Title: A Traveler at Forty

Author: Theodore Dreiser

Illustrator: William J. Glackens

Release date: July 5, 2021 [eBook #65765]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Charlie Howard and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team (https://www.pgdp.net) from page images generously made available by Internet Archive (https://archive.org)

The Project Gutenberg eBook, A Traveler at Forty, by Theodore Dreiser, Illustrated by William Glackens

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See https://archive.org/details/traveleratforty00drei |

Transcriber’s Note

Larger versions of most illustrations may be seen by right-clicking them and selecting an option to view them separately, or by double-tapping and/or stretching them.

A TRAVELER

AT FORTY

BY

THEODORE DREISER

Author of “Sister Carrie,” “Jennie Gerhardt,”

“The Financier,” etc., etc.

ILLUSTRATED BY

W. GLACKENS

NEW YORK

THE CENTURY CO.

1913

Copyright, 1913, by

The Century Co.

Published, November, 1913

TO

“BARFLEUR”

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I | BARFLEUR TAKES ME IN HAND | 3 |

| II | MISS X. | 16 |

| III | AT FISHGUARD | 24 |

| IV | SERVANTS AND POLITENESS | 32 |

| V | THE RIDE TO LONDON | 37 |

| VI | THE BARFLEUR FAMILY | 47 |

| VII | A GLIMPSE OF LONDON | 57 |

| VIII | A LONDON DRAWING-ROOM | 66 |

| IX | CALLS | 72 |

| X | SOME MORE ABOUT LONDON | 77 |

| XI | THE THAMES | 89 |

| XII | MARLOWE | 95 |

| XIII | LILLY: A GIRL OF THE STREETS | 113 |

| XIV | LONDON; THE EAST END | 128 |

| XV | ENTER SIR SCORP | 136 |

| XVI | A CHRISTMAS CALL | 148 |

| XVII | SMOKY ENGLAND | 171 |

| XVIII | SMOKY ENGLAND (continued) | 180 |

| XIX | CANTERBURY | 188 |

| XX | EN ROUTE TO PARIS | 198 |

| XXI | PARIS! | 211 |

| XXII | A MORNING IN PARIS | 225 |

| XXIII | THREE GUIDES | 238 |

| XXIV | “THE POISON FLOWER” | 247 |

| XXV | MONTE CARLO | 255 |

| XXVI | THE LURE OF GOLD! | 264 |

| XXVII | WE GO TO EZE | 275 |

| XXVIII | NICE | 288 |

| XXIX | A FIRST GLIMPSE OF ITALY | 295 |

| XXX | A STOP AT PISA | 306 |

| XXXI | FIRST IMPRESSIONS OF ROME | 315 |

| XXXII | MRS. Q. AND THE BORGIA FAMILY | 327 |

| XXXIII | THE ART OF SIGNOR TANNI | 337 |

| XXXIV | AN AUDIENCE AT THE VATICAN | 345 |

| XXXV | THE CITY OF ST. FRANCIS | 354 |

| XXXVI | PERUGIA | 365 |

| XXXVII | THE MAKERS OF FLORENCE | 371 |

| XXXVIII | A NIGHT RAMBLE IN FLORENCE | 380 |

| XXXIX | FLORENCE OF TO-DAY | 387 |

| XL | MARIA BASTIDA | 398 |

| XLI | VENICE | 409 |

| XLII | LUCERNE | 415 |

| XLIII | ENTERING GERMANY | 424 |

| XLIV | A MEDIEVAL TOWN | 437 |

| XLV | MY FATHER’S BIRTHPLACE | 449 |

| XLVI | THE ARTISTIC TEMPERAMENT | 454 |

| XLVII | BERLIN | 462 |

| XLVIII | THE NIGHT-LIFE OF BERLIN | 474 |

| XLIX | ON THE WAY TO HOLLAND | 486 |

| L | AMSTERDAM | 494 |

| LI | “SPOTLESS TOWN” | 501 |

| LII | PARIS AGAIN | 507 |

| LIII | THE VOYAGE HOME | 515 |

| Piccadilly Circus | Frontispiece |

| FACING PAGE |

|

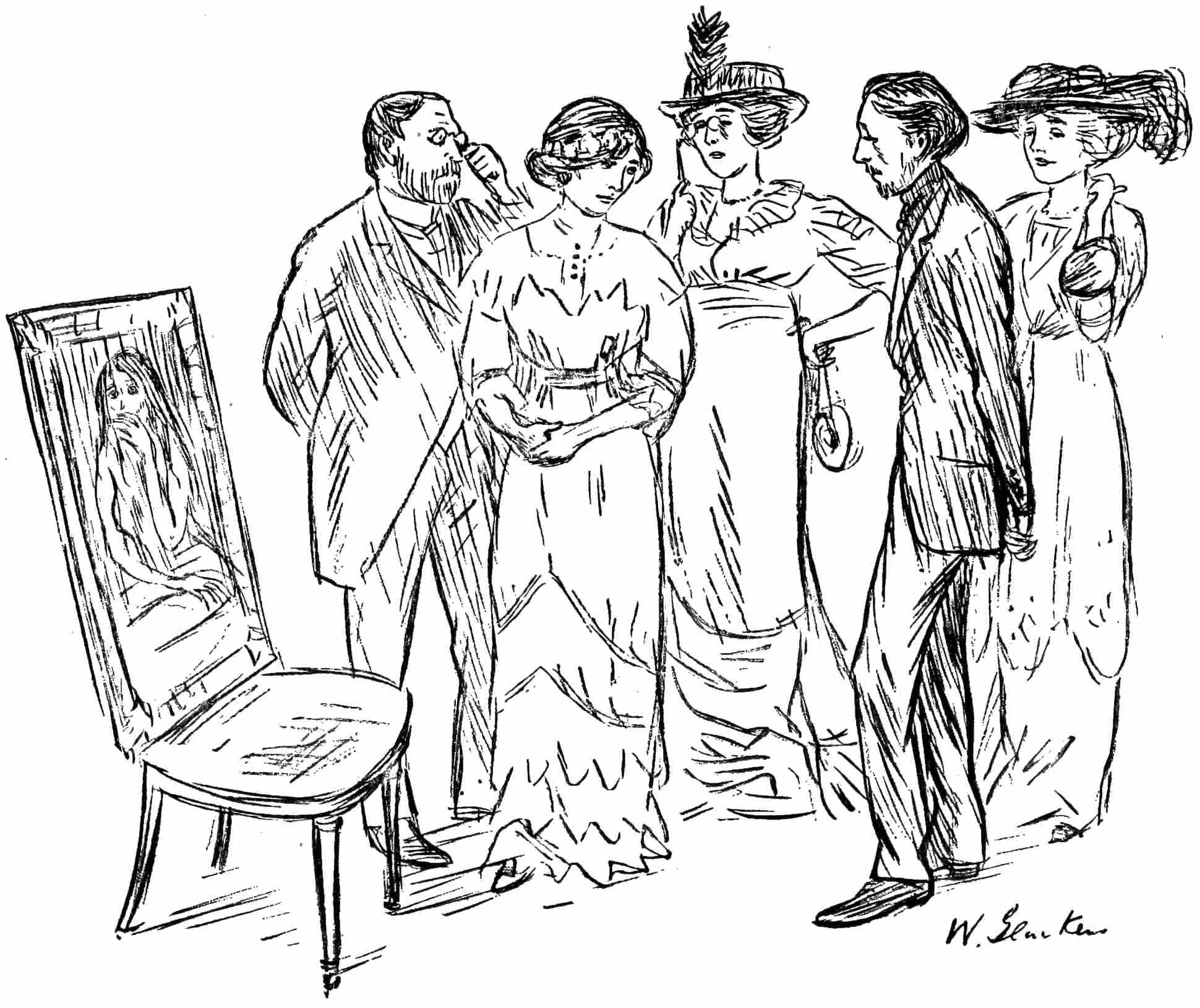

| I saw Mr. G. conversing with Miss E. | 8 |

| One of those really interesting conversations between Barfleur and Miss X. | 20 |

| “I like it,” he pronounced. “The note is somber, but it is excellent work” | 70 |

| Hoped for the day when the issue might be tried out physically | 74 |

| Here the Thames was especially delightful | 90 |

| Barfleur | 156 |

| The French have made much of the Seine | 228 |

| One of the thousands upon thousands of cafés on the boulevards of Paris | 236 |

| These places were crowded with a gay and festive throng | 244 |

| I looked to a distant table to see the figure he indicated | 252 |

| “My heavens, how well she keeps up!” | 290 |

| I sated myself on the house fronts or backs below the Ponte Vecchio | 384 |

| There can only be one Venice | 404 |

| A German dance hall, Berlin | 464 |

| Teutonic bursts of temper | 482 |

3

I have just turned forty. I have seen a little something of life. I have been a newspaper man, editor, magazine contributor, author and, before these things, several odd kinds of clerk before I found out what I could do.

Eleven years ago I wrote my first novel, which was issued by a New York publisher and suppressed by him, Heaven knows why. For, the same year they suppressed my book because of its alleged immoral tendencies, they published Zola’s “Fecundity” and “An Englishwoman’s Love Letters.” I fancy now, after eleven years of wonder, that it was not so much the supposed immorality, as the book’s straightforward, plain-spoken discussion of American life in general. We were not used then in America to calling a spade a spade, particularly in books. We had great admiration for Tolstoi and Flaubert and Balzac and de Maupassant at a distance—some of us—and it was quite an honor to have handsome sets of these men on our shelves, but mostly we had been schooled in the literature of Dickens, Thackeray, George Eliot, Charles Lamb and that refined company of English sentimental realists who told us something about life, but not everything. No doubt all of these great men knew how shabby a thing this world is—how full of lies, make-believe, seeming and false pretense it4 all is, but they had agreed among themselves, or with the public, or with sentiment generally, not to talk about that too much. Books were always to be built out of facts concerning “our better natures.” We were always to be seen as we wish to be seen. There were villains to be sure—liars, dogs, thieves, scoundrels—but they were strange creatures, hiding away in dark, unconventional places and scarcely seen save at night and peradventure; whereas we, all clean, bright, honest, well-meaning people, were living in nice homes, going our way honestly and truthfully, going to church, raising our children believing in a Father, a Son and a Holy Ghost, and never doing anything wrong at any time save as these miserable liars, dogs, thieves, et cetera, might suddenly appear and make us. Our books largely showed us as heroes. If anything happened to our daughters it was not their fault but the fault of these miserable villains. Most of us were without original sin. The business of our books, our church, our laws, our jails, was to keep us so.

I am quite sure that it never occurred to many of us that there was something really improving in a plain, straightforward understanding of life. For myself, I accept now no creeds. I do not know what truth is, what beauty is, what love is, what hope is. I do not believe any one absolutely and I do not doubt any one absolutely. I think people are both evil and well-intentioned.

While I was opening my mail one morning I encountered a now memorable note which was addressed to me at my apartment. It was from an old literary friend of mine in England who expressed himself as anxious to see me immediately. I have always liked him. I like him because he strikes me as amusingly English, decidedly literary and artistic in his point of5 view, a man with a wide wisdom, discriminating taste, rare selection. He wears a monocle in his right eye, à la Chamberlain, and I like him for that. I like people who take themselves with a grand air, whether they like me or not—particularly if the grand air is backed up by a real personality. In this case it is.

Next morning Barfleur took breakfast with me; it was a most interesting affair. He was late—very. He stalked in, his spats shining, his monocle glowing with a shrewd, inquisitive eye behind it, his whole manner genial, self-sufficient, almost dictatorial and always final. He takes charge so easily, rules so sufficiently, does so essentially well in all circumstances where he is interested so to do.

“I have decided,” he observed with that managerial air which always delights me because my soul is not in the least managerial, “that you will come back to England with me. I have my passage arranged for the twenty-second. You will come to my house in England; you will stay there a few days; then I shall take you to London and put you up at a very good hotel. You will stay there until January first and then we shall go to the south of France—Nice, the Riviera, Monte Carlo; from there you will go to Rome, to Paris, where I shall join you,—and then sometime in the spring or summer, when you have all your notes, you will return to London or New York and write your impressions and I will see that they are published!”

“If it can be arranged,” I interpolated.

“It can be arranged,” he replied emphatically. “I will attend to the financial part and arrange affairs with both an American and an English publisher.”

Sometimes life is very generous. It walks in and says, “Here! I want you to do a certain thing,” and it proceeds to arrange all your affairs for you. I felt curiously6 at this time as though I was on the edge of a great change. When one turns forty and faces one’s first transatlantic voyage, it is a more portentous event than when it comes at twenty.

I shall not soon forget reading in a morning paper on the early ride downtown the day we sailed, of the suicide of a friend of mine, a brilliant man. He had fallen on hard lines; his wife had decided to desert him; he was badly in debt. I knew him well. I had known his erratic history. Here on this morning when I was sailing for Europe, quite in the flush of a momentary literary victory, he was lying in death. It gave me pause. It brought to my mind the Latin phrase, “memento mori.” I saw again, right in the heart of this hour of brightness, how grim life really is. Fate is kind, or it is not. It puts you ahead, or it does not. If it does not, nothing can save you. I acknowledge the Furies. I believe in them. I have heard the disastrous beating of their wings.

When I reached the ship, it was already a perfect morning in full glow. The sun was up; a host of gulls were on the wing; an air of delicious adventure enveloped the great liner’s dock at the foot of Thirteenth Street.

Did ever a boy thrill over a ship as I over this monster of the seas?

In the first place, even at this early hour it was crowded with people. From the moment I came on board I was delighted by the eager, restless movement of the throng. The main deck was like the lobby of one of the great New York hotels at dinner-time. There was much calling on the part of a company of dragooned ship-stewards to “keep moving, please,” and the enthusiasm of farewells and inquiries after this person and that, were delightful to hear. I stopped awhile in the writing-room7 and wrote some notes. I went to my stateroom and found there several telegrams and letters of farewell. Later still, some books which had been delivered at the ship, were brought to me. I went back to the dock and mailed my letters, encountered Barfleur finally and exchanged greetings, and then perforce soon found myself taken in tow by him, for he wanted, obviously, to instruct me in all the details of this new world upon which I was now entering.

At eight-thirty came the call to go ashore. At eight fifty-five I had my first glimpse of a Miss E., as discreet and charming a bit of English femininity as one would care to set eyes upon. She was an English actress of some eminence whom Barfleur was fortunate enough to know. Shortly afterward a Miss X. was introduced to him and to Miss E., by a third acquaintance of Miss E.’s, Mr. G.—a very direct, self-satisfied and aggressive type of Jew. I noticed him strolling about the deck some time before I saw him conversing with Miss E., and later, for a moment, with Barfleur. I saw these women only for a moment at first, but they impressed me at once as rather attractive examples of the prosperous stage world.

It was nine o’clock—the hour of the ship’s sailing. I went forward to the prow, and watched the sailors on B deck below me cleaning up the final details of loading, bolting down the freight hatches covering the windlass and the like. All the morning I had been particularly impressed with the cloud of gulls fluttering about the ship, but now the harbor, the magnificent wall of lower New York, set like a jewel in a green ring of sea water, took my eye. When should I see it again? How soon should I be back? I had undertaken this voyage in pell-mell haste. I had not figured at all on where I was8 going or what I was going to do. London—yes, to gather the data for the last third of a novel; Rome—assuredly, because of all things I wished to see Rome; the Riviera, say, and Monte Carlo, because the south of France has always appealed to me; Paris, Berlin—possibly; Holland—surely.

I stood there till the Mauretania fronted her prow outward to the broad Atlantic. Then I went below and began unpacking, but was not there long before I was called out by Barfleur.

“Come up with me,” he said.

We went to the boat deck where the towering red smoke-stacks were belching forth trailing clouds of smoke. I am quite sure that Barfleur, when he originally made his authoritative command that I come to England with him, was in no way satisfied that I would. It was a somewhat light venture on his part, but here I was. And now, having “let himself in” for this, as he would have phrased it, I could see that he was intensely interested in what Europe would do to me—and possibly in what I would do to Europe. We walked up and down as the boat made her way majestically down the harbor. We parted presently but shortly he returned to say, “Come and meet Miss E. and Miss X. Miss E. is reading your last novel. She likes it.”

I went down, interested to meet these two, for the actress—the talented, good-looking representative of that peculiarly feminine world of art—appeals to me very much. I have always thought, since I have been able to reason about it, that the stage is almost the only ideal outlet for the artistic temperament of a talented and beautiful women. Men?—well, I don’t care so much for the men of the stage. I acknowledge the distinction of such a temperament as that of David Garrick or Edwin Booth. These were great actors and, by the same token, they were great artists—wonderful artists. But in the main the men of the stage are frail shadows of a much more real thing—the active, constructive man in other lines.

On the contrary, the women of the stage are somehow, by right of mere womanhood, the art of looks, form, temperament, mobility, peculiarly suited to this realm of show, color and make-believe. The stage is fairyland and they are of it. Women—the women of ambition, aspiration, artistic longings—act, anyhow, all the time. They lie like anything. They never show their true colors—or very rarely. If you want to know the truth, you must see through their pretty, petty artistry, back to the actual conditions behind them, which are conditioning and driving them. Very few, if any, have a real grasp on what I call life. They have no understanding of and no love for philosophy. They do not care for the subtleties of chemistry and physics. Knowledge—book knowledge, the sciences—well, let the men have that. Your average woman cares most—almost entirely—for the policies and the abstrusities of her own little world. Is her life going right? Is she getting along? Is her skin smooth? Is her face still pretty? Are there any wrinkles? Are there any gray hairs in sight? What can she do to win one man? How can she make herself impressive to all men? Are her feet small? Are her hands pretty? Which are the really nice places in the world to visit? Do men like this trait in women? or that? What is the latest thing in dress, in jewelry, in hats, in shoes? How can she keep herself spick and span? These are all leading questions with her—strong, deep, vital, painful. Let the men have knowledge, strength, fame, force—that is their business. The real man, her man, should have some one of these things if she is really going to love him very much.10 I am talking about the semi-artistic woman with ambition. As for her, she clings to these poetical details and they make her life. Poor little frail things—fighting with every weapon at their command to buy and maintain the courtesy of the world. Truly, I pity women. I pity the strongest, most ambitious woman I ever saw. And, by the same token, I pity the poor helpless, hopeless drab and drudge without an idea above a potato, who never had and never will have a look in on anything. I know—and there is not a beating feminine heart anywhere that will contradict me—that they are all struggling to buy this superior masculine strength against which they can lean, to which they can fly in the hour of terror. It is no answer to my statement, no contradiction of it, to say that the strongest men crave the sympathy of the tenderest women. These are complementary facts and my statement is true. I am dealing with women now, not men. When I come to men I will tell you all about them!

Our modern stage world gives the ideal outlet for all that is most worth while in the youth and art of the female sex. It matters not that it is notably unmoral. You cannot predicate that of any individual case until afterward. At any rate, to me, and so far as women are concerned, it is distinguished, brilliant, appropriate, important. I am always interested in a well recommended woman of the stage.

What did we talk about—Miss E. and I? The stage a little, some newspapermen and dramatic critics that we had casually known, her interest in books and the fact that she had posed frequently for those interesting advertisements which display a beautiful young woman showing her teeth or holding aloft a cake of soap or a facial cream. She had done some of this work in the past—and had been well paid for it because she was11 beautiful, and she showed me one of her pictures in a current magazine advertising a set of furs.

I found that Barfleur, my very able patron, was doing everything that should be done to make the trip comfortable without show or fuss. Many have this executive or managerial gift. Sometimes I think it is a natural trait of the English—of their superior classes, anyhow. They go about colonizing so efficiently, industriously. They make fine governors and patrons. I have always been told that English direction and English directors are thorough. Is this true or is it not? At this writing, I do not know.

Not only were all our chairs on deck here in a row, but our chairs at table had already been arranged for—four seats at the captain’s table. It seems that from previous voyages on this ship Barfleur knew the captain. He also knew the chairman of the company in England. No doubt he knew the chief steward. Anyhow, he knew the man who sold us our tickets. He knew the head waiter at the Ritz—he had seen him or been served by him somewhere in Europe. He knew some of the servitors of the Knickerbocker of old. Wherever he went, I found he was always finding somebody whom he knew. I like to get in tow of such a man as Barfleur and see him plow the seas. I like to see what he thinks is important. In this case there happens to be a certain intellectual and spiritual compatibility. He likes some of the things that I like. He sympathizes with my point of view. Hence, so far at least, we have got along admirably. I speak for the present only. I would not answer for my moods or basic change of emotions at any time.

Well, here were the two actresses side by side, both charmingly arrayed, and with them, in a third chair, the short, stout, red-haired Mr. G.

I covertly observed the personality of Miss X. Here12 was some one who, on sight, at a glance, attracted me far more significantly than ever Miss E. could. I cannot tell you why, exactly. In a way, Miss E. appeared, at moments and from certain points of view—delicacy, refinement, sweetness of mood—the more attractive of the two. But Miss X., with her chic face, her dainty little chin, her narrow, lavender-lidded eyes, drew me quite like a magnet. I liked a certain snap and vigor which shot from her eyes and which I could feel represented our raw American force. A foreigner will not, I am afraid, understand exactly what I mean; but there is something about the American climate, its soil, rain, winds, race spirit, which produces a raw, direct incisiveness of soul in its children. They are strong, erect, elated, enthusiastic. They look you in the eye, cut you with a glance, say what they mean in ten thousand ways without really saying anything at all. They come upon you fresh like cold water and they have the luster of a hard, bright jewel and the fragrance of a rich, red, full-blown rose. Americans are wonderful to me—American men and American women. They are rarely polished or refined. They know little of the subtleties of life—its order and procedures. But, oh, the glory of their spirit, the hope of them, the dreams of them, the desires and enthusiasm of them. That is what wins me. They give me the sense of being intensely, enthusiastically, humanly alive.

Miss X. did not tell me anything about herself, save that she was on the stage in some capacity and that she knew a large number of newspaper men, critics, actors, et cetera. A chorus girl, I thought; and then, by the same token, a lady of extreme unconventionality.

I think the average man, however much he may lie and pretend, takes considerable interest in such women. At the same time there are large orders and schools13 of mind, bound by certain variations of temperament, and schools of thought, which either flee temptation of this kind, find no temptation in it, or, when confronted, resist it vigorously. The accepted theory of marriage and monogamy holds many people absolutely. There are these who would never sin—hold unsanctioned relations, I mean—with any woman. There are others who will always be true to one woman. There are those who are fortunate if they ever win a single woman. We did not talk of these things but it was early apparent that she was as wise as the serpent in her knowledge of men and in the practice of all the little allurements of her sex.

Barfleur never ceased instructing me in the intricacies of ship life. I never saw so comforting and efficient a man.

“Oh”—who can indicate exactly the sound of the English “Oh”—“Oh, there you are.” (His are always sounded like ah.) “Now let me tell you something. You are to dress for dinner. Ship etiquette requires it. You are to talk to the captain some—tell him how much you think of his ship, and so forth; and you are not to neglect the neighbor to your right at table. Ship etiquette, I believe, demands that you talk to your neighbor, at least at the captain’s table—that is the rule, I think. You are to take in Miss X. I am to take in Miss E.” Was it any wonder that my sea life was well-ordered and that my lines fell in pleasant places?

After dinner we adjourned to the ship’s drawing-room and there Miss X. fell to playing cards with Barfleur at first, afterwards with Mr. G., who came up and found us, thrusting his company upon us perforce. The man amused me, so typically aggressive, money-centered was he. However, not he so much as Miss X. and her mental and social attitude, commanded my attention. Her card playing and her boastful accounts of adventures at Ostend,14 Trouville, Nice, Monte Carlo and Aix-les-Bains indicated plainly the trend of her interests. She was all for the showy life that was to be found in these places—burning with a desire to glitter—not shine—in that half world of which she was a smart atom. Her conversation was at once showy, naïve, sophisticated and yet unschooled. I could see by Barfleur’s attentions to her, that aside from her crude Americanisms which ordinarily would have alienated him, he was interested in her beauty, her taste in dress, her love of a certain continental café life which encompassed a portion of his own interests. Both were looking forward to a fresh season of it—Barfleur with me—Miss X. with some one who was waiting for her in London.

I think I have indicated in one or two places in the preceding pages that Barfleur, being an Englishman of the artistic and intellectual classes, with considerable tradition behind him and all the feeling of the worth-whileness of social order that goes with class training, has a high respect for the conventions—or rather let me say appearances, for, though essentially democratic in spirit and loving America—its raw force—he still clings almost pathetically, I think, to that vast established order, which is England. It may be producing a dying condition of race, but still there is something exceedingly fine about it. Now one of the tenets of English social order is that, being a man you must be a gentleman, very courteous to the ladies, very observant of outward forms and appearances, very discreet in your approaches to the wickedness of the world—but nevertheless you may approach and much more, if you are cautious enough.

After dinner there was a concert. It was a dreary affair. When it was over, I started to go to bed but, it being warm and fresh, I stepped outside. The night was beautiful. There were no fellow passengers on15 the promenade. All had retired. The sky was magnificent for stars—Orion, the Pleiades, the Milky Way, the Big Dipper, the Little Dipper. I saw one star, off to my right as I stood at the prow under the bridge, which, owing to the soft, velvety darkness, cast a faint silvery glow on the water—just a trace. Think of it! One lone, silvery star over the great dark sea doing this. I stood at the prow and watched the boat speed on. I threw back my head and drank in the salt wind. I looked and listened. England, France, Italy, Switzerland, Germany—these were all coming to me mile by mile. As I stood there a bell over me struck eight times. Another farther off sounded the same number. Then a voice at the prow called, “All’s well,” and another aloft on that little eyrie called the crow’s nest, echoed it. “All’s well.” The second voice was weak and quavering. Something came up in my throat—a quick unbidden lump of emotion. Was it an echo of old journeys and old seas when life was not safe? When Columbus sailed into the unknown? And now this vast ship, eight hundred and eighty-two feet long, eighty-eight feet beam, with huge pits of engines and furnaces and polite, veneered first-cabin decks and passengers!

16

It was ten o’clock the next morning when I arose and looked at my watch. I thought it might be eight-thirty, or seven. The day was slightly gray with spray flying. There was a strong wind. The sea was really a boisterous thing, thrashing and heaving in hills and hollows. I was thinking of Kipling’s “White Horses” for a while. There were several things about this great ship which were unique. It was a beautiful thing all told—its long cherry-wood, paneled halls in the first-class section, its heavy porcelain baths, its dainty staterooms fitted with lamps, bureaus, writing-desks, washstands, closets and the like. I liked the idea of dressing for dinner and seeing everything quite stately and formal. The little be-buttoned call-boys in their tight-fitting blue suits amused me. And the bugler who bugled for dinner! That was a most musical sound he made, trilling in the various quarters gaily, as much as to say, “This is a very joyous event, ladies and gentlemen; we are all happy; come, come; it is a delightful feast.” I saw him one day in the lobby of C deck, his legs spread far apart, the bugle to his lips, no evidence of the rolling ship in his erectness, bugling heartily. It was like something out of an old medieval court or a play. Very nice and worth while.

Absolutely ignorant of this world of the sea, the social, domestic, culinary and other economies of a great ship like this interested me from the start. It impressed me no little that all the servants were English, and that17 they were, shall I say, polite?—well, if not that, non-aggressive. American servants—I could write a whole chapter on that, but we haven’t any servants in America. We don’t know how to be servants. It isn’t in us; it isn’t nice to be a servant; it isn’t democratic; and spiritually I don’t blame us. In America, with our turn for mechanics, we shall have to invent something which will do away with the need of servants. What it is to be, I haven’t the faintest idea at present.

Another thing that impressed and irritated me a little was the stolidity of the English countenance as I encountered it here on this ship. I didn’t know then whether it was accidental in this case, or national. There is a certain type of Englishman—the robust, rosy-cheeked, blue-eyed Saxon—whom I cordially dislike, I think, speaking temperamentally and artistically. They are too solid, too rosy, too immobile as to their faces, and altogether too assured and stary. I don’t like them. They offend me. They thrust a silly race pride into my face, which isn’t necessary at all and which I always resent with a race pride of my own. It has even occurred to me at times that these temperamental race differences could be quickly adjusted only by an appeal to arms, which is sillier yet. But so goes life. It’s foolish on both sides, but I mention it for what it is worth.

After lunch, which was also breakfast with me, I went with the chief engineer through the engine-room. This was a pit eighty feet deep, forty feet wide and, perhaps, one hundred feet long, filled with machinery. What a strange world! I know absolutely nothing of machinery—not a single principle connected with it—and yet I am intensely interested. These boilers, pipes, funnels, pistons, gages, registers and bright-faced register boards speak of a vast technique which to me is tremendously impressive. I know scarcely anything of the history of18 mechanics, but I know what boilers and feed-pipes and escape-pipes are, and how complicated machinery is automatically oiled and reciprocated, and there my knowledge ends. All that I know about the rest is what the race knows. There are mechanical and electrical engineers. They devised the reciprocating engine for vessels and then the turbine. They have worked out the theory of electrical control and have installed vast systems with a wonderful economy as to power and space. This deep pit was like some vast, sad dream of a fevered mind. It clanked and rattled and hissed and squeaked with almost insane contrariety! There were narrow, steep, oil-stained stairs, very hot, or very cold and very slippery, that wound here and there in strange ways, and if you were not careful there were moving rods and wheels to strike you. You passed from bridge to bridge under whirling wheels, over clanking pistons; passed hot containers; passed cold ones. Here men were standing, blue-jumpered assistants in oil-stained caps and gloves—thin caps and thick gloves—watching the manœuvers of this vast network of steel, far from the passenger life of the vessel. Occasionally they touched something. They were down in the very heart or the bowels of this thing, away from the sound of the water; away partially from the heaviest motion of the ship; listening only to the clank, clank and whir, whir and hiss, hiss all day long. It is a metal world they live in, a hard, bright metal world. Everything is hard, everything fixed, everything regular. If they look up, behold a huge, complicated scaffolding of steel; noise and heat and regularity.

I shouldn’t like that, I think. My soul would grow weary. It would pall. I like the softness of scenery, the haze, the uncertainty of the world outside. Life is better than rigidity and fixed motion, I hope. I trust the universe is not mechanical, but mystically blind.19 Let’s hope it’s a vague, uncertain, but divine idea. We know it is beautiful. It must be so.

The wind-up of this day occurred in the lounging- or reception-room where, after dinner, we all retired to listen to the music, and then began one of those really interesting conversations between Barfleur and Miss X. which sometimes illuminate life and make one see things differently forever afterward.

It is going to be very hard for me to define just how this could be, but I might say that I had at the moment considerable intellectual contempt for the point of view which the conversation represented. Consider first the American attitude. With us (not the established rich, but the hopeful, ambitious American who has nothing, comes from nothing and hopes to be President of the United States or John D. Rockefeller) the business of life is not living, but achieving. Roughly speaking, we are willing to go hungry, dirty, to wait in the cold and fight gamely, if in the end we can achieve one or more of the seven stars in the human crown of life—social, intellectual, moral, financial, physical, spiritual or material supremacy. Several of the forms of supremacy may seem the same, but they are not. Examine them closely. The average American is not born to place. He does not know what the English sense of order is. We have not that national esprit de corps which characterizes the English and the French perhaps; certainly the Germans. We are loose, uncouth, but, in our way, wonderful. The spirit of God has once more breathed upon the waters.

Well, the gentleman who was doing the talking in this instance and the lady who was coinciding, inciting, aiding, abetting, approving and at times leading and demonstrating, represented two different and yet allied points of view. Barfleur is distinctly a product of the English20 conservative school of thought, a gentleman who wishes sincerely he was not so conservative. His house is in order. You can feel it. I have always felt it in relation to him. His standards and ideals are fixed. He knows what life ought to be—how it ought to be lived. You would never catch him associating with the rag-tag and bobtail of humanity with any keen sense of human brotherhood or emotional tenderness of feeling. They are human beings, of course. They are in the scheme of things, to be sure. But, let it go at that. One cannot be considering the state of the underdog at any particular time. Government is established to do this sort of thing. Statesmen are large, constructive servants who are supposed to look after all of us. The masses! Let them behave. Let them accept their state. Let them raise no undue row. And let us, above all things, have order and peace.

This is a section of Barfleur—not all, mind you, but a section.

Miss X.—I think I have described her fully enough, but I shall add one passing thought. A little experience of Europe—considerable of its show places—had taught her, or convinced her rather, that America did not know how to live. You will hear much of that fact, I am afraid, during the rest of these pages, but it is especially important just here. My lady, prettily gowned, perfectly manicured, going to meet her lover at London or Fishguard or Liverpool, is absolutely satisfied that America does not know how to live. She herself has almost learned. She is most comfortably provided for at present. Anyhow, she has champagne every night at dinner. Her equipment in the matter of toilet articles and leather traveling bags is all that it should be. The latter are colored to suit her complexion and gowns. She is scented, polished, looked after, and all men pay her attention. She is vain, beautiful, and she thinks that America is raw, uncouth; that its citizens of whom she is one, do not know how to live. Quite so. Now we come to the point.

It would be hard to describe this conversation. It began with some “have you been’s,” I think, and concerned eating-places and modes of entertainment in London, Paris and Monte Carlo. I gathered by degrees, that in London, Paris and elsewhere there were a hundred restaurants, a hundred places to live, each finer than the other. I heard of liberty of thought and freedom of action and pride of motion which made me understand that there is a free-masonry which concerns the art of living, which is shared only by the initiated. There was a world in which conventions, as to morals, have no place; in which ethics and religion are tabooed. Art is the point. The joys of this world are sex, beauty, food, clothing, art. I should say money, of course, but money is presupposed. You must have it.

“Oh, I went to that place one day and then I was glad enough to get back to the Ritz at forty francs for my room.” She was talking of her room by the day, and the food, of course, was extra. The other hotel had been a little bit quiet or dingy.

I opened my eyes slightly, for I thought Paris was reasonable; but not so—no more so than New York, I understood, if you did the same things.

“And, oh, the life!” said Miss X. at one point. “Americans don’t know how to live. They are all engaged in doing something. They are such beginners. They are only interested in money. They don’t know. I see them in Paris now and then.” She lifted her hand. “Here in Europe people understand life better. They know. They know before they begin how much it will take to do the things that they want to do and they start22 out to make that much—not a fortune—just enough to do the things that they want to do. When they get that they retire and live.”

“And what do they do when they live?” I asked. “What do they call living?”

“Oh, having a nice country-house within a short traveling distance of London or Paris, and being able to dine at the best restaurants and visit the best theaters once or twice a week; to go to Paris or Monte Carlo or Scheveningen or Ostend two or three or four, or as many times a year as they please; to wear good clothes and to be thoroughly comfortable.”

“That is not a bad standard,” I said, and then I added, “And what else do they do?”

“And what else should they do? Isn’t that enough?”

And there you have the European standard according to Miss X. as contrasted with the American standard which is, or has been up to this time, something decidedly different, I am sure. We have not been so eager to live. Our idea has been to work. No American that I have ever known has had the idea of laying up just so much, a moderate amount, and then retiring and living. He has had quite another thought in his mind. The American—the average American—I am sure loves power, the ability to do something, far more earnestly than he loves mere living. He wants to be an officer or a director of something, a poet, anything you please for the sake of being it—not for the sake of living. He loves power, authority, to be able to say, “Go and he goeth,” or, “Come and he cometh.” The rest he will waive. Mere comfort? You can have that. But even that, according to Miss X., was not enough for her. She had told me before, and this conversation brought it out again, that her thoughts were of summer and winter resorts, exquisite creations in the way of clothing, diamonds,23 open balconies of restaurants commanding charming vistas, gambling tables at Monte Carlo, Aix-les-Bains, Ostend and elsewhere, to say nothing of absolutely untrammeled sex relations. English conventional women were frumps and fools. They had never learned how to live; they had never understood what the joy of freedom in sex was. Morals—they are built up on a lack of imagination and physical vigor; tenderness—well, you have to take care of yourself; duty—there isn’t any such thing. If there is, it’s one’s duty to get along and have money and be happy.

24

While I was lying in my berth the fifth morning, I heard the room steward outside my door tell some one that he thought we reached Fishguard at one-thirty.

I packed my trunks, thinking of this big ship and the fact that my trip was over and that never again could I cross the Atlantic for the first time. A queer world this. We can only do any one thing significantly once. I remember when I first went to Chicago, I remember when I first went to St. Louis, I remember when I first went to New York. Other trips there were, but they are lost in vagueness. But the first time of any important thing sticks and lasts; it comes back at times and haunts you with its beauty and its sadness. You know so well you cannot do that any more; and, like a clock, it ticks and tells you that life is moving on. I shall never come to England any more for the first time. That is gone and done for—worse luck.

So I packed—will you believe it?—a little sadly. I think most of us are a little silly at times, only we are cautious enough to conceal it. There is in me the spirit of a lonely child somewhere and it clings pitifully to the hand of its big mama, Life, and cries when it is frightened; and then there is a coarse, vulgar exterior which fronts the world defiantly and bids all and sundry to go to the devil. It sneers and barks and jeers bitterly at times, and guffaws and cackles and has a joyous time laughing at the follies of others.

Then I went to hunt Barfleur to find out how I should25 do. How much was I to give the deck-steward; how much to the bath-steward; how much to the room-steward; how much to the dining-room steward; how much to “boots,” and so on.

“Look here!” observed that most efficient of all managerial souls that I have ever known. “I’ll tell you what you do. No—I’ll write it.” And he drew forth an ever ready envelope. “Deck-steward—so much,” it read, “Room steward—so much—” etc.

I went forthwith and paid them, relieving my soul of a great weight. Then I came on deck and found that I had forgotten to pack my ship blanket, and a steamer rug, which I forthwith went and packed. Then I discovered that I had no place for my derby hat save on my head, so I went back and packed my cap. Then I thought I had lost one of my brushes, which I hadn’t, though I did lose one of my stylo pencils. Finally I came on deck and sang coon songs with Miss X., sitting in our steamer chairs. The low shore of Ireland had come into view with two faint hills in the distance and these fascinated me. I thought I should have some slight emotion on seeing land again, but I didn’t. It was gray and misty at first, but presently the sun came out beautifully clear and the day was as warm as May in New York. I felt a sudden elation of spirits with the coming of the sun, and I began to think what a lovely time I was going to have in Europe.

Miss X. was a little more friendly this morning than heretofore. She was a tricky creature—coy, uncertain and hard to please. She liked me intellectually and thought I was able, but her physical and emotional predilections, so far as men are concerned, did not include me.

We rejoiced together singing, and then we fought. There is a directness between experienced intellects which26 waves aside all formalities. She had seen a lot of life; so had I.

She said she thought she would like to walk a little, and we strolled back along the heaving deck to the end of the first cabin section and then to the stern. When we reached there the sky was overcast again, for it was one of those changeable mornings which is now gray, now bright, now misty. Just now the heavens were black and lowering with soft, rain-charged clouds, like the wool of a smudgy sheep. The sea was a rich green in consequence—not a clear green, but a dark, muddy, oil-green. It rose and sank in its endless unrest and one or two boats appeared—a lightship, anchored out all alone against the lowering waste, and a small, black, passenger steamer going somewhere.

“I wish my path in life were as white as that and as straight,” observed Miss X., pointing to our white, propeller-churned wake which extended back for half a mile or more.

“Yes,” I observed, “you do and you don’t. You do, if it wouldn’t cost you trouble in the future—impose the straight and narrow, as it were.”

“Oh, you don’t know,” she exclaimed irritably, that ugly fighting light coming into her eyes, which I had seen there several times before. “You don’t know what my life has been. I haven’t been so bad. We all of us do the best we can. I have done the best I could, considering.”

“Yes, yes,” I observed, “you’re ambitious and alive and you’re seeking—Heaven knows what! You would be adorable with your pretty face and body if you were not so—so sophisticated. The trouble with you is—”

“Oh, look at that cute little boat out there!” She was talking of the lightship. “I always feel sorry for a27 poor little thing like that, set aside from the main tide of life and left lonely—with no one to care for it.”

“The trouble with you is,” I went on, seizing this new remark as an additional pretext for analysis, “you’re romantic, not sympathetic. You’re interested in that poor little lonely boat because its state is romantic; not pathetic. It may be pathetic, but that isn’t the point with you.”

“Well,” she said, “if you had had all the hard knocks I have had, you wouldn’t be sympathetic either. I’ve suffered, I have. My illusions have been killed dead.”

“Yes. Love is over with you. You can’t love any more. You can like to be loved, that’s all. If it were the other way about—”

I paused to think how really lovely she would be with her narrow lavender eyelids; her delicate, almost retroussé, little nose; her red cupid’s-bow mouth.

“Oh,” she exclaimed, with a gesture of almost religious adoration. “I cannot love any one person any more, but I can love love, and I do—all the delicate things it stands for.”

“Flowers,” I observed, “jewels, automobiles, hotel bills, fine dresses.”

“Oh, you’re brutal. I hate you. You’ve said the cruelest, meanest things that have ever been said to me.”

“But they’re so.”

“I don’t care. Why shouldn’t I be hard? Why shouldn’t I love to live and be loved? Look at my life. See what I’ve had.”

“You like me, in a way?” I suggested.

“I admire your intellect.”

“Quite so. And others receive the gifts of your personality.”

“I can’t help it. I can’t be mean to the man I’m with.28 He’s good to me. I won’t. I’d be sinning against the only conscience I have.”

“Then you have a conscience?”

“Oh, you go to the devil!”

But we didn’t separate by any means.

They were blowing a bugle for lunch when we came back, and down we went. Barfleur was already at table. The orchestra was playing Auld Lang Syne, Home Sweet Home, Dixie and the Suwannee River. It even played one of those delicious American rags which I love so much—the Oceana Roll. I felt a little lump in my throat at Auld Lang Syne and Dixie, and together Miss X. and I hummed the Oceana Roll as it was played. One of the girl passengers came about with a plate to obtain money for the members of the orchestra, and half-crowns were universally deposited. Then I started to eat my dessert; but Barfleur, who had hurried off, came back to interfere.

“Come, come!” (He was always most emphatic.) “You’re missing it all. We’re landing.”

I thought we were leaving at once. The eye behind the monocle was premonitory of some great loss to me. I hurried on deck—to thank his artistic and managerial instinct instantly I arrived there. Before me was Fishguard and the Welsh coast, and to my dying day I shall never forget it. Imagine, if you please, a land-locked harbor, as green as grass in this semi-cloudy, semi-gold-bathed afternoon, with a half-moon of granite scarp rising sheer and clear from the green waters to the low gray clouds overhead. On its top I could see fields laid out in pretty squares or oblongs, and at the bottom of what to me appeared to be the east end of the semi-circle, was a bit of gray scruff, which was the village no doubt. On the green water were several other boats—steamers, much smaller, with red stacks, black sides, white rails and29 funnels—bearing a family resemblance to the one we were on. There was a long pier extending out into the water from what I took to be the village and something farther inland that looked like a low shed.

This black hotel of a ship, so vast, so graceful, now rocking gently in the enameled bay, was surrounded this hour by wheeling, squeaking gulls. I always like the squeak of a gull; it reminds me of a rusty car wheel, and, somehow, it accords with a lone, rocky coast. Here they were, their little feet coral red, their beaks jade gray, their bodies snowy white or sober gray, wheeling and crying—“my heart remembers how.” I looked at them and that old intense sensation of joy came back—the wish to fly, the wish to be young, the wish to be happy, the wish to be loved.

But, my scene, beautiful as it was, was slipping away. One of the pretty steamers I had noted lying on the water some distance away, was drawing alongside—to get mails, first, they said. There were hurrying and shuffling people on all the first cabin decks. Barfleur was forward looking after his luggage. The captain stood on the bridge in his great gold-braided blue overcoat. There were mail chutes being lowered from our giant vessel’s side, and bags and trunks and boxes and bales were then sent scuttling down. I saw dozens of uniformed men and scores of ununiformed laborers briskly handling these in the sunshine. My fellow passengers in their last hurrying hour interested me, for I knew I should see them no more; except one or two, perhaps.

While we were standing here I turned to watch an Englishman, tall, assured, stalky, stary. He had been soldiering about for some time, examining this, that and the other in his critical, dogmatic British way. He had leaned over the side and inspected the approaching30 lighters, he had stared critically and unpoetically at the gulls which were here now by hundreds, he had observed the landing toilet of the ladies, the material equipment of the various men, and was quite evidently satisfied that he himself was perfect, complete. He was aloof, chilly, decidedly forbidding and judicial.

Finally a cabin steward came hurrying out to him.

“Did you mean to leave the things you left in your room unpacked?” he asked. The Englishman started, stiffened, stared. I never saw a self-sufficient man so completely shaken out of his poise.

“Things in my room unpacked?” he echoed. “What room are you talking about? My word!”

“There are three drawers full of things in there, sir, unpacked, and they’re waiting for your luggage now, sir!”

“My word!” he repeated, grieved, angered, perplexed. “My word! I’m sure I packed everything. Three drawers full! My word!” He bustled off stiffly. The attendant hastened cheerfully after. It almost gave me a chill as I thought of his problem. And they hurry so at Fishguard. He was well paid out, as the English say, for being so stalky and superior.

Then the mail and trunks being off, and that boat having veered away, another and somewhat smaller one came alongside and we first, and then the second class passengers, went aboard, and I watched the great ship growing less and less as we pulled away from it. It was immense from alongside, a vast skyscraper of a ship. At a hundred feet, it seemed not so large, but more graceful; at a thousand feet, all its exquisite lines were perfect—its bulk not so great, but the pathos of its departing beauty wonderful; at two thousand feet, it was still beautiful against the granite ring of the harbor; but, alas, it was moving. The captain31 was an almost indistinguishable spot upon his bridge. The stacks—in their way gorgeous—took on beautiful proportions. I thought, as we veered in near the pier and the ship turned within her length or thereabouts and steamed out, I had never seen a more beautiful sight. Her convoy of gulls was still about her. Her smoke-stacks flung back their graceful streamers. The propeller left a white trail of foam. I asked some one: “When does she get to Liverpool?”

“At two in the morning.”

“And when do the balance of the passengers land?” (We had virtually emptied the first cabin.)

“At seven, I fancy.”

Just then the lighter bumped against the dock. I walked under a long, low train-shed covering four tracks, and then I saw my first English passenger train—a semi-octagonal-looking affair—(the ends of the cars certainly looked as though they had started out to be octagonal) and there were little doors on the sides labeled “First,” “First,” “First.” On the side, at the top of the car, was a longer sign: “Cunard Ocean Special—London—Fishguard.”

32

Right here I propose to interpolate my second dissertation on the servant question and I can safely promise, I am sure, that it will not be the last. One night, not long before, in dining with a certain Baron N. and Barfleur at the Ritz in New York this matter of the American servant came up in a conversational way. Baron N. was a young exquisite of Berlin and other European capitals. He was one of Barfleur’s idle fancies. Because we were talking about America in general I asked them both what, to them, was the most offensive or objectionable thing about America. One said, expectorating; the other said, the impoliteness of servants. On the ship going over, at Fishguard, in the train from Fishguard to London, at London and later in Barfleur’s country house I saw what the difference was. Of course I had heard these differences discussed before ad lib. for years, but hearing is not believing. Seeing and experiencing is.

On shipboard I noticed for the first time in my life that there was an aloofness about the service rendered by the servants which was entirely different from that which we know in America. They did not look at one so brutally and critically as does the American menial; their eyes did not seem to say, “I am your equal or better,” and their motions did not indicate that they were doing anything unwillingly. In America—and I am a good American—I have always had the feeling that the American hotel or house servant or store clerk—particularly33 store clerk—male or female—was doing me a great favor if he did anything at all for me. As for train-men and passenger-boat assistants, I have never been able to look upon them as servants at all. Mostly they have looked on me as an interloper, and as some one who should be put off the train, instead of assisted in going anywhere. American conductors are Czars; American brakemen and train hands are Grand Dukes, at least; a porter is little less than a highwayman; and a hotel clerk—God forbid that we should mention him in the same breath with any of the foregoing!

However, as I was going on to say, when I went aboard the English ship in question I felt this burden of serfdom to the American servant lifted. These people, strange to relate, did not seem anxious to fight with me. They were actually civil. They did not stare me out of countenance; they did not order me gruffly about. And, really, I am not a princely soul looking for obsequious service. I am, I fancy, a very humble-minded person when traveling or living, anxious to go briskly forward, not to be disturbed too much and allowed to live in quiet and seclusion.

The American servant is not built for that. One must have great social or physical force to command him. At times he needs literally to be cowed by threats of physical violence. You are paying him? Of course you are. You help do that when you pay your hotel bill or buy your ticket, or make a purchase, but he does not know that. The officials of the companies for whom he works do not appear to know. If they did, I don’t know that they would be able to do anything about it. You can not make a whole people over by issuing a book of rules. Americans are free men; they don’t want to be servants; they have despised the idea for years. I think the early Americans who lived in America after the Revolution—the34 anti-Tory element—thought that after the war and having won their nationality there was to be an end of servants. I think they associated labor of this kind with slavery, and they thought when England had been defeated all these other things, such as menial service, had been defeated also. Alas, superiority and inferiority have not yet been done away with—wholly. There are the strong and the weak; the passionate and passionless; the hungry and the well-fed. There are those who still think that life is something which can be put into a mold and adjusted to a theory, but I am not one of them. I cannot view life or human nature save as an expression of contraries—in fact, I think that is what life is. I know there can be no sense of heat without cold; no fullness without emptiness; no force without resistance; no anything, in short, without its contrary. Consequently, I cannot see how there can be great men without little ones; wealth without poverty; social movement without willing social assistance. No high without a low, is my idea, and I would have the low be intelligent, efficient, useful, well paid, well looked after. And I would have the high be sane, kindly, considerate, useful, of good report and good-will to all men.

Years of abuse and discomfort have made me rather antagonistic to servants, but I felt no reasonable grounds for antagonism here. They were behaving properly. They weren’t staring at me. I didn’t catch them making audible remarks behind my back. They were not descanting unfavorably upon any of my fellow passengers. Things were actually going smoothly and nicely and they seemed rather courteous about it all.

Yes, and it was so in the dining-saloon, in the bath, on deck, everywhere, with “yes, sirs,” and “thank you, sirs,” and two fingers raised to cap visors occasionally for good measure. Were they acting? Was this a35 fiercely suppressed class I was looking upon here? I could scarcely believe it. They looked too comfortable. I saw them associating with each other a great deal. I heard scraps of their conversation. It was all peaceful and genial and individual enough. They were, apparently, leading unrestricted private lives. However, I reserved judgment until I should get to England, but at Fishguard it was quite the same and more also. These railway guards and porters and conductors were not our railway conductors, brakemen and porters, by a long shot. They were different in their attitude, texture and general outlook on life. Physically I should say that American railway employees are superior to the European brand. They are, on the whole, better fed, or at least better set up. They seem bigger to me, as I recall them; harder, stronger. The English railway employee seems smaller and more refined physically—less vigorous.

But as to manners: Heaven save the mark! These people are civil. They are nice. They are willing. “Have you a porter, sir? Yes, sir! Thank you, sir! This way, sir! No trouble about that, sir! In a moment, sir! Certainly, sir! Very well, sir!” I heard these things on all sides and they were like balm to a fevered brain. Life didn’t seem so strenuous with these people about. They were actually trying to help me along. I was led; I was shown; I was explained to. I got under way without the least distress and I began actually to feel as though I was being coddled. Why, I thought, these people are going to spoil me. I’m going to like them. And I had rather decided that I wouldn’t like the English. Why, I don’t know; for I never read a great English novel that I didn’t more or less like all of the characters in it. Hardy’s lovely country people have warmed the cockles of my heart; George Moore’s English characters have appealed to me. And here was36 Barfleur. But the way the train employees bundled me into my seat and got my bags in after or before me, and said, “We shall be starting now in a few minutes, sir,” and called quietly and pleadingly—not yelling, mind you—“Take your seats, please,” delighted me.

I didn’t like the looks of the cars. I can prove in a moment by any traveler that our trains are infinitely more luxurious. I can see where there isn’t heat enough, and where one lavatory for men and women on any train, let alone a first-class one, is an abomination, and so on and so forth; but still, and notwithstanding, I say the English railway service is better. Why? Because it’s more human; it’s more considerate. You aren’t driven and urged to step lively and called at in loud, harsh voices and made to feel that you are being tolerated aboard something that was never made for you at all, but for the employees of the company. In England the trains are run for the people, not the people for the trains. And now that I have that one distinct difference between England and America properly emphasized I feel much better.

37

At last the train was started and we were off. The track was not so wide, if I am not mistaken, as ours, and the little freight or goods cars were positively ridiculous—mere wheelbarrows, by comparison with the American type. As for the passenger cars, when I came to examine them, they reminded me of some of our fine street cars that run from, say Schenectady to Gloversville, or from Muncie to Marion, Indiana. They were the first-class cars, too—the English Pullmans! The train started out briskly and you could feel that it did not have the powerful weight to it which the American train has. An American Pullman creaks audibly, just as a great ship does when it begins to move. An American engine begins to pull slowly because it has something to pull—like a team with a heavy load. I didn’t feel that I was in a train half so much as I did that I was in a string of baby carriages.

Miss X. and her lover, Miss E. and her maid, Barfleur and I comfortably filled one little compartment; and now we were actually moving, and I began to look out at once to see what English scenery was really like. It was not at all strange to me, for in books and pictures I had seen it all my life. But here were the actual hills and valleys, the actual thatched cottages, and the actual castles or moors or lovely country vistas, and I was seeing them!

As I think of it now I can never be quite sufficiently grateful to Barfleur for a certain affectionate, thoughtful, sympathetic regard for my every possible mood on this occasion. This was my first trip to this England of which,38 of course, he was intensely proud. He was so humanly anxious that I should not miss any of its charms or, if need be, defects. He wanted me to be able to judge it fairly and humanly and to see the eventual result sieved through my temperament. The soul of attention; the soul of courtesy; patient, long-suffering, humane, gentle. How I have tried the patience of that man at times! An iron mood he has on occasion; a stoic one, always. Gentle, even, smiling, living a rule and a standard. Every thought of him produces a grateful smile. Yet he has his defects—plenty of them. Here he was at my elbow, all the way to London, momentarily suggesting that I should not miss the point, whatever the point might be, at the moment. He was helpful, really interested, and above all and at all times, warmly human.

We had been just two hours getting from the boat to the train. It was three-thirty when the train began to move, and from the lovely misty sunshine of the morning the sky had become overcast with low, gray—almost black—rain clouds. I looked at the hills and valleys. They told me we were in Wales. And, curiously, as we sped along first came Wordsworth into my mind, and then Thomas Hardy. I thought of Wordsworth first because these smooth, kempt hills, wet with the rain and static with deep gray shadows, suggested him. England owes so much to William Wordsworth, I think. So far as I can see, he epitomized in his verses this sweet, simple hominess that tugs at the heart-strings like some old call that one has heard before. My father was a German, my mother of Pennsylvania Dutch extraction, and yet there is a pull here in this Shakespearian-Wordsworthian-Hardyesque world which is precisely like the call of a tender mother to a child. I can’t resist it. I love it; and I am not English but radically American.

39

I understand that Hardy is not so well thought of in England as he might be—that, somehow, some large conservative class thinks that his books are immoral or destructive. I should say the English would better make much of Thomas Hardy while he is alive. He is one of their great traditions. His works are beautiful. The spirit of all the things he has done or attempted is lovely. He is a master mind, simple, noble, dignified, serene. He is as fine as any of the English cathedrals. St. Paul’s or Canterbury has no more significance to me than Thomas Hardy. I saw St. Paul’s. I wish I could see the spirit of Thomas Hardy indicated in some such definite way. And yet I do not. Monuments do not indicate great men. But the fields and valleys of a country suggest them.

At twenty or thirty miles from Fishguard we came to some open water—an arm of the sea, I understood—the Bay of Bristol, where boats were, and tall, rain-gutted hills that looked like tumbled-down castles. Then came more open country—moorland, I suppose—with some sheep, once a flock of black ones; and then the lovely alternating hues of this rain-washed world. The water under these dark clouds took on a peculiar luster. It looked at times like burnished steel—at times like muddy lead. I felt my heart leap up as I thought of our own George Inness and what he would have done with these scenes and what the English Turner has done, though he preferred, as a rule, another key.

At four-thirty one of the charming English trainmen came and asked if we would have tea in the dining-car. We would. We arose and in a few moments were entering one of those dainty little basket cars. The tables were covered with white linen and simple, pretty china and a silver tea-service. It wasn’t as if you were traveling at all. I felt as though I were stopping at the house40 of a friend; or as though I were in the cozy corner of some well-known and friendly inn. Tea was served. We ate toast and talked cheerfully.

This whole trip—the landscape, the dining-car, this cozy tea, Miss X. and her lover, Miss E. and Barfleur—finally enveloped my emotional fancy like a dream. I realized that I was experiencing a novel situation which would not soon come again. The idea of this pretty mistress coming to England to join her lover, and so frankly admitting her history and her purpose, rather took my mind as an intellectual treat. You really don’t often get to see this sort of thing. I don’t. It’s Gallic in its flavor, to me. Barfleur, being a man of the world, took it as a matter of course—his sole idea being, I fancy, that the refinement of personality and thought involved in the situation were sufficient to permit him to tolerate it. I always judge his emotion by that one gleaming eye behind the monocle. The other does not take my attention so much. I knew from his attitude that ethics and morals and things like that had nothing to do with his selection of what he would consider interesting personal companionship. Were they interesting? Could they tell him something new? Would they amuse him? Were they nice—socially, in their clothing, in their manners, in the hundred little material refinements which make up a fashionable lady or gentleman? If so, welcome. If not, hence. And talent! Oh, yes, he had a keen eye for talent. And he loves the exceptional and will obviously do anything and everything within his power to foster it.

Having started so late, it grew nearly dark after tea and the distant landscapes were not so easy to descry. We came presently, in the mist, to a place called Carmarthen, I think, where were great black stacks and41 flaming forges and lights burning wistfully in the dark; and then to another similar place, Swansea, and finally to a third, Cardiff—great centers of manufacture, I should judge, for there were flaming lights from forges (great, golden gleams from open furnaces) and dark blue smoke, visible even at this hour, from tall stacks overhead, and gleaming electric lights like bright, lucent diamonds.

I never see this sort of place but I think of Pittsburgh and Youngstown and the coke ovens of western Pennsylvania along the line of the Pennsylvania Railroad. I shall never forget the first time I saw Pittsburgh and Youngstown and saw how coke was fired. It was on my way to New York. I had never seen any mountains before and suddenly, after the low, flat plains of Indiana and Ohio, with their pretty little wooden villages so suggestive of the new life of the New World, we rushed into Youngstown and then the mountains of western Pennsylvania (the Alleghanies). It was somewhat like this night coming from Fishguard, only it was not so rainy. The hills rose tall and green; the forge stacks of Pittsburgh flamed with a red gleam, mile after mile, until I thought it was the most wonderful sight I had ever seen. And then came the coke ovens, beyond Pittsburgh mile after mile of them, glowing ruddily down in the low valleys between the tall hills, where our train was following a stream-bed. It seemed a great, sad, heroic thing then, to me,—plain day labor. Those common, ignorant men, working before flaming forges, stripped to the waist in some instances, fascinated my imagination. I have always marveled at the inequalities of nature—the way it will give one man a low brow and a narrow mind, a narrow round of thought, and make a slave or horse of him, and another a light, nimble mind, a quick wit and42 air and make a gentleman of him. No human being can solve either the question of ability or utility. Is your gentleman useful? Yes and no, perhaps. Is your laborer useful? Yes and no, perhaps. I should say obviously yes. But see the differences in the reward of labor—physical labor. One eats his hard-earned crust in the sweat of his face; the other picks at his surfeit of courses and wonders why this or that doesn’t taste better. I did not make my mind. I did not make my art. I cannot choose my taste except by predestined instinct, and yet here I am sitting in a comfortable English home, as I write, commiserating the poor working man. I indict nature here and now, as I always do and always shall do, as being aimless, pointless, unfair, unjust. I see in the whole thing no scheme but an accidental one—no justice save accidental justice. Now and then, in a way, some justice is done, but it is accidental; no individual man seems to will it. He can’t. He doesn’t know how. He can’t think how. And there’s an end of it.

But these queer, weird, hard, sad, drab manufacturing cities—what great writer has yet sung the song of them? Truly I do not recall one at present clearly. Dickens gives some suggestion of what he considered the misery of the poor; and in “Les Miserables” there is a touch of grim poverty and want here and there. But this is something still different. This is creative toil on a vast scale, and it is a lean, hungry, savage, animal to contemplate. I know it is because I have studied personally Fall River, Patterson and Pittsburgh, and I know what I’m talking about. Life runs at a gaunt level in those places. It’s a rough, hurtling world of fact. I suppose it is not any different in England. I looked at the manufacturing towns as we flashed by in the night and got the same feeling of sad commiseration43 and unrest. The homes looked poor and they had a deadly sameness; the streets were narrow and poorly lighted. I was eager to walk over one of these towns foot by foot. I have the feeling that the poor and the ignorant and the savage are somehow great artistically. I have always had it. Millet saw it when he painted “The Man with the Hoe.” These drab towns are grimly wonderful to me. They sing a great diapason of misery. I feel hunger and misery there; I feel lust and murder and life, sick of itself, stewing in its own juice; I feel women struck in the face by brutal men; and sodden lives too low and weak to be roused by any storm of woe. I fancy there are hungry babies and dying mothers and indifferent bosses and noble directors somewhere, not caring, not knowing, not being able to do anything about it, perhaps, if they did. I could weep just at the sight of a large, drab, hungry manufacturing town. I feel sorry for ignorant humanity. I wish I knew how to raise the low foreheads; to put the clear light of intellect into sad, sodden eyes. I wish there weren’t any blows, any hunger, any tears. I wish people didn’t have to long bitterly for just the little thin, bare necessities of this world. But I know, also, that life wouldn’t be as vastly dramatic and marvelous without them. Perhaps I’m wrong. I’ve seen some real longing in my time, though. I’ve longed myself and I’ve seen others die longing.

Between Carmarthen and Cardiff and some other places where this drab, hungry world seemed to stick its face into the window, I listened to much conversation about the joyous side of living in Paris, Monte Carlo, Ostend and elsewhere. I remember once I turned from the contemplation of a dark, sad, shabby world scuttling by in the night and rain to hear Miss E. telling of some Parisian music-hall favorite—I’ll call her Carmen—rivaling44 another Parisian music-hall favorite by the name of Diane, let us say, at Monte Carlo. Of course it is understood that they were women of loose virtue. Of course it is understood that they had fine, white, fascinating bodies and lovely faces and that they were physically ideal. Of course it is understood that they were marvelous mistresses and that money was flowing freely from some source or other—perhaps from factory worlds like these—to let them work their idle, sweet wills. Anyhow they were gambling, racing, disporting themselves at Monte Carlo and all at once they decided to rival each other in dress. Or perhaps it was that they didn’t decide to, but just began to, which is much more natural and human.

As I caught it, with my nose pressed to the carriage window and the sight of rain and mist in my eyes, Carmen would come down one night in splendid white silk, perhaps, her bare arms and perfect neck and hair flashing priceless jewels; and then the fair Diane would arrive a little later with her body equally beautifully arrayed in some gorgeous material, her white arms and neck and hair equally resplendent. Then the next night the gowns would be of still more marvelous material and artistry, and more jewels—every night lovelier gowns and more costly jewels, until one of these women took all her jewels, to the extent of millions of francs, I presume, and, arraying her maid gorgeously, put all the jewels on her and sent her into the casino or the ballroom or the dining-room—wherever it was—and she herself followed, in—let us hope—plain, jewelless black silk, with her lovely flesh showing voluptuously against it. And the other lady was there, oh, much to her chagrin and despair now, of course, decked with all her own splendid jewels to the extent of an45 equally large number of millions of francs, and so the rivalry was ended.

It was a very pretty story of pride and vanity and I liked it. But just at this interesting moment, one of those great blast furnaces, which I have been telling you about and which seemed to stretch for miles beside the track, flashed past in the night, its open red furnace doors looking like rubies, and the frosted windows of its lighted shops looking like opals, and the fluttering street lamps and glittering arc lights looking like pearls and diamonds; and I said: behold! these are the only jewels of the poor and from these come the others. And to a certain extent, in the last analysis and barring that unearned gift of brain which some have without asking and others have not at all, so they do.

It was seven or eight when we reached Paddington. For one moment, when I stepped out of the car, the thought came to me with a tingle of vanity—I have come by land and sea, three thousand miles to London! Then it was gone again. It was strange—this scene. I recognized at once the various London types caricatured in Punch, and Pick Me Up, and The Sketch, and elsewhere. I saw a world of cabs and ‘busses, of porters, gentlemen, policemen, and citizens generally. I saw characters—strange ones—that brought back Dickens and Du Maurier and W. W. Jacobs. The words “Booking Office” and the typical London policeman took my eye. I strolled about, watching the crowd till it was time for us to board our train for the country; and eagerly I nosed about, trying to sense London from this vague, noisy touch of it. I can’t indicate how the peculiar-looking trains made me feel. Humanity is so very different in so many little unessential things—so utterly the same in all the large ones. I46 could see that it might be just as well or better to call a ticket office a booking office; or to have three classes of carriages instead of two, as with us; or to have carriages instead of cars; or trams instead of street railways; or lifts instead of elevators. What difference does it make? Life is the same old thing. Nevertheless there was a tremendous difference between the London and the New York atmosphere—that I could see and feel.

“A few days at my place in the country will be just the thing for you,” Barfleur was saying. “I sent a wireless to Dora to have a fire in the hall and in your room. You might as well see a bit of rural England first.”

He gleamed on me with his monocled eye in a very encouraging manner.

We waited about quite awhile for a local or suburban which would take us to Bridgely Level, and having ensconced ourselves first class—as fitting my arrival—Barfleur fell promptly to sleep and I mused with my window open, enjoying the country and the cool night air.

47

I am writing these notes on Tuesday, November twenty-eighth, very close to a grate fire in a pretty little sitting-room in an English country house about twenty-five miles from London, and I am very chilly.

We reached this place by some winding road, inscrutable in the night, and I wondered keenly what sort of an atmosphere it would have. The English suburban or country home of the better class has always been a concrete thought to me—rather charming on the whole. A carriage brought us, with all the bags and trunks carefully looked after (in England you always keep your luggage with you), and we were met in the hall by the maid who took our coats and hats and brought us something to drink. There was a small fire glowing in the fireplace in the entrance hall, but it was so small—cheerful though it was—that I wondered why Barfleur had taken all the trouble to send a wireless from the sea to have it there. It seems it is a custom, in so far as his house is concerned, not to have it. But having heard something of English fires and English ideas of warmth, I was not greatly surprised.

“I am going to be cold,” I said to myself, at once. “I know it. The atmosphere is going to be cold and raw and I am going to suffer greatly. It will be the devil and all to write.”