Title: George Edmund Street: Unpublished Notes and Reprinted Papers

Author: George Edmund Street

Contributor: Georgiana Goddard King

Release date: December 10, 2018 [eBook #58450]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Sonya Schermann, Charlie Howard, and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

PUBLICATIONS OF

THE HISPANIC SOCIETY OF AMERICA

No. 100

WITH AN ESSAY

BY

GEORGIANA GODDARD KING

QUAM DILECTA TABERNACULA TUA DOMINE VIRTUTUM

THE HISPANIC SOCIETY

OF AMERICA

1916

COPYRIGHT, 1916, BY

THE HISPANIC SOCIETY

OF AMERICA

| I. | 1 | |

| II. | Notes of a Tour in Central Italy | 59 |

| III. | Notes on French Churches | 97 |

| Some French Churches Chiefly in the Royal Domain | 99 | |

| Architectural Notes in France | 127 | |

| Some Churches of Le Puy en Velay and Auvergne | 201 | |

| Appendix | 253 | |

| S. Mary’s Stone | 255 | |

| Churches in Northern Germany | 270 | |

| Index | 333 | |

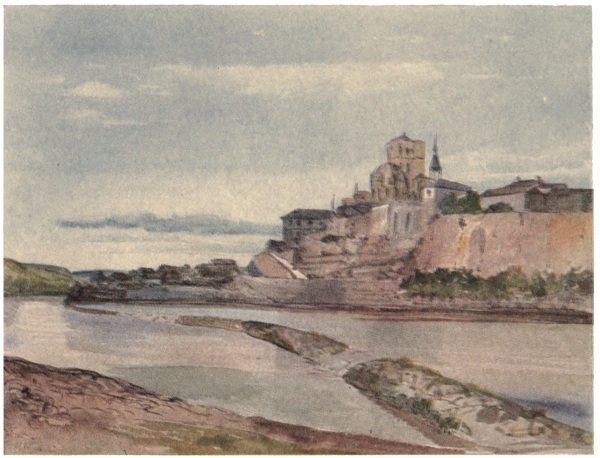

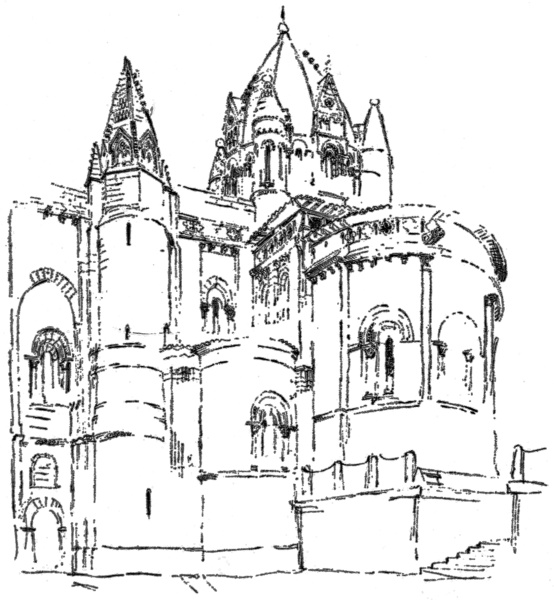

| Zamora on the Douro | Frontispiece |

| PAGE | |

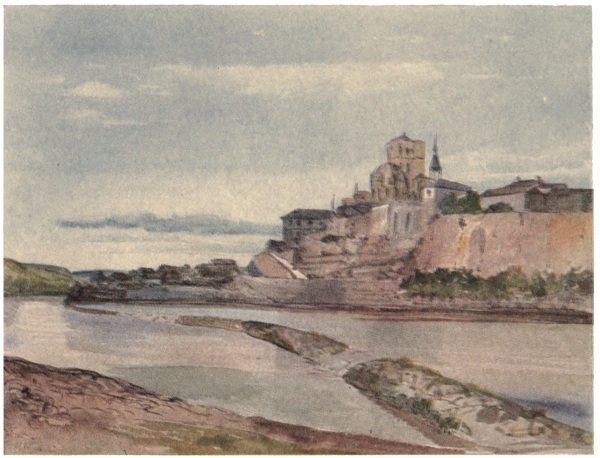

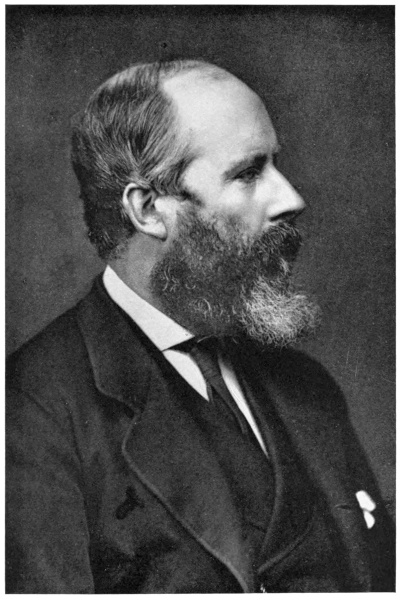

| George Street at about twenty-five | 8 |

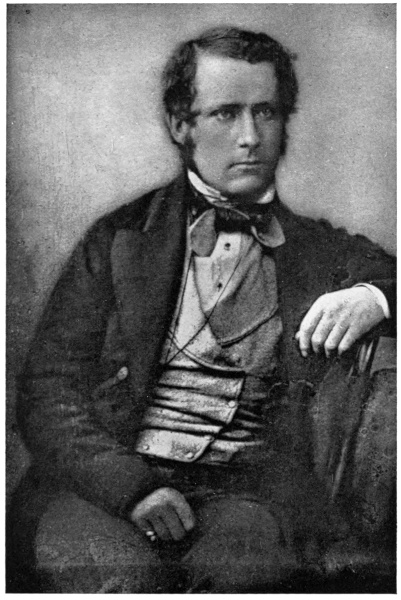

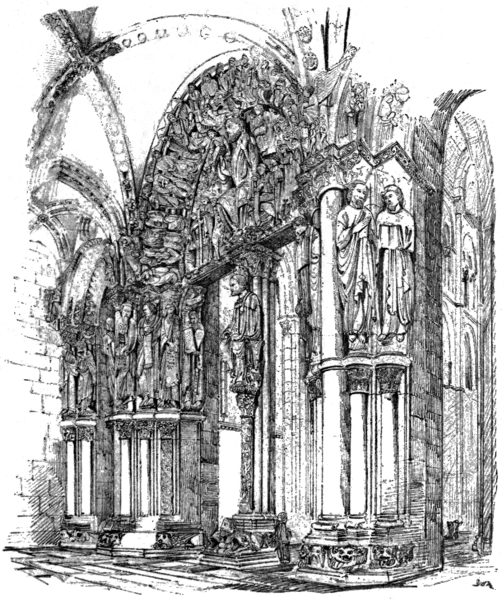

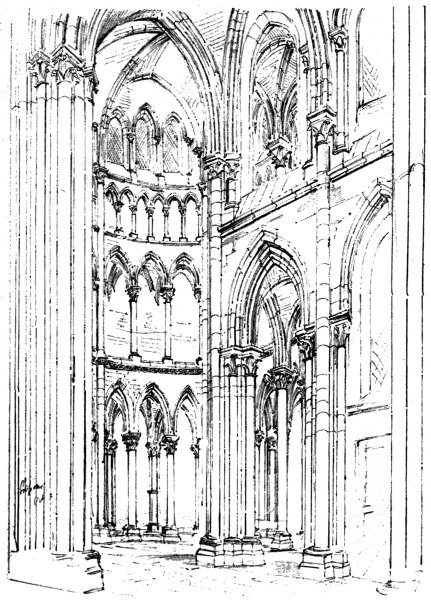

| In Leon Cathedral | 29 |

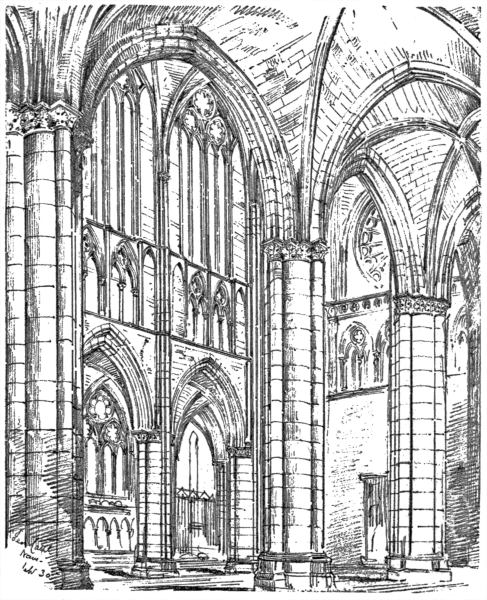

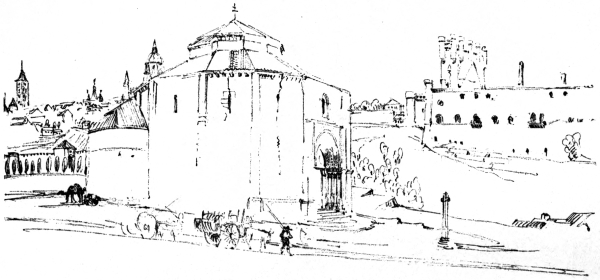

| The Old Cathedral of Salamanca | 46 |

| George Edmund Street in 1877 | 57 |

| Master Matthew’s Porch at Santiago | 92 |

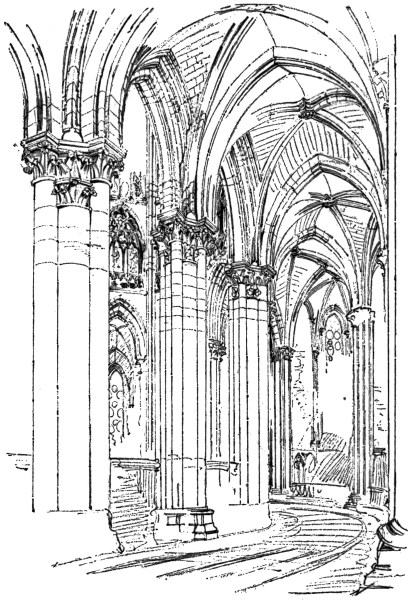

| The Ambulatory, Cathedral of Tours | 127 |

| The South Transept at Soissons | 162 |

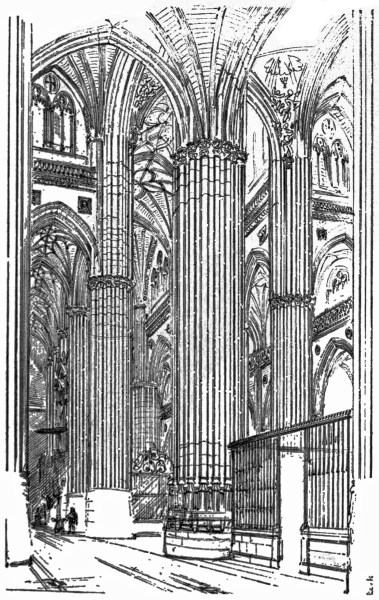

| Nave and Transept, Salamanca | 196 |

| The Templars’ Church at Segovia | 227 |

| The Western Porch, Saumur | 249 |

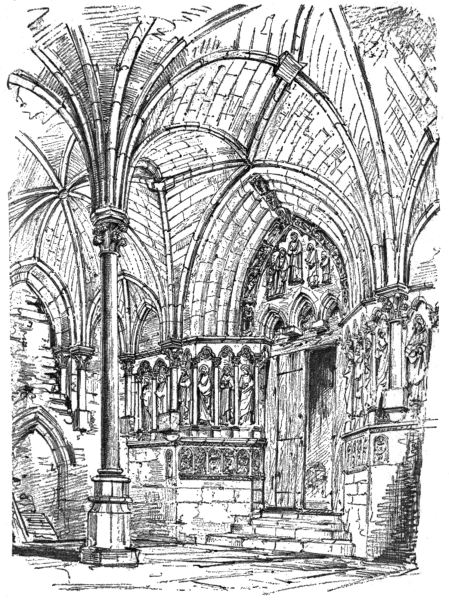

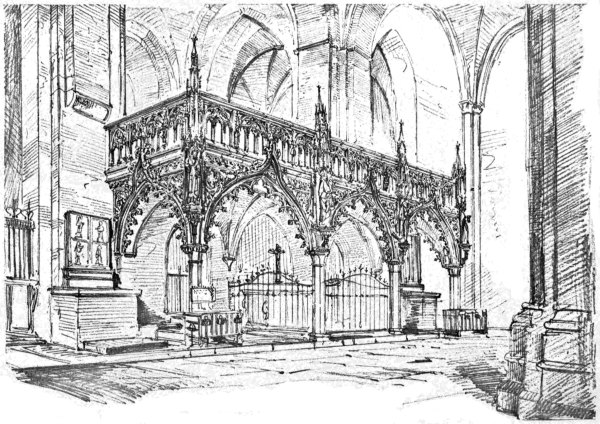

| Rood-screen in Lübeck Cathedral | 271 |

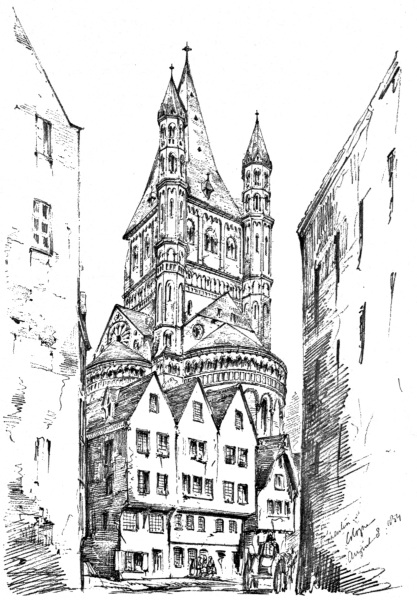

| The Great S. Martin, Cologne | 307 |

I have to thank Arthur Edmund Street, Esq., of London, for the generous loan of some notebooks and drawings, and through these for a more intimate knowledge of his great father’s fine temper and manly art.

Bryn Mawr, Epiphany, 1915

“And he that talked with me had a golden reed to measure the city, and the gates thereof and the walls thereof. And the city lieth foursquare, and the length is as large as the breadth. And the building of the wall of it was of jasper; every several gate was of one pearl.”

1

I have written the memorial, brief enough and all inadequate, of a man who died more than thirty years ago, who lived a Tory and a High Churchman, who worked to revive Gothic architecture in England. His books are out of print, his occasional papers and pamphlets so entirely dispersed and forgotten that not even a bibliography can be recovered. His name goes unrecognized in general talk; his party is wasted to a wraith or transformed beyond recognition; his Church is menaced by Disestablishment in Wales, and Modernism on the Continent; his strong and sincere architecture is superseded by steel and concrete; yet no man ever less fought a losing fight, no figure ever less evoked regret or toleration. He prospered, but his personality made that a kind of happy consequence; he served God, but his genius made that a kind of crowning grace; he was an Englishman, but was that in no mean or halfway fashion. Rather, George Street embodied and expressed in his own temper the very genius of the northern kind.

2 His people were substantial, of the strong British stock which is good for grafting on. In the sixteenth century they were respected in and about Worcester; one of the name went to Parliament in 1563, and another had been Mayor in 1535. In the eighteenth century some of them went to Surrey, and early in the nineteenth Thomas Street was a solicitor in London. He had moved into the suburbs, however, before his youngest son, George Edmund Street, was born. This was in 1824. The boy did well enough at school, but at fifteen he was taken away, when his father removed from Camberwell to Crediton. No school was at hand, and a solicitor would not send his son to Eton and Oxford. Instead, he sent him to the London office. This was in 1840. After the father’s death, in that year, young Street was anxious to go to college and to prepare for Holy Orders, but want of money made the hope impossible, and the strong vocation proved to be for the Third Order—a layman’s part in building up the house of the Lord and making fair the ministry therein.

It seems to have mattered not at all, in the event, that Street was not a University man. In reading the correspondence of Keats, we must deplore that he had not had certain conventions of good taste and good feeling sharply imposed upon him at a great public school; in reading the poetry of Browning we must regret that he missed the tradition of self-criticism and academic stability which would have saved him from the fantasticality of his Greek names and the dullness of his longer Parleyings; but Street seems to have got out of his profession and his associates all that Oxford would have given, and escaped whatever harm it could have done.3 He saved, meanwhile, nearly ten years of life, and spent these on churches, chiefly old. He has not the marks of the University man, but for that he is none the worse. No more in truth has Morris. Instead of culture he has energy, instead of urbanity he has self-control, instead of classical he has professional reading behind him. It is only in a very special sense, after all, that he did without what we call culture and what we call urbanity; in the sense of Newman’s rather malicious definition of a gentleman as a University man who is too indifferent for enthusiasms and too sceptical for prejudices. If young Street never went to school after he was fifteen, and no record remains of his reading regularly or under direction, yet he read irregularly all his life; by middle age he had read everything that a man must have read. Beyond this, in the subjects that he had at heart he had gone wide and deep. He must have mastered and spoken, besides French and German, both Italian and Spanish, and he carried on his research into Latin documents, it seems, with ease and speed. After meals and on journeys the busy man found his opportunity; he took up and took in a vast deal of contemporary thinking; finished the newspaper quickly, and reviews and the graver sort of periodical literature almost as fast. In his case, as rarely happens, another art could give what most men seek in literature if they ever seek it, and the taste was refined and the spirit inspired not so much by fine poetry as by pure Gothic. The churches of England and the cathedrals of France taught him that perfect measure, that economy of force, that high seriousness, that austerity of beauty, for which others are sent to the Iliad and the Divine Comedy. Barring4 belles-lettres and biology, there is little indeed, whether in science or in mathematics, that the University can offer, which the arts do not exact. If architecture is on the one side an art, it is on the other a profession, and partakes as little of the tradesman’s mean-mindedness as of the artist’s irresponsibility. It is probable, moreover, that his passion for landscape had as much to do in forming the character as Wordsworth’s. By the living rock and the ancient wall, by the perfect fabric of Notre Dame and S. Marco, by the worship in chanted psalm and antiphonal prayer, his spirit was forged and tempered.

At school he had sketched and scrawled, and when after his father’s death in 1840 he was recalled to live with his mother and sister at Exeter, he studied painting for a while as painting was taught in the provinces, learning the management of oils and the science of perspective. No harm could come from this except that in landscape sketching later he was shy of strong colour, and set down Spain and Italy more pallid than he liked; but already the current of his life was running by church walls. In the year before, his brother, who was eight years his senior and was brim-full of mediaevalism, had taken him on a short walking trip for what they called ecclesiologizing. For a while he lived near Exeter cathedral, drawn to it at that time by every sentiment: grief for his father—since his domestic affections were stable—and anxiety for the future, strong religious feeling, aesthetic feeling as strong, the beauty of the service and the beauty of the building. Thence he made another trip with this same brother, Thomas, around about through the West of England to Barnstaple, Bideford,5 Torrington and Clovelly. The diary of that tour, written shortly after his sixteenth birthday, is simply the first of the always happy notebooks which record his many journeys in the interest of landscape and art. It sets down the lay of the land and the aspect of the streets where they passed; it notes that he got up at six to sketch out of his bedroom window; and it preserves more fact than comment, and less of the trivial than of the significant. Within another year he was articled to an architect in Winchester, studying the cathedral from every point and at every hour. The two brothers tramped the country for twenty miles about, and as they could pushed further, for the most part on foot still. In the spring of 1843 they walked to Chichester; in the autumn into Lincolnshire; the next year into Sussex. In 1845 they reached Northampton, returning thither in 1846 and again in 1850. The same autumn he went to the Lake Country and thence across to Durham and home by the Yorkshire dales and abbeys. Jervaulx, however, he missed at this time, nor does it appear among the sketches of other abbeys in a notebook of 1875. In the spring of 1847 the two brothers were among the churches of the fen-land in Norfolk and Cambridgeshire. Meanwhile in 1844 Thomas, who was the eldest of the brothers, and had succeeded to his father’s practice, took a house near London and fetched his mother and sister to live with him there.

George, who was lonely and heartily sick of Winchester, came up to share it, with a letter for G. G. Scott and drawings of his own to show. Taken on because work was pressing, he was kept on because his6 work was good, and stayed in the office of Scott and Moffatt until he was ready to set up for himself five years later. Thomas Street by 1849 was married; the requirements of his profession, if not more serious, were more exacting. He made fewer tours, but his taste for architecture, and apparently his taste in architecture, remained sound. “At this time, they were all living together at Lee, and afterwards at Peckham,” says the Memoir written in 1888 by George Street’s son. “My aunt relates how the two young men used to arrive with sketch-books full and rolls of rubbings of brasses, and would then sit up till the small hours, in all the excitement of archaeological discussions and arguments. My uncle [Thomas] was quite untaught. His love for and appreciation of good architecture were quite spontaneous, and the proficiency which he attained with his pencil and the knowledge he had of this subject, more than considerable.”

As the first knowledge of architecture had come through a brother, so Street’s first commission came through the sister. Miss Street worked at ecclesiastical embroidery. She heard through another lady embroiderer of a clergyman who intended building a church in Cornwall. The story turns prettily on the scrupulous girl’s anxieties. Mr. Prynne, the clergyman, begins—“Has your brother got much work going on?” The sister, who wants to make him out as important as possible, yet cannot bring herself to a fib; and the sorry truth that he is quite at leisure from affairs of his own, unexpectedly satisfies the impatient projector. The commission for Biscovey church led to others in Cornwall. Between restorations and new churches and7 schools, commissions accumulated, and Street at this period was in those parts for several weeks together, three or four times a year, overseeing the work in progress and finding new work ready always at hand. In 1849 he had chambers in London and was “on his own”: at the end of 1850 he went to Wantage to be within reach of Cuddesden, being appointed by the Bishop of Oxford, diocesan architect.

Two main interests mark this time. He was engaged to be married, and he was at the well-spring of the Oxford Movement. He spent his Sundays at Maidenhead with Marquita Proctor, on the river, seeing churches and sketching; he spent his working days at Wantage.

“Mr. Street, having no special ties to any locality, desired to live at Wantage where daily service and weekly celebration had been established at a time when such were rare. He took, therefore, in conjunction with Mr. Stillingfleet—one of the clergy of the parish—a little house in Wallingford Street. During the time he lived there I saw him almost daily.” This is Dr. William Butler, later Dean of Lincoln. “When not called from Wantage on business, he regularly attended my service, and took his part in the choir. He had, I remember, a baritone voice, and took a tenor part. He was much interested in the improvement of services, and, although at this time far from wealthy, he offered a large annual subscription, I think it was £20, toward the payment of an organist.... Never was there a man of simpler or less luxurious habits. In those two years he dined with us and the clergy of the parish, he drank no wine, and had only the plainest food.”

It was an energetic wholesome life, simple not so much8 by limitation as by renunciation, full of interest and expression, keeping a right line, as always, by the force of the initial impulse. The energetic, wholesome figure stands firm in a clear sunlight that is hardly dimmed by the space of sixty-odd years intervening. With nothing of the prig, as little of the aesthete, he was alien to both types by virtue of his vitality, his mirth, his essential soundness. A daguerreotype taken about 1850 shows quiet strength with a sort of sweet gravity. The hands are strong and flexible, not large, with tapering fingers and fine modelling on the back. You would have turned in the street to look after the head, with a big square brow jutting over blue eyes, brown hair very soft and round chin very firm, a mouth poetic and self-controlled. If poetry were (as once was rashly said) merely an affair of genius, and genius the affair of energy, Street would have been infallibly a poet. Energy and beauty in him were mingled in unusual measure, and he found expression in active more than in abstract creation: in loving landscape and sketching it, in hearing music and singing it, in building Gothic churches and restoring them.

His invention was inexhaustible; he designed not only all the mouldings for his churches, and all delicately various, not only reredos and pulpit, baldachin and font, and once a whole book of organs, but equally as a matter of course the windows, the stalls, the ironwork, the very altar-cloths. About this time he painted the ceilings to some of his churches after Fra Angelico, and elsewhere from his own designs. His early work may have been a trifle severe at times, and at times a trifle daring, but it had always freshness, vitality, one might say vibration. His capitals ring clearer than9 glass when it is struck; his mouldings sound as true a note as a violin when it is tuned. His building expresses, beyond possibility of mistake, as specific a sentiment as any composition of Palestrina or Fra Angelico:—viz., religious emotion, a combination of reverence and action, a solemn joy. But with this power to express an emotion from within himself and furthermore to create it in others, went an indefatigable energy. He was tall and very ready of movement, thickset and thin-skinned, blue-eyed and brown-bearded, ruddy, compact of strength and gentleness.

The energy found outlet normal and adequate in three directions—his work, his affections and his religion. He worked apparently as a young dog runs, from accumulated motor impulses, from strength that brims over. You have never the pang of our brother the ass, over-ridden, over-laden, that agonizes under the goad. You have never the fever craving for work as anodyne, that drives on desperately at the straining task as the only escape from the hell-hounds that bay hard after the sickening soul. The work is never done for work’s sake. It is a pleasure always, but only by the way. It is done to support some one he loves and to add to the glory of God.

The affections are close and sweet, those of the hearth. His mother was a good Christian but even more a Stoic, and Street held her the better for it. Theirs was a love undemonstrative but recognized, of the most exacting sort, neither of them accepting from the other anything short of the very best. After he went to Winchester, being then seventeen, she treated him like a man, and rarely praised him for doing what he should. If a pleasure10 was renounced, she said, “I knew that under the circumstances you would be Philosopher enough to give it up.” Her grandson wrote: “It is enough to read the mother’s letters to see the source of the son’s strength and steadfastness of character. She was one of those women who, in some indefinable way, have a powerful influence for good on all those into whose company they are thrown; who, themselves rather sparing in outward signs of affection, create in others a warm love and a perfect confidence. Her pride in her son was unbounded, but was left to be inferred rather than expressed; while her love was shown more in the demand for sacrifices, in the confidence with which she appealed to her son’s sense of duty and obedience, however severe the test.”

Besides a wide and wakeful kindness and untiring interest in others of his own profession, he had full, warm friendships, but where he could he took his pleasure with his nearest of kin. The early journeys were made in his brother’s company, the continental with his wife, and later with his son. The brothers, George and Thomas, were married to cousins, and up to the very last the longest and most frequent visits abroad were made to his son’s grandfather. After his wife’s death he took for a second wife her close friend, an intimate of the household and frequent companion.

The relations not of choice, the intimacies sweetened and consecrated by tender use and wont and all the sanctities of the hearth, the blind impulses of the blood and yearnings of the flesh toward kindred flesh and blood, were for him alike inevitable and dear. Here also he expresses the genius of the English stock. The northern race stood out long for the righteousness of the married11 life even in the priesthood, and the English church has at all times tended toward the family life as distinguished from the cloistered, and elaborated and adorned those services and sacraments which celebrate marriage and the birth of children and their coming to maturity.

The Church of England may be in a position undignified, uncomfortable, or even ridiculous, coupled up with the State as it is; the doctrine of the great English churchmen may be honeycombed with Erastianism; but the English church has the virtue of providing for every one of her children, lay not less than clerical, a daily office in which they may take an intelligent, a personal, and a common share. The first characteristic of the primitive church was apparently the fact of worship done in common, action in some sort not merely simultaneous but mutual. There are some—the Society of Friends for instance—who define religion by that collectivity of feeling, and in expectation of the Holy Ghost assemble themselves together. They draw most profit from thirty minutes of silent meditation where a hundred people in presence make up that silence and meditate each one. The monastic life, with its multiplied choir offices, met in another way this same desire for the warmth of human contact, this same enhancement of the experience of the whole far beyond the several experiences. The Roman church, with its sodalities and confraternities meeting regularly for special services, its litanies and rosaries recited by tired, troubled women together after nightfall, has recognized this and is busy recovering hereby what has been lost out of the Sacrament of the Mass. I remember after three weeks’ incessant travel finding myself in Siena cathedral, among12 women unquestionably devout, who held well-thumbed books, and, having lost count of the Sundays after Pentecost, as I opened my Paroissien I asked my neighbour on the right what Sunday it was. She shook her head and questioned her neighbour; I turned to the one on my left, but there was no one within decent whispering distance who knew what the priests and the choir were singing that day. Against such a chance, their church service assures Anglicans. The English Prayer Book may be a compromise, the office for morning and evening prayer may be patched up and anomalous, but it is an order of common prayer. The instinct of kind enhances the personal expression of psalm and antiphon, and daily service and saints’-day celebration have the sweetness and warmth of the family life, the dearness of the sacred ritual of the hearth.

Into his religion Street was born, as he was born into his family. In the dawn of consciousness he found it about him; with adolescence he felt it an influence and a motive. In the months at Exeter he was anxious often, but always there was the cathedral. In the last year at Winchester he was lonely and sick for home, but at hand there was the cathedral. While in Scott’s office he used to go with his sister to mattins before walking into town; in the later years in London he never missed with his wife the early celebration on saints’-days. Church-going was as natural as eating, and as satisfactory. He loved God as consciously as he loved his mother and his wife; and said even less about it. After he gave up the hope of taking Holy Orders he made a plan for a sort of half-monastic fraternity of artists and architects, who should be in art what the Templars13 were, selected, set apart, and dedicated. It was patterned after his own life unawares.

Younger than any of the great men of the Oxford Movement, he was born in the Promised Land. What they had hardly won, he inherited untroubled. Among the many things the average Englishman would rather go without than talk about, even to himself, may be counted his religion, but the strain of enthusiasm in the temper of Street, the genius that leavens his English substance, would not let him rest without a reason for the faith that was in him. He read and thought much at this time. In later years, while the phrasing is reticent yet the architecture is eloquent. In carved stone and hewn timber, in chant and carol, in the colour and contour of his records of the visible world, he let loose the strong inward impulse that burned upward like a flame. His natural element was creation not conflict, and though he could strike a good blow at “pagan” architecture and services restricted to the clergy and the seventh day, he seems to have had small joy in fighting and it, perhaps, killed him at the last. On the ground, already won, of English Catholicity, he stood firm and built strong and fair. Webbe and Neale and Wilberforce, and I suppose Keble and Pusey, were friends and advisers, but his real contemporaries were the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood with their allies and admirers who launched the Aesthetic Movement.

How that was born at Oxford, and was baptized into the English church with the Heir of Redclyffe for godfather, is hard to keep in mind. But Morris and Burne-Jones knew each other there and knew Street, who had married in the June of 1852 and taken his wife to a house14 in Beaumont Street. To us in another century it seems that in those years, from 1852 when the two boys from Walthamstow and Birmingham met and matriculated together at Exeter College, even to 1857 when Rossetti brought them back to paint the walls of the Union, Oxford must have been a place of lightnings and splendours. It sheds the same radiance that a great city just beyond the horizon’s bound throws up at night against low-hanging clouds. To them it seemed spiritually grey and dull enough. The Oxford Movement was in a sense ended; some men had broken away, some had got to cover, and in the rest religious emotion, having gone past the stage of smoke and flame, glowed clear but very still. Burne-Jones, according to his wife, “had thought to find the place still warm from the fervour of the learned and pious men who had shaken the whole land by their cry of danger within and without the Church.... But when he got there the whole life seemed to him languid and indifferent, with scarcely anything left to show the fiery times so lately past.”

“Oxford is a glorious place,” he wrote home, “Godlike. At night I have walked round the colleges under the full moon and thought it would be heaven to live and die here.” He described it later:—

“It was a different Oxford in those days from anything that a visitor would now dream of. On all sides, except where it touched the railway, the city ended abruptly, as if a wall had been about it, and you came suddenly upon the meadows. There was little brick in the city, it was either grey with stone or yellow with the wash of the pebble-dash in the poorer streets. It was an endless delight with us to wander about the streets where were15 still many old houses with wood-carving and a little sculpture here and there. The chapel of Merton College had been lately renovated by Butterfield, and Pollin, a former fellow of Merton, had painted the roof of it. Indeed, I think the buildings of Merton and the cloisters of New College were our chief shrines in Oxford.”

These two undergraduates, both alike so young and so typically English, lived at a high pitch in those years; each strong impetus pushing hard upon the foregoing. There was, to begin, an intention to take Orders, with a real and inward sense of dedication in both. Out of that flowered Burne-Jones’s dream of a Brotherhood very like that which Street had earlier nursed. “A small conventual society of cleric and lay members working in the heart of London,” his wife called it soberly, many years later, but he himself, at the time, “the Order of Sir Galahad.” To a friend he wrote at the end of a letter—and the postscript is like one of his own exquisite pencil drawings, all archaic, and altogether lovely: “You have as yet taken no vows, therefore you are as yet perfectly at liberty to decide your own fate. If your decision involve the happiness of another you know your course, follow nature, and remember the soul is above the mind and the heart greater than the brain; for it is mind that makes man, but soul that makes man angel. Man as the seat of mind is isolated in the universe, for angels that are above him and hearts that are below him are mindless, but it is soul that links him with higher beings and distinguishes him from the lower also, therefore develops it to the full, and if you have one who may serve for a personification of all humanity, expand your love there, and it will orb from its centre wider and16 wider, like circles in water when a stone is thrown therein. But self-denial and self-disappointment, though I do not urge it, is even better to the soul than that. If we lose you from the cause of celibacy, you are no traitor; only do not be hasty. Pax vobiscum in æternum—Edouard.”

That summer they went to France and saw Amiens. Their companion said: “Morris surveyed it with calm joy and Jones was speechless with admiration. It did not awe me until it got quite dark, for we stayed till after seven, but it was so solemn, so human and divine in its beauty that love cast out fear.” They went to Beauvais, Paris and Chartres. “There we were for two days, spending all our time in the church, and thence made northward for Rouen, travelling gently and stopping at every church we could find. Rouen was still a beautiful mediaeval city, and we stayed awhile and had our hearts filled. From there we walked to Caudebec, then by diligence to Havre, on our way to the churches of the Calvados; and it was while walking on the quay at Havre at night that we resolved definitely that we would begin a life of art and put off our decision no longer—he should be an architect and I a painter. It was a resolve only needing final conclusion; we were bent on that road for the whole past year and after that night’s talk we never hesitated more—that was the most memorable night of my life.”

They were to start The Oxford and Cambridge Magazine, and Burne-Jones was to meet Rossetti and very heartily worship him but never to be drawn, even by that blazing, fiery star, out of his own orbit of art deliberate and devout. Morris meanwhile, as soon as he had17 taken his degree, addressed himself to work under Street. Afterwards, as we know, he tried painting, before he found his happiest outlet in decorative designing, in dyeing and printing, and surely his finest and most enduring expression in the writing that came so easily we can only wish that he had taken it harder. A note of Burne-Jones’s in the year 1856 is so charming and so characteristic that it may well serve as the note of the whole set when they had really found themselves. “There was a year in which I think it never rained nor clouded, but was blue summer from Christmas to Christmas, and London streets glimmered, and it was always morning, and the air sweet and full of bells.”

Their lives were, however, what could not be called less than intense. Their emotions were all fervid and their sentiments all impassioned, their enthusiasms fairly militant, their convictions even intransigent. Lady Burne-Jones communicates an exquisite sense of their way of being something better than human nature’s daily food:

“I wish it were possible to explain the impression made upon me as a young girl.... The only approach I can make to describing it is by saying that I felt in the presence of a new religion. Their love of beauty did not seem to me unbalanced, but as if it included the whole world and raised the point from which they regarded everything.” Again she quotes from a letter of her husband’s, written long afterwards, an impression of that first journey into France. “Do you know Beauvais, which is the most beautiful church in the world? I must see it again some day—one day I must. It is thirty-seven years since I saw it and I remember it all—and18 the processions—and the trombones—and the ancient singing—more beautiful than anything I had ever heard and I think I have never heard the like since. And the great organ that made the air tremble—and the greater organ that pealed out suddenly and I thought the Day of Judgement had come—and the roof, and the long lights that are the most graceful thing man has ever made. What a day it was, and how alive I was, and young—and a blue dragon-fly stood still in the air so long that I could have painted him. Yes, if I took account of my life and the days in it that went to make me, the Sunday at Beauvais would be the first day of creation.”

Emotion exquisite and almost as frail as the dragon-fly, almost as quick to pass as the Sunday sunlight! It is the impression of a boy, an aesthete and a poet, who kept to the end of his days the same sensibility and the same delight in beauty tangible. What he expresses, however, he felt with his generation; his associates had a like organization and a like attitude. In that very year Street, who had gone first to France, at a like age, not so long before, wrote from recollection, in a paper that was read at Oxford and published at Cambridge:

“One of the first elements is height. I know of no one thing in which one is so much astonished, in all one’s visits to foreign churches, as by the luxury of that art which could afford to be so daringly grand. From the small chapel, not forty feet long, to the glorious minster of some four hundred, one feels more and more impressed with the sense which the old men evidently entertained of its value; and exaggerated as it often is, even to the most curious extent, it is never contemptible. It is indeed19 a glorious element of grandeur, and not the less to be admired by Englishmen because we seem always to have preferred length to it; whilst they, so they could have height, cared little as to the length to which they could draw out a long arcade, and prolong the infinite perspective of a roof. And there is perhaps this advantage of height over length, that whilst the one seems entirely done for the glory of God, the other is always more apparently for use. So in a church, height in excess seems to typify the excess of their adoration who so built; whilst the greater length makes one think of possible calculations as to how many thousands of men and women might pass through, or how long a procession.... And as I have said so much about foreign examples I will but observe that the wonderful beauty of the apsidal east ends abroad ought to be gladly seized upon.... No one who has stood as I have at the west end of such a cathedral as that at Chartres, and watched the last rays die out from all other windows and at last gradually fade away from the eastern crown of light in its five windows; or who has seen the mounting sun come through all those openings one after the other, with matchless and continued brilliancy, would deny that such glorious beauties are catholic of necessity, and not to be confined by custom or etiquette to one age or one nation.”

There is the expression of the man, mustering his facts, enforcing his conclusions, weighing his estimates, recording of his pleasure the least possible part. The comparison is hardly fair to painter or builder either, but it is none the less significant. His power of expression, to be sure, is less, and his determination toward20 self-control is greater, but all the while the source of delight, though stiller, is no less deep. Street’s private notebooks are as reticent as his public papers. Like everything else that he did, they illustrate the characteristic maxim which opens The Christian Year, that, next to a sound rule of faith, there is nothing of so much consequence as a sober standard of feeling—strong feeling, but sober. A better notion of his response to beauty could be formed from some personal letters that he wrote in 1845, being then twenty-one years of age.

“I got out at Milton station and trudged off for Lanercost Abbey, an enthusiastic ecclesiologist, with everything upon earth to make my enthusiasm higher than usual—a glorious autumn day, a beautiful walk and an abbey in prospect, in ruins it is true, but so lovely and admirable in its ruin that in my admiration of it, the day, and the scenery, I had almost forgotten to be enraged with its iconoclastic destroyers; but it was not in mortal temper, after having seen and sketched it and studied it carefully and lovingly as I did, to ascend the hill away from it, to look at the river still rushing along as beautiful and as swift as when holy men planned its bridge of yore, to look at the sunny fields first cultivated by them, and not to feel sorrow and indignation at the thought that avarice and sin could so far have transported men as to lead them to the destruction of so fair a scene.” “O that the abusers of the monastic system would trouble themselves to examine this once happy valley, and watch the soothing influence of the lovely building and landscape, and would ask themselves whether they did not, in looking, feel more of reverence,21 more of awe and of love for the religions and for the men than they have heretofore felt.”

Street was twenty-six before he crossed the Channel. A foreigner may be pardoned for feeling it a piece of his good luck that he should have learned and loved the English Gothic before seeing the larger beauties and the grander styles of France, lest otherwise his own should have seemed to him fair but pallid, pure but cold, bearing much the same relation to the continental that the English service bears to the Roman use. It was not in him, however, to withdraw the affection once given for due cause, nor yet to withhold that just devotion the larger excellence could command. For him the greater glory would not dim the less. Both shared henceforth in his life.

The foreign journey was omitted only twice, in the year 1855, when his son was born in October, and in 1870, when the Germans had invaded France. In the latter year Street went to Scotland; in the former he stayed at home on the Thames with Mrs. Street’s people, bringing out his Italian book and working on the buildings for the Bishop of Oxford at Cuddesden. Towards the end of the year he moved to London and took a house in Montague Place. The plans which he submitted in competition for a new cathedral at Lille won a second prize, and the Frenchman to whom the actual building was given in the end had been rated originally below him. He had by this time at least three assistants working under him regularly, Edmund Sedding, Philip Webbe, and William Morris. He was perpetually occupied with parishes and private persons—on schools, chapels, restorations, residences even, country churches22 fitted to a village community, town churches designed for the artisan populace and their employers. He had finished Cuddesden College and carried work far already on the whole important cluster of diocesan buildings; he had begun building for the Anglican sisterhood at East Grinstead; he had been praised not a little in the competition at Lille; he was to take a second place, the next year, with his design for the Crimean Memorial and in the end to build the church; and shortly thereafter he sent in plans for new Government Offices. About this last he reasoned, with the spendthrift logic of youth, that while he could hardly expect to win the commission with a Gothic design, the premium offered to him among others of the best was a hundred pounds and would give him another trip to Italy, while he would gain, furthermore, from the public exhibition of the drawings.

The undertaking cost, to be sure, time and strength, but of these he was never stingy. He seems to have known how to be at once thrifty and generous of himself—generous perhaps because thrifty. All his life he seems to have done three men’s work in a day and all work in a third of the time that other men would take. He mentions once, being on a journey, that “it rained, so we read, wrote, and occupied the many hours in the rumbling diligence as best we might.” The notes were written often in diligence or train, as the firm clear writing betrays, while it remains characteristic and legible. He worked habitually till half-past twelve at night, yet with all the incessant occupation of the most exacting sort, in large measure creative labour, you never think of him, as he never can have thought of himself, as23 overworked. The essential soundness, the vital force made his way of life spontaneous and inevitable. The strong, even, white teeth, the strong, curling, brown beard, were the visible token of bodily sanity and power, a sort of physical validity of which the cause was not merely physical.

As the mediaeval builders reared and poised their great churches by a calculated balance of thrust and strain, and hung aloft in stone a proposition in proportion, so, you feel, with Street, it must have been some extraordinarily just measure, some perfect balance of temper, some secret of self-control, only comparable to the engineer’s control of his crane or hammer or locomotive, that gave him life so abounding and yet so temperate, so huge in accomplishment and yet so undistressed. If we know that at times the pulse and the invention flagged, yet it is only because we know by testimony that tasks designed in hours of gloom were not, indeed, fulfilled in hours of insight, but instead they were destroyed, to be replaced later by designs better because of more vitality and more élan.

Doubtless in this a fine natural constitution played a large part, but even a larger part, one is tempted to think, belongs to faith. Nisi Dominum, says the Psalmist, but here the Lord did keep the house and their labour was not lost that built it. One thinks of Huxley coming home exhausted from his lectures to lie on a sofa at one side of the hearth, that on the other side being permanently occupied by his wife. There can be little question which of the two men did more for his generation, but also there can be no question which found more substantial and untroubled happiness. “It is not24 lost labour that ye rise up so early, and so late take rest, and eat the bread of carefulness, for so He giveth His beloved sleep.” By every reasonable standard of happiness we must admit that Street’s work, untiring, joyous, faithful, done in direct loyalty to God Almighty, bore the fruit of a constant blessing.

The domestic affections and the service of religion filled up a life singularly pleasant to contemplate. Boating, cricket matches and riding, plain-song meetings and the Philharmonic Society, opera, exhibitions and sales of pictures, all found place without crowding. If he did not ride he wrote letters for an hour and a half or two hours before breakfast. He had his office in the house and kept long hours in it without interruption except from clients, but his little son was admitted as something less than a trouble, and watched him designing. An assistant said, later: “We worked hard, or thought we did. We had to be at the office at nine o’clock and our hour of leaving was six o’clock, long hours—but he never encroached on our time and as a matter of fact I am sure I never stayed a minute past six o’clock.”

After dinner there might be music, at home or abroad, cards or reading, or a cigar and talk on the balcony over the square—a London balcony, dingy and flower-beset, above a London square in summer, dim with twilight and coal-smoke, smelling of soot and dewfall on green leaves. At half-past nine came tea and thereafter three hours more of good work alone. He travelled, of course, more than a little, and on the journey put in the normal day’s work. The same friend goes on: “I well remember a little tour de force that fairly took our breath away. He told us one morning that he was just off to measure25 an old church, I think in Buckinghamshire, and he left by the ten o’clock train. About half-past four he came back and into the office for some drawing paper; he then retired to his own room, reappearing in about an hour’s time with the whole church carefully drawn to scale, with his proposed additions to it, margin lines and title as usual, all ready to ink in and finish. Surely this was a sufficiently good day’s work. Two journeys, a whole church measured, plotted to scale, and new parts designed, in about seven hours and a half. He was the beau-ideal of a perfect enthusiast. He believed in his own work, and in what he was doing at the time, absolutely; and the charm of his work is that when looking at it you may be certain that it is entirely his own, and this applies to the smallest detail as to the general conception.... No wonder we were enthusiastic with such performances going on under our eyes daily.”

Yes, it is good to know that such lives can be, filled with pleasure in the exercise of conscious strength, sufficient unto the day, with enough for all needs and to spare. It is like watching a blooded dog or a thoroughbred horse. As a rule we compare men to pleasant animals only when they are unpleasant men, and say they are engaging only when we cannot say they are trustworthy. Here was one singularly engaging. Every one in remembering him recalls his wit, fireside mirth, good temper, ready answer. When a dull gentleman, having dissected at great length the old mare’s nest about mediaeval irregularities in design, wound up after a pompous question about the secrets of freemasonry: “Now Mr. Street, what do you think?” Street flashed back: “What do I think? I think the beggars could not26 build straight.” When a young architect consulted him about going to law to recover his designs from a client—would it be wise? Street answered, “That depends on what sort of man your client is and whether you have any expectation of further commissions from him.” “His experience and natural shrewdness,” wrote an acquaintance at the time of his death, “made him a valuable adviser on points of professional practice, and he had a humour very often caustic, which one could not help sympathizing with.”

He was a good son and brother, a good husband and father, without loss of manliness. No man was less a prig. No man, indeed, was ever more respectable, but the touch of genius makes respectability itself engaging. He was not subtle, but his directness can make subtlety look devious and insincere. He was not complex, but his straightness can make complexity look morbid and mean-minded. In 1863 Crabbe Robinson wrote in his diary:

“October 17. Dined with the Streets. Our amusement was three-handed whist. Both Mr. and Mrs. Street very kind. On every point of public interest he and I differ, but it does not affect our apparent esteem for one another. I hold him in very great respect, indeed admiration. He has first-rate talent in his profession as an architect. He will be a great man in act—he is so in character already.”

He lived afterwards in Russell Square and then in Cavendish Square; always in the dear, unspoiled, substantial, smoke-stained professional quarter, the London of those that live there all the year, where autumn lights vistas of tawny splendour down every street, and27 spring offers nosegays of early wall-flower and narcissus from the Scilly Isles at every corner; where the air perpetually tastes of soft coal, damp mud, and warm malt; where in December the moist pavement glistens with a permanent slime, and in May the porch roofs burgeon into azaleas pied and trailing pink geraniums.

His life thenceforth falls into such periods as Ezekiel counted,—a time and a time and half a time. Ten years, from 1855 to 1865, were given to church-building, to travel for the sake of study, to writing, beginning with the Brick and Marble in Italy and culminating in the Gothic Architecture in Spain. Mainly within the next ten fall the great commissions—for the Law Courts, for building the nave of Bristol cathedral, for rebuilding the cathedral at Dublin, for restoring that of York. If this period is closed with the death of his second wife, in 1876, there will remain just five years for bringing all to a conclusion, finishing wholly or very nearly the great works, lending a strong hand to such public undertakings as saving London Bridge, adorning S. Paul’s, rescuing S. Marco at Venice, and serving on the council of the Royal Academy. Finally, he was President of the Royal Institute of British Architects. He delivered, as Professor of Architecture to the Royal Academy, six lectures on Gothic Architecture in the spring of 1881. Those were widely read at the time, printed in the weekly journal, the Builder, as they were delivered, and in the Architect; and reprinted by his son as an appendix to the Memoir. In that same year he died and on the twenty-ninth of December was buried in Westminster Abbey. He was only fifty-seven and he had been ill only a month.

28 With Street’s actual building I have little here to do. Immense in quantity, admirable in kind, it stands and long will stand, not only amid the dense green of English hedgerows and in the bitter grime of English towns, but beside the graves of Alpine valleys and in the Stranger’s Quarter of continental cities. Of its technical excellence, the way it meets and happily resolves the builder’s problems, I am not competent to speak. Architects have praised him well. The distinguished American who has devoted his own rich and exquisite talent to the quest of Gothic, tells me that Street, of them all, had the most genius. To the mere ecclesiologist, who comes to the American church at Paris, or the church and schools of S. James the Less, in Westminster, or the village spire of Holmbury S. Mary, it seems that if new churches must be at all, they should be thus. Where Scott’s work seems colder than death and Butterfield’s trivial or thin, Street’s alone has a kind of present life, a pulse, an inner glow. It is again the abounding life of the man which communicates of itself. Many have put their heart into their work, but only a great heart lives and burns in it.

Of architecture, apart from technical questions, structural or archaeological, there is little profitable to be said. Like the other arts which deal directly with bodily experience, it suffers from the necessity of translating into an alien speech. You may talk about Shelley forever, since poetry is made of words, or about Plato, since philosophy is made of ideas, but the truest praise of the Passion according to St. Matthew is reserved for the organ, and the real right comment on any Perugino is the Granducal Madonna. Criticism may take a29 lawful pleasure in explaining, first, how a given work of art came to be what it is—which is matter of history; and, second, why we enjoy it as much as we do,—which is matter of psychology; but the enjoyment itself criticism cannot express except by a laborious process of transmutation and translation. Of all the arts architecture is least apt for this sort of evocation. Even Pater hardly knows that song to which the memory of Chartres would, like a mist, rise into towers, though he could reweave by his magic the very spell of Botticelli, and recall with his subtle harmonies the very presence that rose so strangely by the waters of Leonardo. Those who have lingered at nightfall in the nave of Chartres until through mounting darkness the blue windows burned as by their own proper light, may know, some of them, that a great church, like the deep sea, like the ancient woods, like the starry heavens, can liberate for an instant the soul from the limitations of the conscious intelligence. But even if a man would tell of that, and no man would, there are no words for the telling. To put the matter another way:—the experience of music is a matter of the auditory sensations and their recall in memory; the experience of painting a matter of the visual, for the most part; that of architecture is a very curious combination of the tactual and muscular with certain respiratory and vaso-motor functions. Words, in each of the cases, are at the second and third remove from the actual appreciation; and moreover architecture shares with music, except where figure-sculpture enters in, the supreme condition that representation merges in presentation, that form and content coincide.

30 The love of thirteenth century France flowered in the beauty of Street’s designing; the knowledge of Catalan city churches bore fruit in the frequent use of the lofty nave arcade, which barely marks the aisle off, and opens all the church to sight and hearing of the preacher; the long acquaintance with Italian brick construction led to his perpetual endeavour by bands of colour to lighten the monotony of English stone. But marbles under a southern sun will fade and stain and modulate together, where other material and other skies will not effect the combination, and while I feel that some of Street’s essays in colour have been less happy than his other audacities, I feel stronglier yet that the fault lies more with the material at hand than with the shaping spirit of imagination.

He is supposed to have been at his best in designing middle-sized churches for general use, like All Saints’ at Clifton, and S. Margaret’s, Liverpool. I know he felt that he never worked more to his own mind than when he built his own church at Holmbury. The American churches in Paris and Rome, the English churches in Rome and Genoa, the Anglican churches at Lausanne, Vevey and Mürren are all his. The list of his buildings published in his son’s Memoir stretches from Constantinople to Trinidad. I notice that at the time of his death some called the new nave of Bristol cathedral his most entirely successful work. That may in a way be reckoned as restoration, if one likes, and remain equally characteristic, for Street did much work of restoring, and the list of original work is followed in the Memoir by a longer list of ancient work to which he lent a reverent hand. Against any restoration but the most reverent31 he protested, both generally and in such particular cases as that of the Lincoln doorways. He was a member of Morris’s “Anti-scrape” society, though once at least that body fell foul of him. The mere ecclesiologist in this case is again disposed to admit that if, to keep a church above ground, some restoration must be done, it had better be in such hands as his.

In truth all the best work of Street was done in the spirit and in the terms of mediaeval work, as the best poetry of Morris was written. Each by a rare chance found himself of blood kin, born to the same language, gesture and emotion, with those long dead. I do not know that Street’s church building was ever blamed for not being of its own age: certainly such a criticism would be peculiarly unjust, for it is the translation into brick and stone of The Christian Year. The Tractarians and Street gave their lives to the same task, and they patched up their churches so well that these will stand for generations yet.

His knowledge, in truth, of the Middle Ages was often enough made a reproach. He was accused by competitors, by church-wardens and committees, by journalists and critics, of allowing an undue influence over his work to foreign styles. No one would be likely now to hold that for a ground of grievance, but the charge is the less plausible considering how early mature were both the man and his workmanship. It was in 1850 that he went to the Continent for the first time, already knowing his England well. Rarely, thereafter, he let a year go by without crossing the Channel, and often he added, especially in later life, an autumn or a winter holiday. There would be interest in32 drawing up a table of his journeys, if one could be made complete, year by year, and in supplying from letters and diaries his fresh impressions, if these were available. With the help of old notebooks, even without other material, may be made out a list tentative and imperfect, indeed, but still suggestive,—by the change in recurrence, for instance, by the perpetual discovery of fresh interest on ground no matter how familiar. From what he saw he took refreshment and suggestion, never precisely a model. There would be no use in setting off, against the table of his travels, a table of his buildings. These were the growth of English soil, and from his masters, the cathedral builders of France and Spain, the masons of Germany and Lombardy, he asked not what they did but how. More often, the direct outcome of travel, the transformation of observation into activity, was not the high-reared vault but the written word—figuring in the Ecclesiologist, in the Transactions of Diocesan Societies and Architectural Associations, in the Italian and the Spanish volumes, and in at least two more that he projected but did not live to finish.

Street never went to Greece or Russia, nor, I think, to Dalmatia. The Gothic lands he loved, there his genius renewed its mighty youth. For him as for the young Pre-Raphaelites in 1845 and then for the young Aesthetes in 1855, the first sight of a great French church, say of Amiens, marked as much the close of one stage and the commencement of another, as if they all had not known Westminster and York Minster, Iffley and Fountains Abbey; as if they were, in effect, young Americans fed on nothing more ancient than those33 white wood pillars of a front porch, that rough-dressed stone or bluish brick of a central square with flanking wings, which appear in our earliest and only, our “Colonial,” style.

If one is tempted to press the American parallel in the matter of enthusiasm, as the only one adequate to express the degree of it and the surprise, fresh as a May morning, irrevocable as falling in love for the first time, one is even more tempted to push the same parallel in the matter of method—of “doing” churches and “doing” towns at an incredible rate. Burne-Jones and Morris on their memorable trip arrived at Abbeville late Thursday night after a Channel crossing, and on Friday had an hour in Amiens cathedral before dinner and stayed there afterwards till nine, reached Beauvais on Saturday and went to Sunday Mass and vespers, thence on to Paris the same night, spent sixteen hours Monday in sightseeing, and had only three days there in all with which to see the Beaux-Arts exhibition, the Cluny, Notre Dame, the Louvre, and hear Le Prophète. Thursday and Friday they gave to Chartres—a longer time, one likes to remember, than they spared for any other cathedral. So, of Street, his son writes: “In September, 1850, ... in ten days he saw Paris, Chartres, Alençon, Caen, Rouen and Amiens, sketching all the time with might and main.” That would be a fair record now for any but the shameless, even if you substituted kodak and motor-car for sketch-book and infrequent trains. “In the summer of 1851 three weeks sufficed to make him acquainted with Mayence, Frankfort, Wurtzburg, Hamburg, Nuremberg, Ratisbon, Munich, Ulm, [Constance], Freiburg, Strasburg, Heidelberg,34 [Cologne], and three or four of the best of the Belgian towns.” The next trip was his wedding tour and reached the great churches of what might be called in architecture, conveniently, the Burgundian March—Dijon, Auxerre, Sens, Troyes; and the year after that, late in August, the pair came to Italy. The things done and seen, and, even more the things thought, in something like five weeks, crammed the notebooks and bore fruit in a volume that Murray published in 1855, Brick and Marble in the Middle Ages.

The first thing, and, even on reflexion, the most surprising, in all this travel, is of course the quality and the quantity of what Street did in his vacations, the incredibly rapid and inconceivably hard work, no less than the enthusiasm and endurance of the man. The labour, in the very doing, passes into creation. Besides the great sketch-block he carried a leather-bound luxurious notebook or two, of heavy and beautiful paper, some five or six inches by eight, and thick as would go into a coat pocket, in which he put down alternately sketches and notes, plans and measurements, names of local building-stone or extracts from a parish register, and occasionally a memorandum of railway trains or addresses and dates for forwarding letters. These worn little volumes are evocative, are potent. He begins sketching, always, the moment he reaches the Continent and keeps it up till he touches the Channel again, but he rarely repeats a subject or an observation. The text records facts and inferences, judgements and estimates, more often than impressions; and emotions, I think, never. The drawings preserve more often a plan, a detail, a profile, than a façade or an interior—in short, a picture. In a sense35 everything is a picture, in its vitality of line and unerring selection. For the rest, the great views of ambulatory and transept, west front and apse, were done on a larger sheet, and such of them as were not later used up or given away still preserve in books the itinerary of the successive years. Whoever has known churches hitherto by photographs only will turn the leaves of these with strong delight. It is hard ever to say fully why all drawings of architecture should satisfy more than any photographs, and these overpass comparison. The camera, after all cannot see around a corner and an artist can.

The solar print is a dead thing, and here is the living line. Street can afford, with great economy of line, immense vitality; his son says that he never carried an india rubber and never put in a line that he was not sure of, and on the pages of the dusty note-books the line lives and vibrates. One of 1874 may open at a chapel of the abbey at Vézelay or a capital from the choir arcade of Auxerre, or another of 1860, at the church of Ainay or the gateway of Nevers; but all the work of all the years is interchangeable in respect of firmness and life, certainty and authority; and what you see on the page is not merely knowledge, accuracy, dexterity, it is genius. The quick notes, as surely as the large studies and the great original designs, show never lack of it. Architecture is a craft, a thing a man by application can learn, like journalism, and architectural drawings may be merely exact, neat and compact, and give pleasure. But genius is like the grace of God in a man’s work, it is all in all and all in every part. The vitality of the line in sketching, the vitality of the design36 in building, are the outcome of it. The very handwriting, rapid but neither negligent nor meticulous, is as much a part of him as a man’s hair.

The original notes, written from day to day, are never slight, or stupid, or cock-sure. The Brick and Marble volume has kept their fresh, quick finality. Thanks in part most likely to Modern Painters, landscape in the early journeys counted nearly as much as cities. Street had seen the Alps in 1851 from the Lake of Constance, and looked at them and stuck to his work. The next year, apparently, he visited Switzerland with his wife and walked up as many as possible. On the Italian journey two years later he literally made the most of the mountains, going and coming—through the Rhineland and the Vosges, by the lakes of Zurich and Wallenstadt, down the canton of the Grisons and over the Splügen to the lake of Como, one way, and the other by Lake Maggiore and the S. Gothard, climbing the Furka and including the lake of Lucerne. As, on another visit, he comes down through the Tyrol by Grauenfels and the Pustertal, the bare hints are electrical, the reader’s imagination catches fire. In this first book, the landscape gets more attention than ever again in print, but all his life he loved a mountain about as well as a cathedral, he saw the Alps as often as Amiens. His pencil was almost as often and as happily set to landscape sketching as to any other; it caught the profile of a bluff and traced the swelling and subsidence of a mountain’s flank. Now that in the pursuit of colour and light most painters have abandoned form, and second-rate Impressionists are content to let a landscape welter in blues and mauves like a basket of dying fish,37 his forcible contours and cool washes awake a tingling of reality.

In 1854 he went to Münster and Soest, and wrote for the Ecclesiologist during the following year three pieces on the architecture of northern Germany, besides another for the Oxford Architectural Society. Summary as are these brief and practical papers, they remain still so entirely and beyond dispute the fullest and most suggestive account of German brick work, they are so good to steal from and so indispensable as adjuncts to Baedeker, and finally, so characteristically foreshadow and supplement the Spanish volume, that they are reprinted bodily in the appendix here. It is precisely sixty years since they were written, and they are not only not superseded, they are still unapproached. Back of the energy which enabled him to cover a vast deal of ground and never miss a detail, beyond the personal acquaintance, and not mere book-knowledge, of the twelfth, thirteenth, fourteenth and fifteenth centuries in England, France, Germany, Switzerland, Italy (to which later he was to add Spain)—beneath all this learning lay the happiest instinct for what was either first-rate or important or both. He rarely went out of his way to look at a church that was not worth his while, he rarely failed to look at every church in a town that would repay him. The Memoir quotes a letter from this journey, with the characteristic prelude, “he worked hard, as he always did, up early and in late”:—“I have got a great budget of sketches; indeed, I have done pretty well, for in a fortnight I have mustered about fifty-five large sketches besides filling a goodly memorandum book. We enjoyed Lübeck immensely, and amongst other feats38 astonished the natives by making rubbings of some magnificent brasses, of which Marique did her share, to the delight of the sacristan.”

His interest in German building was more practical than aesthetic; he found suggestive parallels to his own problems in those of the rich merchant cities, set down, often, in a country without accessible stone. He recurs a dozen times, in his writings, to the similar solutions found in S. Mary’s at Barcelona and S. Elizabeth’s at Marburg, and the same type of building in brick developed about Lübeck and Saragossa, Toulouse and Cremona—in the great plains of the north of Germany, the north of Spain, and the north of Italy.

Though in 1855 he took no summer holiday, he went over in the fall to see the designs at Lille with William Morris, and pushed on to S. Omer. The notebook of that journey is particularly rich in detail, both personal and architectural. The trip supplied material for papers in the Ecclesiologist, supplemented by another two years later, through Normandy, the Soissonnais and the German border. Even to-day when that country has been written to death, ploughed up by pedants and harrowed by illiterate motorists and photographers, the papers are almost too good to leave in the dust of old libraries, with their tang of a spring morning early enough to taste of frost. The notebook still is more than half a journal, coloured with detail not so irrelevant as the writer fancied, and I have snatched out a bit about Laon to reprint.1

39 Far more brief are the notebooks, however, of 1860, when he went to the Bernese Oberland and took in the country that lies westward from Lyons—Le Puy, Brioude, Clermont-Ferrand, Nevers,—and many of the smaller churches of that curious Auvergnat type which was to help him so well in the interpretation of Spanish Gothic during the following years. There are sketches and plans aplenty, with the scantiest jottings of fact, and then a few fragments of bibliography; lastly terse notes of reading done, I fancy, in Paris on the way home. These served for an essay on The Churches of Velay, which has been printed twice in the Transactions of the Royal Institute of British Architects, once at the time, and again, long after his death, in 1889. It is still inaccessible to most, and I reprint it once more, partly for the bearing on his interpretation of Spanish building, and partly because I know nothing better on Auvergne.

Nothing missed him, not the paintings on the wall at Brioude nor the Liberal Arts on the pavement at Ainay. A scrawled road-map on one page would be still the ecclesiologist’s best guide for the region. The village of Monistrol which harbours, thereabouts, a characteristic church, and to which he refers again for comparison in the Spanish volume, is not, I take pleasure in noting, the scene of the first meeting with Modestine. If it had been, you should not know from Stevenson that a church stood thereby, for the good creature had no great taste in churches, and though the Inland Voyage lay through a cathedral country, small good was that to him.

The volume shows how Street’s published books were made, and it shows furthermore, what any other of40 these little leather books could equally illustrate, how his instinct drove straight at the truth and needed from documents only confirmation. He wrote once:

“For that period of just five hundred years so regular was the development that it is not too much to say that a well-informed architect or antiquary ought always to be able to give, within ten or at most twenty years, the date of any, however small a portion, of Mediaeval architecture with almost absolute certainty of being correct when his judgement can be tested by documentary evidence.”

That was his practice, the élan of his own judgement, as certain as the stroke of his pencil, which other architects, of other nations, have delighted to honour.

Señor Lampérez, in his great book on Spanish architecture, bears generous and graceful witness to the justness and certitude of Street’s conjectures. He even gives him the credit of finding the date of S. Maria at Benavente, now known to be 1220, though in point of fact Street had set down as opinion and not knowledge that the church must have been built between 1200 and 1220. The only case in which I know his instinct at fault is that of the belated churches of Galicia, where Romanesque forms persisted sometimes even into the fifteenth century. There, knowing few dates of buildings and fewer of builders, he hardly estimated them enough of laggards, and guesses wrong sometimes by a century, or nearly.

Precisely in a case like this, where an unknown condition vitiates the experiment, one sees how just is his method and how right in all but the actual year of our Lord, even here, is the outcome. The steady judgement,41 the wide knowledge, the happy divination, which we call genius, cannot play false. While the saint, by ancient dogma, cannot sin, the foredamned cannot do right; and the provincial-minded, even though all the data lie before him, is foredoomed by his campanilismo to come out wrong. It is, moreover, a trifle ungrateful in a few young Spaniards and a few fretful Hispanophils to scold at Street, for he was the best friend and the most practical, outside the Peninsula, that Spain had ever had—not forgetting either the Duke of Wellington or Murray’s Ford. Let me quote again Señor Lampérez, what he has to say at the opening of his admirable Historia de la Arquitectura Española Cristiana:

“Two foreigners deserve especial place and mention in this survey, the English Street and the French Enlart. Street was an architect, profoundly versed in Christian art, Gothic in chief; he had studied the monuments of it all over Europe; he visited Spain and before her churches he sketched and took notes with so sure a vision that his book on Gothic Art [sic] in Spain has come to be, if I may say so, classic. It is the greater pity that Street saw of Spain only one very small part. On any count, his work is of exceptional importance. His text is too widely known for me to need to analyze it here; suffice it to say that his method is based on a technical study of each building, without any divagation into poetic descriptions or literary lucubrations.”

Some account of Gothic Architecture in Spain, published in 1865, was the outcome of the journeys in 1861, ’62 and ’63 and (I suppose) of two more summers spent at home in research and actual composition and42 publication. At any rate I find no record of autumn travel in ’64 and ’65.

It is hardly fair, in truth, for Señor Lampérez to say that he saw only a small part of Spain. His journeys covered, geographically speaking, much more than two-fifths of the Peninsula, and archaeologically speaking, all the best of the Romanesque and Gothic, both Gallegan, Castilian, and Catalan. What he missed was the pre-Romanesque, as it is found in the Asturias, and the true Moorish, i.e. the Asiatic and non-Christian. If he neglected the Mudejar work and the Renaissance period, it was deliberately, because when he looked at them he misliked them. The real difference between his field of labour and that of Señor Lampérez consists not so much in the latter’s possession of Estremadura and la Mancha, Seville and the south-east coast, as in his fuller knowledge and more minute experience of the northern provinces. The Castiles and Leon, Galicia and Navarre, and the ancient domain of the kings of Aragon, have been examined league by league and published both fully and frequently, since 1865. The peculiar styles which give their importance to the regions of the Biscay shore and the Sierra Morena, the Latin-Byzantine of Asturias and the Mohammedan of Andalusia, are special phenomena and must always be treated apart; they may therefore at need be omitted, without grave loss, from the general consideration of mediaeval building in Spain; and if these are struck out, for instance from the lists of Señor Lampérez, there will remain, as the significant monuments and the important regions, precisely those which Street had already treated. Cuenca and Soria, Poblet and Ripoll, Tuy and Orense, Toro, Jaca, the43 Seo de Urgel, were all unvisited and other churches yet; but the list is not long nor are the places vastly important.

Some of them, if it must be known, are still but little studied; and with all the fine enthusiasm of Spanish architects, and societies learned and popular, treasures of the great age still remain unexplored. Only last summer the present writer rode over the flank of a hill to salute, all unprepared, a superb transitional church of the thirteenth century. It was not cathedral nor even collegiate, but mere parroquia, and perhaps the finest parish church in Spain:—and it is even to this hour, so far as may be ascertained, completely inédite. When Street went to Santiago he was much in the same case. “I had been able to learn nothing whatever about the cathedral before going there,” he records, with ironic amusement; “in all my Spanish journeys there had been somewhat of this pleasant element of uncertainty as to what I was to find; but here my ignorance was complete, and as the journey was a long one to make on speculation, it was not a little fortunate that my faith was rewarded by the discovery of a church of extreme magnificence and interest.”

The three journeys were so planned as not only to find out much that was new each time but to repeat and verify earlier impressions. With his usual sobriety he sets down the itinerary in the opening pages:

“In my first Spanish tour I entered the country from Bayonne, travelled thence by Vitoria to Burgos, Palencia, Valladolid, Madrid, Alcalá, Toledo, Valencia, Barcelona, Lérida, and by Gerona to Perpiñan. In the second I went again to Gerona, thence to Barcelona,44 Tarragona, Manresa, Lérida, Huesca, Zaragoza, Tudela, Pamplona, and so to Bayonne; and in the third and last I went by Bayonne to Pamplona, Tudela, Tarazona, Sigüenza, Guadalajara, Madrid, Toledo, Segovia, Avila, Salamanca, Zamora, Benavente, Leon, Astorga, Lugo, Santiago, la Coruña, and thence back by Valladolid and Burgos to San Sebastian and Bayonne. Tours such as these have, I think, given me a fair chance of forming a right judgement as to most of the features of Spanish architecture; but it would be worse than foolish to suppose that they have been in the slightest degree exhaustive, for there are large tracts of country which I have not visited at all, others in which I have seen one or two only out of many towns which are undoubtedly full of interesting subjects to the architect, and others again in which I have been too much pressed for time.”

Street is too modest here: his acquaintance with Spain if not indeed exhaustive, like that with France and England, is entirely representative; and however pressed for time, he never scamps his work. The present writer may testify, having followed his tracks with an exact piety all the way, that he exhausted every town. He passed through Miranda at dawn, but he described, classified and dated the church; he went up the coast, from Barcelona to Port Vendres, by train, but he saw more churches and towers than the careful observer after him. He continues:

“Yet I hardly know that I need apologize for my neglect to see more, when I consider that, up to the present time, so far as I know, no architect has ever described the buildings which I have visited and indeed45 no accurate or reliable information is to be obtained as to their exact character, age, or history.”

In that sentence is written down the debt Spain owes to Street.

He took his wife on the first journey but not afterwards. She was both patient and spirited, but it was a little too rough for a lady. His own endurance and good temper are unfailing, and infallible his sense of due proportion. He never tells you what was for dinner, or how the bed ailed, or when he quarrelled with the landlord. It is much if he mentions, in a sort of postscript, that the journey to Compostela in diligence took sixty-six hours, and, elsewhere, that in autumn a man can live largely on bread and grapes. He is not, like Mr. Hewlitt or Mr. Hutton when they go on the road, writing a picaresque romance, but an account of Gothic architecture in Spain. The structural analysis of Santiago, the discussion of the date of Avila, the appreciation of the Catalan type of church-building—everyone knows that famous parallel with “our own Norfolk middle-pointed”—such passages provoke comparison and command praise, for substantiality and lucidity, with the very best of writing on a technical subject. The dexterity with which he singles out the English or Angevine elements at Las Huelgas, and those of the Isle-of-France at Toledo, and signals there the gradual interpenetration of local influences, has the happiest certainty and the most admired ease. It is hard to say where he is at his best,—whether in dealing with a style like the Romanesque of Cluny or the Gothic of Paris, where he has a vast store of experience long accumulated, and makes comparisons and illustrates distinctions from England or46 Italy indifferently, or whether coming upon fresh matter like the domed churches about Zamora or the brick building around Saragossa, or even something so much out of his line as the Mudejar work scattered about in the Castiles, he applies reason and method to the unknown, and, arriving at conviction, he enforces it. Nothing could be more succinct and more satisfying than his dealing with the dates of Don Patricio de la Escosura, in España Artistica y Monumental. “I see no reason,” he writes easily, “for believing that the plaster decorations are earlier than 1350 or thereabouts.”

Only once in a very long while, a slight twist or tang of perversity relieves the even good sense and good taste. Of the lovely sepulchre in Avila of that young brother of Joanna the Mad, too early dead, he remarks that the great tomb “is one of the most tender, fine, and graceful works I have ever seen, and worthy of any school of architecture. The recumbent effigy, in particular, is as dignified, graceful and religious as it well could be, and in no respect unworthy of a good Gothic artist.” The quaint anti-climax has the very, sweet, gaucherie of a woodcut by Rossetti or a bit out of Scripture by the young, unspoiled Holman Hunt. We have come, since that could be said, a very long way.