Title: The Canary Islands

Author: Florence Du Cane

Illustrator: Ella Du Cane

Release date: September 21, 2021 [eBook #66355]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Original publication: GB: A. and C. Black Ltd, 1911

Credits: Fay Dunn, Fiona Holmes and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

In the Contents List, a V has been added to show VI.

Page 35 — swalwart changed to stalwart (two stalwart girls).

Page 41 — form changed to from (entirely hidden from our eyes).

Page 165 — iberty changed to liberty (“fly-flappers” were set at liberty).

Hyphenation has been standardised.

BY FLORENCE DU CANE

WITH 16 FULL-PAGE ILLUSTRATIONS

IN COLOUR BY ELLA DU CANE

A. & C. BLACK LTD.

4, 5 & 6 SOHO SQUARE, LONDON, W.1.

PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN

First published in 1911

[v]

| PAGE | ||

| I | ||

| TENERIFFE | 1 | |

| II | ||

| TENERIFFE (continued) | 21 | |

| III | ||

| TENERIFFE (continued) | 32 | |

| IV | ||

| TENERIFFE (continued) | 50 | |

| V | ||

| TENERIFFE (continued) | 68 | |

| VI | ||

| TENERIFFE (continued) | 84 | |

| VII | ||

| TENERIFFE (continued) | 93 | |

| [vi] | ||

| VIII | ||

| GRAND CANARY | 105 | |

| IX | ||

| GRAND CANARY (continued) | 115 | |

| X | ||

| GRAND CANARY (continued) | 127 | |

| XI | ||

| LA PALMA | 136 | |

| XII | ||

| GOMERA | 146 | |

| XIII | ||

| FUERTEVENTURA, LANZAROTE AND HIERRO | 151 | |

| XIV | ||

| HISTORICAL SKETCH | 160 | |

[vii]

| 1. | A Patio | Frontispiece | |||

| FACING PAGE | |||||

| 2. | A Street in Puerto Orotava | 16 | |||

| 3. | The Peak, from Villa Orotava | 21 | |||

| 4. | Realejo Alto | 28 | |||

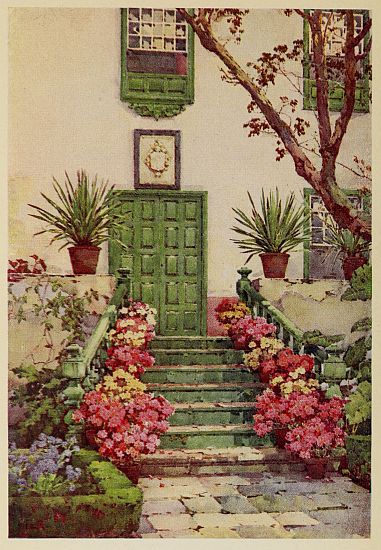

| 5. | Entrance to a Spanish Villa | 49 | |||

| 6. | Statices and Pride of Teneriffe | 64 | |||

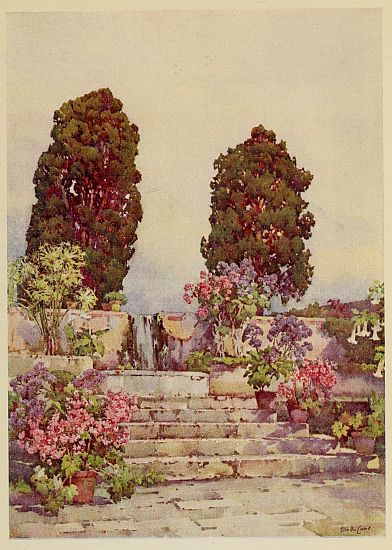

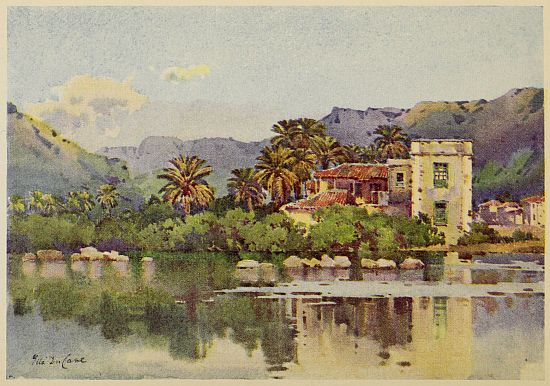

| 7. | La Paz | 69 | |||

| 8. | Botanical Gardens, Orotava | 76 | |||

| 9. | El Sitio del Gardo | 81 | |||

| 10. | Convent of Sant Augustin, Icod de Los Vinos | 96 | |||

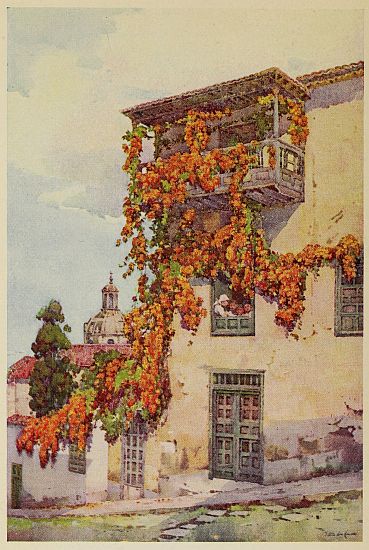

| 11. | An Old Balcony | 113 | |||

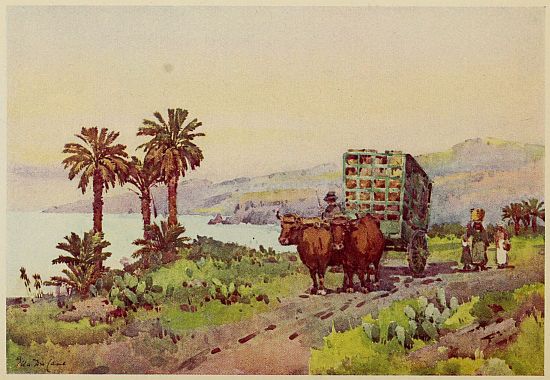

| 12. | A Banana Cart | 117 | |||

| 13. | An Old Gateway | 124 | |||

| 14. | The Canary Pine | 128 | |||

| 15. | San Sebastian | 149 | |||

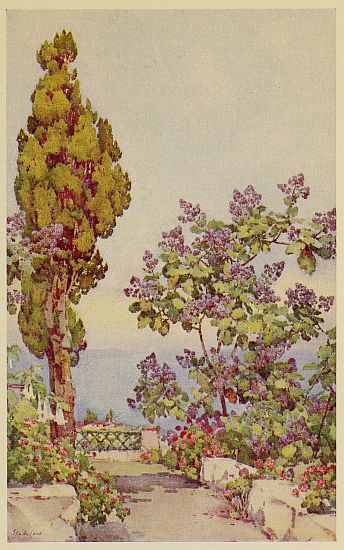

| 16. | A Spanish Garden | 156 | |||

| Sketch Map at end of volume | |||||

[1]

I

TENERIFFE

Probably many people have shared my feeling of disappointment on landing at Santa Cruz. I had long ago realised that few places come up to the standard of one’s preconceived ideas, so my mental picture was not in this case a very beautiful one; but even so, the utter hideousness of the capital of Teneriffe was a shock to me.

Unusually clear weather at sea had shown us our first glimpse of the Peak, rising like a phantom mountain out of the clouds when 100 miles distant, but as we drew nearer to land the clouds had gathered, and the cone was wrapped in a mantle of mist. There is no disappointment attached to one’s first impression of the Island as seen from the sea. The jagged range of hills seemed to come sheer down to the coast, and appeared to have been[2] torn and rent by some extraordinary upheaval of Nature; the deep ravines (or barrancos as I afterwards learnt to call them) were full of dark blue mysterious shadows, a deeply indented coast-line stretched far away in the distance, and I thought the land well deserved to be called one of the Fortunate Islands.

Santa Cruz, or to give it its full title, Santa Cruz de Santiago, though one of the oldest towns in the Canaries, looked, as our ship glided into the harbour, as though it had been built yesterday, or might even be still in course of construction. Lying low on the shore the flat yellow-washed houses, with their red roofs, are thickly massed together, the sheer ugliness of the town being redeemed by the spires of a couple of old churches, which look down reprovingly on the modern houses below. Arid slopes rise gradually behind the town, and appear to be utterly devoid of vegetation. Perched on a steep ridge is the Hotel Quisisana, which cannot be said to add to the beauty of the scene, and all my sympathy went out to those who were condemned to spend a winter in such desolate surroundings in search of health.

Probably no foreign town is entirely devoid of[Pg 3] interest to the traveller. On landing, the picturesque objects which meet the eye make one realise that once one’s foot has left the last step of the gangway of the ship, England and everything English has been left behind. The crowd of swarthy loafers who lounge about the quay in tight yellow or white garments, are true sons of a southern race, and laugh and chatter gaily with handsome black-eyed girls. Sturdy country women are settling heavy loads on their donkeys, preparatory to taking their seat on the top of the pack for their journey over the hills. Their peculiar head-dress consists of a tiny straw hat, no larger than a saucer, which acts as a pad for the loads they carry on their heads, from which hangs a large black handkerchief either fluttering in the wind, or drawn closely round the shoulders like a shawl.

Here and there old houses remain, dating from the days when the wine trade was at its zenith, and though many have now been turned into consulates and shipping offices, they stand in reproachful contrast to the buildings run up cheaply at a later date. Through many an open doorway one gets a glimpse of these cool spacious old houses, whose broad staircases and deep balconies surround[4] a shady patio or court-yard. On the ground floor the wine was stored and the living rooms opened into the roomy balconies on the first floor. Here and there a small open Plaza, where drooping pepper trees shade stone seats, affords breathing-space, but over all and everything was a thick coating of grey dust, which gave a squalid appearance to the town. Narrow ill-paved streets, up which struggle lean, over-worked mules, dragging heavy rumbling carts, lead out of the town, and I was thankful to shake the dust of Santa Cruz off my feet; not that one does, as unless there has been very recent rain the dust follows everywhere. An electric tramway winds its way up the slopes behind the town at a very leisurely pace, giving one ample time to survey the scene.

The only vegetation which looks at home in the dry dusty soil is prickly pear, a legacy of the cochineal culture. In those halcyon days arid spots were brought into cultivation and the cactus planted everywhere. In the eighteenth century the islanders had merely regarded cochineal as a loathsome form of blight, and it was forbidden to be landed for fear it should spoil their prickly pears, but prejudice was overcome, and[5] when it was realised that a possible source of wealth was to be found in the cultivation of the cactus, Opuntia coccinellifera, which is the most suited to the insect, the craze began. Land was almost unobtainable; the amount of labour was enormous which was expended in breaking up the lava to reach the soil below, in terracing hills wherever it was possible to terrace; property was mortgaged to buy new fields; in fact, the islanders thought their land was as good as a gold-mine. The following figures are given by Mr. Samler Brown to show the extraordinary rapidity with which the trade developed. “In 1831 the first shipment was 8 lb., the price at first being about ten pesetas a lb.; in ten years it had increased to 100,566 lb., and in 1869 the highest total, 6,076,869 lb., with a value of £789,993.” The rumour of the discovery of aniline dyes alarmed the islanders, but for a time they were not sufficiently manufactured seriously to affect the cochineal trade, though the fall in prices began to make merchants talk of over-production. The crisis came in 1874, when the price in London fell to 1s. 6d. or 2s., and the ruin to the cochineal industry was a foregone conclusion. Aniline[6] dyes had taken the public taste, and though cochineal has been proved to be the only red dye to resist rain and hard wear, the demand is now small, and merchants who had bought up and stored the dried insect were left with unsaleable stock on their hands. Retribution, we are told, was swift, sudden, and universal, and the farmer who had spent so much on bringing land into cultivation foot by foot, realised that the cactus must be rooted up or he must face starvation.

Possibly there are many other people as ignorant as I was myself on my first visit to the Canaries on the subject of cochineal. Beyond the fact that cochineal was a red dye and used occasionally as a colouring-matter in cooking, I could not safely have answered any question concerning it. I was much disgusted at finding that it is really the blood of an insect which looks like a cross between a “wood-louse” and a “mealy-bug,” with a fat body rather like a currant. The most common method of cultivation, I believe, was to allow the insect to attach itself to a piece of muslin in the spring, which was then laid on to a box full of “mothers” in a room at a very high temperature.

[7]

The muslin was then fastened on to the leaf of the cactus by means of the thorns of the wild prickly pear. When once attached to the leaf the madre cannot move again. There were two different methods of killing the insect to send it to market, one by smoking it with sulphur and the other by shaking it in sacks. A colony of the insects on a prickly pear leaf looks like a large patch of lumpy blight, most unpleasant, and enough to make any one say they would never again eat anything coloured with cochineal.

This terraced land is now cultivated with potatoes and tomatoes for the English market, but the shower of gold in which every one shared in the days of the cochineal boom is no more, though the banana trade in other parts of the island seems likely to revive those good old days.

La Laguna, about five miles above Santa Cruz, is one of the oldest towns in Teneriffe; it was the stronghold of the Guanches and the scene of the most desperate fighting with the Spanish invaders. To-day it looks merely a sleepy little town, but can boast of several fine old churches, besides the old Convente de San Augustin which has been turned into the official seat of learning, containing a very[8] large public library, and the Bishop’s Palace which has a fine old stone façade. The cathedral appears to be in a perpetual state of repairing or rebuilding, and though begun in 1513 is not yet completed. One of the principal sights of La Laguna is the wonderful old Dragon tree in the garden of the Seminary attached to the Church of Santo Domingo, of which the age is unknown. The girth of its trunk speaks for itself of its immense age, and I was not surprised to hear that even in the fifteenth century it was a sufficiently fine specimen to cause the land on which it stood to be known as “the farm of the Dragon tree.”

Foreigners regard the town chiefly as being a good centre for expeditions, which, judging by the list in our guide-book, are almost innumerable. One ride into the beautiful pine forest of La Mina should certainly be undertaken, and unless the smooth clay paths are slippery after rain the walking is easy. After a long stay in either Santa Cruz or even Orotava, where large trees are rare, there is a great enchantment in finding oneself once more among forest trees, and what splendid trees are these native pines, Pinus canariensis, and in damp spots one revels in the ferns and mosses,[9] which form such a contrast to the vegetation one has grown accustomed to.

Alexander von Humboldt who spent a few days in Teneriffe, on his way to South America, landing in Santa Cruz on June 19, 1799, was much struck by the contrast of the climate of La Laguna to that of Santa Cruz. The following is an extract from his account of the journey he made across the island in order to ascend the Peak: “As we approached La Laguna, we felt the temperature of the atmosphere gradually become lower. This sensation was so much the more agreeable, as we found the air of Santa Cruz very oppressive. As our organs are more affected by disagreeable impressions, the change of temperature becomes still more sensible when we return from Laguna to the port, we seem then to be drawing near the mouth of a furnace. The same impression is felt when, on the coast of Caracas, we descend from the mountain of Avila to the port of La Guayra.... The perpetual coolness which prevails at La Laguna causes it to be regarded in the Canaries as a delightful abode.

“Situated in a small plain, surrounded by gardens, protected by a hill which is crowned by a[10] wood of laurels, myrtles and arbutus, the capital of Teneriffe is very beautifully placed. We should be mistaken if, relying on the account of some travellers, we believed it rested on the border of a lake. The rain sometimes forms a sheet of water of considerable extent, and the geologist, who beholds in everything the past rather than the present state of nature, can have no doubt but that the whole plain is a great basin dried up.”

“Laguna has fallen from its opulence, since the lateral eruptions of the volcano have destroyed the port of Garachico, and since Santa Cruz has become the central point of the commerce of the island. It contains only 9000 inhabitants, of whom nearly 400 are monks, distributed in six convents. The town is surrounded with a great number of windmills, which indicate the cultivation of wheat in these higher countries....”

“A great number of chapels, which the Spaniards call ermitas, encircle the town of Laguna. Shaded by trees of perpetual verdure, and erected on small eminences, these chapels add to the picturesque effect of the landscape. The interior of the town is not equal to the external appearance. The houses are solidly built but very antique, and the streets[11] seem deserted. A botanist should not complain of the antiquity of the edifices, as the roofs and walls are covered with Canary house leek and those elegant trichomanes mentioned by every traveller. These plants are nourished by the abundant mists....”

“In winter the climate of Laguna is extremely foggy, and the inhabitants complain often of the cold. A fall of snow, however, has never been seen, a fact which may seem to indicate that the mean temperature of this town must be above 15° R., that is to say higher than that of Naples....”

“I was astonished to find that M. Broussonet had planted in the midst of this town in the garden of the Marquis de Nava, the bread-fruit tree (Artocarpus incise) and cinnamon trees (Laurus cinnamonum). These valuable productions of the South Sea and the East Indies are naturalised there as well as at Orotava.”

The most usual route to Tacoronte en route to Orotava, the ultimate destination of most travellers, is by the main road or carretera, which reaches the summit of the pass shortly after leaving La Laguna, at a height of 2066 feet. The redeeming feature of the otherwise uninteresting[12] road is the long avenue of eucalyptus trees, which gives welcome shade in summer. If time and distance are of no account, and the journey is being made by motor, the lower road by Tejina is far preferable. The high banks of the lanes are crowned with feathery old junipers, in spring the grassy slopes are gay with wild flowers, and here and there stretches of yellow broom (spartium junceum) fill the air with its delicious scent. Turns in the road reveal unexpected glimpses of the Peak on the long descent to the little village of Tegueste, and below lies the church of Tejina, only a few hundred feet above the sea. Here the road turns and ascends again to Tacoronte, and the Peak now faces one, the cone often rising clear above a bank of clouds which covers the base.

At Tacoronte the tram-line ends and either a carriage or motor takes the traveller over the remaining fifteen miles down through the fertile valley to Puerto Orotava. The valley is justly famous for its beauty, and in clear winter weather, when the Peak has a complete mantle of snow, no one can refrain from exclaiming at the beauty of the scene, when at one bend of the road the whole valley lies stretched at one’s feet, bathed in sunshine[13] and enclosed in a semi-circle of snow-capped mountains. The clouds cast blue shadows on the mountain sides, and here and there patches of white mist sweep across the valley; the dark pine woods lie in sharp contrast to the brilliant colouring of the chestnut woods whose leaves have been suddenly turned to red gold by frost in the higher land. In the lower land broad stretches of banana fields are interspersed with ridges of uncultivated ground, where almond, fig trees and prickly pears still find a home, and clumps of the native Canary palm trees wave their feathery heads in the wind. Small wonder that even as great a traveller as Humboldt was so struck with the beauty of the scene that he is said to have thrown himself on his knees in order to salute the sight as the finest in the world. Without any such extravagant demonstration as that of the great traveller, it is worth while to stop and enjoy the view; though, to be sure, carriages travel at such a leisurely rate in Teneriffe, one has ample time to survey the scene. The guardian-angel of the valley—the Peak—dominates the broad expanse of land and sea, in times of peace, a placid broad white pyramid. But at times the mountain has become angry and waved[14] a flaming sword over the land, and for this reason the Guanches christened it the Pico de Teide or Hell, though they appear to have also regarded it as the Seat of the Deity.

Humboldt himself describes the scene in the following words: “The valley of Tacoronte is the entrance into that charming country, of which travellers of every nation have spoken with rapturous enthusiasm. Under the torrid zone I found sites where Nature is more majestic and richer in the display of organic forms; but after having traversed the banks of the Orinoco, the Cordilleras of Peru, and the most beautiful valleys of Mexico, I own that I have never beheld a prospect more varied, more attractive, more harmonious in the distribution of the masses of verdure and rocks, than the western coast of Teneriffe.

“The sea-coast is lined with date and cocoa trees; groups of the musa, as the country rises, form a pleasing contrast with the dragon tree, the trunks of which have been justly compared to the tortuous form of the serpent. The declivities are covered with vines, which throw their branches over towering poles. Orange trees loaded with flowers, myrtles and cypress trees encircle the chapels[15] reared to devotion on the isolated hills. The divisions of landed property are marked by hedges formed of the agave and the cactus. An innumerable number of cryptogamous plants, among which ferns most predominate, cover the walls, and are moistened by small springs of limpid water.

“In winter, when the volcano is buried under ice and snow, this district enjoys perpetual spring. In summer as the day declines, the breezes from the sea diffuse a delicious freshness....

“From Tegueste and Tacoronte to the village of San Juan de la Rambla (which is celebrated for its excellent Malmsey wine) the rising hills are cultivated like a garden. I might compare them to the environs of Capua and Valentia, if the western part of Teneriffe were not infinitely more beautiful on account of the proximity of the Peak, which presents on every side a new point of view.

“The aspect of this mountain is interesting, not merely from its gigantic mass; it excites the mind, by carrying it back to the mysterious source of its volcanic agency. For thousands of years no flames or light have been perceived on the summit of the Piton, nevertheless enormous lateral eruptions, the last of which took place in 1798, are proofs of the[16] activity of a fire still far from being extinguished. There is also something that leaves a melancholy impression on beholding a crater in the centre of a fertile and well-cultivated country. The history of the globe tells us that volcanoes destroy what they have been a long series of ages in creating. Islands which the action of submarine fires has raised above the water, are by degrees clothed in rich and smiling verdure; but these new lands are often laid waste by the renewed action of the same power which caused them to emerge from the bottom of the ocean. Islets, which are now but heaps of scoriæ and volcanic ashes, were once perhaps as fertile as the hills of Tacoronte and Sauzal. Happy the country where man has no distrust of the soil on which he lives.”

A STREET IN PUERTO OROTAVA

Low on the shore lies the little sea-port town of Orotava, known as the Puerto to distinguish it from the older and more important Villa Orotava lying some three miles away inland, at a higher altitude. Further along the coast is San Juan de la Rambla, and on the lower slopes of the opposite wall of the valley are the picturesque villages of Realejo Alto and Bajo, while Icod el Alto is perched at the very edge of the dark cliffs of the Tigaia at a height of about 1700 ft. A gap in the further mountain [17]range is known as the Portillo, the Fortaleza rises above this “gateway,” and from this point begins the long gradual sweep of the Tigaia, which, from the valley, hides all but the very cone of the Peak. Above Villa Orotava towers Pedro Gil and the Montaña Blanca, with the sun glittering on its freshly fallen snow, and near at hand are the villages of Sauzal, Santa Ursula, Matanza and La Victoria.

Though Humboldt describes them as “smiling hamlets,” he comments on their names which he says are “mingled together in all the Spanish colonies, and they form an unpleasing contract with the peaceful and tranquil feelings which these countries inspire.

“Matanza signifies slaughter, or carnage, and the word alone recalls the price at which victory has been purchased. In the New World it generally indicates the defeat of the natives; at Teneriffe the village Matanza was built in a place where the Spaniards were conquered by those same Guanches who soon after were sold as slaves in the markets of Europe.”

In early winter the terraced ridges, which are cultivated with wheat and potatoes, are a blot in the landscape, brown and bare, but in spring, after[18] the winter rains, these slopes will be transformed into sheets of emerald green, and it is then that the valley looks its best. For a few days, all too few, the almond trees are smothered with their delicate pale pink blooms, but one night’s rain or a few hours’ rough wind will scatter all their blossoms, and nothing will remain of their rosy loveliness but a carpet of bruised and fallen petals.

The valley soon reveals traces of the upheavals of Nature in a bygone age; broad streams of lava, which at some time poured down the valley, remain grey and desolate-looking, almost devoid of vegetation, and the two cinder heaps or fumaroles resembling huge blackened mole-hills, though not entirely bare, cannot be admired. No one seems to know their exact history or age, but it appears pretty certain that they developed perfectly independently of any eruption of the Peak itself, though perhaps not “growing in a single night,” as I was once solemnly assured they had done. One theory, which sounded not improbable, was that the bed of lava on which several English villas, the church and the Grand Hotel have been built, was originally spouted out of one of these cinder heaps, and the hill on which the hotel stands was in former[19] days the edge of the cliff. The lava is supposed to have flowed over the edge and accumulated to such a depth in the sea below that it formed the plateau of low-lying ground on which the Puerto now stands.

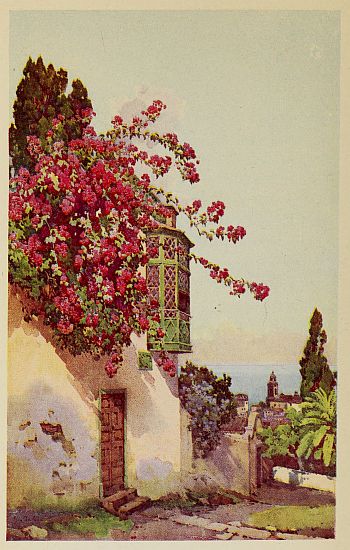

The little town is not without attraction, though its streets are dusty and unswept, being only cleaned once a year, in honour of the Feast of Corpus Christi, on which day at the Villa carpets of elaborate design, arranged out of the petals of flowers, run down the centre of the streets where the processions are to pass. My first impression of the town was that it appeared to be a deserted city, hardly a foot passenger was to be seen, and my own donkey was the only beast of burden in the main street of the town. Gorgeous masses of bougainvillea tumbled over garden walls, and glimpses were to be seen through open doorways of creeper-clad patios. The carved balconies with their little tiled roofs are inseparable from all the old houses, more or less decorated according to the importance of the house. The soft green of the woodwork of the houses, and more especially of the solid green shutters or postijos, behind which the inhabitants seem to spend many hours gazing into the streets, was always a source of admiration to[20] me. The main street ends with the mole, and looking seawards the surf appears to dash up into the street itself. The town wakes to life when a cargo steamer comes into the port, and then one long stream of carts, drawn by the finest oxen I have ever seen, finds its way to the mole, to unload the crates of bananas which are frequently sold on the quay itself to the contractors.

THE PEAK, FROM VILLA OROTAVA

[21]

TENERIFFE (continued)

About a thousand feet above the Puerto de Orotava, on the long gradual slope which sweeps down from Pedro Gil forming the valley of Orotava, lies the villa or town of Orotava. This most picturesque old town is of far more interest than the somewhat squalid port, being the home of many old Spanish families, whose beautiful houses are the best examples of Spanish architecture in the Canaries. Besides their quiet patios, which are shady and cool even on the hottest summer days, the exterior of many of the houses is most beautiful. The admirable work of the carved balconies and shutters, the iron-work and carved stone-work cannot fail to make every one admire houses which are rapidly becoming unique. The Spaniards have, alas! like many other nations, lost their taste in architecture, and the modern houses which are springing up all too quickly make one[22] shudder to contemplate. Some had been built to replace those which had been burnt, others were merely being built by men who had made a fortune in the banana trade. Not satisfied with their old solid houses, with their fine old stone doorways and overhanging wooden balconies, they are ruthlessly destroying them to build a fearsome modern monstrosity, possibly more comfortable to live in, but most offending to the eye. The love of their gardens seems also to be dying out, and as I once heard some one impatiently exclaim, “They have no soul above bananas,” and it is true that the culture of bananas is at the moment of all-absorbing interest.

Though the patios of the houses may be decked with plants, the air being kept cool and moist by the spray of a tinkling fountain, many of the little gardens at the back of these old family mansions have fallen into a sad state of disorder and decay. The myrtle and box hedges, formerly the pride of their owners, are no longer kept trim and shorn, and the little beds are no longer full of flowers. One garden remains to show how, when even slightly tended, flowers grow and flourish in the cooler air of the Villa. In former days a giant[23] chestnut tree was the pride of this garden, only its venerable trunk now remains to tell of its departed glories; but the poyos (double walls) are full of flowers all the year, and the native Pico de paloma (Lotus Berthelotii) flourishes better here than in any other garden; it drapes the walls and half smothers the steps and stone seats with its garlands of soft grey-green, and in spring is covered with its deep red “pigeons’ beaks.” The walls are gay with stocks, carnations, verbenas, lilies, geraniums, and hosts of plants. Long hedges of Libonia floribunda, the bandera d’España of the natives, as its red and yellow blossoms represent the national colours of Spain, line the entrance, and in unconsidered damp corners white arum lilies grow, the rather despised orejas de burros, or donkeys’ ears, of the country people, who give rather apt nick-names to not only flowers, but people.

Though the higher-class Spaniards are a most exclusive race, I met with nothing but civility from their hands when asking permission to see their patio or gardens; as much cannot be said for the middle and lower classes of to-day, who are distinctly anti-foreign. The lower classes appear to regard an incessant stream of pennies as their[24] right, and hurl abuse or stones at your head when their persistent begging is ignored, and even tradesmen are often insolent to foreigners. A spirit of independence and republicanism is very apparent. An employer of labour can obviously keep no control over his men, who work when they choose, or more often don’t work when they don’t choose, and the mother or father of a family keeps no control over the children. One day I asked our gardener why he did not send his children to school to learn to read and write, as he was deploring that he could not read the names of the seeds he was sowing. I thought it was a good moment to point a moral, but he shrugged his shoulders, and said they did not care to go, and also they had no shoes and could not go to school barefoot. The man was living rent free, earning the same wages as an average English labourer, and two sons in work contributed to the expenses of the house, besides the money he got for the crop on a small piece of land which the whole family cultivated on Sundays, and still he could not afford to provide shoes in order that his children should learn to read and write. Another man announced with pride that one of his children[25] attended school. Knowing he had two, I inquired, “Why only one?” On which he owned that the other one used to go, but now she refused to do so, and neither he nor his wife could make her go. This independent person was aged nine!

One of the great curiosities of the Villa was the great Dragon Tree, and though it stands no more, visitors are still shown the site where it once stood and are told of its immense age. Humboldt gave the age of the tree at the time of his visit as being at least 6000 years, and though this may have been excessive, there is no doubt that it was of extreme age. It was blown down and the remains accidentally destroyed by fire in 1867, and only old engravings remain to tell of its wondrous size. The hollow trunk was large enough for a good-sized room or cave, and in the days of the Guanches, when a national assembly was summoned to create a new chief or lord, the meeting place was at the great Dragon Tree. The land on which it stood was afterwards enclosed and became the garden of the Marques de Sauzal.

The ceremony of initiating a lord was a curious one, and the Overlord of Taoro (the old name of[26] Orotava), was the greatest of these lords, having 6000 warriors at his command. Though the dignity was inherited, it was not necessary that it should pass from father to son, and more frequently passed from brother to brother. “When they raised one to be lord they had this custom. Each lordship had a bone of the most ancient lord in their lineage wrapped in skins and guarded. The most ancient councillors were convoked to the ‘Tagoror,’ or place of assembly. After his election the king was given this bone to kiss. After having kissed it he put it over his head. Then the rest of the principal people put it over his shoulder, and he said, ‘Agoñe yacoron yñatzahaña Chacoñamet’ (I swear by the bone on this day on which you have made me great). This was the ceremony of the coronation, and on the same day the people were called that they might know whom they had for their lord. He feasted them, and there were general banquets at the cost of the new lord and his relations. Great pomp appears to have surrounded these lords, and any one meeting them in the road when they progressed to change their summer residence in the mountains to one by the sea in winter, was expected to prostrate himself on the[27] ground, and on rising to cleanse the king’s feet with the edge of his coat of skins.” (See “The Guanches of Teneriffe,” by Sir Clement Markham.) After the conquest the Spaniards turned the temple of the Guanches into a chapel, and Mass was said within the tree.

In the Villa are several fine old churches, whose spires and domes are her fairest adornment. The principal church is the Iglesia de la Concepcion, whose domes dominate the whole town. The exterior of the church is very fine, though the interior is not so interesting. It is curious to think how the silver communion plate, said to have belonged to St. Paul’s Cathedral in London, can have come into the possession of this church. The theory that this and similar plate in the Cathedral at Las Palmas are the scattered remains of the magnificent church plate which was sold and dispersed by the order of Oliver Cromwell is generally accepted.

The fine old doorway and tower of the Convent and Church of Santo Domingo date from a time when the Spaniards had more soul for the beautiful than they have at the present time.

The narrow steep cobbled streets are hardly any[28] of them without interest, and the old balconies, the carved shutters and glimpses of flowery patios, with a gorgeous mass of creeper tumbling over a garden wall or wreathing an old doorway, combine to make it a most picturesque town. A feature of almost every Spanish house is the little latticed hutch which covers the drip stone filter. In many an old house creepers and ferns, revelling in the dampness which exudes from the constantly wet stone, almost cover the little house, and even the stone itself grows maiden-hair or other ferns, and their presence is not regarded as interfering with the purifying properties of the stone, in which the natives place great faith. I never could believe that clean water could in any way benefit by being passed through the dirt of ages which must accumulate in these stones, there being no means of cleaning them except on the surface. The red earthenware water-pots of decidedly classical shape are made in every size, and a tiny child may be seen learning to carry a diminutive one on her head with a somewhat uncertain gait which she will soon outgrow, and in a year or two will stride along carrying a large water-pot all unconscious of her load, leaving her two hands free to carry another burden.

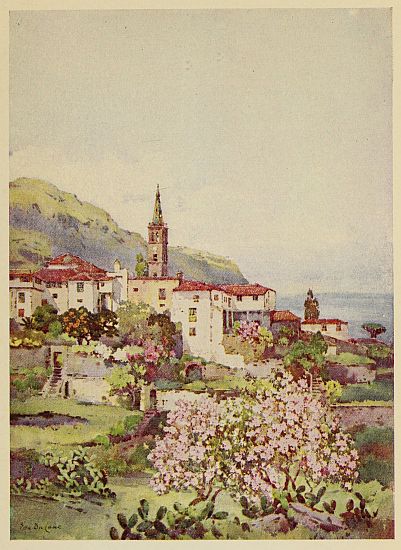

REALEJO ALTO

[29]

A charming walk or donkey-ride leads from the Villa along fairly level country to Realejo Alto, passing through the two little villages of La Perdoma and La Cruz Santa. In early spring the almond blossom gives a rosy tinge to many a stretch of rough uncultivated ground, and in the villages over the garden walls was wafted the heavy scent of orange blossoms. The trees at this altitude seemed freer of the deadly black blight which has ravaged all the orange groves on the lower land, and altogether the vegetation struck one as being more luxuriant and more forward. The cottage-garden walls were gay with flowers: stocks, mauve and white, the favourite alelis of the natives, long trails of geraniums and wreaths of Pico de paloma, pinks and carnations and hosts of other flowers I noticed as we rode past.

The village of Realejo Alto is, without doubt, the most picturesque village I ever saw in the Canaries. Its situation on a very steep slope with the houses seemingly piled one above the other is very suggestive of an Italian mountain village. Part of the Church of San Santiago, the portion next the tower, is supposed to be the oldest church in the island, and the spire, the most prominent[30] feature of the village and neighbourhood, is worthy of the rest of the old church. The interior of the church is not without interest when seen in a good light, and a fine old doorway is said to be the work of Spanish workmen shortly after the conquest. The carved stone-work round this doorway and a very similar one in the lower village are unique specimens of this style of work in the islands.

The barranco which separates the upper and lower villages of Realejo was the scene of a great flood in 1820 which severely damaged both villages. Realejo Bajo, though not quite as picturesque as the upper village, is well worth a visit, and its inhabitants are justly proud of their Dragon Tree, a rival to the one at Icod which may possibly some day become as celebrated as the great tree at Orotava.

These two villages are great centres of the calado or drawn-thread-work industry. Through every open doorway may be seen women and girls bending over the frames on which the work is stretched. It is mostly of very inferior quality, very coarsely worked and on poor material, and it seems a pity that there is no supply of better[31] and finer work. Visitors get tired of the sight of the endless stacks of bed-covers and tea-cloths which are offered to them, and certainly the work compares badly both in price and quality with that done in the East.

[32]

TENERIFFE (continued)

A spell of clear weather, late in February, made us decide to make an expedition to the Cañadas, which, except to those who are bent on mountain climbing and always wish to get to the very top of every height they see, appeals to the ordinary traveller more than ascending the Peak itself. In spite of the promise of fine weather the day before, the morning broke cloudy and at dawn, 6 A.M., we started full of doubts and misgivings as to what the sunrise would bring. We had decided to drive as far as the road would allow, as we had been warned that we should find nine or ten hours’ mule riding would be more than enough, in fact, our friends were rather Job’s comforters. Some said the expedition was so tiring that they had known people to be ill for a week after undertaking it. Others said it was never clear at the top, we must be prepared to be soaked to the skin in the mist,[33] for the mules to stumble and probably roll head over heels, in fact that strings of disasters were certain to overtake us. Our mules were to join us at Realejo Alto, about an hour’s drive from the port, and there we determined we would decide whether we would continue, or content ourselves with a shorter expedition on a lower level.

Sunrise did not improve the prospect, a heavy bank of clouds lay over Pedro Gil, while ominous drifts of light white clouds were gathering below the Tigaia, and the prospect out to sea was not more encouraging. The mules were late, in true Spanish fashion, and we consulted a few weather-wise looking inhabitants who gathered round our carriage in the Plaza, shivering in the morning air, with their mantas or blanket cloaks wrapped closely round them. They looked pityingly at these mad foreigners who had left their beds at such an hour when they were not forced to—for the Spaniard is no early riser—and were proposing to ride up into the clouds. The optimistic members of the party said: “It is nothing but a little morning mist,” while the pessimist remarked, “Morning mists make mid-day clouds in my experience.”

The arrival of the mules put an end to further[34] discussion. The muleteers were full of hope and confident that the clouds would disperse, or anyway that we should get above the region of cloud and find clear weather at the top, so though our old blanket-coated friend murmured “Pobrecitas” (poor things) below his breath, we made a start armed with wraps for the wet and cold we were to encounter. The clattering of the mules as we rode up the steep village street brought many heads to the windows; the little green shutters, or postijos, were hastily pushed open to enable the crowd, which appeared to inhabit every house, to catch a sight of the “Inglezes.” Inquiry as to where we were bound for, I noticed, generally brought an exclamation of “Very bad weather” (“Tiempo muy malo”), to the great indignation of our men, who muttered, “Don’t say so!”

The stony path from Realejo leads in a fairly steep ascent to Palo Blanco, a little scattered village of charcoal-burners’ huts at a height of 2200 feet. The wreaths of blue smoke from their fires mingled with the mist, but already there was a promise of better things to come, as the sun was breaking through and the clouds were thinner. The chant of the charcoal-burners is a sound one[35] gets accustomed to in these regions, and I never quite knew whether it was merely a song which cheered them on their downward path, or whether it was to announce their approach and ask ascending travellers to move out of their way, as the size of the loads they carry on their heads makes them often very difficult to pass. Presently two stalwart girls came into sight, swinging along at a steady trot; their bare feet apparently even more at home along the stony track than the unshod feet of the mules, as there is no stopping to pick their way, on they go, only too anxious to reach their journey’s end, and drop the crushing load off their heads. We anxiously inquired as to the state of the weather higher up, and to our great relief, with no hesitation, came the answer: “Muy claro” (very clear), and in a few minutes a puff of wind blew all the mist away as if by magic, and there was a shout of triumph from the men.

Below lay the whole valley of Orotava, and we were leaving the picturesque town of the Villa Orotava far away below us on the left. The little villages of La Perdoma, La Cruz Santa, and the two Realejos, Alto and Bajo, were more immediately below us, and far away in the distance[36] beyond the Puerto were to be seen Santa Ursula, Sauzal and the little scattered town of Tacoronte. Pedro Gil and all the range of mountains on the left had large stretches of melting snow, shining with a dazzling whiteness in the sun. It had been an unusual winter for snow, so we were assured, and it was rare to find it still lying at the end of February, but we were glad it was so, for it certainly added greatly to the beauty of the scene. At the Monte Verde, the region of green things, we called a halt, for the sake of man and beast, and while our men refreshed themselves with substantial slices of sour bread and the snow white local cheese, made from goats’ milk, and our mules enjoyed a few minutes’ breathing-space with loosened girths, we took a short walk to look down into the beautiful Barranco de la Laura. Here the trees have as yet escaped destruction at the hands of the charcoal-burners and the steep banks are still clad with various kinds of native laurel mixed with large bushes of the Erica arborea, the heath which covers all the region of the Monte Verde. The almost complete deforestation by the charcoal-burners is most deeply to be deplored, and it is sad to think how far more beautiful all this region[37] must have been before it was stripped of its grand pine and laurel trees. The authorities took no steps to stop this wholesale destruction of the forests until it was too late, and even now, though futile regulations exist, no one takes the trouble to see that they are enforced. The law now only allows dead wood to be collected, but it is easy enough to make dead wood—a man goes up and breaks down branches of trees or retama, and a few weeks later goes round and collects them as dead wood, and so the law is evaded. As there is a never-ending demand for charcoal, it being the only fuel the Spaniard uses, so matters will continue until there is nothing left to cut.

No doubt we were on the same path as that by which Humboldt had travelled when he visited Teneriffe in 1799 and ascended the Peak. His description of the vegetation shows how the ruthless axe of the charcoal-burners has destroyed some of the most beautiful forests in the world. Humboldt had been obliged to abandon his travels in Italy in 1795 without visiting the volcanic districts of Naples and Sicily, a knowledge of which was indispensable for his geological studies. Four years later the Spanish Court had given him a splendid welcome[38] and placed at his disposal the frigate Pizarro for his voyage to the equinoctial regions of New Spain. After a narrow escape of falling into the hands of English privateers the Trade winds blew him to the Canaries. The 21st day of June, 1799, finds him on his way to the summit of the Peak accompanied by his friend Bonpland, M. le Gros, the secretary of the French Consulate in Santa Cruz, and the English gardener of Durasno (the botanical gardens of Orotava). The day appears not to have been happily chosen. The top of the Peak was covered in thick clouds from sunrise up to ten o’clock. Only one path leads from Villa Orotava through the retama plains and the mal pays. “This is the way that all visitors must follow who are only a short time in Teneriffe. When people go up the Peak” (these are Humboldt’s words) “it is the same as when the Chamounix or Etna are visited, people must follow the guides and one only succeeds in seeing what other travellers have seen and described.” Like others he was much struck by the contrast of the vegetation in these parts of Teneriffe and in that surrounding Santa Cruz, where he had landed. “A narrow stony path leads through Chestnut woods to regions full of Laurel[39] and Heath, and then further to the Dornajito springs; this being the only fountain that is met with all the way to the Peak. We stopped to take our provision of water under a solitary fir tree. This station is known in the country by the name of Pino del Dornajito. Above this region of arborescent heaths called Monte Verde, is the region of ferns. Nowhere in the temperate zones have I seen such an abundance of the Pteris, Blechium and Asplenium; yet none of these plants have the stateliness of the arborescent ferns which, at the height of 500 and 600 toises, form the principal ornaments of equinoctial America. The root of the Pteris aquilina serves the inhabitants of Palma and Gomera for food. They grind it to powder, and mix it with a quantity of barley meal. This composition when boiled is called gofio; the use of so homely an aliment is proof of the extreme poverty of the lower classes of people in the Canary Islands. (Gofio is still largely consumed).

“The region of ferns is succeeded by a wood of juniper trees and firs, which has suffered greatly from the violence of hurricanes (not one is now left). In this place, mentioned by some travellers under the name of Caraveles, Mr. Eden states that[40] in the year 1705, he saw little flames, which according to the doctrines of the naturalists of his time, he attributes to sulphurous exhalations igniting spontaneously. We continued to ascend, till we came to the rock of La Gayta and to the Portillo: traversing this narrow pass between two basaltic hills, we entered the great plain of Spartium.... We spent two hours in crossing the Llano del Retama, which appears like an immense sea of white sand. In the midst of the plain are tufts of the retama, which is the Spartium nubigenum of Aiton. M. de Martinière wished to introduce this beautiful shrub into Languedoc, where firewood is very scarce. It grows to a height of 9 ft. and is loaded with odoriferous flowers, with which the goat-hunters who met in our road had decorated their hats. The goats of the Peak, which are of a dark brown colour, are reckoned delicious food; they browse on the spartium and have run wild in the deserts from time immemorial.” Spending the night on the mountain, though in mid summer, the travellers complained bitterly of the cold, having neither tents nor rugs. At 3 A.M. they started by torch-light to make the final ascent to the summit of the[41] Piton. “A strong northerly wind chased the clouds, the moon at intervals shooting through the vapours exposed its disk on a firmament of the darkest blues, and the view of the volcano threw a majestic character over the nocturnal scenery.

“Sometimes the peak was entirely hidden from our eyes by the fog, at other times it broke upon us in terrific proximity: and like an enormous pyramid, threw its shadow over the clouds rolling at our feet.”

Scaling the mountain on the north-eastern side, in two hours the party reached Alta Vista, following the same course as travellers of to-day, passing over the mal pays (a region devoid of vegetable mould and covered with fragments of lava) and visiting the ice caves. After the Laurels follow ferns of great size, Junipers and Pines (not one is now left of either) all the way up to the Portillo.

The Portillo was still towering far above us, the gateway of the range, as its name implies, through which we had to pass to get to the Cañadas, and the stony path, though a well defined one, meanders on, not at a very steep incline, past rough hillocks where here and there pumice stone[42] appears. Gradually the heath, which was just coming into flower, and in a few weeks would be covered with its rather insignificant little white or pinkish blossoms, becomes interspersed with codeso, Adenocarpus viscosus, with its peculiar flat spreading growth and tiny leaves of a soft bluish-green. During all the long ascent there is no sign of the Peak; the path lies so immediately beneath the dividing range that it is not until the Portillo itself is reached, that it suddenly bursts into view. It is a grand scene which lies before one. The foreground of rocky ground is interspersed with great bushes of retama (Sparto-cytisus nubigens), a species of broom said to be peculiar to this district. In growth it somewhat resembles Spartium junceum, commonly known in England as Spanish broom, but is more stubby and perhaps not so graceful. When in flower in May its sweet scent is so powerful that not only does it fill the whole air in this mountain district, but sailors are said to smell it miles out at sea. Our guides told us some bushes had white flowers and others white tinged with rose colour. At this season large patches of thawing snow take the place of flowers, but the bushes of retama can be seen piercing the Peak’s[43] dense mantle of snow up to a height of quite 10,000 feet.

I had been told that all the beauty of the Peak was lost when seen from so near, that the beautiful pyramid of rock and snow which rises some 12,000 feet and stands towering above the valley of Orotava would look like a mere hill when seen rising from the moat of fine sand, which is what the Cañadas most resemble, that in fact, all enchantment would be gone. One writer even has gone so far as to call the Peak an ugly cinder-heap when seen from the Cañadas on the other side, and to say they found themselves “in a lifeless, soundless world, burnt out, dead, the very abomination of desolation, where once raged a fiery inferno over a lake of boiling lava.” I cannot help thinking that the writer of the above must have been travelling under adverse circumstances; it is curious how being overtired, wet and cold will make one find no beauty in a scene, which others, who like ourselves have seen it in glorious sunshine, will describe as one of the most beautiful sights in the world.

The path just beyond the Portillo (7150 ft.) divides, and those who propose to ascend the Peak follow the track up the side of the Montaña Blanca, a[44] snow-clad hump at the east base of the Peak. The cone itself is locally called Lomo Tiezo, and rises at an angle of 28°. The stone hut at the Alta Vista (10,702 ft.) is where many a weary traveller spends the night, before ascending the final 1400 ft. on foot, as the mules are left at the hut. No doubt in clear weather the traveller is well repaid, and the scene is well described as follows by Mr. Samler Brown: “Those who cannot ascend the mountain would probably greatly help their imagination by looking at a lunar crater through a telescope. The surroundings are the essence of desolation and ruin. On one side the rounded summit of the Montaña Blanca, on the other the threatening craters of the Pico Viejo and of Chahorra, the latter three-quarters of a mile in diameter, 10,500 ft. high, once a boiling cauldron and even now ready to burst into furious life at any moment. Below, the once circular basin of the Cañadas, seamed with streams of lava and surrounded by its jagged and many-coloured walls. Around, a number of volcanoes, standing, as Piazzi Smyth says, like fish on their tails with widely gaping mouths. On the upper slopes the pine forests and far beneath the sea, with the Six Satellites (the islands of La Palma,[45] Gomera, Hierro, Grand Canary, Fuerteventura and Lanzarote) floating in the distance, the enormous horizon giving the impression that the looker-on is in a sort of well rather than on a height which, taken in relation to its surroundings is second to none in the world.”

To attain the rude little shrine at the Fortaleza where a rest was to be taken, the path leads down into the Cañadas itself. A stretch of fine yellow sand, like the sand of the Sahara, thoroughly sun-baked, proved too great a temptation to one of the mules, and regardless of its rider and luncheon-basket, it enjoyed a good roll in the soft warm bed—luckily with no untoward results. After a welcome rest in the grateful shade of a retama bush, we turned our backs to the Peak and left this beautiful solitary scene. The island of La Palma seemed to be floating in the sky; the line of the horizon dividing sea and sky appeared to be all out of place, in fact it seems to be a weird uncanny world in these parts, and though to-day the Peak may be standing calm and serene, bathed in sunshine and clad in snow, still it reminds one of the death and destruction it has caused by fire and flood, and who knows when it may some day awake[46] from its long sleep and shake the whole island to its foundations.

It is an accepted theory that the Cañadas themselves were originally an immense crater, the second largest in the world, and during a period of activity they threw up the Peak which became the new crater. Probably during this process the Cañadas themselves subsided, and left the wall of rock which appears to form a perfect protection to the Valley of Orotava in case the Peak should some day again spout forth burning lava.

It was in the early winter of 1909 that the inhabitants of Teneriffe were reminded that their volcano was not dead. For nearly a year previously frequent slight shocks of earthquake had warned geological experts that some upheaval was to be expected, which in November were followed by loud detonations, each one shaking the houses in Orotava. One of the inhabitants has described the sensation as one of curious instability, that the houses felt as though they were built on a foundation of jelly. An entirely new crater opened twenty miles from the Peak, and though so far distant from Orotava, the flashes of light were distinctly visible above the lower mountains on the south[47] side of the Peak. Very little damage seems to have been done, as luckily there were no villages near enough to be annihilated by the streams of lava, but most exaggerated reports of the eruptions were circulated in Europe, and it is even said that a message was sent to the Spanish Government asking for men-of-war to be sent at once to take away the inhabitants as the island was sinking into the sea! Many geological authorities have given it as their opinion that it is most unlikely that there will be another eruption in less than another hundred years, which is consoling and reassuring.

As the paths were dry we were able to return by a different route, which though rather longer is far more beautiful, and to those who prefer walking to riding downhill is highly to be recommended. The mules appear to be more sure-footed in the stony paths and once the region of the Monte Verde begins again and the path is smooth their unshod feet get no hold, and in wet weather the path is a mere “mud slide” and should not be attempted. It was a beautiful walk along the crest of the range; the Peak was lost to sight but the valley below lay filled with drifting patches of light mist, through which could just be seen the[48] Villa bathed in the afternoon light, and above, all was clear. Pedro Gil, and the Montaña Blanca beyond, glowed in a red light, and right away in the distance the mountains round La Laguna were just visible.

ENTRANCE TO A SPANISH VILLA

From La Corona the view is perhaps at its best. On the left the pine woods above Icod de los Vinos stretch away into the distance to the extreme west of the island, and on the right the valley of Orotava lies spread out like a map. Just below La Corona one gets back into cultivated regions and the sight of a country-woman with the usual burden on her head reminded us how many hours it was since we had seen a sign of life—not, indeed, since we had passed the two charcoal-burners in the early morning who had given such welcome news of clear weather ahead. Icod el Alto, with the roughest village street it has ever been my fate to encounter, was soon left behind, and the mules trudged wearily down as steep a path as we had met with anywhere, to Realejo Bajo and back to civilisation and the prosaic. A rickety little victoria with three lean but gallant little horses took us home exactly twelve hours from the time we started. We had not meant to break records, and on[49] the homeward path had certainly taken things easily—the ride from Realejo Alto to the Cañadas was exactly four hours, one hour’s rest, five hours’ ride down, partly walking, and two hours’ driving—and we were neither wet through nor so tired that we were ill for a week. I had heard a good description of mule riding by some one who was consulted as to whether it was very tiring, and his answer was, [50]“It is not riding, you just sit, and leave the rest to the mule and Providence!”

TENERIFFE (continued)

I know nothing more enjoyable than a ramble along the coast or up one of the many barrancos in the neighbourhood of Orotava. I had always heard that the Canary Islands were rich in native plants, but I hardly realised that almost each separate barranco (literally meaning a mountain torrent, but now applied to any ravine or deep gully) would have its own special treasures, and that the cliffs by the sea are so rich in vegetation that in many places they look like the most perfect examples of rock gardens.

One of the best walks is up the steep little path, hardly more than a goats’ track, which leads from the Barranco Martinez to the cliffs below the terrace of La Paz. It is possible to wander for miles in this direction; occasionally, it is true, the spell of enchantment in the way of plant collecting will be broken by the path suddenly coming to[51] vast stretches of banana cultivation, but luckily there is still a good deal of unbroken ground, and the path leads back again to the verge of the cliffs and inaccessible places. There are so many plants that will be strangers to the newcomer that it is hard to know which to mention and which to leave out, as far be it from me to pretend to give a full list of Canary plants, and the longer I stayed in the islands the less surprised I was to hear that a learned botanist had been four years collecting material for a full and complete account of the flora of the Canaries, and that still his work was not completed. I think the first place must be given to Euphorbia canariensis as one of the most conspicuous and ornamental of the cliff plants. Great clumps of this “candelabra plant,” as the English have christened it (or cardon in Spanish), are so characteristic that it will always be associated in my mind with the cliffs of Teneriffe. Its great square fluted columns may rise to 10 or 12 ft. leafless, but bearing near the top a reddish fruit or flower, and having vicious-looking hooks down the edges of its stout branches. If you gash one of the columns with a knife out spurts its sticky, milky juice, which if not really poisonous is[52] a strong irritant, and there is a legend that the Guanches used it to stupefy fish, but precisely in what manner I never ascertained. One feature of the cliff vegetation cannot fail to strike every one, and that is the soft bluish-green of nearly all the plants. The prickly pears, as both the Cactuses are commonly called, Opuntia Dillenii and Opuntia coccinellifera—the latter especially appears to have been introduced for the cultivation of cochineal, and has remained as a weed—the sow thistles (Sonchus), Kleinias, Artemerias, and nearly all the succulent plants have grey-green colouring, which is in such beautiful contrast to the dark cliffs. The overhanging cliffs just below La Paz are of most beautiful formation and colouring, in places a deep brick red colour, owing to a deposit of yellow ochre, and in others a tawny yellow, and so deep are the hollows in the volcanic rocks and the air chambers exposed by the inroads of the sea that they have been made into dwellings. Apparently more than one family and all their goods and chattels are ensconced in the recesses of the rocks, and here they live a real open air life, free from house tax or any burden in the way of repairs to their dwellings. The best of water-supplies is close at hand, indeed[53] the stream which gushes out of the rock provides drinking water for the whole town, and when I was told that one of these cave-dwellers was a harmless lunatic, I thought there was a good deal of method in his madness when I remembered the vile-smelling, stuffy cottages that most of the poor inhabit.

Senecio Kleinia, or Kleinia neriifolia, has the habit of a miniature dragon tree, its gouty-forked branches having tufts of blue-green leaves. It remains a shrubby plant about 5 ft. high, and Plocama pendula, with its light weeping form and lovely green colour, makes a charming contrast to the stiff growth of the Euphorbias and Kleinias, and all three are so thoroughly typical of the cliff vegetation that they will probably be the first to attract the attention of the newcomer. Artemesia canariensis (Canary wormwood) is easily recognised by its whitish leaf and very strong aromatic scent, which is far from pleasant when crushed. The native Lavender and various Chrysanthemums, the parents probably of the so-called “Paris Daisy” in cultivation, are common weeds, but in March and April, the months of wild flowers, many more interesting treasures may be found, and while sitting on the rocks, within reach[54] of one’s hand a bunch of flowers or low-growing shrubs may be collected, all probably new to a traveller from northern climes. On the shady damp side of many a miniature barranco or crevasse will be seen nestling in the shadow of the rocks which protect them from the salt spray, broad patches of the wild Cineraria tussilaginis, in every shade of soft lilac, prettier by far than any of the cultivated hybrids. In one inaccessible spot they were interspersed with a yellow Ranunculus, and close by was one of the many sow-thistles with its showy yellow flowers. On some of the steep slopes, too steep happily for the cultivation of the everlasting banana, the great flower stems of the Agave rigida rear their proud heads twenty feet in the air, and are the remains of a plantation of these agaves, which was originally made with a view to cultivating them in order to extract fibre from their leaves. This variety is the true Sisal from the Bahamas, botanically known as var. sisalana, and the rapidity with which it increases once the plants are old enough to bloom may be imagined when it is said that from one single flower-spike will drop 2000 new plants. Like many other agricultural experiments in this island, fibre extrac[55]tion was abandoned, but I heard of some attempt being made to revive it in the arid island of Lanzarote. Among the beautiful strata of rock, besides the Euphorbias and prickly pears, are to be found many low-growing spreading bushes of the succulent, Salsola oppositæ folia, Ruba fruticosa, a white-flowering little Micromeria, Spergularia fimbriata, whose bright mauve flowers would be considered a most valuable addition to a so-called “rock garden” in England, and the low-growing violet-blue Echium violaceum, which is a dreaded weed in Australia, where the seed was probably accidentally introduced. I often used to think when rambling over this natural rock garden what lessons might be learnt by studying rock formation before attempting to lay out in England one of those feeble imitations of Nature which usually result in lamentable failure, not only in failure to please the eye, but failure to cultivate the plants through not providing them with suitable positions.

Those who have a steady head and do not mind scrambling down steep narrow paths can get right down on to the rugged rocks, and when a high sea is running the spray dashes high on to the cliffs, and[56] one sits in a haze of white mist wondering how any vegetation can stand the salt spray. The small lilac Statice pectinata grew and flourished in such surroundings, reminding one that in England statices are generally called Sea Lavenders because the native English Statice, S. Limonium, grows on marsh land. The miniature-flowered heath-like Frankenia ericifolia was also at home amid the spray.

As the path in our wanderings frequently led us back among large farms or fincas entirely devoted to the cultivation of bananas, it may be of interest to mention something of the history of this most lucrative industry. It used to go to my heart to see charming pieces of broken ground being ruthlessly stripped of their natural vegetation, old gnarled and twisted fig trees cut down, and an army of men set to work to break up the soil ready for planting. In most cases the top soil is removed, and the soft earth-stone underneath is broken up and the top soil replaced; but the system appears to differ according to the nature of the soil. Walls are constructed for the protection of the plants, or in order to terrace the land and get the level necessary for the system of irrigation[57] concrete channels being made for the water. So the initial outlay of bringing land into cultivation is heavy, but then the reward reaped is almost beyond the dreams of avarice. Good land with water used to fetch over £40 an acre per annum—indeed, I have even heard of as high a price as £60 having been obtained; that, even if true, was exceptional; but perhaps nowhere else in the world is land let for agricultural purposes at such a rate. Land, however good, which was not irrigated, was only fetching £4 to £6 an acre, and though I was never able to ascertain exactly how much per acre the water would cost, there is no doubt the rate is a very high one; so the rent is not all profit to the landlord. The life of a banana plantation averages from twelve to fourteen years, but for eighteen months no return is obtained, except from the potato crop which is planted in between the young plants, or, rather, the old stumps, from which a young sucker will spring up and bear fruit. That shoot will again be cut down, and by that time several suckers will spring up, about three being left as a rule on a plant, which will each bear fruit in nine or ten months. An acre of land in full bearing will produce over 2000 bunches, which[58] have to be gathered, carted, and carefully packed for export.

Much of the labour on the plantations is done by women, and long processions of them make their way to the packing-houses, bearing the immense bunches of green fruit on their heads. Bare-footed, sturdy, handsome girls many of them, with curiously deep voices in which they chant with a sing-song note as they trip along with a splendid upright carriage. Unfortunately their song is instantly broken when they catch sight of a foreigner, and a chorus of Peni, peni, peni, either getting louder and louder if no attention is paid to the demand, or turned to a bleating whine for una perrita (a little penny), accompanied frequently by a volley of stones. Foreigners complain bitterly of this begging, but they have brought it on themselves by throwing coins to children as they drive along the road. Or when a crowd of urchins collects, as if to reward them for their bright black eyes and pretty faces, which many of them have, a shower of coppers is thrown to them, so it is small wonder that a race has grown up whose earliest instinct teaches it to beg, and I feel sure that Peni is often the first word that a toddling child is taught.

[59]

The packing-houses are also a blot on the landscape, sometimes great unsightly sheds tacked on to what has once been the summer residence of an old Spanish family, and here crowds of men, women and girls are wrapping up the bunches, which are shipped in wooden crates by the thousand, and tens or even hundreds of thousands, I should imagine, judging by the endless procession of carts drawn by immense bullocks which wend their way down to the mole, when a steamer comes in to take a whole cargo of the fruit to England. I used often to wonder that it was possible to find such an unlimited market for bananas when one thinks that Grand Canary ships as many as Teneriffe, and they have a formidable rival also in Jamaica. It is to be hoped that the trade will not be overdone and the markets fall, or that a blight will not come on the plants, and that the Islands will not again suffer from the ruin which followed the cochineal boom. Bananas are said to have been introduced to the Canaries from the Gulf of Guinea, but that was not their real home, and no one knows how they were originally brought from the Far East. From the Canaries they were sent to the West Indian Islands in 1516, and on from there to Central[60] America. Oviedo, writing about the natural history of the West Indies, mentions having seen bananas growing in the orchard of a monastery at Las Palmas in 1520. The botanical name of the Banana, Musa sapientum, was given in the old belief that it was the fruit of the tree of knowledge of good and evil. The variety now under cultivation is Musa Cavendishii, the least tropical and most suitable for cool climates. Locally they are called Plátano, a corruption of the original name Plántano, from plantain in English, under which name they are always known in the East. Though the plant has been known in the islands for nearly four centuries, it was of no use as a crop before the water which is so absolutely necessary for its cultivation was brought down from the mountains. Some residents—those, I noticed, who did not own banana plantations—lament that the excessive irrigation has made the climate of Orotava damper than it used to be, but if the cultivation has brought about a climatic change, it has also brought about a financial change in the fortunes of the farmers and landlords, and many an enterprising man, who a few years ago was just a working medianero, satisfied with his potato or tomato crop, has[61] little by little built up a very substantial fortune.

A medianero is a tenant or bailiff who cultivates the ground and receives a share of the profits. The contract between the landlord and the medianero varies a good deal on different estates, and the system is rather complicated, but as a rule he provides his tenant with a house rent free, pays for half the seed of a cereal, potato or vegetable crop, but none of the labour for cultivation, and the profits made on the crop are equally divided. Sometimes, especially in the case of banana cultivation, the proprietor pays for half the labour of planting and gathering the crop for sending to market, but never for any of the intermediate labour. The landlord provides the all-important water-supply, but all the labour of irrigation has to be done by the medianero, who also pays a share of taxes. The loss of a crop through blight or a storm is equally shared. The trouble of the system, which in some ways seems a good one, must come in over the division of the profits, as either the honesty of the tenant must be implicitly trusted or an overseer must be present when the crop is gathered to see that the landlord gets his true medias.

[62]

At a higher altitude, some 800 or 900 ft. below the village of Santa Ursula, which is justly famous for its groups of Canary Palms, is a large estate, as yet uncultivated from lack of sufficient water. Besides the natural vegetation which stands the summer drought, the owner has collected together many drought-resisting plants, among which are several natives of Australia. The Golden Wattle seemed quite at home, though the trees have not yet attained the size they would in their native country, and small groves of Eucalyptus Lehmanni, with their curious fluffy balls of flower, gave welcome shade, and Australian salt bushes were being grown as an experiment with a view to providing a new fodder plant. The stony ground was covered with a low-growing Cystus monspeliensis closely resembling the variety much prized in England as florentina, its white blossoms covering the bushes. Many of the plants were the same as on the lower cliffs, but Convolvulus scoparius I was much interested to find growing in its natural state. The growth so closely resembles that of the retama that it might easily be mistaken for it; the natives call it Leña Noel or Palo de rosa, but the flower is like a miniature convolvulus growing all down[63] the stems. Both this and Convolvulus floridus are known as Canary Rosewoods, and scoparius has become rare owing to the digging of its roots from which the oil was distilled. Dr. Morris of Kew was a great admirer of C. floridus, and describes guadil, as it is known locally, as “a most attractive plant. When in flower it appears as if covered with newly fallen snow. It is one of the few native plants which awaken the enthusiasm of the local residents.” Many Sempervivums were to be seen, but S. Lindleyi is most curious. Its fleshy transparent leaves grow in clusters and it has received the local and very apt name of Guanche grapes. Little Scylla iridifolium grew everywhere, and one could have spent days collecting treasures, and I felt torn in two between admiring the splendid views which the headland commands, and trying to add something to my most insufficient knowledge of the native plants. Near the house in cultivated ground were to be seen the two most ornamental native brooms, Genista rhodorrhizoides and Cytisus filipes; both are of drooping habit, with very sweet-scented white flowers, and should be more widely cultivated. The former very closely resembles the variety mono-sperma, [64] which grows near the Mediterranean coast.

STATICES AND PRIDE OF TENERIFFE

Here too were to be seen some splendid clumps of the true native Statice arborea which for many years gave rise to such botanical discussions. For a long time this variety was lost and a hybrid of arborea and macrophylla did duty for the true variety, which was definitely pronounced extinct. It was, I believe, Francis Messon who first collected this plant in Teneriffe on his way to the Cape in 1773, and describes its locality as “on a rock in the sea opposite the fountain which waters Port Orotava.” These rocks were the Burgado Cove to the east of Rambla del Castro, and it was again found growing in this neighbourhood in 1829 by Berthelot and Webb, who describe it in their admirable book on the “Histoire Naturelle des Iles Canaries.” Before this date another French botanist, Broussonet, had “discovered” the plant a few miles further along the coast, at Dauté near Garachico, and after its complete disappearance from the Burgado rocks, owing probably to goats having destroyed it, it was re-discovered in the Dauté locality a few years ago, through the untiring efforts and perseverance of Dr. George [65]Perez. Having heard of the plants growing on inaccessible rocks, he got a shepherd to secure the specimens for him, the plants being hauled up by means of ropes to which hooks were attached, and it was no doubt thanks to their position that even goats were not able to destroy them. So Statice arborea was rescued and is once more in cultivation, and one of the most ornamental and effective garden plants it is possible to see. The loose panicles of deep purple flower-heads last for weeks in perfection, and are so freely produced that even one plant of it seems to give colour to a whole garden. The statices endemic to the various islands form quite a long list and are all ornamental, and prove the fact I have already mentioned of the extremely restricted area in which many native plants are found. The true Statice macrophylla finds a home in only a small area on the north-east coast of Teneriffe and is another very showy species. Statice frutescens is very similar to Statice arborea, but is of much smaller stature; its native home appears to be—or to have been—on the rocky promontory of El Freyle, to the extreme west of Teneriffe.

From a single high rock, known as Tabucho,[66] near Marca, also on the west coast, came in 1907 a new variety, at first thought to be Preauxii, but it was eventually found to be an entirely new contribution and was named Statice Perezii after Dr. Perez who discovered the plant and sent the specimen to Kew.

The island of Gomera contributes the very blue-flowered S. brassicifolia, its winged stems making it easy to recognise, and from Lanzarote comes S. puberula, a more dwarf kind, very varying in colour. These appear to comprise the statices best known now in cultivation, though there are several other less interesting varieties.

Here, at Santa Ursula, great interest is also taken in the Echiums, another race of Canary plants. Echium simplex must be accorded first place, as it is commonly called Pride of Teneriffe; it bears one immense spike of white flowers, and like the aloe, after this one supreme effort the plant dies. The seed luckily germinates freely. From the island of La Palma had come seed of Echium pininana, and tales of a deep blue flower-spike said to rise from 9 ft. to 15 ft. in the air, and though the plants were only one year old some showed promise of flowering. The pinkish[67] flowered E. auberianum, like so many of the statices, has made its home in almost inaccessible places among the rocks on the Fortaleza at a height of some 7000 ft., close to the Cañadas.

Over the walls were hanging masses of Lotus Berthelotii, one of the native plants I most admired. Its long trails of soft grey leaves hang in garlands and in spring come the deep red flowers. The plant is known locally as Pico de paloma (pigeon’s beak) and I found one seldom gave it its true botanical name, which does not seem to fit it. Here again is another plant whose native lair has been lost. A stretch of country between Villa Orotava and La Florida is known to have been its home, but for years past botanists have hunted for it in vain. A variety which differed slightly found a home in the Pinar above Arico, but that equally has disappeared.

[68]

TENERIFFE (continued)