Very truly your friend,

Wm. Wells Brown.

ii

Title: My Southern Home: Or, the South and Its People

Author: William Wells Brown

Release date: March 23, 2019 [eBook #59114]

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by hekula03, Wayne Hammond, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team (http://www.pgdp.net) from page images generously made available by the Google Books Library Project (https://books.google.com)

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through the Google Books Library Project. See https://books.google.com/books?id=-q5EAQAAMAAJ&hl=en |

i

Very truly your friend,

Wm. Wells Brown.

ii

Copyright, 1880,

BY ANNIE G. BROWN.

electrotyped and printed by

Duffy, Cashman & Co., Fayette Court, Boston.

iv

No attempt has been made to create heroes or heroines, or to appeal to the imagination or the heart.

The earlier incidents were written out from the author’s recollections. The later sketches here given, are the results of recent visits to the South, where the incidents were jotted down at the time of their occurrence, or as they fell from the lips of the narrators, and in their own unadorned dialect.

Boston, May, 1880. v

| I. |

|---|

| Poplar Farm and its occupants. Southern Characteristics. Coon-Hunting and its results. Sunny side of Slave life on the Plantation. |

| II. |

| The Religious Teaching at Poplar Farm. Rev. Mr. Pinchen. A Model Southern Preacher. Religious Influence among the Southerners of the olden time. Genuine negro wit. |

| III. |

| A Southern country Doctor. Ancient mode of “pulling teeth.” Dinkie the King of the Voudoos. |

| IV. |

| The Parson and the Slave Trader. Slave life. Jumping the Broomstick. Plantation humor. |

| V. |

| An attempt to introduce Northern ideas. The new Plough. The Washing-Machine. Cheese-making. |

| VI. |

| Southern Amusements,—Wit and Humor. Superstition. Fortune-Telling in the olden time. |

| VII. |

| The Goopher King—his dealings with the Devil; he is feared by Whites and Blacks. How he mastered the Overseer. Hell exhibited in the Barn. |

| VIII. |

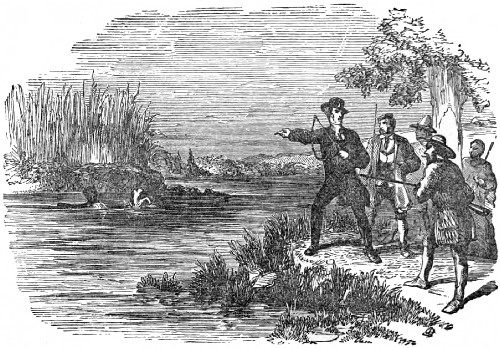

| Slave-Hunting. The Bloodhounds on the Track. The poor “white Trash.” A Sunday Meeting. A characteristic Sermon by one of their number.vi |

| IX. |

| Old-Fashioned Corn-Shucking. Plantation Songs: “Shuck that corn before you eat” an’ “Have that possum nice and sweet.” Christmas Holidays. |

| X. |

| The mysterious, veiled Lady. The white Slave Child. The beautiful Quadroon,—her heroic death. The Slave Trader and his Victim. Lola, the white Slave,—the Law’s Victim. |

| XI. |

| The introduction of the Cotton Gin, and its influence on the Price of Slaves. Great rise in Slave property. The great Southern Slave Trader. How a man got flogged when intended for another. |

| XII. |

| New Orleans in the olden time. A Congo Dance. Visiting the Angels, and chased by the Devil. A live Ghost. |

| XIII. |

| The Slave’s Escape. He is Captured, and again Escapes. How he outwitted the Slave-Catchers. Quaker Wit and Humor. |

| XIV. |

| The Free colored people of the South before the Rebellion. Their hard lot. Attempt to Enslave them. Re-opening of the African Slave Trade. Sentiments of distinguished Southern Fire-Eaters. |

| XV. |

| Southern control of the National Government. Their contempt for Northerners. Insult to Northern Statesmen. |

| XVI. |

| Proclamation of Emancipation. The last night of Slavery. Waiting for the Hour. Music from the Banjo on the Wall. Great rejoicing. Hunting friends. A Son known, Twenty Years after separation, by the Mark on the bottom of his Foot. vii |

| XVII. |

| Negro equality. Blacks must Paddle their own Canoe. The War of Races. |

| XVIII. |

| Blacks enjoying a Life of Freedom. Alabama negro Cotton-Growers. Negro street Peddlers; their music and their humors. A man with One Hundred Children. His experience. |

| XIX. |

| The whites of Tennessee,—their hatred to the negro,—their antecedents. Blacks in Southern Legislatures,—their brief Power. Re-converting a Daughter from her new Religion. Prayer and Switches do the work. |

| XX. |

| The Blacks. Their old customs still hang upon them. Revival Meetings. A characteristic Sermon. Costly churches for the Freedmen. Education. Return of a Son from College. |

| XXI. |

| The Freedmen’s Savings Bank. Confidence of the Blacks in the Institution. All thought it the hope for the negro of the South. The failure of the Bank and its bad influence. |

| XXII. |

| Old Virginia. The F. F. V’s of the olden times,—ex-millionaires carrying their own Baskets of Provisions from Market. John Jaspar, the eloquent negro Preacher; his Sermon, “The Sun does Move.” A characteristic Prayer. |

| XXIII. |

| Norfolk Market. Freedmen costermongers. Musical Hawkers. The Strawberry Woman. Humorous incidents. |

| XXIV. |

| The Education of the Blacks. Freedmen’s schools, colleges. White Teachers in Colored schools. Schools in Tennessee. Black pupils not allowed to Speak to White Teachers in the street. viii |

| XXV. |

| Oppressive Laws against Colored People. Revival of the Whipping Post. The Ku-Klux—their operations in Tennessee. Lynch Law triumphant. |

| XXVI. |

| Colored men as Servants,—their Improvidence. The love of Dress. Personal effort for Education. |

| XXVII. |

| Need of Combination. Should follow the Example set by the Irish, Germans, Italians, and Chinese who come to this country. Should patronize their own Race. Cadet Whittaker. Need of more Pluck. |

| XXVIII. |

| Total Abstinence from Intoxicating Drinks a necessary object for Self-Elevation. Intemperance and its Evils. Literary Associations. The Exodus. Emigration a Necessity. Should follow the Example of other Races. Professions and Trades needed. |

| XXIX. |

| Mixture of Races. The Anglo-Saxon. Isolated Races: The Negro—the Irish—the Coptic—the Jews—the Gypsies—the Romans, Mexicans, and Peruvians. Progressive Negroes,—Artists and Painters. Pride of Race.ix |

GREAT HOUSE AT POPLAR FARM. 1

Ten miles north of the city of St. Louis, in the State of Missouri, forty years ago, on a pleasant plain, sloping off toward a murmuring stream, stood a large frame-house, two stories high; in front was a beautiful lake, and, in the rear, an old orchard filled with apple, peach, pear, and plum trees, with boughs untrimmed, all bearing indifferent fruit. The mansion was surrounded with piazzas, covered with grape-vines, clematis, and passion flowers; the Pride of China mixed its oriental-looking foliage with the majestic magnolia, and the air was redolent with the fragrance of buds peeping out of every nook, and nodding upon you with a most unexpected welcome.

The tasteful hand of art, which shows itself in the grounds of European and New-England villas, was not seen there, but the lavish beauty and harmonious disorder of nature was permitted to take its own course, and exhibited a want of taste so commonly witnessed in the sunny South.

The killing effects of the tobacco plant upon the lands of “Poplar Farm,” was to be seen in the rank growth of the brier, the thistle, the burdock, and 2 the jimpson weed, showing themselves wherever the strong arm of the bondman had not kept them down.

Dr. Gaines, the proprietor of “Poplar Farm,” was a good-humored, sunny-sided old gentleman, who, always feeling happy himself, wanted everybody to enjoy the same blessing. Unfortunately for him, the Doctor had been born and brought up in Virginia, raised in a family claiming to be of the “F. F. V.’s,” but, in reality, was comparatively poor. Marrying Mrs. Sarah Scott Pepper, an accomplished widow lady of medium fortune, Dr. Gaines emigrated to Missouri, where he became a leading man in his locality.

Deeply imbued with religious feeling of the Calvinistic school, well-versed in the Scriptures, and having an abiding faith in the power of the Gospel to regenerate the world, the Doctor took great pleasure in presenting his views wherever his duties called him.

As a physician, he did not rank very high, for it was currently reported, and generally believed, that the father, finding his son unfit for mercantile business, or the law, determined to make him either a clergyman or a physician. Mr. Gaines, Senior, being somewhat superstitious, resolved not to settle the question too rashly in regard to the son’s profession, therefore, it is said, flipped a cent, feeling that “heads or tails” would be a better omen than his own judgment in the matter. Fortunately for the cause of religion, the head turned up in favor of 3 the medical profession. Nevertheless, the son often said that he believed God had destined him for the sacred calling, and devoted much of his time in exhorting his neighbors to seek repentance.

Most planters in our section cared but little about the religious training of their slaves, regarding them as they did their cattle,—an investment, the return of which was only to be considered in dollars and cents. Not so, however, with Dr. John Gaines, for he took special pride in looking after the spiritual welfare of his slaves, having them all in the “great house,” at family worship, night and morning.

On Sabbath mornings, reading of the Scriptures, and explaining the same, generally occupied from one to two hours, and often till half of the negroes present were fast asleep. The white members of the family did not take as kindly to the religious teaching of the doctor, as did the blacks.

For his Christian zeal, I had the greatest respect, for I always regarded him as a truly pious and conscientious man, willing at all times to give of his means the needful in spreading the Gospel.

Mrs. Sarah Gaines was a lady of considerable merit, well-educated, and of undoubted piety. If she did not join heartily in her husband’s religious enthusiasm, it was not for want of deep and genuine Christian feeling, but from the idea that he was of more humble origin than herself, and, therefore, was not a capable instructor.

This difference in birth, this difference in antecedents does much in the South to disturb family relations 4 wherever it exists, and Mrs. Gaines, when wishing to show her contempt for the Doctor’s opinions, would allude to her own parentage and birth in comparison to her husband’s. Thus, once, when they were having a “family jar,” she, with tears streaming down her cheeks, and wringing her hands, said,—

“My mother told me that I was a fool to marry a man so much beneath me,—one so much my inferior in society. And now you show it by hectoring and aggravating me all you can. But, never mind; I thank the Lord that He has given me religion and grace to stand it. Never mind, one of these days the Lord will make up His jewels,—take me home to glory, out of your sight,—and then I’ll be devilish glad of it!”

These scenes of unpleasantness, however, were not of everyday occurrence, and, therefore, the great house at the “Poplar Farm,” may be considered as having a happy family.

Slave children, with almost an alabaster complexion, straight hair, and blue eyes, whose mothers were jet black, or brown, were often a great source of annoyance in the Southern household, and especially to the mistress of the mansion.

Billy, a quadroon of eight or nine years, was amongst the young slaves, in the Doctor’s house, then being trained up for a servant. Any one taking a hasty glance at the lad would never suspect that a drop of negro blood coursed through his blue veins. A gentleman, whose acquaintance Dr. Gaines had 5 made, but who knew nothing of the latter’s family relations, called at the house in the Doctor’s absence. Mrs. Gaines received the stranger, and asked him to be seated, and remain till the host’s return. While thus waiting, the boy, Billy, had occasion to pass through the room. The stranger, presuming the lad to be a son of the Doctor, exclaimed, “How do you do?” and turning to the lady, said, “how much he looks like his father; I should have known it was the Doctor’s son, if I had met him in Mexico!”

With flushed countenance and excited voice, Mrs. Gaines informed the gentleman that the little fellow was “only a slave and nothing more.” After the stranger’s departure, Billy was seen pulling up grass in the garden, with bare head, neck and shoulders, while the rays of the burning sun appeared to melt the child.

This process was repeated every few days for the purpose of giving the slave the color that nature had refused it. And yet, Mrs. Gaines was not considered a cruel woman,—indeed she was regarded as a kind-feeling mistress. Billy, however, a few days later, experienced a roasting far more severe than the one he had got in the sun.

The morning was cool, and the breakfast table was spread near the fireplace, where a newly-built fire was blazing up. Mrs. Gaines, being seated near enough to feel very sensibly the increasing flames, ordered Billy to stand before her.

The lad at once complied. His thin clothing 6 giving him but little protection from the fire, the boy soon began to make up faces and to twist and move about, showing evident signs of suffering.

“What are you riggling about for?” asked the mistress. “It burns me,” replied the lad; “turn round, then,” said the mistress; and the slave commenced turning around, keeping it up till the lady arose from the table.

Billy, however, was not entirely without his crumbs of comfort. It was his duty to bring the hot biscuit from the kitchen to the great house table while the whites were at meal. The boy would often watch his opportunity, take a “cake” from the plate, and conceal it in his pocket till breakfast was over, and then enjoy his stolen gain. One morning Mrs. Gaines, observing that the boy kept moving about the room, after bringing in the “cakes,” and also seeing the little fellow’s pocket sticking out rather largely, and presuming that there was something hot there, said, “Come here.” The lad came up; she pressed her hand against the hot pocket, which caused the boy to jump back. Again the mistress repeated, “Come here,” and with the same result.

This, of course, set the whole room, servants and all, in a roar. Again and again the boy was ordered to “come up,” which he did, each time jumping back, until the heat of the biscuit was exhausted, and then he was made to take it out and throw it into the yard, where the geese seized it and held a carnival over it. Billy was heartily laughed at by his companions in the kitchen and the quarters, 7 and the large blister, caused by the hot biscuit, created merriment among the slaves, rather than sympathy for the lad.

Mrs. Gaines, being absent from home one day, and the rest of the family out of the house, Billy commenced playing with the shot-gun, which stood in the corner of the room, and which the boy supposed was unloaded; upon a corner shelf, just above the gun, stood a band-box, in which was neatly laid away all of Mrs. Gaines’ caps and cuffs, which, in those days, were in great use.

The gun having the flint lock, the boy amused himself with bringing down the hammer and striking fire. By this action powder was jarred into the pan, and the gun, which was heavily charged with shot, was discharged, the contents passing through the band-box of caps, cutting them literally to pieces and scattering them over the floor.

Billy gathered up the fragments, put them in the box and placed it upon the shelf,—he alone aware of the accident.

A few days later, and Mrs. Gaines was expecting company; she called to Hannah to get her a clean cap. The servant, in attempting to take down the box, exclaimed: “Lor, misses, ef de rats ain’t bin at dees caps an’ cut ’em all to pieces, jes look here.” With a degree of amazement not easily described the mistress beheld the fragments as they were emptied out upon the floor.

Just then a new idea struck Hannah, and she said: “I lay anything dat gun has been shootin’ off.” 8

“Where is Billy? Where is Billy?” exclaimed the mistress; “Where is Billy?” echoed Hannah; fearing that the lady would go into convulsions, I hastened out to look for the boy, but he was nowhere to be found; I returned only to find her weeping and wringing her hands, exclaiming, “O, I am ruined, I am ruined; the company’s coming and not a clean cap about the house; O, what shall I do, what shall I do?”

I tried to comfort her by suggesting that the servants might get one ready in time; Billy soon made his appearance, and looked on with wonderment; and, when asked how he came to shoot off the gun, declared that he knew nothing about it; and “ef de gun went off, it was of its own accord.” However, the boy admitted the snapping of the lock or trigger. A light whipping was all that he got, and for which he was well repaid by having an opportunity of telling how the “caps flew about the room when de gun went off.”

Relating the event some time after in the quarters he said: “I golly, you had aughty seen dem caps fly, and de dust and smok’ in de room. I thought de judgment day had come, sure nuff.” On the arrival of the company, Mrs. Gaines made a very presentable appearance, although the caps and laces had been destroyed. One of the visitors on this occasion was a young Mr. Sarpee, of St. Louis, who, although above twenty-one years of age, had never seen anything of country life, and, therefore, was very anxious to remain over night, and go on a 9 coon hunt. Dr. Gaines, being lame, could not accompany the gentleman, but sent Ike, Cato, and Sam; three of the most expert coon-hunters on the farm. Night came, and off went the young man and the boys on the coon hunt. The dogs scented game, after being about half an hour in the woods, to the great delight of Mr. Sarpee, who was armed with a double barrel pistol, which, he said, be carried both to “protect himself, and to shoot the coon.”

The halting of the boys and the quick, sharp bark of the dogs announced that the game was “treed,” and the gentleman from the city pressed forward with fond expectation of seeing the coon, and using his pistol. However, the boys soon raised the cry of “polecat, polecat; get out de way”; and at the same time, retreating as if they were afraid of an attack from the animal. Not so with Mr. Sarpee; he stood his ground, with pistol in hand, waiting to get a sight of the game. He was not long in suspense, for the white and black spotted creature soon made its appearance, at which the city gentleman opened fire upon the skunk, which attack was immediately answered by the animal, and in a manner that caused the young man to wish that he, too, had retreated with the boys. Such an odor, he had never before inhaled; and, what was worse, his face, head, hands and clothing was covered with the cause of the smell, and the gentleman, at once, said: “Come, let’s go home; I’ve got enough of coon-hunting.” But, didn’t the boys enjoy the fun. 10

The return of the party home was the signal for a hearty laugh, and all at the expense of the city gentleman. So great and disagreeable was the smell, that the young man had to go to the barn, where his clothing was removed, and he submitted to the process of washing by the servants. Soap, scrubbing brushes, towels, indeed, everything was brought into requisition, but all to no purpose. The skunk smell was there, and was likely to remain. Both family and visitors were at the breakfast table, the next morning, except Mr. Sarpee. He was still in the barn, where he had slept the previous night. Nor did there seem to be any hope that he would be able to visit the house, for the smell was intolerable. The substitution of a suit of the Doctor’s clothes for his own failed to remedy the odor.

Dinkie, the conjurer, was called in. He looked the young man over, shook his head in a knowing manner, and said it was a big job. Mr. Sarpee took out a Mexican silver dollar, handed it to the old negro, and told him to do his best. Dinkie smiled, and he thought that he could remove the smell.

His remedy was to dig a pit in the ground large enough to hold the man, put him in it, and cover him over with fresh earth; consequently, Mr. Sarpee was, after removing his entire clothing, buried, all except his head, while his clothing was served in the same manner. A servant held an umbrella over the unhappy man, and fanned him during the eight hours that he was there.

Taken out of the pit at six o’clock in the evening, 11 all joined with Dinkie in the belief that Mr. Sarpee “smelt sweeter,” than when interred in the morning; still the smell of the “polecat” was there. Five hours longer in the pit, the following day, with a rub down by Dinkie, with his “Goopher,” fitted the young man for a return home to the city.

I never heard that Mr. Sarpee ever again joined in a “coon hunt.”

No description of mine, however, can give anything like a correct idea of the great merriment of the entire slave population on “Poplar Farm,” caused by the “coon hunt.” Even Uncle Ned, the old superannuated slave, who seldom went beyond the confines of his own cabin, hobbled out, on this occasion, to take a look at “de gentleman fum de city,” while buried in the pit.

At night, in the quarters, the slaves had a merry time over the “coon hunt.”

“I golly, but didn’t de polecat give him a big dose?” said Ike.

“But how Mr. Sarpee did talk French to hissef when de ole coon peppered him,” remarked Cato.

“He won’t go coon huntin’ agin, soon, I bet you,” said Sam.

“De coon hunt,” and “de gemmen fum de city,” was the talk for many days. 12

I have already said that Dr. Gaines was a man of deep religious feeling, and this interest was not confined to the whites, for he felt that it was the Christian duty to help to save all mankind, white and black. He would often say, “I regard our negroes as given to us by an All Wise Providence, for their especial benefit, and we should impart to them Christian civilization.” And to this end, he labored most faithfully.

No matter how driving the work on the plantation, whether seed-time or harvest, whether threatened with rain or frost, nothing could prevent his having the slaves all in at family prayers, night and morning. Moreover, the older servants were often invited to take part in the exercises. They always led the singing, and, on Sabbath mornings, were permitted to ask questions eliciting Scriptural explanations. Of course, some of the questions and some of the prayers were rather crude, and the effect, to an educated person, was rather to call forth laughter than solemnity.

Leaving home one morning, for a visit to the city, the Doctor ordered Jim, an old servant, to do some mowing in the rye-field; on his return, finding the rye-field as he had left it in the morning, he called Jim up, and severely flogged him without giving the man an opportunity of telling why the work had 13 been neglected. On relating the circumstance at the supper-table, the wife said,—

“I am very sorry that you whipped Jim, for I took him to do some work in the garden, amongst my flower-beds.”

TROPICAL LUXURIANCE.

To this the Doctor replied, “Never mind, I’ll make it all right with Jim.” 14

And sure enough he did, for that night, at prayers, he said, “I am sorry, Jim, that I corrected you, to-day, as your mistress tells me that she set you to work in the flower-garden. Now, Jim,” continued he, in a most feeling manner, “I always want to do justice to my servants, and you know that I never abuse any of you intentionally, and now, to-night, I will let you lead in prayer.”

Jim thankfully acknowledged the apology, and, with grateful tears, and an overflowing heart, accepted the situation; for Jim aspired to be a preacher, like most colored men, and highly appreciated an opportunity to show his persuasive powers; and that night the old man made splendid use of the liberty granted to him. After praying for everything generally, and telling the Lord what a great sinner he himself was, he said,—

“Now, Lord, I would specially ax you to try to save marster. You knows dat marster thinks he’s mighty good; you knows dat marster says he’s gwine to heaven; but Lord, I have my doubts; an’ yet I want marster saved. Please to convert him over agin; take him, dear Lord, by de nap of de neck, and shake him over hell and show him his condition. But, Lord, don’t let him fall into hell, jes let him see whar he ought to go to, but don’t let him go dar. An’ now, Lord, ef you jes save marster, I will give you de glory.”

The indignation expressed by the doctor, at the close of Jim’s prayer, told the old negro that for once he had overstepped the mark. “What do you 15 mean, Jim, by insulting me in that manner? Asking the Lord to convert me over again. And praying that I might be shaken over hell. I have a great mind to tie you up, and give you a good correcting. If you ever make another such a prayer, I’ll whip you well, that I will.”

Dr. Gaines felt so intensely the duty of masters to their slaves that he, with some of his neighbors, inaugurated a religious movement, whereby the blacks at the Corners could have preaching once a fortnight, and that, too, by an educated white man. Rev. John Mason, the man selected for this work, was a heavy-set, fleshy, lazy man who, when entering a house, sought the nearest chair, taking possession of it, and holding it to the last.

He had been employed many years as a colporteur or missionary, sometimes preaching to the poor whites, and, at other times, to the slaves, for which service he was compensated either by planters, or by the dominant religious denomination in the section where he labored. Mr. Mason had carefully studied the character of the people to whom he was called to preach, and took every opportunity to shirk his duties, and to throw them upon some of the slaves, a large number of whom were always ready and willing to exhort when called upon.

We shall never forget his first sermon, and the profound sensation that it created both amongst masters and slaves, and especially the latter. After taking for his text, “He that knoweth his master’s 16 will, and doeth it not, shall be beaten with many stripes,” he spoke substantially as follows:—

“Now when correction is given you, you either deserve it, or you do not deserve it. But whether you really deserve it or not, it is your duty, and Almighty God requires that you bear it patiently. You may, perhaps, think that this is hard doctrine, but if you consider it right you must needs think otherwise of it. Suppose then, that you deserve correction, you cannot but say that it is just and right you should meet with it. Suppose you do not, or at least you do not deserve so much, or so severe a correction for the fault you have committed, you, perhaps, have escaped a great many more, and are at last paid for all. Or suppose you are quite innocent of what is laid to your charge, and suffer wrongfully in that particular thing, is it not possible you may have done some other bad thing which was never discovered, and that Almighty God, who saw you doing it, would not let you escape without punishment one time or another? And ought you not, in such a case, to give glory to Him, and be thankful that he would rather punish you in this life for your wickedness, than destroy your souls for it in the next life? But suppose that even this was not the case (a case hardly to be imagined), and that you have by no means, known or unknown, deserved the correction you suffered, there is this great comfort in it, that if you bear it patiently, and leave your cause in the hands of God, he will reward you for it in heaven, and the punishment you suffer 17 unjustly here, shall turn to your exceeding great glory, hereafter.”

At this point, the preacher hesitated a moment, and then continued, “I am now going to give you a description of hell, that awful place, that you will surely go to, if you don’t be good and faithful servants.

“Hell is a great pit, more than two hundred feet deep, and is walled up with stone, having a strong, iron grating at the top. The fire is built of pitch pine knots, tar barrels, lard kegs, and butter firkins. One of the devil’s imps appears twice a day, and throws about half a bushel of brimstone on the fire, which is never allowed to cease burning. As sinners die they are pitched headlong into the pit, and are at once taken up upon the pitchforks by the devil’s imps, who stand, with glaring eyes and smiling countenances, ready to do their master’s work.”

Here the speaker was disturbed by the “Amens,” “Bless God, I’ll keep out of hell,” “Dat’s my sentiments,” which plainly told him that he had struck the right key.

“Now,” continued the preacher, “I will tell you where heaven is, and how you are to obtain a place there. Heaven is above the skies; its streets are paved with gold; seraphs and angels will furnish you with music which never ceases. You will all be permitted to join in the singing and you will be fed on manna and honey, and you will drink from fountains, and will ride in golden chariots.”

“I am bound for hebben,” ejaculated one. 18

“Yes, blessed God, hebben will be my happy home,” said another.

These outbursts of feeling were followed, while the man of God stood with folded arms, enjoying the sensation that his eloquence had created.

After pausing a moment or two, the reverend man continued, “Are there any of you here who would rather burn in hell than rest in heaven? Remember that once in hell you can never get out. If you attempt to escape little devils are stationed at the top of the pit, who will, with their pitchforks, toss you back into the pit, curchunk, where you must remain forever. But once in heaven, you will be free the balance of your days.” Here the wildest enthusiasm showed itself, amidst which the preacher took his seat.

A rather humorous incident now occurred which created no little merriment amongst the blacks, and to the somewhat discomfiture of Dr. Gaines,—who occupied a seat with the whites who were present.

Looking about the room, being unacquainted with the negroes, and presuming that all or nearly so were experimentally interested in religion, Mr. Mason called on Ike to close with prayer. The very announcement of Ike’s name in such a connection called forth a broad grin from the larger portion of the audience.

Now, it so happened that Ike not only made no profession of religion, but was in reality the farthest off from the church of any of the servants at “Poplar Farm”; yet Ike was equal to the occasion, and at 19 once responded, to the great amazement of his fellow slaves.

Ike had been, from early boyhood, an attendant upon whites, and he had learned to speak correctly for an uneducated person. He was pretty well versed in Scripture and had learned the principal prayer that his master was accustomed to make, and would often get his fellow-servants together at the barn on a rainy day and give them the prayer, with such additions and improvements as the occasion might suggest. Therefore, when called upon by Mr. Mason, Ike at once said, “Let us pray.”

After floundering about for a while, as if feeling his way, the new beginner struck out on the well-committed prayer, and soon elicited a loud “amen,” and “bless God for that,” from Mr. Mason, and to the great amusement of the blacks. In his eagerness, however, to make a grand impression, Ike attempted to weave into his prayer some poetry on “Cock Robin,” which he had learned, and which nearly spoiled his maiden prayer.

After the close of the meeting, the Doctor invited the preacher to remain over night, and accepting the invitation, we in the great house had an opportunity of learning more of the reverend man’s religious views.

When comfortably seated in the parlor, the Doctor said, “I was well pleased with your discourse, I think the tendency will be good upon the servants.”

“Yes,” responded the minister, “The negro is eminently a religious being, more so, I think, than 20 the white race. He is emotional, loves music, is wonderfully gifted with gab; the organ of alimentativeness largely developed, and is fond of approbation. I therefore try always to satisfy their vanity; call upon them to speak, sing, and pray, and sometimes to preach. That suits for this world. Then I give them a heaven with music in it, and with something to eat. Heaven without singing and food would be no place for the negro. In the cities, where many of them are free, and have control of their own time, they are always late to church meetings, lectures, or almost anything else. But let there be a festival or supper announced and they are all there on time.”

“But did you know,” said Dr. Gaines, “that the prayer that Ike made to-day he learned from me?”

“Indeed?” responded the minister.

“Yes, that boy has the imitative power of his race in a larger degree than most negroes that I have seen. He remembers nearly everything that he hears, is full of wit, and has most excellent judgment. However, his dovetailing the Cock Robin poetry into my prayer was too much, and I had to laugh at his adroitness.”

The Doctor was much pleased with the minister, but Mrs. Gaines was not. She had great contempt for professional men who sprung from the lower class, and she regarded Mr. Mason as one to be endured but not encouraged. The Rev. Henry Pinchen was her highest idea of a clergyman. This gentleman was then expected in the neighborhood, 21 and she made special reference to the fact, to her husband, when speaking of the “negro missionary,” as she was wont to call the new-comer.

The preparation made, a few days later, for the reception of Mrs. Gaines’ favorite spiritual adviser, showed plainly that a religious feast was near at hand, and in which the lady was to play a conspicuous part; and whether her husband was prepared to enter into the enjoyment or not, he would have to tolerate considerable noise and bustle for a week.

“Go, Hannah,” said Mrs. Gaines, “and tell Dolly to kill a couple of fat pullets, and to put the biscuit to rise. I expect Brother Pinchen here this afternoon, and I want everything in order. Hannah, Hannah, tell Melinda to come here. We mistresses do have a hard time in this world; I don’t see why the Lord should have imposed such heavy duties on us poor mortals. Well, it can’t last always. I long to leave this wicked world, and go home to glory.”

At the hurried appearance of the waiting maid the mistress said: “I am to have company this afternoon, Melinda. I expect Brother Pinchen here, and I want everything in order. Go and get one of my new caps, with the lace border, and get out my scolloped-bottomed dimity petticoat, and when you go out, tell Hannah to clean the white-handled knives, and see that not a speck is on them; for I want everything as it should be while Brother Pinchen is here.”

Mr. Pinchen was possessed with a large share of the superstition that prevails throughout the South, 22 not only with the ignorant negro, who brought it with him from his native land, but also by a great number of well educated and influential whites.

On the first afternoon of the reverend gentleman’s visit, I listened with great interest to the following conversation between Mrs. Gaines and her ministerial friend.

“Now, Brother Pinchen, do give me some of your experience since you were last here. It always does my soul good to hear religious experience. It draws me nearer and nearer to the Lord’s side. I do love to hear good news from God’s people.”

“Well, Sister Gaines,” said the preacher, “I’ve had great opportunities in my time to study the heart of man. I’ve attended a great many camp-meetings, revival meetings, protracted meetings, and death-bed scenes, and I am satisfied, Sister Gaines, that the heart of man is full of sin, and desperately wicked. This is a wicked world, Sister Gaines, a wicked world.”

“Were you ever in Arkansas, Brother Pinchen?” inquired Mrs. Gaines; “I’ve been told that the people out there are very ungodly.”

Mr. P. “Oh, yes, Sister Gaines. I once spent a year at Little Rock, and preached in all the towns round about there; and I found some hard cases out there, I can tell you. I was once spending a week in a district where there were a great many horse thieves, and, one night, somebody stole my pony. Well, I knowed it was no use to make a fuss, so I told Brother Tarbox to say nothing about it, and I’d 23 get my horse by preaching God’s everlasting gospel; for I had faith in the truth, and knowed that my Saviour would not let me lose my pony. So the next Sunday I preached on horse-stealing, and told the brethren to come up in the evenin’ with their hearts filled with the grace of God. So that night the house was crammed brimfull with anxious souls, panting for the bread of life. Brother Bingham opened with prayer, and Brother Tarbox followed, and I saw right off that we were gwine to have a blessed time. After I got ’em pretty well warmed up, I jumped on to one of the seats, stretched out my hands and said: ‘I know who stole my pony; I’ve found out; and you are in here tryin’ to make people believe that you’ve got religion; but you ain’t got it. And if you don’t take my horse back to Brother Tarbox’s pasture this very night, I’ll tell your name right out in meetin’ to-morrow night. Take my pony back, you vile and wretched sinner, and come up here and give your heart to God.’ So the next mornin’, I went out to Brother Tarbox’s pasture, and sure enough, there was my bob-tail pony. Yes, Sister Gaines, there he was, safe and sound. Ha, ha, ha!”

Mrs. G. “Oh, how interesting, and how fortunate for you to get your pony! And what power there is in the gospel! God’s children are very lucky. Oh, it is so sweet to sit here and listen to such good news from God’s people? [Aside.] ‘You Hannah, what are you standing there listening for, and neglecting your work? Never mind, my lady, I’ll whip 24 you well when I am done here. Go at your work this moment, you lazy huzzy! Never mind, I’ll whip you well.’ Come, do go on, Brother Pinchen, with your godly conversation. It is so sweet! It draws me nearer and nearer to the Lord’s side.”

Mr. P. “Well, Sister Gaines, I’ve had some mighty queer dreams in my time, that I have. You see, one night I dreamed that I was dead and in heaven, and such a place I never saw before. As soon as I entered the gates of the celestial empire, I saw many old and familiar faces that I had seen before. The first person that I saw was good old Elder Pike, the preacher that first called my attention to religion. The next person I saw was Deacon Billings, my first wife’s father, and then I saw a host of godly faces. Why, Sister Gaines, you knowed Elder Goosbee, didn’t you?”

Mrs. G. “Why, yes; did you see him there? He married me to my first husband.”

Mr. P. “Oh, yes, Sister Gaines, I saw the old Elder, and he looked for all the world as if he had just come out of a revival meetin’.”

Mrs. G. “Did you see my first husband there, Brother Pinchen?”

Mr. P. “No, Sister Gaines, I didn’t see Brother Pepper there; but I’ve no doubt but that Brother Pepper was there.”

Mrs. G. “Well, I don’t know; I have my doubts. He was not the happiest man in the world. He was always borrowing trouble about something or another. Still, I saw some happy moments with Mr. 25 Pepper. I was happy when I made his acquaintance, happy during our courtship, happy a while after our marriage, and happy when he died.” [Weeps.]

Hannah. “Massa Pinchen, did you see my ole man Ben up dar in hebben?”

Mr. P. “No, Hannah, I didn’t go amongst the niggers.”

Mrs. G. “No, of course Brother Pinchen didn’t go among the blacks. What are you asking questions for? [Aside.] ‘Never mind, my lady, I’ll whip you well when I’m done here. I’ll skin you from head to foot.’ Do go on with your heavenly conversation, Brother Pinchen; it does my very soul good. This is indeed a precious moment for me. I do love to hear of Christ and Him crucified.”

Mr. P. “Well, Sister Gaines, I promised Sister Daniels that I’d come over and see her a few moments this evening, and have a little season of prayer with her, and I suppose I must go.”

Mrs. G. “If you must go, then I’ll have to let you; but before you do, I wish to get your advice upon a little matter that concerns Hannah. Last week Hannah stole a goose, killed it, cooked it, and she and her man Sam had a fine time eating the goose; and her master and I would never have known anything about it if it had not been for Cato, a faithful servant, who told his master all about it. And then, you see, Hannah had to be severely whipped before she’d confess that she stole the goose. Next Sabbath is sacrament day, and I want to know if you 26 think that Hannah is fit to go to the Lord’s Supper, after stealing the goose.”

“Well, Sister Gaines,” responded the minister, “that depends on circumstances. If Hannah has confessed that she stole the goose, and has been sufficiently whipped, and has begged her master’s pardon, and begged your pardon, and thinks she will not do the like again, why then I suppose she can go to the Lord’s Supper; for—

But she must be sure that she has repented, and won’t steal any more.”

“Do you hear that, Hannah?” said the mistress. “For my part,” continued she, “I don’t think she’s fit to go to the Lord’s Supper; for she had no cause to steal the goose. We give our servants plenty of good food. They have a full run to the meal-tub, meat once a fortnight, and all the sour milk on the place, and I am sure that’s enough for any one. I do think that our negroes are the most ungrateful creatures in the world. They aggravate my life out of me.”

During this talk on the part of the mistress, the servant stood listening with careful attention, and at its close Hannah said:—

“I know, missis, dat I stole de goose, an’ massa whip me for it, an’ I confess it, an’ I is sorry for it. But, missis, I is gwine to de Lord’s Supper, next 27 Sunday, kase I ain’t agwine to turn my back on my bressed Lord an’ Massa for no old tough goose, dat I ain’t.” And here the servant wept as if she would break her heart.

Mr. Pinchen, who seemed moved by Hannah’s words, gave a sympathizing look at the negress, and said, “Well, Sister Gaines, I suppose I must go over and see Sister Daniels; she’ll be waiting for me.”

After seeing the divine out, Mrs. Gaines said, “Now, Hannah, Brother Pinchen is gone, do you get the cowhide and follow me to the cellar, and I’ll whip you well for aggravating me as you have to-day. It seems as if I can never sit down to take a little comfort with the Lord, without you crossing me. The devil always puts it into your head to disturb me, just when I am trying to serve the Lord. I’ve no doubt but that I’ll miss going to heaven on your account. But I’ll whip you well before I leave this world, that I will. Get the cowhide and follow me to the cellar.”

In a few minutes the lady returned to the parlor, followed by the servant whom she had been correcting, and she was in a high state of perspiration, and, on taking a seat, said, “Get the fan, Hannah, and fan me; you ought to be ashamed of yourself to put me into such a passion, and cause me to heat myself up in this way, whipping you. You know that it is a great deal harder for me than it is for you. I have to exert myself, and it puts me all in a fever; while you have only to stand and take it.” 28

On the following Sabbath,—it being Communion,—Mr. Pinchen officiated. The church being at the Corners, a mile or so from “Poplar Farm,” the Communion wine, which was kept at the Doctor’s, was sent over by the boy, Billy. It happened to be in the month of April, when the maple trees had been tapped, and the sap freely running.

Billy, while passing through the “sugar camp,” or sap bush, stopped to take a drink of the sap, which looked inviting in the newly-made troughs. All at once it occurred to the lad that he could take a drink of the wine, and fill it up with sap. So, acting upon this thought, the youngster put the decanter to his mouth, and drank freely, lowering the beverage considerably in the bottle.

But filling the bottle with the sap was much more easily contemplated than done. For, at every attempt, the water would fall over the sides, none going in. However, the boy, with the fertile imagination of his race, soon conceived the idea of sucking his mouth full of the sap, and then squirting it into the bottle. This plan succeeded admirably, and the slave boy sat in the church gallery that day, and wondered if the communicants would have partaken so freely of the wine, if they had known that his mouth had been the funnel through which a portion of it had passed.

Slavery has had the effect of brightening the mental powers of the negro to a certain extent, especially those brought into close contact with the whites. 29

It is also a fact, that these blacks felt that when they could get the advantage of their owners, they had a perfect right to do so; and the boy, Billy, no doubt, entertained a consciousness that he had done a very cunning thing in thus drinking the wine entrusted to his care.

Dr. Gaines’ practice being confined to the planters and their negroes, in the neighborhood of “Poplar Farm,” caused his income to be very limited from that source, and consequently he looked more to the products of his plantation for support. True, the new store at the Corners, together with McWilliams’ Tannery and Simpson’s Distillery, promised an increase of population, and, therefore, more work for the physician. This was demonstrated very clearly by the Doctor’s coming in one morning somewhat elated, and exclaiming: “Well, my dear, my practice is steadily increasing. I forgot to tell you that neighbor Wyman engaged me yesterday as his family physician; and I hope that the fever and ague, which is now taking hold of the people, will give me more patients. I see by the New Orleans papers that the yellow fever is raging there to a fearful extent. Men of my profession are reaping a harvest in that section this 30 year. I would that we could have a touch of the yellow fever here, for I think I could invent a medicine that would cure it. But the yellow fever is a luxury that we medical men in this climate can’t expect to enjoy; yet we may hope for the cholera.”

“Yes,” replied Mrs. Gaines, “I would be glad to see it more sickly, so that your business might prosper. But we are always unfortunate. Everybody here seems to be in good health, and I am afraid they’ll keep so. However, we must hope for the best. We must trust in the Lord. Providence may possibly send some disease amongst us for our benefit.”

On going to the office the Doctor found the faithful servant hard at work, and saluting him in his usual kind and indulgent manner, asked, “Well, Cato, have you made the batch of ointment that I ordered?”

Cato. “Yes, massa; I dun made de intment, an’ now I is making the bread pills. De tater pills is up on the top shelf.”

Dr. G. “I am going out to see some patients. If any gentlemen call, tell them I shall be in this afternoon. If any servants come, you attend to them. I expect two of Mr. Campbell’s boys over. You see to them. Feel their pulse, look at their tongues, bleed them, and give them each a dose of calomel. Tell them to drink no cold water, and to take nothing but water gruel.”

Cato. “Yes, massa; I’ll tend to ’em.”

The negro now said, “I allers knowed I was a doctor, an’ now de ole boss has put me at it; I 31 muss change my coat. Ef any niggers comes in, I wants to look suspectable. Dis jacket don’t suit a doctor; I’ll change it.”

Cato’s vanity seemed at this point to be at its height, and having changed his coat, he walked up and down before the mirror, and viewed himself to his heart’s content, and saying to himself, “Ah! now I looks like a doctor. Now I can bleed, pull teef, or cut off a leg. Oh, well, well! ef I ain’t put de pill stuff an’ de intment stuff togedder. By golly, dat ole cuss will be mad when he finds it out, won’t he? Nebber mind, I’ll make it up in pills, and when de flour is on dem, he won’t know what’s in ’em; an’ I’ll make some new intment. Ah! yonder comes Mr. Campbell’s Pete an’ Ned; dem’s de ones massa sed was comin’. I’ll see ef I looks right. [Goes to the looking-glass and views himself.] I ’em some punkins, ain’t I? [Knock at the door.] Come in.” Enter Pete and Ned.

Pete. “Whar is de Doctor?”

Cato. “Here I is; don’t you see me?”

Pete. “But whar is de ole boss?”

Cato. “Dat’s none you business. I dun tole you dat I is de doctor, an’ dat’s enuff.”

Ned. “Oh, do tell us whar de Doctor is. I is almos’ dead. Oh, me! oh, dear me! I is so sick.” [Horrible faces.]

Pete. “Yes, do tell us; we don’t want to stan’ here foolin’.”

Cato. “I tells you again dat I is de doctor. I larn de trade under massa.” 32

Ned. “Oh! well den; give me somethin’ to stop dis pain. Oh, dear me! I shall die.”

Cato. “Let me feel your pulse. Now, put out your tongue. You is berry sick. Ef you don’t mine, you’ll die. Come out in de shed, an’ I’ll bleed you.” [Taking them out and bleeding them.] “Dar, now, take dese pills, two in de mornin’, and two at night, and ef you don’t feel better, double de dose. Now, Mr. Pete, what’s de matter wid you?”

Pete. “I is got de cole chills, an’ has a fever in de night.”

“Come out in de shed, an’ I’ll bleed you,” said Cato, at the same time viewing himself in the mirror, as he passed out. After taking a quart of blood, which caused the patient to faint, they returned, the black doctor saying, “Now, take dese pills, two in de mornin’, and two at night, an’ ef dey don’t help you, double de dose. Ah! I like to forget to feel your pulse, and look at your tongue. Put out your tongue. [Feels his pulse.] Yes, I tells by de feel ob your pulse dat I is gib you de right pills?”

Just then, Mr. Parker’s negro boy Bill, with his hand up to his mouth, and evidently in great pain, entered the office without giving the usual knock at the door, and which gave great offence to the new physician.

“What you come in dat door widout knockin’ for?” exclaimed Cato.

Bill. “My toof ache so, I didn’t tink to knock. Oh, my toof! my toof! Whar is de Doctor?”

Cato. “Here I is; don’t you see me?” 33

Bill. “What! you de Doctor, you brack cuss! You looks like a doctor! Oh, my toof! my toof! Whar is de Doctor?”

Cato. “I tells you I is de doctor. Ef you don’t believe me, ax dese men. I can pull your toof in a minnit.”

Bill. “Well, den, pull it out. Oh, my toof! how it aches! Oh, my toof!” [Cato gets the rusty turnkeys.]

Cato. “Now lay down on your back.”

Bill. “What for?”

Cato. “Dat’s de way massa does.”

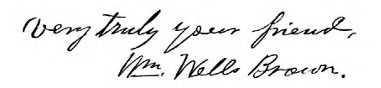

Bill. “Oh, my toof! Well, den, come on.” [Lies down. Cato gets astraddle of Bill’s breast, puts the turnkeys on the wrong tooth, and pulls—Bill kicks, and cries out]—Oh, do stop! Oh, oh, oh! [Cato pulls the wrong tooth—Bill jumps up.]

Cato. “Dar, now, I tole you I could pull your toof for you.”

Bill. Oh, dear me! Oh, it aches yet! Oh, me! Oh, Lor-e-massy! You dun pull de wrong toof. Drat your skin! ef I don’t pay you for this, you brack cuss! [They fight, and turn over table, chairs, and bench—Pete and Ned look on.]

During the melée, Dr. Gaines entered the office, and unceremoniously went at them with his cane, giving both a sound drubbing before any explanation could be offered. As soon as he could get an opportunity, Cato said, “Oh, massa! he’s to blame, sir, he’s to blame. He struck me fuss.” 34

Bill. “No, sir; he’s to blame; he pull de wrong toof. Oh, my toof! oh, my toof!”

NEGRO DENTISTRY.

Dr. G. “Let me see your tooth. Open your mouth. As I live, you’ve taken out the wrong tooth. I am amazed. I’ll whip you for this; I’ll whip you well. You’re a pretty doctor. Now, lie 35 down, Bill, and let him take out the right tooth; and if he makes a mistake this time, I’ll cowhide him well. Lie down, Bill.” [Bill lies down, and Cato pulls the tooth.] “There, now, why didn’t you do that in the first place?”

Cato. “He wouldn’t hole still, sir.”

Bill. “I did hole still.”

Dr. G. “Now go home, boys; go home.”

“You’ve made a pretty muss of it, in my absence,” said the Doctor. “Look at the table! Never mind, Cato; I’ll whip you well for this conduct of yours to-day. Go to work now, and clear up the office.”

As the office door closed behind the master, the irritated negro, once more left to himself, exclaimed, “Confound dat nigger! I wish he was in Ginny. He bite my finger, and scratch my face. But didn’t I give it to him? Well, den, I reckon I did. [He goes to the mirror, and discovers that his coat is torn—weeps.] Oh, dear me! Oh, my coat—my coat is tore! Dat nigger has tore my coat. [He gets angry, and rushes about the room frantic.] Cuss dat nigger! Ef I could lay my hands on him, I’d tare him all to pieces,—dat I would. An’ de old boss hit me wid his cane after dat nigger tore my coat. By golly, I wants to fight somebody. Ef ole massa should come in now, I’d fight him. [Rolls up his sleeves.] Let ’em come now, ef dey dare—ole massa, or anybody else; I’m ready for ’em.”

Just then the Doctor returned and asked, “What’s all this noise here?”

Cato. “Nuffin’, sir; only jess I is puttin’ things 36 to rights, as you tole me. I didn’t hear any noise, except de rats.”

Dr. G. “Make haste, and come in; I want you to go to town.”

Once more left alone, the witty black said, “By golly, de ole boss like to cotch me dat time, didn’t he? But wasn’t I mad? When I is mad, nobody can do nuffin’ wid me. But here’s my coat tore to pieces. Cuss dat nigger! [Weeps.] Oh, my coat! oh, my coat! I rudder he had broke my head, den to tore my coat. Drat dat nigger! Ef he ever comes here agin, I’ll pull out every toof he’s got in his head—dat I will.”

During the palmy days of the South, forty years ago, if there was one class more thoroughly despised than another, by the high-born, well-educated Southerner, it was the slave-trader who made his money by dealing in human cattle. A large number of the slave-traders were men of the North or free States, generally from the lower order, who, getting a little money by their own hard toil, invested it in slaves purchased in Virginia, Maryland, or Kentucky, and sold them in the cotton, sugar, or rice-growing States. And yet the high-bred planter, through mismanagement, or other causes, was compelled to sell his slaves, or some of 37 them, at auction, or to let the “soul-buyer” have them.

Dr. Gaines’ financial affairs being in an unfavorable condition, he yielded to the offers of a noted St. Louis trader by the name of Walker. This man was the terror of the whole South-west amongst the black population, bond and free,—for it was not unfrequently that even free colored persons were kidnapped and carried to the far South and sold. Walker had no conscientious scruples, for money was his God, and he worshipped at no other altar.

An uncouth, ill-bred, hard-hearted man, with no education, Walker had started at St. Louis as a dray-driver, and ended as a wealthy slave-trader. The day was set for this man to come and purchase his stock, on which occasion, Mrs. Gaines absented herself from the place; and even the Doctor, although alone, felt deeply the humiliation. For myself, I sat and bit my lips with anger, as the vulgar trader said to the faithful man,—

“Well, my boy, what’s your name?”

Sam. “Sam, sir, is my name.”

Walk. “How old are you, Sam?”

Sam. “Ef I live to see next corn plantin’ time I’ll be twenty-seven, or thirty, or thirty-five,—I don’t know which, sir.”

Walk. “Ha, ha, ha! Well, Doctor, this is rather a green boy. Well, mer feller, are you sound?”

Sam. “Yes, sir, I spec I is.”

Walk. “Open your mouth and let me see your teeth. I allers judge a nigger’s age by his teeth, 38 same as I dose a hoss. Ah! pretty good set of grinders. Have you got a good appetite?”

Sam. “Yes, sir.”

Walk. “Can you eat your allowance?”

Sam. “Yes, sir, when I can get it.”

Walk. “Get out on the floor and dance; I want to see if you are supple.”

Sam. “I don’t like to dance; I is got religion.”

Walk. “Oh, ho! you’ve got religion, have you? That’s so much the better. I likes to deal in the gospel. I think he’ll suit me. Now, mer gal, what’s your name?”

Sally. “I is Big Sally, sir.”

Walk. “How old are you, Sally?”

Sally. “I don’t know, sir; but I heard once dat I was born at sweet pertater diggin’ time.”

Walk. “Ha, ha, ha! Don’t you know how old you are? Do you know who made you?”

Sally. “I hev heard who it was in de Bible dat made me, but I dun forget de gentman’s name.”

Walk. “Ha, ha, ha! Well, Doctor, this is the greenest lot of niggers I’ve seen for some time.”

The last remark struck the Doctor deeply, for he had just taken Sally for debt, and, therefore, he was not responsible for her ignorance. And he frankly told him so.

“This is an unpleasant business for me, Mr. Walker,” said the Doctor, “but you may have Sam for $1,000, and Sally for $900. They are worth all I ask for them. I never banter, Mr. Walker. 39 There they are; you can take them at that price, or let them alone, just as you please.”

Walk. “Well, Doctor, I reckon I’ll take ’em; but it’s all they are worth. I’ll put the handcuffs on ’em, and then I’ll pay you. I likes to go accordin’ to Scripter. Scripter says ef eatin’ meat will offend your brother, you must quit it; and I say ef leavin’ your slaves without the handcuffs will make ’em run away, you must put the handcuffs on ’em. Now, Sam, don’t you and Sally cry. I am of a tender heart, and it allers makes me feel bad to see people cryin’. Don’t cry, and the first place I get to, I’ll buy each of you a great big ginger cake,—that I will.”

And with the last remark the trader took from a small satchel two pairs of handcuffs, putting them on, and with a laugh said: “Now, you look better with the ornaments on.”

Just then, the Doctor remarked,—“There comes Mr. Pinchen.” Walker, looking out and seeing the man of God, said: “It is Mr. Pinchen, as I live; jest the very man I wants to see.” And as the reverend gentleman entered, the trader grasped his hand, saying: “Why, how do you do, Mr. Pinchen? What in the name of Jehu brings you down here to Muddy Creek? Any camp-meetins, revival meetins, death-bed scenes, or anything else in your line going on down here? How is religion prosperin’ now, Mr. Pinchen? I always like to hear about religion.”

Mr. Pin. “Well, Mr. Walker, the Lord’s work is in good condition everywhere now. I tell you, 40 Mr. Walker, I’ve been in the gospel ministry these thirteen years, and I am satisfied that the heart of man is full of sin and desperately wicked. This is a wicked world, Mr. Walker, a wicked world, and we ought all of us to have religion. Religion is a good thing to live by, and we all want it when we die. Yes, sir, when the great trumpet blows, we ought to be ready. And a man in your business of buying and selling slaves needs religion more than anybody else, for it makes you treat your people as you should. Now, there is Mr. Haskins,—he is a slave-trader, like yourself. Well, I converted him. Before he got religion, he was one of the worst men to his niggers I ever saw; his heart was as hard as stone. But religion has made his heart as soft as a piece of cotton. Before I converted him he would 41 sell husbands from their wives, and seem to take delight in it; but now he won’t sell a man from his wife, if he can get any one to buy both of them together. I tell you, sir, religion has done a wonderful work for him.”

REV. HENRY PINCHEN.

Walk. “I know, Mr. Pinchen, that I ought to have religion, and I feel that I am a great sinner; and whenever I get with good pious people like you and the Doctor, it always makes me feel that I am a desperate sinner. I feel it the more, because I’ve got a religious turn of mind. I know that I would be happier with religion, and the first spare time I get, I am going to try to get it. I’ll go to a protracted meeting, and I won’t stop till I get religion.”

The departure of the trader with his property left a sadness even amongst the white members of the family, and special sympathy was felt for Hannah for the loss of her husband by the sale. However, Mrs. Gaines took it coolly, for as Sam was a field hand, she had often said she wanted her to have one of the house servants, and as Cato was without a wife, this seemed to favor her plans. Therefore, a week later, as Hannah entered the sitting-room one evening, she said to her:—“You need not tell me, Hannah, that you don’t want another husband, I know better. Your master has sold Sam, and he’s gone down the river, and you’ll never see him again. So go and put on your calico dress, and meet me in the kitchen. I intend for you to jump the broomstick with Cato. You need not tell me you don’t want 42 another man. I know there’s no woman living that can be happy and satisfied without a husband.”

Hannah said: “Oh, missis, I don’t want to jump de broomstick wid Cato. I don’t love Cato; I can’t love him.”

Mrs. G. “Shut up, this moment! What do you know about love? I didn’t love your master when I married him, and people don’t marry for love now. So go and put on your calico dress, and meet me in the kitchen.”

As the servant left for the kitchen, the mistress remarked: “I am glad that the Doctor has sold Sam, for now I’ll have her marry Cato, and I’ll have them both in the house under my eyes.”

As Hannah entered the kitchen, she said: “Oh, Cato, do go and tell missis dat you don’t want to jump de broomstick wid me,—dat’s a good man. Do, Cato; kase I nebber can love you. It was only las week dat massa sold my Sammy, and I don’t want any udder man. Do go tell missis dat you don’t want me.” To which Cato replied: “No, Hannah, I ain’t a-gwine to tell missis no such thing, kase I does want you, and I ain’t a-gwine to tell a lie for you ner nobody else. Dar, now you’s got it! I don’t see why you need to make so much fuss. I is better lookin’ den Sam; an’ I is a house servant, an’ Sam was only a fiel hand; so you ought to feel proud of a change. So go and do as missis tells you.”

As the woman retired, the man continued: “Hannah needn’t try to get me to tell a lie; I ain’t a-gwine 43 to do it, kase I dose want her, an’ I is bin wantin’ her dis long time, an’ soon as massa sold Sam, I knowed I would get her. By golly, I is gwine to be a married man. Won’t I be happy? Now, ef I could only jess run away from ole massa, an’ get to Canada wid Hannah, den I’d show ’em who I was. Ah! dat reminds me of my song ’bout ole massa and Canada, an’ I’ll sing it. Dis is my moriginal hyme. It comed into my head one night when I was fass asleep under an apple tree, looking up at de moon.”

While Hannah was getting ready for the nuptials, Cato amused himself by singing—

44

Mrs. Gaines, as she approached the kitchen, heard the servant’s musical voice and knew that he was in high glee; entering, she said, “Ah! Cato, you’re ready, are you? Where is Hannah?”

Cato. “Yes, missis; I is bin waitin’ dis long time. Hannah has bin here tryin’ to swade me to tell you dat I don’t want her; but I telled her dat you sed I must jump de broomstick wid her, an’ I is gwine to mind you.”

Mrs. G. “That’s right, Cato; servants should always mind their masters and mistresses, without asking a question.”

Cato. “Yes, missis, I allers dose what you and massa tells me, an’ axes nobody.”

While the mistress went in search of Hannah, Dolly came in saying, “Oh, Cato, do go an’ tell missis dat you don’t want Hannah. Don’t yer hear how she’s whippin’ her in de cellar? Do go an’ tell missis dat you don’t want Hannah, and den she’ll stop whippin’ her.”

Cato. “No, Dolly, I ain’t a gwine to do no such a thing, kase ef I tell missis dat I don’t want Hannah, den missis will whip me; an’ I ain’t a-gwine to be whipped fer you, ner Hannah, ner nobody else. No, I’ll jump the broomstick wid every woman on de place, ef missis wants me to, before I’ll be whipped.”

Dolly. “Cato, ef I was in Hannah’s place, I’d see you in de bottomless pit before I’d live wid you, you great, big, wall-eyed, empty-headed, knock-kneed fool. You’re as mean as your devilish old missis.” 45

Cato. “Ef you don’t quit dat busin’ me, Dolly, I’ll tell missis as soon as she comes in, an’ she’ll whip you, you know she will.”

As Mrs. Gaines entered she said, “You ought to be ashamed of yourself, Hannah, to make me fatigue myself in this way, to make you do your duty. It’s very naughty in you, Hannah. Now, Dolly, you and Susan get the broom, and get out in the middle of the room. There, hold it a little lower—a little higher; there, that’ll do. Now, remember that this is a solemn occasion; you are going to jump into matrimony. Now, Cato, take hold of Hannah’s hand. There, now, why could n’t you let Cato take hold of your hand before? Now, get ready, and when I count three, do you jump. Eyes on the broomstick! All ready. One, two, three, and over you go. There, now you’re husband and wife, and if you don’t live happy together, it’s your own fault; for I am sure there’s nothing to hinder it. Now, Hannah, come up to the house, and I’ll give you some whiskey, and you can make some apple-toddy, and you and Cato can have a fine time. Now, I’ll go back to the parlor.”

Dolly. “I tell you what, Susan, when I get married, I is gwine to have a preacher to marry me. I ain’t a-gwine to jump de broomstick. Dat will do for fiel’ hands, but house servants ought to be ’bove dat.”

Susan. “Well, chile, you can’t spect any ting else from ole missis. She come from down in Carlina, from ’mong de poor white trash. She don’t know any 46 better. You can’t speck nothin’ more dan a jump from a frog. Missis says she is one ob de akastocacy; but she ain’t no more of an akastocacy dan I is. Missis says she was born wid a silver spoon in her mouf; ef she was, I wish it had a-choked her, dat’ what I wish.”

The mode of jumping the broomstick was the general custom in the rural districts of the South, forty years ago; and, as there was no law whatever in regard to the marriage of slaves, this custom had as binding force with the negroes, as if they had been joined by a clergyman; the difference being the one was not so high-toned as the other. Yet, it must be admitted that the blacks always preferred being married by a clergyman.

Dr. Gaines and wife having spent the heated season at the North, travelling for pleasure and seeking information upon the mode of agriculture practised in the free States, returned home filled with new ideas which they were anxious to put into immediate execution, and, therefore, a radical change was at once commenced.

Two of the most interesting changes proposed, were the introduction of a plow, which was to take the place of the heavy, unwieldy one then in use, 47 and a washing-machine, instead of the hard hand-rubbing then practised. The first called forth much criticism amongst the men in the field, where it was christened the “Yankee Dodger,” and during the first half a day of its use, it was followed by a large number of the negroes, men and women wondering at its superiority over the old plow, and wanting to know where it was from.

But the excitement in the kitchen, amongst the women, over the washing-machine, threw the novelty of the plow entirely in the shade.

“An’ so dat tub wid its wheels an’ fixin’ is to do de washin’, while we’s to set down an’ look at it,” said Dolly, as ten or a dozen servants stood around the new comer, laughing and making fun at its ungainly appearance.

“I don’t see why massa didn’t buy a woman, out dar whar de ting was made, an’ fotch ’em along, so she could learn us how to wash wid it,” remarked Hannah, as her mistress came into the kitchen to give orders about the mode of using the “washer.”

“Now, Dolly,” said the mistress, “we are to have new rules, hereafter, about the work. While at the North, I found that the women got up at four o’clock, on Monday mornings, and commenced the washing, which was all finished, and out on the lines, by nine o’clock. Now, remember that, hereafter, there is to be no more washing on Fridays, and ironing on Saturdays, as you used to do. And instead of six of you great, big women to do the washing, two of you with the ‘washer,’ can do the 48 work.” And out she went, leaving the negroes to the contemplation of the future.

“I wish missis had stayed at home, ’stead of goin’ round de world, bringin’ home new rules. Who she tinks gwine to get out of bed at four o’clock in de mornin’, kase she fotch home dis wash-box,” said Dolly, as she gave a knowing look at the other servants.

“De Lord knows dat dis chile ain’t a-gwine to git out of her sweet bed at four o’clock in de mornin’, for no body; you hears dat, don’t you?” remarked Winnie, as she gave a loud laugh, and danced out of the room.

Before the end of the week, Peter had run the new plow against a stump, and had broken it beyond the possibility of repair.

When the lady arose on Monday morning, at half-past nine, her usual time, instead of finding the washing out on the lines, she saw, to her great disappointment, the inside works of the “washer” taken out, and Dolly, the chief laundress, washing away with all her power, in the old way, rubbing with her hands, the perspiration pouring down her black face.

“What have you been doing, Dolly, with the ‘washer?’” exclaimed the mistress, as she threw up her hands in astonishment.

“Well, you see, missis,” said the servant, “dat merchine won’t work no way. I tried it one way, den I tried it an udder way, an’ still it would not work. So, you see, I got de screw-driver an’ I took 49 it to pieces. Dat’s de reason I ain’t got along faster wid de work.”

Mrs. Gaines returned to the parlor, sat down, and had a good cry, declaring her belief that “negroes could not be made white folks, no matter what you should do with them.”

Although the “patent plow” and the “washer” had failed, Dr. and Mrs. Gaines had the satisfaction of knowing that one of their new ideas was to be put into successful execution in a few days.

While at the North, they had eaten at a farm-house, some new cheese, just from the press, and on speaking of it, she was told by old Aunt Nancy, the black mamma of the place, that she understood all about making cheese. This piece of information gave general satisfaction, and a cheese-press was at once ordered from St. Louis.

The arrival of the cheese-press, the following week, was the signal for the new sensation. Nancy was at once summoned to the great house for the purpose of superintending the making of the cheese. A prouder person than the old negress could scarcely have been found. Her early days had been spent on the eastern shores of Maryland, where the blacks have an idea that they are, by nature, superior to their race in any other part of the habitable globe. Nancy had always spoken of the Kentucky and Missouri negroes as “low brack trash,” and now, that all were to be passed over, and the only Marylander on the place called in upon this “great occasion,” her cup of happiness was filled to the brim. 50

“What do you need, besides the cheese-press, to make the cheese with, Nancy?” inquired Mrs. Gaines, as the old servant stood before her, with her hands resting upon her hips, and looking at the half-dozen slaves who loitered around, listening to what was being said.

“Well, missis,” replied Nancy, “I mus’ have a runnet.”

“What’s a runnet?” inquired Mrs. Gaines.

“Why, you see, missis, you’s got to have a sheep killed, and get out of it de maw, an’ dat’s what’s called de runnet. An’ I puts dat in de milk, an’ it curdles the milk so it makes cheese.”

“Then I’ll have a sheep killed at once,” said the mistress, and orders were given to Jim to kill the sheep. Soon after the sheep’s carcass was distributed amongst the negroes, and “de runnet,” in the hands of old Nancy.

That night there was fun and plenty of cheap talk in the negro quarters and in the kitchen, for it had been discovered amongst them that a calf’s runnet, and not a sheep’s, was the article used to curdle the milk for making cheese.

The laugh was then turned upon Nancy, who, after listening to all sorts of remarks in regard to her knowledge of cheese-making, said, in a triumphant tone, suiting the action to the words,—

“You niggers tink you knows a heap, but you don’t know as much as you tink. When de sheep is killed, I knows dat you niggers would git de meat to eat. I knows dat.” 51

With this remark Nancy silenced the entire group. Then putting her hand a-kimbo, the old woman sarcastically exclaimed: “To-morrow you’ll all have calf’s meat for dinner, den what will you have to say ’bout old Nancy?” Hearing no reply, she said: “Whar is you smart niggers now? Whar is you, I ax you?”

“Well, den, ef Ant Nancy ain’t some punkins, dis chile knows nuffin,” remarked Ike, as he stood up at full length, viewing the situation, as if he had caught a new idea. “I allers tole yer dat Ant Nancy had moo in her head dan what yer catch out wid a fine-toof comb,” exclaimed Peter.

“But how is you going to tell missis ’bout killin’ de sheep?” asked Jim.

Nancy turned to the head man and replied: “De same mudder wit dat tole me to get some sheep fer you niggers will tell me what to do. De Lord always guides me through my troubles an’ trials. Befoe I open my mouf, He always fills it.”

The following day Nancy presented herself at the great house door, and sent in for her mistress. On the lady’s appearing, the servant, putting on a knowing look, said: “Missis, when de moon is cold an’ de water runs high in it, den I have to put calf’s runnet in de milk, instead of sheep’s. So, lass night, I see dat de moon is cold an’ de water is runnin’ high.”

“Well, Nancy,” said the mistress, “I’ll have a calf killed at once, for I can’t wait for a warm moon. Go and tell Jim to kill a calf immediately, 52 for I must not be kept out of cheese much longer.” On Nancy’s return to the quarters, old Ned, who was past work, and who never did anything but eat, sleep and talk, heard the woman’s explanation, and clapping his wrinkled hands exclaimed: “Well den, Nancy, you is wof moo den all de niggers on dis place, fer you gives us fresh meat ebbry day.”

After getting the right runnet, and two weeks’ work on the new cheese, a little, soft, sour, hard-looking thing, appearing like anything but a cheese, was exhibited at “Poplar Farm,” to the great amusement of the blacks, and the disappointment of the whites, and especially Mrs. Gaines, who had frequently remarked that her “mouth was watering for the new cheese.”

No attempt was ever made afterwards to renew the cheese-making, and the press was laid under the shed, by the side of the washing machine and the patent plow. While we had three or four trustworthy and faithful servants, it must be admitted that most of the negroes on “Poplar Farm” were always glad to shirk labor, and thought that to deceive the whites was a religious duty.

Wit and religion has ever been the negro’s forte while in slavery. Wit with which to please his master, or to soften his anger when displeased, and religion to enable him to endure punishment when inflicted.

Both Dr. and Mrs. Gaines were easily deceived by their servants. Indeed, I often thought that Mrs. Gaines took peculiar pleasure in being misled 53 by them; and even the Doctor, with his long experience and shrewdness, would allow himself to be carried off upon almost any pretext. For instance, when he retired at night, Ike, his body servant, would take his master’s clothes out of the room, brush them off and return them in time for the Doctor to dress for breakfast. There was nothing in this out of the way; but the master would often remark that he thought Ike brushed his clothes too much, for they appeared to wear out a great deal faster than they had formerly. Ike, however, attributed the wear to the fact that the goods were wanting in soundness. Thus the master, at the advice of his servant, changed his tailor.

MRS. SARAH PEPPER GAINES. 54

About the same time the Doctor’s watch stopped at night, and when taken to be repaired, the watchmaker found it badly damaged, which he pronounced had been done by a fall. As the Doctor was always very careful with his time-piece, he could in no way account for the stoppage. Ike was questioned as to his handling of it, but he could throw no light upon the subject. At last, one night about twelve o’clock, a message came for the Doctor to visit a patient who had a sudden attack of cholera morbus. The faithful Ike was nowhere to be found, nor could any traces of the Doctor’s clothes be discovered. Not even the watch, which was always laid upon the mantle-shelf, could be seen anywhere.

It seemed clear that Ike had run away with his master’s daily wearing apparel, watch and all. Yes, and further search showed that the boots, with one heel four inches higher than the other, had also disappeared. But go, the Doctor must; and Mrs. Gaines and all of us went to work to get the Doctor ready.

While Cato was hunting up the old boots, and Hannah was in the attic getting the old hat, Jim returned from the barn and informed his master that the sorrel horse, which he had ordered to be saddled, was nowhere to be found; and that he had got out the bay mare, and as there was no saddle on the place, Ike having taken the only one, he, Jim, had put the buffalo robe on the mare.

It was a bright moonlight night, and to see the Doctor on horseback without a saddle, dressed in 55 his castaway suit, was, indeed, ridiculous in the extreme. However, he made the visit, saved the patient’s life, came home and went snugly to bed. The following morning, to the Doctor’s great surprise, in walked Ike, at his usual time, with the clothes in one hand and the boots nicely blacked in the other. The faithful slave had not seen any of the other servants, and consequently did not know of the master’s discomfiture on the previous night.

“Were any of the servants off the place last night?” inquired the Doctor, as Ike laid the clothes carefully on a chair, and was setting down the boots.

“No, I speck not,” answered Ike.

“Were you off anywhere last night?” asked the master.

“No, sir,” replied the servant.

“What! not off the place at all?” inquired the Doctor sharply. Ike looked confused and evidently began to “smell a mice.”

“Well, massa, I was not away only to step over to de prayer-meetin’ at de Corners, a little while, dat’s all,” said Ike.

“Where’s my watch?” asked the Doctor.