Title: The attaché at Peking

Author: Baron Algernon Bertram Freeman-Mitford Redesdale

Release date: April 5, 2023 [eBook #70467]

Language: English

Original publication: United Kingdom: Macmillan and Co, 1900

Credits: MWS, Quentin Campbell, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/Canadian Libraries)

Transcriber’s Note

The cover image was restored by Thiers Halliwell and is placed in the public domain.

See end of this document for details of corrections and other changes.

THE ATTACHE AT PEKING

BY

A. B. FREEMAN-MITFORD, C.B.

AUTHOR OF ‘TALES OF OLD JAPAN,’ ‘THE BAMBOO GARDEN,’ ETC.

London

MACMILLAN AND CO., Limited

new york: the macmillan company

1900

All rights reserved.

[v]

These letters were written many years ago, but in China, and especially at Peking, the old order changes slowly, and they are at any rate a faithful record of the life which was led by those whose duties lay, as the Chinese say, “within the walls.” They profess no more than that. Those who wish to learn more about China and Chinese manners must go to that monumental work of the late Dr. Wells Williams, The Middle Kingdom, to Sir John Davies’s fascinating book, The Chinese, or to Professor Douglas’s book on Chinese society.

It will occur to many people to ask how it comes that we should have lived for so many years peacefully, travelling through the country unarmed, in the midst of a people capable of[vi] the atrocities which have recently taken place. China is of all countries the land of contradiction and of paradox. But I think that those who read these letters will see that though, for obvious reasons, they were written in a spirit of optimism, there was an undercurrent of feeling that at any moment things might become very different. For instance, if the insurrection in Shantung had not been quelled, and the rebels had marched upon Peking, which was undoubtedly part of their programme, the tragedy of 1900 might, and probably would, have been anticipated in 1865. Moreover, although we were riding at anchor in smooth water, there were from time to time uncomfortable signs of disturbance below. I remember how on more than one occasion we were warned that on such and such a day there would be a massacre of Europeans for the old reason, the murder of babies whose eyes were used for purposes of photography. These stories were put about by intriguing mandarins, who succeeded in deceiving even some of the more ignorant of[vii] their own class. The famous General Tsêng Kwo Fan (father of the Marquis Tsêng, who was afterwards minister in London) was talking one day with an English doctor on the subject of this babies’-eyes fraud, when suddenly he said, “It is no use your attempting to deny it, for I have here some of the dried specimens,” and he pulled out a packet of those gelatine capsules which are used for covering castor oil and other nauseous drugs! We paid little heed to these warnings, though, as recent events have proved, there was perhaps more in them than we supposed. We were sitting on a volcano, for experience has often shown how swiftly this seemingly mild and almost childlike people can be lashed into a fury like that of the flaming legions of hell. One thing we knew for certain. If a rising should take place, we were in a death-trap from which there could be no escape. Those grim and frowning gates once shut, rescue was impossible, for what could a mere handful of men—in those days there were but some seventy or eighty Europeans, all told, in Peking—avail[viii] against the seething mob of enraged devils? When years afterwards, in 1879, there came the horror of Sir Louis Cavagnari’s murder, with all his company, at Cabul, I could but think how much the position of the Legations at Peking resembled his.

It is the fashion to belaud Japan for the spirit of progress which she has shown, at the expense of China, which remains wedded to old ways and worn-out customs. Much as we may admire the marvellous headway which Japan has made, this is hardly quite fair. It must be remembered that Japan has never originated anything. All that she knew, up to the time of her first real intercourse with foreigners forty years ago, she owed to China. Buddhism, which replaced and in some sort throve hand-in-hand with the old ancestor worship, the Shintô, reading and writing, every art and accomplishment, from music and dancing down to the game of football, all filtered through Corea from China to Japan, and the dates of their advent are solemnly recorded as important facts in the O Dai Ichi Ran.[ix] “A Glance at the Generation of the Kings,” the native history. Borrowers from the beginning of time, it mattered little to the Japanese whether they borrowed once more or once less, and so when they saw that if they wished to hold a place among the nations their only chance was to get rid of ancient Chinese forms and adopt the civilisation of the West, they did not hesitate—they took a leap into the light and left the thirteenth for the nineteenth century. To hear some enthusiasts talk one would almost be led to believe that the Japanese invented the nineteenth century. They found it ready made to their hand. It was impossible to go through the intermediate centuries. They had to skip, and they did it with a will. The transformation scene was as sudden as it was complete. But it cost the Japanese no sacrifice of national pride. What they gave up was none of their own invention.

The Chinese, on the other hand, have an autochthon civilisation of which they are justly proud. Five hundred years before Christ[x] came into the world—when the inhabitants of these islands were hopeless savages clad in skins, or stained with woad according to the seasons, if the old stories be true—Confucius was teaching respect for customs which were already ancient. Since his day there have been thirteen changes of capital and no fewer than thirty dynasties, but even when Tartar[1] emperors have sat upon the Dragon Throne they have been compelled to follow the rules of the Chinese, and civilisation has remained what it was “under the shadow” of the great Teacher. No wonder that the son of Han thinks a good many times before he will scatter his past to the four winds of heaven, as the Japanese did without a sigh!

In one sense the mandarins have been wiser in their generation than the men who made the Japanese revolution of 1868. These were the daimios, such men as Satsuma, Tosa, Choshiu,[xi] and their karôs (elders or councillors), who thinking to overthrow the Tycoon and his rule, were blind to the fact that in so doing they were working their own downfall as well as his. For they, no less than he, were the embodiment of the feudal system. Where are they now? Où sont les neiges d’antan? They have vanished, and their places are filled by a mushroom growth of dukes, marquises, counts, viscounts, and barons. For Japan has stopped short at nothing; not content with adopting the cocked hat, which as we all know is the very marrow of all good government, giving the entrée to the comity of nations, she has actually invented a full and complete peerage. Far more astute is the mandarin. Such wily anachronisms as Li Hung Chang and his compeers know full well that under the sun of Western civilisation they must melt away, and it is no matter for surprise that they die hard. All the myriads of officials, from the highest to the lowest, swarming like ants over that vast empire, are alive to the fact that their very existence depends on keeping up a constant animosity against the Hung Kwei[xii] Tzŭ, the red devils. That has always appeared to me as the keynote of the situation.

Various causes are commonly assigned for the fanaticism against foreigners, which has from time to time broken out with fatal consequences in different parts of China. Some blame missionary enterprise; some commerce in general; others the opium trade in particular. My belief is that it is due to neither of these in itself, but to the dread of reform which haunts the official mind, and which in the end must win its way.

The Chinese are not by nature a people of strong religious convictions, nor have they any strong religious antipathies. If it were otherwise, how is it that a colony of Jews[2] has dwelt among them unmolested for two thousand years, and still remains, dwindling in numbers, it is[xiii] true, at Kai Fêng in the province of Ho Nan? How is it that the Mohammedans have flourished exceedingly in certain provinces, even to becoming a danger to the empire? On the walls of the Imperial palace at Peking there is a pavilion richly decorated with Arabic inscriptions from the Koran in honour of a Mohammedan lady who was a wife, or favourite, of one of the emperors. This does not look like persecution for religion’s sake. And, more than these, Buddhism? Ever since the Emperor Ming Ti dreamt a dream, nearly nineteen centuries ago, and sent for Buddhist books and images to China, Buddhism has been the popular religion, as Confucianism is the popular school of moral philosophy. Tao-ism, the native religion of Lao Tsŭ, cannot hold its own with it. Troublous days, indeed, it has gone through at various times, but it has outlived them, and now, to quote Dr. Morrison, “Buddhism in China is decried by the learned, laughed at by the profligate, yet followed by all.” (See further Wells Williams, ut suprà.)

Why, then, this tolerance in certain cases, [xiv]side by side with the cruellest intolerance where Christianity is concerned? If it is not religious conviction, it must be political antipathy. And there is the rub. The bitter hatred of Christianity is not inborn in the people, who have in many instances, indeed, shown a sort of limp willingness, not altogether unconnected with better wages, to embrace its tenets; but the hostility is bred, fostered, and fomented by the mandarins to whom it means the end of their rule. Under a Christian dispensation the whole tottering fabric of their power must inevitably fall to the ground. The poor Jews were to them a negligible quantity. The Mohammedan creed, the sacred book of which may not be translated, presents for that reason but small terrors to the lettered class, though we hear of an old prophecy to the effect that there will be a great Mohammedan revolution, and that a Hui-Hui (Mohammedan) dynasty shall rule over China. Buddhism, on the other hand, except in Tibet, aims at no temporal power, and even there the Chinese Emperor is the Suzerain. But Christianity is a very real terror, to be put [xv]down at any cost, however bloody. And yet, strange to say, there was a time when it seemed as if it were destined to conquer everything and to become the state religion. Internal dissensions and ambitions amongst its sects alone stopped its course.

The history of the early missions to China is full of interest; it is not possible, however, to do more than glance at it here. Putting on one side the dim legend that St. Thomas, the doubting apostle, was the first to preach the Gospel to the Chinese, there is no doubt that missionaries did visit them in very remote ages. It was two Nestorian monks who carried the first Eastern silkworms’ eggs to Justinian in the sixth century (see my Bamboo Garden, pp. 31–33). It is strange at the present time to read how at the end of the thirteenth century John of Monte Corvino was sent by Pope Nicholas the Fourth to the court of Kublai Khan at Kambaluk (the ancient name of Peking); how he was kindly entreated there, building a church “which had a steeple and belfry, with three bells that were rung every hour to summon the new converts [xvi]to prayer”; how he baptized nearly six thousand persons during that time, “and bought one hundred and fifty children, whom he instructed in Greek and Latin, composing for them several devotional books.” Clement the Fifth made him an archbishop, and sent him seven suffragan bishops. He died full of years in 1328, “having converted more than thirty thousand infidels.” All Kambaluk is said to have mourned for him, Christians and heathen rending their garments at his funeral, and his tomb became the resort of pious pilgrims. This account, which will be found given at length in the third volume of the Chinese Repository, is probably not a little exaggerated; but even discounting it largely, it is very striking as an evidence of devotion on the one side and toleration on the other. “It is now twelve years,” he wrote, “since I have heard any news of the west. I am become old and gray-headed, but it is rather through labours and tribulations than through age, for I am only fifty-eight years old. I have learned the Tartar language and literature, into which I have translated the whole New Testament[xvii] and the Psalms of David, and have caused them to be transcribed with the utmost care. I write and read and preach openly and freely the testimony of the law of God.” Until the year 1368, when the Yuan or Tartar dynasty was driven out by the Chinese, and the Ming Emperors ruled first at Nanking and afterwards at Peking, Dr. Williams says “there is no reasonable doubt that the greater part of Central Asia and Northern China was the scene of many flourishing Christian communities.” From that time forth, during upwards of two hundred years, they dwindled away so that nothing more was heard of them.

It was at the end of the sixteenth century that the Jesuits first began to exercise an influence which was very nearly overwhelming all rivalry in China. Saint François Xavier, the gospeller of India and Japan, had marked China as the special field of his future labours, but he died of fever at the island of Shang Chuen, near Macao, being only forty-six years old at the time of his death—a wonderful man, truly! But his work was destined to fall into[xviii] hands no less competent for the task than his own.

Matteo Ricci, the famous Jesuit father, was born at Macerata, in the Papal States, in 1552. At the age of nineteen he was sent to Rome to study law, which career he quickly abandoned, to his father’s great displeasure, to enter the Society of Jesus. Here he came under the orders of Father Valignani, the Inspector-General of Eastern Missions, with whom, before he had even finished his noviciate, he went to India, continuing his studies at Goa, where he became professor of philosophy. In 1580 he followed Father Ruggiero to Macao, where the two priests gave themselves up to the study of the Chinese language. They availed themselves of the trading privileges of the Portuguese to visit Canton, and some two years later, not without encountering some difficulties and disappointments, they obtained the permission of the Viceroy of Kwang Tung to build a house at Shao Ching Fu, and a church. Ricci soon saw that a reputation for learning was then, as now, the only passport[xix] to high consideration among the lettered classes. He published a map of China and a catechism, in which he set forth the moral teaching of Christianity, excluding carefully all that pertains to the doctrines of revealed religion. He had his reward, for many learned men came to consult him, and his fame spread far and wide. For some years the Jesuit fathers adopted the garments of Buddhist priests, but finding that these were treated with anything but respect, they, upon the advice of Father Valignani, dropped the yellow robes and assumed the garb of the men of letters, whom above all it was their wise endeavour to conciliate. Ricci paid three visits to Nanking, but on the second occasion he was expelled, and forced to go to Nanchang, where he established a school and published two treatises, the Art of Memory and a Dialogue on Friendship. This last work was a marvellous success, for it became famous not only “for the loftiness of its thoughts, but even for the purity of its style,” a feat perhaps unique in a country where literary style is so much thought of, and so[xx] difficult to attain, even by native scholars. In the year 1600 he achieved his ambition of going to Peking charged with presents for the Emperor Wan Li from the Portuguese at Macao. But the mission was not accomplished without difficulty. A eunuch of the court had offered himself as his escort, and with him Ricci set out in a native junk. But the presents of which he was the bearer had aroused the cupidity of the eunuch, who contrived to imprison Ricci and his companion Pantoja at Tientsing for six months. Happily the affair came to the ears of the Emperor, who ordered him to be released and brought to Peking, where he was kindly received by Wan Li, who assigned him a house and salary. Ricci soon made many friends and converts, of whom one named Sü helped him in the translation of Euclid. His secret of success was being all things to all men, and he contrived so to edit Christianity as to make it fit in with existing manners and customs, and to give offence to none. Among other things he allowed the rites of ancestral worship to be continued,[xxi] affecting to consider them as being of a civil and not of a religious character. In short, he followed the Buddhist system of incorporating, not condemning, those articles of native faith to have fought against which would have been fatal to his schemes. Father Ricci died in 1610, being fifty-eight years of age. If, on account of the laxity of his theological concessions, he cannot be called a great Christian missionary, he was at any rate a great conciliator, and it was no fault of his that the seed which he successfully sowed did not bring forth good fruit. He was possessed of rare talents, his learning was conspicuous in many branches, and his winning charm of manner commended him to the favour of high and low. He was perhaps the only European who ever acquired the Chinese literary style to such a degree as to call forth the admiration of native critics. To such an extent was this recognised, that about 150 years after his death his treatise on The True Doctrine of God, revised by a minister of state named Sin, was included in the collection of the best Chinese works[xxii] made by the order of the Emperor Chien Lung.

To follow a man so various and so plastic as Ricci was no easy task; but the Society of Jesus has never been wanting in men possessed at any rate of the latter quality, and Father Longobardi proved an efficient successor, though he did not make history. But there were troubles in store for the missionaries. Their successes aroused the jealousies of courtiers and officials, whose intrigues led to the publication of an edict banishing the Christian teachers. This decree, however, was never carried into effect. They had made many converts who protected them, and foremost among these were Sü (Ricci’s special friend) and his daughter, christened under the name of Candida. These two Chinese converts were so famous for their virtues and so beloved for their charity, that they are actually worshipped to this day by the people at Shanghai, and the Roman Catholic Mission at Sü Chia Wei, near that city, occupies the property once held by the Christian Sü.[xxiii] Candida was indeed a saintly woman. She built no fewer than thirty-nine churches; she published upwards of one hundred books; she established a foundling hospital for babies whom, then as now, their unnatural parents were in the habit of abandoning; and she employed the blind improvisatori of the streets to substitute Gospel stories for their obscenities and inanities. The Emperor himself conferred upon her the title of “The Virtuous Woman,” and sent her a robe and headgear embroidered with pearls, which she stripped off to further her religious works with their price.

The beginning of the seventeenth century was a time of internal trouble and revolution in China. The old Chinese dynasty of the Mings was about to be replaced by the present Tartar dynasty, the Chi̔ng. That the Jesuits had become a real power in the land is proved by the fact that the claimant to the Ming throne was supported by the missionaries, his troops being led by two native Christian generals, Kiu who was called Thomas, and Chin who was baptized Luke. His mother,[xxiv] wife, and son were christened as Helena, Maria, and Constantine, and Helena went so far as to write to Pope Alexander VII. “expressing her attachment to the cause of Christianity, and wishing to put the country, through him, under the protection of God”! (Wells Williams).

The Jesuits held a high position in the early days of the Tartar rule. This was due to the pre-eminent abilities of their leader, Johann Adam Schall, a man of good family, native of Cologne. This great priest was born in A.D. 1591, and entered the Society of Jesus at Rome in 1611. There he became a student of theology and mathematics, and left for China in 1622. His great learning won for him such renown that he was sent for by the Emperor in 1631, installed at Peking as court astronomer, and charged with the revision of the Chinese calendar. Needless to say this position was not won without exciting great jealousy among the native men of science, who attacked him fiercely, both openly and in secret. But his correct calculation of an eclipse, as to[xxv] which they were hopelessly wrong, defeated all their intrigues, and he was more than ever in favour with the Emperor Chung Ch’êng (the last of the Mings), who, in dread of the Tartars, caused him, much against his will, to start a cannon foundry, rewarding him with a pompous autograph inscription in praise of his science and virtue. When at last the Tartars became masters of Peking, Schall, though in continual danger himself, was able to give effectual protection to the Christian converts. It cannot fail to strike us with amazement that, like the Vicar of Bray, when matters settled down, Schall should have enjoyed even more favour under the Tartar Emperor Shun Chih than he had done under his Ming predecessor; and when, at that sovereign’s death in 1662, he actually was holding the post of tutor to the young Emperor Káng Hsi, who became one of the most famous monarchs that ever ruled in China, it seemed as if nothing could arrest the progress of Jesuit influence.

But the supreme power was for a time in the hands of four regents who were opposed to[xxvi] the Christians, and a memorial was presented to court denouncing the new sect as dangerous to the state. The Dominicans and Franciscans, of whom I shall speak presently, had, during a quarter of a century and more, been working in opposition to the Jesuits, and the internal dissensions of the sects gave their enemies an opportunity of which they were not slow to avail themselves. The memorial, a remarkable document, calls attention to the strife between the orders as to the worship of Ti̔en (Heaven) and Shang Ti (God), which dissensions as to the principle of doctrine show the true aspirations of the rival sects to be political; and in this connection the memorialists call attention to the schisms and civil war to which Christianity gave rise in Japan, evils which could not fail to occur sooner or later in China if the missionaries were allowed to remain there. The regents, nothing loth, yielded to the wishes of the memorialists, and in 1665 the Christian teachers were proscribed as seducers of the people, leading them into a false path. Father Schall died miserably at[xxvii] the age of seventy-eight, after having been for thirty-seven years the trusted and favoured servant of five emperors. His converts were degraded, and his colleagues imprisoned or banished.

Among those who were held in chains, beaten, and subjected to every indignity, was Father Verbiest, a native of Flanders, partly educated at Seville, the third of the great triad of priests who, by their talents, their learning, and their personal charm, so nearly succeeded in turning the current of Chinese history. For six long years who shall say what he suffered? Six years of the horrors of a Chinese prison! At last, however, the minority of the Emperor Ka̔ng Hsi came to an end. He had not forgotten the good teaching of Father Schall, and one of his earliest acts, on assuming the power in 1671, was to release the priests, with Father Verbiest at their head. Ka̔ng Hsi was not a Christian; but though he forbade his subjects to follow the new teaching, he was sufficiently liberal to put an end to persecution, and to recognise the value of Western learning.[xxviii] There is a myth to the effect that an earthquake was the immediate cause of the release, but the truth is that the Emperor wanted Verbiest’s astronomical science to set straight the crooked inventions of the native professors. The father was appointed court astronomer and chief mathematician. He was also ordered, as Schall had been, to cast cannon, which, with much pomp and ceremony, robed as for mass, he blessed, in the presence of the court, sprinkling them with holy water, and giving to each the name of a female saint which he had himself drawn on the breech. This brought him a letter from Pope Innocent XI., praising him for having so wisely brought the profane sciences into play for the salvation of Chinese souls. To Father Verbiest are due the wonderful mathematical instruments of bronze, beautiful as works of art, which are still one of the sights of Peking. They are in the Observatory at the southern corner of the Tartar city, where they remain as the last witnesses of the Jesuit greatness. Verbiest died in 1688, and the Emperor himself composed[xxix] the funeral oration, which was read with great pomp before his coffin. No three men ever succeeded in obtaining the favour of the Chinese court so signally as the three Jesuit fathers, Ricci, Schall, and Verbiest. When Father Verbiest died there was no man with a sufficiently commanding intellect to fill his place and continue his work.

It is conceivable that if they had not been thwarted by the Dominicans and the Franciscans, the Jesuits might have succeeded in their ambition even to the extent of Christianising China. But those two sects effectually put a stop to the process of conversion. The great bone of contention was the so-called worship of ancestors and of Confucius. Another point was the translation of the name of God by Ti̔en, literally Heaven, and Shang Ti, for which there is indeed no other rendering. This last controversy, which has in it much that is childish, and mere splitting of hairs, is not worth discussing. The great point was to render the Sacred Name by some term that should be intelligible to the Chinese mind. Both seemed[xxx] to fulfil that condition. As regards the former question, we have seen how Father Ricci dealt with it. He saw the wisdom of not repelling the Chinese by at once condemning a custom to which they were so wedded that any attempt to do away with it would evidently alienate them altogether, so he, a true Jesuit, effected a clever compromise, treating the rites in honour of ancestors and of Confucius as civil and not as religious ceremonies. It always has seemed to me that he acted wisely, for in no other way could he have hoped to obtain any hearing. By degrees the Christianised Chinese might have been weaned from their old practices, and Christianity in all its purity have been made a dominant religion. This, however, is mere speculation.

When the Dominicans and Franciscans became aware of the successes of the Jesuits, they too resolved to have their share in the work, and they promptly sent out missions to China on their own account. But their school lacked the liberality and plastic nature of the Jesuits. They resolutely refused any[xxxi] compromise. They accused the Jesuits of countenancing idolatry and heathen practices, and one Morales, a Spanish Dominican, sent home a report to the Propaganda to that effect. This produced a decree from Pope Innocent the Tenth, in which the conduct of the Jesuits was censured and their doctrine condemned in 1645. It took the Jesuits eleven years to procure from Pope Alexander VII. another Bull, not indeed contradicting that of Pope Innocent, but one which might be so read as to give them a free hand. But the battle was not over, for in 1693 Bishop Maigrot, Vicar Apostolic in China, declared in the face of the Inquisition and the Pope that Ti̔en meant the material heaven, and not God, and that the worship of ancestors was idolatrous. In this difficulty it is not a little strange to find that the Jesuits appealed to the Emperor Ka̔ng Hsi to show them the way out. They addressed him in a memorial which is quoted at length by Wells Williams from the Life of St. Martin, and which is so curious that I am tempted to transcribe it, the more so as [xxxii]it shows so clearly all the points of the great controversy:—

“We, your faithful subjects, although originally from distant countries, respectfully supplicate your Majesty to give us clear instructions on the following points. The scholars of Europe have understood that the Chinese practise certain ceremonies in honour of Confucius; that they offer sacrifices to Heaven, and that they observe peculiar rites towards their ancestors; but persuaded that these ceremonies, sacrifices, and rites are founded in reason, though ignorant of their true intention, earnestly desire us to inform them. We have always supposed that Confucius was honoured in China as a legislator, and that it was in this character alone, and with this view solely, that the ceremonies established in his honour were practised. We believe that the rites in honour of ancestors are only observed in order to exhibit the love felt for them, and to hallow the remembrance of the good received from them during their life. We believe that the sacrifices offered to Heaven are not tendered[xxxiii] to the visible heavens which are seen above us, but to the Supreme Master, Author, and Preserver of heaven and earth, and of all they contain. Such are the interpretation and the sense which we have always given to these Chinese ceremonies; but as strangers cannot be considered competent to pronounce on these important points with the same certainty as the Chinese themselves, we presume to request your Majesty not to refuse to give us the explanations which we desire concerning them. We wait for them with respect and submission.”

Ka̔ng Hsi cut the Gordian knot by declaring that “Ti̔en means the true God, and that the customs of China are political.” In spite of this Imperial opinion Pope Clement XI. upheld Bishop Maigrot, declared that Ti̔en Chu, Lord of Heaven, must be the name for God, Ti̔en and Shang Ti being altogether inadmissible.

Tournon, Patriarch of Antioch, was sent to Peking, where at an audience of Ka̔ng Hsi the Emperor demanded to be informed of the[xxxiv] decision of the Pope. When Ka̔ng Hsi learnt that a Pope of Rome had ventured to give an opinion contrary to his own in a matter which was altogether Chinese, and in part purely linguistic, he was furious, and issued a decree declaring that the Jesuits should be protected, but the followers of Bishop Maigrot should be persecuted. The Patriarch Tournon was banished to Macao, where further difficulties arose between him and the bishop of that diocese, who went so far as to imprison the legate in a private house, where he died. A second legate was sent to Peking in 1715 in the person of one Mezzabarba. Ka̔ng Hsi received him civilly, but would not talk about rites, and after six years fruitlessly spent he returned to Europe.

At the beginning of the eighteenth century it is claimed that there were in the provinces of the two Chiangs alone one hundred churches and a hundred thousand Christians. Those were the palmy days of missionary enterprise, but they did not last long. The quarrels of the missionaries amongst themselves, their[xxxv] political ambitions, which it was represented constituted a danger to the state, disgusted Ka̔ng Hsi. The Jesuits, indeed, he continued to tolerate, forbidding any priests but those who would follow the rules of Ricci to remain in China. In 1723 Ka̔ng Hsi died, and was succeeded by his son Yung Chêng, who in the following year issued an edict strictly forbidding the propagation of the Christian religion. A few missionaries were retained at Peking on account of their scientific acquirements, but the majority were banished to the south. The native Christians in the north were left as a flock without shepherds; they were subjected to extortion and blackmailing of the worst description, and although many remained faithful and even contrived to harbour their teachers secretly, this edict of Yung Chêng gave the death-blow to an energy which had made itself powerfully felt for a century and a quarter.

I have been led further afield than I intended in this sketch of the Jesuit enterprise (based mainly upon Dr. Wells Williams’s book[xxxvi] and on the Biographie Universelle), but it is a fascinating subject, and few people outside of those personally interested in China know how nearly at one time the Christian religion seemed to be reaching a great triumph. The story of Ricci, Schall, and Verbiest teaches one great truth. If missionaries are to be successful it must be by the power of masterly talent and knowledge. They can only work on any scale through the lettered class, and in order to dominate them must be able to give proof of superior attainments as the old Jesuits did. With courage, devotion, self-sacrifice, our missionaries are largely endowed. They have given proofs of these, even to the laying down of their lives; but these qualities are as nothing in the eyes of the cultivated Confucian. One such convert as Schall’s friend Sü and his daughter Candida would do more towards Christianising China than thousands of poor peasants. To make such a convert needs qualifications which are rare indeed. Above all things an accurate and scholarly knowledge of the language is necessary. There have[xxxvii] been not a few excellent scholars among our missionaries. But there are many more whose ignorance in that respect has been fatal, covering themselves and the religion which they preach with ridicule. Fancy a Chinese Buddhist mounting on the roof of a hansom cab at Charing Cross and preaching Buddhism to the mob in pidgin English! That would give some measure of the effect produced on a Chinese crowd by a missionary whom I have seen perched upon a cart outside the great gate of the Tartar City at Peking, haranguing a yellow crowd of gapers in bastard Chinese, delivered with a strong Aberdonian accent. The Jesuits knew better than that.

Not an uncommon argument in support of the truths of Christianity is to call attention to the purity of the lives of the missionaries. I find a note of a conversation on this subject in my Journals. “Venerable sir,” answered the learned and respectable Kung, “the goodness of a dumpling does not depend upon the pucker at the top of it. You can no more judge a man’s merits by his outward seeming than you[xxxviii] can mete out the sea in a bushel measure. It is true that to all appearance your missionaries lead very pure lives; but to all appearance so do our people. Look at Mr. Li and Mr. Pao, who live in my street. Nothing can be more respectable than their outward demeanour, yet we know perfectly well that Mr. Li sleeps in flowers and closes his eyes in willows” (a metaphorical expression for leading a dissolute life), “while as for Mr. Pao, the less said about him the better. What guarantee have I that these men, whose excellence you extol, are not like my neighbours Li and Pao? Since I must doubt even that which passes before my eyes, how can I believe that which comes to me only by hearsay? The proverb says, ‘If your front teeth are knocked out, swallow them.’ Nobody publishes his own misfortune or his own disgrace.”

The Chinaman knew his own country well. Virtue without the supremest power of science and education is not enough to carry conviction to the man of letters.

At any rate, the history of the great Jesuit[xxxix] movement proves my point that the spirit of religious intolerance is not a fault which can fairly be laid to the charge of “The Hundred Names,” as the οἱ πολλοί of China call themselves, and that where it has shown itself it has been engendered and fostered by the fears of the officials. It is the same with trade. The rulers and not the ruled are the authors of all difficulties. The Chinaman is a born trader. Buying, selling, and barter are the very joy of his life, and so long as he can get the better of a bargain what cares he with whom he deals? Foreigner or fellow-countryman, it is all one to him.

The third source to which hatred of foreigners is ascribed is opium. That has been dealt with so recently by a Royal Commission that there is nothing new to be said upon the subject. All I can say, speaking from personal observation, is that I have known some hundreds of Chinese of all classes who were opium smokers. None of them abused the drug. They regarded it as a most valuable prophylactic against fever and ague, and would[xl] have been very loth to do without it. Some were literary men and officials doing hard brainwork; others, like a travelling pedlar whom I met on one of my Mongolian excursions, were doing equally hard bodily work. The abuse of opium has, so far as I can judge, been grossly exaggerated. It cannot be denied that there are to be seen in the opium dens of great cities a few poor wretches who have reduced themselves to a state of abject degradation by their intemperance; but their percentage must be small indeed compared to that of the victims of alcohol who are the disgrace of our own towns, and at any rate, as has been cunningly observed, they do not go home and beat their wives. To deprive the Chinaman of the finest qualities of Indian opium would be to condemn him to the use of the miserable substitute which he grows in his own fields. It would be like forbidding the importation of champagne and Château Lafitte into England, and driving our epicures and invalids to the necessity of falling back upon cheap and nasty stimulants. If the opium trade were to be abolished[xli] to-morrow it is my firm conviction that it would spring up again immediately, but under altered conditions and in native hands. If it be thought that I am wrong in what I say as to the use of opium, read what Dr. Morrison says in his delightful book, An Australian in China. There you have the independent testimony of a competent physician who has travelled over the whole of China from east to west, and who has dealt exhaustively with the question. No one has had better opportunities of judging. No opinion is worthy of more respect.

My conclusion then is that neither the religion of the missionaries, nor the trade of the merchants, nor even the much-abused drug, can honestly be counted as the cause of the anti-foreign movement in China, though one and all have been used as levers to envenom it. Foreign intercourse in any shape is the bugbear of the mandarin, as being the one standing danger threatening abolition of himself and his privileges, of which the two most dearly prized are robbery and cruelty.

[xlii]

Let us be just, however, even to the mandarin. It often happens that the missionaries are surrounded by natives of bad character, who hang on to them for protection. Especially is this the case with certain Roman Catholics, who have always endeavoured to “extra-territorialise” their converts, that is, to exact for them the same privileges of immunity from Chinese jurisdiction as are granted to the subjects of their own country. It is easy to see how this may give just cause of offence to the officials, and how readily a cunning malefactor will run to his priest to shelter his back from the bamboo rod, swearing that the charge brought against him is a mere pretext, his profession of the Christian faith, in which he is protected by treaty, being the real offence. Full of righteous indignation and confidence in the truth of his convert, who, being a Christian, must necessarily be believed before his heathen accuser, the priest rushes off to the magistrate’s office to plead the cause of his protégé. The magistrate finds the man guilty and punishes him; the priest is stout in his defence;[xliii] a diplomatic correspondence ensues, and on both sides the vials of wrath are poured out. How can a priest who interferes, and the mandarin who is interfered with, love one another? Some instances there have been where the priests have gone a step farther, and have actually urged their disciples to own no allegiance to their native authorities, but to obey only themselves as representatives of the Sovereign Pontiff of Rome.

The missionaries, on the other hand, of the China Inland Mission put forth no such pretensions, and excite no such animosities.

The jealousies of the different sects of Christianity among themselves throw as great difficulties in the way of conversion to-day as they did in Ka̔ng Hsi’s time. A highly-educated Chinese gentleman, who had been making inquiries into the doctrines of Christianity, once appealed to me on the subject. “How is it,” he asked, “that if I go to one teacher and talk to him of what I have learnt from another he answers me, ‘No, that is not right; that is the doctrine preached by So-and-So;[xliv] if you follow him you will go to hell’?” But that one missionary should speak of the Church of another Christian as a “Scarlet Woman” appeared to him to be altogether lacking in decorum. It must be a puzzle—yet not worse than the various schools of Buddhism.

It used to be a cardinal article of faith among Europeans in China during the fifties, that if once we could throw Peking open to foreign diplomacy all would be well. That was to be the sovereign cure for all the ills of which we had to complain. We should be in touch with the Emperor and his court, and we could not fail to convert the most recalcitrant of mandarins to the adoption of our Western civilisation: perhaps even China might become a Christian country. We have now been at Peking for forty years, during which time successive ministers of all countries have preached, flattered, scolded, and threatened over the sweetmeats and tea of the Tsung-Li Yamên, and what is the result to-day?

What really was wanted was not to [xlv]get into Peking ourselves, but to get the Emperor with his court and Government out of it. This is no new theory of mine. So confident have I always been that Peking is the worst capital on all grounds for China, that thirty years ago, writing in Macmillan’s Magazine of the Tientsing massacre in 1870, I said, “This time we hope that the past will be a lesson for the future, and that such conditions will be imposed as will secure our countrymen, be they laymen or missionaries, from outrage, and will prevent China from remaining the one bar to the progress and civilisation of the world. It is not within the province of a magazine article to suggest what those conditions should be; but we cannot help hinting that if the treaty powers were to treat China as Peter the Great did Russia, and transplant the capital and court from Peking back to Nanking, whence it was removed by the Emperor Tai Tsung, who reigned under the style of Yung Lo at the beginning of the fifteenth century, the headquarters of obstructiveness and mandarinism would be destroyed, the power of[xlvi] the viceroys would be brought under the control of the central Government, and a new era might be inaugurated which should be as conducive to the welfare and happiness of the Chinese people as to the safety and profits of the European trader. Above all, the representatives of European powers, instead of being boxed up in Peking like rats in a trap, would in the not improbable event of their having from time to time certain demands and requisitions to make of the Chinese Government, be backed up by the presence of their men of war on the spot. It is wonderful how distance weakens a threat, and how wholesomely the sight of power acts upon the Oriental mind.”

Subsequent events have not led me to alter an opinion formed so many years ago. So long as Peking remains the capital so long will it be impossible to bring home to the Government certain facts which are well known to many of the provincial governors, but which only in rare instances they dare to report to headquarters. It is not conceivable that,[xlvii] if the Empress Tsŭ Hsi had known what a hornet’s nest she was stirring, she would have acted as she must have done in encouraging Prince Tuan and the Boxers. But it is a far cry to Peking.

It cannot be said that the policy of foreign governments in China has been calculated to raise the powers in the estimate of those very Chinese whom it ought to be our chief duty to impress. Take the outrages upon missionaries and the constant murders of which we have had to complain—until the German Emperor seized Kwei Chao we have always been content to accept a money indemnity as reparation; so that the local mandarins must have looked upon the death of a few missionaries—the most sweet-smelling offering that could be made to Tsŭ Hsi and her eunuchs—as a mere question of cost, and that moreover not to be defrayed by themselves, but squeezed out of the people. If some poor wretch or wretches were decapitated, the instigator, the real culprit, could enjoy the luxury of sitting in judgment over his own[xlviii] crime, and sentencing to death some victim caught at random out of the prisons, or perhaps even—for Chinese methods are ingenious—paying off an old score.

As regards intercourse with the ruling classes, or obtaining any influence with the court, our presence at Peking has been useless—perhaps worse than useless, actually mischievous. For what can a Chinese gentleman think when he sees the filthiest beggar pass freely without let or hindrance in parts of the city where the presence of the minister of the proudest nation in Europe would be deemed a pollution? We have been tolerated in Peking as a necessary evil—accepted we have never been. The receptions at court have been so rare, and made such a great favour of, that they have been a mere farce, and in some cases, such as the visit of the ladies of the Corps diplomatique to the Empress Tsŭ Hsi, a degradation. Compare with the position of the British Minister at Peking—stoned and insulted in the streets, and unable to obtain protection or redress—the reception[xlix] of Li Hung Chang by all Europe three years ago. How that astute old intriguer must have laughed in his sleeve when he found himself petted, coaxed, and flattered, treated like a royal personage! and what must have been the inference drawn by every ignorant Chinese, from Tsŭ Hsi and the poor down-trampled Emperor Kwang Hsu down to the meanest beggar on the bridge? Crystal is not so clear as the fact that the Son of Heaven is the ruler of the world, and all other monarchs mere vassals, doing homage to the steps of the Jasper Throne.

Peking has exercised upon foreign representatives a sort of unholy glamour. They have been bewitched. Some have fallen down and worshipped before its scholastic and historical traditions; others have treated the great city and its rulers as a sort of gigantic “curio”; optimism has been the bane of all. If any serious attempt has been made to bring the mandarins into the pale of statesmanship it has been singularly unsuccessful. They remain as retrograde and as hopelessly obstructive as[l] ever. They have occasionally been clever enough, like Li, to throw dust in the eyes of foreigners, and that is all. Unless a radical change is effected European diplomacy will continue to be abortive; to effect that change it is absolutely necessary that the court should be removed from the headquarters of obstruction, and brought into actual contact with our civilisation and with the material evidence of Western power. The old-world prejudices of Moscow were a hindrance to Peter the Great; the Kugés buried for centuries at Kiyôto were a drag upon the reformers of Japan; the capitals were moved. These are the two great precedents for such a policy.

In spite of protesting princes and potentates, it seems as if the partition of China, that unwieldy monster, was at hand. When the phrases “Sphere of Influence” and “Hinterland,” diplomatic expressions recently invented for the benefit of savage Africa, came, three or four years ago, to be applied to China, then nominally a friendly power, it was not difficult to foresee what must follow. The events of[li] the last three months have precipitated matters. Germany is in honour bound to exact exemplary retribution for the murder of her minister, the deadliest insult that could be offered to a great nation. If she were minded to take Shantung, where she might establish a flourishing colony, she would act as a buffer state between Central China and Russia, who has already to all intents possessed herself of Manchuria, and has for many a year cast longing eyes upon Chihli; and after all, if Russia were to annex Chihli with Peking would the world have any great cause for lamentation? Apart from all other considerations, Russia with a nucleus of co-religionists in the Albazines, of whom there is a short account at p. 211 of these letters, would have more in hand towards Christianising the people than any other nation or sect; and it seems to me that Peking Russian, and possibly Christian, would be far better than Peking Chinese, and certainly heathen. If further encroachment were guarded against by Germany in Shantung we should not be losers. Should France want[lii] a rectification of frontier for her great Asiatic colony—why should we interfere? The restoration of the old frontier of Burmah and the freedom of the Yangtze region should suffice us.

As for a change of dynasty in China, which some writers are crying for, that is an impossibility, because there is no Chinese pretender ready to replace the Manchus. It would mean chaos such as the world has never seen.

Freed from the incubus of the Empress Tsŭ Hsi and her eunuchs, freed from Prince Tuan and the other bloodguilty Manchus, the Emperor, surrounded by a more enlightened court, and acting under capable advisers, would be enabled to rule peacefully and honestly over an immense and prosperous empire; while the removal of the capital would, without any act of vandalism, such as the suggested destruction of the Tombs, read China that lesson which is so sorely needed, and which the absurd reprisals of 1860 utterly failed to convey. After the second occupation of Peking we should not again hear of the Barbarians bringing tribute to the Son of Heaven from his vassals.

[liii]

The idea of a change of capital is not one that is of itself strange or repugnant to the Chinese mind. It has even, apparently, been contemplated by the Dowager-Empress herself, though her choice would not unnaturally fall upon a spot like Hsi An Fu, near which town, at Hao, at Hsien Yang, and at Chang An, the emperors of the Chou dynasty (B.C. 1122–781), the Tsin (B.C. 249–200), and the Sui (A.D. 582–904) held their courts. But the chief charm of such a capital would be its inaccessibility and remoteness from the haunts of the foreign devil. Hsi An Fu would be Peking over again, and worse. It would give the coup de grâce to all hope of civilising the court.

In a letter published in the Times newspaper of June 22 I advocated once more the choice of Nanking as a new seat of Government, and I said that such a change would be hailed with joy by many millions of Chinese. A few days after that letter appeared my arguments received a very remarkable confirmation. A telegram from Yokohama informed us that the Chinese[liv] community in Japan, a highly intelligent, educated, and respectable body of men, of first-rate business capacity, had presented a petition urging the foreign powers to take advantage of the settlement which must follow upon the present troubles, to insist upon the removal of the capital from Peking to Nanking. Now these men know what they are talking about. They know that such a change would work wonders in the direction of good government; that it would take the power out of the fossilised hands of the court; that the light of day would be fatal to the bats and owls of the forbidden city; that the secret societies would be deprived of their chief support; that the viceroys and the whole descending scale of mandarins, brought under control of an intelligible and intelligent Government, would no longer be able to squeeze and persecute the people, paralysing trade by their extortions and blackmailing, and setting up insuperable barriers to the progress of civilisation.

In the Blue Book published recently (July 30) we have the first instalment of the official[lv] history of the tragedy of Peking—most melancholy reading, truly! But there is one bright spot in this miserable record. The attitude of our Foreign Office in all the negotiations which have taken place appears to have been altogether admirable. In spite of the cold water thrown by international jealousies upon Lord Salisbury’s efforts to retrieve the situation, he has held his own position, and he has succeeded in using the best means which were available without in any way compromising the future. Japan is to furnish troops, but there are no vague promises, no encouragement of inordinate ambitions, and no raising of hopes, which, if realised, might be fraught with dangers beside which even the horrors of the last few weeks would be as child’s play. Lord Salisbury boldly promises to find the money, and England will honour his bill. That is all. “Her Majesty’s Government wish to draw a sharp distinction between immediate operations which may be still in time to save the Legations, and any ulterior operations which may be undertaken.” No language could be clearer or more[lvi] satisfactory than this. Is it too much to hope that when the final settlement comes, the counsels of the same master-mind may devise a solution which shall bring about a happier era for China, without endangering the harmony of those nations which are now united in their resentment of outrages, for which the history of the world finds no parallel?

Besides the Blue Book, recent events have produced a plentiful crop of letters to the newspapers, many of them written with great ability and knowledge of Chinese affairs. The deposition of the undoubtedly guilty Empress, and the restoration to power of the Emperor, with a Government composed of the progressive party to which he is inclined, are with most of the writers a sine qua non. To this I say Amen. “The murderer Tuan must be executed” is a favourite cry. By all means; but we know what is the first postulate in the cooking of a hare. Prince Tuan will hardly be more easy to catch than was Nana Sahib in 1857. If the Emperor, a weakling at best, be left at Peking in a hotbed of harem intrigues[lvii] and secret societies, how can he be protected? Will his life be worth many days’ purchase? Will a progressive ministry be able to exercise any authority over the great provincial satraps? The foreign representatives will be locked up in the old death-trap, and in ten, twenty, thirty years history will repeat itself. The inviolable sanctity of Legations with such surroundings becomes a most miserable farce.

The return to the status quo ante, with all its possibility of tragic repetitions, is just the sort of lame and impotent conclusion to which we have accustomed the Chinese, and in their dealings with us they count upon a moderation which, like all Asiatics, they construe into fear, and despise accordingly. A barren conquest like that of 1860, which left things as they were, is something which they cannot understand. When Li Hung Chang, who knows exactly what string it is best to harp upon, sweetly urges us to arouse “the gratitude of millions” by abstention from revenge, be sure his gentle mind sees its way to turn such magnanimity to good account. The horrors of[lviii] to-day were begotten of the mistakes of 1860 and 1870. Let us hope that 1900 may be the parent of a less ill-omened brood.

Those who desire to study the political problems of the Far East will find admirable instruction in Mr. Chirol’s the Far Eastern Question (Macmillan), in Mr. Colquhoun’s Overland to China, and in the same writer’s more recently published The Problem in China and British Policy.

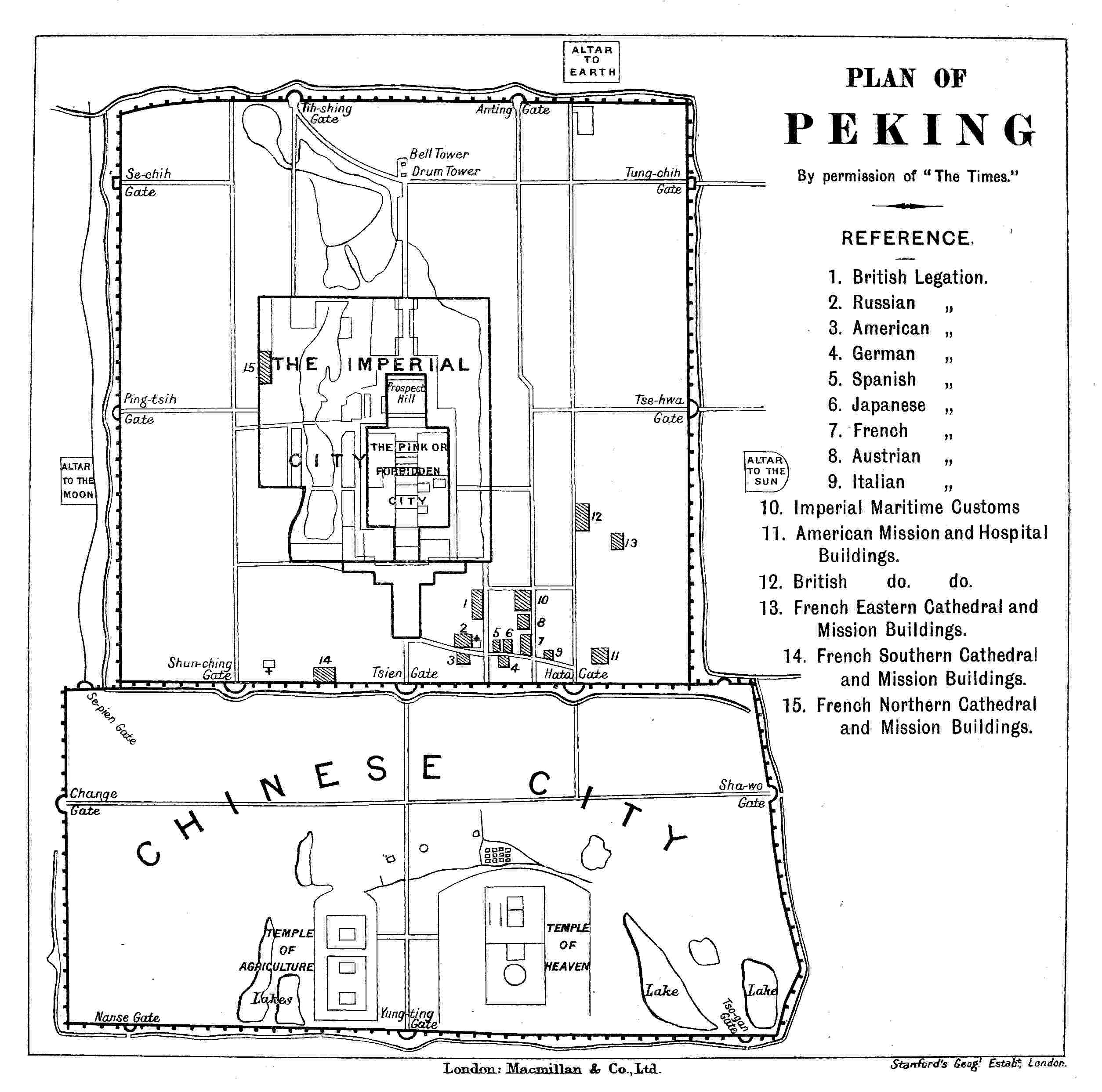

My best thanks are due to the proprietors of the Times newspaper for permission to reproduce here their admirable plan of Peking.

[1]

Hong-kong, 23rd April 1865.

Life at sea may be a very pleasant one for those who like it, but I doubt whether any one ever arrived at the end of a voyage of a month and a half by one of the P. and O. Co.’s steamers without uttering an expression of thanksgiving, hearty and sincere. The monotony of the ever-recurring daily occupations is killing. However,

even Hong-kong is reached at last.

We rush up on deck after breakfast to see the first of the brown, sun-scorched island. It is shrouded in mist, however, and there is not much to look at. But every one is excited and flurried, and in the happiness of realising the[2] luxury of being on land, we feel kindly towards all mankind, and bid a cordial farewell to our fellow-passengers. In a short while we are in harbour, and the little colony, planted at the foot of wild and rugged hills matching those of the mainland opposite, lies before us. A crowd of boats plying for hire, and partly manned, to use a bull, by women often pulling away lustily with a baby slung across their backs, hail us with cries of “Wanchee boat?” “Wanchee big boat?” These Chinese boatwomen are real wonders. Hardy, strong, and burnt by the sun, they look and probably are as sturdy as any of the men. At any rate I saw one woman fight and thrash a couple of stalwart young boatmen; and a good stand-up fight it was, give and take. They did not spare her, and she belaboured them most lustily, screaming and chattering all the while in a way that would have frightened Billingsgate itself into silence. The boats seem to hold whole families,—even the nursery,—the small boys wearing corks or bottles to keep them afloat when they tumble overboard. The girls, being reckoned of no value, take their chance, and wear nothing to protect them. As soon[3] as we came to an anchor the boats of the great commercial firms came alongside, each probably steered by a partner eager to hear the latest news or to welcome a friend. One by one the passengers disappear, and he who has letters for one of the merchant princes of China may look forward to luxurious quarters and a warm welcome, for nowhere else is hospitality carried to such an extent as it is here.

The houses in Hong-kong are large and airy. Lofty and spacious rooms not overloaded with furniture (for everything is dispensed with an eye to the getting the most air and coolness) look out on to a broad verandah, which is shaded with green rush blinds to keep out the glare. Here bamboo lounging chairs, of indescribable comfort, hold out arms that invite one to doze away the sultry afternoon, or sit smoking a cheroot and sipping cool drinks in the most luxurious laziness. The clean and neat matting on the floors, the rare curiosities and jars which decorate the principal rooms, the quiet, mouse-like steps of the China boys in their blue dresses, who act as servants, coming in to take an order or deliver a message in their quaint pidgin English, give [4]a peculiar and original stamp to the whole, which is of itself immensely refreshing. Everything speaks of rest and quiet, and yet it is in these quiet, idle-seeming houses—very castles of Indolence they appear—that busy brains are at work, toiling all day, calculating rises and falls, watching chances by which thousands are won or lost in a day. In the old days when the opium trade was unlawful, and therefore at its height, when the rival houses had each their fast sailing clippers racing against one another from Bombay and Calcutta, and the first to arrive would lie hidden round the corner of the bay, and send a man on shore across the hills with the all-important intelligence, only showing itself when a price had been made, the life of a man of business at Hong-kong must have been one of untold excitement. Nowadays every man gets his letters by the mail, the opium trade is legitimatised, and there is no longer the same amount of “go” and dash about the thing. Still, a venture of tea to the tune of a million of dollars, upon which 40 or 50 per cent may be made or lost, must be exciting enough for most men. Just at present the China trade is in a singularly bad way; vast[5] sums have been lost in tea speculations; some of the larger houses have been very hard hit, but with plenty of capital at their backs have stood the shock well. Smaller firms, however, not having the same elasticity, have sunk under it; smashes and rumours of smashes are rife; and the only men who have not suffered are those who, with wise prescience, have folded their hands and done nothing, waiting for better times.

Hong-kong presents perhaps one of the oddest jumbles in the whole world. It is neither fish, flesh, fowl, nor good red-herring. The Government and principal people are English—the population are Chinese—the police are Indians—the language is bastard English mixed with Cantonese—the currency is the Mexican dollar, and the elements no more amalgamate than the oil and vinegar in a salad. The Europeans hate the Chinese, and the latter return the compliment with interest. In the streets Chinamen, Indian policemen, Malays, Parsees, and half-castes jostle up against Europeans, naval and military officers, Jack-tars, soldiers, and loafers of all denominations. Constantinople, Smyrna, and[6] Cairo show more picturesque and varied crowds, but nothing can be more grotesque than the street life of Hong-kong. The local cab is a green chair[3] open in front and covered in at the top, in which you may sit Yankeewise, with your feet sprawling above your head, and be carried along at a good pace by a couple of strong-shouldered coolies with shaven polls, long tails, and huge umbrella hats. Plenty of these are waiting for hire at every corner. They have a fixed tariff of ten cents the trip. The weights that these coolies carry slung on their bamboo-poles are something surprising. I have seen Turkish hamals bent nearly double under the most impossible loads, such as no London railway porter would look at; but it makes one’s shoulders ache to see the Chinamen fetch and carry, for they do not hold the poles in their hands with the support of a shoulder-strap, like the chairmen who used to take old ladies out to tea and scandal in English country towns, but the bamboo poles are fastened at the ends, and the men simply hoist them on to their shoulders and stagger off under them. Both men and women of the lower orders are[7] certainly to our eyes mightily ill-favoured, and have villainous countenances which, if all tales be true, do not belie their characters; but now and then one comes across a pretty creature enough, some Cantonese, probably, as frail as fair—for St. Antony is not generally worshipped in seaside garrison towns. The long plaited tails worn by the men, and eked out with silk until they reach nearly to the heels, are a never-ending source of wonder to the new-comer. But there is one fashion of shaving the poll, leaving here and there a hair like the bristles on a gooseberry, which is peculiarly droll in its effect—a “coiffure à la groseille.” The Chinaman is very careful of his tail, and no cat has a greater horror of wetting her coat than he has of a drop of rain falling on his back hair. To cut it off is the height of indignity; and when the Chinese sailors on board the P. and O. ships have been stealing opium from the cargo, which they find it very hard to keep their hands off, they are tied up by their tails to the capstan and summarily flogged; in which case they become useful as well as ornamental. The barber drives a brisk trade; nor does he confine himself to shaving, clipping, and plaiting;[8] he has also cunning instruments with which he cleans the eyes and ears of his clients, the result of which is that the drums of their ears are often injured, and the poor patients afflicted with chronic deafness.

In this island of contrasts none is greater than that between the European and Chinese quarters of the town. In the former the houses are large and well built of gray slate-coloured bricks and fine granite, and others, some of which will be real palaces, are in course of construction. In the latter, on the contrary, the houses are low and mean. They are generally built with one story: on the ground floor is the shop with its various goods and quaint perpendicular inscriptions and advertisements; on the first floor, which is thrown out over the footway and supported by wooden posts, so as to form a covered walk, the family live, and here the ugly old women—uglier in China than anywhere—and queer little yellow children may be seen peering out of their dens at the passers-by. Towards evening, when the paper lanterns are lighted and the shops are shut up, not by doors and shutters as with us, but by a sort of cage of bamboo poles,[9] through which the interior is visible, the Chinese house looks very fantastic and strange. This quarter of the town bears a very bad name. It swarms with houses of the worst repute, and low grog-shops which are largely patronised by the sailors. The coolies in the street are a most ruffianly looking lot, not pleasant to meet in a by-road alone and unarmed. Indeed, life and property seem to be by no means so safe in the colony as they should be, considering the force which is kept here. A short time since a gentleman was attacked in broad daylight in the middle of the town, knocked down and robbed; and it is downright dangerous to venture on the hills alone without the moral influence of a revolver. The Chinamen are very clever thieves and housebreakers, and will even venture into barracks, smuggle themselves into the officers’ quarters, burn a little opium under the nose of some sleeping hero, and in double-quick time clear the room of watch, chain, loose cash, and valuables. Sometimes, however, they get caught. The other night a young officer was too quick for one of these light-fingered gentlemen, and pinned him just as he was making off. A mighty pretty dressing[10] he got too—for when the officers were tired of thrashing him, with ingenious cruelty they turned him into the lock-up where the drunken soldiers were, and I leave you to guess what sort of a night he spent. It is said that a Hindoo will rob a man of the sheet he is sleeping on without disturbing him, but I think to clear the goods out of a large warehouse under the owner’s nose, and with the police looking on, is at least as great a feat. This happened in this wise. A “godown” or storehouse full of valuable goods was fixed upon, a number of coolies walked in one fine day with a “comprador” (headman, bailiff, steward, and factotum), and with the utmost innocence set to work emptying the place, the pretended comprador all the while, in the most businesslike manner, making notes of the bales which were sent down to the quay and shipped off in small boats. One coolie is so like another that no wonder the policeman who was standing by thought it was all right, and the very audacity of the robbery put him off his guard. By the time the theft was discovered, goods, coolies, and comprador were well out of reach, and the owner was left lamenting over his empty godown.

[11]

It is rather hard on a man when he first comes to these parts to have to learn a new dialect of his own language more bizarre than broad Somersetshire, more unintelligible than that of Tennyson’s northern farmer. This is the Cantonese or “pidgin” English. Pidgin means business, of which word it is not difficult to see that it is a corruption, and the jargon is the patois that has invented itself for transacting affairs with the natives. Use a plain English word to a Chinaman, and he will stare and “no sabé”; but distort it, add a syllable or two, put it in its wrong place, and, in short, make it so unlike itself that its own root would not acknowledge it, and he will catch your meaning at once. Several Chinese, Portuguese, and other words of doubtful pedigree, mixed up with this maltreated English, make up the lingo, which is a literal translation of Chinese syntax, and puzzling enough at first. Here is a specimen. I should tell you that in pidgin bull is male, cow female. An English gentleman from Shanghai went to call at a friend’s house in Hong-kong. The door was opened by the head Chinese boy. “Mississee have got?” said the gentleman.[12] “Have got,” answered the boy, “but just now no can see.” “How fashion no can see?” The boy answered, grinning from ear to ear, “Last night have catchee one number one piecee bull chilo!” The lady of the house had been safely brought to bed during the night of a fine baby boy! Sometimes the boy will dot his I’s and cross his T’s with unfortunate distinctness as to the occupations in which his master or mistress is engaged, putting one in mind of Gavarni’s Enfants Terribles. It is not to be wondered at that the coolies and servant boys should talk this lingo, but that clever, intelligent fellows like the compradors in big houses should not have acquired a better form of English is indeed strange.

Life at Hong-kong passes away pleasantly enough. The residents are very rich, and they spend their money like princes. Their hospitality is boundless, and open house is the rule. I can fancy no better quarters for a naval or military man. The climate is very different from what it used to be, and has become very healthy; but if a man should fall ill he can get away north to Peking, or run up to Japan, or choose between a dozen trips[13] nearer at hand. The usual daily routine here at this season of the year is as follows:—At six your boy wakes you with a cup of tea; you rise and bathe, and read or write till it is time to dress for breakfast at twelve (the merchants, of course, go to their offices at ten or even much earlier). Breakfast, as it is called, is a regular set meal with several courses, and champagne or claret; any one comes in who pleases, and is sure of a cordial welcome, and probably an invitation to return to dinner. After a cup of coffee and a cheroot, office work begins again, and goes on until about five, when every one turns out to ride, drive, or walk until seven, which is the hour for gossip, and sherry and bitters at the club, a first-rate establishment to which strangers are admitted as visitors, and where a man may put up if he pleases. Dinner is at eight, and a very serious affair it is, for Hong-kong is fond of good living and fine vintages; and this rule does not apply only to the heads of houses, for their clerks are lodged and boarded exactly on the same scale as themselves, and a boy who has been content to dine for a shilling at a London chop-house, sits down here to a dinner fit for a duke,[14] criticises the champagne and claret with the air of a connoisseur, and rattles in his pocket £300 or £400 a year for his menus plaisirs. Which shows the superiority of vulgar fractions to genteel Latin and Greek.

The rides and drives about Hong-kong are in their way very pretty, though the almost entire absence of trees presents a violent contrast to the rich tropical vegetation of Singapore and Penang. On the other hand, both on the mainland and in the island itself, there are bold, rugged mountain outlines, often shrouded in a mist that reminds one of Scotland and Ireland; huge boulders of rock from which beautiful ferns of every variety (fifty-two species have been classed) grow in profusion; a bay studded with wild barren islands; and to the east, where the colony is only separated from the mainland by about a mile of sea, the picturesque peninsula of Kowloon. The racecourse in the Happy Valley is a lovely spot. It is surrounded by hills on three sides, and from the fourth, which is close to the bay, one looks up a blue glen such as Sir Walter Scott might have described. Here on the slope of the hill is the cemetery, and here and[15] at Government House there are some trees, among which the graceful bamboo is conspicuous. But it is the south-west of the island that is most affected by the residents. At a place called Pok Fo Lum, about four miles off, several of the rich merchants have built bungalows to which in summer-time, after stewing all day in their offices, it is their wont to resort of an afternoon, and let the fresh sea-breeze clear their brains of tea, opium, silk, rises and falls, and such-like cobwebs. On a fine evening these gardens are a very pleasant lounge. At the back rises the Peak, a fine bold rock some 1700 feet high; all around are sweet-scented tropical flowers teeming with strange, many-coloured insects and gorgeous butterflies; while in front the view stretches to the mainland hills across the brilliant sea rippling against little islands, and covered with flotillas of native boats, peaceful enough to all appearance, but ever ready for any little piece of light piracy that may turn up.

I was very anxious before leaving the south of China to see Canton, and accordingly on the 28th April I started with a friend in one of the huge house-steamers that ply between[16] Hong-kong and Canton, and are of themselves curiosities. They are divided into separate parts for Europeans, Parsees, and natives of the poorer class, with loose boxes into which bettermost Chinese families are put. You may form some idea of their size when I tell you that three weeks ago, on the occasion of a festival, our boat the Kin Shan took up 2063 Chinamen to Canton, whither they were bound to “chin-chin” the graves of their ancestors. In all American steamers—and this is a Yankee venture—speed is the great object, and we accomplished the distance, between 80 and 90 miles, under the six hours.

We had a bright sunny morning for our expedition, and the harbour of Hong-kong appeared to great advantage, for there were plenty of fleecy clouds in the sky throwing fantastic shadows over the hills around. The sea was as calm and transparent as a lake, and we could sit in the best cabin, which is a huge building on the forecastle, catching every breath of air, and enjoying the scenery. The river-banks are at first wild, barren, and hilly, like Hong-kong, but higher up there begin to be signs of cultivation. Plantains[17] and rice, which is the greenest of all green grasses, grow in profusion among the snipe marshes. Bamboos spring up close to the water’s edge, and the hills are lower, less savage-looking, and more fruitful. Ruined forts, destroyed when we forced our trade upon the unwilling Chinese, numberless boats and junks, here and there a pagoda with different sorts of plants peeping out of its many stories, tell us that we are drawing near a town, and after about four hours and a half we reach Wampoa, a miserable place, with about as dirty and degraded-looking a population as could be seen anywhere. A few lime kilns, soy or ketchup factories, and dry docks where ships are brought to have their keels cleaned of barnacles and sea-muck, seem to constitute all the business of the place. I shall always henceforth look upon soy as the essence of the dirt of Wampoa.

Canton itself does not present a very clean face to be washed by the unsavoury river. If any one should come here expecting to see a fine city of quays and palaces, he will be grievously disappointed. Myriads of low dirty wooden houses, built almost in the very water[18] itself, are crowded together higgledy piggledy, without order or method. As if these were not enough, there are whole streets, alleys, and quarters of the foulest boat-houses, all swarming with human, and probably other, life. Junks in numbers, carrying guns for defence, and if a safe opportunity occurs, for offence, are moored in the stream. Strange, grotesque craft they are, with their huge bows built to represent the heads of sea-monsters; a great eye is painted on each side, for the Chinese treat their ships as reasoning beings, and say, “S’pose no got eye, no can see; s’pose no can see, no can walkee,” which is unanswerable—even the Kin Shan carries an eye on each paddle-box in deference to this idea. But as at Hong-kong, the chief peculiarity of the river scene here is the crowd of small boats with female crews. The mother pulls the stroke oar, the aunt the bow, and grandmamma is at the helm with a third. I am sure there must have been several hundreds of these yellow ladies round the steamer at one time. The parrot-house at the Zoological Gardens was silence itself by comparison, for hard work, and strong pulling, have given them lungs of leather. They all claim acquaintance,[19] and employment on the strength of it. “My boatee, my boatee, my no see you Cheena side long tim.” We had our own boat, however, and with patience cleared a way and got to shore. But no description of the Canton River would be complete without an allusion to the famous “flower-boats.” Huge, unwieldy barges they are, moored by the river-side, and tricked out with every paltry decoration of cheap gilding, paper lanterns, and bizarre ornament that the Owen Jones of China can invent. These are the temples of Venus. The priestesses are mostly brown ugly little women in sad-coloured garments, upon whose flat yellow faces the rosy paint looks even more ghastly than on Europeans; some are almost pretty, however, and all have beautiful hands and feet (when the latter have not been wantonly deformed), indeed this is the one gift of beauty common to all the Chinese, and the very men-servants who wait upon one have hands kept delicately clean, and so well formed that many an European lady might envy them; they have no need to wrap a napkin round their thumbs, nor to wear white cotton gloves; their taper fingers and filbert nails are pleasant to look upon. At night,[20] when the lanterns are lighted, and the tawdriness of the decorations is less offensive, the flower-boats look gay enough, and they are one of the sights of Canton. The trade that their denizens ply is not looked upon as disgraceful, nor does it prevent their marrying respectably afterwards,—at least so it is said.