Title: History for ready reference, Volume 4, Nicæa to Tunis

Author: J. N. Larned

Release date: October 30, 2022 [eBook #69262]

Most recently updated: October 19, 2024

Language: English

Original publication: United States: C. A. Nichols Co, 1895

Credits: Don Kostuch

[Transcriber's Notes: These modifications are intended to provide

continuity of the text for ease of searching and reading.

1. To avoid breaks in the narrative, page numbers (shown in curly

brackets "{1234}") are usually placed between paragraphs. In this

case the page number is preceded and followed by an empty line.

To remove page numbers use the Regular Expression:

"^{[0-9]+}" to "" (empty string)

2. If a paragraph is exceptionally long, the page number is

placed at the nearest sentence break on its own line, but

without surrounding empty lines.

3. Blocks of unrelated text are moved to a nearby break

between subjects.

5. Use of em dashes and other means of space saving are replaced

with spaces and newlines.

6. Subjects are arranged thusly:

Main titles are at the left margin, in all upper case

(as in the original) and are preceded by an empty line.

Subtitles (if any) are indented three spaces and

immediately follow the main title.

Text of the article (if any) follows the list of subtitles (if

any) and is preceded with an empty line and indented three

spaces.

References to other articles in this work are in all upper

case (as in the original) and indented six spaces. They

usually begin with "See", "Also" or "Also in".

Citations of works outside this book are indented six spaces

and in italics (as in the original). The bibliography in

Volume 1, APPENDIX F on page xxi provides additional details,

including URLs of available internet versions.

----------Subject: Start--------

----------Subject: End----------

indicates the start/end of a group of subheadings or other

large block.

To search for words separated by an unknown number of other

characters, use this Regular Expression to find the words

"first" and "second" separated by between 1 and 100 characters:

"first.{1,100}second"

End Transcriber's Notes.]

----------------------------------

History For Ready Reference, Volume 4 of 6

From The Best

Historians, Biographers, And Specialists

Their Own Words In A Complete

System Of History

For All Uses, Extending To All Countries And Subjects,

And Representing For Both Readers And Students The Better

And Newer Literature Of History In The English Language.

BY J. N. LARNED

With Numerous Historical Maps From Original Studies

And Drawings By Alan C. Reiley

In Five Volumes

VOLUME IV—NICÆA TO TUNIS

SPRINGFIELD, MASSACHUSETTS.

THE C. A. NICHOLS COMPANY, PUBLISHERS

MDCCCXCV

COPYRIGHT, 1894.

BY J. N. LARNED.

The Riverside Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts., U. S. A.

Printed by H. O. Houghton & Company.

LIST OF MAPS AND PLANS.

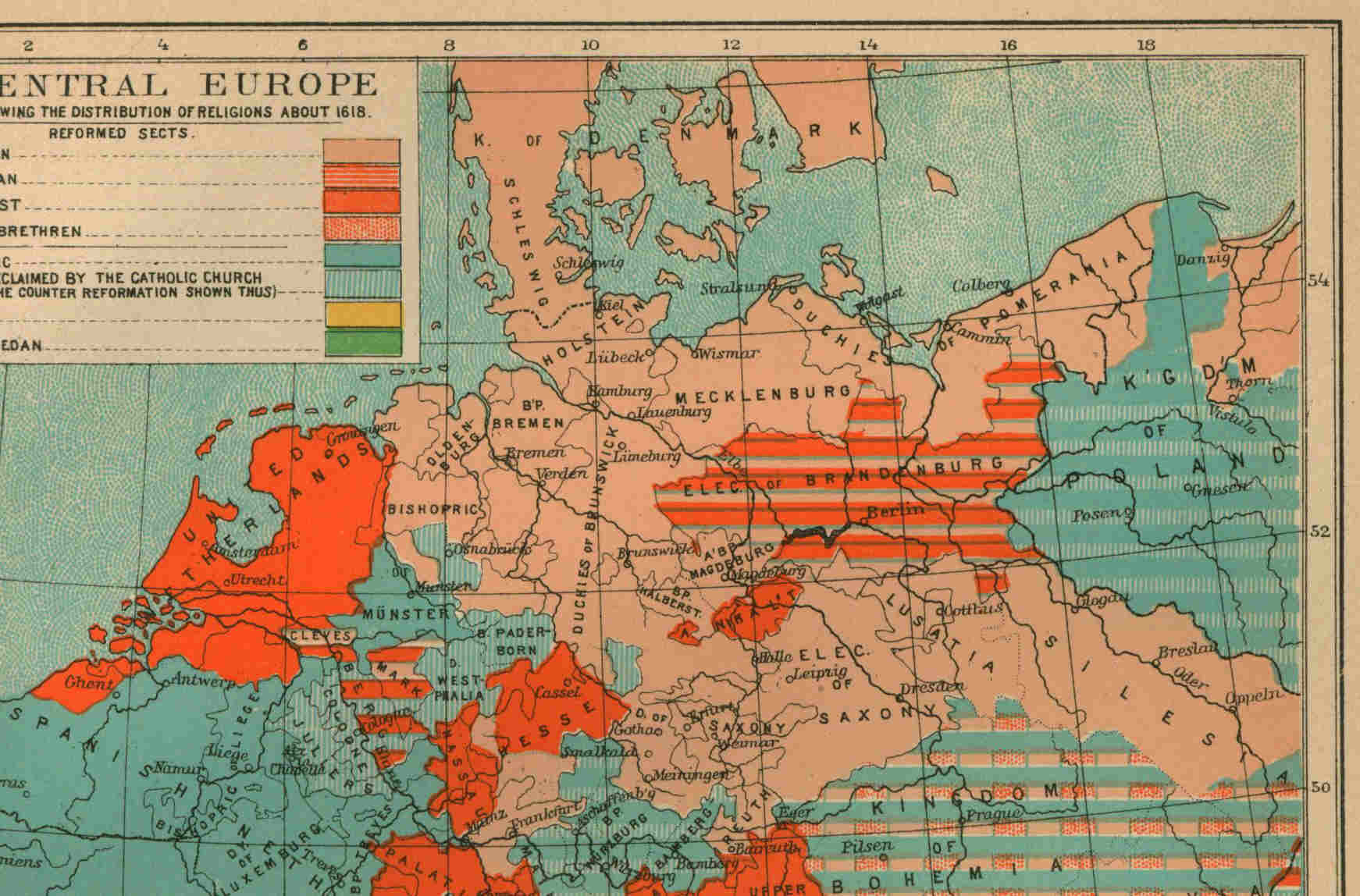

Two maps of Central Europe, at the abdication of Charles V.

(1556), and showing the distribution of Religions about 1618,

To follow page 2458

Map of Eastern Europe in 1768, and of Central Europe at

the Peace of Campo Formio (1797),

To follow page 2554

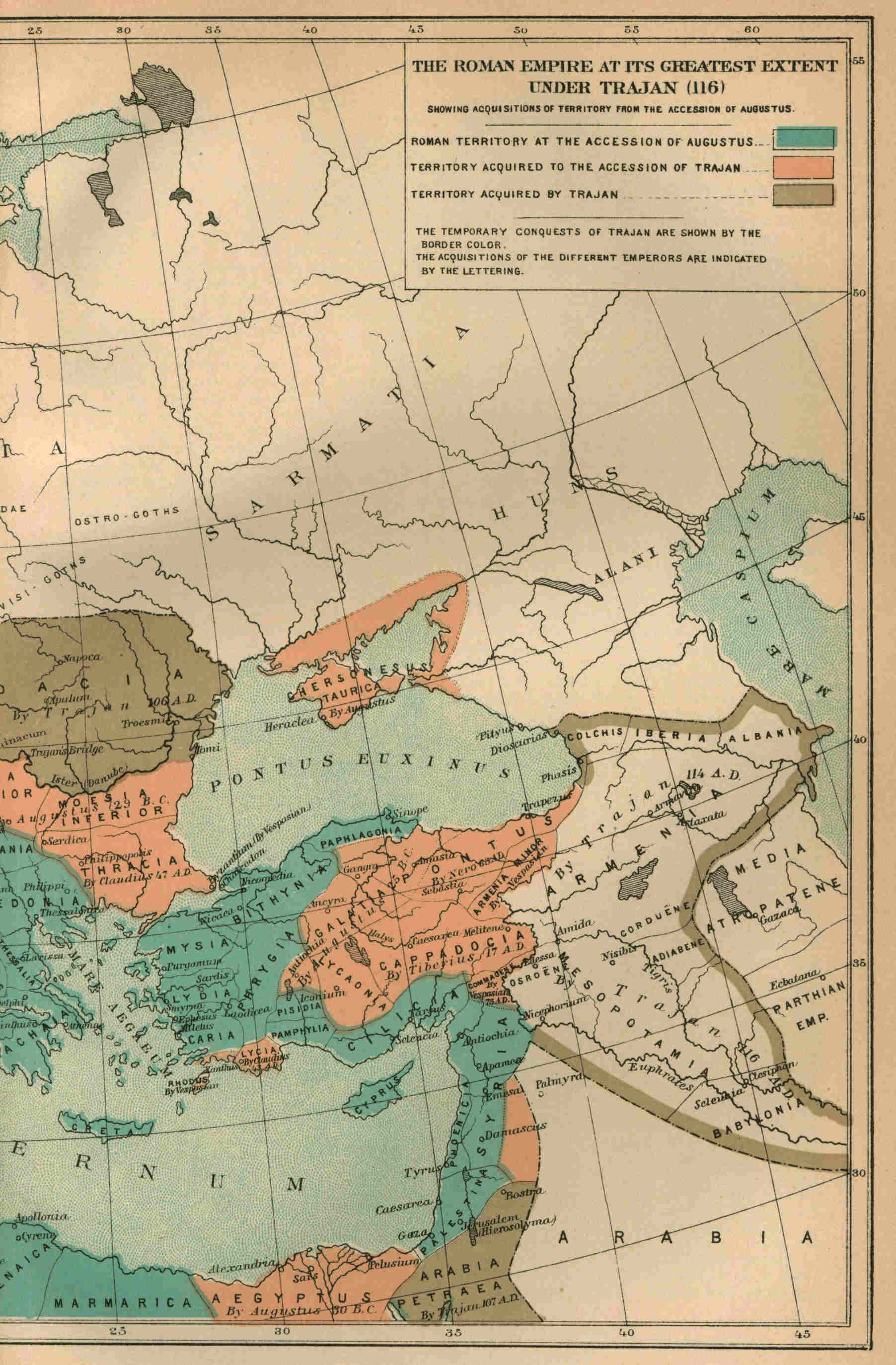

Map of the Roman Empire at its greatest extent,

under Trajan (A. D. 116),

To follow page 2712

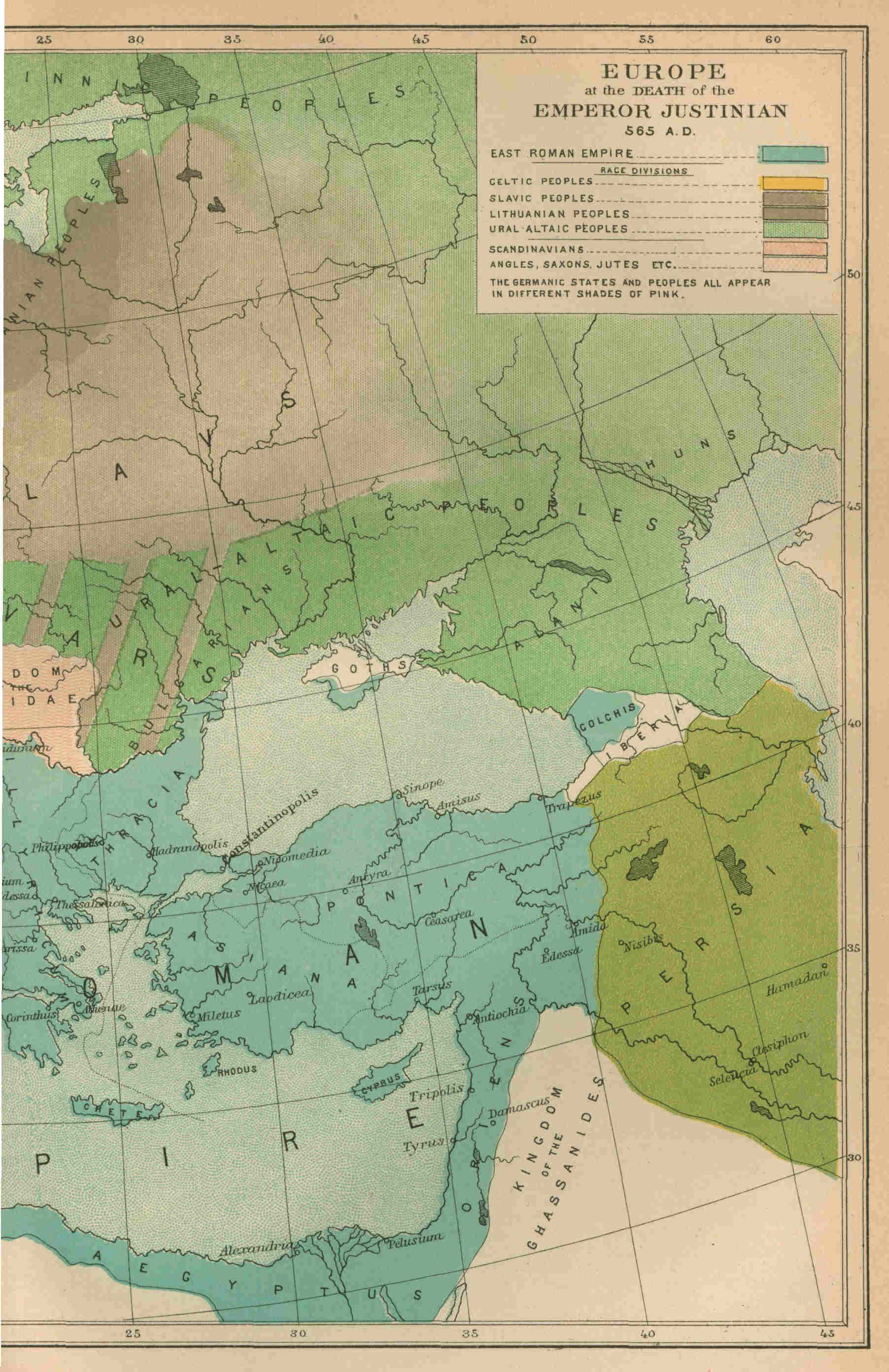

Map of Europe at the death of Justinian (A. D. 565),

To follow page 2742

Two maps, of Eastern Europe and Central Europe, in 1715,

To follow page 2762

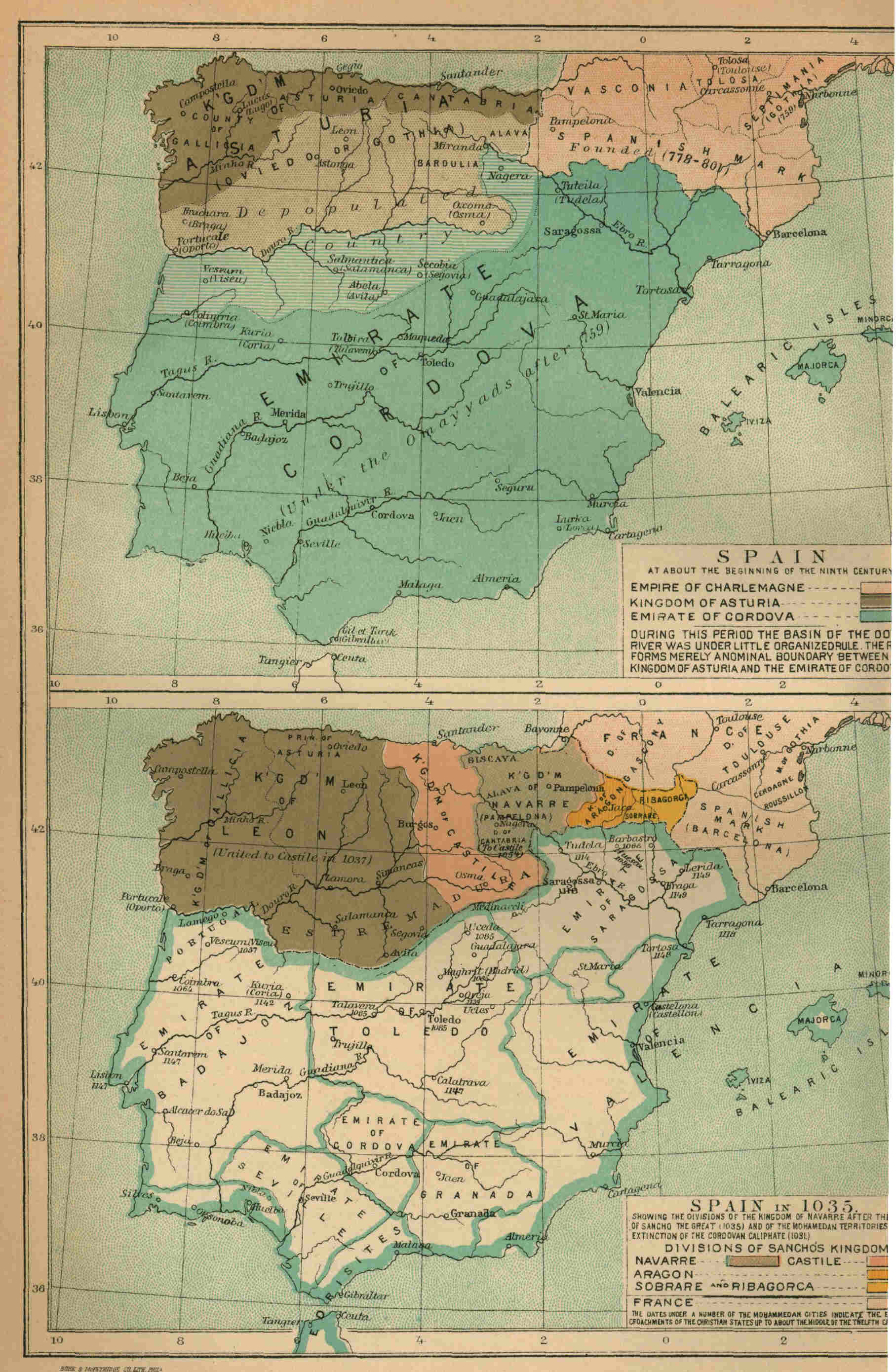

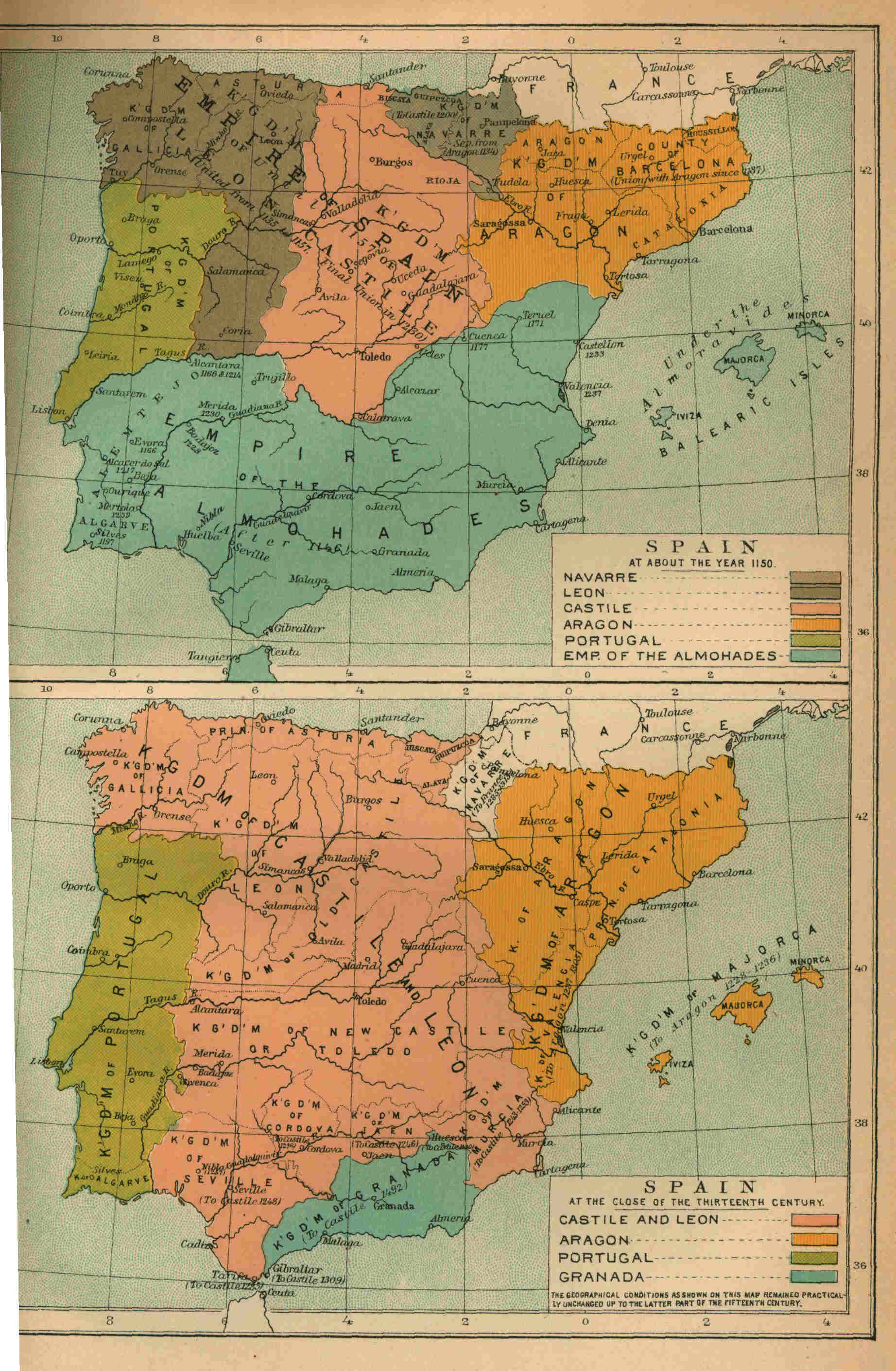

Four development maps of Spain,

9th, 11th, 12th and 13th centuries,

To follow page 2976

LOGICAL OUTLINE, IN COLORS.

Roman history,

To follow page 2656

CHRONOLOGICAL TABLES.

Ninth and Tenth Centuries,

To follow page 2746

{2359}

NICÆA OR NICE:

The founding of the city.

Nicæa, or Nice, in Bithynia, was founded by Antigonus, one of

the successors of Alexander the Great, and received originally

the name Antigonea. Lysimachus changed the name to Nicæa, in

honor of his wife.

NICÆA OR NICE:

Capture by the Goths.

See GOTHS: A. D. 258-267.

NICÆA OR NICE: A. D. 325.

The First Council.

"Constantine … determined to lay the question of Arianism [see

ARIANISM] before an Œcumenical council. … The council met [A.

D. 325] at Nicæa—the 'City of Victory'—in Bithynia, close to

the Ascanian Lake, and about twenty miles from Nicomedia. … It

was an Eastern council, and, like the Eastern councils, was

held within a measurable distance from the seat of government.

… Of the 318 bishops … who subscribed its decrees, only eight

came from the West, and the language in which the Creed was

composed was Greek, which scarcely admitted of a Latin

rendering. The words of the Creed are even now recited by the

Russian Emperor at his coronation. Its character, then, is

strictly Oriental. … Of the 318 members of the Council, we are

told by Philostorgius, the Arian historian, that 22 espoused

the cause of Arius, though other writers regard the minority

as still less, some fixing it at 17, others at 15, others as

low as 13. But of those 318 the first place in rank, though

not the first in mental power and energy of character, was

accorded to the aged bishop of Alexandria. He was the

representative of the most intellectual diocese in the Eastern

Church. He alone, of all the bishops, was named 'Papa,' or

'Pope.' The 'Pope of Rome' was a phrase which had not yet

emerged in history; but 'Pope of Alexandria' was a well-known

title of dignity."

R. W. Bush,

St. Athanasius,

chapter 6.

ALSO IN:

A. P. Stanley,

Lectures on the History of the Eastern Church,

lectures 3-5.

NICÆA OR NICE: A. D. 1080.

Acquired by the Turks.

The capital of the Sultan of Roum.

See TURKS (THE SELJUK): A. D. 1073-1092.

NICÆA OR NICE: A. D. 1096-1097.

Defeat and slaughter of the First Crusaders.

Recovery from the Turks.

See CRUSADES: A. D. 1096-1099.

NICÆA OR NICE: A. D. 1204-1261.

Capital of the Greek Empire.

See GREEK EMPIRE OF NICÆA.

NICÆA OR NICE: A. D. 1330.

Capture by the Ottoman Turks.

See TURKS (OTTOMAN): A. D. 1326-1359.

NICÆA OR NICE: A. D. 1402.

Sacked by Timour.

See TIMOUR.

----------NICARAGUA: Start--------

NICARAGUA:

The Name.

Nicaragua was originally the name of a native chief who ruled

in the region on the Lake when it was first penetrated by the

Spaniards, under Gil Gonzalez, in 1522. "Upon the return of

Gil Gonzalez, the name Nicaragua became famous, and besides

being applied to the cacique and his town, was gradually given

to the surrounding country, and to the lake."

H. H. Bancroft,

History of the Pacific States,

volume 1, page. 489, foot-note.

NICARAGUA: A. D. 1502.

Coasted by Columbus.

See AMERICA: A. D. 1498-1505.

NICARAGUA: A. D. 1821-1871.

Independence of Spain.

Brief annexation to Mexico.

Attempted federations and their failure.

See CENTRAL AMERICA: A. D. 1821-1871.

NICARAGUA: A. D. 1850.

The Clayton-Bulwer Treaty.

Joint protectorate of the United States and

Great Britain over the proposed inter-oceanic canal.

"The acquisition of California in May, 1848, by the treaty of

Guadalupe-Hidalgo, and the vast rush of population, which

followed almost immediately on the development of the gold

mines, to that portion of the Pacific coast, made the opening

of interoceanic communication a matter of paramount importance

to the United States. In December, 1846, had been ratified a

treaty with New Granada (which in 1862 assumed the name of

Colombia) by which a right of transit over the isthmus of

Panama was given to the United States, and the free transit

over the isthmus 'from the one to the other sea' guaranteed by

both of the contracting powers. Under the shelter of this

treaty the Panama Railroad Company, composed of citizens of

the United States, and supplied by capital from the United

States, was organized in 1850 and put in operation in 1855. In

1849, before, therefore, this company had taken shape, the

United States entered into a treaty with Nicaragua for the

opening of a ship-canal from Greytown (San Juan), on the

Atlantic coast, to the Pacific coast, by way of the Lake of

Nicaragua. Greytown, however, was then virtually occupied by

British settlers, mostly from Jamaica, and the whole eastern

coast of Nicaragua, so far at least as the eastern terminus of

such a canal was concerned, was held, so it was maintained by

Great Britain, by the Mosquito Indians, over whom Great

Britain claimed to exercise a protectorate. That the Mosquito

Indians had no such settled territorial site; that, if they

had, Great Britain had no such protectorate or sovereignty

over them as authorized her to exercise dominion over their

soil, even if they had any, are positions which … the United

States has repeatedly affirmed. But the fact that the

pretension was set up by Great Britain, and that, though it

were baseless, any attempt to force a canal through the

Mosquito country, might precipitate a war, induced Mr.

Clayton, Secretary of State in the administration of General

Taylor, to ask through Sir H. L. Bulwer, British minister at

Washington, the administration of Lord John Russell (Lord

Palmerston being then foreign secretary) to withdraw the

British pretensions to the coast so as to permit the

construction of the canal under the joint auspices of the

United States and of Nicaragua. This the British Government

declined to do, but agreed to enter into a treaty for a joint

protectorate over the proposed canal." This treaty, which was

signed at Washington April 19, 1850, and of which the

ratifications were exchanged on the 4th of July following, is

commonly referred to as the Clayton-Bulwer Treaty. Its

language in the first article is that "the Governments of the

United States and of Great Britain hereby declare that neither

the one nor the other will ever obtain or maintain for itself

any exclusive control over the said ship-canal; agreeing that

neither will ever erect or maintain any fortifications

commanding the same, or in the vicinity thereof, or occupy, or

fortify, or colonize, or assume or exercise any dominion over

Nicaragua, Costa Rica, the Mosquito coast, or any part of

Central America; nor will either make use of any protection

which either affords, or may afford, or any alliance which

either has or may have to or with any state or people, for the

purpose of erecting or maintaining any such fortifications, or

of occupying, fortifying, or colonizing Nicaragua, Costa Rica,

the Mosquito coast, or any part of Central America, or of

assuming or exercising dominion over the same;

{2360}

nor will the United States or Great Britain take advantage of

any intimacy, or use any alliance, connection, or influence

that either may possess, with any State or Government through

whose territory the said canal may pass, for the purpose of

acquiring or holding, directly or indirectly, for the citizens

or subjects of the one, any rights or advantages in regard to

commerce or navigation through the said canal which shall not

be offered on the same terms to the citizens or subjects of

the other." Since the execution of this treaty there have been

repeated controversies between the two governments respecting

the interpretation of its principal clauses. Great Britain

having maintained her dominion over the Belize, or British

Honduras, it has been claimed by the United States that the

treaty is void, or, has become voidable at the option of the

United States, on the grounds (in the language of a dispatch

from Mr. Frelinghuysen, Secretary of State, dated July 19,

1884) "first, that the consideration of the treaty having

failed, its object never having been accomplished, the United

States did not receive that for which they covenanted; and,

second, that Great Britain has persistently violated her

agreement not to colonize the Central American coast."

F. Wharton,

Digest of the International Law of the United States,

chapter 6, section 150 f. (volume 2).

ALSO IN:

Treaties and Conventions between the United States

and other Powers (edition of 1889),

page 440.

NICARAGUA: A. D. 1855-1860.

The invasion of Walker and his Filibusters.

"Its geographical situation gave … importance to Nicaragua. It

contains a great lake, which is approached from the Atlantic

by the river San Juan; and from the west end of the lake there

are only 20 miles to the coast of the Pacific. Ever since the

time of Cortes there have been projects for connecting the two

oceans through the lake of Nicaragua. … Hence Nicaragua has

always been thought of great importance to the United States.

The political struggles of the state, ever since the failure

of the confederation, had sunk into a petty rivalry between

the two towns of Leon and Granada. Leon enjoys the distinction

of being the first important town in Central America to raise

the cry of independence in 1815, and it had always maintained

the liberal character which this disclosed. Castellon, the

leader of the Radical party, of which Leon was the seat,

called in to help him an American named William Walker.

Walker, who was born in 1824, was a young roving American who

had gone during the gold rush of 1850 to California, and

become editor of a newspaper in San Francisco. In those days

it was supposed in the United States that the time for

engulfing the whole of Spanish America had come. Lopez had

already made his descent on Cuba; and Walker, in July, 1853,

had organized a band of filibusters for the conquest of

Sonora, and the peninsula of California, which had been left

to Mexico by the treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. This wild

expedition … was a total failure; but when Walker came back to

his newspapers after an absence of seven months, he found

himself a hero. His fame, as we see, had reached Central

America; and he at once accepted Castellon's offer. In 1855,

having collected a band of 70 adventurers in California, he

landed in the country, captured the town of Granada, and,

aided by the intrigues of the American consul, procured his

own appointment as General-in-Chief of the Nicaraguan army.

Walker was now master of the place: and his own provisional

President, Rivas, having turned against him, he displaced him,

and in 1856 became President himself. He remained master of

Nicaragua for nearly two years, levying arbitrary customs on

the traffic of the lake, and forming plans for a great

military state to be erected on the ruins of Spanish America.

One of Walker's first objects was to seize the famous

gold-mines of Chontales, and the sudden discovery that the

entire sierra of America is a gold-bearing region had a good

deal to do with his extraordinary enterprise. Having assured

himself of the wealth of the country, he now resolved to keep

it for himself, and this proved in the end to be his ruin. The

statesmen of the United States, who had at first supposed that

he would cede them the territory, now withdrew their support

from him: the people of the neighbouring states rose in arms

against him, and Walker was obliged to capitulate, with the

remains of his filibustering party, at Rivas in 1857. Walker,

still claiming to be President of Nicaragua, went to New

Orleans, where he collected a second band of filibusters, at

the head of whom he again landed near the San Juan river

towards the end of the year: this time he was arrested and

sent back home by the American commodore. His third and last

expedition, in 1860, was directed against Honduras, where he

hoped to meet with a good reception at the hands of the

Liberal party. Instead of this he fell into the hands of the

soldiers of Guardiola, by whom he was tried as a pirate and

shot, September 12, 1860."

E. J. Payne,

History of European Colonies,

chapter 21, section 8.

"Though he never evinced much military or other capacity,

Walker, so long as he acted under color of authority from the

chiefs of the faction he patronized, was generally successful

against the pitiful rabble styled soldiers by whom his

progress was resisted. … But his very successes proved the

ruin of the faction to which he had attached himself, by

exciting the natural jealousy and alarm of the natives who

mainly composed it; and his assumption … of the title of

President of Nicaragua, speedily followed by a decree

reestablishing Slavery in that country, exposed his purpose

and insured his downfall. As if madly bent on ruin, he

proceeded to confiscate the steamboats and other property of

the Nicaragua Transit Company, thereby arresting all American

travel to and from California through that country, and

cutting himself off from all hope of further recruiting his

forces from the throngs of sanguine or of baffled

gold-seekers, who might otherwise have been attracted to his

standard. Yet he maintained the unequal contest for about two

years."

H. Greeley,

The American Conflict,

volume 1, chapter 19.

ALSO IN:

H. H. Bancroft,

History of the Pacific States,

volume 3, chapters 16-17.

J. J. Roche,

The Story of the Filibusters,

chapters 5-18.

----------NICARAGUA: End--------

NICE (NIZZA), Asia Minor.

See NICÆA.

----------NICE, France: Start--------

NICE (NIZZA), France: A. D. 1388.

Acquisition by the House of Savoy.

See SAVOY: 11-15TH CENTURIES.

{2361}

NICE: A. D. 1542.

Siege by French and Turks.

Capture of the town.

Successful resistance of the citadel.

See FRANCE: A. D. 1532-1547.

NICE: A. D. 1792.

Annexation to the French Republic.

See FRANCE: A. D. 1792 (SEPTEMBER-DECEMBER).

NICE: A. D. 1860.

Cession to France.

See ITALY: A. D. 1859-1861.

----------NICE, France: End--------

NICEPHORUS I.,

Emperor in the East (Byzantine or Greek), A. D. 802-811.

Nicephorus II.,

Emperor in the East (Byzantine or Greek), 963-969.

Nicephorus III.,

Emperor in the East (Byzantine or Greek), 1078-1081.

NICHOLAS, Czar of Russia, A. D. 1825-1855.

Nicholas I., Pope, 858-867.

Nicholas II., Pope, 1058-1061.

Nicholas III., Pope, 1277-1280.

Nicholas IV., Pope, 1288-1292.

Nicholas V., Pope, 1447-1455.

Nicholas Swendson, King of Denmark, 1103-1134.

NICIAS (NIKIAS), and the Siege of Syracuse.

See SYRACUSE: B. C. 415-413.

NICIAS (NIKIAS), The Peace of.

See GREECE: B. C. 424-421.

NICOLET, Jean, Explorations of.

See CANADA: A. D. 1634-1673.

----------NICOMEDIA: Start--------

NICOMEDIA: A. D. 258.

Capture by the Goths.

See GOTHS: A. D. 258-267.

NICOMEDIA: A. D. 292-305.

The court of Diocletian.

"To rival the majesty of Rome was the ambition … of

Diocletian, who employed his leisure, and the wealth of the

east, in the embellishment of Nicomedia, a city placed on the

verge of Europe and Asia, almost at an equal distance between

the Danube and the Euphrates. By the taste of the monarch, and

at the expense of the people, Nicomedia acquired, in the space

of a few years, a degree of magnificence which might appear to

have required the labour of ages, and became inferior only to

Rome, Alexandria, and Antioch, in extent or populousness. …

Till Diocletian, in the twentieth year of his reign,

celebrated his Roman triumph, it is extremely doubtful whether

he ever visited the ancient capital of the empire."

E. Gibbon,

Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire,

chapter 13.

See ROME: A. D. 284-305.

NICOMEDIA: A. D. 1326.

Capture by the Turks.

See TURKS (OTTOMAN): A. D. 1326-1359.

----------NICOMEDIA: End--------

NICOPOLIS.

Augustus gave this name to a city which he founded, B. C. 31,

in commemoration of the victory at Actium, on the site of the

camp which his army occupied.

C. Merivale,

History of the Romans,

chapter 28.

----------NICOPOLIS: Start--------

NICOPOLIS, Armenia, Battle of (B. C. 66).

The decisive battle in which Pompeius defeated Mithridates and

ended the long Mithridatic wars was fought, B. C. 66, in

Lesser Armenia, at a place near which Pompeius founded a city

called Nicopolis, the site of which is uncertain.

G. Long,

Decline of the Roman Republic,

volume 3, chapter 8.

NICOPOLIS: Battle of (B. C. 48).

See ROME: B. C. 47-46.

----------NICOPOLIS, Armenia: End--------

NICOPOLIS, Bulgaria, Battle of (A. D. 1396).

See TURKS (THE OTTOMAN): A. D. 1389-1403.

NICOSIA:

Taken and sacked by the Turks (1570).

See TURKS: A. D. 1566-1571.

NIEUPORT, Battle of (1600).

See NETHERLANDS: A. D. 1594-1609.

NIGER COMPANY, The Royal.

See AFRICA: A. D. 1884-1891.

NIHILISM.

NIHILISTS.

"In Tikomirov's work on Russia seven or eight pages are

devoted to the severe condemnation of the use of the

expressions 'nihilism' and 'nihilist.' Nevertheless … they are

employed universally, and all the world understands what is

meant by them in an approximate and relative way. … It was a

novelist who first baptized the party who called themselves at

that time, 'new men.' It was Ivan Turguenief, who by the mouth

of one of the characters in his celebrated novel, 'Fathers and

Sons,' gave the young generation the name of nihilists. But it

was not of his coinage; Royer-Collard first stamped it; Victor

Hugo had already said that the negation of the infinite led

directly to nihilism, and Joseph Lemaistre had spoken of the

nihilism, more or less sincere, of the contemporary

generations; but it was reserved for the author of 'Virgin

Soil' to bring to light and make famous this word; which after

making a great stir in his own country attracted the attention

of the whole world. The reign of Nicholas I. was an epoch of

hard oppression. When he ascended the throne, the conspiracy

of the Decembrists broke out, and this sudden revelation of

the revolutionary spirit steeled the already inflexible soul

of the Czar. Nicholas, although fond of letters and an

assiduous reader of Homer, was disposed to throttle his

enemies, and would not have hesitated to pluck out the brains

of Russia; he was very near suppressing all the universities

and schools, and inaugurating a voluntary retrocession to

Asiatic barbarism. He did mutilate and reduce the instruction,

he suppressed the chair of European political laws, and after

the events of 1848 in France he seriously considered the idea

of closing his frontiers with a cordon of troops to beat back

foreign liberalism like the cholera or the plague. … However,

it was under his sceptre, under his systematic oppression,

that, by confession of the great revolutionary statesman

Herzen, Russian thought developed as never before; that the

emancipation of the intelligence, which this very statesman

calls a tragic event, was accomplished, and a national

literature was brought to light and began to flourish. When

Alexander II. succeeded to the throne, when the bonds of

despotism were loosened and the blockade with which Nicholas

vainly tried to isolate his empire was raised, the field was

ready for the intellectual and political strife. … Before

explaining how nihilism is the outcome of intelligence, we

must understand what is meant by intelligence in Russia. It

means a class composed of all those, of whatever profession or

estate, who have at heart the advancement of intellectual

life, and contribute in every way toward it. It may be said,

indeed, that such a class is to be found in every country; but

there is this difference,—in other countries the class is not

a unit; there are factions, or a large number of its members

shun political and social discussion in order to enjoy the

serene atmosphere of the world of art, while in Russia the

intelligence means a common cause, a homogeneous spirit,

subversive and revolutionary withal. … Whence came the

revolutionary element in Russia?

{2362}

From the Occident, from France, from the negative,

materialist, sensualist philosophy of the Encyclopædia,

imported into Russia by Catherine II.; and later from Germany,

from Kantism and Hegelianism, imbibed by Russian youth at the

German universities, and which they diffused throughout their

own country with characteristic Sclav impetuosity. By 'Pure

Reason' and transcendental idealism, Herzen and Bakunine, the

first apostles of nihilism, were inspired. But the ideas

brought from Europe to Russia soon allied themselves with an

indigenous or possibly an Oriental element; namely, a sort of

quietist fatalism, which leads to the darkest and most

despairing pessimism. On the whole, nihilism is rather a

philosophical conception of the sum of life than a purely

democratic and revolutionary movement. … Nihilism had no

political color about it at the beginning. During the decade

between 1860 and 1870 the youth of Russia was seized with a

sort of fever for negation, a fierce antipathy toward

everything that was,—authorities, institutions, customary

ideas, and old-fashioned dogmas. In Turguenief's novel,

'Fathers and Sons,' we meet with Bazarof, a froward,

ill-mannered, intolerable fellow, who represents this type.

After 1871 the echo of the Paris Commune and emissaries of the

Internationals crossed the frontier, and the nihilists began

to bestir themselves, to meet together clandestinely, and to

send out propaganda. Seven years later they organized an era

of terror, assassination, and explosions. Thus three phases

have followed upon one another,—thought, word, and deed,—along

that road which is never so long as it looks, the road that

leads from the word to the act, from Utopia to crime. And yet

nihilism never became a political party as we understand the

term. It has no defined creed or official programme. The

fulness of its despair embraces all negatives and all acute

revolutionary forms. Anarchists, federalists, cantonalists,

covenanters, terrorists, all who are unanimous in a desire to

sweep away the present order, are grouped under the ensign of

nihil."

E. P. Bazan,

Russia, its People and its Literature,

book 2, chapters 1-2.

"Out of Russia, an already extended list of revolutionary

spirits in this land has attracted the attention and kept

curiosity on the alert. We call them Nihilists,—of which the

Russian pronunciation is neegilist, which, however, is now

obsolete. Confined to the terrorist group in Europe, the

number of these persons is certainly very small. Perhaps, as

is thought in Russia, there are 500 in all, who busy

themselves, even if reluctantly, with thoughts of resorting to

bombs and murderous weapons to inspire terror. But it is not

exactly this group that is meant when we speak of that

nihilistic force in society which extends everywhere, into all

circles, and finds support and strongholds at widely spread

points. It is indeed not very different from what elsewhere in

Europe is regarded as culture, advanced culture: the profound

scepticism in regard to our existing institutions in their

present form, what we call royal prerogative, church,

marriage, property."

Georg Brandes,

Impressions of Russia,

chapter 4.

"The genuine Nihilism was a philosophical and literary

movement, which flourished in the first decade after the

Emancipation of the Serfs, that is to say, between 1860 and

1870. It is now (1883] absolutely extinct, and only a few

traces are left of it, which are rapidly disappearing. …

Nihilism was a struggle for the emancipation of intelligence

from every kind of dependence, and it advanced side by side

with that for the emancipation of the labouring classes from

serfdom. The fundamental principle of Nihilism, properly

so-called, was absolute individualism. It was the negation, in

the name of individual liberty of all the obligations imposed

upon the individual by society, by family life, and by

religion. Nihilism was a passionate and powerful reaction, not

against political despotism, but against the moral despotism

that weighs upon the private and inner life of the individual.

But it must be confessed that our predecessors, at least in

the earlier days, introduced into this highly pacific struggle

the same spirit of rebellion and almost the same fanaticism

that characterises the present movement."

Stepniak,

Underground Russia,

introduction.

ALSO IN:

Stepniak,

The Russian Storm-Cloud.

L. Tikhomirov,

Russia, Political and Social,

books 6-7 (volume 2).

E. Noble,

The Russian Revolt.

A. Leroy-Beaulieu,

The Empire of the Tsars,

part 1, book 3, chapter 4.

See, also, RUSSIA: A. D. 1879-1881;

and ANARCHISTS.

NIKA SEDITION, The.

See CIRCUS, FACTIONS OF THE ROMAN.

NIKIAS.

See NICIAS.

NILE, Naval Battle of the.

See FRANCE: A. D. 1798 (MAY-AUGUST).

NIMEGUEN:

Origin.

See BATAVIANS.

NIMEGUEN: A. D. 1591.

Siege and capture by Prince Maurice.

See NETHERLANDS: A. D. 1588-1593.

NIMEGUEN, The Peace of (1678-1679).

The war which Louis XIV. began in 1672 by attacking Holland,

with the co-operation of his English pensioner, Charles II.,

and which roused against him a defensive coalition of Spain,

Germany and Denmark with the Dutch (see NETHERLANDS: A. D.

1672-1674, and 1674-1678), was ended by a series of treaties

negotiated at Nimeguen in 1678 and 1679. The first of these

treaties, signed August 10, 1678, was between France and

Holland. "France and Holland kept what was in their

possession, except Maestricht and its dependencies which were

restored to Holland. France therefore kept her conquests in

Senegal and Guiana. This was all the territory lost by Holland

in the terrible war which had almost annihilated her. The

United Provinces pledged themselves to neutrality in the war

which might continue between France and the other powers, and

guaranteed the neutrality of Spain, after the latter should

have signed the peace. France included Sweden in the treaty;

Holland included in it Spain and the other allies who should

make peace within six weeks after the exchange of

ratifications. To the treaty of peace was annexed a treaty of

commerce, concluded for twenty-five years."

H. Martin,

History of France: Age of Louis XIV.,

(translated by M. L. Booth),

volume 1, chapter 6.

The peace between France and Spain was signed September 17.

France gave back, in the Spanish Netherlands and elsewhere,

"Charleroi, Binch, Ath, Oudenarde, and Courtrai, which she had

gained by the Peace of Aix-la-Chapelle; the town and duchy of

Limburg, all the country beyond the Meuse, Ghent, Rodenhus,

and the district of the Waes, Leuze, and St. Ghislain, with

Puycerda in Catalonia, these having been taken since that

peace.

{2363}

But she retained Franche Comté, with the towns of

Valenciènnes, Bouchain, Condé, Cambrai and the Cambresis,

Aire, St. Omer, Ypres, Werwick, Warneton, Poperinge, Bailleul,

Cassel, Bavai, and Maubeuge. … On February 2, 1679, peace was

declared between Louis, the Emperor, and the Empire. Louis

gave back Philippsburg, retaining Freiburg with the desired

liberty of passage across the Rhine to Breisach; in all other

respects the Treaty of Munster, of October 24, 1648, was

reestablished. … The treaty then dealt with the Duke of

Lorraine. To his restitution Louis annexed conditions which

rendered Lorraine little more than a French province. Not only

was Nancy to become French, but, in conformity with the treaty

of 1661, Louis was to have possession of four large roads

traversing the country, with half a league's breadth of

territory throughout their length, and the places contained

therein. … To these conditions the Duke refused to subscribe,

preferring continual exile until the Peace of Ryswick in 1697,

when at length his son regained the ancestral estates."

Treaties between the Emperor and Sweden, between Brandenburg

and France and Sweden, between Denmark and the same, and

between Sweden, Spain and Holland, were successively concluded

during the year 1679. "The effect of the Peace of Nimwegen

was, … speaking generally, to reaffirm the Peace of

Westphalia. But … it did not, like the Peace of Westphalia,

close for any length of time the sources of strife."

O. Airy,

The English Restoration and Louis XIV.,

chapter 22.

ALSO IN:

Sir W. Temple,

Memoirs,

part 2 (Works, volume 2).

NINE WAYS, The.

See AMPHIPOLIS;

also, ATHENS: B. C. 466-454.

NINETY-FIVE THESES OF LUTHER, The.

See PAPACY: A. D. 1517.

NINETY-TWO, The.

See UNITED STATES OF AMERICA: A. D. 1767-1768.

NINEVEH.

"In or about the year before Christ 606, Nineveh, the great

city, was destroyed. For many hundred years had she stood in

arrogant splendor, her palaces towering above the Tigris and

mirrored in its swift waters; army after army had gone forth

from her gates and returned laden with the spoils of conquered

countries; her monarchs had ridden to the high place of

sacrifice in chariots drawn by captive kings. But her time

came at last. The nations assembled and encompassed her around

[the Medes and the Babylonians, with their lesser allies].

Popular tradition tells how over two years lasted the siege;

how the very river rose and battered her walls; till one day a

vast flame rose up to heaven; how the last of a mighty line of

kings, too proud to surrender, thus saved himself, his

treasures and his, capital from the shame of bondage. Never

was city to rise again where Nineveh had been." The very

knowledge of the existence of Nineveh was lost so soon that,

two centuries later, when Xenophon passed the ruins, with his

Ten Thousand retreating Greeks, he reported them to be the

ruins of a deserted city of the Medes and called it Larissa.

Twenty-four centuries went by, and the winds and the rains, in

their slow fashion, covered the bricks and stones of the

desolated Assyrian capital with a shapeless mound of earth.

Then came the searching modern scholar and explorer, and began

to excavate the mound, to see what lay beneath it. First the

French Consul, Botta, in 1842; then the Englishman Layard, in

1845; then the later English scholar, George Smith, and

others; until buried Nineveh has been in great part brought to

light. Not only the imperishable monuments of its splendid art

have been exposed, but a veritable library of its literature,

written on tablets and cylinders of clay, has been found and

read. The discoveries of the past half-century, on the site of

Nineveh, under the mound called Koyunjik, and elsewhere in

other similarly-buried cities of ancient Babylonia and

Assyria, may reasonably be called the most extraordinary

additions to human knowledge which our age has acquired.

Z. A. Ragozin,

Story of Chaldea,

introduction, chapters 1-4.

ALSO IN:

A. H. Layard,

Nineveh and its Remains;

and Discoveries among the Ruins of Nineveh and Babylon.

G. Smith,

Assyrian Discoveries

See, also, ASSYRIA;

and LIBRARIES, ANCIENT.

NINEVEH, Battle of (A.D. 627).

See PERSIA: A. D. 226-627.

NINFEO, Treaty of.

See GENOA: A. D. 1261-1299.

NINIQUIQUILAS, The.

See AMERICAN ABORIGINES: PAMPAS TRIBES.

NIPAL

NEPAUL:

English war with the Ghorkas.

See INDIA: A. D. 1805-1816.

NIPMUCKS,

NIPNETS, The.

See AMERICAN ABORIGINES: ALGONQUIAN FAMILY;

also, NEW ENGLAND: A. D. 1674-1675, 1675,

and 1676-1678 KING PHILIP'S WAR.

NISÆAN PLAINS, The.

The famous horse-pastures of the ancient Medes. "Most probably

they are to be identified with the modern plains of Khawah and

Alishtar, between Behistun and Khorramabad, which are even now

considered to afford the best summer pasturage in Persia. …

The proper Nisæa is the district of Nishapur in Khorasan,

whence it is probable that the famous breed of horses was

originally brought."

G. Rawlinson,

Five Great Monarchies: Media,

chapter 1, with foot-note.

NISCHANDYIS.

See SUBLIME PORTE.

NISHAPOOR:

Destruction by the Mongols (1221).

See KHORASSAN: A. D. 1220-1221.

NISIB, Battle of (1839).

See TURKS: A. D. 1831-1840.

NISIBIS, Sieges of (A. D. 338-350).

See PERSIA: A. D. 226-627.

NISIBIS, Theological School of.

See NESTORIANS.

----------NISMES: Start--------

NISMES:

Origin.

See VOLCÆ.

NISMES: A. D. 752-759.

Recovery from the Moslems.

See MAHOMETAN CONQUEST: A. D. 752-759.

----------NISMES: End--------

NISSA, Siege and battle (1689-1690).

See HUNGARY; A. D. 1683-1699.

NITIOBRIGES, The.

These were a tribe in ancient Gaul whose capital city was

Aginnum, the modern town of Agen on the Garonne.

G. Long,

Decline of the Roman Republic,

volume 4, chapter 17.

NIVELLE, Battle of the (1813).

See SPAIN: A. D. 1812-1814.

NIVÔSE, The month.

See FRANCE: A. D. 1793 (OCTOBER)

THE NEW REPUBLICAN CALENDAR.

NIZAM.

Nizam's dominions.

See INDIA: A. D. 1662-1748.

NIZZA.

See NICE.

NO.

NO AMON.

See THEBES, EGYPT.

NO MAN'S LAND, Africa.

See GRIQUAS.

{2364}

NO MAN'S LAND, England.

In the open or common field system which prevailed in early

England, the fields were divided into long, narrow strips,

wherever practicable. In some cases, "little odds and ends of

unused land remained, which from time immemorial were called

'no man's land,' or 'anyone's land,' or 'Jack's land,' as the

case might be."

F. Seebohm,

English Village Community,

chapter 1.

NO POPERY RIOTS, The.

See ENGLAND: A. D. 1778-1780.

NOBLES, Roman:

Origin of the term.

"When Livy in his first six books writes of the disputes

between the Patres or Patricians and the Plebs about the

Public Land, he sometimes designates the Patricians by the

name Nobiles, which we have in the form Nobles. A Nobilis is a

man who is known. A man who is not known is Ignobilis, a

nobody. In the later Republic a Plebeian who attained to a

curule office elevated his family to a rank of honour, to a

nobility, not acknowledged by any law, but by usage. … The

Patricians were a nobility of ancient date. … The Patrician

nobility was therefore independent of all office, but the new

Nobility and their Jus Imaginum originated in some Plebeian

who first of his family attained a curule office. … The true

conclusion is that Livy in his first six books uses the word

Nobiles improperly, for there is no evidence that this name

was given to the Patres before the consulship of L. Sextius."

G. Long,

Decline of the Roman Republic,

volume 1, chapter 11.

See, also, ROME: B. C. 146.

NOËTIANS AND SABELLIANS.

"At the head of those in this century [the 3d] who explained

the scriptural doctrine of the Father, Son, and holy Spirit,

by the precepts of reason, stands Noëtus of Smyrna; a man

little known, but who is reported by the ancients to have been

cast out of the church by presbyters (of whom no account is

given), to have opened a school, and to have formed a sect. It

is stated that, being wholly unable to comprehend how that

God, who is so often in Scripture declared to be one and

undivided, can, at the same time, be manifold, Noëtus

concluded that the undivided Father of all things united

himself, with the man Christ, was born in him, and in him

suffered and died. On account of this doctrine his followers

were called Patripassians. … After the middle of this century,

Sabellius, an African bishop, or presbyter, of Ptolemais, the

capital of the Pentapolitan province of Libya Cyrenaica,

attempted to reconcile, in a manner somewhat different from

that of Noëtus, the scriptural doctrine of Father, Son, and

holy Spirit, with the doctrine of the unity of the divine

nature." Sabellius assumed "that only an energy or virtue,

emitted from the Father of all, or, if you choose, a particle

of the person or nature of the Father, became united with the

man Christ. And such a virtue or particle of the Father, he

also supposed, constituted the holy Spirit."

J. L. von Mosheim,

Historical Commentaries, 3d Century,

sections 32-33.

NÖFELS,

NAEFELS, Battle of (1388).

See SWITZERLAND: A. D. 1386-1388.

Battle of (1799).

See FRANCE: A. D. 1799 (AUGUST-DECEMBER).

NOLA, Battle of (B. C. 88).

See ROME: B. C. 90-88.

NOMBRE DE DIOS:

Surprised and plundered by Drake (1572).

See AMERICA: A. D. 1572-1580.

NOMEN,

COGNOMEN,

PRÆNOMEN.

See GENS.

NOMES.

A name given by the Greeks to the districts into which Egypt

was divided from very ancient times.

NOMOPHYLAKES.

In ancient Athens, under the constitution introduced by

Pericles, seven magistrates called Nomophylakes, or

"Law-Guardians," "sat alongside of the Proedri, or presidents,

both in the senate and in the public assembly, and were

charged with the duty of interposing whenever any step was

taken or any proposition made contrary to the existing laws.

They were also empowered to constrain the magistrates to act

according to law."

G. Grote,

History of Greece,

part 2, chapter 46.

NOMOTHETÆ, The.

A legislative commission, elected and deputed by the general

assembly of the people, in ancient Athens, to amend existing

laws or enact new ones.

G. F. Schömann,

Antiquity of Greece: The State,

part 3, chapter 3.

NONCONFORMISTS,

DISSENTERS, English:

First bodies organized.

Persecutions under Charles II. and Anne.-

Removal of Disabilities.

See ENGLAND: A. D. 1559-1566; 1662-1665; 1672-1673;

1711-1714; 1827-1828.

NONES.

See CALENDAR, JULIAN.

NONINTERCOURSE LAW OF 1809, The American.

See UNITED STATES OF AMERICA: A. D. 1804-1809.

NONJURORS, The.

See ENGLAND: A. D. 1689 (APRIL-AUGUST).

NOOTKAS, The.

See AMERICAN ABORIGINES: WAKASHAN FAMILY.

NOPH.

See MEMPHIS.

NÖRDLINGEN,

Siege and Battle (1634).

See GERMANY: A. D. 1634-1639.

Second Battle, or Battle of Allerheim (1645).

See GERMANY: A. D. 1640-1645.

NORE, Mutiny at the.

See ENGLAND: A. D. 1797.

NOREMBEGA.

See NORUMBEGA.

----------NORFOLK, VIRGINIA: Start--------

NORFOLK, VIRGINIA: A. D. 1776.

Bombardment and destruction.

See VIRGINIA: A. D. 1775-1776.

NORFOLK, VIRGINIA: A. D. 1779.

Pillaged by British marauders.

See UNITED STATES OF AMERICA:

A. D. 1778-1779 WASHINGTON GUARDING THE HUDSON.

NORFOLK, VIRGINIA: A. D. 1861 (April).

Abandoned by the United States commandant.

Destruction of ships and property.

Possession taken by the Rebels.

See UNITED STATES OF AMERICA: A. D. 1861 (APRIL).

NORFOLK, VIRGINIA: A. D. 1862 (February).

Threatened by the Federal capture of Roanoke Island.

See UNITED STATES OF AMERICA:

A. D. 1862 (JANUARY-APRIL: NORTH CAROLINA).

NORFOLK, VIRGINIA: A. D. 1862 (May).

Evacuated by the Confederates.

See UNITED STATES OF AMERICA:

A. D. 1862 (MAY: VIRGINIA) EVACUATION OF NORFOLK.

----------NORFOLK, VIRGINIA: End--------

NORFOLK ISLAND PENAL COLONY.

See AUSTRALIA: A. D. 1601-1800.

NORICUM.

See PANNONIA;

also, RHÆTIANS.

----------NORMANDY: Start--------

NORMANDY: A. D. 876-911.

Rollo's conquest and occupation.

See NORMANS.

NORTHMEN: A. D. 876-911.

{2365}

NORMANDY: A. D. 911-1000.

The solidifying of Rollo's duchy.

The Normans become French.

The first century which passed after the settlement of the

Northmen along the Seine saw "the steady growth of the duchy

in extent and power. Much of this was due to the ability of

its rulers, to the vigour and wisdom with which Hrolf forced

order and justice on the new community, as well as to the

political tact with which both Hrolf and William Longsword

[son and successor of Duke Rollo or Hrolf, A. D. 927-943]

clung to the Karolings in their strife with the dukes of

Paris. But still more was owing to the steadiness with which

both these rulers remained faithful to the Christianity which

had been imposed on the northmen as a condition of their

settlement, and to the firm resolve with which they trampled

down the temper and traditions which their people had brought

from their Scandinavian homeland, and welcomed the language

and civilization which came in the wake of their neighbours'

religion. The difficulties that met the dukes were indeed

enormous. … They were girt in by hostile states, they were

threatened at sea by England, under Æthelstan a network of

alliances menaced them with ruin. Once a French army occupied

Rouen, and a French king held the pirates' land at his will;

once the German lances were seen from the walls of their

capital. Nor were their difficulties within less than those

without. The subject population which had been trodden under

foot by the northern settlers were seething with discontent.

The policy of Christianization and civilization broke the

Normans themselves into two parties. … The very conquests of

Hrolf and his successor, the Bessin, the Cotentin, had to be

settled and held by the new comers, who made them strongholds

of heathendom. … But amidst difficulties from within and from

without the dukes held firm to their course, and their

stubborn will had its reward. … By the end of William

Longsword's days all Normandy, save the newly settled

districts of the west, was Christian, and spoke French. … The

work of the statesman at last completed the work of the sword.

As the connexion of the dukes with the Karoling kings had

given them the land, and helped them for fifty years to hold

it against the House of Paris, so in the downfall of the

Karolings the sudden and adroit change of front which bound

the Norman rulers to the House of Paris in its successful

struggle for the Crown secured the land for ever to the

northmen. The close connexion which France was forced to

maintain with the state whose support held the new royal line

on its throne told both on kingdom and duchy. The French dread

of the 'pirates' died gradually away, while French influence

spread yet more rapidly over a people which clung so closely

to the French crown."

J. R. Green,

The Conquest of England,

chapter 8.

NORMANDY: A. D. 1035-1063.

Duke William establishes his authority.

Duke Robert, of Normandy, who died in 1035, was succeeded by

his young son William, who bore in youth the opprobrious name

of "the Bastard," but who extinguished it in later life under

the proud appellation of "the Conqueror." By reason of his

bastardy he was not an acceptable successor, and, being yet a

boy, it seemed little likely that he would maintain himself on

the ducal throne. Normandy, for a dozen years, was given up to

lawless strife among its nobles. In 1047 a large part of the

duchy rose in revolt, against its objectionable young lord.

"It will be remembered that the western part of Normandy, the

lands of Bayeux and Coutances, were won by the Norman dukes

after the eastern part, the lands of Rouen and Evreux. And it

will be remembered that these western lands, won more lately,

and fed by new colonies from the North, were still heathen and

Danish some while after eastern Normandy had become Christian

and French-speaking. Now we may be sure that, long before

William's day, all Normandy was Christian, but it is quite

possible that the old tongue may have lingered on in the

western lands. At any rate there was a wide difference in

spirit and feeling between the more French and the more Danish

districts, to say nothing of Bayeux, where, before the Normans

came, there had been a Saxon settlement. One part of the duchy

in short was altogether Romance in speech and manners, while

more or less of Teutonic character still clave to the other.

So now Teutonic Normandy rose against Duke William, and

Romance Normandy was faithful to him. The nobles of the Bessin

and Cotentin made league with William's cousin Guy of

Burgundy, meaning, as far as one can see, to make Guy Duke of

Rouen and Evreux, and to have no lord at all for themselves. …

When the rebellion broke out, William was among them at

Valognes, and they tried to seize him. But his fool warned him

in the night; he rode for his life, and got safe to his own

Falaise. All eastern Normandy was loyal; but William doubted

whether he could by himself overcome so strong an array of

rebels. So he went to Poissy, between Rouen and Paris, and

asked his lord King Henry [of France] to help him. So King

Henry came with a French army; and the French and those whom

we may call the French Normans met the Teutonic Normans in

battle at Val-ès-dunes, not far from Caen. It was William's

first pitched battle," and he won a decisive victory. "He was

now fully master of his own duchy; and the battle of

Val-ès-dunes finally fixed that Normandy should take its

character from Romance Rouen and not from Teutonic Bayeux.

William had in short overcome Saxons and Danes in Gaul before

he came to overcome them in Britain. He had to conquer his own

Normandy before he could conquer England. … But before long

King Henry got jealous of William's power, and he was now

always ready to give help to any Norman rebels. … And the

other neighbouring princes were jealous of him as well as the

King. His neighbours in Britanny, Anjou, Chartres, and

Ponthieu, were all against him. But the great Duke was able to

hold his own against them all, and before long to make a great

addition to his dominions." Between 1053 and 1058 the French

King invaded Normandy three times and suffered defeat on every

occasion. In 1063 Duke William invaded the county of Maine,

and reduced it to entire submission. "From this time he ruled

over Maine as well as over Normandy," although its people were

often in revolt. "The conquest of Maine raised William's power

and fame to a higher pitch than it reached at any other time

before his conquest of England."

E. A. Freeman,

Short History of the Norman Conquest,

chapter 4.

ALSO IN:

E. A. Freeman,

History of the Norman Conquest,

chapter 8.

Sir F. Palgrave,

History of Normandy and England,

book 2, chapter 4.

{2366}

NORMANDY: A. D. 1066.

Duke William becomes King of England.

See ENGLAND: A. D. 1042-1066; 1066; and 1066-1071.

NORMANDY: . D. 1087-1135.

Under Duke Robert and Henry Beauclerc.

See ENGLAND: A. D. 1087-1135.

NORMANDY: A. D. 1096.

The Crusade of Duke Robert.

See CRUSADES: A. D. 1096-1099.

NORMANDY: A. D. 1203-1205.

Wrested from England and restored to France.

See FRANCE: A. D. 1180-1224;

and ENGLAND: A. D. 1205.

NORMANDY: A. D. 1419.

Conquest by Henry V. of England.

See FRANCE: A. D. 1417-1422.

NORMANDY: A. D. 1449.

Recovery from the English.

See FRANCE: A. D. 1431-1453.

NORMANDY: 16th Century.

Spread of the Reformation.

Strength of Protestantism.

See FRANCE: A. D. 1559-1561.

----------NORMANS: Start--------

NORMANS.

NORTH MEN:

Name and Origin.

"The northern pirates, variously called Danes or Normans,

according as they came from the islands of the Baltic Sea or

the coast of Norway, … descended from the same primitive race

with the Anglo-Saxons and the Franks; their language had roots

identical with the idioms of these two nations: but this token

of an ancient fraternity did not preserve from their hostile

incursions either Saxon Britain or Frankish Gaul, nor even the

territory beyond the Rhine, then exclusively inhabited by

Germanic tribes. The conversion of the southern Teutons to the

Christian faith had broken all bond of fraternity between them

and the Teutons of the north. In the 9th century the man of

the north still gloried in the title of son of Odin, and

treated as bastards and apostates the Germans who had become

children of the church. … A sort of religious and patriotic

fanaticism was thus combined in the Scandinavian with the

fiery impulsiveness of their character, and an insatiable

thirst for gain. They shed with joy the blood of the priests,

were especially delighted at pillaging the churches, and

stabled their horses in the chapels of the palaces. … In three

days, with an east wind, the fleets of Denmark and Norway,

two-sailed vessels, reached the south of Britain. The soldiers

of each fleet obeyed in general one chief, whose vessel was

distinguished from the rest by some particular ornament. … All

equal under such a chief, bearing lightly their voluntary

submission and the weight of their mailed armour, which they

promised themselves soon to exchange for an equal weight of

gold, the Danish pirates pursued the 'road of the swans,' as

their ancient national poetry expressed it. Sometimes they

coasted along the shore, and laid wait for the enemy in the

straits, the bays, and smaller anchorages, which procured them

the surname of Vikings, or 'children of the creeks'; sometimes

they dashed in pursuit of their prey across the ocean."

A. Thierry,

Conquest of England by the Normans,

book 2 (volume 1).

ALSO IN:

T. Carlyle,

The Early Kings of Norway.

NORMANS: 8-9th Centuries.

The Vikings and what sent them to sea.

"No race of the ancient or modern world have ever taken to the

sea with such heartiness as the Northmen. The great cause

which filled the waters of Western Europe with their barks was

that consolidation and centralization of the kingly power all

over Europe which followed after the days of Charlemagne, and

which put a stop to those great invasions and migrations by

land which had lasted for centuries. Before that time the

north and east of Europe, pressed from behind by other

nationalities, and growing straitened within their own bounds,

threw off from time to time bands of emigrants which gathered

force as they slowly marched along, until they appeared in the

west as a fresh wave of the barbarian flood. As soon as the

west, recruited from the very source whence the invaders came,

had gained strength enough to set them at defiance, which

happened in the time of Charlemagne, these invasions by land

ceased after a series of bloody defeats, and the north had to

look for another outlet for the force which it was unable to

support at home. Nor was the north itself slow to follow

Charlemagne's example. Harold Fairhair, no inapt disciple of

the great emperor, subdued the petty kings in Norway one after

another, and made himself supreme king. At the same time he

invaded the rights of the old freeman, and by taxes and tolls

laid on his allodial holding drove him into exile. We have

thus the old outlet cut off and a new cause for emigration

added. No doubt the Northmen even then had long been used to

struggle with the sea, and sea-roving was the calling of the

brave, but the two causes we have named gave it a great

impulse just at the beginning of the tenth century, and many a

freeman who would have joined the host of some famous leader

by land, or have lived on a little king at home, now sought

the waves as a birthright of which no king could rob him.

Either alone, or as the follower of some sea-king, whose realm

was the sea's wide wastes, he went out year after year, and

thus won fame and wealth. The name given to this pursuit was

Viking, a word which is in no way akin to king. It is derived

from 'Vik,' a bay or creek, because these sea-rovers lay

moored in bays and creeks on the look-out for merchant ships;

the 'ing' is a well known ending, meaning, in this case,

occupation or calling. Such a sea-rover was called 'Vikingr,'

and at one time or another in his life almost every man of

note in the North had taken to the sea and lived a Viking

life."

G. W. Dasent,

Story of Burnt Njal,

volume 2, appendix.

"Western viking expeditions have hitherto been ascribed to

Danes and Norwegians exclusively. Renewed investigations

reveal, however, that Swedes shared widely in these

achievements, notably in the acquisition of England, and that,

among other famous conquerors, Rolf, the founder of the

Anglo-Norman dynasty, issued from their country. … Norwegians,

like Swedes, were, in truth, merged in the terms Northmen and

Danes, both of which were general to all Scandinavians abroad.

… The curlier conversion of the Danes to Christianity and

their more immediate contact with Germany account for the

frequent application of their name to all Scandinavians."

W. Roos,

The Swedish Part in the Viking Expeditions

(English History Review, April, 1892).

ALSO IN:

S. Laing,

Preliminary Dissertation to Heimskringla.

C. F. Keary,

The Vikings of Western Christendom,

chapter 5.

P. B. Du Chaillu,

The Viking Age.

See, also, SCANDINAVIAN STATES.

{2367}

NORMANS: 8-9th Centuries.

The island empire of the Vikings.

We have hitherto treated the Norwegians, Swedes, and Danes

under the common appellation of Northmen; and this is in many

ways the most convenient, for it is often impossible to decide

the nationality of the individual settlement. Indeed, it would

appear probable that the devastating bands were often composed

indiscriminately of the several nationalities. Still, in

tracing the history of their conquests, we may lay it down as

a general rule that England was the exclusive prey of the

Danes; that Scotland and the islands to the north as far as

Iceland, and to the south as far as Anglesea and Ireland, fell

to the Norwegians, and Russia to the Swedes; while Gaul and

Germany were equally the spoil of the Norwegians and the

Danes. … While England had been overcome by the Danes, the

Norwegians had turned their attention chiefly to the north of

the British Isles and the islands of the West. Their

settlements naturally fell into three divisions, which tally

with their geographical position.

1. The Orkneys and Shetlands, lying to the N. E. of Scotland.

2. The isles to the west as far south as Ireland.

3. Iceland and the Faroe Isles.

The Orkneys and Shetlands: Here the Northmen first appear as

early as the end of the 8th century, and a few peaceful

settlements were made by those who were anxious to escape from

the noisy scenes which distracted their northern country. In

the reign of Harald Harfagr [the Fairhaired] they assumed new

importance, and their character is changed. Many of those

driven out by Harald sought a refuge here, and betaking

themselves to piracy periodically infested the Norwegian coast

in revenge for their defeat and expulsion. These ravages

seriously disturbing the peace of his newly acquired kingdom,

Harald fitted out an expedition and devoted a whole summer to

conquering the Vikings and extirpating the brood of pirates.

The country being gained, he offered it to his chief adviser,

Rögnwald, Jarl of Möri in Norway, father of Rollo of Normandy,

who, though refusing to go himself, held it during his life as

a family possession, and sent Sigurd, his brother, there. …

Rögnwald next sent his son Einar, and from his time [A. D.

875] we may date the final establishment of the Jarls of

Orkney, who henceforth owe a nominal allegiance to the King of

Norway. … The close of the 8th century also saw the

commencement of the incursions of the Northmen in the west of

Scotland, and the Western Isles soon became a favourite resort

of the Vikings. In the Keltic annals these unwelcome visitors

had gained the name of Fingall, 'the white strangers,' from

the fairness of their complexion; and Dugall, the black

strangers, probably from the iron coats of mail worn by their

chiefs. … By the end of the 9th century a sort of naval empire

had arisen, consisting of the Hebrides, parts of the western

coasts of Scotland, especially the modern Argyllshire, Man,

Anglesea, and the eastern shores of Ireland. This empire was

under a line of sovereigns who called themselves the Hy-Ivar

(grandsons of Ivar), and lived now in Man, now in Dublin.

Thence they often joined their kinsmen in their attacks on

England, and at times aspired to the position of Jarls of the

Danish Northumbria."

A. H. Johnson,

The Normans in Europe,

chapter 2.

"Under the government of these Norwegian princes [the Hy Ivar]

the Isles appear to have been very flourishing. They were

crowded with people; the arts were cultivated, and

manufactures were carried to a degree of perfection which was

then thought excellence. This comparatively advanced state of

society in these remote isles may be ascribed partly to the

influence and instructions of the Irish clergy, who were

established all over the island before the arrival of the

Norwegians, and possessed as much learning as was in those

ages to be found in any part of Europe, except Constantinople

and Rome; and partly to the arrival of great numbers of the

provincial Britons flying to them as an asylum when their

country was ravaged by the Saxons, and carrying with them the

remains of the science, manufactures, and wealth introduced

among them by their Roman masters. Neither were the Norwegians

themselves in those ages destitute of a considerable portion

of learning and of skill in the useful arts, in navigation,

fisheries, and manufactures; nor were they in any respect such

barbarians as those who know them only by the declamations of

the early English writers may be apt to suppose them. The

principal source of their wealth was piracy, then esteemed an

honourable profession, in the exercise of which these

islanders laid all the maritime countries of the west part of

Europe under heavy contributions."

D. Macpherson,

Geographical Illustrations of Scottish History

(Quoted by J. H. Burton, History of Scotland,

chapter 15, volume 2, foot-note).

See, also,

IRELAND: 9-10TH CENTURIES.

NORMANS: A. D. 787-880.

The so-called Danish invasions and settlements in England.

"In our own English chronicles, 'Dena' or Dane is used as the

common term for all the Scandinavian invaders of Britain,

though not including the Swedes, who took no part in the

attack, while Northman generally means 'man of Norway.' Asser

however uses the words as synonymous, 'Nordmanni sive Dani.'

Across the channel 'Northman' was the general name for the

pirates, and 'Dane' would usually mean a pirate from Denmark.

The distinction however is partly a chronological one; as,

owing to the late appearance of the Danes in the middle of the

ninth century, and the prominent part they then took in the

general Wiking movement, their name tended from that time to

narrow the area of the earlier term of 'Nordmanni.'"

J. R. Green,

The Conquest of England,

page 68, foot-note.

Prof. Freeman divides the Danish invasions of England into

three periods:

1. The period of merely plundering incursions, which

began A. D. 787.

2. The period of actual occupation and settlement, from 866 to

the Peace of Wedmore, 880.

3. The later period of conquest, within which England was

governed by Danish kings, A. D. 980-1042.

See ENGLAND: A. D. 855-880.

ALSO IN:

C. F. Keary,

The Vikings in Western Christendom,

chapters 6 and 12.

NORMANS: A. D. 841.

First expedition up the Seine.

In May, A. D. 841, the Seine was entered for the first time by

a fleet of Norse pirates, whose depredations in France had

been previously confined to the coasts. The expedition was

commanded by a chief named Osker, whose plans appear to have

been well laid. He led his pirates straight to the rich city

of Rouen, never suffering them to slacken oar or sail, or to

touch the tempting country through which they passed, until

the great prize was struck. "The city was fired and plundered.

Defence was wholly impracticable, and great slaughter ensued.

… Osker's three days' occupation of Rouen was remuneratingly

successful.

{2368}

Their vessels loaded with spoil and captives, gentle and

simple, clerks, merchants, citizens, soldiers, peasants, nuns,

dames, damsels, the Danes dropped down the Seine, to complete

their devastation on the shores. … The Danes then quitted the

Seine; having formed their plans for renewing the encouraging

enterprize,—another time they would do more. Normandy dates

from Osker's three days' occupation Of Rouen."

Sir F. Palgrave,

History of Normandy and England,

book 1, chapter 2 (volume 1).

ALSO IN:

C. F. Keary,

The Vikings in Western Christendom,

chapter 9.

NORMANS: A. D. 845-861.

Repeated ravages in the Seine.

Paris thrice sacked.

See PARIS; A. D. 845; and 857-861.

NORMANS: A. D. 849-860.

The career of Hasting.

"About the year of Alfred's birth [849] they laid siege to

Tours, from which they were repulsed by the gallantry of the

citizens, assisted by the miraculous aid of Saint Martin. It

is at this siege that Hasting first appears as a leader. His

birth is uncertain. In some accounts he is said to have been

the son of a peasant of Troyes, the capital of Champagne, and

to have forsworn his faith, and joined the Danes in his early

youth, from an inherent lust of battle and plunder. In others

he is called the son of the jarl Atte. But, whatever his

origin, by the middle of the century he had established his

title to lead the Northern hordes in those fierce forays which

helped to shatter the Carlovingian Empire to fragments. … When

the land was bare, leaving the despoiled provinces he again

put to sea, and, sailing southwards still, pushed up the Tagus

and Guadalquiver, and ravaged the neighbourhoods of Lisbon and

Seville. But no settlement in Spain was possible at this time.

The Peninsula had lately had for Caliph Abdalrahman the

Second, called El Mouzaffer, 'The Victorious,' and the vigour

of his rule had made the Arabian kingdom in Spain the most

efficient power for defence in Europe. Hasting soon recoiled

from the Spanish coasts, and returned to his old haunts. The

leaders of the Danes in England, the Sidrocs and Hinguar and

Hubba, had, as we have seen, a special delight in the

destruction of churches and monasteries, mingling a fierce

religious fanaticism with their thirst for battle and plunder.

This exceeding bitterness of the Northmen may be fairly laid

in great measure to the account of the thirty years of

proselytising warfare, which Charlemagne had waged in Saxony,

and along all the northern frontier of his empire. … Hasting

seems to have been filled with a double portion of this

spirit, which he had indulged throughout his career in the

most inveterate hatred to priests and holy places. It was

probably this, coupled with a certain weariness—commonplace

murder and sacrilege having grown tame, and lost their

charm—which incited him to the most daring of all his

exploits, a direct attack on the head of Christendom, and the

sacred city. Hasting then, about the year 860, planned an

attack on Rome, and the proposal was well received by his

followers. Sailing again round Spain, and pillaging on their

way both on the Spanish and Moorish coasts, they entered the

Mediterranean, and, steering for Italy, landed in the bay of

Spezzia, near the town of Luna. Luna was the place where the

great quarries of the Carrara marble had been worked ever

since the times of the Cæsars. The city itself was, it is

said, in great part built of white marble, and the 'candentia

mœnia Lunæ' deceived Hasting into the belief that he was

actually before Rome; so he sat down before the town which he

had failed to surprise. The hope of taking it by assault was

soon abandoned, but Hasting obtained his end by guile. … The

priests were massacred, the gates thrown open, and the city

taken and spoiled. Luna never recovered its old prosperity

after the raid of the Northmen, and in Dante's time had fallen

into utter decay. But Hasting's career in Italy ended with the

sack of Luna; and, giving up all hope of attacking Rome, he

re-embarked with the spoil of the town, the most beautiful of

the women, and all the youths who could be used as soldiers or

rowers. His fleet was, wrecked on the south coasts of France

on its return westward, and all the spoil lost; but the devil

had work yet for Hasting and his men, who got ashore in

sufficient numbers to recompense themselves for their losses

by the plunder of Provence."

T. Hughes,

Alfred the Great,

chapter 20.

NORMANS: A. D. 860-1100.

The discovery and settlement of Iceland.

Development of the Saga literature.

The discovery of Iceland is attributed to a famous Norse

Viking named Naddodd, and dated in 860, at the beginning of

the reign, in Norway, of Harald Haarfager, who drove out so

many adventurers, to seek fortune on the seas. He is said to

have called it Snowland; but others who came to the cold

island in 870 gave it the harsher name which it still bears.

"Within sixty years after the first settlement by the Northmen

the whole was inhabited; and, writes Uno Von Troil (p. 64),

'King Harold, who did not contribute a little towards it by

his tyrannical treatment of the petty kings and lords in

Norway, was obliged at last to issue an order, that no one

should sail to Iceland without paying four ounces of fine

silver to the Crown, in order to stop those continual

emigrations which weakened his kingdom.' … Before the tenth

century had reached its half-way period, the Norwegians had

fully peopled the island with not less, perhaps, than 50,000

souls. A census taken about A. D. 1100 numbered the franklins

who had to pay Thing-tax at 4,500, without including cotters

and proletarians."

R. F. Burton,

Ultima Thule, introduction,

section 3 (volume 1).

"About sixty years after the first settlement of the island, a

step was taken towards turning Iceland into a commonwealth,

and giving the whole island a legal constitution; and though

we are ignorant of the immediate cause which led to this, we

know enough of the state of things in the island to feel sure,

that it could only have been with the common consent of the

great chiefs, who, as Priests, presided over the various local

Things.

See THING.

The first, want was a man who could make a code of laws." The

man was found in one Ulfljót, who came from a Norwegian family

long famous for knowledge of the customary law, and who was

sent to the mother country to consult the wisest of his kin.

"Three years he stayed abroad; and when he returned, the

chiefs, who, no doubt, day by day felt more strongly the need

of a common centre of action as well as of a common code, lost

no time in carrying out their scheme. … The time of the annual

meeting was fixed at first for the middle of the month of June,

but in the year 999 it was agreed to meet a week later, and

the Althing then met when ten full weeks of summer had passed.

{2369}

It lasted fourteen days. … In its legal capacity it [the

Althing] was both a deliberative and executive assembly; both

Parliament and High Court of Justice in one. … With the

establishment of the Althing we have for the first time a

Commonwealth in Iceland."

G. W. Dasent,

The Story of Burnt Njal,

introduction (volume 1).

"The reason why Iceland, which was destitute of inhabitants at

the time of its discovery, about the middle of the 9th

century, became so rapidly settled and secured so eminent a

position in the world's history and literature, must be sought

in the events which took place in Norway at the time when

Harald Hárfragi (Fairhair), after a long and obstinate

resistance, succeeded in usurping the monarchical power. … The

people who emigrated to Iceland were for the most part the

flower of the nation. They went especially from the west coast

of Norway, where the peculiar Norse spirit had been most

perfectly developed. Men of the noblest birth in Norway set

out with their families and followers to find a home where

they might be as free and independent as their fathers had

been before them. No wonder then that they took with them the

cream of the ancient culture of the fatherland. … Toward the

end of the 11th century it is expressly stated that many of

the chiefs were so learned that they with perfect propriety

might have been ordained to the priesthood [Christianity

having been formally adopted by the Althing in the year 1000],

and in the 12th century there were, in addition to those to be

found in the cloisters, several private libraries in the

island. On the other hand, secular culture, knowledge of law

and history, and of the skaldic art, were, so to speak, common

property. And thus, when the means for committing a literature

to writing were at hand, the highly developed popular taste

for history gave the literature the direction which it

afterward maintained. The fact is, there really existed a

whole literature which was merely waiting to be put in

writing. … Many causes contributed toward making the

Icelanders preeminently a historical people. The settlers were

men of noble birth, who were proud to trace their descent from

kings and heroes of antiquity, nay, even from the gods

themselves, and we do not therefore wonder that they