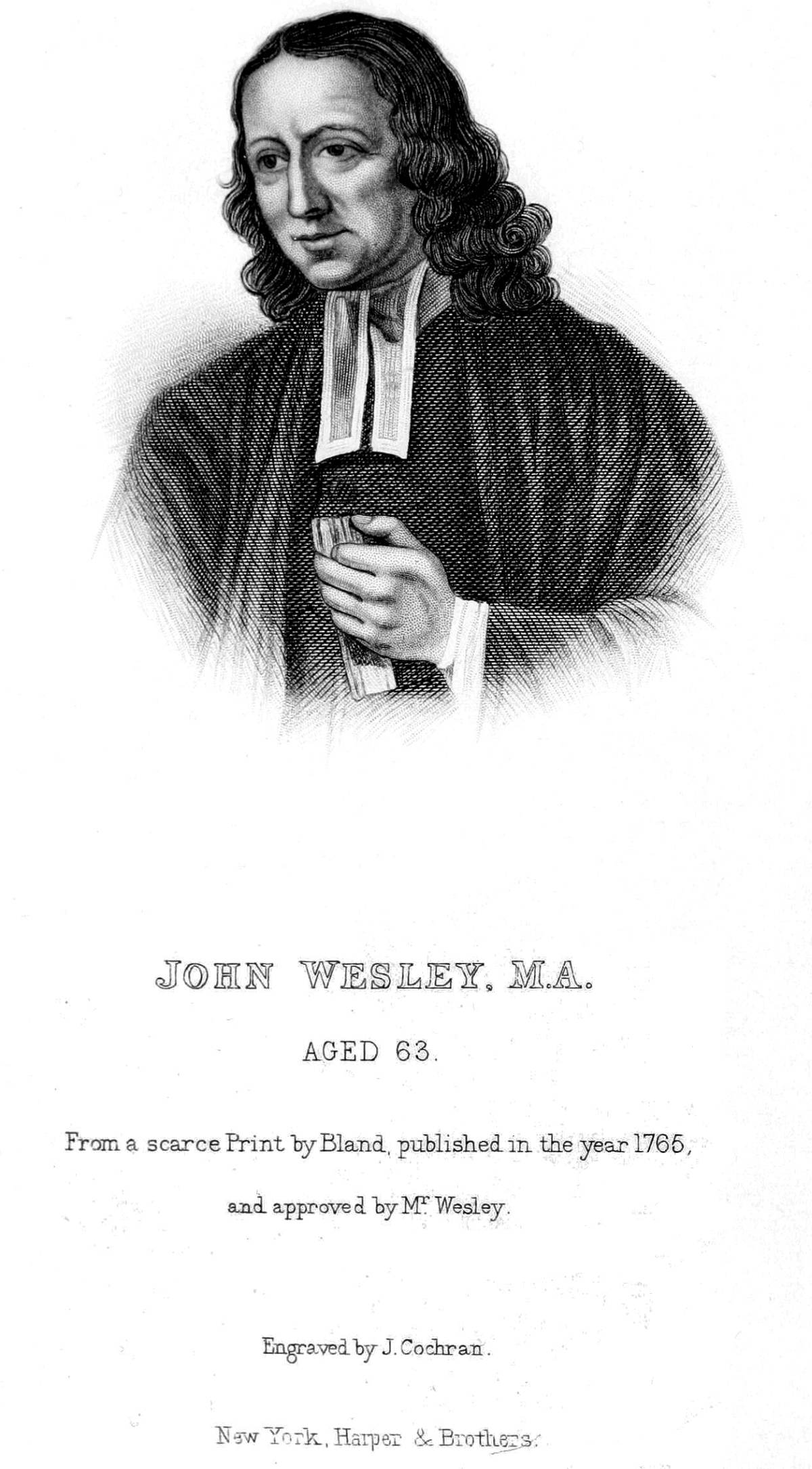

From a scarce Print by Bland, published in the year 1765, and approved by Mr. Wesley.

Engraved by J. Cochran. New York, Harper & Brothers.

Title: The life and times of the Rev. John Wesley, M.A., founder of the Methodists. Vol. 2 (of 3)

Author: L. Tyerman

Release date: July 6, 2023 [eBook #71130]

Language: English

Original publication: United States: Harper & Brothers, Publishers, 1872

Credits: Brian Wilson, Les Galloway, MFR and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

Obvious typographical errors have been silently corrected. All other spelling and punctuation remains unchanged, except inconsistencies in hyphenation.

Founder of the Methodists.

BY THE

Rev. L. TYERMAN,

AUTHOR OF “THE LIFE AND TIMES OF REV. S. WESLEY, M.A.,”

(Father of the Revds. J. and C. Wesley).

IN THREE VOLUMES.

VOL. II.

NEW YORK:

HARPER & BROTHERS, PUBLISHERS,

FRANKLIN SQUARE.

1872.

[Pg v]

VOL. II.

1748.

PAGE

Narrow Escapes—Bristol Chapel—Murderous Persecutions in Ireland—Dublin Society—A Carmelite Friar—First Methodist Chapel in Dublin—London Conference—“Thoughts on Marriage”—Kingswood School—Journey to the North—William Grimshaw—Thomas Colbeck—Horrible Outrages at Roughlee and Barrowford—A Popish Renegado—Grimshaw’s Answer to White—Stoning at Bolton—Wesley among Unitarians—“Drummer Jack”—Whitefield and Wesley—Countess of Huntingdon—Whitefield in Trouble—Bishop Lavington in a Rage—An Unknown Friend—“Christian Library”—Ebenezer Blackwell—Converted Convicts—Sarah Peters—Publications—Wesley on Quakerism

1-31

1749.

Horace Walpole on Methodism—Whitefield and the Wesleys, a Threefold Cord—Wesley gives Lectures to Seventeen Preachers—Charles Wesley Married—Wesley in Ireland—Slanderous Falsehoods—Terrible Persecutions in Cork—Butler, the Ballad Singer—Letter in Bath Journal—John Bennet—Whitefield’s Letter to Bennet—The First Methodist Agitator—Grace Murray—Wesley’s Courtship with Grace Murray—Coquetry—Rival Lovers—Wesley’s Reasons for Marrying—A Wedding—Painful Scenes—Who was Blamable?—A Fire Put Out—Rough Usage in Lancashire—Wesley again in Trouble with Moravians—Original Letter by Wesley—Moravian Balderdash—Wesley’s Publications—Elocution—Dr. Conyers Middleton—Wesley on the Clergy and Learning—“The Christian Library”

32-67

1750.

Fraternization—Whitefield—“The Impostor Detected”—Rev. Charles Manning—Earthquakes—London in Sackcloth—Bishop Sherlock’s Warning—Hymns on Earthquakes—Death of (Mehetabel Wesley) Mrs. Wright—John Jane—Jonah on Board—An Overgrown Brute leading a Drunken Rabble—Roger Ball—Lætitia Pilkington—Wesley in Ireland—Rev. Richard Lloyd—Renewed Outrages in Cork—Drunken Parson at Bandon—Long Rides—Two Termagants—Letters[Pg vi] on Irish Methodism—On Preaching—Complaints against Preachers—The “Gifted Itinerants” in Bristol Weekly Intelligencer—Wesley in the West of England—Zinzendorf—Spitalfields Chapels—Publications—Logic—Rev. Mr. Bailey, of Cork, Castigated—Bishop Lavington’s Vulgar Outpourings—Wesley’s Reply to Lavington

68-94

1751.

Moravianism—Abominations at Leeds and Bedford—“The Contents of a Folio History of the Moravians”—Zinzendorf and the British Parliament—Letter by John Cennick—Wesley’s Marriage—Mrs. Vazeille—A curious Episode—Wesley’s Marriage a great Blunder—Wesley Resigns his Fellowship—Wesley’s Wife and Brother—Connubial Sorrows—Foolish Correspondence with Sarah Ryan—Jealousy and Cruelty—A manly Letter—Original Letter by Wesley’s Wife—Wesley on the Wing—A Bolton Barber—Rev. J. Milner—Benjamin Ingham—Wesley’s First Visit to Scotland—Scottish Methodism—Conference at Leeds—Kingswood Troubles—James Wheatley Tried and Expelled—Strange Proceedings at Norwich—Wheatley condemned to do Public Penance—Number of Itinerant Preachers—A Serious Sifting—Wesley’s Complaints—An Agreement—Mischievous “Gospel Preachers”—Whitefield becomes a Slaveowner—Wesley at Tiverton—John Downes—Wesley on Languages—Calvinistic Fallacies

95-136

1752.

Written Covenants—Journey to the North—Richard Ellison—Rough Reception at Hull—Pocklington—Cursed at York—Maniac at Osmotherley—Mrs. Armstrong at Wickham—Fire Engine at Barnard castle—Extracts from Todmorden Circuit Book—Bedroom at Mellar Barn—Horses—Persecution at Chester—Printing—Letters from Ireland—Charles Wesley charged with being a Calvinist—The first Irish Conference—Philip Guier—A Note of Discord—Publications—Predestination—Rev. John Gill, D.D.—Lavington, the Lampooning Bishop—A marvellous Epitaph

137-153

1753.

Letter from Howel Harris—Whitefield’s Tabernacle—Moravian Debts—Peter Bohler—Zinzendorf charged with Falsehood—Fanatical Fopperies—Letters of Defence—Moravianism at Bedford—Marshalsea Prison—Scenes of Suffering—Benjamin Franklin—Electricity—Wesley’s Electrifying Machines—Advice to Preachers—Incidents—Rev. John Gillies—Alnwick—First Methodist Quarterly Meeting at Newcastle—Conference at Leeds—Original Letter to Whitefield—Minutes of Conference—Methodism at Leicester—Methodism in Isle of Wight—Rioting at Bristol—Wesley Ill—Stephen[Pg vii] Plummer—Wesley and his Friends—Dr. John Fothergill—Wesley’s Epitaph—Dangerous Illness—Whitefield’s loving Letter—Circular of Wesley’s Book Stewards—Thomas Butts—William Briggs—Publications—Dr. John Parkhurst—“Principles and Preaching of the Methodists considered”—“Hymns and Spiritual Songs”—“The Complete English Dictionary”—Wesley a Lover of Plainness

154-183

1754.

Wesley’s “Notes on the New Testament”—Wesley an Invalid—Rev. Henry Venn—Rev. Samuel Furley—Annual Conference—Conference Preaching Plan—Society Ticket—Wesley’s First Visit to Norwich—Chapel at Trowbridge—“The Mechanic Inspired”—Publications—Satirical Poem

184-193

1755.

“Theron and Aspasio”—Journey to the North—A Dance at Hayfield—Methodism in Liverpool—“A Gentleman’s Reasons for his Dissent from the Church of England”—Conference at Leeds—Faithful Dealing—Separation from the Church—Unpublished Letters—Extracts from C. Wesley’s shorthand Diary—Original Letter by C. Wesley—A Poetical Epistle—Letter to Rev. Mr. Baddiley—Other Letters—Rev. Samuel Walker—Rev. Thomas Adam—Whiston Cliff Phenomenon—Rev. John Langhorne, D.D.—Wesley’s Review of the Work of God in England and America—Richard Tompson—“An Apology for the Clergy”—“A Dissertation on Enthusiasm”—Wesley in London, and in Cornwall—A Sunday’s Work—Rev. John Fletcher—Wesley catechizes Zinzendorf—Earthquake at Lisbon—“Catholic Spirit”; “Notes on the New Testament”

194-227

1756.

Whitefield in Long Acre—“History of Modern Enthusiasm”—Another hostile Publication—Letter to Joseph Cownley—Methodist Soldiers at Canterbury—Dr. Dodd—Christian Perfection—Threatened Invasion of the French—Methodist Volunteers—Wesley, and Bristol Election—Visit to Howel Harris—Wesley in Ireland—The Palatines—Methodism at Lisburn—Conference at Bristol—Methodists becoming Dissenters—“The Mitre”—Letters on Separation from the Church—C. Wesley, and his Northern Mission—Original Letter—Proposal to Ordain Preachers—Further Correspondence on Separation from the Church—Debt Incurred—Forbidden Marriages—Wesley on the French Language—Hutchinsonianism—Wesley criticises “Theron and Aspasio”—Fletcher Ordained—Fletcher on Methodist Sacraments—Publications—Baptismal Regeneration—Jacob Behmen—William Law, a[Pg viii] Behmenite—Controversy—“Address to the Clergy”—Hostile Pamphlets

228-270

1757.

C. Wesley ceases to Itinerate—Whitefield Mobbed in Dublin—Sabbath Work in London—The first Methodist Mayor—Wesley in Liverpool, and in Huddersfield—David Lacy—A Woman at Padiham threatens Wesley’s Life—Grand Service at Haworth—Wesley in Scotland—Three Weeks at Newcastle—Return Southwards—Death of Persecutors—Conference in London—Rev. Mr. Vowler—Correspondence on Separation from the Church—Wesley on Methodist Worship—Rev. Martin Madan—Sarah Ryan—Rules for Kingswood School—Wesley’s Wife leaves him—Miss Bosanquet’s Home, at Leytonstone—Wesley in Cornwall—Fire at Kingswood School—Fine Chapels—Hostile Pamphlets—London Magazine—Wesley’s Publications—John Glass and Robert Sandeman—“Doctrine of Original Sin”—Letter to Dr. Taylor

271-296

1758.

African Converts—Nathaniel Gilbert—Sermon at Bedford Assizes—Rough Journey—“Dame Cross”—Rev. Francis Okeley—Wesley in Ireland—Conference at Bristol—Christian Perfection—Methodism at Warminster—Rev. John Berridge—Remarkable Scenes at Everton—Rev. John Newton—Rev. Augustus Montague Toplady—Leeds Society—Wesley’s Publications—Separation from the Church—“Preservative against Unsettled Notions in Religion”—Rev. Dr. Free

297-322

1759.

Great National Excitement—Prayer-Meetings at Lady Huntingdon’s—Methodist Clergymen—Rev. Thomas Jones—Norwich Methodism—Journey to the North—Methodism at Stockport—Methodism in Sunderland—A Fisherwoman at Newcastle—Trances at Everton—Letter from Berridge—Conference in London—Norwich Methodists—Rev. Thomas Goodday—Rev. Richard Conyers, LL.D.—Rev. Walter Shirley—Ecclesiastical Dress—French Prisoners—Methodism at Bedford—Wesley, on the Work at Everton—First Lovefeast for the whole Society—Savage Onslaught by Rev. John Downes—Wesley’s Publications—Suicides—“Advices with respect to Health”—Christian Perfection

323-347

1760.

Letter to Lloyd’s Evening Post—Wesley on the Wing—Wesley and John Newton—Strange Incident in Ireland—General Cavignac—Methodism in Ireland—Wesley mobbed at Carrick upon Shannon—A[Pg ix] Tour of thirteen Weeks—Racing against Time—Letters—A Lawsuit—Original Letter by Walter Sellon—A noble Scheme—Wesley in Cornwall—Catechumen Classes at Bristol—Death of George II.—John Newton declines to become a Methodist Preacher—Execution of Earl Ferrars—Dastardly Attack on Methodism by Samuel Foote—Hostile Publications—Separation from the Church—C. Wesley in a Frenzy—Queries in Lloyd’s Evening Post—Wesley’s Publications—Dress—Results

348-392

PART III.

1761.

Distinguished Men—England from 1760 to 1791—Newgate Prison—Westminster Journal—London Methodists—Methodism’s first Female Preacher—Journey to the North—Real Antinomian Methodists—James Relly—Rev. Henry Venn’s Irregularities—Separation from the Church—Methodism in Aberdeen—Letter to Mrs. Hall—John MacGowan—Methodism in Darlington, Yarm, Scarborough, Otley, Bingley, Rotherham, etc.—Wesley admonishing an Itinerant—Alexander Coates—A Compromise—Conference in London—Original Letter by J. Manners—Christian Perfection—London Magazine—Lloyd’s Evening Post—St. James’s Chronicle—Two Sermons before University of Oxford—Wesley’s Publications—Methodist Tunes and Singing

393-430

1762.

Rev. Benjamin Colley—Christian Perfection—Thomas Maxfield—George Bell—Wesley admonishing Fanatics—Sad Confusion—A false Prophecy—“Philodemas”—Good educed from Evil—Cautions to greatest Professors—Maxfield’s Whinings—End of Bell—Wesley and his Brother on Christian Perfection—Wesley at Everton—Wesley in Ireland—A starving Player—Methodist Professors of Sanctification—Conference at Leeds—A Cornish Magistrate—Letters on Christian Perfection—Hostile Publications—Wesley’s Publications

431-458

1763.

Wesley the only Clerical Itinerant—Letters in London Chronicle—Fanatical Methodists—Wesley’s Friends desert him—Rev. J. Fletcher—Rev. W. Romaine—“Farther Thoughts on Christian Perfection”—Advice to the Sanctified—Distress in London—“Society for the Reformation of Manners”—A “Pious Fraud”—Scottish Ladies—Methodism in Edinburgh, Dunbar, Barnard castle, etc.—Letter from Dr. Conyers—“A kind of Gentleman”—Matthew Mayer—Conference Minutes, between 1753 and 1763—Howel Harris at Conference of 1763—Welsh Jumpers—Danger of[Pg x] rich Methodists—Methodism in Norwich and London—Rev. Jacob Chapman—Dr. Byrom—Increase of Methodism creates a Difficulty—Erasmus and his Ordination—Wesley and Dr. Rutherforth—Wesley and Bishop Warburton—Jane Cooper—Wesley’s Publications

459-496

1764.

Whitefield in Ill Health—The half insane Watchmaker—Blandford Park—Oratorios—Wesley on his northern Journey—Unpublished Letter by Wesley to Lady Maxwell—An adventurous Ride—Riding in Carriages—Difficulty—Unpublished Letter by Wesley to Countess of Huntingdon—Proposed Clerical Union—On Consecrating Churches—Defraying Debts on London Chapels—Proposed new Theatre at Bristol—A Pastoral Address—A Methodist Orphanage—Rev. Thomas Hartley—The Mystics—Millenarianism—Attacks on Methodism—Wesley’s last letter to Hervey—Hervey’s “Eleven Letters to Wesley”—Old Friends divided—Quarrelling and its Results—Letters to Thomas Rankin—Methodist Manifesto

497-533

1765.

Methodism at High Wycombe—A Long Tour—Alexander Knox, Esq.—Opinions and essential Doctrines—Conference of 1765—Methodism at Huddersfield—Important Letter to Rev. H. Venn—Disgraceful Scene in Devonshire—Faults of Cornish Methodism—Professors of Sanctification—Captain Webb—Methodism in Kent—A serious Accident—“Mumbo Chumbo”—“The Scripture Way of Salvation”—Imputed Righteousness—Celibacy—Wesley’s “Notes on the Old Testament”

534-554

1766.

Methodism at Yarmouth—A quadruple Alliance—Horace Walpole on Wesley—Methodism in Bath, Cheltenham, Burton on Trent, Nottingham, and Sheffield—Christian Perfection—Unpublished Letters by Fletcher and Wesley—Methodism at Warrington—Trust Deed of Pitt Street Chapel, Liverpool—Chapel Architects—Wesley in Scotland—An Adventure—A mad Woman in Weardale—Letter to the Dean of Ripon—A vindictive Parson—An odd Mistake—Methodism at Pateley Bridge, Bradford, Halifax, and Haworth—Coolness between Wesley and his Brother—Are Methodists Dissenters?—Methodist public Worship—Wesley’s autocratic Power—An unflattering Picture of the Methodists—Pastoral Visitation—The Way to make Useless Preachers Useful—Conference of 1766—A Mob Defeated—Methodism at Helstone—Methodist Soldiers at Northampton—Miss Lewen—Attacks on Methodism—“Plain Account of Christian Perfection”

555-594

[Pg xi]

1767.

Whitefield—Letter to C. Wesley—Wesley and Dr. Dodd—Irish Superstition—Wesley in Ireland—Methodist Success—Letter to Lady Maxwell—Wesley defending the Methodists—First Methodist Missionary Collection—First Methodist Chapel in America—Methodist Statistics in 1767—Yorkshire Methodism—“Primitive Methodism”—Conference of 1767—Chapel Debts—Wesley on the Wing—Methodism in Sheerness—“Methodism Triumphant”—“The Troublers of Israel”—Smuggling—Wesley’s Publications

595-618

[Pg xii]

[Pg 1]

THE LIFE AND TIMES

OF

THE REV. JOHN WESLEY, M.A.

WESLEY writes: “January 1, 1748.—We began the year at four in the morning, with joy and thanksgiving. The same spirit was in the midst of us, both at noon and in the evening.”

On January 25, he set out for Bristol, and at Longbridge-Deverill, three miles from Warminster, by being thrown from his horse, had a narrow escape from an untimely death. These dangers and escapes were numerous and remarkable. Near Shepton-Mallet, while descending a steep bank, he had another accident of a similar kind to the former, his horse and himself tumbling one over the other, and imperilling the lives of both. And, a few weeks later, when in Ireland, his horse became restive and “fell head over heels.” With almost literal exactness might Wesley have made the apostle’s language his own: “In journeyings often, in perils of waters, in perils of robbers, in perils by countrymen, in perils by the heathen, in perils in the city, in perils in the wilderness, in perils in the sea, in perils among false brethren; in weariness and painfulness, in watchings often, in hunger and thirst, in fastings often, in cold and nakedness; besides those things that are without, that which cometh upon us daily, the care of all the churches.”

The chapel at Bristol, though built only nine years ago, was in great danger of falling upon the people’s heads; and, moreover, it was now too small to accommodate the congregation attending. Accordingly, Wesley took instant steps to repair[Pg 2] and to enlarge the building, and obtained a subscription of £230, towards defraying the expense.

While here, he also made a visit to Shepton-Mallet, where a hired and drunken mob pelted him and his companion, Robert Swindells, with “dirt, stones, and clods in abundance”; broke the windows of the house in which they were staying, took it by storm, and threatened to make it a heap of burning ruins.

Still, the Methodist revival spread. Writing to his friend Blackwell, under the date of February 2, Wesley says:—“Both in Ireland, and in many parts of England, the work of our Lord increases daily. At Leeds only, the society, from a hundred and eighty, is increased to above five hundred persons.”[1]

Charles Wesley and Charles Perronet had been in Ireland for the last six months, and, on the Moravians being ejected from the chapel in Skinner’s Alley, had become the tenants of that building. They had made an excursion to Tyrrell’s Pass, and, from among proverbial swearers, drunkards, thieves, and sabbath breakers, had formed a society of nearly one hundred persons. At Athlone, a gang of ruffians knocked Jonathan Healey off his horse, beat him with a club, and were about to murder him with a knife, when a poor woman, from her hut, came to his assistance, and, for her interference, was half killed with a blow from a heavy whip. The hedges were all lined with papists; the dragoons came out, the mob fled, Healey was rescued, and was taken into the woman’s cabin, where Charles Wesley found him in his blood, and attended to his wounds. A congregation of above two thousand assembled in the market; Charles Wesley preached to them from the window of a ruined house; and then the knot of brave-hearted Methodists marched to the field of battle, stained with Healey’s blood, and sang a song of triumph and of praise to God.

Having completed his business at Bristol, Wesley, on the 15th of February, started for Ireland, but the weather was such, that three weeks elapsed before he was able to set sail from Holyhead. Winds were boisterous, and snow lay thick upon the ground; but, on the way, besides preaching in[Pg 3] churches, chapels, and roadside inns, Wesley, at Builth and other places, took his stand in the open air, immense congregations making surrounding woods and mountains echo, as they sung:—

Attending a service in the Welsh language, he wrote: “What a curse was the confusion of tongues! and how grievous are the effects of it! All the birds of the air, all the beasts of the field, understand the language of their own species. Man only is a barbarian to man, unintelligible to his own brethren!”

At length, Wesley, accompanied by Robert Swindells and the Rev. Mr. Meriton, set sail, and, on March 8, arrived in Dublin, where they found Charles Wesley meeting the society, the members of which made so much noise in shouting, and in praising God, that, for a time, Wesley was unable to obtain a hearing.

Charles returned to England. Wesley spent the next ten weeks in Ireland. These were long absences, to which the leaders in London objected; but Wesley’s almost prophetic answer was, “Have patience, and Ireland will repay you.”[2]

Wesley’s first business was to begin preaching at five o’clock in the morning, “an unheard of thing in Ireland”; his next, to inquire into the state of the Dublin society. He writes: “Most pompous accounts had been sent me, from time to time, of the great numbers added; so that I confidently expected to find six or seven hundred members. And how is the real fact? I left three hundred and ninety-four members; and I doubt if there are now three hundred and ninety-six.” This seems to be a reflection on his brother; but was there not a cause? Ten days later, he remarks: “I finished the classes, and found them just as I expected. I left three hundred and ninety-four persons united together in August; I had now admitted between twenty and thirty, who had offered themselves since my return to Dublin; and the whole[Pg 4] number is neither more nor less than three hundred and ninety-six.” He adds: “Let this be a warning to us all, how we give in to that hateful custom of painting things beyond the life. Let us make a conscience of magnifying or exaggerating anything. Let us rather speak under, than above, the truth. We, of all men, should be punctual in all we say, that none of our words may fall to the ground.”

At Philip’s Town, “a poor, dry, barren place,” he found a society, of whom forty were troopers.[3] At Tullamore, he preached to most of the inhabitants of the town; and at Clara, to “a vast number of well behaved people, some of whom came in their coaches, and were of the best quality in the country.” At Athlone, he writes: “Almost all the town appeared to be moved, full of good will and desires of salvation; but I found not one under any strong conviction, much less had any one attained the knowledge of salvation, in hearing above thirty sermons.”

At Birr, he preached “in the street, to a dull, rude, senseless multitude.” A Carmelite friar cried out, “You lie! you lie!” but the protestants present cried, “Knock the friar down”; and Wesley adds, “it was no sooner said than done.”

At Aughrim, he heard “a warm sermon against enthusiasts”; and, to the same congregation, preached another as an antidote. Mr. Simpson, a magistrate, invited him to dinner; and he, and his wife and daughter, were the first at Aughrim to join the Methodists.[4]

These and other places were soon formed into a circuit, extending on the Leinster side as far as Tyrrell’s Pass and Mountmellick, and on the Connaught side as far as Ballinrobe, Castlebar, and Sligo, the quarterly meetings being held at Coolylough, the residence of Mr. Handy, where hospitable entertainment was abundantly provided, and many a season of spiritual refreshing was religiously enjoyed.[5]

In Dublin, the Methodists had two meeting-houses, one in Dolphin Barn Lane, and the other in Skinner’s Alley; but they were both rented, and therefore of uncertain tenure. Wesley was not satisfied with this, and used his utmost[Pg 5] endeavours to obtain a freehold site, for the erection of a chapel of his own. On the 15th of March, he wrote to Ebenezer Blackwell as follows: “We have not found a place yet that will suit us for building. Several we have heard of, and seen some; but they are all leasehold land, and I am determined to have freehold, if it is to be had in Dublin; otherwise we must lie at the mercy of our landlord whenever the lease is to be renewed.”[6]

Some time after, the freehold site was obtained, and, with Mr. Lunell’s munificent assistance, the first Methodist meeting-house in Dublin was erected in Whitefriar Street, and was opened for public worship in 1752.

Wesley returned to England at the end of the month of May, and on the 2nd of June, and three or four, following days, held, in London, his annual conference. The number present was twenty-three, including about half-a-dozen clergymen, three stewards, some local preachers, and Howel Harris.

At the opening of the conference, it was agreed that there would be no time to consider points of doctrine, and therefore that the attention of those present should be wholly confined to discipline.

The principle was reiterated, that, wherever they preached, they should form societies. They were to visit the poor members of society as much as the rich. Every alternate society-meeting in London, Bristol, Kingswood, and Newcastle, was to be kept inviolably private. At the other meetings strangers might be admitted with caution. It was thought, that they were in danger of making too long prayers, and it was agreed that, though exceptional cases must arise, yet, in general, they would do well not to pray in public above eight or ten minutes at a time. Directions were given to the assistants to guard against jealousy and envy, and against despising each other’s gifts. They were to try to avoid popularity, that is, “the gaining a greater degree of esteem or love from the people than is for the glory of God.” They were to examine the leaders of classes, and were to send to the Wesleys a circumstantial account of every remarkable[Pg 6] conversion, and of every triumphant death. Assisted by the stewards, they were, every Easter, to make exact lists of all the members in each of the nine circuits into which the societies were divided, and to send the lists to the ensuing conference.[7]

In addition to these matters, there was another debated, of great interest and importance. Five years before, Wesley had published his “Thoughts on Marriage and Celibacy,” in which, to say the least, he strongly commended a single life. His brother Charles was now courting Miss Sarah Gwynne, and wished to marry her. Charles writes:—“How know I, whether it be best for me to marry, or no? Certainly better now than later; and, if not now, what security that I shall not then? It should be now, or not at all.” This was sound sense. Charles was now forty years old, and, like a wise man, he concluded, that he must either marry now, or never. Before he left Ireland, he communicated his intentions to his brother; and, in the month of April, he rode to Shoreham, and “told all his heart” to Vincent Perronet.[8] Difficulties existed. Among others, there was his brother’s tract. The Conference of 1747 had agreed to read all the tracts which had been published, and to make a note of everything that was thought objectionable. The Conference of 1748 was about to meet, and, of course, had a perfect right to review and to revise the “Thoughts on Marriage.” The question was introduced, and the result of the discussion upon Wesley’s mind may be found in the following sentence from a manuscript in the British Museum, which, though not written by Wesley, was corrected by him. “In June, 1748, we had a conference in London. Several of our brethren then objected to the ‘Thoughts on Marriage’; and, in a full and friendly debate, convinced me, that a believer might marry without suffering loss in his soul.” This was a great point gained. Charles’s courtship proceeded; and, in April, 1749, John writes: “Saturday, April 8.—I married my brother and Sarah Gwynne. It was a solemn day, such as became the dignity of a Christian marriage.” A stranger said, it looked more like a funeral than a wedding; but Charles remarks,[Pg 7] “We were cheerful without mirth, serious without sadness; and my brother seemed the happiest person among us.”[9]

A few days after the conference was closed, Wesley and his brother proceeded to Bristol for the purpose of opening Kingswood school.

Kingswood school! a sacred spot, surrounded with unequalled Methodistic memories; once one of the homes of the Wesleys and their friends; the place of not a few remarkable revivals of religion; an academic grove, whose scenery was at first beautiful and inviting, and from which have issued many of the most distinguished ministers that Methodism has ever had, and not a few highly accomplished scholars, whose names stand honourably associated with the legal and other high professions, and with England’s chief seats of learning; an upretending edifice, with associations to which no other Methodist building (except the Broadmead meeting-house in Bristol) can make pretensions; for above half a century Methodism’s only college; to the end of life one of Wesley’s favourite haunts; the alma mater of scores still living, who will always love its memory; a homestead in which Methodism lingered perhaps as long as was expedient; and which, when Methodism left it, in 1852, became a place of discipline for young thieves and vagabonds, a reformatory for youthful criminals, whose presence in public society was a nuisance and a curse, and yet whose minds and morals were most likely to be improved, not in a prison, but in a school.

We have already seen, that Wesley built a school at Kingswood in 1740. Myles, in his Chronological History, says, that the school opened in 1748 was the old school “enlarged;”[10] and that, though the school commenced in 1740 was intended for the children of colliers, yet, for some years, several of the Methodists in other places had sent their children to be educated here.[11]

This was an encroachment upon Wesley’s original design, but one which he had no disposition to resist. Besides this, he found it necessary to make some provision for the education of the children of his preachers. Their fathers[Pg 8] were almost constantly from home. Their mothers, in many cases, were unequal to their management. Funds did not exist to send them to a boarding school. And hence Wesley found it imperative to provide a school himself.

To meet this necessity, he “enlarged” the existing school at Kingswood, an unknown lady giving him £800 towards defraying the expenses.[12] The school for the children of the colliers was not closed. It continued to exist for more than sixty years subsequent to the period of which we are writing, and was supported by the subscriptions of the Kingswood society.[13] But now, in 1748, another school, for another class of children, was attached to this, and really became the Kingswood school, so famed in Methodistic annals, and whose memory will last as long as Methodism lasts.

Wesley selected Kingswood for his school because “it was private, remote from all high roads, on a small hill sloping to the west, sheltered from the east and north, and affording room for large gardens.” He made it capable of accommodating fifty children, besides masters and servants; reserving one room and a small study for himself.[14] On the front of the building was placed a tablet, with the inscription, “In Gloriam Dei Optimi Maximi, in Usum Ecclesiæ et Reipublicæ”; and under this, “Jehovah Jireh,” in Hebrew characters.[15] The great defect of the situation was the want of water. Vincent Perronet, in a letter to Walter Sellon, in 1752, writes: “My dear brother John Wesley wonders at the bad taste of those, who seem not to be in raptures with Kingswood school. If there was no other objection, but the want of good water upon the spot, this would be insuperable to all wise men, except himself and his brother Charles.”[16] For more than a hundred years, this was a radical defect, and was one of the chief reasons which induced the Conference to remove the school to another place in 1852.

It has been already stated, that the school was designed[Pg 9] not only for the sons of preachers, but for the children of those Methodists who were able and wishful to give their offspring an education, superior to that imparted in the villages or towns in which they respectively resided. If it be asked, why Wesley did not advise such Methodists to send their children to the boarding schools then existing? the answer is—1. Because most of these schools were in large towns, to which he greatly objected. 2. Because all sorts of children, religious and irreligious, were admitted. 3. Because, in many instances, the masters were regardless of the principles and practice of Christianity, and were utterly indifferent whether their scholars were papists or protestants, Turks or Christians. 4. Because, in most of the great schools, the education given was exceedingly defective, and the class books were imperfect in style and sense, and, in some cases, absolutely profane and polluting.[17]

For such reasons, Wesley opened his new school in Kingswood, on the 24th of June, 1748, by preaching on the text, “Train up a child,” etc.; after which he and his brother administered the sacrament to the crowd who had come from distant places; and then drew up the scholastic rules, which were published soon after.

The object of the school was “to train up children in every branch of useful learning.” None but boarders were to be admitted, and “these were to be taken in, between the years of six and twelve, in order to be taught reading, writing, arithmetic, English, French, Latin, Greek, Hebrew, history, geography, chronology, rhetoric, logic, ethics, geometry, algebra, physics, and music.” They were all to “be brought up in the fear of God; and at the utmost distance, as from vice in general, so in particular from idleness and effeminacy.” Wesley adds: “The children of tender parents, so called (who are indeed offering up their sons and their daughters unto devils), have no business here; for the rules will not be broken, in favour of any person whatsoever. Nor is any child received unless his parents agree that he shall observe all the rules of the house; and that they[Pg 10] will not take him from school, no, not a day, till they take him for good and all.”

Wesley’s design, in founding the school, was, in the highest degree, benevolent and pure; but some of his rules were as absurd as inexperienced philosophy could make them. The diet, consisting of bacon, beef, and mutton, bread and butter, greens, water gruel, and apple dumplings, was unexceptionable. Going to bed at eight, and sleeping on mattresses, were also commendable arrangements. But what can be said of the rule, that every child was to rise, the year round, at four o’clock, and spend the time till five in private, reading, singing, meditating, and praying? Who will defend the rule, that no play days were to be permitted, and no time allowed, on any day, for play, on the ground that he who plays when he is a child will play when he becomes a man? What again about the rule, that every child, if healthy, should fast every Friday till three o’clock in the afternoon? No wonder that Wesley complains of his rules being habitually broken. With such a programme, the school became to him a source of inexpressible annoyance. Children were removed by their parents, and some were dismissed as incorrigible. Enforced religion created a disgust for it, and this imperious way of making saints, in some instances, made the children hypocrites.

At five every morning, they attended public religious service, and again at seven every night. At six, they breakfasted; at seven, school began; at eleven, they walked or worked; at twelve, they dined, and then worked in the garden or sang till one; from one till five, they were again in school; from five to six, was their hour for private prayer; and from six to seven, they again walked or worked; when they all had supper on bread and butter, and milk by turns; and at eight, marched off to bed. On Sundays, they dressed and breakfasted at six; at seven, learnt hymns or poems; at eight, attended public service; at nine, went to the parish church; at one, dined and sang; at two, attended public service; and at four, were privately instructed. Six masters were employed; one for teaching French, two for reading and writing, and three for the ancient languages. The charge for each boy’s board and education, including books, pens, ink, and paper,[Pg 11] was £14 a year.[18] Walter Sellon, John Jones, and James Roquet, all of whom obtained ordination in the Established Church, together with Richard Moss, Monsieur Grou, and William Spencer were the first batch of masters.[19]

Does history record a school parallel to Wesley’s school at Kingswood? We doubt it. It will often require notice in succeeding chapters; but suffice it to add here, that, for a few months at least, the school was worked to Wesley’s satisfaction. In August, several of the boys were converted;[20] and in October, the housekeeper, in a letter to Wesley, wrote:—“The spirit of this family is a resemblance of the household above. They are given up to God, and pursue but the one great end. If any is afraid this school will eclipse others, or that it will train up soldiers to proclaim open war against the god of this world, I believe it is not a groundless fear. If God continue to bless us, one of these little ones shall chase a thousand. I doubt not but, from this obscure spot, there will arise ambassadors for the King of kings.”[21]

On June 27, three days after the opening of Kingswood school, Wesley set out for the north of England. On his way, he preached at Wallbridge “to a lively congregation”; and at Stanley, “in farmer Finch’s orchard.” He spent two days at dear old Epworth; preached four times; heard Mr. Romley, whose “smooth, tuneful voice,” so often used in blaspheming the work of God, was now nearly lost; and received the sacrament from Mr. Hay, the rector. The Methodist society, though not large, had been useful, and sabbath breaking and drunkenness, cursing and swearing, were hardly known. At Hainton, “chiefly owing to the miserable diligence of the poor rector,” the congregation was small. At Coningsby, he preached to one of the largest congregations he had seen in Lincolnshire, and disputed, for an hour and a half, with a Baptist minister upon baptism. At Grimsby, the congregation not only filled the room, but the stairs and adjoining rooms, and many stood in the street below, notwithstanding Mr. Prince had bitterly cursed the[Pg 12] poor Methodists in the name of the Lord. At Laseby, he had “a small, earnest congregation”; and, at Crowle, a wilder one than he had lately seen. Thus preaching at almost every place where he halted, he reached Newcastle on Saturday, July 9.

Here, and in all the country societies round about, he found an increase of members, and more of the life and power of religion among them, than he had ever found before. The boundaries of the Newcastle circuit were,—Allandale on the west, Sunderland on the east, Berwick on the north, and Osmotherley on the south,[22]—an immense tract of country, situated in, at least, four different counties. This Wesley traversed, preaching, visiting classes, and founding societies.

Having spent more than five weeks among these northern Methodists, Wesley, on the 16th of August, started southwards, taking Grace Murray with him, to whom he had proposed marriage. During the first day’s journey, he preached at Stockton, near the market place, “to a very large and very rude congregation;” again in the market place at Yarm; and again, in the midst of a continuous rain, in the street at Osmotherley.

Proceeding to Wakefield, he became the guest of Francis Scott, a local preacher, part of whose joiner’s shop was used as a preaching room.[23] Thence he went to Halifax, where he attempted to preach at the market cross to “an immense number of people, roaring like the waves of the sea.” A man threw money among the crowd, creating great disturbance. Wesley was besmeared with dirt, and had his cheek laid open by a stone. Finding it impossible to make himself heard, he adjourned to a meadow near Salterhebble, and spent an hour with those that followed him “in rejoicing and praising God.”[24] He then went to Bradford, where the only person who misbehaved was the parish curate.

At Haworth, even at five o’clock in the morning, the church was nearly filled. Grimshaw read prayers, and Wesley[Pg 13] preached. A Methodist society was already formed, as appears from the following item in the Haworth society book:—“1748, Jan. 10: A pair of boots for William Darney, 14s. 0d.”[25] Grimshaw was now as much a Methodist as Wesley was, with this difference, the former had a church, the latter not.

For six years, Grimshaw had been incumbent of Haworth. His church was crowded, and no wonder. In the surrounding hamlets, he was accustomed to preach from twelve to thirty sermons weekly. His congregations were rude and rough; but they caught the fervour of his spirit, and hundreds of his hearers were converted. He loved labour, and, for his Master’s sake, cheerfully encountered hard living. One day he would be the guest of Lady Huntingdon; at another time, he would be found sleeping in his own hayloft, simply to find room for strangers in his parsonage. In all sorts of weather, upon the bleak mountains, often drenched by rain, or benumbed by frost, with no regular meals, and frequently nothing better than a crust, he never wearied in his evangelistic wanderings, but pursued his onward course with a blithesome spirit, singing praises to his Divine Redeemer. His dress was plain, and sometimes shabby. Often he had literally only one coat and one pair of shoes, not from affectation, or eccentricity, but from a benevolent desire to benefit the poor. Possessed of strong mental power, and with a Cambridge education, he was capable of rising above the rank of ordinary preachers; but, to accommodate himself to his rustic hearers, there was a homeliness in his forms of speech, which was sometimes scarcely dignified. He preached in the same style as that in which Albert Durer painted. His power in prayer was marvellous. “He was like a man with his feet on earth and his soul in heaven.” As one of Wesley’s “assistants,” he visited classes, gave tickets, held lovefeasts, attended quarterly meetings, entertained the “itinerants,” and let them preach in the kitchen of his parsonage. He was oft eccentric, but always honest, earnest, and devout. Strong of frame, and robust in health, his study was under the wide canopy of heaven, among hills and dales;[Pg 14] and the weariness of his wanderings was relieved by Divinely imparted thoughts, and communings with his God. He died April 7, 1763; some of his last words being, “I am as happy as I can be on earth, and as sure of heaven as if I was in it.” He was a rare man; and in him was fully exemplified his favourite motto, which was inscribed upon his coffin, “For me to live is Christ, and to die is gain.”

In the same neighbourhood was another man, who, though not so eminent, deserves honourable mention,—Thomas Colbeck, of Keighley, now twenty-five years of age, long a faithful and laborious local preacher, and whose memory is still precious among the west Yorkshire mountains. He was one of Grimshaw’s faithful travelling companions; and, by his instrumentality, Methodism was introduced into not a few of the villages in the neighbourhood where he lived. His house was Wesley’s home, and the resting place of Wesley’s itinerants. While praying with a person afflicted with a fever he caught the infection, and died on November 5, 1779.[26]

On leaving Haworth, Wesley proceeded to Roughlee, a village in the vicinity of Colne, Grimshaw and Colbeck going with him. While Wesley was preaching, a drunken rabble came, with clubs and staves, led on by a deputy constable, who said he was come for the purpose of taking Wesley to a justice of the peace at Barrowford. Wesley went with him. On the way a miscreant struck him in the face; another threw a stick at his head; and a third cursed and swore, and flourished his club about Wesley’s person as if he meant to murder him. On reaching the public house, where his worship was waiting, he was required to promise not to come to Roughlee again. He answered, he would sooner cut off his head than make such a promise. For above two hours, he was detained in the magisterial presence; but, at length, he was allowed to leave. The deputy constable went with him. The mob followed with oaths, curses, and stones. Wesley was beaten to the ground, and was forced back into the house. Grimshaw and Colbeck were used with the utmost violence, and covered with all kinds of sludge. Mr. Mackford, who had come with Wesley from Newcastle, was dragged by[Pg 15] the hair of his head, and sustained injuries from which he never fully recovered. Some of the Methodists, who were present, were beaten with clubs; others were trampled in the mire; one was forced to leap from a rock ten or twelve feet high, into the river; and others had to run for their lives, amidst all sorts of missiles thrown after them. The magistrate saw all this; and, so far from attempting to hinder it, seemed well pleased with the murderous proceedings. Next day Wesley wrote him as follows:—“All this time you were talking of justice and law! Alas, sir, suppose we were Dissenters (which I deny), suppose we were Jews or Turks, are we not to have the benefit of the laws of our country! Proceed against us by the law, if you can or dare; but not by lawless violence; not by making a drunken, cursing, swearing, riotous mob, both judge, jury, and executioner. This is flat rebellion against God and the king, as you may possibly find to your cost.”

This horrible outrage was chiefly fomented by a popish renegado, who was now the curate of Colne. The following proclamation for raising mobs against the Methodists was issued:—

“Notice is hereby given, that if any men be mindful to enlist into his majesty’s service, under the command of the Rev. George White, commander-in-chief, and John Bannister, lieutenant-general of his majesty’s forces, for the defence of the Church of England, and the support of the manufactory in and about Colne, both of which are now in danger, etc., etc., let them now repair to the drumhead at the cross, where each man shall have a pint of ale for advance, and other proper encouragements.”[27]

Besides this, White, within the last month, had preached an inflammatory sermon which, at the end of the year, was published, with a dedicatory epistle to the Archbishop of Canterbury. The title is, “A Sermon against the Methodists, preached at Colne and Marsden, to a very numerous audience; by George White, M.A., minister of Colne and Marsden; and author of ‘Mercurius Latinus.’ Published at the request of the audience.” Octavo, 24 pages.

This clerical railer tells the archbishop that, by means of Methodism, there was, in this remote part of the country,[Pg 16] “a schismatical rebellion against the best of churches; a defiance of all laws, civil and ecclesiastical; a professed disrespect to learning and education; a visible ruin of trade and manufacture; a shameful progress of enthusiasm; and a confusion not to be paralleled in any other Christian dominion.” He adds, that he has taken pains to “inquire into the characters of these new sectaries, and has found their teachers shamefully ignorant, and criminally arrogant, while many of them have been prevented arriving at the order of priesthood by early immoralities.”

The text he professes to expound is 1 Corinthians xiv. 33, and the following are a specimen of his spicy sentences concerning the Methodists and their system:—“A weak illiterate crowd,”—“a labyrinth of wild enthusiasm,”—preachers are “bold, visionary rustics, setting up to be guides in matters of the highest importance, without any other plea but uncontrollable ignorance,”—these officious haranguers cozen a handsome subsistence out of their irregular expeditions. Mr. Wesley has in reality a better income than most of our bishops. The under lay praters, by means of a certain allowance from their schismatic general, a contribution from their very wise hearers, and the constant maintenance of themselves and horses, are in a better way of living than the generality of our vicars and curates; and doubtless find it much more agreeable to their constitution, to travel abroad at the expense of a sanctified face and a good assurance, than to sweat ignominiously at the loom, anvil, and various other mechanic employments, which nature had so manifestly designed them for.”

But enough of the oracular utterances of Mr. White. Who was he? First of all, he was educated at Douay, for orders in the Church of Rome. Renouncing popery, he was noticed by Archbishop Potter, and made a priest of the Church of England. An itch for scribbling made him the author of about half-a-dozen worthless ungrammatical publications, including “a burlesque poem on a miraculous sheep’s eye at Paris.” A devoted son of “the best of churches,” he frequently abandoned his church for weeks together; and, on one occasion, read the funeral service more than twenty times in a single night over the dead bodies which had been interred, without ceremony, during his absence from home. He married an Italian[Pg 17] governess in 1745; was imprisoned for debt in Chester castle; and there died on April 29, 1751.[28]

If White’s sermon had not given birth to the murderous outrage at Roughlee and Barrowford, it would have been too worthless to be noticed. As it was, a brainless and ungrammatical production became of such importance, that Grimshaw thought it his duty, in 1749, to publish an answer to it. Grimshaw was not the man to be mealy mouthed. On his title page he put the following: “Why boastest thou thyself in mischief, O mighty man? The goodness of God endureth continually. Thy tongue deviseth mischief; like a sharp razor, working deceitfully. Thou lovest evil more than good; and lying words rather than to speak righteousness. Thou lovest all devouring words, O thou deceitful tongue; God shall likewise destroy thee for ever. He shall take thee away, and pluck thee out of thy dwelling place, and root thee out of the land of the living. The righteous also shall see and fear, and laugh at him.” (Psalm lii. 1-6.) This was strong language for the incumbent of Haworth to use respecting the perpetual curate of Colne. Grimshaw tells him, that his sermon is “full of palpable contradictions, absurdities, falsities, groundless suggestions, and malicious surmises, and, in some sort, vindicates the people it was intended to asperse.” Grimshaw’s “Answer” extends to eighty-six pages, 12mo, closely printed, and is an able and well written defence of the poor, persecuted Methodists. White was no match for Grimshaw, at least, in literary conflict. The one was a braggadocio, the other was a giant; and, with a giant’s knotted club, he belabours the pompous priest with anything but the gentleness of a carpet knight. White, however, deserved all he got. The man was a popish cheat. Besides his disgraceful imprisonment in Chester castle, he had, as Grimshaw reminds him, been acting the rake, in London and elsewhere, for the last three years; and now forsooth! all at once, the cheat and rake becomes the virtuous and indignant champion of mother church. No wonder that Grimshaw wrote: “Bombalio! Clangor! Stridor! Taratantara! Murmur!” The terrible text on Grimshaw’s title page was a graphic description of the[Pg 18] miserable priest who raised the Roughlee mob, and its prophetic utterances were soon fearfully fulfilled. Within three years White was dead. “For some years,” says Wesley, “he was a popish priest. Then he called himself a protestant. He drank himself first into a jail, and then into his grave.”[29]

Leaving Barrowford, Wesley and his friends went to Heptonstall, where he preached, with unexampled power, in an oval surrounded with spreading trees, and scooped out of a hill, which rose round him and his congregation like a rural theatre. He then made his way, through Todmorden and Rossendale, to Bolton, where with the cross for his pulpit, and a vast number of “utterly wild” people for his audience, he began to preach. Once or twice they thrust him down from the steps on which he was standing, but he still continued his discourse. Then stones were thrown, which seem to have done more injury to the mob themselves than they did to Wesley. One man was bawling in his ear, when his bawling was silenced by a missile striking him on the cheek. A second was forcing his way to the preacher, when another stone hit him on his forehead, and disfigured him with blood. A third stretched out his hand to lay hold on Wesley, when a sharp flint struck him on the knuckles, and made him quiet till Wesley concluded his discourse and went away. It was either on this, or some subsequent occasion, that six papists, from Standish, near Wigan, rode right through the midst of Wesley’s congregation; and tradition states, that two of the horsemen, brothers of the name of Lyon, were afterwards hanged for burglary.[30]

Wesley and his friends proceeded from Bolton to Shackerley, six miles farther, where he preached to a large congregation, including not a few Unitarians, the disciples of Dr. Taylor, the divinity tutor of the Unitarian academy founded at Warrington. Wesley, always hopeful, remarks: “O what a providence is it, which has brought us here also, among these silver tongued antichrists!” Wesley visited Shackerley three times after this, and wrote, in 1751: “Being now in the very midst of Mr. Taylor’s disciples, I enlarged much more than I am accustomed to do, on the doctrine of[Pg 19] original sin; and determined, if God should give me a few years’ life, publicly to answer his new gospel.” This was done six years afterwards; and Shackerley must always have a place in Methodistic annals, inasmuch as to Wesley’s visits here Methodism is indebted for the most elaborated work he ever wrote.

In his onward progress, Wesley came to Astbury, where a lawless mob, headed by “Drummer Jack,” surrounded the preaching house, and endeavoured, by discordant noises, to drown his voice. Some years after, the same Drummer Jack was escorting a wedding party to Astbury church, and, on reaching the spot where he had attempted to disturb Wesley’s congregation, suddenly expired.[31]

Thus preaching on his way, Wesley, on September 4, got back to London.

Meanwhile, on July 5, Whitefield, after nearly a four years’ absence, returned to England from America. On the day he landed, he wrote to his friends, the two Wesleys; but an immediate interview was impracticable, for Wesley himself was on his northern journey, and his brother Charles, besides attending to his ministerial duties, was paying loving attentions to Sarah Gwynne. Three days before Wesley got back to London, Whitefield wrote to him as follows:—

“London, September 1, 1748.

“Reverend and dear Sir,—My not meeting you in London has been a disappointment to me. What have you thought about an union? I am afraid an external one is impracticable. I find, by your sermons, that we differ in principles more than I thought; and I believe we are upon two different plans. My attachment to America will not permit me to abide very long in England; consequently, I should but weave a Penelope’s web, if I formed societies; and if I should form them, I have not proper assistants to take care of them. I intend therefore to go about preaching the gospel to every creature. You, I suppose, are for settling societies everywhere; but more of this when we meet. I hope you don’t forget to pray for me. You are always remembered by, reverend and dear sir, yours most affectionately in Christ Jesus,

“George Whitefield.”[32]

Whitefield left London for Scotland before Wesley’s arrival,[Pg 20] and the two evangelists had no opportunity of meeting until the end of November, when, it is possible, they might, in their hurried ramblings, have a brief interview in town. They were still the warmest friends; but their courses of action were separate. Whitefield was a Calvinist; Wesley was not. Whitefield thought an external union, of the Tabernacle and other congregations with the congregations raised by Wesley, was impracticable; Wesley, so far as there is evidence to show, did not desire it. Whitefield had no societies, for the societies in Wales really belonged not to him but to Howel Harris; Wesley had already societies from one end of the kingdom to the other. Whitefield intended to spend his time chiefly in America; Wesley meant to stay in England. Whitefield, for the reasons he assigns, resolved to form no societies, but to be a mere evangelist; Wesley was resolved, for reasons stated at more than one of his annual conferences, to form societies wherever he and his preachers preached. Here the two friends parted, one in one direction, the other in another, both of them with hearts as warm as ever, and both equally animated with zeal for God and benevolence for man; but each, henceforth, cheerily pursuing his own chosen path, until both, laden with the spoils of a victorious war, were welcomed to the tranquillities and joys of their Father’s house in heaven.

Hitherto Whitefield’s preaching had chiefly been in fields and lanes, squares and streets, woods and wildernesses; but now, oddly enough, he was admitted into the drawing rooms of the rich and great.

The Right Honourable Selina, Countess of Huntingdon, wife of the Earl of Huntingdon, and sister of the Earl of Ferrars, was now in the forty-second year of her age. Her noble husband was a man of extensive learning, was most exemplary in his character, and treated his wife with great affection. At his death, in 1746, ninety-eight elegies were written concerning him, and were published under the title of “Lacrymæ Musarum.”

For two years past, the countess had been a widow. Hitherto, she had admirably fulfilled her duties in the higher circles of society. At Donnington Park, she had been the “Lady Bountiful” among her neighbours and dependants;[Pg 21] she had evinced great interest in their temporal and eternal welfare; and, besides encouraging the clergy in her own immediate neighbourhood, she had, more than once, dared to give a hearty welcome to the outcast Wesleys and their friends. Her heart was now pierced with the deepest sorrow, and was highly susceptible of religious impressions. Just at this juncture, Whitefield came back to England; his fervid eloquence attracted her attention; she made him her chaplain; and what Whitefield had resolved not to do, she did herself,—she founded societies, built chapels, appointed ministers, and formed a Methodist connexion apart from that which was formed by Wesley. She never renounced the Church of England; but she embraced views hardly compatible with its practices and well being. She was a child of emotion, carried onwards by an impulse not easily resisted or described. She had her annual conferences; the preachers whom she stationed were called “Lady Huntingdon’s preachers”; and the connexion over which she presided was known by the name of “Lady Huntingdon’s connexion.” Perhaps her people were less efficiently organised; but she held to them the same relation that Wesley did to his. Her authority was parental and decisive. No one doubted the purity of her motives, and all trusted the general soundness of her judgment. Chapels were erected in London, Brighton, Tunbridge Wells, Bath, Bristol, Birmingham, and other places. Again and again, revivalists were sent from one end of the land to the other, preaching everywhere, and almost everywhere winning souls for Christ. A college, the first that Methodism had, was opened at Trevecca, for the training of young ministers. The countess was the empress of the new connexion, and Whitefield was her prime minister. Wesley’s connexion was Arminian; hers was Calvinist. His continues, and is more extended and powerful than ever; hers has long been broken up into Independent churches. Wesley died March 2, 1791; she on the 17th of June next ensuing.

The Countess of Huntingdon was, in many respects, the most remarkable woman of her age and country. She was far from faultless; but she was neither the gloomy fanatic, the weak visionary, nor the abstracted devotee, which different parties have painted her. Her endowments were above the[Pg 22] ordinary standard, and were much improved by reading, conversation, study, and observation. Though not a beauty, she was not without the charms of the female sex. Her devotion to the work of God was almost unexampled. Her house was used for Methodist meetings, which were attended by large numbers of the nobility and higher classes, including the Duchesses of Argyll, Bedford, Grafton, Hamilton, Montagu, Queensberry, Richmond, and Manchester, and Lords Burlington, Townshend, North, March, Trentham, Weymouth, Tavistock, Hertford, Trafford, Northampton, Lyttelton, and others,—even William Pitt. During the last forty years of her life, she gave, at least, £100,000 for the support and extension of her system; and actually sold her jewels to find means for the building of Brighton chapel. Her life was a beautiful course of hallowed labour. Her death was the serene setting of a brilliant sun. Almost her last words were: “My work is done; I have nothing to do but to go to my Father.” She was a mother in Israel, whose decease left a vacancy not filled up. Her person, endowments, energy, and spirit were all uncommon. Accustomed to assume great responsibilities and to be deferred to in matters of great importance, she necessarily cultivated self reliance to such an extent as sometimes made her seem obstinate, haughty, and dogmatical. Still, dignity and ease met in her; and in manners she was refined, elegant, and engaging. Honour, heroism, and magnanimity were always conspicuous in her remarkable career; and, for intrepidity in the cause of God, and success in winning souls to Christ, Selina, Countess of Huntingdon, stands unequalled among women.

Six weeks after his return from America, Whitefield commenced preaching in her ladyship’s mansion. Among his earliest hearers was the celebrated Lord Chesterfield, “a wit among lords, and a lord among wits.” Twice a week, Whitefield preached to these conclaves of nobility and rank, his congregations usually consisting of about thirty persons.[33]

In London, he preached at St. Bartholomew’s, and helped[Pg 23] to administer the sacrament to a thousand communicants;[34] but, in other instances, his congregations were thin. He found that antinomianism had made sad havoc; but the scattered troops began to unite again.[35] He writes November 19: “Matters were in great confusion by reason of Mr. Cennick’s going over to the Moravians”; and again on December 21: “I suppose not less than four hundred, through the practices of the Moravians, have left the Tabernacle. I have also been forsaken in other ways. I have not had above a hundred to hear me, where I had twenty thousand; and hundreds now assemble within a quarter of a mile of me, who never come to see or speak to me; though they must own, at the great day, that I was their spiritual father. All this I find but little enough to teach me to cease from man, and to wean me from that too great fondness which spiritual fathers are apt to have for their spiritual children.”[36]

No doubt, this was exceedingly distressing. But there was more than this to annoy the once popular preacher. Just at the time when Wesley got back to London, Whitefield set out for Scotland, where, on former occasions, he had won some of his greatest triumphs; but now a synod of his old friends, the Seceders, met in Edinburgh, on November 16, to adopt the “new modelled scheme and covenant.” Hundreds took the oath, and solemnly engaged to use all lawful means to extirpate, not only “popery, prelacy, Arminianism, Arianism, tritheism, and Sabellianism,” but also “George Whitefieldism”; and similar decisions were adopted at the synods of Lothian, Ayr, and Glasgow.[37]

And added to all this, there was another trouble of a different kind, in which Wesley was involved as well as Whitefield. Dr. Lavington was bishop of Exeter, and was a fervent hater of the Methodists. He had recently delivered a charge to the clergy of his diocese, and some mischievous person had published a piece, which falsely pretended to be the same as that which the bishop had addressed to his assembled ministers. This fictitious charge contained such a declaration[Pg 24] of doctrines as exposed Lavington to the stigma of a Methodist, and produced several pamphlets in reply and congratulation. His lordship was enraged; and advertised, in the public papers, that the pamphlet which had been affiliated upon himself was false; that the Methodist leaders were the authors of the fraud; and that, though there might be among the Methodists a few well meaning, ignorant people, yet the sect, as a whole, were deluded enthusiasts, and their teachers something worse than that.[38] Whitefield was accused as the principal, and the Wesleys were suspected as being his accomplices, in the spurious production. This was utterly untrue, but it occasioned Whitefield considerable annoyance. It so happened that the pamphlet had been sent to him in manuscript; but he denied its genuineness, and strongly condemned the injustice of its publication.[39] Still, the bishop persisted in his accusation. Lady Huntingdon wrote to him, assuring him that Whitefield and the Wesleys were innocent, and demanded a candid and honourable retraction of the charges against them. Her letter was accompanied by an acknowledgment, on the part of the printer, that no one was to blame for the publication except himself; and, that he received the manuscript from one who had no connection with the Methodists. His lordship maintained a sullen silence. The countess wrote again, declaring that, unless Lavington complied with her request, she would make the transaction public. This extorted a recantation, and an apology “to her ladyship, and to Messrs. Whitefield and Wesley for the harsh and unjust censures which he had passed upon them, and a wish that they would accept his unfeigned regret for having unjustly wounded their feelings, and exposed them to the odium of the world.”[40]

The prelate recanted and apologized; but, henceforth, he became the most bitter and implacable reviler that the Methodist leaders had; and, within two years, began to publish his ribald and infamous attack, entitled “The Enthusiasm of Methodists and Papists compared.”

[Pg 25]

Some good, however, arose out of this disreputable fracas. Among other pamphlets published, the following was one: “A Letter to the Right Rev. Father in God, George, Lord Bishop of Exeter. By a Clergyman of the Church of England.” The writer states, that he has no acquaintance whatever with either Wesley or Whitefield; but he had read their books, and rejoiced in their revival of the grand old doctrine of justification by faith alone. He then proceeds to defend them against three accusations—1. That they had left the Church. 2. That they refused to be under political government. 3. That, though their preaching was right in the main, they were immethodical in their practice.

The pamphlet is chiefly remarkable for its being a defence of the Methodists by a clergyman, who had no connection with the Wesleys. It breathes piety, but lacks power.

Having spent a week in London, Wesley set out, on September 12, for Cornwall. He preached to a “multitude” near St. Stephen’s Down, who were as silent as death, while he was speaking; but the moment he concluded, “the chain fell off their tongues. Never,” says he, “was such a cackling made on the banks of Cayster, or the common of Sedgmoor.” The St. Just society consisted “of one hundred and fifty persons of whom more than a hundred were walking in the light of God’s countenance.” At Newlyn, his congregation were “a rude, gaping, staring rabble rout; some or other of whom were throwing dirt or stones continually.”

On his return, he examined the Bristol society, and “left out every careless person, and every one who wilfully and obstinately refused to meet his brethren weekly. By this means the number of members was reduced from nine hundred to about seven hundred and thirty.” He got back to London on the 15th of October, and remained in town and its immediate neighbourhood till the year expired. A short excursion was made to Windsor and Wycombe, and also to Leigh. He likewise preached at Wandsworth, where a little company had begun to seek and to serve God, though the rabble had pelted them with dirt and stones, and abused both men and women in the grossest manner.

His time, however, was partly occupied in writing. He had already formed the project of publishing “The Christian[Pg 26] Library.” Hence the following letter to Mr. Ebenezer Blackwell.

“Newcastle, August 14, 1748.

“Dear Sir,—I have had some thoughts of printing, on a finer paper, and with a larger letter, not only all that we have published already, but it may be, all that is most valuable in the English tongue, in threescore or fourscore volumes, in order to provide a complete library for those that fear God. I should print only a hundred copies of each. Brother Downes would give himself up to the work; so that whenever I can procure a printing press, types, and some quantity of paper, I can begin immediately. I am inclined to think several would be glad to forward such a design; and if so, the sooner the better; because my life is far spent, and I know not how soon the night cometh wherein no man can work.

“I am, dear sir,

“Your affectionate brother and servant,

“John Wesley.”[41]

This was a bold design, which he began to execute in the ensuing year, and for which he was already preparing materials. Mr. Blackwell was a partner in a banking house in Lombard Street, London; and though, for his plain honesty, he was often called the “rough diamond,”[42] he was one of Wesley’s kindest and most valuable friends. To his country house, at Lewisham, Wesley was accustomed to retire, when writing for the press. Here he found an asylum during his serious illness in 1754. To him, Blackwell was wont to entrust considerable sums of money, for distribution among the poor.[43] Under such circumstances, no wonder that Wesley, with his small purse and large project, should submit his scheme to the London banker, for the purpose of ascertaining his willingness to help in its execution.

Happy deaths among the Methodists were now not unfrequent. Wesley mentions several; and the sanctified muse of his brother Charles never attained to loftier poetic heights than when celebrating such events. There were, however, at the end of 1748, a number of deaths painful as well as pleasing. John Lancaster had been a regular attendant at the Foundery’s five o’clock morning service, and had been converted; but,[Pg 27] by degrees, had left off coming; and had rejoined his old companions, and, fallen into sin. One day, when playing at skittles, he became the accomplice of a thief, and soon after broke into the Foundery, and stole two of the chandeliers. In this instance, he escaped detection; but, emboldened by success, he proceeded to steal nineteen yards of velvet, the property of Mr. Powell; and, for this, was tried at the Old Bailey sessions, in the month of August, and was sentenced to be hanged.[44] The poor wretch sent for Sarah Peters and some other of his old Methodist companions, to visit him in his cell. At the time, there were nine others in the same prison awaiting execution. Six or seven of them joined Lancaster and the Methodists in prayer, reading the Scriptures, and singing hymns. A pestilential fever was raging in the prison; but the visits were oft repeated. Lancaster professed to find peace with God. Thomas Atkins, a youth, nineteen years of age, condemned for highway robbery, said: “I bless God, I have laid my soul at the feet of Jesus, and am not afraid to die.” Thomas Thompson, a horse stealer, exceedingly ignorant, was brought into the same state of mind. John Roberts, a burglar, at first utterly careless and sullen, became penitent and believing. William Gardiner, convicted of rape, said on his way to execution, “I have nothing to trust to but the blood of Christ! If that won’t do, I am undone for ever.” Sarah Cunningham, who had stolen a purse of twenty-seven guineas, at first went raving mad, but, in her lucid intervals, earnestly implored Christ to pity her. Samuel Chapman, a smuggler, seemed to fear neither God nor devil, but, after Sarah Peters had talked to him, he began to cry aloud for mercy, was seized with the jail distemper, and was confined to his bed till carried to the gallows. Ten poor wretches, the above included, were executed at Tyburn, on October 28.[45] Six of them spent their last night together, in continuous prayer; and, on Sarah Peters visiting them early in the morning, several of them exclaimed, with a transport not to be expressed, “O what a happy night we have had! What a blessed morning is this!” The turnkey said he had never seen such people before; and, when the[Pg 28] bellman came at noon, to tell them, as usual, “Remember, you are to die to-day!” they cried out, “Welcome news! welcome news!” When brought out for execution, Lancaster exclaimed, “O that I could tell a thousandth part of the joys I feel!” Atkins said, “Blessed be God, I am ready”; Gardiner cried, “I am happy, and think the moments long; for I want to die, to be with Christ”; Thompson witnessed the same confession. Spectators wept; and the officers looked like men affrighted. On their way to Tyburn, the convicts sang several hymns, and especially—

Thus died Lancaster, a condemned felon, a quondam Methodist, one of his last prayers being, that the Foundery congregation might abound more and more in the knowledge and love of God, and that God would bless and keep the Wesleys, and that neither men nor devils might ever hurt them.

And what became of Sarah Peters? Six days after the execution, she was seized with malignant fever; and, ten days after that, she died. She was, says Wesley, “a lover of souls, a mother in Israel. During a close observation of several years, I never saw her, upon the most trying occasions, in any degree ruffled or discomposed; she was always loving, always happy. It was her peculiar gift, and her continual care, to seek and to save that which was lost; and, in doing this, God endued her, above her fellows, with the love that believeth, hopeth, and endureth all things.”

Before closing the present chapter, all that remains is to note Wesley’s publications during the year 1748. They were the following:—

1. “Thomæ à Kempis de Christo Imitando Libri Tres. Interprete Sebast. Castellione. In Usum Juventutis Christianæ. Edidit Ecclesiæ Anglicanæ Presbyter.” 12mo, 143 pages.

[Pg 29]

2. “Historiæ et Precepta selecta. In Usum Juventutis Christianæ. Edidit Ecclesiæ Anglicanæ Presbyter.” 12mo, 79 pages.

3. “Marthurini Corderii Colloquia selecta. In Usum Juventutis Christianæ. Edidit Ecclesiæ Anglicanæ Presbyter.” 12mo, 51 pages.

4. “Instructiones Prælectiones Pueriles. In Usum Juventutis Christianæ. Edidit Ecclesiæ Presbyter.” 12mo, 39 pages.

5. “A Short English Grammar.” 12mo, 12 pages.

6. “Lessons for Children.” Part III., 12mo, 124 pages. The lessons are fifty-seven in number, and are taken from the books of Ezra, Nehemiah, Job, the Psalms, and Proverbs.

The whole of the above were class books in Kingswood school.

7. “Sermons on several Occasions.” Vol. II., 12mo, 312 pages.

8. “A Word to a Methodist.” 12mo, 8 pages. This was written in Wales, and was published in the Welsh language. The following is Wesley’s account of it. “1748, March 27: Holyhead. Mr. Swindells informed me, that Mr. E——, the minister, would take it a favour, if I would write some little thing, to advise the Methodists not to leave the Church, and not to rail at their ministers. I sat down immediately and wrote, ‘A Word to a Methodist,’ which Mr. E—— translated into Welsh, and printed.” In a letter to Howel Harris, dated “Holyhead, February 28, 1748,” he says:—“I presume you know how bitter Mr. Ellis, the minister here, used to be against the Methodists. On Friday, he came to hear me preach, I believe with no friendly intention. Brother Swindells spoke a few words to him, whereupon he invited him to his house. Since then, they have spent several hours together; and, I believe, his views of things are greatly changed. He commends you much for bringing the Methodists back to the Church; and, at his request, I have wrote a little thing to the same effect. He will translate it into Welsh, and then I design to print it, both in Welsh and English.”[46]

9. “A Letter to a Friend concerning Tea.” 12mo, 24 pages. This tract is a strongly worded condemnation of the use of[Pg 30] tea; but, as the substance of it has been already given, a further description is unneeded.

10. “A Letter to a Clergyman.” Dublin: Printed by S. Powell, Crane Lane. 12mo, 8 pages. This was written at Tullamore, in Ireland, on the 4th of May, 1748; and was occasioned by a conversation with the clergyman to whom it is addressed. Its object is to show, that the preacher whose preaching saves souls is a true minister of Christ, though he has not had a university education, is without learning, has never been ordained, and receives no temporal reward.

11. “A Letter to a Person lately joined with the People called Quakers. In answer to a Letter wrote by him.” 12mo, 20 pages. Wesley takes his account of Quakerism from the writings of Robert Barclay, and shows wherein the system differs from Christianity; namely—1. Because it teaches that the revelations of the Spirit of God, to a Christian believer, “are not to be subjected to the examination of the Scriptures as to a touchstone.” 2. Because it teaches justification by works. 3. Because it sets aside ordination to the ministry by laying on of hands. 4. Because it allows women to be preachers. 5. Because it affirms that we ought not to pray or preach except when we are moved thereto by the Spirit; and that all other worship, both praises, prayers, and preachings, are superstitious, will worship, and abominable idolatries. 6. Because it alleges that “silence is a principal part of God’s worship.” 7. Because it ignores the sacraments of baptism and the Lord’s supper. 8. Because it denies that it is lawful for Christians to give or receive titles of honour. 9. Because it makes it a part of religion to say thee or thou,—a piece of egregious trifling, which naturally tends to make all religion stink in the nostrils of infidels and heathens. 10. Because it teaches that it is not lawful for Christians to kneel, or bow the body, or uncover the head to any man; nor to take an oath before a magistrate.

In his wide wanderings, Wesley met with numbers of friendly Quakers, of whom he speaks in terms of commendation; but their system was one which he abhorred, and, in his “Appeal to Men of Reason and Religion,” he speaks of the inconsistencies of their community in the most withering terms. “A silent meeting,” said he in a letter to a young[Pg 31] lady, “was never heard of in the church of Christ for sixteen hundred years.”[47] And, in one of his letters to Archbishop Seeker, he remarks: “Between me and the Quakers there is a great gulf fixed. The sacraments of baptism and the Lord’s supper keep us at a wide distance from each other; insomuch that, according to the view of things I have now, I should as soon commence deist as Quaker.”[48]

[Pg 32]

IN 1749, Wesley spent four months in London and its vicinity, nearly four in Ireland, ten weeks in Bristol, Wales, and the surrounding neighbourhood, and two months in his tour to the north of England.

His brother employed the year principally in Bristol, Wales, and London, and in visiting intermediate towns and villages.