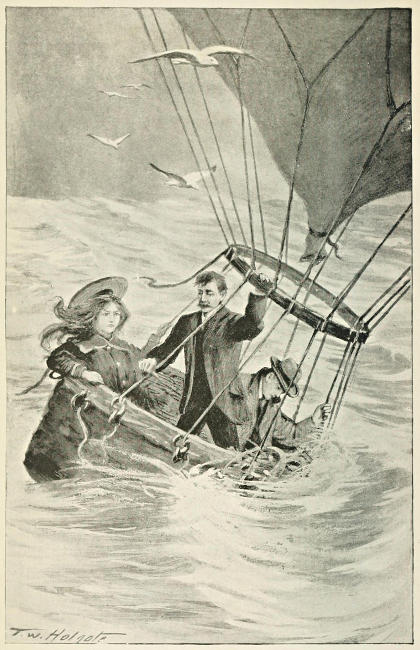

A Terrible Danger.

Title: Pride and His Prisoners

Author: A. L. O. E.

Illustrator: T. W. Holgate

Release date: August 21, 2019 [eBook #60149]

Most recently updated: October 17, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Richard Hulse and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

PRIDE AND HIS PRISONERS

Pride and his

prisoners BY

A. L. O. E.

LONDON, EDINBURGH,

AND NEW YORK

THOMAS NELSON

AND SONS

| I. | The Haunted Dwelling | 5 |

| II. | Resisted, yet Returning | 16 |

| III. | Snares | 26 |

| IV. | A Glance into the Cottage | 33 |

| V. | Both Sides | 43 |

| VI. | The Visit to the Hall | 51 |

| VII. | A Misadventure | 60 |

| VIII. | A Brother’s Effort | 75 |

| IX. | Disappointment | 88 |

| X. | On the Watch | 96 |

| XI. | The Quarrel | 102 |

| XII. | The Unexpected Guest | 111 |

| XIII. | The Friend’s Mission | 119 |

| XIV. | A Fatal Step | 128 |

| XV. | The Deserted Home | 140 |

| XVI. | Pleading | 147 |

| XVII. | Conscience Asleep | 157 |

| [2]XVIII. | The Magazine | 162 |

| XIX. | Expectation | 170 |

| XX. | A Sunny Morn | 178 |

| XXI. | The Ascent | 187 |

| XXII. | In the Clouds | 193 |

| XXIII. | Regrets | 201 |

| XXIV. | Soaring above Pride | 208 |

| XXV. | A Broken Chain | 217 |

| XXVI. | The Awful Crisis | 222 |

| XXVII. | Tidings | 234 |

| XXVIII. | The Wheel Turns | 242 |

| XXIX. | Two Words | 252 |

| XXX. | The Spirit Laid | 263 |

| A Terrible Danger | Frontispiece |

| Her greeting to Dr. and Miss Bardon was most gracious and cordial | 57 |

| Tearing the Manuscript | 107 |

| An Unwelcome Surprise | 168 |

Bright and joyous was the aspect of nature on a spring morning in the beautiful county of Somersetshire. The budding green on the trees was yet so light, that, like a transparent veil, it showed the outlines of every twig; but on the lowlier hedges it lay like a rich mantle of foliage, and clusters of primroses nestled below, while the air was perfumed with violets. Already was heard the hum of some adventurous bee in search of early sweets, the distant low of cattle from the pasture, the mellow note of the[6] cuckoo from the grove,—every sight and sound told of enjoyment on that sunny Sabbath morn.

Yet let me make an exception. There was one spot which reserved to itself the unenviable privilege of looking gloomy all the year round. Nettleby Tower, a venerable edifice, stood on the highest summit of a hill, like some stern guardian of the fair country that smiled around it. The tower had been raised in the time of the Normans, and had then been the robber-hold of a succession of fierce barons, who, from their strong position, had defied the power of king or law. The iron age had passed away. The moat had been dried, and the useless portcullis had rusted over the gate. The loop-holes, whence archers had pointed their shafts, were half filled up with the rubbish accumulated by time. Lichens had mantled the grey stone till its original hue was almost undistinguishable; silent and deserted was the courtyard which had so often echoed to the clatter of hoofs, or the ringing clank of armour.

Silent and deserted—yes! It was not time alone that had wrought the desolation. Nettleby Tower had stood a siege in the time of the Commonwealth, and the marks of bullets might still be traced on its walls; but the injuries which had been inflicted by the slow march of centuries, or the more rapid visitation of war, were slight compared to those which had been wrought by litigation and family dissension. The property had been for years the subject of a [7]vexatious lawsuit, which had half ruined the unsuccessful party, and the present owner of Nettleby Tower had not cared to take personal possession of the gloomy pile. Perhaps Mr. Auger knew that the feeling of the neighbourhood would be against him, as the sympathies of all would be enlisted on the side of the descendant of that ancient family which had for centuries dwelt in the Tower, who had been deprived of his birthright by the will of a proud and intemperate father.

The old fortress had thus been suffered to fall into decay. Grass grew in the courtyard; the wallflower clung to the battlements; the winter snow and the summer rain made their way through the broken casements, and no hand had removed the mass of wreck which lay where a furious storm had thrown down one of the ancient chimneys. Parties of tourists occasionally visited the gloomy place, trod the long, dreary corridors, and heard from a wrinkled woman accounts of the moth-eaten tapestry, and the time-darkened family portraits that grimly frowned from the walls. They heard tales of the last Mr. Bardon, the proud owner of the pile; how he had been wont to sit long and late over his bottle, carousing with jovial companions, till the hall resounded with their oaths and their songs; and how, more than thirty years back, he had disinherited his only son for marrying a farmer’s daughter. Then the old woman would, after slowly showing the way up the worn[8] stone steps which led round and round till they opened on the summit of the tower, direct her listener’s attention to a small grey speck in the wide-spreading landscape below, and tell them that Dr. Bardon lived there in needy circumstances, in actual sight of the place where, if every man had his right, he would now be dwelling as his fathers had dwelt. And the visitors would sigh, shake their heads, and moralize on the strange changes in human fortunes.

The old woman who showed strangers over Nettleby Tower lived in a cottage hard by; neither she nor any other person was ever to be found in the old halls after the sun had set. The place had the repute of being haunted, and was left after dark to the sole possession of the rooks, the owls, and the bats. I must tax the faith of my readers to believe that the old tower was actually haunted; not by the ghosts of the dead, but by the spirits of evil that are ever moving amongst the living. I must attempt with a bold hand to draw aside the mysterious veil which divides the invisible from the visible world, and though I must invoke imagination to my aid, it is imagination fluttering on the confines of truth. Bear with me, then, while I personify the spirits of Pride and Intemperance, and represent them as lingering yet in the pile in which for centuries they had borne sway over human hearts.

Standing on the battlements of the grey tower, behold two dim, but gigantic forms, like dark clouds,[9] that to the eye of fancy have assumed a mortal shape. The little rock-plant that has found a cradle between the crumbling stones bends not beneath their weight,—and yet how many deep-rooted hopes have they crushed! Their unsubstantial shapes cast no shadow on the wall, and yet have darkened myriads of homes! The natural sense cannot recognise their presence; the eye beholds them not, the human ear cannot catch the low thunder of their speech; and yet there they stand, terrible realities,—known, like the invisible plague, by their effects upon those whom they destroy!

There is a wild light in the eyes of Intemperance, not caught from the glad sunbeams that are bathing the world in glory; it is like a red meteor playing over some deep morass, and though there is often mirth in his tone, it is such mirth as jars upon the shuddering soul like the laugh of a raving maniac! Pride is of more lofty stature than his companion, perhaps of yet darker hue, and his voice is lower and deeper. His features are stamped with the impress of all that piety abhors and conscience shrinks from, for we behold him without his veil. Human infirmity may devise soft names for cherished sins, and even invest them with a specious glory which deceives the dazzled eye; but who could endure to see in all their bare deformity those two arch soul-destroyers, Intemperance and Pride?

“Nay, it was I who wrought this ruin!” exclaimed[10] the former, stretching his shadowy hand over the desolated dwelling. “Think you that had Hugh Bardon possessed his senses unclouded by my spell, he would ever have driven forth from his home his own—his only son?”

“Was it not I,” replied Pride, “who ever stood beside him, counting up the long line of his ancestry, inflaming his soul with legends of the past, making him look upon his own blood as something different from that which flows in the veins of ordinary mortals, till he learned to regard a union with one of lower rank as a crime beyond forgiveness?”

“I,” cried Intemperance, “intoxicated his brain”—

“I,” interrupted Pride, “intoxicated his spirit. You fill your deep cup with fermented beverage; the fermentation which I cause is within the soul, and it varies according to the different natures that receive it. There is the vinous fermentation, that which man calls high spirit, and the world hails with applause, whether it sparkle up into courage, or effervesce into hasty resentment. There is the acid fermentation; the sourness of a spirit brooding over wrongs and disappointments, irritated against its fellow-man, and regarding his acts with suspicion. This the world views with a kind of compassionate scorn, or perhaps tolerates as something that may occasionally correct the insipidity of social intercourse. And there is the third, the last stage of fermentation, when hating and hated of all, wrapt up in[11] his own self-worship, and poisoning the atmosphere around with the exhalations of rebellion and unbelief, my slave becomes, even to his fellow-bondsmen, an object of aversion and disgust. Such was my power over the spirit of Hugh Bardon. I quenched the parent’s yearning over his son; I kept watch even by his bed of death; and when holy words of warning were spoken, I made him turn a deaf ear to the charmer, and hardened his soul to destruction!”

“I yield this point to you,” said Intemperance, “I grant that your black badge was rivetted on the miserable Bardon even more firmly than mine. And yet, what are your scattered conquests to those which I hourly achieve! Do I not drive my thousands and tens of thousands down the steep descent of folly, misery, disgrace, till they perish in the gulf of ruin? Count the gin-palaces dedicated to me in this professedly Christian land; are they not crowded with my victims? Who can boast a power to injure that is to be compared to mine?”

“Your power is great,” replied Pride, “but it is a power that has limits, nay, limits that become narrower and narrower as civilization and religion gain ground. You have been driven from many a stately abode, where once Intemperance was a welcome guest, and have to cower amongst the lowest of the low, and seek your slaves amongst the vilest of the vile. Seest thou yon church,” continued Pride, pointing to the spire of a small, but beautiful edifice, embowered[12] amongst elms and beeches; “hast thou ever dared so much as to touch one clod of the turf on which falls the shadow of that building?”

“It is, as you well know, forbidden ground,” replied Intemperance.

“To you—to you, but not to me!” exclaimed Pride, his form dilating with exultation. “I enter it unseen with the worshippers, my voice blends with the hymn of praise; nay, I sometimes mount the pulpit with the preacher,[1] and while a rapt audience hang upon his words, infuse my secret poison into his soul! When offerings are collected for the poor, how much of the silver and the gold is tarnished and tainted by my breath! The very monuments raised to the dead often bear the print of my touch; I fix the escutcheon, write the false epitaph, and hang my banner boldly even over the Christian’s tomb!”

“Your power also has limits,” quoth Intemperance. “There is an antidote in the inspired Book for every poison that you can instil.”

“I know it, I know it,” exclaimed Pride, “and marks it not the extent of my influence and the depth of the deceptions that I practise, that against no spirit, except that of Idolatry, are so many warnings given in that Book as against the spirit of Pride? For every denunciation against Intemperance, how[13] many may be found against me! Not only religion and morality are your mortal opponents, but self-interest and self-respect unite to weaken the might of Intemperance; I have but one foe that I fear, one that singles me out for conflict! As David with his sling to Goliath, so to Pride is the Spirit of the Gospel!”

“How is it, then,” inquired Intemperance, “that so many believers in the Gospel fall under your sway?”

“It is because I have so many arts, such subtle devices, I can change myself into so many different shapes; I steal in so softly that I waken not the sentinel Conscience to give an alarm to the soul! You throw one broad net into the sea where you see a shoal within your reach; I angle for my prey with skill, hiding my hook with the bait most suited to the taste of each of my victims. You pursue your quarry openly before man; I dig the deep hidden pit-fall for mine. You disgust even those whom you enslave; I assume forms that rather please than offend. Sometimes I am ‘a pardonable weakness,’ sometimes ‘a natural instinct,’ sometimes,” and here Pride curled his lip with a mocking smile, “I am welcomed as a generous virtue!”

“It is in this shape,” said Intemperance angrily, “that you have sometimes even taken a part against me! You have taught my slaves to despise and break from my yoke!”

“Pass over that,” replied Pride; “or balance against[14] it the many times when I have done you a service, encouraging men to be mighty to mingle strong drink.”

“Nay, you must acknowledge,” said Intemperance, “that we now seldom work together.”

“We have different spheres,” answered Pride. “You keep multitudes from ever even attempting to enter the fold; I put my manacles upon tens of thousands who deem that they already have entered. I doubt whether there be one goodly dwelling amongst all those that dot yonder wide prospect, where one, if not all of the inmates, wears not my invisible band round the arm.”

“You will except the pastor’s, at least,” said Intemperance. “Yonder, on the path that leads to the school, I see his gentle daughter. She has warned many against me; and with her words, her persuasions, her prayers, has driven me from more than one home. I shrink from the glance of that soft, dark eye, as if it carried the power of Ithuriel’s spear. Ida seems to me to be purity itself; upon her, at least, you can have no hold.”

“Were we nearer,” laughed the malignant spirit, “you would see my dark badge on the saint! Since her childhood I have been striving and struggling to make Ida Aumerle my own. Sometimes she has snapped my chain, and I am ofttimes in fear that she will break away from my bondage for ever. But methinks I have a firm hold over her now.”

“Her pride must be spiritual pride,” observed Intemperance.

“Not so,” replied his evil companion; “I tried that spell, but my efforts failed. While with sweet voice and winning persuasion Ida is now guiding her class to Truth, and warning her little flock against us both, would you wish to hearken to the story of the maiden, and hear all that I have done to win entrance into a heart which the grace of God has cleansed?”

“Tell me her history,” said Intemperance; “she seems to me like the snowdrop that lifts its head above the sod, pure as a flake from the skies.”

“Even the snowdrop has its roots in the earth,” was the sardonic answer of Pride.

[1] “What a beautiful sermon you gave us to-day!” exclaimed a lady to her pastor. “The devil told me the very same thing while I was in the pulpit,” was his quaint, but comprehensive reply.

“Ida Aumerle,” began the dark narrator, “at the age of twelve had the misfortune to lose her mother, and was left, with a sister several years younger than herself, to the sole care of a tender and indulgent father. Ever on the watch to strengthen my interests amongst the children of men, I sounded the dispositions of the sisters, to know what chance I possessed of making them prisoners of Pride. Mabel, clever, impulsive, fearless in character, with a mind ready to receive every impression, and a spirit full of energy and emulation, I knew to be one who was likely readily to come under the power of my spell. Ida was less easily won; she was a more thoughtful, contemplative girl, her temper was less quick, he[17] passions were less easily roused, and I long doubted where lay the weak point of character on which Pride might successfully work.

“As Ida grew towards womanhood my doubts were gradually dispelled. I marked that the fair maiden loved to linger opposite the mirror which reflected her tall, slight, graceful form, and that the gazelle eyes rested upon it with secret satisfaction. There was much time given to braiding the hair and adorning the person; and the fashion of a dress, the tint of a ribbon, became a subject for grave consideration. There are thousands of girls enslaved by the pride of beauty with far less cause than Ida Aumerle.”

“But this folly,” observed Intemperance, “was likely to give you but temporary power. Beauty is merely skin-deep, and passes away like a flower!”

“But often leaves the pride of it behind,” replied his companion. “There is many a wrinkled woman who can never forget that she once was fair,—nay, who seems fondly to imagine that she can never cease to be fair; and who makes herself the laughing-stock of the world by assuming in age the attire and graces of youth. It will never be thus with Ida Aumerle.

“I thought that my chain was firmly fixed upon her, when one evening I found it suddenly torn from her wrist, and trampled beneath her feet! The household at the Vicarage had retired to rest; Ida[18] had received her father’s nightly blessing, and was sitting alone in her own little room. The lamp-light fell upon a form and face that might have been thought to excuse some pride, but Ida’s reflections at that moment had nothing in common with me. She was bending eagerly over that Book which condemns, and would destroy me,—a book which she had ofttimes perused before, but never with the earnest devotion which was then swelling her heart. Her hands were clasped, her dark eyes swimming in joyful tears, and her lips sometimes moved in prayer,—not cold, formal prayer, such as I myself might prompt, but the outpouring of a spirit overflowing with grateful love. That was the birthday of a soul! I stood gloomily apart; I dared not approach one first conscious of her immortal destiny, first communing in spirit with her God!”

“You gave up your designs, then, in despair?”

“You would have done so,” answered Pride with haughtiness; “I do not despair, I only delay. I found that pride of beauty had indeed given way to a nobler, more exalting feeling. Ida had drunk at the fountain of purity, and the petty rill of personal vanity had become to her insipid and distasteful. She was putting away the childish things which amuse the frivolous soul. Ida’s time was now too well filled up with a succession of pious and charitable occupations, to leave a superfluous share to the toilette. The maiden’s dress became simple, because[19] the luxury which she now esteemed was that of assisting the needy. Many of her trinkets were laid aside, not because she deemed it a sin to wear them, but because her mind was engrossed by higher things. One whose first object and desire is to please a heavenly Master by performing angels’ offices below, is hardly likely to dwell much on the consideration that her face and her figure are comely.”

“Ida is, I know, reckoned a model of every feminine virtue,” said Intemperance. “I can conceive that your grand design was now to make her think herself as perfect as all the rest of the world thought her.”

“Ay, ay; to involve her in spiritual pride! But the maiden was too much on her knees, examined her own heart too closely, tried herself by too lofty a standard for that. When the faintest shadow of that temptation fell upon her, she started as though she had seen the viper lurking under the flowers, and cast it from her with abhorrence! ‘A sinner, a weak, helpless sinner, saved only by the mercy, trusting only in the strength of a higher power;’ this Ida Aumerle not only calls herself, but actually feels herself to be. The power of Grace in her heart is too strong on that point for Pride.”

“And yet you hope to subject her to your sway?

“About two years after the night which I have mentioned,” resumed Pride, “after Ida had attained the age of eighteen, she resided for some time at[20] Aspendale, the home of her uncle, Augustine Aumerle.”

“One of your prisoners?” inquired Intemperance.

“Of him anon,” replied the dark one, “our present subject is his niece. At his dwelling Ida met with one who had been Augustine’s college companion, Reginald, Earl of Dashleigh. You can just discern the towers of his mansion faint in the blue distance yonder.”

“I know it,” replied Intemperance; “I frequented the place in his grandfather’s time. The present earl, as I understand, is your votary rather than mine.”

“Puffed up with pride of rank,” said the stern spirit; “but pride of rank could not withstand a stronger passion, or prevent him from laying his fortune and title at the feet of Ida Aumerle.”

“An opportunity for you!” suggested Intemperance.

“A golden opportunity I deemed it. What woman is not dazzled by a coronet? what girl is insensible to the flattering attentions of him who owns one, even if he possess no other recommendation, which, with Dashleigh, is far from being the case? There was a struggle in the mind of Ida. I whispered to her of all those gilded baubles for which numbers have eagerly bartered happiness here, and forfeited happiness hereafter. I set before her grand images of earthly greatness, the pomp and trappings[21] of state, the homage paid by the world to station. I strove to inflame her mind with ambition. But here Ida sought counsel of the All-wise, and she saw through my glittering snare. The earl, though of character unblemished in the eyes of man, and far from indifferent to religion, is not one whom a heaven-bound pilgrim like Ida would choose as a companion for life. Dashleigh’s spirit is too much clogged with earth; he is too much divided in his service; he wears too openly my chain, as if he deemed it an ornament or distinction. Ida prayed, reflected, and then resolved. She declined the addresses of her uncle’s guest, and returned home at once to her father.”

“The wound which she inflicted was not a deep one,” remarked Intemperance. “Dashleigh was speedily consoled, without even seeking comfort from me.”

“I poisoned his wound,” exclaimed Pride, “and drove him to seek instant cure. Dashleigh’s rejection aroused in his breast as much indignation as grief; and I made the disappointed and irritated man at once offer his hand to one who was not likely to decline it, Annabella, the young cousin of Ida.”

“And what said the high-souled Ida to the sudden change in the object of his devotion?”

“I breathed in her ear,” answered Pride, “the suggestion, ‘He might have waited a little longer.’ I called up a flush to the maiden’s cheek when she[22] received tidings of the hasty engagement. But still I met with little but repulse. With maidenly reserve Ida concealed even from her own family a secret which pride might have led her to reveal, and none more affectionately congratulated the young countess on her engagement, than she who might have worn the honours which now devolved upon another.”

“Ida Aumerle appears to be gifted with such a power of resisting your influence and repelling your temptations, that I can scarcely imagine,” quoth Intemperance, “upon what you can ground your assurance that you hold her captive at length. Pride of beauty, pride of conquest, pride of ambition, she has subdued; to spiritual pride she never has yielded. What dart remains in your quiver when so many have swerved from the mark?”

“Or rather, have fallen blunted from the shield of faith,” gloomily interrupted Pride. “Ida’s real danger began when she thought the dart too feeble to render it needful to lift the shield against it. Ida, on her return home, found her father on the point of contracting a second marriage with a lady who had been one of his principal assistants in arranging and keeping in order the machinery of his parish. Miss Lambert, by her activity and energy, seemed a most fitting help-meet for a pastor. She was Aumerle’s equal in fortune and birth, and not many years his junior in age. She had been always[23] on good terms with his family, and the connection appeared one of the most suitable that under the circumstances could have been formed. And so it might have proved,” continued Pride, “but for me!”

“Is Mrs. Aumerle, then, under your control?”

“She is somewhat proud of her good management, of her clear common sense, of her knowledge of the world,” was the dark one’s reply; “and this is one cause of the coldness between her and the daughters of her husband. Ida, from childhood, had been accustomed to govern her own actions and direct her own pursuits. Steady and persevering in character, she had not only pursued a course of education by herself, but had superintended that of her more impetuous sister. Since her mother’s death Ida had been subject to no sensible control, for her father looked upon her as perfection, and left her a degree of freedom which to most girls might have been highly dangerous. Thus her spirit had become more independent, and her opinions more formed than is usual in those of her age. On her father’s marriage Ida found herself dethroned from the position which she so long had held. She was second where she had been first,—second in the house, second in the parish, second in the affections of a parent whom she almost idolatrously loved. I saw that the moment had come for inflicting a pang; you will believe that the opportunity was not trifled[24] away! Ida had been accustomed to lead rather than to follow. She exercised almost boundless influence over her sister Mabel, and was regarded as an oracle by the poor. Another was now taking her place, and another whose views on many subjects materially differed from her own, who saw various duties in a different light, and whose character disposed her to act in petty matters the part of a zealous reformer. I marked Ida’s annoyance at changes proposed, improvements resolved on, and I silently pushed my advantage. I have now placed Ida in the position of an independent state, armed to resist encroachments from, and owning no allegiance to a powerful neighbour. There is indeed no open war; decency, piety, and regard for the feelings of a husband and father alike forbid all approach to that; but there is secret, ceaseless, determined opposition. I never suffer Ida to forget that her own tastes are more refined, her ideas more elevated than those of her step-mother; and I will not let her perceive that in many of the affairs of domestic life, Mrs. Aumerle, as she had wider experience, has also clearer judgment than herself. I represent advice from a step-mother as interference, reproof from a step-mother as persecution, and draw Ida to seek a sphere of her own as distinct as possible from that of the woman whom her father has chosen for his wife.”

“Doubtless you occasionally remind the fair maid,” suggested Intemperance, “that but for her[25] own heroic unworldliness she might have been a peeress of the realm.”

“I neglect nothing,” answered Pride, “that can serve to elevate the spirit of one whom I seek to enslave. I have need of caution and reserve, though hitherto I have met with success, for it is no easy task thoroughly to blind a conscience once enlightened like that of Ida. She does even now in hours of self-examination reproach herself for a feeling towards Mrs. Aumerle which almost approaches dislike. She feels that her own peace is disturbed; for the lightest breath of sin can cloud the bright mirror of such a soul. But in such hours I hover near. I draw the penitent’s attention from her own faults to those of the woman she loves not, till I make her pity herself where she should blame, and account the burden which I have laid upon her as a cross appointed by Heaven.”

“O Pride, Pride!” exclaimed Intemperance with a burst of admiration, “I am a child in artifice compared with you!”

“Rest assured that when any young mortal is disposed to look down upon one placed above her by the will of a higher power, that pride is lingering near.”

“And by what name may you be known in this particular phase of your being?” inquired Intemperance.

“The pride of self-will in the language of truth; but Ida would call me sensitiveness,” replied the dark spirit with a gloomy smile.

“The pastor and his wife I see approaching the church,” observed Intemperance, glancing down in the direction of the path along which advanced a rather stout lady, with large features and high complexion, who was leaning on the arm of a tall, handsome, but rather heavily-built man, in whose mild, dark eyes might be traced a resemblance to those of his daughter.

“They come early,” said Pride; “he, to prepare for service; his wife, to hear the school children rehearse the hymns appointed for the day. This was once Ida’s weekly care; she is far more qualified for the charge than her step-mother, and the music has suffered from the change.”

“Ida showed humility, at least, in yielding up that charge,” remarked Intemperance.

“Humility,” exclaimed Pride, an expression of ineffable scorn convulsing his shadowy features as the word was pronounced. “I should not marvel if Ida thought so; but hear the real state of the case. The maiden had taken extreme pains to teach her choir a beautiful anthem, in which a trio is introduced, which she instructed three of the girls who had the finest voices and the most perfect taste to sing. Mrs. Aumerle, on hearing the anthem, at once condemned it. It was time wasted, she averred, to teach cottage-children to sing like choristers in a cathedral; and to make a whole congregation cease singing in order to listen to the voices of three, was to turn the heads of the girls, and make them fancy themselves far above the homely duties of the state in which Providence had been pleased to place them. There was common sense in the observations; but Ida saw in it simply want of taste, and at my suggestion,—at my suggestion,” repeated Pride in triumph, “she gave up charge of the music altogether, because she was offended at any fault having been found in it by one who knew so little of the subject.”

“Is the minister himself a good man?” inquired Intemperance.

“Good! yes, good, if any of the worms of earth can be called so,” replied Pride, with gloomy bitterness, “for he does not regard himself as good. Naturally weak and corrupt are the best of mortals, prone to fall, and liable to sin, yet I succeed in persuading[28] many that the gold which is intrusted to their keeping imparts some intrinsic merit to the clay vessel which contains it; that the cinder, glowing bright from the fire which pervades it, is in itself a brilliant and beautiful thing!”

“But Lawrence Aumerle was never your captive?”

“I thought once that he would be so,” replied Pride, his features darkening at the recollection of disappointment and failure. “Aumerle had been a singularly prosperous man—his life had appeared one uninterrupted course of success. Easy in circumstances, cherished in his family, a favourite in society, beloved by the poor, with a disposition easy and tranquil, disturbed by no violent passion,—the lot of Aumerle was one which might well render him a subject of envy. In the pleasantness of that lot lay its peril. Aumerle was not the first saint who in prosperity has thought that he should never be moved, who has been tempted to regard earthly blessings as tokens of Heaven’s peculiar favour. He knew little of the burden and heat of the day, still less of the strife and the struggle. Self-satisfaction was beginning to creep over his soul, as vegetation mantles a standing pool over which the rough winds never sweep. ‘He is mine!’ I thought, ‘mine until death, and indolence and apathy shall soon add their links to the chain forged by pride of prosperity.’ But mine was not the only eye that was watching the Vicar of Ayrley. There is an ever-wakeful[29] Wisdom which ofttimes defeats my most subtle schemes, leading the blind by a way they know not, drawing back wandering souls to the orbit of duty, even as that same Wisdom hangs the round world upon nothing, and guides the stars in their courses! My chain was suddenly snapped asunder by a blow which came from a hand of love, but which, in its needful force, laid prostrate the soul which it saved. Aumerle’s loved partner was smitten with sickness, smitten unto death, and the doating husband wrestled in agonizing prayer for her who was dearer to him than life. The prayer was not granted, for the wings of the saint were fledged. She escaped, like a freed bird, from the power of temptation, for ever! Her husband remained behind,—Lawrence Aumerle was an altered man. Earth had lost for him its alluring charm, and enchained his affections no more. He was softened—humbled,” continued Pride, with the bitterness of one who records his own defeat, “and in another world he will reckon as the most signal mercy of his life the tempest which scattered his joys, and dashed his hopes to the ground! Let us not speak of him more,” continued the fierce spirit with impatience; “his younger brother, the stately Augustine, will not shake off my yoke so lightly.”

“His pride may well be personal pride,” said Intemperance, following the direction of the glance of his stern companion, “if that be he who, with the rest of the congregation, is now obeying the[30] summons of the church bells. Mine eyes never rested on a more goodly man.”

“Personal pride!” repeated the dark one with a mocking laugh, “Augustine Aumerle is by far too proud for that. He would not stoop to so childish a weakness. No, his is the pride of intellect, the pride of conscious genius, the pride to mortals, perhaps, the most perilous of all, which trusts its own power to explore impenetrable mystery, and thereby involves in a hopeless labyrinth; that seeks to sound unfathomable depths, and may sink for ever in the attempt.”

“Is he then a sceptic?” inquired Intemperance.

“No, not yet, not yet,” murmured the tempter; “but I am leading him in the way to become one. I am leading him as I have before led some of the most brilliant sons of genius. I have made them trust their own waxen wings, rely on the strength of their own reason, and the higher they have risen in their flight, the deeper and darker has been their fall.” A gleam of savage triumph, like a flash from a dark cloud, passed over the evil spirit as he spoke.

“Who is he with the long white hair,” asked his companion, “who even now glanced up at these old towers with an expression so stern and so sad?”

“He who was once their heir,” replied Pride. “You see Timon Bardon, whom you and I disinherited through the power which we possessed over his father.”

“Have you not thereby lost the son?” asked Intemperance. “Would not the pride of wealth—”

He was rudely interrupted by his associate—“Know you not that there is also a pride of poverty?” he cried. “Have you forgotten that there is the acid fermentation as well as the vinous? Ha! ha! my influence is recognised over the rich and the great; but who knows—who knows,” he repeated, clenching his shadowy hand, “in how heavy a grasp I can hold down the poor! But I can no longer linger here,” continued Pride; “I must mingle with yon crowd of worshippers, even as they enter the house of prayer. Unless I keep close at the side of each, they may derive some benefit from the sermon, from forgetting to criticise the preacher.”

“And I,” exclaimed Intemperance, “must now away to do my work of death amongst such as never enter a house of prayer.”

And so the two evil spirits parted, each on his own dark errand. My tale deals only with Pride, and rather as his influence is seen in the actions and characters of the human beings to whom the preceding conversation related, than as possessing any distinct existence of his own. Let these three first chapters be regarded as a preface in dialogue, explaining the design of my little volume; or as a glimpse of the hidden clockwork which, itself unseen, directs the movements of everyday life. Most thankful should I be if such a glimpse could induce[32] my reader to look nearer at home; if, when ubiquitous Pride speaks to the various characters in this tale, the reader should ask himself whether there be not something familiar in the tone of that voice, and with a searching glance examine whether his own soul be clogged with no link of the tyrant’s chain,—whether he himself be not a prisoner of Pride.

The “small grey speck” just visible from the summit of Nettleby Tower, on nearer approach expands into a stone cottage, which, excepting that it has two storeys instead of one, and can boast an iron knocker to the door, and an apology for a verandah round the window, has little that could serve to distinguish it from the dwelling of a common labourer.

We will not pause in the little garden, even to look at the bed of polyanthus in which its possessor takes great pride; we will at once enter the single sitting-room which occupies almost the whole of the ground floor, and after taking a glance at the apartment, give a little attention to its occupants.

It is evident, even on the most superficial survey, that different tastes have been concerned in the fitting up of the cottage. Most of the furniture is plain, even to coarseness; the table is of deal, and so are the chairs, but over the first a delicate cover[34] has been thrown, and the latter—to the annoyance of the master of the house—are adorned with a variety of tidies, which too often form themselves into superfluous articles of dress for those who chance to occupy the seats. The wall is merely white-washed, but there has been an attempt to make it look gay, by hanging on it pale watercolour drawings of flowers, bearing but an imperfect resemblance to nature. One end of the room is devoted to the arts, and bears unmistakable evidence of the presence of woman in the dwelling. A green guitar-box, from which peeps a broad pink ribbon, occupies a place in the corner, half hidden by a little table, on which, most carefully arranged, appear several small articles of vertu. A tiny, round mirror occupies the centre, attached to an ornamental receptacle for cards; two or three miniatures in morocco cases, diminutive cups and saucers of porcelain, and a pair of china figures which have suffered from time, the one wanting an arm and the other a head,—these form the chief treasures of the collection, if I except a few gaily bound books, which are so disposed as to add to the general effect.

At this end of the room sits a lady engaged in cutting out a tissue paper ornament for the grate; for though the weather is cold, no chilliness of atmosphere would be thought to justify a fire in that room from the 1st of April to that of November. The lady, who is the only surviving member of the[35] family of Timon Bardon and his late wife the farmer’s daughter, seems to have numbered between thirty and forty years of age,—it would be difficult to say to which date the truth inclines, for Cecilia herself would never throw light on the subject. Miss Bardon’s complexion is sallow; her tresses light, the eye-lashes lighter, and the brows but faintly defined. There is a general appearance of whity brown about the face, which is scarcely redeemed from insipidity by the lustre of a pair of mild, grey eyes.

But if there be a want of colour in the countenance, the same fault cannot be found in the attire, which is not only studiously tasteful and neat, but richer in texture, and more fashionable in style, than might have been expected in the occupant of so poor a cottage. The fact is, that Cecilia Bardon’s pride and passion is dress; it has been her weakness since the days of her childhood, when a silly mother delighted to deck out her first-born in all the extravagance of fashion. It is this pride which makes the struggle with poverty more severe, and which is the source of the selfishness which occasionally surprises her friends in one, on all other points, the most kindly and considerate of women. Cecilia would rather go without a meal than wear cotton gloves, and a silk dress affords her more delight than any intellectual feast. She had a sore struggle in her mind whether to expend the little savings of her allowance on a much-needed curtain to the window[36] to keep out draughts in winter and glare in summer, a subscription to the village school, or a pair of fawn-coloured kid boots, which had greatly taken her fancy. Prudence, Charity, Vanity, contended together, but the fawn-coloured boots carried the day! One of them is now resting on a footstool, shewing off as neat a little foot as ever trod on a Brussels carpet,—at least, such is the opinion of its possessor. Grim Pride must have laughed when he framed his fetters of such flimsy follies as these!

Opposite to Cecilia sits her father, whose appearance, as well as character, offers a strong contrast to that of his daughter. Dr. Bardon is a man who, though his dress be of the commonest description, could hardly be passed in a crowd without notice. His dark eyes flash under thick, beetling, black brows with all the fire of youth; and but for the long white hair which falls almost as low as his shoulders, and furrows on each side of the mouth, caused by a trick of frequently drawing the corners downwards, Timon Bardon would appear almost too young to be the father of Cecilia. There is something leonine in the whole cast of his countenance, something that conveys an impression that he holds the world at bay, will shake his white mane at its darts, and make it feel the power of his claws. The doctor’s occupation, however, at present is of the quietest description,—he is reading an old volume of theology, and his mind is absorbed in his subject.[37] Presently a muttered “Good!” shows that he is satisfied with his author, and Bardon, after vainly searching his pockets, rises to look for a pencil to mark the passage that he approves.

He saunters up to Cecilia’s show-table, and examines the ornamental card-rack attached to the tiny round mirror.

“Never find anything useful here!” he growls to himself; then, addressing his daughter, “Why don’t you throw away these dirty cards, I’m sick of the very sight of them!”

Cecilia half rises in alarm, which occasions a shower of little pink paper cuttings to flutter from her knee to the floor. “O papa! don’t, don’t throw them away; they’re the countess’s wedding cards!”

Down went the corners of the lips. “Were they a duchess’s,” said Dr. Bardon, “there would be no reason for sticking them there for years.”

“Only one year and ten months since Annabella married,” timidly interposed Cecilia.

“What is it to me if it be twenty!” said the doctor, walking up and down the room as he spoke; “she’s nothing to us, and we’re nothing to her!”

“O papa! you used always to like Annabella.”

“I liked Annabella well enough, but I don’t care a straw for the countess; and if she had cared for me, she’d have managed to come four miles to see me.”

“She has been abroad for some time, and—”

“And she has done with little people like us,” said the doctor, drawing himself up to his full height, and looking as if he did not feel himself to be little at all. “I force my acquaintance on no one, and would not give one flower from my garden for the cards of all the peerage.”

Cecilia felt the conversation unpleasant, and did not care to keep it up. She bent down, and picked up one by one the scraps of pink paper which she had scattered. Something like a sigh escaped from her lips.

Dr. Bardon was the first to speak.

“I saw Augustine Aumerle yesterday at church; I suppose he’s on a visit to his brother the vicar.”

“How very, very handsome he is!” remarked Cecilia.

“You women are such fools,” said the doctor, “you think of nothing but looks.”

“But he’s so clever too, so wonderfully clever! They say he carried off all the honours at Cambridge.”

“Much good they will do him,” growled the doctor, throwing himself down on his chair; “I got honours too when I was at college, and I might better have been sowing turnips for any advantage I’ve had out of them. It’s the fool that gets on in the world!”

This, by the way, was a favourite axiom of[39] Bardon’s, first adopted at the suggestion of Pride, as being highly consolatory to one who had never managed to get on in the world.

“I think that I see Ida and Mabel Aumerle crossing the road,” said Cecilia, glancing out of the window. “How beautiful Ida is, and so charming! I declare I think she’s an angel!”

“She’s well enough,” replied the doctor, in a tone which said that she was that, but nothing more.

In a short time a little tap was heard at the door, and the vicar’s daughters were admitted. Ida indeed looked lovely; a rapid walk in a cold wind had brought a brilliant rose to her cheek, and as she laid on the table a large paper parcel which she and her sister had carried by turns, her eyes beamed with benevolent pleasure. Mabel was far less attractive in appearance than her sister, a small upturned nose robbing her face of all pretensions to beauty beyond what youth and good-humour might give; but she also looked bright and happy, for the girl’s errand was one of kindness. The want of a curtain in Bardon’s cold room had been noticed by others than Cecilia, and the parcel contained a crimson one made up by the young ladies themselves.

“Oh! what a beauty! what a love!” exclaimed Cecilia, in the enthusiasm of grateful admiration. “Papa, only see what a splendid curtain dear Ida and Mabel have brought us!”

The doctor was not half so enthusiastic. It has[40] been said that there are four arts difficult of attainment,—how to give reproof, how to take reproof, how to give a present, and how to receive one. This difficulty is chiefly owing to pride. Timon Bardon was more annoyed at a want having been perceived, than gratified at its having been removed. He would gladly enough have obliged the daughters of his pastor, but to be under even a small obligation to them was a burden to his sensitive spirit. He could hardly thank his young friends; and a stranger might have judged from his manner that the Aumerles were depriving him of something that he valued, rather than adding to his comforts. But Ida knew Bardon’s character well, and made allowance for the temper of a peevish, disappointed man. She seated herself by Cecilia, and began at once on a different topic.

“I have a message for you, Miss Bardon. I saw Annabella on Saturday.”

“The countess!” cried the expectant Cecilia.

“She was at our house, and regretted that the threatening weather prevented her driving on here.”

“I’d have been so delighted!” interrupted Cecilia, while the doctor muttered to himself some inaudible remark.

“But she desired me to say, with her love, how much pleasure it would give her if you and her old friend the doctor (these were her words) would come to see her at Dashleigh Hall.”

The grey eyes of Miss Bardon lighted up with irrepressible pleasure, and even the gruff old doctor uttered a rather complacent grunt.

“She begged,” said Mabel, “that you would drive over some morning and take luncheon, and let her show you over the garden and park.”

“Then she’s not changed, dear creature!” exclaimed Cecilia.

“And she hopes before long,” continued Mabel, “to find herself again at Milton Cottage.”

“Mill Cottage,” said the doctor gruffly; for the name of his tenement had for many years been a disputed subject between him and his daughter Cecilia;—“there’s common sense in that name: Mill Cottage, because it was once connected with a mill. To turn it into ‘Milton’ is pure nonsense and affectation. A fine title would hang about as well on this place as knee-buckles and ruff on a ploughman!” And having thus given his oracular opinion, Dr. Bardon strolled out into his garden, leaving the young ladies to pursue uninterrupted conversation together, none the less agreeable for his absence.

“You will excuse papa,” said Cecilia, feeling that some apology was required for her father’s abrupt departure.

Dr. Bardon’s manner was far rougher and less courteous than it would have been had he appeared as the lord of Nettleby Tower, instead of a poor[42] surgeon with indifferent practice. Whether it were that he was soured by disappointment, or that his pride shrank from the idea of appearing to cringe to those more favoured by fortune than himself, it would be perhaps difficult to determine; he appeared to consider that true dignity consisted in despising those outward advantages which he would probably have overvalued had he himself possessed them. Thus, while Cecilia’s pride led her to make the best possible appearance, and catch any reflected gleam of grandeur from opulent or titled acquaintance, Dr. Bardon rather gloried in the meanness of his home, never cared to hide the patch upon his coat, and considered himself equal in his poverty to any peer who wore the garter and the George.

The doctor appeared to have walked off his ill-humour, for when Ida and Mabel bade adieu to Miss Bardon, they found him ready to escort them to his gate. With not ungraceful courtesy he presented the young ladies with a nosegay of his choicest hyacinths, and even condescended to say that he valued their present for the sake of the fair hands that had worked it! There was something of the “fine old English gentleman” lingering yet about the disinherited man.

“Now the doctor’s happy! he has got rid of his gratitude! I knew how it would be!” laughed Mabel, as soon as the girls had walked beyond reach of hearing.

“What do you mean?” asked Ida.

“Did you not see how uncomfortable the poor man was under the weight of even such a little obligation? It was steam high pressure with him, till he opened a safety-valve, and off flew all his debt discharged in the shape of a bunch of hyacinths!”

“How you talk!” said her sister with a smile; “he intended these poor little flowers as a mark of attention; they were no return for our present.”

“O Ida, how little you know! Why, Dr. Bardon does not think that there are hyacinths in the world that can bear comparison with his. He thinks them worth any money. He carries[44] a mental glass of very singular construction, patented by the maker, Pride. Look through the one end, everything is small; look through the other, everything is big! He turns the magnifier to what he does himself, the diminisher to what others do for him; and it is wonderful how he thus manages to economize gratitude, and keep himself out of debt to his friends. Depend upon it, seen through his glass, his hyacinths swelled to the size of hollyhocks, and our curtain diminished to that of a sampler!”

“You are a sad satirical girl!” said Ida.

“Not I, I’ve only practised the ‘vigilance of observation and accuracy of distinction, which neither books nor precepts can teach,’ which the famous Mr. Jenkins used to recommend to papa when he was young. I am merely distinguishing between the kindnesses which a man does to please a friend, and those which he does to gratify his own pride. Dr. Bardon, in spite of his poverty, is as proud as the Earl of Dashleigh can be.”

“But he is one who deserves much indulgence.”

“I am not saying anything against him,” interrupted Mabel; “I rather like a dash of pride in a character; I know I have plenty of it myself.”

“Mabel—”

“Why, darling, I’m proud of you!” exclaimed Mabel, turning her eyes affectionately on her sister; “and I’m proud of my excellent father, proud of my glorious uncle, but I am not proud,”—here Mabel[45] laughed,—“I’m not proud of my step-mother at all.”

“Mabel, dearest—”

“I’m convinced that the world may be divided into two classes—those made of porcelain, and those of crockery. There seems such a wonderful difference in the nature of minds, into whatever shape education may twist them! Now, my father, uncle, and you, are made of real Sevres porcelain, and Mrs. Aumerle—”

“Really, Mabel, you do wrong to speak thus of her.”

“Well, I won’t if you don’t like it, darling, but she’s so intensely common-place and matter-of-fact! I don’t believe that she understands or could enter into our feelings any more than if we had been born in different planets!”

Ida sighed. “It is our appointed trial,” she replied; and these few words, though well intended, did more to impress upon her young sister the hardship of having an uncongenial stepmother, than open complaint might have done. Mabel regarded her gentle sister as a suffering saint, and had no idea that there might be two sides even to such a question as this.

Ida’s conscience warned her that the preceding conversation had been unprofitable, to say the least of it, and she knew well what Scripture saith against every idle word. She therefore turned the channel[46] of discourse, and told Mabel of her new plan of having a class for farm-boys, which she intended herself to conduct.

“You can’t manage more upon Sundays, Ida; you have two classes already, you know.”

“True; this must be on the Saturday evening, when the lads have left off work.”

“You can’t have the school-room, then; that’s Mrs. Aumerle’s time for the mother’s class.”

“I have been thinking about that,” said Ida, gravely; “but there is really no other hour that will be suitable at all for mine. I must ask Mrs. Aumerle to have her women a little earlier in the afternoon.”

“I would not ask a favour of her!” said Mabel proudly.

“It is never pleasant to ask favours,” replied Ida; “but it is sometimes our duty to do so.”

It was growing dark before the sisters reached their home. They found Mrs. Aumerle busily engaged in cutting out clothes for the poor, wielding her large, bright scissors with quick hand, and directing its operations with an experienced eye. She looked up from her occupation as Ida and Mabel entered the room.

“What has made you so late?” asked the lady.

“Oh! we have had a nice, long chat with Cecily Bardon,” replied Mabel; “we never thought of the hour.”

“I hope that you will think of it another time,” said Mrs. Aumerle, resuming her cutting and clipping; “it is not proper for young ladies to be crossing the fields after sunset without an escort.”

“Not proper!” repeated Mabel half aloud, her cheek suffused with an angry flush.

“We have been always accustomed,” said Ida more calmly, “to walk whither and at what hour we pleased, and we have never found the smallest inconvenience arise from so doing.”

“Your having done so is no reason why you should do so,” said the lady firmly; “you have been too much left to yourselves, and it is well that you have now some one of a little experience to judge what is suitable or unsuitable for two young girls of your age.”

Mabel turned down the corners of her mouth after the fashion of Dr. Bardon; happily Mrs. Aumerle was too busy with a jacket-sleeve to look at her step-daughter’s face. Ida seated herself without reply; but Pride stole up at that moment and whispered in her ear, “You can manage quite as well for yourself as the meddling dame can manage for you. She might be content to let well alone, and confine herself to her own affairs.”

Ida now entered upon the subject of the class for farmers’ boys and labouring lads, and explained the necessity for holding it on the particular day and hour on which the mothers’ meeting usually took[48] place. She dwelt with gentle eloquence upon the difficulties and temptations of the youths who would be benefited by the new arrangement; but it tried her patience not a little to hear the snip-snip of the scissors all the time that she was speaking.

“Well, I’ll consider the matter,” said Mrs. Aumerle, stopping at length in her occupation; “it will cause me a little inconvenience, but I think that the thing may be managed. But,” she continued, as Ida, having gained her point, was about to leave the apartment, “but we have not thought of the most important thing—who is to conduct the class?”

“I had thought of it,” replied Ida; “I am going to conduct it myself.”

“You!” exclaimed Mrs. Aumerle, turning towards Ida a face whose naturally high colour was heightened by stooping over her cutting; “you! the thing is not to be dreamed of! Your father’s daughter to be teaching and preaching to a set of hulking farm lads, as if they were a parcel of little schoolboys! It would not become a young lady like you.”

“I have yet to learn what can become a lady, be she old or young, better than teaching the ignorant and helping the poor,” said Ida with forced calmness, but great constraint and coldness of manner.

“Oh! that’s very fine talking, my dear; the thing may be a very good thing in itself, but we must choose different instruments for different kinds of work. One would not mend quills with scissors,[49] or cut out flannel with a penknife. I can’t hear of your holding such a class.”

Commanding herself sufficiently not to reply, but with an angry and swelling heart Ida sought her own room, followed by the indignant Mabel. No sooner had they reached it than Mabel threw her arms around Ida, and exclaimed, “My own darling, angel sister! how dared she speak so to you!”

“She will grieve one day,” said Ida, struggling to keep down tears, “that she has put any stumbling-block in the way of such a work. Mabel, we must pity and pray for her!”

“And never let yourselves be led by her,” suggested Pride.

“That girl wants somebody to guide her;” such were the reflections of Mrs. Aumerle, as she went on with her work for the poor. “There’s a great deal of good in her, but she wants ballast,—she wants common-sense. She is spoilt by being so long without the control of a mother, and needs, almost as much as saucy Mabel, a good firm hand over her. With all Ida’s gentleness and meekness, there’s in her a world of obstinacy and pride. I wish that I had brought one verse to her recollection, which she seems to leave out when she reads the Bible—Likewise ye younger, submit yourselves unto the elder; yea, all of you be subject one to another, and be clothed with humility; for God resisteth the proud, and giveth grace to the humble. Ida has a wonderful[50] conceit of her own opinion, as most inexperienced young people have; and it’s almost impossible to convince her that she ever can be wrong. She is not wrong, however, about the duty of having a class for these poor farm lads; I must consult Lawrence as to how it can be done.” The lady went on with her cogitations upon the subject. “We could not expect our schoolmaster to undertake such an addition to his labours. The clerk, Ashby—no, no, he’s not fitted for it; he’d set the young fellows yawning,—no one would come twice for his teaching. Perhaps the best plan would be for me to take the lads myself, and give up my mother’s meeting to Ida. It would be far more suitable for a pretty young creature like her. But I must keep the cutting out and shaping of the poor-clothes still, for clever as she is in reading and talking, that is a business which poor Ida never could manage with all the goodwill in the world.”

And so the plain, practical stepmother settled the matter in her own mind; and only Pride could suggest that her plan was inconvenient, inconsiderate, or unkind. It was ultimately adopted by Ida, but with a reluctance and coldness which deprived both ladies of the encouragement and pleasure which they would have derived from cheerful, hearty, co-operation with each other in labours of love.

The visit of the sisters Aumerle, or rather the message which they had brought, had caused great excitement in the mind of Cecilia Bardon. One thought was now uppermost there, thrusting itself forward at all times, interfering with domestic duties, taking her attention even from her prayers; that thought was—how should she persuade her father to pay a visit to Dashleigh Hall!

Dr. Bardon held out against entreaties for two days; on the third he yielded, having probably all along only made show of fight to avoid seeming eagerly to catch at an invitation from a titled acquaintance.

The next question was—How was the visit to be paid? Four miles was a distance too great to be traversed on foot by Cecilia Bardon.

“We could get a neat clarence from Pelton,” suggested the lady.

“Pelton!” exclaimed the doctor,—“why, Pelton is six miles off! You’ll not find me paying for a clarence to go twenty miles to carry me to a place to which I could walk any fine morning. I’ve not money to fling away after that fashion.”

“If only the Aumerles kept a carriage!” sighed Cecilia.

“If they kept fifty I’d not ask for the loan of one,” said the doctor, with all the pride of poverty.

“Dear me! how shall we ever get to Dashleigh Hall!” cried Cecilia.

“I’ll tell you what, I’ll hire our neighbour the farmer’s donkey-chaise,—that won’t ruin even a poor man like me.”

“A donkey-chaise!” exclaimed Miss Bardon in horror.

“Why, you’ve been glad enough of it before now to carry you over to Pelton, when you had shopping to do in the town.”

“Pelton,—why, yes,—shopping,—but to call on a countess!”

“A countess, I suppose, is made of flesh and blood like other people; if she’s such an idiot as to care whether her friends come to her in chariots or donkey-chaises, the less we have to do with her the better, say I.”

“But to drive through the park—to go up to the grand hall, to—to—to be seen by all the fine liveried servants—”

The doctor actually stamped with impatience. “What is it to us,” he cried, “if all the lackeys in Christendom were to see us? We’re doing nothing wrong—nothing to be ashamed of. I should be as much a gentleman in a chaise, or a cart, drawn by a donkey or a dog, as if I’d fifty racers in my stables, and a handle a mile long to my name.”

The pride of the father and the daughter were at variance, but it was the same passion that worked in both. Cecilia sought dignity in accessories, Dr. Bardon found it in self. She would climb up to distinction in the world by grasping at every advantage held out by the rank and wealth of her friends; he would rise also, but by trampling under foot rank and wealth as things to be despised. The pride of the daughter was most ridiculous—that of the father most deadly. Reader, do you know nothing of either?

One of the things on which Bardon prided himself was on being master in his own house—no very difficult matter, as his subjects consisted but of one gentle-tempered daughter, and one old deaf domestic. On the present occasion Cecilia soon found that she must go to Dashleigh Hall in a donkey-carriage, if she intended to go at all; and after a longer struggle than usual, which ended in something like tears, she yielded to the pressure of circumstances, and consented to accompany her father the next day in the ignoble vehicle which he had selected. This point settled, her mind was free to give itself to the[54] darling subject of dress. Half the day was devoted to touching and retouching last summer’s bonnet, which looked rather the worse for wear, and selecting such articles of attire as might give a distinguished and fashionable air to the lady of Milton Cottage. Cecilia was not unsuccessful. Never, perhaps, had a more elegantly dressed woman stepped into a donkey-chaise before. Her flounced silk dress expanded to such fashionable dimensions as scarcely to leave space in the humble conveyance for the accommodation of the doctor.

If her dress was an object of triumph to Miss Bardon, it was also one of solicitude and care. Never, surely, were roads so dusty, and never was dust more annoying. Her nervous anxiety and precautions irritated the temper of the doctor, who found more than enough to try it in the obstinacy of the animal that he drove, without further provocation from his companion. Both father and daughter were well pleased when they at length reached the ornamental lodge of Dashleigh Park.

“Papa,” suggested Cecilia timidly, “could we not leave the donkey to graze in the lane, and go through the grounds on foot?”

“Leave the hired donkey to be carried off by any party of tramping gipsies! I’m not such a fool,” said the doctor.

The lodge-keeper obeyed the summons of the bell, which was rung with more force than was needful;[55] he stood still, however, without opening the gate, to inquire what the occupants of the donkey-chaise wanted.

“Open the gate, will you?” cried the doctor, in his rough, domineering manner.

“For Dr. and Miss Bardon, of Milton Cottage, friends of the countess,” said Cecilia nervously, feeling very uncomfortable at her own position.

The gate-keeper looked hesitatingly at the lady, then at the chaise, then at the lady again. It is possible that her appearance decided his doubts, or that the impatience of the doctor overbore them, for the gate slowly rolled back on its hinges, and the donkey-chaise entered the park.

Cecilia could scarcely find any charm in the beautiful drive, magnificent timber, verdant glades, broad avenues affording glimpses of distant prospects, sunny knolls on which grazed the light-footed deer. She could not, however, refrain from an exclamation of delight as a sudden bend in the road brought her unexpectedly in sight of the lordly Hall.

Dr. Bardon surveyed the splendid building before him with a gloomy, dissatisfied eye. What was it compared to Nettleby Tower, in the mind of the disinherited man? “Mere gingerbread! mere gingerbread!” he muttered to himself, as he drew up at the lofty entrance. He saw more beauty in a ruined buttress of the ancient home of his fathers than in all the florid decorations of the countess’s magnificent abode.

Cecilia Bardon was well-nigh overpowered by the sense of the grandeur before her. The presence of three or four of the earl’s powdered footmen was enough in itself to make her seat in the donkey-chaise almost intolerable to the lady.

“Lady Dashleigh at home?” inquired the doctor from his low seat, in a tone that would have sounded haughty from a prince.

The countess was happily at home; and Cecilia, hastily descending, breathed more freely when no longer in contact with the odious conveyance. She felt something as a prisoner may feel when he has left the jail behind, his connection with which he desires to forget, wishing that all others could do so likewise. Dr. Bardon flung the rein on the neck of the donkey, and followed his daughter into the Hall.

They were introduced into a splendid apartment, fitted up with magnificence and taste. Poor Cecilia, as she there awaited the countess, painfully contrasted the room with its glittering mirrors and gilded ceiling, painted panels and velvet cushions, with the homeliness of her own humble abode. Pride, who revels in human misery, would not omit the opportunity of inflicting an envious pang. But his barbed dart went deeper—far deeper into the heart of the unhappy Bardon—the man who would have scornfully laughed at the idea of the possibility of such as he envying any mortal in the world.

Cecilia had scarcely time to gaze around her, shake out her dusty flounces, and glance in a mirror to see if her scarf fell gracefully, when Annabella herself appeared from an inner apartment.

The appearance of the youthful countess was rather attractive than striking. Her figure was below the middle height, and so light and delicate in its proportions as to have earned for Annabella in girlhood the title of Titania, queen of the fairies. Her complexion had not the purity of that of her cousin Ida; but any emotion or excitement suffused her cheek with a beautiful crimson, and lit up the vivacious dark eyes, which were the only decidedly pretty feature in a face whose chief charm lay in its ever-varying expression. The irregular outline of the countess’s profile deprived her countenance of all claim to absolute beauty, but no one when under the spell of her winning conversation, could pause to criticise or even notice defects where the general effect was so pleasing. The dress of the countess was not such as might have been expected in one of her rank. It was picturesque rather than costly, fanciful rather than fashionable. Annabella had just been bending over her desk, busy with a romance which she was writing; her tresses were slightly disordered, and a small ink stain actually soiled the whiteness of one little delicate finger.

Her greeting to Dr. and Miss Bardon was most gracious and cordial. She came forward with both[58] hands extended, and welcomed her old friends to Dashleigh Hall with a frank kindliness which at once set Cecilia at her ease. “She is not changed in the least; she is the same fascinating being as ever,” was the reflection of the gratified guest.

Dr. Bardon was not so easily won. He was out of temper with himself and all the world. The touch of pride had turned indeed his wine of life into a concentrated acid. Annabella could not but notice the hardness of his manner, but she was neither surprised nor offended, for she knew the character of the man. “I will conquer the old lion!” thought she, and she exerted all her powers to do so. How thoughtfully attentive the countess became, how she humoured her guest’s little fancies, how she avoided jarring upon his prejudices, and talked of old times, old scenes, old friends, till she fairly beat down, one after another, every barrier behind which ill-humour could lurk!

Annabella took the arm of the doctor, and with Cecilia at her side, sauntered down the marble terrace into the garden. She consulted Timon Bardon about the disposition of her flower-beds, asked advice concerning the management of plants, and finally overcame the old lion altogether by begging for a slip from his Venice Sumach. The moment that the doctor found that he could confer a favour instead of accepting one, all his equanimity returned; and when the party re-entered the beautiful drawing-room,[59] the only shadow on the enjoyment of any of the three was Cecilia’s consciousness that the gravel-walks had impaired the beauty of her fawn-coloured boots.

“What a sweet creature the countess is!” was Miss Bardon’s silent reflection; “prosperity has done her no harm; she has not a particle of pride!”

“She has not a particle of pride!” Such may be the judgment of the world, which looks not below the surface, but the recording angel may give a very different account. Let us examine a little more closely into the character of the countess, and see if she may fairly be ranked amongst the poor in spirit, of whom is the kingdom of heaven.

Annabella had been an orphan almost from her birth, and had been brought up by a tender grandmother, since deceased, who had made an idol of her little darling, the heiress to all her wealth. As soon as the child had power to frame a sentence, that sentence was law to the household. Annabella, the fairy queen, acquired a habit of ruling, which gave a permanent cast to her mind. Gifted with joyous spirits, a sweet temper, and a strong desire to please, her pride was seldom offensive. Annabella’s subjects were willing, for the sovereign was beloved.

As the child grew into the woman, her views began to expand; she desired a wider sway. Annabella was not contented to rule merely in a household, to influence only a small circle of friends. Like those who cut their names on a pyramid, she was ambitious of leaving her mark on the world. The only instrument by which it seemed possible to accomplish this object of ambition was the pen. If “the press” is the fourth power in the state, Annabella resolved to have a share in that power. She had a lively fancy, a ready wit, and, to her transporting delight, her first essay was successful. The young lady’s contributions to a monthly periodical were indeed sent under a nom de guerre, but Annabella’s darling hope was to make that adopted title of “Egeria” famous throughout the land.

It was at this point of her history that the Earl of Dashleigh, smarting under the sting of mortified pride, and casually thrown much into the charming society of Annabella, made her the offer of his hand. The eye of the young heiress had not, like that of her cousin Ida, been fixed upon objects so high that the glare of earthly grandeur died away before it like the sparkles of fireworks below. Annabella was completely dazzled by the idea of such a brilliant alliance. Her imagination immediately invested the young earl with every great and glorious quality. Love threw a halo around him, and the maiden fancied that she saw realized in her noble suitor every[62] poetical dream of her girlhood. Nor was love the only chord that vibrated to rapture in the heart of Dashleigh’s young bride. Did not this elevation to rank and dignity offer at once a wider sphere to her eager ambition? From the rapidity of her conquest, Annabella deemed that her power over the earl would be unbounded, little imagining how much that conquest was owing to the effect of his pride and pique.

Marriage soon undeceived Annabella. She found herself united to a man at least as proud as herself, though his pride took a different form. As long as the bride was contented simply to please, there was domestic harmony; Annabella was happy in her husband, and he thought that no companion could be so agreeable as his witty and lively wife. But the moment that the countess attempted to rule, the elements of discord began to work. The earl, who never lost consciousness of high birth and distinguished rank, was aware that he had married one who, though of good family, was yet considerably below himself in social position. This, however, would have mattered little, had Annabella readily accommodated herself to the new circumstances in which she was placed. The nobleman, in the famous old tale, had deigned to wed even the humble Griselda; he had had no reason to regret his choice, but then there was a difference, wide as north from south, between Griselda and Annabella! As soon as the[63] young countess became aware that her husband felt that he had stooped a little when he raised her to share his rank, all her pride at once rose in arms. She was more determined than ever to assert the independence which she regarded as the right of her sex.

The bond which pride had first helped to form was ill fitted to bear the daily strain which was now put upon it. Annabella, all the romance of courtship over, saw her idol without its gilding, the halo of fancy faded away, and he over whom its lustre had been thrown, appeared but as an ordinary mortal. In a thousand little ways, scarcely apparent to any but the parties immediately concerned, the habits and wishes of the ill-assorted couple jarred painfully on each other. Pride revelled in his work of mischief as he glided from the one to the other.

“Your wife,” he would whisper to the earl, “with all her talents, and all her charms, is ill fitted for the station which she holds. She has not the dignity, the stateliness of mien which would beseem the lady of Dashleigh Hall. She has vulgar tastes, vulgar friends, vulgar amusements. Her very dress is not such as becomes the wife of a peer of the realm. She is giddy, fantastic, and vain, and altogether devoid of a due sense of your condescension in placing her at the head of your splendid establishment. Your choice has been a mistake.”

Then the spirit of mischief would breathe out his[64] treason to Annabella: “Your husband, if superior to you in descent, you have now discovered to be so in no single other point. He has neither your wit nor your spirit. He is rather a weak, though an obstinate man, and thinks much more than common-sense warrants of what has been called ‘the accident of birth.’ Have you not much more reason to exult in belonging to the aristocracy of talent, than that of mere rank like him? Do you glory in the name of Countess as you do in that of ‘Egeria,’ by which alone you are known to reading thousands?”

Having thus given my readers a glimpse of “the skeleton in the house” where all appears outwardly so full of enjoyment, I will take up my thread where I laid it down, and return to the drawing-room of Dashleigh Hall.

Dr. Bardon, as we have seen, had been restored to good humour by the tact and attentions of the countess, and Cecilia exhausted all her superlatives in admiration of everything that she saw. The conversation flowed pleasantly between Annabella and the doctor, for Bardon was a well read and intelligent man, and literature was the countess’s passion. Cecilia, however, found the discourse assuming too much of the character of a tête-a-tête, and not being content to remain exclusively a listener, watched eagerly for an opportunity to drop in her little contribution to “the feast of reason and the flow of soul.”

“Yes, the world is much like a library,” said[65] Annabella, in reply to an observation from the doctor, “but most persons enter it rather to give a superficial glance at the binding of the books, than to make themselves masters of the contents.”

“They are satisfied if the gilding lie thick enough on the backs of the tomes,” said the doctor.

“But what a deep, what a curious study would every character be, if we could read it through from beginning to end (skipping the preface, of course, for school-boys and school-girls are objects of natural aversion). What romances would some lives disclose—while others would offer the most forcible sermons that ever were written. What exquisite beauty, what touching poetry we might find in the daily course of some whom now we regard with little attention!”

“Your lovely Cousin Ida, for instance,” chimed in Cecilia, trying to catch the tone of the conversation, “I always think of her as a living poem!”

“If Ida be a poem,” said Annabella rather coldly, “she is certainly one in blank verse,—a new version of ‘Young’s Night Thoughts,’ exceedingly admirable and sublime!”