Title: The Builder, No. 2, February 18, 1843

Author: Various

Release date: September 1, 2023 [eBook #71540]

Language: English

Original publication: London: Publishing Office 2 York Stree Covent Garden, 1844

Credits: Charlene Taylor, David Garcia, Jon Ingram and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Library of Early Journals. Noted on site that this resource is no longer available.)

The various speculations and expressions of opinion to which our movements have given rise would, if accurately noted, supply the most interesting exposition of what we have to contend with on the one hand, and what we have to encourage us on the other. We should gather from it the most convincing testimony of the necessity of some such effort as that which we are now making to remove the general ignorance on all points connected with Building, whether as regards the science or its professors and practitioners. Grave and experienced men are to be found who hold up their hands in astonishment at the rashness, as they consider it, of our enterprise—men who argue upon general principles against the success of our plan. They say the Builders are not a reading class, nor a class at all, either in themselves or their connection, to support a periodical like the one we propose to give. The publishers in particular, and they, in their experience on all points connected with publication, are certainly entitled to be considered oracles—the publishers generally have but a mean opinion, or say they can form no opinion at all of the probabilities of success. They confess themselves astonished at the numbers of the Building Class; but they mistrust the conclusions to which we have come upon the data which these numbers supply. So little have publishers had to do with the Building Class, and so little the Builders with the publishers, that they might have lived on the opposite sides of the same globe as regards the acquaintance each has with the other for any practical interchange of their mutual special interests; but we propose to bring them into more intimate union, and to make the publisher at least confess that he knew not one half the territory over which his appointment was designed to extend.

But there are parties connected with the arts who might have been supposed to have lived in something like a consciousness of the immense, as it is intimate, alliance that subsists between them and the Builders as members, it may be said, of one common fraternity; and these are as ignorant of the more important facts as it is possible to suppose men to be. An eminent sculptor addressed us the other day in a strain of this character: “The Builders,” said he, “are too small a body to support a class paper; look around you,” he continued, “and you find them dotted here and there only, and not like the Shoemakers, or the Publicans, or the Butchers, meeting you at every turn.” It should be stated that he had seen our Precursor Number. We asked him if he was aware of the fact the Carpenters alone outnumbered the Shoemakers, and that the whole body of Builders are as five to one of that very numerous class: that in round numbers we had 130,000 Carpenters, 60,000 Masons, 40,000 Bricklayers, 30,000 Painters, Plumbers, and Glaziers, and so on. And that these were an intelligent, a reading, a thinking, and provident class, and well to do in the world. At this he expressed his surprise, but yet in such terms as to shew us that there was a leaven of incredulity mixed with it. Again we referred to them as an advertising class, on which he seemed amazed, but more so when we pointed out to him seventy-one advertisements in the Precursor, and expressed our belief that shortly it would amount to five times that number. On this head, indeed, it would be easy for us to give convincing proof, were we so disposed, and we know not but we may, for the curiosity of the matter, some day do it; we could print the largest part of a paper in thickly-set advertisements pertaining to building, and all selected from the London and provincial papers of one week: sales and falls of timber, of brick earth, and minerals; of building land and general building materials; businesses to be disposed of, contracts to let, situations wanted, and the like; indeed, there is no such class, no class so much in need of, and so well able to support their own weekly paper. Other parties we have met with, and reports have been brought to our ears, from men moving in the very ranks of the workmen themselves, who express a most disparaging opinion, not of our objects, or our exertions, but of their fellow-workmen; they say, in as many words, that “we are throwing pearls before swine.” The plan is good, they admit; but they urge that the mass of the workmen are too fond of amusements, and so given to low and sensual indulgences, as to deny the hope that they will, to any extent of numbers, seek to benefit by it. These people, we are afraid, measure their class by themselves. Others again urge, that the reading appetite is vitiated and depraved, and that unless we pander to the passions of the multitude “by strong and exciting and vulgar matter” (we use their own words), we may look in vain for subscribers. Against all these we have to contend, and we are utterly opposed to them in opinion on all such grounds as the foregoing; but in one point we agree,—we certainly have an uphill affair. The ground we have chosen is unoccupied and untrodden. We have a great task in reversing the usage of centuries. We must, therefore, call upon the workmen themselves to aid us in fighting their own battle,—not a battle against interests or individuals, but against ignorance and exclusion. And we reiterate our call on the friends of the working classes, for whose satisfaction, and the satisfaction of all who care to know it, we now make our profession of purpose as regards the end and object of our labours.

We do not want to inflame the mind of the workman with discontent; we do not want to unsettle or disturb the relations of society; we do not wish to raise any man above his proper condition. On the contrary, we would promote and teach contentment; we would settle and consolidate; we would give every man his own proper level. We consider that it is too much the tendency of the agitation of these times to effect the opposite of all this. The best words are perverted from their true meaning or misunderstood; a false principle pervades and regulates our intentions, and the world runs counter to its own wishes, by reason of its neglect of simple truths, which he who runs may read.

As regards that much abused word education, and as to our purpose to educate the workman, a right understanding will suffice to disarm it of its terrors in the minds of many who have seen in its perversion or abuse that which they have ascribed to education itself. What is an educated man? Here we fancy we hear ten thousand voices exclaim, What a question! And yet we challenge the whole of that ten thousand to give the true answer, if they reply in the generally accepted meaning of the term. Education is too frequently confounded with book-learning, and that is considered to be knowledge which is only the key to it. Take your educated man, as he is called, and put him into the workshop or the sphere of operation in that art on which he descants so learnedly, and he must give way (at first at least) to the unlettered, or, as he is termed, the uneducated artificer and labourer. A mind well stored with the facts that bear upon any particular art, may be likened to a well-furnished chest of tools; but it requires a practised hand to apply those tools with skill and to a useful purpose—all the rest is mere theory; and of this sort of theory we have a great deal too much now-a-days.

Aye! we will take the rude, unlettered Carpenter of the most obscure country workshop, and match him as an educated man against the most learned pundit of our universities. We do not mean to say that the Carpenter is a better man for his rudeness, or because he may read or write badly, or not at all; but we take this as an illustration of the meaning we attach to the word education in its practical sense, and we will now say a word as to its bearing on the course we have chalked out for ourselves.

It is true that the relations of society and its workings in these times appear very mysterious, confused, and complicated; but what does it arise from? Does any man imagine it to be more difficult to regulate domestic or civic government now, than it was in the simplest state of pastoral life? Not a whit the more, provided the education of the heart, the bringing out of its virtuous tendencies be properly studied and promoted. Teach the workman his duties in the several relations in which he is placed, as much as you aim at making his skilful in the handling of his tools, or the fashioning of his materials, and you have educated him for the whole end of his existence; but he wants few or none of the theories of matters that are above him.

It is to settle then, to calm or quell the agitation of purpose which now disturbs the public mind, to do our part in this, as we conceive, great work of national repair, to bring into harmony the now contending powers and forces, and to assist in our humble way to direct them to one end and object, of peaceful and profitable action, that our exertions will be directed.

And how do we propose to do this? how do we aim to be useful in this work of charity,—for surely charity it must be called which shall effect the ends of peace? Why, by bearing in mind and acting upon the old proverb, “Charity begins at home.” We begin with our class—we begin at home.

Oh! there are conquests more bright, achievements higher, glory greater to be reaped in this sphere than in all the turmoil of politics, or the dread strife of war! Let us wean our countrymen, but particularly that great body of which we have the honour of being a member,—the building class,—from the fretting and exciting consideration of subjects which only tend to unhinge the mind and distract it from acquiring that solid profit which a skilful exercise of his craft procures from every intelligent workman, let the quiet habits of a steady industry be enforced upon ourselves; let our curious and admiring thoughts be bent, so far as business goes, upon the investigation of the principles in science, and the properties in nature which affect the things we construct, and the materials of which they are constructed; let the workshop and the building have our working hours, and our homes and families the rest, even to a participation in our studies, for these in most instances may be made the interest, and now and then the delight of every family circle.

Is it nothing, good countrymen and esteemed fellow-craftsmen, that we have to boast of honours and achievements such as neither military daring, or statesmanlike craft or wisdom has ever attained, or can attain to. What are[18] all the doings of the science of war or government compared with the building up, on clear and well-defined principles, abstract as well as tangible, those stupendous and imperishable memorials of a country’s history which the works of the Architect and the Building Artificer supply. After the lapse of ages of obscurity, we recover, by means of the indelible tracings of the hand of the long departed, a knowledge of the habits, character, and condition of the countries in which they lived and worked. How much of the tale of British history of the fourteenth century, and of following centuries, have to be recorded by the architect and builder of these days? and by those whom their present conduct will influence? How important then it is that there should be none of the trifling in our department, and that we should be alive to the importance of the functions we are called upon to exercise.

The humblest workman of the building class is charged with the duties of the same mission. It will be our part to show them how this duty was discharged in times gone by, and to engage them in the consideration of such subjects, and in the labour of acquiring a similar mastery in their craft with those whose works we call upon them to join us in investigating.

It is thus that we propose to educate—the standard of mechanical and moral excellence must be raised at the same time, and good citizens, as well as able artisans and artists, be trained under one system and together.

It is a pleasing part of our duty to acknowledge the flattering testimonials we have received in favour of our work. Certain of our approving friends have taken the trouble to write, but many more have called at the office, and expressed the warmest interest in the success of The Builder, with a determination to do all in their power to insure it. The Royal Institute of British Architects have, by a special resolution, directed their Honorary Secretary (Mr. Bailey) to acknowledge the reception of our first number, and the Society of Arts have placed it in their library, and thanked us for the presentation. These matters are noted as shewing that a work of this class is recognized by important public bodies as deserving of their especial regard; and we feel assured that as we advance we shall find not only an admission but a welcome to every public and private library in which the literature of art obtains a place.

We have letters of encomium from architects as well as from builders and working men; and as it is for the latter that we are most anxious, feeling assured that when matters are right at the base of the social structure, the ornaments are firmly fixed and supported, so we feel the greater pride in perceiving the interest which the workman takes in our labours. It is the architect, however, and the experienced and liberal master builder, the clerk of works, and foreman, who can assist us to the enlightening of the body of the craft; and we have one grateful specimen of this species of co-operation, from a learned and eminent architect, an extract from which we cannot forbear committing to print.

“I should like to know whether The Builder will assume the character of Loudon’s Magazine, or whether you intend it entirely for the working classes—if for the latter, shall you endeavour to bring before them the principles of what they are called upon to labour at, or shall you endeavour to give them a taste for those acquirements which at present are supposed to be possessed by those who direct them? I do not fear any ill from raising the mental condition of the artisan, but see in it much good, at the same time, feel the difficulty of elevating the social condition of so large a mass of the community, and am desirous that when the attempt is made, it should be followed by success.

“To inform the working classes how their labour was performed in ancient days, would be instructive and amusing, and would lead to a better style of workmanship. I will instance the carpenter’s employment—describe the tools, the style of setting out and executing roofs of the middle ages, where neither iron-work nor nails of any kind were employed. The scarfing, the manner of uniting the timbers, &c. &c., are all at variance with modern practice. Then the beautiful manner in which the whole is put together and balanced would be a study calculated to raise him in his own estimation, and satisfy him that he belonged to a superior class of artificers. Emulation would encourage him to do as well or better, to carry the same excellence into minor employments, or, at all events, to understand sufficient to derive pleasure from the examination of many of the specimens left us. A vast deal might be written upon the mere handicraft—much more upon the principles—more still upon the art; and when the design is taken up, the field is too spacious to put bounds to.”

The foregoing so well expresses many of our views that we can hardly encumber it by a comment. We have in another place given our own opinions on the question of “raising the mental condition of the artisan,” and we have also in the same paper attempted to sketch out by what means and for what end we propose to raise it. We shall, therefore, proceed to the letter of another architect, which, as it regards the “getting up,” as it is termed, of the paper, has a practical value in that sense, and will enable us to explain a point or two in reference to it, that may give satisfaction to many.

“Sir,

“As you have invited opinions of your precursor number of The Builder, I take the liberty, as an architect, to express my gratification at the publication of so useful and desirable a periodical, and have very little doubt, if continued as promised in the address, of its becoming a work of great circulation, and one which will effect much benefit to the numerous classes connected with the building art, more particularly to the workman, providing you publish it at a price within his means, for at present, it is much to be regretted, this great class of persons are wholly denied the advantages derived by perusal of works on this science, owing to the high price at which they are from necessity published. I would therefore suggest you give this the fullest consideration, as I feel sixpence will be too high to give The Builder the circulation you desire. Another point requiring attention will be as to the advertisements, both as to quantity and description. If general advertisements are received, it will not so well admit of the title you give to the paper, which should exclude many such as are in the Precursor; and I fear, without much less space is devoted, or that the number of advertisements is compressed by smaller type, you will experience a disappointment in the success of your undertaking. I again beg you will accept the thanks and best wishes of an

“Architect.”

Now as to price, we think the best answer we can give is the present number. We have been advised to steer clear of too low a price at the commencement, because of the admitted difficulty of alteration in such cases, when found necessary to raise it. We hope no such necessity will arise in this; that the largeness of the subscription-list and of the number of purchasers will fully compensate us for any sacrifice we may make in the outset. With regard to advertisements, it was our wish to confine the list to such as bore directly on building, but to be stringent in this respect would be to deprive the paper of a large power of usefulness. Builders want almost every thing, and are consumers to an immense amount of all sorts of commodities; wherefore, then, should we refuse our columns to advertisements that inform the workman and the master alike of the ready means of supplying their general daily wants? But we make this promise, that the space given to advertisements shall not defraud the inquiring reader of his full share of information and of matter of trade interest; nor shall our friends the advertisers be treated with less consideration for this resolve—the more they bestow their favours upon us, the more shall we study to cater for their advantage, and for every page they add to our sheet we shall in some way or other give a page to the reader, so that the mutual workings of both parties shall be for the mutual good.

We give the next letter, though of some length, entire. It, like the first from which we made an extract, embodies so much of our views and plans, that we would give Mr. Harvey the full credit of his own clear perceptions, by letting it be seen how well he understands the subject upon which he writes, as will be exemplified in the carrying out.

“Sir,

“The general invitation conveyed through the ‘precursor number’ has induced me to offer a few remarks in reference to The Builder.

“‘The discovery of the disease is half the cure;’ so in this instance, the primary point to ascertain is, what class stands most in need of the kind of publication contemplated in The Builder. When the vast number directly and indirectly connected with building and mechanical pursuits is considered, there is certainly much cause for encouragement in such a project: at all events, it may be fairly concluded that there is a good site; and if the foundation be well studied, there is but little fear of erecting a durable structure.

“I have no doubt that The Builder may be rendered worthy the patronage of all the numerous grades named in the list given in the ‘precursor number;’ but bearing in mind ‘the old man and his ass,’ I am of opinion, that out of these several grades, some particular class should be specially borne in view, and that upon the selection of this class mainly depends the success of The Builder.

“Upon a review of such literary works extant as may be deemed the property of that body to whom The Builder is addressed, I think it will be found that no class of men are so ill provided for as journeymen mechanics generally, and this is the class that I would recommend to your preference in the conduct of The Builder; to this class The Builder ought to be considered invaluable in the dissemination of practical knowledge,—extracts from works made inaccessible by their cost,—experiments,—hints on construction,—design,—enrichment, and similar topics; which at the same time would be very acceptable to the more enlightened portion of the building community, and produce inquiry and improvement in the minds of the less experienced and youthful.

“With this view but little will be expected or required of The Builder in the character of a newspaper. Further than the limited notice of occurrences appertaining to its title, I would suggest the insertion of the markets, or current prices of building materials, &c. &c., and in particular, that an allotted space be given up to the subjects just referred to, to the exclusion of advertisements or any other matter. Probably once a fortnight might suffice for such a work; this point, however, with its price, I will not now enter upon, having already, I fear, trespassed too long on your attention.

“Be assured of my interest in the success of The Builder; to the aid of which my humble tribute will be given with much pleasure.

“I am, Sir, your obedient Servant,

“Sidney Harvey.”

The next letter is from a plasterer, and we make it the occasion of reiterating our intention to give designs of ornaments for plasterers. There is a field of novelty and propriety open to them which we venture to say has scarcely yet been touched upon. Hitherto architectural ornament in plaster-work has been principally confined to imitations of marble, or stone-work and wood. Now this is a perversion and a deception, and a better principle will inevitably obtain, since just and sound views of the principles of design and ornament are beginning to be inculcated. So beautifully plastic a material has its own peculiar province in decoration, and we shall take occasion, as we advance, to throw out practical suggestions for ascertaining and working in it.

“Sir,

“It is with much satisfaction I have read the precursor of The Builder, which I think will be well received by all persons in that line of business, for nothing can possibly be so much wanted for the trade in general as a publication of the sort you are about to send into the world. I have been a practical plasterer these thirty years, and have often expressed a wish that a useful intelligent paper might be published. I shall be most happy to become a subscriber. I am fearful there will be thousands read the Precursor, like myself, that will be proud to subscribe, but will not take the trouble to express themselves by letter, and then you may fancy it will not be taken up with spirit, though I am convinced, by the many persons, indeed all, that I have conversed with, that it is their intention to become purchasers the moment it is fairly out. Wishing you success,

“I am Sir, your obedient servant,

“B. J. Maskall.”

We will insert two more of what we may term the professional, and conclude with a complimentary note, lately received, from a gentleman whom we have not the pleasure of knowing, and extracts from the first that came to hand, as proofs, along with a great number of others, of a deep interest being taken in The Builder, as we predicted would be the case, by the amateur.

“Sir,

“You invite a reply from your readers of the ‘Builder’s Magazine.’

“To make a newspaper answer, it must be numerously circulated. I should advise to make it a weekly paper, to suit every mechanic or person engaged in the trade. I should recommend that it be like the Illustrated London News, to contain sketches of works in progress, new buildings, amounts of contracts, and other news relating to building. Also, to make it general (for nearly every workman takes a weekly paper), it must contain the heads of the news for the week. This would answer, without doubt, and I should like my name as a weekly subscriber.—Yours, &c.

“J. Nesham.”

“Sir,

“I approve much the plan of your proposed publication, and cheerfully offer myself a subscriber in whichever form it may appear; but would prefer it as a weekly magazine and advertiser, in which character I hope soon to see it, and wishing it all possible success.

“I am, Sir, yours respectfully,

“Thomas Allen.”

“Sir,

“I have only just had time to look into your valuable and most interesting work, The Builder, which I took up by accident this morning. I am so convinced of its excellence, that I should feel greatly obliged if you would allow me to become a subscriber of the unstamped number, from the first, and supply me regularly with it, if you are in the habit of sending it to this neighbourhood.

“I am, Sir, &c.

“J. R. W.”

“Sir,

“Last Saturday evening I bought the precursor number of The Builder, and was so pleased with the contents, that I called again at your office to say that I meant to take it in myself, and that I had shewn it to a bookseller, who told me that he also would order it at once for his shop. At that time I had only taken a very cursory glance at the number, but on further inspection, I feel convinced that it must have a very great sale, and I am sure I heartily wish you every success. My answer to your question, as to whether a magazine or simple newspaper would be the better form of publication is this,—that though many would prefer it as a magazine only, yet many more would rather see the news of the week blended in its columns. I am no artist, I am no mechanic, but I am a very great admirer of architecture, particularly of country houses and rustic cottages, churches, gardens, &c.

“I wish your new work was called ‘The Builder and Landscape Gardener.’ Views of parks and garden grounds, &c., ornamented with their castles, halls, cottages, &c., both of this and other countries, are at all times highly instructive and interesting.

“To the greatest talent is united in your work that kindly feeling towards those who have to labour for their daily food that will carry you on triumphantly. That your undertaking may meet with a deserved and most abundant reward, is the sincere hope of yours, &c.,

“M. B.”

The suggestion contained in the last extract, as to the title, is one upon which we are glad to make a few remarks, because the same suggestion has been embodied in the observations of other friends, in different ways.

We have confined ourselves to the simple term “Builder,” as best descriptive of all classes and crafts concerned in the art of building itself, and the arts with which it is intimately allied. Were we to attempt to give a title that should specifically explain the branches of art and science to be treated in this work, we should occupy half a page. Not only setting up houses or edifices, but, as we have said before, preparing the materials—aye, even to the very question of the planting and the culture of the oak and the pine, on which the future carpenter is to exercise his ingenuity. As to the brick-field, the quarry, the limekiln, the mine, the forest—consider what enters into the composition and completion of a building, what machines and implements are employed in working and preparing the materials, and its erection—what in the furnishing and fittings—what in the garden and other appurtenances. Consider all these, and you have engineering and machinery, cabinet-work and upholstery, and finally landscape art, included. And as to building science, or architecture, consider also its extensive range: the cottage, the middle-rate dwelling-house, the mansion, the villa, the palace—there is the labourer’s house of the country, and the labourer’s and workman’s house of the town; the farmer’s dwelling in the one, and the tradesman’s in the other—the farm-yard buildings and the corresponding workshop, warehouse, and factory—the country “box” and the citizen’s suburban retreat—the mansion of the country squire and that of the wealthy town merchant—the parsonage, the church—the humble village church!—the street of the pretty country village, the formal lines and gay shops of the crowded city—the traveller’s way-side inn, the town hotel—the petty sessions house, the county courts, prisons, workhouses, almshouses, asylums, barracks—the halls of our cities, the concert-rooms, the theatres, the great market-houses, the exchange for our merchants, the parliament-houses, the palace, the cathedral!

Our subterranean structures, in drains and tunnellings; our pavements and highways; our bridges, aqueducts, and viaducts; our railroads, our lighthouses, harbours, docks, ports, defences. Consider these, and we have not half exhausted the list—we dare not longer particularize—consider these, and the numerous crafts and callings engaged in them, and it will be at once seen that we should only weaken the force and destroy the comprehensiveness of our title, The Builder, by any attempt to make it more comprehensive.

The following excellent letter has come to hand since the foregoing summary was penned:—

“Sir,

“The delight with which any one connected with the erection of an edifice seizes a book or paper, bearing the title (The Builder) heading your new publication, can be duly appreciated by those who have carefully studied the ‘Practical Builder,’ as published by Mr. Peter Nicholson, in the enlarged edition of 1822.

“In the perusal of which the idea of a work similar to the one shewn forth in the precursor number of The Builder, has very often engaged my most serious attention, leaving no doubt on my mind of the very favourable reception the work would have from all parties engaged in the Building department.

“Begin and continue on the broad principle of practical utility, making most prominent, works already executed, or in the course of erection, with a copious description, as also, plans, elevations, sections, and details of the most prominent features of the building or structure, illustrated, and the work, from its great utility, will take a place amongst the magazines of the present day, second only to the great magazine of the north.[1]

“A large and beautiful field lies open before you, and by bringing before the public some of the noble metropolitan structures, the beautiful street architecture, and suburban villas, you will create a love for reading and study amongst a most important class, that will force The Builder on, till it has attained the ‘Corinthian order’ as a magazine, and the companion of every artizan.

“A magazine has always occurred to me as the best mode to bring the architecture of this country in its best form before the public, always acknowledging the name of the professional gentlemen employed in the erection illustrated; so much so, that I have often been tempted to suggest the idea to some of the London publishers, as there the erections are as a source inexhaustible.

“Though The Builder may be an instrument of much good, if correctness of plans and details are guaranteed, its fall will be as certain, if it should be a medium of ‘book-making,’ so often seen thrown before the public.

“It will likewise add to the value of The Builder, by continuing the portraitures of men so eminent in architectural skill as the noble-minded William of Wykeham, already illustrated in the Precursor number.

“I would respectfully suggest the propriety of detaching the advertisements from The Builder, so far as to allow a separate binding of the work.

“Reviews of architectural works are also highly commendable in The Builder, as they increase in quantity of late years; and a guidance to purchasers therefore is valuable.

“With best wishes for the prosperity of the undertaking, in a continual increasing circulation, I must beg the forwarding to your correspondent here, such of the numbers as have been issued.

“I remain, most respectfully,

“Joseph J. Roebuck, Joiner.”

“Manchester-Road, Huddersfield, Feb. 13, 1843.”

[1] Chambers’s.

“Sir,

“Judging from a perusal of The Builder that it is your intention to give to the building world the first information upon all matters connected with its interests, I beg therefore to apprize you that at this moment, a bill is preparing very secretly (at least the ground-work for one) for Parliament, upon which it is presumed, as secretly will be obtained, a New Building Act.

“Whatever objections there may be (and I readily admit there are many) to our present Building Act, yet I do not think it requires altogether to be superseded.

“From private information I learn, that the majority of clauses in the intended new bill, are exceedingly arbitrary, and calculated only to oppress the Builders without the least additional benefit to the public, and indeed, I am of opinion that if adopted, it will prove a source of great inconvenience and expense to all parties in any way connected with building. I should, therefore, recommend a Meeting of speculative Builders immediately, to take into consideration the best means to oppose the bill in Parliament.

“I shall be most happy to give my best assistance in this matter, as also to forward the views of the proprietor of The Builder.

“I am, Sir, your obedient servant,

“John Reid, Surveyor.”

“90, Canterbury-buildings, Lambeth,

“February 14th, 1843.”

The foregoing letter came to hand as we were going to press. We have only time to assure our correspondent that we will pay immediate attention to the subject it refers to, and we invite further information from all those who may be in the way of procuring it. At the same time we would urge a calm and steady purpose in the pursuit of this or any similar object of our vigilance.

Legislation on matters affecting building interests, above all things, should be deliberate and not capricious. Much mischief may be done by over anxious meddlings, indeed, we may say in this respect with Shakspeare in Hamlet,

“Better bear the ills we have than fly to others that we know not of,”

or run the risk of so doing.

(From Pugin’s principles of Pointed Architecture.)

We now come to the consideration of works in metal; and I shall be able to shew that the same principles of suiting the design to the material and decorating construction, were strictly adhered to by the artists of the middle ages, in all their productions in metal, whether precious or common.

In the first place, hinges, locks, bolts, nails, &c., which are always concealed in modern designs, were rendered in Pointed Architecture, rich and beautiful decorations; and this, not only in the doors and fittings of buildings, but in cabinet and small articles of furniture. The early hinges covered the whole face of the door with varied and flowing scroll-work. Of this description are those of Notre Dame at Paris, St. Elizabeth’s church at Marburg, the western doors of Litchfield cathedral, the Chapter House at York, and hundreds of other churches, both in England and on the Continent.

Hinges of this kind are not only beautiful in design, but they are practically good. We all know that on the principle of a lever, a door may be easily torn off its modern hinges, by a strain applied at its outward edge. This could not be the case with the ancient hinges, which extended the whole width of the door, and were bolted through in various places. In barn doors and gates these hinges are still used, although devoid of any elegance of form; but they have been most religiously banished from all public edifices as unsightly, merely on account of our present race of artists not exercising the same ingenuity as those of ancient times, in rendering the useful a vehicle for the beautiful. The same remarks will apply to locks which are now concealed, and let into the styles of doors, which are often more than half cut away to receive them.

A lock was a subject on which the ancient smiths delighted to exercise the utmost resources of their art. The locks of chests were generally of a most elaborate and beautiful description. A splendid example of an old lock still remains at Beddington Manor House, Surrey, and is engraved in my father’s work of examples. In churches we not unfrequently find locks with sacred subjects chased upon them, with the most ingenious mechanical contrivances to conceal the keyhole. Keys were also highly ornamented with appropriate decorations referring to the locks to[20] which they belonged; and even the wards turned into beautiful devices and initial letters. Railings were not casts of meagre stone tracery, but elegant combinations of metal bars, adjusted with a due regard to strength and resistance.

There were many fine specimens of this style of railing round tombs, and Westminster Abbey was rich in such examples, but they were actually pulled down and sold for old iron by the order of the then dean, and even the exquisite scroll-work belonging to the tomb of Queen Eleanor was not respected. The iron screen of King Edward the Fourth’s tomb, at St. George’s Chapel, Windsor, is a splendid example of ancient iron-work. The fire-dogs or Andirons, as they were called, which supported either the fuel-logs where wood was burnt, or grates for coal, were frequently of splendid design. The ornaments were generally heraldic, and it was not unusual to work the finer parts in brass, for relief of colour and richness of effect. These form a striking contrast with the inconsistencies of modern grates, which are not unfrequently made to represent diminutive fronts of castellated or ecclesiastical buildings with turrets, loopholes, windows, and doorways, all in the space of forty inches. The fender is a sort of embattled parapet, with a lodge-gate at each end; the end of the poker is a sharp pointed finial; and at the summit of the tongs is a saint. It is impossible to enumerate half the absurdities of modern metal-workers; but all these proceed from the false notion of disguising instead of beautifying articles of utility. How many objects of ordinary use are rendered monstrous and ridiculous because the artist, instead of seeking the most convenient form and then decorating it, has embodied some extravagancies to conceal the real purpose for which the article was made! If a clock is required it is not unusual to cast a Roman warrior in a flying chariot, round one of the wheels of which, on close inspection, the hours may be descried; or the whole of a cathedral church reduced to a few inches in height, with the clock-face occupying the position of a magnificent rose window. Surely the inventor of this patent clock-case could never have reflected that according to the scale on which the edifice was reduced, his clock would be about 200 feet in circumference, and that such a monster of a dial would crush the proportions of any building that could be raised. But this is nothing when compared to what we see continually produced from those inexhaustible mines of bad taste, Birmingham and Sheffield; staircase turrets for inkstands, monumental crosses for light shades, gable ends hung on handles for door porters, and four doorways and a cluster of pillars to support a French lamp; while a pair of pinnacles supporting an arch is called a Gothic-pattern scraper, and a wiry compound of quatrefoils and fan tracery an abbey garden seat. Neither relative scale, form, purpose, nor unity of style, is ever considered by those who design these abominations; if they only introduce a quatrefoil or an acute arch, be the outline and style of the article ever so modern and debased, it is at once denominated and sold as Gothic.

TO THE EDITOR OF THE BUILDER.

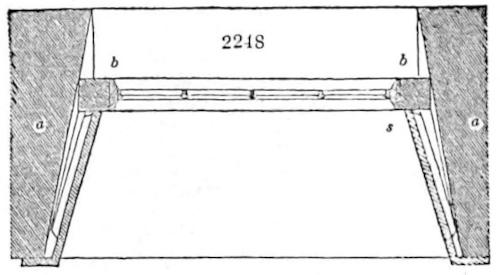

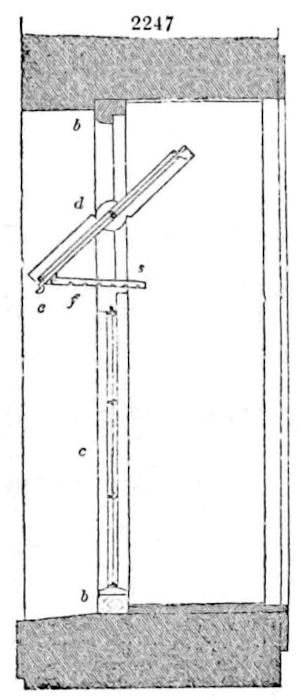

Sir—I have introduced the suspension principle in two or three instances with great success, where nothing else could have answered the purpose; and as it was through you that the first impression was made upon my mind of its practicability for building purposes, I at once send you a rude sketch of the last one I have used. It is to carry a roof, lead-flat, and ceiling; it is in connection with the old mansion, an enlargement of the cooking kitchen, taking out the whole of the end wall, 16 feet wide, and making or adding to the same a large bow, which is covered with lead. I have marked the different parts as follows:

A. Suspension-rods secured to walls, 1 inch round, iron, flat in the walls.

B. Screw bolts, 1 inch round, iron.

C. Nuts at bottom of bolts, and brace.

D. Brace, ½ inch round, iron.

E. Head to brace.

F. Iron plate under wood plate, 3 inches by ½ inch, flat.

G. Wood plate, 3 inches thick.

H. Lead-flat.

I. Joists to ditto.

J. Ceiling-joists.

K. Principal beam of roof.

I must give you to understand the bow, lead-flats, &c., were done before I came here, and supported in a manner that gave offence to every one; you will now perceive there is a straight ceiling and no obstruction to light or any thing else.

The suspension-rods are fixed to the bolts as the link of a chain, the brace screws them tight together, and the bottom nuts screw up and camber the plate, which renders the whole complete and very strong. I had it put together and fixed in about two hours, so that you will perceive it can be applied in any situation without doing any damage, by merely boring the holes and making good the joint round the bolts on either a floor, roof, or flat.

I have applied others in different places, and have made them as circumstances required, to carry scores of tons weight. They have given the greatest satisfaction possible to all concerned.

I am happy to inform you that our architect and the master-builder will both be subscribers to your valuable work. I think from this neighbourhood you will have a dozen names.

Yours most obediently,

T. P. Hope,

Clerk of Works, Richmond.

We beg to introduce the Enthusiast to our readers, for such the world is pleased now and then to call him; his real character, however, shall be judged of by the reflecting and considerate; the name may stick to him as a matter of small account, for a wiser man than ourselves has said “there’s nothing in a name.”

When we speak of the reflecting and considerate, it is not to be implied that all persons do not at times and in their way reflect and consider; but it is hard to do so while we are involved in the business of ordinary life; like players at cards, we are absorbed in the calculations that affect them, and in the consideration of the “hand” we hold. We find even the most skilful, straining to recollect himself of the past progress, and speculating on the future chances of the game—so it is with the mass of human beings. Could we look but on as cool spectators of the games, and shifts, and moves of general life, we should pity, smile, expostulate, reprove, where now at best we give a vacant look, an unmeaning sigh, rage and burn, as in turns we feel the instinct of weakness or passion, and are driven to act under their impulses—but we are drawing the portrait of the multitude, and losing sight of the Enthusiast.

How shall we catch his likeness and how present it to our readers? It must be drawn with many lines and a patient hand. We are not limners, or choose not to be, who cut out profiles in black, with a pair of scissors; nor can we daguerrotype him at a glance. No! The Enthusiast must be the subject of many sittings, though we may give a complete feature or, sketch at each of his aspect for the day; and in doing so, we promise ourselves what we hope will be largely shared in by our readers, a fair amount of interest and gratification.

Enthusiast has some eccentricities, or to speak more plainly, has his oddities. Tell him so however, tell him as a friend, and he is enthusiastic to rid himself of his oddities. He has friends who now and then tell him so; he has enemies who also take the same liberty; but it is ten to one, if you examine it, that both friends and enemies, in specifying some particular oddity, confront and contradict each other, and leave the poor Enthusiast not wiser, but more perplexed, between them. Indeed, so much do they themselves blunder, and so much of guess-work is there in their opinions, that to give things their right names, judging from effects, we should call the friend an enemy, and the enemy a friend. The only conclusion we can come to is by canvassing the motives of each, to decide that the well-meaning and evil-doing are ranged on the one side, and the evil-meaning and well-doing on the other. So odd are many things and many persons besides Enthusiast; but we are again sketching from the crowd, and Enthusiast sits impatient, or rather his friends are impatient, which with them is much the same thing.

Enthusiast is an architect! Upon my word, some one will exclaim, what is coming to us now-a-days?—architects and architecture are obtruded upon us at every turn; and a certain lady of a certain age (which means, as everybody knows, no very large portion of a century) indignantly expostulates against this attempt to engross the public mind and attention with these “new fanglements” of a profession and an art which her father and grandfather’s days could very well do without. “Formerly,” she says (which means about the ancient period of her youth), “we hardly heard the mention of such things. Architects, indeed! formerly the word even was scarcely so much as known among us. I recollect,” says she, “having my attention forced upon it somewhere in my school readings, in some out of the way chapter or exercise, which poor Mrs. Cross-stitch imposed on me at the ‘finishing’ of my education. I recollect reading something about architecture, and how I mispronounced the word, and how Mrs. Letterhead, our class mistress, told me to pronounce the ch like k; and how she gave us a spelling task with that and several other hard words to learn at home in the evening, and how my poor father, when he heard me my task at my bed-time, had a dispute with our neighbour, Percy Fullpurse, as to which was the greater personage, the archdeacon or the architect; for they both insisted that Miss Letterhead was wrong in her pronounciation, as Percy had it; and how Percy, who was a great authority with us, for we thought riches and wisdom went very much together, decided that[21] the archdeacon and the architect had nothing to do with each other, but that the architect was something he could not exactly tell what or how, but he believed had something to do with the quarter of the Archipelago, with which also he had nothing to do. All this I recollect, and certainly, though I may now smile at the ignorance of my poor father and neighbour Percy, yet I am not bound to hold with all that we are hearing and having dinned into our ears every day. Almost every third person I meet with has some friend or friend’s friend who is an architect, or is acquainted with an architect—and I meet with them at parties; and there is Cousin Symmetry has placed his son by his first wife as pupil to an architect; but what call can there be, or what to do for so many architects? Architects, like Proctors, should keep their places, and some two or three of them inhabit a cathedral town, to take care of those fine old buildings and the churches, for the churchwardens, they say, do not look to those things properly; but, Lord bless us, do not let us be bored with architecture at every turn. Let them have a bookseller specially to themselves, if they will—and now I think of it, I recollect something of an old established shop in that way somewhere in Holborn; but here I see Messrs. Longman are publishing works on architecture, and Mr. Tilt pushing them before one’s noses, and Bell & Wood, and others, as the advertisements tell us. Nay, to crown all! there is that very Boz, in his new work, Martin Chuzzlewit, beginning with an architect, which, by the way, proves what I have always said, that he is wearing out his subjects—and mind what I say again, it will break down! He should take popular characters and popular subjects; but an architect! Why, not one in a thousand knows or cares any thing about architects. Trash! and now just do look at this—a weekly paper, called The Builder! and another character to be drawn out—an Enthusiast, who is also an architect! Well, upon my word, that is good! We have heard of castles in the air; I suppose we are going to have a builder of them, and that this Enthusiast is to be the architect. Well, that is as it should be—the clouds for the architects, and the architects for the clouds.”

But when shall we sit down to our business?—Miss Fatima Five-and-forty has had the turn of our pencil, and Enthusiast still awaits its return.

Enthusiast is an architect; that is, he is so for this limning; for Enthusiast enters into most things, and is the life and soul of them. We cannot go into his parentage, to shew how he is allied to, or of the family of, the Geniuses; but really it is a difficult task this sketching that we have undertaken, and reminds us of one of George Cruikshank’s humours, under the head of “Ugly Customers;” not that we are so much out of love with our subject as with the task we have undertaken.

Do excuse us, good readers, for a while longer, and we will tell you a story about this same Enthusiast. It is a trick of some of our contemporary painters, to beguile the sitter by a conversation on some topic which throws him from the restraint of posture-making; perhaps if we try it, Enthusiast may be caught in a more favourable attitude, and we may close the day with some success for our hitherto failing and disappointed pencil.

Enthusiast was one day engaged in a discussion with a lady friend, and had, in the usual warmth of his manner, been descanting on the beauties and properties of Church Architecture in connection with the proposed erection of a suitable structure of this class in a wealthy manufacturing town. “It should be a cathedral,” said he, “at least in dimension, in aspect, in decorations and appointments.” He had dwelt on the peculiar features it should possess, on the facilities that could be commanded, on the energies that ought to be exerted, and so on, when he was cut short in his rhapsody by the cruel observation of the lady,—and a common one it is,—“There is no money for such things now-a-days.”

Casting his eyes around, as if in a reverie of thought, he scanned the character of the various luxuries of the well-appointed drawing-room in which they sat. Glancing from the broad mirror boldly superposed on the massive carved chimney-piece of Carrara marble, which in its turn enclosed the highly-polished steel and burnishings of a costly Sheffield grate and its furniture, to the rich silk hangings of the windows—their gilded cornices and single sheets of plate-glass—thence to the chairs of rosewood and ivory inlaid, the seats of silken suit—the companion couch and ottoman of most ample dress—the curious and costly cabinet, the screens, the gold-mounted harp, the “grand piano.”—Pacing once the length of the room on the gay velvet of the carpet, he turned again and rested his view on the table, choicely decked with books, most expensive in all the appliances of paper, type, illustration, and binding—having done all this, with breath suppressed and stiflings of emotion, which fain had broken out with a scornful repetition of the lady’s words, “there is no money for such things now-a-days,” he quietly disengaged himself of his passion, and by an apparently easy transition ran on thus:

“I have been calling to mind some of my early readings, and most prominent just now is the recollection of the observations of Hope when treating the subject of Egyptian Architecture and commenting on the vastness of the Pyramids; he enters into a speculation as to the means by which the people of that country under the Pharaohs were enabled to find the leisure, or the time necessary for the construction of such stupendous works, and he ventures to ascribe it to the natural fertility of the soil caused by the annual over-flowings of the Nile, thus demanding less from the Egyptians of the labour and care of agriculture; and hence the drift of their exertions in the direction of architecture. True, the bounty of nature would go a long way in supplying to the cravings of art the leisure and opportunity for gratification. True, those pyramids are evidence of the direction of great means and great powers to an end which astounds more than it edifies us, but what were the bounties of Egypt’s irrigating water, what the greatness of their pyramids compared with that bounty which Providence has given us in the mineral and the out-growing mechanical characteristics of this favoured country, and the pyramids which we erect as if in emulation of Egyptian vanity and inutility?” “Pyramids!” interrupted the lady, “Ah, it is always so with you, to propound to us first some extravagant project, and when driven from your ground by a common sense and practical answer, to take shelter in some ambiguity or paradox. Pyramids, Sir,—what is your meaning?” “Here,” said the Enthusiast, “here, madam, are stones from some of the English pyramids, of which your Scotts, and Byrons, and Bulwers, and Marryatts have been the architects. Compare the labours, and the end of the labours of these ingenious minds with those of the architects of the Egyptian pyramids, and tell me then the difference in amount. See the glories and untiring industry of him of Abbotsford, devoted to an incessant wearing out of the energies of his mind in designing pyramids of fiction—look on the ant-like bustle and activity of the thousands whom he brought into requisition to be engaged in the building—look at the millions of devotees who have prostrated and continue to prostrate themselves at these great entombments of his genius.—The paper-makers—the printers—the artists employed in illustration—the binders—the booksellers—the advertizing—the correspondence—the carrying—volumes, pyramids of volumes to advertize alone—an endless train of carriages and lines of road for the conveyance—the Builders and makers employed on all these—and on the establishments of printers, booksellers, &c.—and then the excited million of expectants, the absorbed and half-entranced readers—the hours, days, weeks, months, and years of reading—the impatience of interruption till the whole delusion is swallowed—the readings again and again—the contagion from the elders to the younger—children even bewildered with the passion to peep into, to pore over, and last, to read as rote-books these little better than idle fables—bootless in their aim and object, and pointless in all but their rival obtuseness of the mountain-mocking pyramids. The fertility, the leisure, and the vanities of Egypt!—oh, madam, their country was sterility—their leisure, incessant bustle compared with what we enjoy; and their vain direction of labour and thought not to be named after this enumeration of vanities. Pyramids!—where they had one we have ten. Where ages were required by the Egyptians, we in as many years outvie them, and yet your answer to my aspirations is, “We have no money for such things as these!”

Reader, we have beguiled ourselves and you, and not the Enthusiast, into a sitting; and one feature is sketched of his likeness and his character.

We give the following notice in connexion with the subject of Wood Pavements, believing, as we do, that the efficiency of that mode of paving greatly depends upon its being kept clean; an object which this invention will materially facilitate.

Patent Self-Loading Cart, or Street-Sweeping Machine.

The Self-loading Cart has been lately brought into operation in the town of Manchester, where it has excited a considerable degree of public attention. It is the invention of Mr. Whitworth, of the firm of Messrs. Joseph Whitworth & Co., engineers, by whom it has been patented, and is now in process of manufacture. The principle of the invention consists in employing the rotatory motion of locomotive wheels, moved by horse or other power, to raise the loose soil from the surface of the ground, and deposit it in a vehicle attached.

It will be evident that the self-loading principle is applicable to a variety of purposes. Its most important application, however, is to the cleaning of streets and roads. The apparatus for this purpose consists of a series of brooms suspended from a light frame of wrought iron, hung behind a common cart, the body of which is placed as near the ground as possible, for the greater facility of loading. As the cart-wheels revolve, the brooms successively sweep the surface of the ground, and carry the soil up an inclined plane, at the top of which it falls into the body of the cart.

The apparatus is extremely simple in construction, and will have no tendency to get out of order, nor will it be liable to material injury from accident. The draught is not severe on the horse. Throughout the process of filling, a larger amount of force is not required that would be necessary to draw the full cart an equal distance.

The success of the operation is no less remarkable than its novelty. Proceeding at a moderate speed through the public streets, the cart leaves behind it a well-swept track, which forms a striking contrast with the adjacent ground. Though of the full size of a common cart, it has repeatedly filled itself in the space of six minutes from the principal thoroughfares of the town before mentioned.

The state of the streets in our large towns, and particularly in the metropolis, it must be admitted, is far from satisfactory. It is productive of serious hindrance to traffic, and a vast amount of public inconvenience. The evil does not arise from the want of a liberal expenditure on the part of the local authorities. In the township of Manchester, the annual outlay for scavenging is upwards of 5,000l. This amount is expended in the township alone. In the remaining districts of the town, the expense is considerable. Other towns are burdened in an equal or still greater proportion. Yet, notwithstanding the amount of outlay, the effective work done is barely one-sixth part of what would be necessary to keep the public streets in proper order. In the district before referred to, they were a short time ago distributed into the following classes, according to the frequency of cleaning them:—Class A,—once a week; B,—once a fortnight; C,—once a month. It may be safely asserted, that all these streets should be swept, at least, six times oftener. The main thoroughfares, as well as the back streets and confined courts, crowded with the poorer part of the population, absolutely require cleaning out daily. But the expense already incurred effectually prevents a more frequent repetition of the process. The expensiveness of the present system, in fact, renders it altogether inefficient; nor is there any chance of material improvement in this important department of public police, unaccompanied by a corresponding reduction in the rate of expenditure.

According to the Kunctsblatt, a German painter, Edward Hansen, of Basle, has been commissioned to prepare cartoons for the oil paintings intended to decorate the church at Oscott, which Mr. Pugin is about to build at the Earl of Shrewsbury’s expense. One of the designs, “The Last Judgment,” is spoken of as exceedingly beautiful. On the same authority, we learn that Thorwalsden has sustained a loss by the wreck of a ship, bound from Leghorn to Hamburg. On board were several of his works, most of which were saved, but were completely spoiled by the sea-water; from which we infer that they were plaster casts.

Westminster Hall Roof.

We now beg to draw attention to what we consider will be found the most important feature in this number, inasmuch as it is the commencement of the task with which we have charged ourselves to enter upon the investigation and elucidation of the character and principles of Gothic Architecture.

We use this unhappy term, Gothic, for no other reason than that as we address ourselves mainly to the workmen, and as the style of architecture so designated (originally in opprobrium) has now and for long obtained the appellation in a popular sense, we feel unwilling to depart from it until a thoroughly correct epithet shall have been devised and accepted amongst us; that we are justified in this decision, or rather indecision, we think may be shewn by the various opinions of parties who may be said to rank as the authorities on such points. Mr. Pugin is anxious that it should be called “Pointed, or Christian Architecture.” Mr. Whewell and others have lately been pleading for a title which the prevalence of vertical lines and principles of construction, as in contradistinction to the horizontal character of Greek architecture, appear to them to justify; others again have contended for the term “English Architecture.” Now, without committing ourselves to an opinion of our own, we think there is sufficient ground for hesitating as to the adoption of this or that novelty, notwithstanding our strong objection to the inapt and absurd term “Gothic.”

Our task will be formidable, as to the length of time it will occupy, the pains-taking it will require, the expense it will entail upon us, and, above all, the system with which it must be conducted. But what good thing is to be accomplished without some one or more of all these? We only hope to be cheered on by the approving smiles and the patient co-operation of those for whom we undertake it.

And how do we commence this task, so as to give promise that a system may be observed, without which the best efforts in other respects are likely to fail? It will not do to enter upon it at random, or without due preparation, both on our own part and that of our readers. We shall, therefore, proceed to state our object in selecting the illustration we have done as the heading of this paper.

Let the carpenters look to it, and let them look on it with pride—nay, let them look on it as we have done, with reverence. Let them remember that this was the work of great spirits of their department. It is a master-piece, and we have chosen it on this account, as we shall continue, for some weeks to come, to make choice of similar master-pieces, in the masons’ department. Oh! we have such glorious examples at our hands. And then, again, as to ornamental brickwork, and brass and latten work, and that gorgeous coloured glazing, and such mastery in the carvers’ and sculptors’ art; these we choose, to fire the breasts of our readers. We would excite them by such glowing description of the land of promise into which we propose to lead them, that the future steps, however irksome or laborious, may be trodden with a light and gladsome foot. For the present, then, and as we have said, for weeks to come, we shall select the instances of varied excellence in roofs, vaults, arching, in traceried windows, doorways, screens, in elaborate specimens of “bench carpentry,” such as stalls, pulpits, railings, tabernacle and screen work, in monumental brasses and other memorials of sepulture, in moulded and enriched brickwork; the encaustic and coloured pavements, the staining in glass, and generally all such matter in the province of the artificer as may be regarded with the admiring eye of the discerning practitioner.

Borrowing a similitude from what we are otherwise bound to deprecate, we would speak of these as the trophies of our predecessors in campaigns of glory, bidding every good soldier in this day of later, though of similar service, to burn with ardour until he may have successfully emulated the doings of his ancestry.

Yes, every carpenter should feel proud of a calling which enrols him in the ranks of a craft whose arms are emblazoned and charged with insignia such as these; but we promise the same evidences of distinction to every department of the building fraternity.

This Westminster-Hall roof, spanning over an area of 74 feet wide and 270 feet in length, rearing its ridge to the height of 90 feet, exhibits in its application a proof of the progress of working upon a principle which is, in the present day, somewhat too much decried. Originally that Hall was otherwise covered in; doubtless, in the same manner as the halls at Norwich and York; that is, with a roof supported by pillars; but the decay, or perhaps destruction by fire, of the original roof, gave scope to the genius of advanced science, which, disdaining to merely restore, applied this noble emendation,—with such happy effect, however, as not only to reconcile us to a departure from the original models, but to lead us to applaud the “innovator.”

The illustration we have given has been made pictorial rather than simply geometrical; because, as we have already observed, our object now is not to enter into a critical examination, which would with such a subject be beginning at the wrong end, but to give a comprehensive glimpse of that end to which we must by another process patiently steer. This plan will enable us, too, to give much more effect to our future instruction, inasmuch as it will enable a greater number of readers to become our companions in the paths of study and research. After we have occupied what appears on all hands to be a sufficient number of our series in illustrations of this class, we shall commence with the simple rudiments of Gothic art, citing first from the most ancient specimens the various features of the edifices of the period, and accompanying it by a glossary of terms and such matter of description as will give the series the character of a workman’s hand-book or manual.

Take, for instance, the subject of Roofs as now brought before us. We have in this draught or picture, a kind of summing up of that which it will be our duty to go through in detail, as to style, construction, and workmanship. In Masonry, though the end may be one of those embodied marvels of the imagination, the almost over-wrought canopy of a stone ceiling or roof; and which end, as in the case of this week’s carpentry, we may present to view; yet the beginning of our studies will be some rude effort of a Saxon chisel, and their continuation, to trace through the various eras the change and progress, until we arrive, skilled as masters, to analyze and fully understand the intricacies of science and art involved in these objects of our setting out.

By this we hope to give a thoroughly practical character and value to our pages, and that this will be in nowise diminished, if we shew ourselves now and then susceptible of emotions of almost ecstatic delight, while we contemplate those almost superhuman efforts of the skill of the mid-æval architects and workmen.

In concluding the present chapter, we beg to state that we have copied the drawing at its head from the beautiful work known as Britton and Brayley’s Westminster.

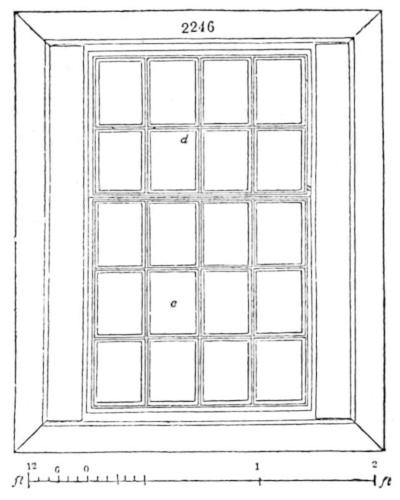

First Additional Supplement to the Encyclopædia of Cottage, Farm, and Villa Architecture and Furniture. By J. C. Loudon, F.L.S., &c. London: Longman and Co.

It was said by the Times, of the Encyclopædia to which this is a supplement, that “no single work had ever effected so much in improving the arrangement and the external appearance of country dwellings, generally,” and nothing that was ever said by that influential journal had in it greater truth. We scruple not to go out of our way to subscribe in full to this opinion. And we say more, that no man living has ever laboured more assiduously, generously, and usefully, to effect every practical improvement in the building art, than our good and worthy friend Mr. Loudon.

And why should we scruple or be ashamed to confess the strength of our partialities for one of whom we entertain such an opinion? It may be said,—but no! we will not do any man the injustice to suppose that he will say any thing in disparagement of our motives, and certainly none will be so ungrateful as to undervalue the honest disinterestedness of our friend. See him, read his works, and if any one after that retires with a feeling of less reverential respect than our own, we will give him license to bate us for a partiality of an over-measured and unfair amount.

What if he has put at our service in the Precursor Number and in this review the choice of those pleasing illustrations that adorn his works? We point to these as additional proofs of his title to the respect and esteem of our readers. He was influenced, we know full[23] well, by that same generous purpose which has sustained him through life, which has made him to triumph over physical difficulties and to stand now a living, and to be a memorable instance of the supremacy of mental over material power. He will pardon us, if in the honest excess of our gratitude on personal grounds, but much more in our humble capacity as of the “craft” for whom he has so well laboured—a gratitude which took possession of our minds through the reading of his works long before we knew him—he will pardon us, if, unrestrained by a sense of the little pain we may cause him on the one hand, we thus tender to him that which we are assured, will on the other be acceptable—our honest and undisguised, but feeble expression of grateful esteem.

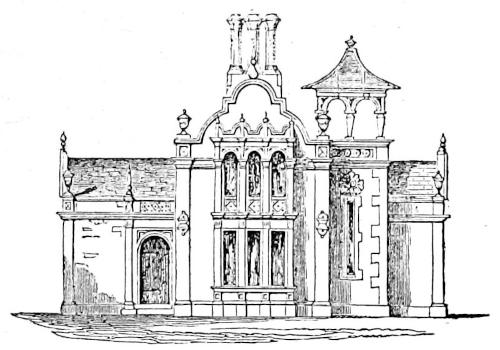

As we profess to teach not so much by criticisms, which after all can have but little weight, or at any rate little more than the opinion of an individual, and when delivered with an air of authority that the test of inquiry would dissipate, only make criticism ridiculous, and confirms error; as we teach not so much by criticisms as by joining in the commendations of generally acknowledged good; and as every one who has travelled on the North Midland Railway has acknowledged, that the station-buildings on that line have more of the picturesque and attractive than any thing of the kind on our other railways, we have a pleasure in transferring from Mr. Loudon’s Supplement the accompanying elevation of “a cottage in the style of the Ambergate Railway Station,” by Mr. Francis Thompson, who was also the architect of that station, and it will readily be admitted that there is a meritoriousness which entitles this design to the regard which that gentleman’s other works have obtained.

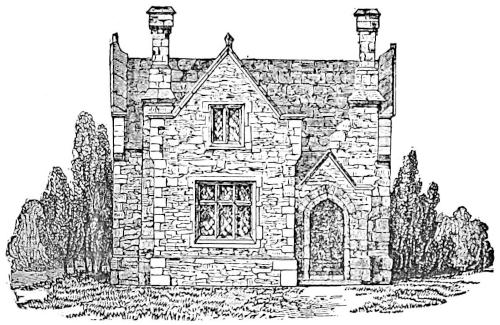

The next selection which we make is a design, by Mr. E. B. Lamb, of “the Keeper’s Lodge at Bluberhouses,” which, it appears, was built, with some slight variations, for Sir F. R. Russell, Bart., on his estate of Thirkleby Park, Thirsk, Yorkshire.

In Mr. Loudon’s text there are some judicious remarks on the elevations; the construction is also described, and plans likewise given, as indeed with all the designs, both of this supplement and its parent or precursor volume. The supplement alone contains nearly 300 engravings.

The next design is also by Mr. Lamb, and is one out of a number of “small villas in the Gothic style,” originally intended to be built near Gravesend. We have not space to transfer Mr. Loudon’s critique, and are precluded by the rule we have laid down from any observations of our own.

In a future number it is our intention to return to this subject, and, in connection with the question of the improvement of labourers’ and workmen’s dwelling houses, several plans for which are now before us, we shall have the assistance of Mr. Loudon’s matured lucubrations, as given in the Encyclopædia and the Supplement.

An Architectural College was founded in London, on Advent Eve, 1842, for the cultivation of the various branches of the art, under the denomination of the “Free-Masons of the Church, for the Recovery, Maintenance, and Furtherance of the True Principles and Practice of Architecture.”

It appears that the objects contemplated in the foundation of this Institution are the rediscovery of the ancient principles of architecture; the sanction of good principles of building, and the condemnation of bad ones; the exercise of scientific and experienced judgment in the choice and use of the most proper materials; the infusion, maintenance, and advancement of science throughout architecture; and, eventually, by developing the powers of the College upon a just and beneficial footing, to reform the whole practice of architecture, to raise it from its present vituperated condition, and to bring around it the same unquestioned honour which is at present enjoyed by almost every other profession.

It is proposed, by having numerous professors, contributors, and co-labourers, to acquire a great body of practical information; and that, whenever any knowledge of value shall be obtained by the College, the same shall be immediately communicated to each of its members, without waiting for the production of a whole volume, and before the subject-matter shall have lost any of its professional interest.

By the appointment of a “Professor of Architectural Dynamics,” the gravitation of materials will be taught to the student in practical architecture: thence in all designs the present mystery, in which the quantity of materials merely absolutely requisite to cause a building to hold firmly together, may be ended; architectural designs may in future be made on certain principles of stability, and therefore on principles of natural and philosophical taste; and through the economy of discharging from buildings all lumber, as is the case with all living members of the creation, the architect will be enabled to restore to his work, frequently without extra expense, the carving and other exquisite beauties for which ancient architecture has in every age been celebrated.

By the appointment of a “Professor of Architectural Jurisprudence,” it is judged that the practical profession of architecture will be rendered more sure, through the acquirement of fixed and certain rules relative to contracts, rights of property, dilapidations, and other legal matters.

By having a “Professor of Architectural Chemistry,” it is confidently expected that a more certain method will be assured to the practitioner in the choice of proper and durable materials.

By the appointment of the various other professors and officers, it is judged that the very best information will be obtained upon all material matters connected with the science and the practice of architecture, and that a degree of perfection will be thus induced, and will thus mix itself with the practice and execution of the art in a manner which is not now very often the case.

As a first labour of the College, it is proposed that the present unsatisfactory division and nomenclature of pointed architecture shall be remedied, and that all the publications of the society upon that subject shall be issued according to such classification and nomenclature. Not indeed that the perfecting of so desirable a project can be expected at once; but such a nomenclature can be laid down as shall immediately distinguish the different members of the art, which are as numerous as those of heraldry; and these can be superseded by more primitive or more simple and energetic terms, as they shall be recovered from ancient contracts and other documents, or shall be invented by more judicious and mature consideration. But to prevent doubt or future mistake, it is proposed that a cut of each intended object shall be executed, and that a reference shall be made to where exemplars of it are to be found, and also to its chronology.

Further, it is proposed to render this College still more useful, by joining with it a charitable foundation, for the behoof of those and their families over whom it shall please Providence, after a life devoted to the service and practice of architecture and its dependant arts, that need shall fall.

This institution, the scope of which is most extensive, is silently, but rapidly forming, and has already connected with it many of the chief men of the literature and science of architecture: few of those whose names will be found amid the subjoined list have not distinguished themselves by the authorship of some eminent architectural work, and many of them are well known in the sciences and arts connected with architecture. A power, an order, and a propriety previously unknown in the profession since the fall of pointed architecture in the sixteenth century, are being worked out, by having every man at his post, and with ability to fill that post well.

Twelve meetings of the College are appointed to take place in every year, and four have already been held.

The following elections have taken place:—

Advent-Eve, 1842.

1. Edward Cresy, Esq., F.S.A., Architect of Trafalgar-square, as Professor of Pointed Architecture.

2. Thomas Parker, Jun., Esq., of Lincoln’s-Inn, as Professor of Architectural Jurisprudence.

3. Valentine Bartholomew, Esq., F.R.B.S., Flower-Painter in Ordinary to the Queen, of 23, Charlotte-street, Portland-place, as Professor of Fruit and Flower Painting.

4. George Aitchison, Esq., Architect, A.I.C.E., Surveyor to the St. Katharine’s Dock Company, and to the Honourable the Commissioners of Sewers for the Precinct of St. Katharine, as Professor of Concreting and Opus Incertum.

5. W. R. Billings, Esq., of Manor House, Kentish Town, as Itinerant Delineator.

6. William Bartholomew, Esq., of Gray’s Inn, Vestry Clerk of St. John, Clerkenwell, as Honorary Solicitor.

7. W. P Griffith, Esq., F.S.A., Architect, St. John’s-square, as Baptisterographer, or Delineator of Fonts and Baptisteries.

8. Frederick Thatcher, Esq., A.R.I.B.A., Architect, of Furnival’s Inn, as Recorder, or Clerk of Proceedings.

9. William Fisk, Esq., of Howland-street, as Professor of Historical Painting.

10. C.H. Smith, Esq., of Clipstone-street, as Architectural Sculptor.

11. Thomas Deighton, Esq., of Eaton-place, Belgrave-square, Architectural Modeller to her Majesty and Prince Albert, as Modeller of Buildings.

12. W. G. Rogers, Esq., of Great Newport-street, as Gibbons Carver.

13. J. G. Jackson, Esq., Architect, of Leamington Priors, as Correspondent Delineator for the County of Warwick.

14. T. L. Walker, Esq., F.R.I.B.A., Architect, of Nuneaton, Warwick, as Correspondent Delineator for the County of Warwick.