Title: The Girl's Own Paper, Vol. VIII, No. 366, January 1, 1887

Author: Various

Release date: June 25, 2021 [eBook #65696]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Susan Skinner and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

{209}

Vol. VIII.—No. 366.

Price One Penny.

JANUARY 1, 1887.

[Transcriber’s Note: This Table of Contents was not present in the original.]

NEW YEAR’S GIFTS.

MERLE’S CRUSADE.

HERALDRY, HISTORICALLY AND PRACTICALLY CONSIDERED.

THE BRIDE’S FIRST DINNER PARTY.

GIRTON GIRL.

THE SHEPHERD’S FAIRY.

THE ROMANCE OF THE BANK OF ENGLAND.

GIRLS’ FRIENDSHIPS.

ANSWERS TO CORRESPONDENTS.

By MARY ROWLES.

“OLD SONGS.”

All rights reserved.]

{210}

By ROSA NOUCHETTE CAREY, Author of “Aunt Diana,” “For Lilias,” etc.

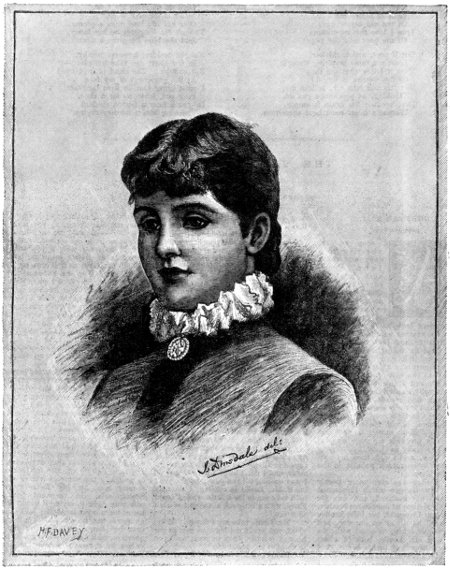

GAY CHERITON.

was afraid Mrs. Markham did not understand children. Nothing would induce Reggie to let her kiss him; he beat her off in his usual fashion, with a sulky “go, go,” and hid his face on my shoulder. I could see this vexed her immensely, for she had praised his beauty in most extravagant terms.

Joyce listened with a perplexed expression on her face.

“Have you ever seed an angel, Aunt Adda?” this being her childish abbreviation of Adelaide.

“Dear me, nurse! how badly the child speaks. She is more than six years old, you say. Why my Rolf is only seven, and speaks beautifully! What did you say, Joyce?”—very sharply—“seen an angel? What unhealthy nonsense to put into a child’s head! This comes of new-fangled ideas on your mother’s part”—with a glance in my direction. “No, child! of course not. No one has seen an angel.”

Joyce looked so shocked at this that I hastened to interpret Mrs. Markham’s speech.

“No one sees angels now, Joyce; not as the good people in the Bible used to see them; perhaps we are not good enough. But what put angels into your head, my dear?”

“Only Aunt Adda said Reggie was like an angel, and I thought she had seed one. What is a cherub, nurse, dear? Something good to eat?”

I saw a smile hovering on Mrs. Markham’s thin lips. Evidently she found Joyce amusing, but just then a loud peevish voice was distinctly audible in the passage.

“Mother, mother, I say! Go away, Juddy, I tell you. You are a nasty disagreeable old cat—and I will go to mother”—this accompanied by ominous kicks.

I signed to Hannah to take the children into the adjoining room. It was Reggie’s bedtime, and Joyce was tired with her journey. The door was scarcely closed upon them before the same violent kicking was heard against the nursery door.

“It is only Rolf. I am afraid he is very cross,” observed Mrs. Markham, placidly, shivering a little after the fashion of people who have lived in India, as she moved away from the open window, and drew a lace scarf round her. “Judson is such a bad manager. She never does contrive to amuse him, or keep him quiet.”

“He will frighten Reggie,” I remonstrated, for she did not offer to stop the noise, and I went quickly to the door.

There was a regular scuffle going on in the passage. A little boy in Highland dress was endeavouring to escape from a young woman, who was holding him back from the door with some difficulty.

“Master Rolf—Master Rolf, what will your mamma say? You will make her head ache, and then you will be sorry.”

“I shan’t be a bit sorry, Juddy, I tell you! I will go in, and——” Here he stopped and stared up in my face. He was a pale, sickly-looking child, rather plain, as Miss Cheriton had said, but he had beautiful grey eyes, only they were sparkling with anger. The young woman who held him by the arm had a thin, careworn face—probably her post was a harassing one, with an exacting mistress and that spoilt boy.

“Who are you?” demanded the boy, rudely.

“I am Miss Fenton, the nurse,” I returned. “Your little cousins are just going to bed, and I cannot have that noise to disturb them.”

“I shall kick again, unless you let me come in and see them.”

“For shame, Master Rolf. Whatever makes you so naughty to-night?”

“I mean to be naughty. Hold your stupid old tongue, Juddy. You are a silly woman. That is what mother calls you. I am a gentleman, and shall be naughty if I like. Now then, Mrs. Nurse, may I come in?”

“Not to-night, Master Rolf. To-morrow, if you are good.”

“Nurse,” interrupted Mrs. Markham’s voice, behind me, “I do not know what right you have to exclude my boy. Let him come in and bid good-night to his cousins. You will behave prettily, Rolf, will you not?”

One look at the surly face before me made me incredulous of any pretty behaviour on Rolf’s part. I knew Joyce was a nervous child, and easily frightened, and already the loud voices were upsetting Reggie. I could hear him crying, in spite of Hannah’s coaxing. I felt I must be firm. The nursery was my private domain. I was determined Rolf should not cross the threshold to-night.

“Excuse me, Mrs. Markham,” I returned quickly, “I cannot have the children disturbed at bedtime; it is against Mrs. Morton’s rules. Master Rolf may pay us a visit to-morrow, if he be good”—laying a stress on good—“but I cannot admit him to-night.”

She looked at me with haughty incredulity.

“I consider this very impertinent,” she muttered, half to herself. But Judson must have heard her.

“Come with me, Rolf darling. Never mind about your cousins. I daresay we shall find something nice downstairs,” and she held out her hand to him, but he pushed it away.

“Bring him to the drawing-room, Judson,” she said, coolly, not at all discomposed by his rudeness; but I could see my firmness had offended her. She would not soon forgive my excluding Rolf.

Rolf waited till she was out of sight, and then he recommenced his kicks. I exchanged a glance with Judson; her harassed face seemed to appeal to me for help.

“Master Rolf,” I said, indignantly, “you call yourself a gentleman, but you are acting like an ill-tempered baby, and I shall treat you like one,” and to his intense astonishment I lifted him off the ground, and, being pretty strong, managed to carry him, in spite of his kicks and pinches, down to the hall, followed by Judson. Probably he had never been so summarily dealt with, for his kicks diminished as we descended the stairs; and I left him on the hall mat, looking rather subdued and ashamed of himself.

I had gained my point, but I felt out of heart as I went back to the nursery. I had entered the house prejudiced against Mrs. Markham, and our first interview had ended badly. My conscience justified me in my refusal to admit Rolf; but all the same, I felt I had made Mrs. Markham my enemy. Her cold eyes had measured me superciliously from the first moment. Very probably she disapproved of my appearance. With women of this calibre—cold, critical, and domineering—poor gentlewomen would have a chance of being sent to the wall.

When the children were asleep I seated myself rather disconsolately by the low nursery window. Hannah had been summoned to the housekeeper’s room to see her sister Molly, and had left me alone.

I felt too tired and dispirited to settle to my work or book; besides, it was a shame to shut out the moonlight. The garden seemed transformed into a fairy scene. A broad silvery pathway stretched across the park; curious shadows lurked under the elms; an indescribable stillness and peace seemed to pervade everything; the flowers and birds were asleep; nothing stirred but a night moth, stretching its dusky wings in the scented air, and in the distance the soft wash of waves against the shore.

I laid my head against the window frame, and let the summer breeze blow over my face, and soon forgot my worries in a long, delicious day-dream. Were my thoughts foolish, I wonder!—mere cobwebs of girls’ fancies woven together with moonbeams and rose scents!

“A girl’s imagination,” as Aunt Agatha once said, “resembles an unbroken colt, that must be disciplined and trained, or it will run away with her.” I have a notion that my Pegasus soared pretty{211} high and far that night. I imagined myself an old woman with wrinkles and grey hair, and cap border that seemed to touch my face, and I was sitting alone by a fire reviewing my past life. “It has not been so long, after all,” I thought; “with the day’s work came the day’s strength. The manna pot was never empty, and never overflowed. Who is it said, ‘Life is just a patchwork?’ I have read it somewhere. I like that idea. ‘How badly the children sew in their little bits—a square here and a star there. We work better as we go on.’ Yes, that queer comparison is true. The beauty and intricacy of the pattern seem to engross our interest as the years go on. When rest-time comes we fold up our work. Well done or badly done, there will be no time for unpicking false stitches then. Shall I be satisfied with my life’s work, I wonder? Will death be to me only the merciful nurse that call us to rest?”

“Why, Miss Fenton, are you asleep? I have knocked and knocked until I was tired.”

I started up in some confusion. Had I fallen asleep, I wonder? for there was Miss Cheriton standing near me, with an oddly-shaped Roman lamp in her hand, and there was a gleam of fun in her eyes, as though she were pleased to catch me napping.

“You must have been tired,” she said, smiling. “The room looked quite eerie as I entered it, with streaks of moonlight everywhere. Dinner is just over, and I slipped away to see if you are comfortable. I am afraid you are rather dull.”

But I would not allow that, for what business has a nurse to be subject to moods like idle people? but I could not deny that it was very pleasant to see Miss Cheriton. She was certainly very pretty—a good type of a fresh, healthy, happy English girl, and there is nothing in the world to equal that. The creamy Indian muslin gown suited her perfectly, and so did the knot of crimson roses and maidenhair, against the full white throat; and the small head, with its coil of dark shiny hair, was almost classical in its simplicity. A curious idea came to me as I looked at her. She reminded me of a picture I had seen of one of the ten virgins—ready or unready, I wonder which! The bright-speaking face, the festive garb, the quaint lamp, recalled to me the figure in the foreground, but in a moment the vague image faded away.

“How I wonder what you do with yourself in the evening, when the children are asleep!” observed Gay, glancing at me curiously. Then, as I looked surprised at that, she continued, sitting down beside me in the window-seat, in the most friendly way imaginable:

“Oh, Violet has told me all about you. I am quite interested, I assure you. I know you are not just an ordinary nurse, but have taken up the work from terribly good motives. Now I like that; it interests me dreadfully to see people in earnest, and yet I am never in earnest myself.”

“I shall find it difficult to believe that, Miss Cheriton.”

“Oh, please don’t call me Miss Cheriton; I am Miss Gay to everyone. People never think me quite grown-up, in spite of my nineteen years. Adelaide treats me like a child, and father makes a pet of me. By the bye, you have contrived to offend Adelaide. Now, don’t look shocked—I think you were quite right. Rolf is insufferable; but you see no one has mastered him before.”

“I was very sorry to contradict Mrs. Markham, but I am obliged to be so careful of Joyce—she is so nervous and excitable; I should not have liked her to see Rolf in that passion.”

“Of course you were quite right; I am glad you acted as you did; but you see Rolf is his mother’s idol—her ‘golden image,’ and she expects us all to bow down to him. Rolf can be a nice little fellow when he is not in his tantrums; but he is fearfully mismanaged, and so he is more of a plague than a pleasure to us.”

“What a pity!” I observed; but Gay broke into a laugh at my grave face.

“Yes, but it cannot be helped, and his mother will have to answer for it. He will be a horribly disagreeable man when he grows up, as I tell Adelaide when I want to make her cross. Don’t trouble yourself about Rolf, Miss Fenton; we shall all forgive you if you do box his ears.”

“But I should not forgive myself,” I returned, smiling; “the blow would do Rolf more harm than good.” But she shrugged her shoulders and changed the subject, chattering to me a little while about the house and the garden, and her several pets, treating me just as though she felt I was a girl of her own age.

“It is nice to have someone in the house to whom one can talk,” she said at last, very frankly; “Adelaide is so much older, and our tastes do not agree. Now, though you are so dreadfully sensible and matter-of-fact, I like what I have heard of you from Violet, and I mean to come and talk to you very often. I told Adelaide that it was an awfully plucky thing of you to do; for of course we can see in a moment you have not been used to this sort of thing.”

“All dependent positions have their peculiar trials,” I replied. “I am beginning to think that in some ways my lot is superior to many governesses. Perhaps I am more isolated, but I gain largely in independence. I live alone, perhaps, but then no one interferes with me.”

“Don’t be too sure of that when Adelaide is in the house.”

“The work is full of interest,” I continued, warming to my subject, as Gay’s face wore an expression of intelligent curiosity and sympathy. “The children grow, and one’s love grows also. It is beautiful to watch the baby natures developing, like seedlings, in the early summer; it is not only ministering to their physical wants, a nurse has higher work than that. Forgive me if I am wearying you,” breaking off from my subject with manifest effort, “one must not ride a hobby to death, and this is my hobby.”

“You are a strange girl,” she said, slowly, looking at me with large puzzled eyes. “I did not know before that girls could be so dreadfully in earnest, but I like to listen to you. I am afraid my life will shock you, Miss Fenton; not that I do any harm—oh, no harm at all—only I am always amusing myself. Life is such a delicious thing, you see, and we cannot be young for ever.”

“Surely it is not wrong to amuse yourself.”

“Not wrong, perhaps,” with a little laugh; “but I lead a butterfly existence, and yet I am always busy, too. How is one to find time for reading and improving oneself or working for the poor, when there are all my pets to feed, and the flower vases to fill, and the bees and the garden; and in the afternoon I ride with father; and there is tennis, or archery or boating; and in the evening if I did not sing to him—well, he would be so dull, for Adelaide always reads to herself; and if I do not sing I talk to him, or play at chess; and then there is no time for anything; and so the days go on.”

“Miss Gay, I do not consider you are leading a perfectly useless life,” I observed, when she had finished.

“Not useless; but look at Violet’s life beside mine.”

“In my opinion your sister works too much; she is using up health and energy most recklessly. Perhaps you might do more with your time, but it cannot be a useless life if you are your father’s companion. By your own account you ride with him, sing to him, and talk to him. This may be your work as much as being a nurse is mine.”

“You are very merciful in your judgment,” she said, with a crisp laugh, as she rose from the window-seat. “What a strange conversation we have had! What would Adelaide have thought of it! She is always scolding me for being irresponsible and wasting time, and even father calls me his ‘humming bird.’ You have comforted me a little, though I must confess my conscience endorses their opinion. Good night, Miss Fenton. Violet calls you Merle, does she not? and it is such a pretty name. The other sounds dreadfully stiff.” And she took up her lamp and left the room, humming a Scotch ballad as she went, leaving me to take up my neglected work, and ponder over our conversation.

“Were they right in condemning her as a frivolous idler?” I wondered; but I knew too little of Gay Cheriton to answer that question. Only in creation one sees beautiful butterflies and humming birds as well as working bees. All are not called upon to labour. A happy few live in the sunshine, like gauzy-winged insects in the ambient air. Surely to cultivate cheerfulness; to be happy with innocent happiness; to love and minister to those we love, may be work of another grade. We must be careful not to point out our own narrow groove as the general footway. The All-Father has diversity of work for us to do, and all is not of the same pattern.

(To be continued.)

{212}

The world-wide existence and remote antiquity of heraldic insignia—before heraldry emerged from its infancy, and developed into a science—is an established fact. To enter exhaustively into this branch of my subject, its historic and artistic interest, and valuable practical uses; its institution by Divine ordinance; together with its various accessories—comprising war-cries, badges, mottoes, seals, and devices—would demand far more space than could be allocated in a weekly magazine.

Some of my readers, it may be, will inquire, “What is Heraldry?” and lest this should be the case, I must commence by stating that it is the practice, art, or science of recording genealogies, the blazoning of arms or ensigns armorial, and all that relates to the marshalling of state ceremonies, processions, and cavalcades; the devising, also, of suitable arms and badges for families, guilds, cities, and regiments. This brief explanation supplied to the uninitiated, we may enter at once on the historical department.

The antiquity of distinctive badges and ensigns dates back, as I have premised, to long-ago ages of the world. No exact period can be assigned to their first adoption by Eastern nations; from whence the custom spread to the West. It would appear that in the first instance only nations, or tribes of one and the same people, distinguished themselves by special emblems displayed on their banners; although certain princes and warriors adopted personal devices. In later times, such distinctions were granted to families likewise, as hereditary honours, in reward for chivalrous service rendered to their country. Such rewards were more esteemed by many than gifts of money or lands, as they sacrificed life or limb as patriots, and needed no pecuniary compensation.

And here I must draw attention to the fact that the granting of such rewards for distinguished service as should commemorate that service for all generations, and confer hereditary honour on the hero’s descendants, was, in its character, in accordance with the just and liberal dispensations of the All-wise Himself. He is “a rewarder of them that do well;” and while visiting the sins of the fathers upon the children, unto the third and fourth generation, He “shows mercy unto thousands in them that love Him.” To such He says: “The promises are to you, and to your children” (Acts ii. 39), because “they are the seed of the blessed of the Lord; and their offspring with them” (Isa. lxv. 23)—a clear case of hereditary blessing; for, “as touching election,” we are told “they are beloved for the fathers’ sakes.” Duly considering the Divine example, it seems to me that ample precedent exists for the reward of well-doing in a man’s descendants; more especially as, in most cases, those commemorative rewards exist in a title only, or an escutcheon on his seal.

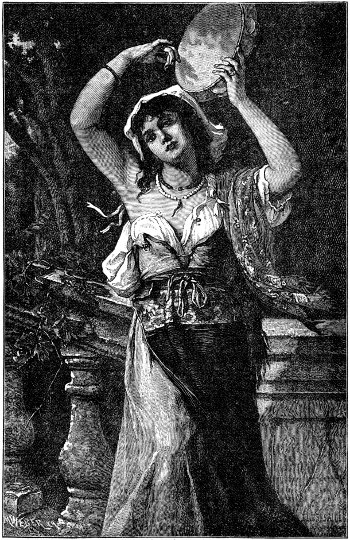

A TOURNAMENT.

We return now to our historical data, in reference to the infancy of the art in question. Those who are acquainted with the classics will find many references to the use of heraldic emblems before that use was reduced to a complete and perfect science. According to Herodotus, the Carians were the first who put crests upon their helmets and sculptured devices on their shields. These Carians inhabited a country in the south-west angle of Asia Minor, of which Halicarnassus was the capital and Miletus its rival—both famous cities of antiquity. The princes of Caria reigned under Persian protection, but the kingdom was annexed to Rome about 129 years before Christ. Herodotus further observes that Sophanes “bare on his shield, as a device, an anchor,” and Tacitus speaks of the standard, eagles, and other ensigns in use of the Romans. Xenophon, also, says that the Median kings bore on their shields the representation of a golden eagle. The Greeks adopted crests from the Carians, and had flags adorned with images of animals, or other devices bearing a peculiar and distinctive relation to the cities to which they belonged. For instance, the Athenians chose an owl, that bird being sacred to the goddess Minerva, the patron and protector of their city, while the Thebans were represented by a sphinx, in memory of the monster overcome by Œdipus. The emblem of Persia was the sun, of the Romans an eagle; the Teutonic invaders of England bore a horse on their standards, and the Norsemen a raven.

The figure-heads on the prows of our own ships owe their origin to the times of the Phœnicians and Bœtians, who distinguished theirs by a figure of one of their gods, being thenceforth the tutelar god and protector of the vessel. Thebes was the principal city of Bœtia; and their tutelar divinity, Cadmus, having been the founder of that city, was represented on their flags, having a dragon in his hand. They also used flags to distinguish one ship from another, which were placed in the prow or stern; and these were sometimes painted to represent a flower, tree, or mountain; and the names of the vessels were taken from the devices respectively portrayed upon them.

Before our system of heraldry was organised, even in a yet imperfect degree, we read that the ancient British kings, Brute, Lud, Bladud, and others, all assumed their respective insignia. Brute bore on a golden shield a “Lion rampant gules, charged on the neck and shoulder with three crowns in pale.” Camber, another British monarch, bore on a silver shield two lions passant gardant, gules.

Even to this day, the descendants of the British Prince Cadogan-ap-Elystan bear the arms of their warrior ancestors—“gules, a lion rampant regardant or,” and combined with them the badge of the three Saxon chiefs (brothers), i.e. “three boars’ heads couped sable, on a silver field”—which chiefs he slew in battle with his own hand.

In the same way, the Saxons, who succeeded, and partially exterminated our ancient British ancestors, are still memorialised by the badges of their thanes; and later on, the Normans—so reputed in the annals of chivalry—were all individually distinguished by their armorial bearings.

As time went on, ripening all arts and sciences—or is supposed to do so—heraldry began to develop, and to be regulated by certain rules under State control, and the spirit of chivalry, that grew with the institution of the crusades, jousts, and tournaments, may be credited with that development. The English knights under Cœur de Lion, and the French under Philip Augustus, wore emblazoned shields; and such of my readers who may visit the Museum at Versailles may see a fine collection of those worn by the crusaders, arranged in proper order. There are (or were some thirty years ago) no less than 74 of these “écussons,” which belonged to “seigneurs les plus illustrés et les plus puissants,” including those of our lion-hearted king, and Philip Augustus, before named. These all date from the first Crusade, in 1095, down to the time of Philip “le Hardi,” 1270. But, over and above these emblazoned shields, once used by the grandest examples of Middle Age chivalry, the visitor to this museum will find some 240 others, bearing heraldic insignia worn by crusaders of less exalted rank than the illustrious personages better known to fame comprised in the seventy-four first-named. The better to appreciate such an exhibition, the student should previously acquaint herself with the curious and charming “Chronicles of Froissart,” than which no romance could ever prove half as interesting, and certainly not as desirable for study, being a faithful and graphic history of those warlike times.

To obtain an appreciable idea of a field prepared for a tournament, we refer the reader to the eighth chapter of Sir Walter Scott’s “Ivanhoe.” The picture he gives of the scene is worth notice. Imagine the gay{213} pavilions ranged side by side, and the arms of the several knights, emblazoned on their shields, suspended before the entrance of each and guarded by their squires, the latter being curiously attired, according to his lord’s particular fancy. Then picture to yourselves the knights, armed cap-à-pie, mounted on splendidly caparisoned chargers, and riding up and down the lines, and the whole field glittering with arms and bright with gorgeous banners.

But perhaps some reader may say, “Cui bono? What a vain exhibition and useless expenditure of money!” Nay, such condemnation is scarcely just. In those half-civilised, warlike times danger threatened the country on every side, at home and abroad, and at any unexpected moment; and such practice in the science of arms and reviews of the efficiency of the knights and leaders of our armies were absolutely essential. Even in our own day it is a thoroughly well recognised fact that such a terrible service as that of arms needs all the external attraction with which it can possibly be invested to induce volunteers to enter its ranks. Were there no band, no uniform, no decorations nor rewards for gallantry in prospect, thousands who, when face to face with the enemy, would give their lives for their country without a moment’s hesitation, would be revolted if, in the first instance and in cold blood, they were invited to dress in a butcher’s apron, and were presented with a mallet or cleaver. But these few reflections may suffice in reply to objectors, and we will return to the history under review.

It was not until the latter end of the twelfth century, about the time of Philip le Hardi, that the science of mediæval armory developed into a system. In the thirteenth century it had gained in growth and in favour, the uses of the art being more fully recognised. Thus, under the reign of Henry III. a regular system, classification, and technical language of its own were devised and organised.

The earliest heraldic roll of arms actually still existing is dated at the time of Henry III. It is a copy, of which the original was compiled (according to Sir Harris Nicholas) between the years 1240 and 1249, and the regular armorial bearings of the king, princes of the blood, chief barons, and knights of England were correctly blazoned. Moreover, most of the principal terms in use in the present perfected state of the art are to be found on this roll. A second of the same period still exists, comprising nearly seven hundred coats of arms, besides other and similar heraldic records, which are likewise preserved to this day, belonging to the several reigns of the first, second, and third Edwards and of Richard II. It appears that the right to bear arms was inaugurated at some time in or about the reign of Henry II.

In the reign of Henry V. a registry of armorial bearings was inaugurated, rendered essential for the avoidance of confusion and the just settlement of disputations; but the incorporation of the officers of this College of Arms by royal charter was granted in 1483 by Richard III. The several titles and duties of these officers shall be duly recorded in another part of this series; for to the apparent origin and antiquity of heraldic insignia, and the gradual development of their use into a science, I must for the present confine my attention.

Cold Harbour was the name of the mansion allocated to the heralds as soon as incorporated into a college. It was erected between Blackfriars and St. Paul’s Wharf by Sir John Poulteney, who was four times elected Lord Mayor of London. This mansion was successively known as York Inn, Poulteney’s Inn, and thirdly as Cold Harbour. In the reign of Mary I. she removed the college to Derby House, previously the palace of the Stanleys, and bestowed it on them by charter, Dethick being Garter King-of-Arms at that time. This ancient building stood on St. Benet’s Hill, and was destroyed in the Great Fire of London, A.D. 1666; but the valuable records were all saved and conveyed to Whitehall, Charles II. sending his private carriages for the purpose. Thither also the heralds removed and continued to reside until upon the original site the present college was erected. Of this building Sir Christopher Wren was the architect, the north-western portion having been built at his own expense by Dugdale. It was constructed in the form of a quadrangle, but the formation of a new street caused the removal of the southern side, and the form was changed. To obtain further particulars respecting this interesting institution and all its treasures we recommend a visit to the college, if the means of admission can be procured through acquaintance with some one of the officers connected with it.

So far I have given a brief account of the remote origin and growth of heraldry. I now proceed to name a few of the leading uses claimed for armorial insignia, and still further for the institution of a regularly organised system in connection with them under the authority of the State.

In the first place, when a knight was encased in armour and wore (as the hand-to-hand warfare of the times necessitated) a visor to protect the face, it became equally essential that some external sign should identify him as a friend or foe and distinguish him as a leader and the lord of his special retainers and squires. Thus the rewards granted in the form of heraldic escutcheons emblazoned on his shield, and the crest that surmounted his helmet identified him, and even in the thick of a close encounter, when the shield might be hidden from view, the crest could be seen and his identity recognised.

Thus, likewise, the standards used by the conflicting hosts served to distinguish at a distant point of view the friendly or hostile forces one from the other, whence the shields and crests would have been indistinguishable. To those individually engaged in mortal combat, and to the countries whose woe or weal hung on the issue of a battle, the usefulness of employing emblazoned standards and shields and the wearing of crests was sufficiently self-evident.

Again, amongst the uses of heraldry, as at present existing and developed into a science, I may name the service rendered to private families by the records preserved, the investigation of claims to property, the identification of relationships, and finding of next of kin; the distinguishing between one branch of a family from another, proved by some trifling differences in the arms they respectively bear, or in the crests or mottoes; usurpation of arms and titles, and unjust pretensions to the privileges due only to legitimacy, to the injury of real heirs—all these are rights or evils which the College of Heralds alone is in a position to investigate, prove and maintain, or expose and frustrate, respectively. Such public services as these, not confined to the titled or untitled aristocracy, nor even to the upper commoners of the country, but available to all classes when seeking relationships, and through relationships property, or when searching for registries of births, deaths, or marriages—such public services as these, I say, ought surely to be duly recognised by all.

Lastly, so long as public pageants and processions continue to exist—no less interesting and attractive to the poorer spectator than to the great personages that are fêted—so long as there are royal presentations, investitures with orders of knighthood, coronations, and grand State ceremonies to be conducted, and processions marshalled in suitable order—just so long the offices of the College of Heralds will be essential to the requirements of the State and country.

And now I have reached the last part of my subject with which this, my first chapter, has to deal, i.e., that in its broad features heraldry is supported by the highest possible authority. The formation of pedigrees, the use of emblematic signs and figures, and of emblazoned standards, as distinctive badges, was not merely permitted, but was Divinely ordained. To many customs of the world around them the “elect people of God” were forbidden to conform. In the case in question it was otherwise.

In proof of this assertion, let me refer the reader to the Book of Numbers, chap. i., 2, 18, 52. There we read as follows: “Take ye the sum of all the congregations of the children of Israel, after their families, by the house of their father, with the number of their names.” “And they declared their pedigrees, after their families, by the house of their fathers, according to the number of the names.” “And the children of Israel shall pitch their tents, every man by his own camp, and every man by his own standard, throughout their hosts.” Again, in the same book, chap. ii., 2, 34, we read thus: “Every man of the children of Israel shall pitch by his own standard, with the ensign of their father’s house.” “And the children of Israel did according to all that the Lord commanded Moses; so they pitched by their standards, and so they set forward; everyone after their families, according to the house of their fathers.”

What some of these several standards represented, so as to distinguish one tribe from another, we have not far to seek, although we have no data whereby to determine the devices of the several families they each comprised. Jacob, the patriarch and father of these elect tribes, allocates to each its fitting symbol. To ascertain what these were I refer the reader to the blessing he gave them when his pilgrimage was rapidly drawing to its close. (See Gen. xlix. 10, 13, 14, 17, 19, 20, 21, 22, 27.) Some of the tribes had two emblems, as in the case of Judah—a lion and a sceptre (or kingly crown)—and Joseph—a bunch of grapes and a bow—these two sons of the patriarch inheriting respectively the birthright and the blessing. Other emblems of a representative character were attributed to these Hebrew tribes by Moses also, for which I refer the reader to Deut. xxxiii.

In my next chapter I propose to enter on what is designated the “grammar of heraldry,” and without further taxing the reader’s patience, I now take my leave.

(To be continued.)

{214}

By PHILLIS BROWNE, Author of “The Girl’s Own Cookery Book.”

A certain young lady, a member of The Girl’s Own Cookery Class (in other words, an individual who has educated herself in cookery, with the assistance of articles published in this journal), was married a few weeks ago. Her husband is an exceedingly good fellow, and holds a salaried position in a mercantile establishment. He has plenty of common sense and energy, and, if all goes well, he will make his way; but at the present moment he is not very well off. He has, however, managed to save enough to furnish the small home very prettily and very well, while his wife has received from her father a handsome trousseau, a good supply of house linen of every sort and kind, and a good many odds and ends of things. Besides this, the young couple, having a large circle of friends, have been presented with a considerable number of wedding presents.

Young beginners in these days are really very fortunate; for they get so much friendly help in starting life. It very much simplifies matters if, just as one has arrived at the conclusion that a dinner service is imperatively required, but that the money for purchasing the same is not immediately forthcoming, a knock is heard at the door, and a box is brought in containing a handsome dinner service of the newest pattern and latest fashion, as a small proof of the affection of a friend. The young people now referred to have been most lucky in this way. They must have received scores of presents, all useful, all judiciously chosen, and with only two duplicates, which were speedily exchanged for something else. That delightful Parcel Post has been a messenger of good fortune to them. Pretty things for the table have arrived in profusion; ornaments, pictures, silver, glass, china, cutlery have appeared upon the scene as if by magic; and the result of it all is that the home of this newly-wedded pair is as thoroughly well appointed all the way through as anyone need wish a home to be.

The routine of married life in these days is first the wedding day, then the honeymoon, and then any amount of visiting—dinner parties and supper parties without limit. Old-fashioned individuals may disapprove of this, and say that it would be better for the newly-wedded to settle down quietly, look at life from a serious standpoint, read improving books aloud to each other in the evenings, and save up every available halfpenny for a future rainy day. Without doubt, the old-fashioned individuals are right; but, unfortunately, few young married people see as they do. Experience is the great teacher, and its lessons can never be learnt by proxy. These young people have not yet been to that school. They have their charming home, their many friends, their limited income, and their pretty table appliances; and the question has now arisen—How shall they entertain their friends? They plume themselves on being prudent; they have no wish to run into extravagance, and they have no thought of entertaining everyone whom they know; but they are hospitably inclined, and they have deliberately arrived at the conclusion that there are one or two special friends whom they must invite, and whom they must make a little fuss over. The result of it all has been the bride’s first dinner party.

When first the subject of an entertainment was mooted, the young bride, whom we will call Mabel, was much exercised as to whether it would be wiser to have high tea or dinner. There was much to be said in favour of both. With high tea it was possible to have everything cold, and put on the table all at once, and this would enable the mistress to see the table laid, and be sure that everything was right before the guests arrived, a consideration not to be disregarded where there was only one little maid, and that one only eighteen, though clever for her age. The bride thought of the anxiety which she would have to go through if there were to be an awful pause between the courses, and then Emma were to come to her side and say, “Please, mum, the pudding won’t turn out!” What should she do? Then too, high tea was quieter, and less pretentious, and the young housekeeper had no desire to make a display beyond her means. On the other hand, dinner would be pleasanter; and, best of all, it would furnish an occasion for bringing out all the pretty presents, the bright silver, the exquisite glass, the artistic table ornaments, the elegant dinner and dessert services. Where was the good of being possessed of all these treasures if they were always to be kept locked up in a cupboard? With these presents a dinner-table could be laid out so effectively that the food would be quite a minor detail. Besides, “the master” preferred dinner. In his bachelor days he had been accustomed to dine on leaving business, and had learnt to regard high tea as a nondescript sort of meal, only to be accepted as a painful discipline when it could not well be avoided. Of course, the master’s likes and dislikes counted for a good deal with the mistress, and dinner was almost decided upon. But then came the question, “Which meal would be the more expensive of the two?” Expense was the chief consideration after all. Everything had to be paid for with ready money, and a committee of two of ways and means had decided that a sovereign must cover all expenses apart from beverages. There were to be six guests, eight in all with master and mistress; could the thing be done for £1 sterling? The young lady was doubtful.

At this stage of the cogitation, a double knock was heard, and in a minute or two the maid, young but clever for her age, came up and announced that Mrs. Jones had called to see Mrs. Smith. Amy Jones! exactly the person to consult. Amy was an old school-mate of the bride’s, had been married a couple of years ago, enjoyed almost the same yearly income, and deserved the reputation of having arrived at Dora Greenwell’s idea of perfection; that is, she had, up to this point, not merely made both ends meet, but made them tie over in a handsome bow. Yet she had been hospitable, too. A person of such abundant experience would be sure to know what was best.

“Amy, if you were in my place, which should you decide upon, a high tea or a small dinner?”

“You have begun to consider the claims of hospitality, have you, Mabel! What is your maid like?”

“She is a very good little girl, and she does her best, but she is very slow. If all goes on quietly, she manages excellently, but if she were to be flurried, I do not know what would happen.”

“That’s bad,” remarked experienced Amy Jones.

“Yet she means well, and really does her best,” continued the young mistress, anxiously eager to defend her first domestic. “She can cook plain dishes fairly, and is interested in her work. If I tell her a thing, she never forgets.”

“That’s good; almost good enough to make up for the slowness. Can she wait?”

“Not properly. She can bring dishes and plates into the room and take them out again quickly, but that is almost the extent of her power; she could not hand round dishes or remain in the room during a dinner to be a credit or help. If we were to decide on dinner, don’t you think you would hire a waitress if you were me?”

“If you want my advice, dear, I should say, decidedly, do nothing of the kind. It would be an exhibition of effort which would involve pretence, and the slightest pretence would be a mistake. Whatever you do, don’t go beyond the resources of your own modest establishment. At present, all your friends know exactly what your position is; they will respect you if you make the best of it, but if you seem to wish to go beyond it they will begin to criticise, while the people you care for most will blame you.”

“Then you would give up all thought of dinner?”

“I don’t say so. Why should you not have a small dinner? Prepare everything yourself, altogether dispense with regular waiting, show Emma exactly what she has to do, and let her do her best. Supposing there should be a little contretemps, never mind; laugh at it, and your friends will laugh with you. They will only say that you are inexperienced. If all should go well, how pleased your husband will be! You are sure you don’t mind the trouble?”

“Mind the trouble! I like it. I think it is fun. I am only uneasy about the expense.”

“Well, dear, I should say that high tea, though less troublesome, is quite as expensive as dinner. We can easily ascertain the truth, however. Let us take paper and pencil, and draw up a statement of the cost of both. We will begin with the high tea. I suppose we are to take it for granted that you must have something extra? It would not do to have a thoroughly simple meal.”

“Oh, no. If we ask six people on such an occasion, we must make a sort of feast. Let me think. You put the items down as I decide on them. We might have a lobster salad, a couple of boiled fowls with egg sauce, a beefsteak and oyster pie, a strawberry cream, a jelly of some sort, a few tarts and cheesecakes, some fruit and fancy biscuits. Then, of course, tea and coffee and thin bread and butter, brown and white. That would do well enough. We could not well have less.”

“A very excellent menu, indeed,” said Amy, while a rather amused look passed over her face. “What do you suppose it will cost?”

“I don’t know,” said Mabel. “You cast it out and see. You understand prices better than I do.”

For a while there was silence, and nothing was heard but the scratching of a pencil. Then Amy read aloud:—“Lobster salad, 3s. 3d.; boiled fowls and egg sauce, 7s. 11d.”

“Oh, dear!” said Mabel.

“Well, you see, it is spring, and fowls are dear in the spring. I do not suppose you could get a fine pair for less than 3s. 6d. each. Beefsteak and oyster pie, 5s.; strawberry cream (made with your own jam), 1s. 8d.; orange jelly, 1s. 4d.; tarts and cheesecakes we will calculate roughly at 1s. 4d.; a little fruit, 2s.; tea and coffee (say 2d. per person), 1s. 4d.; bread and butter, 2s. Altogether say £1 5s. 10d.”

{215}

“That will never do,” said Mabel. “We must take something away.”

“For one thing, you might take the tarts and cheesecakes. Surely they are not necessary.”

“One wants a little trifle of the sort to conclude the meal,” said Mabel.

“Then make jam sandwich. I can give you a simple recipe, by following which you can produce a dishful for less than sixpence.”

“Thanks. But that will not make matters right. We must reduce much more than that.”

“Suppose that before doing so we draw up a dinner, and see what we can make of that. I will furnish the menu this time.”

“Very good. Only remember to take into consideration Emma’s limited capacity,” said Mabel.

Again there was silence. After a few minutes Amy read aloud once more:—

Menu.

Estimate.

Potato soup, 11d.; tomatoes farcies, 1s.; mutton, forcemeat, gravy, &c., 6s. 9d.; potatoes and celery, 6d.; orange jelly, 1s. 4d.; ready-made pudding, 1s. 3d.; macaroni cheese, 9d.; dessert, 3s.; coffee, 10d. Altogether, 16s. 4d.

Mabel was silent for a moment from amazement. Then she said—

“That is very extraordinary. I would not have believed it.”

“Yes, dear. But you must take into account that you drew up rather a luxurious tea; and my dinner is a very simple and homely one. Therefore you were scarcely fair to yourself.”

“I only described the sort of high tea we should have had at home before I was married.”

“And you forgot that your mother did not need to make a sovereign cover all expenses.”

“And yet your dinner sounds more satisfactory than my tea, and I am sure it would look more. I wonder if Emma could manage a dinner like that; she is not entirely ignorant. She can roast a joint, and boil potatoes very well, and she can bake a pudding——”

“Then I am sure she could manage, for everything else you could yourself prepare beforehand. Of course, if she were more of a cook, you might have a little fish, or perhaps a trifle of game after the mutton, and still keep within the sovereign.”

“I feel that I should be wiser to experiment first in a small way,” said Mabel.

“Very well. The potato soup you know well. It is good, and cheap; you can get it ready beforehand, so that Emma will only have to make it hot. The mutton you can get the butcher to bone, and then stuff it with veal forcemeat, and roll it early in the day, leaving Emma to roast it. The gravy, also, you can make ready, and put, nicely seasoned and free from fat, in a cup, so that Emma will need only to put it in a saucepan to get hot when she begins to dish the meat. The tomatoes you can prepare. The celery and potatoes you may leave with her, I should think.”

“Decidedly; she boils vegetables very well, and she can mash potatoes, and put browned potatoes round quite easily. I had better make the sauce for the celery, though.”

“You might make it, and put it in a gallipot in a saucepan with boiling water round, to keep hot. Then surely if you make the soup, if you prepare the meat, and make the gravy, make the sauce, get the tomatoes ready, make the jelly, mix the pudding, three parts cook the macaroni, dish the dessert, and altogether make the coffee, there can be no danger.”

“I shall be rather tired by the time our friends arrive,” said Amy, looking a little grave as she realised the responsibilities which she was proposing to take upon herself.

“Oh, yes; you will have to be very quick, and to do all the head-work. But you said you did not mind the trouble. And besides, remember this, if once you can succeed in your attempt you will find that you are not at all more tired with providing dinner than you are with providing high tea. But there are just two things you would do well to try for, in my opinion.”

“What are they?”

“One is to make Emma well acquainted with every dish beforehand. Let her understand how things ought to be and to look when properly cooked; on no account let the final touches be the product of her imagination as exercised in carrying out your descriptive order.”

“No, that would scarcely do,” said Mabel, laughing.

“Well, the only way to prevent it is to make the most of the time between now and the important day. Have potato soup one day, rolled mutton another, tomatoes farcies, and ready-made pudding a third, and macaroni cheese a fourth, and so make her familiar with what is coming.”

“And the second point?”

“I was going to suggest that if you have anything served in a style superior to your ordinary mode, you should try to keep Emma up to the better way as a regular thing. This will really be a great kindness to her. It will make her more skilful, and fit her for taking a better situation afterwards, and, strange to say, she will be all the happier for it. Right-minded girls (and I should quite think Emma is one) are glad to be shown refined ways, and they respect a mistress who understands and insists upon the best modes of doing things far more than they respect a mistress who lets things go, and puts up with slipshod fashions just for the sake of peace and quiet. And really you will find that when Emma knows what ought to be, all you will need to impress upon her is the time required for the various dishes.”

“That is it precisely,” said Mabel, who had been listening very quietly to her friend’s remarks, but who was evidently giving all her thoughts to the subject in hand. “I can see now exactly what I shall have to do. I shall make out a list of every ingredient, and have everything where it will be close to my hand, the day but one before the dinner. The day before I shall make the jelly and, with Emma’s help, brighten all the glass and silver, and look out any pretty ornaments and services. Then quite early on the eventful morning I shall make the soup, and put it ready for making hot; yes, I shall even fry and dish the sippets and chop the parsley, which will have to be sprinkled in at the last moment. I shall stuff and roll the mutton, dish the sour plums (those delightful sour plums! they were there without needing to be in the estimate; how good it was of Frau Bergmann to give them to me). I shall stuff the tomatoes, turn out the jelly, dish the dessert, arrange the coffee cups and saucers—but, oh, the coffee, what shall I do for that? Emma never makes it properly.”

“Few servants do; and if I were you I should look after it yourself in this case. The coffee is so very important. Really good coffee, served at the close even of an unsuccessful dinner, almost atones for disaster, while inferior coffee spoils the most recherché repast. Why should you not steal away for a minute or two when your friends leave the dining-room, make the coffee, and send Emma in with it. Then all is sure to be right.”

“Yes, that will be best. Well, as I was saying, I must be as busy as possible before luncheon. Then, after luncheon——”

“After luncheon I should lie down for an hour,” said Amy.

“Oh!” said Mabel, dubiously.

“Yes. It would be unfortunate if the dinner were a success, and the hostess laid up next day through fatigue.”

“May be. Yes, I will certainly rest awhile after luncheon. Then, while Emma prepares her vegetables, tidies the kitchen, and attends to the roast, I will lay the table; and I know I can make it beautiful.”

“What shall you do for flowers? We did not allow for them in our estimate.”

“I planted some corn a week ago in a large fancy bowl, and it will be lovely. Have you never done that? You get a few ears of corn, pack them in a bowl full of water, so that the ears are close together and are partially covered with the water. Put the bowl in a warm room, and in about a fortnight the delicate blades will peep out and grow to be very pretty. There could not be anything more effective for the middle of the table, and the grass lasts five or six weeks, and it is a most convenient decoration when flowers are scarce. We always used to provide ourselves with corn in harvest time for this purpose.”

“I will remember to do the same,” said Amy. “I never heard of growing corn in a bowl.”

“I can give you a little meanwhile to experiment with. Then, when the table is laid, I will dress, and when I come down will present Emma first with a written menu, giving a list of what is to go in with each course, and a few notes of reminder—something of this sort:—

“Remember—

“To put the pudding and tomatoes in the oven, also to pour the sauce over the macaroni and set it to brown, as soon as the last guest arrives.

“To put the plates for soup, meat, tomatoes, ready-made pudding, and cheese to heat half an hour before the dinner hour.

“To make the milk boil before stirring it into the boiling soup, and to sprinkle in the chopped parsley at the last moment.

“To shut the dining-room door after taking in or removing dishes, &c., and to move about as quietly as possible.

“To begin to dish the meat and vegetables and make the gravy hot the moment soup is in, so that everything may be quite ready when the bell rings.

“To put the coffee (left ready ground on the dresser) into the oven, to get hot, as soon as dessert is in, and at the same time to set a jug of milk in a saucepan of boiling water.”

“What is that for?” said Amy.

“It is to scald the milk. Coffee tastes so much more delicious when the milk is scalded, not boiled. There, I think that is all. I will write the notes early, and then, if anything else occurs to me, I can put it down. But, Amy, for safety’s sake would you mind giving me the recipes for the dishes in your menu. I have one or two, but they may be mislaid, and I should not like there to be a mistake.”

“There is not much fear of a mistake, if you take all that trouble. But I will give you the recipes with pleasure. In return, will you give me the recipe for the sour plums? I should like to have it, for I intend to make some when plums are in season.”

The arrangements thus laid down were implicitly carried out, and the “Bride’s First Dinner Party” was a great success—so much so that every guest remarked, when the evening was over, “What a clever little woman Mrs. Smith is! How fortunate her husband is to have a wife thus domesticated.” Then,{216} in a moment, “What lovely wedding presents!”

For the benefit of those who may care to have them, I subjoin a copy of the recipes which were exchanged between Amy and Mabel.

Potato Soup.—Melt a piece of butter the size of an egg in a stewpan. Throw in two pounds of potatoes, weighed after they have been peeled, the white parts of two leeks, and a stick of celery, all cut up. Sweat for a few minutes without browning. Pour on a quart of cold stock or water; boil gently till the vegetables are tender, and pass through a sieve. When wanted, make hot in a clean stewpan, and add salt and pepper. Boil separately half a pint of milk; stir this into the boiling soup. At the last moment sprinkle on the top of the soup a dessertspoonful of chopped parsley. If cream is allowed, the soup will be greatly improved.

Tomatoes Farcies.—Take eight smooth red tomatoes; cut the stalks off evenly, and slice off the part that adheres to them; scoop out the seeds from the centre without breaking the sides. Melt an ounce of butter in a stewpan. Put in two tablespoonfuls of cooked ham chopped, two tablespoonfuls of chopped mushrooms, two shalots, two teaspoonfuls of chopped parsley, pepper and salt, and two ounces of grated Parmesan. Mix thoroughly over the fire, fill the tomatoes with the mixture, and bake on a greased baking tin in a moderate oven for ten or fifteen minutes. The tomatoes should be tender, but not broken. If the ingredients for this forcemeat are not at hand, a little ordinary veal forcemeat may be used, but the taste will be inferior.

Rolled Loin of Mutton.—Get the butcher from whom the meat is bought to bone the loin; spread veal stuffing inside, roll it up, bind it with tape, and bake in the usual way. Thick, smooth gravy should be served with it. This may be made of the bones.

Mashed and Browned Potatoes.—Mash potatoes in the usual way. Prepare beforehand six or eight good sized potatoes of uniform size. Parboil them, then put them into the dripping-tin round the meat for about three-quarters of an hour—less, if small—and baste them every now and then till brown. Pile the mashed potatoes in the middle of the tureen, put browned potatoes round, and sprinkle chopped parsley on the white centre.

Stewed Celery.—Wash the celery carefully, and boil it till tender in milk and water, to which salt and a little butter have been added. The time required will depend on the quality. Young, tender portions will be ready in half an hour or less; the coarse outer stalks will need to boil a long time. Drain thoroughly, dish on toast, and pour white sauce over.

Sour Plums (a substitute for red currant jelly served with meat; to be made in the autumn).—Take three pounds of the long, blue autumn plums, almost the last to come into the market, called in Germany zwetschen. Rub off the bloom and prick each one with a needle. Boil a pint of vinegar for a quarter of an hour with a pound and a-half of sugar, a teaspoonful of cloves, three blades of mace, and half an ounce of cinnamon. Pour the vinegar through a strainer over the plums, and let them stand for twenty-four hours. Next day boil the vinegar, and again pour it over the fruit. Put all over the fire together to simmer for a few minutes until the plums are tender and cracked without falling to pieces. Tie down while hot.

Ready-Made Pudding.—Mix two tablespoonfuls of flour, an ounce of sugar, and a very little grated nutmeg, with a spoonful of cold milk to make a smooth paste, then add boiling milk to make a pint. When cold, beat two eggs with a glass of sherry, mix and bake in a buttered dish for half an hour.

Orange Jelly.—Soak an ounce of gelatine in water to cover it for an hour, and put with the gelatine the very thin rind of three oranges. Squeeze the juice from some sweet oranges to make half a pint, then add the juice of two lemons, and strain to get out all pips, etc. Take as much water as there is fruit juice, put this into a stewpan with the gelatine, and a quarter of a pound of loaf sugar, and simmer for a few minutes till the gelatine is entirely dissolved. Remove any scum that may rise, then add the juice; boil up once, and strain into a damp mould. This jelly has a delicious taste, and is not supposed to be clear.

Macaroni Cheese.—Wash half a pound of Naples macaroni, break it up and throw it into boiling water with a lump of butter in it, and boil it for about half an hour, till the macaroni is tender. Drain it well. Melt an ounce of butter in a stewpan, stir in one ounce of flour, and, when smooth, half a pint of cold milk. Stir the sauce till it boils, add salt and pepper, an ounce of grated Parmesan, and the macaroni drained dry. Pour all upon a dish, sprinkle an ounce of macaroni over, and brown in the oven or before the fire.

Simple Jam Sandwich.—Beat three eggs, and add a breakfastcupful of flour, to which has been added a teaspoonful of cream of tartar. Beat the mixture till it bubbles. Add a scant breakfastcupful of sifted sugar. Beat again, and add half a teaspoonful of carbonate of soda. Turn into a shallow baking tin, greased, and bake for a few minutes in a quick oven. With the oven ready, this cake can be made and baked in half an hour.

By CATHERINE GRANT FURLEY.

{217}

A GIRTON GIRL.

{218}

A PASTORALE.

By DARLEY DALE, Author of “Fair Katherine,” etc.

HOPE AND FEAR.

s soon as the shearing company was gone, John Shelley went into the house to watch by Charlie’s couch, and to take counsel with his wife as to what must be done about Jack, as to whose safety he was as anxious as about Charlie’s, for if the latter died Jack would inevitably be tried for manslaughter, though the shepherd felt sure the fall on the stone gate-post was a far more serious matter than the blow Jack had dealt, and which had accidentally, and quite unintentionally, caused the fall.

All Jack had meant to do, as the shepherd and his wife knew well enough, was to give Charlie a good bang across the shoulders, but if the boy died it might be a difficult matter to persuade a coroner’s jury that no more was intended, especially as Jack, by keeping himself aloof, as he did, from his own class, was by no means popular in the neighbourhood.

Mrs. Shelley was even more keenly alive to the danger which threatened Jack than her husband, and was for sending him away at once to her brother, who lived at Liverpool, but John Shelley never acted hastily or on impulse, and he suggested taking counsel with the doctor and Mr. Leslie, both of whom were good friends of Jack’s, before they decided on any course of action.

“We’ll send Jack round to the rectory as soon as he comes back; he will be glad of something to do, tired and hungry as he must be, for I see he has not had his supper yet,” said the shepherd.

“No, he won’t touch anything till there is some hope of Charlie, I daresay. He has been unconscious nearly an hour now, John. Do you think there is any hope?”

“Yes, I do; while there is life there is hope. I expect it is concussion of the brain, and if so, people are often unconscious for hours. He is breathing, you see. But where is Fairy? Why does not the child come in? Is she frightened?”

“I don’t know, I am sure; I had forgotten all about her. Just see, John, will you? She has had no supper either,” replied Mrs. Shelley.

John went to the door to look for Fairy just as Jack and Dr. Bates came up together. The shepherd brought the doctor in, and sent Jack to the rectory, and then went to talk to Fairy, who was still sitting on the bench outside.

“Why have you sent for Mr. Leslie? Is Charlie worse?” asked Fairy, anxiously, as she beckoned to the shepherd to sit by her side.

“No, he is just the same, but I want to ask Mr. Leslie’s advice about Jack; I am afraid we shall have to send poor Jack away. Shall you be sorry, Fairy?”

“Sorry! Of course I shall; but, John, why must Jack go as well as I? Mother says it is all my fault, and I am to go away, and I don’t know where to go, so I was waiting till you came, to ask you; but if Mr. Leslie is coming, I daresay he’ll take me in for a little while,” said Fairy, with a little sob at the end of each sentence.

“Mr. Leslie take my Fairy in. Why, child, you would not leave us now in our hour of trouble, when we most want you to comfort us, would you?”

“I don’t want ever to leave you, unless, of course, I find my own parents; but mother says I am to go, and she is sorry she ever took me in, because it is all my fault. So you see, John, of course I must go away after that,” said Fairy, gently.

“I can’t spare my little Fairy now. Mother did not mean what she said; she was so upset at seeing poor Charlie insensible, I expect she hardly knew what she was doing, so you must forgive her—will you, little one?—and stay and cheer us in our sorrow,” said John.

“Of course I will, if you are quite sure mother didn’t mean it, but she should not have said it was my fault, should she? For she knows as well as you do, John, how fond I am of both the boys, and how I never let them quarrel; only this was done in such a minute I could not stop it; it really was more an accident than anything else. Poor Jack didn’t mean to knock Charlie down, or to hurt him really, only he was so angry about that lamb that he lost his temper. How grave you look, John; you don’t think it was my fault, do you?”

Now the shepherd understood perfectly what his wife had meant by saying it was Fairy’s fault; but it was evident the child had not the remotest suspicion of Mrs. Shelley’s meaning; she was too childlike and innocent (children of that day were less precocious and more like children than they are now), too free from vanity and self-consciousness to be aware that Jack had any other feeling for her than a brotherly affection, and it was equally evident that at present, at any rate, Fairy’s affection for Jack was of precisely the same character as her sisterly love for her foster-brother. Seeing this, the shepherd felt his wife was right in saying it would be far better for many reasons that Jack should go away; but he was so lost in thought that he forgot to reply to Fairy’s question, which, after waiting a minute or two, for she was accustomed to John’s slowness of speech, she repeated.

“No, my child, no, I am sure it was no fault of yours; don’t think any more about it. Here comes Jack with Mr. Leslie; I will go in and hear what the doctor says. Ask Mr. Leslie to wait in the kitchen for a minute, if he does not mind,” and the shepherd went indoors to hear the doctor’s report just as Jack and Mr. Leslie appeared.

“‘COME, CHILD, YOU HAVE HAD NO SUPPER YET.’”

See “The Shepherd’s Fairy,” p. 219.

{219}

They both looked very grave, for Jack was a great pet of the rector’s, and he had already told him exactly how the accident had occurred; and Mr. Leslie was almost as anxious as Jack to hear the doctor’s report, for Jack seemed so absorbed in his anxiety about Charlie as to be unconscious of his own danger.

“How is he?” they exclaimed in a breath.

“I don’t know; Dr. Bates is still with him,” said Fairy; but a minute or two later John Shelley came out with the doctor’s report.

“Well, what news?” asked Mr. Leslie.

“He is still unconscious, and the doctor can’t say how it will go with him,” replied the shepherd.

“Is there no hope, father?” asked Jack, turning very white and speaking very low.

“Yes, lad, yes, there is hope, thank God; he may rally; it is the fall on the gate-post that has done the mischief. He struck the back of his head against the stone; the place on the temple is a mere trifle. But will you walk in, Mr. Leslie? Dr. Bates wants to speak to you, and you too, Jack.”

Accordingly these four went into the kitchen and shut themselves up to discuss the matter, leaving Fairy feeling very miserable and in the way, for she did not know where to go, on the bench outside. But a few minutes later Mrs. Shelley came to the door to look for her, wondering what had become of her, having forgotten her hasty speech on seeing Charlie lying prostrate on the ground.

“Why, Fairy, where have you been all this time? Come, child, you have had no supper yet. How pale you look; and your hands are quite cold. You are not frightened, are you?” said Mrs. Shelley, as Fairy reluctantly followed her into the house.

“No, I am not frightened, but it is all so miserable,” said Fairy, sobbing, as she looked at the unconscious Charlie, who was breathing almost imperceptibly on the sofa.

“Come, this won’t do; I shall have you ill next; why, the child has cried more to-night than she ever cried all the sixteen years she has been here,” said Mrs. Shelley, taking Fairy in her arms.

“You were never unkind to me before,” sobbed Fairy.

Suddenly Mrs. Shelley remembered how she had turned on Fairy in her anxiety and pity for Jack.

“There, child, don’t cry any more; I don’t know what I said; but at any rate I can’t let you quarrel with me when I may lose one, if not both, of my sons; for I am sure they will decide to send Jack away—indeed, I hope they will,” said Mrs. Shelley.

“You hope so, mother?” asked Fairy, in astonishment.

“Yes; if anything happened to poor Charlie, Jack might get into terrible trouble, so, for his sake, I hope Mr. Leslie will let him go; besides, he is not fit for a shepherd; he never has liked the work, and he may get on far better at something else.”

Just as Mrs. Shelley said this, the kitchen door opened, and John Shelley asked his wife to come in to the discussion which was being held in the kitchen, and Fairy was left to watch by Charlie. It seemed an interminable time to Fairy, though it was not really half an hour before the door opened and they all came out. Mr. Leslie went home; the doctor came in to look at Charlie again; Mrs. Shelley went upstairs with Jack; and the shepherd called Fairy into the kitchen to tell her what had been decided.

“Jack is going away to-night; he is going to America.”

“To America!” exclaimed Fairy, for in those days going to America was indeed going to another world.

“Yes, for two years; perhaps for longer if he likes it. Mr. Leslie has friends out there, and he knows of something he thinks will do for Jack. There is a ship sails on Monday from Liverpool, so he is to go to Brighton to-night with Mr. Leslie, and be off by the London coach at five to-morrow morning. Mr. Leslie will go to Liverpool with him and see him off if he can get anyone to take his duty here on Sunday; anyhow, he will go to London and put him into the Liverpool coach.”

John had not time to enter into further details as to what had passed at the meeting in the kitchen; but, in truth, both Dr. Bates and Mr. Leslie had strongly urged getting Jack out of the way as quickly as possible. Dr. Bates because he was very anxious and by no means hopeful about Charlie; Mr. Leslie partly on the same account, but also because he knew the state of Jack’s feelings with regard to Fairy, and had long wished to see the boy in a position where he would have some opportunity of using the talents he possessed, and, by dint of his own abilities and exertions, rising in the world. It so happened that he had friends in New York, and a relation of his; a banker there had, in answer to his inquiries whether he had an opening for a clever, self-educated young man, lately written to say he had a vacancy for a clerk which he would keep for Mr. Leslie’s young protégé. Mr. Leslie had only been waiting till the shearing season was over to offer this post to Jack, knowing that he could not very well be spared till it was finished. Jack was delighted at the idea; a salary of fifty pounds a year seemed to him untold wealth, and to have all the rest of the day from five in the afternoon till ten the next morning to himself, a perpetual holiday; and then to go to America, to him who had never been much farther than Brighton, would, under any other circumstances, have been all that he could have wished for, except Fairy to accompany him. The post was offered him for two years, and the option of remaining, if he liked the work, at the end of the two years. The only difficulty was the money for his passage, but, to the surprise of Jack, his father said he had plenty in the savings bank for that and to get him a few necessaries as well.

But leaving as he was leaving, took all pleasure out of Jack’s good fortune; if he felt any pleasure at all it was only from the excitement of the journey, and the occupation of both mind and body, which prevented him from dwelling on the sorrow he had brought on them all, and diverted his mind from the terrible anxiety Charlie’s state caused him.

If it had not been for Dr. Bates, Jack would have remained at home for the night, and walked over to Brighton at daybreak to catch the coach, but the doctor was rather a nervous man, and knowing that it was quite possible Charlie might not live till the morning, he urged Mr. Leslie to take Jack to Brighton that evening, adding in an undertone that if anything happened Jack had better learn it in America. Perhaps it was as well for all parties that the doctor’s advice was acted upon, for it prevented any prolonged leave-takings, and gave no one time to fret over Jack’s departure; indeed, an hour after the council held in the kitchen, Jack was standing already to start, folding his mother in his arms as he bade her good-bye. Then he went to the sitting-room, in which Charlie was lying, and took a long, long look at him as he lay with closed eyes, just breathing, all the colour gone from his usually rosy cheeks. What would not Jack have given to see those merry blue eyes open once more before he went away, perhaps never to see them again? But no, the eyelids remained firmly closed, and Jack waited in vain for any hopeful sign. He was alone in the room, and before he left he knelt down by the side of the sofa and prayed until a footstep outside startled him, and he rose hastily, for, proud and reserved as he was, he would have hated even his mother to have seen him on his knees, for, like many young men of his age, he had a great deal more religion than the world gave him credit for. The footstep was Mrs. Shelley’s; she was come to warn her darling son that it was time he started or he would keep Mr. Leslie waiting.

“Mother, may I have a lock of his hair?” asked Jack. And Mrs. Shelley cut one of Charlie’s fair curls for him; and then Jack stooped, and, for the first time for many years, kissed the boy’s pale cheeks, and then, once more embracing his mother, he left the room. But there was another person to say good-bye to—Fairy—who was waiting in the passage, and now came forward, putting both her hands in Jack’s and lifting up her sweet, delicate little face to be kissed as naturally as though Jack was her own brother; and though poor Jack blushed crimson as he stooped and kissed her, Fairy, if she changed colour at all, grew paler, for she felt very sad and lonely at the loss of her favourite companion.

“You will think of me sometimes, Fairy, won’t you?” whispered Jack, holding her hands.

“Yes, often, Jack; and mind you write to us directly you get to America; we shall be longing to know how you are getting on.”

“Jack, my boy, it is time to start,” cried John Shelley, who was waiting outside to walk to the rectory with his son, and the next moment they were off.

(To be continued.)

{220}

By EMMA BREWER.

After having tided over my difficulties, which had been brought about partly by the ill-feeling and envy of the Land Bank, and partly by another matter to be explained later, I went on successfully in my old home, gradually increasing my powers and responsibilities, and, if I may be allowed to add, daily growing more attractive.

Everybody courted my smiles, and were wretched if they failed to find favour. Among those who paid me attention were members of the royal family, bishops, clergy, ministers of state, merchants, and philosophers; and, strange to say, I was as great a favourite with the women as with the men, and I think I influenced their lives not a little, for if a girl were known to be on my visiting list, even though she were very plain, she found no difficulty in marrying well. Did a mother hold in her arms her first-born, she was more restful and content concerning its future if it had an opportunity of being placed in my good books; and, certainly if a person died who had during his life stood well with me, he was buried with more pomp and ceremony for the fact.

It seems wonderful, does it not, that I should have kept my head amid so much flattery and attention, and I very much doubt if I should have done so but for the healthy tone of my home and the constant care of my people.

Every now and then I got a fright, which prevented my becoming frivolous, and which, but for my good constitution, would have gone far to shake the life out of me. One I remember well.

It occurred in 1707, when I was but thirteen years old. It came in the form of a “run,” and certainly, but for timely help, I should have been torn to pieces.

The word run may be suggestive to you merely of a race between me and another bank; but in bank language it has a most terrifying and disagreeable meaning.

It is a sudden demand from everybody to whom you owe money to pay up on the spot, and without hesitation.

Your office is filled and refilled with people angrily and defiantly demanding their money. Such was the case with me, and in my one room in the Grocers’ Hall, at the date I mentioned.

I tried to console myself with the thought that if the people would but give me time I would pay everyone to the full, but, alas! I was old enough to know that this was not sufficient—my existence depended upon the whole world believing me to be safe and worthy of confidence, and their test of my trustworthiness was that I should pay everyone in full at a moment’s notice.

I was nearly wild, and, for the moment, utterly powerless. To me confidence was money, and by money I lived and breathed.

It was no use disguising the fact—I had not sufficient in my chests to pay the reckless demands.

Not that I had misused the money entrusted to me, but that I had lent it out again, that it might work and earn for me the means to pay interest to the depositors and afford me something for my trouble; all this was quite honourable and above board, and yet how frightened I was! Had I wished it I could not have run away, for you know I had but one room, without private doors and staircases; I was, therefore, compelled to stand and face the excited and unreasonable crowd.

In the case of a run, it is absolutely necessary to find the money somewhere, in order to meet the demand made by the public; for if once payment is suspended credit is gone, career blasted, and business at an end.

When a person asks me in confidence my definition of a run, I always answer, “A reckless, senseless attack on a bank—one in which self-interest is so overpowering as utterly to cover and blot out reason for the time being.”

Of course the news spread like wildfire that I was surrounded by a clamorous people whom more than likely I should not be able to satisfy, and who, in that case, would not hesitate to take my life.

This roused my friends, who without loss of time came to my assistance with the only commodity that could save me.

Godolphin (the Lord Treasurer in the reign of Queen Anne) declared that the credit of the country was bound up together with mine, and that help must be at once offered, for which phrase, when I had time to think of it, I was thankful; but, better than words, my friends, the Dukes of Marlborough and Newcastle, and others of the nobility, at once came to my rescue with large sums of money, and gentlemen of all ranks came with their offering of such cash as they had in hand.