceeded thirty-five hundred men, exclusive of Indians.

According to the weekly return of June 22, 1814, Major-General Riall, who commanded the right division of the British army, had a force of four thousand rank-and-file present for duty; but of this number the larger part were in garrison at York, Burlington Heights, and Fort Niagara. His headquarters were at Fort George, where he had nine hundred and twenty-seven rank-and-file present for duty. Opposite Fort George, in Fort Niagara on the American side, five hundred and seventy-eight rank-and-file were present for duty. At Queenston were two hundred and fifty-eight; at Chippawa, four hundred and twenty-eight; at Fort Erie, one hundred and forty-six. In all, on the Niagara River Riall commanded two thousand three hundred and thirty-seven rank-and-file present for duty. The officers, musicians, etc., numbered three hundred and thirty-two. At that time only about one hundred and seventy men were on the sick list. All told, sick and well, the regular force numbered two thousand eight hundred[39] and forty men.[49] They belonged chiefly to the First, or Royal Scots; the Eighth, or King’s; the Hundredth, the Hundred-and-third regiments, and the Artillery, with a few dragoons.

As soon as Porter’s volunteers were ready, the whole American army was thrown across the river. The operation was effected early in the morning of July 3; and although the transport was altogether insufficient, the movement was accomplished without accident or delay. Scott’s brigade with the artillery landed below Fort Erie; Ripley landed above; the Indians gained the rear; and the Fort, which was an open work, capitulated at five o’clock in the afternoon. One hundred and seventy prisoners, including officers of all ranks,[50] being two companies of the Eighth and Hundredth British regiments were surrendered by the major in command.

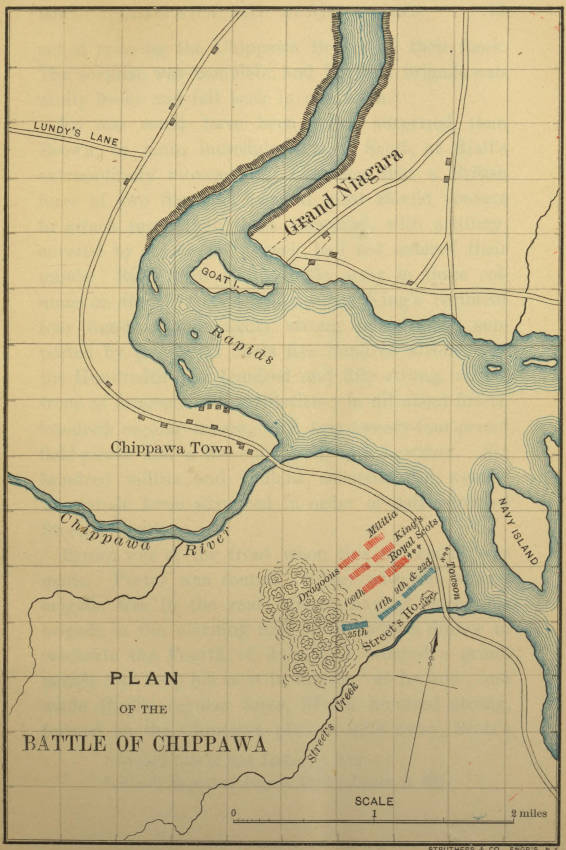

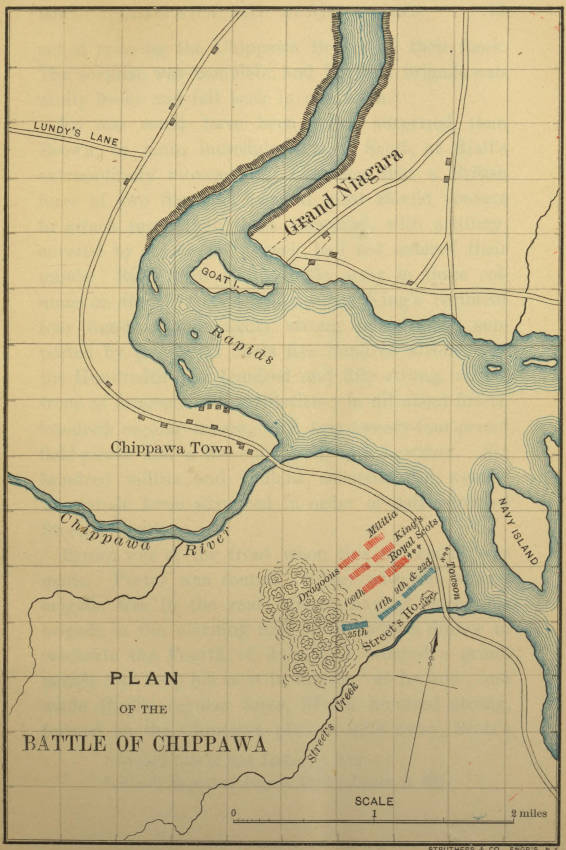

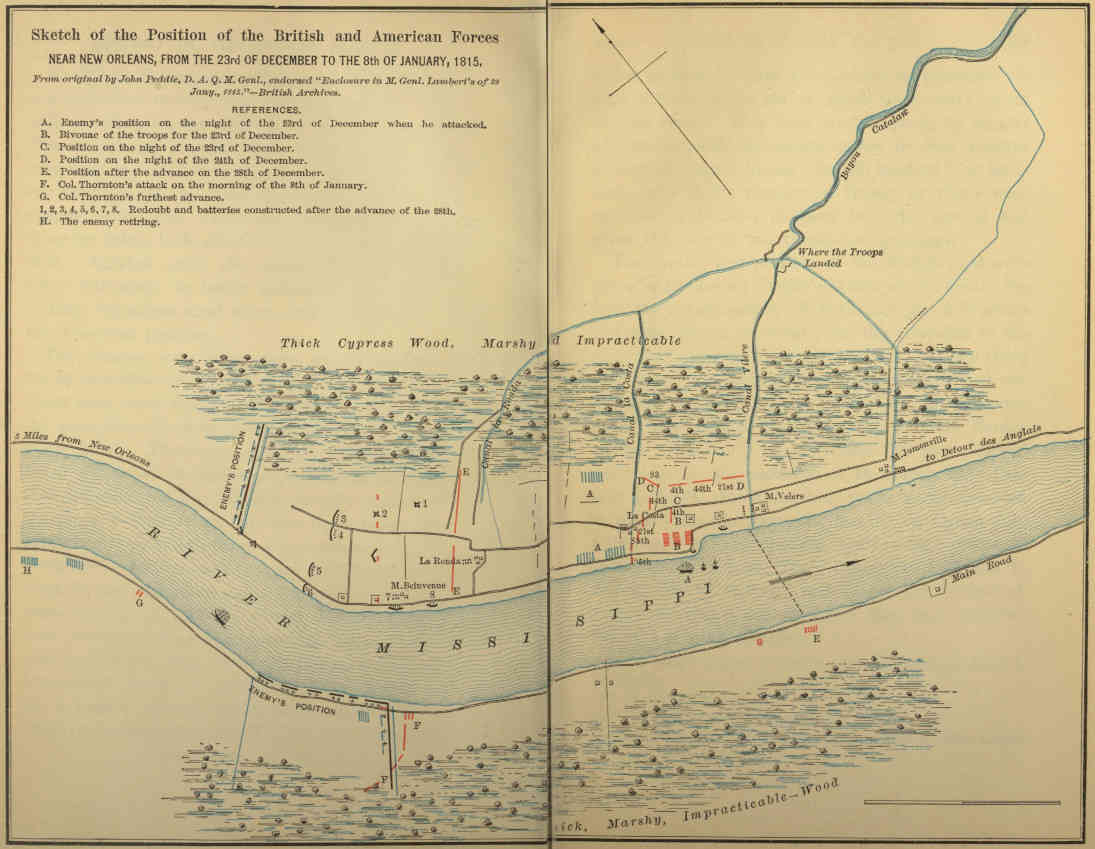

The next British position was at Chippawa, about sixteen miles below. To Chippawa Major-General Riall hastened from Fort George, on hearing that the American army had crossed the river above; and there, within a few hours, he collected about fifteen hundred regulars and six hundred militia and Indians, behind the Chippawa River, in a position not to be assailed in front. The American army also hastened toward Chippawa. On the morning of July 4 Scott’s brigade led the way, and after an exhausting[40] march of twelve hours, the enemy tearing up the bridges in retiring, Scott reached Chippawa plain toward sunset, and found Riall’s force in position beyond the Chippawa River. Scott could only retire a mile or two, behind the nearest water,—a creek, or broad ditch, called Street’s Creek,—where he went into camp. Brown and Ripley, with the second brigade and artillery, came up two or three hours later, at eleven o’clock in the night.[51] Porter followed the next morning.

Brown, knowing his numbers to be about twice those of Riall, was anxious to attack before Riall could be reinforced; and on the morning of July 5, leaving Ripley and Porter’s brigades encamped in the rear, he reconnoitred the line of the Chippawa River, and gave orders for constructing a bridge above Riall’s position. The bridge was likely to be an affair of several days, and Riall showed a disposition to interfere with it. His scouts and Indians crossed and occupied the woods on the American left, driving in the pickets and annoying the reconnoitring party, and even the camp. To dislodge them, Porter’s volunteers and Indians were ordered forward to clear the woods; and at about half-past four o’clock in the afternoon, Porter’s advance began to drive the enemy’s Indians back, pressing forward nearly to the Chippawa River. There the advancing volunteers and Indians suddenly became aware that the whole British army was in the [41]act of crossing the Chippawa Bridge on their flank. The surprise was complete, and Porter’s brigade naturally broke and fell back in confusion.[52]

PLAN

OF THE

BATTLE OF CHIPPAWA

STRUTHERS & CO., ENGR’S, N. Y.

No one could have been more surprised than Brown, or more incredulous than Scott, at Riall’s extraordinary movement. The idea that a British force of two thousand men at most should venture to attack more than three thousand, with artillery, covered by a deep, miry creek, had not entered their minds. Riall drew up his little army in three columns on the Chippawa plain,—the King’s regiment four hundred and eighty strong in advance, supported by the Royal Scots five hundred strong, and the Hundredth four hundred and fifty strong, with a troop of dragoons and artillerists; in all about fifteen hundred regular troops, with two twenty-four-pound field-pieces and a five-and-a-half inch howitzer. Six hundred militia and Indians occupied the woods.[53] The whole force advanced in order of battle toward Street’s Creek.

Brown was at the front when this movement was made. Porter was routed. Ripley with the second brigade was in the rear. Scott, having rested his brigade in the morning and given them a dinner to celebrate the Fourth of July, had ordered a grand parade “to keep his men in breath,” as he said; and while Riall’s regular force, fifteen hundred strong, formed on the Chippawa plain a mile away, Scott’s[42] brigade—which a week before had been reported as containing thirteen hundred men present for duty, and if all its details had been called in could hardly have exceeded thirteen hundred men in the ranks on the afternoon of July 5—was forming, before crossing the little bridge over Street’s Creek to parade on the plain already occupied by the British. Owing to the brushwood that lined the creek Scott could not see the plain, and received no notice of danger until he approached the bridge at the head of his brigade. At that moment General Brown in full gallop from the front rode by, calling out in passing, “You will have a battle!”[54] Scott remarked that he did not believe he should find three hundred British to fight, and crossed the bridge.

If Riall was unwise to attack, Scott tempted destruction by leaving his secure position behind the creek; but at that moment he was in his happiest temper. He meant to show what he and his brigade could do. As his thin column crossed the bridge, the British twenty-four-pound guns opened upon it; but the American line moved on, steady as veterans, and formed in order of battle beyond. Towson’s three twelve-pounders were placed in position near the river on the extreme right, and opened fire on the heavier British battery opposite. The infantry deployed in three battalions,—the right, under Major Leavenworth of the Ninth; the centre, under Major McNeil of the Eleventh; the left, under Major Jesup of the[43] Twenty-fifth. Throwing the flanks obliquely forward, and extending Jesup’s battalion into the woods on the left to prevent outflanking, Scott ordered an advance; and at the same time Riall directed the Royal Scots and the Hundredth to charge.[55] The two lines advanced, stopping alternately to fire and move forward, while Towson’s guns, having blown up a British caisson, were turned on the British column. The converging American fire made havoc in the British ranks, and when the two lines came within some sixty or seventy paces of each other in the centre, the flanks were actually in contact. Then the whole British line broke and crumbled away.[56] Ripley’s brigade, arriving soon afterward, found no enemy on the plain. The battle had lasted less than an hour.

Riall’s report made no concealment of his defeat.[57]

“I placed two light twenty-four-pounders and a five-and-a-half inch howitzer,” he said, “against the right of the enemy’s position, and formed the Royal Scots and Hundredth regiment with the intention of making a movement upon his left, which deployed with the greatest regularity and opened a very heavy fire. I immediately moved up the King’s regiment to the right, while the Royal Scots and Hundredth regiments were directed to charge the enemy in front, for which they advanced with the greatest gallantry under a most destructive fire. I am sorry to say, however, in this attempt[44] they suffered so severely that I was obliged to withdraw them, finding their further efforts against the superior numbers of the enemy would be unavailing.”

For completeness, Scott’s victory at Chippawa could be compared with that of Isaac Hull over the “Guerriere;” but in one respect Scott surpassed Hull. The “Constitution” was a much heavier ship than its enemy; but Scott’s brigade was weaker, both in men and guns, than Riall’s force. Even in regulars, man against man, Scott was certainly outnumbered. His brigade could not have contained, with artillerists, more than thirteen hundred men present on the field,[58] while Riall officially reported his regulars at fifteen hundred, and his irregular corps at six hundred. Scott’s flank was exposed and turned by the rout of Porter. He fought with a creek in his rear, where retreat was destruction. He had three twelve-pound field-pieces, one of which was soon dismounted, against two twenty-four-pounders and a five-and-a-half inch howitzer. He crossed the bridge and deployed under the enemy’s fire. Yet the relative losses showed that he was the superior of his enemy in every respect, and in none more than in the efficiency of his guns.

Riall reported a total loss in killed, wounded, and missing of five hundred and fifteen men,[59] not including Indians. Scott and Porter reported a total loss of two hundred and ninety-seven, not including Indians. Riall’s regular regiments and artillery lost[45] one hundred and thirty-seven killed, and three hundred and five wounded. Scott’s brigade reported forty-eight killed and two hundred and twenty-seven wounded. The number of Riall’s killed was nearly three times the number of Scott’s killed, and proved that the battle was decided by the superior accuracy or rapidity of the musketry and artillery fire, other military qualities being assumed to be equal.

The battle of Chippawa was the only occasion during the war when equal bodies of regular troops met face to face, in extended lines on an open plain in broad daylight, without advantage of position; and never again after that combat was an army of American regulars beaten by British troops. Small as the affair was, and unimportant in military results, it gave to the United States army a character and pride it had never before possessed.

Riall regained the protection of his lines without further loss; but two days afterward Brown turned his position, and Riall abandoned it with the whole peninsula except Fort George.[60] Leaving garrisons in Fort George and Fort Niagara, he fell back toward Burlington Bay to await reinforcements. Brown followed as far as Queenston, where he camped July 10, doubtful what next to do. Fretting under the enforced delay, he wrote to Commodore Chauncey, July 13, a letter that led to much comment:[61]—

[46]

“I have looked for your fleet with the greatest anxiety since the 10th. I do not doubt my ability to meet the enemy in the field, and to march in any direction over his country, your fleet carrying for me the necessary supplies.... There is not a doubt resting in my mind but that we have between us the command of sufficient means to conquer Upper Canada within two months, if there is a prompt and zealous co-operation and a vigorous application of these means.”

Brown, like Andrew Jackson, with the virtues of a militia general, possessed some of the faults. His letter to Chauncey expressed his honest belief; but he was mistaken, and the letter tended to create a popular impression that Chauncey was wholly to blame. Brown could not, even with Chauncey’s help, conquer Upper Canada. He was in danger of being himself destroyed; and even at Queenston he was not safe. Riall had already received, July 9, a reinforcement of seven hundred regulars;[62] at his camp, only thirteen miles from Brown, he had twenty-two hundred men; in garrison at Fort George and Niagara he left more than a thousand men; Lieutenant-General Drummond was on his way from Kingston with the Eighty-ninth regiment four hundred strong, under Colonel Morrison, who had won the battle of Chrystler’s Field, while still another regiment, DeWatteville’s, was on the march. Four thousand men were concentrating on Fort George, and Chauncey, although he might have delayed, could not have prevented their attacking Brown, or stopping his advance.

[47]

Brown was so well aware of his own weakness that he neither tried to assault Fort George nor to drive Riall farther away, although Ripley and the two engineer officers McRee and Wood advised the attempt.[63] After a fortnight passed below Queenston, he suddenly withdrew to Chippawa July 24, and camped on the battle-field. Riall instantly left his camp at eleven o’clock in the night of July 24, and followed Brown’s retreat with about a thousand men, as far as Lundy’s Lane, only a mile below the Falls of Niagara. There he camped at seven o’clock on the morning of July 25, waiting for the remainder of his force, about thirteen hundred men, who marched at noon, and were to arrive at sunset.

The battle of Chippawa and three weeks of active campaigning had told on the Americans. According to the army returns of the last week in July, Brown’s army at Chippawa, July 25, numbered twenty-six hundred effectives.[64]

| Present for Duty. | Aggregate. | |

| Non-com. Officers, rank-and-file. |

Present and absent. |

|

| Scott’s Brigade | 1072 | 1422 |

| Ripley’s Brigade | 895 | 1198 |

| Porter’s Brigade | 441 | 538 |

| Artillery | 236 | 260 |

| Total | 2644 | 3418 |

[48]

Thus Brown at Chippawa bridge, on the morning of July 25, with twenty-six hundred men present for duty, had Riall within easy reach three miles away at Lundy’s Lane, with only a thousand men; but Brown expected no such sudden movement from the enemy, and took no measures to obtain certain information. He was with reason anxious for his rear. His position was insecure and unsatisfactory except for attack. From the moment it became defensive, it was unsafe and needed to be abandoned.

The British generals were able to move on either bank of the river. While Riall at seven o’clock in the morning went into camp within a mile of Niagara Falls, Lieutenant-General Gordon Drummond with the Eighty-ninth regiment disembarked at Fort George, intending to carry out a long-prepared movement on the American side.[65]

Gordon Drummond, who succeeded Major-General de Rottenburg in the command of Upper Canada in December, 1813, and immediately distinguished himself by the brilliant capture of Fort Niagara and the destruction of Buffalo, was regarded as the ablest military officer in Canada. Isaac Brock’s immediate successors in the civil and military government of Upper Canada were Major-Generals Sheaffe and De Rottenburg. Neither had won distinction; but Gordon Drummond was an officer of a different character. Born in 1772, he entered the army in 1789 as[49] an ensign in the First regiment, or Royal Scots, and rose in 1794 to be lieutenant-colonel of the Eighth, or King’s regiment. He served in the Netherlands, the West Indies, and in Egypt, before being ordered to Canada in 1808. In 1811 he became lieutenant-general. He was at Kingston when his subordinate officer, Major-General Riall, lost the battle of Chippawa and retired toward Burlington Heights. Having sent forward all the reinforcements he could spare, Drummond followed as rapidly as possible to take command in person.

No sooner did Drummond reach Fort George than, in pursuance of orders previously given, he sent a detachment of about six hundred men across the river to Lewiston. Its appearance there was at once made known to Brown at Chippawa, only six or seven miles above, and greatly alarmed him for the safety of his base at Fort Schlosser, Black Rock, and Buffalo. Had Drummond advanced up the American side with fifteen hundred men, as he might have done, he would have obliged Brown to re-cross the river, and might perhaps have destroyed or paralyzed him; but Drummond decided to join Riall, and accordingly, recalling the detachment from Lewiston at four o’clock in the afternoon, he began his march up the Canadian side with eight hundred and fifteen rank-and-file to Lundy’s Lane.[66]

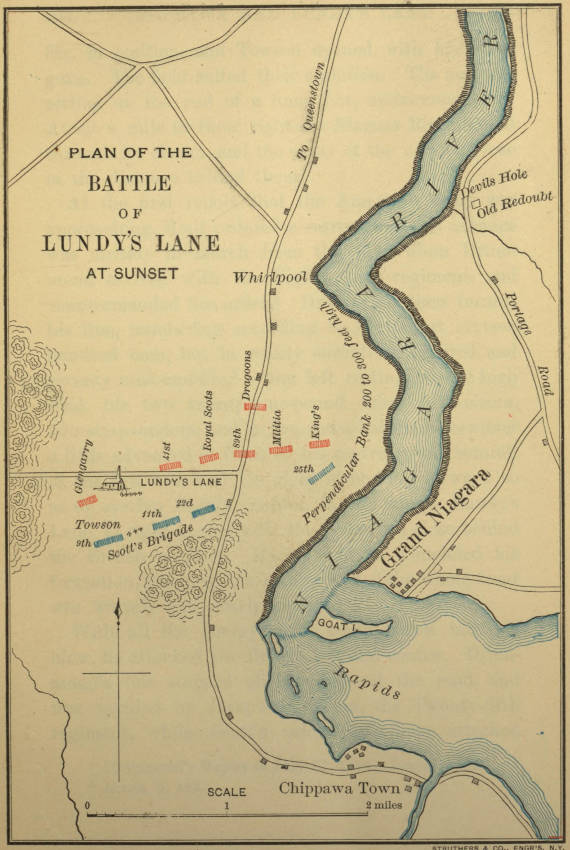

At five o’clock, July 25, the British army was nearly concentrated. The advance under Riall at Lundy’s[50] Lane numbered nine hundred and fifty rank-and-file, with the three field-pieces which had been in the battle of Chippawa, and either two or three six-pounders.[67] Drummond was three miles below with eight hundred and fifteen rank-and-file, marching up the river; and Colonel Scott of the One Hundred-and-third regiment, with twelve hundred and thirty rank-and-file and two more six-pound field-pieces, was a few miles behind Drummond.[68] By nine o’clock in the evening the three corps, numbering three thousand rank-and-file, with eight field-pieces, were to unite at Lundy’s Lane.

At a loss to decide on which bank the British generals meant to move, Brown waited until afternoon, and then, in great anxiety for the American side of the river, ordered Winfield Scott to march his brigade down the road toward Queenston on the Canadian side, in the hope of recalling the enemy from the American side by alarming him for the safety of his rear. Scott, always glad to be in motion, crossed Chippawa bridge, with his brigade and Towson’s battery, soon after five o’clock, and to his great surprise, in passing a house near the Falls, learned that a large body of British troops was in sight below. With his usual audacity he marched directly upon them, and reaching Lundy’s Lane, deployed to the left in line of battle. Jesup, Brady, Leavenworth, and McNeil placed their little battalions, numbering at the utmost a thousand rank-and-file,[51] in position, and Towson opened with his three guns. The field suited their ambition. The sun was setting at the end of a long, hot, midsummer day. About a mile to their right the Niagara River flowed through its chasm, and the spray of the cataract rose in the distance behind them.

PLAN OF THE

BATTLE

OF

LUNDY’S LANE

AT SUNSET

STRUTHERS & CO., ENGR’S, N. Y.

At the first report that the American army was approaching, Riall ordered a retreat, and his advance was already in march from the field when Drummond arrived with the Eighty-ninth regiment, and countermanded the order.[69] Drummond then formed his line, numbering according to his report sixteen hundred men, but in reality seventeen hundred and seventy rank-and-file,[70]—the left resting on the high road, his two twenty-four-pound brass field-pieces, two six-pounders, and a five-and-a-half-inch howitzer a little advanced in front of his centre on the summit of the low hill, and his right stretching forward so as to overlap Scott’s position in attacking. Lundy’s Lane, at right angles with the river, ran close behind the British position. Hardly had he completed his formation, when, in his own words, “the whole front was warmly and closely engaged.”

With all the energy Scott could throw into his blow, he attacked the British left and centre. Drummond’s left stopped slightly beyond the road, and was assailed by Jesup’s battalion, the Twenty-fifth regiment, while Scott’s other battalions attacked[52] in front. So vigorous was Jesup’s assault that he forced back the Royal Scots and Eighty-ninth, and got into the British rear, where he captured Major-General Riall himself, as he left the field seriously wounded. “After repeated attacks,” said Drummond’s report, “the troops on the left were partially forced back, and the enemy gained a momentary possession of the road.” In the centre also Scott attacked with obstinacy; but the British artillery was altogether too strong and posted too high for Towson’s three guns, which at last ceased firing.[71] There the Americans made no impression, while they were overlapped and outnumbered by the British right.

From seven till nine o’clock Scott’s brigade hung on the British left and centre, charging repeatedly close on the enemy’s guns; and when at last with the darkness their firing ceased from sheer exhaustion, they were not yet beaten. Brady’s battalion, the Ninth and Twenty-second, and McNeil’s, the Eleventh, were broken up; their ammunition was exhausted, and most of their officers were killed or wounded. The Eleventh and Twenty-second regiments lost two hundred and thirty men killed, wounded, and missing, or more than half their number; many of the men left the field, and only with difficulty could a battalion be organized from the debris.[72] McNeil and Brady were wounded, and[53] Major Leavenworth took command of the remnant. With a small and exhausted force which could not have numbered more than six hundred men, and which Drummond by a vigorous movement might have wholly destroyed, Scott clung to the enemy’s flank until in the darkness Ripley’s brigade came down on the run. The American line was also reinforced by Porter’s brigade; by the First regiment, one hundred and fifty strong, which crossed from the American side of the river; and by Ritchie’s and Biddle’s batteries.

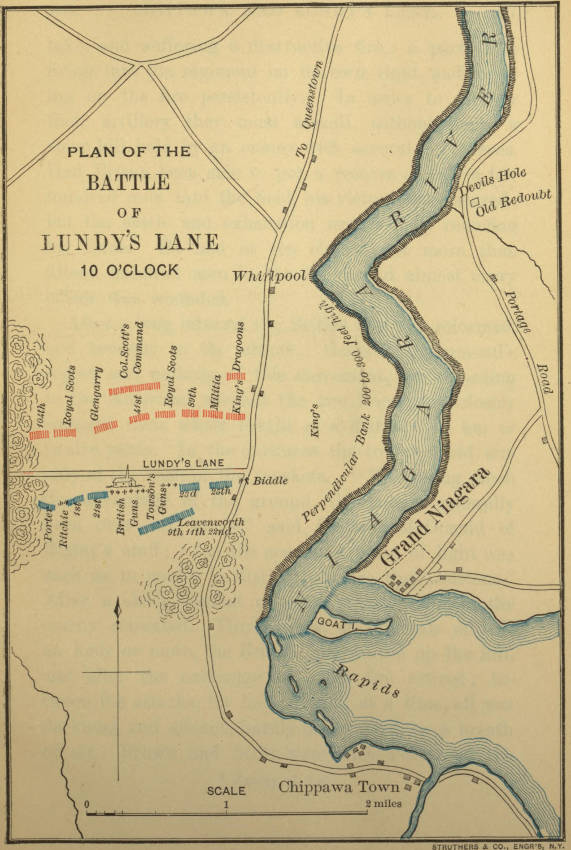

At about the same time the rest of Riall’s force, twelve hundred and thirty rank-and-file, with two more six-pound guns, appeared on the field, and were placed in a second line or used to prolong the British right. If Scott had lost four hundred men from the ranks Drummond had certainly lost no more, for his men were less exposed. Brown was obliged to leave details of men for camp duty; Drummond brought three thousand rank-and-file on the field. At nine o’clock Drummond could scarcely have had fewer than twenty-six hundred men in Lundy’s Lane, with seven field-pieces, two of which were twenty-four-pounders. Brown could scarcely have had nineteen hundred, even allowing Porter to have brought five hundred of his volunteers into battle.[73] He had also Towson’s, Ritchie’s, and Biddle’s batteries,—seven twelve-pound field-pieces in all.

[54]

As long as the British battery maintained its fire in the centre, victory was impossible and escape difficult.[74] Ripley’s brigade alone could undertake the task of capturing the British guns, and to it the order was given. Colonel Miller was to advance with the Twenty-first regiment against the British battery in front.[75] Ripley himself took command of the Twenty-third regiment on the right, to lead it by the road to attack the enemy’s left flank in Lundy’s Lane. According to the story that for the next fifty years was told to every American school-boy as a model of modest courage, General Brown gave to Miller the order to carry the enemy’s artillery, and Miller answered, “I’ll try!”[76]

The two regiments thus thrown on the enemy’s centre and left numbered probably about seven hundred men in the ranks, according to Ripley’s belief. The Twenty-first regiment was the stronger, and may have contained four hundred and fifty men, including officers; the Twenty-third could scarcely have brought three hundred into the field. In a few minutes both battalions were in motion. The Twenty-third, advancing along the road on the right, instantly attracted the enemy’s fire at about one hundred and fifty yards from the hill, and was thrown back. Ripley reformed the column, and in five minutes it[55] advanced again.[77] While the Twenty-third was thus engaged on the right, the Twenty-first silently advanced in front, covered by shrubbery and the darkness, within a few rods of the British battery undiscovered, and with a sudden rush carried the guns, bayoneting the artillery-men where they stood.

So superb a feat of arms might well startle the British general, who could not see that less than five hundred men were engaged in it; but according to the British account[78] the guns stood immediately in front of a British line numbering at least twenty-six hundred men in ranks along Lundy’s Lane. Drummond himself must have been near the spot, for the whole line of battle was but five minutes’ walk; apparently he had but to order an advance, to drive Miller’s regiment back without trouble. Yet Miller maintained his ground until Ripley came up on his right. According to the evidence of Captain McDonald of Ripley’s staff, the battle was violent during fifteen or twenty minutes:—

“Having passed the position where the artillery had been planted, Colonel Miller again formed his line facing the enemy, and engaged them within twenty paces distance. There appeared a perfect sheet of fire between the two lines. While the Twenty-first was in this situation, the Twenty-third attacked the enemy’s flank, and advanced within twenty paces of it before the first volley was discharged,—a measure adopted by command of General Ripley, that the fire might be effectual and more[56] completely destructive. The movement compelled the enemy’s flank to fall back immediately by descending the hill out of sight, upon which the firing ceased.”[79]

Perhaps this feat was more remarkable than the surprise of the battery. Ripley’s Twenty-third regiment, about three hundred men, broke the British line, not in the centre but on its left, where the Eighty-ninth, the Royal Scots, King’s, and the Forty-first were stationed,[80] and caused them to retire half a mile from the battle-field before they halted to reform.

When the firing ceased, Ripley’s brigade held the hill-top, with the British guns, and the whole length of Lundy’s Lane to the high-road. Porter then brought up his brigade on the left; Hindman brought up his guns, and placed Towson’s battery on Ripley’s right, Ritchie’s on his left, while Biddle’s two guns were put in position on the road near the corner of Lundy’s Lane. Jesup with the Twenty-fifth regiment was put in line on the right of Towson’s battery; Leavenworth with the remnants of the Ninth, Eleventh, and Twenty-second formed a second line in the rear of the captured artillery; and thus reversing the former British order of battle, the little army stood ranked along the edge of Lundy’s Lane, with the British guns in their rear.

PLAN OF THE

BATTLE

OF

LUNDY’S LANE

10 O’CLOCK

STRUTHERS & CO., ENGR’S, N.Y.