TEMPLE OF ZEUS AT OLYMPIA

PAINTED FOR THE CENTURY BY JULES GUÉRIN

Title: The Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine (June 1913)

Author: Various

Release date: April 13, 2017 [eBook #54545]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Jane Robins, Reiner Ruf, and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

Transcriber’s Notes

This e-text is based on ‘The Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine,’ from June 1913. The table of contents has been added by the transcriber.

Inconsistent spelling and hyphenation have been retained, but punctuation and typographical errors have been corrected. Passages in English dialect and in languages other than English have not been altered.

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

Copyright, 1913, by THE CENTURY CO. All rights reserved.

TRAVEL NUMBER

| PAGE | ||

| THE GREAT ST. BERNARD. | Ernst von Hesse-Wartegg | 161 |

| Pictures by André Castaigne. | ||

| THE TRAINING OF A JAPANESE CHILD. | Frances Little | 170 |

| Pictures from photographs. | ||

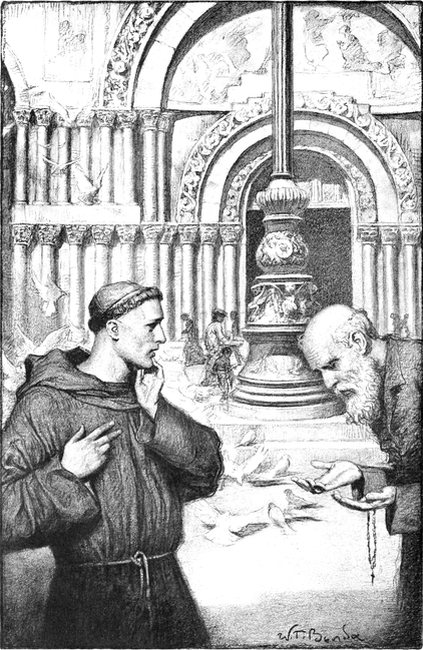

| BROTHER LEO. | Phyllis Bottome | 181 |

| Pictures by W. T. Benda. | ||

| THE CENTURY’S AFTER-THE-WAR SERIES. | ||

| Another View of “The Hayes-Tilden Contest”. | George F. Edmunds | 192 |

| Portrait of Ex-Senator Edmunds. | ||

| THE GRAND CAÑON OF THE COLORADO. | Joseph Pennell | 202 |

| Six lithographs drawn from nature for “The Century.” | ||

| IF RICHARD WAGNER CAME BACK. | Henry T. Finck | 208 |

| Portrait of Wagner from photograph. | ||

| PORTRAIT OF DOROTHY MCK——. | Wilhelm Funk | 211 |

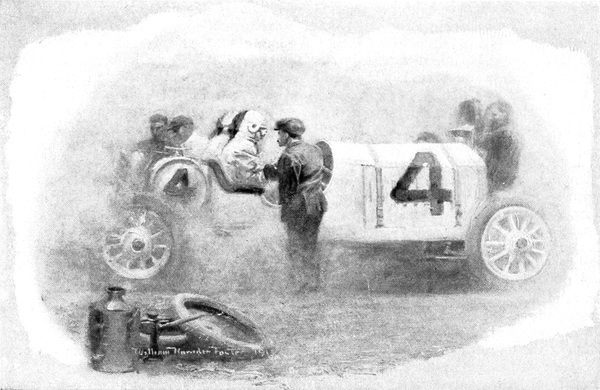

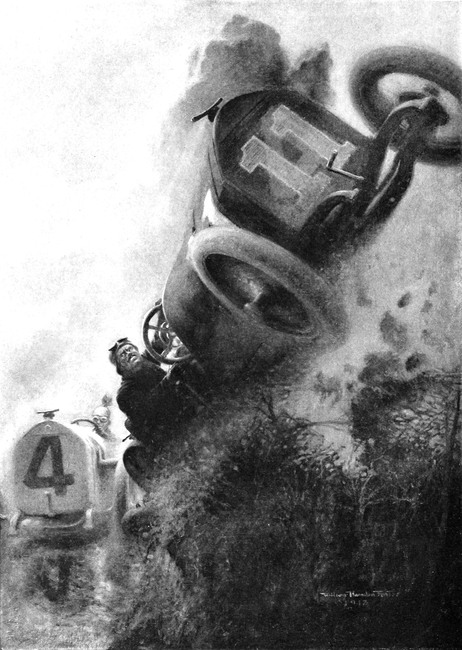

| “BLACK BLOOD.” | Edward Lyell Fox | 213 |

| Pictures by William H. Foster. | ||

| SKIRTING THE BALKAN PENINSULA | Robert Hichens | |

| IV. Delphi and Olympia. | 224 | |

| Pictures by Jules Guérin and from photographs. | ||

| NOOSING WILD ELEPHANTS. | Charles Moser | 240 |

| Pictures from photographs. | ||

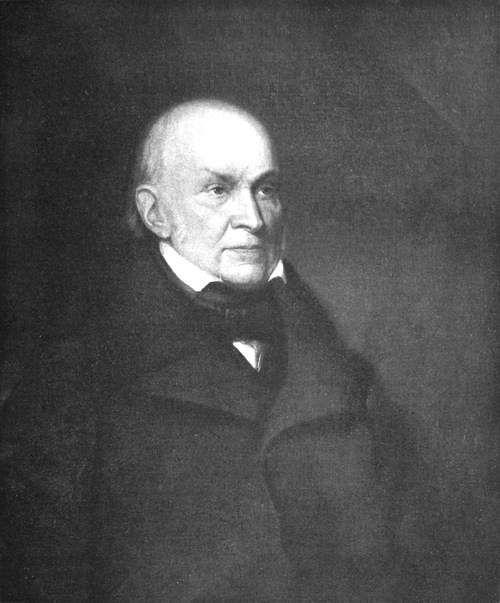

| JOHN QUINCY ADAMS IN RUSSIA. (Unpublished letters.) | ||

| Introduction and notes by Charles Francis Adams. Portraits of John Quincy Adams and Madame de Staël | 250 | |

| THE CENTURY’S AMERICAN ARTISTS SERIES. | ||

| Frank W. Benson: My Daughter. | 264 | |

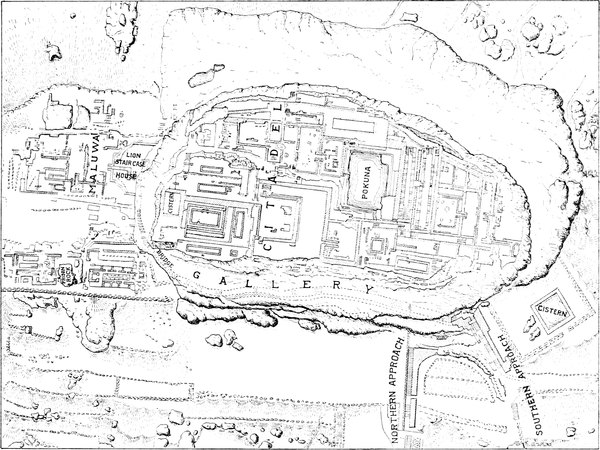

| SIGIRIYA, “THE LION’S ROCK” OF CEYLON. | Jennie Coker Gay | 265 |

| Pictures by Duncan Gay. | ||

| NOTEWORTHY STORIES OF THE LAST GENERATION. | ||

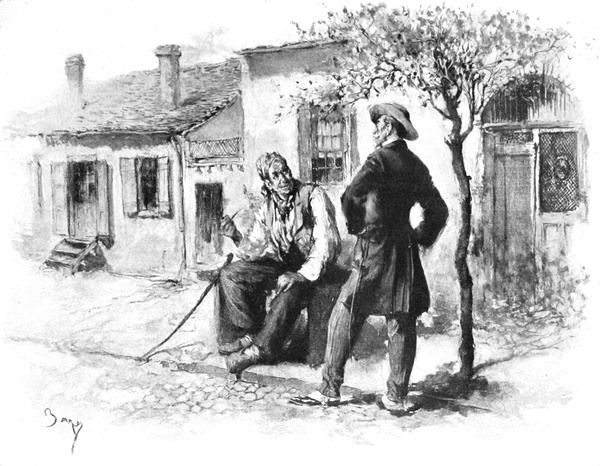

| Belles Demoiselles Plantation. | George W. Cable | 273 |

| With portrait of the author, and new pictures by W. M. Berger. | ||

| COLONEL WATTERSON’S REJOINDER TO EX-SENATOR EDMUNDS. | Henry Watterson | 285 |

| Comments on “Another View of ‘The Hayes-Tilden Contest.’” | ||

| A PAPER OF PUNS | Brander Matthews | 290 |

| Head-piece by Reginald Birch. | ||

| T. TEMBAROM. | Frances Hodgson Burnett | |

| Drawings by Charles S. Chapman. | 296 | |

| UNDER WHICH FLAG, LADIES, ORDER OR ANARCHY? | Editorial | 309 |

| NEWSPAPER INVASION OF PRIVACY. | Editorial | 310 |

| THE CHANGING VIEW OF GOVERNMENT. | Editorial | 311 |

| THE TWO-BILLION-DOLLAR CONGRESS. | Editorial | 313 |

| ON THE LADY AND HER BOOK. | Helen Minturn Seymour | 315 |

| ON THE USE OF HYPERBOLE IN ADVERTISING. | Agnes Repplier | 316 |

| AFTER-DINNER STORIES. | ||

| An Anecdote of McKinley. | Silas Harrison | 319 |

VERSE

| OFF CAPRI. | Sara Teasdale | 223 |

| AT THE CLOSED GATE OF JUSTICE. | James D. Corrothers | 272 |

| FINIS. | William H. Hayne | 295 |

| INVULNERABLE. | William Rose Benét | 308 |

| A CUBIST ROMANCE. | Oliver Herford | 318 |

| Picture by Oliver Herford. | ||

| OLD DADDY DO-FUNNY’S WISDOM JINGLES. | Ruth McEnery Stuart | 319 |

| LIMERICKS: | ||

| Text and pictures by Oliver Herford. | ||

| XXIX. The Kind Armadillo. | 320 | |

BY ERNST VON HESSE-WARTEGG

WITH PICTURES BY ANDRÉ CASTAIGNE

IN a popular guide-book to Switzerland, it is stated that of all Alpine passes the Great St. Bernard is the least interesting. With this view the traveling public does not seem to agree, for the St. Bernard is crossed every year by more people than any other pass. On an average, twenty thousand annually arrive at the hospice on the summit, and nine tenths of them during the short summer season, from the beginning of July to the end of August, which means over three hundred daily.

Now, the whole district of the St. Bernard for many miles around possesses not one of the vast caravansaries characteristic of the picturesque mountain-tops in Switzerland,—indeed, not even a modest inn,—where tourists may find shelter for a few days. Why, then, should these armies of tourists invade the pass every summer, if it really offers little of interest?

To me, who have seen almost all the passes from one end of the Alps to the other, the trip over the Great St. Bernard was most enjoyable. Though the scenery may not be so beautiful as that of the St. Gotthard, for instance, it surpasses by far even that and most of the others in wild grandeur; for nowhere else in the Alps can be found mountains of bolder aspect and greater height. On the west, near the French boundary, I need only mention Mont Blanc and Mont Dolent; on the east, the glacier-covered peaks of Mont Velan, and the towering masses of the Grand Combin.

The valley of the river Dranse, which is followed by the traveler from Martigny, in the Rhone valley, to very near the summit, more than eight thousand feet above the sea, is full of romantic beauty and wildness, closed in by snow-covered mountains of fantastic shapes, their steep slopes partly covered with dark pine forests. Nestling on the rocks or sleeping in the valleys there are a few straggling settlements, with heavy-visaged natives, apparently of a different race from the Swiss, and entirely untouched by modern life. They live in tottering, wooden houses of the quaintest shapes, dark brown with age, and with wooden barns on stilts attached to them. Only a few villages, as Orsières,[Pg 162] Liddes, and Bourg St. Pierre on the Swiss side, and St. Rémy on the Italian side, have stone houses along their narrow main thoroughfares.

During the summer months these roads are daily traversed by a motley crowd of tourists from all parts of the world, traveling on foot, or in private carriages or postal diligences, for the road is kept in capital order. Many wayfarers stop at the modest inns to rest and take a glass of kirsch, or even to seek shelter in the old houses when storms spring up suddenly, blowing furiously down the valleys; or they may repose on the rotten thresholds of the houses side by side with old matrons working at their spinning-wheels or with young girls knitting stockings, and converse with them in their French patois. The men are frequently employed as guides, and all are in constant intercourse with modern people from the great capitals of both continents, yet they do not depart from their ancient manners and ways.

The uncommon tenacity of these mountaineers is surprising, as the St. Bernard traffic is by no means new. True, the new carriage-road connecting central Europe, by way of Switzerland, with Italy was opened only in the first days of August, 1905, when the King of Italy himself was present, together with the authorities of the neighboring countries. But the St. Bernard has been a highway for thousands of years; it has seen many armies in war-time and many caravans with merchandise in times of peace. More than two hundred years before Christ, the great Hannibal passed over it with his Carthaginian legions; over the winding road which Hannibal had constructed Julius Cæsar led his Roman army down the valley of the Dranse for the conquest of Gallia and Germania. Emperor Augustus II improved and rebuilt the road, portions of which are still seen by the side of the new carriage-road wherever the latter has not been built on the foundation of the Roman highway.

At the beginning of the Christian era, the summit of the pass was crowned with a temple in honor of Jupiter, with rest-houses for travelers. Vestiges of this temple still exist, and in the large and well-stocked library of the present Hospice of St. Bernard the prior of the religious order in charge showed me a number of gold and silver coins, ex-voto figures, tablets, vessels, statuettes, and other objects found by the priests on the temple site. Indeed, owing to its situation on the direct geographical line between Italy and the North, the St. Bernard has been crossed in the course of time by more people than has any other pass.

The traveler of to-day, arriving at the hospice in a comfortable carriage within ten hours from the nearest railway-station, and provided with all the luxuries of modern life, can hardly picture to himself the terrible privations of the traveler in ancient times, when settlements were scarce. Provisions had to be carried along for many miles to these icy regions, most of the time covered with deep snow which obliterated every trace of roads.

On the evening of my arrival, I went to the plateau where once Jupiter was worshiped. The small lake beyond which it is situated had still some ice-cakes floating on its placid surface. Resting there on a stone, my fancy enlivened this scene of solitude and desolation with the savage soldiers of heathen times. I imagined that I heard the cracking and screaking of heavy cart-wheels, the clattering of armor, the clanking of spears, as the legions toiled wearisomely upward to the beating of drums and blowing of trumpets. My eyes pictured strange, stalwart warriors, exhausted from the arduous pull up those steep valleys, shivering with intense cold, fainting, sinking into the deep snow. And then an avalanche, breaking loose from the towering mountains above, came thundering down, dispersing this glittering array, and burying many under the soft, white, yet deadly, mass.

It was with the object of offering shelter to the weary and of rescuing those who succumbed to the inclemencies of these forbidding heights that in the year 962 a pious monk, Bernard, Count of Menthon, whose home was in Savoy, near Annecy, resolved to devote his life and fortune to the founding of a hospice on the summit of the pass. He succeeded in persuading other monks to share with him the dreary life, and thus founded a holy order, named to-day “Les Chanoines reguliers de St. Augustin.” Bernard of Menthon himself, afterward canonized by the pope, was elected first prior, and lived[Pg 164] forty years at the hospice. His tomb is still standing in the Italian town of Novara. According to the keeper of the royal archives at Turin, whom I consulted on the history of the hospice, it is first mentioned in a document in the year 1108.

Drawn by André Castaigne. Half-tone plate engraved by R. Varley

AN AVALANCHE ON THE ST. BERNARD PASS

In the Middle Ages the hospice, being of great importance in the intercourse between the north and south of Europe, enjoyed the powerful support and protection of the great rulers of that period, notably the German emperors. In return for valuable services, the order was richly endowed, and became in time exceedingly wealthy and prosperous. At the beginning of the sixteenth century it possessed no fewer than ninety-eight livings. The Reformation, however, ended this prosperity, and since then various misfortunes have carried away most of its once very large revenues. Its total income is now about eight thousand dollars, and without the aid received from the Italian and Swiss governments it would be impossible to offer hospitality to the large number of tourists that come every year. As many as five hundred have received free board and lodging in a single day.

It is to be regretted that so few visitors take notice of the collection-box in the pretty little church. Many well able to pay for the hospitality they receive do not give even so much as they would pay for their entertainment in a third-rate inn. The total amount given by tourists is only a small fraction of the actual expense incurred in entertaining them. The present King of England, who visited the hospice when Prince of Wales, sent a piano, and I could not help wondering how this bulky instrument was brought up the steep mountains. Emperor Frederick of Germany, with his consort, came in 1883, and the prior showed me one of their valuable gifts—a volume of Thomas à Kempis, bearing their signatures.

One must bear in mind that provisions, wood, and all other necessities of life have to be brought up eight thousand feet from the valleys below. For miles about the hospice there is not a tree, not a bush or a single blade of grass, and the view from my window offered nothing but barren rocks, bleak mountains, glaciers, and snow-fields. The mean annual temperature is below the freezing-point, being about the same as Spitzbergen, within the Arctic Ocean! One cannot help admiring the little group of monks, about twelve in number, who, with an equal number of lay brothers and servants, live here, in this highest human habitation of Europe, summer and winter, year after year, till they die. They do not wear the monk’s capouch, but the ordinary black sacerdotal robe, with a white cord falling from the neck as a special distinction.

Their sufferings are sometimes intense. The climate is so severe, and their duties are so arduous, that their constitutions would soon be broken down if they were not allowed to recuperate temporarily at their house in Martigny, their places being taken by other members of this brave and devoted brotherhood.

On the St. Bernard summit the seasons are unknown. Winter is, so to speak, perpetual, without spring or autumn or summer, the only indication of our warm seasons being the melting of the snow, which sometimes drifts about the three tall stone buildings to a height of forty feet. The cold is often twenty degrees below zero Fahrenheit and has been in one instance twenty-nine degrees. When I stayed at the hospice early in August, the lake behind it was frozen over during the night, and the monks told me that there have been years when the ice on its surface did not melt.

Under these conditions, I was not surprised to find among the occupants of the hospice mostly young men, only one of them being over fifty, and he had spent twenty consecutive years on the St. Bernard. The hardest labors of these pious men are during the winter months, notably in November and February, when numerous poor laborers from Italy venture to cross in search of work. Unfamiliar with the hardships and dangers they have to face, they ascend from Aosta over St. Rémy, plodding wearily through the deep snow, which obliterates all traces of the road, sometimes covering even the telegraph-poles. At last their strength gives out, or they are buried under an avalanche, or they lose their way and cannot proceed from sheer exhaustion. Those who do not perish owe their lives to the zeal of the monks and the alertness of the famous dogs of St. Bernard.

Day after day all the monks are out on their beat through the “Valley of Death” on the north side opening immediately below the hospice, and the steep snow-fields to the south, each accompanied by a servant and a dog. They search the surroundings, where every dell, every rock is familiar to them, with powerful field-glasses. Breaks or dark spots are detected at once on the white surface, but the surest and never-failing discoverers of unfortunate victims are the dogs. Their extraordinary fine scent indicates to them the exact direction in which it is necessary to search, and the men follow on snow-shoes. Arrived at the supposed spot, the dogs begin to bark and to scratch in the snow, the men take to their shovels, and soon the poor wayfarer is discovered. If life has fled from him, the body is carried up to the hospice and placed in the little low, desolate stone hut standing at a short distance from the buildings, the abode of the dead. In this “morgue” rest the victims of the Alps till their bodies crumble to ashes. There is no other way of disposing of the dead, since for miles about the hospice not enough soil can be found to furnish a grave.

At the time of my visit, only one body of the preceding winter was lying among the remains of the victims of former years. The others who had been found had been restored to life.

Many thousands have been rescued[Pg 165] from certain death, principally owing to the cleverness of the dogs, carefully trained to their work. According to the register kept at the hospice, these dogs, originally a cross between Newfoundland and Pyrenean, were employed first in the fifteenth century, and the present breed is undoubtedly descended from them. To preserve it pure, several dogs are also kept at the two other settlements of the brotherhood, the Simplon hospice and Martigny. The expediency of this is shown by the accident of 1825, when nearly all the dogs at the St. Bernard hospice, together with three lay brothers, perished in a terrible avalanche on the Swiss slope near the present “Cantine de Proz,” the highest inn on the way to the hospice, kept by the Swiss Government as a postal station. Only two or three dogs survived, and they perpetuated the race.

Now there are about fifteen dogs at the hospice. They are objects of much petting on the part of travelers, especially ladies, to which they indulgently submit. In appearance they differ considerably from what we picture them to be. They are much smaller than the St. Bernard dog of other countries, but heavier-set and stronger. The hair is white, coarse, and tight to the skin, with large yellow or reddish-brown spots, the chest and the lower part of the body being always white. The long tail is heavy and shaggy, the[Pg 166] neck short-set and uncommonly strong, carrying a large head, with the muzzle short and broad. The front teeth are mostly visible, and the dogs would look rather ferocious without the intelligent and withal docile expression of their large, bright eyes. Many of them have been reproduced on postal cards, for sale in the large reception-room, one of the few rooms furnished with a stove. The prior, who is also Swiss postmaster, told me that on the average one thousand postal cards, mostly with pictures of the dogs, are daily sent “with hearty greetings” to all parts of the world. But in the “season,” as many as fifteen hundred have been mailed in a single afternoon, especially when snow-storms or rain keep the tourists indoors with nothing to do.

The best type of a St. Bernard dog was famous Bary, who, after saving thirty-nine lives, was unfortunately shot by an English traveler he was trying to rescue, who mistook him for a wolf. His stuffed skin is now in the museum at Bern. Since then there has always been a “Bary” among the dogs. The present dog of that name has already saved three lives, while Pallas and Diana have saved two each.

St. Bernard dogs, imported mostly from England in recent years, have become decidedly popular in America. They are chiefly of the long-haired kind, much larger and with rather flatter heads and longer muzzles than the dogs at the St. Bernard hospice. Nevertheless, they are genuine St. Bernards, and are descended from those originally brought to England from Switzerland for Lord Dashwood, about one hundred years ago.

In their home country this breed of dogs is by no means confined to the St. Bernard mountain. Raised in most Alpine valleys, they have become, so to speak, the[Pg 167] national dog of Switzerland, and are foremost in public favor. While the long-haired type prevails in the lower cantons, nothing but the short-haired variety are employed at the hospice, the former type being unfitted for the peculiar mountain work. Enormous snowfalls in spring and autumn force them sometimes to dig their way under the snow for two or three days; on occasions they remain in the icy fields for a week or two, returning to the hospice reduced to mere skeletons. The coat of the long-haired dogs dries much slower, and the dripping from the fur congeals, causing rheumatism and other ailments and making them soon unfit for their work.

The general belief that the original St. Bernard race died out long ago is unfounded. There can be no doubt that the present dogs are descended from those kept at the hospice in the Middle Ages, crossed with Danish bulldogs and Pyrenean dogs about five centuries ago, that they might inherit size and strength from the former and intelligence and keen scent from the latter. St. Bernard, the founder of the hospice, is represented in ancient pictures accompanied by a large white dog. The insecurity of the much frequented route between Italy and the North in early times caused the monks to keep dogs for their own protection, till their usefulness for life-saving purposes made them indispensable companions.

Drawn by André Castaigne. Half-tone plate engraved by H. C. Merrill

A BAND OF GIPSIES TRAVELING ALONG THE ST. BERNARD PASS

Unfortunately, most of the early documents in regard to the dogs were destroyed by fire, but the existing traditions of the antiquity of the race are confirmed by the escutcheon of an ancient Swiss family which I discovered in the archives of the city of Zurich. Four families of the fourteenth century have dogs as ornaments of the escutcheon helmet. They are Stubenweg, Aichelberg, Hailigberg, and the counts of Toggenburg, the latter famous in history and still flourishing in Austria. The escutcheons are most carefully painted, and show four distinct and clearly defined types of dogs. The type over the escutcheon of the family of Hailigberg shows a striking resemblance to the St. Bernard dog of to-day, with all the characteristic signs. Mountains crowned by hospices used to be called sacred mountains or Hailigberg (present style Heiligberg) during the Middle Ages, and from this it may safely be deducted that the knights of Hailigberg, took the picture of a hospice dog for their helmet ornament.

For ages the St. Bernard dogs have been trained for their service in a peculiar manner: one old and one young dog are sent together daily down the Valley of Death toward the nearest human habitation; two others on the south side toward St. Rémy, their footprints in the snow indicating to lost travelers with unfailing certainty the exact line of the road buried under the snow. The younger dogs are taught by the older ones to show to travelers the way to the hospice by barking and jumping and running ahead of them toward the summit of the pass. If they happen to find a poor half-frozen victim, they try to restore animation by licking the hands and face. Then they hasten back to the hospice and announce their discovery by barking.

Great credit is due to the Kynological Society of Switzerland for the preservation, improvement, and popularization of the hospice dogs in their pure type. In the latter part of the last century the English type, as described above, threatened to become generally established as the correct one. At an international Kynological Congress convened by that society in Zurich in 1887, the characteristic marks of the pure hospice type were laid down and acknowledged by the delegates of all countries, England included. In 1885 the first pure St. Bernard dogs were introduced into Germany by Prince Albrecht of Solms-Braunfels, and as they became very popular in a short time, a St. Bernard Club was organized in Munich in 1891 for the express purpose of improving the St. Bernard breed by organizing an exposition with competent judges, and publishing annually a book of genealogy.

The first Napoleon, who crossed the St. Bernard with his army, cavalry, artillery, and all, between the fifteenth and twenty-first of May, 1800, was very fond of these dogs and kept some in his room while resting at the hospice. Near the entrance of the largest building, erected in the seventeenth century, there is a big bell, rung by travelers to announce their arrival. Opposite the bell a large marble tablet commemorates the passage of Napoleon, dedicated by the government of the then republic, now the Swiss canton of Valais. His army was the last to cross the St. Bernard, and in the place of armies of soldiers, those of tourists invade the historic pass every year. They are most numerous in August, for the snow rarely melts before July and begins to fall again early in September, to stay till the following July. The poor priests are then left to themselves for about ten months, when the next summer’s sun makes the carriage-road again practicable.

The founder of the hospice, with its brotherhood, has at last received a monument, which he well deserved. His statue was unveiled during the summer of 1905, and stands on the spot which the many thousands have had to pass who, after being rescued by his successors, have resumed their journey to the valleys below and to renewed life.

BY FRANCES LITTLE

Author of “The Lady of the Decoration,” “The Lady and Sada San,” etc.

THE stork has no vacation in Japan, neither does he sleep; and if he rests, the time and place are known of no man. On the stroke of the hour, nay, of the quarter, he is faithfully at his work distributing impartially among rich and poor small bits of humanity. He may be a wise bird, but if he thinks by the swiftness of his wings to find a home beneath roof of straw or palace tile unprepared for his coming, he is mistaken. He will discover that he has failed utterly to comprehend the joy of the mother to be. A childless woman is of no value in a land where the perpetuation of the family name is the most vital law prescribed in its religious and moral teachings. For a Japanese woman, therefore, the pinnacle of desire is reached when the white bird taps at her door and lays its precious bundle in her outstretched arms. For a time at least she has been able to forget the great terror of her life, divorce, and to make ready for the coming of the child with high hope and tender joy.

Only two little garments are prepared previously. For the inside, a tiny kimono of bright yellow, the color supposed to give health and strength to the body; and for an outer covering, a coat of red, which color means congratulation. Until the sex of the baby is known, the wardrobe is thus limited as a matter of economy in time and cloth. If a boy, he has the sole right to every shade of blue. To the girl fall the softest pinks and reds. Whichever the sex, every available member of the family lends a willing hand to the busy task of cutting and stitching into many shapes the flowered cloth necessary to decorate the small body.

The tiny wardrobe complete, the household turns its attention to the preparation of the feast with which to make merry and give thanks to the gods for so good a gift as a little child, whether it be boy or girl. The house is swept and garnished. Out in the kitchen, maids run hither and thither, hurrying the boiling pot, cleansing the already spotless rice, and scampering to bring the best wine. It is glad service. The happiness in the coming of the baby is shared by everybody from the parents to the water-coolie. Hence the eagerness with which the little house shrine is decorated and offerings of food and sake set before the benign old image who is responsible for this great favor. For days preparations go joyfully on, and though the small guest cannot indulge, a special table is set for him at the feast given in his honor, when neighbors and friends as[Pg 172]semble to offer congratulations and presents. Later, each present must be acknowledged by the parents sending one in return.

The baby is excused from being present at the festival, but custom demands that no other engagement interfere with the shaving of his head on the third day. In the olden days styles in hair-cutting were as rigidly adhered to as the wearing of a samurai’s sword, but progress must needs tamper even with the down on a baby’s head. Now the fashion has lost much of its quaintness, and is mostly uniform. The sides and back of the head are shaved smooth, while from the crown a fringe is left to sprout like the long petals of a ragged chrysanthemum. The length and seriousness of the hair-cutting ceremony depend upon the self-control of the young gentleman. Regardless of conduct, however, or of the cost to the nervous system, certain fixed rules are enforced, which are virtually the only training the child receives in early years.

After the little stranger, all shaven and shorn, is returned to his private apartments, the elders of the family consult on the grave matter of choosing a name for him. Often the naming of the baby is a simple matter, the father or grandfather speaking before the company the name of some famous man, if the child is a boy, or of some favorite flower, if it is a girl. For girls, Hana, flower, Yuki, snow, Ai, love, are the favorites of parents with a poetical strain. The sterner country-folk choose for their daughters, Matsu, pine, Take, bamboo (the bamboo joints are exact; hence the exactness of virtue), Ume, plum, since the plum bears both cold and snow bravely. For boys, Ichiro, first boy, Toshio, smart, Iwao, strong, and Isamu, brave, are very popular.

Where belief is strong in the power of a name, the family, in holiday dress, often assembles in a large room. Each writes a name upon a slip of paper and lays it reverently before the house shrine. From the group a very young child is chosen and led before this shrine, and the fate of the name is decided by the small hand which reaches out for a slip. Though it is a festive occasion, the selection of a name is made with a seriousness worthy the election of a bishop. Many believe devoutly that this rite influences the baby’s entire future, and therefore the one whose[Pg 173] slip is chosen incurs from the moment of choice great responsibility for the child’s welfare.

The next great event in the baby’s existence is on the thirtieth day, when he is taken to the temple to be offered to the god that rules over that particular village or city. Dressed in his best suit of clothes, he is strapped to the back of his mother or nurse, with his body wrapped almost to suffocation, and usually with his head dangling from side to side with no protection for face or eyes. Why all Japanese babies are not blind is one of the secrets of nature’s provision. With tender women for mothers and affectionate servants for nurses, it is strange that the little face is seldom shielded from the direct rays of the sun or the piercing winds of winter. Possibly it is a training for physical endurance that later in life is a part of his education.

Arrived at the temple, the child is presented to the priest. This dignitary, with shaven head and clad in a purple gown, reads very solemnly a special prayer to the god whose image, enshrined in gilt and ebony, rests within the deep shadows of the temple. He asks his care and protection for the helpless little creature that lies before him. At the end of the reading the priest shakes a gohei to and fro over the child. A gohei resembles nothing so much as a paper feather duster. Its fluffy whiteness is supposed to represent the pure spirit of the god, and through some mysterious agency a part of this spirit is transferred to the child by the vigorous shaking.

For a few more coins, further protection can be purchased for the little wayfarer. The guaranty of his success and happiness comes in two small paper amulets on which the priest has drawn curious characters decipherable only to the priest and the god. Both amulets are given to the mother, who, with the baby on her back, trots home on her high wooden geta, or clogs, her face aglow with the contentment possible only to one whose faith in prayer and priest is sublime. One amulet, carefully wrapped with the cuttings of the first hair and with the name, is laid away safely in the house shrine, that the god may not forget. The other is carried in a gay little bag of colored crape, which is tied to the sash of the child; for it is believed that it will ward off sickness and hold all evil spirits at bay.

It must be with a sigh of relief that the baby comes to this stage of his existence. The numerous rites necessary to a fair start on life’s highway have been conscientiously performed, the watchful care of the spirits invoked. Now it is his sole business to kick and grow and feed like any small healthy animal, to be served as a young prince and to be adored as a young god. He is the pivot on which the whole household turns. Often, in the soft shadows of evening, on the paper doors of a Japanese house is silhouetted a picture where the child is the center about which the family is grouped in the great act of adoration. It is a bit of inner life that finds a tender response in the heart of any beholder.

The attitude of the usual family is that obedience is not to be expected of one so young, consequently nobody is disappointed, and the effect on the child is telling. He quickly learns his power, and becomes in turn the trainer and the ruler of the household. In fact, he is a small king, with only a soft ring of dark hair for a crown, and a chop-stick in his chubby fist for a scepter. His lightest frown or smile is a command to all the house, from the poodle with the ingrown nose to the bent old grandmother. But more willing subjects never bent before a king of maturer growth. Father and mother, with a train of relatives, yield glad obedience and stand ever ready for action at the merest suggestion of a wish.

Alas! for the tried and true theories on early training that have held for generations in other countries! Alas! for the scores of learned volumes on child culture! Useless the work of the greatest psychologists, who sound grave warning as to the direful results should one fail to observe certain hard-and-fast rules in the training of mind and body. Grant a few months to a fat, well-fed Japanese baby, and with one wave of his pink heels he will kick into thin air every tested theory that scholarly men have grown gray in proving. He snaps in twain the old saw, “As the twig is bent,” and sends to eternal oblivion that oft-repeated legend, “Give me a child till its seventh year, and neither friend nor foe can change his tendencies.” Even the promise of old, “Children, obey your parents,” loses its value as a recipe for long life when applied to the baby citizen of old Nippon. It is a rare exception if he obeys. He lives neither by rule nor regulation, eats when, where, and what he pleases, then cuddles down to sleep in peace.

To the specialist, one such ill-regulated day in a baby’s life would augur a morning after with digestion in tatters and a ragged temper. He does not take into account the strange mental and physical contradictions of the race. Unchecked, the baby has been permitted to shatter every precept of health, but he awakens as happy as a young kitten. Fresh, sweet, and wholesome, he crawls from his soft nest of comfortables and goes about seeking some object on which to bestow his adorable smile. He is ready to thrive on another lawless day.

There is a mistaken, but popular, belief that a Japanese baby never cries. There is really no reason why he should. Replete with nourishment and rarely denied a wish, he blossoms like a wild rose on the sunny side of the hedge, as sweet and as unrestrained. His life is full of rich and varied interests. From his second day on earth, tied safely to his mother’s back under an overcoat made for two, he finds amusement for every waking hour in watching the passing show. He is the honored guest at every family picnic. No matter what the hour or the weather, he is the active member in all that concerns the household amusements or work. From his perch he participates in the life of the neighborhood, and is a part of all the merry festivals that turn the streets into fairy-land. Later, his playground is the gay market-place or the dim old temples.

Up to this time the child has had no suggestion of real training. His innate deftness in the art of imitation has taught him much. Continual contact with a wide-awake world has effectively quickened the growth of his brain, but the strings that have held him steadily to his mother’s back have stunted the growth of his body. The result is that when the time comes for that wonderful first day in the kindergarten, into the play-room often toddles a self-confident youngster whose legs refuse to coöperate when he makes his quaint bow, but whose keen brain and correspondingly deft hand work small miracles with blocks and paint-brush.

In Japan only a blind child could be insensible to color, after long days under the pink mist of the cherry-blossoms and the crimson glory of the maples, in the sunny green and yellow fields, or with mountain slopes of wild azalea for a romping-place and a wonderful sky of blue for a cover. By inheritance and environment he is an artist in the use of color. Form, too, is as easy, for when crude toys have failed to please, it is his privilege to build ships, castles, gunboats, and temples with every conceivable household article from the spinning-wheel to the family rice-bucket.

His instinct for play is strong, and after his legs grow steady he quickly masters games, and to his own satisfaction he can sing any song without tune or words. In the kindergarten he finds at first new joys in a play paradise of which he is, as at home, the ruler. Alas! for the swift coming of grief! For the first time in his life his will clashes with law, and for the first time he meets defeat, though he rises to conquer with all his fighting blood on fire. The struggle is swift and fierce, then behold the mystery of a small Ori[Pg 176]ental! After the first encounter, and often before the tears of passion have dried, he bends to authority, and with only occasional lapses soon becomes a devotee of the thing he has so bitterly fought. Henceforth kisoku, or law, becomes his meat and drink, the very foundation of living.

It is difficult to say whether this sudden change of heart comes from an inherited belief in the divine right of rulers or is the first cropping-out of that Eastern fatalism forcibly expressed in the word “Shikataganai” (“There is no help for it”). A partial explanation might be found in the attitude of most Japanese parents to the teacher in both kindergarten and school. By some strange reasoning they argue that it is the teacher’s business in life to train children; therefore from its earliest days the teacher is held before the child as a power from whose word there is no appeal. Frequently a mother says to her unmanageable offspring:

“What will happen when the sensei [teacher] hears of your rudeness?” or, “I shall speak to your teacher to command you to obey me.” Often the appeal is made direct to the teacher: “My daughter does not bow correctly,” or “She is neglectful of duty. Please remind her.”

The value of using the teacher as a prop or commander-in-chief lies in the fact that most of the profession realize their responsibility and earnestly endeavor to live up to the trust. They seek to share every experience of the pupil’s life, and are faithful leaders to the highest ideals they know.

There is a tendency in most Japanese kindergartens to make of them elementary schools in which much of the spirit of play is lost in an effort on the part of the teachers to give formal instruction. The inclination is to fit the child to the rule; to follow to the last detail a written law, at the sacrifice of spontaneity. Formality finds steady resistance in the buoyancy of youth; and how childhood will have its fling, refusing to wear the shackles till it must, is expressed in the despair of a little Japanese teacher who had worked in vain to make an unessential point in posture: “I have the great trouble. They just will kick up their heels spiritually [spiritedly].”

In addition to the gifts, games, and[Pg 177] songs usually found in the kindergartens, there is a specific training in patriotism, loyalty, and physical endurance by the constant repetition of certain stories emphasizing these virtues that have been told from generation to generation. Stories of brave men and women are dramatized. Day after day the child takes part in these simple plays. So earnest is the acting, so unwavering are the ideals presented at this very early age, that the mind is saturated with the principle of the sacrifice of the individual for the good of the whole.

In all circumstances, stress is laid upon outward courtesy, regardless of time or consequences. The key-note in the mimic plays is kindness to a fallen foe. Often there is an organized band of tiny Red Cross workers, who in full uniform are ever on the alert in the games to render quick aid to the supposedly wounded. The play is very real and sincere, and it fosters a spirit of kindness and sympathy never wholly lost in later years.

From babyhood the diminutive subject hears stories of his glorious ruler; but sometimes it is in the kindergarten that he is trained to perform his first great act of reverence to the throne in bowing before the picture of the emperor. It is a ceremony that touches deeply the most skeptical heart. On certain days groups of little children, many still unsteady on their feet, dressed in gay holiday clothes, come before the pictured image and pay homage to his Majesty by a low, reverent bow. It is like a flower-garden bending before the greater brilliancy of the sun. It is the tribute of innocence to power, and no sovereign lives who would not be a better man for having seen it.

As the first day in the kindergarten is wonderful, so to the child is the last. He is leaving babyhood behind, and half a day is barely sufficient for the imposing ceremonies. For weeks he has been patiently drilled. At the proper hour, with the precision of a mechanical doll and the dignity of a field-marshal, he graciously accepts from the hand of the teacher a roll of parchment only slightly shorter than himself. It is his certificate of graduation, stamped with a large seal, which inspires a deeper joy than comes later with the Order of the Rising Sun.

The transition from the kindergarten[Pg 178] to the primary grade is accomplished easily, and as the pupil is never supposed or expected to take the initiative, he has only to follow where he is led. A Japanese child is as responsive as are the strings of a samisen to the fingers of a skilled musician, and the leader has only to touch the notes to create the harmony desired.

During the period of elementary school, the training for boys and girls is much the same except in special cases when very young boys are instructed in fencing and jiu-jutsu. In these first years it is a sharing of all experiences, and the girls pluckily take their chances in the rough-and-tumble games with the boys. Then comes the parting of the ways. The sign-post for each points to a difference in school and subjects. For the boys, the road leads to the sterner things of life. Every step of the girls’ path is trained for the inevitable end—marriage. Whatever the future, it never yields—to the girl, at least—the same golden hours of freedom and equal right to joy and pleasure as in the glory days of youth. Every boy in Japan is a prospective soldier or sailor, every girl, a wife; and a training toward the end best fitting each for the duties involved is the principal aim of the carefully planned curriculum. In all grades the teaching is en masse; individual attention is rare.

From the first year of the primary course, through every grade, the study of morals heads the list. This rather formidable subject is presented to the very youthful in a most attractive way. Large pictures are shown illustrating in a charming manner the virtues to be emphasized. The teacher tells a set story. It is short, but so dramatic is the manner of telling it, so alluring the trick of hand and voice, the child’s interest is held as if by magic. The subjects of these early moral lessons are the “Teacher,” the “Flag,” “Attitude.” Later, family relations are studied; as, for instance, that of father and mother, grandparents, etc.

Training in pronunciation and simple lessons in drawing are included in the first year, with manual work for the boys. The girls begin preparation for their calling with the first principles of sewing and the first stitches of crocheting or knitting. In the latter part of the year practice begins in writing the kana, gradually intermixed with the Chinese ideographs. There are many thousands of these characters, and they are usually difficult. Necessarily the first steps are simple. The awkward little fist must be trained to lightness and poise of brush, delicacy and sureness in touch, for one false stroke in the intricate structure brings grief. Ignorant of the difficulties in store for him, the child begins his task merrily, delighted with the lines, big and bold at first, which resemble funny pictures more than an alphabet. He practises on everything at hand, from the fresh sand on the playground to the nearest new, white shoji.

A system of calisthenics, too, is begun early with the child, and only the unconquerable grace of childhood saves it from a permanent stiffening of bone and muscle. Happily, studies and gymnastics are interspersed with generous hours for free play. In all the training of Japanese children a great deal of outdoor life is planned. There are historical excursions, geographical excursions for practical instruction, and jolly ones merely for pleasure, when with a luncheon of cold rice and pickled plum tied in a furoshiki, or handkerchief, everybody scampers away to the river or mountain for a long happy day.

Every year at school means increased hours and more difficult studies. Added to these long periods are special lessons for the young in how to bow, how to stand, how to enter a room, how to lower the eyes, the placing of each finger on a book when reading, and endless other regulations. These rules are published in a text-book for the teacher, who is expected to drill them into the student to the minutest detail. It seems folly to expect anything from such training but a group of automata; but underlying this fixed formality is an air of controlled freedom that is really the foundation of the tremendous respect for law cherished by the entire nation. Nor is it to be imagined that continuous training in repression means permanent suppression of high spirits. This light-hearted race takes joy in the simplest pleasures, and the imp of mischief finds fertile soil in the brain of any healthy boy or girl.

During these years the hand of discipline is lightly laid in the home. The attitude of father and mother is kindly indulgent, and punishments, if any, cause[Pg 179] neither pain nor inconvenience. Current topics involving the welfare of the country and intimate matters of family life are freely discussed in the child’s presence. At an early age he absorbs much information, both wholesome and other. But whatever else may be neglected in his training, so insistently is held before the heir day by day the requirements necessary as a man to bear the honors of the family name, it often works something of a miracle in regulating conduct.

Next in reverence for the emperor is veneration for ancestors. There is one form of entertainment and instruction in the home which as an educative factor plays a large and delightful part in the life of the children. In the evenings, after the books have been put away, they gather around the glowing hibachi to hear the grandfather or grandmother weave the nondescript tales of gods and goddesses, of loyal, wise, and brave men. If any deed of the day calls for emphasis, it is skilfully marked by a special story cleverly worded by the aged narrator. Thus reward or punishment is effectively recited rather than administered.

But the training of the Japanese child is not all play and easy studies. Very soon the girls in the home begin lessons in light household duties, sewing, weaving, and cooking. Koto-playing is an accomplishment in the education of a girl, flower arrangement a necessity. To this most difficult art is usually allotted a period of five years. By tedious and patient practice the small hand must learn delicacy of touch and deftness in twists, that each leaf and blossom may express the symbol for which it stands. Every home festival and feast calls for a certain “poem” in arrangement. This is the duty of the young daughter of the house, who early must be well versed in the legends and meaning of flowers.

In ceremonial tea, “O Cha No Yu,” there are especial lessons in etiquette, which mean days and months of constant application and repetition of certain attitudes and definite postures, before supple muscles and youthful spirits are toned to the graceful formality and modest reserve requisite to every well-bred Japanese girl. Should the girl’s destiny point to the calling of geisha, or professional entertainer, the training is severe. At the age of three or four she is taken in hand by an expert in the business, and the strict discipline of the training soon robs childhood of its rights. Should a foolish law compel attendance for a year or so at school, it does not in the least interfere with long hours of music lessons, dancing lessons, flower arrangement, lessons in tea-serving, and the etiquette peculiar to tea-houses. The girl is persuaded or forced into quiet submission to the hard, tedious work by the glowing pictures of the butterfly life that awaits her. There is only one standard in the training of a geisha—attractiveness, and often the price of its attainment is an irretrievable tragedy.

Education for the child of the East calls for different methods from that of the West, and fully to understand the training of the Japanese child one must know the influence and demand for ancestor-worship, ethics, and the passion for patriotism. In fact, to understand any part of the system of training, it must be remembered that the whole moral and national education of the Japanese is based on the imperial rescript given the people by the emperor in 1890. The rescript is read in all the schools four times a year. The manner of reading, the silence, breathless with reverence, in which it is received by the students, young and old, is a profound testimony to the sacredness of the emperor’s desires for his people.

The following is a translation, given by the president of the Tokio University:

Know ye, Our Subjects:

Our Imperial Ancestors have founded Our Empire on a basis broad and everlasting, and have deeply and firmly implanted virtue; Our Subjects, ever united in loyalty and filial piety, have from generation to generation illustrated the beauty thereof. This is the glory of the fundamental character of Our Empire, and herein also lies the source of Our education. Ye, Our Subjects, be filial to your parents, affectionate to your brothers and sisters; as husbands and wives be harmonious; as friends, true; bear yourselves in modesty and moderation; extend your benevolence to all; pursue learning and cultivate the arts, and thereby develop intellectual faculties and perfect moral powers; furthermore, advance public good and promote common interests; always respect the Constitution and observe[Pg 180] the laws; should emergency arise, offer yourselves courageously to the State; and thus guard and maintain the prosperity of Our Imperial Throne coeval with heaven and earth.

So shall ye not only be Our good and faithful subjects, but render illustrious the best traditions of your forefathers.

The Way here set forth is indeed the teaching bequeathed by Our Imperial Ancestors, to be observed alike by Their Descendants and the subjects, infallible for all ages, and true in all places. It is Our Wish to lay it to heart in all reverence, in common with you, Our Subjects, that we may all attain to the same virtue.

From the early days to the present, the educational system, which enters more vitally into the training of a Japanese child than any other influence, has survived many changes. The authorities have sought earnestly in every country for the plan best adapted to the peculiar demands of a country that was progressing by leaps. After the Restoration, when every sentiment was swinging away from old customs and traditions, there was a reorganization with the American plan as a model. Soon, however, the wholesale doctrine of freedom proved too radical for a country lately emerged from isolation and feudalism, and much of the German system was introduced, and more rigid control was exercised over the students. The schools assumed something of a military atmosphere and the dangers of a too new liberty were laid low for a while.

It would be difficult in a brief space to estimate the whole influence of European and American methods on Japanese education. While these influences, especially those of America, have enjoyed successive waves of favor and disrepute, it is undoubtedly true that the educational department is slowly but surely feeling its way to the final adoption of a general American plan. So far, the most marked tendency of the Western spirit has been a bolder assertion of individual freedom, less tolerance of the teacher’s supreme authority, a demand for a more practical education and not so much eagerness for the Chinese classics.

While to an outsider the present system in many instances seems needlessly complex, and in frequent danger of a sad and sudden death from strangulation by its endless red tape, yet a glimpse of the internal workings of the department is reassuring.

Whatever criticism might be offered as to the methods of training or defects thereof in school or home, one undeniable truth stands out boldly: despite its faults, or because of its virtues, the system has produced men splendidly brave and noble, and women whose lives stand for all that is tender and beautiful in womanhood and motherhood.

BY PHYLLIS BOTTOME

WITH PICTURES BY W. T. BENDA

IT was a sunny morning, and I was on my way to Torcello. Venice lay behind us a dazzling line, with towers of gold against the blue lagoon. All at once a breeze sprang up from the sea; the small, feathery islands seemed to shake and quiver, and, like leaves driven before a gale, those flocks of colored butterflies, the fishing-boats, ran in before the storm. Far away to our left stood the ancient tower of Altinum, with the island of Burano a bright pink beneath the towering clouds. To our right, and much nearer, was a small cypress-covered islet. One large umbrella-pine hung close to the sea, and behind it rose the tower of the convent church. The two gondoliers consulted together in hoarse cries and decided to make for it.

“It is San Francesco del Deserto,” the elder explained to me. “It belongs to the little brown brothers, who take no money and are very kind. One would hardly believe these ones had any religion, they are such a simple people, and they live on fish and the vegetables they grow in their garden.”

We fought the crooked little waves in silence after that; only the high prow rebelled openly against its sudden twistings and turnings. The arrowy-shaped gondola is not a structure made for the rough jostling of waves, and the gondoliers put forth all their strength and skill to reach the tiny haven under the convent wall. As we did so, the black bars of cloud rushed down upon us in a perfect deluge of rain, and we ran speechless and half drowned across the tossed field of grass and forget-me-nots to the convent door. A shivering beggar sprang up from nowhere and insisted on ringing the bell for us.

The door opened, and I saw before me a young brown brother with the merriest eyes I have ever seen. They were unshadowed, like a child’s, dancing and eager, and yet there was a strange gentleness and patience about him, too, as if there was no hurry even about his eagerness.

He was very poorly dressed and looked thin. I think he was charmed to see us, though a little shy, like a hospitable country hostess anxious to give pleasure, but afraid that she has not much to offer citizens of a larger world.

“What a tempest!” he exclaimed. “You have come at a good hour. Enter, enter, Signore! And your men, will they not come in?”

We found ourselves in a very small rose-red cloister; in the middle of it was an old well under the open sky, but above us was a sheltering roof spanned by slender arches. The young monk hesitated for a moment, smiling from me to the two gondoliers. I think it occurred to him that we should like different entertainment, for he said at last:

“You men would perhaps like to sit in the porter’s lodge for a while? Our Brother Lorenzo is there; he is our chief fisherman, with a great knowledge of the lagoons; and he could light a fire for you to dry yourselves by—Signori. And you, if I mistake not, are English, are you not, Signore? It is probable that you would like to see our chapel. It is not much. We are very proud of it, but that, you know, is because it was founded by our blessed father, Saint Francis. He believed in poverty, and we also believe in it, but it does not give much for people to see. That is a misfortune, to come all this way and to see nothing.” Brother Leo looked at me a little wistfully. I think he feared that I should be disappointed. Then he passed before me with swift, eager feet toward the little chapel.

It was a very little chapel and quite bare; behind the altar some monks were chanting an office. It was clean, and there were no pictures or images, only, as I knelt there, I felt as if the little island in its desert of waters had indeed secreted some vast treasure, and as if the chapel, empty as it had seemed at first, was full of invisible possessions. As for Brother Leo, he had stood beside me nervously for a moment; but on seeing that I was prepared to kneel, he started, like a bird set[Pg 182] free, toward the altar steps, where his lithe young impetuosity sank into sudden peace. He knelt there so still, so rapt, so incased in his listening silence, that he might have been part of the stone pavement. Yet his earthly senses were alive, for the moment I rose he was at my side again, as patient and courteous as ever, though I felt as if his inner ear were listening still to some unheard melody.

We stood again in the pink cloister. “There is little to see,” he repeated. “We are poverelli; it has been like this for seven hundred years.” He smiled as if that age-long, simple service of poverty were a light matter, an excuse, perhaps, in the eyes of the citizen of a larger world for their having nothing to show. Only the citizen, as he looked at Brother Leo, had a sudden doubt as to the size of the world outside. Was it as large, half as large, even, as the eager young heart beside him which had chosen poverty as a bride?

The rain fell monotonously against the stones of the tiny cloister.

“What a tempest!” said Brother Leo, smiling contentedly at the sky. “You must come in and see our father. I sent word by the porter of your arrival, and I am sure he will receive you; that will be a pleasure for him, for he is of the great world, too. A very learnèd man, our father; he knows the French and the English tongue. Once he went to Rome; also he has been several times to Venice. He has been a great traveler.”

“And you,” I asked—“have you also traveled?”

Brother Leo shook his head.

“I have sometimes looked at Venice,” he said, “across the water, and once I went to Burano with the marketing brother; otherwise, no, I have not traveled. But being a guest-brother, you see, I meet often with those who have, like your Excellency, for instance, and that is a great education.”

We reached the door of the monastery, and I felt sorry when another brother opened to us, and Brother Leo, with the most cordial of farewell smiles, turned back across the cloister to the chapel door.

“Even if he does not hurry, he will still find prayer there,” said a quiet voice beside me.

I turned to look at the speaker. He was a tall old man with white hair and eyes like small blue flowers, very bright and innocent, with the same look of almost superb contentment in them that I had seen in Brother Leo’s eyes.

“But what will you have?” he added with a twinkle. “The young are always afraid of losing time; it is, perhaps, because they have so much. But enter, Signore! If you will be so kind as to excuse the refectory, it will give me much pleasure to bring you a little refreshment. You will pardon that we have not much to offer?”

The father—for I found out afterward that he was the superior himself—brought me bread and wine, made in the convent, and waited on me with his own hands. Then he sat down on a narrow bench opposite to watch me smoke. I offered him one of my cigarettes, but he shook his head, smiling.

“I used to smoke once,” he said. “I was very particular about my tobacco. I think it was similar to yours—at least the aroma, which I enjoy very much, reminds me of it. It is curious, is it not, the pleasure we derive from remembering what we once had? But perhaps it is not altogether a pleasure unless one is glad that one has not got it now. Here one is free from things. I sometimes fear one may be a little indulgent about one’s liberty. Space, solitude, and love—it is all very intoxicating.”

There was nothing in the refectory except the two narrow benches on which we sat, and a long trestled board which formed the table; the walls were whitewashed and bare, the floor was stone. I found out later that the brothers ate and drank nothing except bread and wine and their own vegetables in season, a little macaroni sometimes in winter, and in summer figs out of their own garden. They slept on bare boards, with one thin blanket winter and summer alike. The fish they caught they sold at Burano or gave to the poor. There was no doubt that they enjoyed very great freedom from “things.”

It was a strange experience to meet a man who never had heard of a flying-machine and who could not understand why it was important to save time by using the telephone or the wireless-telegraphy system; but despite the fact that the father seemed very little impressed by our modern urgencies, I never have met a more[Pg 183] intelligent listener or one who seized more quickly on all that was essential in an explanation.

“You must not think we do nothing at all, we lazy ones who follow old paths,” he said in answer to one of my questions. “There are only eight of us brothers, and there is the garden, fishing, cleaning, and praying. We are sent for, too, from Burano to go and talk a little with the people there, or from some island on the lagoons which perhaps no priest can reach in the winter. It is easy for us, with our little boat and no cares.”

“But Brother Leo told me he had been to Burano only once,” I said. “That seems strange when you are so near.”

“Yes, he went only once,” said the father, and for a moment or two he was silent, and I found his blue eyes on mine, as if he were weighing me.

“Brother Leo,” said the superior at last, “is our youngest. He is very young, younger perhaps than his years; but we have brought him up altogether, you see. His parents died of cholera within a few days of each other. As there were no relatives, we took him, and when he was seventeen he decided to join our order. He has always been happy with us, but one cannot say that he has seen much of the world.” He paused again, and once more I felt his blue eyes searching mine. “Who knows?” he said finally. “Perhaps you were sent here to help me. I have prayed for two years on the subject, and that seems very likely. The storm is increasing, and you will not be able to return until to-morrow. This evening, if you will allow me, we will speak more on this matter. Meanwhile I will show you our spare room. Brother Lorenzo will see that you are made as comfortable as we can manage. It is a great privilege for us to have this opportunity; believe me, we are not ungrateful.”

It would have been of no use to try to explain to him that it was for us to feel gratitude. It was apparent that none of the brothers had ever learned that important lesson of the worldly respectable—that duty is what other people ought to do. They were so busy thinking of their own obligations as to overlook entirely the obligations of others. It was not that they did not think of others. I think they thought only of one another, but they thought without a shadow of judgment, with that bright, spontaneous love of little children, too interested to point a moral. Indeed, they seemed to me very like a family of happy children listening to a fairy-story and knowing that the tale is true.

After supper the superior took me to his office. The rain had ceased, but the wind howled and shrieked across the lagoons, and I could hear the waves breaking heavily against the island. There was a candle on the desk, and the tiny, shadowy cell looked like a picture by Rembrandt.

“The rain has ceased now,” the father said quietly, “and to-morrow the waves will have gone down, and you, Signore, will have left us. It is in your power to do us all a great favor. I have thought much whether I shall ask it of you, and even now I hesitate; but Scripture nowhere tells us that the kingdom of heaven was taken by precaution, nor do I imagine that in this world things come oftenest to those who refrain from asking.”

“All of us,” he continued, “have come here after seeing something of the outside world; some of us even had great possessions. Leo alone knows nothing of it, and has possessed nothing, nor did he ever wish to; he has been willing that nothing should be his own, not a flower in the garden, not anything but his prayers, and even these I think he has oftenest shared. But the visit to Burano put an idea in his head. It is, perhaps you know, a factory town where they make lace, and the people live there with good wages, many of them, but also much poverty. There is a poverty which is a grace, but there is also a poverty which is a great misery, and this Leo never had seen before. He did not know that poverty could be a pain. It filled him with a great horror, and in his heart there was a certain rebellion. It seemed to him that in a world with so much money no one should suffer for the lack of it.

“It was useless for me to point out to him that in a world where there is so much health God has permitted sickness; where there is so much beauty, ugliness; where there is so much holiness, sin. It is not that there is any lack in the gifts of God; all are there, and in abundance, but He has left their distribution to the[Pg 184] soul of man. It is easy for me to believe this. I have known what money can buy and what it cannot buy; but Brother Leo, who never has owned a penny, how should he know anything of the ways of pennies?

“I saw that he could not be contented with my answer; and then this other idea came to him—the idea that is, I think, the blessèd hope of youth: that this thing being wrong, he, Leo, must protest against it, must resist it! Surely, if money can do wonders, we who set ourselves to work the will of God should have more control of this wonder-working power? He fretted against his rule. He did not permit himself to believe that our blessèd father, Saint Francis, was wrong, but it was a hardship for him to refuse alms from our kindly visitors. He thought the beggars’ rags would be made whole by gold; he wanted to give them more than bread, he wanted, poverino! to buy happiness for the whole world.”

The father paused, and his dark, thought-lined face lighted up with a sudden, beautiful smile till every feature seemed as young as his eyes.

“I do not think the human being ever has lived who has not thought that he ought to have happiness,” he said. “We begin at once to get ready for heaven; but heaven is a long way off. We make haste slowly. It takes us all our lives, and perhaps purgatory, to get to the bottom of our own hearts. That is the last place in which we look for heaven, but I think it is the first in which we shall find it.”

“But it seems to me extraordinary that, if Brother Leo has this thing so much on his mind, he should look so happy,” I exclaimed. “That is the first thing I noticed about him.”

“Yes, it is not for himself that he is searching,” said the superior. “If it were, I should not wish him to go out into the world, because I should not expect him to find anything there. His heart is utterly at rest; but though he is personally happy, this thing troubles him. His prayers are eating into his soul like flame, and in time this fire of pity and sorrow will become a serious menace to his peace. Besides, I see in Leo a great power of sympathy and understanding. He has in him the gift of ruling other souls. He is very young to rule his own soul, and yet he rules it. When I die, it is probable that he will be called to take my place, and for that it is necessary he should have seen clearly that our rule is right. At present he accepts it in obedience, but he must have more than obedience in order to teach it to others; he must have a personal light.

“This, then, is the favor I have to ask of you, Signore. I should like to have you take Brother Leo to Venice to-morrow, and, if you have the time at your disposal, I should like you to show him the towers, the churches, the palaces, and the poor who are still so poor. I wish him to see how people spend money, both the good and the bad. I wish him to see the world. Perhaps then it will come to him as it came to me—that money is neither a curse nor a blessing in itself, but only one of God’s mysteries, like the dust in a sunbeam.”

“I will take him very gladly; but will one day be enough?” I answered.

The superior arose and smiled again.

“Ah, we slow worms of earth,” he said, “are quick about some things! You have learned to save time by flying-machines; we, too, have certain methods of flight. Brother Leo learns all his lessons that way. I hardly see him start before he arrives. You must not think I am so myself. No, no. I am an old man who has lived a long life learning nothing, but I have seen Leo grow like a flower in a tropic night. I thank you, my friend, for this great favor. I think God will reward you.”

Brother Lorenzo took me to my bedroom; he was a talkative old man, very anxious for my comfort. He told me that there was an office in the chapel at two o’clock, and one at five to begin the day, but he hoped that I should sleep through them.

“They are all very well for us,” he explained,[Pg 186] “but for a stranger, what cold, what disturbance, and what a difficulty to arrange the right thoughts in the head during chapel! Even for me it is a great temptation. I find my mind running on coffee in the morning, a thing we have only on great feast-days. I may say that I have fought this thought for seven years, but though a small devil, perhaps, it is a very strong one. Now, if you should hear our bell in the night, as a favor pray that I may not think about coffee. Such an imperfection! I say to myself, the sin of Esau! But he, you know, had some excuse; he had been hunting. Now, I ask you—one has not much chance of that on this little island; one has only one’s sins to hunt, and, alas! they don’t run away as fast as one could wish! I am afraid they are tame, these ones. May your Excellency sleep like the blessed saints, only a trifle longer!”

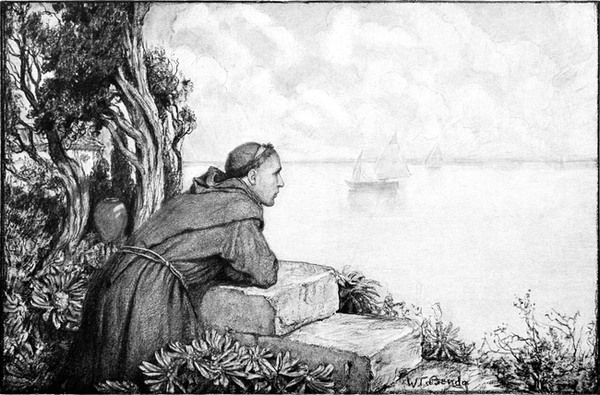

Drawn by W. T. Benda Half-tone plate engraved by R. C. Collins

“HE WAS LOOKING OUT OVER THE BLUE STRETCH OF LAGOON INTO THE DISTANCE, WHERE VENICE LAY LIKE A MOVING CLOUD AT THE HORIZON’S EDGE”

I did sleep a trifle longer; indeed, I was quite unable to assist Brother Lorenzo to resist his coffee devil during chapel-time. I did not wake till my tiny cell was flooded with sunshine and full of the sound of St. Francis’s birds. Through my window I could see the fishing-boats pass by. First came one with a pair of lemon-yellow sails, like floating primroses; then a boat as scarlet as a dancing flame, and half a dozen others painted some with jokes and some with incidents in the lives of patron saints, all gliding out over the blue lagoon to meet the golden day.

I rose, and from my window I saw Brother Leo in the garden. He was standing under St. Francis’s tree—the old gnarled umbrella-pine which hung over the convent-wall above the water by the island’s edge. His back was toward me, and he was looking out over the blue stretch of lagoon into the distance, where Venice lay like a moving cloud at the horizon’s edge; but a mist hid her from his eyes, and while I watched him he turned back to the garden-bed and began pulling out weeds. The gondoliers were already at the tiny pier when I came out.

“Per Bacco, Signore!” the elder explained. “Let us hasten back to Venice and make up for the Lent we have had here. The brothers gave us all they had, the holy ones—a little wine, a little bread, cheese that couldn’t fatten one’s grandmother, and no macaroni—not so much as would go round a baby’s tongue! For my part, I shall wait till I get to heaven to fast, and pay some attention to my stomach while I have one.” And he spat on his hands and looked toward Venice.

“And not an image in the chapel!” agreed the younger man. “Why, there is nothing to pray to but the Signore Dio Himself! Veramente, Signore, you are a witness that I speak nothing but the truth.”

The father superior and Leo appeared at this moment down the path between the cypresses. The father gave me thanks and spoke in a friendly way to the gondoliers, who for their part expressed a very pretty gratitude in their broad Venetian patois, one of them saying that the hospitality of the monks had been like paradise itself, and the other hasting to agree with him.

The two monks did not speak to each other, but as the gondolier turned the huge prow toward Venice, a long look passed between them—such a look as a father and son might exchange if the son were going out to war, while his father, remembering old campaigns, was yet bound to stay at home.

It was a glorious day in early June; the last traces of the storm had vanished from the serene, still waters; a vague curtain of heat and mist hung and shimmered between ourselves and Venice; far away lay the little islands in the lagoon, growing out of the water like strange sea-flowers. Behind us stood San Francesco del Deserto, with long reflections of its one pink tower and arrowy, straight cypresses, soft under the blue water.

The father superior walked slowly back to the convent, his brown-clad figure a shining shadow between the two black rows of cypresses. Brother Leo waited till he had disappeared, then turned his eager eyes toward Venice.

As we approached the city the milky sea of mist retreated, and her towers sprang up to greet us. I saw a look in Brother Leo’s eyes that was not fear or wholly pleasure; yet there was in it a certain awe and a strange, tentative joy, as if something in him stretched out to greet the world. He muttered half to himself:

“What a great world, and how many children il Signore Dio has!”

When we reached the piazzetta, and he looked up at the amazing splendor of the ducal palace, that building of soft yellow, with its pointed arches and double loggias of white marble, he spread out both his hands in an ecstasy.

“But what a miracle!” he cried.[Pg 187] “What a joy to God and to His angels! How I wish my brothers could see this! Do you not imagine that some good man was taken to paradise to see this great building and brought back here to copy it?”

“Chi lo sa?” I replied guardedly, and we landed by the column of the Lion of St. Mark’s. That noble beast, astride on his pedestal, with wings outstretched, delighted the young monk, who walked round and round him.

“What a tribute to the saint!” he exclaimed. “Look, they have his wings, too. Is not that faith?”

“Come,” I said, “let us go on to Saint Mark’s. I think you would like to go there first; it is the right way to begin our pilgrimage.”

The piazza was not very full at that hour of the morning, and its emptiness increased the feeling of space and size. The pigeons wheeled and circled to and fro, a dazzle of soft plumage, and the cluster of golden domes and sparkling minarets glittered in the sunshine like flames. Every image and statue on St. Mark’s wavered in great lines of light like a living pageant in a sea of gold.

Brother Leo said nothing as he stood in front of the three great doorways that lead into the church. He stood quite still for a while, and then his eyes fell on a beggar beside the pink and cream of the new campanile, and I saw the wistfulness in his eyes suddenly grow as deep as pain.

“Have you money, Signore?” he asked me. That seemed to him the only question. I gave the man something, but I explained to Brother Leo that he was probably not so poor as he looked.

“They live in rags,” I explained, “because they wish to arouse pity. Many of them need not beg at all.”

“Is it possible?” asked Brother Leo, gravely; then he followed me under the brilliant doorways of mosaic which lead into the richer dimness of St. Mark’s.

When he found himself within that great incrusted jewel, he fell on his knees. I think he hardly saw the golden roof, the jeweled walls, and the five lifted domes full of sunshine and old gold, or the dark altars, with their mysterious, rich shimmering. All these seemed to pass away beyond the sense of sight; even I felt somehow as if those great walls of St. Mark’s were not so great as I had fancied. Something greater was kneeling there in an old habit and with bare feet, half broken-hearted because a beggar had lied.

I found myself regretting the responsibility laid on my shoulders. Why should I have been compelled to take this strangely innocent, sheltered boy, with his fantastic third-century ideals, out into the shoddy, decorative, unhappy world? I even felt a kind of anger at the simplicity of his soul. I wished he were more like other people; I suppose because he had made me wish for a moment that I was less like them.

“What do you think of Saint Mark’s?” I asked him as we stood once more in the hot sunshine outside, with the strutting pigeons at our feet and wheeling over our heads.

Brother Leo did not answer for a moment, then he said:

“I think Saint Mark would feel it a little strange. You see, I do not think he was a great man in the world, and the great in paradise—” He stooped and lifted a pigeon with a broken foot nearer to some corn a passer-by was throwing for the birds. “I cannot think,” he finished gravely, “that they care very much for palaces in paradise: I should think every one had them there or else—nobody.”