Title: Hippodrome Skating Book

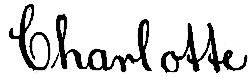

Author: Charlotte Oelschlager

Release date: March 29, 2020 [eBook #61693]

Most recently updated: October 17, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Richard Tonsing, deaurider, and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

Transcriber’s Note:

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

HIPPODROME SKATING BOOK, by “Charlotte”

To CHARLES DILLINGHAM, Esq., TO WHOM I OWE A DEBT OF GRATITUDE FOR MY AMERICAN FAME, AND TO WHOM ALL SKATERS ARE THANKFUL FOR THE STIMULATING INFLUENCE HIS ENTERPRISE HAS HAD IN REVIVING INTEREST IN AMERICA IN THE GREATEST OF ALL ATHLETIC PASTIMES, THIS LITTLE VOLUME IS RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED,

SALUTATION.

“CHARLOTTE.”

| Chapter | ||

|---|---|---|

| 1— | THE RIGHT EQUIPMENT, Skates, Shoes, Costumes, etc. | Page 11 |

| 2— | Correct Form of Skating | Page 15 |

| Illustrated | Page 17 | |

| 3— | Outside Circles, forward | Page 18 |

| 4— | PLAIN CIRCLES, Inside Edge Forward | Page 22 |

| Illustrated | Page 22 | |

| 5— | OUTSIDE CIRCLES, Backward | Page 26 |

| Illustrated | Page 27 | |

| 6— | INSIDE CIRCLES, Backward | Page 30 |

| Illustrated | Page 33 | |

| 7— | CHANGE OF EDGE; Forward; Outside to Inside | Page 34 |

| 8— | CHANGE OF EDGE; Forward; Inside to Outside | Page 36 |

| Illustrated | Pages 36–37–38 | |

| 9— | CHANGE OF EDGE; Backward; Outside to Inside and Inside to Outside | Page 40 |

| Illustrated | Pages 40–44 | |

| 10— | THREES—Forward and Backward | Page 45 |

| Illustrated | Pages 46–47 | |

| 11— | DOUBLE THREES Forward | Page 49 |

| 12— | DOUBLE THREES Backward | Page 53 |

| 13— | LOOPS, Forward | Page 55 |

| Illustrated | Pages 56–58 | |

| 14— | LOOPS, Backward | Page 59 |

| Illustrated | Pages 60–61 | |

| 15— | BRACKETS | Page 63 |

| Illustrated | Page 65 | |

| 16— | ROCKERS; Outside Forward and Outside Backward | Page 67 |

| 17— | ROCKERS; Inside Forward and Inside Backward | Page 70 |

| 18— | COUNTERS | Page 73 |

| Illustrated | Page 74 | |

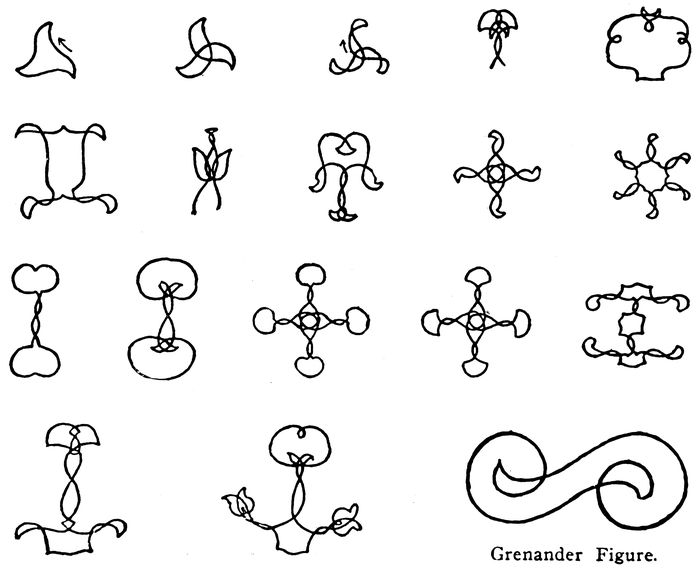

| 19— | The Advanced School Figures | Page 75 |

| Illustrated | Page 76 | |

| 20— | Other Important Figures | Page 77 |

| Illustrated | Pages 69–72–83 | |

| 21— | FREE SKATING | Page 79 |

| Illustrated | Page 80 | |

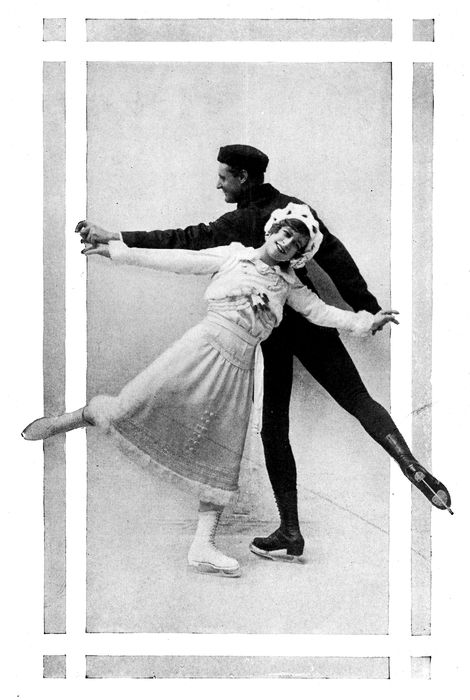

| 22— | Pair Skating | Page 81 |

| 23— | Competitions and Judging | Page 90 |

| 24— | Skating Ponds and Rinks | Page 92 |

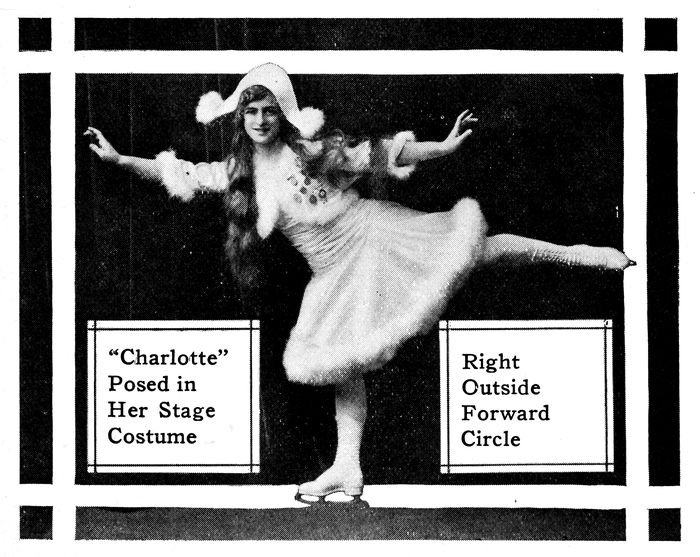

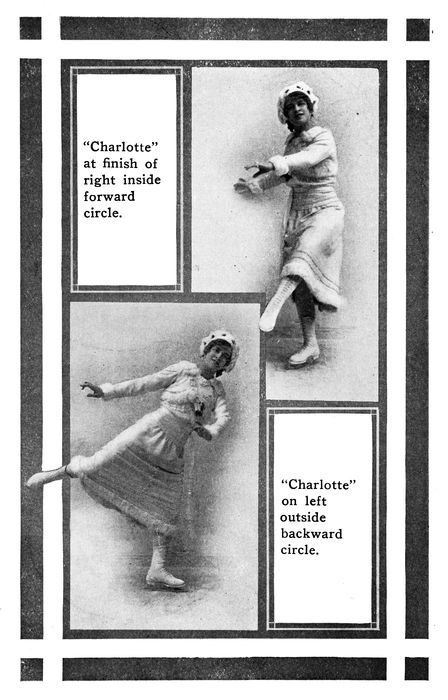

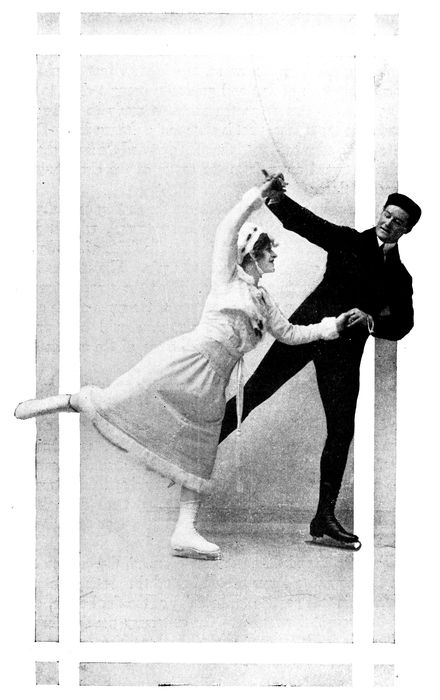

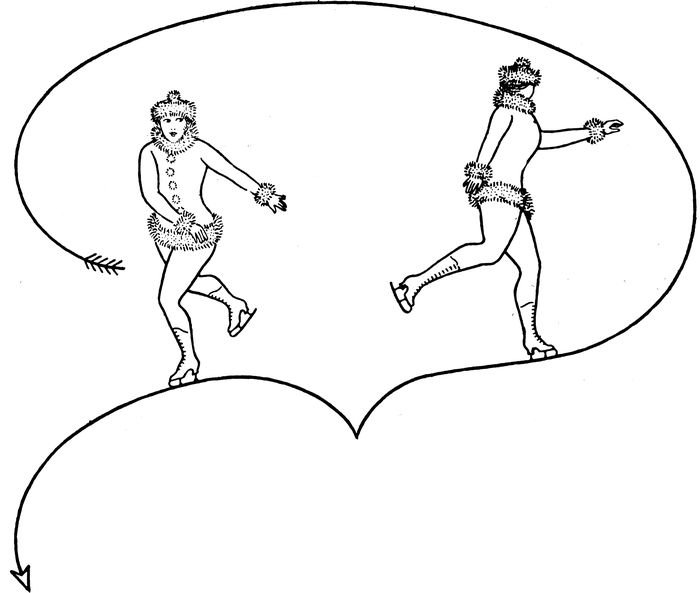

“CHARLOTTE” starting the right inside edge forward.

Americans ought to be the greatest skaters in the world. They are athletic people, lovers of outdoor sports and their country is situated in the largest tract of the North Temperate zone occupied by any one nation in the world. In this zone is found sufficient cold weather to produce a great deal of natural ice and at the same time such agreeable weather as to render the use of that ice, for sport, attractive and exhilarating. In this respect the United States is more fortunately situated than any of the countries of northern Europe.

This little book is intended as a stimulus and encouragement toward ice skating among Americans. It is intended as much for women as for men. There are no physical reasons why women should not skate quite as well as men. Skating is a matter of balance and grace, not strength. Young girls often become very expert skaters, doing all the difficult feats that grown men accomplish. Up to within a few years ago, the figure skating championships of Europe were open to both men and women on equal terms. Perhaps the fact that women excelled in grace was partially responsible for the separation of the sexes in these championships.

Much attention is paid in the book to the fundamental strokes, called school figures. These are the foundation of all figure skating. After they have been fully mastered the skater will probably discover a tendency to adopt an individual style and make up special figures suited to individual physical or temperamental characteristics. One skater, for instance, will especially enjoy spins and whirls; another will incline toward big, showy spirals; another will develop individual skill in two-foot movements such as grapevines, etc. Skating, like every other fine sport, becomes an expression of individuality. The foundation rules must first be learned, after which personal choice will direct the skater toward special figures most to his or her liking.

Skating is a sport for everybody—girls and boys, young people and old people. It can be started in extreme childhood and enjoyed far into old age. It can be a fast, strenuous exercise or a gentle enjoyment of poetic motion. It stimulates health, prompts to wholesome life out of doors, is a social diversion and, in its best development, requires considerable mental application. In every respect it is an ideal sport for people of any nation, especially those situated where natural ice is found or artificial ice is provided.

Frontispiece and cover design by Mr. Karl Struss.

Portrait Study, page four, by Count Streclecki.

All other photographs posed for at White’s Studio.

I wish to thank my American skating friend, Mr. James A. Cruikshank of New York, for his assistance in the arrangement of this book and for preparation of the manuscript for the printer.

“CHARLOTTE” on right inside edge forward.

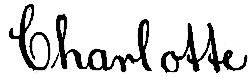

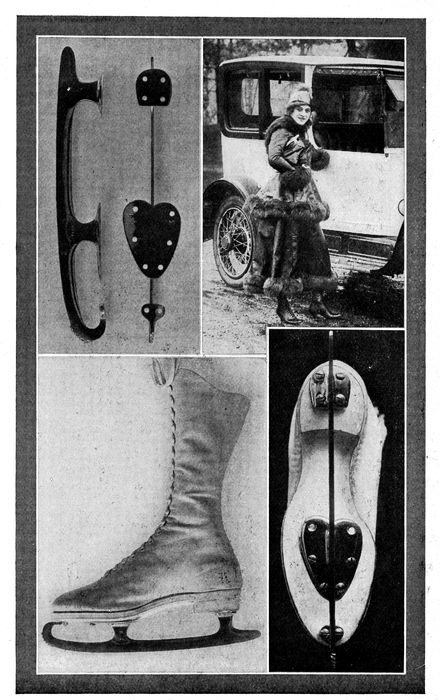

CHARLOTTE’S personal equipment for skating.

Skating on ice is the best sport in the world. It is also the best method in the world for developing grace of carriage, supple muscles and fine health through a fascinating exercise. I have tried all the various sports, including swimming, fencing, dancing, tennis and mountain climbing, and there is none to compare with ice skating.

Strange as it may seem, ice skating will both reduce fat and add fat; if mildly followed as a regular exercise it will stimulate appetite, digestion and that zest in life which makes for healthy, rounded physique without superfluous fat. If persisted in vigorously, it will reduce flabby fat into smooth muscle. It is especially good for the reduction of fat around the waist and hips.

Skating to music is the most rhythmic of all exercises and far surpasses dancing in enjoyment and benefit. Dancing generally implies the need of a partner who dances equally well, while skating is a sport which can be enjoyed with a partner or without one. In fact, the more expert one becomes in skating the less one is dependent upon any one else for the pleasure of the sport.

To skate properly or to learn to skate, the right equipment is absolutely essential. The skate is the first essential; one may skate fairly well with shoes which are inappropriate or costume which retards free action, but with the wrong skates it is impossible to learn the art.

The proper skate has two stanchions or uprights running from the blade to the foot and heel plates. There seems to be scientific warrant for the statement that this method of construction makes it “run farther.” The old pattern having three stanchions or supports has been discarded by the best skaters of all skating countries for years.

The toe of the skate should curve up and around the toe of the shoe, in many patterns even touching the sole of the shoe in front. This curved front is deeply cut in with very sharp 12sawteeth, and it is on these sawteeth that so many of my pirouettes and pivots and dance steps are made. The height of the foot plate from the ice is much less than that of the heel plate from the ice, which naturally throws the skater into a forward balance. Most of the time I am skating upon the part of the skate directly under the ball of my foot. The curve of the blade from toe to heel is about a nine foot radius.

My skates are very light, weighing only four ounces. I advocate a light skate, and I think that most of the skates being used are too heavy. As one becomes more expert, lighter skates become more important, for in spins and turns on one foot the weight of the shoe and skate can seriously affect the balance and throw the skater into a false curve.

For about two inches along the blade of my skate, almost directly under the ball of my foot, I have a slightly flattened space which permits the immense curves and spirals I execute. These would be impossible with a sharply curved blade. The blade of my skate is splayed—that is, it is wider at the centre than at the toe and heel.

I have quite a deep groove ground in my skates, and I have the outer edge of the skate slightly lower than the inner edge. The height of the skate above the ice is not very important. Some of the experts favor great height. My skates are built comparatively low.

The flat bladed skate ought not to be used by any one who wishes to learn figure skating. The hockey skate is the right skate for hockey, but the wrong skate for anything else. To learn on that type of skate means that the skater must learn all over again when figure skating is attempted.

I am glad to hear that some of the American manufacturers are even making their hockey skates with a curved blade, so that the simple curves can be learned on that type of skate. There are several excellent models of skates now being made in the United States.

The skating shoe should fit very snug around the heel and over the instep, and should be comparatively high, seven or eight inches being my preference. The heel of the shoe should be higher than that of the sporting or tramping or golf shoe now being worn by the American woman.

It is important to get such skates and shoes as will throw 13the balance of the body forward onto the ball of the foot when one stands on the ice. This can only be done by raising the heel of the foot, partly through the design of the skate and partly through the height of the heel of the shoe. But no such thing as French heels are intended or advocated, of course.

The shoe should lace from close to the toes up and should be a comparatively straight last. A strong, stiff leather lined shoe should be the first choice. Afterward, as the ankles strengthen, a lighter shoe can be worn. I often skate in low shoes, my ankles are so strong, and the only trouble I find with my low shoes is that the heel slips out in the toe spin.

Artificial braces are sometimes valuable aids to the beginner. The best braces consist of a bandage wrapped carefully around the ankle and foot under the stocking. A stiff piece of leather set inside the shoe between the stocking and the shoe is an excellent brace. It can be removed as the skater gains strength.

The shoe should not be laced so tight as to stop circulation or to interfere with the play of the toes, but it should be capable of being laced with rigid firmness around the instep. Skating is hard on the feet at first and makes them sore and tender. A thin lisle or wool stocking is advisable for the beginner, and cold baths will soothe and strengthen the foot muscles.

The costume for skating may now include practically all varieties of design and material, ranging from silk to leather, the latest fad. Nowhere can a woman look prettier and nowhere can she look less attractive than on the ice. Some items are essential, however. The material of the skating costume ought to be something which does not bulk up, something which falls into naturally graceful curves and straightens out quickly.

An undergarment of silk or satin in the form of a petticoat, bloomers or knickerbockers is important in skating any difficult or spectacular figures, since it serves to keep the gown from bunching around the legs. The skirt should be comparatively snug around the hips and free, even slightly flaring, around the edge. Fur bands around the edge of the skirt give an air of appropriateness.

The new unrestrained and somewhat bold way of skating necessitates skirts which permit freedom in the swinging and spread of the legs. A petticoat or short skirt of thin woven 14elastic goods, especially if of silk, makes an ideal undergarment for the skater, whether beginner or expert.

The length of the skirt should be about to the tops of the skating shoes. Sensible costumes are now being adopted by the best skaters of all countries. One should as soon think of swimming in a long skirt as skating in one. The skirt which reaches to the middle of the calf will be found both comfortable and graceful.

My skating costume at the Hippodrome is probably regarded as very daring, but I wish every woman who skates might test for herself how comfortable it is. There is a stimulus in suitable costumes which it is impossible to get any other way. Skating is worth a pretty and appropriate costume, and such a costume will last for years and be always in style.

Note:—The CHARLOTTE SKATE, designed and used by CHARLOTTE, is not as yet being manufactured in America, but it will be on the market next winter. Those who desire this skate should accept none as the genuine CHARLOTTE Skate unless stamped with her trade-mark on the side of the runner.

The tracing of certain set figures on the ice is by no means all there is to figure skating. The correct carriage of the head and body, the arms and the balance leg are not merely an important part of the sport; they are even the very basis on which good marks are given in all serious competitions. No skater wishes to look like a freak on the ice. To avoid it one must cultivate the right carriage and balance from the start. Certain accepted rules are in vogue among the European skaters which tend to make skating graceful. They should be memorized carefully and followed every time the skater goes on the ice.

The head should be carried erect. Momentary looking down at the ice to see where to place a figure is permitted but the habit of a drooping carriage of the head should be carefully avoided. It is as unnecessary as it is ungraceful.

The arms should not be held close to the body nor should they be flung violently about. If the former position is taken the skater looks stiff and awkward. If too wide reaching out of the arms is permitted the skater appears to be grasping at imaginary straws like a drowning man. Both extremes are bad but of the two it is better to allow the arms freedom of poise and carry them gracefully extended than stiffly hung to the sides of the body. Fencing and interpretive or folk dancing furnish interesting examples of the right use of the arms during vigorous action. The individuality of the skater is often revealed by the carriage of the arms as much as by the tracing of the figures.

Bending of the body from the hips, sidewise, is neither necessary nor permissible. It is a fault which beginners adopt from 16fear of falling. But the sharp edge of the skate sustains the body in its temporary violation of the law of gravitation. Take a firm edge and let the body lean as much as is necessary or desired. Some skaters take a much stronger edge than others and therefore lean more than others.

The men ought to be told that there is nothing more ungraceful or unsuitable for skating than long trousers. Knickerbockers and tight fitting coats with just a bit of military cut are the right costume for the men who would skate well and look well. The best European skaters among the men all skate in woolen tights, but they are a little theatrical and do not always serve to increase one’s admiration for the wearer.

Bending the body forward or backward from the waist is generally only temporary and for the purpose of obtaining strong impetus for an initial stroke or adding power to a stroke already started. In general the carriage of the body should be upright, with the chest expanded and the shoulders held back.

The skating leg should be bent at the knee. This bending may be increased occasionally to gain power but the straightening up of the body should almost immediately follow. Too much bending of the skating knee makes an ungraceful appearance. The balance leg should be carried somewhat away from the skating leg, with the knee well bent and the foot turned outward and downward. The knees should seldom touch in skating and should never be held close together for any considerable length of time. In some figures there are temporary and necessary violations of both of these rules.

The position and carriage of the hands have very much to do with the effect created by the skater. They should be extended gracefully, with the fingers neither stretched out nor clenched and with the palms turned down or toward the body.

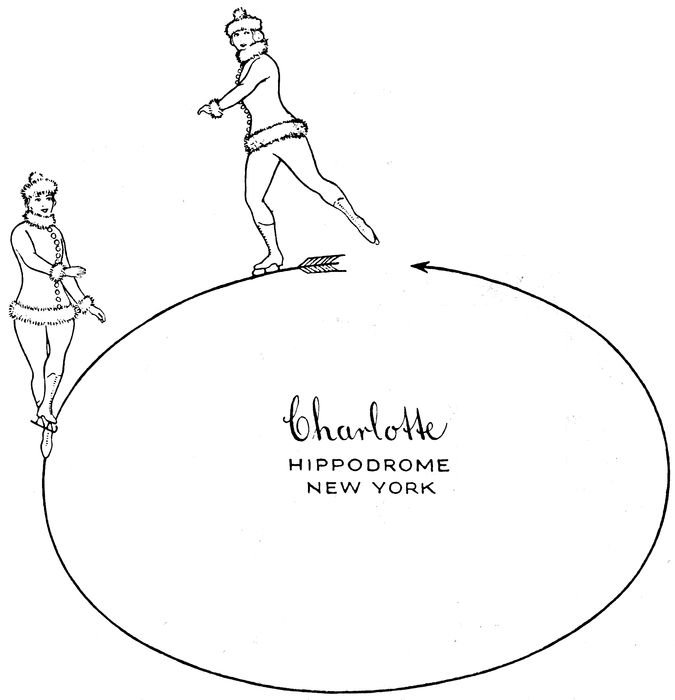

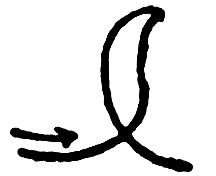

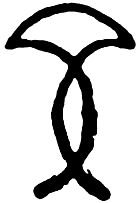

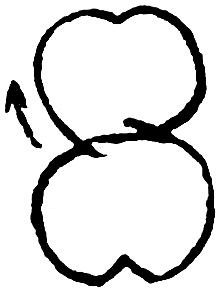

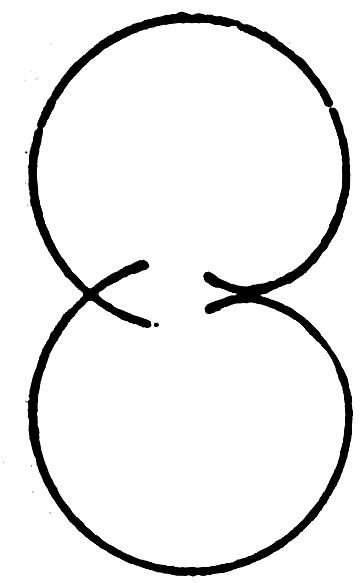

CIRCLE. Right outside edge, forward. (ROF)

Start with the idea that good skating is a hard thing to acquire. It is. For the same reason it is interesting. Easy things never hold their interest very long. Graceful skating implies perseverance and determination. It requires close application to right principles from the very start and rigid concentration upon a number of important rules, several of which the skater will have to keep in mind during the moment of execution of any figures. But the fact that it is the chosen sport of most of the people dwelling in the northern parts of the world, women as well as men, proves that it is not too difficult to permanently hold the enthusiasm of lovers of outdoor sport.

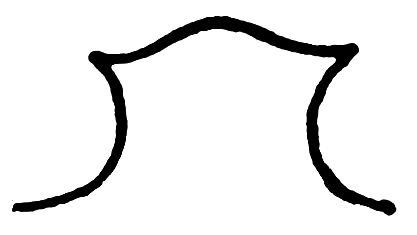

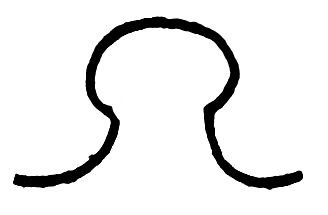

Curves are the fundamental figures in skating. True, the racing skate and the hockey skate permit only straight strokes, but these skates are a development of the sport by which greater speed or steadier position against attack is obtained. Graceful skating and the execution of figures on the ice are impossible without the proper skate.

The first figures to learn, and the basis of all further progress in the art, are the outside edge circles. The outside edge of the skate is the edge furthest away from the body. There is an outside edge on each skate and this edge can be used to skate forward or backward; there are, therefore, four outside edge circles, one on right forward, one on left forward, one on right backward and one on left backward. For convenience and simplicity these edges are often designated thus: ROF, meaning right outside forward, etc.

The most important things to have in mind as one skates the elementary figure are carriage, poise and deliberation. If the body is correctly poised a slight stroke will carry the skater in the right direction; no amount of straining or kicking will cause the skate to execute the right figures if the body over that skate is in the wrong position or wrong balance.

19My own skating as head of the ice ballet at the New York Hippodrome is fast and spectacular, I admit; it has to be so to be theatric, to catch the crowd, to startle the sensation seeker. But it is not quite so fast when I am skating for my own amusement.

Size is the next most important consideration in skating the elementary or school figures. All the plain circles should be made as large as possible without sacrificing correct balance all the way to the end of the curve. The European skaters make the plain circles, in the form of an eight, with a diameter of fifteen to twenty feet. The beginner will find about eight feet as large a circle as can be made without loss of poise, but this depends also upon the question of size and strength of the skater and whether man or woman.

It is essential that the skater learn to use both feet equally well. If one foot is harder than the other to manage, it must be skated with more often until equal skill is attained. It will generally be found that right handed persons are more proficient in skating with the left foot and vice versa. To skate each figure equally well on either foot is not merely the right standard to set; it will be found fundamental to the correct execution of figures implying a reverse direction, and it is the basis of success in pair skating.

Now we are ready to strike out on the right outside edge. Stand with feet together. Get your start on the right foot by pressing the left skate, by its edge, not by its point, firmly against the ice. Bend the skating knee a good deal, almost sink on it, something in the manner of the dancing dip, and lunge strongly forward, leaning toward the centre of the circle. The left leg should follow well behind, and a little across the print, with the knee bent and the toe turned out, and the body should be turned or twisted so that the right shoulder is almost directly over the right foot. This will bring the body flatly in line with the mark on the ice which the skate is making. This mark is called the print. (See the diagram for the first skating position near the feathers of the arrow.)

The arms will take their correct, natural position, the right arm being held well up and curved around the breast at a distance of about six inches and the left arm well extended directly behind the body.

20This general position should be sustained during one-half of the circle. Then slowly bring the balance foot past the skating foot, turning the toe in and bending the knee of the balance foot as it is carried forward. It must be kept very close to the skating foot in passing, otherwise there will be a tendency for its weight to swing the skater out of the true circle he is making.

The fact that the balance leg, which was being carried behind the body, has now been brought in front of it, implies that a complete change in the balance of the body has taken place. Up to a little more than one-half of the circle the body has been held strongly forward; as the foot passes the skating leg the body assumes first a straight and then a slightly backward balance. The arms, too, have been serving to compensate the balance. At first they are held well toward the left or behind. As the body twists or turns into the new position and the shoulders are brought square with the direction of the print, the arms slowly swing forward and, from being held on the outside of the circle at the beginning of the stroke, are found on the inside of the circle at the end of the stroke.

The general principle of skating implies that the arms and the legs are used for compensating balances in almost every stroke. When the arms are on one side of the body the leg is on the other. There are a very few violations of this broad principle, but they are associated with the execution of extremely complicated figures.

The body performs a gradual and almost complete rotation during the execution of the forward outside circles. At the beginning of the stroke the back is toward the centre of the circle, at the end of the stroke one faces the centre. The twisting of the body during the stroke should be first at the shoulders and afterward at the hips. But care must be exercised not to make this twisting conspicuous. It must be gradual, deliberate and almost unnoticeable. In fact, it is difficult to believe as one writes about the stroke that all these changes of poise and balance are taking place. It is excellent practice to stand in the various positions on one’s floor and get them clearly in mind.

“CHARLOTTE” in novel kid skating costume.

Next to the outside edges in importance are the inside edges. Indeed, it is more accurate to say that they are of equal importance. For some reasons the inside edge deserves the premier position in skating.

Spectacular and exhibition skating probably draws into use more bold inside edges than it does outside edges. There is a certain attraction about the poised body executing the inside edge that the outside edge lacks.

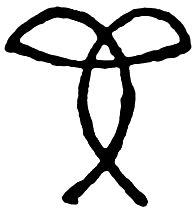

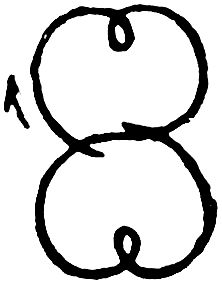

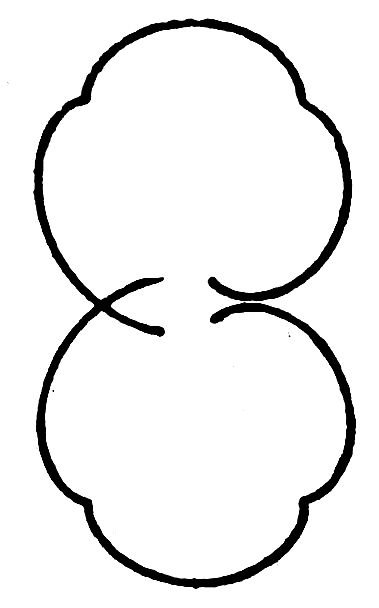

CIRCLE. Right inside edge, forward. (RIF)

23Many of my own big sweeping curves following quick dance steps are on the inside edges and they have come to me without any especial analysis of the reasons for their introduction. The fact that they have worked themselves into my varied programme implies that I find them both agreeable and natural.

The outside edge may be said to be an unnatural balance, almost a false balance. The weight of the body, if it is held erect over the print or mark which is being executed in the outside edge circle, is outside of the circle, where it has a natural tendency to pull the skater away from the circle he is trying to execute.

This pull has to be counteracted by leaning the body well toward the centre of the circle which is being skated. There are many compensating and at the same time conflicting balances in the outside edge circles which make them more difficult than the inside edge circles.

The inside edge circles, on the other hand, especially those skated forward, are in some respects the most natural and easy balances in the whole school of skating figures. They are the most natural stroke for any beginner to take. It is sometimes well to allow a beginner to start with these inside circles merely for the encouragement which their comparatively easy accomplishment will bring to the pupil. The more difficult outside edges can be gradually worked into the practice.

The reason why the inside plain circles forward are easy, is found in the fact that the natural balance of the body, poised on either skate, has a strong tendency to the inner curve. The weight of the body is in the inside of the circle which it is proposed to execute, not outside, where a pull out of the direction of right progress is constantly at work.

On the inside edges the body has opportunity to swing as a pendulum in a natural curve which has a tendency to end in a spiral. The fact that a spiral almost invariably results from the uncorrected inside edge serves to prove that the stroke is a natural and correct skating position. But since the spiral is the very thing that must not be permitted to enter into the execution of the plain inside circles, at least until the skater has fully mastered all the school figures, there must be careful correction of the balance to round out the inside edges into full circles and prevent them from becoming spirals.

24The outside edges which we studied in the last lesson are hard. The inside edges are much easier. But there are certain fundamental things to remember in the inside edge circles. And unless they are remembered the figure cannot be executed properly. The circle will insist upon becoming a spiral in spite of all the skater can do unless these few foundation principles are mastered. An excellent method for learning to skate, seen constantly on the skating floors of Europe, is the little book or even the page from the book, held in the hand of the skater and studied constantly as the figure is practised. It is difficult to remember the various poses and changes of carriage.

The most important item to remember in the inside forward edges is the carriage of the shoulders and the manner in which they are slowly turned during the execution of the circle. Next to that in importance is the carriage of the balance leg. Here let me repeat that it is almost invariably true in skating that the correct balance as well as the most graceful poise is found when the arms and hands are used to compensate the weight of the balance leg. If the balance leg is inside the circle which is being skated, the arms will generally be carried outside and vice versa. When the balance leg is forward of the body there will be a slightly backward poise; when the balance leg is carried far behind the body there will be a strong forward leaning of the body. If this general principle is remembered by the ambitious beginner much will be gained in progress toward correct carriage.

Now start out on the right inside forward circle. Start from the push of the left skate squarely pressed against the ice, not from the toe of the skate. Bend the skating knee considerably, take a firm hold of the ice with the inside edge of the skate, lunge strongly forward with the leg carried well behind, knee bent and toe turned out. The shoulders, at the start of the figure, should be twisted toward the right, which will bring the left shoulder forward; this position is maintained for about one-fourth of the circle, when the shoulders are slowly brought square with the print and from this point to the end of the circle the right shoulder continues to be brought forward until, at the end of the circle, the shoulders are almost in line with the print.

When one-half of the circle has been completed, the balance leg, which up to this time has been carried well behind, is slowly 25brought forward and carried past the skating leg, the body meanwhile swaying from a forward to a backward balance to compensate the weight of the leg in front. As the balance foot passes the skating foot the knee of the balance leg is well bent, the toe turned out, and the foot carried as close to the skating foot as possible. Then the balance leg is carried well to the right, across the print and considerably elevated above the skating knee.

The arms, which were carried on the right of the body, well elevated, at the start of the figure, are slowly swung across to the left of the body as the balance leg swings forward and across the print. The close of the figure is one of the most striking and effective poses in the whole list of school figures. Unless the balance leg is carried well forward and across the print, the body straightened up and the arms carried across simultaneous with the bringing forward of the balance leg, the figure will degenerate into a spiral. Finish the figure as close to the starting point as possible. Do it at least three times on each foot and practise most on the weaker foot.

Most spectacular and most applauded of all the items on my programme in the ice ballet in “Flirting at St. Moritz,” at the Hippodrome, are the backward outside edges or circles. Probably the very simplicity of them adds to the effect which they create in the mind of the crowds. The series of jumps which I make from a forward outside edge to a backward outside edge, is nowhere near as hard as it appears. And the complete revolution in the air which I make from one outside backward edge to the same edge again is dependent upon the accuracy and firmness of the outside edges. These are but two of the simple, yet very spectacular features of my exhibition which are based on the outside backward edges.

The outside edges backward are very popular for exhibition and spectacular purposes. But they are fundamental figures which must be mastered by every skater who hopes to make real progress in the most beautiful of all sports.

First the beginner must get a little confidence in skating backward by what is called “sculling.” The friend or helper is more important in learning the fundamental backward figures than in the forward figures. The best position for the helper when one is learning the backward strokes is facing the beginner; thus the beginner will skate backward and the instructor or friend will skate forward, right hands joined to left hands.

By a gentle push from the instructor or friend, the beginner is sent backward. Then should begin the waving lines made by the skates on the ice as the learner sways from side to side and throws the balance of the body from one foot to the other and from one edge to the other. Probably the beginner will not realize that he is making a sculling or waving mark on the ice until he has examined the print of the skates. It is an excellent practice to look at the marks which you have made in the ice. Often the accuracy of a curve or circles, or the correct tracing of a three or counter or rocker will be impossible to determine until the print has been examined. The judges in all great contests study the print on the ice as much as they do the carriage of the skater.

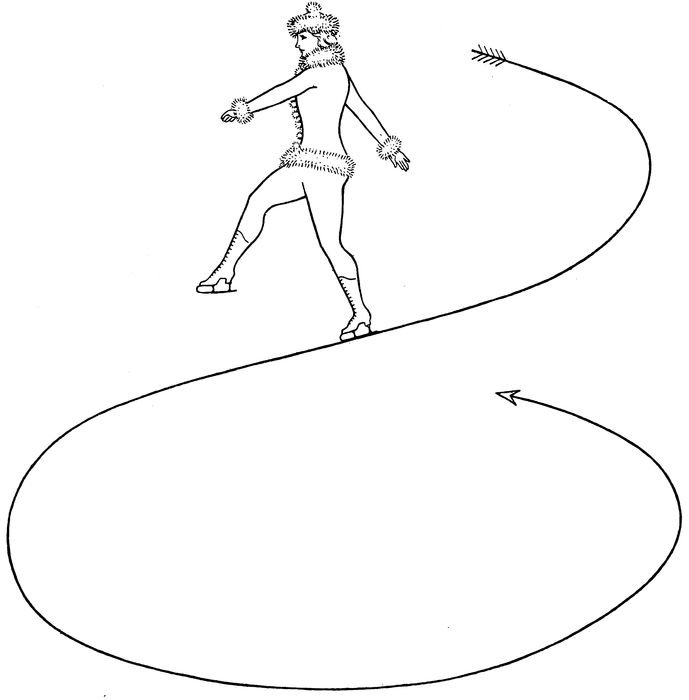

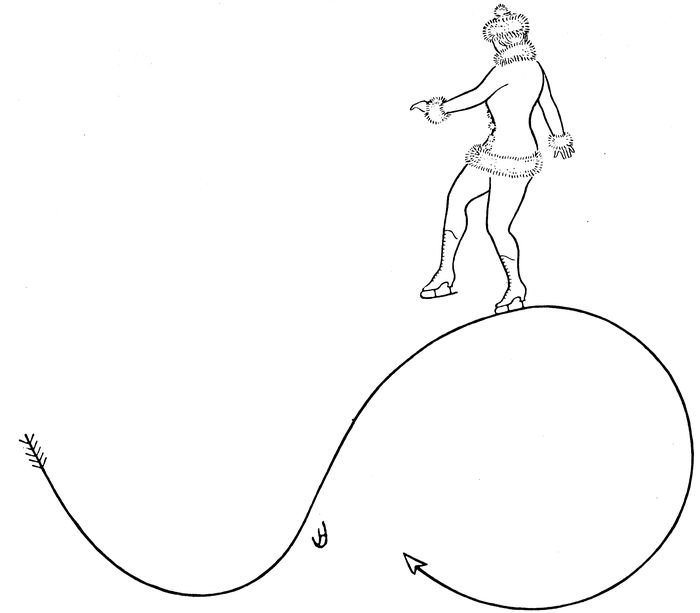

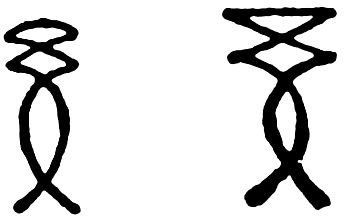

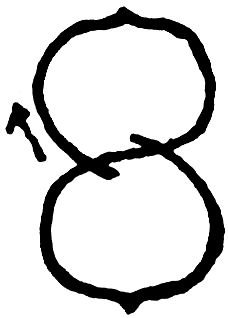

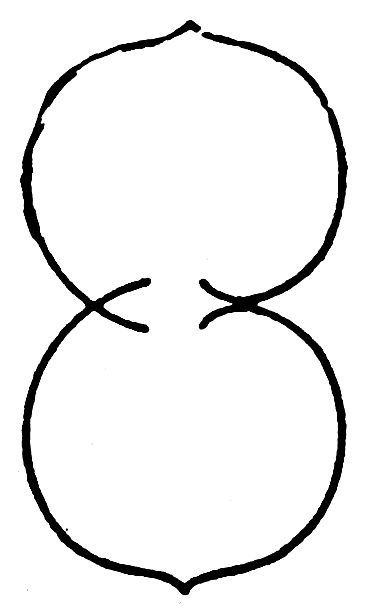

CIRCLE. Right outside edge, backward. (ROB)

28The sculling motion and strokes should be continued until the skater realizes that he is making a slight outside edge with each skate as his body changes its balance. Then learn to take the foot which is not being skated on, off the ice, carry it forward of the body toward the helper and trust to the outside edge of the skating foot.

When some considerable practice has been done in this manner and a part of a circle can be accomplished on the outside edge backward it is time for the beginner to start the full circles, or at least to learn to make the figure large and try to get back to the starting point.

The backward outside edges require nerve and daring. Here the skater’s qualifications for the sport will often come out. Skating backward in any circumstances is trying work to the beginner, and the curious balance of the outside backward circles is a hard thing to learn when one is at the same time distressed by the perfectly natural fear of skating backward. But make up your mind, clench your fists, grit your teeth and pluckily go at it.

Standing with both feet together on the ice, the starting stroke is made by pressing firmly with the flat part of the left skate on the ice and lunging backward strongly on the outside edge of the right skate. The chief difficulty in mastering this important figure comes from the innate hesitancy of the beginner to throw his balance backward. If this backward lunge is firm and strong, more than half the difficulty of the stroke has been mastered.

The balance left foot is carried across the right leg with the 29knee bent and the toe turned out and the leg carried fairly high in the air, not dragging behind. The shoulders rotate during all the circle edges, as we have seen in those which have already been studied. In the backward circle eights on the right foot, the left shoulder should be held well in front; this position, holding the shoulders almost square with the print, should be maintained through the circle.

The left foot, which is carried across the right leg and in front of the skater at the start of the stroke, should be brought slowly past the skating foot when about one-third of the circle has been completed, then carried well extended in a “spread-eagle” position to the end of the circle. This is one of the few strokes in skating where but little change of the position of the arms occurs during the completion of the circle. They slowly turn with the shoulders and maintain a graceful pose, with hands extended and palms downward. The general idea of the backward circle is to keep the entire body, arms and legs, almost directly over and slightly inside the print; its weight will tend to swing the body around as a revolving pendulum. The outside circle eights, either forward or backward, are somewhat forced or false balance, since the body has to lean considerably toward the centre of the circle to get the centre of gravity in the right place.

These articles are for beginners, and they ought not to hold me too closely to the rules I lay down. Many of my exhibition figures are so unusual and contain such unexpected combinations of jumps, counter rockers and spins that I have to violate rules or the figures could not be done. I have been accused of having no rules for skating, as I do so many things my own way. And when you have progressed to the point where they want newspaper articles from you which they head with the flattering remark that you are the greatest woman skater in the world, you will be in a position to violate rules a little bit. My pet philosopher says that rules were made for slaves.

All backward skating is difficult to acquire. After it is acquired it is more interesting than forward skating.

Some of the very difficult jumps in mid-air which I do are taken backward because it is really easier to do them that way than forward. There is one jump where I am skating backward on the outside edge on the right foot, swing the left foot violently around, spring into the air, make a complete revolution of my body, land on the outside edge of the right foot again and continue on a big sweeping curve. It is in some respects the most popular number that I introduce. It is done that way solely for the reason that it is much easier backward than forward and yet at the same time it looks more difficult backward than forward.

Most skating figures will be found easier forward than backward. Probably that is partly due to the fact that not as much time is spent by any skater learning backward skating as is spent learning forward strokes. The art of skating backward requires pluck and courage. When one attempts the full backward circles without a helper it is an occasion to mark in one’s diary.

The plunge is the main thing in learning to skate backward. Make up your mind some fine morning that you are going to practise outside edges backward or inside edges backward all of the skating session of that day. Then do it. Skating is a matter of will power after all and not at all a matter of strength. I took up skating just because I was not strong and the doctors said it was outdoor life or a little narrow box for me.

It is hard to catch one’s self during a fall when one is on the outside circles backward; the position during much of the inside circles backward makes it easier to get ready for the fall after you feel sure it is coming. Not that I mean there is any special instruction necessary in the matter of falling for there is not. Just let go and sit down as meekly as you can, smile and look about helplessly and some chivalrous American is sure to hurry to your aid. This is much more dignified and less liable to be embarrassing than scrambling to all fours, stepping on your gown and, perhaps, falling over again.

“CHARLOTTE” in spectacular backward stroke.

32To get a strong start for the inside circle backward is the hardest part of the acquirement of the figure. Stand on the flat of the left skate, swing the right foot in front of you, just as if you were going to make a little jump backward onto that foot, bend the right knee a good deal and lunge onto the right skate on the inside edge. The left foot as it leaves the ice should then be carried across the right leg, with the knee bent and the toe turned out and down. It should be carried well across the print or mark that the skate is making on the ice and somewhat high, not dragging along. The body should lean strongly backward.

As the stroke is begun the shoulders are turned well toward the right and both arms are carried on the right of the body outside of the print. This is one of the very few cases where the arms are carried on the same side of the print as the balance leg and it is due to the fact that the body naturally inclines toward the center of the circle when it is on the inside edges. The head should be facing the starting point throughout the execution of the circle.

When about one-third of the circle has been skated then slowly bring the balance foot past the skating foot, knee bent and toe turned strongly out and down. Simultaneously the shoulders should be turned toward the left until the body faces the center of the circle and maintained in that position to the end of the figure with both arms, one forward and the other following, almost directly over the print. As the balance foot passes the skating foot the body is straightened and for a moment the arms are drawn close to the body. This straightening of the body and change in the carriage of the balance foot will make it possible for the skater to round out the circle to its correct proportions. All inside edge circles have a strong tendency to become spirals. At the close of the stroke the skater will be in the right position for the start of the same stroke on the opposite foot.

CIRCLE. Right inside edge, backward. (RIB)

The change of edge is one of the most important school figures and should be carefully practised by every skating pupil. It is not spectacular, although it is very graceful and very easy to acquire.

I like the changes of edge and, like all other expert skaters, find them of the greatest importance at certain times. When one has an audience of skaters I find these figures much better appreciated than at other times. At a private party given on the stage of the Hippodrome, I was skating a difficult figure where there were three small circles at the four corners of a square. I went from one of the corners to the other by a change of edge and a three after it. The skaters who were watching me applauded this figure as generously as any figure of a more spectacular character that I do during the regular performances of matinees and evenings during the week. But they were all skaters and appreciated the difficulty and the beauty of the figure.

The right outside edge forward is the best way to start to learn the changes of edge. It is easier than the change of edge which begins with the right inside edge forward, for the reasons which I have explained in previous chapters concerning the way that the body tends to swing around toward the circle on inside edges and tends to swing away from it on outside edges.

The start of the right outside forward change of edge is the same as for the right outside forward circles and it seems unnecessary to repeat those directions. The drawings, too, will be found precisely similar in the pose for some of the figures as for some other figures. This is one way to get double practise. Every time one practises the outside change of edge forward he is practising the right start of the outside forward circles. Every time he is practising the inside forward change of edge he is practising the start of the inside forward circles.

Start the right outside forward edge circle, as we have seen, 35by pressing the left skate squarely against the ice and thrusting onto the right foot outside edge. The left foot should be carried well behind and a little across the print with the knee bent and the foot turned out and down. The skating knee should be strongly bent at the start of the stroke. The shoulders should be turned so that the right shoulder is almost over the right foot and the left shoulder twisted well to the back. When nearly half of the circle has been completed gradually turn the shoulders toward the right, which will bring them square across the print or direction in which the skater is moving.

When half the circle is complete the change of edge from the right outside forward to the right inside forward occurs. The balance of the body is here changed from an outside to an inside circle and the general directions which have been given for the execution of an inside edge circle will be found applicable. But the manner of making the change from the outside to the inside edge is most important and this portion of the figure is new to the pupil.

As the outside forward half circle is nearly completed and the change of edge about to occur, the body, which has been carried on a slightly forward balance, is slowly changed to a backward balance, and the left foot, which has been carried behind during the completion of the outside forward circle, is slowly swayed past, close to the skating foot, and carried well in front, somewhat high. Sinking on the skating knee at the time of the change of edge will much assist the full rounding out of the figure. The arms should not be allowed to swing the body around during this change of edge as they are liable to do if carried too high or too far from the body.

Follow same directions for left forward outside change of edge.

I feel convinced no one can be called a skater until he can do the school figures. Every day I practise the simplest of the school figures—outside circles, forward and backward; threes, changes of edge, loops, and the rest of them. I do this because I am sure they are the best practice for keeping the skater in right form and correct balance. You may not see many of them on the ice of the Hippodrome pool, so you must take my word for their importance to me. When one has but a few moments in which to crowd a skating performance, which shall be just as thrilling as you know how to make it, little time can be spent on the A, B, C’s of skating.

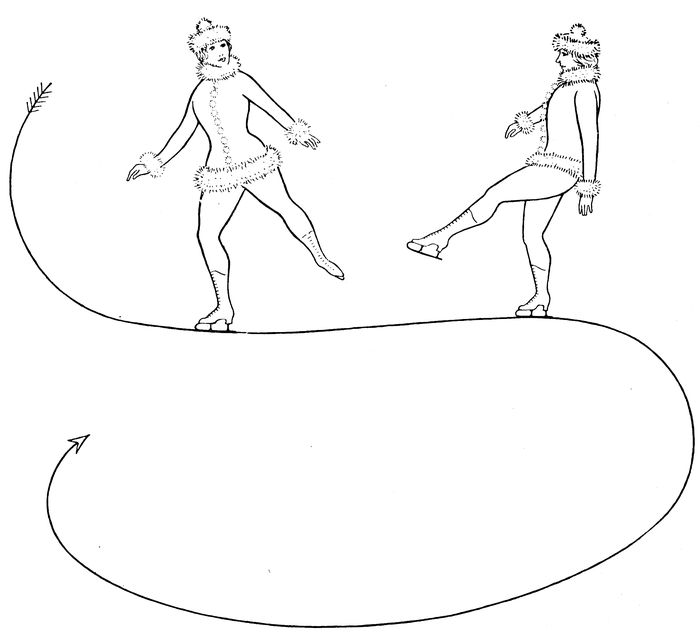

CHANGE OF EDGE OR SERPENTINE. Right outside edge, forward, change edge, inside forward. (ROIF)

37The lesson to-day is again on the change of edge. There are really four of these to learn on each foot. Beginning on the outside edge forward and changing to the inside forward we had last time. This time we begin on the inside edge forward and change to the outside edge forward.

The difference between the execution of to-day’s lesson and the last one is that the figure to-day is easier to start and harder to finish, while the last one taught, from outside to inside edge, is harder to start and easier to finish. That is, it is harder to round out the circle after the change of edge from inside to outside has been made than it is to round out the circle after the change from outside to inside has been made. I have explained the reason for this in speaking of the inside edges in several former lessons.

CHANGE OF EDGE OR SERPENTINE. Left inside edge, forward, change edge, outside forward. (LIOF)

38This time I have had the drawing illustrate me on the left foot. The start may be on either foot first. I advocate starting on the foot with which one can skate best, for the sake of encouragement and the acquisition of right carriage more quickly. Then practise oftener on the foot which is less perfect, so as to bring both up to the same standard of efficiency.

As the change of edge occurs, the balance leg is brought back, past the skating leg and outside the print, the shoulders are slightly turned toward the left, facing more the centre of the circle, and the general position described for the inside edge circle forward assumed. When the inside circle has been about half completed, the balance foot is brought slowly forward and carried there to the end of the figure.

CHANGE OF EDGE OR SERPENTINE. Right outside edge backward, change edge, inside backward. (ROIB)

39The chief difficulty in learning this figure is found in making the sway of the balance foot and leg forward and backward again deliberate. To use the swing of the balance foot for the purpose of jumping the body into any position is a glaring error. The body should roll over the change of edge and the sway of the foot past the other be almost unnoticed.

Start, this time on the left foot, let us say, by thrusting out from the flat of the right skate, assuming the position described for the correct inside circle, with the right foot behind, slightly across the print, both shoulders in line with the print and the arms raised. Just before making the change of edge the balance foot is brought past the skating foot, close to it and extended well in front and somewhat high. As the change of edge is made, the centre of gravity should be brought directly over the print and at the same time the balance foot, which has been in front, should be brought back and carried well behind and well across the print. This is the right position for the forward outside circle, as will be seen by reference to former lesson and diagram on that figure.

Immediately after the change of edge has occurred the body should be straightened up, the shoulders kept flat and the head erect and facing the centre of the circle which is being executed. A little before the centre of the circle is reached the balance foot, which has been carried behind, should be slowly moved in front of the skating foot. Great care must be exercised to keep the shoulders in right position before, after and especially during the changes of edge, for on the right carriage of the shoulders and the balance leg the rounding out of the figure depends.

The changes of edge are performed in three lobed eights. One half of the centre circle is performed on one leg, then the change of edge occurs and then a full circle on the second edge. The main difficulty will be found with the full circle after the change of edge. Follow the same directions for the right foot inside to outside change of edge.

We have now reached the place in the school figures where they are of sufficient difficulty and interest for their introduction into my programme as premiere of the ice skating ballet in “Flirting at St. Moritz” at the Hippodrome. But of course they may be done so fast that they will be missed by any except the most observing attendants. Theatrical skating, such as I do, has to be fast and sensational. The easy transition strokes from one figure to another furnish about the only example of school figures which the public will quickly catch in my work, although I am constantly doing threes and double threes both forward and backward. These school figures are so interesting and pretty when well done that I have put several of them in my programme.

CHANGE OF EDGE OR SERPENTINE. Left inside edge, to outside edge, backward. (LIVB)

The lesson to-day covers two school figures—the changes of edge backward, executed on, first, the outside and then the 41inside edges. Both these figures include strokes which have been fully described in former lessons. The new thing to learn is the combination of the two strokes which have already been learned into one continuous movement or figure. A change of edge either forward or backward implies considerable loss of power or momentum at the place where the change of edge occurs. The most important thing to learn in all changes of edge is the manner of retaining or even of increasing this momentum at the time of the change. That the momentum of a skating stroke can be added to during its execution may surprise some persons who are unfamiliar with skating; nevertheless it not only can be done but is done by all who skate the school figures correctly. This momentum is added to, sometimes by lowering and raising the body, sometimes by rocking the body over a change of edge, sometimes by the swinging of the balance foot to a new position.

To skate the backward change of edge, beginning on the right outside edge, start off as described for the plain outside edge circle backward, with a strong push from the left foot. All strokes beginning backward require a stronger start than the same strokes started forward. It is easier to walk forward than backward; the unnatural stroke is harder to learn than the natural one.

The outside backward circle has been fully described in a previous lesson. Start the change of edge backward by making this stroke, remembering that one is to skate not merely a single circle but a circle and a half and that the stroke must needs be strong and firm. There should be strong backward leaning in the first half circle of this figure, as in the start of all backward outside edges. The balance foot should be slowly brought backward during the execution of the first half circle close to and past the skating foot to the correct position for the outside backward circle. Slight bending of the skating knee before the change of edge is advisable; straightening of the body after the change of edge increases momentum.

As the change of edge is made, which should be an almost imperceptible swinging over of the body from the outside to the inside edge, not a quick upset of the balance, the balance foot is brought slowly forward, past and close to the skating foot, and carried in this position until about one-third of the circle has 42been completed. Then the balance foot is again brought back, past the skating foot, and correct inside edge backward position assumed.

The second figure consists of a reversal of the stroke which has been above described. It starts on the inside edge backward and changes to outside edge backward. These strokes are almost equally difficult. The former is easier to start and harder to finish, while the latter is harder to start and easier to finish.

It is customary, when following the procedure of the European skating teachers, to skate first an outside backward change to inside backward and then skate an inside backward change to outside backward. All changes of edge both forward and backward, therefore, will be skated in an eight having three lobes, as per the diagram. If the start of one figure has been on an inside edge and change has been made to the outside edge, then the next figure will be started on the outside edge and changed to inside edge.

Lunge boldly on to the inside edge, as if to make an inside edge circle backward. But before the half circle has been completed bring the balance foot slightly past the skating foot and close to it. When the change of edge occurs the balance foot should be brought forward directly over the print, with the balance knee bent and the toe turned out. The location of the balance foot throughout all of the changes of edge is of the utmost importance. If it is allowed to swing wide from the print uneven curves and spirals will result. The described position for the outside backward circle is maintained until about half of the circle has been skated, when the balance foot is brought slowly backward and maintained in this position to the end of the circle. The carriage of the body, the arms and the head are of the greatest importance in the execution of changes of edge and must be carefully memorized and simultaneously changed. There should be no jerky movements of the balance leg during the execution of the figures but a deliberate swing of the body to the new edge and the new carriage. A good way of determining whether the figure has been executed correctly is by inspection of the print; it should be accurate as to half circle and circle, and there should be no snow turned up as the change of edge is made.

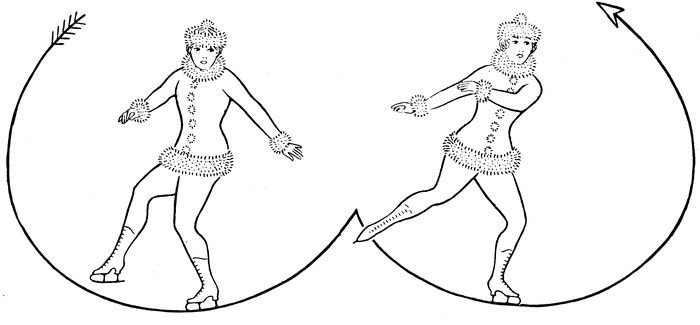

THREE. Right outside edge forward, to inside backward. (ROFTIB)

THREE. Left inside edge backward, to outside forward. (LIBTOF)

Skated in a series, as I do them, backward, threes always interest even those who know nothing about skating. They are necessary to the mastery of the ice waltz and all the other dance steps. In their simplest form, either forward or backward, they are generally graceful.

There are two ways of regarding the three. Some of the best skaters make it very deeply indented, as if there were two circles, in the middle of which was placed the threes. Others make the three a quick turn, almost unnoticeable on the ice, in the execution of a big circle. The latter design seems to me to be right. I regard the three as a movement which occurs and should occur only as part of the execution of a big circle. This is the way that I skate it. My style is my own and is a combination of the best style I have seen. Every skater becomes more or less individual as he becomes expert and in some of the best skaters it is difficult to tell where they learned or who their teacher was.

There are eight threes for the beginner to learn—one on outside edge forward to inside edge backward, one on inside edge forward to outside edge backward, one on outside edge backward to inside edge forward and one on inside edge backward to outside edge forward. These must be duplicated on each foot, making eight in all. They are progressively difficult in the order in which they have been named.

The outside forward to inside backward three is started as one would start a plain circle, on the outside forward edge. But gradual rotation of the shoulders toward the center should begin as soon as the figure is started. On approaching the three the shoulders should be in line with the circle of which the three is a part. This position of the shoulders should be maintained until the latter half of the figure is nearly completed; it will be found of great assistance to the skater in continuing the circle to its full shape. It will be noticed from the diagram 46that the general position of the shoulders, the arms and the legs is almost identical after the turn as before the turn; the figure is being finished on another edge, that is all.

In all forward threes the balance foot maintains its position behind the skating foot, both before, during and after the three. In the outside backward three the balance foot, which at the start of the three took a position slightly across the print and over the skating foot, retains that position to the end of the figure. In the execution of the inner backward three the balance foot may remain in front or may be carried behind; either position is correct. If it is carried behind, there should be strong sinking on the skating leg at the time the three is made and a straightening of the body immediately afterward.

THREE. Right inside edge forward three, outside backward. (RIFTOB)

47The inside forward, outside backward three is the easiest for the amateur to learn. The inside backward, outside forward three is the most difficult to learn and extremely difficult to place accurately. It should be practised persistently until mastered thoroughly.

The inside backward, outside forward three is started as for the inside circle backward, but the shoulder over the skating foot is turned strongly away from the centre of the circle. As the three turn is made the balance of the body should be strongly backward and the turn executed on the back or heel of the skate. This is the three where the balance foot may either be swung around in front of the body or allowed to remain behind the body as the turn is made. The illustration shows the latter method of making this three.

THREE. Right outside edge, backward, three, inside forward. (ROBTIF)

THREE. After the three, right outside backward, three, inside, forward. (ROBTIF)

48All threes should be placed most carefully at the correct position at the top of the indented eight. Imagine two circles with a dent inward at the top of each circle and you have the right design for threes. In competitions or in serious practise of the threes for progress in skating school figures they are skated in pairs, starting first forward and then backward. For instance, right outside forward, three; left inside backward, three.

The carriage of the balance foot is most important in assisting in the execution of full, round curves after the threes. In every case the balance foot should be carried well outside the print after the three has been made; this will tend to enlarge the portion of the circle following the three. The arms should be carried low for all three turns, otherwise they will have a tendency to swing the skater out of the true curve and into a spiral.

SAINT LIEDWI, Of Scheidam, Holland, A. D. 1396; from ancient wood-cut.

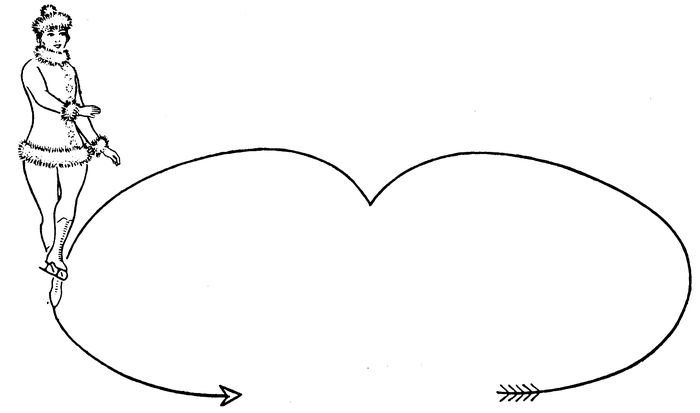

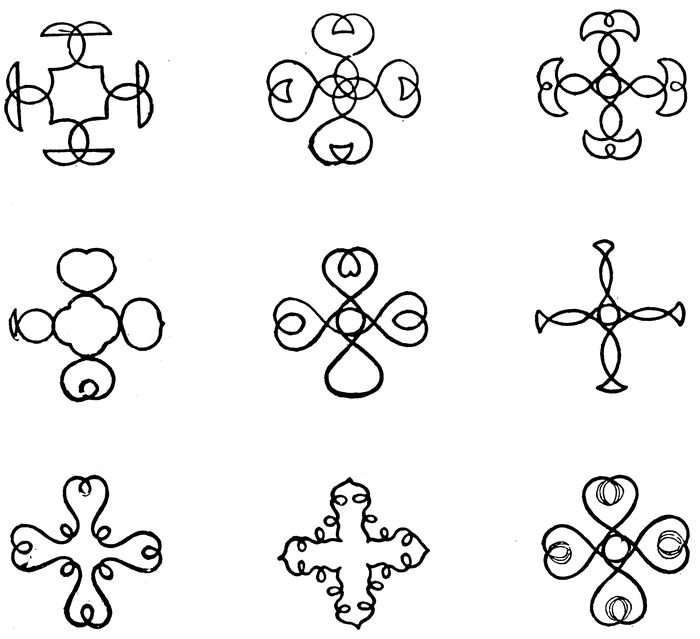

Double threes make a very pretty tracing on the ice and are especially useful in determining if the skater has learned the correct carriage for the various turns comprising them. Unless that correct balance has been learned, the correct execution of the double threes is impossible. There is an agreeable swing to the double threes which is lacking in some of the other school figures. They form what one might call a finished figure of themselves, both as to the tracing on the ice and the position of the skater after the figure has been performed. They leave the skater in a naturally correct and agreeable pose for the following half of the figure.

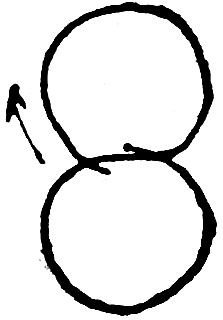

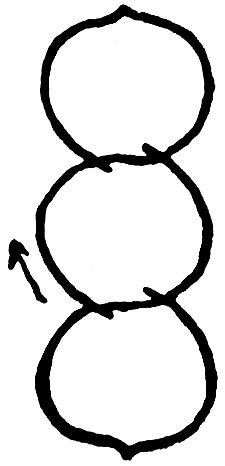

The double threes have this peculiar difference from other school figures—they are very much easier forward than backward. But the carriage of the balance foot is much easier in the backward than in the forward half of the figures. To-day we have the forward half of the double threes—that is, starting on each foot forward, first outside and then inside edge. The completed figure makes a trefoil, or clover leaf, as will be seen from the diagram, one of the prettiest of the school figures.

Start the double three on the outside forward edge with not too vigorous thrust from the foot on the ice, since a certain amount of power can and should be gained by the correct turns which will be made during the progress of the figure. Too strong a thrust will tend to make the skater spin on the first three. It is better to start practise of the double threes somewhat slowly, learn where the greatest difficulty lies, and then practise overcoming that difficulty by independent skating of the most difficult portion of the figure.

“CHARLOTTE” in pirouette.

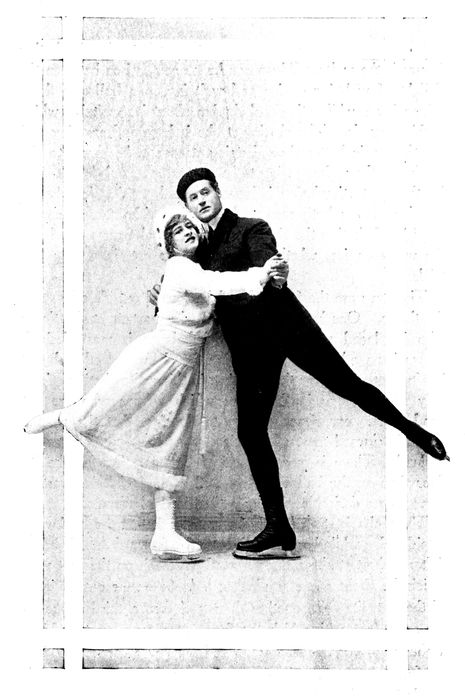

“CHARLOTTE” and IRVING BROKAW in hand-over-head pair skating.

52The general directions for the start of the threes forward on the outside edge apply to the start of the double threes. After the first three has been made, which will bring the skater on to the inside edge backward, the balance foot should be carried fairly high at first and gradually brought close to the skating foot, so that when the skater is ready to make the second three the balance foot is close to the skating foot. During the inside edge backward the shoulders and the body should be slowly turned away from the centre of the circle toward the second three.

At the moment of the second three the skating knee should be bent rather strongly and the body turned, without perceptible jerk, into the right position for the finish of the figure, which is on the outside edge forward again. The balance foot is allowed to remain slightly behind as the second three is performed and, when the third portion of the curve of the completed figure is about one-half skated, should be brought forward into the usual position for the end of the outside forward circle.

The inside edge double threes forward are started as for the inside forward threes, but with more bending of the skating knee and with less inward turn of the body toward the circle. When the first three has been executed and the skater is then on the outside backward edge, the balance foot should be carried fairly close to the skating foot and the body should lean strongly backward. At the moment of the second three the balance foot should be brought close to the skating foot and directly over it.

When the second three has been executed, the balance foot may be allowed to linger a little behind the skating foot and be carried in that position to the finish of the third curve, or it may be brought forward into the customary position for the finish of the inside forward circle. Both positions are used by the best experts of Europe.

The second half of the double threes are skated backward. That is, both parts of the lesson of the day start backward. Double threes have the interesting peculiarity of finishing on the same edge and in the same direction as they are started. They are clover leaf in pattern, and should be skated with great care to have the leaves equal in size and accurately placed as to the axis of the two large circles of which they form a part. The placing of all school figures is most important and is the basis of the marking which obtains in European competitions.

Start the figure on the outside edge backward, with a fairly strong thrust from the foot on the ice. The general position is that which has been described for the outside backward circle of three, with a little less turn of the shoulders away from the centre of the circle. Gradually turn the body so that, as the first three is being made almost the right position for the second curve, on the inside edge forward, is obtained. As the first three is performed, the balance foot should be in front of the body, over the print and not far from the skating foot. A slight swing of the balance foot is customary as the first three is performed, but the balance foot must not be permitted to stray from the skating foot, or there will be a tendency to revolve the body from the right position for the second curve.

The balance foot is carried forward of the body during the second curve in the customary position during the inside forward circle and up to the moment when the second three is performed, when it should be brought close to the skating foot 54and directly over it. There should be considerable bending of the skating knee as this second three is made. The balance foot drops slightly forward of the body after the three is made, as in the usual backward outside edge circle, and the figure is so finished.

The inside backward double threes are started as for the inside backward threes, but with more vigorous thrust and more bending of the skating knee. The balance foot is carried well across the print up to the moment of the first three, when it is brought close to and over the skating foot. After the three is made there should be general straightening of the skating knee and of the body, which will greatly add to the momentum. The second curve of the figure, on the outside forward edge, furnishes one of the places where much power can be added during the execution of a figure. The second three is performed exactly as described in the forward outside three and the figure finished on the inside backward edge.

Many skaters find that the double threes are easier than the single threes, and that a series of threes are easier than a single three, carried out correctly to the starting point. Such skaters should not get the bad habit of doing the more elaborate double or chain threes to the neglect of the fundamental single or double threes. In time ignorance of the right balance for the simpler figures cannot fail to get the skater into trouble.

The importance of loops cannot be exaggerated. They are in some respects more important than the threes, which precede them. They are an entirely different balance from figures to which they are very similar and for that reason alone are important. If, for instance, one has been practising threes and then goes to loops, the different balance is so great as to disturb the proper execution of either figure. Of course, when one becomes expert they can do any figure they select, in any order. The amateur and the beginner, however, will do well to separate the time of practising certain contrasting figures.

One day make special effort to master the threes, forward and backward. Do but little else. Memorize the correct balance, the correct carriage of the balance foot, the body and the arms. Do no loops that day. Another day specialize on loops, making no threes, but studying most carefully the correct carriage for loops. Threes and loops are hard figures to practise in sequence although there will come a time in the progress of the amateur when one of the most interesting and beautiful figures he can do will be a combination of three, loop and three. The single threes, however, and the single loops are a different balance from combination three, loop and threes.

In learning the placing of either threes or loops or brackets, it is important that the beginner have in mind the fact that they should be executed at the far ends of the figure in which they are placed. The length of the curve or part of the circle after the three or loop ought to be the same as before the three or loop. The loop ought not to be at the end of a long spiral. Correct tracing of the figure on the ice is a fundamental part of true continental form in skating.

LOOP. Right outside edge forward, loop, outside forward. (ROFLOF)

57Start on the right foot, outside edge, forward, as for the circle eight on that foot, but soon begin to twist the shoulders toward the centre of the circle. The balance leg should be carried behind and not far out or it will have a tendency to swing the skater into a three instead of a loop. As the loop is started the skating leg should be bent considerably. When the loop is half finished the balance foot which has been swinging around is brought past the skating foot, close to it and vigorously but deliberately thrust forward outside the curve which forms the finish of the figure. At the same time the arms should be brought in close to the body and the body straightened up, which will give added impetus for the correct curve to the starting point.

The difficulties in the performance of the loops will be met in the correction of balance at the middle of the loop and the completion of a full curve after the loop. These difficulties can be lessened by much careful study of the right principles before the figure is attempted and by repeated practising over and over again after the correct balance has been learned. When the correct loop movements are once attained it is best to continue practising them before other different balances are allowed to interfere with their complete mastery.

The inside forward loops are started differently from the inside circles as the shoulders should face the centre of the circle right from the start. The skating knee should be well bent and the balance of the body should be strongly forward until half of the loop has been completed. Then the balance foot, which has been carried behind and outside the print, describes a small, quick circle directly over the loop and is thrust well forward, across and outside the print. The shoulders, however, remain twisted toward the centre of the circle. The balance of the body before the inside forward loop is strongly forward; after the loop it is strongly backward. After the loop is made straighten the body up and bring the arms quickly to the sides of the body; the first movement adds impetus and the second tends to prevent the following curve from becoming a spiral. Loops should be made on a strong edge. After the loop is made less edge is required; in fact as little edge as can be used to follow the correct curve of the circle back to the starting point.

LOOP. Left inside forward, loop, inside forward. (LIFLIF)

Loops are somewhat dependent upon the freedom with which the skater is able to control his ankles. They should not be held too stiffly in these figures since a firm edge is needed even in the small circles which will be formed and there is change of the balance from the forward to the backward part of the blade, or vice versa, in the various loops. There should be no noticeable pause at the centre of the loop. The balance foot should not be employed to jerk the skater out of the loop into the finish of the circle.

Loops are so very important a part of the equipment of the finished skater that I have divided them into two chapters. They should have large place in the careful, studious skating of all who are ambitious to make good progress in this most graceful of sports.

There are some interesting peculiarities of loops which may be set down as worth remembering. For instance, all loops are skated with the balance foot following the skating foot before the loop and preceding it after the loop. Again, all loops are skated with the balance of the body strongly forward before the loop and strongly backward after the loop. The balance foot should pass the skating foot very close to it in all loops or there will be strong tendency to swing the skater into too small a curve after the loop has been made. Loops should be almost round as to shape.

The outside backward loop is in some respects the easiest of the four loops. But it is not easy to get the right start for this loop. Perhaps more daring is required in the strike off of the outside backward loop than in any other school figure. For this reason, while championship competitions insist that the start of all figures shall be from rest, the beginner may find it encouraging to start the backward outside loops after he has taken a slight backward outside stroke on the opposite foot. This merely for encouragement. After a good start has been learned, lessen the times that the assisting motion from the stroke on the other foot are used and finally discard it altogether and start, as one should, from rest.

Thrust out boldly on the outside backward edge as for the outside backward circle, twisting the shoulders so that they are flat with the centre of the circle of which the loop is to be a part. Turn the head even more than the shoulders, looking almost over the unemployed shoulder toward the spot where the loop is to be placed. At the moment of commencing the loop the face should be almost directly toward the loop and 60both arms twisted well toward the centre of the circle as in the diagram. The twist of the shoulders and a sharp swing of the balance foot around the skating foot, close to it, will give the right rotation for the loop. After the loop has been made the head and the shoulder over the balance foot should be kept turned well toward the direction of the curve which is being skated. It will be found very difficult to round out this finishing curve of the outside backward loop. The twist of the shoulders and the carriage of the balance foot outside of the print are the secrets of its accomplishment.

The inside backward loops, as has been said of the inside edges in general, are easier to start and harder to get out of than any similar strokes. To make a clean inside edge loop backward and get out of it with a resulting curve of full size and true radius is an indication of real proficiency in figure skating. Many good skaters fail in this difficult figure. Yet it must be learned or other following and combination figures cannot be accomplished.

This loop requires more edge than any of the others. It is about the only loop which the experts of Europe agree upon as to the place on the blade of the skate with which it should be executed. This is the forward part of the blade.

LOOP. Right outside edge, backward, loop, outside backward. (ROBLOB)

61The start is made like the start of the inside edge circle backward except that the head is turned over the employed shoulder instead of over the unemployed shoulder. That is the face is turned away from the centre of the circle of which the loop is to be a part instead of toward the start of the stroke. The position is similar to that for the execution of the three or the backward inside edge but there should be more twist to the shoulders. The balance foot should be carried well in front of the body, not too high, and over the print. The arm of the employed shoulder should be extended well out from the body compensating the weight of the balance leg which is on the other side of the centre of gravity, as shown in the diagram. There should be strong backward leaning of the body, as in all backward loops, up to the middle of the loop when the balance foot swings past making a small circle, almost a flip of the foot, and is carried well out, over the print. The curve is finished like the inside backward circle. There is less use of the shoulders, and more use of the balance foot in the execution of the inside backward loops than in any of the other loops.

LOOP. Right inside edge, backward, loop, inside backward. (LIBLIB)

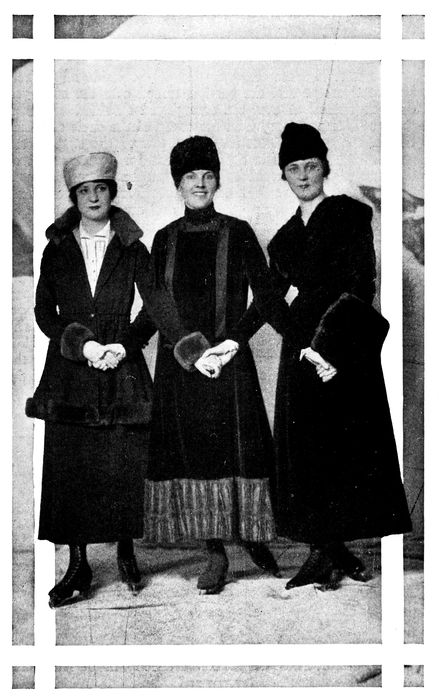

MRS. JULIEN M. GERARD, MRS. CHARLES B. DILLINGHAM and MISS MADELINE COCHRANE at Hippodrome Skating Tea.

It is most important, in learning the school figures in the correct continental style, to remember that all the school figures should be done in large size. The matter of size is, in fact, one of the first essentials in the correct performance of the continental school figures. It is told me that the American tendency is to skate all figures much smaller than they are skated in Europe. When the fact is realized that after the figures are learned in large size it is comparatively easy to skate them small, and that it is almost impossible to skate them large after they have been learned small, the importance of practising all figures large is realized.

In all simple figures of large size the carriage of the head and shoulders is of the utmost importance. For the purposes of this argument the brackets may be regarded as simple figures; they are much less difficult than many somewhat similar school figures. In the execution of small figures the carriage of the balance leg and the arms is of greater importance than the carriage of the shoulders and head. It is, of course, true that no figures can be done correctly, either small or large, unless both head and shoulders and balance leg are correctly poised, but the relative importance of the parts of the body is as stated.

While the turn of the threes is a natural turn, the turn of the brackets is an unnatural turn. That is, the tendency of the body when one strikes out on a right outside forward edge is to revolve toward the right. But to make a bracket on that foot and that edge the turn of the body must be toward the left. It will be seen, therefore, that the stroke is similar, as to the edges employed, to the threes, but that the turn of the body is in the opposite direction. The diagram clearly explains this peculiar turn. There are eight brackets for the skater to master—four on each foot—two beginning forward and two beginning backward; two starting on outside and two starting on inside edges.

64There are slight differences of opinion among the experts of Europe as to the manner in which the balance foot should be carried in some of the brackets. When one reaches a certain degree of proficiency in skating there is reasonable freedom allowed for individual preferences in balance. Sometimes these preferences are purely physical and sometimes they are based upon a difference of opinion as to which is the more graceful or effective performance.

The difference between the execution of the threes and the brackets is illustrated in the matter of carrying the shoulders better than in any other way. For the threes the shoulders are turned well toward the three; for the brackets they are turned away from, that is, flat with it. It is a most important difference to remember, and on its remembrance is based all successful skating of brackets. Another general truth of bracket skating is that the balance foot should be very close to, sometimes directly over, the skating foot at the time when the bracket is being made. This is done by bringing the balance foot slowly up to and sometimes slightly in front of the skating foot just before the bracket is made.

For the outside forward bracket start as for the outside forward circle, but begin immediately to flatten the shoulders with the print. Just before the bracket bring the balance foot, which has been carried behind, past the skating foot, close to it and glance momentarily at the place where the bracket is to be located. At the bracket the body should be flat with the circle, the balance on the forward part of the blade and strongly leaning toward the centre of the circle. After the bracket the balance foot should follow the skating foot, across the print, and the general position for the inside backward circle be maintained to the end of the curve.

The complementary half of this figure is skated backward, and begins therefore on an inside backward edge in which a bracket is made to the outside forward edge on the same foot. The general directions for the inside edge circles backward should be followed at the start, always remembering that the body must be turned gradually so as to be flat with the circle at the time the bracket is made.

BRACKET. Right outside edge, forward, bracket, inside backward. (ROFBIB)