Title: History for ready reference, Volume 3, Greece to Nibelungen

Author: J. N. Larned

Release date: June 13, 2022 [eBook #68302]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Original publication: United States: C. A. Nichols Co, 1895

Credits: Don Kostuch

[Transcriber's Notes: These modifications are intended to provide

continuity of the text for ease of searching and reading.

1. To avoid breaks in the narrative, page numbers (shown in curly

brackets "{1234}") are usually placed between paragraphs. In this

case the page number is preceded and followed by an empty line.

To remove page numbers use the Regular Expression:

"^{[0-9]+}" to "" (empty string)

2. If a paragraph is exceptionally long, the page number is

placed at the nearest sentence break on its own line, but

without surrounding empty lines.

3. Blocks of unrelated text are moved to a nearby break

between subjects.

5. Use of em dashes and other means of space saving are replaced

with spaces and newlines.

6. Subjects are arranged thusly:

Main titles are at the left margin, in all upper case

(as in the original) and are preceded by an empty line.

Subtitles (if any) are indented three spaces and

immediately follow the main title.

Text of the article (if any) follows the list of subtitles (if

any) and is preceded with an empty line and indented three

spaces.

References to other articles in this work are in all upper case

(as in the original) and indented six spaces. They usually

begin with "See", "Also" or "Also in".

Citations of works outside this book are indented six spaces

and in italics (as in the original). The bibliography in Volume

1, APPENDIX F on page xxi provides additional details,

including URLs of available internet versions.

----------Subject: Start--------

----------Subject: End----------

indicates the start/end of a group of subheadings or other

large block.

To search for words separated by an unknown number of other

characters, use this Regular Expression to find the words "first"

and "second" separated by between 1 and 100 characters:

"first.{1,100}second"

End Transcriber's Notes.]

----------------------------------

History For Ready Reference, Volume 3 of 6

From The Best

Historians, Biographers, And Specialists

Their Own Words In A Complete

System Of History

For All Uses, Extending To All Countries And Subjects,

And Representing For Both Readers And Students The Better

And Newer Literature Of History In The English Language.

BY J. N. LARNED

With Numerous Historical Maps From Original Studies

And Drawings By Alan C. Reiley

In Five Volumes

Volume III—Greece To Nibelungen Lied

Springfield, Mass.

The C. A. Nichols Co., Publishers

MDCCCXCV

Copyright, 1894.

By J. N. Larned.

The Riverside Press, Cambridge, Mass., U. S. A.

Printed by H. O. Houghton & Company.

List Of Maps.

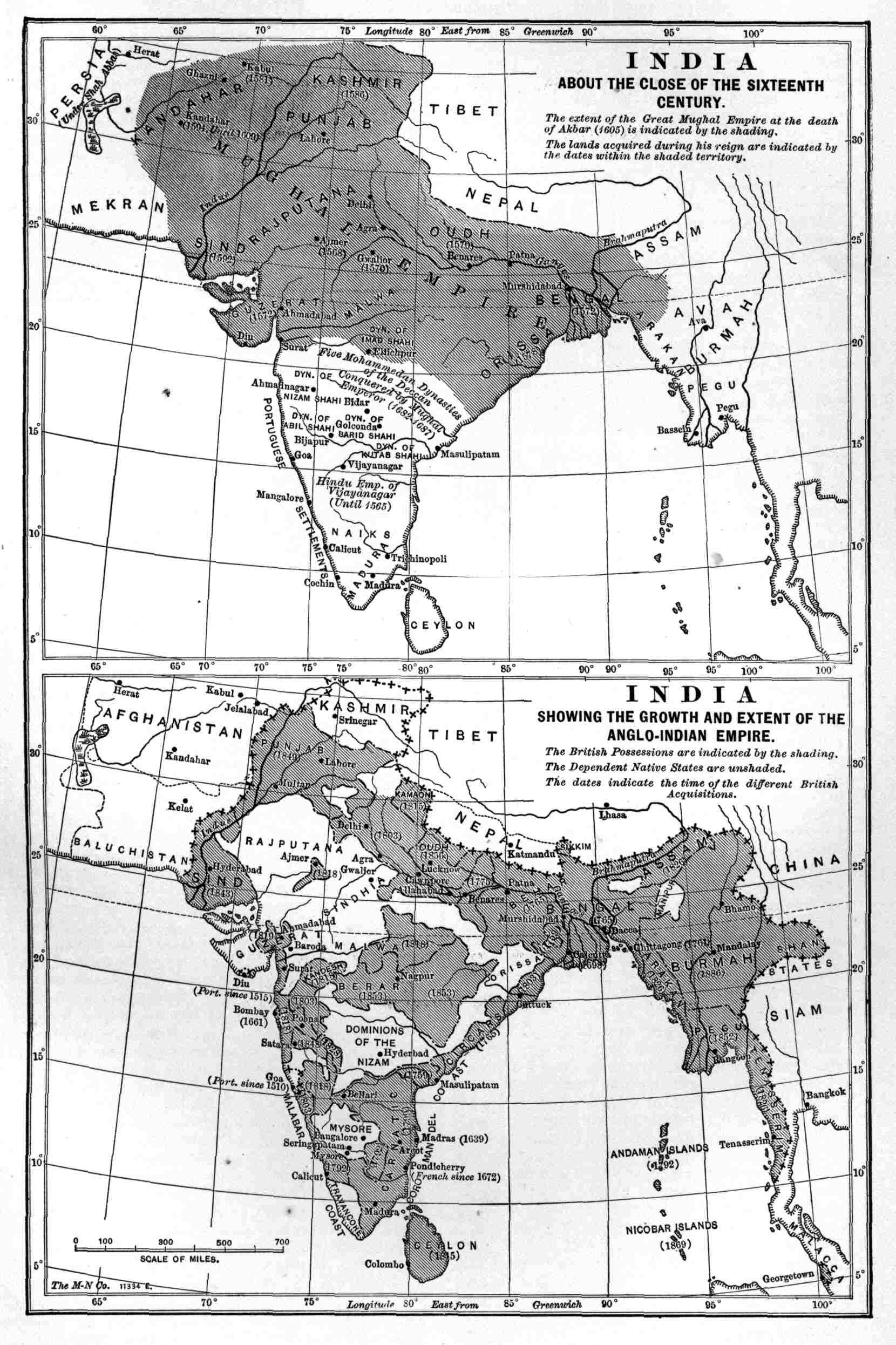

Map of India, about the close of the Sixteenth Century,

and map of the growth of the Anglo-Indian Empire,

To follow page 1708.

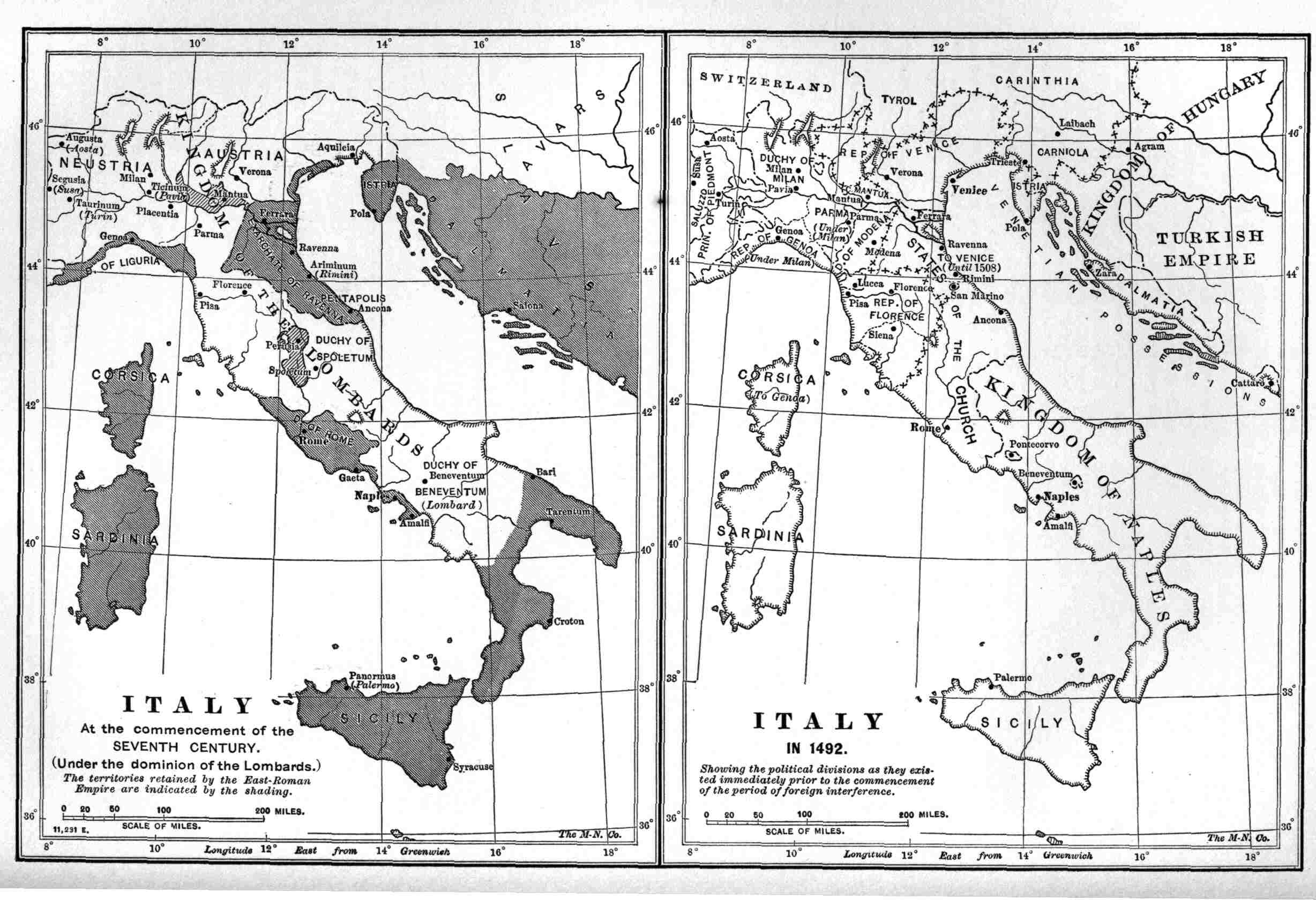

Two maps of Italy, at the beginning of the Seventh Century,

and A. D. 1492, To follow page 1804.

TWO maps of Italy, A. D. 1815 to 1859, and 1861,

To follow page 1864.

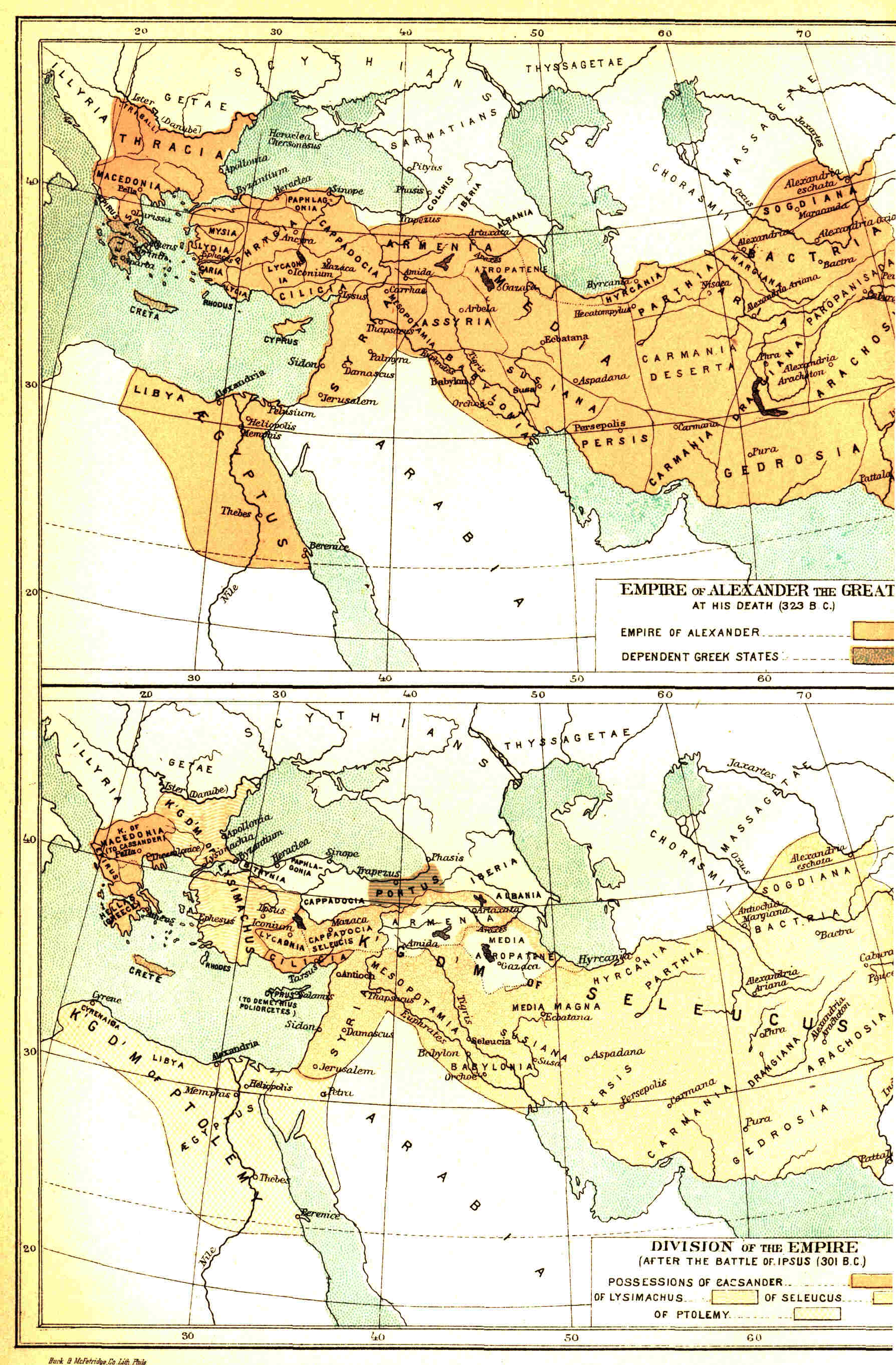

Four maps of the Empire of Alexander the Great

and his successors, To follow page 2061.

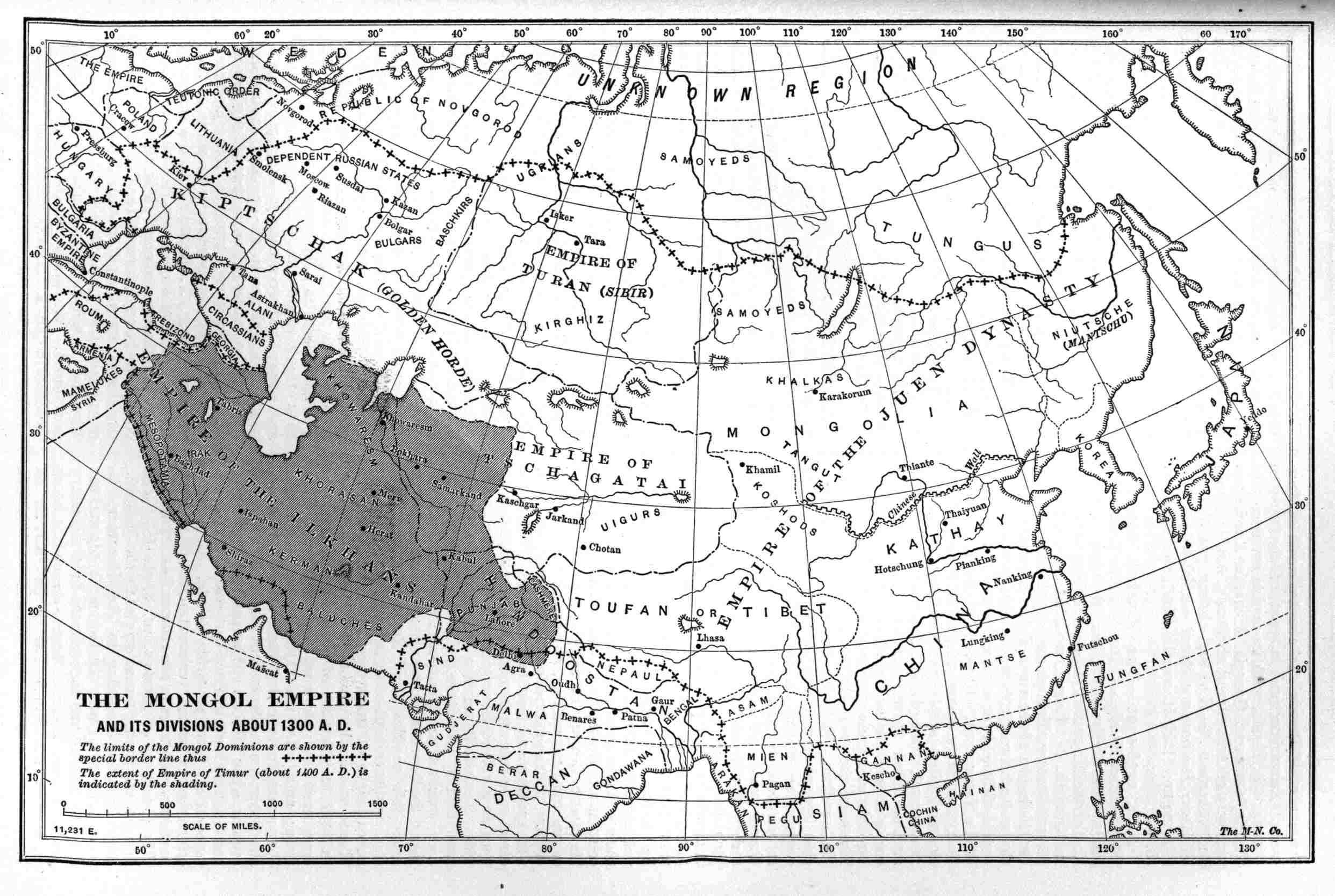

Map of the Mongol Empire, A. D. 1300, On page 2223.

Logical Outline, In Colors.

Irish History, To follow page 1754

Chronological Tables.

The Seventh Century, On page 2073

The Eighth Century, On page 2074

{1565}

----------GREECE: Start----------

[Footnote: An important part of Greek history is treated

more fully under the heading "ATHENS" (in Volume 1), to

which the reader is referred.

https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/65306]

GREECE:

The Land.

Its geographical characteristics, and their influence upon the

People.

"The considerable part played by the people of Greece during

many ages must undoubtedly be ascribed to the geographical

position of their country. Other tribes having the same

origin, but inhabiting countries less happily situated—such,

for instance, as the Pelasgians of Illyria, who are believed

to be the ancestors of the Albanians—have never risen above a

state of barbarism, whilst the Hellenes placed themselves at

the head of civilised nations, and opened fresh paths to their

enterprise. If Greece had remained for ever what it was during

the tertiary geological epoch—a vast plain attached to the

deserts of Libya, and run over by lions and the

rhinoceros—would it have become the native country of a

Phidias, an Æschylos, or a Demosthenes? Certainly not. It

would have shared the fate of Africa, and, far from taking the

initiative in civilisation, would have waited for an impulse

to be given to it from beyond. Greece, a sub-peninsula of the

peninsula of the Balkans, was even more completely protected

by transverse mountain barriers in the north than was Thracia

or Macedonia. Greek culture was thus able to develop itself

without fear of being stifled at its birth by successive

invasions of barbarians. Mounts Olympus, Pelion, and Ossa,

towards the north and east of Thessaly, constituted the first

line of formidable obstacles towards Macedonia. A second

barrier, the steep range of the Othrys, runs along what is the

present political boundary of Greece. To the south of the Gulf

of Lamia a fresh obstacle awaits us, for the range of the Œta

closes the passage, and there is but the narrow pass of the

Thermopylæ between it and the sea. Having crossed the

mountains of the Locri and descended into the basin of Thebæ,

there still remain to be crossed the Parnes or the spurs of

the Cithæron before we reach the plains of Attica. The

'isthmus' beyond these is again defended by transverse

barriers, outlying ramparts, as it were, of the mountain

citadel of the Peloponnesus, that acropolis of all Greece.

Hellas has frequently been compared to a series of chambers,

the doors of which were strongly bolted; it was difficult to

get in, but more difficult to get out again, owing to their

stout defenders. Michelet likens Greece to a trap having three

compartments. You entered, and found yourself taken first in

Macedonia, then in Thessaly, then between the Thermopylæ and

the isthmus. But the difficulties increase beyond the isthmus,

and Lacedæmonia remained impregnable for a long time. At an

epoch when the navigation even of a land-locked sea like the

Ægean was attended with danger, Greece found herself

sufficiently protected against the invasions of oriental

nations; but, at the same time, no other country held out such

inducements to the pacific expeditions of merchants. Gulfs and

harbours facilitated access to her Ægean coasts, and the

numerous outlying islands were available as stations or as

places of refuge. Greece, therefore, was favourably placed for

entering into commercial intercourse with the more highly

civilised peoples who dwelt on the opposite coasts of Asia

Minor. The colonists and voyagers of Eastern Ionia not only

supplied their Achæan and Pelasgian kinsmen with foreign

commodities and merchandise, but they also imparted to them

the myths, the poetry, the sciences, and the arts of their

native country. Indeed, the geographical configuration of

Greece points towards the east, whence she has received her

first enlightenment. Her peninsulas and outlying islands

extend in that direction; the harbours on her eastern coasts

are most commodious, and afford the best shelter; and the

mountain-surrounded plains there offer the best sites for

populous cities. … The most distinctive feature of Hellas,

as far as concerns the relief of the ground, consists in the

large number of small basins, separated one from the other by

rocks or mountain ramparts. The features of the ground thus

favoured the division of the Greek people into a multitude of

independent republics. Every town had its river, its

amphitheatre of hills or mountains, its acropolis, its fields,

pastures, and forests, and nearly all of them had, likewise,

access to the sea. All the elements required by a free

community were thus to be found within each of these small

districts, and the neighbourhood of other towns, equally

favoured, kept alive perpetual emulation, too frequently

degenerating into strife and battle. The islands of the Ægean

Sea, likewise, had constituted themselves into miniature

republics. Local institutions thus developed themselves

freely, and even the smallest island of the Archipelago has

its great representatives in history. But whilst there thus

exists the greatest diversity, owing to the configuration of

the ground and the multitude of islands, the sea acts as a

binding element, washes every coast, and penetrates far

inland. These gulfs and numerous harbours have made the

maritime inhabitants of Greece a nation of sailors—amphibiæ,

as Strabo called them. From the most remote times the passion

for travel has always been strong amongst them. When the

inhabitants of a town grew too numerous to support themselves

upon the produce of their land, they swarmed out like bees,

explored the coasts of the Mediterranean, and, when they had

found a site which recalled their native home, they built

themselves a new city. … The Greeks held the same position

relatively to the world of the ancients which is occupied at

the present time by the Anglo-Saxons with reference to the

entire earth. There exists, indeed, a remarkable analogy

between Greece, with its archipelago, and the British Islands,

at the other extremity of the continent. Similar geographical

advantages have brought about similar results, as far as

commerce is concerned, and between the Ægean and the British

seas time and space have effected a sort of harmony."

E. Reclus,

The Earth and its Inhabitants: Europe,

volume 1, pages 36-38.

"The independence of each city was a doctrine stamped deep on

the Greek political mind by the very nature of the Greek land.

How truly this is so is hardly fully understood till we see

that land with our own eyes. The map may do something; but no

map can bring home to us the true nature of the Greek land

till we have stood on a Greek hill-top, on the akropolis of

Athens or the loftier akropolis of Corinth, and have seen how

thoroughly the land was a land of valleys cut off by hills, of

islands and peninsulas cut off by arms of sea, from their

neighbours on either side.

{1566}

Or we might more truly say that, while the hills fenced them

off from their neighbours, the arms of the sea laid them open

to their neighbours. Their waters might bring either friends

or enemies; but they brought both from one wholly distinct and

isolated piece of land to another. Every island, every valley,

every promontory, became the seat of a separate city; that is,

according to Greek notions, the seat of an independent power,

owning indeed many ties of brotherhood to each of the other

cities which helped to make up the whole Greek nation, but

each of which claimed the right of war and peace and separate

diplomatic intercourse, alike with every other Greek city and

with powers beyond the bounds of the Greek world. Corinth

could treat with Athens and Athens with Corinth, and Corinth

and Athens could each equally treat with the King of the

Macedonians and with the Great King of Persia. … How close

the Greek states are to one another, and yet how physically

distinct they are from one another, it needs, for me at least,

a journey to Greece fully to take in."

E. A. Freeman,

The Practical Bearings of European History

(Lectures to American Audiences),

pages 243-244.

GREECE: Ancient inhabitants.

Tribal divisions.

See PELASGIANS; HELLENES; ACHAIA; ÆOLIANS;

and DORIANS AND IONIANS.

GREECE: The Heroes and their Age.

"The period included between the first appearance of the

Hellenes in Thessaly and the return of the Greeks from Troy,

is commonly known by the name of the heroic age, or ages. The

real limits of this period cannot be exactly defined. The date

of the siege of Troy is only the result of a doubtful

calculation [ending B. C. 1183, as reckoned by Eratosthenes,

but fixed at dates ranging from 33 to 63 years later by

Isocrates, Callimachus and other Greek writers]; and … the

reader will see that it must be scarcely possible to ascertain

the precise beginning of the period: but still, so far as its

traditions admit of anything like a chronological connexion,

its duration may be estimated at six generations, or about 200

years [say from some time in the 14th to some time in the 12th

century before Christ]. … The history of the heroic age is

the history of the most celebrated persons belonging to this

class, who, in the language of poetry, are called 'heroes.'

The term 'hero' is of doubtful origin, though it was clearly a

title of honour; but, in the poems of Homer, it is applied not

only to the chiefs, but also to their followers, the freemen

of lower rank, without, however, being contrasted with any

other, so as to determine its precise meaning. In later times

its use was narrowed, and in some degree altered: it was

restricted to persons, whether of the heroic or of after ages,

who were believed to be endowed with a superhuman, though not

a divine, nature, and who were honoured with sacred rites, and

were imagined to have the power of dispensing good or evil to

their worshippers; and it was gradually combined with the

notion of prodigious strength and gigantic stature. Here,

however, we have only to do with the heroes as men. The

history of their age is filled with their wars, expeditions,

and adventures, and this is the great mine from which the

materials of the Greek poetry were almost entirely drawn."

C. Thirlwall,

History of Greece,

chapter 5 (volume 1).

The legendary heroes whose exploits and adventures became the

favorite subjects of Greek tragedy and song were Perseus,

Hercules, Theseus, the Argonauts, and the heroes of the Siege

of Troy.

GREECE:

The Migrations of the Hellenic tribes in the Peninsula.

"If there is any point in the annals of Greece at which we can

draw the line between the days of myth and legend and the

beginnings of authentic history, it is at the moment of the

great migrations. Just as the irruption of the Teutonic tribes

into the Roman empire in the 5th century after Christ marks

the commencement of an entirely new era in modern Europe, so

does the invasion of Southern and Central Greece by the

Dorians, and the other tribes whom they set in motion, form

the first landmark in a new period of Hellenic history. Before

these migrations we are still in an atmosphere which we cannot

recognize as that of the historical Greece that we know. The

states have different boundaries, some of the most famous

cities have not yet been founded, tribes who are destined to

vanish occupy prominent places in the land, royal houses of a

foreign stock are established everywhere, the distinction

between Hellene and Barbarian is yet unknown. We cannot

realize a Greece where Athens is not yet counted as a great

city, while Mycenae is a seat of empire; where the Achaian

element is everywhere predominant, and the Dorian element is

as yet unknown. When, however, the migrations are ended, we at

once find ourselves in a land which we recognize as the Greece

of history. The tribes have settled into the districts which

are to be their permanent abodes, and have assumed their

distinctive characters. … The original impetus which set the

Greek tribes in motion came from the north, and the whole

movement rolled southward and eastward. It started with the

invasion of the valley of the Peneus by the Thessalians, a

warlike but hitherto obscure tribe, who had dwelt about Dodona

in the uplands of Epirus. They crossed the passes of Pindus,

and flooded down into the great plain to which they were to

give their name. The tribes which had previously held it were

either crushed and enslaved, or pushed forward into Central

Greece by the wave of invasion. Two of the displaced races

found new homes for themselves by conquest. The Arnaeans, who

had dwelt in the southern lowlands along the courses of

Apidanus and Enipeus, came through Thermopylae, pushed the

Locriams aside to right and left, and descended into the

valley of the Cephissus, where they subdued the Minyae of

Orchomenus [see MINYI], and then, passing south, utterly

expelled the Cadmeians of Thebes. The plain country which they

had conquered received a single name. Boeotia became the

common title of the basins of the Cephissus and the Asopus,

which had previously been in the hands of distinct races. Two

generations later the Boeotians endeavoured to cross

Cithaeron, and add Attica to their conquests; but their king

Xanthus fell in single combat with Melanthus, who fought in

behalf of Athens, and his host gave up the enterprise. In

their new country the Boeotians retained their national unity

under the form of a league, in which no one city had authority

over another, though in process of time Thebes grew so much

greater than her neighbours that she exercised a marked

preponderance over the other thirteen members of the

confederation. Orchomenus, whose Minyan inhabitants had been

subdued but not exterminated by the invaders, remained

dependent on the league without being

at first amalgamated with it.

{1567}

A second tribe who were expelled by the irruption of the

Thessalians were the Dorians, a race whose name is hardly

heard in Homer, and whose early history had been obscure and

insignificant. They had till now dwelt along the western slope

of Pindus. Swept on by the invaders, they crossed Mount

Othrys, and dwelt for a time in the valley of the Spercheius

and on the shoulders of Oeta. But the land was too narrow for

them, and, after a generation had passed, the bulk of the

nation moved southward to seek a wider home, while a small

fraction only remained in the valleys of Oeta. Legends tell us

that their first advance was made by the Isthmus of Corinth,

and was repulsed by the allied states of Peloponnesus, Hyllus

the Dorian leader having fallen in the fight by the hand of

Echemus, King of Tegea. But the grandsons of Hyllus resumed

his enterprise, and met with greater success. Their invasion

was made, as we are told, in conjunction with their neighbours

the Aetolians, and took the Aetolian port of Naupactus as its

base. Pushing across the narrow strait at the mouth of the

Corinthian Gulf, the allied hordes landed in Peloponnesus, and

forced their way down the level country on its western coast,

then the land of the Epeians, but afterwards to be known as

Elis and Pisatis. This the Aetolians took as their share,

while the Dorians pressed further south and east, and

successively conquered Messenia, Laconia, and Argolis,

destroying the Cauconian kingdom of Pylos and the Achaian

states of Sparta and Argos. There can be little doubt that the

legends of the Dorians pressed into a single generation the

conquests of a long series of years. … It is highly probable

that Messenia was the first seized of the three regions, and

Argos the latest … but of the details or dates of the Dorian

conquests we know absolutely nothing. Of the tribes whom the

Dorians supplanted, some remained in the land as subjects to

their newly found masters, while others took ship and fled

over sea. The stoutest-hearted of the Achaians of Argolis,

under Tisamenus, a grandson of Agamemnon, retired northward

when the contest became hopeless, and threw themselves on the

coast cities of the Corinthian Gulf, where up to this time the

Ionic tribe of the Aegialeans had dwelt. The Ionians were

worsted, and fled for refuge to their kindred in Attica, while

the conquerors created a new Achaia between the Arcadian

Mountains and the sea, and dwelt in the twelve cities which

their predecessors had built. The rugged mountains of Arcadia

were the only part of Peloponnesus which were to escape a

change of masters resulting from the Dorian invasion. A

generation after the fall of Argos, new war-bands thirsting

for land pushed on to the north and west, led by descendants

of Temenus. The Ionic towns of Sicyon and Phlius, Epidaurus

and Troezen, all fell before them. Even the inaccessible

Acropolis which protected the Aeolian settlement of Corinth

could not preserve it from the hands of the enterprising

Aletes. Nor was it long before the conquerors pressed on from

Corinth beyond the isthmus, and attacked Attica. Foiled in

their endeavour to subdue the land, they at least succeeded in

tearing from it its western districts, where the town of

Megara was made the capital of a new Dorian state, and served

for many generations to curb the power of Athens. From

Epidaurus a short voyage of fifteen miles took the Dorians to

Aegina, where they formed a settlement which, first as a

vassal to Epidaurus, and then as an independent community,

enjoyed a high degree of commercial prosperity. It is not the

least curious feature of the Dorian invasion that the leaders

of the victorious tribe, who, like most other royal houses,

claimed to descend from the gods and boasted that Heracles was

their ancestor, should have asserted that they were not

Dorians by race, but Achaians. Whether the rude northern

invaders were in truth guided by princes of a different blood

and higher civilization than themselves, it is impossible to

say. … In all probability the Dorian invasion was to a

considerable extent a check in the history of the development

of Greek civilization, a supplanting of a richer and more

cultured by a poorer and wilder race. The ruins of the

prehistoric cities, which were supplanted by new Dorian

foundations, point to a state of wealth to which the country

did not again attain for many generations. On the other hand,

the invasion brought about an increase in vigour and moral

earnestness. The Dorians throughout their history were the

sturdiest and most manly of the Greeks. The god to whose

worship they were especially devoted was Apollo, the purest,

the noblest, the most Hellenic member of the Olympian family.

By their peculiar reverence for this noble conception of

divinity, the Dorians marked themselves out as the most moral

of the Greeks."

C. W. C. Oman,

History of Greece,

chapter 5.

ALSO IN:

M. Duncker,

History of Greece,

book 2 (volume 1).

C. O. Müller,

History and Antiquity of the Doric Race,

introduction, and book 1, chapters 1-5.

G. Grote,

History of Greece,

part 2, chapters 3-8 (volume 2).

See, also, DORIANS AND IONIANS;

ACHAIA; ÆOLIANS; THESSALY;

and BŒOTIA.

GREECE:

The Migrations to Asia Minor and the Islands of the Ægean.

Æolian, Ionian and Dorian colonies.

See ASIA MINOR: THE GREEK COLONIES.

GREECE:

Mycenæ and its kings.

The unburied memorials.

"Thucydides says that before the Dorian conquest, the date of

which is traditionally fixed at B. C. 1104, Mycenae was the

only city whence ruled a wealthy race of kings. Archaeology

produces the bodies of kings ruling at Mycenae about the

twelfth century and spreads their wealth under our eyes.

Thucydides says that this wealth was brought in the form of

gold from Phrygia by the founder of the line, Pelops.

Archaeology tells us that the gold found at Mycenae may very

probably have come from the opposite coast of Asia Minor which

abounded in gold; and further that the patterns impressed on

the gold work at Mycenae bear a very marked resemblance to the

decorative patterns found on graves in Phrygia. Thucydides

tells us that though Mycenae was small, yet its rulers had the

hegemony over a great part of Greece. Archæology shews us that

the kings of Mycenae were wealthy and important quite out of

proportion to the small city which they ruled, and that the

civilisation which centred at Mycenae spread over south Greece

and the Aegean, and lasted for some centuries at least. It

seems to me that the simplest way of meeting the facts of the

case is to suppose that we have recovered at Mycenae the

graves of the Pelopid race of monarchs. It will not of course

do to go too far. … It would be too much to suppose that we

have recovered the bodies of the Agamemnon who seems in the

Iliad to be as familiar to us as Caesar or Alexander, or of

his father Atreus, or of his charioteer and the rest.

{1568}

We cannot of course prove the Iliad to be history; and if we

could, the world would be poorer than before. But we can

insist upon it that the legends of heroic Greece have more of

the historic element in them than anyone supposed a few years

ago. … Assuming then that we may fairly class the Pelopidae

as Achaean, and may regard the remains at Mycenae as

characteristic of the Achaean civilisation of Greece, is it

possible to trace with bolder hand the history of Achaean

Greece? Certainly we gain assistance in our endeavour to

realize what the pre-Dorian state of Peloponnesus was like. We

secure a hold upon history which is thoroughly objective,

while all the history which before existed was so vague and

imaginative that the clear mind of Grote refused to rely upon

it at all. But the precise dates are more than we can venture

to lay down, in the present condition of our knowledge. …

The Achaean civilisation was contemporary with the eighteenth

Egyptian dynasty (B. C. 1700-1400). It lasted during the

invasions of Egypt from the north (1300-1100). When it ceased

we cannot say with certainty. There is every historical

probability that it was brought to a violent end in the Dorian

invasion. The traditional date of that invasion is B. C. 1104.

But it is obvious that this date cannot be relied upon."

P. Gardner,

New Chapters in Greek History,

chapters 2-3.

ALSO IN:

R. Schliemann,

Mycenæ.

C. Schuchhardt,

Schliemann's Excavations,

chapter 4.

GREECE:

Ancient political and geographical divisions.

"Greece was not a single country. … It was broken up into

little districts, each with its own government. Any little

city might be a complete state in itself, and independent of

its neighbours. It might possess only a few miles of land and

a few hundred inhabitants, and yet have its own laws, its own

government, and its own army. … In a space smaller than an

English county there might be several independent cities,

sometimes at war, sometimes at peace with one another.

Therefore when we say that the west coast of Asia Minor was

part of Greece, we do not mean that this coast-land and

European Greece were under one law and one government, for

both were broken up into a number of little independent

States: but we mean that the people who lived on the west

coast of Asia Minor were just as much Greeks as the people who

lived in European Greece. They spoke the same language, and

had much the same customs, and they called one another

Hellenes, in contrast to all other nations of the world, whom

they called barbarians … , that is, 'the unintelligible

folk,' because they could not understand their tongue."

C. A. Fyffe,

History of Greece (History Primers),

chapter 1.

"The nature of the country had … a powerful effect on the

development of Greek politics. The whole land was broken up by

mountains into a number of valleys more or less isolated;

there was no central point from which a powerful monarch could

control it. Hence Greece was, above all other countries, the

home of independence and freedom. Each valley, and even the

various hamlets of a valley, felt themselves possessed of a

separate life, which they were jealous to preserve."

E. Abbott,

History of Greece,

part 1, chapter 1.

See AKARNANIANS; ACHAIA;

ÆGINA; ÆTOLIA; ARCADIA; ARGOS; ATHENS;

ATTICA; BŒOTIA; CORINTH; DORIS AND

DRYOPIS; ELIS; EPIRUS; EUBŒA; KORKYRA;

LOCRI; MACEDONIA; MANTINEA; MEGALOPOLIS;

MEGARA; MESSENE; OLYNTHUS; PHOKIANS;

PLATÆA; SICYON; SPARTA; THEBES;

and THESSALY.

GREECE:

Political evolution of the leading States.

Variety in the forms of Government.

Rise of democracy at Athens.

"The Hellenes followed no common political aim. …

Independent and self-centred, they created, in a constant

struggle of citizen with citizen and state with state, the

groundwork of those forms of government which have been

established in the world at large. We see monarchy,

aristocracy, democracy, rising side by side and one after

another, the changes being regulated in each community by its

past experience and its special interests in the immediate

present. These forms of government did not appear in their

normal simplicity or in conformity with a distinct ideal, but

under the modifications necessary to give them vitality. An

example of this is Lakedæmon. If one of the families of the

Heracleidæ [the two royal families-see SPARTA: THE

CONSTITUTION] aimed at a tyranny, whilst another entered into

relations with the native and subject population, fatal to the

prerogatives of the conquerors, we can understand that in the

third case, that, of the Spartan community, the aristocratic

principle was maintained with the greatest strictness.

Independently of this, the divisions of the Lakedæmonian

monarchy between two lines, neither of which was to have

precedence, was intended to guard against the repetition in

Sparta of that which had happened in Argos. Above all, the

members of the Gerusia, in which the two kings had only equal

rights with the rest, held a position which would have been

unattainable to the elders of the Homeric age. But even the

Gerusia was not independent. There existed in addition to it a

general assembly, which, whilst very aristocratic as regards

the native and subject population, assumed a democratic aspect

in contrast with the king and the elders. The internal life of

the Spartan constitution depended upon the relations between

the Gerusia and the aristocratic demos. … The Spartan

aristocracy dominated the Peloponnesus. But the constitution

contained a democratic clement working through the Ephors, by

means of which the conduct of affairs might be concentrated in

a succession of powerful hands. Alongside of this system, the

purely aristocratic constitutions, which were without such a

centre, could nowhere hold their ground. The Bacchiadæ in

Corinth, two hundred in number, with a prytanis at their head,

and inter-marrying only among themselves, were one of the most

distinguished of these families. They were deprived of their

exclusive supremacy by Kypselus, a man of humble birth on his

father's side, but connected with the Bacchiadæ through his

mother. … As the Kypselidæ rose in Corinth, the metropolis

of the colonies towards the west, so in the corresponding

eastern metropolis, Miletus, Thrasybulus raised himself from

the dignity of prytanis to that of tyrant; in Ephesus,

Pythagoras rose to power, and overthrew the Basilidæ; in

Samos, Polycrates, who was master also of the Kyklades, and of

whom it is recorded that he confiscated the property of the

citizens and then made them a present of it again. By

concentrating the forces of their several communities the

tyrants obtained the means of surrounding themselves with a

certain splendor, and above all of liberally encouraging

poetry and art.

{1569}

To these Polycrates opened his citadel, and in it we find

Anacreon and Ibycus; Kypselus dedicated a famous statue to

Zeus, at Olympia. The school of art at Sikyon was without a

rival, and at the court of Periander were gathered the seven

sages—men in whom a distinguished political position was

combined with the prudential wisdom derived from the

experience of life. This is the epoch of the legislator of

Athens, Solon, who more than the rest has attracted to himself

the notice of posterity.

See ATHENS: B. C. 594.

He is the founder of the Athenian democracy. … His proverb

'Nothing in excess' indicates his character. He was a man who

knew exactly what the time has a right to call for, and who

utilized existing complications to bring about the needful

changes. It is impossible adequately to express what he was to

the people of Athens, and what services he rendered them. That

removal of their pecuniary burdens, the seisachtheia, made

life for the first time endurable to the humbler classes.

See DEBT, LAWS CONCERNING: ANCIENT GREEK.

Solon cannot be said to have introduced democracy, but, in

making the share of the upper classes in the government

dependent upon the good pleasure of the community at large, he

laid its foundations. The people were invested by him with

attributes which they afterwards endeavored to extend. …

Solon himself lived long enough to see the order which he

established serve as the basis of the tyranny which he wished

to avoid; it was the Four Hundred themselves who lent a hand

to the change. The radical cause of failure was that the

democratic element was too feebly constituted to control or to

repress the violence of the families. To elevate the democracy

into a true power in the state other events were necessary,

which not only rendered possible, but actually brought about,

its further development. The conflicts of the principal

families, hushed for a moment, were revived under the eyes of

Solon himself with redoubled violence. The Alemæonidæ

[banished about 595 B. C.—see ATHENS: B. C. 612-595] were

recalled, and Æthelred around them a party consisting mainly

of the inhabitants of the seacoast, who, favored by trade, had

the money in their hands; the genuine aristocrats, described

as the inhabitants of the plains, who were in possession of

the fruitful soil, were in perpetual antagonism to the

Alemæonidæ; and, whilst these two parties were bickering, a

third was formed from the inhabitants of the mountain

districts, inferior to the two others in wealth, but of

superior weight to either in the popular assemblies. At its

head stood Peisistratus, a man distinguished by warlike

exploits, and at an earlier date a friend of Solon. It was

because his adherents did not feel themselves strong enough to

protect their leader that they were induced to vote him a

body-guard chosen from their own ranks. … As soon, however,

as the first two parties combined, the third was at a

disadvantage, so that after some time sentence of banishment

was passed upon Peisistratus. … Peisistratus … found means

to gather around him a troop of brave mercenaries, with whom,

and with the support of his old adherents, he then invaded

Attica. His opponents made but a feeble resistance, and he

became without much trouble master both of the city and of the

country.

See ATHENS: B. C. 560-510.

He thus attained to power; it is true, with the approbation of

the people, but nevertheless by armed force. … We have

almost to stretch a point in order to call Peisistratus a

tyrant—a word which carries with it the invidious sense of a

selfish exercise of power. No authority could have been more

rightly placed than his; it combined Athenian with

Panhellenist tendencies. But for him Athens would not have

been what she afterwards became to the world. …

Nevertheless, it must be admitted that Peisistratus governed

Athens absolutely, and even took steps to establish a

permanent tyranny. He did, in fact, succeed in leaving the

power he possessed to his sons, Hippias and Hipparchus. … Of

the two brothers it was the one who had rendered most service

to culture, Hipparchus, who was murdered at the festival of

the Panathenæa. It was an act of revenge for a personal

insult. … In his dread lest he should be visited by a

similar doom, Hippias actually became an odious tyrant and

excited universal discontent. One effect, however, of the loss

of stability which the authority of the dominant family

experienced was that the leading exiles ejected by

Peisistratus combined in the enterprise which was a necessary

condition of their return, the overthrow of Hippias. The

Alcmæonidæ took the principal part. … The revolution to

which this opened the way could, it might seem, have but one

result, the establishment of an oligarchical government. …

But the matter had a very different issue," resulting in the

constitution of Cleisthenes and the establishment of democracy

at Athens, despite the hostile opposition and interference of

Sparta.

L. von Ranke,

Universal History:

The oldest Historical Group of Nations and the Greeks,

chapter 5.

See, also,

ATHENS: B. C. 510-507,

and 509-506.

GREECE: B. C. 752.

The Archonship at Athens thrown open to the whole body of the

people.

See ATHENS: FROM THE DORIAN MIGRATION TO B. C. 683.

GREECE: B. C. 624.

The Draconian legislation at Athens.

See ATHENS: B. C. 624.

GREECE: B. C. 610-600.

War of Athens and Megara for Salamis.

Spartan Arbitration.

See ATHENS: B. C. 610-586.

GREECE: B. C. 595-586.

The Cirrhæan or first Sacred War.

See ATHENS: B.C. 610-586; and DELPHI.

GREECE: B. C. 500-493.

Rising of the Ionians of Asia Minor against the Persians.

Aid rendered to them by the Athenians.

Provocation to Darius.

The Ionic Greek cities, or states, of Asia Minor, first

subjugated by Crœsus, King of Lydia, in the sixth century B.

C., were swallowed up, in the same century, with all other

parts of the dominion of Crœsus, in the conquests of Cyrus,

and formed part of the great Persian Empire, to the

sovereignty of which Cambyses and Darius succeeded. In the

reign of Darius there occurred a revolt of the Ionians (about

502 B. C.), led by the city of Miletus, under the influence of

its governor, Aristagoras. Aristagoras, coming over to Greece

in person, sought aid against the Persians, first at Sparta,

where it was denied to him, and then, with better success, at

Athens. Presenting himself to the citizens, just after they

had expelled the Pisistratidæ, Aristagoras said to them "that

the Milesians were colonists from Athens, and that it was just

that the Athenians, being so mighty, should deliver them from

slavery.

{1570}

And because his need was great, there was nothing that he did

not promise, till at the last he persuaded them. For it is

easier, it seems, to deceive a multitude than to deceive one

man. Cleomenes the Spartan, being but one man, Aristagoras

could not deceive; but he brought over to his purpose the

people of Athens, being thirty thousand. So the Athenians,

being persuaded, made a decree to send twenty ships to help

the men of Ionia, and appointed one Melanthius, a man of

reputation among them, to be captain. These ships were the

beginning of trouble both to the Greeks and the barbarians.

… When the twenty ships of the Athenians were arrived, and

with them five ships of the Eretrians, which came, not for any

love of the Athenians, but because the Milesians had helped

them in the old time against the men of Chalcis, Aristagoras

sent an army against Sardis, but he himself abode in Miletus.

This army, crossing Mount Tmolus, took the city of Sardis

without any hindrance; but the citadel they took not, for

Artaphernes held it with a great force of soldiers. But though

they took the city they had not the plunder of it, and for

this reason. The houses in Sardis were for the most part built

of reeds, and such as were built of bricks had their roofs of

reeds; and when a certain soldier set fire to one of these

houses, the fire ran quickly from house to house till the

whole city was consumed. And while the city was burning, such

Lydians and Persians as were in it, seeing they were cut off

from escape (for the fire was in an the outskirts of the

city), gathered together in haste to the market-place. Through

this market-place flows the river Pactolus, which comes down

from Mount Tmolus, having gold in its sands, and when it has

passed out of the city it flows into the Hermus, which flows

into the sea. Here then the Lydians and Persians were gathered

together, being constrained to defend themselves. And when the

men of Ionia saw their enemies how many they were, and that

these were preparing to give battle, they were stricken with

fear, and fled out of the city to Mount Tmolus, and thence,

when it was night, they went back to the sea. In this manner

was burnt the city of Sardis, and in it the great temple of

the goddess Cybele, the burning of which temple was the cause,

as said the Persians, for which afterwards they burnt the

temples in Greece. Not long after came a host of Persians from

beyond the river Halys; and when they found that the men of

Ionia had departed from Sardis, they followed hard upon their

track, and came up with them at Ephesus. And when the battle

was joined, the men of Ionia fled before them. Many indeed

were slain, and such as escaped were scattered, every man to

his own city. After this the ships of the Athenians departed,

and would not help the men of Ionia any more, though

Aristagoras besought them to stay. Nevertheless the Ionians

ceased not from making preparations of war against the King,

making to themselves allies, some by force and some by

persuasion, as the cities of the Hellespont and many of the

Carians and the island of Cyprus. For all Cyprus, save Amathus

only, revolted from the King under Onesilus, brother of King

Gorgus. When King Darius heard that Sardis had been taken and

burned with fire by the Ionians and the Athenians, with

Aristagoras for leader, at the first he took no heed of the

Ionians, as knowing that they would surely suffer for their

deed, but he asked, 'Who are these Athenians?' And when they

told him he took a bow and shot an arrow into the air, saying,

'O Zeus, grant that I may avenge myself on these Athenians.'

And he commanded his servant that every day, when his dinner

was served, he should say three times, 'Master, remember the

Athenians.' … Meanwhile the Persians took not a few cities

of the Ionians and Æolians. But while they were busy about

these, the Carians revolted from the King; whereupon the

captains of the Persians led their army into Caria, and the

men of Caria came out to meet them; and they met them at a

certain place which is called the White Pillars, near to the

river Mæander. Then there were many counsels among the

Carians, whereof the best was this, that they should cross the

river and so contend with the Persians, having the river

behind them, that so there being no escape for them if they

fled, they might surpass themselves in courage. But this

counsel did not prevail. Nevertheless, when the Persians had

crossed the Meander, the Carians fought against them, and the

battle was exceeding long and fierce. But at the last the

Carians were vanquished, being overborne by numbers, so that

there fell of them ten thousand. And when they that

escaped—for many had fled to Labranda, where there is a great

temple of Zeus and a grove of plane trees—were doubting

whether they should yield themselves to the King or depart

altogether from Asia, there came to their help the men of

Miletus with their allies. Thereupon the Carians, putting away

their doubts altogether, fought with the Persians a second

time, and were vanquished yet more grievously than before. But

on this day the men of Miletus suffered the chief damage. And

the Carians fought with the Persians yet again a third time;

for, hearing that these were about to attack their cities one

by one, they laid an ambush for them on the road to Pedasus.

And the Persians, marching by night, fell into the ambush, and

were utterly destroyed, they and their captains. After these

things, Aristagoras, seeing the power of the Persians, and

having no more any hope to prevail over them—and indeed, for

all that he had brought about so much trouble, he was of a

poor spirit—called together his friends and said to them, 'We

must needs have some place of refuge, if we be driven out of

Miletus. Shall we therefore go to Sardinia, or to Myrcinus on

the river Strymon; which King Darius gave to Histiæus?' To

this Hecateus, the writer of chronicles, made answer, 'Let

Aristagoras build a fort in Leros (this Leros is an island

thirty miles distant from Miletus) and dwell there quietly, if

he be driven from Miletus. And hereafter he can come from

Leros and set himself up again in Miletus.' But Aristagoras

went to Myrcinus, and not long afterwards was slain while he

besieged a certain city of the Thracians."

Herodotus,

The Story of the Persian War

(version of A. J. Church, chapter 2).

See, also,

PERSIA: B. C. 521-493;

and ATHENS: B. C. 501-490.

GREECE: B. C. 496.

War of Sparta with Argos.

Overwhelming reverse of the Argives.

See ARGOS: B. C. 496-421.

GREECE: B. C. 492-491.

Wrath of the Persian king against Athens.

Failure of his first expedition of invasion.

Submission of 'Medizing' Greek states.

Coercion of Ægina.

Enforced union of Hellas.

Headship of Sparta recognized.

{1571}

The assistance given by Athens to the Ionian revolt stirred

the wrath of the Persian monarch very deeply, and when he had

put down the rebellion he prepared to chastise the audacious

and insolent Greeks. "A great fleet started from the

Hellespont, with orders to sail round the peninsula of Mt.

Athos to the Gulf of Therma, while Mardonius advanced by land.

His march was so harassed by the Thracians that when he had

effected the conquest of Macedonia his force was too weak for

any further attempt. The fleet was overtaken by a storm off

Mt. Athos, on whose rocks 300 ships were dashed to pieces, and

20,000 men perished. Mardonius returned in disgrace to Asia

with the remnant of his fleet and army. This failure only

added fury to the resolution of Darius. While preparing all

the resources of his empire for a second expedition, he sent

round heralds to the chief cities of Greece, to demand the

tribute of earth and water as signs of his being their

rightful lord. Most of them submitted: Athens and Sparta alone

ventured on defiance. Both treated the demand as an outrage

which annulled the sanctity of the herald's person. At Athens

the envoy was plunged into the loathsome Barathrum, a pit into

which the most odious public criminals were cast. At Sparta

the herald was hurled into a well, and bidden to seek his

earth and water there. The submission of Ægina, the chief

maritime state of Greece, and the great enemy of Athens,

entailed the most important results. The act was denounced by

Athens as treason against Greece, and the design was imputed

to Ægina of calling in the Persians to secure vengeance on her

rival. The Athenians made a formal complaint to Sparta against

the 'Medism' of the Æginetans; a charge which is henceforth

often repeated both against individuals and states. The

Spartans had recently concluded a successful war with Argos,

the only power that could dispute her supremacy in

Peloponnesus; and now this appeal from Athens, the second city

of Greece, at once recognized and established Sparta as the

leading Hellenic state. In that character, her king Cleomenes

undertook to punish the Medizing party in Ægina 'for the

common good of Greece'; but he was met by proofs of the

intrigues of his colleague Demaratus in their favour. …

Cleomenes obtained his deposition on a charge of illegitimacy,

and a public insult from his successor Leotychides drove

Demaratus from Sparta. Hotly pursued as a 'Medist,' he

effected his escape to Darius, whose designs against Athens

and Sparta were now stimulated by the councils of their exiled

sovereigns, Hippias and Demaratus. Meanwhile, Cleomenes and

his new colleague returned to Ægina, which no longer resisted,

and having seized ten of her leading citizens, placed them as

hostages in the hands of the Athenians. Ægina was thus

effectually disabled from throwing the weight of her fleet

into the scale of Persia: Athens and Sparta, suspending their

political jealousies, were united when their disunion would

have been fatal; their conjunction drew after them most of the

lesser states: and so the Greeks stood forth for the first

time as a nation prepared to act in unison, under the

leadership of Sparta (B. C. 491). That city retained her proud

position till it was forfeited by the misconduct of her

statesmen."

P. Smith,

History of the World: Ancient,

chapter 13 (volume 1).

ALSO IN:

G. W. Cox,

The Greeks and the Persians,

chapter 6.

G. Grote,

History of Greece,

chapter 36 (volume 4.)

See, also, ATHENS: B. C. 501-490.

GREECE: B. C. 490.

The Persian Wars: Marathon.

The second and greater expedition launched by Darius against

the Greeks sailed from the Cilician coast in the summer of the

year 490 B. C. It was under the command of two generals,—a

Mede, named Datis, and the king's nephew, Artaphernes. It made

the passage safely, destroying Naxos on the way, but sparing

the sacred island and temple of Delos. Its landing was on the

shores of Eubœa, where the city of Eretria was easily taken,

its inhabitants dragged into slavery, and the first act of

Persian vengeance accomplished. The expedition then sailed to

the coast of Attica and came to land on the plain of Marathon,

which spreads along the bay of that name. "Marathon, situated

near to a bay on the eastern coast of Attica, and in a

direction E. N. E. from Athens, is divided by the high ridge

of Mount Pentelikus from the city, with which it communicated

by two roads, one to the north, another to the south of that

mountain. Of these two roads, the northern, at once the

shortest and the most difficult, is 22 miles in length. …

[The plain] 'is in length about six miles, in breadth never

less than about one mile and a half. Two marshes bound the

extremities of the plain; the southern is not very large and

is almost dry at the conclusion of the great heats; but the

northern, which generally covers considerably more than a

square mile, offers several parts which are at all seasons

impassable. Both, however, leave a broad, firm sandy beach

between them and the sea. The uninterrupted flatness of the

plain is hardly relieved by a single tree; and an amphitheatre

of rocky hills and rugged mountains separates it from the rest

of Attica."

G. Grote,

History of Greece,

part 2, chapter 36 (volume 4).

The Athenians waited for no nearer approach of the enemy to

their city, but met them at their landing-place. They were few

in number—only 10,000, with 1,000 more from the grateful city

of Platæa, which Athens had protected against Thebes. They had

sent to Sparta for aid, but a superstition delayed the march

of the Spartans and they came the day after the battle. Of all

the nearer Greeks none came to the help of Athens in that hour

of extreme need; and so much the greater to her was the glory

of Marathon. The ten thousand Athenian hoplites and the one

thousand brave Platæans confronted the great host of Persia,

of the numbers in which there is no account. Ten generals had

the right of command on successive days, but Miltiades was

known to be the superior captain and his colleagues gave place

to him. "On the morning of the seventeenth day of the month of

Metagitnion (September 12th), when the supreme command

according to the original order of succession fell to

Miltiades, he ordered the army to draw itself up according to

the ten tribes. … The troops had advanced with perfect

steadiness across the trenches and palisadings of their camp,

as they had doubtless already done on previous days. But as

soon as they had approached the enemy within a distance of

5,000 feet they changed their march to a double-quick pace,

which gradually rose to the rapidity of a charge, while at the

same time they raised the war-cry with a loud voice.

{1572}

When the Persians saw these men rushing down from the heights,

they thought they beheld madmen: they quickly placed

themselves in order of battle, but before they had time for an

orderly discharge of arrows the Athenians were upon them,

ready in their excitement to begin a closer contest, man

against man in hand-to-hand fight, which is decided by

personal courage and gymnastic agility, by the momentum of

heavy-armed warriors, and by the use of lance and sword. Thus

the well-managed and bold attack of the Athenians had

succeeded in bringing into play the whole capability of

victory which belonged to the Athenians. Yet the result was

not generally successful. The enemy's centre stood firm. …

But meanwhile both wings had thrown themselves upon the enemy;

and after they had effected a victorious advance, the one on

the way to Rhamnus, the other towards the coast, Miltiades …

issued orders at the right moment for the wings to return from

the pursuit, and to make a combined attack upon the Persian

centre in its rear. Hereupon the rout speedily became general,

and in their flight the troubles of the Persians increased;

… they were driven into the morasses and there slain in

numbers."

E. Curtius,

History of Greece,

book 3, chapter 1 (volume 2).

The Athenian dead, when gathered for the solemn obsequies,

numbered 192; the loss of the Persians was estimated by

Herodotus at 6,400.

Herodotus,

History,

book 6.

ALSO IN:

E. S. Creasy,

Fifteen Decisive Battles,

chapter 1.

C. Thirlwall,

History of Greece,

chapter 14 (volume 2).

G. W. Cox,

The Greeks and Persians,

chapter 6.

Sir E. Bulwer Lytton,

Athens: Its Rise and Fall,

book 2, chapter 5.

GREECE: B. C. 489-480.

The Æginetan War.

Naval power of Athens created by Themistocles.

SEE ATHENS: B. C. 489-480.

GREECE: B. C. 481-479.

Congress at Corinth.

Hellenic union against Persia.

Headship of Sparta.

"When it was known in Greece that Xerxes was on his march into

Europe, it became necessary to take measures for the defence

of the country. At the instigation of the Athenians, the

Spartans, as the acknowledged leaders of Hellas and head of

the Peloponnesian confederacy, called on those cities which

had resolved to uphold the independence of their country to

send plenipotentiaries to a congress at the Isthmus of

Corinth. When the envoys assembled, a kind of Hellenic

alliance was formed under the presidency of Sparta, and its

unity was confirmed by an oath, binding the members to visit

with severe penalties those Greeks who, without compulsion,

had given earth and water to the envoys of Xerxes. This

alliance was the nearest approach to a Hellenic union ever

seen in Greece; but though it comprised most of the

inhabitants of the Peloponnesus, except Argos and Achæa, the

Megarians, Athenians, and two cities of Bœotia, Thespiæ and

Platæa, were the only patriots north of the Isthmus. Others,

who would willingly have been on that side, such as the common

people of Thessaly, the Phocians and Locrians, were compelled

by the force of circumstances to 'medize.' From the time at

which it met in the autumn or summer of 481 to the autumn of

480 B. C., the congress at the Isthmus directed the military

affairs of Greece. It fixed the plan of operations. Spies were

sent to Sardis to ascertain the extent of the forces of

Xerxes; envoys visited Argos, Crete, Corcyra, and Syracuse, in

the hope, which proved vain, of obtaining assistance in the

impending struggle. As soon as Xerxes was known to be in

Europe, an army of 10,000 men was sent to hold the pass of

Tempe, but afterwards, on the advice of Alexander of Macedon,

this barrier was abandoned; and it was finally resolved to

await the approaching forces at Thermopylæ and Artemisium. The

supreme authority, both by land and sea, was in the hands of

the Spartans; they were the natural leaders of any army which

the Greeks could put into the field, and the allies refused to

follow unless the ships also were under their charge. … When

hostilities were suspended, the congress re-appears, and the

Greeks once more meet at the Isthmus to apportion the spoil

and adjudge the prizes of valour. In the next year we hear of

no common plan of operations, the fleet and army seeming to

act independently of each other; yet we observe that the

chiefs of the medizing Thebans were taken to the Isthmus

(Corinth) to be tried, after the battle of Platæa. It appears

then that, under the stress of the great Persian invasion, the

Greeks were brought into an alliance or confederation; and for

the two years from midsummer 481 to midsummer 479 a congress

continued to meet, with more or less interruption, at the

Isthmus, consisting of plenipotentiaries from the various

cities. This congress directed the affairs of the nation, so

far as they were in any way connected with the Persian

invasion. When the Barbarians were finally defeated, and there

was no longer any alarm from that source, the congress seems

to have discontinued its meetings. But the alliance remained;

the cities continued to act in common, at any rate, so far as

naval operations were concerned, and Sparta was still the

leading power."

E. Abbott,

Pericles and the Golden Age of Athens,

chapter 3.

ALSO IN:

C. O. Müller,

History and Antiquity of the Doric Race,

volume 1, appendix 4.

GREECE: B. C. 480.

The Persian War: Thermopylæ.

"Now when tidings of the battle that had been fought at

Marathon [B. C. 490] reached the ears of King Darius, the son

of Hystaspes, his anger against the Athenians," says

Herodotus, "which had been already roused by their attack on

Sardis, waxed still fiercer, and he became more than ever

eager to lead an army against Greece. Instantly he sent off

messengers to make proclamation through the several states

that fresh levies were to be raised, and these at an increased

rate; while ships, horses, provisions and transports were

likewise to be furnished. So the men published his commands;

and now all Asia was in commotion by the space of three

years." But before his preparations were completed Darius

died. His son Xerxes, who ascended the Persian throne, was

cold to the Greek undertaking and required long persuasion

before he took it up. When he did so, however, his

preparations were on a scale more stupendous than those of his

father, and consumed nearly five years. It was not until ten

years after Marathon that Xerxes led from Sardis a host which,

Herodotus computes at 1,700,000 men, besides half a million

more which manned the fleet he had assembled. "Was there a

nation in all Asia," cries the Greek historian, "which Xerxes

did not bring with him against Greece? Or was there a river,

except those of unusual size, which sufficed for his troops to

drink?" By a bridge of boats at Abydos the army crossed the

Hellespont, and moved slowly through Thrace, Macedonia and

Thessaly; while the fleet, moving on the

coast circuit of the same countries, avoided the perilous

promontory of Mount Athos by cutting a canal.

{1573}

The Greeks had determined at first to make their stand against

the invaders in Thessaly, at the vale of Tempe; but they found

the post untenable and were persuaded, instead, to guard the

narrower Pass of Thermopylæ. It was there that the Persians,

arriving at Trachis, near the Malian gulf, found themselves

faced by a small body of Greeks. The spot is thus described by

Herodotus: "As for the entrance into Greece by Trachis, it is,

at its narrowest point, about fifty feet wide. This, however,

is not the place where the passage is most contracted; for it

is still narrower a little above and a little below

Thermopylae. At Alpeni, which is lower down than that place,

it is only wide enough for a single carriage; and up above, at

the river Phœnix, near the town called Anthela, it is the

same. West of Thermopylæ rises a lofty and precipitous hill,

impossible to climb, which runs up into the chain of Œta;

while to the east the road is shut in by the sea and by

marshes. In this place are the warm springs, which the natives

call 'The Cauldrons'; and above them stands an altar sacred to

Hercules. A wall had once been carried across the opening; and

in this there had of old times been a gateway. … King Xerxes

pitched his camp in the region of Malis called Trachinia,

while on their side the Greeks occupied the straits. These

straits the Greeks in general call Thermopylæ (the Hot Gates);

but the natives and those who dwell in the neighbourhood call

them Pylæ (the Gates). … The Greeks who at this spot awaited

the coming of Xerxes were the following:—From Sparta, 300

men-at-arms; from Arcadia, 1,000 Tegeans and Mantineans, 500

of each people; 120 Orchomenians, from the Arcadian

Orchomenus; and 1,000 from other cities; from Corinth, 400

men; from Phlius, 200; and from Mycenæ 80. Such was the number

from the Peloponnese. There were also present, from Bœotia,

700 Thespians and 400 Thebans. Besides these troops, the

Locrians of Opus and the Phocians had obeyed the call of their

countrymen, and sent, the former all the force they had, the

latter 1,000 men. … The various nations had each captains of

their own under whom they served; but the one to whom all

especially looked up, and who had the command of the entire

force, was the Lacedæmonian, Leonidas. … The force with

Leonidas was sent forward by the Spartans in advance of their

main body, that the sight of them might encourage the allies

to fight, and hinder them from going over to the Medes, as it

was likely they might have done had they seen Sparta backward.

They intended presently, when they had celebrated the Carneian

festival, which was what now kept them at home, to leave a

garrison in Sparta, and hasten in full force to join the army.

The rest of the allies also intended to act similarly; for it

happened that the Olympic festival fell exactly at this same

period. None of them looked to see the contest at Thermopylæ

decided so speedily." For two days Leonidas and his little

army held the pass against the Persians. Then, there was found

a traitor, a man of Malis, who betrayed to Xerxes the secret

of a pathway across the mountains, by which he might steal

into the rear of the post held by the Greeks. A thousand

Phocians had been stationed on the mountain to guard this

path; but they took fright when the Persians came upon them in

the early dawn, and fled without a blow. When Leonidas learned

that the way across the mountain was open to the enemy he knew

that his defense was hopeless, and he ordered his allies to

retreat while there was yet time. But he and his Spartans

remained, thinking it "unseemly" to quit the post they had

been specially sent to guard. The Thespians remained with

them, and the Thebans—known partisans at heart of the

Persians—were forced to stay. The latter deserted when the

enemy approached; the Spartans and the Thespians fought and

perished to the last man.

Herodotus,

History

(translated by Rawlinson), book 7.

ALSO IN:

E. Curtius,

History of Greece,

book 3, chapter 1.

G. Grote,

History of Greece,

part 2, chapter 40 (volume 4).

See, also,

ATHENS: B. C. 480-479.

GREECE: B. C. 480.

The Persian Wars: Artemisium.

On the approach of the great invading army and fleet of

Xerxes, the Greeks resolved to meet the one at the pass of

Thermopylæ and the other at the northern entrance of the

Eubœan channel. "The northern side of Eubœa afforded a

commodious and advantageous station: it was a long beach,

called, from a temple at its eastern extremity, Artemisium,

capable of receiving the galleys, if it should be necessary to

draw them upon the shore, and commanding a view of the open

sea and the coast of Magnesia, and consequently an opportunity

of watching the enemy's movements as he advanced towards the

south; while, on the other hand, its short distance from

Thermopylæ enabled the fleet to keep up a quick and easy

communication with the land force."

C. Thirlwall,

History of Greece,

chapter 15 (volume 1).

The Persian fleet, after suffering heavily from a destructive

storm on the Magnesian coast, reached Aphetæ, opposite

Artemisium, at the mouth of the Pagasæan gulf. Notwithstanding

its losses, it still vastly outnumbered the armament of the

Greeks, and feared nothing but the escape of the latter. But,

in the series of conflicts which ensued, the Greeks were

generally victorious and proved their superior naval genius.

They could not, however, afford the heavy losses which they

sustained, and, upon hearing of the disaster at Thermopylæ and

the Persian possession of the all-important pass, they deemed it

necessary to retreat.

W. Mitford,

History of Greece,

chapter 8, section 4 (volume 2).

GREECE: B. C. 480.

The Persian Wars: Salamis.

Leonidas and his Spartan band having perished vainly at

Thermopylæ, in their heroic attempt to hold the pass against

the host of Xerxes, and the Greek ships at Artemisium having

vainly beaten their overwhelming enemies, the whole of Greece

north of the isthmus of Corinth lay completely at the mercy of

the invader. The Thebans and other false-hearted Greeks joined

his ranks, and saved their own cities by helping to destroy

their neighbors. The Platæans, the Thespians and the Athenians

abandoned their homes in haste, conducted their families, and

such property as they might snatch away, to the nearer islands

and to places of refuge in Peloponnesus. The Greeks of

Peloponnesus rallied in force to the isthmus and began there

the building of a defensive wall. Their fleet, retiring from

Artemisium, was drawn together, with some re-enforcements,

behind the island of Salamis, which stretches across the

entrance to the bay of Eleusis, off the inner coast of Attica,

near Athens.

{1574}

Meantime the Persians had advanced through Attica, entered the

deserted city of Athens, taken the Acropolis, which a small

body of desperate patriots resolved to hold, had slain its

defenders and burned its temples. Their fleet had also been

assembled in the bay of Phalerum, which was the more easterly

of the three harbors of Athens. At Salamis the Greeks were in

dispute. The Corinthians and the Peloponnesians were bent upon

falling back with the fleet to the isthmus; the Athenians, the

Eginetans and the Megarians looked upon all as lost if the

present combination of the whole naval power of Hellas in the

narrow strait of Salamis was permitted to be broken up. At

length Themistocles, the Athenian leader, a man of fertile

brain and overbearing resolution, determined the question by

sending a secret message to Xerxes that the Greek ships had

prepared to escape from him. This brought down the Persian

fleet upon them at once and left them no chance for retreat.

Of the memorable fight which ensued (September 20 B. C. 480)

the following is a part of the description given by Herodotus:

"Against the Athenians, who held the western extremity of the

line towards Eleusis, were placed the Phœnicians; against the

Lacedæmonians, whose station was eastward towards the Piræus,

the Ionians. Of these last, a few only followed the advice of

Themistocles, to fight backwardly; the greater number did far

otherwise. … Far the greater number of the Persian ships

engaged in this battle were disabled, either by the Athenians

or by the Eginetans. For as the Greeks fought in order and

kept their line, while the barbarians were in confusion and

had no plan in anything that they did, the issue of the battle

could scarce be other than it was. Yet the Persians fought far

more bravely here than at Eubœa, and indeed surpassed

themselves; each did his utmost through fear of Xerxes, for

each thought that the king's eye was upon himself. … During

the whole time of the battle Xerxes sat at the base of the

hill called Ægaleos, over against Salamis; and whenever he saw

any of his own captains perform any worthy exploit he inquired

concerning him; and the man's name was taken down by his

scribes, together with the names of his father and his city.

… When the rout of the barbarians began, and they sought to

make their escape to Phalêrum, the Eginetans, awaiting them in

the channel, performed exploits worthy to be recorded. Through

the whole of the confused struggle the Athenians employed

themselves in destroying such ships as either made resistance

or fled to shore; while the Eginetans dealt with those which

endeavoured to escape down the straits; so that the Persian

vessels were no sooner clear of the Athenians than straightway

they fell into the hands of the Eginetan squadron. … Such of

the barbarian vessels as escaped from the battle fled to

Phalêrum, and there sheltered themselves under the protection

of the land army. … Xerxes, when he saw the extent of his

loss, began to be afraid lest the Greeks might be counselled

by the Ionians, or without their advice might determine, to

sail straight to the Hellespont and break down the bridges

there; in which case he would be blocked up in Europe and run

great risk of perishing. He therefore made up his mind to

fly."

Herodotus,

History

(edited and translated by Rawlinson),

book 8, sections 85—97 (volume 4).

ALSO IN:

E. Curtius,

History of Greece,

book 3, chapter 1 (volume 2).

G. Grote,

History of Greece,

part 2, chapter 4 (volume 4).

W. W. Goodwin,

The Battle of Salamis

(Papers of the American School at Athens, volume 1).

GREECE: B. C. 479.

The Persian Wars: Platæa.

When Xerxes, after the defeat of his fleet at Salamis, fled

back to Asia with part of his disordered host, he left his

lieutenant, Mardonius, with a still formidable army, to repair

the disaster and accomplish, if possible, the conquest of the

Greeks. Mardonius retired to Thessaly for the winter, but

returned to Attica in the spring and drove the Athenians once

more from their shattered city, which they were endeavoring to

repair. He made overtures to them which they rejected with

scorn, and thereupon he destroyed everything in city and

country which could be destroyed, reducing Athens to ruins and

Attica to a desert. The Spartans and other Peloponnesians who

had promised support to the Athenians were slow in coming, but

they came in strong force at last. Mardonius fell back into

Bœotia, where he took up a favorable position in a plain on

the left bank of the Asopus, near Platæa. This was in

September, B. C. 479. According to Herodotus, he had 300,000

"barbarian" troops and 50,000 Greek allies. The opposing

Greeks, who followed him to the Asopus, were 110,000 in

number. The two armies watched one another for more than ten

days, unwilling to offer battle because the omens were on both

sides discouraging. At length the Greeks undertook a change of

position and Mardonius, mistaking this for a movement of

retreat, led his Persians on a run to attack them. It was a

fatal mistake. The Spartans, who bore the brunt of the Persian

assault, soon convinced the deluded Mardonius that they were

not in flight, while the Athenians dealt roughly with his

Theban allies. "The barbarians," says Herodotus, "many times

seized hold of the Greek spears and brake them; for in

boldness and warlike spirit the Persians were not a whit

inferior to the Greeks; but they were without bucklers,

untrained, and far below the enemy in respect of skill in

arms. Sometimes singly, sometimes in bodies of ten, now fewer

and now more in number, they dashed forward upon the Spartan

ranks, and so perished. … After Mardonius fell, and the

troops with him, which were the main strength of the army,

perished, the remainder yielded to the Lacedæmonians and took

to flight. Their light clothing and want of bucklers were of

the greatest hurt to them: for they had to contend against men

heavily armed, while they themselves were without any such

defence." Artabazus, who was second in command of the

Persians, and who had 40,000 immediately under him, did not

strike a blow in the battle, but quitted the field as soon as

he saw the turn events had taken, and led his men in a retreat

which had no pause until they reached and crossed the

Hellespont. Of the remainder of the 300,000 of Mardonius'

host, only 3,000, according to Herodotus, outlived the battle.

It was the end of the Persian invasions of Greece.

Herodotus,

History

(translated by Rawlinson), book 9.

G. Grote,

History of Greece,

part 2, chapter 42 (volume 5).

C. Thirlwall,

History of Greece,

chapter 16 (volume 1).

G. W. Cox,

History of Greece,

book 2, chapter 7 (volume 1).

{1575}

In celebration of the victory an altar to Zeus was erected and

consecrated by the united Greeks with solemn ceremonies, a

quintennial festival, called the Feast of Liberty, was

instituted at Platæa, and the territory of the Platæans was

declared sacred and inviolable, so long as they should