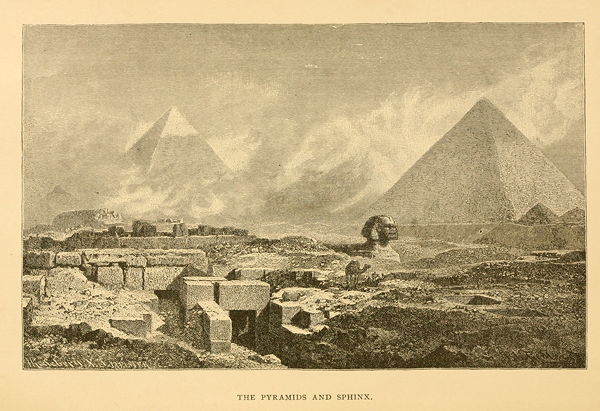

THE PYRAMIDS AND SPHINX.

Title: The Boys' and Girls' Herodotus

Author: Herodotus

Editor: John S. White

Release date: October 16, 2017 [eBook #55758]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Turgut Dincer, Chris Pinfield and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

Transcriber's Note

Apparent typographical errors have been corrected. The inconsistent use of hyphens has been retained, as has the use of both "king" and "King". A phrase in black letter font has been bolded.

An advertisement for another work by the same author has been shifted to the back of the book.

The illustration titled "ALPHABET" does not identify which alphabet it is, but it appears to illustrate Egyptian hieroglyphics.

The "Synchronistical Table of the Principal Events in Herodotus" towards the end of the book extends over two pages in small font: one on the Greeks and one on the "Barbarians". The text on the Persian Empire is spread over several columns on the second page. In this version the table on each page has been split into two, and the text on the Persian Empire placed at the end.

THE PYRAMIDS AND SPHINX.

BEING

PARTS OF THE HISTORY OF HERODOTUS

Edited for Boys and Girls, with an Introduction

BY

JOHN S. WHITE, LL.D.

HEAD-MASTER,

BERKELEY SCHOOL; EDITOR OF THE BOYS' AND GIRLS' PLUTARCH

WITH FIFTY ILLUSTRATIONS

NEW YORK & LONDON

G. P. PUTNAM'S SONS

The Knickerbocker Press

1884

COPYRIGHT BY

G. P. PUTNAM'S SONS

1884

Imagine yourself in the city of Athens near the close of the year 446 B.C. The proud city, after many years of supremacy over the whole of Central Greece, has passed her zenith, and is surely on the decline. She has never recovered from the blow received at Coronea. The year has been one of gloom and foreboding. The coming spring will bring the end of the five years' truce; and an invasion from the Peloponnesus is imminent. But, as the centre of learning, refinement, and the arts, the lustre of her fame is yet undimmed, and men of education throughout the world deem their lives incomplete until they have sought and reached this intellectual Mecca. During this year a stranger from Halicarnassus, in Asia Minor, after many years of travel in Asia, Scythia, Libya, Egypt, and Magna Græcia, has taken up his abode at Athens. He is still a young man, hardly thirty-seven, yet his fame is that of the first and greatest of historians. Dramatists and poets immortal there have been, but never man has written such exquisite prose. Twenty centuries and more shall wear away, and his history will be read in a hundred different tongues, as well as in the beautiful and simple Greek that he wrote. His name will grow into a household word; the school-boy will revel in his delightful tales, and wise men will call him the Father of History! For weeks the people of Athens have listened entranced to the public reading of his great work, and now the Assembly has passed a decree tendering to him the city's thanks, together with a most substantial gift in recognition of his talents—a purse of money equal to twelve thousand American dollars.

{iv} Such is the account which Eusebius gives, and others to whom we may fairly accord belief; and it adds no slight tinge of romance to the picture to discover among the listening throng the figure of the boy Thucydides, moved to tears by the recital, who then and there received the impulse that made of him also a great student and writer of history. Herodotus, noticing how intensely his reading had affected the youth, turned to Olorus, the father of Thucydides, who was standing near, and said: "Olorus, thy son's soul yearns after knowledge."

Herodotus was born at Halicarnassus, 484 B.C., and died at Thurium in Italy, about the year 425. As in the case of Plutarch, our knowledge of his personal history is very meagre, aside from the little we glean from his own writings. His parents, Lyxes and Rhœo, appear to have been of high rank and consideration in Halicarnassus, and possessed of ample means; and his acquaintance both at home and in Athens was of the best. A lover of poetry and a poet by nature, the whole plan of his work, the tone and character of his thoughts, and a multitude of words and expressions, show him to have been perfectly familiar with the Homeric writings. There is scarcely an author previous to his time with whose works he does not appear to have been thoroughly acquainted. Hecatæus, to be sure, was almost the only writer of prose who had attained any distinction, for prose composition was practically in its infancy; but from him and from several others, too obscure even to be named, he freely quotes, while the poets, Hesiod, Olen, Musæus, Archilochus, the authors of the "Cypria" and the "Epigoni," Alcæus, Sappho, Solon, Æsop, Aristeas, Simonides of Ceos, Phrynichus, Æschylus, and Pindar, are referred to, or quoted, in such a way as to show an intimate acquaintance with their works.

The design of Herodotus was to record the struggles between the Greeks and barbarians, but, in carrying it out, as Wheeler, the English analyst of the writings of Herodotus, has happily expressed it, he is perpetually led to trace the causes of the great events of his history; to recount the origin of that mighty contest between {v} liberty and despotism which marked the whole period; to describe the wondrous manners and mysterious religions of nations, and the marvellous geography and fabulous productions of the various countries, as each appeared on the great arena; to tell to an inquisitive and credulous people of cities vast as provinces and splendid as empires; of stupendous walls, temples and pyramids; of dreams, omens, and warnings from the dead; of obscure traditions and their exact accomplishment;—and thus to prepare their minds for the most wonderful story in the annals of men, when all Asia united in one endless array to crush the states of Greece; when armies bridged the seas and navies sailed through mountains; when proud, stubborn-hearted men arose amid anxiety, terror, confusion, and despair, and staked their lives and homes against the overwhelming power of a foreign despot, till Heaven itself sympathized with their struggles, and the winds and waves delivered their country, and opened the way to victory and revenge.

The personal character of Herodotus, reflected from every page that he wrote, renders his vivid story all the more happily suited to the reading and study of boys and girls. He is as honest as the sun; equally impartial to friends and foes; candid in the statement of both sides of a question; and an artist withal in the gift of delineating a character or a people with a few rapid strokes, so bold and masterly that the sketch is placed before you with stereoscopic distinctness. For so early a writer he presents a surprising unity of plan, combined with a variety of detail that is amazing. What if he does crowd and enrich his story with a world of anecdote? What if he feels bound always to paint for you the customs, manners, dress, and peculiarities of a people before he begins their history? This very biographical style is the charm of his pen. Like the flowers of the magnolia-tree, his bright stories and vivid descriptions at times almost overwhelm the root and branch of his narrative; yet, after all, we remember the magnolia more because of its cloud of snowy bloom in the few fleeting days of May than for all its green and shade in the other months.

{vi} Herodotus, to be sure, lacks that far-seeing faculty of discerning accurately the real causes of great movements, wars, and migrations of men—a faculty possessed pre-eminently by Thucydides and largely by Xenophon, but he is equally far removed from the coldness of the one and the ostentatious display of the other. He is above all things natural, simple, and direct. "He writes," says Aristotle, "sentences which have a continuous flow, and which end only when the sense is complete."

I have allowed Herodotus, as I did Plutarch, to tell you his story in his own words, as closely as the English idiom can reproduce the spirit and flow of the Greek, calling gratefully to my aid the labors of such students, analysts, and translators of Herodotus as Rawlinson, Dahlmann, Cary, and Wheeler; and I have discarded from the text only what is indelicate to the modern ear, or what the young reader might find tedious, redundant, or irrelevant to the main story. But so small a part comes under this head, that I am sure I can fairly say to you: "This is Herodotus himself." If you read him through and do not like him, who will be the disappointed one? Not you, but I!

New York, June 15, 1884.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| BOOK I.—CLIO | ||

| I. | Origin of the War between the Greeks and Barbarians | 1 |

| II. | History of Lydia | 4 |

| III. | Origin of Athens and Sparta | 17 |

| IV. | Conquest of Lydia by Cyrus | 25 |

| V. | History of the Medes to the Reign of Cyrus | 35 |

| VI. | The Asiatic Greeks and the Lydian Revolt | 54 |

| VII. | The Conquest of Assyria and the War with the Massagetæ | 65 |

| BOOK II.—EUTERPE. | ||

| I. | Physical History of Egypt | 83 |

| II. | Religion, Manners, Customs, Dress, and Animals of the Egyptians | 91 |

| III. | God-Kings Prior to Menes | 107 |

| IV. | First Line of 330 Kings, only Three Mentioned | 108 |

| V. | From Sesostris to Sethon | 110 |

| VI. | Third Line from the Twelve Kings to Amasis | 127 |

| BOOK III.—THALIA. | ||

| I. | Expeditions of Cambyses | 138 |

| II. | Usurpation of Smerdis the Magus and Accession of Darius | 157 |

| III. | Indians, Arabians, and Ethiopians | 169 |

| IV. | Reign of Darius to the Taking of Babylon | 174 |

| BOOK IV.—MELPOMENE. | ||

| I. | Description of Scythia and the Neighboring Nations | 188 |

| II. | Invasion of Scythia by Darius | 203 |

| III. | Description of Libya | 210 |

| BOOK V.—TERPSICHORE. | ||

| I. | Conquests of the Generals of Darius | 219 |

| II. | The Ionian Revolt | 229 |

| BOOK VI.—ERATO. | ||

| I. | The Suppression of the Ionian Revolt | 236 |

| II. | Expedition of Mardonius | 246 |

| III. | Expedition of Datis and Artaphernes; The Battle of Marathon | 252 |

| BOOK VII.—POLYMNIA. | ||

| I. | Death of Darius and Reign of Xerxes | 261 |

| II. | Battle of Thermopylæ | 280 |

| BOOK VIII.—URANIA. | ||

| I. | The Invasion of Attica and the Battle of Salamis | 292 |

| II. | Xerxes' Retreat | 302 |

| BOOK IX.—CALLIOPE. | ||

| I. | The War Continued; Battle of Platæa and Siege of Thebes | 307 |

| II. | The Battle of Mycale | 321 |

| Synchronistical Table of the Principal Events in Herodotus | 326 | |

| Herodotean Weights and Money, Dry and Liquid Measures, and Measurements of Lengths | 328 | |

| PAGE | |

| The Pyramids and Sphinx | Frontispiece |

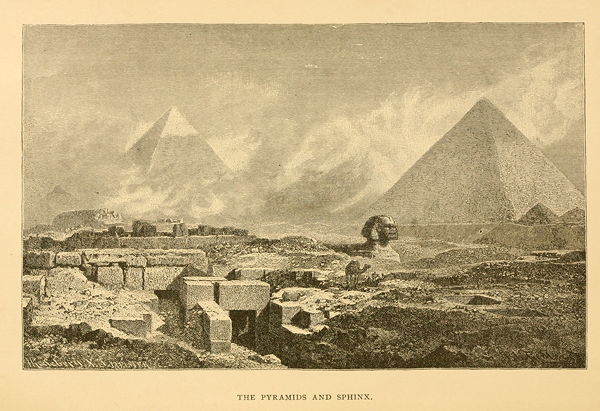

| Offering at the Temple of Delphi | 14 |

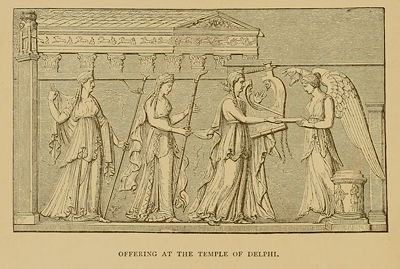

| Athens from Mount Hymettus | 19 |

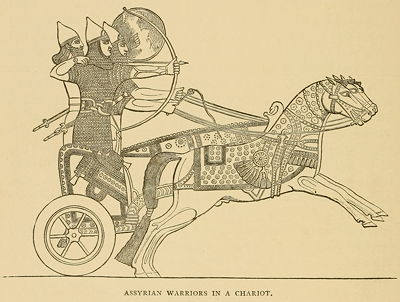

| Assyrian Warriors in a Chariot | 38 |

| Sphinx from S. W. Palace (Nimroud) | 39 |

| Egyptian Hare | 47 |

| Winged Human-Headed Lion | 69 |

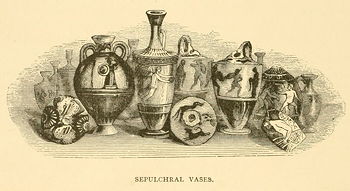

| Sepulchral Vases | 80 |

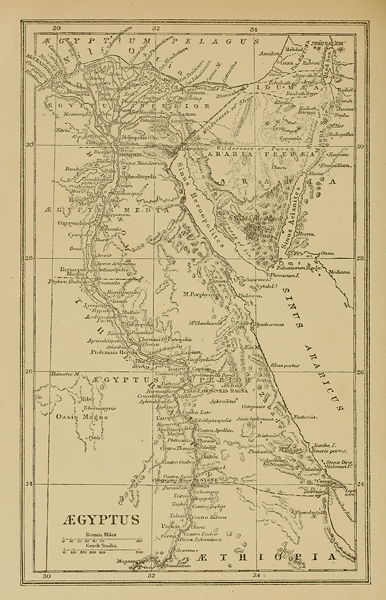

| Map of Ægyptus | 82 |

| The Two Great Pyramids at the Time of the Inundation | 85 |

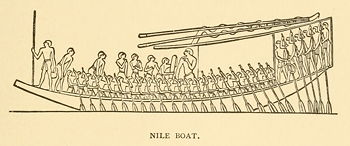

| Nile Boat | 89 |

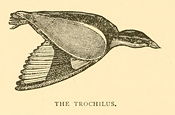

| The Trochilus | 98 |

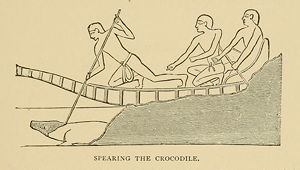

| Spearing the Crocodile | 99 |

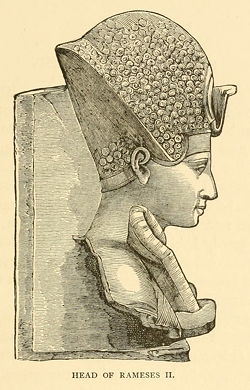

| Head of Rameses II. | 109 |

| Bust of Thothmes I. | 111 |

| Paris Carrying Away Helen | 113 |

| Bes and Hi | 117 |

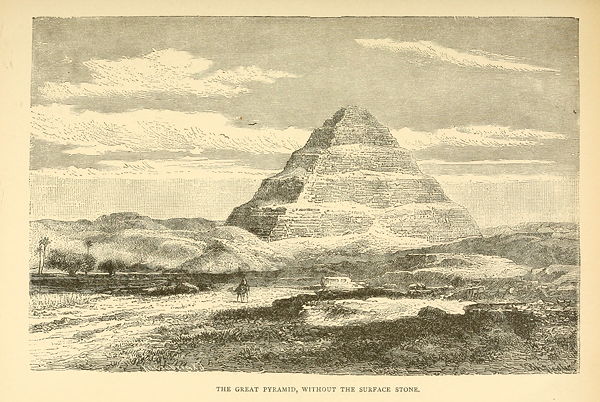

| The Great Pyramid, without the Surface Stone | 119 |

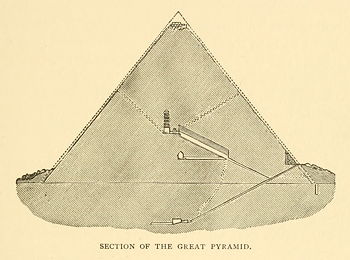

| Section of the Great Pyramid | 121 |

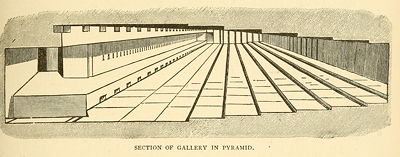

| Section of Gallery in Pyramid | 123 |

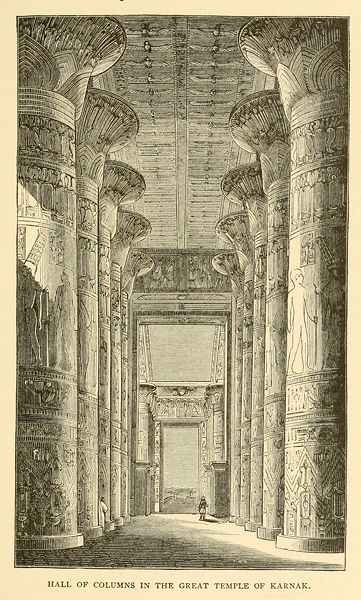

| Hall of Columns in the Great Temple of Karnak | 125 |

| Egyptian Bell Capitals | 129 |

| Harpoon and Fish-Hooks | 129 |

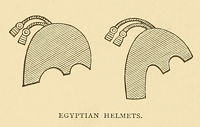

| Egyptian Helmets | 131 |

| The Great Sphinx | 135 |

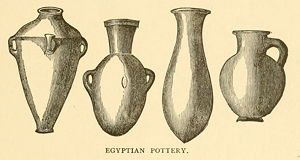

| Egyptian Pottery | 139 |

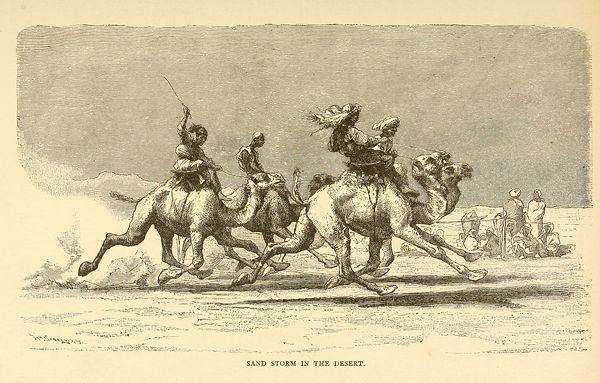

| Sand Storm in the Desert | 147 |

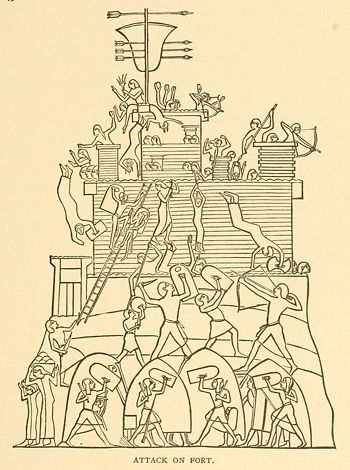

| Attack on Fort | 153 |

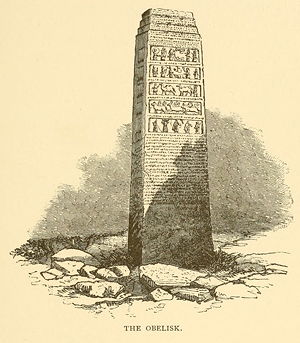

| The Obelisk | 155 |

| Mameluke Tomb, Cairo | 163 |

| Egyptian War Chariot, Warrior, and Horse | 167 |

| Military Drum | 171 |

| Alphabet | 175 |

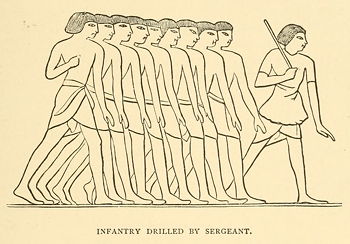

| Infantry Drilled by Sergeant | 185 |

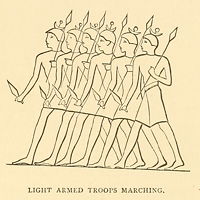

| Light-Armed Troops Marching | 187 |

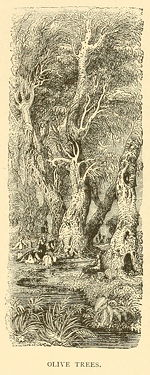

| Olive Trees | 217 |

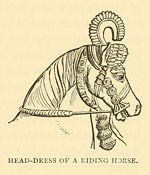

| Head-Dress of a Riding Horse | 221 |

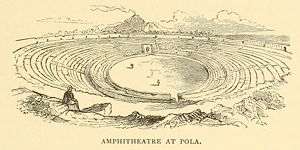

| Amphitheatre at Pola | 241 |

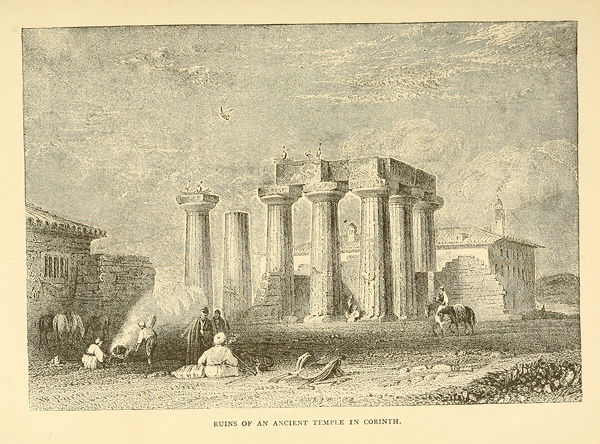

| Ruins of an Ancient Temple in Corinth | 249 |

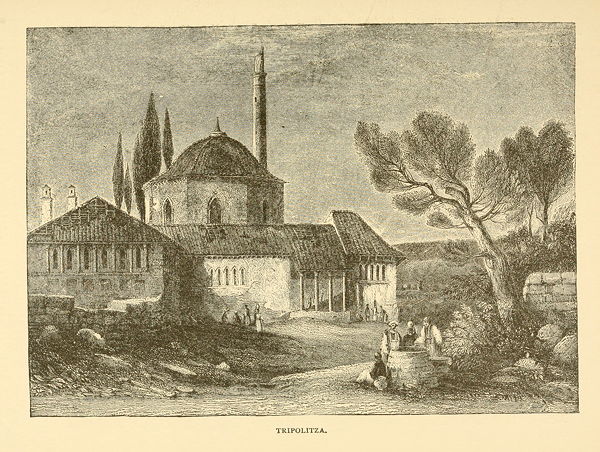

| Tripolitza | 267 |

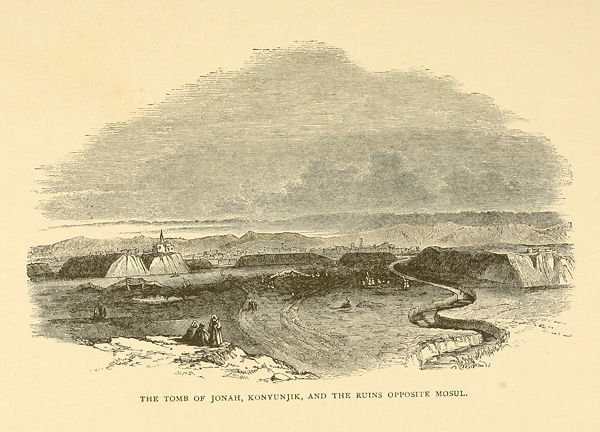

| The Tomb of Jonah, Konyunjik, and the Ruins Opposite Mosul | 273 |

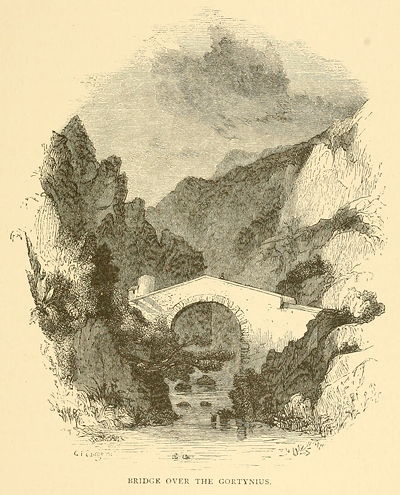

| Bridge over the Gortynius | 277 |

| Cyclopean Walls at Cephalloma | 281 |

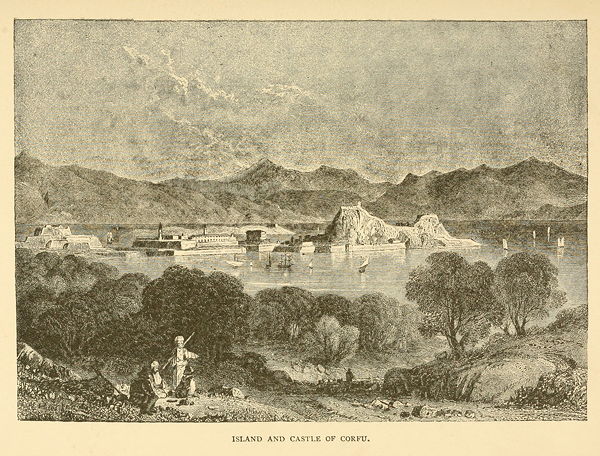

| Island and Castle of Corfu | 283 |

| Bridge at Corfu | 287 |

| Plains of Argos | 289 |

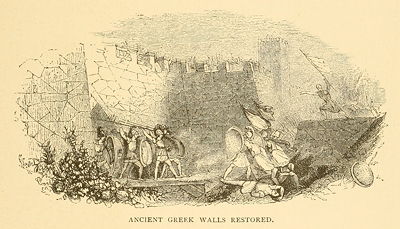

| Ancient Greek Walls Restored | 293 |

| Celes Ridden by a Cupid | 303 |

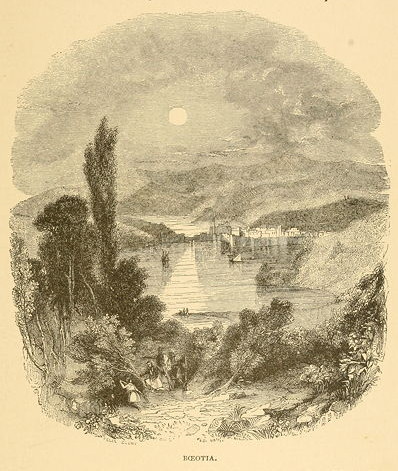

| Bœotia | 309 |

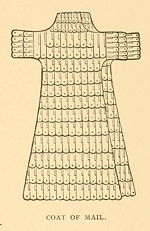

| Coat of Mail | 311 |

| The Fisherman | 313 |

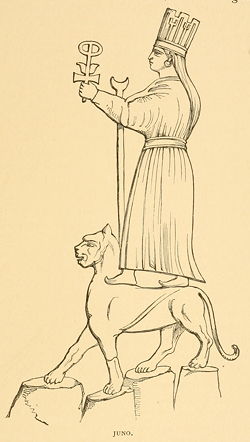

| Juno | 315 |

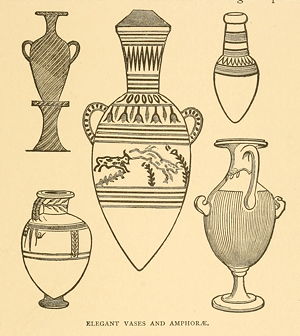

| Elegant Vases and Amphoræ | 317 |

| Bas-Relief of the Muses | 325 |

HERODOTUS.

This is a publication of the researches of Herodotus of Halicarnassus, made in order that the actions of men may not be effaced by time, and that the great and wondrous deeds displayed both by Greeks and barbarians[1] may not be deprived of renown; and, furthermore, that the cause for which they waged war upon each other may be known.

The learned among the Persians assert that the Phœnicians were the original authors of the quarrel; that they migrated from that which is called the Red Sea to the Mediterranean and, having settled in the country which they now inhabit, forthwith applied themselves to distant voyages; and that they exported Egyptian and Assyrian merchandise, touching at other places, and also at Argos. Argos, at that period, surpassed in every respect all those states which are now comprehended under the general appellation of Greece. They say, that on their arrival at Argos, the Phœnicians exposed their merchandise for sale, and that on the fifth or sixth day after their arrival, when they had almost disposed of their cargo, a great number of women came down to the sea-shore, and among them Io the daughter of the king Inachus. While these women {2} were standing near the stern of the vessel, and were bargaining for such things as most pleased them, the Phœnicians made an attack upon them. Most of the women escaped, but Io with some others was seized. Then the traders hurried on board and set sail for Egypt. Thus the Persians say that Io went to Egypt, and that this was the beginning of wrongs. After this certain Greeks (for they are unable to tell their name), having touched at Tyre in Phœnicia, carried off the king's daughter Europa. These must have been Cretans. Thus far they say that they had only returned like for like, but that after this the Greeks were guilty of the second provocation; for having sailed down in a vessel of war to Æa, a city of Colchis on the river Phasis, when they had accomplished the more immediate object of their expedition, they carried off the king's daughter Medea; and the king of Colchis, having despatched a herald to Greece, demanded satisfaction and the restitution of the princess; but the Greeks replied, that as they of Asia had not given satisfaction for the stealing of Io, they would not give any to them. In the second generation after this, Alexander, the son of Priam, having heard of these events, was desirous of obtaining a wife from Greece by means of violence, being fully persuaded that he should not have to give satisfaction, since the Greeks had not done so. When, therefore, he had carried off Helen, the Greeks immediately sent messengers to demand her back again and require satisfaction; but when they brought forward these demands they were met with this reply: "You who have not yourselves given satisfaction, nor made it when demanded, now wish others to give it to you." After this the Greeks were greatly to blame, for they levied war against Asia before the Asiatics did upon Europe. Now, to carry off women by violence the Persians think is the act of wicked men; to trouble one's self about avenging them when so carried off is the act of foolish ones; and to pay no regard to them when carried off, of wise men: for it is clear, that if they had not been willing, they could not have been carried off. Accordingly the Persians say, that they of Asia made no account of women that were carried off; but that the {3} Greeks for the sake of a Lacedæmonian woman assembled a mighty fleet, sailed to Asia, and overthrew the empire of Priam. From this event they had always considered the Greeks as their enemies: for the Persians claim Asia, and the barbarous nations that inhabit it, as their own, and consider Europe and the people of Greece as totally distinct.

Such is the Persian account; and to the capture of Troy they ascribe the commencement of their enmity to the Greeks. As relates to Io, the Phœnicians do not agree with this account of the Persians but affirm that she voluntarily sailed away with the traders. I, however, am not going to inquire further as to facts; but having pointed out the person whom I myself know to have been the first guilty of injustice toward the Greeks, I will then proceed with my history, touching as well on the small as the great estates of men: for of those that were formerly powerful many have become weak, and some that were formerly weak became powerful in my time. Knowing, therefore, the precarious nature of human prosperity, I shall commemorate both alike.

Crœsus was a Lydian by birth, son of Alyattes, and sovereign of the nations on this side the river Halys. This river flowing from the south between the Syrians[2] and Paphlagonians, empties itself northward into the Euxine Sea. This Crœsus was the first of the barbarians whom we know of that subjected some of the Greeks to the payment of tribute, and formed alliances with others. He subdued the Ionians and Æolians, and those of the Dorians who had settled in Asia, and formed an alliance with the Lacedæmonians; but before his reign all the Greeks were free.

The government, which formerly belonged to the Heraclidæ, passed to the family of Crœsus, who were called Mermnadæ. Candaules, whom the Greeks call Myrsilus, was tyrant of Sardis, and a descendant of Alcæus, son of Hercules. For Agron, son of Ninus, grandson of Belus, great-grandson of Alcæus, was the first of the Heraclidæ who became king of Sardis; and Candaules, son of Myrsus, was the last. They who ruled over this country before Agron, were descendants of Lydus, son of Atys, from whom this whole people, anciently called Mæonians, derived the name of Lydians. The Heraclidæ, descended from a female slave of Jardanus and Hercules, having been intrusted with the government by these princes, retained the supreme power in obedience to the declaration of an oracle: they reigned for twenty-two generations, a space of five hundred and five years, the son succeeding to the father to the time of Candaules, son of Myrsus. Candaules was murdered by his favorite, Gyges, who thus obtained the kingdom, and was confirmed in it by the oracle at Delphi. For when the Lydians resented the murder of Candaules, and were up in arms, the partisans of Gyges and the other Lydians came to the following agreement, that if the oracle should pronounce him king of the Lydians, he should reign; if not, he should restore the power to the Heraclidæ. The oracle answered that Gyges should become king. But the Pythian added this, "that the Heraclidæ should be avenged on the fifth descendant of Gyges." Of this prediction neither the Lydians nor their kings took any notice until it was actually accomplished.

Thus the Mermnadæ deprived the Heraclidæ of the supreme {5} power. Gyges sent many offerings to Delphi; indeed most of the silver offerings at Delphi are his; and besides the silver, he gave a vast quantity of gold; among the rest six bowls of gold, which now stand in the treasury of the Corinthians, and are thirty talents in weight; though, to tell the truth, this treasury does not belong to the people of Corinth, but Cypselus son of Eetion. Gyges was the first of the barbarians of whom we know who made offerings at Delphi, except Midas, son of Gordius, the king of Phrygia, who dedicated the royal throne, on which he used to sit and administer justice, a piece of workmanship deserving of admiration. The throne stands in the same place as the bowls of Gyges.

Periander the son of Cypselus was king of Corinth, and the Corinthians say (and the Lesbians confirm their account) that a wonderful prodigy occurred in his life-time. Arion of Methymna, second to none of his time in accompanying the harp, and the first who composed, named, and represented the dithyrambus at Corinth, was carried to Tænarus on the back of a dolphin. Arion, having continued a long time with Periander, made a voyage to Italy and Sicily, acquired great wealth there, and determined to return to Corinth. He set out from Tarentum, and hired a ship of some Corinthians, because he put more confidence in them than in any other nation; but these men, when they were in the open sea, conspired together to throw him overboard and seize his money. Learning of this he offered them his money, and entreated them to spare his life. But he could not prevail on them; the sailors ordered him either to kill himself, that he might be buried ashore, or to leap immediately into the sea. Arion, reduced to this strait, entreated them, since such was their determination, to permit him to stand on the stern of the vessel in his full dress and sing, and he promised when he had sung to make way with himself. The seamen, pleased that they should hear the best singer in the world, retired from the stern to the middle of the vessel. Arion put on all his robes, took his harp in his hands, stood on the rowing benches and went through the Orthian strain; {6} the strain ended, he leaped into the sea as he was, in full dress; the sailors continuing their voyage to Corinth: but a dolphin caught him upon his back, and carried him to Tænarus; so that, having landed, he proceeded to Corinth in his full dress, and upon his arrival there, related all that happened. Periander gave no credit to his relation, put Arion under close confinement, and watched anxiously for the arrival of the seamen. When they appeared, he summoned them and inquired if they could give any account of Arion. They answered that he was safe in Italy, and that they had left him flourishing at Tarentum. At that instant Arion appeared before them just as he was when he leaped into the sea; at which they were so astonished that, being fully convicted, they could no longer deny the fact. These things are reported by the Corinthians and Lesbians; and there is a little bronze statue of Arion at Tænarus, representing a man sitting on a dolphin.

Alyattes the Lydian and father of Crœsus, having waged a long war against the Milesians, died after a reign of fifty-seven years. Once upon recovery from an illness he dedicated at Delphi a large silver bowl, with a saucer of iron inlaid; an object that deserves attention above all the offerings at Delphi. It was made by Glaucus the Chian, who first invented the art of inlaying iron.

At the death of Alyattes, Crœsus, then thirty-five years of age, succeeded to the kingdom. He attacked the Ephesians before any other Greek people. The Ephesians being besieged by him, consecrated their city to Diana, by fastening a rope from the temple to the wall. The distance between the old town, which was then besieged, and the temple, is seven stadia. Crœsus afterward attacked the several cities of the Ionians and Æolians in succession, alleging different pretences against the various states. After he had reduced the Greeks in Asia to the payment of tribute, he formed a design to build ships and attack the Islanders. But when all things were ready for the building of ships, Bias of Priene (or, as others say, Pittacus of Mitylene) arriving at Sardis, put a stop to his ship-building by making this reply, when Crœsus {7} inquired if he had any news from Greece: "O king, the Islanders are enlisting a large body of cavalry, with the intention of making war upon you and Sardis." Crœsus, thinking he had spoken the truth, said: "May the gods put such a thought into the Islanders, as to attack the sons of the Lydians with horse." The other answering said: "Sire, you appear to wish above all things to see the Islanders on horseback upon the continent; and not without reason. But what can you imagine the Islanders more earnestly desire, after having heard of your resolution to build a fleet to attack them, than to catch the Lydians at sea, that they may revenge on you the cause of those Greeks who dwell on the continent, whom you hold in subjection?" Crœsus, much pleased with the conclusion, and convinced, (for he appeared to speak to the purpose,) put a stop to the ship-building, and made an alliance with the Ionians that inhabit the islands.

In course of time, when nearly all the nations that dwell within the river Halys, except the Cilicians and Lycians, were subdued, and Crœsus had added them to the Lydians, all the wise men of that time, as each had opportunity, came from Greece to Sardis, which had then attained to the highest degree of prosperity; and amongst them Solon, an Athenian, who made laws for the Athenians at their request, and absented himself for ten years, sailing away under pretence of seeing the world, that he might not be compelled to abrogate any of the laws he had established: for the Athenians could not do it themselves, since they were bound by solemn oaths to observe for ten years whatever laws Solon should enact for them. On his arrival Solon was hospitably entertained by Crœsus, and on the third or fourth day, by order of the king, the attendants conducted him round the treasury, and showed him all their grand and costly contents. After he had seen and examined every thing sufficiently, Crœsus asked him this question: "My Athenian guest, the great fame as well of your wisdom as of your travels has reached even to us; I am therefore desirous of asking you who is the most happy man you have seen?" He asked this question because he thought himself the most happy {8} of men. But Solon, speaking the truth freely, without any flattery, answered, "Tellus, the Athenian." Crœsus, astonished at his answer, eagerly asked him: "On what account do you deem Tellus the happiest?" He replied: "Tellus, in the first place, lived in a well-governed commonwealth; had sons who were virtuous and good; and he saw children born to them all, and all surviving. In the next place, when he had lived as happily as the condition of human affairs will permit, he ended his life in a most glorious manner. For coming to the assistance of the Athenians in a battle with their neighbors of Eleusis, he put the enemy to flight and died nobly. The Athenians buried him at the public charge in the place where he fell, and honored him greatly."

When Solon had roused the attention of Crœsus by relating many happy circumstances concerning Tellus, Crœsus, expecting at least to obtain the second place, asked, whom he had seen next to him. "Cleobis," said he, "and Biton, natives of Argos, for they possessed a sufficient fortune, and had withal such strength of body, that they were both alike victorious in the public games; and moreover the following story is related of them:—When the Argives were celebrating a festival of Juno, it was necessary that their mother should be drawn to the temple in a chariot; but the oxen did not come from the field in time, the young men therefore put themselves beneath the yoke, and drew the car in which their mother sat; and having conveyed it forty-five stades, they reached the temple. After they had done this in sight of the assembled people, a most happy termination was put to their lives; and in them the Deity clearly showed that it is better for a man to die than to live. For the men of Argos, who stood round, commended the strength of the youths, and the women blessed her as the mother of such sons; but the mother herself, transported with joy both on account of the action and its renown, stood before the image and prayed that the goddess would grant to Cleobis and Biton, her own sons, who had so highly honored her, the greatest blessing man could receive. After this prayer, when they had sacrificed and partaken of the feast, the youths fell asleep in the {9} temple itself, and never woke more, but met with such a termination of life. Upon this the Argives, in commemoration of their filial affection, caused their statues to be made and dedicated at Delphi."

Thus Solon adjudged the second place of felicity to these youths. Then Crœsus was enraged, and said: "My Athenian friend, is my happiness then so slighted by you as worth nothing, that you do not think me of so much value as private men?" He answered: "Crœsus, do you inquire of me concerning human affairs—of me, who know that the divinity is always jealous, and delights in confusion. For in lapse of time men are constrained to see many things they would not willingly see, and to suffer many things they would not willingly suffer. Now I put the term of man's life at seventy years; these seventy years then give twenty-five thousand two hundred days, without including the intercalary months of the leap years, and if we add that month to every other year, in order that the seasons arriving at the proper time may agree, the intercalary months will be thirty-five more in the seventy years, and the days of these months will be one thousand and fifty. Yet in all this number of twenty-six thousand two hundred and fifty days, that compose these seventy years, one day produces nothing exactly the same as another. Thus, then, O Crœsus, man is altogether the sport of fortune. You appear to me to be master of immense treasures, and king of many nations; but as relates to what you inquire of me, I cannot say, till I hear that you have ended your life happily. For the richest of men is not more happy than he that has a sufficiency for a day, unless good fortune attend him to the grave, so that he ends his life in happiness. Many men who abound in wealth are unhappy; and many who have only a moderate competency are fortunate. He that abounds in wealth, and is yet unhappy, surpasses the other only in two things; but the other surpasses the wealthy and the miserable in many things. The former indeed is better able to gratify desire and to bear the blow of adversity. But the latter surpasses him in this; he is not indeed equally able to bear misfortune {10} or satisfy desire, but his good fortune wards off these things from him; and he enjoys the full use of his limbs, he is free from disease and misfortune, he is blessed with good children and a fine form, and if, in addition to all these things, he shall end his life well, he is the man you seek and may justly be called happy; but before he die we ought to suspend our judgment, and not pronounce him happy, but fortunate."

When Solon had spoken thus to Crœsus, Crœsus did not confer any favor on him, but holding him in no account, dismissed him as a very ignorant man, because he overlooked present prosperity, and bade men look to the end of every thing.

After the departure of Solon, the indignation of the gods fell heavily upon Crœsus, probably because he thought himself the most happy of all men. A dream soon after visited him while sleeping, which pointed out to him the truth of the misfortunes that were about to befall him in the person of one of his sons. For Crœsus had two sons, of whom one was grievously afflicted, for he was dumb; but the other, whose name was Atys, far surpassed all the young men of his age. Now the dream intimated to Crœsus that he would lose this Atys by a wound inflicted with the point of an iron weapon. When he awoke, and had considered the matter with himself, he relieved Atys from the command of the Lydian troops, and never after sent him out on that business; and causing all spears, lances, and such other weapons as men use in war, to be removed from the men's apartments, he had them laid up in private chambers, that none of them being suspended might fall upon his son. While Crœsus was engaged with the nuptials of his son, a man oppressed by misfortune, and whose hands were polluted, a Phrygian by birth, and of royal family, arrived at Sardis. This man, having come to the palace of Crœsus, sought permission to obtain purification according to the custom of the country. Crœsus purified him, performing the usual ceremony, and then inquired: "Stranger, who art thou, and from what part of Phrygia hast thou come as a suppliant to my hearth? and what man or woman hast thou slain?" The stranger answered: "I am the son of Gordius, {11} and grandson of Midas, and am called Adrastus. I unwittingly slew my own brother, and being banished by my father and deprived of every thing, I have come hither." Then said Crœsus: "You were born of parents who are our friends, and you have come to friends, among whom, if you will stay, you shall want nothing; and by bearing your misfortune as lightly as possible you will be the greatest gainer." So Adrastus took up his abode in the palace of Crœsus.

At this time a boar of enormous size appeared in Mysian Olympus, and rushing down from that mountain, ravaged the fields of the Mysians. The Mysians, though they often went out against him, could not hurt him, but suffered much from him. At last deputies from the Mysians came to Crœsus and said: "O king, a boar of enormous size has appeared in our country, and ravages our fields: though we have often endeavored to take him, we cannot. We therefore earnestly beg, that you will send with us your son and some chosen youths with dogs, that we may drive him from the country." But Crœsus, remembering the warning of his dream, answered: "Make no further mention of my son; I shall not send him with you, because he is lately married, but I will give you chosen Lydians, and the whole hunting train, and will order them to assist you with their best endeavors in driving the monster from your country." The Mysians were content with this, but Atys, who had heard of their request, came in, and earnestly protested: "Father, you used to permit me to signalize myself in the two most noble and becoming exercises of war and hunting; but now you keep me excluded from both, without having observed in me either cowardice or want of spirit. How will men look on me when I go or return from the forum? What kind of a man shall I appear to my fellow-citizens? What to my newly married wife? Either let me then go to this hunt, or convince me that it is better for me to do as you would have me." "My son," said Crœsus, "I act thus, not because I have seen any cowardice, or any thing else unbecoming in you; but a vision in a dream warned me that you would be short-lived, and would die by the point of {12} an iron weapon. It was on account of this that I hastened your marriage, and now refuse to send you on this expedition; taking care to preserve you, if by any means I can, as long as I live; for you are my only son; the other, who is deprived of his hearing, I consider as lost." The youth answered: "You are not to blame, my father, if after such a dream you take so much care of me; but you say the dream signified that I should die by the point of an iron weapon. What hand, or what pointed iron weapon has a boar, to occasion such fears in you? Had it said I should lose my life by a tusk, you might do as you have, but it said by the point of a weapon; then since we have not to contend against men, let me go." "You have outdone me," replied Crœsus, "in explaining the import of the dream, you shall go to the chase."

Then turning to the Phrygian Adrastus, he exclaimed: "Adrastus, I beg you to be my son's guardian, when he goes to the chase, and take care that no skulking villains show themselves in the way to do him harm. Besides, you ought to go for your own sake, where you may signalize yourself by your exploits; this was the glory of your ancestors, and you are besides in full vigor." Adrastus answered: "On no other account, my lord, would I take part in this enterprise; it is not fitting that one in my unfortunate circumstances should join with his prosperous compeers. But since you urge me, I ought to oblige you. Rest assured, that your son, whom you bid me take care of, shall, as far as his guardian is concerned, return to you uninjured."

Then all went away, well provided with chosen youths and dogs, and, having arrived at Mount Olympus, they sought the wild beast, found him and encircled him around. Among the rest, the stranger, Adrastus, throwing his javelin at the boar, missed him, and struck the son of Crœsus; thus fulfilling the warning of the dream. Upon this, some one ran off to tell Crœsus what had happened, and having arrived at Sardis, gave him an account of the action, and of his son's fate. Crœsus, exceedingly distressed by the death of his son, lamented it the more bitterly, because he fell by the hand of one, whom he himself had purified from blood; and vehemently {13} deploring his misfortune, he invoked Jove the Expiator, attesting what he had suffered by this stranger. He invoked also the same deity, by the name of the god of hospitality and private friendship: as the god of hospitality, because by receiving a stranger into his house, he had unawares fostered the murderer of his son; as the god of private friendship, because, having sent him as a guardian, he found him his greatest enemy. Soon the Lydians approached, bearing the corpse, and behind it followed the murderer. He, having advanced in front of the body, delivered himself up to Crœsus, stretching out his hands and begging him to kill him upon it; for he ought to live no longer. When Crœsus heard this, though his own affliction was so great, he pitied Adrastus, and said to him: "You have made me full satisfaction by condemning yourself to die. You are not the author of this misfortune, except as far as you were the involuntary agent; but that god, whoever he was, that long since foreshowed what was about to happen." Crœsus buried his son as the dignity of his birth required; but the son of Gordius, when all was silent around, judging himself the most heavily afflicted of all men, killed himself on the tomb.

Some time after, the overthrow of the kingdom of Astyages, son of Cyaxares, by Cyrus, son of Cambyses, and the growing power of the Persians, put an end to the grief of Crœsus; and it entered into his thoughts whether he could by any means check the growing power of the Persians before they became formidable. After he had formed this purpose, he determined to make trial as well of the oracles in Greece as of that in Lydia; and sent different persons to different places, some to Delphi, some to Abæ of Phocis, and some to Dodona.

OFFERING AT THE TEMPLE OF DELPHI.

He endeavored to propitiate the god at Delphi by magnificent sacrifices; for he offered three thousand head of cattle of every kind fit for sacrifice, and having heaped up a great pile, he burned on it beds of gold and silver, vials of gold, and robes of purple and garments; hoping by that means more completely to conciliate the god. When the sacrifice was ended, having melted down a vast quantity of gold, he cast half-bricks from it; of which the {14} longest were six palms in length, the shortest three, and in thickness one palm: their number was one hundred and seventeen: four of these, of pure gold, weighed each two talents and a half; the other half-bricks of pale gold, weighed two talents each. He made also the figure of a lion of fine gold, weighing ten talents. This lion, when the temple of Delphi was burned down, fell from the half-bricks, for it had been placed on them; and it now lies in the treasury of the Corinthians, weighing six talents and a half; for three talents and a half were melted from it. Crœsus, having finished these things sent them to Delphi, and with them these following: two large bowls, one of gold, the other of silver; that of gold was placed on the right hand as you enter the temple, and that of silver on the left; but these also were removed when the temple was burnt down; and the golden one weighing eight talents and a half and twelve minæ, is placed in the treasury of Clazomenæ; the silver one, containing six hundred amphoræ, lies in a corner of the vestibule, and is used by the Delphians for mixing the wine on the Theophanian festival. The Delphians say it {15} was the workmanship of Theodorus the Samian; and I think so too, for it appears to be no common work. He also sent four casks of silver, which stand in the treasury of the Corinthians; and he dedicated two lustral vases, one of gold, the other of silver: on the golden one is an inscription, OF THE LACEDÆMONIANS, who say that it was their offering, but wrongfully, for it was given by Crœsus: a certain Delphian made the inscription, in order to please the Lacedæmonians; I know his name, but forbear to mention it. The boy, indeed, through whose hand the water flows, is their gift; but neither of the lustral vases. At the same time Crœsus sent many other offerings without an inscription: amongst them some round silver covers; and a statue of a woman in gold three cubits high, which the Delphians say is the image of Crœsus's baking woman; and to all these things he added the necklaces and girdles of his wife.

These were the offerings he sent to Delphi; and to Amphiaraus, having ascertained his virtue and sufferings, he dedicated a shield all of gold, and a lance of solid gold, the shaft as well as the points being of gold. These are now at Thebes in the temple of Ismenian Apollo.

To the Lydians appointed to convey these presents to the temples, Crœsus gave it in charge to inquire of the oracles, whether he should make war on the Persians, and if he should invite any other nation as an ally. Accordingly, when the Lydians arrived at the places to which they were sent, and had dedicated the offerings, they consulted the oracles, saying: "Crœsus, king of the Lydians and of other Nations, esteeming these to be the only oracles among men, sends these presents in acknowledgment of your discoveries; and now asks whether he should lead an army against the Persians, and whether he should join any auxiliary forces with his own?" Such were their questions; and the opinions of both oracles concurred, foretelling: "That if Crœsus should make war on the Persians, he would destroy a mighty empire;" and they advised him to engage the most powerful of the Greeks in his alliance. When Crœsus heard the answers that {16} were brought back, he was beyond measure delighted with the oracles; and fully expecting that he should destroy the kingdom of Cyrus, he again sent to Delphi, and having ascertained the number of the inhabitants, presented each of them with two staters of gold. In return for this, the Delphians gave Crœsus and the Lydians the right to consult the oracle before any others, and exemption from tribute, and the first seats in the temple, and the privilege of being made citizens of Delphi, to as many as should desire it in all future time. Crœsus, having made these presents to the Delphians, sent a third time to consult the oracle. For after he had ascertained the veracity of the oracle, he had frequent recourse to it. His demand now was whether he should long enjoy the kingdom? to which the Pythian gave this answer: "When a mule shall become king of the Medes, then, tender-footed Lydian, flee over pebbly Hermus, nor tarry, nor blush to be a coward." With this answer, when reported to him, Crœsus was more than ever delighted, thinking that a mule should never be king of the Medes instead of a man, and consequently that neither he nor his posterity should ever be deprived of the kingdom. In the next place he began to enquire carefully who were the most powerful of the Greeks whom he might gain over as allies; and on inquiry found that the Lacedæmonians and Athenians excelled the rest, the former being of Dorian, the latter of Ionic descent: for these were in ancient time the most distinguished, the latter being a Pelasgian, the other an Hellenic nation.

What language the Pelasgians used I cannot with certainty affirm; but if I may form a conjecture from those Pelasgians who now exist, and inhabit the town of Crestona above the Tyrrhenians, and from those Pelasgians settled at Placia and Scylace on the Hellespont, they spoke a barbarous language. And if the whole Pelasgian body did so, the Attic race, being Pelasgic, must at the time they changed into Hellenes have altered their language. The Hellenic race, however, appears to have used the same language from the time they became a people. At first insignificant, yet from a small beginning they have increased to a multitude of nations, chiefly by a union with many other barbarous nations. But the Pelasgic race, being barbarous, never increased to any great extent.

Of these nations Crœsus learnt that the Attic was oppressed and distracted by Pisistratus, then reigning in Athens. When a quarrel happened between those who dwelt on the sea-coast and the Athenians, the former headed by Megacles, the latter by Lycurgus, Pisistratus aiming at the sovereign power, formed a third party; and having assembled his partisans under color of protecting those of the mountains, he contrived this stratagem. He wounded himself and his mules, drove his chariot into the public square, as if he had escaped from enemies that designed to murder him in his way to the country, and besought the people to grant him a guard, having before acquired renown in the expedition against Megara, by taking its port, Nisæa, and displaying other illustrious deeds. The people of Athens, deceived by this, gave him such of the citizens as he selected, who were not to be {18} his javelin men, but club-bearers, for they attended him with clubs of wood. These men, joining in revolt with Pisistratus seized the Acropolis, and Pisistratus assumed the government of the Athenians, neither disturbing the existing magistracies, nor altering the laws; but he administered the government according to the established institutions, liberally and well. Not long after, the partisans of Megacles and Lycurgus became reconciled and drove him out. In this manner Pisistratus first made himself master of Athens, and, his power not being firmly rooted, lost it. But those who expelled Pisistratus quarrelled anew with one another; and Megacles, harassed by the sedition, sent a herald to Pisistratus to ask if he was willing to marry his daughter, on condition of having the sovereignty. Pisistratus having accepted the proposal and agreed to his terms, in order to his restitution, they contrive the most ridiculous project that, I think, was ever imagined; especially if we consider, that the Greeks have from old been distinguished from the barbarians as being more acute and free from all foolish simplicity, and more particularly as they played this trick upon the Athenians, who are esteemed among the wisest of the Greeks. In the Pæanean tribe was a woman named Phya, four cubits high, wanting three fingers, and in other respects handsome; this woman they dressed in a complete suit of armor, placed her on a chariot, and having shown her beforehand how to assume the most becoming demeanor, they drove her to the city, with heralds before, who, on their arrival in the city, proclaimed what was ordered in these terms: "O Athenians, receive with kind wishes Pisistratus whom Minerva herself honoring above all men now conducts back to her own citadel." The report was presently spread among the people that Minerva was bringing back Pisistratus; and the people in the city believing this woman to be the goddess, both adored a human being, and received Pisistratus.

ATHENS FROM MOUNT HYMETTUS.

Pisistratus having recovered the sovereignty in the manner above described, married the daughter of Megacles in accordance with his agreement, but Pisistratus soon hearing of designs that were being formed against him, withdrew entirely out of the {20} country, and arriving in Eretria, consulted with his sons. The opinion of Hippias prevailing, to recover the kingdom, they immediately began to collect contributions from those cities which felt any gratitude to them for benefits received; and though many gave large sums, the Thebans surpassed the rest in liberality. At length (not to give a detailed account) time passed, and every thing was ready for their return, for Argive mercenaries arrived from Peloponnesus; and a man of Naxos, named Lygdamis, who had come as a volunteer, and brought both men and money, showed great zeal in the cause. Setting out from Eretria, they came back in the eleventh year of their exile, and first of all possessed themselves of Marathon. While they lay encamped in this place, their partisans from the city joined them, and others from the various districts, to whom a tyranny was more welcome than liberty, crowded to them. The Athenians of the city, on the other hand, had shown very little concern all the time Pisistratus was collecting money, or even when he took possession of Marathon. But when they heard that he was marching from Marathon against the city, they at length went out to resist him; and marched with their whole force against the invaders. In the mean time Pisistratus's party, advanced towards the city, and arrived in a body at the temple of the Pallenian Minerva, and there took up their position. Here Amphilytus, a prophet of Acarnania, moved by divine impulse, approached Pisistratus, and pronounced this oracle in hexameter verse:

He, inspired by the god, uttered this prophecy; and Pisistratus, comprehending the oracle, and saying he accepted the omen, led on his army. The Athenians of the city were then engaged at their breakfast, and some of them after breakfast had betaken themselves to dice, others to sleep; so that the army of Pisistratus, falling upon them by surprise, soon put them to flight. As they were flying, Pisistratus contrived a clever stratagem to prevent their rallying again, and forced them thoroughly to disperse. {21} He mounted his sons on horseback and sent them forward. They, overtaking the fugitives, spoke as they were ordered by Pisistratus, bidding them be of good cheer, and to depart every man to his own home. The Athenians yielded a ready obedience, and thus Pisistratus, having a third time possessed himself of Athens, secured his power, more firmly, both by the aid of auxiliary forces, and by revenues partly collected at home and partly drawn from the mines along the river Strymon. He seized as hostages the sons of the Athenians who had held out against him, and had not immediately fled, and settled them at Naxos. He moreover purified the island of Delos, in obedience to an oracle, and having dug up the dead bodies, as far as the prospect from the temple reached, he removed them to another part of Delos.

Crœsus was informed that such was, at that time, the condition of the Athenians; and that the Lacedæmonians, having extricated themselves out of great difficulties, had gained the mastery over the Tegeans in war. They had formerly been governed by the worst laws of all the people in Greece, both as regarded their dealings with one another, and in holding no intercourse with strangers. But they changed to a good government in the following manner: Lycurgus, a man much esteemed by the Spartans, having arrived at Delphi to consult the oracle, no sooner entered the temple, than the Pythian spoke as follows:

Some men say that, besides this, the Pythian also communicated to him that form of government now established among the Spartans. But, as the Lacedæmonians themselves affirm, Lycurgus being appointed guardian to his nephew Leobotis,[3] king of Sparta, brought those institutions from Crete. For as soon as he had taken the guardianship, he altered all their customs, and took {22} care that no one should transgress them. Afterwards he established military regulations, and instituted the ephori and senators. Thus, having changed their laws, they established good institutions in their stead. They erected a temple to Lycurgus after his death, and held him in the highest reverence. As they had a good soil and abundant population, they quickly sprang up and flourished. And now they were no longer content to live in peace; but proudly considering themselves superior to the Arcadians, they sent to consult the oracle at Delphi, touching the conquest of the whole country of the Arcadians; and the Pythian gave them this answer: "Dost thou ask of me Arcadia? thou askest a great deal; I cannot grant it thee. There are many acorn-eating men in Arcadia, who will hinder thee. But I do not grudge thee all; I will give thee Tegea to dance on with beating of the feet, and a fair plain to measure out by the rod." When the Lacedæmonians heard this answer reported, they laid aside their design against all Arcadia; and relying on an equivocal oracle, led an army against Tegea only, carrying fetters with them, as if they would surely reduce the Tegeans to slavery. But being defeated in an engagement, as many of them as were taken alive, were compelled to work, wearing the fetters they had brought, and measuring the lands of the Tegeans with a rod. Those fetters in which they were bound, were, even in my time, preserved in Tegea, suspended around the temple of Alean Minerva.

In the first war, therefore, they had constantly fought against the Tegeans with ill success, but in the time of Crœsus, and during the reign of Anaxandrides and Ariston at Lacedæmon, they at length became superior in the following manner: When they had always been worsted in battle by the Tegeans, they sent to enquire of the oracle at Delphi, what god they should propitiate, in order to become victorious over the Tegeans. The Pythian answered, they should become so, when they had brought back the bones of Orestes the son of Agamemnon. But as they were unable to find the sepulchre of Orestes, they sent again to inquire of the god in what spot Orestes lay interred, and the Pythian gave this answer to the inquiries of those who came to consult her:

When the Lacedæmonians heard this, they were as far off the discovery as ever, though they searched every where, till Lichas, one of the Spartans who are called Agathoergi, found it. These Agathoergi consist of citizens who are discharged from serving in the cavalry, such as are senior, five in every year. It is their duty during the year in which they are discharged from the cavalry, not to remain inactive, but go to different places where they are sent by the Spartan commonwealth. Lichas, who was one of these persons, discovered it in Tegea, both meeting with good fortune and employing sagacity. For as the Lacedæmonians had at that time intercourse with the Tegeans, he, coming to a smithy, looked attentively at the iron being forged, and was struck with wonder when he saw what was done. The smith perceiving his astonishment desisted from his work, and said: "O Laconian stranger, you would certainly have been astonished had you seen what I saw, since you are so surprised at the working of iron. For as I was endeavoring to sink a well in this enclosure, in digging, I came to a coffin seven cubits long; and because I did not believe that men were ever taller than they now are, I opened it and saw that the body was equal to the coffin in length, and after I had measured it I covered it up again." The man told him what he had seen, and Lichas, reflecting on what was said, conjectured from the words of the oracle, that this must be the body of Orestes, forming his conjecture on the following reasons: seeing the smith's two bellows he discerned in them the two winds, and in the anvil and hammer the stroke answering to stroke, and in the iron that was being forged the woe that lay on woe; representing it in this way, that iron had been invented to the injury of man. He then returned to Sparta, and gave the Lacedæmonians an account of the whole matter; but they brought a feigned charge against him and sent {24} him into banishment. He, going back to Tegea, related his misfortune to the smith, and wished to hire the enclosure from him, but he would not let it. But in time, when he had persuaded him, he took up his abode there; and having opened the sepulchre and collected the bones, he carried them away with him to Sparta. From that time, whenever they made trial of each other's strength, the Lacedæmonians were by far superior in war; and the greater part of Peloponnesus had been already subdued by them.

Crœsus being informed of all these things, sent ambassadors to Sparta, with presents, and to request their alliance, having given them orders what to say; and when they were arrived they spoke as follows: "Crœsus, king of the Lydians and of other nations, has sent us with this message: 'O Lacedæmonians, since the deity has directed me by an oracle to unite myself to a Grecian friend, therefore (for I am informed that you are pre-eminent in Greece), I invite you in obedience to the oracle, being desirous of becoming your friend and ally, without treachery or guile.'" But the Lacedæmonians, who had before heard of the answer given by the oracle to Crœsus, were gratified at the coming of the Lydians, and exchanged pledges of friendship and alliance; and indeed certain favors had been formerly conferred on them by Crœsus; for when the Lacedæmonians sent to Sardis to purchase gold, wishing to use it in erecting the statue of Apollo that now stands at Thornax in Laconia, Crœsus gave it as a present to them. For this reason, and because he had selected them from all the Greeks, and desired their friendship, the Lacedæmonians accepted his offer of alliance; and in the first place they promised to be ready at his summons; and in the next, having made a great bronze bowl, capable of containing three hundred amphoræ, and covered it outside to the rim with various figures, they sent it to him, being desirous of making Crœsus a present in return. But this bowl never reached Sardis, for one of the two following reasons: the Lacedæmonians say, that when the bowl, on its way to Sardis, was off Samos, the Samains having heard of it, sailed out in long ships, and took it away by force. On the other hand the Samains affirm, that when the Lacedæmonians {26} who were conveying the bowl found they were too late, and heard that Sardis was taken and Crœsus a prisoner, they sold the bowl in Samos, and that some private persons, who bought it dedicated it in the temple of Juno.

Crœsus, mistaking the oracle, prepared to invade Cappadocia, hoping to overthrow Cyrus and the power of the Persians. Whilst Crœsus was preparing for his expedition against the Persians, a Lydian named Sandanis, who before that time was esteemed a wise man, and on this occasion acquired a very great name in Lydia, gave him advice in these words: "O king, you are preparing to make war against a people who wear leather trousers, and the rest of their garments of leather; who inhabit a barren country, and feed not on such things as they choose, but such as they can get. Besides they do not habitually use wine, but drink water; nor have they figs to eat, nor any thing that is good. In the first place, then, if you should conquer, what will you take from them, since they have nothing? On the other hand, if you should be conquered, consider what good things you will lose. For when they have tasted of our good things, they will become fond of them, nor will they be driven from them. As for me, I thank the gods, that they have not put it into the thoughts of the Persians to make war on the Lydians." Sandanis did not, however, persuade Crœsus, for he proceeded to invade Cappadocia, as well from a desire of adding it to his own dominions, as a wish to punish Cyrus on account of Astyages. For Cyrus, son of Cambyses, had subjugated Astyages, son of Cyaxares, who was brother-in-law of Crœsus, and king of Medes.

Crœsus, alleging this against him, sent to ask the oracle, if he should make war on the Persians; and when an ambiguous answer came back, he, interpreting it to his own advantage, led his army against the territory of the Persians. When he arrived at the river Halys, Crœsus transported his forces, as I believe, by the bridges which are now there. But the common opinion of the Greeks is, that Thales the Milesian procured him a passage in the following way: Whilst Crœsus was in doubt how his army should {27} pass over the river, for they say that these bridges were not at that time in existence, Thales, who was in the camp, caused the stream, which flowed along the left of the army, to flow on the right instead. He contrived it thus: having begun above the camp, he dug a deep trench, in the shape of a half-moon, so that the river, being turned into this from its old channel, might pass in the rear of the camp pitched where it then was, and afterward, having passed by the camp, might fall into its former course; so that as soon as the river was divided into two streams it became fordable in both. Some say, that the ancient channel of the river was entirely dried up; but this I cannot assent to; for how then could they have crossed it on their return?

However, Crœsus, having passed the river with his army, came to a place called Pteria, in Cappadocia. (Now Pteria is the strongest position of the whole of this country, and is situated over against Sinope, a city on the Euxine Sea.) Here he encamped and ravaged the lands of the Syrians; and took the city of the Pterians, and enslaved the inhabitants; he also took all the adjacent places, and expelled the inhabitants, who had given him no cause for blame. But Cyrus, assembling his own army, and taking with him all who inhabited the intermediate country, went to meet Crœsus. But before he began to advance, he sent heralds to the Ionians, to persuade them to revolt from Crœsus, which the Ionians refused to do. When Cyrus had come up and encamped opposite Crœsus, they made trial of each other's strength on the plains of Pteria; but when an obstinate battle took place, and many fell on both sides, they at last parted, on the approach of night, neither having been victorious.

Crœsus laying the blame on his own army on account of the smallness of its numbers, for his forces that engaged were far fewer than those of Cyrus,—marched back to Sardis, designing to summon the Egyptians according to treaty, and to require the presence of the Lacedæmonians at a fixed time: having collected these together, and assembled his own army, he purposed, when winter was over, to attack the Persians in the beginning of the spring. {28} With this design, when he reached Sardis, he despatched ambassadors to his different allies, requiring them to meet at Sardis before the end of five months; but the army that was with him, and that had fought with the Persians, which was composed of mercenary troops, he entirely disbanded, not imagining that Cyrus, who had come off on such equal terms, would venture to advance upon Sardis. While Crœsus was forming these plans the whole suburbs were filled with serpents, and when they appeared, the horses, forsaking their pastures, came and devoured them. When Crœsus beheld this, he considered it to be, as it really was, a prodigy, and sent immediately to consult the interpreters at Telmessus; but the messengers having arrived there, and learnt from the Telmessians what the prodigy portended, were unable to report it to Crœsus, for before they sailed back to Sardis, Crœsus had been taken prisoner. The Telmessians had pronounced as follows: "that Crœsus must expect a foreign army to invade his country, which, on its arrival, would subdue the natives, because, they said, the serpent is a son of the earth, but the horse is an enemy and a stranger."

Cyrus, as soon as Crœsus had retreated after the battle at Pteria, having discovered that it was the intention of Crœsus to disband his army, saw that it would be to his advantage to march with all possible expedition on Sardis, before the forces of the Lydians could be a second time assembled. Whereupon Crœsus, thrown into great perplexity, seeing that matters had turned out contrary to his expectations, drew out the Lydians to battle. At that time no nation in Asia was more valiant and warlike than the Lydians. Their mode of fighting was from on horseback; they were armed with long lances, and managed their horses with admirable address.

The place where they met was the plain that lies before the city of Sardis, which is extensive and bare; the Hyllus and several other rivers flowing through it force a passage into the greatest, called the Hermus, which, flowing from the sacred mountain of mother Cybele, falls into the sea near the city of Phocæa. Here Cyrus, {29} when he saw the Lydians drawn up in order of battle, alarmed at the cavalry, had recourse to the following stratagem, on the suggestion of Harpagus, a Mede. Collecting together all the camels that followed his army with provisions and baggage, and causing their burdens to be taken off, he mounted men upon them equipped in cavalry accoutrements, and ordered them to go in advance of the rest of his army against the Lydian horse; his infantry he bade follow the camels, and placed the whole of his cavalry behind the infantry. When all were drawn up in order, he charged them not to spare any of the Lydians, but to kill every one they met; but on no account to kill Crœsus, even if he should offer resistance when taken. He drew up the camels in the front of the cavalry for this reason: a horse is afraid of a camel, and cannot endure either to see its form or to scent its smell; this then would render the cavalry useless to Crœsus, by which the Lydian expected to signalize himself. Accordingly, when they joined battle, the horses no sooner smelt the camels and saw them, than they wheeled round, and the hopes of Crœsus were destroyed. Nevertheless, the Lydians were not discouraged, but leaped from their horses and engaged with the Persians on foot; but at last, when many had fallen on both sides, the Lydians were put to flight, and being shut up within the walls, were besieged by the Persians.

Sardis was taken in the following manner. On the fourteenth day after Crœsus had been besieged, Cyrus sent horsemen throughout his army, and proclaimed that he would liberally reward the man who should first mount the wall; upon this several attempts were made, and as often failed; till, after the rest had desisted, a Mardian, whose name was Hyrœades, endeavored to climb up on that part of the citadel where no guard was stationed, for on that side the citadel was precipitous and impracticable. Hyrœades had seen a Lydian the day before come down this precipice for a helmet that had rolled down, and carry it up again. He thereupon ascended the same way, followed by divers Persians; and when great numbers had gone up, Sardis was thus taken, and the whole town plundered.

{30} The following incidents befel Crœsus himself. He had a son of whom I have before made mention, who was dumb. Now, in the time of his former prosperity, Crœsus had done every thing he could for him, and among other expedients had sent to consult the oracle of Delphi concerning him; but the Pythian gave him this answer:

When the city was taken, one of the Persians, not knowing Crœsus, was about to kill him; Crœsus, though he saw him approach, took no heed of him, caring not if he should die by the blow; but this speechless son of his, when he saw the Persian advancing against him, through dread and anguish, burst into speech, and said: "Man, kill not Crœsus." These were the first words he ever uttered; but from that time he continued to speak during the remainder of his life. So the Persians got possession of Sardis, and made Crœsus prisoner, after he had reigned fourteen years, been besieged fourteen days, and lost his great empire, as the oracle had predicted. The Persians, having taken him, conducted him to Cyrus; and he, having heaped up a great pile, placed Crœsus upon it, bound with fetters, and with him fourteen young Lydians; designing either to offer this sacrifice to some god, as the first fruits of his victory, or wishing to perform a vow; or perhaps, having heard that Crœsus was a religious person, he placed him on the pile for the purpose of discovering whether any deity would save him from being burned alive. When Crœsus stood upon the pile, notwithstanding the weight of his misfortunes, the words of Solon recurred to him, as spoken by inspiration of the deity, that "No living man could be justly called happy." When this occurred to him, it is said, that after a long silence he recovered himself, and uttering a groan, thrice pronounced the name of Solon; when Cyrus heard him, he commanded his interpreters to ask Crœsus whom it was he called upon; Crœsus for {31} some time kept silence; but at last, being constrained to speak, said: "I named a man, whose discourses I more desire all tyrants might hear, than to be possessor of the greatest riches." When he gave them this obscure answer, they again inquired what he said, and were very importunate; he at length told them that Solon, an Athenian, formerly visited him, and having viewed all his treasures, made no account of them; telling, in a word, how every thing had befallen him as Solon had warned him, though his discourse related to all mankind as much as to himself, and especially to those who imagine themselves happy. The pile now was kindled, and the outer parts began to burn; when Cyrus, informed by the interpreters of what Crœsus had said, relented, considering that being but a man, he was yet going to burn another man alive, who had been no way inferior to himself in prosperity; and moreover, fearing retribution, and reflecting that nothing human is constant, commanded the fire to be instantly extinguished, and Crœsus, with those who were about him, to be taken down. But they with all their endeavors were unable to master the fire. Crœsus, perceiving that Cyrus had altered his resolution, when he saw every man endeavoring to put out the fire, but unable to get the better of it, shouted aloud, invoking Apollo, and besought him, if ever any of his offerings had been agreeable to him, to protect and deliver him from the present danger. And the Lydians relate, as he with tears invoked the god, on a sudden clouds were seen gathering in the air, which before was serene, and that a violent storm burst forth and vehement rain fell and extinguished the flames; by which Cyrus perceiving that Crœsus was beloved by the gods, and a good man, when he had had him taken down from the pile, asked him the following question: "Who persuaded you, Crœsus, to invade my territories, and to become my enemy instead of my friend?" He answered: "O king, I have done this for your good but my own evil fortune, and the god of the Greeks who encouraged me to make war is the cause of all. For no man is so void of understanding as to prefer war before peace; for in the latter children bury their fathers; in the former, fathers bury their children. {32} But, I suppose, it pleased the gods that these things should be so."

Cyrus, having set him at liberty, placed him by his own side, and showed him great respect. But Crœsus, absorbed in thought remained silent; and presently turning round and beholding the Persians sacking the city of the Lydians, he said, "Does it become me, O king, to tell you what is passing through my mind, or to keep silence?" Cyrus bade him say with confidence whatever he wished; upon which Crœsus asked him, "What is this vast crowd so earnestly employed about?" He answered, "They are sacking your city, and plundering your riches." "Not so," Crœsus replied, "they are neither sacking my city, nor plundering my riches, for they are no longer mine; they are ravaging what belongs to you." The reply of Crœsus attracted the attention of Cyrus; he therefore ordered all the rest to withdraw, and asked Crœsus what he thought should be done in the present conjuncture. He answered: "Since the gods have made me your servant, I think it my duty to acquaint you, if I perceive anything deserving of remark. The Persians, who are by nature overbearing, are poor. If, therefore, you permit them to plunder and possess great riches, you may expect the following results; whoso acquires the greatest riches, be assured, will be ready to rebel. Therefore, if you approve what I say, adopt the following plan: place some of your body-guard as sentinels at every gate, with orders to take the booty from all those who would go out, and to acquaint them that the tenth must of necessity be consecrated to Jupiter; thus you will not incur the odium of taking away their property; and they, acknowledging your intention to be just, will readily obey." Cyrus was exceedingly delighted at this suggestion, and ordered his guards to carry it out, then turning to Crœsus, he said: "Since you are resolved to display the deeds and words of a true king, ask whatever boon you desire on the instant." "Sir," he answered, "the most acceptable favor you can bestow upon me is, to let me send my fetters to the god of the Greeks, whom I have honored more than any other deity, and to ask him, {33} if it be his custom to deceive those who deserve well of him." Certain Lydians were accordingly sent to Delphi, with orders to lay his fetters at the entrance of the temple, and to ask the god, if he were not ashamed to have encouraged Crœsus by his oracles to make war on the Persians assuring him that he would put an end to the power of Cyrus, of which war such were the first-fruits (commanding them at these words to show the fetters), and at the same time to ask if it were the custom of the Grecian gods to be ungrateful. When the Lydians arrived at Delphi, and had delivered their message, the Pythian is reported to have made this answer: "The god himself even cannot avoid the decrees of fate; and Crœsus has atoned for the crime of Gyges his ancestor in the fifth generation, who, being one of the body-guard of the Heraclidæ, murdered his master, Candaules, and usurped his dignity, to which he had no right. But although Apollo was desirous that the fall of Sardis might happen in the time of the sons of Crœsus, and not during his reign, yet it was not in his power to avert the fates; but so far as they allowed he accomplished, and conferred the boon on him; for he delayed the capture of Sardis for the space of three years. Let Crœsus know, therefore, that he was taken prisoner three years later than the fates had ordained; and in the next place, he came to his relief, when he was upon the point of being burnt alive. Then, as to the prediction of the oracle, Crœsus has no right to complain; for Apollo foretold him that if he made war on the Persians, he would subvert a great empire; and had he desired to be truly informed, he ought to have sent again to inquire, whether his own or that of Cyrus was meant. But since he neither understood the oracle, nor inquired again, let him lay the blame on himself. And when he last consulted the oracle, he did not understand the answer concerning the mule; for Cyrus was that mule; inasmuch as he was born of parents of different nations, the mother superior, but the father inferior. For she was a Mede, and daughter of Astyages, king of Media; but he was a Persian, subject to the Medes." When Crœsus heard this reply of the priestess of Apollo, he acknowledged the fault to be his and not the god's.

{34} The customs of the Lydians differ little from those of the Greeks. They are the first of all nations we know of that introduced the art of coining gold and silver; and they were the first retailers. The Lydians themselves say that the games which are now common to themselves and the Greeks, were invented by them during the reign of Atys, when a great scarcity of corn pervaded all Lydia. For when they saw famine staring them in the face they sought for remedies, and some devised one thing, some another; and at that time the games of dice, knucklebones, ball, and all other kinds of games except draughts, were invented, (for the Lydians do not claim the invention of this ancient game,) and having made these inventions to alleviate the famine, they employed them as follows: they used to play one whole day that they might not be in want of food; and on the next, they ate and abstained from play. Thus they passed eighteen years; but when the evil did not abate, but on the contrary, became still more virulent, their king divided the whole people into two parts, and cast lots which should remain and which quit the country, and over that part whose lot it should be to stay he appointed himself king; and over that part which was to emigrate he appointed his own son, whose name was Tyrrhenus. Those to whose lot it fell to leave their country went down to Smyrna, built ships, and having put all their movables which were of use on board, set sail in search of food and land, till having passed by many nations, they reached the Ombrici, where they built towns, and dwell to this day. From being called Lydians, they changed their name to one after the king's son, who led them out; from him they gave themselves the appellation of Tyrrhenians.