click here for larger image.

click here for larger image.

of the

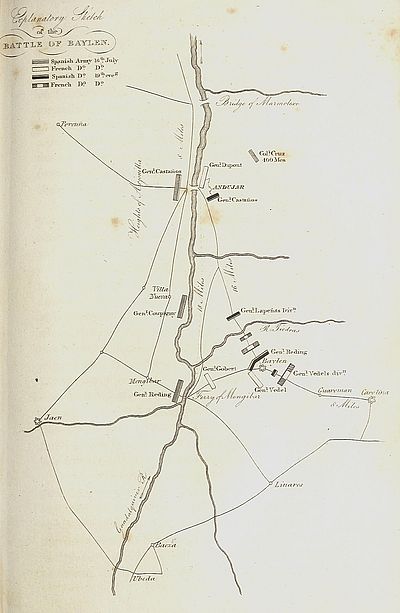

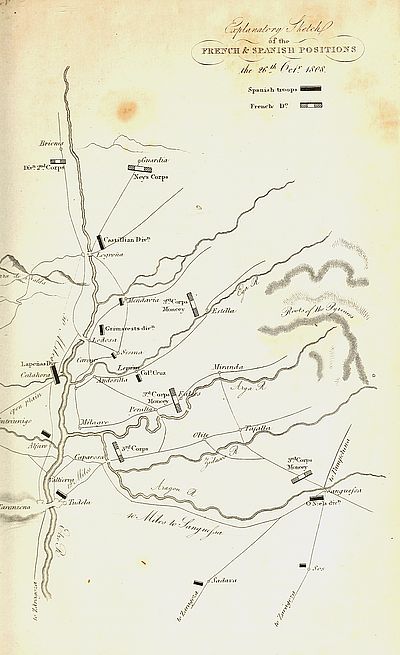

BATTLE OF BAYLEN.

London. Published March 1828, by John Murray, Albermarle Street.

Title: History of the war in the Peninsula and in the south of France from the year 1807 to the year 1814, vol. 1

Author: William Francis Patrick Napier

Release date: February 4, 2022 [eBook #67318]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Original publication: United Kingdom: John Murray, 1828

Credits: Brian Coe, John Campbell and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

TRANSCRIBER’S NOTE

When indicating an underline, a horizontal parenthesis symbol is denoted by several equal signs =====.

Omitted text is indicated by three asterisks, * * *.

Footnote anchors are denoted by [number], and the footnotes have been placed at the end of the book.

All changes noted in the CORRIGENDA have been applied to the etext. Each change is indicated by a dashed blue underline.

With a few exceptions noted at the end of the book, variant spellings of place names have not been changed.

The LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS was created by the transcriber and has been placed in the public domain.

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

Some minor changes to the text are noted at the end of the book. These are indicated by a dotted gray underline.

AND IN THE

SOUTH OF FRANCE,

FROM THE YEAR 1807 TO THE YEAR 1814.

BY

W. F. P. NAPIER, C. B.

LT. COLONEL H. P. FORTY-THIRD REGIMENT.

VOL. I.

LONDON:

JOHN MURRAY, ALBEMARLE-STREET.

MDCCCXXVIII.

TO

FIELD-MARSHAL

THE DUKE OF WELLINGTON.

This History I dedicate to your Grace, because I have served long enough under your command to feel, why the Soldiers of the Tenth Legion were attached to Cæsar.

W. F. P. NAPIER.

For six years the Peninsula was devastated by the war of independence. The blood of France, Germany, England, Portugal, and Spain, was shed in the contest; and in each of those countries, authors, desirous of recording the sufferings, or celebrating the valour of their countrymen, have written largely touching that fierce struggle. It may therefore happen that some will demand, why I should again relate “a thrice-told tale?” I answer, that two men observing the same object, will describe it diversely, following the point of view from which either beholds it. That which in the eyes of one is a fair prospect, to the other shall appear a barren waste, and yet neither may see aright! Wherefore, truth being the legitimate object of history, I hold it better that she should be sought for by many than by few, lest, for want of seekers, amongst the mists of prejudice and the false lights of interest, she be lost altogether.

That much injustice has been done, and much justice left undone, by those authors who have hitherto written concerning this war, I can assert from personal knowledge of the facts. That I have been able to remedy this without falling into similar errors, is more than I will venture to assume; but I have endeavoured to render as impartial an account of the[viii] campaigns in the Peninsula as the feelings which must warp the judgment of a contemporary historian will permit.

I was an eye-witness to many of the transactions that I relate; and a wide acquaintance with military men has enabled me to consult distinguished officers, both French and English, and to correct my own recollections and opinions by their superior knowledge. Thus assisted, I was encouraged to undertake the work, and I offer it to the world with the less fear because it contains original documents, which will suffice to give it interest, although it should have no other merit. Many of those documents I owe to the liberality of marshal Soult, who, disdaining national prejudices, with the confidence of a great mind, placed them at my disposal, without even a remark to check the freedom of my pen. I take this opportunity to declare that respect which I believe every British officer who has had the honour to serve against him feels for his military talents. By those talents the French cause in Spain was long upheld, and after the battle of Salamanca, if his counsel had been followed by the intrusive monarch, the fate of the war might have been changed.

Military operations are so dependent upon accidental circumstances, that to justify censure it should always be shown that an unsuccessful general has violated the received maxims and established principles of war. By that rule I have been guided; but to preserve the narratives unbroken, my own observations are placed at the end of certain transactions of magnitude, where their real source being known they will[ix] pass for as much as they are worth, and no more: when they are not well supported by argument, I freely surrender them to the judgment of abler men.

Of those transactions which, commencing with “the secret treaty of Fontainebleau” ended with “the Assembly of Notables” at Bayonne, little is known except through the exculpatory and contradictory publications of men interested to conceal the truth; and to me it appears that the passions of the present generation must subside, and the ultimate fate of Spain be known, before that part of the subject can be justly and usefully handled. I have, therefore, related no more of those political affairs than would suffice to introduce the military events that followed, neither have I treated largely of the disjointed and ineffectual operations of the native armies; for I cared not to swell my work with apocryphal matter, and neglected the thousand narrow winding currents of Spanish warfare; to follow that mighty stream of battle which, bearing the glory of England in its course, burst the barriers of the Pyrenees, and left deep traces of its fury in the soil of France.

The Spaniards have boldly asserted, and the world has believed, that the deliverance of the Peninsula was the work of their hands: this assertion so contrary to the truth I combat. It is unjust to the fame of the British general, injurious to the glory of the British arms. Military virtue is not the growth of a day, nor is there any nation so rich and populous, that, despising it, can rest secure. The imbecility of Charles IV., the vileness of Ferdinand, and the corruption of Godoy, were undoubtedly the proximate[x] causes of the calamities that overwhelmed Spain; but the primary cause, that which belongs to history, was the despotism arising from the union of a superstitious court and a sanguinary priesthood, which, repressing knowledge and contracting the public mind, sapped the foundation of all military as well as civil virtues, and prepared the way for invasion. No foreign potentate would have attempted to steal into the fortresses of a great kingdom, if the prying eyes, and the thousand clamorous tongues belonging to a free press, were ready to expose his projects, and a well-disciplined army present to avenge the insult; but Spain being destitute of both, was first circumvented by the wiles, and then ravaged by the arms, of Napoleon. She was deceived and fettered because the public voice was stifled, but she was scourged and torn because her military institutions were decayed.

From the moment that an English force took the field, the Spaniards ceased to act as principals in a contest carried on in the heart of their country, and involving their existence as an independent nation; they were self-sufficient, and their pride was wounded by insult; they were superstitious, and their religious feelings were roused to fanatic fury by an all-powerful clergy, who feared to lose their own rich endowments; but after the first burst of indignation the cause of independence created little enthusiasm. Horrible barbarities were exercised on those French soldiers that sickness or the fortune of war exposed to the rage of the invaded, and a dreadful spirit of personal hatred was kept alive by the exactions and severe retaliations of the invaders, but no great and general[xi] exertion to drive the latter from the soil was made, or at least none was sustained with steadfast courage in the field. Manifestoes, decrees, and lofty boasts, like a cloud of canvas covering a rotten hull, made a gallant appearance, but real strength and firmness were nowhere to be found.

The Spanish insurrection presented indeed a strange spectacle; patriotism was seen supporting a vile system of government; a popular assembly working for the restoration of a despotic monarch; the higher classes seeking a foreign master; the lower armed in the cause of bigotry and misrule. The upstart leaders secretly abhorring freedom, yet governing in her name, trembled at the democratic activity they had themselves excited. They called forth all the bad passions of the multitude, but repressed the patriotism that would regenerate as well as save. The country suffered the evils, without enjoying the benefits, of a revolution! Tumults and assassinations terrified and disgusted the sensible part of the community; a corrupt administration of the resources extinguished patriotism, and neglect ruined the armies: the peasant-soldier, usually flying at the first onset, threw away his arms and returned to his home, or, attracted by the license of the partidas, joined the banners of men who, for the most part originally robbers, were as oppressive to the people as the enemy. The guerilla chiefs would, in their turn, have been quickly exterminated, but that the French, pressed by lord Wellington’s battalions, were obliged to keep in large masses. This was the secret of Spanish constancy! Copious supplies from England, and the valour of[xii] the Anglo-Portuguese troops, these were the supports of the war! and it was the gigantic vigour with which the duke of Wellington resisted the fierceness of France, and sustained the weakness of three inefficient cabinets, that delivered the Peninsula. Faults he committed, and who in war has not? but his reputation stands upon a sure foundation, a simple majestic structure, that envy cannot undermine, nor the meretricious ornaments of party panegyric deform. The exploits of his army were great in themselves, and great in their consequences: abounding with signal examples of heroic courage and devoted zeal, they should neither be disfigured nor forgotten, being worthy of more fame than the world has yet accorded them—worthy also of a better historian.

| BOOK I. | ||

| CHAPTER I. | ||

| Introduction | Page 1 |

|

| CHAPTER II. | ||

| Dissensions in the Spanish court—Secret treaty and convention of Fontainebleau—Junot’s army enters Spain—Dupont’s and Moncey’s corps enter Spain—Duhesme’s corps enters Catalonia—Insurrections of Aranjuez and Madrid—Charles the fourth abdicates—Ferdinand proclaimed king—Murat marches to Madrid—Refuses to recognise Ferdinand as king—The sword of Francis the first delivered to the French general—Savary arrives at Madrid—Ferdinand goes to Bayonne—Charles the fourth goes to Bayonne—The fortresses of St. Sebastian, Figueras, Pampeluna, and Barcelona, treacherously seized by the French—Riot at Toledo, 23d April—Tumult at Madrid, 2d of May—Charles the fourth abdicates a second time in favour of Napoleon—Assembly of notables at Bayonne—Joseph Buonaparte declared king of Spain—Arrives at Madrid. | 12 | |

| CHAPTER III. | ||

| Council of Castile refuses to take the oath of allegiance—Supreme junta established at Seville—Marquis of Solano murdered at Cadiz, and the Conde d’Aguilar at Seville—Intercourse between Castaños and sir Hew Dalrymple—General Spencer and admiral Purvis offer to co-operate with the Spaniards—Admiral Rossily’s squadron surrenders to Morla—General insurrection—Massacre at Valencia—Horrible murder of Filanghieri. | 32 | |

| CHAPTER IV. | ||

| New French corps formed in Navarre—Duhesme fixes himself at Barcelona—Importance of that city—Napoleon’s military plan and arrangements. | 45 | |

| CHAPTER V. | ||

| First operations of marshal Bessieres—Spaniards defeated at Cabeçon, at Segovia, at Logroño, at Torquemada—French take St. Ander—Lefebre Desnouettes defeats the Spaniards on the Ebro, on the Huecha, on the Xalon—First siege of Zaragoza—Observations. | 62 | |

| CHAPTER VI. | ||

| Operations in Catalonia—General Swartz marches against the town of Manresa, and general Chabran against Taragona—French defeated at Bruch—Chabran recalled—Burns Arbos—Marches against Bruch—Retreats—Duhesme assaults Gerona—Is repulsed with loss—Action on the Llobregat—General insurrection of Catalonia—Figueras blockaded—General Reille relieves it—First siege of Gerona—The marquis of Palacios arrives in Catalonia with the Spanish troops from the Balearic isles, declared captain-general under St. Narcissus, re-establishes the line of the Llobregat—The count of Caldagues forces the French lines at Gerona—Duhesme raises the siege and returns to Barcelona—Observations—Moncey marches against Valencia, defeats the Spaniards at Pajaso, at the Siete Aguas, and at Quarte—Attacks Valencia, is repulsed, marches into Murcia, forces the passage of the Xucar, defeats Serbelloni[xiv] at San Felippe, arrives at San Clemente—Insurrection at Cuenca, quelled by general Caulincourt—Observations | 74 | |

| CHAPTER VII. | ||

| Second operations of Bessieres—Blake’s and Cuesta’s armies unite at Benevente—Generals disagree—Battle of Rio Seco—Bessieres’ endeavours to corrupt the Spanish generals fail—Bessieres marches to invade Gallicia, is recalled, and falls back to Burgos—Observations | 101 | |

| CHAPTER VIII. | ||

| Dupont marches against Andalusia, forces the bridge of Alcolea, takes Cordoba—Alarm at Seville—Castaños arrives, forms a new army—Dupont retreats to Andujar, attacks the town of Jaen—Vedel forces the pass of Despeñas Perros, arrives at Baylen—Spanish army arrives on the Guadalquivir—General Gobert defeated and killed—Generals Vedel and Darfour retire to Carolina—General Reding takes possession of Baylen—Dupont retires from Andujar—Battle of Baylen—Dupont’s capitulation, eighteen thousand French troops lay down their arms—Observations—Joseph holds a council of war, resolves to abandon Madrid—Impolicy of so doing | 112 | |

| BOOK II. | ||

| CHAPTER I. | ||

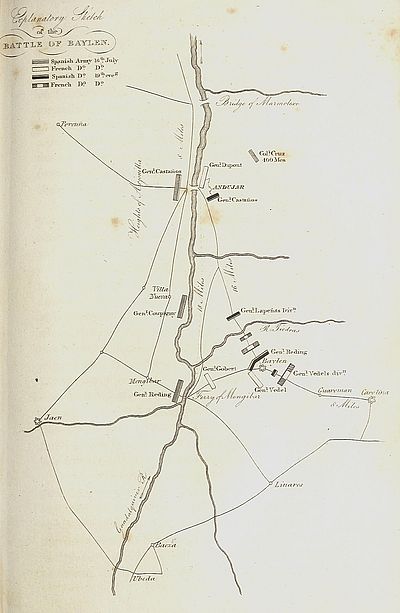

| The Asturian deputies received with enthusiasm in England—-Ministers precipitate—Imprudent choice of agents—Junot marches to Alcantara, joined by the Spanish contingent, enters Portugal, arrives at Abrantes, pushes on to Lisbon—Prince regent emigrates to the Brazils, reflections on that transaction—Dangerous position of the French army—Portuguese council of regency—Spanish contingent well received—General Taranco dies at Oporto, is succeeded by the French general Quesnel—Solano’s troops retire to Badajos—Junot takes possession of the Alemtejo and the Algarves; exacts a forced loan; is created duke of Abrantes; suppresses the council of regency; sends the flower of the Portuguese army to France—Napoleon demands a ransom from Portugal—People unable to pay it—Police of Lisbon—Junot’s military position; his character; political position—People discontented—Prophetic eggs—Sebastianists—-The capture of Rossily’s squadron known at Lisbon—Pope’s nuncio takes refuge on board the English fleet—Alarm of the French | 136 | |

| CHAPTER II. | ||

| Spanish general Belesta seizes general Quesnel and retires to Gallicia—Insurrection at Oporto—Junot disarms and confines the Spanish soldiers near Lisbon—General Avril’s column returns to Estremos—General Loison marches from Almeida against Oporto; is attacked at Mezam Frias; crosses the Douero; attacked at Castro d’Año; recalled to Lisbon—French driven out of the Algarves—The fort of Figueras taken—Abrantes and Elvas threatened—Setuval in commotion—General Spencer appears off the Tagus—Junot’s plan—Insurrection at Villa Viciosa suppressed—Colonel Maransin takes Beja with great slaughter of the patriots—The insurgents advance from Leria, fall back—Action at Leria—Loison arrives at Abrantes—Observations on his march—French army concentrated—The Portuguese general Leite, aided by a Spanish corps, takes post at Evora—Loison crosses the Tagus; defeats Leite’s advanced guard at Montemor—Battle of Evora—Town taken and pillaged—Unfriendly conduct of the Spaniards—Loison reaches Elvas; collects provisions; is recalled by Junot—Observations | 155 | |

| CHAPTER III. | ||

| Political and military retrospect—Mr. Fox’s conduct contrasted with that of his successors—General Spencer sent to the Mediterranean—Sir John Moore withdrawn from thence; arrives in England; sent to Sweden—Spencer arrives at Gibraltar—Ceuta, the object of his expedition—Spanish insurrection diverts his attention to Cadiz; wishes to occupy that city—Spaniards averse to it—Prudent[xv] conduct of sir Hew Dalrymple and lord Collingwood—Spencer sails to Ayamonte; returns to Cadiz; sails to the mouth of the Tagus; returns to Cadiz—Prince Leopold of Sicily and the duke of Orleans arrive at Gibraltar—Curious intrigue—Army assembled at Cork by the whig administration, with a view to permanent conquest in South America, the only disposable British force—Sir A. Wellesley takes the command—Contradictory instructions of the ministers—Sir John Moore returns from Sweden; ordered to Portugal—Sir Hew Dalrymple appointed commander of the forces—Confused arrangements made by the ministers | 169 | |

| CHAPTER IV. | ||

| Sir A. Wellesley quits his troops and proceeds to Coruña—Junta refuse assistance in men, but ask for and obtain money—Sir Arthur goes to Oporto; arranges a plan with the bishop; proceeds to the Tagus; rejoins his troops; joined by Spencer; disembarks at the Mondego; has an interview with general Freire d’Andrada; marches to Leria—Portuguese insurrection weak—Junot’s position and dispositions—Laborde marches to Alcobaça, Loison to Abrantes—General Freire separates from the British—Junot quits Lisbon with the reserve—Laborde takes post at Roriça—Action of Roriça—Laborde retreats to Montachique—Sir A. Wellesley marches to Vimiero—Junot concentrates his army at Torres Vedras | 187 | |

| CHAPTER V. | ||

| Portuguese take Abrantes—Generals Ackland and Anstruther land and join the British army at Vimiero—Sir Harry Burrard arrives—Battle of Vimiero—Junot defeated—Sir Hew Dalrymple arrives—Armistice—Terms of it—Junot returns to Lisbon—Negotiates for a convention—Sir John Moore’s troops land—State of the public mind in Lisbon—The Russian admiral negotiates separately—Convention concluded—the Russian fleet surrenders upon terms—Conduct of the people at Lisbon—The Monteiro Mor requires sir Charles Cotton to interrupt the execution of the convention—Sir John Hope appointed commandant of Lisbon; represses all disorders—Disputes between the French and English commissioners—Reflections thereupon | 207 | |

| CHAPTER VI. | ||

| The bishop and junta of Oporto aim at the supreme power; wish to establish the seat of government at Oporto; their intrigues; strange proceedings of general Decken; reflections thereupon—Clamour raised against the convention in England and in Portugal; soon ceases in Portugal—The Spanish general Galluzzo refuses to acknowledge the convention; invests fort Lalippe; his proceedings absurd and unjustifiable—Sir John Hope marches against him; he alters his conduct—Garrison of Lalippe—March to Lisbon—Embarked—Garrison of Almeida; march to Oporto; attacked and plundered by the Portuguese—Sir Hew Dalrymple and sir Harry Burrard recalled to England—Vile conduct of the daily press—Violence of public feeling—Convention, improperly called, of Cintra—Observations—On the action of Roriça—On the battle of Vimiero—On the convention | 236 | |

| BOOK III. | ||

| CHAPTER I. | ||

| Comparison between the Portuguese and Spanish people—The general opinion of French weakness and Spanish strength and energy, fallacious—Contracted policy of the English cabinet—Account of the civil and military agents employed—Many of them act without judgment—Mischievous effects thereof—Operations of the Spanish armies after the battle of Baylen—Murcian army arrives at Madrid—Valencian army marches to the relief of Zaragoza—General Verdier raises the siege—Castaños enters Madrid—Contumacious conduct of Galluzzo—Disputes between Blake and Cuesta—Dilatory conduct of the Spaniards—Sagacious observation of Napoleon—Insurrection at Bilbao; quelled by general Merlin—French corps approaches Zaragoza—Palafox alarmed, threatens the council of Castille—Council of war held at Madrid—Plan of operations—Castaños unable to march from want of money—Bad[xvi] conduct of the junta of Seville—Vigorous conduct of major Cox—Want of arms—Extravagant project to procure them | 269 | |

| CHAPTER II. | ||

| Internal political transactions—Factions in Gallicia, Asturias, Leon, and Castile—Flagitious conduct of the junta of Seville—Mr. Stuart endeavours to establish a northern cortes—Activity of the council of Castile, proposes a supreme government agreeable to the public—Local juntas become generally odious—Cortes meet at Lugo, declare for a central and supreme government—Deputies appointed—Clamours of the Gallician junta and bishop of Orense—Increasing influence of the council of Castile—Underhand proceedings of the junta of Seville, disconcerted by the quickness of the Baily Valdez—Character of Cuesta, he denies the legality of the northern cortes, abandons the line of military operations, returns to Segovia, arrests the Baily Valdez and other deputies from Lugo—Central and supreme government established at Aranjuez, Florida Blanca president—Vile intrigues of the local juntas—Cuesta removed from the command of his army, ordered to Aranjuez—Popular feeling in favour of the central junta, vain and interested proceedings of that body, its timidity, inactivity, and folly, refuses to name a generalissimo—Foreign relations—Mr. Canning leaves Mr. Stuart without any instructions for three months—Mr. Frere appointed envoy extraordinary, &c. | 292 | |

| CHAPTER III. | ||

| Political position of Napoleon; he resolves to crush the Spaniards; his energy and activity; marches his armies from every part of Europe towards Spain; his oration to his soldiers—Conference at Erfurth—Negotiations for peace—Petulant conduct of Mr. Canning—160,000 conscripts enrolled in France—Power of that country—Napoleon’s speech to the senate—He repairs to Bayonne—Remissness of the English cabinet—Sir John Moore appointed to lead an army into Spain; sends his artillery by the Madrid road, and marches himself by Almeida—The central junta impatient for the arrival of the English army—Sir David Baird arrives at Coruña; is refused permission to disembark his troops—Mr. Frere and the marquis of Romana arrive at Coruña; account of the latter’s escape from the Danish Isles—Central junta resolved not to appoint a generalissimo—Gloomy aspect of affairs | 315 | |

| CHAPTER IV. | ||

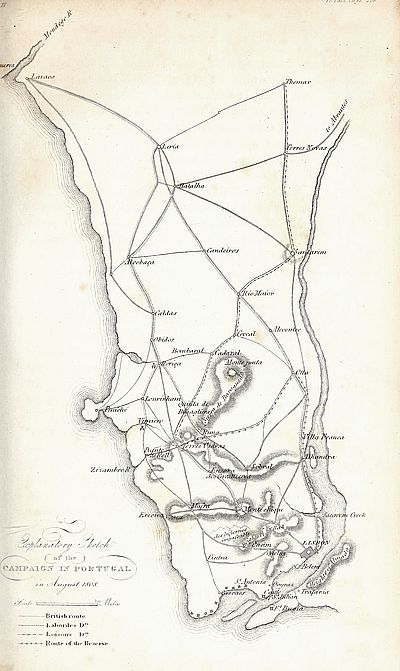

| Movements of the Spanish generals on the Ebro, their absurd confidence, their want of system and concert—General opinion that the French are weak—Real strength of the king—Marshal Ney and general Jourdan join the army—Military errors of the king exposed by Napoleon, who instructs him how to make war—Joseph proposes six plans of operation—Observations thereupon | 342 | |

| CHAPTER V. | ||

| Position and strength of the French and Spanish armies—Blake moves from Reynosa to the Upper Ebro; sends a division to Bilbao; French retire from that town—Ney quits his position near Logroña, and retakes Bilbao—The armies of the centre and right approach the Ebro and the Aragon—Various evolutions—Blake attacks and takes Bilbao—Head of the grand French army arrives in Spain—The Castilians join the army of the centre—The Asturians join Blake—Apathy of the central junta—Castaños joins the army; holds a conference with Palafox; their dangerous position; arrange a plan of operations—The Spaniards cross the Ebro—The king orders a general attack—Skirmish at Sanguessa, at Logroño, and Lerim—The Spaniards driven back over the Ebro—Logroño taken—Colonel Cruz, with a Spanish battalion, surrenders at Lerim—Francisco Palafox, the military deputy, arrives at Alfaro; his exceeding folly and presumption; controls and insults Castaños—Force of the French army increases hourly; how composed and disposed—Blake ascends the valley of Durango—Battle of Zornosa—French retake Bilbao—Combat at Valmaceda—Observations | 361 | |

| BOOK IV.[xvii] | ||

| CHAPTER I. | ||

| Napoleon arrives at Bayonne—Blake advances towards Bilbao—The count Belvedere arrives at Burgos—The first and fourth corps advance—Combat of Guenes—Blake retreats—Napoleon at Vittoria; his plan—Soult takes the command of the second corps—Battle of Gamonal—Burgos taken—Battle of Espinosa—Flight from Reynosa—Soult overruns the Montagna de St. Ander, and scours Leon—Napoleon fixes his head-quarters at Burgos, changes his front, lets 10,000 cavalry loose upon Castile and Leon—Marshals Lasnes and Ney directed against Castaños—Folly of the central junta—General St. Juan occupies the pass of the Somosierra—Folly of the generals on the Ebro—Battle of Tudela | 385 | |

| CHAPTER II. | ||

| Napoleon marches against the capital; forces the pass of the Somosierra—St. Juan murdered by his men—Tumults in Madrid—French army arrives there; the Retiro stormed—Town capitulates—Remains of Castaños’s army driven across the Tagus; retire to Cuenca—Napoleon explains his policy to the nobles, clergy, and tribunals of Madrid—His vast plans, enormous force—Defenceless state of Spain | 407 | |

| CHAPTER III. | ||

| Sir John Moore arrives at Salamanca; hears of the battle of Espinosa—His dangerous position; discovers the real state of affairs; contemplates a hardy enterprise; hears of the defeat at Tudela; resolves to retreat; waits for general Hope’s division—Danger of that general; his able conduct—Central junta fly to Badajos—Mr. Frere, incapable of judging rightly, opposes the retreat; his weakness and levity; insults the general; sends colonel Charmilly to Salamanca—Manly conduct of sir John Moore; his able and bold plan of operations | 425 | |

| CHAPTER IV. | ||

| British army advances towards Burgos—French outposts surprised at Rueda—Letter from Berthier to Soult intercepted—Direction of the march changed—Mr. Stuart and a member of the junta arrive at head-quarters—Arrogant and insulting letter of Mr. Frere—Noble answer of sir John Moore—British army united at Majorga; their force and composition—Inconsistent conduct of Romana; his character—Soult’s position and forces; concentrates his army at Carrion—Combat of cavalry at Sahagun—The British army retires to Benevente—The emperor moves from Madrid, passes the Guadarama, arrives at Tordesillas, expects to interrupt the British line of retreat, fails—Bridge of Castro Gonzalo destroyed—Combat of cavalry at Benevente—General Lefebre taken—Soult forces the bridge of Mansilla, takes Leon—The emperor unites his army at Astorga; hears of the Austrian war; orders marshal Soult to pursue the English army, and returns to France | 450 | |

| CHAPTER V. | ||

| Sir John Moore retreats towards Vigo; is closely pursued—Miserable scene at Bembibre—Excesses at Villa Franca—Combat at Calcabellos—Death of general Colbert—March to Nogales—Line of retreat changed from Vigo to Coruña—Skilful passage of the bridge of Constantino; skirmish there—The army halts at Lugo—Sir John Moore offers battle; it is not accepted; he makes a forced march to Betanzos; loses many stragglers; rallies the army; reaches Coruña—The army takes a position; two large stores of powder exploded—Fleet arrives in the harbour; army commences embarking—Battle of Coruña—Death of sir John Moore—His character | 473 | |

| CHAPTER VI.[xviii] | ||

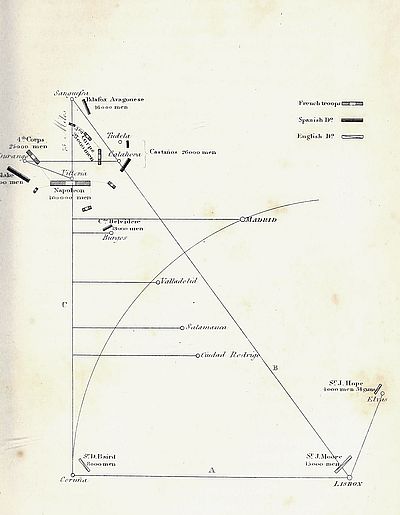

| Observations—The conduct of Napoleon and that of the English cabinet compared—The emperor’s military dispositions examined—Propriety of sir John Moore’s operations discussed—Diagram, exposing the relative positions of Spanish, French, and English armies—Propriety of sir John Moore’s retreat discussed, and the question whether he should have fallen back on Portugal or Gallicia investigated—Sir John Moore’s judgment defended; his conduct calumniated by interested men for party purposes—Eulogised by marshal Soult, by Napoleon, by the duke of Wellington | 502 | |

| No. | ||

| 1. | Observations on Spanish affairs by Napoleon | Page i |

| 2. | Notes on Spanish affairs ditto | v |

| 3. | Ditto ditto ditto | xiii |

| 4. | Ditto ditto ditto | xvii |

| 5. | Ditto ditto ditto | xxiii |

| 6. | Plan of campaign by king Joseph | xxvi |

| 7. | Five Sections, containing four letters from Berthier to general Savary—One from marshal Berthier to king Joseph | xxx |

| 8. | Four letters.—Mr. Drummond to sir A. Ball—Ditto to sir Hew Dalrymple—Sir Hew Dalrymple to lord Castlereagh—Lord Castlereagh to sir Hew Dalrymple | xxxv |

| 9. | Two letters from sir Arthur Wellesley to sir Harry Burrard | xxxvii |

| 10. | Articles of the convention for the evacuation of Portugal | xlii |

| 11. | Three letters from brigadier-general Von Decken to sir Hew Dalrymple | xlvi |

| 12. | Two letters.—General Leite to sir Hew Dalrymple—Sir Hew Dalrymple to lieutenant-general Hope | li |

| 13. | Nine Sections, containing justificatory extracts from sir John Moore’s correspondence.—Section 1st. Want of money—2d. Relating to roads—3d. Relating to equipments and supplies—4th. Relating to the want of information—5th. Relating to the conduct of the local juntas—6th. Central junta—7th. Relating to the passive state of the people—8th. Miscellaneous | liii |

| 14. | Justificatory extracts from sir John Moore’s correspondence | lxviii |

| 15. | Despatch from the conde de Belvedere relative to the battle of Gamonal | lxxi |

| 16. | Extract of a letter from the duke of Dalmatia to the author | ib. |

| 17. | Letters from Mr. Canning to Mr. Frere | lxxii |

| 18. | Return of British troops embarked for Portugal and Spain | lxxviii |

| 19. | Return of killed, &c. sir Arthur Wellesley’s army | lxxix |

| 20. | British order of battle—Roriça | ib. |

| 21. | British order of battle—Vimiero | lxxx |

| 22. | Return of sir Hew Dalrymple’s army | ib. |

| 23. | Embarkation return of the French under Junot | lxxxi |

| 24. | Detail of troops—Extracted from a minute made by the duke of York | ib. |

| 25. | Order of battle—Sir John Moore’s army—Return of ditto December 19th, 1808 | lxxxii |

| 26. | Especial return of loss during sir John Moore’s campaign | lxxxiii |

| 27. | States of the Spanish armies | lxxxiv |

| 28. | Five sections, containing returns of the French armies in Spain and Portugal | lxxxvi |

| 29. | Three letters from lord Collingwood to sir Hew Dalrymple | xc |

| Explanatory Sketch of the BATTLE OF BAYLEN. | 124 |

| SKETCH OF THE COMBAT OF RORIÇA. | 203 |

| SKETCH OF THE BATTLE OF VIMIERO. | 216 |

| Explanatory Sketch of the CAMPAIGN IN PORTUGAL | 258 |

| Explanatory Sketch of the FRENCH & SPANISH POSITIONS | 372 |

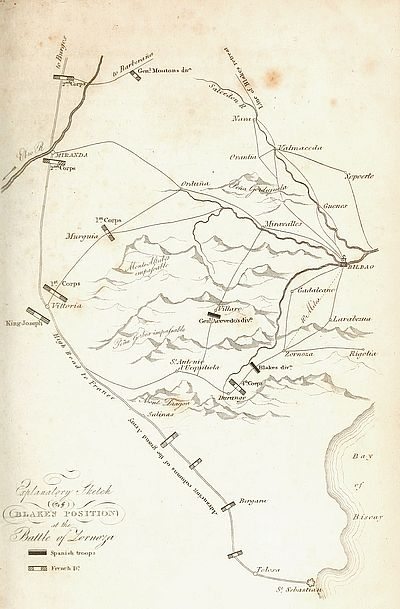

| Explanatory Sketch of BLAKE’S POSITION | 382 |

| SKETCH OF THE BATTLE OF CORUÑA | 498 |

| Plate VIII | 516 |

Of the manuscript authorities consulted for this history, those marked with the letter S. the author owes to the kindness of marshal Soult.

For the notes dictated by Napoleon, and the plans of campaign sketched out by king Joseph, he is indebted to his grace the duke of Wellington.

The returns of the French army were extracted from the original half monthly statements presented by marshal Berthier to the emperor Napoleon.

Of the other authorities it is unnecessary to say more than that the author had access to the original papers, with the exception of Dupont’s memoir, of which a copy only was obtained.

| Page 92, | line 27, for | Agnas, read Aguas. | |

| 202, | __ 30, __ | Catlin’s, Craufurd’s, read Catlin Craufurd’s. | |

| 214, | __ 32, __ | above ridge, read ridge above. | |

| 215, | __ 2, __ | deep, read steep. | |

| 256, | __ 17, __ | Alhambra, read Alhandra. | |

| 274, | __ 9, __ | of the first class to be erased: it is an error. | |

| 289, | __ 27, __ | tlme, read time. | |

| 343, | __ 7, __ | Orma, read Osma. | |

| 365, | __ 16, __ | Carella, read Corella. | |

| 374, | __ 1, __ | Montejo, read Montijo. | |

| 381, | __ 9, __ | were, read was. | |

| 394, | __ 11, __ | Sahugan, read Sahagun. | |

| 424, | __ 30, __ | wnose, read whose. | |

| 425, | __ 3, __ | communications, read communication. | |

| 428, | __ 6, __ | transports, read transport. | |

| 426, | __ 1, __ | one hundred thousand, read one hundred and seventy thousand. | |

| 464, | __ 20, __ | fine plain, read plain. | |

| 468, | __ 26, __ | six guns, read two guns. | |

| 481, | __ 2, __ | who, having turned Villa Franca and scoured the valley of the Syl, read who, after turning Villa Franca and scouring the valley of the Syl. | |

| 483, | __ 21, __ | three or four hundred, read three and four hundred. |

The hostility of the European aristocracy caused the enthusiasm of republican France to take a military direction, and forced that powerful nation into a course of policy which, however outrageous it might appear, was in reality one of necessity. Up to the treaty of Tilsit, the wars of France were essentially defensive; for the bloody contest that wasted the continent so many years was not a struggle for pre-eminence between ambitious powers, not a dispute for some accession of territory, nor for the political ascendancy of one or other nation, but a deadly conflict to determine whether aristocracy or democracy should predominate; whether equality or privilege should henceforth be the principle of European governments.

The French revolution was pushed into existence before the hour of its natural birth. The power of the aristocratic principle was too vigorous and too much identified with that of the monarchical principle, to be successfully resisted by a virtuous democratic effort, much less could it be overthrown by a[2] democracy rioting in innocent blood, and menacing destruction to political and religious establishments, the growth of centuries, somewhat decayed indeed, yet scarcely showing their grey hairs. The first military events of the revolution, the disaffection of Toulon and Lyons, the civil war of La Vendee, the feeble, although successful resistance made to the duke of Brunswick’s invasion, and the frequent and violent change of rulers whose fall none regretted, were all proofs that the French revolution, intrinsically too feeble to sustain the physical and moral force pressing it down, was fast sinking when the wonderful genius of Buonaparte, baffling all reasonable calculation, raised and fixed it on the basis of victory, the only one capable of supporting the crude production.

Sensible, however, that the cause he upheld was not sufficiently in unison with the feelings of the age, Napoleon’s first care was to disarm or neutralize monarchical and sacerdotal enmity, by restoring a church establishment, and by becoming a monarch himself. Once a sovereign, his vigorous character, his pursuits, his talents, and the critical nature of the times, inevitably rendered him a despotic one; yet while he sacrificed political liberty, which to the great bulk of mankind has never been more than a pleasing sound, he cherished with the utmost care political equality, a sensible good, that produces increasing satisfaction as it descends in the scale of society; but this, the real principle of his government, the secret of his popularity, made him the people’s monarch, not the sovereign of the aristocracy; hence, Mr. Pitt called him, “the child and the champion of democracy,” a truth as evident as that Mr. Pitt and his successors were the children and the champions of aristocracy;[3] hence also the privileged classes of Europe consistently transferred their natural and implacable hatred of the French revolution to his person, for they saw that in him innovation had found a protector; that he alone had given pre-eminence to a system so hateful to them, and that he really was what he called himself, “the State.”

The treaty of Tilsit, therefore, although it placed Napoleon in a commanding situation with regard to the potentates of Europe, unmasked the real nature of the war, and brought him and England, the respective champions of equality and privilege, into more direct contact; peace could not be between them while both were strong, and all that the French emperor had hitherto gained only enabled him to choose his future field of battle.

When the catastrophe of Trafalgar forbade him to think of invading England, his fertile genius conceived the plan of sapping her naval and commercial strength, by depriving her of the continental market for her manufactured goods; he prohibited the reception of English wares in any part of the continent, and he exacted from allies and dependants the most rigid compliance with his orders; but this “continental system,” as it was called, became inoperative when French troops were not present to enforce his commands. It was thus in Portugal, where British influence was really paramount, although the terror inspired by the French arms seemed at times to render this doubtful; fear however is momentary, self-interest lasting, and Portugal was but an unguarded province of England.

From Portugal and Gibraltar, English goods freely passed into Spain; and to check this traffic by force[4] was not easy, and otherwise impossible. Spain stood nearly in the same position with regard to France that Portugal did to England; a warm feeling of friendship Monsieur de Champagny’s Report, 21st Oct. 1807. for the enemy of Great Britain was the natural consequence of the unjust seizure of the Spanish frigates in a time of peace; but although this rendered the French cause popular in Spain, and that the court of Madrid was from weakness subservient to the French Emperor, nothing could induce the people to refrain from a profitable contraband trade; they would not pay that respect to the wishes of a foreign power, which they refused to the regulations of their own government; neither was the aristocratical enmity to Napoleon asleep in Spain. A proclamation issued by the Prince of Peace previous to the battle of Jena, although hastily recalled when the result of that conflict was known, sufficiently indicated the tenure upon which the friendship of the Spanish court was to be held.

This state of affairs drew the French Emperor’s attention towards the Peninsula; a chain of remarkable circumstances fixed it there, and induced him to remove the reigning family, and to place his brother Joseph on the throne of Spain. He thought that the people of that country, sick of an effete government, would be quiescent under such a change; and although it should prove otherwise, the confidence he reposed in his own fortune, unrivalled talents, and vast power, made him disregard the consequences, while the cravings of his military and political system, the danger to be apprehended from the vicinity of a Bourbon dynasty, and above all the temptations offered by a miraculous folly which outrun even his desires, urged him to a deed, that well accepted by[5] the people of the Peninsula, would have proved beneficial; but being enforced contrary to their wishes, was unhallowed either by justice or benevolence.

In an evil hour, for his own greatness and the happiness of others, he commenced this fatal project; founded in violence, executed with fraud and cruelty, it spread desolation through the fairest portions of the Peninsula; it was calamitous to France and destructive to himself. The conflict between his hardy veterans and the bloody vindictive race he insulted, assumed a character of unmitigated ferocity disgraceful to human nature; for the Spaniards did not fail to defend their just cause with hereditary cruelty, and the French army struck a terrible balance of barbarous actions.

Napoleon observed with surprise the unexpected energy of the people, and bent his whole force to the attainment of his object; while England coming to the assistance of the Peninsula employed all her resources to frustrate his efforts. Thus the two leading nations of the world were brought into contact at a moment when both were disturbed by angry passions, eager for great events, and possessed of surprising power.

The extent and population of the French empire, including the kingdom of Italy, the confederation of the Rhine, the Swiss Cantons, the Duchy of Warsaw, and the dependent states of Holland and Naples, enabled Buonaparte through the medium of the conscription to array an army, in number nearly equal to the great host that followed the Persian of old against Greece; like that multitude also his troops were gathered from many nations, but they were trained in a Roman discipline, and ruled by a Carthaginian[6] genius. The organization[1] of Napoleon’s army was simple, the administration vigorous, the manipulations well contrived. The French officers, accustomed to success, were bold, enterprising, of great reputation, and feared accordingly. By a combination of discipline and moral excitement, admirably adapted to the mixed nature of his troops, the Emperor had created a power that appeared to be resistless, and, in truth, it would have been so, if applied to one great object at a time; but this the ambition of the man, or rather the force of circumstances, would not permit.

The ships of France were chained up in her harbours, and her naval strength was rebuked, but not destroyed; inexhaustible resources for building vessels, vast marine establishments, a coast line of many thousand miles, and the creative genius of Napoleon were nursing up a navy, formidable as a secondary arm; and the war then pending between the United States and Great Britain promised to nurture its growth, and to increase its efficacy.

Maritime commerce was indeed fainting in France, but her internal and continental traffic was robust; her manufactures were rapidly improving; her debt was small; her financial operations conducted on a prudent plan, and with exact economy. Ibid. 6th part. The supplies were all raised within the year without any very great pressure of taxation, and from a sound metallic currency; thus there seemed to be no reasonable doubt, that any war undertaken by Napoleon might be by him brought to a favourable termination.

On the other hand, England, omnipotent at sea, was little regarded as a military power. Her enormous debt was yearly increasing in an accelerated ratio; and this necessary consequence of anticipating the resources of the country, and dealing in a factitious currency, was fast eating into the vital strength of the state; for although the merchants and great manufacturers were thriving from the accidental circumstances of the times, the labourers were suffering and degenerating in character; pauperism and its sure attendant crime were spreading over the land, and the population was fast splitting into distinct classes,—the one rich and arbitrary, the other poor and discontented: the former composed of those who profited, the latter of those who suffered by the war. Of Ireland it is unnecessary to speak; her wrongs and her misery, peculiar and unparalleled, are too well known, and too little regarded, to call for remark.

This general comparative statement, so favourable to France, would however be a false criterion of the relative strength of the belligerents, with regard to the approaching struggle in the Peninsula. A cause manifestly unjust is a heavy weight upon the operations of a general: it reconciles men to desertion—it sanctifies want of zeal—is a pretext for cowardice—renders hardships more irksome, dangers more obnoxious, and glory less satisfactory to the mind of the soldier. Now the invasion of the Peninsula, whatever might have been its real original, was an act of violence on the part of Napoleon repugnant to the feelings of mankind. The French armies were burthened with a sense of its iniquity, the British troops exhilarated by a contrary sentiment. All the continental nations had smarted under the sword of Napoleon, but, with the exception of Prussia, none[8] were crushed; a common feeling of humiliation, the hope of revenge, and the ready subsidies of England, were bonds of union among their governments stronger than the most solemn treaties. France could only calculate on their fears, England was secure in their self-love.

The hatred to what were called French principles was at this period in full activity. The privileged classes of every country hated Napoleon, because his genius had given stability to the institutions that grew out of the revolution, because his victories had baffled their calculations, and shaken their hold of power. As the chief of revolutionary France he was constrained to continue his career until the final accomplishment of her destiny, and this necessity, overlooked by the great bulk of mankind, afforded plausible ground for imputing insatiable ambition to the French government and to the French nation, of which ample use was made. Rapacity, insolence, injustice, cruelty, even cowardice, were said to be inseparable from the character of a Frenchman; and, as if such vices were nowhere else to be found, it was more than insinuated that all the enemies of France were inherently virtuous and disinterested. Unhappily history is but a record of crimes, and it is not wonderful that the arrogance of men, buoyed up by a spring-tide of military glory, should, as well among allies, as among vanquished enemies, have produced sufficient disgust to ensure a ready belief in any accusation, however false and absurd.

Napoleon was the contriver and the sole support of a political system that required time and victory to consolidate; he was the connecting link between the new interests of mankind and what of the old were left in a state of vigour; he held them together strongly, but he was no favourite with either, and[9] consequently in danger from both. His power, unsanctified by time, depended not less upon delicate management than upon vigorous exercise; he had to fix the foundations of, as well as to defend, an empire, and he may be said to have been rather peremptory than despotic. There were points of administration with which he durst not meddle even wisely, much less arbitrarily; customs, prejudices, and the dregs of the revolutionary licence interfered with his policy, and rendered it complicated and difficult. It was not so with his inveterate adversaries; the delusion of parliamentary representation enabled the English government safely to exercise an unlimited power over the persons and the property of the nation, and through the influence of an active and corrupt press they exercised nearly the same power over the public mind.

The vast commerce of England, penetrating by a thousand channels (open or secret) as it were into every house on the face of the globe, supplied unequalled sources of intelligence. The spirit of traffic, which seldom acknowledges the ties of country, was universally on the side of Great Britain, and those twin curses, paper-money and public credit, so truly described as “strength in the beginning but weakness in the end,” were recklessly used by statesmen whose policy regarded not the interests of posterity. Such were the adventitious causes of England’s power; and her natural, legitimate resources were many and great.

If any credit is to be given to the census, the increasing population of the United Kingdom, amounted at this period to nearly twenty millions: France reckoned but twenty-seven millions when Frederick the Great declared that if he were her king, “not a gun should be fired in Europe without his leave.”

The French army was undoubtedly very formidable from numbers, discipline, skill, and bravery; but contrary to the general opinion, the British army was inferior to it in none of these points save the first, and in discipline it was superior, because a national army will always bear a sterner code than a mixed force will suffer. With the latter, the military not the moral crimes can be punished; men will submit to death for a breach of great regulations which they know by experience to be useful, but the constant restraint of petty though wholesome rules they will escape from by desertion, or resist by mutiny, when the ties of custom and country are removed; for the disgrace of bad conduct attaches not to them, but to the nation under whose colours they serve; great indeed is that genius that can keep men of different nations firm to their colours, and preserve a rigid discipline at the same time. Napoleon’s military system was, from this cause, inferior to the British, which, if it be purely administered, combines the solidity of the Germans with the rapidity of the French, excluding the mechanical dulness of the one, and the dangerous vivacity of the other; yet, before the campaign in the Peninsula had proved its excellence in every branch of war, the English army was absurdly under-rated in foreign countries, and absolutely despised in its own. It was reasonable to suppose that it did not possess that facility of moving in large bodies which long practice had given to the French; but the individual soldier was (and is still) most falsely stigmatized as deficient in intelligence and activity, the officers ridiculed, and the idea that a British could cope with a French army, even for a single campaign, considered chimerical.

The English are a people very subject to receive and to cherish false impressions; proud of their credulity[11] as if it were a virtue, the majority will adopt any fallacy, and cling to it with a tenacity proportioned to its grossness. Thus an ignorant contempt for the British soldiery had been long entertained, before the ill success of the expeditions in 1794 and 1799 appeared to justify the general prejudice. The true cause of those failures was not traced, and the excellent discipline afterwards introduced and perfected by the duke of York was despised. England, both at home and abroad, was, in 1808, scorned as a military power, when she possessed, without a frontier to swallow up large armies in expensive fortresses, at least two hundred thousand[2] of the best equipped and best disciplined soldiers in the universe, together with an immense recruiting establishment, and through the medium of the militia, the power of drawing upon the population without limit. It is true that of this number many were necessarily employed in the defence of the colonies, but enough remained to compose a disposable force greater than that with which Napoleon won the battle of Austerlitz, and double that with which he conquered Italy. In all the materials of war, the superior ingenuity and skill of the English mechanics were visible, and that intellectual power that distinguishes Great Britain amongst the nations, in science, arts, and literature, was not wanting to her generals in the hour of danger.

For many years antecedent to the French invasion, the royal family of Spain was distracted with domestic quarrels; the son’s hand was against his mother, the father’s against his son, and the court was a scene of continual broils, under cover of which artful men, as is usual in such cases, pushed their own interest forward, while they seemed to act only for the sake of the party whose cause they espoused. Nellerto.[3] Charles IV. attributed this unhappy state of his house to the intrigues of his sister-in-law, the queen of the Two Sicilies. He himself, a weak and inefficient old man, was governed by his wife, and she again by don Manuel Godoy, of whose person she was enamoured even to folly. Vide Doblado’s Letters. From the rank of a simple gentleman of the Royal Guards, this person had, through her influence, been raised to the highest dignities; and the title of Prince of the Peace was conferred upon a man whose name must be for ever connected with one of the bloodiest wars that fill the page of history.

Ferdinand prince of the Asturias, naturally hated this favourite, and the miserable death of his young wife, his own youth and apparently forlorn condition created such an interest in his favour, that the people partook of his feelings; and the disunion of the royal family extending its effects beyond the precincts of the court, involved the nation in ruin. Those who know how a Spaniard hates, will readily comprehend why Godoy, who was really a mild, good-natured man, although a sensual and corrupt one, has been so overloaded[13] with imprecations, as if he, and he alone, had been the cause of the disasters of Spain.

The canon, Escoiquiz, a daring and subtile politician, appears to have been the chief of Ferdinand’s party; finding the influence of the Prince of the Peace too strong, he looked for support in a powerful quarter; Nellerto.and under his tuition, Ferdinand wrote upon the 11th of October, 1807, to the emperor Napoleon; in this letter he complained of the influence which bad men had obtained over his father, prayed for the interference of the “hero destined by Providence,” so run the text, “to save Europe and to support thrones;” asked an alliance by marriage with the Buonaparte family, and finally desired that his communication might be kept secret from his father, lest it should be taken as a proof of disrespect. To this letter he received no answer, and fresh matter of quarrel being found by his enemies at home, he was placed in arrest, and upon the 29th of October, Charles denounced him to the Emperor as guilty of treason, and of having projected the assassination of his own mother. Napoleon caught eagerly at this pretext for interfering in the domestic policy of Spain, and thus the honour and independence of a great people were placed in jeopardy by the squabbles of two of the most worthless persons in the nation.

Some short time before this, Godoy, either instigated by an ambition to found a dynasty, or fearing that the death of the king would expose him to the vengeance of Ferdinand, had made proposals to the French court to concert a plan for the conquest and division of Portugal, promising the assistance of Spain, on condition that a principality for himself should be set apart from the spoil. At least such is the turn given by Napoleon to this affair; but the[14] article which provided an indemnification for the king of Etruria a minor, who had just been obliged to surrender his Italian dominions to France, renders it very doubtful if the first offer came from Godoy. That, however, is a point of small interest, for Napoleon eagerly adopted the project if he did not propose it; and the advantages were all on his side. Under the pretext of supporting his army in Portugal, he might fill Spain with his troops; the dispute between the father and the son, now referred to his arbitration, placed the golden apples within his reach, and he resolved to gather the fruit if he had not planted the tree.

A secret treaty was immediately concluded at Fontainebleau, between marshal Duroc on the part of France, and Eugenio Izquerdo on the part of Spain. This treaty, together with a convention dependant on it, was signed the 27th, and ratified by Napoleon on the 29th of October; the contracting parties agreeing to the following conditions.

The house of Braganza to be driven forth of Portugal, and that kingdom divided into three portions, of which the province of Entre Minho e Duero and the town of Oporto, forming one, was to be given as an indemnification to the dispossessed king of Etruria, and to be called the kingdom of North Lusitania.

The Alemtejo and the Algarves to be erected into a principality for Godoy, who taking the title of prince of the Algarves, was still to be in some respects dependant upon the Spanish crown.

The central provinces of Estremadura, Beira, and the Tras os Montes, together with the town of Lisbon, to be held in deposit until a general peace, and then to be exchanged under certain conditions for English conquests.

The ultra-marine dominions of the exiled family to be equally divided between the contracting parties, and in three years at the longest, the king of Spain to be gratified with the title of Emperor of the Two Americas. Thus much for the treaty. The terms of the convention were:

That France should employ 25,000 infantry and 3,000 cavalry. Spain 24,000 infantry, 30 guns, and 3,000 cavalry.

The French contingent to be joined at Alcantara by the Spanish cavalry, artillery, and one-third of the infantry, and from thence to march at once to Lisbon. Of the remaining Spanish infantry 10,000 were to take possession of the Entre Minho e Duero and Oporto, and 6,000 were to invade Estremadura and the Algarves. In the mean time a reserve of 40,000 men was to be assembled at Bayonne, ready to take the field by the 20th of November, if England should interfere, or the Portuguese people resist.

If the king of Spain or any of his family joined the troops, the chief command was to be vested in the person so joining, but with that exception, the French general was to be obeyed whenever the armies of the two nations came into contact, and during the march through Spain the French soldiers were to be fed by that country, but paid by their own government.

The revenues of the conquered provinces were to be administered by the general actually in possession, and for the benefit of the nation in whose name the province was held.

Although it is evident that this treaty and convention favoured Napoleon’s ulterior operations in Spain, by enabling him to mask his views, and introduce large bodies of men into that country without creating much suspicion of his real intention; it does[16] not follow, as some authors have asserted, that they were contrived by the emperor for the sole purpose of rendering the Spanish royal family odious to the world, and by this far-fetched expedient to prevent other nations from taking an interest in their fate when he should find it convenient to apply the same measure of injustice to his associates that they had accorded to the family of Braganza.

To say nothing of the weakness of such a policy, founded as it must be on the error that governments acknowledge the dictates of justice at the expense of their supposed interests; it must be observed that Portugal was intrinsically a great object. History does not speak of the time when the inhabitants of that country were deficient in spirit; the natural obstacles to an invasion had more than once frustrated the efforts of large armies, and the long line of communication between Bayonne and the Portuguese frontier could only be supported by Spanish co-operation. Add to this, the facility with which England could, and the probability that she would, succour her ancient ally, and the reasonable conclusion is, that Napoleon’s first intentions were in accordance with the literal meaning of the treaty of Fontainebleau, Voice from St. Helena, vol. ii. and that his subsequent proceedings were the result of new projects conceived as the wondrous imbecility of the Spanish Bourbons became manifest.

Again, the convention provided for the organization of a large Spanish force, to be stationed in the north and south of Portugal, that is, in precisely the two places from whence they could most readily march to the assistance of their country, if it was invaded; and in fact the division of the marquis of Solano in the south, and that of general Taranco in the north of Portugal, did afterwards (when the Spanish insurrection[17] broke out) form the strength of the Andalusian and Gallician armies, the former of which gained the victory at Baylen, while the latter contended for it, although ineffectually, at Rio Seco.

The French force destined to invade Portugal was already assembled at Bayonne, under the title of the first army of the Garonne. It was commanded by general Junot, a young man of a bold ambitious disposition, but of greater reputation for military talent than he was able to support. The men were principally conscripts, and ill fitted to endure the hardships which awaited them.

At first, by easy marches and in small divisions, Junot led his army through Spain; the inhabitants were by no means friendly to their guests; but whether from any latent fear of what was to follow, or from a dislike of foreign soldiers common to all secluded people, does not clearly appear. When the head of the columns reached Salamanca, Junot halted, intending to complete the organization of his troops in that rich country, and there to await the most favourable moment for penetrating the sterile frontier which guarded his destined prey; but political events marched faster than his calculations, and fresh instructions from the emperor prescribed an immediate advance upon Lisbon. Junot obeyed, and the family of Braganza, at his approach, fled to the Brazils. The series of interesting transactions which attended this invasion will be treated of hereafter; at present I must return to Spain already bending to the first gusts of that hurricane, which was soon to sweep over her with such destructive violence.

The accusation of treason and intended parricide, preferred by Charles IV. against his son Ferdinand,[18] gave rise to some judicial proceedings which ended in the submission of the latter; and Ferdinand being Historia de la Guerra contra Nap. absolved of the imputed crime, wrote a letter to his father and mother, acknowledging his own faults, but accusing the persons who surrounded him of being the instigators of deeds which he abhorred. The intrigues of his advisers, however, continued, and the plans of Napoleon advanced as a necessary consequence of the divisions in the Spanish court.

By the terms of the convention of Fontainebleau,

forty thousand men were to be held in reserve at

Bayonne; but a greater number were assembled on

different points of the frontier; and in the course of

December, two corps had entered the Spanish territory,

and were quartered in Vittoria, Miranda, Briviesca,

and the neighbourhood. The one, commanded

by general Dupont, was called the second army of observation

of the “Gironde.” The other, commanded

by marshal Moncey, took the title of the army of observation

of the “Côte d’Ocean.”

Return of the French army.Appendix.

Journal of Dupont’s Operations MSS.

In the gross they

amounted to fifty-three thousand men, of which above

forty thousand were fit for duty; and in the course of

the month of December, Dupont advanced to Valladolid,

while a reinforcement for Junot, four thousand

seven hundred in number, took up their quarters at

Salamanca.

It thus appeared as if the French troops were quietly following the natural line of communication between France and Portugal; but in reality Dupont’s position cut off the capital from all intercourse with the northern provinces, while Moncey secured the direct road from Bayonne to Madrid. Small divisions Notes of Napoleon. Appendix, No. 2. under different pretexts continually reinforced these two bodies, and through the Eastern Pyrenees[19] twelve thousand men, commanded by general Duhesme, penetrated into Catalonia, and established themselves in Barcelona.

In the mean time the dispute between the king and his son, or rather between the Prince of the Peace and the advisers of Ferdinand, was brought to a crisis by insurrections at Aranjuez and Madrid, which took place upon the 17th, 18th, and 19th of March, 1808. The old king, deceived by intrigues, or frightened at the difficulties which surrounded him, had determined, as it is supposed by some, to quit Spain, and, in imitation of his brother of Portugal, to retire from the turmoil of European politics, and take refuge in his American dominions. Certain it is that every thing was prepared for a flight to Seville, when the prince’s grooms commenced a tumult, in which the populace of Aranjuez joined, and were only pacified by the assurance that no journey was in contemplation.

Upon the 18th the people of Madrid, following the example of Aranjuez, sacked the house of the obnoxious favourite, Manuel Godoy. Upon the 19th the riots recommenced in Aranjuez: the Prince of the Peace secreted himself from the fury of the mob; but his retreat being discovered, he was maltreated, and on the point of being killed, when the soldiers of the royal guard rescued him. Upon the 18th Charles IV., terrified by the violent proceedings of his subjects, abdicated. This event was proclaimed at Madrid on the 20th, and Ferdinand was declared king, to the great joy of the nation at large: little did the people know what they rejoiced at, time has since taught them that the fable of the frogs and their monarch had its meaning.

During these transactions, Murat, grand duke of Berg, who had taken the command of all the French[20] troops in Spain, quitted his quarters at Aranda de Duero, passed the Somosierra, and entered Madrid the 23d, with Moncey’s corps and a fine body of cavalry, Dupont at the same time deviating from the road to Portugal, crossed the Duero and occupied Segovia, the Escurial, and Aranjuez.

Ferdinand arrived at Madrid on the 24th, but was not recognised by Murat as king; nevertheless, at the demand of that powerful guest, he surrendered the sword of Francis I., which was delivered with much ceremony to the French general. Charles, who had sent a paper to Murat, declaring that his abdication had been the result of force, wrote also to Napoleon in the same strain; and this state of affairs being unexpected by the emperor, he employed general Savary Napoleon in Las Casas. to conduct his plans, which appear to have been considerably deranged by the vehemence of the people, and the precipitation of Murat in taking possession of the capital.

Before Savary’s arrival, don Carlos the brother of Ferdinand, departed from Madrid hoping to meet the emperor Napoleon, whose presence in that city was confidently expected; and upon the 10th of April, Ferdinand, having first appointed a supreme junta, of which his uncle, don Antonio, was president, and Murat a member, commenced his own remarkable journey to Bayonne, the true causes of which certainly have not yet been developed; and perhaps when they shall be known, some petty personal intrigue may be found to have had a greater share in producing it, than the grand machinations attributed to Napoleon, who could not have anticipated, much less have calculated, a great political measure upon such a surprising example of weakness.

The people everywhere manifested their repugnance to this journey; at Vittoria they cut the traces of Ferdinand’s carriage, and at different times several gallant men offered, at the risk of their lives, to carry him off, in defiance of the French troops quartered along the road. But Ferdinand, unmoved by their entreaties and zeal, and regardless of the warning contained in a letter that he received at this period from Napoleon (who, withholding the title of majesty, sharply reproved him for his past conduct, and scarcely expressed a wish to meet him), continued his progress, and on the 20th of April, 1808, found himself a prisoner in Bayonne. In the mean time Charles, who, under the protection of Murat, had resumed his rights, and obtained the liberty of Godoy, quitted Spain, and also threw himself, his cause, and kingdom, into the hands of the emperor.

These events were in themselves quite enough to urge a more cautious people than the Spaniards into action; but other measures had been pursued, which proved beyond the possibility of doubt, that the country was destined to be the spoil of the French. The troops of that nation had been admitted without reserve or precaution into the different fortresses upon the Spanish frontier, and, taking advantage of this hospitality to forward the views of their chief, they got possession, by various artifices, of the citadels of St. Sebastian in Guipuscoa, of Pampeluna in Navarre, and of that of Figueras, and the forts of Monjuik, and citadel of Barcelona in Catalonia; and thus, under the pretence of mediating between the father and the son, in a time of profound peace, a foreign force was suddenly established in the capital—on the communications—and in the principal frontier fortresses; its chief was admitted to a share[22] of the government, and a fiery, proud, and jealous nation was laid prostrate at the feet of a stranger, without a blow being struck, without one warning voice being raised, without a suspicion being excited in sufficient time to guard against those acts, upon which all were gazing in stupid amazement.

It is idle to attribute this surprising event to the subtlety of Napoleon’s policy, to the depth of his deceit, or to the treachery of Godoy. Such a fatal calamity could only be the result of bad government, and a consequent degradation of public feeling; and it matters but little to those who wish to derive a lesson from experience, whether it be a Godoy or a Savary that strikes the last bargain of corruption, the silly father or the rebellious son that signs the final act of degradation and infamy. Fortunately, it is easier to oppress the people of all countries, than to destroy their generous feelings; when all patriotism is lost among the upper classes, it may still be found among the lower. In the Peninsula it was not found, but started into life, and with a fervour and energy that ennobled even the wild and savage form in which it appeared; nor was it the less admirable that it burst forth attended by many evils. The good feeling displayed was the people’s own; their cruelty, folly, and perverseness, were the effects of bad government.

There are many reasons why Napoleon should have meddled with the interior affairs of Spain; there seems to be no good one for his manner of doing it. It is true that the Spanish Bourbons could never have been sincere friends to France while Buonaparte held the sceptre, and the moment that the fear of his power ceased to operate, it was quite certain that their apparent friendship would change to active hostility; the proclamation issued by the Spanish cabinet just before the[23] battle of Jena, is evidence of this feeling; but if the Bourbons were his enemies, it did not follow that the people sympathised with their rulers. The resources of the country were, it is said, already at his disposal; but that availed him little, as the corruption and weakness of the administration had reduced those resources to the lowest ebb. His great error was, that he looked only to the court, and treated the nation with contempt. Had Napoleon taken care to bring the people and their government into hostile contact first,—and how many points of contact would not such a government have afforded!—instead of appearing as the treacherous arbitrator in a domestic quarrel, he would have been hailed as the deliverer of a great people.

The journey of Ferdinand, the liberation of Godoy, and the flight of Charles, the appointing Murat to be a member of the governing Junta, and the movements of the French troops, who were advancing from all parts towards Madrid, roused the indignation of the Spanish people; tumults and assassinations had Journal of Dupont’s Operations. MSS. taken place in various parts; and at Toledo a serious riot occurred on the 23d of April; the peasants joined the inhabitants of the town, and it was only by the advance of a division of infantry and some cavalry of Dupont’s corps (then quartered at Aranjuez) that order was restored. The agitation of the public mind, however, increased, the French troops were all young men, or rather boys, taken from the last conscription, and disciplined after they had entered Spain, their youth and apparent feebleness excited the contempt of the Spaniards, who pride themselves much upon individual prowess; and the swelling indignation at last broke out.

Upon the 2d of May, a carriage being prepared (as the people supposed) to convey don Antonio, the[24] uncle of Ferdinand, to France, a crowd collected about it, and their language indicated a determination not to permit the last of the royal family to be spirited away: the traces of the carriage were cut, and loud imprecations against the French burst forth on every side. At that moment, colonel La Grange, an aide-de-camp of Murat’s, appearing amongst them, was assailed and maltreated; in an instant the whole city was in commotion, and the French soldiers expecting no violence, were taken unawares and killed in every quarter: above seven hundred fell. The hospital was attacked by the populace; but the attendants and the sick beat them off; and the alarm having spread to the camp outside the town, the French cavalry came to the assistance of their countrymen by the gate of Alcala; while general Lanfranc, with a column of three thousand infantry, descending from the heights on the north-west quarter, entered the Calle Ancha de Bernardo. As this column crossed the street of Maravelles, in which the arsenal was situated, two Spanish officers, named Daois and Velarde, who were in a state of great excitement, discharged some guns upon the passing troops, and were immediately put to death by the voltigeurs; meanwhile, the column, continuing its march, released, as it advanced, several superior French officers, who were in a manner besieged in the houses by the mob. The cavalry at the other end of the town, treating the affair as a tumult, Memoir of Azanza and O’Farril. and not as an action, made some hundred prisoners; and by the exertions of marshal Moncey, general Harispe, Gonzalvo O’Farril, and some others, order was soon restored.

After night-fall, the peasantry of the neighbourhood came armed and in considerable numbers towards the city, and the French guards at the different[25] gates firing upon them, killed twenty or thirty, and wounded others, some few were also crushed to death or lamed by the cavalry in the morning.

In the first moment of irritation, Murat ordered all the prisoners to be tried by a military commission, which condemned them to death; but the municipality interfered, and represented to that prince the extreme cruelty of visiting this angry ebullition of an injured and insulted people with such severity. Murat admitted the weight of their arguments, and forbade any executions on the sentence; but it is said that general Grouchy, in whose immediate power the prisoners remained, exclaiming that his own life had been attempted! that the blood of the French soldiers was not to be spilt with impunity! and that the prisoners having been condemned by a council of war, ought and should be executed! proceeded to shoot them in the Prado; and forty were thus slain before Murat could cause his orders to be effectually obeyed. The next day some of the Spanish authorities having discovered that a colonel commanding the imperial guards still retained a number of prisoners in the barracks, applied to the duke of Berg to have them released. Murat consented to have those prisoners also enlarged: but the colonel getting intelligence of what was passing, and being enraged at the loss of so many choice soldiers, put forty-five of the captives to death before the order could arrive to stay his bloody proceedings[4].

Such were nearly the circumstances that attended[26] this celebrated tumult, in which the wild cry of Spanish warfare was first heard; but as many authors, adopting without hesitation all the reports of the day, have represented it sometimes as a wanton and extensive massacre on the part of the French, at another as a barbarous political stroke to impress a dread of their power, I think it necessary to make the following observations.

That it was commenced by the Spaniards is undoubted: their fiery tempers, the irritation produced by passing events, and the habits of violence which they had acquired by their late successful insurrection against Godoy, rendered an explosion inevitable. But if the French had secretly stimulated this disposition, and had prepared in cold blood to make a terrible example, undoubtedly they would have prepared some check on the Spanish soldiers of the garrison, and they would scarcely have left their hospital unguarded; still less have arranged the plan so that their own loss should far exceed that of the Spaniards; and surely nothing would have induced them to relinquish the profit of such policy after having suffered all the injury. Yet marshal Moncey and general Harispe were actively engaged in restoring order; Manifesto of the council of Castile. Page 28. and it is certain that, including the peasants shot outside the gates, the executions on the Prado and in the barracks of the imperial guards, the whole number of Spaniards slain did not amount to one hundred and twenty persons, while more than seven hundred French fell. Of the imperial guards seventy Surgical Campaigns of Baron Larrey. men were wounded, and this fact alone would suffice to prove that there was no premeditation on the part of Murat; for if he was base enough to sacrifice his own men with such unconcern, he would not have exposed the select soldiers of the French empire in preference[27] to the conscripts who abounded in his army. The affair itself was certainly accidental, and not very bloody for the patriots, but policy induced both sides to attribute secret motives, and to exaggerate the slaughter. The Spaniards in the provinces, impressed with an opinion of French atrocity, were thereby excited to insurrection on the one hand; and, on the other, the French, well aware that such an impression could not be effaced by an accurate relation of what did happen, seized the occasion to convey a terrible idea of their power and severity; but, while it is the part of history to reduce such amplifications, it is impossible to remain unmoved in recording the gallantry and devotion of a populace that could thus dare to assail the force commanded by Murat, rather than abandon one of their princes; such, however, was the character of the lower classes of Spain throughout this war; fierce, confident, and prone to sudden and rash actions, they had an intuitive perception of all that was great and noble, but were miserably weak in execution.