This text is a compilation of the six numbers of the first Volume of

Lucifer, spanning September 1887 through February 1888.

Footnotes have been collected at the end of each issue of the

magazine, and are linked for ease of reference. They have been resequenced for

uniqueness across the text.

Minor errors, attributable to the printer, have been corrected. Please

see the transcriber’s note at the end of this text

for details regarding the handling of any textual issues encountered

during its preparation.

Any corrections are indicated using an underline

highlight. Placing the cursor over the correction will produce the

original text in a small popup.

Any corrections are indicated as hyperlinks, which will navigate the

reader to the corresponding entry in the corrections table in the

note at the end of the text.

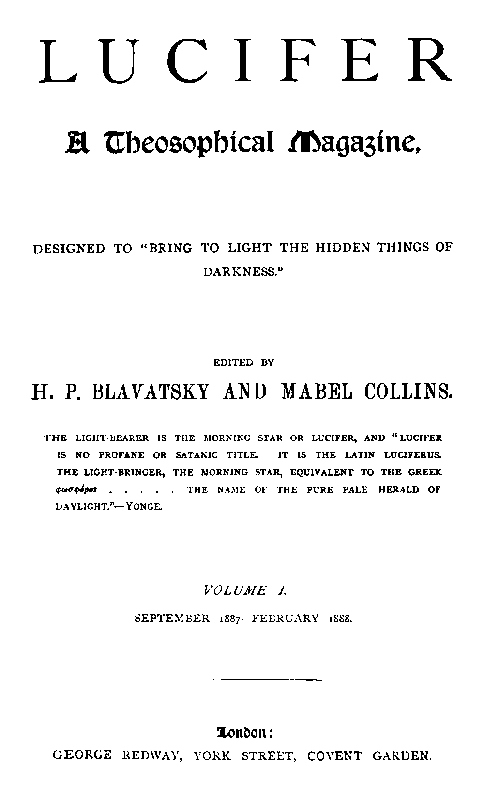

LUCIFER

A Theosophical Magazine,

DESIGNED TO “BRING TO LIGHT THE HIDDEN THINGS OF DARKNESS.”

EDITED BY

H. P. BLAVATSKY AND MABEL COLLINS.

THE LIGHT-BEARER IS THE MORNING STAR OR LUCIFER, AND “LUCIFER

IS NO PROFANE OR SATANIC TITLE. IT IS THE LATIN LUCIFERUS.

THE LIGHT-BRINGER, THE MORNING STAR, EQUIVALENT TO THE GREEK

φωσφορος ... THE NAME OF THE PURE PALE HERALD OF

DAYLIGHT.”—Yonge.

VOLUME I.

SEPTEMBER 1887-FEBRUARY 1888.

London:

GEORGE REDWAY, YORK STREET, COVENT GARDEN.

KELLY & CO., PRINTERS

1 & 3, GATE STREET, LINCOLNS INN FIELDS, LONDON, W.C.

AND MIDDLE MILL, KINGSTON-ON-THAMES.

CONTENTS.

| Astrological Notes |

158, 512 |

| Auto-Hypnotic Rhapsody, An |

472 |

| Birth of Light, The |

52 |

| Blood Covenanting |

216 |

| Blossom and the Fruit, The. The True Story of a Magician |

23, 123, 193, 258, 347, 443 |

| Brotherhood |

212 |

| Buddhism, The Four Noble Truths of |

49 |

| Christian Dogma, Esotericism of the |

368 |

| Christmas Eve, A Remarkable |

274 |

| Correspondence |

76, 136, 228, 311, 412, 502 |

| Emerson and Occultism |

252 |

| Evil, The Origin of |

109 |

| Fear |

298 |

| Freedom |

185 |

| Ghost’s Revenge, A |

63, 102 |

| God Speaks for Law and Order |

292 |

| Gospels, The Esoteric Character of the |

173, 299, 490 |

| Hand, The “Square” in the |

181 |

| Hauntings, A Theory of |

486 |

| Healing, The Spirit of |

267 |

| Hylo-Idealism and “The Adversary” |

507 |

| Infant Genius |

296 |

| Interlaced Triangles, The Relation of Colour to the |

481 |

| Invisible World, The |

186 |

| Lady of Light, The |

81 |

| Lama, The Last of a Good |

51 |

| Law of Life, A: Karma |

39, 97 |

| Let Every Man Prove His Own Work |

161 |

| “Light on the Path,” Comments on |

8, 90, 170, 379 |

| Literary Jottings |

71, 329 |

| Love with an Object |

391 |

| “Lucifer” To the Archbishop of Canterbury Greeting, 241; To the Readers of |

340 |

| Luniolatry |

440 |

| Morning Star, To the |

339 |

| Mystery of all Time, The |

46 |

| Mystic Thought, The |

192 |

| Paradox, The Great |

120 |

| Planet, History of a |

15 |

| Quest, The Great |

288, 375 |

| Reviews |

143, 232, 395, 497 |

| Science of Life, The |

203 |

| Signs of the Times, The |

83 |

| Soldier’s Daughter, The |

432 |

| Some Words on Daily Life |

344 |

| Theosophical and Mystic Publications |

77, 156, 335 |

| Theosophist, A True (Count Tolstoi) |

55 |

| Theosophy, Thoughts on, 134; and Socialism |

282 |

| Three Desires, The 476 |

| Twilight Visions |

365, 461 |

| Unpopular Philosopher, From the Note-Book of an |

80, 160, 238 |

| What is Truth? |

425 |

| What’s in a Name? Why is the Magazine called “Lucifer”? |

1 |

| White Monk, The |

384, 466 |

| 1888 |

337 |

1

LUCIFER

Vol. I. LONDON, SEPTEMBER 15TH, 1887. No. 1.

WHAT’S IN A NAME?

WHY THE MAGAZINE IS CALLED “LUCIFER.”

What’s in a name? Very often there is more in it than the

profane is prepared to understand, or the learned mystic to

explain. It is an invisible, secret, but very potential influence

that every name carries about with it and “leaveth wherever it

goeth.” Carlyle thought that “there is much, nay, almost all, in names.”

“Could I unfold the influence of names, which are the most important

of all clothings, I were a second great Trismegistus,” he writes.

The name or title of a magazine started with a definite object, is,

therefore, all important; for it is, indeed, the invisible seedgrain, which

will either grow “to be an all-over-shadowing tree” on the fruits of

which must depend the nature of the results brought about by the said

object, or the tree will wither and die. These considerations show

that the name of the present magazine—rather equivocal to orthodox

Christian ears—is due to no careless selection, but arose in consequence

of much thinking over its fitness, and was adopted as the best symbol

to express that object and the results in view.

Now, the first and most important, if not the sole object of the

magazine, is expressed in the line from the 1st Epistle to the Corinthians,

on its title page. It is to bring light to “the hidden things of darkness,”

(iv. 5); to show in their true aspect and their original real meaning

things and names, men and their doings and customs; it is finally to

fight prejudice, hypocrisy and shams in every nation, in every class of

Society, as in every department of life. The task is a laborious one

but it is neither impracticable nor useless, if even as an experiment.

Thus, for an attempt of such nature, no better title could ever be

found than the one chosen. “Lucifer,” is the pale morning-star, the

precursor of the full blaze of the noon-day sun—the “Eosphoros” of the

Greeks. It shines timidly at dawn to gather forces and dazzle the eye

after sunset as its own brother ‘Hesperos’—the radiant evening star, or

2the planet Venus. No fitter symbol exists for the proposed work—that

of throwing a ray of truth on everything hidden by the darkness of

prejudice, by social or religious misconceptions; especially by that idiotic

routine in life, which, once that a certain action, a thing, a name, has

been branded by slanderous inventions, however unjust, makes respectable

people, so called, turn away shiveringly, refusing to even look at it from

any other aspect than the one sanctioned by public opinion. Such an

endeavour then, to force the weak-hearted to look truth straight in the

face, is helped most efficaciously by a title belonging to the category of

branded names.

Piously inclined readers may argue that “Lucifer” is accepted by all

the churches as one of the many names of the Devil. According to

Milton’s superb fiction, Lucifer is Satan, the “rebellious” angel, the

enemy of God and man. If one analyzes his rebellion, however, it will

be found of no worse nature than an assertion of free-will and independent

thought, as if Lucifer had been born in the XIXth century. This

epithet of “rebellious,” is a theological calumny, on a par with that other

slander of God by the Predestinarians, one that makes of deity an

“Almighty” fiend worse than the “rebellious” Spirit himself; “an

omnipotent Devil desiring to be ‘complimented’ as all merciful when he

is exerting the most fiendish cruelty,” as put by J. Cotter Morison.

Both the foreordaining and predestining fiend-God, and his subordinate

agent are of human invention; they are two of the most morally repulsive

and horrible theological dogmas that the nightmares of light-hating

monks have ever evolved out of their unclean fancies.

They date from the Mediæval age, the period of mental obscuration,

during which most of the present prejudices and superstitions have been

forcibly inoculated on the human mind, so as to have become nearly

ineradicable in some cases, one of which is the present prejudice now

under discussion.

So deeply rooted, indeed, is this preconception and aversion to the name

of Lucifer—meaning no worse than “light-bringer” (from lux, lucis,

“light,” and ferre “to bring”)[1]—even among the educated classes, that

by adopting it for the title of their magazine the editors have the

prospect of a long strife with public prejudice before them. So absurd

and ridiculous is that prejudice, indeed, that no one has seemed to ever

ask himself the question, how came Satan to be called a light-bringer,

unless the silvery rays of the morning-star can in any way be made

suggestive of the glare of the infernal flames. It is simply, as Henderson

showed, “one of those gross perversions of sacred writ which so extensively

obtain, and which are to be traced to a proneness to seek for more

3in a given passage than it really contains—a disposition to be influenced

by sound rather than sense, and an implicit faith in received interpretation”—which

is not quite one of the weaknesses of our present age.

Nevertheless, the prejudice is there, to the shame of our century.

This cannot be helped. The two editors would hold themselves as

recreants in their own sight, as traitors to the very spirit of the proposed

work, were they to yield and cry craven before the danger. If one

would fight prejudice, and brush off the ugly cobwebs of superstition

and materialism alike from the noblest ideals of our forefathers, one has

to prepare for opposition. “The crown of the reformer and the innovator

is a crown of thorns” indeed. If one would rescue Truth in all her

chaste nudity from the almost bottomless well, into which she has been

hurled by cant and hypocritical propriety, one should not hesitate to

descend into the dark, gaping pit of that well. No matter how badly

the blind bats—the dwellers in darkness, and the haters of light—may

treat in their gloomy abode the intruder, unless one is the first to show

the spirit and courage he preaches to others, he must be justly held as a

hypocrite and a seceder from his own principles.

Hardly had the title been agreed upon, when the first premonitions of

what was in store for us, in the matter of the opposition to be

encountered owing to the title chosen, appeared on our horizon. One

of the editors received and recorded some spicy objections. The scenes

that follow are sketches from nature.

A Well-known Novelist. Tell me about your new magazine. What class do you

propose to appeal to?

Editor. No class in particular: we intend to appeal to the public.

Novelist. I am very glad of that. For once I shall be one of the public, for

I don’t understand your subject in the least, and I want to. But you must remember

that if your public is to understand you, it must necessarily be a very small one.

People talk about occultism nowadays as they talk about many other things, without

the least idea of what it means. We are so ignorant and—so prejudiced.

Editor. Exactly. That is what calls the new magazine into existence. We

propose to educate you, and to tear the mask from every prejudice.

Novelist. That really is good news to me, for I want to be educated. What is

your magazine to be called?

Editor. Lucifer.

Novelist. What! Are you going to educate us in vice? We know enough about

that. Fallen angels are plentiful. You may find popularity, for soiled doves are in

fashion just now, while the white-winged angels are voted a bore, because they are not

so amusing. But I doubt your being able to teach us much.

A Man of the World (in a careful undertone, for the scene is a dinner-party). I

hear you are going to start a magazine, all about occultism. Do you know, I’m very

glad. I don’t say anything about such matters as a rule, but some queer things have

happened in my life which can’t be explained in any ordinary manner. I hope you

will go in for explanations.

4Editor. We shall try, certainly. My impression is, that when occultism is in any

measure apprehended, its laws are accepted by everyone as the only intelligible

explanation of life.

A M. W. Just so, I want to know all about it, for ’pon my honour, life’s a mystery.

There are plenty of other people as curious as myself. This is an age which is afflicted

with the Yankee disease of ‘wanting to know.’ I’ll get you lots of subscribers. What’s

the magazine called?

Editor. Lucifer—and (warned by former experience) don’t misunderstand the

name. It is typical of the divine spirit which sacrificed itself for humanity—it was

Milton’s doing that it ever became associated with the devil. We are sworn enemies

to popular prejudices, and it is quite appropriate that we should attack such a

prejudice as this—Lucifer, you know, is the Morning Star—the Lightbearer,...

A M. W. (interrupting). Oh, I know all that—at least I don’t know, but I take

it for granted you’ve got some good reason for taking such a title. But your first

object is to have readers; you want the public to buy your magazine, I suppose.

That’s in the programme, isn’t it?

Editor. Most decidedly.

A M. W. Well, listen to the advice of a man who knows his way about town.

Don’t mark your magazine with the wrong colour at starting. It’s quite evident, when

one stays an instant to think of its derivation and meaning, that Lucifer is an excellent

word. But the public don’t stay to think of derivations and meanings; and the first

impression is the most important. Nobody will buy the magazine if you call it

Lucifer.

A Fashionable Lady Interested in Occultism. I want to hear some more about the

new magazine, for I have interested a great many people in it, even with the little you

have told me. But I find it difficult to express its actual purpose. What is it?

Editor. To try and give a little light to those that want it.

A F. L. Well, that’s a simple way of putting it, and will be very useful to me.

What is the magazine to be called?

Editor. Lucifer.

A F. L. (After a pause) You can’t mean it.

Editor. Why not?

A F. L. The associations are so dreadful! What can be the object of calling it

that? It sounds like some unfortunate sort of joke, made against it by its enemies.

Editor. Oh, but Lucifer, you know, means Light-bearer; it is typical of the Divine

Spirit——

A F. L. Never mind all that—I want to do your magazine good and make it

known, and you can’t expect me to enter into explanations of that sort every time I

mention the title? Impossible! Life is too short and too busy. Besides, it would

produce such a bad effect; people would think me priggish, and then I couldn’t talk at

all, for I couldn’t bear them to think that. Don’t call it Lucifer—please don’t. Nobody

knows what the word is typical of; what it means now is the devil, nothing more or less.

Editor. But then that is quite a mistake, and one of the first prejudices we propose

to do battle with. Lucifer is the pale, pure herald of dawn——

Lady (interrupting). I thought you were going to do something more interesting

and more important than to whitewash mythological characters. We shall all have to

go to school again, or read up Dr. Smith’s Classical Dictionary. And what is the use

of it when it is done? I thought you were going to tell us things about our own lives

and how to make them better. I suppose Milton wrote about Lucifer, didn’t he?—but

nobody reads Milton now. Do let us have a modern title with some human meaning

in it.

A Journalist (thoughtfully, while rolling his cigarette). Yes, it is a good idea, this

magazine of yours. We shall all laugh at it, as a matter of course: and we shall cut

it up in the papers. But we shall all read it, because secretly everybody hungers after

the mysterious. What are you going to call it?

Editor. Lucifer.

Journalist (striking a light). Why not The Fusee? Quite as good a title and not

so pretentious.

The “Novelist,” the “Man of the World,” the “Fashionable Lady,”

and the “Journalist,” should be the first to receive a little instruction.

A glimpse into the real and primitive character of Lucifer can do them

no harm and may, perchance, cure them of a bit of ridiculous prejudice.

They ought to study their Homer and Hesiod’s Theogony if they would

do justice to Lucifer, “Eosphoros and Hesperos,” the Morning and the

Evening beautiful star. If there are more useful things to do in this

life than “to whitewash mythological characters,” to slander and blacken

them is, at least, as useless, and shows, moreover, a narrow-mindedness

which can do honour to no one.

To object to the title of Lucifer, only because its “associations are

so dreadful,” is pardonable—if it can be pardonable in any case—only

in an ignorant American missionary of some dissenting sect, in one

whose natural laziness and lack of education led him to prefer ploughing

the minds of heathens, as ignorant as he is himself, to the more

profitable, but rather more arduous, process of ploughing the fields of his

own father’s farm. In the English clergy, however, who receive all a

more or less classical education, and are, therefore, supposed to be

acquainted with the ins and outs of theological sophistry and casuistry,

this kind of opposition is absolutely unpardonable. It not only smacks

of hypocrisy and deceit, but places them directly on a lower moral level

than him they call the apostate angel. By endeavouring to show the

theological Lucifer, fallen through the idea that

“To reign is worth ambition, though in Hell;

Better to reign in Hell than serve in Heaven,”

they are virtually putting into practice the supposed crime they would

fain accuse him of. They prefer reigning over the spirit of the masses

by means of a pernicious dark LIE, productive of many an evil, than

serve heaven by serving TRUTH. Such practices are worthy only of the

Jesuits.

But their sacred writ is the first to contradict their interpretations and

the association of Lucifer, the Morning Star, with Satan. Chapter

XXII. of Revelation, verse 16th, says: “I, Jesus ... am the

root ... and the bright and Morning Star” (ὀρθρινὸς “early rising”):

hence Eosphoros, or the Latin Lucifer. The opprobrium attached to

6this name is of such a very late date, that the Roman Church found

itself forced to screen the theological slander behind a two-sided

interpretation—as usual. Christ, we are told, is the “Morning Star,”

the divine Lucifer; and Satan the usurpator of the Verbum, the “infernal

Lucifer.”[2] “The great Archangel Michael, the conqueror of Satan, is

identical in paganism[3] with Mercury-Mithra, to whom, after defending

the Sun (symbolical of God) from the attacks of Venus-Lucifer, was

given the possession of this planet, et datus est ei locus Luciferi.

And since the Archangel Michael is the ‘Angel of the Face,’ and ‘the

Vicar of the Verbum’ he is now considered in the Roman Church as

the regent of that planet Venus which ‘the vanquished fiend had

usurped.’” Angelus faciei Dei sedem superbi humilis obtinuit, says

Cornelius à Lapide (in Vol. VI. p. 229).

This gives the reason why one of the early Popes was called Lucifer,

as Yonge and ecclesiastical records prove. It thus follows that the title

chosen for our magazine is as much associated with divine and pious

ideas as with the supposed rebellion of the hero of Milton’s “Paradise

Lost.” By choosing it, we throw the first ray of light and truth on a

ridiculous prejudice which ought to have no room made for it in this our

“age of facts and discovery.” We work for true Religion and Science,

in the interest of fact as against fiction and prejudice. It is our duty, as

it is that of physical Science—professedly its mission—to throw light on

facts in Nature hitherto surrounded by the darkness of ignorance. And

since ignorance is justly regarded as the chief promoter of superstition,

that work is, therefore, a noble and beneficent work. But natural

Sciences are only one aspect of Science and Truth. Psychological

and moral Sciences, or theosophy, the knowledge of divine truth,

wheresoever found, are still more important in human affairs, and real

Science should not be limited simply to the physical aspect of life and

nature. Science is an abstract of every fact, a comprehension of every

truth within the scope of human research and intelligence. “Shakespeare’s

deep and accurate science in mental philosophy” (Coleridge),

has proved more beneficent to the true philosopher in the study of the

human heart—therefore, in the promotion of truth—than the more

accurate, but certainly less deep, science of any Fellow of the Royal

Institution.

Those readers, however, who do not find themselves convinced that the

Church had no right to throw a slur upon a beautiful star, and that it did

so through a mere necessity of accounting for one of its numerous loans

from Paganism with all its poetical conceptions of the truths in Nature,

are asked to read our article “The History of a Planet.” Perhaps, after

its perusal, they will see how far Dupuis was justified in asserting that

7“all the theologies have their origin in astronomy.” With the modern

Orientalists every myth is solar. This is one more prejudice, and a

preconception in favour of materialism and physical science. It will be

one of our duties to combat it with much of the rest.

Occultism is not magic, though magic is one of its tools.

Occultism is not the acquirement of powers, whether psychic or

intellectual, though both are its servants. Neither is occultism the pursuit

of happiness, as men understand the word; for the first step is

sacrifice, the second, renunciation.

Life is built up by the sacrifice of the individual to the whole. Each

cell in the living body must sacrifice itself to the perfection of the

whole; when it is otherwise, disease and death enforce the lesson.

Occultism is the science of life, the art of living.

8

COMMENTS ON “LIGHT ON THE PATH.”

“Before the eyes can see they must be incapable of tears.”

It should be very clearly remembered by all readers of this volume

that it is a book which may appear to have some little philosophy

in it, but very little sense, to those who believe it to be written in

ordinary English. To the many, who read in this manner it will be—not

caviare so much as olives strong of their salt. Be warned and read

but a little in this way.

There is another way of reading, which is, indeed, the only one of

any use with many authors. It is reading, not between the lines but

within the words. In fact, it is deciphering a profound cipher.

All alchemical works are written in the cipher of which I speak; it has

been used by the great philosophers and poets of all time. It is used

systematically by the adepts in life and knowledge, who, seemingly

giving out their deepest wisdom, hide in the very words which frame

it its actual mystery. They cannot do more. There is a law of nature

which insists that a man shall read these mysteries for himself. By no

other method can he obtain them. A man who desires to live must

eat his food himself: this is the simple law of nature—which applies

also to the higher life. A man who would live and act in it cannot

be fed like a babe with a spoon; he must eat for himself.

I propose to put into new and sometimes plainer language parts of

“Light on the Path”; but whether this effort of mine will really

be any interpretation I cannot say. To a deaf and dumb man, a

truth is made no more intelligible if, in order to make it so, some misguided

linguist translates the words in which it is couched into every

living or dead language, and shouts these different phrases in his

ear. But for those who are not deaf and dumb one language is generally

easier than the rest; and it is to such as these I address myself.

The very first aphorisms of “Light on the Path,” included under

Number I. have, I know well, remained sealed as to their inner meaning

to many who have otherwise followed the purpose of the book.

There are four proven and certain truths with regard to the entrance

to occultism. The Gates of Gold bar that threshold; yet there are some

who pass those gates and discover the sublime and illimitable beyond.

In the far spaces of Time all will pass those gates. But I am one

who wish that Time, the great deluder, were not so over-masterful. To

those who know and love him I have no word to say; but to the

others—and there are not so very few as some may fancy—to whom the

9passage of Time is as the stroke of a sledge-hammer, and the sense of

Space like the bars of an iron cage, I will translate and re-translate

until they understand fully.

The four truths written on the first page of “Light on the Path,” refer

to the trial initiation of the would-be occultist. Until he has passed

it, he cannot even reach to the latch of the gate which admits to knowledge.

Knowledge is man’s greatest inheritance; why, then, should

he not attempt to reach it by every possible road? The laboratory

is not the only ground for experiment; science, we must remember,

is derived from sciens, present participle of scire, “to know,”—its origin

is similar to that of the word “discern,” “to ken.” Science does

not therefore deal only with matter, no, not even its subtlest and

obscurest forms. Such an idea is born merely of the idle spirit of

the age. Science is a word which covers all forms of knowledge.

It is exceedingly interesting to hear what chemists discover, and to see

them finding their way through the densities of matter to its finer

forms; but there are other kinds of knowledge than this, and it is not

every one who restricts his (strictly scientific) desire for knowledge to

experiments which are capable of being tested by the physical senses.

Everyone who is not a dullard, or a man stupefied by some predominant

vice, has guessed, or even perhaps discovered with some

certainty, that there are subtle senses lying within the physical

senses. There is nothing at all extraordinary in this; if we took the

trouble to call Nature into the witness box we should find that everything

which is perceptible to the ordinary sight, has something even

more important than itself hidden within it; the microscope has opened

a world to us, but within those encasements which the microscope

reveals, lies a mystery which no machinery can probe.

The whole world is animated and lit, down to its most material

shapes, by a world within it. This inner world is called Astral by some

people, and it is as good a word as any other, though it merely

means starry; but the stars, as Locke pointed out, are luminous

bodies which give light of themselves. This quality is characteristic

of the life which lies within matter; for those who see it, need no

lamp to see it by. The word star, moreover, is derived from the

Anglo-Saxon “stir-an,” to steer, to stir, to move, and undeniably it is

the inner life which is master of the outer, just as a man’s brain

guides the movements of his lips. So that although Astral is no very

excellent word in itself, I am content to use it for my present purpose.

The whole of “Light on the Path” is written in an astral cipher and

can therefore only be deciphered by one who reads astrally. And its

teaching is chiefly directed towards the cultivation and development

of the astral life. Until the first step has been taken in this development,

the swift knowledge, which is called intuition with certainty, is impossible

to man. And this positive and certain intuition is the only form of

10knowledge which enables a man to work rapidly or reach his true and

high estate, within the limit of his conscious effort. To obtain knowledge

by experiment is too tedious a method for those who aspire to

accomplish real work; he who gets it by certain intuition, lays hands on

its various forms with supreme rapidity, by fierce effort of will; as a

determined workman grasps his tools, indifferent to their weight or

any other difficulty which may stand in his way. He does not stay for

each to be tested—he uses such as he sees are fittest.

All the rules contained in “Light on the Path,” are written for all

disciples, but only for disciples—those who “take knowledge.” To none

else but the student in this school are its laws of any use or interest.

To all who are interested seriously in Occultism, I say first—take

knowledge. To him who hath shall be given. It is useless to wait for it.

The womb of Time will close before you, and in later days you will remain

unborn, without power. I therefore say to those who have any

hunger or thirst for knowledge, attend to these rules.

They are none of my handicraft or invention. They are merely the

phrasing of laws in super-nature, the putting into words truths as absolute

in their own sphere, as those laws which govern the conduct of the earth

and its atmosphere.

The senses spoken of in these four statements are the astral, or inner

senses.

No man desires to see that light which illumines the spaceless soul

until pain and sorrow and despair have driven him away from the life of

ordinary humanity. First he wears out pleasure; then he wears out pain—till,

at last, his eyes become incapable of tears.

This is a truism, although I know perfectly well that it will meet with

a vehement denial from many who are in sympathy with thoughts which

spring from the inner life. To see with the astral sense of sight is a form

of activity which it is difficult for us to understand immediately. The

scientist knows very well what a miracle is achieved by each child that is

born into the world, when it first conquers its eye-sight and compels it

to obey its brain. An equal miracle is performed with each sense

certainly, but this ordering of sight is perhaps the most stupendous effort.

Yet the child does it almost unconsciously, by force of the powerful

heredity of habit. No one now is aware that he has ever done it at all;

just as we cannot recollect the individual movements which enabled us to

walk up a hill a year ago. This arises from the fact that we move and

live and have our being in matter. Our knowledge of it has become

intuitive.

With our astral life it is very much otherwise. For long ages past,

man has paid very little attention to it—so little, that he has practically

lost the use of his senses. It is true, that in every civilization the star

arises, and man confesses, with more or less of folly and confusion, that

he knows himself to be. But most often he denies it, and in being a

11materialist becomes that strange thing, a being which cannot see its own

light, a thing of life which will not live, an astral animal which has eyes,

and ears, and speech, and power, yet will use none of these gifts. This

is the case, and the habit of ignorance has become so confirmed, that

now none will see with the inner vision till agony has made the physical

eyes not only unseeing, but without tears—the moisture of life. To be

incapable of tears is to have faced and conquered the simple human

nature, and to have attained an equilibrium which cannot be shaken by

personal emotions. It does not imply any hardness of heart, or any

indifference. It does not imply the exhaustion of sorrow, when the

suffering soul seems powerless to suffer acutely any longer; it does not

mean the deadness of old age, when emotion is becoming dull because

the strings which vibrate to it are wearing out. None of these conditions

are fit for a disciple, and if any one of them exist in him, it must be

overcome before the path can be entered upon. Hardness of heart

belongs to the selfish man, the egotist, to whom the gate is for ever closed.

Indifference belongs to the fool and the false philosopher; those whose

lukewarmness makes them mere puppets, not strong enough to face the

realities of existence. When pain or sorrow has worn out the keenness

of suffering, the result is a lethargy not unlike that which accompanies

old age, as it is usually experienced by men and women. Such a condition

makes the entrance to the path impossible, because the first step

is one of difficulty and needs a strong man, full of psychic and physical

vigour, to attempt it.

It is a truth, that, as Edgar Allan Poe said, the eyes are the windows

for the soul, the windows of that haunted palace in which it dwells.

This is the very nearest interpretation into ordinary language of

the meaning of the text. If grief, dismay, disappointment or

pleasure, can shake the soul so that it loses its fixed hold on the calm

spirit which inspires it, and the moisture of life breaks forth, drowning

knowledge in sensation, then all is blurred, the windows are darkened,

the light is useless. This is as literal a fact as that if a man, at the edge

of a precipice, loses his nerve through some sudden emotion he will

certainly fall. The poise of the body, the balance, must be preserved,

not only in dangerous places, but even on the level ground, and with

all the assistance Nature gives us by the law of gravitation. So it is

with the soul, it is the link between the outer body and the starry spirit

beyond; the divine spark dwells in the still place where no convulsion

of Nature can shake the air; this is so always. But the soul may lose

its hold on that, its knowledge of it, even though these two are part of

one whole; and it is by emotion, by sensation, that this hold is loosed.

To suffer either pleasure or pain, causes a vivid vibration which is, to

the consciousness of man, life. Now this sensibility does not lessen

when the disciple enters upon his training; it increases. It is the

first test of his strength; he must suffer, must enjoy or endure, more

12keenly than other men, while yet he has taken on him a duty which

does not exist for other men, that of not allowing his suffering to

shake him from his fixed purpose. He has, in fact, at the first step

to take himself steadily in hand and put the bit into his own mouth;

no one else can do it for him.

The first four aphorisms of “Light on the Path,” refer entirely to astral

development. This development must be accomplished to a certain extent—that

is to say it must be fully entered upon—before the remainder

of the book is really intelligible except to the intellect; in fact, before it

can be read as a practical, not a metaphysical treatise.

In one of the great mystic Brotherhoods, there are four ceremonies,

that take place early in the year, which practically illustrate and

elucidate these aphorisms. They are ceremonies in which only novices

take part, for they are simply services of the threshold. But it will

show how serious a thing it is to become a disciple, when it is

understood that these are all ceremonies of sacrifice. The first one

is this of which I have been speaking. The keenest enjoyment, the

bitterest pain, the anguish of loss and despair, are brought to bear on

the trembling soul, which has not yet found light in the darkness,

which is helpless as a blind man is, and until these shocks can be

endured without loss of equilibrium the astral senses must remain

sealed. This is the merciful law. The “medium,” or “spiritualist,”

who rushes into the psychic world without preparation, is a law-breaker,

a breaker of the laws of super-nature. Those who break

Nature’s laws lose their physical health; those who break the laws of

the inner life, lose their psychic health. “Mediums” become mad,

suicides, miserable creatures devoid of moral sense; and often end as

unbelievers, doubters even of that which their own eyes have seen.

The disciple is compelled to become his own master before he

adventures on this perilous path, and attempts to face those beings

who live and work in the astral world, and whom we call masters,

because of their great knowledge and their ability to control not only

themselves but the forces around them.

The condition of the soul when it lives for the life of sensation as

distinguished from that of knowledge, is vibratory or oscillating, as

distinguished from fixed. That is the nearest literal representation of

the fact; but it is only literal to the intellect, not to the intuition.

For this part of man’s consciousness a different vocabulary is needed.

The idea of “fixed” might perhaps be transposed into that of “at

home.” In sensation no permanent home can be found, because change

is the law of this vibratory existence. That fact is the first one which

must be learned by the disciple. It is useless to pause and weep for

a scene in a kaleidoscope which has passed.

It is a very well-known fact, one with which Bulwer Lytton dealt

with great power, that an intolerable sadness is the very first experience

13of the neophyte in Occultism. A sense of blankness falls

upon him which makes the world a waste, and life a vain exertion.

This follows his first serious contemplation of the abstract. In gazing,

or even in attempting to gaze, on the ineffable mystery of his own

higher nature, he himself causes the initial trial to fall on him. The

oscillation between pleasure and pain ceases for—perhaps an instant

of time; but that is enough to have cut him loose from his fast

moorings in the world of sensation. He has experienced, however

briefly, the greater life; and he goes on with ordinary existence

weighted by a sense of unreality, of blank, of horrid negation. This

was the nightmare which visited Bulwer Lytton’s neophyte in

“Zanoni”; and even Zanoni himself, who had learned great truths,

and been entrusted with great powers, had not actually passed the

threshold where fear and hope, despair and joy seem at one moment

absolute realities, at the next mere forms of fancy.

This initial trial is often brought on us by life itself. For life is

after all, the great teacher. We return to study it, after we have

acquired power over it, just as the master in chemistry learns more

in the laboratory than his pupil does. There are persons so near

the door of knowledge that life itself prepares them for it, and no

individual hand has to invoke the hideous guardian of the entrance.

These must naturally be keen and powerful organizations, capable

of the most vivid pleasure; then pain comes and fills its great duty.

The most intense forms of suffering fall on such a nature, till at last

it arouses from its stupor of consciousness, and by the force of its

internal vitality steps over the threshold into a place of peace. Then

the vibration of life loses its power of tyranny. The sensitive nature

must suffer still; but the soul has freed itself and stands aloof, guiding

the life towards its greatness. Those who are the subjects of

Time, and go slowly through all his spaces, live on through a long-drawn

series of sensations, and suffer a constant mingling of pleasure

and of pain. They do not dare to take the snake of self in a steady

grasp and conquer it, so becoming divine; but prefer to go on fretting

through divers experiences, suffering blows from the opposing

forces.

When one of these subjects of Time decides to enter on the path of

Occultism, it is this which is his first task. If life has not taught it

to him, if he is not strong enough to teach himself, and if he has

power enough to demand the help of a master, then this fearful trial,

depicted in Zanoni, is put upon him. The oscillation in which he

lives, is for an instant stilled; and he has to survive the shock of

facing what seems to him at first sight as the abyss of nothingness.

Not till he has learned to dwell in this abyss, and has found its

peace, is it possible for his eyes to have become incapable of tears.

The difficulty of writing intelligibly on these subjects is so great that

14I beg of those who have found any interest in this article, and are yet

left with perplexities and doubts, to address me in the correspondence

column of this magazine. I ask this because thoughtful questions

are as great an assistance to the general reader as the answers to them.

Δ

Harmony is the law of life, discord its shadow, whence springs suffering,

the teacher, the awakener of consciousness.

Through joy and sorrow, pain and pleasure, the soul comes to a

knowledge of itself; then begins the task of learning the laws of life,

that the discords may be resolved, and the harmony be restored.

The eyes of wisdom are like the ocean depths; there is neither joy

nor sorrow in them; therefore the soul of the occultist must become

stronger than joy, and greater than sorrow.

15

THE HISTORY OF A PLANET.

No star, among the countless myriads that twinkle over the sidereal

fields of the night sky, shines so dazzlingly as the planet Venus—not

even Sirius-Sothis, the dog-star, beloved by Isis. Venus

is the queen among our planets, the crown jewel of our solar system.

She is the inspirer of the poet, the guardian and companion of the lonely

shepherd, the lovely morning and the evening star. For,

“Stars teach as well as shine.”

although their secrets are still untold and unrevealed to the majority of

men, including astronomers. They are “a beauty and a mystery,” verily.

But “where there is a mystery, it is generally supposed that there must

also be evil,” says Byron. Evil, therefore, was detected by evilly-disposed

human fancy, even in those bright luminous eyes peeping at our wicked

world through the veil of ether. Thus there came to exist slandered

stars and planets as well as slandered men and women. Too often

are the reputation and fortune of one man or party sacrificed for the

benefit of another man or party. As on earth below, so in the heavens

above, and Venus, the sister planet of our Earth,[4] was sacrificed to the

ambition of our little globe to show the latter the “chosen” planet of the

Lord. She became the scapegoat, the Azaziel of the starry dome, for the

sins of the Earth, or rather for those of a certain class in the human

family—the clergy—who slandered the bright orb, in order to prove

what their ambition suggested to them as the best means to reach

power, and exercise it unswervingly over the superstitious and ignorant

masses.

This took place during the middle ages. And now the sin lies black

at the door of Christians and their scientific inspirers, though the error

was successfully raised to the lofty position of a religious dogma, as

many other fictions and inventions have been.

Indeed, the whole sidereal world, planets and their regents—the

ancient gods of poetical paganism—the sun, the moon, the elements,

and the entire host of incalculable worlds—those at least which happened

to be known to the Church Fathers—shared in the same fate. They

have all been slandered, all bedevilled by the insatiable desire of

proving one little system of theology—built on and constructed out of

16old pagan materials—the only right and holy one, and all those which

preceded or followed it utterly wrong. Sun and stars, the very air

itself, we are asked to believe, became pure and “redeemed” from

original sin and the Satanic element of heathenism, only after the year

I, A.D. Scholastics and scholiasts, the spirit of whom “spurned laborious

investigation and slow induction,” had shown, to the satisfaction of

infallible Church, the whole Kosmos in the power of Satan—a poor

compliment to God—before the year of the Nativity; and Christians

had to believe or be condemned. Never have subtle sophistry and

casuistry shown themselves so plainly in their true light, however, as in

the questions of the ex-Satanism and later redemption of various

heavenly bodies. Poor beautiful Venus got worsted in that war of so-called

divine proofs to a greater degree than any of her sidereal colleagues.

While the history of the other six planets, and their gradual

transformation from Greco-Aryan gods into Semitic devils, and finally

into “divine attributes of the seven eyes of the Lord,” is known but to

the educated, that of Venus-Lucifer has become a household story

among even the most illiterate in Roman Catholic countries.

This story shall now be told for the benefit of those who may have

neglected their astral mythology.

Venus, characterised by Pythagoras as the sol alter, a second Sun, on

account of her magnificent radiance—equalled by none other—was the

first to draw the attention of ancient Theogonists. Before it began to

be called Venus, it was known in pre-Hesiodic theogony as Eosphoros

(or Phosphoros) and Hesperos, the children of the dawn and twilight. In

Hesiod, moreover, the planet is decomposed into two divine beings,

two brothers—Eosphoros (the Lucifer of the Latins) the morning, and

Hesperos, the evening star. They are the children of Astrœos and

Eos, the starry heaven and the dawn, as also of Kephalos and Eos

(Theog: 381, Hyg: Poet: Astron: 11, 42). Preller, quoted by Decharme,

shows Phaeton identical with Phosphoros or Lucifer (Griech: Mythol:

1. 365). And on the authority of Hesiod he also makes Phaeton the son

of the latter two divinities—Kephalos and Eos.

Now Phaeton or Phosphoros, the “luminous morning orb,” is carried

away in his early youth by Aphrodite (Venus) who makes of him the

night guardian of her sanctuary (Theog: 987-991). He is the “beautiful

morning star” (Vide St. John’s Revelation XXII. 16) loved for its radiant

light by the Goddess of the Dawn, Aurora, who, while gradually eclipsing

the light of her beloved, thus seeming to carry off the star, makes it

reappear on the evening horizon where it watches the gates of heaven.

In early morning, Phosphoros “issuing from the waters of the Ocean,

raises in heaven his sacred head to announce the approach of divine

light.” (Iliad, XXIII. 226; Odyss: XIII. 93; Virg: Æneid, VIII. 589;

Mythol: de la Grèce Antique. 247). He holds a torch in his hand and

flies through space as he precedes the car of Aurora. In the evening he

17becomes Hesperos, “the most splendid of the stars that shine on the

celestial vault” (Iliad, XXII. 317). He is the father of the Hesperides,

the guardians of the golden apples together with the Dragon; the

beautiful genius of the flowing golden curls, sung and glorified in all the

ancient epithalami (the bridal songs of the early Christians as of the

pagan Greeks); he, who at the fall of the night, leads the nuptial

cortège and delivers the bride into the arms of the bridegroom. (Carmen

Nuptiale. See Mythol: de la Grèce Antique. Decharme.)

So far, there seems to be no possible rapprochement, no analogy to be

discovered between this poetical personification of a star, a purely

astronomical myth, and the Satanism of Christian theology. True, the

close connection between the planet as Hesperos, the evening star, and

the Greek Garden of Eden with its Dragon and the golden apples may,

with a certain stretch of imagination, suggest some painful comparisons

with the third chapter of Genesis. But this is insufficient to justify the

building of a theological wall of defence against paganism made up of

slander and misrepresentations.

But of all the Greek euhemerisations, Lucifer-Eosphoros is, perhaps,

the most complicated. The planet has become with the Latins, Venus,

or Aphrodite-Anadyomene, the foam-born Goddess, the “Divine Mother,”

and one with the Phœnician Astarte, or the Jewish Astaroth. They

were all called “The Morning Star,” and the Virgins of the Sea, or Mar

(whence Mary), the great Deep, titles now given by the Roman Church

to their Virgin Mary. They were all connected with the moon and the

crescent, with the Dragon and the planet Venus, as the mother of Christ

has been made connected with all these attributes. If the Phœnician

mariners carried, fixed on the prow of their ships, the image of the goddess

Astarte (or Aphrodite, Venus Erycina) and looked upon the evening

and the morning star as their guiding star, “the eye of their Goddess

mother,” so do the Roman Catholic sailors the same to this day. They

fix a Madonna on the prows of their vessels, and the blessed Virgin

Mary is called the “Virgin of the Sea.” The accepted patroness of

Christian sailors, their star, “Stella Del Mar,” etc., she stands on the

crescent moon. Like the old pagan Goddesses, she is the “Queen of

Heaven,” and the “Morning Star” just as they were.

Whether this can explain anything, is left to the reader’s sagacity.

Meanwhile, Lucifer-Venus has nought to do with darkness, and everything

with light. When called Lucifer, it is the “light bringer,” the first

radiant beam which destroys the lethal darkness of night. When named

Venus, the planet-star becomes the symbol of dawn, the chaste Aurora.

Professor Max Müller rightly conjectures that Aphrodite, born of the

sea, is a personification of the Dawn of Day, and the most lovely of all

the sights in Nature (“Science of Language”) for, before her naturalisation

by the Greeks, Aphrodite was Nature personified, the life and light

of the Pagan world, as proven in the beautiful invocation to Venus by

18Lucretius, quoted by Decharme. She is divine Nature in her entirety,

Aditi-Prakriti before she becomes Lakshmi. She is that Nature before

whose majestic and fair face, “the winds fly away, the quieted sky pours

torrents of light, and the sea-waves smile,” (Lucretius). When referred

to as the Syrian goddess Astarte, the Astaroth of Hieropolis, the

radiant planet was personified as a majestic woman, holding in one

outstretched hand a torch, in the other, a crooked staff in the form of

a cross. (Vide Lucian’s De Dea Syriê, and Cicero’s De Nat: Deorum,

3 c.23). Finally, the planet is represented astronomically, as a globe

poised above the cross—a symbol no devil would like to associate with—while

the planet Earth is a globe with a cross over it.

But then, these crosses are not the symbols of Christianity, but the

Egyptian crux ansata, the attribute of Isis (who is Venus, and Aphrodite,

Nature, also) ♀ or ♀ the planet; the fact that the Earth has the crux

ansata reversed, ♁ having a great occult significance upon which there

is no necessity of entering at present.

Now what says the Church and how does it explain the “dreadful

association.” The Church believes in the devil, of course, and could not

afford to lose him. “The Devil is the chief pillar of the Church” confesses

unblushingly an advocate[5] of the Ecclesia Militans. “All the Alexandrian

Gnostics speak to us of the fall of the Æons and their Pleroma, and

all attribute that fall to the desire to know,” writes another volunteer in

the same army, slandering the Gnostics as usual and identifying the

desire to know or occultism, magic, with Satanism.[6] And then, forthwith,

he quotes from Schlegel’s Philosophie de l’Histoire to show that the seven

rectors (planets) of Pymander, “commissioned by God to contain the

phenomenal world in their seven circles, lost in love with their own

beauty,[7] came to admire themselves with such intensity that owing to

this proud self-adulation they finally fell.”

Perversity having thus found its way amongst the angels, the most

beautiful creature of God “revolted against its Maker.” That creature

is in theological fancy Venus-Lucifer, or rather the informing Spirit or

Regent of that planet. This teaching is based on the following speculation.

The three principal heroes of the great sidereal catastrophe

mentioned in Revelation are, according to the testimony of the Church

fathers—“the Verbum, Lucifer his usurper (see editorial) and the grand

Archangel who conquered him,” and whose “palaces” (the “houses”

19astrology calls them) are in the Sun, Venus-Lucifer and Mercury. This is

quite evident, since the position of these orbs in the Solar system correspond

in their hierarchical order to that of the “heroes” in Chapter xii of

Revelation “their names and destinies (?) being closely connected in

the theological (exoteric) system with these three great metaphysical

names.” (De Mirville’s Memoir to the Academy of France, on the

rapping Spirits and the Demons).

The outcome of this was, that theological legend made of Venus-Lucifer

the sphere and domain of the fallen Archangel, or Satan before his

apostacy. Called upon to reconcile this statement with that other fact,

that the metaphor of “the morning star,” is applied to both Jesus, and his

Virgin mother, and that the planet Venus-Lucifer is included, moreover,

among the “stars” of the seven planetary spirits worshipped by the

Roman Catholics[8] under new names, the defenders of the Latin dogmas

and beliefs answer as follows:—

“Lucifer, the jealous neighbour of the Sun (Christ) said to himself in his

great pride: ‘I will rise as high as he!’ He was thwarted in his design

by Mercury, though the brightness of the latter (who is St. Michael) was

as much lost in the blazing fires of the great Solar orb as his own was,

and though, like Lucifer, Mercury is only the assessor, and the guard of

honour to the Sun.”—(Ibid.)

Guards of “dishonour” now rather, if the teachings of theological

Christianity were true. But here comes in the cloven foot of the Jesuit.

The ardent defender of Roman Catholic Demonolatry and of the worship

of the seven planetary spirits, at the same time, pretends great wonder

at the coincidences between old Pagan and Christian legends, between

the fable about Mercury and Venus, and the historical truths told of

St. Michael—the “angel of the face,”—the terrestrial double, or ferouer

of Christ. He points them out saying: “like Mercury, the archangel

Michael, is the friend of the Sun, his Mitra, perhaps, for Michael is a

psychopompic genius, one who leads the separated souls to their appointed

abodes, and like Mitra, he is the well-known adversary of the demons.”

This is demonstrated by the book of the Nabatheans recently discovered

20(by Chwolson), in which the ZoroastrianZoroastrian Mitra is called the “grand enemy

of the planet Venus.”[9] (ibid p. 160.)

There is something in this. A candid confession, for once, of

perfect identity of celestial personages and of borrowing from every pagan

source. It is curious, if unblushing. While in the oldest Mazdean

allegories, Mitra conquers the planet Venus, in Christian tradition

Michael defeats Lucifer, and both receive, as war spoils, the planet of

the vanquished deity.

“Mitra,” says Dollinger, “possessed, in days of old, the star of Mercury,

placed between the sun and the moon, but he was given the planet of

the conquered, and ever since his victory he is identified with Venus.”

(“Judaisme and Paganisme,” Vol. II., p. 109. French transl.)

“In the Christian tradition,” adds the learned Marquis, “St. Michael

is apportioned in Heaven the throne and the palace of the foe he has vanquished.

Moreover, like Mercury, during the palmy days of paganism,

which made sacred to this demon-god all the promontories of the

earth, the Archangel is the patron of the same in our religion.” This

means, if it does mean anything, that now, at any rate, Lucifer-Venus is

a sacred planet, and no synonym of Satan, since St. Michael has become

his legal heir?

The above remarks conclude with this cool reflection:

“It is evident that paganism has utilised beforehand, and most marvellously,

all the features and characteristics of the prince of the face of

the Lord (Michael) in applying them to that Mercury, to the Egyptian

Hermes Anubis, and the Hermes Christos of the Gnostics. Each of these

was represented as the first among the divine councillors, and the

god nearest to the sun, quis ut Deus.”

Which title, with all its attributes, became that of Michael. The

good Fathers, the Master Masons of the temple of Church Christianity,

knew indeed how to utilize pagan material for their new dogmas.

The fact is, that it is sufficient to examine certain Egyptian

cartouches, pointed out by Rossellini (Egypte, Vol. I., p. 289), to find

Mercury (the double of Sirius in our solar system) as Sothis, preceded

by the words “sole” and “solis custode, sostegnon dei dominanti, e

forte grande dei vigilanti,” “watchman of the sun, sustainer of dominions,

and the strongest of all the vigilants.” All these titles and attributes

are now those of the Archangel Michael, who has inherited them from

the demons of paganism.

Moreover, travellers in Rome may testify to the wonderful presence in

the statue of Mitra, at the Vatican, of the best known Christian symbols.

Mystics boast of it. They find “in his lion’s head, and the eagle’s

wings, those of the courageous Seraph, the master of space (Michael);

in his caduceus, the spear, in the two serpents coiled round the body,

21the struggle of the good and bad principles, and especially in the two

keys which the said Mitra holds, like St. Peter, the keys with which this

Seraph-patron of the latter opens and shuts the gates of Heaven,

astra cludit et recludit.” (Mem: p. 162.)

To sum up, the aforesaid shows that the theological romance of

Lucifer was built upon the various myths and allegories of the pagan

world, and that it is no revealed dogma, but simply one invented to

uphold superstition. Mercury being one of the Sun’s assessors, or the

cynocephali of the Egyptians and the watch-dogs of the Sun, literally,

the other was Eosphoros, the most brilliant of the planets, “qui mane

oriebaris,” the early rising, or the Greek ὀρθρινὸς. It was identical

with the Amoon-ra, the light-bearer of Egypt, and called by all

nations “the second born of light” (the first being Mercury), the beginning

of his (the Sun’s) ways of wisdom, the Archangel Michael being

also referred to as the principium viarum Domini.

Thus a purely astronomical personification, built upon an occult

meaning which no one has hitherto seemed to unriddle outside the

Eastern wisdom, has now become a dogma, part and parcel of Christian

revelation. A clumsy transference of characters is unequal to the task

of making thinking people accept in one and the same trinitarian

group, the “Word” or Jesus, God and Michael (with the Virgin occasionally

to complete it) on the one hand, and Mitra, Satan and Apollo-Abbadon

on the other: the whole at the whim and pleasure of Roman

Catholic Scholiasts. If Mercury and Venus (Lucifer) are (astronomically

in their revolution around the Sun) the symbols of God the Father, the

Son, and of their Vicar, Michael, the “Dragon-Conqueror,” in Christian

legend, why should they when called Apollo-Abaddon, the “King of

the Abyss,” Lucifer, Satan, or Venus—become forthwith devils and

demons? If we are told that the “conqueror,” or “Mercury-Sun,” or

again St. Michael of the Revelation, was given the spoils of the

conquered angel, namely, his planet, why should opprobrium be any

longer attached to a constellation so purified? Lucifer is now the

“Angel of the Face of the Lord,”[10] because “that face is mirrored in it.”

We think rather, because the Sun is reflecting his beams in Mercury

seven times more than it does on our Earth, and twice more in Lucifer-Venus:

the Christian symbol proving again its astronomical origin. But

whether from the astronomical, mystical or symbological aspect, Lucifer

is as good as any other planet. To advance as a proof of its demoniacal

character, and identity with Satan, the configuration of Venus, which

gives to the crescent of this planet the appearance of a cut-off horn is

rank nonsense. But to connect this with the horns of “The Mystic

22Dragon” in Revelation—“one of which was broken”[11]—as the two

French Demonologists, the Marquis de Mirville and the Chevalier des

Mousseaux, the champions of the Church militant, would have their

readers believe in the second half of our present century—is simply

an insult to the public.

Besides which, the Devil had no horns before the fourth century of

the Christian era. It is a purely Patristic invention arising from their

desire to connect the god Pan, and the pagan Fauns and Satyrs, with

their Satanic legend. The demons of Heathendom were as hornless

and as tailless as the Archangel Michael himself in the imaginations of

his worshippers. The “horns” were, in pagan symbolism, an emblem

of divine power and creation, and of fertility in nature. Hence the

ram’s horns of Ammon, of Bacchus, and of Moses on ancient medals,

and the cow’s horns of Isis and Diana, etc., etc., and of the Lord God of

the Prophets of Israel himself. For Habakkuk gives the evidence that

this symbolism was accepted by the “chosen people” as much as by the

Gentiles. In Chapter III. that prophet speaks of the “Holy One from

Mount Paran,” of the Lord God who “comes from Teman, and whose

brightness was as the light,” and who had “horns coming out of his

hand.”

When one reads, moreover, the Hebrew text of Isaiah, and finds

that no Lucifer is mentioned at all in Chapter XIV., v. 12, but simply

הֵילֵל, Hillel, “a bright star,” one can hardly refrain from wondering that

educated people should be still ignorant enough at the close of our century

to associate a radiant planet—or anything else in nature for the

matter of that—with the Devil![12]

H. P. B.

23

THE BLOSSOM AND THE FRUIT:

A TALE OF LOVE AND MAGIC.

Author of “The Prettiest Woman in Warsaw,” &c., &c., And Scribe of “The Idyll of the White Lotus,” and “Through the Gates of Gold.”

Only—

One facet of the stone,

One ray of the star,

One petal of the flower of life,

But the one that stands outermost and faces us, who are men and women.

This strange story has come to me from a far country and

was brought to me in a mysterious manner; I claim only to

be the scribe and the editor. In this capacity, however, it is

I who am answerable to the public and the critics. I therefore

ask in advance, one favour only of the reader; that he will

accept (while reading this story) the theory of the reincarnation

of souls as a living fact.

M. C.

INTRODUCTION.

Containing two sad lives on earth,

And two sweet times of sleep in Heaven.

Overhead the boughs of the trees intermingle, hiding the deep blue

sky and mellowing the fierce heat of the sun. The boughs are so

covered with white blossoms that it is like a canopy of clustered

snow-flakes, tinged here and there with a soft pink. It is a natural orchard,

a spot favoured by the wild apricot. And among the trees, wandering

from shine to shade, flitting to and fro, is a solitary figure. It is that of a

young woman, a savage, one of a wild and fierce tribe dwelling in the

fastnesses of an inaccessible virgin forest. She is dark but beautiful.

Her blue-black hair hangs far down over her naked body; its masses

shield the warm, quivering, nervous brown skin from the direct rays

of the sun. She wears neither clothing nor any ornament. Her eyes

are dark, fierce and tender: her mouth soft and natural as the lips of

an opening flower. She is absolutely perfect in her simple savage

beauty and in the natural majesty of her womanhood, virgin in herself

and virgin in the quality of her race, which is untaught, undegraded.

But in her sublimely natural face is the dawn of a great tragedy. Her

24soul, her thought, is struggling to awake. She has done a deed that

seemed to her quite simple, quite natural; yet now it is done a dim

perplexity is rising within her obscure mind. Wandering to and fro

beneath the rich masses of blossom-laden boughs, she for the first time

endeavours to question herself. Finding no answer within she goes

again to look on that which she has done.

A form lies motionless upon the ground within the thickest shade

of the rich fruit trees. A young man, one of her own tribe, beautiful

like herself, and with strength and vigour written in every line of his

form. But he is dead. He was her lover, and she found his love sweet,

yet with one wild treacherous movement of her strong supple arm she

had killed him. The blood flowed from his forehead where the sharp

stone had made the death wound. The life blood ebbed away from his

strong young form; a moment since his lips still trembled, now they

were still. Why had she in this moment of fierce passion taken that

beautiful life? She loved him as well as her untaught heart knew how

to love; but he, exulting in his greater strength, tried to snatch her

love before it was ripe. It was but a blossom, like the white flowers

overhead: he would have taken it with strong hands as though it were a

fruit ripe and ready. And then in a sudden flame of wondrous new

emotion the woman became aware that the man was her enemy, that

he desired to be her tyrant. Until now she had thought him as herself,

a thing to love as she loved herself, with a blind unthinking trust.

And she acted passionately upon the guidance of this thing—feeling—which

until now she had never known. He, unaccustomed to any

treachery or anger, suspected no strange act from her, and thus, unsuspicious,

unwarned, he was at her mercy. And now he lay dead at

her feet. And still the fierce sun shone through the green leaves and

silvern blossoms and gleamed upon her black hair and tender brown

skin. She was beautiful as the morning when it rose over the tree tops

of that world-old forest. But there is a new wonder in her dark eyes;

a question that was not there until this strange and potent hour came

to her. What ages must pass over her dull spirit ere it can utter the

question; ere it can listen and hear the answer?

The savage woman, nameless, unknown save of her tribe, who regard

her as indifferently as any creature of the woods, has none to help her

or stay in its commencement the great roll of the wave of energy she

has started. Blindly she lives out her own emotions. She is dissatisfied,

uneasy, conscious of some error. When she leaves the orchard of wild

fruit trees and wanders back to the clearer part of the forest beneath the

great trees, where her tribe dwells, when she returns among them her lips

are dumb, her voice is silent. None ever heard that he, the one she

loved, had died by her hand, for she knew not how to frame or tell this

story. It was a mystery to her, this thing which had happened. Yet it

made her sad, and her great eyes wore a dumb look of longing. But

25she was very beautiful and soon another young and sturdy lover was

always at her side. He did not please her; there was not the glow in

his eyes that had gladdened her in those of the dead one whom she

had loved. And yet she shrunk not from him nor did she raise her arm

in anger, but held it fast at her side lest her passion should break loose

unawares. For she felt that she had brought a want, a despair upon

herself by her former deed; and now she determined that she would act

differently. Blindly she tried to learn the lesson that had come upon her.

Blindly she let herself be the agent of her own will. For now she

became the willing slave and serf of one whom she did not love, and

whose passion for her was full of tyranny. Yet she did not, she dared

not, resist this tyranny; not because she feared him, but because she

feared herself. She had the feeling that one might have who had come

in contact with a new and hitherto unknown natural force. She feared

lest resistance or independence should bring upon her a greater wonder,

a greater sadness and loss than that which she had already brought

upon herself.

And so she submitted to that which in her first youth would no more

have been endured by her than the bit by the wild horse.

The apricot blossom has fallen and fruit has followed it; the leaves

have fallen and the trees are bare. The sky is grey and wild above, the

ground dank and soft with fallen leaves below. The aspect of the

place is changed, but it is the same; the face and form of the woman

have changed; but she is the same. She is alone again in the wild

orchard, finding her way by instinct to the spot where her first lover

died. She has found it. What is there? Some white bones that lie

together; a skeleton. The woman’s eyes fasten and feed on the sight

and grow large and terrible. Horror at last is struck into her soul.

This is all that is left of her young love, who died by her hand—white

bones that lie in ghastly order! And the long hot days and sultry

nights of her life have been given to a tyrant who has reaped no gladness

and no satisfaction from her submission; for he has not learned yet

even the difference between woman and woman. All alike are mere

creatures like the wild things; creatures to hunt and to conquer.

Dumbly in her dark heart strange questionings arise. She turns from

this graveyard of her unquestioning time and goes back to her slavery.

Through the years of her life she waits and wonders, looking blankly

at the life around her. Will no answer come to her soul?

Splendid was the veil that shielded her from that other soul, the soul

she knew and of which she showed her recognition by swift and sudden

love. But the veil separated them; a veil heavy with gold and

shining with stars of silver. And as she gazed upon these stars, with

26delighted admiration of their brilliance, they grew larger and larger, till

at length they blended together, and the veil became one shining sheen

gorgeous with golden broideries. Then it became easier to see through

the veil, or rather it seemed easier to these lovers. For before the veil

had made the shape appear dim; now it appeared glorious and ideally

beautiful and strong. Then the woman put out her hand, hoping to

obtain the pressure of another hand through the shining gossamer.

And at the same instant he too put out his hand, for in this moment

their souls communicated, and they understood each other. Their

hands touched; the veil was broken; the moment of joy was ended

and again the struggle began.

Sitting, singing, on the steps of an old palace, her feet paddling in

the water of a broad canal, was a child who was becoming more than a

child; a creature on the threshold of life, of awakening sensation.

A girl, with ruddy gold hair, and innocent blue eyes, that had in their

vivid depths the strange startled look of a wild creature. She was as

simple and isolated in her happiness as any animal of the woods or

hills—the sunshine, the sweet air with the faint savour of salt in it, her

own pure clear girlish voice, and the gay songs of the people that she

sang—these were pleasure enough and to spare for her.

But the space of unconscious happiness or unhappiness which

heralds the real events of a life was already at an end. The great wave

which she had set in motion was increasing in volume ceaselessly; how

long before it shall reach the shore and break upon that far off coast?

None can know, save those whose eyesight is more than man’s. None

can tell; and she is ignorant, unknowing. But though she knows

nothing of it, she is within the sweep of the wave, and is powerless

to arrest it until her soul shall awake.

“My blossom, my beautiful wild flower,” said a voice close beside her.

A young boatman had brought his small vessel so gently to the steps

she had not noticed his approach. He leaned over his boat towards

her, and touched her bare white feet with his hand.

“Come away with me, Wild Blossom,” he said. “Leave that

wretched home you cling to. What is there to keep you there now

your mother is dead? Your father is like a savage, and makes you live

like a savage too. Come away with me, and we will live among people

who will love you and find you beautiful as I do. Will you come?

How often have I asked you, Wild Blossom, and you have never

answered. Will you answer now?”

“Yes,” said the girl, looking up with grave, serious eyes, that had

beneath their beauty a melancholy meaning, a sad question.

27The man saw this strange look and interpreted it as clearly as he

could.

“Trust me,” he said, “I am not a savage like your father. When you

are my little wife I will care for you far more dearly than myself.

You will be my soul, my guide, my star. And I will shield you as

my soul is shielded within my body, follow you as my guide, look up

to you as to a star in the blue heavens. Surely you can trust my love,

Wild Blossom.”

He had not answered the doubt in her heart, for he had not guessed

what it was, nor could she have told him. For she had not yet learned

to know what it was, nor to know of it more than that it troubled her.

But she put it aside and silenced it now, for the moment had come to

do so. Not till she had learned her lesson much more fully could the

question ever be expressed even to her own soul, and before this could

be, the question must be silenced many times.

“Yes,” she said, “I will come.”

She held out her hand to him as if to seal the compact. He

interpreted the gesture by his own desire, and taking her hand in his

drew her towards him. She yielded and stepped into the boat. And

then he quickly pushed away from the steps, and, dipping his oars in

the water, soon had gone far away down the canal. Blossom looking

earnestly back, watched the old palace disappear. In some of its old

rooms and on its sunny steps her child-life had been spent. Now she

knew that was at an end. She understood that all was changed henceforth,

though she could not guess into what she was going, and she

waited for her future with a strange confidence in the companion she

had accepted. This puzzled her dimly. Yet how should she lack

confidence, having known him long ago and thrown away his love and

his life beneath the wild apricot trees, having seen afterwards the

steadfastness of his love when her soul stood beside his in soul life?

A long way they went in the little boat. They left the canals and

went out upon the open sea, and still the boatman rowed unwearyingly,

his eyes all the while upon the beautiful wild blossom he had plucked

and carried away with him to be his own, his dear and adored possession.

Far away along the coast lay a small village of fishermen’s cots.

It was to this that the young man guided his boat, for it was here

he dwelled.

At the door of his cot stood his old mother, a quaint old woman