are the largest Furniture Makers in the Metropolis of the South.

We shipped more car loads of furniture last year than any other factory in this section. This is proof that

Title: Bob Taylor's Magazine, Vol. I, No. 1, April 1905

Author: Various

Release date: May 6, 2021 [eBook #65270]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Richard Tonsing, hekula03, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This book was produced from images made available by the HathiTrust Digital Library.)

Transcriber’s Note:

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

The Contents of this Magazine are protected by copyright and must not be used without the consent of the publishers.

| Cover Design | Mayna Treanor Avent | ||

| Frontispiece—The Late Hon. John H. Reagan | 2 | ||

| The Old South | Robert L. Taylor | 3 | |

| Illustrated with photographs. | |||

| Popular Education in the South | Henry N. Snyder, LL.D. | 9 | |

| With portrait of the Author. | |||

| To Helen Keller | 14 | ||

| Men of Affairs | 15 | ||

| Illustrated with photographs. | |||

| The Lost Herd | Joseph A. Altsheler | 23 | |

| With portrait of Author. | |||

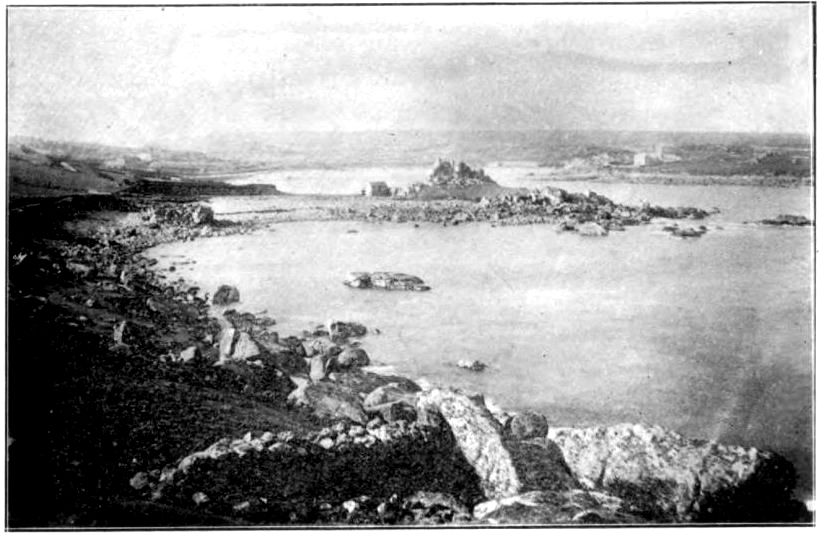

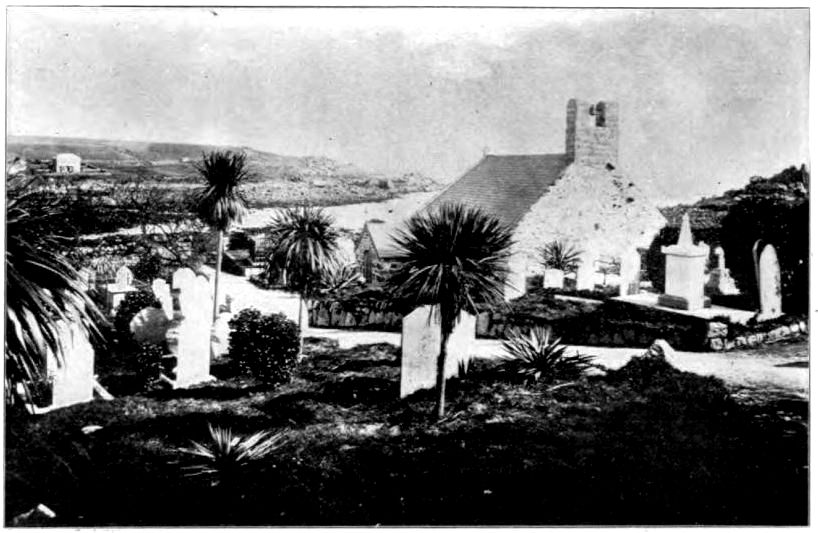

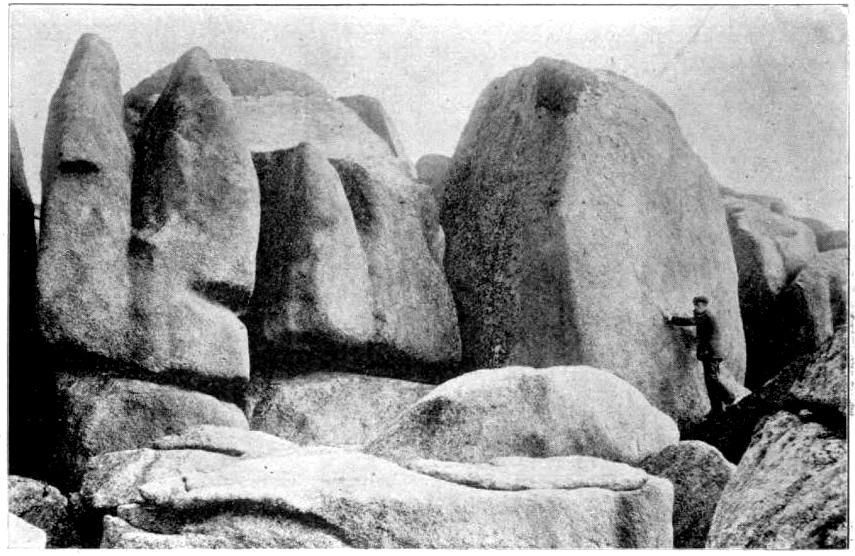

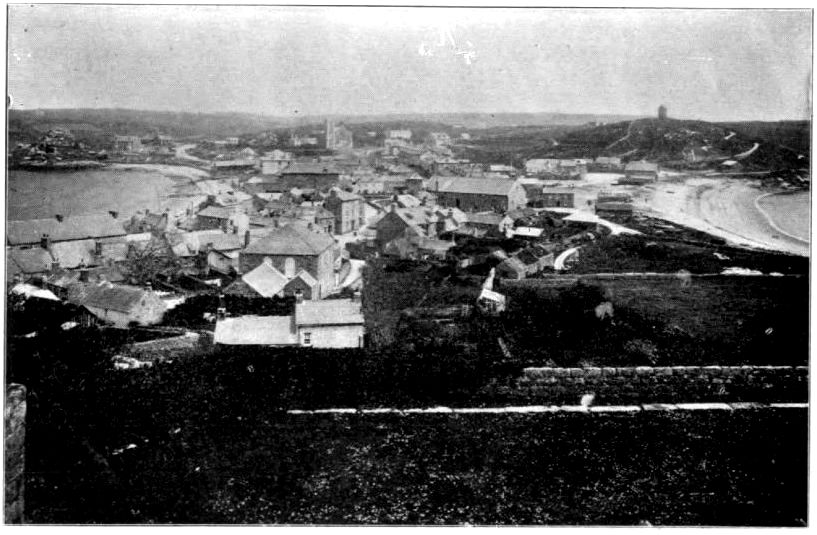

| The Isles of Scilly | J. H. Stevenson, Ph.D. | 32 | |

| Illustrated with photographs. | |||

| Labor Problems in the South | Herman Justi | 39 | |

| With portrait of the Author. | |||

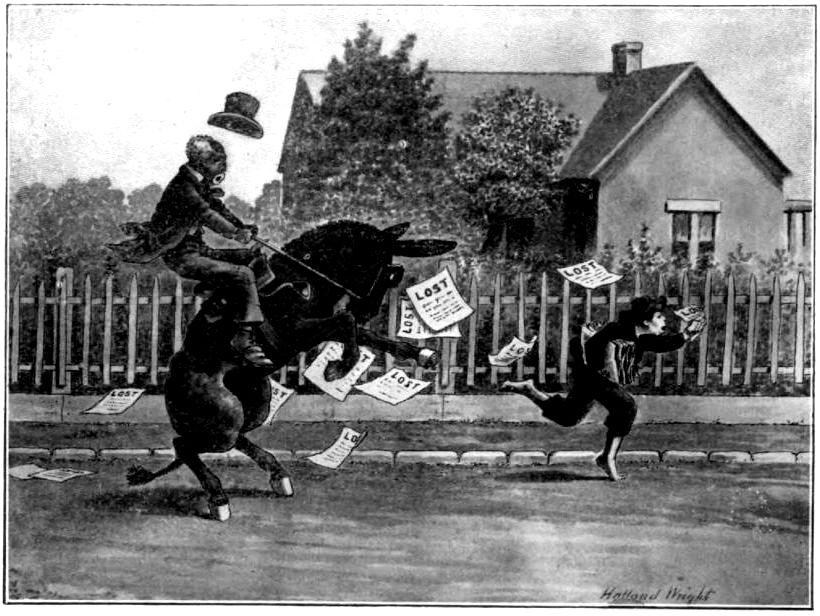

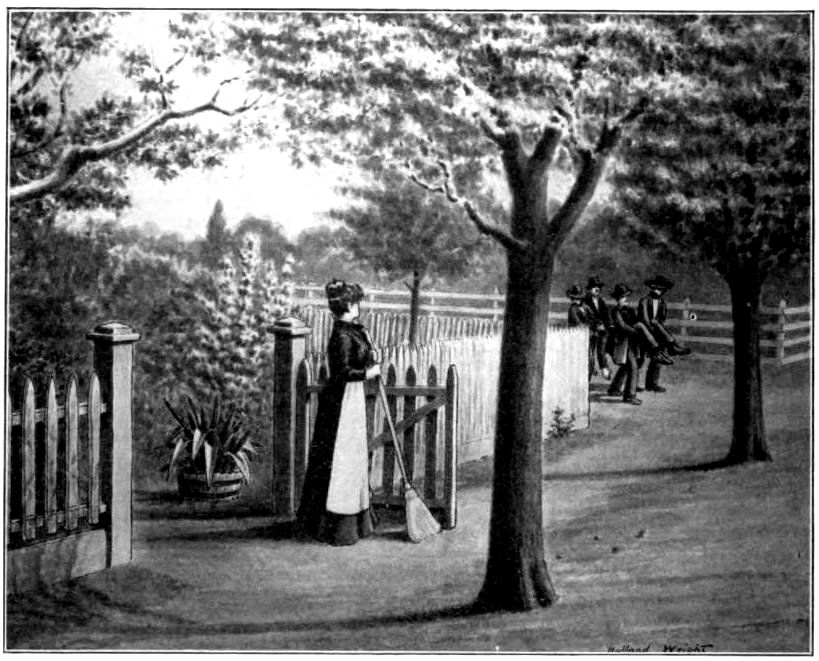

| Tildy Binford’s Advertisement | Holland Wright | 46 | |

| Story. Illustrated by the Author. | |||

| The Man and the Matinee | Sybil Stewart | 54 | |

| Story. Illustrated. | |||

| The Old Order Passeth | Grace McGowan Cooke | 61 | |

| Poem. Illustrated with photograph. | |||

| Sources of Southern Wealth | Austin P. Foster | 62 | |

| Society of the Forest | M. W. Connolly | 66 | |

| Illustrated by Mayna Treanor Avent. | |||

| Sunshine—Conducted by the Editor in Chief | 80 | ||

| Greeting. | |||

| Fly in your Own Firmament. | |||

| The Governor. | |||

| The Lieutenant-Governor. | |||

| The Commercial Traveler. | |||

| Lyrical and Satirical—Conducted by Vermouth | 87 | ||

| A Cuban Sketch | Harvey Hannah | 90 | |

| Within a Valley Narrow | Ingram Crockett | 91 | |

| Leisure Hours | 92 | ||

| Books and Authors—Conducted by Mrs. Genella Fitzgerald Nye | 95 | ||

| The Fiddle and the Bow | Robert L. Taylor | 103 | |

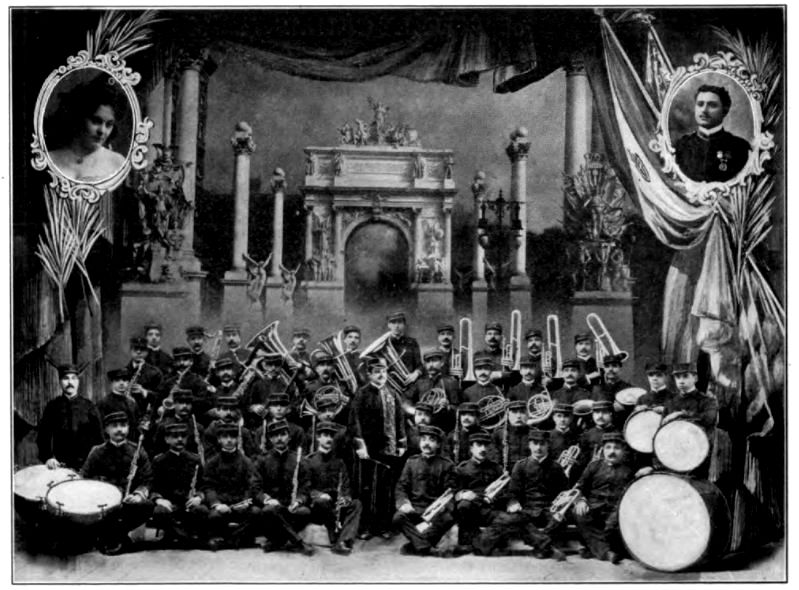

| Illustrated. | |||

| The Southern Platform | 107 | ||

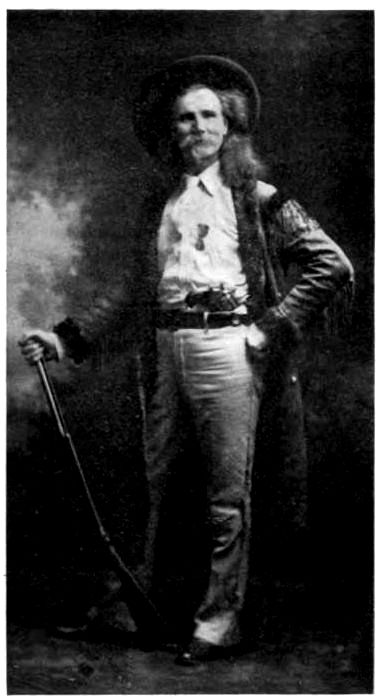

| Poem | Capt. Jack Crawford. | ||

| The Story of Joseph | Ida Benfey. | ||

| The Mocking-bird | Mary H. Flanner. | ||

| The Youth of Shakespeare | Frederick Warde. | ||

| A Critique of the Masquerader | James Hunt Cook. | ||

are the largest Furniture Makers in the Metropolis of the South.

We shipped more car loads of furniture last year than any other factory in this section. This is proof that

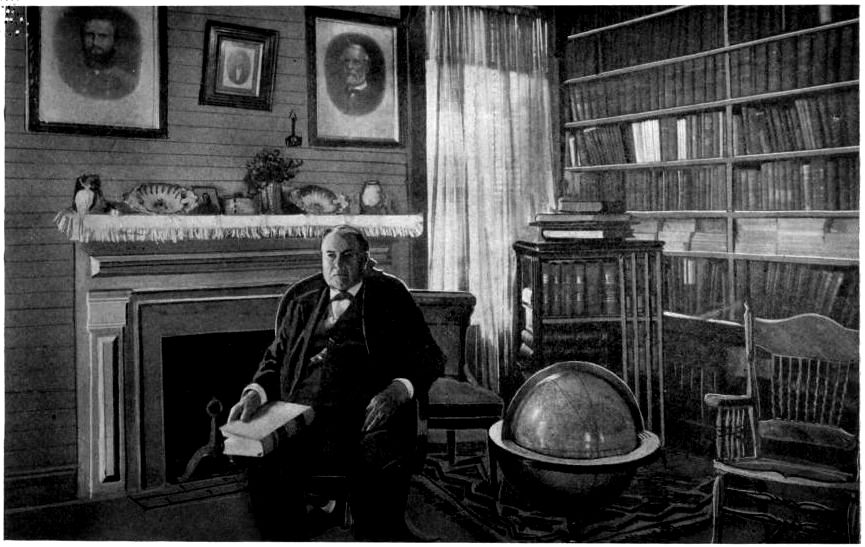

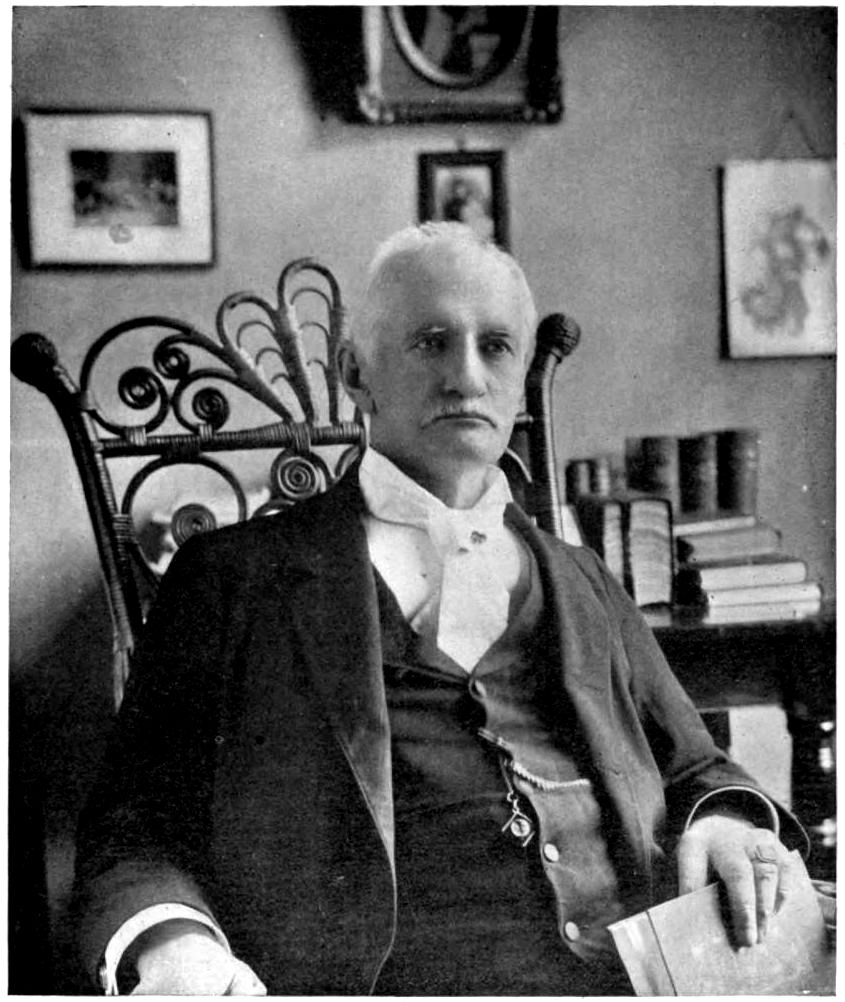

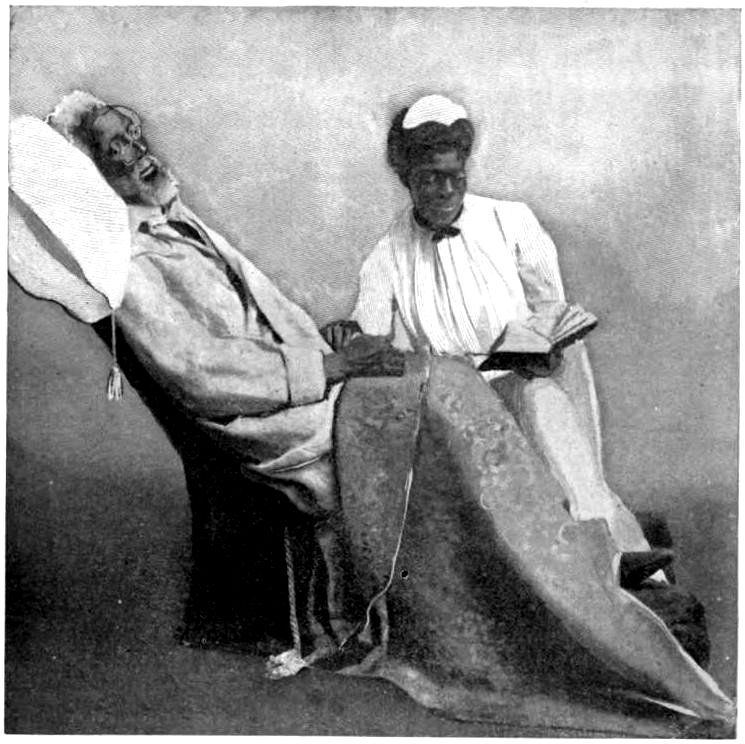

THE LATE HON. JOHN H. REAGAN IN HIS STUDY AT PALESTINE, TEXAS.

BOB TAYLOR’S MAGAZINE

| VOL. I | APRIL, 1905 | NO. 1 |

One of the most brilliant civilizations that ever flourished in the history of the world staggered and fell with broken sword and shattered shield on that dark day when the flag of Southern hope and glory went down in blood and tears. Its decimated armies, too exhausted from loss of blood to longer pull the trigger, too weak from starvation to charge the enemy, too footsore and too proud to run, stacked their old, bent and battered muskets in the anguish of defeat and went limping back to their ruined homes in Dixie.

There is nothing left of that civilization now but a few remnants of its gray columns—themselves grown gray as if in honor of the uniforms they wore—and the thrilling and pathetic story of its vanished prestige and power lingering among its tombstones and monuments like the fragrance of roses that are faded and gone. Never again will the white-columned mansions of the masters glorify the groves of live oak and the orange and the palm where Southern beauty was wooed and won by Southern chivalry, and life was an endless chain of pleasure. Never again will the snowy cotton fields and rice fields, stretching away to the Gulf or to the river, teem with happy slaves and ring with their old time plantation melodies. Hushed forever is the music of the Old South! Closed are the lips of its matchless orators! The dust of its statesmen mingles with the dust of the heroes who died to save it. Only three are left in the counsels of the nation: Morgan, the brave and the true, the able, the eloquent and learned Senator from Alabama; Pettus from the same state, the peer of Morgan in all the exalted traits of character that distinguish the unswerving and incorruptible representative and defender of Southern ideals and Southern traditions; and Bate, that grand old man of dauntless courage, that fearless soldier with many scars, the hero of Shiloh, the strong and faithful Senator who in private life is as pure and gentle as the mother of his children, and in war as bold and daring a cavalier as ever drew a sword![1] It is true there are other splendid men from the land of cotton and cane in Congress, whose heads are silvered o’er, and who have nobly led Southern thought and sentiment. They are superb exponents of the old ante-bellum civilization, but they were too young to taste the sweets of its glory. Some of them were born soon enough to listen to the lullaby of the old black mammy and to sit in the negro cabin and listen to the blood-curdling tales of uncle ’Rastus about ghosts and goblins; some, like Daniel of Virginia, Berry of Arkansas, and Blackburn of Kentucky, were old enough to follow Lee and Jackson and to fight to the finish; but their youth forbade them from sitting on the throne of living ebony with these older men, who, in reality, are all that is left of the Old South in the national legislature; and in whose presence all men, whether of the North or of the South, delight to lift their hats with that profound reverence which true nobility of character always commands. What a shame there are not four!

1. Senator Bate has died since this was penned.

SENATOR WILLIAM B. BATE.

GOVERNOR JAMES B. FRAZIER, OF TENNESSEE.

A sigh of deep regret came from the Southern heart when Missouri registered the decree that Cockrell, the soul of honor, the impersonation of truth and integrity, the soldier and the statesman, must cease to reflect honor upon that great commonwealth as one of its representatives in the United States Senate. But it must be a sweet consolation to him to go back among the people whom he has served so faithfully and so well, with the consciousness of a clean life behind him, both private and public, and with the prestige of a glorious record in the service of his country.

GOVERNOR JOHN C. W. BECKHAM, OF KENTUCKY

To those who have marked the passing of men in recent years, how solemn the thought that there are so few left to tell the tale of the manhood, the wealth and the influence of that chivalrous race who staked all and lost all save honor in the struggle to preserve its institutions. There is only one remaining who served in the cabinet of Jefferson Davis, in the person of the venerable and beloved John H. Reagan of the Lone Star State. The dews of life’s evening are condensing on his brow and its shadows are lengthening around him, but the burden of his fourscore years and five still rests lightly upon him. The snows that never melt have fallen upon his head, but there’s no snow upon his heart; ’tis always summer there! He has been distinguished through life for his rigid honesty and the fearless discharge of duty, and he will die, as he has lived, the idol of his people. May God lengthen the twilight of his declining years far into the twentieth century![2]

2. Since this article was set up, Judge Reagan, too, has passed away.

One by one the great majority of the star actors in the thrilling drama of the past have made their exit behind the sable curtain of death, and in all probability another decade will clear the stage.

GOVERNOR ANDREW J. MONTAGUE, OF VIRGINIA.

GOVERNOR EDWIN WARFIELD, OF MARYLAND.

GOVERNOR J. M. TERRELL, OF GEORGIA.

It is one of the purposes of this magazine to aid in keeping ever fresh and green the history and traditions of the Old South; to keep alive its chivalrous spirit, and to tell the pathetic story of the lion-hearted men around whose names are woven some of the greatest events of history. It has been beautifully said that “literature loves a lost cause.” If this be true, the South will yet be a flower garden of the most enchanting literature that ever blossomed in any age or in any land. Some Homer will rise, greater than the Greek, and dream among the cemeteries where its heroes sleep and sing the sweetest Iliad ever sung! The spirit of another Hugo will brood over its battle fields and gather tales of valor and reckless courage; of grim visaged men scorning shot and shell and riding to the cannon’s mouth; of bayonets mixed and crossed; of angry armies clinching and rolling together in the bloody mire of the awful strife; of Death on the pale horse, beckoning the flower of the Old South to the opening grave! He will gather up the tears and prayers and the withered hopes of a dying nation; the piteous wails of pale and haggard maidens for lovers slain in battle; the shrieks of brides for grooms of a day brought back with pallid lips sealed forever and jackets all stained with blood; and the swoons of mothers with the kisses of fallen sons still warm upon their wrinkled brows. He will gather them up and weave them all into volumes of romantic love more vivid and terrible than the story of Waterloo! He will paint in burning words a picture, not of all the horrors that followed the blunder of Grouchy in that battle upon which hung the fate of empires, but of Stonewall Jackson falling in the noontide of his brilliant career and passing over the river to rest under the shade of the trees; a picture, not of Wellington seizing the fallen Napoleon and banishing him to solitude and death on a rock in the sea, but of the great and generous Grant receiving our own immortal Lee like a king at Appomattox, declining to accept his sword and bidding him return to the peaceful walks of private life among the green hills of old Virginia; a picture, not of Ney, who had fought so long and so bravely for the triumph of his beloved France, shot through the heart by cowards within the very walls of Paris, but of Gordon, with golden tongue portraying the last days of the Confederacy amid the shouts and tears of the brave men who had faced him with booming cannon and rattling musketry on a hundred fields of glory; a picture, not of the English Channel as the dividing line between the drawn swords of France and Britain, but of Mason and Dixon’s line healing into a red scar of honor across the breast of the great Republic and marking the unity of a once divided country!

GOVERNOR NEWTON C. BLANCHARD, OF LOUISIANA.

GOVERNOR N. B. BROWARD, OF FLORIDA.

GOVERNOR JAMES K. VARDEMAN, OF MISSISSIPPI.

SENATOR JOHN T. MORGAN.

Not very long ago, during the Spanish-American War, there was commotion in a far Southern town, caused by a coterie of young men bitterly protesting against the sons of Confederate veterans wearing the blue and fighting under the old flag. An elderly man with “crow’s feet” at the comers of his eyes and silver in his hair, listened for a while in silence, but finally arose from his chair and said: “Young men, you are wrong. I followed the stars and bars for four long, weary years! I saw its colors go down at last and I straggled back to my native state, barefooted and in rags, only to find my home in ashes. I swore eternal enmity to the stars and stripes and to the blue. But one day, after the battle of Manila Bay had been fought, a Mississippi regiment went marching up the main street of my town and lo! my boy was in the ranks dressed in the Federal uniform. In my rage I rushed to the Colonel and shouted, “Take that blue uniform off these young men and let them put on the gray and show the world how the sons of Confederate veterans can fight!” but the Colonel smiled and shook his head and the regiment marched on eager for the fray. I went home in my fury more bitter against the North than ever before. But when one day they brought my boy home in his coffin and I looked down upon him pale and motionless, in his blue uniform and wrapped in the old flag, my animosity vanished in a moment and in my tears I said: ‘Henceforth that uniform is my uniform, that flag is my flag and this whole country is my country.’” This sentiment is not incompatible with loyalty to the gray nor to the folded stars and bars, but it is the expression of the only feeling that will ever unite all the sections of the Union.

SENATOR B. F. PETTUS.

We must recognize the fact that a new civilization has arisen in the South from the ashes of the old, and while her people cherish the past for its precious memories, their faces are turned toward the morning. They are not only producing more cotton than ever before, but building gigantic plants among its snow-white fields, and with the magic of modern machinery are transforming the raw material into finished fabrics; they are pulling down the hills and dragging forth their treasures of coal and iron, of marble, zinc and lead, and are converting them into all the finished implements of peace; they are harnessing their beautiful rivers to the thunder-clad steeds of the storm and turning the myriad wheels of industry with electric power; and they will some day out-herod Herod in the marts of the world.

The representatives and governors of the South, confronted with new and perilous problems, have had the courage to grapple with them, the brain to control them and the heart to turn many of them into blessings. They have brought wealth out of poverty and prosperity out of desolation; and Hope stands on the horizon with a new crown in her hand, beckoning this new civilization to a throne of power never dreamed of by the old. And yet, while the Southern people rejoice in the resurrection of their country from the dead and in the bright prospects spread out before them, let them never forget to worship at the shrine of memory nor to permit the glory of the blessed past to be dimmed by the splendor of the future.

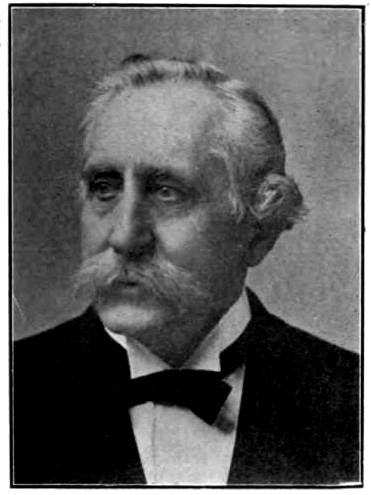

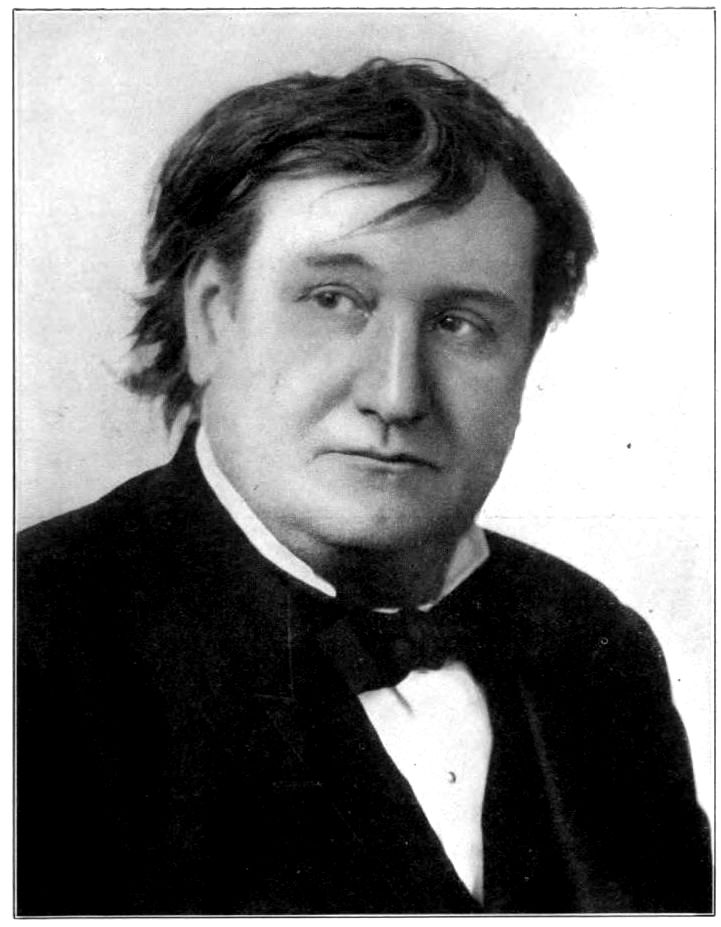

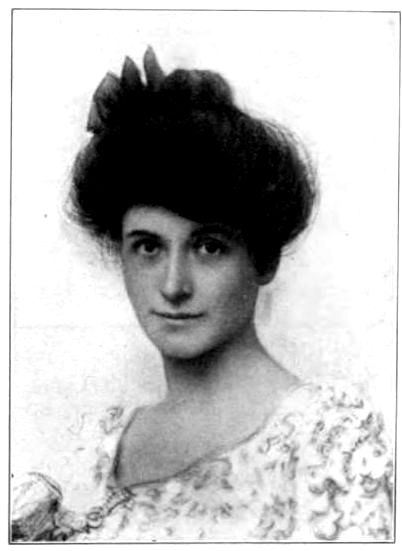

HENRY NELSON SNYDER, M.A., LITT.D., LL.D.

President Henry N. Snyder, of Wofford College, speaks to our readers in a thoughtful and commanding way on a question, that with the rapid and general development of the South is becoming more and more recognized as a vital popular problem.

As the executive head of one of the South’s most representative denominational colleges and as a lecturer on the subject before representative summer schools for teachers, President Snyder has had occasion to bestow upon his theme serious and special study and his intelligent and earnest treatment of his topic tends to present it in a practical and popular form and to eliminate from it those speculative and academic qualities that have so generally characterized its discussion.

A native of Macon, Ga., where he was born during the final year of the Civil War, President Snyder was reared and educated in Nashville where, after completing the course of the city high schools he entered Vanderbilt University in 1883, and from which he graduated in arts, with both his bachelor’s and master’s degrees.

He was until 1890 connected with his alma mater, the last three years of which time he was instructor in Latin and student of graduate subjects. He subsequently pursued advanced special work in German and English universities, since which time, until 1902, he was professor of the English Language and Literature in Wofford College. He has been president of this institution since 1902.

President Snyder’s contribution to the actual promotion and solution of his subject has been considerable, as he has served as lecturer on English Literature at the South Carolina State Summer School and the Summer School of the South, at Knoxville, Tenn.

He is a frequent contributor to magazines on literary and educational subjects and is a member of the Modern Language Association of America, and the Religious Education Association.

The American democracy is not so much an achievement as a prophecy. Its chief glory cannot be in what it is, but in what it is to be. It has not attained the measure of its growth till every man in it has a fair chance and an open field to make the most of himself, and has done so with reasonable completeness. It is therefore essentially idealistic, and, however deeply concerned with the present hour’s duty and work, its face is ever set toward a larger future for itself. But this larger future can only be realized in a finer and more efficient quality of the men and women who are to do the work and continue the unfolding life of this free democracy of equal opportunity,—equal opportunity not for the few favored by fortune or circumstance, but for every child born in it. No democracy dare have any other mind with reference to itself.

The most necessary, as the most inspiring, work therefore which a democracy assumes to do is that of seeing to it that all its children are rightly trained for intelligent service and skilled efficiency. This task it undertakes not only that it may live as a collective body but also that each citizen may in the best and fullest manner express his own individual life. In this two-fold view of the matter popular education, the putting of all the children of all the people into the best possible schools, under the best possible teachers, for the longest possible time, becomes the sacred and imperative duty of a democracy that cares for to-morrow as well as for to-day. And the to-morrow of a democracy, in all the manifold activities of its complex life, is determined by what it does for the child of to-day.

From this viewpoint no democracy ever had a better opportunity to test itself and its ability to control the future than that phase of democratic life working out its destiny here at the South. For the conditions are such as to make the task of training the citizenship of the future almost the one thing to be done. The figures representing those conditions have been so often used of late that one is really inclined to resent the very mention of them. Nevertheless, a proper understanding of the conditions entering into this, as into any problem, is the first step toward the solution. Moreover, in this struggle now on for popular education at the South, it is no part of courage to blink a fact because it is ugly, nor of sane judgment to let anything or anybody beguile us into fighting our battle in the dark. We should keep steadily before us the facts as they are, the stupendous nature of the work that lies ahead and how it is to be done, and withal the eternally vital need of doing it now and in the right way.

Now as far as figures can give one anything like an adequate conception, the situation is about this: In 1900 there were 8,683,762 persons of school age in what we are used to call the Southern states,—5,594,284 white persons and 3,089,478 black. It should be said in passing, yet with all emphasis, that the South may as well get used to reckoning the children of its former slaves in both its educational assets and educational liabilities. Justice and expediency are both vitally involved in this view of the situation. Now, of this future citizenship only sixty out of every hundred were actually in process of school training, and of this enrollment only forty-two were, on the average, in daily attendance. The only comfort that one can get in this situation is by looking back and seeing that conditions have been worse and forward to see that they are bound to be better.

These figures, then, represent the mass of material that popular education has to deal with and the actual portion upon which it is really working. Now when one considers the machinery of instruction, the teachers, the school-property, the length of terms, and the capital invested, one sees even more vividly that the democracy of the immediate future must be limited in its development, not alone because its children are not in process of training but because the means themselves are inadequate and inefficient. The entire country pays, on the average, for its men teachers a salary of $49.00 per month, for its women $40.00. The South gets its men for $35.63 and its women for $30.47. Leaving out of consideration the quality of service to be had at such a pitifully low price, one can be perfectly sure that no high professional ideals and standards can be maintained at such rates. But let us look at the matter from another standpoint; upon every child in its schools the South spends $6.95 as against $10.57 for the entire country; while some states of the West spend $31.49, some Southern states are spending only $4.50. It is not surprising therefore to see what this means as to the average length of school term among us: in the entire country every child has a chance to be in school at least 145 days, while the child of the South has open to him only 99 days. Clear enough is it, then, that democracy in this section is, in comparison with the rest of the Union, handicapped in the very beginning of its race. Moreover, the relation of popular education to its best life, in the light of the situation revealed by these figures, is a deep and fundamental one.

How deep and fundamental this is, can be best realized by the comparative density of illiteracy already prevailing at the South. Fifty out of every hundred negroes ten years old and over can neither read nor write, and nearly thirteen out of every hundred whites are in the same condition of darkness. In the United States as many as 231 counties report a proportion of twenty per cent of illiterate white men of voting age, and of the total, 210 of these counties are in the South. Now the conditions represented by all these figures—and at best they can only bring the matter vaguely to our conception—in one sense, on account of the magnitude of the work to be done and the difficulties in the way, are of a nature almost to take hope and courage from us. On the other hand, the absolute need of doing the work, the fruits that must follow, and the progress already made are a clarion call to patience, patriotism, faith, and unresting effort.

But before taking up the progress already made, it would be well to remind ourselves once more of some of the causes which have brought about the present state of affairs and render the Southern situation as to popular education a peculiar one. In the first place, there was the all but disheartening poverty due to the collapse of the entire social and industrial system of the South. War, followed by Reconstruction, did the work with ruthless thoroughness. From 1860 to 1880 taxable property at the South suffered a decrease in value of $2,167,000,100, that is, to less than one-half its value at the breaking out of the War. Indeed, in 1870 the one little state of Massachusetts paid considerably over one-half the amount of taxes paid by the entire South. It is clear, then, that for nearly twenty years the South was under the simple yet stern and inexorable compulsion of how to live. In this light, therefore, what it did accomplish in the matter of training its children is to be regarded as a really heroic achievement, and is no occasion of blame because, by comparison, it seems so little. Absolutely, it is worthy of all praise.

It should be remembered, too, that in spite of its poverty, in spite of the fact that its energies have been given to a pressing struggle for its very existence, the South has had to maintain a two-fold system of popular education. It has had to care for the children of its former slaves in separate schools, and bear virtually all the expense. This has both complicated its problem and necessarily limited its educational advancement. But at this time it can be asserted with emphasis, that the South, in spite of certain reactionary eddies in the current of its thinking, will still continue to support Negro schools. Our best thought is fast fixing itself in the unalterable conviction that to keep the black man in ignorance is an injustice to ourselves as well as to him; and, moreover, that expediency itself dictates that he shall neither remain sunken in the night of illiteracy nor mistrained for the sphere of life for which he is, in his present stage of advancement, fitted. Therefore popular education has meant, will continue to mean, with the South a two-fold system of education. And the Southern white man, with his own taxes, is largely to maintain it,—at least for many years to come.

But above everything else, the chief consideration with reference to the whole question of popular education in the South, both as to its needs and difficulties, is that we are dealing with a rural folk and rural conditions. More than eighty-three per cent of the Southern people live in the country,—a pure, wholesome Anglo-Saxon stock of unwasted, if untrained, physical, intellectual and moral qualities. The problem of popular education in villages, towns, and cities is virtually solved. The task therefore is concerned wholly with what we shall do for and with the saving, and in this case, the larger remnant which draws its support from the fields. No democracy ever had better or richer assets from which to recuperate itself, or a more inspiring duty to perform in giving this class opportunity for training and development. But from the very nature of the case the proper performance of this duty is a task of stupendous magnitude, and even an approximate accomplishment of it must wait upon necessarily slow processes. The deep-seated conservatism of the people, the extent to which illiteracy prevails and the narrow poverty in many sections, remote and widely-sundered homes, roads almost impassable at certain seasons of the year, the immediate need of the children in the fields, even if the best of schools were at their doors,—here are conditions which would discourage any but a brave and patient people who believe in the divine right of all to whatever power there is in knowledge and the bounden duty of the state to offer to all its opportunities.

However, neither the pressure of poverty, nor the double burden of caring for two races in separate schools, nor the special difficulty growing out of the peculiar nature of conditions, nor the huge magnitude of the task, has daunted courage or enfeebled effort. On every hand there are inspiring marks of progress, and results prophetic of greater advances yet to follow. In the first place, the last six or eight years have been a period of quite remarkable educational agitation throughout the entire South. Every kind of leadership has been systematically at work to quicken the conscience and stir the sentiment of the people on this subject. Pulpit, press, organized philanthropy, and civil authority have combined with professional educators in a campaign whose rallying-cry has been the uplifting of democracy through the power of the schoolhouse. The general result is an interest both wide and intelligent, an awakened conscience, and an aroused sentiment throughout all this Southern land, all of which tends to put behind special and definite efforts of improvement an irresistible public opinion. The South is therefore keenly realizing its sense of civic obligation and its duty to its own future, and when the South once sees its duty and that rich vein of sentimentality, which lies at the basis of its temperament, is once touched, there will be no turning back. And surely it has now seen its duty and its sentimentality is thoroughly alive to all that popular education means to the child of to-day and the state of to-morrow.

For this condition we have to thank, not only the church, the press, and organized philanthropy, but a strikingly courageous and far-sighted political leadership, which the situation has called forth,—men, for example, like Governor Frazier of Tennessee, Governor Aycock of North Carolina, Governor Heyward of South Carolina, and Governor Montague of Virginia, men who have convincingly fought for the inalienable right of every child to be trained by the state at public expense. To their influence must also be added the skilled patriotic service of such State Superintendents of Public Instruction as Mynders, Martin, MacMahan, Merritt, Whitefield and Joyner,—men who seemed to regard their office as peculiarly the most sacred of all trusts committed by a people to public servants. The people have listened to such as these when they might have turned deaf ears to voices from any other source.

Too much importance cannot be attached to the sentiment which has been thus created in the last half-dozen years. It was the necessary step in the preparation for more definite things. Its immediate value has been in the awakening of people to such an extent that they will not only put their children in school but will also tax themselves for educational purposes. General and local taxation, as a result, has been increasing at a significant rate. Indeed, some of the Southern states are now giving a larger proportion of their income from taxes to the use of education than the states of the North and West. They are everywhere building better schoolhouses, furnishing better equipment, and demanding better trained teachers. Consolidation of schools, free transportation, longer terms, expert supervision, the removal of educational matters from the blight of political influence, are the things which now make the educational atmosphere fairly electric with reform, and the next few years will show a growth that will please even the most ardent optimist.

This general agitation has thus connected with it certain definite aims and methods of educational policy, which have already taken shape and are bearing fruit. Not the least important among them has been the effort to secure, above everything, trained teachers. Many of the states have either established Normal Schools for this purpose or have added to their Universities departments of Education. But it has been felt that even these were not sufficient to meet the demands for a trained teaching force. Hence in some of the states, in Georgia, Mississippi, and South Carolina, for example, summer schools with an attendance of from four to six hundred have been running for a number of years, and at Knoxville the great Summer School has been drawing from all over the South a choice body of teachers to the number of two thousand, and offering them the best instruction to be had, North or South. To the influence of these general schools is to be added that of the County Institutes, which of themselves have been an inestimable source of power. All have stood for an intelligent knowledge of the situation, for the missionary spirit of propaganda, for a broader and more accurate scholarship on the part of the teacher, for the application of expert, up-to-date methods of instruction and organization, and for the raising of the teacher’s work to the dignity of a great profession. The significance of all this is that this movement for popular education is laying its foundations in wisdom in that it sees that the teacher himself must first be taught.

And the work has already begun to tell to a degree that can even now be measured. In the last score of years Virginia has reduced its ratio of white illiteracy by 7 per cent, Georgia and Mississippi by 8, Kentucky by 10, Alabama by 11, North Carolina and Florida, by 12, Tennessee by 13, and Arkansas by 14 per cent. These figures are eloquent of present progress and inspiringly suggestive of the future. Democracy is really caring for its own. It is told that a famous German teacher of the Reformation once stepped into his schoolroom and greeted his pupils with these words: “Hail, reverend pastors, doctors, superintendents, judges, chancellors, magistrates, professors.” Some there were who laughed at him as a joker and mocker. But he was wiser than they, and in his wisdom was the prophet of that true democracy which sees not merely the child in the school, but the future man in the state. The South therefore views in this way the progress already made and realizes that what it now does and will do with its children in the schools of the people is the true measure of its own life in the coming years.

With the commercial awakening of the South and the increased importance of the section as a factor in the national life, has developed a new citizenship—a sub-structure of the Old South with a modernized superstructure—in which with the sterling and standard traits of the old regime is strongly blended the nervous activity of the new. As a means of paying special tribute to the work being accomplished in the local and general fields by new generation of the South it is the intention of this magazine to devote a department toward setting forth their achievements as well for public information as for acknowledgment of their services, and in offering the initial installment of this special column it is desired to direct attention to the highly representative types herein noticed with the significant intimation that all are yet in the prime of life with greater opportunities ahead of them.

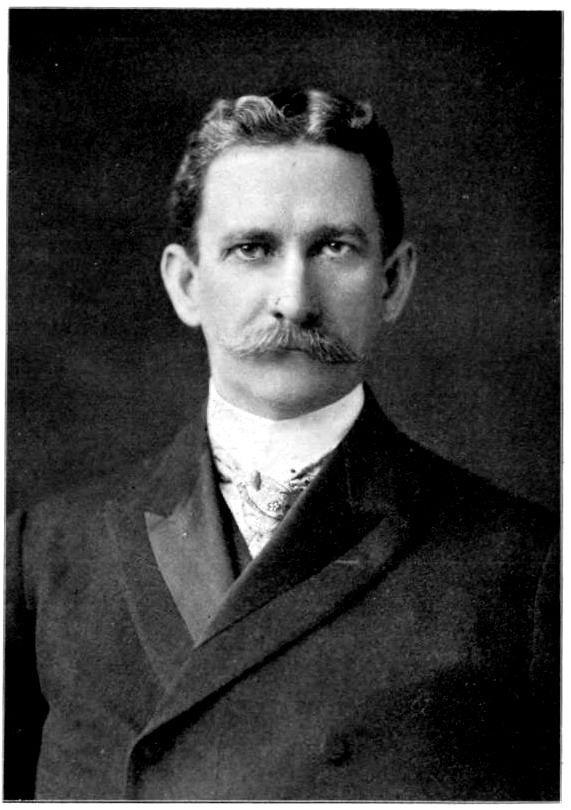

The Manufacturers’ Record, the South’s, if not the country’s, most representative trades journal, had a modest origin less than a quarter of a century ago in a small desk in an obscure business office in Baltimore. Its founder and guiding spirit was Richard M. Edmonds, who from nothing in the way of working capital save sagacity, energy and determination, has developed a magnificent journalistic property, occupying its own seven-story building and has himself become a man of large affairs and wide influence.

In the development of the now admittedly fertile field of trades journalism, no one point may be more emphasized as having been significantly demonstrated than that it holds peculiar and pronounced opportunities for those desirous of actively participating in the vital activities of commerce.

In no less than three distinct phases of Southern development have Mr. Edmonds and his paper conspicuously figured—in the encouragement of industrial and technical education, in the promotion of the cause of immigration from among the most desirable domestic elements and the diverting of the cotton manufacturing business from New England to the cotton fields. It was Mr. Edmonds’ editorial columns that first started the now irresistible southward migration of the mills by pointing out the many and conclusive reasons why the advantages for cotton manufacturing were all in favor of the South.

As a commercial and financial figure it may be noted that Mr. Edmonds is now a member of the executive committee of the International Trust Company, a three million dollar Baltimore corporation, and is chairman of the executive committee of the Alabama Consolidated Coal and Iron Company, with a capitalization twice that of the former. He is a member of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, the American Academy of Political and Social Science, the Southern History Association, the Maryland Historical Society, the Southern Society of New York, and other organizations.

Mr. Edmonds was born in Norfolk, Va., in 1857, receiving a common school education in Baltimore, where he started life as a clerk in the office of the old Journal of Commerce.

RICHARD M. EDMONDS.

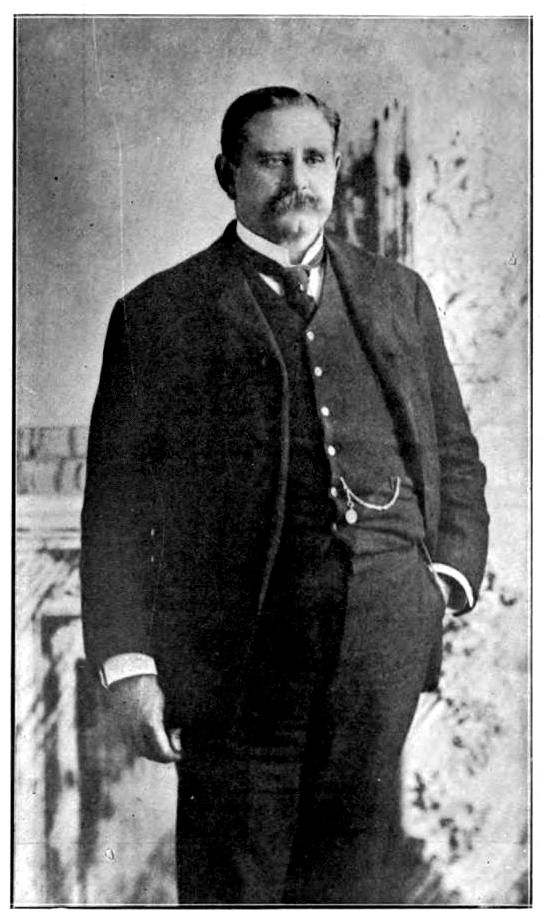

Successively a teacher, a practitioner of law, a railroad attorney, a teacher of law, Assistant Attorney General of the United States, general counsel for one of the country’s large railroad systems and a leading legal representative of the nation’s interests before the Alaskan boundary tribunal,—this is the record of this distinguished Southerner, yet in his physical and mental prime.

A native of Mississippi and a product of ultra Southern environment, himself a soldier of the gray at the very early age of fourteen, Mr. Dickinson’s evolution into a representative type of national citizenship comprises an interesting study in contemporary American life.

Educated at the old University of Nashville and at the Columbia Law School, New York, with a capstone of extensive travel abroad and special work in law and economics at the universities of Leipsic and Paris, Mr. Dickinson has combined an ideal working equipment with a tremendous energy and a capacity for laborious and sustained mental effort.

As a practitioner his unusual ability was several times recognized by gubernatorial appointments as special judge on the Tennessee Supreme Bench, to which he declined a permanent appointment, shortly thereafter being called to the very high duties of the position of Assistant Attorney General of the United States. After his retirement from this position he became District Attorney for Tennessee and northern Alabama for the Louisville and Nashville Railroad Company, from which he was promoted to his present position as Chief Counsel for the Illinois Central, with headquarters at Chicago.

His greatest public service, as is well known, was his representation of the government in the Alaskan boundary dispute, wherein his presentation of the nation’s claims is admitted to have had a material influence in the successful outcome of that famous piece of international litigation.

JAMES McGAVOCK DICKINSON.

Judge Dickinson maintains a close identity with Southern matters by keeping up his connection with various societies and organizations, among the number being the Isham Harris Confederate Bivouac, at his native town, Columbus, Miss.

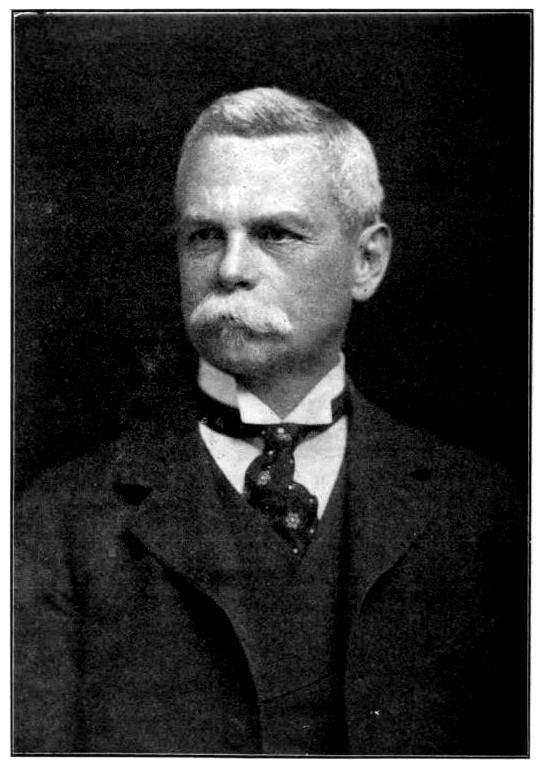

In the executive feature of railroad operation Samuel Spencer is a prominent national figure. From an humble position in the ranks, a combination of native ability, splendid equipment and consistent application has resulted in his promotion to the presidency of six large roads, while he is in addition a member of the board of directors of nearly a score of others and of nearly a dozen of the country’s most representative banking and other corporations.

SAMUEL SPENCER.

A native of Georgia, where he was born at Columbus, in 1847, Mr. Spencer entered the Confederate army, serving the last two years and with much credit, after which he graduated from the University of Georgia with A.B., and subsequently from the University of Virginia with his engineering degree.

Since leaving college in 1869 Mr. Spencer has devoted his energies uniformly to his ambition to rise to the highest round of the railroad ladder, with the result that he is now president of the Southern, the Mobile and Ohio, the Alabama and Great Southern, the Cincinnati, New Orleans and Texas Pacific, the Georgia Southern and Florida, and the Northern Alabama, aggregating a mileage of over nine thousand miles and employing more than forty thousand men.

Besides innumerable other roads, in the management of which Mr. Spencer is director, he is also a director of the Western Union Telegraph Company, the Old Dominion Steamship Company, three large New York Trust companies, the Hanover National Bank of New York, and one of Boston’s large street railway systems.

Mr. Spencer is identified with the American Society of Civil Engineers and other representative political, scientific and forestry associations, and is socially very much of a cosmopolite, being a member of New York, Chicago, Cincinnati, Atlanta and Macon clubs, besides that wealthy sportsman’s paradise, the Jekyl Island Club.

One of the very few Southerners who have advanced into the circles of millionairedom, Mr. Spencer resides principally in New York and Washington, but is much in the South and is still in feeling and sentiment very much a Southerner.

JAMES C. McREYNOLDS

In the appointment of James C. McReynolds to be Assistant Attorney General of the United States the President followed his revolutionary precedent in the selection of Judge Thomas G. Jones, of Alabama, as occupant of the Federal Bench. In this instance conventional custom was further ignored in the elevation of a man considerably younger than the age generally considered requisite.

Born at Elkton, Ky., a little over forty years ago, Mr. McReynolds was graduated from Vanderbilt University and the University of Virginia with his academic and law degrees, respectively, in both of which institutions he ranked high in scholarship and character.

His initial experience in public life was gained as the private secretary of Judge Howell E. Jackson of the United States Supreme Bench, which, with his already ample legal equipment, served him in good stead in the general practice in Nashville where his career at the bar was characterized by ability, integrity and a high order of fidelity to the many large interests that he represented.

In civic and political movements Mr. McReynolds’ record was signalized by a notably courageous, independent and unselfish interest.

Since his promotion to the duties of Assistant Attorney General of the United States he has established principles of large governmental significance and his able presentation of the government’s litigation before the Supreme Court has elicited the unanimous commendation of that impartial and august body.

Mr. McReynolds’ appreciation by the President would have been further displayed by his appointment as United States District Judge to succeed Judge Hammond, had not a technicality involving residence interfered.

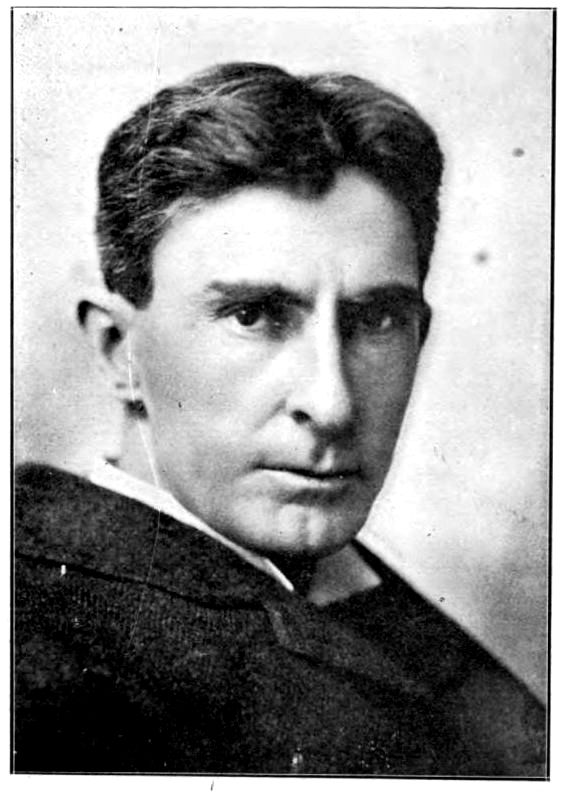

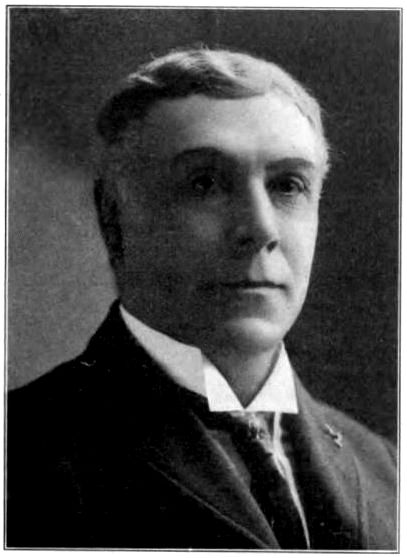

THOMAS DIXON, JR.

One of the most picturesque and dramatic figures in the limelight of to-day is the Rev. Thomas Dixon, Jr., a man who has at his age probably succeeded in as many different lines of endeavor as any other man of the times.

An intense product of the new South, Mr. Dixon speaks his opinions on his section’s great and peculiar problems with an incisive virility and a fearless conviction, and with his novels, “The Leopard’s Spots” and “The Clansman” has gained a popular audience for the Southern point of view, before unreached. He has also illumined the divorce evil and the subject of socialism in his dramatic story, “The One Woman.”

Born in North Carolina just forty years ago, and educated at Wake Forest, a Baptist denominational school, Mr. Dixon has in rapid succession essayed the fields of law, the ministry, lecturing and authorship, and has been prominently identified with each. He was a member of the North Carolina legislature at one time and is said to have essayed the histrionic for a brief spell.

First attaining more than casual prominence as a Baptist minister in New York, Mr. Dixon felt the opportunity of a non-sectarian evangelist fraught with higher possibilities in the metropolis and more in keeping with his temperament and convictions, founding a popular church wherein as a religious and civic free lance he attracted a large and influential hearing.

On the lecture platform he found a broader and more congenial labor still, and from lecturing he took to literature, to which he is now devoting his time exclusively. He has planned a trilogy of novels in exposition of the negro question, the second of which, “The Clansman,” takes its text from the vital role played by the Ku Klux in the redemption of the South from the triple scourge of the carpet bagger, the scalawag and their irresponsible tool, the ignorant African.

Mr. Dixon’s late successes have constituted him a man of affairs and he now resides upon his extensive Virginia plantation, where he does much of his literary work and incidentally lives the life of the Virginia planter and gentleman of the olden day.

He is proud to admit the valuable assistance rendered him by his wife, not only as literary critic but as a ready helper in the physical construction of his productions.

JOHN TEMPLE GRAVES.

As lecturer, orator and editor, John Temple Graves, of Atlanta, is well known to the country at large. As a lecturer he is classed by George R. Wendling as being in a class with Governor Taylor at the head of the Southern field; as an orator he has had the distinction of presenting his section’s sentiments and peculiar problems to the national ear as has no other man since Henry W. Grady; and as an editor he has by the forcefulness of his personality developed in a brief period of time an extensive business enterprise and a material public influence in his section.

Mr. Graves’ most telling work on the platform has doubtless been his contribution to the enlightenment of the Northern mind on the negro question, while on this and various other subjects he has appeared three times as the orator of the New England Society of Boston, twice of the Merchants’ Club of Boston, once of the New England Society of Philadelphia and twice of the Southern Society of New York. In the capacity of journalist he has officially represented the South as spokesman before the World’s Congress of Journalists at Chicago, in 1893, and also before the World’s Press Parliament at St. Louis, last summer.

As a memorial orator Mr. Graves is entitled to distinguished rank, it having devolved upon him to deliver the funeral orations over the remains of his state’s most eminent sons—Grady and Gordon.

Mr. Graves is still a young man and is a native of Rome, Ga., and a graduate of his state institution at Athens, of which he is a devoted alumnus. He now devotes his time chiefly to his journalistic interests and resides in Atlanta.

Though not a politician Mr. Graves has been twice elector at large in two consecutive presidential campaigns in different states, and has led the Democratic ticket in both instances.

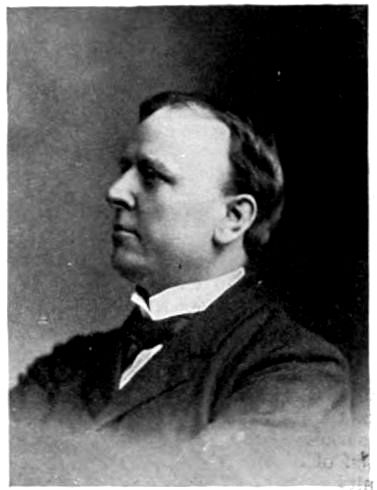

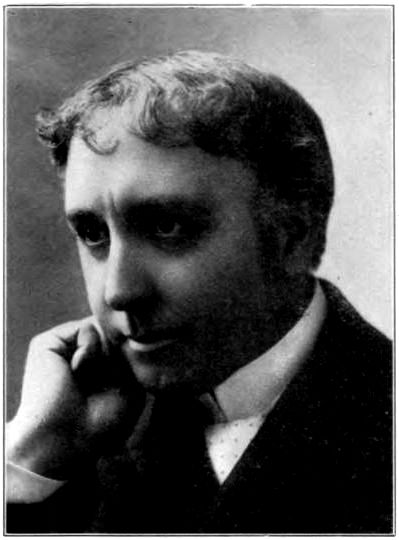

Joseph A. Altsheler, whose story, “The Lost Herd,” follows, is a representative type of the new generation of Southerners in contemporary literature.

Born, reared and educated in the South, he has won successive and substantial laurels in both journalism and literature, and is at present the unusual combination of a successful figure in both fields.

Born in Kentucky, that commonwealth that has contributed so many distinguished workers to the literary history of the day, he attended the local schools of his native heath in the southern part of the state until entering Vanderbilt University, where he ranked high in class work, being a Latin scholarship man.

After leaving college, he immediately took up journalistic work in Louisville with The Evening Post, subsequently going with the Courier-Journal, with which paper he remained several years, gaining wide journalistic experience as legislative correspondent, dramatic critic, city editor and editorial writer.

In 1892 Mr. Altsheler followed the almost inevitable ambition of the American with pronounced literary attainments, migrating to the broad and inviting field of the metropolis, since which time he has successively filled responsible positions with the New York World, being at present in charge of its tri-weekly edition.

About nine years ago Mr. Altsheler turned his attention seriously to fiction, since which time he has produced no less than ten novels, in many of which he has drawn largely upon his own extensive personal experiences as a journalist.

His first book was “The Sun of Saratoga,” while his latest is “Guthrie of the Times,” a contemporary romance with a strong political flavor. He has now in press “The Candidate,” also a novel of the day, and likewise treating of political life, this time in the West instead of in Kentucky.

Redfield parted the twining bushes with both hands, and pushed his body through the cleft, while I stood by to see the issue. He took but a single step and then threw himself back like a soldier who would escape a bullet, his face, now turned toward me, showing a yellowish hue in the moonlight. He raised his hand and wiped his damp forehead, while I gazed at him in silence, seeing fear, sudden and absolute, in his gaze, as if death had faced him, with no warning.

We stood so, for a few moments, until the terror died slowly in his eyes, when he took another step back, and laughing a little, in a nervous way, pointed before him with a long forefinger.

I advanced, but he put a restraining hand upon my shoulder, and bade me take only a single step. I obeyed and, with his hand still on my shoulder, looked down a drop of a thousand feet, steep like the side of a house, the hard stone of the wall showing gray and bronze, where the light of the moon fell upon it.

I saw at the bottom masses of foliage like the tops of trees, and running through them a thread of silver, which I felt sure was the stream of a brook or creek. We were looking into a green valley, and now I understood Redfield’s terror, when instinct or quickness of eye, or both, saved him from the next step, which would have taken him to sure death.

The valley looked pleasant, with green trees and running water, and I suggested that it would furnish a good camp to us who were weary of mountains and ravines and stony paths.

Redfield pointed straight before us, and three miles away rose the mountain wall again, steep and bare, the hard stone gleaming in the moonlight. I followed his finger as he moved it around in a circle, and the wall was there, everywhere. The valley seemed to be enclosed by steep mountains as completely as the sea rings around a coral island.

I said that I had never heard of such a place in these mountains, and Redfield reminded me that there were many things of which neither he nor I had ever heard, and perhaps never would hear.

His retort did not dim my curiosity, in which he shared fully, and, lying down for greater security, we stared over the brink into the valley, which looked like a huge bowl, sunk there by nature. The sky was clear, the moon was rising, and we could see the boughs of the trees below waving in the gentle wind. The silver thread of the brook widened, cutting across the valley like a sword blade, and we almost believed that we saw soft green turf by its banks. But on all sides of the bowl towered the stone walls, carved into fantastic figures by the action of time and mountain torrents.

The green valley below could not remove the sense of desolation which the walls, grim and hard, inspired. My eyes turned from the foliage to the sweep of stone rising above, black where the light could not reach it, then gray and bronze and purple and green as if the moon’s rays had been tinted by some hidden alchemy. I assisted nature with my own imagination and carved definite shapes—impish faces and threatening armies in the solid stone of the walls. I felt the shiver of Redfield’s hand, which was still upon my shoulder, and he complained that he was chilled. I knew it to be the stony desolation of the walls, and not the cold of the night, that made him shiver, for I, too, felt it in my bones, and I proposed that we look no more, at least not then, but build a fire, and rest and sleep.

We did as I proposed, but while we gathered the fallen brushwood, each knew what was in the other’s mind; the mystery of the valley was upon us, and we would wait only until daylight to enter it and see what it held.

Redfield lighted the fire, and the blaze, rising above the heaps of dry sticks and boughs, was twisted into coils of red ribbon by the wind; a thin cloud of smoke gathered and floated off over the valley, where it hung like a mist, while the wind moaned in the great cleft.

Redfield complained that he was still cold, and wrapping his blanket tightly around him, sat close to the fire, where I noticed that he did not cease to shiver. I spread out my own blanket, and by and by both of us lay down on the grass seeking sleep.

When I awoke far in the night, the fire had burned down, the moon was gone, and Redfield’s figure, beyond the bed of coals, was almost hidden by the darkness. Damp mists had gathered on the mountain, and my hand, as I drew the corners of the blanket around my throat, shook with cold.

Not being able to sleep again just then, I rose and put more wood on the heap of coals. But the fire burned with a languid, drooping blaze, giving out little warmth and offering no resistance to the encroaching darkness. Redfield slept heavily and was so still that he lay like one dead. The flickering light of the fire fell over his face sometimes and tinted it with a pale red.

I sat by the coals a little while, looking around at the dim forest, and then the attraction of the great pit, or valley, drew me toward it.

I knelt down at the brink, holding to the scrubby bushes with each hand, and looked over, but I could no longer see the trees and brook below. The valley was filled with mists and vapors, and from some point beneath came the loud moan of the wind.

I stayed there a long time, gazing down at the clouds and vapors, which heaped upon each other and dissolved, showing denser vapors below, and then heaped up in terraces again. The stone walls, when I caught glimpses of them, seemed wholly black in the darkness of the night, and the queer shapes which took whatever form my fancy wished were exaggerated and distorted by the faintness of the light. The place put a spell upon me; if Redfield would not go with me in the morning to explore it, though knowing well he would, I resolved to go alone, and see what, if anything, was there besides grass and trees and water. I felt the strange desire to throw myself from a height which sometimes lays hold of people, and instantly pulling myself back from the brink I returned to the fire. Redfield was yet sleeping heavily and the flames had sunk again, flickering and nodding as they burned low. I lay down and slept until morning, when I awoke to find that Redfield was already cooking our breakfast. He proposed that we begin the descent in an hour, and like myself he seemed to have accepted the conclusion that we had agreed upon the attempt, though neither had said a word about it.

The valley assumed a double aspect in the bright light of the morning, green and pleasant far down where the grass grew and the brook flowed, but grim and gaunt as ever in its wide expanse of rocky wall. The rising sun broke in a thousand colored lights upon the cliffs, and the stony angles and corners threw off tiny spear points of flame. The majesty of the place which had taken hold of us by night held its sway by day.

We had no doubt that we should find a slope suitable for descent if we sought long enough, and we pushed our way through the bushes and over the masses of sharp and broken stone along the brink until our bones ached and our spirit was weak. Yet we encouraged each other with the hope that we would soon reach such a place, though the circle of the valley was soon proved to be much greater than we had expected.

Noon came and we were forced to rest and eat some of the cold food that we had wisely brought with us. The sun was hot on the mountains and the stone walls of the valley threw the light back in our eyes until, dazzled, we were forced to look away. But we had no thought of ceasing the quest; such a discovery was not made merely to leave the valley unexplored, and rising again after food and rest we resumed our task. About the middle of the afternoon I saw a break in the wall which we thought to be a ravine or gully of sufficient slope to permit of our descent into the valley, but it was nearly night when we reached the place and found our opinion was correct.

The ravine was well lined with short bushes which seemed to ensure a safe descent, even in twilight, and we began the downward climb, seeking a secure resting place among the rocks for each footstep and holding with both hands to the bushes and vines.

The sun, setting in a sky of unbroken blue, poured a flood of red and golden light into the valley. The walls blazed with vivid colors, and the green of the trees and grass was deepened. Redfield stopped, and touching me on the shoulder pointed with his finger to the little plain in the center of the valley where a buffalo herd was grazing. Such they were we knew at the first glance, for one could not mistake the great forms, the humped shoulders and shaggy necks.

Neither of us sought to conceal his surprise, and perhaps neither would have believed what his eyes told him had it not been for the presence and confirmation of the other. We knew, as everybody else knew, that the wild buffalo had been exterminated in this region years ago, and that even now the only herd left in the whole United States was somewhere in the tangled mountains of Colorado, and yet here we were gazing upon another herd of these great animals, at least fifty of them, for we could count them as they moved placidly about and cropped the short turf.

We remained a quarter of an hour in that notch in the wall exulting over our second discovery, for we considered the tenants of the valley of as great importance as the valley itself, and exchanged with each other sentences of surprise and wonder. The sun hovered directly over the further brink, and poised there, a huge globe of red, shot through with orange light, it seemed to pour all its rays upon the valley.

Every object was illumined and enlarged. The buffaloes rose to a gigantic height, the trees were tipped with fire, and the brook gleamed red and yellow where the rays of the sun struck directly upon it. Again we said to each other what a wonderful discovery was ours and looked to the rifles that we had strapped across our backs, for seeing the great game of the valley we had it in mind to enjoy unequalled sport. I lamented the speedy departure of the day, but Redfield thought the night would give us a better chance to stalk the big game, and thus talking we resumed the descent. The sun sank behind the mountains, the red and golden lights faded, and the valley lay below us in darkness. The buffalo herd had disappeared from our sight, but feeling sure that we should find it we continued our descent, clinging to the bushes and vines, and wary with our footing.

The twilight was not so deep that the gray mountain walls did not show through it, and as we painfully continued our descent the trees and the brook rose again out of the dusk. Nearing the last steps of the slope we could see that the valley was much larger than it had looked from above, and our wonder at the presence of the herd was equalled by our wonder at the manner in which it had ever reached such a place, as there seemed to be no entrance save the perilous path by which we had come.

At last we left the bushes and stones of the ravine and, standing with feet half buried in the soft turf of the valley, looked up at the sky as if from the bottom of a pit.

The twilight was as clear around us as it had been on the mountain above, and we could see a pleasant stretch of sward, the land rolling gently, with clumps of bushes and large trees clustering here and there.

We did not pause to look about, both being filled with the ardor of the chase, and we walked quickly toward the little bit of prairie in which we had seen the buffaloes, examining our rifles to be sure that they were loaded properly. I felt that sense of unreality which strange surroundings always give.

The night, now fully come, was not dark, the stars were appearing and a pale light glimmered along the edges of the cliffs, which seemed, as I looked up, to overhang and threaten us.

We reached the brook that we had seen from above, a fine stream of clear water, a foot deep and a dozen or more across. We paused there to drink and refresh ourselves, and found it cool and natural to the taste. I supposed that it flowed into some cave through the mountain, since I could not imagine any other outlet; but the matter remained for only a few seconds in my mind, as Redfield began to tug at my sleeve and urge me on to the chase, to which I was nothing loth.

Yet I noticed that there were no other signs of animal life in the valley. Not a rabbit popped up in the grass; the trees were fresh with foliage, but no birds flew among the boughs. All around us was silence, save for the soft crush of our own footsteps and our breathing, now quickened by our exertions. I called Redfield’s attention to this silence and absence of life, and we stopped again and listened but heard nothing. The night was without wind; I could not see a leaf on the trees stir, the air felt close and heavy, and Redfield told me that my face was without color; I had noticed that fact already in his.

Fifty yards farther and we came to the open space in which we had seen the herd, and we felt sure that it was not far beyond us, for the heads of the animals had been turned south and we believed they had continued to move in that direction as they nibbled the grass. We paused to take another look at our rifles, our ardor for the chase rising to the highest, leaving us no thought of anything but to kill.

I had never before hunted such big game and I felt now the thrill which leads men to risk their own lives that they may take those of the most dangerous wild beasts. The twilight had deepened somewhat, and though of a grayer tone in the valley, where mists seemed to be collected and hemmed, it was not dense enough to hinder our pursuit.

Redfield paused suddenly and put his hand upon my shoulder though I had seen them as soon as he. The herd was grazing in the edge of a little grove a few hundred yards ahead of us, but within plain sight. This closer view confirmed our count from the mountain-side that they were about fifty in number, and admiration mingled with our wonder, for they were magnificent in size, true monarchs of the wilderness, grazing, unseen by man, while the rush of civilization passed around their mountains and pressed on, hundreds of miles into the Farther West. Their figures stood out in the gray twilight, huge and somber, surpassing in size anything that I had imagined. I felt a joy that I was one of the two whose fortune it was to find such game, a proud anticipation of the trophies that I would show. I saw the same exhilaration in Redfield’s eyes, and again we spoke to each other of our fortune.

I held up a wet finger, and finding that the wind was blowing from the herd toward us we resumed our advance, sure that we could approach near enough for rifle shot. The herd was noiseless, like ourselves, the huge beasts seeming to step lightly as they cropped the grass, the scraping of the bushes as they pushed through them not reaching our ears. Again the sense of silence, of desolation oppressed me. The grayness over everything, the trees, the grass, the mountains, Redfield, myself even, the unreality of the place and our situation seized me and clung to me, though I strengthened my will and went on, the zeal of the chase directing all else.

Our stalking proceeded with a success that was encouraging to novices like ourselves, and a few more cautious steps would take us within good rifle shot. We marked two of the animals, the largest two of the herd, standing near a clump of bushes, and we agreed that we should fire first upon these, Redfield taking the one on the right. If we failed to slay at the first shot, which was very likely, the chase would be sure to lead us directly down the valley, and we could easily slip fresh cartridges into our rifles as we ran. Nor could the game escape us within such restricted limits; and thus, feeling secure of our triumph, we slipped forward with the greatest caution until we were within the fair range that we wished. Then we stood motionless until we could secure the best aim, each selecting the target upon which we had agreed.

The herd seemed to have no suspicion of our presence. However acute might be the buffalo’s sense of smell, it had brought to them no warning of our presence. Their heads were half buried in the long grass, and as I looked along the barrel of my rifle, I felt again the stillness of the valley, the utter sense of loneliness which made me creep a little closer to Redfield, even as I sought the vital spot in the animal at which I aimed my rifle.

Redfield whispered that we could hardly miss at such good range, and then we pulled trigger so close together that our two rifles made one report.

We were good marksmen, but both the buffaloes whirled about, untouched as far as we could see, and looked at us. The entire herd followed these two leaders, and in an instant fifty pairs of red eyes confronted Redfield and myself. Then they charged us like a troop of cavalry, heads down, their great shoulders heaving up. We slipped hasty cartridges into our rifles and fired again, but the shots, like the first, seemed to have no effect, and, in frightened fancy, feeling the breath of the angry beasts already in our faces, we turned and ran with all speed up the valley, in fear of our lives and praying silently for refuge. I hung to my rifle with a kind of instinct, and I noticed that Redfield, too, carried his. I looked once over my shoulder and saw the herd pursuing, not fifty feet away, in solid line like the front of an attacking square. I shouted to Redfield to dart to one side among some trees, hoping that the heavy brutes would rush past us as we could not hope to outrun them in a straight course, and he obeyed with promptness. We gained a little by the trick, but the buffaloes turned again presently, and then we seized the hanging boughs of two convenient trees, and, managing to retain our rifles, climbed hastily up and out of present danger.

The buffaloes stopped about a hundred feet away, still in unbroken phalanx, and stared at us with red eyes. I was filled with fear; I will not deny it, I felt it in every fiber. I had heard always that these beasts, however huge, were harmless, their first rush over, but they were looking at us now with eyes of human intelligence and even more than human rage; a steady, tenacious anger that threatened us, and seemed to demand our lives as the price of our attempt upon theirs. I felt cold to the bone, and the angry gaze of the besieging beasts held my own eyes until I turned them away, with an effort, and looked at Redfield. Then I saw that he was as white and afraid as I knew myself to be. I told him that we were besieged, and he rejoined that the attitude, the look of our besiegers, betokened persistency.

While we talked, the buffaloes began to move and we hoped that we had been mistaken in our belief, and that they would abandon us, but the hope was idle. They formed a complete circle around us, a ring of sentinels, each motionless after he had assumed his proper position, the red eyes shining out of the massive, lowered heads, and fixed on us. Redfield laughed, but it was not the laugh of mirth. He asked me what we had to fear from the buffalo, which was not a beast of prey; they would turn away presently and begin to crop the grass again, but his tone did not express a belief in his own words.

The night had not darkened, but the curious grayness which was the prevailing quality of the atmosphere in the valley had deepened, and the forms of the beasts on guard became less distinct. Yet it seemed only to increase the penetrating gaze of their eyes, which flamed at us like a circle of watch fires. The sentinels were noiseless as well as motionless. The wind whimpered gently through the leaves of the trees, but there was nothing else to be heard in the valley, and saving ourselves and the buffaloes, nothing of human or animal life to be seen. Redfield said to me that he wished our guards would move, that while they stayed in such fixed attitudes he felt as if we were watched by so many human beings. His voice was at a higher pitch than usual, and I felt a strange pleasure in noticing it, for I knew then that he had been affected as I by our peculiar position. He burst suddenly into a laugh, and when I asked him where he found amusement, he reminded me that both of us yet carried our rifles, though we seemed to have forgotten the use for which they were made. He added that the sentinels were within easy range, and since our object was now self-preservation and not sport, we could sit on the boughs in perfect safety and shoot as many of them as we chose, unless they retired.

It was the power of surprise and fear that had prevented us from thinking of this before, though the weapons were in our hands, and I felt a sense of shame that we had permitted ourselves to be overwhelmed in such a manner. I waited before raising my own rifle, to see the effect of Redfield’s shot. I saw him select his target and look down the barrel of his rifle as he sought to make his aim true. The eyes of the buffalo had seemed so human in their intelligence and anger that I expected to see the animal, knowing his danger, retreat when the rifle was raised. But he made no motion, looking straight into the muzzle of the weapon which was threatening him. Redfield pulled the trigger and fired, and then both of us cried out in surprise and displeasure.

The buffalo did not move, and if the bullet had touched him there was no mark upon him that we could see to tell of its passage. Redfield said it was the bad light that had made him miss, but I believed it was a trembling hand—that the chill, though the night was warm, which affected me had seized him, too. Yet I steadied myself now that my own time to fire had come, and took good aim at the buffalo nearest to my tree. It may have been the strength of my imagination, and in reality the eyes of the brute may not have been visible at all at such a distance and in the night, but I was sure that they were staring at me with human malice, and another expression, too, that I interpreted as defiance. I was seized with a sudden and fierce anger—anger because I had been afraid, anger because there was a taunt in the eyes of the beast.

I pulled the trigger and looked eagerly at the result of my shot; then I cried aloud in disappointment, as Redfield had done. The buffalo, untouched, was staring at me with the same malicious eyes, not even moving his head when I fired.

Redfield laughed once more in a mirthless way, and I told him angrily to hush; that he was afraid but I was not, and I would fire again. I put in a second cartridge but the shot was as futile as the first, and Redfield, who tried once more, had a similar lack of success. But we told each other, and with all the greater emphasis because we were not sure of it, that it was the imperfect light and our nerves strained by the descent of the rough cliff. I noticed that Redfield’s voice was growing louder and more uneven as we talked, and his eyes were gleaming.

At last we exhausted our cartridges without touching the silent ring of sentinels, or making any of them move, and Redfield, throwing his rifle to the ground, laughed in the curious, unnatural way that makes one shiver. I bade him stop and I spoke with anger, but he paid no attention either to my words or my manner. His laughter ended shrilly, and then he said that he understood it all: that these animals had been hunted from the face of the earth except this lone herd, which was left here to hunt any man who came against it. Behold the present as the proof of what he said!

I laughed at him, yet my laughter, like his, sounded strange even in my own ears, and looking at the silent ring of sentinels, I believed his words to be true. When or how we should escape I could not foresee, and I did not feel the fear of death; and yet there was nothing that I had in the world which I would not have given to be out of the valley. The rifle which I had used to such little purpose burned my hands, and I let it drop to the ground.

Redfield laughed again in a shrill, acrid way, and when I asked him to stop, jeered at me and bade me notice how faithful our besiegers were to their duty.

Not one of them had moved from the circle, their forms becoming duskier as the night deepened, but growing larger in the thick atmosphere. The sky above was cloudless, and we seemed to see it from interminable depths; the huge cliffs rose out of the mists, shapeless walls, and the trees became gray and shadowy. Redfield began to talk, volubly and about nothing, varying his chatter with the same shrill, unpleasant laughter, and I, finding it useless to bid him hush, said nothing. Yet I wished that he would cease, and I might hear other sounds, the leap of a rabbit or the scamper of a deer, anything to disturb that horrible chatter, and the equally horrible silence, otherwise. Securing myself in the crook of a bough and the tree I tried to sleep, and I think that at last I fell into a kind of stupor, in which I heard only Redfield’s shrill laugh. But I awoke from it to find a clear moon, and our silent line of sentinels still there. The wind, risen somewhat, was moaning up the valley and the night was cold.

Redfield was silent then, but when I called to him he answered in a natural tone for the first time in hours and asked me if I had anything to suggest, as we must change our present position very soon. I told him that we must descend from the trees, find the path out of the valley and leave by it, at once. He pointed to the sentinels and said nothing would induce him to face them, but I told him we must do it since it was the only thing left for us, though I will admit that my own sense of fear was of such strength that my words were braver than myself.

The moon came out again and the forms of our guards grew more distinct, ceasing to have the shadowy quality which at times in the last hour had made them waver before me. Nevertheless, the light still served to distort them and enlarge them to gigantic size, and my imagination gave further aid in the task.

Redfield became silent again, and I thought he might be asleep, but when I looked at him I saw his eyes shining with the same unnatural light that I had marked there before, and I felt with greater force than ever that we must not long delay our attempt to leave the valley. But I remained for a while without movement or without thought of what we should do. The belief that we had come there to be hunted by the survivors of the millions whom we had hunted out of existence became a conviction, and I felt a reluctance to meet the eyes of the avenging beasts, eyes that I could always see with my imagination if not with my own gaze. The light of the moon struck fairly on the sides of the great cliffs and the grotesque and threatening faces which my fancy had carved there in the rock lowered at us again. I could even distort the trees into gigantic half-human shapes, leaning toward us and taunting us, but I shut my eyes and drove them away. I had not forgotten the curious light gleaming in Redfield’s eyes.

An hour later I told Redfield that we must descend, that we could not stay forever where we were and it was foolish for us to delay, wearing out our strength and weakening our wills with so long and heavy a vigil. He said no, that he would not stir while those beasts were there watching; he could see a million red eyes all turned upon him and he knew that as soon as he touched the earth the owners of those eyes would rush upon him and trample him to death. I felt some of his own reluctance, but knowing that it was no time to waste words I told him that he could stay where he was, if he chose, but I was going; I had seen enough of the valley and certainly I would never come near it again. So speaking I began to descend the tree, and Redfield instantly began to tremble and beg me, like a child, not to go. He said he could not be left there alone and he would not be for all the world. Strengthened in my purpose by his pleadings and believing that my method would compel him to come I again bade him stay if he wished, it was nothing to me; but while I said these things I continued to descend. When he saw that I was in truth going he began to lower himself from his tree, though still begging me not to make the attempt.

My foot struck the ground and I stood there afraid, but resolute. Our guards still gazed at us but made no movement to attack, and I drew courage from the fact.

Redfield was shivering, and perhaps my own courage was not of the best, but I pointed to a dark line in the face of a distant cliff where the moonlight fell clearly, and asked if it were not the ravine by which we had come. He said yes, and not giving him time to think and to hesitate about it I seized him by the arm and pulled him on, telling him that we must reach the ravine as quickly as we could and leave the valley. Then we advanced directly toward that segment of the watchful circle which stood between us and the point we desired to reach.

I retained my firm grasp upon Redfield’s arm and I felt the flesh trembling under my fingers. We did not recall until long afterward that we had forgotten our rifles. As we advanced, the line of buffaloes parted and we passed through it. Redfield cried out in childish delight and said they were afraid of us, but I shook him, more in anger than from any wiser motive, and hastened our steps. Fear rolled away from me and I felt an exhilaration that made me walk with buoyant step. I dropped my hand from Redfield’s arm and we walked on at a swift pace, my eyes fixed on the dark line in the cliff which marked the ravine, our avenue of escape from the valley. Redfield suddenly put his hand upon my shoulder and motioned me to look back. When I obeyed I saw the buffaloes following us in a long line, as regular and even as a company of soldiers. Redfield laughed in the mirthless way which marked him that night and said we had an escort who would see that we did not linger in the valley. I could not say that he was wrong, but I grew impatient with him when he tried to make a jest of it and talked of our bodyguard. I knew that he was trembling, and I asked angrily, though not in words, why they could not let us alone. We were leaving as fast as we could, and as for coming back, nothing could drag me to that valley again; no, nothing, and I said the “nothing” aloud with angry emphasis.

Our guard did not desert us, but followed at fifty or sixty yards with noiseless step. And again I noticed that there was no other animal life in the valley, though the grass was green and the woods abundant, a place that the birds and rabbits should love.

The outlines of the pass grew more distinct, the tracery of bushes and vines that lined it was revealed, and in a few minutes we would arrive at the first slope. I felt like a criminal, a murderer, taken in disgrace from the place of his crime, and this feeling once having seized me would not leave, but grew in strength and held me. Redfield was my brother in crime, and certainly his face, his nerveless manner, showed his guilt.