Title: Mary: The Queen of the House of David and Mother of Jesus

Author: A. Stewart Walsh

Author of introduction, etc.: T. De Witt Talmage

Release date: August 1, 2019 [eBook #60028]

Most recently updated: October 17, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by MFR and the Online Distributed Proofreading

Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from

images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

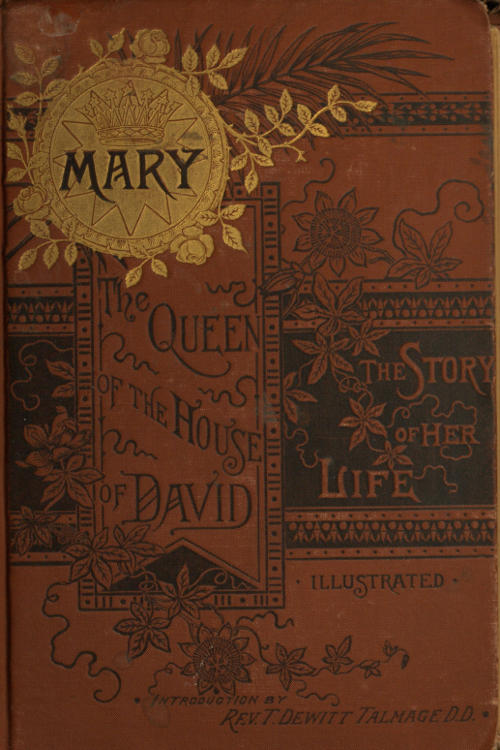

By Frederick Goodall.

MARY AND THE INFANT SAVIOUR.

MARY:

THE

QUEEN OF THE HOUSE OF DAVID

AND

MOTHER OF JESUS.

THE STORY OF HER LIFE.

BY

Rev. A. STEWART WALSH, D.D.

WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY

Rev. T. DE WITT TALMAGE, D.D.

ILLUSTRATED.

PUBLISHED EXCLUSIVELY BY

A. S. GRAY & CO.

SUCCESSORS TO

Central Publishing House and Keystone Publishing Co.

Pittsburgh, Pa.

1889.

COPYRIGHT BY H. S. ALLEN,

1886.

COPYRIGHT OWNED BY

A. S. GRAY.

1889.

ARGYLE PRESS,

Printing and Bookbinding,

265 & 267 CHERRY ST., N. Y.

TO WOMANKIND THROUGHOUT THE WORLD

THIS

STORY OF A LIFE

MOST

BEAUTIFUL, BENEFICENT, AND INSPIRING

Is Dedicated

BY THE AUTHOR.

By Rev. T. De Witt Talmage, D.D.

I have been asked to open the front door of this book. But I must not keep you standing too long on the threshold. The picture-gallery, the banqueting hall and the throne-room are inside. All the fascinations of romance are, by the able author, thrown around the facts of Mary’s life. Much-abused tradition is also called in for splendid service. The pen that the author wields is experienced, graceful, captivating, and multipotent. As perhaps no other book that was ever written, this one will show us woman as standing at the head of the world. It demonstrates in the life of Mary what woman was and what woman may be. Woman’s position in the world is higher than man’s; and although she has often been denied the right of suffrage, she always does vote and always will vote—by her influence; and her chief desire ought to be that she should have grace rightly to rule in the dominion which she has already won.

She has no equal as a comforter of the sick.[viii] What land, what street, what house has not felt the smitings of disease? Tens of thousands of sick beds! What shall we do with them? Shall man, with his rough hand, and heavy foot, and impatient bearing, minister? No; he cannot soothe the pain. He can not quiet the nerves. He knows not where to set the light. His hand is not steady enough to pour out the drops. He is not wakeful enough to be watcher. You have known men who have despised women, but the moment disease fell upon them, they did not send for their friends at the bank or their worldly associates. Their first cry was, “Take me to my wife.” The dissipated young man at the college scoffs at the idea of being under home influence; but at the first blast of typhoid fever on his cheek he says, “Where is mother?” I think one of the most pathetic passages in all the Bible is the description of the lad who went out to the harvest fields of Shunem and got sunstruck; throwing his hands on his temples, and crying out, “Oh, my head! my head!” and they said, “Carry him to his mother.” And the record is “He sat on her knees till noon and then died.”

In the war men cast the cannon, men fashioned the muskets, men cried to the hosts “Forward, march!” men hurled their battalions on the sharp edges of the enemy, crying “Charge! charge!” but woman scraped the lint, woman administered the cordials, woman watched by the dying couch, woman wrote the last message to the home circle, woman wept at the solitary burial, attended by herself and four men with a spade. Men did their work with shot and shell, and carbine and howitzer; women did their[ix] work with socks and slippers, and bandages, and warm drinks, and scripture texts, and gentle soothings of the hot temples, and stories of that land where they never have any pain. Men knelt down over the wounded and said, “On which side did you fight?” Women knelt down over the wounded and said, “Where are you hurt? What nice thing can I make for you to eat? What makes you cry?” To-night, while we men are soundly asleep in our beds, there will be a light in yonder loft; there will be groaning down that dark alley; there will be cries of distress in that cellar. Men will sleep and women will watch.

No one as well as a woman can handle the poor. There are hundreds and thousands of them in all our cities. There is a kind of work that men cannot do for the destitute. Man sometimes gives his charity in a rough way, and it falls like the fruit of a tree in the East, which fruit comes down so heavily that it breaks the skull of the man who is trying to gather it. But woman glides so softly into the house of want, and finds out all the sorrows of the place, and puts so quietly the donation on the table, that all the family come out on the front steps as she departs, expecting that from under her shawl she will thrust out two wings and go right up to Heaven, from whence she seems to have come down. O, Christian young woman, if you would make yourself happy and win the blessings of Christ, go out among the poor! A loaf of bread or a bundle of socks may make a homely load to carry, but the angels of God will come out to watch, and the Lord Almighty will give His messenger hosts a charge, saying, “Look[x] after that woman, canopy her with your wings, and shelter her from all harm.” And while you are seated in the house of destitution and suffering, the little ones around the room will whisper, “Who is she? is she not beautiful?” and if you will listen right sharply, you will hear dripping through the leaky roof, and rolling over the broken stairs, the angel chant that shook Bethlehem: “Glory to God in the highest, and on earth peace and good will to man.” Can you tell why a Christian woman, going down among the haunts of iniquity on a Christian errand, seldom meets with any indignity?

I stood in the chapel of Helen Chalmers, the daughter of the celebrated Dr. Chalmers, in the most abandoned part of the city of Edinburg; and I said to her, as I looked around upon the fearful surroundings of that place, “Do you come here nights to hold a service?” “Oh, yes,” she said; “I take my lantern and I go through all these haunts of sin, the darkest and the worst; and I ask all the men and women to come to the chapel, and then I sing for them, and I pray for them, and I talk to them.” I said, “Can it be possible that you never meet with an insult while performing this Christian errand?” “Never,” she said; “never.” That young woman, who has her father by her side, walking down the street, and an armed policeman at each corner is not so well defended as that Christian woman who goes forth on Gospel work into the haunts of iniquity carrying the Bible and bread.

Some one said, “I dislike very much to see that Christian woman teaching these bad boys in the mission school. I am afraid to have her instruct[xi] them.” “So,” said another man, “I am afraid too.” Said the first, “I am afraid they will use vile language before they leave the place.” “Ah,” said the other man, “I am not afraid of that; what I am afraid of is, that if any of those boys should use a bad word in her presence, the other boys would tear him to pieces—killing him on the spot.”

Woman is especially endowed to soothe disaster She is called the weaker vessel, but all profane as well as sacred history attests that when the crisis comes she is better prepared than man to meet the emergency. How often have you seen a woman who seemed to be a disciple of frivolity and indolence, who, under one stroke of calamity, changed to be a heroine. There was a crisis in your affairs, you struggled bravely and long, but after a while there came a day when you said, “Here I shall have to stop;” and you called in your partners, and you called in the most prominent men in your employ, and you said, “We have got to stop.” You left the store suddenly; you could hardly make up your mind to pass through the street and over on the ferry-boat; you felt everybody would be looking at you and blaming you and denouncing you. You hastened home; you told your wife all about the affair. What did she say? Did she play the butterfly; did she talk about the silks and the ribbons and the fashions? No; she came up to the emergency; she quailed not under the stroke. She helped you to begin to plan right away. She offered to go out of the comfortable house into a smaller one, and wear the old cloak another winter. She was one who understood your affairs[xii] without blaming you. You looked upon what you thought was a thin, weak woman’s arm holding you up; but while you looked at that arm there came into the feeble muscles of it the strength of the eternal God. No chiding. No fretting. No telling you about the beautiful house of her father, from which you brought her, ten, twenty, or thirty years ago. You said, “Well, this is the happiest day of my life. I am glad I have got from under my burden. My wife don’t care—I don’t care.” At the moment you were utterly exhausted, God sent a Deborah to meet the host of the Amalekites and scatter them like chaff over the plain. There are scores and hundreds of households to-day where as much bravery and courage are demanded of woman as was exhibited by Grace Darling or Marie Antoinette or Joan of Arc.

Woman is further endowed to bring us into the Kingdom of Heaven. It is easier for a woman to be a Christian than for a man. Why? You say she is weaker. No. Her heart is more responsive to the pleadings of divine love. The fact that she can more easily become a Christian, I prove by the statement that three-fourths of the members of the churches in all Christendom are women. So God appoints them to be the chief agencies for bringing this world back to God. The greatest sermons are not preached on celebrated platforms; they are preached with an audience of two or three and in private home-life. A patient, loving, Christian demeanor in the presence of transgression, in the presence of hardness, in the presence of obduracy and crime, is an argument from the[xiii] throne of the Lord Almighty; and blessed is that woman who can wield such an argument. A sailor came slipping down the ratlin one night as though something had happened, and the sailors cried, “What’s the matter?” He said, “My mother’s prayers haunt me like a ghost.”

In what a realm is every mother the queen. The eagles of heaven can not fly across that dominion. Horses, panting and with lathered flanks, are not swift enough to run to the outpost of that realm, and death itself will only be the annexation of heavenly principalities. When you want your grandest idea of a queen you do not think of Catherine of Russia, or of Anne of England, or Maria Theresa of Germany: but when you want to get your grandest idea of a queen you think of the plain woman who sat opposite your father at the table or walked with him, arm in arm, down life’s pathway; sometimes to the Thanksgiving banquet, sometimes to the grave, but always together; soothing your petty griefs, correcting your childish waywardness, joining in your infantile sports, listening to your evening prayer, toiling for you with needle or at the spinning wheel, and on cold nights wrapping you up snug and warm; and then, at last, on that day when she lay in the back room dying, and you saw her take those thin hands with which she had toiled for you so long, and put them together in a dying prayer that commended you to the God whom she had taught you to trust—oh, she was the queen! The chariots of God came down to fetch her, and as she went in, all heaven rose up. You can not think of her now without a rush of[xiv] tenderness that stirs the deep foundations of your soul, and you feel as much a child again as when you cried on her lap; and if you could bring her back to life again to speak, just once more, your name as tenderly as she used to speak it, you would be willing to throw yourself on the ground and kiss the sod that covers her, crying, “Mother! mother!” Ah, she was the queen!

Home influences are the mightiest of all influences upon the soul. There are men who have maintained their integrity, not because they were any better naturally than some other people, but because there were home influences praying for them all the time. They got a good start. They were launched on the world with the benedictions of a Christian mother. They may track Siberian snows, they may plunge into African jungles, they may fly to the earth’s end, they can not go so far and so fast but the prayer will keep up with them. Oh, what a multitude of women in heaven. Mary, Christ’s mother, in heaven. Elizabeth Fry in heaven. Charlotte Elizabeth in heaven. The mother of Augustine in heaven. The Countess of Huntingdon is in heaven—who sold her splendid jewels to build chapels—in heaven; while a great many others who have never been heard of on earth, or known but little of, have gone into the rest and peace of heaven. What a rest. What a change it was from the small room with no fire and one window, the glass broken out, and the aching side and worn out eyes, to the “house of many mansions.” Heaven for aching heads. Heaven for broken hearts. Heaven for anguish-bitten frames.[xv] No more sitting up until midnight for the coming of staggering steps. No more rough blows on the temples. No more sharp, keen, bitter curses.

Some of you will have no rest in this world; it will be toil and struggle all the way up. You will have to stand at your door fighting back the wolf with your own hand red with carnage. But God has a crown for you. He is now making it, and whenever you weep a tear, He sets another gem in that crown; whenever you have a pang of body or soul, He puts another gem in that crown, until after a while in all the tiara there will be no room for another splendor; and God will say to his angel, “The crown is done; let her up that she may wear it.” And as the Lord of righteousness puts the crown upon your brow, angel will cry to angel, “Who is she?” and Christ will say, “I will tell you who she is; she is the one that came up out of great tribulation and had her robe washed and made white in the blood of the Lamb.” And then God will spread a banquet, and He will invite all the principalities of heaven to sit at the feast, and the tables will blush with the best clusters from the vineyards of God and crimson with the twelve manner of fruits from the tree of life, and water from the fountains of the rock will flash from the golden tankards; and the old harpers of heaven will sit there, making music with their harps, and Christ will point you out amid the celebrities of heaven, saying, “She suffered with me on earth, now we are going to be glorified together.” And the banquetters, no longer able to hold their peace, will break forth with congratulation. “Hail! hail!” And there will be a handwriting on the wall;[xvi] not such as struck the Persian noblemen with horror, but with fire-tipped fingers writing in blazing capitals of light and love and victory: “God has wiped away all tears from all faces.”

And now I leave you in the hands of Dr. Walsh, the author of this book. He will show you Mary, the model of all womanly, wifely, motherly excellence—the Madonna hanging in the Louvre of admiration for all Christendom, and for many millions in the higher Vatican of their worship.

T. De Witt Talmage.

| Chapter I.—The Queen’s Portrait. | ||

| “A form beloved comes again”—Inspired painters in a voyage of discovery—Tributes to Mary, honoring all womankind—Guido’s wish—Madonnas of many climes. Raphael’s “Transfigured Woman”—Savonarola’s bonfire—St. Luke’s picture of the Virgin—The Vandal spirit. | Page 29 | |

| Chapter II.—The Pilgrim, Crusader and Virgin. | ||

| Life a pilgrimage—Pilgrims of many faiths—A struggle for holy places between the Pilgrim-Crusaders and Moslem—The harem and the home—The rise of Chivalry—The Knights and “Our Lady”—The results of the Crusades. | Page 36 | |

| Chapter III.—Armageddon! “The Key and Sickle.” | ||

| “The wandering hermit wakes the storms of war”—Acre and Esdrælon, the “Armageddon” or “Mountain of the Gospel” of the Scriptures—The battle-field of nations—The City of Jeanne d’Arc. The jewel in the sickle-haft—Prince Edward, the Crusade leader—Sultan Kha-tel—The sacking of Acre—Actors introduced. | Page 48 | |

| Chapter IV.—Sir Charleroy; The Soldier of Fortune and Knight of Saint Mary. | ||

| The flight from Acre to Nazareth—The born-leader—Life estimates with Death holding the scales—A prince honors, a bishop blesses, and a mother loves—An epitome of paradoxes. | Page 53[xviii] | |

| Chapter V.—Nazareth. | ||

| Nazareth, the place of Mary’s nativity—The choice of a leader—The coward king—The Virgin’s Fount—English songsters—The Knights’ mountain Litany—Longings for home and mother—Nain and Endor’s lessons. | Page 61 | |

| Chapter VI.—The Fugitives. | ||

| A night bivouac amid sacred scenes—The “Knight of the Holy-Sepulcher” who fled on “a white charger with black wings”—The funeral at dawn—Mary’s palm-bearing angel-guard—The twelve knights separate into two parties—Will-makings and farewells—By Endor to oblivion. | Page 74 | |

| Chapter VII.—Ichabod. | ||

| Sir Charleroy’s band approach Shunem, the City of Elijah—The surprise—Sir Charleroy the captive of Azrael the Mameluke—The Mohammedan heaven depicted—“A hair, the bridge over hell”—The odoriferous houris—A gorgeous charnel-house blasted—The prodigal becomes the herald of purity—The Knight of Saint Mary and the Jewish Spy—Adversity makes the Knight and the Jew friends—The Knight instructing Ichabod—“’Till Shiloh comes”—“The true, refined and final Judaism”—“The east and the west embracing; truth leading.”—An honest doubt is a real prayer. | Page 82 | |

| Chapter VIII.—From Jericho to Jordan. | ||

| The radiant proselyte—Climbing to glory—The ghostly forms hovering over submerged Sodom—Jordan’s sweetening—Siddim-angels among the willows and oleanders by the Dead Sea—Summonsed to fight for the Crescent or go to the slave mart—Nourahmal “The light of the harem” becomes the disciple and friend of Ichabod—A debate concerning women—A rarity and a wonder—“I told her women had souls; she laughed like a monkey”—The flight from Jericho by night—The lightning—God’s torch—“Canst thou dance rocks[xix] into camels?”—A mummy’s flight, and the burial of a live man—“Unclean”—The solemn passage of Jordan. | Page 93 | |

| Chapter IX.—The Feast of The Rose. | ||

| A breakfast of lentils and barley in the wilderness—The gloom of the Knight and the joy of the Jew—Sermons on fate and songs in flowers—The poetry of Ichabod—Celibacy a reward at Rome—Kneph “The father of his mother”—The heathen and the Christian “Feast of the Rose”—The summary of the events in Mary’s life and in the life of Jesus—The Egyptian Rosary—Neb-ta the maiden sister—The egg and the cross, ancient signs of immortality—The Copt priest—The insights of the Egyptians symbolized by the Sphinx. | Page 113 | |

| Chapter X.—After Eve, Esther or Mary? | ||

| By Jabbock, in the native place of Ichabod—Israelitish maidens keeping the feast of Esther—Religious love, filial love and lover’s love—The poetic Jew’s rhapsody concerning affection—God’s voice in the Garden—The ideal women of the Old Testament and of the New—The Jew’s cry for mother—Vacillating Sir Charleroy—“Echo’s Magic”—Jewish customs. | Page 135 | |

| Chapter XI.—The Feast of Purim. | ||

| A night-scene by Jabbock—Harrimai the priest, and his daughter Rizpah—The religious ceremonial and the revel—Sir Charleroy and Rizpah as “Ahasuerus and Esther”—The Knight’s secret discovered—Conquest of a woman’s heart through pity—“Of what metals Jewish maidens are.” | Page 152 | |

| Chapter XII.—Astarte or Mary? | ||

| The Knight of Saint Mary enslaved by a Hebrew beauty—The journey toward Bozrah—The Mameluke attack—The hand to hand fight—Sir Charleroy wounded and Ichabod slain—Rizpah’s heroism in peril—Espousal in the face of death—A wonderful vision. | Page 170[xx] | |

| Chapter XIII.—From Ramoth Gilead to Damascus. | ||

| Teacher and pupil become patient and nurse—Perilous relations—Delights, assurances, fears and clouds—Harrimai’s discovery and his malediction—Love’s debate and decision—Elopement by night—the Knight and the Jewess wedded at Damascus. | Page 182 | |

| Chapter XIV.—The Theater of the Giants. | ||

| The death of Harrimai—A honey-moon in the “Eye of the East”—To Bashan with the Mecca chaplet-seekers—Nature, art and desolation—Lejah’s black lava-sea—The frenzies of Gerash’s passion-flower—Reaction after exaltation—“A camel voyage in-sea”—Rizpah’s challenge—Jealous of Sir Charleroy’s love for Mary—“Illusion”—The church of Saint George at Edrei—Recrimination—Ridicule costly to pride—Neither Christian, Jew nor Pagan—A woman with unsettled faith—A babe poisoned by its mother’s passion—The lamp and the palm-trees—The Knight’s appeals—Omens—A beacon needed—Fleeing the Lejah—To Bozrah. | Page 195 | |

| Chapter XV.—The Revels of Men and the rites of Their Goddesses. | ||

| Kunawat at the City of Job—The Shrine of Astarte—The Cyclopean image—Questioning the Soul, Time and God—Hugeness, greatness; littleness, caricature—The naked worshipers of the golden calf—Sins exposed—Purity’s vision—Phallic mysteries—Khem—Female deities—Dualism—Immortality by progeny and by regeneration—The fire-worshiper’s mystic number eight, and the Jewish covenant number seven. | Page 212 | |

| Chapter XVI.—A Battle of Giants at Bozrah. | ||

| Houses forty centuries old—The old stone-house of an ancient giant becomes the home of the knight and his wife—How circumstances change people—Recriminations and reconciliation—“The gall taken from animals offered to Juno, goddess of marriage”—Rizpah’s temper that seemed brilliant before wedlock, afterward seems to[xxi] Sir Charleroy very like that of a virago—The charming nonsense of those for the first time parents—Shall she be named Davidah, Angela, Marah or Mary?—The Christian and Jewish faith battle about the cradle—The separation of husband and wife, in anger—The sick child and the desolated, deserted wife—Rizpah longs for a mother, such as Mary of Bethlehem. | Page 224 | |

| Chapter XVII.—Rizpah the Ancient Mother of Sorrows. | ||

| After many years, Rizpah dwells in Bozrah with her three children—Rizpah of Bozrah fascinated by Rizpah of Gibeah—Miriamne the daughter of Rizpah—The daughter appalled by her mother’s mysterious hallucinations—The wonders of mother-love—The story of the ancient, Jewish “Mother of Sorrows”—The omen of the bat and the parable of the stars. | Page 245 | |

| Chapter XVIII.—The Queen Proclaimed in the Giant City. | ||

| The old and the young Jews—The old Christian priest and his Jewess proselyte—Attacked by Mamelukes—The “Old Clock Man”—The Balsam Band—Miriamne, the Jewess proselyte, questions concerning the queen of the old priest’s heart—The miraculous picture of Mary at Damascus—Silver hands and feet—Crown jewels. | Page 264 | |

| Chapter XIX.—The Story of Mary’s Childhood. | Page 282 | |

| Chapter XX.—The Wedding—The Birth and the Flight. | ||

| The birth of Jesus and the flight to Egypt—Miriamne reads to her mother a Christian account of Mary’s espousal—Rizpah curious but doubtful. | Page 293 | |

| Chapter XXI.—The Queen and Her Family in Egypt. | ||

| Father Adolphus and Miriamne converse of the Holy Family’s sojourn in Egypt—Heliopolis and the Temple[xxii] of the Sun—Fire-worshipers—At Memphis, the shrine of Apis the sacred bull—The red heifer of Israel—The Holy Family rescued in Egypt by a robber who afterward died on the cross next to the Savior—The legend of a gipsy’s prophecy concerning Jesus—Zingarella won by the Virgin. | Page 312 | |

| Chapter XXII.—The Shadow of the Cross. | ||

| Rizpah dreading heresy yet charmed by the story of the “Girl Wife”—“Behold my mother and brethren”—Christ’s message to his widowed mother—The “Church of the Terror”—Rizpah’s vision of “Glad Tidings.” Rizpah of Bozrah allured from Rizpah of Gibeah—A hot-chase after an old love—The sword that pierced Mary—The shadow of the cross horrifies Rizpah—The faith of the Nazarene denounced—Miriamne driven from home by her mother. | Page 322 | |

| Chapter XXIII.—The Miserere and the Easter Anthem. | ||

| Miriamne alone at night in the giant city—A refuge at the Christian priest’s—The midnight Miserere—Penitents—Easter at Bozrah—Finding the mother-love in God’s heart. | Page 337 | |

| Chapter XXIV.—A Heroine’s Pilgrimage. | ||

| The convert’s yearnings—“Go and tell”—When parents oppose each other which shall the child follow?—A child of the kingdom in a new family circle—Jesus, Mary and the elect—Miriamne’s two great ambitions—Living apart may be as sinful as actual divorcement—Father Adolphus encourages and Rizpah opposes Miriamne—Rizpah recounts to Miriamne the story of her love for Sir Charleroy, his madness and her own futile visit to London in the effort to win him back—The curse of heredity—“I’ll disown thee with tears in my voice and kisses in my heart.” | Page 351 | |

| Chapter XXV.—Consolatrix Afflictorum. | ||

| Miriamne’s welcome by the London Palestineans—The daughter meets her father in a mad-house—Disappointment—The[xxiii] flight—The search—The White Madonna of the Asylum Park—Love the remedy of minds perturbed by hate—Pallas-Athene the virgin of the heathen—Miriamne’s letter to her mother and its grim answer. | Page 367 | |

| Chapter XXVI.—The Wedding at Cana. | ||

| Sir Charleroy giving signs of recovery under Miriamne’s Ministries—A remarkable service in the chapel of the Palestineans—The knight interested in the story of Cana—The address of Cornelius, on “Home” and “Marriage”—“Is this London or Bozrah?”—Sir Charleroy’s sudden relapse—Miriamne’s adroit ministries—Memories that awaken hopes—The clouds again lifting—Mary’s life motto. | Page 381 | |

| Chapter XXVII.—The Star of the Sea. | ||

| Sir Charleroy, partially restored, with Miriamne and Cornelius journeying toward Syria—Passing Cyprus—Olympus—A storm rising on the Mediterranean—Cornelius presses his love suit on Miriamne—Miriamne pledges love, but pleads her mission as a barrier to marriage—Conflicts below, tempests aloft—A dream; Venus’s court and Mary’s triumph—Sir Charleroy in frenzy defying the billows—An hour of peril—The “Lightning Song” of the sailors—The twin stars—“Mary, Star of the Sea”—The victims of fabricated consciences—Parting. | Page 397 | |

| Chapter XXVIII.—The Queen in the Valley of Sorrows. | ||

| Father and daughter at Acre—The mysterious Hospitaler—From Acre to Joppa—“The myths are as full of women as the women are full of myths”—The wars of men about women—At Jerusalem—The wonderful words of the Knight-Hospitaler, turned preacher—The Via Dolorosa—The Valley of Jehosaphat—The mountain outlook—“Soldiers Speed the Cross”—Mary, the sun of women, rising in moral grandeur above the women of the grove-shrines—The panorama of the ages, passing before Mary’s mind. | Page 419[xxiv] | |

| Chapter XXIX.—Two Dead Hearts Uniting Two Living Ones. | ||

| From Jerusalem to Bozrah—The tomb of Ichabod—Sir Charleroy argues against meeting Rizpah—Miriamne’s strong argument in behalf of the lasting obligations of marriage—A husband reaching the climax of revenges—Joseph by kindness kept Mary in sweet mood and so blessed the unborn Christ—“Miriamne, I am a bundle of contradictions!”—The news-rider—A plague at Bozrah—De Griffin’s twins nigh death—Miriamne meets her mother—Reconciliation—A strange funeral; only two women as mourners and pall-bearers. | Page 437 | |

| Chapter XXX.—The “Knight of Saint Mary” and Rizpah at the Grave of their Sons. | ||

| Father Adolphus and Sir Charleroy—A ruined temple and a ruined man—“A woman, a woman leading in religion!”—Jesus and Magdalena—The twelve appearings of the lingering Christ—The Savior’s love-letter from heaven to His mother—Lucifer’s attempt at suicide—The kiss befouled by treason—The meeting of Sir Charleroy and Rizpah—“The tomb of giant-love grown to mad-hate.” | Page 453 | |

| Chapter XXXI.—The Rose, Queen of Hearts in Bozrah. | ||

| A scene of domestic happiness—Love the vassal of the will—Neb-ta in the “Judgment Hall of Truth”—The lambs that are offered by sectarian hates—The Arcana of glorious wedded love—Rizpah transformed—Miriamne’s public profession of Christ—Cornelius Woelfkin again appeals for union in wedlock—An inner and an outer Miriamne—The coronation of love—The solemn espousal. | Page 467 | |

| Chapter XXXII.—The Queen and the Grail-seekers. | ||

| “The gold of my heart to the man that piloted me to happiness”—Miriamne yearns for a world in sin—Has the Church or God failed?—A revolutionary reformer—The story of the grail quest—The quest of a heavenly cure[xxv] for human ills—The triumphant Adam and Eve—The queenly women of patriarchal times—The mother of the Savior as the wife of a carpenter—What kept her young heart from breaking—Miriamne’s farewell to Bozrah. | Page 484 | |

| Chapter XXXIII.—The Hospitaler’s Oration. | ||

| The secret meeting of the Knights at the house of Phebe—Swords bent sickle-like and spears crossed—After war, social victories—Sunrise at midnight—Each career determined by the life that gives life—The girdle of Venus—Next after God, Mary chiefly instrumental in giving the world a Savior. | Page 498 | |

| Chapter XXXIV.—Memorials at Bozrah. | ||

| The death of Dorothea—The priest of the wayside—The wedding of Cornelius and Miriamne—A pilgrimage to the tombs of Adolphus, Charleroy and Rizpah. Backlook, and outlooks. | Page 510 | |

| Chapter XXXV.—The Sisters of Bethany. | ||

| The Missioners at Bethany—The site of the Home of Jesus—Miriamne’s ideal society—The miracle age—A home, not a throne, the place of Ascension—Will Jesus so return?—The angel bivouac. | Page 522 | |

| Chapter XXXVI.—The Queen of the House of David. | ||

| The Knight’s Pentecost—In the upper room of Joseph of Arimathæa—Mary’s title and realm—Luke, the word-painter—The smoke side and the fire side of Pentecost. | Page 529 | |

| Chapter XXXVII.—The Coronation of the Queen. | ||

| The Hospitaler deemed a prophet at Bethany. The legitimacy of Jesus as the “son of David” assured through His mother—“The reign of blood”—First born—Pagan Rome made sponsor for Mary’s son—Doomsday books and royal charters. | Page 538[xxvi] | |

| Chapter XXXVIII.—The “light of the Harem” in the “Temple of Allegory.” | ||

| The old church at Bethany—A dedication—The wonders of symbolism—Idolatry and Mariolatry. | Page 548 | |

| Chapter XXXIX.—Crown Jewels. | ||

| The Hospitaler warns the Missioners of the Sheik of Jerusalem’s designs—The son of Azrael—Immunity purchased—The wedding of Beulah, Nourahmal’s grand-daughter to a Jewish convert—The wedding address—Juno-Moneta—Crown jewels of maidens and mothers—Mary sounding the depths of woman’s miseries—A malediction for lust—“Knights of the White Cross”—The lost woman dreaming of how it seems to have a mother’s arms infolding her—The Virgin’s potent example. | Page 568 | |

| Chapter XL.—The Queen’s Vision of the Age of Gold and Fire. | ||

| Nourahmal wed to the Druse camel-driver—the Druse converted—The Hospitaler’s message—Ezekiel prophecies fulfilled at Olivet—The “Mother’s pillow”—Gabriel, the “Angel of Mothers and of Victories.” | Page 581 | |

| Chapter XLI.—A Chime and a Dirge at Christmas-Time. | ||

| “Motherhood priced”—“Thou shalt be saved in child-bearing”—Sylvan gods of Rome—“The Miriamites,”—“In Rama, weeping and great mourning”—Joachim’s bleating lamb slain—Woman’s supreme hour—Maternity’s crucifixion—“The Cæsarian Section”—The ebbing tide and the stranded wreck, at midnight. | Page 595 | |

| Chapter XLII.—The Mother of Sorrows Triumphant at Last. | ||

| The funeral of Miriamne—The Hospitaler tells the traditions of Mary’s death and assumption—What the Druse convert said to his camel—“The beatings of mighty wings”—The tomb of Miriamne in Gethsemane. | Page 611[xxvii] | |

| Chapter XLIII.—A Coffin Full of Flowers, and a Girdle with Wings. | ||

| Cornelius and his son at Bethany—Changed scenes—Under the lights and shadows of Chemosh—A widower’s grief—Azrael’s putative son razes to the ground Miriamne’s home and temple—The legend of Mary’s coffin and girdle—The last of the new grail-knights—A sad and dramatic tableau. | Page 618 |

| I. | |

| Mary and the Infant Jesus, | Frontispiece |

| (The original painted by Goodall.) | |

| PAGE | |

| II. | |

| The Birth of Mary | 60 |

| (The original painted by Murillo.) | |

| III. | |

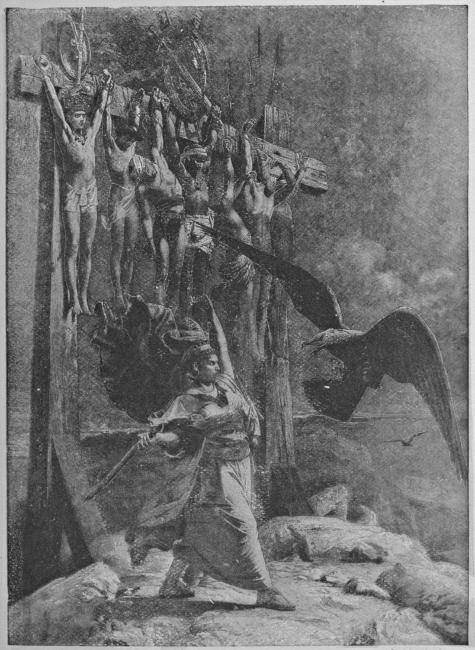

| Rizpah Defending the Dead Bodies of Her Relations, | 250 |

| (The original painted by Becker.) | |

| IV. | |

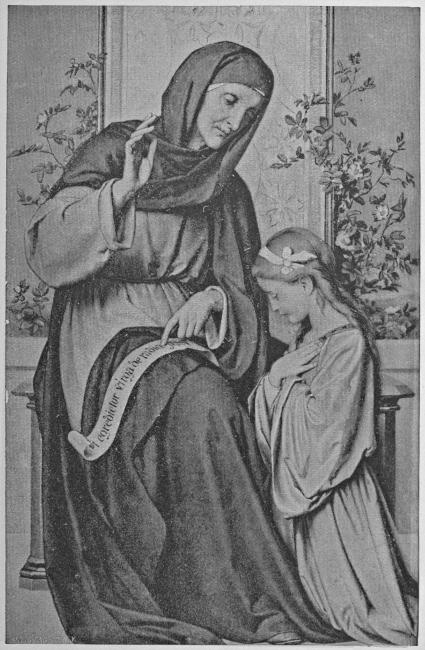

| The Education of Mary, | 282 |

| (The original painted by Carl Muller.) | |

| V. | |

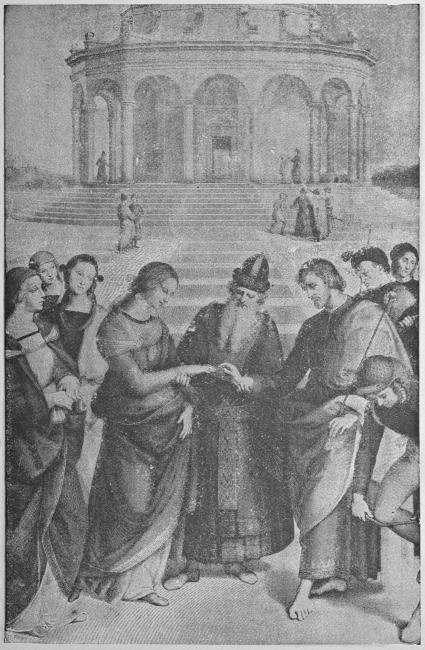

| The Marriage of Mary and Joseph, | 294 |

| (The original painted by Raphael.) | |

| VI. | |

| The Shadow of the Cross, | 332 |

| (The original painted by Morris.) | |

| VII. | |

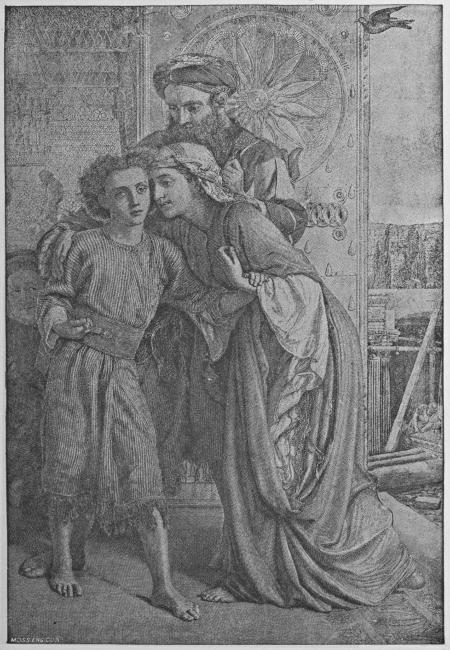

| Jesus at the Age of Twelve with Mary and Joseph on their way to Jerusalem, | 350 |

| (The original painted by Mengelburg.) | |

| VIII. | |

| The Youth Jesus Yielding to the Wishes of His Mother, | 366 |

| (The original painted by W. Holman Hunt.) | |

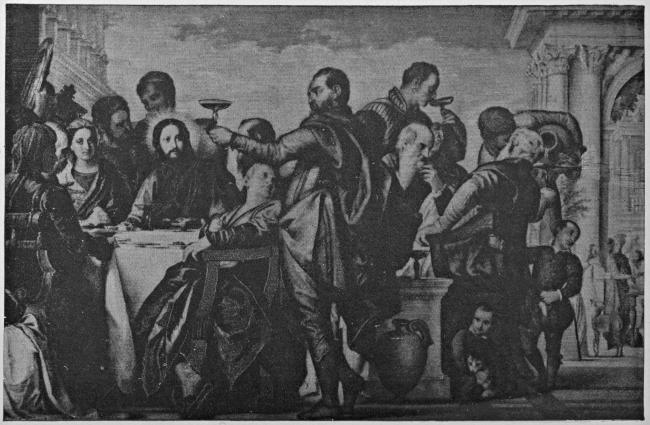

| IX. | |

| The Wedding at Cana, | 380 |

| (The original painted by Paul Veronese.) | |

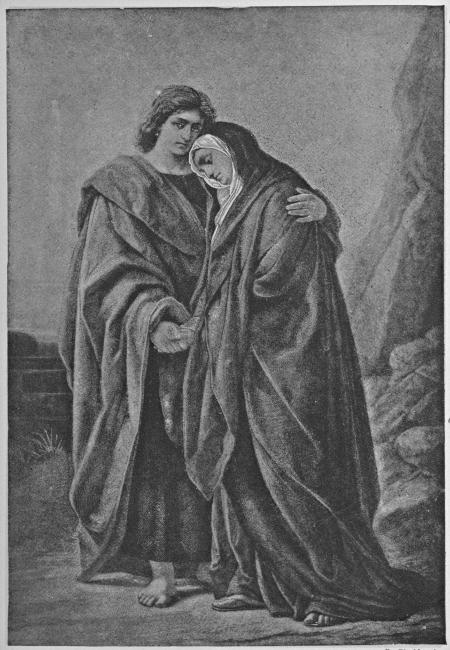

| X. | |

| Mary and St. John, | 433 |

| (The original painted by Plockhorst.) | |

Master, we would see a sign from Thee, was the cunning challenge of the Scribes and Pharisees. They were certain that, in this at least, the hearts of the people would be with them. A sign, a scene, a symbol, were the constant demand and quest of the olden times, as of all times. Even Jehovah led forth to victory and trust, as necessity was upon Him in leading human followers,[30] “with an outstretched arm, and with signs and with wonders.” The Jews, seemingly so doubtful and so querulous, after all articulated the longings of the universal humanity. The longing stimulated the effort to gratify it, and forthwith the artist became the teacher of the people. Presentments of Mary, as she might have been, and as she was imagined to have been by those most devout, were multiplied. Piety sought to express its regard for her by making her more real to faith through the instrumentality of the speaking canvas, but beyond this there was the desire to embody certain charms and virtues of character dear to all pure and devout ones. These were expressed by pictured faces, ideally perfect. They called each such “Mary”; and if there had never been a real Mary, still these handiworks would have had no small value. Who can say that those consecrated artists were in no degree moved by the Spirit which guided David when “he opened dark sayings on the harp,” and rapturously extolled that other Beloved of God, the Church? Music and painting—twin sisters—equal in merit, and both from Him who displays form, color and harmony as among the chief rewards and glories of His upper kingdom. These also meet a want in human nature as God created it. The artists did not beget this desire for presentments through form and color of the woman deemed most blessed; the desire rather begot the artists. Stately theology has never ceased truly to proclaim from the day Christ cried “It is finished!” that “in Him all fullness dwells;” but no theology, has been able to silence the cry of woman’s heart in woman and woman’s nature in man which pleads through the long years, “Show us the mother and[31] it sufficeth us.” It has happened sometimes that gross minds have strayed from the ideal or spiritual imports of Mary’s life and fallen into idolizing her effigies. That was their fault, and must not be taken as full proof that nothing but evil came from the portrayings of our queen. The facts are conclusively otherwise. The painters that made glorious ideals shine forth from the canvas unconsciously painted the shadows largely out of the conditions of all women. Before this second advent of the Virgin, the paganish idea that women were the “weaker sex,” the inferiors of men, at best only useful, handsome animals, prevailed. The renaissance of Mary, as the ideal woman, was an event seeded with the germs of revolutionary impulses socially. Like sunrise it began in the East, at first dimly manifest, then it became effulgent and quickly coursed westward along the pathways of Christianity’s conquests. Like sweet, grateful light then there came to the hearts of men the braver true persuasion, that the woman who not only bore the Christ but won His reverent love must have been morally beautiful and great. In the track of this persuasion, and as its sequence, there came the conviction that the sex, of which Mary was one, had within it possibilities beyond what its sturdier companions had dreamed. After this it came about that the painters, often the interpreters of human feelings, began to represent all goodness under the form of a Madonna. Not knowing the contour of Mary’s face they began gathering here and there, from the women they knew, features of beauty. They combined these in one harmonious presentment. They set out to represent the ideal woman,[32] but had to go to women to find her parts. It became a tribute to womankind to do this. It was like a voyage of discovery, and the artist voyagers depicted not only the best things in womankind, but by putting these things together illustrated what woman could be and should be at her best.

It was thus that Guido produced a picture of the Madonna which enravished all that beheld it. Once he had said, “I wish I’d the wings of an angel to behold the beatified spirits, which I might have copied.” After, here and there, he picked out fragments of color and form on earth; then put them into one ideal composition. It was a heart-expanding work; the work of a prophet, since it told of what might be in woman wholly at her best. Then he said, “the beautiful and pure idea must be in the head” of the artist. It was a deep saying. Given the ideal, and the worker will need only proper ambition to present a grand composition, whether on canvas or in the patternings of the inner life. The presentments of the Virgin rose in fineness when priests turned from their exegesis to kneel and paint for men. The great Saint Augustine, held in high honor by Christians of every name, redeemed from a youth of darkest sinning, revered as his guiding star two lovely women, Monica, his mother, and Mary, the mother of Jesus. He argues, in stalwart polemics, that through the acknowledgment of Mary’s pre-eminence all womankind was elevated. Her presentment, so as to be fully comprehended, was in the beginning a blessing to every soul in being an inspiration to purer, sweeter living. So far as such presentment now conserves the same[33] results the work is worthy and profitable. In all times the representations of the Virgin, whether by the historian or the master of the studio, varied; but the piety they awakened always seemed to be of one type, and that lofty. Thus we have “the stern, awful quietude of the old Mosaics, the hard lifelessness of the degenerate Greeks, the pensive sentiment of the Siena, the stately elegance of the Florentine Madonnas, the intellectual Milanese, with their large foreheads and thoughtful eyes, the tender, refined mysticism of the Umbrian, the sumptuous loveliness of the Venetian; the quaint, characteristic simplicity of the early German, so stamped with their nationality that I never looked round me in a room full of German girls without thinking of Albert Durer’s Virgins; the intense, life-like feeling of the Spanish, the prosaic, portrait-like nature of the Flemish schools, and so on.” Each time and place produced its own ideal, but all tried to express the one thought uppermost; pious regard for the Queen and model. All seemed to feel that in this devotion there was somehow comfort and exaltation—and there generally were both.

The writer of the foregoing quotation, a woman of widest culture and admirable good sense, attested the need that many feel by her own rapturous description of the Madonna of Raphael in the Dresden Gallery. “I have seen my own ideal once where Raphael—inspired, if ever painter was inspired—projected on the space before him that wonderful creation.” “There she stands, the transfigured woman; at once completely human and completely divine, an abstraction of power, purity and love; poised on the[34] empurpled air, and requiring no other support; with melancholy, loving mouth, her slightly dilated sibylline eyes looking out quite through the universe to the end and consummation of all things; sad, as if she beheld afar off the visionary sword that was to reach her heart through him, now resting as enthroned on that heart; yet already exalted through the homage of the redeemed generations who were to salute her as blessed. Is it so indeed? Is she so divine? or does not rather the imagination lend a grace that is not there? I have stood before it and confessed that there is more in that form and face than I have ever yet conceived. The Madonna di San Sisto is an abstract of all the attributes of Mary.”

The foregoing representation marked a step forward in things spiritual. Before Raphael, painters numberless, under the influence of the luxurious and vicious Medici, had filled the churches of Florence with painted presentments of the Virgin, characterized by an alluring beauty which seemed next door to blasphemy. Then came that Luther of his times, Savonarola. He thundered for purity, simplicity and reform; aiming his blows at the depraving, sensuous conceptions of the grosser artists. He made a bonfire in the Piazza of Florence, there consuming these false madonnas. He was, for this, persecuted to death by the Borgia family. They could not bear his trumpet call to Florentines, “Your sins make me a prophet; I have been a Jonah warning Nineveh; I shall be a Jeremiah weeping over the ruins; for God will renew His church and that will not take place without blood—” Art heard his voice, the painters became disgusted with their[35] meaner handiwork, the rude, the obscene, the mischievous was obliterated; finer, more spiritual and loftier concepts of the Virgin appeared as proof of a reformation of morals. And Raphael, later on, seeing these productions, felt the influence that begot them, and then produced that masterpiece. Tradition says Saint Luke painted a picture of the Virgin from life. The picture, reputed to have been so painted, was found by the Turks in Constantinople when that city fell into their conquering hands. They despoiled it of its princely jewel-decorations, then tramped it contemptuously beneath their feet. The latter act was typical, and the Turk still lives to trample in contempt on honest efforts to portray with amplitude and finished details this splendid character, whose outlines alone are presented by the Gospels. But though the Vandal spirit survives, there survives also the strong yearning for the representation of that woman beyond compare, and some will still revel amid the ideals of painters, and some will be gladdened still more by truth’s complete presentment which words alone can make.

There is something very fascinating about the contemplation of life as a continuous pilgrimage, and the fascination grows on one as the conviction of the truth of the conception is deepened by study of it. The course of our race has been a series of processions from continent to continent, from age to age, from barbarism to refinement, from darkness toward light. Whether measuring the little arcs of individuals from birth to dust, or following along the mighty marches of our universe with all its grouping hosts of whirling constellations, we have before us ever this constant truth; man moves willingly or unwillingly onward, as a pilgrim amid pilgrims. “Move on” is the constant mandate and necessity of being. Man’s course is mapped; onward from the swaddling clothes to the shroud, from[37] life to dust; then onward again; while all the mighty planet fleets of which the earth-ship is but one, move along their courses, over trackless oceans, toward destinations, all unknown, yet concededly in a grand as well as in an inexorable pilgrimage. Partly because the motions of his earth-ship makes him restless, partly because he is a being that hopes and so comes to try to find by distant quests hope’s fruitions, and more largely because he is of a religious nature, which impels him to seek things beyond himself, the man becomes a pilgrim. He that is content as and where he is, always, is regarded as a fool playing with the toys of a child, by wise men; by religionists, lack of holy restlessness is ever adjudged to be a sign of depravity. Hence almost all religions, whether false or true, have given birth to the pilgrim spirit. The zeal to express and to utilize this spirit has been often pitiful to behold. Multitudes, failing to grasp the fact that life itself is a pilgrimage, have invented other pilgrimages and gone aside to useless, needless miseries. But all the time they attested human nature seeking something beyond itself, better than its present. So the tribes that lived in the lowlands nourished traditions of descent from gods or ancestors who abode on the mountains, and they inaugurated pilgrimages to seek inspiration or a golden age “on high places, far away.” The chosen people of God thus constantly were allured from the worship of the Everywhere and One Jehovah by the enthusiasm of the heathen devotees who flocked to the mountain fanes. Turn which way one will in the night of the ages and the spectacle of the pilgrim is before him.[38] Ancient Hinduism, followed by that of to-day, witnessed annually, pilgrims counted by hundreds of thousands to the temple of murderous Juggernaut, the Ganga Sagor, or isle of Sacred Ganges. The Buddhists journey to Adam’s Peak in Ceylon, and the Lamaists of Thibet travel adoringly to their Lha-Isa; the Japanese have their pilgrim shrines amid perilous approaches at Istje, while the Chinese, who claim to be sons of the mountains, clamber with naked knees the rugged sides of Kicou-hou-chan. The pilgrimages of the Jews occupy many chapters of Holy Writ, for all their ancient worthies “not having received the promises, but seeing them afar off ... confessed that they were pilgrims and strangers.” Christ confronted the pilgrim spirit perverted in the person of the woman of Samaria, at the eastern foot of Gerezim. She and her people rested their hopes in pilgrimages to their supposed to be sacred places, but the Saviour declared to her by Jacob’s well, truths, both grand and revolutionary, in these words: “The hour ... now is when the true worshiper shall worship the Father in spirit ... not in this mountain nor in Jerusalem.” “Go call thy husband and come hither. Whosoever drinketh the water I shall give shall never thirst.” There were volumes in the golden sentences and they plainly said no need to travel far to find the Everywhere God Who ever comes where men are to satisfy their every thirst. “Go call thy husband.” Go to thy home and find the water of life through doing God’s will; it is better to be a missionary than a pilgrim unless the pilgrim be also missioner. But the truths of that hour have found tardy acceptance among many. The children of[39] Jacob are pilgrims throughout the earth, and the disciples of Christ, since His departure, have gone pilgriming often, as did their fathers before them. Constantine, the Roman emperor, and his mother, Helena, by example and precept, urged Christendom to re-embark in such pious journeys, and at the end of the first thousand years of its existence, Christianity had hosts of disciples actuated by the same old passion that sent religionists everywhere to seek shrines, fanes and blessings. Then the belief began to be held everywhere among Christians that the millennial period was at hand. Multitudes abandoned friends, sold or gave away their possessions, and hastened toward the Holy Land, where they believed Jesus Christ was to appear to judge the world. Here two pilgrim tides, utterly opposed to each other, met; the Christian and the Mohammedan. The followers of the False Prophet, like other men, were imbued with the pilgrim spirit. Some of these thought perfection could be attained only within the precincts of Babylon or Bagdad, and others sincerely believed that they could find peculiar nearness to heaven about the stone-walled Kaaba of Mecca. It was held to be not only a privilege but a duty, incumbent upon all, to take these religious journeys; hence men and women, young and old, undertook them. Even the decrepit were under the obligation, and they must either undertake the work, though failure by death were certain, or hire a proxy to go in their behalf. So was rolled up stupendously the numbers of pilgrim graves which have marked this earth of ours. The Christian pilgrims for a time thronged toward Palestine, first as a small stream, then as[40] a torrent. Europe at large was aroused, and all impulses converged toward the Holy Sepulcher. The soldiers of the Cross soon added swords to their equipments; the flashing of spears outshone the altar lights, and almost before they realized it the priests and pious pilgrims were transformed to mailed knights. There was a root to the impulse, and that the universally felt need of ideals, patterns, personages of heroic mold in all goodness, to show men how to live. The pilgrims turned their eyes to the worthies of the past, and soon came to believe that they could best imbibe their spirit amid their tombs and former abodes. Like most religionists they grew to believe God their especial friend, and they therefore soon came to feel that, against all odds, He would help them to victory. Then they easily grew to believe that death in their crusades would merit the martyr’s crown. Their courage was unbounded, for many went out with a passion to die in the cause they had embraced. The following crusades were marked by conflicts between Moslem and Christian, filled with fanatical and merciless fury, though both the opposing hosts claimed to be doing all they did in God’s name and under his especial direction. “Deus vult,” “God wills it,” was the war-cry of a mighty army, each of which bore on his banner and on his breast the sign of the Cross, the emblem eternally exalted by the Prince of Peace, who willingly died that others might live; but these soldiers were bent on slaying those they could not convert. They were in a transitional state, passing from being pilgrims to being missionaries, but the course was a bloody one. They promoted their self-complacency by persuading themselves[41] that it was a heaven-offending wrong to continue to suffer heretics to occupy the places made sacred by the Saviour when in the world. Then multitudes of Christian priests taught that the pious needed free course to visit the holy places of the East, that they might upbuild their faith and their grasp of theological abstractions by beholding objects associated with the tenets they had adopted. The Moslems had no interest in these proceedings beyond a desire to thwart them. The Christians, to be sure, had the moral disadvantage of being invaders, but then censure of them is mitigated by the fact that Syria was stolen property to the Turk. The latter held it by the stern title deed of the sword. The reader of this summary will be chiefly advantaged by remembering that this conflict was one of the mightiest efforts in the direction of missionary work ever attempted by man, and that being attempted by force it failed utterly. Now the Crusaders were believers in Christ and devoted to Mary. These facts awaken questions as to how, since the spirits of these twain are finally to conquer all hearts, their champions were so defeated? The Crusaders desired to promote the glory of the Man of men and the woman of women, but sought it by aims only weakly worthy, and means often atrocious. It never matters to Christ’s kingdom who possesses His grave if He only possesses all hearts. The Crusaders, beginning with a warm sentiment of respect for the Virgin, suffered their sentimentality to run mad, and mad sentiment is ripe for folly and defilement. An opal, they say, will change its color when its wearer is sick; so a man wearing a priceless virtue on the sleeve of his creed,[42] will find its luster bedimmed when evil sickens his heart. The Crusaders had grand banners, mottoes, war-cries and ideals, but they did not know how to honestly and truly apply them. Their efforts and results well serve to emphasize the truth that moral advances are made with grander forces than those of the sword; that in the end the heroes and heroines of the world’s regeneration will appear potent and regnant solely in the sweetness, truth and exaltation of personal character. Crusader and Moslem, at heart, were each desirous of making the world better, but they each, in fact for a time made it fearfully worse. Probably the followers of the Cross and the followers of the Crescent would have been glad to have bestowed all kindness each on the other, if only the one would have accepted the creed of the other. But the humanity and charity of each were as to the other eclipsed utterly by a zeal for theories. There was need to both that there arise a harmonizing ideal. It would seem as if Providence suffered these opposing pilgrims to peel each other until each in sheer disgust was driven to seek some better way. An able historian affirms that the Crusades did not “change the fate of a single dynasty, nor the boundaries and relative strength of a nation”—but they did leave a history, the contemplation of which affords rare thought-food. The conflict ended in the utter route and flight of the Christians. The tragedy ended at Acre, but there were left some things that took shape in men’s thinking, and the world was made thereby better. The populations and properties of Christian Europe had been squandered to a startling degree in these religious wars, and it was fitting[43] that there be some return to compensate. The result of all others, that grew out of the Crusades, and was indeed also a leading cause of their vigor, was the rising of the spirit of chivalry. The dawn of chivalry first begat brave fighting, but in time the chivalrous discovered a theater for their activity amid the amenities of peace. Chivalry was a rebound from the rugged, barbarous belief of the semi-civilized, whose trust was in brute force and whose constant dictum was, “Might makes right.” Men became impressed with a spirit of tenderness, and, little by little the duty and beauty of the strong’s helping the weak dawned upon humanity. To be chivalrous, by the unwritten laws of custom, became the obligation of every man who sought popular respect. Chivalry was in the creed of the noble and brave, and men delighted to become the companions of lone pilgrims, patrons of beggars, protectors of children and defenders of women. Toward the gentler sex, the spirit of chivalry finely expressed itself by not only defending helpless females amid physical perils, but by according to womankind distinguished courtesy, refined politeness, and all those proper respects that so appropriately garnish and ornament the social intercourse of the sexes in properly cultivated societies. Before the advent of this chivalric time, women had been deemed as generally every way inferior to men; chiefly desirable as ministers to the necessities or appetites of their lords; useful as mothers, but worthy of very little respect, confidence or lasting admiration. The dawn of this new and fine gallantry was a step toward woman’s disinthrallment. Chivalry tried to express itself in the Crusades; defeated, its ardor still burned, and Europe[44] felt its beneficent glow long after the conflict for Syrian sepulchers had ceased. And here it is of the utmost importance that the reader forget not the key fact, that before the advent of the attractive spirit of chivalry, men’s minds in Christian communities were profoundly penetrated and wondrously incited by a deep and new regard for the Queenly woman Mary, the mother of Jesus! She had been almost rediscovered. By a common consent, Christian pulpits had begun sounding her praises, as the ideal woman; a woman worthy of the veneration and emulation of all. The various religious communities vied with each other in doing her honor. The Cistercians declared her purity by wearing white, the Servi wore black to commemorate her touching sorrows, and other bodies elected as their distinguishing badges, various garbs or signs solely to proclaim their allegiance to their ideal woman. A popular moral coronation of Mary resulted. The Crusaders outran all others in their adulation of, and committal to, the wondrous woman. They were the first to call her “Our Lady.” She was the Lady of the hearts of all. These chivalrous soldiers to her spoke their pious vows, from her besought holy favors, and in her name, with sacred oaths, committed their all to effort to wrest all Palestine from the enemies of Mary’s Son.[1] Now these millions of men were not mad, nor in pursuit of a phantom. It was all very real to them. They desired to express a long pent-up natural feeling, and they found an object all satisfactory in Mary. The Crusaders returned finally and for good from battling with Moslem; they returned[45] thoroughly, disastrously defeated: but with their love for Mary all aglow. When they first called her “Our Lady,” there may have been an admixture of irreverence and dilettante in the thought of many; they were purged of these in the hurricane of battle and in the terrors of that inhospitable land of their pilgrimages. Amid trials, far away from his home, often in severe want, frequently confronting slavery and death, the Christian knight while adding “Ave Marie” to his “Patre Nostre,” learned to think of the Madonna as his mother. Missing the latter keenly, worshiping the other unfeignedly, woman took a high throne in his esteem. Sword conquest began to seem to the war-wearied soldier very insignificant as compared to a ministry of comfort, peace and good will. The defeated Crusaders returned to scatter through all Europe a new gospel of humanity. They exalted the Queen of David’s line and forgot to recount the fortunes of war in the East in expounding the dawning beauties of the woman that entranced them and the queenship this ideal had gained over their minds. So they prepared multitudes of the sterner sex for a lasting belief in the worthfulness of true womanhood at its best. The Christian world was ripe for such a revival, when the priests began to thunder “On to Jerusalem!” but men needed not so much war as conversion; not so much relics and tombs as loving principles exemplified. It is wonderful how conversion womanizes some men. That is a triumph of the spiritual over the sensual, the beautiful over the gross. It will make a man of brutal, selfish fiber, in time, as tender as a mother toward her child and as self-denying[46] as a maid toward her lover. The Crusaders started out to rescue the tomb of the dead Saviour from unbelievers and failed, but they returned to herald the renaissance of Mary, the disenslaving of woman; to call the state, the home and individuals to all the refinements which the exaltation of such an ideal of necessity offered. Toward this advening the rising spirit of chivalry was bending the finest hearts when the clarions of war, sounded from altar and baptistry, summoned all to raise the red banner against the Moslem. Right here it is worthy of notice that God’s providence presented other, though allied, principles in the conflict against the Orientals. Two pilgrim hosts, thinking to choose their own ways, were wisely led to better goals than they knew. The Turk presented the throng of the harem as his family; the Christian was committed to the union of only two in holy wedlock. One party presented a banner with a Cross, forever the emblem of self-sacrifice; the other the Crescent, emblem of youthfulness increasing, a hint ever of the hope of endless lust, whether borne of the master of a harem or by the heathen follower of the ancient moon-horned Astarte. The last at Acre, by the Syrian border of the Mediterranean Sea, the Saracen hugged victory and the Cross-bearers were utterly routed. So reads human history, but in truth the defeat was only apparent and local. The followers of the Crescent, holding the creed of lust and making pleasure of sense their end came surely toward their destruction when successes encouraged them in their courses; the followers of the Cross, on the other hand, had within some germs of truth, life-giving in themselves and too beautiful[47] to be suffered to die from the earth. Trial and defeat watered these germs and the knightly hosts returned to Europe by thousands to proclaim finer doctrines than those by which the priest had incited them to war. The returning soldiers were transformed from pilgrims to missionaries, from being taught to teaching, from restorers of Palestine’s graves to restorers of European society. Of the “Teutonic Knights of Saint Mary,” a fine and representative order, an impartial historian writes: “They defended Christianity against the barbarians of Eastern Europe.” “After many bloody encounters introduced German manners, language and morals.” Of the Knighthood, as a whole, says another, “the institution that could breed such characters as these, obviously rendered an enduring service to humanity. Its spirit lives on, offering examples which the young still welcome in their joyous, dreamy days. The ideal still remains, purified by time, freed from its frailties, and aids in fashioning modern sentiment to the conception and admiration of the Christian gentleman.”

As a traveler climbs the mountain to see the sunrise, so he that would overlook the past or present must needs clamber to some lofty point of vision in a significant era or historic location. There are two plains in Syria; one lying along the Mediterranean, the other jutting out from the base of the former toward Jordan; the two together, in shape very like a sickle, have witnessed events wonderfully instructive and determinate to the student of the philosophy of time’s course. These two plains are known respectively as Esdrælon and Acre. The sea and the mountains give these plains their sickle shape, and the geographical outlines are constantly suggestively before the mind as one remembers these plateaus not only as the highways but the battle-fields of the ancient nations. For while, as one says, “the face of nature smiles”—“no spot on earth more fertile,” he also says “no field on earth was so[49] fattened by the blood of the slain.” There the Philistines, the Ptolemys, Antiochus, the Maccabees, Herod, Baldwin, King of Jerusalem, Salah-ed-din, Cœur-de-Lion, Melek-Seruf and Napoleon, each in turn, put their ambitions and their beliefs to the stern arbitrament of swords. There the kingdom of the House of David struggled for life; there the splendid dream of the Crusaders ended as a nightmare.

As a jewel in the haft of the sickle, at the northerly end of the plain by the sea, sits the city of Acre. This city compels the attention of the preacher and student of history and gives theme to him who blends symbol into song. Acre gave its name to its adjacent country round about, and though both city and plain witnessed many a change of master in the past, those changing masters, to gratify their whims or strengthen their policies from time to time, giving the places various names. The Knights of Saint John made it their elect city, honoring it as Saint Jean de Acre, the martyr maid of France. From the city itself one may look out over the sea-highway of nations; from the drear and lofty mountains of its surrounding country one may look over many memorable places. Acre was often called the “Key of Palestine” by the soldier strategists and by the chroniclers of events. To their testimony is added that of the inspired writers and prophets who made it their key and mountain of outlook frequently.

These plains, dotted all about by sacred places, memorable for two great victories; Barak over the Canaanites and Gideon over the Midianites; and two[50] great disasters, the death of Saul and the death of Josiah, became to the Jews the symbol of the conflict of right and wrong. Prophetically, and in the serene hope that righteousness at last would prevail, the plain was called Armageddon, “the Mountain of the Gospel.” We hear the rapt Zechariah thus descanting: “The Lord also shall save the glory of the house of David and the house of David shall be as God.” “And it shall come to pass in that day, that I will seek to destroy all the nations that come against Jerusalem. And I will pour upon the house of David, and upon the inhabitants of Jerusalem, the spirit of grace and of supplications; and they shall look upon me whom they have pierced, and they shall mourn for him, as one mourneth for his only son, and shall be in bitterness for him, as one that is in bitterness for his first-born.”

The prophet looked forth to the Pentecostal day of salvation and the assured victories of David’s great successor. Following this ancient seer, John the beloved, in the Visions of the Apocalypse repeats, these oracles. During the wars of the Crusaders, Acre was sometimes in their possession and sometimes held by their Turkish foes. In the year 1191 Richard the Lion Heart wrested it from the infidel leader Salah-ed-din. The Christians held it firmly until 1291, the time when the last wave of the Crusader advance ebbed, in bloody defeat, from the shores of the Holy Land. For two hundred years the believer of the West and the Moslem grappled with each other in deadly conflict; war’s fortunes often changing, but the awful price in human misery and human blood was inexorably exacted at every stage of the conflict. Acre was the focus toward[51] which the eddying tides ever and anon moved; therefore it saw not only the end but the worst of the Crusades.

Our story begins A. D. 1291 at Acre, the Key of Palestine, in Armageddon, “the mountain of the Gospel.” The situation may be briefly depicted: Acre was filled with a mixed and un-homogeneous population. There were the ubiquitous Galilean traders, without politics; shrewd to the last degree in traffic and courtly as a Parisian; there some secret, sullen, silent enemies of the Christian invaders, awaiting the coming end; there hundreds of those camp-following nondescript “good lord and good devil” characters, and there the remnants of the Crusader armies. The latter were not only diminished as to numbers but greatly degraded in moral tone. Their warfare had been belittled to a defense and a retreat. The adventurers were uppermost; courts-martial, intrigues and fanfaronade were their occupation daily. Prince Edward, the Christian leader, had made a sworn treaty with the Moslems long before this time; but his pious followers had quickly, wickedly violated it. Thereupon the Sultan, Kha-tel, had made an irrevocable treaty with himself, sealed with the most awful oath he could register, that he would never tire until he had exterminated the last of the Western invaders now circumscribed and besieged in Acre. With 200,000 dusky followers the Sultan besieged the last stronghold of the Crusaders. The hearts of the defenders sank within them, and scores sought safety in homeward flight, loading down every vessel bound for Europe. Among the first fugitives was the chief leader, Hugh de Lusignan, who wore the phantom title, “King of Jerusalem.” He preferred the safety of distant[52] Cyprus to the doubtful regality which was overshadowed with nearing death. Only 12,000 were left to represent the Crusade cause which once mustered millions. May 18, 1291, the devoted city was stormed by the Turks; an entrance was effected and a murderous carnage, heaping the streets with the dead, and redding the foam of the moaning sea, followed. But there was no easy victory to the Moslem, for the steady, vigorous, brilliant, desperate fighting of the knights, laying low piles of their foes for every one of themselves that fell, compelled the respect of the Sultan’s host. The Turks attempted to gain a surrender by offering bribes; these failing, terms were offered. The latter, which included permission for the Crusade remnant to depart the country in peace, were accepted. But the Sultan, taught, if he needed the lesson, by the perfidy of Prince Edward’s Christian truce-breakers, quickly broke his promise of safe conduct. Though the retreating band was in no way party to the wrong he sought to avenge, they were mercilessly ambuscaded. There followed another struggle to the death, a handful against a host and but few succeeded in cutting their way through the cordon of death. History has often recounted the preceding events up to the point; from this point it is proposed to lead the reader along the career of a fragment tossed out of the foregoing whirlpool of disaster.

The course of the knights fleeing from Acre was turned toward Nazareth. There being but one way open to them, they took that way quickly and with one accord. The fugitives from Acre represented various knightly orders, but they were disorganized, without any definite destination and without an authorized leader. Among them was Sir Charleroy de Griffin, a knight famed for valor, a central and commanding personage; one that would have attracted attention in almost any assembly of men. As he went, so went the rest of the fleeing Christians, and when he reined in his panting steed,[54] after a time, at the top of a fir-crested knoll not far from Nazareth, the knights following him did likewise. Then they drew around him in a semi-circle, without command, and simultaneously, as if to solicit his direction. They had followed the course he took because he took it, and now with one accord they halted because he had done so. There is to some a subtile influence that makes them leaders of men; so the disorganized Crusaders, by an unvoiced but fully expressed concession, admitted the leadership of this dashing horseman. Some may designate this a triumph of personal magnetism, but be that as it may, it was a fact that Sir Charleroy was chief. Sir Charleroy, just at the time of the foregoing incident, presented an admirable study for the philosopher or painter. From his saddle he was able to overlook leagues of bright landscape, but he could not claim the protection of a foot of it; for the first time in his life he yearned for home, now a spreading sea, and a wall of death shut it out from him apparently for ever; by circumstances absolute sovereign almost of the men about him, but doubt and danger were confounding all his ability to give commands. He fell into a train of thought, leaving his comrades to converse with their pawing steeds and to questionings within themselves as to the future. Sir Charleroy had reached an eminence in life, one of those points of out-look where a man’s past meets him and demands review, that it may explain the present. He believed that he had reached very nearly the end of his career, and in that belief he began to weigh it for what it was worth. In imagination he saw one writing the story of his life.[55] Sir Charleroy, the refugee, began faithfully to review Sir Charleroy, the wayward youth, pleasure-seeker and reckless man. The former dictated mentally to the imaginary scribe: “Write, Charleroy de Griffin was the son of a stalwart French Baron, used to duels and trained to war. The boy inherited from his father a splendid physique, of which he was unduly proud, and a restless disposition that he never sincerely asked God to control. By the death of the baron, his son, an infant, was left to the sole tutelage of his English mother. The latter was of high birth, by nature a noble woman, and in every way worthy of a better son than the one whom he had turned out to be. She had idolized her brawny spouse in his lifetime, and when she had recovered from the shock his death caused, her yearning heart, little by little, turned from the idol in the tomb to the child he had left her. Ere long she lived again in the rapture of a love all absorbing, all bestowing, all ruling. She lavished her affection on the youth, not because he was particularly lovable, for he was not, but because he was the only one left her to love, and she was so constituted that she must love; the necessity of loving to her made it easy.

“Then there were many things in the features and form of her son that reminded her of the man who, in brighter days, had won entirely her maiden heart and her young wife love. The child was wont to wonder why his mother embraced him as she did sometimes, with a wondering, startled, wild, passionate embrace; but when he got older he discerned the meaning of these outbreaks. He knew that the mother-heart was having a vision of past wifehood, memory’s grace-given[56] solace of widowhood. Besides this the embraces were her appealings or warnings to death; her heart suddenly seizing as if to shelter and save her last and only idol; for the thought would sometimes come with shadows deep enough, that perhaps the boy might also die. Such love would have been a prized wealth and blessing to some; but in this case, on the one hand, it unfitted this mother for the proper disciplining of this son, and this son though, sometimes, when his conceit permitted it, realizing that the love was given, not won, began to expect it as his due or despise it for its lavishness. In due time he entered the period expressively designated, ‘The monster age.’ This is the time when expanding young life has outgrown the tenderness of infancy and failed of putting on manly and womanly graces; a time when there is a mighty ambition to put on the characteristics of adult life and a mighty lack of ability gracefully to wear them. At this period, perhaps, the majority of youths of both sexes, are interesting chiefly for what they have been, or what it is hoped they will be. They feel, conscious of their growing powers, great self-conceit, and with their growth comes an expansion of their capacities and wants. The plenitude of their wantings makes them avaricious, hence parsimonious toward others of every thing, especially of gratitude. Reverence for elders, respect for fathers, holy regard for mothers, tenderness toward women, chief charms of youth, are buried in the tomb of other virtues by great, selfish, ugly demons of desire. The monster age came to Charleroy in its full virulence, but his mother discerned little of his monstrosity; what she did discern, all unasked, she condoned. She[57] believed all things, hoped all things good of him, although seldom comforted by an expression or act of gratitude on his part. She was to be pitied; but it may be said that the lad was to be pitied almost as much as herself. It was the old story over; she unconsciously went about destroying her own happiness and though she would have willingly died if need be in his behalf, she harmed him beyond estimate by her indulgent loving. Then the youth was surrounded by those who sought the favor of the baroness by constantly sounding in her ears, and in the ears of the boy, praises of the dead baron. They told of his daring, they descanted upon his adventures, his powers, his wisdom. He was the widow’s idol, and the incense was grateful to her, but the worst of it was that they befooled the lad by continually assuring him that he was the image of his father, and surely destined to equal, if not surpass, his sire in deeds of valor. A dangerous burden is wealth; whether it come as great name or great intellect, great physical strength or as much gold, it is a fateful load which few can gracefully support. The youth had wealth in all the foregoing directions; if he had had a mother whose love loved wisely enough to save, if it need be by pain, he might have been saved; but her love infatuated her. The youth’s folly brought him frequently into shameful entanglements; but she extricated him each time. Nobody ever heard of her even rebuking him; as to chastising him, that were a thing abhorrent to her thoughts. His face always bespoke his pardon in advance with her. She would have smitten her husband’s corpse, as it lay in its coffin, as soon as she would have smitten the one[58] whose features constantly reminded her of him her heart had held most dear. Then she hoped, with a mother’s large-hearted faith, that each escapade would be the last. But as the youth grew older his acts were bolder. Again and again, without notice and with heartless inconsiderateness, he left his home to pursue some adventure, and again and again, mother’s love followed him, ever to find him at last in some sore plight, and then quickly to forgive him. By the time Charleroy had reached his majority, the family fortune had been severely tried and depleted in paying the penalty of his follies. He himself had become an old young man, with too many gray hairs and too much experience for one of his years.