Title: Climate and Health in Hot Countries and the Outlines of Tropical Climatology

Author: George Michael James Giles

Release date: May 9, 2018 [eBook #57122]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Charlene Taylor, Harry Lamé and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

Please see the Transcriber’s Notes at the end of this text.

The cover images has been created for this text, and is placed in the public domain.

A Popular Treatise on Personal Hygiene in the Hotter Parts

of the World, and on the Climates that will be

met with within them

BY

LIEUT.-COL. G. M. GILES, M.B., F.R.C.S.

Indian Medical Service (Retd.)

Author of

“A Handbook of the Gnats or Mosquitoes,” “Kala Azar,” and

“Beri-Beri,” &c., &c.

NEW YORK

WILLIAM WOOD AND COMPANY

MDCCCCV

[I-iii]

A hundred years ago a prolonged residence in the Tropics was regarded with well-founded horror. The best the white settler in the lands of the sun dared hope for was “a short life and a merry one,” but too often the merriment was sadly lacking.

When Clive’s father made interest to get his son a writership under “Old John Company,” and packed off the troublesome lad to India, he probably regarded it as a last resource, and felt much as if he had signed the youth’s doom; but an age that hanged for sheep-stealing, or less, was like to be stern in its dealings with its children.

We know now that what the father took for vice was but evidence of the superabundant vitality of a genius, and being one, Clive naturally possessed the originality to modify his habits to his new surroundings, and so survived to become an Empire-builder and hero. Nor was the case exceptional, for looking back on the history of our great Indian dependency, one cannot fail to be struck with the high average ability of the few who survived to attain leading positions.

Furlough to Europe was almost impossible, and the hills were unknown, but in spite of this, many of these seasoned veterans who had learned their lesson lived, in the land of their adoption, to a green old age. But the rank and file, who could not or would not learn, died off like rotten sheep; and to this day it is the young and inexperienced, who have as yet not learned to adapt and protect themselves, who fall the readiest victims. At home it is, I believe, generally recognised that at the age of 26 a man[I-iv] is rather past his best from the athletic point of view, and it is hardly to be supposed that he is not equally at his fittest before that age, simply because he has shifted his domicile a couple of thousand miles to the south; but so fatal is the want of caution and intolerance of precaution inherent in early manhood, that most authorities recommend that, if possible, emigration to a hot climate should be postponed till the age of 25. This obstinate determination to carry to tropical parts habits of life suitable only to the more temperate parts of Europe was carried in old times to an almost incredible extent.

Now and again, in the guest-chamber of some native noble’s house, one may come across quaint old paintings and engravings which show our great grandfathers fighting or playing cricket in exactly the same costume as their contemporaries at home. No alteration whatever was made in the soldier’s dress, and his officers duelled, drank, and gambled in the same old Ramillies wigs that led such portentous gravity to those charming discussions with the enemy as to who should “fire first.” Even the earlier files of the Illustrated London News show the same things, and looking at these old pictures, the wonder is not so much that many succumbed as that any survived. Even in Europe the conditions of military service were terribly unhealthy, and when transplanted to the Tropics the mortality was such as to give to India and other hot countries an evil reputation which they have not yet lived down.

The dire struggle of the Indian Mutiny led to the first attempts to clothe and treat the soldier in a somewhat more rational fashion, and since then great improvements have been effected; but a great deal more remains to be done, especially in the matter of utilising our recently gained knowledge of the causation of malaria, before our military statistics can be expected to show how little this evil reputation is due to the climate itself, and how much has really been caused by human misdirection. No amount of sanitary improvement can be expected to render Bombay a comfortable place of residence in the dog days, and apart from localities at considerable elevations, where the climate is[I-v] really temperate, it is hopeless to expect that anything in the way of actual colonisation can succeed in the climates with which we are dealing; but with due care and attention to sanitary laws, as modified by the altered conditions, there is no reason why the rates of sickness and mortality should be much more formidable than elsewhere.

In the following pages the writer has endeavoured to put into popular form the principal points of personal hygiene as applied to hot countries, and as they are intended mainly for the non-professional reader, all technical terms have been, as far as possible, avoided, and words in popular use, such as germs, &c., have been substituted for the more exact nomenclature of science. Should any of his medical colleagues care to read a merely popular work, they can easily supply for themselves, in place of these vague, popular words, the more precise terminology in use amongst ourselves.

The climates of the hotter parts of the world vary even more widely than those of the temperate zone, so that it is often impossible to offer suggestions applicable to all of them; and on this account it is extremely important that the intending resident or visitor to them should be able to ascertain what is the exact nature of the climatic conditions with which he will have to cope, so that it is absolutely essential to include within the scope of a work like the present some account of the climates of the various countries included in the enormous area under consideration. On this account the little book has been divided into two distinct parts, the first of which is devoted to personal tropical hygiene, while the second, which deals with climate, is necessarily mainly a dry mass of tabulated information, of which only the few pages devoted to the country he proposes to visit is likely to interest the individual reader.

The inclusion of information of the sort is, however, quite essential, as it is by no means easily accessible, and, as a matter of fact, scarcely exists, except in the form of the official records of the various meteorological observatories, so that when collecting data for the compilation of this[I-vi] second part, or appendix, on tropical climates, the writer was a good deal surprised to find that he was engaged in the preparation of what is really a pioneer work on the subject in the English language.

This being the case, it has been thought well to publish these outlines of tropical climatology also in a separate form for the use of the professional reader who may not care to be burdened with a booklet on health treated from the popular point of view; a step which has further necessitated that the paging and indexing of the two parts should be kept separate from each other, a plan which, in view of the moderate dimensions of the book, might otherwise have appeared rather superfluous.

[I-vii]

Bicarbonate of soda.

Bismuthi salicyl., in tabuloids of grains x. each.

Book of litmus paper.

Boracic acid, in powder.

Calomel, in tabuloids of 1⁄2 grain each.

Carbolic acid, with sufficient glycerine added to keep it in a fluid condition.

Castor oil.

Castor oil with resorcin:—

| ℞ | Ol. ricini | ℥viii. |

| Resorcin | ʒii. | |

| Mix, and dissolve the resorcin by standing the bottle in hot water. | ||

Citrate of potash.

Easton’s syrup, put up in a bottle marked to its dosage.

Ether sulphuric. This drug is too volatile for storage in the ordinary way in the Tropics and so should be put up in glass capsules each holding a drachm.

“Fever” or diaphoretic mixture:—

| ℞ | Liq. ammon. acetatis fortior, B.P., 1885 | ʒss. | |

| Sp. eth. nitrosi | ♏xx. | ||

| Potas. nitratis | gr. i. | ||

| Water | to ʒii for each dose. | ||

| Dose.—To be put up in a bottle graduated to that dosage containing 8 oz. of the mixture, and taken diluted with four or five times its quantity of water. | |||

Goa ointment:—

| Goa powder | - | āā ʒss. | |

| Acid salicylic | |||

| Lanolin | ad ℥i. | ||

Gregory’s powder.

Hydrochloric acid, preferably in the dilute form.

Opium, in tabuloids of 1 grain each.

The “Patna” drug is preferable as a sedative before the administration of ipecacuanha.

Paint for “Dhobi’s itch”:—

| Liquor iodi fortior | - | partes æquales ad ℥ii. | |

| Pure carbolic acid | |||

| Glycerine |

[I-viii]

Perchloride of mercury, in tabuloids:—

| 1⁄40 grain | - | for internal administration. | |

| 1⁄64 grain | |||

| 21⁄2 grain “soloids” for compounding an antiseptic solution. | |||

Permanganate of potash, put up in packets of 2 oz. each, wrapped in waterproof paper, for disinfecting wells.

Phenacetin; tabuloids of grains v. each.

Phenyle, “Little’s soluble.”

Pills for hill diarrhœa and similar disturbances of the bowel:—

| ℞ | Euonymini | - | āā grain i. | |

| Pil. hydrargyri | ||||

| Pulv. ipecac. |

Pulv. hydrargyri cum creta, popularly known as grey powder.

Pulv. ipecacuanhæ, in tabuloids of 5 grains each.

Quinine sulphate (or hydrochloride) in powder. The cork should be fitted with a small wooden cup, to measure 5 grains approximately.

Resorcin, in tabuloids of grains v. each.

Thymol, in tabuloids of grains x. each.

Tinct. camphoræ composita, popularly known as “paregoric elixir.”

[I-ix]

[For Index to Part II., “Outlines of Tropical Climatology,” see end of volume.]

[I-xix]

[I-1]

Climate and Health in Hot Countries.

PART I.

In hot climates, as elsewhere, people are rarely in a position to exercise much choice in their selection of a habitation, as its site must usually depend on considerations of business, and in the majority of cases, the number of available dwellings is limited. Oftener still, it is a matter of “Hobson’s choice,” and one must needs occupy the house that has served one’s predecessors in the work in which one may happen to be engaged. On this account it will be superfluous to do more than generally indicate the general principles on which it is desirable, that houses designed to afford shelter in hot climates, should be placed and constructed.

In the matter of choice of site, the same general considerations as to soil and configuration of the ground that determine our choice in temperate climates, as a rule, hold good. A gravelly or sandy soil, and gradients favourable to natural drainage, are even greater desiderata in the Tropics than in Europe, and this is especially the case in climates characterised by a heavy rainfall; but ideal sites are rare in all countries, and as a rule, one must be content to make the best of less favourably placed spots. In the countries which we are at present considering, the especial danger against which we have to guard is always that of malaria, and hence, in choosing the site for a house or[I-2] station, the great point is to select one, which is, as far as possible, free from natural or artificial collections of water, within a radius of a quarter of a mile; or at any rate, including such only as can be easily filled in, drained, or otherwise dealt with. The site should also be sufficiently raised above the level of some natural watercourse to afford an adequate outfall for its surface drainage.

For a single house, no better position can be selected than the summit of a mound, whether natural or artificial; and such situations are generally to be preferred to the slope of a hill, even where the latter affords a considerably greater elevation. On the sea coast, and not unfrequently in the neighbourhood of some of the great rivers, sand dunes, where sufficiently clad with vegetation to afford a sufficiently stable foundation, form excellent sites for single houses, good examples of which are to be found in Chittagong, where nearly every European residence has its own little hill, on which it is perched by itself; and it is doubtless to this circumstance that the comparative healthiness of the European population of the town, under otherwise unfavourable surroundings, is mainly due. The neighbourhood of jungle, and even of trees, should be as far as possible avoided, for trees undoubtedly harbour mosquitoes, and their presence is generally equivalent to that of malaria: moreover, the appearance of coolness, associated with trees, is deceptive rather than real. As a rule, even when numerous and thickly set, they throw no actual shade on the walls of the house, which hence receives as fully the power of the sun as it would in an open plain, and added to this they obstruct the breeze and generally impede ventilation; so that a house placed in the midst of a glaring, treeless space is often really far cooler than one surrounded with fine timber. Even a garden is by no means too desirable an adjunct to a tropical residence, for unless there is abundant labour to keep it in a condition of perfect neatness, and constant intelligent supervision to ensure that the cultivation of flowers and vegetables be not associated with the breeding of mosquitoes, it is only too likely to originate fever of a luxuriance at least equalling that of its roses and salads.

[I-3]

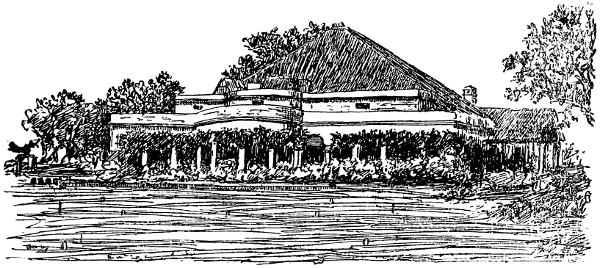

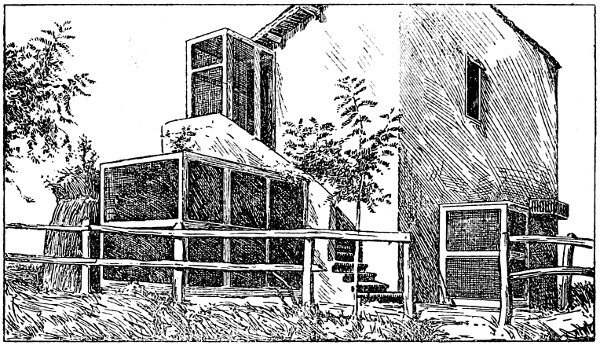

It must not of course be forgotten, that the provision of a free supply of good vegetables is everywhere an essential to health, and is in many localities obtainable in no other way than by the maintenance of a garden, and that under such circumstances, it is probably safest to keep their cultivation under personal supervision; but where such an accessory is indispensable, its attendant dangers should always be carefully borne in mind, and care should be taken that the garden should be so worked as to avoid its becoming a breeding place for mosquitoes. A house for example, such as that shown in the subjoined sketch, makes, doubtless, a very inviting picture, but when lived in, it would be found that the fine trees almost completely cut off the breeze, that the beautiful creepers render the verandahs and the rooms behind them “stuffy,” and that the wealth of vegetation, combined with the arrangements for irrigation, render it a veritable paradise of mosquitoes.

Fig. 1.—A Regular Mosquito-trap Bungalow.

Coming now to questions of general plan, one of the first essentials is that the floor level should be well raised above that of the surrounding ground. In most localities this object is attained by simply forming a platform of earth dug from some situation hard by, so as to form a plinth; and too often, the excavations for the purpose are made absolutely without plan or method, and result in the production of a number of irregular depressions, close by the[I-4] habitation; which during rainy weather are always full of water, and form ideal breeding places for mosquitoes, besides too often serving as depositories for refuse. The earth for forming the plinth should, however, never be allowed to be obtained in this way, but previously to laying out the plan of the house or station, a careful survey of the levels and contours of the site should be made, and the alignment of a series of deep cuttings, so designed as to form an efficient system of surface drains extending from the site to the nearest natural effluent, should be laid out, so that the spoil wherewith to form plinths should be taken in a systematic manner in the digging of these cuttings, and from no other situations. The cuttings should be made as deep and narrow as they can be without expensive revetting of the sides, as experience has shown that the larvæ of the really dangerous species of mosquitoes, the Anopheletes, avoid collections of water shielded from the sun and light. As the station develops, it may perhaps become possible to pave these channels with some permanent material, such as brick or concrete, but as a rule the expense of such a proceeding is prohibitory. When, however, a certain amount of money is available for this purpose, it should be devoted to paving the smaller shallow surface drains close to the dwelling, and the deeper distant cuttings close to the effluent left to the last. No house should ever be allowed to be constructed with a plinth of less than one foot, and provided the material be obtainable without making undesirable excavations, it cannot well be too high, a fact well understood by the earlier European residents in India, whose fine old houses, however wanting their work may be in the matter of finish, form an admirable contrast, in this and many others of the essentials of a healthy residence, to the cramped, low-lying heat traps of admirably pointed brickwork in which the occupant of a “sealed pattern” government quarter is now doomed to live.

The writer is personally strongly of opinion that all tropical residences should be at least two storied, so that the sleeping apartments should be raised at least some 12 or 15 feet above the ground, and of course, where this is the case,[I-5] the provision of a high plinth is less essential, but in any case, the minimum of at least a foot should be insisted upon.

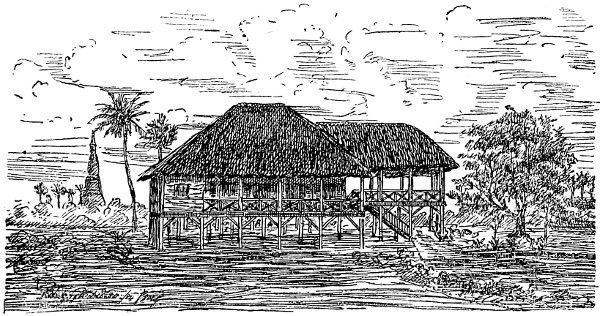

In regions such as Assam and Burmah, where the rains are so heavy as to reduce the entire country to a chronic condition of flooding, any adequate plinth would be so costly that both natives and settlers build their houses perched up on poles, and the numerous sanitary advantages of the plan are undeniable; which is also, I understand, adopted in Honduras.

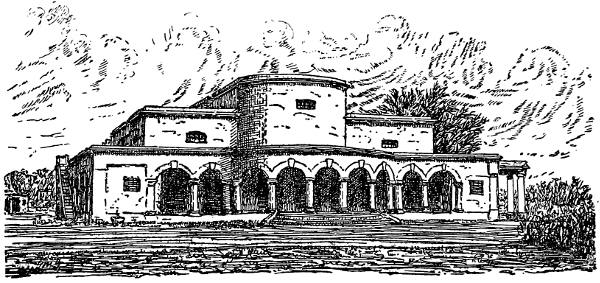

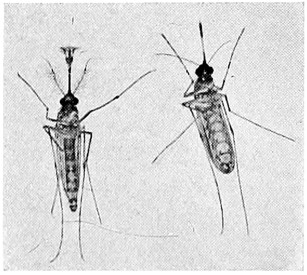

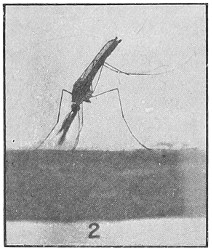

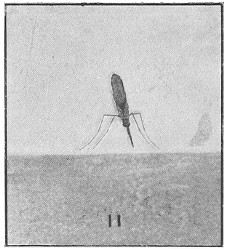

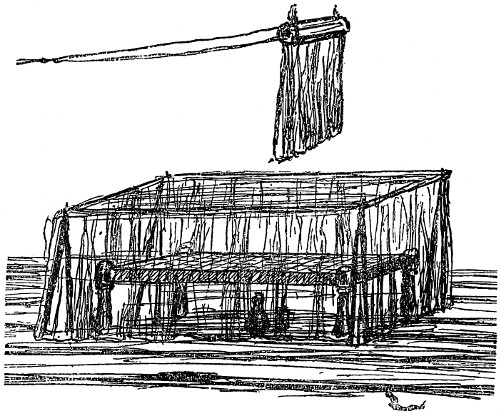

Fig. 2.—In the above sketch of an ordinary Anglo-Burman bungalow, it will be noticed that the large projecting porch is raised higher than the rest of the house so as to admit of a carriage being driven beneath it to the foot of the steps to the platform of the house. These porches form a sort of open-air sitting room, and are more usually on the same level as the rest of the house. They form a most attractive feature of most Burmese bungalows, but it would be very difficult to protect them against mosquitoes by means of wire gauze.

The general characteristics of these “chang” houses may be gathered from the above sketch. In the cottages of the peasantry the “chang,” or platform, is rarely raised more than 4 or 5 feet above the ground, but 10, or even 15 feet is no uncommon height in the case of the houses of people of means and position. Even in the case of houses occupied by planters and officials, the walls are largely composed of bamboo matting, while in those of the populace, the floor itself is formed of a stouter variety of the same material; and on account of the growing cost of timber of[I-6] a class that will resist white ants, I have little doubt that ere long steel girders will replace the wooden framework and corrugated iron will take the place of the picturesque thatched roof, at any rate in the coast towns. A chang of concrete carried on stout corrugated iron, 8-inch walls of the “Elizabethan” pattern, and a double corrugated iron roof, with a large intervening air space, would form a most comfortable, if not very beautiful, residence, for the combination of heat and moisture with the evils of which the chang house is intended to cope; but walls of such flimsy materials would be of little avail to withstand the furnace-heated air of hot dry climates, such as are met with in the Punjab and the deserts of Rajputana.

One of the great sanitary advantages of the chang house is the circulation of air beneath the floors, and the comparative immunity from vermin secured by its isolation on the top of high posts, and though there is no objection to the storing beneath it of carriages and other articles frequently moved, because in daily request, the covered space beneath the house should on no account be allowed to degenerate into a lumber room, as not only will lumber attract dangerous vermin, but with the inevitable numerous native dependants, the lumber room will soon develop into a refuse heap, or worse. Although there is no need to construct a regular plinth, the ground below the chang should always be slightly raised by laying down a layer of gravel, as any collection of water would be obviously unhealthy; besides which, if kept in proper order, the large shady space forms an excellent playground for children, where such charming encumbrances form part of the household.

In actually desert climates, a plinth is less essential, but there are comparatively few countries in which heavy rain does not occur at some time of the year, and any dampness of the soil immediately underlying a house is always unhealthy.

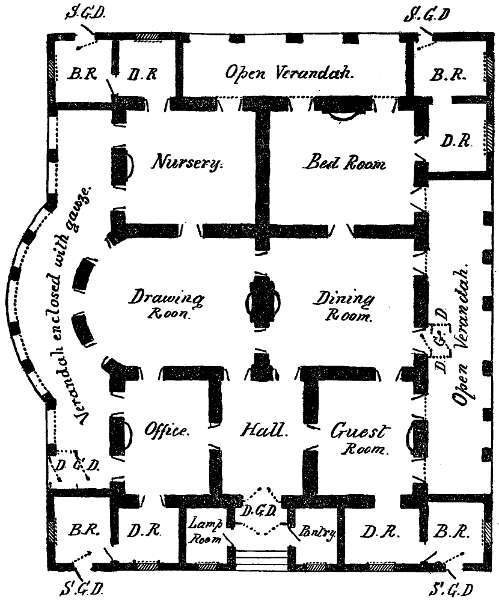

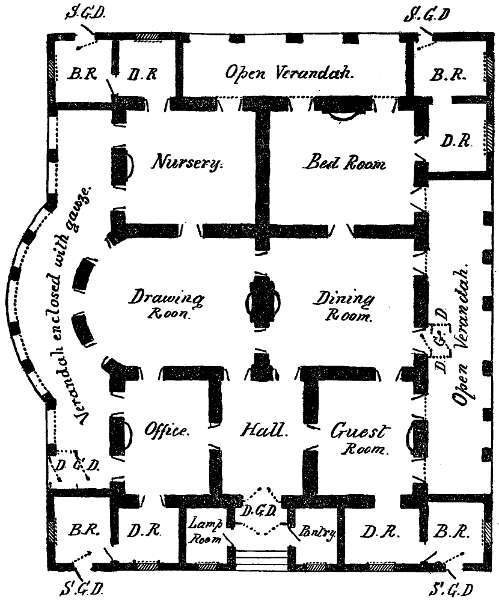

Fig. 3.—Ground plan of an existing “up-country” Indian Bungalow, in which the doors and windows are well placed. (The dotted lines represent wire gauze screens.) Scale, 18′ = 1″

The second great desideratum of a tropical house is free ventilation, to secure which at least one, and preferably two, sides of each room should be in free communication with the outer air by means of doors or windows, and some at least of these should extend to the floor level or near it.[I-7] Many Indian houses are spoilt by want of attention to this point, especially those of long standing; for though the original plan may have been fairly sound, the desire for additional accommodation generally, in course of time, leads to additions, and especially to the enclosure of verandahs, whereby rooms, originally light and airy, are quite cut off[I-8] from all exterior ventilation. Many of these enclosed rooms have small dormer or clerestory windows, close up to the roof; but openings of this sort are no real substitute for proper windows and doors in the usual position, and where choice can be exercised, a house with inner rooms should be rejected in favour of one affording freer ventilation.

The subjoined plan is a good example of an existing, well-planned bungalow of one floor, in which every room has external doors and windows, and several have them on two sides. It should be added that every room has one or more clerestory windows to give exit to the heated air that always finds its way to the top of any enclosed space.

In the best class of houses in Persia this principle of free external ventilation is often carried to the extent of all four sides of the rooms being provided with several openings—the different rooms being separated from each other by open passages, running right across the building from verandah to verandah.

As there are often several doors on each side, one easily realises that Aladdin’s hundred-doored palace may have been no mere creation of the fancy, but was probably based on some actual palace—indeed, as a matter of fact, the Subsabad Residency at Bushire has, I believe, a good deal over the allowance of doors assigned to Aladdin’s palace, and I know that the room I occupied there had no less than nine doors, though two of them gave access respectively to a dressing-room and bath-room.

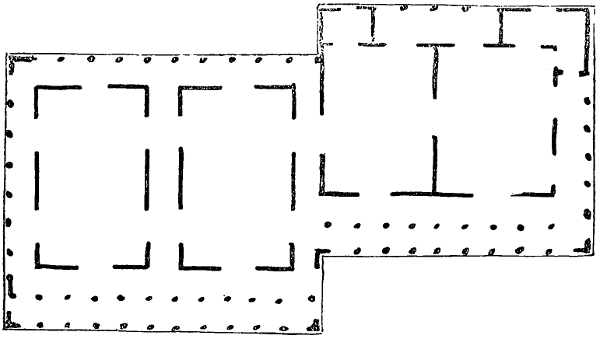

The outline (fig. 4) will give some idea of the way in which the rooms are arranged; but it is needless to say that the plan is a very expensive one. It will be noticed that the southern verandahs are double. Practically speaking, indeed, a Persian house is little else than a series of colonnades, with the spaces between certain of the pillars filled in with door frames, so that it would be an expensive business to fortify one against the invasion of mosquitoes.

Houses of this type are well suited to climates usually blessed with a good breeze, and in which the heat during the day does not reach such a degree as to necessitate shutting it out, and are specially adapted to places where,[I-9] from scarcity of labour, there is a difficulty about the pulling of punkahs. When, however, the midday heat reaches into the nineties, such a plan of building becomes unsuitable, and it is necessary to adopt the thick-walled type of house, with comparatively few floor level openings; the object being to keep imprisoned the cooler night air, so that the interior may never approach the maximum shade temperature of the day. It is obvious that the adoption of this principle quite precludes all proper ventilation, and that unless the rooms are exceptionally large and lofty it must be positively unhealthy. At the same time, heat beyond a certain degree induces such severe nervous and physical prostration that the adoption of this course is almost unavoidable during the worst hours of the day in such climates as the Punjab; but the shorter the period the better, and as the same reasons that render the house cooler than the outer air in the day, make it hotter at night; it is always well to compensate for the lack of ventilation during the day by sleeping absolutely in the open at night.

Fig. 4.—Rough ground plan of an European Bungalow in Persia.

Too often, not only the air, but the light is shut out, a course of action which is as pernicious as it is futile, for unless the sun be shining directly into the room its temperature will be in no way raised by admitting an ample amount of light.

[I-10]

There can be no doubt that this baneful practice of keeping children shut up in darkened rooms is one of the principal causes of the blanched and enfeebled little ones so often met with in India; for they suffer promptly from deprivation of light, though they are wonderfully tolerant of heat, and if unchecked by their anxious mothers, will follow their own wholesome instincts, and be found romping and tumbling about with the servants and orderlies in the verandah, at temperatures that make their parents devote anxious consideration to the question of crossing a room.

Fig. 5.—Sketch of bungalow with terraced roof, of a type very common in the Punjab and United Provinces in India. Speaking generally, this bungalow is well planned. Its faults are that the verandah is too low-pitched, leaving a needlessly large proportion of the external walls exposed to the full power of the sun. The dormer or ventilating windows also are too low down, as they leave several feet of confined “dead” air at the top of the rooms. They should have been placed close up to the cornice.

The third important consideration in planning a good tropical house is that the outer walls should, as far as possible, be shielded from the direct rays of the sun by ample verandahs. Objects exposed to the full glare of the sun soon become so hot that it is difficult to handle them, reaching a temperature 40° or 50° F. higher than that of the air, and though building materials conduct heat but slowly, they do so very surely, so that the air within any building with extensive unshielded sunward walls cannot fail to be considerably[I-11] hotter than that of one so planned that as small an area of wall as possible is directly exposed. Within the true Tropics, the sun must necessarily come to the northward of any localities for a longer or shorter portion of the year, and in such low latitudes it is desirable that the verandah should extend all round the house; but outside the equatorial zone the side looking away from the noon-day sun may be left unprotected as far as the coolness of the house is concerned; though a northern verandah is still desirable, as affording the most eligible position for an open air lounge during the day. Within practicable limits, a verandah can hardly be too wide, and as one of its main functions is to shield the main wall, it is also important that it should be high pitched, but this point is too often lost sight of, although the additional cost of constructing a higher-pitched verandah is very small, as the supports of these structures cost but little, in comparison with the roof. Of course the oblique rays of the sun will search into a high verandah for a longer time than they can in a low one, but this defect is easily obviated by closing the upper part of the colonade with wooden jalousies or with mats, but in this case openings should be provided in the roof to give exit to what must be almost dead air. Verandahs of less than six feet width are of comparatively little use, and 10 feet may be considered to be a fair average standard, but 15 feet is by no means excessive, if it can be afforded, and as shown in the diagram on page 9, double verandahs, consisting of two colonnades, each about 12 feet wide, are by no means uncommon in Persia.

To attain an equivalent standard of comfort, the rooms of a tropical house require to be much higher pitched than is needful in temperate climates, but it is quite possible to carry this to excess, as over a certain height, the pendulum swing of the punkah is too slow; and it is well known to students of ventilation that spaces of dead air, unsearched by the currents normally circulating through the room, are very apt to be found in too lofty apartments. From 16 to 18 feet is a good average standard, and if the height be carried many feet above the higher figure, it is desirable[I-12] that a strong beam should be carried across the room, at about that level, to carry the punkah. As far as ventilation is concerned, there is probably little advantage in any height of ceiling above 13 feet, but this does not give an adequate swing for a punkah.

As already incidentally mentioned, the writer holds a strong preference for houses of two or more floors. While residents of Calcutta or Bombay will never, if they can avoid it, live on the ground floor, there is a general but quite unfounded idea, amongst up-country residents in India, that upper floors are necessarily hotter.

It is needless to say that the reverse is actually the case, and that other things being equal, upper storey rooms are necessarily cooler and more healthy, on account of their better exposure to the breeze and their being to a great extent raised above dust and other more subtle emanations from the soil. The reason for this misapprehension is that, outside the Presidency towns, upper rooms are almost universally makeshift additions, with no proper verandah protection, and often flimsy roofs. Now it is obvious that to gain the full advantage of an upper storey, all verandahs should be carried right up, so that except in being elevated above the soil, the upper rooms are exact reproductions of those below them. I cannot recall, however, a single instance of a properly planned two-storied house “up-country,” and it is absurd to expect that a room with thin brick walls, exposed directly to the sun’s rays, can be as comfortable as one with massive walls and broad verandahs. It may be admitted that during the day, when the doors are shut to keep out the heat, the upper rooms of a two-storied house will be hotter than the lower ones, because one has but a single roof overhead in place of two, but they will be cooler than the lower ones would be, assuming the upper story to be removed.

It is also extremely desirable that the plan of the house should include a stair giving access to the roof, as during the hot dry season, there can be no doubt that it is by far the healthiest plan to sleep there.

A small area of thatched roof supported on four pillars[I-13] should be erected on the roof to protect the sleeper from dew, and to prevent his being worried by the glare of the moon, which to say the least of it makes it very difficult to sleep. Whether there is any truth in the belief that exposure to the moon’s rays may cause blindness or not, I cannot say, but I certainly have met with a number of cases of temporary blindness for which it was, to say the least of it, extremely difficult to find any plausible explanation other than the popular one. Moreover, as we are quite in the dark as to the modus operandi of true sunstroke, it seems unscientific to deny that over-stimulation of the retina by the moon’s rays can be capable of producing the symptoms in question, and at any rate it is preferable to act on the assumption that “moon-blindness” may be a possible contingency.

It is, further, a matter of great importance that the upper limits of the air-space included within a room should be ventilated by means of openings placed close up to the ceiling, as otherwise a stratum of impure, heated air will lodge there, which can only be removed by the slow action of diffusion. In one-storied houses this is usually effected by means of small windows, and in order to admit of a sufficient number of these being provided, it is a common expedient to carry the walls of rooms situated in the interior of the house above those of the lateral rooms, as shown in fig. 4. There should, however, be no necessity for doing this, as no room should be ever built with no external wall; and though upper openings on more sides than one may be desirable, this is not so essential as to warrant the large increase of cost involved in building in this way. Where a house has an upper storey, the top ventilation of the lower rooms is usually effected by openings into the verandahs; but this is by no means a satisfactory outlet, and it would be far preferable to effect the purpose by means of shafts carried up in the thickness of the walls to the roof, the long column of air within which would favour the production of a good current.

In certain parts of the East, subterranean chambers (taikhana) are used as a refuge during periods of extreme[I-14] heat, and are occasionally to be met with in very old European bungalows, though I have never seen one in actual use. Good examples are to be seen in the ruins of the historical Residency at Lucknow; and it was within them that many of the women and children were sheltered during the memorable siege. They can, of course, be ventilated only from above; but there can be no doubt that they are cooler than rooms above ground, and it is possible that the principle might be adopted with advantage under certain extreme climatic conditions.

The materials appropriate for house-building necessarily vary according to the character of the climate, but it is desirable to consider briefly the advantages and disadvantages of those in most common use. Taking first the structure of the walls, it may be noted that in rainy climates near the coast, where very high temperatures are seldom registered, the materials can hardly be too flimsy and permeable; but as one recedes from the coast and meets with the extreme climates characteristic of the interior of continents, it will be found that the buildings become progressively more massive; so that while the Bengali or Malay inhabits a shanty formed of thatch and matting, the peasant of the Punjab shelters himself within mud halls some two feet thick. These differences in domestic architecture are the necessary outcome of differing environment, and to be comfortable, European houses must be built of very much the same materials as those of the natives around them.

In dry climates, sun-dried bricks make an excellent wall, which resists heat even better than one of burnt brick, and provided it be protected from rain, it is wonderfully permanent and much stronger than would be expected; so that heavy, terraced roofs are easily carried by a two-feet thickness of this material, and they are even quite adequate to sustain a second story of lighter materials. The great drawback of the material is that it forms a favourite haunt for white ants, which tunnel it in all directions; but this can easily be obviated by introducing, just at the floor level, a single course of some damp and insect-proof material,[I-15] such as burnt brick, laid on cement and tarred. Owing to its extreme cheapness a large house can be built for the same expenditure as a small one of burned brick, and as air space is of the greatest importance in hot climates, it is unfortunate that this material is not more utilised in Government buildings.

—The most suitable material is stone flagging, marble, of course, being preferable. After these come hard tiles, brick on edge, and cement, in order of desirability. Besides these there are, of course, various special modern inventions, but they hardly come into practical consideration, outside large seaports. Wooden floors should be generally avoided, as owing to decay and the attacks of insects, they are apt to become dangerous, and may give way unexpectedly at any time. For upper floors, by far the most suitable material is the narrow brick arch supported on steel girders, which are now so generally obtainable and cheap, that they can be economically substituted for wooden beams in any locality tolerably accessible from a railway.

One great advantage of this form of construction of flooring and terraced roofs, is the entire absence of nooks and crannies which can harbour vermin, for even the equally massive roofs of concrete, laid on flat tiles supported by a system of beams and battens, afford most dangerous refuges for disagreeable intruders, and I well remember an inmate of my house being put to intense suffering on two successive nights by vermin that fell from such a roof; the first disturber of our rest being an enormous centipede, and the second a hornet. For the same reason, all cornices and similar architectural adornments are distinctly to be deprecated.

The roofing materials generally employed in tropical countries are thatch, tiling, terraced constructions, and corrugated iron. Thatch is, from many points of view, an excellent material, as while it favours ventilation by being extremely pervious to air, it gives excellent shelter from rain, and is quite unequalled as a protection against the sun; in addition to which it does not, to any appreciable[I-16] extent, throw out into the house during the night the heat absorbed during the day.

With all this, it has great and, it is to be feared, preponderating disadvantages, the principal of which is that it forms a perfectly ideal refuge for vermin of all sorts, vertebrate and invertebrate. As a rule, owing to the high pitch necessary in this form of roofing, the lower edge of the roof is rarely more than a few feet from the ground, and owing to the usual existence of creepers, trellises and similar facilities, is usually easily accessible to any animal endowed with the most moderate powers of climbing. Owing to this, such roofs are usually honeycombed with the nests of squirrels, rats, civet cats, and half wild domestic cats, to say nothing of snakes, and birds and other flying things. The large empty space between the ceilings and the rafters is usually alive with bats, and as all this extensive population is quite without any system of conservancy, an old thatched roof is simply permeated with guano; and the emanations from this necessarily find their way into the house, and indeed are always plainly perceptible in a thatched house that, for any reason, has been shut up for any length of time.

Besides this, the substance of the thatching is always slowly decomposing under the slow action of mildew, and this adds further musty exhalations to the bouquet. Hence, if used at all, the thatch should be completely renewed at frequent intervals, and its employment should be confined to situations which cannot be scaled by large vertebrate vermin.

Where it is used, the interior of the rooms should be completely cut off from the cavity of the roof by some fairly impervious ceiling, such as one formed of match-boarding, and not, as is commonly the case, by a “ceiling cloth” of ill-stretched canvas.

These “ceiling cloths” are utter abominations, and, even when their untidy appearance is ameliorated by subdividing the cloth into a number of small panels, the improvement is purely one of appearance, and in no way diminishes their sanitary defects, so that no effort should[I-17] be spared to induce landlords to replace them with match-boarding or any material that will shut out the emanations from the thatch and its inhabitants.

For some reason, the lath-and-plaster ceilings and partitions, so commonly used in Europe, are never employed in Indian house-building. It is difficult to understand why this is so, as the natives are skilful plasterers, and there would be no difficulty whatever in teaching them this particular application of their trade, which would be a valuable and inexpensive expedient in this and a number of other cases.

Tiles of the old-fashioned sort present few of the advantages of thatch, and most of its disadvantages, besides numerous special objections of their own, but these remarks do not apply to roofs formed of large tiles of European patterns laid on a properly graded framework of squared battens. To these latter the only objection is that they let in too much heat unless they are supplemented with a tolerably substantial ceiling; and the same remarks apply even more to corrugated iron, but both these materials, and especially tiles, are excellent materials for verandahs, especially those of upper stories, where weight is a consideration.

Corrugated iron, however, is scarcely tolerable in extreme climates unless it is actually doubled, and the most scientific way of doing this is to form a ceiling of corrugated iron of a thin gauge screwed up to light joists and painted white below. On the upper surface, should be spread about an inch of dry sand, to retain which it is necessary that any ventilation openings should be protected with a wooden edging. The outer roof should be of stouter gauge, and must of course be pitched at an appropriate slope, and it is of the first importance that the space between the two roofs should be freely ventilated by large openings placed at the apices of the gables, but these openings should be secured against the entry of birds and cats by means of wire netting, and all other openings by which they can enter should be carefully closed with plaster. The coolness of a roof so planned depends largely on the thickness of the layer of dry sand, and, provided the joists that carry the sheets are fairly[I-18] strong, there is no difficulty in raising this to even a couple of inches. The preceding materials all have the disadvantage that they must be pitched at a considerable slope, and hence cannot be used as a platform for sleeping on.

All considered, however, a terraced roof, formed of brick arches supported on steel girders, covered with concrete, is by far the best for most tropical climates. It forms an excellent protection against sun and rain, and the smooth finish of both its upper and lower surfaces offers absolutely no hiding place for even insects; besides which it forms an excellent elevated platform on which to sleep during periods of intense dry heat. Its one disadvantage is that a great deal of the heat absorbed during the day is radiated into the rooms at night, and that it generally is inferior as a non-conductor either to thatch, or to double roofs of any description.

Another form of terraced roof commonly found in dry climates consists of a considerable thickness of beaten clay, spread on mats supported on a system of beams and battens.

Owing to their great thickness and the fact that the clay conducts heat much less easily than burnt bricks, such roofs are very cool, and they form a good sleeping platform; but they give endless trouble during periods of rain, as they always leak at the beginning of one, and vermin are apt to harbour amongst the matting and battens that carry the mud. Owing to their immense weight, too, they are not free from danger, especially as they are usually found in combination with walls of unburnt brick, which offer no obstacle whatever to the tunnelling of white ants, which thus can readily reach the beams, the interior of which may be entirely eaten away by these mischievous insects without any sign of the mischief appearing externally.

All the above considerations appear at first sight tolerably obvious and would, one would think, be adopted wherever not rendered impracticable by consideration of cost, and yet it is perfectly wonderful to notice how frequently every consideration of common-sense sanitation and comfort is ignored in buildings, on which neither space nor expense have been stinted.

[I-19]

Quite recently the writer halted in a large hotel which illustrated this point in a most pitiable manner. The masonry was admirable, being worthy almost of an Egyptian monument, and speaking generally, it was obvious that expense had been almost disregarded by the enterprising proprietors. The management showed every desire to secure the comfort of their guests, and the cuisine was excellent. In spite of this the bulk of the rooms were scarcely habitable, as they seemed contrived to give a tropical sun the best possible chance to make itself felt. Save for a verandah of paltry width to the magnificent dining-room, these indispensable adjuncts of a tropical residence were absolutely wanting.

Moreover, this omission was clearly not due to any desire or necessity for economising space, for the area absolutely wasted in the form of corridors was astonishing, and could not have fallen short of half the space occupied by the sleeping rooms, though these were exceptionally spacious. Facing south-east, the full glare of the sun and the dazzling reflection from the sea glared directly into the windows of the most desirably placed rooms, without even the protection of an ordinary “jalousie,” while the magnificent view was shut out by windows of granulated greenish glass, the sashes being pivoted in such a way as to make it difficult to enjoy either the breeze or the prospect, even when they were opened. Apart from these latter details, the building would be admirably adapted for the accommodation of winter visitors in Italy, where the sun is made to do duty for artificial heat, and the whole is a striking example of the way in which the most lavish expenditure may be rendered futile by a want of due appreciation of the principles that should govern tropical domestic architecture. I give this instance mainly to show that, however self-evident the principles described above may appear, they are far from being generally appreciated.

These principles may be briefly epitomised as follows:—

(1) Through ventilation of all rooms.

(2) The elevation of all rooms, and especially of sleeping chambers, to as great a height as practicable above the ground.

[I-20]

(3) The selection of appropriate building materials which cannot harbour vermin.

(4) The shielding of outer walls from becoming heated by the direct rays of the sun by the provision of adequate verandahs.

(5) The application of the same principle to the construction of roofs by planning them so as to secure a well-ventilated air space between the actual roof and a fairly substantial ceiling, or by constructing them of massive materials, if single.

(6) The admission of sufficient light.

In the case of a house of moderate dimensions, these principles might be carried out as follows:—

Basement of brick arches ten feet high, including a low plinth and thickness of floor. These arches would be utilised for the accommodation of the kitchen, cook room, pantry, lamp room, store room, coach house, and well house, the well being placed beneath the house, and so well protected from any neighbouring fouling of the soil. The platform of the house supported on these arches would be pierced only by a concealed staircase for the use of the sweeper, but this would not be in communication with the other offices, though a hand lift might advantageously be arranged between kitchen and dining room. First floor 18 feet high-dining room, drawing room, office, and one or more bedrooms with dressing and bathrooms communicating with them, if large accommodation is required. Verandah all round not less than 10 feet wide. Second floor, 17 feet in height—principal bedrooms with dressing and bathrooms, some of the central rooms provided with terraced roof; the rest, together with the verandahs, with tiles of good pattern, the rooms having substantial ceilings. On terraced roof-large iron water-tank, with windmill to work force pump from well; small sleeping shelter, and protected with corrugated iron roof, supported on pillars.

It would be well to have the southern verandahs (in the northern hemispheres) of greater width than the others, and to place in them the stairs giving access to the second storey and to the roof.

[I-21]

The first floor would be reached by means of a flight of steps leading from the carriage drive, which might, if desired, be protected by a sloping porch. Such a house would, of course, be somewhat costly, but not much more so than one of equal accommodation constructed on the ordinary plan, and would undoubtedly be far more healthy than those of the usual type.

It is needless to remark that this imaginary residence would be completely protected against mosquitoes by means of metallic gauze, but the point is not dealt with here, as it is fully considered in the chapter on the prevention of malaria.

[I-22]

The principles that should guide us in the contrivance of tropical costume may be epitomised in a single sentence. Keep the head cool and the abdomen warm:—and most of the costumes of the more civilised tropical races usually meet these requirements.

It is of course generally true that it is well in matters of costume to take as a general guide the habits of the inhabitants of the country we are visiting; but the recommendation cannot be taken too literally, as, apart from questions of cut and fashion, a too slavish imitation might be as hazardous to health as it would be fatal to decency, as there are places where the Paris fashions consist only of a hoop of cane or a liberal smearing of clay. Nor can the question be lightly solved by simply adopting lighter materials, as, in addition to adaptation to altered meteorological conditions, our dress should be so contrived as to afford protection against certain other dangers which are only indirectly the outcome of climatic conditions, notably against the attacks of mosquitoes, which are now known to be no mere irritating annoyances, but to undoubtedly serve as the carriers of several of the most deadly of tropical diseases.

Moreover, although very pleasant, it is by no means safe to knock about the house bare-footed in countries where scorpions and centipedes, to say nothing of poisonous snakes, are every-day vermin.

The “flannel next the skin” doctrine, too, is applicable only to those blessed with hides sufficiently phlegmatic to tolerate the material; and enthusiasts in its favour are apt to forget that our powers of resistance to extreme heat[I-23] depend entirely on the healthy action of the skin, so that, if that important portion of our anatomy be kept in a condition of chronic inflammation by “prickly heat,” it must necessarily be more or less incapacitated from performing its proper functions.

The substratum of truth that underlies most doctrines, good, bad and indifferent, depends in this case on the fact that in hot climates it is especially important that clothing should be absorbent and porous; but, provided this be secured by the plan of manufacture, the nature of the fibre used is of little moment.

It must be admitted that the well-known Jaeger materials are in all respects admirable for all but the higher grades of atmospheric temperature, but when the thermometer gets up in the nineties, unadulterated wool becomes too irritating for the majority, and an admixture of silk, as in the so-called “Anglo-Indian gauze,” is preferable. Pure silk gets too easily sodden with perspiration, and in that state is too good a conductor of heat to form by itself a desirable material, but the combination of the two fibres forms an ideal material for wear during periods of excessive heat.

This material is necessarily rather costly, though it is surprisingly strong in proportion to its weight, and with ordinary care in washing lasts a long time, whereas the cheaper material of mixed cotton and wool is apt to shrink, and hence requires to be frequently replaced.

All materials into the composition of which wool enters, require great care in washing if they are to retain the properties which render them, in one form or another, so valuable in all climates. It need hardly be pointed out that they are at once hopelessly spoiled by a short immersion in boiling, or even very hot water. For the frequently changed garments of European residents of the Tropics little else is required than immersion and rinsing about in luke-warm or cold soap and water, and there is rarely need to guard against their being spoiled by heat, as neither soap nor hot water are much used by persons following the trade of washing in semi-civilised lands; but the severe beating and[I-24] manipulation to which they subject everything that comes into their hands is almost as effectual in felting and spoiling woollen goods as great heat. It is pretty well impossible to induce a native to so alter his methods as to wash such articles in the orthodox European fashion, unless, indeed, one were disposed to occupy one’s time in personally superintending the process; but by cautioning against rough and excessive manipulation, and steadily refusing to pay for articles spoiled, it is generally possible to minimise the evil.

While touching on the subject of the washing of clothes, it may be well to remark, that although personal superintendence of the process may be out of the question, it is certainly important to find out and inspect the place where the washing is done, which in such countries as India and China, and doubtless elsewhere, will too often be found to be some filthy stagnant pool, redolent with the accumulated dirt of all classes of the population. But for the powerful germ-killing powers of the tropical sun to which the articles are subjected in the process of drying, there can be no doubt that disease would be spread in this way much more frequently than is actually the case, but it will not do to trust this natural disinfection too far, and without counting suspected instances of the transmission of really serious diseases, there can be no doubt that the troublesome skin disease known as “dhobie’s itch,” is often contracted by Europeans in this way. The policy of sparing the imagination by shutting the eyes is, in this case again, a fallacy which may lead to considerable personal inconvenience and perhaps to danger.

If, as is not unfrequently the case, all the public washing places are undesirable, it is well worth while providing the simple arrangements required by natives following this calling within one’s own enclosure.

All that is required is a masonry platform about 6 feet square, connected by a channel with the well and enclosed with walls about a foot high, the whole being lined with cement. A short length of metal pipe, capable of being closed with a wooden plug, must be built into the wall at the lowest edge of the platform, so as to admit of the dirty water[I-25] being drained off. A piece of smoothly-worked plank, about 4 feet by 2 feet, with rounded corrugations athwart it, formed like those of corrugated iron roofing on a smaller scale, is all the additional apparatus required, and I feel sure that these simple appliances would be found much more frequently within our compounds than they are, if Anglo-Indians in general had any idea of the filthy conditions under which their clothing is commonly washed. Of course, such a matter as the cleanliness of public washing places ought to be a matter of superintendence and regulation by the authorities, but as yet everything is usually left to individual initiative, and those who wish to protect themselves must take their own precautions.

A not uncommon mistake of persons making their first sally into these warm climates is to leave behind them all their everyday European apparel, under which circumstances the one or two old suits that were taken to see them through the chops of the Channel and “Bay” become most treasured possessions, for there are very few parts of the world where, at some season or another, our ordinary English outfit will not be found convenient and suitable. Even the “Equatorial Rowing Club” probably find it well to put on their sweaters on returning to Singapore, after a spurt along “the line.”

Within intertropical limits no doubt, the occasions on which the garb of temperate climates is required are rare, but everywhere outside them there are ample opportunities of comfortably wearing out clothing adapted to life in Europe. In the Northern Punjab one’s heaviest English clothing is required for two or three months in the year, while in South Africa the diurnal range of temperature is so great that a light overcoat is required after sunfall in the hottest time of the year, and even in the Persian Gulf stout woollen clothing is required from December to early March. A glance at the meteorological data furnished in the second part of the book devoted to climate, will give the best idea of what will be required, as it may be taken as certain that in any case where the mean monthly temperature approximates at any season to that of our native island, clothing[I-26] appropriate to the corresponding season of the year will be desirable.

In choosing a costume for really hot weather it must be remembered that any material requiring to be starched is about as suitable for the purpose as mackintosh sheeting, because linen and cotton fabrics, starched and ironed, are, as long as they retain their appearance, quite as impervious to transpiration. After they have lost their stiffness their appearance is most objectionable and disgusting, and it is a fortunate circumstance that they become so soon sodden, as there can be no doubt, that but for this, their use would be clung to by the conservative Briton, far more than he is able to do.

For this reason the loss of popularity of late years of the old-fashioned white “American drill” clothing, once universally adopted, is hardly to be regretted. Without a considerable amount of starching they never looked fresh after an hour or two’s wear, and with it the material ceased to be suitable. It is, indeed, a mistake to provide oneself with clothing of this sort in England, as even “American drill” of the right sort, cannot be obtained, and the light cotton tweeds and checks which are now in use in India do not appear to be found in the home market. It is, of course, necessary to obtain two or three suits for use on the outward voyage, but to obtain more than this, is only to burden oneself with what will, as likely as not, prove to be useless, and perhaps noticeably out of the fashion of the country.

A few shirts of soft cotton “twilled lining,” made with turned down collars, like a cricketing shirt, perhaps three pairs of white drill trousers (the material used by merchant seamen and known as “Dungaree” is the most suitable) and an alpaca coat and waistcoat will suffice. Unless one belongs to the clerical profession, the alpaca should be fawn-coloured, or, at any rate, not black, as in this colour the material is a sort of badge of missionary enterprise, and it is embarrassing to be asked to conduct service on the main deck, under false pretences. For the sub-tropical portion of the voyage, light flannel suits, made with as little lining as possible, are most suitable, and will prove useful, in any warm climate, at certain seasons of the year.

[I-27]

In really hot weather, however, if thin enough to be cool, flannel becomes too flimsy to serve for outer garments, and one is practically restricted to cotton fabrics. Of late years a variety of cotton materials have been made in India in imitation of the woollen tweeds in general use in Europe, and have the great advantage that the little deception is all the better maintained if they are kept unstarched.

Without desiring to furnish a gratuitous advertisement to any individual enterprise, missionary or otherwise, I see no harm in mentioning that I have met with no fabrics so suitable for tropical wear as those manufactured by the admirable Basel Mission at Cannanore, and though their energies are presumably mostly confined to the Indian market, I have little doubt they would export parcels if asked to do so.

They have shown great ingenuity in contriving light porous materials, almost indistinguishable at a short distance from those to which we are accustomed at home, and there can be no doubt that the short-fibred Indian cotton possesses certain properties that cause materials manufactured from it to be softer and more absorbent than those made from the harder and longer American fibre. At any rate I can account in no other way for the marked difference that exists between the fabric known as “twilled lining,” manufactured in Cawnpore, and what appears to the eye the same article obtained in England, though the latter is by no means to be despised.

It is but ten or twelve years since some bold innovator made the discovery that the cheap and despised “twilled lining” formed an admirable underwear for hot climates, and whoever he may have been, he was certainly a great benefactor to the Anglo-tropical community, for none of the numerous expensive patent materials that have from time to time been brought out, combine the same good qualities to anything like the same degree. It absorbs moisture quite as well as flannel of the same substance, and can be comfortably tolerated by the most irritable skin, while I doubt if it exposes one to greater danger of chilling than any other material of like weight. It can be safely worn next the[I-28] skin without the intervention of a vest, which is indispensable with the ordinary starched linen shirt, and is, all considered, the best material for shirts, and for pyjamas for night wear, as various striped patterns are made specially suitable for the latter purpose. While speaking of night clothes, it may be well to remark that the ordinary pattern of short coat, commonly worn with pyjamas, is a distinctly dangerous garment, as it is very liable to ruck up during sleep, and so leave exposed the abdominal organs, which are of all parts of the body the most vulnerable to chill. To leave any portion of the abdomen exposed for even a short time while at rest is an extremely hazardous matter, so that in place of the usual coat it is far better to wear a shirt which can be safely tucked into the pyjamas.

I was glad to hear, during a recent visit to India, that the rational and cleanly custom of adopting white for evening dress was again coming into vogue, for even the lightest cloth clothing is undesirably hot, and the idea of wearing, night after night, garments which cannot be washed, in a climate so productive of perspiration, is, to say the least of it, somewhat repulsive.

It is, I understand, now the custom to have them cut after the pattern of the now almost universal “dress jacket,” but it is probably better to have them made by an English tailor of white drill, when fitting out, as the cut of the native workman is hardly to be relied on, though he may be trusted fairly well for nether garments. A broad silk sash or kamarband is usually substituted for the waistcoat; and to protect the ankles from the attacks of mosquitoes, which bite easily through a thin sock, it is a good anti-malarial precaution to have the trousers fitted with straps.

For riding, either stout khaki drill or the admirable cotton cords made at Cannanore are most suitable, and they are best cut after the pattern of the very handy “Puttialla” breeches, in which the breeches are prolonged below the knee into a closely fitting extension formed like a gaiter, as this does away with the necessity of wearing the very hot and unsanitary long boot. These garments would also be very useful, either at the Cape on account of ticks, or in[I-29] parts of Burmah and Assam as a protection against leeches, as in both these, and no doubt in many other localities, these pests swarm so amongst the herbage that it is impossible to go abroad in ordinary trousers unless they be tucked into the socks. It is true that knickerbockers and long stockings will serve the same purpose, but few can bear the irritation caused by stockings thick enough to be worn in this way, in climates of this sort.

Another very suitable class of material for outer garments is to be found in the coarse wild silk that is met with and manufactured in parts of India, under the name of Tussur serge, and I have no doubt that many other parts of the world produce materials equally adaptable to our needs.

The matter of head covering requires special consideration, as there is a quite unaccountable difference as to the risk of sunstroke in climates which, as judged by the thermometer and the brilliancy of the sunlight, appear quite similar.

Accidents of this sort are almost unknown at the Cape of Good Hope; even as far north as Natal, and throughout our colonies there, and I believe also in America and Australia, a broad-leaved felt hat appears to afford quite adequate protection, always provided that it be not looped up in the idiotic “smartness” of an Imperial yeoman’s headgear. It is wonderful, too, how European officers contrive to go about in Egypt in the singularly unpractical “fez,” which, save as a protection for the bald within the house, appears about the most ill-contrived headgear yet contrived.

To wear one in June in most parts of India, would be certain death to the majority of Europeans, and few could venture to wear it at any time of the year.

For India, however, and other climates where sunstroke is common, a good sun-hat is indispensable, and there is undoubtedly no material that at all equals pith or solah for the purpose; and the bigger, the thicker, and uglier, the better it is for the purpose. Thick stiffened felt also answers very well, but is not reliable under extreme conditions, unless made double with an intervening air space throughout. Whatever the material, it is essential that the[I-30] interior should be well ventilated, and this is most efficiently secured by the hat itself being attached to a comparatively narrow band that encircles the head, by the means of a few widely separated pieces of cork; no lining or other material being allowed to obstruct the passage of air.

The ordinary brass bound eyelet holes and squat top ventilator, so often seen in home-made “helmets,” are generally, for all practical purposes, absolutely useless.

Of the various shapes of solah hat in use, I am inclined to think the “Cawnpore tent club hat” is the best. This is made with the brim almost horizontal in front so as not to interfere with vision, and well sloped elsewhere, and is quite comfortable to ride, shoot, or work in. It has been adopted for the troops for tropical field service, but is I notice, already commencing to undergo evolution in the direction of smart inefficiency so dear to the heart of the military milliner.

Constructed as they are of strips of pith glued together, solah hats naturally go to pieces in rainy weather, but this can be obviated by covering with some waterproof material instead of the alpaca, or brown holland, usually used. The padded and quilted coverings to solah hats sometimes seen are absurd, as quilted cotton is far inferior as a non-conductor of heat to a similar thickness of pith, and the padding greatly increases the weight of the head gear.

In case of emergency, the oriental pugaree or turban is a very fair protection, though it requires a good deal of practice to tie it properly. Five or six yards of coarse muslin can, however, be got even in small native towns, and such accidents as one’s hat blowing out of a railway carriage, or off the head into a river, may occur to any one, so that the expedient may obviate one’s either incurring considerable risk, or submitting to the alternative of returning with one’s errand unperformed.

Many persons are well nigh as sensitive to insolation of the spine as of the brain, and suffer at once from the exposure of the back to the sun’s rays. I have never personally experienced inconvenience on this score, but know that many find that the sun playing on this part of the person[I-31] causes a dull, heavy aching:—an oppression rather than pain. Persons subject to such symptoms should wear a broad pad of the same material as the coat, thickly padded with cotton wool. The pad should not form part of the coat, but be made separately to button on, as it is cooler worn thus. Turning to the opposite extremity of the body, it must be admitted that, owing to the entire want of ventilation, our European foot gear is very unsuited for use in hot climates. Every one knows the discomfort that is caused by boots that “draw” the feet, and these symptoms are entirely caused by the comparative imperviousness of leather, as is clearly shown by the greater discomfort caused by patent leather, which is practically air-proof. On this account, shoes are more generally useful than boots, though the latter are required for shooting, or work in the jungle; as shoes do not sufficiently protect the ankle from thorns, or the possible attacks of a snake. During the hot weather, the most comfortable form of foot-gear is a canvas shoe, but as made by the ordinary English shoemaker with leather lining and elaborate leather toe-caps and cross straps, they present no real advantages over an ordinary leather shoe. They should be made of stout but open woven canvas, with no lining except over the stiffener at the heel, and quite without toe-caps or other ornamentation; though the sole should be as stout as that of an ordinary walking shoe, and it is better to choose a brown canvas, as the “blanco” used for giving a clean appearance to white canvas, soon fills up the pores of the fabric and makes it almost as impervious as leather. The Persians wear a sort of ankle boot, the upper of which is formed of knitted twine, and these “málikis,” made up on an European last, form ideal “uppers” for hot climates, for they are admirably porous, though so strong that they will outlast half-a-dozen leather “uppers.” Can not our European manufacturers devise something similar? In hot wet weather, it is a mistake to try to keep the water out, as the sock, if enclosed in a water-tight boot, will very soon become so saturated with perspiration that one has simply subjected oneself to heat and discomfort to no purpose. Whether for rainy weather, or for wading after[I-32] snipe, or when fishing, the only desideratum is that the water should be able to ran out as easily as it gets in. Provided that clothing is changed as soon as one gets into shelter, no harm need be feared from getting either clothing or the feet wet, as long as one is on the move, in the climates with which we have to do. For the same reason the advantages of a waterproof are very doubtful, the fact being that, with a combination of heat and rain, one is bound to get wet anyhow, and whether the moisture comes from the outside or the inside of our garments is a matter of little moment. One other point in connection with foot-gear remains to be noticed, and that is that as one’s feet and hands become a full size larger under tropical conditions, it is necessary that those included in our outfit should be full large; for a shoe so loose as to be almost slipshod in England, will be found to be quite tight when tried on in India. The best way is not to confuse your shoemaker with directions, but to put on a couple of pairs of thick woollen socks and get measured over them.

At night, the main object is to have as little in contact with the skin as possible, so that mattresses of all sorts are best put aside during the hot months and a smooth mat substituted. Most tropical races actually prefer to sleep on a hard surface, such as the floor, during periods of heat, and though few Europeans can habituate themselves to so hard a couch, the majority prefer a cot formed of tightly strained cordage or webbing to the more modern spring bed of woven wire, the yielding character of which causes the surface laid upon to follow too closely the curves of the body. Personally, I prefer the woven wire, covered only with a loosely-made reed mat. Costing only a few pence, such mats may be frequently renewed, and they are far cooler than the fine and closely-woven “China” mats, which are rather costly, and in the finest quality almost impervious to air.

Assuming that one is properly protected against mosquitoes, the feet and chest may be left bare, but a light blanket or rug, folded to about 2 feet wide, should be thrown across the abdomen, as nothing is more dangerous than chill to this portion of the body.

[I-33]

Ladies’ costume lends itself more readily to coolness than that of the sterner sex, though its advantages are usually thrown away, by their obstinate adherence to the corset, a garment which is even more pernicious in hot climates than elsewhere. Apart from this, their most common mistake is to err on the side of over-coolness, and medical men who practise in the Tropics are constantly meeting with serious and obstinate cases arising from inadequate protection to the abdominal and pelvic organs.

Ladies too often expose the head to the sun in a most foolhardy way. It may be admitted that a safe sun-hat is not particularly becoming to either sex, but in the presence of the girl graduate, often surpassing her male competitors, no one can doubt that a substratum of brains underlies the golden hair, and this being admitted, it is clearly morally incumbent on ladies not only to make themselves attractive, but to take proper care of thinking organs of such high quality. Besides, a woman with a headache is seldom charming, and a very genuine one—no mere boredom—is too often contracted by the conscientious performance of the quasi-religious duty of paying calls at noon in a picture hat.

Even where a covered conveyance is available—and many of us do not run to anything more ambitious than a dog-cart in the East—it is quite possible to contract a headache in crossing a pavement, and when a lady drives herself, it is almost impossible for her groom to so hold an umbrella over her as to afford protection, without obstructing her view. On this account, it is better that on such expeditions she should submit to be driven, so that she may have her hands free to carry an umbrella or sunshade; and it is well to remember that a fairly large sunshade with a padded cover is really more efficient than the largest single umbrella, or even one provided with the customary thin outer white cover.

Mothers have a general tendency to overclothe their children. Provided that the abdomen be properly protected by a flannel “binder,” the less they are hampered during the day the better. A child’s extremities rapidly become clammy if it be inadequately clothed, and as long as these[I-34] feel comfortably warm, nothing but harm can result from stifling them with coverings which cause prickly heat, with attendant loss of rest and all the evils that result from chronic nervous irritation. Above all things, the face should never be covered, even with a handkerchief, in the case of the youngest of infants; as this pernicious fad of nurses and mothers necessarily leads to the rebreathing of air already rendered impure by passing through the lungs, than which few things are more destructive to health, even in adults, let alone in an infant, where the rapid chemical changes involved in growth and development demand a supply of oxygen proportionately far in excess of that required by a grown-up person.

In children much troubled with prickly heat, who have reached the age of intelligence, a pair of silk drawers should be worn under the binder; and during the day, and at night under the mosquito net, nothing more than this is really required. At dusk, when they go out for their airing, and at any time when mosquitoes are in evidence, their costume should be contrived so as to protect them from the attacks of the insects as far as possible.

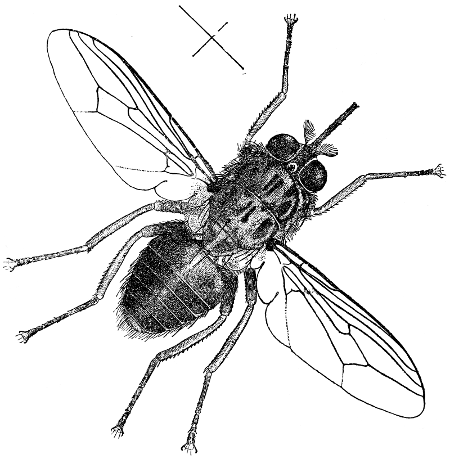

In countries where ophthalmia is common, protection from flies during the day is almost as essential as against mosquitoes at night, and if the child falls asleep it should at once be placed under a mosquito net, as the eyes of children seem to have a peculiar attraction for flies, and there can be no doubt that these insects are often instrumental in carrying infectious matter from the eyes of the diseased to those of the healthy.

[I-35]

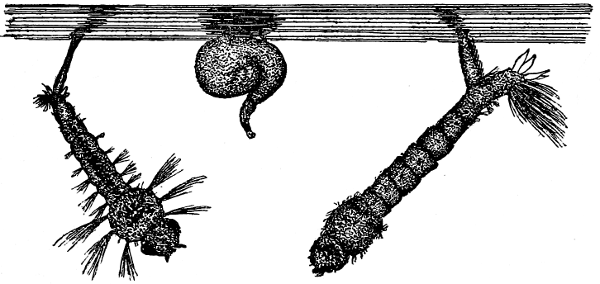

The importance of attention to personal hygiene in the matter of what to eat, drink and avoid, may be judged by the fact that three of the greatest scourges of tropical life—cholera, dysentery, and typhoid fever—are conveyed exclusively by the agency of germs that find their way into the body along with ordinary articles of diet; and even putting aside diseases of so dramatically striking a character, bad food, careless cooking, and impure water may set up such minor troubles as dyspepsia, with all its prolonged attendant miseries of body and mind. Those who do not die from an attack of cholera or typhoid usually recover fairly completely, but he who has once suffered from a bad attack of dysentery is as truly lamed for life as if he had suffered mutilation of a limb.