Title: The Soil (La terre): A Realistic Novel

Author: Émile Zola

Editor: Ernest Alfred Vizetelly

Release date: March 6, 2018 [eBook #56687]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Clare Graham & Marc D'Hooghe at Free Literature

(Images generously made available by the Internet Archive.)

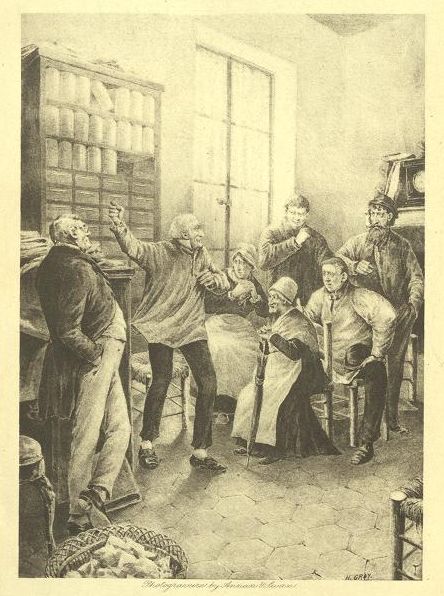

Hold your tongue or I strike. Am I not the master? P. 27.

| Page | |

| PART I. | |

| CHAPTER I. | 5 |

| CHAPTER II. | 16 |

| CHAPTER III. | 29 |

| CHAPTER IV. | 44 |

| CHAPTER V. | 59 |

| PART II. | |

| CHAPTER I. | 76 |

| CHAPTER II. | 90 |

| CHAPTER III. | 100 |

| CHAPTER IV. | 112 |

| CHAPTER V. | 123 |

| CHAPTER VI. | 141 |

| CHAPTER VII. | 155 |

| PART III. | |

| CHAPTER I. | 167 |

| CHAPTER II. | 176 |

| CHAPTER III. | 186 |

| CHAPTER IV. | 201 |

| CHAPTER V. | 215 |

| CHAPTER VI. | 226 |

| PART IV. | |

| CHAPTER I. | 243 |

| CHAPTER II. | 256 |

| CHAPTER III. | 272 |

| CHAPTER IV. | 293 |

| CHAPTER V. | 315 |

| CHAPTER VI. | 333 |

| PART V. | |

| CHAPTER I. | 355 |

| CHAPTER II. | 370 |

| CHAPTER III. | 386 |

| CHAPTER IV. | 403 |

| CHAPTER V. | 429 |

| CHAPTER VI. | 454 |

| NOTES. | 472 |

That morning Jean, with a seed-bag of blue linen tied round his waist, held its mouth open with his left hand, while with his right, at every three steps, he drew forth a handful of corn, and flung it broadcast. The rich soil clung to his heavy shoes, which left holes in the ground, as his body lurched regularly from side to side; and each time he threw you saw, amid the ever-flying yellow seed, the gleam of two red stripes on the sleeve of the old regimental jacket he was wearing out. He strode forward in solitary state; and behind him, to bury the grain, there slowly came a harrow, to which were harnessed two horses, driven by a waggoner, who cracked his whip over their ears in long, regular sweeps.

The patch of ground, scarcely an acre and a quarter in extent, was of such little importance that Monsieur Hourdequin, the master of La Borderie, had not cared to send the drill-plough, which was in use elsewhere. Jean, then journeying due north over the field, had the farm-buildings exactly in front of him, a mile and a quarter off. On reaching the end of the furrow, he raised his eyes with a vacant look as he paused for a moment to take breath.

Before him were the low farm walls, and a patch of old slate, isolated on the outskirts of the plain of La Beauce, which stretched towards Chartres. Under a dull, late October sky lay ten leagues of arable land, where, at that time of year, great ploughed squares of bare, rich, yellow soil alternated with green expanses of lucern and clover; there was here not a slope, not a tree; the plain extended into the dim distance, curving down beyond the horizon, which was level as at sea. Westward, a small wood just edged the sky with a band of russet. In the centre a road—the road from Châteaudun to Orleans—of chalk-like whiteness, stretched four leagues straight[Pg 6] ahead, displaying as it went a geometrical row of telegraph-posts. Nothing else but three or four wooden mills on log foundations, with their sails at rest; some villages forming islets of stone; and a distant steeple emerging from a depression in the landscape, the church itself being hidden among the gentle undulations of the wheat-fields.

Jean turned and lurched back again due south, his left hand holding the seed-bag, and his right slashing the air with an unbroken sheet of grain. He now had in front of him, quite near, and cutting trench-like through the plain, the narrow valley of the Aigre, beyond which the district of La Beauce resumed its unconfined course on to Orleans. Meadows and shady places could only be inferred from a range of tall poplars, the yellowish tops of which rose out of the dell, looking, as they just cleared the edge, like short bushes. Of the little village of Rognes, built upon the declivity, a few roofs only were in view, near the church, which raised on high its grey stone steeple, the dwelling-place of ancient families of ravens. And eastward, beyond the valley of the Loir,—where Cloyes, the chief town of the canton[1] nestled at two leagues' distance,—the far-off hills of Le Perche were visible, tinged with violet in the slate-grey light. There the old Dunois, now become the arrondissement of Châteaudun, lay between Le Perche and La Beauce, on the very frontier of the latter, at a spot which has obtained the name of Beauce the "Lousy," the soil there being less fertile. When Jean got to the end of the field, he stopped again, and glanced down along the stream of the Aigre, rippling bright and clear through the meadows, side by side with the road to Cloyes, which on that Saturday was furrowed by the carts of peasants going to market; then he turned up again.

And still, with the same step, with the same gesture, he set out north and returned south, wrapped in a living dust-cloud of seed; while, behind him the whip cracked and the harrow buried the germs, at the same quiet, contemplative rate. Heavy rains had retarded the autumn sowing; the season's manuring had been done in August, and the deep-lying fallows, duly cleared of weeds, had long been ready for a fresh yield of corn, after the clover and oats of the triennial rotation. Now the farmers were urged on by fear of coming frost, which threatened after the storms. The weather had suddenly turned cold and gloomy: there was no breath of wind, and[Pg 7] but a dull light was distributed over all this ocean of land. Seed was being sown on all sides; there was a sower to the left, three hundred yards away; another farther off to the right; others, and yet others, lost to sight in the receding vista of the level fields. They formed little black silhouettes, mere strokes which became slimmer and slimmer, till they vanished in the distance. All made the same gesture, as they strewed the seed, which the mind's eye still saw encircling them, as with a wave of life. It was like a quiver passing over the plain, even into the dim distance, where the scattered sowers could no longer be seen.

Jean was coming down for the last time when he perceived, approaching from Rognes, a large red and white cow, the halter of which was held by a young girl, almost a child. The little peasant-girl and the animal were coming along the path which skirted the valley at the top of the plateau; and, with his back turned to them, he had gone up and finished the field, when a sound of running, mingled with stifled cries, made him look round, just as he was untying his seed-bag to depart. It was the cow running away, galloping over a field of lucern, and followed by the girl, who was exhausting her strength in trying to keep it back. Fearing an accident, he shouted:

"Leave go; why don't thee?"

But she did nothing of the kind, only panting and abusing her cow in angry, frightened tones.

"Coliche! Would you, then, Coliche? Ah, you foul brute! Ah, you cursed beast!"

So far, running and leaping to the full extent of her little legs, she had managed to follow. But she stumbled, fell once, then rose only to fall again farther on; and from that point, the animal growing frantic, she was dragged along. Then she began to shriek, while her body left a furrow in the lucern.

"Leave go, in God's name!" Jean continued shouting. "Leave go, why don't thee?"

He shouted thus mechanically, out of fright; for he also had started running, grasping, at length, the situation. The rope had evidently got entangled round her waist, and was being more closely twined at each fresh effort. Fortunately he took a short cut across a ploughed field, and made for the cow with such speed that the frightened and perplexed animal stopped dead. Jean was already undoing the rope, and seating the girl upon the grass.

"Thou hast broken nothing?" he asked.

No; she had not so much as swooned. She stood up, felt[Pg 8] herself all over, and coolly lifted her petticoats up to her thighs, to look at her knees, which smarted. Meanwhile, she was still so breathless that she could not speak.

"See, it's there it hurts me," she said at last. "All the same, I'm alive and kicking; there's nothing the matter. Oh! I was frightened. Over on the road there I was a regular jelly!"

And, examining the circle of red on her strained wrist, she moistened it with spittle and applied her lips to it; then, comforted and restored, she added with a deep sigh:

"She's not vicious, Coliche. Only since yesterday she has plagued us to death, because she's in heat. I'm taking her to the bull at La Borderie."

"At La Borderie?" repeated Jean. "That's capital; I'm going back there; I'll go with thee."

He still used the second person singular, treating her as a little urchin, so slight was she for her fourteen years of age. She, raising her chin, looked seriously at the big, ruddy, crop-haired, full-faced, regular-featured young fellow, whose twenty-nine years made him in her eyes an old man.

"Hullo! I know you. You are Corporal, the carpenter who stopped as farm-hand with Monsieur Hourdequin."

Hearing the nickname, which the peasants had given him, the young fellow smiled; and he contemplated her in turn, surprised to find her almost a woman so soon, with her little bust firm and taking shape, her oval face, her deep, black eyes; and full lips, fresh and rosy as ripening fruit. She was clad in a grey skirt and black woollen bodice; on her head there was a round cap; and she had a very dark skin, scorched and burnished by the sun.

"Why, thou'rt old Mouche's youngest!" cried he. "I didn't call thee to mind. Isn't that so? Thy sister was keeping company with Buteau last spring, when he worked with me at La Borderie?"

She replied simply:

"Yes, I'm Françoise. My sister Lise went with cousin Buteau, and is now six months with child. He's bolted; he's down Orgères way, at the farm of La Chamade."

"That's it," concluded Jean; "I have seen them together."

And they remained an instant mute, face to face; he smiling at having one evening surprised the two lovers behind a mill, she still sucking her bruised wrist, as if the moisture of her lips allayed its smarting; whilst, in an adjoining field, the cow quietly plucked tufts of lucern. The waggoner and the harrow had gone off by a roundabout way, to reach the road.[Pg 9] Two ravens, which kept wheeling round and round the steeple, were heard to caw. The three notes of the angelus rang through the still air.

"Hullo! Twelve o'clock already!" cried Jean. "Let's make haste!"

Then, noticing La Coliche in the field: "Eh, but thy cow is doing damage! Suppose any one saw her! Wait a bit, I'll make it lively for her!"

"Nay, let be," said Françoise, stopping him. "The plot is ours. Our folk own the whole bank as far as Rognes. We reach from here up to yonder; the next to that is uncle Fouan's; then comes aunt Grande's."

While indicating the patches she had led the cow back into the path. And not till then, when she again held her, fearlessly, by the rope, did she think of thanking the young fellow.

"Anyhow, I owe you a pretty debt of gratitude! Thanks, you know, thanks, very much!"

They had started walking along the narrow road which skirted the valley before cutting through the fields. The final peal of the angelus had just died away, the ravens alone kept on cawing. They trudged on behind the cow tugging at her rope, neither of the two conversing, for they had relapsed into the silence of rustics who travel for leagues, side by side, without exchanging a word. On their right their glance fell on a drill-plough, the horses of which turned close by them; the ploughman bade them good-day, and they answered him in the same sober tone. Down on their left, along the road to Cloyes, carts continued to file by, the market not opening till one o'clock. These vehicles jolted heavily along on their two wheels, like jumping insects, so diminished in the distance as to leave merely the white specks of the women's caps distinguishable.

"There's uncle Fouan and aunt Rose over there, on their way to the notary's," said Françoise, gazing at a conveyance the size of a nutshell, which sped along nearly a mile off.

She had a sailor's eye, the long sight of those bred in the country, trained in details, and capable of identifying man or beast even when they were but little moving specks afar off.

"Oh, yes; I've been told so," resumed Jean. "So it's settled that the old man divides his property among his daughter and two sons?"

"It's settled. They've all agreed to meet to-day at Monsieur Baillehache's."

She again watched the cart in its course, and then resumed:

"We don't care one way or the other; it won't make us any fatter or thinner. Only, on account of Buteau, sister thinks he'll marry her, perhaps, when he gets his share. He says one can't start housekeeping on nothing."

Jean laughed.

"Me and Buteau were pals, hang him! Oh, he don't think twice about telling girls lies! And he must have 'em, by hook or by crook; he gets at 'em by foul means, if they won't by fair."

"He's a pig, that's flat!" declared Françoise, peremptorily. "People have no business to play dirty tricks like that, putting their cousins in the family-way and then leaving 'em in the lurch."

But suddenly, in a fit of rage, she exclaimed:

"You wait, Coliche! I'll make you dance! There she is at it again; she's mad, the brute, when she gets that way."

She had violently jerked the cow back. At that spot the road left the edge of the plateau, and the cart disappeared from view, while they both continued their walk on the level, now having in front of them, and on either side, only the endless expanse of arable land. Between the fallows and the artificial meadows the path ran flat and bushless, terminating at the farm, which you might have thought within reach of the hand, but which kept receding under the ashen-grey sky. They had relapsed into silence again, no longer opening their mouths, as if impressed by the contemplative gloominess of La Beauce, so sad and yet so fruitful.

When they arrived, the large square yard of La Borderie, shut in on three sides by cow-sheds, sheep-cots, and barns, was deserted. But there immediately appeared upon the kitchen door-step a short, bold, pretty-looking young woman.

"How's this, Jean, you're not eating this morning?"

"I'm just going to, Madame Jacqueline."

Since the daughter of Cognet, the Rognes road-labourer,—La Cognette, as they called her when she washed up the farm dishes at twelve years of age—had been raised to the honours of servant-mistress, she despotically required that every one should treat her as a lady.

"Oh, it is you, Françoise," she resumed. "You've come for the bull. Well, you must wait. The neatherd is at Cloyes with Monsieur Hourdequin. But he'll be back; he ought to be here now."

And as Jean was making for the kitchen, she took him round the waist and fondled him smilingly, regardless of[Pg 11] spectators, hungering, as it were, for love, and not satisfied with having the master.

Françoise, left alone, waited patiently, sitting on a stone bench in front of the manure-pit, which took up a third of the yard. She was listlessly watching a group of fowls, pecking and warming their feet in the broad low layer of manure, which in the cold air began to steam with a slight bluish vapour. At the end of half-an-hour, when Jean re-appeared, finishing a slice of bread and butter, she had not stirred. He sat down near her, and as the cow fidgeted, lashed its tail and lowed, he finally said:

"It's tiresome he doesn't come back."

The girl shrugged her shoulders, as though to say that she was in no hurry. Then, after a fresh silence:

"So, Corporal, they call you Jean, and nothing else?"

"Why, no; Jean Macquart."

"And you don't belong to our part of the country?"

"No, I'm a Provençal, from Plassans, a town over yonder."

She had raised her eyes to examine him, surprised that any one could come from so far off.

"After Solferino," continued he, "eighteen months since, I came back from Italy with my discharge, and a fellow-soldier brought me here. Then, d'ye see, my old trade of carpenter no longer suited me, and, what with one thing and another, I stopped at the farm."

"Ah!" said she, simply, without taking her big, black eyes off him, "it's curious, all the same."

At that moment, as La Coliche gave a prolonged, despairing low of desire, a hoarse murmur came from the cow-house, the door of which was shut.

"Hullo!" cried Jean, "that brute of a Cæsar has heard her. Hark! he's talking inside there. Oh, he knows his business. You can't bring one of 'em into the yard but he smells her out, and knows what he's wanted for."

Then, breaking off:

"I say, the neatherd must have stopped with Monsieur Hourdequin. If thee liked, I would bring thee the bull, and thee needn't come back again. We could manage it all right by ourselves."

"Not half a bad idea," said Françoise, getting up.

As he opened the door of the cow-house, he paused to ask:

"Must thy animal be tied up?"

"Tied up? No, no! not worth while. She is quite ready; she won't so much as stir."

When the door was opened you saw, in two rows on either side of the central path, the thirty farm cows, some lying in the litter, others crunching the beets in their manger; and, from the corner where he stood, one of the bulls, a black Dutch, spotted with white, stretched out his head in anticipation of his task.

As soon as he was untied, he slowly emerged. Then stopping short, as though surprised by the fresh air and sunlight, he remained motionless for a minute, bracing himself up, his sinewy tail swinging, his neck inflated, his muzzle outstretched to sniff. La Coliche, without stirring, turned towards him her large, fixed eyes, and lowed more softly. Then he advanced, pressed against her, and laid his head on her hind-quarters, abruptly and roughly; with his tongue, which was hanging out, he put her tail aside, and licked her as far as the thighs; she letting him do as he pleased, and keeping quite still, save for a slight quivering of her skin. Jean and Françoise waited gravely, their arms hanging beside them.

When Cæsar was ready, he got upon La Coliche with a jerk, and with such weighty force as to shake the ground. She had not given way, and he compressed her flanks with his two feet. But she, a strapping animal from the Cotentin, was so tall, so broad for him, who was of a smaller breed, that he could not reach. He was conscious of it, and made a vain effort to raise himself and to bring her nearer.

"He is too small," said Françoise.

"Yes, a little," said Jean. "But that don't matter; he'll do it all the same."

She shook her head in doubt; and, as Cæsar still fumbled about, and seemed to be getting exhausted, she came to a resolution.

"No, he must be helped," she said. "If he goes wrong, it'll be waste of time."

Calmly and carefully, as if bent on a serious piece of work, she had drawn near. Her intentness made the pupils of her eyes retreat, left her red lips half open, and kept her features motionless. Raising her arm with a sweep she aided the animal in his efforts, and he, gathering up his strength, speedily accomplished his purpose. It was done. Firmly, with the impassive fertility of land which is sown with seed the cow had unflinchingly received the fruitful stream of the male. Indeed, she had not even trembled at the shock; and he had already dropped again to the ground, shaking the earth once more.

Françoise having withdrawn her hand, remained with her arm in the air. Finally she lowered it, saying:

"That's all right."

"Yes, and neatly done," replied Jean, with an air of conviction, mingled with a good workman's satisfaction at seeing work well and expeditiously performed.

It did not occur to him to indulge in any of the spicy remarks with which the farm-servants used to chaff the girls who brought their cows for this purpose. The child seemed to consider it all so simple and necessary that there was, indeed, nothing to laugh at fairly. It was Nature.

However, Jacqueline had been standing at the door again for an instant or so, and with a chuckle which was habitual to her, she cried jestingly:

"Eh! poke your nose everywhere! So you hold the candle now!"

Jean having burst into a horse-laugh, Françoise suddenly flushed all over, quite confused; and to hide her embarrassment—while Cæsar returned of his own accord into the cow-house, and La Coliche munched a stalk of oats which had grown in the manure-pit—she dived into her pockets, fumbled about, eventually produced her handkerchief, untied the corner of it, in which she had wrapped up the two-franc fee, and said:

"Here! There's the money! And good day to you!"

She set out with her cow, and Jean took his bag again and followed her, telling Jacqueline that he was going to the Poteau field, according to the instructions issued by Monsieur Hourdequin, for the day.

"Good!" she replied. "The harrow ought to be there."

Then as the young man came up with the girl, and they went off in single file down the narrow path, she called out to them again, in her coarse, bantering voice:

"No danger, eh? If you lose yourselves together the chit knows her way about."

Behind them the farmyard was again deserted. Neither had laughed this time. They walked on slowly, and the only sound was that of their shoes striking against the stones. All that Jean noticed of Françoise was the nape of her child-like neck, over which curled some short black hair under her round cap. At last, after going some fifty paces:

"She does wrong to chaff others about the men," said Françoise, sedately. "I might have answered her——"

And turning towards the young fellow with a mischievous upward glance:

"It's true, isn't it, that she is false to Monsieur Hourdequin, just as if she were already his wife? You know as much about that, maybe, as most people."

His eyes fell, and he looked sheepish. "Lord! she does as she likes; it's her affair," he answered.

Françoise had turned her back and was pursuing her road.

"That's true enough. I was only in fun, because you're old enough to be my father, and because it's of no consequence one way or the other. But there's one thing, since Buteau played that dirty trick on my sister, I've taken an oath that I'd rather be cut in two than have a lover."

Jean bent his head, and they spoke no more. The little Poteau field lay at the bottom of the path, half way to Rognes. When the young fellow got there he stopped. The harrow was waiting for him, and a sack of seed had been emptied out into a furrow. He filled his bag, saying:

"Good-bye, then!"

"Good-bye," replied Françoise. "Thanks again!"

But, in sudden apprehension, he drew himself up and called out:

"I say! suppose La Coliche began again; shall I go with you all the way?"

She was already some distance off, but she turned round, and through the deep stillness of the country air came the sound of her calm, steady voice:

"No, no! There's no need, it's all right! She's got quite as much as she can carry!"

Jean, with his seed-bag at his waist, had started down the piece of plough land, with his ceaseless gesture of throwing the grain; he raised his eyes and looked at Françoise diminishing in height among the fields, looking quite small behind her lazy cow, which was swinging heavily from side to side. When he turned up again, he ceased to see her; but, as he came back, there she was again, but smaller still, so slim as to seem like some new kind of dandelion, with her slight figure and her white cap. Thrice she dwindled thus; then, when he once more looked for her, she had apparently turned down by the church.

Two o'clock struck. The sky remained grey, dull, and cold, as if the sun were buried under spadefuls of ashes for weary months, till the spring-time returned. The dreariness of the clouds was relieved by one lighter patch towards Orleans, as if the sun were shining somewhere in that direction, leagues away; and against that glimmering patch the steeple of Rognes stood out, the village itself sloping down[Pg 15] from view into the fold made by the valley of the Aigre. But on the north, towards Chartres, the level line of the horizon clearly separated the leaden uniformity of the waste sky from the endless vista of La Beauce, like an ink-stroke across a monochrome sketch. Since the mid-day meal, the number of sowers seemed to have increased. Now each patch of the little farm-lands had one to itself; they multiplied and teemed like black laborious ants roused to activity by some heavy piece of work, and straining every nerve over a mighty task, giant-like in size as compared with their littleness. And still you might descry, even in the most remote, the one persistent never-varying gesture; still did the pertinacious insect-like sowers wrestle with the vast earth, and become eventually the victors over space and life.

Till night-fall Jean sowed. After the Poteau field there were the Rigoles and the Quatre-Chemins. To and fro, to and fro, he paced the fields, with long, rhythmical steps, till the corn in his bag came to an end; while, in his wake, the seed strewed all the soil.

The house of Maître Baillehache, notary at Cloyes, was situated in the Rue Grouaise, on the left hand going to Châteaudun. A little white, one-storey house it was, at the corner of which a bracket was riveted for the rope of the single lantern which lighted this broad, paved street, deserted during the week, but on Saturday nights crowded with a living tide of peasants coming to market. From afar might be seen the gleam of the two professional escutcheons against the chalk-like wall of the low buildings; and, behind, a narrow garden stretched down to the Loir.

On that Saturday, in the room which served as an office, and which looked out upon the street to the right of the entrance hall, the youngest clerk, a pale, wizened boy of fifteen, had drawn up one of the muslin curtains to see the people pass. The other two clerks—one old, corpulent, and very dirty; one younger, scraggy, and a hopeless victim to liver complaint—were writing at a double desk of ebonised deal, there being no other furniture except seven or eight chairs and a cast-iron stove, which was never lit till December, even if it snowed a month before. Rows of pigeon-holes decorated the walls, with greenish pasteboard boxes, broken at the corners and full to repletion with bundles of yellow papers, and the room was pervaded with an unwholesome smell of ink gone bad and dust-eaten documents.

However, seated side by side, two peasants, man and wife, were waiting in deep respect, like statues of Patience. So many papers, and, more than all, the gentlemen who wrote so fast, with their pens all scratching away at once, sobered them by evoking vague visions of law-suits and money. The woman, aged thirty-four, very dark, with a countenance which would have been pleasant but for a large nose, had her horny, toil-worn hands crossed over her black cloth, velvet-edged body, and was scanning every corner with her keen eyes, evidently musing on the many title-deeds which reposed here. In the meanwhile the man, five years older, red-haired and stolid, in black trousers and a long, bran-new blue linen blouse, held[Pg 17] his round felt hat on his knees, with not a spark of intelligence illuminating his broad, clean-shaven, terra-cotta-like face, which was perforated with two large eyes of porcelain blue, having a fixed stare that reminded one of a somnolent ox.

A door opened, and Maître Baillehache, who had just breakfasted with his brother-in-law, farmer Hourdequin, made his appearance; ruddy and fresh-complexioned despite his fifty-five years, with thick lips and crow's feet, which gave him a perpetually amused expression. He carried a double eye-glass, and had a lunatic habit of always pulling at his long, grizzled whiskers.

"Ah! it's you, Delhomme," said he. "So, old Fouan has consented to divide the property?"

The reply came from the woman.

"Yes, sure, Monsieur Baillehache. We have all made an appointment, so that we may come to an agreement, and that you may tell us how we are to proceed."

"Good, good, Fanny; we'll see about it. It's hardly more than one o'clock, we must wait for the others."

The notary stopped an instant to chat, asking about the price of corn, which had fallen during the last two months, and showing Delhomme the friendly consideration due to a farmer who owned fifty acres of land, and kept a servant and three cows. Then he returned to his inner room.

The clerks had not raised their heads, but were scratching away with their pens more vigorously than ever; and, once more, the Delhommes waited motionless. Fanny had been a lucky girl to marry a respectable, rich lover without even getting into the family-way beforehand, she whose only expectations had been some seven or eight acres of land from old Fouan. Her husband, however, had not repented of his bargain, for he could not anywhere have found a more active or intelligent housekeeper. Hence he followed her lead in everything, being of a narrow mind, but so steady and straightforward as to be frequently selected as an umpire by the Rognes people.

At that moment the little clerk, who was looking out into the street, stifled a laugh behind his hand, and murmured to his old, corpulent, and very dirty neighbour: "Here's Hyacinthe the saint coming!"

Fanny bent down quickly to whisper to her husband: "Now, leave everything to me. I am fond enough of papa and mamma, but I won't have them rob us; and keep a sharp eye on Buteau and that rascal Hyacinthe."

She referred to her two brothers, having seen one of them[Pg 18] approach as she looked out of the window: Hyacinthe, the elder, whom the whole neighbourhood knew as an idler and a drunkard, and who, at the close of his military service, after going through the Algerian campaigns, had taken to a vagabond life, refusing all regular work, and subsisting by poaching and pillage, as if he were still extortioner-in-ordinary among a terrified people of Bedouins.

A tall, strapping fellow came in, rejoicing in the brawny strength of his forty years; he had curly hair, and a pointed, long, unkempt beard, with the face of a saint laid waste, a saint sodden with strong drink, addicted to forcing girls, and to robbing folks on the highway. He had already got tipsy at Cloyes since the morning, and wore muddy trousers, a filthily-stained blouse, and a ragged cap stuck on the back of his neck. He was smoking a damp, black, pestilential halfpenny cigar. Yet, in the depths of his fine liquid eyes lurked a spirit of fun free from ill-feeling, the open-heartedness of good-natured blackguardism.

"So father and mother haven't turned up yet?" he asked.

When the thin, jaundiced clerk responded testily by a shake of the head, he stared for an instant at the wall, while his cigar smouldered in his hand. He had not so much as glanced at his sister and his brother-in-law, who, themselves, did not appear to have seen him enter. Then, without a word, he left the room, and went to hang about on the pavement.

"Hyacinthe! Hyacinthe!" droned the little clerk, turning streetwards, and seeming to find infinite amusement in this name, which brought many a funny tale back to his memory.

Hardly five minutes had passed before the Fouans made their tardy appearance, two old folk of slow, prudential gait. The father, once very robust, now seventy years of age, had shrivelled and dwindled down under such hard work, such a keen land-hunger, that his form was bowed as if in a wild impulse to return to that earth which he had coveted and possessed. Nevertheless, in all save the legs, he was still hale and well-knit, with spruce little white mutton-chop whiskers, and the long family nose, which lent an air of keenness to his thin, leathery, deeply-wrinkled face. In his wake, following him as closely as his shadow, came his wife; shorter and stouter, swollen as if by an incipient dropsy, with a drab-coloured face perforated with round eyes, and a round mouth pursed up into an infinity of avaricious wrinkles. A household drudge, endowed with the docile, hard-working stupidity of a beast of burden, she had always stood in awe of the despotic authority of her husband.

"Ah, so it's you!" cried Fanny, getting up. Delhomme, also, had risen from his chair. Behind the old people, Hyacinthe had just lounged in again without a word. Compressing the cigar end to put it out, he thrust the pestiferous stump into a pocket of his blouse.

"So we're here," said Fouan. "There's only Buteau missing. Never in time, never like other people, the beast!"

"I saw him in the market," asserted Hyacinthe in a husky voice due to drink. "He's coming."

Buteau, the younger son, owed his nickname to his pigheadedness, being always up in arms in obstinate defence of his own ideas, which were never those of anybody else. Even when an urchin, he had not been able to get on with his parents; and, later on, having drawn a lucky number in the conscription, he had run away from home to go into service, first at La Borderie, subsequently at La Chamade.

While his father was still grumbling, he skipped cheerfully into the room. In him, the large Fouan nose was flattened out, while the lower part of his face, the maxillaries, projected like the powerful jaws of a carnivorous beast. His temples retreated, all the upper part of his head was contracted, and, behind the boon-companion twinkle of his grey eyes, there lurked deceit and violence. He had inherited the brutish desires and tenacious grip of his father, aggravated by the narrow meanness of his mother. In every quarrel, whenever the two old people heaped reproaches upon his head, he replied: "You shouldn't have made me so!"

"Look here, it's five leagues from La Chamade to Cloyes," replied he to their complaints; "and besides, hang it all, I'm here at the same time as you. Oh, at me again, are you?"

They all disputed, shouted in shrill, high-pitched voices, and argued over their private matters exactly as if they had been at home. The clerks, disturbed, looked at them askance, till the tumult brought in the notary, who re-opened the door of his private office.

"You are all assembled? Then come in!"

This private office looked on to the garden, a narrow strip of ground running down to the Loir, the leafless poplars along which were visible in the distance. On the mantelpiece, between some packets of papers, there was a black marble clock; the furniture simply comprised the mahogany writing-table, a set of pasteboard boxes, and some chairs. Monsieur Baillehache at once installed himself at his writing-table, like a judge on the bench, while the peasants who had entered in a file hesitated[Pg 20] and squinted at the chairs, feeling embarrassed as to where and how they were to sit down.

"Come, seat yourselves!" said the notary.

Then Fouan and Rose were pushed forward by the rest on to the two front chairs; Fanny and Delhomme got behind, also side by side; Buteau established himself in an isolated corner against the wall; while Hyacinthe alone remained standing, in front of the window, blocking out the light with his broad shoulders. The notary, out of patience, addressed him familiarly.

"Sit down, do, Hyacinthe!"

He had to broach the subject himself.

"So, Fouan, you have made up your mind to divide your property before your death, between your two sons and your daughter?"

The old man made no reply. The rest were as if frozen to stone; there was deep silence.

On his part, the notary, accustomed to such sluggishness, did not hurry himself. His office had been in his family two hundred and fifty years. Baillehache, son, had succeeded Baillehache, father, at Cloyes, the line being of ancient Beauceron extraction, and they had contracted from their rustic connection that ponderous reflectiveness, that artful circumspection, which protract the most trivial debates with long pauses and irrelevant talk. Having taken up a penknife the notary began paring his nails.

"Haven't you? It would appear that you have made up your mind," he repeated at length, looking hard at the old man.

The latter turned, looked round at everybody, and then said, hesitatingly:

"Yes; that may be so, Monsieur Baillehache. I spoke to you about it at harvest-time. You told me to think it over; and I have thought it over, and I can see that it will have to come to that."

He explained the why and wherefore, in faltering phrases, interspersed with constant digressions. But there was one thing which he said nothing about, but which was obvious from the repressed emotion which choked his utterance—and that was the infinite distress, the smothered rancour, the rending asunder, as it were, of his whole frame, which he felt in parting with the property so eagerly coveted before his father's death, cultivated later on with the violent avidity of lust, and then added to, bit by bit, at the cost of the most sordid avarice. Such-and-such a plot represented months of bread and cheese, tireless[Pg 21] winters, summers of scorching toil, with no other sustenance than a few gulps of water. He had loved the soil as it were a woman who kills, and for whose sake men are slain. No spouse, nor child, nor any human being; but the soil! However, being now stricken in years, he must hand his mistress over to his sons, as his father, maddened by his own impotence, had handed her over to him.

"You see, Monsieur Baillehache, one has to look at things as they are. My legs are not what they used to be; my arms are hardly better; and, of course, the land suffers accordingly. Things might still have gone on if one could have come to an understanding with one's children."

He glanced at Buteau and Hyacinthe, who made no sign, however; their eyes were looking into vacancy, as though they were a hundred miles away from him and his words.

"Well, am I to be expected to take strange people under our roof, to pick and steal? No, servants now-a-days cost too much; they eat one out of house and home. As for me, I am used up. This year, look you, I have hardly had the strength to cultivate a quarter of the nineteen setiers[2] I possess; just enough to provide corn for ourselves and fodder for the two cows. So, you understand, it's breaking my heart to see good land spoiled by lying idle. I had rather let everything go than look on at such sinful waste."

His voice faltered; his gestures were those of resigned anguish. Near him listened his submissive wife, crushed by more than half a century of obedience and toil.

"The other day," he continued, "Rose, while making her cheeses, fell into them head first. It wears me out only to jog to market. And then, we can't take the land away with us when we go. It must be given up—given up. After all, we have done enough work, and we want to die in peace. Don't we, Rose?"

"That's true enough; true as we sit here," said the old woman.

There fell a new and prolonged silence. The notary finished trimming his nails, and at last he put the knife back on his desk, saying:

"Yes, those are very good reasons; one is frequently forced to resolve on a deed of gift. I should add that it saves expense, for the legacy duties are heavier than those on the transference of property."

Buteau, despite his affectation of indifference, could not help exclaiming:

"Then it's true, Monsieur Baillehache?"

"Most certainly. You will save some hundreds of francs."

There was a flutter among the others; even Delhomme's countenance brightened, while the parents also shared in the general satisfaction. The moment they knew it was cheaper, the thing was as good as done.

"It remains for me to make the usual observations," continued the notary. "Many thoughtful persons condemn such transfers of property, and regard them as immoral, in that they tend to sever family ties. Deplorable instances might, in fact, be mentioned, children having sometimes behaved very badly, when their parents had stripped themselves of all."

The two sons and the daughter listened to him, open-mouthed, with trembling eyelids and quivering cheeks.

"Let papa keep everything himself, if those are his ideas," brusquely interrupted the very susceptible Fanny.

"We have always been dutiful," said Buteau.

"And we're not afraid of work," added Hyacinthe.

With a wave of his hand Maître Baillehache restored calm.

"Pray, let me finish! I know you are good children, and honest workers; and, in your case, there is not the slightest danger of your parents ever repenting of their resolution."

He spoke without a tinge of irony, repeating the conciliatory phrases which five-and-twenty years of professional practice had made smooth upon his tongue. However, the mother, although seeming not to understand, glanced with her small eyes from her daughter to her two sons. She had brought them up, without any show of fondness, amid the chill parsimony which reproaches the little ones with diminishing the household savings. She had a grudge against the younger son for having run away from home just when he was capable of earning wages; the daughter she had never been able to get on with, encountering in her a strain too like her own, a robust activity made haughty and unyielding by the intermingled intelligence of the father; and her gaze only softened as it rested upon the elder son, the ruffian who took neither after her nor after her husband—the ill weed sprung none knew whence, and, perhaps, excused and favoured on that account.

Fouan also had looked at his children, one after the other, with an uneasy mistrust of the uses they might make of his property. The laziness of the drunkard was not so keen an anguish to him as the covetous yearning of the two others for[Pg 23] possession. However, he bent his trembling head. What was the good of kicking against the pricks?

"The partition being thus resolved upon," resumed the notary, "the question becomes one of terms. Are you agreed upon the allowance which is to be paid?"

Everybody suddenly relapsed into mute rigidity. Their sun-burnt faces assumed a stony look, an air of impenetrable gravity, like that of diplomatists entering on the appraisement of an empire. Then they threw out tentative glances one to another, but nobody spoke. At last the father once more explained matters.

"No, Monsieur Baillehache, we have not entered on the subject; we were waiting till we met all together, here. But it's quite simple, isn't it? I have nineteen setiers, or, as people now say, nine hectares and a half (about twenty-three acres). So that, if I rented them out, it would come to nine hundred and fifty francs, at a hundred francs per hectare (two and a half acres)."

Buteau, the least patient, leapt from his chair.

"What! A hundred francs per hectare! Do you take us for fools, papa?"

And a preliminary discussion began on the question of figures. There was a setier of vineyard; that, certainly, would let for fifty francs. But would that price ever be got for the twelve setiers of plough-land, still less for the six setiers of natural meadow-land, the fields along the Aigre, the hay of which was worth nothing? The plough-land itself was hardly of good quality, especially at the end which edged the plateau, for the arable layer got thinner and thinner as it neared the valley.

"Come, come, papa," said Fanny, reproachfully, "you mustn't take an unfair advantage of us."

"It's worth a hundred francs a hectare," repeated the old man stubbornly, slapping his thigh. "I could let it out to-morrow at a hundred francs if I wanted to. And what's it worth to you, now? Just let's hear what it's worth to you?"

"It's worth sixty francs," said Buteau, but Fouan, greatly put out, sustained his price, and launched into fervent eulogy of his land—such fine land as it was, yielding wheat of itself—when Delhomme, silent till then, declared in his blunt, honest way: "It's worth eighty francs, not a copper more, and not a copper less."

The old man immediately calmed down.

"All right, say eighty. I don't mind making a sacrifice for my children."

Rose, twitching at a corner of his blouse, expressed in one word the outraged instincts of her mean nature—"No!"

Hyacinthe held himself aloof. Land had been no object to him since the five years he had spent in Algeria. He had but one aim: to get his share at once, whatever it might be, and to turn it into money. Accordingly, he went on swinging to and fro with an air of amused superiority.

"I said eighty," cried Fouan, "and eighty it is. I have always been a man of my word; I swear it. Nine hectares and a half, look you, come to seven hundred and sixty francs, or, in round numbers, eight hundred. Well, the allowance shall be eight hundred francs, that's fair enough?"

Buteau burst into a violent fit of laughter, while Fanny protested by a shake of the head, as if dumbfounded. Monsieur Baillehache, who, since the discussion began, had been looking vacantly into the garden, again turned to his clients and seemed to listen, tugging in his lunatic way at his whiskers, and dreamily digesting the excellent meal he had just made.

This time the old man was right, it was fair. But the children, heated and possessed by the one idea of concluding the bargain on the lowest possible terms, grew absolutely ferocious, and haggled and cursed with the bad faith of yokels buying a pig.

"Eight hundred francs!" sneered Buteau. "Seems you want to live like gentle folks——Oh, indeed! Eight hundred francs, when you might live on four! Why not say at once that you want to gorge till you burst?"

Fouan had not yet lost his temper, considering the higgling natural, and simply facing the expected storm, himself excited, but making straight for the goal he had in view.

"Stop a bit! that's not all. Till the day of our death we keep the house and garden, of course. Then, as we shall no longer get anything from the crops, or have our two cows, we want every year a cask of wine and a hundred faggots; and every week eight quarts of milk, a dozen eggs, and three cheeses."

"Oh, papa!" groaned Fanny in piteous consternation. "Oh, papa!"

As for Buteau, he had done with discussion. He had sprung to his feet, and was striding brusquely to and fro; he had even jammed his cap on his head as if he were about to go. Hyacinthe also had likewise got up from his chair, disquieted by the idea that this fuss might prevent the partition after all. Delhomme[Pg 25] alone remained impassive, with his finger laid against his nose, in an attitude of deep thought and extreme boredom.

At this point Maître Baillehache felt it necessary to help matters forward a little. Rousing himself up, and fidgeting more energetically with his whiskers:

"You know, my friends," said he, "that wine, faggots, cheese, and eggs are customary."

But he was cut short by a volley of bitter phrases.

"Eggs with chickens inside, perhaps!"

"We don't drink our wine, do we? We sell it!"

"It's jolly convenient not to do a blasted thing and be made warm and comfortable, while your children are toiling and moiling!"

The notary, who had heard the same thing often enough before, continued unmoved:

"All that is no argument. Come, come, Hyacinthe, sit down, will you? You're keeping out the light; you're a perfect nuisance! So that's settled, isn't it, all of you? You will pay the dues in kind, because otherwise you would become a by-word. We have, therefore, only to discuss the amount of the allowance."

Delhomme at length indicated that he had something to say. Everybody having resumed his place, he began slowly, amid general attention:

"Excuse me; what the father asks seems fair: he might be allowed eight hundred francs on the ground that he could let the property for eight hundred francs—only we don't reckon like that on our side. He is not letting us the land, but giving it to us, and what we have to calculate is: how much do he and his wife require to live on? That is all. How much do they require to live on?"

"That is, certainly," chimed in the notary, "the usual basis of calculation."

Another endless dispute set in. The two old folks' lives were dissected, exposed, and discussed, need by need. Bread, vegetables, and meat were weighed out; clothing appraised, linen and woollen, to the utmost farthing; even such trivial luxuries as the father's tobacco—cut down, after interminable recriminations, from two sous a day to one—were not beneath notice. When people were beyond work, they ought to reduce their expenditure. The mother, again; could she not do without her black coffee? It was like their twelve-year-old dog, who ate, and ate, and made no return; he ought to have had a bullet put through his head long ago! The calculation was[Pg 26] no sooner finished than it was begun all over again, on the chance of finding some other item to suppress: two shirts or six handkerchiefs in the year. And thus, by cutting closer and closer, by pinching and scraping in the paltriest matters, they got down to five hundred and fifty odd francs, which left the children in a state of uncontrollable agitation, for they had set their hearts upon not giving more than five hundred.

Fanny, however, was growing tired. She was not a bad sort, having more of the milk of human kindness than the men, and not yet having had her heart or her skin hardened by rough life in the open air. Accordingly she spoke of making an end of it, and resigned herself to some concessions. Hyacinthe, for his part, shrugged his shoulders, in a most liberal, not to say maudlin mood; ready to offer, out of his own share, any little balance which, be it remarked, he would never have paid.

"Come," asked the daughter, "shall we let it go at five hundred and fifty?"

"Right you are!" answered he. "The old 'uns must have a little pleasant time!"

The mother turned to her elder son with a smiling and yet almost tearful look of affection, while the father continued his contention with the younger. He had only given way step by step, disputing every reduction, and making a stubborn stand on certain items. But, beneath his ostensibly cool pertinacity, his wrath rose high within him as he confronted the mad desire of his own flesh and blood to fatten on his flesh, and to drain his blood dry while he was yet alive. He forgot that he had thus fed upon his own father. His hands had begun to tremble; and he growled out:

"Ah, the rascals! To think that one has brought 'em up, and then they turn round and take the bread out of one's mouth! On my word, I'm sick of it. I'd rather be already rotting under ground. So there's no getting you to behave decently; you won't give more than five hundred and fifty?"

He was about to accept the sum, when his wife again twitched his blouse and whispered:

"No, no!"

"And that's not all," resumed Buteau, after a little hesitation. "How about the money you have saved up? If you've any money of your own you don't want ours, do you?"

He looked steadily at his father, having reserved this shot for the last. The old man had grown very pale.

"What money?" he asked.

"Why, the money invested; the money you hold bonds for."

Buteau, who only suspected the hoard, wanted to make sure. One evening, he had thought he saw his father take a little roll of papers from behind a looking-glass. The next day and the days following he had been on the watch, but nothing had turned up; the empty cavity alone remained.

Fouan's pallor now suddenly changed to a deep red as his torrent of wrath at length burst forth. He rose up, and shouted with a furious gesture:

"Great heaven! You go rummaging in my pockets now. I haven't a sou, a copper invested; you've cost too much for that, you brute. But, in any case, is it any business of yours? Am I not the master, the father?"

He seemed to grow taller in the re-assertion of his authority. For years everybody, wife and children alike, had quailed before him, under his rude despotism as chief of the family. If they fancied all that at an end, they made a mistake.

"Oh, papa!" began Buteau, with an attempt at a snigger.

"Hold your tongue, in God's name!" resumed the old man, with his hand still uplifted. "Hold your tongue, or I strike!"

The younger son stammered, and shrank into himself on his chair. He had felt the blow approaching and had raised his elbow to ward it off, seized once more with the terrors of infancy.

"And you, Hyacinthe, leave off smirking! And you, Fanny, look me in the face, if you dare! True as the sun's shining, I'll make it lively for some of you; see if I don't!"

He stood, threateningly, over them all. The mother shivered, as if apprehensive of stray buffets. The children neither stirred nor breathed, they were conquered and submissive.

"Understand, the allowance shall be six hundred francs; or else I shall sell my land and invest in an annuity. Yes, an annuity! All shall be spent, and you sha'n't come into a copper. Will you give the six hundred francs?"

"Why, papa," murmured Fanny, "we will give whatever you ask."

"Six hundred francs. Right!" said Delhomme.

"What suits the rest, suits me," declared Hyacinthe.

Buteau, setting his teeth viciously, gave the consent of silence. Fouan still held them in check, with the stern look of one accustomed to obedience. Finally, he sat down again, saying: "Good! Then we are agreed."

Maître Baillehache had begun to doze again, unconcernedly awaiting the issue of the quarrel. Now, opening his eyes, he brought the interview to a peaceful close.

"Well, then, as you're agreed, that's enough! Now I know the terms, I will draw up the deed. For your part, get the surveying done, portion out the lots, and tell the surveyor to forward me a note containing the description of the lots. Then, when you've drawn your numbers, all we shall have to do will be to write the number drawn against each name, and sign."

He had risen from his arm-chair to see them out. But they, hesitating, and reflecting, would not stir. Was it really over? Was nothing forgotten? Had they not made a bad bargain, which there was yet time, perhaps, to cancel?

Four o'clock struck; they had been there nearly three hours.

"Aren't you going?" said the notary to them at last. "There are others waiting."

He precipitated their decision by hustling them into the next room, where, indeed, a number of patient rustics were sitting still and rigid upon their chairs, while the small clerk watched a dog-fight out of the window, and the two others still drove their pens, sulkily and scratchily, over stamped paper.

Once outside, the family stood for a moment stock-still in the middle of the street.

"If you like," declared the father, "the measuring shall take place on the day after to-morrow—Monday."

They nodded assent, and went down the Rue Grouaise in scattered file.

Then, old Fouan and Rose, having turned down the Rue du Temple, towards the church, Fanny and Delhomme went off through the Rue Grande. Buteau had stopped on the Place Saint-Lubin, wondering if his father had a hidden hoard or not; and Hyacinthe, left by himself, relighted his cigar-end, and went into the Jolly Ploughman café.

The Fouans house was the first in Rognes, on the high-road from Cloyes to Bazoches-le-Doyen, which passes through the village. On Monday, the old man was going out at seven o'clock in the morning to keep the appointment in front of the church, when, in the next doorway, he perceived his sister, "La Grande," who was already astir, despite her eighty years.

These Fouans had propagated and grown there for centuries, like some sturdy luxuriant vegetation. Serfs in the old times of the Rognes-Bouquevals—of whom not a trace survived save the few half-buried stones of a ruined château—they had been emancipated, it appeared, under Philip the Fair; becoming thenceforward landowners of an acre or so, which they had bought from the lord of the manor when in difficulties, and paid for with tears and blood at ten times the value. Then had set in the long struggle of four hundred years to defend and enlarge the property, in a frenzy of passion transmitted from father to son: odd corners were lost and bought back, the ownership was unremittingly called into question, the inheritances were subject to such a list of dues that they almost ate their own heads off; but in spite of all, both arable and plough-lands grew, bit by bit, in the ever-prevailing, stubborn craving for possession. Generations passed away, the lives of many men enriched the soil; but when the Revolution of '89 set its seal upon his rights, the Fouan of the time, Joseph Casimir, possessed about twenty-six acres, wrested in the course of four centuries from the old seignorial manor.

In '93, this Joseph Casimir was twenty-seven years of age, and on the day when what remained of the manor was declared national property and sold in lots by auction, he yearned to acquire a few acres of it. The Rognes-Bouquevals, ruined and in debt, after letting the last tower of the château crumble into dust, had long since given up to their creditors the right of receiving the revenues of La Borderie, three quarters of which property lay fallow. In particular, adjacent to one of Fouan's bits of land there was a large field, on which he looked with the fierce covetousness of his race. But the harvest had[Pg 30] been poor, and in the old pipkin behind his oven he had barely a hundred crowns saved up. Moreover, although it had momentarily occurred to him to borrow off a Cloyes money-lender, a distrustful prudence had stood in the way: he was afraid to touch these lands of the nobility; who knew whether they would not be claimed again later on? So it happened that, divided between desire and apprehension, he had the agony of seeing La Borderie bought at auction, field by field, and for a tenth of its value, by Isidore Hourdequin, a townsman of Châteaudun, formerly employed in the collection of excise duties.

Joseph Casimir Fouan, in his old age, had divided his twenty-six acres equally among his eldest child, Marianne, and his two sons, Louis and Michel; a younger daughter Laure, brought up to dressmaking and employed at Châteaudun, being indemnified in hard cash. But marriage destroyed this equality. While Marianne Fouan, surnamed "La Grande," wedded a neighbour, Antoine Péchard, with about twenty-two acres; Michael Fouan, surnamed "Mouche," encumbered himself with a sweetheart who only expected from her father two and a half acres of vineyard. On the other hand, Louis Fouan, joined in matrimony to Rose Maliverne, the heiress to fifteen acres, had acquired that total of twenty-three acres or so, which, in his turn, he was about to divide among his three children.

La Grande was respected and dreaded in the family, not for her advanced age, but for her fortune. Still very upright, tall, thin, wiry, and large-boned, she had the fleshless head of a bird of prey set on a long, shrivelled, blood-coloured neck. In her, the family nose curved into a formidable beak; she had round fixed eyes, with not a trace of hair under the yellow silk handkerchief she always wore, though she possessed her full complement of teeth, and jaws that might have masticated flints. She never went out without her thornwood stick, which she held on high as she walked, only making use of it to strike animals and human beings. Left a widow at an early age, she had turned her one daughter out of doors, because the wretch had insisted, against her mother's will, on marrying a poor youth, Vincent Bouteroue; and even when this daughter and her husband had died of want, leaving behind them a grand-daughter and a grandson, Palmyre and Hilarion, aged respectively thirty-two and twenty-four, she had refused her forgiveness and let them starve to death, allowing no one so much as to remind her of their existence. Since her goodman's death she presided in person over the cultivation of her land; she had three cows, a pig,[Pg 31] and a farm-hand, all fed out of a common trough; and she was obeyed by those about her with the most abject submission.

Fouan, seeing her on her threshold, had drawn near out of respect. She was ten years older than he, and he regarded her sternness, her avarice, her obstinate resolution to possess and to live, with an admiring deference, shared by the whole village.

"I was just wanting to tell you about it, La Grande," said he. "I have made up my mind, and am going up yonder to see about the division."

She made no reply, but tightened her grasp upon the stick which she was flourishing.

"The other night I wanted to ask your advice again, but I knocked and no one answered."

Then she broke out in shrill tones:

"Idiot! Advice, indeed! I gave you advice. The fool, the poltroon you must be to give your property up as long as you can get about. They might have bled me to death, but, under the knife, I would still have refused. To see what belongs to one in the hands of others, to turn one's self out of doors for the benefit of rascally children.—No! No! No!"

"But," put in Fouan, "if you're incapable of farming, and the land suffers accordingly."

"Well, let it suffer. Rather than lose half an acre of it, I would go and watch the thistles grow every morning."

She drew herself up grimly, in her featherless, old vulture-like way, and, drumming on his shoulder with her stick, as if to impress her words upon him more deeply, she resumed:

"Listen, and mark me. When you have nothing and they have everything, your children will refuse you a mouthful of bread. You'll end with a beggar's wallet, like a road-tramp. And when that happens, don't come knocking at my door, for I give you fair warning, it'll be the worse for you. Would you like to know what I shall do, eh? Would you?"

He waited submissively, as behoved a younger brother; and she returned indoors, banging the door behind her and screaming:

"I shall do that! Die in a ditch!"

Fouan stood for an instant motionless before the closed door. Then, with a gesture of resigned decision, he went up the path leading to the Place de l'Eglise. On that very spot stood the old family residence of the Fouans, which, in the division of property, had fallen to his brother Michel, called Mouche; his own house, lower down along the road, had come to[Pg 32] him from his wife Rose. Mouche, who had long been a widower, lived alone with his two daughters, Lise and Françoise, embittered by disappointments, still humiliated by his lowly marriage, and accusing his brother and sister, after forty years, of having cheated him when the allotments were drawn for. He was for ever telling the tale how the worst lot had been left for him at the bottom of the hat; and, in the course of time, this seemed to have become true, for he proved so excellent at excuses and such a sluggard at work that his share lost half its value in his hands. "The man makes the land," as folks say in La Beauce.

That morning Mouche also was on the watch at his door when his brother came round the corner of the square. The division roused his spleen, reviving old grudges, although he had nothing to expect from it. However, to demonstrate his utter indifference, he, too, turned his back and shut the door with a slam.

Fouan had suddenly caught sight of Delhomme and Hyacinthe, who were waiting twenty yards apart from each other. He made for the former, while the latter made for him. The three, without speaking, scanned the path which skirted the edge of the plateau.

"There he is," said Hyacinthe, at last. "He" was Grosbois, the local surveyor, a peasant from Magnolles, a little village near Cloyes. His knowledge of reading and writing had ruined him. When summoned from Orgères to Beaugency, on surveying business, he used to leave to his wife the management of his property, and he had contracted during his constant pilgrimages such drunken habits that he was now never sober. Very stout, very sturdy for his sixty years, he had a broad red face budding all over into purple pimples; and, despite the early hour, he was, on the day in question, in a state of abominable intoxication, the result of a merry-making held the night before by some Montigny vine-growers in honour of a divided inheritance. But that mattered nothing: the tipsier he was, the clearer his brain. He never measured incorrectly, and never added up incorrectly. He was held in deference and honour, advisedly, for he had the reputation of being extremely spiteful.

"All here, eh?" said he. "Then come along."

A dirty, bedraggled urchin of twelve was in attendance, carrying the chain under his arm and the stand and the staves over his shoulder, while with his free hand he swung the square, which was in an old burst cardboard case.

They all set out without waiting for Buteau, whom they[Pg 33] had just descried in the distance, standing still before the largest field of the holding. That field, some five acres in extent, was immediately adjacent to the one along which La Coliche had dragged Françoise a few days before. Buteau, thinking it useless to proceed further, had stopped there in a brown study. When the others arrived, they saw him stoop down, take up a handful of earth, and gradually filter it through his fingers, as though to estimate its weight and flavour.

"There," resumed Grosbois, taking a greasy memorandum-book from his pocket: "I have already drawn up an accurate little plan of each lot, as you asked me to do, Fouan. It now devolves upon us to divide the whole into three portions; and that, my children, we will do together, eh? Just tell me how you intend it to be done."

The day had worn on. A ripping wind was driving continuous masses of thick clouds across the pale sky; and La Beauce lay sullen and gloomy, lashed by the keen air. Yet not one of them seemed conscious of that breeze from the offing, which inflated their blouses and threatened to carry off their hats. Not one of the five, in holiday attire, as befitted the gravity of the occasion, spoke a word. As they stood on the confines of the field, amid the boundless expanse, their lineaments had a dreamy, frozen fixedness, the musing expression of mariners who live alone in large open spaces. La Beauce, flat and fertile, easily tilled but demanding continuous effort, has made the Beauceron calm and reflective, without passion save for the land itself.

"It'll all have to be divided into three," said Buteau at length.

Grosbois shook his head, and a discussion set in. An apostle of progress, by virtue of his connection with large farms, he occasionally went so far as to set himself up against his smaller clients, by condemning extreme subdivision. Would not the labour and cost of transport from place to place become a ruinous thing, when there were only odds and ends of land left that might be covered by a handkerchief? Was it farming at all, with paltry garden-plots on which it was impossible either to improve the system of crops or to introduce machinery? No: the only sensible thing to do was to make a mutual arrangement, not to adopt the murderous course of chopping a field up like so much pastry. If one of them would be content with the plough-land, another might manage with the meadows; the portions could eventually be equalised, and the distribution decided by lot.

Buteau, with the natural liveliness of youth, adopted a jocose tone. "And, with only some meadow-land, what shall I have to eat? Grass, I suppose? No, no; I want some of everything, hay for cow and horse, corn and grape for myself."

Fouan, who was listening, nodded assent. For generations, such had been the mode of partition; and fresh acquisitions, by marriage or otherwise, had subsequently swollen the plots anew.

Delhomme, passing rich with his fifty acres or so, had broader views; but he was in a conciliatory mood, and had indeed only come, in his wife's interest, to see that she was not cheated in the measurements. As for Hyacinthe, he had gone off in pursuit of a flight of larks, with his hands crammed full of pebbles. Whenever one of the birds, distressed by the wind, stopped still a couple of seconds in mid-air with quivering wings, he felled it to the ground with the skill of a savage. Three fell, and he thrust them bleeding into his pocket.

"Come, stop your talk, and let's have it cut up into three!" said the lively Buteau, addressing the surveyor familiarly; "and not into six, mind, for you seem to me this morning to have both Chartres and Orleans in your eye at once."

Grosbois, feeling hurt, drew himself up with much dignity.

"When you've had as much to drink as I have, young shaver, see whether you can keep your eyes open at all. Which of you clever people would like to take the square instead of me?"

As no one ventured to take up the challenge, he called out harshly and triumphantly to the boy, who was rapt with admiration of Hyacinthe's pebble-shooting. The square duly installed on its stand, the stakes were being set up, when a new dispute arose over the method of dividing the field. The surveyor, supported by Fouan and Delhomme, wanted to divide the five acres into three strips parallel with the Aigre valley; while Buteau insisted on the strips being taken perpendicular to the valley, on the plea that the arable layer got thinner and thinner as it neared the slope. In this way every one would have his share of the worse end; whereas, in the other case, the third lot would be altogether of inferior quality.

But Fouan grew heated; swore that the depth was the same everywhere, and reminded them that the former partition between himself, Mouche, and La Grande had been made in the direction he indicated; in proof of which, Mouche's five acres lay adjacent to the third of the proposed lots. Delhomme, on his side, made a decisive remark: even admitting that the[Pg 35] one lot was inferior, the owner would be benefited as soon as the authorities decided to open the road that was to skirt the field at that point.

"Oh, yes; I daresay!" cried Buteau. "The celebrated road from Rognes to Châteaudun, by way of La Borderie! And a jolly long time you'll have to wait for it!"

His importunity being, nevertheless, disregarded, he entered a protest from between his clenched teeth.

Hyacinthe himself had drawn near, and they were all absorbed in watching Grosbois trace out the lines of division. They kept a sharp eye on him, as if they suspected him of trying by unfair means to make one share half-an-inch bigger than the others. Three times did Delhomme put his eye to the slit in the square, to make quite sure that the line fairly intersected the stave. Hyacinthe swore at the "d——d youngster" because he did not hold the chain right. But Buteau, in particular, followed the process step by step, counting the feet, and going over the calculations again in his own way with trembling lips. With this consuming desire to possess, with the joy he felt at getting at last a grip of the land, his bitterness and sullen rage at not being able to keep the whole grew and grew. Those five acres, all of one piece, made such a fine field. He had insisted on the division, so that no one might have what he couldn't get; and yet the wholesale destruction drove him distracted. He again tried to find frivolous causes of quarrel.

Fouan, standing in a listless attitude, had been looking on at the dismemberment of his property without a word.

"It's finished!" said Grosbois. "And look at it how you will, you won't find a pound difference between the lots."

There were still, on the plateau, ten acres of plough-land divided into a dozen plots, none of which were much more than an acre in size. Indeed, one was only about a rood, and the surveyor having inquired, with a sneer, whether that also was to be sub-divided, a fresh dispute arose.

Buteau, with his instinctive gesture, had stooped down and taken up a handful of earth, which he raised to his face as if to try its flavour. A complacent wrinkling of his nose seemed to pronounce it better than all the rest; and, after gently filtering it through his fingers, he said that if they left the lot to him it was all right, otherwise he insisted on a division. Delhomme and Hyacinthe angrily refused, and likewise wanted their share. Yes, yes! A third of a rood each; that was the only fair way. By sub-dividing every plot, they were[Pg 36] sure that none of the three could have anything which the other two lacked.

"Come on to the vineyard," said Fouan, and as they turned towards the church, he threw a last glance over the vast plain, pausing for an instant to look at the distant buildings of La Borderie. Then, with a cry of inconsolable regret, alluding to the old lost opportunity of buying up the national property:

"Ah!" said he, "if father had only chosen, Grosbois, you would now be measuring all that!"

The two sons and the son-in-law turned sharply round, and there was a new halt and a lingering look at the seven hundred and fifty acres of the farm spread out before them.

"Ugh!" grunted Buteau, as he set off again: "Much good it does us, that story! It's always our fate to be the prey of the townsfolk."

Ten o'clock struck. The main part of the work was over. But they hastened their steps, for the wind had fallen, and a heavy dark cloud had just discharged itself of a premonitory shower. The various Rognes vineyards were situated beyond the church, on the hill-side which sloped down to the Aigre. In former times, the château had stood there with its grounds; and it was barely more than a century since the peasantry, encouraged by the success of the Montigny vineyards, near Cloyes, had decided to plant vines on this declivity, though it was specially adapted for the purpose by its Southern aspect and the steepness of its slope. The wine it yielded was thin but of a pleasantly acid taste, and resembled the minor Orléanais vintages. Each owner only secured a few casks, Delhomme, the wealthiest, possessing some seven acres of vine-land; the rest of the country-side was entirely given up to cereals and plants for fodder.

They turned down behind the church, skirted the old ruined presbytery which had been turned into a lodging for the rural constable, and gained the narrow chequered patches. As they crossed a piece of stony ground, covered with shrubs, a shrill voice cried through a gap:

"Father, it's raining! and I've brought out my geese."

It was the voice of "La Trouille,"[3] Hyacinthe's daughter, a girl of twelve, thin and wiry like a holly branch, with fair towzled hair. Her large mouth had a twist to the left, her green eyes stared so boldly that she might have been taken for a boy, and her dress consisted of an old blouse of her[Pg 37] father's, tied round her waist with some string. The reason everybody called her La Trouille—although she bore, by right, the fair name of Olympe—was that Hyacinthe, who used to yell at her from morning till night, could never say a word to her without adding:

"Just wait, you dirty troll, and I'll make it hot for you!"

He had begotten this wilding of a drab, whom he had picked up in a ditch after a fair, and whom he had installed in his den, to the great scandal of all Rognes. For nearly three years the household had been at sixes-and-sevens, and one harvest evening the baggage went off the way she came, in company with another man. The child, then scarcely weaned, had grown apace after the manner of ill weeds; and, as soon as she could walk, she got the meals ready for her father, whom she both dreaded and worshipped. Her chief passion, however, was for geese. At first she had only had two, male and female, stolen when quite young from behind a farm hedge. Then, thanks to her maternal care, the flock had increased, and she now possessed twenty birds, which she fed by pillage.

When La Trouille made her appearance, with her brazen, goat-like look, driving the geese before her with a stick, Hyacinthe flew into a temper.

"Be sure you're back for dinner, or else you'll catch it! And mind you keep the house carefully locked up, you dirty troll, for fear of robbers!"

Buteau sniggered, and even Delhomme and the others could not help laughing, they were so tickled at the idea of Hyacinthe being robbed. His house was a sight; an old cellar consisting of three walls crumbled to their original clay, a regular fox-hole, amid heaps of fallen stones and under a cluster of old lime-trees. It was all that remained of the château; and when our poaching friend, falling out with his father, had ensconced himself in this stony corner belonging to the village, he had had to close up the cellar by building a fourth wall of rough stones, in which he left two openings for window and door. The place was overgrown with brambles, and a large sweet briar hid the window. The country folk called it the Château.

A new deluge poured down. Luckily the acre or so of vineyard was close by, and the division into three was effected straightforwardly, without any new ground for a quarrel arising. There now only remained seven or eight acres of meadow down by the river side; but at this moment the rain became so heavy, and fell in such torrents, that the surveyor,[Pg 38] passing the gate of a residence, suggested that they should go in.

"What if we took shelter for a minute at Monsieur Charles's?"

Fouan had come to a standstill, wavering, full of respect for his brother-in-law and sister, who had made their fortune, and lived in a retired way in this middle-class residence.

"No, no," he muttered; "they breakfast at twelve. It would disturb their arrangements."

But Monsieur Charles put in an appearance on his stone steps under the verandah, taking an interest in the fall of rain, and, on recognising them, he called out:

"Come in, come in, do!"

Then, as they were all dripping wet, he bade them go round and enter by the kitchen, where he joined them. He was a fine man of sixty-five summers, close-shaven, with heavy eyelids over his lack-lustre eyes, and the solemn, sallow face of a retired magistrate. He was clad in deep-blue swan-skin flannel, with furred shoes, and an ecclesiastical skull-cap, which he wore with the dignified air of one whose life had been spent in duties of delicacy and authority.