Title: Isis unveiled, Volume 1 (of 2), Science

A master-key to mysteries of ancient and modern science and theology

Author: H. P. Blavatsky

Release date: August 7, 2022 [eBook #68705]

Most recently updated: September 19, 2025

Language: English

Original publication: United States: J. W. Bouton, 1878

Credits: David Edwards, Les Galloway and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

Obvious typographical errors have been silently corrected. Variations in hyphenation have been standardised but all other spelling and punctuation remains unchanged with the exception of Greek and Hebrew which have been extensively corrected. The corrections are listed at the end of the book. The index appears only in Volume 2 of this work. A copy was added to this volume for the convenience of readers.

The cover was prepared by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

A MASTER-KEY

TO THE

Mysteries of Ancient and Modern

SCIENCE AND THEOLOGY.

BY

H. P. BLAVATSKY,

CORRESPONDING SECRETARY OF THE THEOSOPHICAL SOCIETY.

“Cecy est un livre de bonne Foy.”—Montaigne.

Vol. I.—SCIENCE.

FOURTH EDITION.

NEW YORK:

J. W. BOUTON, 706 BROADWAY.

LONDON: BERNARD QUARITCH.

1878.

Copyright, by

J. W. BOUTON.

1877.

Trow’s

Printing and Bookbinding Co.,

PRINTERS AND BOOKBINDERS,

205-213 East 12th. St.,

NEW YORK.

THE AUTHOR

Dedicates these Volumes

TO THE

THEOSOPHICAL SOCIETY,

WHICH WAS FOUNDED AT NEW YORK, A.D. 1875,

To Study the Subjects on which they Treat.

| PAGE | |

| Preface | v |

| BEFORE THE VEIL | |

| Dogmatic assumptions of modern science and theology | ix |

| The Platonic philosophy affords the only middle ground | xi |

| Review of the ancient philosophical systems | xv |

| A Syriac manuscript on Simon Magus | xxiii |

| Glossary of terms used in this book | xxiii |

| Volume first. | |

| THE “INFALLIBILITY” OF MODERN SCIENCE. | |

| CHAPTER I. | |

| OLD THINGS WITH NEW NAMES. | |

| The Oriental Kabala | 1 |

| Ancient traditions supported by modern research | 3 |

| The progress of mankind marked by cycles | 5 |

| Ancient cryptic science | 7 |

| Priceless value of the Vedas | 12 |

| Mutilations of the Jewish sacred books in translation | 13 |

| Magic always regarded as a divine science | 25 |

| Achievements of its adepts and hypotheses of their modern detractors | 25 |

| Man’s yearning for immortality | 37 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| PHENOMENA AND FORCES. | |

| The servility of society | 39 |

| Prejudice and bigotry of men of science | 40 |

| They are chased by psychical phenomena | 41 |

| Lost arts | 49 |

| The human will the master-force of forces | 57 |

| Superficial generalizations of the French savants | 60 |

| Mediumistic phenomena, to what attributable | 67 |

| Their relation to crime | 71 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| BLIND LEADERS OF THE BLIND. | |

| Huxley’s derivation from the Orohippus | 74 |

| Comte, his system and disciples | 75 |

| The London materialists | 85 |

| Borrowed robes | 89 |

| Emanation of the objective universe from the subjective | 92 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| THEORIES RESPECTING PSYCHIC PHENOMENA. | |

| Theory of de Gasparin | 100 |

| Theory of Thury | 100 |

| Theory of des Mousseaux, de Mirville | 100 |

| Theory of Babinet | 101 |

| Theory of Houdin | 101 |

| Theory of MM. Royer and Jobart de Lamballe | 102 |

| The twins—“unconscious cerebration” and “unconscious ventriloquism.” | 105 |

| Theory of Crookes | 112 |

| Theory of Faraday | 116 |

| Theory of Chevreuil | 116 |

| The Mendeleyeff commission of 1876 | 117 |

| Soul blindness | 121 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| THE ETHER, OR “ASTRAL LIGHT.” | |

| One primal force, but many correlations | 126 |

| Tyndall narrowly escapes a great discovery | 127 |

| The impossibility of miracle | 128 |

| Nature of the primordial substance | 133 |

| Interpretation of certain ancient myths | 133 |

| Experiments of the fakirs | 139 |

| Evolution in Hindu allegory | 153 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| PSYCHO-PHYSICAL PHENOMENA. | |

| The debt we owe to Paracelsus | 163 |

| Mesmerism—its parentage, reception, potentiality | 165 |

| “Psychometry” | 183 |

| Time, space, eternity | 184 |

| Transfer of energy from the visible to the invisible universe | 186 |

| The Crookes experiments and Cox theory | 195 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| THE ELEMENTS, ELEMENTALS, AND ELEMENTARIES. | |

| Attraction and repulsion universal in all the kingdoms of nature | 206 |

| Psychical phenomena depend on physical surroundings | 211 |

| Observations in Siam | 214 |

| Music in nervous disorders | 215 |

| The “world-soul” and its potentialities | 216 |

| Healing by touch, and healers | 217 |

| “Diakka” and Porphyry’s bad demons | 219 |

| The quenchless lamp | 224 |

| Modern ignorance of vital force | 237 |

| Antiquity of the theory of force-correlation | 241 |

| Universality of belief in magic | 247 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| SOME MYSTERIES OF NATURE. | |

| Do the planets affect human destiny? | 253 |

| Very curious passage from Hermes | 254 |

| The restlessness of matter | 257 |

| Prophecy of Nostradamus fulfilled | 260 |

| Sympathies between planets and plants | 264 |

| Hindu knowledge of the properties of colors | 265 |

| “Coincidences” the panacea of modern science | 268 |

| The moon and the tides | 273 |

| Epidemic mental and moral disorders | 274 |

| The gods of the Pantheons only natural forces | 280 |

| Proofs of the magical powers of Pythagoras | 283 |

| The viewless races of ethereal space | 284 |

| The “four truths” of Buddhism | 291 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| CYCLIC PHENOMENA. | |

| Meaning of the expression “coats of skin” | 293 |

| Natural selection and its results | 295 |

| The Egyptian “circle of necessity” | 296 |

| Pre-Adamite races | 299 |

| Descent of spirit into matter | 302 |

| The triune nature of man | 309 |

| The lowest creatures in the scale of being | 310 |

| Elementals specifically described | 311 |

| Proclus on the beings of the air | 312 |

| Various names for elementals | 313 |

| Swedenborgian views on soul-death | 317 |

| Earth-bound human souls | 319 |

| Impure mediums and their “guides” | 325 |

| Psychometry an aid to scientific research | 333 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| THE INNER AND OUTER MAN. | |

| Père Félix arraigns the scientists | 338 |

| The “Unknowable” | 340 |

| Danger of evocations by tyros | 342 |

| Lares and Lemures | 345 |

| Secrets of Hindu temples | 350 |

| Reïncarnation | 351 |

| Witchcraft and witches | 353 |

| The sacred soma trance | 357 |

| Vulnerability of certain “shadows” | 363 |

| Experiment of Clearchus on a sleeping boy | 365 |

| The author witnesses a trial of magic in India | 369 |

| Case of the Cevennois | 371 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| PSYCHOLOGICAL AND PHYSICAL MARVELS. | |

| Invulnerability attainable by man | 379 |

| Projecting the force of the will | 380 |

| Insensibility to snake-poison | 381 |

| Charming serpents by music | 383 |

| Teratological phenomena discussed | 385 |

| The psychological domain confessedly unexplored | 407 |

| Despairing regrets of Berzelius | 411 |

| Turning a river into blood a vegetable phenomenon | 413 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| THE “IMPASSABLE CHASM.” | |

| Confessions of ignorance by men of science | 417 |

| The Pantheon of nihilism | 421 |

| Triple composition of fire | 423 |

| Instinct and reason defined | 425 |

| Philosophy of the Hindu Jaïns | 429 |

| Deliberate misrepresentations of Lemprière | 431 |

| Man’s astral soul not immortal | 432 |

| The reïncarnation of Buddha | 437 |

| Magical sun and moon pictures of Thibet | 441 |

| Vampirism—its phenomena explained | 449 |

| Bengalese jugglery | 457 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| REALITIES AND ILLUSION. | |

| The rationale of talismans | 462 |

| Unexplained mysteries | 466 |

| Magical experiment in Bengal | 467 |

| Chibh Chondor’s surprising feats | 471 |

| The Indian tape-climbing trick an illusion | 473 |

| Resuscitation of buried fakirs | 477 |

| Limits of suspended animation | 481 |

| Mediumship totally antagonistic to adeptship | 487 |

| What are “materialized spirits”? | 493 |

| The Shudâla Mâdan | 495 |

| Philosophy of levitation | 497 |

| The elixir and alkahest | 503 |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| EGYPTIAN WISDOM. | |

| Origin of the Egyptians | 515 |

| Their mighty engineering works | 517 |

| The ancient land of the Pharaohs | 521 |

| Antiquity of the Nilotic monuments | 529 |

| Arts of war and peace | 531 |

| Mexican myths and ruins | 545 |

| Resemblances to the Egyptian | 551 |

| Moses a priest of Osiris | 555 |

| The lessons taught by the ruins of Siam | 563 |

| The Egyptian Tau at Palenque | 573 |

| CHAPTER XV. | |

| INDIA THE CRADLE OF THE RACE. | |

| Acquisition of the “secret doctrine” | 575 |

| Two relics owned by a Pali scholar | 577 |

| Jealous exclusiveness of the Hindus | 581 |

| Lydia Maria Child on Phallic symbolism | 583 |

| The age of the Vedas and Manu | 587 |

| Traditions of pre-diluvian races | 589 |

| Atlantis and its peoples | 593 |

| Peruvian relics | 597 |

| The Gobi desert and its secrets | 599 |

| Thibetan and Chinese legends | 600 |

| The magician aids, not impedes, nature | 617 |

| Philosophy, religion, arts and sciences bequeathed by Mother India to posterity | 618 |

[Pg v]

The work now submitted to public judgment is the fruit of a somewhat intimate acquaintance with Eastern adepts and study of their science. It is offered to such as are willing to accept truth wherever it may be found, and to defend it, even looking popular prejudice straight in the face. It is an attempt to aid the student to detect the vital principles which underlie the philosophical systems of old.

The book is written in all sincerity. It is meant to do even justice, and to speak the truth alike without malice or prejudice. But it shows neither mercy for enthroned error, nor reverence for usurped authority. It demands for a spoliated past, that credit for its achievements which has been too long withheld. It calls for a restitution of borrowed robes, and the vindication of calumniated but glorious reputations. Toward no form of worship, no religious faith, no scientific hypothesis has its criticism been directed in any other spirit. Men and parties, sects and schools are but the mere ephemera of the world’s day. Truth, high-seated upon its rock of adamant, is alone eternal and supreme.

We believe in no Magic which transcends the scope and capacity of the human mind, nor in “miracle,” whether divine or diabolical, if such imply a transgression of the laws of nature instituted from all eternity. Nevertheless, we accept the saying of the gifted author of Festus, that the human heart has not yet fully uttered itself, and that we have never attained or even understood the extent of its powers. Is it too much to believe that man should be developing new sensibilities and a closer relation with nature? The logic of evolution must teach as much, if carried to its legitimate conclusions. If, somewhere, in the line of ascent from vegetable or ascidian to the noblest man a soul was evolved, gifted with intellectual qualities, it cannot be unreasonable to infer and believe that a faculty of perception is also growing in man, enabling him to descry facts and truths even beyond our ordinary ken. Yet we do not hesitate to accept the assertion of Biffé, that “the essential is forever the same. Whether we cut away the marble inward that hides the statue in the[Pg vi] block, or pile stone upon stone outward till the temple is completed, our NEW result is only an old idea. The latest of all the eternities will find its destined other half-soul in the earliest.”

When, years ago, we first travelled over the East, exploring the penetralia of its deserted sanctuaries, two saddening and ever-recurring questions oppressed our thoughts: Where, WHO, WHAT is GOD? Who ever saw the IMMORTAL SPIRIT of man, so as to be able to assure himself of man’s immortality?

It was while most anxious to solve these perplexing problems that we came into contact with certain men, endowed with such mysterious powers and such profound knowledge that we may truly designate them as the sages of the Orient. To their instructions we lent a ready ear. They showed us that by combining science with religion, the existence of God and immortality of man’s spirit may be demonstrated like a problem of Euclid. For the first time we received the assurance that the Oriental philosophy has room for no other faith than an absolute and immovable faith in the omnipotence of man’s own immortal self. We were taught that this omnipotence comes from the kinship of man’s spirit with the Universal Soul—God! The latter, they said, can never be demonstrated but by the former. Man-spirit proves God-spirit, as the one drop of water proves a source from which it must have come. Tell one who had never seen water, that there is an ocean of water, and he must accept it on faith or reject it altogether. But let one drop fall upon his hand, and he then has the fact from which all the rest may be inferred. After that he could by degrees understand that a boundless and fathomless ocean of water existed. Blind faith would no longer be necessary; he would have supplanted it with KNOWLEDGE. When one sees mortal man displaying tremendous capabilities, controlling the forces of nature and opening up to view the world of spirit, the reflective mind is overwhelmed with the conviction that if one man’s spiritual Ego can do this much, the capabilities of the Father Spirit must be relatively as much vaster as the whole ocean surpasses the single drop in volume and potency. Ex nihilo nihil fit; prove the soul of man by its wondrous powers—you have proved God!

In our studies, mysteries were shown to be no mysteries. Names and places that to the Western mind have only a significance derived from Eastern fable, were shown to be realities. Reverently we stepped in spirit within the temple of Isis; to lift aside the veil of “the one that is and was and shall be” at Saïs; to look through the rent curtain of the Sanctum Sanctorum at Jerusalem; and even to interrogate within the crypts which once existed beneath the sacred edifice, the mysterious Bath-Kol. The Filia Vocis—the daughter of the divine voice—responded[Pg vii] from the mercy-seat within the veil,[1] and science, theology, every human hypothesis and conception born of imperfect knowledge, lost forever their authoritative character in our sight. The one-living God had spoken through his oracle—man, and we were satisfied. Such knowledge is priceless; and it has been hidden only from those who overlooked it, derided it, or denied its existence.

From such as these we apprehend criticism, censure, and perhaps hostility, although the obstacles in our way neither spring from the validity of proof, the authenticated facts of history, nor the lack of common sense among the public whom we address. The drift of modern thought is palpably in the direction of liberalism in religion as well as science. Each day brings the reactionists nearer to the point where they must surrender the despotic authority over the public conscience, which they have so long enjoyed and exercised. When the Pope can go to the extreme of fulminating anathemas against all who maintain the liberty of the Press and of speech, or who insist that in the conflict of laws, civil and ecclesiastical, the civil law should prevail, or that any method of instruction solely secular, may be approved;[2] and Mr. Tyndall, as the mouthpiece of nineteenth century science, says, “... the impregnable position of science may be stated in a few words: we claim, and we shall wrest from theology, the entire domain of cosmological theory”[3]—the end is not difficult to foresee.

Centuries of subjection have not quite congealed the life-blood of men into crystals around the nucleus of blind faith; and the nineteenth is witnessing the struggles of the giant as he shakes off the Liliputian cordage and rises to his feet. Even the Protestant communion of England and America, now engaged in the revision of the text of its Oracles, will be compelled to show the origin and merits of the text itself. The day of domineering over men with dogmas has reached its gloaming.

Our work, then, is a plea for the recognition of the Hermetic philosophy, the anciently universal Wisdom-Religion, as the only possible key to the Absolute in science and theology. To show that we do not at all conceal from ourselves the gravity of our undertaking, we may say in advance that it would not be strange if the following classes should array themselves against us:

[Pg viii]

The Christians, who will see that we question the evidences of the genuineness of their faith.

The Scientists, who will find their pretensions placed in the same bundle with those of the Roman Catholic Church for infallibility, and, in certain particulars, the sages and philosophers of the ancient world classed higher than they.

Pseudo-Scientists will, of course, denounce us furiously.

Broad Churchmen and Freethinkers will find that we do not accept what they do, but demand the recognition of the whole truth.

Men of letters and various authorities, who hide their real belief in deference to popular prejudices.

The mercenaries and parasites of the Press, who prostitute its more than royal power, and dishonor a noble profession, will find it easy to mock at things too wonderful for them to understand; for to them the price of a paragraph is more than the value of sincerity. From many will come honest criticism; from many—cant. But we look to the future.

The contest now going on between the party of public conscience and the party of reaction, has already developed a healthier tone of thought. It will hardly fail to result ultimately in the overthrow of error and the triumph of Truth. We repeat again—we are laboring for the brighter morrow.

And yet, when we consider the bitter opposition that we are called upon to face, who is better entitled than we upon entering the arena to write upon our shield the hail of the Roman gladiator to Cæsar: Moriturus te Salutat!

New York, September, 1877.

[Pg ix]

Joan.—Advance our waving colors on the walls!—King Henry VI. Act IV.

“My life has been devoted to the study of man, his destiny and his happiness.”

—J. R. Buchanan, M.D., Outlines of Lectures on Anthropology.

It is nineteen centuries since, as we are told, the night of Heathenism and Paganism was first dispelled by the divine light of Christianity; and two-and-a-half centuries since the bright lamp of Modern Science began to shine on the darkness of the ignorance of the ages. Within these respective epochs, we are required to believe, the true moral and intellectual progress of the race has occurred. The ancient philosophers were well enough for their respective generations, but they were illiterate as compared with modern men of science. The ethics of Paganism perhaps met the wants of the uncultivated people of antiquity, but not until the advent of the luminous “Star of Bethlehem,” was the true road to moral perfection and the way to salvation made plain. Of old, brutishness was the rule, virtue and spirituality the exception. Now, the dullest may read the will of God in His revealed word; men have every incentive to be good, and are constantly becoming better.

This is the assumption; what are the facts? On the one hand an unspiritual, dogmatic, too often debauched clergy; a host of sects, and three warring great religions; discord instead of union, dogmas without proofs, sensation-loving preachers, and wealth and pleasure-seeking parishioners’ hypocrisy and bigotry, begotten by the tyrannical exigencies of respectability, the rule of the day, sincerity and real piety exceptional. On the other hand, scientific hypotheses built on sand; no accord upon a single question; rancorous quarrels and jealousy; a general drift into materialism. A death-grapple of Science with Theology for infallibility—“a conflict of ages.”

At Rome, the self-styled seat of Christianity, the putative successor to the chair of Peter is undermining social order with his invisible but omnipresent net-work of bigoted agents, and incites them to revolutionize Europe for his temporal as well as spiritual supremacy. We see him who calls himself the “Vicar of Christ,” fraternizing with the anti-Christian Moslem against another Christian nation, publicly invoking the blessing of God upon the arms of those who have for centuries withstood, with[Pg x] fire and sword, the pretensions of his Christ to Godhood! At Berlin—one of the great seats of learning—professors of modern exact sciences, turning their backs on the boasted results of enlightenment of the post-Galileonian period, are quietly snuffing out the candle of the great Florentine; seeking, in short, to prove the heliocentric system, and even the earth’s rotation, but the dreams of deluded scientists, Newton a visionary, and all past and present astronomers but clever calculators of unverifiable problems.[4]

Between these two conflicting Titans—Science and Theology—is a bewildered public, fast losing all belief in man’s personal immortality, in a deity of any kind, and rapidly descending to the level of a mere animal existence. Such is the picture of the hour, illumined by the bright noon-day sun of this Christian and scientific era!

Would it be strict justice to condemn to critical lapidation the most humble and modest of authors for entirely rejecting the authority of both these combatants? Are we not bound rather to take as the true aphorism of this century, the declaration of Horace Greeley: “I accept unreservedly the views of no man, living or dead”?[5] Such, at all events, will be our motto, and we mean that principle to be our constant guide throughout this work.

Among the many phenomenal outgrowths of our century, the strange creed of the so-called Spiritualists has arisen amid the tottering ruins of self-styled revealed religions and materialistic philosophies; and yet it alone offers a possible last refuge of compromise between the two. That this unexpected ghost of pre-Christian days finds poor welcome from our sober and positive century, is not surprising. Times have strangely changed; and it is but recently that a well-known Brooklyn preacher pointedly remarked in a sermon, that could Jesus come back and behave in the streets of New York, as he did in those of Jerusalem, he would find himself confined in the prison of the Tombs.[6] What sort of welcome, then, could Spiritualism ever expect? True enough, the weird stranger seems neither attractive nor promising at first sight. Shapeless and uncouth, like an infant attended by seven nurses, it is coming out of its teens lame and mutilated. The name of its enemies is legion; its friends and protectors are a handful. But what of that? When was ever truth accepted à priori? Because the champions of Spiritualism have in their fanaticism magnified its qualities, and remained blind to its imperfections, that gives no excuse to doubt its reality. A forgery is impossible when we have no model to forge after. The fanaticism of Spiritualists is itself[Pg xi] a proof of the genuineness and possibility of their phenomena. They give us facts that we may investigate, not assertions that we must believe without proof. Millions of reasonable men and women do not so easily succumb to collective hallucination. And so, while the clergy, following their own interpretations of the Bible, and science its self-made Codex of possibilities in nature, refuse it a fair hearing, real science and true religion are silent, and gravely wait further developments.

The whole question of phenomena rests on the correct comprehension of old philosophies. Whither, then, should we turn, in our perplexity, but to the ancient sages, since, on the pretext of superstition, we are refused an explanation by the modern? Let us ask them what they know of genuine science and religion; not in the matter of mere details, but in all the broad conception of these twin truths—so strong in their unity, so weak when divided. Besides, we may find our profit in comparing this boasted modern science with ancient ignorance; this improved modern theology with the “Secret doctrines” of the ancient universal religion. Perhaps we may thus discover a neutral ground whence we can reach and profit by both.

It is the Platonic philosophy, the most elaborate compend of the abstruse systems of old India, that can alone afford us this middle ground. Although twenty-two and a quarter centuries have elapsed since the death of Plato, the great minds of the world are still occupied with his writings. He was, in the fullest sense of the word, the world’s interpreter. And the greatest philosopher of the pre-Christian era mirrored faithfully in his works the spiritualism of the Vedic philosophers who lived thousands of years before himself, and its metaphysical expression. Vyasa, Djeminy, Kapila, Vrihaspati, Sumati, and so many others, will be found to have transmitted their indelible imprint through the intervening centuries upon Plato and his school. Thus is warranted the inference that to Plato and the ancient Hindu sages was alike revealed the same wisdom. So surviving the shock of time, what can this wisdom be but divine and eternal?

Plato taught justice as subsisting in the soul of its possessor and his greatest good. “Men, in proportion to their intellect, have admitted his transcendent claims.” Yet his commentators, almost with one consent, shrink from every passage which implies that his metaphysics are based on a solid foundation, and not on ideal conceptions.

But Plato could not accept a philosophy destitute of spiritual aspirations; the two were at one with him. For the old Grecian sage there was a single object of attainment: REAL KNOWLEDGE. He considered those only to be genuine philosophers, or students of truth, who possess the knowledge of the really-existing, in opposition to the mere seeing; of[Pg xii] the always-existing, in opposition to the transitory; and of that which exists permanently, in opposition to that which waxes, wanes, and is developed and destroyed alternately. “Beyond all finite existences and secondary causes, all laws, ideas, and principles, there is an INTELLIGENCE or MIND [νοῦς, nous, the spirit], the first principle of all principles, the Supreme Idea on which all other ideas are grounded; the Monarch and Lawgiver of the universe; the ultimate substance from which all things derive their being and essence, the first and efficient Cause of all the order, and harmony, and beauty, and excellency, and goodness, which pervades the universe—who is called, by way of preëminence and excellence, the Supreme Good, the God (ὁ θεός) ‘the God over all’ (ὁ επι πασι θεός).”[7] He is not the truth nor the intelligence, but “the father of it.” Though this eternal essence of things may not be perceptible by our physical senses, it may be apprehended by the mind of those who are not wilfully obtuse. “To you,” said Jesus to his elect disciples, “it is given to know the mysteries of the Kingdom of God, but to them [the πολλοὶ] it is not given; ... therefore speak I to them in parables [or allegories]; because they seeing, see not, and hearing, they hear not, neither do they understand.”[8]

The philosophy of Plato, we are assured by Porphyry, of the Neo-platonic School was taught and illustrated in the MYSTERIES. Many have questioned and even denied this; and Lobeck, in his Aglaophomus, has gone to the extreme of representing the sacred orgies as little more than an empty show to captivate the imagination. As though Athens and Greece would for twenty centuries and more have repaired every fifth year to Eleusis to witness a solemn religious farce! Augustine, the papa-bishop of Hippo, has resolved such assertions. He declares that the doctrines of the Alexandrian Platonists were the original esoteric doctrines of the first followers of Plato, and describes Plotinus as a Plato resuscitated. He also explains the motives of the great philosopher for veiling the interior sense of what he taught.[9]

[Pg xiii]

As to the myths, Plato declares in the Gorgias and the Phædon that they were the vehicles of great truths well worth the seeking. But commentators are so little en rapport with the great philosopher as to be compelled to acknowledge that they are ignorant where “the doctrinal ends, and the mythical begins.” Plato put to flight the popular superstition concerning magic and dæmons, and developed the exaggerated notions of the time into rational theories and metaphysical conceptions. Perhaps these would not quite stand the inductive method of reasoning established by Aristotle; nevertheless they are satisfactory in the highest degree to those who apprehend the existence of that higher faculty of insight or intuition, as affording a criterion for ascertaining truth.

Basing all his doctrines upon the presence of the Supreme Mind, Plato taught that the nous, spirit, or rational soul of man, being “generated by the Divine Father,” possessed a nature kindred, or even homogeneous, with the Divinity, and was capable of beholding the eternal realities. This faculty of contemplating reality in a direct and immediate manner belongs to God alone; the aspiration for this knowledge constitutes what is really meant by philosophy—the love of wisdom. The love of truth is inherently the love of good; and so predominating over every desire of the soul, purifying it and assimilating it to the divine, thus governing every act of the individual, it raises man to a participation and communion with Divinity, and restores him to the likeness of God. “This flight,” says Plato in the Theætetus, “consists in becoming like God, and this assimilation is the becoming just and holy with wisdom.”

The basis of this assimilation is always asserted to be the preëxistence of the spirit or nous. In the allegory of the chariot and winged steeds, given in the Phædrus, he represents the psychical nature as composite and two-fold; the thumos, or epithumetic part, formed from the substances of the world of phenomena; and the θυμοειδές, thumoeides, the essence of which is linked to the eternal world. The present earth-life is a fall and punishment. The soul dwells in “the grave which we call the body,” and in its incorporate state, and previous to the discipline of education, the noëtic or spiritual element is “asleep.” Life is thus a dream, rather than a reality. Like the captives in the subterranean cave, described in The Republic, the back is turned to the light, we perceive only the shadows of objects, and think them the actual realities. Is not this[Pg xiv] the idea of Maya, or the illusion of the senses in physical life, which is so marked a feature in Buddhistical philosophy? But these shadows, if we have not given ourselves up absolutely to the sensuous nature, arouse in us the reminiscence of that higher world that we once inhabited. “The interior spirit has some dim and shadowy recollection of its antenatal state of bliss, and some instinctive and proleptic yearnings for its return.” It is the province of the discipline of philosophy to disinthrall it from the bondage of sense, and raise it into the empyrean of pure thought, to the vision of eternal truth, goodness, and beauty. “The soul,” says Plato, in the Theætetus, “cannot come into the form of a man if it has never seen the truth. This is a recollection of those things which our soul formerly saw when journeying with Deity, despising the things which we now say are, and looking up to that which REALLY IS. Wherefore the nous, or spirit, of the philosopher (or student of the higher truth) alone is furnished with wings; because he, to the best of his ability, keeps these things in mind, of which the contemplation renders even Deity itself divine. By making the right use of these things remembered from the former life, by constantly perfecting himself in the perfect mysteries, a man becomes truly perfect—an initiate into the diviner wisdom.”

Hence we may understand why the sublimer scenes in the Mysteries were always in the night. The life of the interior spirit is the death of the external nature; and the night of the physical world denotes the day of the spiritual. Dionysus, the night-sun, is, therefore, worshipped rather than Helios, orb of day. In the Mysteries were symbolized the preëxistent condition of the spirit and soul, and the lapse of the latter into earth-life and Hades, the miseries of that life, the purification of the soul, and its restoration to divine bliss, or reünion with spirit. Theon, of Smyrna, aptly compares the philosophical discipline to the mystic rites: “Philosophy,” says he, “may be called the initiation into the true arcana, and the instruction in the genuine Mysteries. There are five parts of this initiation: I., the previous purification; II., the admission to participation in the arcane rites; III., the epoptic revelation; IV., the investiture or enthroning; V.—the fifth, which is produced from all these, is friendship and interior communion with God, and the enjoyment of that felicity which arises from intimate converse with divine beings.... Plato denominates the epopteia, or personal view, the perfect contemplation of things which are apprehended intuitively, absolute truths and ideas. He also considers the binding of the head and crowning as analogous to the authority which any one receives from his instructors, of leading others into the same contemplation. The fifth gradation is the most perfect felicity arising from hence, and, according[Pg xv] to Plato, an assimilation to divinity as far as is possible to human beings.”[10]

Such is Platonism. “Out of Plato,” says Ralph Waldo Emerson, “come all things that are still written and debated among men of thought.” He absorbed the learning of his times—of Greece from Philolaus to Socrates; then of Pythagoras in Italy; then what he could procure from Egypt and the East. He was so broad that all philosophy, European and Asiatic, was in his doctrines; and to culture and contemplation he added the nature and qualities of the poet.

The followers of Plato generally adhered strictly to his psychological theories. Several, however, like Xenocrates, ventured into bolder speculations. Speusippus, the nephew and successor of the great philosopher, was the author of the Numerical Analysis, a treatise on the Pythagorean numbers. Some of his speculations are not found in the written Dialogues; but as he was a listener to the unwritten lectures of Plato, the judgment of Enfield is doubtless correct, that he did not differ from his master. He was evidently, though not named, the antagonist whom Aristotle criticised, when professing to cite the argument of Plato against the doctrine of Pythagoras, that all things were in themselves numbers, or rather, inseparable from the idea of numbers. He especially endeavored to show that the Platonic doctrine of ideas differed essentially from the Pythagorean, in that it presupposed numbers and magnitudes to exist apart from things. He also asserted that Plato taught that there could be no real knowledge, if the object of that knowledge was not carried beyond or above the sensible.

But Aristotle was no trustworthy witness. He misrepresented Plato, and he almost caricatured the doctrines of Pythagoras. There is a canon of interpretation, which should guide us in our examinations of every philosophical opinion: “The human mind has, under the necessary operation of its own laws, been compelled to entertain the same fundamental ideas, and the human heart to cherish the same feelings in all ages.” It is certain that Pythagoras awakened the deepest intellectual sympathy of his age, and that his doctrines exerted a powerful influence upon the mind of Plato. His cardinal idea was that there existed a permanent principle of unity beneath the forms, changes, and other phenomena of the universe. Aristotle asserted that he taught that “numbers are the first principles of all entities.” Ritter has expressed the opinion that the formula of Pythagoras should be taken symbolically, which is doubtless correct. Aristotle goes on to associate these numbers with the “forms” and “ideas” of Plato. He even declares that Plato said:[Pg xvi] “forms are numbers,” and that “ideas are substantial existences—real beings.” Yet Plato did not so teach. He declared that the final cause was the Supreme Goodness—το ἀγαθόν. “Ideas are objects of pure conception for the human reason, and they are attributes of the Divine Reason.”[11] Nor did he ever say that “forms are numbers.” What he did say may be found in the Timæus: “God formed things as they first arose according to forms and numbers.”

It is recognized by modern science that all the higher laws of nature assume the form of quantitative statement. This is perhaps a fuller elaboration or more explicit affirmation of the Pythagorean doctrine. Numbers were regarded as the best representations of the laws of harmony which pervade the cosmos. We know too that in chemistry the doctrine of atoms and the laws of combination are actually and, as it were, arbitrarily defined by numbers. As Mr. W. Archer Butler has expressed it: “The world is, then, through all its departments, a living arithmetic in its development, a realized geometry in its repose.”

The key to the Pythagorean dogmas is the general formula of unity in multiplicity, the one evolving the many and pervading the many. This is the ancient doctrine of emanation in few words. Even the apostle Paul accepted it as true. “Εξ αυτοὺ, και δι᾽ αυτοῦ, και εις αυτὸν τὰ πάντα”—Out of him and through him and in him all things are. This, as we can see by the following quotation, is purely Hindu and Brahmanical:

“When the dissolution—Pralaya—had arrived at its term, the great Being—Para-Atma or Para-Purusha—the Lord existing through himself, out of whom and through whom all things were, and are and will be ... resolved to emanate from his own substance the various creatures” (Manava-Dharma-Sastra, book i., slokas 6 and 7).

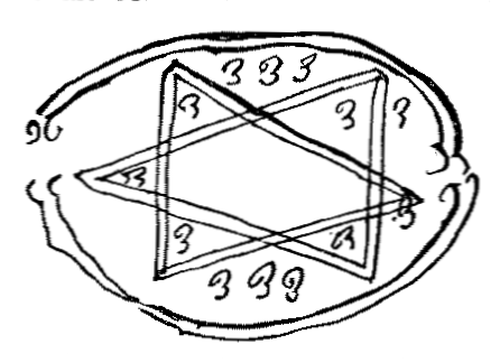

The mystic Decad 1 + 2 + 3 + 4 = 10 is a way of expressing this idea. The One is God, the Two, matter; the Three, combining Monad and Duad, and partaking of the nature of both, is the phenomenal world; the Tetrad, or form of perfection, expresses the emptiness of all; and the Decad, or sum of all, involves the entire cosmos. The universe is the combination of a thousand elements, and yet the expression of a single spirit—a chaos to the sense, a cosmos to the reason.

The whole of this combination of the progression of numbers in the idea of creation is Hindu. The Being existing through himself, Swayambhu or Swayambhuva, as he is called by some, is one. He emanates from himself the creative faculty, Brahma or Purusha (the divine male), and the one becomes Two; out of this Duad, union of the purely[Pg xvii] intellectual principle with the principle of matter, evolves a third, which is Viradj, the phenomenal world. It is out of this invisible and incomprehensible trinity, the Brahmanic Trimurty, that evolves the second triad which represents the three faculties—the creative, the conservative, and the transforming. These are typified by Brahma, Vishnu, and Siva, but are again and ever blended into one. Unity, Brahma, or as the Vedas called him, Tridandi, is the god triply manifested, which gave rise to the symbolical Aum or the abbreviated Trimurty. It is but under this trinity, ever active and tangible to all our senses, that the invisible and unknown Monas can manifest itself to the world of mortals. When he becomes Sarira, or he who puts on a visible form, he typifies all the principles of matter, all the germs of life, he is Purusha, the god of the three visages, or triple power, the essence of the Vedic triad. “Let the Brahmas know the sacred Syllable (Aum), the three words of the Savitri, and read the Vedas daily” (Manu, book iv., sloka 125).

“After having produced the universe, He whose power is incomprehensible vanished again, absorbed in the Supreme Soul.... Having retired into the primitive darkness, the great Soul remains within the unknown, and is void of all form....

“When having again reünited the subtile elementary principles, it introduces itself into either a vegetable or animal seed, it assumes at each a new form.”

“It is thus that, by an alternative waking and rest, the Immutable Being causes to revive and die eternally all the existing creatures, active and inert” (Manu, book i., sloka 50, and others).

He who has studied Pythagoras and his speculations on the Monad, which, after having emanated the Duad retires into silence and darkness, and thus creates the Triad can realize whence came the philosophy of the great Samian Sage, and after him that of Socrates and Plato.

Speusippus seems to have taught that the psychical or thumetic soul was immortal as well as the spirit or rational soul, and further on we will show his reasons. He also—like Philolaus and Aristotle, in his disquisitions upon the soul—makes of æther an element; so that there were five principal elements to correspond with the five regular figures in Geometry. This became also a doctrine of the Alexandrian school.[12] Indeed, there was much in the doctrines of the Philaletheans which did not appear in the works of the older Platonists, but was doubtless taught in substance by the philosopher himself, but with his usual reticence was not committed to writing as being too arcane for promiscuous publication. Speusippus and Xenocrates after him, held, like their great master, that the[Pg xviii] anima mundi, or world-soul, was not the Deity, but a manifestation. Those philosophers never conceived of the One as an animate nature.[13] The original One did not exist, as we understand the term. Not till he had united with the many—emanated existence (the monad and duad) was a being produced. The τίμιον, honored—the something manifested, dwells in the centre as in the circumference, but it is only the reflection of the Deity—the World-Soul.[14] In this doctrine we find the spirit of esoteric Buddhism.

A man’s idea of God, is that image of blinding light that he sees reflected in the concave mirror of his own soul, and yet this is not, in very truth, God, but only His reflection. His glory is there, but, it is the light of his own Spirit that the man sees, and it is all he can bear to look upon. The clearer the mirror, the brighter will be the divine image. But the external world cannot be witnessed in it at the same moment. In the ecstatic Yogin, in the illuminated Seer, the spirit will shine like the noon-day sun; in the debased victim of earthly attraction, the radiance has disappeared, for the mirror is obscured with the stains of matter. Such men deny their God, and would willingly deprive humanity of soul at one blow.

No God, No Soul? Dreadful, annihilating thought! The maddening nightmare of a lunatic—Atheist; presenting before his fevered vision, a hideous, ceaseless procession of sparks of cosmic matter created by no one; self-appearing, self-existent, and self-developing; this Self no Self, for it is nothing and nobody; floating onward from nowhence, it is propelled by no Cause, for there is none, and it rushes nowhither. And this in a circle of Eternity blind, inert, and—CAUSELESS. What is even the erroneous conception of the Buddhistic Nirvana in comparison! The Nirvana is preceded by numberless spiritual transformations and metempsychoses, during which the entity loses not for a second the sense of its own individuality, and which may last for millions of ages before the Final No-thing is reached.

Though some have considered Speusippus as inferior to Aristotle, the world is nevertheless indebted to him for defining and expounding many things that Plato had left obscure in his doctrine of the Sensible and Ideal. His maxim was “The Immaterial is known by means of scientific thought, the Material by scientific perception.”[15]

Xenocrates expounded many of the unwritten theories and teachings of his master. He too held the Pythagorean doctrine, and his system of numerals and mathematics in the highest estimation. Recognizing but three degrees of knowledge—Thought, Perception, and Envisagement (or knowledge by Intuition), he made the former busy itself with all that[Pg xix] which is beyond the heavens; Perception with things in the heavens; Intuition with the heavens themselves.

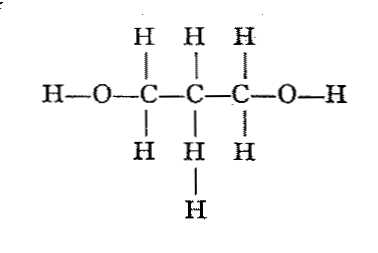

We find again these theories, and nearly in the same language in the Manava-Dharma-Sastra, when speaking of the creation of man: “He (the Supreme) drew from his own essence the immortal breath which perisheth not in the being, and to this soul of the being he gave the Ahancara (conscience of the ego) sovereign guide. Then he gave to that soul of the being (man) the intellect formed of the three qualities, and the five organs of the outward perception.”

These three qualities are Intelligence, Conscience, and Will; answering to the Thought, Perception, and Envisagement of Xenocrates. The relation of numbers to Ideas was developed by him further than by Speusippus, and he surpassed Plato in his definition of the doctrine of Invisible Magnitudes. Reducing them to their ideal primary elements, he demonstrated that every figure and form originated out of the smallest indivisible line. That Xenocrates held the same theories as Plato in relation to the human soul (supposed to be a number) is evident, though Aristotle contradicts this, like every other teaching of this philosopher.[16] This is conclusive evidence that many of Plato’s doctrines were delivered orally, even were it shown that Xenocrates and not Plato was the first to originate the theory of indivisible magnitudes. He derives the Soul from the first Duad, and calls it a self-moved number.[17] Theophrastus remarks that he entered and eliminated this Soul-theory more than any other Platonist. He built upon it the cosmological doctrine, and proved the necessary existence in every part of the universal space of a successive and progressive series of animated and thinking though spiritual beings.[18] The Human Soul with him is a compound of the most spiritual properties of the Monad and the Duad, possessing the highest principles of both. If, like Plato and Prodicus, he refers to the Elements as to Divine Powers, and calls them gods, neither himself nor others connected any anthropomorphic idea with the appellation. Krische remarks that he called them gods only that these elementary powers should not be confounded with the dæmons of the nether world[19] (the Elementary Spirits). As the Soul of the World permeates the whole Cosmos, even beasts must have in them something divine.[20] This, also, is the doctrine of Buddhists and the Hermetists, and Manu endows with a living soul even the plants and the tiniest blade of grass.

The dæmons, according to this theory, are intermediate beings[Pg xx] between the divine perfection and human sinfulness,[21] and he divides them into classes, each subdivided in many others. But he states expressly that the individual or personal soul is the leading guardian dæmon of every man, and that no dæmon has more power over us than our own. Thus the Daimonion of Socrates is the god or Divine Entity which inspired him all his life. It depends on man either to open or close his perceptions to the Divine voice. Like Speusippus he ascribed immortality to the ψυχη, psychical body, or irrational soul. But some Hermetic philosophers have taught that the soul has a separate continued existence only so long as in its passage through the spheres any material or earthly particles remain incorporated in it; and that when absolutely purified, the latter are annihilated, and the quintessence of the soul alone becomes blended with its divine spirit (the Rational), and the two are thenceforth one.

Zeller states that Xenocrates forbade the eating of animal food, not because he saw in beasts something akin to man, as he ascribed to them a dim consciousness of God, but, “for the opposite reason, lest the irrationality of animal souls might thereby obtain a certain influence over us.”[22] But we believe that it was rather because, like Pythagoras, he had had the Hindu sages for his masters and models. Cicero depicted Xenocrates utterly despising everything except the highest virtue;[23] and describes the stainlessness and severe austerity of his character.[24] “To free ourselves from the subjection of sensuous existence, to conquer the Titanic elements in our terrestrial nature through the Divine one, is our problem.” Zeller makes him say:[25] “Purity, even in the secret longings of our heart, is the greatest duty, and only philosophy and the initiation into the Mysteries help toward the attainment of this object.”

Crantor, another philosopher associated with the earliest days of Plato’s Academy, conceived the human soul as formed out of the primary substance of all things, the Monad or One, and the Duad or the Two. Plutarch speaks at length of this philosopher, who like his master believed in souls being distributed in earthly bodies as an exile and punishment.

Herakleides, though some critics do not believe him to have strictly adhered to Plato’s primal philosophy,[26] taught the same ethics. Zeller presents him to us imparting, like Hicetas and Ecphantus, the Pythagorean doctrine of the diurnal rotation of the earth and the immobility of the fixed stars, but adds that he was ignorant of the annual revolution of the[Pg xxi] earth around the sun, and of the heliocentric system.[27] But we have good evidence that the latter system was taught in the Mysteries, and that Socrates died for atheism, i. e., for divulging this sacred knowledge. Herakleides adopted fully the Pythagorean and Platonic views of the human soul, its faculties and its capabilities. He describes it as a luminous, highly ethereal essence. He affirms that souls inhabit the milky way before descending “into generation” or sublunary existence. His dæmons or spirits are airy and vaporous bodies.

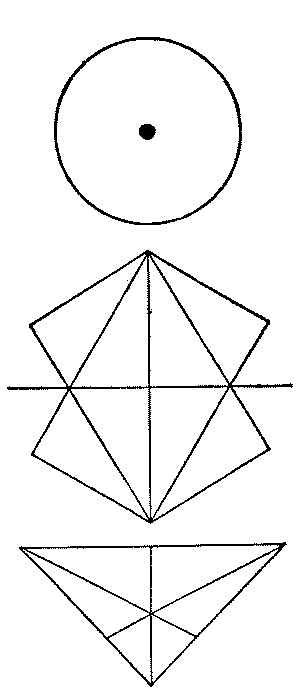

In the Epinomis is fully stated the doctrine of the Pythagorean numbers in relation to created things. As a true Platonist, its author maintains that wisdom can only be attained by a thorough inquiry into the occult nature of the creation; it alone assures us an existence of bliss after death. The immortality of the soul is greatly speculated upon in this treatise; but its author adds that we can attain to this knowledge only through a complete comprehension of the numbers; for the man, unable to distinguish the straight line from a curved one will never have wisdom enough to secure a mathematical demonstration of the invisible, i. e., we must assure ourselves of the objective existence of our soul (astral body) before we learn that we are in possession of a divine and immortal spirit. Iamblichus says the same thing; adding, moreover, that it is a secret belonging to the highest initiation. The Divine Power, he says, always felt indignant with those “who rendered manifest the composition of the icostagonus,” viz., who delivered the method of inscribing in a sphere the dodecahedron.[28]

The idea that “numbers” possessing the greatest virtue, produce always what is good and never what is evil, refers to justice, equanimity of temper, and everything that is harmonious. When the author speaks of every star as an individual soul, he only means what the Hindu initiates and the Hermetists taught before and after him, viz.: that every star is an independent planet, which, like our earth, has a soul of its own, every atom of matter being impregnated with the divine influx of the soul of the world. It breathes and lives; it feels and suffers as well as enjoys life in its way. What naturalist is prepared to dispute it on good evidence? Therefore, we must consider the celestial bodies as the images of gods; as partaking of the divine powers in their substance; and though they are not immortal in their soul-entity, their agency in the economy of the universe is entitled to divine honors, such as we pay to minor gods. The idea is plain, and one must be malevolent indeed to misrepresent it. If the author of Epinomis places these fiery gods higher than the animals, plants, and even mankind, all of which, as earthly creatures, are assigned by him[Pg xxii] a lower place, who can prove him wholly wrong? One must needs go deep indeed into the profundity of the abstract metaphysics of the old philosophies, who would understand that their various embodiments of their conceptions are, after all, based upon an identical apprehension of the nature of the First Cause, its attributes and method.

Again when the author of Epinomis locates between these highest and lowest gods (embodied souls) three classes of dæmons, and peoples the universe with invisible beings, he is more rational than our modern scientists, who make between the two extremes one vast hiatus of being, the playground of blind forces. Of these three classes the first two are invisible; their bodies are pure ether and fire (planetary spirits); the dæmons of the third class are clothed with vapory bodies; they are usually invisible, but sometimes making themselves concrete become visible for a few seconds. These are the earthly spirits, or our astral souls.

It is these doctrines, which, studied analogically, and on the principle of correspondence, led the ancient, and may now lead the modern Philaletheian step by step toward the solution of the greatest mysteries. On the brink of the dark chasm separating the spiritual from the physical world stands modern science, with eyes closed and head averted, pronouncing the gulf impassable and bottomless, though she holds in her hand a torch which she need only lower into the depths to show her her mistake. But across this chasm, the patient student of Hermetic philosophy has constructed a bridge.

In his Fragments of Science Tyndall makes the following sad confession: “If you ask me whether science has solved, or is likely in our day to solve the problem of this universe, I must shake my head in doubt.” If moved by an afterthought, he corrects himself later, and assures his audience that experimental evidence has helped him to discover, in the opprobrium-covered matter, the “promise and potency of every quality of life,” he only jokes. It would be as difficult for Professor Tyndall to offer any ultimate and irrefutable proofs of what he asserts, as it was for Job to insert a hook into the nose of the leviathan.

To avoid confusion that might easily arise by the frequent employment of certain terms in a sense different from that familiar to the reader, a few explanations will be timely. We desire to leave no pretext either for misunderstanding or misrepresentation. Magic may have one signification to one class of readers and another to another class. We shall give it the meaning which it has in the minds of its Oriental students and practitioners. And so with the words Hermetic Science, Occultism, Hierophant, Adept, Sorcerer, etc.; there has been little agreement of late as to their meaning. Though the distinctions between the terms are very often[Pg xxiii] insignificant—merely ethnic—still, it may be useful to the general reader to know just what that is. We give a few alphabetically.

Æthrobacy, is the Greek name for walking or being lifted in the air; levitation, so called, among modern spiritualists. It may be either conscious or unconscious; in the one case, it is magic; in the other, either disease or a power which requires a few words of elucidation.

A symbolical explanation of æthrobacy is given in an old Syriac manuscript which was translated in the fifteenth century by one Malchus, an alchemist. In connection with the case of Simon Magus, one passage reads thus:

“Simon, laying his face upon the ground, whispered in her ear, ‘O mother Earth, give me, I pray thee, some of thy breath; and I will give thee mine; let me loose, O mother, that I may carry thy words to the stars, and I will return faithfully to thee after a while.’ And the Earth strengthening her status, none to her detriment, sent her genius to breathe of her breath on Simon, while he breathed on her; and the stars rejoiced to be visited by the mighty One.”

The starting-point here is the recognized electro-chemical principle that bodies similarly electrified repel each other, while those differently electrified mutually attract. “The most elementary knowledge of chemistry,” says Professor Cooke, “shows that, while radicals of opposite natures combine most eagerly together, two metals, or two closely-allied metalloids, show but little affinity for each other.”

The earth is a magnetic body; in fact, as some scientists have found, it is one vast magnet, as Paracelsus affirmed some 300 years ago. It is charged with one form of electricity—let us call it positive—which it evolves continuously by spontaneous action, in its interior or centre of motion. Human bodies, in common with all other forms of matter, are charged with the opposite form of electricity—negative. That is to say, organic or inorganic bodies, if left to themselves will constantly and involuntarily charge themselves with, and evolve the form of electricity opposed to that of the earth itself. Now, what is weight? Simply the attraction of the earth. “Without the attractions of the earth you would have no weight,” says Professor Stewart;[29] “and if you had an earth twice as heavy as this, you would have double the attraction.” How then, can we get rid of this attraction? According to the electrical law above stated, there is an attraction between our planet and the organisms upon it, which holds them upon the surface of the ground. But the law of gravitation has been counteracted in many instances, by levitations of persons and inanimate objects; how account[Pg xxiv] for this? The condition of our physical systems, say theurgic philosophers, is largely dependent upon the action of our will. If well-regulated, it can produce “miracles;” among others a change of this electrical polarity from negative to positive; the man’s relations with the earth-magnet would then become repellent, and “gravity” for him would have ceased to exist. It would then be as natural for him to rush into the air until the repellent force had exhausted itself, as, before, it had been for him to remain upon the ground. The altitude of his levitation would be measured by his ability, greater or less, to charge his body with positive electricity. This control over the physical forces once obtained, alteration of his levity or gravity would be as easy as breathing.

The study of nervous diseases has established that even in ordinary somnambulism, as well as in mesmerized somnambulists, the weight of the body seems to be diminished. Professor Perty mentions a somnambulist, Koehler, who when in the water could not sink, but floated. The seeress of Prevorst rose to the surface of the bath and could not be kept seated in it. He speaks of Anna Fleisher, who being subject to epileptic fits, was often seen by the Superintendent to rise in the air; and was once, in the presence of two trustworthy witnesses (two deans) and others, raised two and a half yards from her bed in a horizontal position. The similar case of Margaret Rule is cited by Upham in his History of Salem Witchcraft. “In ecstatic subjects,” adds Professor Perty, “the rising in the air occurs much more frequently than with somnambulists. We are so accustomed to consider gravitation as being a something absolute and unalterable, that the idea of a complete or partial rising in opposition to it seems inadmissible; nevertheless, there are phenomena in which, by means of material forces, gravitation is overcome. In several diseases—as, for instance, nervous fever—the weight of the human body seems to be increased, but in all ecstatic conditions to be diminished. And there may, likewise, be other forces than material ones which can counteract this power.”

A Madrid journal, El Criterio Espiritista, of a recent date, reports the case of a young peasant girl near Santiago, which possesses a peculiar interest in this connection. “Two bars of magnetized iron held over her horizontally, half a metre distant, was sufficient to suspend her body in the air.”

Were our physicians to experiment on such levitated subjects, it would be found that they are strongly charged with a similar form of electricity to that of the spot, which, according to the law of gravitation, ought to attract them, or rather prevent their levitation. And, if some physical nervous disorder, as well as spiritual ecstasy produce[Pg xxv] unconsciously to the subject the same effects, it proves that if this force in nature were properly studied, it could be regulated at will.

Alchemists.—From Al and Chemi, fire, or the god and patriarch, Kham, also, the name of Egypt. The Rosicrucians of the middle ages, such as Robertus de Fluctibus (Robert Fludd), Paracelsus, Thomas Vaughan (Eugenius Philalethes), Van Helmont, and others, were all alchemists, who sought for the hidden spirit in every inorganic matter. Some people—nay, the great majority—have accused alchemists of charlatanry and false pretending. Surely such men as Roger Bacon, Agrippa, Henry Kunrath, and the Arabian Geber (the first to introduce into Europe some of the secrets of chemistry), can hardly be treated as impostors—least of all as fools. Scientists who are reforming the science of physics upon the basis of the atomic theory of Demokritus, as restated by John Dalton, conveniently forget that Demokritus, of Abdera, was an alchemist, and that the mind that was capable of penetrating so far into the secret operations of nature in one direction must have had good reasons to study and become a Hermetic philosopher. Olaus Borrichias says, that the cradle of alchemy is to be sought in the most distant times.

Astral Light.—The same as the sidereal light of Paracelsus and other Hermetic philosophers. Physically, it is the ether of modern science. Metaphysically, and in its spiritual, or occult sense, ether is a great deal more than is often imagined. In occult physics, and alchemy, it is well demonstrated to enclose within its shoreless waves not only Mr. Tyndall’s “promise and potency of every quality of life,” but also the realization of the potency of every quality of spirit. Alchemists and Hermetists believe that their astral, or sidereal ether, besides the above properties of sulphur, and white and red magnesia, or magnes, is the anima mundi, the workshop of Nature and of all the cosmos, spiritually, as well as physically. The “grand magisterium” asserts itself in the phenomenon of mesmerism, in the “levitation” of human and inert objects; and may be called the ether from its spiritual aspect.

The designation astral is ancient, and was used by some of the Neo-platonists. Porphyry describes the celestial body which is always joined with the soul as “immortal, luminous, and star-like.” The root of this word may be found, perhaps, in the Scythic aist-aer—which means star, or the Assyrian Istar, which, according to Burnouf has the same sense. As the Rosicrucians regarded the real, as the direct opposite of the apparent, and taught that what seems light to matter, is darkness to spirit, they searched for the latter in the astral ocean of invisible fire which encompasses the world; and claim to have traced the equally invisible divine spirit, which overshadows every man and is erroneously called soul, to the very throne of the Invisible and Unknown[Pg xxvi] God. As the great cause must always remain invisible and imponderable, they could prove their assertions merely by demonstration of its effects in this world of matter, by calling them forth from the unknowable down into the knowable universe of effects. That this astral light permeates the whole cosmos, lurking in its latent state even in the minutest particle of rock, they demonstrate by the phenomenon of the spark from flint and from every other stone, whose spirit when forcibly disturbed springs to sight spark-like, and immediately disappears in the realms of the unknowable.

Paracelsus named it the sidereal light, taking the term from the Latin. He regarded the starry host (our earth included) as the condensed portions of the astral light which “fell down into generation and matter,” but whose magnetic or spiritual emanations kept constantly a never-ceasing intercommunication between themselves and the parent-fount of all—the astral light. “The stars attract from us to themselves, and we again from them to us,” he says. The body is wood and the life is fire, which comes like the light from the stars and from heaven. “Magic is the philosophy of alchemy,” he says again.[30] Everything pertaining to the spiritual world must come to us through the stars, and if we are in friendship with them, we may attain the greatest magical effects.

“As fire passes through an iron stove, so do the stars pass through man with all their properties and go into him as the rain into the earth, which gives fruit out of that same rain. Now observe that the stars surround the whole earth, as a shell does the egg; through the shell comes the air, and penetrates to the centre of the world.” The human body is subjected as well as the earth, and planets, and stars, to a double law; it attracts and repels, for it is saturated through with double magnetism, the influx of the astral light. Everything is double in nature; magnetism is positive and negative, active and passive, male and female. Night rests humanity from the day’s activity, and restores the equilibrium of human as well as of cosmic nature. When the mesmerizer will have learned the grand secret of polarizing the action and endowing his fluid with a bi-sexual force he will have become the greatest magician living. Thus the astral light is androgyne, for equilibrium is the resultant of two opposing forces eternally reacting upon each other. The result of this is Life. When the two forces are expanded and remain so long inactive, as to equal one another and so come to a complete rest, the condition is Death. A human being can blow either a hot or a cold breath; and can absorb either cold or hot air. Every child knows how to regulate[Pg xxvii] the temperature of his breath; but how to protect one’s self from either hot or cold air, no physiologist has yet learned with certainty. The astral light alone, as the chief agent in magic, can discover to us all secrets of nature. The astral light is identical with the Hindu akâsa, a word which we will now explain.

Akâsa.—Literally the word means in Sanscrit sky, but in its mystic sense it signifies the invisible sky; or, as the Brahmans term it in the Soma-sacrifice (the Gyotishtoma Agnishtoma), the god Akâsa, or god Sky. The language of the Vedas shows that the Hindus of fifty centuries ago ascribed to it the same properties as do the Thibetan lamas of the present day; that they regarded it as the source of life, the reservoir of all energy, and the propeller of every change of matter. In its latent state, it tallies exactly with our idea of the universal ether; in its active state it became the Akâsa, the all-directing and omnipotent god. In the Brahmanical sacrificial mysteries it plays the part of Sadasya, or superintendent over the magical effects of the religious performance, and it had its own appointed Hotar (or priest), who took its name. In India, as in other countries in ancient times, the priests are the representatives on earth of different gods; each taking the name of the deity in whose name he acts.

The Akâsa is the indispensable agent of every Krityâ, (magical performance) either religious or profane. The Brahmanical expression “to stir up the Brahma”Brahma jinvati—means to stir up the power which lies latent at the bottom of every such magical operation, for the Vedic sacrifices are but ceremonial magic. This power is the Akâsa or the occult electricity; the alkahest of the alchemists in one sense, or the universal solvent, the same anima mundi as the astral light. At the moment of the sacrifice, the latter becomes imbued with the spirit of Brahma, and so for the time being is Brahma himself. This is the evident origin of the Christian dogma of transubstantiation. As to the most general effects of the Akâsa, the author of one of the most modern works on the occult philosophy, Art-Magic, gives for the first time to the world a most intelligible and interesting explanation of the Akâsa in connection with the phenomena attributed to its influence by the fakirs and lamas.

Anthropology—the science of man; embracing among other things:

Physiology, or that branch of natural science which discloses the mysteries of the organs and their functions in men, animals, and plants; and also, and especially,

Psychology, or the great, and in our days, so neglected science of the[Pg xxviii] soul, both as an entity distinct from the spirit and in its relations with the spirit and body. In modern science, psychology relates only or principally to conditions of the nervous system, and almost absolutely ignores the psychical essence and nature. Physicians denominate the science of insanity psychology, and name the lunatic chair in medical colleges by that designation.

Chaldeans, or Kasdim.—At first a tribe, then a caste of learned kabalists. They were the savants, the magians of Babylonia, astrologers and diviners. The famous Hillel, the precursor of Jesus in philosophy and in ethics, was a Chaldean. Franck in his Kabbala points to the close resemblance of the “secret doctrine” found in the Avesta and the religious metaphysics of the Chaldees.

Dactyls (daktulos, a finger).—A name given to the priests attached to the worship of Kybelé (Cybelè). Some archæologists derive the name from δάκτυλος, finger, because they were ten, the same in number as the fingers of the hand. But we do not believe the latter hypothesis is the correct one.

Dæmons.—A name given by the ancient people, and especially the philosophers of the Alexandrian school, to all kinds of spirits, whether good or bad, human or otherwise. The appellation is often synonymous with that of gods or angels. But some philosophers tried, with good reason, to make a just distinction between the many classes.

Demiurgos, or Demiurge.—Artificer; the Supernal Power which built the universe. Freemasons derive from this word their phrase of “Supreme Architect.” The chief magistrates of certain Greek cities bore the title.

Dervishes, or the “whirling charmers,” as they are called. Apart from the austerities of life, prayer and contemplation, the Mahometan devotee presents but little similarity with the Hindu fakir. The latter may become a sannyasi, or saint and holy mendicant; the former will never reach beyond his second class of occult manifestations. The dervish may also be a strong mesmerizer, but he will never voluntarily submit to the abominable and almost incredible self-punishment which the fakir invents for himself with an ever-increasing avidity, until nature succumbs and he dies in slow and excruciating tortures. The most dreadful operations, such as flaying the limbs alive; cutting off the toes, feet, and legs; tearing out the eyes; and causing one’s self to be buried alive up to the chin in the earth, and passing whole months in this posture, seem child’s play to them. One of the most common tortures is that of Tshiddy-Parvâdy.[31] It consists in suspending the fakir to one of the[Pg xxix] mobile arms of a kind of gallows to be seen in the vicinity of many of the temples. At the end of each of these arms is fixed a pulley over which passes a rope terminated by an iron hook. This hook is inserted into the bare back of the fakir, who inundating the soil with blood is hoisted up in the air and then whirled round the gallows. From the first moment of this cruel operation until he is either unhooked or the flesh of his back tears out under the weight of the body and the fakir is hurled down on the heads of the crowd, not a muscle of his face will move. He remains calm and serious and as composed as if taking a refreshing bath. The fakir will laugh to scorn every imaginable torture, persuaded that the more his outer body is mortified, the brighter and holier becomes his inner, spiritual body. But the Dervish, neither in India, nor in other Mahometan lands, will ever submit to such operations.

Druids.—A sacerdotal caste which flourished in Britain and Gaul.

Elemental Spirits.—The creatures evolved in the four kingdoms of earth, air, fire, and water, and called by the kabalists gnomes, sylphs, salamanders, and undines. They may be termed the forces of nature, and will either operate effects as the servile agents of general law, or may be employed by the disembodied spirits—whether pure or impure—and by living adepts of magic and sorcery, to produce desired phenomenal results. Such beings never become men.[32]

Under the general designation of fairies, and fays, these spirits of the elements appear in the myth, fable, tradition, or poetry of all nations, ancient and modern. Their names are legion—peris, devs, djins, sylvans, satyrs, fauns, elves, dwarfs, trolls, norns, nisses, kobolds, brownies, necks, stromkarls, undines, nixies, salamanders, goblins, ponkes, banshees, kelpies, pixies, moss people, good people, good neighbors, wild women, men of peace, white ladies—and many more. They have been seen, feared, blessed, banned, and invoked in every quarter of the globe and in every age. Shall we then concede that all who have met them were hallucinated?

[Pg xxx]

These elementals are the principal agents of disembodied but never visible spirits at seances, and the producers of all the phenomena except the subjective.

Elementary Spirits.—Properly, the disembodied souls of the depraved; these souls having at some time prior to death separated from themselves their divine spirits, and so lost their chance for immortality. Eliphas Levi and some other kabalists make little distinction between elementary spirits who have been men, and those beings which people the elements, and are the blind forces of nature. Once divorced from their bodies, these souls (also called “astral bodies”) of purely materialistic persons, are irresistibly attracted to the earth, where they live a temporary and finite life amid elements congenial to their gross natures. From having never, during their natural lives, cultivated their spirituality, but subordinated it to the material and gross, they are now unfitted for the lofty career of the pure, disembodied being, for whom the atmosphere of earth is stifling and mephitic, and whose attractions are all away from it. After a more or less prolonged period of time these material souls will begin to disintegrate, and finally, like a column of mist, be dissolved, atom by atom, in the surrounding elements.

Essenes—from Asa, a healer. A sect of Jews said by Pliny to have lived near the Dead Sea “per millia sæculorum” for thousands of ages. Some have supposed them to be extreme Pharisees; and others—which may be the true theory—the descendants of the Benim nabim of the Bible, and think they were “Kenites” and “Nazarites.” They had many Buddhistic ideas and practices; and it is noteworthy that the priests of the Great Mother at Ephesus, Diana-Bhavani with many breasts, were also so denominated. Eusebius, and after him De Quincey, declared them to be the same as the early Christians, which is more than probable. The title “brother,” used in the early Church, was Essenean: they were a fraternity, or a koinobion or community like the early converts. It is noticeable that only the Sadducees, or Zadokites, the priest-caste and their partisans, persecuted the Christians; the Pharisees were generally scholastic and mild, and often sided with the latter. James the Just was a Pharisee till his death; but Paul or Aher was esteemed a schismatic.

Evolution.—The development of higher orders of animals from the lower. Modern, or so-called exact science, holds but to a one-sided physical evolution, prudently avoiding and ignoring the higher or spiritual evolution, which would force our contemporaries to confess the superiority of the ancient philosophers and psychologists over themselves. The ancient sages, ascending to the UNKNOWABLE, made their starting-point from the first manifestation of the unseen, the unavoidable, and from a strict logical reasoning, the absolutely necessary creative Being, the[Pg xxxi] Demiurgos of the universe. Evolution began with them from pure spirit, which descending lower and lower down, assumed at last a visible and comprehensible form, and became matter. Arrived at this point, they speculated in the Darwinian method, but on a far more large and comprehensive basis.

In the Rig-Veda-Sanhita, the oldest book of the World[33] (to which even our most prudent Indiologists and Sanscrit scholars assign an antiquity of between two and three thousand years B.C.), in the first book, “Hymns to the Maruts,” it is said:

“Not-being and Being are in the highest heaven, in the birthplace of Daksha, in the lap of Aditi” (Mandala, i., Sûkta 166).

“In the first age of the gods, Being (the comprehensible Deity) was born from Not-being (whom no intellect can comprehend); after it were born the Regions (the invisible), from them Uttânapada.”

“From Uttânapad the Earth was born, the Regions (those that are visible) were born from the Earth. Daksha was born of Aditi, and Aditi from Daksha” (Ibid.).

Aditi is the Infinite, and Daksha is dáksha-pitarah, literally meaning the father of gods, but understood by Max Müller and Roth to mean the fathers of strength, “preserving, possessing, granting faculties.” Therefore, it is easy to see that “Daksha, born of Aditi and Aditi from Daksha,” means what the moderns understand by “correlation of forces;” the more so as we find in this passage (translated by Prof. Müller):