Title: The boy mechanic, book 3

800 things for boys to do

Editor: H. H. Windsor

Release date: October 12, 2023 [eBook #71856]

Most recently updated: September 20, 2025

Language: English

Original publication: Chicago: Popular Mechanics Co, 1919

Credits: Charlene Taylor, Harry Lamé and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

Please see the Transcriber’s Notes at the end of this text.

New original cover art included with this eBook is granted to the public domain.

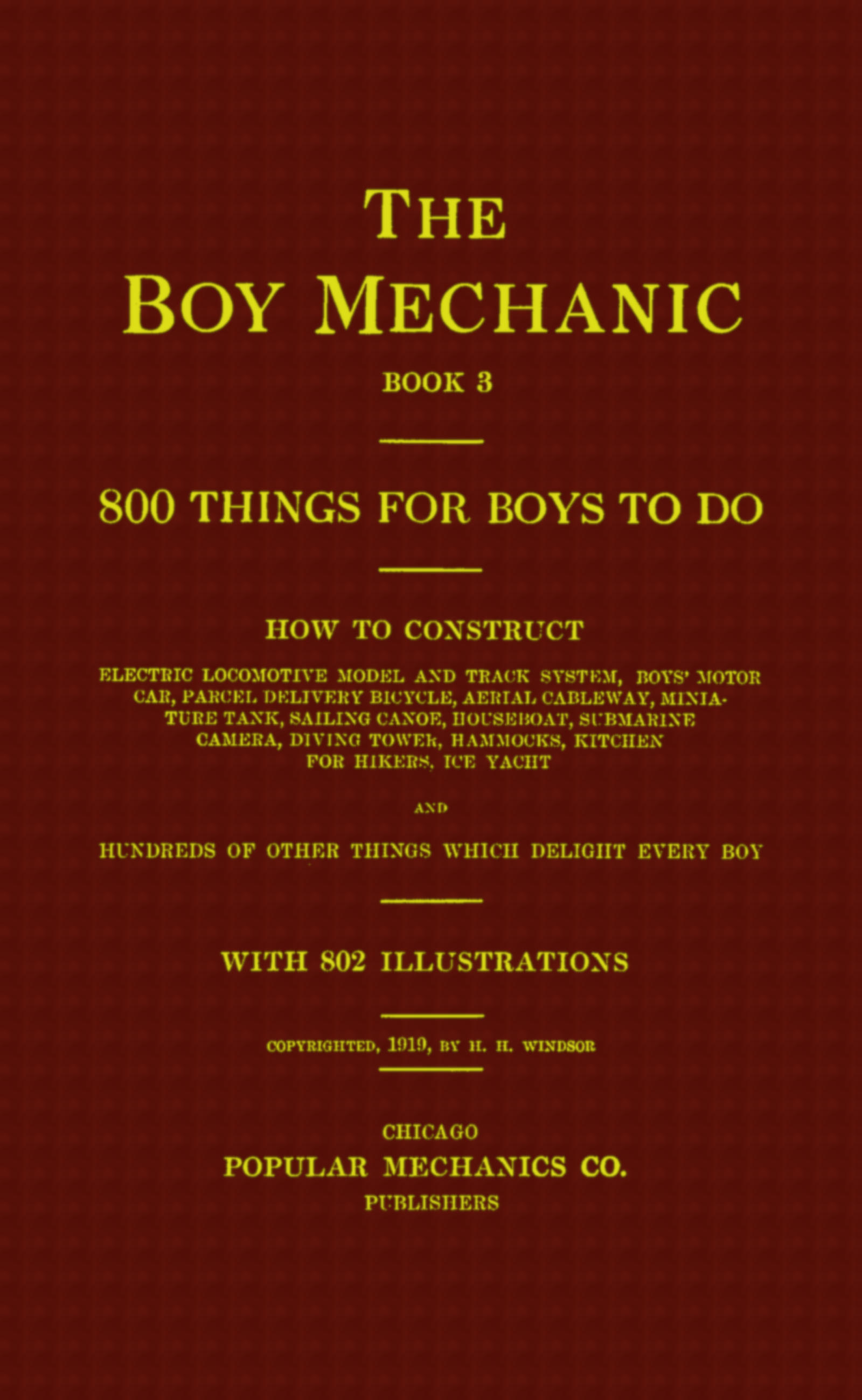

See Page 86

The

Boy Mechanic

BOOK 3

800 THINGS FOR BOYS TO DO

HOW TO CONSTRUCT

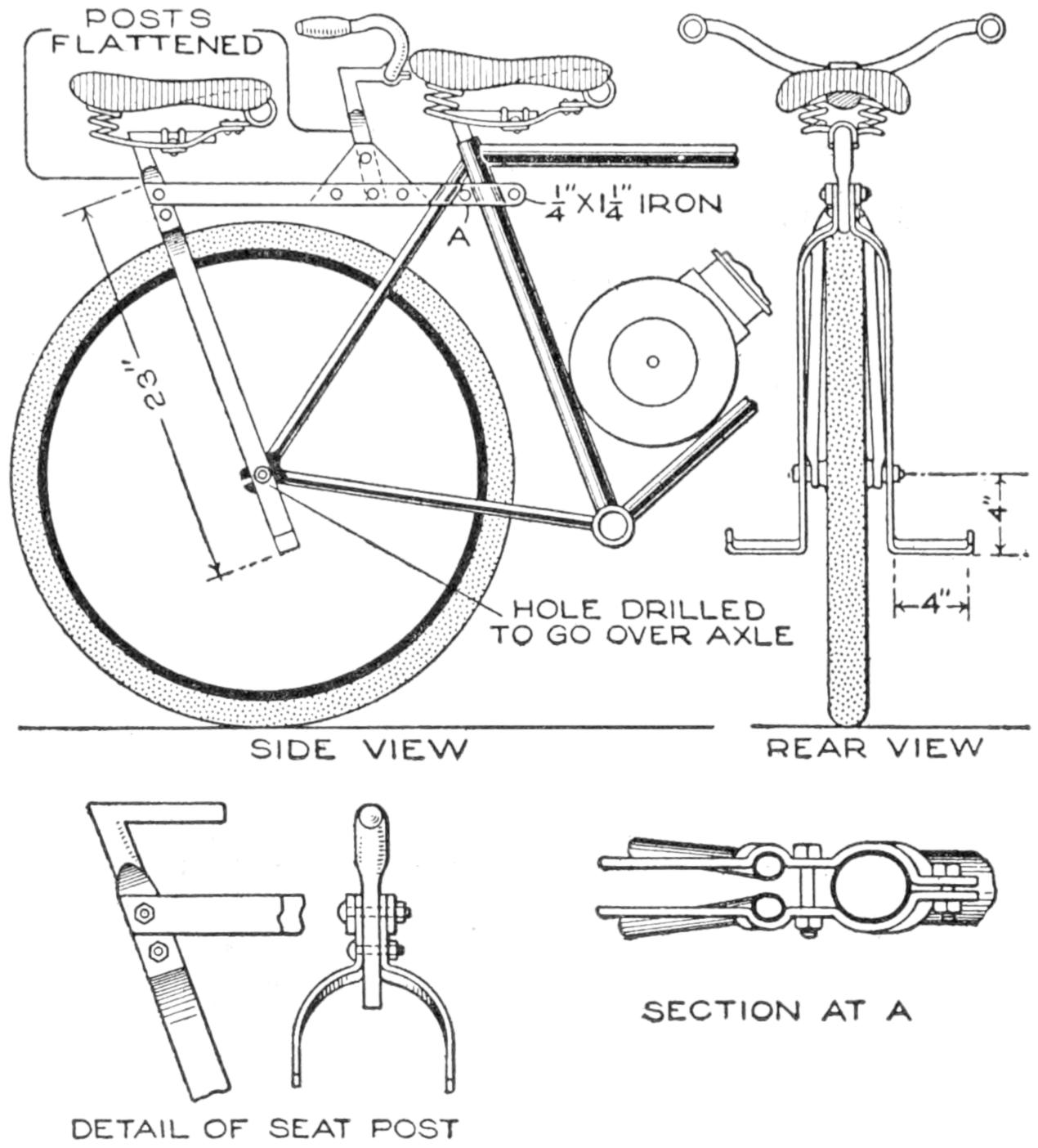

ELECTRIC LOCOMOTIVE MODEL AND TRACK SYSTEM, BOYS’ MOTOR

CAR, PARCEL DELIVERY BICYCLE, AERIAL CABLEWAY, MINIA-

TURE TANK, SAILING CANOE, HOUSEBOAT, SUBMARINE

CAMERA, DIVING TOWER, HAMMOCKS, KITCHEN

FOR HIKERS, ICE YACHT

AND

HUNDREDS OF OTHER THINGS WHICH DELIGHT EVERY BOY

WITH 802 ILLUSTRATIONS

COPYRIGHTED, 1919, BY H. H. WINDSOR

CHICAGO

POPULAR MECHANICS CO.

PUBLISHERS

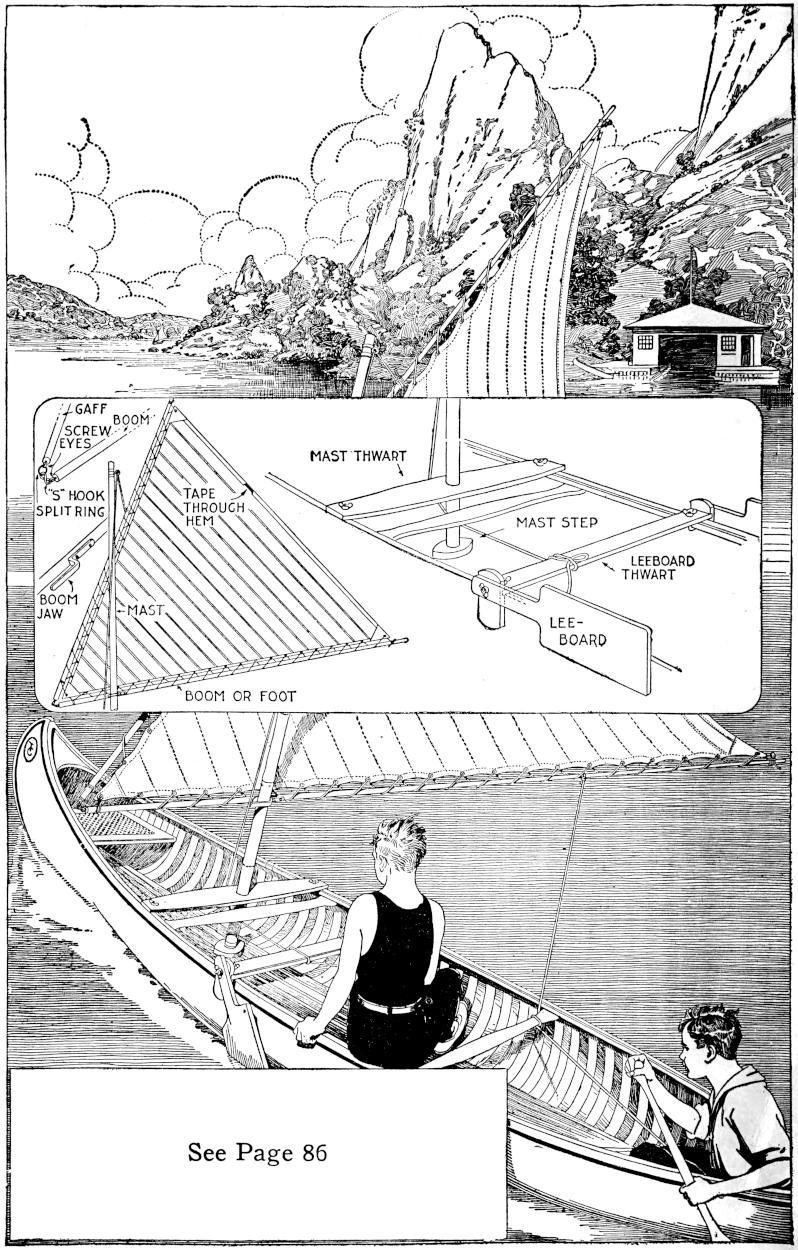

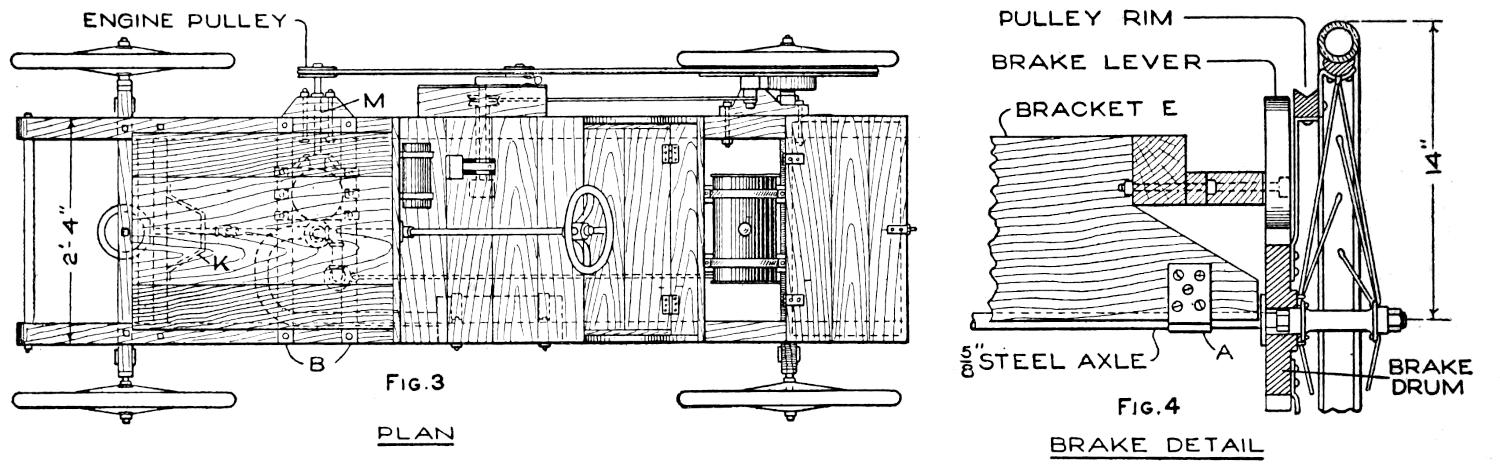

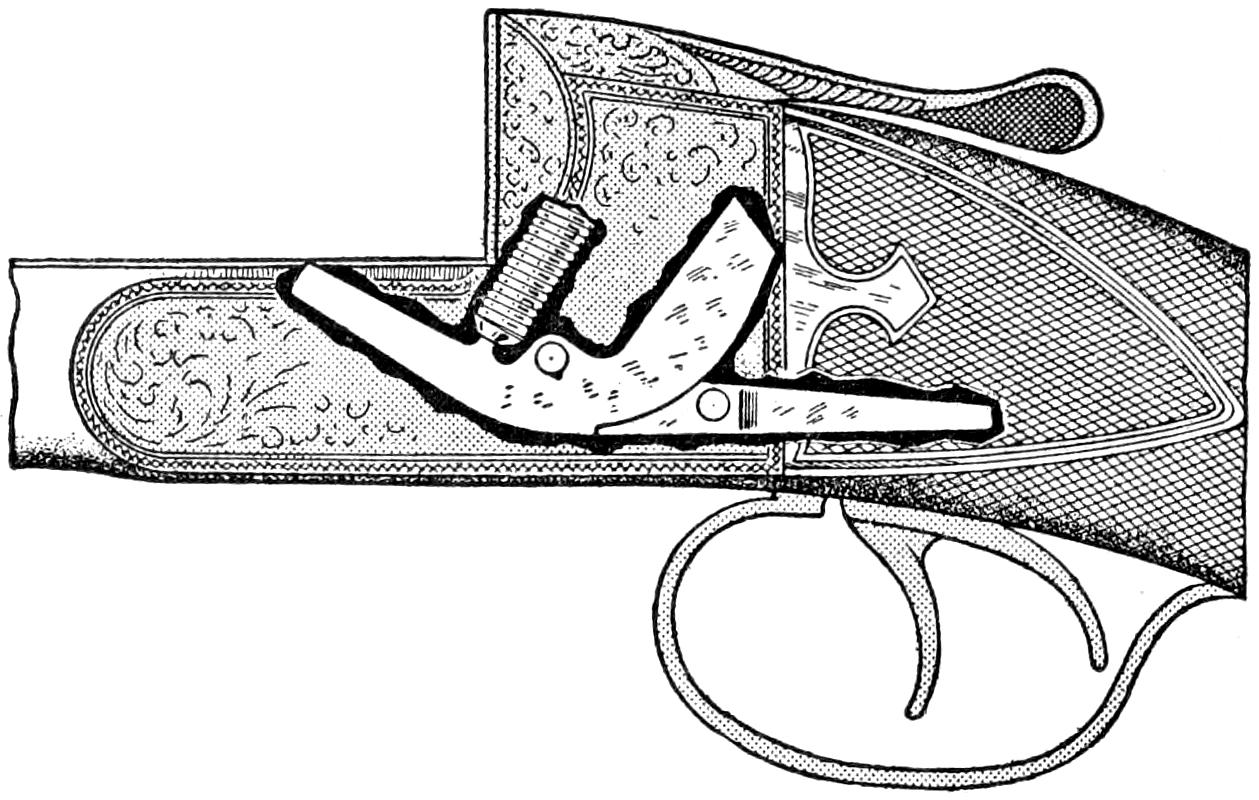

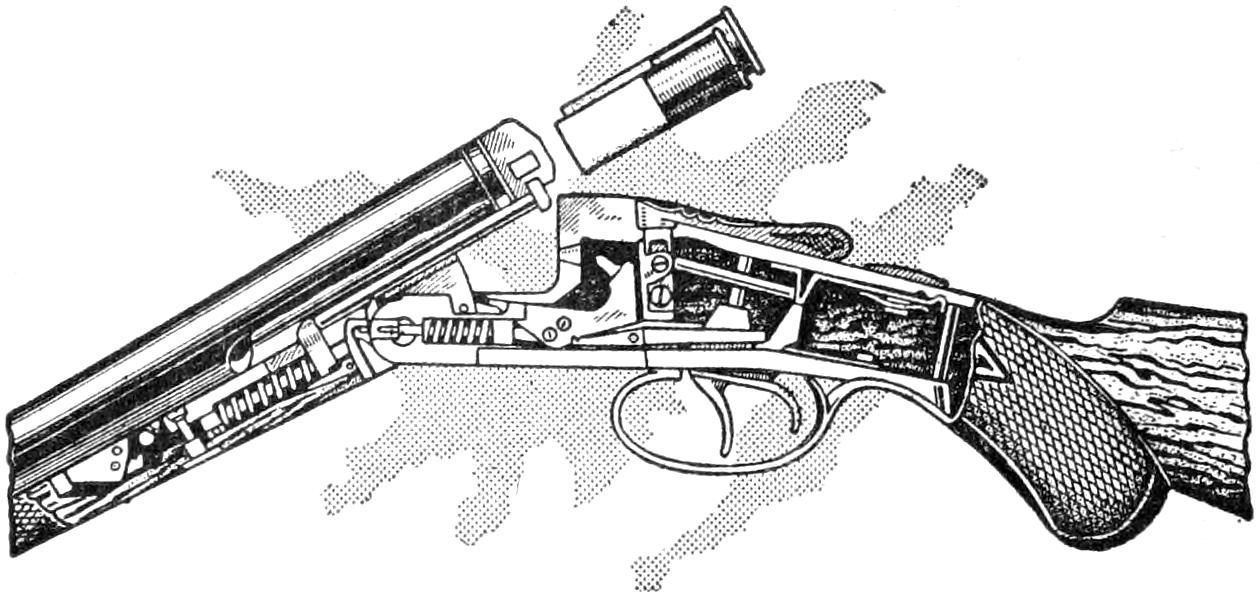

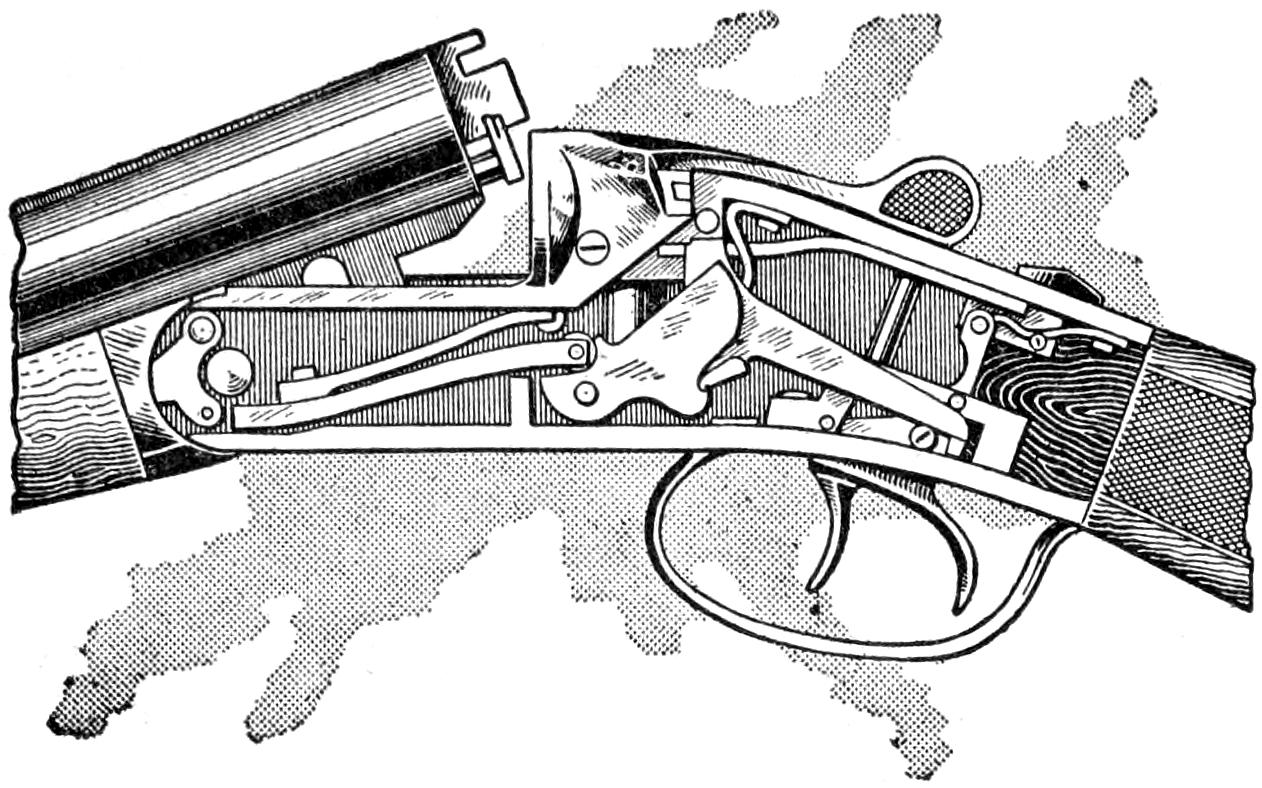

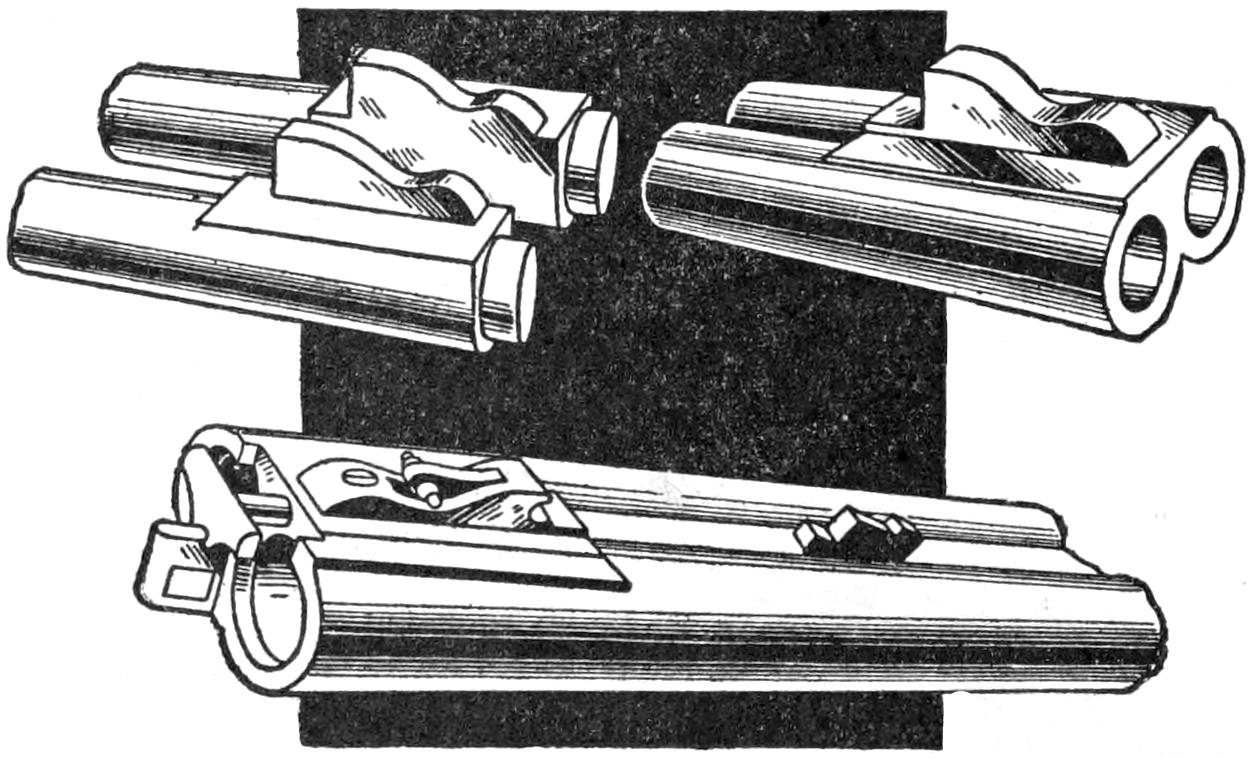

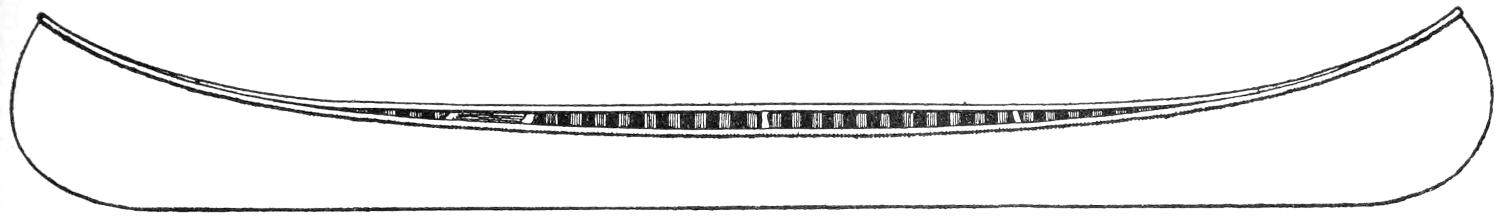

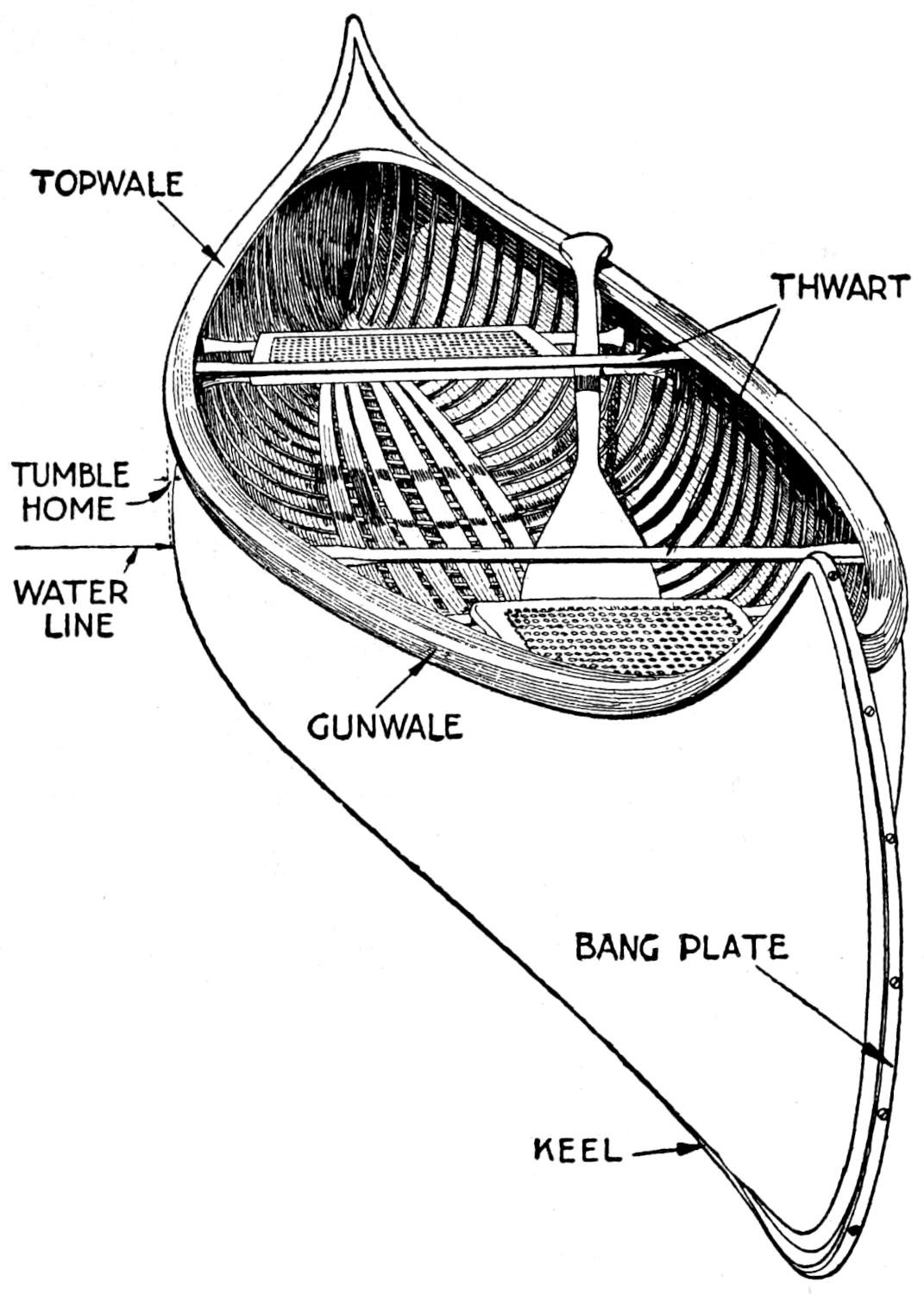

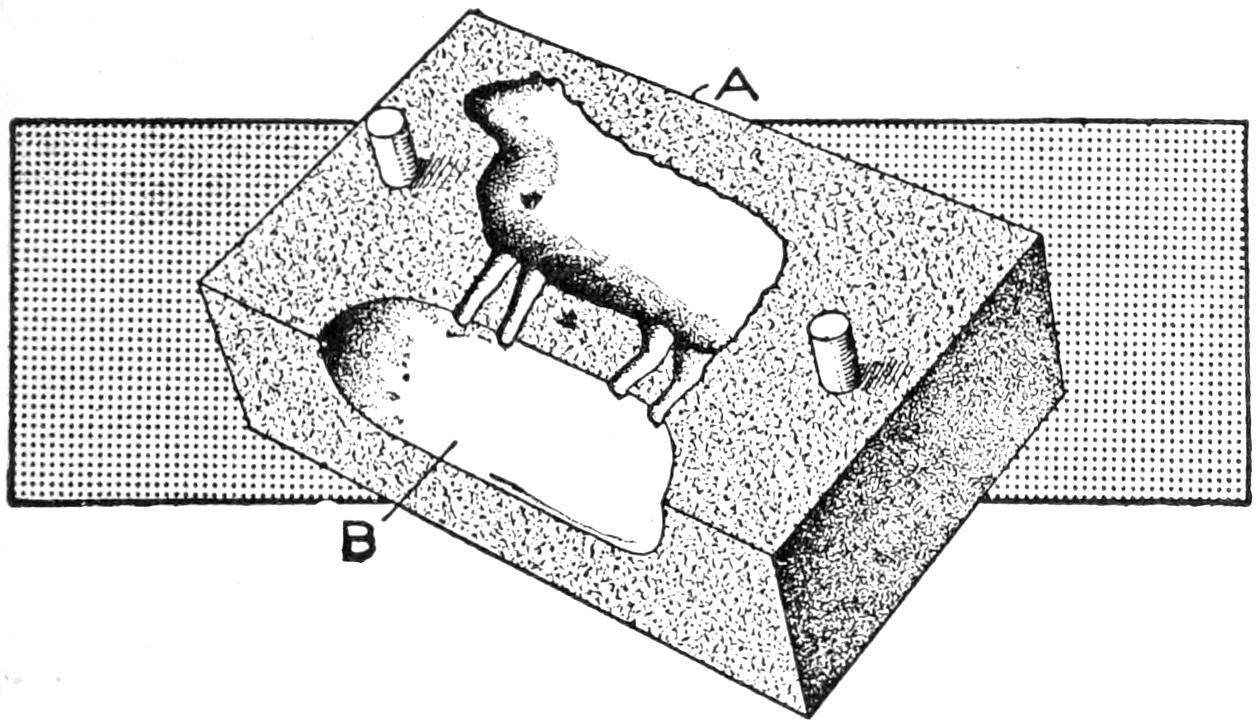

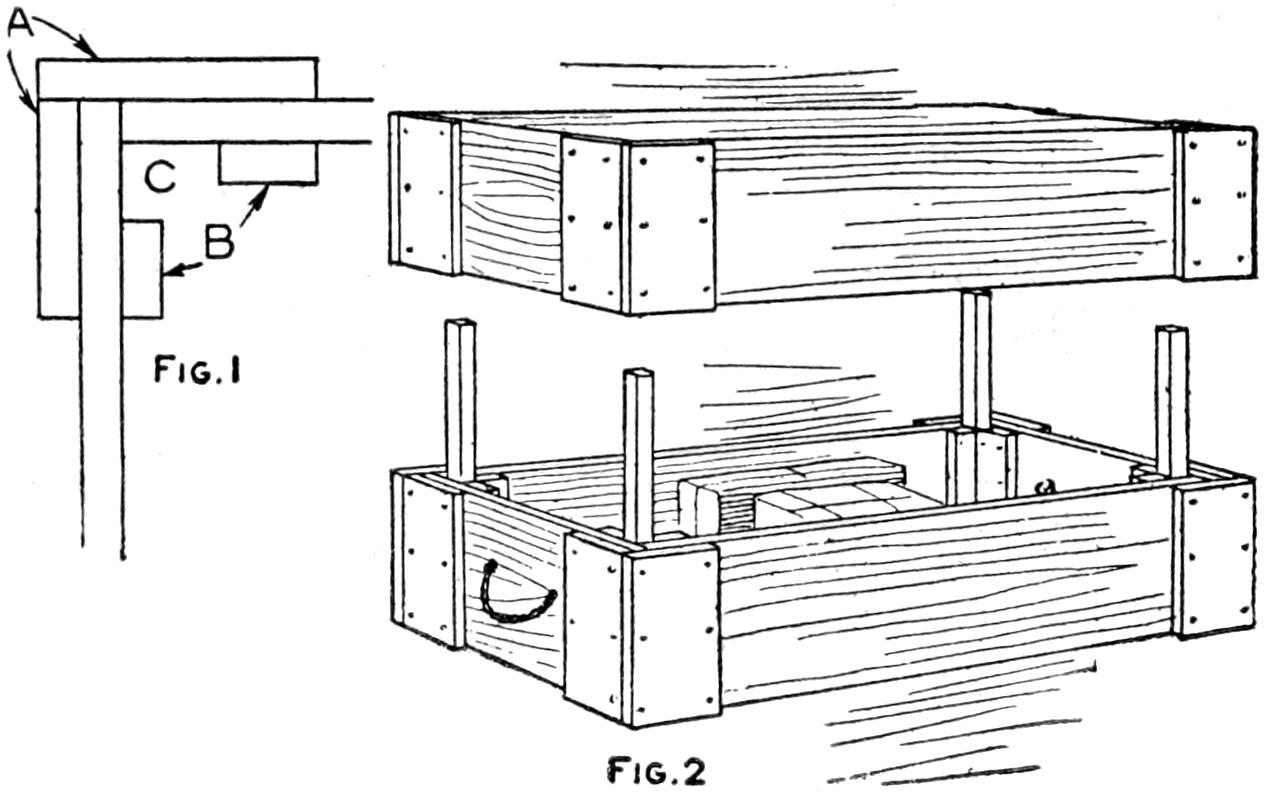

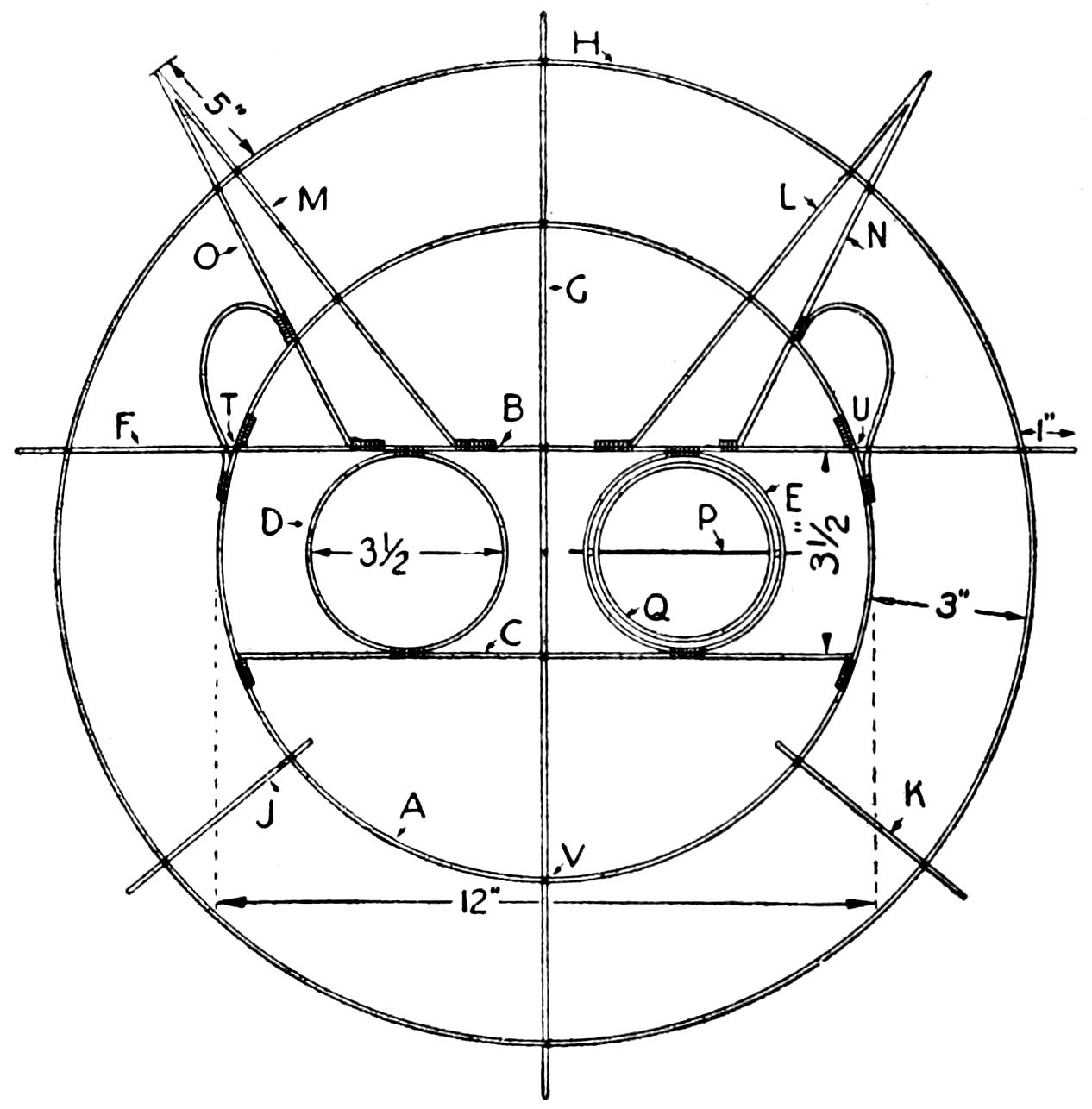

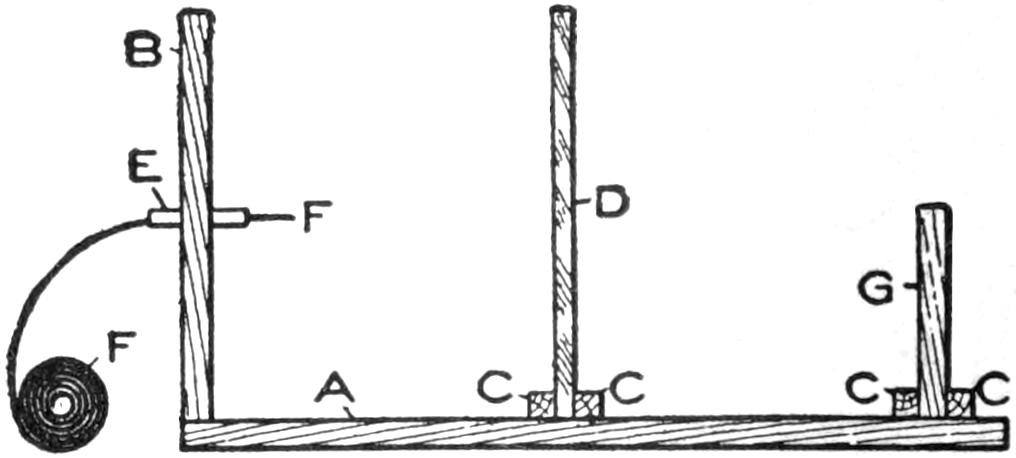

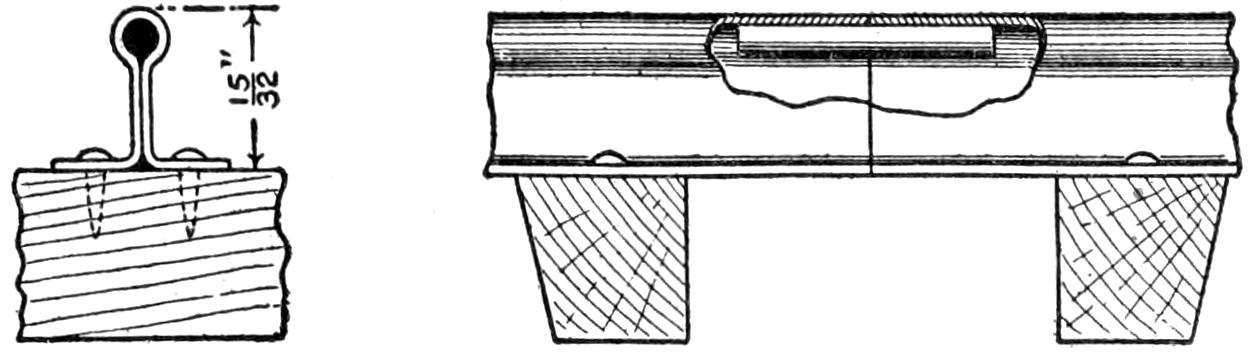

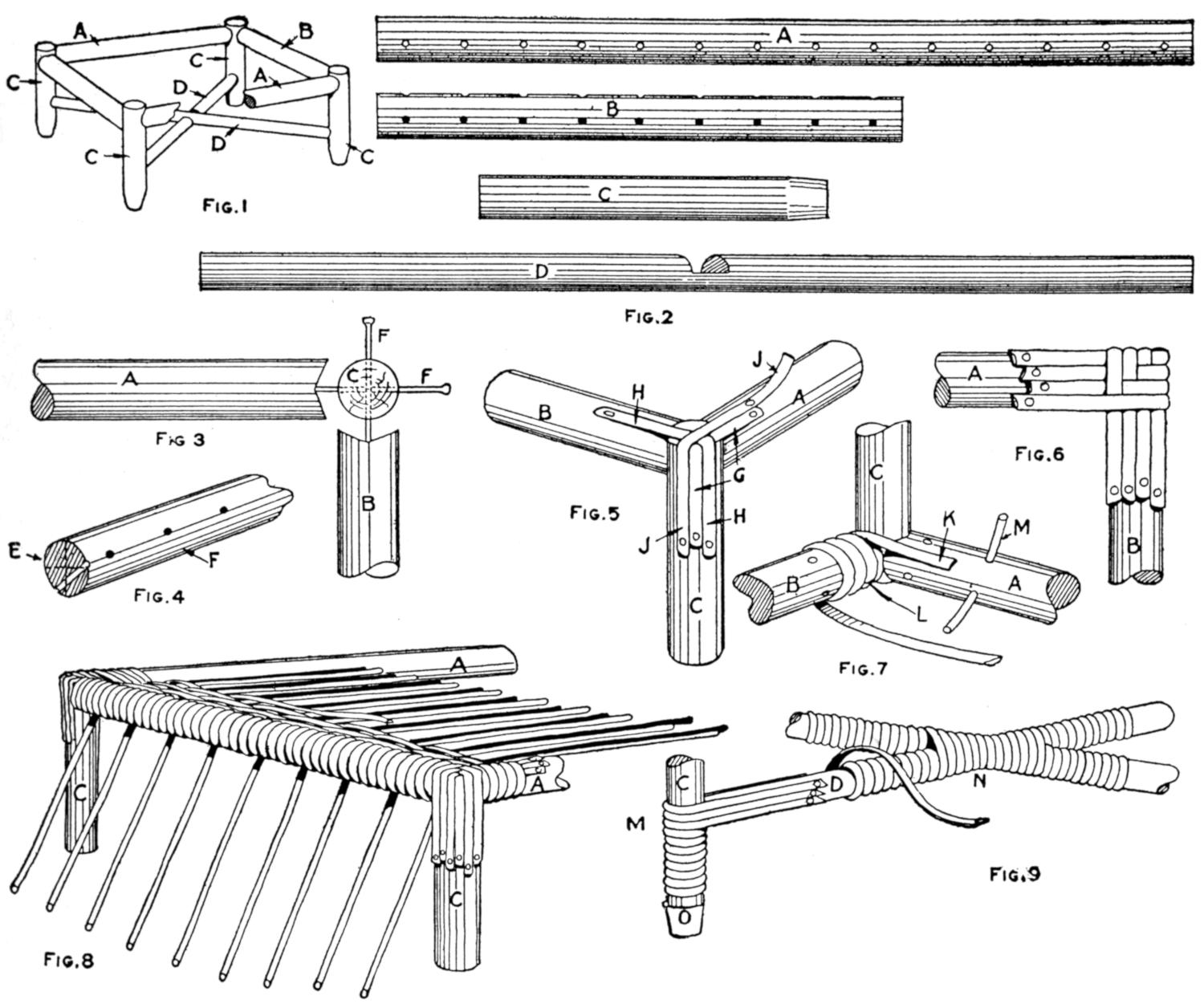

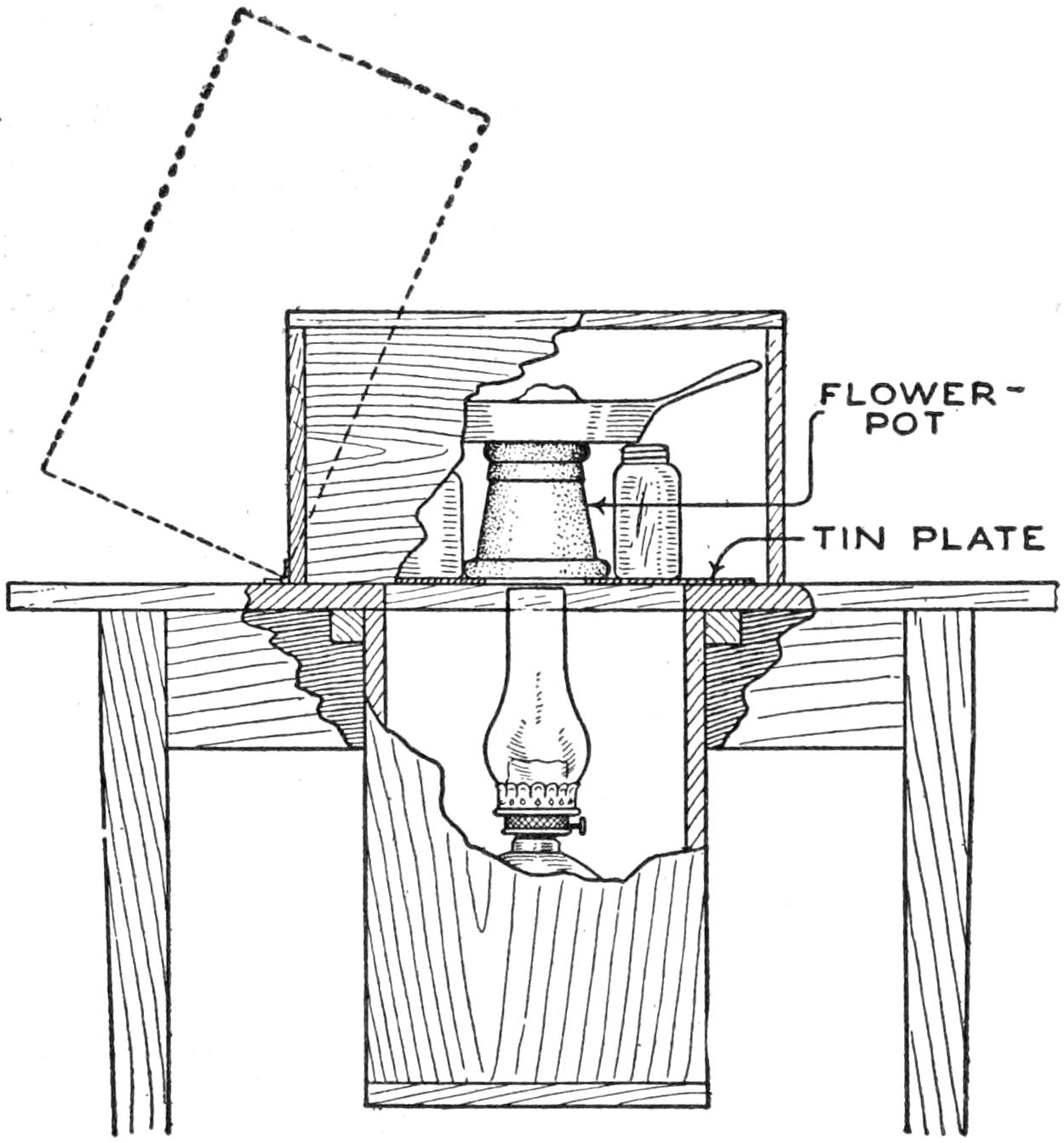

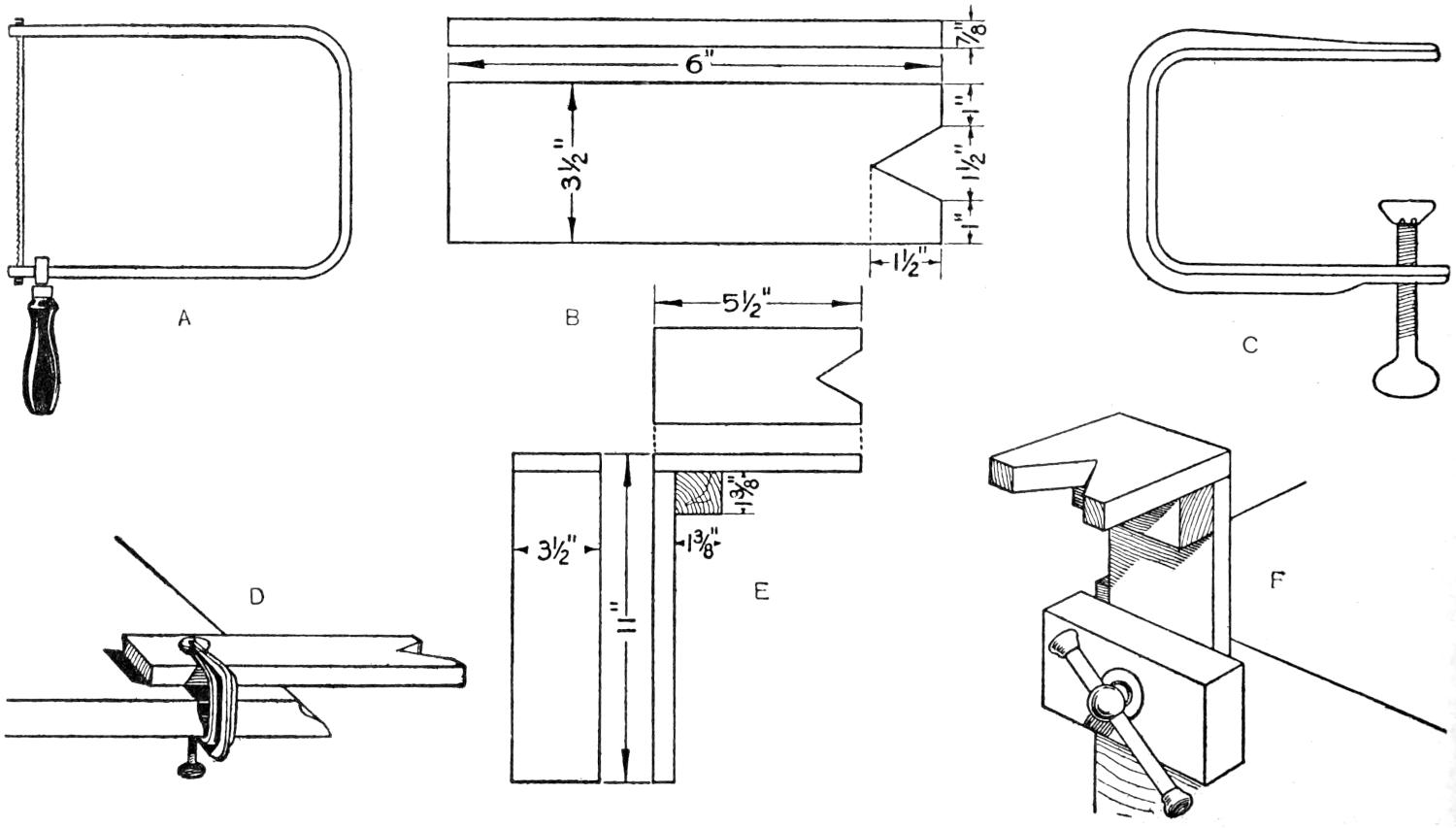

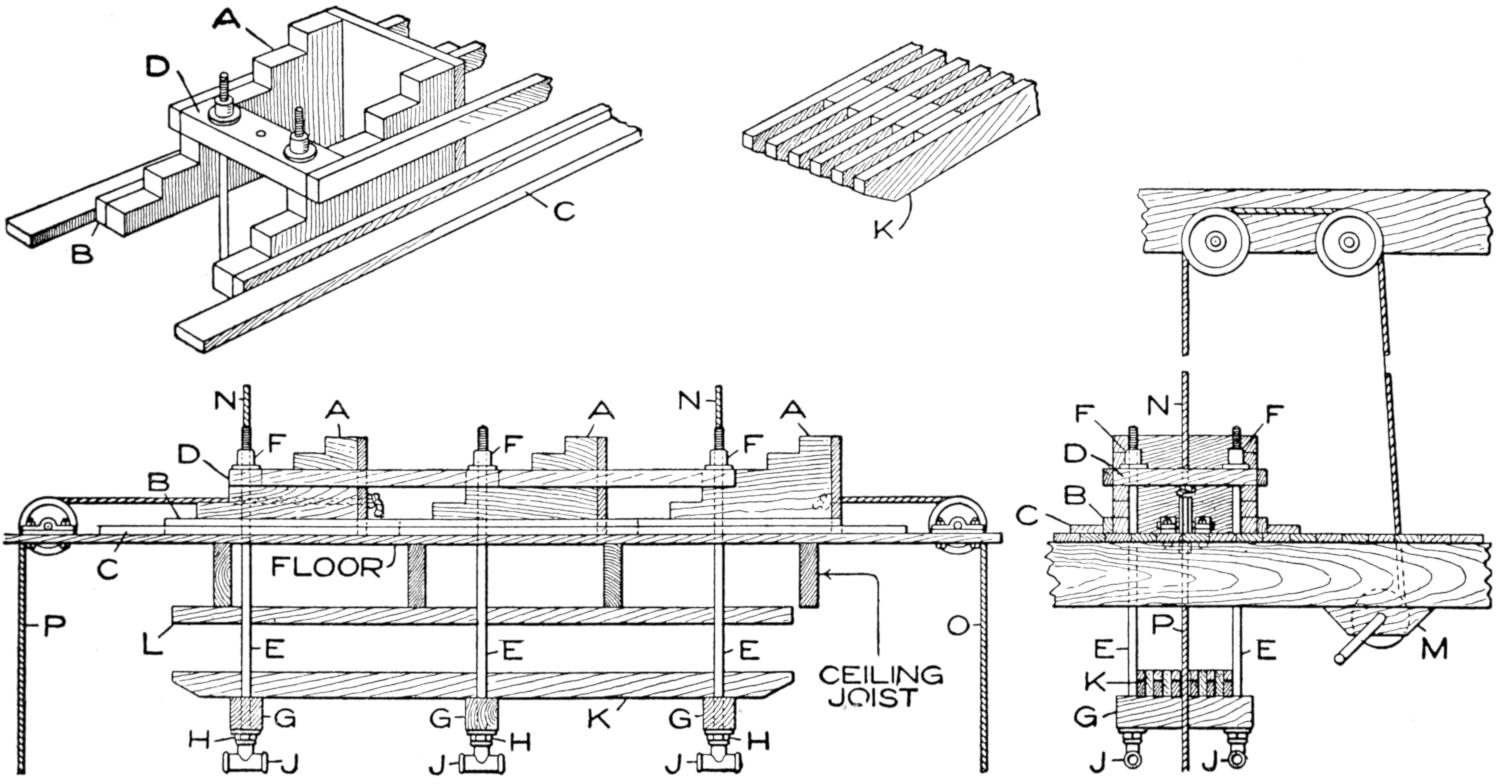

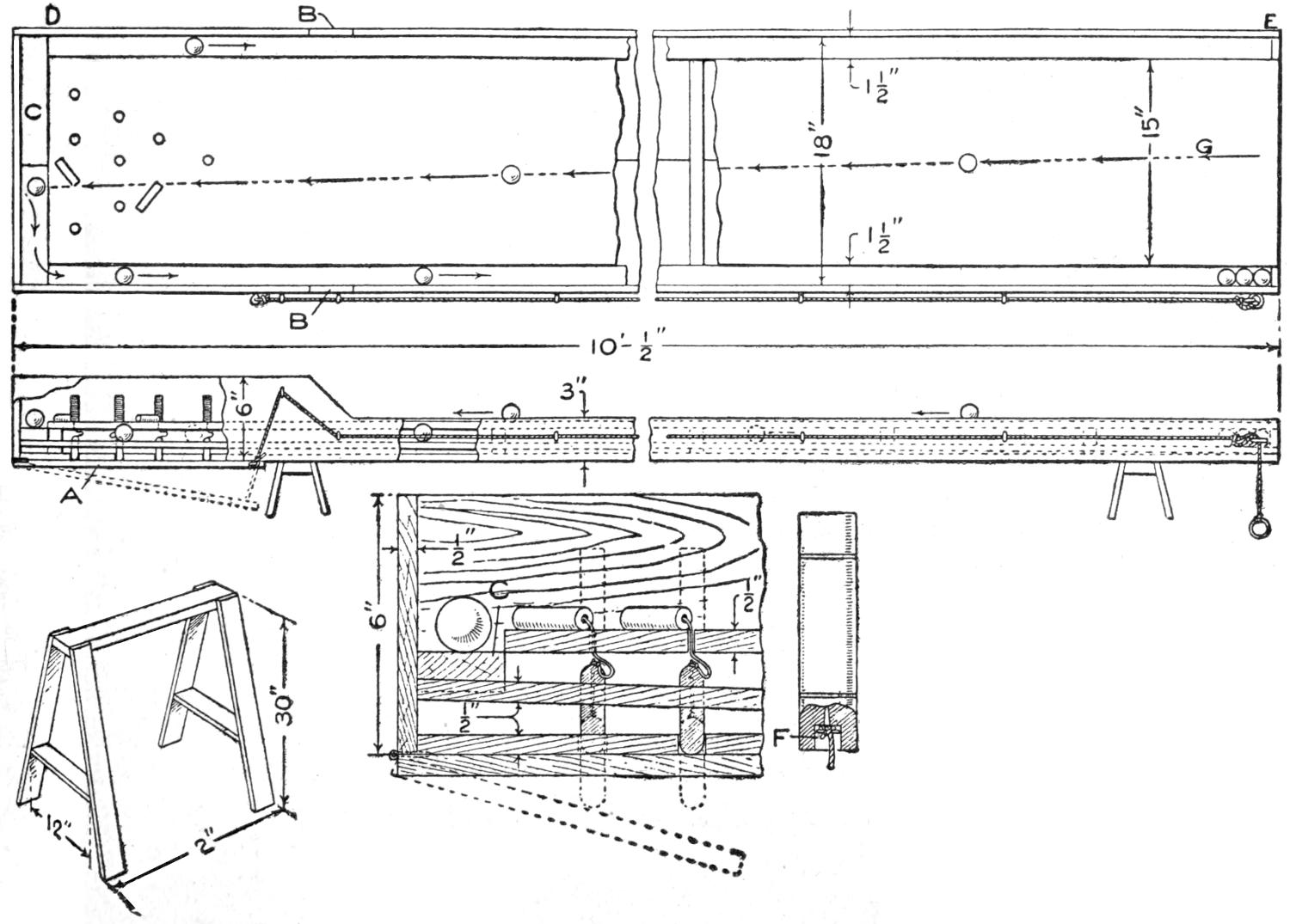

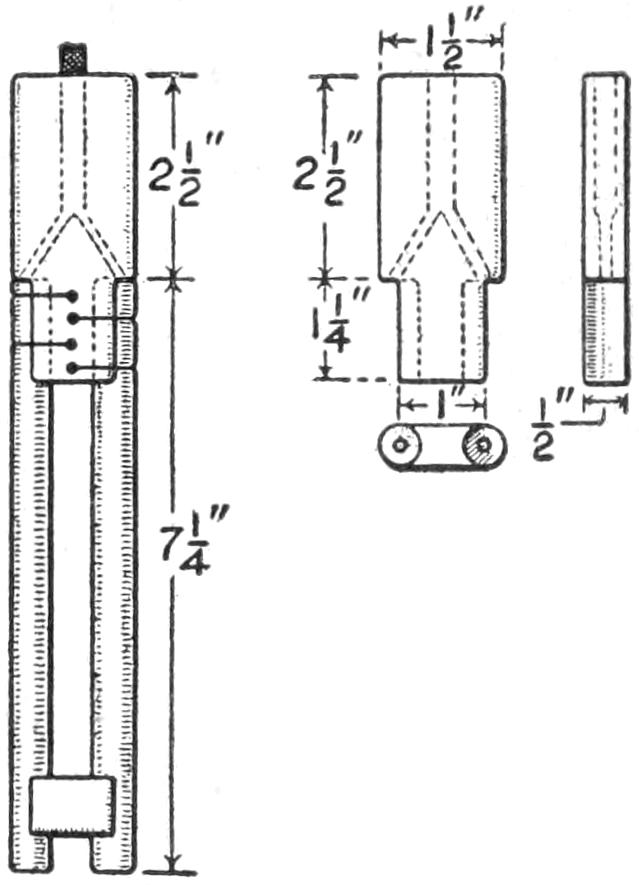

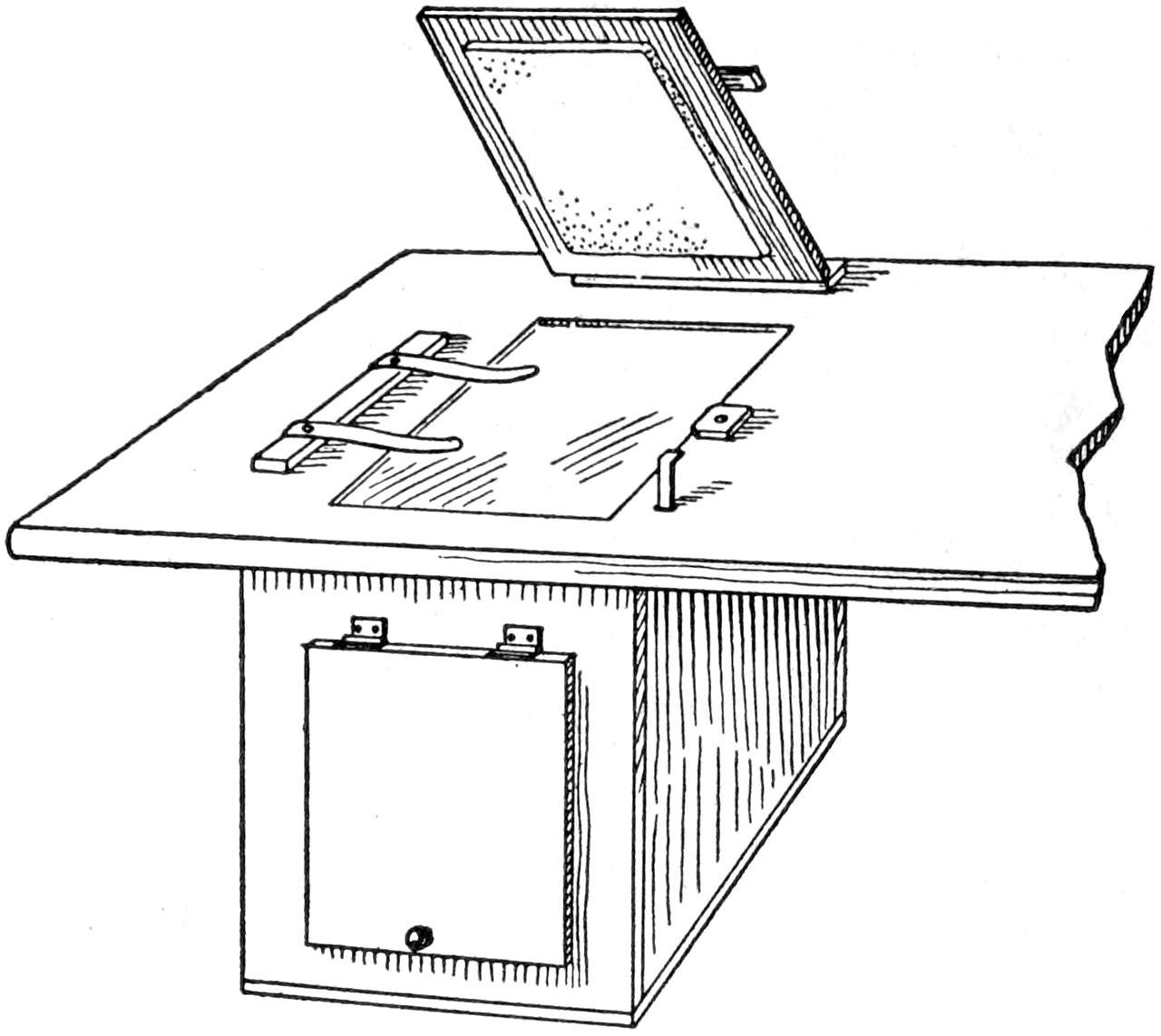

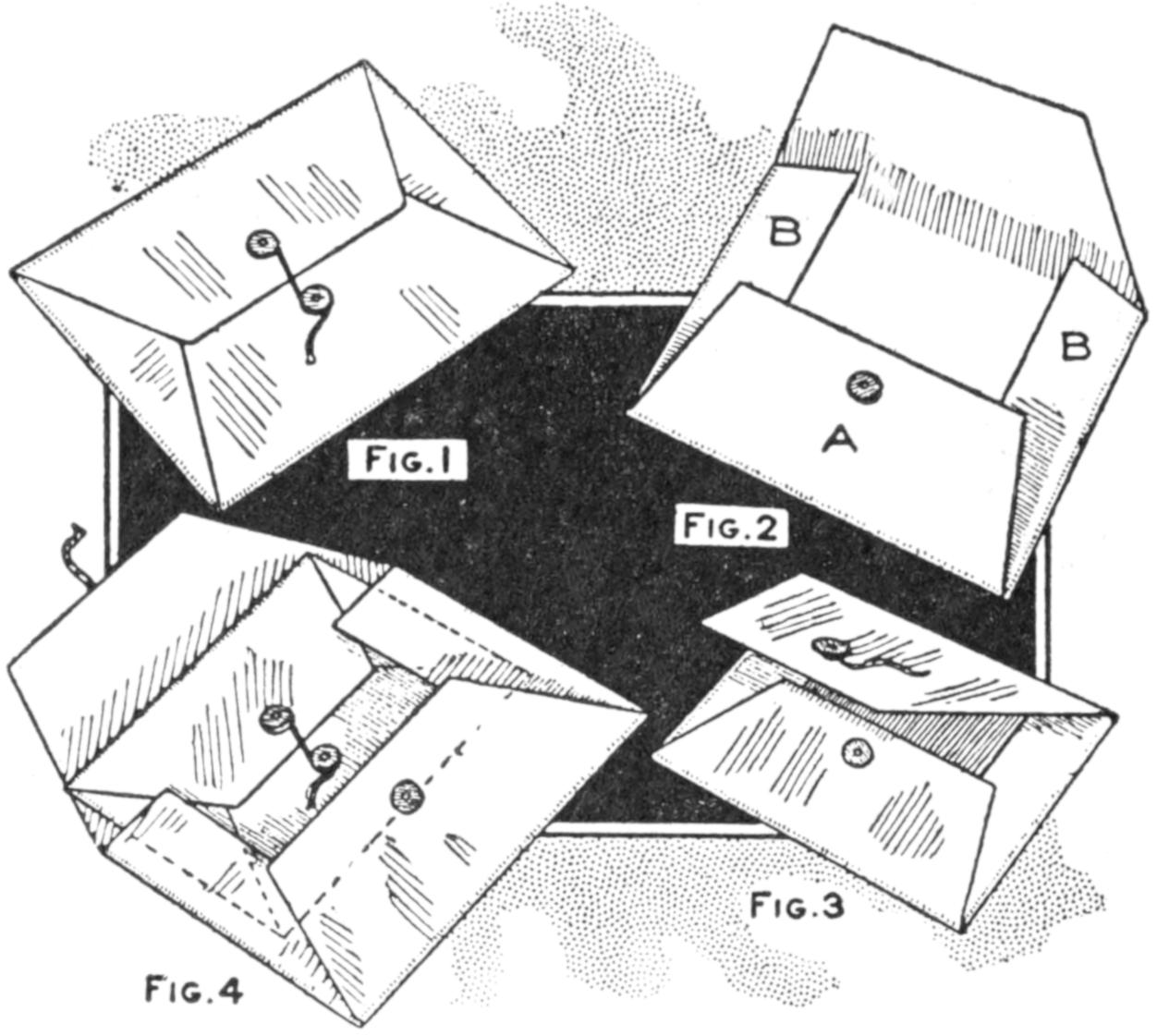

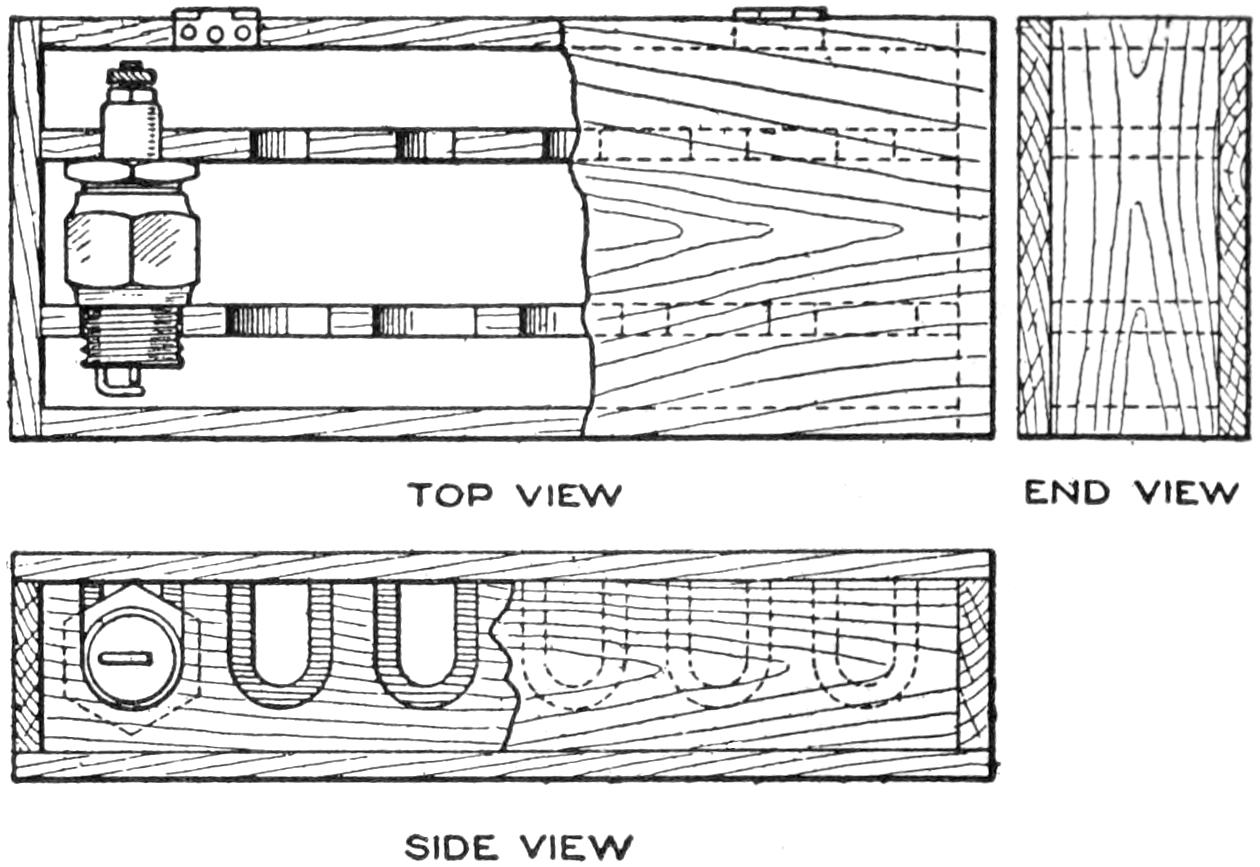

| Fig. 1 SECTIONAL SIDE VIEW |

Fig. 2 FRONT VIEW |

|

| Fig. 3 PLAN |

Fig. 4 BRAKE DETAIL |

|

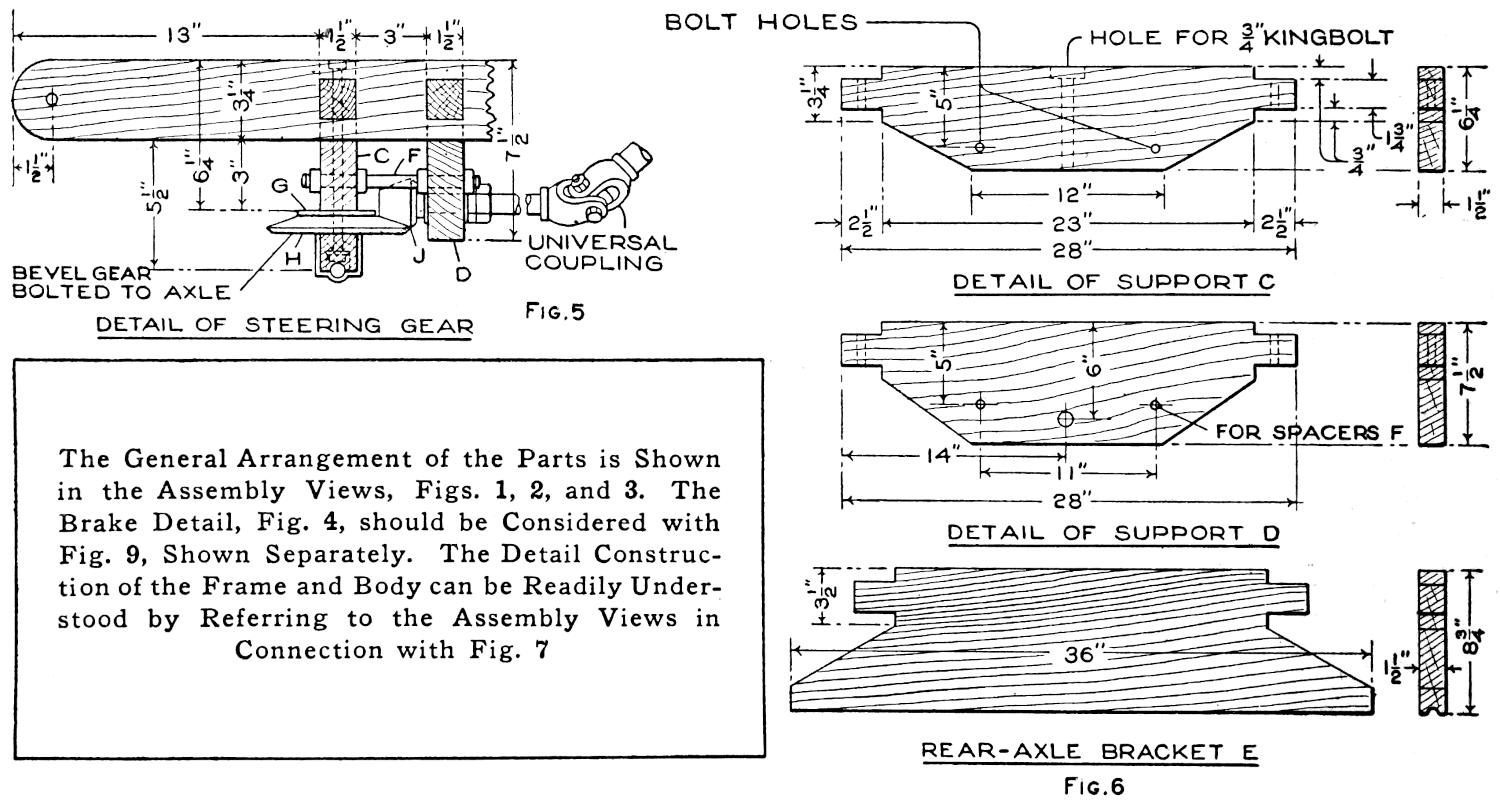

| Fig. 5 DETAIL OF STEERING GEAR |

DETAIL OF SUPPORT C | |

| The General Arrangement of the Parts is Shown in the Assembly Views, Figs. 1, 2, and 3. The Brake Detail, Fig. 4, should be Considered with Fig. 9, Shown Separately. The Detail Construction of the Frame and Body can be Readily Understood by Referring to the Assembly Views in Connection with Fig. 7 | DETAIL OF SUPPORT D | |

| REAR-AXLE BRACKET E Fig. 6 |

||

| Fig. 7 DETAIL OF FRAME AND BODY |

||

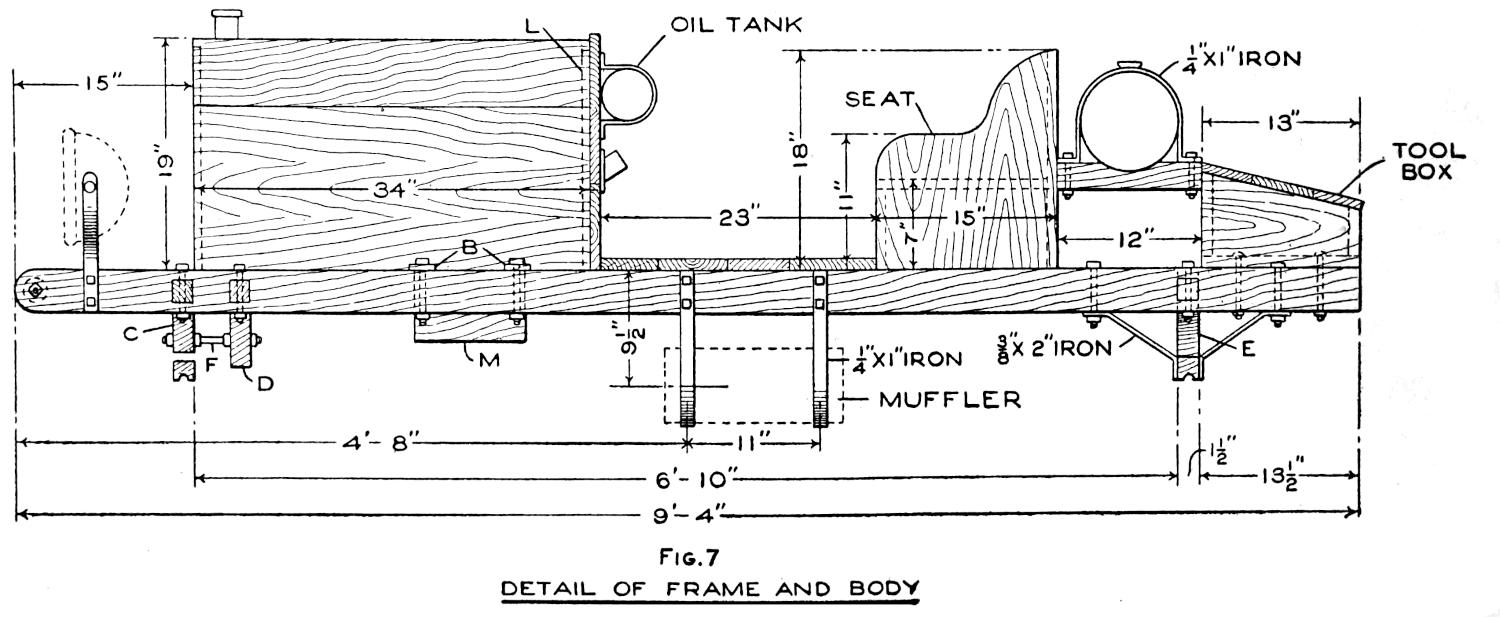

[1]

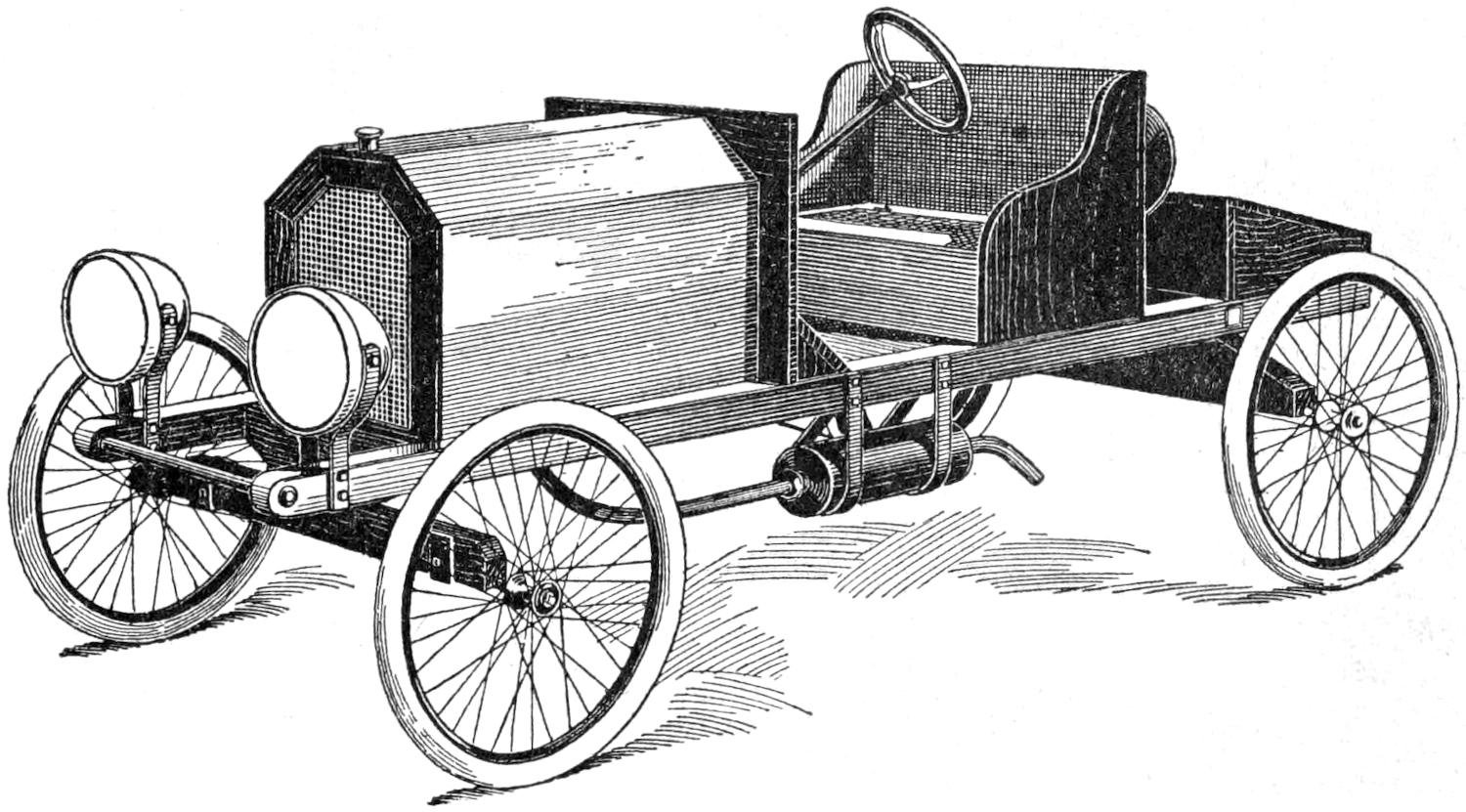

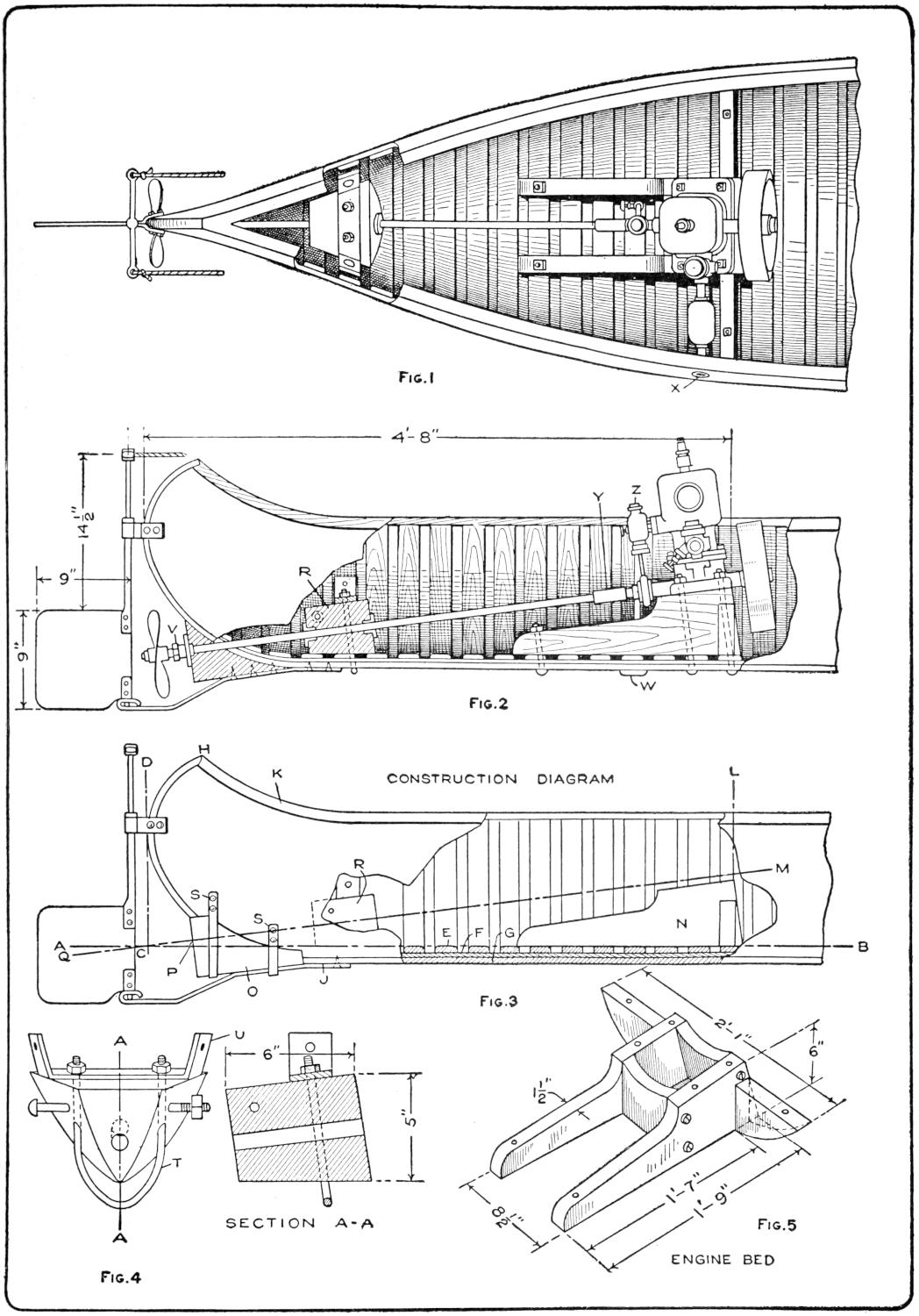

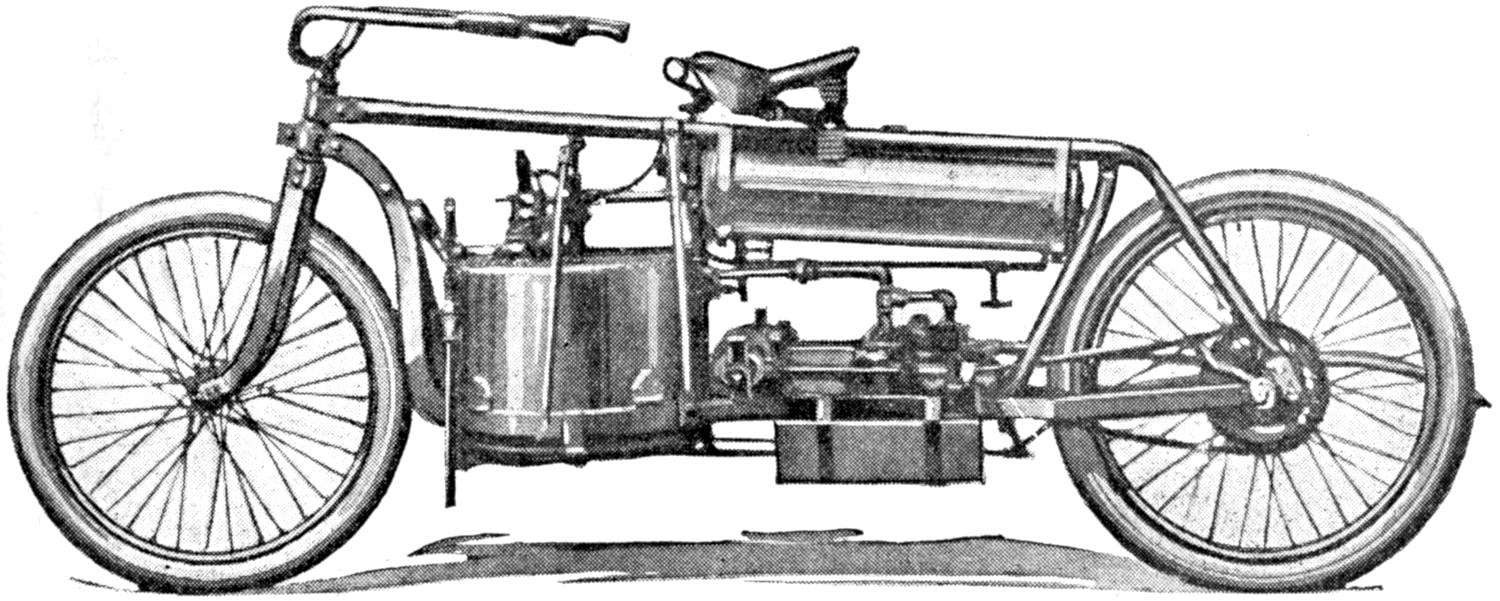

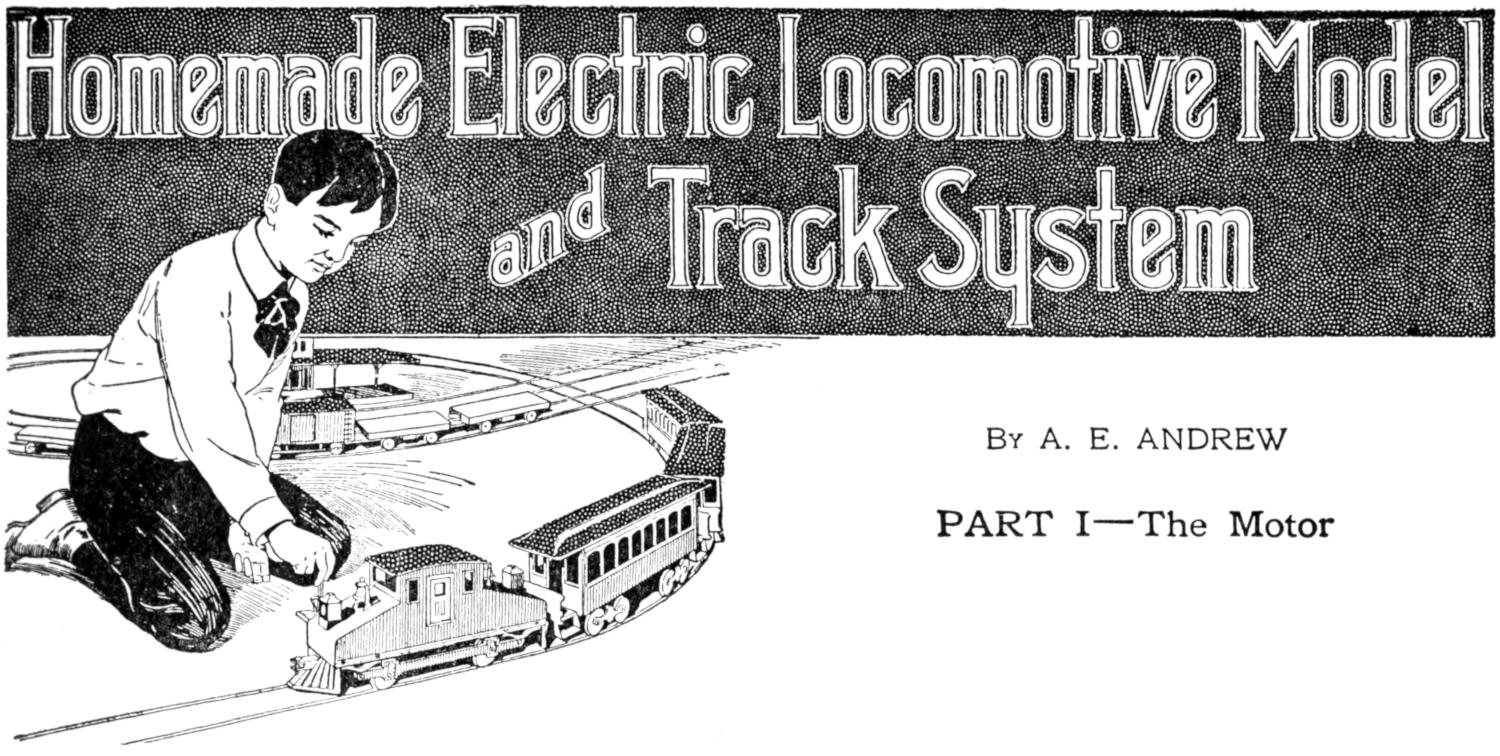

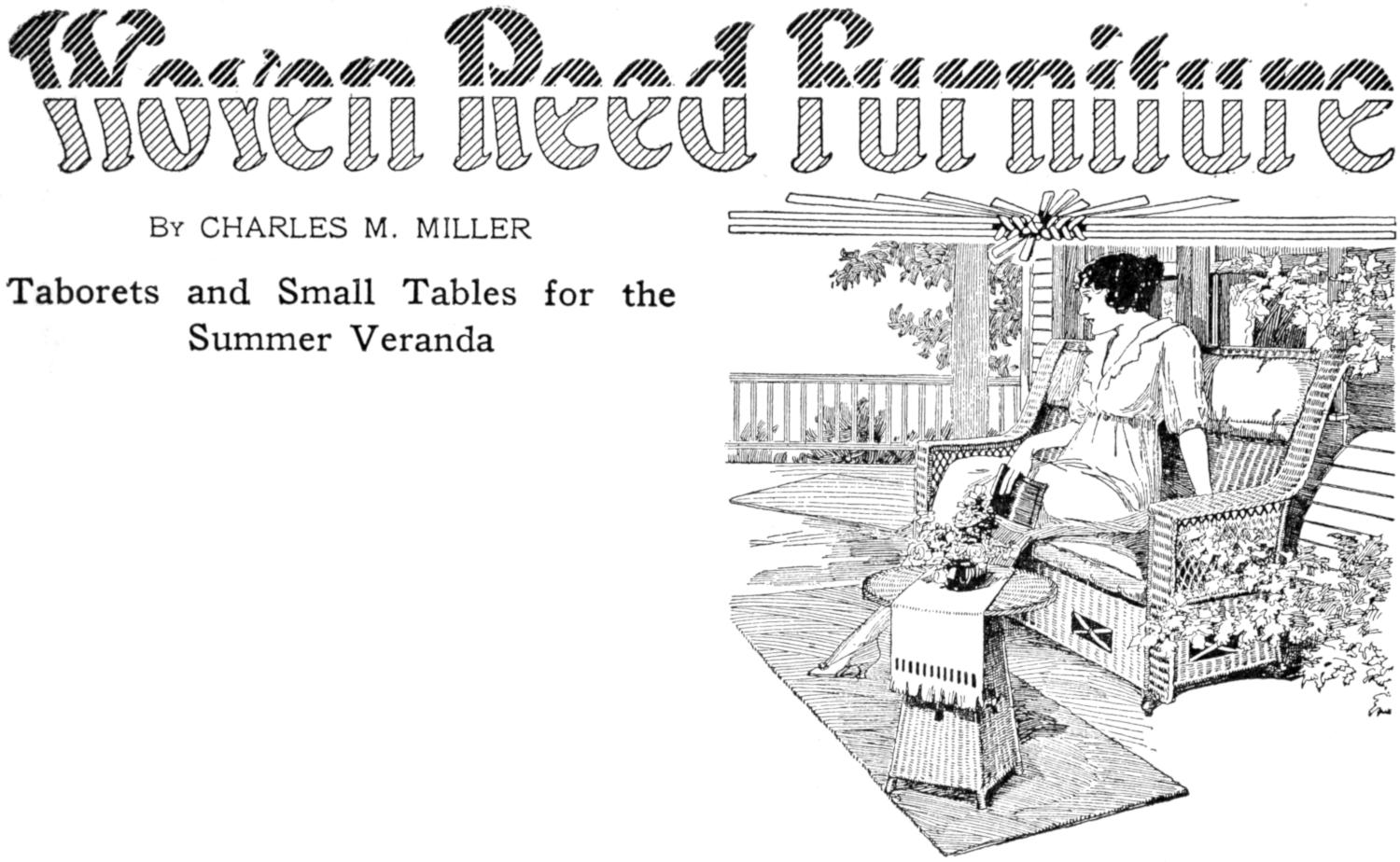

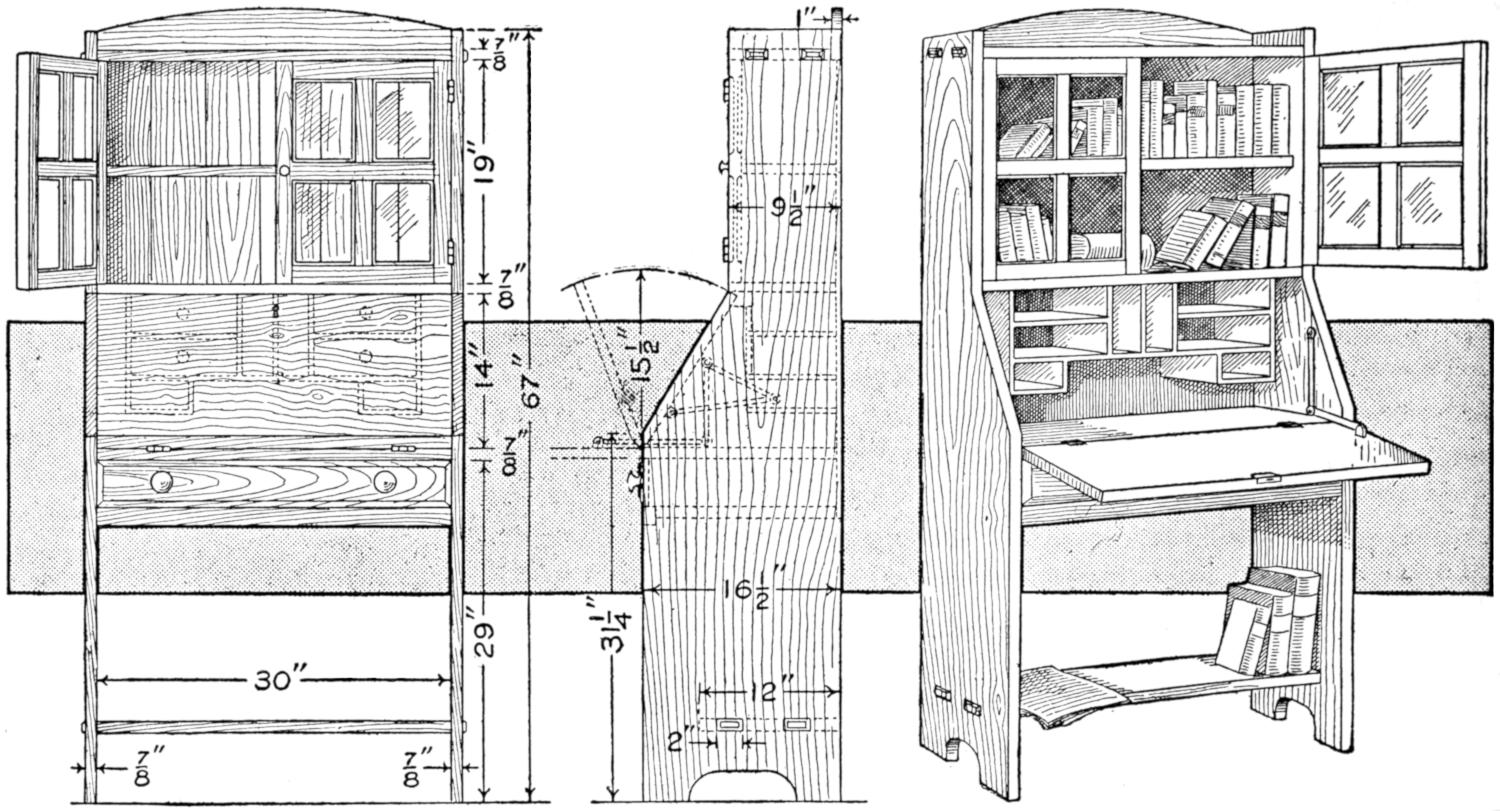

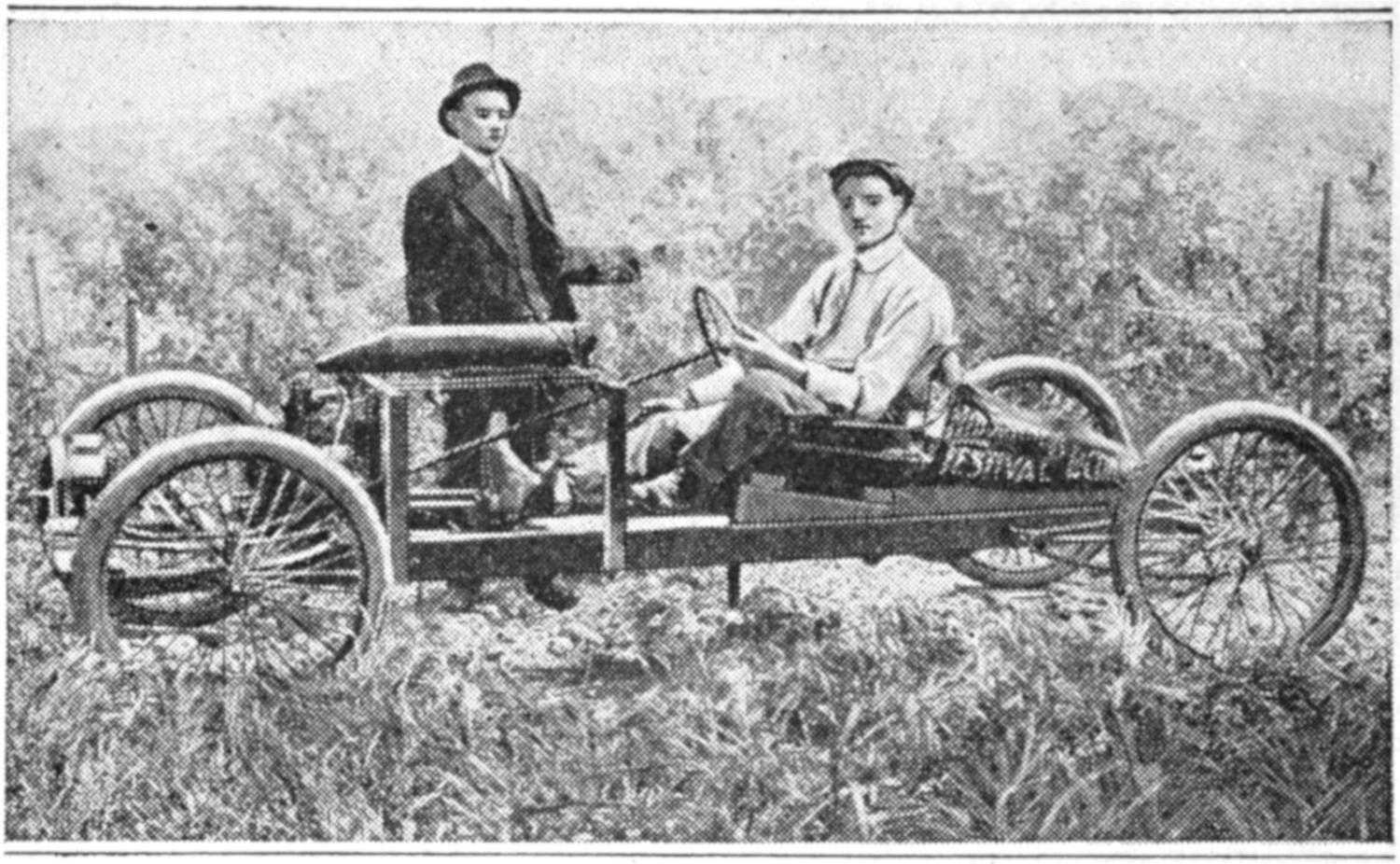

A Boys’ Motor Car

HOMEMADE

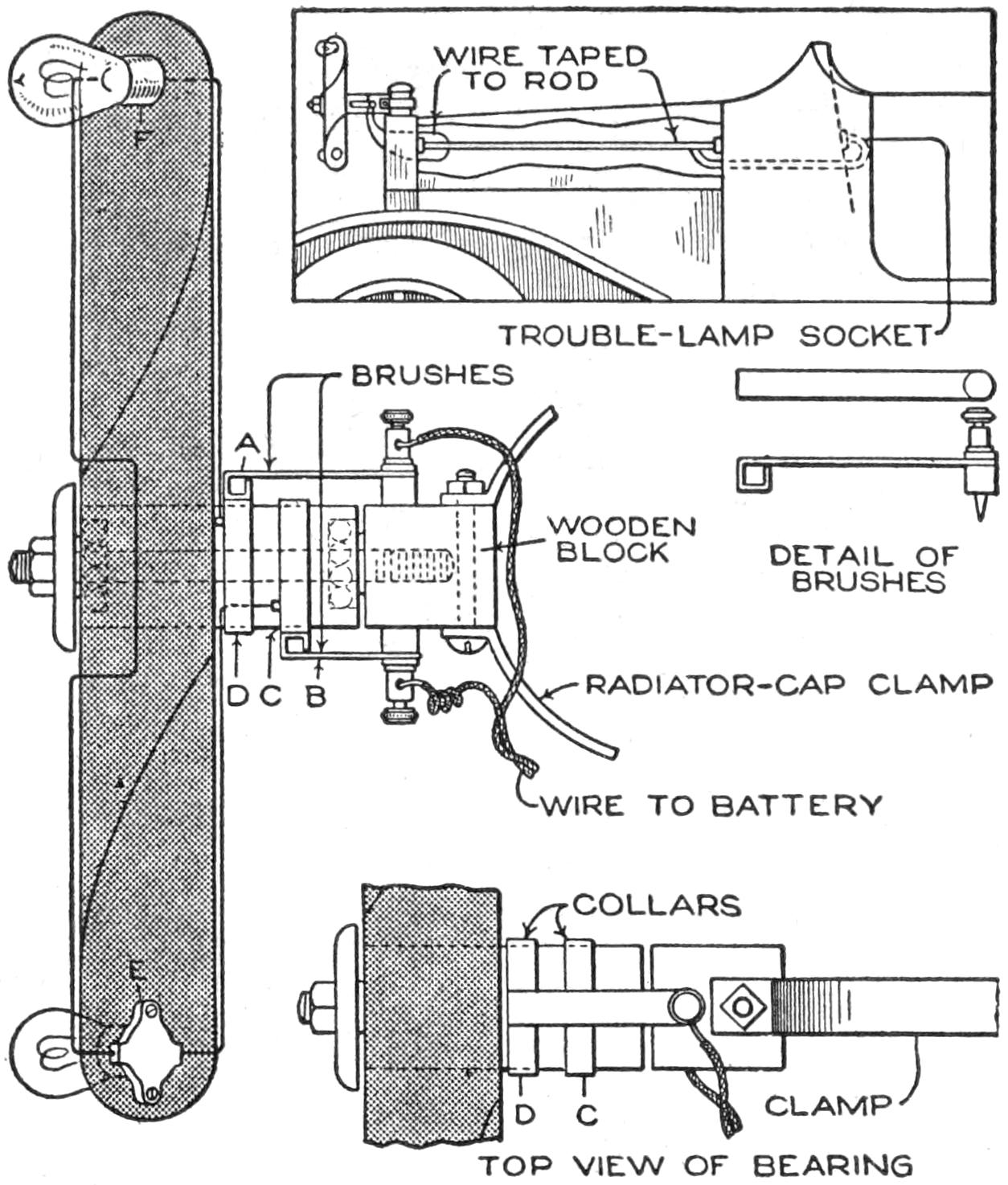

by P.P. Avery

Even though the home-built “bearcat” roadster, or other favorite model, does not compare in every detail with the luxurious manufactured cars, it has an individuality that puts it in a class by itself. The amateur mechanic, or the ambitious boy, who is fairly skilled with tools, can build at least the main parts for his own small car, of the simple, practical design shown in the sketch and detailed in the working drawings. If necessary, he can call more skilled mechanics to his aid. A motorcycle engine, or other small gasoline motor, is used for the power plant. The control mechanism of the engine and the electrical connections are similar to those of a motorcycle. They are installed to be controlled handily from the driver’s seat. The car is built without springs, but these may be included, if desired, or the necessary comfort provided—in part at least—by a cushioned seat. Strong bicycle wheels are used, the 1¹⁄₂ by 28-in. size being suitable. The hood may be of wood, or of sheet metal, built over a frame of strap iron. The top of the hood can be lifted off, and the entire hood can also be removed, when repairs are to be made. The tool box on the rear of the frame can be replaced by a larger compartment, or rack, for transporting loads, or an extra seat for a passenger.

To Simplify This Small but Serviceable Motor Car for Construction by the Young Mechanic, Only the Essential Parts are Considered. Other Useful and Ornamental Features may be Added as the Skill and Means of the Builder Make Possible

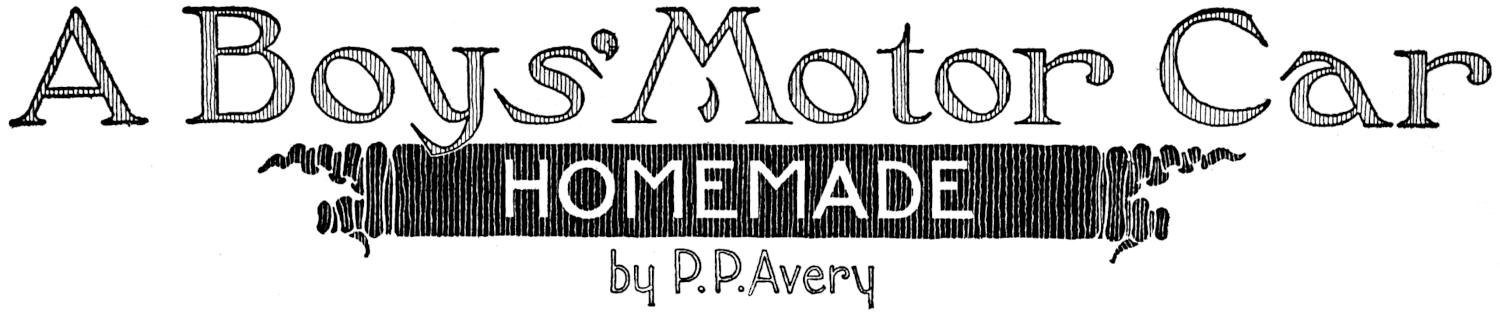

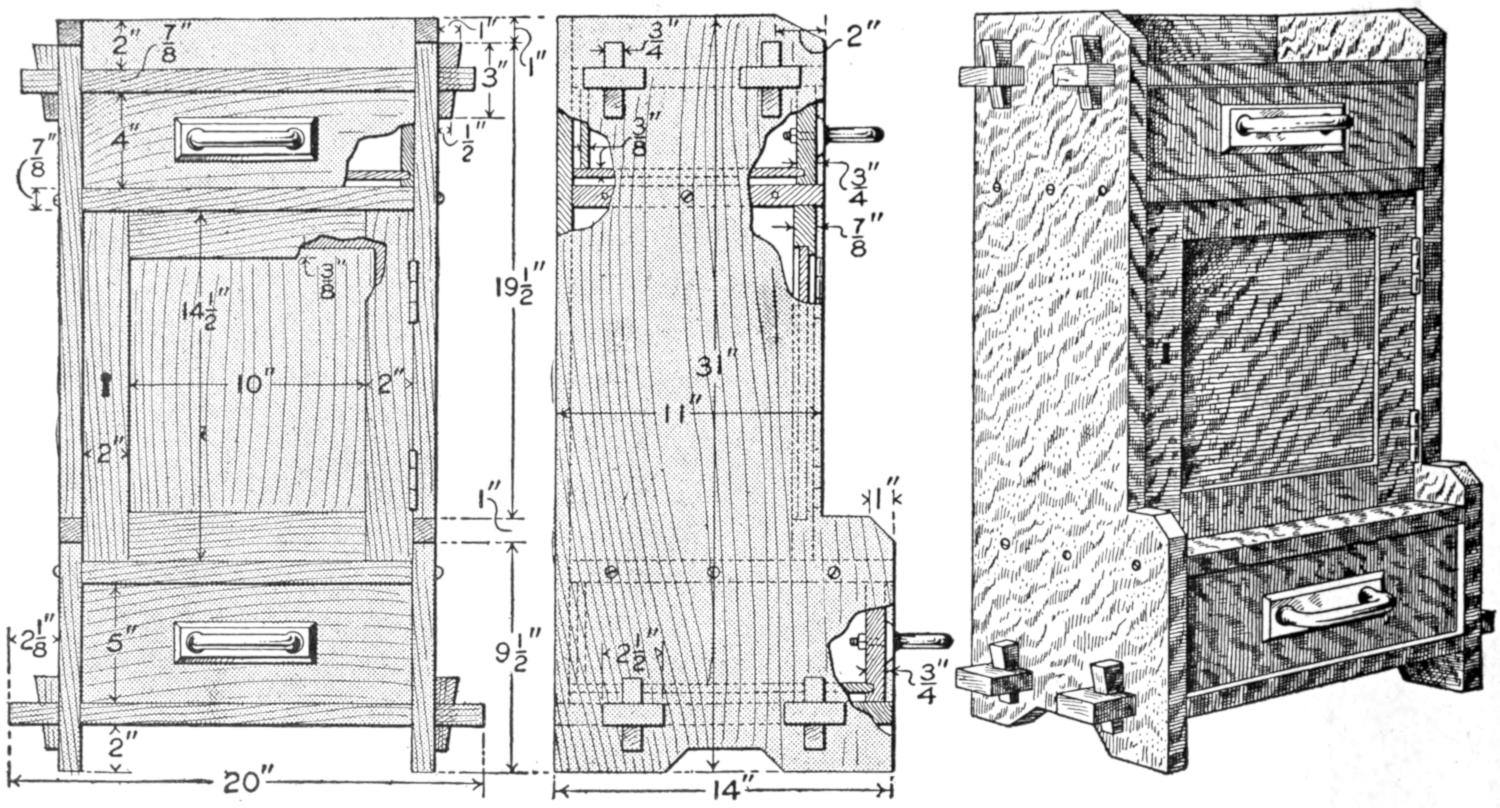

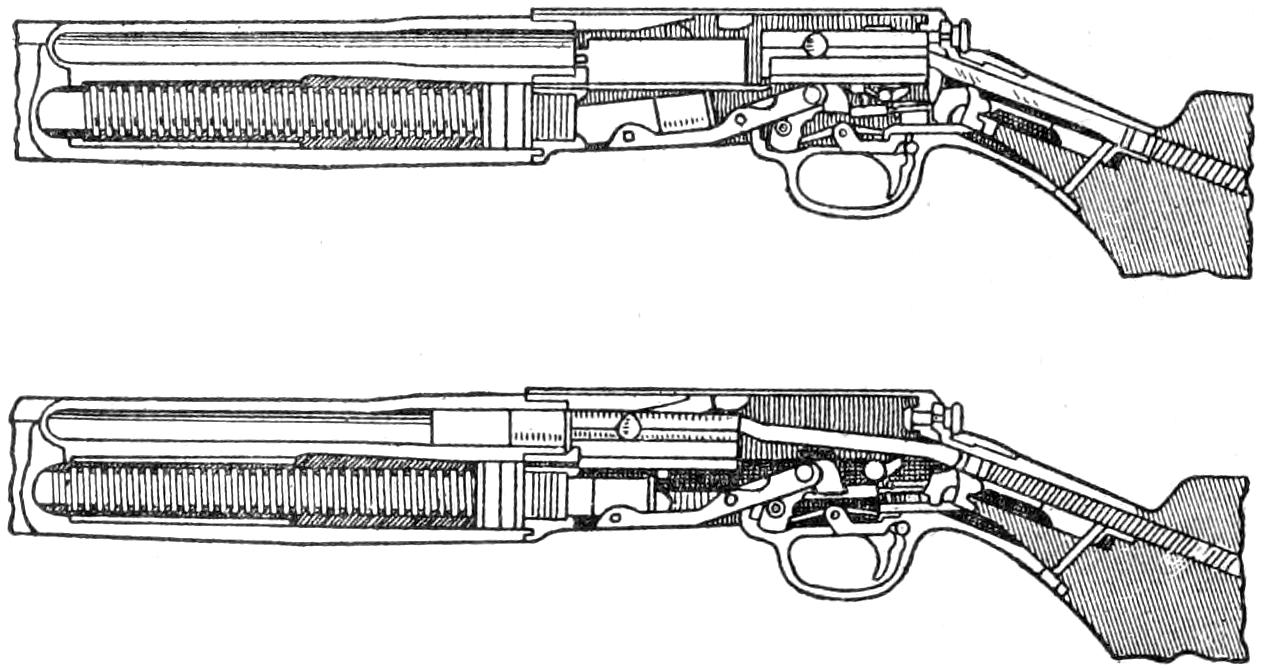

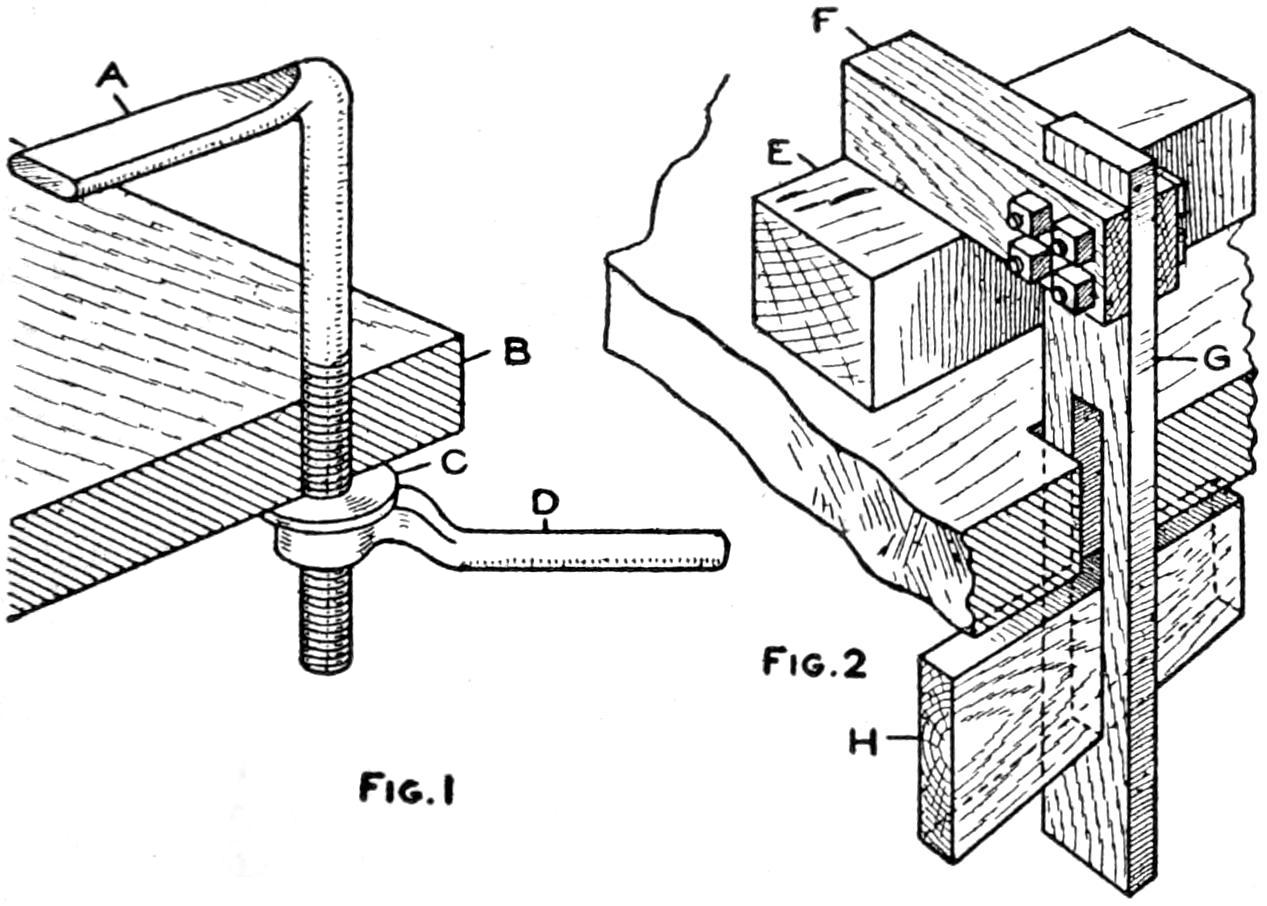

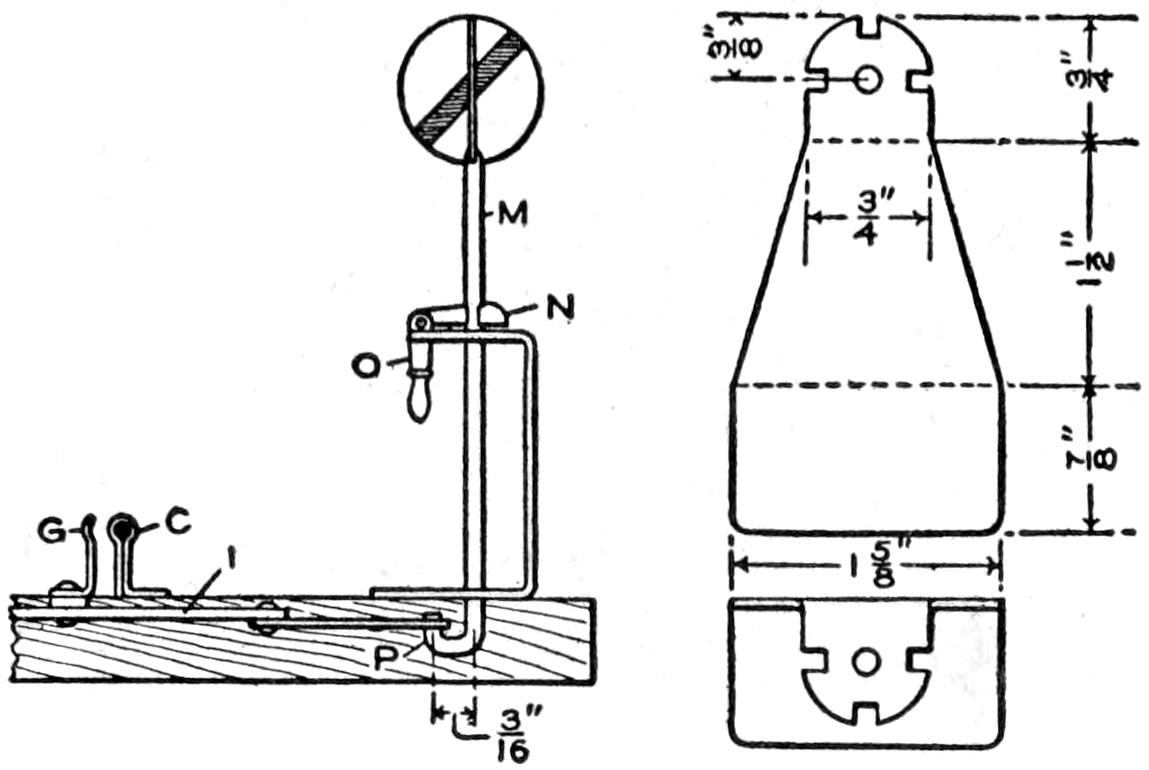

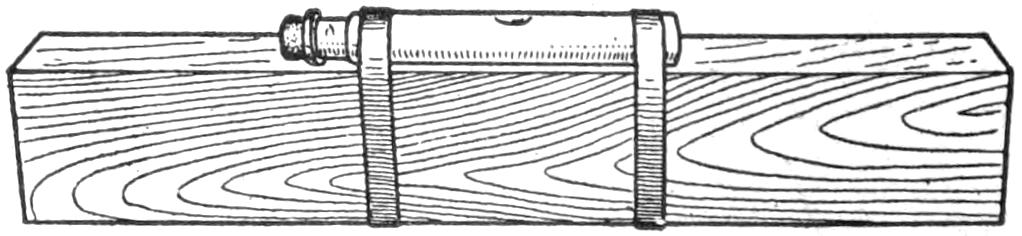

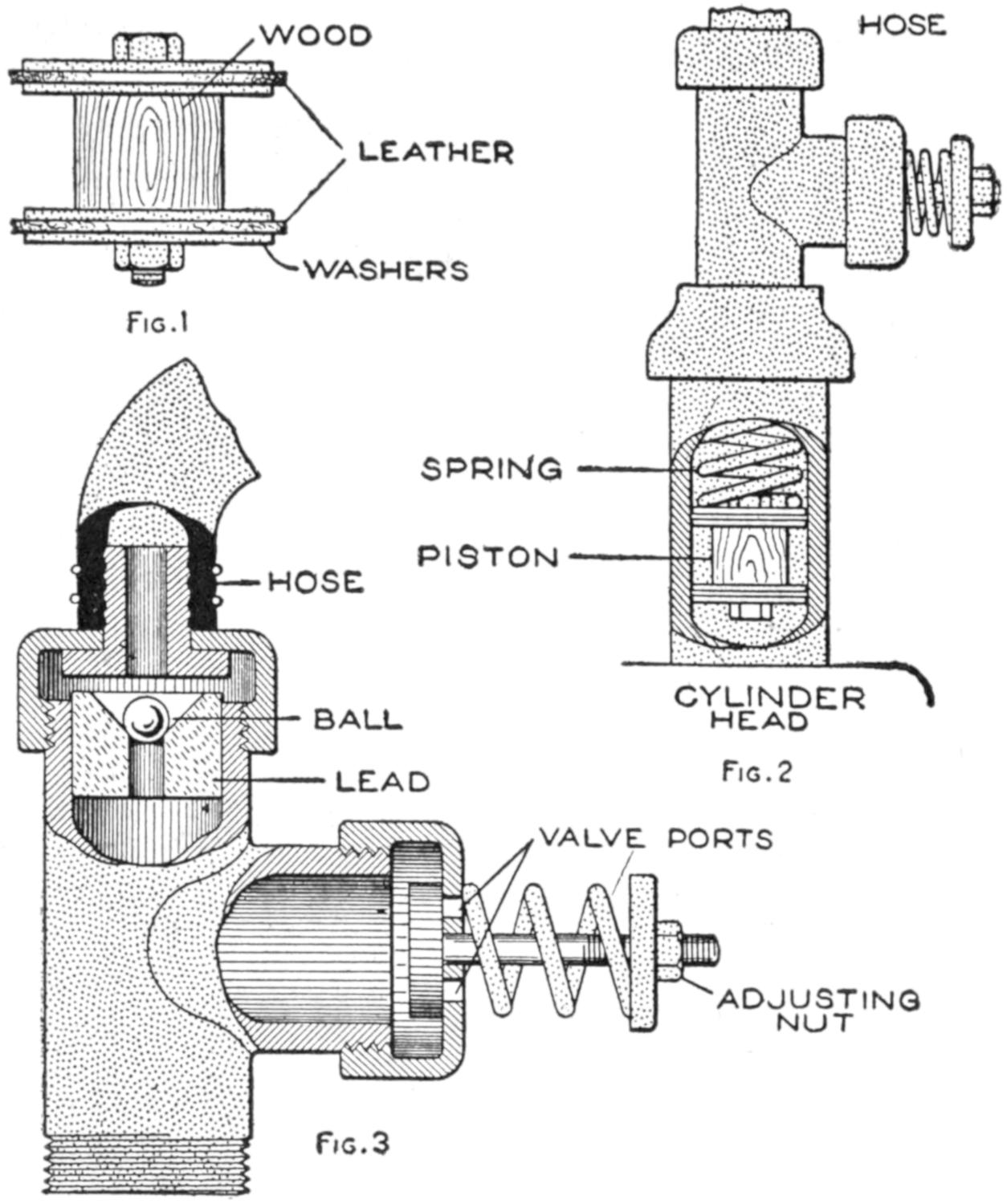

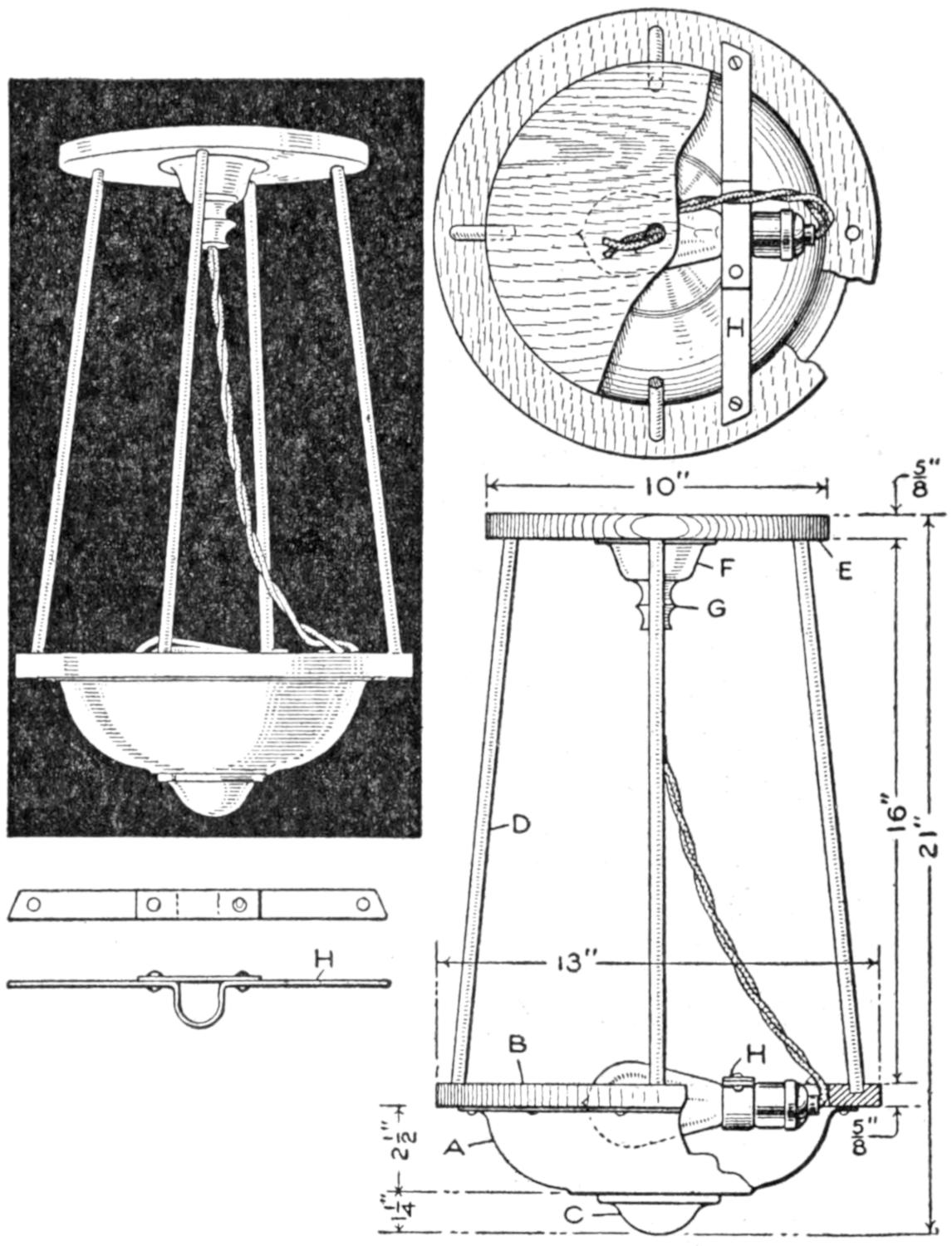

The construction may be begun with the chassis and the running gear. Fit the wheels with ⁵⁄₈-in. axles, as shown in the assembly views, Figs. 1, 2, and 3, and detailed in Fig. 4. Fit the ends of the axles to the hubs of the wheels, providing the threaded ends with lock nuts. Make the wooden supports for the frame, as detailed in Fig. 6. The axles are fastened into half-round grooves, cut in the bottoms of the supports, and secured by iron straps, as shown in Fig. 4, at A. Make the sidepieces for the main frame 2¹⁄₂ by 3¹⁄₄ in. thick, and 9 ft. 4 in. long, as detailed in Fig. 7. Mortise the supports through the sidepieces, and bore the holes for the bolt fastenings and braces. Glue the mortise-and-tenon joints before the bolts are finally secured. Provide the bolts with washers, and lock the nuts with additional jam nuts where needed. Keep the woodwork clean, and apply a coat of linseed oil, so that dirt and grease cannot penetrate readily.

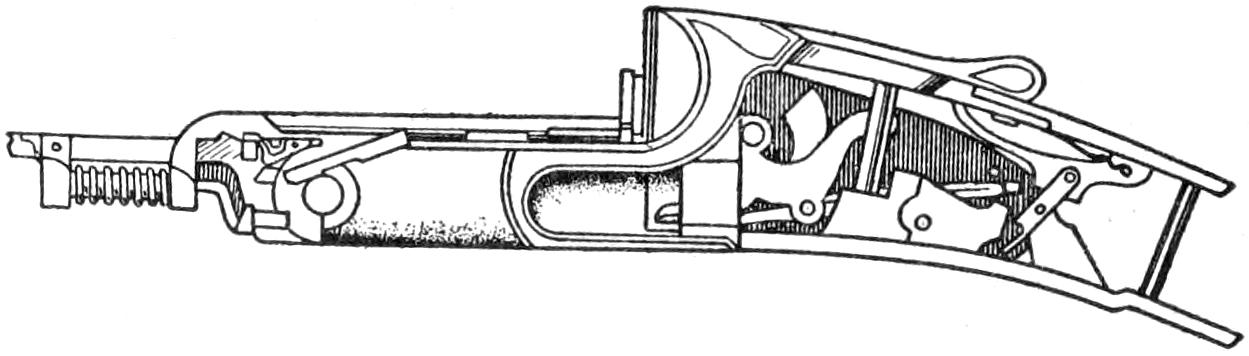

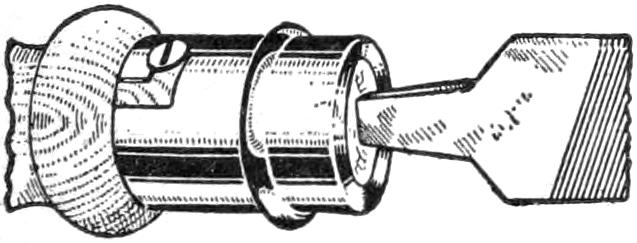

Finish only the supporting structure of the chassis in the preliminary woodwork. Set the front-axle and steering-rigging supports C and D, and adjust the spacers F between them. Bore the hole for the kingbolt, as detailed in Fig. 6, and fit the bevel gears and the fifth wheel G, of ¹⁄₄-in. steel, into place, as shown in Fig. 5. The gear H is bolted to the axle support. The[2] pinion J is set on the end of a short ³⁄₄-in. shaft. The latter passes through the support D, and is fitted with washers and jam nuts, solidly, yet with sufficient play. A bracket, K, of ¹⁄₄ by 1³⁄₄-in. strap iron, braces the shaft, as shown in Fig. 3. The end of this short shaft is joined to one section of the universal coupling, as shown, and, like the other half of the coupling, is pinned with a ³⁄₁₆-in. riveted pin. The pinion is also pinned, and the lower end of the kingbolt provided with a washer and nut, guarded by a cotter pin. Suitable gears can be procured from old machinery. A satisfactory set was obtained from an old differential of a well-known small car.

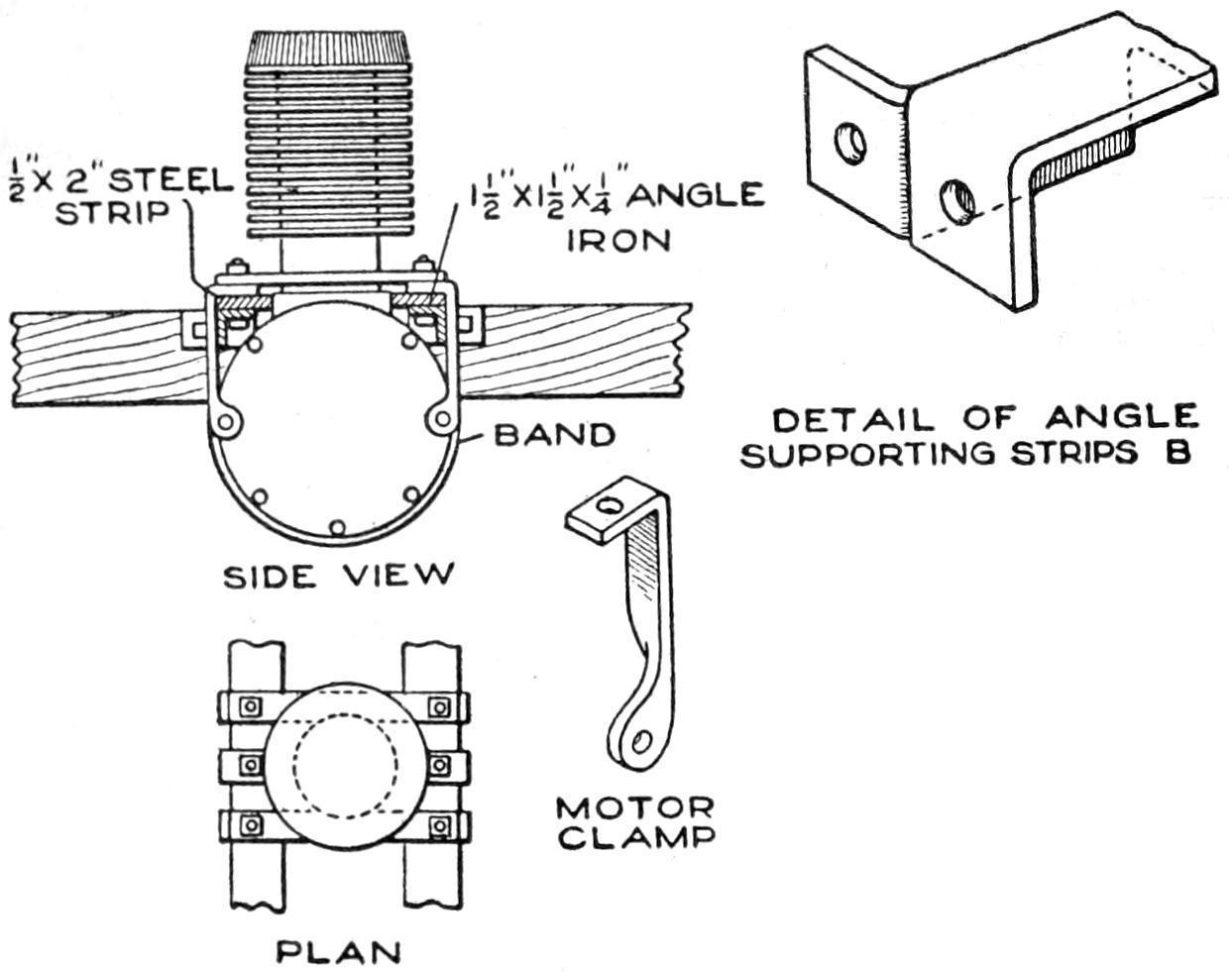

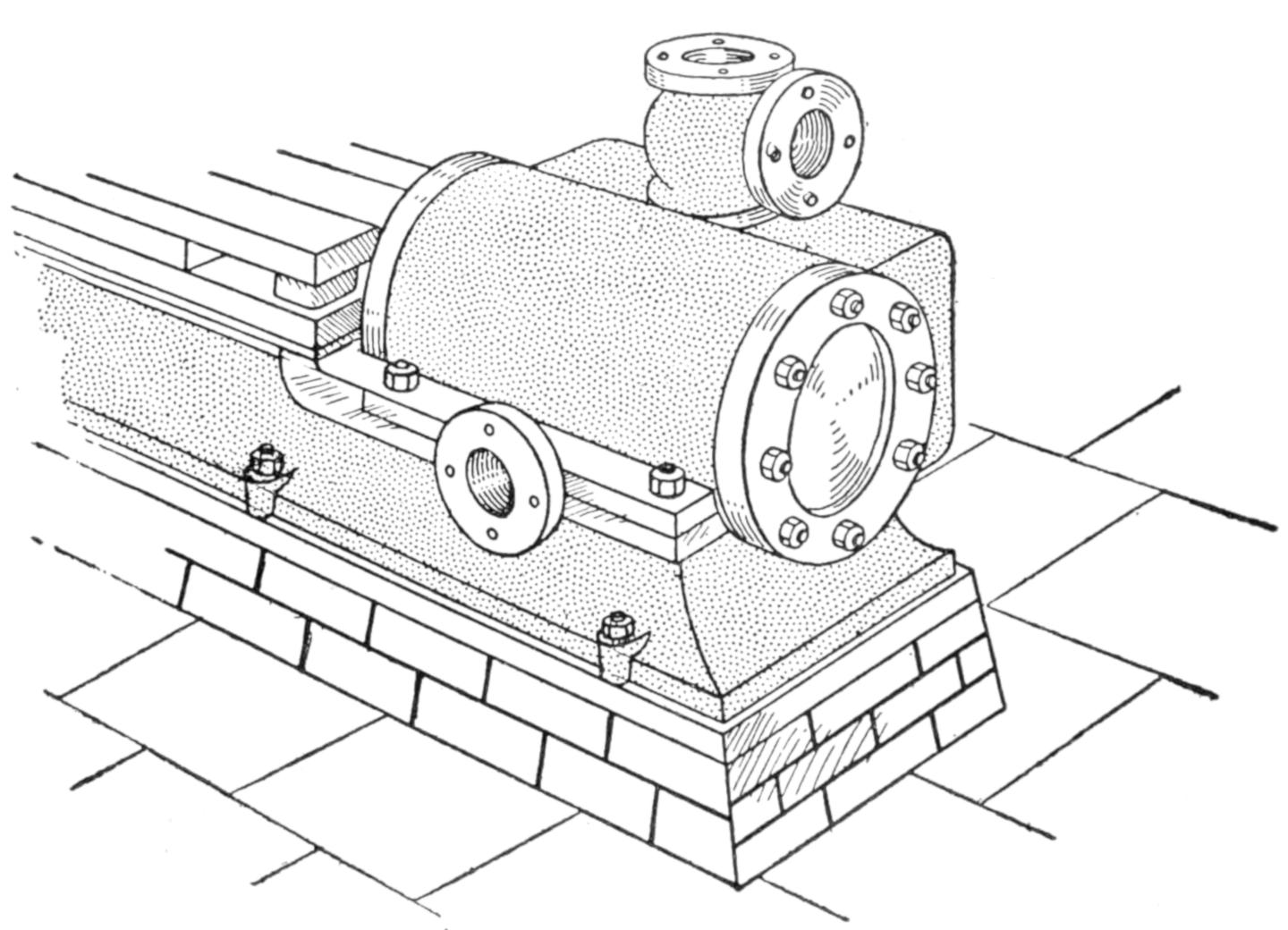

Fig. 8

Detail of the Motor

Support: The Engine

is Mounted on

Reinforced Angle

Irons, and Secured

by Clamps and a

Supporting Band

under the Crank

Case

Before fitting the steering column into place, make the dashboard, of ⁷⁄₈-in. oak, as shown in the assembly view, and in detail in Fig. 7. It is 19¹⁄₂ in. high and 2 ft. 4 in. wide, and set on the frame and braced to it with 4 by 4 by 1¹⁄₂-in. angle irons, ¹⁄₄ in. thick. Fit a ⁷⁄₈-in. strip of wood around the edge of the dashboard, on the front side, as a rest for the hood, as shown in Figs. 1 and 7, at L. A brass edging protects the dashboard, and gives a neat appearance. Lay out carefully the angle for the steering column, which is of ⁷⁄₈-in. shafting, so as to be convenient for the driver. Mark the point at which it is to pass through the dashboard, and reinforce the hole with an oak block, or an angle flange, of iron or brass, such as is used on railings, or boat fittings. A collar at the flange counteracts the downward pressure on the steering post. The 12-in. steering wheel is set on the column by a riveted pin.

The fitting of the engine may next be undertaken. The exact position and method of setting the engine on the frame will depend on the size and type. It should be placed as near the center as possible, to give proper balance. The drawings show a common air-cooled motor of the one-cylinder type. It is supported, as shown in Figs. 1 and 3 and detailed in Fig. 8. Two iron strips, B, riveted to 1¹⁄₂ by 1¹⁄₂-in. angle irons, extend across the main frame, and support the engine by means of bolts and steel clamps, designed to suit the engine. Cross strips of iron steady the engine, and the clamps are bolted to the crank case. The center clamp is a band that passes under the crank case.

The engine is set so that the crankshaft extends across the main frame. Other methods may be devised for special motors, and the power transmission changed correspondingly. One end of the crankshaft is extended beyond the right side of the frame, as shown in Fig. 3. This extension is connected to the shaft by means of an ordinary setscrew collar coupling. A block M, Figs. 3 and 7, is bolted to the frame, and a section of heavy brass pipe fitted as a bearing.

The ignition and oiling systems, carburetor, and other details of the engine control and allied mechanism, are the same as those used on the motorcycle engine originally, fitted up as required. The oil tank is made of a strong can, mounted on the dashboard, as shown in Figs. 1 and 2. It is connected with the crank case by copper tubing. A cut-out switch for the ignition system is mounted on the dashboard. The controls used for the engine of the motorcycle can be extended with light iron rods, and the control handles mounted on the dashboard or in other convenient position. The throttle can be mounted on the steering column by fitting an iron pipe around the post and mounting this[3] pipe in the angle flange at the dashboard. A foot accelerator may also be used, suitable mountings and pedal connections being installed at the floor.

In setting the gasoline tank, make only as much of the body woodwork as is necessary to support it, as shown in Figs. 1, 3, and 7. The tank may be made of a can, properly fitted, and heavy enough, as determined by comparison with gasoline tanks in commercial cars. The feed is through a copper tube, as shown in Fig. 1. A small venthole, to guard against a vacuum in the tank, should be made in the cap. The muffler from a motorcycle is used, fitted with a longer pipe, and suspended from the side of the frame.

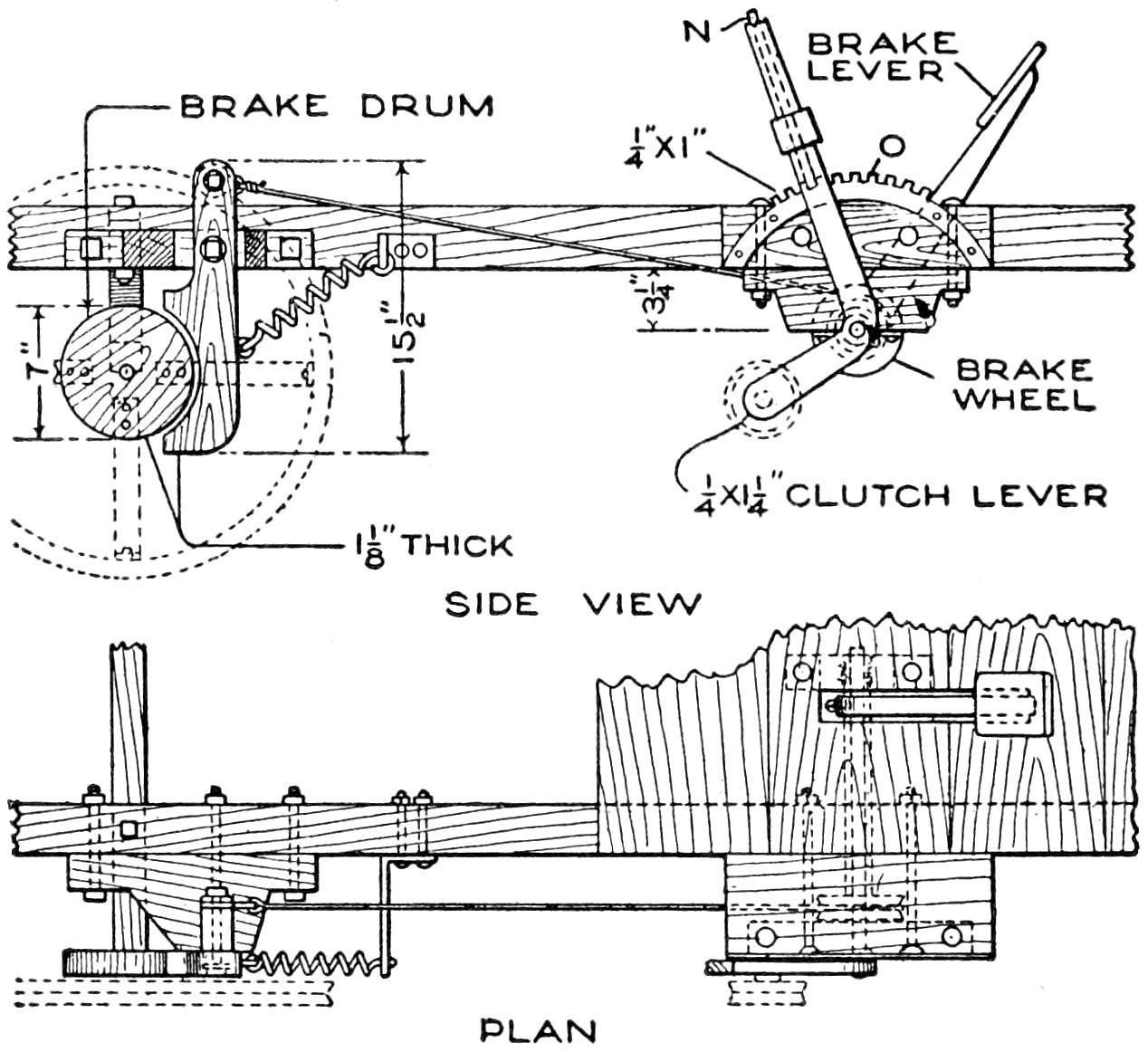

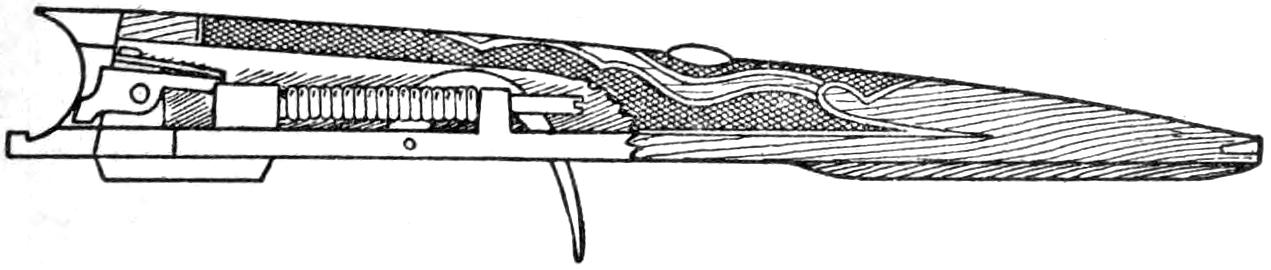

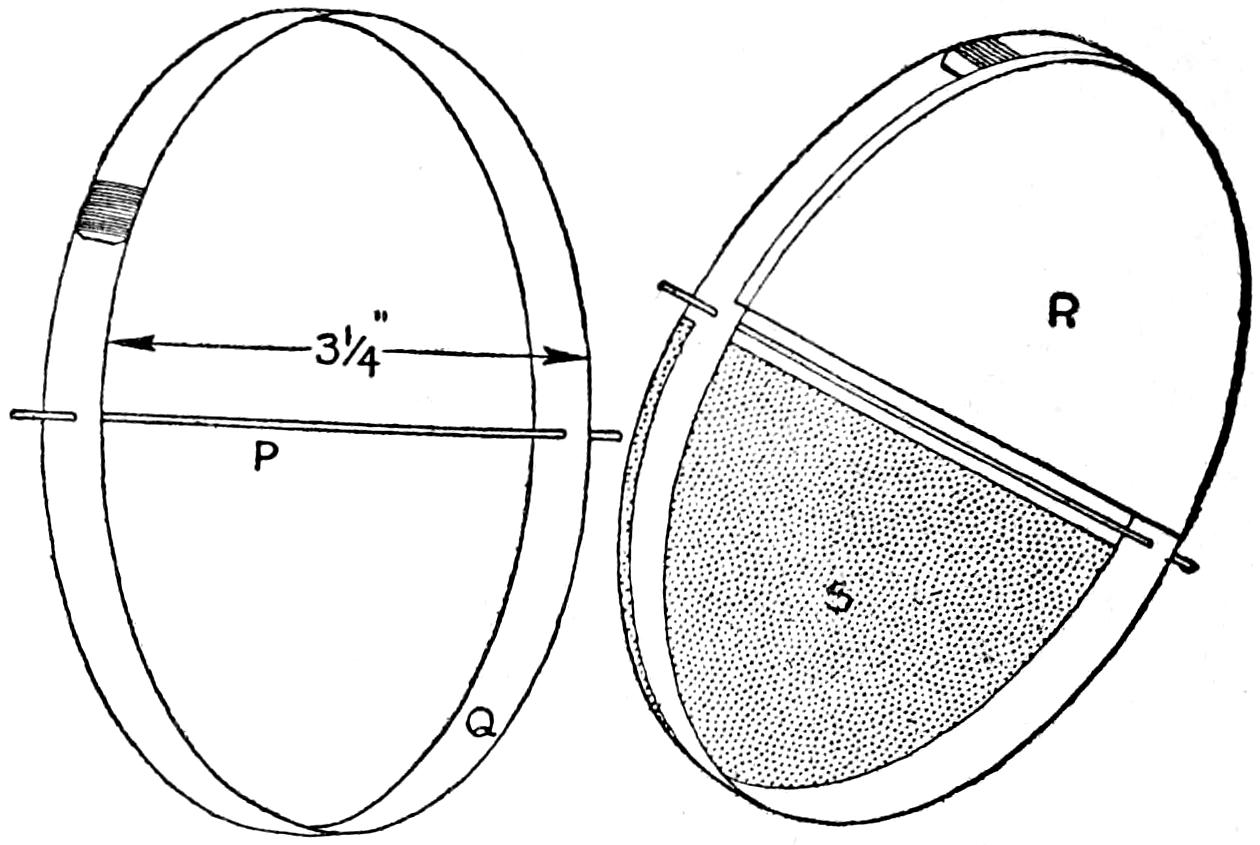

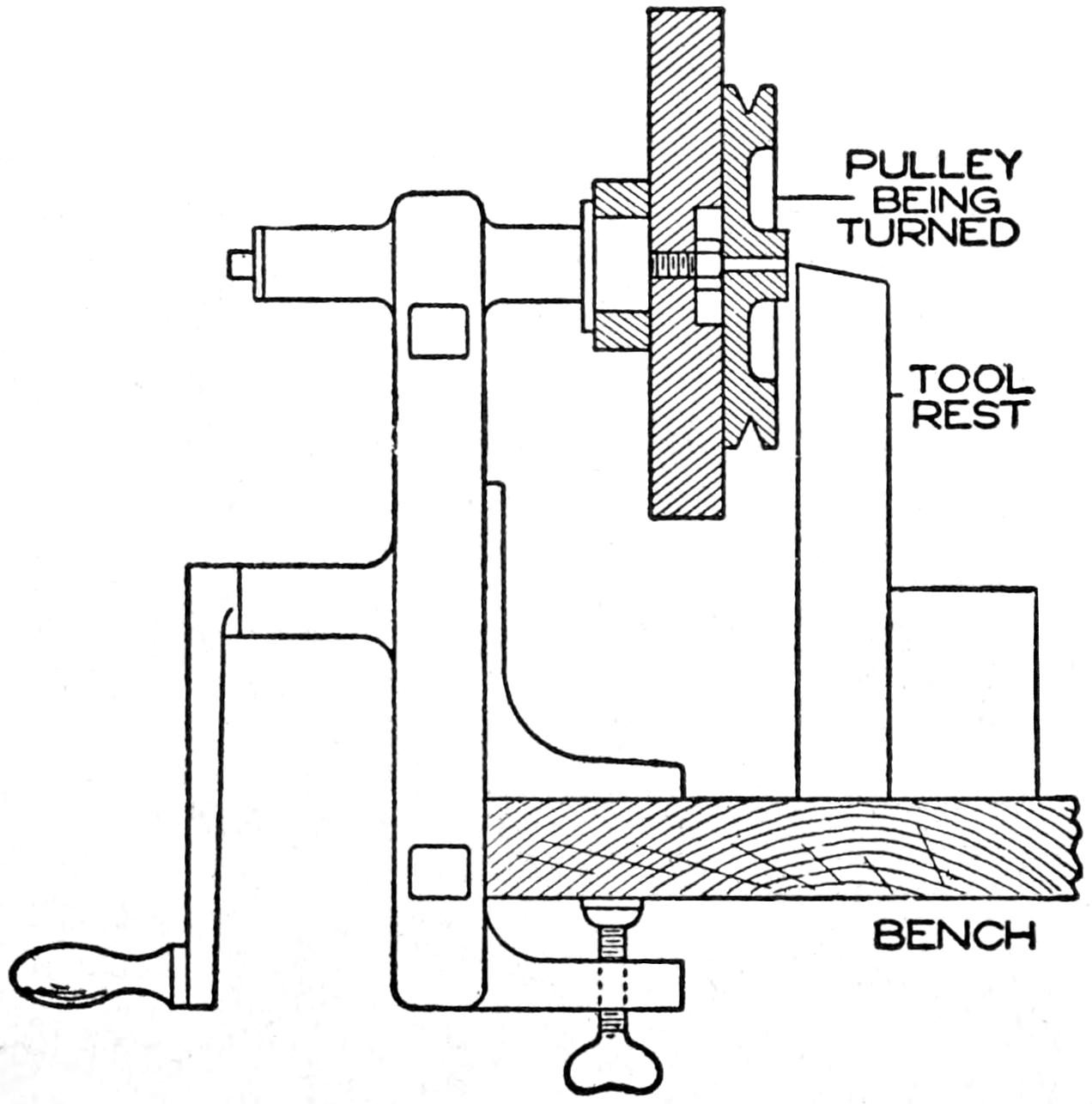

The transmission of the power from the motor shaft to the right rear wheel is accomplished by means of a leather motorcycle belt, made by fitting leather washers close together over a bicycle chain, oiling the washers with neat’s-foot oil. A grooved iron pulley is fitted on the end of the motor shaft, and a grooved pulley rim on the rear wheel, as shown in Figs. 1 and 3, and detailed in Fig. 4. The motor is started by means of a crank, and the belt drawn up gradually, by the action of a clutch lever and its idler, detailed in Fig. 9. The clutch lever is forged, as shown, and fitted with a ratchet lever, N, and ratchet quadrant, O. The idler holds the belt to the tension desired, giving considerable flexibility of speed.

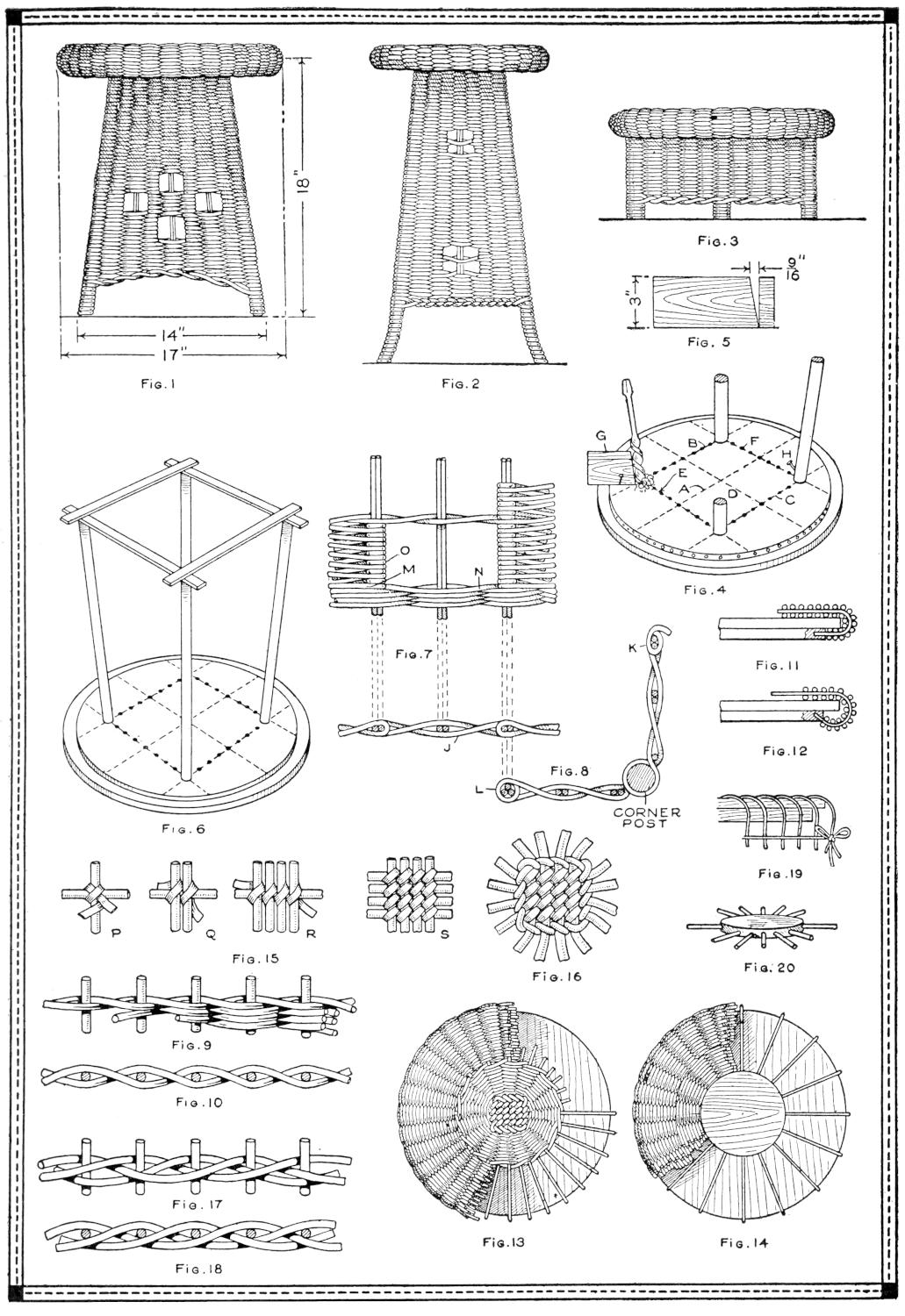

The brake is shown in Figs. 1 and 3, and detailed in Figs. 4 and 9. The fittings on the rear wheel and axle are made of wood, and bolted, with a tension spring, as shown. The brake drum is supported on iron bands, riveted to the wheel, and to the pulley rim. The brake arm is connected to the brake wheel by a flexible wire. When the pedal is forced down, the wire is wound on the brake wheel, thus permitting of adjustment. The pedal is of iron and fixed on its shaft with a setscrew. An iron pipe is used as a casing for the central shaft, the shaft carrying the clutch lever, and the pipe carrying the brake pedal and the brake wheel. The quadrant O is mounted on a block, fastened to the main frame. The central shaft is carried in wooden blocks, with iron caps. A catch of strap iron can be fitted on the floor, to engage the pedal, and lock the brake when desired.

DETAIL OF BRAKE AND CLUTCH LEVER

Fig. 9

The Brake is Controlled by a Pedal, and a Clutch Lever is Mounted on the Central Shaft, and Set by Means of a Ratchet Device and Grip-Release Rod

The engine is cooled by the draft through the wire-mesh opening in the front of the hood, and through the openings under the hood. If desirable, a wooden split pulley, with grooved rim and rope belt, may be fitted on the extension of the engine shaft, and connected with a two-blade metal fan, as shown in Fig. 2.

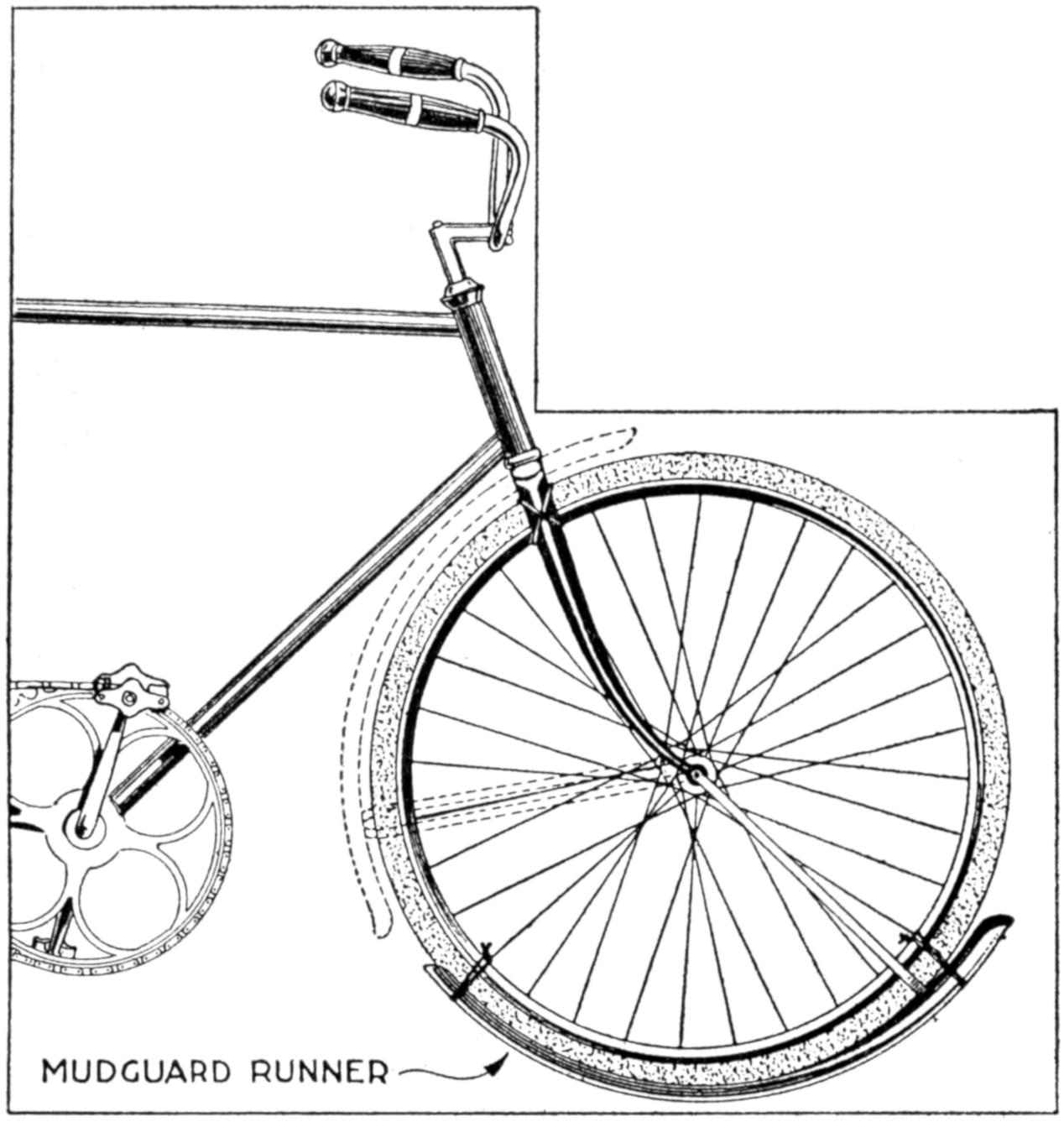

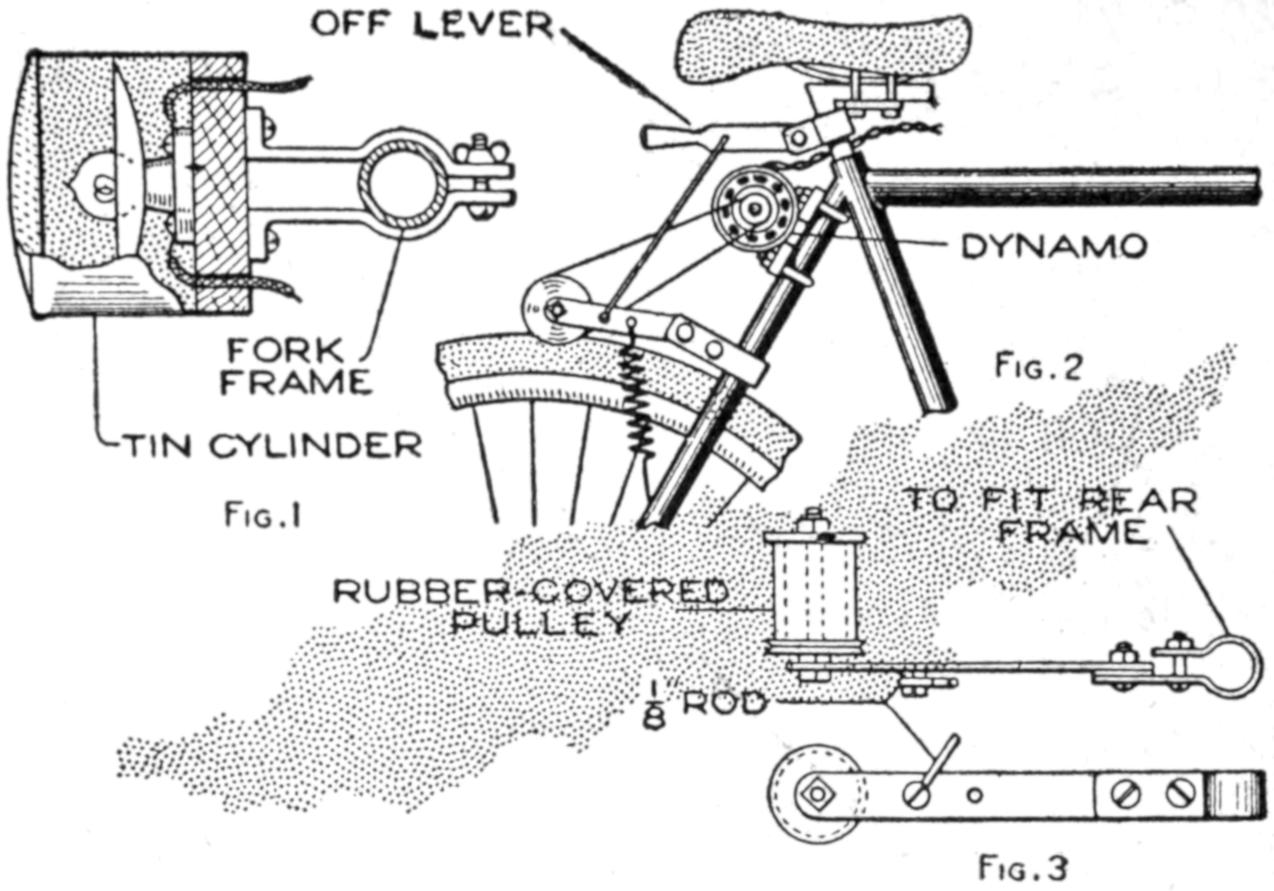

The lighting arrangement may next be installed, gas or electric lamps, run on batteries, being used. Mudguards are desirable if the car is to be used on muddy roads. Strong bicycle mudguards can be installed, the guard braces being bolted on the axles. A strong pipe, with a drawbolt passing through its length, is mounted across the front of the frame. The body is built of ⁷⁄₈-in. stock, preferably white wood, and is 2 ft. 4 in. wide. A priming coat should be applied to the woodwork, followed by two coats of the body color, and one or two coats of varnish. The metal parts, except at the working surfaces, may be painted, or enameled.

[4]

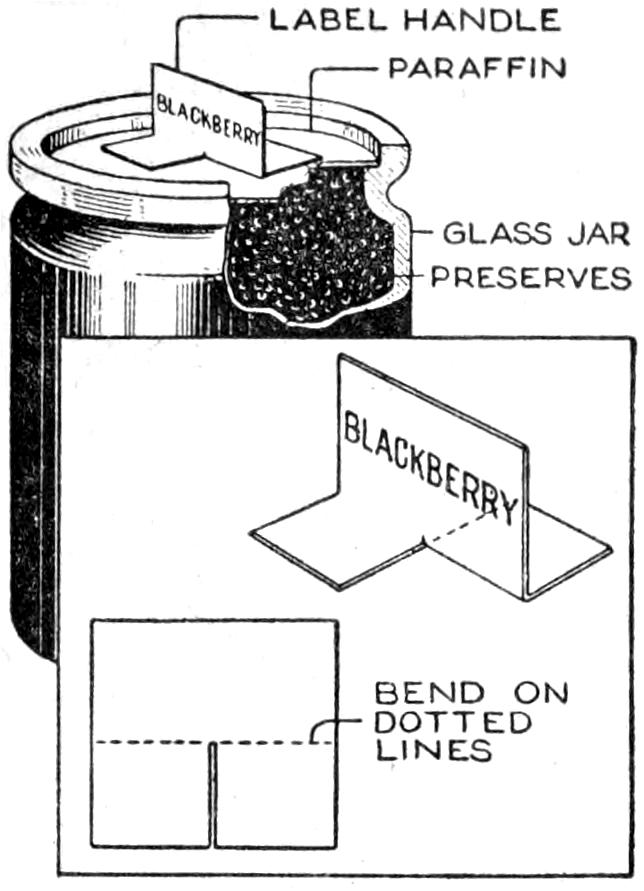

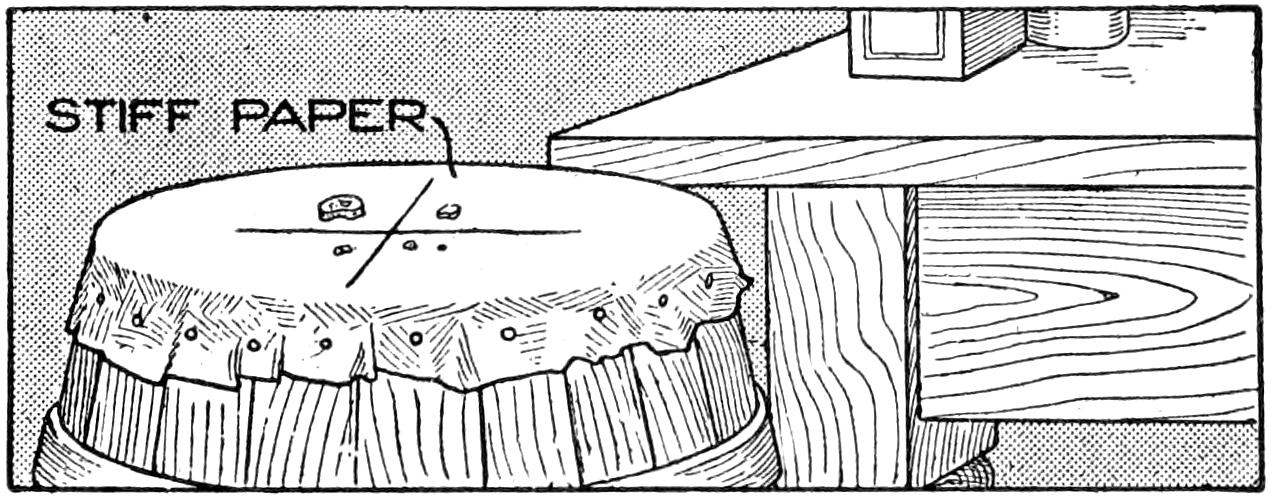

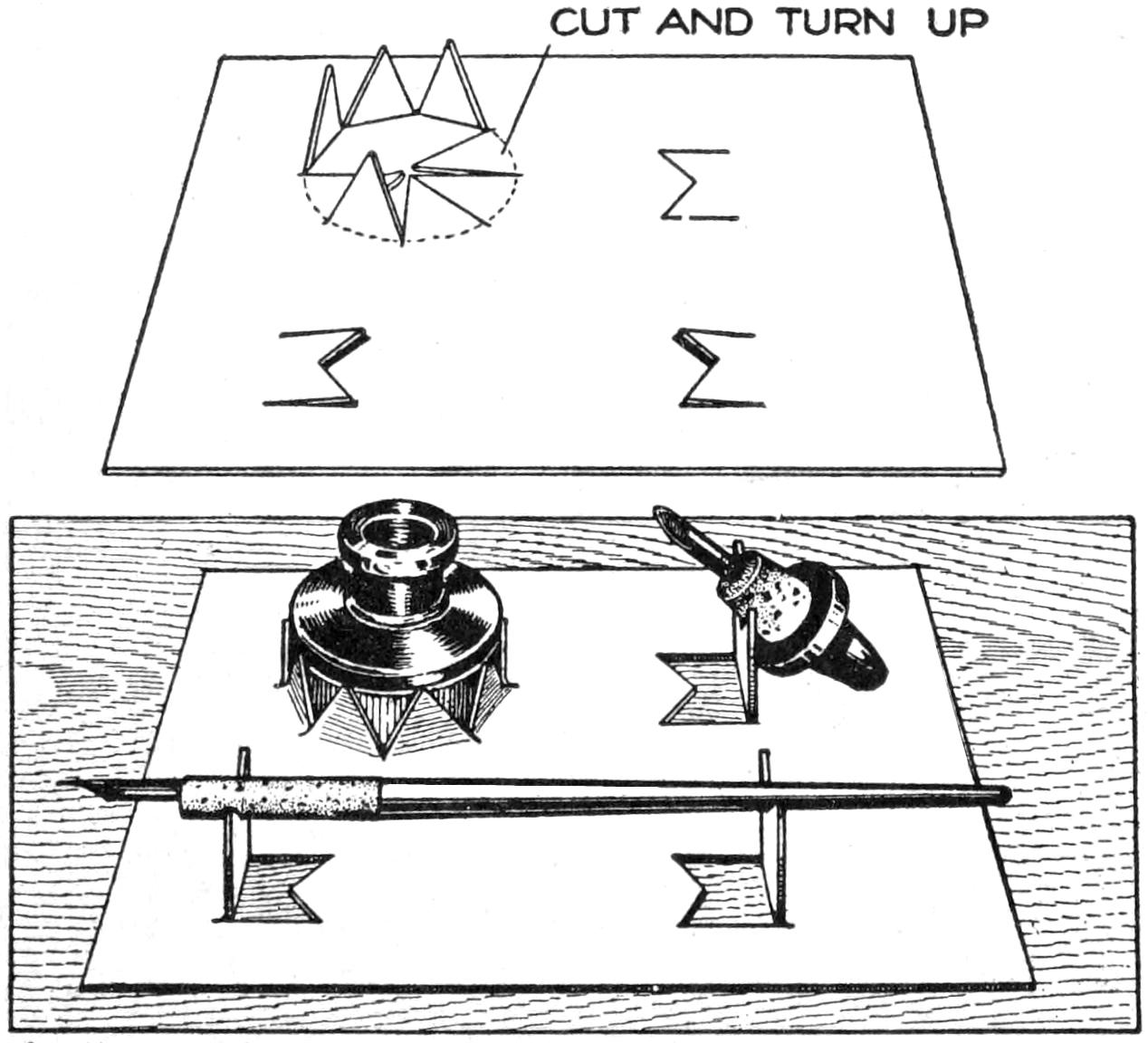

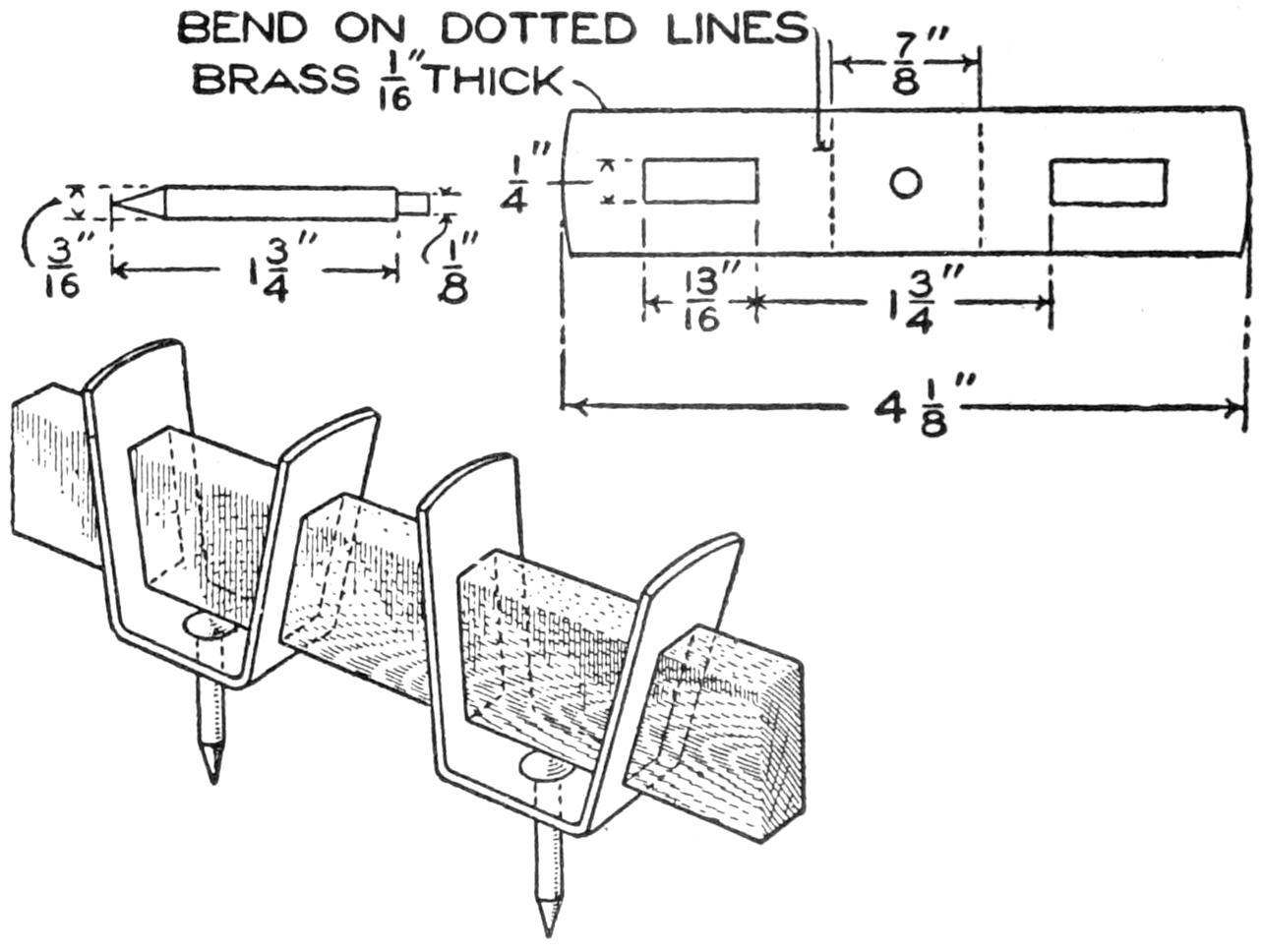

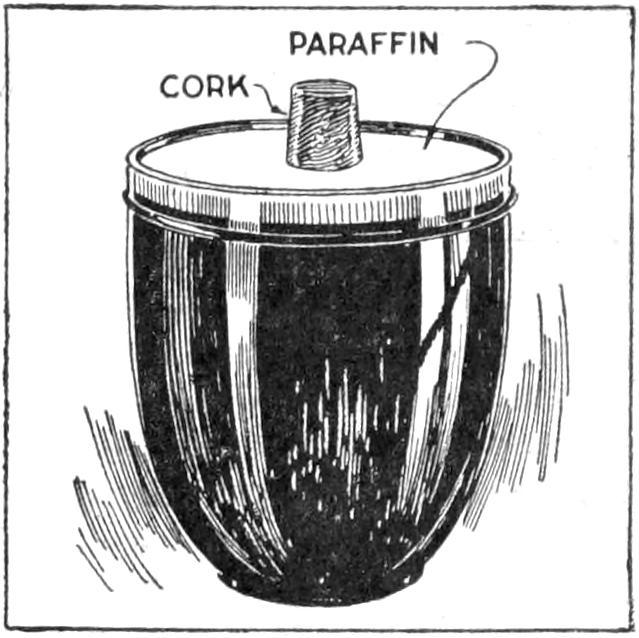

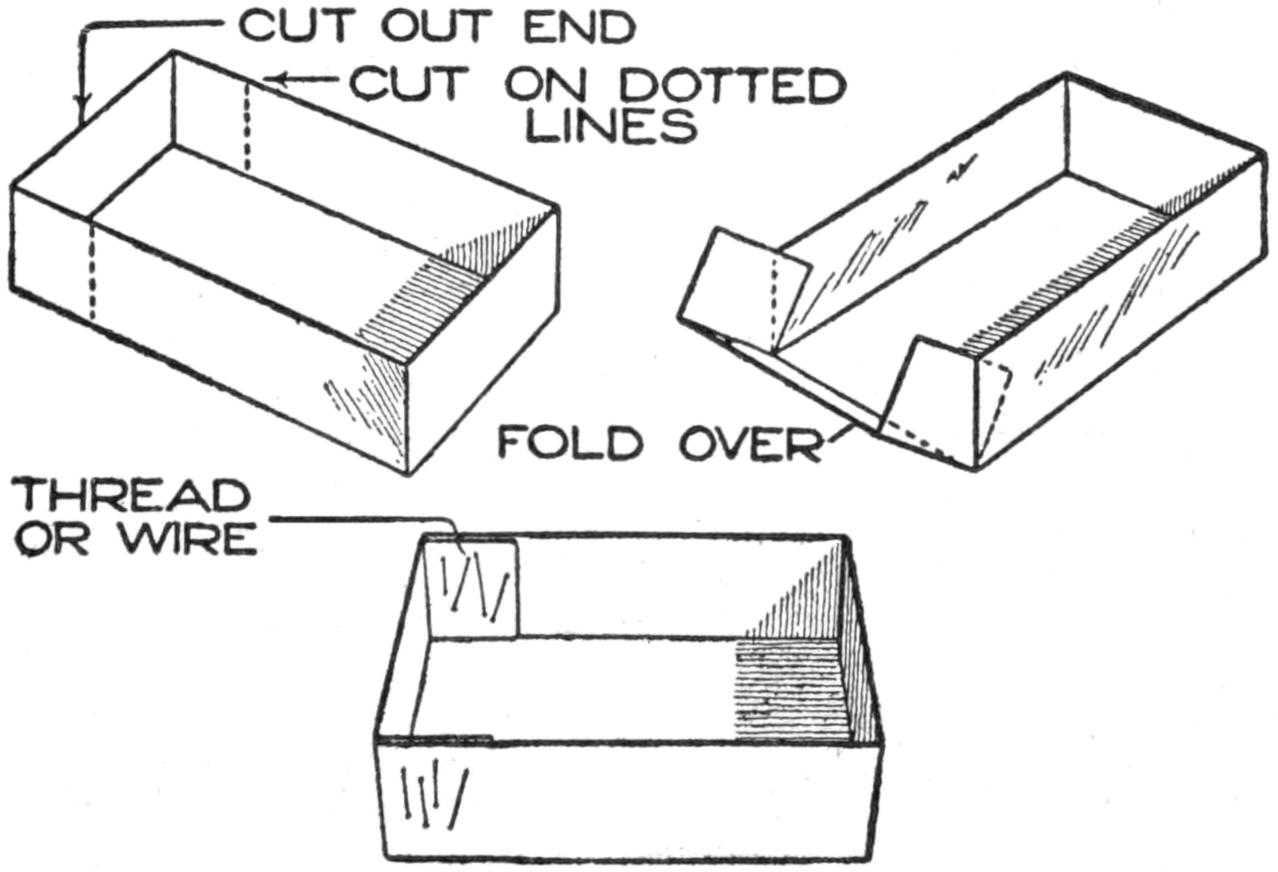

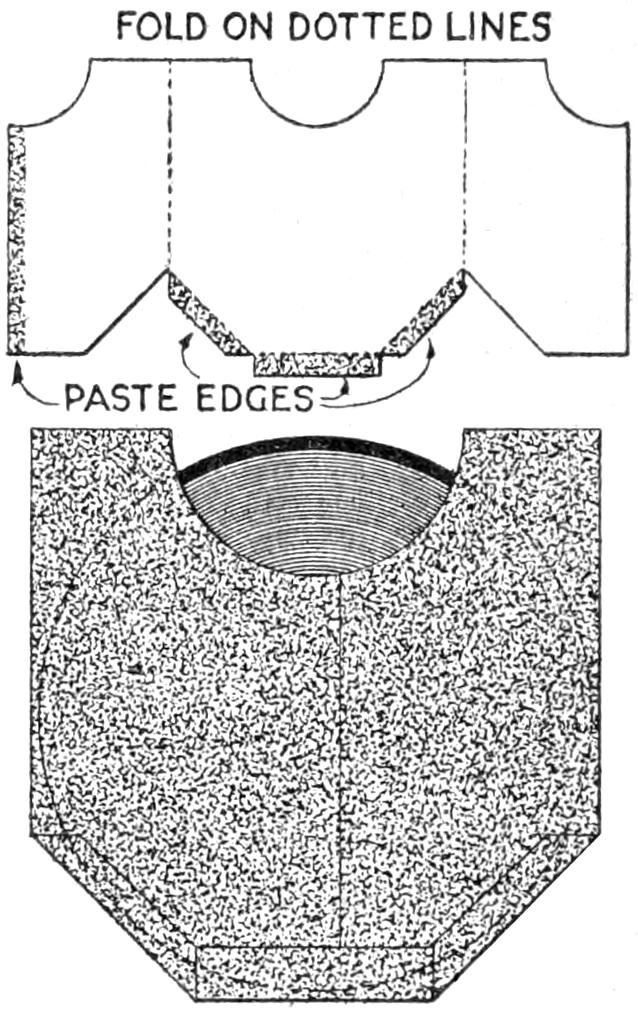

A neat and convenient method of making a label for jars of preserves, or similar preparations, to serve as a tab for removing the cover of paraffin on the glass, or dish, is shown in the sketch. The tabs are cut from tag board, notched, as shown, and bent on the dotted line. When melted paraffin is poured on top of the material in the jar, the tab is imbedded in it. To remove the paraffin cover intact, a pointed knife is run around the edge, or the glass warmed sufficiently to loosen the cover, which is then easily removed.—Arthur M. Cranford, St. Louis, Mo.

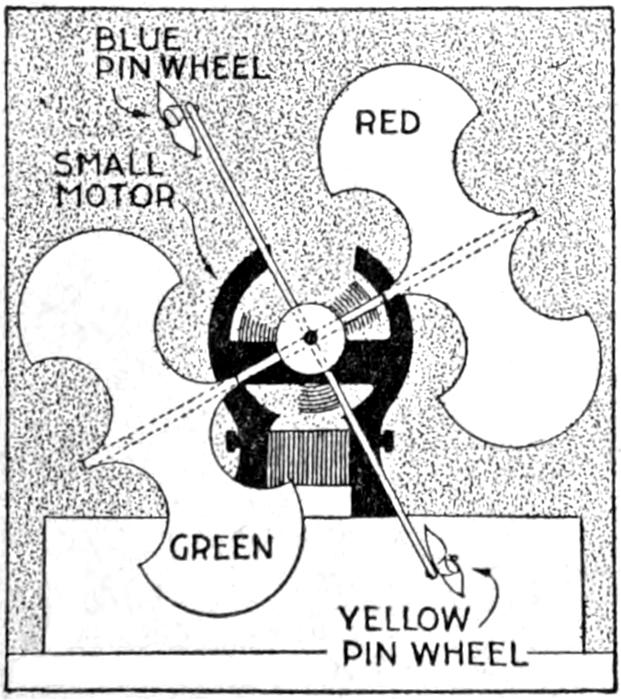

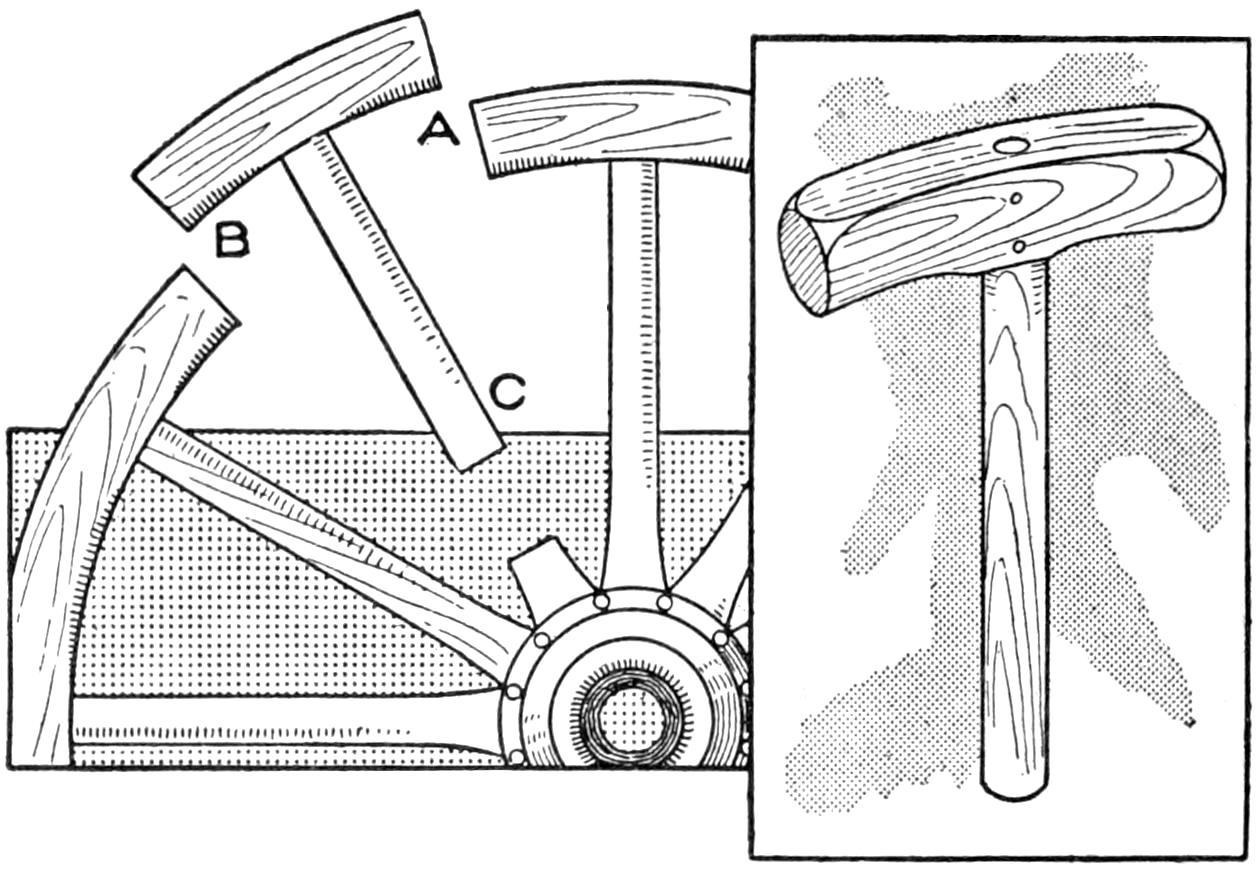

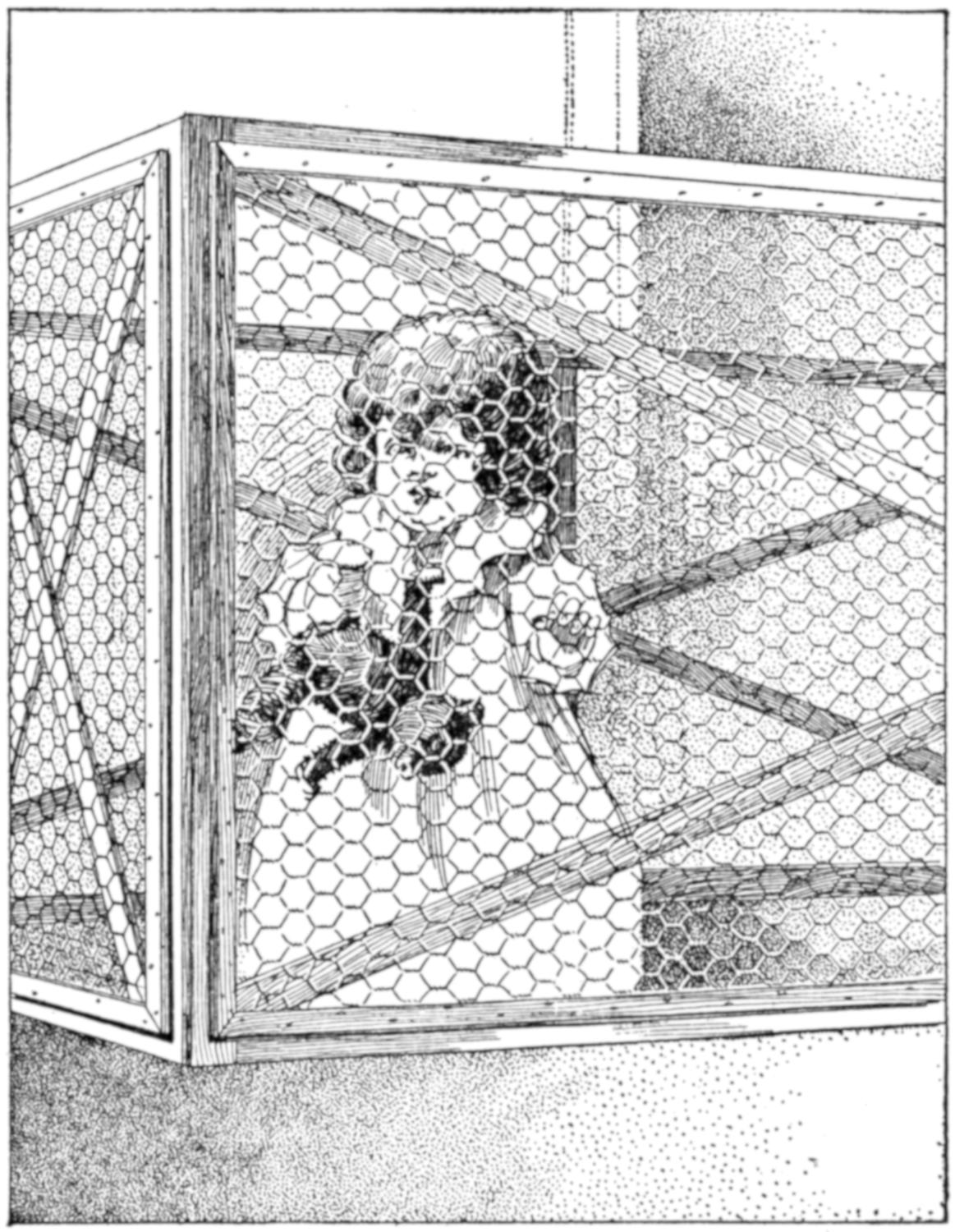

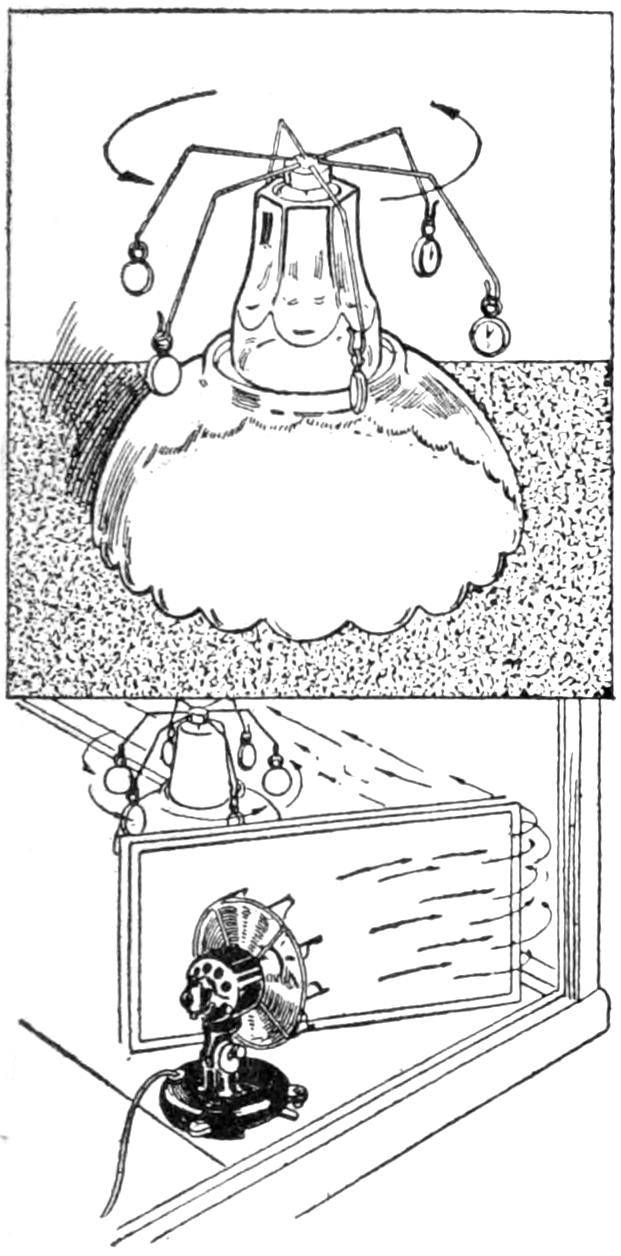

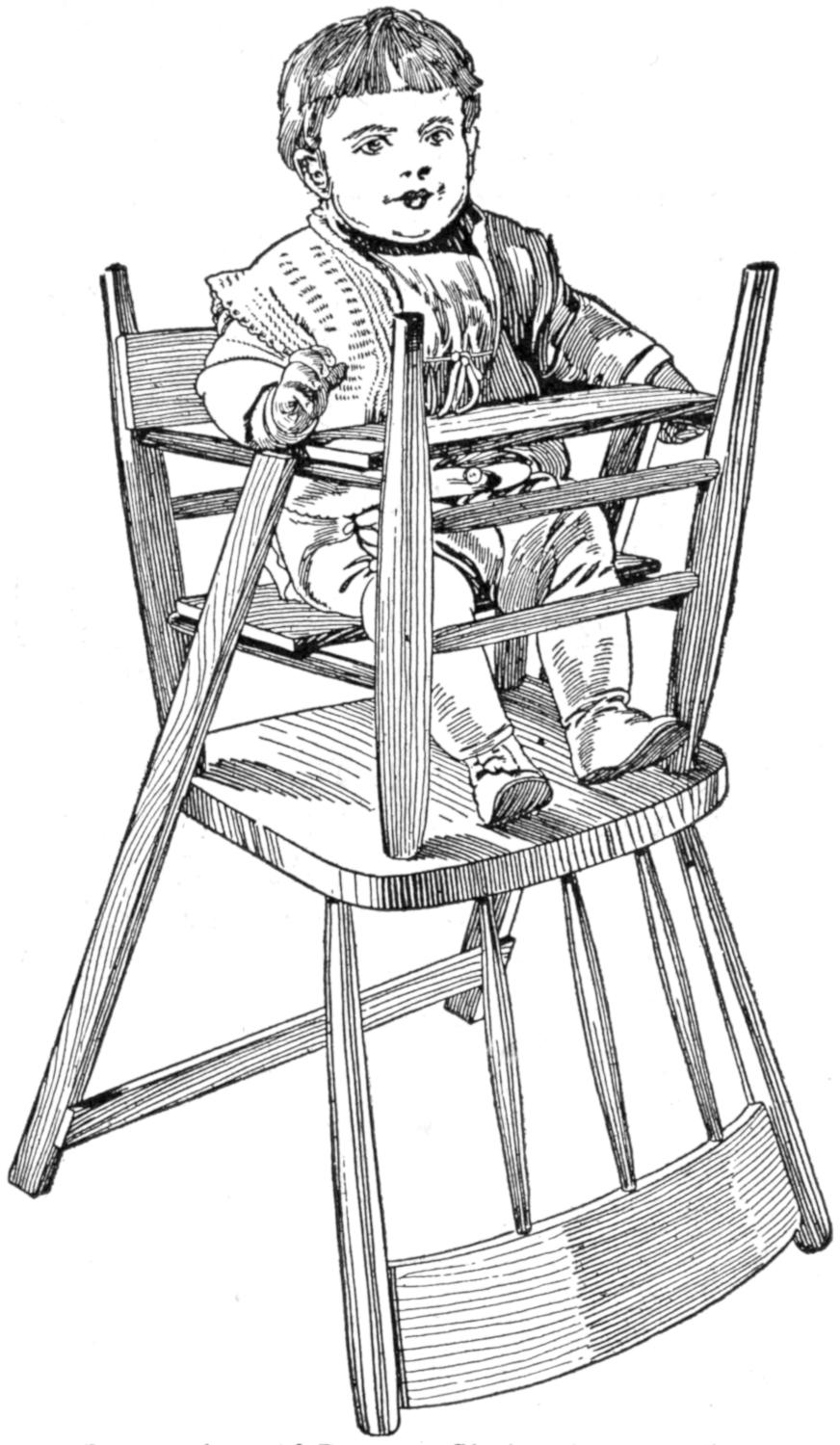

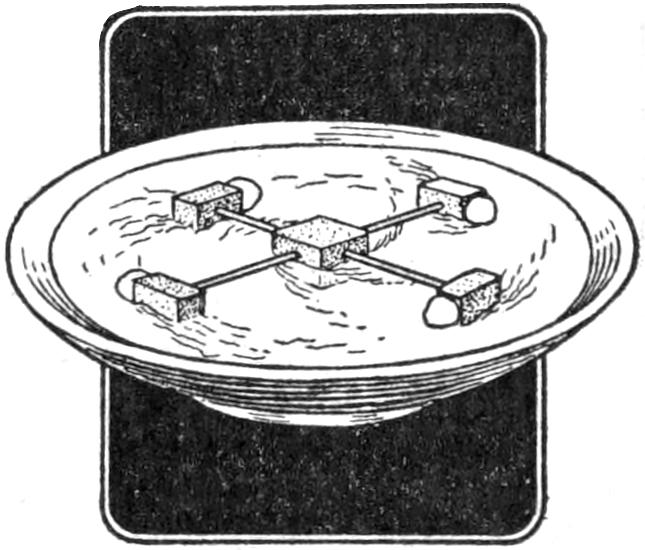

A contrivance that keeps the baby entertained, by the hour, at intervals, and is a big help to a busy mother, was made in a short time. I mounted four wooden arms on a small motor, as shown. On the ends of two of the arms, I fixed small pin wheels, one blue and the other yellow. The other arms hold curious-shaped pieces of bright cardboard, one red and the other green. The driving motor is run by one two-volt cell. The revolving colored pin wheels amuse baby in his high chair, and the device has well repaid the little trouble of making it.—A. H. Lange, St. Paul, Minn.

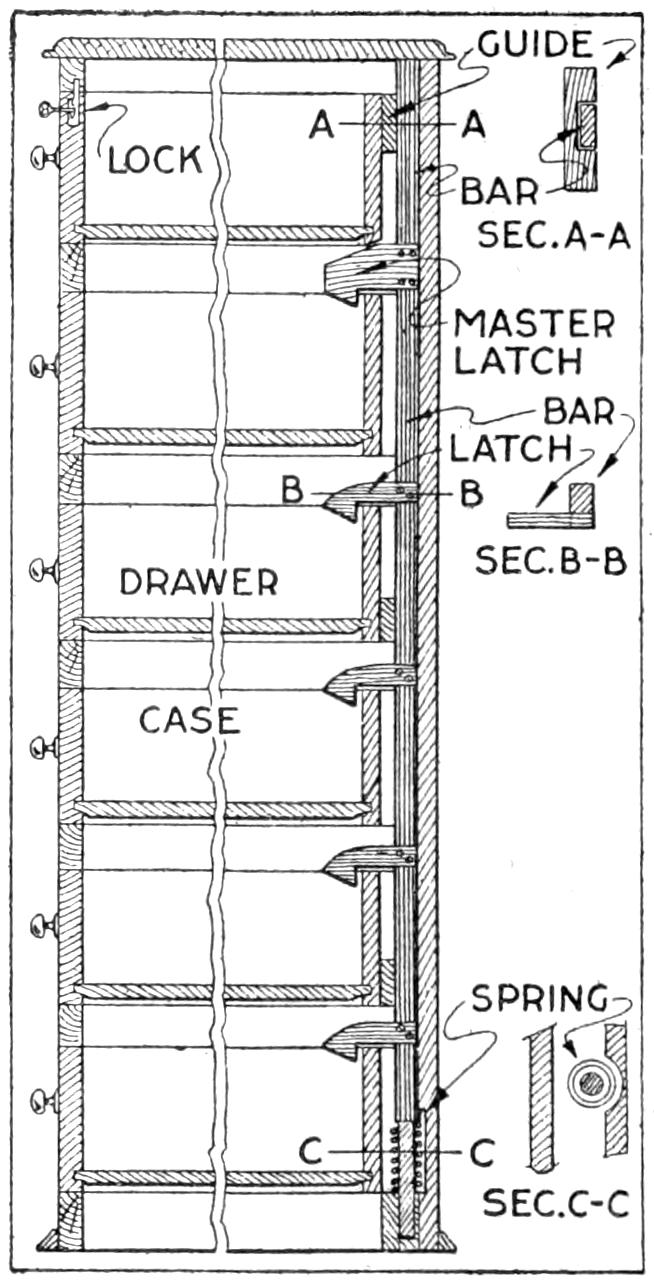

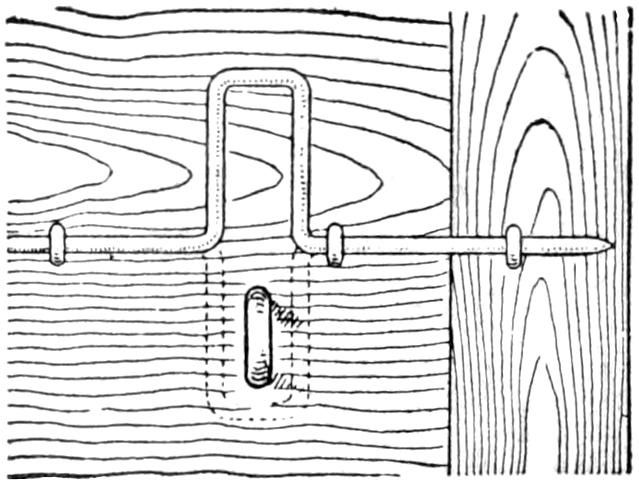

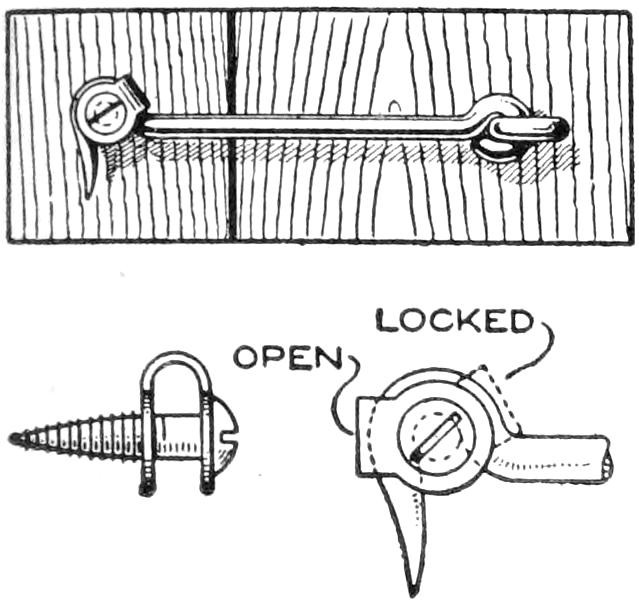

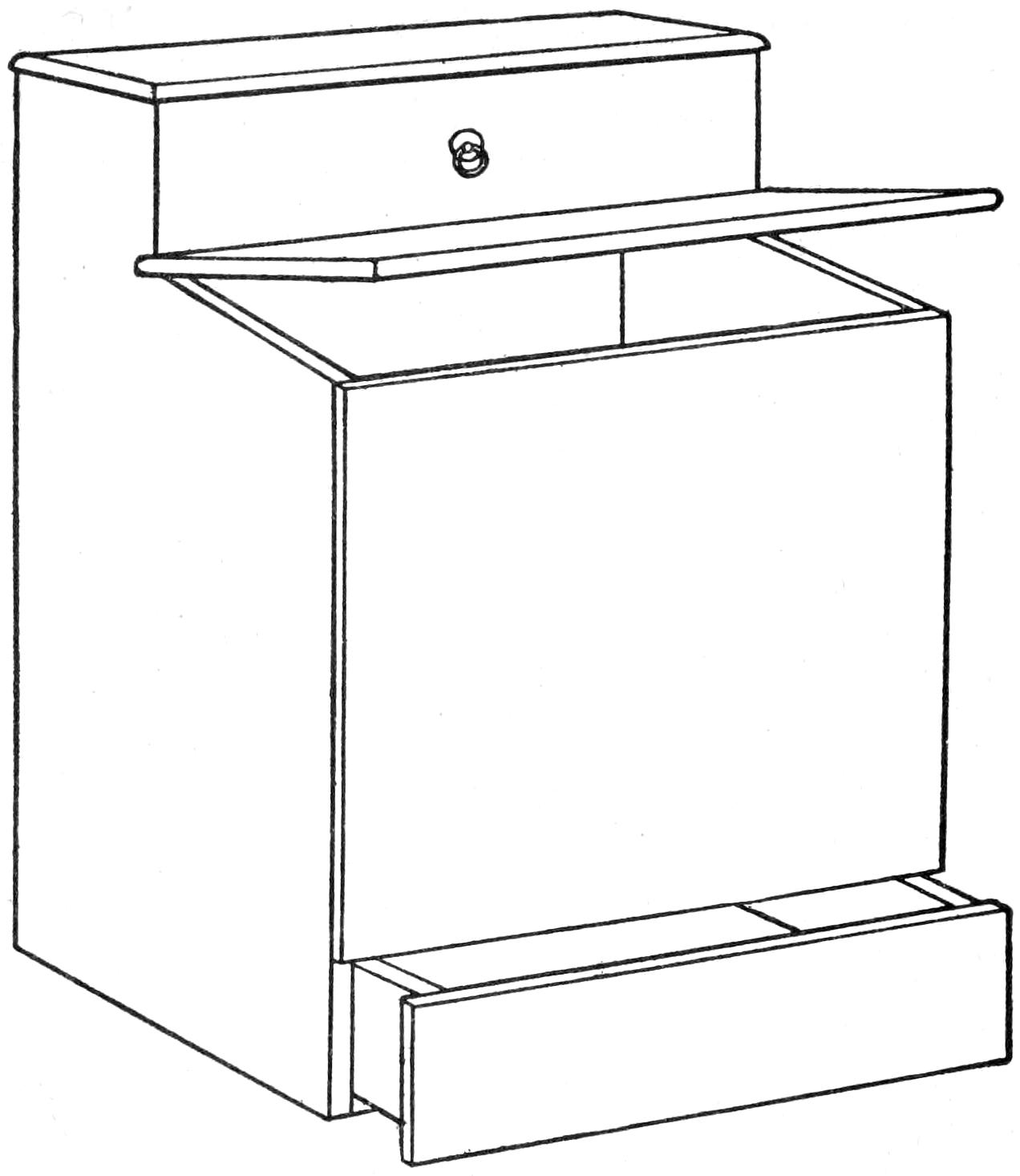

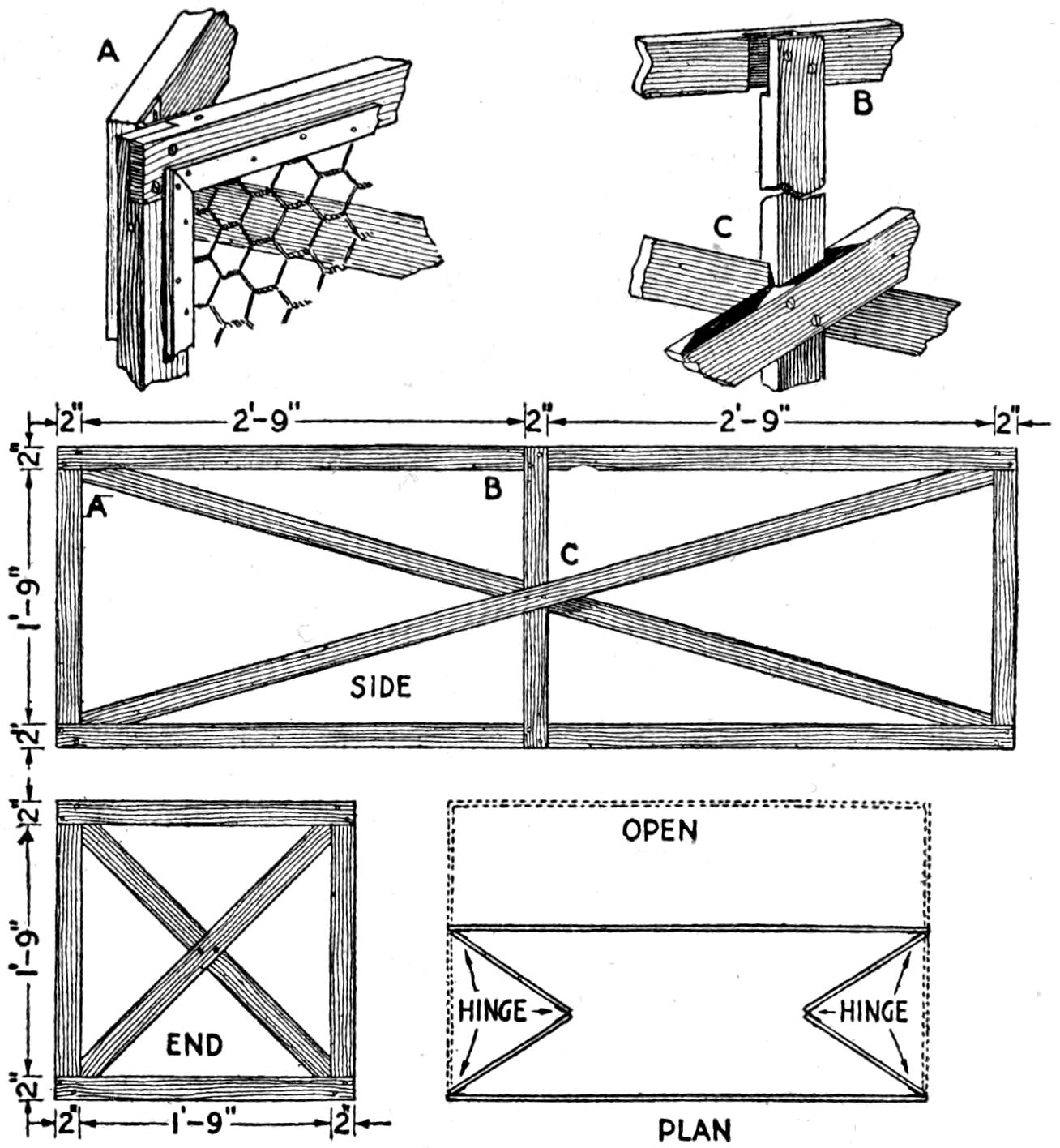

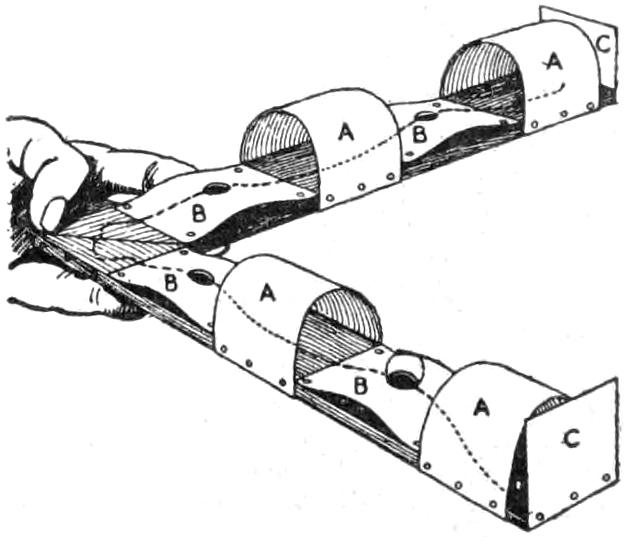

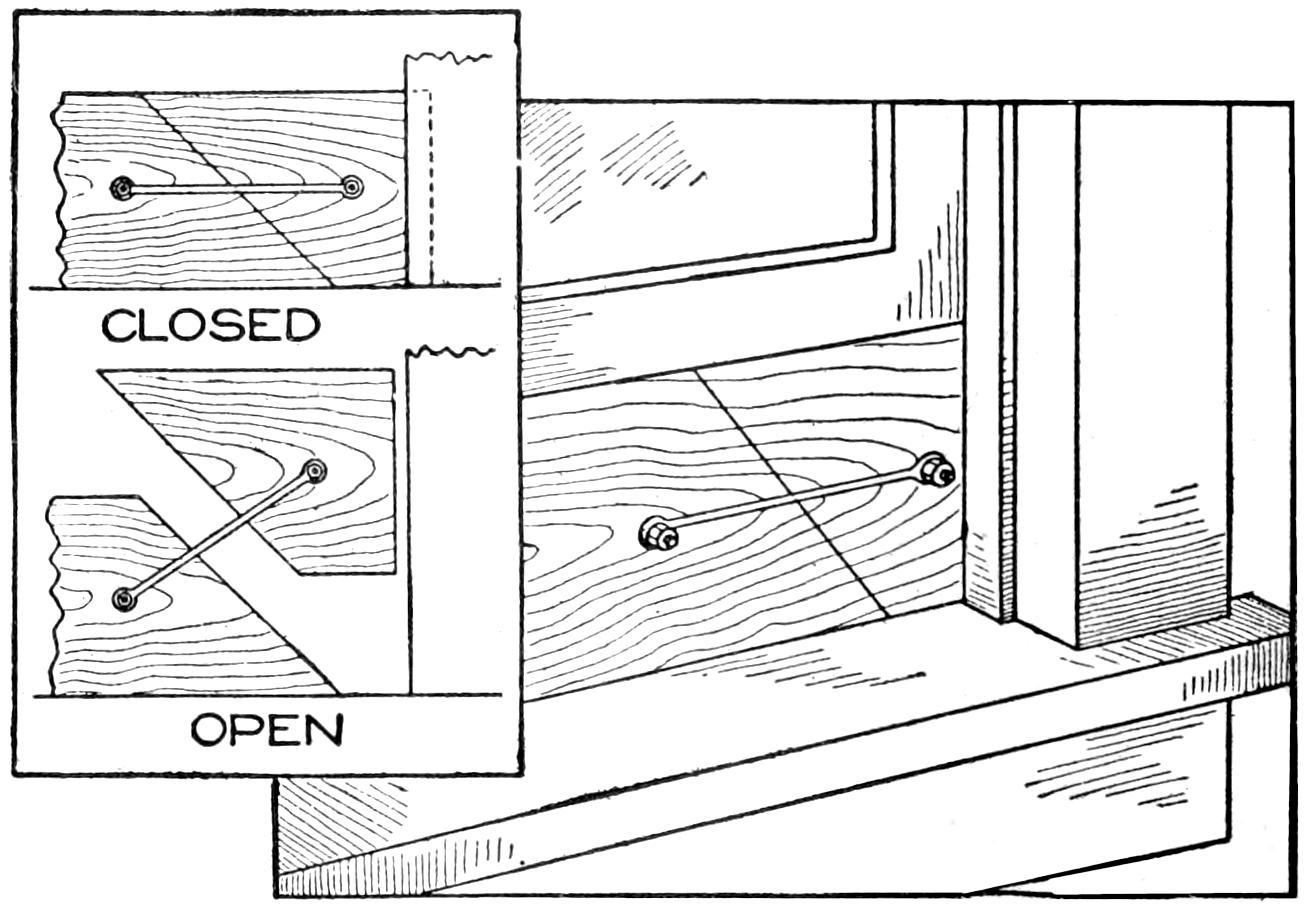

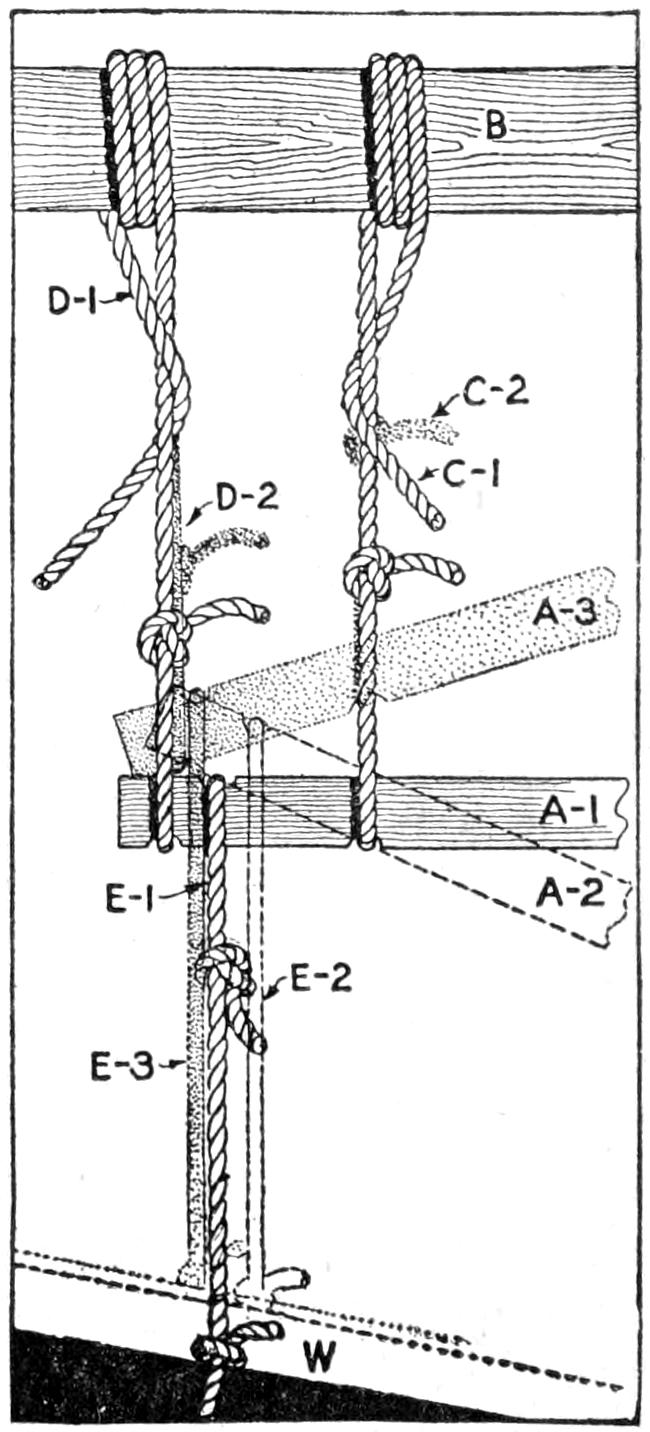

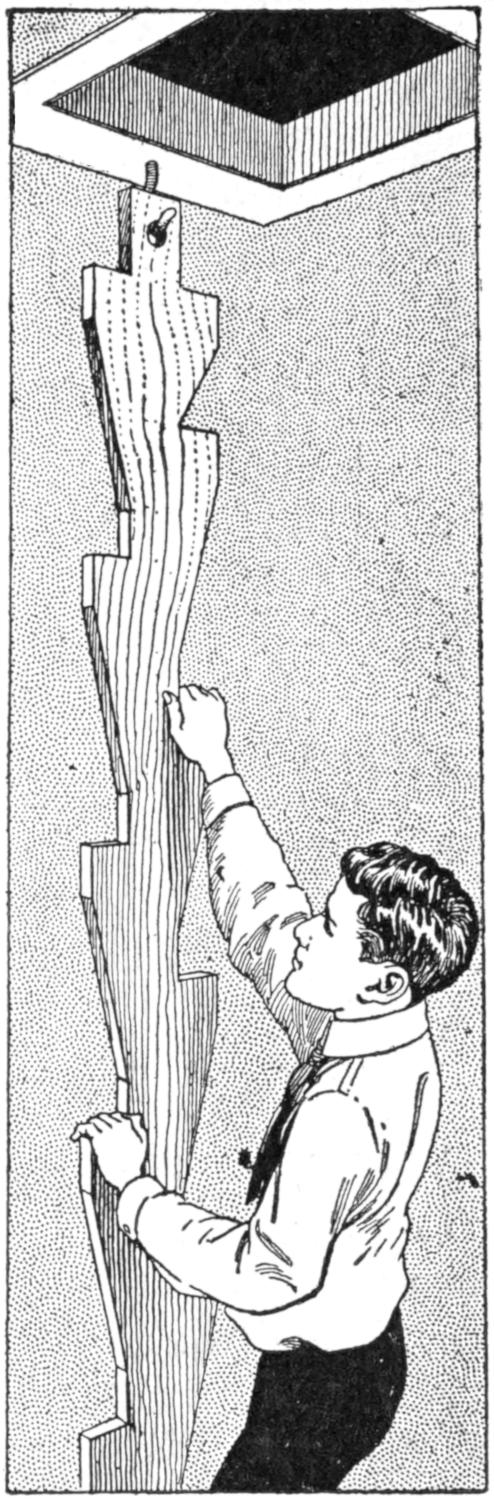

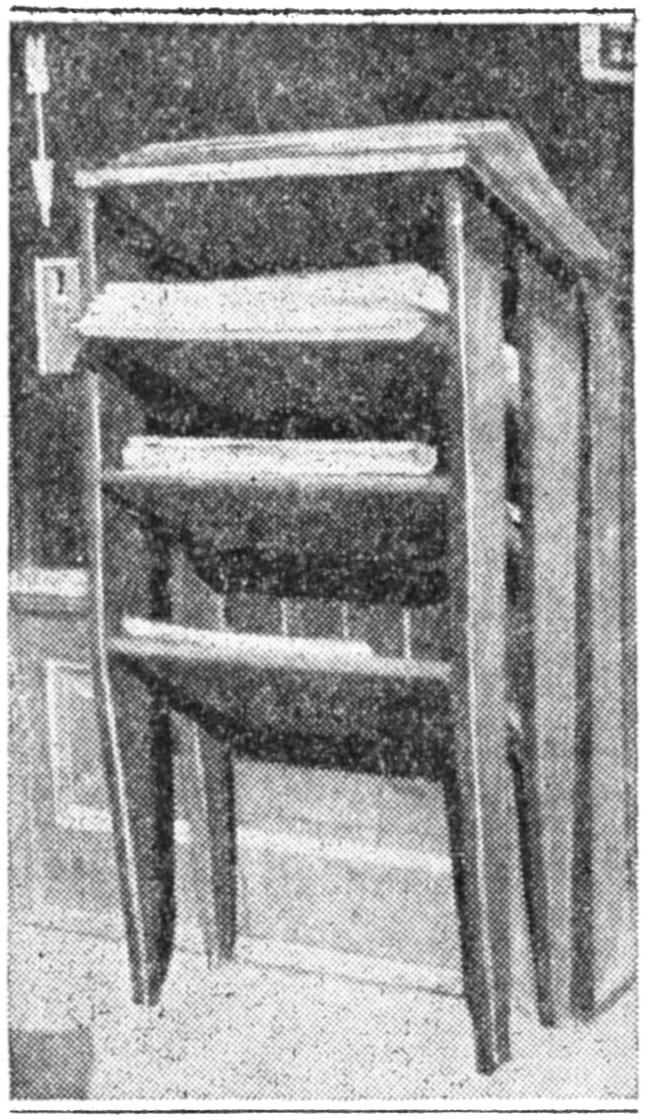

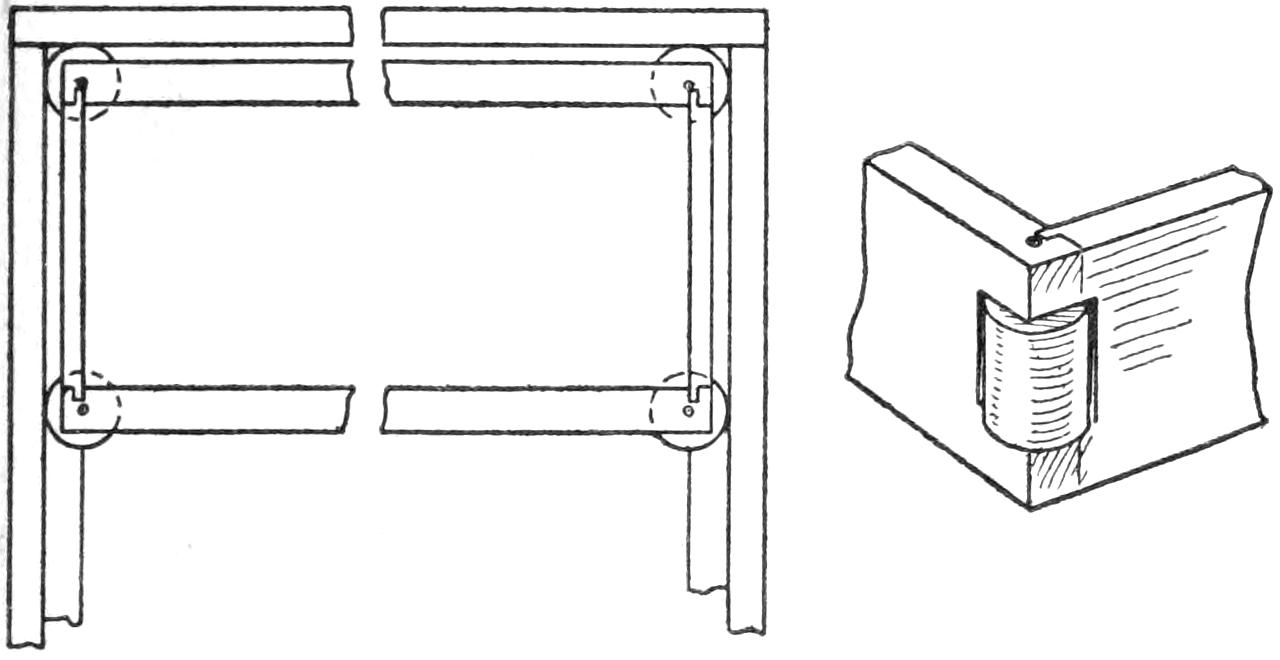

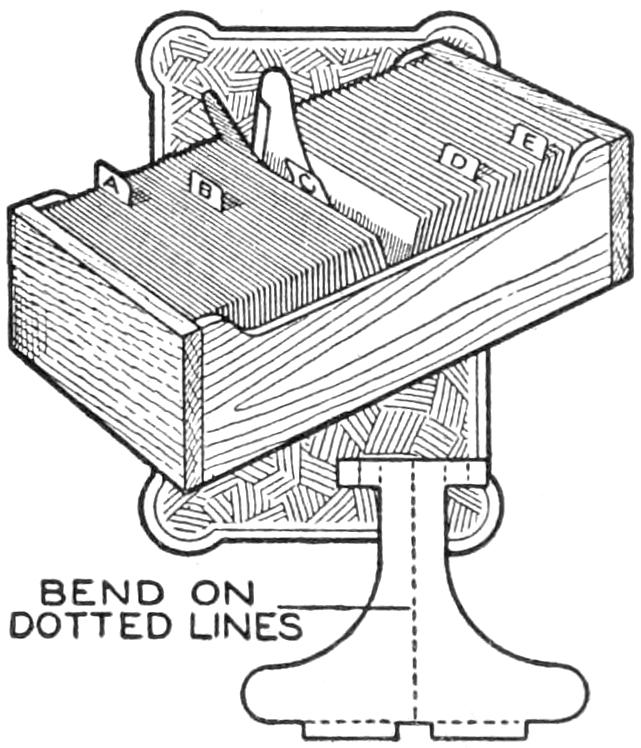

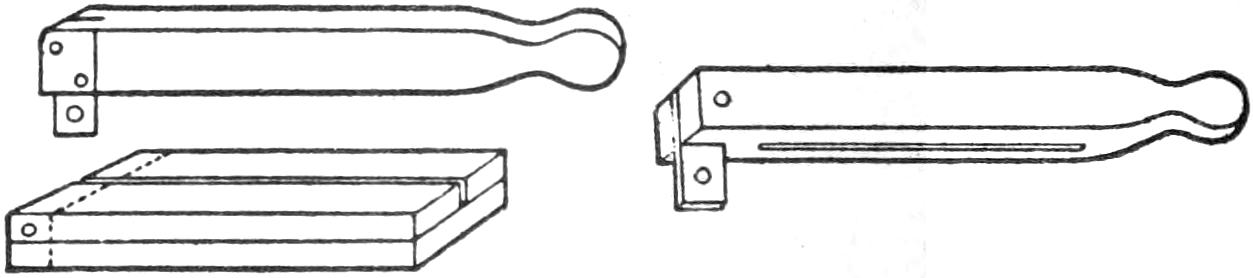

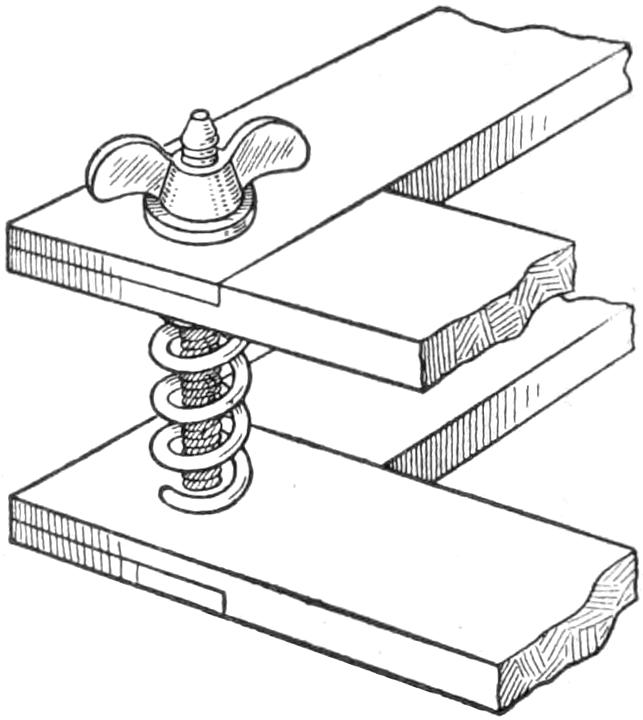

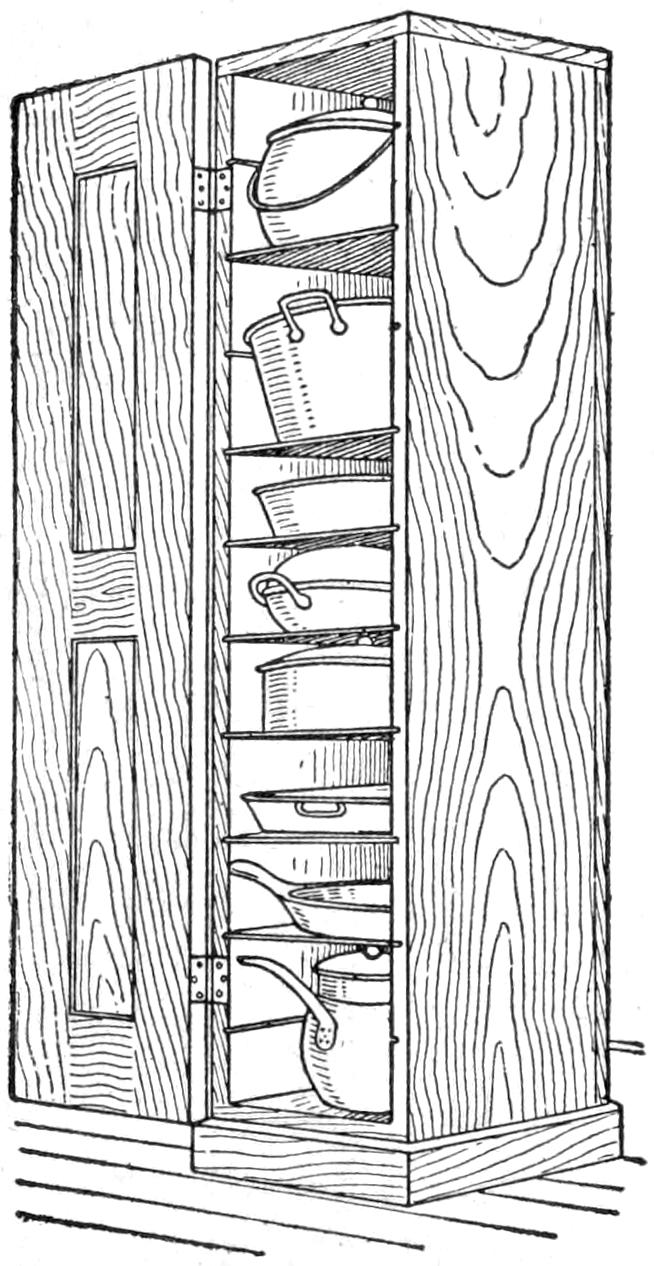

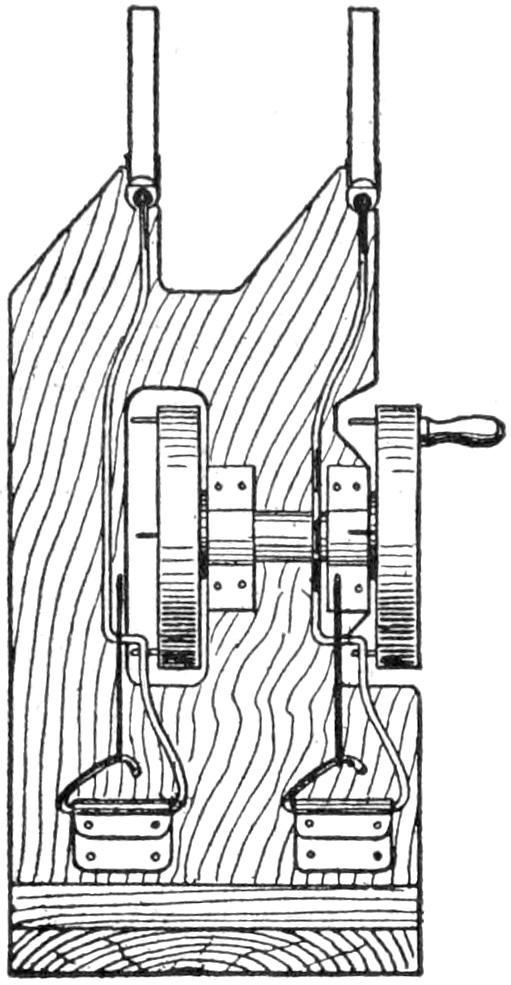

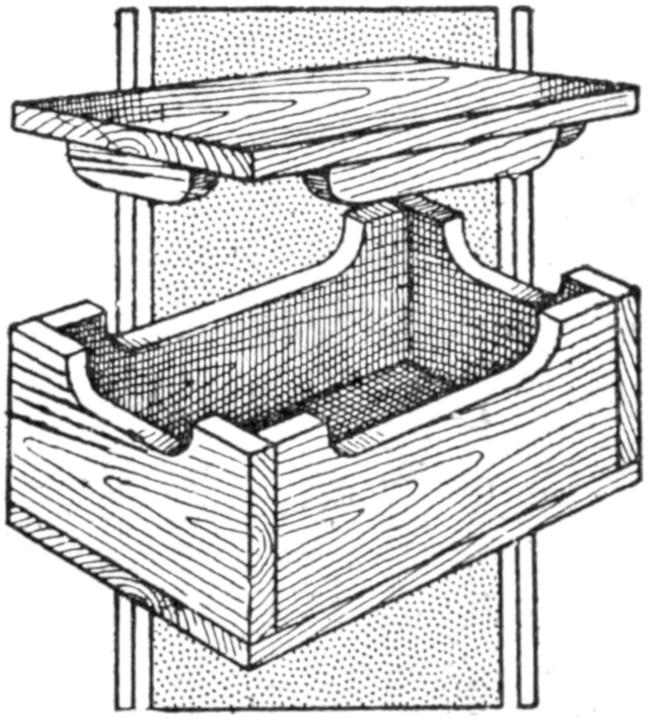

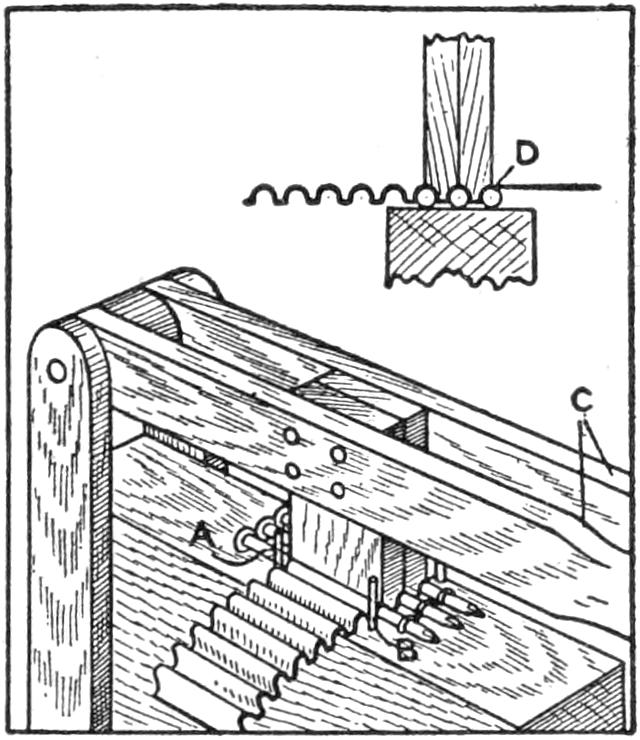

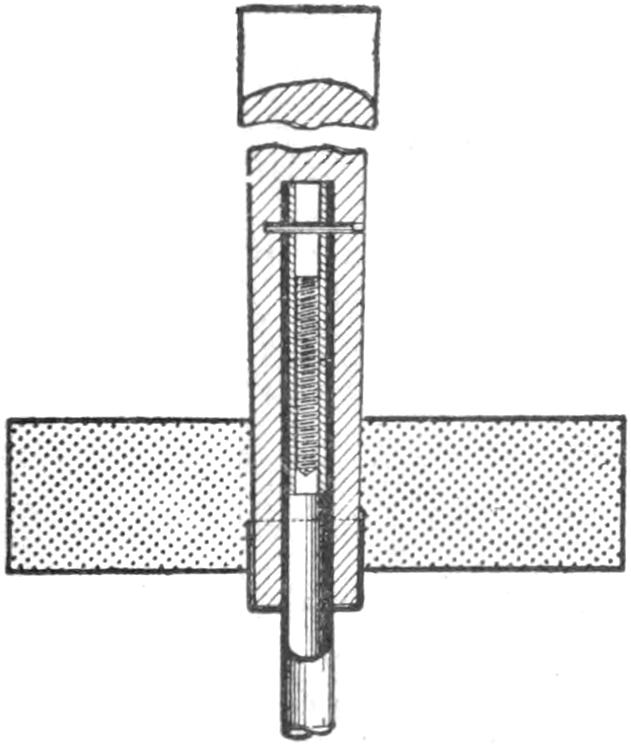

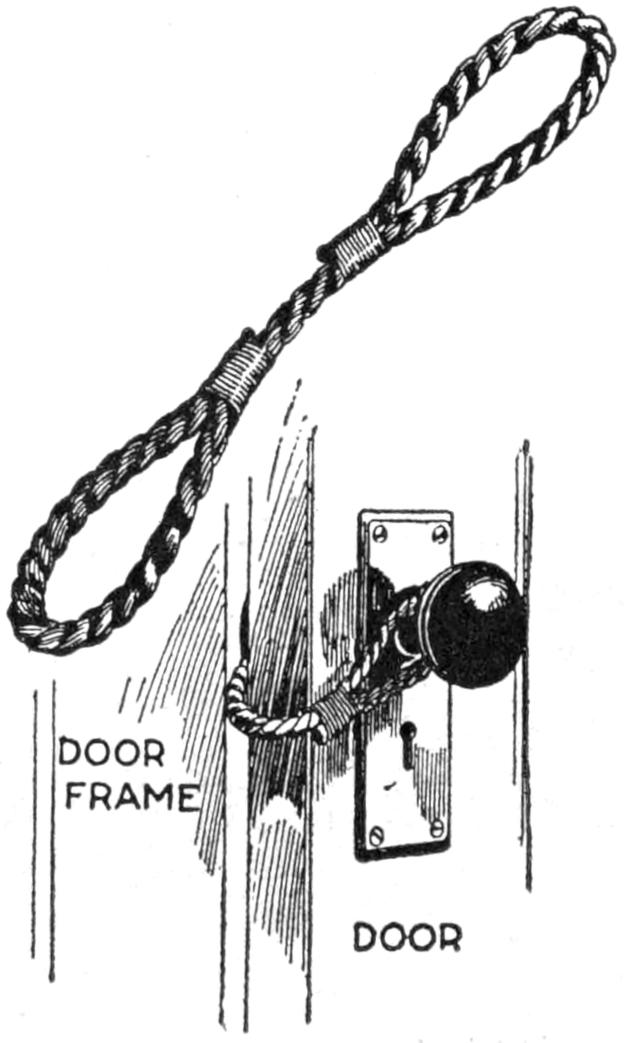

A simple method of providing a homemade locking device for a tier of drawers, the use of only one keyed lock being necessary, as is common in manufactured cases, is shown in the sketch. This is applicable to new or old cases, where a space of about 1¹⁄₂ in. is available between the back of the drawers and the rear of the case.

The device, as detailed, consists of a locking bar sliding in guides, screwed or fastened to the back of the case. Attached to the bar are latches one less in number than there are drawers, and spaced apart the distance that each drawer top is above the one below. The upper latch is the master feature. The top of this is beveled off, forcing it downward when the top drawer is closed. The locking bar, with the other latches, also moves down, and the latch fingers engage the backs of the drawers. The connecting bar is operated by a light coil spring, set on a shouldered rod at the bottom of the bar, as detailed.

The master latch may be attached at any place on the bar, and should be placed at the bottom drawer, for cases too high to be reached handily. To make the device for a small space, a ¹⁄₄-in. metal rod, with metal fingers clamped on, can be used. Metal striking plates are then put on the back edges of the drawers.—G. A. Luers, Washington, D. C.

¶Steam-pipe drains should be provided at all points in the line where water is likely to accumulate.

[5]

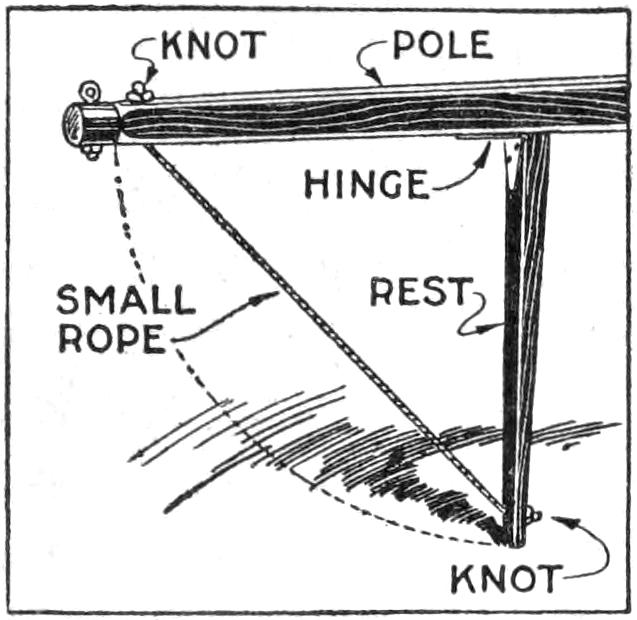

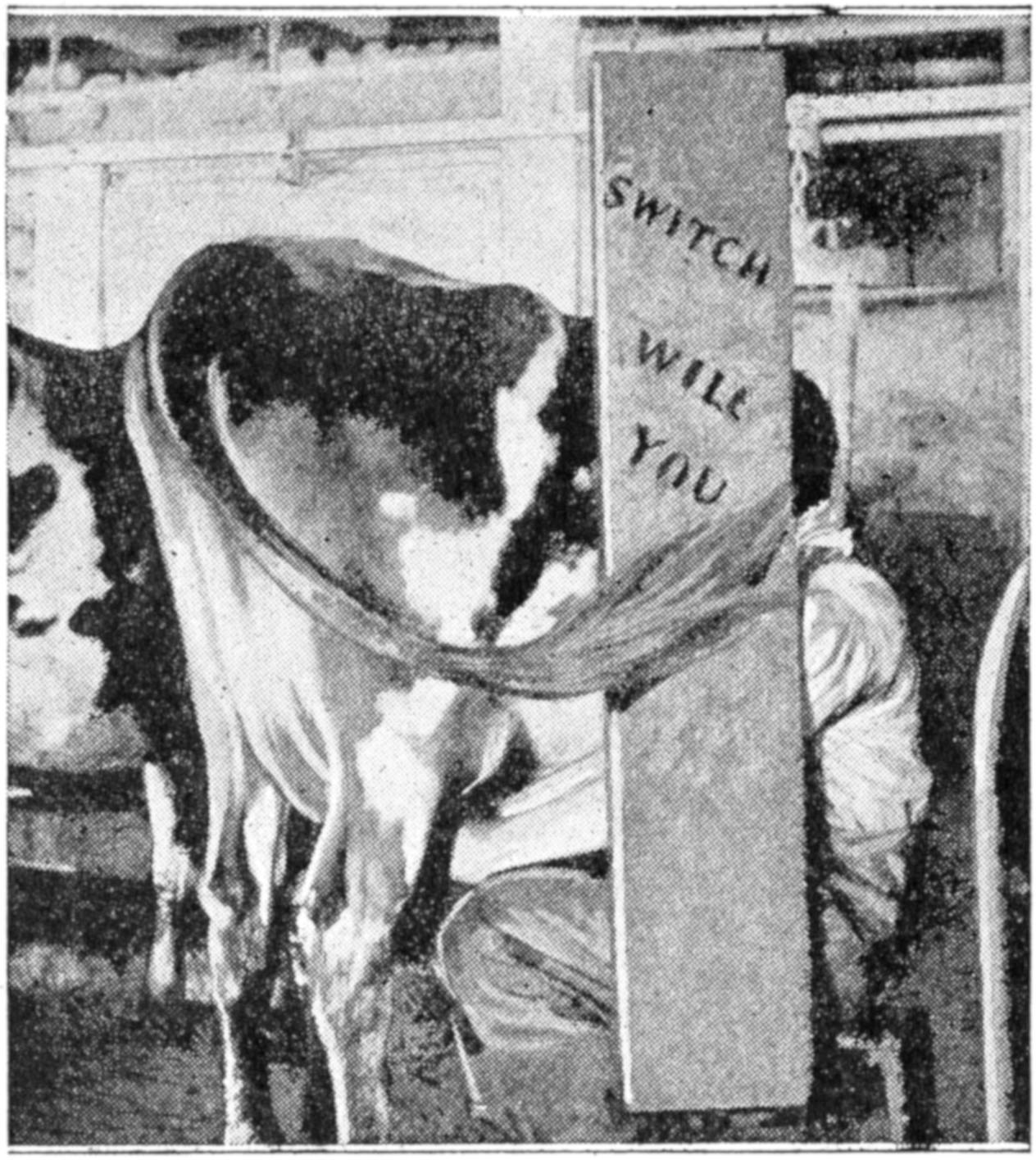

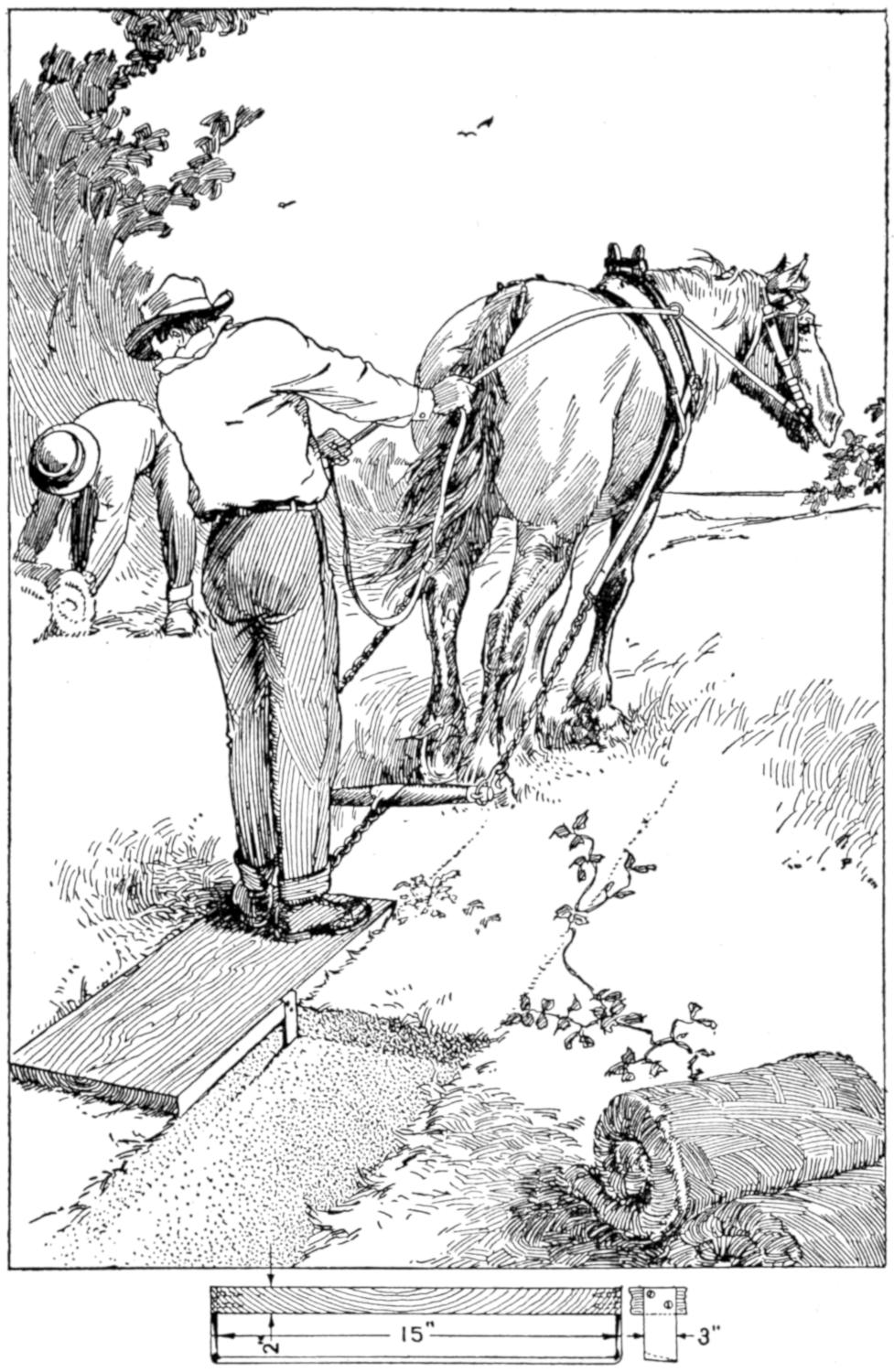

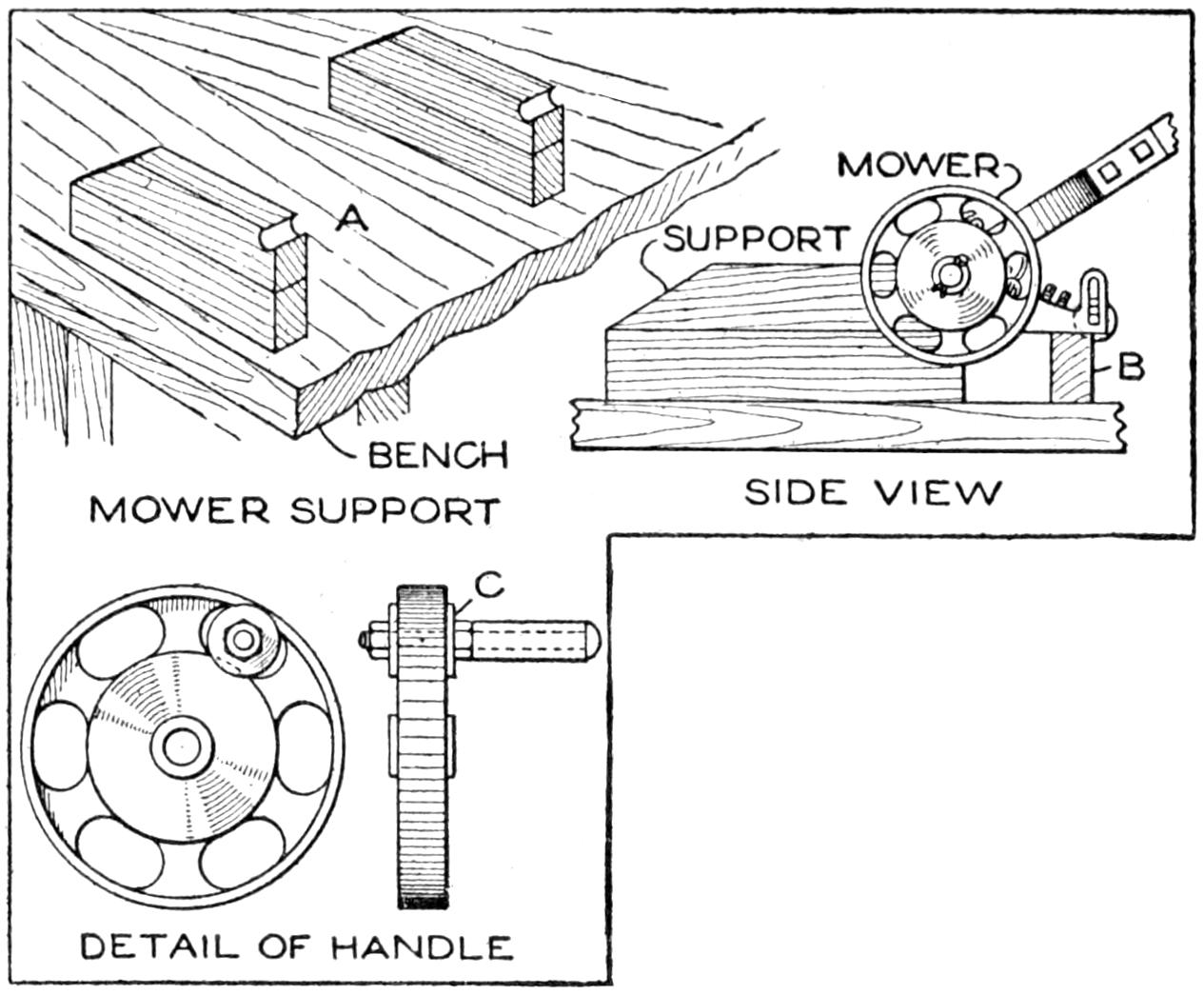

To do away with the annoyance and strain of holding up the heavy pole of a mowing machine while fastening the yoke strap to the hames of a restless team of horses, I equipped the pole with a drop stick, or rest. This was made of a 30-in. piece of an old carriage shaft. One end of the rod was hinged to the underside of the pole as shown. When the machine is in operation, the stick is tied up out of the way by means of a rope. This appliance also lengthens the life of the pole, and can be used on various kinds of vehicles.—T. H. Linthicum, Annapolis, Maryland.

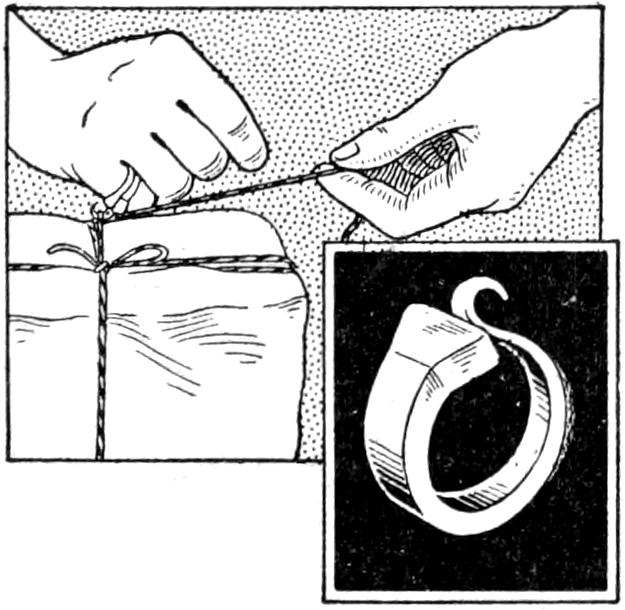

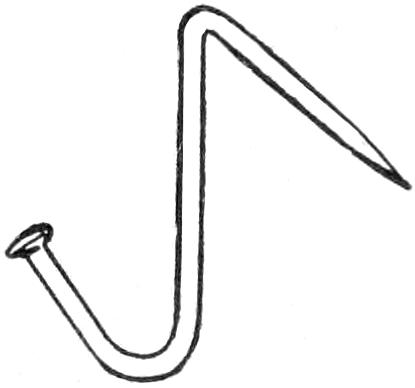

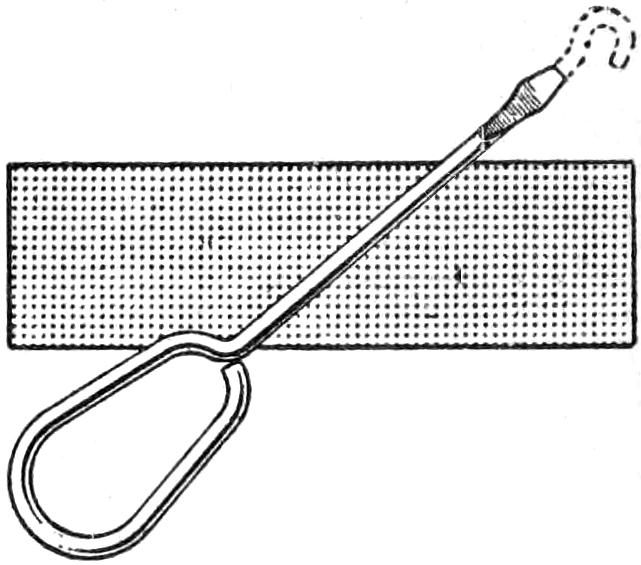

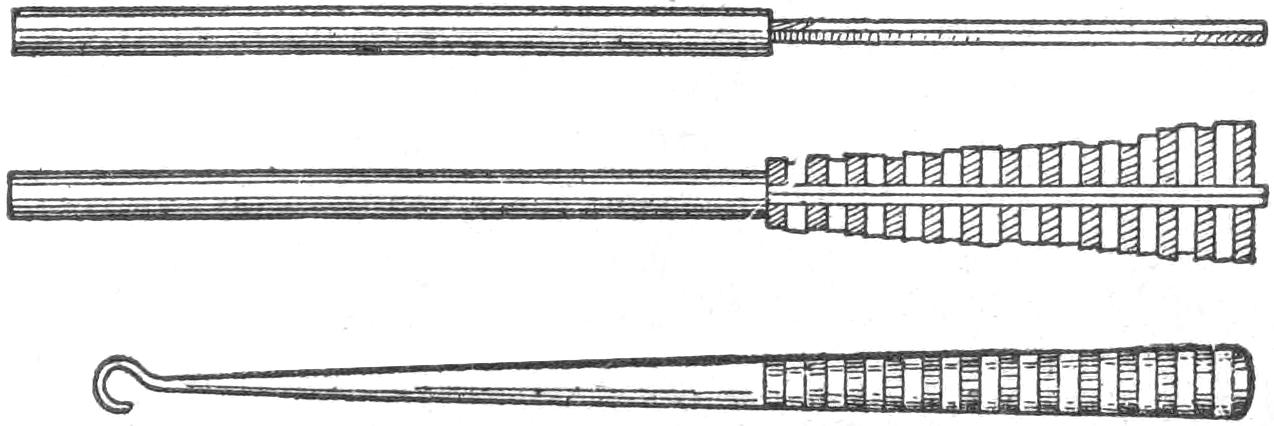

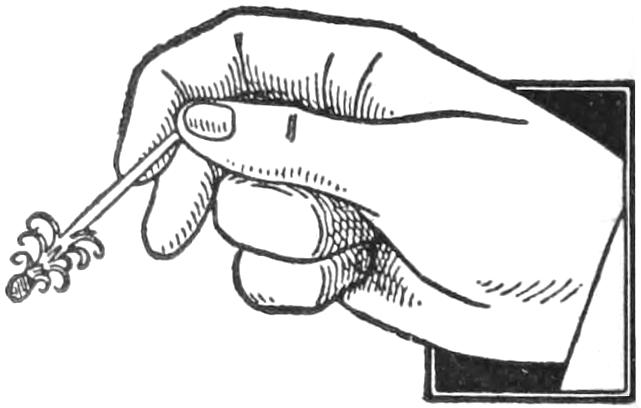

Persons having to tie a large number of packages or parcels soon find that their fingers become sore from breaking the heavy cord in the usual manner by wrapping it around the finger to form a cutting loop. A handy device, that can easily be made, is a string-cutting ring fashioned from a horseshoe nail, as shown. The point of the nail is curled into a hook, and the inner edge of the hook is sharpened. The string is quickly looped around the hook and cut by a slight pull on the free end. The ring is worn on the little finger.—C. C. Spreen, Flint, Mich.

¶A block of soft rubber, 1¹⁄₂ by 3 by 5 in., is useful as a pad for sandpaper in smoothing curved surfaces.

To prevent kettle covers from dropping off, and the fingers from being burned by the escaping steam, make a small dent in the edge of the lid, as shown. In setting the lid into place, arrange it so that the dent is at the point opposite the spout. Thus, when the water is poured from the kettle, the lid cannot easily tip forward.—W. J. Parks, LaSalle, Ill.

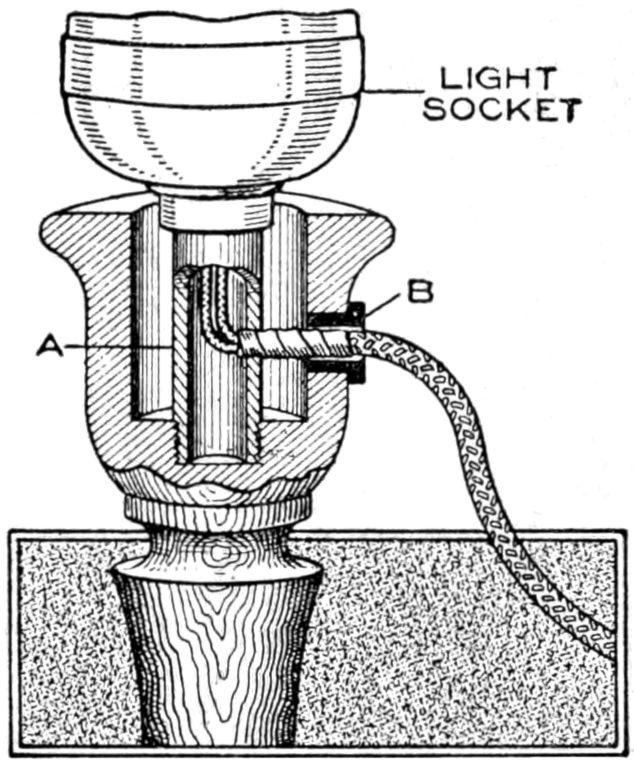

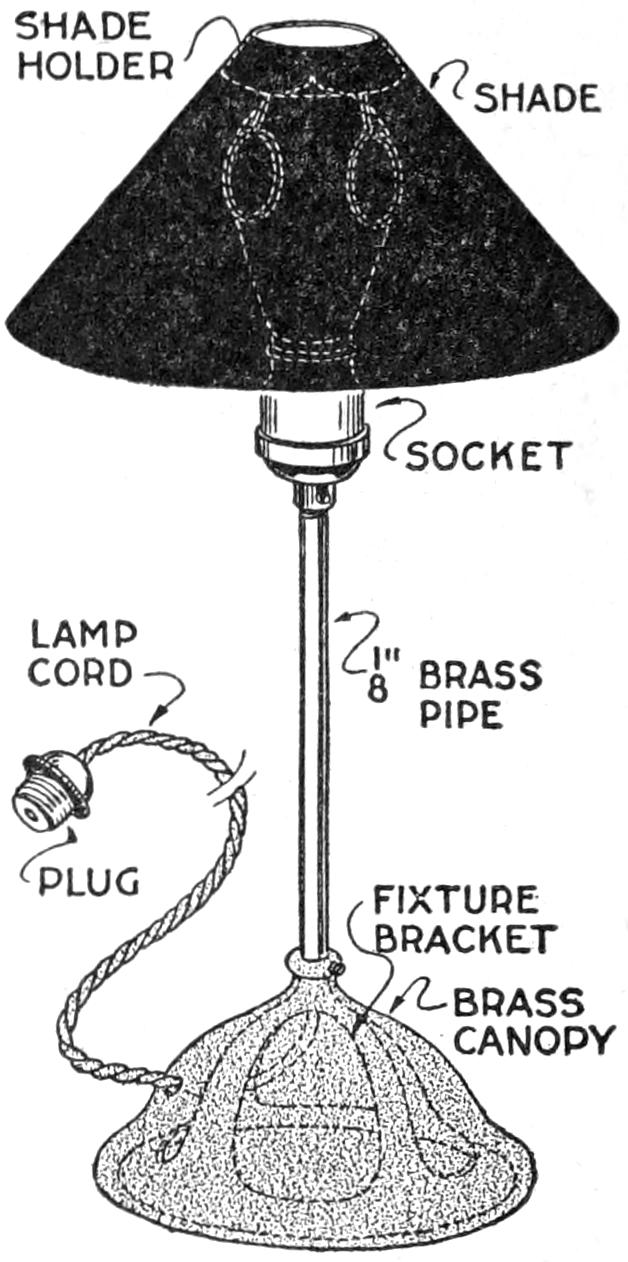

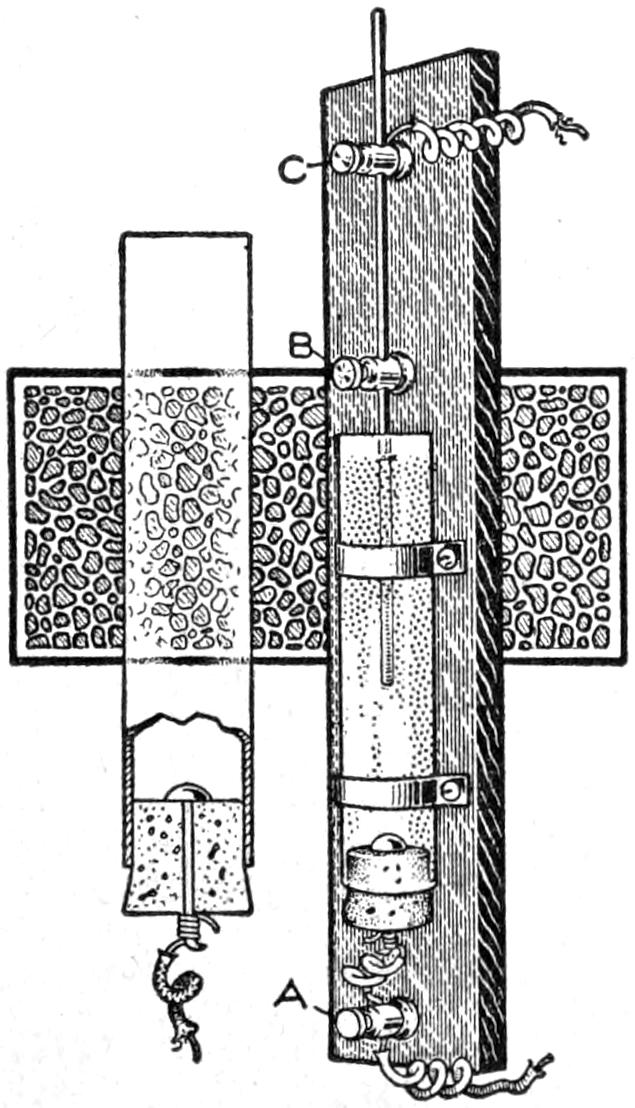

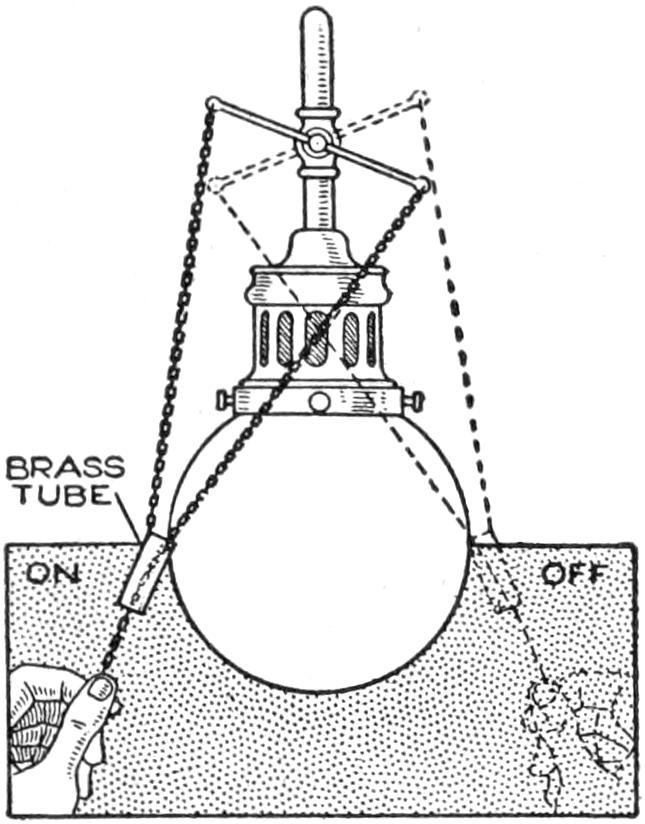

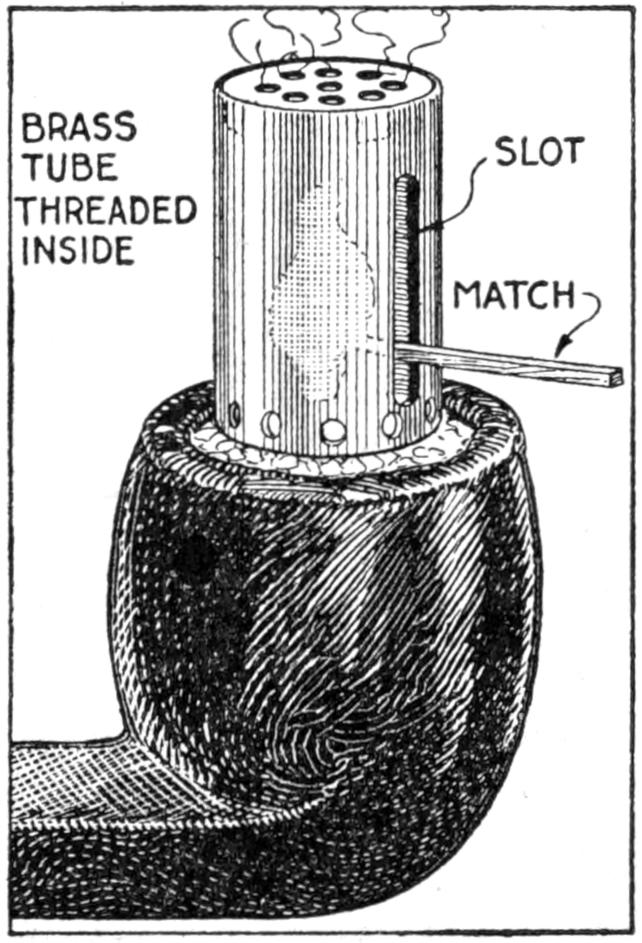

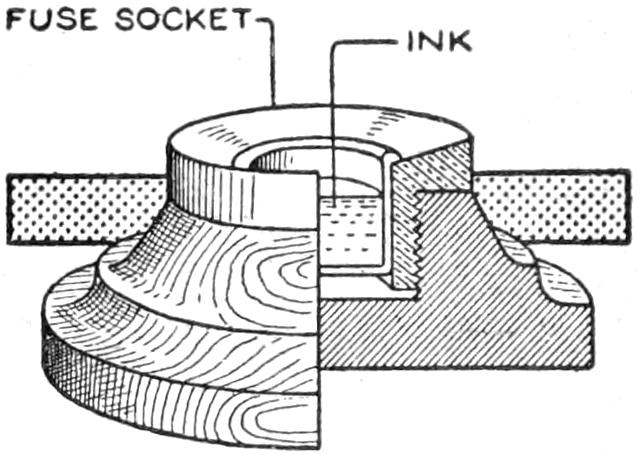

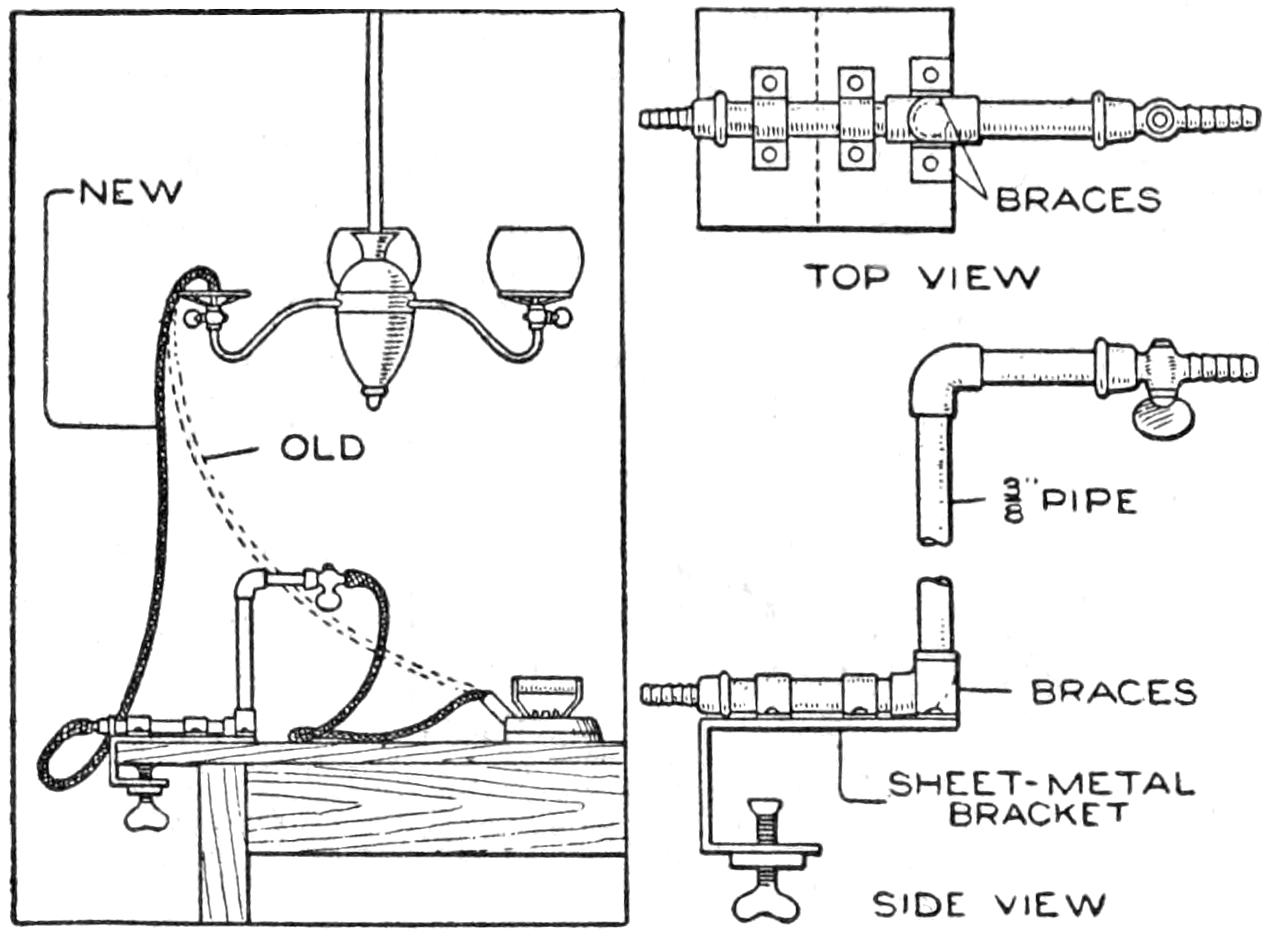

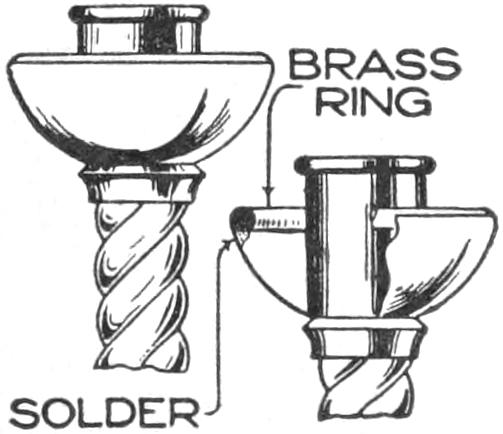

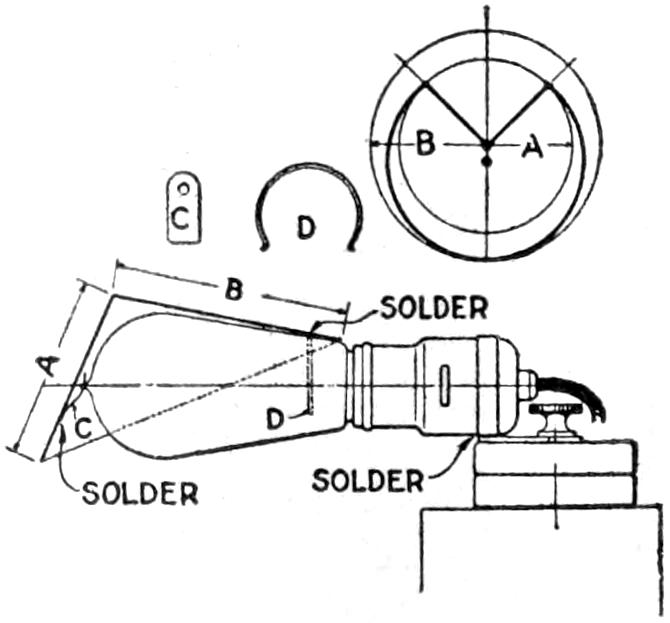

A number of wooden candlesticks were to be fitted with fixtures for electric lights, and it was found that the types ordinarily available could not be attached in the usual manner. A simple method was, therefore, devised, as shown in the sketch, and proved practical. A short length of brass tubing, A, was screwed into a hole drilled in the bottom of the candle socket, both ends of the tube being threaded. A hole was drilled through the side of the tube, and another through the side of the candlestick cup, as indicated. The hole in the wood was fitted with an insulation ring, B. The wiring, suitably taped, was carried through the opening for it, into the tube, and fastened in the usual manner to a standard keyless socket, which was then screwed to the end of the tube, making a substantial support. The lights were controlled conveniently at the usual wall switches.—Livingston Haviland, Buffalo, N. Y.

[6]

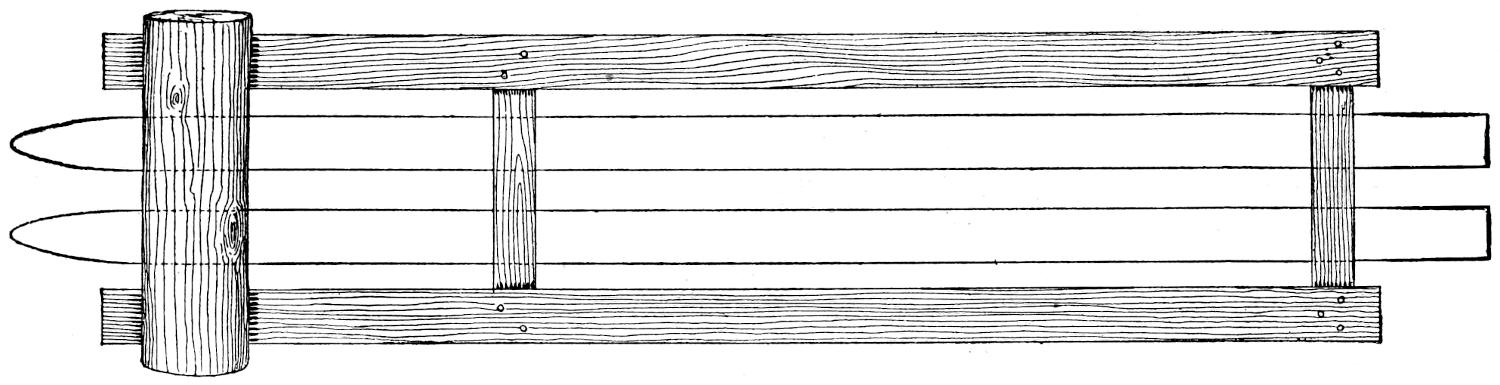

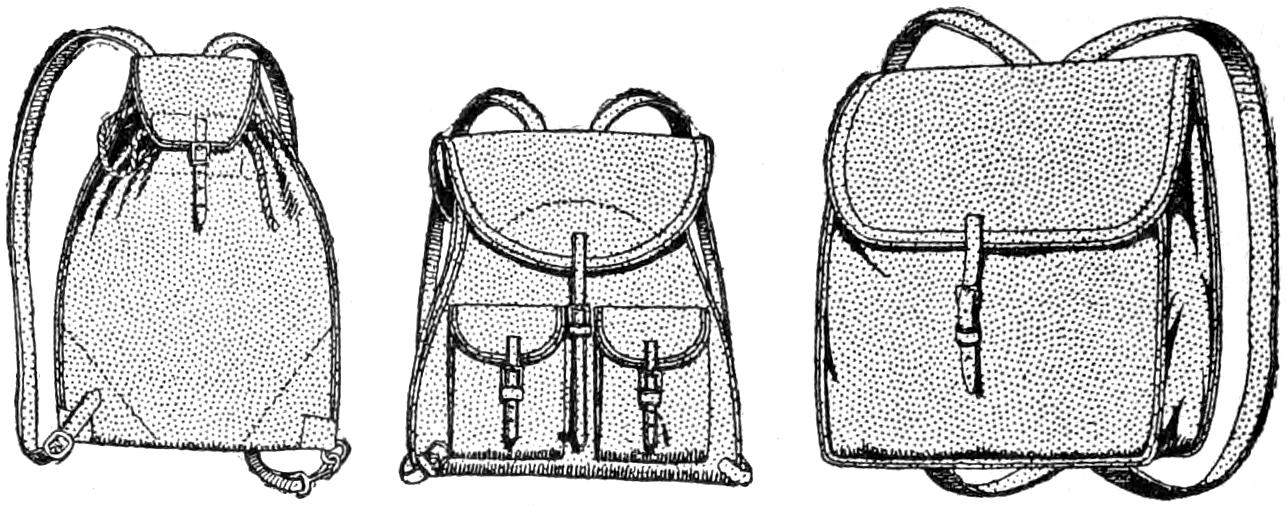

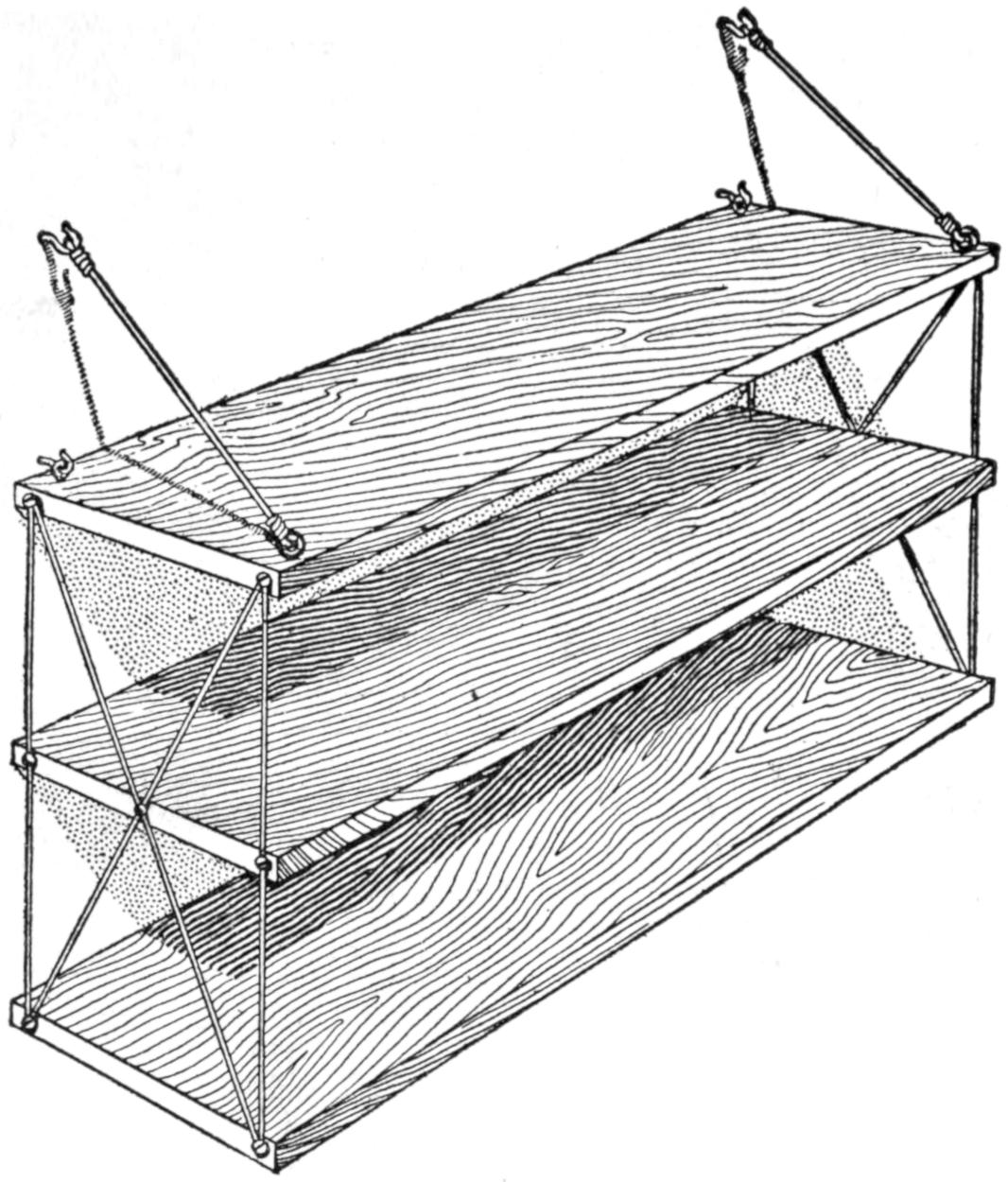

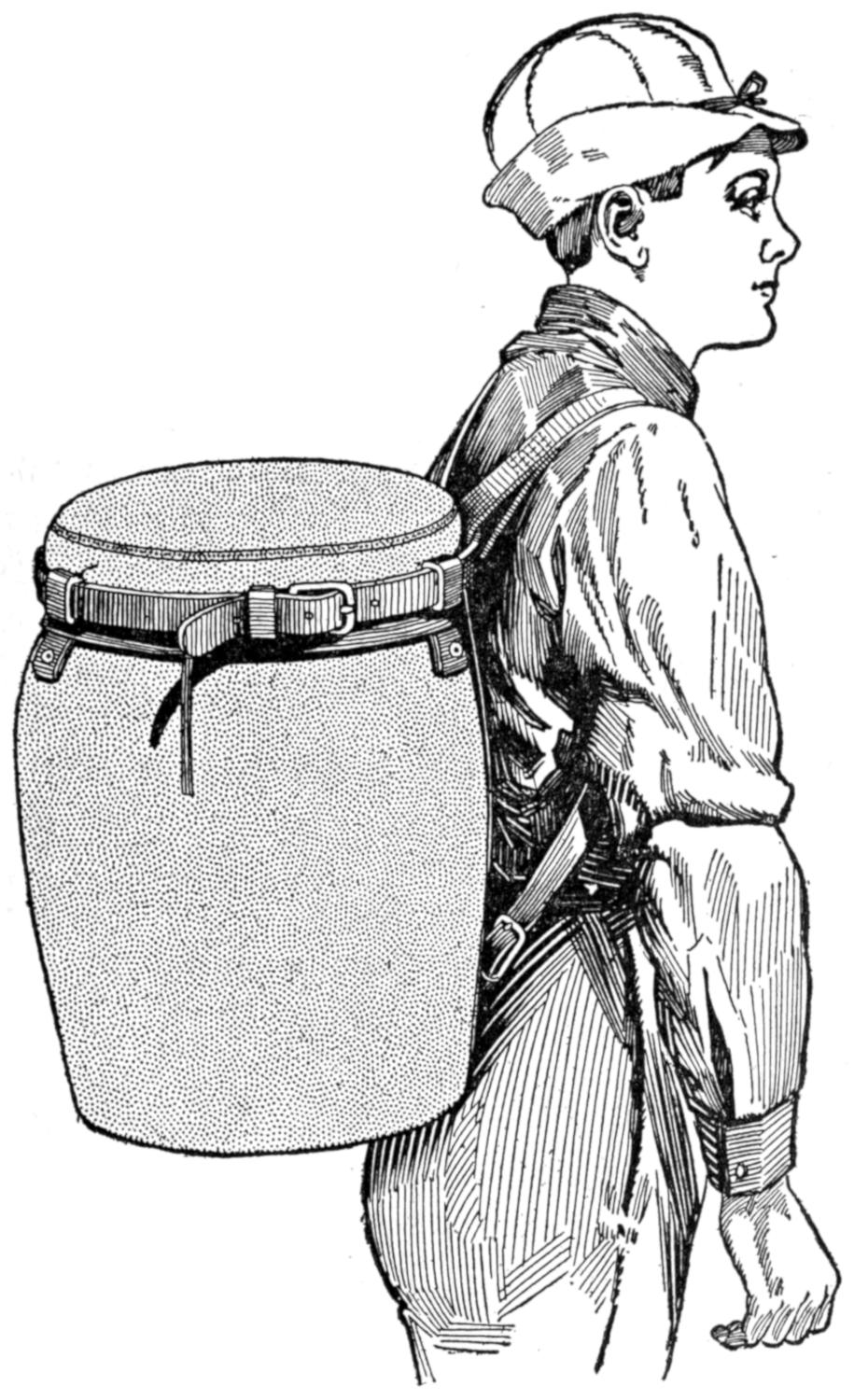

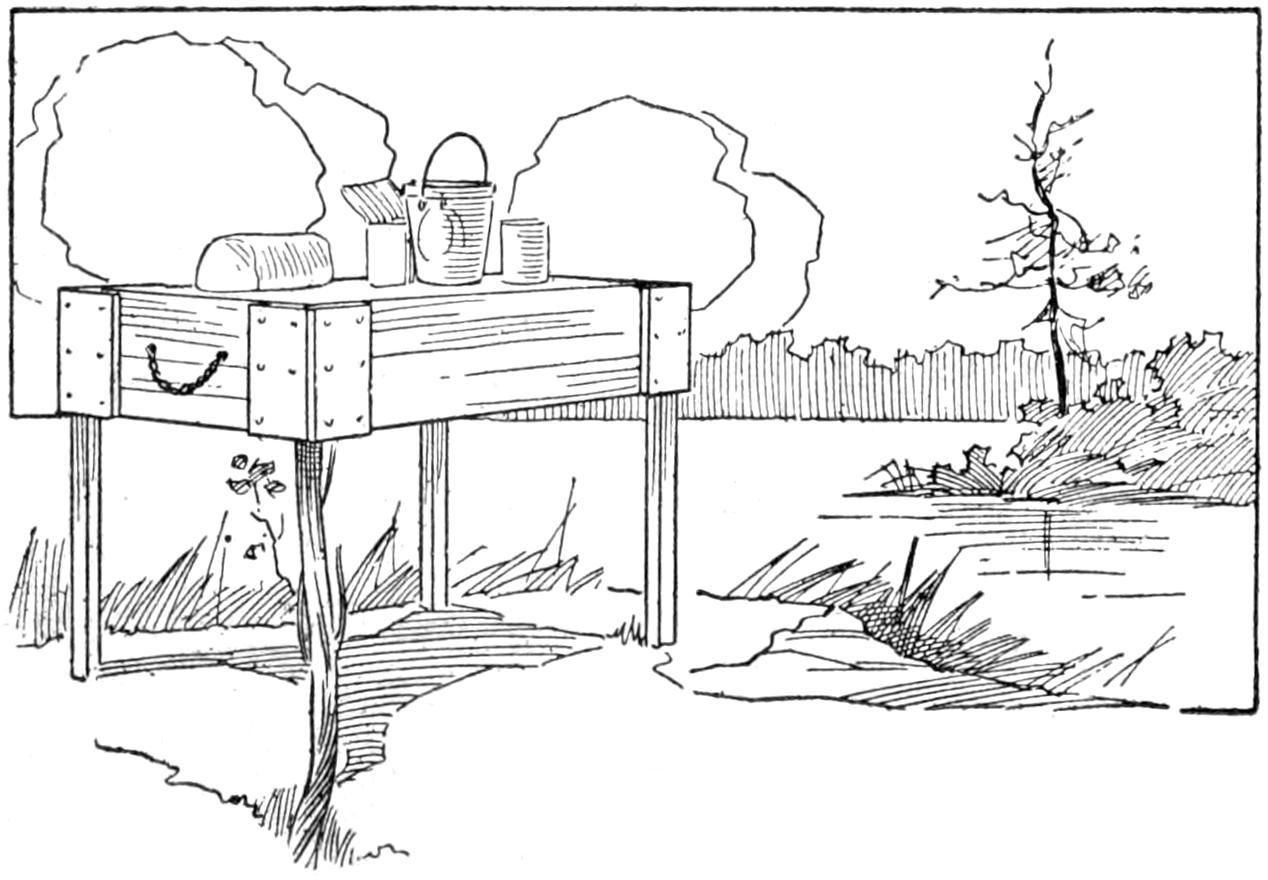

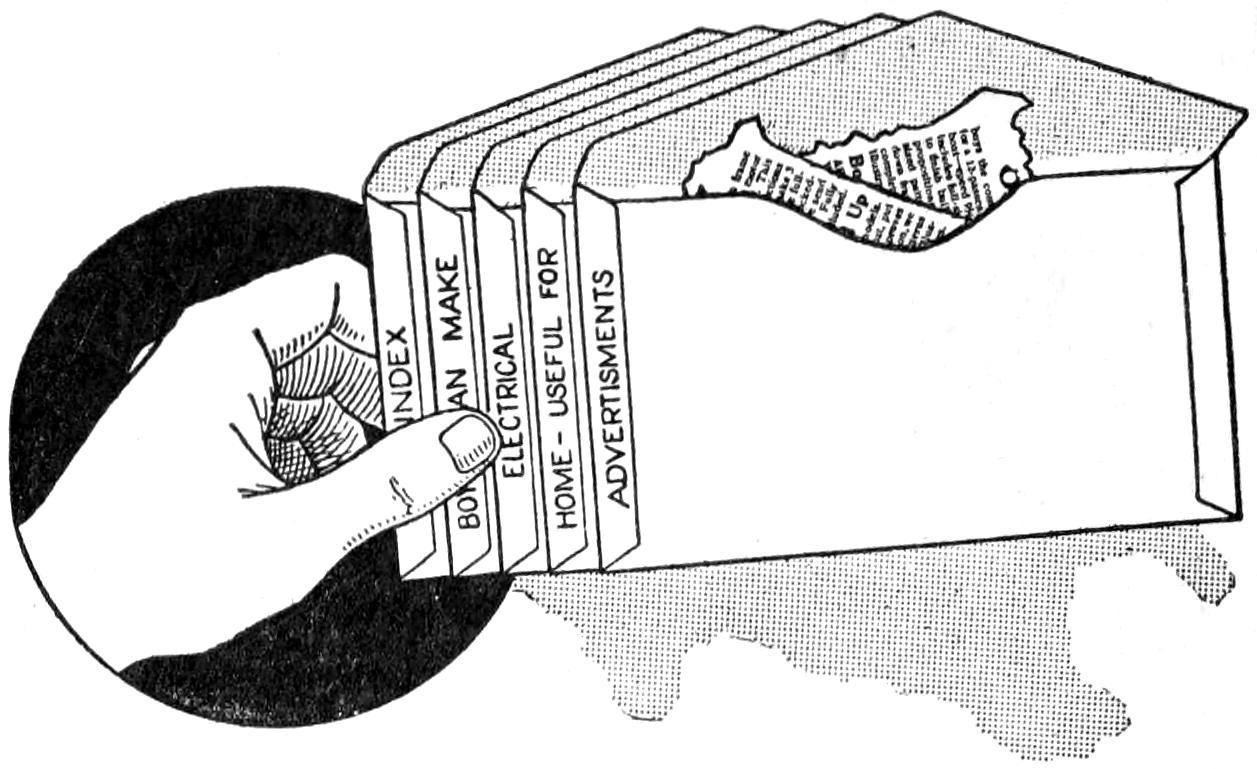

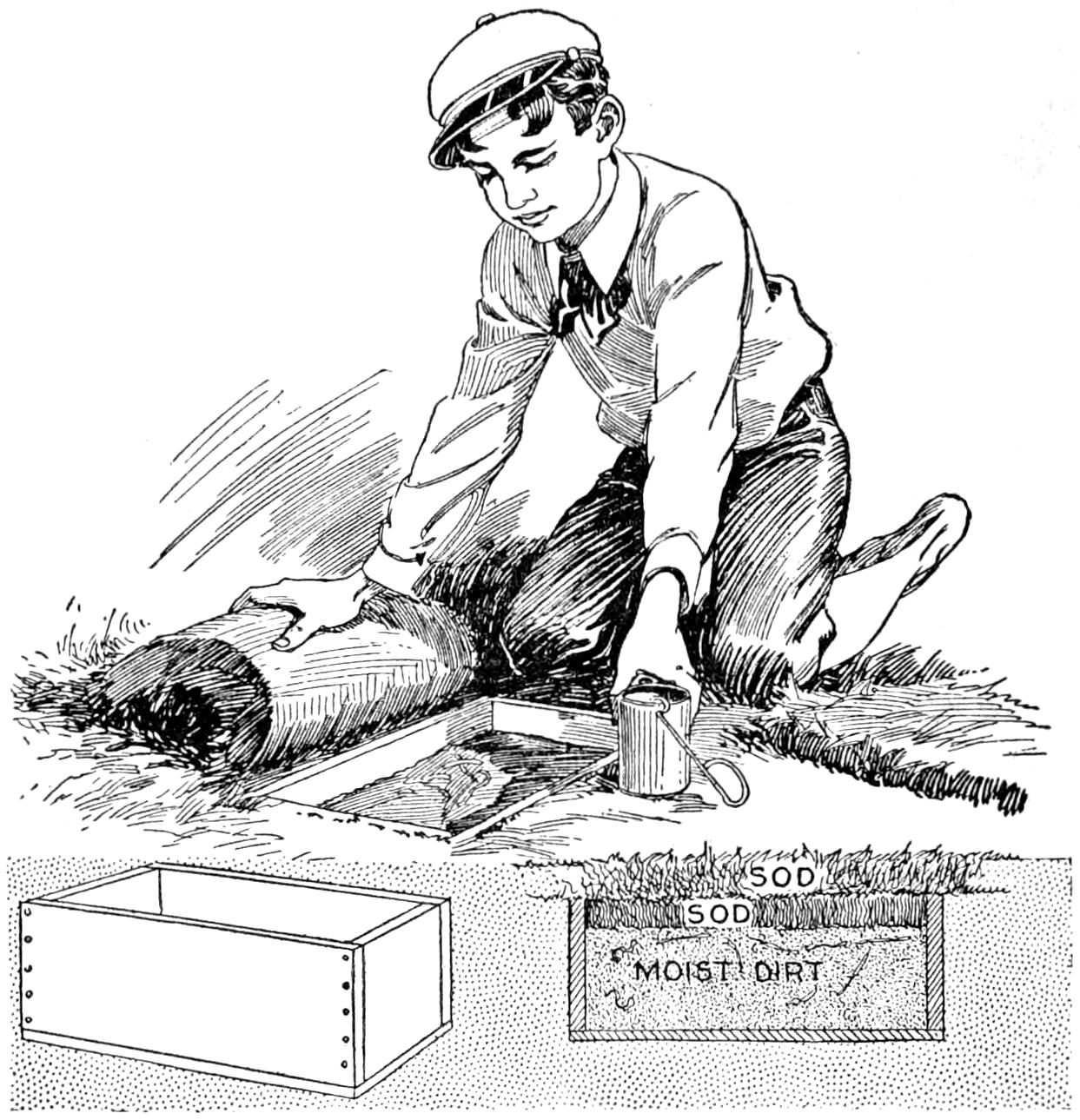

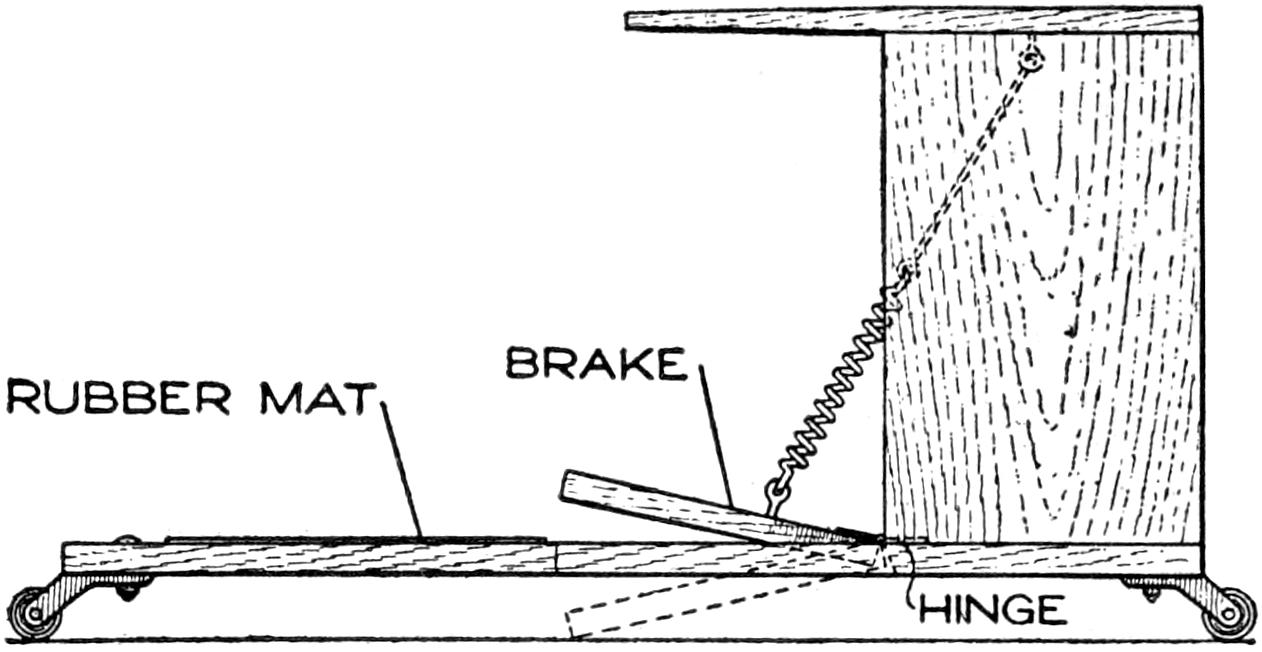

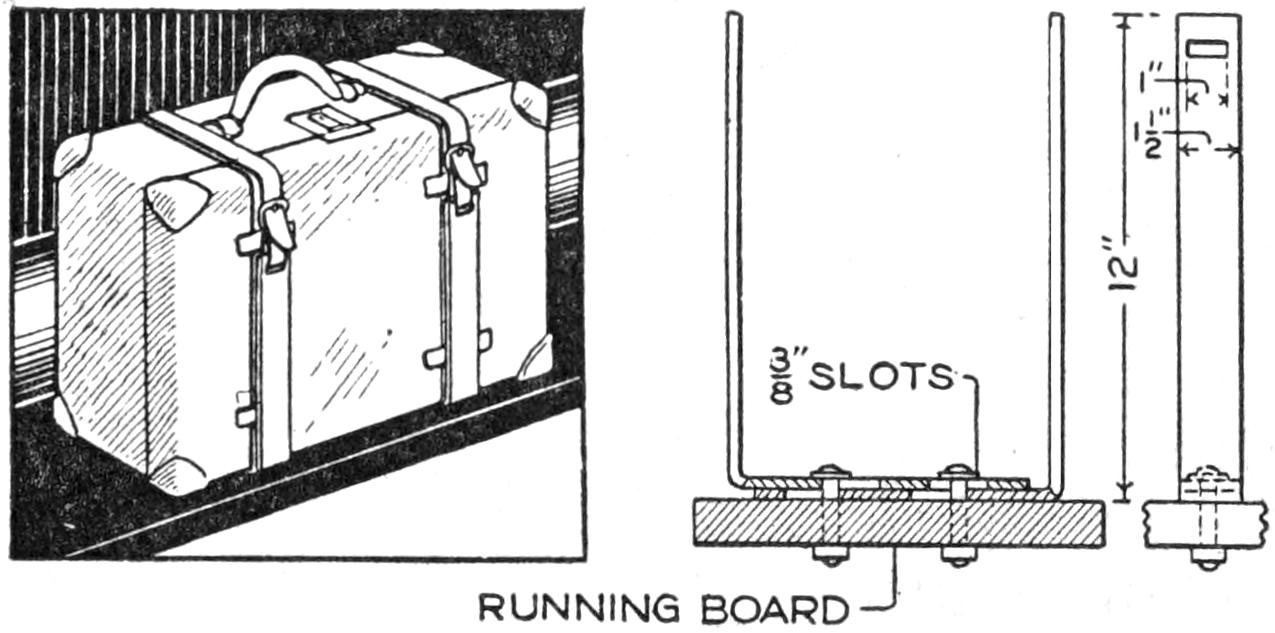

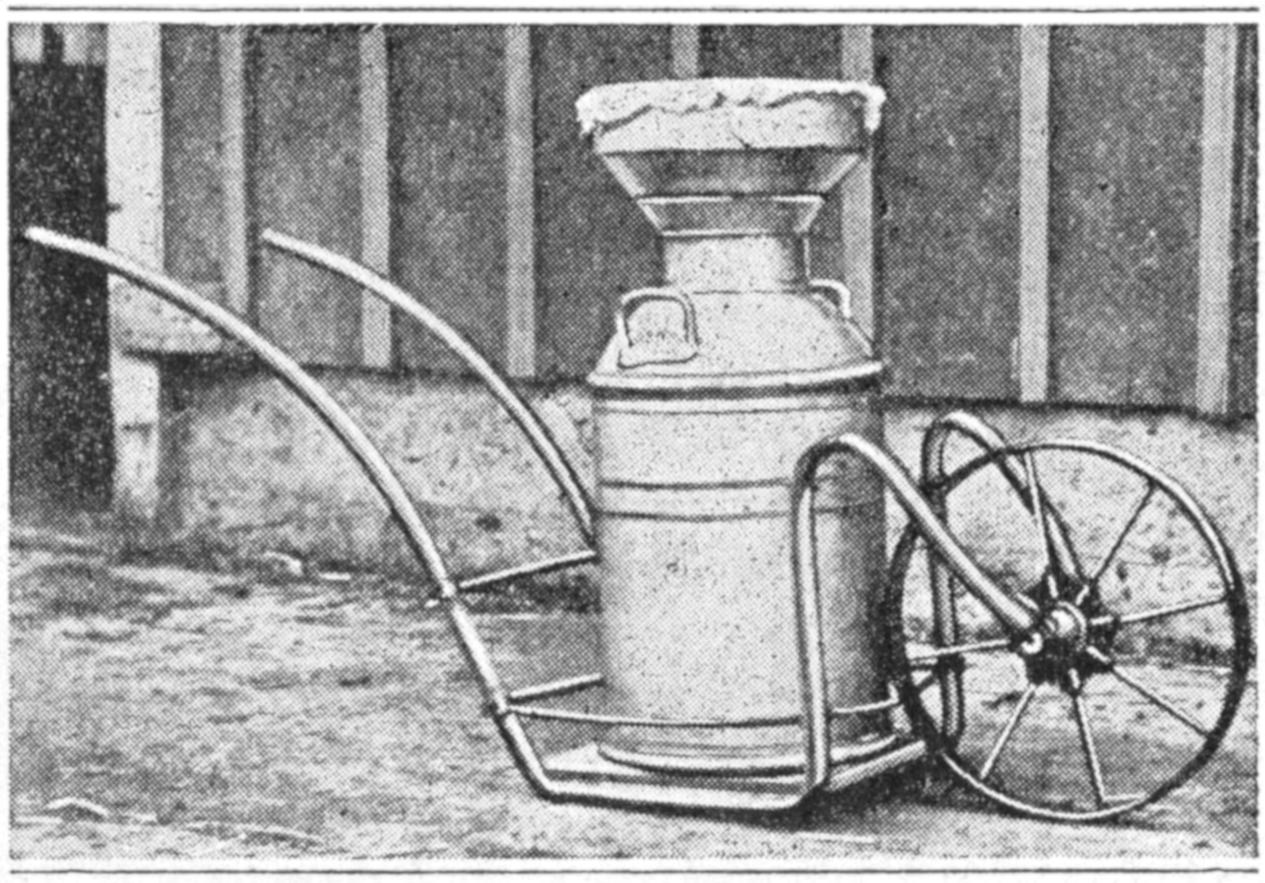

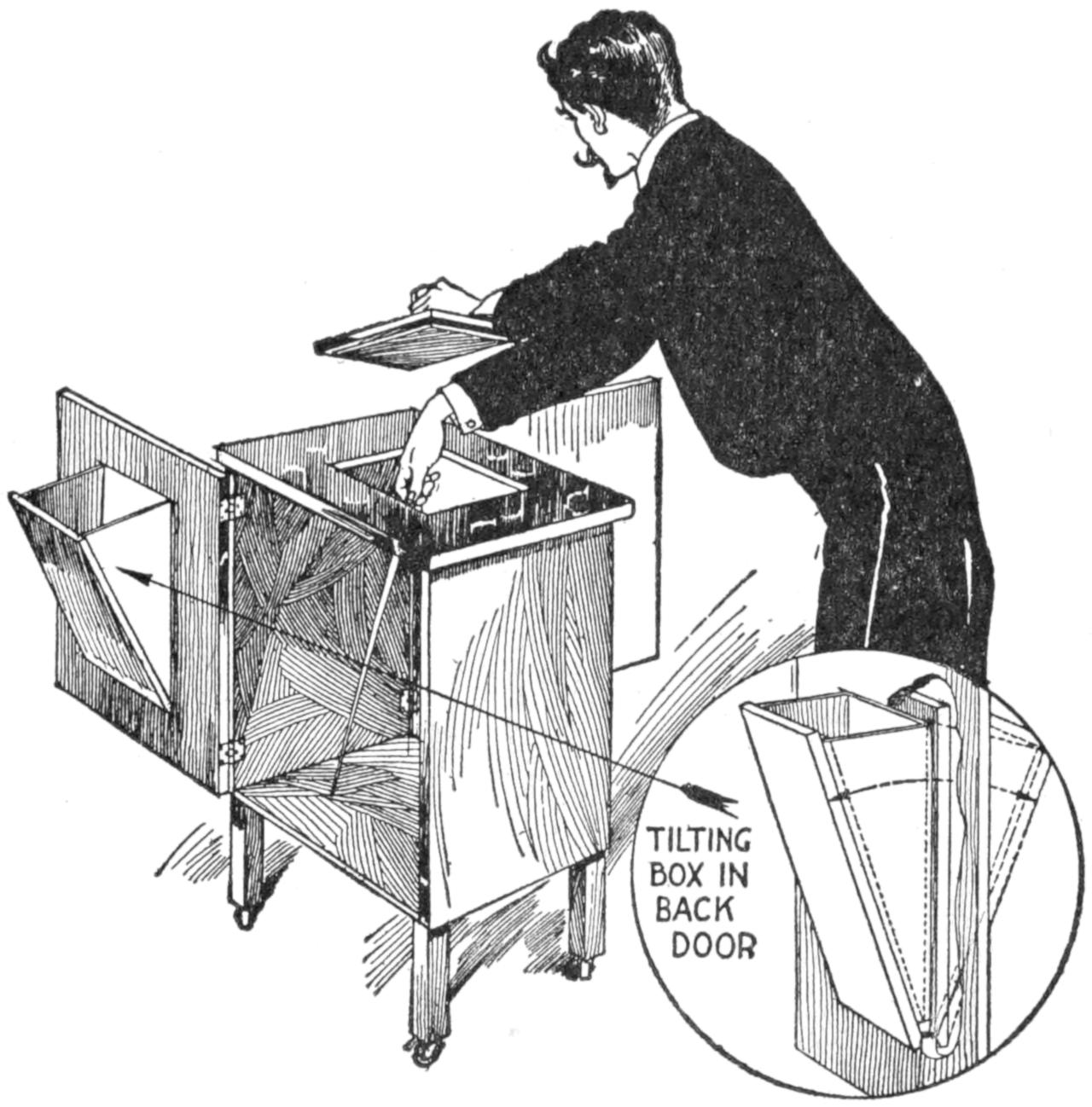

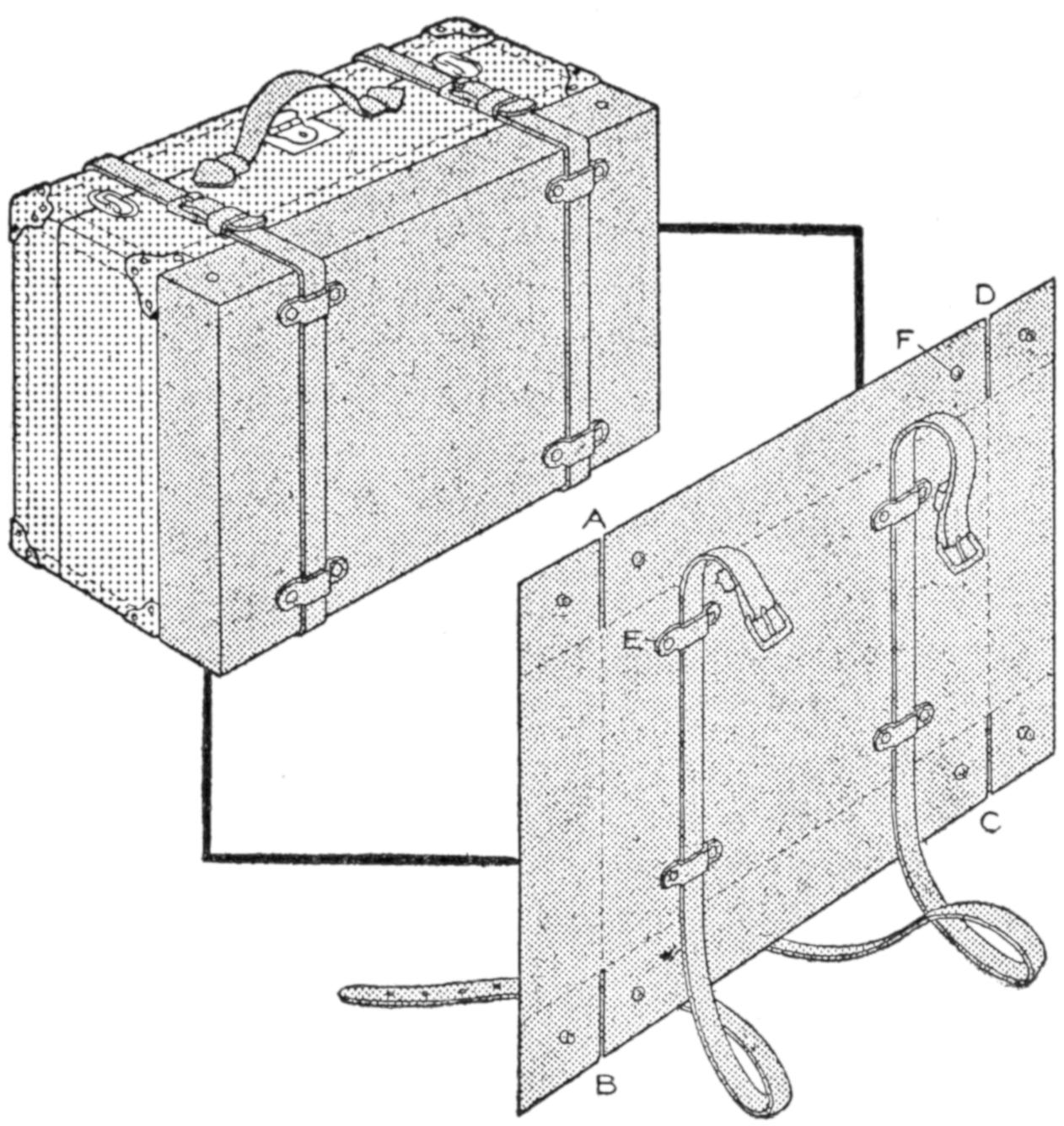

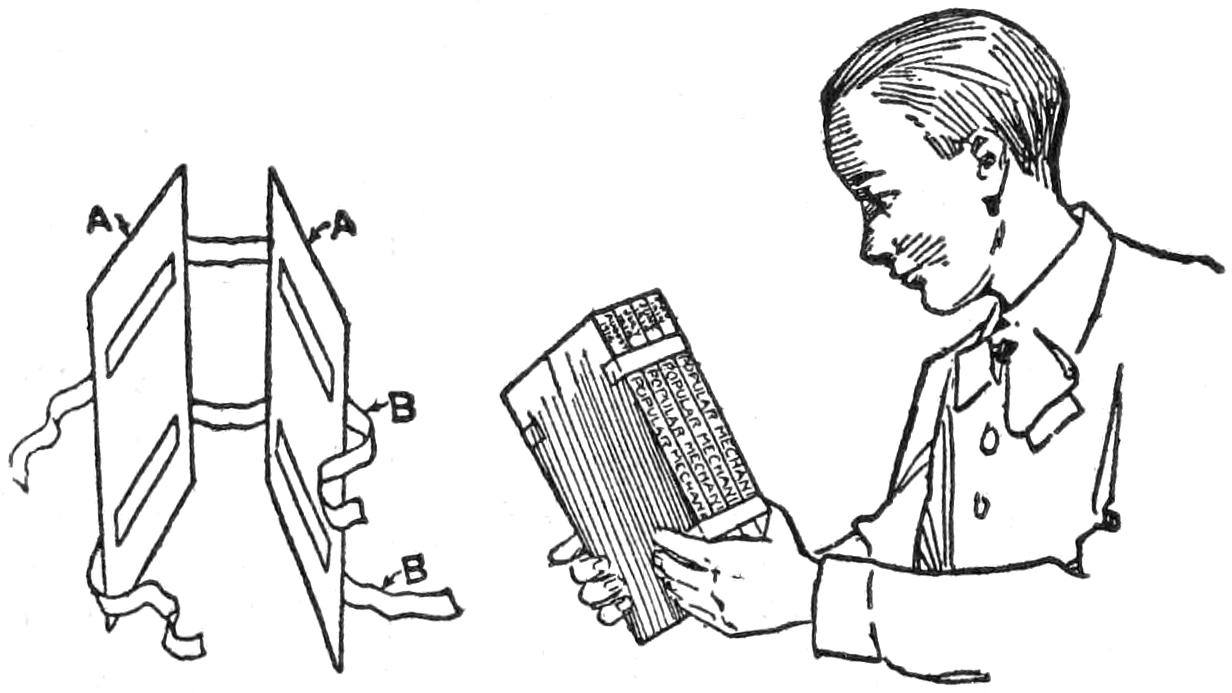

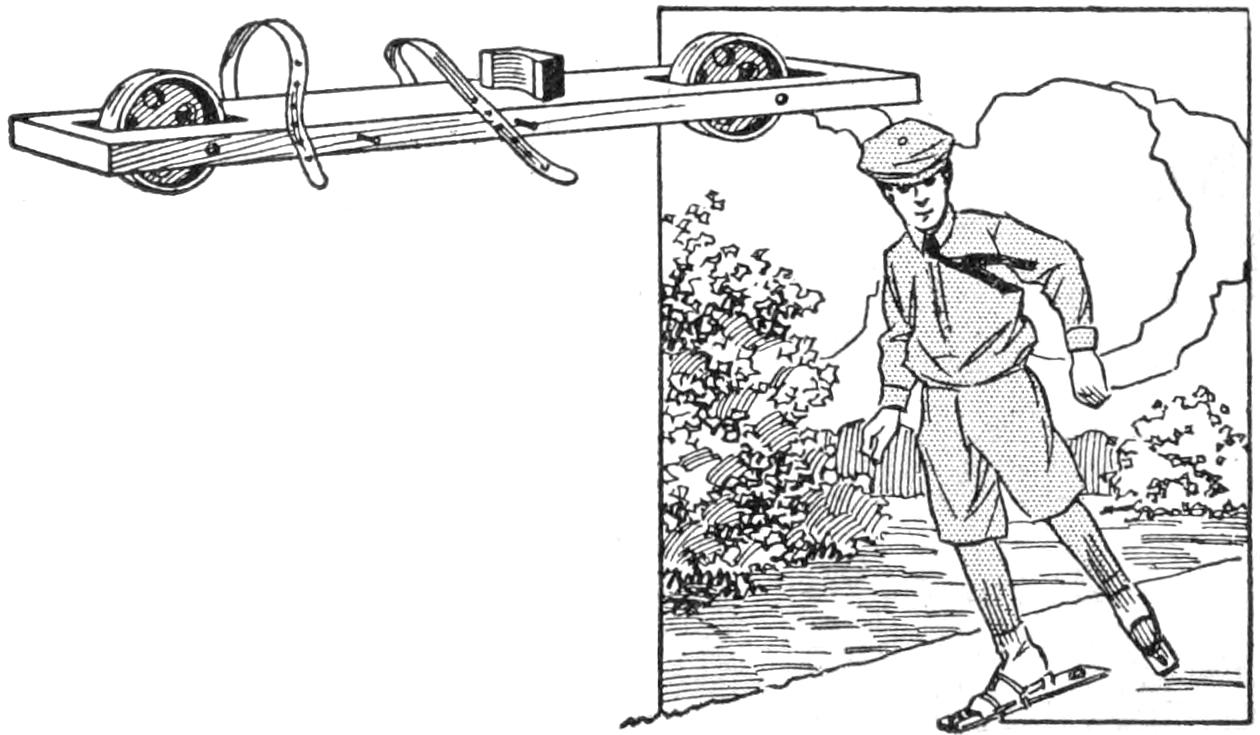

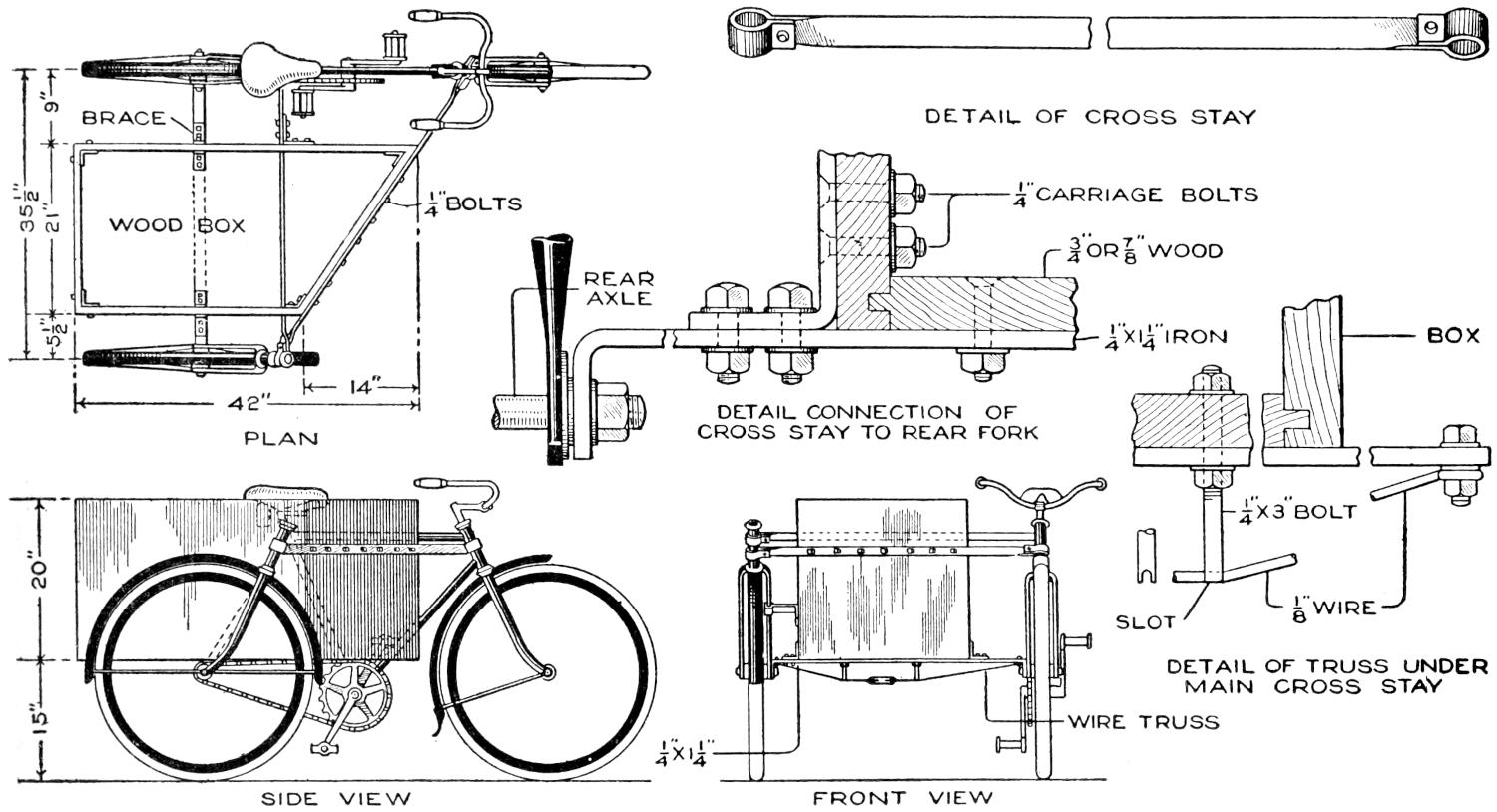

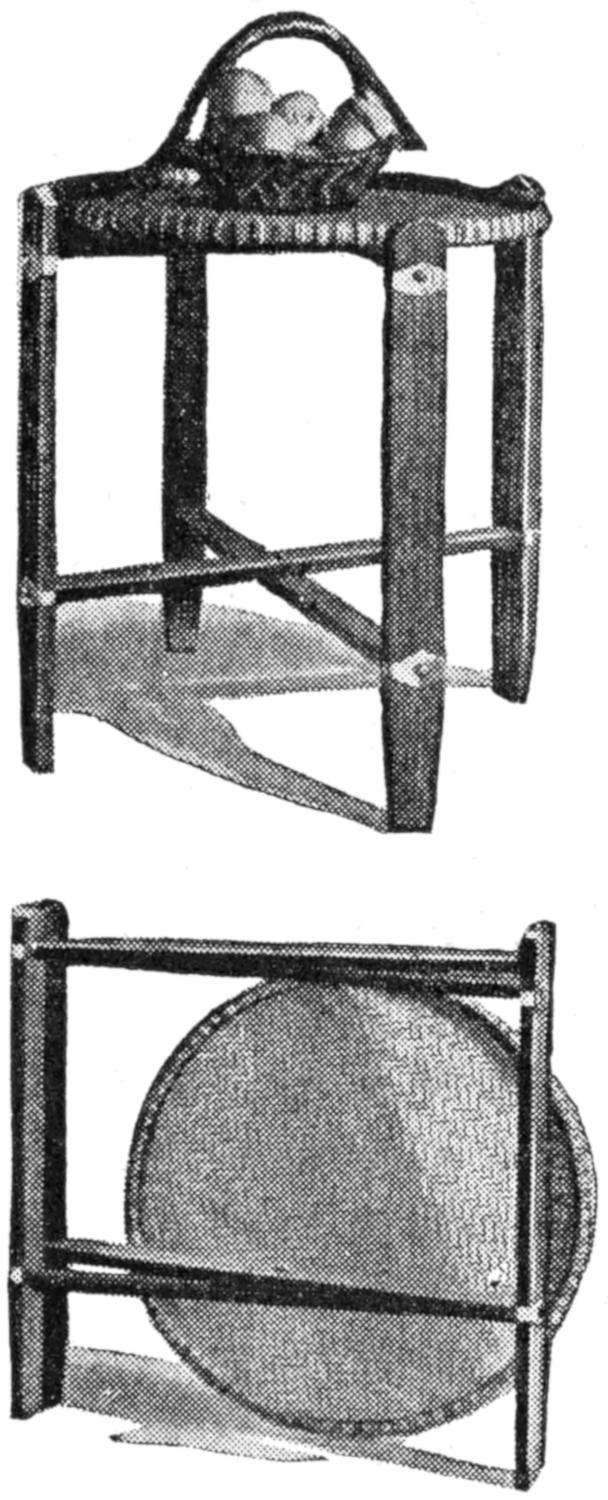

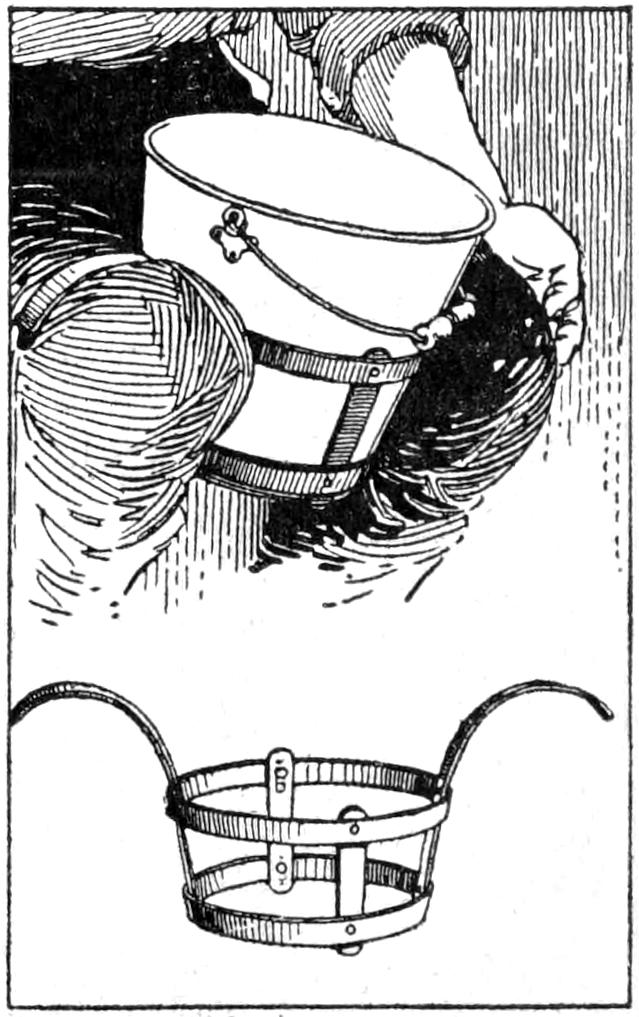

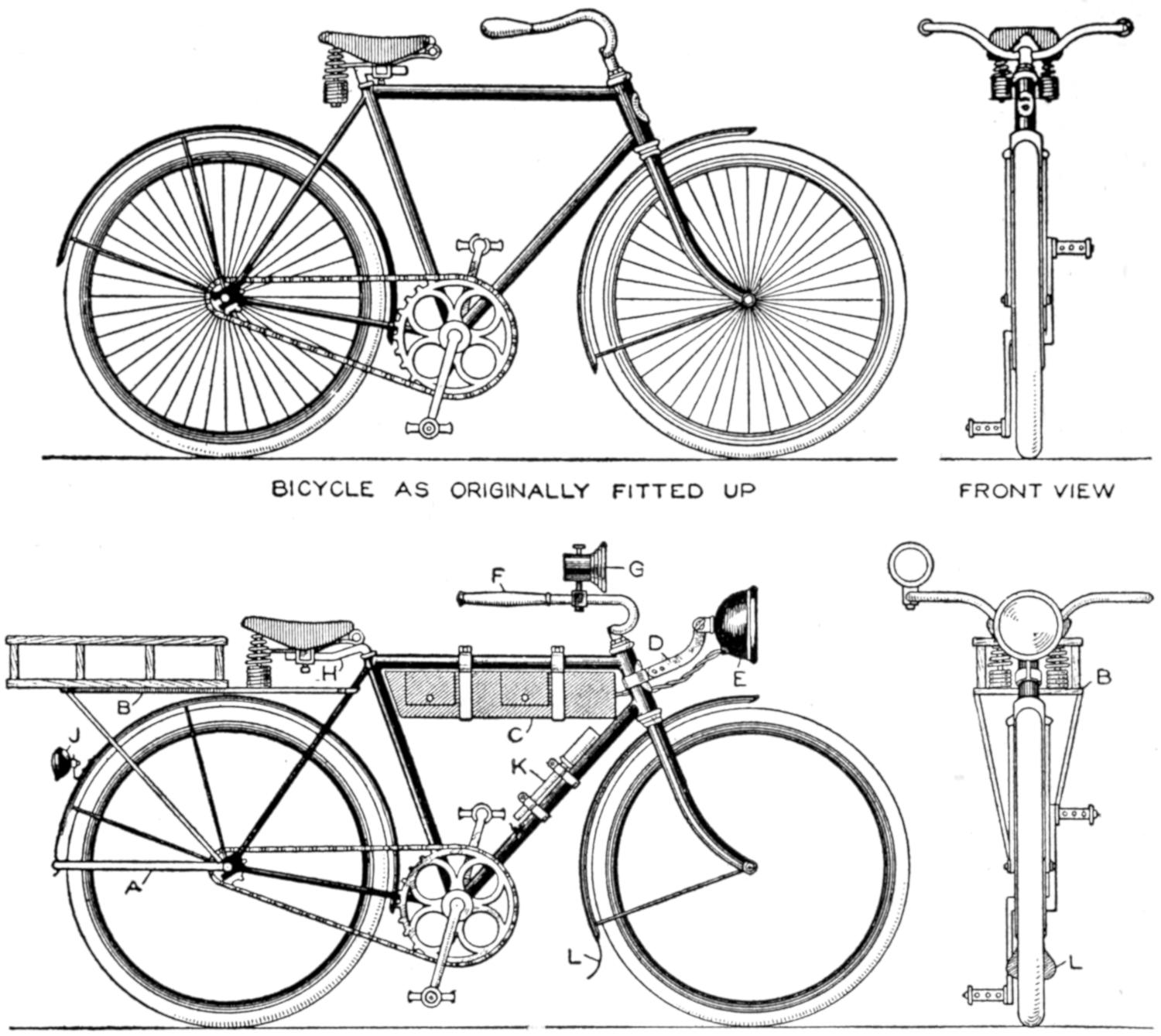

The Parcels are Handled Easily and with Little Danger of Damage by the Use of This Homemade Carrier

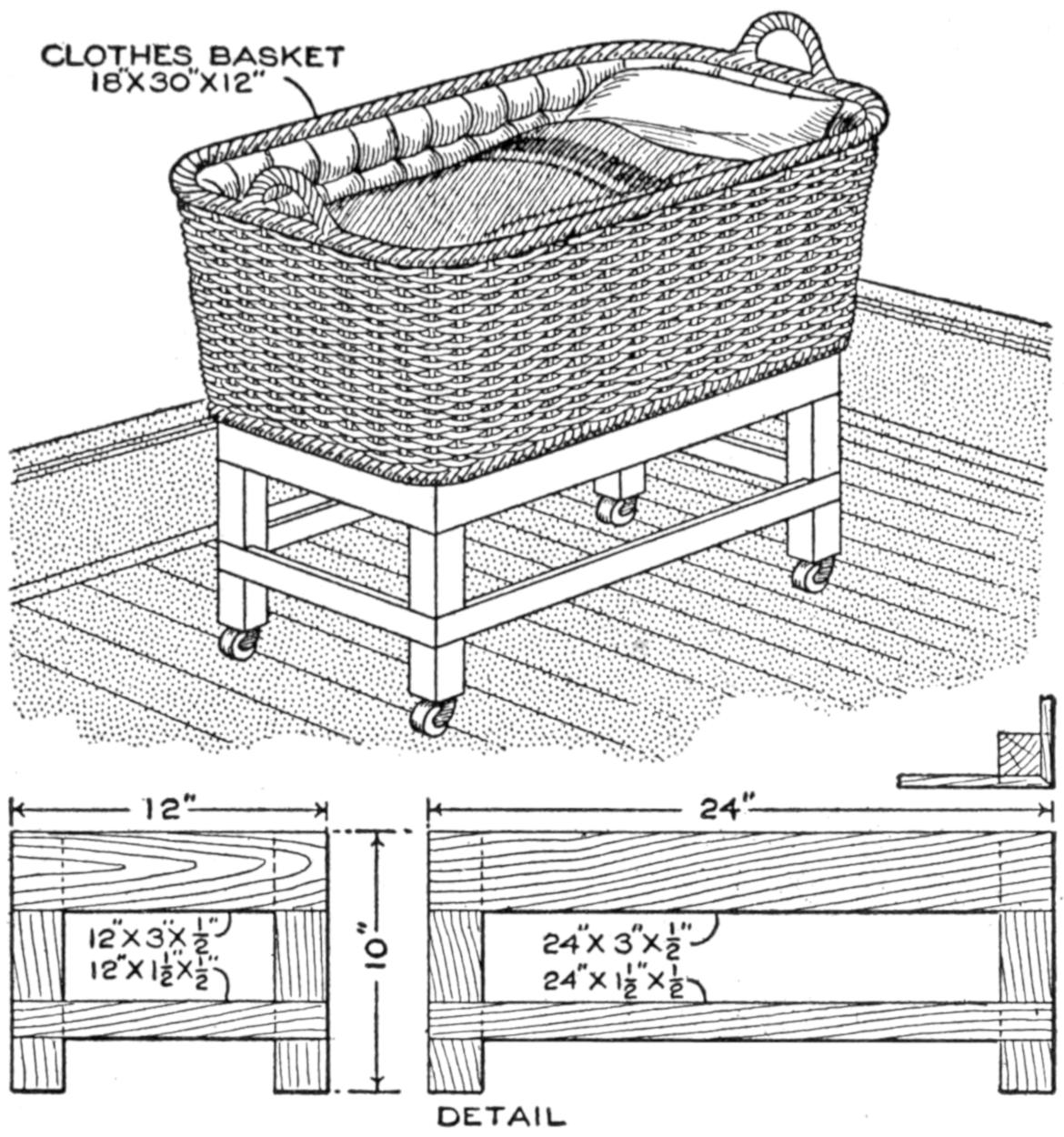

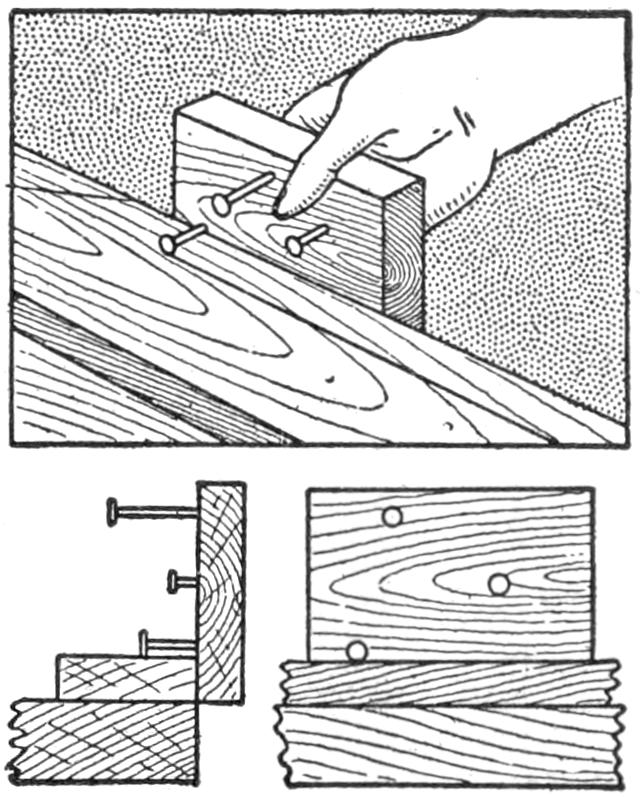

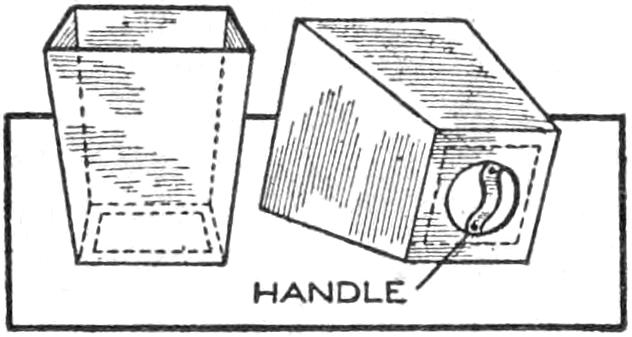

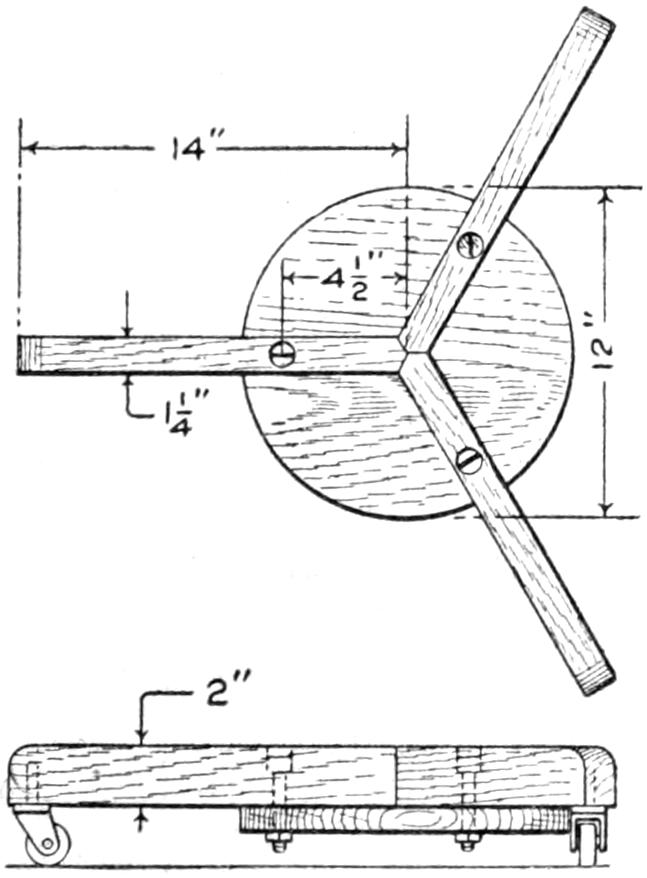

Instead of carrying out an armload, or a boxful, of miscellaneous parcels to the delivery wagon or the customer’s vehicle, an enterprising grocery clerk made a parcel carrier fitted with casters, as shown in the sketch. An ordinary wooden box was used for the tray, and handles were fitted at the ends. The legs were made of light strips nailed as shown. The parcels are loaded into the tray and the arrangement carried or rolled along on the casters, as is convenient. Besides making the work of handling the articles easier, they are kept clean, since it is not necessary to lay them on the walk or other undesirable place.—Avis Gordon Vestal, Chicago, Ill.

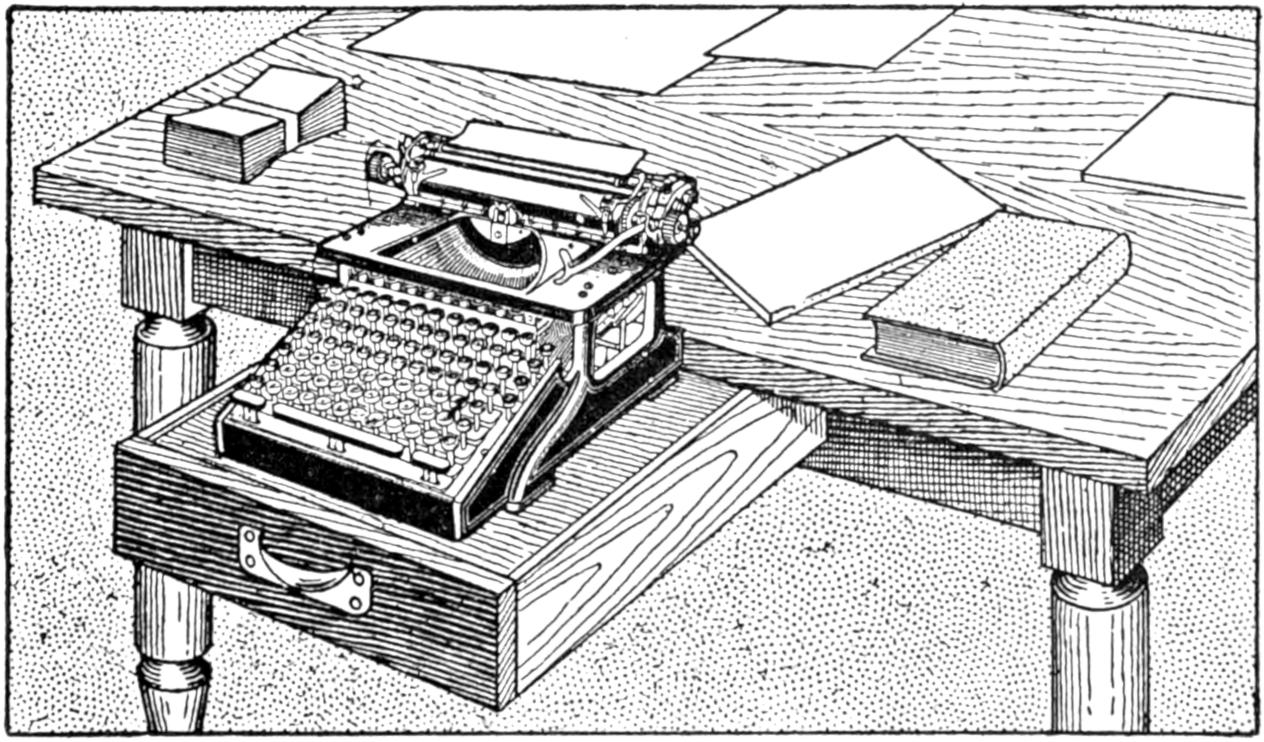

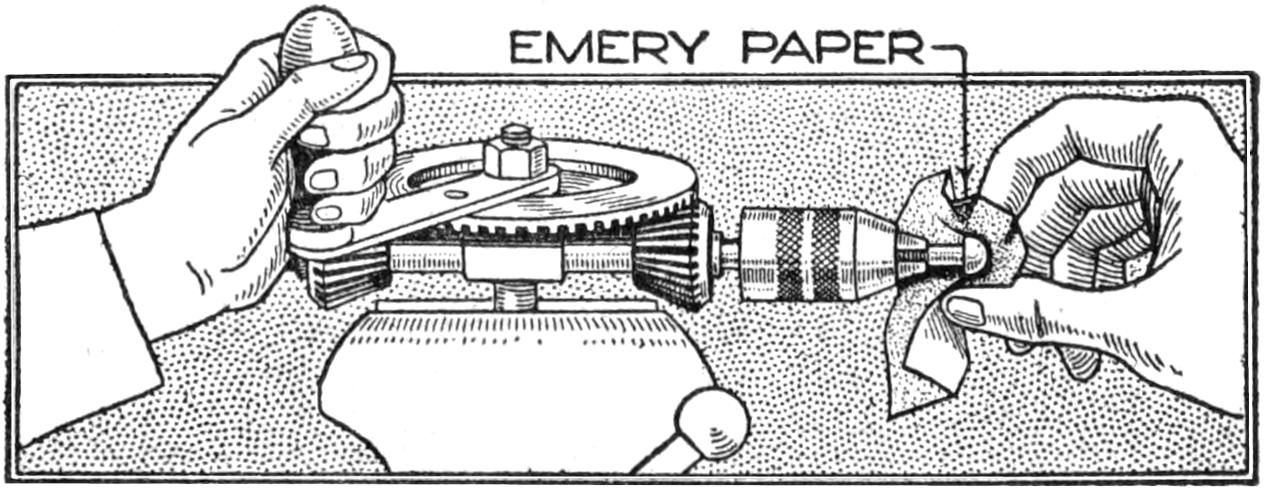

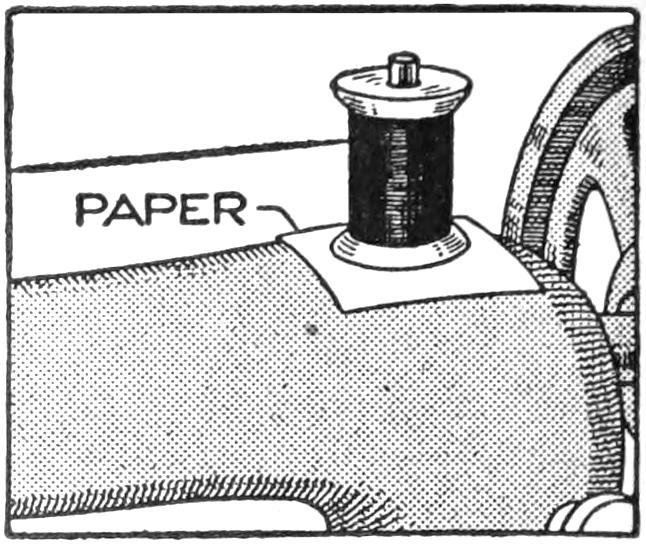

Irregularities in the feeding of the paper into a typewriter are often due to slippery spots on the platen. To overcome this trouble, clean the platen thoroughly with a mixture of two parts of denatured alcohol to one part of ether. Rub the polished parts with No. 2 emery cloth, then smooth the surface with No. 0 emery cloth. In cleaning a typewriter with gasoline, the effect is to leave the parts dry. A better method is to use a mixture of one part of typewriter oil to 50 parts gasoline. This will leave a fine coating of oil, which is too fine to collect dust, on the working parts.—William Doenges, Fort Sam Houston, Texas.

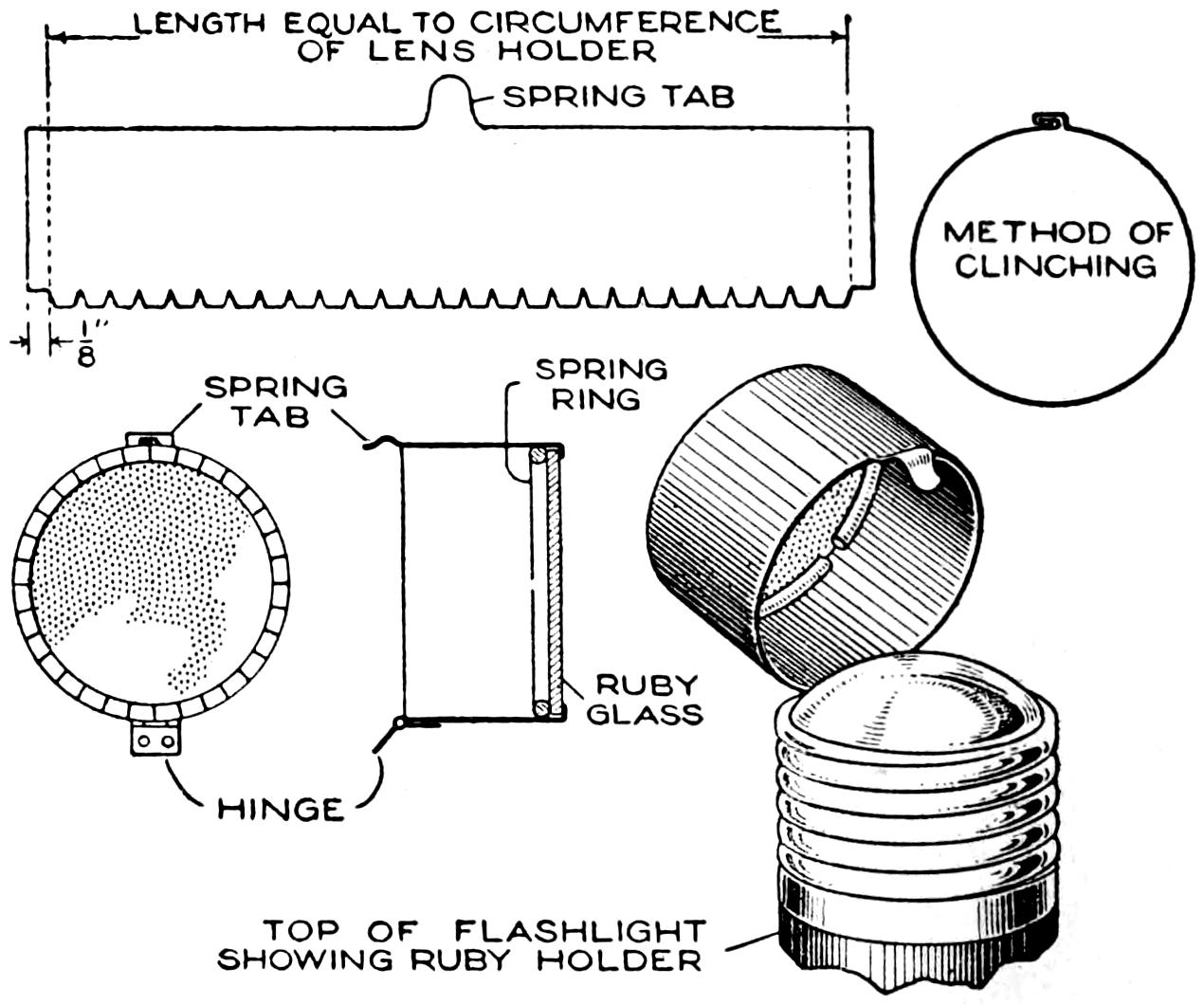

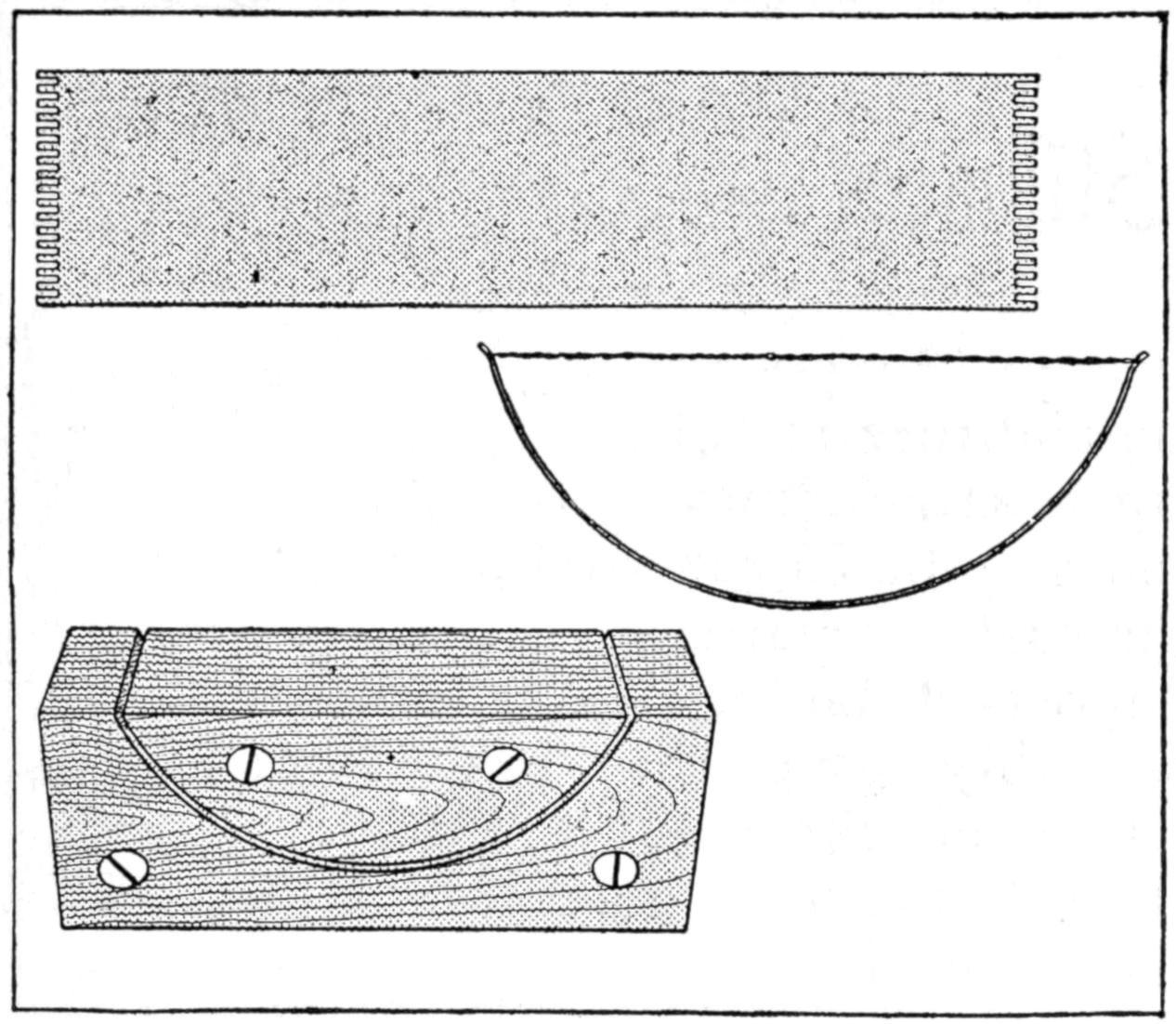

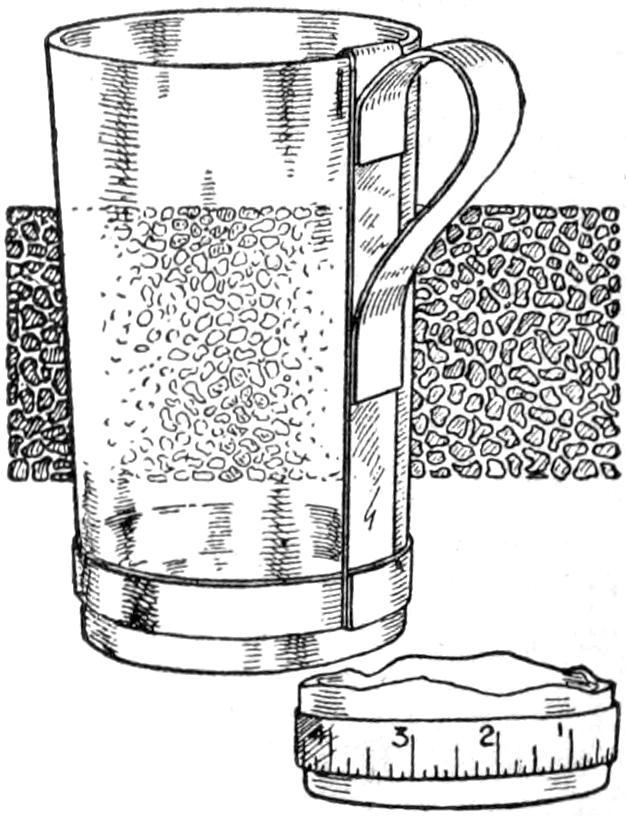

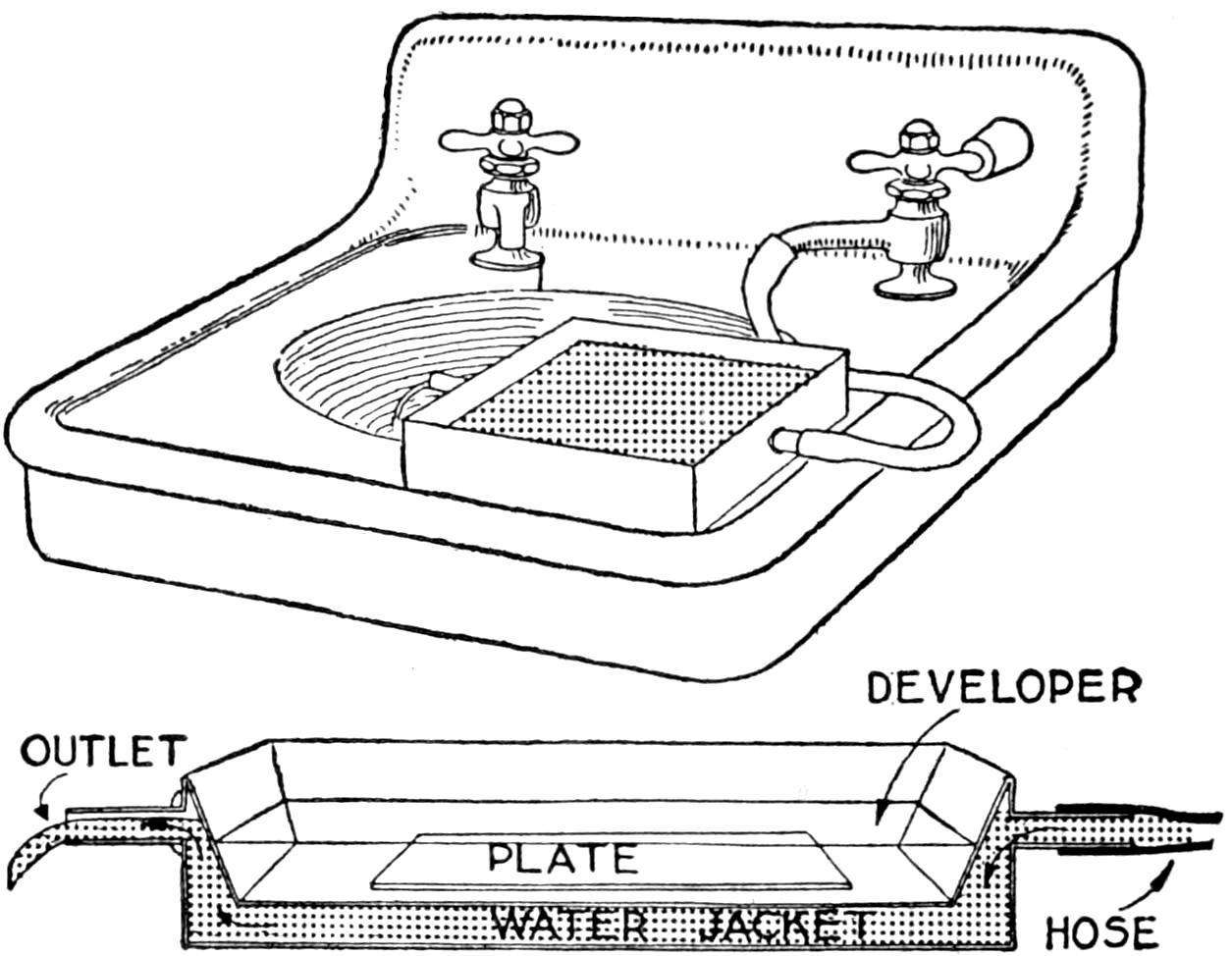

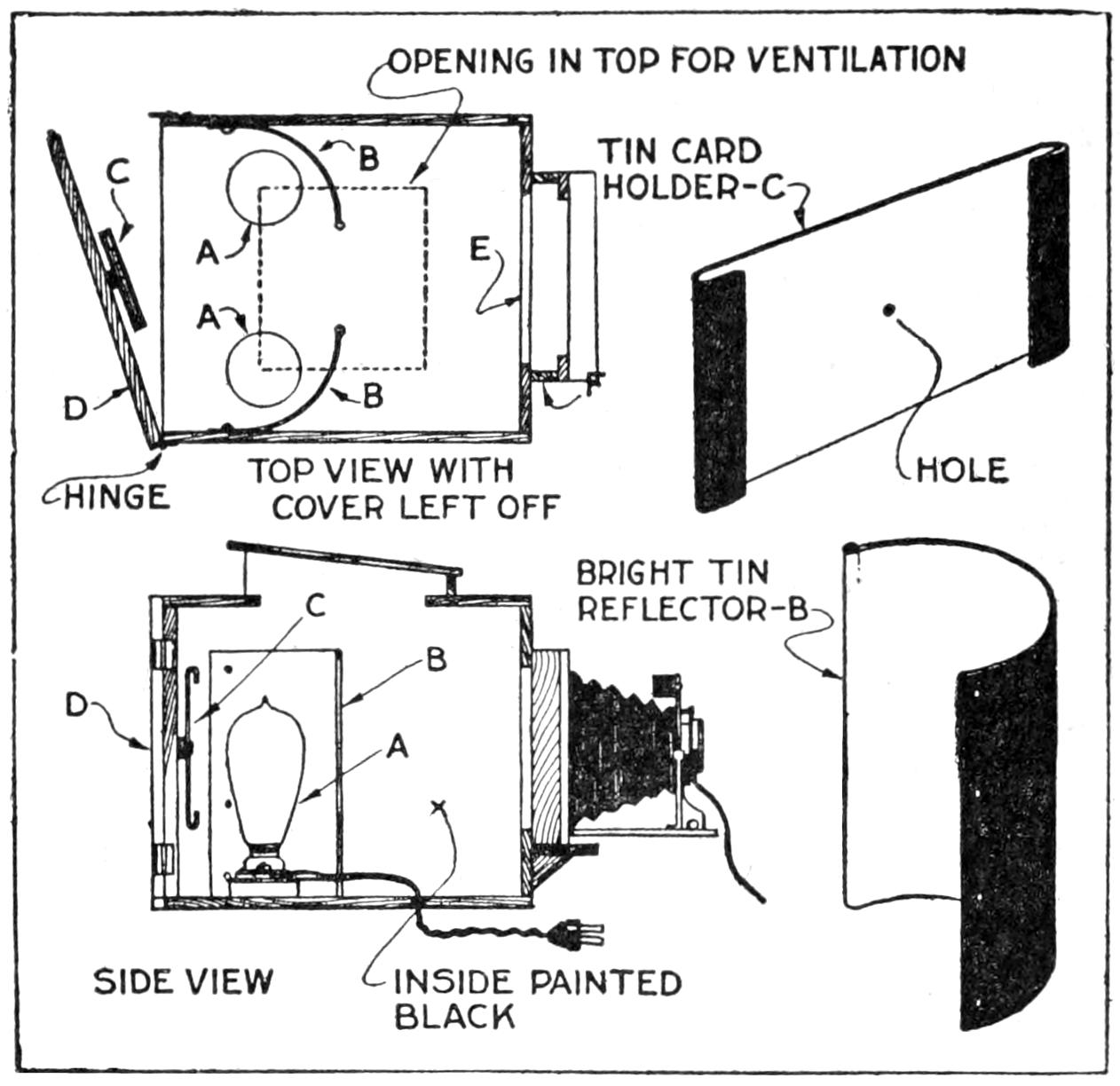

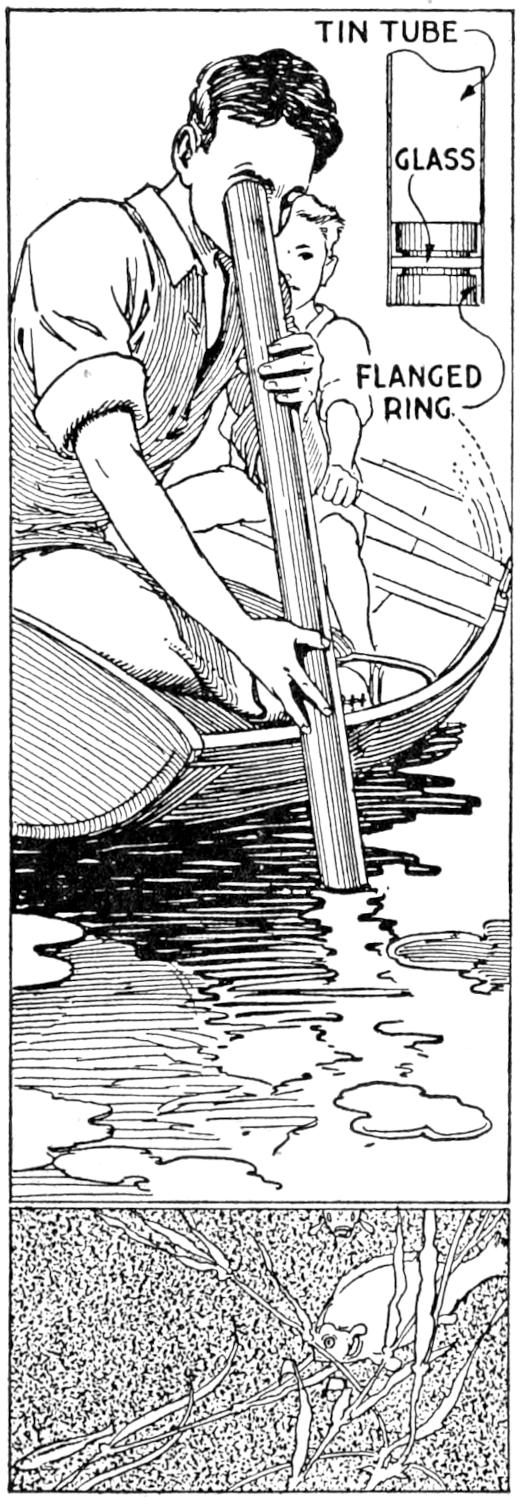

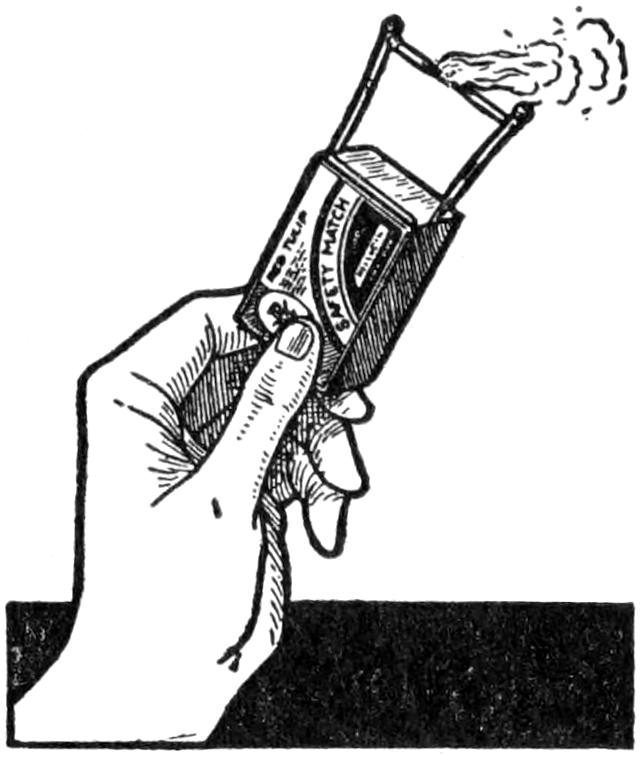

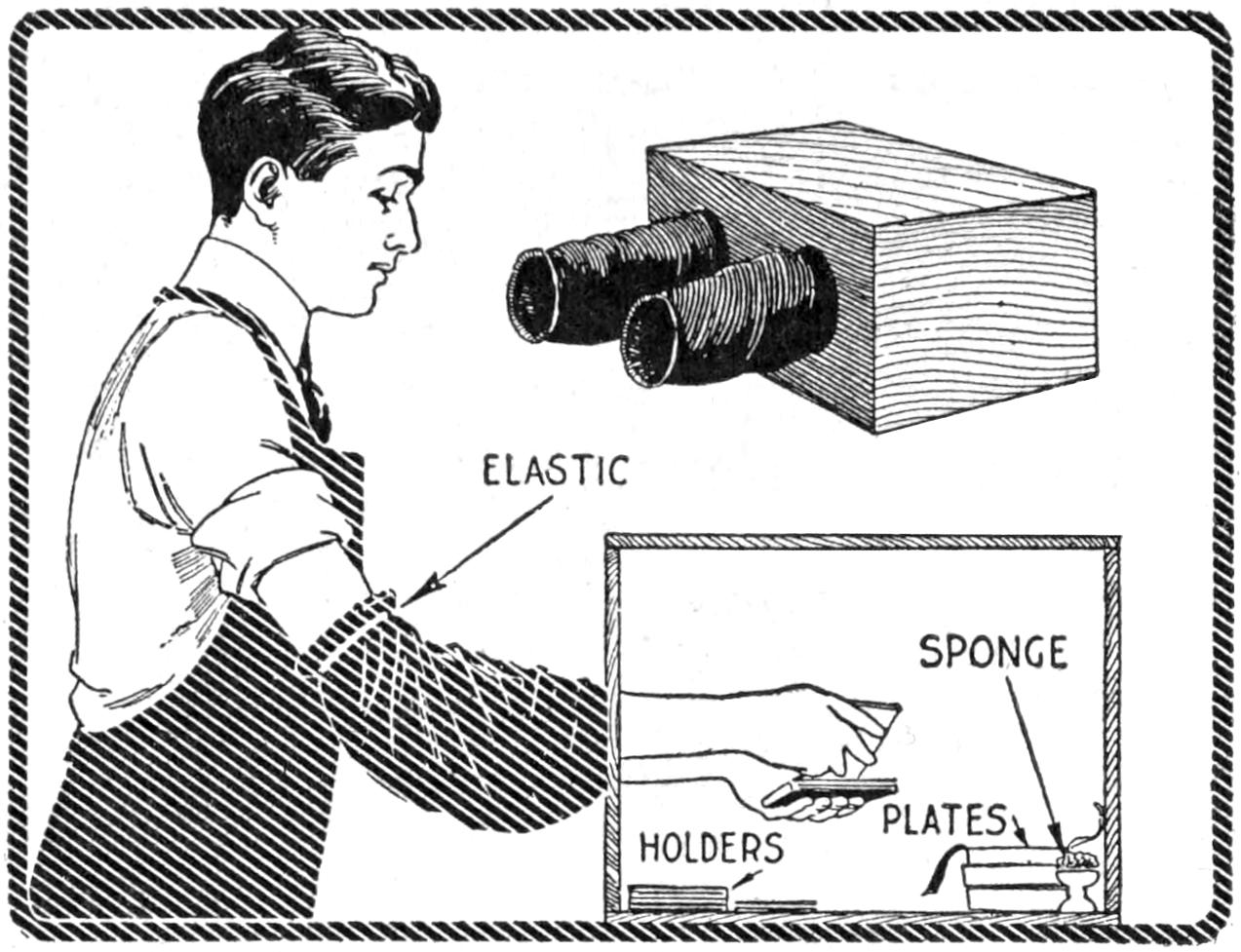

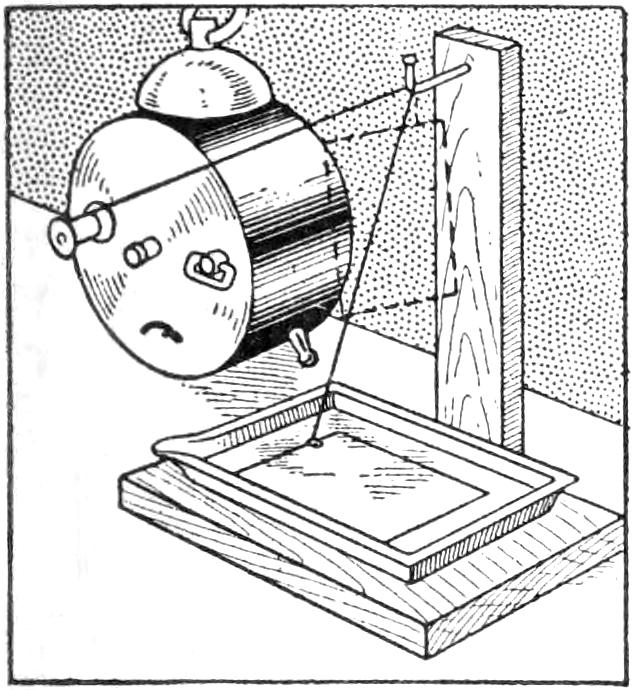

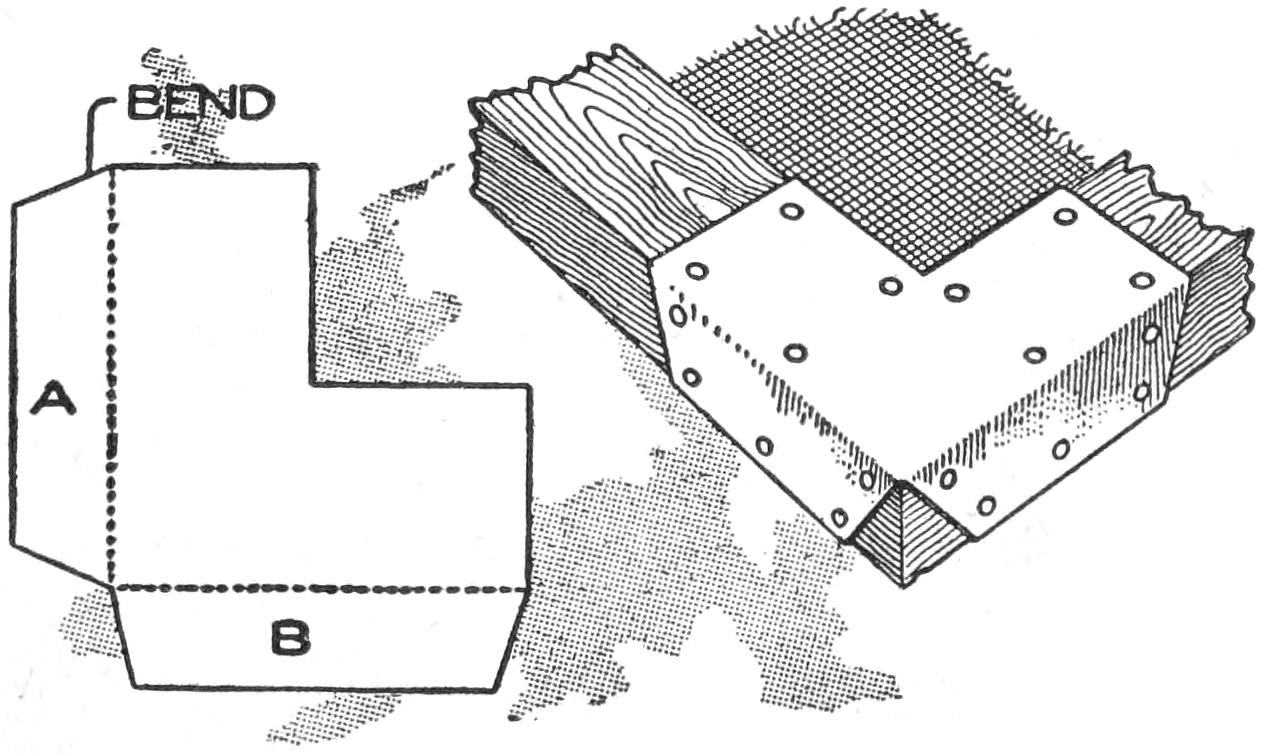

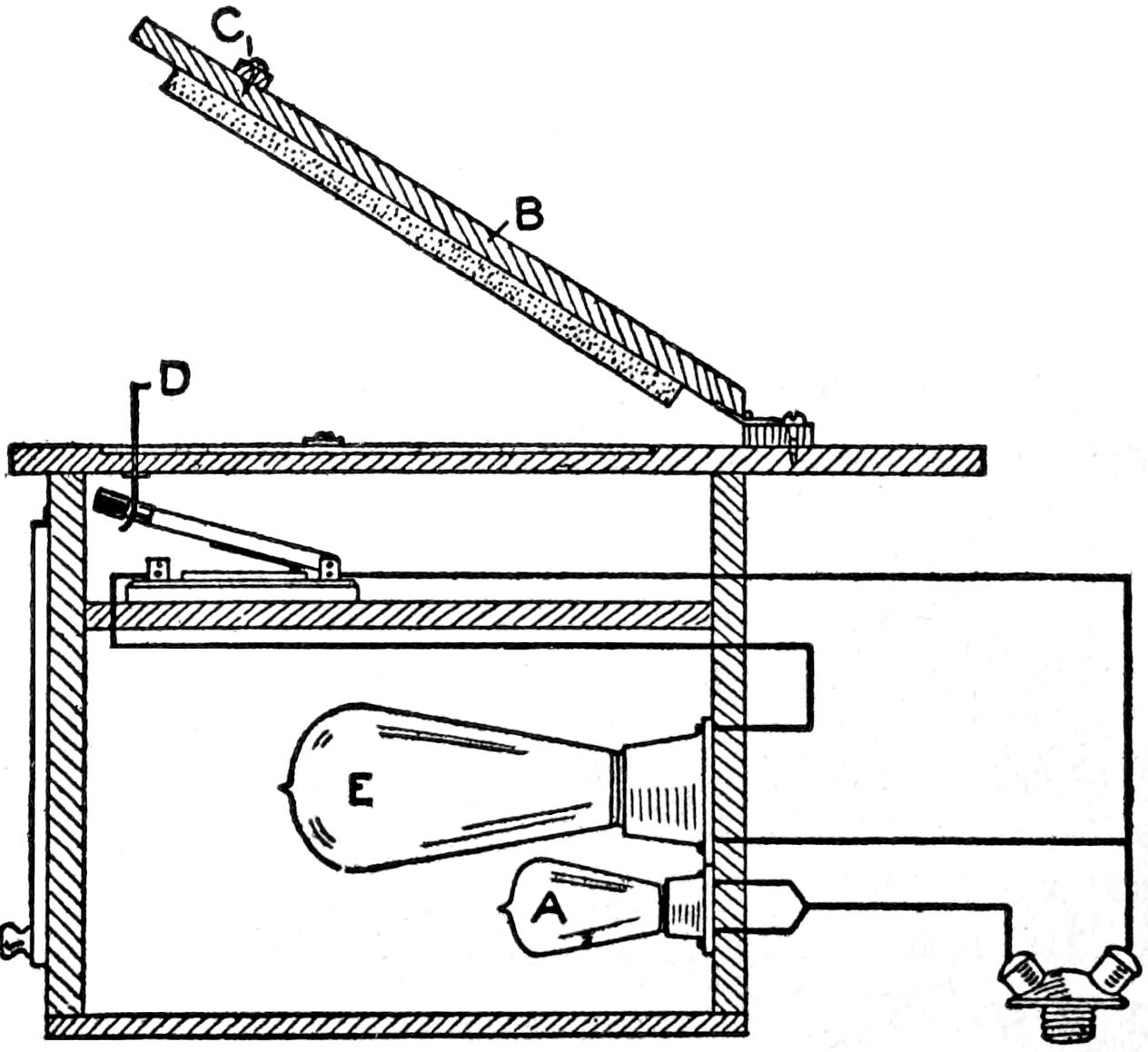

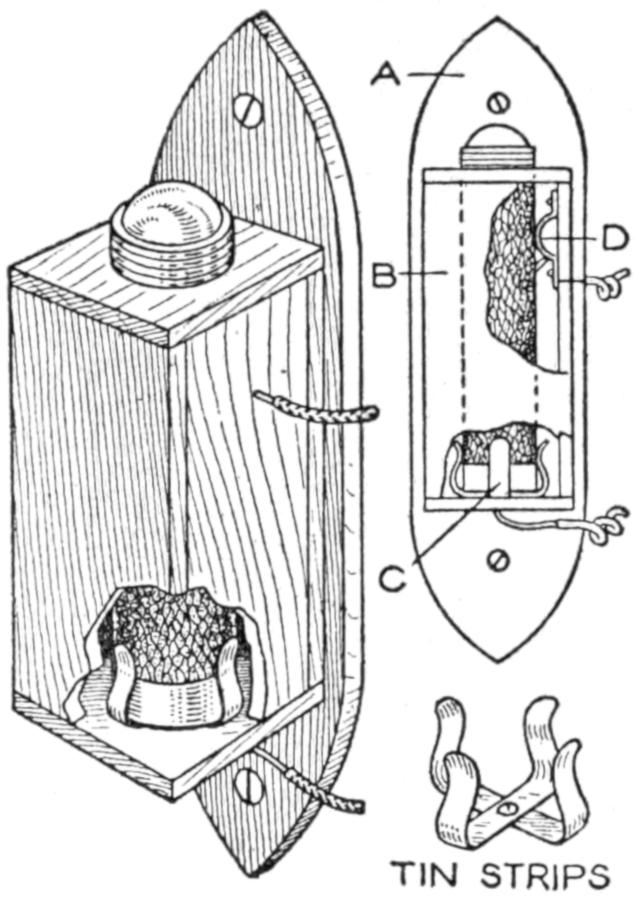

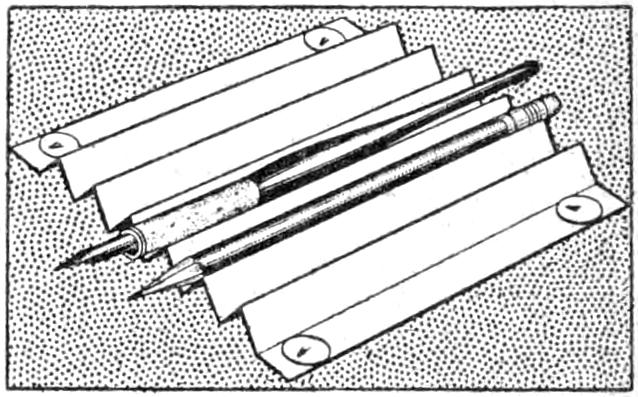

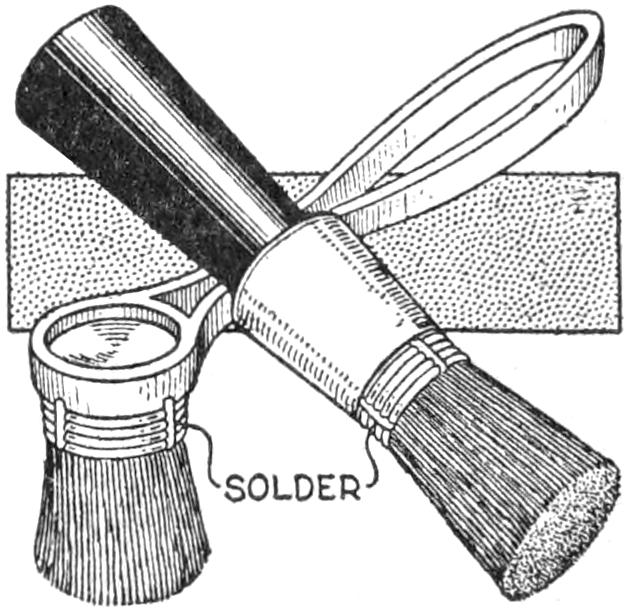

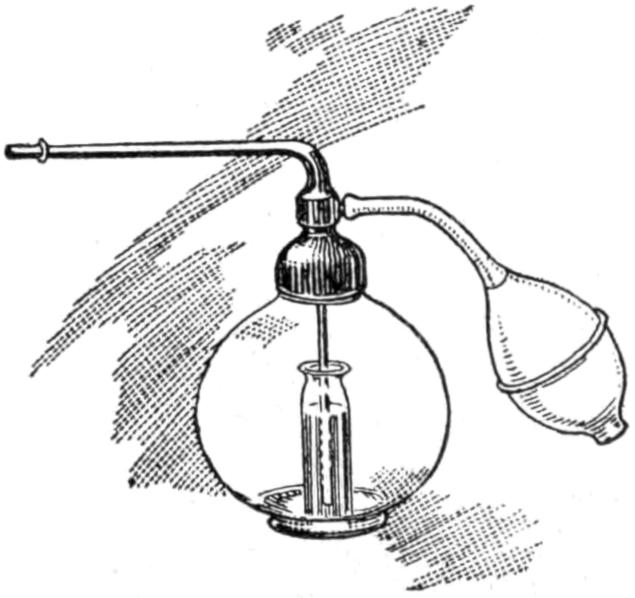

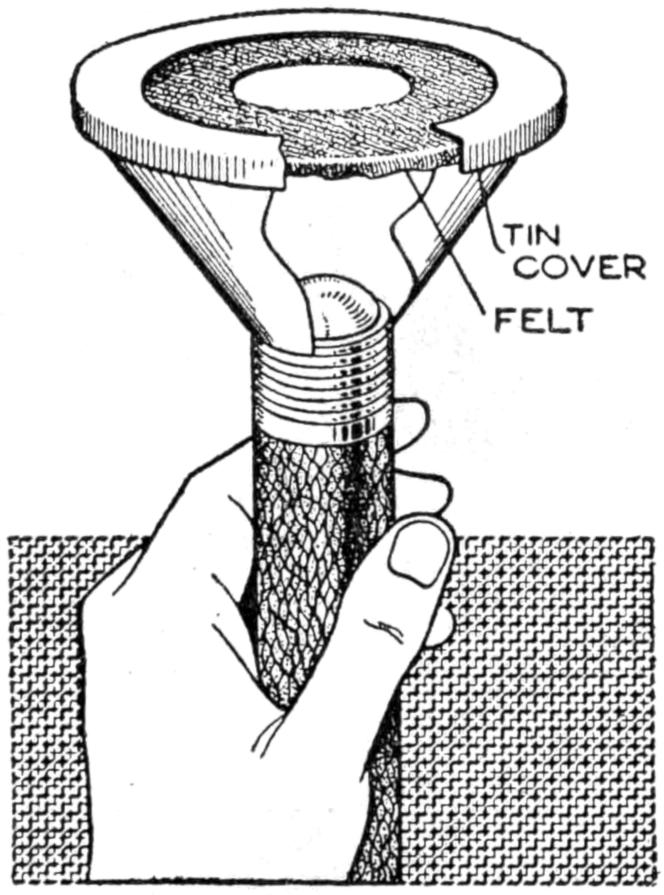

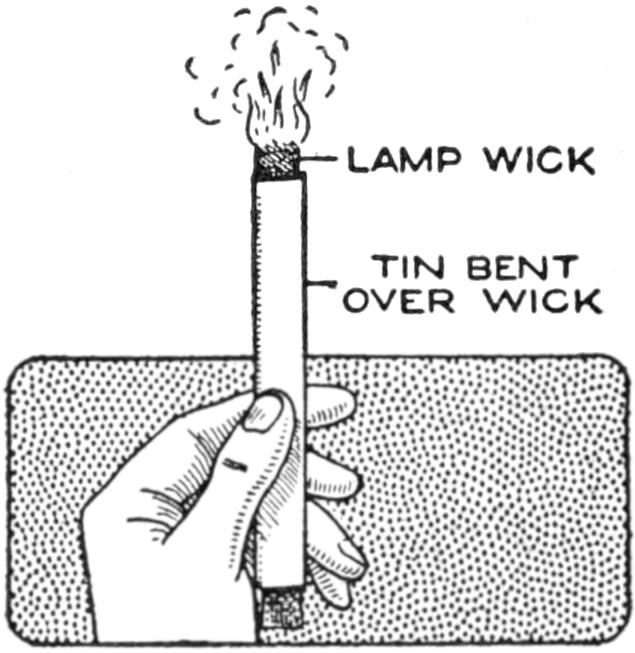

A Ruby Cap Hinged over the Lens of an Ordinary Flash Light Is a Convenience for the Dark Room

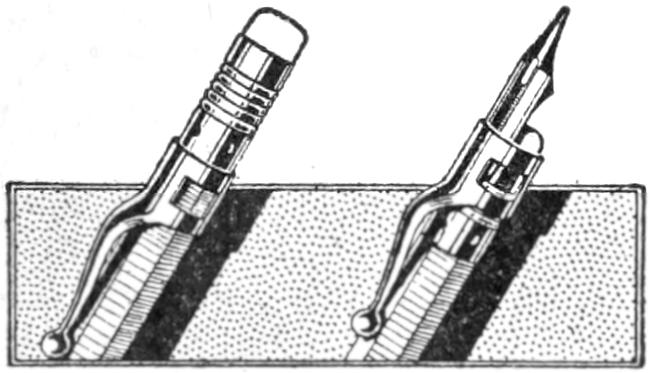

Amateur photographers will find a red lens attachment for a hand flash light a useful arrangement for the dark room, when going in or out, and during the process of developing, especially in temporary quarters. To fit the device in place, measure the distance around the outside of the lens holder, and lay out this dimension on a strip of tin, or other metal, 1 in. wide, as shown. Then add ¹⁄₈ in. at each end, and an extra strip, which should be cut into ¹⁄₄-in. sections, along the whole length. A spring tab, midway along the top edge of the metal, is also made. Curl the piece to a cylindrical form and clinch the joint as detailed, and bend the notched tabs into place. Slip a piece of ruby glass into the cylinder and hold it against the notched tabs with a spring ring. Then solder a small hinge to the edge of the cylinder and to the lens holder on the flash light, so that the spring tab will snap into place. When a white light is wanted, the red-glass fitting is released, as shown.

[7]

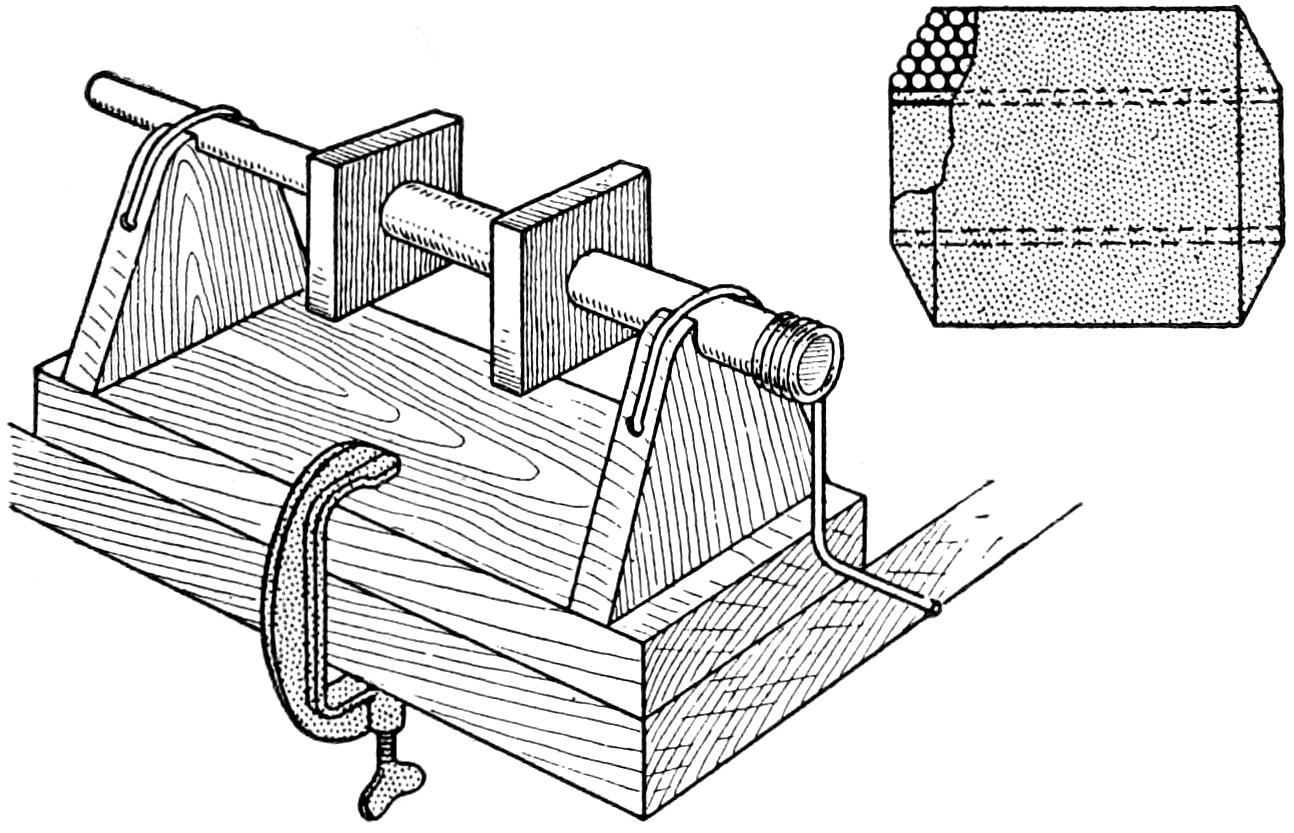

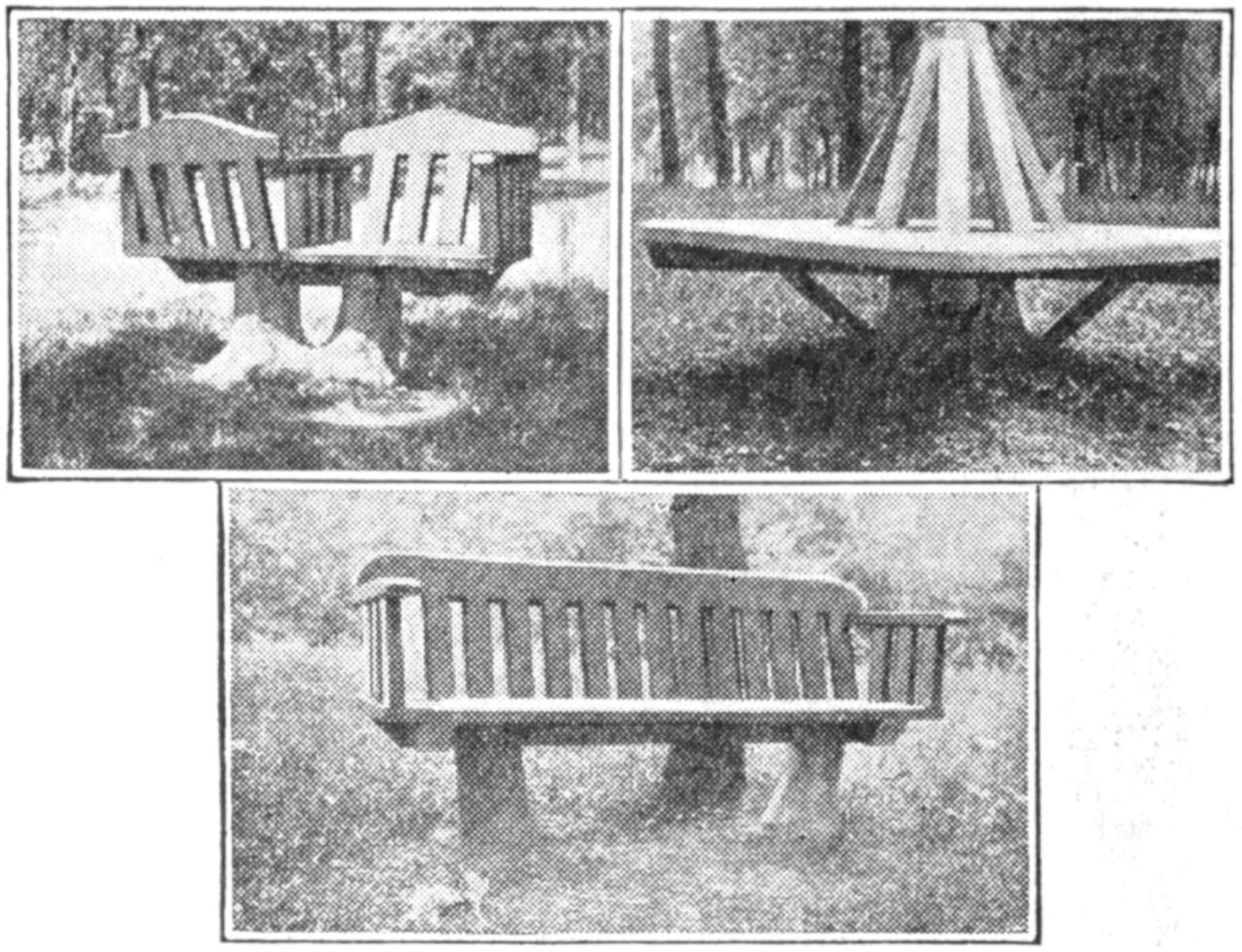

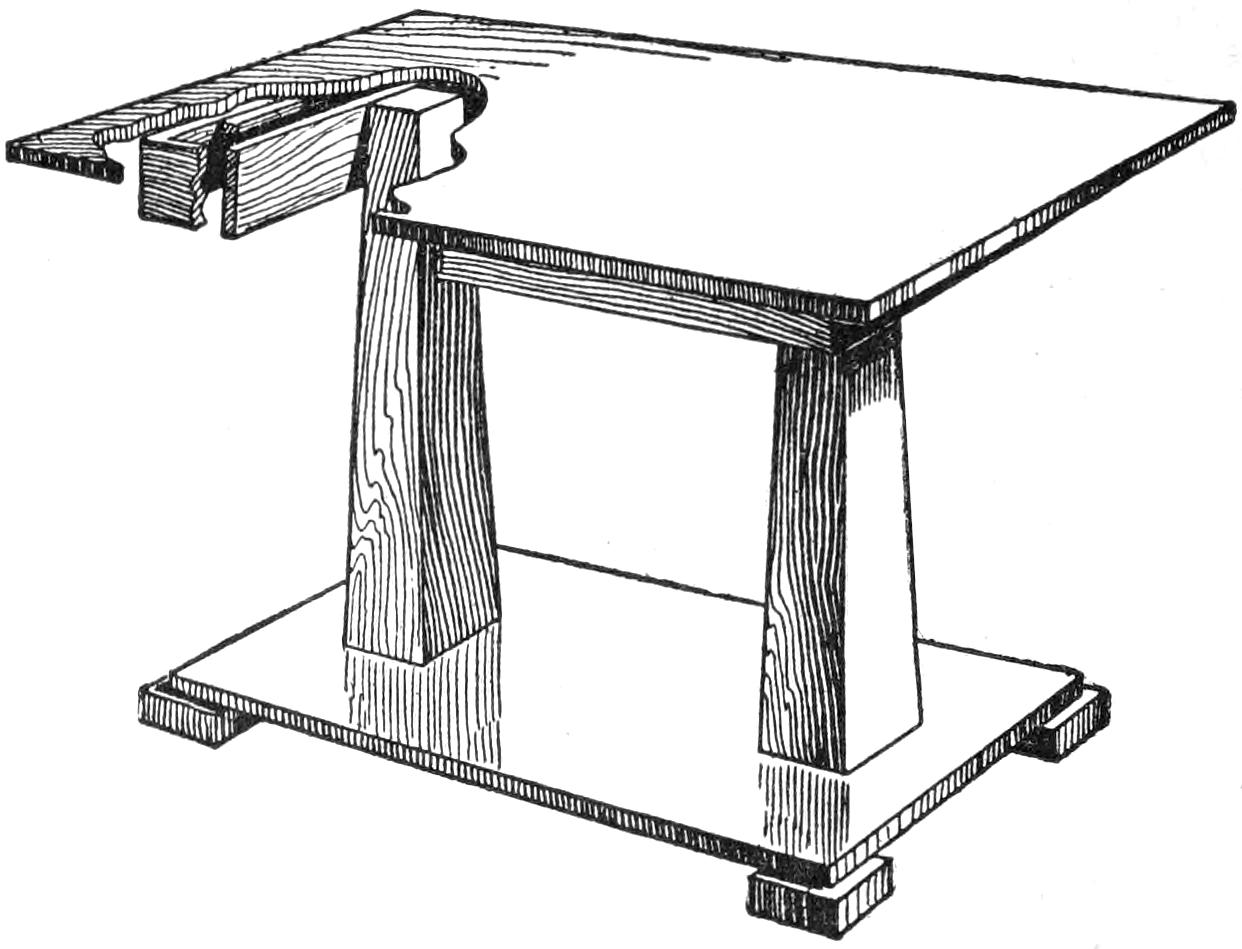

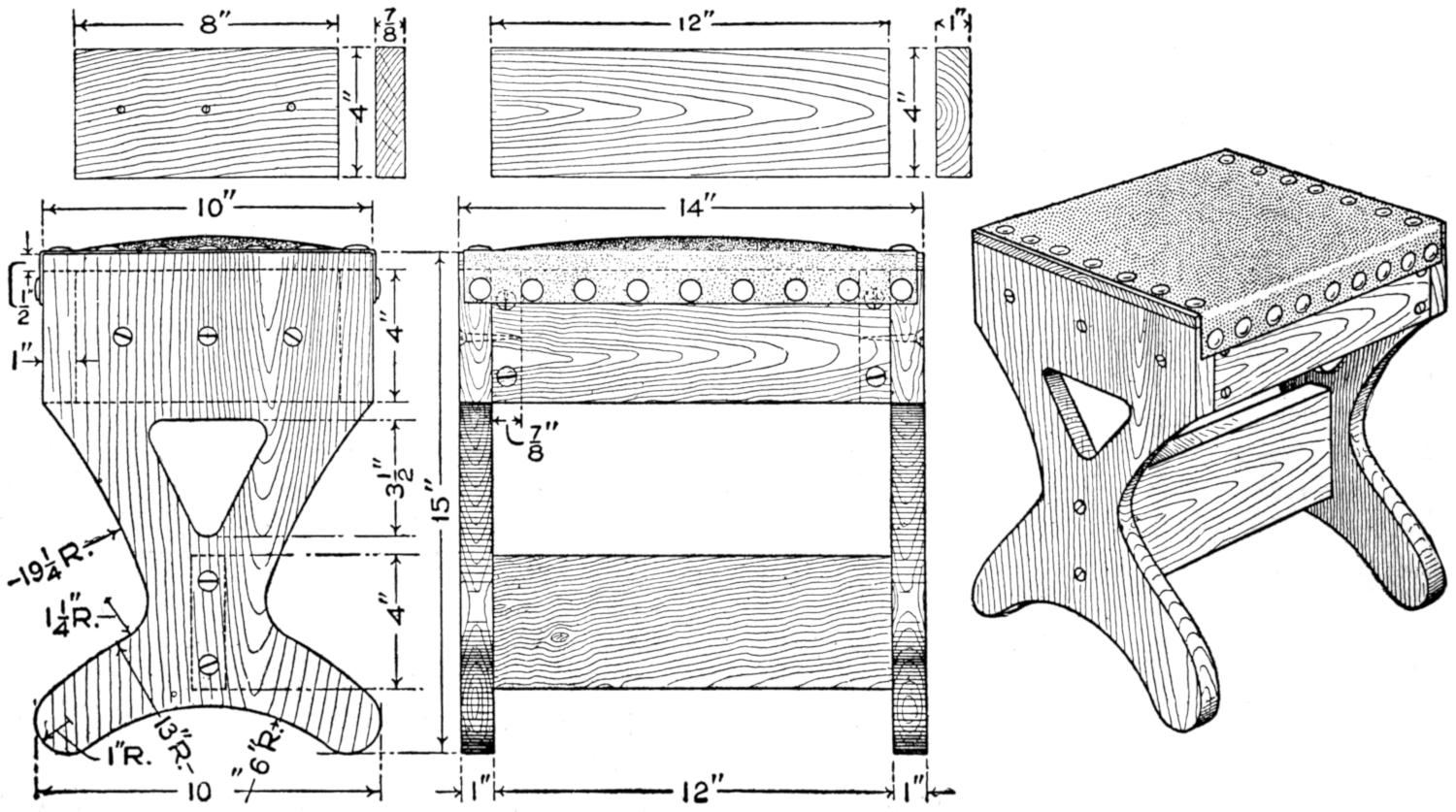

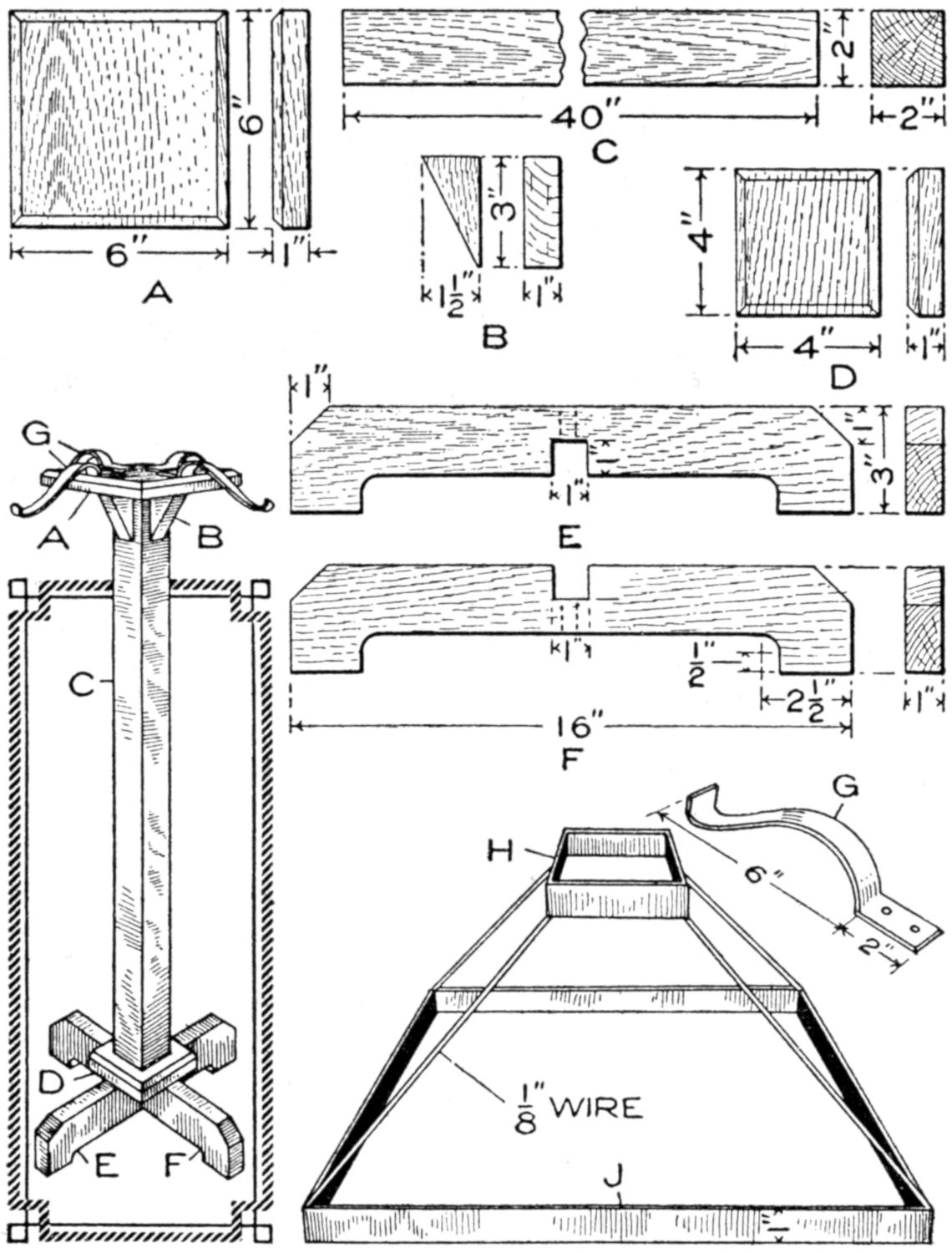

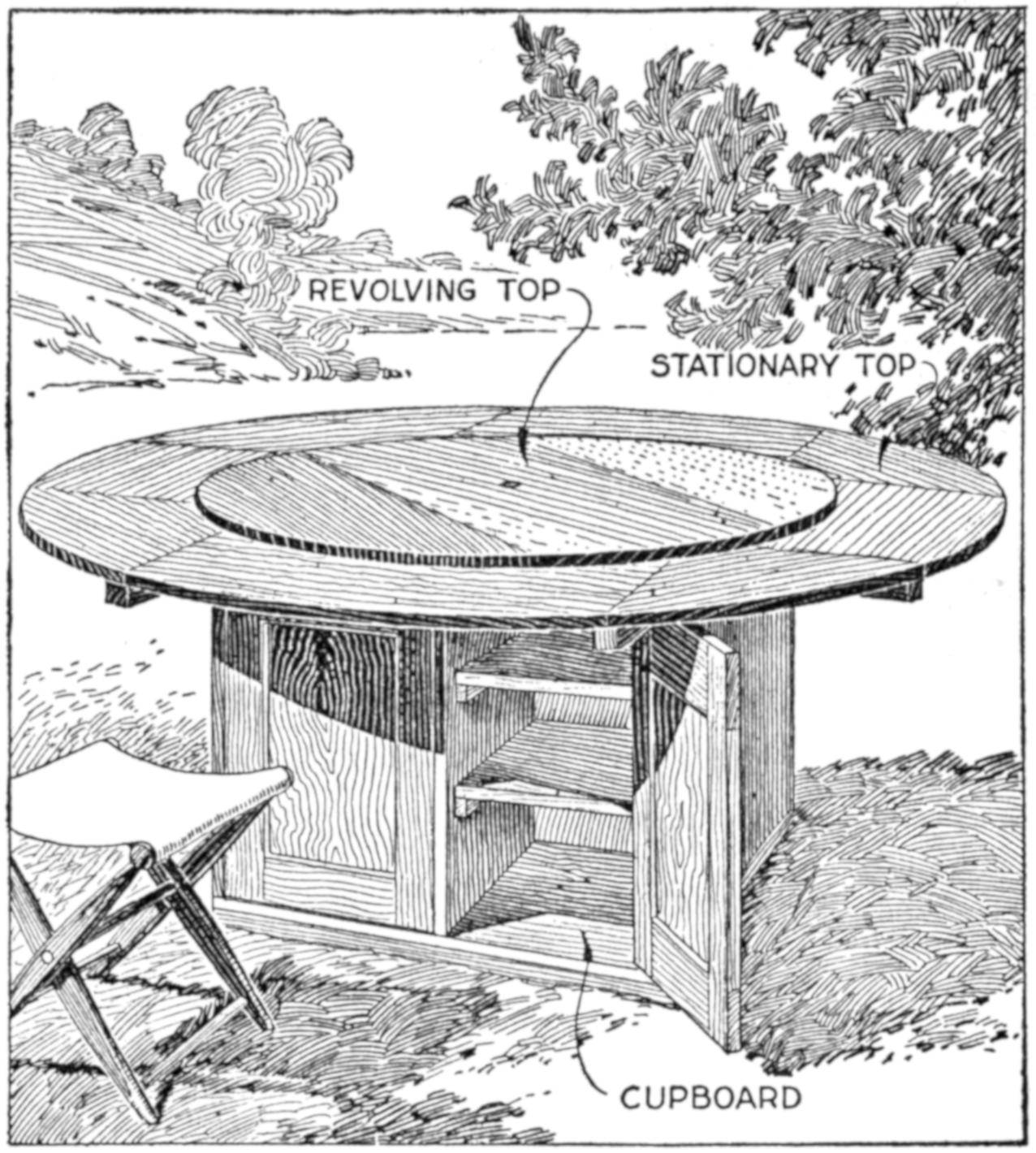

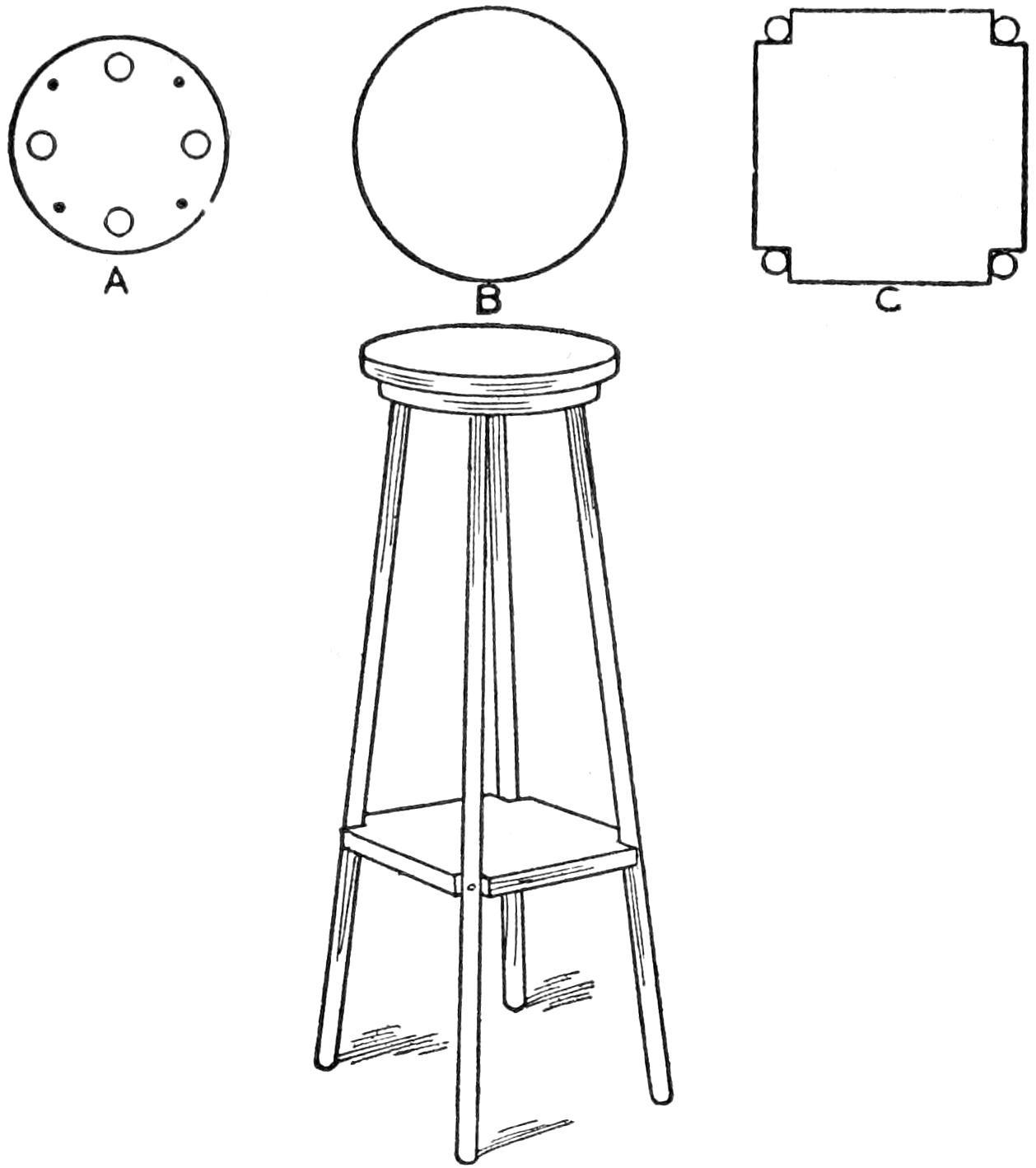

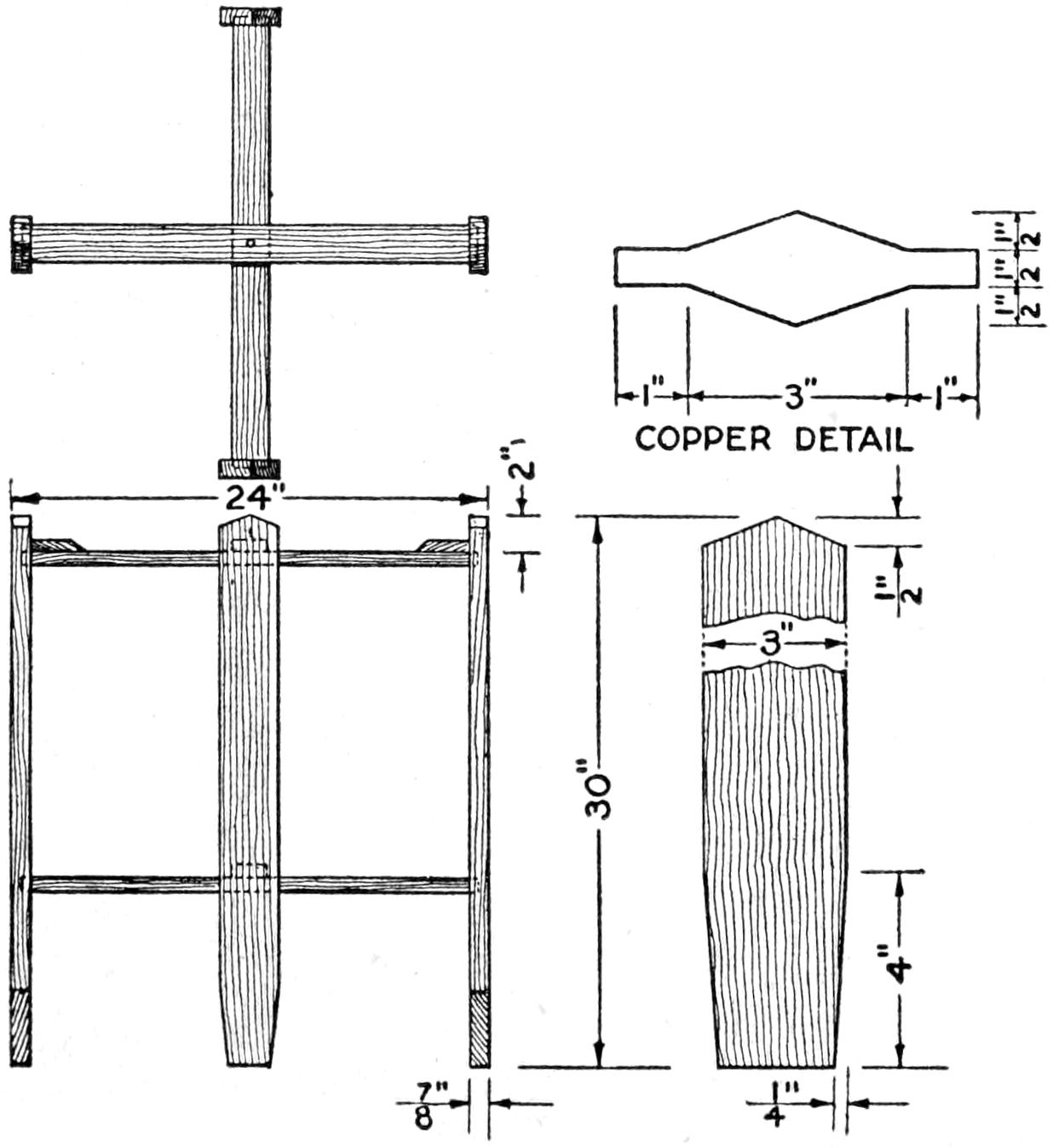

The home craftsman who is fairly skilled with woodworking hand tools will be well repaid for a little extra care in making this mission center table, of unusual design. Most of the woodwork involved in its construction is quite simple, the element calling for careful work being the laying out and shaping of the octagonal top and the shelf. Because of the wide surfaces exposed it will also pay the maker to plane, scrape, and sand down these surfaces carefully. By selecting the best pieces of wood and setting their better sides out, the effect is also enhanced. The table can be finished in a variety of ways to suit the furniture of the room where it is used. Various kinds of hard wood are suitable, quarter-sawed oak being preferable.

The Home Craftsman will Find the Making of This Octagonal Mission Center Table a Novel Piece of Construction. It Offers No Special Difficulties if Care is Taken in the Shaping of the Top and Shelf

Begin the construction by gluing up the pieces for the top and the shelf. While they are drying, make the pieces for the legs, the lower braces, and the strips for the edging of the top. The upper portion of the legs is of double thickness, ⁷⁄₈-in. stock being used throughout. Fit the lower supporting framework together as shown in the bottom view of the shelf, two of the braces extending across the bottom and the others butting against them.

When the top and shelf are dry, brace the top with cleats screwed on underneath, as shown in the bottom view of the top. Lay out the shelf accurately, and shape it to a perfect octagon, 25 in. across from opposite parallel sides. Make a strip, 1⁵⁄₈ in. wide, and use it in marking the layout for the top, from the shelf as a pattern, the edges of the top being parallel with those of the shelf and 1⁵⁄₈ in. from them.

Assemble the parts as shown, using glue and screws where practicable, and properly set nails for places where the fastening will be exposed. All the stock should be cleaned up thoroughly both before and after assembling. Four pieces for the casters are fastened to the legs with screws. The edging for the top may be mitered, with a rounded corner, as shown in the detail, or butted square against the edge of the top, as indicated in the photograph and the plan of the top, the latter method being far easier.

¶The nuisance of tracking dust and ashes from the basement can be overcome, to a considerable extent, by providing carpet mats on two or three lower treads of the stairs leading from the basement to the rooms above.

[8]

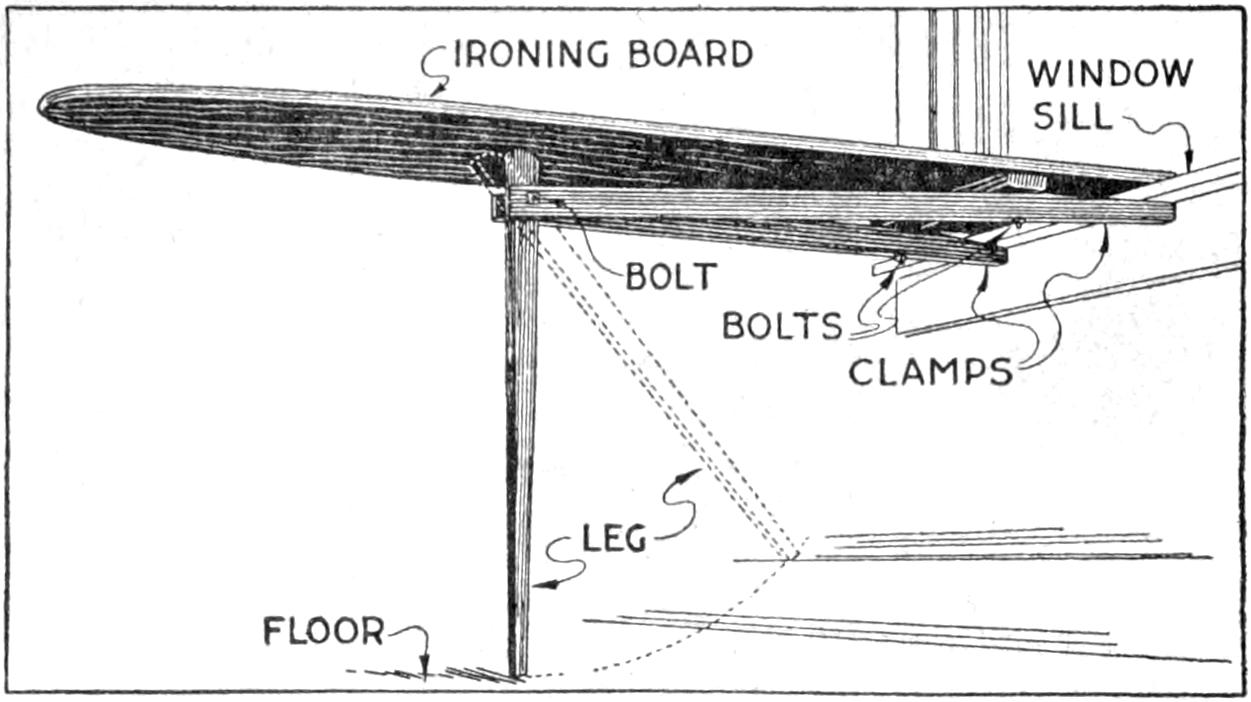

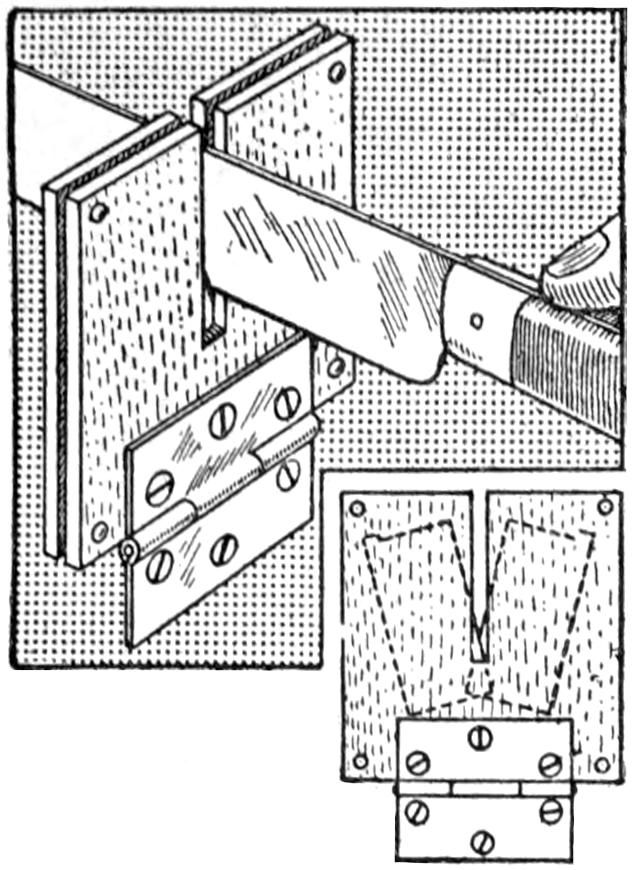

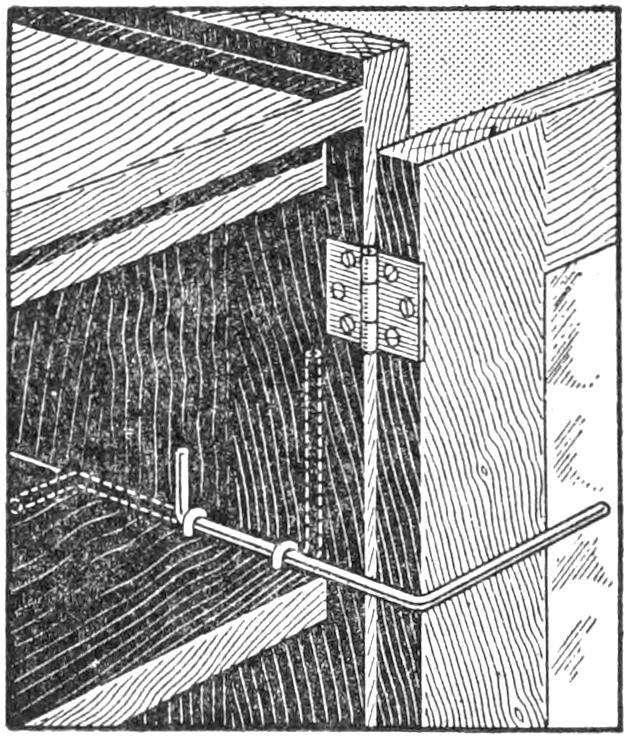

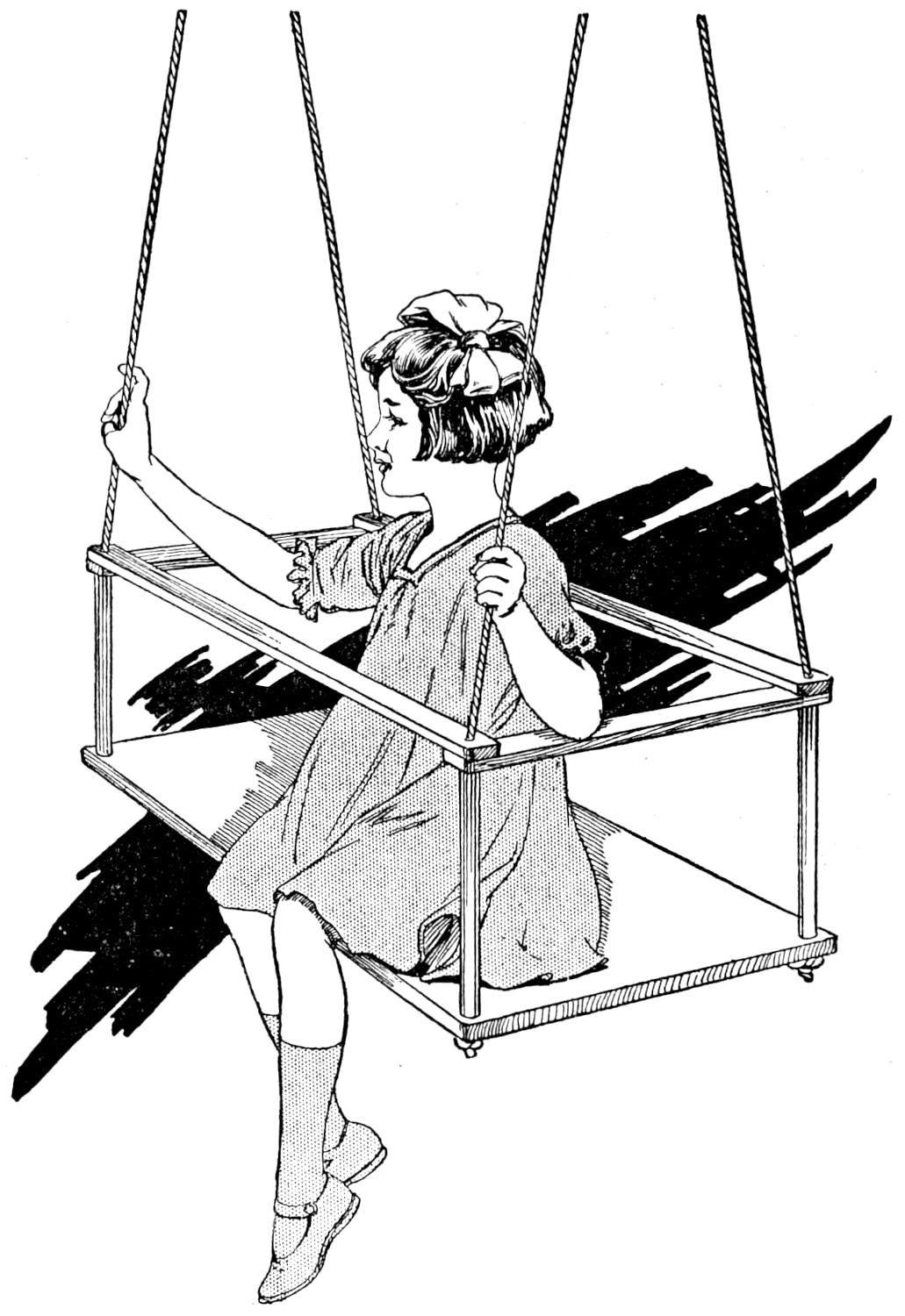

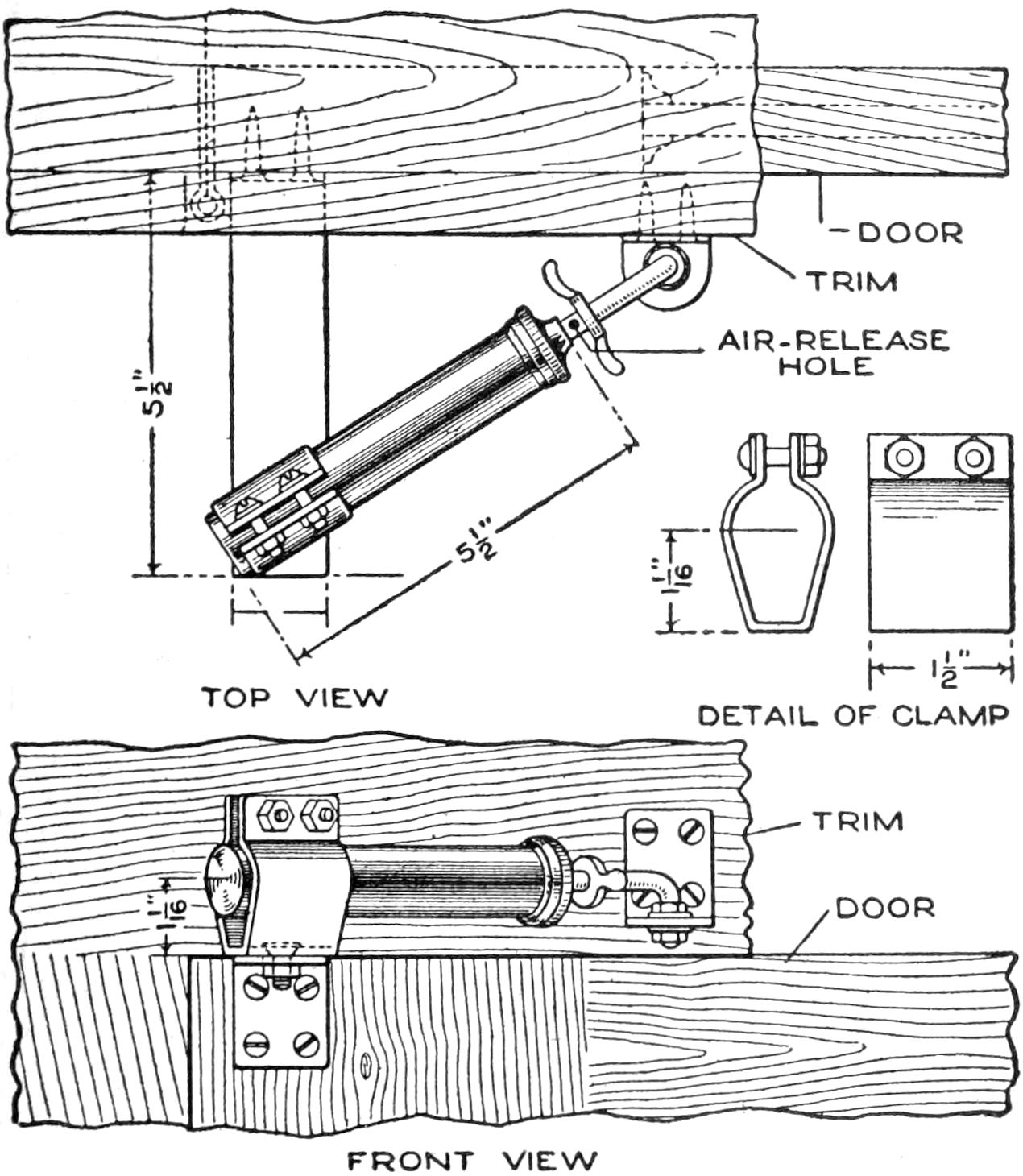

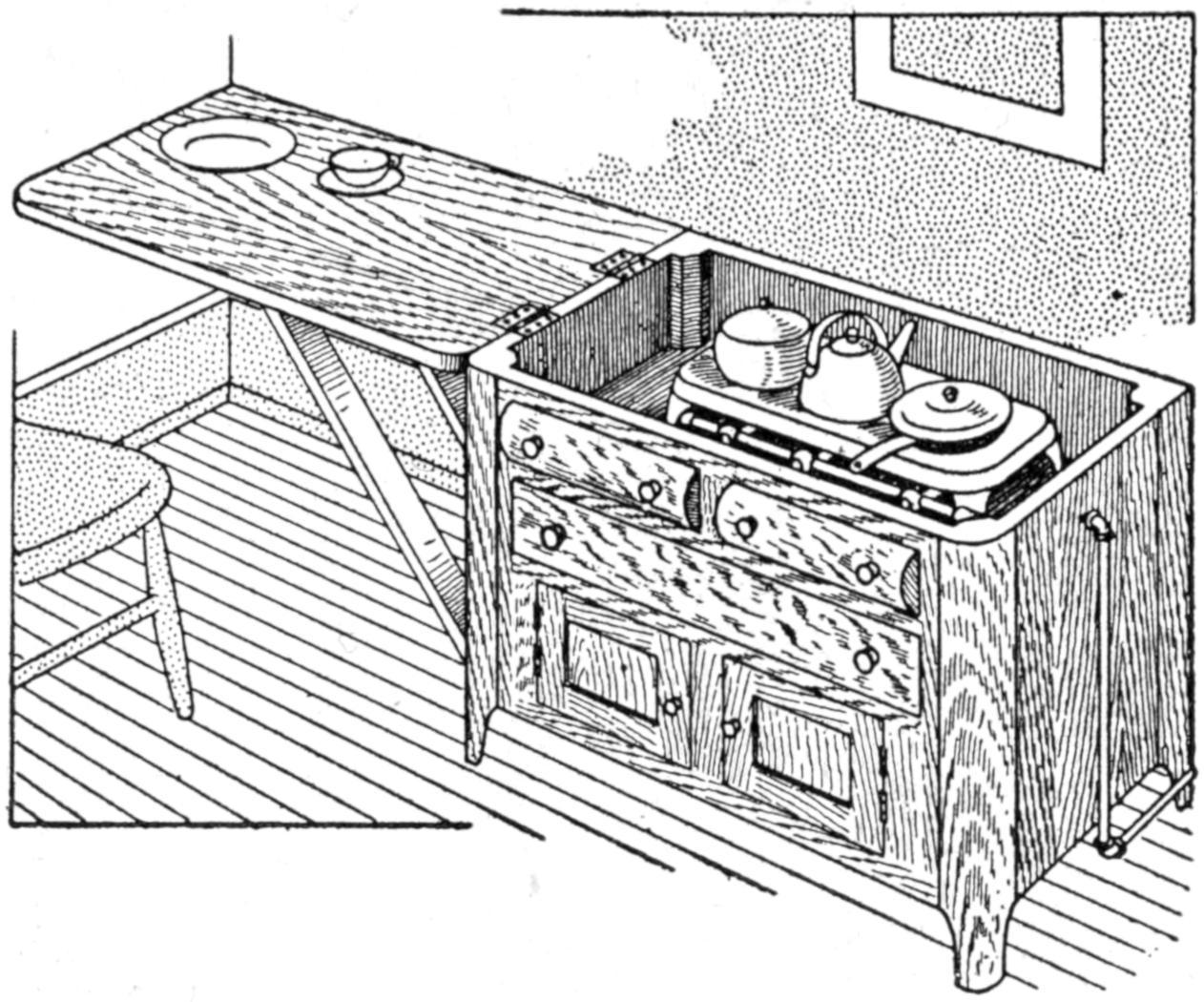

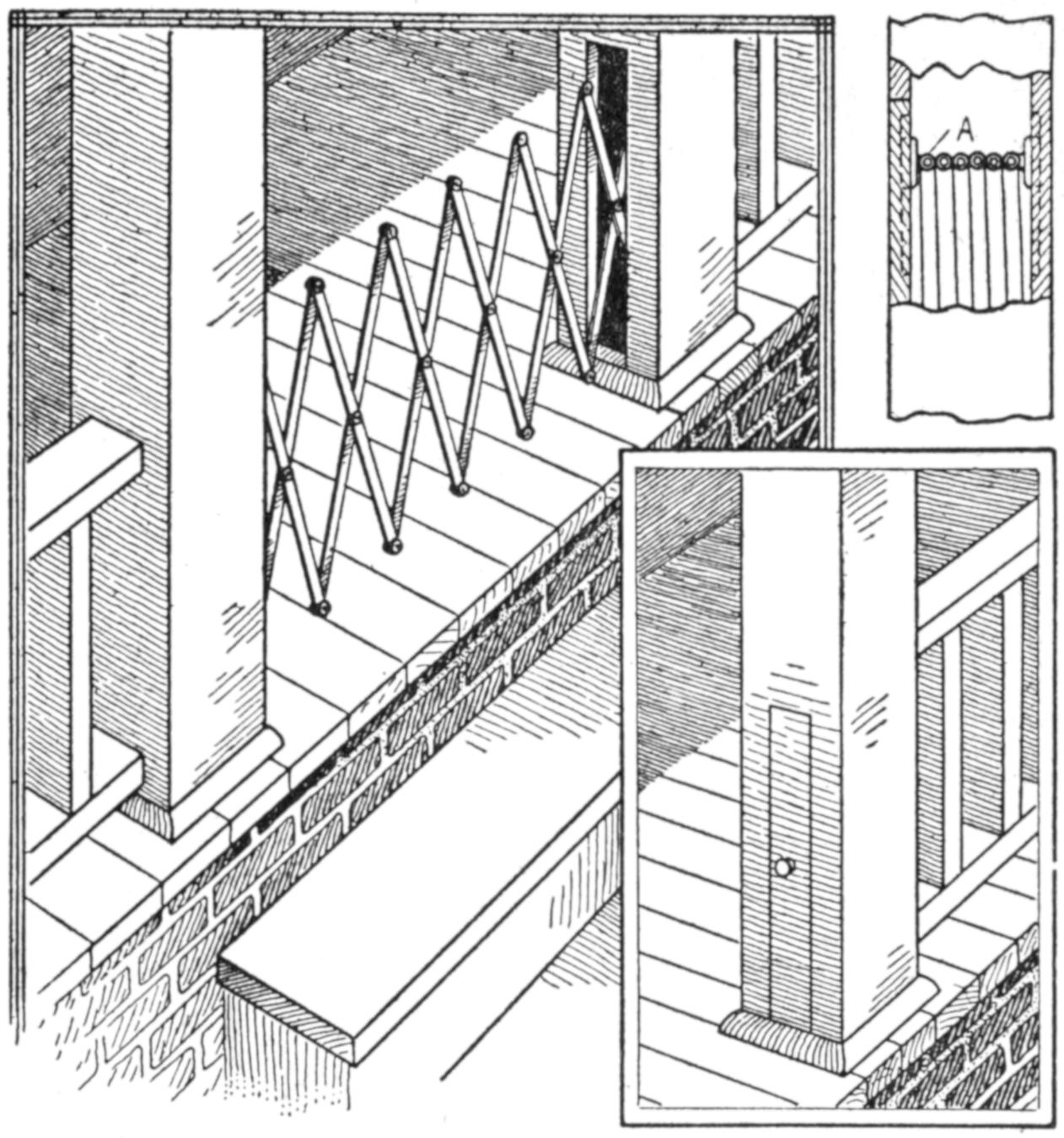

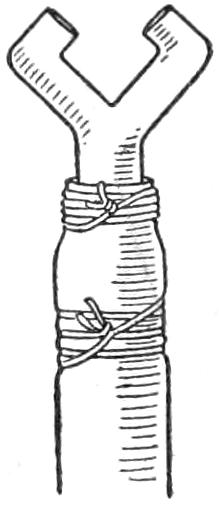

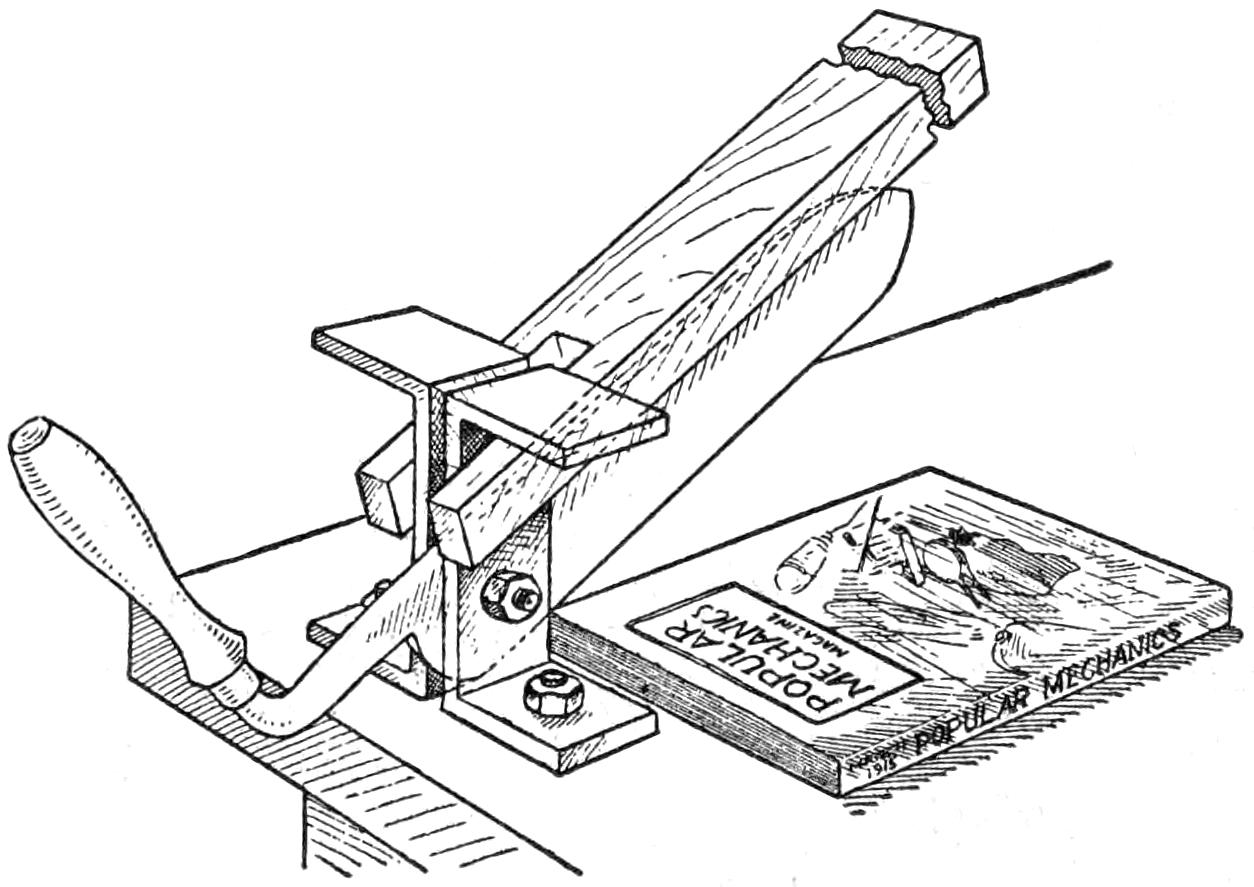

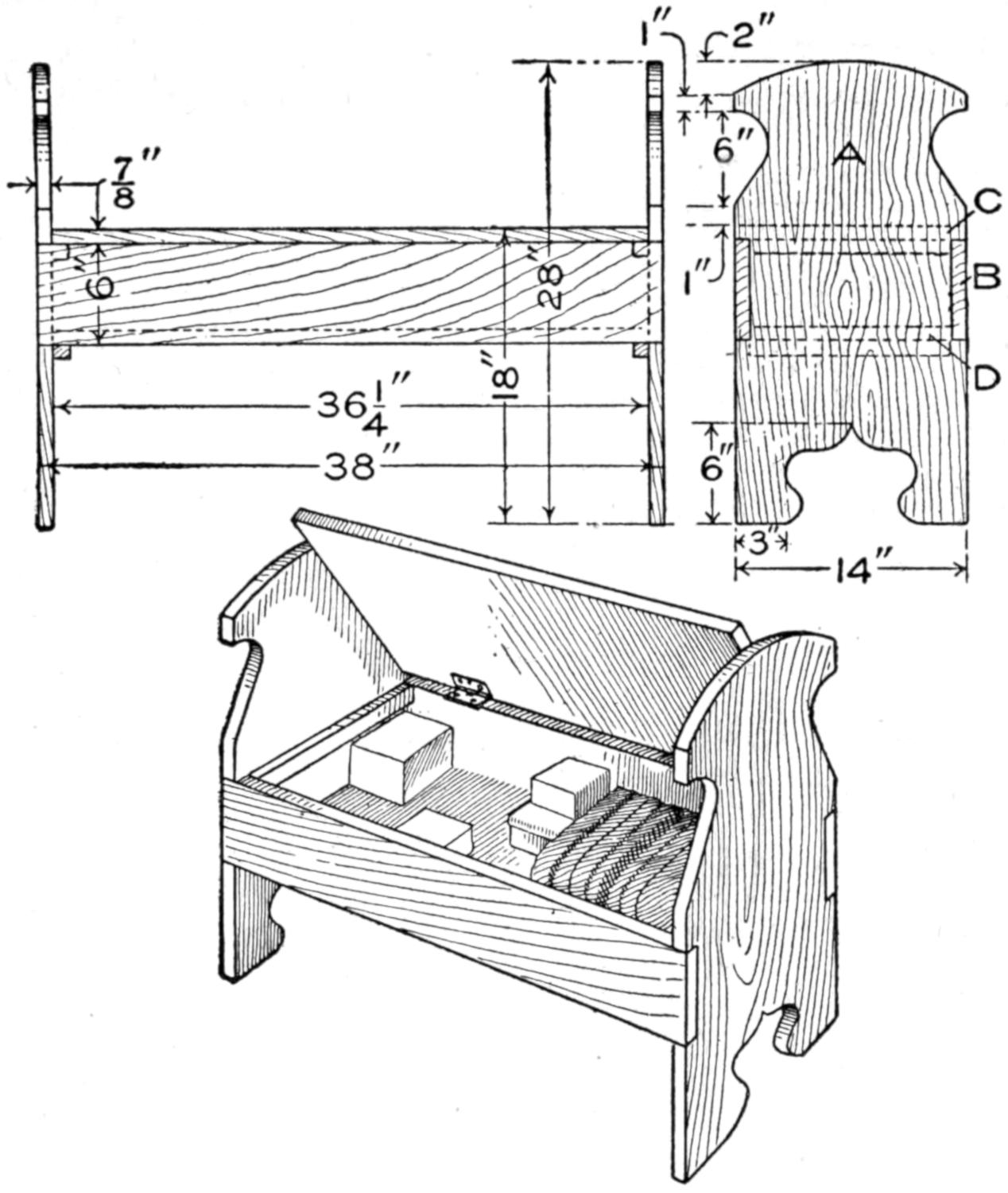

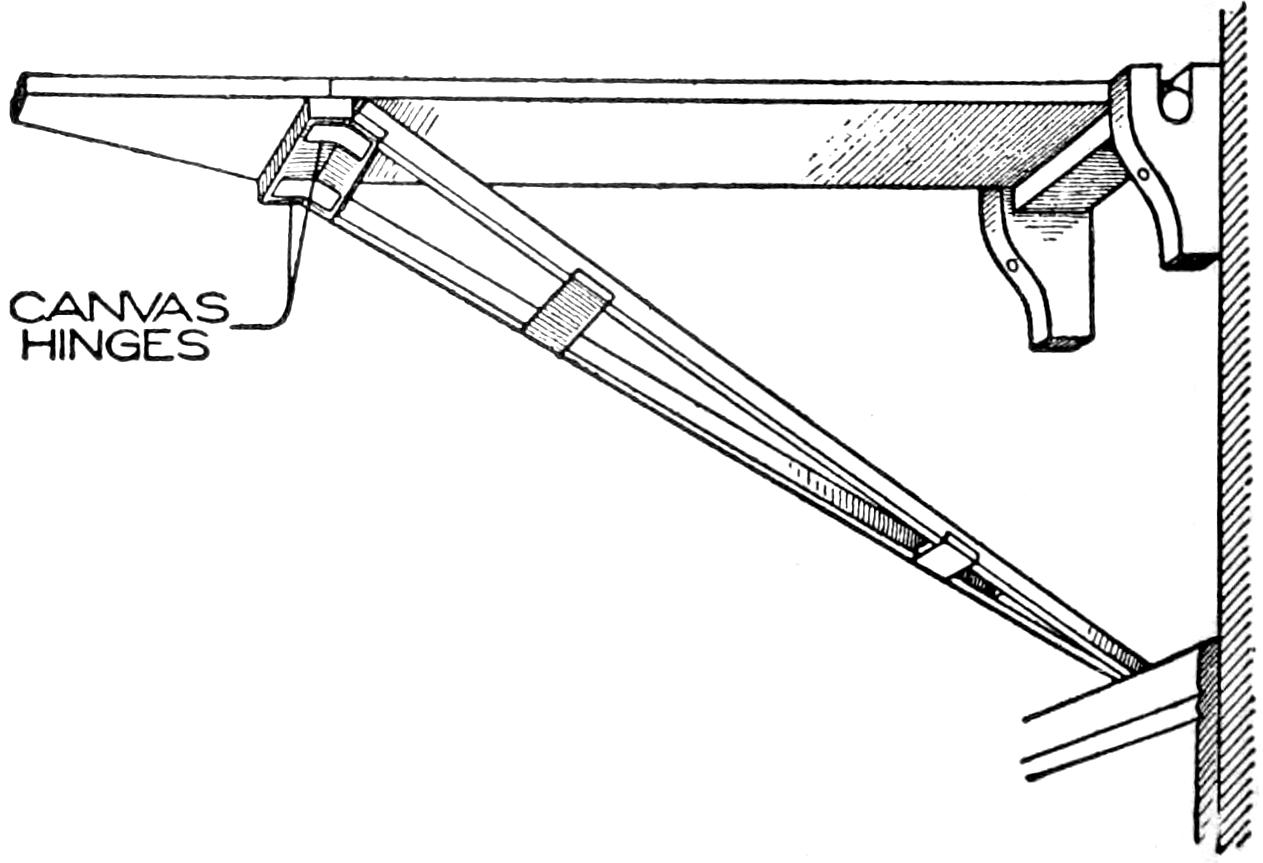

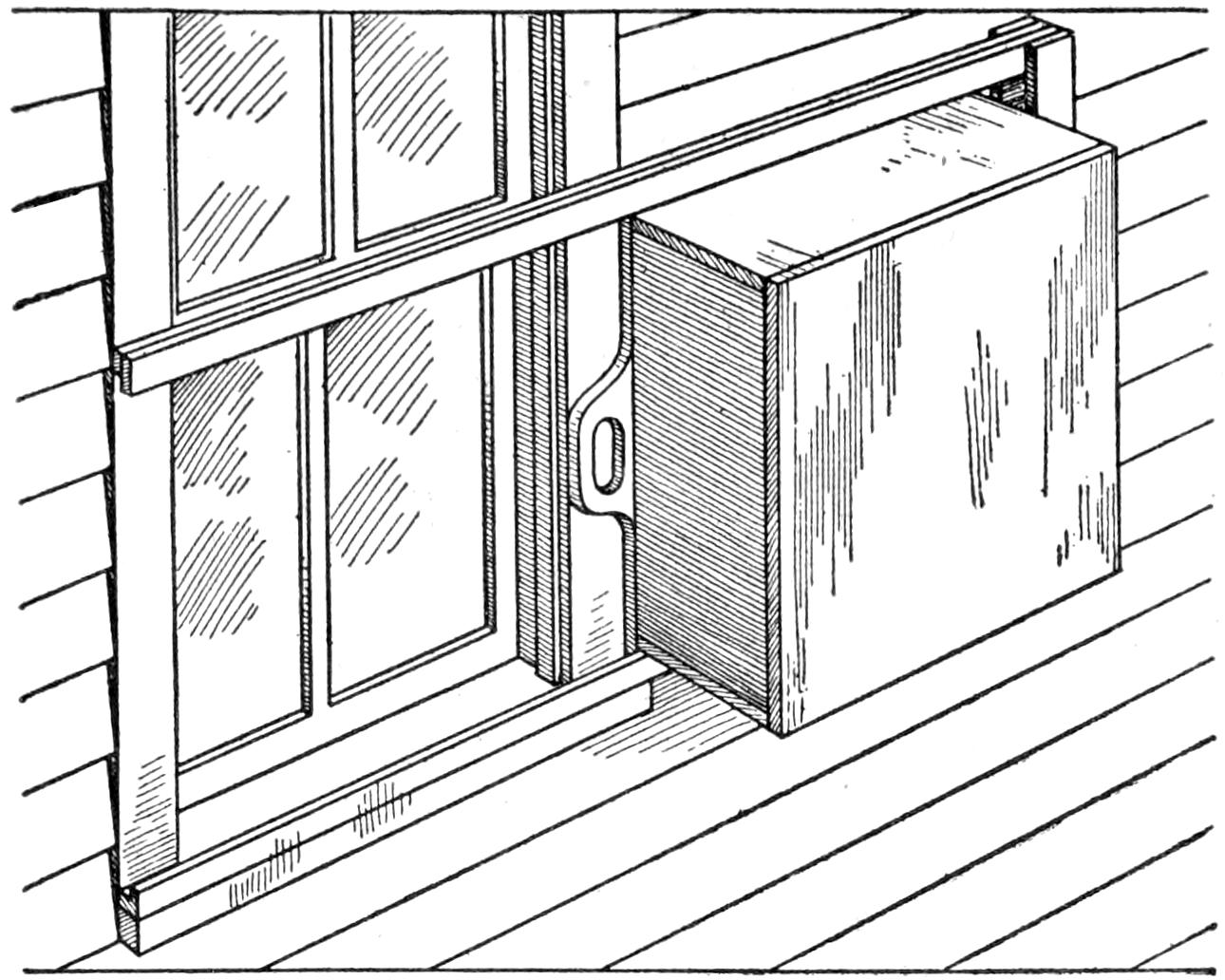

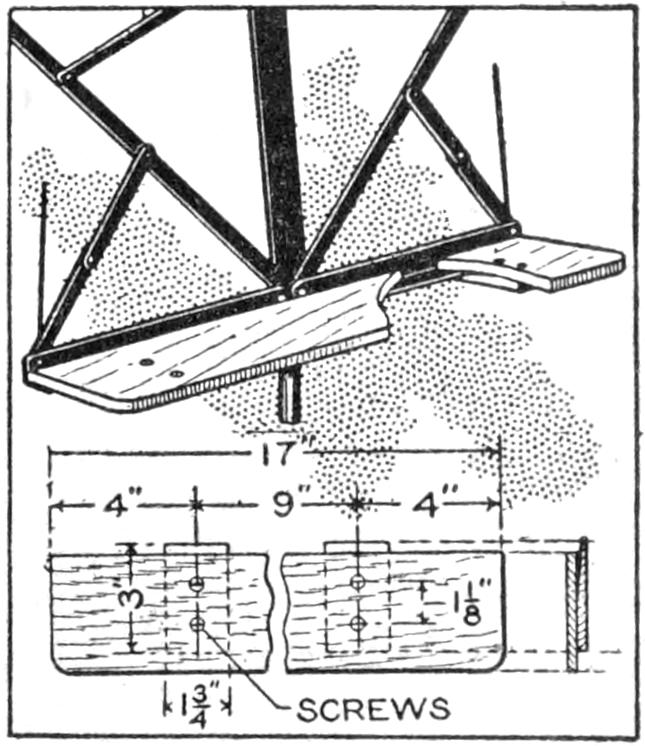

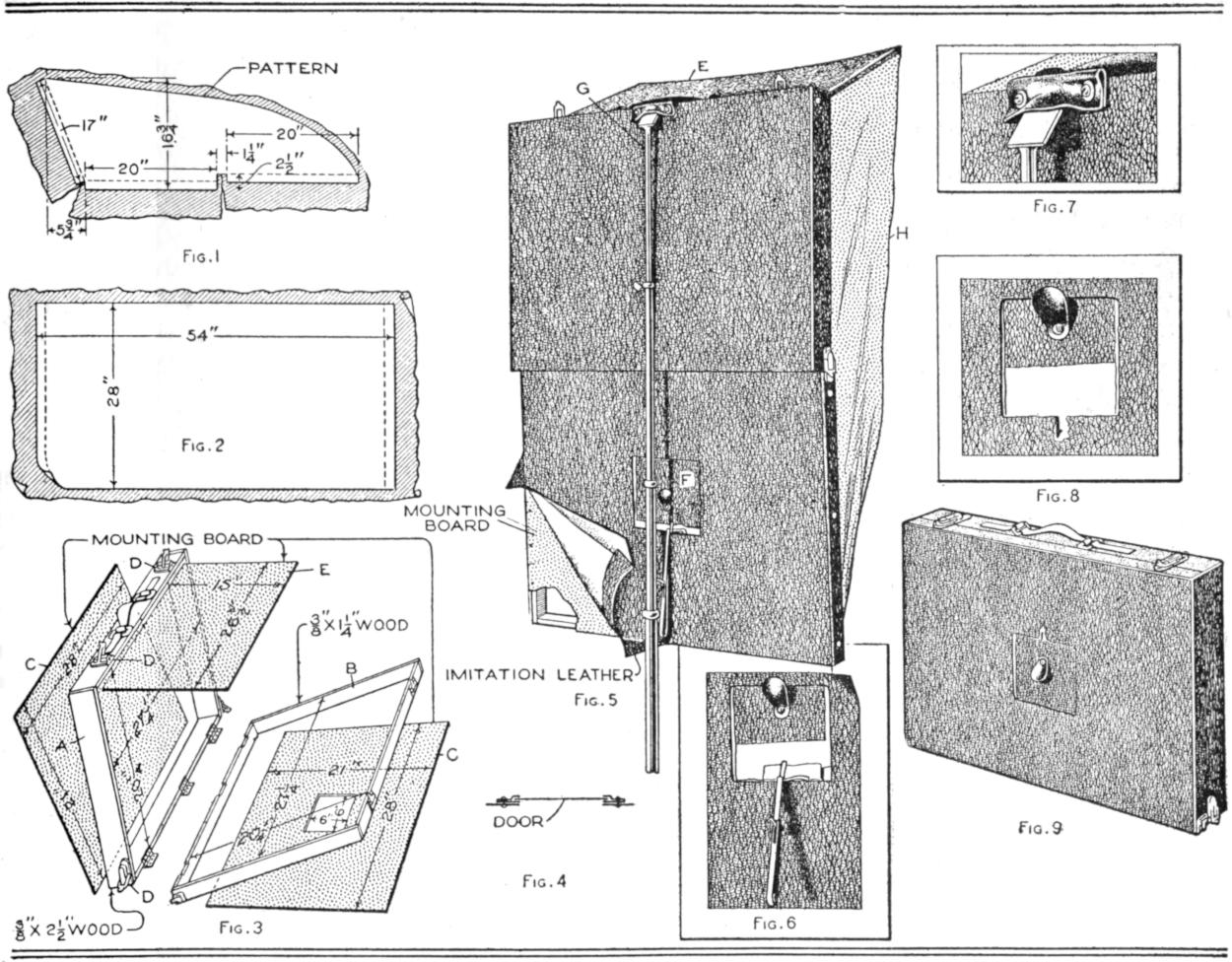

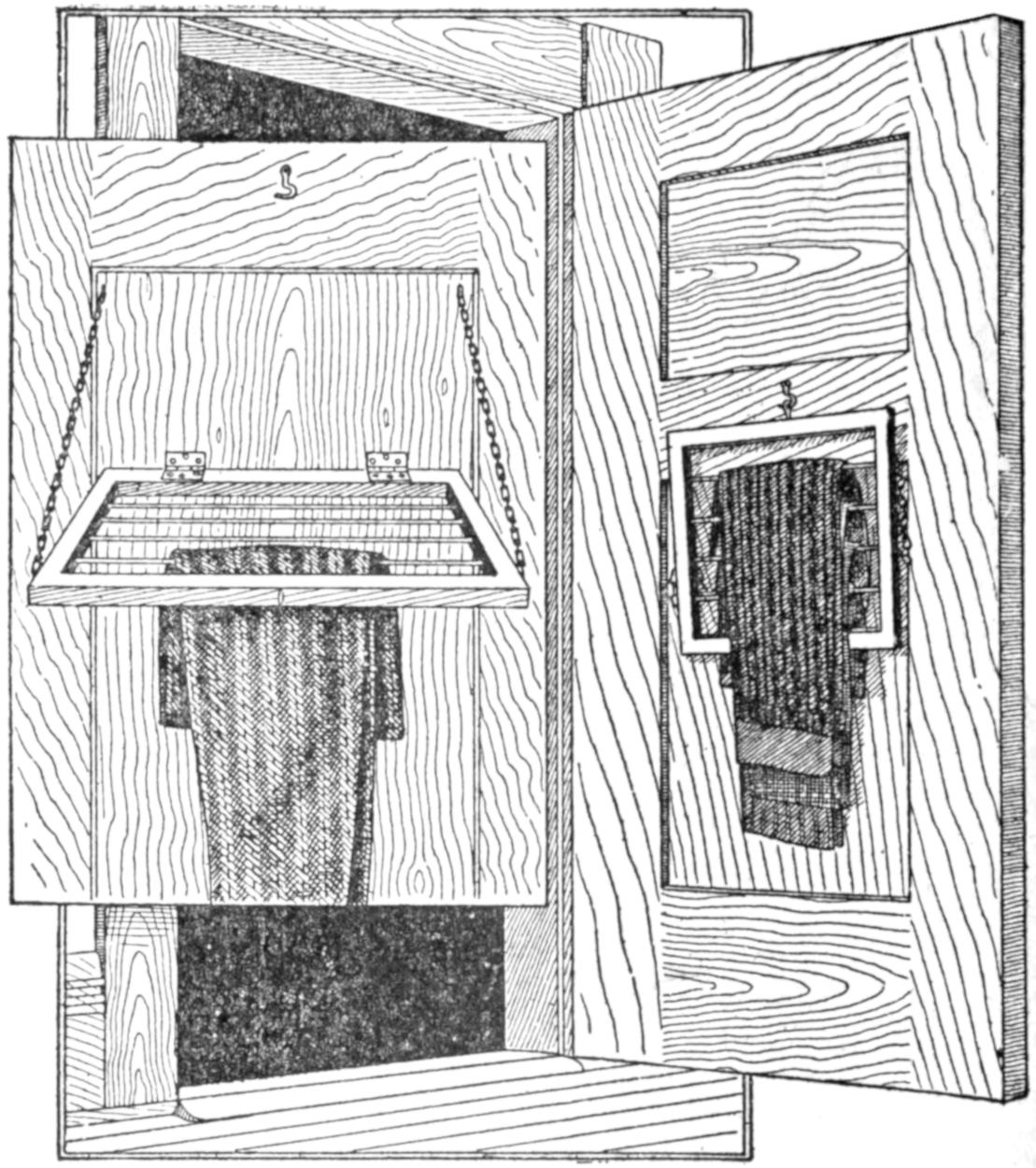

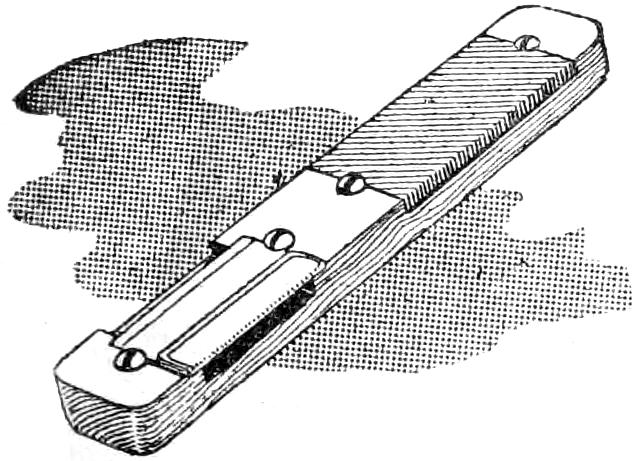

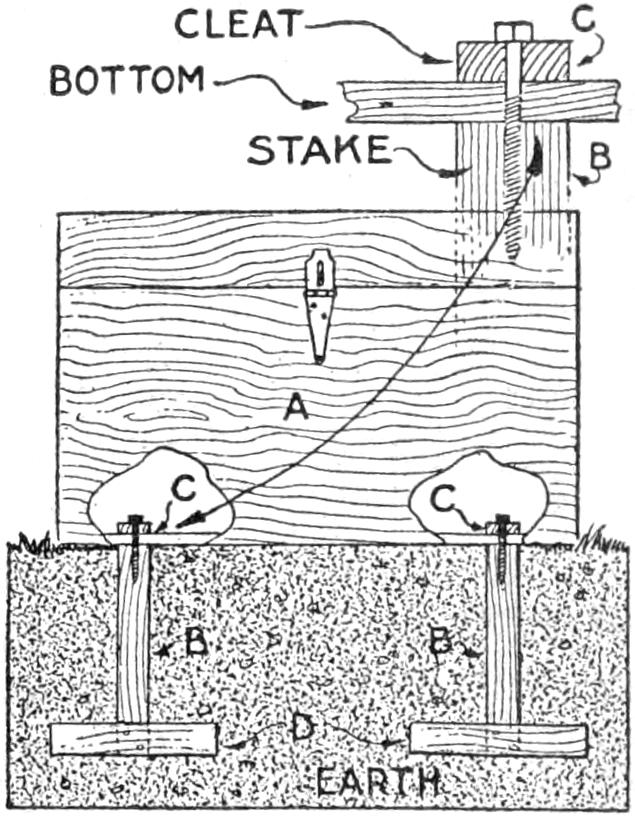

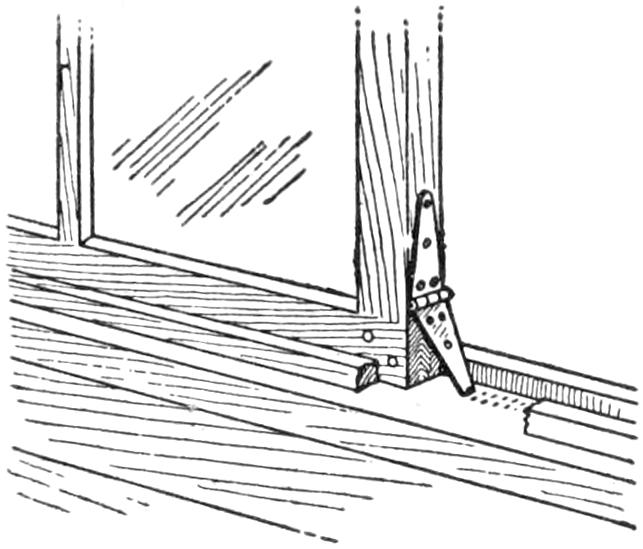

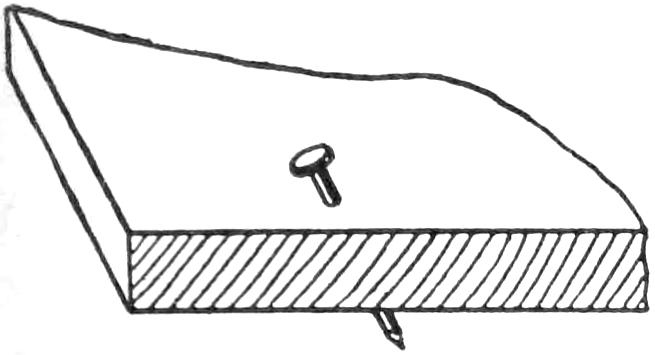

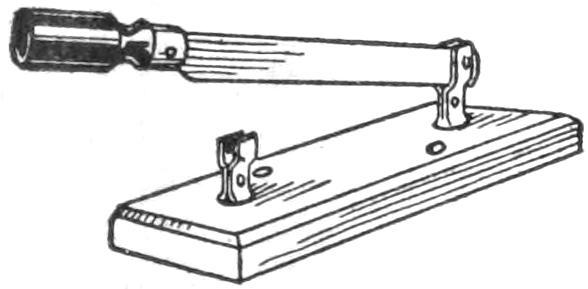

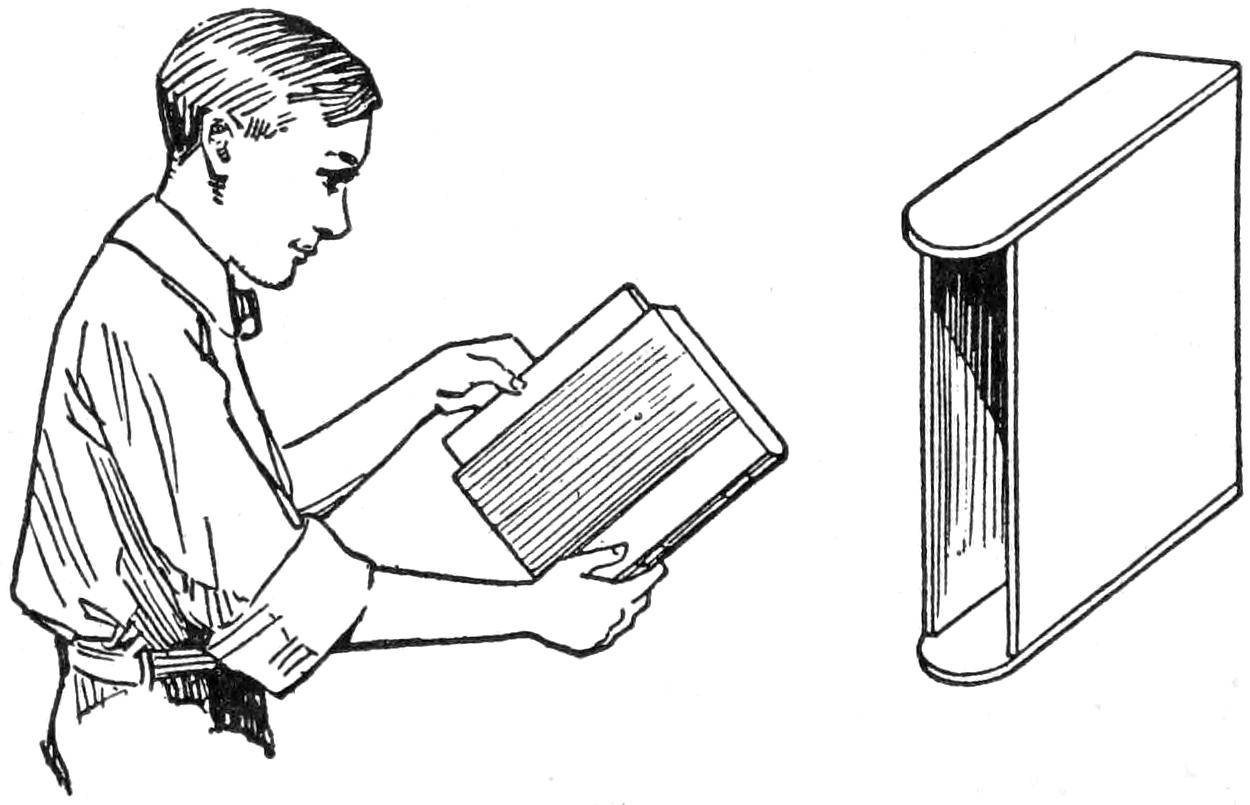

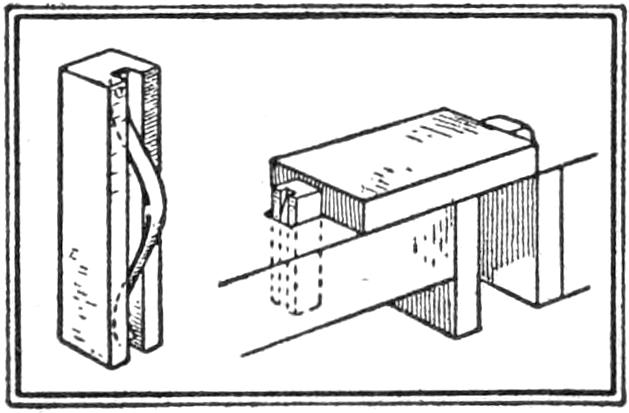

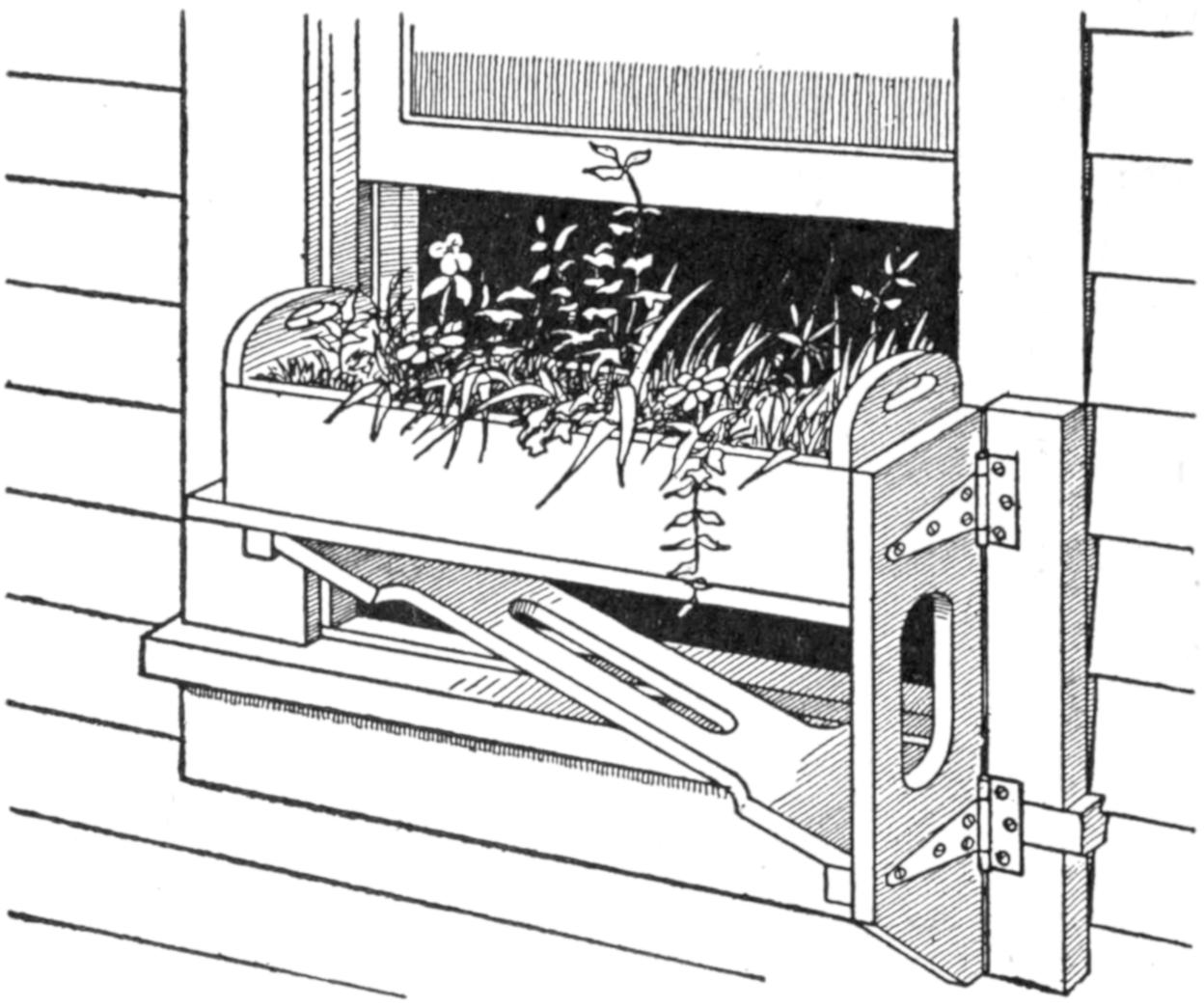

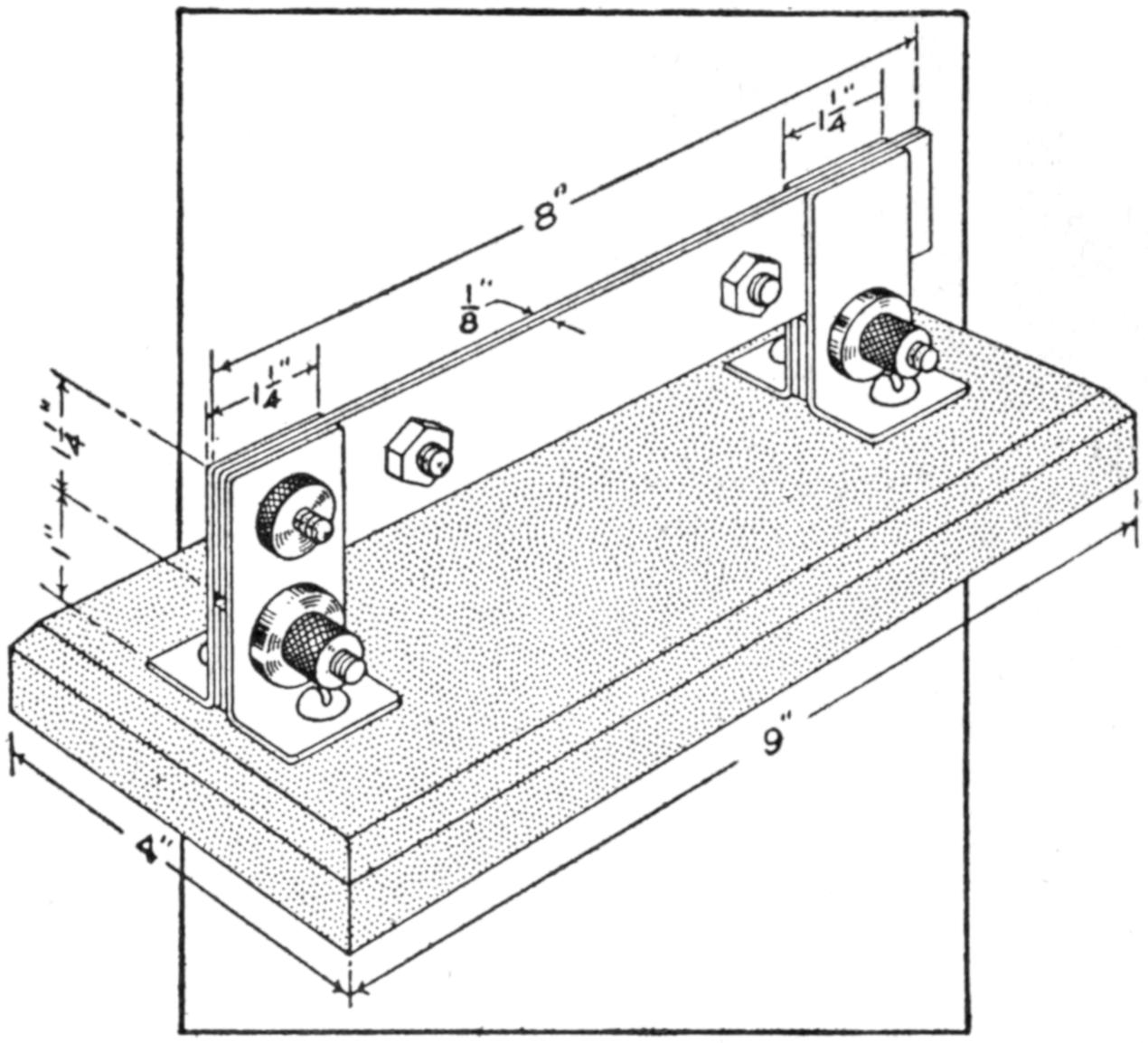

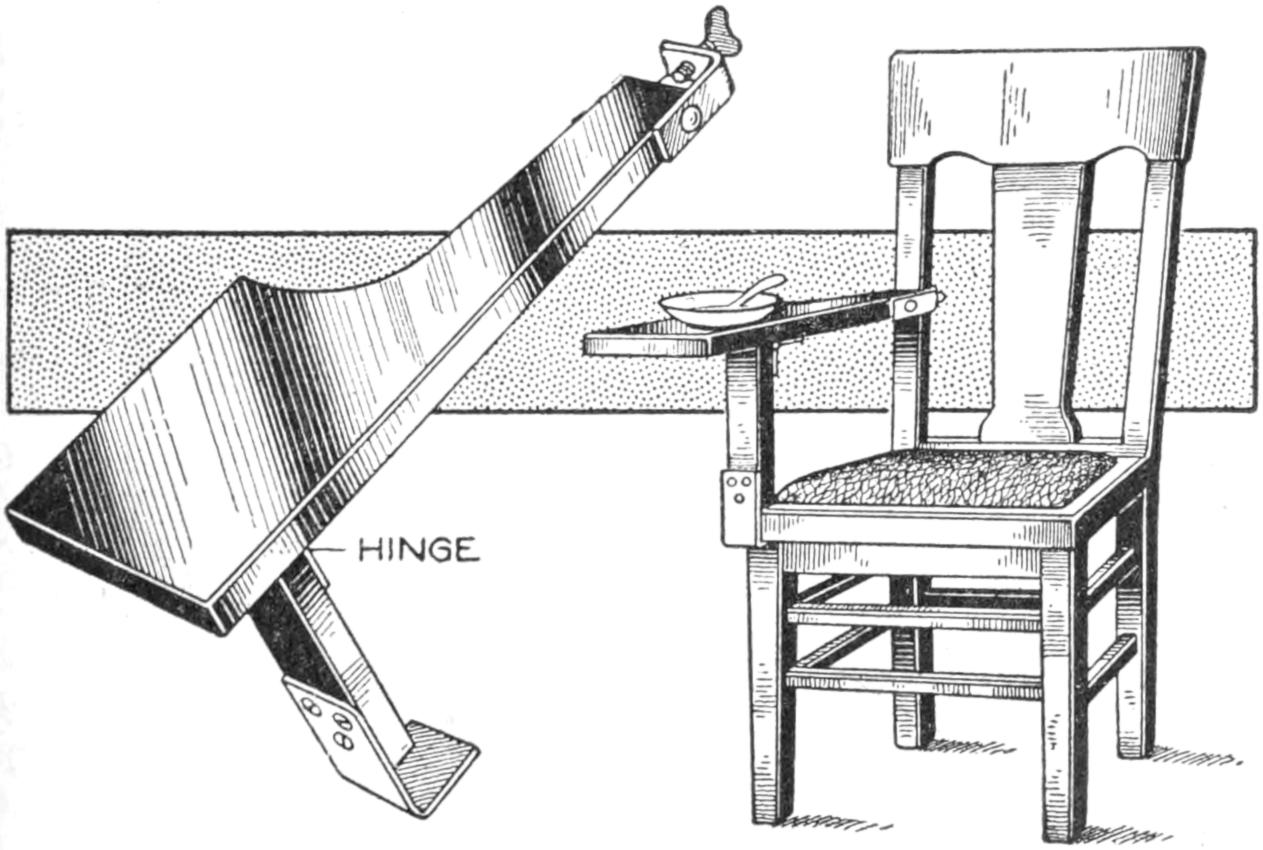

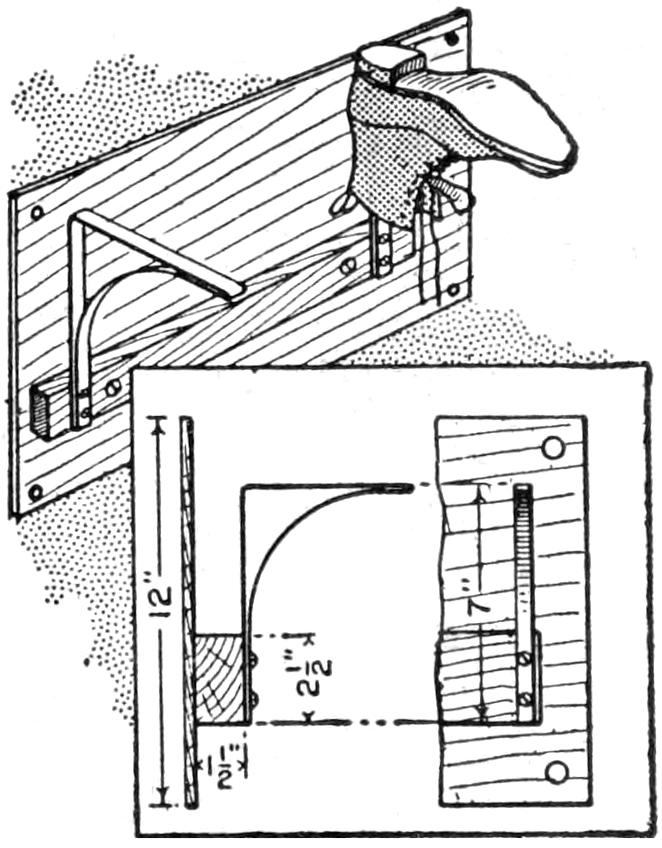

This Rigid Ironing Board Folds Compactly and can be Set Up with Ease at the Window Sill

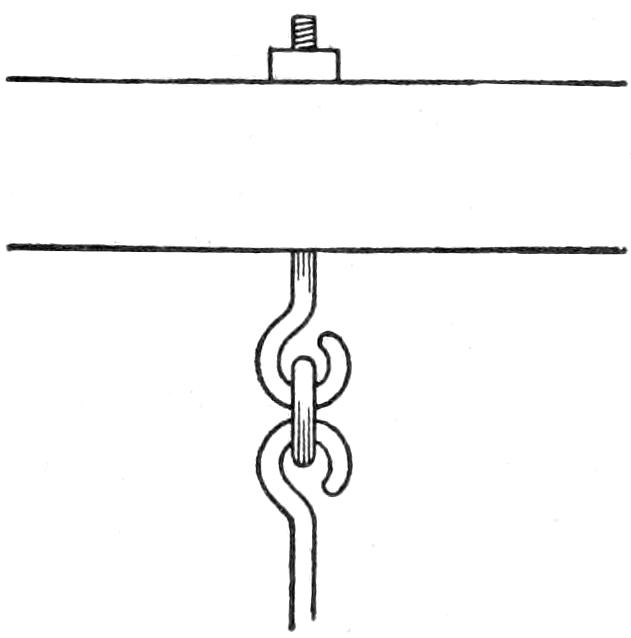

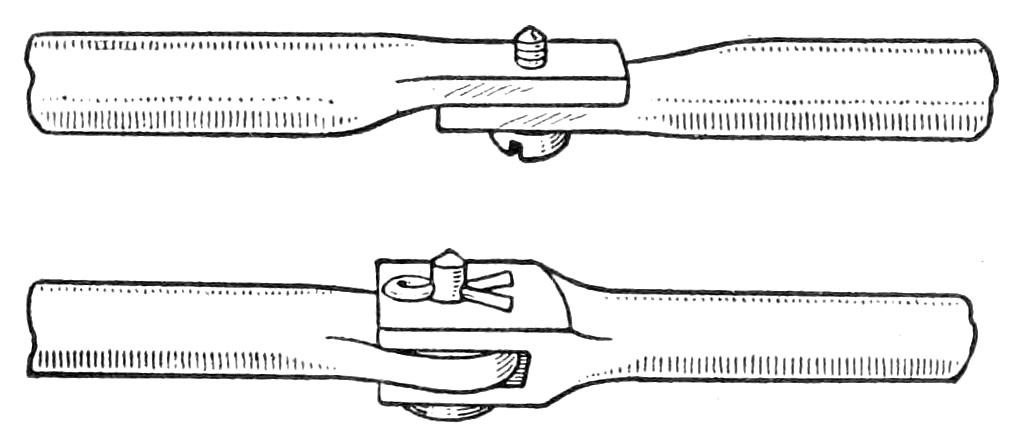

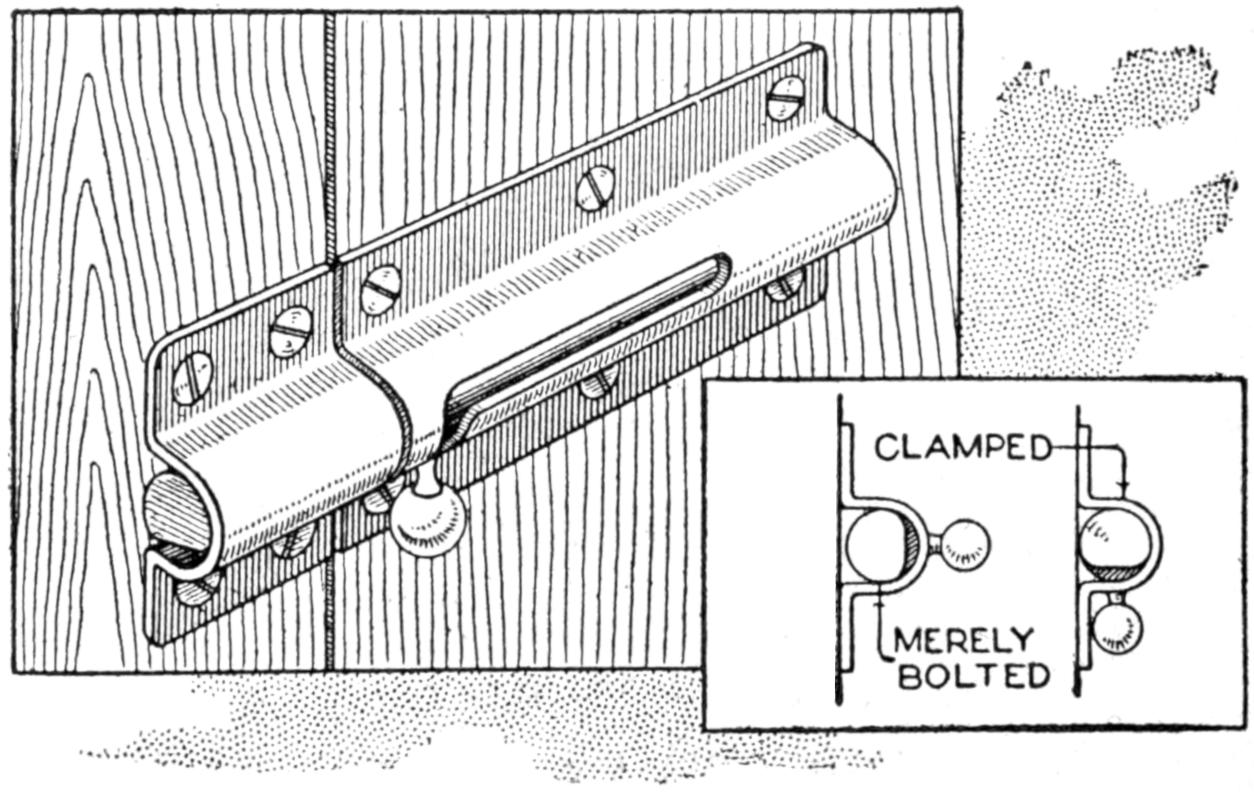

An ironing board is usually most convenient for use when its left end is set near a window, or other source of light. The arrangement shown in the sketch was designed with this in mind, and other interesting features were added. The top is of the usual type. Arranged underneath it is a cross cleat near one end. Bolted through this are two clamps which engage the edge of the window sill or table. They are clamped by lowering the leg from its folded position, underneath the top, as indicated. The bolts at the clamps are adjustable for gripping various thicknesses of table tops, etc., between the clamps and the top. The lower end of the leg can be fitted with a sliding adjustment, if the board is used at different heights, the design being otherwise the same.—T. J. Hubbard, Mendota, Ill.

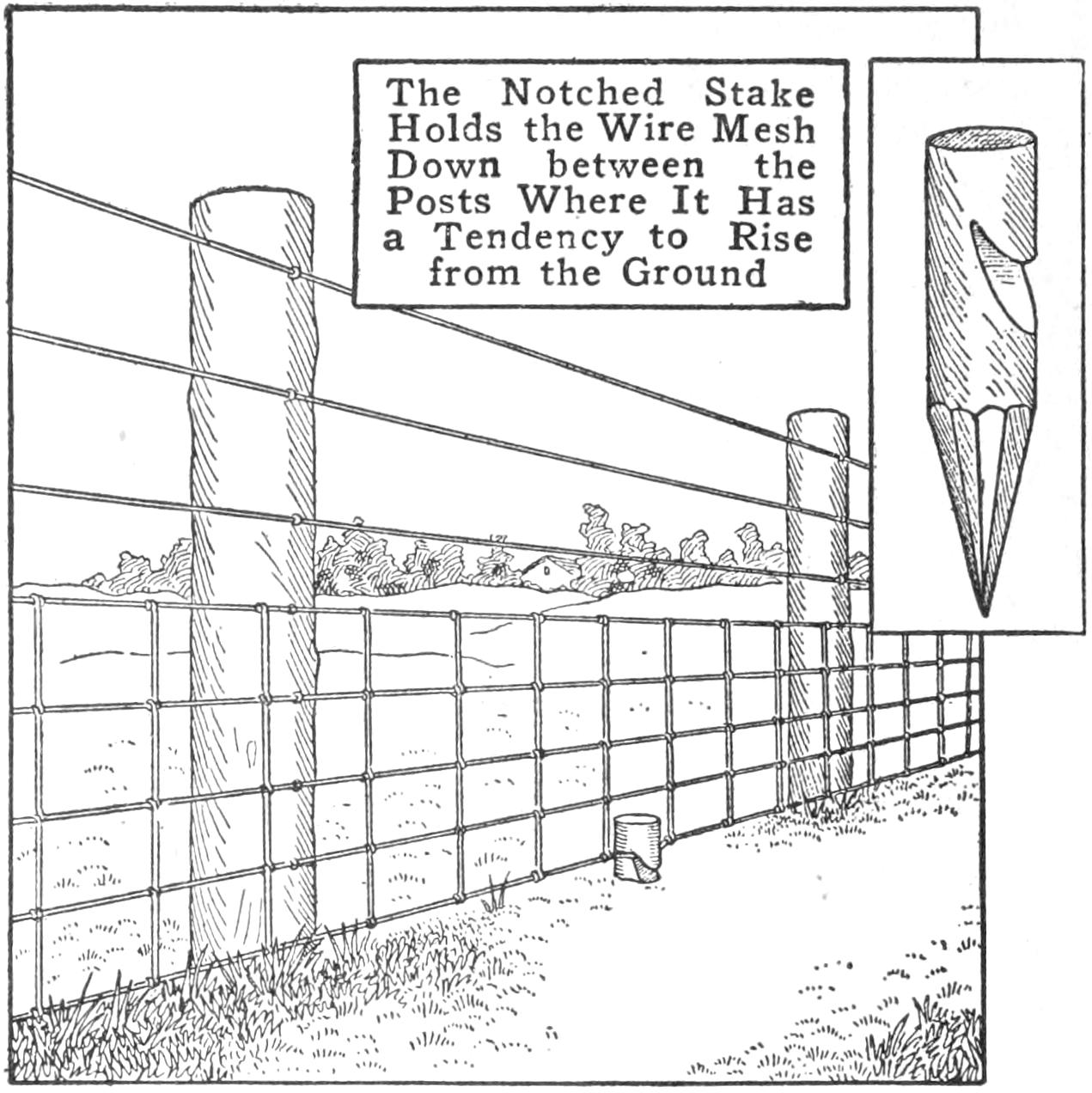

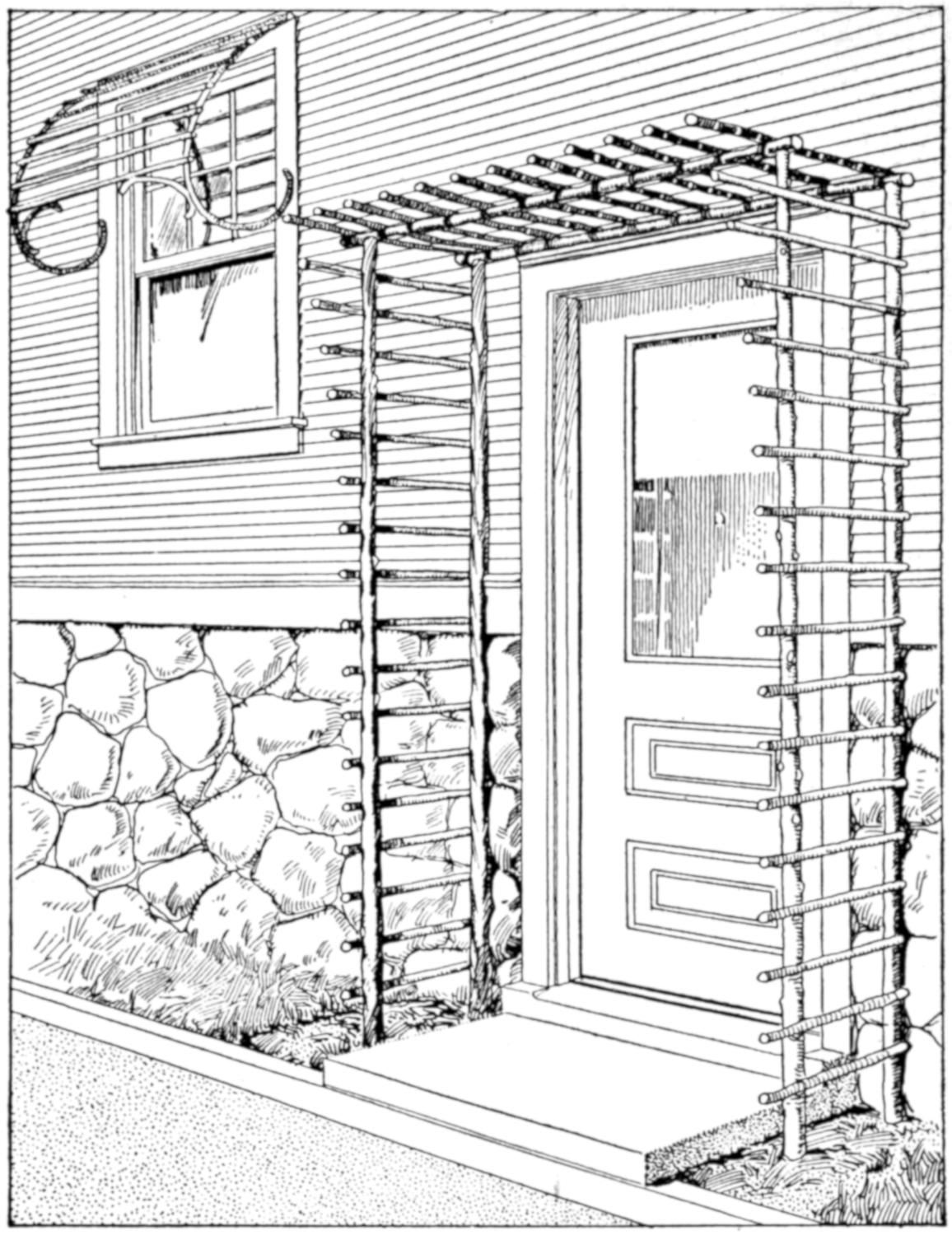

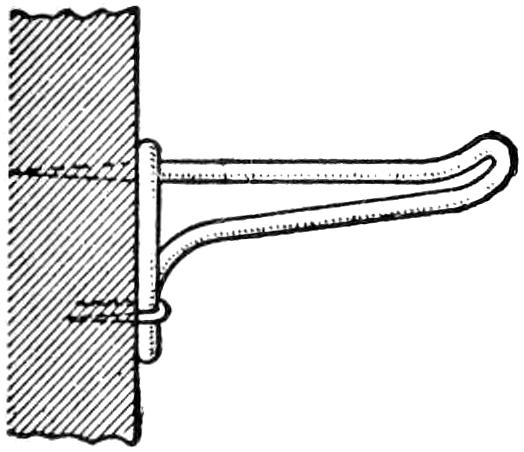

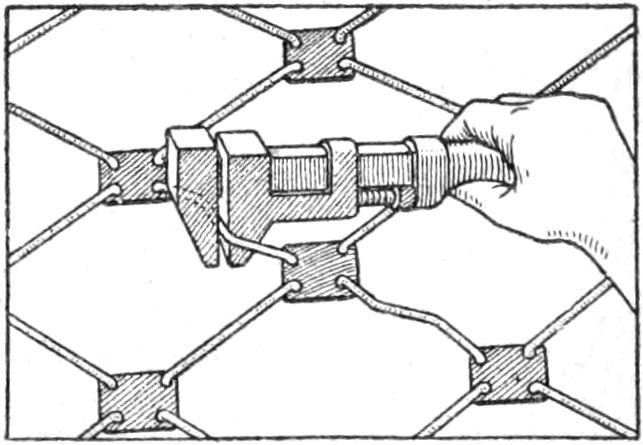

A desirable vine often has not the natural ability for clinging to stone, and other walls, and a suitable aid must be provided to support it. Fastening a wire trellis to such a wall is a good method. Screw anchors are used, which fit into holes drilled for them and expand under the pressure of the screw. Staples may also be used in walls laid up in mortar. A ⁵⁄₁₆-in. screw anchor will hold an ordinary fence staple, and requires a ⁷⁄₁₆-in. hole. After the staple has been placed over the wire its ends are pinched together and driven into the anchor socket. The staple is held firmly, and will support a considerable load. First fasten the trellis of wire mesh to the wall, at the top, very securely. A chalk line aids in setting the wire straight. If carefully done, the trellis will be hardly noticeable, and the wall will be unmarred.—C. L. Meller, Fargo, N. D.

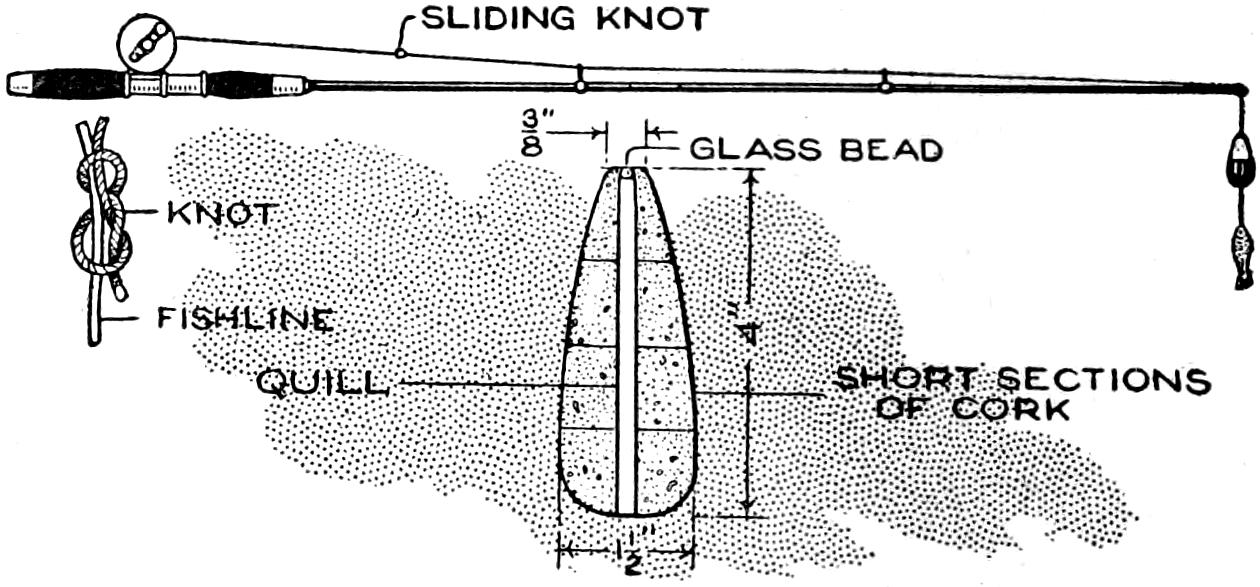

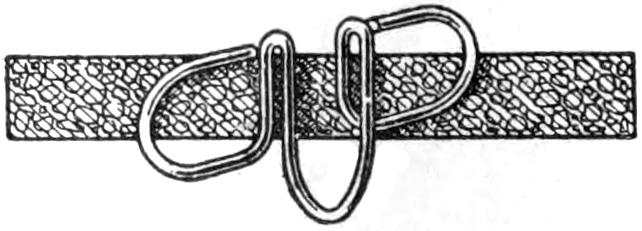

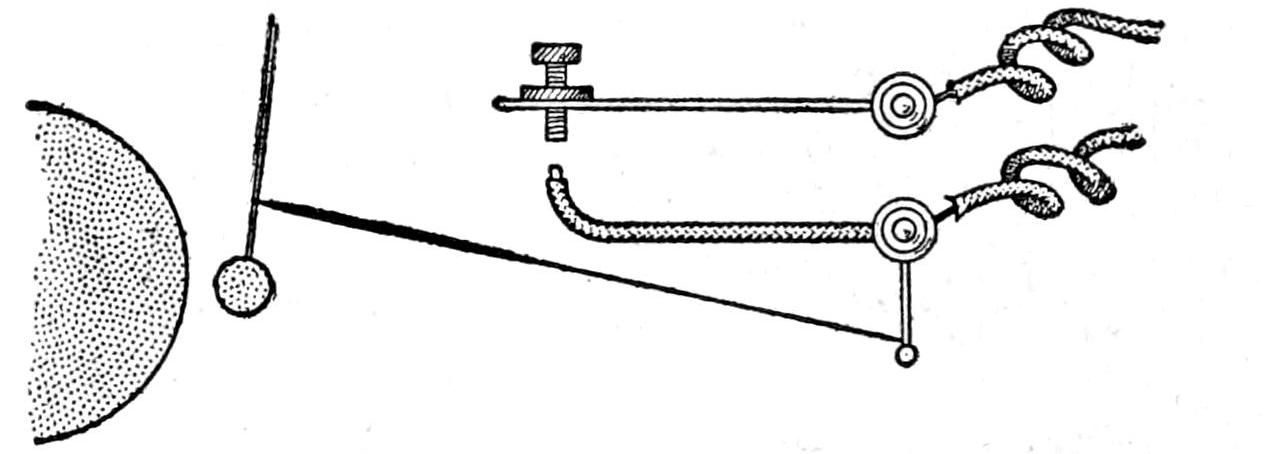

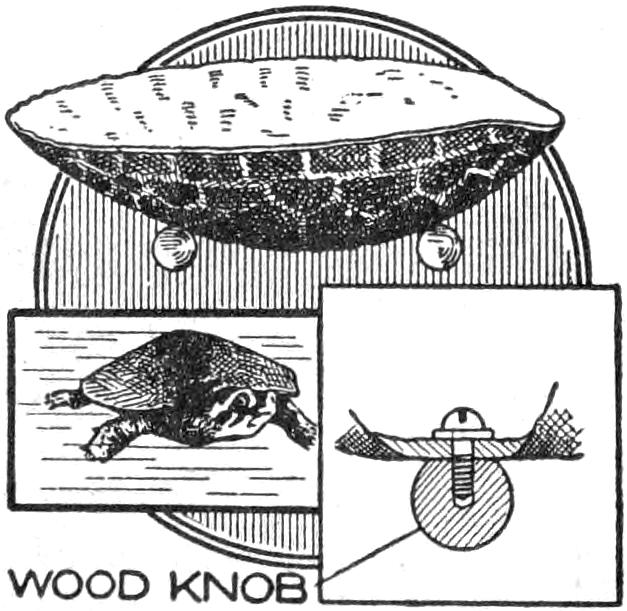

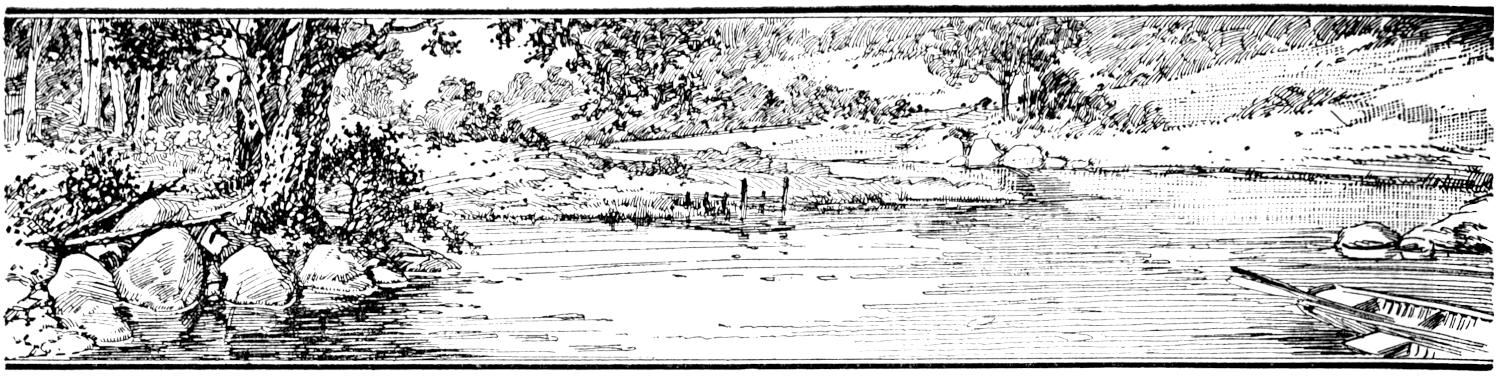

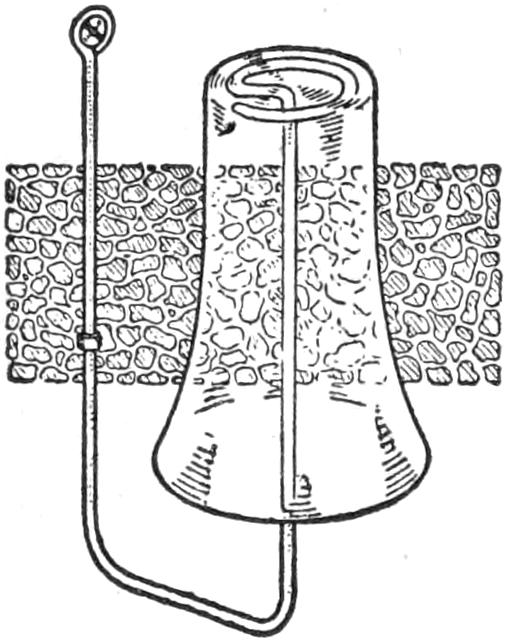

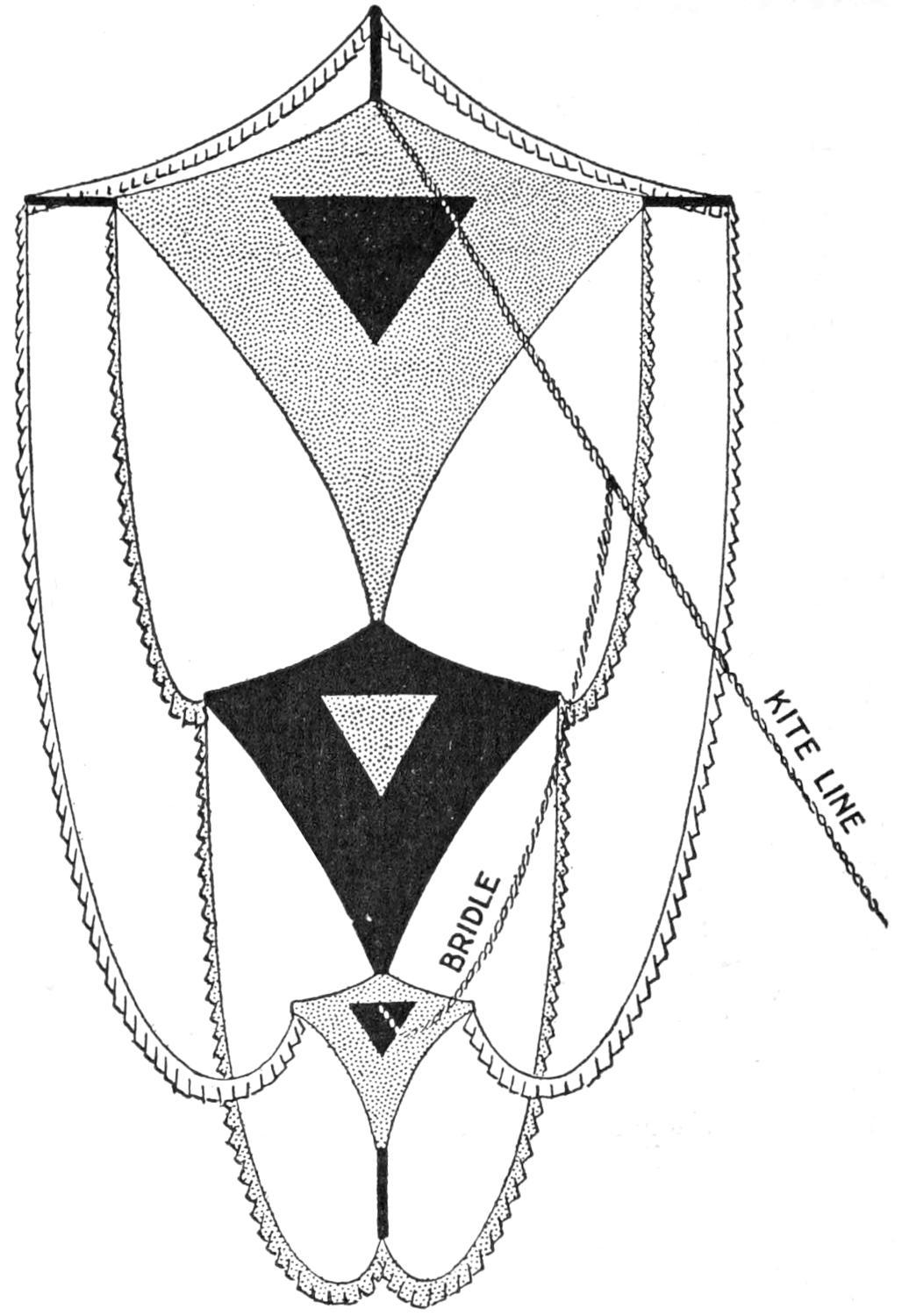

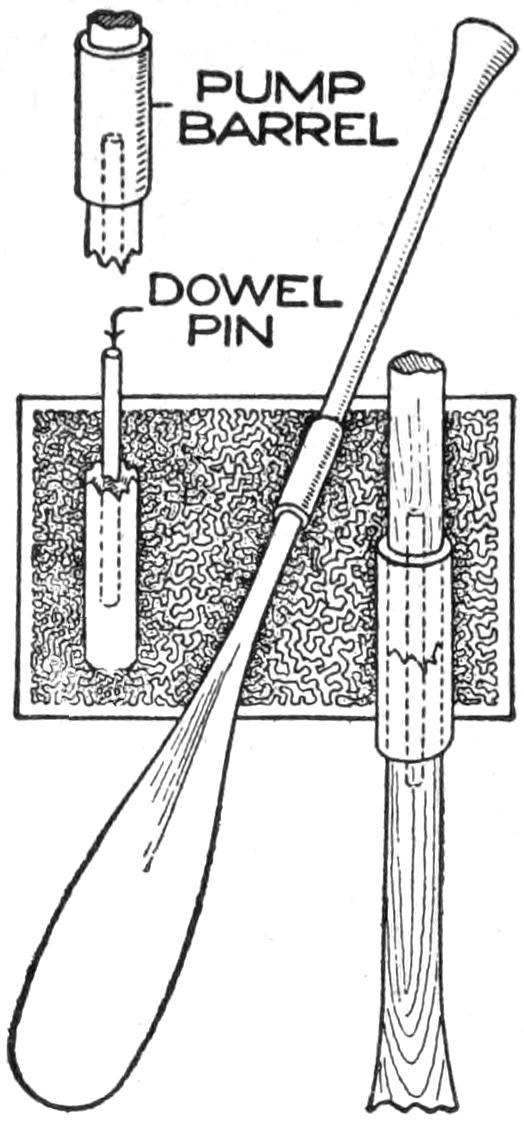

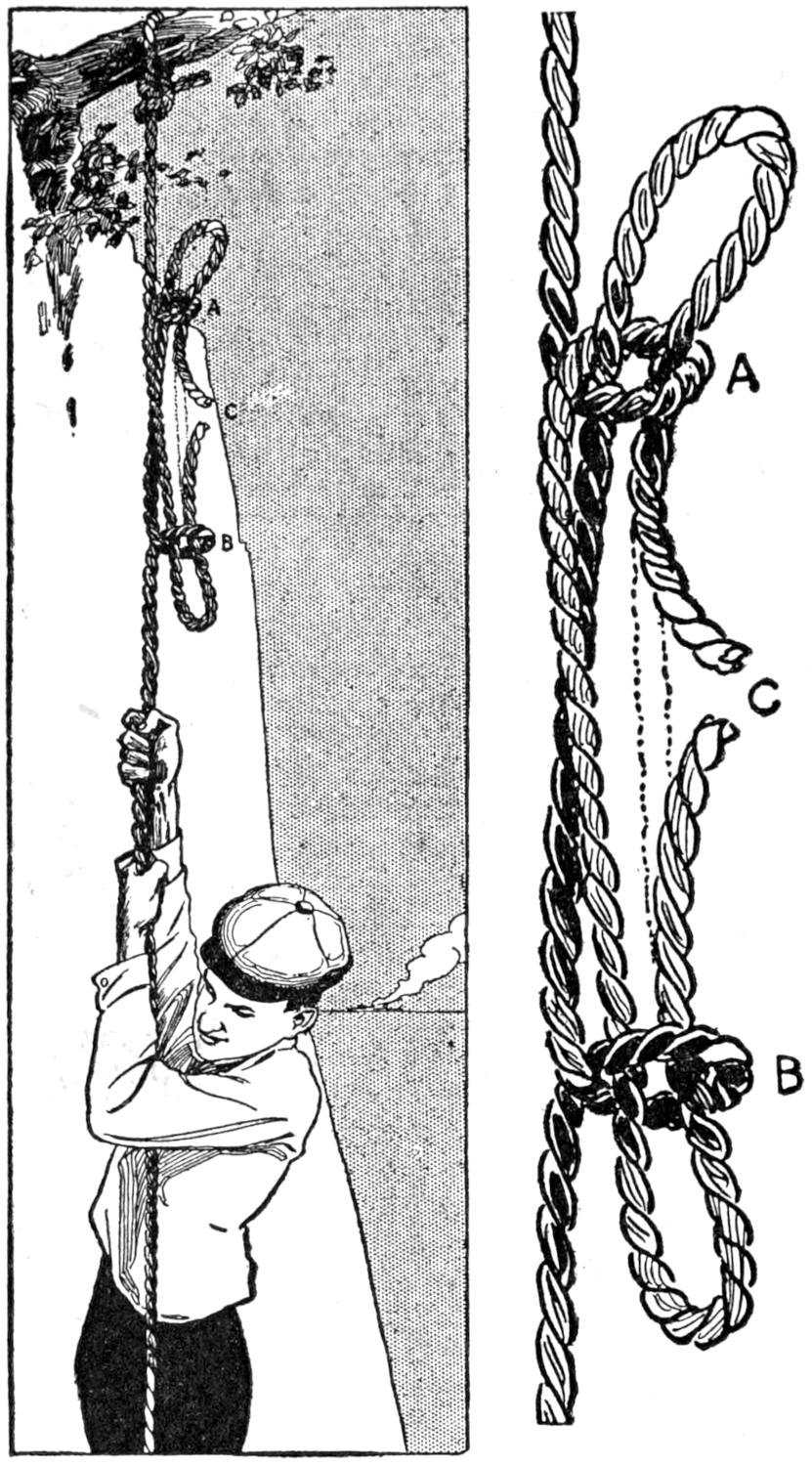

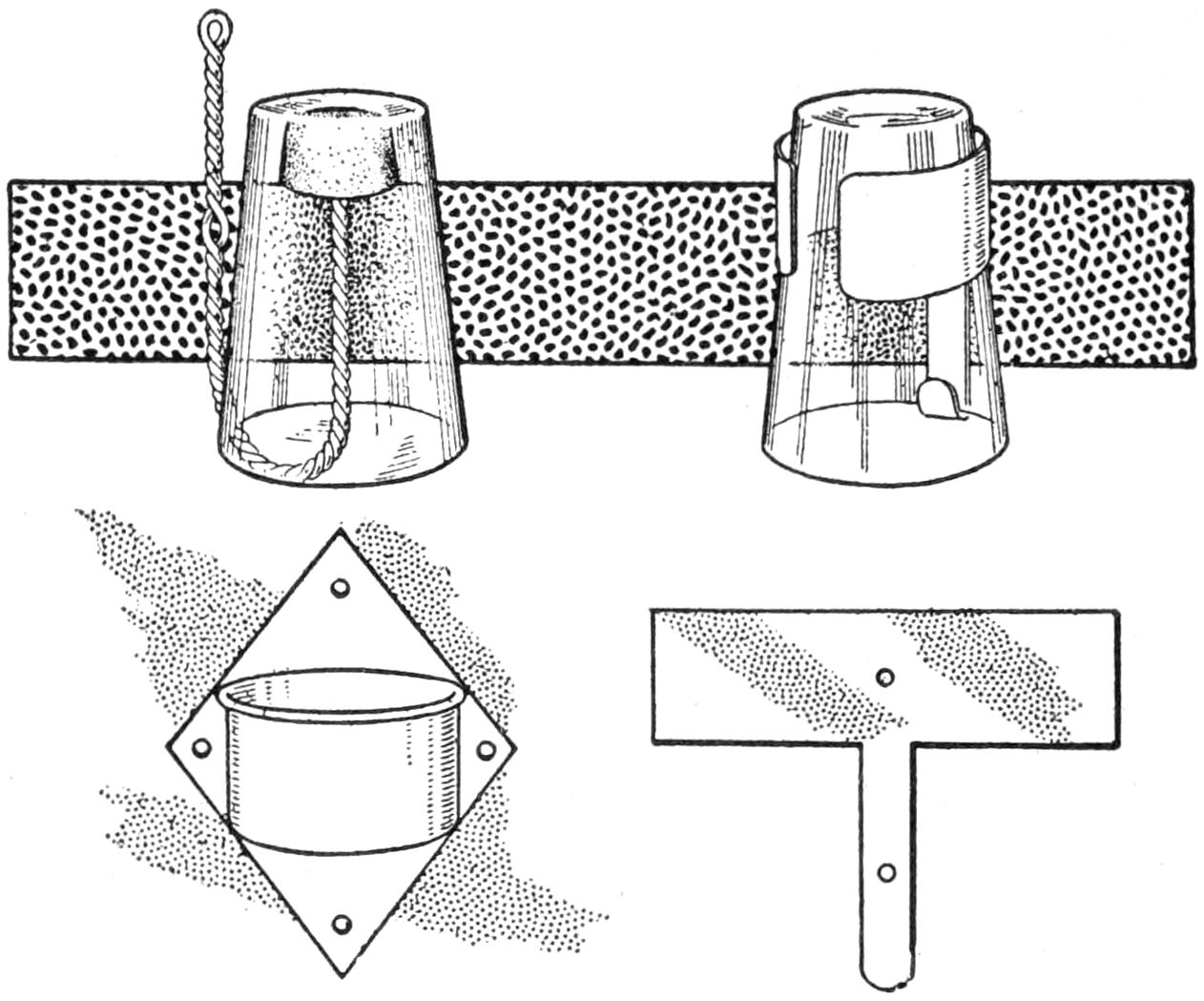

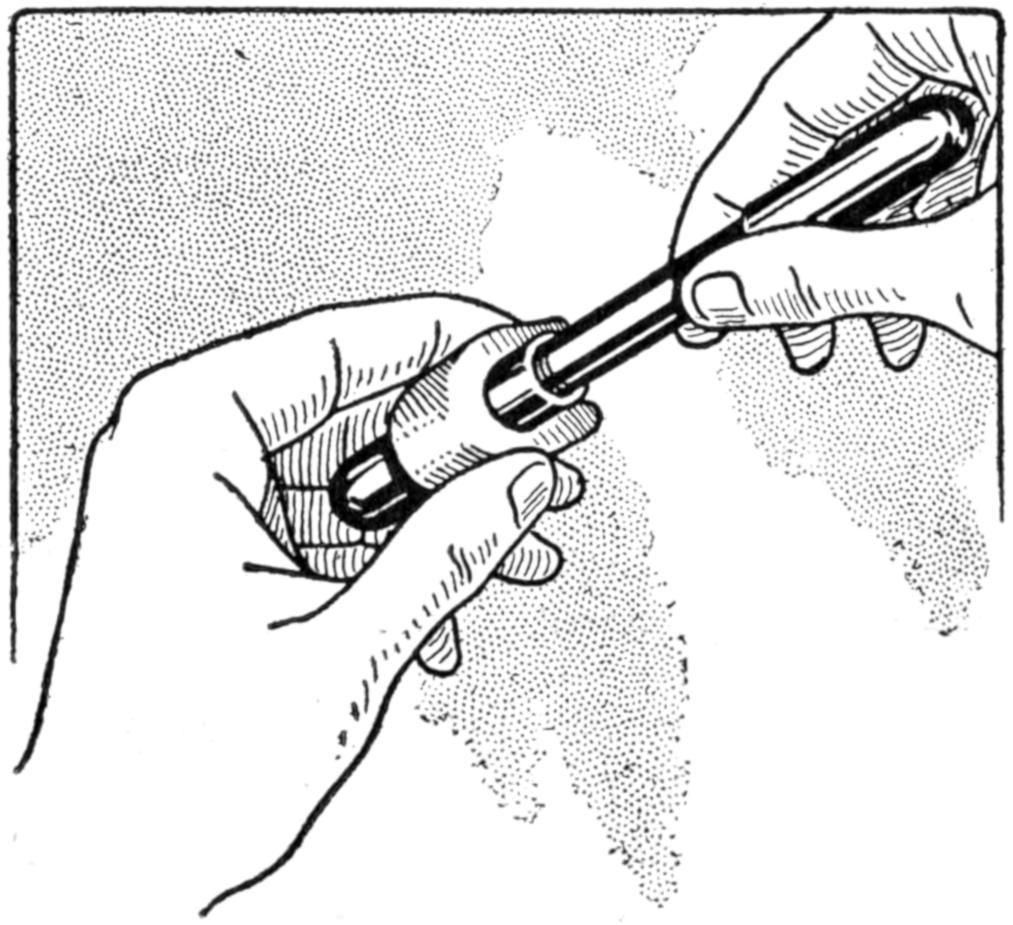

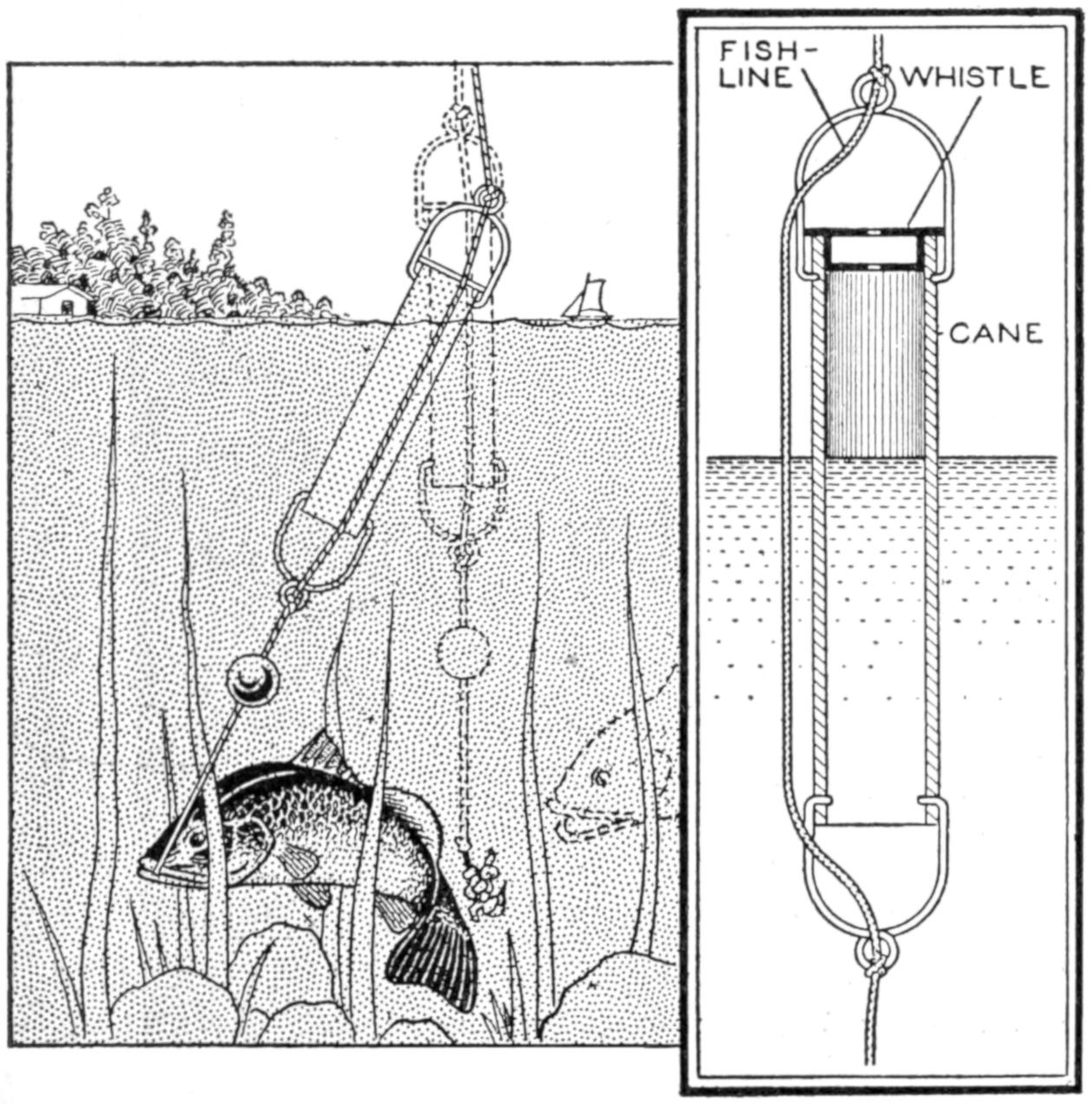

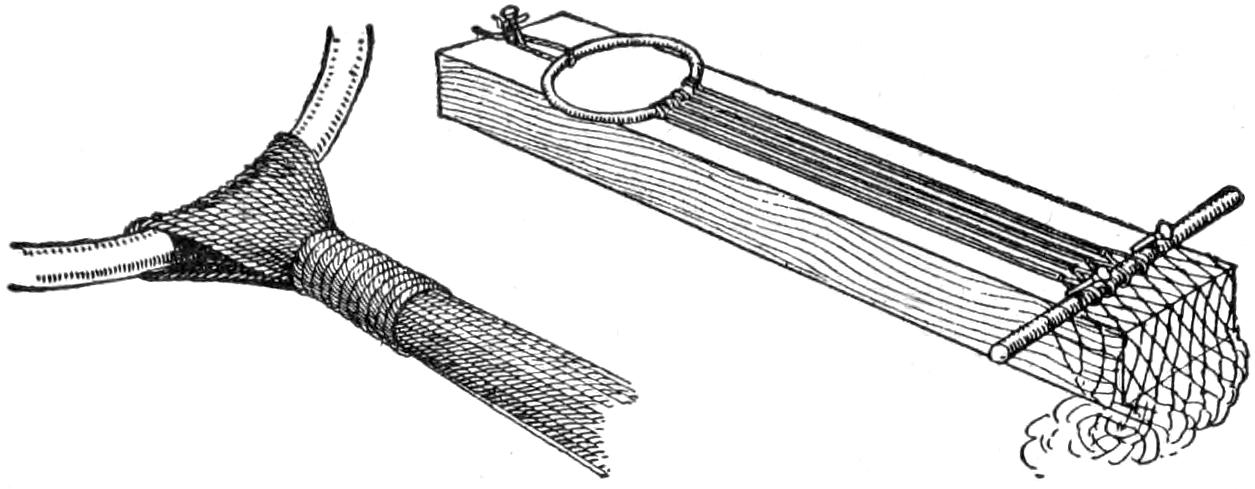

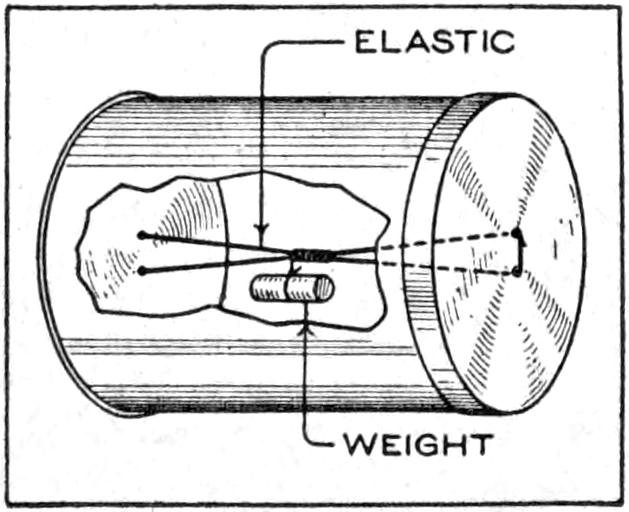

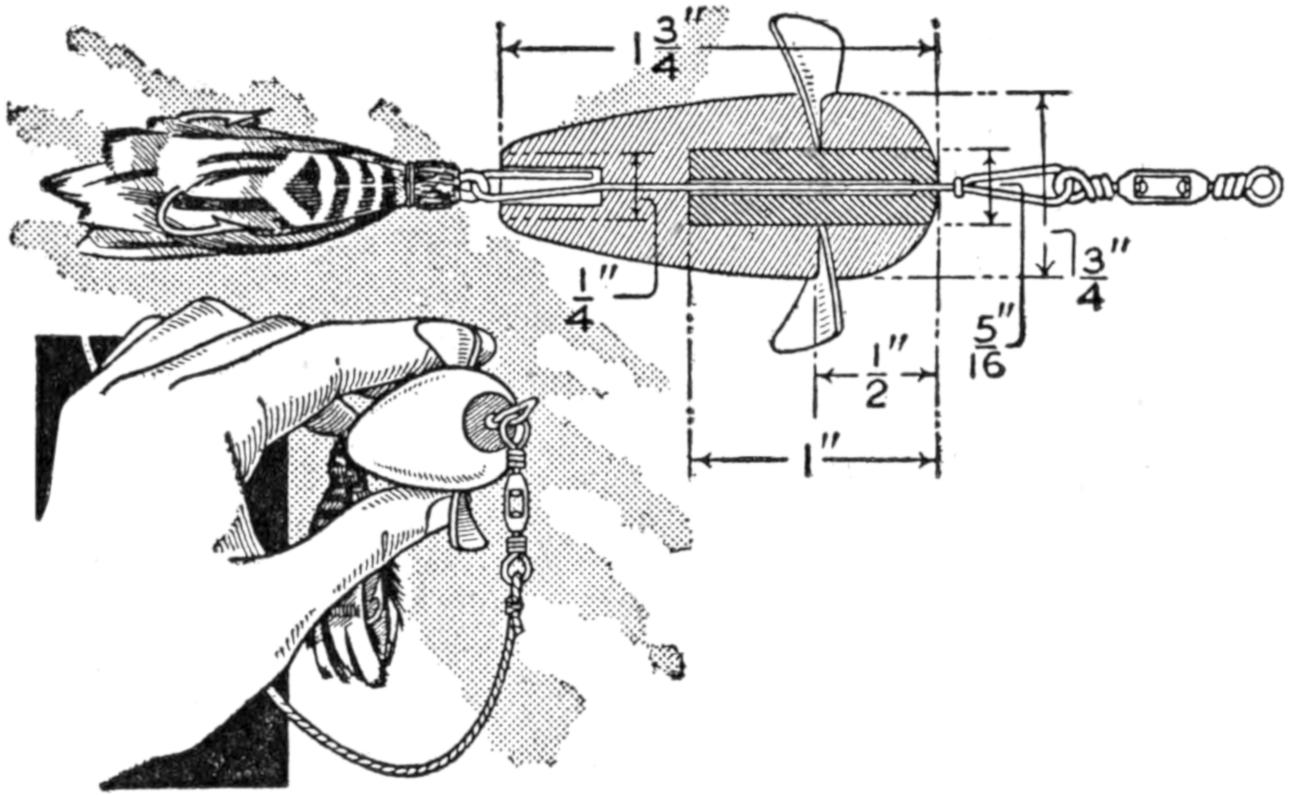

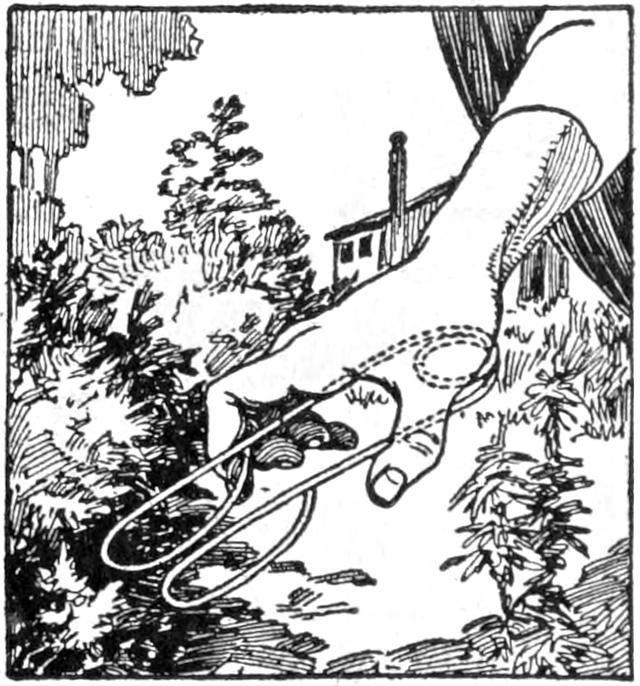

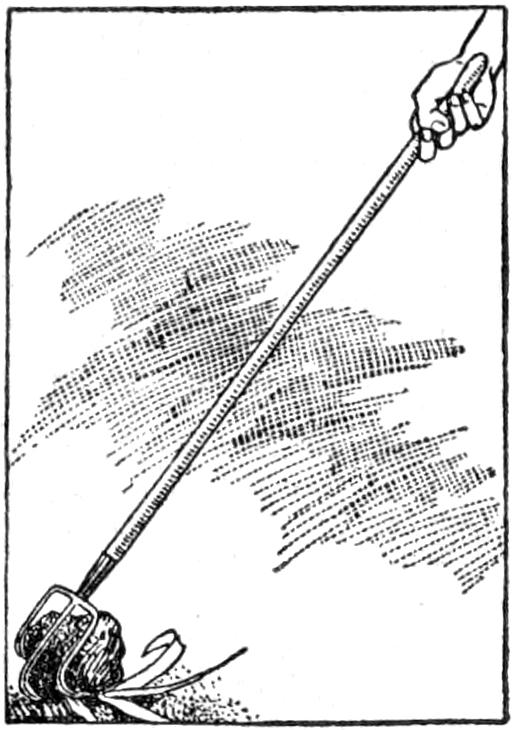

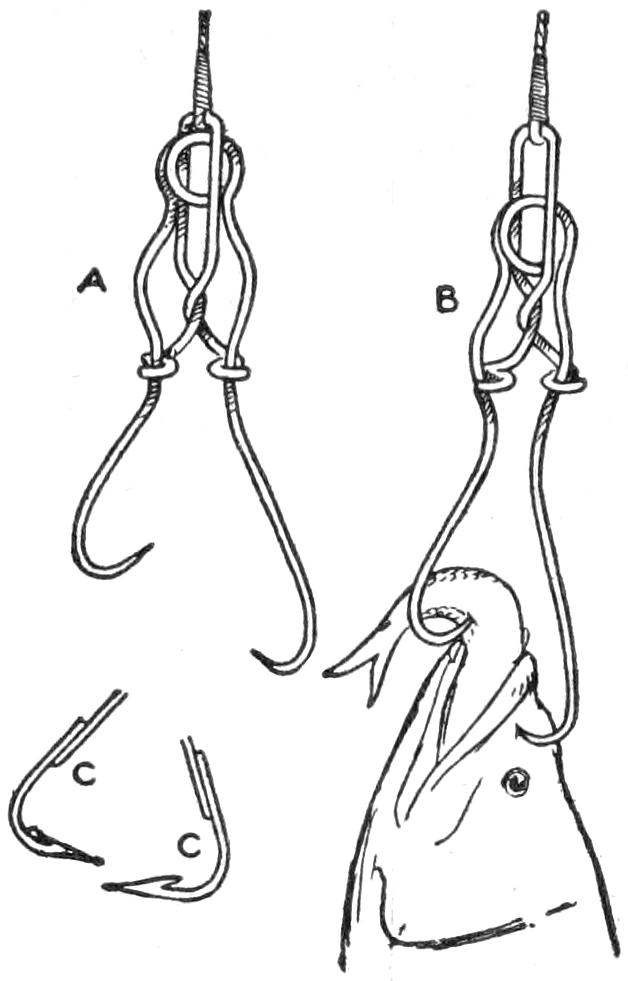

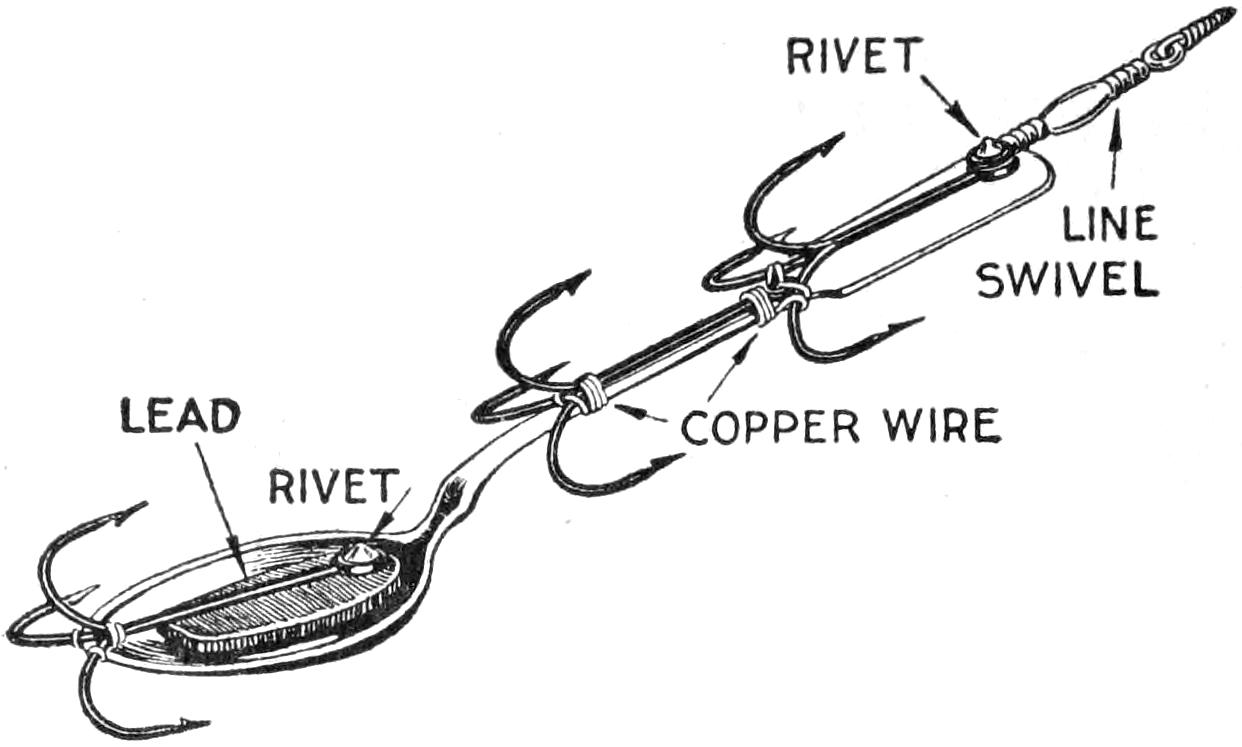

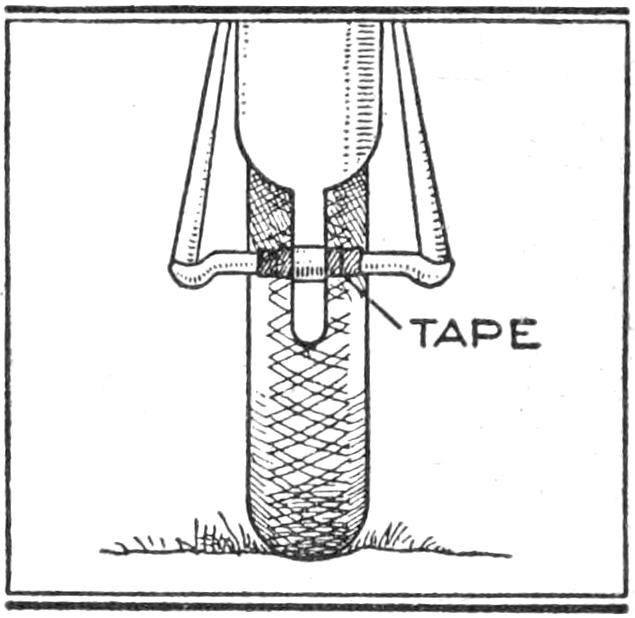

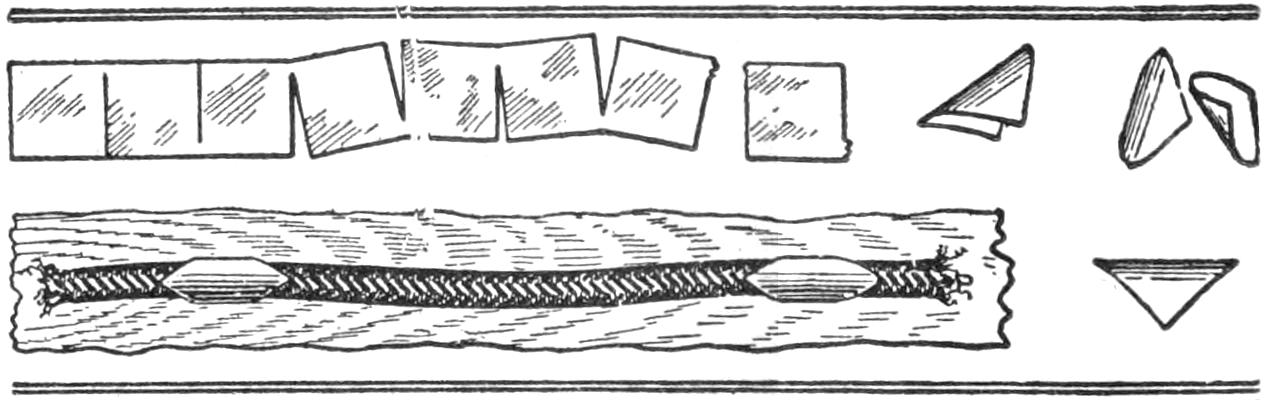

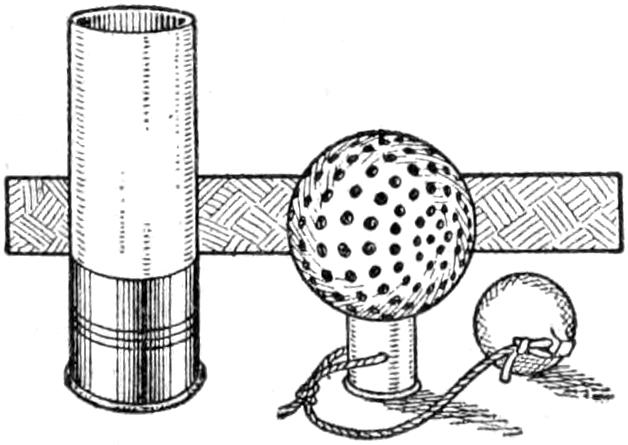

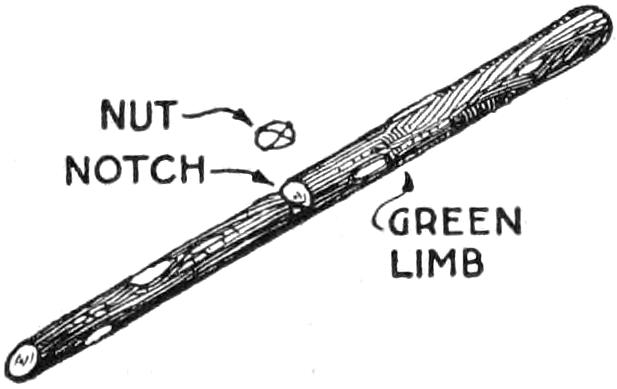

A novel device for fishing, especially with a short bait-casting rod, is a float that can be adjusted to the depth of water in which it is desired to fish. The float is hollow and slides on the line. To use it, the casting lead and hooks are adjusted as usual, and a sliding knot on the line is set for the depth desired, and the cast made. The float will stop at the sliding knot, and remain on the surface. In reeling the line, the knot passes freely through the guides, and the float slides down on the line until it reaches the casting weight.

By Setting a Sliding Knot on the Line, as a Stop for the Float, the Depth at Which the Sinker is Desired can be Easily Regulated

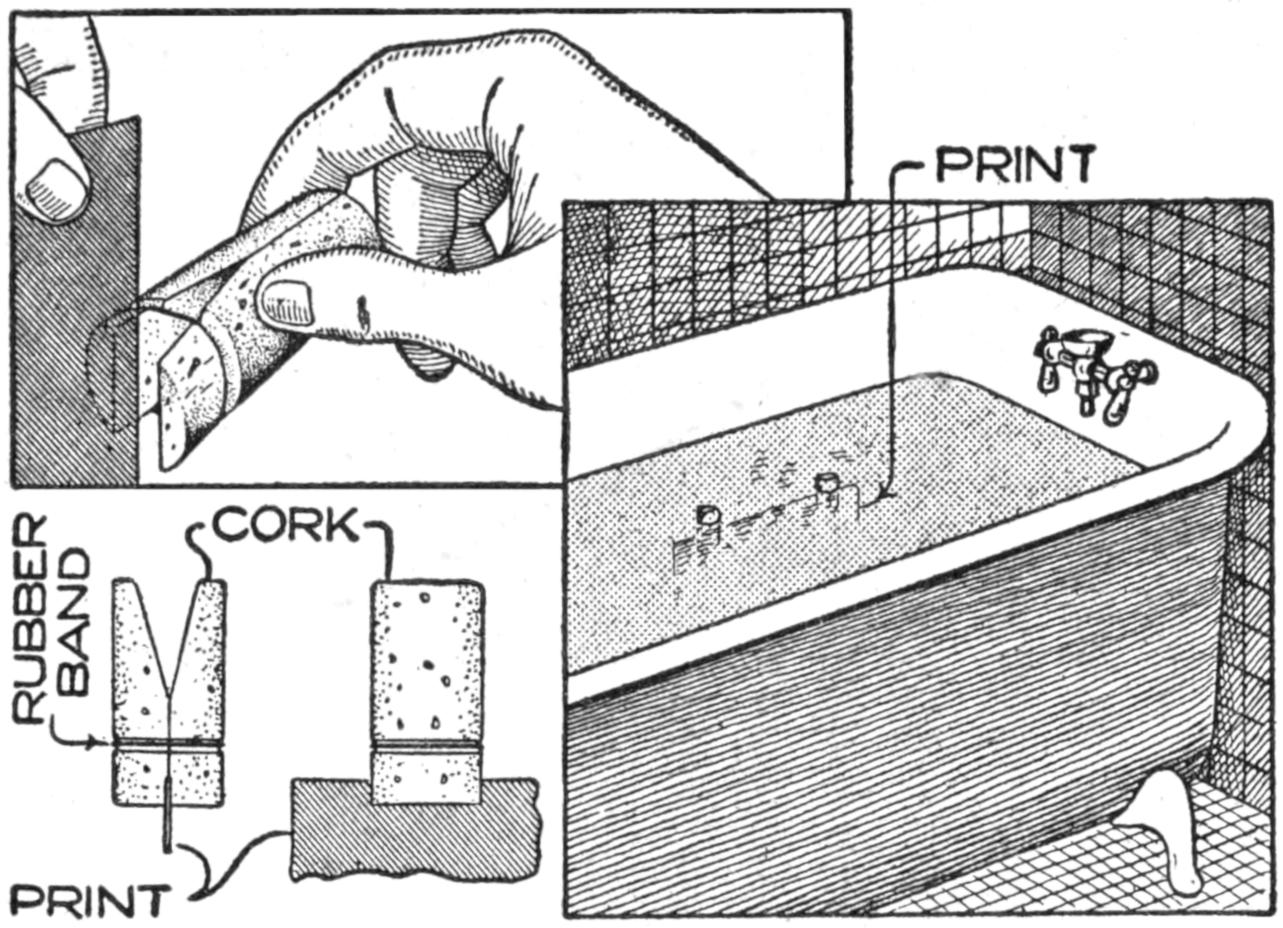

Cork is a good material from which to make the float. Cut the cork in sections, as shown, and fit it over a large quill, which provides a smooth-running hole through the float. Fit a small glass bead in the upper end of the float, as a stop for the knot. The knot is of the figure-eight type, and tied as shown in the detail at the left. It slides easily, but grips the line tightly enough to stop the float. An ordinary float can be altered for use as described.—Charles Carroll, Baltimore, Maryland.

[9]

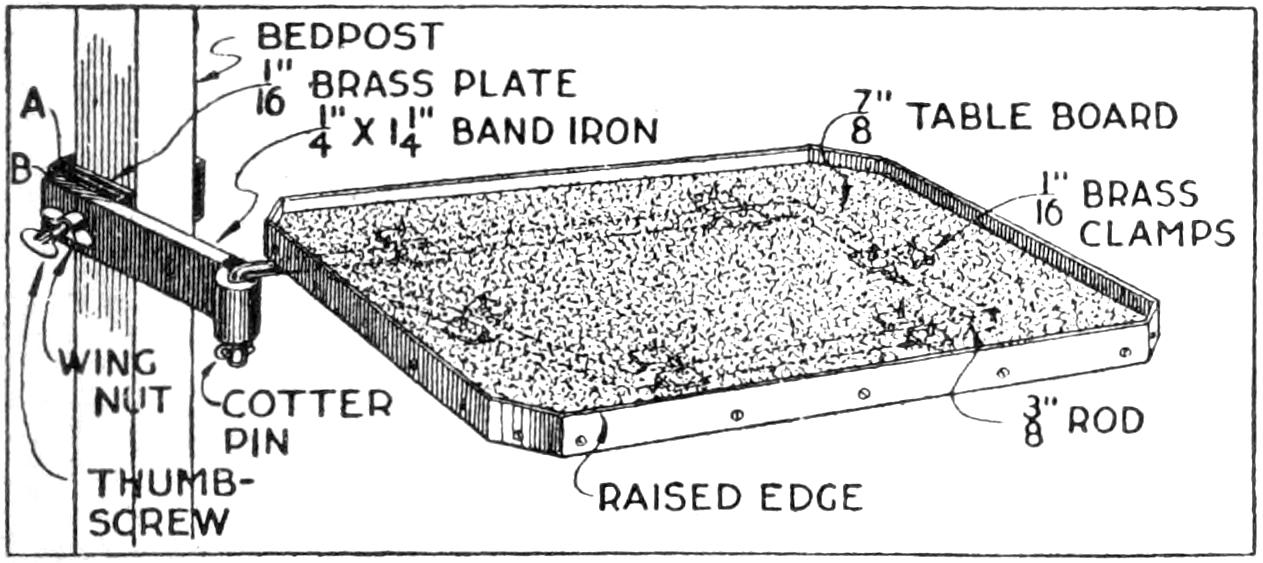

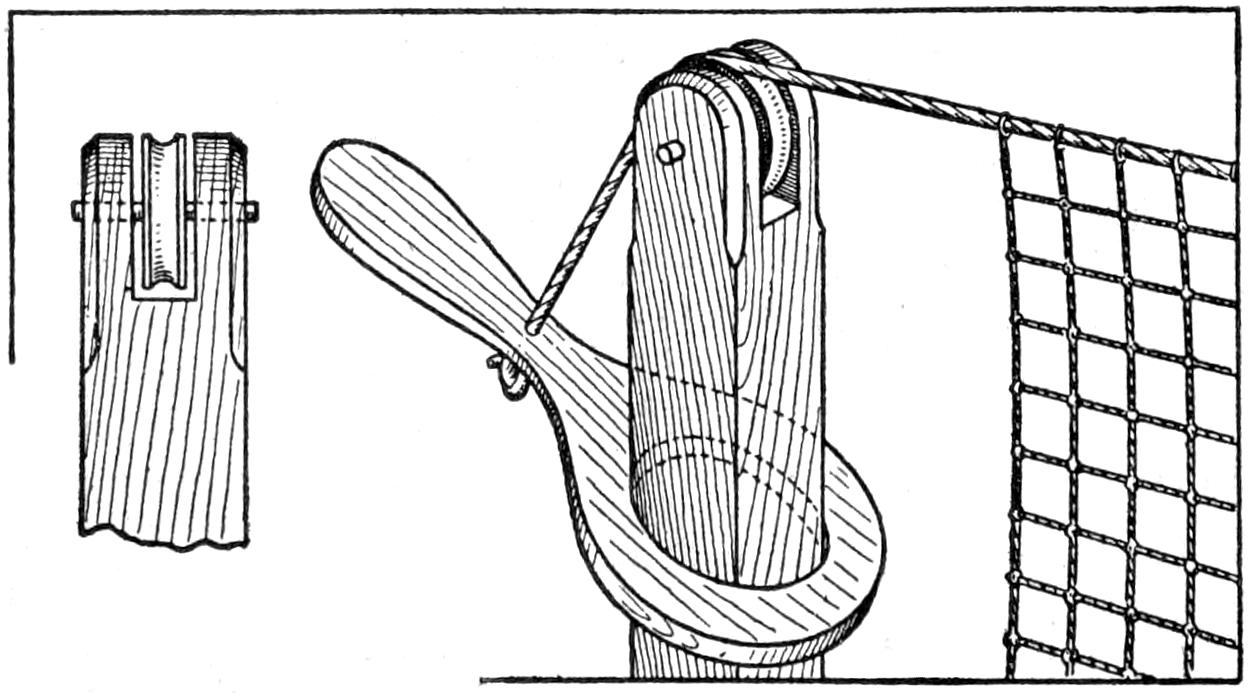

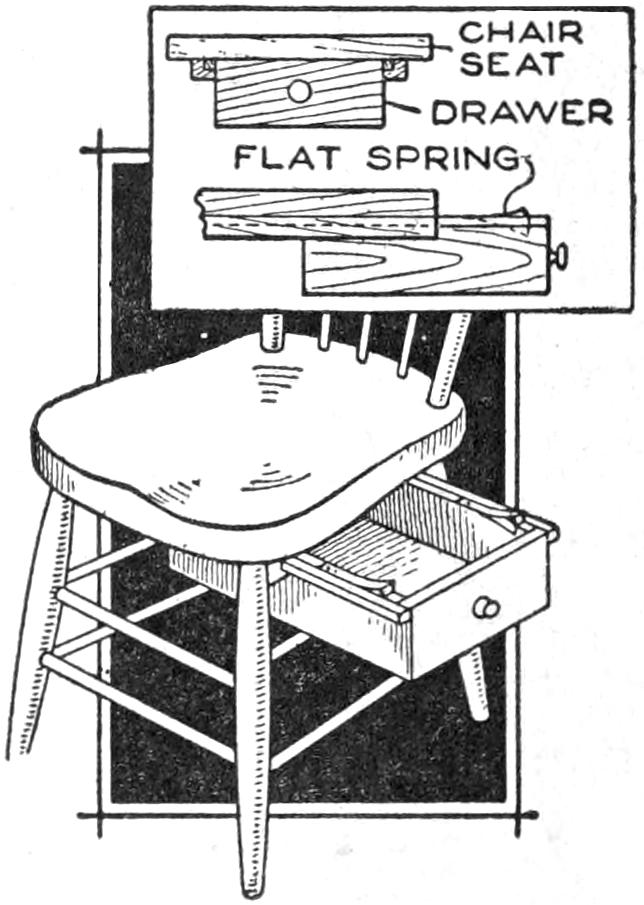

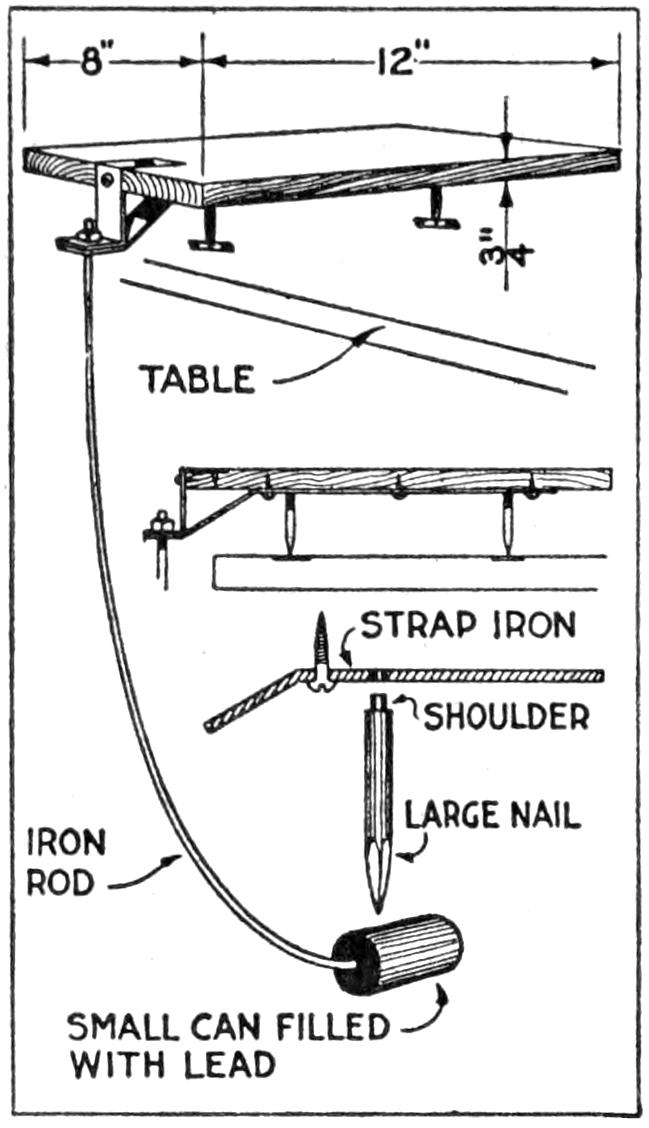

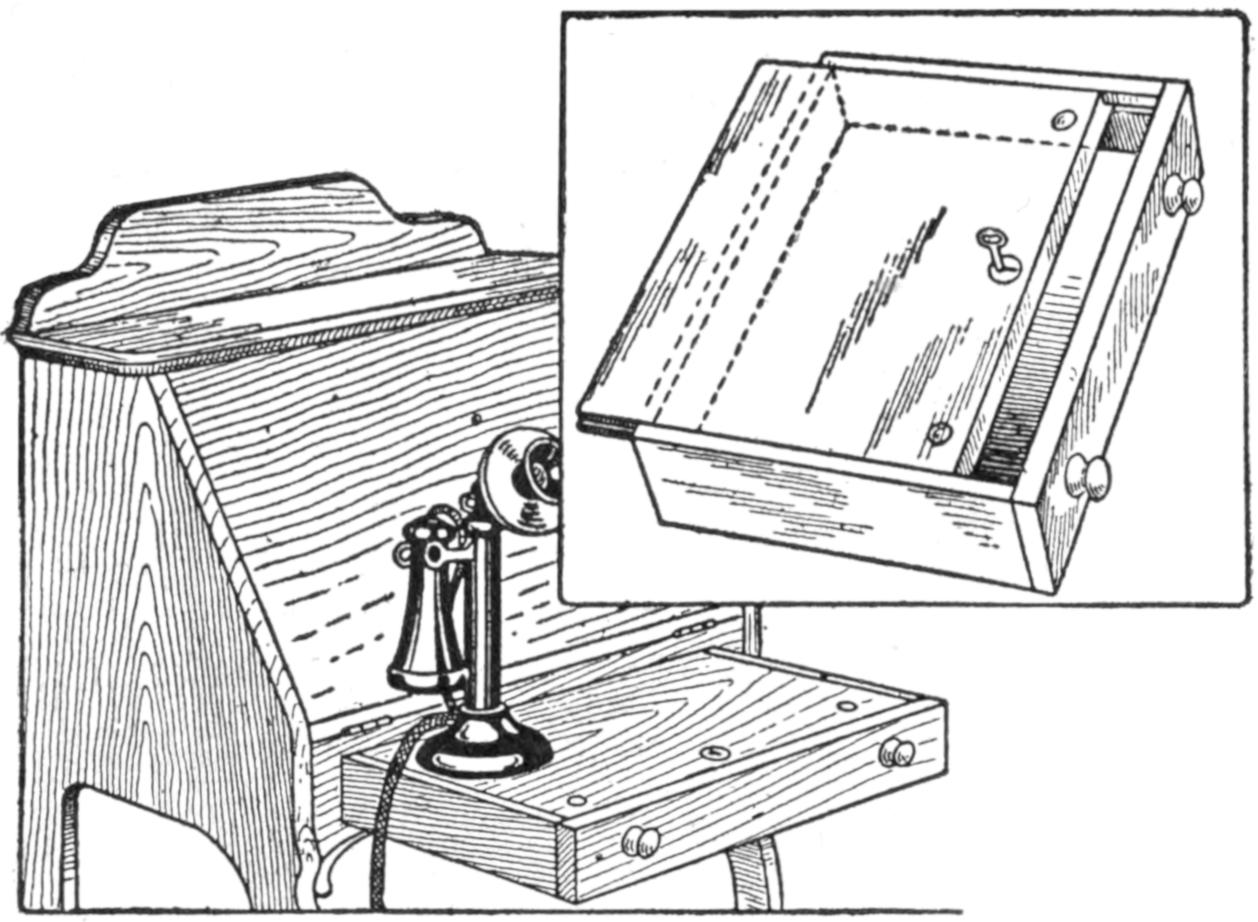

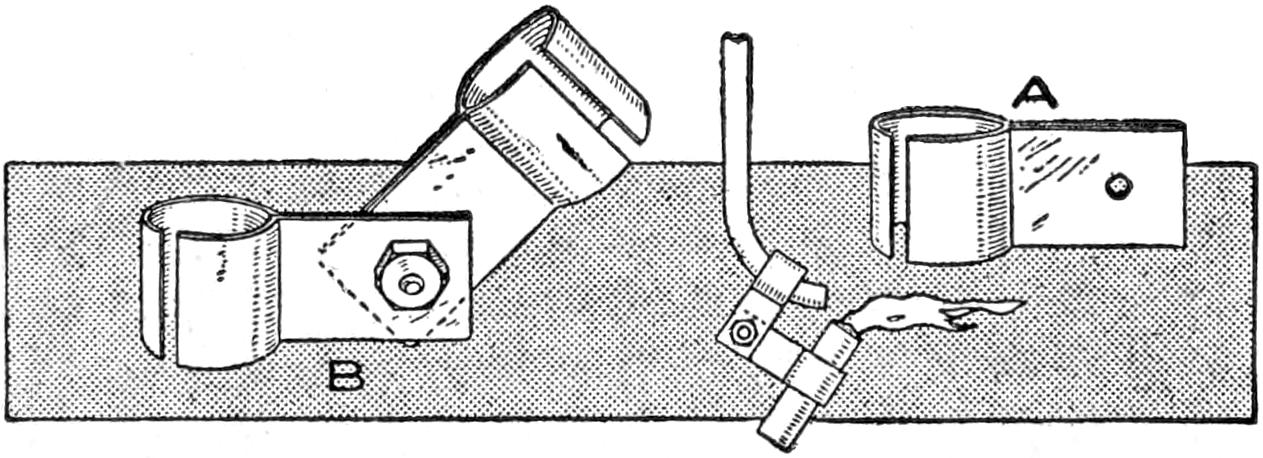

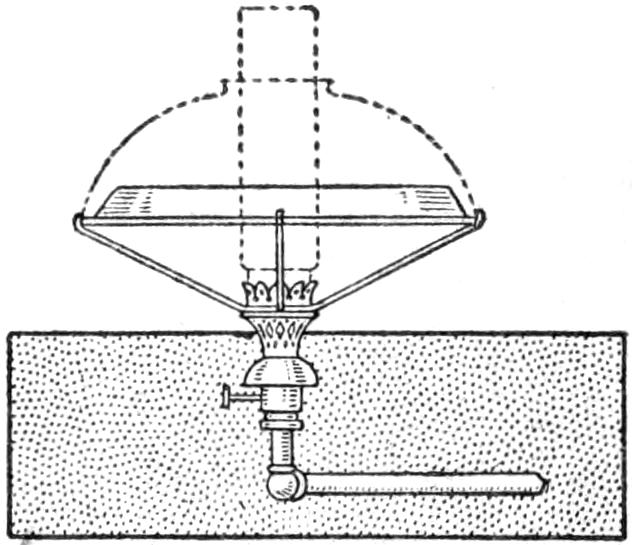

This Handy Table Clamps on the Bedpost and can be Swung Aside Conveniently, or Removed Altogether

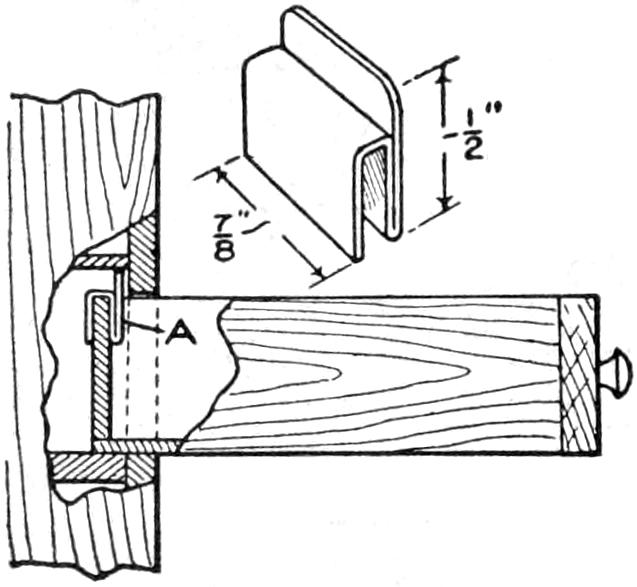

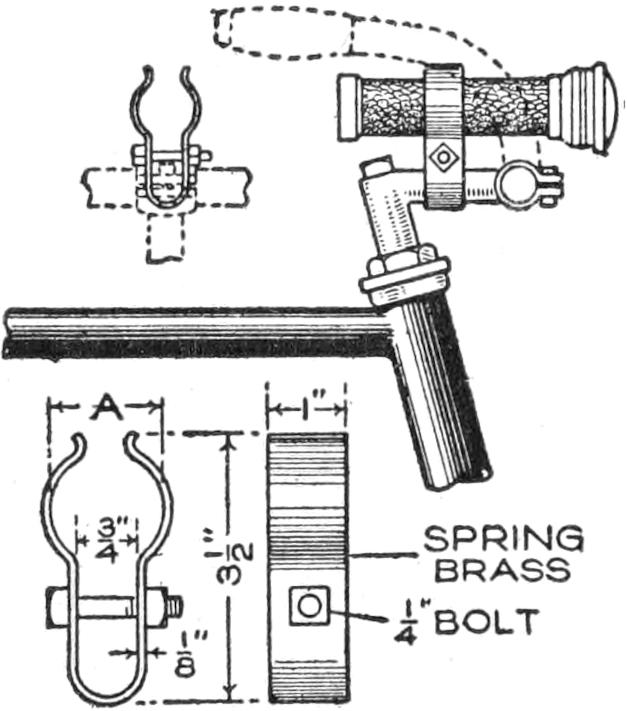

A table arrangement which can be clamped handily to the bedpost and swung out of the way or removed altogether when not in use, is a convenience that has a wide use in the home. A device of this kind, which requires no floor support and can be folded compactly for storage, is shown in the illustration. The table proper consists of a ⁷⁄₈-in. board, of suitable size, the edges of which are banded with metal or thin wooden strips. The board is supported on a frame of iron rod, bent to the form indicated in the dotted lines, and clamped with ¹⁄₁₆-in. brass clamps. The end of this frame rod is bent at an angle and pivoted in a metal bracket. A cotter pin guards against accidental loosening of the joint. The clamping device is made of ¹⁄₄ by 1¹⁄₄-in. band iron, and is bent to fit loosely around the bedpost. A brass plate, A, is fitted inside of the main piece B, as shown. A thumbscrew is threaded into the piece B, its point engaging the brass plate, which acts as a guard. In fastening the piece B on the bedpost, the thumbscrew is set, and the wing nut also tightened.—A. Lavery, Garfield, N. J.

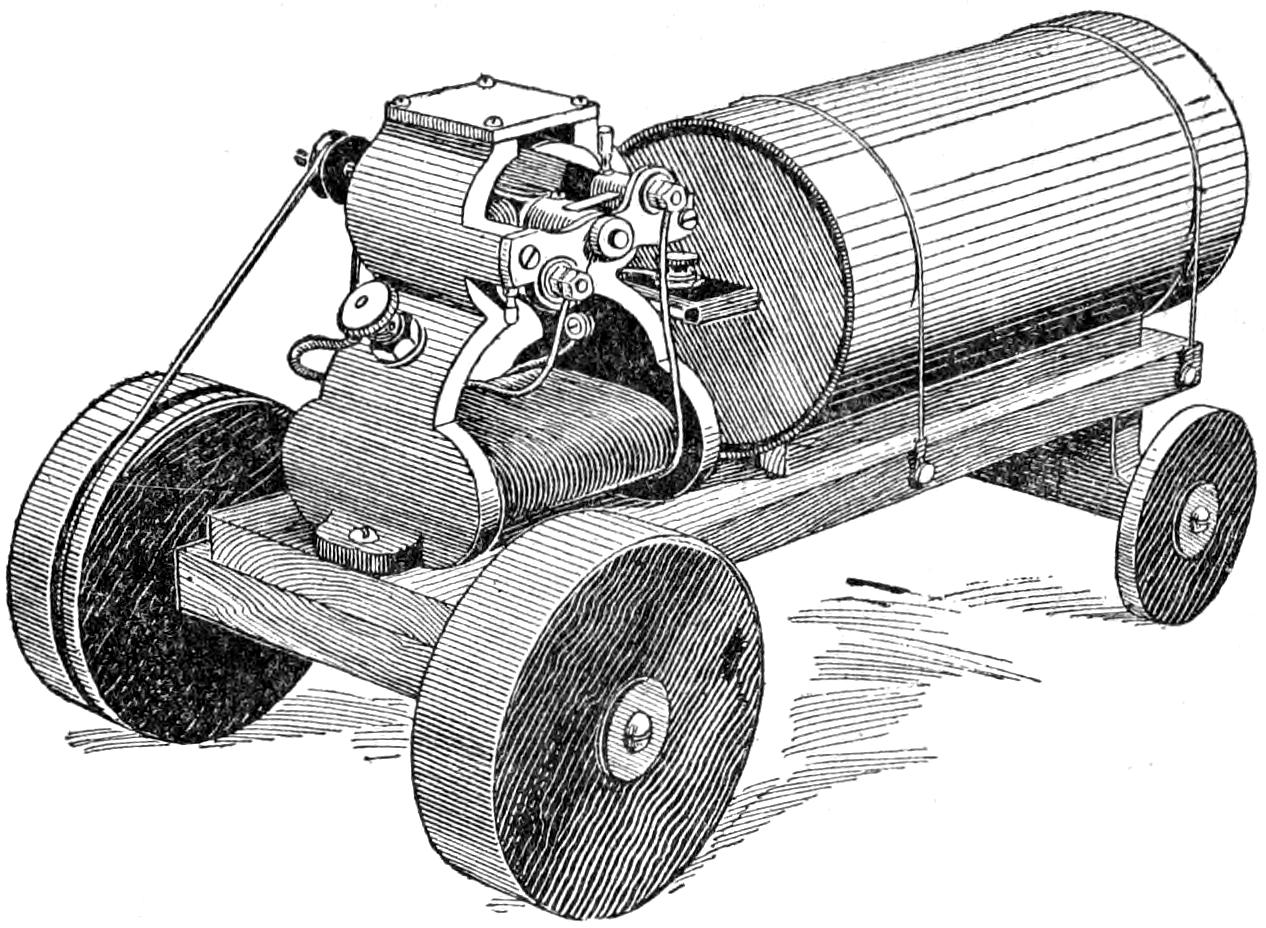

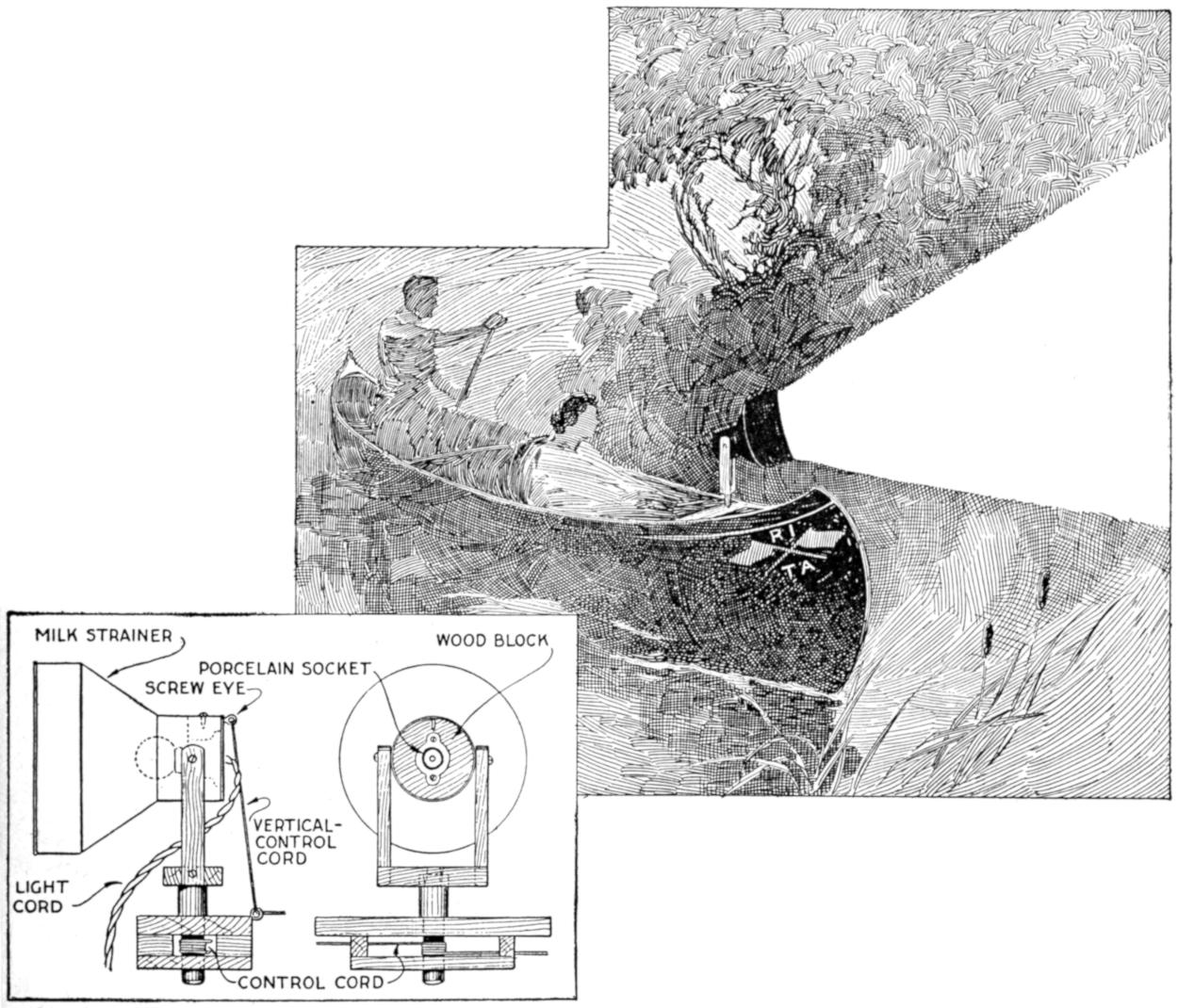

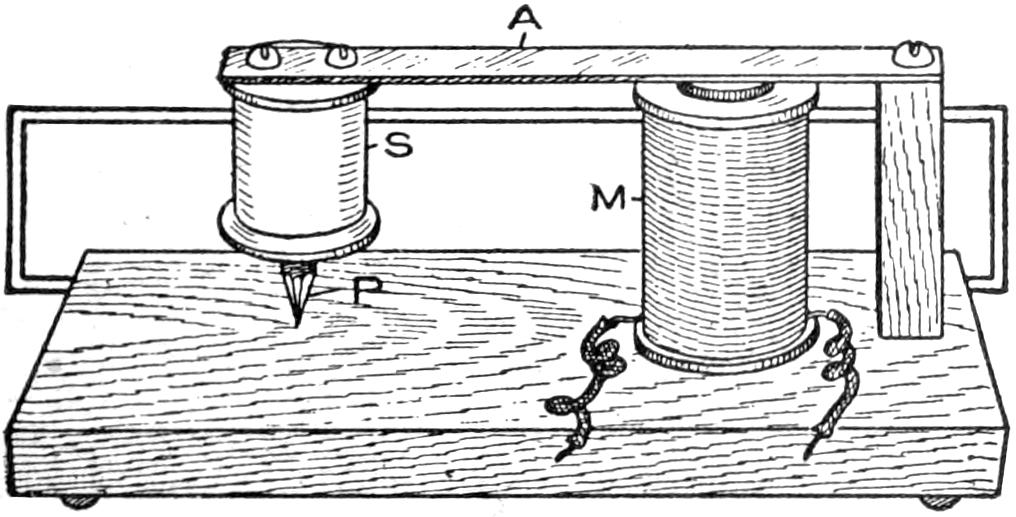

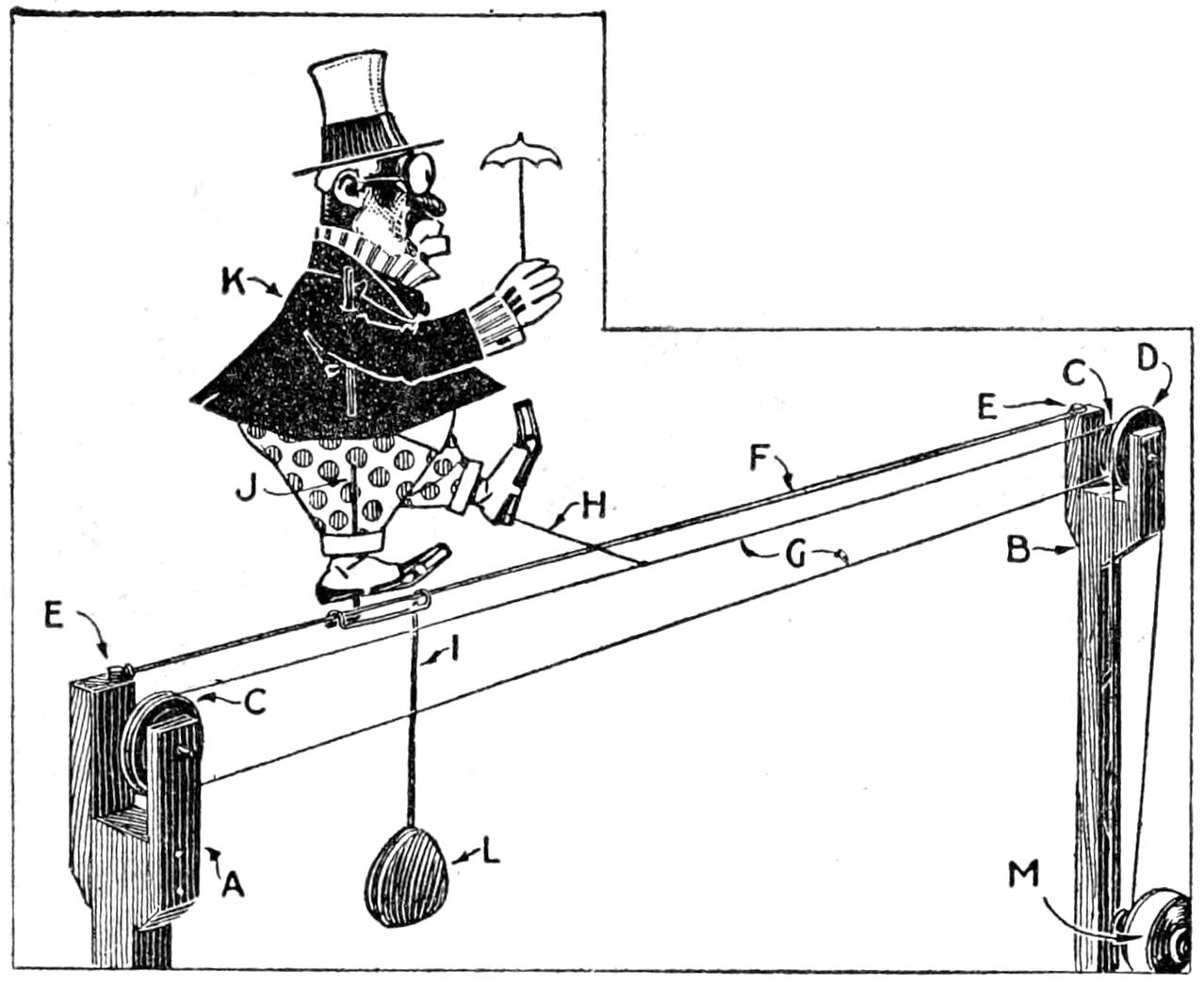

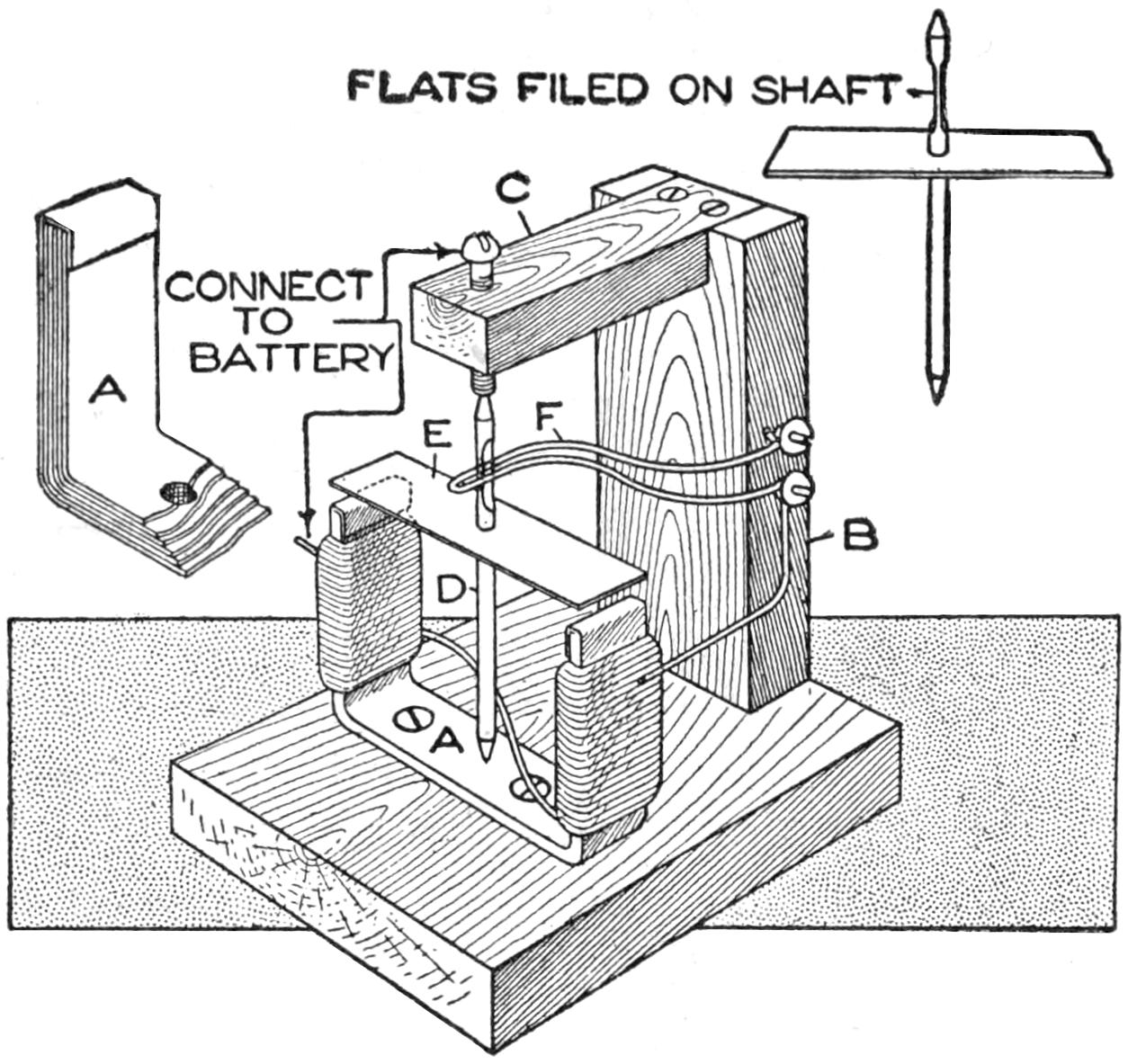

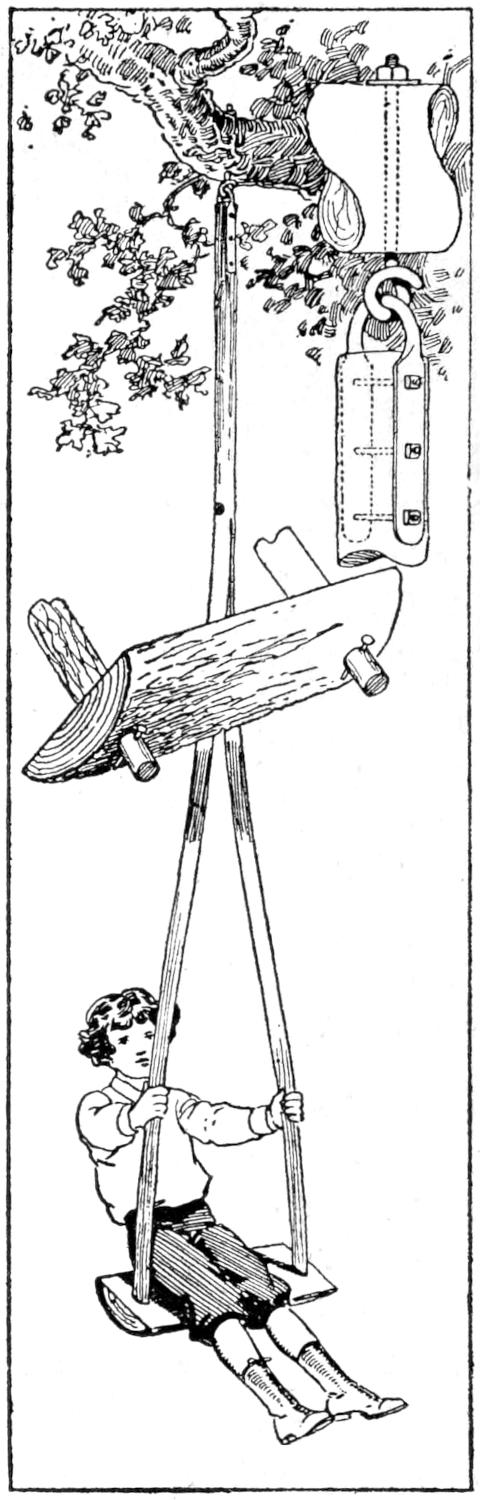

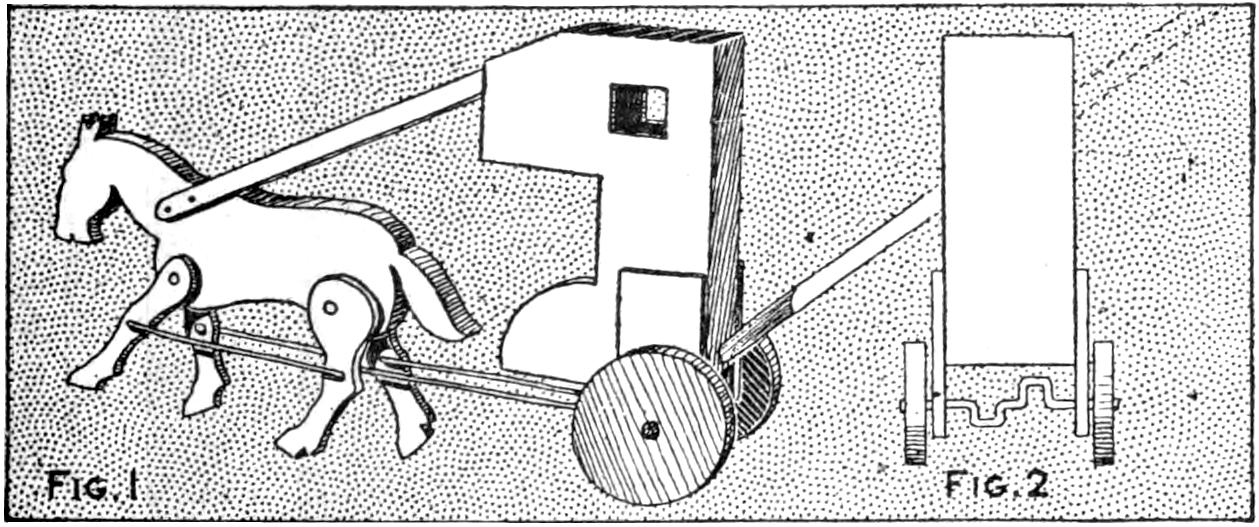

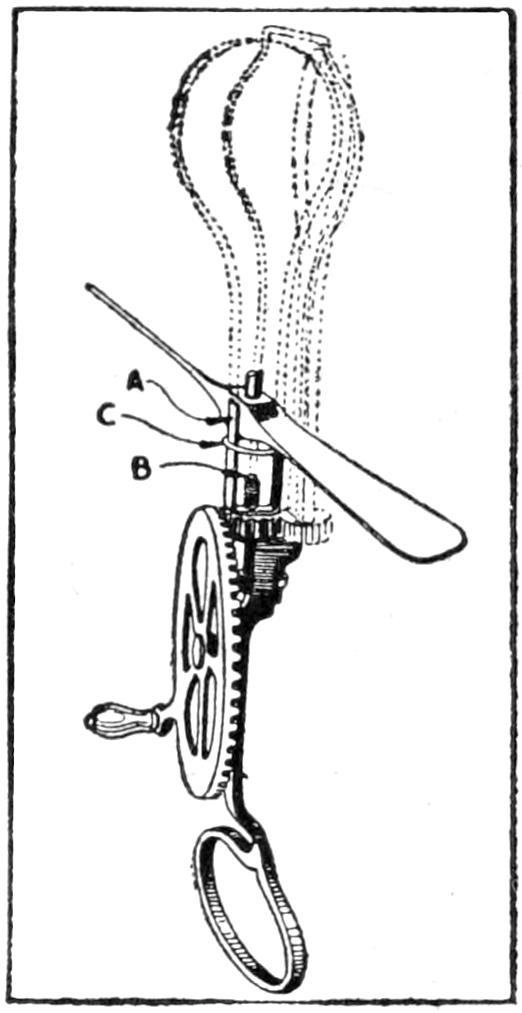

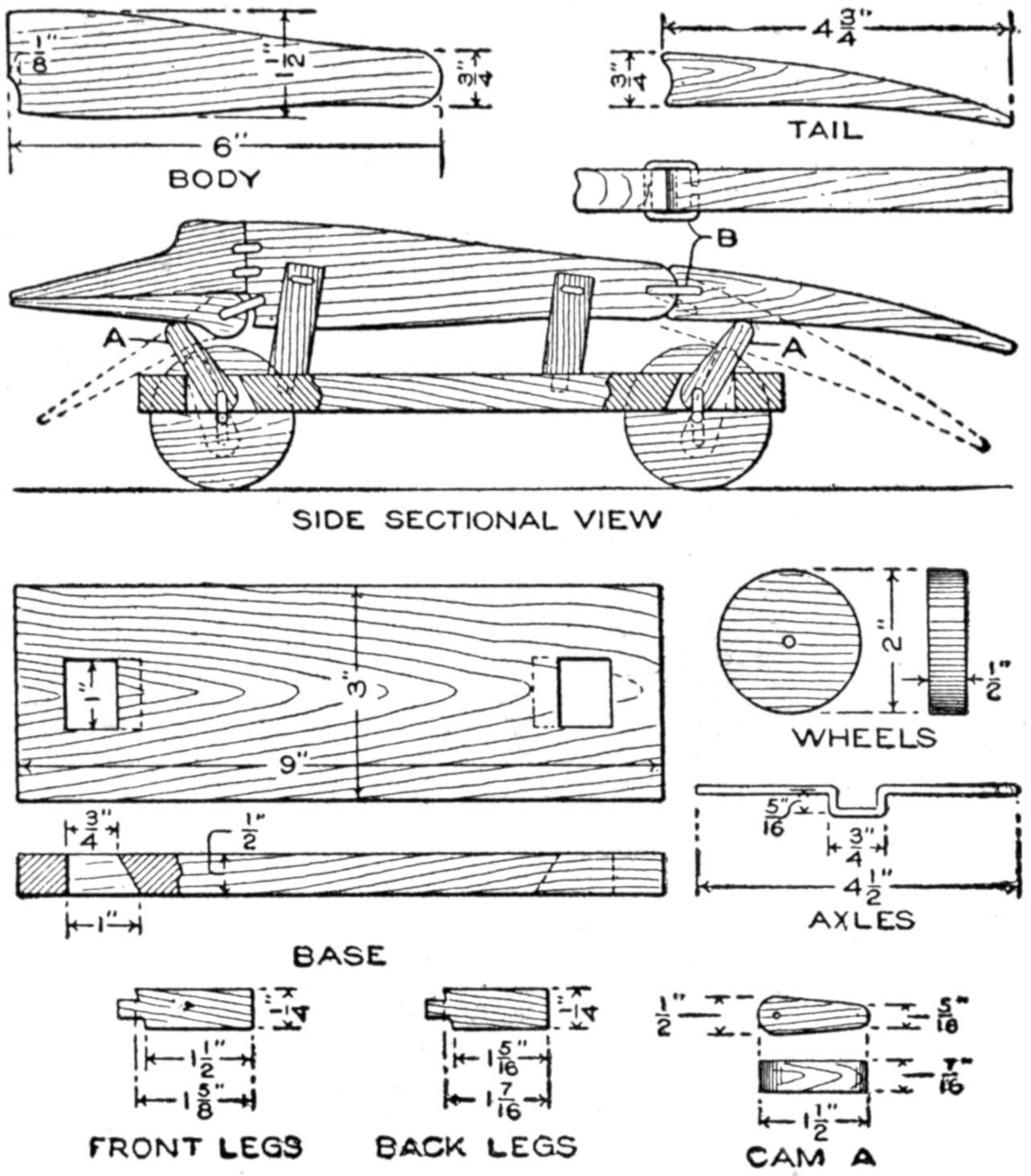

A Boy can Make This Simple Electric Tractor in a Short Time, and will Get Much Fun Out of It

An ordinary two-volt dry cell, a small motor, and the necessary wooden parts, as shown in the illustration, are all that is needed for the making of a toy tractor that will give its builder a great deal of fun. A good feature is that the parts can be taken down quickly and used for other purposes when desired. A base, ¹⁄₂ by 3 by 9 in. long, is made of wood, and two axles of the same thickness are set under it, as shown. The wheels are disks cut from spools, or cut out of thin wood for the rear wheels, and heavier wood for the front ones. They are fastened with screws and washers, or with nails. The dry cell is mounted on small strips and held by wires. The motor is fastened with screws and wired to the dry cell in the usual manner. One of the front wheels serves as the driver, and is grooved to receive the cord belt.—J. E. Dalton, Cleveland, O.

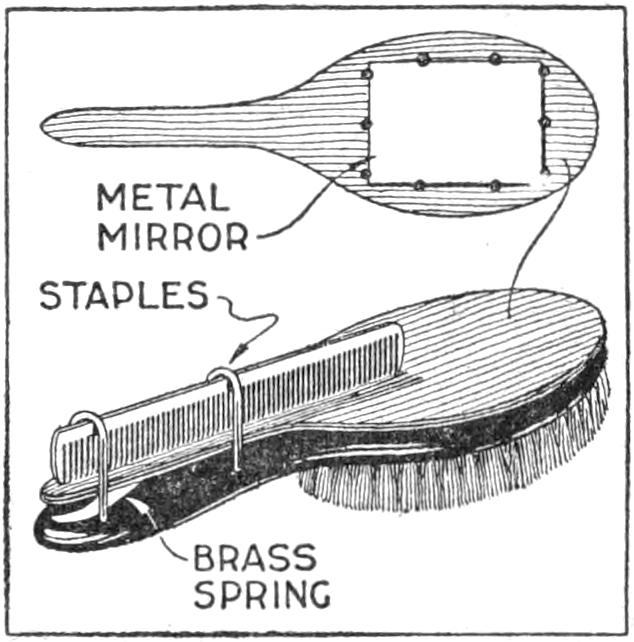

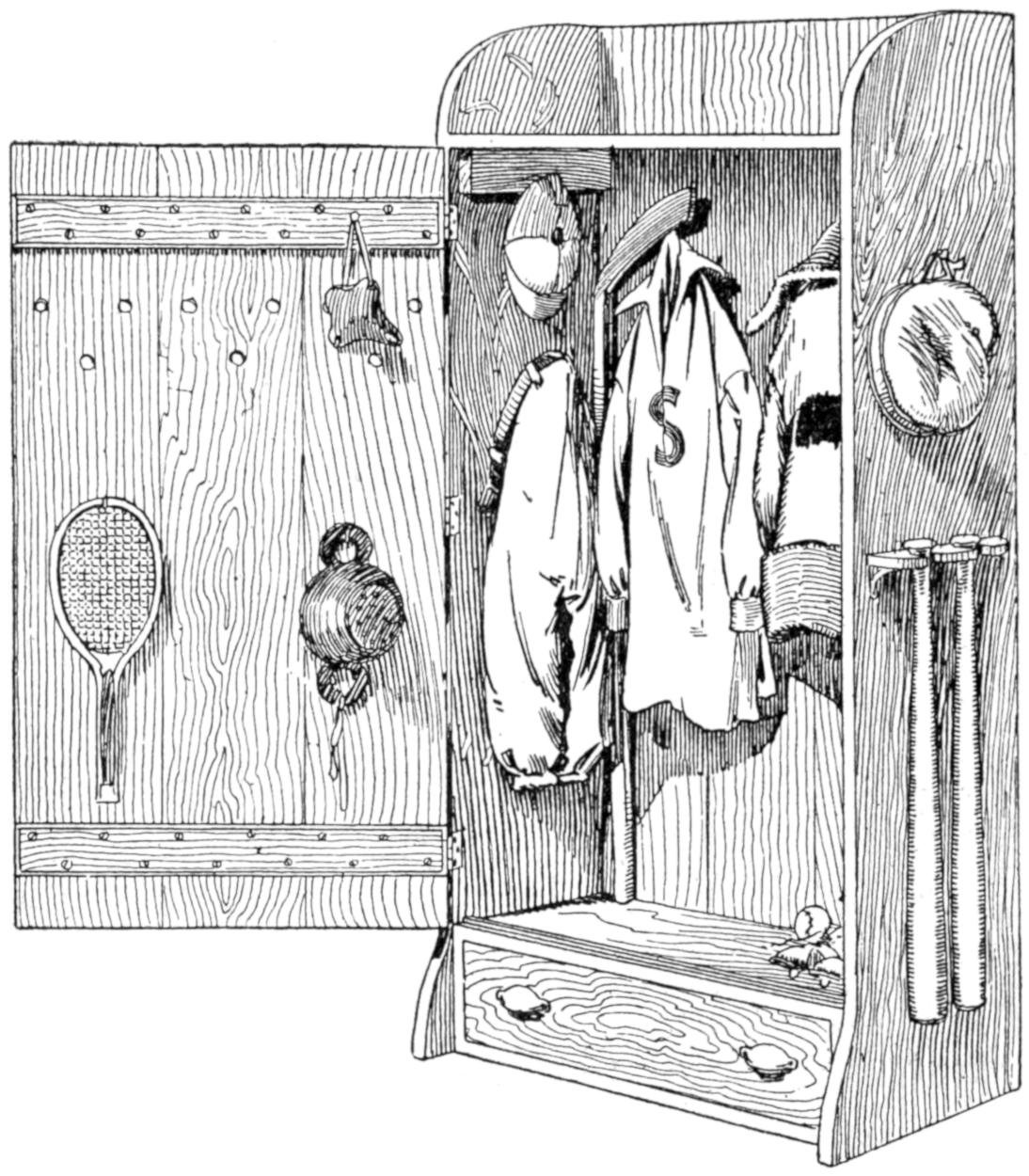

A compact outfit, which the soldier or camper will appreciate, consists of a comb, brush, and mirror, clamped together, as shown in the sketch. Two long staples are set into the back of the brush handle, as indicated. From a board, ¹⁄₄ in. thick, the backing for the metal “trench mirror” is made, with the handle portion small enough to fit into the staples. A small brass strip acts as a spring when placed near the end of the mirror handle, and holds the outfit snugly.

[10]

The common method of preserving leaves by pressing them with an iron rubbed on beeswax may be improved by substituting the following process. Paint the under side of each leaf with linseed oil, ironing it immediately, and then paint and iron the upper side in the same way. This treatment gives the leaves sufficient gloss, while they remain quite pliable. It is not necessary to press and dry the leaves beforehand, but this may be done if desired. The tints may even be well preserved by painting only the upper side of the leaves with the oil and then placing them, without ironing, between newspapers, under weights, to dry.—Caroline Bollerer, New Britain, Conn.

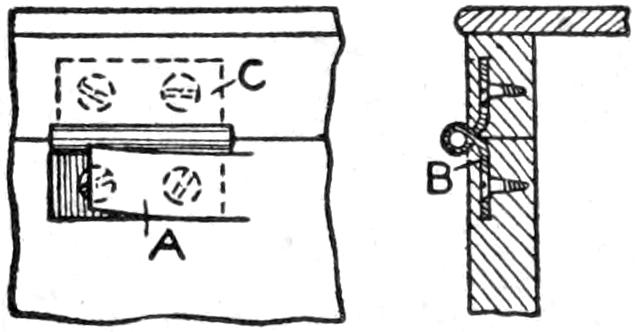

When I least expected it, the small-tool drawers of my tool chest have often dropped out, after I had left them partly open. The result was a waste of time in picking up the tools, not to mention the possible injury to them. I made small clips, like that shown in the sketch, and fitted them to the back of the drawers, as at A. When it is desired to remove the clips, the portion that extends above the drawer may be bent forward. This is necessary only where the space above the drawer is small. The clips may be made large enough to fit drawers of various sizes.—J. Harger, Honolulu, H. I.

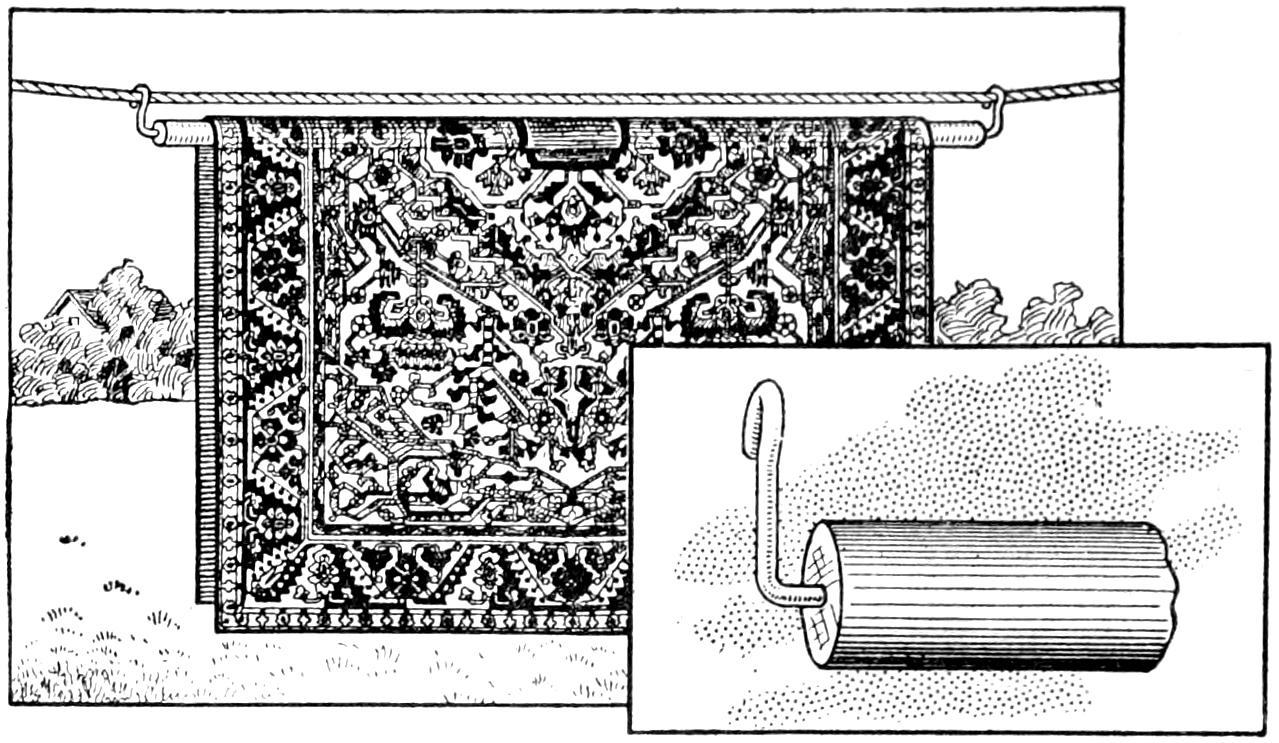

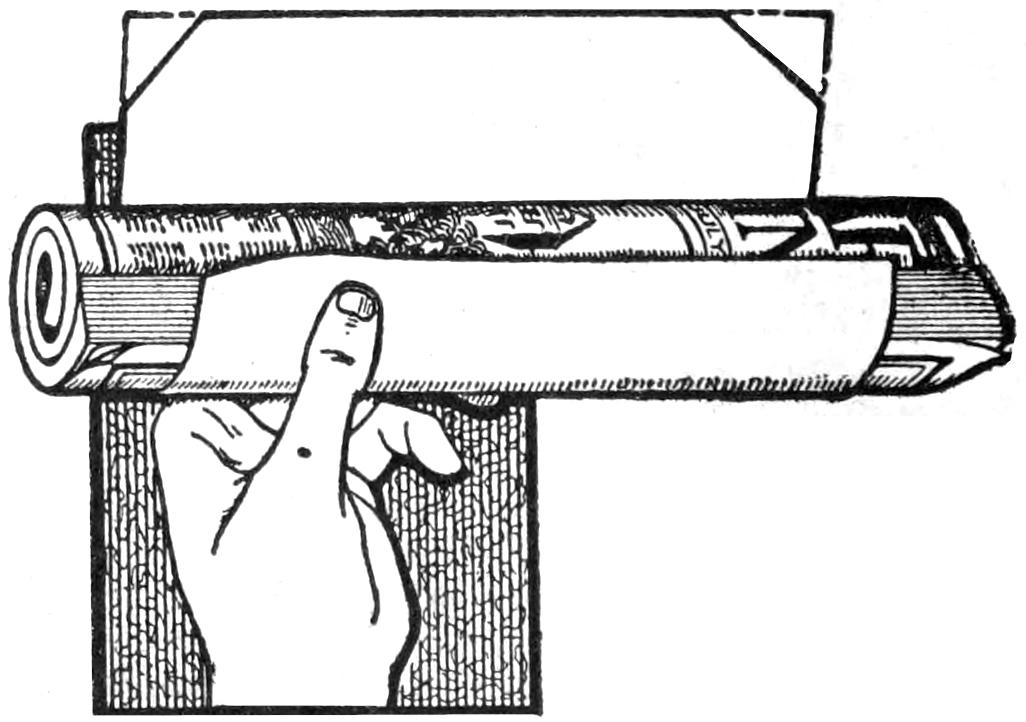

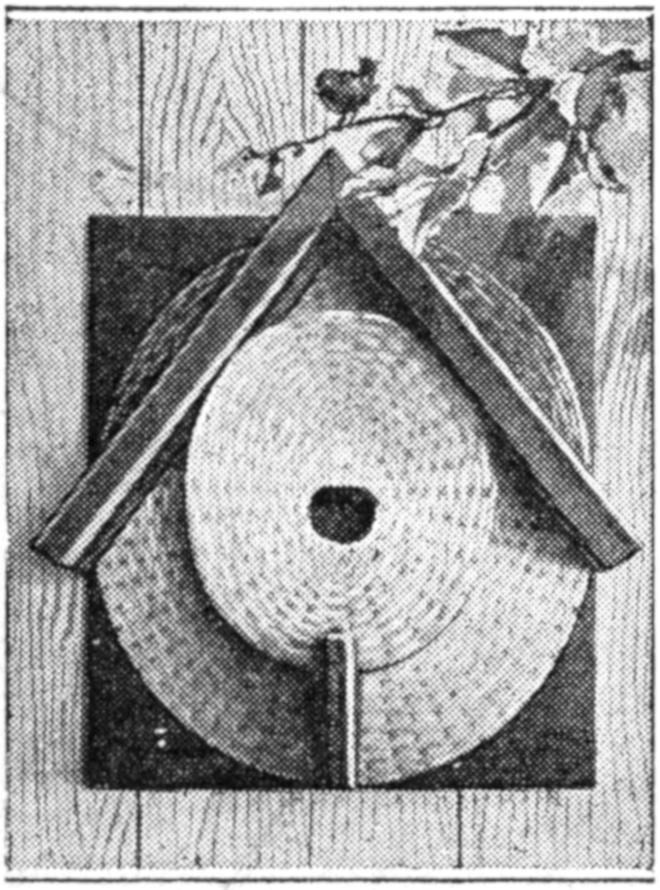

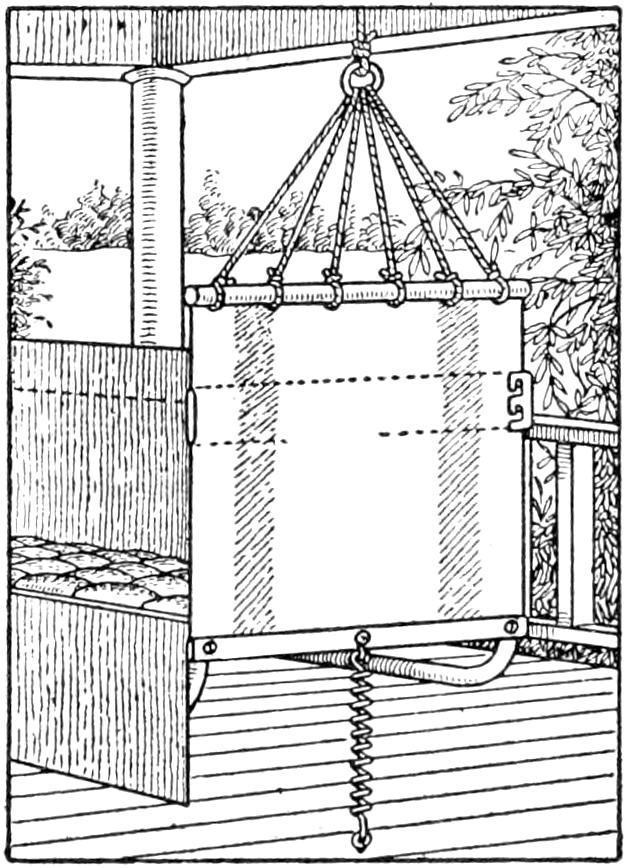

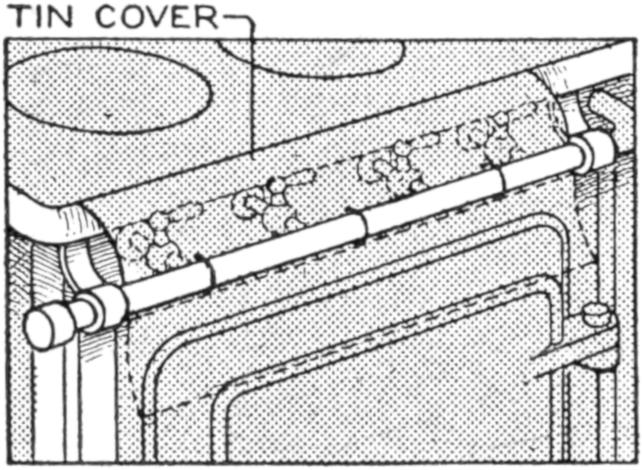

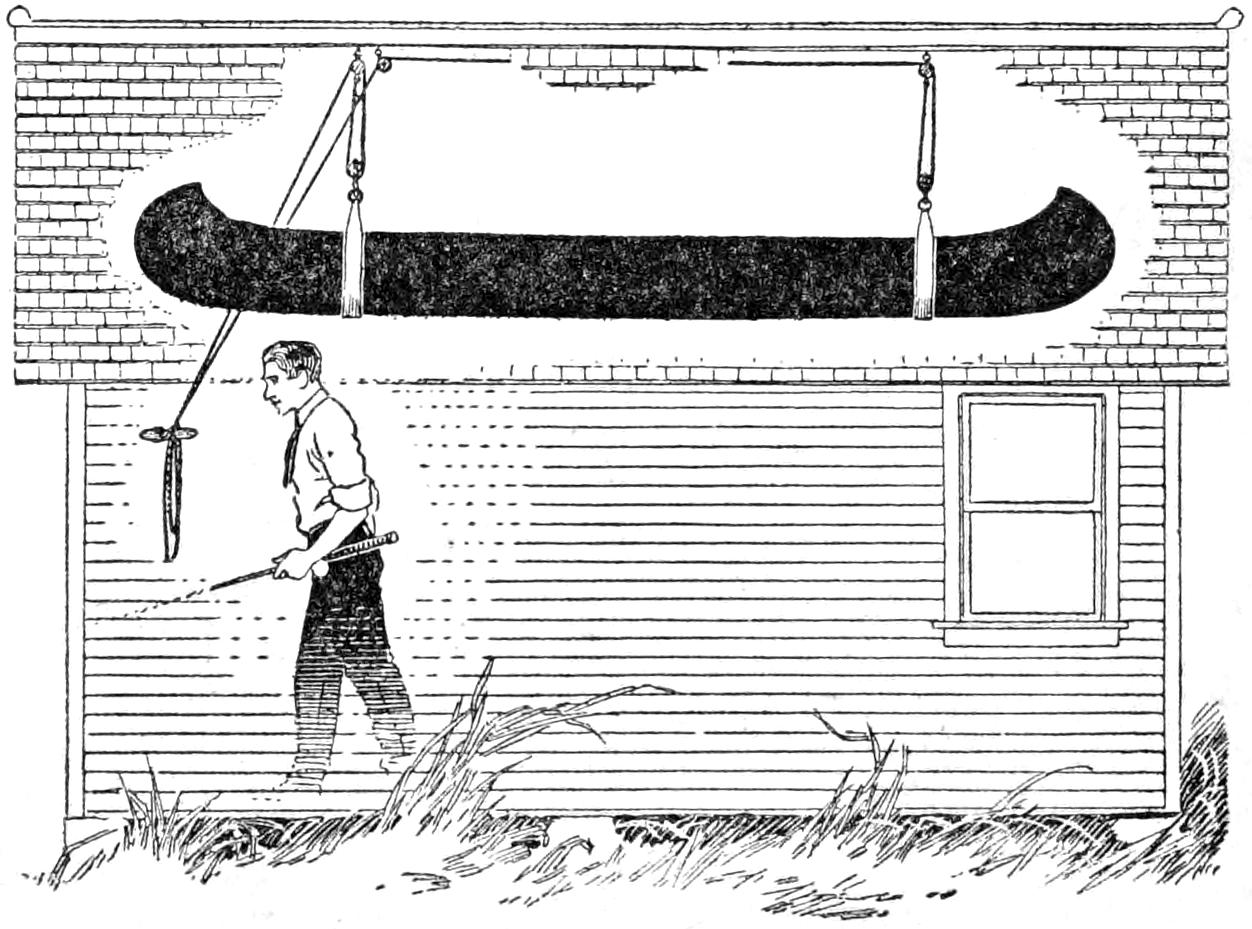

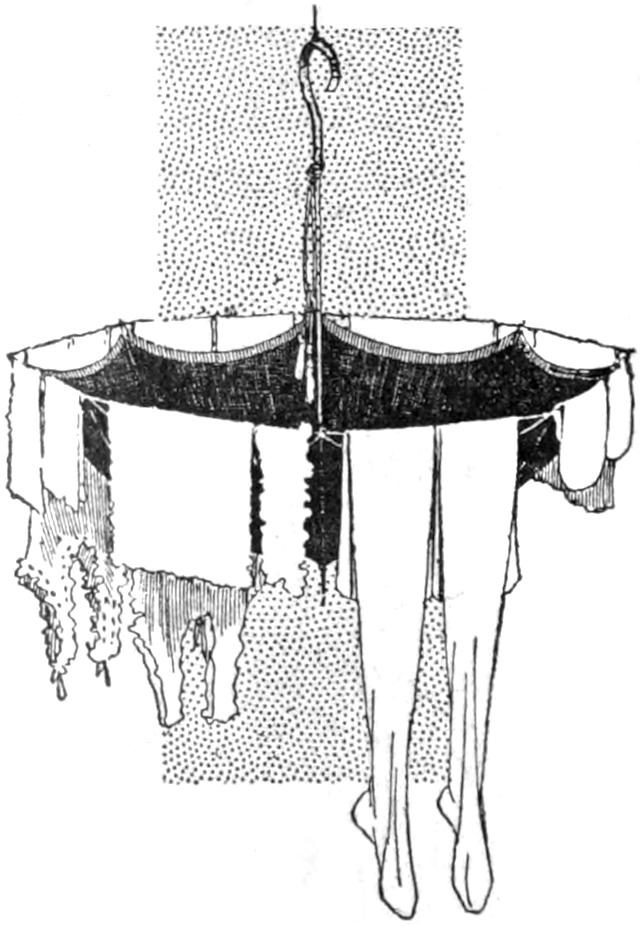

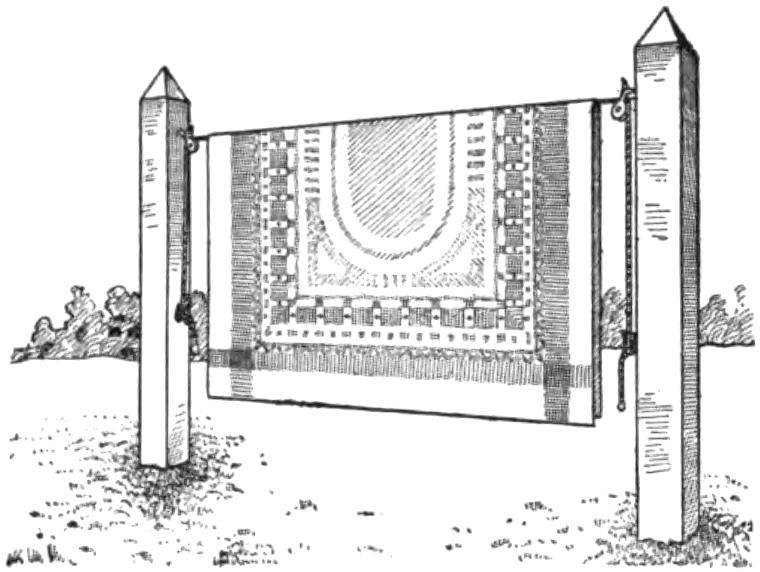

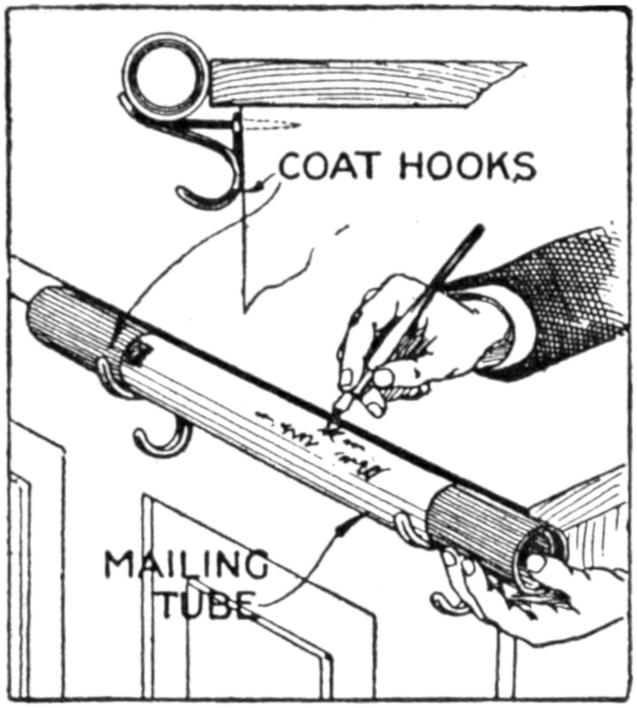

A rug may be handled easily for cleaning if the pole on which it is rolled when purchased is used as a support, as shown in the illustration. Two stout wires are fastened into the ends of the pole and hooked over the tightly stretched clothesline. The rug is suspended on the roller and is thus kept straight while it is cleaned, the tendency being, when only a clothesline is used, to crumple at the middle.—John V. Loeffler, Evansville, Ind.

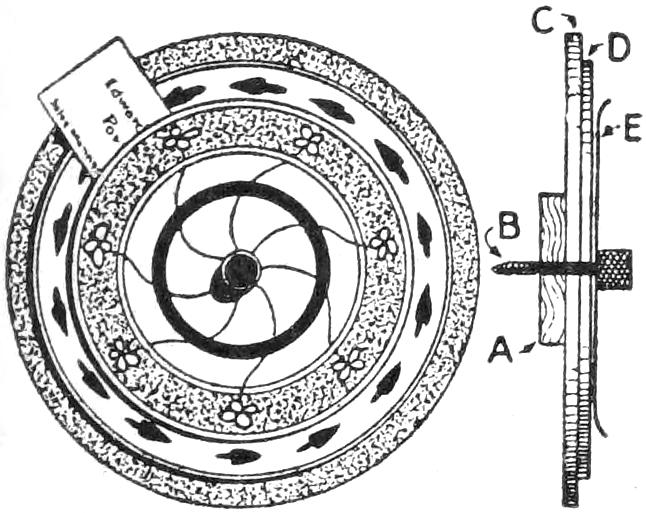

The Roller on Which the Rug is Rolled When Purchased is Used to Advantage as a Support While Cleaning It

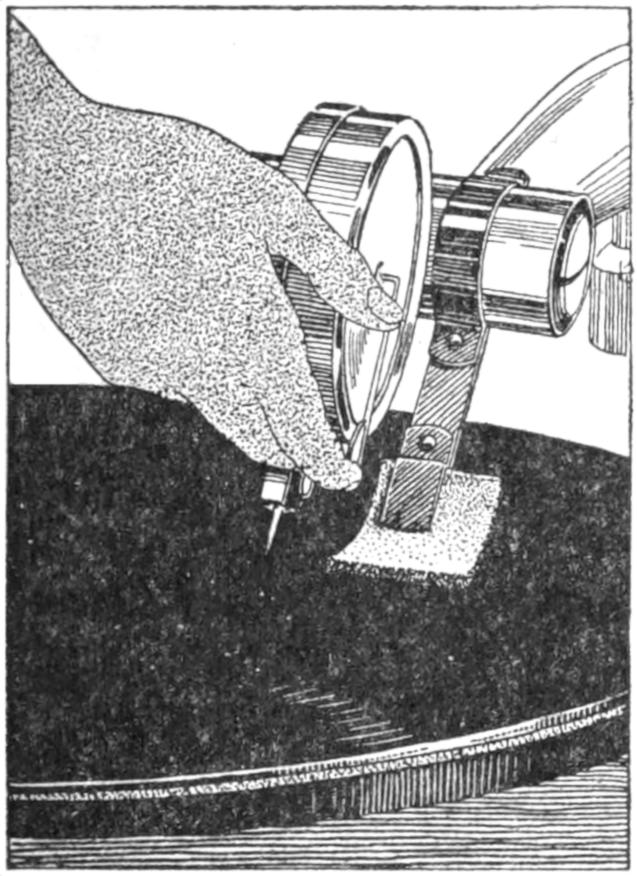

A serviceable wheel for banding hand-painted china may be had by adapting a disk talking machine for the purpose. Three old records are placed on the wheel, so as to bring the surface of the upper one slightly higher than the center pin. The piece of china to be banded is set on the exact center of the disk, with the rings on the record as a guide, and the brush may be rested on the arm of the machine. Care must, of course, be taken not to injure the talking machine.—Mrs. W. Read Elmer, Bridgeton, N. J.

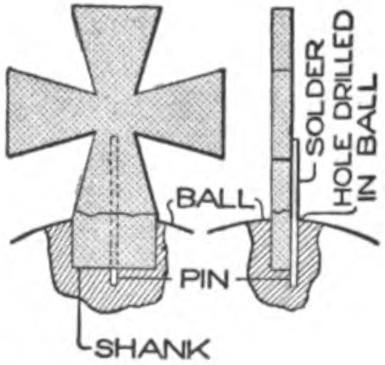

Requiring a collar button, and, as usual, having no extra one on hand, I devised the holder shown in the illustration. It proved to be better than a collar button for use at the back of the neckband. It was bent into shape from a hairpin and has the advantage of keeping the collar fixed with little chance of becoming unfastened.—William S. Thompson, Hopkinsville, Ky.

[11]

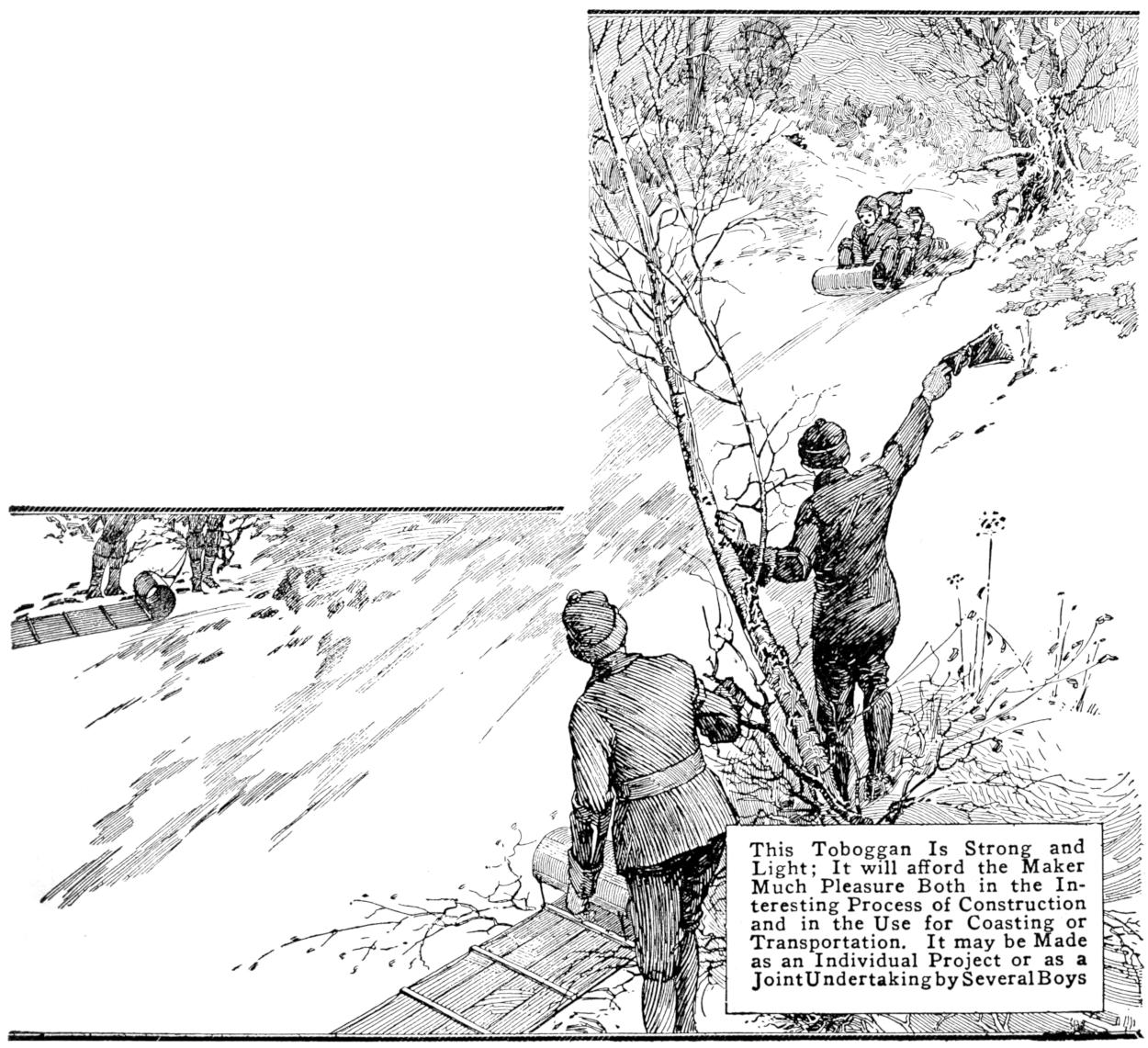

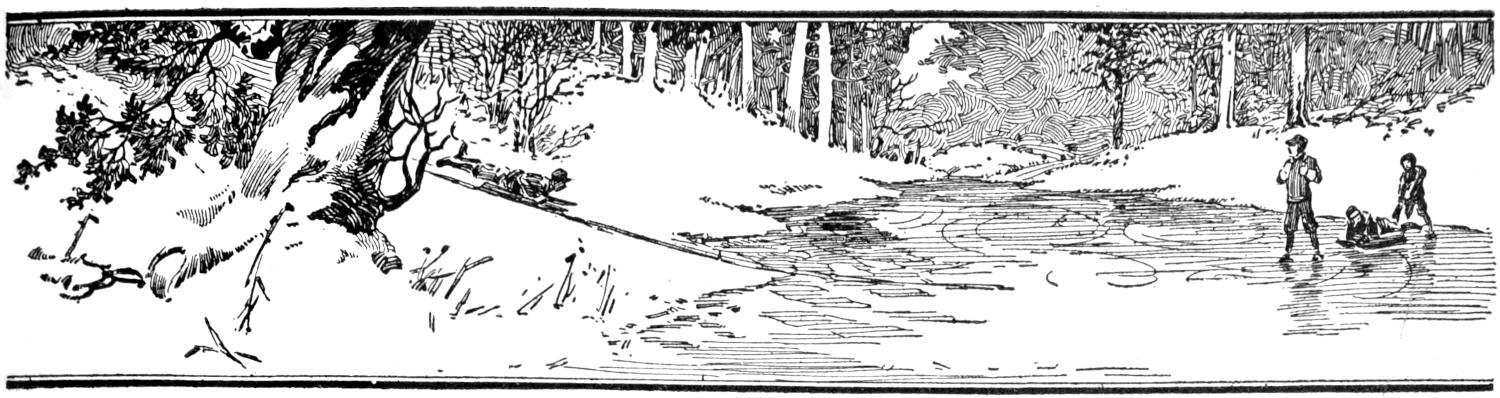

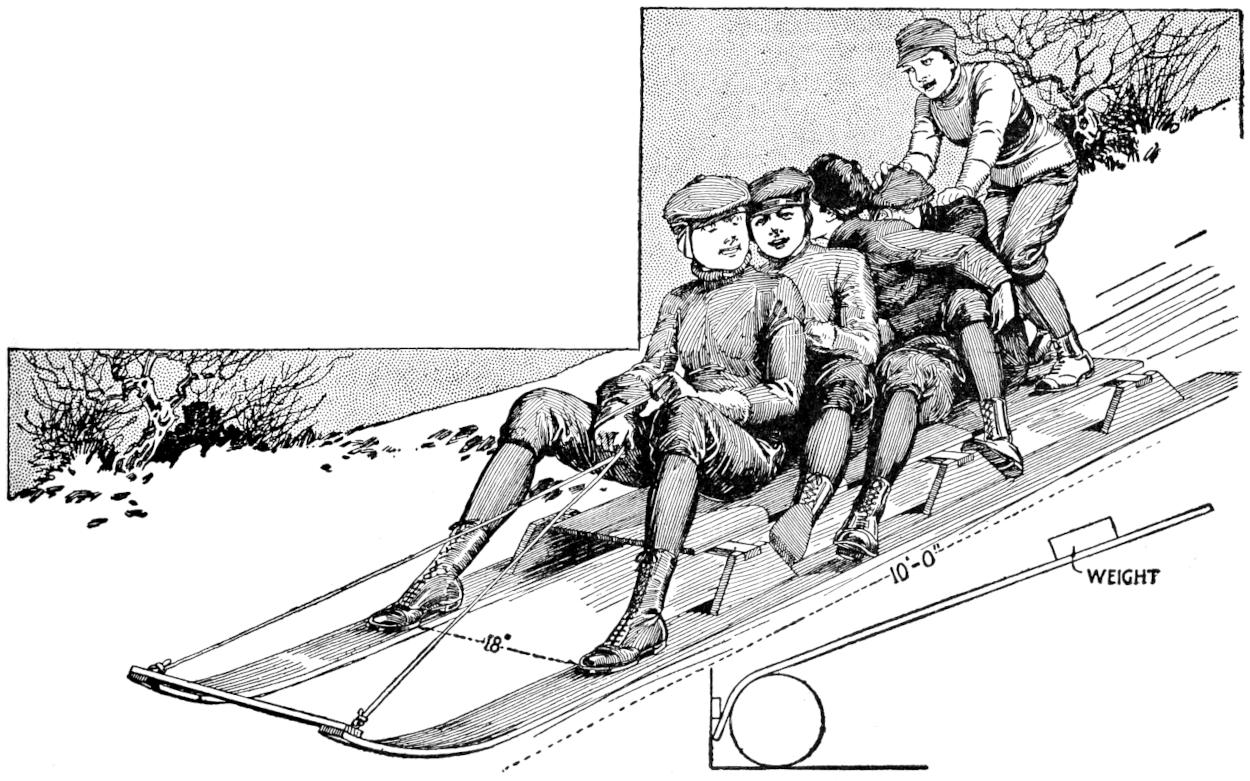

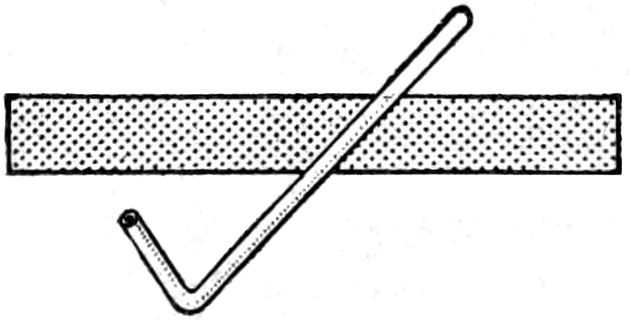

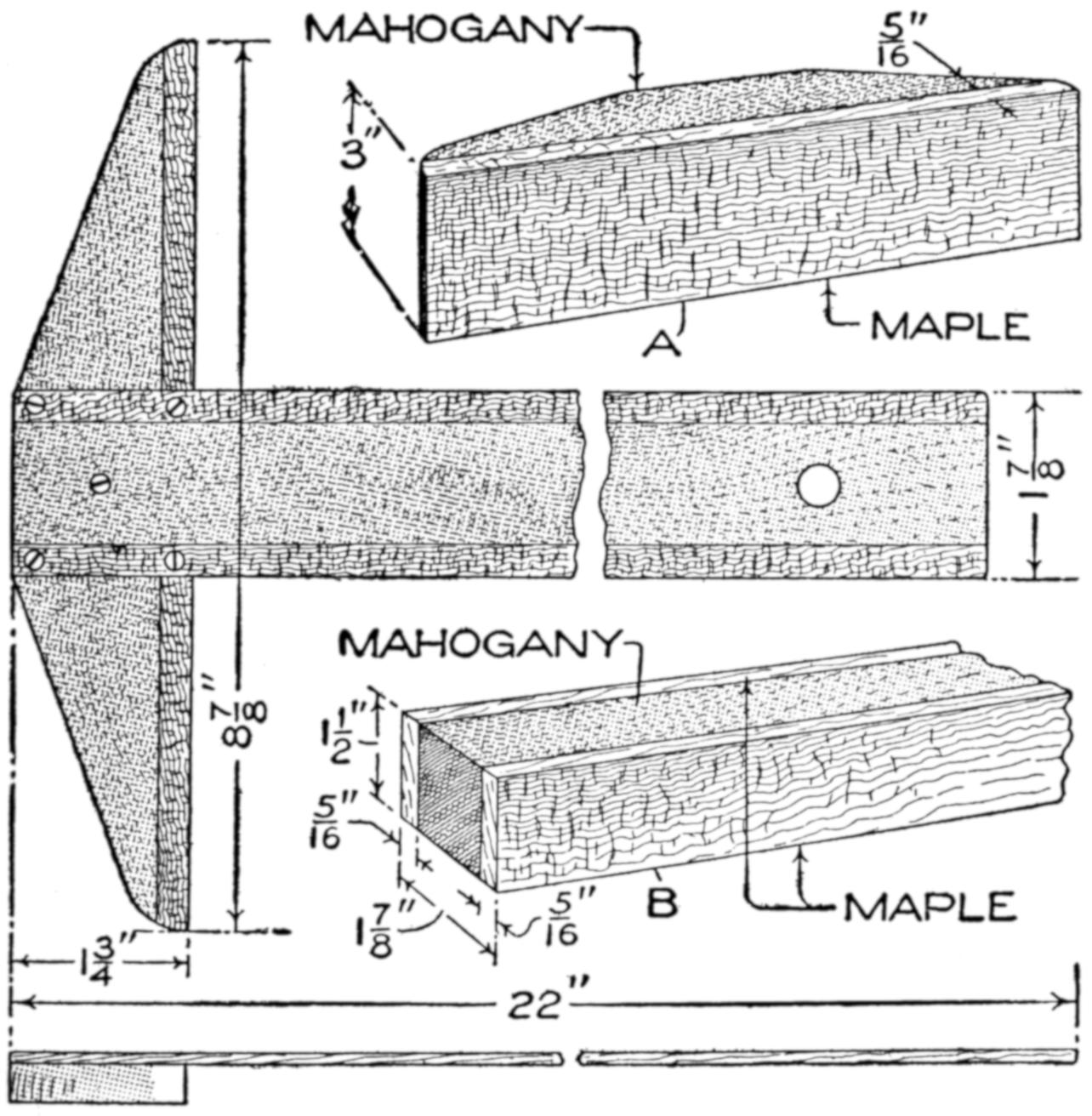

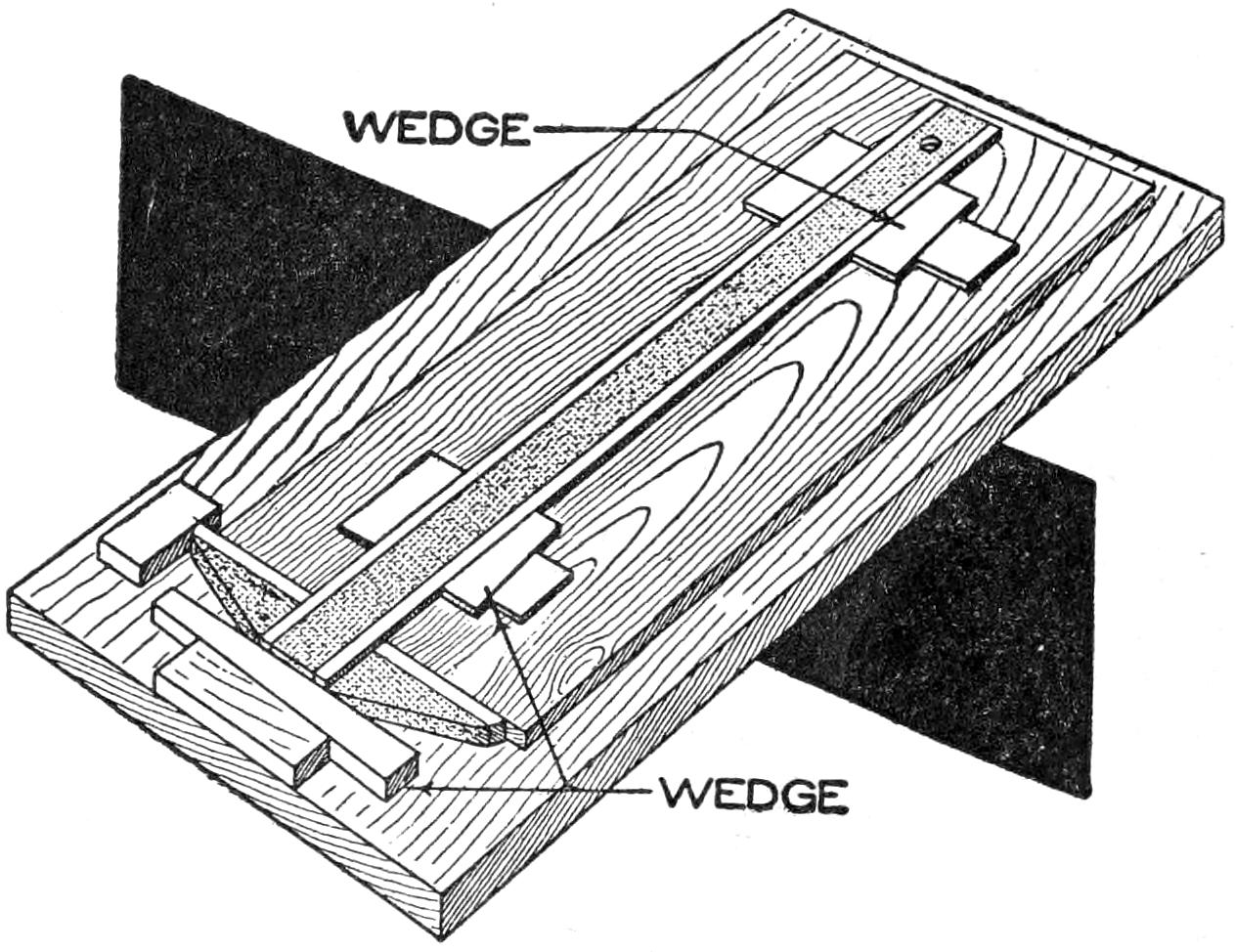

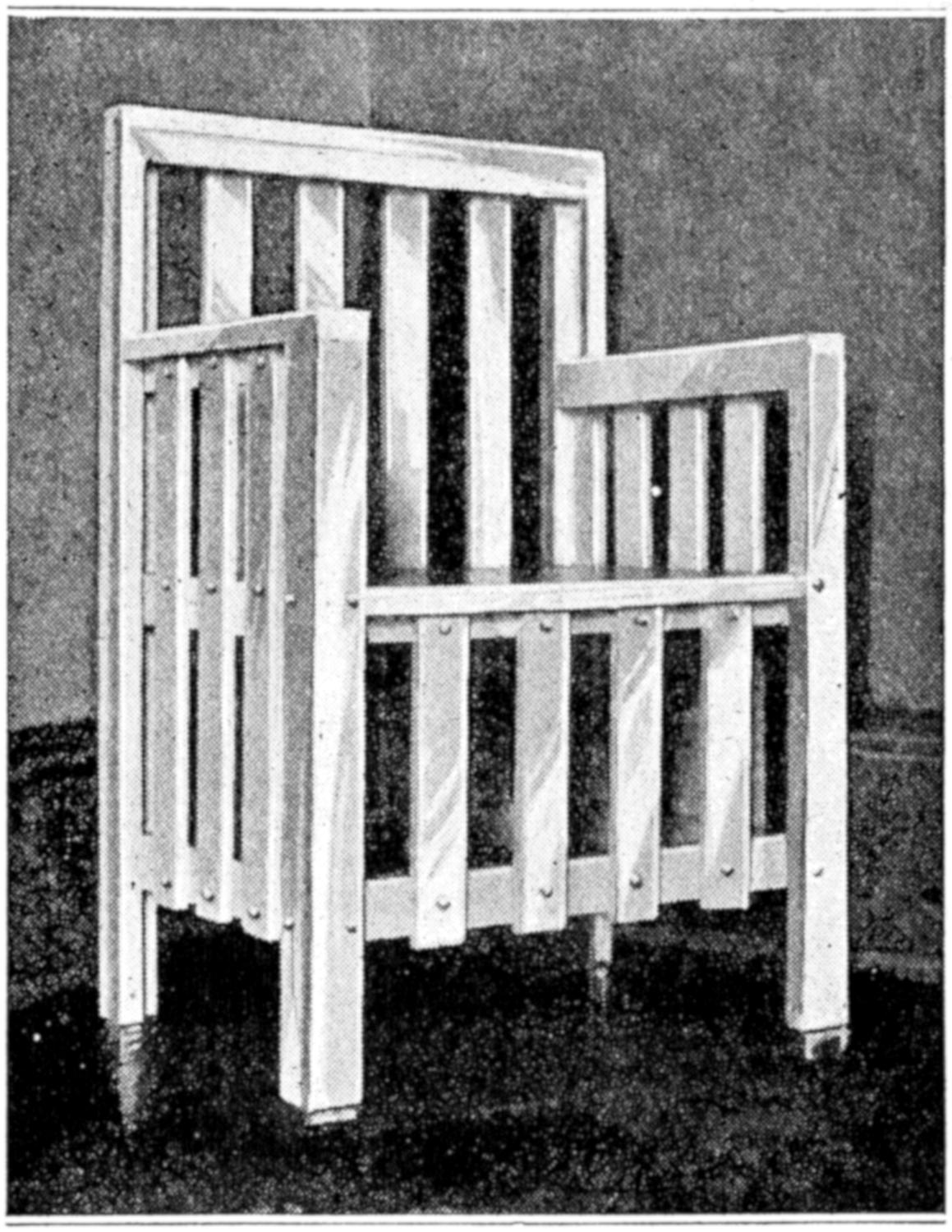

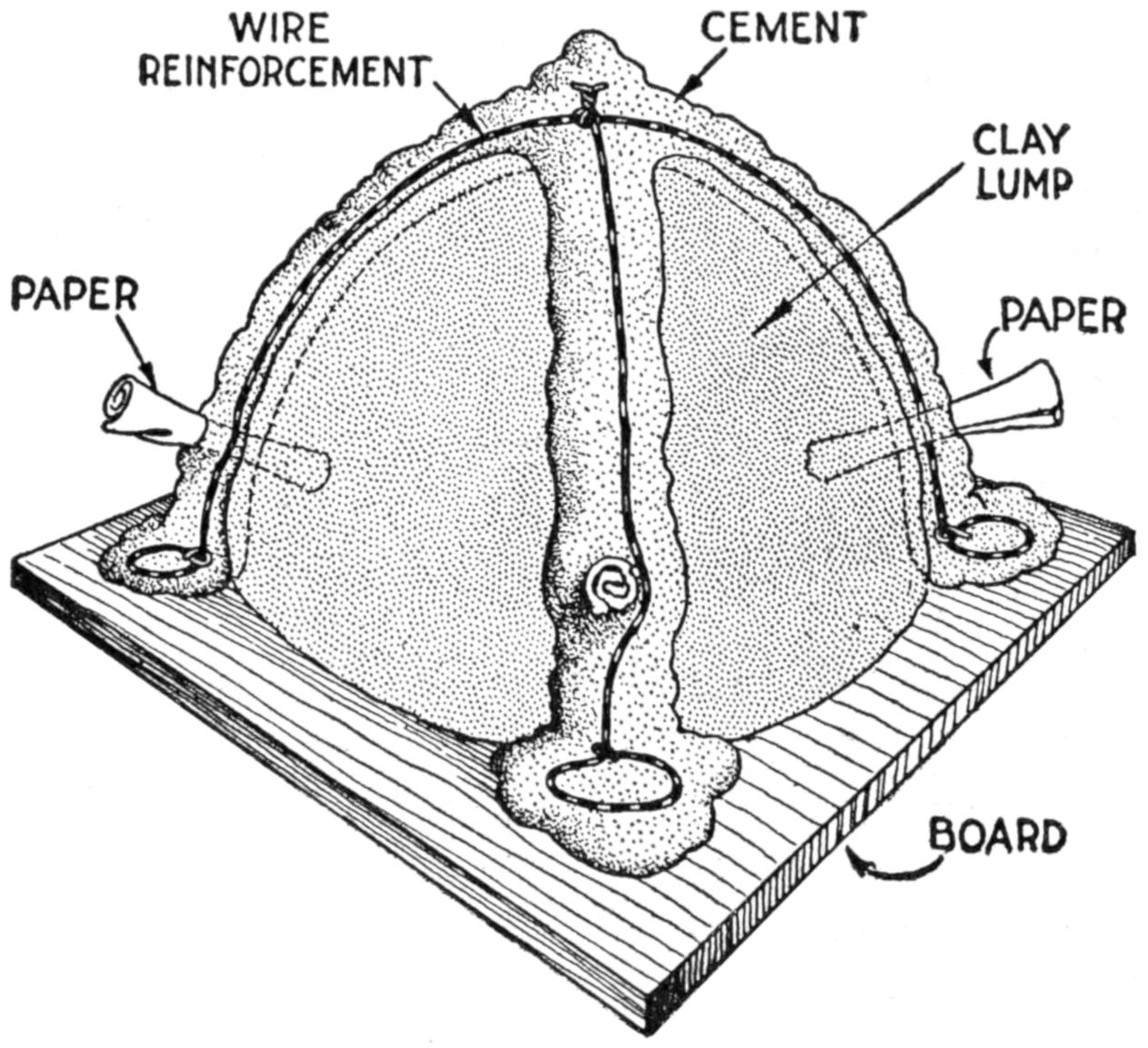

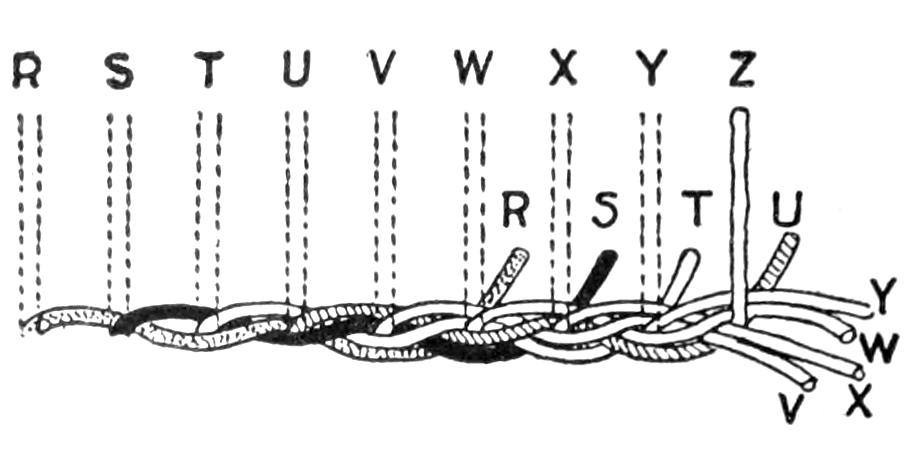

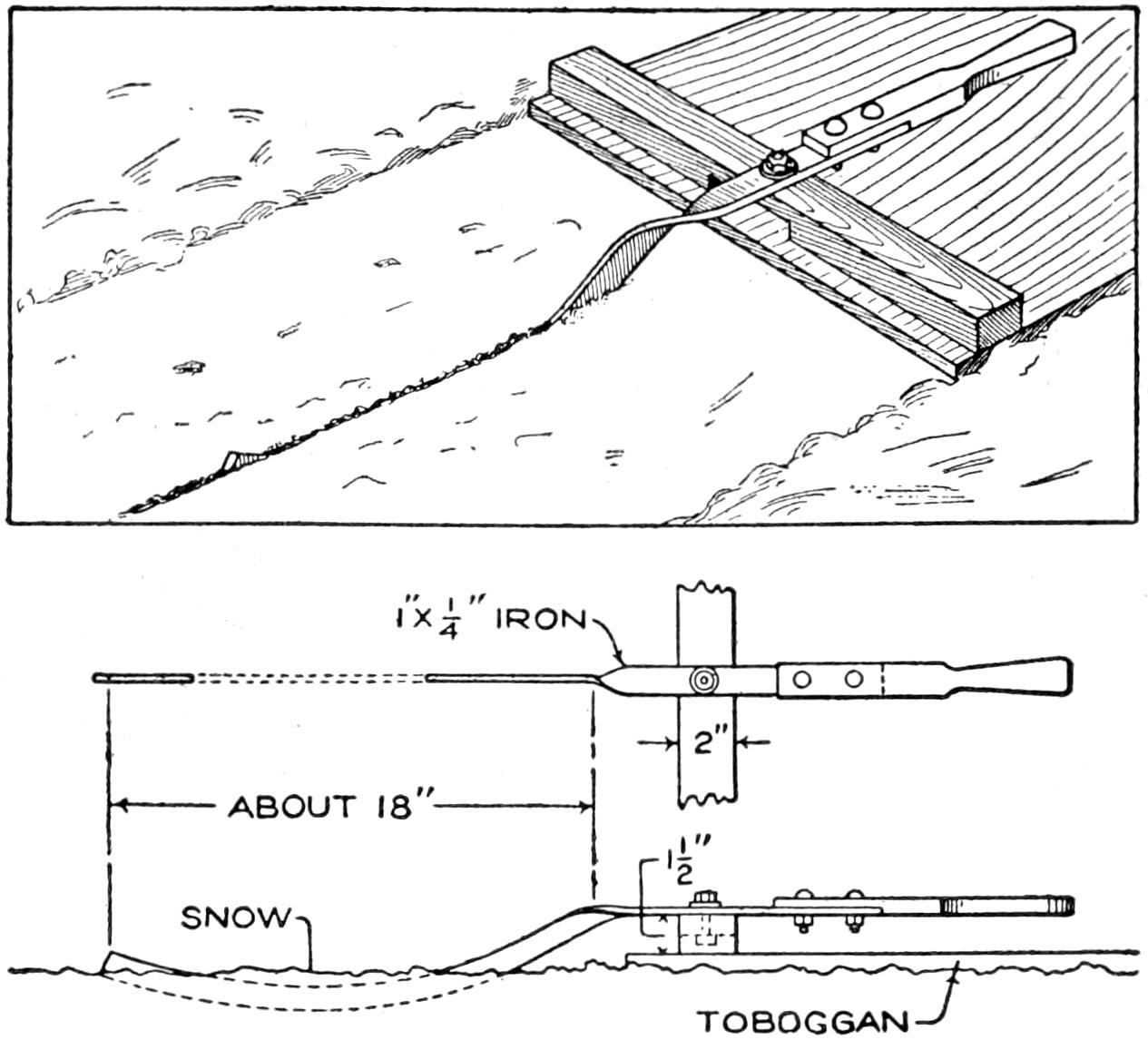

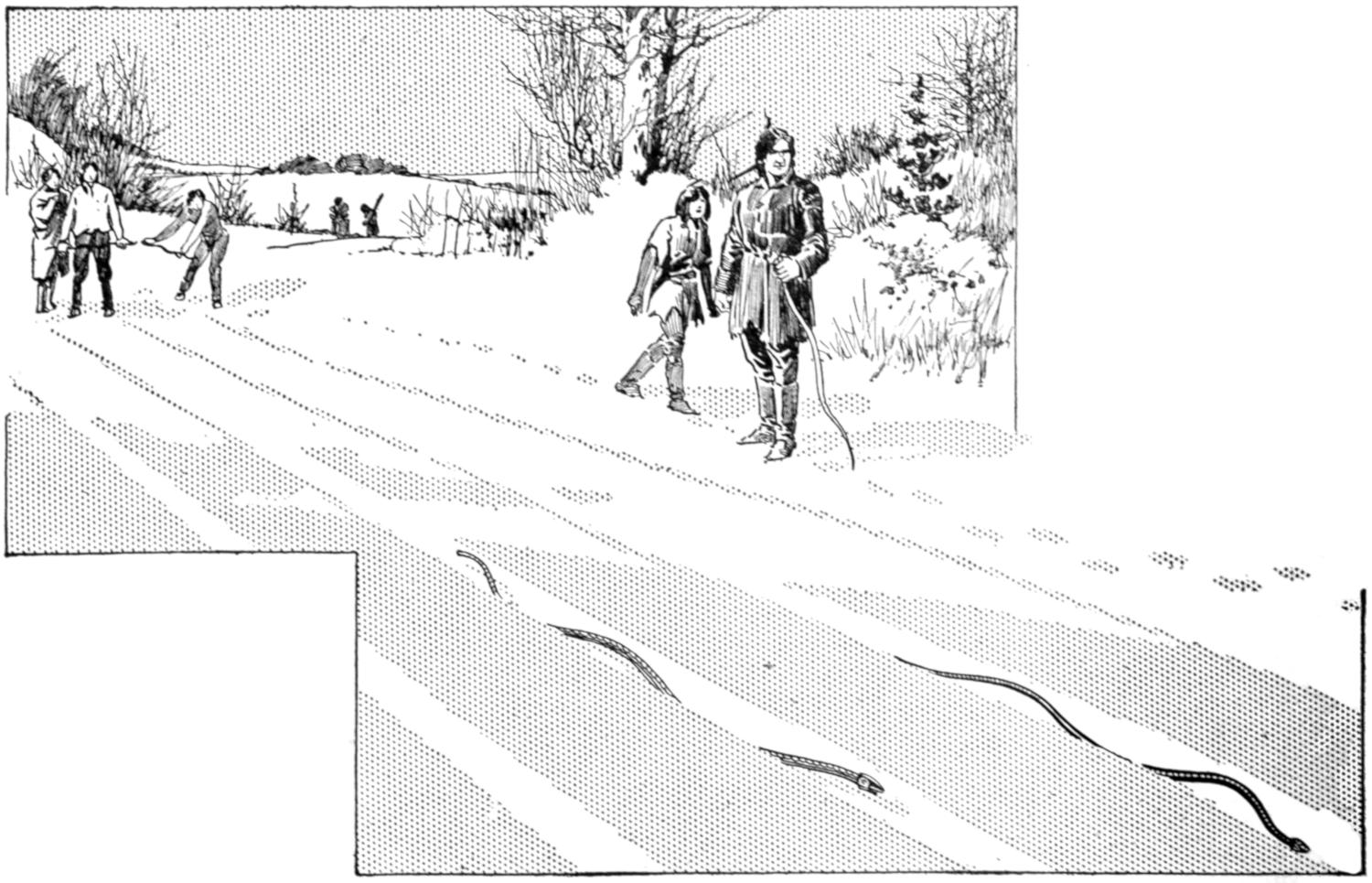

Essentials of a good toboggan, whether for coasting or use in transportation, are strength and lightness, and when it is to be made in the home shop, the construction must be simple. That shown in the illustration, and detailed in the working sketches, was designed to meet these requirements. The materials for the toboggan proper and the forms over which it is bent, may be obtained at small expense.

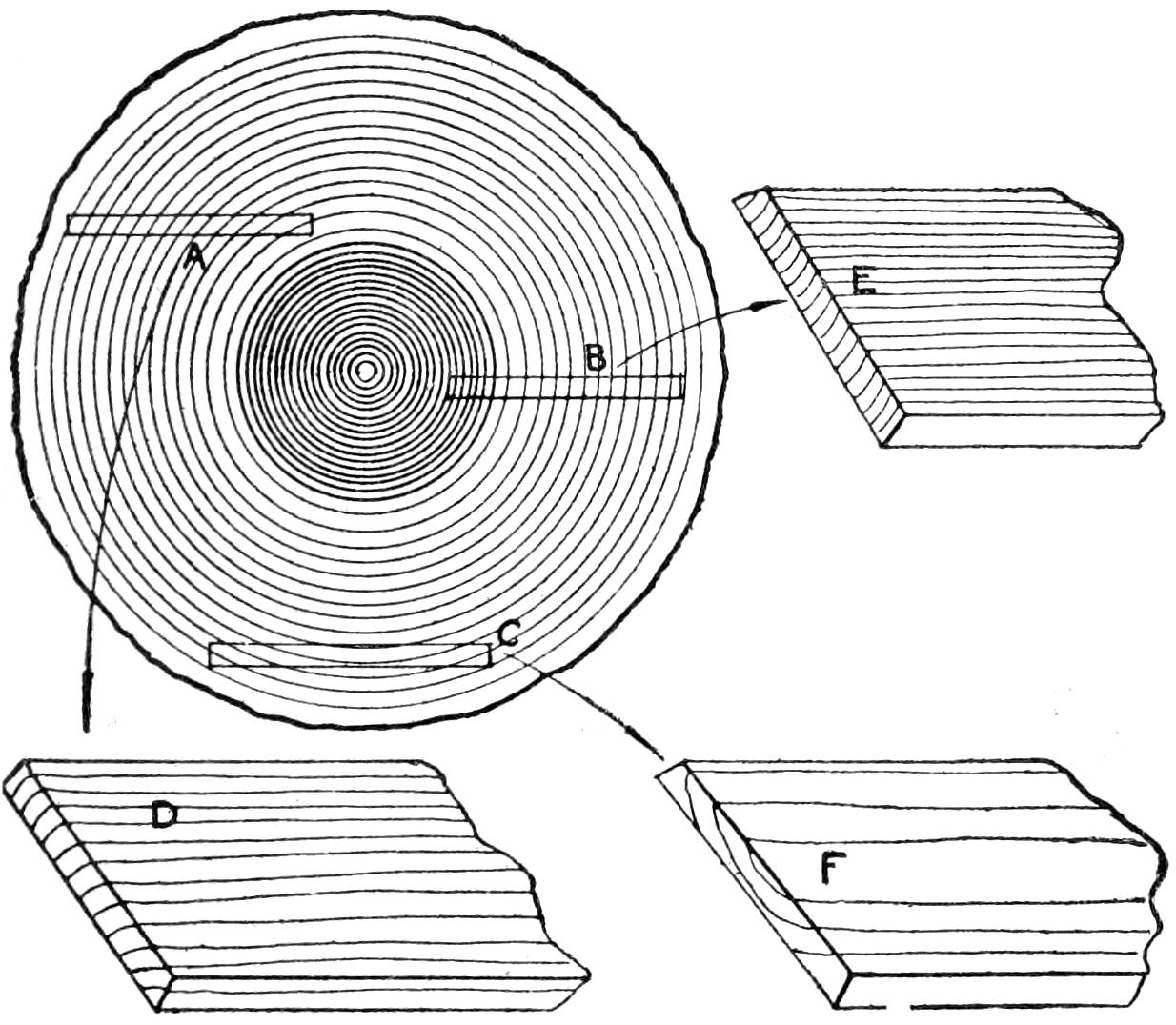

Smoothness of finished surface, freedom from tendency to splinter, and ability to stand up under abuse being requisite qualities in the wood used to make a toboggan, three varieties may be mentioned in their order of merit: hickory, birch, and oak. Birch is softer than hickory and easily splintered, but acquires an excellent polish on the bottom. Oak stands bending well, but does not become as smooth on the running surface as close-grained woods. Do not use quarter-sawed oak because of the cross-grain flakes in its structure.

While the best toboggan is made of a single board, both the securing of material and its construction are rather difficult. Narrow strips are easily bent to shape, but do not make a durable article. A toboggan made of four boards is practical. The mill bill for one 7¹⁄₂ ft. long by 16 in. wide and for the bending frame, is as follows:

| 4 | pieces, | ⁵⁄₁₆ | by | 4 | in. | by | 10 | ft., | hard | wood. | |

| 7 | „ | 1 | by | 1 | in. | by | 16 | in., | „ | „ | |

| 2 | „ | ¹⁄₂ | by | 1 | in. | by | 16 | in., | „ | „ | |

| 2 | „ | 1 | by | 6 | in. | by | 6 | ft., | common boards. | ||

| 6 | „ | 1 | by | 2 | in. | by | 18 | in., | „ | „ | |

| 1 | cylindrical block, 12 in. diameter by 18 in. long. | ||||||||||

This Toboggan Is Strong and Light; It will afford the Maker Much Pleasure Both in the Interesting Process of Construction and in the Use for Coasting or Transportation. It may be Made as an Individual Project or as a Joint Undertaking by Several Boys

[12]

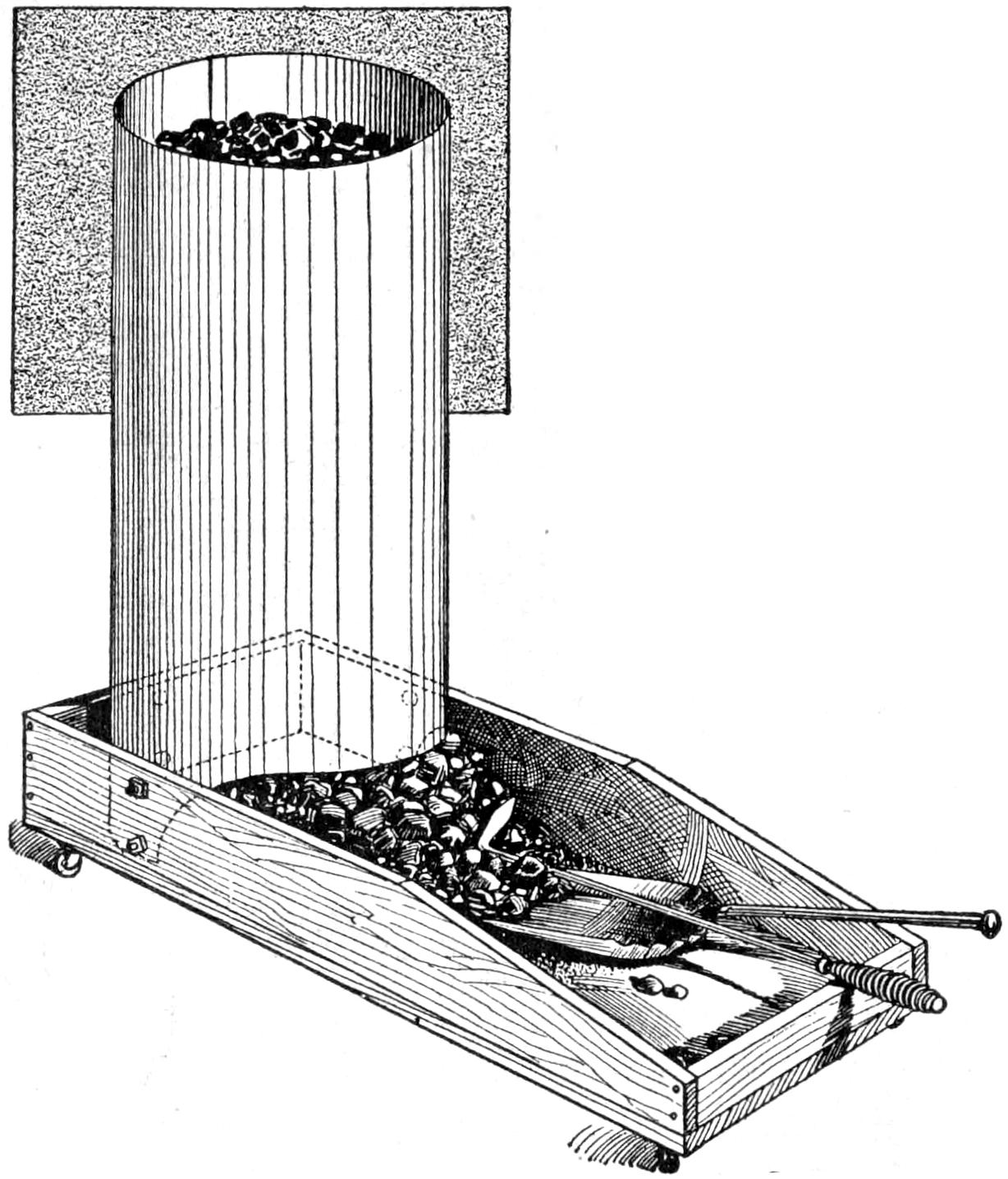

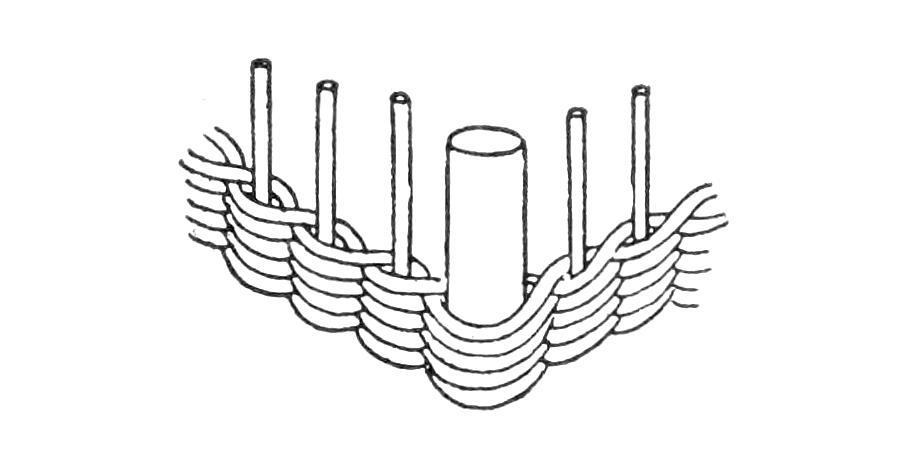

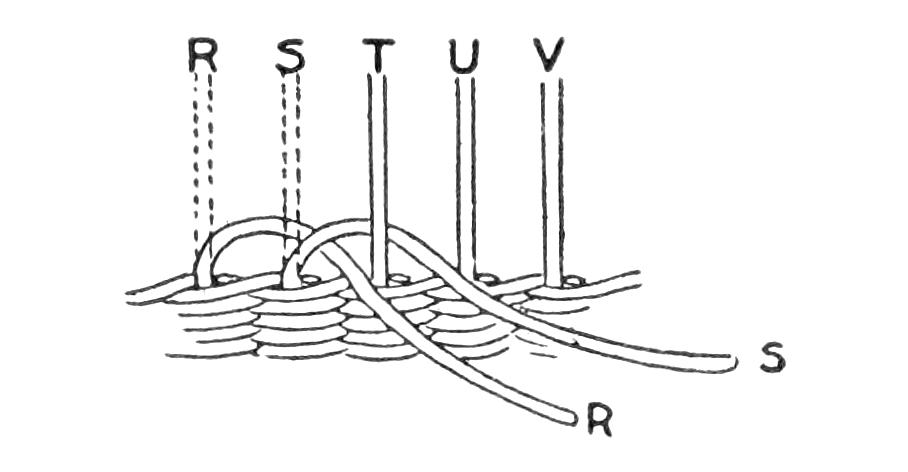

The form for the bending of the pieces is made of the common boards and the block. A block sawed from the end of a dry log is excellent. Heat it, if convenient, just before bending the strips. The boards for the bottom should be selected for straightness of grain and freedom from knots and burls. Carefully plane the side intended for the wearing surface, and bevel the edges so that, when placed together, they form a wide “V” joint, half the depth of the boards. The 1 by 1-in. pieces are for cross cleats and should be notched on one side, 1 in. from each end, to receive the side ropes. The two ¹⁄₂ by 1-in. pieces are to be placed one at each side of the extreme end of the bent portion, to reinforce it.

The Boards for the Bottom are Steamed or Boiled at the Bow Ends and Bent over the Form. As the Bending Operation Progresses, the Boards are Nailed to the Form with Cleats, and Permitted to Dry in This Position

Bore a gimlet hole through the centers of the 1 by 2 by 18-in pieces, and 4¹⁄₄ in. each side of this hole, bore two others. Nail the end of one of the 6-ft. boards to each end of the block, so that their extended ends are parallel. With 3-in. nails, fasten one of the bored pieces to the block between the boards, inserting, temporarily, a ¹⁄₂-in. piece to hold it out that distance from the block.

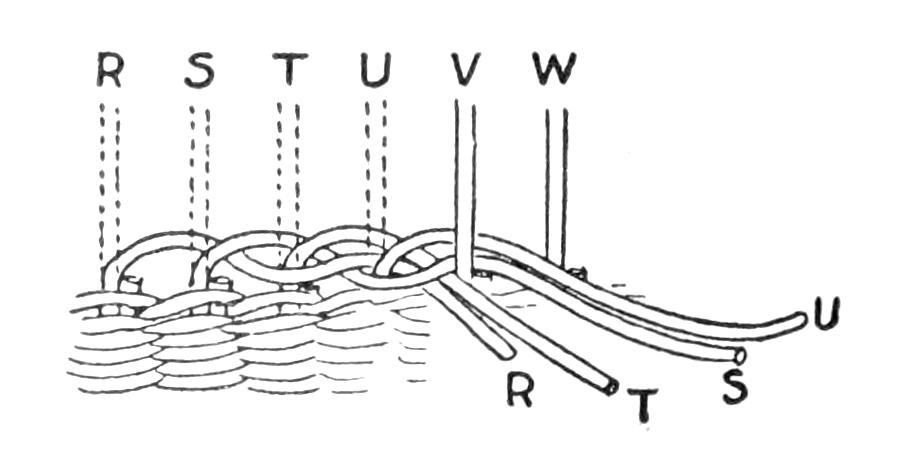

Steam about 3 ft. of the ends of the boards, or boil them in a tank. Clamp, or nail, the boards together, at the dry ends, edge to edge, between two of the 1 by 2-in. pieces, leaving about ¹⁄₄-in. opening between boards. Thrust the steamed ends under the cleat nailed on the block, the nails which hold it slipping up between the boards. Bear down on the toboggan carefully, nailing on another of the bored cleats, when the toboggan boards have been curved around the block as far as the floor will permit. The nails, of course, go between the boards.

Now, turn the construction over and bend up the toboggan, following the boards around the block with more of the nailed cleats, until the clamped end is down between the two 6-ft. boards,[13] where it can be held by a piece nailed across. More of the cleats may be nailed on if desired; in fact, the closer together the cleats are the less danger there is of splintering the boards, and the more perfect the conformity of the boards to the mold.

Allow at least four days for drying before removing the boards from the form. Clamp the ¹⁄₂ by 1-in. pieces one each side of the extreme ends of the bent bows, drill holes through, and rivet them. A 1 by 1-in. crossbar is riveted to the inside of the bow at the extreme front and another directly under the extremity of the curved end. These cleats are wired together to hold the bend of the bow. The tail end crossbar should be placed not nearer than 2¹⁄₂ in. from the end of the boards, while the remainder of the crossbars are evenly spaced between the front and back pieces, taking care that the notched side is always placed down. Trim off uneven ends, scrape and sandpaper the bottom well, and finish the toboggan with oil. Run a ³⁄₈-in. rope through the notches under the ends of the cross pieces, and the toboggan is completed.

Screws are satisfactory substitutes for rivets in fastening together the parts, and wire nails, of a length to allow for about ¹⁄₄-in. clinch, give a fair job. Indians overcome the lack of hardware by the use of rawhide, laced through diagonally staggered holes bored through the crosspieces and bottom boards. Rawhide, which they sometimes stretch over the bow as a protection, affords an opportunity for elaborate ornamentation.

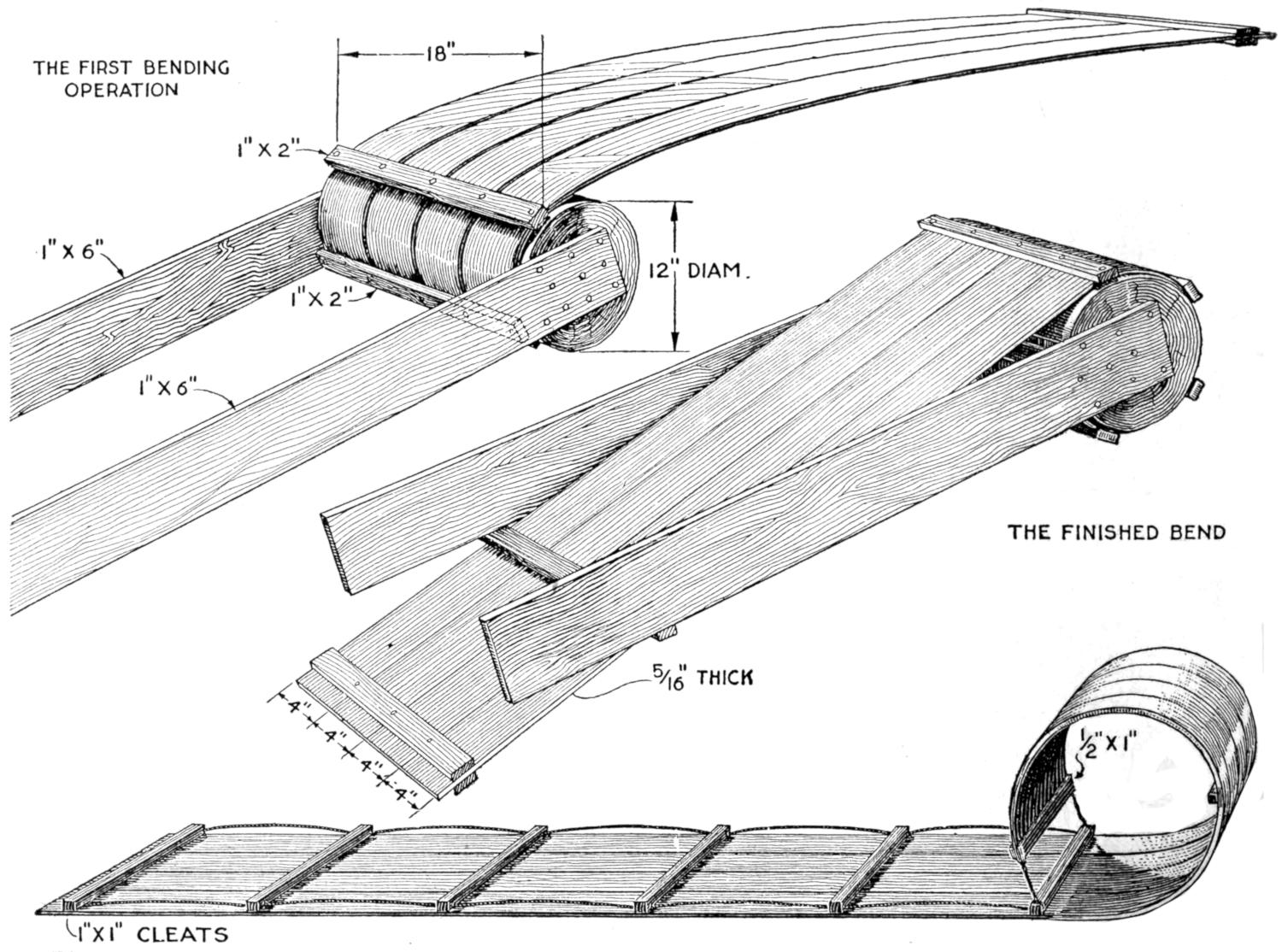

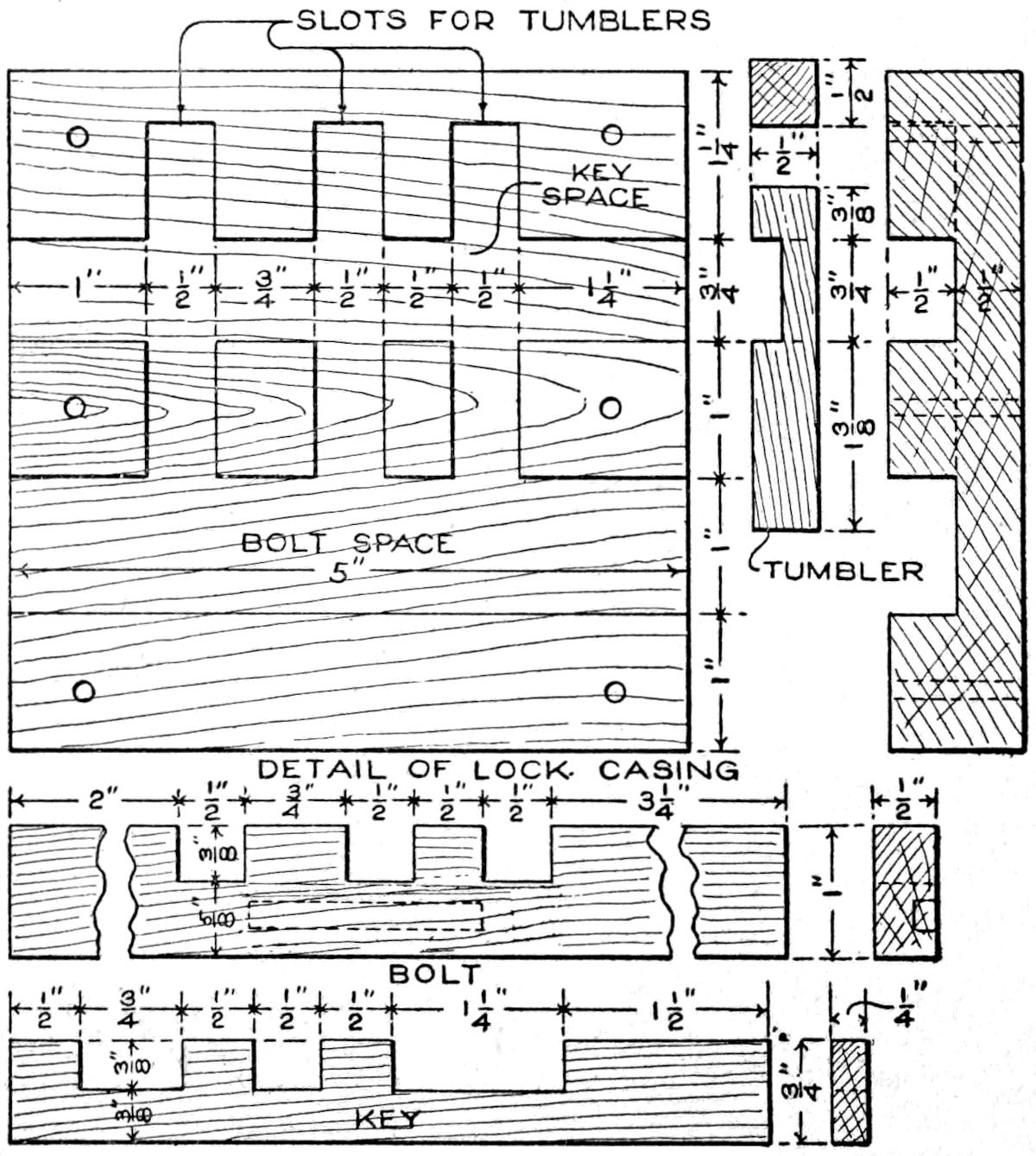

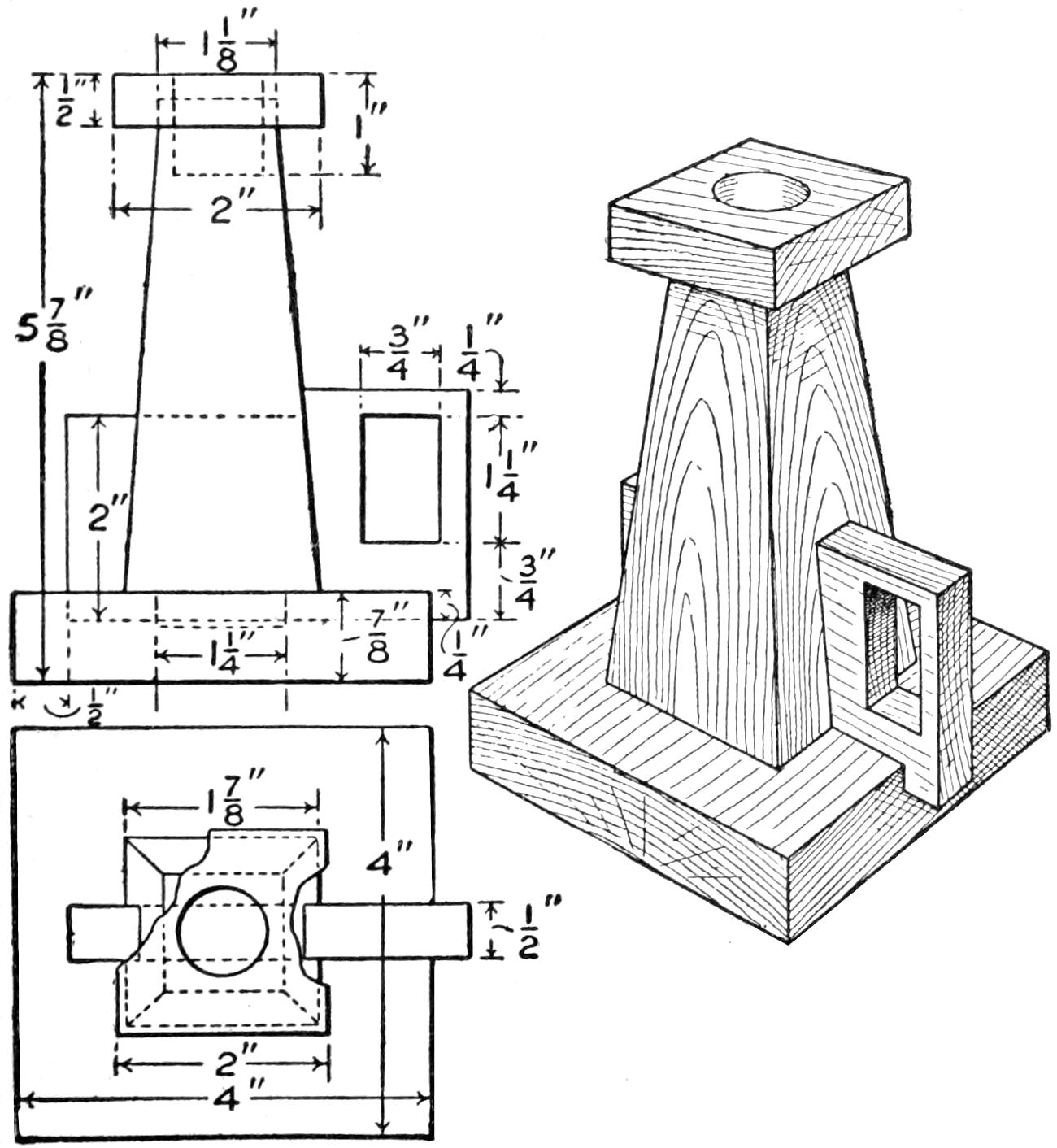

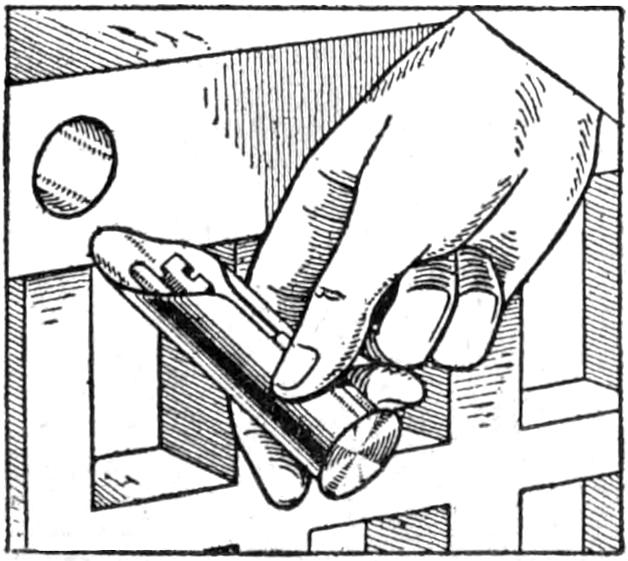

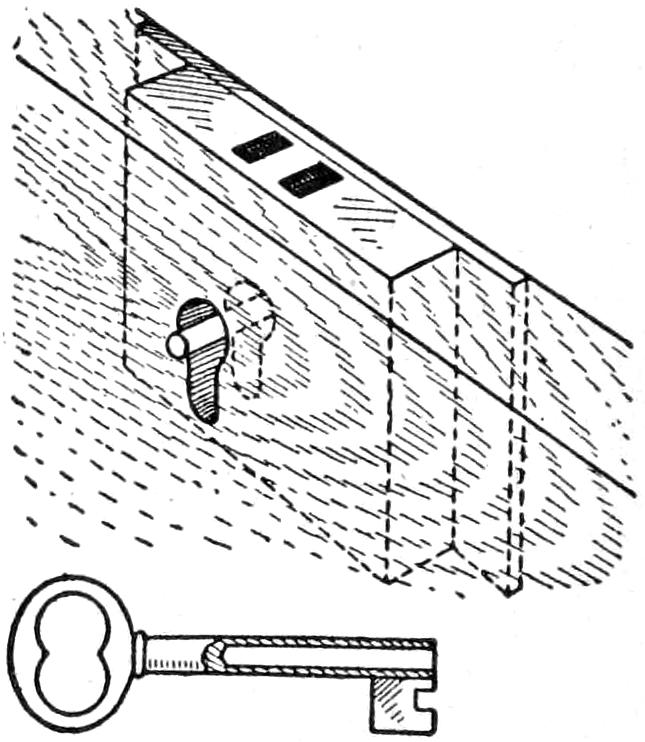

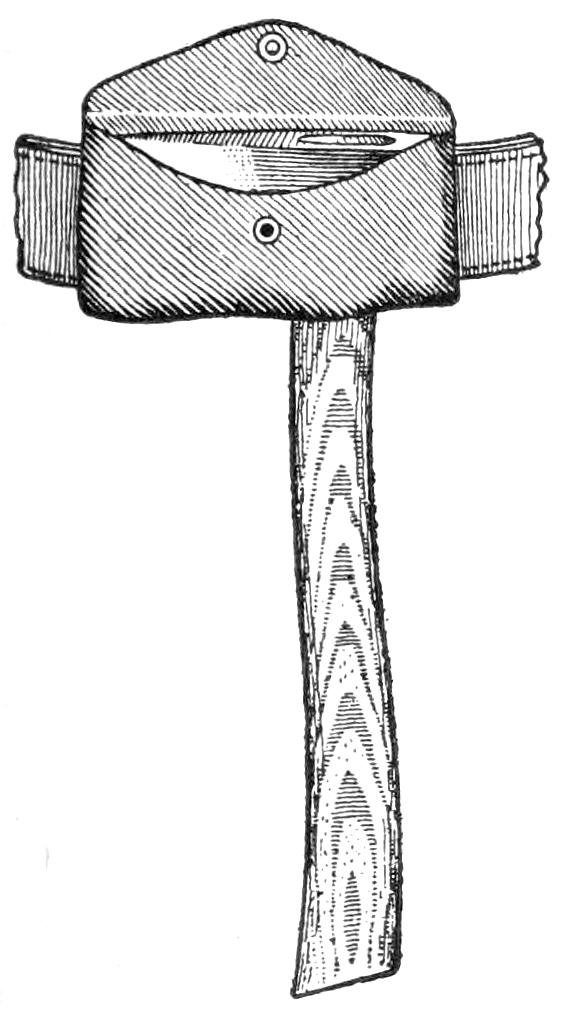

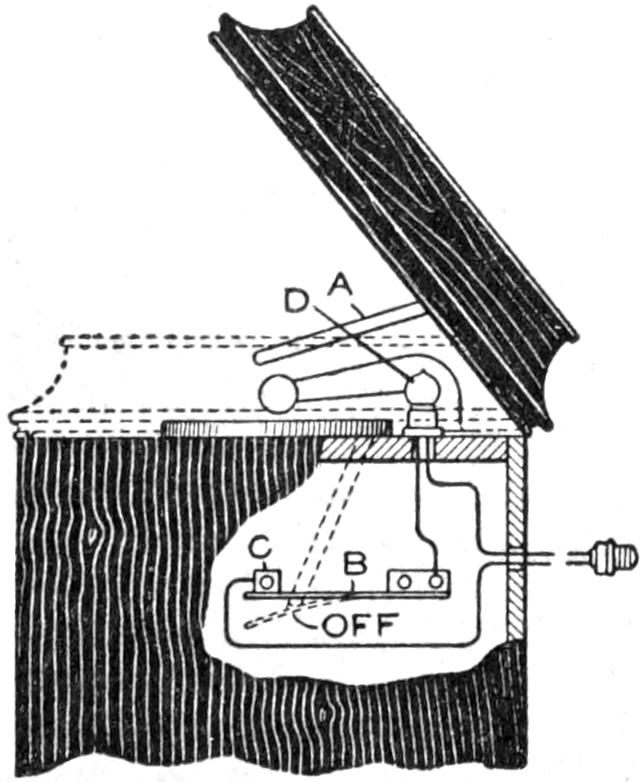

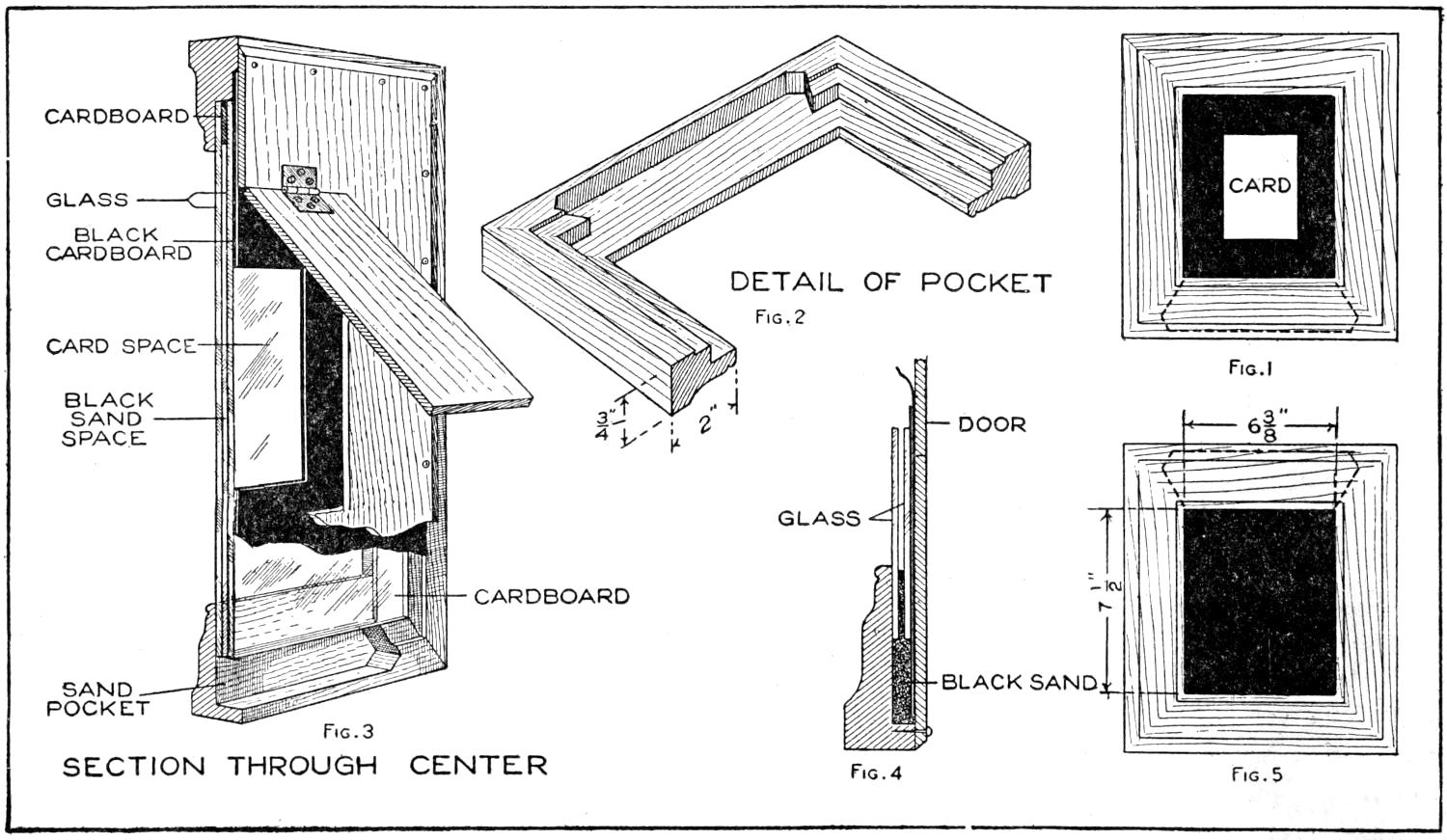

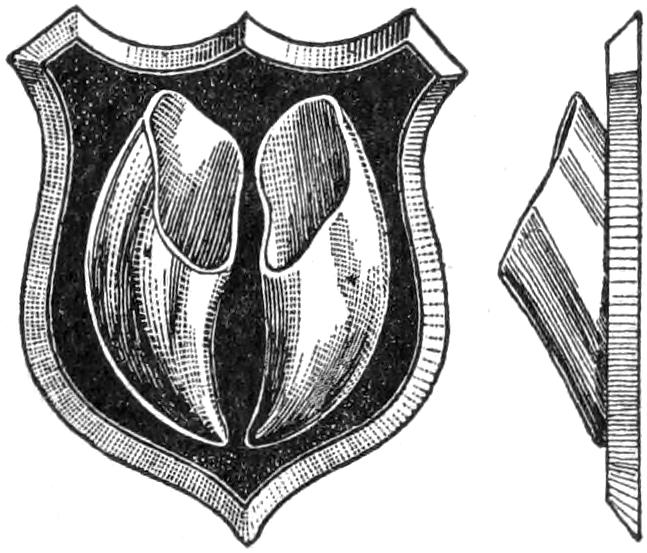

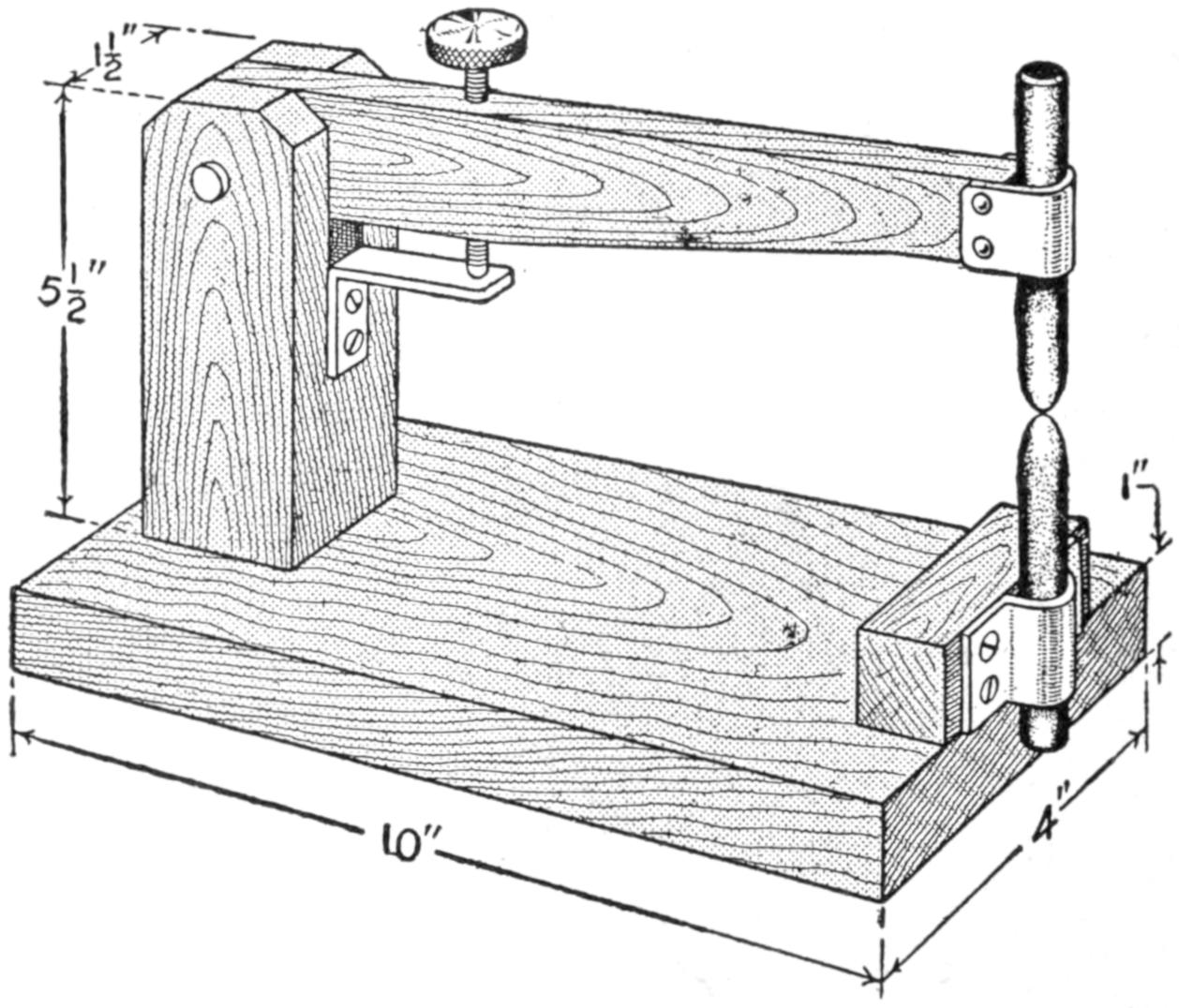

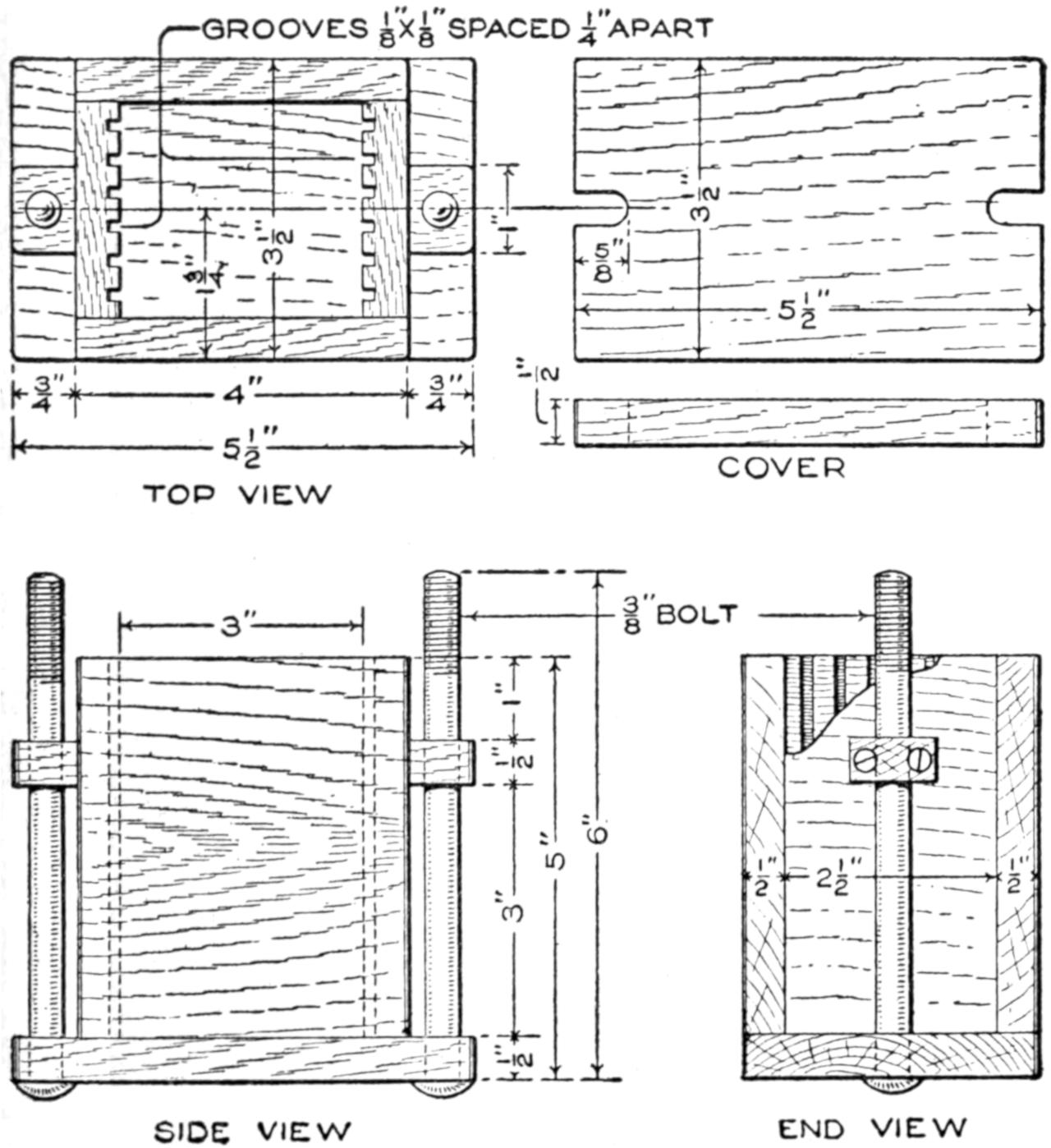

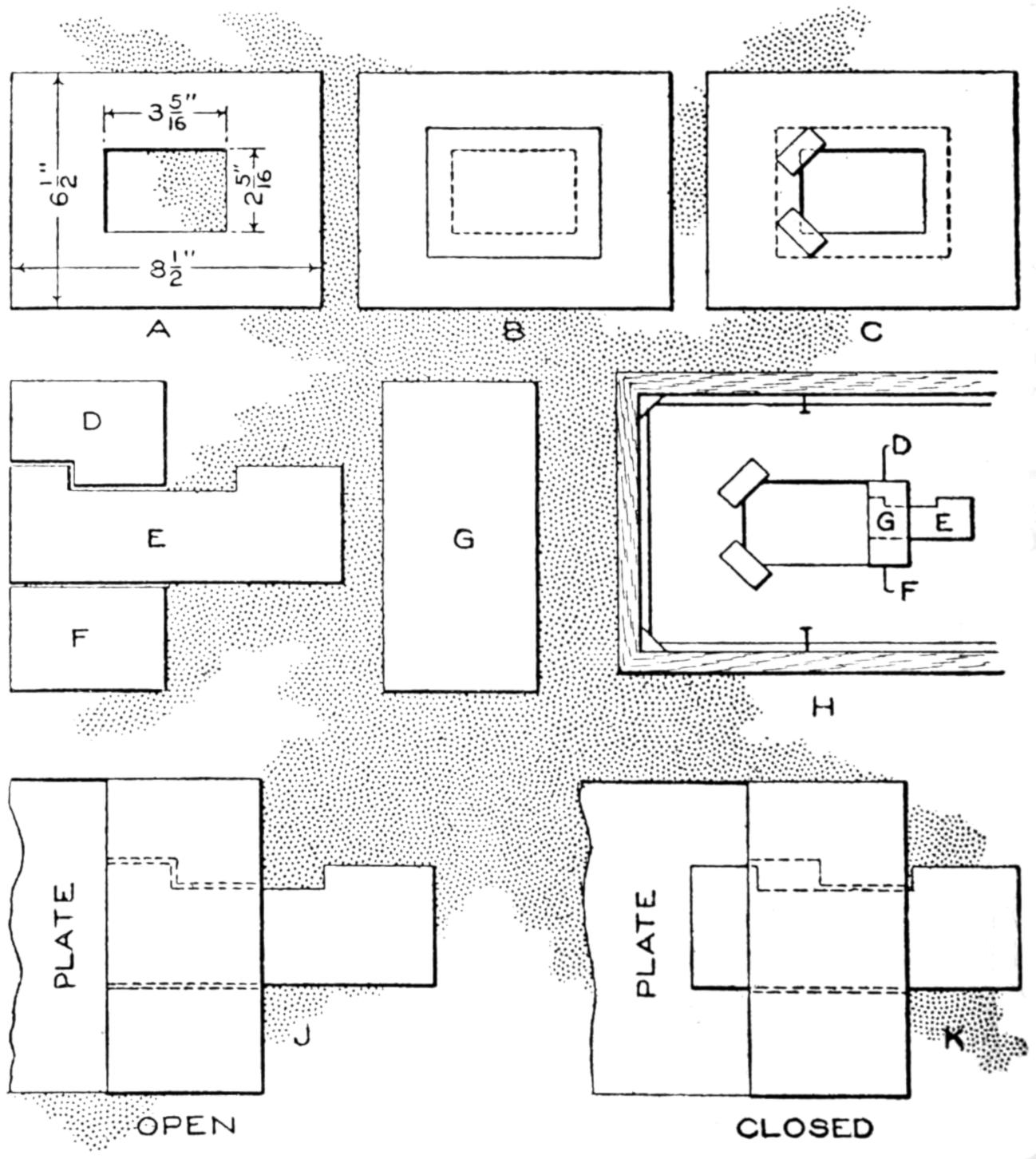

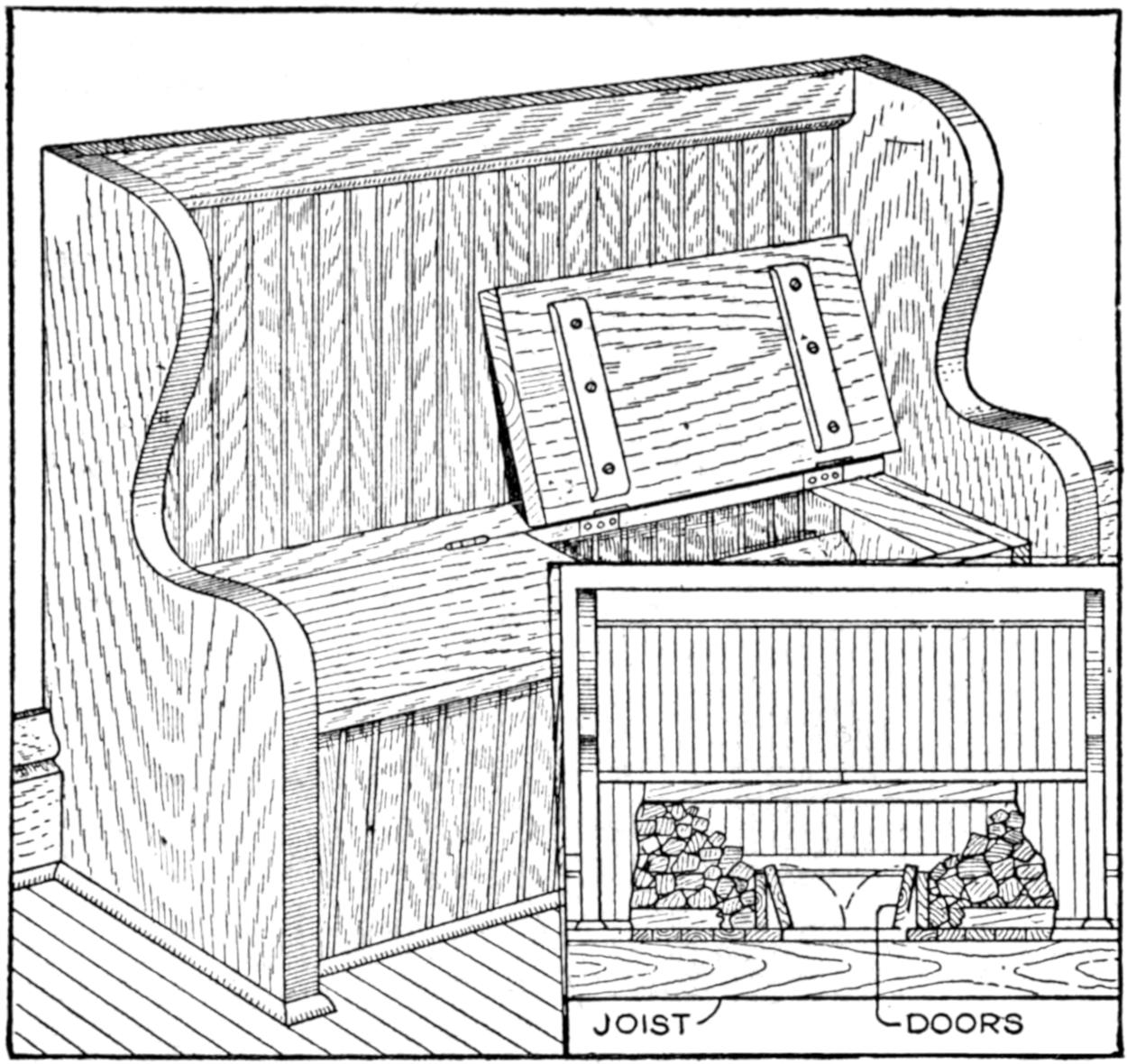

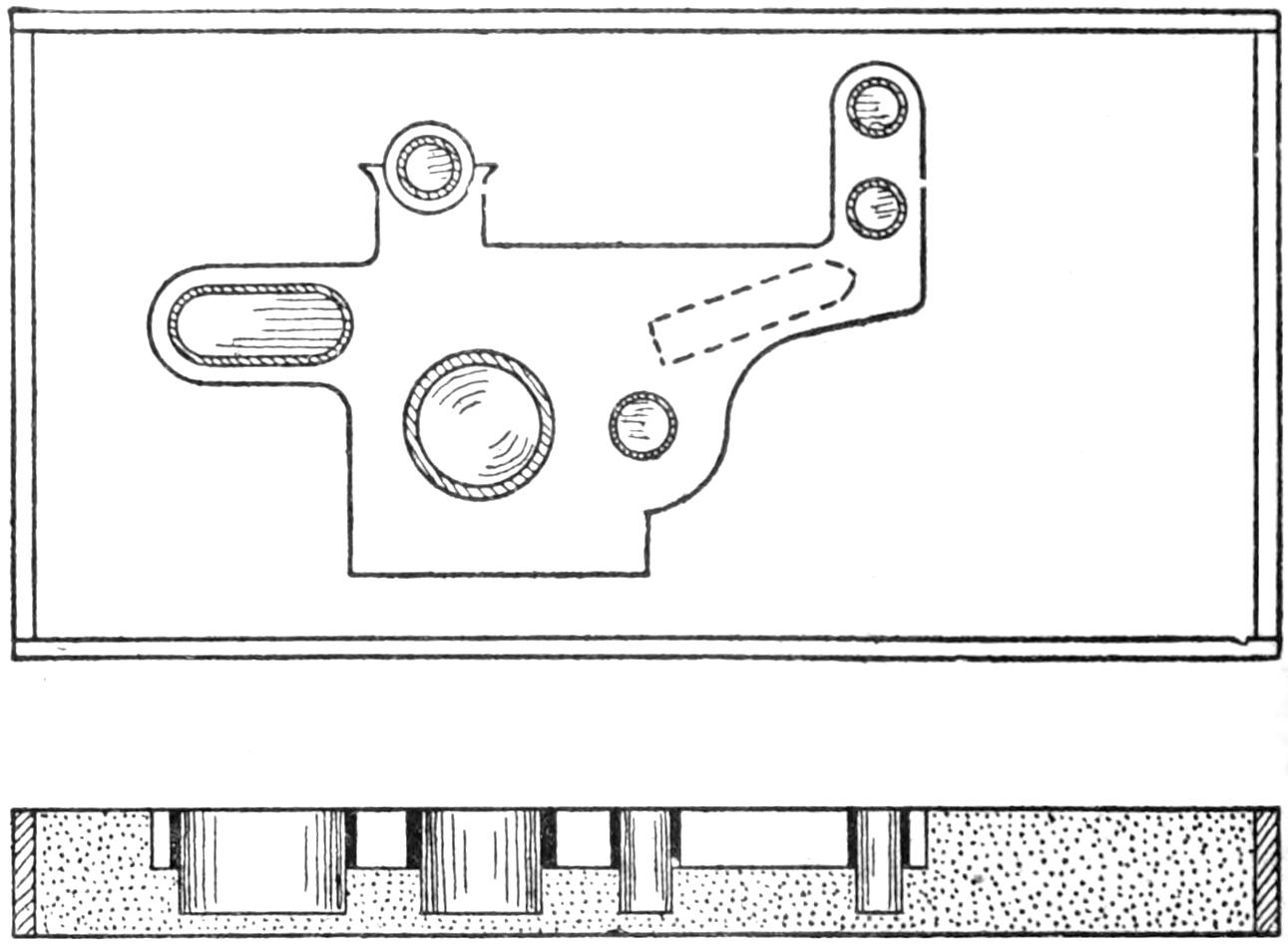

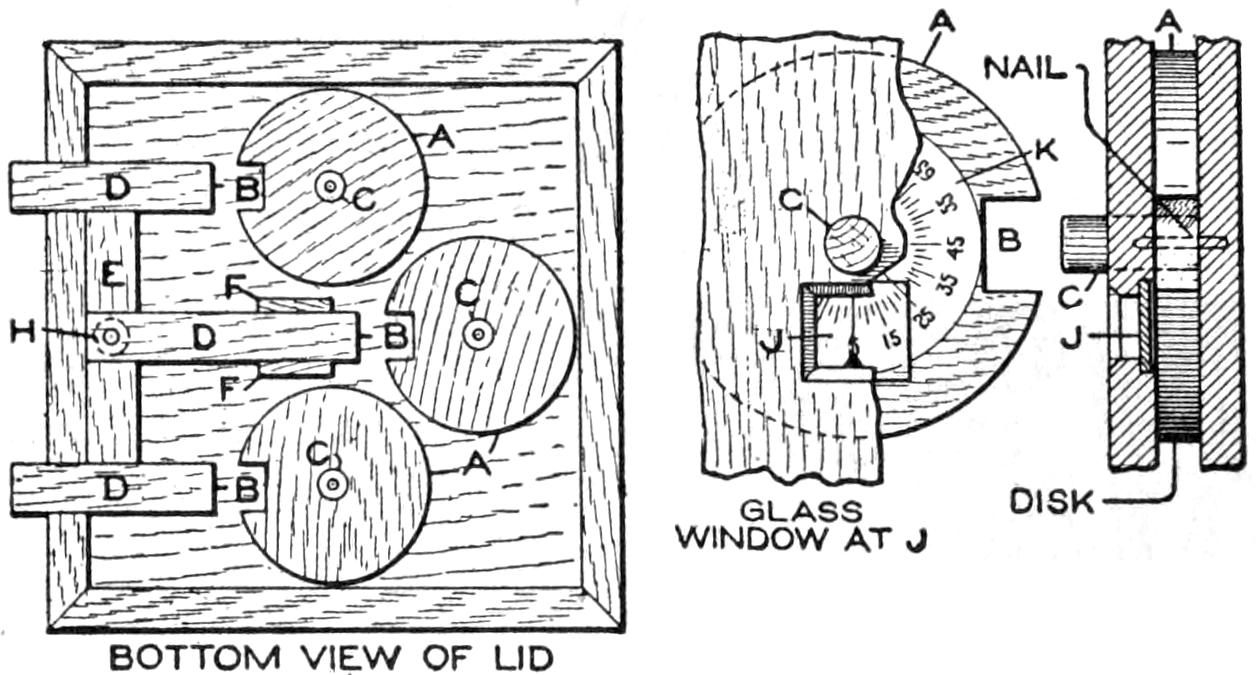

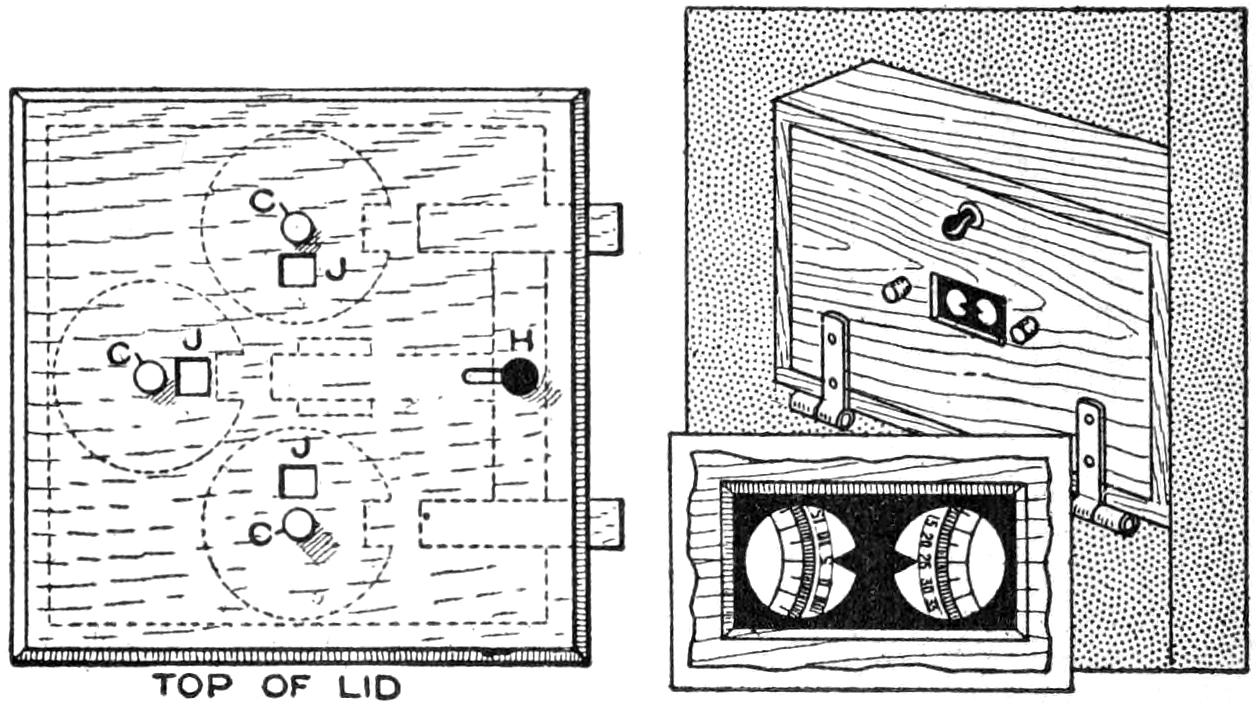

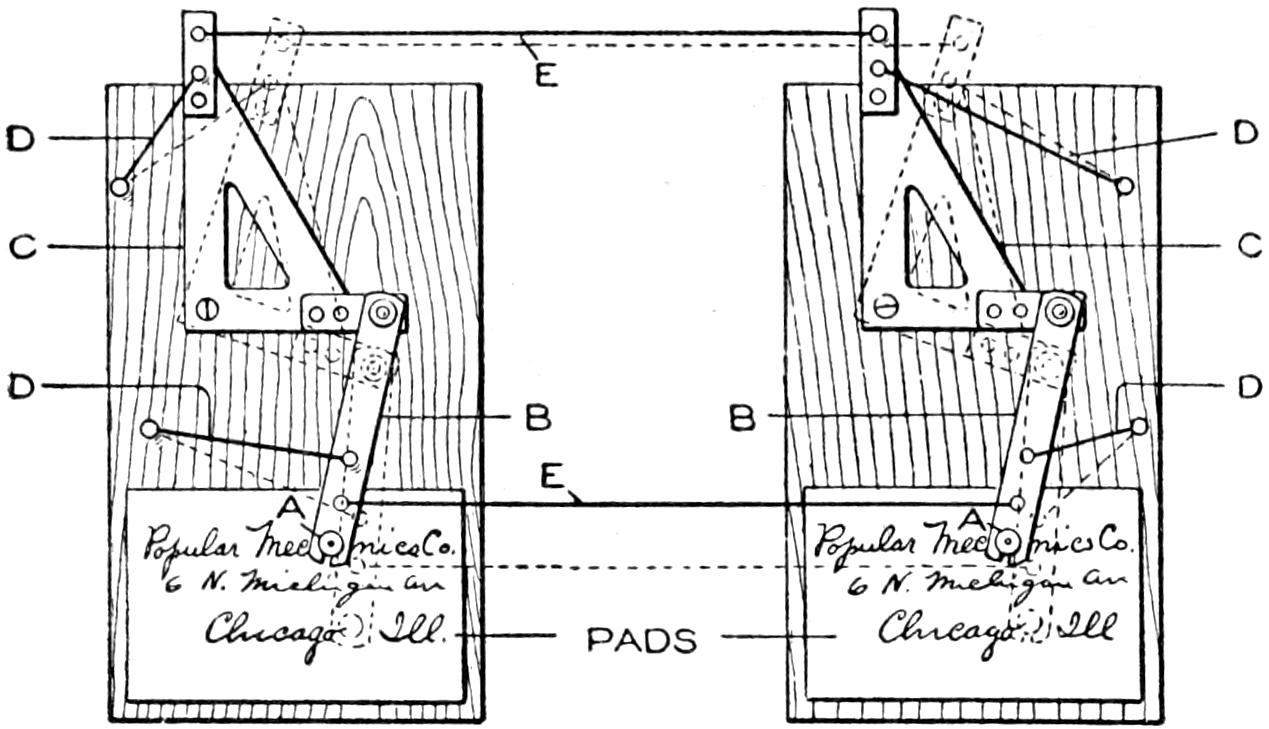

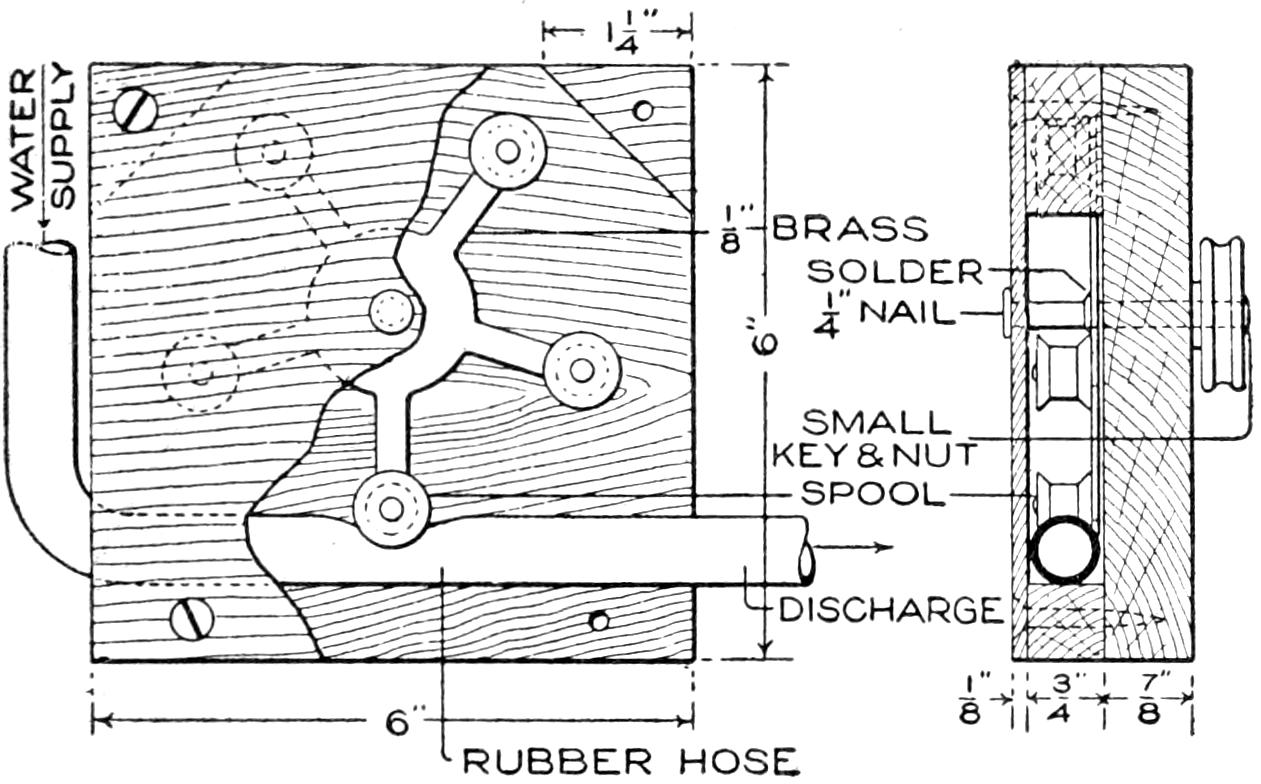

This Lock is Made Entirely of Wood and cannot be Picked Easily

The lock shown in the sketch and detailed drawings is made entirely of wood, and it is nearly impossible to pick or open it without the use of the key. The casing of the lock is 5 by 5 in. and 1 in. thick, of hard wood, oak being suitable for this as well as for the other parts. Three tumblers, a bolt, and a keeper are required. The key is shown inserted, indicating how the tumblers are raised by it. The bolt is slotted and a screw placed through it to prevent it from being moved too far. The lock and keeper are bolted into place on a door with carriage bolts, the heads being placed on the outer side.

The Details of Construction must be Observed Carefully and the Parts Made Accurately to Insure Satisfactory Operation

The detailed drawing shows the parts, together with the dimensions of each, which must be followed closely.

The lock casing is grooved with two grooves, extending the length of the grain and connected by open mortises,[14] all ¹⁄₂ in. in depth. The spacing of the mortises and the grooves is shown in the views of the casing. Three tumblers, ¹⁄₂ in. square and 2¹⁄₂ in. long, are required. The bolt is ¹⁄₂ by 1 by 8 in., and the key ¹⁄₄ by ³⁄₄ by 5¹⁄₂ in., and notched as shown. All the parts of the lock must be fitted carefully, sandpapered smooth, and oiled to give a finish that will aid in the operation, as well as protect the wood. Aside from its practical use, this lock is interesting as a piece of mechanical construction.—B. Francis Dashiell, Baltimore, Md.

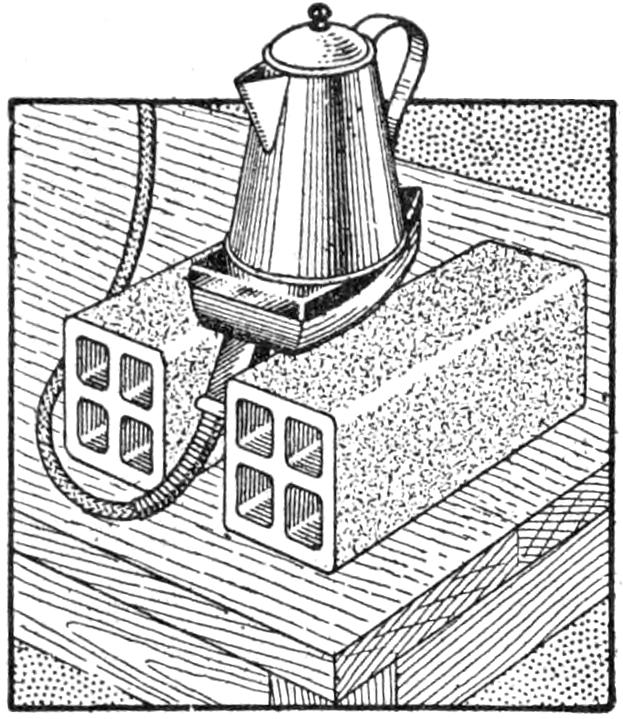

A milliner, in addition to using her electric iron for ordinary purposes of ironing and pressing, inverts it between two hollow tiles and thus makes use of it in steaming velvet trimmmings. The tiles not only hold the iron securely in this position, but also insulate it from overheating or scorching adjoining objects or surfaces. The iron is also used inverted for heating water, cooking coffee, and other liquids, as well as in providing a warm lunch.

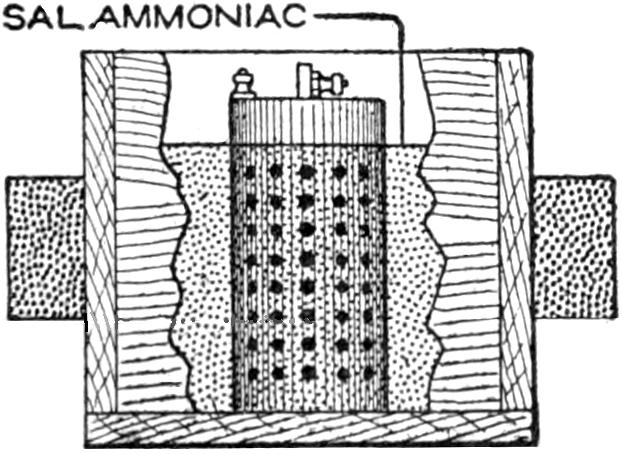

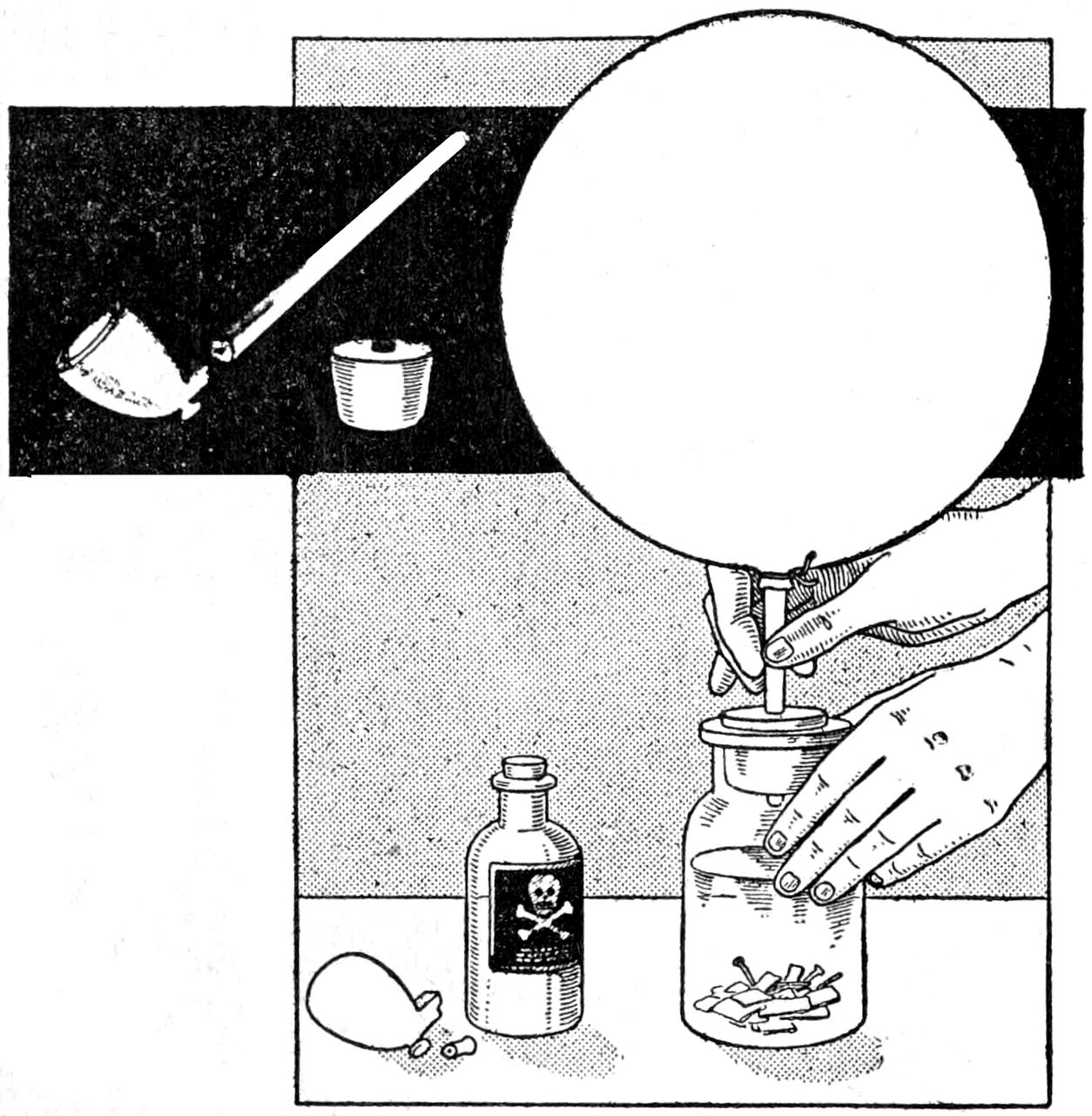

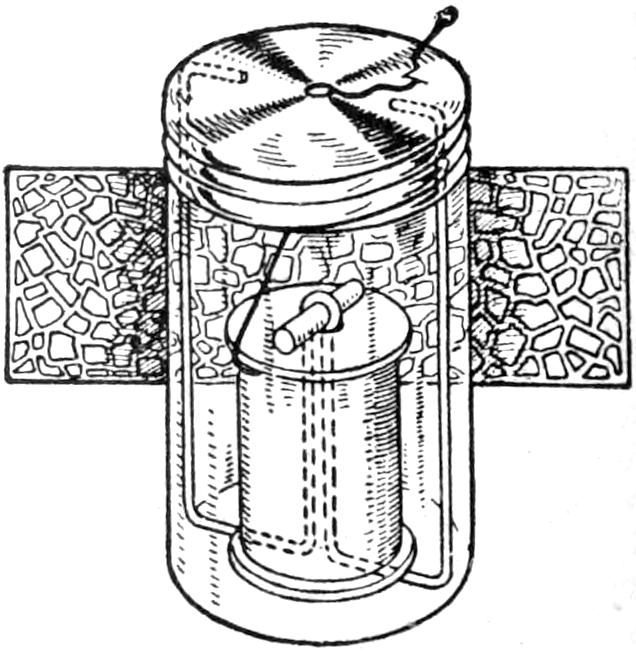

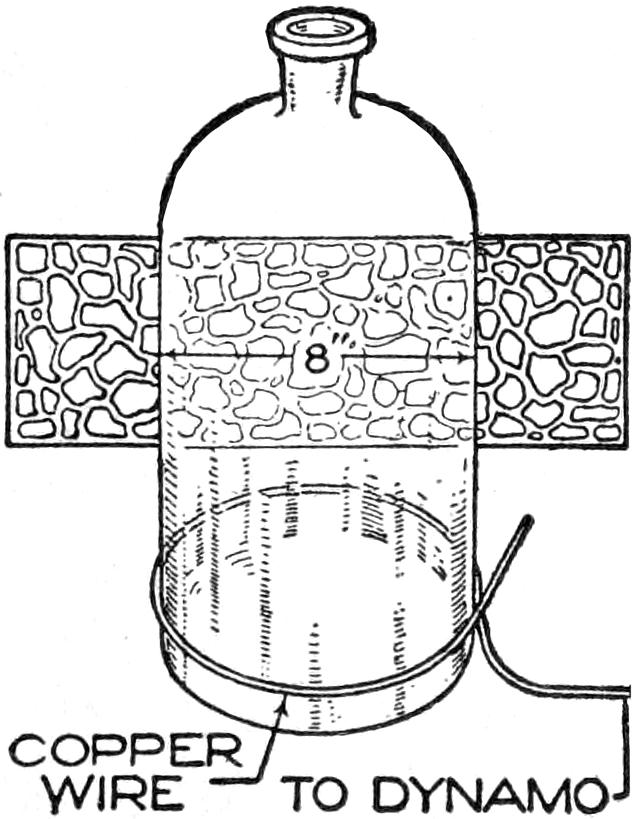

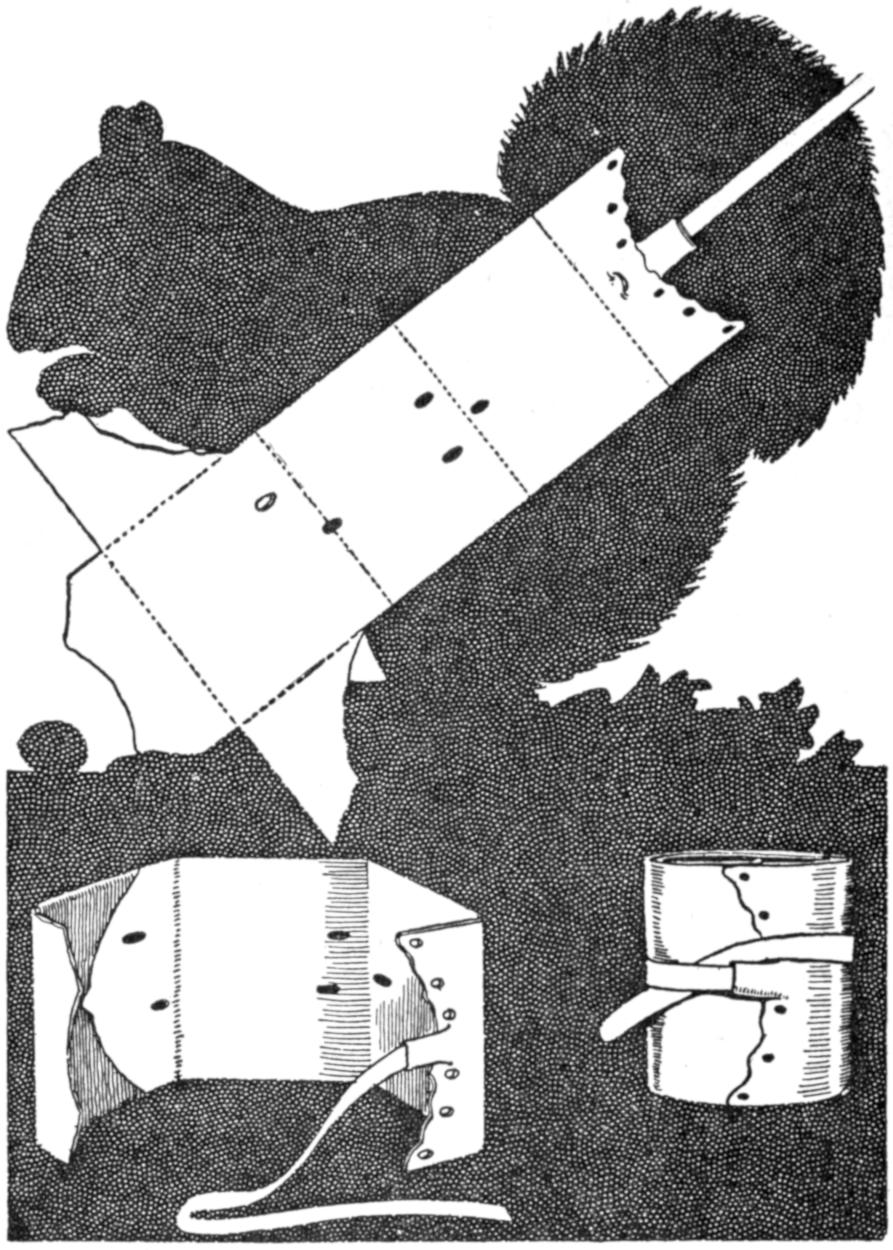

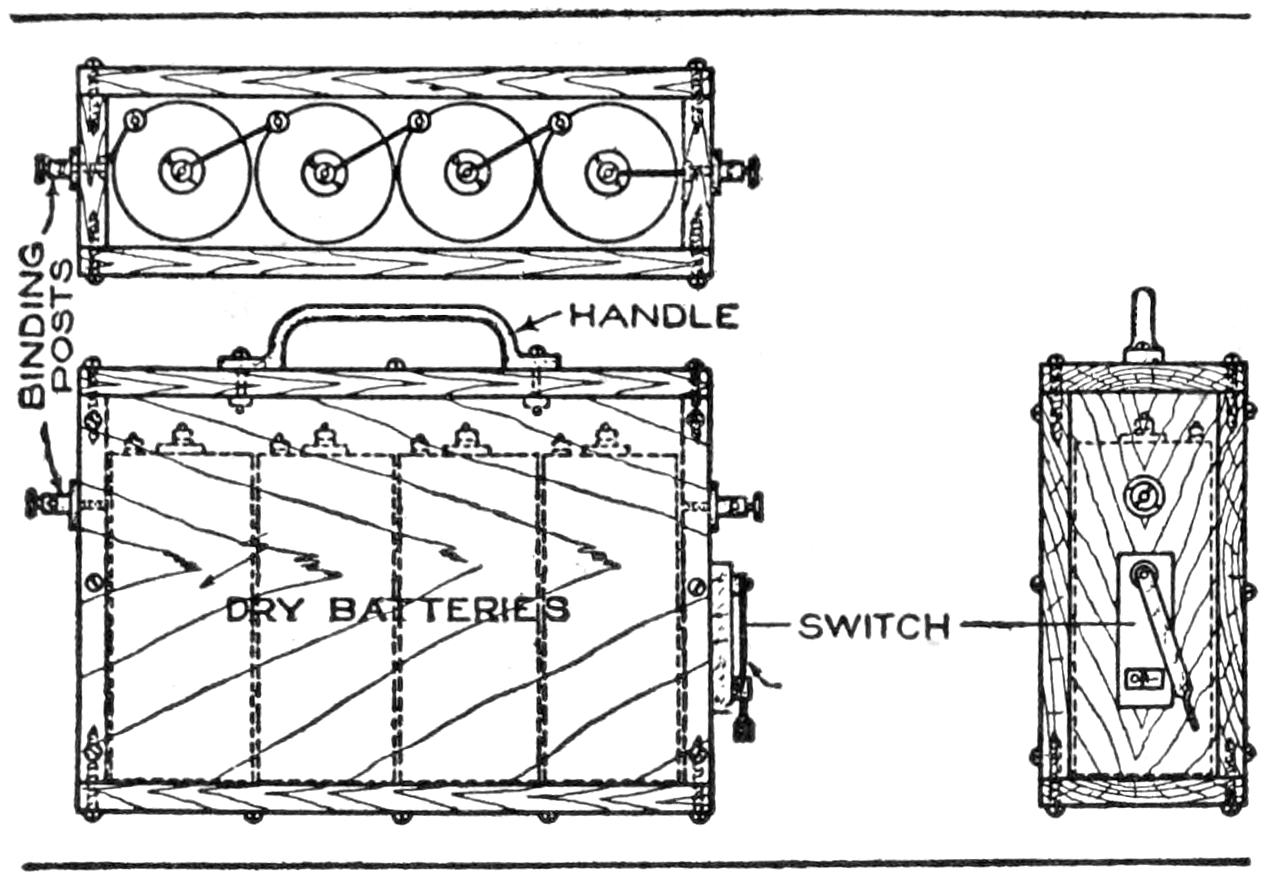

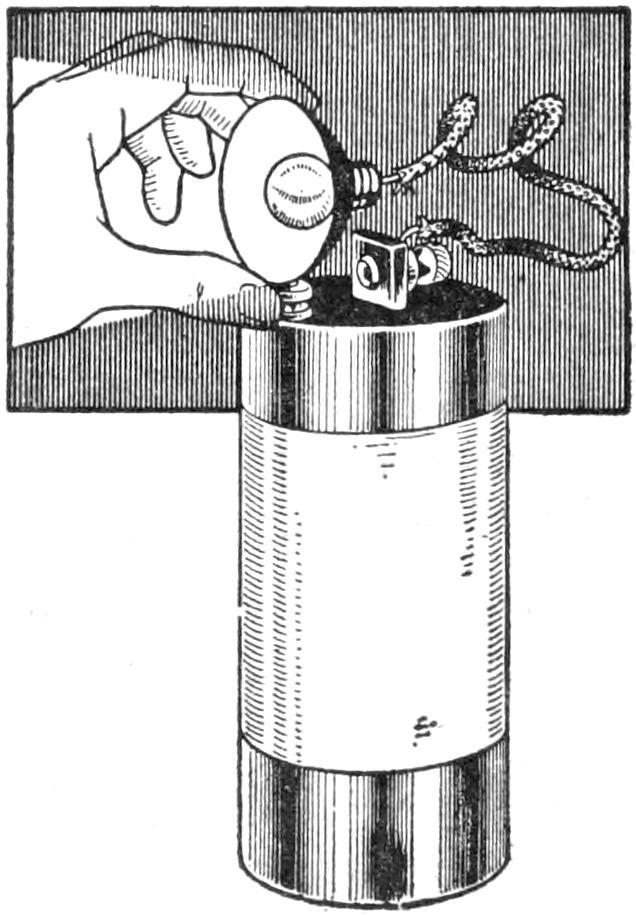

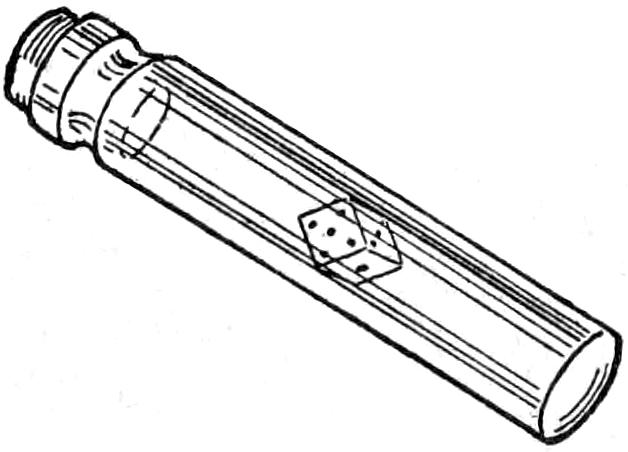

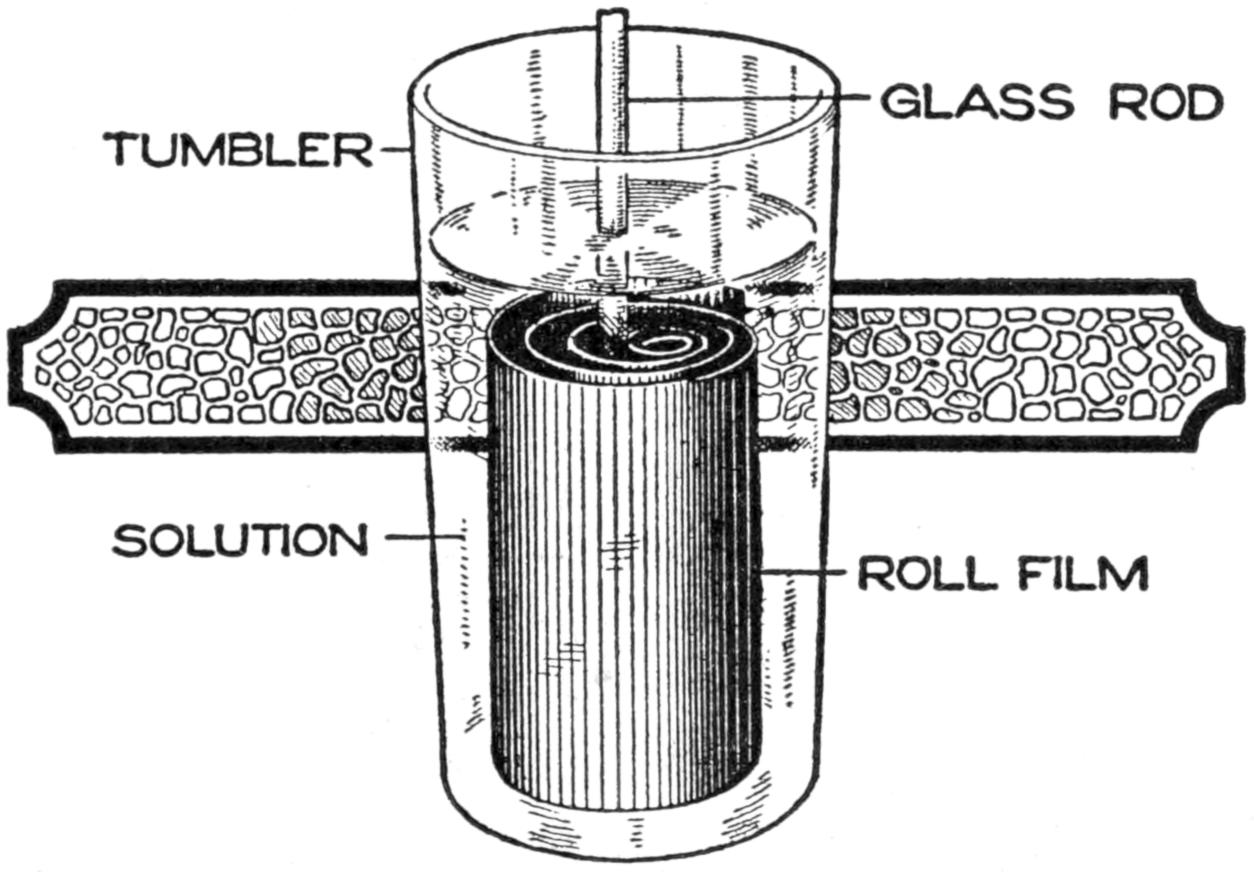

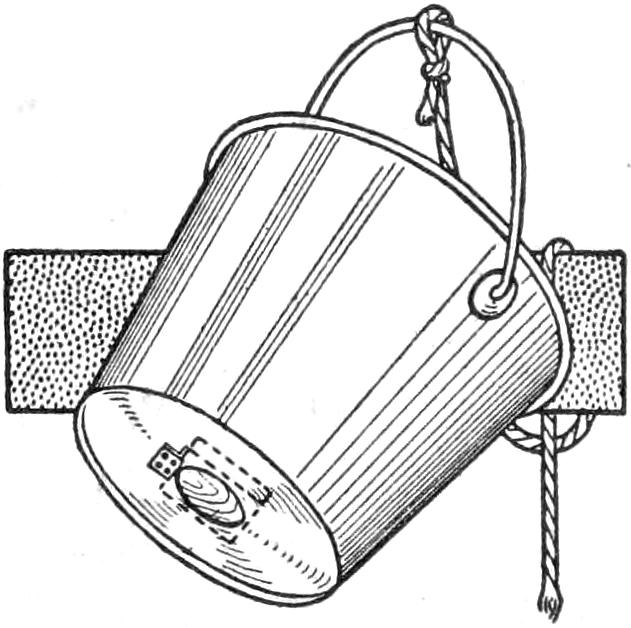

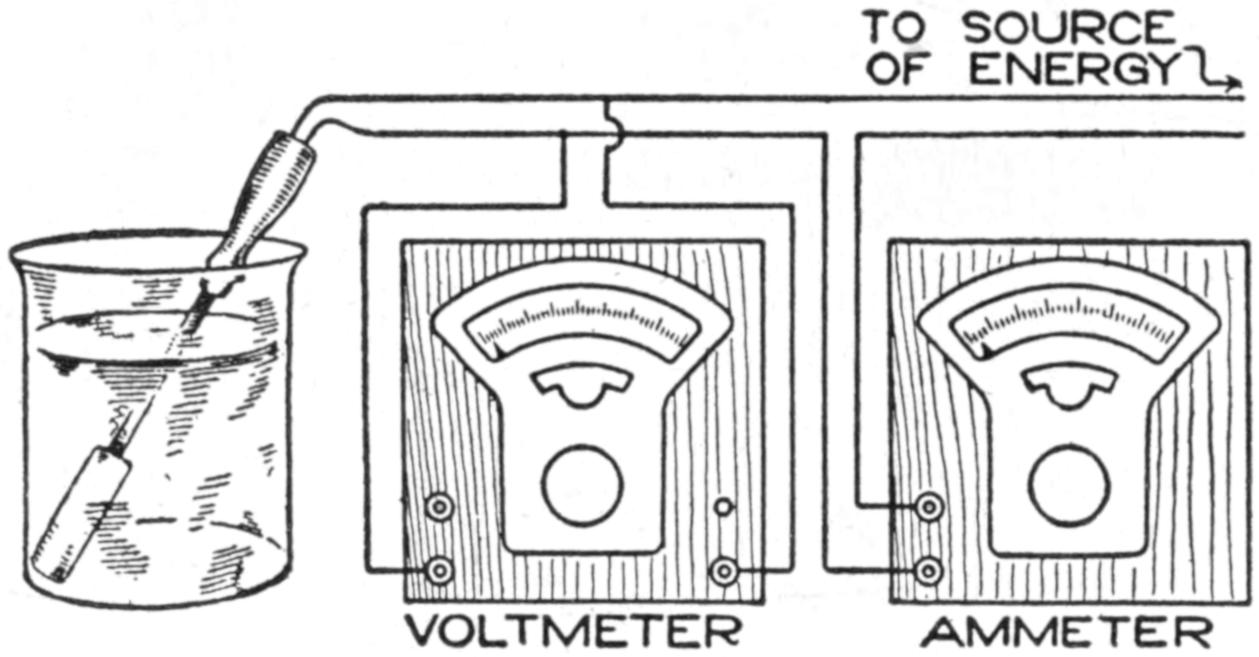

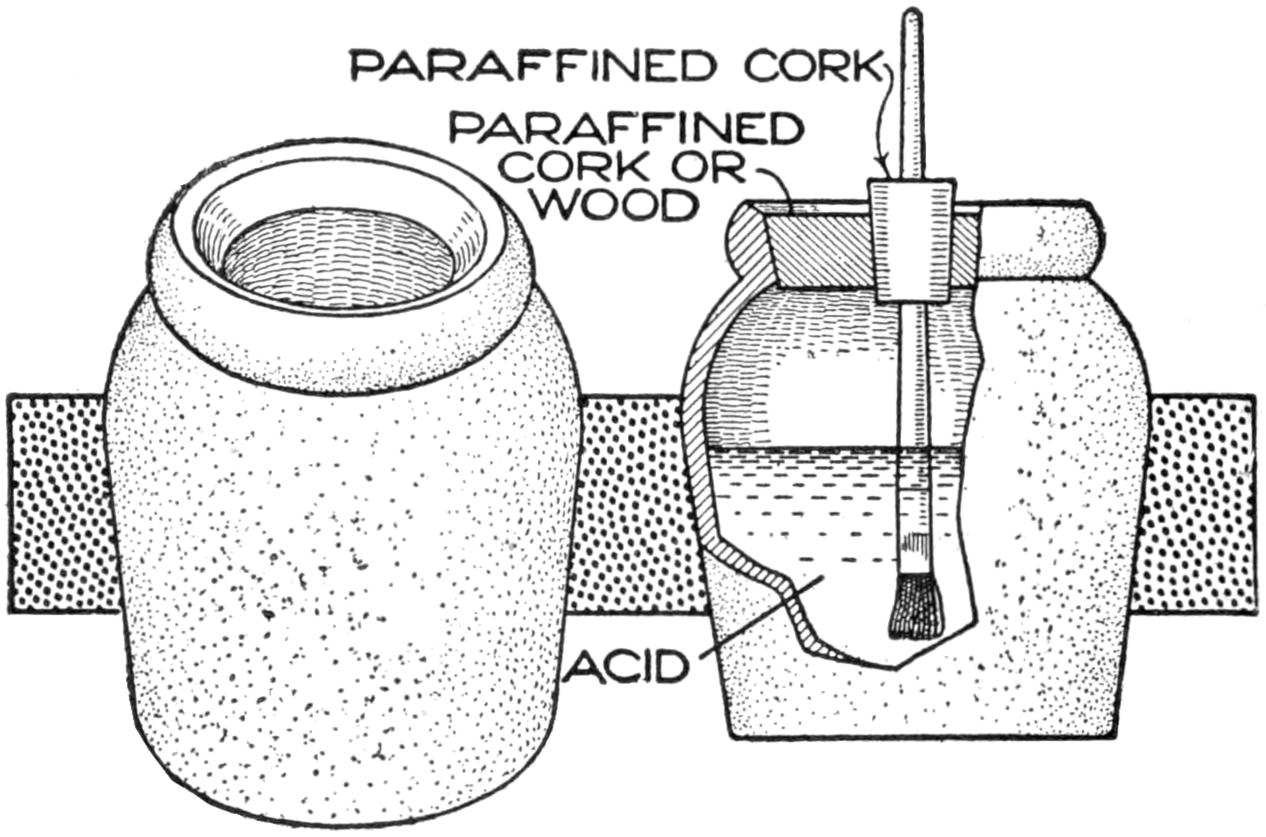

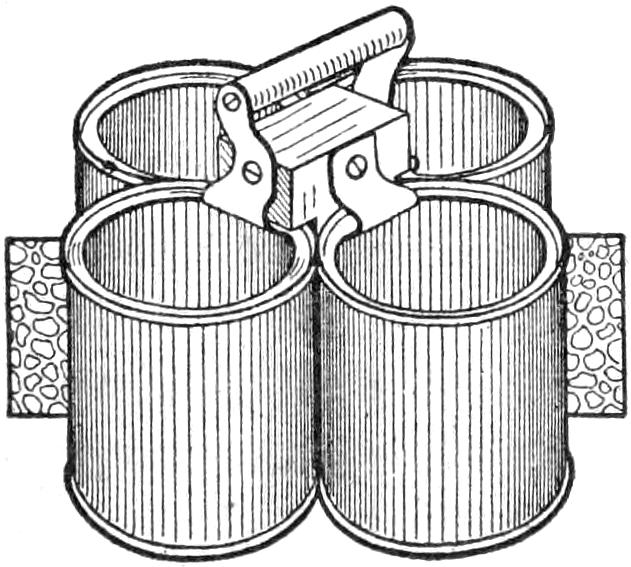

Finding that dry batteries had increased in price, and requiring a number for experimental purposes, I devised the following method by which I was able to use the old batteries for a considerable period: When the dry cells were nearly exhausted, I punched holes through the zinc covering with a nail, as shown in the sketch. The holes were placed about 1¹⁄₂ in. apart, and care was taken not to punch them near the upper edge of the container, or the black insulation might thus be injured. The cells were then placed in a saturated solution of sal ammoniac. The vessel containing the liquid must be filled only to within ¹⁄₂ in. from the top of the cell, otherwise the binding posts will be corroded, and the cell probably short-circuited. The cells were left in the solution six hours, and then became remarkably live. They must not be connected or permitted to come into contact with each other while in the solution.—H. Sterling Parker, Brooklyn, N. Y.

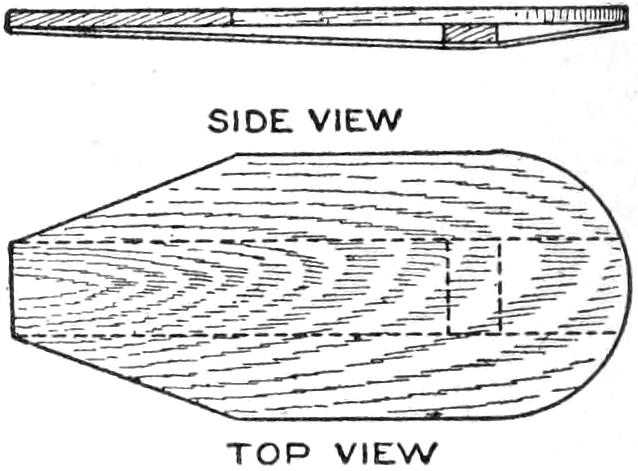

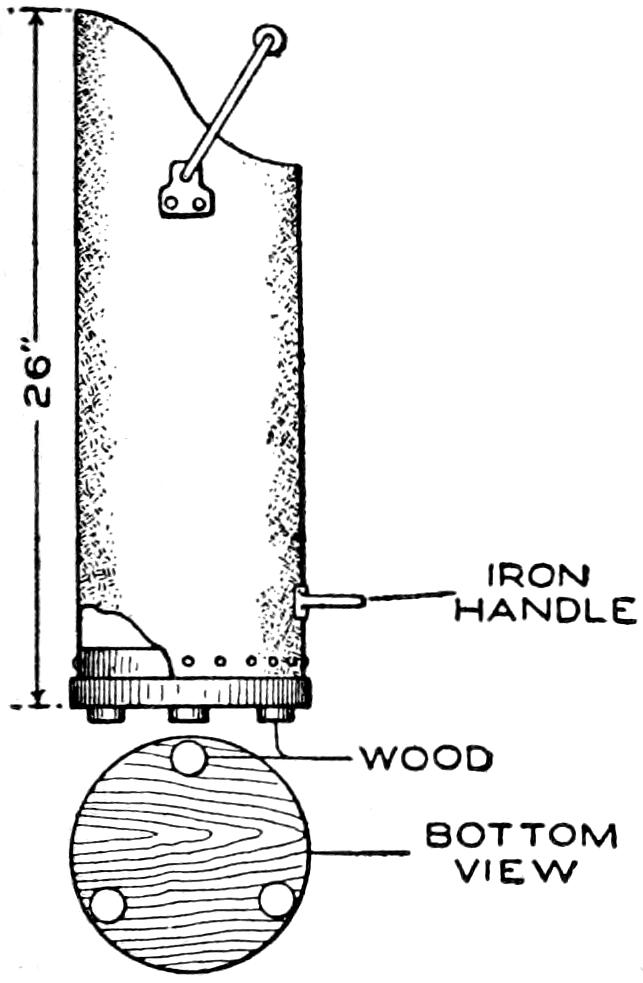

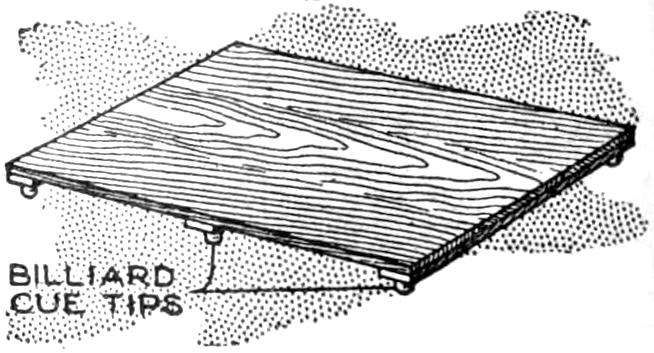

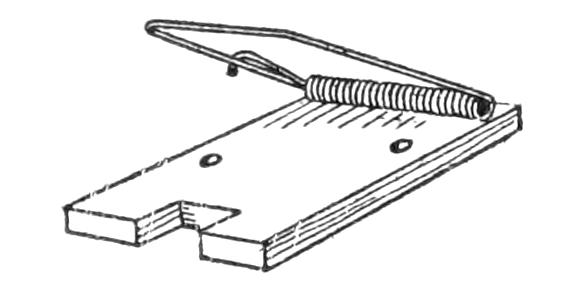

The simple device shown in the sketch can afford youngsters much amusement in coasting down inclines or small hills, either on the snow or on surfaces slightly crusted with ice. The board is intended for individual use only and should be about 10 in. wide and 26 in. long. It is reinforced underneath by a strip of wood, about ¹⁄₄ in. thick and smoothed on its lower side. This piece is fastened in the form of a bow by placing a small cleat between it and the upper piece. The strip should be about 3 in. wide, and aids in keeping the sliding board in its course.—John F. Long, Springfield, Mo.

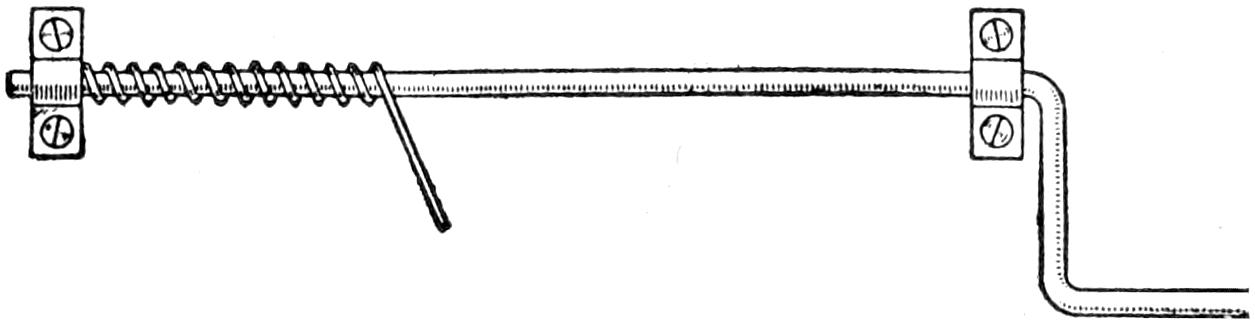

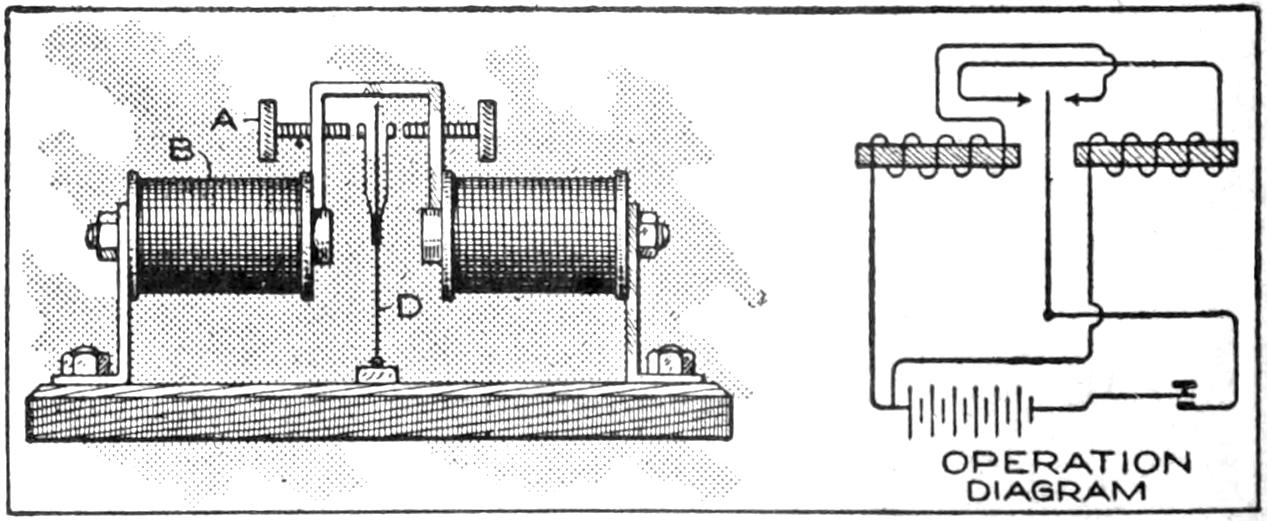

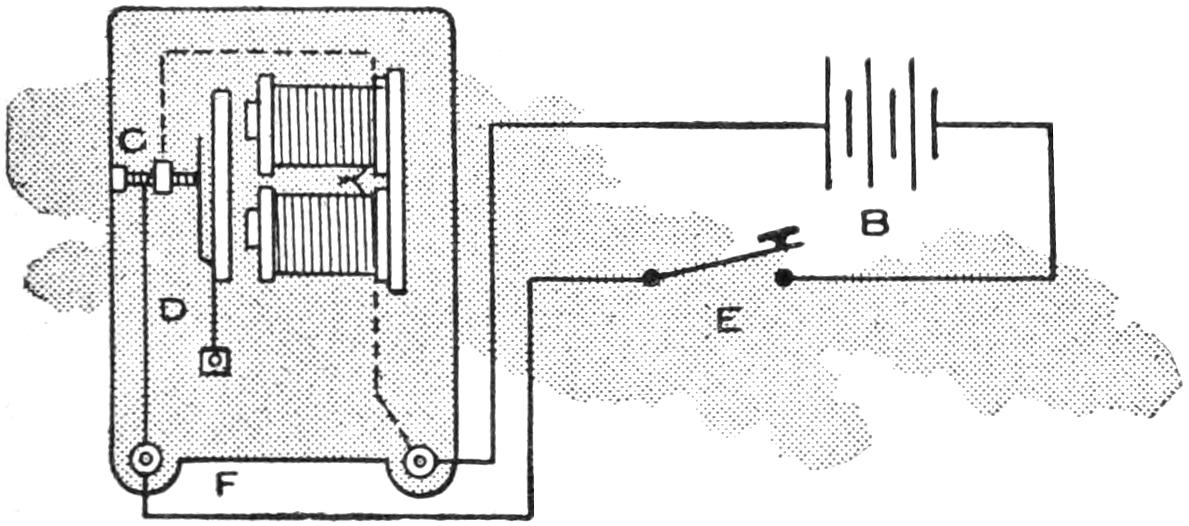

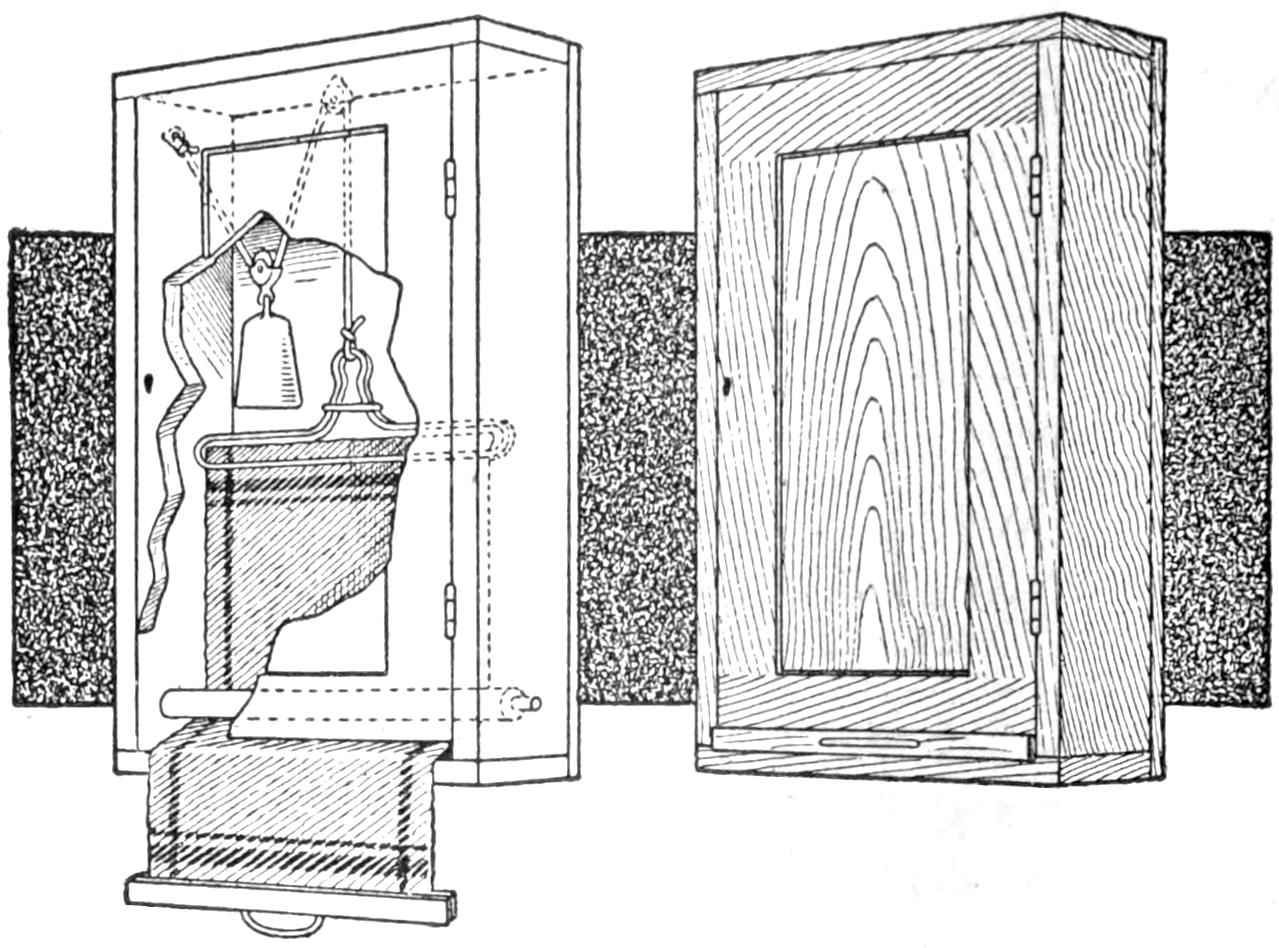

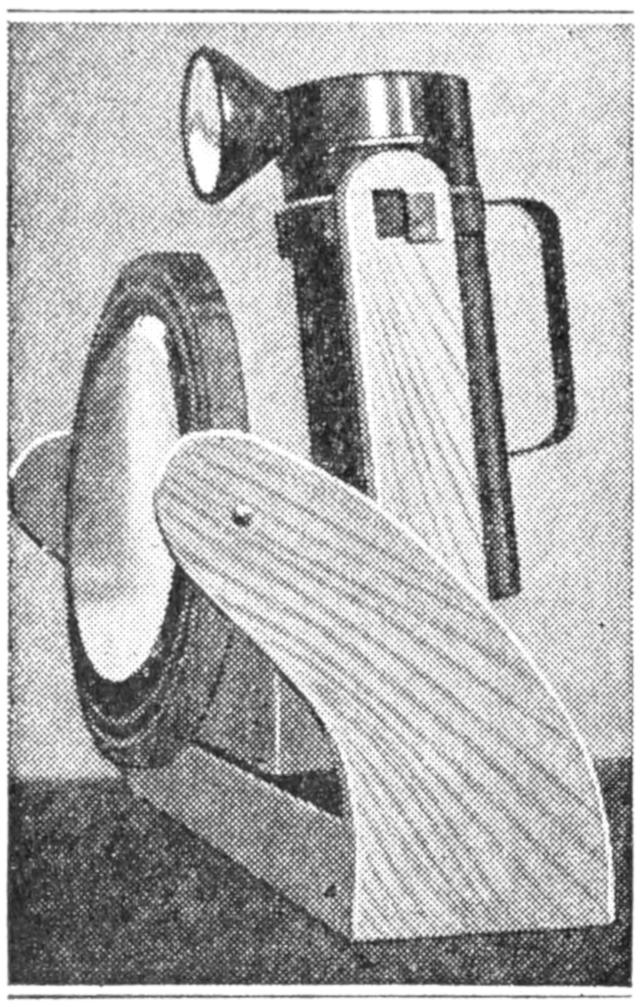

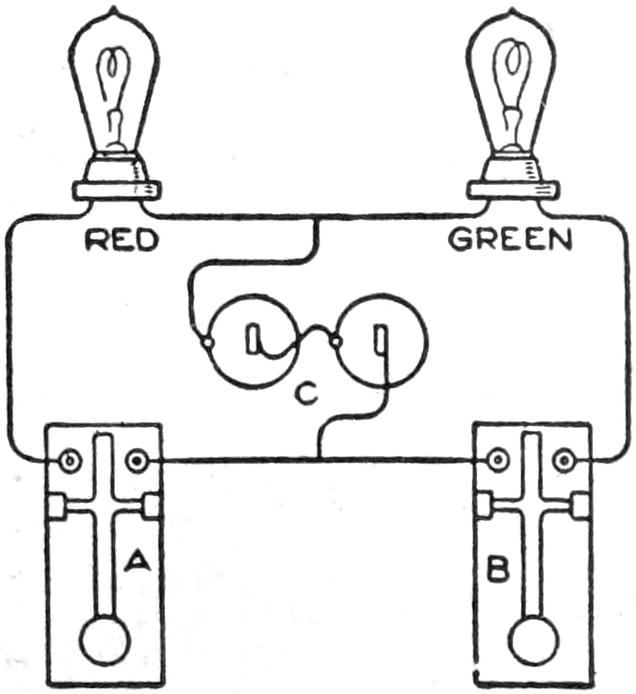

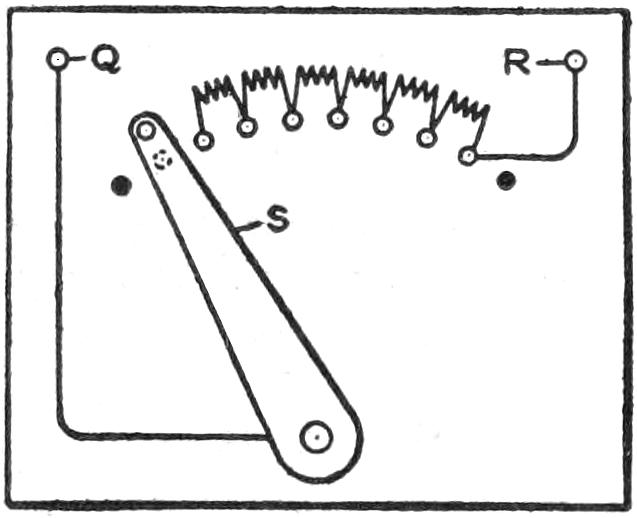

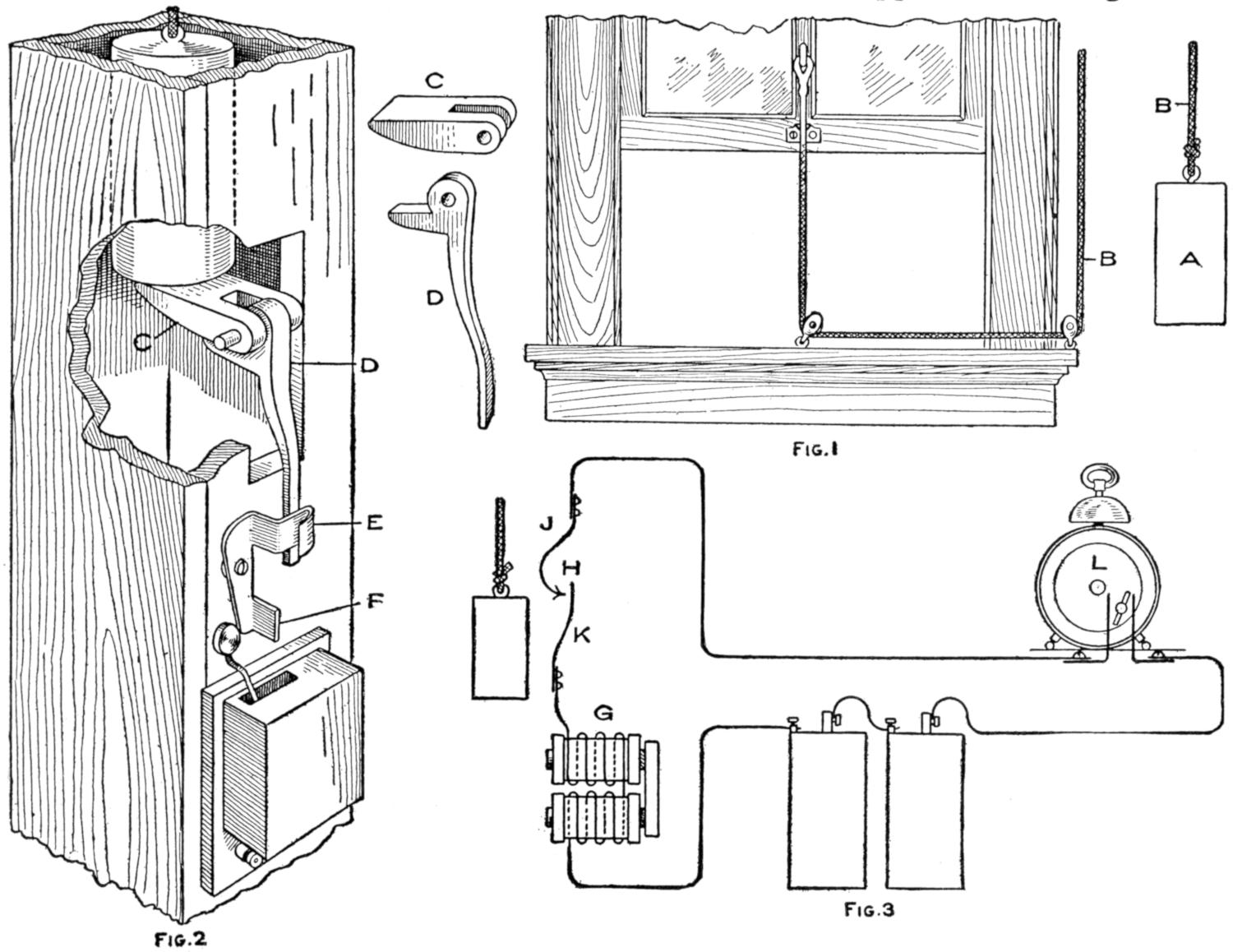

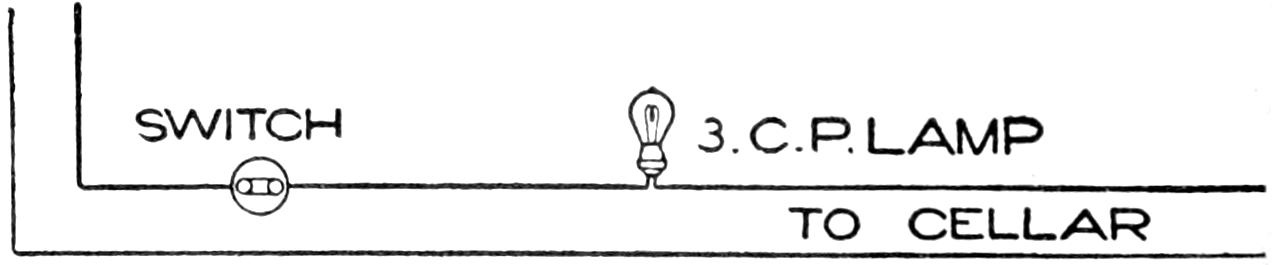

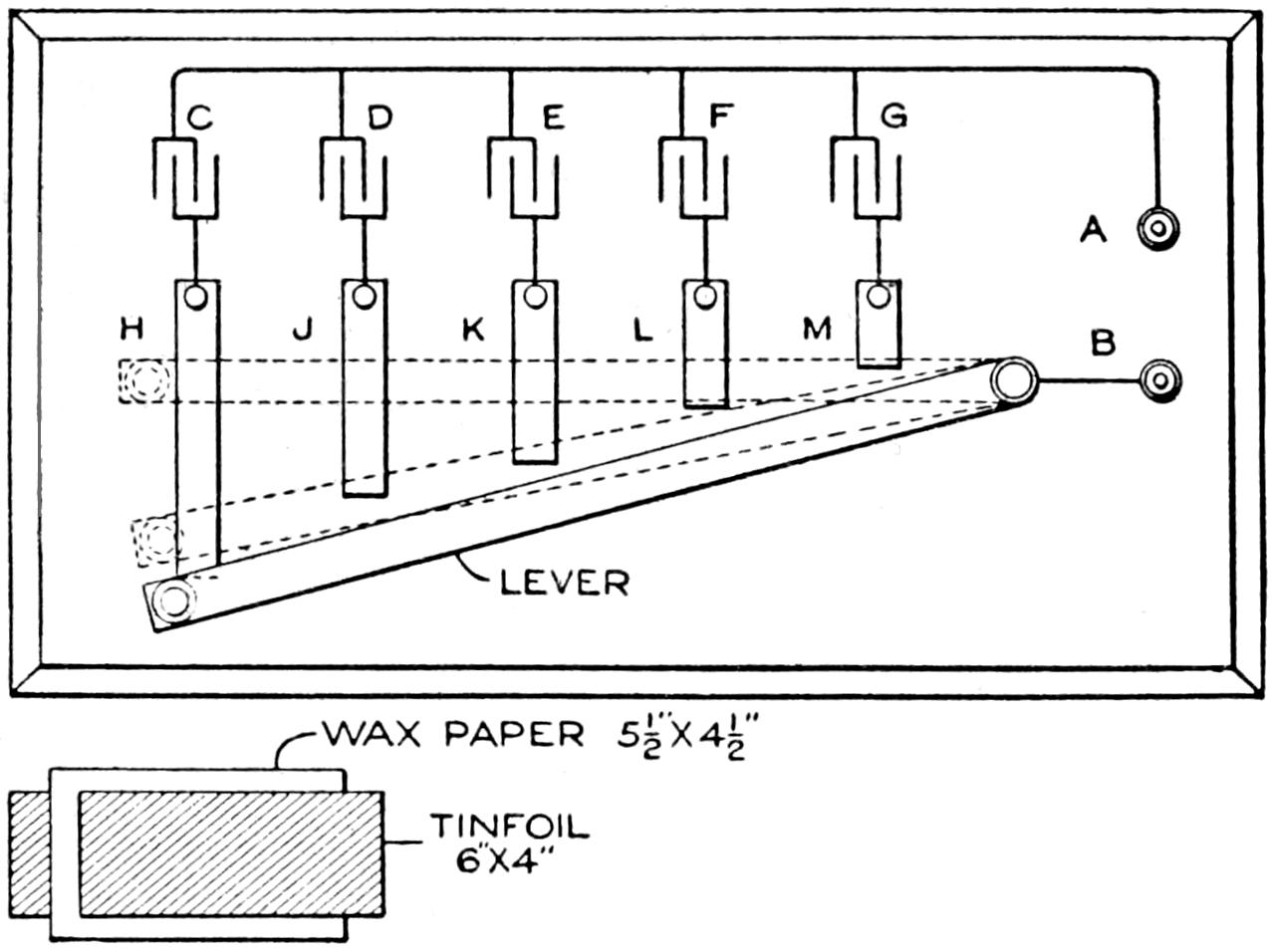

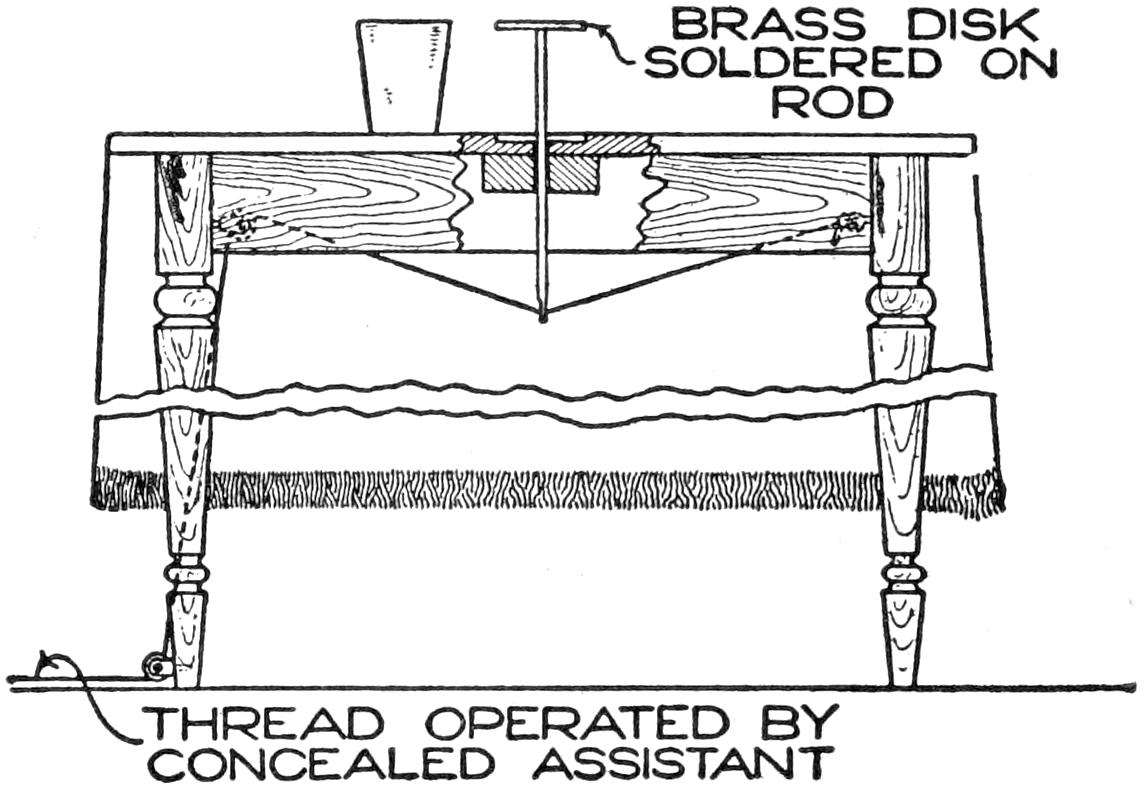

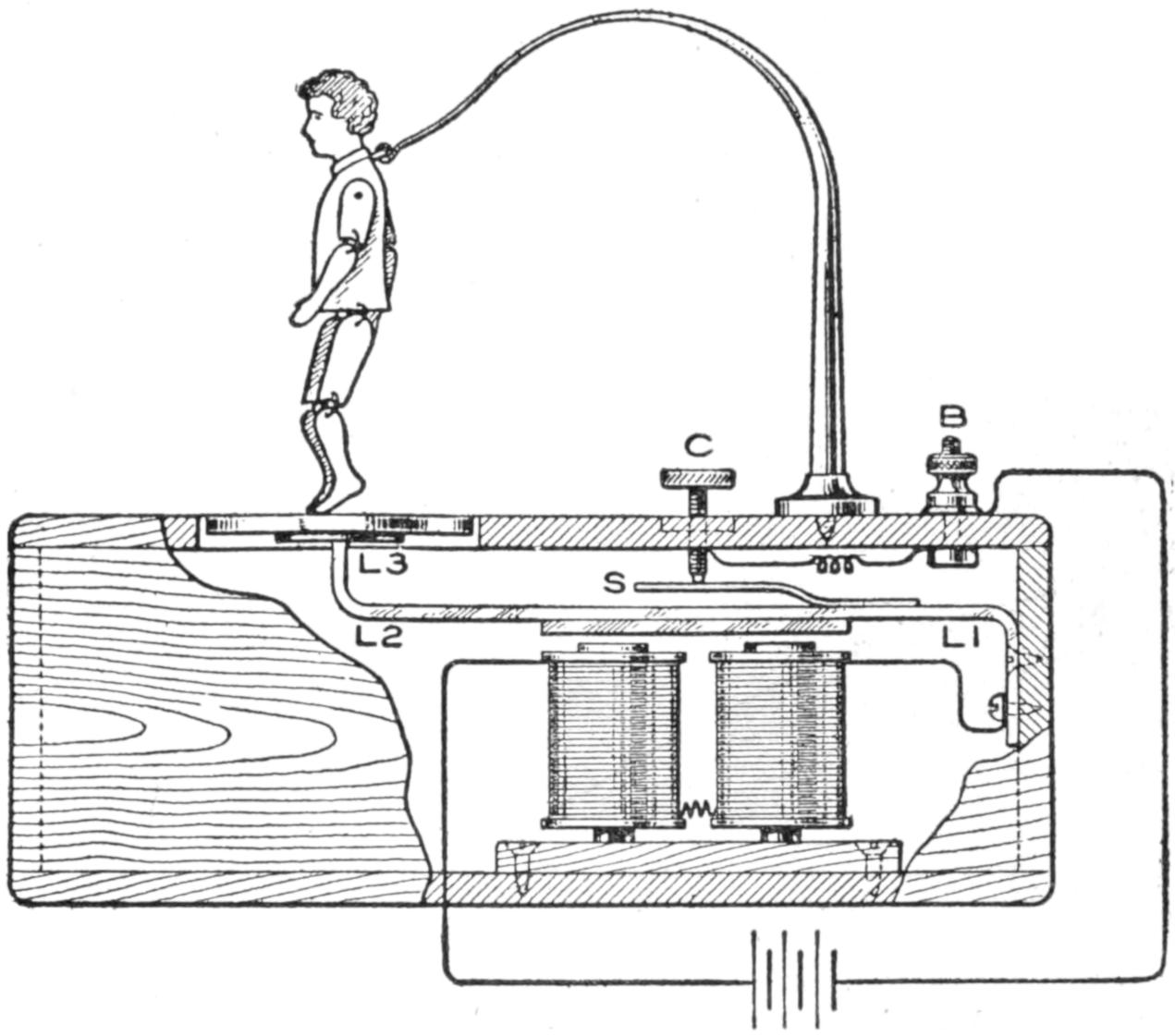

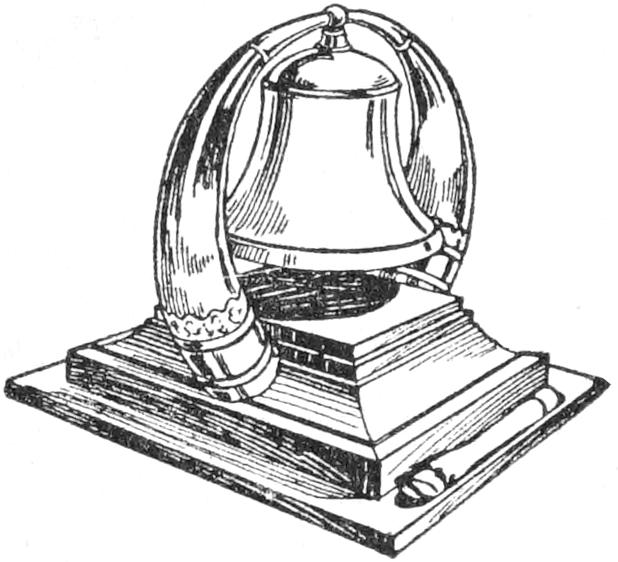

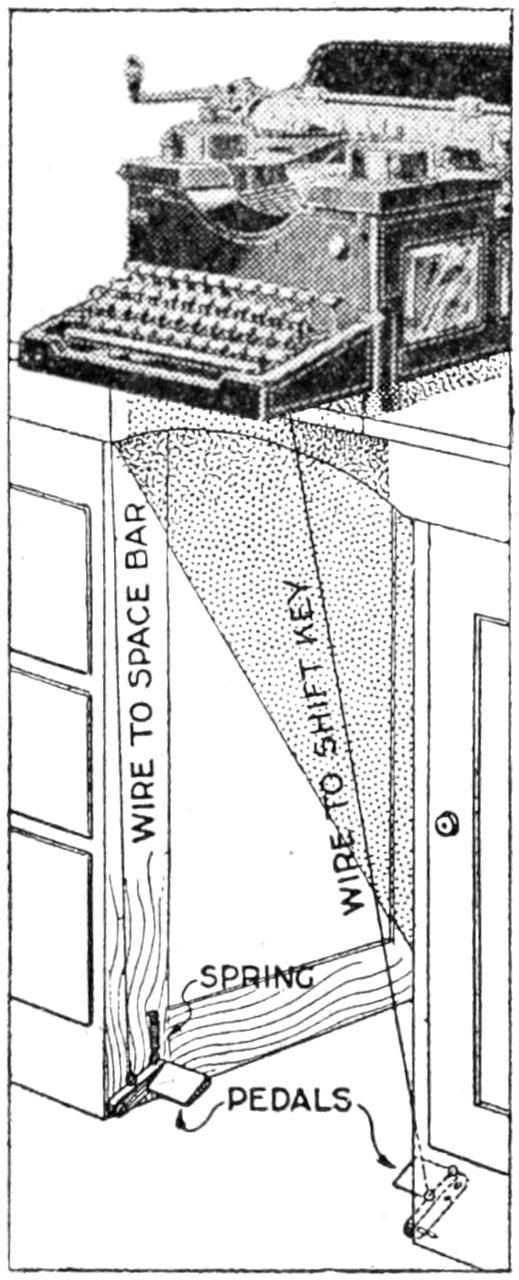

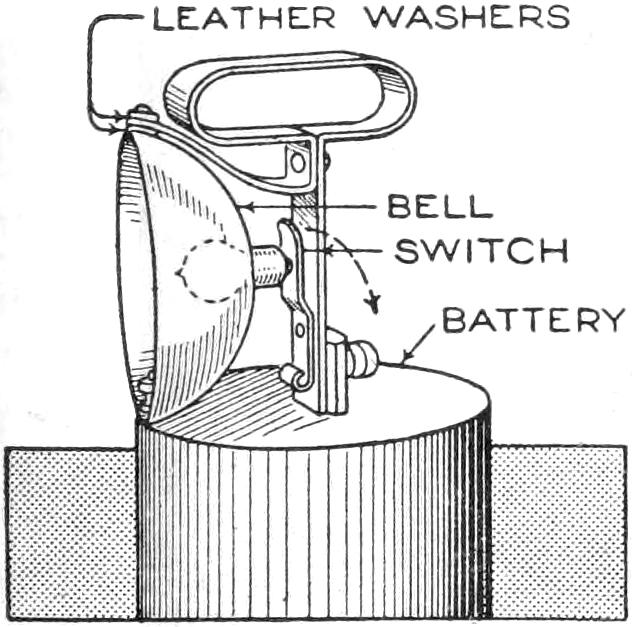

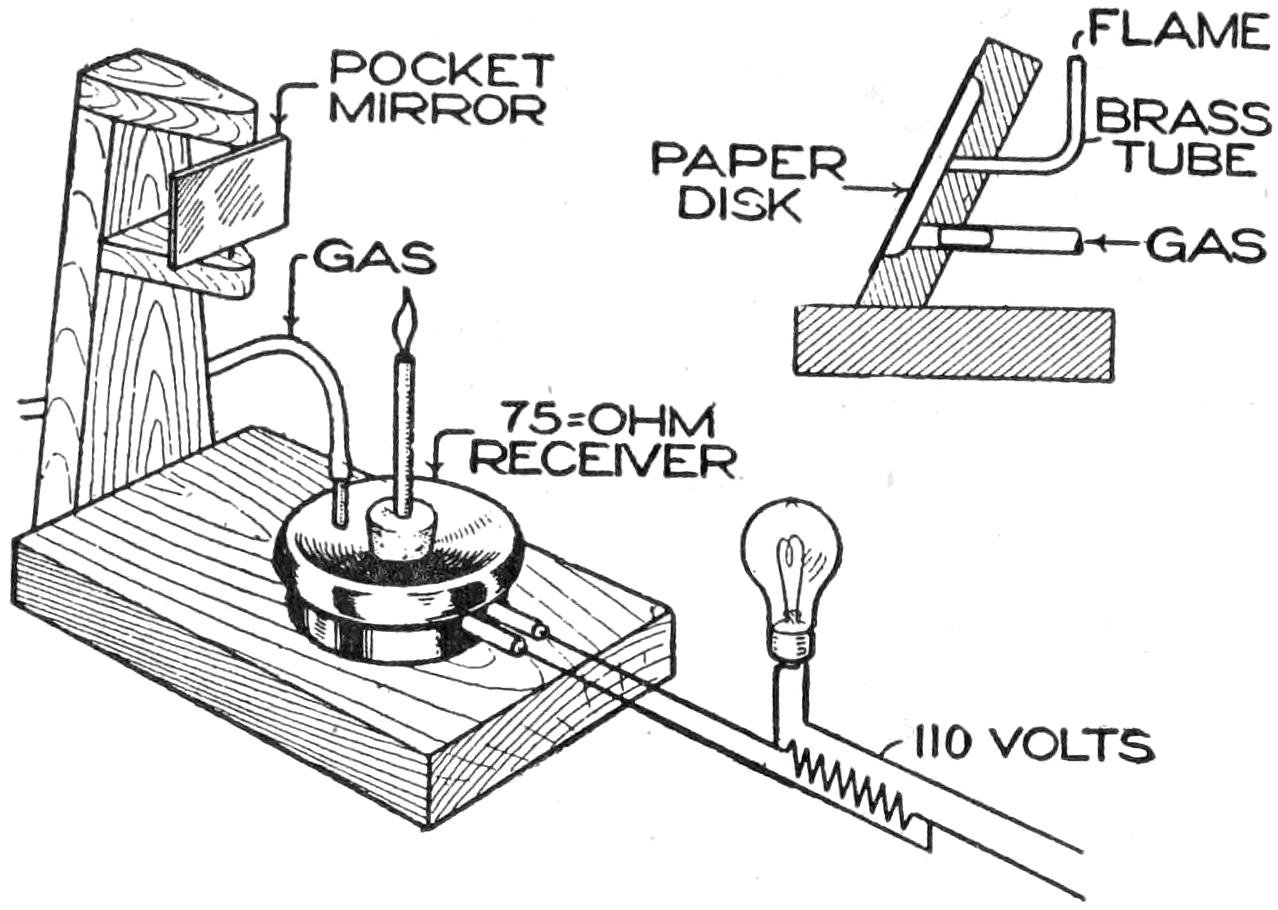

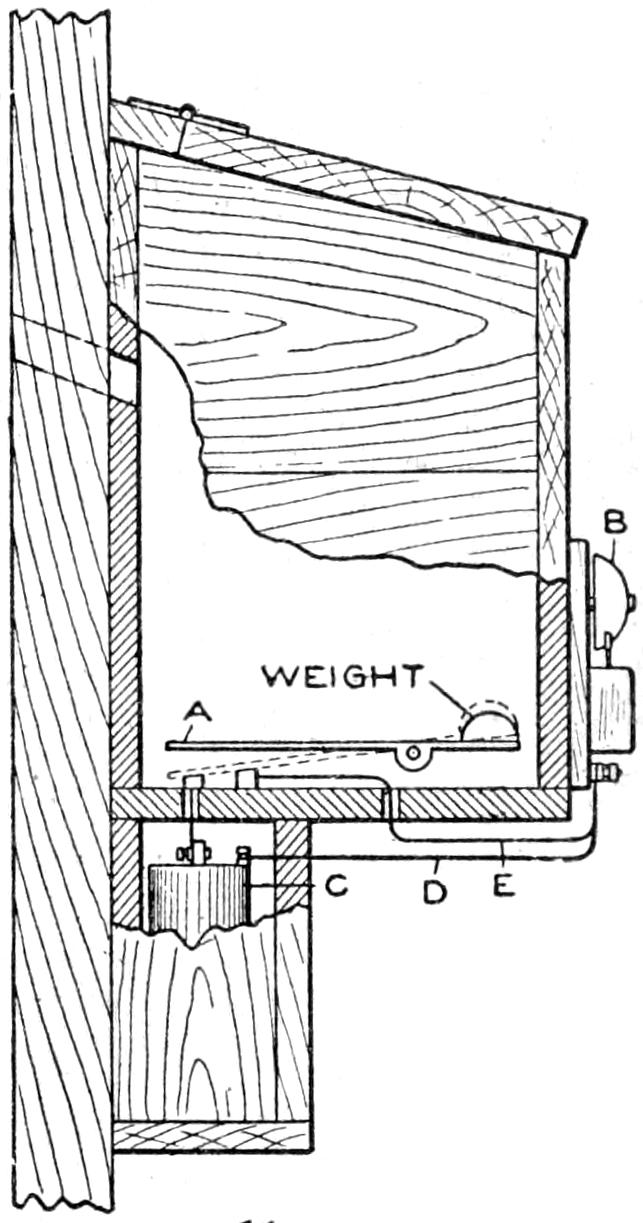

Converting an ordinary parlor, or mantel, clock into a master clock, from which the striking of the gong is transmitted to various parts of the home, may be accomplished by fitting it with a simple electrical device, as shown in the sketch. The general arrangement of the batteries, single-stroke bells, and[15] the contact device within the clock case is shown in Fig. 1; a detail of the silk cord and other connections of the contact key and the gong hammer, is shown in Fig. 2. This arrangement has been in operation for several years, and has been found practical.

Fig. 1

Fig. 2

The General Arrangement of the Apparatus for Transmitting the Striking of a Clock Gong is Shown in Fig. 1, and a Detail of the Contact Device in Fig. 2

The various rooms to which the striking of the gong is to be transmitted are wired with No. 18 annunciator wire, run carefully behind picture moldings and in corners. Where the wires must be carried through a partition, a ¹⁄₄-in. hole is sufficiently large for the purpose. The single-stroke bells are wired up as shown in the sketch. The number of dry batteries necessary varies with the number of bells in the circuit, and also depends on the length of wire through which the current is carried. A trial should be made with several batteries and more added until the bells are rung properly.

The connecting device may be fitted into the clock case without defacing it by boring holes in its side, and the binding posts are fixed into place neatly. The two sections of the contact key, shown in detail in Fig. 2, are fastened to the back of the clock case with bolts. The upper member is fitted with an adjustable thumbscrew and is stationary on the bolt fastening. The lower arm is made of covered wire and is pivoted on the supporting bolt. Attached to its lower edge, at the pivot, is a small lever arm. This is connected to the hammer rod of the gong with a silk cord. The length of the cord must be determined by careful adjustment so that it will not hinder the action of the hammer H, but will bring the swinging arm into proper contact with the thumbscrew. The contact should be made at the instant the hammer strikes the bell. The contact of the platinum point of the thumbscrew and the swinging arm must be close, but not too strong. Metal posts or tubes fitted over the bolts, at the points where the arms are attached to the back of the clock case, may be used to bring the arms the proper distance forward in the case, so that they will be in alinement with the hammer rod. The silk cord must not interfere with the action of the pendulum P. To hold the silk cord in place on the hammer rod, drop a small piece of melted sealing wax or solder on the rod.—W. E. Day, Pittsfield, Mass.

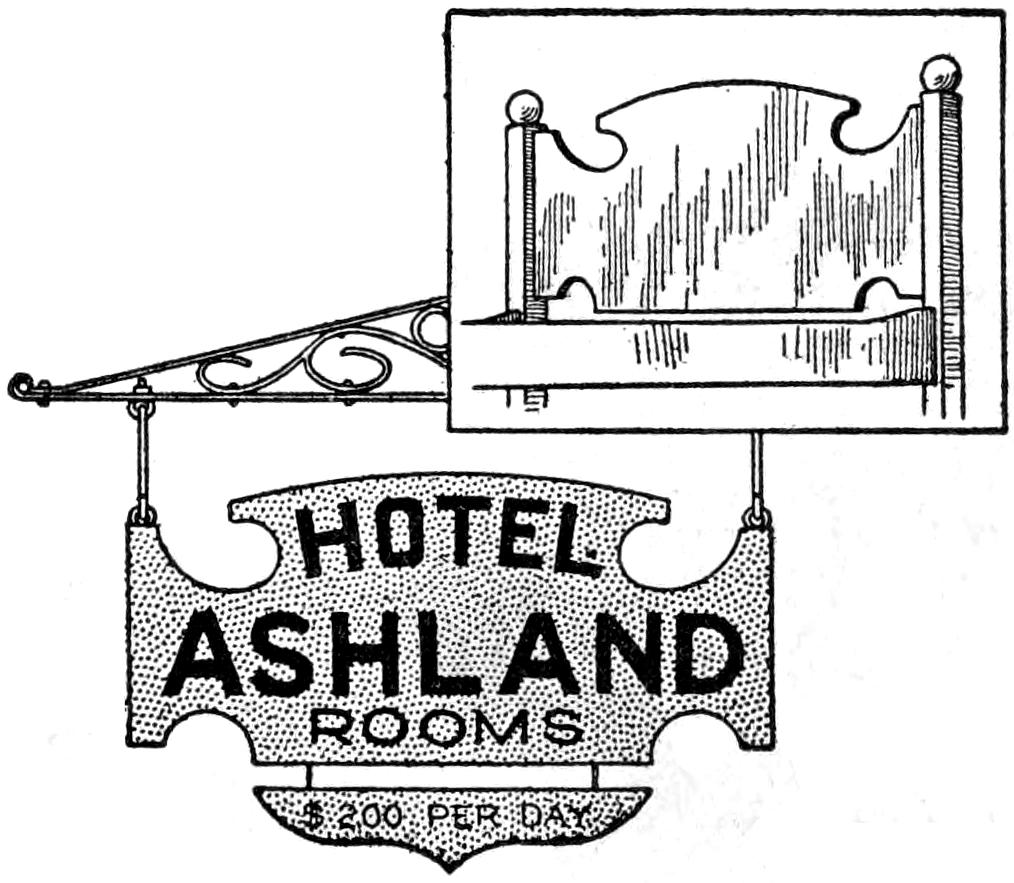

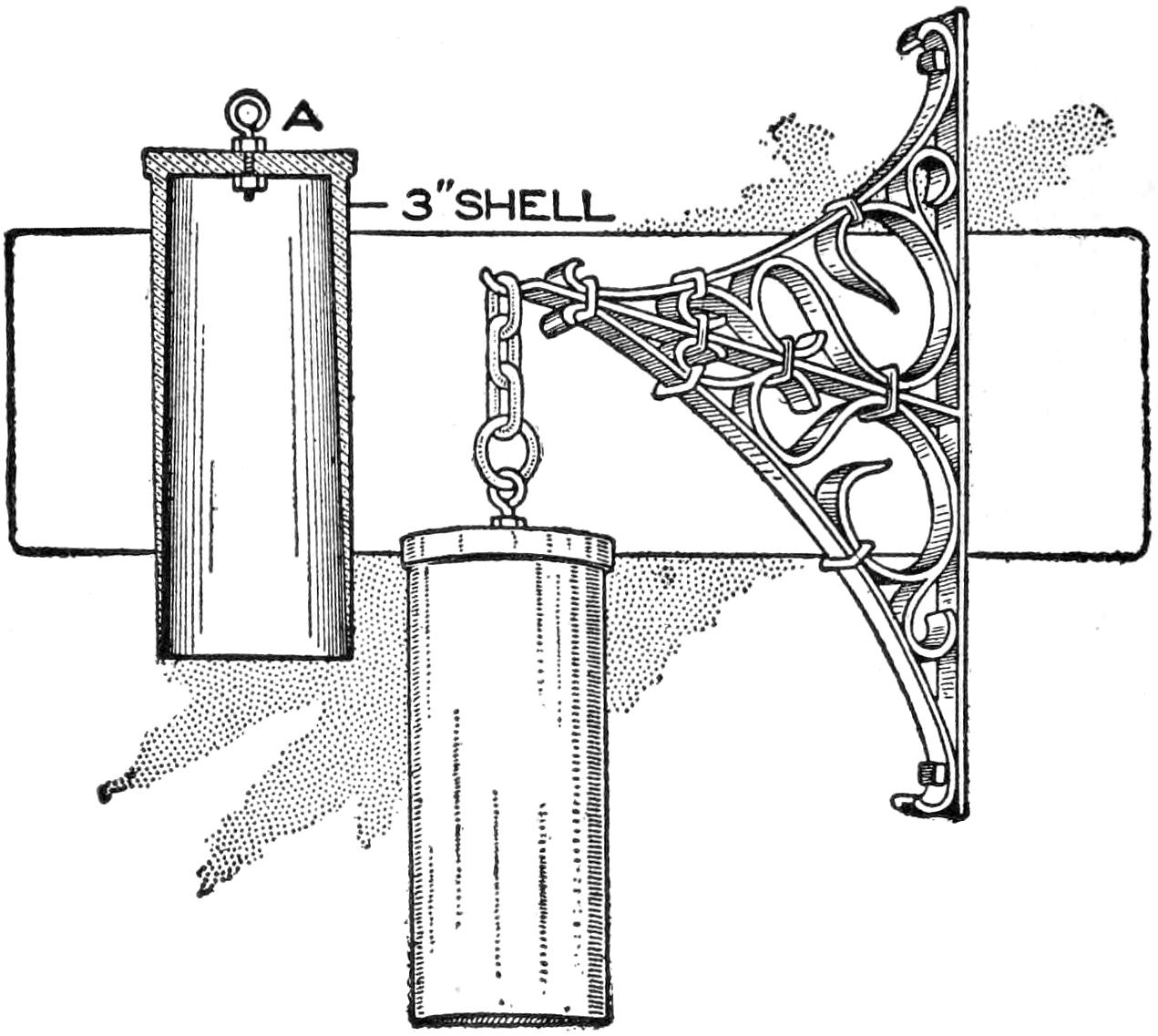

Some old headboards of beds are of such a pattern that they lend themselves readily for use as signboards, with only slight alteration. Such an adaptation is shown in the sketch, and was fitted to a bracket of ornamental iron, the whole producing a striking effect. The sign was made of black walnut and was, by reason of its age, well seasoned. It was treated with several coats of linseed oil to withstand the action of the weather better.

A Signboard Which Attracts Attention was Made of the Headboard of a Walnut Bed

[16]

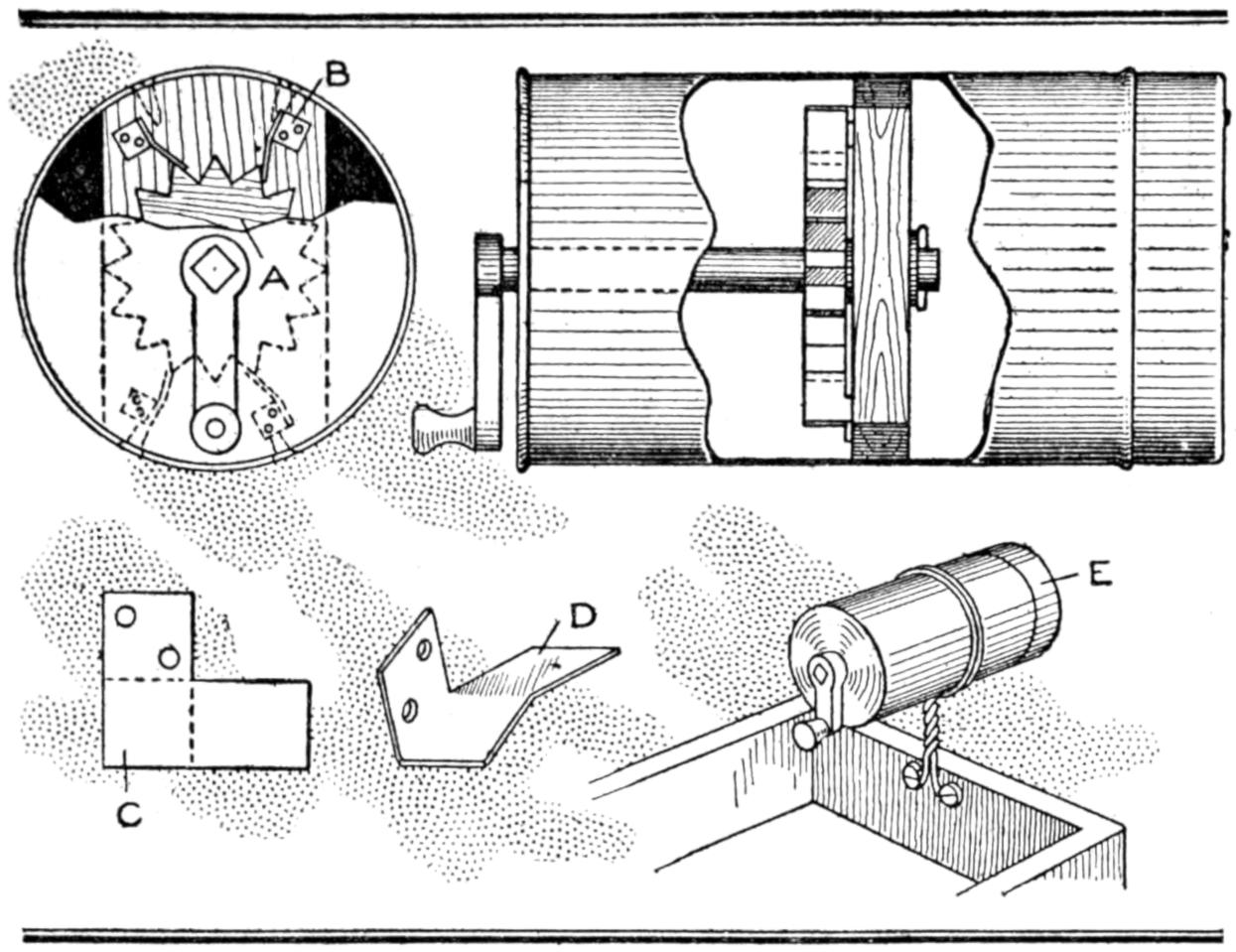

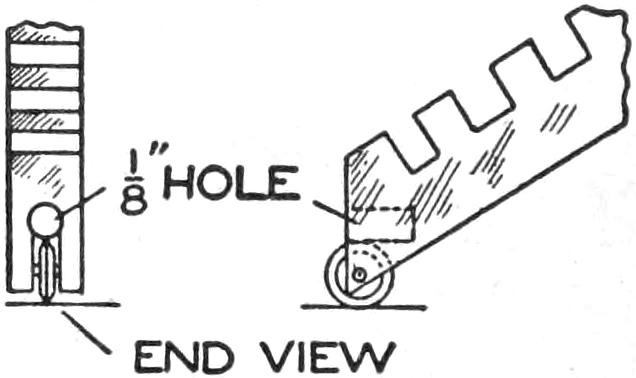

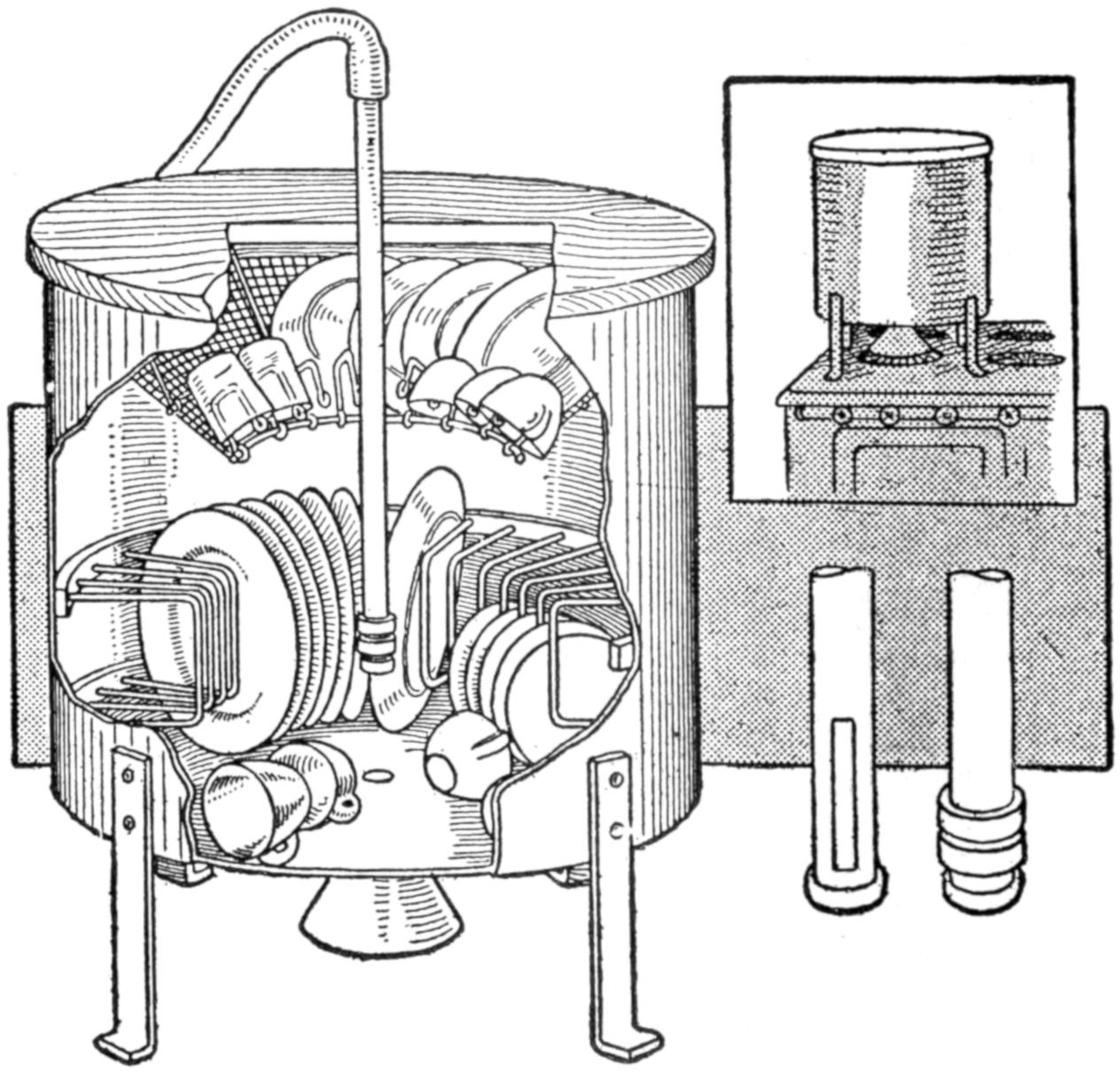

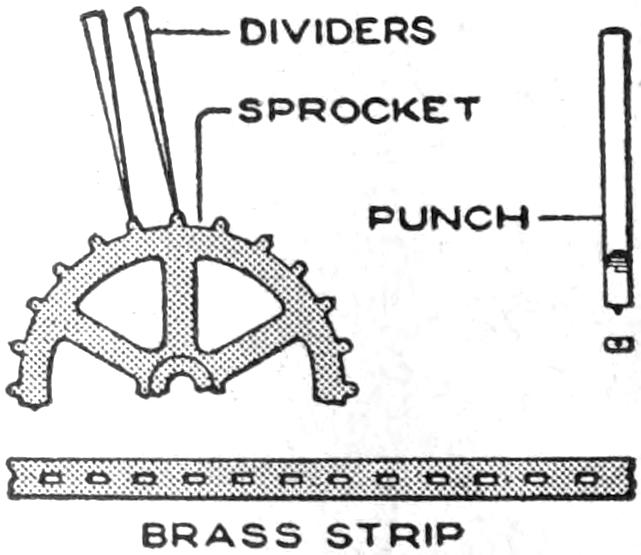

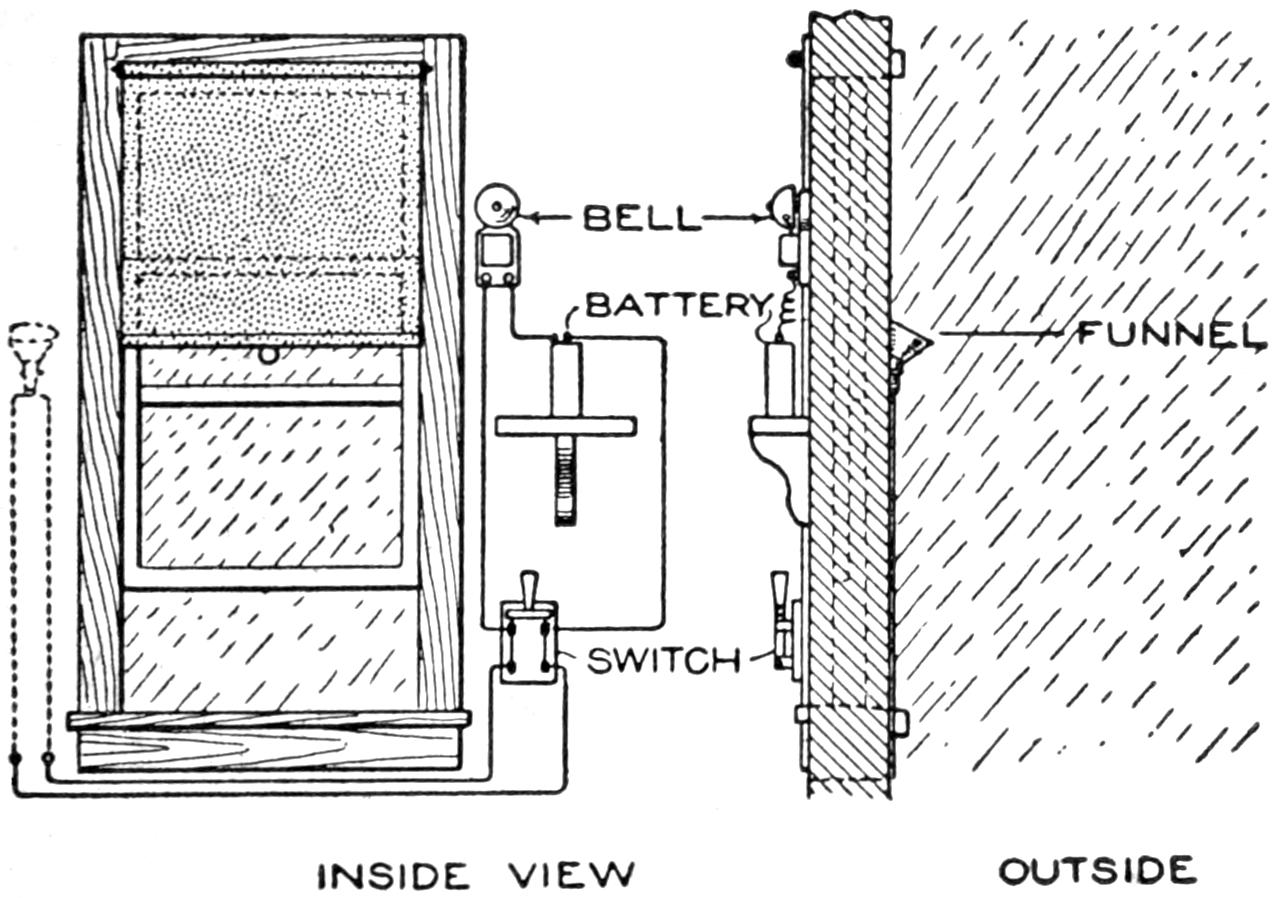

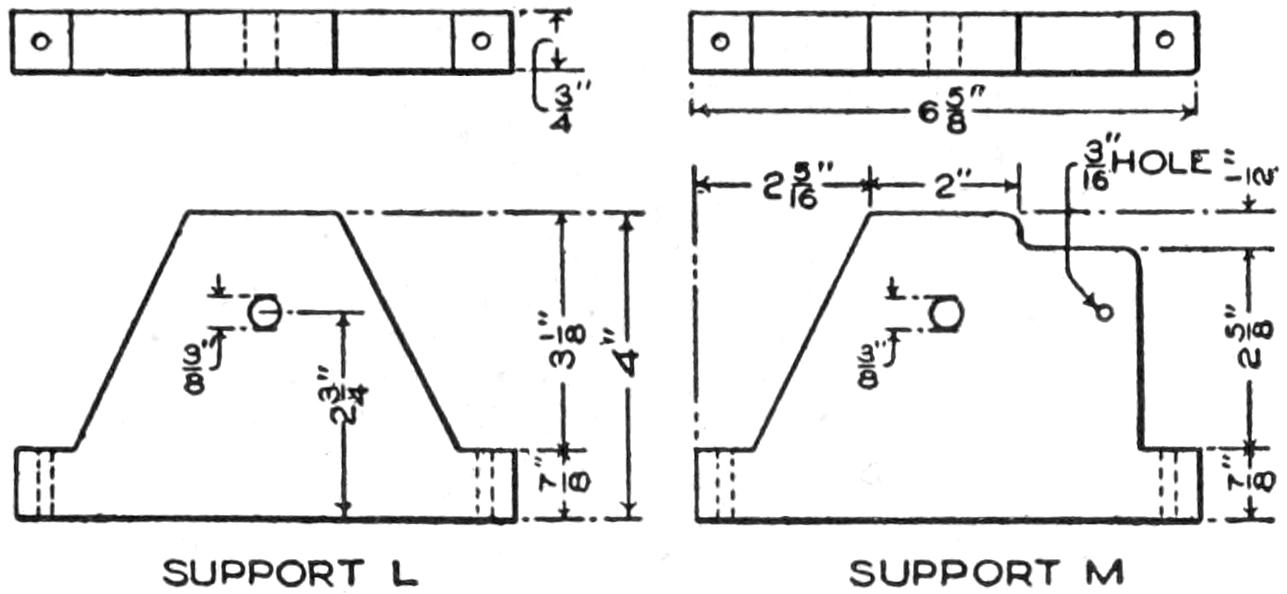

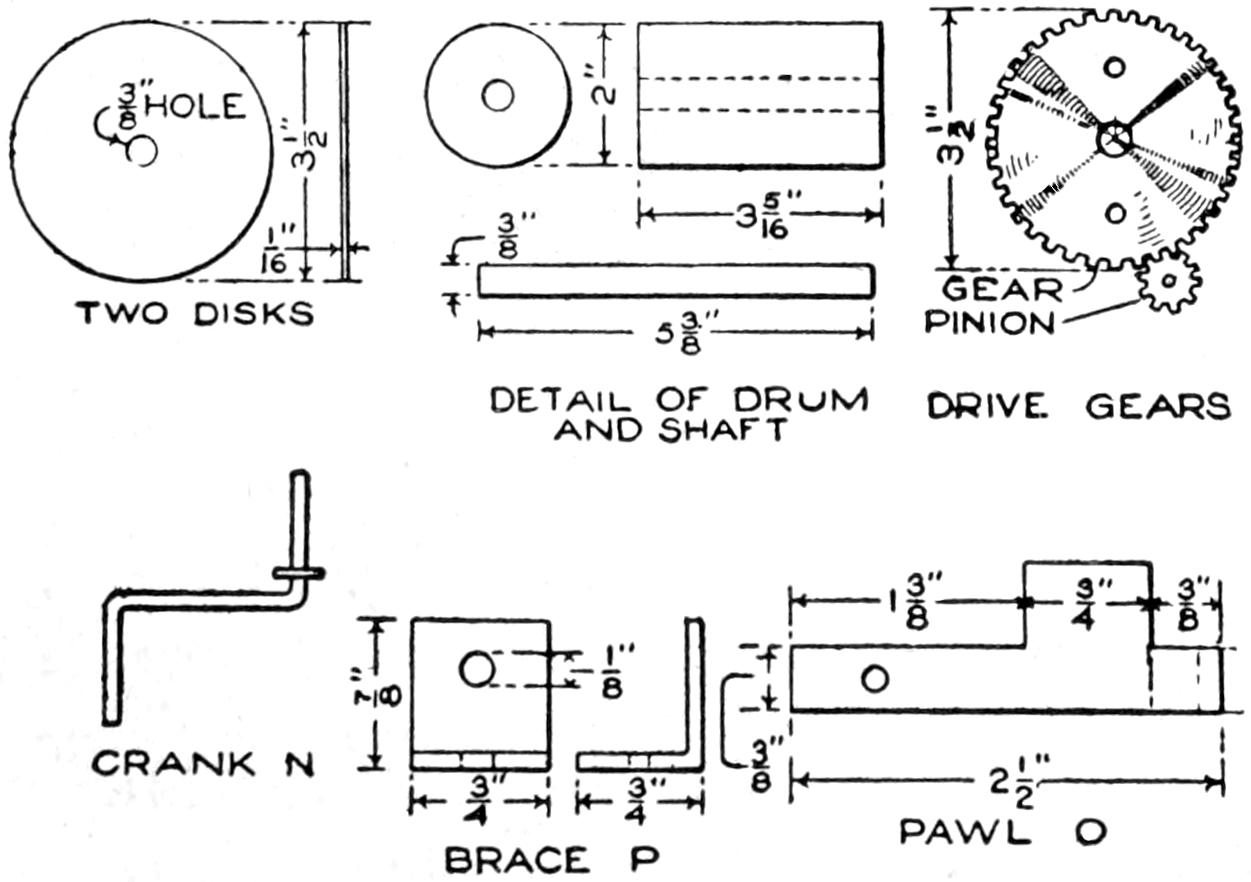

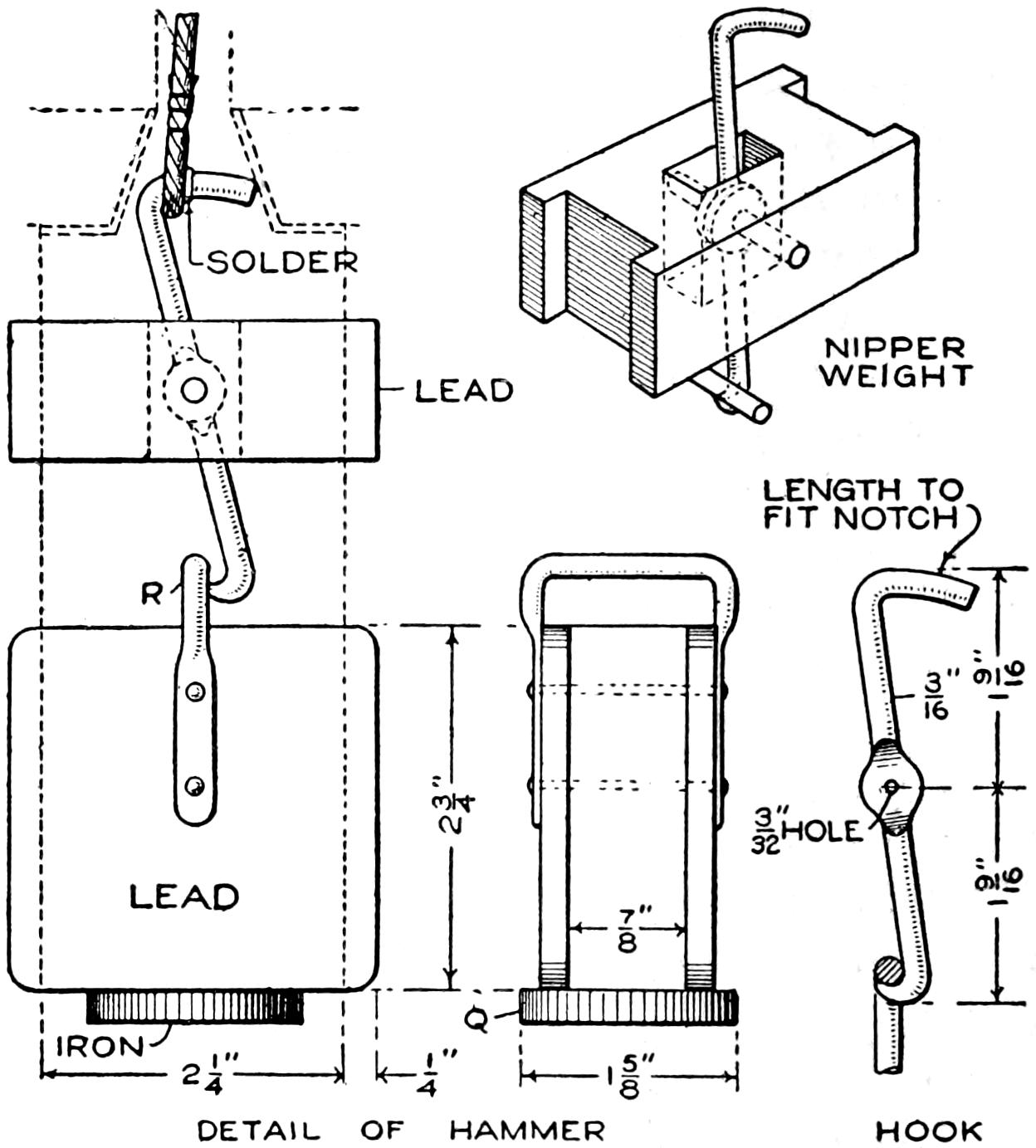

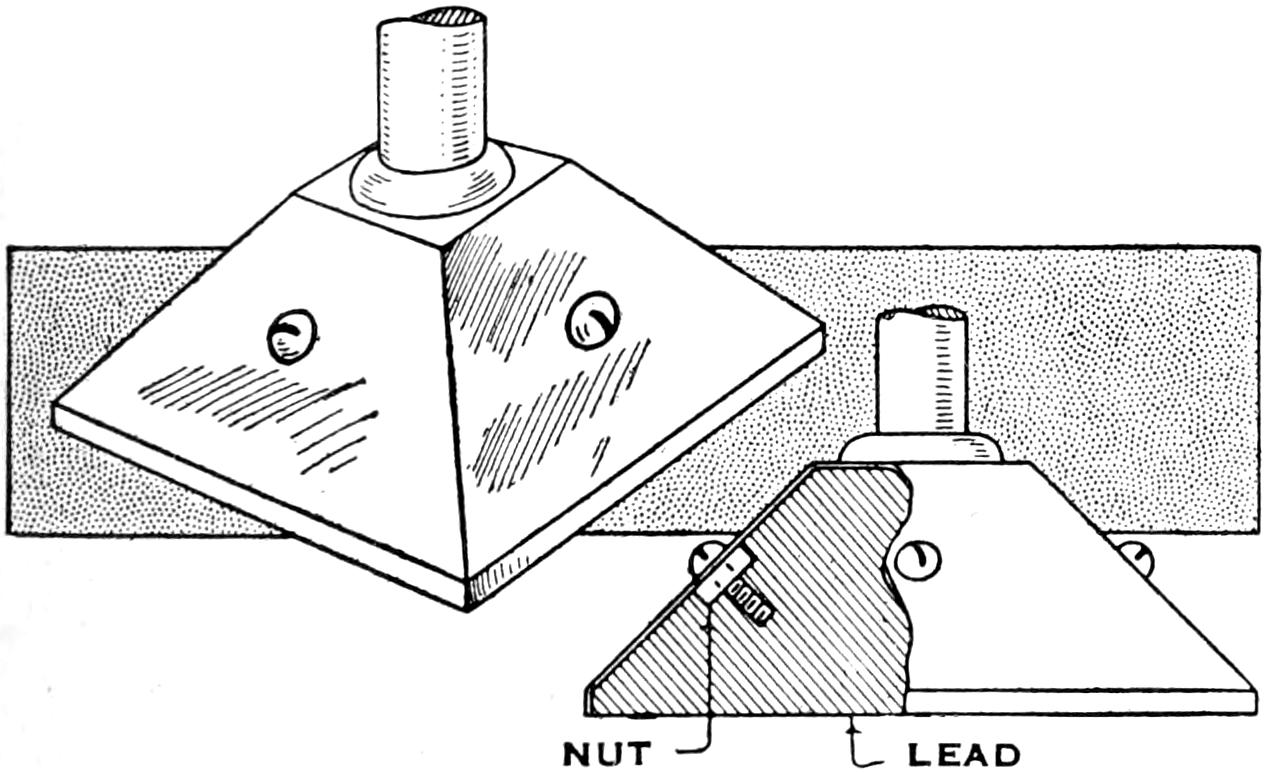

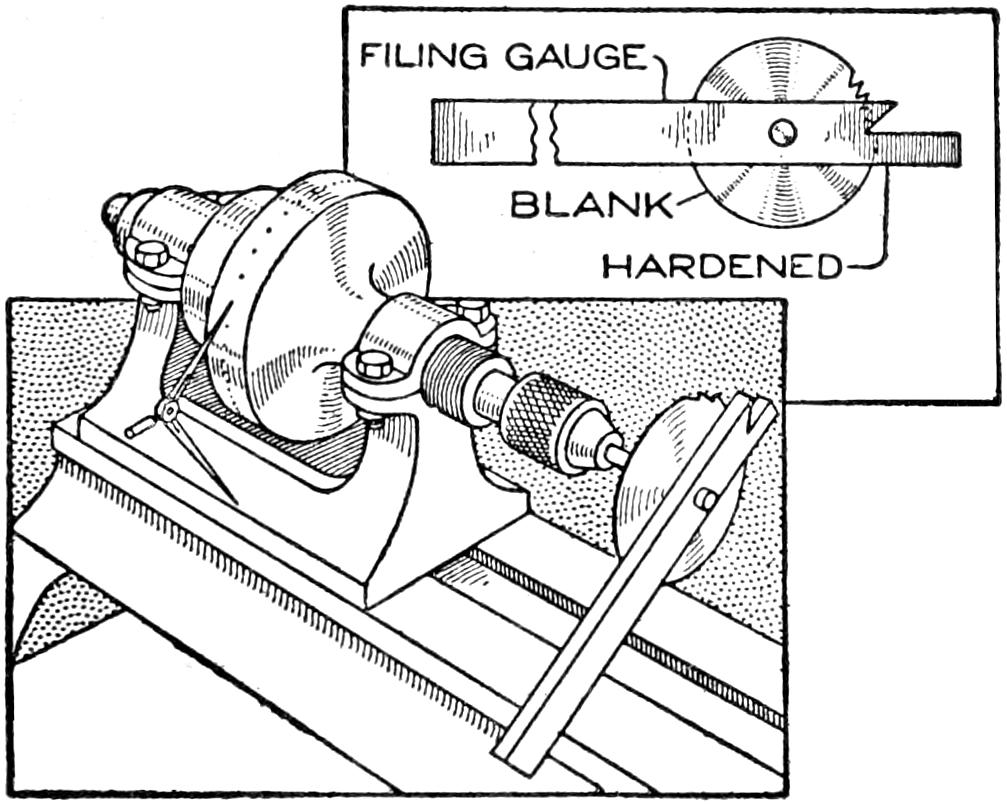

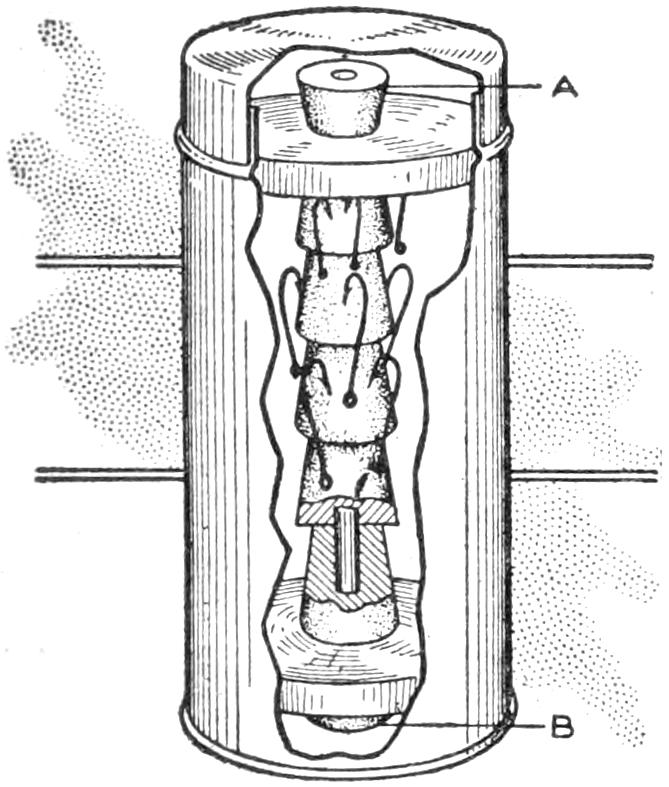

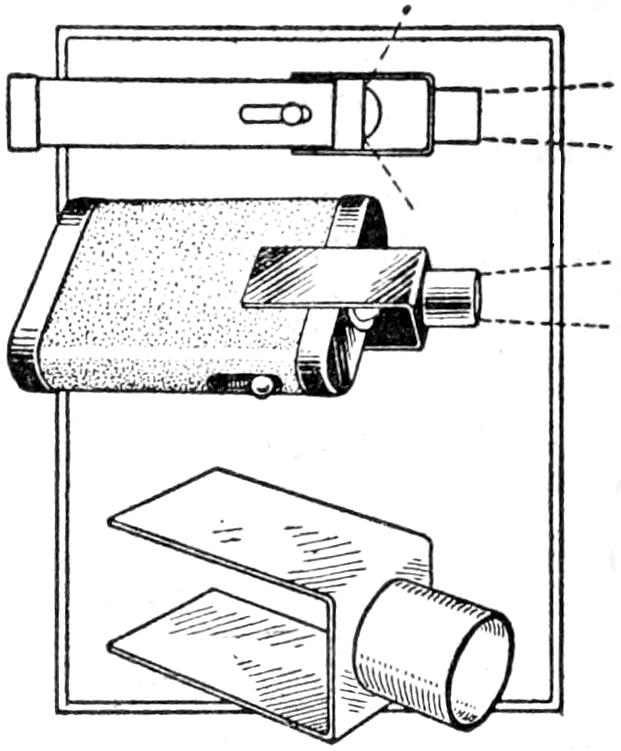

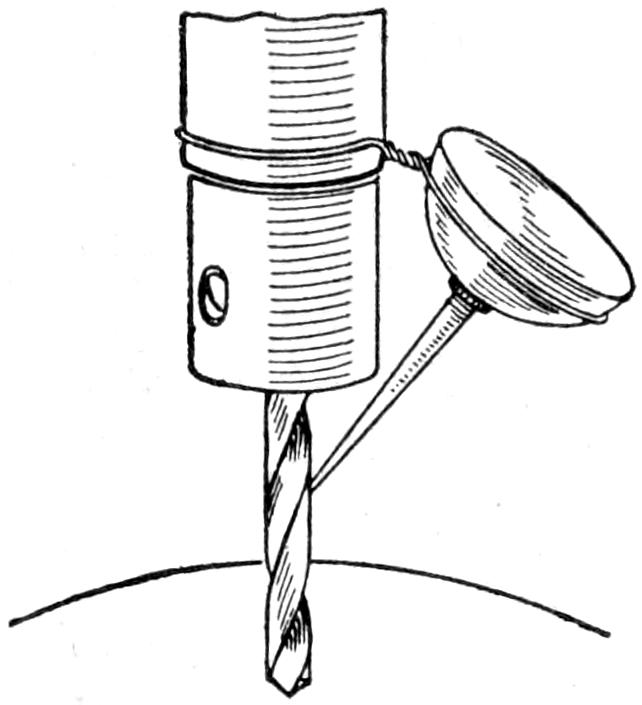

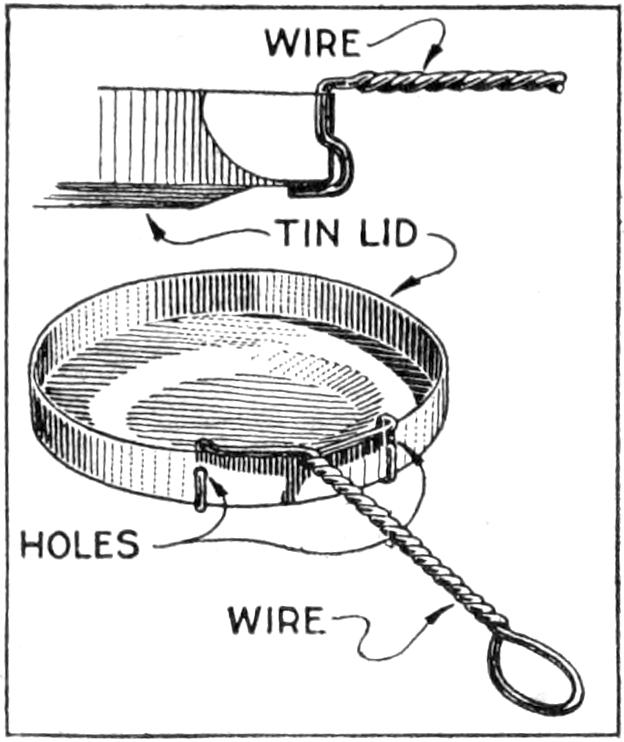

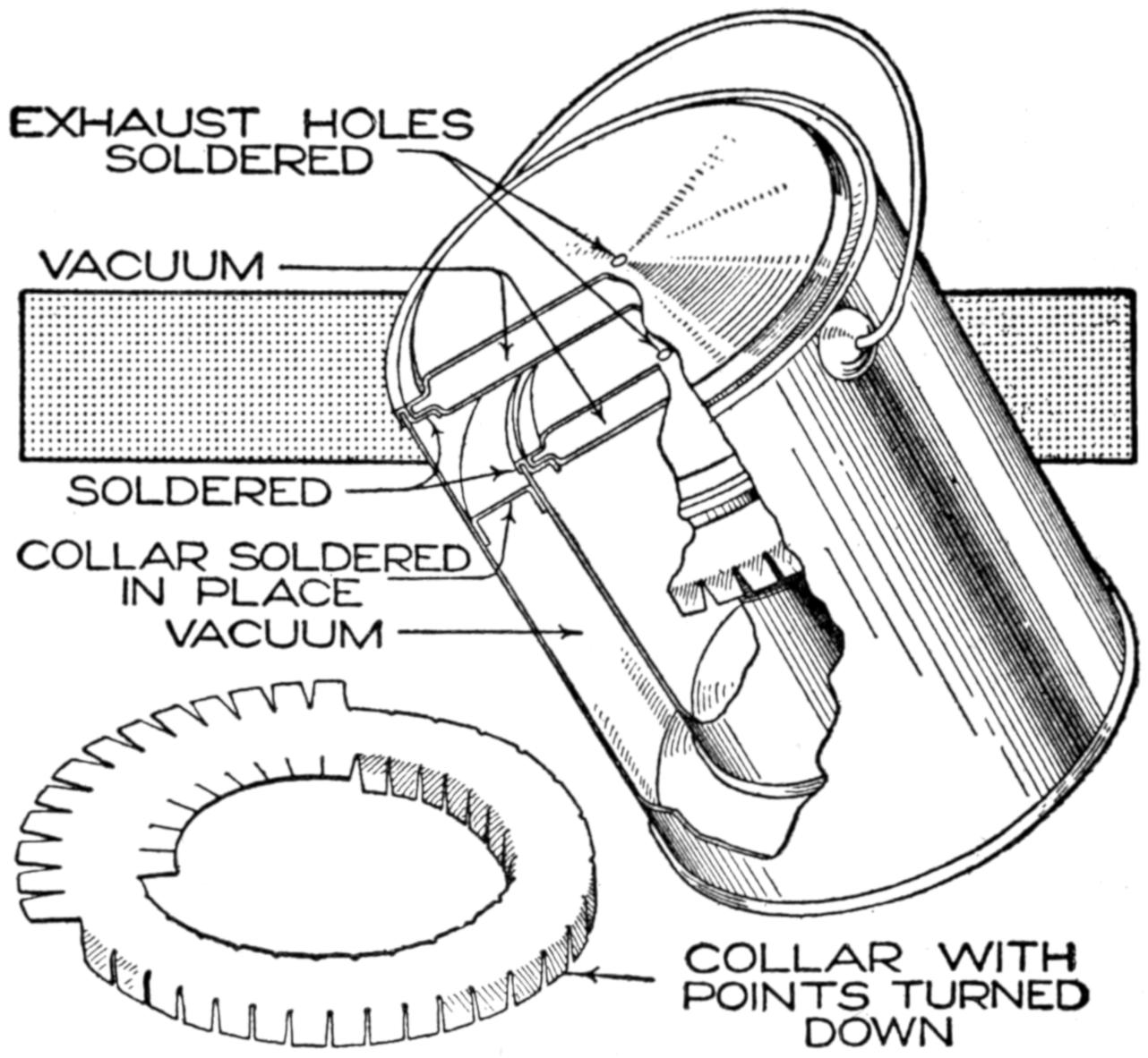

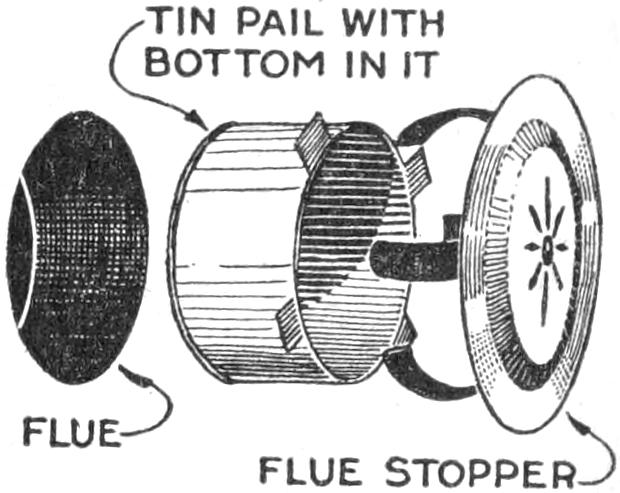

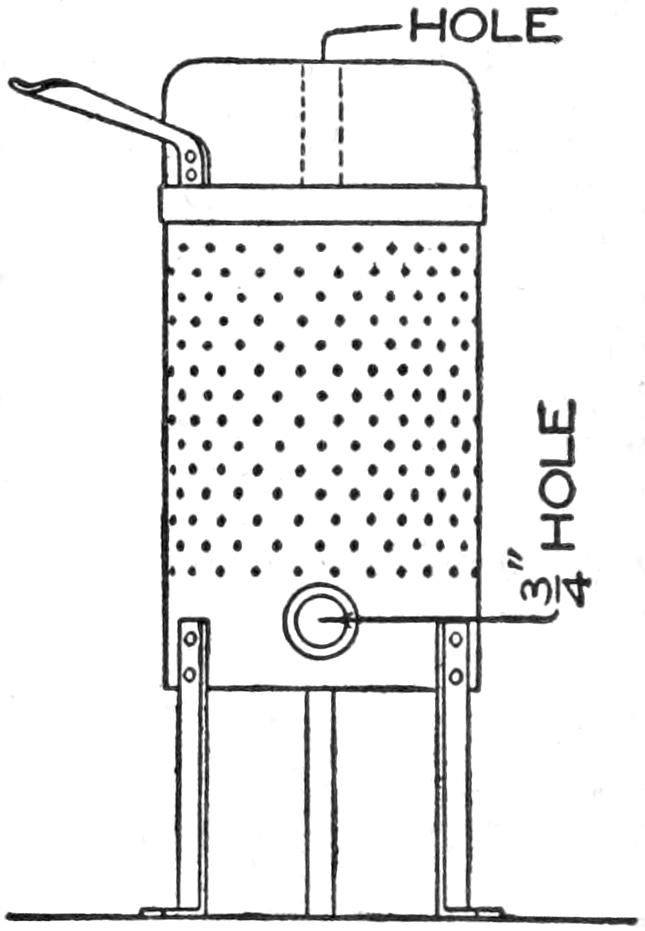

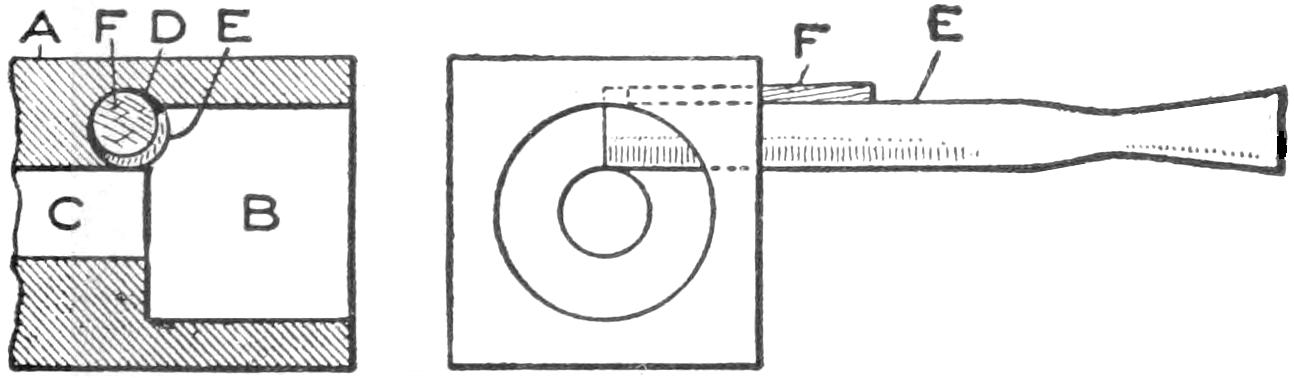

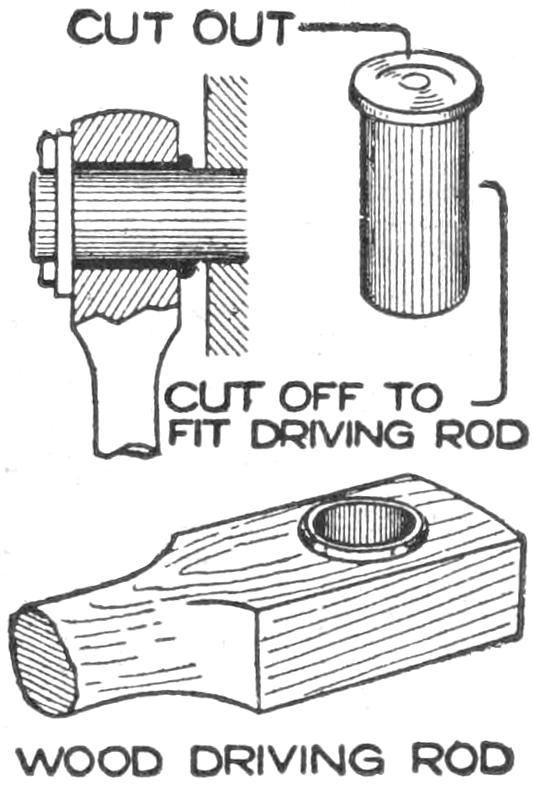

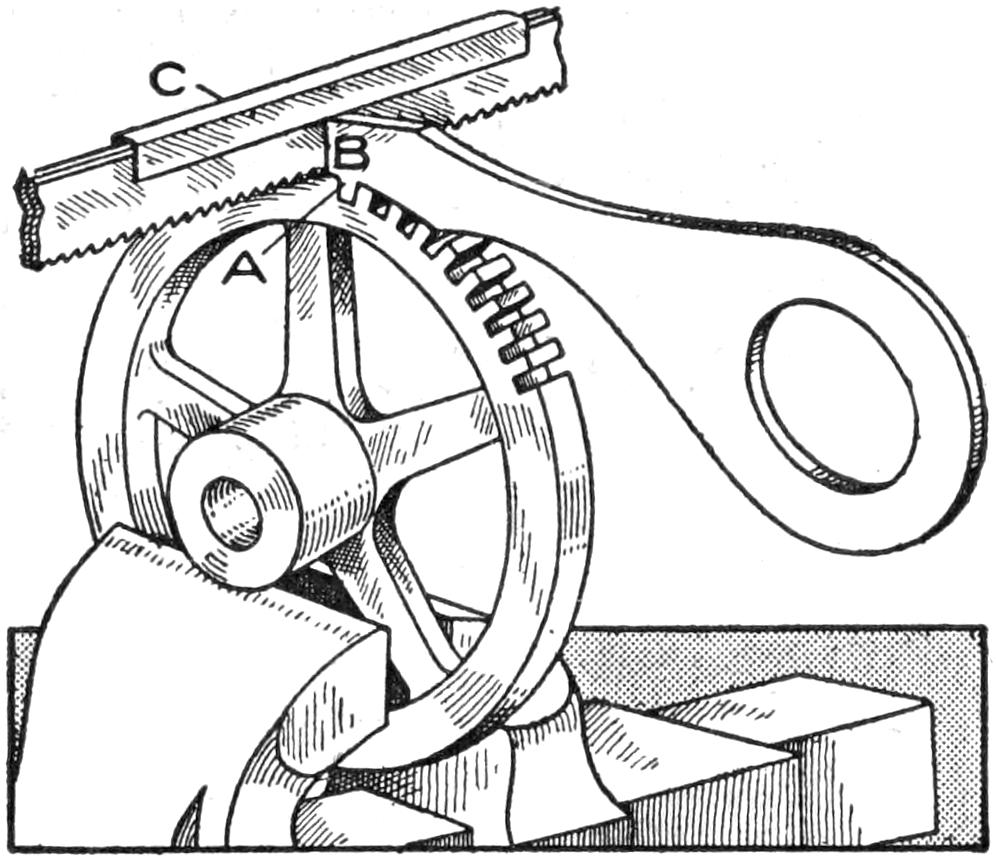

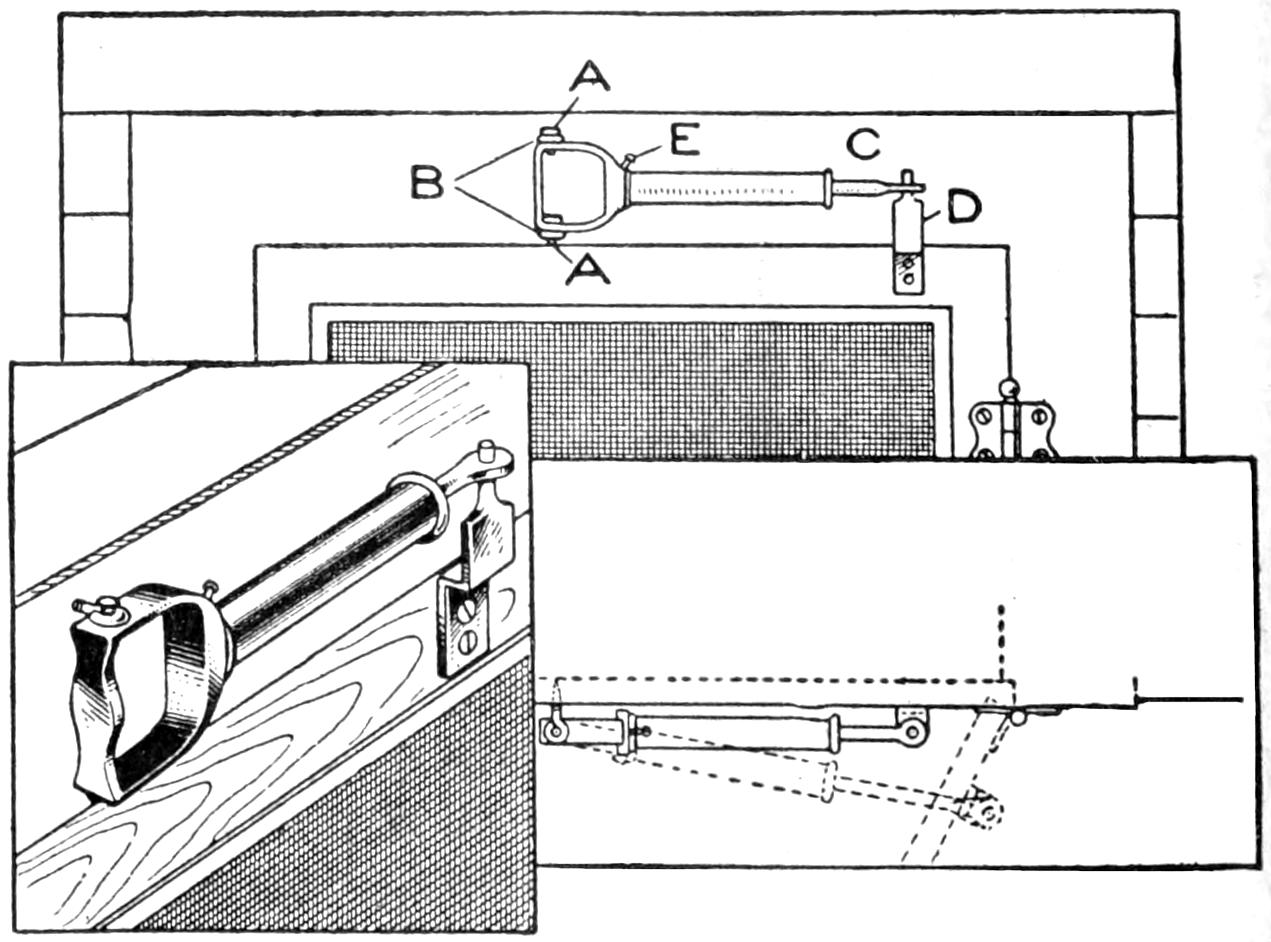

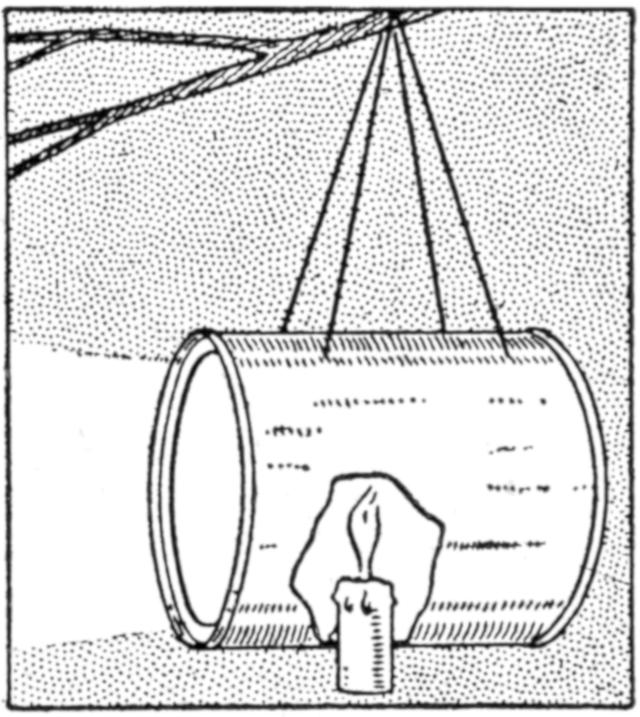

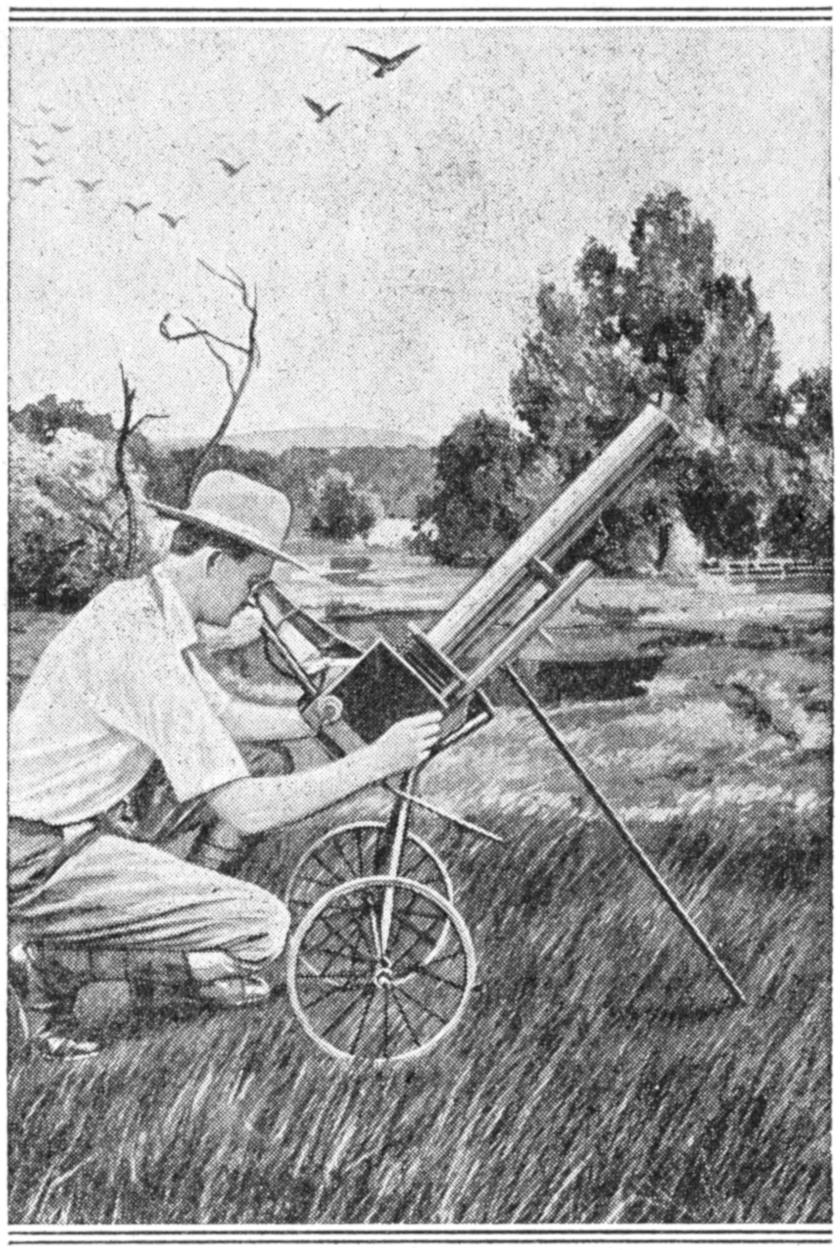

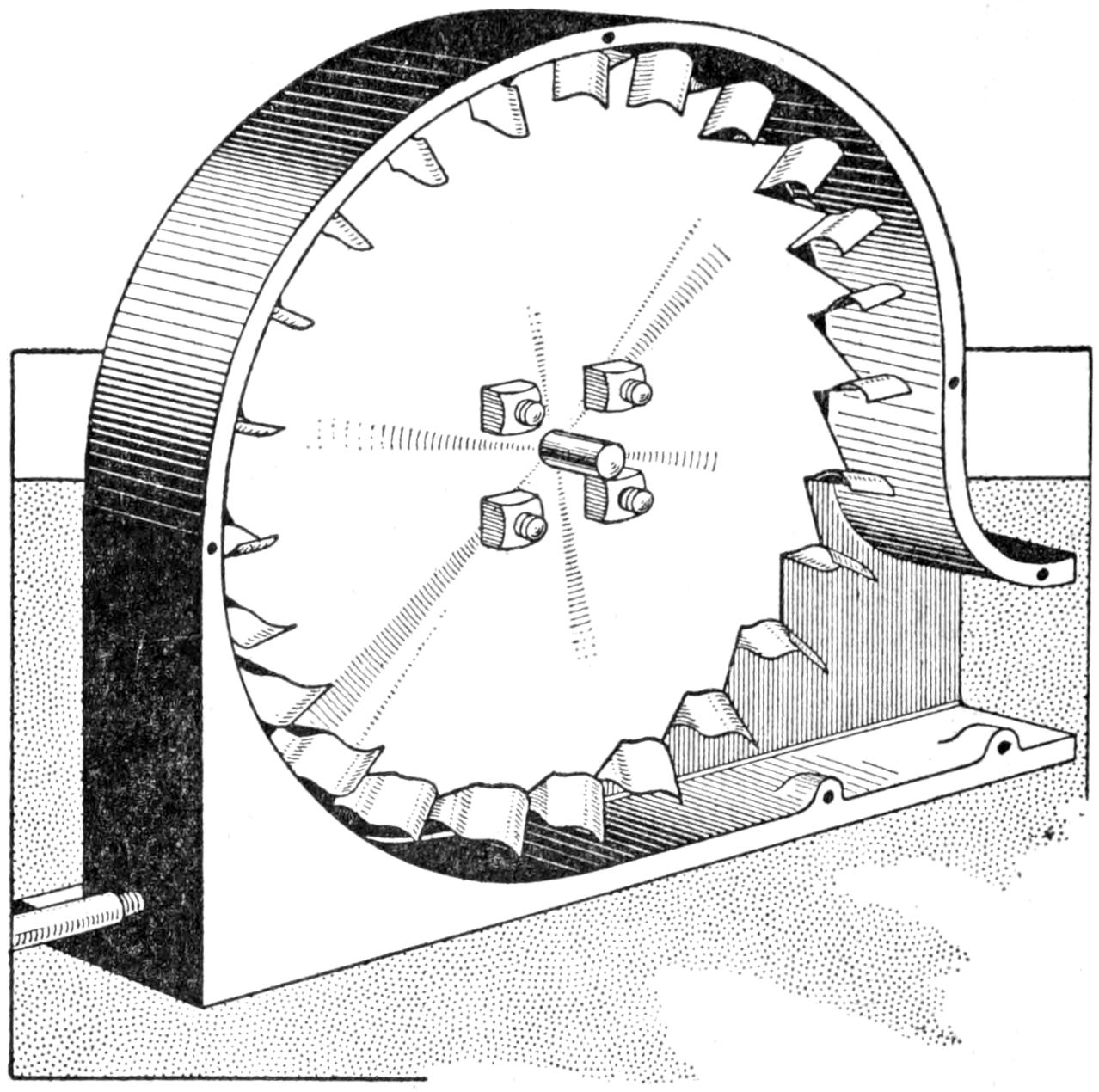

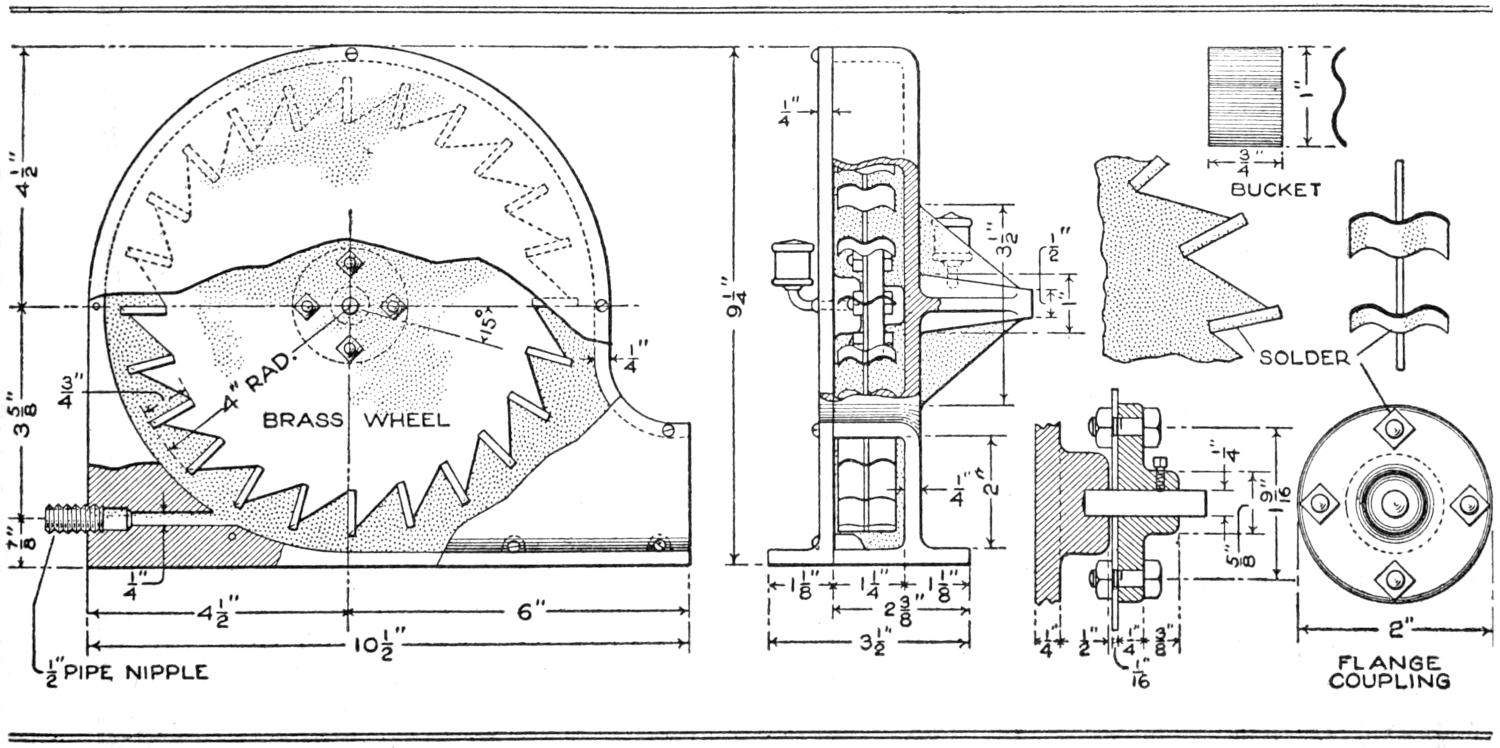

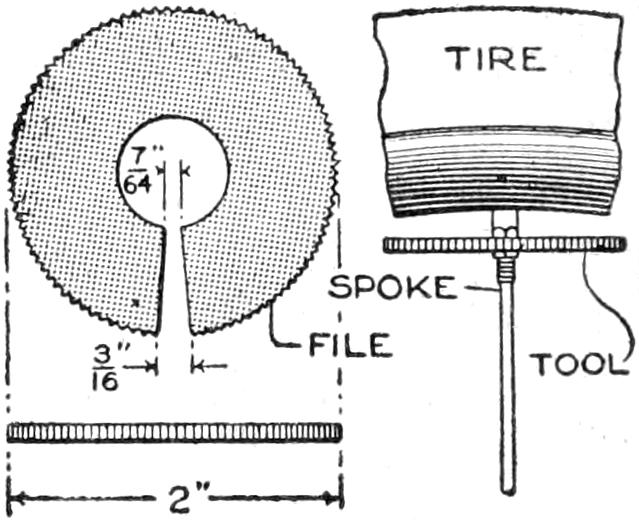

A baking-powder, or other tinned, can may be used to make the small automobile horn shown in the illustration, for use on a child’s coaster wagon. The device consists of a toothed wheel operating against several metal pawls within the can, and the warning sound is produced by turning a small crank at the end of the can. The can is fixed to the side of the vehicle by means of a wire or strap-iron bracket, as shown in the sketch at E.

This Small Auto Horn was Made of a Tinned Can Fitted with a Notched Wheel and Pawls

A piece of wood is fitted into the can, to support the ratchet wheel. It is bored to carry a shaft, which bears in the end of the can, and at the exposed end of which is fixed a crank. A disk of wood, about ¹⁄₂ in. thick, is cut to have a notched edge, as shown at A. The notched wheel is placed upon the shaft, and fastened securely to it, so that the ratchet wheel revolves with the shaft when the crank on the latter is turned. Four small pawls of sheet metal, are fixed on the inner support, as shown at B. They are made by cutting pieces of metal to the shape shown at C, and folding them, as shown at D. They are fastened to the support with small screws or nails. The cover is placed on the end of the can when the device is used. The action of the ratchet wheel against the pawls is to produce a loud grating sound, resembling that of a horn of the siren type.—William Freebury, Buffalo, N. Y.

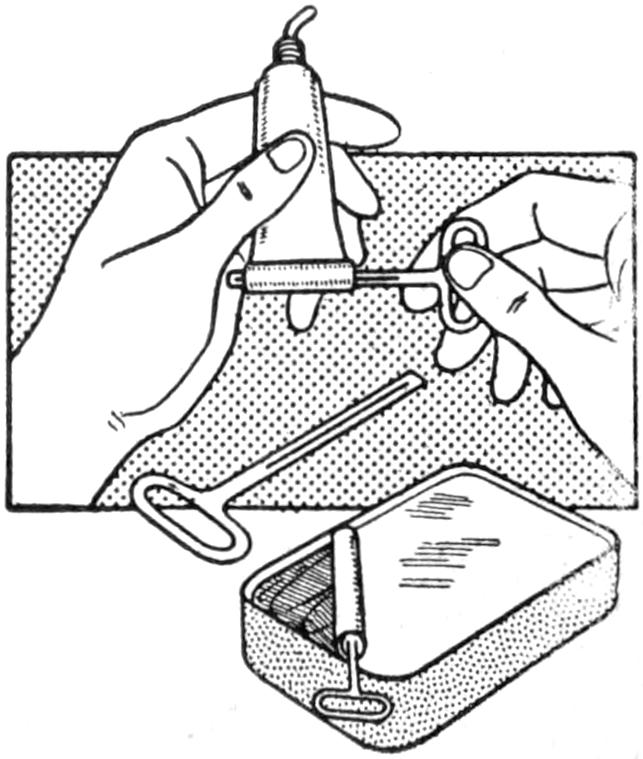

A small paste tube of the collapsible variety is hard to keep at hand on the desk and occasionally, if left uncovered, the contents may be forced out on papers or on the table. A simple container may be made for the tube by cutting the carton in which the tube is packed with a penknife, so as to expose the upper end of the tube. The cover and upper end of the back of the carton is doubled over to provide an extra thickness for a support, by which the contrivance may be suspended on the wall.—T. H. Linthicum, Annapolis, Md.

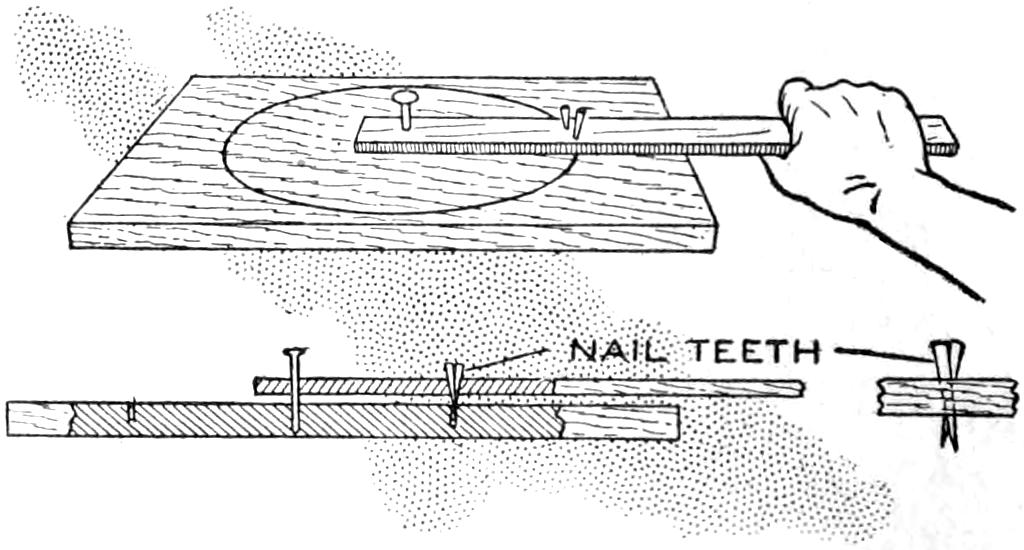

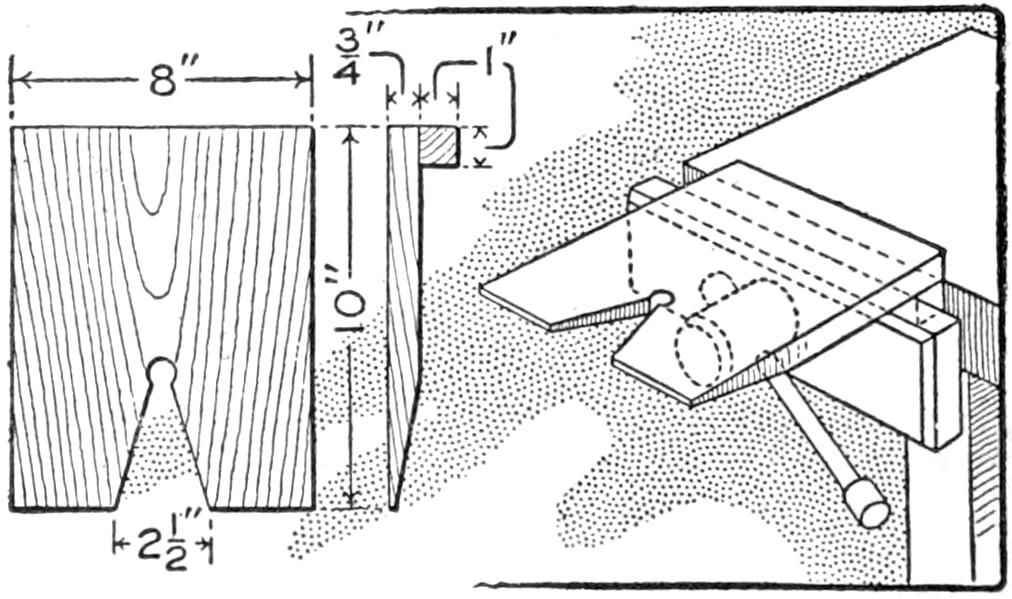

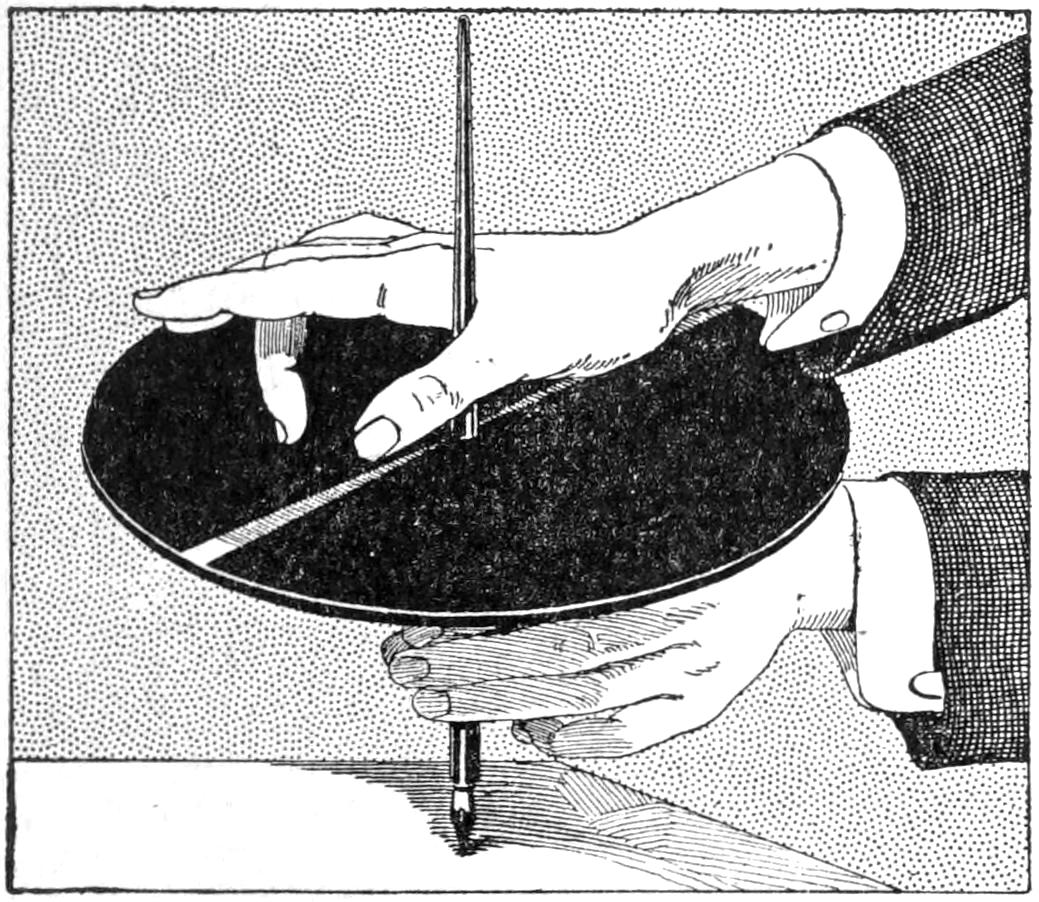

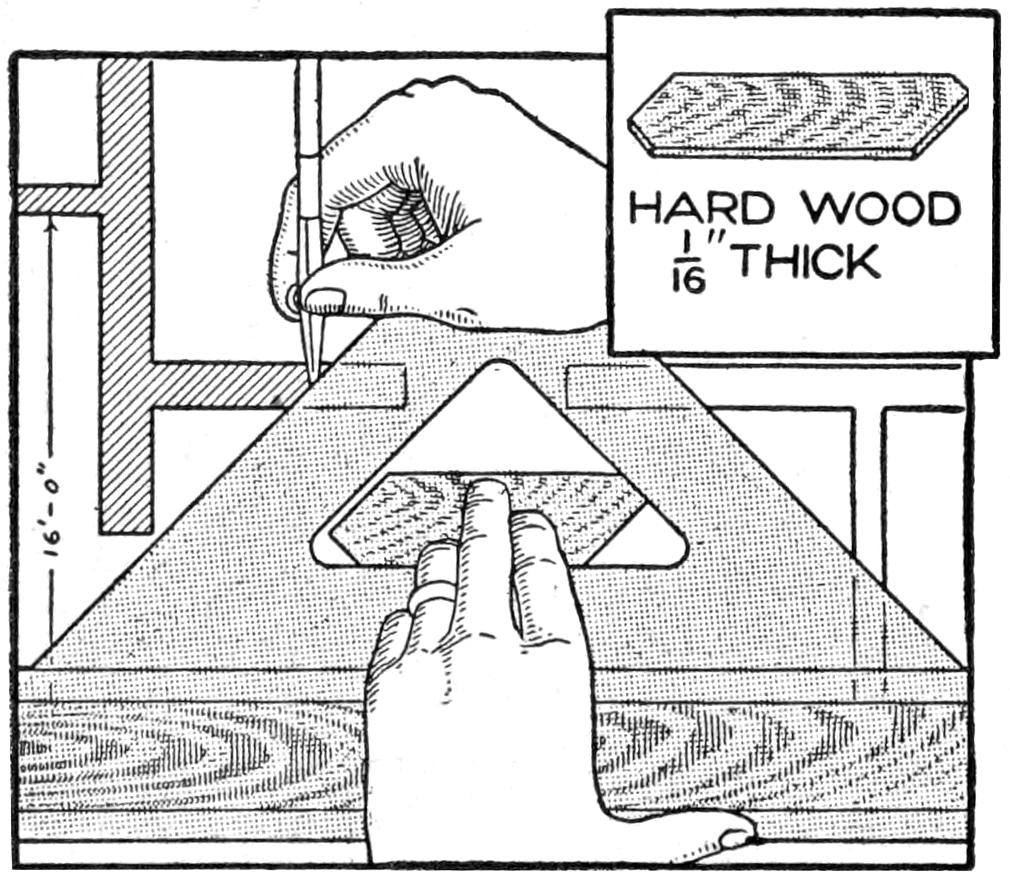

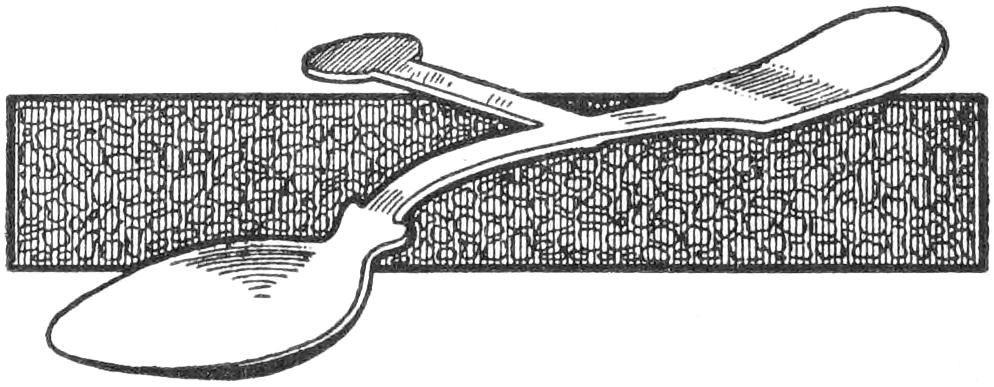

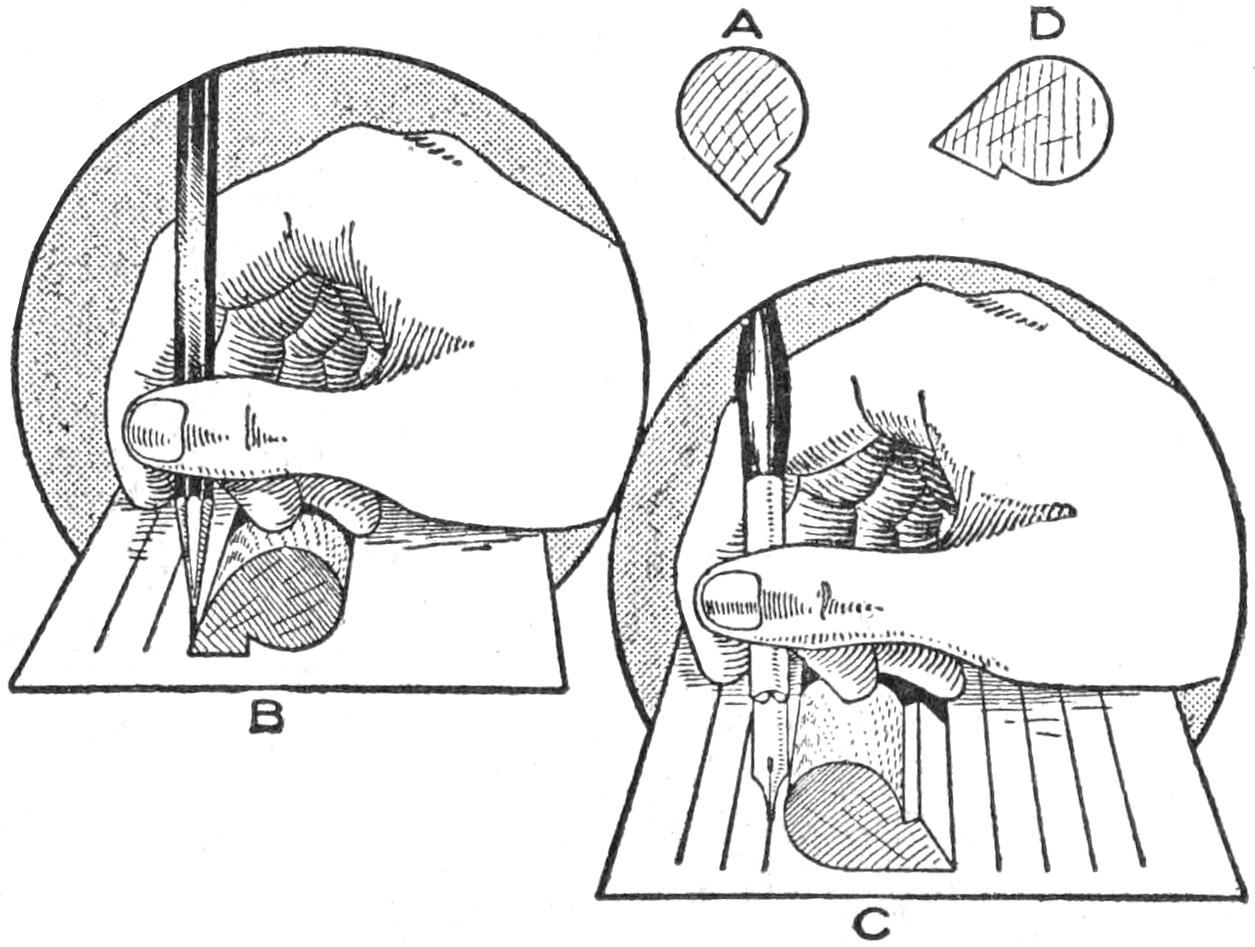

Draw the Strip with Its Saw-Tooth Brads around the Center, Cutting Out the Disk

Instead of cutting thin wooden disks with a coping saw, making it necessary to smooth off the circumference of the disk, more satisfactory results may be had by the following method: Determine the center from which the circumference of the disk is to be struck. Drive a nail through a strip of wood about 1 in. wide and ¹⁄₄ in. thick, and into the center of the proposed disk. At a point on the strip, so as to strike the circumference of the disk, drive two sharp brads, as shown in the sectional view of the sketch, arranging them to act as saw teeth, by driving them at an angle, with a slight space between the points. By grasping the end of the strip and drawing it carefully around the center a number of times, the disk may be cut cleanly. By cutting from one side nearly through the board, and then finishing the cut from the other, an especially good job results.—S. E. Woods, Seattle, Wash.

[17]

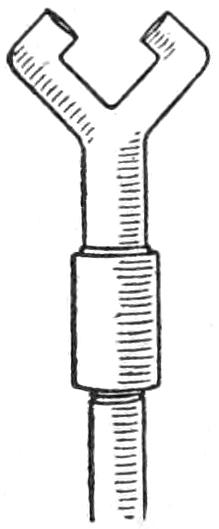

A WISHBONE-MAST

ICE YACHT

by John F. Pjerrou

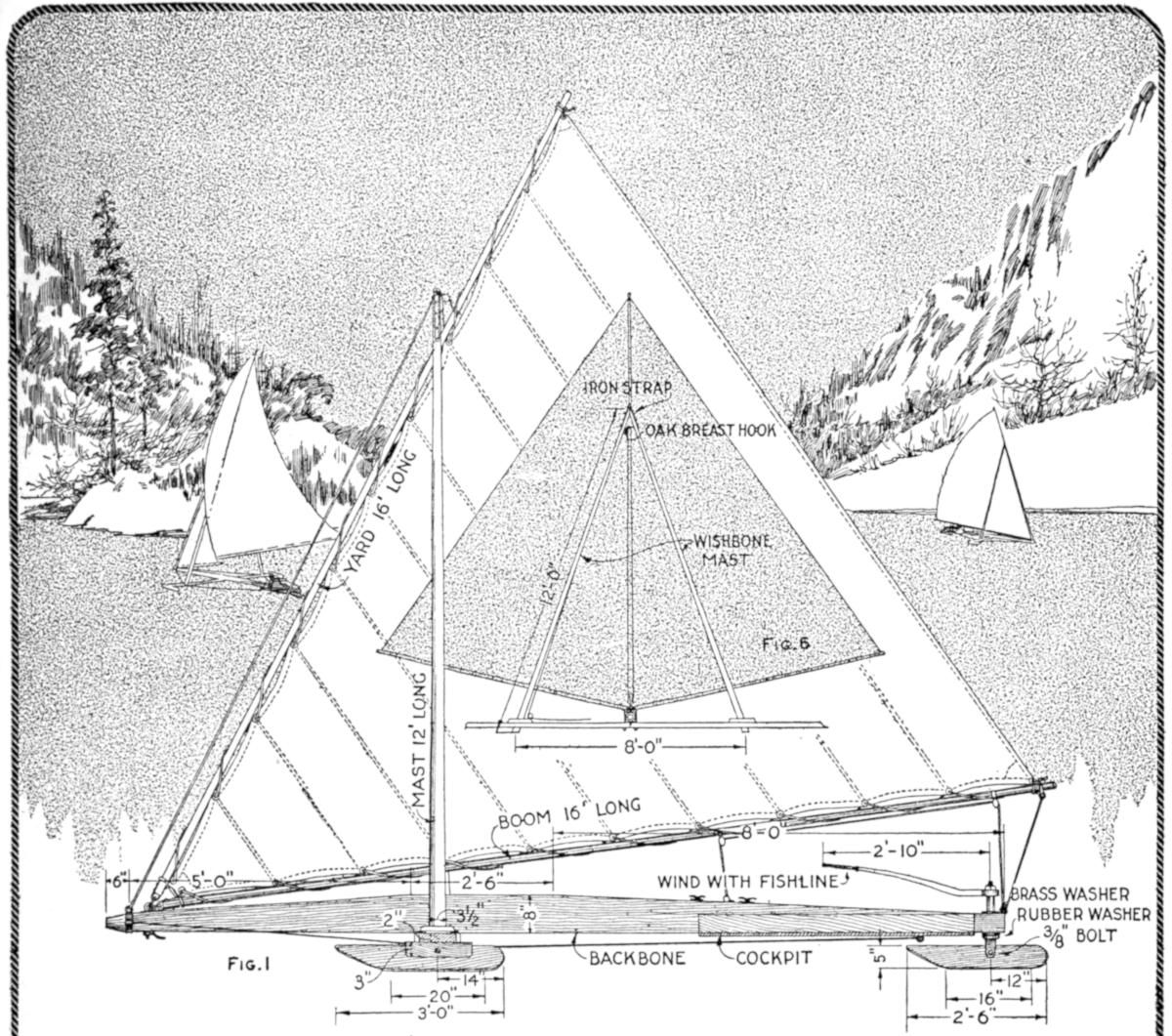

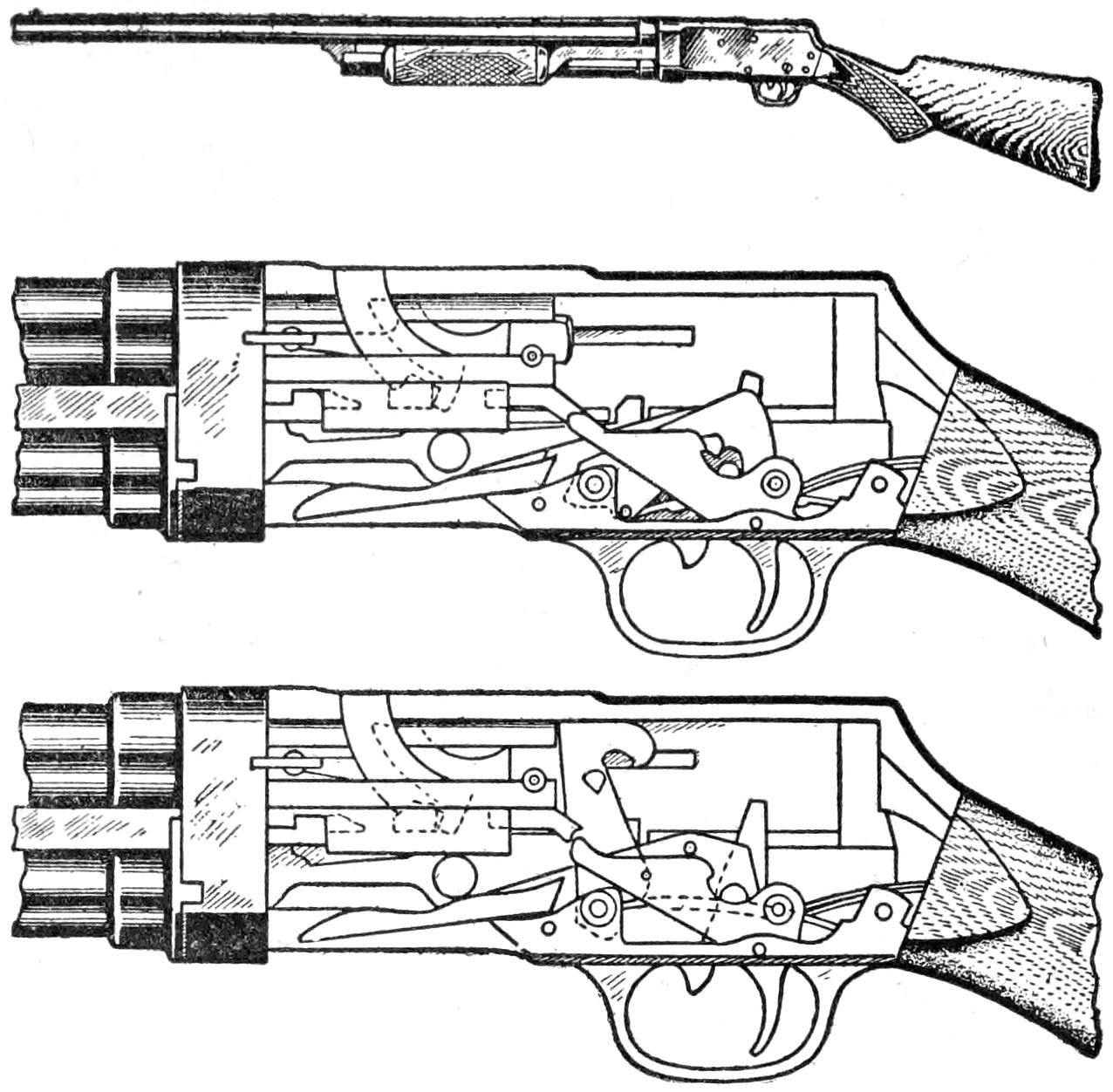

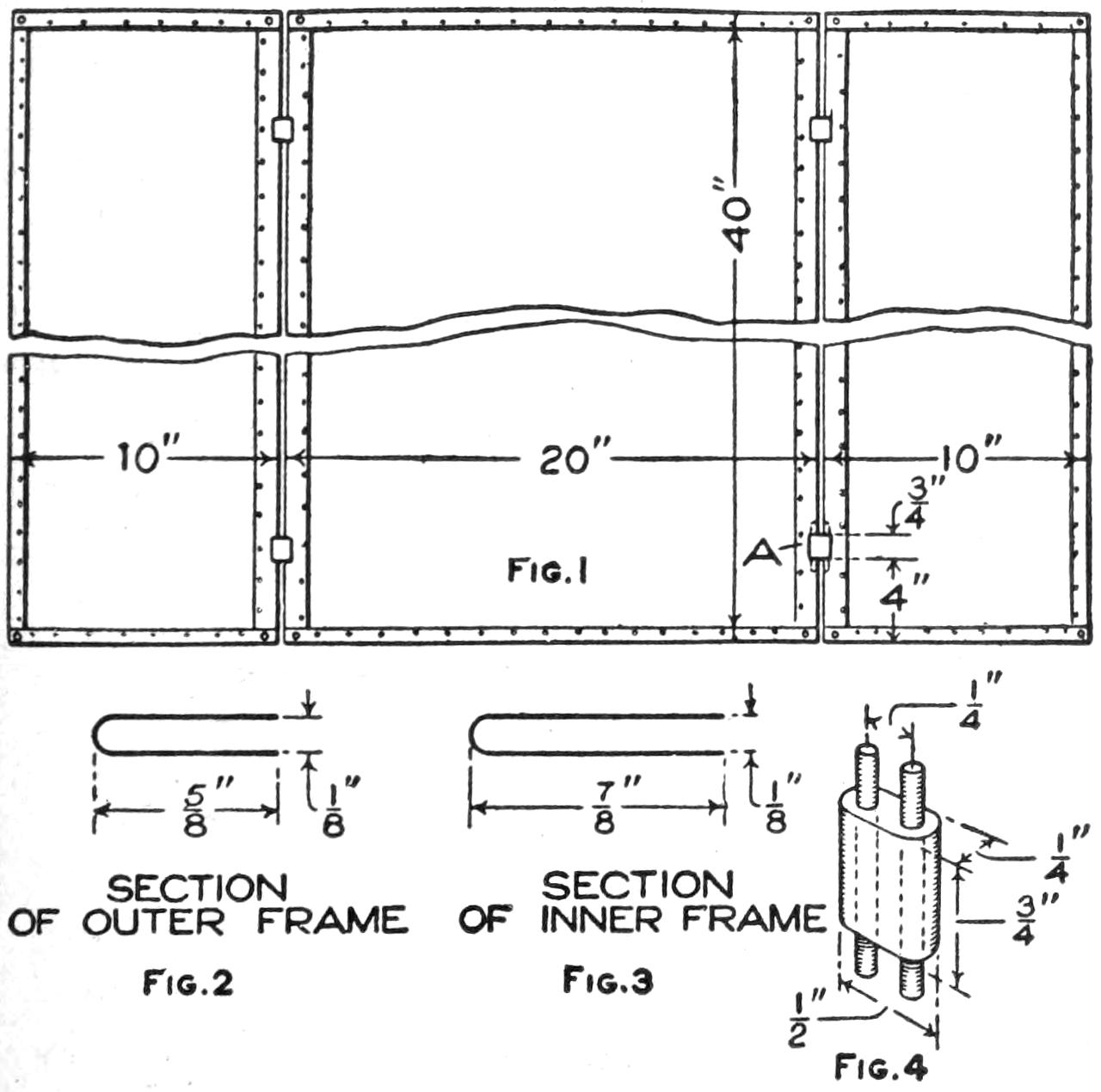

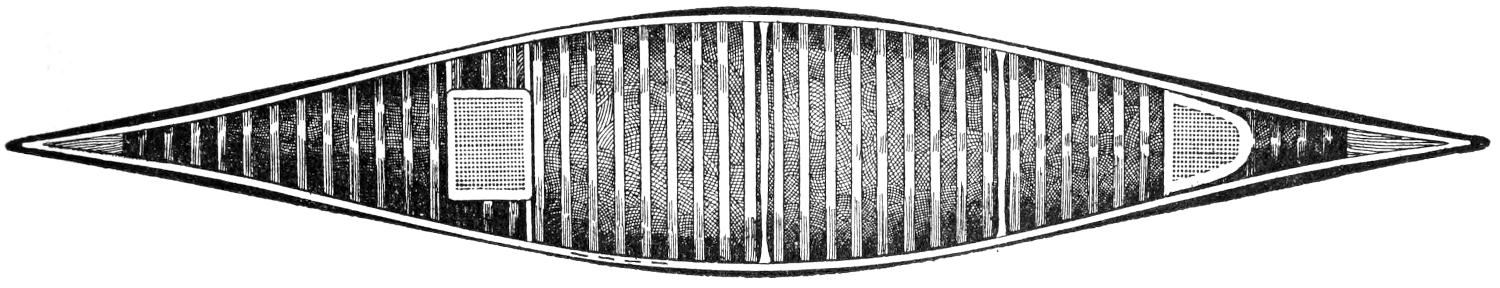

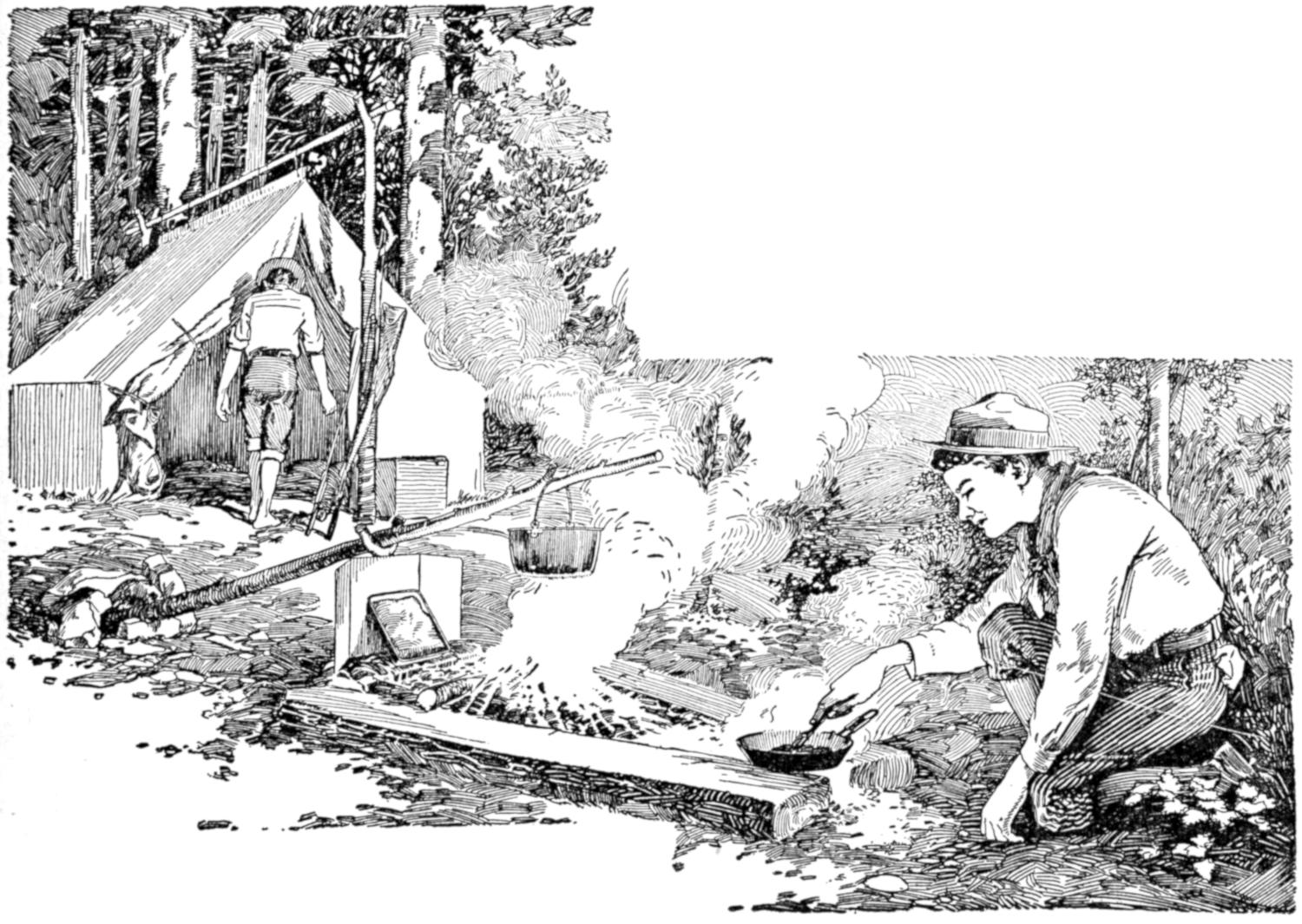

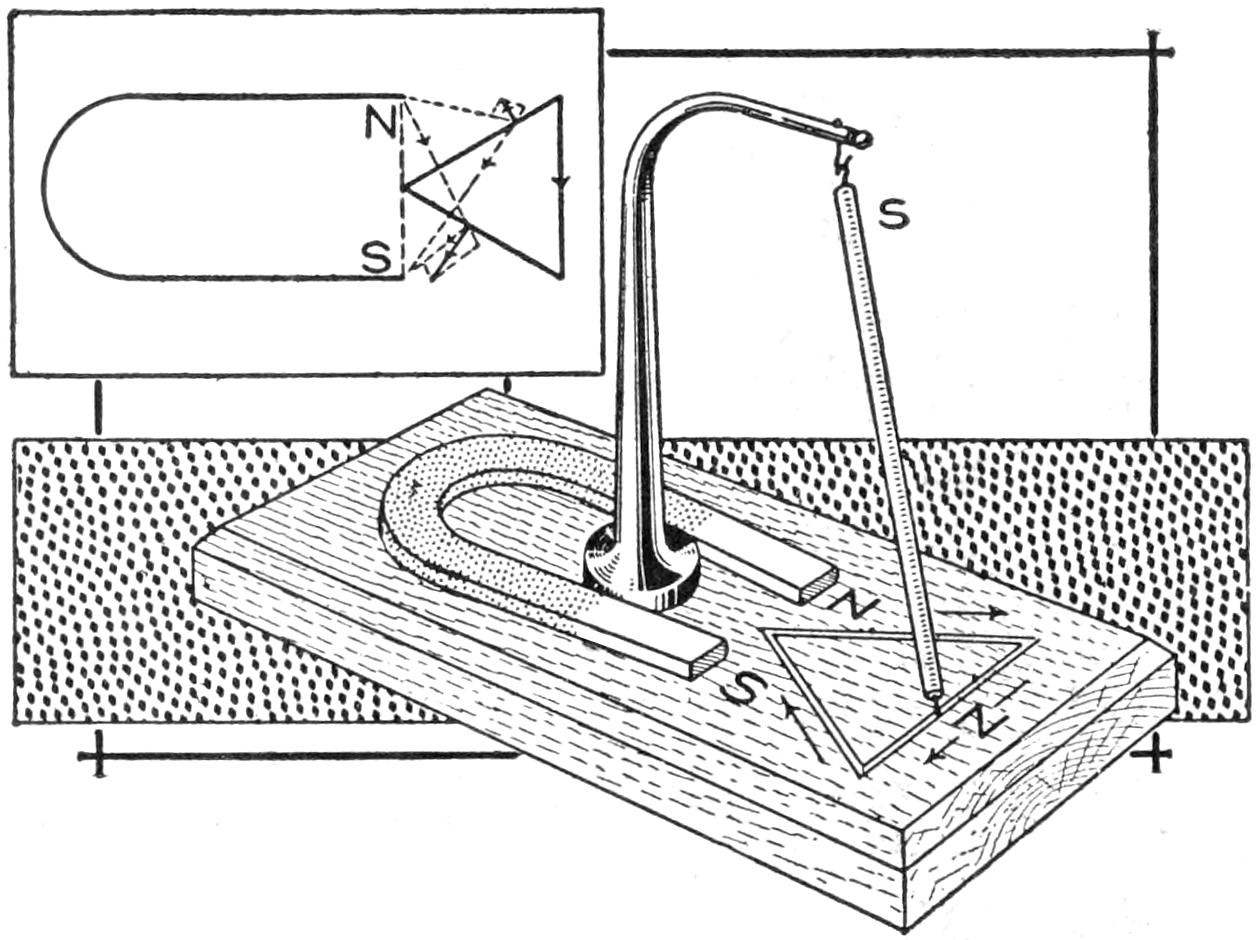

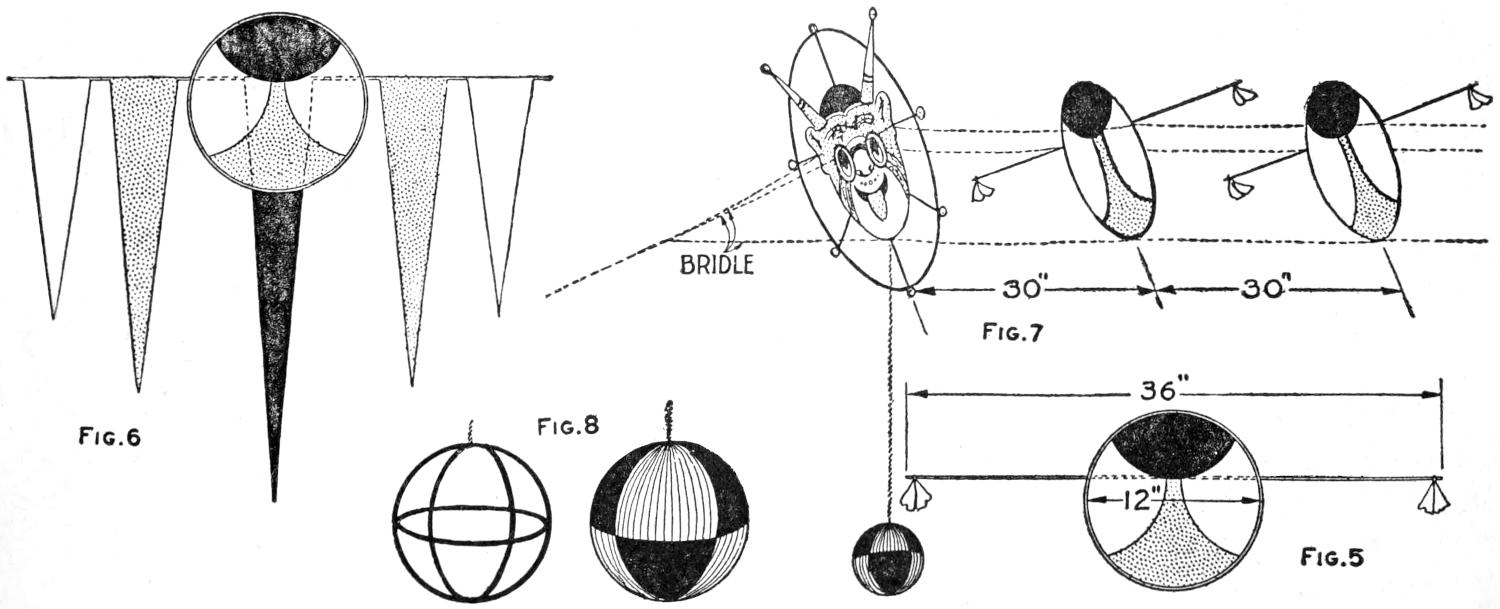

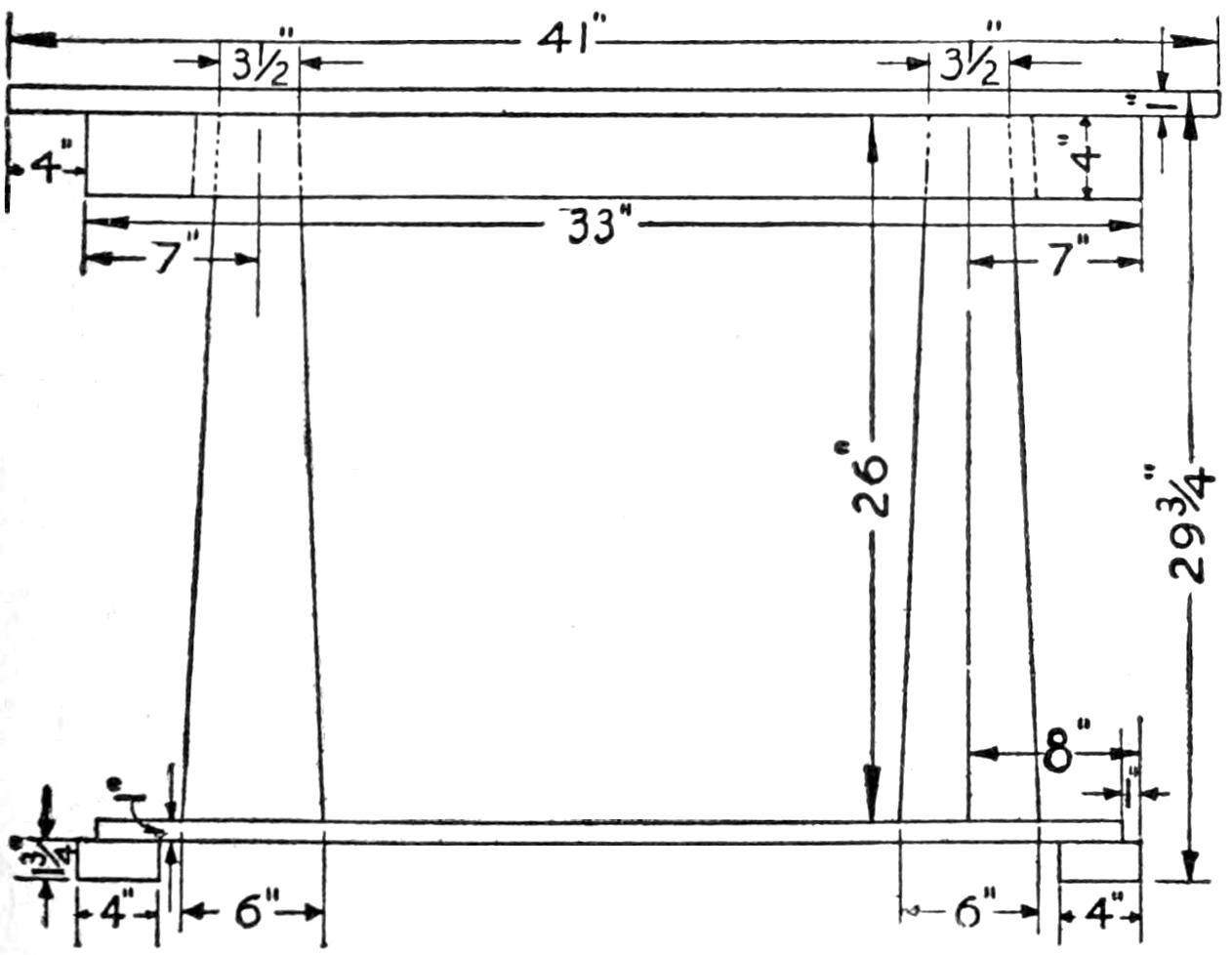

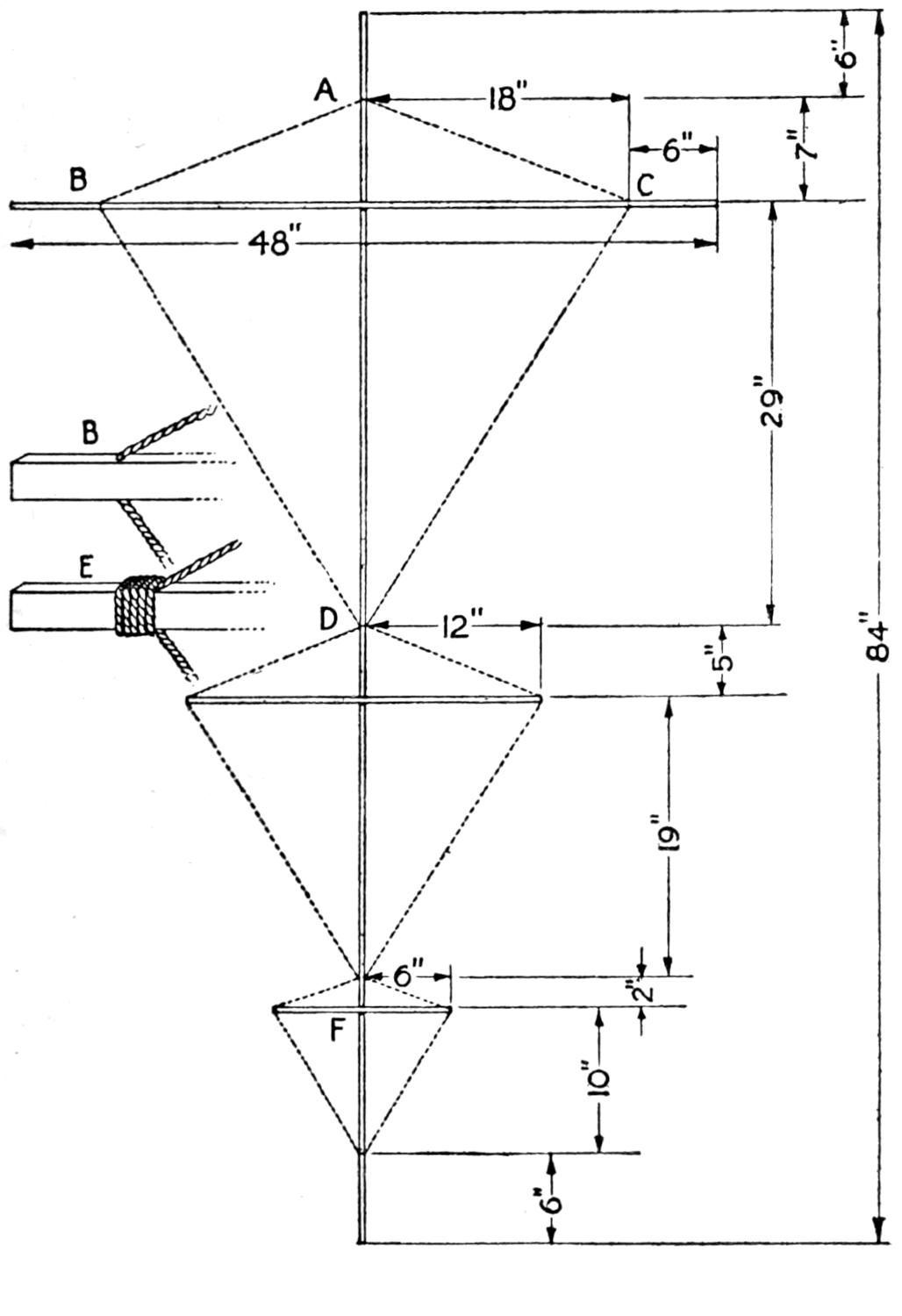

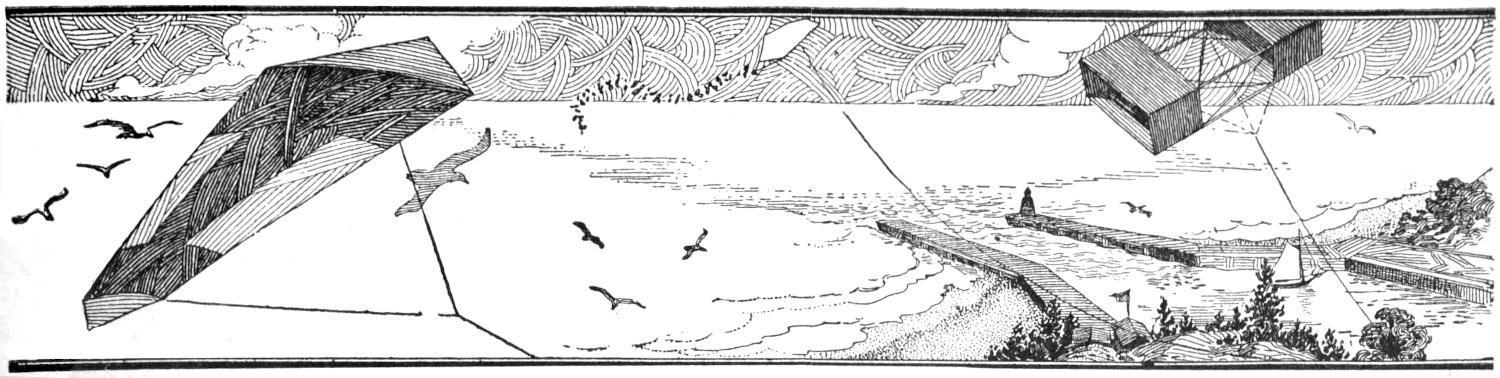

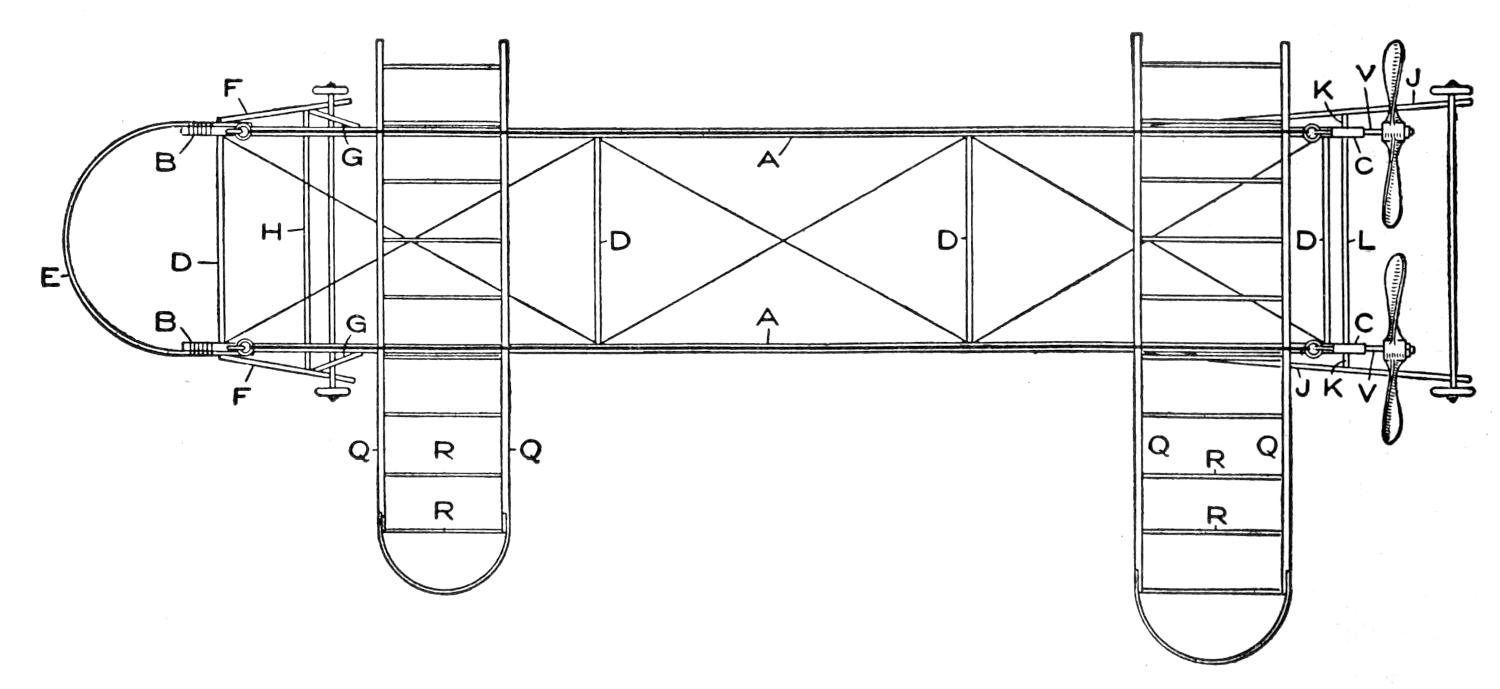

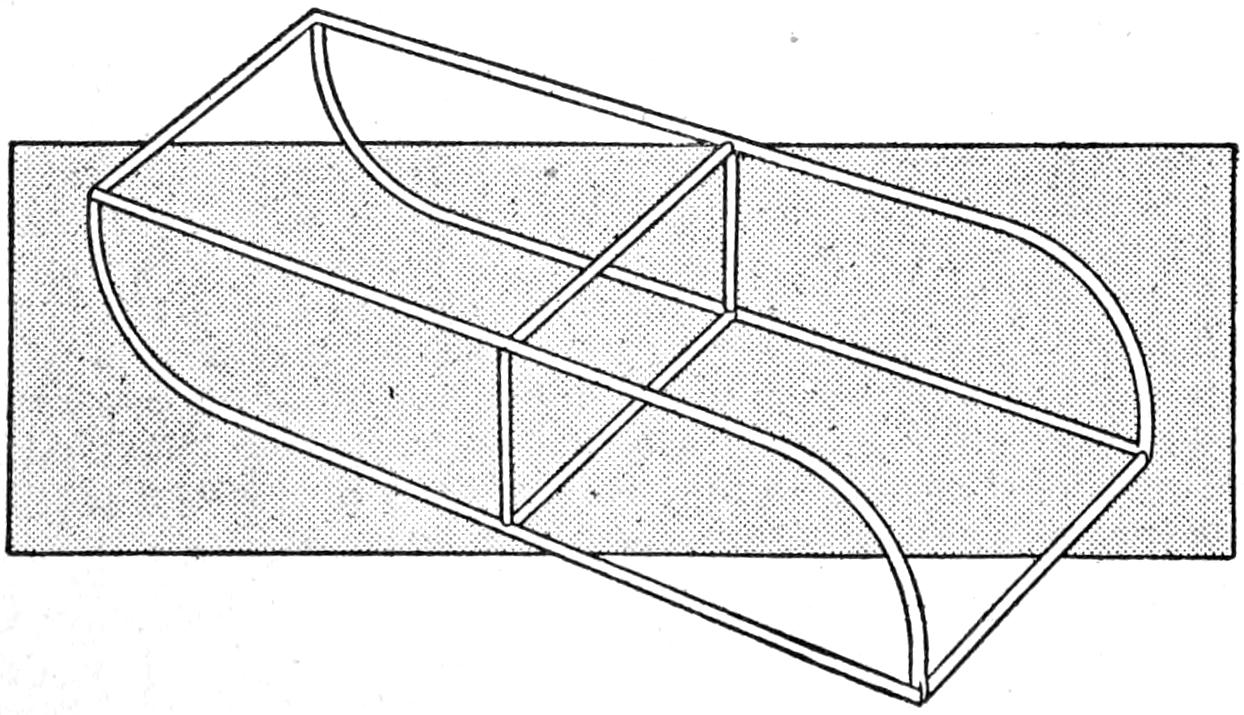

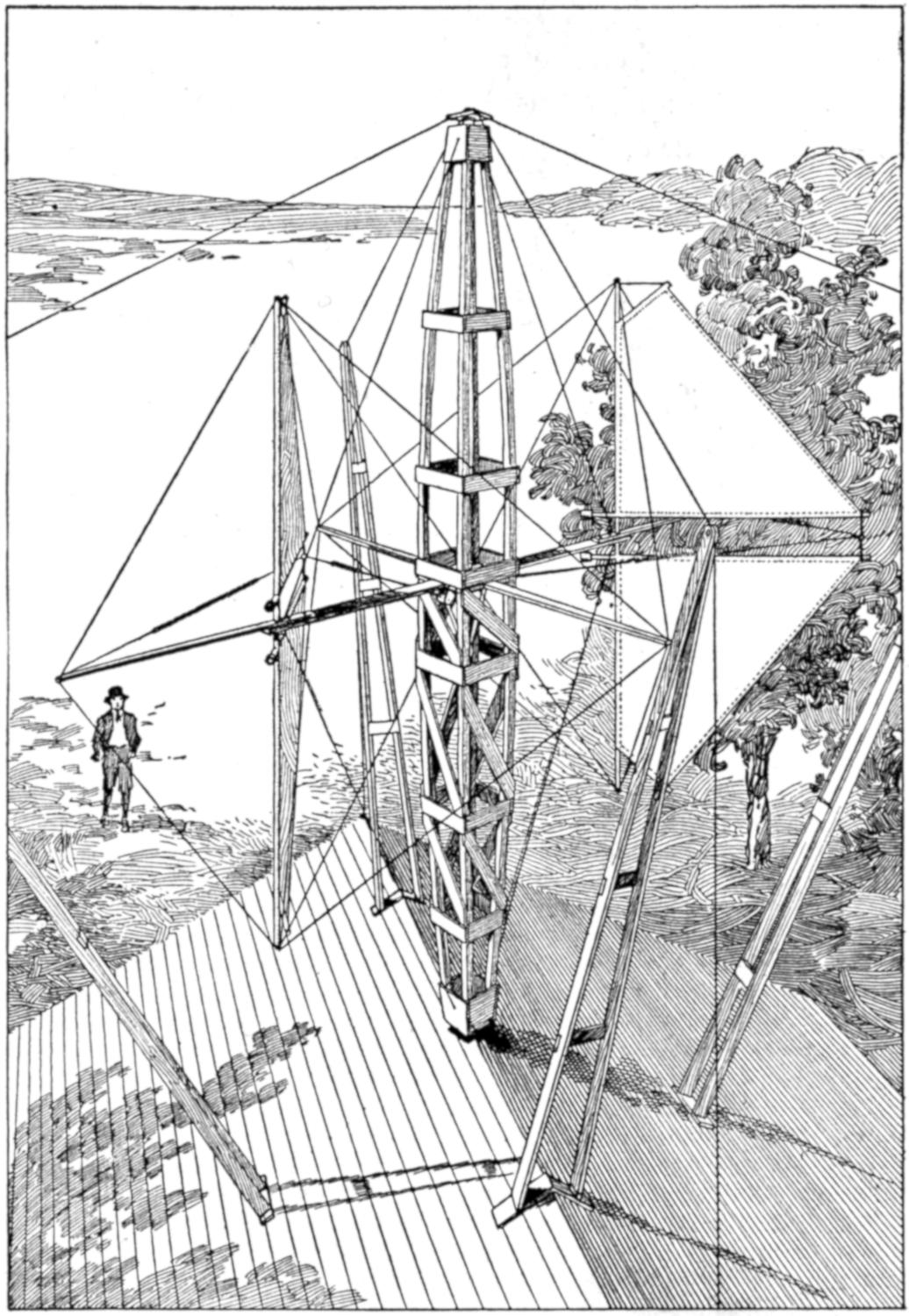

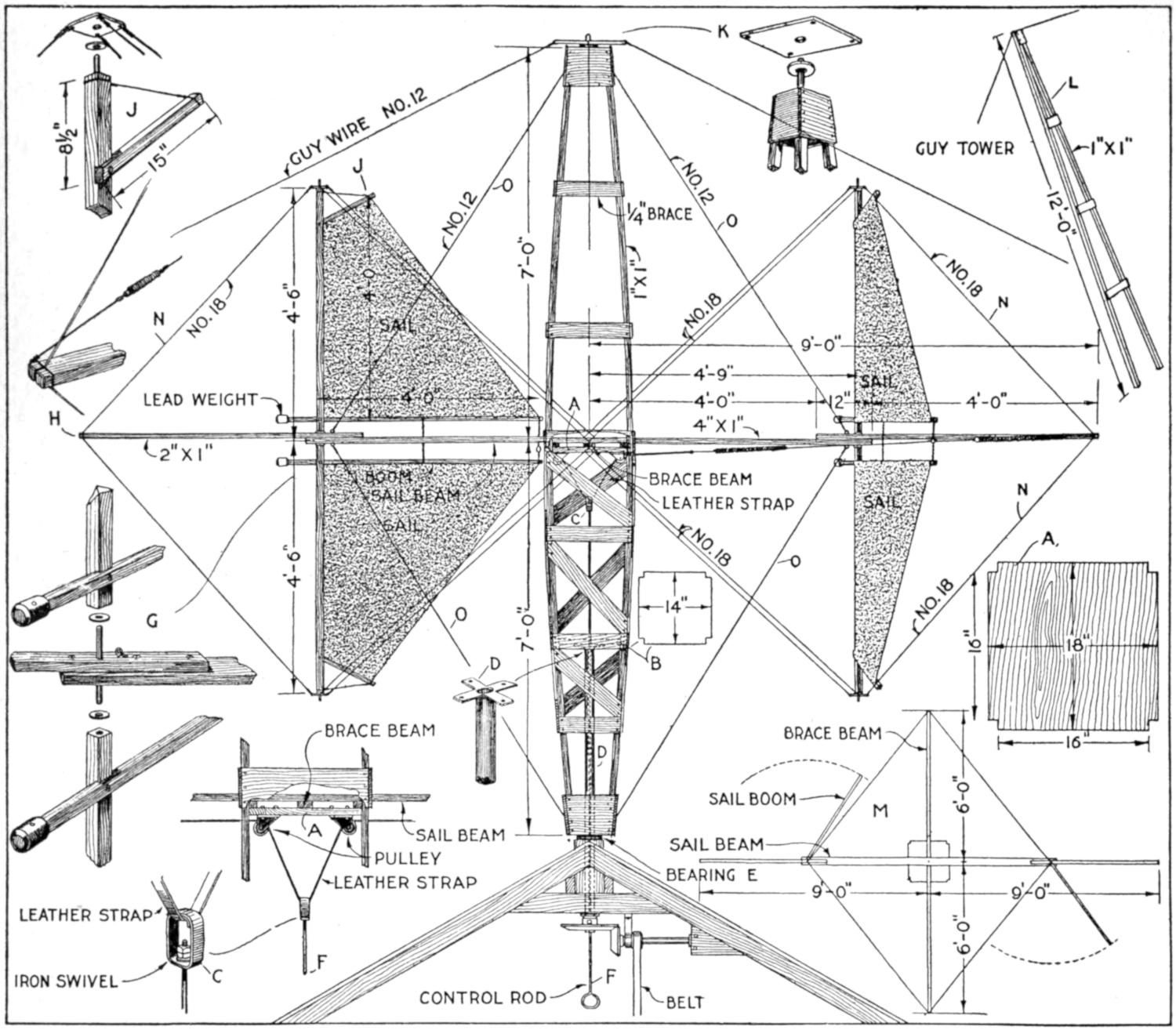

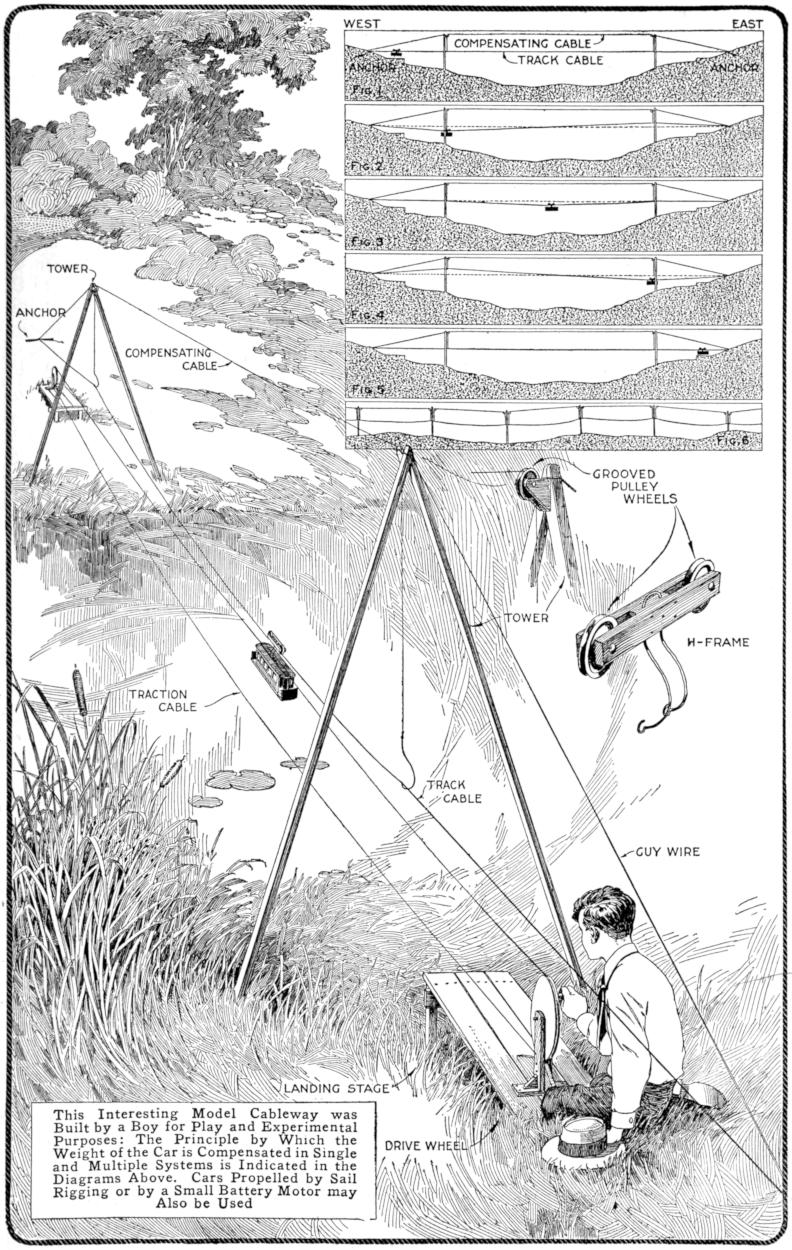

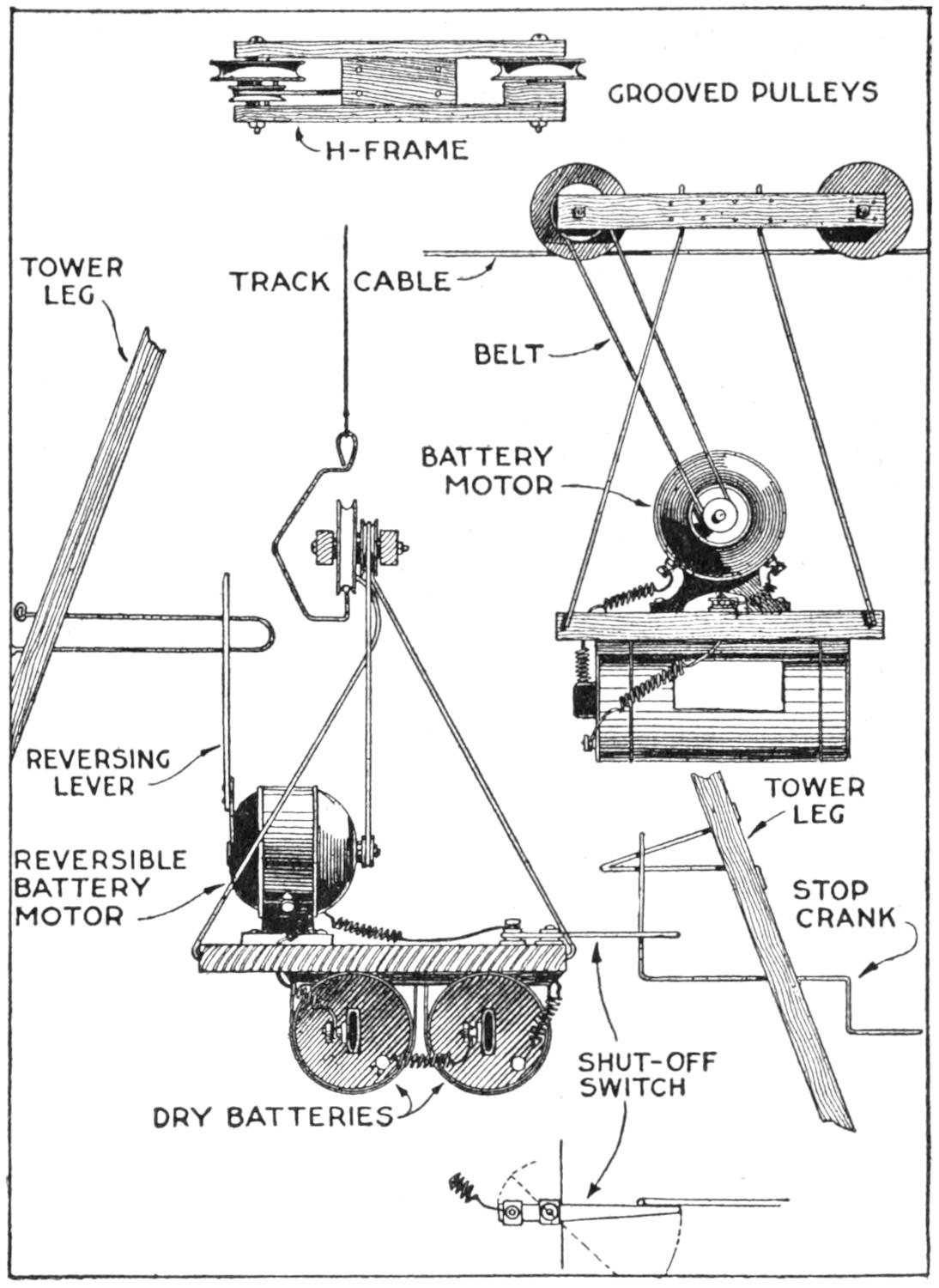

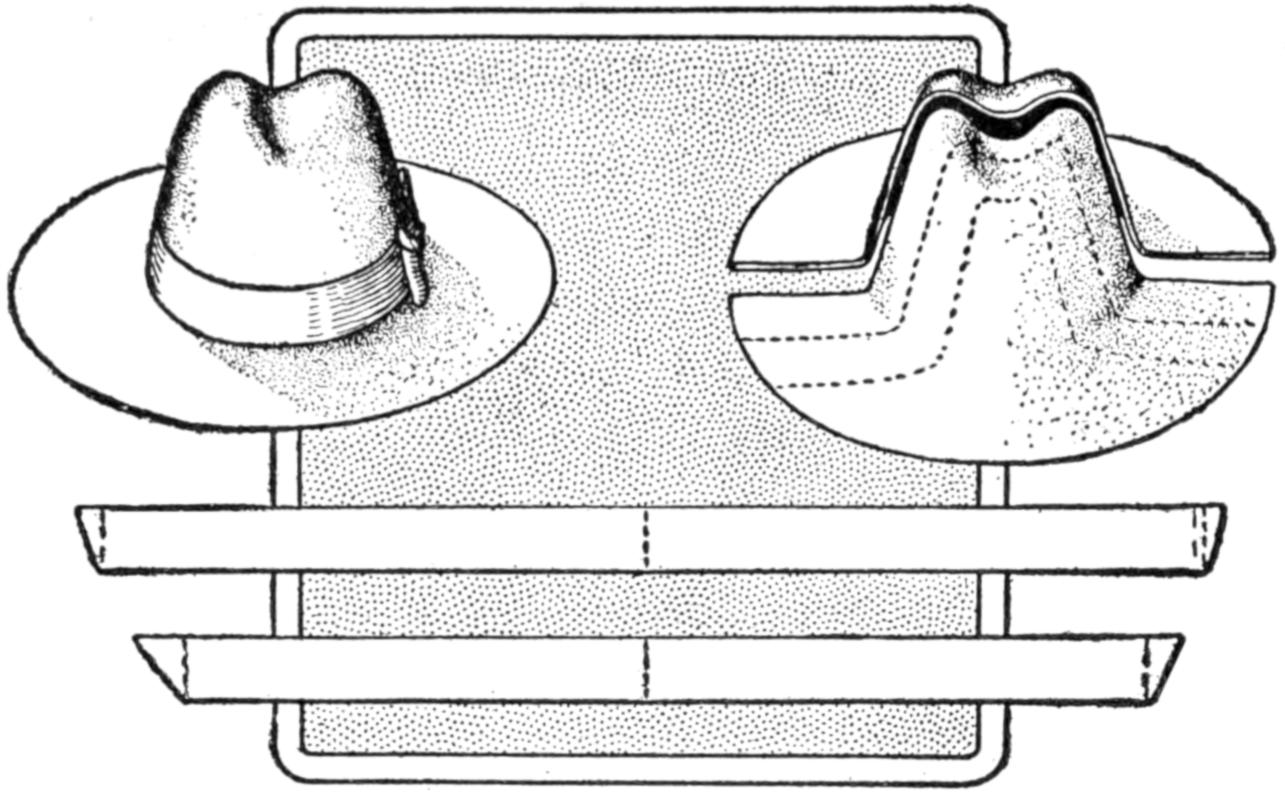

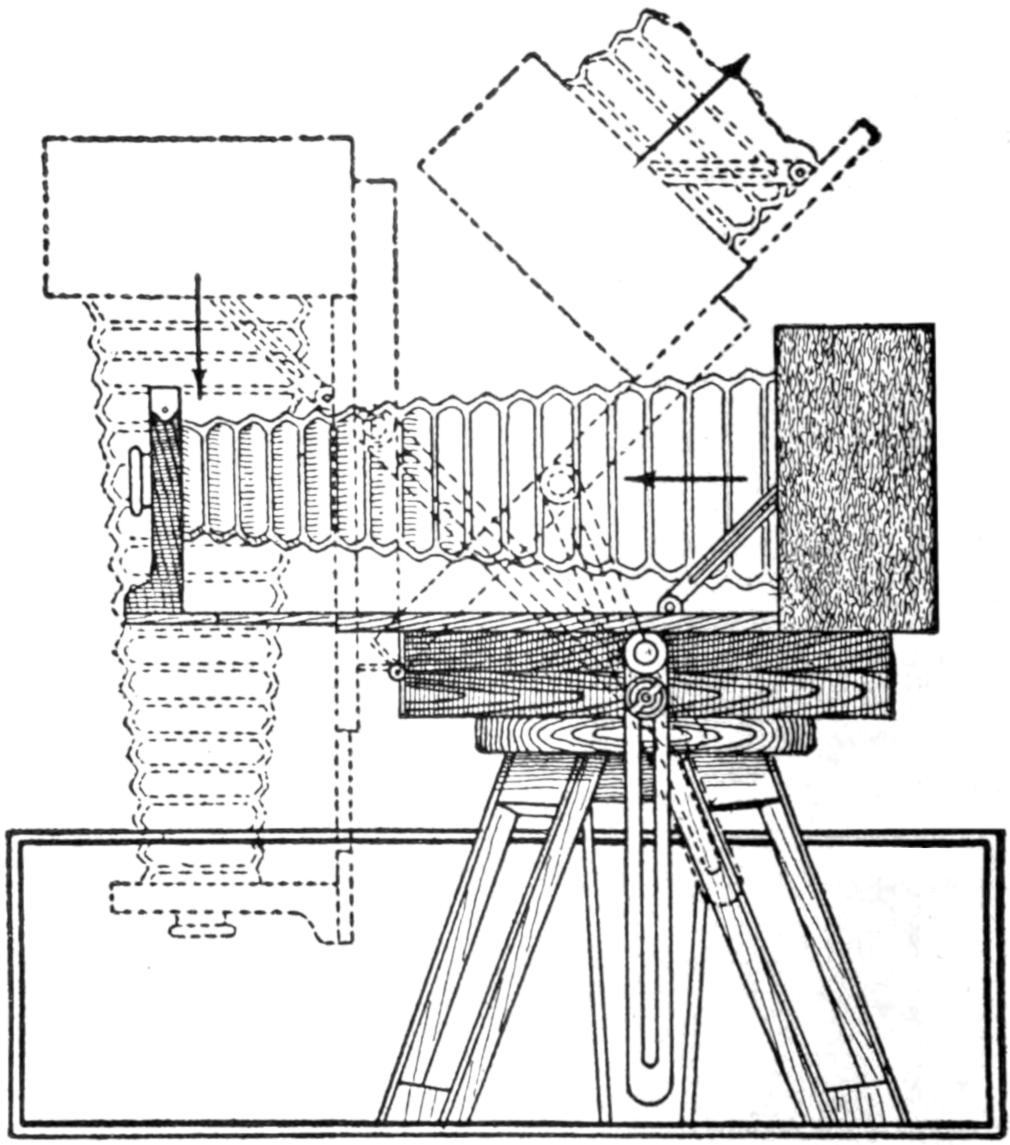

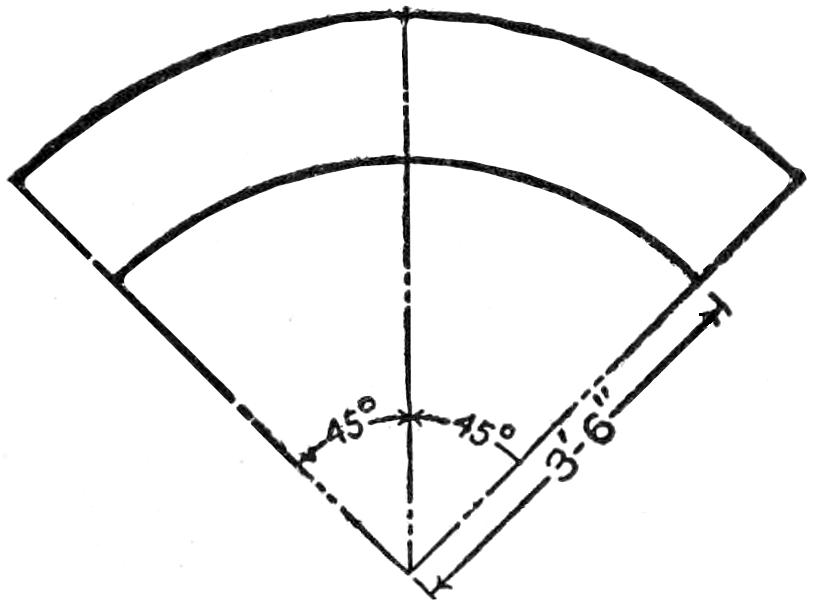

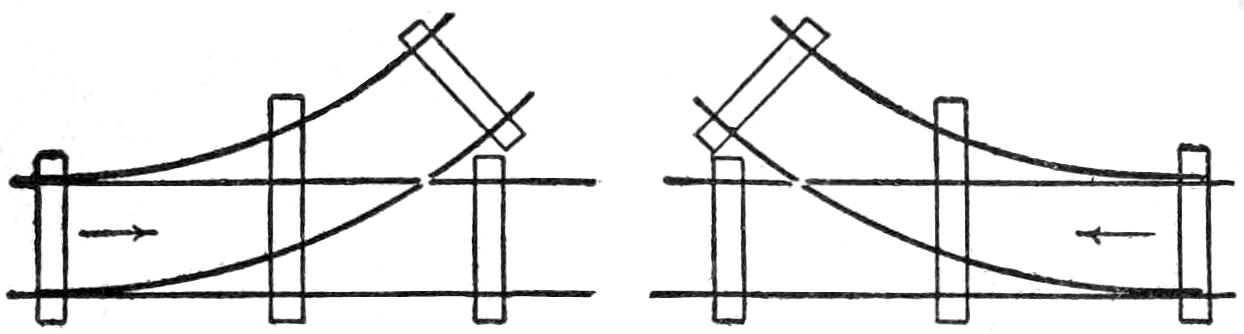

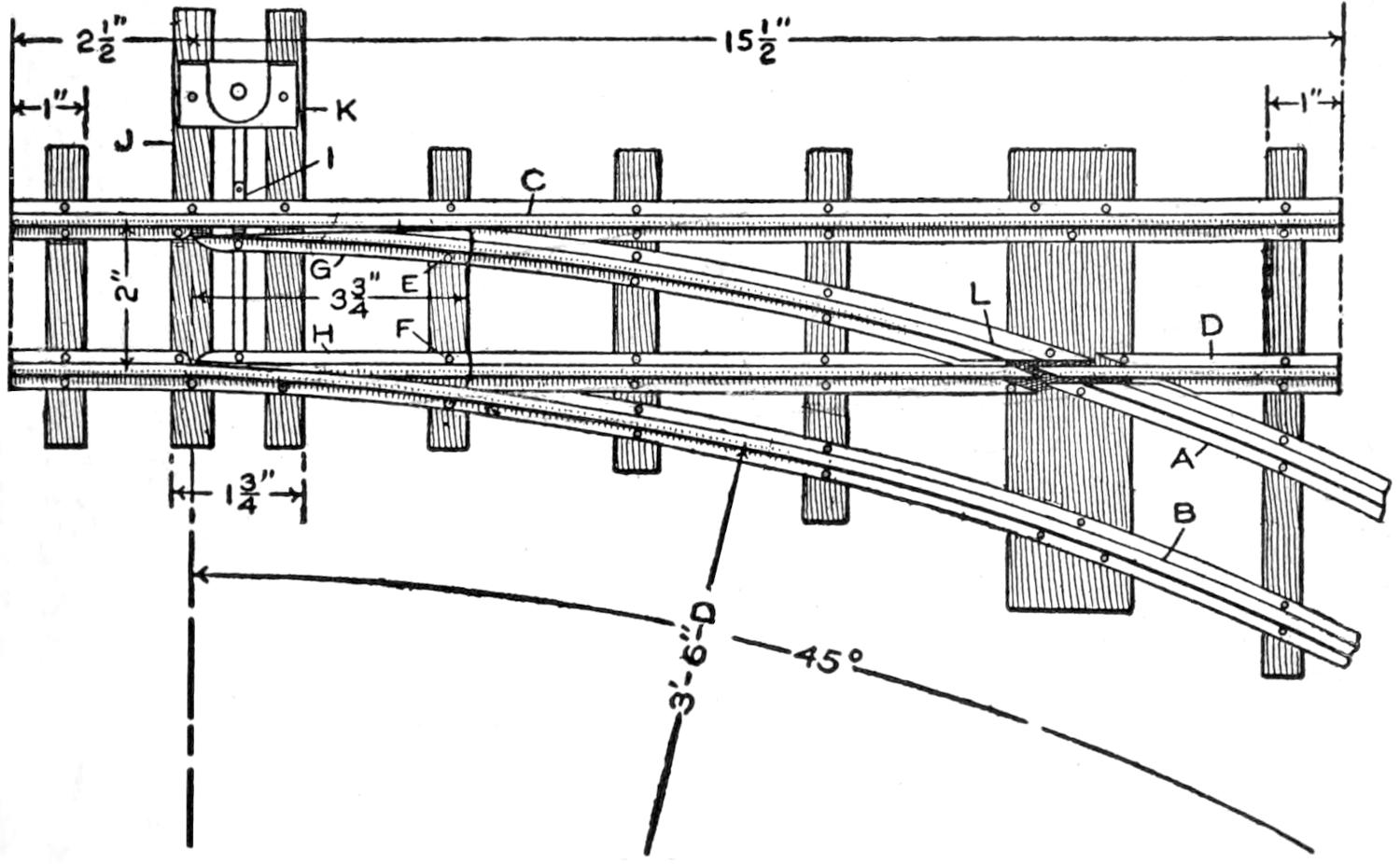

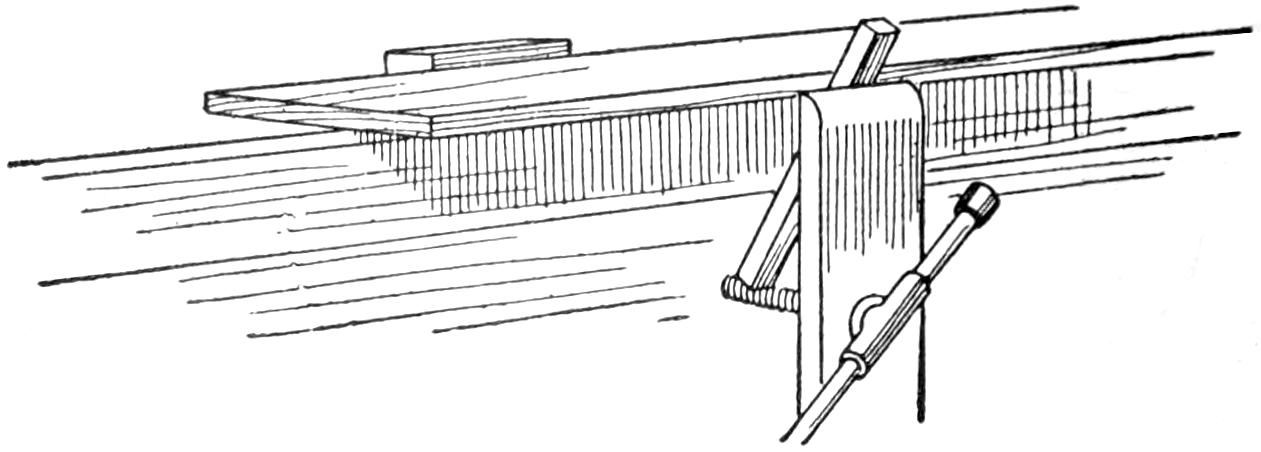

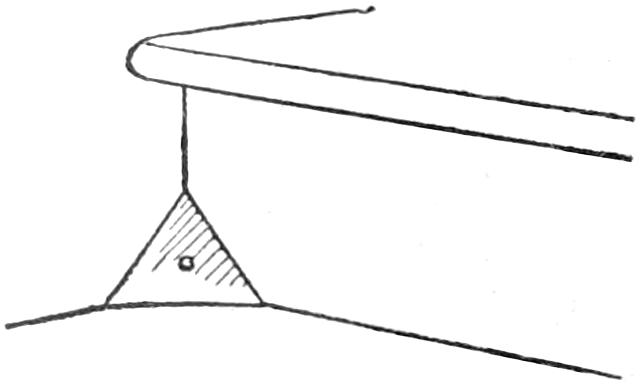

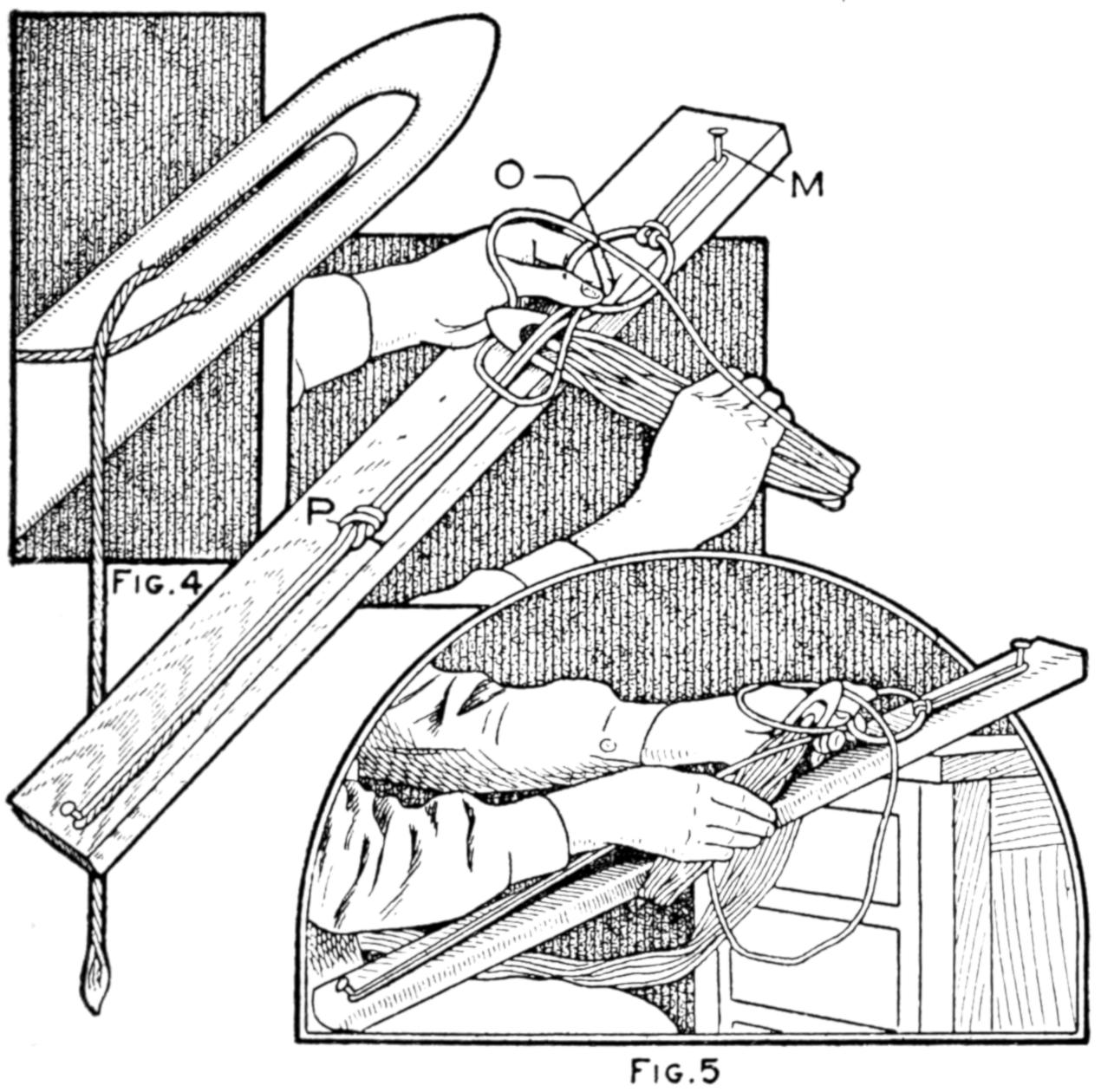

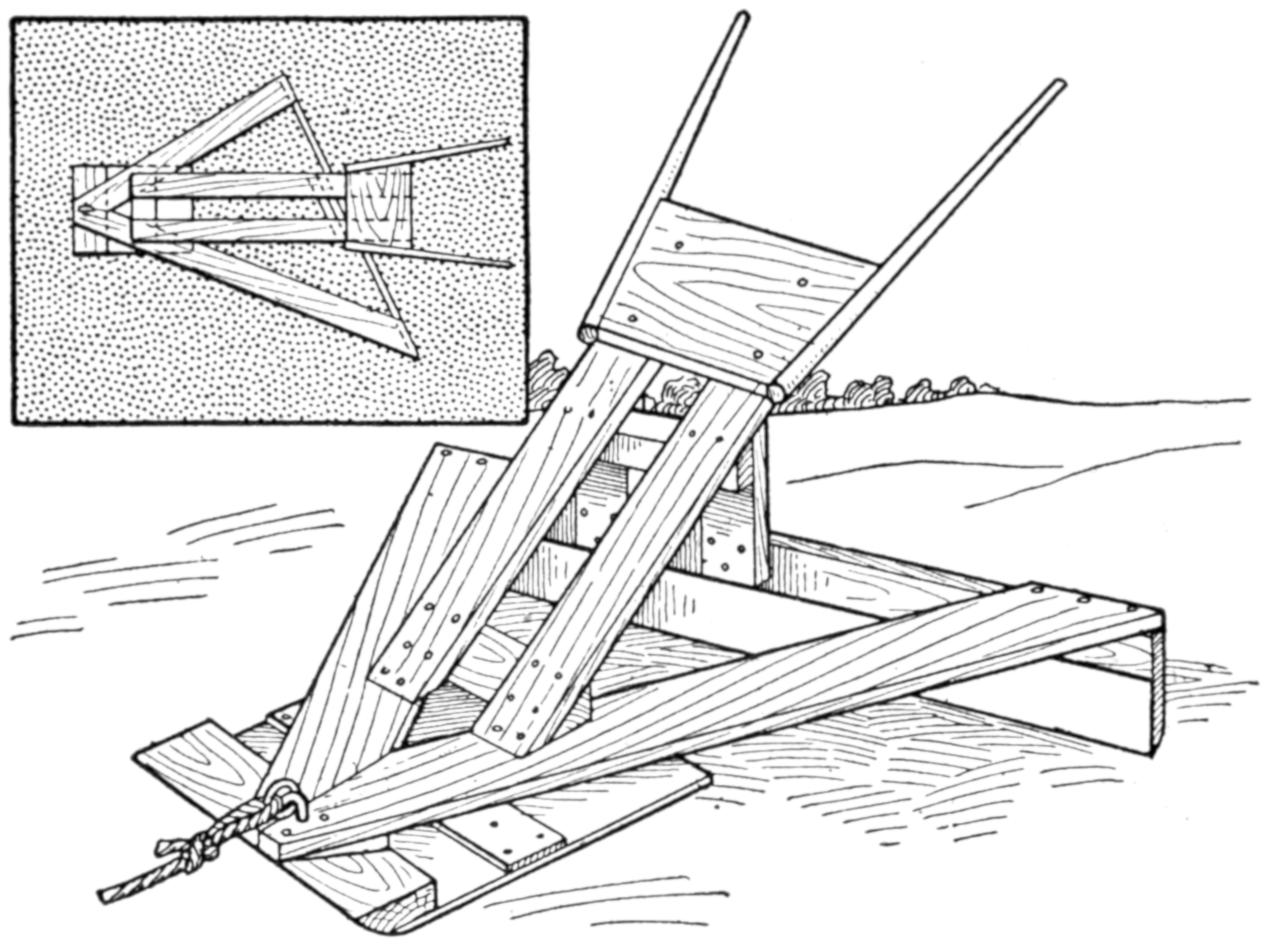

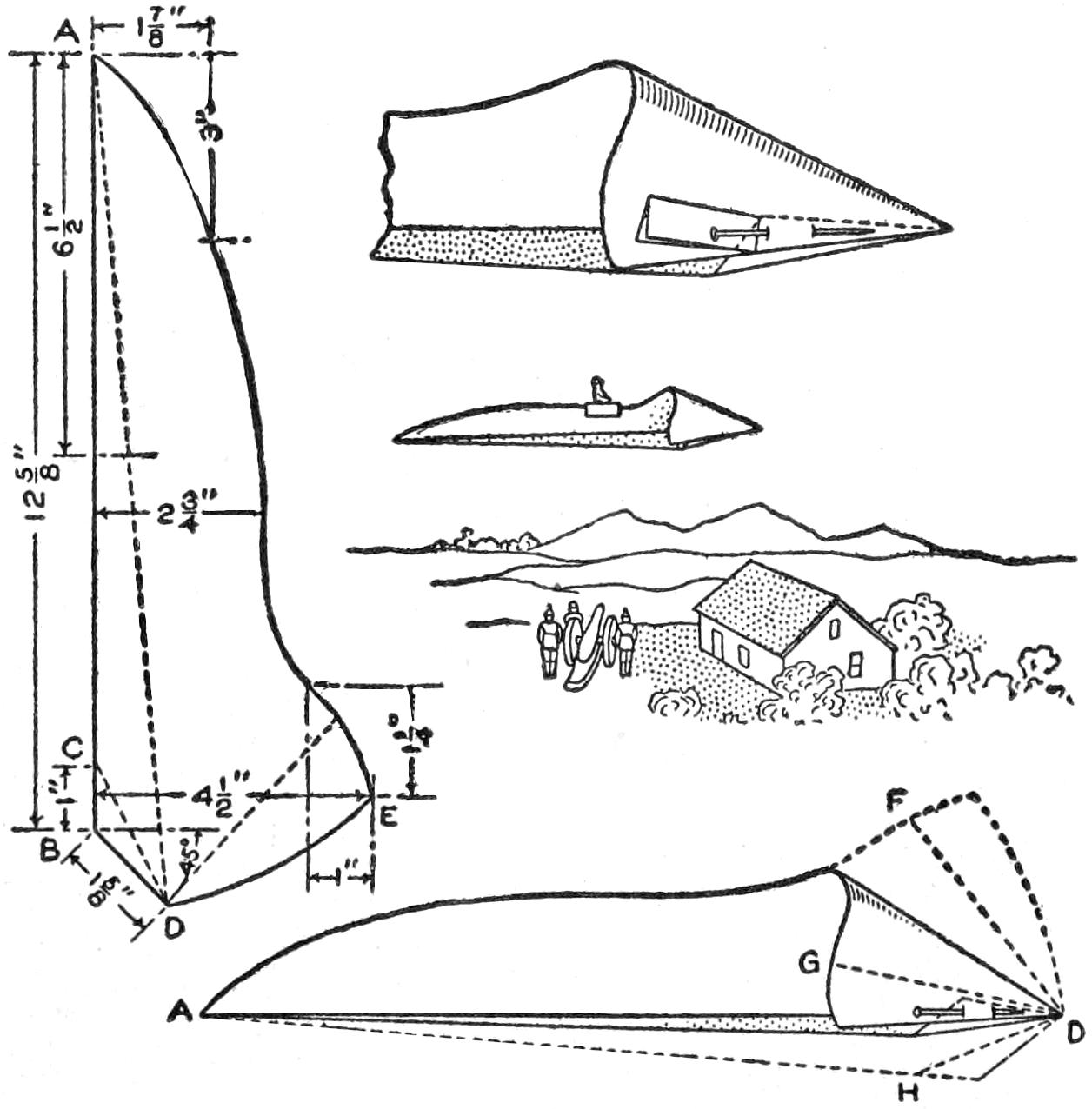

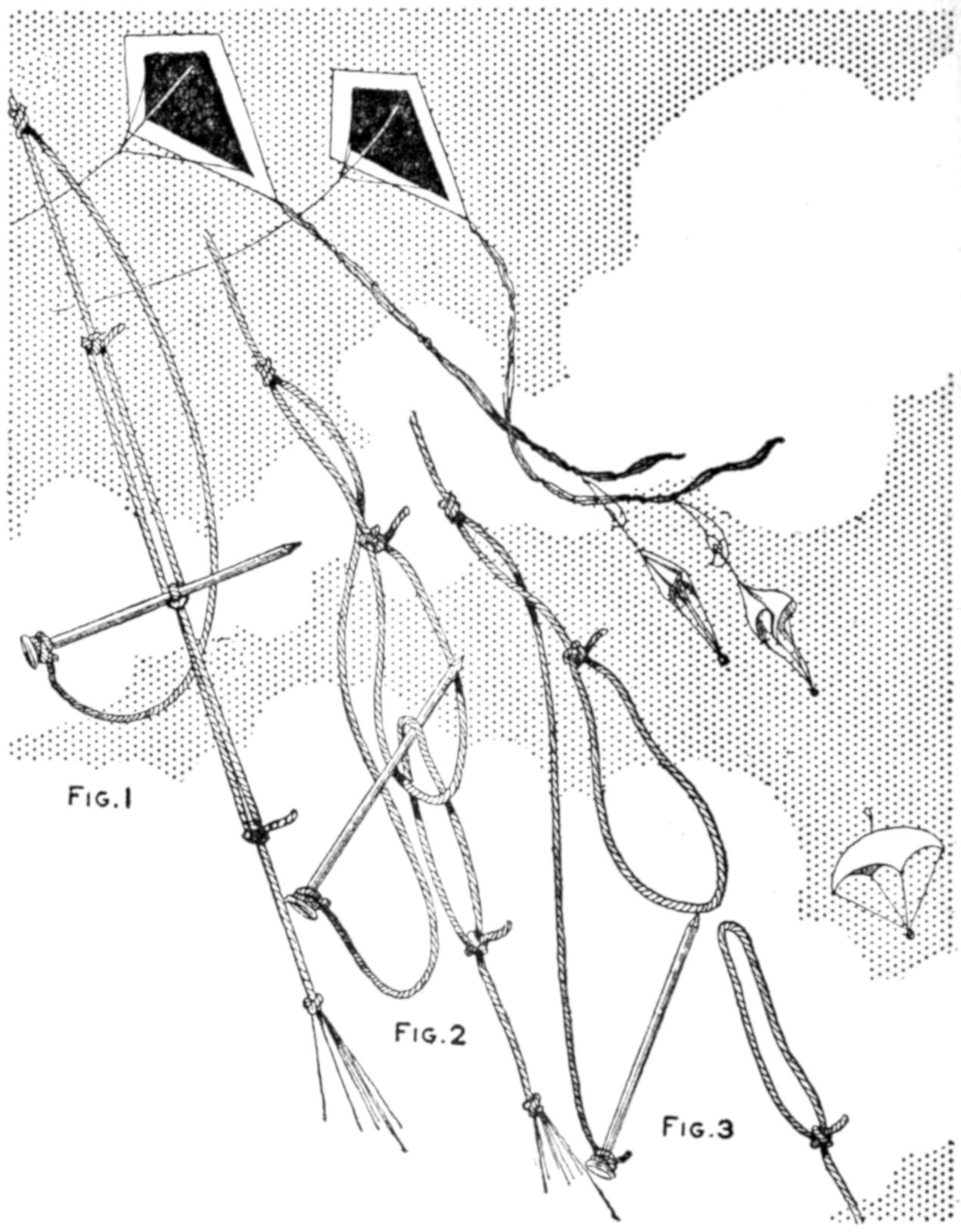

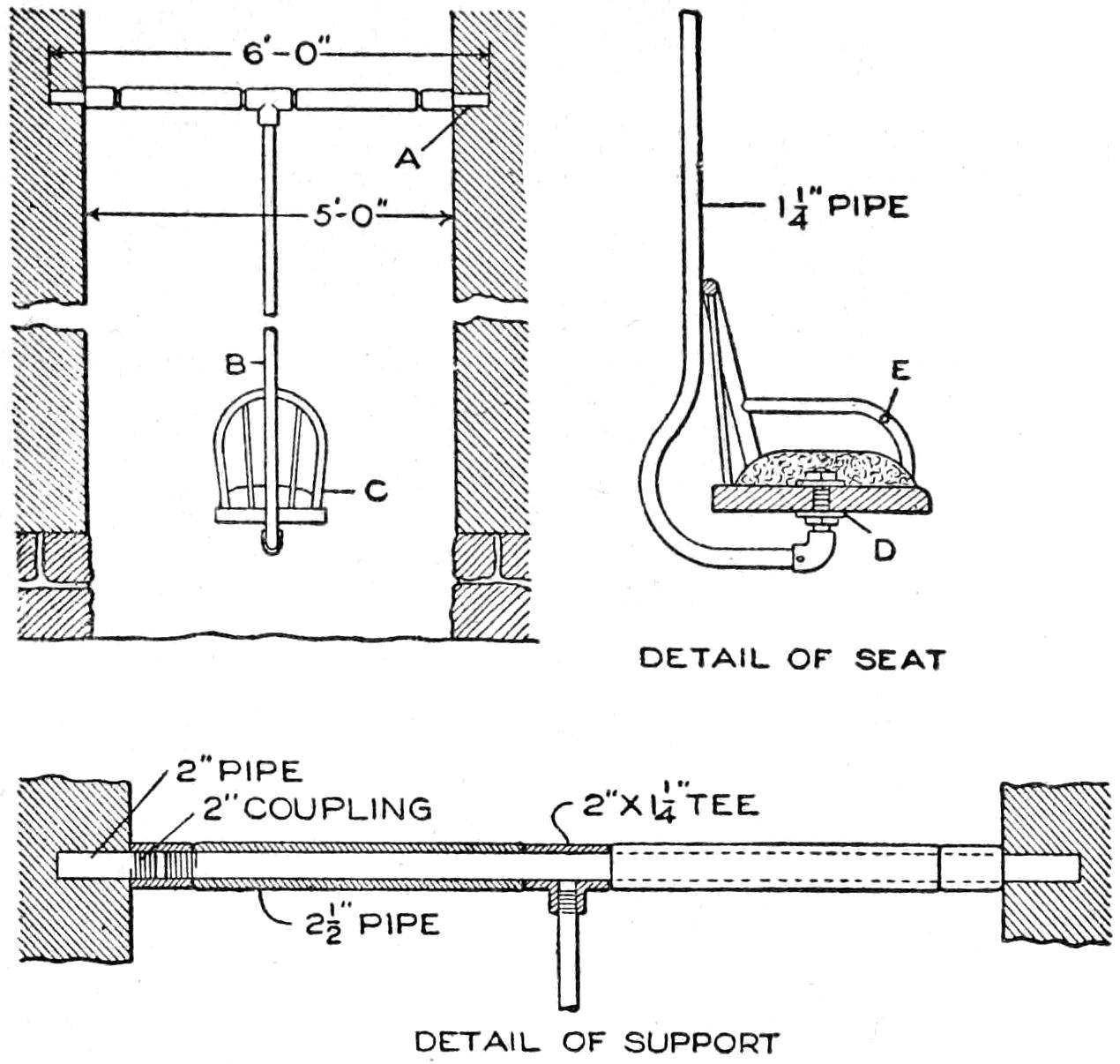

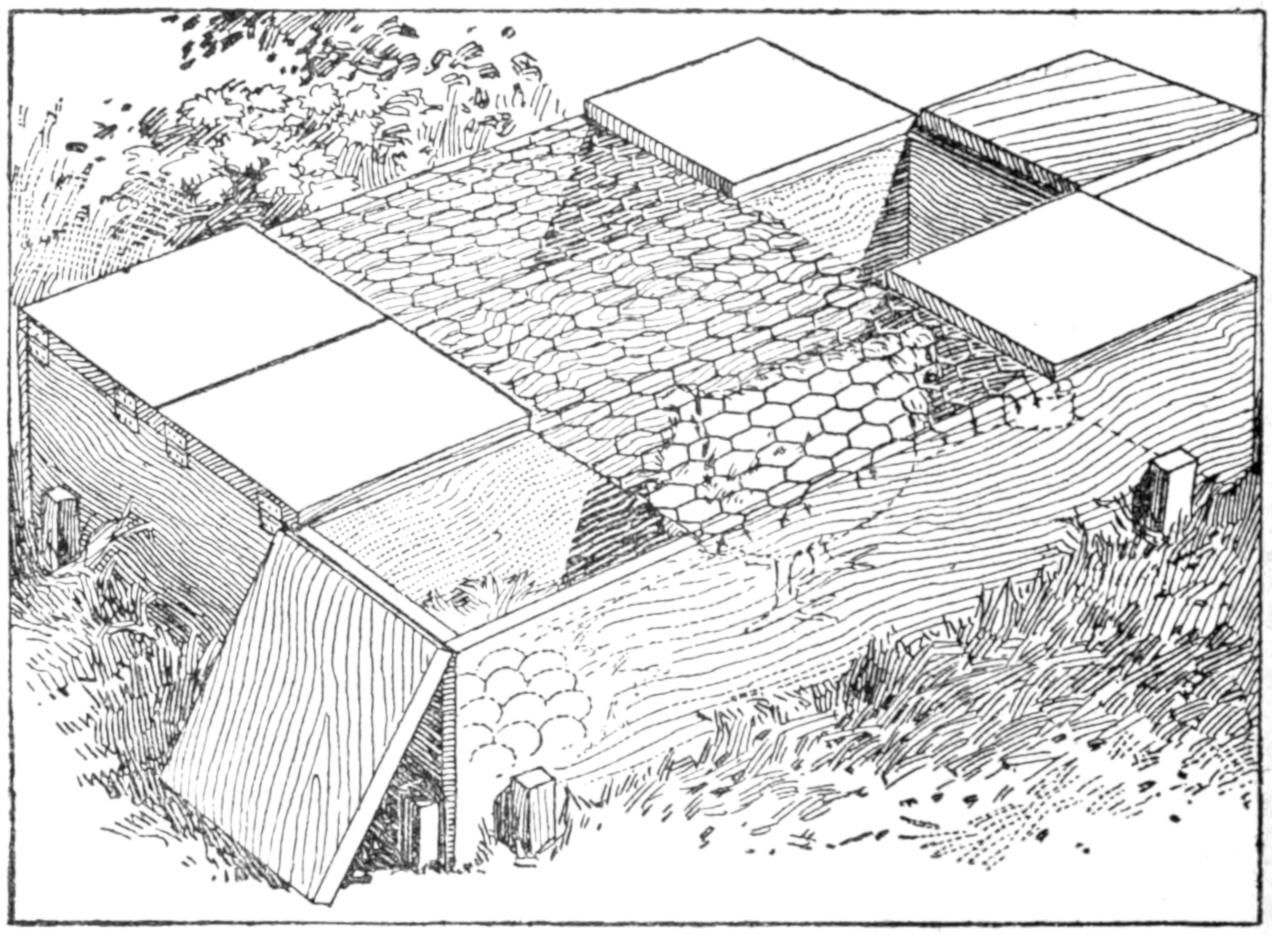

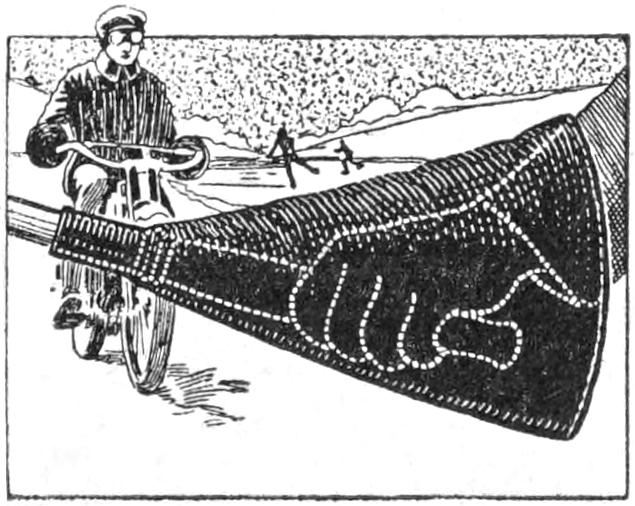

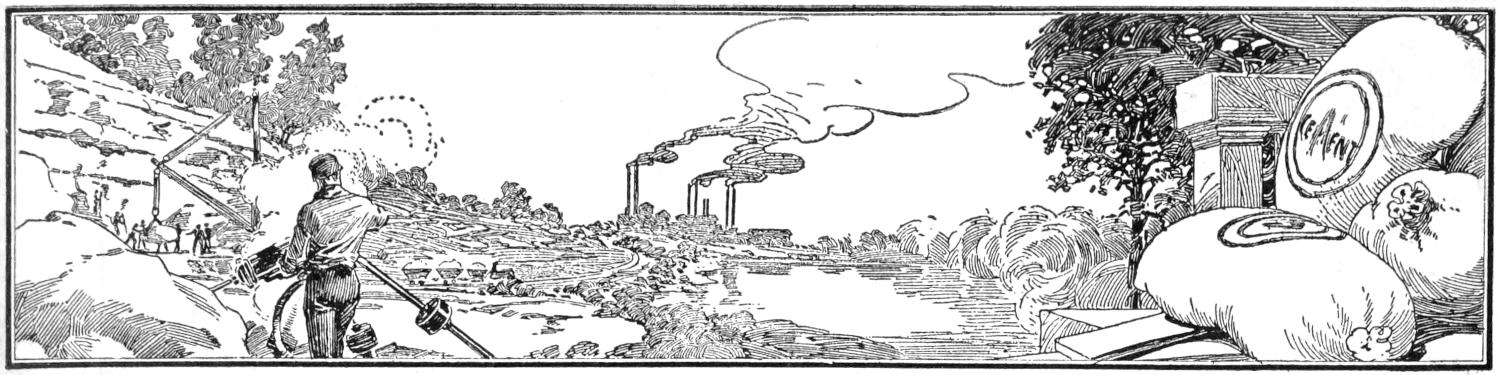

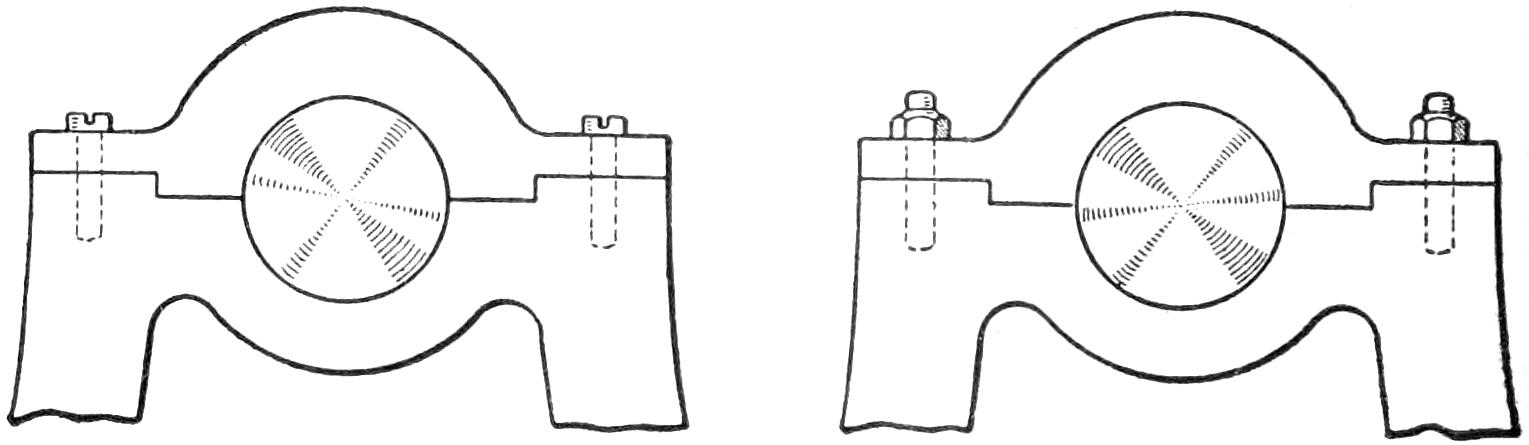

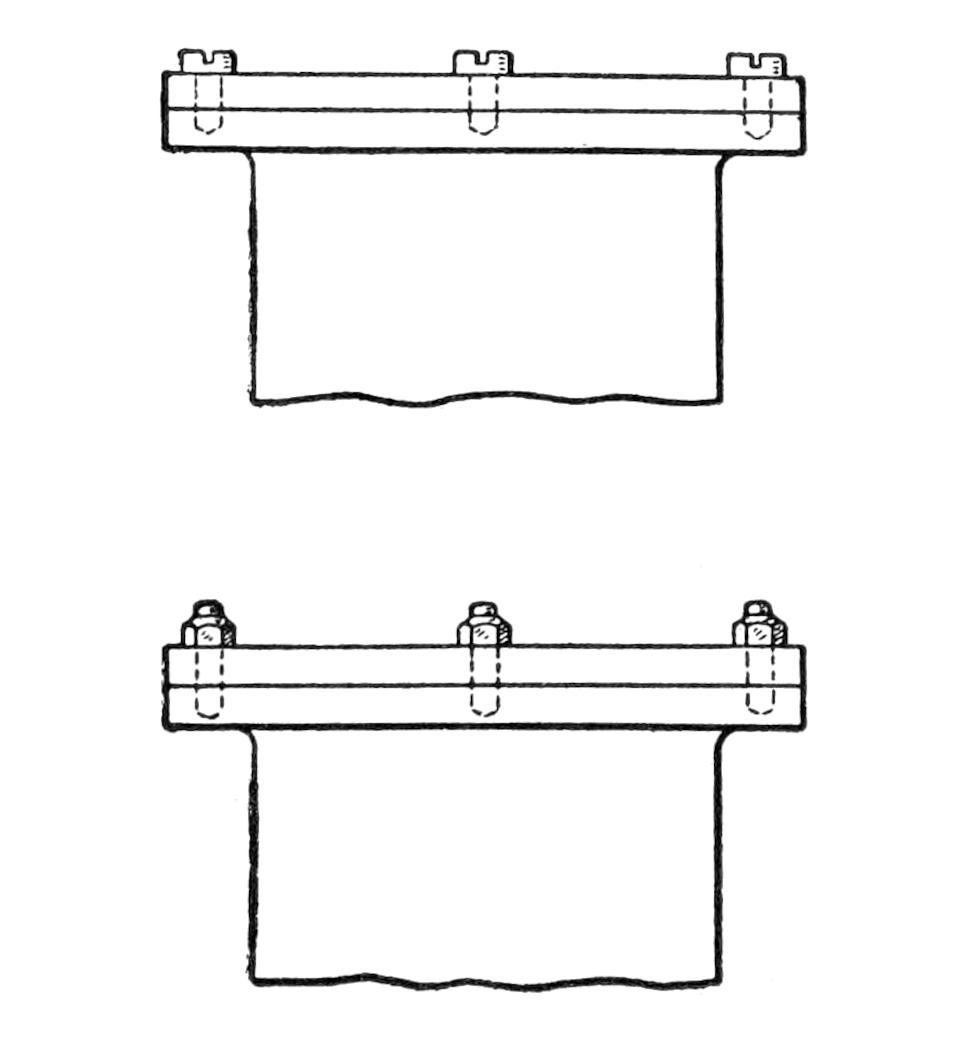

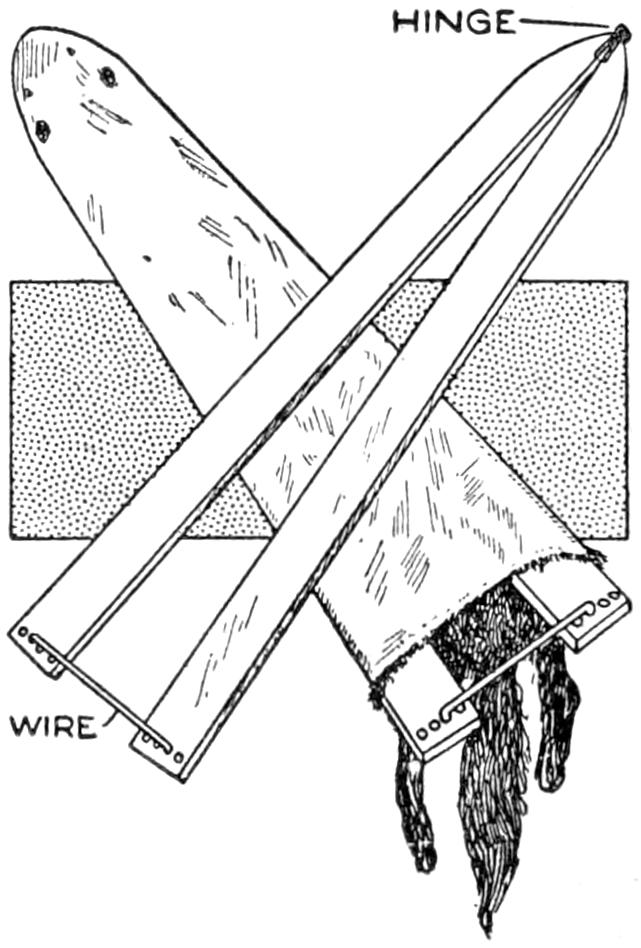

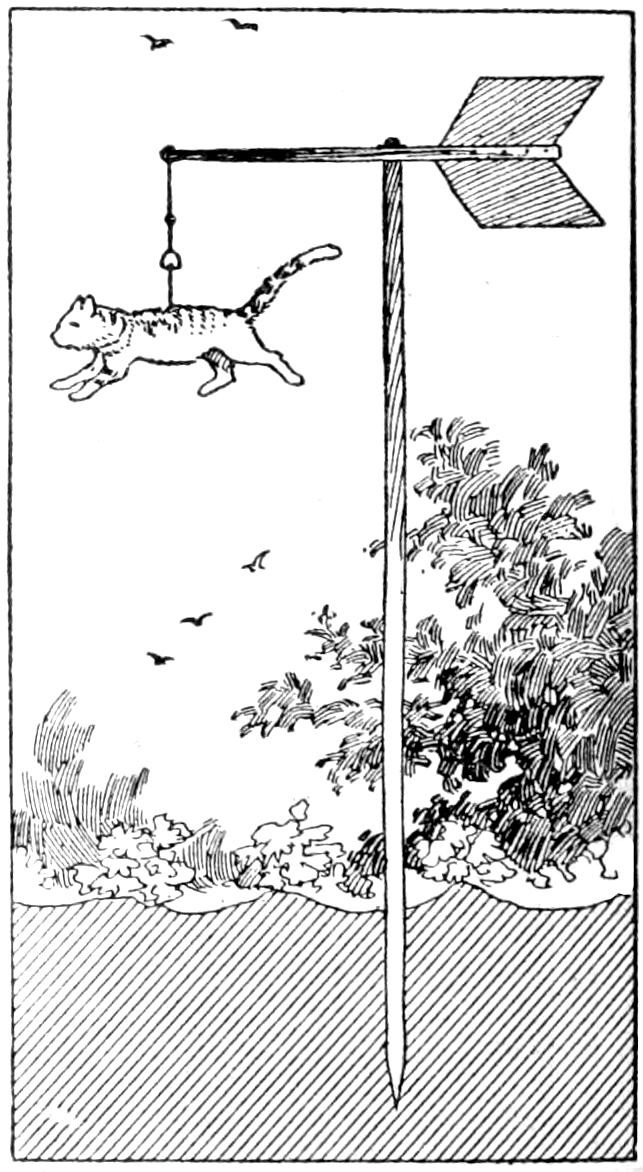

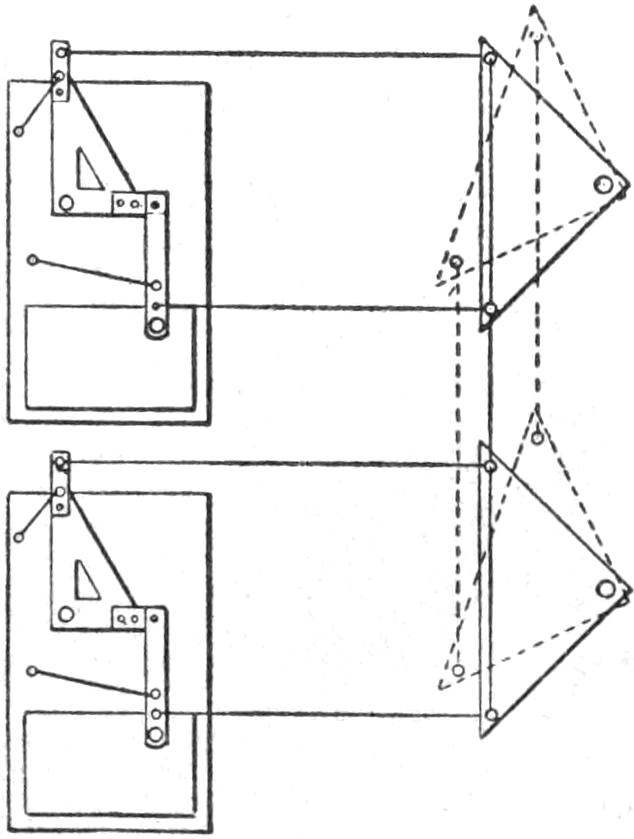

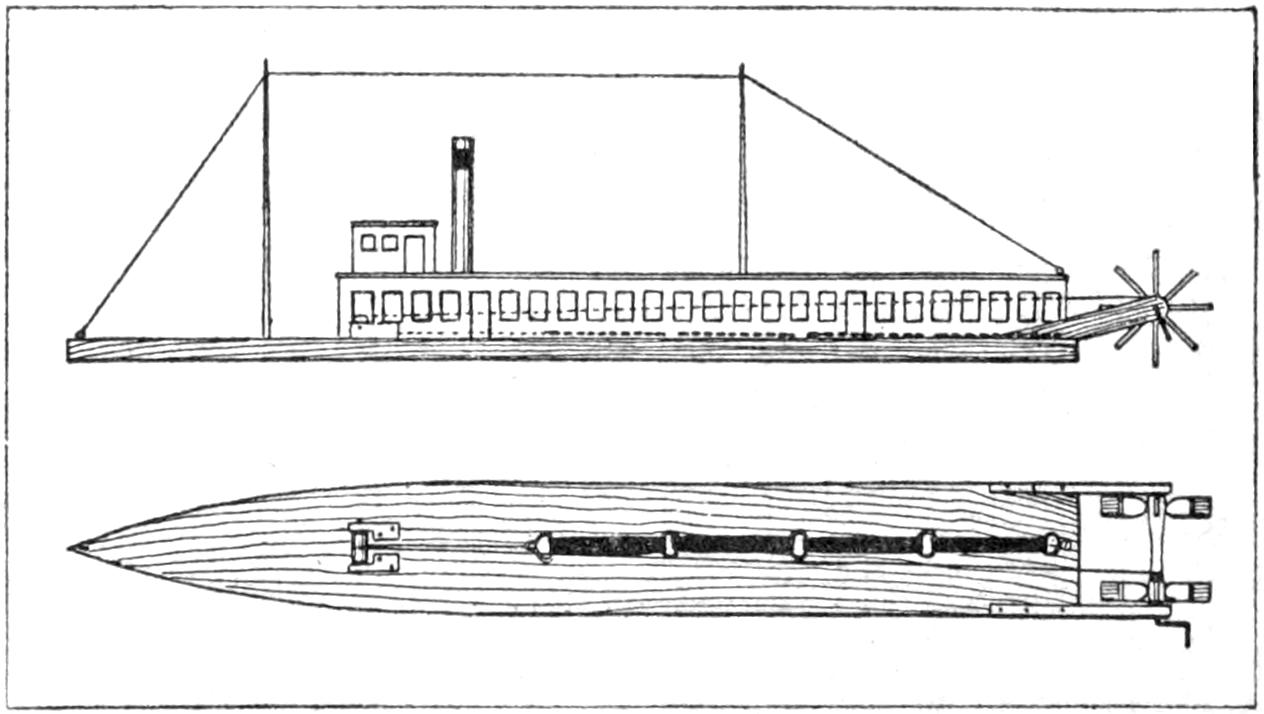

Large spread of canvas and great speed when running with the wind, or “free”; stability under heavy wind, and adaptability to sailing under conditions similar to those of the common, single-boom-and-sheet ice boat, are the features of the ice yacht shown in the illustration. The runner and frame structure is in general typical of ice-boat construction. The double, or wishbone, mast is distinctive, as is the double-boom and sail arrangement, shown in Figs. 1 and 6. The booms are pivoted at the bow of the craft, and controlled at the stern by the usual line and pulley rigging. The booms may be spread so that a V-shaped cavity is afforded for taking the wind when running free, or they may be brought together and both sails manipulated as a single sheet. Reefing and lowering of the sails are accomplished in the usual manner. The framework is very substantial and the proportions are of moderate range, so that the craft may be constructed economically for one or two passengers. The double-boom feature may be omitted if the craft is to be used where little or no opportunity is afforded for running before the wind, by reason of the particular ice areas available. For the experimenter with sailing craft, the wishbone-mast ice yacht affords opportunity for adaptation of the various elements of the craft described, and is a novelty. The dimensions given are for a small yacht, and care must be taken, in adapting the design, to maintain proper proportions for stability and safety. A side view with working dimensions is shown in Fig. 1; inset into it is Fig. 6, showing a front view of the mast and sail arrangement. Figure 2 shows a view of the framework from below. A detail of the fastening of the backbone and runner plank is shown in Fig. 3; a detail of the fastening of the masts and the forward runners into the runner plank, in Fig. 4, and the fixture by which the booms and the yard are attached to the forward end of the backbone, in Fig. 5.

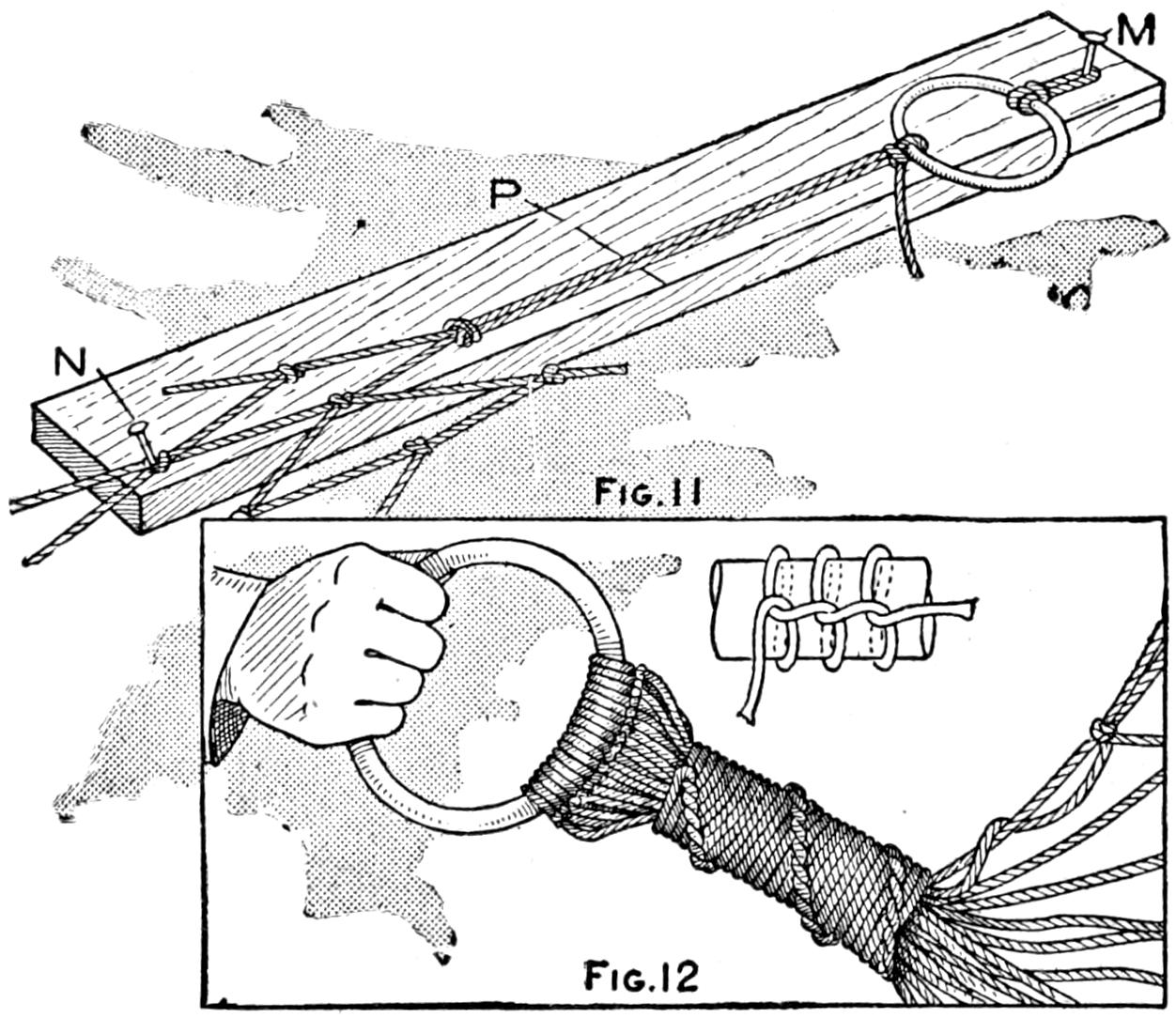

The construction should begin with the making of the lower framework, as shown in Fig. 2 viewed from the lower side. The main frame consists of a backbone, of spruce or white pine, 4 in. thick, 8 in. high at the center, and 16 ft. long, clamped accurately at right angles to a runner plank, of the same material, 2 in. thick, 10 in. wide, and 12 ft. 6 in. long. The backbone is tapered from the middle portion, 5 ft. 6 in. from the forward end, and with a ridge, 8 in. high and 2 ft. 6 in. long, measured from the end of the taper at this end, as shown in Fig. 1. It is tapered to 4 in. at each end, and the bow end is fitted with a three-eye metal ring, as shown in detail in Fig. 5. The runner plank and the backbone are clamped together firmly at their crossing, the backbone being set upon the plank, by means of two strap bolts, with washers and nuts, as shown in detail in Fig. 3. Only the best material should be used in the backbone and runner plank, and the stock should be straight-grained, to give the greatest strength.

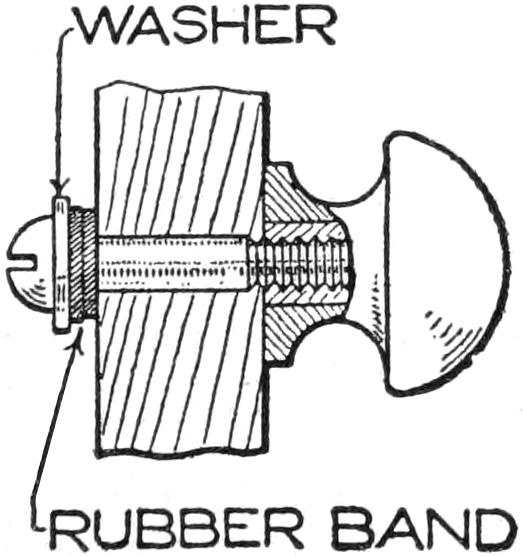

The runner plank is tapered down to 8 in. at its ends, to which the guides for the forward runners are fixed. The guides are of straight-grained oak, 1¹⁄₂ by 3 by 14 in., bolted to the runner plank with ⁵⁄₁₆-in. carriage bolts, as[18] shown in the detail sketch, Fig. 4, and in Fig. 2. The guides and the ends of the plank are reinforced with oak chocks, bolted in place at each of the tapered edges of the plank. The forward runners are of oak, 1¹⁄₂ by 5 by 36 in., shaped at their ends as shown, and shod with half-round strap iron. The heads of the screws used for this purpose are countersunk carefully. The runners are pivoted on ⁵⁄₈-in. bolts, the nuts being set to the inner side. Washers and jam nuts should be provided, or the ends of the bolts riveted slightly, to prevent the nuts from becoming loosened.

The stern runner is of oak, 1¹⁄₂ by 5 by 30 in., shod like the forward runners, and is pivoted in a forged wrought-iron hanger. The lower portion of the hanger may be made of a strip of heavy iron, bent into a U-shape, and drilled to receive a ³⁄₈-in. bolt, on which the runner pivots. The U-shaped piece is riveted firmly to a vertical shaft, provided with a heavy rubber washer, protected from wear by a metal one, as indicated at the right in Fig. 1. The upper end of the shaft is threaded to receive a washer and nut. A section of pipe is fitted over the shaft, and the steering handle, fitted to a square section of the shaft, is clamped securely.

The cockpit is fixed to the lower side of the backbone, and is 5 ft. long and 3 ft. wide, with coaming, 4 in. high. It is shown with square corners, since this construction is convenient, though not as good as the type having the ends of the cockpit rounded, and fitted with coaming steamed and bent to the curve. The floor of the cockpit is fastened to the backbone with lag screws, and the coaming is also fastened securely; this construction, if carefully made, will afford ample strength. If desired, especially in larger craft, ribs may be fixed to the backbone, to carry the cockpit.

The runners, the runner plank, and the backbone must be alined carefully, so that they are at right angles, and track properly; otherwise the craft will not keep a true course, and cannot be controlled properly by the rudder runner. The backbone and runner plank are held rigidly by four ¹⁄₄-in. wire-rope stays, shown in Fig. 2. They are fixed to eyes on the bands at the bow, near the ends of the runner plank, and to an eyebolt below the cockpit. The stays are provided with turnbuckles, so that they may be adjusted as required. The bands near the ends of the runner plank are fixed to the lower ends of the masts, as shown in detail in Fig. 4, and are reinforced with oak blocks. The ends of the guy wires are fastened to the eyes by looping them and clamping the resulting eye with steel clamps made for this purpose. Metal thimbles may be fitted into the loop of the rope, to make a better finish; other fastenings may easily be devised by one skilled enough to make such a construction.

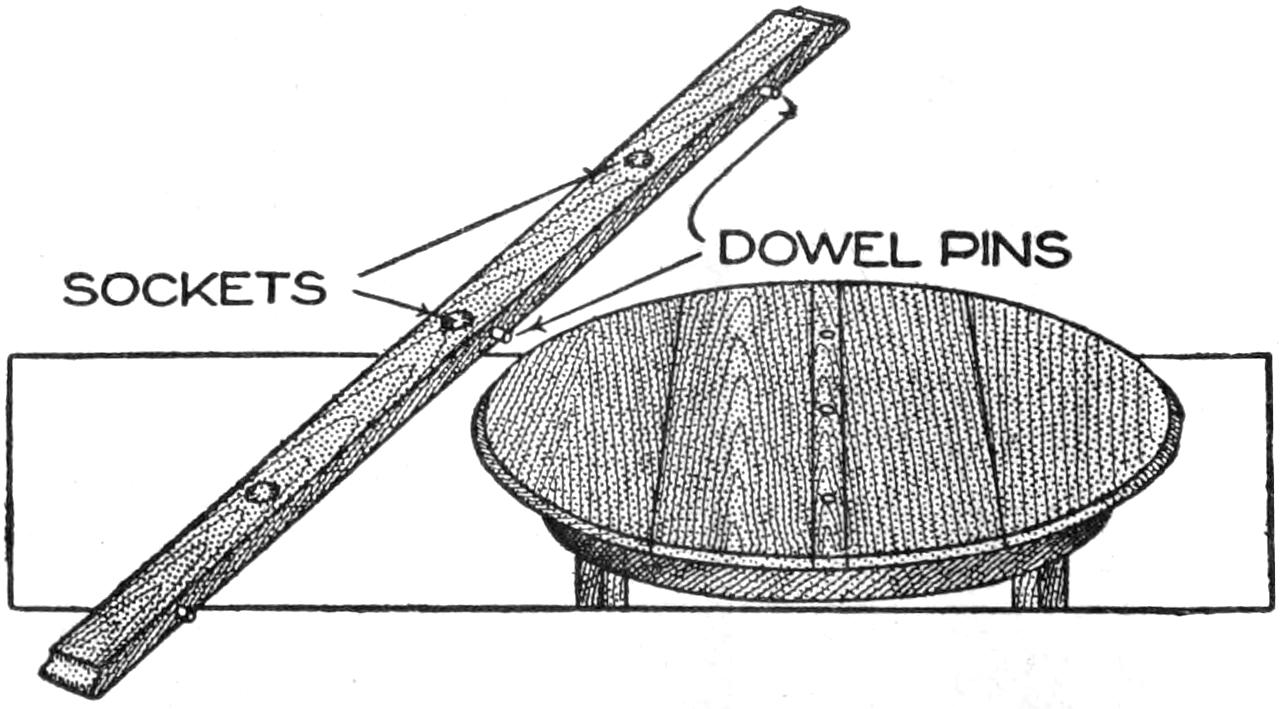

The wishbone mast is made of two poles of hickory or ash, 3¹⁄₂ in. thick at the base, and tapered to 2 in. at the top. The poles are joined carefully at the masthead, bolted together, and fitted to an oak breast hook, as shown in Fig. 6. An iron strap reinforces the joint, and an eye, fashioned at its upper end, affords a point of attachment for the forward stay of the mast. The lower ends of the poles forming the mast are fitted into sockets in the runner plank, which is reinforced with mast blocks, as shown in Fig. 4. The ends of the mast, projecting beyond the lower side of the runner plank, are fitted with eye bands, used in guying the runner plank and backbone.

The sails are carried on a yard and two booms, of the same material as the masts, each 16 ft. long, 2³⁄₄ in. at the middle and tapering to 1¹⁄₂ in. at the ends. They are fitted with metal rings at the ends to prevent splitting. The yard and booms are fitted to the backbone at the bow by means of loops bolted to them and engaging an eyebolt and ring on the backbone. The eyebolt is fitted into a slotted plate of ³⁄₁₆-in. sheet iron, and fastened by a lever nut, as shown in Fig. 5. The sheets are fastened to the yard and booms in the usual manner, being fitted with grommets, and tied with line. The yard is suspended from the masthead by means of a line and pulley, the former being cleated to the backbone. The booms are controlled by the operator from the cockpit, by the use of lines and pulleys, similar to the arrangement used on sailboats, except that a duplicate set is required for the additional boom. The lines are cleated on the backbone convenient to the cockpit.

[19]

| Fig. 1 Fig. 6 |

||

| Fig. 5 | Fig. 2 | Fig. 4 |

| Fig. 3 | The Wishbone Mast Provides a Strong Construction of Marked Stability, and the Double Booms and Sails Permit of Great Speed When Running before the Wind. When Tacking, the Sails and Booms are Used as One Boom and Sheet. Figure 1 Shows the Side Elevation; Fig. 2 a View of the Lower Side, and the Details are Shown in the Other Figures | |

[20]

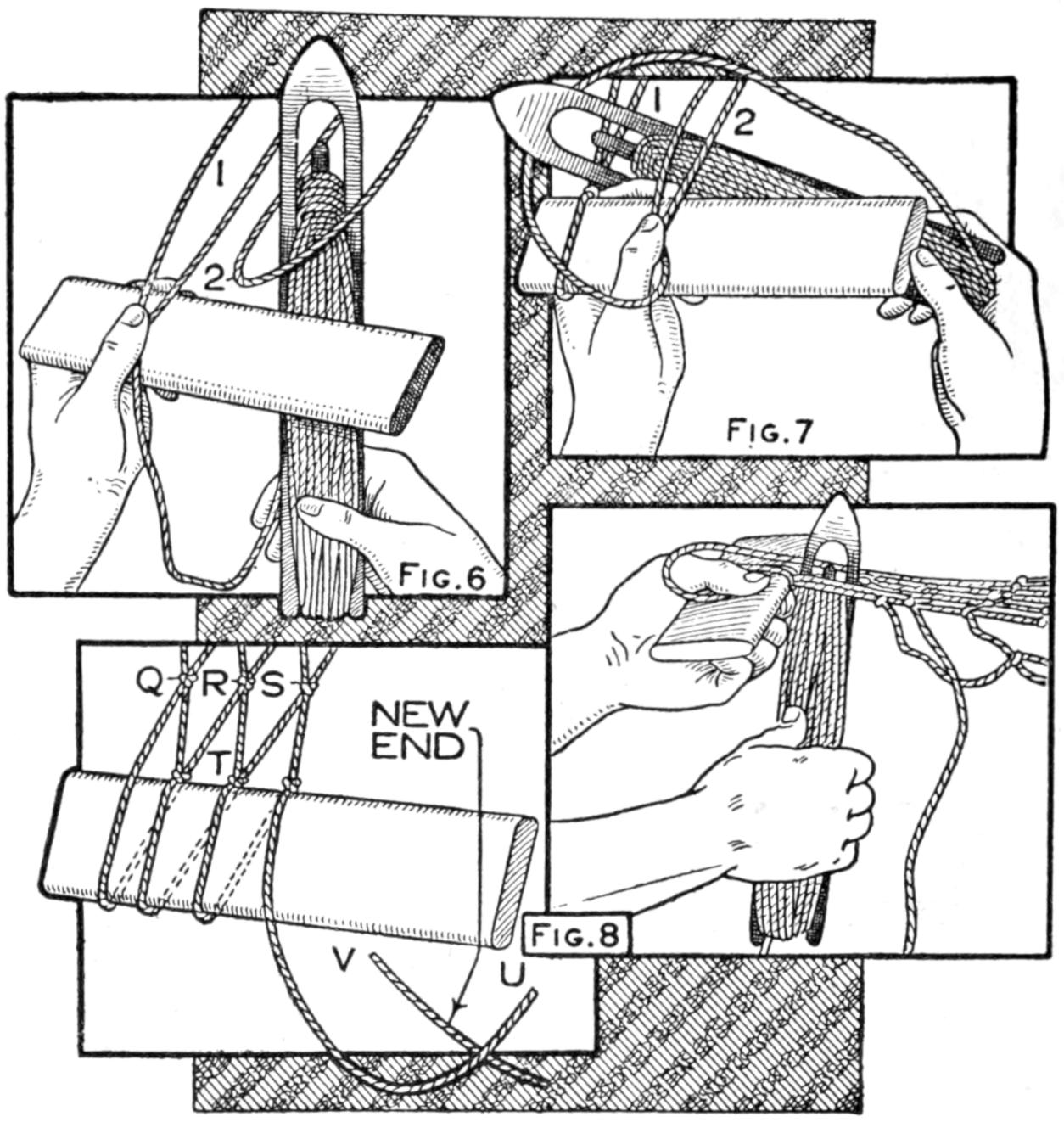

The sails are of the lateen type, and should be made of 8-oz. unbleached cotton duck. The breadths are sewn together by lapping one edge over the other about 1 in., and sewing or stitching along the edge. Yard-wide material is satisfactory, and if narrower laps or bights are desired, simply fold over 1 in. of the goods and double-stitch the seam. The bights should run parallel with the after, or leach, edge of the sail, as shown in Fig. 1. Each corner of the sail should be reinforced with a triangular patch of duck, so that it will stand up under the severe strain of winter usage. The edges of the sail may be bound with ¹⁄₄-in. tarred rope, which is not difficult if a sailor’s palm and a diamond-pointed needle are used. Sail twine, well waxed, should be used for the sewing of the sails.

The edges of the sails adjoining the yard and booms are provided with grommet holes by means of which the sails are attached to their supports. The grommets are made by punching holes in the sails, at the proper points, fitting two ³⁄₄-in. brass grommet rings into the holes, one at each side, and overcasting them with a buttonhole stitch. The sail needle and waxed sail twine are used. The reef points are of the usual type, and are made of ¹⁄₈-in. cotton rope, whipped at the ends to prevent raveling, and sewed to the sails at intervals.

The craft is designed to be taken down when not in use, particularly between seasons, and can be stored in comparatively small space, in the knockdown form. The method of setting up the ice yacht will serve to illustrate, also, the method of taking it down, in that the process is practically reversed. First, the backbone is fitted with the forward ring and the strap bolts are fastened at the crossing of the backbone and runner plank. The runners are fitted into place, and the steering rigging is adjusted. The wishbone mast is set into its steps, clamped at its masthead, and the bands fitted to the lower ends. The guy wires at the bottom and that at the masthead are then set, by means of the turnbuckles. The sails are attached to the yard and booms, and the forward end of the latter supports are fixed into place. The pulley at the masthead is fitted with ³⁄₈-in. rope which is fastened to the yard, at the proper point, as indicated in Fig. 1. The rigging by which the booms are controlled is threaded through the pulleys at the stern and the ends fixed on the cleats. The yard may now be hauled up and the craft trimmed so that the sails “set” properly. The halyard is fixed to the yard, as shown, and run through a pulley at the masthead, then down through a second pulley fixed to the runner plank, from which it is conducted to cleats convenient to the operator in the cockpit.

The main sheets are rigged as shown in Fig. 1. The ends of the lines are lashed to the ends of the booms, passed through pulleys, at the stern of the backbone, on the booms, about 1 ft. from the ends, and 5 ft. from the ends, respectively, then down to the cleats at the cockpit. This rigging gives good purchase on the lines and makes it convenient for the operator to attend to the helm and the lines at the same time. The fittings are, as nearly as possible, designed to be standard and may be purchased from ship chandlers, or dealers in marine hardware and fittings. The special metal parts may be made by one of fair mechanical skill, or may be made by local blacksmiths. The woodwork is all comparatively simple. The masts, yard, and booms should be smoothed carefully, sandpapered lightly, and finished with several coats of spar varnish. The other woodwork may be painted suitably, and the metal fittings should be finished with two coats of red lead, or other good paint for use on metals exposed to the weather.

[21]

The manipulation of this craft is in general similar to that of the common lateen-rig, or other sail and ice, boats. When running before the wind—free—the booms are separated and the wind acts against the sails in the pocket between them. When tacking, the booms are brought together, and the sails act as one sheet, on a craft of the ordinary type.

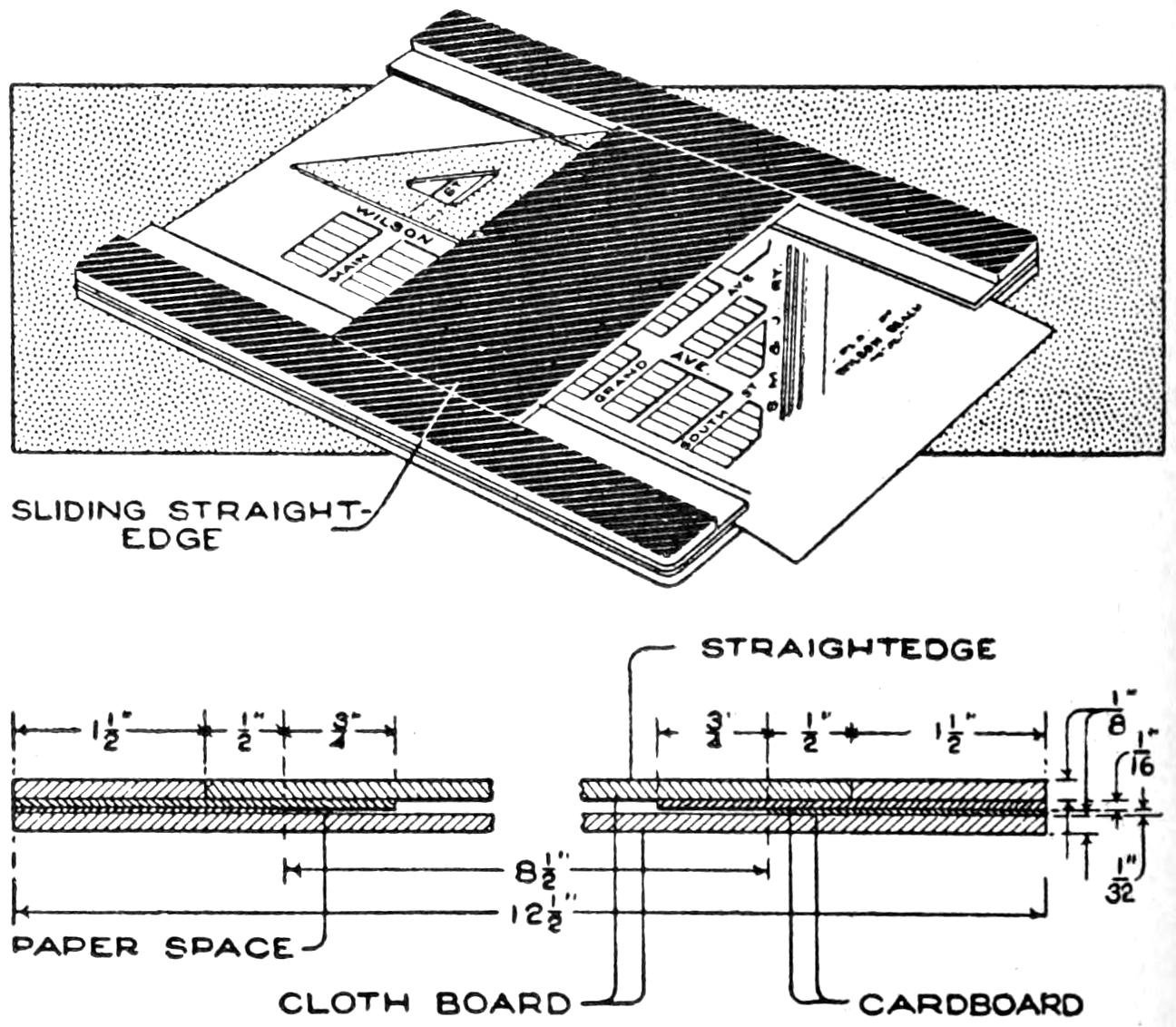

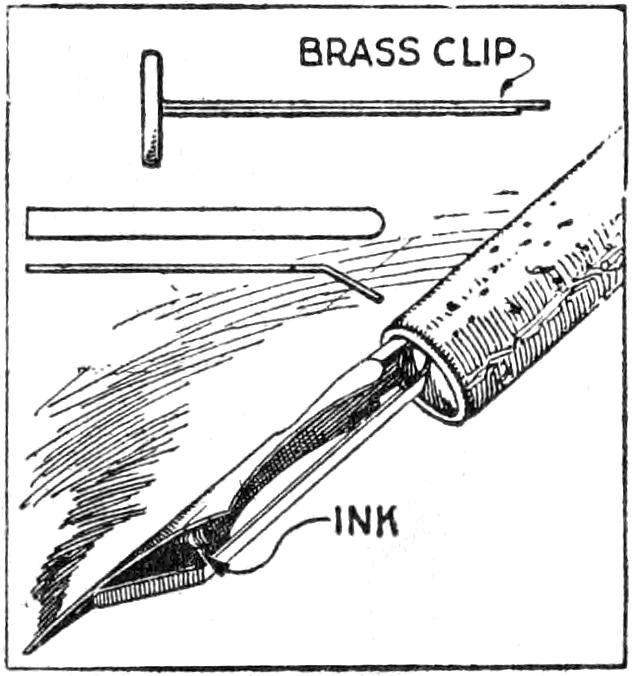

Draftsmen, whose work demands the use of drawing paper of uniform size, sometimes experience difficulty in fixing thumb tacks solidly in the board. This is caused by the continual placing of tacks in the same spot and may be overcome by the use of cork plugs which can be removed when worn. At the four points where the tacks are generally placed, bore 1-in. holes nearly through the board. Insert corks large enough to be forced into the holes and trim them off flush with the surface. Tacks will hold firmly in them and new corks may be inserted as needed. —G. F. Thompson, Pittsburgh, Pa.

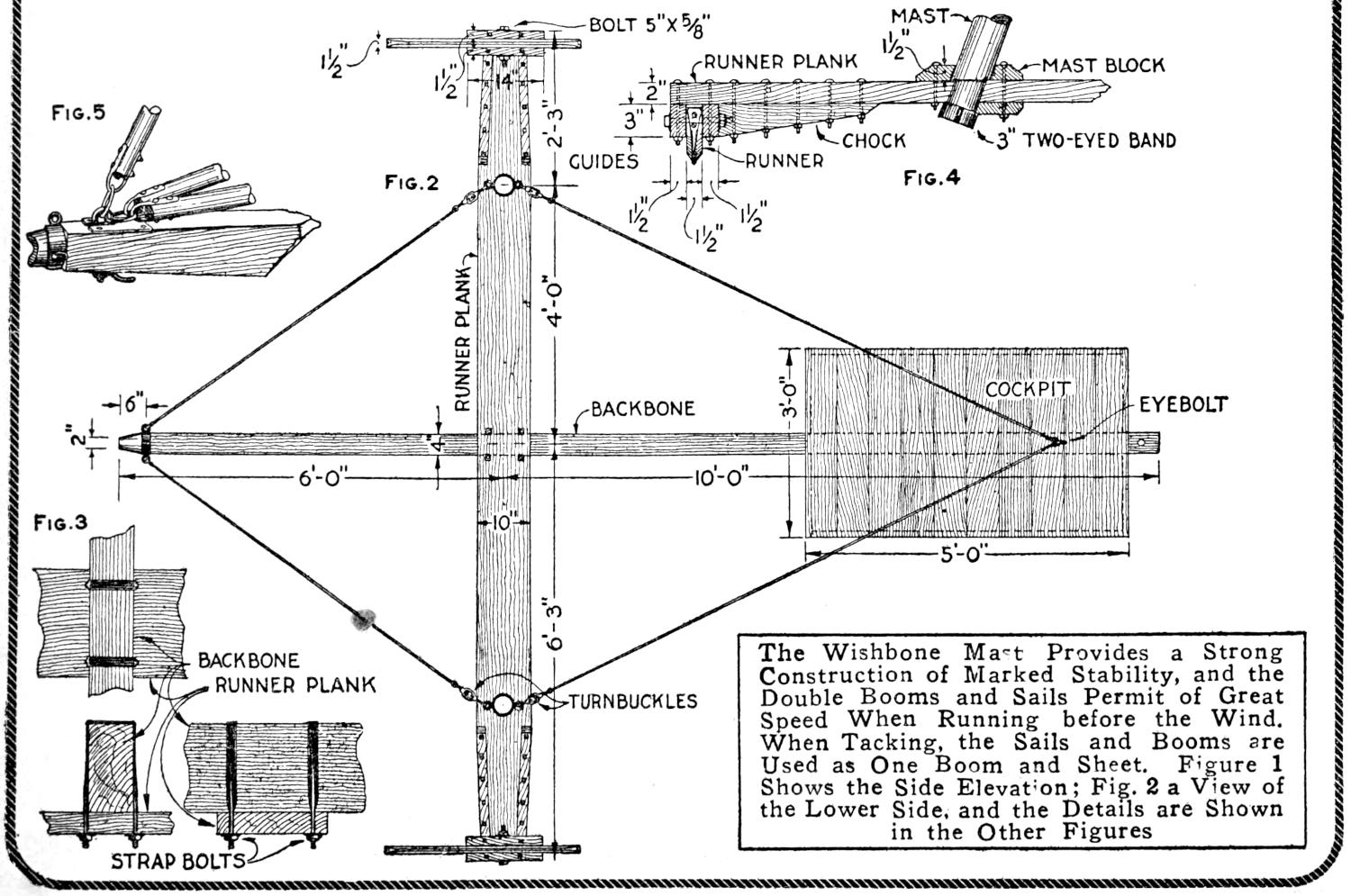

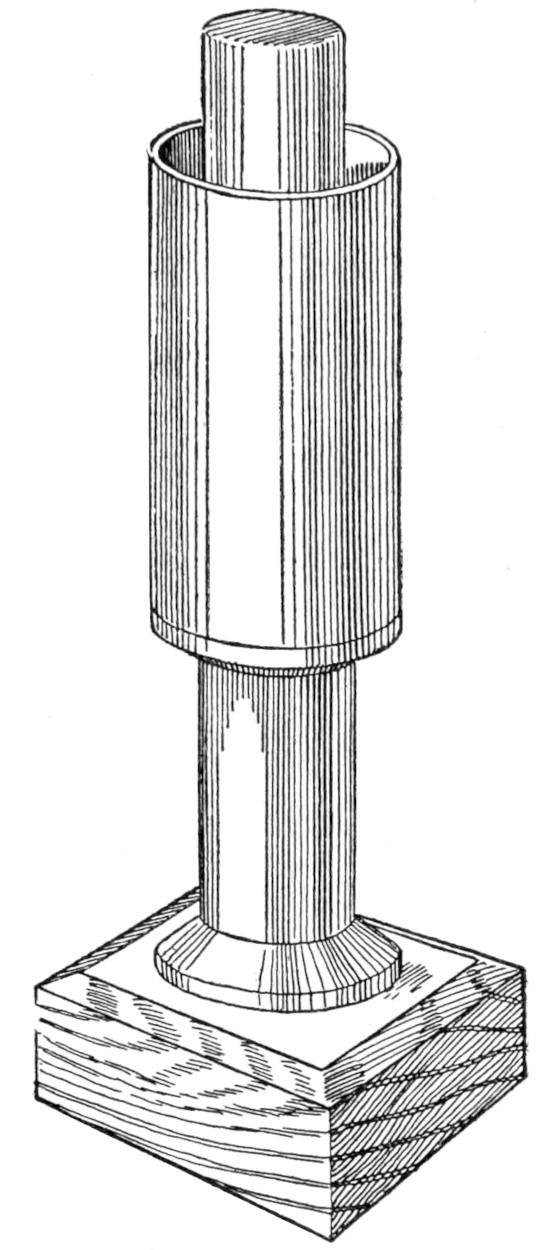

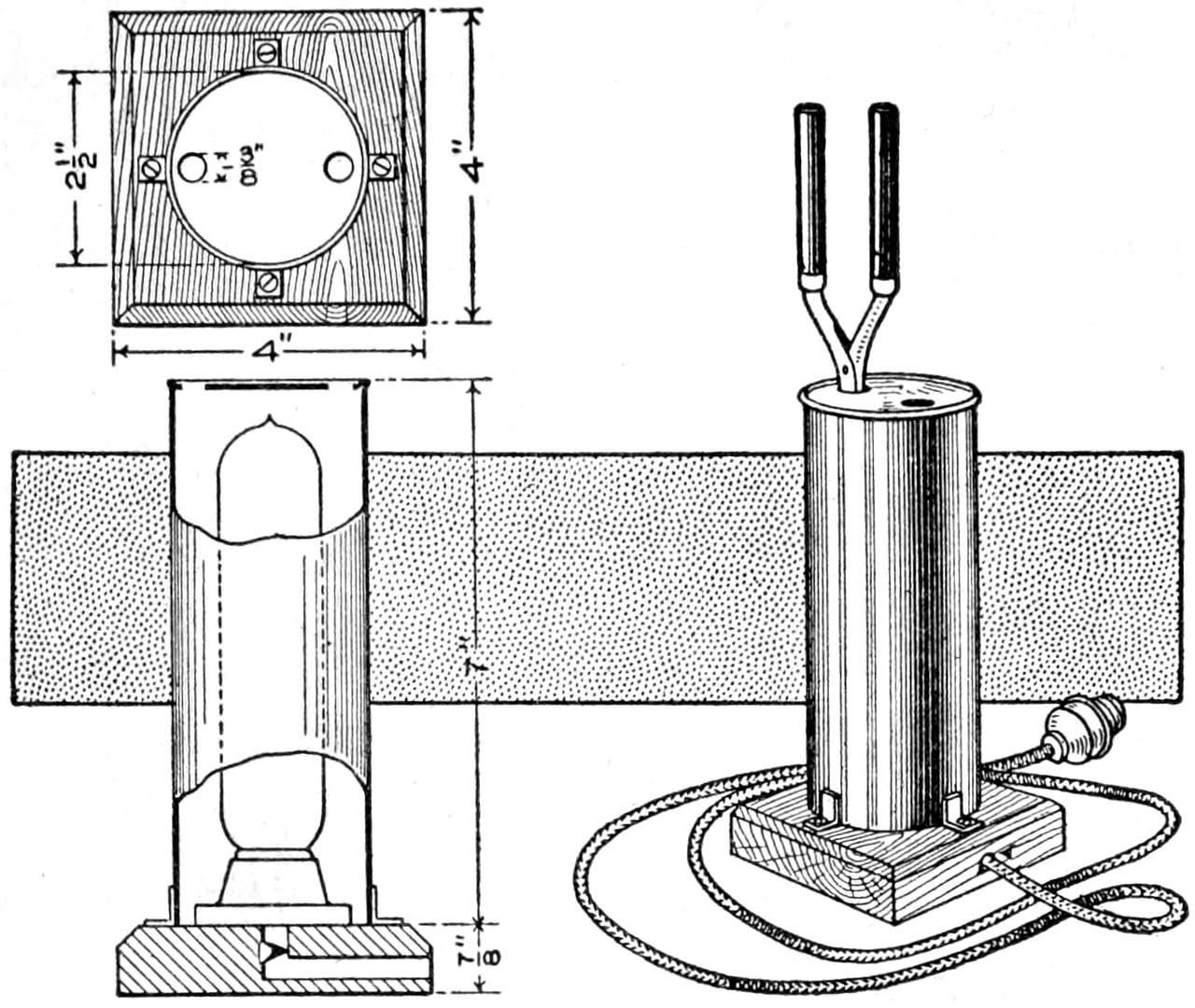

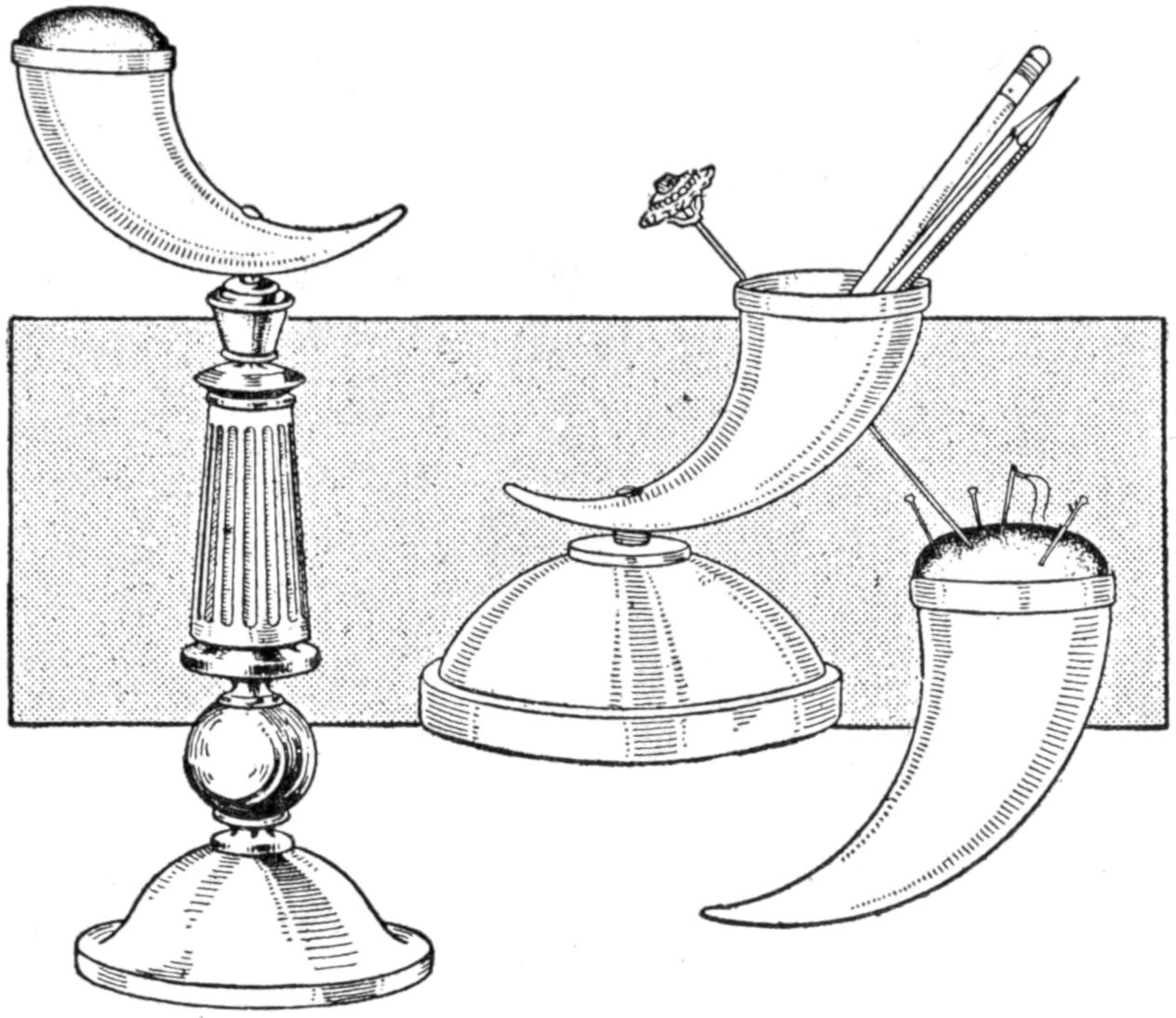

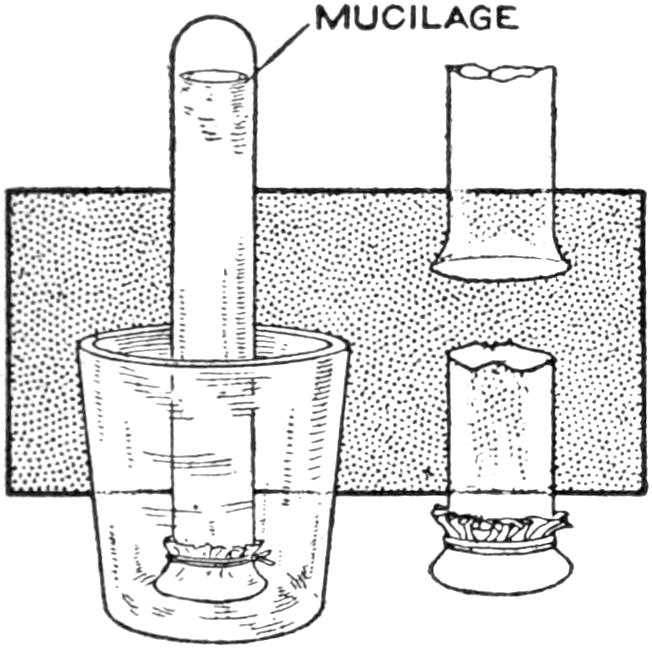

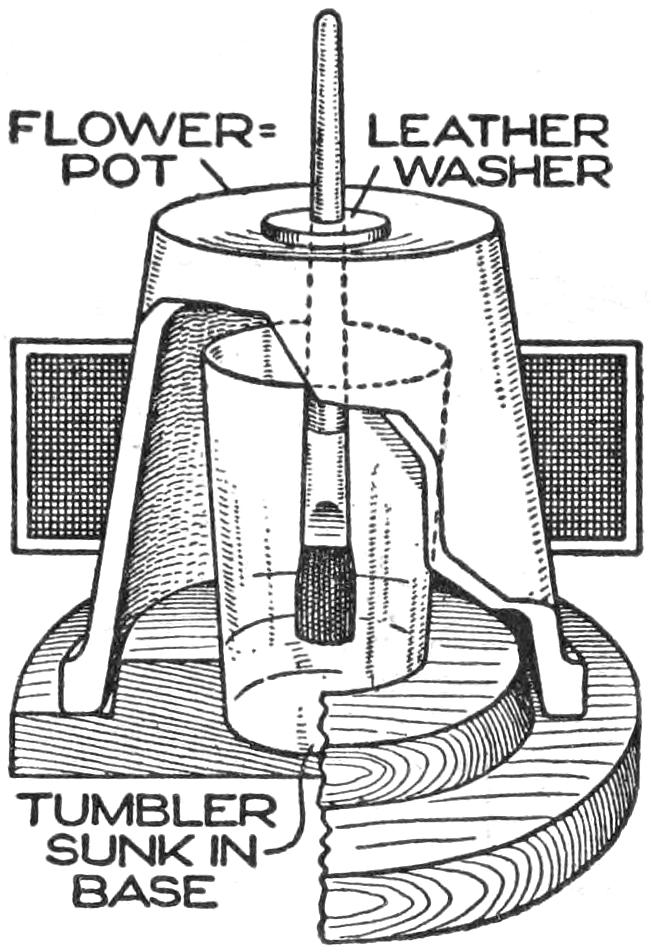

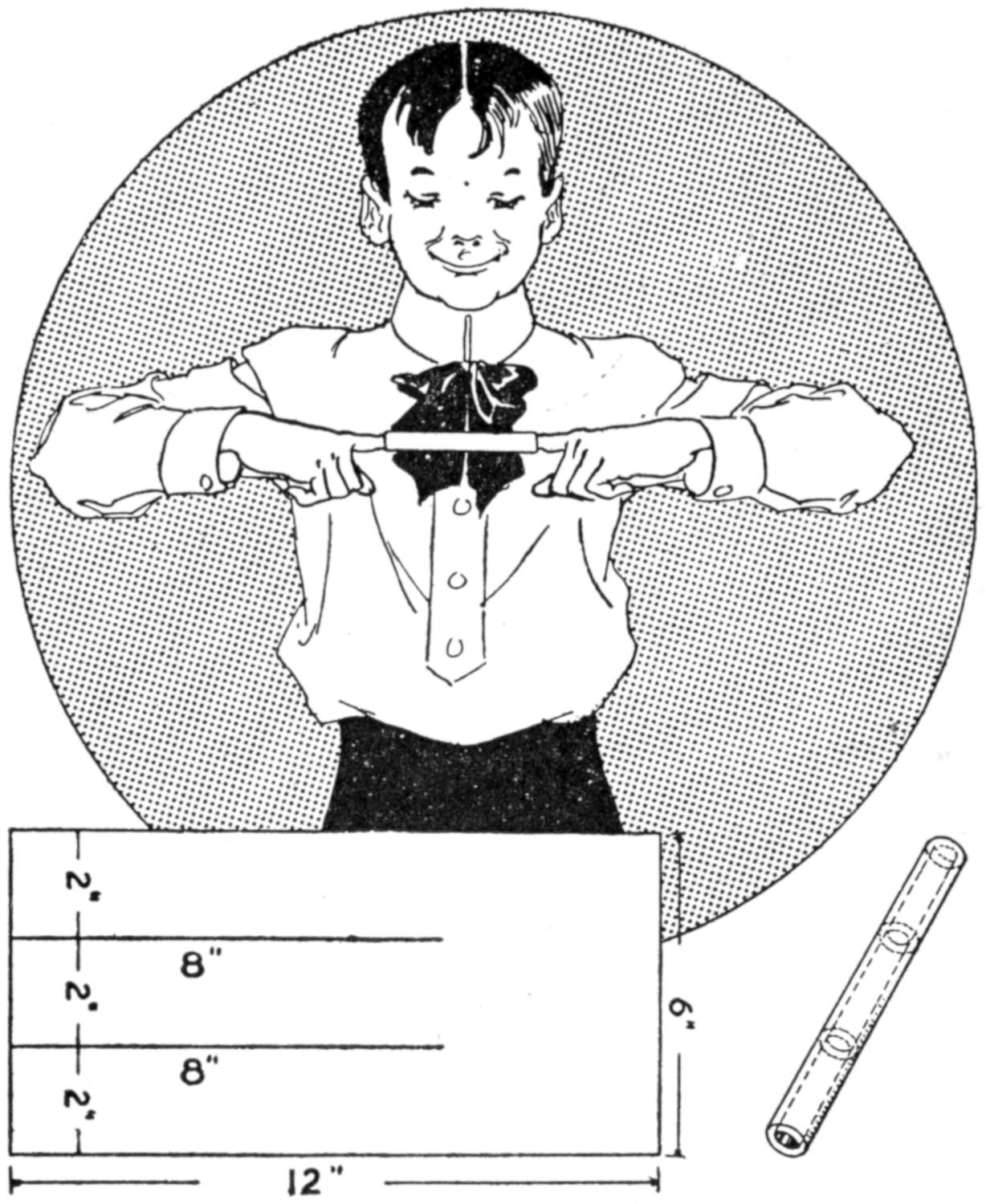

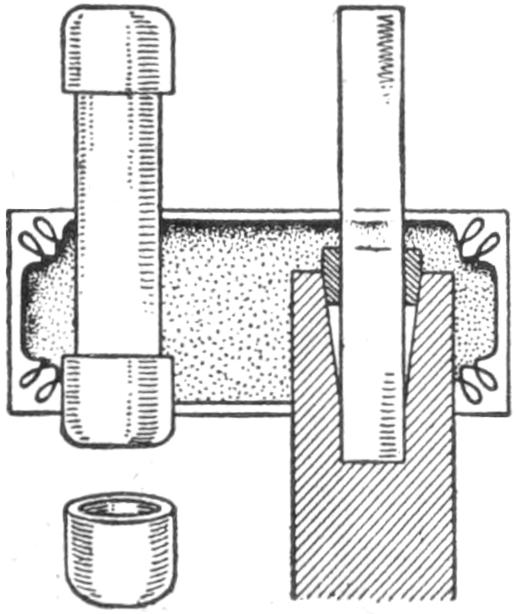

A test-tube vase, containing a single blossom, adds color and a certain individual touch to the business man’s desk, or it may be used with effectiveness in the home. A simple wooden stand, finished to harmonize with the surroundings, may be made easily, and affords a support and protection for the test tube. The sketch shows a small stand of this type, made of oak, in the straight-line mission style. It may be adapted to other woods and to various designs in straight or curved lines.

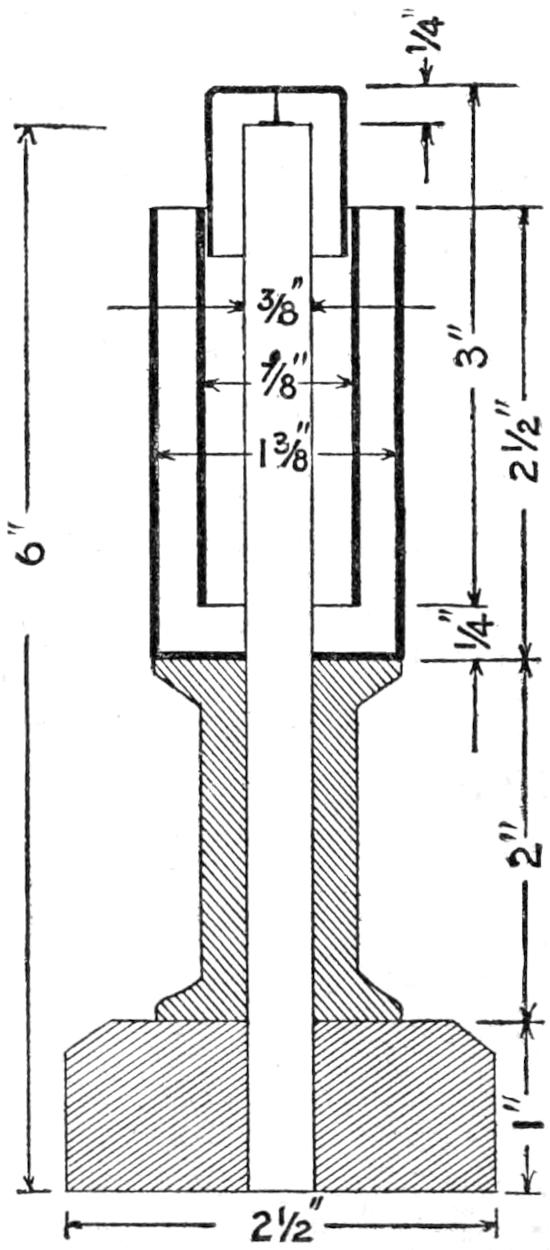

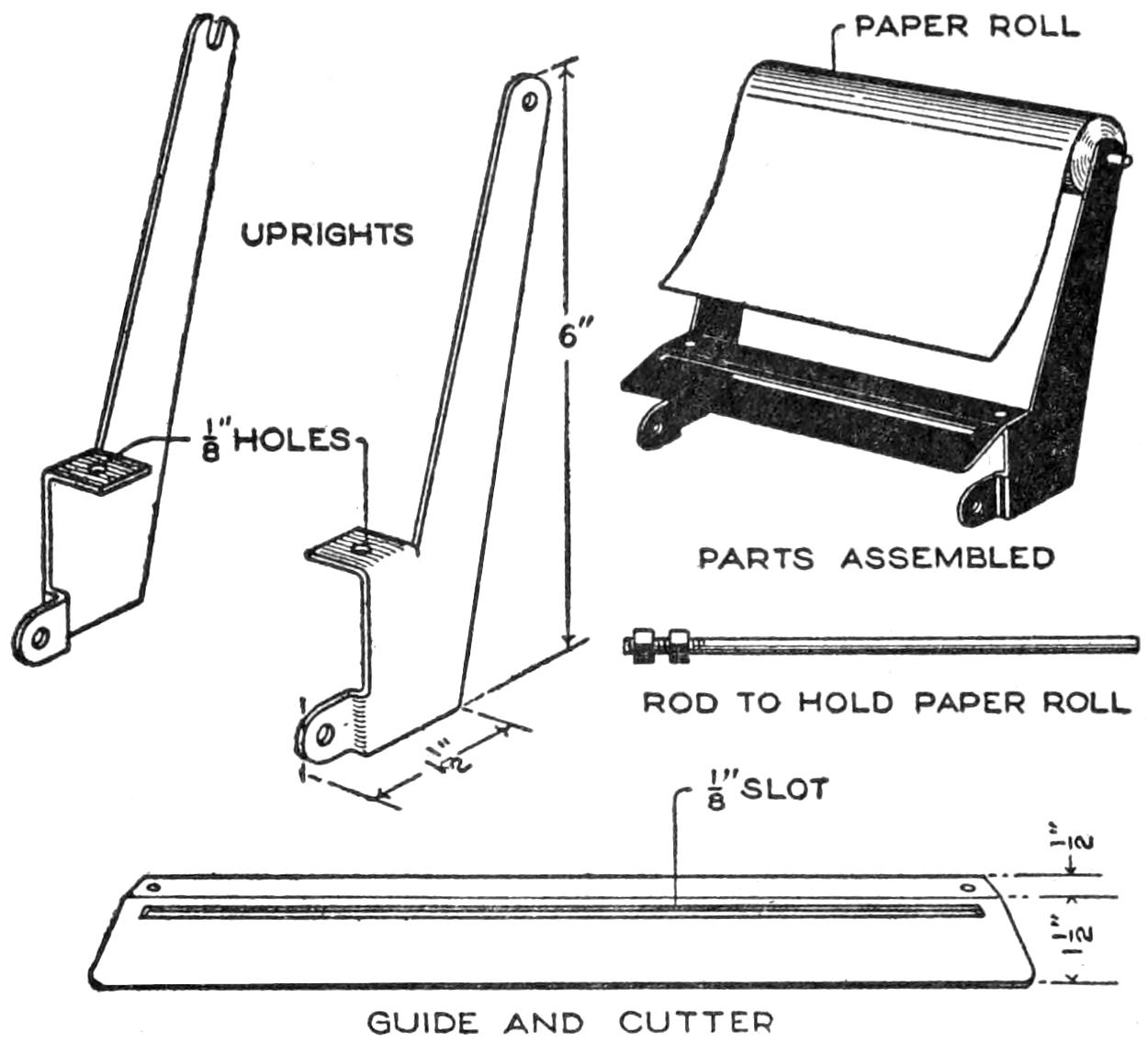

The Stand Provides a Support and Protection for the Test-Tube Vase on the Office Desk or in the Home

The base is 2¹⁄₂ in. square, and rests on two cross strips, 1 in. wide. All the material may be about ¹⁄₄ in. thick, but it is desirable to have the base and cap pieces of thicker stuff. The uprights may be of ¹⁄₈ to ¹⁄₄-in. stuff, and are notched together as shown. They are 1 in. wide and 6¹⁄₄ in. long, a portion being cut out to receive the test tube. The cap is 1¹⁄₂ in. square, and its edges are chamfered slightly, as are those on the upper edge of the base. The pieces are fitted together with small brads, used as hidden dowels, and the joints are glued. Brads may be used to nail the pieces together, and they should be sunk into the wood, and the resulting holes filled carefully. The stand should be stained a dark color, or left natural, and given a coat of shellac or varnish.

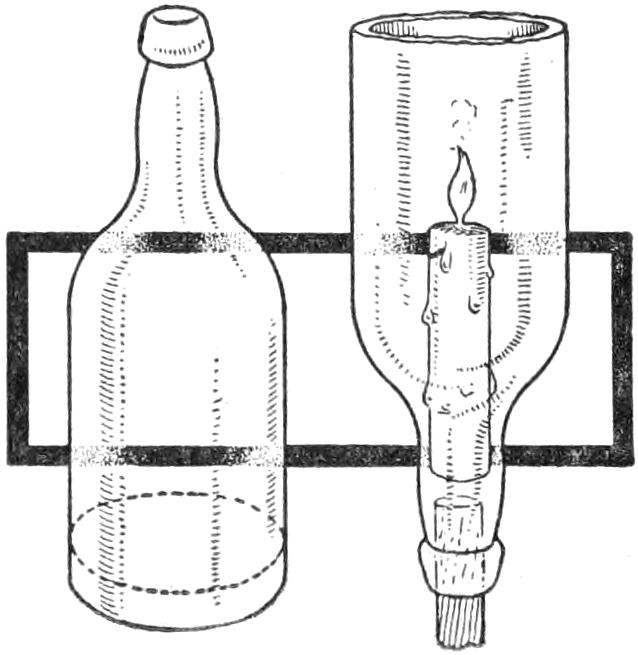

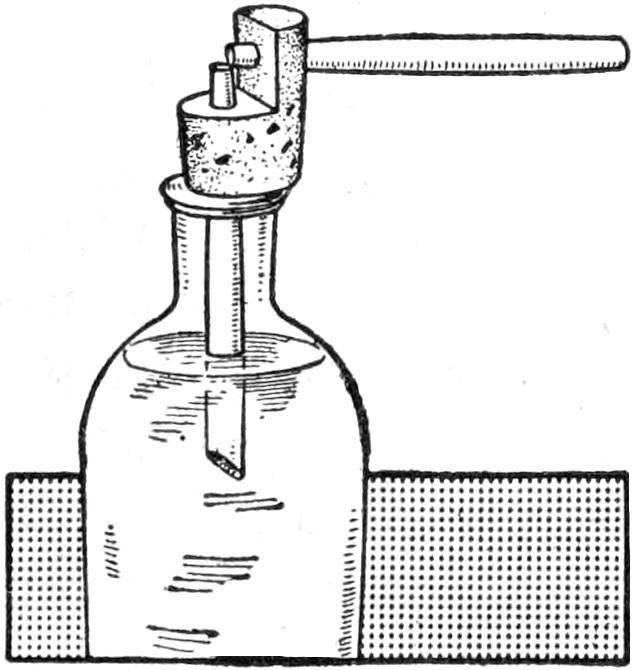

In pouring a liquid from a jug or bottle, the vessel should be held with the opening downward, rather than horizontally, if convenient, and swung quickly with a circular motion. The liquid will rotate and in leaving the opening will permit air to enter continuously, causing the liquid to run out rapidly and without intermittent gurgling sounds. If the opening of the container is at one side it is best to hold the container so that the opening is at the highest point of the end rather than at the bottom. The air may thus enter and permit a continuous flow until the container is empty.—E. F. Koke, Colorado Springs, Colo.

[22]

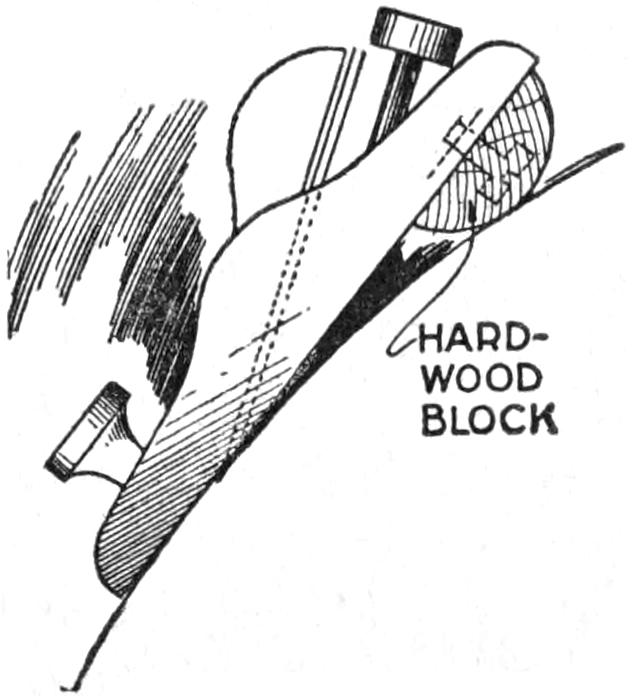

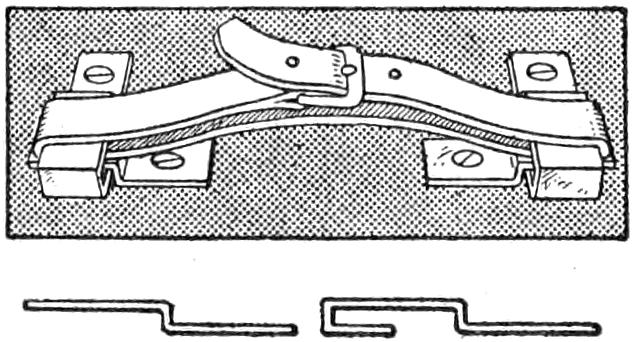

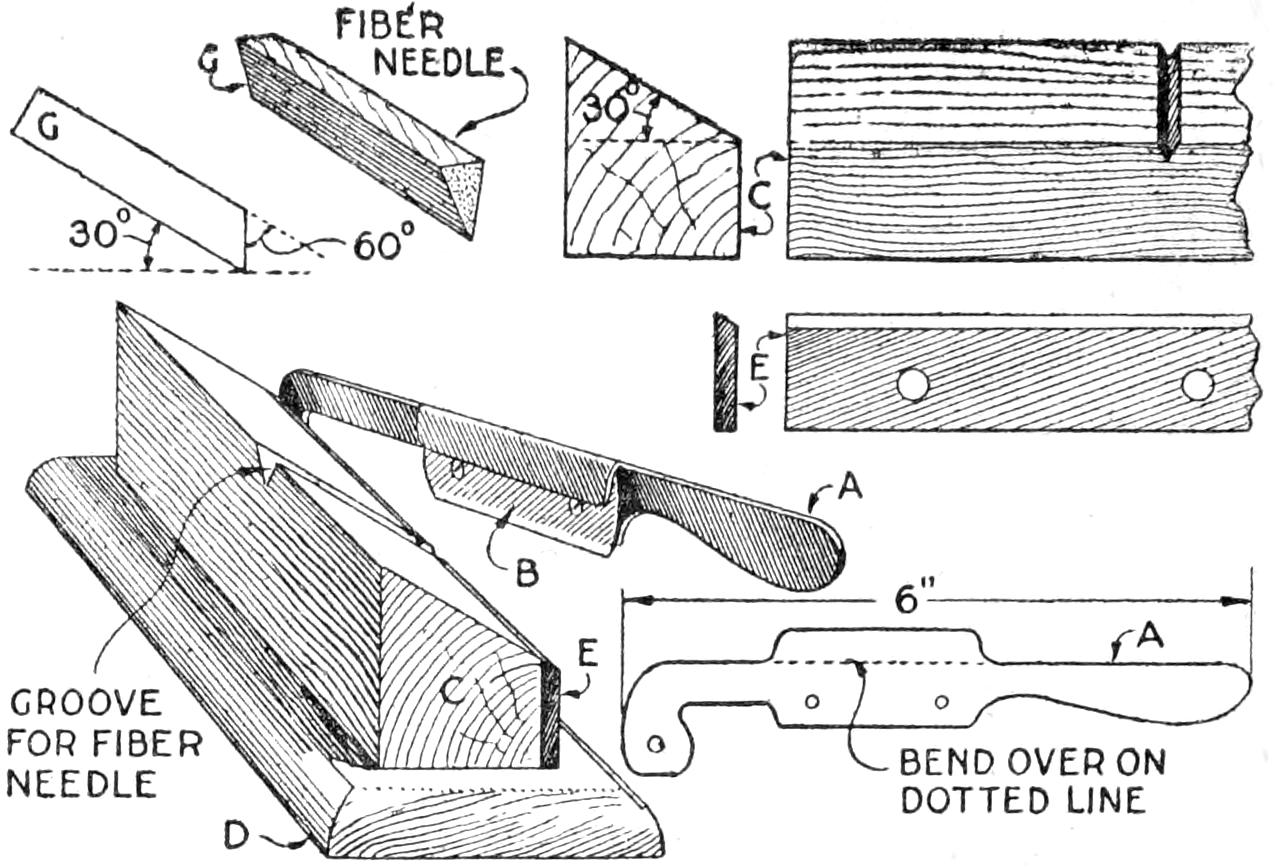

The knife sharpener shown can be easily made of two pieces of thin wood, such as cigar-box covers, about 2 in. wide and 2¹⁄₂ in. long, and two discarded safety-razor blades of the heavier type. Lay the wood pieces together and saw a slot down the center for about 1³⁄₄ in. Lay the two razor blades at an angle of about 2° on each side of the slot, as shown, fasten them to one of the boards, and securely attach the other board over them.

To sharpen a knife, run it through the slot two or three times. The sharpener can be fastened with a hinge so that it will swing inside of the drawer, or box, that the knives are kept in, and it will always be ready for use.—Contributed by Henry J. Marion, Pontiac, Mich.

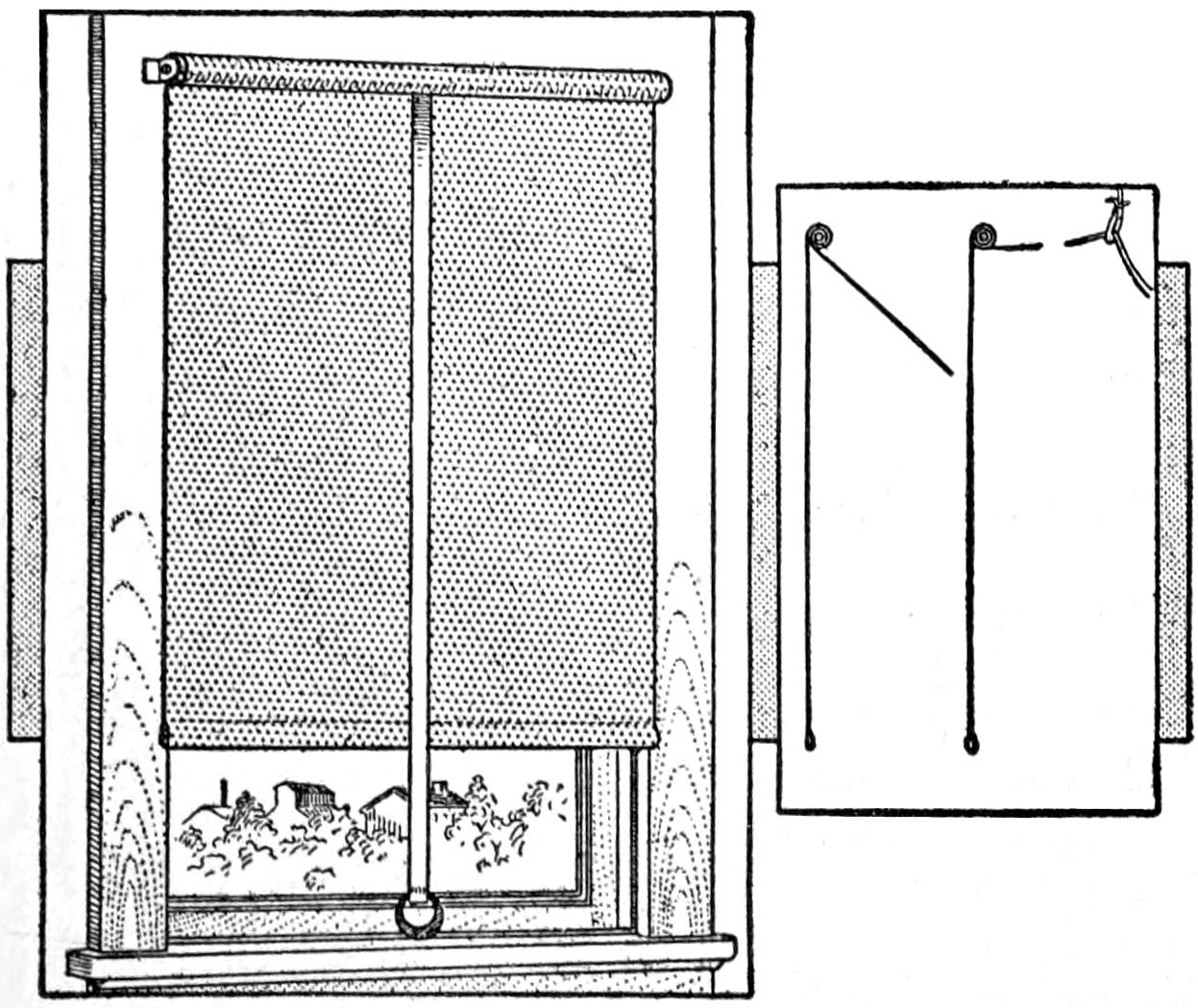

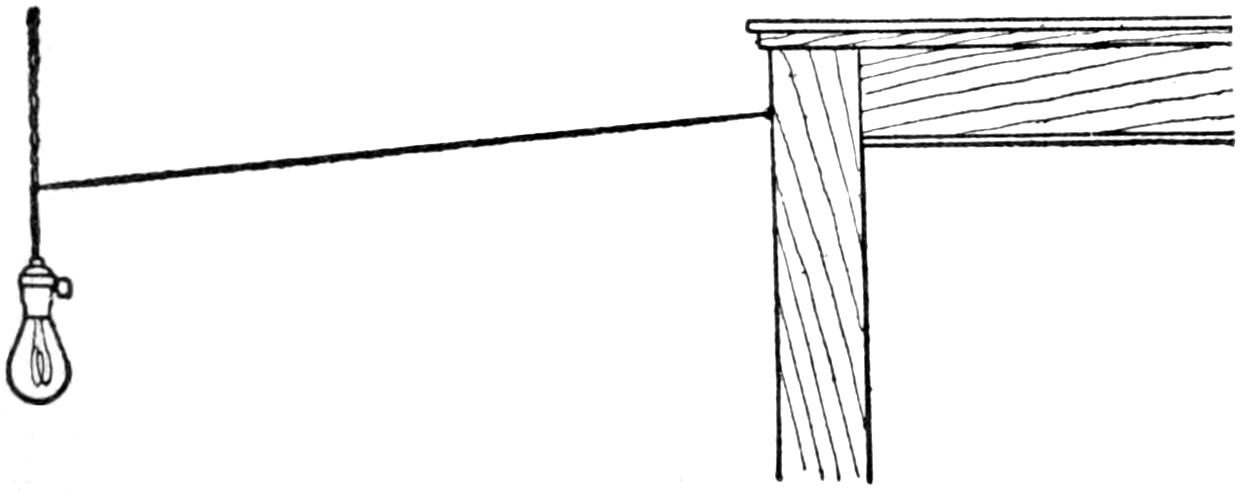

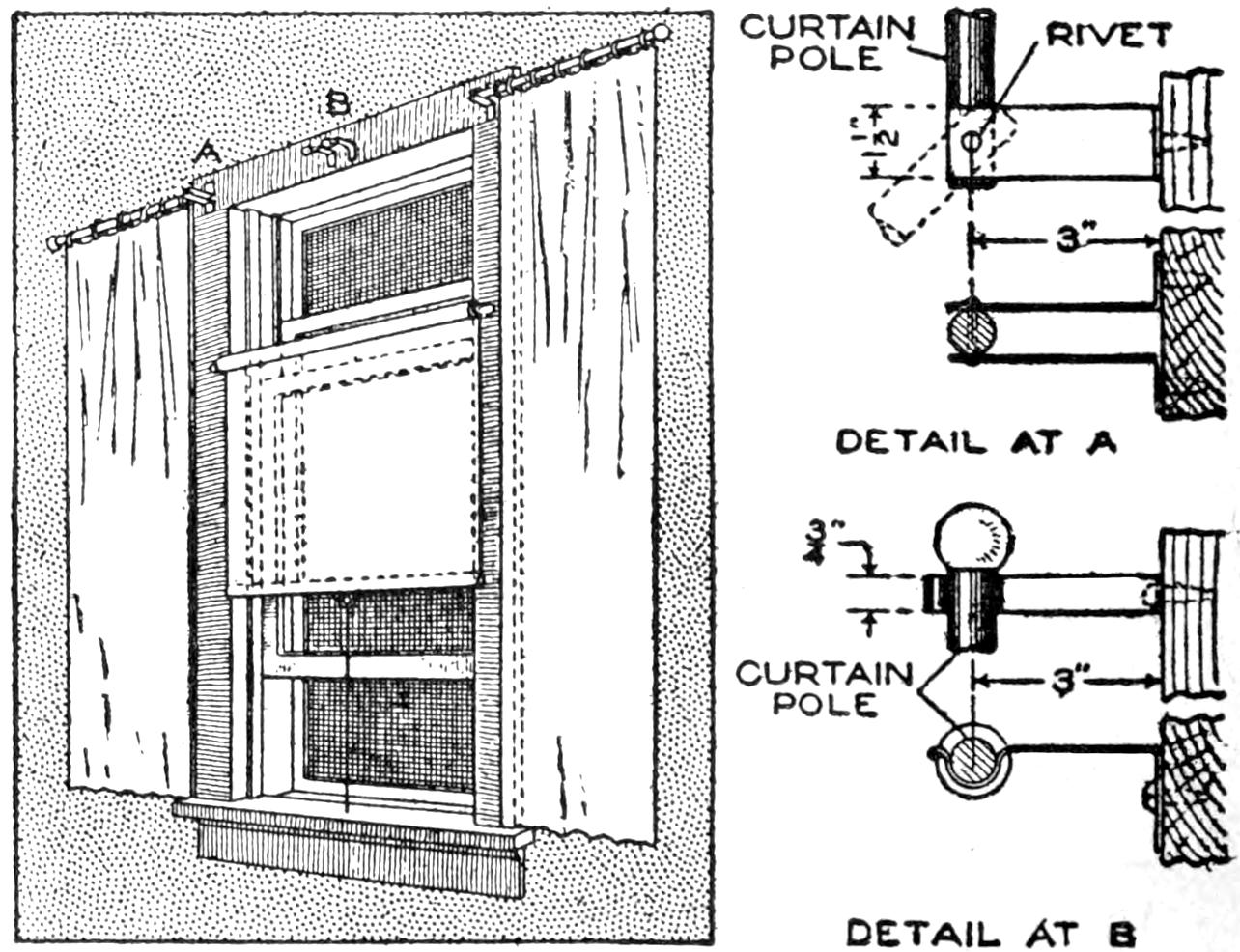

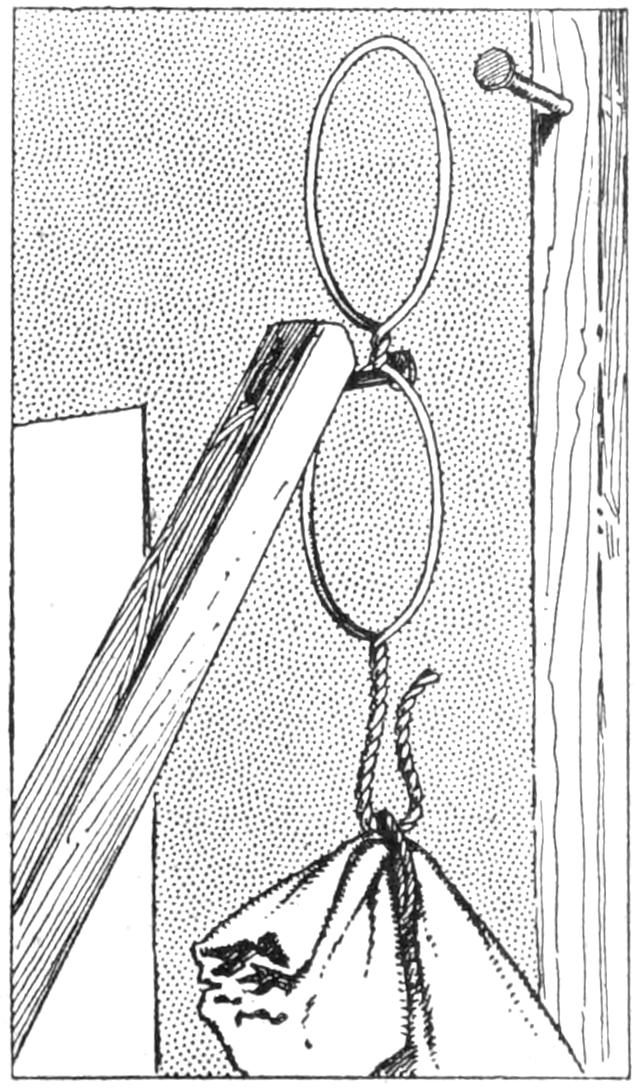

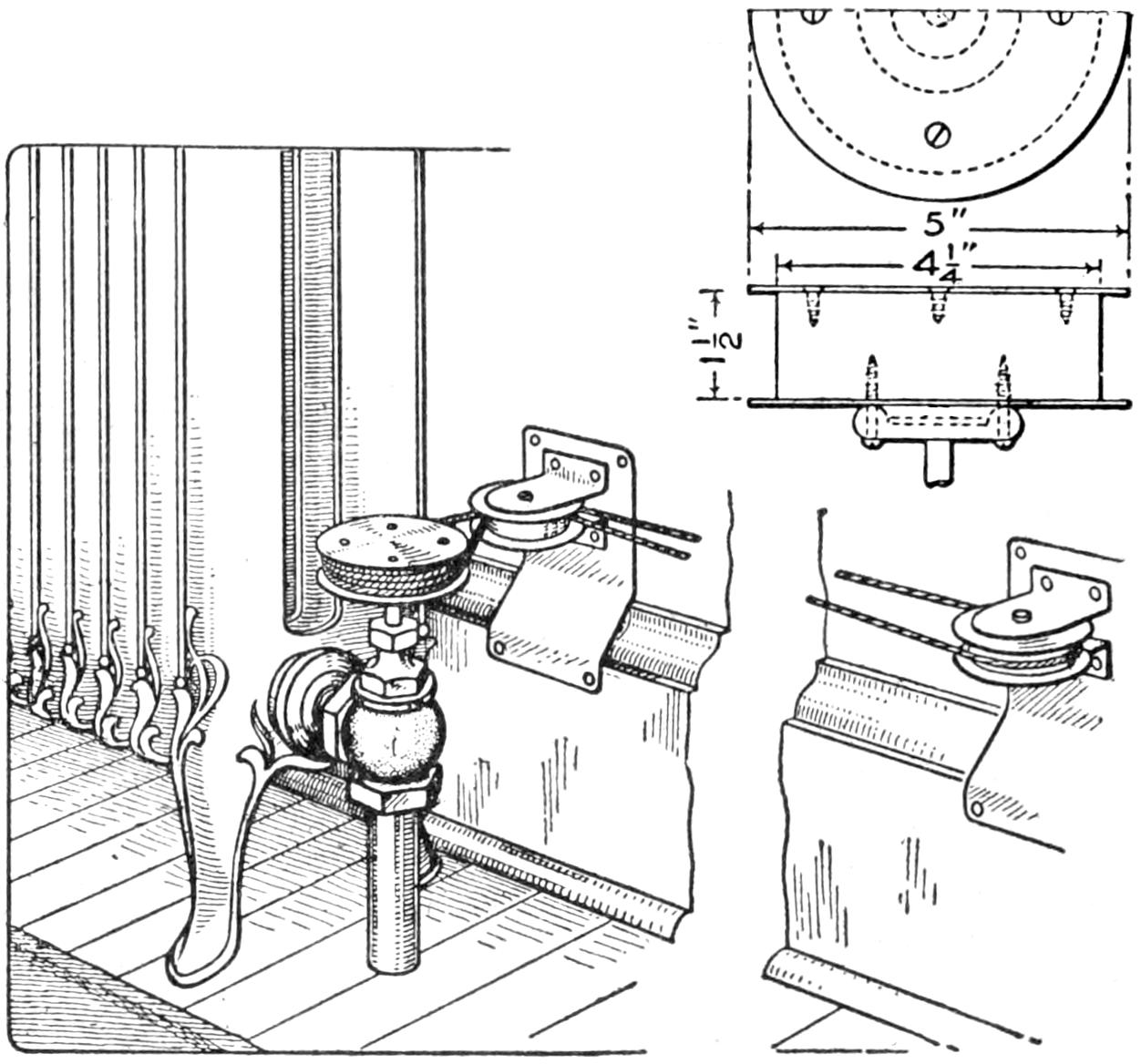

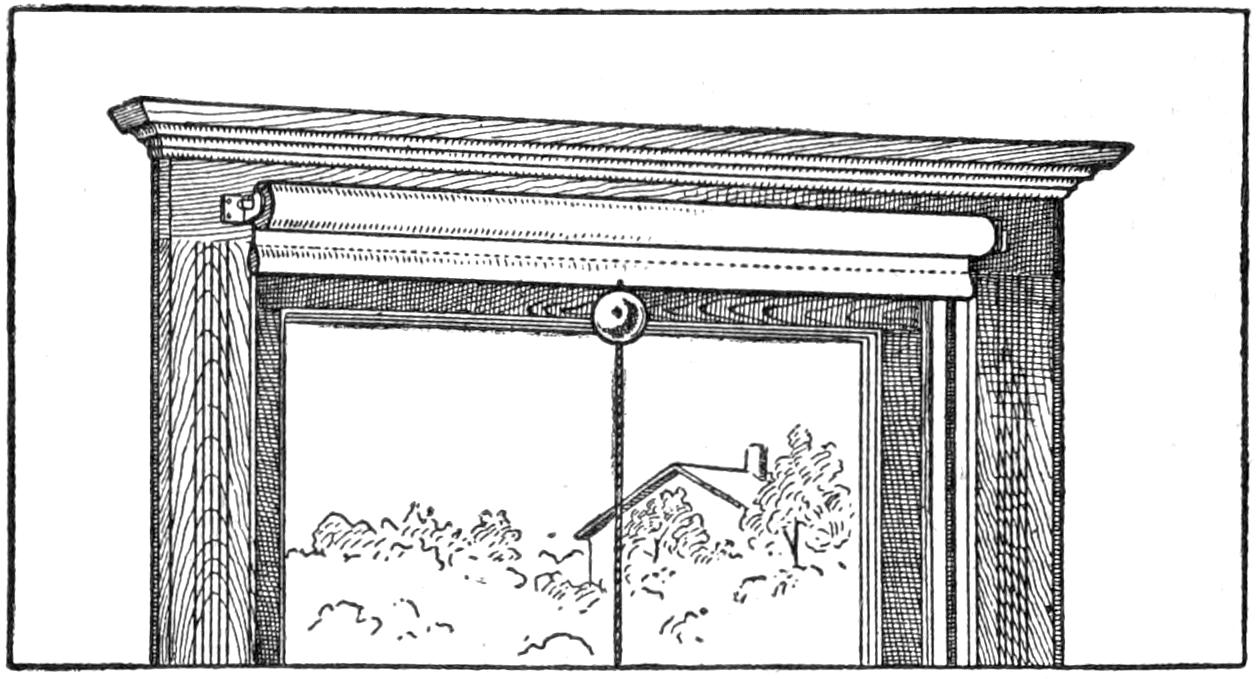

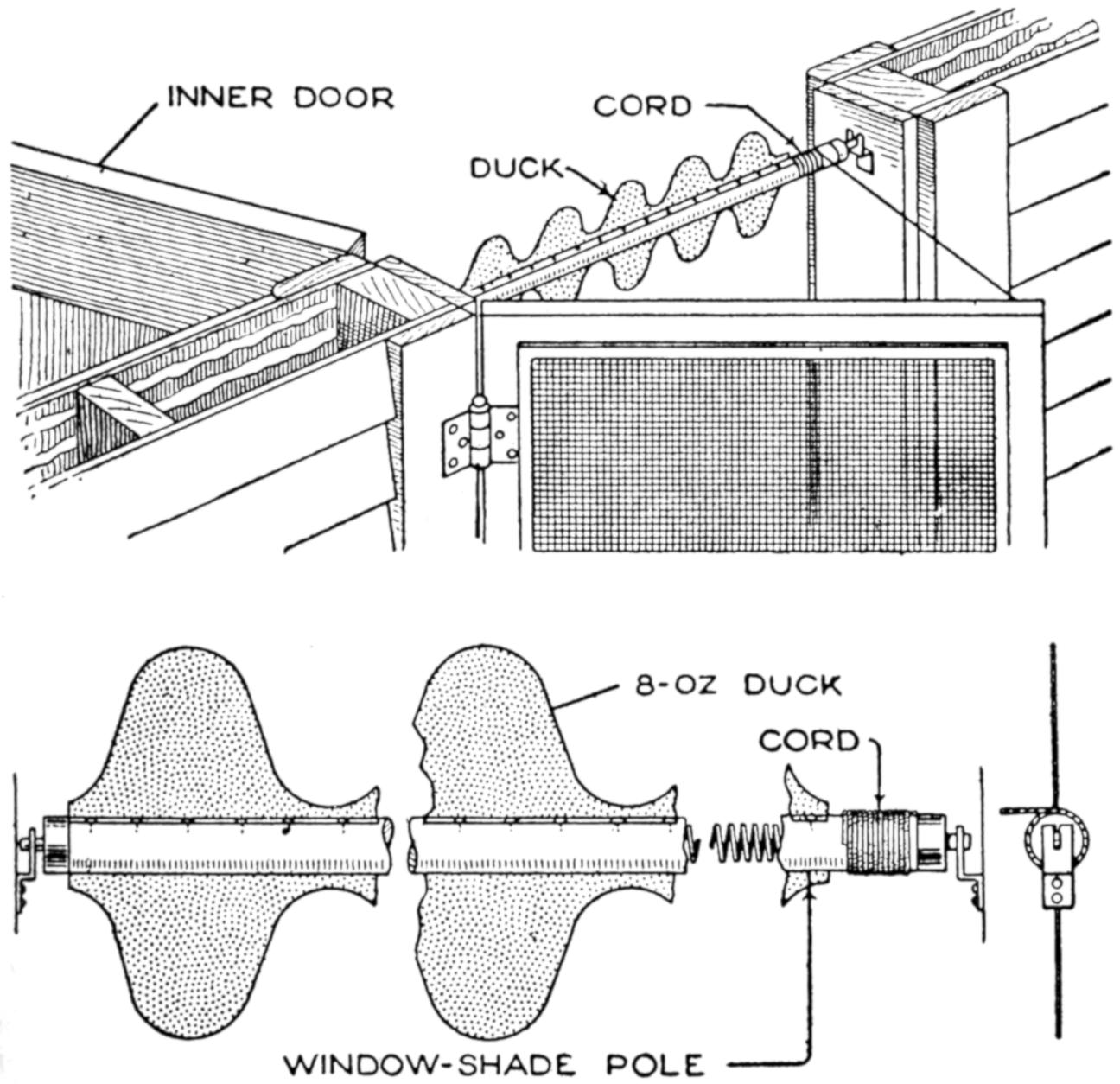

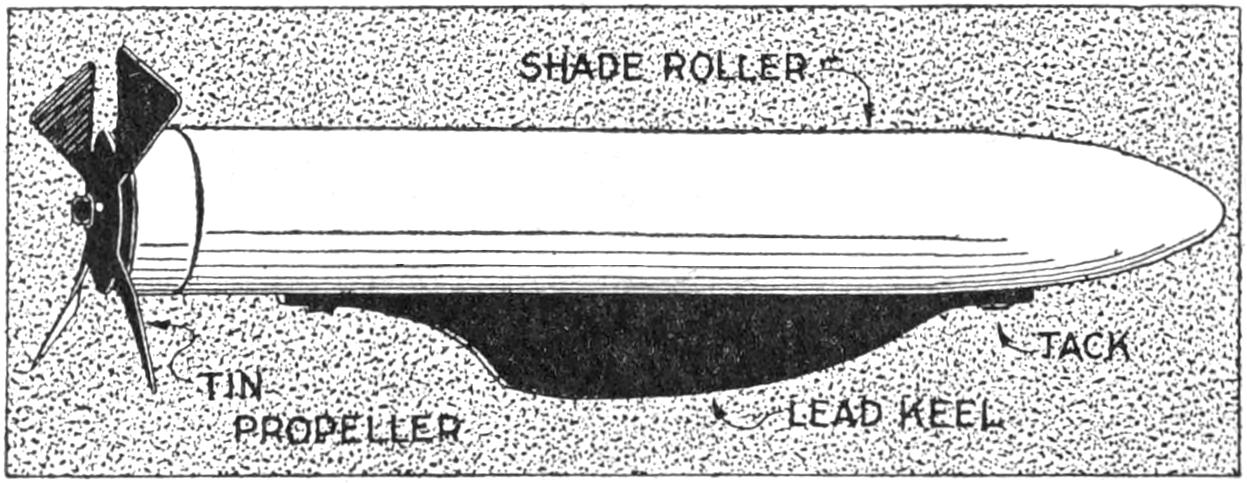

A Ribbon or Tape Attached to a Curtain Roller to Operate It at a Distance

To enable an invalid, or any other person, to easily raise and lower a curtain from a position at a distance from the window, a ribbon can be attached to the roller, at the center and on the inner side of the curtain. The ribbon may extend across the room in line with the window, and still operate the curtain as well as with the regular cord attached to the bottom. If desirable to operate the curtain by a vertical pull, a flat pulley may be conveniently fastened to the ceiling or wall, and the ribbon passed over it, or through a ring, as shown. This plan is especially adapted for show windows where the curtain string would otherwise mar the appearance and be hard to get at.—Contributed by L. E. Turner, New York, N. Y.

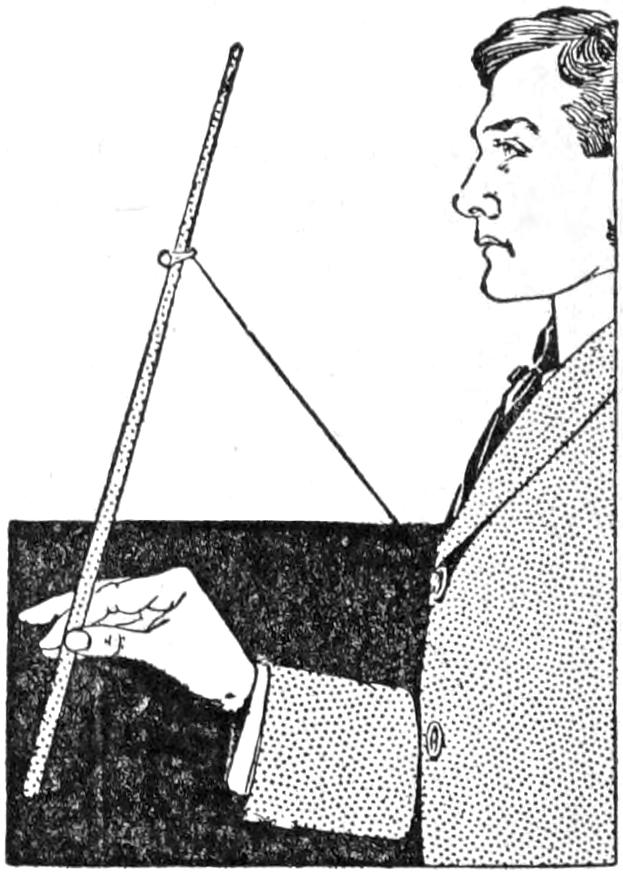

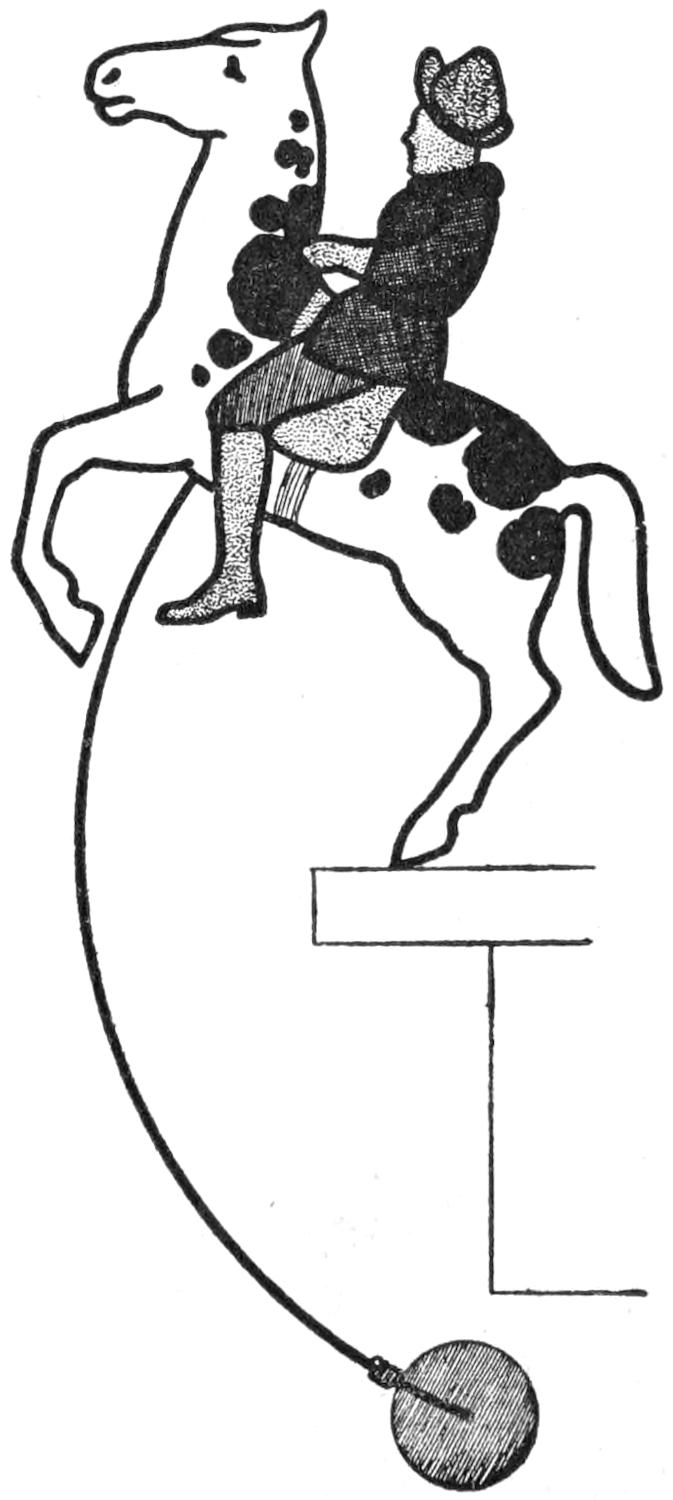

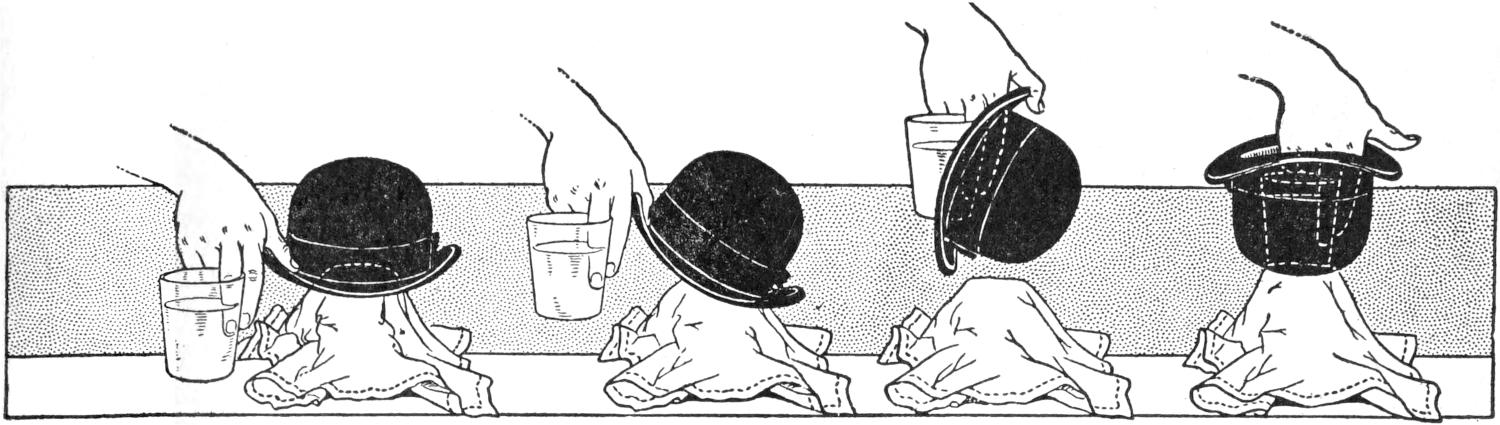

The performer hands out a wand for examination and borrows a finger ring. He holds the wand in his hand, point upward, and drops the ring on it, then makes mesmeric passes over the wand with the other, and causes the ring to climb toward the top, stop at any place desired, pass backward, and at last fall from the wand. The wand and ring are examined again by the audience.

To produce this little trick, the performer must first provide himself with a round, black stick, about 14 in. long, a piece of No. 60 black cotton thread about 18 in. long, and a small bit of beeswax. Tie one end of the thread to the top button on the coat and to the free end stick the beeswax, which is stuck to the lower button until ready for the trick.

After the wand is returned, secretly stick the waxed end to the top of the wand, then drop the ring on it. Moving the wand slightly from oneself will cause the ring to move upward, and relaxing it causes the ring to fall. In the final stage remove the thread and hand out the wand for examination.

[23]

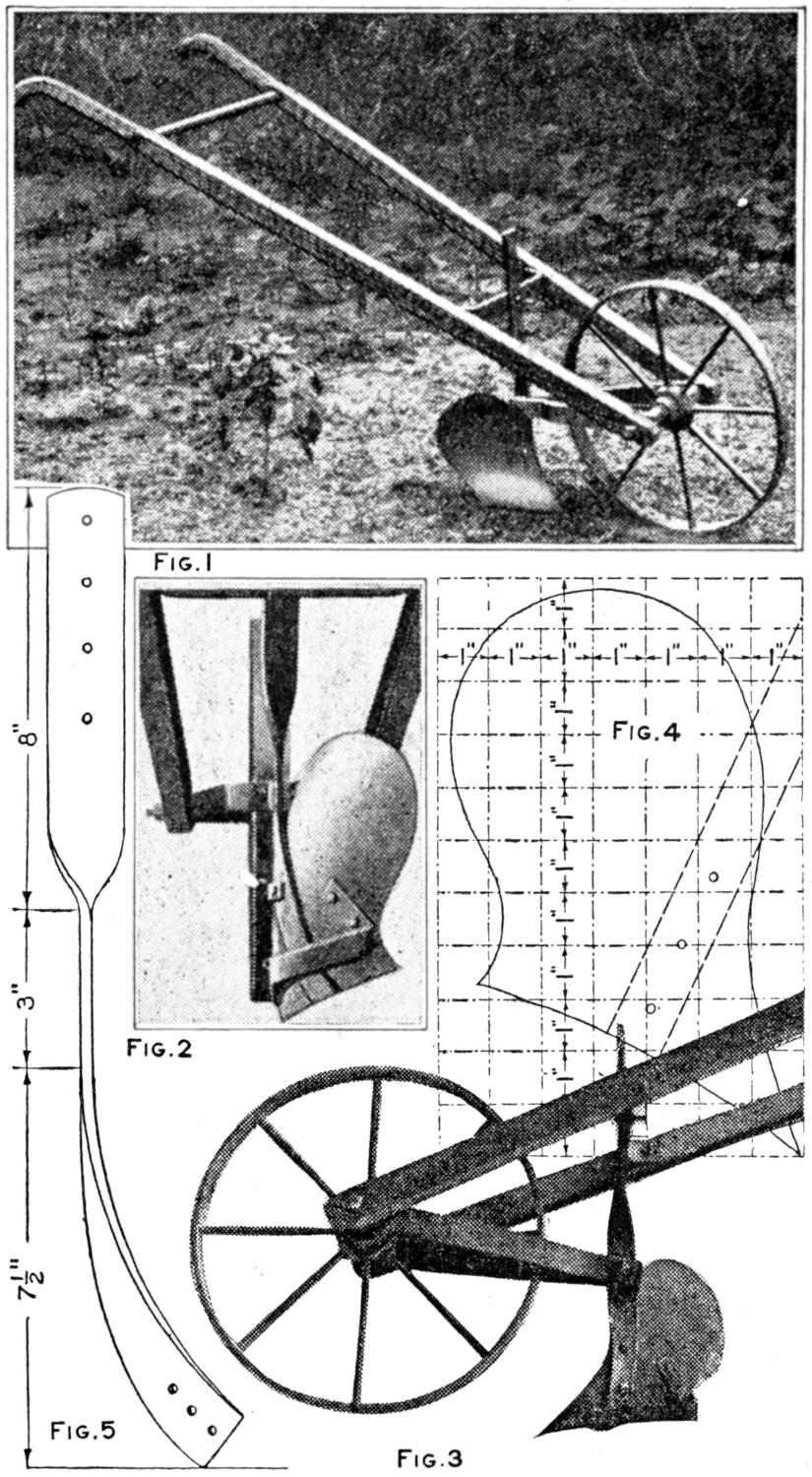

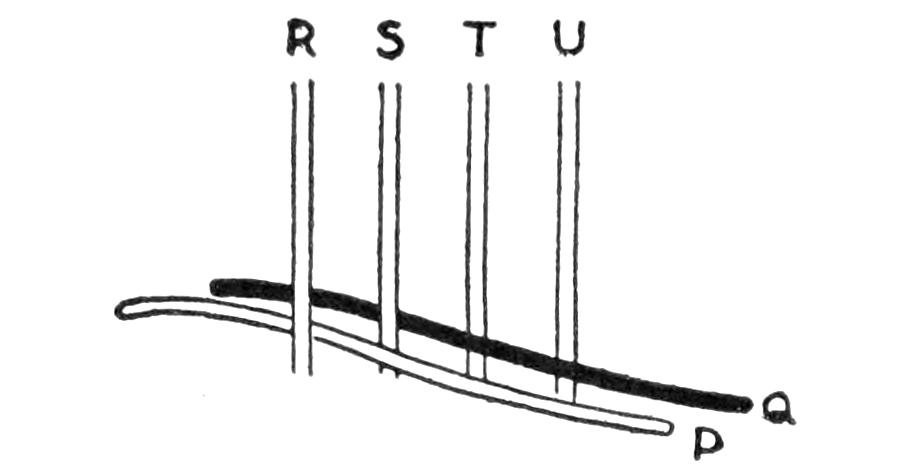

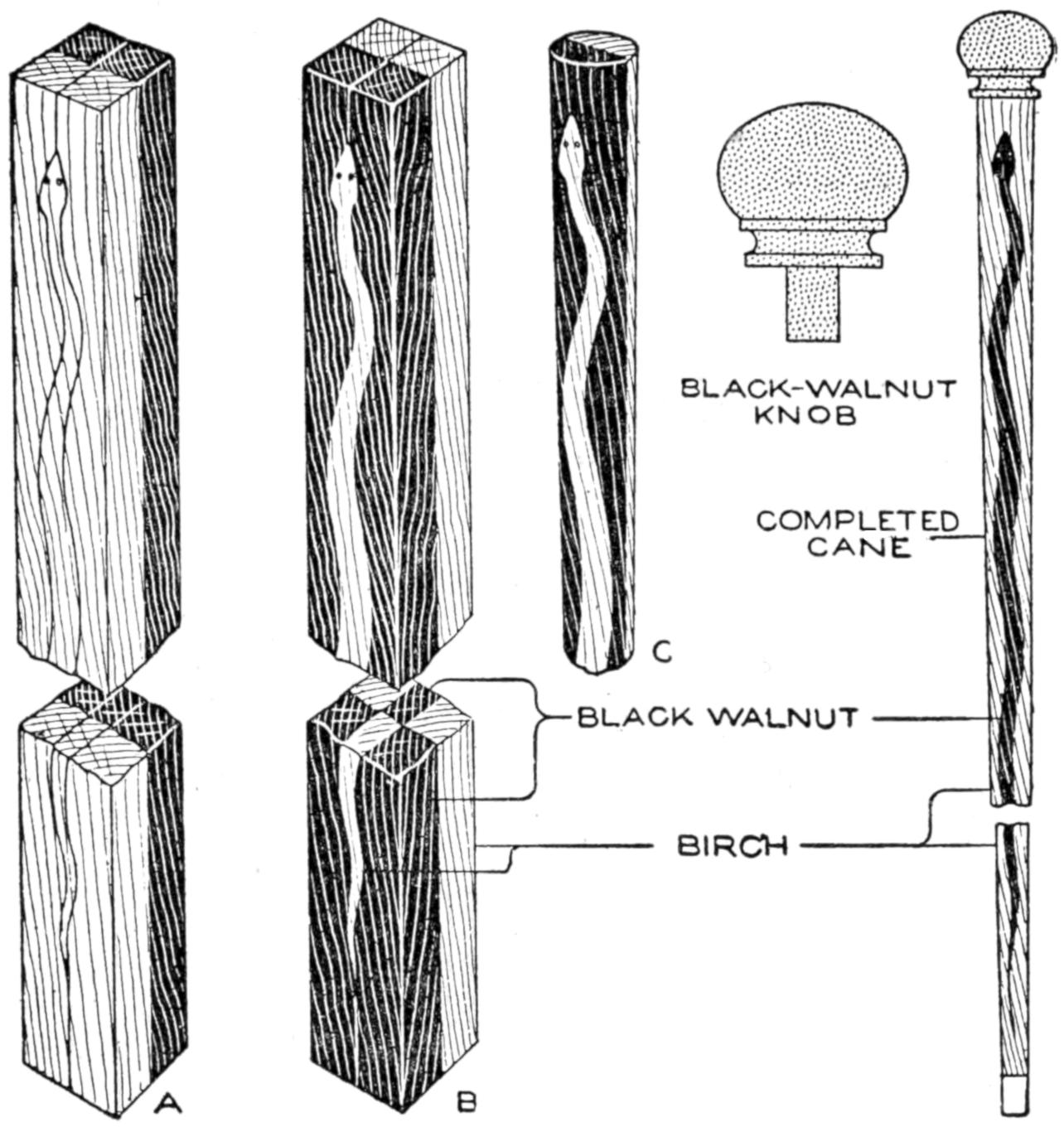

Skis and Ski Running

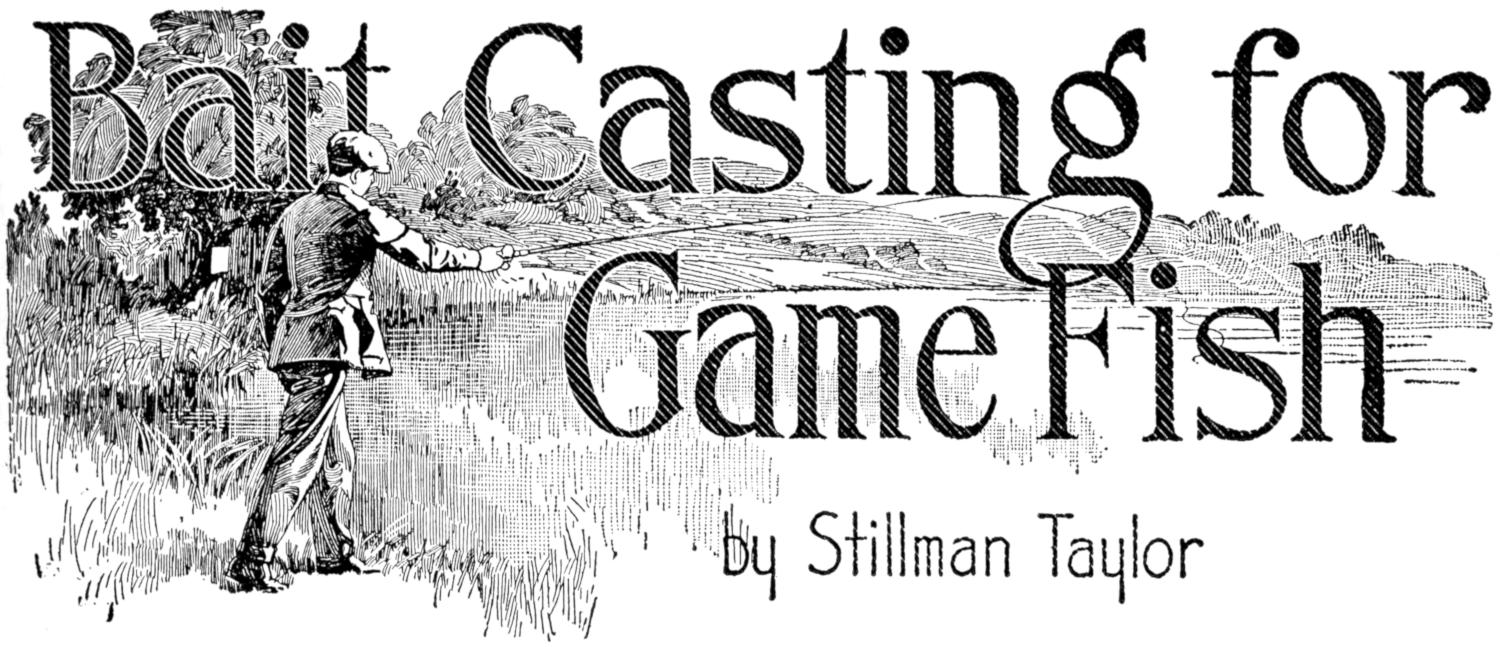

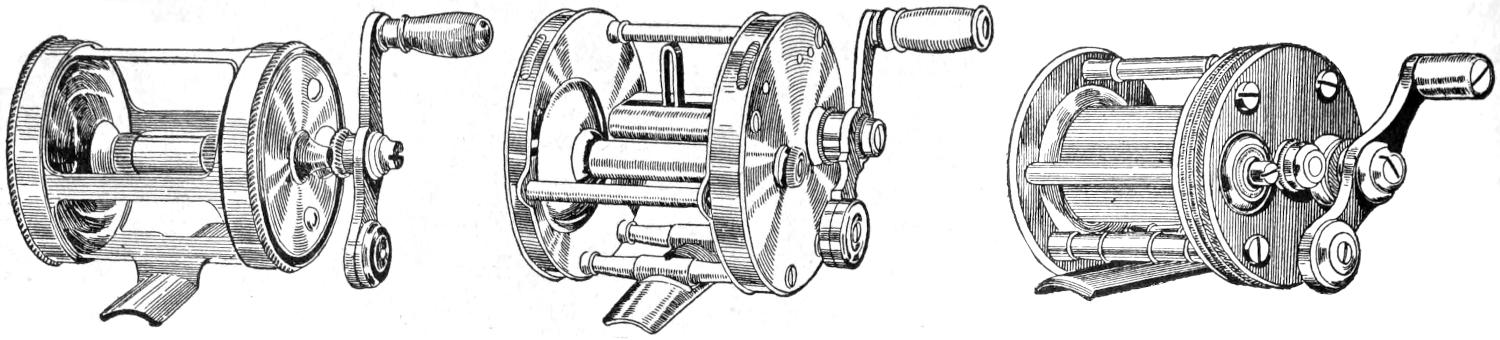

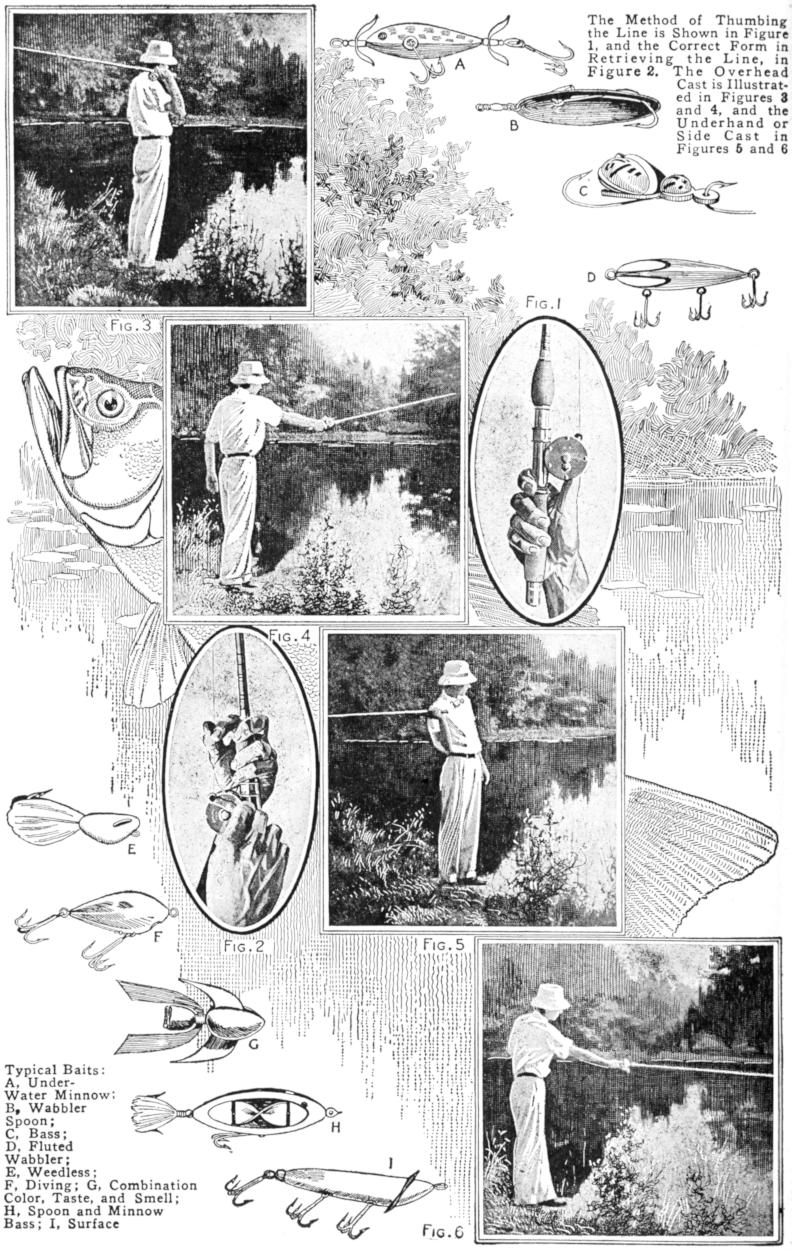

By Stillman Taylor.

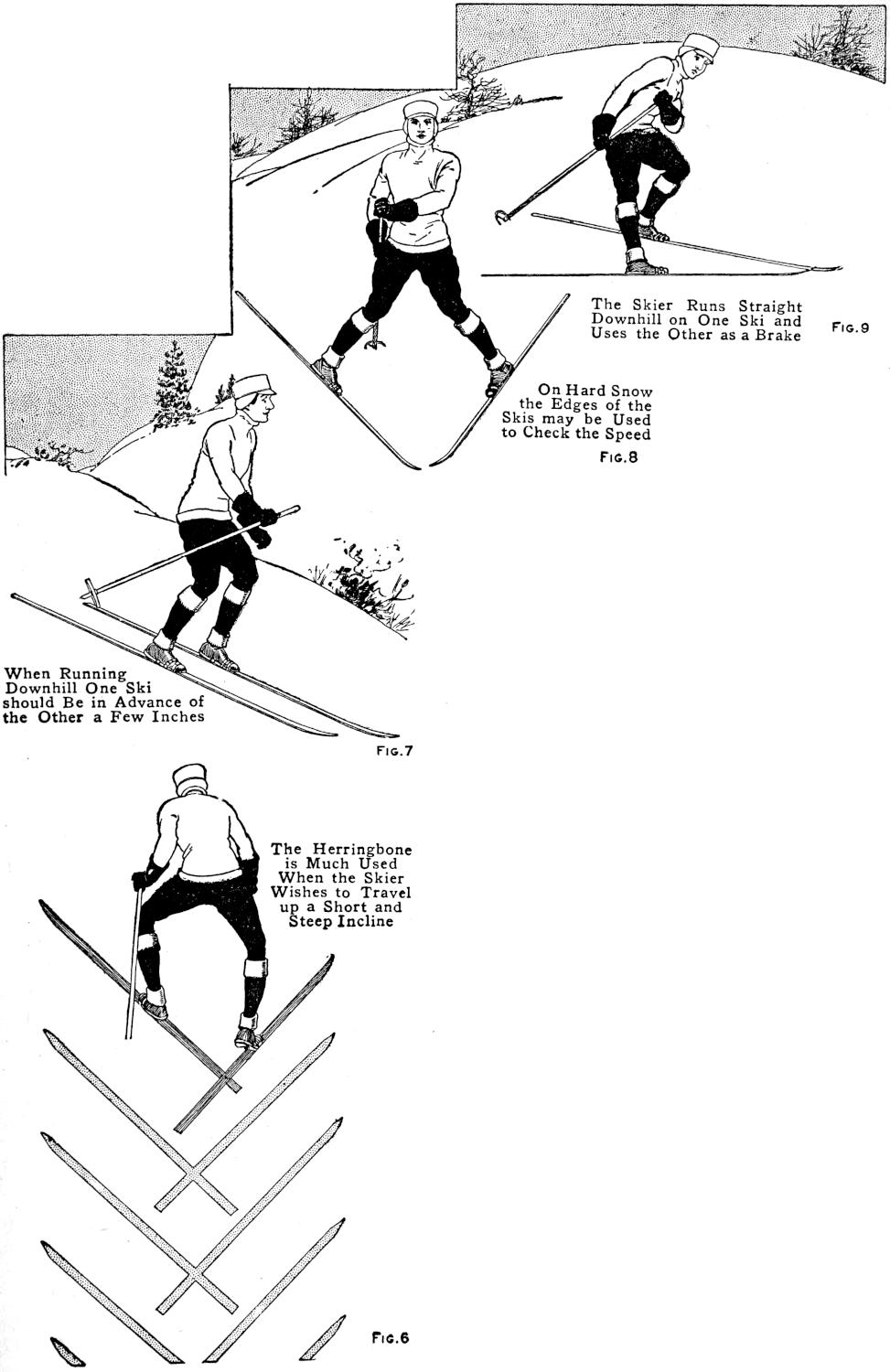

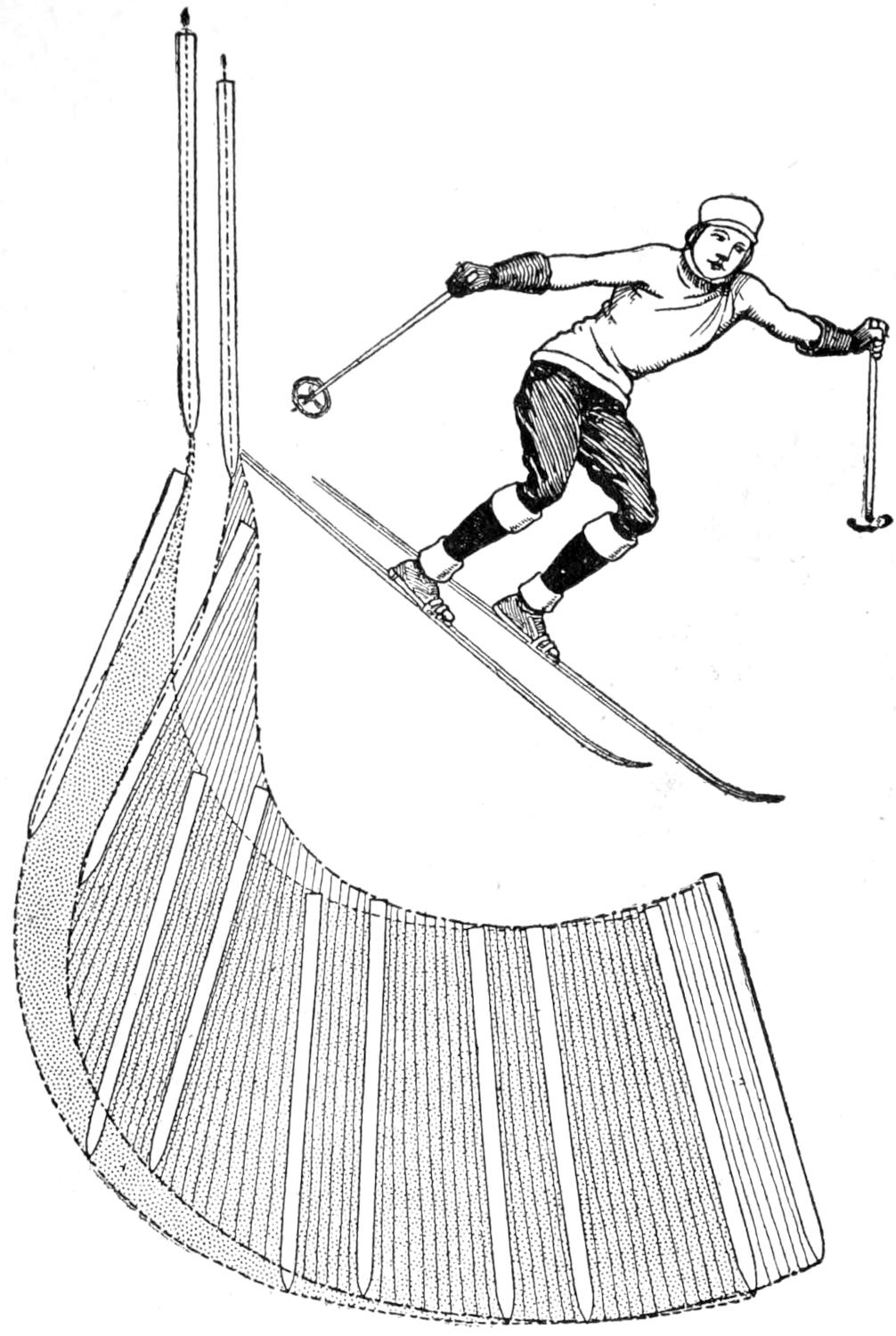

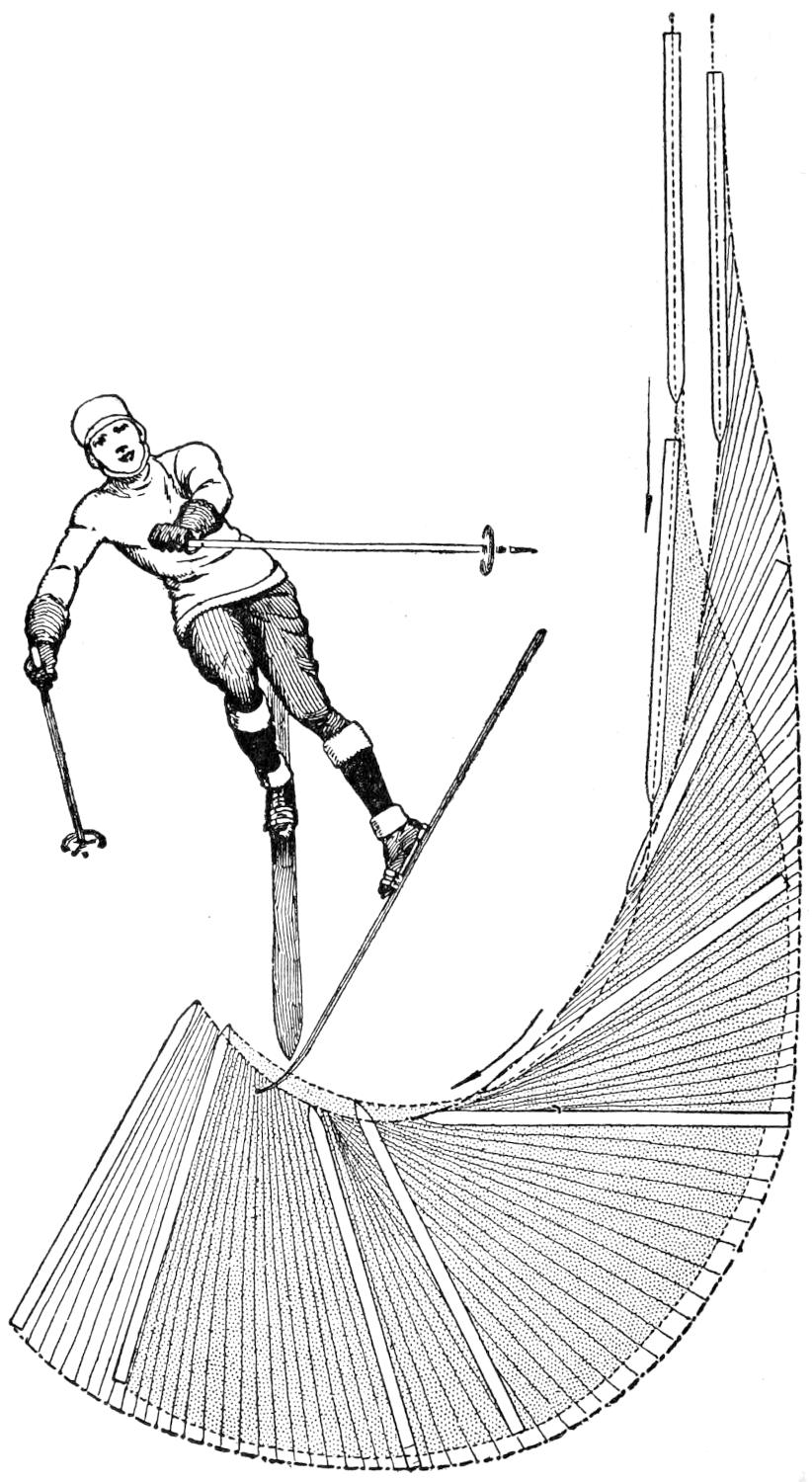

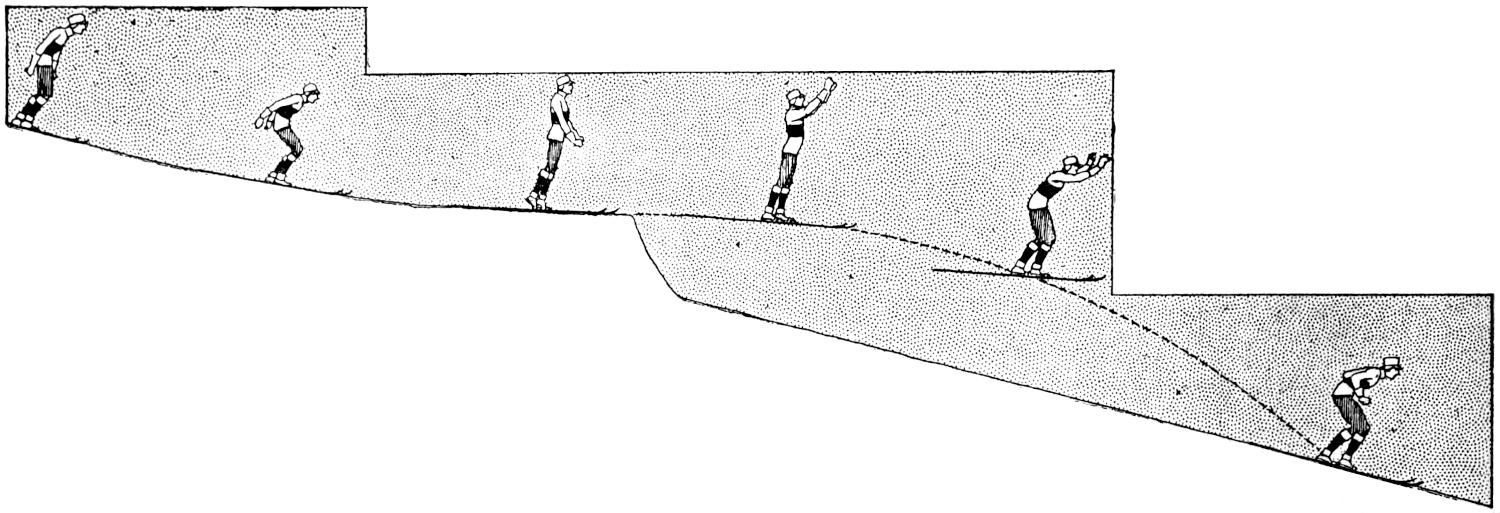

PART I—Prominent Types of

Modern Skis

The requirements of the modern ski call for a hard, flexible, and tough material, and while hickory, white ash, white maple, birch, yellow pine, white pine, and spruce are all used, the experienced ski runner considers hickory and ash to combine in the fullest measure the qualities most desired. Of course, every wood has its limitations as well as merits. Hickory is elastic and fairly tough, but heavy. Ash resembles hickory so far as elasticity is concerned, and its weight is about the same, but the wood contains soft layers. Birch possesses the requisite lightness, but is far too brittle to prove serviceable, and pine is open to the same objection. Maple makes an excellent ski, which can be finished very smooth so as to slide more easily than the other woods, but it is much less flexible than either hickory or ash.

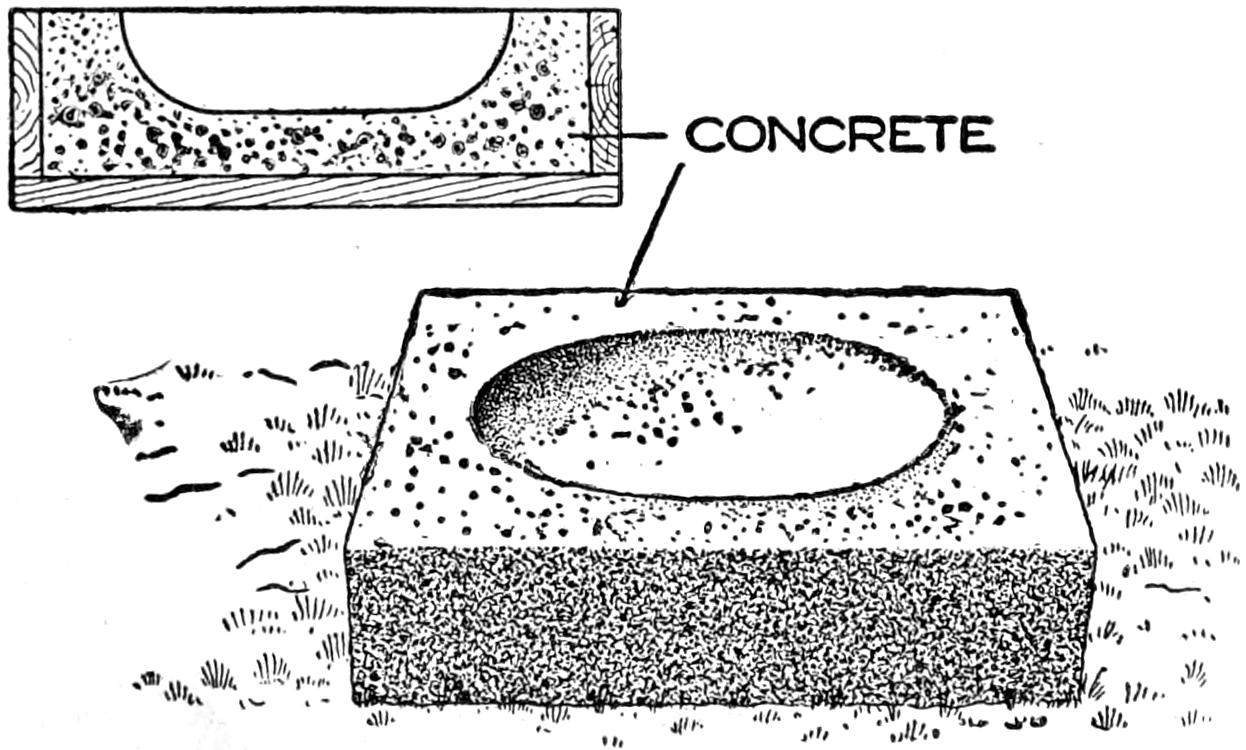

This form of ski, so called from the Telemarken province of Norway, where the art of ski running has reached a high order of skill, is probably the choice of the sportsmen wherever the exhilarating sport of ski running is practiced, and the larger portion of the members of the numerous skiing clubs use the Telemark-model ski. This type is practically identical with the most popular model so long used in Telemarken, and the rule for its selection is to choose a pair whose length reaches the middle joint of the fingers when the arm is stretched above the head. There are various makers of this type of ski, and while the modeling will be found to differ but little, there are numerous brands sold which are fashioned of cheap and flimsy material, and consequently unsatisfactory in every respect.

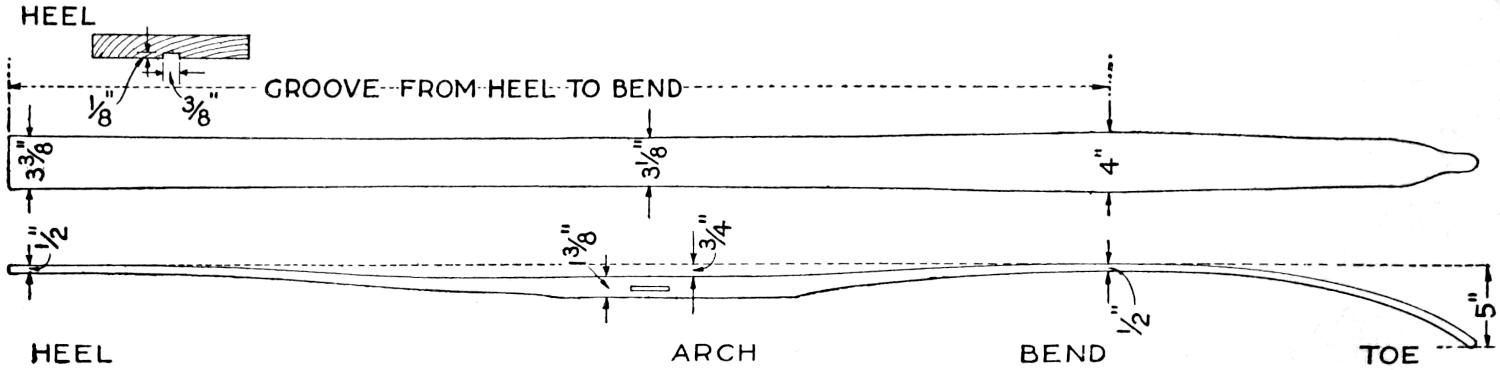

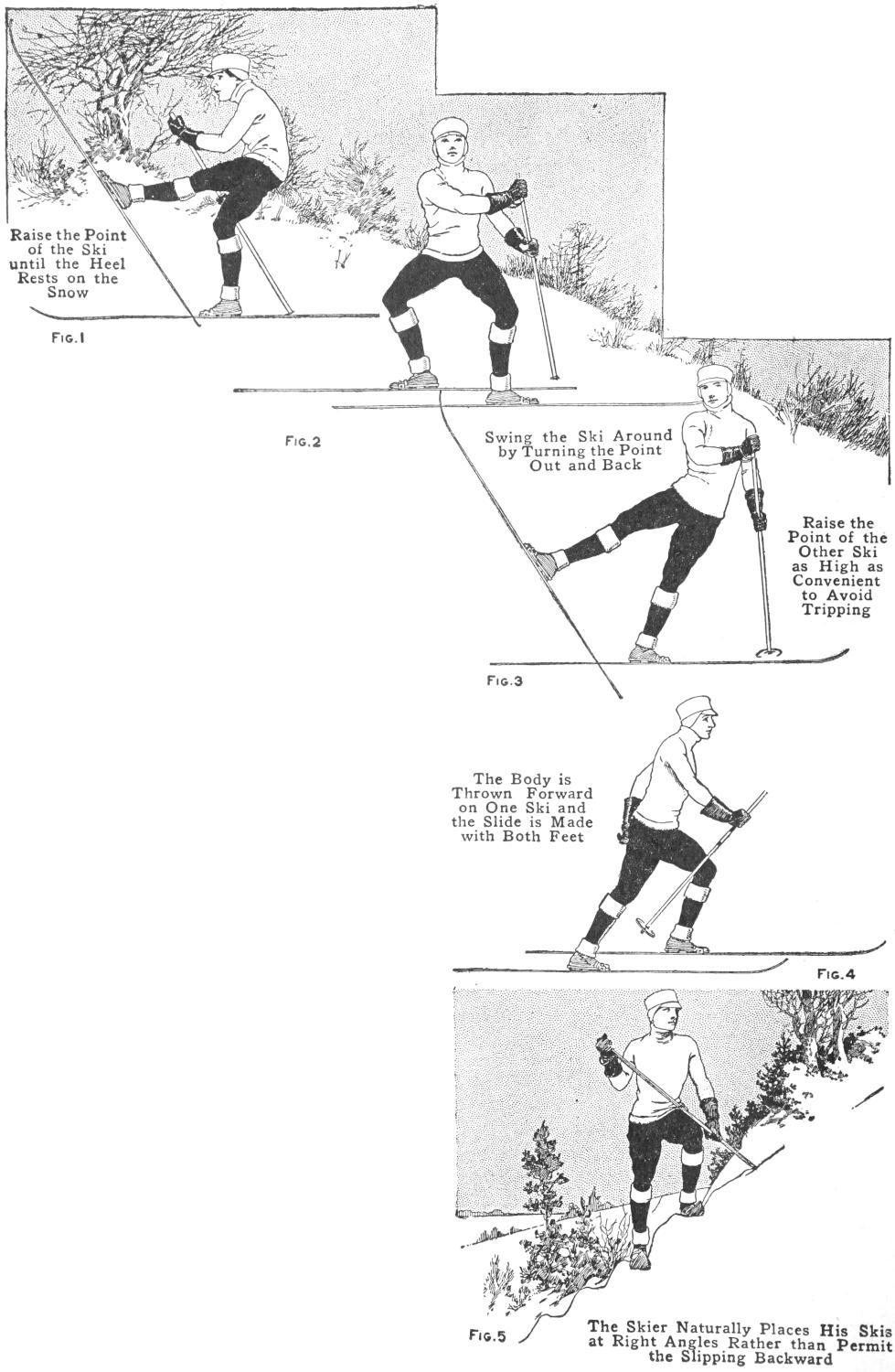

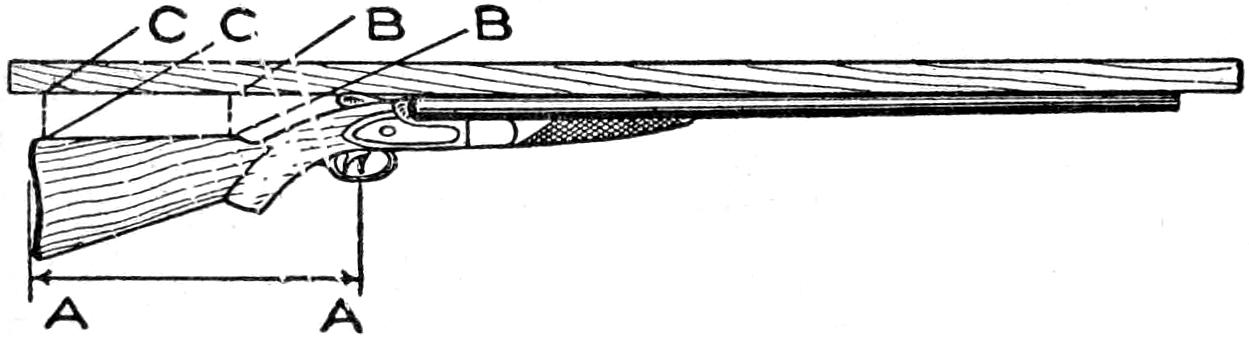

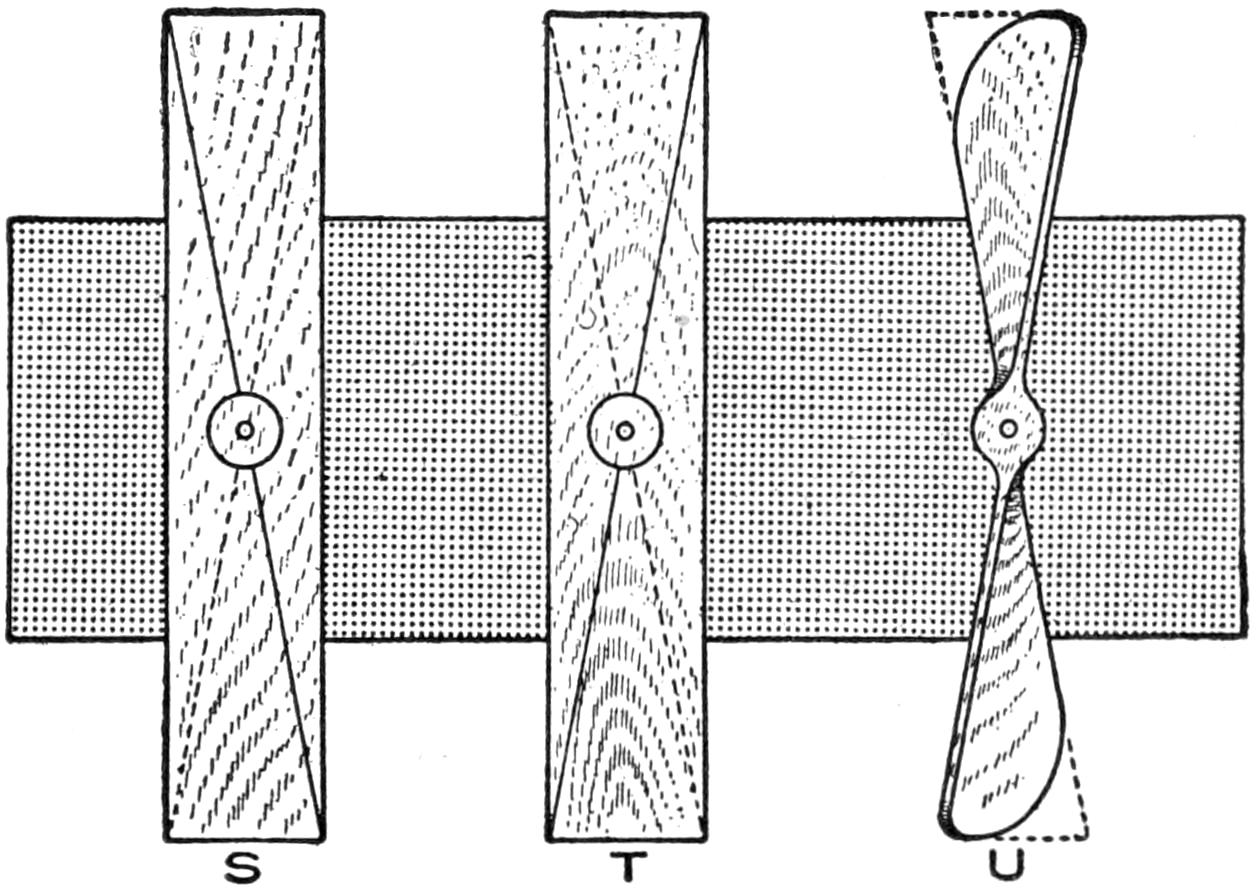

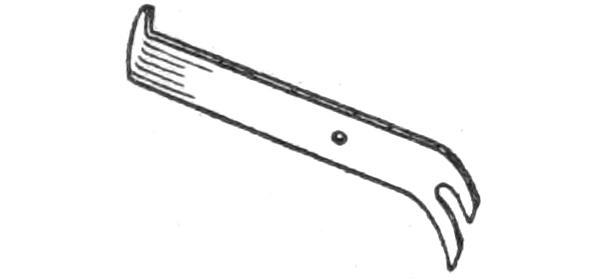

The Telemark model is shown in Fig. 1, and from this sketch it will be seen that the wood has two curves or bends, one running its entire length to form a graceful arch, and the second, at the toe. The first one is technically known as the “arch,” and the other curve the “bend,” while the front or toe end of the ski is called the “point,” and the rear end the “heel.” In almost all skis the under, or running, surface is provided with a hollow, known as the “groove,” which runs from the heel to the bend. It will be noticed in the drawing that the sides also are gently curved, thus making the ski a trifle broader at the ends than in the center. This curve affords a somewhat greater bend at the heel, and while some experts approve, others disapprove of it, but most ski runners agree that the curve should not be pronounced, or it will prove a handicap and make it difficult for the runner to secure a firm grip at the edge when ascending steep slopes covered with hard snow.

The “arch” of the ski is necessary to avoid bending when the weight of the body is on the runner, and the total height of this important curve should not exceed ³⁄₄ in., for a too exaggerated arch will practically form a concave running surface and retard the speed,[24] since it will run on two edges, or points, instead of on the entire running surface. A slight arch may be reckoned necessary to offset the weight of the body, but the utility of the ski, in nearly every instance, will be less affected by too little arch than by too great a curve at this point.

A good ski is told at a glance by its bend, which must never be abruptly formed, nor carried too high. A maximum curve of 6 in. is all that is ever required, and to prevent breaking at this, the weakest, part of the ski, the bend must be gradual like the curve of a good bow, thus making it more flexible and elastic at this point. As a rule, the ski should be fashioned a trifle broader at the bend than at any other point, and the wood should be pared moderately thin, which will make it strong and resilient with plenty of spring, or “backbone.”

The groove in the running surface is so formed as to make the ski steady and prevent “side slip” when running straightaway. In fact this groove may be compared to the keel of a boat, and as the latter may be made too deep, making it difficult to steer the craft and interfering with the turning, so will the badly formed groove interfere with the control of the ski. The Telemark round-faced groove is by far the best form, and for all-around use is commonly made ¹⁄₁₂ or ¹⁄₈ in. deep. Not all Telemark skis are thus fashioned, however, some being made without the groove, while others are provided with two, and I have seen one marked with three parallel hollows. The shallow groove is the most satisfactory for general use, and while a groove, ³⁄₈ or ¹⁄₂ in. deep, is good enough for straightaway running, it makes turning more difficult.

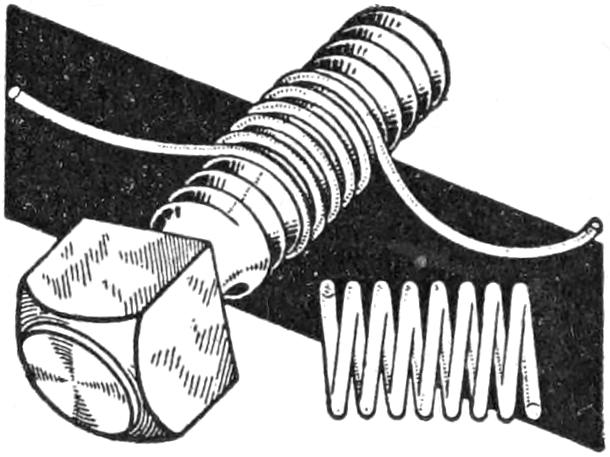

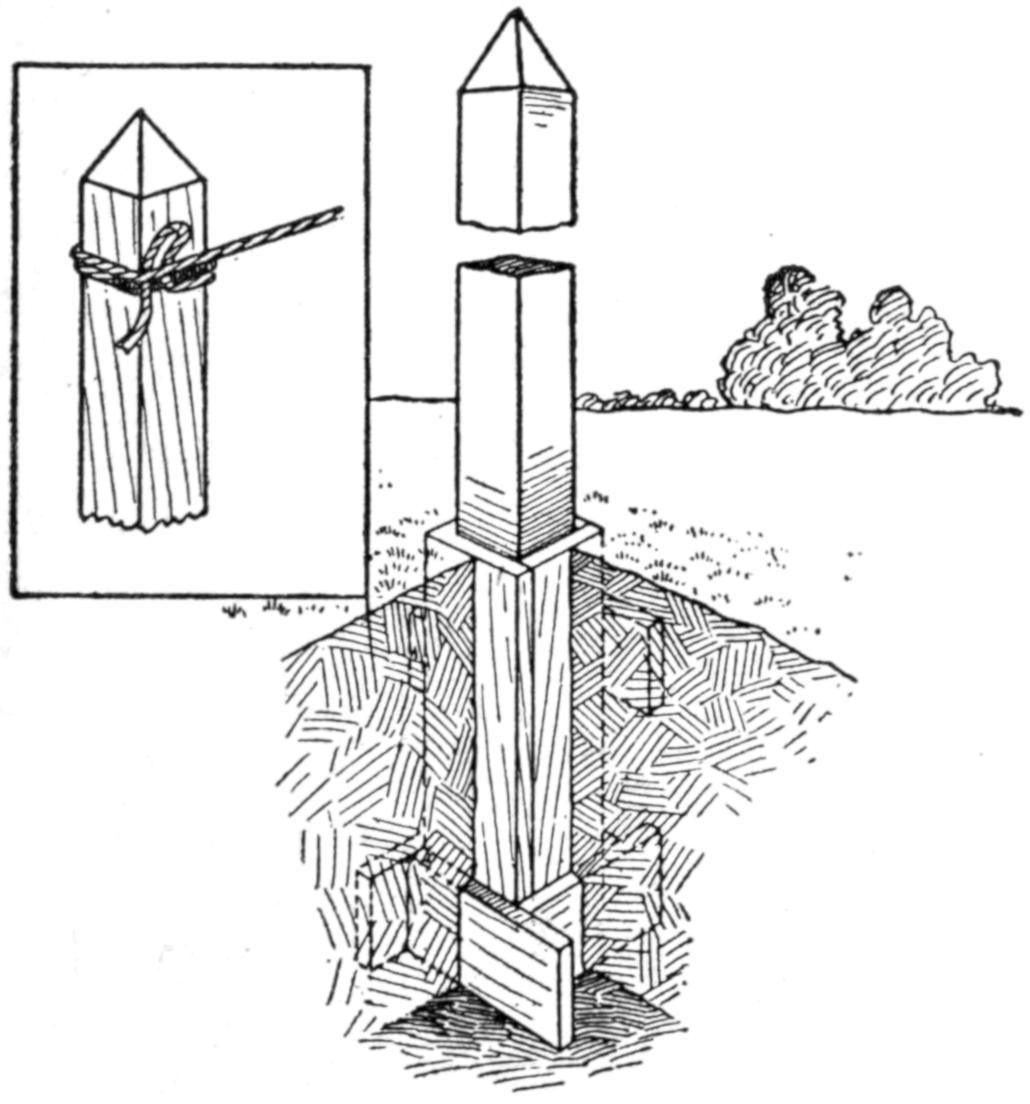

To attach the ski binding, which secures the shoe to the runner, a hole in the form of a narrow slit is made just back of the center. This is the usual manner of attaching the foot binding, and while it cannot but weaken the ski to a certain extent, it is the best method for making a secure foot fastening, and weakens the wood to a much less extent than the use of bolts, or other metal fastening.

So far as finish is concerned, most Norwegian makers finish their skis with a coat of black paint, while other makers stain the wood, and some finish the wood in the natural color by varnishing. This applies to the upper surface only, the running surface being rubbed down with linseed oil and made smooth with wax.

This type of ski is made quite long and comparatively narrow, with a deep groove, and is well adapted for running on the level or for gliding down slight slopes. This type of ski is commonly used in Lapland and to a less extent in the northern parts of Norway, but the great length and quick, short bend make this model less adapted for ordinary use, since the deep, rectangular groove slows down the speed, and the great length makes turning doubly difficult. For special conditions this type is probably useful, but it can scarcely be considered suited to the average use.

This type of ski is favored by but comparatively few ski runners, and the modeling is inferior to the Telemark ski. The arch is excessive in height, the bend is abrupt and stiff, while the round point, fashioned to prevent sticking in loose brush, has apparently little value in actual use. The Lilienfeld ski is made without a groove, and since the whole model is shorter and broader than the usual type of ski, turning is more easily accomplished, but side slipping is, of course, considerably increased. Ease in turning is a desirable quality, to be sure, but steadiness and immunity from side slipping are far more valuable qualities in a ski designed for all-around use. In short, the Lilienfeld model possesses no decided advantages over the Telemark type, but has many points of inferiority. To one who has used both models there can be no question but that the Telemark model is preferable.

When purchasing skis the sportsman[25] will make no mistake in selecting the Telemark model, and for an active person the skis should be long enough to reach to the middle joint of the fingers, when the arms are stretched above the head, and the ski is stood upright on its heel. The length of a pair so selected will be from 7¹⁄₂ to 8 ft. For elderly and less active persons, for individuals of short stature, and for ladies, skis reaching to the wrist joint will be about right; the length ranging from 6¹⁄₂ to 7 ft. For youths and children shorter skis, from 5 to 6 ft. in length, according to the size and strength of the person, are of course required.

Fig. 1

The Telemark, Swedish and Lilienfeld Models with Grooves and Grooveless Bottoms, the Telemark Being

the Standard and Best All-Around Ski; the Swedish is Long and Narrow with Upturned Heel, and

the Lilienfeld Is Short with a Round Point, More Abrupt Bend, and without a Groove

For all-around use where a large amount of straight running is done, the running surface should be provided with a groove, but if there is not much straight work to be done, and ease in turning is regarded as an important factor, the running surface should be made smooth. This necessitates making the skis to order, for practically all ready-made skis of the Telemark model are fashioned with a shallow groove. However, a groove may be easily cut in at any time if wanted later on. While other types are at times preferred for special use in certain localities, the Telemark-model ski is the standard, being equally good for all kinds of work, straight running, uphill skiing, and for jumping.

The best materials are hickory, or white ash, with a straight, even grain running from end to end. Ash is well liked by many experts, but it would indeed be difficult to find a more satisfactory wood than our American hickory. In fact, many of the most prominent makers in Europe are now fashioning their skis from American timber. As a rule, the best well-seasoned ash, or hickory, is heavier in weight than an inferior grade, and this is why the expert skier considers weight as one of the reliable “earmarks” of first-class material. A good hickory, or ash, ski made by any reputable maker will give the fullest measure of satisfaction.

The finish of skis is purely a matter of personal taste, but practically all Norwegian skis are painted black on the upper side, while a few of the cheaper maple and pine implements are stained. The plain varnished finish protects the wood as well as paint, but allows the grain to show through, and is generally preferred by experts. The running surface must be as smooth as possible to obtain the best speed, and it must not be varnished, the wood being filled with several coats of linseed oil to which a little wax has been added.[26] Tar is used to some extent, but this preparation is mostly employed by Swedish makers.

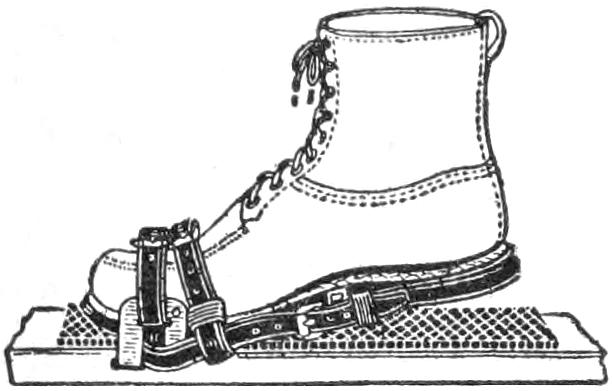

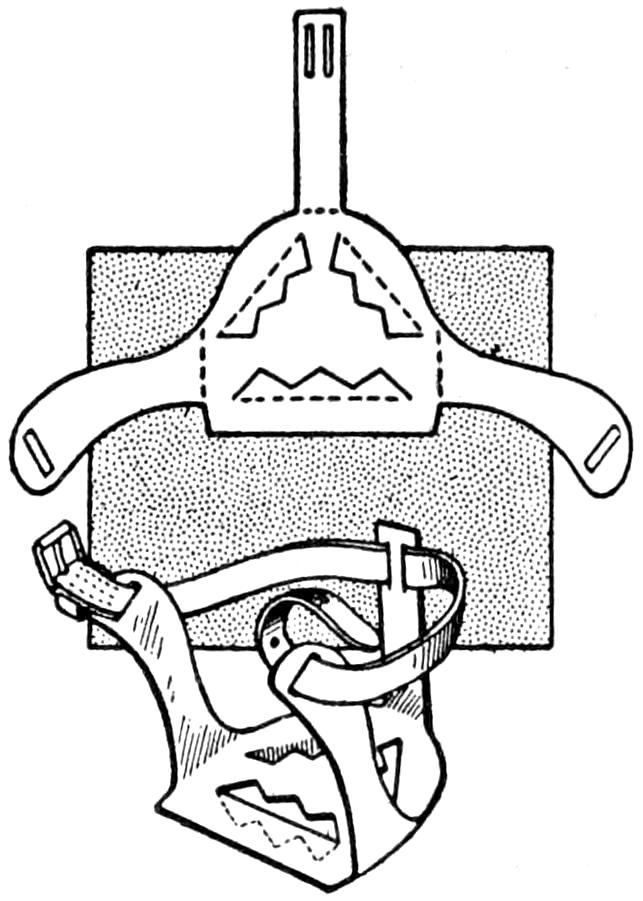

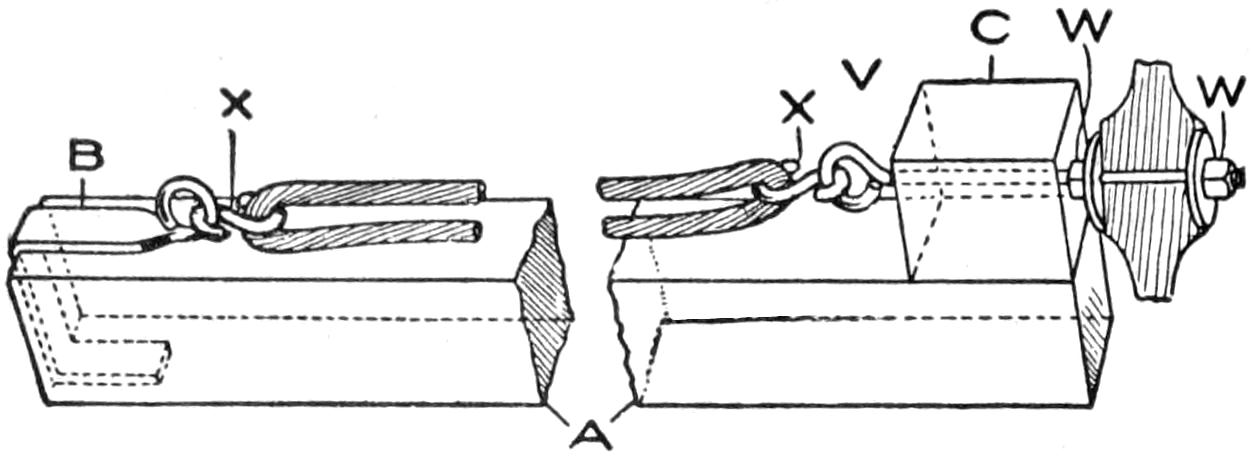

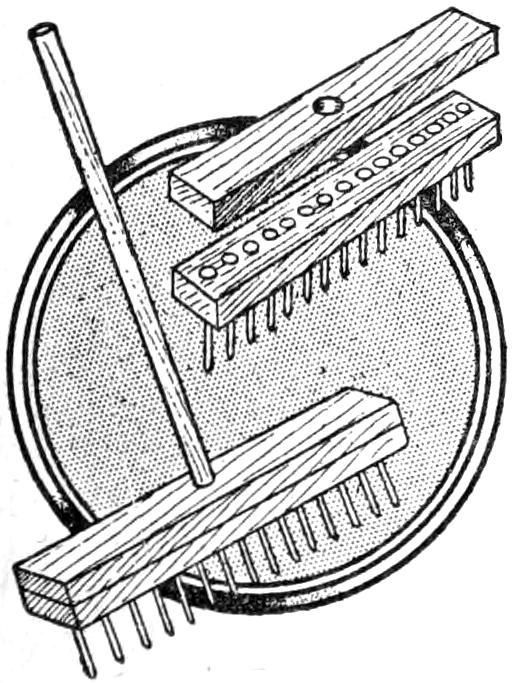

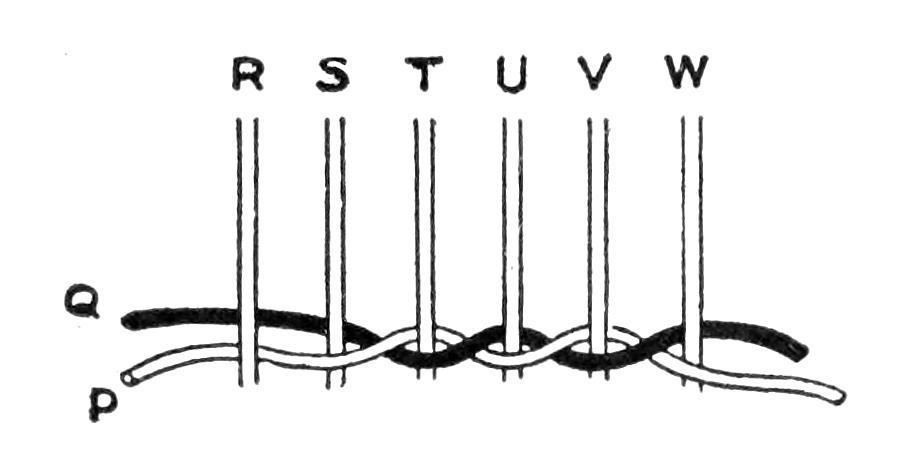

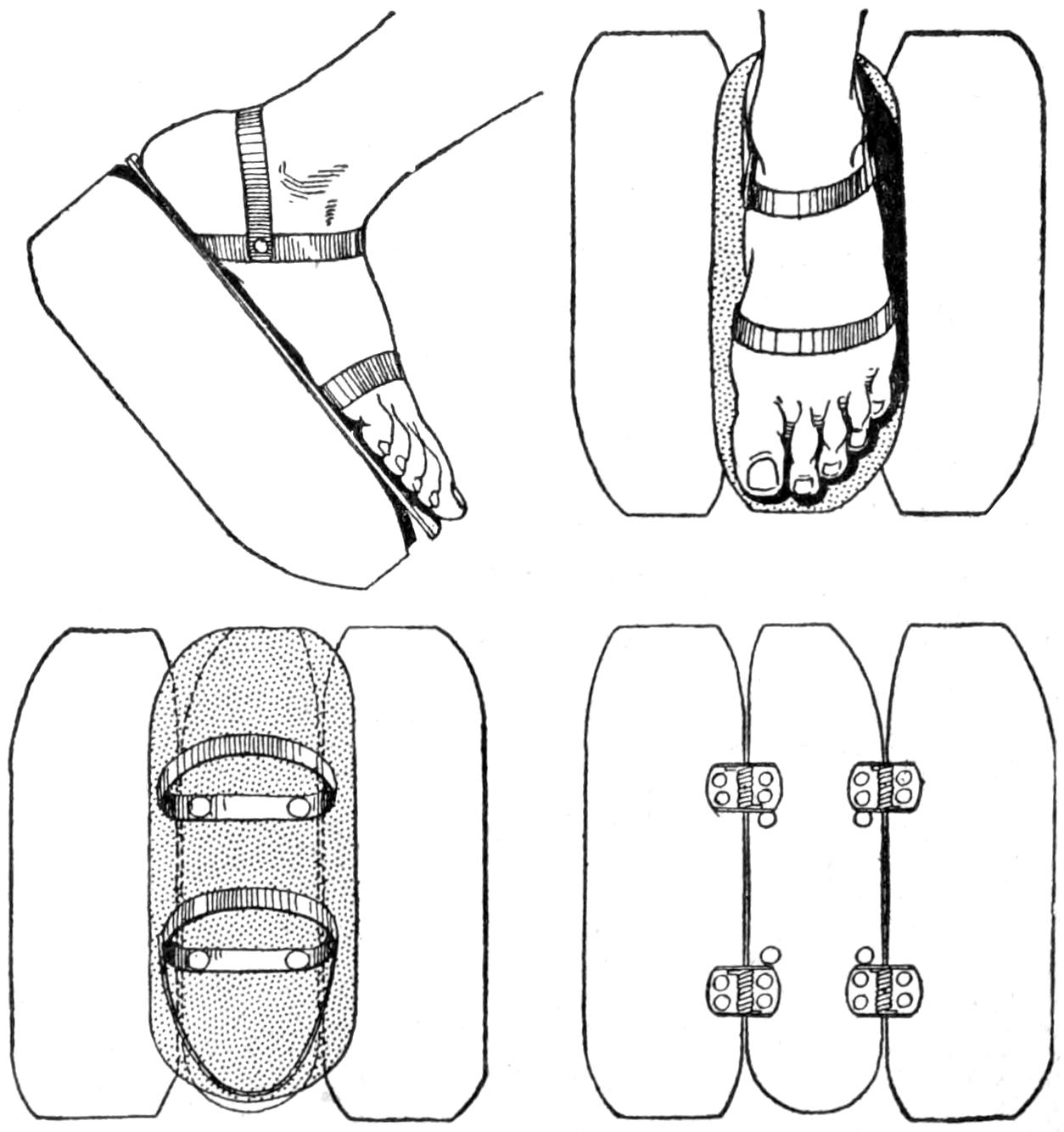

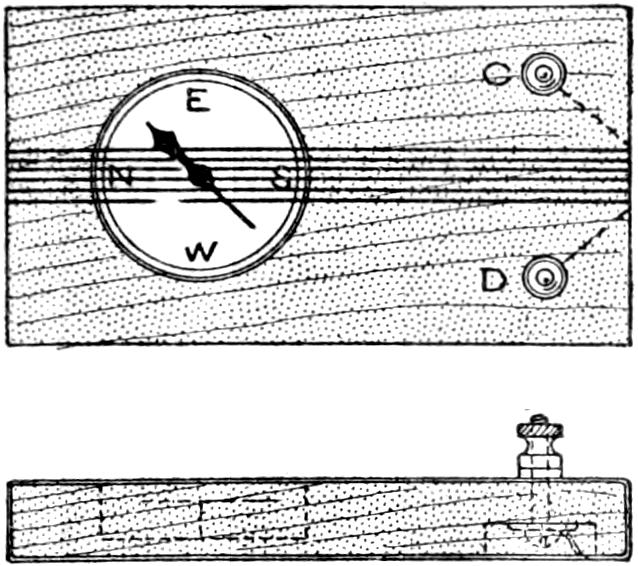

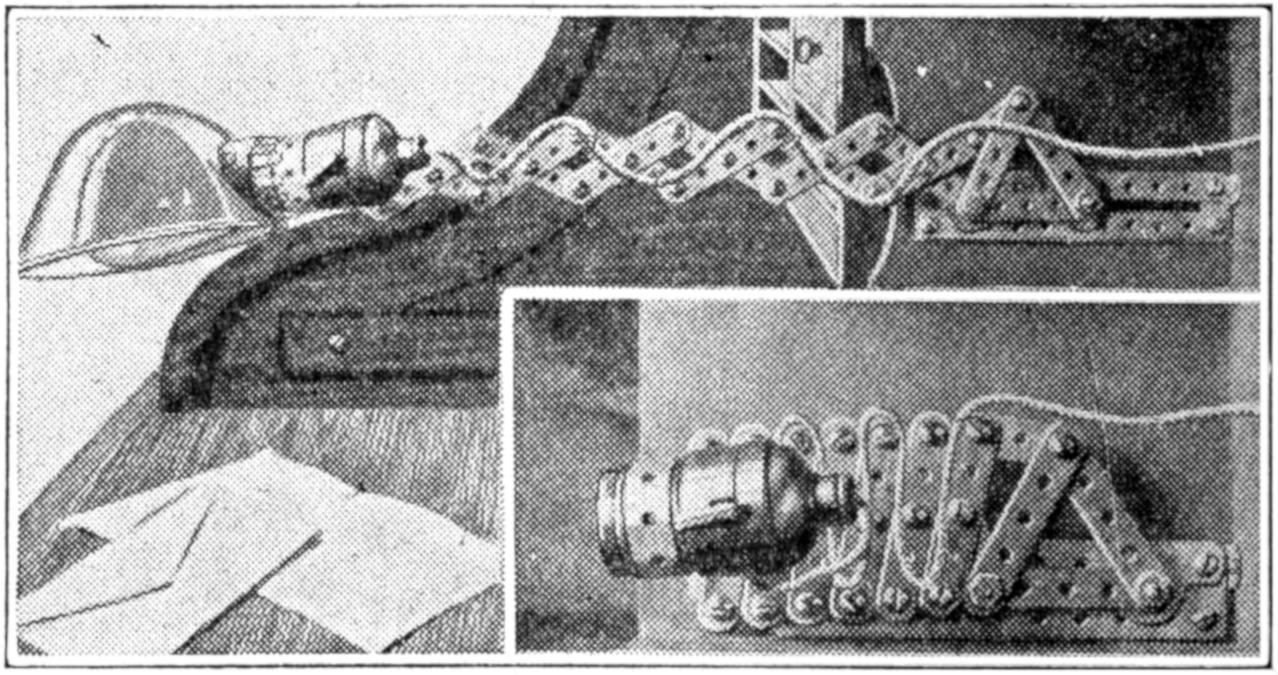

Fig. 2

The manner in which the foot is secured to the ski is highly important, and while various kinds of “bindings” are in use, from the simple cane binding, which marked the first substantial improvement over the twisted birch withes originally used by the peasantry of Telemarken, the Huitfeldt bindings are for many reasons considered the best by experts. The ski runner must have a foot binding that is well secured under all ordinary conditions met with in ski running, and it must be quite rigid and without lateral play. It is desirable also that the foot be freed whenever a fall occurs, thus preventing possible sprains at the ankle and knee, as well as avoiding breakage of the straps. Again the heel of the skier should be free to move up and down for at least 3 in., but the binding should check the vertical movement at this height, thus easing the foot of undue strain when the ski is slid forward, in climbing or working on the level. These essential specifications are so well incorporated in the Huitfeldt model that the description and illustrations of this admirable attachment will suffice. As shown in Fig. 2, the boot is wedged into a firm position between the metal toe piece at the sides. To secure a rigid support, these toe pieces must be firmly wedged in position on the ski, and the skiing shoe should fit between them snugly and well. For this type of binding, a shoe having a stout sole is desirable so that it may keep rigid under the pressure of the body at various angles, and be heavy enough to stand the more or less constant chafing of the metal toe plates. One excellent feature of this binding is the arrangement of the toe and heel straps, which allow all necessary vertical movement of the foot, yet at the same time provide a fairly rigid strong, and reasonably light foot attachment. When fitted with the Ellefsen tightening clamp, and it is a good plan to order the Huitfeldt model so equipped, the skis are easily put on and taken off. A large number of experts prefer this binding above all others, but the Huitfeldt type of binding may be made by the skier if desired. Any metalworker or blacksmith can supply the metal toe pieces, and the binding may be completed by adding suitable straps, or the foot may be secured at the heel by leather thongs.

While there are occasions when the proficient ski runner can dispense with the stick, as in jumping and practicing many fancy turns and swings, a good stick must be reckoned a valuable implement for climbing and downhill running, and often a help on a level. The beginner should not depend too much upon the stick, however, but should acquire the knack of handling the skis without this aid early in his practice. In short, the novice should practice both with and without the stick, that he may learn all the little points of balancing the body unaided, but every skier ought to know how to use the stick, that he may rely upon its assistance whenever necessary.

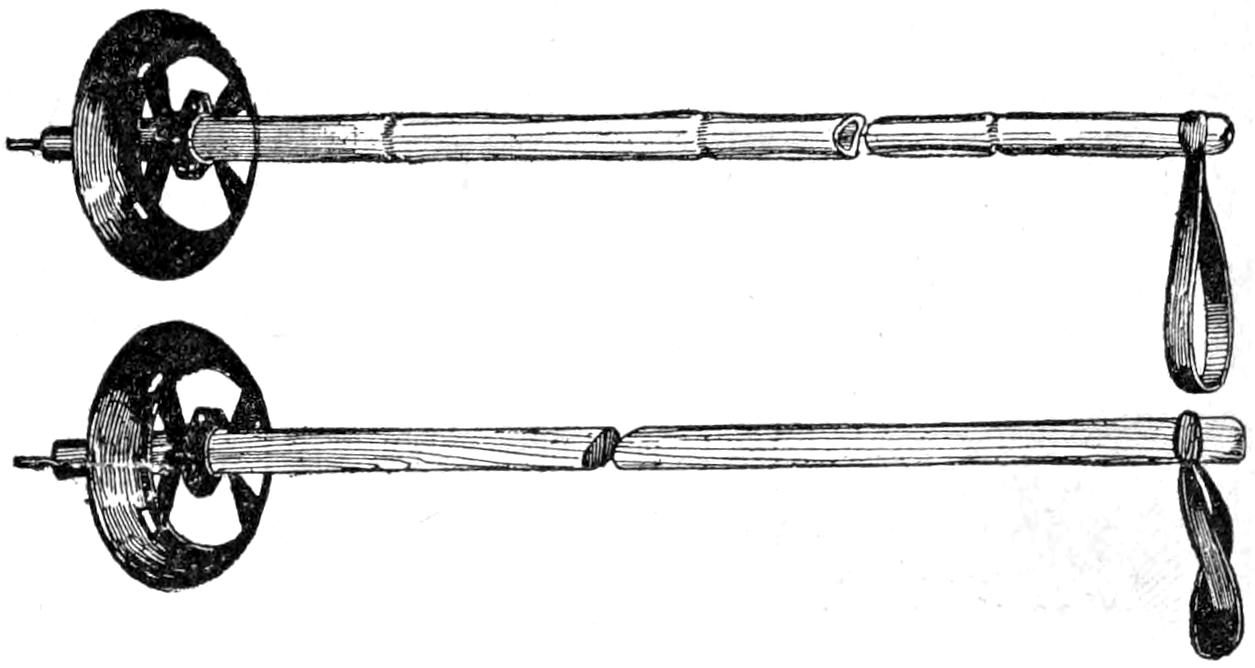

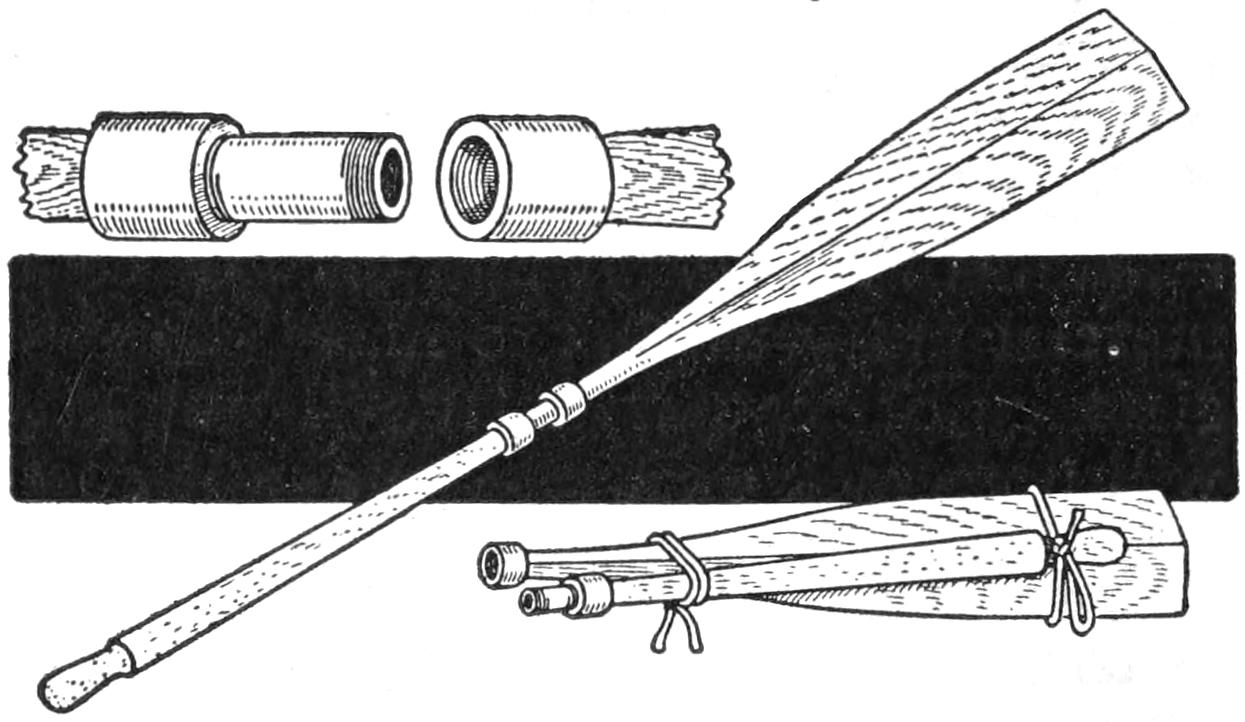

Fig. 3

Skiing Sticks with Staff of Bamboo or Hard Wood

Having an Easily Removable Aluminum Washer

The use of two sticks may be of help for mountain climbing, but the majority of ski runners consider one stout stick to be of more real service. For downhill running, the extra stick is of no value whatever, but rather a hindrance, the one stick being all that is required for braking. In choosing a stick, its height may be such that it will reach to the shoulders of the skier, although many prefer a shorter one. On the average, a stick 5 ft. long will be found about right for most persons, while a proportionately shorter stick will be required for boys and girls. Bamboo of good quality is generally preferred, since it is light, elastic, and very stiff and strong. Hardwood sticks are a trifle heavier, but if fashioned from straight-grain hickory, or ash, are as[27] satisfactory as the bamboo. In any case, the end of the stick should be provided with a metal ice peg, and a ferrule to strengthen the wood at this point. A few inches above the peg a ring, or disk, is fastened, and this “snow washer” serves to keep the stick from sinking too deeply into the snow. Wicker rings, secured with thongs or straps, are much used, as are also disks of metal and hard rubber. A decided improvement over these materials has been brought out in a cup-shaped snow washer made of aluminum, which is flexible and fastened to the stick with clamps so that it can be easily shifted or removed at will. This feature is a good one, since the washer is often useful for assisting braking in soft snow, but is likely to catch and throw the runner if used upon crusted snow, hence the detachable arrangement is of value in that it supplies an easy way to take off the washer whenever desired. The sticks are shown in Fig. 3.

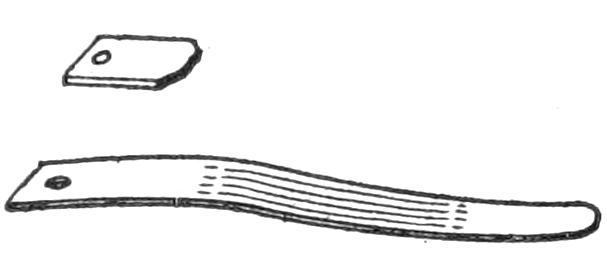

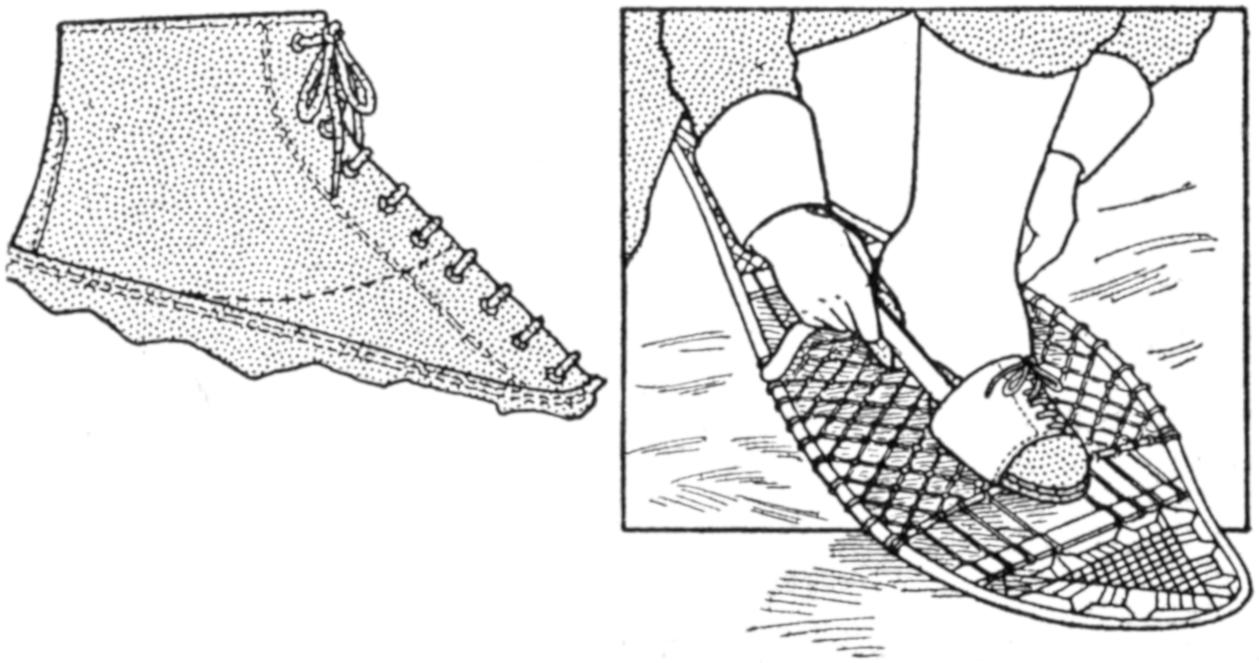

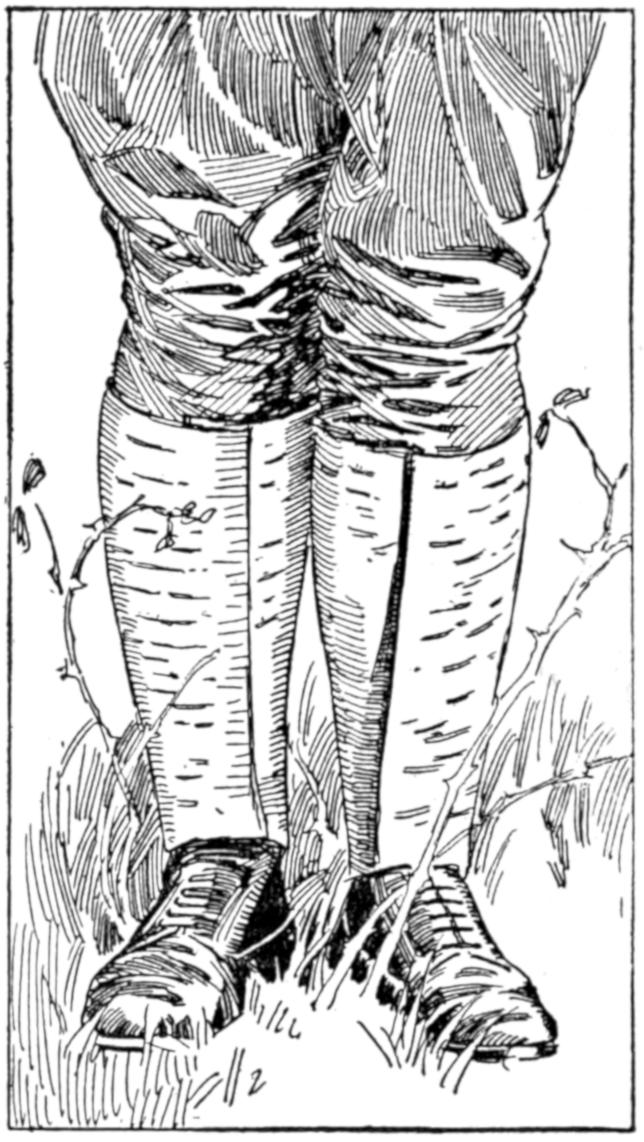

For skiing an ordinary pair of heavy-soled lace shoes that fit well are suitable, but to keep the heel strap of a binding from slipping, the shoes should have broad, concave heels, or a small strap and buckle, firmly sewed in place at the extreme end of the heel, should be fitted to them. Personally, I prefer the heel strap to the special heel, but any cobbler can fit the shoes with either one. Specially designed skiing shoes, or boots, as shown in Fig. 4, are to be had at the sporting-goods dealers’, and while good, are somewhat expensive, because most of them are imported. Of course, shoes for skiing must be amply large so that one or two pairs of woolen socks may be worn; two pairs of thin, woolen stockings being less bulky and very much warmer than one extremely heavy pair.

Fig. 4

Specially Designed Skiing

Boots, Handmade for the

Sport, with and without

Heel Buckles

For clothing, the soft, smooth finish of the regulation mackinaw garments cannot be improved upon for outdoor winter wear, although any suitable material will serve as well. Smooth-finish material is the best in all cases, because cloth of rough texture will cause the snow to stick and make it uncomfortable. Regulation mackinaw trousers, split at the bottom and fastened with tapes to tie close to the ankle, are as good as any, over which cloth puttees, or leggings, may be worn to keep out the snow. For the coat, a mackinaw, made Norfolk-style, with belt and flap pockets secured with a button, has given me the most satisfaction. For ladies, close-fitting knickerbockers and leggings are generally preferred when a short skirt is worn.