Plates in tint, engraved for THE CENTURY by H. C. Merrill and H. Davidson

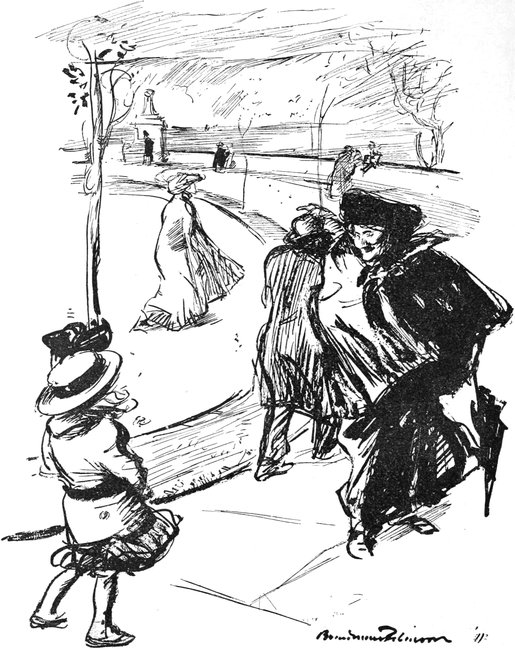

“AND ‘INASMUCH,’ HE SAID. JUST THAT—‘INASMUCH.’

SO THAT’S HOW I HAPPENED TO GO INTO NURSING”

DRAWN BY HERMAN PFEIFER

Title: The Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine, August, 1913

Author: Various

Release date: October 6, 2018 [eBook #58043]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Jane Robins, Reiner Ruf, and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

Transcriber’s Notes

This e-text is based on ‘The Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine,’ from August, 1913. The table of contents, based on the index from the May issue, has been added by the transcriber.

Inconsistent spelling and hyphenation have been retained, but punctuation and typographical errors have been corrected. Passages in English dialect and in languages other than English have not been altered. In some cases, such as in ‘Fresh Light on Washington’ (p. 635), errors seem to be introduced deliberately; here, the text has been retained as printed in the original.

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

Plates in tint, engraved for THE CENTURY by H. C. Merrill and H. Davidson

“AND ‘INASMUCH,’ HE SAID. JUST THAT—‘INASMUCH.’

SO THAT’S HOW I HAPPENED TO GO INTO NURSING”

DRAWN BY HERMAN PFEIFER

MIDSUMMER HOLIDAY NUMBER

Copyright, 1913, by THE CENTURY CO. All rights reserved.

| PAGE | ||

| WHITE LINEN NURSE, THE | Eleanor Hallowell Abbott | 483 |

| Pictures, printed in tint, by Herman Pfeifer. | ||

| ROMAIN ROLLAND. | Alvan F. Sanborn | 512 |

| Picture from portrait of Rolland from a drawing by Granié. | ||

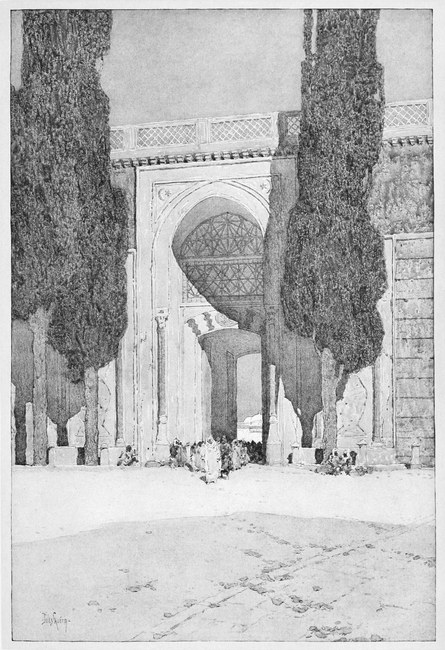

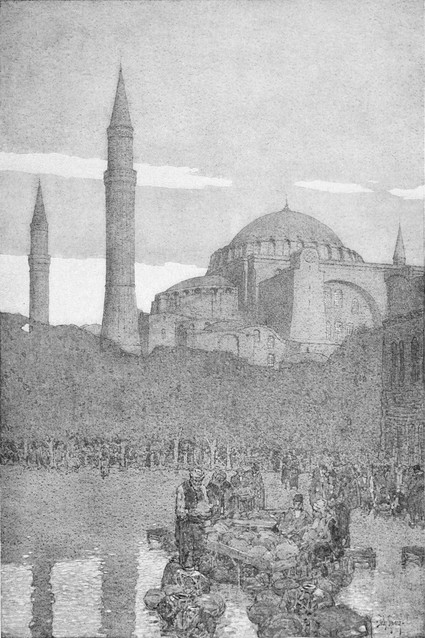

| BALKAN PENINSULA, SKIRTING THE | Robert Hichens | |

| VI. Stamboul, the City of Mosques. | 519 | |

| Pictures by Jules Guérin, two printed in color. | ||

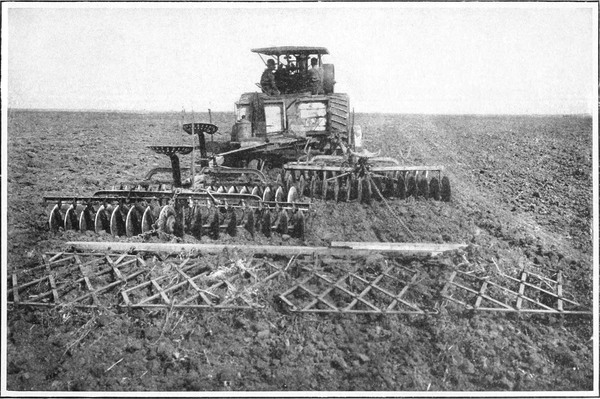

| TRADE OF THE WORLD PAPERS, THE | James Davenport Whelpley | |

| XVII. If Canada were to Annex the United States | 534 | |

| Pictures from photographs. | ||

| IMPRACTICAL MAN, THE | Elliott Flower | 549 |

| Pictures by F. R. Gruger. | ||

| BRITISH UNCOMMUNICATIVENESS. | A. C. Benson | 567 |

| GUTTER-NICKEL, THE | Estelle Loomis | 570 |

| Picture by J. Montgomery Flagg. | ||

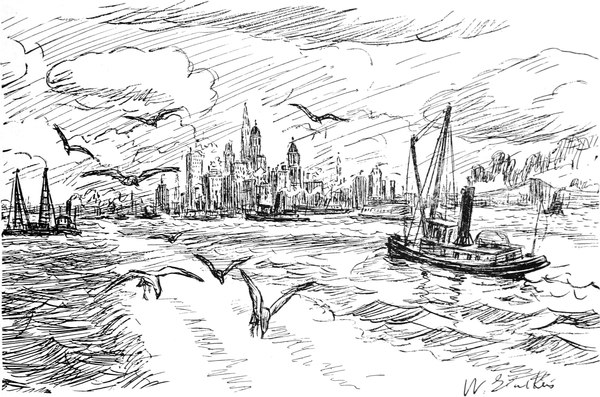

| VOYAGE OVER, THE FIRST | Theodore Dreiser | 586 |

| Pictures by W. J. Glackens. | ||

| JAPAN, THE NEW, AMERICAN MAKERS OF | William Elliot Griffis | 597 |

| Pictures from photographs. | ||

| GOLF, MIND VERSUS MUSCLE IN | Marshall Whitlatch | 606 |

| T. TEMBAROM. | Frances Hodgson Burnett | 610 |

| Drawings by Charles S. Chapman. | ||

| GOING UP. | Frederick Lewis Allen | 632 |

| Picture by Reginald Birch. | ||

| WASHINGTON, FRESH LIGHT ON | 635 | |

| CARTOONS. | ||

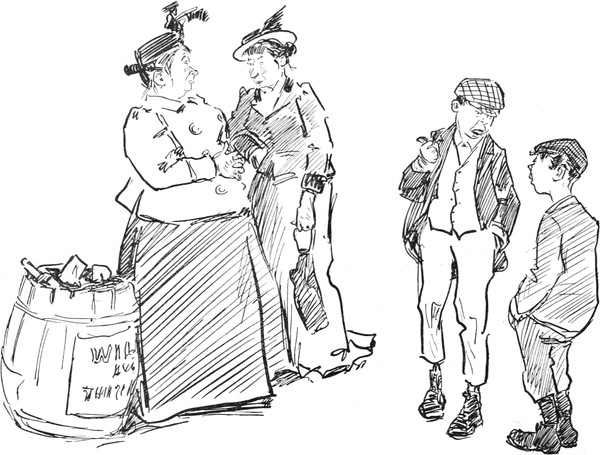

| A Boy’s Best Friend | May Wilson Preston | 634 |

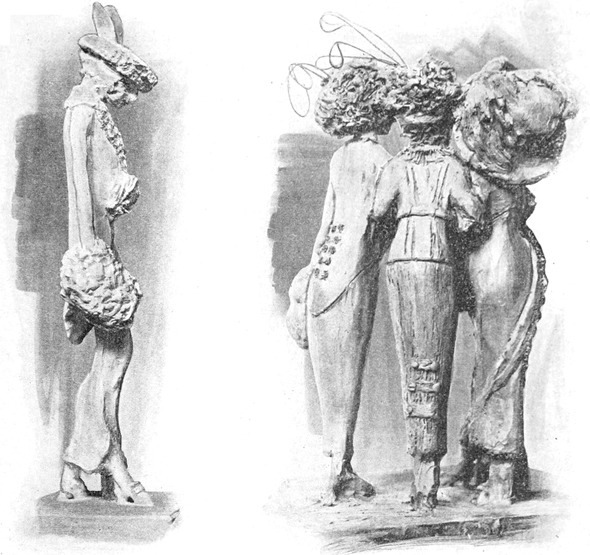

| “The Fifth Avenue Girl” and “A Bit of Gossip.” Sculpture by | Ethel Myers | 635 |

| The Child de Luxe. | Boardman Robinson | 636 |

VERSE

| DOUBLE STAR, A | Leroy Titus Weeks | 511 |

| MESSAGE FROM ITALY, A | Margaret Widdemer | 547 |

| Drawing printed in tint by W. T. Benda. | ||

| MARVELOUS MUNCHAUSEN, THE | William Rose Benét | 563 |

| Pictures by Oliver Herford. | ||

| WINGÈD VICTORY. | Victor Whitlock | 596 |

| Photograph and decoration. | ||

| ROYAL MUMMY, TO A | Anna Glen Stoddard | 631 |

| TRIOLET, A | Leroy Titus Weeks | 636 |

| RYMBELS. | ||

| Pictures by Oliver Herford. | ||

| The Girl and the Raspberry Ice. | Oliver Herford | 637 |

| The Yellow Vase. | Charles Hanson Towne | 637 |

| Tragedy. | Theodosia Garrison | 638 |

| “On Revient toujours à Son Premier Amour”. | Oliver Herford | 638 |

| LIMERICKS. | ||

| Text and pictures by Oliver Herford. | ||

| XXXII. The Eternal Feminine. | 639 | |

| XXXIII. Tra-la-Larceny. | 640 | |

HOW RAE MALGREGOR UNDERTOOK GENERAL HEARTWORK FOR A FAMILY OF TWO

BY ELEANOR HALLOWELL ABBOTT

Author of “Molly Make-Believe,” etc.

IN THREE PARTS: PART ONE

THE White Linen Nurse was so tired that her noble expression ached.

Incidentally her head ached and her shoulders ached and her lungs ached, and the ankle-bones of both feet ached excruciatingly; but nothing of her felt permanently incapacitated except her noble expression. Like a strip of lip-colored lead suspended from her poor little nose by two tugging, wire-gray wrinkles, her persistently conscientious sick-room smile seemed to be whanging aimlessly against her front teeth. The sensation was very unpleasant.

Looking back thus on the three spine-curving, chest-cramping, foot-twinging, ether-scented years of her hospital training, it dawned on the White Linen Nurse very suddenly that nothing of her ever had felt permanently incapacitated except her noble expression.

Impulsively she sprang for the prim white mirror that capped her prim white bureau, and stood staring up into her own entrancing, bright-colored Nova Scotian reflection with tense, unwonted interest.

Except for the unmistakable smirk which fatigue had clawed into her plastic young mouth-lines, there was nothing special the matter with what she saw.

“Perfectly good face,” she attested judicially, with no more than common courtesy to her progenitors—“perfectly good and tidy-looking face, if only—if only—” her breath caught a trifle—“if only it didn’t look so disgustingly noble and—hygienic—and dollish.”

All along the back of her neck little sharp, prickly pains began to sting and burn.

“Silly—simpering—pink-and-white puppet!” she scolded squintingly, “I’ll teach you how to look like a real girl!”

Very threateningly she raised herself to[Pg 484] her tiptoes and thrust her glowing, corporeal face right up into the moulten, elusive, quicksilver face in the mirror. Pink for pink, blue for blue, gold for gold, dollish smirk for dollish smirk, the mirror mocked her seething inner fretfulness.

“Why, darn you!” she gasped—“why, darn you—why, you looked more human than that when you left the Annapolis Valley three years ago! There were at least tears in your face then, and cinders, and your mother’s best advice, and the worry about the mortgage, and the blush of Joe Hazeltine’s kiss.”

Furtively with the tip of her index-finger she started to search her imperturbable pink cheek for the spot where Joe Hazeltine’s kiss had formerly flamed.

“My hands are all right, anyway,” she acknowledged with vast relief. Triumphantly she raised both strong, stub-fingered, exaggeratively executive hands to the level of her childish blue eyes, and stood surveying the mirrored effect with ineffable satisfaction. “Why, my hands are—dandy!” she gloated. “Why, they’re perfectly dandy! Why, they’re wonderful! Why, they’re—” Then suddenly and fearfully she gave a shrill little scream. “But they don’t go with my silly doll-face,” she cried. “Why, they don’t! They don’t! My God! they don’t! They go with the Senior Surgeon’s scowling Heidelberg eyes. They go with the Senior Surgeon’s grim, gray jaw. They go with the—Oh, what shall I do? What shall I do?”

Dizzily, with her stubby finger-tips prodded deep into every jaded facial muscle that she could compass, she staggered toward the air and, dropping down into the first friendly chair that bumped against her knees, sat staring blankly out across the monotonous city roofs that flanked her open window, trying very, very hard, for the first time in her life, to consider the general phenomenon of being a trained nurse.

All about her, as inexorable as anæsthesia, horrid as the hush of tomb or public library, lurked the painfully unmistakable sense of institutional restraint. Mournfully to her ear from some remote kitcheny region of pots and pans a browsing spoon tinkled forth from time to time with soft muffled resonance. Up and down every clammy white corridor innumerable young feet, born to prance and stamp, were creeping stealthily to and fro in rubber-heeled whispers. Along the somber fire-escape just below her windowsill, like a covey of snubbed doves, six or eight of her classmates were cooing and crooning together with excessive caution concerning the imminent graduation exercises that were to take place at eight o’clock that very evening. Beyond her dreariest ken of muffled voices, beyond her dingiest vista of slate and brick, on a far, faint hillside, a far, faint streak of April green went roaming jocundly skyward. Altogether sluggishly, as though her nostrils were plugged with warm velvet, the smell of spring and ether and scorched mutton-chops filtered in and out, in and out, in and out, of her abnormally jaded senses.

Taken all in all, it was not a propitious afternoon for any girl as tired and as pretty as the White Linen Nurse to be considering the general phenomenon of anything except April.

In the real country, they tell me, where the young spring runs as wild and bare as a nymph through every dull-brown wood and hay-gray meadow, the blasé farmer-lad will not even lift his eyes from the plow to watch the pinkness of her passing. But here in the prudish brick-minded city, where the young spring at her friskiest is nothing more audacious than a sweltering, winter-swathed madcap who has impishly essayed some fine morning to tiptoe down street in her soft, sloozily, green-silk-stockinged feet, the whole hobnailed population reels back aghast and agrin before the most innocent flash of the rogue’s green-veiled toes. And then, suddenly snatching off its own cumbersome winter foot-habits, goes chasing madly after her in its own prankish, varicolored socks.

Now, the White Linen Nurse’s socks were black, and cotton at that, a combination incontestably sedate. And the White Linen Nurse had waded barefoot through too many posied country pastures to experience any ordinary city thrill over the sight of a single blade of grass pushing scarily through a crack in the pavement, or a puny, concrete-strangled maple-tree flushing wanly to the smoky sky. Indeed, for three hustling, square-toed, rubber-heeled city years the White Linen Nurse had never even stopped to notice whether[Pg 485] the season was flavored with frost or thunder. But now, unexplainably, just at the end of it all, sitting innocently there at her own prim little bedroom window, staring innocently out across indomitable roof-tops, with the crackle of glory and diplomas already ringing in her ears, she heard instead, for the first time in her life, the gaily daredevil voice of the spring, a hoidenish challenge flung back at her, leaf-green, from the crest of a winter-scarred hill.

“Hello, White Linen Nurse!” screamed the saucy city Spring. “Hello, White Linen Nurse! Take off your homely starched collar, or your silly candy-box cap, or any other thing that feels maddeningly artificial, and come out! And be very wild!”

Like a puppy-dog cocking its head toward some strange, unfamiliar sound, the White Linen Nurse cocked her head toward the lure of the green-crested hill. Still wrestling conscientiously with the general phenomenon of being a trained nurse, she found her collar suddenly very tight, her tiny cap inexpressibly heavy and vexatious. Timidly she removed the collar, and found that the removal did not rest her in the slightest. Equally timidly she removed the cap, and found that even that removal did not rest her in the slightest. Then very, very slowly, but very, very permeatingly and completely, it dawned on the White Linen Nurse that never while eyes were blue, and hair was gold, and lips were red, would she ever find rest again until she had removed her noble expression.

With a jerk that started the pulses in her temples throbbing like two toothaches, she straightened up in her chair. All along the back of her neck the little blond curls began to crisp very ticklingly at their roots.

Still staring worriedly out over the old city’s slate-gray head to that inciting prance of green across the farthest horizon, she felt her whole being kindle to an indescribable passion of revolt against all hushed places. Seething with fatigue, smoldering with ennui, she experienced suddenly a wild, almost incontrollable, impulse to sing, to shout, to scream from the house-tops, to mock somebody, to defy everybody, to break laws, dishes, heads—anything, in fact, that would break with a crash.

And then at last, over the hills and far away, with all the outraged world at her heels, to run, and run, and run, and run, and run, and laugh, till her feet raveled out, and her lungs burst, and there was nothing more left of her at all—ever, ever, any more!

Discordantly into this rapturously pagan vision of pranks and posies broke one of her room-mates all a-whiff with ether, a-whir with starch.

Instantly with the first creak of the door-handle, the White Linen Nurse was on her feet, breathless, resentful, grotesquely defiant.

“Get out of here, Zillah Forsyth!” she cried furiously. “Get out of here quick, and leave me alone! I want to think.”

Perfectly serenely the new-comer advanced into the room. With her pale, ivory-tinted cheeks, her great limpid, brown eyes, her soft dark hair parted madonna-like across her beautiful brow, her whole face was like some exquisite composite picture of all the saints of history. Her voice also was amazingly tranquil.

“Oh, fudge!” she drawled. “What’s eating you, Rae Malgregor? I won’t either get out. It’s my room just as much as it is yours. And Helene’s just as much as it is ours. And, besides,” she added more briskly, “it’s four o’clock now, and, with graduation at eight and the dance afterward, if we don’t get our stuff packed up now, when in thunder shall we get it done?” Quite irrelevantly she began to laugh. Her laugh was perceptibly shriller than her speaking-voice. “Say, Rae,” she confided, “that minister I nursed through pneumonia last winter wants me to pose as ‘Sanctity’ for a stained-glass window in his new church! Isn’t he the softy?”

“Shall you do it?” quizzed Rae Malgregor, a trifle tensely.

“Shall I do it?” mocked the new-comer. “Well, you just watch me! Four mornings a week in June at full week’s wages? Fresh Easter lilies every day? White silk angel-robes? All the high souls and high paints kowtowing around me? Why, it would be more fun than a box of monkeys. Sure I’ll do it.”

Expeditiously as she spoke, the new-comer reached up for the framed motto over her own ample mirror, and yanking it down with one single tug, began to busy[Pg 486] herself adroitly with a snarl in the picture-cord. Like a withe of willow yearning over a brook, her slender figure curved to the task. Very scintillatingly the afternoon light seemed to brighten suddenly across her lap. “You’ll Be A Long Time Dead!” glinted the motto through its sun-dazzled glass.

Still panting with excitement, still bristling with resentment, Rae Malgregor stood surveying the intrusion and the intruder. A dozen impertinent speeches were rioting in her mind. Twice her mouth opened and shut before she finally achieved the particular opprobrium that completely satisfied her.

“Bah! you look like a—trained nurse!” she blurted forth at last with hysterical triumph.

“So do you,” said the new-corner, amiably.

With a little gasp of dismay, Rae Malgregor sprang suddenly forward. Her eyes were flooded with tears.

“Why, that’s just exactly what’s the matter with me!” she cried. “My face is all worn out trying to look like a trained nurse! O Zillah, how do you know you were meant to be a trained nurse? How does anybody know? O Zillah! save me! Save me!”

Languorously Zillah Forsyth looked up from her work and laughed. Her laugh was like the accidental tinkle of sleigh-bells in midsummer, vaguely disquieting, a shiver of frost across the face of a lily.

“Save you from what, you great big overgrown, tow-headed doll-baby?” she questioned blandly. “For Heaven’s sake, the only thing you need is to go back to whatever toy-shop you came from and get a new head. What in creation’s the matter with you lately, anyway Oh, of course you’ve had rotten luck this past month but what of it? That’s the trouble with you country girls. You haven’t got any stamina.”

With slow, shuffling-footed astonishment Rae Malgregor stepped out into the center of the room. “Country girls!” she repeated blankly. “Why, you’re a country girl yourself.”

“I am not,” snapped Zillah Forsyth. “I’ll have you understand that there are nine thousand people in the town I come from, and not a rube among them. Why, I tended soda-fountain in the swellest drug store there a whole year before I even thought of taking up nursing. And I wasn’t as green when I was six months old as you are now.”

Slowly, with a soft-snuggling sigh of contentment, she raised her slim white fingers to coax her dusky hair a little looser, a little farther down, a little more madonna-like across her sweet, mild forehead, then, snatching out abruptly at a convenient shirt-waist, began with extraordinary skill to apply its dangly lace sleeves as a protective bandage for the delicate glass-faced motto still in her lap, placed the completed parcel with inordinate scientific precision in the exact corner of her packing-box, and then went on very diligently, very zealously, to strip the men’s photographs from the mirror on her bureau. There were twenty-seven photographs in all, and for each one she had there already cut and prepared a small square of perfectly fresh, perfectly immaculate, white tissue wrapping-paper. No one so transcendently fastidious, so exquisitely neat in all her personal habits, had ever before been trained in that particular hospital.

Very soberly the doll-faced girl stood watching the men’s pleasant paper countenances smoothed away one by one into their chaste white veilings, until at last, quite without warning, she poked an accusing, inquisitive finger directly across Zillah Forsyth’s shoulder.

“Zillah,” she demanded peremptorily, “all the year I’ve wanted to know, all the year every other girl in our class has wanted to know—where did you ever get that picture of the Senior Surgeon? He never gave it to you in the world. He didn’t, he didn’t! He’s not that kind.”

Deeply into Zillah Forsyth’s pale, ascetic cheek dawned a most amazing dimple.

“Sort of jarred you girls some, didn’t it,” she queried, “to see me strutting round with a photo of the Senior Surgeon?” The little cleft in her chin showed suddenly with almost startling distinctness. “Well, seeing it’s you,” she grinned, “and the year’s all over, and there’s nobody left that I can worry about it any more, I don’t mind telling you in the least that I—bought it out of a photographer’s show-case. There, are you satisfied now?”

With easy nonchalance she picked up[Pg 487] the picture in question and scrutinized it shrewdly.

“Lord! what a face!” she attested. “Nothing but granite. Hack him with a knife, and he wouldn’t bleed, but just chip off into pebbles.” With exaggerated contempt she shrugged her supple shoulders. “Bah! how I hate a man like that! There’s no fun in him.” A little abruptly she turned and thrust the photograph into Rae Malgregor’s hand. “You can have it if you want to,” she said. “I’ll trade it to you for that lace corset-cover of yours.”

Like water dripping through a sieve the photograph slid through Rae Malgregor’s frightened fingers. With nervous apology she stooped and picked it up again, and held it gingerly by one remote corner. Her eyes were quite wide with horror.

“Oh, of course I’d like the—picture well enough,” she stammered, “but it wouldn’t seem—exactly respectable to—to trade it for a corset-cover.”

“Oh, very well,” drawled Zillah Forsyth; “tear it up, then.”

Expeditiously, with frank, non-sentimental fingers, Rae Malgregor tore the tough cardboard across, and again across, and once again across, and threw the conglomerate fragments into the waste-basket. And her expression all the time was no more, no less, than the expression of a person who would vastly rather execute his own pet dog or cat than risk the possible bungling of an outsider. Then, like a small child trotting with great relief to its own doll-house, she trotted over to her bureau, extracted the lace corset-cover, and came back with it in her hand, to lean across Zillah Forsyth’s shoulder again and watch the men’s faces go slipping off into oblivion. Once again, abruptly, without warning, she halted the process with a breathless exclamation.

“Oh, of course this waist is the only one I’ve got with ribbons in it,” she asserted irrelevantly, “but I’m perfectly willing to trade it for that picture.” She pointed out with unmistakably explicit finger-tip.

Chucklingly, Zillah Forsyth withdrew the special photograph from its half-completed wrappings.

“Oh, him?” she said. “Oh, that’s a chap I met on the train last summer. He’s a brakeman or something. He’s a—”

Perfectly unreluctantly Rae Malgregor dropped the fluff of lace and ribbons into Zillah’s lap and reached out with cheerful voraciousness to annex the young man’s picture to her somewhat bleak possessions. “Oh, I don’t care a rap who he is,” she interrupted briskly; “but he’s sort of cute-looking, and I’ve got an empty frame at home just that odd size, and mother’s crazy for a new picture to stick up over the kitchen mantelpiece. She gets so tired of seeing nothing but the faces of people she knows all about.”

Sharply Zillah Forsyth turned and stared up into the younger girl’s face, and found no guile to whet her stare against.

“Well, of all the ridiculous, unmitigated greenhorns!” she began. “Well, is that all you wanted him for? Why, I supposed you wanted to write to him. Why, I supposed—”

For the first time an expression not altogether dollish darkened across Rae Malgregor’s garishly juvenile blondness.

“Maybe I’m not quite as green as you think I am,” she flared up stormily. With this sharp flaring-up every single individual pulse in her body seemed to jerk itself suddenly into conscious activity again, like the soft, plushy pound-pound-pound of a whole stocking-footed regiment of pain descending single file upon her for her hysterical undoing. “Maybe I’ve had a good deal more experience than you give me credit for,” she hastened excitedly to explain. “I tell you—I tell you, I’ve been engaged!” she blurted forth with a bitter sort of triumph.

With a palpable flicker of interest Zillah Forsyth looked back across her shoulder.

“Engaged? How many times?” she asked bluntly.

As though the whole monogamous groundwork of civilization was threatened by the question, Rae Malgregor’s hands went clutching at her breast.

“Why, once!” she gasped. “Why, once!”

Convulsively Zillah Forsyth began to rock herself to and fro.

“Oh, Lordy!” she chuckled. “Oh, Lordy! Lordy! Why, I’ve been engaged four times just this past year.” In a sudden passion of fastidiousness, she bent down over the particular photograph in her hand and, snatching at a handkerchief,[Pg 488] began to rub diligently at a small smutch of dust in one corner of the cardboard. Something in the effort of rubbing seemed to jerk her small round chin into almost angular prominence. “And before I’m through,” she added, at least two notes below her usual alto tones—“and before I’m through, I’m going to get engaged to every profession that there is on the surface of the globe.” Quite helplessly the thin paper skin of the photograph peeled off in company with the smutch of dust. “And when I marry,” she ejaculated fiercely—“and when I marry, I’m going to marry a man who will take me to every place that there is on the surface of the globe. And after that—”

“After what?” interrogated a brand-new voice from the doorway.

It was the other room-mate this time. The only real aristocrat in the whole graduating class, high-browed, high-cheek-boned, eyes like some far-sighted young prophet, mouth even yet faintly arrogant with the ineradicable consciousness of caste, a plain, eager, stripped-for-a-long-journey type of face—this was Helene Churchill. There was certainly no innocuous bloom of country hills and pastures in this girl’s face, nor any seething small-town passion pounding indiscriminately at all the doors of experience. The men and women who had bred Helene Churchill had been the breeders also of brick and granite cities since the world was new.

Like one vastly more accustomed to treading on Persian carpets than on painted floors, she came forward into the room.

“Hello, children!” she said casually, and began at once without further parleying to take down the motto that graced her own bureau-top.

It was the era when almost everybody in the world had a motto over his bureau. Helene Churchill’s motto was “Inasmuch As Ye Have Done It Unto One Of The Least Of These, Ye Have Done It Unto Me.” On a scroll of almost priceless parchment the text was illuminated with inimitable Florentine skill and color. A little carelessly, after the manner of people quite accustomed to priceless things, she proceeded now to roll the parchment into its smallest possible circumference, humming exclusively to herself all the while an intricate little air from an Italian opera.

So the three faces foiled each other, sober city girl, pert town girl, bucolic country girl, a hundred fundamental differences rampant between them, yet each fervid, adolescent young mouth tamed to the same monotonous, drolly exaggerated expression of complacency that characterizes the faces of all people who, in a distinctive uniform, for a reasonably satisfactory living wage, make an actual profession of righteous deeds.

Indeed among all the thirty or more varieties of noble expression which an indomitable Superintendent had finally succeeded in inculcating into her graduating class, no other physiognomies had responded more plastically perhaps than these three to the merciless imprint of the great hospital machine which, in pursuance of its one repetitive design, discipline, had coaxed Zillah Forsyth into the semblance of a lady, snubbed Helene Churchill into the substance of plain womanhood, and, still uncertain just what to do with Rae Malgregor’s rollicking rural immaturity, had frozen her face temporarily into the smugly dimpled likeness of a fancy French doll rigged out as a nurse for some gilt-edged hospital fair.

With characteristic desire to keep up in every way with her more mature, better educated classmates, to do everything, in fact, so fast, so well, that no one would possibly guess that she hadn’t yet figured out just why she was doing it at all, Rae Malgregor now, with quickly reconventionalized cap and collar, began to hurl herself into the task of her own packing. From her open bureau drawer, with a sudden impish impulse toward worldly wisdom, she extracted first of all the photograph of the young brakeman.

“See, Helene! My new beau!” she giggled experimentally.

In mild-eyed surprise Helene Churchill glanced up from her work. “Your beau?” she corrected. “Why, that’s Zillah’s picture.”

“Well, it’s mine now,” snapped Rae Malgregor, with unexpected edginess. “It’s mine now, all right. Zillah said I could have him. Zillah said I could—write to him—if I wanted to,” she finished a bit breathlessly.

Wider and wider Helene Churchill’s eyes dilated.

“Write to a man whom you don’t know?” she gasped. “Why, Rae! Why, it isn’t even very nice to have a picture of a man you don’t know.”

Mockingly to the edge of her strong white teeth Rae Malgregor’s tongue crept out in pink derision.

“Bah!” she taunted. “What’s nice? That’s the whole matter with you, Helene Churchill. You never stop to consider whether anything’s fun or not; all you care is whether it’s nice.” Excitedly she turned to meet the cheap little wink from Zillah’s sainted eyes. “Bah! What’s nice?” she persisted, a little lamely. Then suddenly all the pertness within her crumbled into nothingness. “That’s—the—whole trouble with you, Zillah Forsyth,” she stammered—“you never give a hang whether anything’s nice or not; all you care is whether it’s fun.” Quite helplessly she began to wring her hands. “Oh, how do I know which one of you girls to follow?” she demanded wildly. “How do I know anything? How does anybody know anything?”

Like a smoldering fuse the rambling query crept back into the inner recesses of her brain, and fired once more the one great question that lay dormant there. Impetuously she ran forward and stared into Helene Churchill’s face.

“How do you know you were meant to be a trained nurse, Helene Churchill?” she began all over again. “How does anybody know she was really meant to be one? How can anybody, I mean, be perfectly sure?” Like a drowning man clutching out at the proverbial straw, she clutched at the parchment in Helene Churchill’s hand. “I mean—where did you get your motto, Helene Churchill?” she persisted, with increasing irritability. “If you don’t tell me, I’ll tear the whole thing to pieces.”

With a startled frown, Helene Churchill jerked back out of reach.

“What’s the matter with you, Rae?” she quizzed sharply, and then, turning round casually to her book-case, began to draw from the shelves one by one her beloved Marcus Aurelius, Wordsworth, Robert Browning. “Oh, I did so want to go to China,” she confided irrelevantly; “but my family have just written me that they won’t stand for it. So I suppose I’ll have to go into tenement work here in the city instead.” With a visible effort she jerked her mind back again to the feverish question in Rae Malgregor’s eyes. “Oh, you want to know where I got my motto?” she asked. A flash of intuition brightened suddenly across her absent-mindedness. “Oh,” she smiled, “you mean you want to know just what the incident was that first made me decide to devote my life to humanity?”

“Yes,” snapped Rae Malgregor.

A little shyly Helene Churchill picked up her copy of Marcus Aurelius and cuddled her cheek against its tender morocco cover.

“Really?” she questioned with palpable hesitation—“really, you want to know? Why, why—it’s rather a—sacred little story to me. I shouldn’t exactly want to have anybody—laugh about it.”

“I’ll laugh if I want to,” attested Zillah Forsyth, forcibly, from the other side of the room.

Like a pugnacious boy’s, Rae Malgregor’s fluent fingers doubled up into two firm fists.

“I’ll punch her if she even looks as though she wanted to,” she signaled surreptitiously to Helene.

Shrewdly for an instant the city girl’s narrowing eyes challenged and appraised the country girl’s desperate sincerity. Then quite abruptly she began her little story.

“Why, it was on an Easter Sunday, oh, ages and ages ago,” she faltered. “Why, I couldn’t have been more than nine years old at the time.” A trifle self-consciously she turned her face away from Zillah Forsyth’s supercilious smile. “And I was coming home from a Sunday-school festival in my best white muslin dress, with a big pot of purple pansies in my hand,” she hastened somewhat nervously to explain.[Pg 490] “And just at the edge of the gutter there was a dreadful drunken man lying in the mud, with a great crowd of cruel people teasing and tormenting him. And because—because I couldn’t think of anything else to do about it, I—I walked right up to the poor old creature, scared as I could be, and—and I presented him with my pot of purple pansies. And everybody of course began to laugh—to scream, I mean—and shout with amusement. And I, of course, began to cry. And the old drunken man straightened up very oddly for an instant, with his battered hat in one hand and the pot of pansies in the other, and he raised the pot of pansies very high, as though it had been a glass of rarest wine, and bowed to me as reverently as though he had been toasting me at my father’s table at some very grand dinner. And ‘Inasmuch,’ he said. Just that—‘Inasmuch.’ So that’s how I happened to go into nursing,” she finished as abruptly as she had begun. Like some wonderful phosphorescent manifestation her whole shining soul seemed to flare forth suddenly through her plain face.

With honest perplexity Zillah Forsyth looked up from her work.

“So that’s how you happened to go into nursing?” she quizzed impatiently. Her long straight nose was all puckered tight with interrogation. Her dove-like eyes were fairly dilated with slow-dawning astonishment. “You—don’t—mean,” she gasped—“you don’t mean that just for that?” Incredulously she jumped to her feet and stood staring blankly into the city girl’s strangely illuminated features. “Well, if I were a swell like you,” she scoffed, “it would take a heap sight more than a drunken man munching pansies and rum and Bible texts to—to jolt me out of my limousines and steam-yachts and Adirondack bungalows.”

Quite against all intention, Helene Churchill laughed. She did not often laugh. Just for an instant her eyes and Zillah Forsyth’s clashed together in the irremediable antagonism of caste, the plebeian’s scornful impatience with the aristocrat equaled only by the aristocrat’s condescending patience with the plebeian.

It was no more than right that the aristocrat should recover her self-possession first.

“Never mind about your understanding, Zillah dear,” she said softly. “Your hair is the most beautiful thing I ever saw in my life.”

Along Zillah Forsyth’s ivory cheek an incongruous little flush of red began to show. With much more nonchalance than was really necessary she pointed toward her half-packed trunk.

“It wasn’t Sunday-school I was coming home from when I got my motto,” she remarked dryly, with a wink at no one in particular. “And, so far as I know,” she proceeded with increasing sarcasm, “the man who inspired my noble life was not in any way particularly addicted to the use of alcoholic beverages.” As though her collar was suddenly too tight, she rammed her finger down between her stiff white neck-band and her soft white throat. “He was a New York doctor,” she hastened somewhat airily to explain. “Gee! but he was a swell! And he was spending his summer holidays up in the same Maine town where I was tending soda-fountain. And he used to drop into the drug store nights after cigars and things. And he used to tell me stories about the drugs and things, sitting up there on the counter, swinging his legs and pointing out this and that—quinine, ipecac, opium, hashish—all the silly patent medicines, every sloppy soothing-syrup! Lordy! he knew ’em as though they were people—where they come from, where they’re going to, yarns about the tropics that would kink the hair along the nape of your neck, jokes about your own town’s soup-kettle pharmacology that would make you yell for joy. Gee! but the things that man had seen and known! Gee! but the things that man could make you see and know! And he had an automobile,” she confided proudly. “It was one of those billion-dollar French cars, and I lived just round the corner from the drug store; but we used to ride home by way of—New Hampshire.”

Almost imperceptibly her breath began to quicken.

“Gee! those nights!” she muttered. “Rain or shine, moon or thunder, tearing down those country roads at forty miles an hour, singing, hollering, whispering! It was him that taught me to do my hair like this instead of all the cheap rats and pompadours every other kid in town was wearing,” she asserted quite irrelevantly; then stopped with a furtive glance of suspicion toward both her listeners and mouthed her way delicately back to the beginning of her sentence again. “It was he that taught me to do my hair like this,” she repeated, with the faintest possible suggestion of hauteur.

For one reason or another along the exquisitely chaste curve of her cheek a narrow streak of red began to show again.

“And he went away very sudden at the last,” she finished hurriedly.[Pg 491] “It seems he was married all the time.” Blandly she turned her wonderful face to the caressing light. “And—I hope he goes to hell,” she added.

With a little gasp of astonishment, shock, suspicion, distaste, Helene Churchill reached out an immediate conscientious hand to her.

“O Zillah,” she began, “O poor Zillah dear! I’m so sorry! I’m so—”

Absolutely serenely, through a mask of insolence and ice, Zillah Forsyth ignored the proffered hand.

“I don’t know what particular call you’ve got to be sorry for me, Helene Churchill,” she drawled languidly. “I’ve got my character, same as you’ve got yours, and just about nine times as many good looks. And when it comes to nursing—” Like an alto song pierced suddenly by one shrill treble note, the girl’s immobile face sharpened transiently with a single jagged flash of emotion. “And when it comes to nursing? Ha! Helene Churchill, you can lead your class all you want to with your silk-lined manners and your fuddy-duddy book-talk; but when genteel people like you are moping round all ready to fold your patients’ hands on their breasts and murmur, ‘Thy will be done,’ why, that’s the time that little ‘Yours Truly’ is just beginning to roll up her sleeves and get to work.”

With real passion her slender fingers went clutching again at her harsh linen collar. “It isn’t you, Helene Churchill,” she taunted, “that’s ever been to the Superintendent on your bended knees and begged for the rabies cases and the small-pox! Gee! you like nursing because you think it’s pious to like it; but I like it because I like it!” From brow to chin, as though fairly stricken with sincerity, her whole bland face furrowed startlingly with crude expressiveness. “The smell of ether,” she stammered, “it’s like wine to me. The clang of the ambulance gong? I’d rather hear it than fire-engines. I’d crawl on my hands and knees a hundred miles to watch a major operation. I wish there was a war. I’d give my life to see a cholera epidemic.”

As abruptly as it came, the passion faded from her face, leaving every feature tranquil again, demure, exaggeratedly innocent. With saccharine sweetness she turned to Rae Malgregor.

“Now, little one,” she mocked, “tell us the story of your lovely life. Having heard me coyly confess that I went into nursing because I had such a crush on this world, and Helene here brazenly affirm that she went into nursing because she had such a crush on the world to come, it’s up to you now to confide to us just how you happened to take up so noble an endeavor. Had you seen some of the young house doctors’ beautiful, smiling faces depicted in the hospital catalogue? Or was it for the sake of the Senior Surgeon’s grim, gray mug that you jilted your poor plowboy lover way up in the Annapolis Valley?”

“Why, Zillah,” gasped the country girl—“why, I think you’re perfectly awful! Why, Zillah Forsyth! Don’t you ever say a thing like that again! You can joke all you want to about the flirty young internes,—they’re nothing but fellows,—but it isn’t—it isn’t respectful for you to talk like that about the Senior Surgeon. He’s too—too terrifying,” she finished in an utter panic of consternation.

“Oh, now I know it was the Senior Surgeon that made you jilt your country beau,” taunted Zillah Forsyth, with soft alto sarcasm.

“I didn’t, either, jilt Joe Hazeltine,” stormed Rae Malgregor, explosively. Backed up against her bureau, eyes flaming, breast heaving, little candy-box cap all tossed askew over her left ear, she stood defying her tormentor. “I didn’t, either, jilt Joe Hazeltine,” she reasserted passionately. “It was Joe Hazeltine that jilted me; and we’d been going together since we were kids! And now he’s married the dominie’s daughter, and they’ve got a kid of their own ’most as old as he and I were when we first began courting each other. And it’s all because I insisted on being a trained nurse,” she finished shrilly.

With an expression of real shock, Helene Churchill peered up from her lowly seat on the floor.

“You mean,” she asked a bit breathlessly—“you mean that he didn’t want you to be a trained nurse? You mean that he wasn’t big enough, wasn’t fine enough, to appreciate the nobility of the profession?”

“Nobility nothing!” snapped Rae Malgregor.[Pg 492] “It was me scrubbing strange men with alcohol that he couldn’t stand for, and I don’t know as I exactly blame him,” she added huskily. “It certainly is a good deal of a liberty when you stop to think about it.”

Quite incongruously her big childish blue eyes narrowed suddenly into two dark, calculating slits.

“It’s comic,” she mused, “how there isn’t a man in the world who would stand letting his wife or daughter or sister have a male nurse; but look at the jobs we girls get sent out on! It’s very confusing.” With sincere appeal she turned to Zillah Forsyth. “And yet—and yet,” she stammered, “and yet when everything scary that’s in you has once been scared out of you, why, there’s nothing left in you to be scared with any more, is there?”

“What? What?” pleaded Helene Churchill. “Say it again! What?”

“That’s what Joe and I quarreled about, my first vacation home,” persisted Rae Malgregor. “It was a traveling salesman’s thigh. It was broken bad. Somebody had to take care of it; so I did. Joe thought it wasn’t modest to be so willing.” With a perplexed sort of defiance she raised her square little chin. “But, you see, I was willing,” she said. “I was perfectly willing. Just one single solitary year of hospital training had made me perfectly willing. And you can’t un-willing a willing even to please your beau, no matter how hard you try.” With a droll admixture of shyness and disdain, she tossed her curly blond head a trifle higher. “Shucks!” she attested, “what’s a traveling salesman’s thigh?”

“Shucks yourself!” scoffed Zillah Forsyth. “What’s a silly beau or two up in Nova Scotia to a girl with looks like you? You could have married that typhoid case a dozen times last winter if you’d crooked your little finger. Why, the fellow was crazy about you. And he was richer than Crœsus. What queered it?” she demanded bluntly. “Did his mother hate you?”

Like one fairly cramped with astonishment, Rae Malgregor doubled up very suddenly at the waist-line, and, thrusting her neck oddly forward after the manner of a startled crane, stood peering sharply round the corner of the rocking-chair at Zillah Forsyth.

“Did his mother hate me?” she gasped. “Did—his—mother—hate me? Well, what do you think? With me, who never even saw plumbing till I came down here, setting out to explain to her, with twenty tiled bath-rooms, how to be hygienic though rich? Did his mother hate me? Well, what do you think? With her who bore him—her who bore him, mind you—kept waiting down-stairs in the hospital anteroom half an hour every day on the raw edge of a rattan chair, waiting, worrying, all old and gray and scared, while little, young, perky, pink-and-white me is up-stairs brushing her own son’s hair and washing her own son’s face and altogether getting her own son ready to see his own mother! And then me obliged to turn her out again in ten minutes, flip as you please, ‘for fear she’d stayed too long,’ while I stay on the rest of the night? Did his mother hate me?”

As stealthily as an assassin she crept around the corner of the rocking-chair and grabbed Zillah Forsyth by her astonished linen shoulder.

“Did his mother hate me?” she persisted mockingly. “Did his mother hate me? My God! Is there any woman from here to Kamchatka who doesn’t hate us? Is there any woman from here to Kamchatka who doesn’t look upon a trained nurse as her natural-born enemy? I don’t blame ’em,” she added chokingly. “Look at the impudent jobs we get sent out on! Quarantined up-stairs for weeks at a time with their inflammable, diphtheretic bridegrooms while they sit down-stairs brooding over their wedding teaspoons! Hiked off indefinitely to Atlantic City with their gouty bachelor uncles! Hearing their own innocent little sister’s blood-curdling death-bed deliriums! Snatching their own new-born babies away from their breasts and showing them, virgin-handed, how to nurse them better! The impudence of it, I say, the disgusting, confounded impudence—doing things perfectly, flippantly, right, for twenty-one dollars a week—and washing—that all the achin’ love in the world don’t know how to do right just for love!” Furiously she began to jerk her victim’s shoulder. “I tell you it’s awful, Zillah Forsyth,” she insisted. “I tell you I just won’t stand it!”

With muscles like steel wire, Zillah[Pg 493] Forsyth scrambled to her feet, and pushed Rae Malgregor back against the bureau.

“For Heaven’s sake, Rae, shut up!” she said. “What in creation’s the matter with you to-day? I never saw you act so before.” With real concern she stared into the girl’s turbid eyes. “If you feel like that about it, what in thunder did you go into nursing for?” she demanded not unkindly.

Very slowly Helene Churchill rose from her lowly seat by her precious book-case and came round and looked at Rae Malgregor rather oddly.

“Yes,” she faltered, “what did you go into nursing for?” The faintest possible taint of asperity was in her voice.

Quite dumbly for an instant Rae Malgregor’s natural timidity stood battling the almost fanatic professional fervor in Helene Churchill’s frankly open face, the raw scientific passion, of very different caliber, but of no less intensity, hidden craftily behind Zillah Forsyth’s plastic features; then suddenly her own hands went clutching back at the bureau for support, and all the flaming, raging red went ebbing out of her cheeks, leaving her lips with hardly blood enough left to work them.

“I went into nursing,” she mumbled, “and it’s God’s own truth—I went into nursing because—because I thought the uniforms were so cute.”

Furiously, the instant the words were gone from her mouth, she turned and snarled at Zillah’s hooting laughter.

“Well, I had to do something,” she attested. The defense was like a flat blade slapping the air.

Desperately she turned to Helene Churchill’s goading, faintly supercilious smile, and her voice edged suddenly like a twisted sword.

“Well, the uniforms are cute,” she parried. “They are! They are! I bet you there’s more than one girl standing high in the graduating class to-day who never would have stuck out her first year’s bossin’ and slops and worry and death if she’d had to stick it out in the unimportant-looking clothes she came from home in. Even you, Helene Churchill, with all your pious talk, the day they put your coachman’s son in as new interne and you got called down from the office for failing to stand when Mr. Young Coachman came into the room, you bawled all night. You did, you did, and swore you’d chuck your whole job and go home the next day if it wasn’t that you’d just had a life-size photo taken in full nursing costume to send to your brother’s chum at Vale! So there!”

With a gasp of ineffable satisfaction she turned from Helene Churchill.

“Sure the uniforms are cute,” she slashed back at Zillah Forsyth. “That’s the whole trouble with ’em. They’re so awfully, masqueradishly cute! Sure I could have gotten engaged to the typhoid boy. It would have been as easy as robbing a babe. But lots of girls, I notice, get engaged in their uniforms, feeding a patient perfectly scientifically out of his own silver spoon, who don’t seem to stay engaged so specially long in their own street clothes, bungling just plain naturally with their own knives and forks. Even you, Zillah Forsyth,” she hacked—“even you, who trot round like the ‘Lord’s anointed’ in your pure white togs, you’re just as Dutchy-looking as anybody else come to put you in a red hat and a tan coat and a blue skirt.”

Mechanically she raised her hands to her head as though with some silly thought of keeping the horrid pain in her temples from slipping to her throat, her breast, her feet.

“Sure the uniforms are cute,” she persisted a bit thickly. “Sure the typhoid boy was crazy about me. He called me his ‘holy chorus girl.’ I heard him raving in his sleep. Lord save us! What are we to any man but just that?” she questioned hotly, with renewed venom. “Parson, actor, young sinner, old saint—I ask you frankly, girls, on your word of honor, was there ever more than one man in ten went through your hands who didn’t turn out soft somewhere before you were through with him? Mawking about your ‘sweet eyes’ while you’re wrecking your optic nerves trying to decipher the dose on a poison bottle! Mooning over your wonderful likeness to the lovely young sister they never had! Trying to kiss your finger-tips when you’re struggling to brush their teeth! Teasin’ you to smoke cigarettes with ’em when they know it would cost you your job!”

Impishly, without any warning, she crooked her knee and pointed one homely,[Pg 494] square-toed shoe in a mincing dancing step. Hoidenishly she threw out her arms and tried to gather Helene and Zillah both into their compass.

“Oh, you holy chorus girls!” she chuckled, with maniacal delight. “Everybody all together, now! Kick your little kicks! Smile your little smiles! Tinkle your little thermometers! Steady, there! One, two, three! One, two, three!”

Laughingly, Zillah Forsyth slipped from the grasp.

“Don’t you dare ‘holy’ me!” she cried.

In real irritation Helene released herself.

“I’m no chorus girl,” she said coldly.

With a shrill little scream of pain, Rae Malgregor’s hands went flying back to her temples. Like a person giving orders in a great panic, she turned authoritatively to her two room-mates, her fingers all the while boring frenziedly into her temples.

“Now, girls,” she warned, “stand well back! If my head bursts, you know, it’s going to burst all slivers and splinters, like a boiler.”

“Rae, you’re crazy,” hooted Zillah.

“Just plain vulgar—loony,” faltered Helene.

Both girls reached out simultaneously to push her aside.

Somewhere in the dusty, indifferent street a bird’s note rang out in one wild, delirious ecstasy of untrammeled springtime. To all intents and purposes the sound might have been the one final signal that Rae Malgregor’s jangled nerves were waiting for.

“Oh, I am crazy, am I?” she cried, with a new, fierce joy. “Oh, I am crazy, am I? Well, I’ll go ask the Superintendent and see if I am. Oh, surely they wouldn’t try and make me graduate if I really was crazy!”

Madly she bolted for her bureau, and, snatching her own motto down, crumpled its face securely against her skirt, and started for the door. Just what the motto was no one but herself knew. Sprawling in paint-brush hieroglyphics on a great flapping sheet of brown wrapping-paper, the sentiment, whatever it was, had been nailed face down to the wall for three tantalizing years.

“No, you don’t!” Zillah cried now, as she saw the mystery threatening meanly to escape her.

“No, you don’t!” cried Helene. “You’ve seen our mottos, and now we’re going to see yours!”

Almost crazed with new terror, Rae Malgregor went dodging to the right, to the left, to the right again, cleared the rocking-chair, a scuffle with padded hands, climbed the trunk, a race with padded feet, reached the door-handle at last, yanked the door open, and with lungs and temper fairly bursting with momentum, shot down the hall, down some stairs, down some more hall, down some more stairs to the Superintendent’s office, where, with her precious motto still clutched securely in one hand, she broke upon that dignitary’s startled, near-sighted vision like a young whirlwind of linen and starch and flapping brown paper. Breathlessly, without prelude or preamble, she hurled her grievance into the older woman’s grievance-dulled ears.

“Give me back my own face!” she demanded peremptorily. “Give me back my own face, I say! And my own hands! I tell you, I want my own hands! Helene and Zillah say I’m insane! And I want to go home!”

Like a short-necked animal elongated suddenly to the cervical proportions of a giraffe, the Superintendent of Nurses reared up from her stoop-shouldered desk-work, and stared forth in speechless astonishment across the top of her spectacles.

Exuberantly impertinent, ecstatically self-conscious, Rae Malgregor repeated her demand. To her parched mouth the very taste of her own babbling impudence refreshed her like the shock and prickle of cracked ice.

“I tell you, I want my own face again, and my own hands!” she reiterated glibly. “I mean the face with the mortgage in it, and the cinders—and the other human expressions,” she explained. “And the nice, grubby country hands that go with that sort of a face.”

Very accusingly she raised her finger and shook it at the Superintendent’s perfectly livid countenance.

“Oh, of course I know I wasn’t very much to look at; but at least I matched. What my hands knew, I mean, my face knew. Pies or plowing or May-baskets, what my hands knew my face knew. That’s the way hands and faces ought to work together. But you—you with all your rules and your bossing, and your everlasting ‘’S-’sh! ’S-’sh!’ you’ve snubbed all the know-anything out of my face and made my hands nothing but two disconnected machines for somebody else to run. And I hate you! You’re a monster! You’re a—Everybody hates you!”

Mutely then she shut her eyes, bowed her head, and waited for the Superintendent to smite her dead. The smite, she felt sure, would be a noisy one. First of all, she reasoned, it would fracture her skull. Naturally then, of course, it would splinter her spine. Later, in all probability, it would telescope her knee-joints. And never indeed, now that she came to think of it, had the arches of her feet felt less capable of resisting so terrible an impact. Quite unconsciously she groped out a little with one hand to steady herself against the edge of the desk.

But the blow when it came was nothing but a cool finger tapping her pulse.

“There! There!” crooned the Superintendent’s voice, with a most amazing tolerance.

“But I won’t ‘there, there!’” snapped Rae Malgregor. Her eyes were wide open again now, and extravagantly dilated.

The cool fingers on her pulse seemed to tighten a little.

“’S-’sh! ’S-’sh!” admonished the Superintendent’s mumbling lips.

“But I won’t ‘’S-’sh! ’S-’sh!’” stormed Rae Malgregor. Never before in her three years’ hospital training had she seen her arch-enemy, the Superintendent, so utterly disarmed of irascible temper and arrogant dignity, and the sight perplexed and maddened her at one and the same moment. “But I won’t ‘’S-’sh! ’S-’sh!’” Desperately she jerked her curly blond head in the direction of the clock on the wall. “Here it’s four o’clock now,” she cried, “and in less than four hours you’re going to try and make me graduate, and go out into the world—God knows where—and charge innocent people twenty-one dollars a week, and washing, likelier than not, mind you, for these hands,” she gestured, “that don’t coördinate at all with this face,” she grimaced, “but with the face of one of the house doctors or the Senior Surgeon or even you, who may be ’way off in Kamchatka when I need him most!” she finished, with a confused jumble of accusation and despair.

Still with unexplainable amiability the Superintendent whirled back into place in her pivot-chair, and with her left hand, which had all this time been rummaging busily in a lower desk drawer, proffered Rae Malgregor a small fold of paper.

“Here, my dear,” she said, “here’s a sedative for you. Take it at once. It will quiet you perfectly. We all know you’ve had very hard luck this past month, but you mustn’t worry so about the future.” The slightest possible tinge of purely professional manner crept back into the older woman’s voice. “Certainly, Miss Malgregor, with your judgment—”

“With my judgment?” cried Rae Malgregor. The phrase was like a red rag to her. “With my judgment? Great heavens! that’s the whole trouble! I haven’t got any judgment! I’ve never been allowed to have any judgment! All I’ve ever been allowed to have is the judgment of some flirty young medical student or the house doctor or the Senior Surgeon or you!”

Her eyes were fairly piteous with terror.

“Don’t you see that my face doesn’t know anything?” she faltered, “except just to smile and smile and smile and say ‘Yes, sir,’ ‘No, sir,’ ‘Yes, sir’?” From curly blond head to square-toed, common-sense shoes her little body began to quiver suddenly like the advent of a chill. “Oh, what am I going to do,” she begged, “when I’m ’way off alone—somewhere in the mountains or a tenement or a palace, and something happens, and there isn’t any judgment round to tell me what I ought to do?”

Abruptly in the doorway, as though summoned by some purely casual flicker of the Superintendent’s thin fingers, another nurse appeared.

“Yes, I rang,” said the Superintendent. “Go and ask the Senior Surgeon if he can come to me here a moment, immediately.”

“The Senior Surgeon?” gasped Rae Malgregor. “The Senior Surgeon?” With her hands clutching at her throat she reeled back against the wall for support. Like a shore bereft in one second of its tide, like a tree stripped in one second of its leafage, she stood there, utterly stricken of temper or passion or any animating human emotion whatsoever.

“Oh, now I’m going to be expelled! Oh, now I know I’m going to be expelled!” she moaned listlessly.

Very vaguely into the farthest radiation of her vision she sensed the approach of a man. Gray-haired, gray-suited, as grayly dogmatic as a block of granite, the Senior Surgeon loomed up at last in the doorway.

“I’m in a hurry,” he growled. “What’s the matter?”

Precipitously Rae Malgregor collapsed into the breach.

“Oh, there’s nothing at all the matter, sir,” she stammered. “It’s only—it’s only that I’ve just decided that I don’t want to be a trained nurse.”

With a gesture of ill-concealed impatience the Superintendent shrugged the absurd speech aside.

“Dr. Faber,” she said, “won’t you just please assure Miss Malgregor once more that the little Italian boy’s death last week was in no conceivable way her fault—that nobody blames her in the slightest, or holds her in any possible way responsible?”

“Why, what nonsense!” snapped the Senior Surgeon. “What—”

“And the Portuguese woman the week before that,” interrupted Rae Malgregor, dully.

“Stuff and nonsense!” said the Senior Surgeon. “It’s nothing but coincidence, pure coincidence. It might have happened to anybody.”

“And she hasn’t slept for almost a fortnight,” the Superintendent confided, “nor touched a drop of food or drink, as far as I can make out, except just black coffee. I’ve been expecting this breakdown for some days.”

“And—the—young—drug-store—clerk—the—week—before—that,” Rae Malgregor resumed with singsong monotony.

Bruskly the Senior Surgeon stepped forward and, taking the girl by her shoulders, jerked her sharply round to the light, and, with firm, authoritative fingers, rolled one of her eyelids deftly back from its inordinately dilated pupil. Equally bruskly he turned away again.

“Nothing but moonshine!” he muttered. “Nothing in the world but too much coffee dope taken on an empty stomach—‘empty brain,’ I’d better have said. When will you girls ever learn any sense?” With search-light shrewdness his eyes flashed back for an instant over the haggard, gray lines that slashed along the corners of her quivering, childish mouth. A bit temperishly he began to put on his gloves. “Next time you set out to have a ‘brain-storm,’ Miss Malgregor,” he suggested satirically, “try to have it about something more sensible than imagining that anybody is trying to hold you personally responsible for the existence of death in the world. Bah!” he ejaculated fiercely. “If you are going to fuss like this over cases hopelessly moribund from the start, what in thunder are you going to do some fine day when, out of a perfectly clear and clean sky, security itself turns septic, and you lose the President of the United States or a mother of nine children—with a hang-nail?”

“But I wasn’t fussing, sir!” protested Rae Malgregor, with a timid sort of dignity. “Why, it never had occurred to me for a moment that anybody blamed me for anything.” Just from sheer astonishment her hands took a new clutch into the torn, flapping corner of the motto that she still clung desperately to even at this moment.

“For Heaven’s sake, stop crackling that brown paper!” stormed the Senior Surgeon.

“But I wasn’t crackling the brown paper, sir! It’s crackling itself,” persisted Rae Malgregor, very softly. The great blue eyes that lifted to his were brimming full of misery. “Oh, can’t I make you understand, sir?” she stammered. Appealingly she turned to the Superintendent. “Oh, can’t I make anybody understand? All I was trying to say, all I was trying to explain, was that I don’t want to be a trained nurse—after all.”

“Why not?” demanded the Senior Surgeon, with a rather noisy click of his glove fasteners.

“Because—my face is tired,” said the girl, quite simply.

The explosive wrath on the Senior Surgeon’s countenance seemed to be directed suddenly at the Superintendent.

“Is this an afternoon tea?” he asked tartly. “With six major operations this morning, and a probable meningitis diagnosis ahead of me this afternoon, I think I might be spared the babblings of an hysterical nurse.” Casually over his shoulder he nodded at the girl. “You’re a fool,” he said, and started for the door.

Just on the threshold he turned abruptly and looked back. His forehead was furrowed like a corduroy road, and the one rampant question in his mind at the moment seemed to be mired hopelessly between his bushy eyebrows.

“Lord!” he exclaimed a bit flounderingly, “are you the nurse that helped me last week on that fractured skull?”

“Yes, sir,” said Rae Malgregor.

Jerkily the Senior Surgeon retraced his footsteps into the office and stood facing her as though with some really terrible accusation.

“And the freak abdominal?” he quizzed sharply. “Was it you who threaded that needle for me so blamed slowly and calmly and surely, while all the rest of us were jumping up and down and cursing you for no brighter reason than that we couldn’t have threaded it ourselves if we’d had all eternity before us and all hell bleeding to death?”

“Y-e-s,” said Rae Malgregor.

Quite bluntly the Senior Surgeon reached out and lifted one of her hands to his scowling professional scrutiny.

“God!” he attested, “what a hand! You’re a wonder. Under proper direction you’re a wonder. It was like myself working with twenty fingers and no thumbs. I never saw anything like it.”

Almost boyishly the embarrassed flush mounted to his cheeks as he jerked away again. “Excuse me for not recognizing you,” he apologized gruffly, “but you girls all look so much alike!”

As though the eloquence of Heaven itself had suddenly descended upon a person hitherto hopelessly tongue-tied, Rae Malgregor lifted an utterly transfigured face to the Senior Surgeon’s grimly astonished gaze.

“Yes, yes, sir!” she cried joyously; “that’s just exactly what the trouble is; that’s just exactly what I was trying to express, sir: my face is all worn out trying to ‘look alike.’ My cheeks are almost sprung with artificial smiles. My eyes are fairly bulging with unshed tears. My nose aches like a toothache trying never to turn up at anything. I’m smothered with the discipline of it. I’m choked with the affectation. I tell you, I just can’t breathe through a trained nurse’s face any more. I tell you, sir, I’m sick to death of being nothing but a type. I want to look like myself. I want to see what life could do to a silly face like mine if it ever got a chance. When other women are crying, I want the fun of crying. When other women look scared to death, I want the fun of looking scared to death.” Hysterically again, with shrewish emphasis, she began to repeat: “I won’t be a nurse! I tell you I won’t! I won’t!”

“Pray what brought you so suddenly to this remarkable decision?” scoffed the Senior Surgeon.

“A letter from my father, sir,” she confided more quietly—“a letter about some dogs.”

“Dogs?” hooted the Senior Surgeon.

“Yes, sir,” said the White Linen Nurse. A trifle speculatively for an instant she glanced at the Superintendent’s face and then back again to the Senior Surgeon’s. “Yes, sir,” she repeated with increasing confidence, “up in Nova Scotia my father raises hunting-dogs. Oh, no special fancy kind, sir,” she hastened in all honesty to explain, “just dogs, you know; just mixed dogs, pointers with curly tails, and shaggy-coated hounds, and brindled spaniels, and all that sort of thing; just mongrels, you know, but very clever. And people, sir, come all the way from Boston to buy dogs of him, and once a man came way from London to learn the secret of his training.”

“Well, what is the secret of his training?” quizzed the Senior Surgeon with the sudden eager interest of a sportsman. “I should think it would be pretty hard,” he acknowledged, “in a mixed gang like that to decide just what particular game was suited to which particular dog.”

“Yes, that’s just it, sir,” beamed the White Linen Nurse. “A dog, of course, will chase anything that runs,—that’s just dog,—but when a dog really begins to care for what he’s chasing, he—wags! That’s hunting. Father doesn’t calculate, he says, on training a dog on anything he doesn’t wag on.”

“Yes, but what’s that got to do with you?” asked the Senior Surgeon, a bit impatiently.

With ill-concealed dismay the White Linen Nurse stood staring blankly at the Senior Surgeon’s gross stupidity.

“Why, don’t you see?” she faltered.[Pg 498] “I’ve been chasing this nursing job three whole years now, and there’s no wag to it.”

“Oh, hell!” said the Senior Surgeon. If he hadn’t said “Oh, hell!” he would have grinned. And it hadn’t been a grinny day, and he certainly didn’t intend to begin grinning at any such late hour as that in the afternoon. With his dignity once reassured, he then relaxed a trifle. “For Heaven’s sake, what do you want to be?” he asked not unkindly.

With an abrupt effort at self-control Rae Malgregor jerked her head into at least the outer semblance of a person lost in almost fathomless thought.

“Why, I’m sure I don’t know, sir,” she acknowledged worriedly. “But it would be a great pity, I suppose, to waste all the grand training that’s gone into my hands.” With sudden conviction her limp shoulders stiffened a trifle. “My oldest sister,” she stammered, “bosses the laundry in one of the big hotels in Halifax, and my youngest sister teaches school in Moncton. But I’m so strong, you know, and I like to move things round so, and everything, maybe I could get a position somewhere as general housework girl.”

With a roar of amusement as astonishing to himself as to his listeners, the Senior Surgeon’s chin jerked suddenly upward.

“You’re crazy as a loon!” he confided cordially. “Great Scott! If you can work up a condition like this on coffee, what would you do on malted milk?” As unheralded as his amusement, gross irritability overtook him again. “Will—you—stop—rattling that brown paper?” he thundered at her.

As innocently as a child she rebuffed the accusation and ignored the temper.

“But I’m not rattling it, sir!” she protested. “I’m simply trying to hide what’s on the other side of it.”

“What is on the other side of it?” demanded the Senior Surgeon, bluntly.

With unquestioning docility the girl turned the paper around.

From behind her desk the austere Superintendent twisted her neck most informally to decipher the scrawling hieroglyphics. “Don’t Ever Be Bumptious!” she read forth jerkily with a questioning, incredulous sort of emphasis.

“Don’t ever be bumptious!” squinted the Senior Surgeon perplexedly through his glass.

“Yes,” said Rae Malgregor, very timidly. “It’s my motto.”

“Your motto?” sniffed the Superintendent.

“Your motto?” chuckled the Senior Surgeon.

“Yes, my motto,” repeated Rae Malgregor, with the slightest perceptible tinge of resentment. “And it’s a perfectly good motto, too. Only, of course, it hasn’t got any style to it. That’s why I didn’t want the girls to see it,” she confided a bit drearily. Then palpably before their eyes they saw her spirit leap into ineffable pride. “My father gave it to me,” she announced briskly, “and my father said that, when I came home in June, if I could honestly say that I’d never once been bumptious all my three years here, he’d give me a heifer. And—”

“Well, I guess you’ve lost your heifer,” said the Senior Surgeon, bluntly.

“Lost my heifer?” gasped the girl. Big-eyed and incredulous, she stood for an instant staring back and forth from the Superintendent’s face to the Senior Surgeon’s. “You mean,” she stammered—“you mean that I’ve been bumptious just now? You mean that, after all these years of meachin’ meekness, I’ve lost?”

Plainly even to the Senior Surgeon and the Superintendent the bones in her knees weakened suddenly like knots of tissue-paper. No power on earth could have made her break discipline by taking a chair while the Senior Surgeon stood, so she sank limply down to the floor instead, with two great solemn tears welling slowly through the fingers with which she tried to cover her face.

“And the heifer was brown, with one white ear; it was awful’ cunning,” she confided mumblingly. “And it ate from my hand, all warm and sticky, like loving sand-paper.” There was no protest in her voice, or any whine of complaint, but merely the abject submission to fate of one who from earliest infancy had seen other crops blighted by other frosts. Then tremulously, with the air of one who just as a matter of spiritual tidiness would purge her soul of all sad secrets, she lifted her entrancing, tear-flushed face from her strong, sturdy, utterly unemotional fingers and stared with amazing blueness, amazing blandness, into the Senior Surgeon’s scowling scrutiny.

Plates in tint, engraved for THE CENTURY by H. C. Merrill and H. Davidson

“‘DON’T EVER BE BUMPTIOUS!’ SQUINTED THE SENIOR SURGEON PERPLEXEDLY THROUGH HIS GLASS”

DRAWN BY HERMAN PFEIFER

“And I’d named her for you,” she said—“I’d named her Patience, for you!”

Instantly then she scrambled to her knees to try and assuage by some miraculous apology the horrible shock which she read in the Senior Surgeon’s face.

“Oh, of course, sir, I know it isn’t scientific,” she pleaded desperately. “Oh, of course, sir, I know it isn’t scientific at all; but up where I live, you know, instead of praying for anybody, we—we name a young animal for the virtue that that person seems to need the most. And if you tend the young animal carefully, and train it right, why—it’s just a superstition, of course, but—Oh, sir,” she floundered hopelessly, “the virtue you needed most in your business was what I meant! Oh, really, sir, I never thought of criticizing your character!”

Gruffly the Senior Surgeon laughed. Embarrassment was in the laugh, and anger, and a fierce, fiery sort of resentment against both the embarrassment and the anger, but no possible trace of amusement. Impatiently he glanced up at the fast-speeding clock.

“Good Lord!” he exclaimed, “I’m an hour late now!” Scowling like a pirate, he clicked the cover of his watch open and shut for an uncertain instant. Then suddenly he laughed again, and there was nothing whatsoever in his laugh this time except just amusement.

“See here, Miss—Bossy Tamer,” he said, “if the Superintendent is willing, go get your hat and coat, and I’ll take you out on that meningitis case with me. It’s a thirty-mile run, if it’s a block, and I guess if you sit on the front seat it will blow the cobwebs out of your brain—if anything will,” he finished not unkindly.

Like a white hen sensing the approach of some utterly unseen danger, the Superintendent seemed to bristle suddenly in every direction.

“It’s a bit irregular,” she protested in her most even tone.

“Bah! So are some of the most useful of the French verbs,” snapped the Senior Surgeon. In the midst of authority his voice could be inestimably soft and reassuring; but sometimes on the brink of asserting said authority he had a tone that was distinctly unpleasant.

“Oh, very well,” conceded the Superintendent, with some waspishness.

Hazily for an instant Rae Malgregor stood staring into the Superintendent’s uncordial face. “I’d—I’d apologize,” she faltered, “but I don’t even know what I said. It just blew up.”

Perfectly coldly and perfectly civilly the Superintendent received the overture.

“It was quite evident, Miss Malgregor, that you were not altogether responsible at the moment,” she conceded in common justice.

Heavily then, like a person walking in her sleep, the girl trailed out of the room to get her coat and hat.

Slamming one desk-drawer after another, the Superintendent drowned the sluggish sound of her retreating footsteps.

“There goes my best nurse,” she said grimly, “my very best nurse. Oh, no, not the most brilliant one,—I didn’t mean that,—but the most reliable, the most nearly perfect human machine that it has ever been my privilege to see turned out, the one girl that, week in, week out, month after month and year after year, has always done what she’s told, when she was told, and the exact way she was told, without questioning anything, without protesting anything, without supplementing anything with some disastrous original conviction of her own. And look at her now!” Tragically the Superintendent rubbed her hand across her worried brow. “Coffee you said it was?” she asked skeptically. “Are there any special antidotes for coffee?”

With a queer little quirk to his mouth, the gruff Senior Surgeon jerked his glance back from the open window where, like the gleam of a slim tomboyish ankle, a flicker of green went scurrying through the tree-tops.

“What’s that you asked?” he quizzed sharply. “Any antidotes for coffee? Yes, dozens of them; but none for spring.”

“Spring?” sniffed the Superintendent. A little shiveringly she reached out and gathered a white knitted shawl about her shoulders. “Spring? I don’t see what spring’s got to do with Rae Malgregor or any other young outlaw in my graduating class. If graduation came in November, it would be just the same. They’re a set of ingrates, every one of them.” Vehemently she turned aside to her card-index of names, and slapped the cards through one by one without finding one[Pg 502] single soothing exception. “Yes, sir, a set of ingrates,” she repeated accusingly. “Spend your life trying to teach them what to do and how to do it, cram ideas into those that haven’t got any, and yank ideas out of those who have got too many; refine them, toughen them, scold them, coax them, everlastingly drill and discipline them: and then just as you get them to a place where they move like clockwork, and you actually believe you can trust them, then graduation day comes round, and they think they’re all safe, and every single individual member of the class breaks out and runs amuck with the one daredevil deed she’s been itching to do every day the last three years! Why, this very morning I caught the president of the senior class with a breakfast tray in her hands stealing the cherry out of her patient’s grape-fruit, and three of the girls reported for duty as bold as brass with their hair frizzed tight as a nigger doll’s. And the girl who’s going into a convent next week was trying on the laundryman’s derby hat as I came up from lunch. And now, now—” the Superintendent’s voice became suddenly a little hoarse—“and now here’s Miss Malgregor intriguing to get an automobile ride with you!”

“Eh?” cried the Senior Surgeon, with a jump. “My God! is this an insane asylum? Is it a nervine?” Madly he started for the door. “Order a ton of bromides,” he called back over his shoulder. “Order a car-load of them, fumigate the whole place with them, fumigate the whole damned place!”

Half-way down the lower hall, all his nerves on edge, all his unwonted boyish impulsiveness quenched nauseously like a candle-flame, he met and passed Rae Malgregor without a sign of recognition.

“God! How I hate women!” he kept mumbling to himself as he struggled clumsily all alone into the torn sleeve lining of his thousand-dollar mink coat.

Like a train-traveler coming out of a long, smoky, smothery tunnel into the clean-tasting light, the White Linen Nurse came out of the prudish, smelling hospital into the riotous mud-and-posie promise of the young April afternoon.

The god of hysteria had certainly not deserted her. In all the full effervescent reaction of her brain-storm, fairly bubbling with dimples, fairly foaming with curls, light-footed, light-hearted, most ecstatically light-headed, she tripped down into the sunshine as though the great harsh granite steps that marked her descent were nothing more nor less than a gigantic old horny-fingered hand passing her blithely out to some deliciously unknown Lilliputian adventure.

As she pranced across the soggy April sidewalk to what she supposed was the Senior Surgeon’s perfectly empty automobile, she became aware suddenly that the rear seat of the car was already occupied.

Out from an unseasonable snuggle of sable furs and flaming red hair a small peevish face peered forth at her with frank curiosity.

“Why, hello!” beamed the White Linen Nurse. “Who are you?”

With unmistakable hostility the haughty little face retreated into its furs and its red hair.

“Hush!” commanded a shrill childish voice. “Hush, I say! I’m a cripple and very bad-tempered. Don’t speak to me!”

“Oh, my glory!” gasped the White Linen Nurse. “Oh, my glory, glory, glory!” Without any warning whatsoever, she felt suddenly like nothing at all, rigged out in an exceedingly shabby old ulster and an excessively homely black slouch-hat. In a desperate attempt at tangible tomboyish nonchalance, she tossed her head, and thrust her hands down deep into her big ulster pockets. That the black hat reflected no decent featherish consciousness of being tossed, that the big threadbare pockets had no bottoms to them, merely completed her startled sense of having been in some way blotted right out of existence.

Behind her back the Senior Surgeon’s huge fur-coated approach dawned blissfully like the thud of a rescue-party.

But if the Senior Surgeon’s blunt, wholesome invitation to ride had been perfectly sweet when he prescribed it for her in the Superintendent’s office, the invitation had certainly soured most amazingly in the succeeding ten minutes. Abruptly now, without any greeting, he reached out and opened the rear door of the car, and nodded curtly for her to enter.