Title: A history of the administration of the Royal Navy and of merchant shipping in relation to the Navy from MDIX to MDCLX, with an introduction treating of the preceding period

Author: M. Oppenheim

Release date: August 8, 2022 [eBook #68713]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Original publication: United Kingdom: John Lane, 1896

Credits: MWS and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

VOLUME I

MDIX-MDCLX

A HISTORY OF THE ADMINISTRATION

OF THE ROYAL NAVY

AND OF MERCHANT SHIPPING

IN RELATION TO THE NAVY

BY M. OPPENHEIM

VOL I

MDIX-MDCLX

JOHN LANE THE BODLEY HEAD

LONDON AND NEW YORK

MDCCCXCVI

A HISTORY OF THE ADMINISTRATION

OF THE ROYAL NAVY

AND OF MERCHANT SHIPPING

IN RELATION TO THE NAVY

FROM MDIX TO MDCLX WITH

AN INTRODUCTION TREATING

OF THE PRECEDING PERIOD

BY M. OPPENHEIM

JOHN LANE THE BODLEY HEAD

LONDON AND NEW YORK

MDCCCXCVI

J. MILLER AND SON, PRINTERS, EDINBURGH

| PAGE | |

| List of Illustrations | viij |

| Preface | ix |

| Introduction—The Navy before 1509 | 1 |

| Henry VIII, 1509-1547 | 45 |

| Edward VI, 1547-1553 | 100 |

| Mary and Philip and Mary, 1553-1558 | 109 |

| Elizabeth, 1558-1603 | 115 |

| James I, 1603-1625 | 184 |

| Charles I, 1625-1649, Part I—The Seamen | 216 |

| —— Part II—Royal and Merchant Shipping | 251 |

| —— Part III—The Administration | 279 |

| The Commonwealth, 1649-1660 | 302 |

| Appendix A—Inventory of the Henry Grace à Dieu | 372 |

| —— B—The Mutiny of the Golden Lion | 382 |

| —— C—Sir John Hawkyns | 392 |

| —— D—A Privateer of 1592 | 398 |

| Index | 401 |

| PAGE | |

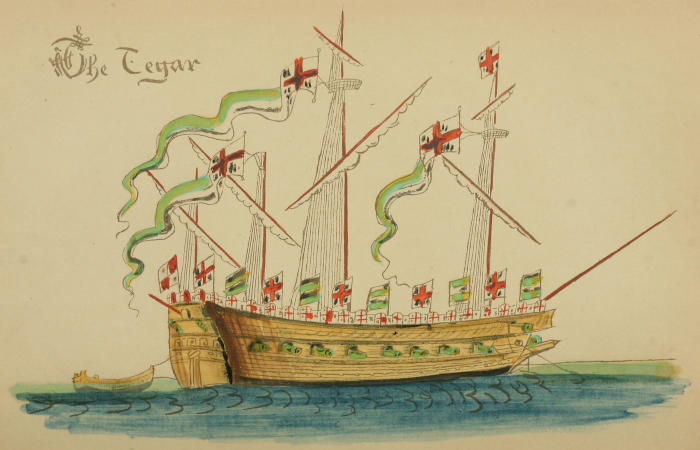

| The Tiger (of Henry VIII). Hand-coloured in facsimile of a portion of the original MS. in the British Museum, (Add. MSS., 22047) | Frontispiece |

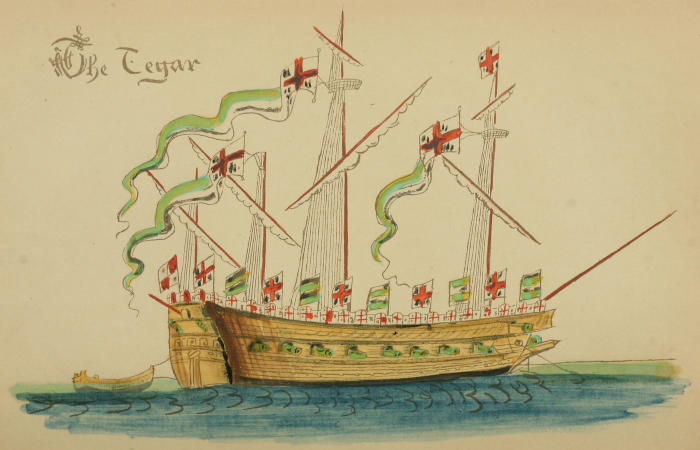

| Wyard’s Medal, 1650. From one of the four Remaining Medals (British Museum) | Title Page |

| The Seal of the Navy Office | xiij |

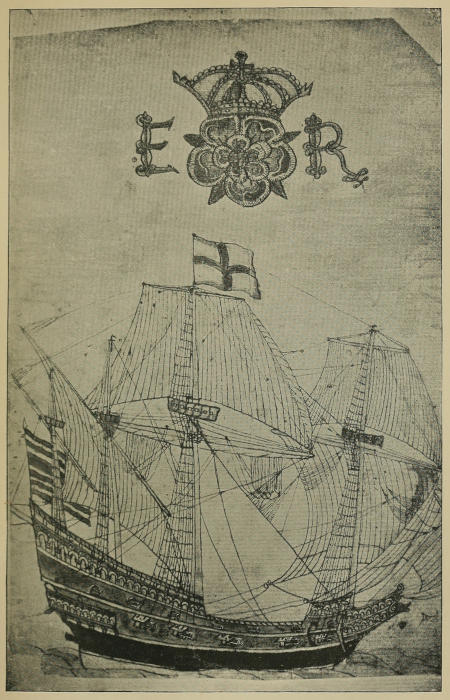

| An Elizabethan Man-of-War. From a contemporary Drawing in the Bodleian Library, Oxford, (Rawlinson MSS., A 192, 20) | 130 |

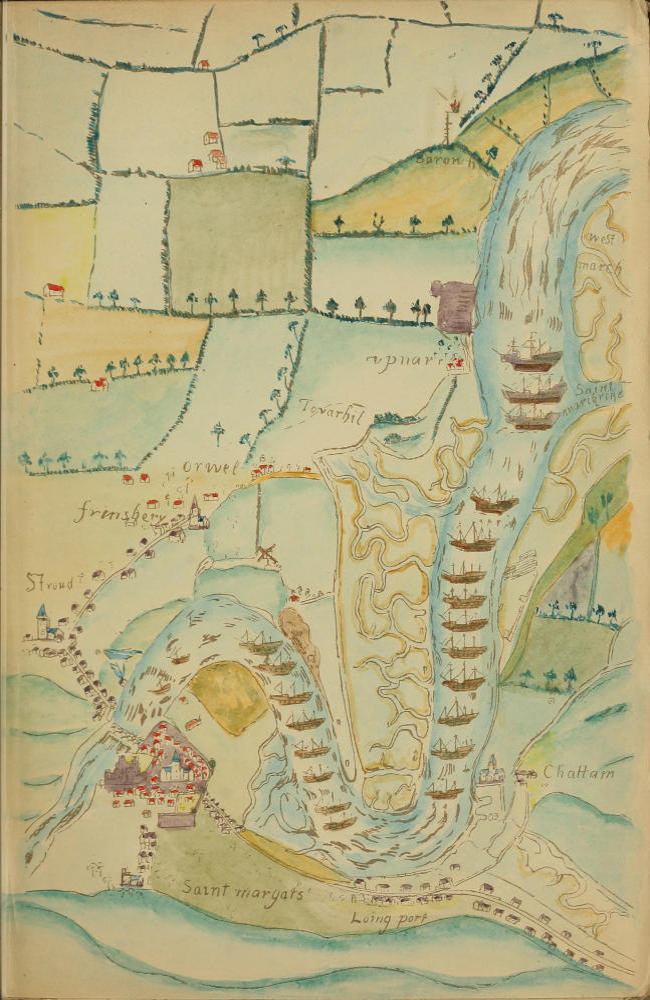

| The Medway Anchorage (temp. Elizabeth). Hand-coloured in facsimile of a portion of the Original MS. in the British Museum, (Cott. MSS., Aug. I, i, 52) | 150 |

Of the following pages the Introduction and the portion dealing with the period 1509-1558 are entirely new. The remainder originally appeared in the English Historical Review, but the Elizabethan section has been rewritten and much enlarged in the light of fresh material found since it was first printed, and many additions and alterations have been made to the other papers. Of the four Appendices three are new.

Sixteen years ago the doyen of our English naval historians, Professor J. K. Laughton, wrote,

‘Every one knows that according to the Act of Parliament, it is on the Navy that “under the good providence of God, the wealth, safety, and strength of the kingdom chiefly depend,” but there are probably few who have realised the full meaning of that grave sentence.’[1]

Since those words were penned, a more widely diffused interest in naval matters has permeated all classes of society, and there is, happily, a vastly increased perception of what the Navy means for England and the Empire.[2] The greater interest[x] taken in naval progress has caused a new attention to be bestowed on the early history of the Navy, and there is little apology required for the plan—however much may be needed for the execution—of a work dealing with the civil organisation under which the executive has toiled and fought. Whole libraries have been written about fleets and expeditions, but there has never yet been any systematic history of the organisation that rendered action on a large scale possible, or of the naval administration generally, and although its record does not appear to the writer to be a matter for national pride, it has its importance as a corollary of—and if only as a foil to—that of the Navy proper. This work as a whole, is therefore intended to be a history of the later Royal Navy, and of naval administration, from the accession of Henry VIII until the close of the Napoleonic wars, in all the details connected with the subject except those relating to actual warfare.

The historical evolution of many of the great administrative offices of the state, as they exist now, can be, in most cases, observed through the centuries and the course and causes of their growth traced with sufficient exactness. Originally a delegation of some one or more of the functions of the monarch, they have developed from small and obscure beginnings in the far off past and increased with the growth of the nation. The naval administration of to-day has no such dignity of antiquity. It will be for the readers of these volumes in their entirety to decide whether it has earned that higher honour which comes of loyal service performed with justice to the subordinates dependent on it,[xi] and with honesty to the British people who have entrusted it with such important duties.

The Board of Admiralty came into power subsequent to the period at which this volume ends. It dates, properly from 1689, or, at the utmost, reaches back to 1673, but its forerunner, the modern administration which is the subject of the present volume, sprang full grown into life in 1546 when the outgrown mediæval system ended. The Admiralty Board is in the place, and administers the duties, of the Lord Admiral, but that officer although the titular head of the Navy never had any very active or continuous part in administration, nor was the post itself a very ancient one. James, Duke of York, afterwards James II, was the first Lord Admiral who really took actual charge of domestic naval affairs and the Admiralty succeeded him, and to his powers, thus overshadowing the Navy Board. Between 1546 and 1618, the Navy was governed by the Principal Officers, controlling the various branches of naval work, who constituted the Navy Board; between 1618 and 1689 we have a transitional period when the Navy Officers, Commissioners of the Admiralty, Parliamentary Committees, Lord Admiral, and the King, were all at different times, and occasionally simultaneously, ruling and directing. The Admiralty now more nearly represents in function and composition the old Navy Board, abolished in ignominy in 1832, than the Board of the seventeenth or eighteenth centuries with which, except in the power still retained by the First Lord, it has little in common but name.

Our subject then in this volume, is the Navy[xii] Board as the predominant authority between 1546 and 1660. Although a history of the modern administration should in exactness, therefore, begin in 1546, an academic preciseness of date would be obtained at the expense of historical accuracy since Henry VIII remodelled the Navy, before he touched the administration. The year of his accession has therefore been chosen as the starting point. But it should be borne in mind that there is very much less difference between the great and complex administration of to-day, and the Navy Board or—as it was then sometimes called—the Admiralty, of 24th April 1546, than between the Board of 24th April and what existed the day before. Within the twenty-four hours the old system had been swept away and replaced; its successor has altered in form but not in principle.

The sources of information are sufficiently indicated by the references. The great majority of them being used for the first time, subsequent inquiry may modify or alter some of the conclusions here reached. Unless a date is given in a double form (e.g. 20th February 1558-9) it will be understood to be new or present style, so far as the year is concerned. Few attempts have been made to give the modern equivalents of the various sums of money mentioned during so many periods when values were continually fluctuating. With one exception all the MS. collections known to the writer, likely to be of value, have been fully examined, but there are also many papers not available for research in the possession of private owners. The one exception referred to is the collection of Pepys MSS., at Magdalene College, Cambridge. An[xiii] application to examine these was refused on the ground that a member of the university was working at them. It is to be hoped that this ingenuous adaptation of the principles of Protection to historical investigation will duly stimulate production.

There remains the pleasant duty of thanking those from whom I have received assistance. To Mr S. R. Gardiner, and Professor J. K. Laughton, I am obliged for various suggestions on historical and naval questions; to Professor F. Elgar for information on the difficult subject of tonnage measurement. I have to thank Mr F. J. Simmons for assistance in the task of index compilation and proof-reading.

As this is the first opportunity I have had of publicly acknowledging my indebtedness to Mr E. Salisbury of the Record Office, I am glad to be now able to express my sincere gratitude to that gentleman for constant and cordially given help in many ways during the five years this book has been in preparation.

September 1896.

The creation of the modern Royal Navy has been variously attributed to Henry VII, to Henry VIII, and to Elizabeth. Whichever sovereign may be considered entitled to the honour, the statement, as applied to either monarch, really means that modification of mediæval conditions, and adoption of improvements in construction and administration, which brought the Navy into the form familiar to us until the introduction of steam and iron. And in that sense no one sovereign can be accredited with its formation. The introduction of portholes in, or perhaps before the reign of Henry VII, differentiated the man-of-war, involved radical alterations in build and armament, and made the future line-of-battle ship possible; the establishment of the Navy Board by Henry VIII, made the organisation of fleets feasible and ensured a certain, if slow, progress because henceforward cumulative and, in the long run, independent of the energy and foresight of any one man under whom, as under Henry V, the Navy might largely advance, to sink back at his death into decay. Under Elizabeth the improvements in building and rigging constituted a step longer than had yet been taken towards the modern type, the Navy Board became an effectively working and flourishing institution, and the wars and voyages of her reign founded the school of successful seamanship of which was born the confidence, daring and self-reliance still prescriptive in the royal and merchant services.

It is not the purpose of this work to deal with the history, of the Navy previous to the accession of Henry VIII, but no real line of demarcation can be drawn in naval more than in other history, and it will be necessary to briefly sketch the conditions generally existing before 1509, and in somewhat[2] more detail, those relating to the fifteenth century.[3] In the widest sense the first Saxon king who possessed galleys of his own may be said to have been the founder of the Royal Navy; in a narrower but truer sense, the Royal Navy as an appanage of imperial power, and an entity of steady growth, really dates from the Norman conquest. The Saxon navy although respectable by way of number, was essentially a coast defence force, mustered temporarily to answer momentary needs, and lacking continuity of existence and purpose. There is but one instance of a Saxon fleet being employed out of the four seas, that which Canute used in the conquest of Norway, and in it the Scandinavian element was probably larger than the Saxon. With the advent of William I, the channel, instead of remaining a boundary, became a means of communication between the divided dominions of one monarch, and a comparatively permanent and reliable naval force, both for military transport and for command of the passage between the insular and continental possessions of the Crown, became a necessity of royal policy. For nearly two centuries this duty was mainly performed by the men of the Cinque Ports who, in return for certain privileges and exemptions, were bound, at any moment, to place fifty-seven ships at the service of the Crown for fifteen days free of cost, and for as much longer time as the king required them at the customary rate of pay.[4] These claims, practically constituting the Cinque Ports fleet a standing force, were ceaselessly exercised by successive monarchs, and, at first sight, such demands might seem to be destructive of that commercial progress which is the primary basis of the growth or maintenance of shipping. But the methods of warfare in those ages were more profitable than commerce, and the decay of the Ports was not due to poverty caused by the calls made upon their shipping for military purposes. The existence of the Cinque Ports service was indirectly a hindrance to the growth of a crown navy, since it was obviously cheaper for the king to order the Ports to act than to man and equip his own vessels; it was not until ships of larger size and stronger build than those belonging to the Ports were required, that the royal ships came into frequent use.

As well as mobilising the Cinque Ports fleet, the sovereign was able to issue writs to arrest the ships of private owners throughout the kingdom, together with the necessary number of[3] sailors, when rival fleets had to be fought or armies to be transported. The Normans, descendants of the Vikings, must have been better shipbuilders and better seamen than the Saxons, and the large number of nautical words that can be traced back to Norman French bear witness to improvements in rigging and handling due to them. The Crusades must have reacted on the English marine by bringing under the observation of our seamen the construction of ships belonging to the Mediterranean powers, then far in advance of the North in the art of shipbuilding. And during the century which followed the Conquest, the foreign trade, which is the nursery of shipping, was steadily growing. Under the Angevin kings the whole coast line of France, from Flanders to Bayonne, was, with the exception of Brittany, subject to English rule, and the inter-coast traffic that naturally followed was the greatest stimulus to maritime enterprise this country had yet experienced. The result was seen in the Crusade of 1190, when the fleet of Richard I for the Mediterranean was made up of vessels drawn from the ports of the empire, but many of them doubtless belonging to the continental possessions of the crown; and as John certainly possessed ships of his own, it may be inferred that Richard, and his predecessors also had some. When a general arrest was ordered, foreign ships were seized as well as English, and this practice continued as late as the first years of Elizabeth. Richard I issued, in 1190, regulations for the government of his fleet. These regulations doubtless only methodised customs already existing, and as they dealt with offences against life and property bear the mark of their commercial origin. Offences against discipline must have been punished by military law and military penalties, and required no new code.

During the reign of John we meet the first sign of a naval administration in the official action of William of Wrotham, like many of his successors a cleric, and the first known ‘Keeper of the king’s ships.’ This office, possibly in its original form of very much earlier date and only reconstituted or enlarged in function by John, and now represented in descent by the Secretaryship of the Admiralty, is the oldest administrative employment in connection with the Navy. At first called ‘Keeper and Governor’ of the king’s ships, later, ‘Clerk of the king’s ships,’ this official held, sometimes really and sometimes nominally, the control of naval organisation until the formation of the Navy Board in 1546. His duties included all those now performed by a multitude of highly placed Admiralty officials. If a man of energy, experience, and capacity, his name stands foremost in the maintenance of the royal fleets during peace and their preparation for war; if, as frequently happened, a merchant or[4] subordinate official with no especial knowledge, he might become a mere messenger riding from port to port, seeking runaway sailors, or bargaining for small parcels of naval stores. Occasionally, under such circumstances, his authority was further lessened by the appointment of other persons, usually such as held minor personal offices near the king, as keepers of particular ships. This was a method of giving a small pecuniary reward to such a one, together with the perquisites he might be able to procure from the supply of stores and provisions necessary for the vessel and her crew.

In the course of centuries the title changed its form. In the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries the officer is called ‘clerk of marine causes,’ and ‘clerk of the navy;’ in the seventeenth century, ‘clerk of the acts.’ Although Pepys was not the last clerk of the acts, the functions associated with the office, which were the remains of the larger powers once belonging to the ‘Keeper and Governor,’ were carried up by him to the higher post of Secretary of the Admiralty.

With the reign of Henry III we find the royal ships large enough to become attractive to merchants, who hired them from the king for freight, perhaps at lower rates than could be afforded by private owners. There is hardly a reign, down to and including that of Elizabeth, in which men-of-war were not hired by merchants, and the earlier trading voyages to Italy and the Levant during the last quarter of the fifteenth century were nearly all performed by men-of-war let out for the voyage. The Navy was mainly made up of sailing vessels even before the reign of Henry III, and by that period many of them possessed two masts, each carrying a single sail. The conversion of a merchantman into a fighting-ship was accomplished by fitting it with temporary fore and after castles, which became later the permanent forecastle and poop, the addition of a ‘top castle’ or fighting top, and the provision of proper armament. Doubtless the king’s own ships were more strongly built, and better adapted by internal arrangements for their work, than the hired merchantmen. The supreme government of the Navy in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries was in the hands of the King’s Council, who ordered, equally, the preparation and fitting of ships and the action of the admirals commanding. These officers, known during the greater part of the thirteenth century as keepers or governors of the sea, were usually knights or nobles in command of the soldiers. While holding commission they appear to have had jurisdiction in the matter of discipline on board their fleets, but not of law suits or maritime causes until 1360; before that date such causes were dealt with at common law.[5] There were usually two, one having charge of the East,[5] the other of the South Coast, but occasionally, an officer had a particular section placed under his care, such as the coasts of Norfolk and Suffolk. Their period of service was commonly short and often only for a special employment. The maintenance of a fleet was a part of the King’s Household expenses; in the Wardrobe Accounts for 1299-1300 are the amounts paid for fifty-four vessels and their crews hired for the conveyance of stores for the Scotch war.

Galleys, although frequently mentioned, were at no time a chief portion of our fleets. Large fleets were mainly composed of impressed merchantmen, and galleys are expensive and useless for trading purposes compared with sailing ships; the natural home of the galley was the landlocked Mediterranean, and even there its utility was limited to the summer months, so that it was still less suitable for Northern latitudes. But the great difficulty was in manning them. Forced labour by captives taken in the continual warfare normal amongst the states on the Mediterranean littoral solved that problem for them, but here the cost of the free oarsman, to whom the drudgery was in any case distasteful, was prohibitive. We shall see that, down to the close of the sixteenth century, attempts were at various times made to form such a service, but always unsuccessfully, and the supreme moment of the galley service, so far as it ever existed here, was the reign of Edward I.[6] This king steadily increased the strength of the Navy. In 1294 and 1295 galleys were built by him at York, Southampton, Lynn, Newcastle and Ipswich, of which at least two pulled 120 oars apiece. Perhaps the experiment was conclusive for, neither as regards number or size do such ever occur again. Although Edward III had one or two built, most of those he employed were temporarily hired from the Genoese or from Aquitainean ports, and the total number bore a very small proportion to the sailing vessels in his fleets. The records of the first years of Edward II show that the crown possessed at least eleven vessels, all sailing ships, but the circumstances of the reign were not conducive to the growth of a Royal Navy, although there seem to have been ten ships in 1322.

A far-seeing statesmanship in relation to the political value of sea-power has been attributed to Edward III on the strength of the victories of 1340 and 1350, and of two lines of a poem, written nearly a century later, referring to the gold noble of[6] 1344.[7] This view assigns to Edward a knowledge, in the modern sense, of ‘the influence of sea-power on history’ greater than that possessed by such a statesman as Edward I, and a policy in connection with maritime matters of which the results, at anyrate, were directly the opposite of his intentions. The claim to be lord of the narrow seas was not a new one, and was as much and merely a title of dignity as any other of the sovereign’s verbal honours, not following the actual enforcement of ownership but consequent to the fact of the channel lying between England and Normandy.[8] And it was a title also claimed by France. There is no sign in the policy of the early kings of any perception of the value of a navy as a militant instrument like an army, or any sense of the importance of a real continuity in its maintenance and use. Society was based on a military organisation, but there was no place in that organisation for the Navy except as a subsidiary and dependent force. Fleets were called into being to transport soldiery abroad, to keep open communications, or to meet an enemy already at sea, but the real work of conquest was always held to be the duty of the knights and archers they carried from one country to another. There is no understanding shewn of the ceaseless pressure a navy is capable of exercising, and the disbandment of all, or the greater part, of the fleet was usually the first step which followed the disembarkation of troops or a successful fleet action. In an age when the land transit of goods was hampered by innumerable disadvantages, the position of England, dominating the natural way of communication between the prosperous cities of the north and their customers, was one of splendid command had its far-reaching political possibilities been realised. That they did not comprehend a function only understood many generations later cannot be made a subject of censure, but it has a distinct bearing on the question of Edward’s superiority in this matter to his predecessors and successors. In the same way as theirs the methods of Edward III were directed to conquests by land, and, once the troops were transported or an opposing fleet actually in existence was crushed, the Channel was left as bare of protection to merchantmen, and as destitute of any power capable of enforcing the reputed sovereignty of the narrow seas, as it remained down to the days of the Commonwealth.[7] Beyond the fact that in 1340 and 1350 Edward commanded in person, where his predecessors had been represented by deputies, his action in relation to the Royal Navy differs in no respects from theirs. The gold noble of 1344, into which so much meaning has been read, was struck in combination with the people of Flanders for political and trading purposes, and in connection with Edward’s intrigues to obtain their financial and military support. It is noteworthy that in December 1339, six months before the battle of Sluys, Flanders, Brabant, and Hainault, agreed that a common coinage should be struck, and this, in all probability, marks the first inception of the noble when Edward realised the purposes to which a common coinage for England and the Low Countries might be made to work. In 1343 the Commons petitioned for a gold coin to run equally in England and Flanders and thus strengthened the king’s purpose. But the ship on this coin, the noble, was obviously an afterthought since the florin, the first issue of the same year, called in on account of its unpopularity, bore the royal leopard on the whole and half noble and the royal crest on the quarter one; if therefore the king meant all that is supposed to be implied by the device it occurred to him very suddenly and subsequent to the first, and deliberately thought out, issue.[9] All that the writer of the Libel of English Policie says is that, in 1436, the noble proves to him four things. Further reasons, in relation to other passages of the poem, will be adduced on a later page to show that his work is only one more instance among the many in which individual and unofficial thinkers have been in advance of the statesmanship of their age and whose views, ignored by their contemporaries have become the accepted opinions of a subsequent period.

The commercial policy of Edward III was emphatically not one of protection to English shipping, being a nearer approach to free trade than existed for centuries after his death. During the greater part of his reign the needs in ships for his campaigns were supplied from the accumulations of the reigns of Edward I and Edward II, the second of which was not necessarily disastrous to commerce. But when these were exhausted it was found that a system which had aimed merely at obtaining a highest possible yearly revenue for the purpose of supporting armies had, whether or not in itself, fiscally praiseworthy resulted in the ruin of English shipping. In 1372 and 1373, the Commons complained of the destruction of shipping and the decay of the port towns, and it is collateral evidence of Edward’s real lack of insight into the value of a marine—its slow creation[8] and its easy loss—that some of the causes to which they attributed these circumstances were directly due to a reckless indifference to, or ignorance of, the only conditions which could render a merchant marine, subject to conscription, possible.[10] Vessels, they said, were pressed long before they were really wanted, and until actually taken into the service of the crown, ships were idle and seamen had to be paid and supported at the expense of the owners; the effect of royal ordinances which had driven many shipowners to other occupations, and the decrease in the number of sailors due to these and other causes, formed further articles of remonstrance.[11]

The year which saw the decease of the ‘Lord of the Sea,’ was marked by the sack of Rye, Lewes, Hastings, Yarmouth, Dartmouth, Plymouth, Folkestone, Portsmouth, and the Isle of Wight, a sufficient commentary on the title, and an adequate illustration of the system which had left absolutely no navy, royal or mercantile, capable of protecting the coasts.

In 1378 the Commons again attributed the defenceless state of the kingdom not so much to the late king’s impressment of ships as to the losses and poverty caused by non-payment, or delay in payment for their use, and lack of compensation for waste of fittings and stores. Every meeting of Parliament was signalised by fresh representations, and that of 1380 obtained a promise that owners should receive 3s 4d a ‘ton-tight’ for every three months, commencing from the day of arrival at the port of meeting; in 1385 this allowance was reduced to two shillings, and remained at that rate, notwithstanding frequent petitions for a return to the older amount, for at least half a century.[12] It is not known when the payment of 3s 4d a ton was first introduced, nor on what principle it was calculated, but, in 1416, the Commons said that it ran ‘from beyond the time of memory.’ The following petition, undated, but probably belonging to one of the early years of Henry IV, shows that it was older than the Edwards, and, incidentally, yields some interesting information:

‘To the very noble and very wise lords of this present Parliament very humbly supplicate all owners of ships in this kingdom. That[9] whereas in the time of the noble King Edward and his predecessors, whenever any ship was commanded for service that the owner of such a ship took 3s 4d per ton-tight in the three months by way of reward for repair of the ship and its gear, and the fourth part of any prize made at sea, by which reward the shipping of this kingdom was then well maintained and ruled so that at that time, 150 ships of the Tower were available in the kingdom;[13] and since the decease of the noble King Edward, in the time of Richard, late King of England, the said reward was reduced to two shillings the ton-tight, and this very badly paid, so that the owners of such ships show no desire to keep up and maintain their ships, but have them lying useless; and by this cause the shipping of this kingdom is so diminished and deteriorated that there be not in all the kingdom more than 25 ships of the Tower.’[14]

They then beg a return to the old rates. We may gather from this document that, at some time during the reign of Edward III there were one hundred and fifty large fighting ships available, and there is some reason to believe that, both in number and size, the fourteenth and fifteenth century navy has been too much underrated when compared with that of the sixteenth century. At least one merchantman of the time of Edward III was of three hundred tons, others were of two hundred, and it will be shown that, in the middle of the fifteenth century, the number and tonnage of merchant vessels will compare favourably with any subsequent period up to, and in fact later, than the accession of Elizabeth.

While, under Richard II, the guard of the seas was maintained with chequered success by hired ships, the French, under the able rule of Charles V, not only possessed a navy but had founded a dockyard at Rouen completely equipped according to the ideas of the age.[15] Thirteen galleys and two barges are mentioned in this account, with all the tools, fittings, and armament necessary for building, repairing, and equipment, and constituting a complete establishment such as did not exist in England until more than a century later.[10] The accession of Charles VI, and the internal dissensions which culminated in Azincourt, determined an essay not again attempted on the Northern or Western coasts until the ministry of Richelieu.

The first Navigation Act,[16] ‘to increase the Navy of England which is now greatly diminished,’ by making it compulsory for English subjects to export and import goods in English ships, with a majority of the crews subjects of the English crown, can only be regarded as a suggestion of future legislation. In fact, it was practically annulled by a permissive amendment the following year. More disastrous to merchants than the losses due to warfare were the operations of the pirates who swarmed on the Northern Coasts of Europe during these centuries, and who appear to have become unbearably successful during the reign of Henry IV. This king appears to have cared little for his titular sovereignty of the seas, ignored every petition of Parliament for redress of the especial grievances affecting shipowners, and used such fleets as he got together, as his predecessors had used them, simply as a means of transporting troops to make weak and useless attacks at isolated points. Tunnage and poundage had been first levied by an order of Council in 1347, and year by year following, by agreement with the merchants; from 1373 it became a parliamentary grant of two shillings on the tun of wine, and sixpence in the pound on merchandise, for the protection of the narrow seas and the support of the Navy.[17] The tunnage and poundage now given was, if applied at all to naval purposes, not used with the least success. It was then, in May 1406, together with the fourth part of a subsidy on wools, handed over to a committee of merchants, who undertook the duty of clearing the seas for a period of sixteen months. The arrangement between the king and the committee was quite an amicable one, but in October of the same year Henry withdrew from the agreement, and it is doubtful whether the members of the committee ever received any portion of their outlay.

If the Norman Conquest gave the first great impulse to English over-sea trade, the events of the close of the fourteenth and first half of the fifteenth centuries may be held to mark the second important era in the development of merchant shipping by the opening up of fresh markets. Hitherto the products of the countries of the Baltic had been mainly obtained through the agency of the merchants of the Hansa, who had their chief factory in London, with branches at York,[11] Lynn, and Boston. In the same way English exports found their way to the north only through Hansa merchants and in Hansa ships. For two centuries they had held a monopoly of the purchase and export of the products of the north, by virtue of treaties with, and payments made to, the northern powers, and an unlicensed, but very effective, warfare waged on all ships which ventured to trade through the Sound. But the war against Waldemar III of Denmark, the depredations of the organised pirate republic known as the Victual brothers, followed by the struggle with Eric XIII of Sweden, were times of disorder lasting through more than half a century, from which the Hansa emerged nominally victorious but with the loss of the prestige and vigour that had made its monopoly possible. While it was fighting to uphold its pretensions the Dutch and English had both seized the opportunity of forcing their way into the Baltic, and when, in 1435, the Hansa extorted from its antagonists a triumphant peace the real utility of the privileges thus obtained had passed away for ever.

Coincidently with these events economic changes were taking place at home which, by favouring the accumulation of capital, had also a direct influence on the demand for shipping. The temporary renewal of possession in the coast line of France was a spur to trade with it in English bottoms. The growth of the towns, the necessity the townsmen experienced for the profitable use of surplus capital, and the slow change, which commenced under Edward III, in the national industry from wool exportation to cloth manufacture, were all elements which found ultimate expression in increased export and import in native shipping.[18] Possibly the most important factor in the change was the commencing manufacture of English cloth, instead of selling the wool to foreign merchants and buying it back from them in the finished state.[19] During the reign of Henry V, English ships were stretching down to Lisbon and the coast of Morocco, and British fishermen were plying their industry off Iceland. Not long afterwards the first English trader entered the Mediterranean, and the numerous entries in the records relating to merchant vessels show the flourishing state of trade. By example, and doubtless by persuasion, Henry himself assisted in the renewal.

Under Henry’s rule the crown navy was increased till in magnitude it exceeded the naval power of any previous reign; the character of the vessels, bought or built, shows that they[12] were provided for seagoing purposes rather than the mere escort or transport of troops which had been the object of preceding kings, and which object would have been equally well served by the hired merchantmen that had contented them. The king himself hired at various times many foreign vessels, but purely for transport purposes.

The following, compiled from the accounts of Catton and Soper, successively keepers of the ships, is a more complete list of Henry’s navy than has yet been printed:—[20]

| SHIPS | Built | Prize | Tons |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jesus of the Tower | 1000 | ||

| Holigost of the Tower | 1414 | 760 | |

| Trinity Royal of the Tower | 1416 | 540 | |

| Grace Dieu of the Tower | 1418 | 400 | |

| Thomas of the Tower[21] | 1420 | 180 | |

| Grande Marie of the Tower | 1416 | 420 | |

| Little Marie of the Tower | 140 | ||

| Katrine of the Tower | |||

| Christopher Spayne of the Tower | 1417 | 600 | |

| Marie Spayne of the Tower | 1417 | ||

| Holigost Spayne of the Tower | 1417 | 290 | |

| Philip of the Tower | |||

| Little Trinity of the Tower | 120 | ||

| Great Gabriel of the Tower | |||

| Cog John of the Tower | |||

| Red Cog of the Tower | |||

| Margaret of the Tower | |||

| CARRACKS | Built | Prize | Tons |

| Marie Hampton | 1416 | 500 | |

| Marie Sandwich | 1416 | 550 | |

| George of the Tower | 1416 | 600 | |

| Agase of the Tower | 1416 | ||

| Peter of the Tower | 1417 | ||

| Paul of the Tower | 1417 | ||

| Andrew of the Tower | 1417 | ||

| BARGES | Built | Prize | Tons |

| Valentine of the Tower | 1418 | 100 | |

| Marie Bretton of the Tower | |||

| BALINGERS | Built | Prize | Tons |

| Katrine Breton of the Tower | 1416 | ||

| James of the Tower | 1417 | ||

| Ane of the Tower | 1417 | 120 | |

| Swan of the Tower | 1417 | 20 | |

| Nicholas of the Tower | 1418 | 120 | |

| George of the Tower | 120 | ||

| Gabriel of the Tower | |||

| Gabriel de Harfleur of the Tower | |||

| Little John of the Tower | |||

| Fawcon of the Tower | 80 | ||

| Roos | 30 | ||

| Cracchere of the Tower | 56 |

It will be noticed that there is no galley in this list; one is referred to in the accounts, but had apparently ceased to[13] exist, her fittings being used for other ships. Oars occur among the equipments, but probably in most cases, for the ‘great boat’ which with a ‘cokk’ was attached to each vessel. Few cannon were carried—if the schedules represent the full armament—the Holigost six, the Thomas four, the George and Grace Dieu three each, the Katrine and Andrew two. The inventories of stores at this date show very little difference from the preceding century in the character of tackle and gear, nor is there any great alteration for some two centuries from 1350. English vessels were, on an average, smaller at this time than either Italian, Spanish, or German. The tomb of Simon of Utrecht, a Hansa admiral who died in 1437, has a sculpture of a three-masted vessel; if any of Henry’s were three-masted they were certainly the first of that class in our service. The statement of Stow, however, that the vessels captured in 1417 ‘were of marvellous greatnesse, yea, greater than ever were seen in those parts before that time,’ is, if patriotic, as absurdly incorrect as some other of his naval information. The payments for hired ships show that vessels of 400 and 450 tons, belonging to Dantzic and other ports, were taken up for the transport of troops and, putting aside the tonnage of some of the English ships, there is no reason to suppose that the North German traders were the largest of their kind. The prizes of 1416 were Spanish and Genoese carracks in French pay, captured by the Duke of Bedford in the action of 15th August off the mouth of the Seine;[22] those of 1417 by the Earl of Huntingdon in that of 25th July.

The tonnage of the English built ships shows that there was now a well marked tendency to increase in size, probably due to Henry’s initiative. The usual measurement, in the fifteenth century, of a barge was about sixty or eighty tons, and of a balinger[23] about forty. But a man-of-war balinger might be much larger as in the Nicholas of the Tower, the George, and the Ane. There is very little information as to the conditions under which Henry’s ships were built. The Trinity Royal, Grace Dieu, Holigost and Gabriel were certainly constructed at Southampton, the two last named under the supervision of William Soper, then merely a merchant of the town, who remained many years unpaid the money advanced by him for that purpose; in April 1417 he was given an annuity of twenty marks a year, doubtless by way of reward.[24] The Thomas of the Tower was rebuilt at[14] Deptford in 1420; the Jesus, and the Gabriel Harfleur were rebuilt at Smalhithe, in Kent, but in years unknown. The hulls of several of the ships were sold or given away before the end of the reign.

At one time the king seems to have commenced building abroad. There is a letter of 25th April 1419 from John Alcetre, his agent at Bayonne, describing the slow progress of the work upon a ship there and the sharp practices of the mayor and his associates who appear to have undertaken the contract. Alcetre anticipated that four or five years would elapse before its completion, and it is quite certain that it was never included in the English navy. The most noteworthy points in the details given, are the lengths over all and of the keel—respectively 186 and 112 feet—so that the fore and aft rakes, together, were 74 feet, just about two-thirds of the keel length.

The only one of Henry’s ships of which the name is still remembered is the Grace Dieu, and she was, if not the largest, probably the best equipped ship yet built in England. She was not constructed under the superintendence of either Catton, the official head of the administration, or of Soper, and with two balingers, the Fawcon and the Valentine, and some other work cost £4917, 15s 3½d.[25] Besides other wood 2591 oaks and 1195 beeches were used among the three vessels and for the various details mentioned, and it is to be remarked that, although the Grace Dieu must have represented the latest improvements, she, like the others, appears to have had only one ‘great mast’ and one ‘mesan,’[26] but two bowsprits. These carried no sails and were probably more of the nature of ‘bumpkins’ than spars. She was supplied with six sails and eleven bonnets, but their position when in use is not described, and some of them were perhaps spare ones. The order to commence her was placed in Robert Berd’s hands in December 1416, when Catton was still keeper and Soper was engaged in naval administration. It would appear to be entirely subversive of discipline and responsibility to distribute the control among three men, each of whom possessed sufficient position and independence to ensure friction, and we can only guess that the motive was pecuniary.

The first keeper of the ships under Henry V was William Catton by Letters Patent of 18th July 1413, who from the third to the eighth year of the reign of Henry IV had been bailiff of Winchelsea, and who subsequently held the bailiffship of Rye conjointly with his naval office. He was succeeded from 3rd February 1420 by the before-mentioned William Soper. Berd’s name only occurs in connection with the Grace Dieu. The river Hamble, on Southampton water, was then, and down to the close of the century, the favourite roadstead[15] for the royal ships lying up, and was defended at its entrance by a tower of wood which cost £40,[27] a storehouse with a workshop[28] was also built at Southampton, and one existed in London near the Tower. If the vessels were not built in royal yards or by royal workmen we may infer the control of a crown officer from the fact of a pension of fourpence a day having been granted, when broken down in health, to John Hoggekyns, ‘master-carpenter of the king’s ships,’ and builder of the Grace Dieu, the first known of the long line of master shipwrights reaching down to the present century.

The fittings of ships do not differ materially from those quoted by Sir N. H. Nicolas under Edward III; we find a ‘bitakyll’[29] covered with lead, and pumps were now in use. Cordage was chiefly from Bridport, but occasionally from Holland, and Oleron canvas was bought abroad. Flags were of St Marie, St Edward, Holy Trinity, St George, the Swan, Antelope, Ostrich Feathers, and the king’s arms. The Trinity Royal had a painted wooden leopard with a crown of copper gilt, perhaps as a figure head. The largest anchor of the Jesus weighed 2224lb. The balingers, besides being fully rigged, carried sometimes forty or fifty oars, twenty-four feet long apiece, for use in calms or to work to windward. But even a vessel like the Trinity Royal had forty oars and a large one called a ‘steering skull,’ to assist the rudder we may suppose. The fore and stern stages were now becoming permanent structures. Two ‘somerhuches’ were built on the Holigost and Trinity Royal. Somerhuche was the summer-castle or poop of the early sixteenth century, and the cost, £4, 11s 3d, equivalent now to some £70, seems too great for a mere timber staging.[30] Sails were sometimes decorated with the king’s arms or badges, but probably only in the chief ships and for holiday use.

After the death of Henry V one of the first orders of the Council was to direct the sale of the bulk of the Royal Navy.[31] Modern writers who hold that the spirit of the ‘Libel of English Policie’ was that representing the ideas of the time must explain this startling contrast between fact and theory. The truth is that the ‘Libel’ described, not existing conditions, but those that the writer desired should exist; the whole poem is a lament over past glories and an exhortation to retrieve[16] the maritime position of the country, but the poet did not look at what lay behind a couple of victories at sea and the capture of Calais.[32] After the real triumphs of Henry V and the memories associated with Edward III, the state of things in the Channel doubtless appeared very evil, although they were hardly worse during the reign of Henry VI than was usual, and not nearly so bad as under James I and Charles I. The poem was really an attempt to obtain continuity in naval policy, a thing of which the meaning is, even now, scarcely understood, and which in 1436, when the man-at-arms was the ideal fighting unit, had as little chance of being accepted and carried out as though it had preached religious toleration.

By Letters Patent of 5th March 1423, William Soper, merchant of Southampton, a collector of customs and subsidies at that port, and mayor of the town in 1416 and 1424, was again appointed ‘Keeper and Governor’ of the King’s ships, under the control[33] of Nicholas Banastre, comptroller of the customs there; no such clause existed in the patent of 1420. For himself and a clerk Soper was allowed £40 a year, but Banastre was not given any salary. The appointment is noteworthy for more than one reason. It is the first, and apparently the only, instance in which a keeper of the ships acted under the supervision of another officer little his superior in the official hierarchy, and it, with the previous patent of 1420, marks the commencement of a custom frequent enough afterwards of naming well-to-do merchants to posts in the administrative service of the navy. Besides greater business capacity such a man was useful to the government in that he was expected to advance money, or purchase stores, on his own credit when the crown finance was temporarily strained. There is little doubt that Soper’s appointment was of this character, and that his salary, was really by way of interest on money advanced by him for the construction of the Holigost and Gabriel, and for other purposes, years before. The first named ship was built in 1414, the other perhaps later, but it was not until 1430 that he received the sum which represented the final instalment of their cost.[34] By the will of Henry V the whole of his personal possessions were ordered to be sold and the proceeds handed over to his executors to pay his debts.[17] They received, in 1430, one thousand marks from the sale of the men-of-war, the remainder of the money obtained from this source being retained by Soper in settlement of his claims dating from 1414.

The transaction is interesting both as showing that the Council did not consider the men-of-war—if compulsorily put up to auction under the will—of sufficient importance to buy in, and as illustrating the fact that the royal ships were personal possessions of the sovereign in which the nation had no interest of ownership. Tunnage and poundage had been granted for ‘the safe keeping of the sea,’ but the application of the money was at the discretion of the king. He might use it to pay hired merchantmen or he might build ships of his own with it, or with the revenue of the crown estates to fulfil the same purpose; in neither case had Parliament any voice in the employment of the money. While calling upon the Cinque Ports to fulfil the conditions of their charters and impressing merchant ships throughout the country, he might keep his own navy idle; there was no national right to profit by its existence. The tunnage and poundage grant did not interfere with the king’s title to seize every ship in the kingdom, and was only an attempt to secure payment to owners, and the wages and victualling of the crews; it in no way placed upon him the responsibility of providing ships, the supply of which was ensured by the unrestricted exercise of the prerogative, and that prerogative was not used any less frequently because of the existence of the tunnage and poundage. As years passed on and the power of the trading classes increased, and the need for specialised fighting ships grew greater, they made their ethical right to the use of the navy for ordinary purposes felt in practice and implicitly recognised by the crown. Hence the distinction became less and less marked but the note of possessive separation between the ‘King’s Navy Royal’ and the trading navy which was, legally, also the king’s and is so referred to in sixteenth century papers, is to be traced to as late as 1649. Since that date the title ‘Royal Navy,’ although associated with our proudest national memories is, historically, a misnomer as applied to the navy of the state.

In 1425, Parliament raised tunnage and poundage to three shillings on the tun of wine and one shilling in the pound on merchandise, at which rate it continued. Probably very little of it was applied to the specific purpose for which it was given, the struggle for the crown of France absorbing every available item of revenue for the support of armies; in 1450 one of the articles against the Duke of Suffolk was that he had caused money given for the defence of the realm and safety of the sea to be otherwise employed. There still remains a sufficient[18] number of complaints and petitions to show to what little purpose our maritime forces were used. In 1432, the Commons formally declared that Danish ships had plundered those of Hull, to the amount of £5000, and others to £20,000 in one year, and requested that letters of reprisal might be issued.[35] Such attempts to clear the Channel as the government recognised sometimes bore a suspicious resemblance to piracy legalised by success. In 1435, Wm. Morfote of Winchelsea petitioned for a pardon, having been, as he euphemistically put it, ‘in Dover Castle a long time and afterward come oute as wele as he myghte,’ and then, ‘of his gode hertly intente,’ had been at sea with 100 men to attack the king’s enemies. He found it difficult to obtain provisions which seems to have been his only motive in asking for a pardon. The answer to the petition, while granting the pardon for ‘an esy fyne,’ more plainly calls him an escaped prisoner.[36] He was member for Winchelsea in 1428.

Although Parliament was continually complaining of foreign piracy there can be no doubt that English seamen had nothing to learn, in that occupation, from their rivals. ‘Your shipping you employ to make war upon the poor merchants and to plunder and rob them of their merchandise, and you make yourselves plunderers and pirates,’ said a contemporary writer.[37] By a statute[38] of Henry V, the breaking of truce and safe conduct was made high treason, and a conservator of safe conducts, who was to be a person of position enjoying not less than £40 in land by the year, was to be appointed in every port. Under Henry VI, safe conducts were freely granted to neutrals to load goods in enemies’ ships, and protests were made by the Commons about their number and that they were not enrolled of record in the court of chancery and so led to loss and litigation.

Notwithstanding the normal drawbacks of piracy and warfare, the over-sea trade of the kingdom seems to have been steadily expanding. A branch of traffic which employed many vessels, and must have been a valuable school of preparation for the longer voyages of the next generation, was what may be called, the pilgrim transport trade. The shrine of St James of Compostella was then the favourite objective of English external pilgrimage and there are innumerable licenses to shipowners to carry passengers out and home. In 1427-8 twenty-two licenses were granted, and in 1433-4 the number reached 65;[39] in 1445, 2100 persons were carried there and back.[40] Some of the licenses were granted to Soper, who was engaged in the business as well as in ordinary trade to[19] Spain, and it is to be remarked that they were sometimes issued during the winter months—January, February, March,—showing that English seamanship was outgrowing the tradition of summer voyages. In 1449 we have the first sign of the bounty system on merchant ships of large size which, in the next century, systematised into five shillings a ton for those of 100 tons and upwards. John Taverner of Hull, had built the Grace Dieu, and in that year, was allowed certain privileges in connexion with lading the vessel in reward for his enterprise.[41] The document seems to imply that she was a new ship, but in 1444-5, she was exempted from the harbour dues at Calais because drawing too much water to enter the harbour,[42] and is probably referred to in 1442.[43]

There are two most valuable papers still existing which enable us to form some idea of the number and size of the merchantmen available for the service of the crown. The first of June 1439[44] is a list of payments for ships taken up for the transport of troops to Aquitaine, and is unfortunately mutilated in some places. Its contents may be thus classified:—

| Tons 100 |

Tons 120 |

Tons 140 |

Tons 160 |

Tons 200 |

Tons 240 |

Tons 260 |

Tons 300 |

Tons 360 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| London | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Hull | 2 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Saltash | 1 | ||||||||

| Plymouth | 1 | ||||||||

| Exeter | 1 | ||||||||

| Fowey | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Bideford | 1 | ||||||||

| Bristol | 2 | ||||||||

| Penzance | 1 | ||||||||

| Barnstaple | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| Southampton | 1 | ||||||||

| Winchelsea | 1 | ||||||||

| Ipswich | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| Ash | 2 | ||||||||

| Lynn | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| Boston | 1 | ||||||||

| Teignmouth[45] | 1 | ||||||||

| Unknown[46] | 1 | 2 | 2 |

Twenty-two other vessels are of eighty tons, twenty of sixty, and six are under forty tons; in two cases the tonnage is not given, nine more are foreign including two from Bayonne, then an English possession, and ten entries are nearly altogether destroyed.

The next list, of 1451,[47] is also one of vessels impressed for an expedition to Aquitaine:—

| Tons 100 |

Tons 120 |

Tons 140 |

Tons 160 |

Tons 180 |

Tons 200 |

Tons 220 |

Tons 260 |

Tons 300 |

Tons 350 |

Tons 400 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| London | 1 | 3 | 1 | ||||||||

| Bristol | 1 | ||||||||||

| Southampton | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||

| Dartmouth[48] | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Plymouth | 2 | 2 | 1 | ||||||||

| Lynn | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| Fowey | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Looe | 1 | 1 | |||||||||

| Weymouth | 1 | 1 | |||||||||

| Penzance | 1 | ||||||||||

| Falmouth | 1 | ||||||||||

| Portsmouth | 1 | ||||||||||

| Winchelsea | 1 | ||||||||||

| Ash | 1 | ||||||||||

| Hoke | 1 | ||||||||||

| Calais | 1 | 2 |

One vessel of one hundred and forty, one of two hundred, and one of two hundred and twenty tons belong to places unnamed, and there are twenty-three ships of from fifty to ninety tons.

There are, then, at least thirty-six ships in the 1439, and fifty in the 1451, list of one hundred tons and upwards. It must be remembered that they are not schedules of the total available reserves drawn up during a naval war, with an enemy’s fleet at sea, or under the pressure of a threatened invasion, but merely represent the number of vessels required to transport a certain military force, and form only a proportion—whether large or small we know not—of the maritime strength of the country. Certainly the numbers for Bristol did not represent the total resources of that city, and Newcastle and Yarmouth, to name only two flourishing ports, do not occur in either list. Assuming the method of tonnage measurement to have been the same during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries we have here registers which will compare favourably, both in number and size of vessels, with those of the earlier twenty years of the reign of Elizabeth,[49] and imply a naval force superior in extent to anything existing during the greater part of the sixteenth century. There is contemporary evidence from a French author, one therefore not likely to be more than just to England, as to the flourishing condition of the merchant marine during the reign of Henry VI.[50] The author makes the English herald claim that his countrymen ‘are more richly[21] and amply provided at sea, with fine and powerful ships than any other nation of Christendom, so that they are kings of the sea, since none can resist them; and they who are strongest on the sea may call themselves kings.’ The answer of the French herald, too long to quote, after admitting that ‘you have a great number of fine ships,’ is only devoted to showing that France possesses all the natural advantages which go to the formation of maritime power, and that the French king, ‘when he pleases,’ would become supreme at sea. Obviously down to the time of the loss of the English conquests in France, and the outbreak of the wars of the Roses, the wave of prosperity which commenced with the century had not altogether spent its force.

Great or small, the progress was, at anyrate, not a bounty-fed one, since shipowners were experiencing the usual difficulties in obtaining payment merely for the use of their vessels. The bill for ships provided in 1450, came to £13,000, nearly one fourth of the yearly revenue of the crown, but the Treasury, exhausted by the ceaseless demands made upon it by the garrisons in France could not pay.[51] The king, therefore, appealed to his creditors and has left it on record that as £13,000 was a sum

‘Wyche myght not esely be perveyed at that tyme wherefore we comauded oure trusty and welbelovid Richard Greyle of London and others to labour and entrete the seyd maistres, possessores, and maryners for agrement of a lasse sume, the wych maistres, possessores, and maryners by laboar and trete made with hem accordyng to our seid comaundement agreed hem to take and reseve the sume of £6,200 in and for ful contentacyon of their seid dutees; and bycause the seid £6,200 myght not at that tyme esely be ffurnysshed in redy mony we graunted to ye seid maistres and possessores by oure several letters patentes conteynyng diveise sumys of money amountyng to the sume of £2,884 that they, their deputees or attornies shold have to reseyve in theire owne handes almaner of custumes and subsidies of wolle, wollefell and other merchaundises comyng into dyverse portes.’[52]

This was perhaps all they obtained of the £13,000, and such incidents, of which this was doubtless only one, explain the discontent of the trading classes with the house of Lancaster. Shipowners and merchants might be trusted, in the long run, to take care of their own interests, but the seamen were more helpless, and it may be supposed that if employers had to accept less than a fourth of their dues the men did not fare better if as well. Their protests were sometimes neither tardy[22] nor voiceless. The murder of Bishop Adam de Moleyns at Portsmouth on July 9, 1450, is directly attributed to an attempt to force sailors to accept a smaller amount than they had earned, and the bias towards the house of York, shown by the maritime population generally, may be ascribed to this cause.

Henry V had not considered it beneath the dignity of the crown to hire out his ships to merchants for voyages to Bordeaux and elsewhere when they were not required for service; the Council of Regency, therefore did not hesitate to follow the same course. In 1423 the Holigost was lent to some Lombard merchants for a journey to Zealand and back for £20; and the Valentine from Southampton to Calais for £10.[53] As the Holigost was of 760 tons a rate of £300, in modern values, or about eight shillings a ton for a voyage probably occupying nearly two months, cannot be considered excessive, and does not imply any great fear of sea risks, whether from man or the elements.

In the meantime, in virtue of the Council order of March 3, 1423, the destruction of a navy progressed merrily. During 1423 the following vessels were sold to merchants of London, Dartmouth, Bristol, Southampton, and Plymouth, and, from the prices, many of them must have been in good condition[54]:—

| George (Carrack), | £133 | 6 | 8 |

| George (Balinger), | 20 | 0 | 0 |

| Christopher, | 166 | 13 | 4 |

| Katrine Breton (Balinger), | 20 | 0 | 0 |

| Thomas, | 133 | 6 | 8 |

| Grande Marie, | 200 | 0 | 0 |

| Holigost (Spayne), | 200 | 0 | 0 |

| Nicholas, | 76 | 13 | 4 |

| Swan, | 18 | 0 | 0 |

| Cracchere, | 26 | 13 | 4 |

| Fawcon, | 50 | 0 | 0 |

Anchors and other stores were sold and, in 1424, the storehouse and forge at Southampton went for £66, 13s 4d; if there were to be no ships there was certainly no reason to keep up any establishment for their repairs. In the same year eight other vessels, mostly described as worn out, followed their sisters. They were sold for very low prices and the description of their state may be exact, although two at least were nearly new, and what we know of administrative methods in later times does not warrant an implicit faith, especially under a Council of Regency. When a 550 ton ship, like the Marie Sandwich, brought only £13, it must be assumed that she was almost worthless even for breaking up, or that the proceedings were not devoid of collusion.

We have no record of the expenditure for the first years of Henry’s reign but, from 31st August 1427 to 31st August 1433, the sum of £809, 10s 2d was spent by Soper for naval purposes, being an average of £134, 18s 4d a year.[55] The[23] Trinity Royal, Holigost, Grace Dieu, and Jesus were still in existence, but dismantled and unrigged at Bursledon. Apparently there were no officers attached to them, or at Southampton, of sufficient experience to assume responsibility, since Peter Johnson, master mariner of Sandwich, was paid for coming to superintend the removal of the masts of the Grace Dieu. The Trinity Royal was so far unseaworthy and useless as to be imbedded in the mud of the river Hamble, and fifteen Genoese and other foreign master mariners were employed about dismasting her. There seems at this time to have been some purpose of rebuilding the Jesus, because she was taken to a dock lately prepared at Southampton, and, of the whole amount before mentioned, £165, 6s 10d was laid out in unrigging her, towing to Southampton, expenses of dock, etc. As the sails and stores of the vessels sold in 1423-4 were still under Soper’s care, a new storehouse, 160 feet long and 14 feet broad, was built at Southampton. That at London had not been closed in 1423, possibly because it may have been within the precincts of the Tower, and much of the equipment of the four great ships still remaining was kept in it.

During the four years ending with the 31st August 1437, £96, 0s 2½d was received from the Exchequer and £72, 1s 6d from the sale of cordage, etc., belonging to the ships;[56] the expenditure was £143, 6s 5¾d. For the two years ending 31st August 1439, the outlay on the Royal Navy was £8, 9s 7d. The ‘Libel of English Policie,’ which is now held to have represented the views of the governing statesmen was therefore given to the world when the estimates for the crown navy averaged £4, 4s 6½d a year.

Economy had been further exercised by the discharge of the shipkeepers as superfluous, and possibly one of the results of this careful thrift was the destruction of the Grace Dieu by fire, while lying on the mud at Bursledon, during the night of the 7th January 1439.[57] Some loose fittings were saved and 15,400lbs. of iron recovered from the burnt wreck. Soper’s next account, from 31st August 1439, ends on 7th April 1442, during which time he received £3, 10s from the Exchequer and £3, 0s 11¾d for 1222lbs. of lead from the ships. The disbursements were £4, 16s 4d, chiefly incurred in breaking up the cabins[58] on the Trinity Royal and Holigost and taking away the timber; the Jesus appears to have been too far perished to experience even this fate.[59]

From 7th April 1442, Soper was succeeded by Richard[24] Clyvedon, a yeoman of the crown[60] by Letters Patent, dated 26th March 1442, but at the smaller fee of one shilling a day which had been received by Soper’s predecessors. In all probability Soper’s salary was very irregularly, if at all paid, and an official outlay which averaged some £1, 10s a year, offered few opportunities in the way of perquisites to a prosperous merchant. For five years and ninety days, from 7th April 1442 until 6th July 1447, the receipts were £61, 2s 7d, all from the sale of stores originally belonging to the vessels sold in 1423-4; no expenses of any sort had to be met since the bare hulks of the Jesus, Trinity, and Holigost, still existing were left to take care of themselves.[61] The next and last accounts continue for the following four years and nine months to the 7th April 1452, when they cease. The amount received was £73, 11s 4½d, again altogether from the sale of stores; the expenditure was £16, 12s 10d, mostly referable to the cost of a chain fixed across the Hamble.[62] As only the rotting hulls of the Trinity and Holigost now remained, it is difficult to estimate its value so far as they were concerned, but for the first time for nearly forty years, there were now fears of French reprisals.

It must not, however, be supposed that because the Royal Navy was not kept up, no measures were taken to protect maritime interests. The predecessors of Henry V had employed a combination of royal and impressed ships; Henry V apparently intended to increase the crown navy until it was powerful enough to enable him to rely on it for every purpose but that of transport. Rightly or wrongly the Protector and Council adopted a different system and one which was continued through all the political changes of the reign. Instead of keeping up a royal force, or of pressing ships and placing them under the crown officers, indentures were entered into now and again with certain persons supposed to be competent to provide under their own command an agreed number of ships and men to keep the sea for a specified time. In favour of this plan it was perhaps argued that it was cheaper than any other, and that it should prove sufficiently effective as the coast of France was either in English occupation or belonged to a neutral or ally in the Duke of Brittany, and that an expensive Royal Navy was unnecessary when a French navy was impossible and only the ordinary rovers of the sea had to be met and destroyed. Against it might be urged that, besides the delay inevitable to the process of collecting merchantmen at a given rendezvous, it was the object of the persons undertaking the work to make a profit on the[25] bargain and that they would probably minimise effort, time, and expense, as much as practicable. So far as the scanty evidence enables us to judge it is possible that, until the loss of the French coastline, the plan, had it been carried on under the authoritative supervision of an able and honest crown official, might have worked successfully. Doubtless the economy promised was the final argument because, once the Royal Navy had been suffered to perish, there was never throughout the reign any financial possibility of restoring it. By 1433 the royal expenses were nearly double the revenue; and the Lord Treasurer, Cromwell, told the King, ‘nowe daily many warrantis come to me of paiementes ... of moche more than all youre revenus wold come to thowe they wer not assigned afore; whereas hit aperith by your bokes of record which have been showed that they have been assigned nygh for this eleven yeere next folowyng.’[63]

As many of the debts of Henry V for hire of ships and men’s wages were still unpaid, the conditions were evidently not favourable to the direct action of the crown either in replacing its own navy or taking ships into pay. An intermediary of recognised position to whom a payment was usually at once made on account, doubtless inspired more confidence in owners and men. Although not the first in point of time, the commission of Sir John Speke by an agreement of 2nd May 1440, is noticeable in that the service was apparently the first in which the men were paid and victualled at a weekly rate, one and sixpence a week wages and the same for victuals.[64] For at least two centuries the rate had been threepence a day, with usually an additional sixpence a week ‘reward,’ and this reduction of pay seems to imply that there were plenty of men to be obtained. In 1442 the Commons themselves arranged the period—2nd February to 11th November—during which a fleet was to be at sea, and even designated the ships which were to serve, together with the allowances to officers and men.[65] There were to be eight ships, all merchantmen, manned by 1200 men, and each of the eight was to be attended by a barge and balinger having respectively 80 and 40 men apiece. There were also four pinnaces. One of the ships is the Nicholas of the Tower of Bristol. ‘Of the Tower’ was the man-of-war mark, and this is the only one found in the lists of merchantmen of the century. The Nicholas of the Tower of Henry V was sold to some purchasers belonging to Dartmouth, but may have passed into Bristol ownership. It was the crew of this vessel, usually described as a man-of-war, who seized and[26] executed the Duke of Suffolk on his passage to Flanders when exiled in 1450.

The seamen’s pay, two shillings a month, if not an error of entry, can only be explained by the expectation of a liberal division of prize-money, one half of which was to be shared among masters, quartermasters, soldiers and sailors. The other half was divided into thirds, of which two went to the owners and one to the captains and under-captains. The victualling was now one and twopence a week. The captains and under-captains were military officers; there was no ship-captain in the modern sense although the master, whose pay was sixpence a day, was his nearest equivalent. The conditions were beginning to slowly change during this century, but hitherto the fighting had been done on board ship by the soldiers embarked for the purpose. The duty of the sailors, whether officers or men, was only to handle the vessel at sea or in action. The fleet does not appear to have put to sea till August, although the undertakers, Sir William Ewe, Miles Stapylton, and John Heron, were receiving money for its preparation in June.[66] In 1445 the charges for the passage of Margaret of Anjou when she came to share the crown do not show the same tendency to lower wages; masters were still paid sixpence a day, but the men received one and ninepence a week and their sixpence ‘reward,’ and pages (boys) one and three halfpence a week.[67] During the winter of 1444-5 a Cinque Ports squadron was in commission from September to the following April, and this must be almost the last instance of the performance of the ancient service of the ports in a complete manner. Twenty-six vessels were provided—four from Hastings, seven from Winchelsea, four from Rye, Lydd, and Romney, two from Hythe, three from Dover, five from Sandwich, and one from Faversham, numbers which perhaps indicate the relative importance of the towns at this time. The whole cost of the fleet was only £672, 9s 1½d, while Margaret’s journey was considered worth £1810, 9s 7½d.[68] The tonnage of the Cinque Ports vessels is not given, but that they were of no great size may be inferred from the small number of men in each.

In 1449 Alexander Eden and Gervays Clifton, afterwards Treasurer of Calais, were entrusted with the care of the Channel and, although their deeds have left no mark in history, they were considered so satisfactory at the time that, in the following year, Clifton was granted a special reward of four hundred marks for his good service. In 1450 Clifton and Eden were again performing the same duty and, in 1452, Clifton and Sir Edward Hull. Certainly there was now every[27] reason for redoubled vigilance. Between 1449 and 1451 the English Conquests in France had gone like a dream; only Calais was left, and that was considered to be imminently threatened. Notwithstanding loans, mortgages of revenues, and money obtained by pawning the crown jewels, the government owed £372,000, while the receipts from the crown estates were not more than £5000 a year, and the yearly charge of the household alone was £23,000. If we add to these facts a saintly king, and an inefficient government, the first mutterings of the storm of civil war, and a foe, exhausted it is true, but eager for vengeance, we are able to partly picture the extent of the losses in honour and prosperity which made one of the first acts of the Duke of York, when created Protector on 27th March 1454, the appointment of a fresh commission to guard the seas. On the following 3rd April, the tunnage and poundage for three years was assigned to the Earls of Salisbury, Shrewsbury, Wiltshire, Worcester, and Oxford, the Lords Stourton and Fitzwalter, and Sir Robert Vere, for that purpose.[69] That immediate action might be taken a loan of £1000 was raised in the proportions of London £300, Bristol £150, Southampton £100, Norwich and Yarmouth £100, Ipswich, Colchester and Malden £100, York and Hull £100, New Sarum, Poole and Weymouth £50, Lynn £50, Boston £30, and Newcastle £20, to be repaid out of the tunnage and poundage.[70]

In 1455, the first battle of St Albans was fought and there was no further question of naval matters until Edward IV was on the throne. Naval power appears to have had but little influence on the result of the wars of the Roses, nor, except at one moment, is the command of the sea shown to be a factor of any great importance in the struggle. Such as it was the Yorkists possessed it, as owners and seamen both affected the white Rose, but the Lancastrians seem never to have experienced any difficulty in obtaining necessary shipping, when in power on land, during the years of war. In 1459, however, when York fled to Ireland, and Warwick to Calais, the attachment the seamen generally felt for the latter enabled him to hold his own there and in the Channel, which perhaps had no inconsiderable influence on the final issue. The naval weakness of the Lancastrians compelled them, instead of protecting the English coasts off the French ports, to issue commissions to array the posse comitatus in the maritime counties to repel invasion, and the sack of Sandwich in 1457, by the Seneschal de Brézé was an outcome of the changed conditions. But Warwick’s fight on 29th May 1458, with a fleet of Spanish[28] ships of more than double his strength, and his capture of six of them, though little better than open piracy, was a sharp reminder that English seamen had not lost the spirit which animated their fathers, and, under the right conditions could still emulate their deeds.[71]

Unless the merchant marine had degenerated very rapidly there must have still been plenty of seagoing ships available in English ports, but the subjoined Treasury warrant perhaps indicates the difficulty the Lancastrians experienced in chartering ships and obtaining men. On 5th April 1460, Henry was once more king and his adversaries in exile, and an order of that date directs the officials of the Exchequer that ‘of suche money as is lent unto us by oure trewe subgittes for keping of the see and othire causes ye do paye to Julyan Cope capitaigne of a carake of Venise nowe beinge in the Tamyse £100 for a moneth, and to Julyan Ffeso capitayne of a nother carrake of Jeane[72] being at Sandwich £105 for a moneth the which two carrakes be entretid to doo us service.’ This is of course not conclusive because foreign vessels were at times hired by all our kings although English ships were available. But in June 1460 the Lancastrian Duke of Exeter, with a superior force, met Warwick at sea, but did not venture to attack him, being unable to trust his men. If, therefore, the men were not reliable there was good reason for the employment of foreigners.