Title: 240,000 miles straight up

Author: L. Ron Hubbard

Illustrator: Virgil Finlay

Release date: March 2, 2023 [eBook #70187]

Language: English

Original publication: United States: Standard Magazines, Inc, 1948

Credits: Greg Weeks, Mary Meehan and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

A NOVELET BY

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Thrilling Wonder Stories December 1948.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

CHAPTER I

Left at the Post

The party was wild. The night was gay. And the "Angel" was very, very drunk.

But who wouldn't have got drunk on such an occasion? The Angel was about to head man's first attempt to conquer space and within a few short hours he would be boring space to the Moon, 240,000 miles straight up.

He had tried to stay sober but this, being without precedent in the Angel's career, was entirely too great a strain. "Don't dare take another grink—well—jush one more—hic!"

The Angel was First Lieutenant Cannon Gray of the United States Army Air Forces, Engineers. He was five feet two inches tall and he had golden curly hair and a face like a choir boy. Old ladies thought him wonderful and beautiful. His superiors, from the moment he had entered West Point, had found him just about the wickedest, hard drinkingest, go-to-hell splinter of steel they'd ever tried to forge.

The army, with a taste of opposites, called him Angel from the first, called it to his face, loved him and was hilarious over his escapades.

This was probably the first time in history that Angel had attempted to stay sober. But it was a wonderful party they were giving in his honor (two floors of the Waldorf plus the ballroom) and people kept insisting that he wouldn't get another chance at a drink for months and maybe never and everyone was so pleasant that good resolutions were very hard to hold—especially for a dashing young officer who had never tried to make any before.

The occasion was gala and his hand was sore from being pumped by brasshats and newsmen and senators. For at zero four zero eight of the dawning, First Lieutenant Cannon Gray, U.S.A., was taking off for the Moon.

It was in all the papers.

Several times Colonel Anthony, a veritable old maid of a flight surgeon, had tried to pry his charge loose and steer him to bed and, while Angel seemed willing and looked blue eyed and agreeable, he always vanished before the hall was reached. Really, it was not Angel's fault.

No less than nineteen frail, charming and truly startling young ladies, all professing undying passion and future faithfulness, had turned up one after the other and it was something of a task making each one unaware of the other eighteen and confirmed in her belief in his lasting fidelity.

Such strains should not be placed upon young men about to fly two hundred and forty thousand miles straight up. And it takes hours to say a proper good-by. And it takes more hours to be respectful to brass. And it takes time, time, time to drink up all the toasts shoved at one. All in all it was a very exhausting evening.

Not until zero one zero six did Colonel Anthony manage to catch the collapsing Angel in such a way as to keep him. Wrapped in the massive grip of Colonel Anthony, Angel said, "Candrin four oh eigh—snore!"

The golden head dropped on the Colonel's eagle and Angel slept.

Cruelly, it was no time at all before somebody was slapping Angel awake again, standing him on his feet, getting him into a uniform, wrapping him up in furs, weighing him down with equipment and generally tangling up a dark, dismal and thoroughly confused morning.

Angel was aware of a howling headache. Small scarlet fiends, especially commissioned by the Prince of Darkness for the purpose, played a gay chorus with red hot hammers just behind Angel's eyes. He was missing between his chin and his knees and his feet wandered off on various courses.

A flight major and two sergeants undeniably capped with horns, danced in high anxiety around him and managed to touch him in all the places that hurt.

He was in horrible condition and no mistake.

And the watch on his wrist gleamed as hugely as a steeple clock and said, "Zero three fifty-one," in an unnecessarily loud voice.

The corridor was at least half the distance to Mars and Angel kept hitting the walls. The casual chairs with which he collided all apologized profusely.

A potted palm fell on him and then became a general who, with idiotic pomposity said, "Fine morning, fine morning lieutenant. You look fit. Fit, sir. No clouds and a splendid full moon."

He felt the call, one which generals too old for command can never resist, to give a young officer the benefit of a wealth of experience but, fortunately, his aide swiftly interposed.

The aide was brilliant with the usual aide's enthusiasm for paper glory and distaste for generals. Angel knew him well. The aide, in Angel's day at the Point, had been an Upperclassman, a noted grind, a shuddery bore and the darling of his seniors. He didn't look any better to Angel this morning.

"Beg pardon, sir," said the aide sidewise to the general, "but we've just time to brief him as we ride down. Here, this way lieutenant." And, abetted by the usherlike habit peculiar to the breed of aides, he got Angel into the car.

"Now," said the aide to Angel, who was hard put to stifle his groans and shivers at the unearthly hour, "you have been thoroughly briefed. But there must be a quick resumé unless you think you are thoroughly cognizant of your duties."

Angel would have answered but the sound came out as a groan.

"Very well," said the aide, just as though his were the really important job and Angel was just a sort of paperweight, very needful to aides but not at all important. "The staff is terribly interested in your surveys.

"You will confine yourself wholly to this one task. It has been thought wisest to entrust a topographer with this first mission because, after all, that's the way things are done. We've insufficient reconnaissance to send up a main body."

Angel would have added that he was a guinea pig. They didn't even know if he could really get to the moon. But aides talk like that and lieutenants somehow let them.

"As soon as you have completed a survey of an elementary sort you will televise your maps, then send a complete set in a pilot rocket and return if you are able. But you are not to risk bringing the maps back personally."

They were little enough sure he'd ever get there, much less get back.

"You will phone all data back to us. Our tests show that the wave can travel much further than that. Anything you may think important, beyond maps and perhaps geology, you are permitted to note and report.

"Under no circumstances are you to attempt to change any control settings in your ship. Everything is all prenavigated and proper setting will be phoned to you for your return.

"All instructions are here in this packet."

Angel shoved the brown envelope into his jacket and felt twinges of pain as he did so.

"My boy," said the general, getting a word in there somehow, "this is a glorious occasion. You have been chosen for your courage and loyalty and it is a great honor. A great honor, my boy. You will, I am sure, be a credit to your country."

Angel didn't mean it to be a groan but that is the way it came out. They had chosen him because he was the smallest man ever to enter West Point, his height having been waived because of the lump of tin—the Congressional Medal of Honor, no less—he had won as an enlisted man (under age) in the war.

They had needed a topographer who wouldn't subtract from pay load. Space travel was to begin with seeming to create a demand for a race of small men. But he didn't tell the general this and they came to the end of the ride.

The aide expertly ushered Angel out into the bleak blackness of the take-off field, where every officer and newspaperman who could wangle it was all buttoned up to the ears and massed about the whitish blob of the ship.

The flight surgeon took over and protected Angel from the back swats and got him through to the ladder. The two smallish master sergeants—Whittaker and Boyd—were waiting at the top in the open door of the ship. Metal glinted beyond them in the lighted interior.

Whittaker was methodically chewing a huge wad of tobacco and Boyd was humming a bawdy tune as he stared up at the romantically round and glowing moon in the west. They were taking off away from it for reasons best known to the U.S. Navy navigators who had set the course.

A commander was hurrying about, muttering sums, and he paused only long enough to glare at Angel. "Don't touch those sets!" he growled, and rushed off to take station at the pushbutton which, when all was well, would fire the assist rockets under the carriage on the rails. These were keyed in with the ship's rockets. The commander glared at his ticking standard chronometer.

The flight surgeon said, "Well, you've got a week to sober up, boy. You won't like this take-off."

Angel gave him a green smile. It hadn't been the champagne. It was the apricot cordial that Alice had brought him to take along. "I'll be fine," said Angel, managing a ghost of his lovely smile.

"Board!" shouted the commander.

Angel went up the ladder. Whittaker spat out his chaw and lent a hand. Boyd was standing by on the stage and, more to avert the necessity of having to see Angel's poor navigation than from interest, turned a powerful navy night glass on the Moon. Boyd was very fond of Angel in a cussing sort of way.

But Angel made it without help and had just turned to give the faces, white blurs there in the floodlights, a parting wave to the click of cameras when Boyd yelled.

"Oh, my aching Aunt!"

There was so much amazed fear in that shout that everyone stared at Boyd and then turned to find what he saw. Angel found Boyd shoving the glasses at him.

"Look, lieutenant!"

Angel hadn't supposed himself able to see a thousand-dollar bill, much less the clear Moon. And then he jumped as if he'd been clipped with a bullet.

The commander was howling at them to batten down but Angel stood and stared, glasses riveted to the lunar glory.

Those with sharper eyes could see it now. And a wail went up interspersed with awful silences. Even the testy commander turned to stare, looked back to the ship and then whipped about to snatch a quartermaster's glass from his gunner. He took one look and froze in silence.

Every face was uplifted now, the field was stunned. For there on the moon in print which must have been a hundred miles high, done in lampblack, were the letters—

U S S R

CHAPTER II

Take-Off

For some days Angel languished in bachelor officers' quarters, all out of gear. He had been nerved up to a job and then it hadn't come off. The frustration resulted in lack of any desire for animation of whatever kind.

It was the sort of feeling one gets when he says good-by, good-by, to all his friends at the curb and then, just as he starts off in the car, runs out of gas and has to call a garage.

His room was littered with newspapers which he had long since perused. The mess-boy brought stacks in every now and then until bed and furniture seemed to be constructed badly of newsprint.

His own personal tragedy was such that he hardly cared for the details. Instead of being the first man to fly to the Moon he was again just a simple lieutenant with nothing more than his deserved reputation for angelic wickedness. It came very hard to him, poor chap.

But it came very hard to the world as well. For events had transpired which made any former event including World War II a petty incident.

The world had been conquered without firing any other shots than those needed to propel Russian forces to the Moon. The head of the Russian state had promptly issued manifestoes in no uncertain terms demanding that all armies and navies be scrapped everywhere and Russian troops admitted as garrisons to every world capital. Russia had plans.

One by one countries had begun to fly the hammer and sickle without ever seeing a single Red army star.

For it was obvious to everyone. Even statesmen. All Russia had to do was launch atom bombs from the Moon at any offender to destroy him wholly.

The mystery of how Russia had solved the atom bomb and had so adroitly manufactured all the plutonium it could ever need was solved when a Russian scientist stated for the press that he had needed but one year and the Smythe report. Everybody began to quiet down, for at first there had been talk of traitors and selling the secret.

But now that it was at last obvious that there never had been any secret and that self-navigating missiles could be very easily launched from the Moon at any Earth target and that, such was the gravity difference, it would be nearly impossible to bomb-saturate the Moon from Earth, even the die-hards could see they were whipped.

A demand on Washington had come from Russia for the entire U.S. atom stockpile and Congress was debating right now, without much enthusiasm, a law to give it up.

It had been very striking the way the morale of the world had collapsed, seeing up there in the sky those giant letters, U.S.S.R. Communists in every land had begun to crawl out from under dubious cover and prepare welcomes for Russian troops (and the Russians had been bidding the foreign communists to crawl right back again).

To understate the matter, there was some little consternation in the nations and peoples of the world. And whatever labor thought about it they at least remembered that of all the civilized nations of Earth, Russia had been the only one after World War II to employ, use, exploit (and let die) slaves.

And then, just as surrender was being accomplished, the U.S. Naval Intelligence, working with the State Department, had done some interception and unscrambling and decoding which again gave everyone pause. By great diligence and watchfulness they had managed to tap in on the Moscow-Moon circuit to discover that all was not well.

Angel had been reading about the Moon commander. The man was General Slavinsky and at first reading Angel had decided, with a bitterness not usually found in celestial sprites, that he hated the trebly-damned intestines of General Slavinsky.

Slavinsky was known as the "Avenger of Stalingrad" and had been a very popular general in his own country. The Germans, however, had not liked him, jealous no doubt of the thorough sadism of the Russian.

When Slavinsky had not been winning battles he had been butchering prisoners and he had turned his men loose to loot in many a neutral town and conquered province. Slavinsky evidently had himself all mixed up with Genghis Khan, complete with pyramids of skulls.

The pictures in the papers showed Slavinsky to be a big, powerful man, meticulously uniformed, always smoking cigarettes. Typical corporal-made-good, Slavinsky had been Moscow's favorite peasant. About as cultured as a bull, he was quite proud of his refinement. And he had been sent with troops, supplies and bombs to command Russia's most trusted post, the Moonbase.

It was here that dictatorship displayed its weakness. Bred by force out of starvation, the Russian state had very scant background of tradition. And trustworthy military forces are trustworthy only by their tradition. Slavinsky owed no debt to anyone but the Russian dictator. The Russian people would not know one dictator from another.

It developed, when Slavinsky was well dug in, that he had been a Trotskyite since boyhood and the murder of his ideal in Mexico had left him festering very privately. At least that was a fine excuse.

Once there Slavinsky began to make certain demands on Moscow. Moscow was beginning to be acrimonious about it. The dictator had ordered Slavinsky home and Slavinsky had told the dictator where he could stuff Moscow. Moscow was now threatening to withhold needed supplies.

U.S. Naval Intelligence and the State Department were very interested and rumors flew amongst the personnel of the U.S. Moon Expedition that something was about to break.

Angel lay on his back, feet against the wall-paper and gloomed. When a knock came on the door he supposed it was another load of papers and sadly said, "Come in."

But it was a colonel who stood there and Angel very hastily bounced up to sharp attention.

"We're having callers, son," said the Colonel. "Be down in the court in five minutes."

Disinterestedly, Angel got himself into a blouse and wandered out. He wondered if he would ever feel human and normal again. All his life he had been a somewhat notorious but really rather unimportant runt and the big chance to be otherwise had passed, it seemed, forever.

He hardly noticed his fellow officers as he lined up in the court. Most of them were of the Moon gang, destined to go, once upon a time, in various capacities on the abandoned expedition. None of them looked very cheerful.

There was hardly a ripple or a glance when the big Cadillac drew up at the curb. Their senior barked attention and the officers drew up. Only then, when ordered to see nothing and be robot, did Angel note that the car had the SecNav's flag on it.

Four civilians, namely the secretary of state, the secretaries of defense, war and the navy, alighted, followed by a five star admiral and a five star general. They were a dispirited group and they cast wilted glances over the lines of young officers.

The colonel in command of the detachment fell in with them behind the secretary of state and proceeded with this strange inspection.

Finally the group drew off and stood beside the Cadillac talking in low tones until they nodded agreement and then waited.

The colonel sang out, "Lieutenant Gray!"

Angel started from his trance, came to attention, paced front and center and automatically saluted the group. The colonel looked baffled as he came forward.

In a voice the others could not overhear, the colonel said, "I have no idea why they chose you, Angel. They were looking specifically for the tamest officer here. God knows how or why, but you won. They couldn't have looked at the records!"

"Thank you, sir," said Angel.

The colonel gave him a hard look and led him off to the car.

They didn't say anything to him. Angel got in beside the driver and, when the doors had shut behind the rest, they moved off at a dispirited speed.

Nothing was said until they arrived in the driveway of the White House and then the general told Angel to follow them.

The abashed lieutenant alighted on the gravel, looked up at the big hanging lantern and the door, then quickly went after his superiors. This was all very deflating stuff to him. The closest he had ever come to the President was leaving his card in the box for the purpose in the Pentagon Building—and he doubted that the President ever read the cards dropped by officers newly come to station or passing through.

He hardly saw the hall and was still dazed when the general again asked his name, sotto voce.

"Mr. President," said the five star, "may I introduce First Lieutenant Cannon Gray."

Angel shook the offered hand and then dizzily found a chair like the rest. All eyes were on him. Nobody was very sure of him, that was a fact. Nobody liked what he was doing.

"Lieutenant Fay—" began the President.

"Gray, sir."

"Oh yes, of course, Lieutenant Gray, we have brought you here to ask you to perform a mission of vital importance to your country. You may withdraw now without stigma to yourself when I tell you that you may not return from this voyage.

"We considered it useless to ask for volunteers since then we would have had to explain a thing which I believe we all agree is the most humiliating thing this country has ever had to do. We are not prepared just now for publicity. You may withdraw."

This, thought Angel, was a hell of a way to force a guy into something. Who could withdraw now? "I am willing," he said.

"Splendid," said the president. "I am happy to see, gentlemen, that you have chosen a brave officer. Here are the despatches."

Angel looked through them quickly and then at the first page of the sheaf, which was a brief summary.

He learned that one Slavinsky, late general of Russia, had finally, forever parted company with his dictator and had declared himself master of Russia and the world. The United States was now addressed in uncompromising fashion by Slavinsky and ordered to do two things.

One, immediately to prepare a land, sea and air attack on Russia—one city in the United States or one city in Russia to pay for the first use of atom bombs by either—in order to secure the government of that nation to Slavinsky. And two, to send instantly a long list of needed supplies by one of the space-ships known to be ready in the United States. Angel knew that he was to be interested in "two."

"This situation," said the President, "is unparalleled." And with that understatement, continued, "Unless we comply we will lose all our cities and still have to obey. We are insufficiently decentralized to avoid these orders.

"Humiliated or not, we must proceed to save ourselves. Slavinsky holds the Moon and is armed with plentiful atom rockets. And he who holds the Moon, we learn too late, controls all the earth below.

"We are asking you," he continued, "to take the supplies to the Moon. We have secretly loaded a space-ship with the required items and need only one officer and two men as crew.

"The reason we send you at all is to ensure the arrival of the supplies in case of breakage on the way and, more important, in the hope that Slavinsky will let you go and you can bring back data which, if accurate enough, may possibly aide us to destroy Slavinsky and his men."

"Mr. President," said the secretary of state, "we have chosen this man not for valor but for reliability. I think it was our intention that whoever we sent should attempt no heroics which would anger Slavinsky. I think Lieutenant May should be so warned."

"Yes, yes," said the President. "This is of the utmost importance. You are only to return if Slavinsky permits it. You are to attempt no heroics. For if you failed in them we would pay the price. Am I understood in that, lieutenant?"

Angel said he was.

"Now then," said the president, "the space-ship is waiting and, when you have picked your two crewmen and Commander Dawson gives the word, you can leave. These despatches"—and he took up a sheaf of them—"are for General Slavinsky and may be considered important only as routine diplomatic exchanges."

Angel took the package and stood up.

"One thing more," said the admiral. "You will be carrying a small pilot rocket aboard. You will take the rolls from the automatic recording machines, place them in it just before you reach the Moon and launch the missile back to Earth before landing. If we have enough data, though it is a forlorn hope, we may some day fight Slavinsky."

"I doubt it," said the secretary of state, "but I won't oppose your thirst for data, admiral."

They shook hands with the President and then Angel found himself back in the Cadillac, rolling through the rush-hour traffic of Washington. Soon they made it to the Fourteenth Street Bridge and went rocketing into Virginia to a secret take-off field.

"Could you get me Master-sergeants Whittaker and Boyd?" said Angel timidly to the general.

"I'll have them picked up on the way by the barracks," said the general. "No word of this to anyone though."

"Yes sir," said Angel.

When darkness had come at the secret field Commander Dawson turned up with a briefcase full of calculations from the U.S. Naval Observatory and began to check instruments.

"Two o'clock," he told the general.

"Two o'clock," said the general to Angel.

Angel walked out of the hangar and joined Whittaker and Boyd.

Whittaker spat reflectively into the dust. "I shore miss the brass band this time, lootenant."

"And the dames," said Boyd, "Boy how I'd like me a drink. We got time to go to town, lootenant?"

Angel was walking around in small circles, his beautiful face twisted in thought. Now and then he kicked gravel and swore most unangelically.

They were handing Slavinsky the world, that was that. And without a scrap. The slaughter of a Russian war was nothing to anyone compared to the loss of Chicago. Maybe it was logical but it just plain didn't seem American to be whipped so quick.

Suddenly he stopped, stared hard at Boyd without seeing him and then socked a fist into his palm.

"What's the matter?" said Boyd.

Angel went into the hangar where the big ship was getting ready to be rolled out on the rails now that her loading was done.

"General," said Angel, "as long as I may never have the chance again—and being young makes it pretty hard—you might at least let me go to town and buy a couple quarts for the ride up."

"You know the value of secrecy," warned the general. And then more kindly, "You can take my car."

Angel stood not. Some fifty seconds later the Cadillac was heading for town at speeds not touched in all its life before.

Whittaker and Boyd, in the back seat, bounced and applied imaginary brakes.

"Listen you guys," said Angel. "Your necks are out as much as mine"—he avoided two street cars at a crossing and screamed on up toward F Street—"and I ought to ask your permission.

"We're going to take a load of food to Slavinsky on the Moon. Very hush-hush, though the only one we've to keep secrets from now is Slavinsky. But I intend to make a try at knocking off that base. Are you with me?"

"Why not?" said Whittaker.

"Your party," said Boyd.

Angel drew up before an apartment house on Connecticut Avenue and rushed out. He was back almost instantly with a grip and considerable lipstick smeared on his cheek.

Boyd thought he heard a feminine voice in the darkness above calling good-by as they hurtled away. He grinned to himself. This Angel!

Their next stop was before a drug store and Angel dashed in. But he was gone longer this time and seemed, according to a glimpse through the window, to be having trouble convincing the druggist. Angel came out empty-handed and beckoned to his two men.

Whittaker and Boyd walked in. A young pharmacist looked scared. There was no one else in the place.

Angel walked around behind the pharmacist. "Close the door," said Angel. Three minutes later the pharmacist was bound quite securely in a back closet.

Angel ransacked the shelves and loaded up a ninety-eight-cent bag. They turned out the lights and closed the door softly behind them and went away.

Twenty-one minutes later a young Chemical Warfare classmate of Angel's was hauled from the bosom of his family and after some argument and several lies from Angel permitted himself to be convinced by SecNav's Cadillac and went away with them.

They halted at an ordnance depot in Maryland at eight-fifteen and the young chemist opened padlocks and finally, with many words of caution, delivered into Angel's hands three small flasks.

It was well before two when Angel and his men came back to the field. They alighted with their burdens and whisked them into the ship.

"Find that drink?" said the general indulgently.

"Yes, sir," said Angel.

"Good-boy!" said the general, chuckling over having been young once himself. He had not missed the lipstick and had applied the school solution.

Commander Dawson was growling and snarling around the ship like a vengeful priest. Behind him came two quartermasters carrying the precious standard chronometer and spyglass.

"Better get aboard," said Dawson roughly. "And don't monkey with those instruments. We're almost ready." His scowl promised that it didn't matter to him what happened: this time he was going to get that rocket upstairs!

CHAPTER III

Moon Meeting

Stark death was the Moon. No half-tones, no softness. Black and white. Knife-edged peaks and sharp rills. Hot enough to fry iron. Cold enough to solidify air. Brutal, savage, dead. Strictly Moussorgsky.

A place you wouldn't want to go on a honeymoon, Angel decided.

For all of Dawson's growling they had not hit the target exactly. Slavinsky had drawn a big, lampblack X below the U.S.S.R. on a plateau near Tycho but the ship had hit nearly eight miles from it.

Hit was the word, for if they had not landed in pumice some thirteen feet thick things would have been dented. The abrasive dust had risen suddenly and drifted down with an unnatural slowness.

For a week they had been lying around in the padded cabin, experiencing space sickness, worn out from accelerations and decelerations, living on K and D and C rations and cursing the engineers who had drawn such a thoroughly uncomfortable design.

Angel had sent off the pilot rocket as ordered, filled with the recording rolls, but he had added a few succinct notes of his own which he hoped the engineers would take to heart. Such things as the way air rarified up front on the take-off and nearly killed Boyd.

Such things as drinking bottles that wouldn't throw water in your face when you got thirsty. Such things as straps to hold you casually down when your body began to wander around and helmets to keep your head from cracking against the overhead when you got up suddenly and found no gravity.

But for all the travail of the past week the Angel was bright-eyed and expectant. It was balanced off in his mind whether he would kill Slavinsky by slow fire or small knife cuts.

For Angel had very far from enjoyed being cheated of the glory of being the first man to fly to the Moon and he distinctly disliked a man who would make a slave country of the United States. Prejudiced perhaps, but the Angel believed America was a fine country and should stay free.

Boyd raked up three packages, tying a line and a C ration can, buoy-like, upon it. Whittaker got a port open, inside pane only, and looked at the scenery.

He turned and spat carefully into another can—experience had taught him, this trip—and then put on his space helmet, screwing the lucite dome down tight. He glanced at his companions.

Angel was having some trouble getting into his suit because of his hair, but when he had managed it he led the way to the space port. The three of them crawled over the supplies and entered the chamber, shutting the airtight behind them.

They checked their air supplies and then their communications. Satisfied, they let the outer door open. With a swoosh the air went out and they began their vacuumatic lives.

It was thirty feet down but they didn't use the built-in rungs. Angel stepped out into space and floated down like a miniature space-ship to plant his ducklike shoes deep into the soft pumice. Boyd followed him. Whittaker, carrying debris in the form of cans and bottles in his hugely gloved hands, came after.

As though on pogo sticks the three small ships bounced around to the rear of the space-ship. Boyd threw the three packages down and stamped them into the pumice. Whittaker scattered the debris around the one can which was the real buoy marker.

The discarded objects floated in slow motion into place and lay there in the deathly stillness.

They looked around and their sighs echoed in their earphones, one to the other. No tomb had ever been this dead.

They were landed in a twilight zone, thanks to Dawson. And if their suits—rather, vehicles—had not been so extremely well insulated they would already be feeling the cold.

The sky was ink. The landscape was a study in Old Dutch cleanser and broken basalt. A mountain range thrust startlingly sharp and high to the west. A king-size grand canyon dived away horribly to their south. A great low plain, once miscalled a sea, stretched endlessly toward Tycho.

Two miles away a meteor landed with a crash which made the pumice ripple like waves. A great column of the stuff, stiffly formed in an explosion pattern, almost stroboscopic, stood for some time, having neither gravity nor wind to disperse it.

A few fragments patted down, making new slow-motion bursts. But the meteor had landed at ten miles a second and they all winced and looked up into the blackness. Having atmosphere was a subtle blessing. Having none was horrible.

Having looked up, Angel saw Earth. It was bigger than a Japanese Moon and a lot prettier. It had colors, diffused and gentle, below its aura of atmosphere. It looked fairylike and unreal. Angel sighed and thought about his favorite bar.

They snowshoed around the ship again. The last of the sun, half visible like an up-ended saucer made of pure arc light, came to them through their leaded lucite helmets. That sun was taking a long, long time to set. Hours later it would still be sitting there. Things obviously took their time on the Moon.

Whittaker, unable to spit, was having difficulties. Heroically, he swallowed his chew.

They weren't on the same wave length with the Russians and the approaching detachment came within a quarter of a mile before they saw it. The group was tearing along, bouncing like a herd of kangaroos, sending up puffs of pumice at each leap. They came alongside the ship in a moment and, without any greeting to the newcomers, scrambled up inside.

The officer came back and peered out at the horizon and then ducked in again. It was very difficult to see through the metal helmets of these people but they looked hungry.

Angel went up and stood in the space door. The Russians had left the inner airtight open and all the atmosphere had rushed from the ship. Like madmen they were ripping at the boxes and stuffing chocolate and biscuit into their capacious bags. This was evidently personal loot and the way they were going at it looked bad for the boys who had stayed behind.

Nobody paid any attention to Angel, not even glancing his way, until the officer motioned Boyd and Whittaker into the ship and then unceremoniously herded the three of them into the forward hold and bolted a door on them.

Through a forward port Angel saw the two tractors approach. They were made of aluminum mostly, and they seemed to run out of a propane type tank. They threw hooks into the skids of the ship and, their huge treads soundlessly clanking, began to yank the ship toward the king-size grand canyon.

After an hour or so of tugging they came to the brink and were snaked around until they fitted on an oblong metal stage which, carrying tractors and all, promptly began to descend.

The ship lurched in the lower blackness and then lights flared up by which the stage could be seen to rise into place above them.

Eager crews of spacesuited men swarmed out of an airtight set in a blank wall and in a few moments a stream of supplies was being shuttled, bucket-brigade fashion, toward the entrance.

It was a weird ballet of monsters in metal. The supplies, so heavy on earth, were tossed lightly from monster to monster which added to the illusion. Big crates of dehydrated sailed along like chips.

The unloading took three hours and eight minutes by Angel's watch and then the line cleared away. Belatedly somebody thought of the crew and unlocked the door. At pistol point they were rushed out, down the ladder and to the airtight. The gutted ship stood forlornly behind them, their only contact with home, associating now with six other monsters, the Stars and Stripes outnumbered.

In the dank corridor behind the second airtight men were standing around in various stages of relaxation and undress. They kept halting to gloat over the supplies which left one Russian still in helmet but without pack or gloves, another stripped to underwear, a third in pack and all. Nobody glanced at them.

Their guard shoved them into another tunnel and they wound down a gentle grade between basalt walls until they came to another series of airtights. At the end they were shoved into a chamber walled all in metal, a sort of giant strongbox with doors at each of the five sides.

A desk made of packing boxes stood in the center. A rubber mattress bed was several feet behind it. A crude hat tree bore the fragments of a space suit. The place was a combination of arsenal, bedroom and office, sealed in, double-bolted, entrenched and triple-guarded.

At the desk sat a singularly dirty man, covered with matted black hair, clad in pants, glistening with perspiration and scowling furiously under crew cut bristles.

This was Slavinsky, Vladimir, one-time general of Russia, currently dictator of the world.

The guard had got out of his clumsy space helmet. "The ship crew, Ruler," he said in English.

Whittaker had taken off his helmet and was biting at a plug of Ole Mule. Boyd was examining his fingernails.

Only Angel was still fully suited and helmeted.

"Who is commander?" barked Slavinsky, black eyes screwing up.

Boyd glanced up.

"I am Lieutenant Cannon Gray," he said with blue eyes wide.

"Don't forget the despatches, lootenant," said Whittaker.

Boyd tossed the packet on the desk. It floated down.

"I am displeased," said Slavinsky.

"I'm sorry to hear it," said bogus Gray. "I'll sure tell the President when I get back."

"You're not going back!" said Slavinsky. "You have failed."

"Looks to me like we brought a lot of supplies," said Boyd.

"You brought no cigarettes!" said Slavinsky.

"Well, if that ain't something," said Boyd. "I tell you them quartermasters ought to be horsewhipped and that's a fact. Well, well. No cigarettes. You sure you checked the inventory, general?"

"The title of address is 'Ruler!' And I'll have no questioning of our actions. You brought no cigarettes and there's not a single pack on the Moon."

"Well, if it's okay with you," said Whittaker, "we'll just trot down and fetch you up a couple cartons."

"That's impertinence! Lieutenant, have you no control over your men? Are you certain we have emptied all storage compartments of your ship?"

"Well, can't say. Back in the tube room we had a little layout for the return trip but you wouldn't want to take that away."

"Aha!" said Slavinsky, jumping up to his full five feet.

He pushed down a communicator button and rattled orders into it.

Just as he finished a small bespectacled man entered timidly, his hands full of reports. "Ruler, I have just checked the supplies and I find them safe. I began when the first case entered and have just finished. The food is not poisoned."

"So!" said Slavinsky to Boyd. "You knew better than to trip us up, did you. Ha!"

"I got to send my report to the President," said Boyd.

"I am afraid," said Slavinsky, "that I shall have to attend to that. Now, to business. You will be separated from your men, of course. And then men we need in our labor gangs. We have all too few men, you see.

"But you, as an officer, according to the usages of war, need not work outside but may have some light job. The meteors have been bad lately and we have lost several people. Guard, take this officer to a cell and put the men to work on the missile emplacements instantly."

"With a guard, Ruler?"

"No, blockhead. Where would they go? Ha, ha. Yes, indeed. Where would they go?"

Angel had been half through the act of unscrewing his helmet. Now he hastily replaced it. He and Whittaker were thrust outside and in a moment found themselves in the hands of a non-com who was organizing a work party.

A radio technician came up and adjusted their radios to proper wave length and in a moment they were drowned in Russian.

Angel sighed with relief and looked back at the last of the doors which had led out from Slavinsky. Ruler of the world, was he?

Well, maybe he could manage to get some good out of it. But as for Angel, give him control over a bar stool of the Madrillon and Slavinsky could keep the Moon.

Musing, he found himself in a column and outward bound.

CHAPTER IV

Wait for the Night

It was still twilight on the surface and the earthlight was quite bright even where the blackness of airless night lay upon the stabbed and pitted world. The pumice-covered plains were upheaved into abrupt cliffs and slashed apart by ugly chasms.

It was a nightmare land where one bobbed in levitation-like gyrations, skating over soft and treacherous pumice bogs, plowing through the basalt dust of rays, all under an indigo sky.

Meteors landed soundlessly with the enormous explosions of bombs and each twenty-four hours millions fell. Sometimes clouds rose up to catch the higher rays of the slow-motion sun and hung there, twisting the light into colors.

Man was experiencing his first contact with the wild, garish, infinitely dangerous power of space, billions of times as strong, as capricious, as his ancient enemy the sea.

All was so slow, so quiet, so vastly untenanted. And far away the aura-crowned Earth hung silent, watchful in the sky, satellite of this dead world.

Their imperishable tracks stretched behind them as they drifted toward the emplacements. It was difficult to believe that these weird metal things were containers for human beings.

In ages to come, in scenes like these, men would sicken and madden and die just as the crews of tempest-driven barques have gripped insanity in the ages past.

Angel plowed through pumice and climbed the final bastion of the emplacement.

The great pilotless missile was shielded by an overhanging cliff against all but a freak meteor. Through a small opening this sleek white tube could fly, rushing to the execution of perhaps a million human beings. It stood quietly, waiting. It had all the dignity of the slave machine. It could wait.

Painted scarlet on its nose was—

CHICAGO

There was a buzz of cheerfulness from the Russians as they got out of the open. Eight of their number here had died—two from sun, one from cold, one from suffocation, four all at once under the smash of a thousand-ton meteor.

The mathematician amongst them sat down and began clumsy figures with his mitten-held pencil. A surveyor set up a transit. They were about to complete the orientation and construction of the rail tracks for Chicago.

Angel supposed he would remain here under guard. But the captain had ideas.

"You Yankees! There is rail material dumped in a small crater a few hundred yards from here. We have too few men as it is. You will begin the task of bringing them."

The ground vibrated for an instant as a meteor struck above.

Angel said, "Come on, Whittaker."

They crawled back over the entrance bulwark and regained the still twilight of the outside.

For a moment they stopped and adjusted the radio dials on each other's helmets.

"I hope Boyd is all right," said Angel.

"I hope we can find the place," said Whittaker.

They turned and in great leaps began to scout for the incoming tracks of their ship. There were many such tracks and Angel had to take a quick orientation. Then they found theirs, neither older nor younger than any other tracks, and began to race back down it, taking broadjumps of forty feet with every step, trying to keep from sailing sky-high. The pumice was indifferent footing and clung to their duck shoes, leaving a slowly settling stream of particles in the half-light behind them.

They had gone five miles before they saw anything on their backtrack. And then it was obvious that somebody in the work party had begun pursuit after missing them.

The pursuit was specklike, unhurried as the weasel stalks. For who could find board and room on the Moon?

Angel's breath was hurtful in his lungs. Whittaker was lagging and the officer stopped to let him catch up. It was then he saw the motor sled. It was coming fast, so fast he could see it grow.

Desperately, Angel sprinted on. Ahead, with a yell of delight, he saw the end of the tracks and the strewn debris. He grabbed cans one after the other until he found the right one and hauled up its string. The first package came to light and then the string broke.

Whittaker dived headlong into the pumice to recover it. The second and third packages came to view.

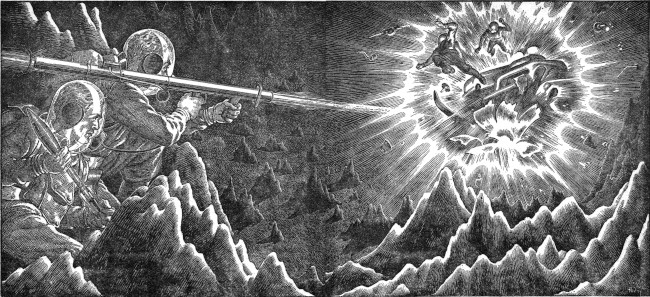

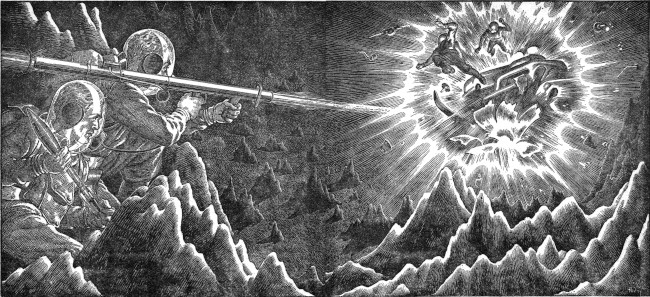

Angel glanced back. The motor sled was almost there. He wrenched off the ties of the heaviest packet. Out rolled the sleek bombs of a bazooka and the instrument itself.

Whittaker seized the barrel and placed it over Angel's shoulder. Angel found the trigger and knelt, sighting on the sled. Whittaker thrust the first rocket in place.

The sled was quite close now, trying to brake, throwing up lazy clouds of pumice.

The rocket trail was red flame in the twilight. The explosion was soundless but like a blow on the chest. Scarlet fire sucked sled and men into its ball and then spewed them forth in fragments which fell lazily, driftingly through the clouds.

Angel got up and would have mopped his brow until his hand, striking against the helmet, reminded him where he was. He turned to find that Whittaker was already slinging the string of grenades over his shoulder.

From the third packet they took the Tommy-guns and ammunition. Armed then and in haste they started the backtrack.

Had they been able to afford more oxygen they would not have been so tired. Weightless walking took little energy and their burdens were feathers. It was rather insecure to feel a Tommy-gun so light.

They oriented themselves and then Angel led off toward the chasm. They gained the shelter of this just as a meteor seemed to explode behind them. But it wasn't a meteor. It was a rocket projectile of small caliber.

They floundered down to a ledge in the giant canyon and then, like two mountain goats of great power, began to leap from outcrop to outcrop.

They made time. The canyon had a bend which would protect them until the last.

But Chicago was there.

A slug struck the bazooka barrel and glanced soundlessly away. They instantly pressed against a jagged break in the wall and Angel adjusted his burdens. He looked up and saw that he could climb.

With a motion to Whittaker to stay put, Angel went up the basalt and found himself crawling over an unburned meteor of glittery sheen. There were diamonds in it.

On top he could crawl forward and peer down over the edge at the Chicago rampart. He glanced ahead and saw that there were fifteen other emplacements but the main entrance to the tunnels interposed.

Cautiously he laid down his weapons and then crept to the edge again, grenades in hand.

With sudden rapidity he teethed out pin after pin and pitched. It was like salvo ranging. How hard it was to estimate throwing distances!

But the cliff wall let them billiard. One, two, three, four they dropped into the emplacement.

He could see space suits down there scrambling back. Any slightest wound would be fatal. A slug tipped his mitten and then the first grenade went up.

The emplacement rocked. Four blasts belched out stone. The imperfectly held rocks folded in and an avalanche began a leisurely curtain into the bottomless canyon. There was no sign of the Chicago entrance.

While particles still drifted, Angel waved to Whittaker and they swiftly resumed their goat travel. The huge steel faces of the main tunnels remained solid and impassive, proof even against meteors.

No shot came.

Whittaker cautiously drew up to their faces until he could touch them. He found no chink in them.

"Up!" said Angel.

They scrambled and leaped and finally came to the plain. A rocket missile shook the ground near them and covered them with dust. They dived headlong into a crater.

Whittaker lifted his head above the rim. "Emplacement to repel ground troops. On that crater rim."

"They must keep one manned continually as an alert," said Angel. He thoughtfully sat down. Somewhere a meteor shook ground. The tip of the last rocket explosion was still rising, catching the sunlight in a turning glitter.

"The only available entrance into the tunnels must be through that guarded emplacement," said Angel. He looked up. "There's very little sun left. It will be dark in half an hour."

Whittaker nodded inside his lucite casque. "It'll get awful dark, lootenant."

"Fine," said Angel. "Take bearings on the emplacement from the two rims of the crater. A man could get hurt stumbling around here without lights."

Whittaker got busy with the engineer's companion, an azimuth compass. It worked fairly well, though heaven knows where the magnetic pole of the Moon might be. He made a small chart of prominent land marks which would be easy to find in the dark.

Now and then a rocket would explode along the crater rim but such was the gravity problem that the alerts did not attempt the mortar effect.

Angel put a piece of chocolate into the miniature space lock of his helmet, closed the outer door, opened the inner one with his chin and worried it dog-fashion out of the compartment. He ate it reflectively.

"I hope Boyd is all right," he said.

CHAPTER V

Now I Lay Me...

Dark came as if someone had shut off an electric light in a coal cellar. The moment was well chosen. Dark wouldn't come in such a fashion to this place again for twenty-nine and a half days, nor would it be light again until half that period had passed.

Soon it would get very cold, down to minus two hundred Centigrade. These space suits were designed for that but they used up their batteries very quickly despite the eight thicknesses of asbestos on their outsides.

"Let's go," said Angel. "They may try a foray on their own." The earthlight was wiped out by their colored helmets.

As nearly as they could calculate they covered the proper chart distances in a wide triangle which would bring them up the side of the alert post.

Soundlessly they made their debouch, fortunately having to take no care of tumbled meteor fragments beyond falling. And a fall was far from fatal.

They came to the slope and groped their way up.

Something round bumped Angel. He felt it and found it to be a metal pole. Some sort of aerial or light stand. He wondered if the Russians had shifted to other helmets which would permit them to see him in the earthlight. That he was still alive made him think not.

He felt the manmade smoothness of the pit edge and drew back. He stopped Whittaker and toothed out the pin of a grenade.

Rapidly they hurled four. The pumice shook like jelly under them under four explosions.

They dived over the edge. Only one Russian was there and nothing much of him was remaining.

"They tried a foray," said Angel. He threw on his chest lights and the metal escape door gleamed.

They lifted it swiftly and plunged down the steps, closing it behind them. An airlock was before them.

"Keep your helmet on," said Angel. He went through.

At the third door they paused and took the safeties off their Tommy-guns. They went through alertly. But no one barred their way and they entered the main tunnel. To their right they could see their big ports beyond which stood their ship.

Supplies were scattered along the walls. Space suits hung on pegs. Weapons were racked.

"Come along," said Angel.

They confronted the first series of doors which led to Slavinsky. In the first, second and third chambers they found no one. The fourth was locked.

Angel waved Whittaker back and from the second chamber sighted with the bazooka on the locked door.

"Look alive in case anybody comes," said Angel.

Whittaker placed the missile and then stepped aside, Tommy-gun ready.

The trajectory of the rocket flamed out. Smoke and dust dissolved the far door. The echoing concussion buffeted them, unheard through their suits.

Angel was up with a rush, cleaving the billows of cordite. His charge brought him straight into the inner sanctum.

And there, pistol gripped but flung back was Slavinsky.

The black eyes glared. The yellow teeth showed. Whatever he yelled Angel could not hear. The pistol jerked and a cartridge empty flipped up.

Angel chopped down with the Tommy-gun.

And discovered the engineering fact that metal still fifty degrees below zero Centigrade does not work well. The firing pin fell short.

The lucite casque fanned out a gauzy pattern but the slug did not penetrate, leaving only a blot.

Angel threw the gun straight at Slavinsky's head. Slavinsky ducked the weapon. But he did not duck the chair which followed it. He staggered back, losing his grip on the pistol.

In Angel's radio, Whittaker's voice yelled, "Three Ruskies are comin'!"

"Use a grenade!" cried Angel. And he flung himself bodily upon Slavinsky.

The metal mittens were clumsy and could not find the general's throat. Slavinsky got a heel into Angel's belt and catapulted him with a smash against the ceiling.

Angel flung himself back. Slavinsky's naked torso was nothing to grip.

"Get him!" howled Whittaker. "They got us penned in!"

Angel grabbed for the sling of the Tommy-gun. The weapon leaped up, amazingly light. But it had mass and mass counted. He drove the butt through Slavinsky's guard, drove in the teeth, the nose, brought sheets of blood into the eyes, crushed the jutting jaw and obliterated the face.

He spun about to find Whittaker holding a bulging door. Angel reached into his kit and pulled out a flask.

"Let them in!"

"They're in!" roared Whittaker.

The bottle of Lewisite exploded against the wall beside the first Russian, spraying out over his naked skin.

The rest plowed forward. They plowed, caught their throats, strangled and dropped.

Angel turned and popped a space cloak and helmet on the remains of Slavinsky. He wanted him alive before the gas reached clear across the chamber. "Stay here," said Angel. And he plunged out.

He found Boyd in a cell, safe enough, carefully garbed in his space helmet.

"It was horrible," said Boyd. "The fools grabbed those cigarettes like you said they would. They distributed all of them to everybody but Slavinsky and he hits marijuana instead. And then they started to light up. Even them that didn't get to take a puff got it from the rest. Lootenant, don't never feed me no Lewisite cigarette!"

"Anybody else you know of back here?" said Angel sweetly.

"Whoever survived rushed up to where you came in. Geez, lootenant, what if that had missed?"

"We'd be working in St. Peter's army," grinned Angel. "Keep that helmet on. This whole place must be full of gas."

They went back to Slavinsky's office and from there made way into the communications center.

Boyd set the wave lengths and called.

When they had Washington as though they were Russians, Angel took the aircraft code from his kit and began to give them news that Russia wouldn't know in time.

"We have met Slavinsky," he coded. "I am in possession of this objective and require reinforcements immediately. The enemy is dead except for stragglers outside who will die. Tell the highest in command to send force quickly. We are victorious!"

Whittaker put an affectionate hand on Angel's shoulder and shook it gently. Angel felt terrible.

"Lieutenant," said the surgeon, "you'd better come around. It's nearly time."

The watch on his wrist gleamed as hugely as a steeple clock and said, "Zero three fifty-one" in an unnecessarily loud voice.

He was dressed somehow and they shoved him into the corridor, which was at least half the distance to Mars. A potted palm fell down and became a general.

"Fine morning, fine morning, lieutenant. You look fit. Fit, sir. No clouds and a splendid full Moon."

The aide was brilliant. Angel knew him well. The aide had been an Upperclassman when Angel was at the Point.

"Beg pardon, sir," said the aide sidewise to the general. "But we've just time to brief him as we ride down. Here, this way, lieutenant."

When they were in the car the aide said, "You have been thoroughly briefed before. But there must be a quick resumé unless you think you are thoroughly cognizant of your duties."

Angel would have answered but all that came out was a groan.

"You will phone all data back to us. Our tests show that the wave can travel much farther than that. Anything you may think important, beyond maps and perhaps geology, you are permitted to note and report.

"Under no circumstances are you to attempt to change any control settings in your ship. All instructions are in this packet."

Angel shoved the brown packet into his pocket with a twinge of pain. What a hangover. And what a dreadfully confused night he had had!

Colonel Anthony got him out of the car, through the crowd and up the ladder.

Whittaker was standing there, indolently chewing tobacco. Metal glinted behind them in the interior. Commander Dawson of the Navy prowled around the ship and then went to take his post.

"You've got a week to sober up, my boy," said Anthony.

"I'll be fine," said Angel, managing a smile.

Angel stepped from the ladder to the platform.

"Board!" shouted Dawson.

Floodlights and cameras and upraised faces. There was a hushed, awed stillness.

Boyd had a big pair of glasses fixed upon the full Moon. He was adjusting them to get the proper focus. Suddenly Angel grabbed the glasses away and stabbed them at the brilliant orb.

With a little sigh of relief he gave the glasses back and with a wave of his hand to the crowd, entered the ship.

The door closed. The spectators were waved hurriedly back.

There was a crash of jets, a flash of metal.

The space-ship was gone.

In spite of nightmares and hangovers, Man had begun his first flight into outer space.