Title: Architecture

nineteenth and twentieth centuries

Author: Henry-Russell Hitchcock

Release date: February 20, 2023 [eBook #70079]

Language: English

Original publication: United States: Penguin Books Inc, 1963

Credits: Tim Lindell, Barry Abrahamsen, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This book was produced from images made available by the HathiTrust Digital Library.)

| LIST OF FIGURES | ix | |

| LIST OF PLATES | xi | |

| ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS | xix | |

| PREFACE TO THE SECOND EDITION | xx | |

| INTRODUCTION | xxi | |

| 1. | ROMANTIC CLASSICISM AROUND 1800 | 1 |

| 2. | THE DOCTRINE OF J.-N.-L. DURAND AND ITS APPLICATION IN NORTHERN EUROPE | 20 |

| 3. | FRANCE AND THE REST OF THE CONTINENT | 43 |

| 4. | GREAT BRITAIN | 59 |

| 5. | THE NEW WORLD | 77 |

| 6. | THE PICTURESQUE AND THE GOTHIC REVIVAL | 93 |

| 7. | BUILDING WITH IRON AND GLASS: 1790-1855 | 115 |

| 8. | SECOND EMPIRE PARIS, UNITED ITALY, AND IMPERIAL-AND-ROYAL VIENNA | 131 |

| 9. | SECOND EMPIRE AND COGNATE MODES ELSEWHERE | 152 |

| 10. | HIGH VICTORIAN GOTHIC IN ENGLAND | 173 |

| 11. | LATER NEO-GOTHIC OUTSIDE ENGLAND | 191 |

| 12. | NORMAN SHAW AND HIS CONTEMPORARIES | 206 |

| 13. | H. H. RICHARDSON AND McKIM, MEAD & WHITE | 221 |

| 14. | THE RISE OF COMMERCIAL ARCHITECTURE IN ENGLAND AND AMERICA | 233 |

| 15. | THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE DETACHED HOUSE IN ENGLAND AND AMERICA FROM 1800 TO 1900 | 253 |

| 16. | THE BEGINNINGS OF THE ART NOUVEAU: VICTOR HORTA | 281 |

| 17. | THE SPREAD OF THE ART NOUVEAU: THE WORK OF C. R. MACKINTOSH AND ANTONI GAUDÍ | 292 |

| 18. | MODERN ARCHITECTS OF THE FIRST GENERATION IN FRANCE: AUGUSTE PERRET AND TONY GARNIER | 307 |

| 19. | FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT AND HIS CALIFORNIA CONTEMPORARIES | 320 |

| 20. | PETER BEHRENS AND OTHER GERMAN ARCHITECTS | 336 |

| 21. | THE FIRST GENERATION IN AUSTRIA, HOLLAND, AND SCANDINAVIA | 349 |

| 22. | THE EARLY WORK OF THE SECOND GENERATION: WALTER GROPIUS, LE CORBUSIER, MIES VAN DER ROHE, AND THE DUTCH | 363 |

| 23. | LATER WORK OF THE LEADERS OF THE SECOND GENERATION | 380 |

| 24. | ARCHITECTURE CALLED TRADITIONAL IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY | 392 |

| 25. | ARCHITECTURE AT THE MID CENTURY | 411 |

| EPILOGUE | 429 | |

| NOTES | 439 | |

| BIBLIOGRAPHY | 473 | |

| The Plates | 484 | |

| INDEX | 677 | |

| 1 | Friedrich Weinbrenner: Karlsruhe, Marktplatz, 1804-24, plan | 17 |

| 3 | J.-N.-L. Durand: ‘Vertical Combinations’ (from Précis des leçons, II, plate 3) | 21 |

| 3 | J.-N.-L. Durand: ‘Galleries’ (from Précis des leçons, II, plate 14) | 24 |

| 4 | Leo von Klenze; Munich, War Office, 1824-6, elevation (from Klenze, Sammlung, III, plate x) | 26 |

| 5 | K. F. von Schinkel: project for Neue Wache, Berlin, 1816 (from Schinkel, Sammlung, I, plate 1) | 29 |

| 6 | K. F. von Schinkel: Berlin, Altes Museum, 1824-8, section (from Schinkel, Sammlung, I, plate 40) | 31 |

| 7 | K. F. von Schinkel: Berlin, Feilner house, 1829, elevation (from Schinkel, Sammlung, plate 113) | 34 |

| 8 | Gottfried Semper: Dresden, Opera House (first), 1837-41, plan (from Semper, Das Königliche Hoftheater, plate 1) | 37 |

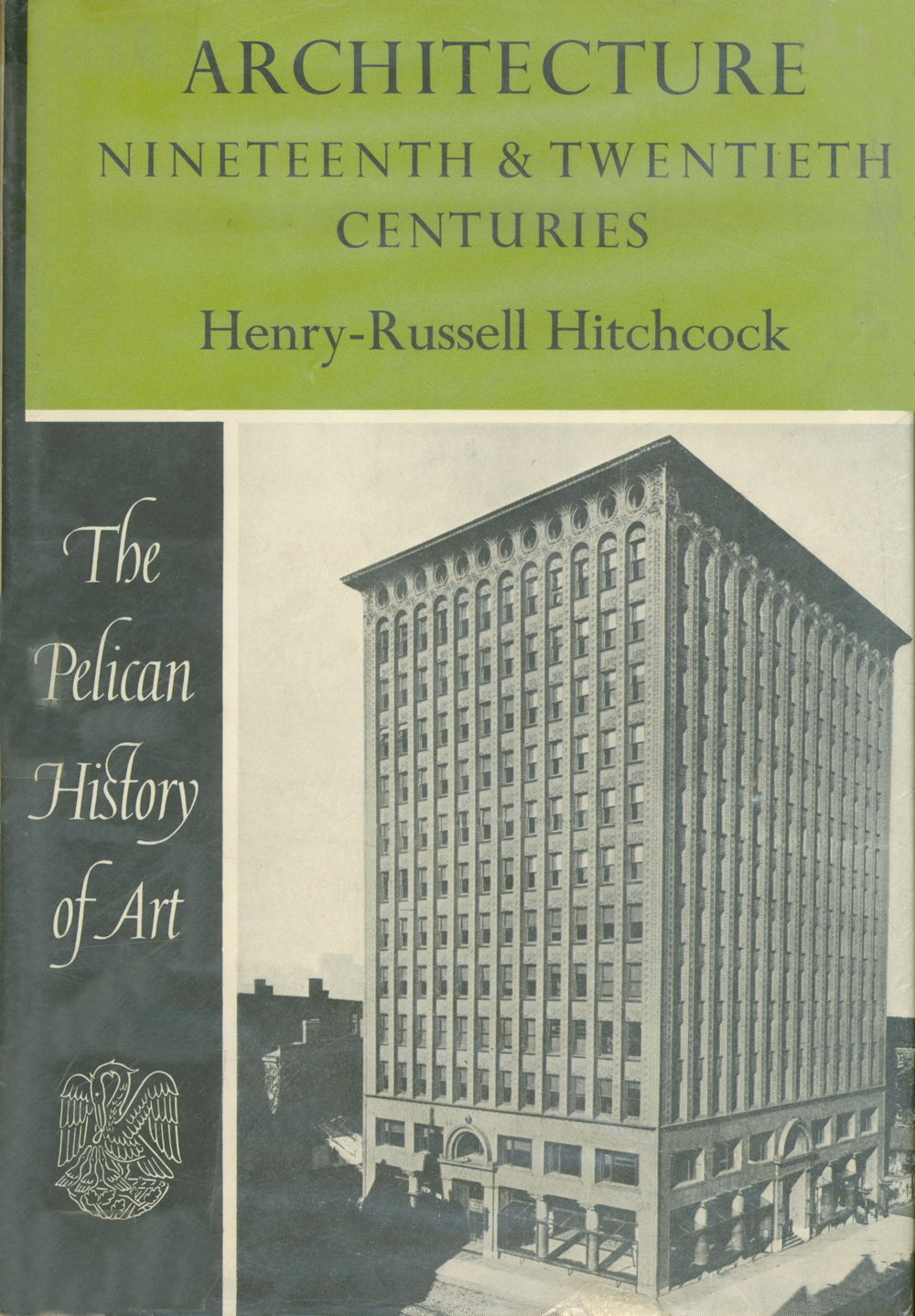

| 9 | J.-I. Hittorff: project for country house for Comte de W., 1830, elevation (from Normand, Paris moderne, I, plate 71) | 47 |

| 10 | John Nash: London, Regent Street and Regent’s Park, 1812-27, plan (from Summerson, John Nash) | 65 |

| 11 | John Haviland: Philadelphia, Eastern Penitentiary, 1823-35, plan (from Crawford, Report, plate 1) | 79 |

| 12 | Thomas Jefferson: Charlottesville, Va., University of Virginia, 1817-26, plan (from Kimball, Thomas Jefferson) | 83 |

| 13 | Isaiah Rogers: Boston, Tremont House, 1828-9, plan (from Eliot, A Description of the Tremont House) | 87 |

| 14 | H.-P.-F. Labrouste: Paris, Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève, (1839), 1843-50, section (from Allgemeine Bauzeitung, 1851, plate 386) | 125 |

| 15 | J.-L.-C. Garnier: Paris, Opéra, 1863-74, plan (from Garnier, Nouvel opéra, I, plate 9) | 139 |

| 16 | Vilhelm Petersen and Ferdinand Jensen: Copenhagen, Søtorvet, 1873-6, elevation (Kunstakademiets Bibliotek, Copenhagen) | 156 |

| 17 | Antoni Gaudí: project for Palau Güell, Barcelona, 1885, elevation (from Ráfols, Gaudí, p. 54) | 203 |

| 18 | W. Eden Nesfield: Kew Gardens, Lodge, 1867, elevation (Courtesy of Victoria and Albert Museum) | 208 |

| 19 | R. Norman Shaw: Leyswood, Sussex, 1868, plan (from Muthesius, Das Englische Haus, I, figure 81) | 210 |

| 20 | D. H. Burnham and F. L. Olmsted: Chicago, World’s Fair, 1893, plan (from Edgell, American Architecture of Today, figure 36) | 231 |

| 21 | T. F. Hunt: house-plan, 1827 (from Hunt, Designs for Parsonage Houses, plate IV) | 255 |

| 22 | A. J. Downing: house-plan, 1842 (from Downing, Cottage Residences, figure 50) | 258 |

| 23 | Philip Webb: Arisaig, Inverness-shire, 1863, plan (Courtesy of J. Brandon-Jones) | 260 |

| 24 | Nesfield & Shaw: Cloverley Hall, Shropshire, 1865-8, plan (from Architectural Review, 1 (1897), p. 244) | 261 |

| 25 | Philip Webb: Barnet, Hertfordshire, Trevor Hall, 1868-70, plan (Courtesy of Victoria and Albert Museum) | 262 |

| 26 | W. R. Emerson: Mount Desert, Maine, house, 1879, plan (from Scully, The Shingle Style, figure 46) | 266 |

| 27 | McKim, Mead & White: Newport, R.I., Isaac Bell, Jr, house, 1881-2, plan (from Sheldon, Artistic Houses) | 268 |

| 28 | Bruce Price: Tuxedo Park, N.Y., Tower House, 1885-6 (from Scully, The Shingle Style, figure 109) | 270 |

| 29 | Frank Lloyd Wright: Chicago, Isidore Heller house, 1897, plan (from Hitchcock, In the Nature of Materials, figure 44) | 272 |

| 30 | Frank Lloyd Wright: Chicago, J. W. Husser house, 1899, plan (from Hitchcock, In the Nature of Materials, figure 46) | 273 |

| 31 | Frank Lloyd Wright: Kankakee, Ill., Warren Hickox house, 1900, plan (from Hitchcock, In the Nature of Materials, figure 54) | 274 |

| 32 | C. F. A. Voysey: Lake Windermere, Broadleys, 1898-9, plan (Courtesy of J. Brandon-Jones) | 277 |

| x33 | M. H. Baillie Scott: Trevista, c. 1905, plan (from Baillie Scott, Houses and Gardens, 1906, p. 155) | 278 |

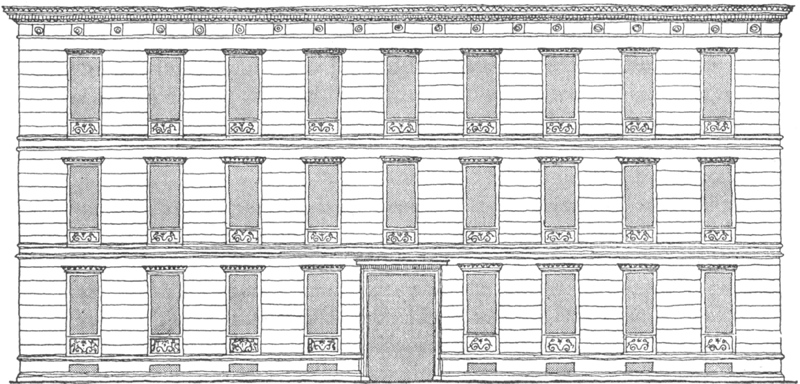

| 34 | Victor Horta: Brussels, Aubecq house, 1900, plan (Courtesy of J. Delhaye) | 290 |

| 35 | Antoni Gaudí: Barcelona, Casa Milá, 1905-10, plan of typical floor (Courtesy of Amics de Gaudí) | 304 |

| 36 | Auguste Perret: Paris, block of flats, 25 bis Rue Franklin, 1902-3, plan (from Architecture d’Aujourd’hui, October 1932, p. 19) | 311 |

| 37 | Auguste Perret: Le Raincy, S.-et-O., Notre-Dame, 1922-3, plan (from Pfammatter, Betonkirchen, p. 38) | 313 |

| 38 | Frank Lloyd Wright: Highland Park, Ill., W. W. Willitts house, 1902, plan (from Hitchcock, In the Nature of Materials, figure 74) | 322 |

| 39 | Frank Lloyd Wright: Glencoe, Ill., W. A. Glasner house, 1905, plan (from Hitchcock, In the Nature of Materials, figure 111) | 323 |

| 40 | Frank Lloyd Wright: Pasadena, Cal., Mrs G. M. Millard house, 1923, plans (from Hitchcock, In the Nature of Materials, figure 251) | 327 |

| 41 | Frank Lloyd Wright: Minneapolis, M. C. Willey house, 1934, plan (from Hitchcock, In the Nature of Materials, figure 317) | 328 |

| 42 | Frank Lloyd Wright: Middleton, Wis., Herbert Jacobs house, 1948, plan (from Hitchcock and Drexler, Built in U.S.A., p. 121) | 331 |

| 43 | Adolf Loos: Vienna, Gustav Scheu house, 1912, plan (Courtesy of Dr Ludwig Münz) | 353 |

| 44 | Le Corbusier: First project for Citrohan house, 1919-20, perspective (from Le Corbusier, Œuvre complète, I, p. 31) | 368 |

| 45 | Le Corbusier: Second project for Citrohan house, 1922, plans and section (from Le Corbusier, Œuvre complète, I, p. 44) | 369 |

| 46 | Le Corbusier: Vaucresson, S.-et-O., house, 1923, plans (from Le Corbusier, Œuvre complète, I, p. 51) | 371 |

| 47 | Le Corbusier: Poissy, S.-et-O., Savoye house, 1929-30, plan (from Hitchcock, Modern Architecture, p. 67) | 372 |

| 48 | Walter Gropius: Dessau, Bauhaus, 1925-6, plans (from Hitchcock, Modern Architecture, p. 67) | 374 |

| 49 | Ludwig Mies van der Rohe: Project for brick country house, 1922, plan (from Johnson, Mies van der Rohe, p. 32) | 375 |

| 50 | Ludwig Mies van der Rohe: Brno, Tugendhat house, 1930, plan (from Hitchcock, Modern Architecture, p. 127) | 376 |

| 51 | Le Corbusier: Marseilles, Unité d’Habitation, 1946-52, section of three storeys (from Le Corbusier, Œuvre complète, V, p. 211) | 386 |

| 52 | Ludwig Mies van der Rohe: Chicago, Illinois Institute of Technology, 1939-41, general plan (from Johnson, Mies van der Rohe, 2nd ed., p. 134) | 389 |

| 53 | Ludwig Mies van der Rohe: Plano, Ill., Dr Edith Farnsworth House, 1950, plan (from Johnson, Mies van der Rohe, p. 170) | 390 |

| 54 | Sir Edwin Lutyens: Hampstead Garden Suburb, London, North and South Squares, 1908 (from Weaver, Houses and Gardens (Country Life), 1913, figure 480) | 406 |

| 55 | Saarinen & Saarinen: Warren, Mich., General Motors Technical Institute, 1946-55, layout (Courtesy of General Motors) | 419 |

| 56 | Osvaldo Arthur Bratke: São Paulo, Morumbí, Bratke house, 1953, plan (from Hitchcock, Latin American Architecture, p. 174) | 425 |

| 57 | Philip Johnson: Wayzata, Minn., Richard S. Davis house, 1954 (from Architectural Review, 1955, pp. 236-47) | 426 |

| 1 | J.-G. Soufflot and others: Paris, Panthéon (Sainte-Geneviève), 1757-90 (Archives Photographiques—Paris) |

| 2 (A) | C.-N. Ledoux: Paris, Barrière de la Villette, 1784-9 (Archives Photographiques—Paris) |

| 2 (B) | C.-N. Ledoux: Project for Coopery, c. 1785 (from Ledoux, L’ Architecture, 1) |

| 2 (C) | L.-E. Boullée: Project for City Hall, c. 1785 (H. Rosenau) |

| 3 | Sir John Soane: London, Bank of England, Consols Office, 1794 (F. R. Yerbury) |

| 4 (A) | Sir John Soane: London, Bank of England, Waiting Room Court, 1804 (F. R. Yerbury) |

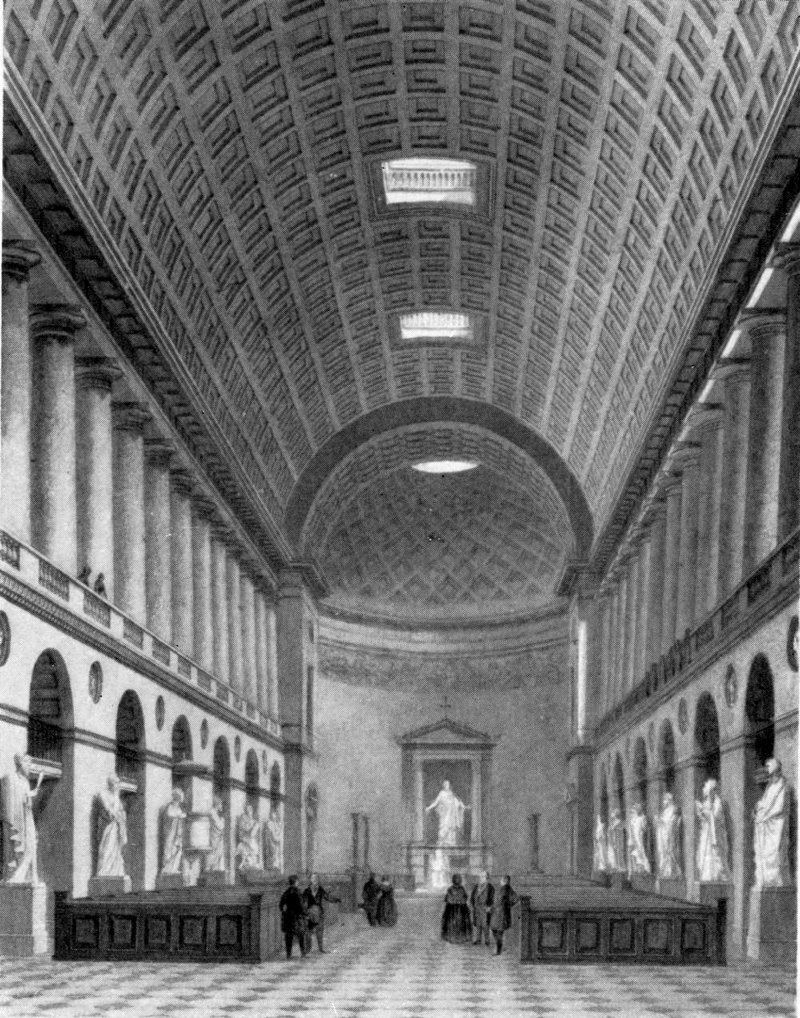

| 4 (B) | C. F. Hansen: Copenhagen, Vor Frue Kirke, 1811-29 (Kongelige Bibliotek, Copenhagen) |

| 5 | Benjamin H. Latrobe: Baltimore, Catholic Cathedral, 1805-18 (J. H. Schaefer & Son) |

| 6 (A) | Sir John Soane: Tyringham, Buckinghamshire, Entrance Gate, 1792-7 (Soane Museum) |

| 6 (B) | Percier and Fontaine: Paris, Rue de Rivoli, 1802-55 (A. Leconte) |

| 7 | J.-F.-T. Chalgrin and others: Paris, Arc de Triomphe de l’Étoile, 1806-35 (Giraudon) |

| 8 (A) | Thomas de Thomon: Petersburg, Bourse, 1804-16 (Courtesy of T. J. McCormick) |

| 8 (B) | A.-T. Brongniart and others: Paris, Bourse, 1808-15 (R. Viollet) |

| 9 (A) | Friedrich Gilly: Project for monument to Frederick the Great, 1797 (F. Stoedtner) |

| 9 (B) | Leo von Klenze: Munich, Glyptothek, 1816-30 (F. Kaufmann) |

| 10 (A) | Friedrich Weinbrenner: Karlsruhe, Marktplatz, 1804-24 (Staatliches Amt für Denkmalpflege, Karlsruhe) |

| 10 (B) | Friedrich von Gärtner: Munich, Ludwigskirche and Staatsbibliothek, 1829-40 and 1831-40 (from an engraving by E. Rauch) |

| 11 (A) | Heinrich Hübsch: Baden-Baden, Trinkhalle, 1840 (H. Kuhn) |

| 11 (B) | Wimmel & Forsmann: Hamburg, Johanneum, 1836-9 (E. Gorsten) |

| 12 | K. F. von Schinkel: Berlin, Schauspielhaus, 1819-21 |

| 13 | K. F. von Schinkel: Berlin, Altes Museum, 1824-8 |

| 14 (A) | K. F. von Schinkel: Potsdam, Court Gardener’s House, 1829-31 |

| 14 (B) | G. L. F. Laves: Hanover, Opera House, 1845-52 (H. Wagner) |

| 15 | Ludwig Persius: Potsdam, Friedenskirche, 1845-8 |

| 16 (A) | Leo von Klenze: Regensburg (nr), Walhalla, 1831-42 (from Klenze, Walhalla, plate VI) |

| 16 (B) | M. G. B. Bindesbøll: Copenhagen, Thorwaldsen Museum, Court, 1839-48 (Jonals) |

| 17 (A) | Friedrich von Gärtner: Athens, Old Palace, 1837-41 (Tensi) |

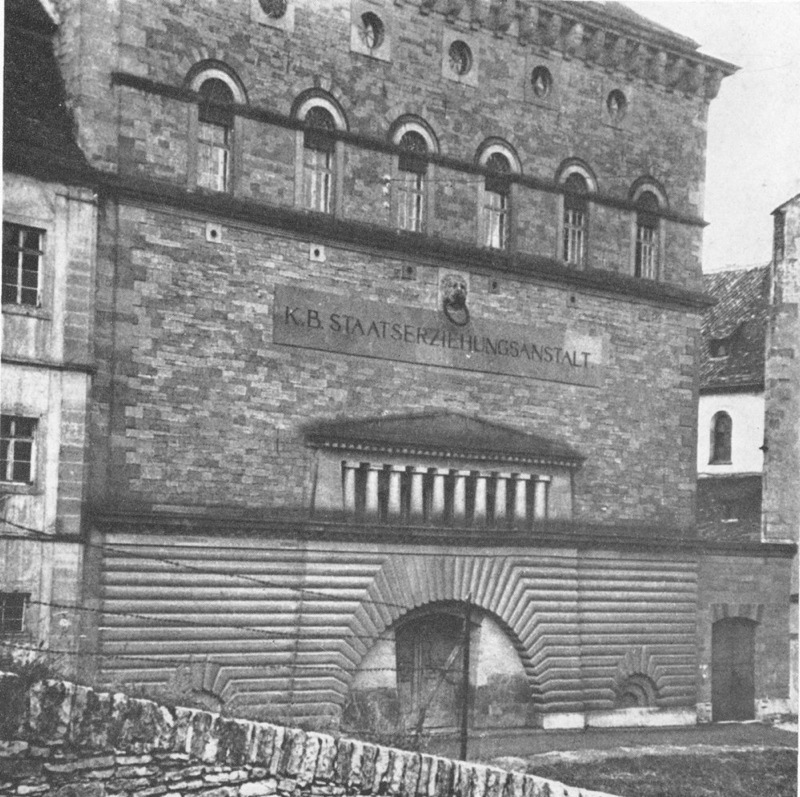

| 17 (B) | Peter Speeth: Würzburg, Frauenzuchthaus, 1809 (F. Stoedtner) |

| 18 (A) | P.-F.-L. Fontaine: Paris, Chapelle Expiatoire, 1816-24 (Archives Photographiques—Paris) |

| 18 (B) | L.-H. Lebas: Paris, Notre-Dame-de-Lorette, 1823-36 (Archives Photographiques—Paris) |

| 19 | J.-B. Lepère and J.-I. Hittorff: Paris, Saint-Vincent-de-Paul, 1824-44 (from Paris dans sa splendeur) |

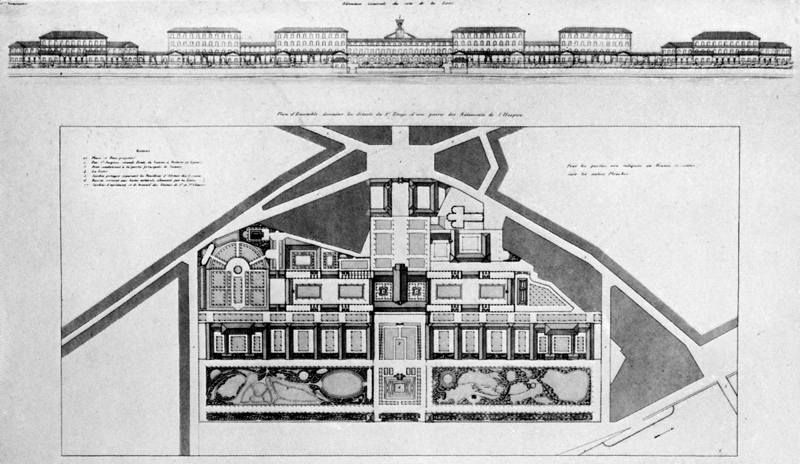

| 20 | Douillard Frères: Nantes, Hospice Général, 1832-6 (from Gourlier, Choix d’édifices publics, III) |

| 21 | H.-P.-F. Labrouste: Paris, Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève, 1843-50 (Bulloz) |

| 22 (A) | É.-H. Godde and J.-B. Lesueur: Paris, extension of Hôtel de Ville, 1837-49 (from a contemporary lithograph) |

| 22 (B) | F.-A. Duquesney: Paris, Gare de l’Est, 1847-52 (Archives Photographiques—Paris) |

| 23 (A) | Giuseppe Jappelli and Antonio Gradenigo: Padua, Caffè Pedrocchi, 1816-31 (Alinari) |

| 23 (B) | Antonio Niccolini: Naples, San Carlo Opera House, 1810-12 (Alinari) |

| 24 | Raffaelle Stern: Rome, Vatican Museum, Braccio Nuovo, 1817-21 (D. Anderson) |

| xii25 | A. de Simone: Caserta, Royal Palace, Sala di Marte, 1807 (Alinari) |

| 26 (A) | Pietro Bianchi: Naples, San Francesco di Paola, 1816-24 (Alinari) |

| 26 (B) | Giuseppe Frizzi and others: Turin, Piazza Vittorio Veneto, laid out in 1818; with Gran Madre di Dio by Ferdinando Bonsignore, 1818-31 (G. Cambursano) |

| 27 (A) | A. A. Monferran: Petersburg, St Isaac’s Cathedral, 1817-57 (Mansell) |

| 27 (B) | A. A. Monferran: Petersburg, Alexander Column, 1829; and K. I. Rossi: Petersburg, General Staff Arches, 1819-29 (Courtesy of T. J. McCormick) |

| 27 (C) | A.-J. Pellechet: Paris, block of flats, 10 Place de la Bourse, 1834 (J. R. Johnson) |

| 28 (A) | Sir John Soane: London, Royal Hospital, Chelsea, Stables, 1814-17 (N.B.R.) |

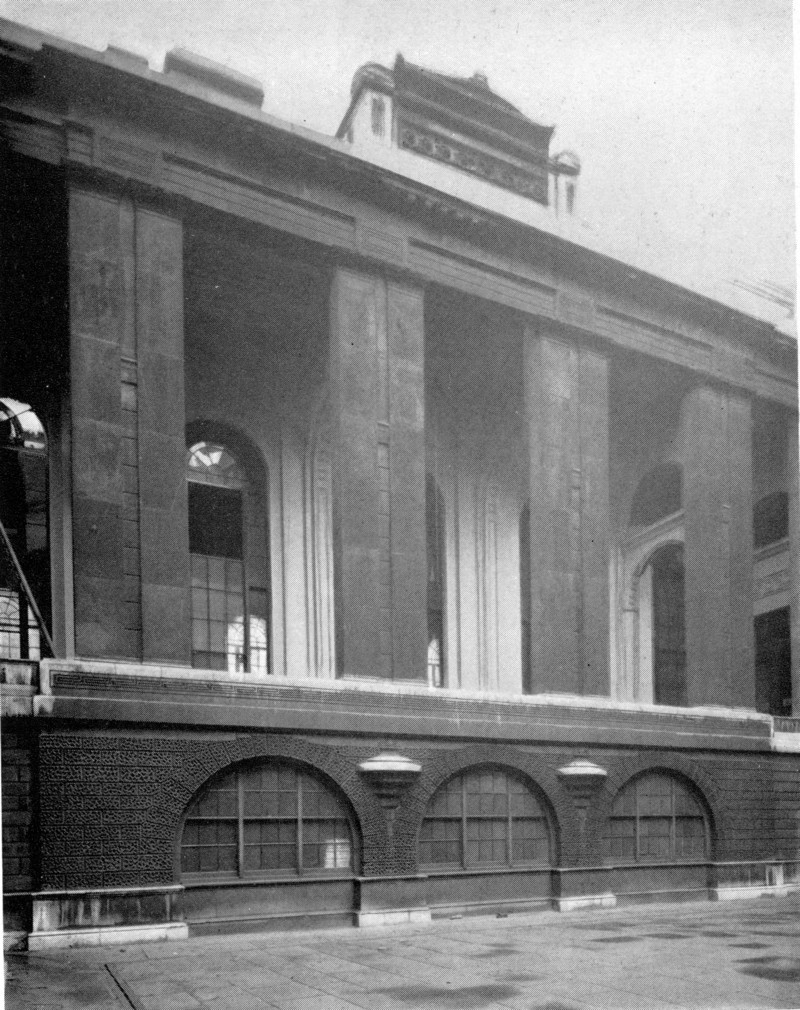

| 28 (B) | Sir John Soane: London, Bank of England, Colonial Office, 1818-23 (F. R. Yerbury) |

| 29 | Alexander Thomson: Glasgow, Caledonia Road Free Church, 1856-7 (T. & R. Annan) |

| 30 | John Nash: London, Piccadilly Circus and Lower Regent Street, 1817-19 (from lithograph by T. S. Boys) |

| 31 | London, Hyde Park Corner: Decimus Burton, Screen, 1825, Arch, 1825; William Wilkins, St George’s Hospital, 1827-8; Benjamin Dean Wyatt, Apsley House, 1828 (from lithograph by T. S. Boys) |

| 32 | John Nash and James Thomson: London, Regent’s Park, Cumberland Terrace, 1826-7 (A. F. Kersting) |

| 33 | Sir Robert Smirke: London, British Museum, south front, completed 1847 (A. F. Kersting) |

| 34 (A) | H. L. Elmes: Liverpool, St George’s Hall, 1841-54 (Hulton Picture Library) |

| 34 (B) | W. H. Playfair: Edinburgh, Royal Scottish Institution, National Gallery of Scotland, and Free Church College, 1822-36, 1850-4, and 1846-50 (F. C. Inglis) |

| 35 (A) | Alexander Thomson: Glasgow, Moray Place, Strathbungo, 1859 (T. & R. Annan) |

| 35 (B) | Sir Charles Barry: London, Travellers’ Club and Reform Club, 1830-2 and 1838-40 (N.B.R.) |

| 36 | J. W. Wild: London, Christ Church, Streatham, 1840-2 (J. R. Johnson) |

| 37 (A) | Sir Charles Barry: original design for Highclere Castle, Hampshire, c. 1840 (S. W. Newbery) |

| 37 (B) | Cuthbert Brodrick: Leeds, Corn Exchange, 1860-3 (N.B.R.) |

| 38 (A) | Robert Mills: Washington, Treasury Department, 1836-42 (Horydczak) |

| 38 (B) | Thomas Jefferson: Charlottesville, Va. University of Virginia, 1817-26 (F. Nichols) |

| 39 (A) | Thomas U. Walter and others: Columbus, Ohio, State Capitol, 1839-61 (Ohio Development and Publicity Commission) |

| 39 (B) | James C. Bucklin: Providence, R.I., Washington Buildings, 1843 (F. Hacker) |

| 40 | William Strickland: Philadelphia, Merchants’ Exchange, 1832-4 (Historical Society of Pennsylvania) |

| 41 | Isaiah Rogers: Boston, Tremont House, 1828-9 (from Eliot, A Description of the Tremont House) |

| 42 (A) | A. J. Davis: New York, Colonnade Row, 1832 (W. Andrews) |

| 42 (B) | Russell Warren: Newport, R.I., Elmhyrst, c. 1833 (from Hitchcock, Rhode Island Architecture) |

| 43 (A) | Henry A. Sykes: Springfield, Mass., Stebbins house, 1849 (R.E. Pope) |

| 43 (B) | Alexander Parris: Boston, David Sears house, 1816 (Southworth & Hawes) |

| 44 | Thomas A. Tefft: Providence, R.I., Union Station, begun 1848 (R.I. Historical Society) |

| 45 | Amherst, Mass., Amherst College, Dormitories, 1821-2, Chapel, 1827 (Courtesy of Amherst College) |

| 46 | William Clarke: Utica, N.Y., Insane Asylum, 1837-43 (Courtesy of Munson-Williams-Proctor Institute) |

| 47 (A) | John Notman: Philadelphia, Atheneum, 1845-7 (W. Andrews) |

| 47 (B) | J. M. J. Rebelo: Rio de Janeiro, Palacio Itamaratí, 1851-4 (G. E. Kidder Smith) |

| 48 | John Nash: Brighton, Royal Pavilion, as remodelled 1815-23 (N.B.R.) |

| 49 | C. A. Busby: Gwrych Castle, near Abergele, completed 1815 |

| 50 (A) | John Nash: Blaise Hamlet, near Bristol, 1811 (N.B.R.) |

| 50 (B) | Thomas Rickman and Henry Hutchinson: Cambridge, St John’s College, New Court, 1825-31 (A. C. Barrington Brown) |

| 51 | G. M. Kemp: Edinburgh, Sir Walter Scott Monument, 1840-6 (F. C. Inglis) |

| 52 (A) | A. W. N. Pugin: Cheadle, Staffordshire, St Giles’s, 1841-6 (M. Whiffen) |

| 52 (B) | Sir G. G. Scott: Hamburg, Nikolaikirche, 1845-63 (Staatliche Landesbildstelle, Hamburg) |

| xiii53 (A) | Richard Upjohn: New York, Trinity Church, c. 1844-6 (W. Andrews) |

| 53 (B) | Richard Upjohn: Utica, N.Y., City Hall, 1852-3 (H. Lott) |

| 54 | Sir Charles Barry: London, Houses of Parliament, 1840-65 (A. F. Kersting) |

| 55 (A) | Salem, Mass., First Unitarian (North) Church, 1836-7 (Courtesy of Essex Institute, Salem) |

| 55 (B) | F.-C. Gau and Théodore Ballu: Paris, Sainte-Clotilde, 1846-57 (from Paris dans sa splendeur) |

| 56 | E.-E. Viollet-le-Duc: Paris, block of flats, 28 Rue de Liège, 1846-8 (J. R. Johnson) |

| 57 (A) | Alexis de Chateauneuf and Fersenfeld: Hamburg, Petrikirche, 1843-9 |

| 57 (B) | G. A. Demmler and F. A. Stüler: Schwerin, Schloss, 1844-57 (Institut für Denkmalpflege, Schwerin) |

| 58 (A) | John Nash: Brighton, Royal Pavilion, Kitchen, 1818-21 (Brighton Corporation) |

| 58 (B) | Thomas Telford: Menai Strait, Menai Bridge, 1819-24 (W. Scott) |

| 59 | Thomas Telford: Craigellachie Bridge, 1815 (A. Reiach) |

| 60 (A) | John A. Roebling: Niagara Falls, Suspension Bridge, 1852 (Courtesy of Eastman House) |

| 60 (B) | Thomas Hopper: London, Carlton House, Conservatory, 1811-12 (from Pyne, Royal Residences, III) |

| 61 | Robert Stephenson and Francis Thompson: Menai Strait, Britannia Bridge, 1845-50 (Hulton Picture Library) |

| 62 (A) | Grisart & Froehlicher: Paris, Galeries du Commerce et de l’Industrie, section, 1838 (from Normand, Paris Moderne, II) |

| 62 (B) | Robert Stephenson and Francis Thompson: Derby, Trijunct Railway Station, 1839-41 (from Russell, Nature on Stone) |

| 63 | J. B. Bunning: London, Coal Exchange, 1846-9 (from Builder, 29 Sept. 1849) |

| 64 | Sir Joseph Paxton and Fox & Henderson: London, Crystal Palace, 1850-1 (from Builder, 4 Jan. 1851) |

| 65 | I. K. Brunel and Sir M. D. Wyatt: London, Paddington Station, 1852-4 (from Illustrated London News, 8 July 1854) |

| 66 (A) | Lewis Cubitt: London, King’s Cross Station, 1851-2 (British Railways) |

| 66 (B) | Karl Etzel: Vienna, Dianabad, 1841-3 (from Allgemeine Bauzeitung, 1843) |

| 67 (A) | Decimus Burton and Richard Turner: Kew, Palm Stove, 1845-7 (N.B.R.) |

| 67 (B) | James Bogardus; New York, Laing Stores, 1849 (B. Abbott) |

| 68 | L.-T.-J. Visconti and H.-M. Lefuel: Paris, New Louvre, 1852-7 (Giraudon) |

| 69 | H.-P.-F. Labrouste: Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale, Reading Room, 1862-8 (Chevojon) |

| 70 (A) | H.-J. Espérandieu: Marseilles, Palais Longchamps, 1862-9 (R. Viollet) |

| 70 (B) | J.-L.-C. Garnier: Paris, Opéra, 1861-74 (Édition Alfa) |

| 70 (C) | Charles Rohault de Fleury and Henri Blondel: Paris, Place de l’Opéra, 1858-64 (Chevojon) |

| 71 | J.-L.-C. Garnier: Paris, Opéra, Foyer, 1861-74 (Bulloz) |

| 72 (A) | J.-A.-E. Vaudremer: Paris, Saint-Pierre-de-Montrouge, 1864-70 (R. Viollet) |

| 72 (B) | J.-F. Duban: Paris, École des Beaux-Arts, 1860-2 (Giraudon) |

| 73 (A) | Gottfried Semper and Karl von Hasenauer: Vienna, Burgtheater, 1874-88 (Österreichische Nationalbibliothek) |

| 73 (B) | Theophil von Hansen: Vienna, Heinrichshof, 1861-3 (from a water-colour by Rudolf von Alt) |

| 74 | Vienna, Ringstrasse, begun 1858 (from a water-colour by Rudolf von Alt) |

| 75 (A) | A.-F. Mortier: Paris, block of flats, 11 Rue de Milan, c. 1860 (J. R. Johnson) |

| 75 (B) | Giuseppe Mengoni: Milan, Galleria Vittorio Emmanuele, 1865-77 (Alinari) |

| 76 (A) | Gaetano Koch: Rome, Esedra, 1885 (Fotorapida Terni) |

| 76 (B) | J.-A.-F.-A. Pellechet: Barnard Castle, Co. Durham, Bowes Museum, 1869-75 (Copyright Country Life) |

| 77 (A) | Friedrich Hitzig: Berlin, Exchange, 1859-63 (F. Stoedtner) |

| 77 (B) | Julius Raschdorf: Cologne, Opera House, 1870-2 (Courtesy of Rheinisches Museum, Cologne) |

| 78 (A) | Cuthbert Brodrick: Leeds, Town Hall, 1855-9 (N.B.R.) |

| 78 (B) | Sir Charles Barry: Halifax, Town Hall, 1860-2 (N.B.R.) |

| 79 | Cuthbert Brodrick: Scarborough, Grand Hotel, 1863-7 (Walkers Studios) |

| 80 (A) | John Giles: London, Langham Hotel, 1864-6 (Bedford Lemere) |

| 80 (B) | London, 1-5 Grosvenor Place, begun 1867 (N.B.R.) |

| 81 | Joseph Poelaert: Brussels, Palace of Justice, 1866-83 (Archives Centrales Iconographiques, Brussels) |

| xiv82 (A) | Thomas U. Walter: Washington, Capitol, Wings and Dome, 1851-65; Central Block by William Thornton and others, 1792-1828 (from American Architect, 30 Jan. 1904) |

| 82 (B) | Arthur B. Mullet; Arthur Gilman consultant: Washington, State, War and Navy Department Building, 1871-5 (Horydczak) |

| 83 (A) | Sir M. D. Wyatt: London, Alford House, 1872 (Victoria and Albert Museum, Crown Copyright) |

| 83 (B) | Francis Fowke: London, Victoria and Albert Museum, Court, begun 1866 (Victoria and Albert Museum, Crown Copyright) |

| 84 | Georg von Dollmann: Schloss Linderhof, near Oberammergau, 1870-86 (L. Aufsberg) |

| 85 | William Butterfield: London, All Saints’, Margaret Street, interior, 1849-59 (S.W. Newbery) |

| 86 (A) | William Butterfield: London, All Saints’, Margaret Street, Schools and Clergy House, 1849-59 (S.W. Newbery) |

| 86 (B) | Deane & Woodward: Oxford, University Museum, 1855-9 |

| 87 | William Butterfield: Baldersby St James, Yorkshire, St James’s, 1856 (R. Cox) |

| 88 | William Burges: Hartford, Conn., project for Trinity College, 1873 (from Pullan, Architectural Designs of William Burges) |

| 89 (A) | Henry Clutton: Leamington, Warwickshire, St Peter’s, 1861-5 (J. E. Duggins) |

| 89 (B) | James Brooks: London, St Saviour’s, Hoxton, 1865-7 (N.B.R.) |

| 90 | Sir G. G. Scott: London, Albert Memorial, 1863-72 (A. F. Kersting) |

| 91 (A) | J. P. Seddon: Aberystwyth, University College, begun 1864 (N.B.R.) |

| 91 (B) | H. H. Richardson: Medford, Mass., Grace Church, 1867-8 (from American Architect, 8 Feb. 1890) |

| 92 (A) | E. W. Godwin: Congleton, Cheshire, Town Hall, 1864-7 (N.B.R.) |

| 92 (B) | G. F. Bodley: Pendlebury, Lancashire, St Augustine’s, 1870-4 (N.B.R.) |

| 93 (A) | J. L. Pearson: London, St Augustine’s, Kilburn, 1870-80 (N.B.R.) |

| 93 (B) | Edmund E. Scott: Brighton, St Bartholomew’s, completed 1875 (N.B.R.) |

| 94 (A) | R. Norman Shaw: Bingley, Yorkshire, Holy Trinity, 1866-7 (N.B.R.) |

| 94 (B) | G. E. Street: London, St James the Less, Thorndike Street, 1858-61 (N.B.R.) |

| 95 (A) | Ware & Van Brunt: Cambridge, Mass., Memorial Hall, 1870-8 (J. K. Ufford) |

| 95 (B) | Frank Furness: Philadelphia, Provident Life and Trust Company, 1879 (J. L. Dillon & Co.) |

| 96 (A) | Russell Sturgis: New Haven, Conn., Yale College, Farnam Hall, 1869-70 (C. L. V. Meeks) |

| 96 (B) | Antoni Gaudí: Barcelona, Palau Güell, 1885-9 (Arxiu Mas) |

| 97 (A) | Fuller & Jones: Ottawa, Canada, Parliament House, 1859-67 (Courtesy of Public Archives of Canada) |

| 97 (B) | William Morris and Philip Webb: London, Victoria and Albert Museum, Refreshment Room, 1867 (Victoria and Albert Museum, Crown copyright) |

| 98 | E.-E. Viollet-le-Duc: St-Denis, Seine, Saint-Denys-de-l’Estrée, 1864-7 (Archives Photographiques—Paris) |

| 99 (A) | Heinrich von Ferstel: Vienna, Votivkirche, 1856-79 (P. Ledermann) |

| 99 (B) | Friedrich von Schmidt: Vienna, Fünfhaus Parish Church, 1868-75 (Österreichische Nationalbibliothek) |

| 100 | G. E. Street: Rome, St Paul’s American Church, 1873-6 (Alinari) |

| 101 (A) | E.-E. Viollet-le-Duc: Paris, block of flats, 15 Rue de Douai, c. 1860 (J. R. Johnson) |

| 101 (B) | P. J. H. Cuijpers: Amsterdam, Maria Magdalenakerk, 1887 (Lichtbeelden Instituut) |

| 101 (C) | P. J. H. Cuijpers: Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, 1877-85 (J. G. van Agtmaal) |

| 102 (A) | Philip Webb: Smeaton Manor, Yorkshire, 1877-9 (O. H. Wicksteed) |

| 102 (B) | R. Norman Shaw: Withyham, Sussex, Glen Andred, 1866-7 (Courtesy of F. Goodwin) |

| 103 | R. Norman Shaw: London, Old Swan House, 1876 (Bedford Lemere) |

| 104 (A) | R. Norman Shaw: London, Albert Hall Mansions, 1879 (N.B.R.) |

| 104 (B) | George & Peto: London, W. S. Gilbert house, 1882 (Bedford Lemere) |

| 105 | R. Norman Shaw: London, Fred White house, 1887 (Bedford Lemere) |

| 106 (A) | R. Norman Shaw: London, Holy Trinity, Latimer Road, 1887-9 (N.B.R.) |

| 106 (B) | R. Norman Shaw: London, New Scotland Yard, 1887 (Bedford Lemere) |

| 107 | R. Norman Shaw: London, Piccadilly Hotel, 1905-8 (Bedford Lemere) |

| 108 (A) | H. H. Richardson: Boston, Trinity Church, 1873-7 (from Van Rensselaer, Henry Hobson Richardson, 1888) |

| xv108 (B) | H. H. Richardson: Pittsburgh, Penna., Allegheny County Jail, 1884-8 |

| 109 (A) | Charles B. Atwood: Chicago, World’s Fair, Fine Arts Building, 1892-3 (from American Architect, 22 Oct. 1892) |

| 109 (B) | McKim, Mead & White: New York, Villard houses, 1883-5 (from Monograph, 1) |

| 110 | H. H. Richardson: Quincy, Mass., Crane Library, 1880-3 (W. Andrews) |

| 111 | McKim, Mead & White: Boston, Public Library, 1888-92 (W. Andrews) |

| 112 (A) | C. R. Cockerell: Liverpool, Bank Chambers, 1849 (J. R. Johnson) |

| 112 (B) | Alexander Parris: Boston, North Market Street, designed 1823 (B. Abbott) |

| 113 | E. W. Godwin: Bristol, 104 Stokes Croft, c. 1862 (N.B.R.) |

| 114 (A) | Peter Ellis: Liverpool, Oriel Chambers, 1864-5 (N.B.R.) |

| 114 (B) | Lockwood & Mawson(?): Bradford, Yorkshire, Kassapian’s Warehouse, c. 1862 (N.B.R.) |

| 115 (A) | George B. Post: New York, Western Union Building, 1873-5 (Courtesy of Museum of the City of New York) |

| 115 (B) | D. H. Burnham & Co.: Chicago, Reliance Building, 1894 (Chicago Architectural Photographing Co.) |

| 116 (A) | H. H. Richardson: Hartford, Conn., Brown-Thompson Department Store (Cheney Block), 1875-6 |

| 116 (B) | H. H. Richardson: Chicago, Marshall Field Wholesale Store, 1885-7 (Chicago Architectural Photographing Co.) |

| 117 (A) | Adler & Sullivan: Chicago, Auditorium Building, 1887-9 (Chicago Architectural Photographing Co.) |

| 117 (B) | William Le B. Jenney: Chicago, Sears, Roebuck & Co. (Leiter) Building, 1889-90 (Chicago Architectural Photographing Co.) |

| 118 | Adler & Sullivan: St Louis, Wainwright Building, 1890-1 (Bill Hedrich, Hedrich-Blessing) |

| 119 | Adler & Sullivan: Buffalo, N.Y., Guaranty Building, 1894-5 (Chicago Architectural Photographing Co.) |

| 120 | Holabird & Roche; Louis H. Sullivan: Chicago, 19-20 South Michigan Avenue; Gage Building, 1898-9 (Chicago Architectural Photographing Co.) |

| 121 | Louis H. Sullivan: Chicago, Carson, Pirie & Scott Department Store, 1899-1901, 1903-4 (Chicago Architectural Photographing Co.) |

| 122 (A) | J. B. Papworth: ‘Cottage Orné’, 1818 (from Rural Residences, plate XIII) |

| 122 (B) | William Butterfield: Coalpitheath, Gloucestershire, St Saviour’s Vicarage, 1844-5 (N.B.R.) |

| 123 | R. Norman Shaw: nr Withyham, Sussex, Leyswood, 1868 (from Building News, 31 March 1871) |

| 124 (A) | Dudley Newton: Middletown, R.I., Sturtevant house, 1872 (W. K. Covell) |

| 124 (B) | H. H. Richardson: Cambridge, Mass., Stoughton house, 1882-3 (from Sheldon, Artistic Country Seats, 1) |

| 125 (A) | McKim, Mead & White: Elberon, N.J., H. Victor Newcomb house, 1880-1 (from Artistic Houses, 2, Pt I) |

| 125 (B) | Bruce Price: Tuxedo Park, N.Y., Pierre Lorillard house, 1885-6 (from Sheldon, Artistic Country Seats, II) |

| 126 | McKim, Mead & White: Newport R.I., Isaac Bell, Jr, house, 1881-2 |

| 127 | McKim, Mead & White: Bristol, R.I., W. G. Low house, 1887 |

| 128 (A) | Frank Lloyd Wright: River Forest, Ill., W. H. Winslow house, 1893 |

| 128 (B) | Frank Lloyd Wright: River Forest, Ill., River Forest Golf Club, 1898, 1901 (from Ausgeführte Bauten und Entwürfe, 1910, pl. xi) |

| 129 (A) | C. F. A. Voysey: Hog’s Back, Surrey, Julian Sturgis house, elevation, 1896 (Courtesy of Royal Institute of British Architects) |

| 129 (B) | C. F. A. Voysey: Lake Windermere, Broadleys, 1898-9 (Courtesy of J. Brandon-Jones) |

| 130 (A) | Gustave Eiffel: Paris, Eiffel Tower, 1887-9 (N. D. Giraudon) |

| 130 (B) | Baron Victor Horta: Brussels, Tassel house, 1892-3 |

| 131 (A) | Baron Victor Horta: Brussels, Solvay house, 1895-1900 (Archives Centrales Iconographiques, Brussels) |

| 131 (B) | Baron Victor Horta: Brussels, L’Innovation Department Store, 1901 (F. Stoedtner) |

| 132 (A) | C. R. Mackintosh: Glasgow, School of Art, 1897-9 (T. & R. Annan) |

| 132 (B) | Baron Victor Horta: Brussels, Maison du Peuple, interior, 1896-9 (F. Stoedtner) |

| 133 | Frantz Jourdain: Paris, Samaritaine Department Store, 1905 (from L’Architecte, II, 1906, plate X) |

| xvi134 (A) | Auguste Perret: Paris, block of flats, 119 Avenue Wagram, 1902 (from L’Architecte, I, 1906, plate XIV) |

| 134 (B) | C. Harrison Townsend: London, Whitechapel Art Gallery, 1897-9 (from Muthesius, Englische Baukunst der Gegenwart) |

| 135 (A) | C. R. Mackintosh: Glasgow, School of Art, 1907-8 (T. & R. Annan) |

| 135 (B) | Antoni Gaudí: Barcelona, Casa Milá, ground storey, 1905-7 (Arxiu Mas) |

| 136 | Antoni Gaudí: Barcelona, Casa Batlló, front, 1905-7 (Arxiu Mas) |

| 137 (A) | Antoni Gaudí: Barcelona, Casa Milá, 1905-7 (Soberanas Postales) |

| 137 (B) | Hector Guimard: Paris, Gare du Métropolitain, Place Bastille, 1900 (R. Viollet) |

| 138 (A) | Otto Wagner: Vienna, Majolika Haus, c. 1898 (from L’Architecte, I, 1905) |

| 138 (B) | H. P. Berlage: London, Holland House, 1914 (from Gratama, Dr H. P. Berlage, Bouwmeester) |

| 139 (A) | Auguste Perret: Paris, Garage Ponthieu, 1905-6 (F. Stoedtner) |

| 139 (B) | Place de la Porte de Passy, 1930-2 (Chevojon) |

| 140 (A) | Auguste Perret: Le Havre, Place de l’Hôtel de Ville, 1948-54 (Chevojon) |

| 140 (B) | Auguste Perret: Paris, Ministry of Marine, Avenue Victor, 1929-30 (Chevojon) |

| 141 | Auguste Perret: Le Rainey, S.-et-O., Notre-Dame, 1922-3 (Chevojon) |

| 142 (A) | Frank Lloyd Wright: Kankakee, Ill., Warren Hickox house, 1900 |

| 142 (B) | Frank Lloyd Wright: Highland Park, Ill., W. W. Willitts house, 1902 (Fuermann) |

| 143 (A) | Frank Lloyd Wright: Delavan Lake, Wis., C. S. Ross house, 1902 |

| 143 (B) | Frank Lloyd Wright: Oak Park, Ill., Unity Church, 1906 (Russo) |

| 144 | Frank Lloyd Wright: Pasadena, Cal., Mrs G. M. Millard house, 1923 (W. Albert Martin) |

| 145 (A) | Frank Lloyd Wright: Falling Water, Pennsylvania, 1936-7 (Hedrich-Blessing Studio) |

| 145 (B) | Frank Lloyd Wright: Pleasantville, N.Y., Sol Friedman house, 1948-9 (Ezra Stoller) |

| 146 (A) | Frank Lloyd Wright: Racine, Wisconsin, S. C. Johnson and Sons, Administration Building and Laboratory Tower, 1936-9 and 1946-9 (Ezra Stoller) |

| 146 (B) | Bernard Maybeck: Berkeley, Cal., Christian Science Church, 1910 (W. Andrews) |

| 147 (A) | Greene & Greene: Pasadena, Cal., D. B. Gamble house, 1908-9 (W. Andrews) |

| 147 (B) | Irving Gill: Los Angeles, Walter Dodge house, 1915-16 (E. McCoy) |

| 148 (A) | Peter Behrens: Berlin, A.E.G. Small Motors Factory, 1910 (F. Stoedtner) |

| 148 (B) | Peter Behrens: Hagen-Eppenhausen, Cuno and Schröder houses, 1909-10 (F. Stoedtner) |

| 149 (A) | Peter Behrens: Berlin, A.E.G. Turbine Factory, 1909 (F. Stoedtner) |

| 149 (B) | Max Berg: Breslau, Jahrhunderthalle, 1910-12 (F. Stoedtner) |

| 150 | H. P. Berlage: Amsterdam, Diamond Workers’ Union Building, 1899-1900 (Lichtbeelden Instituut) |

| 151 | Adolf Loos: Vienna, Kärntner Bar, 1907 (Gerlach) |

| 152 | Bonatz & Scholer: Stuttgart, Railway Station, 1911-14, 1919-27 (Windstosser) |

| 153 (A) | Fritz Höger: Hamburg, Chilehaus, 1923 (Staatliche Landesbildstelle, Hamburg) |

| 153 (B) | Erich Mendelsohn: Neubabelsberg, Einstein Tower, 1921 (F. Stoedtner) |

| 154 (A) | Josef Hoffmann: Brussels, Stoclet house, 1905-11 (Archives Centrales Iconographiques, Brussels) |

| 154 (B) | Otto Wagner: Vienna, Postal Savings Bank, 1904-6 (Österreichische Nationalbibliothek) |

| 155 (A) | Adolf Loos: Vienna, Gustav Scheu house, 1912 (from Glück, Adolf Loos) |

| 155 (B) | Adolf Loos: Vienna, Leopold Langer flat, 1901 (from Glück, Adolf Loos) |

| 156 (A) | Piet Kramer: Amsterdam, De Dageraad housing estate, 1918-23 (Lichtbeelden Instituut) |

| 156 (B) | Michael de Klerk: Amsterdam, Eigen Haard housing estate, 1917 (Lichtbeelden Instituut) |

| 157 (A) | W. M. Dudok: Hilversum, Dr Bavinck School, 1921 (C. A. Deul) |

| 157 (B) | Saarinen & Saarinen: Minneapolis, Minn., Christ Lutheran Church, 1949-50 (G. M. Ryan) |

| 158 (A) | Walter Gropius with Adolf Meyer: Project for Chicago Tribune Tower, 1922 (W. Gropius) |

| 158 (B) | Walter Gropius and Adolf Meyer: Alfeld-an-der-Leine, Fagus Factory, 1911 (Museum of Modern Art) |

| xvii159 | Le Corbusier: Poissy, S.-et-O., Savoye house 1929-30 (L. Hervé) |

| 160 (A) | Le Corbusier: Second project for Citrohan house, 1922 (from Le Corbusier, Œuvre complète, I) |

| 160 (B) | Le Corbusier: Garches, S.-et-O., Les Terrasses, 1927 (Museum of Modern Art) |

| 161 (A) | Walter Gropius: Dessau, Bauhaus, 1925-6 (Museum of Modern Art) |

| 161 (B) | Walter Gropius: Dessau, City Employment Office, 1927-8 (Museum of Modern Art) |

| 162 (A) | Walter Gropius: Berlin, Siemensstadt housing estate, 1929-30 (Museum of Modern Art) |

| 162 (B) | Ludwig Mies van der Rohe: Stuttgart, block of flats, Weissenhof 1927 (Museum of Modern Art) |

| 163 (A) | Brinkman & van der Vlugt: Rotterdam, van Nelle Factory, 1927 (E. M. van Ojen) |

| 163 (B) | J. J. P. Oud: Hook of Holland, housing estate, 1926-7 (Museum of Modern Art) |

| 164 (A) | J. J. P. Oud: Rotterdam, church, Kiefhoek housing estate, 1928-30 (Museum of Modern Art) |

| 164 (B) | Gerrit Rietveld: Utrecht, Schroeder house, 1924 (F. Stoedtner) |

| 165 (A) | Ludwig Mies van der Rohe: Barcelona, German Exhibition Pavilion, 1929 (F. Stoedtner) |

| 165 (B) | Le Corbusier: Paris, Swiss Hostel, Cité Universitaire, 1931-2 (L. Hervé) |

| 166 | Le Corbusier: Marseilles, Unité d’Habitation, 1946-52 (Éditions de France) |

| 167 | Le Corbusier: Ronchamp, Hte-Saône, Notre-Dame-du-Haut, 1950-4 (L. Hervé) |

| 168 (A) | Le Corbusier: Éveux-sur-L’Arbresle, Rhône, Dominican monastery of La Tourette, 1957-61 (C. Michael Pearson) |

| 168 (B) | Eero Saarinen: Warren, Mich., General Motors Technical Institute, 1951-5 (Ezra Stoller) |

| 169 | Howe & Lescaze: Philadelphia, Philadelphia Savings Fund Society Building, 1932 (Museum of Modern Art) |

| 170 | Ludwig Mies van der Rohe: Chicago, Ill., blocks of flats, 845-60 Lake Shore Drive, 1949-51 (Hube Henry, Hedrich-Blessing) |

| 171 | Lúcio Costa, Oscar Niemeyer, and others (Le Corbusier consultant): Rio de Janeiro, Ministry of Education and Health, 1937-43 (G. E. Kidder Smith) |

| 172 (A) | Giuseppe Terragni: Como, Casa del Fascio, 1932-6 (G. E. Kidder Smith) |

| 172 (B) | Tecton: London, Regent’s Park Zoo, Penguin Pool, 1933-5 (Museum of Modern Art) |

| 173 (A) | Martin Nyrop: Copenhagen, Town Hall, 1893-1902 (F. R. Yerbury) |

| 173 (B) | Alvar Aalto: Säynatsälo, Municipal Buildings, 1951-3 (M. Quantrill) |

| 174 (A) | Ragnar Östberg: Stockholm, Town Hall, 1909-23 (Lindquist and Svandesson) |

| 174 (B) | Ragnar Östberg: Stockholm, Town Hall, 1909-23 (Lindquist and Svandesson) |

| 175 (A) | Sigfrid Ericson: Göteborg, Masthugg Church, 1910-14 (Courtesy of G. Paulsson) |

| 175 (B) | P. V. Jensen Klint: Copenhagen, Grundvig Church, 1913, 1921-6 (F. R. Yerbury) |

| 176 (A) | E. G. Asplund: Stockholm City Library, 1921-8 (F. R. Yerbury) |

| 176 (B) | Edward Thomsen and G. B. Hagen: Gentofte Komune, Øregaard School, 1923-4 (F. R. Yerbury) |

| 177 (A) | Cram & Ferguson: Princeton, N.J., Graduate College, completed 1913 (E. Menzies) |

| 177 (B) | Reed & Stem and Warren & Wetmore: New York, Grand Central Station, 1903-13 (New York Central Railroad) |

| 178 | Cass Gilbert: New York, Woolworth Building, 1913 (J. H. Heffren) |

| 179 | McKim, Mead & White: New York, University Club, 1899-1900 (from Monograph, II) |

| 180 | Henry Bacon: Washington, Lincoln Memorial, completed 1917 (Horydczak) |

| 181 | Sir Edwin Lutyens: Delhi, Viceroy’s House, 1920-31 (Copyright Country Life) |

| 182 (A) | Alvar Aalto: Muuratsälo, architect’s own house, 1953 (Kolmio) |

| 182 (B) | Sir Edwin Lutyens: Sonning, Deanery Gardens, 1901 (Copyright Country Life) |

| 183 (A) | Victor Laloux: Paris, Gare d’Orsay, 1898-1900 (F. Stoedtner) |

| 183 (B) | Eugenio Montuori and others: Rome, Termini Station, completed 1951 (Fototeca Centrale F.S.) |

| 184 | Carlos Lazo and others: Mexico City, University City, begun c. 1950 (R. T. McKenna) |

| 185 (A) | Kay Fisker and Eske Kristensen: Copenhagen, Kongegården Estate, 1955-6 (Strüwing) |

| 185 (B) | Eero Saarinen: New Haven, Conn., Ezra Stiles and Samuel F. B. Morse College, 1960-2 (J. W. Molitor) |

| xviii186 (A) | James Cubitt & Partners: Langleybury, Hertfordshire, school, 1955-6 (Architectural Design) |

| 186 (B) | London County Council Architect’s Office: London, Loughborough Road housing estate, 1954-6 (Architectural Review) |

| 187 (A) | Kenzo Tange: Totsuka, Country Club, c. 1960 (Y. Futagawa) |

| 187 (B) | Kunio Maekawa: Tokyo, Metropolitan Festival Hall, 1961 (Akio Kawasumi) |

| 188 (A) and (B) |

Frank Lloyd Wright: New York, Guggenheim Museum, (1943-6), 1956-9 (Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum) |

| 189 | Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (Gordon Bunshaft): New York, Lever House, 1950-2 (Ezra Stoller) |

| 190 (A) | Philip C. Johnson: New Canaan, Conn., Boissonas house, 1955-6 (Ezra Stoller) |

| 190 (B) | Eero Saarinen: Chantilly, Va., Dulles International Airport, 1960-3 (B. Korab) |

| 190 (C) | Oscar Niemeyer: Pampulha, São Francisco, 1943 (M. Gautherot) |

| 191 | Hentrich & Petschnigg: Düsseldorf, Thyssen Haus, 1958-60 (Arno Wrubel) |

| 192 | Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and Philip Johnson: New York, Seagram Building, 1956-8 (A. Georges) |

My Modern Architecture: Romanticism and Reintegration appeared in 1929. It was an early attempt to relate the newest architecture of the nineteen-twenties to that of the preceding century and a half. In the thirty years that followed I have studied, in varying degrees of detail, many aspects of the story of architecture in the last two hundred years, from the ‘Romantic’ gardens of the mid eighteenth century to Latin-American building of the mid twentieth. In the process debts of gratitude have accumulated that can never be discharged, least of all here. Moreover, immediately before writing this book I visited a dozen countries in the New World, and during its composition in London—made possible by a sabbatical leave from Smith College for the academic year 1955-6—I visited another dozen in the Old World. It would be manifestly impossible even to list all those—first of all in England and America, but also all the way from Athens to Bogotá—who assisted me in various ways in the gathering of material. They will, I trust, understand and accept this generalized expression of my thanks.

Not least of the problems of preparing such a book as this is the finding of photographs. The names of the photographers responsible for the plates (or in a few cases those who obtained photographs for me) are given in the list of plates. The material for the figures, mostly redrawn for this book by P. J. Darvall, came largely from books and drawings in the libraries of the Royal Institute of British Architects and the Victoria and Albert Museum, to whose authorities my thanks are due, as also for notable assistance of various other sorts. The co-operation of the National Buildings Record, which was generously ready to add to their so extensive files photographs newly taken for use in this book, deserves specific mention here. In certain other cases I am not quite sure whether photographs were taken especially for me or not, but I must express gratitude in this connexion also to Professor Frederick D. Nichols of the University of Virginia, to the Staatliche Landesbildstelle of Hamburg, to the Institut für Denkmalpflege of Schwerin, and to Professor Donald Egbert of Princeton University.

The notes indicate a considerable number of the fellow scholars who have assisted me in one way or another. But I would like to mention more particularly the following, who were good enough to read chapters or sections covering matters of which they had expert knowledge: John Summerson, Dorothy Stroud, John Brandon-Jones, Fello Atkinson, Robin Middleton, Turpin Bannister, Winston Weisman, James Grady, William Jordy, and Reyner Banham, not to speak of the Editor of the Pelican History of Art, whose contribution in a field especially his own was naturally of the utmost value. Needless to say these friends bear no responsibility for what appears here, but the importance of their contribution will often be very apparent in the notes. Robert Rosenblum did a very large part of the work of gathering the bibliography, a notable service to the author of a book such as this, as well as checking innumerable note references.

Finally I must mention Mary Elkington, whose intelligent typing of successive drafts of the manuscript made revision a pleasure.

The present edition is no drastic revision of the original one. Only a paragraph or two has been omitted or rewritten, and the one wholly new section is the Epilogue. However, very many corrections and additions have been made in detail, following suggestions made by reviewers and including facts supplied by others, notably John Jacobus, Robin Middleton, Pieter Singelenberg, John Harris, Fritz Novotny, Malcolm Quantrill, Carroll Meeks, and Kevin Dynan among a host of correspondents who have kindly answered specific queries or volunteered relevant information. No changes have been made in the Figures and only about a dozen in the Plates, chiefly at the end where it was possible to introduce the influential work of Aalto and characteristic examples of late Japanese work by reducing the Latin-American representation, not to speak of important works by Wright, Le Corbusier, and Mies completed since the original edition was prepared. The sources of the new photographs are indicated in the List of Plates, but I must specially thank Messrs Hentrich and Johnson, among the architects, for their assistance and also J. M. Richards of the Architectural Review from whose files come the Japanese material and one of the Aalto illustrations.

A certain number of new Notes (indicated by a letter after the number) have been added and many were largely rewritten. The Bibliography has been extended to include titles posterior to the date of the original edition.

The round numbers of chronology have no necessary significance historically. Centuries as cultural entities often begin and end decades before or after the hundred-year mark. The years around 1800, however, do provide a significant break in the history of architecture, not so much because of any major shift in style at that precise point as because the Napoleonic Wars caused a general hiatus in building production. The last major European style, the Baroque, had been all but dissolved away in most of Europe. The beginnings of several differing kinds of reaction against it—Academic in Italy, Rococo in France, Palladian in England—go back as far as the first quarter of the century; shortly after the mid century there came a more concerted stylistic revolution.

1750 and 1790 the new style that is called ‘Romantic Classicism’[1] took form, producing by the eighties its most remarkable projects, and even before that some executed work of consequence in France and in England. Thus the nineteenth century could inherit the tradition of a completed architectural revolution, and at its very outset was in possession of a style that had been fully mature for more than a decade. The most effective reaction against the Baroque in the second, and even to some extent the third, quarter of the eighteenth century had taken place in England; the later architectural revolution that actually initiated Romantic Classicism centred in France.

Yet Paris was not the original locus of the new style’s gestation but rather Rome.[2] From the early sixteenth century Rome had provided the international headquarters from which new ideas in the arts, by no means necessarily originated there, were distributed to the Western world. To Rome came generation after generation of young artists, connoisseurs, and collectors to form their taste and to formulate their aesthetic ideals. Some even settled there for life. From the time of Colbert the French State maintained an academic establishment in Rome for the post-graduate training of artists. Thus French hegemony in the arts of the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries was based on a tradition maintained and renewed at Rome. The nationals of other countries came to Rome more informally, and were for the most part supported by their own funds or by private patrons; only in the seventies were young English architects of promise first awarded travelling studentships by George III. In the fifties the number of northern architects studying in Rome notably increased; some of them, beginning with the Scot Robert Mylne (1734-1811) in 1758, won prizes in the competitions held by the Roman Academy of St Luke.[3]

The initiation of Romantic Classicism was by no means solely in the hands of architects. In the mid-century period of Roman gestation, Winckelmann, Gavin Hamilton, and Piranesi—a German archaeologist, a Scottish painter, and a Venetian etcher—played significant roles, as well as various architects, some pensionnaires of the French Academy, others Britons studying on their own. Certain aspects of Romantic Classicism xxii(1720-78), not the projects in his Prima parte di architettura of 1743 or the plates of ruins in his Antichità romane of 1748 but his fanciful Carceri dating from the mid 1740s. On the theoretical side the Essai sur l’architecture of M.-A. Laugier (1713-70), which first appeared anonymously in 1751 with further editions in 1752, 1753, and 1755, had something of real consequence to contribute as a basic critique of the dying Baroque style. In simple terms Laugier may be called both a Neo-Classicist and a Functionalist. The bolder functionalist ideas of an Italian Franciscan Carlo Lodoli (1690-1761) as presented by Francesco Algarotti in his Lettere sopra l’architettura, beginning in 1742, and in his Saggio sopra l’architettura of 1756 were also influential. However, despite all the new archaeological treatises inspired by the Roman milieu, of which the first was the Ruins of Palmyra published in 1753 by Robert Wood (1717-71), and all the excavations undertaken at Herculaneum over the years 1738-65 and those at Pompeii beginning a decade later, the first architectural manifestations of Romantic Classicism did not occur on Italian soil.

Two buildings begun in the late 1750s, one a very large church in France completed only in 1790, the other a mere garden pavilion in England, may be considered to announce the architectural revolution: Sainte-Geneviève in Paris, desecrated and made a secular Panthéon in 1791 immediately after its completion, was designed by J.-G. Soufflot (1713-80);[4] the Doric Temple at Hagley Park in Worcestershire is by his exact contemporary James Stuart (1713-88). The Panthéon remains one of the most conspicuous eighteenth-century monuments of Paris; the Hagley temple is familiar today only to specialists. Yet, historically, Stuart’s importance is rather greater than Soufflot’s, even though his production was almost negligible in quantity. Born and partly trained in Lyons, Soufflot studied early in Rome and returned to Italy again in the middle of the century. Like several of the French theorists of the day, he had had a lively interest in Gothic construction from his Lyons days. He owed his selection to design Sainte-Geneviève in 1755 to his friendship with Louis XV’s Directeur Général des Bâtiments, the Marquis de Marigny, brother of Mme de Pompadour, whom he had accompanied to Italy in 1749 along with the influential critics C.-N. Cochin and the Abbé Leblanc.

The Scottish architect James Stuart had also gone to Rome, and formed there as early as 1748 the project of visiting Athens; by 1751 he was on his way, accompanied by Nicholas Revett (c. 1721-1804), with whom he proposed to produce an archaeological work on the Antiquities of Athens. The publication of the first volume of this epoch-making book was delayed until 1762. In the meantime, in 1758, the year Stuart designed his Hagley temple, J.-D. Leroy (1724-1803) got ahead of him by publishing Les Ruines des plus beaux monuments de la Grèce; but the very pictorial and inaccurate plates in this had little practical effect on architecture.

The significance of Stuart’s temple may be readily guessed; small though it is, this fabrick was the first example of the re-use of the Greek Doric order[5]—so barbarous, or at least so primitive, in appearance to mid-eighteenth-century eyes—and the first edifice to attempt an archaeological reconstruction of a Greek temple. By the fifties many architects and critics were ready to accept the primacy of Greek over Roman art, if not xxiiilittle or no knowledge of Greek architecture several French writers before Laugier had praised it. J. J. Winckelmann also recommended Greek rather than Roman models in his Gedanken über die Nachahmung der Griechischen Werke (Dresden, 1755) published just before he settled in Rome.[6]

Out of Italian chauvinism Piranesi attacked the theory of Grecian primacy in the arts; yet before his death he had prepared an impressive and influential set of etchings of the Greek temples at Paestum which his son Francesco published. In 1760, moreover, Piranesi decorated the Caffè Inglese in Rome in an Egyptian mode. Eventually Greek precedent in detail all but superseded Roman for over a generation; yet a real Greek Revival, at best but one aspect of Romantic Classicism, did not mature until after 1800. There was never a widespread Egyptian Revival,[7] but Egyptian inspiration did play a real part in crystallizing the formal ideals of Romantic Classicism; it also provided certain characteristic architectural forms, such as the pyramid and the obelisk, and occasional decorative details.

Soufflot’s vast cruciform Panthéon provides no such simple paradigm as Stuart’s temple. No longer really Baroque, it is by no means thoroughly Romantic Classical. Like most of the work of the leading British architect of Soufflot’s generation, Robert Adam (1728-92),[8] the Panthéon must rather be considered stylistically transitional. For example, the purity of the temple portico at the front, in any case Roman not Grecian, is diminished by the breaks at its corners. The tall, hemispherical dome[9] over the crossing is even less antique in character, owing its form to Wren’s St Paul’s rather than to the Roman Pantheon, which was the favourite domical model for later Romantic Classicists. In the interior, up to the entablatures, the columniation is Classical enough and the structure entirely trabeated[10]—at least in appearance (Plate 1). Above, the domes in the four arms are perhaps Roman, but hardly the pendentives that carry them; these are, of course, a Byzantine structural device revived in the fifteenth century by Brunelleschi. Over the aisles the cutting away of the masonry and the general statical approach, while not producing anything that looks very Gothic, illustrate the results of Soufflot’s long-pursued study of Gothic vaulting. Many aspects of nineteenth-century architectural development were thus presaged by Soufflot here, as will become very evident later (see Chapters 1-3, 6, and 7).[11]

The Panthéon was finally finished in the decade after Soufflot’s death by his own pupil Maximilien Brébion (1716-c. 1792), J.-B. Rondelet (1743-1829), a pupil of J.-F. Blondel, and Soufflot’s nephew (François, ?-c. 1802). Well before that, a whole generation of French architects had developed a mode, similar to Adam’s in England, which is usually called, despite its initiation long before Louis XV’s death in 1774, the style Louis XVI. Whether or not this mode in its inception owed much to English inspiration is still controversial. In any case it was widely influential outside France from the seventies to the nineties, and in those decades both French-born and French-trained designers were in great demand all over Europe, except in England; and even in England French craftsmen were employed. With that completely eighteenth-century phase of architectural history this book cannot deal, even though most of the architects who xxivafter 1800 had first made their reputation under Louis XVI, or even earlier under Louis XV. The style Louis XVI and the English ‘Adam Style’ were over, except in remote provinces and colonial dependencies, by 1800.

In various executed works of the decades preceding the French Revolution it is possible to trace the gradual emergence of mature Romantic Classicism in France, as also to some extent in the executed buildings and, above all, the projects of the younger George Dance (1741-1825)[12] in England. But it is in the extraordinary designs, dating from the eighties, by two French architects a good deal younger than Soufflot that the new ideals were most boldly and completely visualized. In the last twenty-five years these two men, L.-E. Boullée (1728-99) and C.-N. Ledoux (1736-1806), have increasingly been recognized as the first great masters of Romantic Classical design if not, in the fullest sense, the first great Romantic Classical architects. Boullée built little and few of his projects and none of the manuscript of his book on architecture, both now preserved at the Bibliothèque Nationale, were published—or at least not until modern times.[13] Yet they must have been well known to his many pupils—including J.-N.-L. Durand, who was the author of the most influential architectural treatise of the Empire period, and doubtless to others as well (see Chapters 2 and 3).

Ledoux was from the first a very successful architect, working with assurance and considerable versatility in the style Louis XVI from the late sixties, particularly for Mme du Barry. He became an academician and architecte du roi in 1773 and spent the next few years at Cassel in Germany. His major executed works are in France, however, and belong to the late seventies and eighties. These are the Besançon Theatre of 1775-84, the buildings of the Royal Saltworks at Arc-et-Senans near there of 1775-9—he had been made inspecteur of the establishment in 1771—and the barrières or toll-houses of Paris, which were built in 1784-9 just before the Revolution. In this later work most of the major qualities of his personal style, qualities carried to much greater extremes in his projects, are readily recognizable; his earlier work was of rather transitional character and not at all unlike what many other French architects of his generation were producing.

The massive cube of the exterior of Ledoux’s Besançon Theatre, against which an unpedimented Ionic portico is set, can already be found, however, at his Château de Benouville begun in 1768; the later edifice is nevertheless much more rigidly cubical and much plainer in the treatment of the rare openings. In the interior Ledoux substituted for a Baroque horseshoe with tiers of boxes a hemicycle[14] with rising banks of seats and a continuous Greek Doric colonnade around the rear fronting the gallery. The extant constructions at Arc-et-Senans are less geometrical; instead of Greek orders there is much rustication and also various Piranesian touches of visual drama. It was this commission which set Ledoux to designing his ‘Ville Idéale de Chaux’; that was his greatest achievement, even though it never came even to partial execution, nor could perhaps have been expected to do so, so cosmic was the basic concept.

The barrières varied very widely in character; some were very Classical, others in a modest Italianate vernacular; some were rather Piranesian in their bold rustication, xxvthe Besançon Theatre. The most significant, however, were notable for the crisp and rigid geometry of their flat-surfaced masses. The extant Barrière de St Martin in the Place de Stalingrad in the La Villette district of Paris consists of a tall cylinder rising out of a very low, square block; this is intersected by a cruciform element projecting as three pedimented porticoes beyond the edges of the square (Plate 2A). Although the range of Ledoux’s restricted detail here is not very great, it is varied to the point of inconsistency all the same. The rather heavy piers of the porticoes are square, with capitals simplified from the Grecian Doric; yet around the cylinder extends an open arcade of Italian character carried on delicate coupled columns.

Had Ledoux’s ideas been known only from his executed work, he would probably not have been especially influential; certainly he would not have attained with posterity the very high reputation that is his today. Inactive at building after the Revolution—he was even imprisoned for a while in the nineties—he concentrated on the publication of his designs both executed and projected. His book L’Architecture considérée sous le rapport de l’art, des mœurs et de la législation appeared in 1804, and a second edition was published by Daniel Ramée (1806-87) in 1846-7. This book has a long and fascinating text which is sociological as much as it is architectural; but it is in its plates, both of executed work and projects, that Ledoux’s originality can best be appreciated. By no means all of his ideas, known before the Revolution to his pupils and undoubtedly to many others as well, passed into the general repertory of Romantic Classicism; some of the most extreme are hardly buildable. The ‘House for Rural Guards’ is a free-standing sphere, a form that he utilized as space rather than mass in the interior of a project for a Columbarium. For the ‘Coopery’, the coopers’ products dictated the target-like shape (Plate 2B). The ‘House for the Directors of the Loue River’ is also a cylinder set horizontally, but a much more massive one, through which the whole flood of the river was to pour to the thorough discomfort, one would imagine, of the inhabitants. Even where the forms are more conventional, as in the project for the church of his ‘Ville Idéale’ of Chaux—a purified version of Soufflot’s Panthéon: cruciform, temple-porticoed, and with a Roman saucer dome—or for the bank there—a peristylar rectangle with high, plain attic, flanked at the corners by detached cubic lodges—the clarity and originality of his formal thinking is very evident, and was apparently influential well before his book actually appeared in 1804. Masses are of simple geometrical shapes, discrete and boldly juxtaposed; walls are flat and as little broken as possible, the few necessary openings mere rectangular holes. Minor features are repeated without variation of rhythm in regular reiterative patterns; the top surfaces of the masses, whether flat, sloping, or rounded, are considered as bounding planes, not modelled plastically in the Baroque way.[15]

Much of this is common to the projects of Boullée, more widely known than Ledoux’s in the eighties because of his many pupils. The simple geometrical forms, the plain surfaces, the reiterative handling of minor features, all are even more conspicuous in his designs and generally presented at a scale so grand as to approach megalomania (Plate 2C). Boullée could be, and often was, more conventionally the Classical Revivalist than Ledoux; he was also perhaps somewhat less bold in using such shapes as the sphere xxvicube and the pyramid. His inspiration was on occasion medieval (of a very special South European ‘Castellated’ order), and he thereby laid the foundations for that more widely eclectic use of the forms of the past which makes the Romantic Classical a syncretic style, not a mere revival of Roman or Greek architecture. Various projects of the eighties by younger men, such as Bernard Poyet (1742-1824) and L.-J. Desprez (1743-1804), of whom we will hear again later, were of very similar character.

Both Boullée and Ledoux, but particularly Ledoux, were interested in symbolism. In that sense their architecture was not essentially abstract, despite the extreme geometrical simplicity of their forms, but in their own term parlante or expressive and meaningful. So special and personal is most of their symbolism, however, that even when quite obvious, as with the ‘Coopery’, it was hardly viable for other architects. When Ledoux gave to his Oikema or ‘House of Sexual Education’ an actual plan of phallic outline (which would be wholly unnoticeable except from the air) he epitomized the hermetic quality of much of his architectural speech. It is understandable that, of the many who accepted his architectural syntax, very few really attempted to speak his language. Such symbolism belonged on the whole to an early stage of Romantic Classicism; after 1800 architectural speech was generally of a much less recondite order. Yet to each of the different vocabularies employed by Romantic Classicists—Grecian, Egyptian, Italian, Castellated, etc.—some sort of special meaning was commonly attached. Thus a restricted and codified eclecticism provided, as it were, the equivalent of a system of musical keys that could be chosen according to a conventional code when designing different types of buildings.

One cannot properly say that international Romantic Classicism derives to any major degree from Ledoux and Boullée; one can only say that their projects of the eighties epitomized most dramatically the final ending of the Baroque and the crystallization of the style that succeeded it. Many French architects of the generation of Poyet and Desprez, however, such as J.-J. Ramée, Pompon, A.-L.-T. Vaudoyer, L.-P. Baltard, Belanger, Grandjean de Montigny, Damesme, and Durand (to mention only those whose names will recur later) came close to rivalling even the grandest visions of Ledoux and Boullée in projects prepared in the nineties.[16] After such exalted work on paper, the buildings actually executed by this generation of Romantic Classicists often seem rather tame. So also were the glorious social schemes of the political revolutionaries much diluted by the functioning governments of Consulate and Empire before and after 1800.

Only in England did the decades preceding the French Revolution produce any development in architecture at all comparable in significance to what was taking place then in France. But there also it is the projects rather than the executed work of Dance—of which very little remains except his early London church of All Hallows, London Wall, of 1765-7—that modern investigators have come to realize led most definitely away from the transitional ‘Adam Style’ towards Romantic Classicism. His Piranesian Newgate Prison, begun in 1769, was demolished in 1902. By 1790, both in France and in England, the new ideas had taken firm root, however, and other countries were not slow to accept the mature style once it had been fully adumbrated.

xxviiThe fact that the nineteenth century began with much of Europe under the hegemony of a French Empire does not quite justify calling the particular phase of Romantic Classicism with which the nineteenth century opens Empire, although this is frequently done in most European countries. Yet the prestige of Napoleon’s rule, and indeed its actual extent, ensured around 1800 the continuance of that French leadership in architecture which had started a century earlier under Louis XIV. Beyond the boundaries of Napoleon’s realm and the lands of his nominees and his allies, moreover, French émigrés carried the new architectural ideas of the last years of the monarchy—for many of them were revolutionaries in the arts, although like Ledoux politically unacceptable to the leaders of the Revolution in France. Even in the homeland of Napoleon’s principal opponents, the English, the prestige of French taste, high in the eighties, hardly declined with the Napoleonic wars. The mature Romantic Classicism of England in the last decade of the old century and the first of the new is certainly full of French ideas, even though it is not always clear exactly how they were transmitted across the Channel in war-time.

If Romantic Classicism, the nearly universal style with which nineteenth-century architecture began, was predominantly French in origin and in its continuing ideals and standards, the same decades that saw it reach maturity also saw the rise of another major movement in the arts that was definitely English. The ‘Picturesque’, a critical concept that had been increasing in authority for two generations in England, received the dignity of a capital P in the 1790s. The term Romantic Classicism is a twentieth-century historian’s invention, attempting by its own contradictoriness to express the ambiguity of the dominant mode of this period in the arts; the term Picturesque, on the other hand, was most widely used and the concept most thoroughly examined just before and just after 1800 (see Chapters 1 and 6).

To the twentieth century, on the whole, the aesthetic standards of Romantic Classicism—or perhaps one should rather say the visual results—have been widely acceptable. The results of the application of Picturesque principles in architecture, on the other hand, have not been so generally admired; indeed, until lately the more clearly and unmistakably buildings realized Picturesque ideals, the less was usually the esteem in which they were held by posterity. On the whole, in architecture if not in landscape design, the twentieth century has preferred to see the manifestations of the Picturesque around 1800 as aberrations from a norm considered primarily to have been a ‘Classical Revival’. As the adjectival aspect of the term Romantic Classicism makes evident, however, the Classicism of the end of the eighteenth century and the beginning of the nineteenth was not at all the same as that of the High Renaissance, nor even that of the Academic Reaction of the early and middle decades of the eighteenth century. Romantic Classicism aimed not so much towards the ‘Beautiful’, in the sense of Aristotle and the eighteenth-century aestheticians, as towards what had been distinguished by Edmund Burke in 1756 as the ‘Sublime’.

Posterity has admired in the production of the first decades of the nineteenth century a homogeneity of style which is in fact even more illusory than that of earlier periods. Horrified by the chaos of later nineteenth-century eclecticism, two twentieth-century xxviiihave praised architects and patrons of the years before and after 1800 for a consistency that was by no means really theirs. In some ways, and not unimportant ways, the history of architecture within the period covered by this volume seems to come full circle so that the Austrian art historian Emil Kaufmann could in 1933 write a book entitled Von Ledoux bis Le Corbusier. Kaufmann did not live quite long enough to realize how far from the spheres and cubes of the Ledolcian ideal the revolutionary twentieth-century architect would move in these last years (see Chapter 23). Le Corbusier’s church at Ronchamp, completed in 1955 after Kaufmann’s death, seems more in accord with extreme eighteenth-century illustrations of the Picturesque than with characteristic monuments of Romantic Classicism (Plate 167). Yet in the early works of the American Frank Lloyd Wright in the 1890s and those of the German Mies van der Rohe twenty years later a filiation to early nineteenth-century Classicism can be readily traced; that tradition informed almost the entire production of the French Perret, a good deal of that of the German Behrens, and even some of the best late work of the Austrian Wagner (see Chapters 18-21).

Forgetting for the moment the Picturesque, one may profitably set down here some of the characteristics that the aspirations and the achievements of the architects of 1800 share, or seem to share, with those of the architects of over a century later. The preference for simple geometrical forms and for smooth, plain surfaces is common to both, though the earlier men aimed at effects of unbroken mass and the later ones rather at an expression of hollow volume. The protestations of devotion to the ‘functional’ are similar, if as frequently sophistical in the one case as in the other. The preferred isolation of buildings in space is as evident in the ubiquitous temples of the early nineteenth century as in the towering slabs of the mid twentieth. Monochromy and even monotony in the use of homogeneous wall-surfacing materials and the avoidance of detail in relief is balanced in both periods by an emphasis on direct structural expression, whether the structure be the posts and lintels of a masonry colonnade or the steel or ferro-concrete members of a continuous space-cage. Finally, impersonality and, perhaps even more notably, ‘internationality’ of expression provided around 1800 a universalized sense of period rather than the flavours of particular nations or regions, just as they have done in the last forty years.

The full flood of Romantic Classicism came late, having been dammed so long by the political and economic turmoil of the last years of the eighteenth century and the first of the nineteenth; it also continued late, in some areas even beyond 1850. But dissatisfaction and revolt also started early; it is not a unique stylistic paradox that the greatest masters of Romantic Classicism were often those who were also most ready to explore the alternative possibilities of the Picturesque (see Chapter 6). The architectural production of the first half of the nineteenth century cannot therefore be presented with any clarity in a single chronological sequence. Parallel architectural events, even strictly contemporary works by the same architect, must be set in their proper places in at least two different sequences of development.

The building production of the early decades of the century already divides only too easily under various stylistic headings. A Greek Revival, a Gothic Revival, etc., have xxixfact, these and other ‘revivals’ were but aspects either of the dominant Romantic Classical tide or of the Picturesque countercurrent (see Chapters 1-5 and Chapter 6, respectively). Only the story of the increasing exploitation of new materials, notably iron and glass, reaching some sort of a culmination around 1850, lay outside, though never quite isolated from, the realm of the revivalistic modes (see Chapter 7).

Despite the drastically reduced production of the years just before and after 1800, between the outbreak of the French Revolution and the termination of Napoleon’s imperial career, there are prominent buildings in many countries that provide fine examples of Romantic Classicism in its early maturity; others, generally more modest in size, give evidence of the vitality of the Picturesque at this time. Since England and America were least directly affected by the French Revolution, however much they were drawn into the wars that were its aftermath, they produced more than their share, so to say, of executed work. French architects before 1806 were mostly reduced to designing monuments destined never to be built or to adapting old structures to new uses.

The greatest architect in active practice in the 1790s was Sir John Soane (1753-1837), from 1788 Architect of the Bank of England. The career of his master, the younger Dance, was in decline; he had made what were perhaps his greatest contributions a good quarter of a century earlier. Whatever Soane owed to Dance, and he evidently owed him a great deal, the Bank[17] offered greater opportunities than the older man had ever had. His interiors of the early nineties at the Bank leave the world of academic Classicism completely behind (Plate 3). His extant Lothbury façade of 1795, with the contiguous ‘Tivoli Corner’ of a decade later—now modified almost beyond recognition—and even more the demolished Waiting Room Court (Plate 4A) showed that his innovations in this period were by no means restricted to interiors.

Soane’s style, consonant though it was in many ways with the general ideals of Romantic Classicism, is a highly personal one. At the Bank, however, he was not creating de novo but committed to the piecemeal reconstruction of an existing complex of buildings, and controlled as well by very stringent technical requirements. Thus the grouping of the offices about the Rotunda, like the plan of the Rotunda itself, goes back to the work done by his predecessor Sir Robert Taylor (1714-88) twenty years earlier; while the special need of the Bank for various kinds of security made necessary both the avoidance of openings on the exterior and a fireproof structural system within. The architectural expression that Soane gave to his complex spaces in the offices which he designed in 1791 and built in 1792-4 had very much the same abstract qualities as those to which older masters of Romantic Classicism, such as Ledoux and Dance, had already aspired in the preceding decades (Plate 3). The novel treatment of the smooth plaster 2surfaces of the light vaults made of hollow terracotta pots, where he substituted linear striations for the conventional membering of Classical design, was as notable as the frank revelation of the delicate cast-iron framework of his glazed lanterns (see Chapter 7). These interiors have particularly appealed to twentieth-century taste, while Soane’s columnar confections of this period generally appear somewhat pompous and banal.

The Rotunda of 1794-5 was grander and more Piranesian in effect; thus it shared in the international tendency of this period towards megalomania. So also the contemporary Lothbury façade, with its rare accents of crisply profiled antae and its vast unbroken expanses of flat rustication, is less personal to Soane and more in a mode that was common to many Romantic Classical architects all over the Western world. The original Tivoli Corner of 1805, however, was almost Baroque in its plasticity, with a Roman not a Greek order, and a most remarkable piling up of flat elements organized in three dimensions at the skyline that could only be Soane’s.

On the other hand, the reduction of relief and the linear stylization of the constituent elements of the Loggia in the Waiting Room Court of 1804, equally personal to Soane, illustrated an anti-Baroque tendency to reduce to a minimum the sculptural aspect of architecture (Plate 4A). Planes were emphasized rather than masses, and the character of the detail was thoroughly renewed as well as the basic formulas of Classical design that Soane had inherited. This was even more apparent in the New Bank Buildings, a terrace of houses, begun in 1807, that once stood across Prince’s Street. Except for the paired Ionic columns at the ends, conventional Classical forms were avoided almost as completely as in the Bank offices of the previous decade, and the smooth plane of the stucco wall was broken only by incised linear detail.

Perhaps the most masterly example of this characteristically Soanic treatment is still to be seen in the gateway and lodge of the country house that he built at Tyringham in Buckinghamshire in 1792-7 (Plate 6A). There the simple mass is defined by flat surfaces bounded by plain incised lines. The house itself is both less drastically novel and less successful; various other Soane houses of these decades have more character.

Summerson has claimed that Soane introduced all his important innovations before 1800. However that may be, there is no major break in his work at the end of the first decade of the century, nor did his production then notably increase. It is therefore rather arbitrary to cut off an account of his architecture at this point; but it is necessary to do so if the importance of the Picturesque countercurrent in these same years, not as yet of great consequence as an aspect of Soane’s major works, is to be adequately emphasized. His concern with varied lighting effects, however, if not necessarily Picturesque technically, gave evidence of an intense Romanticism; more indubitably Picturesque was his exaggerated interest in broken skylines.