Title: Harper's Young People, August 15, 1882

Author: Various

Release date: May 1, 2019 [eBook #59410]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Annie R. McGuire

| THE CRUISE OF THE CANOE CLUB. |

| GRAN'MA'S STITCHES. |

| GLUCK. |

| HURRAH! FOUR KINGS! |

| LEO. |

| MR. STUBBS'S BROTHER. |

| MR. THOMPSON AND THE CROWS. |

| SOMETHING ABOUT LIGHTNING. |

| JUBE'S WATER-MELON. |

| OUR POST-OFFICE BOX. |

| vol. iii.—no. 146. | Published by HARPER & BROTHERS, New York. | price four cents. |

| Tuesday, August 15, 1882. | Copyright, 1882, by Harper & Brothers. | $1.50 per Year, in Advance. |

It is a very easy thing for four boys to make up their minds to get four canoes and to go on a canoe cruise, but it is not always so easy to carry out such a project, as Charley Smith, Tom Schuyler, Harry Wilson, and Joe Sharpe discovered.

Canoes cost money; and though some canoes cost more than others, it is impossible to buy a new wooden canoe of an approved model for less than seventy-five dollars. Four canoes, at seventy-five dollars each, would cost altogether three hundred dollars. As the entire amount of pocket-money in the possession of the boys was only seven dollars and thirteen cents, it was clear that they were not precisely in a position to buy canoes.

There was Harry's uncle, who had already furnished his nephew and his young comrades first with a row-boat, and then with a sail-boat. Even a benevolent uncle deserves some mercy, and the boys agreed that it would never do to ask Uncle John to spend three hundred dollars in canoes for them. "The most we can ask of him," said Charley Smith, "is to let us sell the Ghost and use the money to help pay for canoes."

Now the Ghost, in which the boys had made a cruise along the south shore of Long Island, was a very nice sail-boat, but it was improbable that any one would be found who would be willing to give more than two hundred dollars for her. There would still be a hundred dollars wanting, and the prospect of finding that sum seemed very small.

"If we could only have staid on that water-logged brig and brought her into port, we should have made lots of money," said Tom. "The Captain of the schooner that towed us home went back with a steamer and brought the brig in yesterday. Suppose we go and look at her once more?"

While cruising in the Ghost the boys had found an abandoned brig, which they had tried to sail into New York Harbor, but they had been compelled to give up the task, and to hand her over to the Captain of a schooner which towed the partly disabled Ghost into port. They all thought they would like to see the brig again, so they went down to Burling Slip, where she was lying, and went on board her.

The Captain of the schooner met the boys on the dock. He was in excellent spirits, for the brig was loaded with valuable South American timber, and he was sure of receiving as much as ten thousand dollars from her owners. He knew very well that while the boys had no legal right to any of the money, they had worked hard in trying to save the brig, and had been the means of putting her in his way. He happened to be an honest, generous man, and he felt very rich; so he insisted on making each of the boys a present.

The present was sealed up in an envelope, which he gave to Charley Smith, telling him not to look at its contents until after dinner—the boys having mentioned that they were all to take dinner together at Uncle John's house. Charley put the envelope rather carelessly in his pocket; but when it was opened it was found to contain four new one-hundred-dollar bills.

It need hardly be said that the boys were delighted. They showed the money to Uncle John, who told them that they had fairly earned it, and need feel no hesitation about accepting it. They had now money enough to buy canoes and to pay the expenses of a canoe cruise. Mr. Schuyler, Mr. Sharpe, and Charley's guardian were consulted, and at Uncle John's request gave their consent to the canoeing scheme. The first great difficulty in the way was thus entirely removed.

"I don't know much about canoes," remarked Uncle John, when the boys asked his advice as to what kind of canoes they should get, "but I know the Commodore of a canoe club. You had better go and see him, and follow his advice. I'll give you a letter of introduction to him."

No time was lost in finding the Commodore, and Charley Smith explained to him that four young canoeists would like to know what was the very best kind of canoe for them to get.

The Commodore, who, in spite of his magnificent title, wasn't in the least alarming, laughed, and said: "That is a question that I've made up my mind never to try to answer. But I'll give you the names of four canoeists, each of whom uses a different variety of canoe. You go and see them, listen to what they say, believe it all, and then come back and see me, and we'll come to a decision." He then wrote four notes of introduction, gave them to the boys, and sent them away.

The first canoeist to whom the boys were referred received them with great kindness, and told them that it was fortunate they had come to him. "The canoe that you want," said he, "is the 'Rice Lake' canoe, and if you had gone to somebody else, and he had persuaded you to buy 'Rob Roy' canoes or 'Shadows,' you would have made a great mistake. The 'Rice Lake' canoe is nearly flat-bottomed, and so stiff that there is no danger that you will capsize her. She paddles easily, and sails faster than any other canoe. She is roomy, and you can carry about twice as much in her as you can carry in a 'Rob Roy.' She has no keel, so that you can run rapids easily in her, and she is built in a peculiar way that makes it impossible for her to leak. Don't think for a moment of getting any other canoe, for if you do you will never cease to regret it."

He was such a pleasant, frank gentleman, and was so evidently earnest in what he said, that the boys at once decided to get "Rice Lake" canoes. They did not think it worth while to make any farther inquiries; but, as they had three other notes of introduction with them, Tom Schuyler said that it would hardly do to throw them away. So they went to see the next canoeist, though without the least expectation that he would say anything that would alter their decision.

Canoeist No. 2 was as polite and enthusiastic as canoeist No. 1. "So you boys want to get canoes, do you?" said he. "Well, there is only one canoe for you to get, and that is the 'Shadow.' She paddles easily, and sails faster than any other canoe. She's not a flat-bottomed skiff, like the 'Rice Laker,' that will spill you whenever a squall strikes her, but she has good bearings, and you can't capsize her unless you try hard. Then, she is decked all over, and you can sleep in her at night, and keep dry even in a thunder-storm; her water-tight compartments have hatches in them, so that you can stow blankets and things in them that you want to keep dry; and she has a keel, so that when you run rapids, and she strikes on a rock, she will strike on her keel instead of her planks. It isn't worth while for you to look at any other canoe, for there is no canoe except the 'Shadow' that is worth having."

"You don't think much of the 'Rice Lake' canoe, then?" asked Harry.

"Why, she isn't a civilized canoe at all," replied the canoeist. "She is nothing but a heavy, wooden copy of the Indian birch. She hasn't any deck, she hasn't any water-tight compartments, and she hasn't any keel. Whatever else you do, don't get a 'Rice Laker.'"

The boys thanked the advocate of the "Shadow," and when they found themselves in the street again they wondered which of the two canoeists could be right, for each directly contradicted the other, and each seemed to be perfectly sincere. They reconsidered their decision to buy "Rice Lake" canoes, and looked forward with interest to their meeting with canoeist No. 3.

That gentleman was just as pleasant as the other two, but he did not agree with a single thing that they had said. "There are several different models of canoes," he remarked, "but that is simply because there are ignorant people in the world. Mr. Macgregor, the father of canoeing, always uses a 'Rob Roy' canoe, and no man who has once been in a good 'Rob Roy' will ever get into any other canoe. The 'Rob Roy' paddles like a feather, and will outsail any other canoe. She weighs twenty pounds less than those great, lumbering canal-boats, the 'Shadow' and the 'Rice Laker,' and it don't break your back to paddle her or to carry her round a dam. She is decked over, but her deck isn't all cut up with hatches. There's plenty of room to sleep in her, and her water-tight compartments are what they pretend to be—not a couple of leaky boxes stuffed full of blankets."

"We have been advised," began Charley, "to get 'Shadows' or 'Rice—'"

"Don't you do it," interrupted the canoeist. "It's lucky for you that[Pg 659] you came to see me. It's a perfect shame for people to try to induce you to waste your money on worthless canoes. Mind you get 'Rob Roys,' and nothing else. Other canoes don't deserve the name. They are schooners, or scows, or canal-boats, but the 'Rob Roy' is a genuine canoe."

"Now for the last canoeist on the list!" exclaimed Harry, as the boys left the office of canoeist No. 3. "I wonder What sort of a canoe he uses?"

"I'm glad there is only one more of them for us to see," said Joe. "The Commodore told us to believe all they said, and I'm trying my best to do it, but it's the hardest job I ever tried."

The fourth canoeist was, on the whole, the most courteous and amiable of the four. He begged his young friends to pay no attention to those who recommended wooden canoes, no matter what model they might be. "Canvas," said he, "is the only thing that a canoe should be built of. It is light and strong, and if you knock a hole in it, you can mend it in five minutes. If you want to spend a great deal of money and own a yacht that is too small to sail in with comfort and too clumsy to be paddled, buy a wooden canoe; but if you really want to cruise, you will, of course, get canvas canoes."

"We have been advised to get 'Rice Lakers,' 'Shadows,' and 'Rob Roys,'" said Tom, "and we did not know until now that there was such a thing as a canvas canoe."

"It is very sad," replied the canoeist, "that people should take pleasure in giving such advice. They must know better. Take my advice, my dear boys, and get canvas canoes. All the really good canoeists in the country would say the same thing to you."

"We must try," said Joe, as the boys walked back to the Commodore's office, "to believe that the 'Rice Laker,' the 'Shadow,' the 'Rob Roy,' and the canvas canoe is the best one ever built. It seems to me something like believing that four and one are just the same. Perhaps you fellows can do it, but I'm not strong enough to believe as much as that all at one time."

The Commodore smiled when the boys entered his office for the second time, and said, "Well, of course you've found out what is the best canoe, and know just what you want to buy?"

"We've seen four men," replied Harry, "and each one says that the canoe that he recommends is the only good one, and that all the others are good for nothing."

"I might have sent you to four other men, and they would have told you of four other canoes, each of which is the best in existence. But perhaps you have already heard enough to make up your minds."

"We're farther from making up our minds than ever," said Harry. "I do wish you would tell us what kind of canoe is really the best."

"The truth is," said the Commodore, "that there isn't much to choose among the different models of canoes, and you'll find that every canoeist is honestly certain that he has the best one. Now I won't undertake to select canoes for you, though I will suggest that a light 'Rob Roy' would probably be a good choice for the smallest of you boys. Why don't you try all four of the canoes that have just been recommended to you? Then, if you cruise together, you can perhaps find out if any one of them is really better than the others. I will give you the names of three or four builders, all of whom build good strong boats."

This advice pleased the boys, and they resolved to accept it. That evening they all met at Harry's home, and decided what canoes they would get. Harry determined to get a "Shadow," Tom a "Rice Laker," Charley a canvas canoe, and Joe a "Rob Roy"; and the next morning orders for the four canoes were mailed to the builders whom the Commodore had recommended.

"Hush, dear," said mamma, while busy at play

Were three little mischievous witches;

Little Charley and Lulu, and sweet baby May,

"Hush! Gran'ma is counting her stitches.

"Don't chatter so loud. Ah, see her lips move,

To wreathe in that smile which enriches

Your own lives and mine, my dear little elves;

Ah, hear her now counting her stitches.

"See her pearly white ball, and her soft bordered cap,

With little blue bows in the niches,

And the sheath for her glasses that lie on her lap,

While she's busily counting her stitches."

The bright summer sped, and the beautiful snow

Came falling, and filling the ditches,

When warm little toes, wrapped in soft woollen hose,

Showed that grandma had counted her stitches.

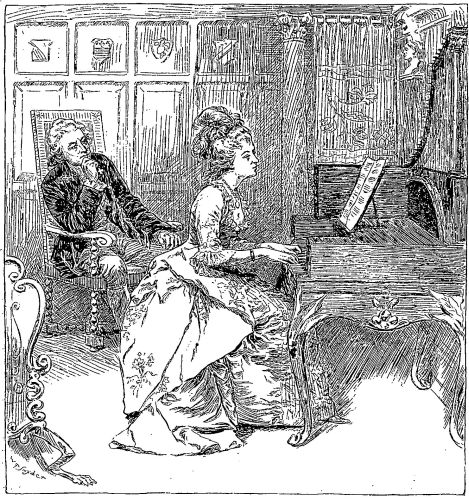

When I was a child I used to be very fond of a faded little picture which hung in my grandmother's house. It was on a staircase, and going up and down we liked to stop and look at it, and make up stories about it.

THE OLD PICTURE ON THE STAIRWAY.

THE OLD PICTURE ON THE STAIRWAY.

The picture represented a fine room, evidently in a palace, and a very splendidly dressed lady, with a tremendous coiffure and a brocaded gown, sitting before a spinet, or old-fashioned piano.

Near her was seated a gentleman, also dressed in the fashion of 1770. He seemed to be teaching her to play. The young lady was charmingly pretty, we thought. The gentleman had a strong, rather stern face, high cheek-bones, and a big forehead; but the look of his eyes was by no means unkindly. Underneath the picture was engraved in script, with any number of flourishes, "Gluck and Marie Antoinette."

The little picture was of no particular merit as a work of art, yet it possessed such an extraordinary fascination for my childish eyes that the other day, when at a concert I listened to some of Gluck's grand music, the strains seemed to bring it back in a flash to my mind's eye. In imagination I saw again clearly the little ebony frame, the faded tints, the pretty smiling young Dauphiness, and the stern, kind-hearted master.

Christoph Willibald, Ritter von Gluck, was born at Weidenwang on July 2, 1714. His destiny was to improve the form and style of operatic music, and to leave behind him some of the most enchanting compositions the world has ever listened to.

Gluck's father was in the service of a Prince, and Christoph had all the musical advantages of the period. He learned the violin, the organ, and the harpsichord, and early tried his hand at composition. His ideas were mainly dramatic, but the opera of that day was very unsatisfactory, and Gluck's first operas were not a great advance on those of other writers. However, he felt quite sure that something much better could be done, and when in 1736 he went to England, he visited Handel, who was then prosperous and busy in the court of George II.

Gluck was only twenty-two, an eager, restless young man, with his head full of ideas and his pockets full of manuscripts. To old Handel he came, and showed him his music, and begging for criticism, but Handel would only admit that it "promised well." Off went Gluck to Paris, and there met with much encouragement from the poets and writers of the day, as well as from the King and Queen. I do not think that, with all his work and his success, his life could have been very happy during those[Pg 660] years. He was easily excited, easily depressed. He hated the wickedness of the people about him, their light ways, their frivolous ideas, even their splendor and riches. Paris in those days was a place in which it was hard for a young man to fear God and himself, and that Gluck lived free from the sins of those about him ought to make us less severe in judging the weakness of his later years. He began to use stimulants for his health, and gradually became addicted to drinking to drown thought and fire him for his work.

Fashion governed art and music very curiously in those days. It was in 1746 that there was a rage in England for what was called the "glasses." This was in reality a harmonica—an instrument made of glasses, and which, by applying a finger moistened with water, produced what were considered agreeable concords. It is odd to think of the great composer Gluck making his bow before the public at the Haymarket Theatre as a performer on the musical glasses. In one of Horace Walpole's famous letters he writes of this event as stirring the fashionable world. The instrument later became very popular, and Mozart and Beethoven did not disdain to write music for it.

Gluck's work went on very steadily in spite of the controversies of his friends and enemies and his personal annoyances. Final success came with his grand opera founded on the mythological story of Orpheus and Eurydice.

I have told you that Gluck reformed the style of the opera. He modelled his work upon the old Greek ideas of dramatic art. He felt that so far the opera had been more like a concert—a mere collection of melodies and ballets. He bent all his energies to making a lyric drama of opera, and he succeeded. To Gluck we owe the best that we have had in opera since his day.

In Vienna much of his time and his work had to be given to the princes and princesses who were his patrons. On one occasion the royal family performed his opera of Il Parnasso. It was about this time he taught the Archduchess Marie Antoinette, and later she wrote from Paris to her sister speaking of him as "notre cher Gluck" (our dear Gluck).

It was Gluck who first introduced cymbals and the big drum into the orchestra. He fought hard over this innovation. His enemies got out satirical pamphlets, in which his "big noises" were ridiculed, but Gluck went his own way, determined to carry his point and prove himself right.

Gluck's last opera was Echo et Narcisse. This was produced in 1779, and soon after he retired to Vienna, where he passed his last years among the kindest friends. In 1787 he died suddenly.

The great object of Gluck's life was thoroughly attained. He made himself felt in every branch of operatic performance. He improved the method, arrangement, and especially its dramatic power. He made it a drama, and its music classical.

This word classical, as applied to music, I am sure many of our young people do not fully understand. To define it completely would be difficult, but I will try and give you some idea of what it means.

Strictly speaking, then, classical music is that which is written according to rule and law: with an intention of producing the most complete harmonies. Bach, Handel, Haydn, Mozart, Gluck, and countless other composers wrote strictly classical music, although Gluck was not remarkable for his counterpoint.

Counterpoint is the "art of combining melodies." The name had a very natural origin. In old times, when notes were designated by little points or pricks, and several of these were joined together to produce a harmony, it was called "point against point," or counterpoint. If the rules of counterpoint are strictly observed, the piece is said to be composed "in perfect counterpoint."

Sometimes you will find a fragment of simple old music with various parts added. This would be "adding counterpoint to a subject."

Handel, when Gluck went to him first, said "he knew no more of counterpoint than his cook," but the master of modern opera had many other strong points, and the music of Orpheus and of Iphigenia will endure while there are hearts to listen.

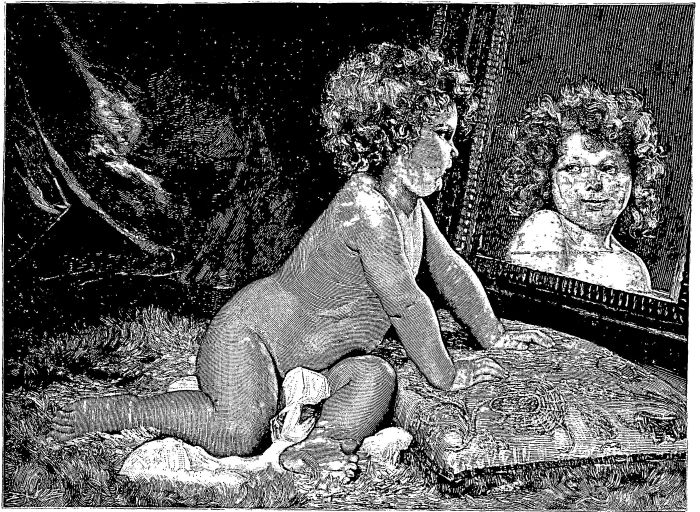

FREDERICK WILLIAM AUGUST VICTOR ERNEST.

FREDERICK WILLIAM AUGUST VICTOR ERNEST.

No less than five long names belong to the little baby Prince who nestles so cozily here on his great-grandfather's lap. The soldierly looking old gentleman is the Emperor William of Germany. The babe is also the great-grandson of the good Queen Victoria, but the little fellow is too young to know to what honors he is born. His father, who stands on the right, is himself the son of the Crown Prince, who will be the successor of the sturdy old Emperor William when he shall have passed away.

"Hurrah! Four Kings!" was the joyous cry with which the royal babe was greeted when he was first presented to the Emperor. You may look at the four in our artist's beautiful picture, and then, perhaps, you will be interested to hear about the christening, which took place in a gallery of the Marble Palace at Potsdam, on the afternoon of June 11, 1882.

This was the anniversary of the Emperor's wedding. Himself and the Empress Augusta, his wife, the Crown Prince and Princess, and the youthful father and mother, stood together before the clergyman, the Emperor receiving and holding the babe in his own arms. Around this group were clustered a great number of stately royal personages, brilliantly dressed, and blazing with jewels and decorations. Among the godfathers and godmothers were included not only Kings, Queens, and Princes, but, to their delight no doubt, the youthful uncles and aunts of the pretty baby.

The minister preached a sermon suitable to the occasion, from the text, "And now abideth faith, hope, charity, these three; but the greatest of these is charity."

Three years ago, when the Emperor's golden wedding was celebrated, the same preacher spoke from the same text, which is certainly a very beautiful one, especially when we remember that charity as here used means love.

Very likely some of you are wondering how the baby Prince behaved during the ceremony. For a while he was very good and patient, but by-and-by he grew very restless, and presently screamed as loud and cried as heartily as though he had been some little peasant Fritz, and not a royal little Frederick William. All the same, the baptismal water was sprinkled on his brow, and he received the blessing from the lips of the good minister. He was called Frederick William August Victor Ernest. These names have long been borne by the Kings of Prussia. May he wear them worthily! After the christening there was a magnificent musical service by the choir, and then the great people sat down together to an imperial dinner. The tired little Prince was taken to his nursery, and put to sleep with many a kiss.

Ford Bonner may live to be a very old man—he is "going on" fifteen now—but it is likely that he will always recollect what occurred upon a certain dark evening in August two years ago. Ford's father and mother were travelling in Europe that summer; hence Ford, who was all the rest of the year a boarding-school-boy of the first water, spent his vacation at his Uncle Pepper's country place.

Ford's chief companion from day to day, as he scrambled among the rocky spurs, was Leo. Leo was a Scotch grayhound, Major Pepper's particular pet. Now one curious trait of his did equal honor to his head and heart. He had been bought at Black's Hollow, a village—if a store, which also was a Post-office, and six or seven dwellings, can be called a village—about two miles further up the road, among the mountains. Regularly once or twice a week would Leo slip innocently off in the morning for a whole day's visiting with any four-legged playmates whose society he had formerly relished at Black's Hollow. On such occasions Ford had to ramble on the heights alone.

Now Amzi Spinner, Major Pepper's hired man, had a brother who kept the Post-office and store at the Hollow. As soon as Amzi discovered Leo's trick of going so frequently thither of his own will, it seemed good to him to teach the dog to carry a letter there with safety and dispatch whenever told to do so. Amzi would tie his missives securely about the bright-eyed, lithe dog's neck, and say in his Yankee drawl:

"Naow, Leo, you jest make tracks for the village, double-quick. Do you[Pg 662] understand? That letter'd ought to git to the store. Be off!"

Leo would leap away, barking joyfully, and in an hour return to seek Amzi in field or barn, collared with an answer from Lot Spinner. In this way the dog became, in a limited sense, the messenger and postman of the family when occasion prompted, and a very quick and faithful one.

It was the last Thursday in August when Major Pepper, finishing his second cup of coffee at breakfast, exclaimed to his wife, "There, Helen. I forgot to tell you last night that if you want to go down to the town in the phaeton with me to-day and give this afternoon to picking out those carpets, it'll suit me capitally."

Aunt Pepper laughed. "Why does a man always choose just the wrong day of all others?" she said, merrily. "Amzi and Mira" (Mira was Amzi's wife and Aunt Pepper's cook) "wanted to go to New York to-day to attend that wedding—her sister's, you recollect. They started early (at four o'clock) for the station, and I don't expect them back until long after we're in bed to-night. I can't leave the house and Ford to take care of themselves."

"Oh yes, you can," laughed Uncle Pepper. "Ford might go along if it wouldn't be a hot and stupid day in town for him—we shall be so busy. Leave him a good luncheon, and let him keep house by himself for once. Leo will help him. You wouldn't mind it, eh, Ford?"

Ford laughed too, and said that he rather guessed not.

"We'll not be later in getting back home than six o'clock, I suppose," said Aunt Pepper, reluctantly consenting.

"Oh dear no," replied the Major, "and Ford will just have a fine appetite for a late dinner."

A half-hour later Ford and Leo, the one with his hand and the other with his active if unimportant tail, waved Major and Mrs. Pepper good-by from the broad piazza, and then turned themselves about to begin the work of passing a jolly day together. Ford did not like to leave the house for any length of time.

A wooden swing he was contriving in the garden, the arrangement of his collection of Indian relics, and a letter to his room-mate at the school—one Harry North—took up all the forenoon.

This latter, or letter business, was still on hand, and Ford was scratching away at it in the summer-house, when Leo suddenly growled. Then he sprang up, barking violently. A strange gentleman was leisurely drawing near the pair of friends. Ford rose and stepped out of his retreat.

"I beg pardon for interrupting you, sir," began the stranger, very pleasantly, "but are your father and mother at home to-day?"

"My father and mother are in Europe, sir," replied Ford, "but—"

"Ah—oh—I see," continued the civil stranger. "I had forgotten that my old friends Major and Mrs. Pepper had no children. Is your uncle at home?"

"I'm sorry, sir," replied Ford, "but they have both driven to town this morning, and will not be back till evening. Be quiet, Leo!" for Leo persisted in showing his teeth, and making sundry impolite noises, not to say growls, while he eyed the polite new-comer very much as if he had been a snake.

"A fine dog that," remarked the stranger, carelessly. "Well, since I am unlucky enough to miss your uncle, could I see that excellent man he employs here, Amzi—-Amzi—dear me, I can not just recall his name." The strange gentleman had a clear, rich voice. He was, by-the-way, a stout, well-made young man, with a dark blue cravat.

"Sorry again, sir," returned Ford, "but Amzi and Mira are away too until quite late this evening. It just happens so. Couldn't I take your message for uncle? Leo, be still, I tell you!"

"You're very kind, my dear boy," said the unknown gentleman, looking at his watch, and backing out from the summer-house gracefully, "but I won't trouble you. I should prefer riding over from my place to-morrow evening. Please tell your good uncle that Mr. Alexander Kingbolt—he will remember my name—called on business, and will see him to-morrow evening if possible, at eight. Good-by." And Mr. Alexander Kingbolt, whistling sweetly "There's one more River to Cross," stepped into a light buggy standing without the gate. Another gentleman sat in it, and the two rode away talking rapidly.

The afternoon shadows grew long; twilight closed in; Ford and Leo sat together, the boy with his hand upon the dog's head. Both began to feel somewhat lonely—at least Ford did. Why in the world did not the phaeton come toiling up the steep mountain road? Halloa! a white owl fluttered across the lawn into an acacia.

Ford had long desired to ascertain that particular owl's private address. He dashed after it, and Leo bore him company. Up through the dark garden bird, boy, and dog sped. Presently Ford slipped and fell. He uttered a cry when he rose, and found that he could put his left foot to the ground only with a pain that sickened him, so severely had his fall strained it.

Very slowly and painfully Ford limped into the garden again, his unlucky foot feeling more miserable with each step. All at once he looked through the trees, and saw lights in the dining-room of his uncle's house.

Major Pepper and Aunt Helen were back, doubtless much disturbed to know where in the world Ford and Leo had gone, or since what hour of the day.

As he drew nearer the closed shutters, he caught the sound of low strange voices, the faint clink of a hammer. Could it be possible anything was amiss? Ford was frightened, but prudent. "Leo," said he, very softly, but almost sternly, to the dog, whose ears were on the alert too, "lie down."

Leo obeyed.

Forgetting his painful foot in his breathless excitement, Ford crept down along the back of the house. The strange voices came clearly from within. "And we'd better be quick about it," somebody was saying.

A robbery it surely was. Ford turned the blind and looked within the dining-room. A lamp was lit. The small safe wherein Major Pepper usually kept his papers and any large sum of money he happened to have in the house for a day or so was rolled out to the middle of the room. Over it leaned a tall well-dressed man, impatiently directing another man who knelt before it, and was working at the old-fashioned lock with some tools he had evidently brought for the purpose.

Ford caught sight of a profile, and the sound of "One more River to Cross," whistled very gently. The man working at the safe door was Mr. Alexander Kingbolt. An exceedingly frightened boy was Ford Bonner.

"So then they can't possibly get over the bridge?" said Mr. Kingbolt, plying his chisel.

"All the planks are up, and hid away till we go down, I tell you," replied the other, "and a red lantern hung across it."

"The bridge," Ford knew at once, must mean a narrow rough structure across a stream just before the road from town wound up the mountain.

"They're likely on their way around by the other one. It'll take them till midnight."

There was a pause. Then said Mr. Kingbolt, out of breath, "Where do you suppose that boy and the dog are?"

"Lost on the mountain, I dare say. But if they come back before we get through, we can fix them somehow."

Ford slipped from below the window. The boy understood all. Many houses in the town had been robbed lately. The "gang" had in some way learned that Major Pepper was occasionally obliged to keep large amounts of money in his lonely country house. They had chosen their day carefully, made or else altered their plans that very morning, thanks to Ford's own politeness in answering Mr. Kingbolt's questions. By a trick they had sent Major and Mrs. Pepper around by their longest route for home. The whole thing was a hastily but cleverly planned scheme. And Ford could do nothing—alone; the nearest houses in the village two miles up the mountain; his swollen foot!

Had he forgotten Leo? The thought darted into his confused mind like a flash. He leaned forward into a ray of light, and drew out gently his pencil, and the envelope, still undirected, in which was his letter to Harry North. He managed to control his excitement and terror enough to scrawl upon it: "There are burglars in our house. Come quick, somebody. Ford Bonner."

The envelope was secured by Ford's shoestring to the greyhound's neck. "Be very quiet, Leo," he kept whispering, almost beseechingly, as he led the dog as well as he could down the far side of the garden, along the fence, and some distance up the road, lest Leo should bark.

"Quick, Leo! To the Post-office—to the Post-office!" he cried, tremblingly, pushing and pointing the dog off.

Leo refused to go. He did not understand all this mystery. Ford felt for a stick, and shook it at him. Leo bounded away silently up the steep. Ford half fell, half sat down, in the darkness on the grass.

He never knew how long it was before he was startled from his stupor by hearing stealthy steps approach down the road. He strained his young eyes to make out a dozen tall figures moving noiselessly toward his hiding-place. They were the astonished men from the village, roused from their circle of gossip around the stoop of the store by Leo's advent and extraordinary excitement.

The letter had been discovered at once by Amzi's brother himself, who, like the rest, with stockings drawn over his boots, headed the party. Ford intercepted them, and made his hurried explanation.

"Stay here," said Lot Spinner, "till we call you."

They leaped the garden wall. A few minutes later Ford heard shouts, and the sound of a gun or two, and a struggle on the house piazza.

"They've got 'em!" he exclaimed, delight and relief getting the best of his long fright and pain.

And so they had; for when Lot Spinner came up and carried the boy down to the house, "Mr. Alexander Kingbolt"—afterward put into jail as Dennis Leary—his comrades, and their tools were all secured under rude guardianship together.

Just as Ford was helped into the house, Leo darted up. The dog had been left behind, lest he should warn the burglars of the party coming from the village, but he had contrived to make his escape.

Ford joined in the cheers for him when at eleven o'clock Major and Mrs. Pepper rode hurriedly up to the brightly lit house to hear the end of the story which the village people up the mountain had stopped them hurrying toward home to tell. Soon after arrived Amzi and Mira; more explanations, and much more ado made over Ford and Leo than either of them relished.

"The scamps would have got away with a couple of thousand dollars, Ford," exclaimed the Major again and again. "It was some money that a man was to call here and get to-morrow morning."

Leo wagged his tail complacently.

So much for a brave boy's coolness, and an obedient dog's intelligence.

After Toby was left alone in the tent he remained for some time looking at the triumphant monkey, and listening to Ben's attempts to crawl around under the barn as fast as the cat could, when suddenly, as if such a thought had not occurred to him before, he cried out,

"Don't you want me to come an' help you, Ben?"

"You keep that monkey back; that's all the helpin' I want," Ben replied, almost sharply; and then the sounds indicated that the cat had suddenly changed her position to one farther under the barn, while the boy was trying to frighten her out.

"Give it up, Ben," shouted Toby, after waiting some time longer, and not seeing any sign of success on the part of his friend. "If you come up here about dark, you'll have a chance to catch her, for she'll have to come out for something to eat."

"You take the monkey into the house, an' I'll get along all right," was the almost savage reply. "She smells him, an' jest as long as he's there, she'll stay under here."

It seemed to Toby almost cruel to desert his friend and partner just at a time when he needed assistance; but he could do no less than go away, since he had been urged so peremptorily to do so, and catching his pet without much difficulty, he carried Mr. Stubbs's brother away from the scene of the ruin he had caused.

Ben's remark that the monkey had "broke the show all up" seemed to be very near the truth, for the boys would not think of going on with so small a number of animals; and even if they decided to do without the menagerie, Bob's calf had wrecked one side of the tent so completely that that particular piece of canvas was past mending.

"I don't know what we'll do," said Toby, mournfully, after he had finished telling the story to Aunt Olive. "The boys act as if they blamed me, because Mr. Stubbs's brother is so bad, and Joe's squirrels an' Bob's mice are all gone. Ben's hen don't look as if she'd ever 'mount to much, an' it don't seem to me that he can get Mrs. Simpson's cat an' every one of the kittens out from under the barn."

"Now don't go to worryin' about that, Toby," said Aunt Olive, as she patted him on the head, and gave him a large piece of cake at the same time. "You can get a dozen cats for Mrs. Simpson if she wants 'em; and as for mice, you tell Bob to set his trap out in the granary two or three times, an' he'll have as many as he can take care of. I'm glad the squirrels did get away, for it seems such a sin to shut them up in a cage when they're so happy in the woods."

Toby was cheered by the very philosophical view that Aunt Olive took of the affair, and came to the conclusion that matters were not more than half so bad as they might have been.

"You be careful that your monkey don't get out again, an' go to cuttin' up as he did last night, for I shall get provoked with him if he hurts my ducks any more;" and with this bit of advice Aunt Olive went upstairs to see Abner.

Toby went out to the shed to assure himself that Mr. Stubbs's brother was tied so that he could not escape, and while he was there Uncle Daniel came in with an armful of strips of board.

"There, Toby boy," he said, as he laid them on the floor, and looked around for the hammer and nails, "I'm going to build a pen for your monkey right up here in one corner, so that we sha'n't be called up again in the night by a false alarm of burglars. Besides, it's almost[Pg 664] time for school to begin again, an' I'm 'most too old to commence chasing monkeys around the country in case he gets out while you're away."

Had it been suggested the day before that Mr. Stubbs's brother was to be shut up in a cage, Toby would have thought it a very great hardship for his pet to endure; but the experience he had had in the last twenty-four hours convinced him that the imprisonment was for the best.

He helped Uncle Daniel in his labor to such purpose that when it was time for him to go to the pasture the cage was built, and Mr. Stubbs's brother was in it, looking as if he considered himself a thoroughly abused monkey, because he was not allowed to play just such pranks as had roused the household as well as broken up the circus scheme.

On his way to the pasture Toby met Joe, and the two had a long talk about the disaster of the afternoon. Joe believed that the enterprise must be abandoned—for that summer at least—as it would take them some time to repair the damage done, and his short experience in the business caused him to believe that they could hardly hope to compete with real circuses until they had more material with which to work.

Joe promised to see the other partners that evening or the next morning, and if they were of the same opinion, the tent should be taken down and returned to its owner.

"Perhaps we can fix it all right next year, an' then Abner will be 'round to help," said Toby, as he parted with Joe that night; and thus was the circus project ended very sensibly, for the chances were that it would have been a failure if they had attempted to give their exhibition.

During that afternoon Toby had worried less about Abner than on any day since he had been sick. He had felt that his friend's recovery was certain, and a load was lifted from his shoulders when he and Joe had decided regarding the circus; for, that out of the way, he could devote all his attention to his sick friend. Surely, with the ponies and the monkey they could have a great deal of sport during the two weeks that yet remained before school would begin, and Toby felt thoroughly happy.

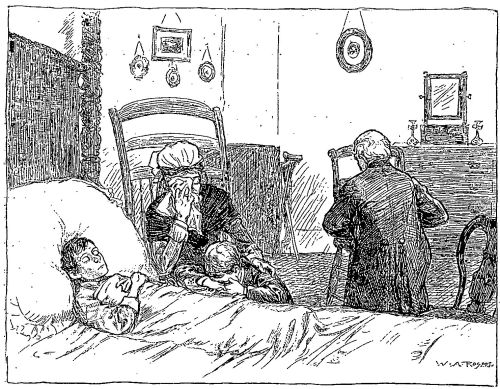

But his happiness was changed to alarm very soon after he entered the house, for the doctor was there again, and from the look on the faces of Uncle Daniel and Aunt Olive he knew Abner must be worse.

"What is it, Uncle Dan'l? is Abner any sicker?" he asked, with quivering lip, as he looked up at the wrinkled face that ever wore a kindly look for him.

Uncle Daniel laid his hand affectionately on the head of the boy whom he had cared for with the tenderness of a father since the day he repented and asked forgiveness for having run away, and his voice trembled as he said:

"It is very likely that the good God will take the crippled boy to Himself to-night, Toby, and there in the heavenly mansions will he find relief from all his pain and infirmities. Then the poor-farm boy will no longer be an orphan or deformed, but with his Almighty Father will enter into such joys as we can have no conception of."

"Oh, Uncle Dan'l! must Abner really die?" cried Toby, while the great tears chased each other down his cheeks, and he hid his face on Uncle Daniel's knee.

"He will die here, Toby boy, but it is simply an awakening into a perfect, glorious life, to which I pray that both you and I may be prepared to go when our Father calls us."

"THE GREAT WHITE-WINGED MESSENGER OF GOD CAME."

"THE GREAT WHITE-WINGED MESSENGER OF GOD CAME."

For some time there was silence in the room, broken only by Toby's sobs; and while Uncle Daniel stroked the weeping boy's head, the great white-winged messenger of God came into the chamber above, bearing away with him the spirit of the poor-farm boy.

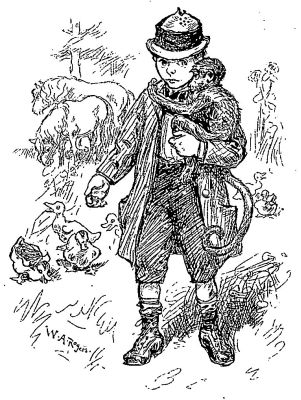

"WHERE DID YOU COME FROM?"

"WHERE DID YOU COME FROM?"

"I reckon them plaguey crows are goin' to eat up all the corn," said 'Lisha one morning during a discussion with Mr. Thompson regarding the weather, the state of the crops, and so forth.

"Hm!" said Mr. Thompson; then paused as if immersed in thought. "Hm!" he continued; "I have read that in England children are employed to keep the crows off the corn."

"Reckon corn can't pay a very big profit there, if they have to take the child's wages out of the price of the crop," commented 'Lisha.

"And it struck me," continued Mr. Thompson, not heeding the interruption, "that I might sit in the field and read, and at the same time keep the crows away."

"I s'pose you could, ef you didn't go to sleep," replied 'Lisha, with a sly laugh.

Mr. Thompson sniffed indignantly, and after a little more talk it was decided that he should take his book and sit in the corner of the field. After he had settled himself comfortably, and read several pages, he began to feel drowsy. His book dropped on his knee, and his thoughts turned to the crows.

"I wonder what they pull up the corn for?" he murmured. "They don't seem to eat it."

"'Cause," replied a coarse voice just behind him.

"'Cause why?" inquired Mr. Thompson.

"'Cause we do eat some, and we pull up the rest for fun," replied the voice.

Mr. Thompson turned to look: there was a big crow sitting on the fence gazing at him curiously, his black head was cocked on one side, and his bead-like eyes were full of mischief.

"Don't you know that is very wicked?" said Mr. Thompson, severely.

"Humph!" croaked the crow, contemptuously. "If you was a crow, you'd feel differently."

"I should always feel like doing right," said Mr. Thompson.

"Try it, and see," croaked the crow.

Mr. Thompson felt himself shrinking, and his black coat was changing to feathers.

No sooner had the change become complete than he felt an irresistible desire to pull up a hill of corn. As soon as he had uprooted one, he was filled with joy and a desire to destroy. He went to work with a will, and in a few minutes had pulled up quite a number.

"I thought that was very wicked," croaked a hoarse voice, with a tone of sarcasm.

Mr. Thompson paused a moment. "It is," he admitted. "But," he added, "it is such fun; and then men shoot us at every possible opportunity. It is no more than fair that we should get even with them."

"You talk like a sensible crow," said his companion. "But here comes a man;" and he uttered a derisive "Caw!" as he flew off, followed by Mr. Thompson.

"Let's go down to the shore," remarked the crow, as they came in sight of Long Island Sound.

Soon they were on the shore of a little creek that came in from the Sound. Mr. Thompson and his companion walked along the edge of the water, when suddenly Mr. Thompson spied a soft crab. He made a quick snatch for it, and caught it. His companion looked on in disdain.

"Humph!" he said, "who wants a crab? I've got a clam."

"What good is a clam?" retorted Mr. Thompson. "You can't open it."

"Can't I, though?" and the crow took the clam in his beak, flew high over the stony beach, and dropped it. The shell cracked, and the crow ate the clam with a relish.

"Look out! here comes a kingbird!"

Suddenly, with an angry cry, a small gray bird swooped down upon them, and making a vigorous peck at Mr. Thompson's eye, dashed off before he could retaliate.

"Come on," cried the old crow: "there is no use of sitting still and getting our eyes picked out."

They flew as rapidly as they could over toward the corn field, the kingbird following them a part of the way. When they reached the field, the crow alighted on the head of a stuffed figure which the farmer had set up for a scarecrow. Mr. Thompson settled on the outstretched arm.

"Yes," said the old crow, as if continuing a previous conversation—"yes, it amuses me to see the way these farmers think to frighten us with their stuffed figures. Now anything that is in motion, like that bunch of feathers over there, really does scare me, for I never know how far it will swing; but the idea of any intelligent crow being frightened at this thing—why, it is preposterous. And then the contemptible way in which they treat us, too—shooting us whenever they have a chance. Now there comes a crowd up the road in a wagon. They won't hurt us; they are afraid to shoot when the horses are around. Hullo! one man is getting out, and, as I live, he has a gun. Let's be off."

But Mr. Thompson got confused, and instead of flying away, he flapped heavily toward the corner of the field, and alighted beside his book. The man with the gun crawled cautiously up to the fence. It was 'Lisha.

"Wa'al, I vow, ef here ain't Mr. Thompson fast asleep!" he muttered. "I'll give him a scare;" and cocking his gun, he discharged it close to Mr. Thompson.

Mr. Thompson jumped up, and looked around savagely. "What are you shooting at?" he demanded, sharply.

"Nothin' in particular," replied 'Lisha, somewhat abashed. "I tried to shoot a crow, but the pesky thing flew off."

"Of course he did. We saw you get out of the wagon, and he knew you had come to murder him," said Mr. Thompson, severely.

'Lisha looked at him in surprise. "I reckon you've been asleep," he ventured. "You cum out to keep the crows off the corn, and when I cum here, thar was two settin' on the scarecrow."

"Yes," replied Mr. Thompson, calmly, "that was my friend and me;" and he walked majestically toward the house.

'Lisha looked at him in open-mouthed amazement. "Wa'al, I vow, he do hev the funniest dreams!" he muttered. "But," he added, after a moment's reflection, "it 'pears to me one of them crows did fly over to this corner." And 'Lisha shouldered his gun and walked home, speculating upon the eccentricities of the "city boarder."

I wonder how many of the readers of the Young People, while watching the vivid flashes of lightning during a summer-storm, have ever asked the question, What is lightning? This problem has puzzled many old and wise heads, and the solution is apparently as far off as ever.

Scientific men are agreed that lightning is electricity, differing in no wise from that which can be produced by rubbing a piece of amber or by an electrical machine, except in power; but of what might be called the inner nature of this electricity they are quite ignorant. They can only observe and study its effects.

Lightning is divided into two kinds, which you will recognize under the names of sheet and forked lightning. Sheet lightning is supposed to be caused by the discharge of electricity over a large space, while forked[Pg 667] lightning consists of a ball of fire rushing with exceeding swiftness through the air, and very often destroying everything in its way.

The passage of one of these fire-balls is nearly always in a zigzag line, and so rapidly does it travel that it always presents to the eye the appearance of an unbroken line. It has not yet been possible to measure its rate of speed, but it exceeds that of light, which is 185,000 miles in a second. Some of the flashes of lightning have been estimated at more than ten miles in length, while those from five to eight miles long are not so uncommon. The brilliancy of some of these flashes is so great that cases are on record where a flash has rendered the beholder incurably blind.

The idea that electricity and lightning were one and the same seems to have been first entertained about the middle of the seventeenth century. Many experiments were made to establish the relationship, but without any decisive result, when one of our own countrymen, Benjamin Franklin, gave a new impulse to the science. After a number of experiments, he was impressed with the idea that a metal point raised to a great height in the air would form a conductor for the electricity stored in the thunder-clouds.

Too impatient to wait for the completion of a church steeple which he intended to make use of in his investigations, he prepared a kite, using silk to enable it to withstand rain, and with it made his early experiments—at first privately, because of the fear that his neighbors would ridicule an old man's kite-flying. He raised the kite during a storm, and was delighted to feel, on applying his finger to the string, a slight spark. For the first time man had succeeded in coaxing the lightning from the clouds, and playing with it. This occurred in 1752.

Scientific men everywhere now began to devote themselves to the study of electricity. It was discovered that lightning burns its way, setting fire even to metals, and melting sand into glass by momentary contact. A striking illustration of its intense heat are the fulgurites, or curious glass tubes, produced from sand by lightning as follows: In certain places, where the ground is formed of a particular kind of sand, and lightning enters it from a cloud, the expansion of the air, as the electricity rushes through, forces it back in all directions, and the heat melts it into glass at the same time. These tubes have a diameter of one or two inches, and ordinarily a length of two or three feet. The interior surface is glazed, while the outside is formed of sand. Many have been taken out of the ground entire, and placed in museums as curiosities. It is said that fulgurites twenty to thirty feet in length have been discovered.

The experiments of the men to whom we are indebted for our knowledge of these marvels of nature are not always unattended with danger. In 1753, Richman, a member of the St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences, had an iron rod for the attraction of electricity erected on his house and continued down into his study, in order to be better able to observe its effects. During a violent storm he was working at some distance from the conductor in order to be out of the way of the large sparks. He at last incautiously approached too near, when a globe of bluish fire struck him on the forehead, killing him instantly.

The following incident illustrates the danger of being in a direct line with any article of iron during a storm. A number of people were assembled in one room of a house, conversing and watching the play of the lightning, when one of their number was struck and instantly killed by a flash that came from overhead. The death of this one man and the escape of all the rest were at first regarded as one of the freaks of which lightning is frequently guilty, but a close search revealed the fact that the accident was strictly in accordance with natural laws. It was found that in the room above, there hung a saw, one end of it nearly touching the floor directly over the man's head, while in the cellar below were a number of iron tools, among them a crowbar standing in such a position that the upper end of it was directly beneath his feet. His body had therefore only been a connecting link in the chain along which the lightning had travelled.

Another incident, but of a less tragic character, is the following. During a violent thunder-storm lightning struck a farm-house; a ball of fire descended through the chimney, and rolled across the floor of a room in which three women and a child were sitting without injuring them. It then rolled out through the kitchen, passing close to the feet of a young man, and passed out through a crevice in the wall. It next appeared in the pig-sty, and killed the pig without burning the straw on which it lay.

In olden times, before the study of the natural sciences was undertaken, every occurrence out of the common was thought to be an act of Divine power. Even in our days this idea has not entirely died out, and in those countries where people are ignorant lightning is still regarded as a mark of God's anger and a visitation sent for the punishment of sin. But with the spread of scientific knowledge it has been robbed of its terrors, and in the lightning-rod a means has been given us of attracting and controlling the electric current, and thus protecting ourselves from harm.

POOR OLD DOBBIN!

POOR OLD DOBBIN!

It was one of the happiest moments of Jube Rosewood's life when, as he was passing Farmer Tappan's melon patch one day, the owner hailed him, and exclaimed:

"Jube, I promised you a reward for driving old Brindle home the other morning, and now if you will jump over that fence and take your pick of those water-melons, you can tote it along home with you."

Jube was one of the blackest little fellows that had ever basked in the sunlight of a Georgia plantation, but his eyes and teeth flashed out such a gleam of joy at this golden promise that his swarthy face seemed like a dark lantern with the slide suddenly turned as he made the delighted response:

"Mars' Tappan, you's fetched me right whar I's lierble ter feel mo' bleedzd to yer dan ef yo'd sot me down in a merlasses bar'l. I'll be dar 'fo' yo' min' gits a chance ter drif out o' dat rut." With this Jube bounded over the old rail fence, and in a moment was at Farmer Tappan's side, gazing critically and with some little wonderment at the streaked delicacies rounding out here and there from their lowly canopies of green.

So eager was the happy boy to show his appreciation of the situation, and of the possibility of the farmer's regretting his generosity, that he sprang toward the first plump specimen of the oblong fruit which he saw, and tapping its dainty shell, exclaimed:

"I reckon dis'n's 'bout my meshur, an' ef yo' sez de word, I'll onhitch de goodie, an' 'scort it down to der Rosewood shanty wid yo' compelments."

"All right, Jube," returned the farmer; "take it along if you can carry it. The fruit isn't any bigger than the thanks I owe you, but I'm afraid it is a size or two beyond your strength to carry."

"Don't let dat onsettle yo', Mars' Tappan," said Jube, as he got down on his "hunkies" to pick his prize package. "Dis chile's 'fection fo' dis wegetable am strong 'nuff ter gar'nty dat it won' get outer reach atter der grip's been tuk on it, an' dat yo' kin 'pen' on." With this remark Jube broke the stem, and thrusting his arms under the curving ends of his game, staggeringly lifted it from the ground.

Now Jube had a little brother at home who was every bit as big as that[Pg 668] water-melon, and because he had carried him about very often in mere play, he thought there would not be any trouble about managing this inoffensive specimen of garden truck. Jube forgot, however, that the water-melon didn't have any arms to catch hold with, and no wrinkly trousers to catch hold of, and besides it was smooth and bunchy, and would spoil a good deal easier if it should happen to drop. He had no more than tottered through the rails that Farmer Tappan had let down for him than he began to feel as if he had a baby elephant in his arms, and before he had struggled a hundred feet down the road, he imagined the elephant had grown big enough to be its own grandfather.

"I 'clar' ter sakes!" he exclaimed, as, turning a bend in the highway, he was enabled unseen by the farmer to put his burden in keeping of a moss bank for a while—"I 'clar' ter sakes ef dat ar' 'freshment don' 'pear ter be stuff' wid cookin'-stoves. 'Pears like ef a man wuz lookin' fo' sumfin dat wuz easy ter drop, dis yarb'd come closer ter de mark dan a bees' nes'." Then, apparently addressing the melon, he continued: "But yo'm gotter come 'long wid me. I sot out ter see yer hum, an' dar's whar yo'm gonter lan' up, 'less yo' grows till yo's de size ob a fo'-hoss wagon."

Hereupon, Jube bent down to gather up his burden again, and after bracing himself as if he was going to pull up a tree by the roots, and gritting his teeth in a way that might have frightened a smaller melon, he began to joggle himself along his journey once more. He had fixed his trophy in such a way that his chest was made to form part of the support, and with arms beneath for a prop, he bobbed along with his head thrown away back to the rear of the procession, and his waist poked far enough out in front to give the idea that he was sending it on ahead to let the folks know he was coming. It was jostle and sway, and tug and stagger, every inch of the way, and I am not sure but it would have suggested to you a lone tumble-bug working his dirt-ball along a dusty highway.

Coming to the top of a hill, the overburdened boy was obliged to rest again, and depositing his responsibility upon a convenient brush heap, he straightened out the kinks in his back, brushed the perspiration from his brow with his shirt sleeve, and taking a long breath, again addressed the unconscious water-melon.

"Well, dar! ef yo' hain't been swallyin' a stun fence, den my gumpshun's slip out froo a crack somewhars sho 'nuff. Whatsumever's inside dat ar' speckle hide o' yo'n dis chile dunno, but ef yo'm as wuff eatin' as yo'm heaby totin', dar's mo' sweetmeats waitin' fo' der fam'ly whar I's gwine ter interduce ye dan dey's had in a mont' er Sund'ys."

Here Jube took another survey of the situation, and as his eye followed the range of the rather steep roadway, and rested on a whitewashed cabin at its foot, a look of pleasure and confidence spread over his face as he said:

"Dar's mammy's cabin, sartin. An' dar's whar dis yar water-million's gwinter fotch up; an' ef dar's any mo' easier way o' gettin' it dar dan losin' it, Jube hain't one o' der Rosewoods dat's 'quainted wid der fac'."

It was but the work of a moment for Jube to get the melon to the brow of the hill, and, poising it there, he gave it a rather smart push with his foot, and away it went down the steep. At the start, the wobbly, end-to-end movement by which it progressed indicated a rather tardy arrival at the Rosewood estate, but rounding the first knoll, and getting the sudden impetus of its dip, the enterprise of that fruit was so remarkable that Jube, with his legs going like a pair of drumsticks, could hardly keep up with it. Another bulge in the roadway jumped, and a livelier pace was imparted to the melon, and, panting like a winded hound, Jube threw out his half-shod feet with frantic energy, shouting all the time:

"Hol' on dar! Hol' on dar! Yo'll lan' in de stun fence sho', an' squash all yo' nat'al senses!"

Alas that the water-melon didn't take warning! As it reached the foot of the hill, and passed the Rosewood cabin, where Jube's brothers and sisters were wonderingly watching the chase, the boy's foot slipped on a cobble-stone, and as the melon rolled into a little gulley, head-first into its bulging surface landed the unfortunate Jube.

Was he hurt? Bless you, no. He was a little staggered, perhaps, but as between him and the water-melon, had you been there to have witnessed the result, you would surely have given your every ounce of sympathy to the melon. It was turned completely inside out, and spread over the grass-plot in every direction. Wasn't there a scene when Jube got himself to rights, shook the melon pits out of his hair, and shouted:

"Hey! Heyo! Clem! Cuffle! Mimy! Zekal! Pheby! Shuffle ober here libely an' he'p me sop up dese 'freshments. Dey's goin' to waste."

Almost in the wink of an eye about a dozen dusky youngsters were assembled at the scene of the wreck, and as they distributed themselves about the remains, and began a-feasting, the looks that gleamed from the eyes bulging over the green rims of an array of fruit fragments told how thoroughly they appreciated the inquest of Jube's water-melon.

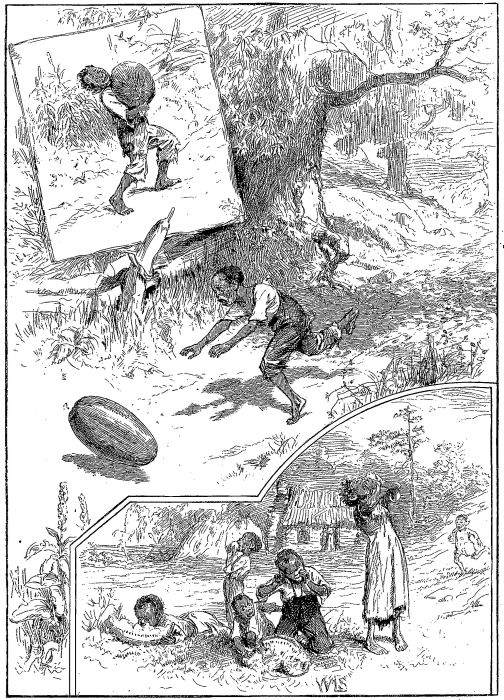

JUBE'S WATER-MELON.

JUBE'S WATER-MELON.

A dear little girl writes the Postmistress that she is very much frightened whenever there is a thunder-shower. The sharp flashes of lightning and the loud claps of thunder terrify her, and she always runs and hides in her mamma's lap.

Well, darling Effie, you could not find a better place to hide. But I want you to remember that the beautiful summer showers do a great deal of good. Have you ever noticed how pure and sweet the air is after the storm is over, and do you not love to watch the rainbow when its arch is in the sky?

Once, dear, a long while ago, when I was a little girl, a very heavy thunder-storm came up in the afternoon. It grew so dark that in the school-room, where we girls were gathered for our lessons, we could not see each other's faces. We put away our books, and our kind teacher told us a story to divert our minds. By-and-by, when the sun shone, and the sky looked blue, and the rain-drops glittered on the bushes and the long blades of grass, we sang a beautiful German choral, and I have never forgotten the opening words:

"It thunders, but I tremble not,

My trust is firm in God;

His arm of strength I ever sought

Through all the way I've trod."

Galveston, Texas.

Galveston is on the sea-coast, and has a splendid beach. There is a beautiful pavilion on it, and a great many bathing-houses. I have been bathing twice this summer, and it is perfectly delightful. Several nights in the week they have music, and sky-rockets are shot off. The beach is a great place for driving. Every evening carriages and vehicles of every description are passing up and down. The last time I was there a buggy ran over a little boy, and he was badly hurt.

Ethel T. S.

New York City.

I am a little St. Louis girl, but am now living in New York.

I am ten years of age, and have taken music lessons three years, and like music very much.

I have a pet bird named Jimmie; he will eat out of my hand, and is very tame.

My little brother Edgar is five years old, and mamma has just put his first pants on him, and he looks so cunning marching round with his hands in his pocket, and thinks he is quite a man. I almost envy the little boys and girls who have nice gardens. I have one, but it is a funny one; it is in a window, for we have no yard. We live in a flat, but I am very fond of flowers, and so keep them in a window. Some of your little readers may laugh at this, but it is the best I can have, and it affords me a great deal of pleasure.

Mamma was reading in No. 138 a letter signed "C. Harold C.," from Mount Vernon, New York, of a little boy who could not pronounce F. If his mamma will take him to a physician and have his tongue examined, she may find that he is tongue-tied, although you would hardly believe it. But my little brother was troubled the same way; he would say sishes for fishes, shogs for frogs, etc, etc. The doctor said he was tongue-tied and cut his tongue, and in a few minutes he said fishes as plain as any one. Mamma used to try and make him say words with F in in this way: she would say, "Edgar, say F." He would pronounce F very distinctly. Now mamma would say, "Say fishes." But he could not. So one day he says to mamma, "Mamma, say F; now say mustard."

Robin D.

The little boy who can not pronounce "f" may be tongue-tied, and then again he may not be. I knew a little girl once who spoke so very peculiarly until she was ten years old that people wondered what queer foreign language Minnie used. But all at once she began to talk plainly, as she has done ever since without the help of a physician.

Montreal, Canada.

I wrote you a letter some time ago, and asked you to print it; but you did not, and you don't know how sorry I felt. I do hope you will print this. I am ten years of age. I have two dear little brothers, one named Mello and the other Garibaldi, and a sweet little sister named Minnie; they all like Young People very much, especially little Mello, who delights to sit for hours looking at the pictures. I have two dear little pet squirrels, which we caught on the mountain in little traps. We put a small piece of apple in the trap, and set it on the fence that runs up the side of the mountain, and it is great fun to watch them go in the traps. We have caught more than a dozen that way. I have been to New York two or three times, and to Philadelphia to see the Centennial Exhibition. Did you go to it? and if so, don't you think it was splendid? I go to school, and like it very much. I got the prize for Grecian history this year. Don't you think that was very well for a little girl only ten? I am going away next week to visit a dear little girl named Dagmar, but I am only to stay about two weeks, and when I return I hope to see my letter in Young People. I think "Toby Tyler" is splendid, but I like Jimmy Brown's letters best.

May R.

Of course, dear May, you set the little squirrels free soon after catching them. Although they are very cunning pets, I can not help feeling sorry for them when shut up in cages, for they so dearly love their liberty, and are so merry when leaping from bough to bough in the woods.

The cunning little letter which follows was the first effort of a wee bit of a girlie whose papa had gone from home on a visit:

Bigelow Place, Cincinnati, Ohio.

Dear Papa,—I miss you so much! We are going to have a water-melon for dinner to-day. I love water-melons. But I love you the best. We had a nawful storm yesterday, and it blew the roof off a house on Walker Street. I guess the people got wet. My neck is tired bending over. I wish you many happy returns.

Your little baby Lula.

Here is another bright little letter from a wee girlie to her papa:

Bridgehamton, Long Island.

Dear Papa,—I hope you will come this afternoon, and bring me home—come after two o'clock; I will be all ready. I want to know how many tricks you have taught Gip [Scotch terrier]? How large is Gip? How are my kittens? I don't know whether they are dead; are they? Are they fed? How is Tom [cat]? Please bring the puppy with you when you come down, but don't fill his stomach with meat—'tis too indigestible. I helped to hunt the eggs yesterday, and we got over a hundred. Papa, I have a great many little mats, pretty as silk, made out of thistles flattened out, and they are the prettiest little thistles you ever did see, but they were the coarsest little thistles when Mary [nurse] picked them, just like "needles and pins." There are some little pet birds here, but we don't have to feed them. We can't bring them home; we will have to leave them here. This is the last of my letter; I can't write any more. Do you want to know why? The flies are bothering me so.

Lisa D.

Utica, New York.

I am nine years old to-day. I received as a present a card album that will hold 700 cards. We have a large yard, and in it a large tent. I had a birthday party last year, and we had a supper in the tent, at which fifty sat down at one time. I like "Mr. Stubbs's Brother," and am so glad Abner did not die.

Arthur E. J.

Bradford, New Hampshire.

Dear Postmistress,—I am a little girl of eleven, living in Massasechem Valley beside a beautiful lake, which affords great pleasure to many. I have three sisters and one brother. We have twelve English Jacobin doves, a little shepherd dog, a lamb, and a kitty for pets. I have taken Harper's Young People ever since it was first published, and I enjoy the stories very much. I think Ninetta's poem was real nice. She is just the age of my sister Ida. I think Toby Tyler has a hard time losing his pets. He must feel very sad and lonesome now Mr. Stubbs's brother is gone, but I hope he will recover him soon.

Marian F. D.

Thyatira, Mississippi.

I have written two letters to Our Post-office Box which have not been published; however, I will try again. I have been taking Young People for nearly two years. I like all the stories, but "Toby Tyler" and "Mr. Stubbs's Brother" are the best of all. I am a little boy ten years old. I work on the farm, but have just finished, and began to go to school last Monday. I have no pets except one sweet little sister; her name is Lucy, and she is just the sweetest child in the world. She is fourteen months old, can walk and talk some, and says, "Just lookie dar," and "Who is dat?"

Jack C.

Salem, Oregon.

I am a little girl twelve years old. I live with my papa and mamma on a large farm. I have three little sisters and one brother. I have been taking Harper's Young People for almost a year now, and like it very much. I have not very many pets. I have a horse, a little colt, and a cow with a calf. Mamma has two little Maltese kittens, and they are very pretty. We spent one winter out in Southern Oregon, where my papa owns a gold mine. It was very lonesome there, as there were very few neighbors. My two sisters and I go to school. The school-house is almost a mile from home. My youngest sister is the baby; she is thirteen months old, but she can not walk yet.

Deadie A.

Summit, New Jersey.

I am a little boy eleven years and a half old. I have been taking Young People since October, 1881, and like it very much. I have a sister and brother, each younger than I, and we have three birds' nests in our yard, and each one of the birds has four little ones. We fed them when they were little, but the mother did not like it, and one rainy day she threw one of them out of the nest, and we put it back again, and she kept it, and we never fed the birds again. I like "Talking Leaves" and Jimmy Brown's stories best, and I hope Jimmy Brown will write some more soon.

R. M. G.

What a naughty mother-bird! But maybe she knew better than you did what was good for her children. I think the little birdie must have fallen out by accident.

Lansing, Michigan.

The schools in our city have closed, and I am so glad, for we are going away to spend vacation. We are going to a pleasant resort called Harbor Point, on Lake Michigan, in the northern part of the State. We have a cottage there, and have delightful times boating and bathing in the surf. Does the Postmistress like the stories of Charles Dickens, and if so, which is her favorite one? Here are two verses I made up to-day:

Only a silver spoon,

Thin and battered and old,

Yet he thought he'd keep it for ever and e'er,

For ever and e'er to hold.

"Oh, take it not," said the maiden—

"Oh, take it not away,"

But the tramp put it in his pocket.

And went upon his way.

Chub.

Yes, dear, I am very fond of all Charles Dickens's stories, and my favorite one is, I think, Our Mutual Friend. Yet I am not sure, for I like The Tale of Two Cities very much, and I am about to read Bleak House for the fifth or sixth time. The little maiden in your verses should have taken better care of her spoon.

Waretown, New Jersey.

I am eight years old. I live in the country. I have a little brother Fred, and a little baby sister Alice. We had for a pet a shepherd dog named Colonel, but he ran away. I took Young People last year, and Fred takes it this. I like "The Cruise of the 'Ghost'" best. Grandpa gave Fred and me a nice fishing-pole, and takes us fishing, and sometimes we catch lots of fish. I have been to school part of a term; it is vacation now. I wrote this myself. I like to read the letters from the little girls and boys.

Ralph H. C.

Carrollton, Missouri.

My papa gave me Young People for a Christmas present; I like it very much. I am ten years old. I have twenty-five dolls; my largest is a wax doll thirty inches long. I have a play-house, a set of furniture, a set of dishes, a little trunk, and a real little cook stove that I can cook on. We have a swing and a hammock. I have a dear papa and mamma, but no brother or sister. We have a canary-bird. I wish the Postmistress would tell Jimmy Brown to write some more.

Edith C.

Twenty-five dolls! Dear me! what a large family! Don't you sometimes feel like the little old woman who lived in her shoe, and had so many children she did not know what to do? She gave them some broth, without any bread, and whipped them all round, poor things! and sent them to bed. You, I am sure, are not so unkind to your dollies as the poor bothered old lady of the shoe.

Brooklyn, New York.

I am going to tell you about my pets. I have a terrier named Jack. I like him very much. If I throw a stick, he will run and bring it to me. I have seven land turtles and two water turtles. There is one big turtle which I call grandfather of them all. I am very fond of them. I sunk half of a barrel in the ground, and I keep it filled with water for them to drink and swim in. They are all the time digging in the ground. I have fifty pigeons of all colors, and I have ten young ones. I like to watch the old ones feed their young; they are so cunning about it. We have a big old cat named Tom, and two canary-birds; so you see I have plenty of pets. My sister took me over to New York to see your big building, and to buy the story of "Toby Tyler." I have been taking Young People two years, and think it is splendid. I think "Mr. Stubbs's Brother" is very nice, and I hope when it is ended that you will publish it as[Pg 671] you did "Toby Tyler." If you do so, my mother intends to give me money to buy it. I think I will close my letter with my best thanks to you and Mr. Otis for writing such nice stories.

Jesse W. P.

They built a fort upon the shore,

With merry heedless din.

They never spied the evening tide

Was rolling, rolling in.

They made it firm and fast without,

They made it firm within.

But evermore along the shore

The tide was rolling in.

Without a fear they slept that night,

But when they went next day,

They found no sign, no stone, no line—

The fort was washed away.

'Tis ever so, my little men; you'll find it, one and all,

That forts, not only those of sand, are very apt to fall.

But if they fall, why, let them fall; away with doubt and dread,

And build again with might and main a better fort instead.

Sanbornton, New Hampshire.

My dear Postmistress,—I was so glad to see your kind answer to my letter in the C. Y. P. R. U. Perhaps you don't remember me, but I am the girl who was reading so many exciting novels, and you kindly suggested more solid and less exciting reading. Mamma said the same things you did, and disliked to have me read so many love stories, but I was so fond of them. Now I am not reading any of them. The only novel I have read for ever so long is one, by Auerbach, called Edelweiss, and it is a lovely book, I think, and so does mamma, but really I don't care so much about reading when here in the country as I did in Worcester, for there are so many other things to take my attention.

We are at the old homestead, where papa used to live when he was a little boy, and there are such lovely walks and drives all about here. A few days ago I ascended my first mountain. Papa and I drove to the first pair of "bars" on the mountain-road, and tied the horse there, and then we climbed the mountain (Mount Atkinson). It was a long hard climb, but the view when we reached the top paid for all our trouble. We could see blue Lake Winnipiseogee in the distance, and on our left was Mount Lafayette, with little Victory Mountain, close beside it. Further east was Chicorowa, Passaconoway, off in the east the Unconoonocks, and then came Monadnock, and even our Worcester mountain, Wachusett, besides a great many others whose names I can not remember.

After we had staid on the summit some time enjoying the beautiful view, we came down, found Leonard (the horse), and drove home. It was a beautiful ride, and we appreciated it after our toil. This afternoon I shall take Leonard, and drive over to the post-office, about two miles away. When it is too warm to walk or ride, I lie in the hammock and read. Isn't Butcher and Lang's translation of the Odyssey beautiful? But I must close this long letter.

We children have our dear Young People forwarded to us here, and we enjoy it so much.

I was very much interested in the beautiful picture and interesting account of St. Elizabeth in the last Young People. I had heard the legend of St. Elizabeth and the Roses before, and think it is a charming story. I never saw a paper with such beautiful pictures in it as Harper's Young People has; and I especially like W. A. Rogers's pictures, because he illustrated dear "Toby Tyler." But, dear Postmistress, I must stop, and I really think I like oth er things besides novels a great deal better than I used to.

Olive R.

It is very pleasant, indeed, to receive such a letter as this, and to find that one's advice has been so willingly taken. You were well repaid, dear, for your trouble in climbing the mountain. Yes, you may send your exchange again.