Title: The Parthenon at Athens, Greece and at Nashville, Tennessee

Author: Benjamin Franklin Wilson

Release date: January 9, 2019 [eBook #58665]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Stephen Hutcheson and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Excerpts

from

The Parthenon of Pericles

and Its

Reproduction in America

Illustrated

By

Benjamin Franklin Wilson, III

Director of the Parthenon

PARTHENON PRESS

NASHVILLE

THE PARTHENON AT ATHENS, GREECE

And

AT NASHVILLE, TENNESSEE

(Excerpts from THE PARTHENON OF PERICLES AND

ITS REPRODUCTION IN AMERICA)

Copyright, MCMXLI

By Benjamin Franklin Wilson III

TO

THE MEMBERS OF THE BOARD OF PARK COMMISSIONERS

1920-1941

Whose intelligent and untiring interest made possible the reproduction of the Parthenon at Nashville; in memory of those who are gone, and in appreciation of those who are living, this booklet is gratefully dedicated

The Parthenon of Pericles, while not thought to be one of the wonders of the world, nevertheless has always been regarded as one of the most wondrously beautiful and inspiring of the world’s buildings. It embraces the best effort of the mind, the heart, and the hand of man. In it are bound up the religion, the history, and the art of Greece.

It has been well said that art is organized emotion, while science is organized knowledge. The field of emotion found its first great development among the Greeks and in the time of Pericles reached its zenith. Assuredly the Greeks have never been excelled in the beauty of their architecture or sculptural art.

The influence of religion was dominant in the life and thought that produced such outstanding men in this period of world history as Phidias and Sophocles, Ictinos and Pericles. Every function of the mind, every activity of the hand, was closely associated with some god or goddess, and to this inspirational incentive the world is greatly indebted for the Parthenon. The mythological stories of the Parthenon largely cover the mythology of Greece. Twenty-eight of the major deities and numerous minor deities and personifications adorn its pediments.

At the time of its destruction in the seventeenth century, a little more than two thousand years after its completion, the Parthenon was almost in as good condition as it was at its beginning. The changes made by the Christians in the fifth century and by the Turks in the fifteenth century had impaired it but little, all of which is eloquent testimony to the thoroughness with which the task was accomplished. The co-ordination of mind, hand, and heart of the Greeks of that age has never been excelled by men of any time and found its culmination in the Parthenon.

The Ruins of the Parthenon at Athens in 1929

The Parthenon was built on the Acropolis, a hill two hundred feet above the streets of Athens, in the year 438 B.C. Not yet had the blight of decay laid its hand upon an outstanding civilization and Athens was at the zenith of her glory and power. The nations she had conquered contributed to her wealth and her slaves furnished the labor for her every great undertaking. It is no wonder that at this time she should turn her heart toward her beloved Athena and honor her with a shrine. Athena Parthenos was her name, hence the word Parthenon. She was the wisest and most beautiful of the Grecian deities and the Parthenon was her temple.

It is thought that the earliest Greeks worshiped their goddess with crude altars of uncut stone and unhewn wood. Gradually, as the Greeks became more intelligent, they began building temples, each lovelier than the one before and all on the same foundation, as attested by excavations at Athens. It is not known just how many temples there were in this series, but it is known that the last one was destroyed by the Persian Xerxes in the year 480 B.C. Then came the Parthenon, begun in 447 and dedicated to the goddess Athena in 438 B.C. Here for a thousand years the Greeks worshiped their goddess, and it was during this period that Greece produced the greatest of her philosophers, warriors, artists, and writers.

The Parthenon was built under the supervision of Phidias, the greatest artist of form the world has ever known. He was a close friend of Pericles, archon of Athens, who, appreciating Phidias’ great executive ability as well as his genius, commissioned him to build the temple. He had built a number of other temples for Pericles, notably the temple of Zeus at Olympia, but the Parthenon was the most ambitious of all his undertakings, as indeed it was the most ambitious of all the Greek temples.

The Greeks were somewhat slow in embracing Christianity but by 426 A.D. they had become a Christian nation. In the meantime Greece had fallen under the dominion of the Roman Empire and the Emperor Theodosius II changed the Parthenon into a Christian church. For a little more than a thousand years the Greeks worshiped Jehovah in the Parthenon. After the conquest by the Turks in 1458 the Parthenon was changed into a Mohammedan mosque.

Except for the minor changes to the interior in the fifth century by the Christians and those to the exterior in the fifteenth century by the Turks, the Parthenon was almost in as good condition at the time of its destruction in 1687 as it was in the beginning. In that year the Turks were driven out of Athens by the Venetians, representing a Christian nation. In this war the Turks temporarily stored gunpowder in the Parthenon for safekeeping, thinking the Greek gods which adorned its pediments would give them good luck. However, a Venetian shot, not so respectful of the gods of the Greeks, struck the Parthenon and rendered it the interesting ruin that, for the most part, remains today.

As a result of the explosion the entire interior was destroyed. The columns, the architrave, the ceiling, the roof, nothing remained except the floor and fragments of the walls. Fortunately the explosive agent was gunpowder, whose power acts upward and outward only; consequently, the floor was not materially injured and the markings on the floor disclose the order of architecture, location, and diameter of the columns.

The exterior did not suffer as much from the force of the explosion as did the interior. Of the fifty-eight columns on the outside, forty-four were left standing. Eight on the northeast corner and six on the south side were entirely blown away. A few of the end columns were damaged slightly. Almost all of the pedimental sculptures were blown off and greatly injured. Only two fragmentary groups of the pedimental sculptures are left on the old ruin.

In 1929 the Greek Government, with the assistance of American capital, began a restoration of the Parthenon. It is to be hoped that the Greeks will not allow anything to prevent the completion of this work.

The Parthenon at Nashville at Night

In 1896 the State of Tennessee attained its full century statehood. To celebrate that important event in the life of the State the Tennessee Centennial Exposition was held in Nashville the following year. Nashville had long been known as the “Athens of the South” because of its many schools and colleges and accompanying culture, and it is not surprising that the director general of the exposition, a man noted for his culture and love of art, conceived the idea of having as the gallery of fine arts for the exposition a reproduction of the Parthenon at Athens.

In the successful prosecution of the work there was no time for research and study. Relying on existing information, a very creditable building was erected of laths and plaster in the few months available.

The “Gallery of Fine Arts” attracted so much favorable attention during the exposition that at its close the people of Nashville, having become greatly attached to it, insisted that it should not be torn down when the exposition buildings were destroyed. The Board of Park Commissioners of the City of Nashville obtained approximately one hundred and fifty acres of land surrounding the building and laid out what is now beautiful Centennial Park. Built to last a year, the much loved building stood for nearly twenty-four years until, in spite of every effort made for its preservation, it became a greater ruin than its prototype in Athens.

The Board of Park Commissioners had long had as a cherished objective the reproduction of the Parthenon in permanent materials. This was an ambitious undertaking for a city much larger than Nashville, and it was not until 1920 that the old building was torn down and on its site the present reproduction of the Parthenon at Athens was begun. Competent architects, artists, and archaeologists were employed, who devoted the best efforts of their careers to the work. No effort was too great, no money was spared, to make the Parthenon as near as was 4 humanly possible a reproduction of the original as it existed as the temple of Athena in the fifth century, B.C.

The chief difference between the original and the reproduction lies in the materials of which they were made. The Parthenon at Athens was built of Pentelic marble quarried near by, while that at Nashville is of reinforced concrete finished by a patented process which, under the influence of electric lights, very closely resembles marble. The Pentelic marble of the original had a small content of iron, which became oxidized and the color of the ruin at Athens is now a brownish yellow from the iron oxide stain.

By the use of concrete in the building at Nashville three important advantages were obtained: durability, economy, and the privilege of seeing the Parthenon in two colors. Concrete is the most durable of all building materials and the most economical. By a careful selection of materials, the color of the Parthenon at Nashville in daylight is brownish yellow, the same as the ruin at Athens. This effect was obtained by using, as the aggregate of the concrete, a brownish yellow gravel from the bottom of the Potomac River in Virginia.

The Parthenon at Nashville is floodlighted for an hour and a half each night and is indeed a beautiful sight, one of the most beautiful in the world; the lighting plan having been carefully designed by the Engineering Staff of the General Electric Company. A writer in one of the leading newspapers in America said, “If I am ever so fortunate as to reach the Pearly Gates of the New Jerusalem, I shall expect to find nothing more radiantly beautiful than the Parthenon at Nashville at night.”

It is regretted that there was no acropolis on which to locate the reproduction in Nashville. However, this defect in the setting was to some extent atoned for by building it adjacent to a small lake and surrounding it with a beautiful park.

The Parthenon at Athens had no basement, but in the reproduction a basement was added to house a museum of fine arts. Thus the spirit of the Parthenon, always a temple of some god, is not violated by the hanging of pictures on its walls.

Begun in 1920, because of the research necessary to make it a reproduction of the original as it was in the beginning, the Parthenon at Nashville required eleven years for completion. The exterior was finished in 1925, and the Parthenon was thrown open to the public on May 20, 1931, six years having been necessary to complete the interior.

Showing a Section of East Portico with Closed Doors

Shadows on the Parthenon at Nashville showing the “Greek Urn” in End of Exterior Corridor

The Parthenon of Pericles has been shown in a new light as a result of the eleven years of study and research made in connection with the reproduction at Nashville. Some of the older conceptions were based on assumptions rather than facts derived from research. For the first time the modern Greek who visits Nashville sees the Parthenon as his ancestors saw and admired it at Athens.

The Parthenon is sixty-five feet high with its superstructure resting on the base or stylobate of the temple, consisting of three steps. The largest dimensions are furnished by the lowest of these steps, which is two hundred and thirty-eight feet long by one hundred and eleven feet wide. The top step, on which the peristyle rests, is two hundred and twenty-eight feet long by one hundred and one feet wide.

One of the most interesting peculiarities, or it might be said subtleties, employed by the Greeks in building the Parthenon is that no two major lines are exactly parallel nor are they exactly equal in length.

The most striking feature of the Parthenon when viewed from any exterior approach is the encircling row of great Doric columns forming the peristyle. There are forty-six of these columns, seventeen on each side, six on each end (not counting the corner columns twice), and six each on the east and west porticos. The columns of the peristyle are thirty-four feet high with an approximate diameter at the base of six feet. They have an average spacing from face to face of eight feet. The columns of the porticos are somewhat smaller, having a base diameter of five and one-half feet.

Top of Treasury or West Room Showing Ionic Columns and Decorations

The main body of the building is called the cella. The exterior walls of the cella on the long sides with the columns form majestic corridors. The shadows falling at certain times of the day on the walls and floors of the corridors are very beautiful.

Another interesting feature connected with the corridors is what has come to be known as the “Greek Urn.” This is the figure cut in the sky by the columns and architrave at the ends of the long exterior corridors. The Greek Urn has been made famous in literature by the poet Keats in his “Ode to a Grecian Urn.”

The only openings to the Parthenon are the two pairs of great bronze doors leading off the east and west porticos. These doors are the largest in America and probably are the largest bronze doors in the world. They can only be challenged as to size by the Congressional Library doors at Washington or by those of one of the old cathedrals in Florence, Italy, and they are slightly larger than either. The doors are twenty-four feet high, seven feet each wide, a foot thick, and weight seven and one-half tons each.

There is no doubt that the front entrance to the Parthenon was through the eastern doors. If there were no documentary evidence to prove this, and there is an abundance, the fact that all of the twenty-two gods of the east pediment are major deities of the Greeks while only four of those on the west pediment are major (the remainder being personifications and minor deities) would be sufficient proof that the eastern end was the front of the building.

Entering the Parthenon through the eastern doors, the visitor most likely would first note the division of the main body of the building, or cella, by a transverse wall into two rooms—the east room and the west room.

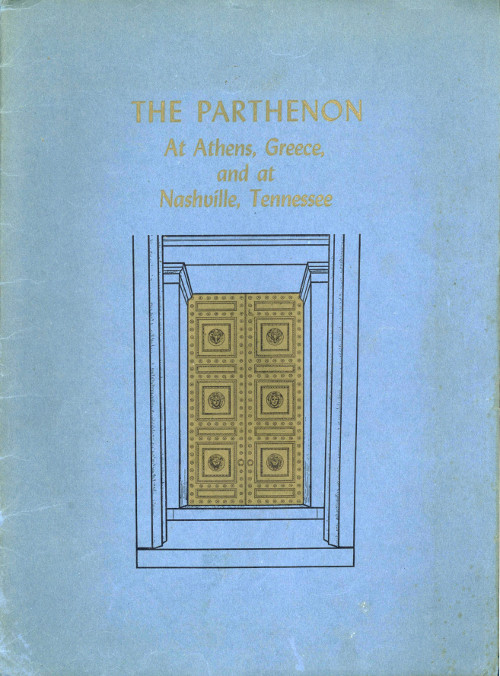

The east room is known as the Naos or temple proper. It is ninety-eight feet long, sixty-three feet wide, and has a ceiling height of forty-three feet. The most striking feature of the Naos is the double row of Doric columns, twenty-three below and twenty-three above, with an architrave between. These form a colonnade surrounding the main floor on three sides. The lower units of the colonnade are three and three-quarter feet in diameter at the base and twenty-one feet high. Those of the upper tier are two and one-quarter feet in diameter and sixteen feet high. The columns on the long side of the colonnade form with the interior cella walls beautiful and impressive corridors. Another interesting feature is that the floor of the corridors is raised an inch and a half above the main floor of the Naos.

In the west end of the Naos, twenty feet from the end columns and facing the eastern doors, stood the Chryselephantine Statue of Athena, the beautiful shrine of the temple, if historians of that day are to be believed. The statue was forty feet high and reached within three feet of the ceiling. It was made, as its name indicates, of gold and ivory. The fleshy parts were carved ivory and the remainder were plates of gold suspended on a framework of cedarwood. It was the masterpiece of Phidias and was worth a king’s ransom.

When Theodosius II changed the Parthenon into a Christian church in the fifth century he moved the statue of Athena to Byzantium, capital of the Roman Empire, as it would have been 7 incongruous to leave it in the Parthenon after the change in religions. After the removal of the Chryselephantine Statue its fate is shrouded in mystery. No part of it and no authentic sketch, drawing, or model of it has ever been found.

Interior of Naos or East Room of Parthenon at Nashville Showing the Ceiling and Plaster Casts of Elgin Marbles

The Greeks entered the eastern doors at the hour of temple worship, always in the early morning, bearing gifts of gold and silver and other valuable articles. There they were met by the priests, who received the gifts. While the worshipers paid their devotions to the goddess at her shrine, the priests took the gifts through the great doors, thence along the exterior corridors, through the western doors, and into the west room where the gifts were deposited. This room is called the Maiden’s Chamber or Treasury.

The west room is forty-four feet long and sixty-three feet wide. As in the east room, its most striking feature is the columns. There are four of these arranged in a rectangle sixteen by twenty-three feet in the center of the room. The columns are Ionic in design and, unlike those of the east room, are monoliths. They are forty-one feet high, six feet in diameter at the base, and three and one-half feet in diameter at the top. The decorations of the room are Ionic also, in contrast with those of the east room.

The decorations of the Parthenon are all authenticated. Fragments of them are preserved in the British Museum and in the Louvre, and some of the colors still show, though dimly, on the protected parts of the ruin at Athens. The decorations at the top of both the interior and exterior architrave, above and between the capitals of the Doric columns are technically known as guttae. The color decorations are principally in shades of blue and red with some yellows. In the interior the colors are found in the fret along the top of the architrave in the east room and in the moldings around the ceilings of both rooms. The colors of the exterior occur in the frets around the top of the cella walls, in the ceiling of the corridors and porticos, and in the decorations of the cornice.

The Greeks lighted the old temple almost 8 wholly through the great doors in each end of the building; at Nashville the lighting comes from above, and this is one of the most prominent of the modern innovations incorporated in the reproduction of the Parthenon. The Greek ceiling was exactly like that at Nashville with this exception: In the Greek temple, between the great cedar beams that span the ceiling and support the roof was an open grillwork of cedarwood, while at Nashville the open spaces have been filled with frosted panes of glass, etched to resemble the rays of the sun. The Greeks might have had glass, as the manufacture of plate glass by the Phoenicians antedated the period of Pericles by some five hundred years. As we have seen, however, they had no incentive to use it, for they obtained their light from below. The incentive at Nashville is to conceal the two hundred and seventy-two high-powered electric lights which give to the interior its beautiful simulation of sunlight, accentuating its beauty and, to a great extent, eliminating the shadows.

The roof at Nashville is like the one at Athens except as to the material used in its construction. The antefixes along the eaves served the purpose of covering the joints between the marble slabs and are of carved ornamental design. At each corner of the roof is a lion’s head, thought to be intended originally as a waterspout. Also at each corner of the roof is a stone block upon which is surmounted a Gryphon monster, standing guard over the temple day and night. The highest points on the Parthenon are the carved ornaments, known as the Acroteria, at each end of the building above the pediments.

It is difficult for anyone to describe the Parthenon and do it justice. Suffice it to say that “it is a thing of beauty and a joy forever.”

The Naos or East Room Showing Symmetry of Columns, the Depressed Floor and Some of the Elgin Marbles

The architecture of Greece was essentially Doric. The Ionic was an exotic in Athens and the Corinthian was more Roman than Grecian and found no place in the Parthenon. There is a total of one hundred and eight columns in the building, and of these all on the exterior and all in the east room, one hundred and four in number, are Doric, while the four in the west room are Ionic.

Taste varies in the beauty of architecture as well as in art generally. Some admire the Gothic cathedrals of Europe, others admire the Taj Mahal in India, and still others prefer the temples of Japan; but to those who admire the architecture of the Greeks and the Romans, the Parthenon is the most beautiful building in the world. Regardless, however, of what may be thought of the beauty of its architecture, it is the most perfect.

The age of Pericles has been known through the centuries as the “Golden Age of Greece,” but the judgment of time has forced us to the conclusion that it was also the golden age of the world as far as the beauty of architecture and sculptural art is concerned.

There is no more intriguing part of the whole narrative of the Parthenon than this story of the subtlety of the Greeks in overcoming optical illusions and neutralizing differences in distance.

Perhaps the most important, certainly the most prominent, of the refinements of the Parthenon is the curvature of the horizontal lines. It is not true, as some textbooks have it, that there is no straight line in the Parthenon. There are a number of them, but all of these straight lines are vertical. What should be said is that there are no straight horizontal lines in the Parthenon.

Another refinement used by the Greeks in adding to the beauty of the Parthenon relates 10 to the columns. The visitor is certain to be impressed by the softness of the Doric columns. This is especially true of those of the Naos where their proximity to each other emphasizes their beauty as they are caught banked against each other. When thus seen all other columns fail by comparison and seem as stiff as pokers. This quality of softness is given them by the fact that all columns, both in the Naos and on the exterior of the building, are different in diameter from those beside them and all are also spaced differently.

Still another refinement pertaining to the columns is technically known as entasis, which is that quality which gives to them their beautiful symmetry.

In discussing the columns in relation to their softness it was suggested that they be seen banked against each other. In the discovery of their symmetrical beauty, however, they should be seen singly. The column apparently rises from the floor at its largest diameter and gradually diminishes in a beautifully fluted shaft, having the very breath of symmetry in every line to the top. That is the way it appears; but, as a matter of fact, if the column had been constructed as it actually looks, then, instead of seeming beautifully symmetrical, because of an optical illusion, it would have appeared concave at a point just below the center of the column. Knowing this from experience, the Greeks filled in just enough to correct the results of the optical illusion and the column in reality is bulged near the center.

It has been noted that the first sight of the Parthenon usually inspires the visitor with a sense of its strength and stability. This effect is produced by another of the subtleties of the Greeks in approaching perfection in the Parthenon. Only one with technical knowledge would ever suspect that its columns and walls are other than perpendicular; yet, with the exception of the transverse wall which divides the cella into its two rooms, all of them are inclined toward the center. If all were projected on their axes, they would meet in a cluster five thousand, eight hundred and fifty-six feet above the base of the temple.

One of the major problems that confronted the builders of the Parthenon at Nashville related to the arrangement of the columns of the Naos. Prior to the research work in connection with the Nashville reproduction, the preponderance of authority favored the theory that the Doric columns of the Naos were monoliths. This matter was settled definitely by the work done by Mr. William Bell Dinsmoor, of New York, who represented the builders in the archaeological end of the work.

As has been said, nothing remained of the interior of the original Parthenon after the explosion of 1687 except the floor and fragments of the walls. One of these fragments happened to be in the end of the building in the southeast corner of the Naos. Sticking in it, Mr. Dinsmoor discovered a small piece of the architrave and a discoloration of the wall revealing where the remainder had been. This discovery fixed the fact of an architrave and, following very closely, the further fact that there were columns superimposed on each other with an architrave between.

The architecture of the Parthenon will always carry with it elements of the mystical and the mysterious to modern minds, accustomed as they are to the solution of engineering problems by rule. The more the Parthenon is considered, the more interesting it seems.

Floor of Treasury or West Room Showing Arrangement of Ionic Columns and Figures from Elgin Marbles of Iris and Heracles

The sculptures of the Parthenon occur in four groups: the Ionic or inner frieze, the Doric or outer frieze, the east pediment, and the west pediment.

As the subtlety of the builders of the Parthenon emphasized their intellect, so the sculptures emphasized their religion. The Greeks were not idolaters in the sense that they bowed down to gold and ivory. They loved to chisel in marble the beautiful forms that represented to them their gods who dwelt on Mount Olympus. A characteristic of the Greeks of this period was that, in their art, they always presented their goddesses fully clothed and, almost always, their gods in the nude.

While the origin of the Parthenon has the most of its roots firmly fixed in Egypt, many of the sculptures were derived from the Assyrians. Particularly is this true of the smaller figures, winged mythical creatures, as well as lions and horses, typical of the Assyrian bas-reliefs. The heavier figures, notably those of the pediments, are essentially Greek.

In the life and times of Phidias, a love for the beautiful was so general that it was comparable to the air which they breathed. It was not difficult, therefore, for him to find men, almost as accomplished as himself, upon whose shoulders he could lay the greater part of the work.

It is a matter of keen regret that so few of the sculptures of the Parthenon have been preserved. For this reason, the most difficult problem in the task of the reproduction of the Parthenon at Nashville was the reproduction of the sculptures.

When the Parthenon was destroyed in 1687 the sculptures were blown off the temple and, to a great extent, broken up by the explosion. As already noted, only two of the pedimental groups remain on the ruin, one on each pediment. Plaster casts of these are now in the British Museum. A much larger proportion of the figures of the friezes remain on the ruin but they are so badly damaged that identification is practically impossible; this is especially true of the Doric frieze.

Interior Corridor, South Side, Showing Elgin Marbles

In 1801, after the fragments of the sculptures had lain in the debris around the temple for approximately one hundred and fifteen years, Lord Elgin, Minister to Turkey from England, persuaded the Turks, who had again conquered the Greeks, to let him go to Athens and dig up all the sculptures that he could find around the ruins. He sold these fragments to the British government, and they are now the most highly prized possessions of the British Museum, known as the Elgin Marbles.

It is popular in some quarters to criticize Lord Elgin for his action in taking the fragments from the Parthenon to England. Some have gone so far as to say that he actually robbed the temple of its sculptures. Unquestionably, the correct view of the matter is that Lord Elgin did the world a great service in salvaging the fragments from the earth in which they had deteriorated for many years and, but for him, might have suffered greater injury.

In the west room of the Parthenon at Nashville and along the corridors of the east room may be seen casts which form the only complete set of the pedimental sculptures outside of the British Museum. Many isolated groups of these may be found in America and in Europe, but all of them may be seen only at Nashville. Here they are mounted on wooden bases forming a most interesting exhibit and were obtained through the courtesy of the British Museum.

In the east room of the Parthenon at the west end of the south corridor is the head of one of Selene’s steeds, considered by many as the finest example of a horse’s head in the world. Just beyond, through the door at the end of the corridor, is seen in the west room the figure of Heracles. It is interesting to note that in the report of the artists who passed on the value of the Elgin marbles a statement was incorporated to the effect that the back muscles of the Heracles represented the finest example of physiological art known to the world of that day. Another most interesting group of sculptures, the three Fates, is seen near by in the west end of the east room. This group, thought to be the work of Phidias, is generally regarded as one of the most beautiful examples of sculptural art existing today.

The casts of the Elgin marbles in the Parthenon at Nashville, which were made by the British Government, were not obtained primarily as an exhibit but as a study for the reproduction of those sculptures now on the building. However, it was not thought inappropriate to mount the fragments and use them as an exhibit so as to permit visitors to compare the completed figures with them. The comparison can only cover approximately half the figures on the pediments as the remainder have been lost beyond recovery. Quite naturally, the question arises in the mind of the reader as to how it was possible for the artists to reproduce all of them.

In 1674, just thirteen years before the explosion which destroyed the Parthenon, young Jacques Carrey, a French artist attached to the French embassay to Turkey, on a voyage from Paris to Constantinople with the ambassador stopped off at Athens and sketched the temple sculptures. These sketches are preserved in the National Library at Paris and were made available for the artists. From a study of the Elgin marbles and the Carrey drawings, supplemented by further study of Greek contemporary art and Greek history, the artists at Nashville succeeded in making a wonderful reproduction of the Parthenon’s sculptures.

Figures from the Ionic Frieze

The inner or Ionic frieze, sometimes erroneously called the frieze, was one of the most beautiful of the groups of sculptures on the original Parthenon. It was almost unknown to distinctly Doric temples and owes its place on the Parthenon to some one or more Ionic temples from which the idea was without doubt copied.

In the Ionic frieze is found most of the atmosphere of ancient Assyria that is associated with the Parthenon. This frieze was low in relief, forty inches in height; and of necessity the figures of the men and women and animals which went to make up the frieze were small, typical of the Assyrian bas-relief.

The Ionic frieze was located along the outer walls of the Parthenon, extending forty inches down from the top of the wall, and rested on a blue fret running all around the building, a distance of five hundred and twenty-four feet. It was a marvelous piece of sculptural art. Although there were approximately six hundred figures in the frieze, men, women, and animals, no two of them were alike—no two men, no two women, and no two animals; yet all were graceful, dignified, and beautiful.

The Ionic frieze of the Parthenon depicted the Panathenaic Procession which occurred every four years in Athens. It was an established part of the Panathenaic Festival and coincident also with the athletic contests held in honor of Athena. On this occasion the Greeks assembled in the downtown streets of Athens; men and women of high and low degree with their slaves, various kinds of animals, chariots with their horsemen, men at arms, wild horses led by Barbarians, dignitaries of state, and maidens. These formed a procession which wound its way up through the streets of Athens leading to the Acropolis, on to that sacred hill, and into the Parthenon, where they invested the figure of Athena with a peplos, or robe, which had been woven by the women of Athens during the previous 14 four-year period. It was at once a gala and a solemn occasion for the Greeks.

Unfortunately, for lack of funds the Ionic frieze has been left off the Parthenon at Nashville, which lacks that much of being completed. It is available, however, as the greater part of it is in the British Museum, some in the Louvre, and the remainder, twenty-four feet in all, is still on the ruin at Athens. There is no doubt that the Ionic frieze will eventually find its place on the temple at Nashville.

The Doric, or outer frieze, is located on the outside of the Parthenon above the architrave that rests on the great Doric columns of the peristyle. It extends along both sides of the building and underneath the pedimental sculptures at each end. It consists of a repeating conventional design called a triglyph which divides the frieze into ninety-two panels, each panel containing a group of sculptures. The panels with their sculptures are known as the metopes and are approximately four feet square.

There were no repetitions in the sculptures of the Doric frieze. They told legendary and mythological stories that were dear to the heart of the Greeks. That part of the frieze on the eastern end of the building pictured scenes from the struggle between the gods and the giants. The war between the Greeks and the Amazons was shown by the figures of the frieze on the western end. On the north side of the building the figures depicted incidents of the Trojan War, while those along the south side told the story of the Lapiths, a tribe of the Greeks, and the Centaurs. The story is that of a princess of this tribe who was to be married. She sent invitations to the Centaurs, mythological creatures part man and part horse, to come to the wedding feast. They came, drank wine, became drunken, and insulted the bride, which brought on a war in which the Centaurs were defeated.

The figures of the Doric frieze are archaic and stiff by comparison with those of the pedimental sculptures or of the Ionic frieze and are therefore thought not to be the work of Phidias and his associates but rather a transfer from one of the earlier temples to the Parthenon. They play their part well in the harmonious whole and reflect the ability and genius of Phidias, who adapted them.

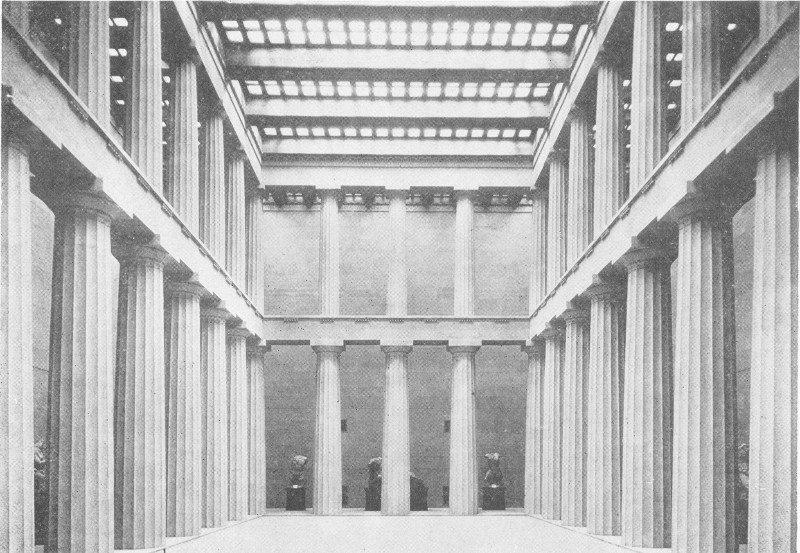

The West Pediment Showing Section of Doric Frieze Underneath the Acroteria Above

The figures of the west pediment were more easily reproduced than those of the east pediment, as they were more completely authenticated by the Elgin marbles and the Carrey drawings.

It should be understood that the explosion that destroyed the Parthenon did its greatest damage to the figures themselves rather than to the base on which they rested, and as a consequence less difficulty was encountered by the artists in placing the sculptures in their proper settings on the west than on the east pediment. In considering the sculptures of the two pediments it must also be borne in mind that the force of the explosion was greatest in the eastern portion of the building, as evidenced by the condition of the ruin, and for that reason also the greatest damage was to the east pediment.

The sculptures of the west pediment tell the story of the struggle between Poseidon, the powerful god of the sea, and his niece Athena, the goddess of wisdom, for the possession of Attica, or ancient Greece.

In the center of the pediment, to the right, is the heroic figure of Poseidon with his three-pronged weapon or trident in his hand, his friends and supporters to the right. Opposing him, and to the left, is the equally heroic figure of Athena with her great spear in her hand, her supporters to the left. Both of these gods coveted the fair land of Attica and desired the worship of its people. They were unable to agree and appealed to the gods for a decision. The gods held their convocation on the Acropolis, the site of the Parthenon, and this assembly is shown by the figures of the west pediment.

As a result of the convocation the gods decreed that the contestant who should most bless Greece would be given the control of Athens and have the worship of the Greeks. It was to be a battle of blessing, rather than blood.

Poseidon, in granting his blessing, struck the solid rock of the Acropolis with his trident, and as he was the god of the sea it obeyed him and came up in a rushing, gushing spring of salt water, symbolic of his promise that if the Greeks would make him their god he would make of them a mighty maritime nation—their glory should be on the sea. When it became Athena’s turn to grant her blessing, she struck her great spear in the earth and withdrew it and from the place sprang an olive tree, the parent of all those which have so greatly blessed Greece from that day to this. The gods, acting wisely, decreed that Athena’s gift was of far greater advantage to the Greeks than any promise of the glory of war as made by Poseidon, and made her the patron goddess of Athens.

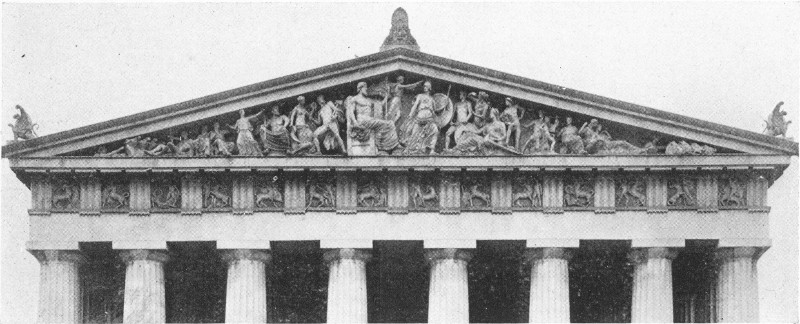

The East Pediment with Section of the Doric Frieze Underneath Showing Gryphon Monsters and Acroteria on Roof

It would be very difficult for a visitor to Nashville to decide which group of sculptures on the Parthenon is the loveliest. Each general group fits so harmoniously into its own particular place that a choice of one could not avoid being unfair to the others. Viewing the west pediment first, one essaying judgment might exclaim, “What could be more beautiful!” Yet on leaving it and looking at the east pediment he might easily be found saying, “Here is the answer.” The presence on the east pediment of the three Fates, the Heracles, and the steeds of Selene probably gives the east pediment the advantage over the other groups, especially in the eyes of the artists.

The story of the east pediment is very beautiful and tells of the birth of Athena and of her reign. In the beginning Zeus, the father of the gods, the king of the gods, had a very severe headache and could find no relief. He had long wanted a child born of the intellect. It is said that he was so disappointed at having a son, Hephaestus, born maimed that he threw him out of Heaven and it took a whole day for him to fall to the earth. Hephaestus was the god of fire, the god of metals, the blacksmith of the gods, and he forged the thunderbolts that Zeus used in his battles of Heaven. Hephaestus sent word to his father that if he would restore him to his rightful position among the gods, he would cure him of his headache. Thereupon Zeus assembled the gods on Mount Olympus and from somewhere, in a thundercloud, came Hephaestus. He struck his father in the back of the head with an axe and from the wound, giving Zeus his wish, sprang Athena, fully grown, clothed, and armed. She was announced and crowned goddess of wisdom by Nike, goddess of victory. It is said that at this event the earth groaned, Mount Olympus trembled, and the gods stood in amazement at the miracle that had been performed. These four figures form the highest pinnacle of the east pediment of the Parthenon.

At the extreme south end of the pediment, representing the beginning of the reign of Athena, in the morning is seen Helios, the god of the sun, the god of the morning, coming up out of the sea driving his four steeds representing the four seasons. As the horses come bounding out of the sea, Helios can scarcely restrain them, so eager are they to mount the skies.

Heracles, the next figure on the pediment, is shown with his club on his shoulder, nonchalantly looking at the horses, paying no attention to what is taking place on Mount Olympus. He is looking at the sun as it rises. Heracles was known as the favorite of the gods. In his early manhood they had permitted him to choose between virtue on the one hand, and vice on the other, both very attractively arrayed. He chose virtue rather than vice, and 17 thus became their favorite. He did many heroic deeds in Grecian history, and was the national hero of Greece. Heracles was himself made a god; Zeus was his father, his mother was a mortal.

Next, on the pediment, may be seen the figures of Demeter, the sister of Zeus, and her daughter Persephone. Demeter was the goddess of the seasons. Ceres was her Roman name, and her daughter, Persephone, was the goddess of the underworld. She became the goddess of the underworld in this wise: One day when Persephone was in the fields plucking violets with her maidens, suddenly the earth opened and through it, in a chariot, came Pluto, the god of Hades. He saw her, fell in love with her, seized her, took her back to Hades, and made her his queen. Her mother grieved sorely and would not be comforted. She had powerful influence with the gods. She sent plagues on the earth and worried the gods, until Zeus was forced to compel Pluto to bring Persephone back to her mother. Thereafter, it is said, under a compromise agreement, Persephone spent six months of each year with her mother among the gods, and six months with her husband, Pluto, in Hades.

The next figure on the pediment is that of Iris, the female messenger of the gods, the rainbow goddess. She is represented on the pediment as being poised, ready to go at a moment’s notice, to tell the story of the birth of Athena to the world. This is the first figure seen among the fragments as the visitor enters the Parthenon door, and is often confused with the Winged Victory of Samothrace. The confusion arises from the fact that in the fragment of the Parthenon figure of Iris, located in the west room, she is holding her scarf at arm’s length in her hands and the fragment is broken through the scarf and through the arms, causing it to look as if it might be a wing, when, as a matter of fact, it is the fragment of a scarf and not a wing; and the figure is not the Winged Victory, but is Iris, the female messenger of the gods, the rainbow goddess.

Next is seen on the pediment the figure of Poseidon, the god of the sea; Neptune was his Roman name. Poseidon was the brother of Zeus, one of the chief deities of the Greeks, and is represented on the east pediment as sitting calmly by, looking on at what is taking place.

The next figure beyond Poseidon is that of Aphrodite, or Venus, the goddess of beauty, the goddess of love. She seems shocked at what she sees, and shrinks a little; but is comforting Hebe, the goddess of youth, who is reclining at her feet, by placing her hand on her head.

Then comes the central group, Hephaestus, Zeus, Nike, and Athena, or Minerva as the Romans called her, illustrating the story of the birth of Athena.

Next is seen Ares, or Mars, the god of war. He is represented on the pediment as looking rather sternly past Athena as though he does not welcome this additional warlike member to the family of the gods.

The next figure is that of Artemis, the twin sister of Apollo. Artemis is the goddess of the fields, the goddess of hunting; Diana is her Roman name. She is represented on the pediment as shading her eyes with her hand from the resplendent glory of the newborn goddess.

Just beyond Artemis is seen Hera, queen of Heaven, also known as Juno, the jealous wife of Zeus. In addition to her jealousy, it is said that she was vain and the peacock, seen near by, was sacred to her. Hera was also the goddess of maternity, and very fittingly was present at the birth of Athena.

The next figure is that of Hermes, the male messenger of the gods, corresponding to Iris, the female messenger. Iris usually executed the commands and carried the messages for Hera, while Hermes performed a like office for Zeus. He is always represented with a magic wand, or caduceus, in his hand, which was given to him by Apollo. One day, when Hermes was a mere child, almost a baby, he was playing in the fields and captured a tortoise. He placed strings across the shell of the tortoise and made a musical instrument (we call it the lyre), and presented it to his brother Apollo. Apollo, who was the god of music, was so delighted with the precociousness of his baby brother that he gave him the magic wand, which had the power of putting gods and mortals to sleep at his will. Hermes is also shown with wings on his ankles and wings on his cap. He was god of business, and also the god of transportation. His figure adorns many of the railway stations of the world. His Roman name is Mercury.

Beyond Hermes, on the pediment, is seen Apollo, the god of music, with his harp. He was also the god of manly youth and the god of healing. Esculapius, his son, was the first doctor of Greece, the father of all the physicians. Apollo was regarded as the most beautiful of the gods. Reclining on him is seen Ganymede, the cupbearer of the gods.

These were the chief deities of the Greeks. There were others which they worshiped also. They were as sacred to the ancient Greek as Jehovah is to us, and it is pertinent to say that they worshiped the beautiful—and the beautiful is the spiritual.

We are not so much interested in the gods of the Greeks in this twentieth century, however, as we are in human life; and the next group of figures to Apollo and Ganymede, the three Fates, brings the Whole matter closer to us, because it represents the Greek idea of life. The first figure in the group is Clotho, who is represented as spinning the thread of life; and as she spins, the second figure, Lachesis, winds it on a spool, and the third figure, Atropos, clips it at will, typifying the beginning, the span, and the end of life—the destiny of us all.

Last, in the extreme north angle of the pediment, in the evening, is seen the gentle Selene, the goddess of the moon, the goddess of the evening, guiding her tired steeds, so different from those seen coming out of the sea in the morning, down into the cool, quiet waters of the deep, typifying not alone the close of the day but the close of the reign of Athena and the end of time.

The gods of the Greeks are no more. They have no single worshiper left on all the face of the earth today to pay them homage, yet their deeds are told in song and story, and their memory is green in the hearts of those who love the beautiful.

And now, we come to the close of the story of the Parthenon.

The period of Pericles marked one of the high points in the history of the world. A comparison of its characteristics serves to emphasize its superiority over other epochs in many ways. The Parthenon at Athens was not merely a wonderful building, but was an expression of Greek mind and heart. It did not spring up in a day as did Athena from the head of Zeus but found its roots in the prehistoric altars of their goddess. It was not built to please individuals but to honor their gods. It is no wonder, then, that when the Parthenon came into full flower in the “Age of Pericles” it should have reached that state which the judgment of succeeding generations has pronounced perfection.

The Parthenon at Nashville stands alone as a portrayal of the Parthenon of Pericles. It would be too much of a challenge to the antiquity of the Parthenon to say that every statement made about it in these pages bears the stamp of absolute authenticity. It can be said, however, that because of the many facts obtained from the research and the records of earlier days and because of the eleven years of research and study in our own times, the Parthenon at Nashville will stand as the last word.

It is difficult to estimate the influence of the Parthenon at Nashville on the world of today. To those who love the beautiful, either by instinct or cultivation, the Parthenon is a thing to be revered; to others it is just another building. To understand and appreciate the Parthenon it must be studied. We may glance at some buildings and pass on, but not so with the Parthenon. It is compelling. A revelation of its balanced lines and its harmony of proportions, its simplicity both delicate and strong, its subtleties, some bordering on the mystical, marks the Parthenon as a thing by itself.

The Naos or East Room as Seen Through the Eastern Doors

The Parthenon is used only for educational and cultural purposes. Over four hundred college, high school, and primary school groups visit the Parthenon each year.

This, then, may be said of the Parthenon: As in the earlier days, even so now, young and old, rich and poor, alike are made happy by its sheer beauty and inspired by its history to reach for a higher and better life.