Title: The Ambassadors From Venus

Author: Kendell Foster Crossen

Illustrator: Herman B. Vestal

Release date: December 13, 2020 [eBook #64045]

Most recently updated: October 18, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Greg Weeks, Mary Meehan and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

A Novelet of Grim New Worlds

Strange. Strange. The empty space ships. The patched

voices. The curt invitation to Venus. But what had Clyde

Ellery and the other atom-plague survivors to lose?

They forgot there are many kinds of death!

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Planet Stories March 1952.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

The first ship landed in a plowed field fifty miles from the city, just beyond the signs that warned of radiation. Rather circular in shape, it was fully sixty feet across and twenty feet in thickness, its color a burnished green. It came down swiftly until it was fifty feet from the ground; then a gush of flame poured from the under side and checked its fall. It settled to the soil, like a giant mushroom, and there was a smell of scorched earth in the air.

Max Carr was the first to see it. He was sitting under the gnarled apple tree in the front yard, and he watched the ship settle down on that tail of fire. He should have been out in the fields planting, but he wasn't. He hadn't worked in months, beyond milking the cows and tossing them wisps of hay. He knew that a hundred million people had died in America the day the bombs fell, that hundreds of millions more had died in Europe the following day, and in Asia and Africa the day after, as American atomic bombs rocketed in reply to the sudden attack.

He knew that millions had died since, and were still dying as the radioactivity bit deep into their bones and flesh. He felt the clutch of death on himself, so he looked at the ship with little curiosity. It was a strange ship, but there was nothing it could do that had not already been done.

But when nothing happened, when no strange warriors came swaggering from the ship, his sluggish interest uncoiled and took on life. He called his wife and children and they cautiously approached the ship. Still nothing happened. It seemed to be made of solid metal, with no windows or doors. They touched the strange metal and stared at the blackened ground, and then returned to the lethargy that was their daily fare.

The ship might have set there in the field, forgotten for months, if a neighbor hadn't stopped by that evening. He saw the ship and asked questions and carried the news away with him. It was the first thing that had happened in months which was at least neutral, and he stopped at three houses to talk about it. He was tired of talking about death.

Three days later, they trudged into Max Carr's farm, some of them coming from as far as twenty miles away. A dozen men and women stood in the field and stared at the ship. Max Carr and his wife joined them.

"Big, huh?" one of the men said, but no one answered him. They were a small community in which everything had been said.

Two more men came along the road, their dragging feet kicking up little spurts of dust, and turned into the field. After fifteen minutes, another arrived. It was when he drew near the ship that it happened.

There was a loud click from somewhere inside the ship and a crack appeared in the side as a panel slid back. Soon there was an opening, large enough for a man to enter or leave. It was dark within. But no one came from the ship, nor was there a single step taken nearer it. The small group stood and waited.

"People of Earth," said a harsh voice from the ship, "you have just come through a war and there are few of you left alive. There is little hope for any of you, for the radioactivity is spreading over the entire face of your planet. This ship has come to invite those of you who are not sick to establish a colony on the planet which you call Venus. You may pick one of your group to represent you. If he is not already a victim of radiation, he will be permitted to enter this ship and learn more of this plan."

The voice cut off with an audible click.

The men and women in the field shuffled about in indecision. They stared at each other in fear. Who among them was not sick? There was doubt on every face and in everyone the thought that it would be better not to know. Then the self-searching ended as though by common consent, with every eye swinging to a man who stood apart from the group.

Clyde Ellery was a scientist, one of the few to escape the death of their own making. On vacation, high in a mountain retreat, he had seen the sky turn angrily red, had watched the pall of smoke. He had hurried back, but there was nothing to do. There was no place that the Geiger counter did not purr its message, and all he could do was mark the dividing line between quick death and slow death. He had watched the faces turned toward him, burning anger checked by the knowledge that there was no punishment to fit the crime. Under the weight of those glances, the burden of being alone, Clyde Ellery's shoulders had stooped and rounded. He walked alone, and recognized its justice.

There was a difference in the looks now turned in his direction. He sensed it, even before he lifted his head. His gaze went swiftly from face to face and in those few silent seconds the appointment was made and accepted. Clyde Ellery's thin shoulders straightened and he stepped forward, walking through the small crowd to the ship. At the doorway, he stopped. There was a queer rigidity to his body, as if he were leaning against an invisible barrier. For a full minute he stood there, unmoving, being tested by others than his neighbors.

"This man has no sickness," the voice from the ship announced suddenly. "He may enter."

Clyde Ellery stepped through the door and was gone into the darkness beyond.

The sun glinted from the burnished green hull, but no light entered the blackness that was the doorway. There was nothing to see or hear. The men and women stood patiently in front of the ship and waited. They seemed unaware of the passage of time, for they lived in the stasis of a minute.

Shadows were longer by a foot or more when Clyde Ellery again appeared among them. There was an expression of hope on his face, but they stared back without understanding.

"We must leave the field," he told them. They followed him across the furrowed ground, accepting for the moment his leadership. Beyond the staggering rail fence, near to the once-red barn, he turned to look back at the strange ship.

The doorway was closed and once again there was only the smooth metal, looking green and alive against the brown earth. As they watched, the ship quivered, then rose a few feet on a single leg of fire. It hung poised in the air as the fire fanned out, grew solid and orange. There was no sound, but they could feel the heat against their faces. The pillar of fire lengthened, pushing the ship against the sky. Then the fire lifted from the earth and the ship was flashing out of sight, leaving only the offal of blackened soil as proof of its visit.

Clyde Ellery turned and walked to where the gnarled apple trees guarded Max Carr's house. He dropped to the ground. The others seated themselves around him and waited. The children grouped near the pump and were silent.

"It'll be back," Clyde Ellery said, and there was confidence in his voice. The strength of words had been redeemed. "It has gone to other communities like this one—all over the world. But it will return—it and other ships like it."

He paused, but there were no questions. The hope that was within him found no new ground. They were aware of no questions that had not been answered by the bursting flame and mushrooming smoke he had helped to make. They expected no answers, yet they respected that which they saw in his face.

"The ship was empty," Clyde Ellery said after a while, "but there was a recording which told me everything. There is to be another chance for Man—for those of us who are not yet radioactive."

They waited patiently, these men and women who had looked too long upon death to recognize life.

"The ship is from Venus—built by what, I don't know. Speech, as we know it, must be unknown, for the recording we all heard, and those that were played for me, were pieced together from words recorded here on Earth. Almost every word was spoken by a different voice. They must have recorded many conversations here, then picked out the needed words and made up their message on new records. It indicates no spoken language, perhaps no vocal cords, but a high degree of intelligence."

He was the only one interested in the high degree of intelligence.

"The ships are apparently remote-controlled," he said, and it was easy to see that he was dreaming of the science that had made such ships possible. "I suspect the ships are magnetic-powered for the record said that the trip to Venus can be made very quickly—a matter of hours." He realized then that among his listeners there was not one who cared how the ship was powered. He said bluntly, "All the people of Earth who are still healthy are invited to go to Venus. One half of the entire planet will be given to us. We must take with us our own animals and our own plant seeds, those that are also healthy. They will provide as many ships as are necessary.

"The ships are somehow built to detect the healthy and the unhealthy. It will be impossible for a person, an animal, or for any seed, to pass within the ship unless it is healthy. There will be no chance for the sickness to take root in the new colony."

They had come to accept death for all, and there was only fear at the thought that some of them might live. They stared stolidly at a point just above Clyde Ellery's head.

"The climate and the atmosphere on Venus are pretty much the same as here," Clyde Ellery continued. "There is more precipitation—more rain, but not too much. The soil is rich, and will not need fertilizers for years. One half of the planet—the half towards Earth—will be ours to cultivate and govern as we please. We may take as many personal possessions with us as we wish, as long as they are free from radioactivity. There—there is—" his voice faltered, then went on—"one other requirement in accepting their help. We cannot take any equipment or literature necessary to the making of weapons of war, including atomic bombs, and the record said that any attempt to make destructive weapons on Venus will bring death to those doing it. Other than that, there will be no interference. The ships will be here within a week."

A bird chirped feebly from the branches of the apple tree, but there was no other sound. The men and women sat quietly in the grass and looked at Clyde Ellery without emotion. From farther off, the children stared in futile imitation.

"That's all," Clyde Ellery said lamely. "The ships for this area will land in the same field. Within a week." He paused, then walked toward the road. He was alone again, a leader with no followers.

By ones and twos, the others left as the sun dropped lower. No words were given, no promises made, in the leaving. No man looked to his neighbor.

It was an uneventful week. The women still cooked meals automatically, and between meals they stared endlessly through windows; the men still did a few chores or sat in the shade and stared. Here and there a man might lift his head to the skies and feel a stirring of something like hope, but then he'd see a withered plant or walk through the fields to find a dead cow and he'd go back to sitting in the shade. And it was the same all over the world, whether the man was black or yellow or white.

The same ship returned to the field on Max Carr's farm. With it were a number of other ships, larger by far. They covered the field, like strange green growths, and the earth was black from their flames.

They stood there, empty and waiting for the people to come. And come they did, without hope and with little curiosity. Still they came, walking through the dry dust, riding in Fords and Cadillacs, driving horses and oxen and even goats. They came for days in an endless stream of plodding humanity, clutching personal possessions, carrying precious bags of seeds, driving livestock before them. Men and women and squawling children. Some wore scars where they could be seen, great livid welts that gave mute testimony to the progress of man; others bore their scars unseen. All were silent and looked away quickly if they met another's eye.

The doors of the ships opened and the recorded voice from the smaller ship told them to enter the other ships, taking with them their seed and their animals. In listless streams they poured through the nearest doorways, and some came out of one door and some from another. Some entered holding a bag of seed and came out holding two. There were husbands and wives who went in holding hands and came out by different doors. As they left the ships, they stood where the voice directed them. Slowly one group grew, one or two at a time adding to its numbers, while the other swelled out over the field.

Those in the smaller group looked to the larger and there were many who saw a beloved, a husband or wife, a child or parent, standing among the rejected. A hand that a moment before had gripped another now clutched the limp throat of a bag filled with dying seed. There were some who gazed across the field, then looked briefly through a mist of sadness and longing at the shimmering ships before stepping across to volunteer for death with those they could not leave. There were others who looked across to the larger group and turned away to weep, but stayed where they were.

For several days the sorting of seed and equipment, animals and people, continued. The two camps became little tent villages with smoldering fires. Thin rays of light, unseen during the day, soft blue at night, reached out from the ships between the two groups. Those from the smaller group could pass through the rays, but when two men tried to sneak in among the chosen they were stopped as though by a brick wall. Others tried going around the fingers of light late at night, but the rays curved and drove them back. None of the rejected left, but camped there in silent resignation. One place was the same as another, and they had nothing to do but wait.

Clyde Ellery worked day and night, helping to form the lines, carrying children and packages, seeing that the campers had enough to eat. He almost forgot himself in the pressing needs of the exodus.

On the third day, the smaller ship again shot into the sky and vanished from sight. On the morning of the fourth day, just as the last of the sorting was being done, it returned. The door yawned blackly and the recorded voice spoke:

"Those who have shown no evidence of radiation will please enter the large ships." The small group stirred into life and began to file into the ships, prodding their animals before them. Here and there a man or woman waved in the direction of the larger group and looked quickly away; but the rest of them looked rigidly ahead as they went.

Clyde Ellery again helped, wondering if he should enter the last ship. Then the chosen were all loaded, while beyond the fence those who were to stay watched wordlessly. Children of the atom, Clyde Ellery thought fleetingly, and turned to enter the ship only to find his way barred by the closing panel. For a swift moment, he felt panic flooding him.

"The man," said the metallic voice from the small ship, "who first entered this ship will now enter again."

Clyde Ellery crossed the field quickly and stepped into the ship. On his first visit, he had turned to the right into a small chamber where the recorded voice had spoken to him. But this time he felt some unseen force turning him to the left. He followed the pressure and entered a large room. Weird flickering lights blazed from niches high on the rounded wall. Scattered around the room were various-sized pads similar in shape to chairs. A number of other men looked up as he entered.

The floor quivered beneath his feet. There was a quick surge of soundless power, and he knew they were taking off. His body was heavy and ungainly; there was a feeling of pressure which brought with it a quick nausea. Then, slowly, he was aware of an adjustment in the room. The pressure eased off, gravity returned to normal. The ringing in his ears stopped and his stomach righted itself. Having seen the ship take off, he knew that they were traveling at a rate of speed never before known on Earth, yet he was soon unaware of movement at all. He stepped forward to become acquainted with the others.

He had seen at a glance that these were men from all over the world—their faces all colors and shapes. Slowly making his way around the room, he learned their names. It was an exotic roll call—Wang Chin Kwang, Anton Dubov, Jean-Paul Monet, David Hellman, Courtland Stokes, Riyad el Khoury, Kano Mbabane, Alexandre Spaak, Boleslaw Rzymowski, Vincent Ravielli, Mohandas Punjab, Konstantinos Piraeus. To it, he added the name of Clyde Ellery. Language was only a minor problem, for there was always someone who could translate when he was unable to understand. There were as many occupations and trades as there were faces. Some wore a look of guilt that faded slowly, and some still held confusion darkly in their eyes. But in all there was the slow-fuse of a new hope.

Each, Clyde Ellery found, had gone through much the same experience as he had. Each of them represented the science of his community, whatever its stage, ranging from Kano Mbabane, a witch doctor, to Ellery who was a nuclear physicist.

As the ship flashed silently on its journey, the men explored. The hull was of a metal unknown on Earth. They were able to groove deep scratches in its surface with an ordinary penknife, but within two minutes the scratch would vanish. It felt almost soft to the touch, but was obviously of great strength. They began to understand its purpose, if not its structure, when a section of the wall suddenly bulged inward more than a foot, then slowly smoothed out.

"Good heavens," exclaimed Courtland Stokes, as they stared at the retreating bulge, "that must have been a small meteorite! Imagine the uses of a metal with the strength to resist such a force. Why if we'd had this metal—"

He broke off, but the thought was there. This was a metal which might have resisted even the atom bomb.

Two of the men translated his remarks into the other languages.

"Djen shi dje yang dy mo?" Wang Chin asked dryly.

There was no need to translate the comment. They all understood the ironic tones. Stokes' thought had reminded them that if they and their kind had used atomic energy for the benefit of the world there would have been no need for a defense against it. They turned to other things within the ship in order to forget the thought.

Light for the interior of the ship came from shoulder-high recesses around the wall. They looked into them, expecting an improved lighting system, surprised at finding only small steady-burning flames. The flames seemed to be coming from the center of a small green plant. One of the men stretched a hand toward a small flame only to withdraw it quickly with an exclamation of pain. The heat was intense for several inches around the flame, but then it dissipated quickly.

The remainder of the ship was just as strange. The seating arrangements around the interior of the ship seemed to be made of broad thick leaves, somehow fused together, yet still feeling alive. In the small compartment, where each of them had originally gone to listen to the recordings, they discovered a number of fibrous cones which were apparently the records. One was still in a position which indicated that it had not yet been used, while the others were dropped to one side. But they were unable to examine them, for there was some sort of energy belt which kept them at a distance.

There was another small compartment which was apparently the engine room, or what would have corresponded to it in an Earth ship. But there were no mighty motors, as might have been indicated by the power of the ship—only a small hopper into which another hopper fed a continuous stream of crimson pellets. Except for their color, these looked like large seeds. The men guessed that in some way the second hopper broke down the atomic structure of the pellets to convert them into power, but again they were frustrated in their attempts at closer examination by an invisible belt of energy.

Hardly had they finished their sketchy inspection when they felt the ship decelerate. A moment later, they were aware that the ship had come to rest. The door did not immediately open, so they turned expectantly toward the compartment of the cones. They did not have long to wait.

"You are now on the planet you know as Venus," the voice said in English, with that strange change of voice on almost every word. "You who have helped to organize your own kind for this trip are the first to arrive. The other ships will begin to arrive within an hour, so there will be time for you to do preliminary planning. As you leave the ship, you will notice that this half of the planet has been cleared of all native vegetation with the exception of a few trees. You will find that they are so arranged as not to interfere with the construction of your housing, so you are requested not to destroy them. They will not cross-breed with your own vegetation. You will notice that arrangements have been made for the protection of the ships which brought you here; but for the rest—you are on your own, Earth-men. You may now leave the ship."

The door opened and the men hurried out, anxious to see the world which would become a new Earth.

"Strange," Stokes muttered to Clyde Ellery, as they filed through the door. "From the way that record was worded, it sounds as if the natives who sent the ships for us do not intend to show themselves at all. Deuced peculiar."

"Maybe not so strange," Clyde Ellery said. "Remember the theories that evolution on other planets may have followed an entirely different line than on Earth? This may be the case, and, knowing the tendency of humans to dislike anything different from themselves, the natives may have wisely decided to stay in hiding for the time being."

"Whatever they are," said David Hellman, who had been listening, "they are certainly more advanced than we, so any contact should be to our advantage."

"If our hosts ever decide that they want anything to do with us," Clyde Ellery said dryly. He waved ahead of them as they stepped to the ground. "And they apparently don't as yet."

Ahead of them stretched the broad, flat continent. With two exceptions, all there was to see was rich-looking, bare soil. There was a looseness to the dirt which made it seem that not so long ago it had been cultivated, but now there was not so much as a blade of grass. The bareness of the black earth made the exceptions even more noticeable. Not far from where their ship was grounded, there were two rows of trees, about the width of an Earth city street apart. The trees were towering, half again as tall as the giant redwoods of Earth. The leaves, a delicate pink in color, were broad and oval, curling at the edges to form almost a perfect ball. These hung down from the limbs, swaying toward the ground. From each rounded leaf there were two waving tendrils, looking almost like antennae, ranging from a deep pink at the base to a light purple at their tips.

Back of where the ship had grounded, there was a rounded, dome-like structure, large enough to house several hundred of the ships. Green in color, it seemed to be built of broad, flat leaves. Around it were a number of trees, their limbs twisting far above the building. Their leaves were long and tapering, a deep orange in color, while the trunk and limbs were dark green. From each limb hung dozens of pods, fully three feet long and a foot thick at the center, tapering to an end which seemed to have an opening three or four inches in diameter.

For the rest, there was only rich dark soil for almost as far as the eye could see. At a distance, where the curve of land met the sky, they could see the edge of what appeared to be almost a jungle. But, except for the tree leaves moving restlessly in the slight breeze, there was no movement, no sound.

Within the hour the other ships began arriving, in groups of two and three. First to land were those which had been loaded with material. As the passenger ships landed, the men were divided into two groups. One was set to putting up tents which could shelter them that night, while the other swiftly unloaded materials and began to throw up the prefabricated walls of the first Earth buildings.

When night came on the strange planet, darkness descending quickly, bringing with it a light pattering of rain. A city of tents had mushroomed across the Venusian plains and skeletal walls were already thrusting skyward near the double line of trees.

The Earthlings were up with the sun the following morning, small fires blazing among the tents as the women busied themselves with breakfast. The men held a hasty meeting, and elected as a temporary council to govern them the men who had come in the first ship. They in turn elected Clyde Ellery as their first chairman.

That second day upon Venus was a hectic one. A hasty tabulation revealed that they were a little more than two hundred thousand strong—counting children and infants—all that were still healthy from Earth's once thriving billions. Architects and city planners were found among them and Earth City began to go up with a rush. As one building was being finished, the plans for the next one were being handed to the workers. Construction crews were followed by electricians; plumbing went into houses as cesspools were still being dug. Farms were laid out around the new city, all of them equal in size, and furrows were being turned while surveyors still sighted through their instruments.

For two weeks the work continued at the same mad pace. And that section of Venus more and more took on the look of Earth. The broad fields were sectioned in geometric patterns where already tender green plants and young grass shoots were thrusting their way through the soil. Within fenced plots, the cows and horses munched on their hay and looked with longing at the tender shoots. Chickens scratched in the black dirt, and roosters greeted the Venusian sunrise with the same clarion voices as on Earth.

Within the city, which had now spread to almost ample size, flowers were already growing in the yards. Clothes, bought in Cleveland and Pinsk, in Surrey and Isfahan, hung side by side to dry in the Venusian sun. The main street, running between the two rows of strange trees with their curved and nodding leaves, was lined with stores bearing signs in almost every language of Earth. The colony had already issued its own money and business was flourishing. Earth City possessed every business and profession save one—they had no use for a mail man.

It was on the fifteenth day of their stay on Venus, when the work was slacking down to normal, that two of the colonists decided that if they had some extra wood they would build corncribs although it was still some time before they would have corn. They shouldered axes, mounted horses and rode off toward the line of jungle that marked the edge of the land given to Earth people.

Hours later, the two horses returned without the riders, and a search party was formed.

It was almost dark when the two men were found, lying unconscious not far from the edge of the strange and exotic forest. When they were revived, they remembered only that there had seemed to be some sort of barrier trying to keep them out of the forest. One of them described it as a strong wind, although there had been no wind blowing. But they had forced their way against it, shoving step by step within the jungle, and that was the last they remembered. Both had the impression that something must have struck them down. Much bruised and shaken, they were helped back to their homes, and the story of their experience spread rapidly.

That evening, a voice spoke to the colonists. It was a voice much like the one heard from the first ship to land on Earth, but this one sounded as if it came through several loudspeakers. Its message was simple.

"People of Earth," the voice said; "you were offered a generous portion of this planet, and ships were sent to bring you from your sickened homes, with the understanding that you would not attempt to enter the other portions, nor would you harm any of the life already existing here. Yet some of you have tried to break this agreement, intending to destroy local trees. Do not let this happen again."

There was no way to tell from where the voice came.

That night there was a Town Meeting; and by the time it was called it seemed that the entire colony was there and waiting. There were angry looks on many of the faces and on some the anger was mixed with fear. It was obvious that they had already talked among themselves about the earlier incident, for little time was lost once the meeting was called to order by Clyde Ellery. A big, red-headed man stood up in the center of the building.

"I'm Lennie Johnson," he said loudly, "but I reckon I'm talking for most of them here. And we don't like the way things are going."

"Are you referring to the accident that happened to Roberts and Sayyid?" Clyde Ellery asked.

"You're damned right I am," the red-headed man said, "and we don't think it was an accident. When we were first invited to come up here, most of us thought it was a pretty neighborly thing. We had the idea that there was a bunch of people up here, pretty much like ourselves, and they were acting the way any of us would if a neighbor was in trouble. But now we ain't so sure. Why was them ships sent down to us and why was this land turned over to us? And why ain't we seen anybody?"

A murmur from the crowd showed that others were thinking the questions he asked. Clyde Ellery rapped for order and said: "I'm afraid that we haven't been in a position to question our gift too strongly. It has been enough that we've had the opportunity of saving our lives."

"Have we now?" shouted the big red-headed man. "We're beginning to get a different idea about it. If this thing was on the up and up—if there was people up here who wanted to help us—why, then, they'd have been around to welcome us when we got here. They'd have showed up like honest men instead of skulking around in that jungle out there to knock out a couple of good men without so much as a by-your-leave."

"But Roberts and Sayyid were breaking the agreement—" Ellery began.

"And whose agreement?" demanded the man in the hall. "We never made no agreement, so it's nothing but orders. It's a free world and we don't have to take no such orders from anybody—on Earth or here. We'll go where we please and stay where we please."

Clyde Ellery was annoyed, but he tried not to show it. A glance at the other council members showed him they shared his reaction. "What do you propose we do about it?" he asked the red-headed man.

"We don't care what you do about it," the man retorted, "but we're going back to Earth. We know where we stand on Earth and we don't have to worry about a bunch of savages ambushing us every time we turn around."

"How do you intend to do this? The ships which brought us were remote-controlled."

"We've got pilots and mechanics. We'll find some way to make the damn things work."

"One more thing," Clyde Ellery said. "If some of you wish to leave, and if the ships can be made to operate, the matter will still have to be taken up by this council. We were duly elected to represent this community for its best interests, and we will not permit a few unruly characters to endanger the entire colony."

"Yeah?" the red-headed man said with a grin. He turned and looked around the hall. "Everybody who wants to go back to Earth," he shouted, "raise your hand, so these wise guys can see where they stand."

Almost every hand in the hall was raised.

"There's been a new election," the red-headed man said, turning back to the council. "You boys want to come along with the rest of us, or stay here until some Venusian cannibal decides you're fat enough to eat?"

"Hey!" a voice shouted from the back of the hall. "Fire!"

There was a red glare visible through the windows, unnoticed until now. The crowd jammed and shoved their way out of the building, the council following as fast as they could. Once outside, they could see the flames leaping toward the sky as something beyond the edge of the city burned.

The crowd ran through the streets but when they reached the limits of Earth City they came to an abrupt halt and stared at the flames which were taking a decision out of their hands.

The huge domed structure which housed the strange space ships was a mass of writhing flames. The fire crackled and roared, flames twisting upward to lick against the orange leaves of the towering trees. And the crowd stood and watched, for they knew that there was nothing to be done. The colony had fire-fighting equipment, but nothing that would handle such a fire as this.

An hour later, the building was a blackened crater, and all that was left of the space ships were smoking lumps of the strange metal. The crowd of colonists turned and walked silently through the streets of the untouched city.

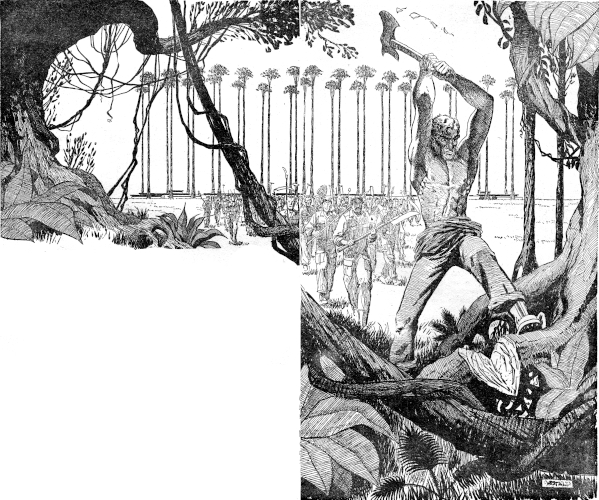

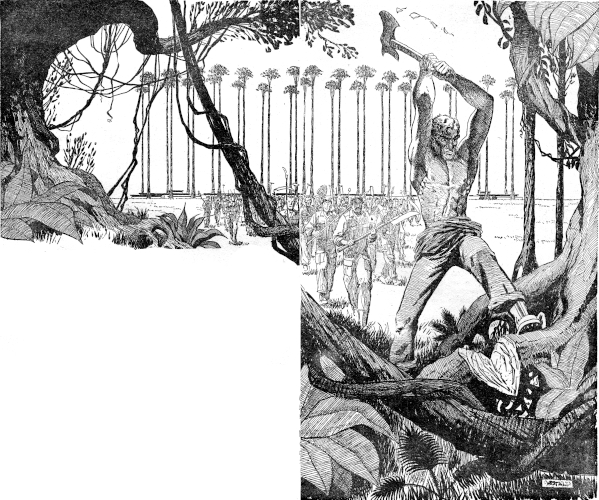

There was a grimness about the Earth men the following morning. Clyde Ellery was first aware of the new note when he awakened to hear the plodding thump of many feet. He looked out of the window to see several hundred men marching down the main street. Every man in the group was armed in some crude fashion. Many carried axes and clubs, while others hefted sledge hammers and crowbars as they marched out of the city in the direction of the Venusian jungle. At the head of the group strode the red-headed man, an axe gleaming brightly over his shoulder.

Clyde Ellery hurriedly dressed and sought the other council members. Most of them had also seen the mob and were ready. Here and there within Earth City they were able to find a small handful of men who had not joined the others and these became the council's posse. Unarmed, they mounted horses and rode after the crowd. None of them was quite sure of what they could do, but felt that something had to be done.

They rode swiftly, but even so too much time had elapsed. They were still several miles from the jungle when they saw the knot of men, the sun glinting from the weapons they carried, move resolutely into the green wall and vanish. As they spurred their horses forward, they heard the distant shout of the red-headed man as he led his troops forward. It seemed to them that the cry was cut off abruptly, and then there was silence except for the hoofbeats and labored breathing of the horses.

As they neared the jungle, the council was greeted by a sight which made them pull their horses up short. From the forest came the mob of men, the red-headed man still leading them, marching with the same vigor with which they had gone in. But the grimness had fled from their faces, to be replaced by a relaxed friendliness. They halted as they recognized the horsemen. The red-headed man looked up at Clyde Ellery with an easy grin.

"Out riding, Councilor Ellery?" he asked pleasantly.

"What happened in there?" Ellery asked, nodding toward the jungle.

"Why, nothing," the red-headed man said with surprise. "Why should anything happen?"

"What were you men doing in there?"

For a moment the red-headed man looked perplexed, his gaze shifting from Ellery to the jungle and then back to Ellery; then his expression cleared. "Why, me and the boys were just looking around," he said. "Since we're going to be living here for the rest of our lives, we thought we might as well take a look at this jungle. We figured there might be some dangerous animals in it and if there was we ought to know about it. But it looks like everything's okay."

The council members exchanged glances. "But what about your idea of going back to Earth?" Clyde Ellery asked.

This time the red-headed man was really surprised. "You must be off your rocker, councilor," he said. "We like it here."

"Well, if you were only looking around," Ellery said, "why did each of you bring a weapon?"

The red-headed man glanced down at the axe he was carrying and frowned. "I'll be damned if I know," he said. "It just seemed like a good idea at the time. Well, councilor, me and the boys better be getting back to work. We'll be seeing you."

The councilors sat on their horses and watched the man march off toward the city with swinging strides. Then they rode silently along behind them.

Back in Earth City, the council members quartered their horses and went straight to the town hall, straight to the private room that served for their council meetings.

"What do you think happened?" Clyde Ellery asked slowly.

"Seems rather obvious," Courtland Stokes said, running a hand through his thinning hair. "They showed all the symptoms of having been hypnotized. Apparently, the minute they entered the forest with the intention of destruction, they were hypnotized and given a post hypnotic block which made them completely forget their original reactions."

"Clever, these—Venusians," said Wang Chin Kwang, privately amused at the new usage of an old expression.

"However," Clyde Ellery said slowly, "the action of these men does bring up something which we have pretty much ignored since we landed—the question of our hosts. I confess I'm not too satisfied with the explanation that they are merely a strange life form which doesn't show itself to us because we may be prejudiced."

"Have any of you thought about that fire last night?" David Hellman asked. "It looked as if some intelligence knew that some of us were planning to leave and so deliberately burned the space ships."

"Yes," Stokes said dryly, "it occurred to me that the fire might be evidence that our—hosts were determined that we stay on Venus."

"But why?" demanded Clyde Ellery. There was no answer, and for a moment the members of the council knew the same fear of the unknown which had been on the faces of the colonists the night before. Clyde Ellery cleared his throat. "For the moment," he said, "it would seem to me that our most pressing problem is one of finding some way of communicating with our hosts and determining the exact status we are to enjoy here. Are there any suggestions?"

There were none. After a few more pointless and nervous remarks, the council adjourned.

It was the next day that they were reminded of the corncribs which had started the whole thing. That morning Arthur Roberts, whose farm was nearest to the jungle, went out to find a number of sheets of metal lying in his field. They were obviously of the same material which had been used in the space ships. Stranger still, they were of the exact sizes to build the corncrib as Arthur Roberts had imagined it.

Most of the colonists took this as evidence of the good intentions of their unseen hosts, but it only served to increase the uneasiness of the council.

Two days later, they were quickly summoned by Jean-Paul Monet. Without offering an explanation, he insisted that they again mount their horses and ride toward the jungle. As they neared the giant wall of green, they heard a strange thumping noise ahead of them and once more pressed Monet for answers.

"You will soon see," he said grimly. "For two days, I have stayed in the fields watching for the secret to the metal. Now, you will see what I witnessed early this morning."

A few minutes later, the men reined their horses to a stop and stared into the jungle, scarcely believing what they saw.

Near the outer edge of lush, living green, there was a huge vine. Its creepers, almost a foot thick and covered with cup-shaped thick leaves, seemed to enter the ground at intervals and then reappear to grow along the top. But the Earth men soon realized that the creepers were moving, as though growing at a tremendous rate. And each time one of the scarlet cup-shaped leaves appeared out of the ground it dumped a greenish lump of something on the ground. On looking closer, they saw that the ground here was covered with the broad flat leaves of some other plant.

Towering above this scene were a number of orange-leafed trees like those which had surrounded the field where the space ships first landed. As they watched, the green limbs of these trees swayed and bent until the huge green pods were directly over the lumps cast up out of the ground. Then, from what they had thought were seed pods, came a gush of white fire, striking the lumps. Under that direct fire, so strong that the horses shied from the heat a hundreds yards away, the lumps took on a fire of their own.

From the edge of the jungle there grew long stalks with what had seemed to be large square flowers on them. But, as the men watched, the stalks whipped forward and the flowers descended upon the heated lumps. It was this which was producing the thumping noise they'd heard, and each blow from the square flowers was helping to pound the lumps into sheets of metal.

As the men watched, the last lump of metal was cast up, heated, flattened and cast aside. The thumping ceased, the flames died out, and once more the jungle was a wall of exotic plants and trees swaying gently in the breeze. If it hadn't been for the sheets of metal on the ground, they might have imagined that what they had seen had been an illusion. But there were a good six-dozen sheets of metal on the ground before them.

It was Clyde Ellery who finally dismounted and approached the jungle. The others sat on their horses and watched him. They saw him stoop to gaze intently at the giant creeper on the ground and then step briskly into the jungle. He did not go far, but seemed to stand there in an attitude of listening for several minutes. Then he turned and walked briskly back to where the others waited. He mounted his horse and turned its head toward the distant city.

"Well?" demanded Courtland Stokes, when Ellery still said nothing. "What happened in there?"

"Nothing," Clyde Ellery said. He seemed surprised that anyone should think that anything had happened. "I merely looked into the jungle and came back. After all, it was part of our agreement that we not enter that part of the planet."

"But you stood there for several minutes," Stokes insisted.

"I'm afraid you must be wrong," Ellery said. "I believe I'm quite aware of what I'm doing when I do it. I merely glanced into the forest to see if there was any more metal there. The minute I saw there wasn't, I turned around. In fact, I distinctly remember that I didn't even stop walking."

The others exchanged glances, but said nothing more. When they reached Earth City, they agreed to hold a meeting that afternoon and then separated.

By the time the council met, Clyde Ellery was aware that he too had been hypnotized when he tried to enter the jungle. But he had no memory of what had happened. It still seemed to him that he had merely glanced into the jungle and had then retraced his steps.

The meeting was delayed because of Alexandre Spaak, who at last came bustling in, his face tense with excitement.

"Wait until you hear this," he said in answer to the questioning looks. "You know my house is at the edge of town, not far from the spot where the space ships were kept? Well, this afternoon, the kids were missing. I went looking for them and finally found them playing under those big Venusian trees with the orange leaves. You know, the same kind of trees we saw with flames shooting out of their pods to melt that metal? Well, take a guess what my kids were doing?"

"What was it?" Ellery said irritably. "Don't make us play guessing games."

"Among the foodstock my wife and I brought to Venus," Spaak said, "was a package of marshmallows. The kids had the marshmallows on the ends of sticks and there were little tiny flames coming out of the tree pods, roasting them. If you remember those trees at all, you'll remember the nearest pods were at least fifteen feet from the ground—which means the tree had to bend its limbs down to reach the marshmallows the children were holding."

"But how did your children control the flames?" Stokes asked. "Those flames we saw this morning would have blasted them to ashes within twenty feet."

"The children weren't controlling the flame," Spaak said. "The tree was controlling the flame for the benefit of the children."

"I have a feeling," said Jean-Paul Monet, "that the colonists were right the other night. We should leave this planet."

"How?" Wang Chin Kwang murmured.

"A minute, gentlemen," Alexandre Spaak broke in. "I believe I have solved the mystery of our hosts." He paused and looked around at the others. "Gentlemen, the intelligent life which invited us to this planet is the plant life of Venus."

"Impossible!" exclaimed Stokes. "The intelligent life which invited us here is one capable of building space ships—an engineering feet beyond even the highly advanced technical skill of Earth. You don't mean to say a plant could do that!"

"You forget," said Spaak, "that all of us stood in a field this morning and watched a plant dig ore out of the ground, another plant smelt the ore, a third plant flatten it into sheets of metal, using a fourth plant as an anvil. After seeing that flame tree in action, there can be no doubt that the flame trees also deliberately destroyed the space ships when some of us were about to use them to leave Venus. No, gentlemen, I tell you that the intelligent and dominant life on this planet consists of trees, bushes, vines, and so on down to the smallest plant. That, incidentally, must be the reason we were told to bring our own plants and not to touch any of the plant life here."

"You are right, Earth-Man."

For a moment, the thirteen men in the room sat, frozen, not daring to look at each other. It had not been a voice speaking this time, yet each had heard the thought within his head. As each of them realized that all had heard it, that the thought had not been a personal hallucination, they relaxed. Quickly, they looked around the room. But there was no one there except themselves.

"I have been expecting this," Alexandre Spaak said. "I knew that my theory was right—and I thought that once it was out, they might communicate with us."

"But who—where?" gasped Stokes. "There's no one else in this room—I mean, there isn't even a plant."

"No, but look out of the window," Spaak said. "Look at the trees lining both sides of the street—the trees with those curling leaves which look almost like heads—with tendrils waving from them, like antennae!"

They looked from the window, and it was true that the leaves on the trees did look like heads. They noticed that the antennae on the leaves of the nearest tree were all bent in the direction of their building, even though the wind was blowing away from it.

"Ih dien buh tso!" exclaimed Wang Chin Kwang.

"But it's impossible, really!" said Stokes. "That space ship, all of those records in the various languages, the clearing of the land here, everything!"

"Even if one does accept the idea of intelligent plants," Clyde Ellery said, "it does seem that some of the things which have happened would be beyond the ability of—say—a tree."

You are wrong, Earth-Man, came the thought. We have been the dominant life on this planet for many thousands of years, by your reckoning of time. Long ago, we knew there was intelligent life on the third planet of our sun, for we could catch an occasional thought, and we knew that your science was less advanced than our own. But we didn't realize until much later that it was animal life which was dominant there. At first, we found it hard to believe our senses.

"Then you did build the space ships?" Spaak asked.

Of course. It was not difficult. The Scarlet Diggers among us dug up the Llantl ore, even as you saw it done this morning. The Flame Tree processed it, and the Great Pounder hammered the hull into shape.

"But how did you power the ship? What were those crimson pellets which we saw pouring into the hopper in the ship?" Clyde Ellery asked.

The seeds of the Flame Tree. They are a more powerful explosive than anything known to your science.

"And the recordings?" asked Ellery.

The seed-bearing cones of our Repeater Tree. It took many trips of our first ship, for our message had to be made up of individual words from your languages. We could not communicate as we are now because of the distance.

"How did you know that we needed help?" Ellery asked.

We felt the waves of force set up by the explosion of what you called atomic energy. We had felt these waves before, coming from other planets, and each time all thoughts gradually died out on those planets and we knew that the intelligent life there had died. The last time it happened was on the fourth planet of our sun, a long time ago.

"And you were unable to save any of them?"

We could have saved them if we'd wished, came the thought.

"Which seems to bring us to the most important question of all," Clyde Ellery said with a wry smile. "Why did you save us?"

There was a hesitation, and then the thought came to them: The animal life on our planet died out because we could not, of course, permit it to feed on us. Yet, as you must know, we needed some form of animal life to maintain the balance of oxygen and carbon dioxide necessary to our lives. You seemed ideal for our purpose, for you could bring with you other animal life and your undeveloped plant life to feed yourselves.

"And you did destroy the ships so that we could not leave?"

Of course.

For several minutes, the men looked silently at each other and considered that which they had received.

"It's hard to accept," Clyde Ellery said to the others, "but I suppose it's not too surprising when you stop to think about it. Even on Earth, the actual boundaries between animals and plants were artificial, as shown by our one-celled animal life which often couldn't be told from a unicell plant. It was just a question of where this evolutionary accident happened."

Not an accident, came the thought swiftly. It was an accident that plants did not become dominant upon your planet. It is logical that we should be highest on the evolutionary scale. We are the only non-destructive form of life there is.

"Oh, I say now!" protested Stokes.

Think, Earth-Men. Animals are in reality a parasite upon plant life, needing to destroy plants in order to exist. But we plants can build our carbohydrates and proteins out of inorganic salt and so need to destroy nothing. Can you do that, Earth-Men?

There was a moment of silence. Clyde Ellery turned to the others. "I suppose, in a way," he said, "they're right. Anyway, the important thing is that we are to live out our lives on a strange planet and must adapt ourselves to the conditions here. We mustn't forget that one of the things which led to the destruction of Earth was our attempt to believe that certain people—certain life forms, shall we say—were inferior to the rest of us. We must not let that happen again.... May I speak for all of us?"

The other twelve men looked to each other and then nodded. Clyde Ellery turned to face the window, looking embarrassed.

"I hardly know the proper way of addressing an intelligent tree," he began, "but you may inform the rest of the life on this planet that we men of Earth have learned our lessons. We are quite prepared to treat you as our equals, and to cooperate with you to our fullest extent."

There was a long moment of silence; and, when the answering thought came, it seemed to be tinged with surprise and something which might have been humor:

You misunderstand. It was pointed out to you that all animal life exists as a parasite upon plant life. In our case, unfortunately, we need you parasites in order to live, but that does not imply special privileges. So long as you continue to supply us with carbon dioxide and do not attempt to destroy any of us, we are content to leave you alone. But should you attempt to step out of your place, we will have to take measures. Those of you who have tried to enter our part of the planet have already experienced the weaker radiations of the one of us which you might call an energy tree. If you persist, you will be exposed to its full strength which will render you incapable of any action except what is needed for your survival. The thought softened. As your hosts—in a double sense, you might say—we do not like to make a point of your inferiority, but we are sure you will understand our present reaction if you will consider how you might have felt if the fleas which infested your bodies, the viruses in your bloodstreams, had offered you equality and cooperation.

The thought ceased. Outside, a heavy Venusian rain began, beating for a second upon the roof, before sliding to the ground and sinking to the level of thirsty roots.

Quietly the council bowed and departed.