"A dimple will be a great handicap in my life."

Title: The Crucible

Author: Mark Lee Luther

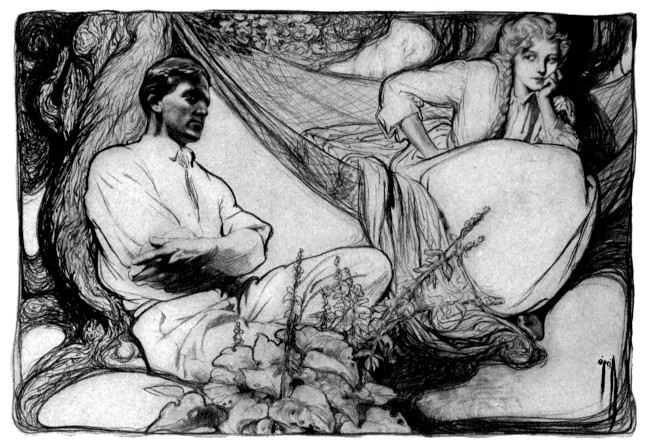

Illustrator: Rose Cecil O'Neill

Release date: August 17, 2022 [eBook #68775]

Most recently updated: October 19, 2024

Language: English, Spanish

Original publication: United States: The Macmillan Company, 1907

Credits: Carlos Colon, Mary Meehan, the University of California and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

Author of "The Henchman," "The Mastery,"

etc., etc.

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS BY

ROSE CECIL O'NEILL

New York

THE MACMILLAN COMPANY

1907

All rights reserved

Copyright, 1907,

By INTERNATIONAL MAGAZINE COMPANY.

Copyright, 1907,

By THE MACMILLAN COMPANY.

Set up and electrotyped. Published October, 1907.

Norwood Press

J. S. Cushing Co.—Berwick & Smith Co.

Norwood, Mass., U.S.A.

THE MACMILLAN COMPANY

NEW YORK - BOSTON - CHICAGO

ATLANTA - SAN FRANCISCO

MACMILLAN & CO., Limited

LONDON - BOMBAY - CALCUTTA - MELBOURNE

THE MACMILLAN CO. OF CANADA, Ltd.

TORONTO

To

E. M. R.

AN OPTIMIST

I

The girl heard the key rasp in the lock and the door open, but she did not turn.

"When I enter the room, rise," directed an even voice.

The new inmate obeyed disdainfully. The superintendent, a middle-aged woman of precise bearing and crisp accent, took possession of the one chair, and flattened a note-book across an angular knee.

"Is Jean Fanshaw your full name?" she began.

"I'm called Jack."

"Jack!" The descending pencil paused disapprovingly in mid-air. "You were committed to the refuge as Jean."

"Everybody calls me Jack," persisted the girl shortly—"everybody."

"Does your mother?"

Her face clouded. "No," she admitted; "but my father did. He began it, and I like it. Why isn't it as good as Jean? Both come from John."

"It is not womanly," said Miss Blair, as one having authority. "Women of refinement don't adopt men's names."

"How about George Eliot?" Jean promptly countered. "And that other George—the French woman?"

The superintendent battled to mask her astonishment. Case-hardened by a dozen years' close contact with moral perverts, budding criminals, and the half-insane, she plumed herself that she was not easily taken off her guard. But the unexpected had befallen. The newcomer had given her a sensation, and moreover she knew it. Jean Fanshaw's dark eyes exulted insolently in her victory.

Miss Blair took formal refuge in her notes. "Birthplace?" she continued.

"Shawnee Springs."

"Age?"

"Seventeen, two months ago—September tenth."

The official jotted "American" under the heading of nationality, and said,—

"Where were your parents born?"

"Father hailed from the South—from Virginia." Her face lighted curiously. "His people once owned slaves."

"And your mother?"

The girl's interest in her ancestry flagged. "Pure Shawnee Springs." She flung off the characterization with scorn. "Pure, unadulterated Shawnee Springs."

But the superintendent was now on the alert for the unexpected. "I want plain answers," she admonished. "What has been your religious training?"

"Mixed. Father was an Episcopalian, I think, but he wasn't much of a churchgoer; he preferred the woods. Mother's a Baptist."

"And you?"

"I don't know what I am. I guess God isn't interested in my case."

The official retreated upon her final routine question.

"Education?"

"I was in my last year at high school when"—her cheek flamed—"when this happened."

Miss Blair construed the flush as a hopeful sign. "You may sit down, Jean," she said, indicating the narrow iron bed. "Let me see your knitting."

The girl handed over the task work which had made isolation doubly odious.

The superintendent pursed her thin lips.

"Have you never set up a stocking before?" she asked.

"No."

"Can you sew?"

"No."

"Or cook?"

"No."

"'No, Miss Blair,' would be more courteous. Have you been taught any form of housework whatsoever?"

Jean looked her fathomless contempt. "We kept help for such drudgery," she explained briefly.

"You must learn, then. They are things which every woman should know."

"I don't care to learn the things every woman should know. I hate women's work. I hate women, too, and their namby-pamby ways. I'd give ten years of my life to be a man."

Her listener contrasted Jean Fanshaw's person with her ideas. Even the flesh-mortifying, blue-and-white-check uniform of the refuge became the girl. Immature in outline, she was opulent in promise. Her features held no hint of masculinity; the mouth, chin, eyes—above all, the defiant eyes—were hopelessly feminine. Miss Blair's own pale glance returned again and again upon those eyes. They made her think of pools which forest leaves have dyed. The brows were brown, too, and delicately lined, but the thick rope of hair, which fell quite to the girl's hips, was fair. The other woman touched the splendid braid covetously.

"You can't escape your sex," she said. "Don't try."

"But I wasn't meant for a girl. They didn't want one when I was born. They'd had one girl, my sister Amelia, and they counted on a boy. They felt sure of it. Why, they'd even picked out his name. It was to be John, after my father. Then I came."

"Nature knew best."

Jean gave a mirthless laugh. "Nature made a botch," she retorted. "What business has a boy with the body of a girl?"

The superintendent lost patience. "You must rid yourself of this nonsense," she declared firmly, and said again, "You can't escape your sex."

"I will if I can."

"But why?"

"Because this is a man's world. Because I mean to do the things men do."

"For some little time to come you'll occupy yourself with the things women do."

Jean's long fingers clenched at the reminder. The hot color flooded back. "Oh, the shame of it!" she cried passionately. "The wicked injustice of it!"

"You did wrong. This is your punishment."

"My punishment!" flashed the girl. "My punishment! Could they punish me in no other way than this? Am I a Stella Wilkes, a common creature of the streets, who—"

The superintendent raised her hand. "Don't go into that," she warned peremptorily. "If you knew Stella Wilkes in Shawnee Springs—"

"I know her!"

"Don't interrupt me. I repeat, if you know anything of Stella's record, keep it to yourself. A girl turns over a new leaf when she enters here. Her past is behind her. And let me caution you personally not to speak of your life to any one but myself. Remember that. Make confidences to no one—not even the matrons—to no one except me."

Jean searched the enigmatic face hungrily. "I doubt if you'd care to listen," she stated simply; "or whether, if you did listen, you'd believe!"

Something in her tone penetrated Miss Blair's official crust. "My dear!" she protested.

The girl was silent a moment. Then, point-blank, "Do you think a mother can hate her child?" she asked.

The superintendent, by virtue of her office, felt constrained to take up the cudgels for humanity. "Of course not," she responded.

"My mother hates me sometimes."

"Nonsense!"

"At other times it's only dislike," Jean went on impassively. "It's always been so. Dad got over the fact that I was a girl. He said he would call me his boy, anyhow. That's where the 'Jack' came from. But mother—she was different. I dare say if I'd been all girl, like Amelia, she could have stood me. She was forever holding up Amelia as a pattern. Amelia would get a hundred per cent. in that quiz you put me through. Amelia can sew; Amelia can embroider; Amelia can make tea-biscuit and angel-cake."

"And what were you doing while your sister was improving her opportunities?"

"Improving mine," came back Jean, with conviction. "Why didn't you ask me if I could swim, and box, and shoot, and hold my own with a gamy pickerel or trout?"

"Did your father teach you those things?"

"Some of them."

"And to affect mannish clothes, and smoke cigarettes with your feet on the table?"

Jean flaunted an unregenerate grin. "You've heard more than you let on, I guess. But you wouldn't have asked that last question if you'd known him. He wasn't that sort. I did those things after—after he went. I didn't really care for the cigarettes; I mainly wanted to shock that sheep, Amelia. Besides, I only smoked in my own room. I had a bully room—all posters and foils and guns. That reminds me," she added, with a quick change of tone. "That woman who comes in here—the matron—took something of mine. I want it back."

"What was it?"

"A little clay bust my father made."

"Was he a sculptor?"

"No, a druggist; but he could model. You'll make her give it back?"

"Is it the likeness of a man?"

"Yes, of dad."

"The matron was right. We allow no men's pictures in the girls' rooms, and the rule would apply here."

Incredulity, resentment, impotent anger drove in rapid sequence across the too mobile face. "But it's dad!" she cried. "Why, he did it for me! I never had a picture. Don't keep it from me; it's only dad."

The official shook her head in stanch conviction of the sacredness of red tape. "The rule is for everybody. Furthermore, you must not refer to men in your letters home. If you make such references, they will be erased. Nor will they be permitted in any letter you may receive from your family."

"You'll read my letters?"

"Certainly."

Jean silently digested this fresh indignity. "Then I'll never write," she declared.

Miss Blair waived discussion. "Never mind about the rules now, my girl," she returned, not unkindly. "You will appreciate the reasons for them in time. Go on with your story. Tell me more of your home life."

"It wasn't a home—at least, not for me. I didn't fit into it anywhere after dad went. Mother couldn't understand me. She said I took after the Fanshaws, not her folks, the Tuttles. Thank heaven for that! I never understood her, it's certain. When she wasn't flint, she was mush. Her softness was all for Amelia, though. They were hand and glove in everything, and always lined up together in our family rows. I think that was at the bottom of half the trouble. If mother'd only let us girls scrap things out by ourselves, we'd have rubbed along somehow, and probably been better friends. But she couldn't do it. She had to take a hand for Saint Amelia, as a matter of course. I can't remember when it wasn't so, from the days when we fought over our toys till the last big rumpus of all."

"And that last affair?" prompted her inquisitor. "What led to it?"

"A box social."

"A box social!"

"Never heard of one? You're not country-bred, I guess. Shawnee Springs pretends to be awfully citified when the summer cottagers are in town, but it's rural enough the rest of the year. Box socials are all the rage. You see, the girls all bring boxes, packed with supper for two, which are auctioned off to the highest bidder. The fellows aren't supposed to know whose box they're buying. Anyhow, that's the theory. I thought it ought to be the practice, too, and when I found that Amelia had fixed things beforehand with Harry Fargo, I planned a little surprise by changing the wrapper. Harry bid in the box she signalled him to buy, and drew his own little sister for a partner. The man who bought Amelia's was a bald-headed old widower she couldn't bear. It wasn't much of a joke, I dare say, and Amelia couldn't see the point of it at all. She told me she hated me, right before Harry Fargo himself, and after we came home she followed me up to my room to say it again."

An unofficial smile tempered Miss Blair's austerity. "But go on," she said, with an access of formality by way of atonement for her lapse.

Jean's own quick-changing eyes gleamed over the memory of Amelia's undoing, but it was for an instant only. "It was a dear joke for me," she continued soberly. "Amelia was sore. She had a nasty way of saying things, for all her angel-food, and she hadn't lost her voice that night, I can assure you. I said I was sorry for playing her the trick, but she kept harping on it like a phonograph, and one of our regular shindies followed. It would have ended in talk, like all the rest, if mother hadn't chimed in, but when they both tuned up with the same old song about my being a hoiden and a family disgrace, why, I got mad myself, and told them to clear out. When they didn't budge, I grabbed a Cuban machete that a Rough Rider friend had given me, and went for them."

"What did you mean to do?"

"Only frighten them. I never knew till afterward that I'd really pinked Amelia's arm. Of course, I didn't mean to do anything like that. I swear it."

"And then?"

"Then mother lost her head completely. She tore shrieking downstairs, Amelia after her, and both of them took to the street. First I knew, in came the officer. The rest seems a kind of nightmare to me—the arrest, the station-house cell, the blundering old fool of a magistrate who sent me here. He said he'd had his eye on me for a long time, and that I was incorrigible. Incorrigible! What did he know about it? He couldn't even pronounce the word! What business has such a man with power to spoil a girl's life! He was only a seedy failure as a lawyer, and got his job through politics. That's what sent me here—politics! Mother never intended matters to go this far. I know she didn't, though she doesn't admit it. She wanted to frighten me, but things slipped out of her hands. Think of it! Three years among the Stella Wilkeses for a joke! My God, I can't believe it! I must be dreaming still."

The superintendent ransacked her stock of homilies for an adequate response, but nothing suggested itself. Jean Fanshaw's case refused to fit the routine pigeonholes. She could only remind the girl that it lay with herself to decide whether she would serve out her full term.

"It is possible to earn your parole in a year and a half, remember," she charged, rising. "Bear that constantly in mind."

Jean seemed not to hear. "The shame of it!" she repeated numbly. "The disgrace of it! I shall never live it down."

She brooded long at her window when her visitor had gone, her wrongs rankling afresh from their rehearsal. The two weeks' isolation had begun to tell upon the nerves which she had prided herself were of stoic fibre. Human companionship she did not want. She had not welcomed the superintendent's coming, nor the physician's before her; and, if contempt might slay, the drear files of her fellow-inmates which traversed the snow-bound paths below would have withered in their tracks. It was the open she craved, and the daily walks under the close surveillance of a taciturn matron had but whetted her great desire.

She had conned the desolate prospect till she felt she knew its every hateful inch. Yonder, at the head of the long quadrangle, was the administration building, whither Miss Blair had taken her precise way. Flanking the court, ran the red brick cottages—each a replica of its unlovely neighbor, offspring all of a single architectural indiscretion—one of which she supposed incuriously would house her in the lost years of her durance. Quite at the end, closing the group, loomed the prison, gaunt, iron-barred, sinister in the gathering dusk.

This last structure had come almost to seem a sensate creature, a grotesque, sprawling monster, with half-human lineaments which nightfall blurred and modelled. Now, as she watched, the central door, that formed its mouth, gaped wide and emitted one of the double files of erring femininity which were continually passing and repassing. She knew that there were degrees of badness here, and reasoned that these from the monster's jaws must be the more refractory, but they appeared to her no worse than the others. Indeed, as looks went, they were, on the whole, superior. She felt no pity for them, only measureless disgust—disgust for the brazen and the dispirited alike; all were despicable. Her pity was for herself that she must breathe the common air.

Hitherto she had not separated them one from the other. This time, however, she passed them in review—the hard, the vicious, the frankly animal, the merely weak; till, coming last of all upon a brunette face of garish good looks, she shrank abruptly from the window. For the first time since her arrival she glimpsed the girl whose name had been a byword in Shawnee Springs, the being who at once symbolized and made concrete to Jean the bald, terrible fact of her degradation. Till now she had gone through all things dry-eyed—manfully, as she would have chosen to say—but the sight of Stella Wilkes plumbed emotional deeps in the womanhood she would have forsworn, and she flung herself, sobbing, upon her bed.

II

So the little secretary found her. Miss Archer was born under a more benignant star than her superior, and habitually tried in such quiet ways as a wise grand vizier may to leaven the ruling autocracy with kindness. She told Jean that she had come to transfer her to the regular routine, bade her bathe her eyes, and made cheerful talk while she collected her few possessions. They crossed the quadrangle in the wintry dusk, turning in at a cottage near the prison just as Jean was gripped by the fear that the monster itself would engulf her.

At the door-sill she felt a hand slip into hers.

"Be willing, dearie, and seem as cheerful as you can," counseled her guide. "I'm anxious to have you make a good first impression here in Cottage No. 6. It's immensely important that you stand well with your matron. Everything depends upon it."

Jean melted before her friendliness.

"I wish I could be under you," she said impulsively. "This place wouldn't seem—what it is."

She framed this wish anew when she faced the matron herself in the bleak cleanliness of the hall. This person was a variant of the superintendent's impersonal type and a slavish plagiarist of her mannerisms. A bundle of prejudices, she believed herself dowered with superhuman impartiality; and now, in muddle-headed pursuit of this notion, she promptly decided that an offender so plainly superior to the average ought in the fitness of things to receive less consideration than the average. Jean accordingly went smarting to her room.

Happily she was given little time to think about it. The incessant round which, day in and day out, was to fill her waking hours, caught her into its mechanism. A querulous bell tapped somewhere, her door, in common with every one in the corridor, was unlocked, and she merged with a uniformed file which, without words, shuffled down two flights of stairs and ranged itself about the tables of a desolate dining-hall. Whereupon the matron, who had taken her station at a small table laid for herself and another black-garbed official, raised her thin voice and repeated,

"The eyes of all wait upon Thee, O Lord!"

An unintelligible mumbling followed, which by dint of strained listening at many ensuing meals Jean finally translated,

"And Thou givest them their meat in due season."

Thirty odd chairs forthwith scraped the bare floor. Thirty odd appetites attacked the food heaped in coarse earthenware upon the oilcloth. Jean fasted. Hash she despised; macaroni stood scarcely higher in her regard; while tea was an essentially feminine beverage which of principle she had long eschewed. This eliminated everything save bread, and it chanced that her share of this staple was of the maiden baking of a young person whose talents till lately had been exclusively devoted to picking pockets.

Jean surveyed the room. It shared the naked dreariness of the corridors; not a picture enlivened its terra-cotta wastes of wall. Another long table, twin in all respects to her own, occupied with hers the greater part of the floor space; but there remained room near the door for two smaller tables, the matron's, which she had remarked on entering, and one occupied by five favorites of fortune, whose uniform, though similar to the general in color, resembled a trained nurse's in its striping, and was further distinguished by white collars and cuffs. This table, like the matron's, was covered with a white cloth and boasted a small jardinière of ferns.

The matron's voice was again heard.

"You may talk now, girls," she announced. "Quietly, remember."

A score of tongues were instantly loosed. The newcomer was astounded. How had they the heart to speak? It was strange table-talk, curiously limited in range, straying little beyond the narrow confines of the reformatory world. A girl opposite said: "One year and five months more!" and set afoot a spirited comparison which crisscrossed the board from end to end and reached its climax in the enviable lot of her whose release was due in thirty-seven days. Jean observed that the head of the first speaker was lop-sided; its neighbor was narrow in the forehead; a third, two places beyond, had peculiar teeth. Nearly all, in fact, were stamped with some queerness, either natural or artificially imposed by an institutional régime wherein the graces of the toilet had no function.

The gossip took another tack, originating this time in some trivial happening in the gymnasium. Jean listened closely at a mention of basket-ball, but lost all interest when the talk veered fitfully to the sewing-school.

"Ain't you hungry?" said a voice at her side.

Jean rounded upon a girl perhaps a year her senior. Her tones were gentle, with a certain lisping appeal, and her face, if not strong, was neither abnormal nor coarse. Outside a refuge uniform she would readily pass as pretty.

"I couldn't stomach it myself, at the start," she went on, without waiting for an answer, "but I got used to it. We all do. Why, the days I work in the laundry I'm half starved."

Jean stared.

"They make you do laundry work!"

"Sure. We all take a turn. Everything on the place is done by the girls, you know—washing, cooking, tailoring, gardening, and a lot besides."

Her auditor relapsed into gloomy silence, a new horror added to her plight. At home, even the factotum they styled the hired girl had been exempt from washing. A strapping negress had come in Mondays for that.

"I'm next door to you upstairs," pursued the new acquaintance, in her deprecating way. "My name is Amy Jeffries. What's yours?"

She gave it after a moment's debate. The old beloved "Jack" was at the tip of her tongue, but she suddenly thought better of it. After all, "Jean" would answer for this place. She regretted that in lieu of Fanshaw she could not use Jones, or Smith, or—master stroke of irony—the abominated Tuttle.

"Jean Fanshaw's a nice name," commented Amy sociably.

Dreading further catechising, Jean struck in with a question of her own.

"Why have those girls over there a better uniform and a table to themselves?" she demanded.

"They're high grade."

"What does that mean?"

"Six months without a mark." Amy Jeffries cast a look of envy upon the group at the side table. "I'd like awfully to be high grade. It must seem like living again to sit down to a tablecloth. I should like the cuffs and collars, too. I just love dress. When I leave here I think I'll go into a dressmaking establishment, or a milliner's."

Jean was reminded of something.

"Tell me how I can get out of here in a year and a half," she requested. "Somebody said it could be done."

Amy smiled wanly.

"I wanted to know, too, when I was green. I could just see the guard holding the gate open as I sailed off the grounds! It was a beautiful dream."

"Why couldn't you do it?"

"Marks," said Amy sententiously. "Parole in eighteen months means a perfect record right from the beginning. I thought I'd try for it, but, mercy, I've never even made high grade! Once I came within six weeks of it, but I let a dress go down to the laundry with a pin in it."

"They mark for a little thing like that?"

"My stars, yes! For less than that—buttons off, wrong apron in the recreation-room, and so on. I got my first mark for wearing my hair 'pomp.' They won't stand for it here. They want to make us as hideous as they can."

A lull threw the remarks of the girl with peculiar teeth into unsought prominence.

"Jim was a swell-looker," she was saying, "and a good spender when he was flush, but I used to tell him—"

"Delia!" The matron was on her feet leveling a rebuking finger at Jim's biographer. "You know better. Leave the room at once. All talking will cease."

The culprit scuffed sulkily out, and no further word was uttered till the end of the meal, when at a signal all rose and the matron observed in pontifical tones,

"Thou openest Thy hand!"

On this occasion Jean caught the response without difficulty. The words, "And Thou fillest all things living with plenteousness," seemed to emanate chiefly from the high-grade table, with a faint echo on the part of Amy Jeffries, in whom the ambition to eat from a cloth still persisted. At "plenteousness" one bold spirit snickered.

The file tramped up the two flights by which it had come, and scattered to its rooms. For twenty minutes Jean sat in darkness and dejection. Then the fretful bell clamored again, the doors yawned as before, the silent ranks re-formed, and the march below stairs was repeated. Their destination proved to be the recreation-room. In a dwelling this chamber would have been shunned. Here, compared with such other parts of the cottage as Jean had seen, it seemed blithesome. Potted geraniums made grateful oases of the window-sills. An innocuous print or two hung upon the walls.

As the girls found seats, the matron handed Jean a letter.

"You will be allowed to answer it next week," she said. "All letter-writing is done upon the third Friday of the month."

The girl took the missive with burning face. The envelope was already slit. The letter itself had undergone inspection, and five whole lines had been expunged. But her anger at this tampering lost itself in the unspeakable bitterness which jaundiced her to the soul as she read. Better that they had blotted every syllable.

Jean: I hope this will find you reconciled to your cross, and resolved to lead a different life. After talking over this great affliction with our pastor, and taking it to the Throne of Grace in prayer, I have come to feel that His hand guides us in this, as in all things. I cannot understand why I have been so chastened, but I bow to the rod. If your father were alive, I should consider it a judgment upon him for his lax principles in religious matters. I never could comprehend his frivolous indifference. I am sure I spared no effort to bring him to a realizing sense of his impiety.

Amelia takes the same view that I do of all that has happened. She has not felt like going out, poor sensitive child, but.... (The hand of the censor lay heavy here. Jean readily inferred, however, that Amelia's retirement had its solace.) The first storm of the winter came yesterday. Snow is six inches deep on a level, and eggs are high.

Your devoted mother,

Marcia Fanshaw.

The matron was reading aloud from a novel which her audience found absorbing. Jean could give it no heed. What were the imaginary woes of Oliver Twist beside her actualities!

The hands of a bland-faced clock crept round to bedtime. The reader marked her place, and, after a moment's pause, began the first line of a familiar hymn. Jean hated hymn-singing out of church. It had depressed her even as a child, while later it evoked choking memories of her father's funeral. So she set her teeth till they made an end of it.

Suggestive also of her father and of vesper services to which they had sometimes gone together, after a Sunday in the fields, were the words presently repeated by the forlorn figures kneeling about her; but she heard them with mute lips and in passionate protest against their personal application. These tawdry creatures might confess that they had erred and strayed like lost sheep, if they would. She was not of their flock. The things she had left undone did not prick her conscience. The things which she ought not to have done were dwarfed to peccadillos by the vast disproportion of their punishment.

III

Life in a reformatory is an ordeal at its doubtful best. It approximated its noxious worst under the martinet whom Cottage No. 6 styled "the Holy Terror." The absolutism of the superintendent was at least founded on a sense of duty; her imitator's was based upon whim. Jean's chimera of parole after eighteen months was promptly dissipated. Disciplined at the outset for breaking a rule of which she was not aware, her obedience became thenceforth a captive's. Scrubwoman, laundress, seamstress, kitchen-drudge—all rôles in which fate, as embodied in the matron, cast her—were one in their odiousness. She slurred their doing where she could, and scorned all such meek spirits as curried favor by trying their best. At times only the fear of the prison deterred her from open mutiny.

She learned presently that there was an inferno lower even than the prison. One day, while clearing paths after a heavy snowfall, she saw a girl dragged past, handcuffed and struggling, her head muffled in the brown refuge shawl, but audibly and fluently blasphemous notwithstanding. Jean recognized Stella Wilkes.

Amy, who was working near, said in furtive undertone:

"I heard she'd cut loose again. She'll get all that's coming to her this time."

Jean eyed the nearest black-clad watcher before replying.

"But she's in prison, anyhow," she commented, with Amy's trick of the motionless lips. "She can't get much worse than she has already."

"Can't she, though! It's the guardhouse this trip."

Jean questioned and Amy answered till the matron's approach stopped communication. It was a lurid saga of the days before the state abolished corporal punishment, handed down with fresh embellishments from girl to girl. The air was full of such bizarre folk-lore, she discovered—tales of superintendents who failed to govern; of matrons, wise and foolish; of delirious riots and hairbreadth escapes. Amy Jeffries was always the channel which conveyed these legends to Jean's willing ears.

From all others Jean held herself aloof. Amy alone seemed a victim of injustice like herself. Jean invited no confidences, and made none; but bit by bit, as the winter passed, the story of this pretty moth, whose world, more than her pleasure-loving self, seemed out of joint, pieced itself together. It was a common story, too hackneyed to detail, though it signified the quintessence of tragedy to its narrator. Of itself, it struck no kindred chord in Jean. Its passions, its temptations, its sin were without glamour or reason; but she divined that nature, rather than Amy, had wrought this coil, and that, after the fashion of a topsy-turvy universe, one was again expiating the lapse of two.

The coming of spring at once brightened and embittered Jean's lot. Outdoor work was no hardship. She knew the times and seasons of all growing things; which soil was fattest; when plowshare, harrow, spade, and hoe should do their appointed parts; when the strawberry-beds should be stripped of their winter coverlets; when potatoes, shorn of their pallid cellar sprouts, should be quartered and dropped; when peas and green corn should be sown; when the drooping tomato plants should be set out and fostered; and she entered upon this dear toil with a zest which nothing indoors had inspired. But she knew also—and here was the pang—precisely what was transpiring out there in the forest which all but touched the refuge boundary. With a heartache she visualized the stir of shy life in pond and field and tree-top; caught in memory the scent of the first arbutus; spied out the earliest violet; beheld jack-in-the-pulpit unbar his shutter; saw the mandrake bear its apple, the ferns uncurl, the dogwood bloom.

The call of the woods rang most insistent when she lay in her iron cot at twilight, for bedtime still came as in the early nights of winter, at an hour when the play of the outside world had just begun. She could see the bit of forest from her narrow window, and in fancy made innumerable forays into its captivating depths with rod or gun. It was these imaginary outings, ending always behind locks and bars, which first set her thoughts coursing upon the idea of escape.

There were precedents galore. The undercurrent of reformatory gossip was rich in these picaresque adventures. But cleverly planned as some of them had been, daringly executed as were others, all save one ended in commonplace recapture. The exception enchained Jean's interest. Amy Jeffries had rehearsed the tale one day when the gardener, concerned with the ravages of an insect invasion of the distant currant bushes, left the lettuce-weeding squad to itself.

"I never knew Sophie Powell," Amy prefaced; "she skipped before I came. But they say she was something on your style—haughty-like and good at throwing a bluff. I heard that the men down at the gatehouse nicknamed her the 'Empress-out-of-a-job.' What she was sent here for, I can't say. She was as close-mouthed as you. Mind you, I'm not criticising. It's risky business, swapping life histories here. You're the only girl that's heard my story. If you never feel like telling me yours, all right. If you do, why, all right, too. I didn't mention names, and you needn't either. I wonder if he would do as much for me!"

Jean checkmated Amy's maneuver without ceremony.

"I've no man's name to hide," she returned bluntly. "But never mind that. It's Sophie Powell I want to hear about."

Amy took no offense.

"My," she laughed admiringly; "you are a riddle! Well, as I say, Sophie had a way with her, and knew how to play her cards. She got high grade within a year, and worked her matron for special privileges. The matron let her have the run of her room a good deal, for Sophie knew to a T just how she liked everything kept; and she wasn't over particular about locking Sophie's door, which was handy to her own. One spring night, earlier than this, I guess, for it was still dark at supper, she played up sick. She timed her spasm for an hour when the doctor was generally busy at the hospital, and let the matron fuss round with hot-water bags till the supper bell rang. Then the matron went downstairs, leaving the door open to give poor Sophie more air. As soon as she heard the dishes rattle, the invalid got busy. She hopped in next door, pinched the matron's best black skirt and a swell white silk shirt-waist she kept for special, grabbed a hat and veil and a long cloak out of the wardrobe and the big bunch of house-keys from a hiding-place she'd spotted, tip-toed downstairs and let herself out of the front door."

Jean drew a long breath.

"But the guards?" she put in.

"She only ran into one—the easy mark at the gate."

"The gate!"

"Sure. Sophie didn't propose to muss her new clothes climbing a ten-foot fence. She marched over to the gatehouse, bold as brass, handed in her keys as she'd seen the matrons do, and was out in no time. Why, the guard even tipped his hat—so he said before they fired him. That was the most comical thing about it all."

Jean threw a glance over her shoulder. The gardener was still beyond earshot.

"Go on," she said eagerly. "How did she manage outside? That's the part I want to hear."

"Then came smoother work still. Sophie hadn't a cent—she missed the matron's purse in her hurry—but she had her nerve along. She streaked it over into town, and asked her way to the priest who comes out here twice a month for confession. She banked on his not remembering her, for she wasn't one of his girls; and he didn't. His sight was poor, anyhow. Well, she told him she was a Catholic and a stranger in town, looking for work, and that she'd just had a telegram from home saying her mother was dying. She pumped up the tears in good style, and put it up to him to ante the car fare if he didn't want her heart to break. It didn't break."

Jean absently fashioned the moist earth beneath her fingers into the semblance of a priest's face, which she instantly obliterated when it stirred Amy's interest.

"Why couldn't they trace her?" she asked.

"Because she was too cute to stick to her train. She must have jumped the express when they slowed up for their first stop."

The fugitive bulked large in Jean's meditations. It occurred to her that possibly the needless rigor of her own treatment in Cottage No. 6 might originate in her chance resemblance to Sophie Powell. She wondered how it fared with the girl; whether she had had to make her way unbefriended; to what she had turned her hand. Was she perhaps living a blameless life, respected, loved, in all ways another personality, yet forever hag-ridden with the fear of recapture? She did not debate whether such freedom were worth its cost, for just then the pungent invitation of the woods was borne to her across the lettuce-rows.

A bit of refuse crystallized her resolve. She spied it toward the end of her day's toil—a large rusty nail half protruding from the loam—and knew it instantly for the tool which should compass her release. Her mind acted on its hint with extraordinary lucidity, and her fingers were scarcely less nimble. Not even Amy at her side saw her slip the treasure trove into the concealing masses of her hair. From that moment till the bolts were shot upon her for the night she was absorbed in her plans.

To duplicate Sophie Powell's exploit was, of course, out of the question. Her own door was never left unlocked; the Holy Terror's graceless clothes, for all practical uses, might as well hang in another planet; while even were these impossibilities surmounted, she could scarcely hope to hoodwink the men at the gate. She must secure a disguise somehow, but she cheerfully left that detail to chance. To escape was the main thing, and if by a rusty nail she might cross that bridge, surely she need borrow no trouble lest her wits desert her afterward.

A tedious-toned clock over in the town struck twelve before she dared begin her attempt. The watchman had just gone beneath her window on his hourly round, and with the cessation of his slow pace upon the gravel the peace of midnight overlay everything. For almost two hours thereafter Jean labored with her rude implement at the staples which held the woven-wire barrier before her window. The first staple came hardest, but she had pried it loose by the time the watch repassed. In a half-hour more she had freed enough of the netting to serve her end, but she deferred the great moment till the man should again have come and gone. It was a difficult wait, centuries long, and anxiety began to cheat and befool her reason. She questioned whether she had not lost count of time. Suppose she had let him come upon her unheeded! Suppose he had caught some hint of her employment! Suppose he were even now lurking, spider-like, in the shadows!

Then the clock struck twice in its deliberative way, the measured footfall recurred, and her brain cleared. Five minutes later she bent back the netting and calculated the distance to the ground. She judged it some sixteen or eighteen feet, all told, or a sheer drop of more than half that space as she would hang by her finger-tips. There could be no leaving a telltale rope of bedclothes to dangle. Such folly would set the telephone wires humming within the hour. She must drop, and drop with good judgment; since the grass plot, which she counted upon to break her fall, gave place directly below to an area, grated over to be sure, but undesirable footing notwithstanding.

She tossed her brown shawl to the ground first, and noted, with some oddly detached segment of her mind, that it spread itself on the sward in the shape of a huge bat. A romping girlhood steadying her nerves, she let herself cautiously over the sill, and for an instant hung motionless, her eyes below. Then, gathering momentum from a double swing, she suddenly relaxed her hold, cleared the danger-point, and alighted, uninjured and almost without sound, upon the springing turf.

IV

For a moment Jean crouched listening where she fell. No sound issuing from within, she caught up her shawl and stole quickly toward the point where she planned to scale the high fence which still shut her from freedom. There was no moon, but the night was luminous with starshine, and she hugged the shadows of the cottages. These buildings shouldered one another closely in most part, but she came presently to a gap in the friendly obscurity where a site awaited a structure for which the state had vouchsafed no funds. It was bare of any sort of screen whatever, and lay in full range not only of the quadrangle, which it broke, but of the gatehouse beyond.

Nor was this all. Drifting round the last sheltering corner came the reek of a pipe. Jean's heart sank. After all, the trap! Then second thought told her that a foe in ambush would not smoke, and she gathered courage to reconnoiter. Across the quadrangle she made out the motionless figure of the watch. He was plainly without suspicion. He had completed his circuit and was lounging against a hydrant, his idle gaze upon the stars.

So for cycling ages he sat. Yet but a quarter of an hour had lapsed when the man knocked the ashes from his pipe, yawned audibly, and turned upon his heel. The instant the door of the gatehouse swallowed him, Jean sped like a phantom across the open ground, skirted the hospital, the tool-sheds, and the hotbeds, and plunged into the recesses of the garden. All else was simple. The high fence had no terrors; her scaling-ladder was a piece of board. The asperities of the barbed wire she softened with her shawl. When the town clock brought forth its next languid announcement she heard it without a tremor. She was resting on a mossy slope a mile or more away.

She made but a brief halt, for the East, toward which she set her face, was already paling. It was no blind flight. She struck for the hills deliberately, since behind the hills ran the boundary of another commonwealth. All fellow-runaways, whose stories she knew, had foolishly held to the railroad or other main-traveled ways, and, barring the brilliant Sophie, had for that very reason come early to disaster. Jean reasoned that they were in all likelihood city girls whom the woods terrified. Their stupidity was incredible. To fear what they should love! She took great breaths of the cool fragrance. She could not get her fill of it.

Nevertheless, it was not yet her purpose to quit the tilled countryside utterly. She hoped first to compel clothing from it somehow—clothing, and then food, of which she began to feel the need. The fact that she must probably come unlawfully by these necessaries gave her slight compunction. In some rose-colored, prosperous future she could make anonymous amends. She haunted the outskirts of three several farmhouses, but without success. At none of them had garments of any kind been left outdoors over night. Some impossible rags fluttered from a scarecrow in a field of young corn; that was all. Things edible, too, were as carefully housed. Near the last place she found a spring with a tin cup beside it. She drank long, and took the cup away with her.

It was too light now for foraging, and Jean took up her eastward march, avoiding the highways and resorting to hedgerows, stone walls, or briers where the woods failed. As the day grew she saw farmhands pass to their work, and once, in the far distance, she caught the seductive glitter of a dinner pail. She was ravenous from her long fast, and nibbled at one or two palatable wild roots which she knew of old. They seemed savorless to-day, almost sickening in fact; and her fancy dwelt covetously upon the resources of orchard, garden, and field, that the next month but one would lavish. Nevertheless, she harbored no regret that she had taken time somewhat too eagerly by the forelock.

Noon found her beside a lake well up among the hills. She knew the region by hearsay. People came here in hot weather, she remembered. Somewhere alongshore should stand log-camps of a species which urban souls fondly thought pioneer, but which snugly neighbored a summer hotel where ice, newspapers, scandal, and like benefits of civilization could be had. These play houses were as yet tenantless, of course—and foodless; but the chance of finding some cast-off garment, possibly too antiquated for a departing summer girl, but precious beyond cloth of gold to a fugitive in blue-and-white check, buoyed Jean's spirits and lent fresh energy to her muscles. Equipped with another dress, be its style and color what they might, she felt that she could cope fearlessly with fate.

She had followed the vagrant shore-line for perhaps a mile when two things, assailing her senses simultaneously, brought her to an abrupt halt. One was the smell of frying bacon; the other was a baritone voice which broke suddenly into the chorus of a rollicking popular air. Jean wheeled for flight, but, beguiled by the bacon which just then wafted a fresh appeal, she turned, cautiously parted the undergrowth, and beheld a young man swaying in a hammock slung between two birch trees. He held in his lap a book into which he dipped infrequently, singing meanwhile; and his attention was further divided between the crackling spider and a fishing-rod propped in a forked stick at the water's edge. Jean viewed his methods with disapproval. It was neither the way to read, sing, fry bacon, nor yet fish.

Possibly some such idea suggested itself to this over versatile person, for he presently rolled out of the hammock and centered his talents upon the line, which he began to reel in as if the mechanism were an amusing novelty. The stern critic in the background perceived the hand of an amateur in the rebaiting, and predicted sorrier bungling still when he should essay the cast. Her gloomiest forebodings, however, fell far short of the amazing event. She expected the recklessly whirling lead to shoot somewhere into the foliage, but nothing prepared her for its sure descent upon herself. There was no disentangling that outlandish collection of hooks at short notice, and she did not try. But neither could she break the line. The bushes separated while she struggled, and a vast silence befell.

Jean straightened slowly.

"You're a prize angler," she said.

The young fellow's bewilderment gave way to an expansive smile.

"I quite agree with you," he admitted. "I ought to have a blue ribbon, or a pewter mug, or whatever they give the duffer who lands the biggest catch. Let me help you with those hooks. I hope they haven't torn your dress?"

Then the blue-and-white check drew him. The girl's eyes had held him first; next, her brows; afterward, her contrasting hair. The uniform compelled his gaze to significant details—the shawl, the coarse shoes, the fallen cup.

Jean flushed under his scrutiny, and brusquely declined his help.

"No, but let me," he urged, and so humbly that she relented.

"I know more about these things than you do," she said. "Do you know you're trying several kinds of fishing with one line?"

"Oh, yes," he smiled. "You see I haven't a notion what sort of fish frequent these waters, and fish vary a lot in their tastes. Some prefer worms, some have a cannibal appetite for minnows, and some, I believe, like a little bunch of colored feathers, which can't be very nourishing, I must say. I couldn't make up my mind which bait to use, and so I spread a kind of lunch-counter for all comers."

This was too much for Jean's gravity. The fisherman was unruffled by her laughter. In fact, he laughed with her.

"Is it so preposterous as all that?" he asked. "I didn't know but I'd hit on something new. This tackle doesn't belong to me; it's the other fellow's."

Jean's glance shot past him. The man saw and understood.

"We planned to camp together," he explained, "but a telegram overtook him on the train. It was highly inconsiderate in a mere great-grandmother to pick out just this time for her funeral. I look for him to-morrow or the day after."

Jean freed her dress at length and searched for her belongings. The young man stooped also. He was too late for the shawl, but gravely restored the tin cup. She thanked him, as gravely, and after a little pause added:—

"The least you can do is to say nothing."

"About seeing you?"

"Yes."

"You're from the other side of the county?"

"Yes."

"From the—" he hesitated.

"From the House of Refuge," stated Jean, looking him squarely in the face.

His own gaze was as direct.

"But not that sort," he commented softly, as if thinking aloud—"not that sort."

Jean, boy-like, offered her hand.

"Thank you," she said simply. "You're quite right. That's exactly why I'm running away. Good-by."

"Don't go!" He detained her hand, his face full of sympathy and perplexity. "I can't begin to tell you how sorry I am. It would be hard lines for a fellow, but when I see a girl"—his eyes added: "And such a girl!"—"roaming the country like a—a homeless—"

"Hobo?" supplied Jean.

He reddened guiltily.

"Hang it all!" he ended, "I can't stand it. You hit the nail on the head when you told me that the least I can do is to say nothing. But I trust that isn't all I can do. I want to help."

The girl's eyes misted.

"You have helped, you believe in me."

"Who wouldn't!" His bearing challenged the world.

"Several people. My family, for instance; most of the officials back there at the refuge. But never mind that."

"No," agreed her new champion. "Never mind that. Let's face the future, the practicalities."

Jean complied with despatch.

"Your bacon is burning," she announced.

He led the way to his camp, and together they surveyed the charred ruin in the spider. Jean could have devoured it as it lay.

"And it's my first warm meal," lamented the camper tragically—"my first warm meal after five days of canned stuff! The other fellow was to be cook as well as fisherman."

Jean promptly mastered the situation.

"Clean that spider while I slice more bacon," she directed, rolling up her sleeves. "If you have potatoes, wash about a dozen."

The victim of a canned diet flung himself blithely into the work, but halted suddenly, halfway to the water, and brandished the spider in air.

"Not a mouthful unless you'll eat too?" he stipulated.

Jean gave a happy laugh.

"Perhaps I can be pressed," she conceded.

With a facility which would have amazed the refuge, and with a secret pride in her new knowledge which she had little dreamed she could come to feel, Jean set the bacon and potatoes frying, evolved a plate of sandwiches from soda crackers and a tin of sardines, discovered a jar of olives which their owner had forgotten, and arranged the whole upon a box-cover laid with a napkin. Nor was this the sum of the miracle. She even garnished the meat with a handful of watercress which she spied and bade her admiring host gather in a neighboring brook.

They said little during the meal, for both were famished; but while they washed the dishes together by the shore Jean, under questioning, sketched the story of her flight. Her listener's ejaculations gained steadily in vigor, till ultimately, moved by a startling thought, he dropped the plate he was polishing.

"Look here!" he cried. "Have you had a wink of sleep?"

"I got in an hour about the middle of the forenoon."

"One hour out of thirty!"

"It was enough."

"I'll sling the hammock anywhere you say."

"I was never more wide awake. There are too many things to think out and plan."

"Take the hammock, anyhow," he urged. "You can plan and rest, too."

She let herself be so far persuaded, and he brought pillows from the tent. As she let herself relax, she first realized how weary she had become, and closed her eyes that she might taste the full luxury of rest. The rhythmic chuckle of the little brook where the watercress grew was ineffably soothing. It seemed almost articulate, an elfish voice to which the small waves, lapping the shore, played a delicate accompaniment. She dreamily fitted words to its chant, and presently, still smiling at the conceit, strayed quite into the delectable land where water-sprites are real, and beautiful impossibilities matter of fact.

The shadows had lengthened when she woke. Her companion sat with his back to a tree trunk as before, but she perceived that he had stretched a bit of canvas to screen her from the slanting sun.

"It was best all round," he said, as she sprang up reproachfully. "It did you good and gave me leisure to think. I felt sorrier than ever while you lay there, smiling and dimpling in your sleep, like a child."

"I despise that dimple," avowed Jean, disgustedly.

"You despise it!"

"It's so—so feminine."

"Of course it is; that is no reason for abusing it."

"I think it's a mighty good reason. A dimple will be a great handicap in my life."

"Great Jupiter!" said the young man softly. "Why, some girls I know would give—But we can't discuss dimples, just now, can we? What I began to say, before you took my breath away, was that I think I've solved the clothes problem. You know there's a town about ten miles to the north—the county seat—and it occurs to me that if I set out to-night, I can be back here early in the morning with everything you'll need. I don't believe they'll suspect me, even if they have happened to read that a refuge girl has escaped. I can buy the skirt in one store, the hat in another, and so on, pretending they're for my sister—or my wife."

Jean's refractory dimple deepened.

"Make it your mother," she advised. "Wives and sisters prefer to do their own shopping."

"Very well, then. If you will jot down the measurements and other technicalities, I'll manage it somehow. As for money," he added, perceiving her falter, "I will take care of that, too, if you'll allow me. You will naturally need a loan."

Jean swallowed a lump.

"You're a brick," she said huskily. "I'll pay you back with the first money I earn."

The brick received her praise with a change of color appropriate to his title.

"Any fellow would be—be glad to help, you know," he stammered. "And you needn't feel that you must hurry to pay up, either. Wait until you're well settled among your friends."

"My friends! I have none."

"No friends!" He stared blankly. "Of course I realized that you could hardly go back home, but I took it for granted that there must be some place—somebody—"

"There isn't."

He sat down abruptly, bewildered with the complexities which beset an apparently simple situation. Jean herself began to entertain some misgiving. For the moment his opinion epitomized the world's.

"Where do you mean to go?" he asked.

"Across the state line first; then to New York."

"New York!"

"Yes; to find work. Why do you stare as if I'd said Timbuctoo?"

"I'm from New York."

"Are you?" She brightened wonderfully. "Then you can tell me where to find work. I'm willing to do anything at the start, but by and by I want to get into some good business. Women are succeeding in business on all sides nowadays. Why do you look so hopeless? Don't you think I can get on?"

"How can I answer you! If there were only some woman to whom I might take you. I've a sister, but—"

"But she wouldn't understand?"

"No, she wouldn't understand. Neither do you understand," he went on anxiously. "To be a stranger in New York, homeless, friendless, without work, the shadow of that place over there dogging your steps; with you what you are—trustful, unsuspicious, open as sunlight—Oh, I daren't advise you. I don't dare."

Jean was awed, but not downcast.

"I'll risk it," she replied stoutly.

Twice he opened his lips to speak, but rose instead and paced among the trees. Finally he confronted her.

"Why not go back?" he asked.

Jean widened her eyes upon him.

"Go back! Go back to the refuge?"

"Yes. Why not go back and see it through? No, no," he entreated, as her lip curled. "Don't think I'm trying to squirm out of my offer. That stands. It's you I'm considering. Remember that no matter how much you may make of yourself those people over there will have the power to take it from you. Should you marry—"

"I shall never marry."

"Should you marry—ah! you will—they can shame you and the man whose name you bear. Could you stand that? After all, isn't the other way better? Wouldn't a clean slate be worth its price?"

She shook her head.

"You don't realize what you ask. I can't go back. I can't. You don't know."

"I suppose I don't," he admitted.

"I'd rather run the risk—the risk of their finding me, the risk, whatever it is, of New York. As for friends—" she smiled upon him radiantly—"well, I'll have you."

"Yes," he promised. "You'll have me."

He accepted her decision, and at once made ready for his tramp across the hills. At parting he reminded her that to him she was still nameless.

"I'm not sure myself," she laughed. "I'll need a new name in New York!"

"But now?"

"Well, then—Jack."

"To offset the dimple, I suppose. Is it short for Jacqueline?"

"No; just Jack."

Jean's knight errant looked back once before the tree-boles shut her wholly away. She had dropped upon a log and was facing the blue reach of the lake. This was about six o'clock in the evening. At nine she had not shifted her position. It was perhaps an hour later when she sprang up abruptly, lit a candle which he had shown her in arranging for the night, and hunting out a pencil and paper, wrote a hurried note which she pinned to the tent-flap.

There were but two lines in all. The first thanked him. The second ran:—

"I've gone back to see it through."

V

The refuge, considered officially, was impressed. That any fugitive, let alone one who had outwitted pursuit, should freely present herself at the gatehouse, spiced its drab annals with originality. Jean Fanshaw, no less than Sophie Powell, had achieved distinction. The refuge dissembled its emotion, however. An escape was an escape, with draconic penalties no more to be stayed than the march of a glacier or the changes of the moon.

But even the refuge—from the vantage-point of a supposed ventilator reached by a secret stair—discerned that the prisoner of the guardhouse was unaccountably not the rebel of Cottage No. 6. The girl who dropped from the window would have found this duress maddening. Four brick walls were its horizon; its furnishing was a mattress thrust through a grudging door at night and withdrawn when the dim glow, filtering through a ground-glass disk in the ceiling, heralded the return of another day. It was always twilight within, for the occupations of a guardhouse require little light. Text-books, no other print, were sometimes permitted, but even these arid pastimes were not for Jean; the school taught nothing she had not mastered. Her resources were two: she might knit or she might think. She usually chose the latter.

Another thing puzzled the refuge—still considered officially. It was no novelty for a song to rise to the pseudo-ventilator (inmates so punished often sang out of bravado when first confined), but it was quite unprecedented for a girl with no couch but the floor, no outlook save the walls, no employment except knitting, companioned solely by her thoughts, to croon the words of a rollicking popular air as if she were content.

Jean, too, wondered unceasingly. Why had her old ideas of life cheapened? Save one chance stranger, men had met her on the footing of boyish good-fellowship which she required of them: why should this no longer seem wholly desirable? Why had she relished a chivalrous insistence on her sex? Why had she taken pride in the practice of a menial feminine art? Why had all things womanly shifted value? Why, above all, did she feel no regret that these things should be? Yet content was scarcely the word for her frame of mind. Her thoughts were a yeasty ferment out of which the unknown youth of the forest, whose very name was a mystery, began presently to emerge as an ideal figure. And this ideal man had on his part a conception of ideal womanhood! Here was the germinal truth at last.

While she pondered, two solitary weeks which by popular account should have been unspeakable, slipped magically away. She dreaded their end, for she knew that in the adamantine scheme of things six months of prison life, at very least, awaited her. Even to the average refuge girl the prison signified degradation; to Jean it also spelled Stella Wilkes. The abhorred contact did not begin at once, however, since it fell out that in runaway cases the powers were wont to decree yet another fortnight of isolation following the transfer from the guardhouse. But isolation in the prison was a relative term. The building's sights could be shut away; its sounds penetrated every cranny.

Such sounds! One of them broke Jean's light slumber her first night under the prison roof. It was a strand in the woof of her dreams at first, a monotonous, tuneless plaint, strangely exotic, like nothing earthly except the wailing of savage women who mourn their dead. She lay half awake for an interval, the weird chant clutching at her heart. Then, as it rose, waxing shriller with each repetition, she sat bolt upright with hair prickling and flesh acreep. It was a menace to the living, not a requiem; a virulent explicit curse.

"The matron to hell! The matron to hell! The matron to hell!"

The prison stirred.

"The matron to hell! The matron to hell! The matron to hell!"

Here a woman laughed; there one began softly to echo the cry; cell warily hailed cell.

"The matron to hell! The matron to hell! The matron to hell!"

The pulsing hate of it now filled the corridors. A door opened somewhere, and a metallic footfall began to echo briskly from iron stairs.

"Is it mesilf ye're wantin', darlin'?" called a fat-throated voice. "I'll not keep ye waitin'. With ye in a jiffy!"

There was a sound of shooting bolts, a brief scuffle, the click of handcuffs, and a ragged retreat. Presently a door slammed, and the matron's steps alone retraced the lower corridors. Far in the distance, muffled by intervening walls, its two emphatic words only audible, the eerie defiance still rose and untiringly persisted until it again entered the fabric of Jean Fanshaw's dreams.

That cry somehow struck the dominant note of the prison. Its bitterness, its mental squalor, its agonizing repression, its smouldering revolt, all focussed in that hysterical out-burst against constituted authority. Jean heard it again and again in the ensuing months, and in each instance it broke the stillness of night. The second time it startled, but did not frighten. The third she thrilled to its message, knowing it at last for her own fiery heartache made articulate. But this was afterward.

In the beginning Stella Wilkes overshadowed their background. She and Jean had had a grammar-school acquaintance in the days before respectability and the Wilkes girl—as Shawnee Springs knew her—parted company; and it was to this period of democratic equality and relative innocence to which Stella chose sentimentally to revert when she first found a chance to speak.

"Can't say I feel a day older than I did then," she went on, sociably. "Do I look it?"

Jean made some answer. Stella indeed seemed no different; looking a mature woman at sixteen, she had simply marked time since. A mole, oddly placed near one corner of her mouth where another girl would dimple, still fascinated by its unexpectedness. Stella noticed this and laughed.

"Remember how all you little kids used to rubber at my mole?" she said. "It made me mad. I don't care now when people stare, but I wish it was on my neck. 'Moles on the neck, money by the peck,' you know. Queer, ain't it, that two of us from the old West Street school should strike this joint together? It's just the same as if we'd gone away to college—I don't think! Any Shawnee Springs news to tell?"

"No," Jean answered, stonily.

Stella saw that her advances were unwelcome, and her mood veered.

"That's your game, is it?" She thrust her hard face closer. "So I ain't in your class, my lady—you that was so keen for the boys! You give me a pain. As if near the whole kit of us wasn't pinched for the same reason. Go tell the marines you're any better than the rest!"

It was Jean's first sharp conception of the brutal truth that the stigma of the reformatory was all-embracing. The world presently emphasized the stern lesson. True to her word on learning of the censorship, she had never written home; but her mother's letters, formal and mutilated as they were, had nevertheless meant more to her than she realized until her degradation to the prison lopped this privilege too away. The cumulative effect of Mrs. Fanshaw's correspondence, when finally read, was not tonic. Despite the censor, Jean gathered that Shawnee Springs now linked her name with Stella Wilkes's. A refuge girl was a refuge girl; degrees and shadings of misconduct lost themselves in the murky sameness of the stain. Her grateful wonder grew that her champion of the forest had had the insight to distinguish. His quixotic young faith and a heartening word now and then from Miss Archer, when some infrequent errand brought the little secretary near, between them redeemed humanity.

A torrid summer dragged into an autumn scarcely less enervating. The kitchen-gardens were arid; the grass-plots sere; the scant wisps of ivy wherewith Miss Archer, unsanctioned by the state, had attempted to soften the more glaring shortcomings of the architect, hung dead beyond all hope of resurrection; and the endless reaches of brick wall, soaked in sunshine by day, reeked like huge ovens the live-long night. The officials' tempers grew short, their decisions arbitrary beyond common; obedience became daily more difficult; riot, full-charged, awaited only its galvanizing spark.

This the prison contributed. Conditions were always hardest here, and the rage they fostered had gathered itself into an ominous hatred of the matron. Nor was this wholly due to her chance embodiment of law. That carried weight, of course, but the prime factor in her unpopularity was a stolid cynicism implanted by some years' prior service in a metropolitan police station. Joined to a temperament like the superintendent's, this could have been endured, though detested; but the former matron of a "sunrise court" mixed her doubt with a lumbering joviality against which sincerity beat itself in vain. Her smile was a goad; her laugh a stinging blow.

The revolt turned upon an old grievance. Breakfast was a scant meal in the prison, and the laundry squad, upon which the severest toil fell, had for months clamored for a mid-forenoon luncheon. This request was reasonable, but an intricate knot of red tape, understood clearly by nobody, had balked its granting, and the matron accordingly reaped a whirlwind which others had sown. All the week it threatened. On Monday perhaps half the workers in the laundry, headed by Stella Wilkes, repeated the old demand, and were sent about their business with heavy sarcasm.

"Lunch, is it!" drawled the matron, with her maddening grin. "Sure it's Vassar College, or Bryn Mawr maybe, these swells think they're attendin'! How triggynomtry, an' dead languidges, an' the pianoforty do tire the brain! Wouldn't you find a club sandwich tasty, young ladies? Or a paddy-de-foy-grass, now? Back to your tubs!"

Jean took no part in the demonstration, and as the Wilkes girl returned to her work she cursed her for a chicken-hearted coward. Since the day of her rebuff she had worn her enmity like a chip upon her shoulder. Jean met this, as she now met everything, with apathy. Stella, her unlovely associates bending over the steaming tubs, the nagging matron—one and all had their being in an unreal world, a nightmare country, which must be stoically endured until the awakening. The tomboy had become a mystic.

With this detachment she incuriously watched the rising storm. From Tuesday to Thursday the unrest spent itself in note-writing, a diversion, following Rabelaisian models in style, which was, of course, forbidden. The contraband pencils found ingenious hiding-places, however, and the notes themselves a lively circulation. One of these missives, written by Stella and mailed with a scuttleful of fresh coal in the laundry stove, fell under Jean's eye Thursday afternoon. It was intended for another, but some delay had bungled its delivery, and the flames unfolded it and betrayed its secret. Stella saw and pressed close.

"If you blab, I'll kill you," she threatened hoarsely. "That's straight."

Jean shrugged her away. She attached no weight to the scrawl's ungrammatical hints of violence. Such vaporings were as common as they were idle. Nor was she moved when, on Friday, during recreation, the matron's alertness checked, though it failed truly to appraise, a catlike dart of Stella's to the rear. She did not escape, however, a certain sympathetic share in the tension which set the last day of the week apart from other days. The nerves of a reformatory are high-pitched. To be always dumb unless bidden to speak, forever aware of a spying eye, eternally the slave of Yea and Nay—such is the common lot. Double the feeling of repression, and you get the prison and hysteria. From the rising-bell, Saturday, till she slept again, Jean's senses were played upon by vague malign influences. All felt them. If sleeve brushed sleeve, a scowl followed; muttered curses sped the passing of every dish at meals; and in the stifling night some one raised the heart-clutching chant against the matron. This was the time Jean hailed it for her own.

Sunday brought no relief. The piping heat held unabated; hard work, the week-day safety-valve, was lacking. Only the matron could muster a smile. That smile! The prison file, passing, chapel bound, in Sunday review, felt the heat hotter and life more bitter because of it. The eyes of one girl blinked nervously; the fingers of a second spread clawlike, then clenched; the jaws of another set. If that woman laughed! The quadrangle peopled rapidly. Every building spun its blue-gray thread into the paths. The earliest comers were quite at the chapel steps when the prison girls, issuing from their frowning archway last, swung reluctantly into the treeless glare. Their smiling matron stood just within the shadow, looking exasperatingly cool in her white linen, and outrageously at peace with herself and her smug, well-ordered world. Then, abruptly, some trifle—perhaps a missing button, possibly a curl where should be puritanic simplicity, nothing more significant—loosed her sarcasm, her laugh and revolt.

A cry, different from the midnight defiance, yet as terrible, burst from one of the prison girls. Shrill, bird-like, prolonged, it was such a sound as the tortured captive at the stake may have heard from the encircling squaws. It was well known in the refuge; decade had bequeathed it to decade; and it was always the signal of mutiny. As throat after throat took it up, the commands of the matrons became mere angry pantomime. Rank upon rank melted in confusion, and the mob, lusting for violence, awaited only its directing fury.

A leader rose. Stella had secretly fomented this outbreak; it was her storm to ride openly if she dared. Yet it was scarcely a question of daring. This was her supreme hour, hers by right of might; and had another seized the lead she would have crushed her. With black locks tumbled, eyes kindled, cheeks afire, wanting only the scarlet gear of anarchy to cap her likeness to those women of other speech who braved barricades like men, she rallied disorder about her as the fiercer flame draws the less. Her following flocked from every quarter of the quadrangle—high-grade girls, girls but just clear of the guardhouse; the mature in years, the tender; the froward, the meek; spawn of the tenements, wayward from the farm; beggars, vagrants, drunkards, felons, wantons, thieves. Hysteria answering to hysteria, madness to madness, like filings to the magnet they came, and, among them, Jean.

VI

Stella hailed the recruit with shrill satisfaction, clutched her by the arm lest her allegiance falter, and beckoned on her amazons.

"Smash the prison first," she screamed. "We'll show 'em."

Back into the grim archway they swept, a frenzied, yelling horde, and flung themselves into a fury of destruction. The window-panes crashed first; then followed fusillades of crockery from dining-room and kitchen. Nothing breakable survived; where glass failed, they demolished furniture; lacking wood, they fell upon the plumbing.

Treading close in Stella's vandal wake, Jean laid waste right and left with hands which she hazily perceived were but mere automata under another unknown self's control. She was a dual being, thinking one thing, doing its opposite. The active personality disquieted yet fascinated the critical real self, and she realized, half dismayed, that if Stella Wilkes should waver in her leadership, the mad, alien Jean Fanshaw would in all likelihood leap to replace her.

But Stella harbored no thought of abdication. Her reign had just begun. What was the too brief interval which had sufficed to wreck the hated prison! There was as good pillage in the cottages, she reminded them; better still in the administration buildings and the chapel. The chapel now! What splendid atrocities they could wreak upon the big organ! And after the chapel, why not storm the gatehouse? What were a handful of guards! The gatehouse and liberty! Fired with this dream of conquest, the mob armed itself with scraps of wreckage and trooped back to the entrance to confront a thorough surprise. Bolted doors blocked their triumphal progress—bolted doors and the matron, calm, resolute, unarmed, and absolutely alone.

The quadrangle, too, had had its happenings. With the superintendent absent, her assistant ill, and the few male guards at the gatehouse but mere creatures of routine, wholly incapable of the generalship which the crisis demanded, the outbreak could scarcely have been more effectively timed; yet order somehow issued from confusion. Officials acting separately bundled such of their charges as had not yielded to hysteria into the cottages, and hurried back to cope with the open mutiny. With this the prison matron demanded the right to deal. It had flamed out in her special province; it was hers to quench if her authority was to mean anything thereafter; and she stubbornly declined aid. Not even the guards might enter with her; she would meet the situation single-handed.

The rioters faced the lonely figure stupidly. Their clamor sank to whispers, then silence. Their eyes blinked and shifted under the cold survey which passed deliberately from girl to girl, missing none, condemning all.

Suddenly the matron levelled a finger at a weak-jawed offender in the van.

"Drop that stick!" she commanded.

The culprit sheepishly complied.

"You too!" She indicated the next, and was again obeyed. In the rear some one whispered.

"Stella Wilkes, come here."

Habit swayed the girl a step forward before she realized that she was tamely submitting, but she caught herself up with an oath, and returned stare for stare.

The matron's voice sharpened.

"Stella," she repeated, "come here."

The rebel's grip upon her cudgel tightened.

"Come yourself," she retorted. "Come if you dast!"

The matron dared. Force rather than psychology had ruled the police station of her schooling, and with the loss of her temper she reverted instinctively to its crude argument. A rush, a glint of handcuffs hitherto concealed, a violent brief struggle, a blow, a heavy fall—such were the kaleidoscopic details of a battle whose whole nobody saw perfectly, but from which Stella, the mob incarnate, emerged unmistakably a victor. Moblike, she was also merciless, and continued to rain blows which the half-stunned woman at her feet had power neither to return nor fend. One of them drew blood, a scarlet thread, which by fantastic approaches and doublings traversed the matron's now pallid cheek and stained the whiteness of her dress.

It was then Jean woke. She was no longer among the foremost. Separated from Stella in the sack of the upper floors, she had fallen late upon a mirror of the matron's, miraculously preserved till her coming, and had busied herself with its joyous ruin till the others had surged below and the rencounter at the door had begun. With her first idle moment apart from the common folly she experienced reaction; one glimpse of the scene below effected a cure. She loved the vanquished as little as the victor, but her every instinct for fair play and decency cried out against the wanton blows, and drove her hotly through the press to the dazed woman's side.

The surprise of the attack, more than its strength, disconcerted Stella, and Jean had pulled the matron to her feet before retaliation was possible. Nimble wits likewise counted most in the immediate sequel. Quite in the moment of her charge Jean spied a coil of fire-hose, which, used not half an hour ago for the sake of coolness, lay still connected with its hydrant, and its possibilities flashed instantly upon her. Before the ringleader's slow brain could divine her purpose she had thrust the nozzle into the matron's fingers and sprung to release the flood. Stella saw the advantages of this neglected weapon now, and plunged to capture it, but a stream as thick as a man's wrist took her squarely in the face with the pent energy of a long descent from the hills, and brought her gasping to her knees. Before she fairly caught her breath she was handcuffed and helpless, and the matron, all bustle and resource with the turning of the tide, was issuing crisp orders to as drenched, frightened, and abjectly obedient a band of rebels as ever made unconditional surrender.