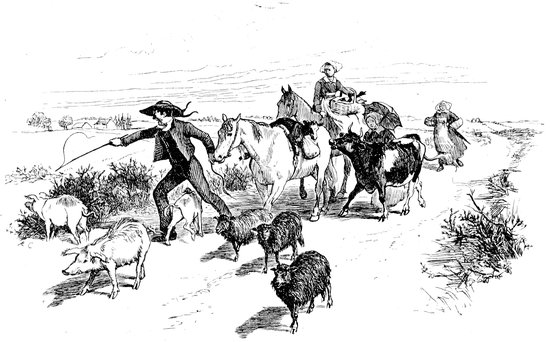

CAVALIERS AND ROUNDHEAD.

Title: Breton Folk: An artistic tour in Brittany

Author: Henry Blackburn

Illustrator: Randolph Caldecott

Release date: November 26, 2016 [eBook #53600]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Richard Tonsing, Suzanne Shell and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

Transcriber's Note:

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

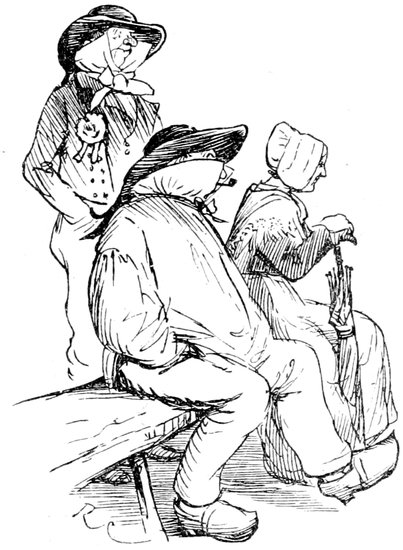

CAVALIERS AND ROUNDHEAD.

The following notes were made during three summer tours in Brittany, in two of which the Author was accompanied by the Artist.

Breton Folk is not a description of the antiquities of Brittany, nor even a book of folk-lore. It is a series of sketches of a “black-and-white country” under its summer aspect; of a sombre land shrouded with white clouds, peopled with peasants in dark costumes, wide white collars and caps, black and white cattle and magpies.

ivThe illustrations, one hundred and seventy in number, have been drawn by the Artist from sketches made on the spot, and, apart from their artistic qualities, have the curious merit of truth. They have been engraved with the utmost care by Mr. J. D. Cooper.

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

|---|---|---|

| I.— | The Western Wing | 1 |

| II.— | St. Malo—St. Servan—Dinard—Dinan | 6 |

| III.— | Lamballe—St. Brieuc—Guingamp | 27 |

| IV.— | Lanleff—Paimpol—Lannion—Perros-Guirec | 45 |

| V.— | Carhaix—Huelgoet | 58 |

| VI.— | Morlaix—St. Pol—Lesneven—Le Folgoet | 69 |

| VII.— | Brest—Plougastel—Châteauneuf du Faou | 83 |

| VIII.— | Quimper—Pont l’Abbé—Audierne—Douarnenez | 100 |

| IX.— | Concarneau—Pont-Aven—Quimperlé | 123 |

| X.— | Hennebont | 143 |

| XI.— | Le Faouet—Gourin—Guéméné | 152 |

| XII.— | Ste. Anne d’Auray—Carnac—Locmariaker | 171 |

| XIII.— | Vannes | 190 |

| Map of Brittany, and Postscript for Travellers, at end. | ||

| PAGE | ||

|---|---|---|

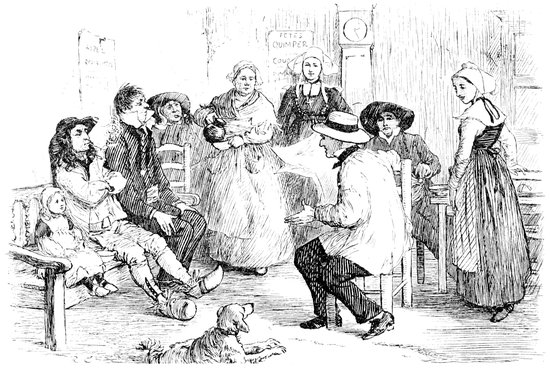

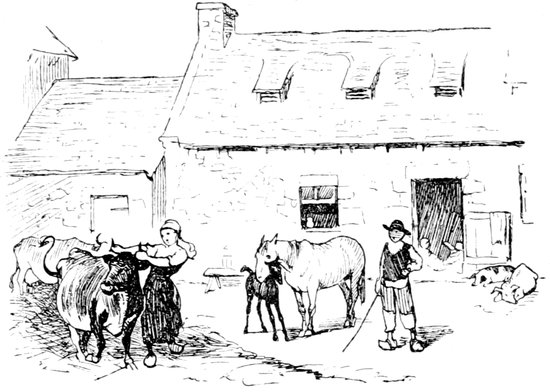

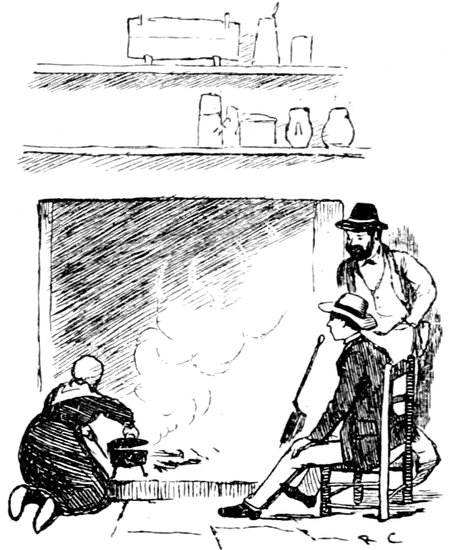

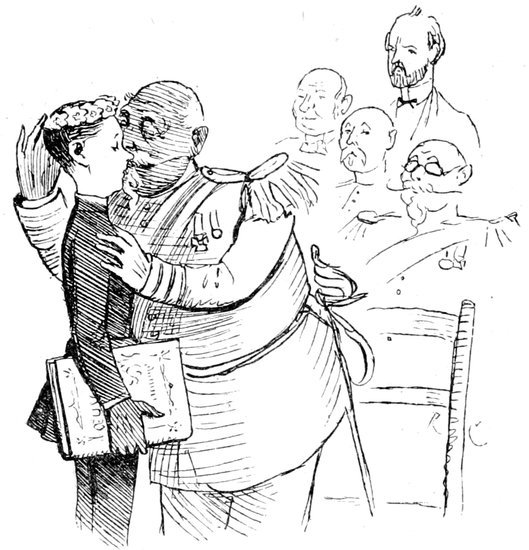

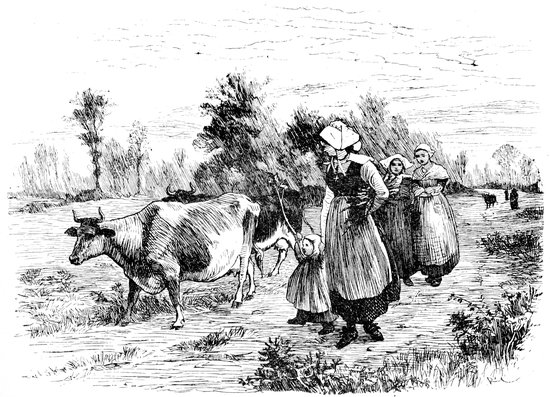

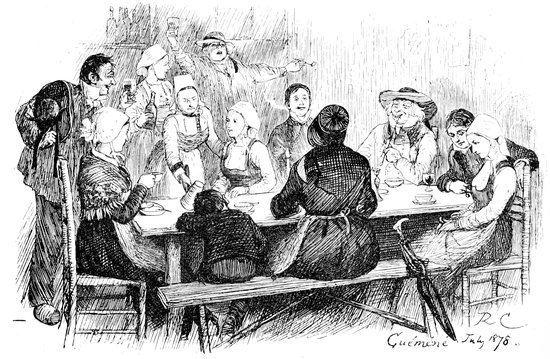

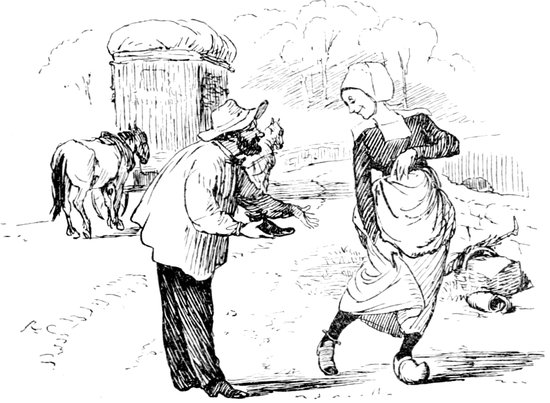

| Cavaliers and Roundhead | Frontispiece | |

| Vignette | Title page | |

| A Breton Gate | iii | |

| Sketching | iv | |

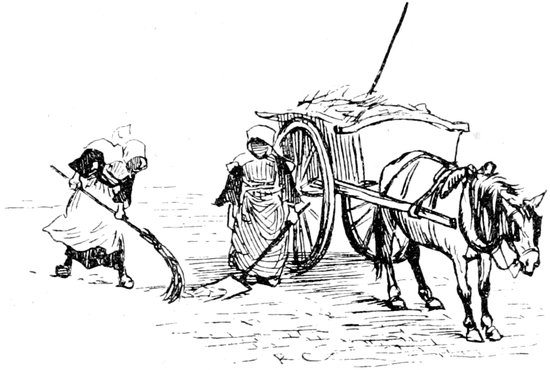

| Carrying Corn | v | |

| Vignette | vi | |

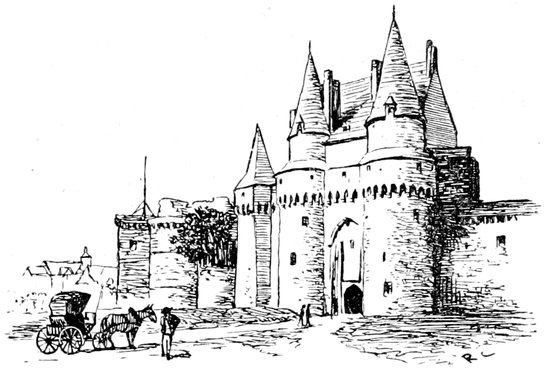

| Old Château | vii | |

| Sheep sheltering from the Wind | xii | |

| CHAPTER I. | ||

| Hill and Dale | 1 | |

| On the Road | 5 | |

| CHAPTER II. | ||

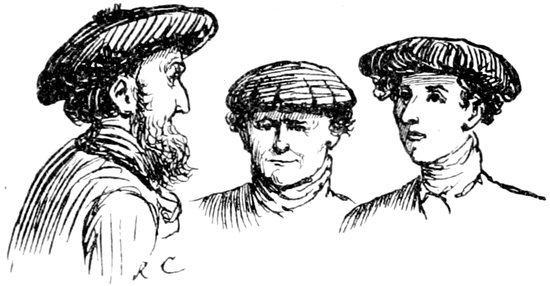

| Caps of Côtes-du-Nord | 6 | |

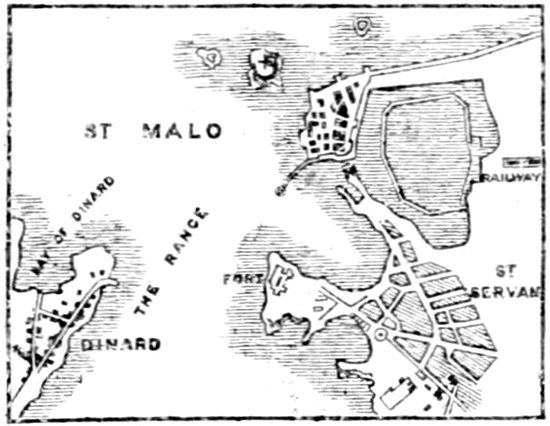

| Map of the Mouth of the Rance | 7 | |

| Peasants of Côtes-du-Nord | 11 | |

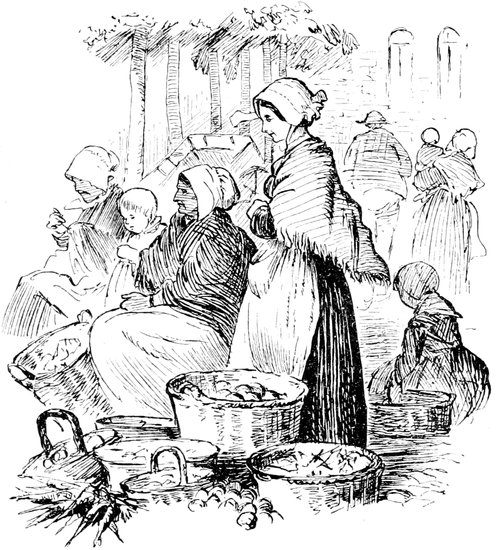

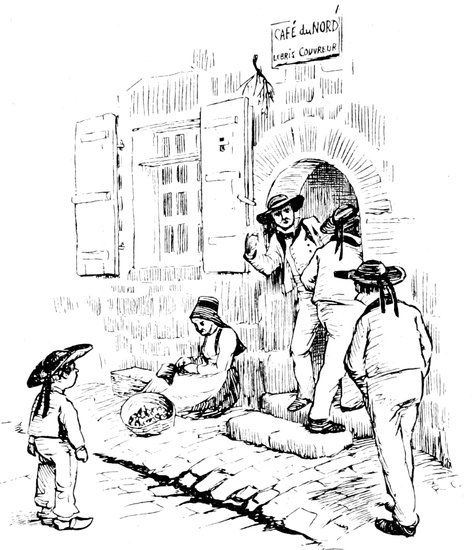

| Fruit Stall at Dinan | 15 | |

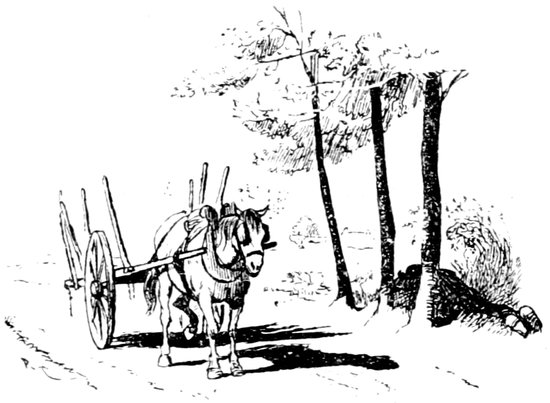

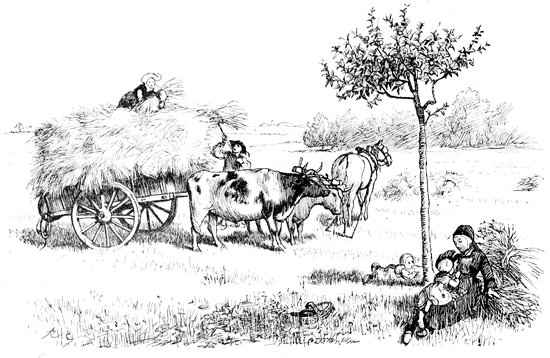

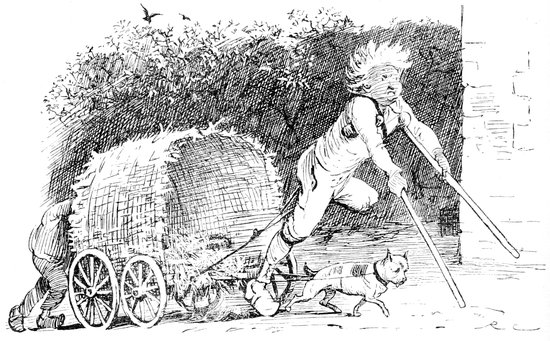

| A Loaded Hay Cart | 16 | |

| viiiOn the Place, Dinan | 17 | |

| Outside the Walls | 18 | |

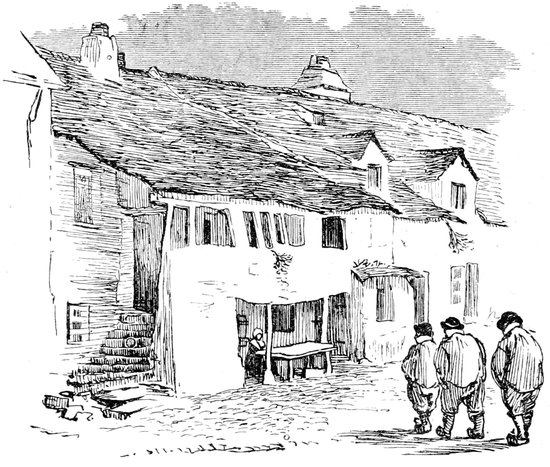

| Old House near Dinan | 20 | |

| Old Woman of Dinan | 21 | |

| Porte de Brest | 22 | |

| A Little Beggar | 23 | |

| “The Hour of Repose” | 24 | |

| Farmhouse of Côtes-du-Nord | 25 | |

| Farmer meditating on his Stock | 26 | |

| CHAPTER III. | ||

| Caps of Côtes-du-Nord | 27 | |

| The Buckwheat Harvest | 30 | |

| A Road Scraper | 31 | |

| Sketch of Château | 32 | |

| On the Sands near St. Brieuc | 33 | |

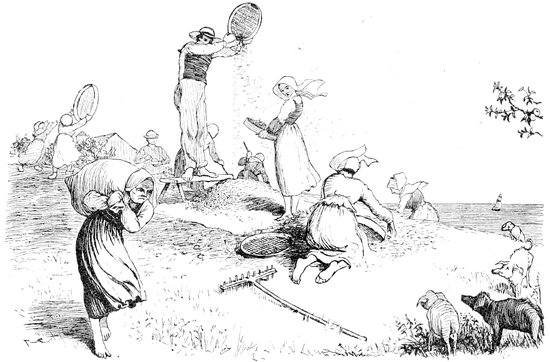

| Winnowing near St. Brieuc | 34 | |

| Mathurine | 35 | |

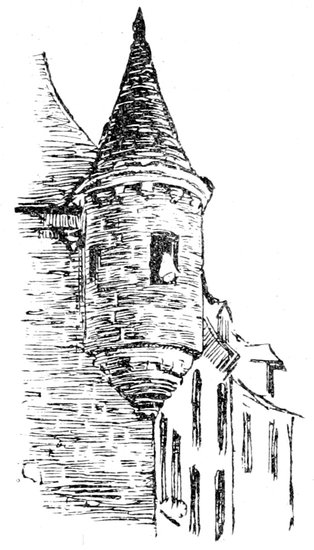

| Corner Turret at Guingamp | 38 | |

| Going to Market | 39 | |

| The Market-place, Guingamp | 40 | |

| Waiting-maid at Hôtel de l’Ouest | 41 | |

| The Ossuary at Guingamp | 42 | |

| By the River | 44 | |

| CHAPTER IV. | ||

| Cap of Côtes-du-Nord | 45 | |

| Three Children | 50 | |

| Riding to Market | 53 | |

| Returning Home | 57 | |

| CHAPTER V. | ||

| Cap of the Monts d’Arrée | 58 | |

| Peasant in Sabots | 60 | |

| Girl tending Sheep | 61 | |

| Old House at Carhaix | 62 | |

| On The Road to Market | face | 62 |

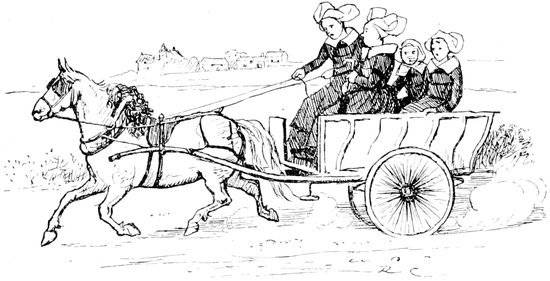

| A Cart Party | 63 | |

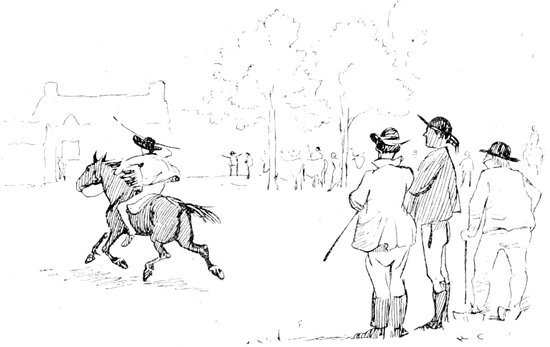

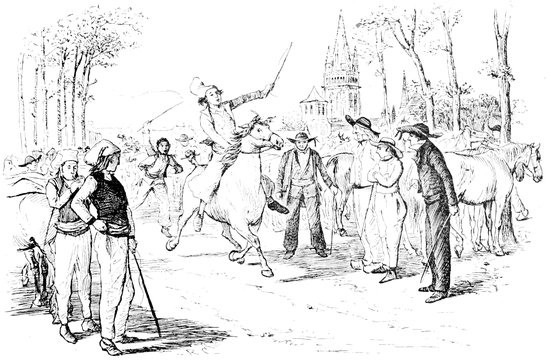

| Trotting out a Horse | 64 | |

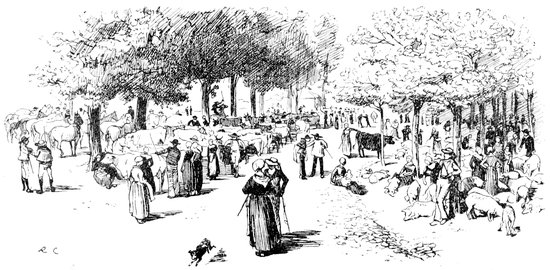

| Cattle Fair at Carhaix | face | 64 |

| ixA Gentleman Farmer | 65 | |

| A Family Party | 66 | |

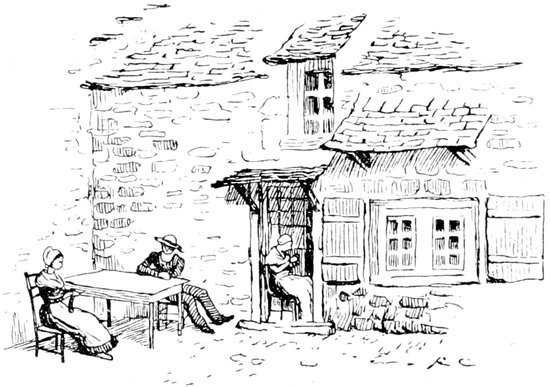

| Waiting for Dinner, Huelgoet | 67 | |

| Shepherd of the Monts d’Arrée | 68 | |

| CHAPTER VI. | ||

| Cap of Morlaix | 69 | |

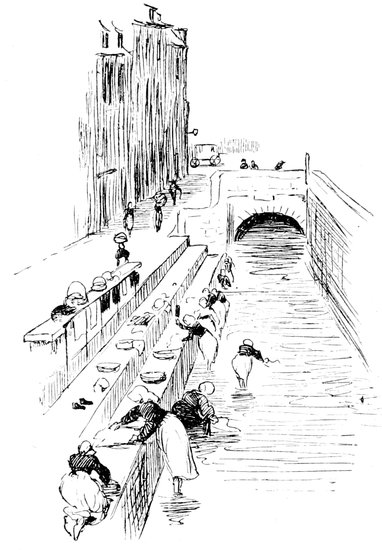

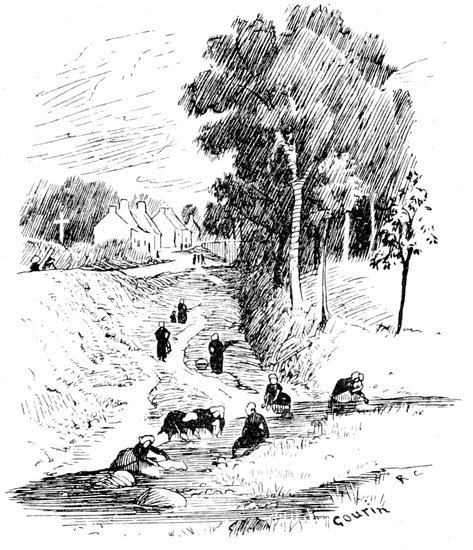

| Washing in the River | 70 | |

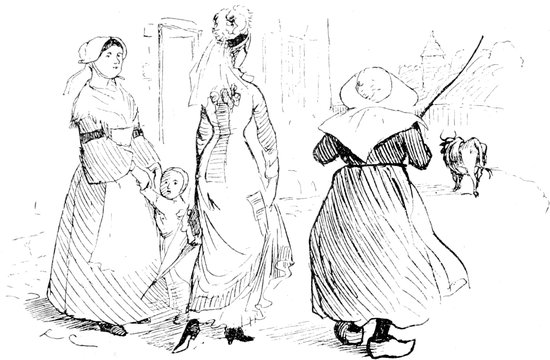

| Women of Morlaix | 72 | |

| Potato-getting near St. Pol de Léon | face | 75 |

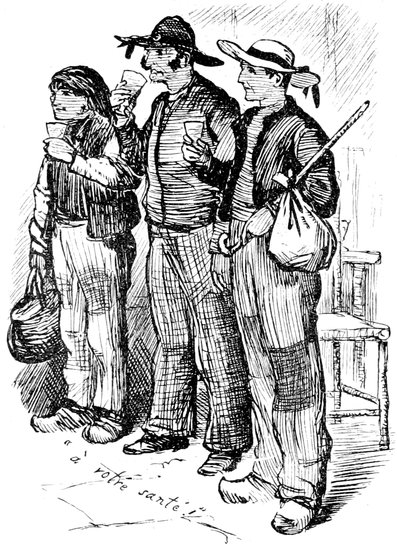

| Three Men of St. Pol de Léon | 76 | |

| Children in Cabbage Garden | 77 | |

| Gurgoyle at Roscoff | 78 | |

| An Owner of the Soil | 79 | |

| “The Fool of the Wood” | 80 | |

| In the Church of Le Folgoet | face | 80 |

| On Horseback | 82 | |

| Horse Fair at Le Folgoet | face | 82 |

| CHAPTER VII. | ||

| Cap of Finistère | 83 | |

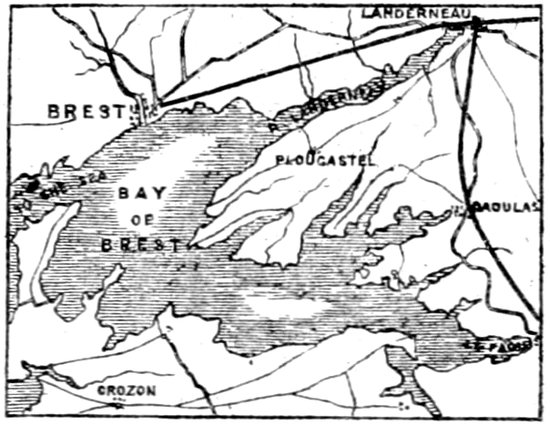

| Map of the Bay of Brest | 84 | |

| “Every Dog has his Day” | 87 | |

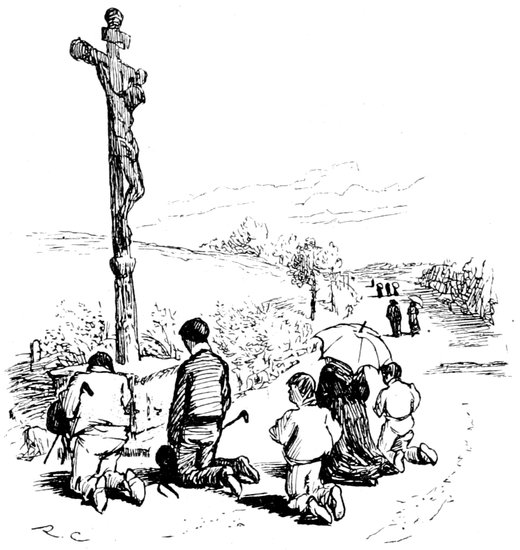

| Wayside Cross | 89 | |

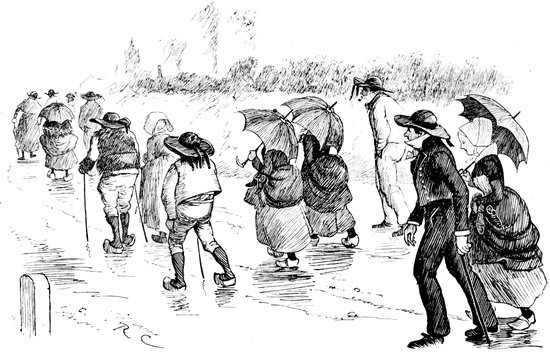

| Going to the Pardon at Châteauneuf du Faou | face | 90 |

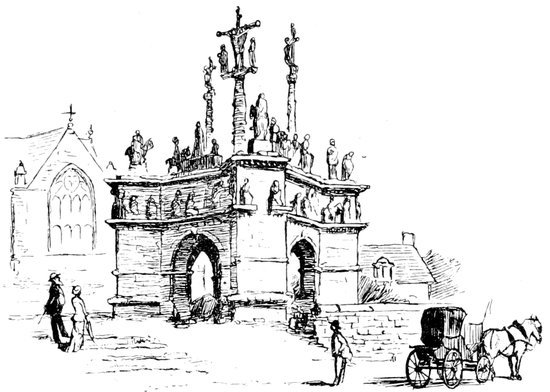

| Calvary at Pleyben | 91 | |

| Street Musicians | 92 | |

| Races at Châteauneuf du Faou | 94 | |

| Two Spectators | 95 | |

| Stewards of the Fête | 96 | |

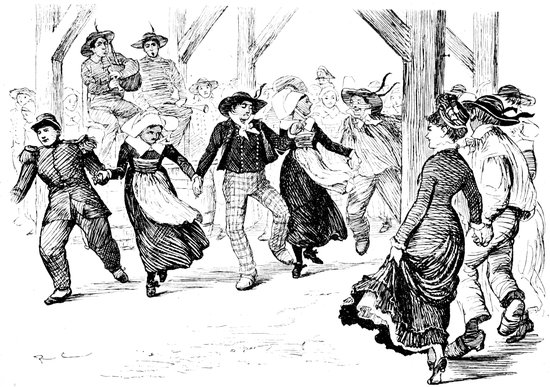

| Dancing the Gavotte | face | 96 |

| Pleased Spectator | 97 | |

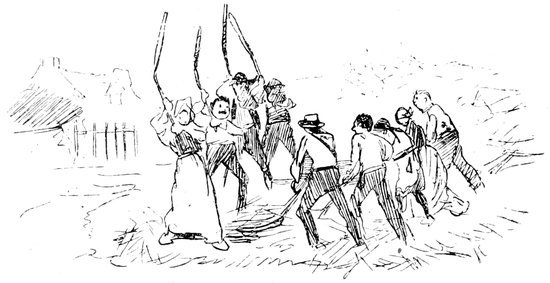

| Threshing Corn |

{ 98 { 99 |

|

| CHAPTER VIII. | ||

| Caps of Finistère | 100 | |

| A Promenade | 101 | |

| On the Place, Quimper | 102 | |

| Towers of Quimper Cathedral | 103 | |

| Waitress at Hôtel de l’Épée | 104 | |

| At a Well | 105 | |

| Professional Beggar | 106 | |

| xA Domestic Scene | 107 | |

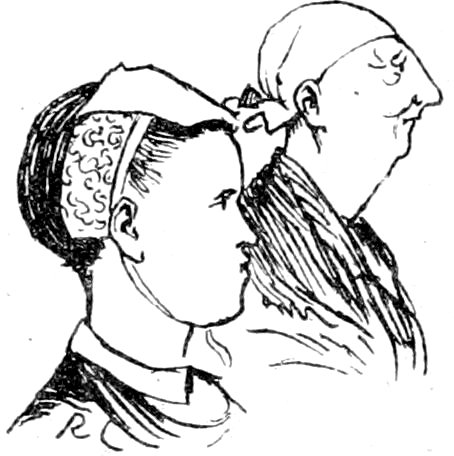

| Two Heads; sketched at Audierne | 108 | |

| Prize-giving at Quimper | 109 | |

| Two Heads; sketched at Audierne | 110 | |

| A Domestic Interior | 111 | |

| River below Pont l’Abbé | 112 | |

| Landscape in Finistère | 114 | |

| Inhabitants of Audierne |

{ 116 { 117 { 117 |

|

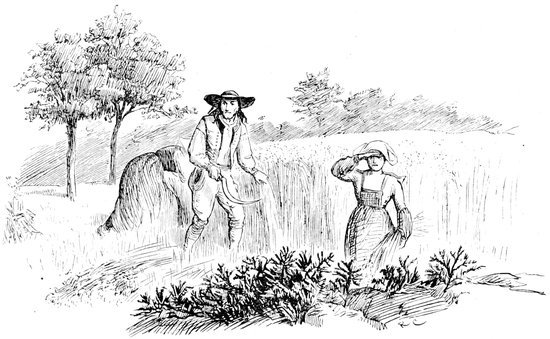

| Cutting the Corn | 118 | |

| Harvesting in Finistère | face | 118 |

| Waiting for the Sardine Boats at Douarnenez | 120 | |

| Waitress at Douarnenez | 121 | |

| Beggar on the Road | 122 | |

| CHAPTER IX. | ||

| Woman and Child, Finistère | 123 | |

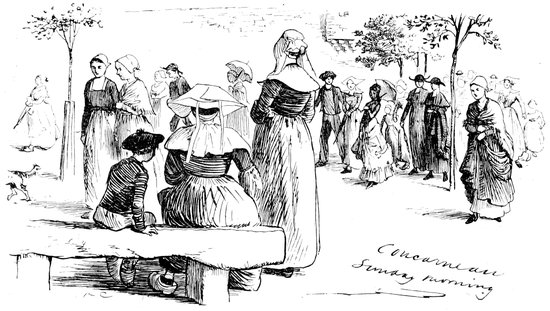

| Concarneau: Coming from Church | 124 | |

| On the Place at Concarneau | face | 124 |

| The Last Touches | 125 | |

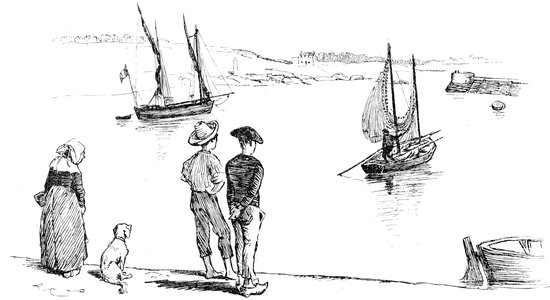

| On the Quay at Concarneau | 126 | |

| A Boating Party | 127 | |

| Old Man and Child | 128 | |

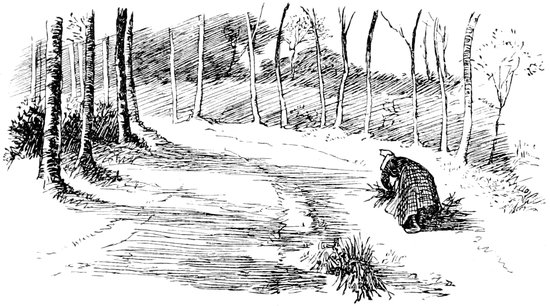

| Pont-Aven: Washing at a Stream | 129 | |

| Pont-Aven | 131 | |

| Returning from Labour, Pont-Aven | 133 | |

| Models | 135 | |

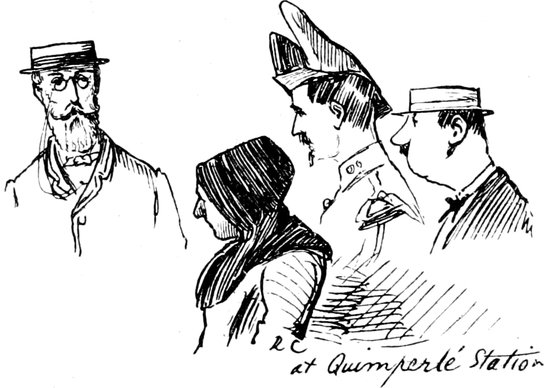

| At Quimperlé Station | 136 | |

| Old Woman at Quimperlé Station | 137 | |

| Gathering Sticks | 138 | |

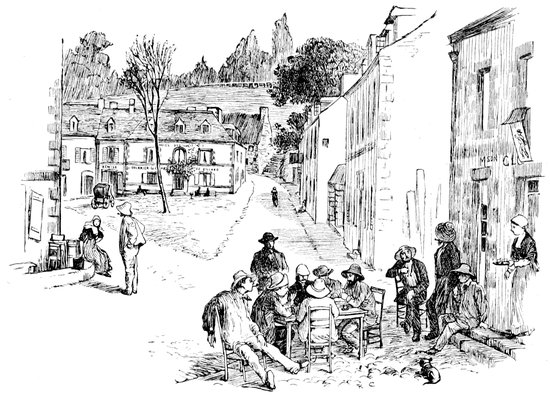

| On the Place at Quimperlé | 139 | |

| A Big Load | 140 | |

| Augustine | 141 | |

| Evening: Near Quimperlé | face | 142 |

| Drawing Water | 142 | |

| CHAPTER X. | ||

| Little Cap of Morbihan | 143 | |

| In the Ville Close, Hennebont | 144 | |

| The High Street of the Ville Neuve | 145 | |

| Poverty and Riches | 146 | |

| xiReapers returning | face | 147 |

| Opposite the Old Inn | 147 | |

| At the Well | 148 | |

| Carrying Water | 149 | |

| Washing Parties | 149 | |

| Old Doorway in the Ville Close | 150 | |

| A Conversation | 151 | |

| CHAPTER XI. | ||

| Cap of Morbihan | 152 | |

| Reaping near Hennebont | 153 | |

| Street In Le Faouet | 155 | |

| A Breton Propriétaire | 156 | |

| Le Faouet | face | 156 |

| Bed-time | 157 | |

| The Man on Two Sticks | 158 | |

| Stairs leading to the Chapel of Ste. Barbe | 160 | |

| Gourin | 161 | |

| “Montez, s’il vous plait, Monsieur!” | 162 | |

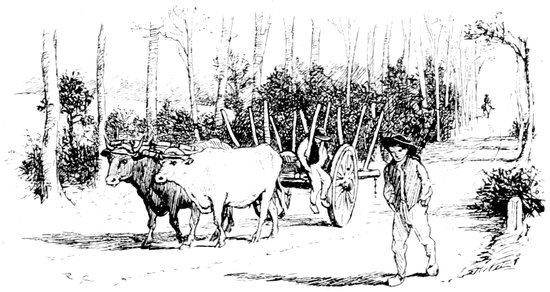

| Bullock Cart on the Road | 163 | |

| Waitress at the Inn | 164 | |

| High Street of Guéméné | 165 | |

| A Meeting | 166 | |

| En Promenade | 167 | |

| Sunday Morning at Guéméné | 168 | |

| A Conversation | 169 | |

| The Bottle | 170 | |

| Betrothal Party | face | 170 |

| CHAPTER XII. | ||

| At the Hôtel Pavillon d’en Haut | 171 | |

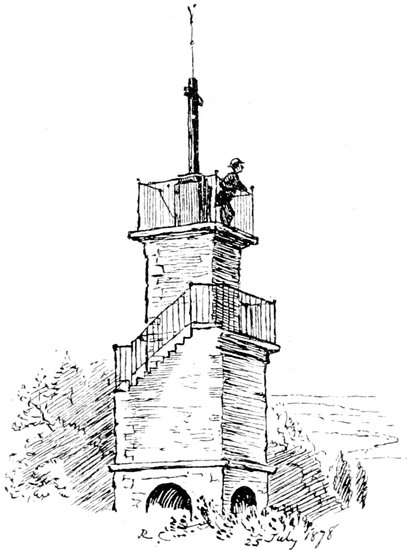

| The Tower on the Belvédère at Auray | 172 | |

| Evening on the Belvédère | 173 | |

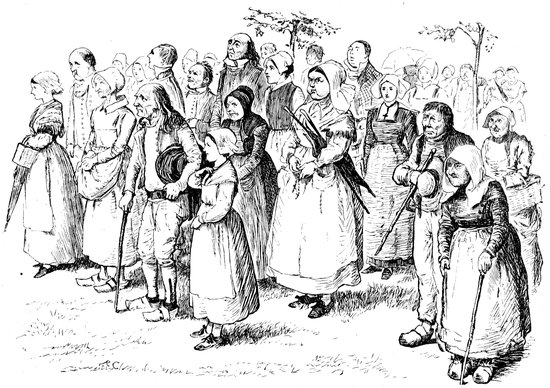

| At the Pardon of Ste. Anne d’Auray | 174 | |

| At the Pardon of Ste. Anne d’Auray | 175 | |

| At the Pardon of Ste. Anne d’Auray | face | 176 |

| At the Pardon of Ste. Anne d’Auray | 177 | |

| At the Pardon of Ste. Anne d’Auray | 180 | |

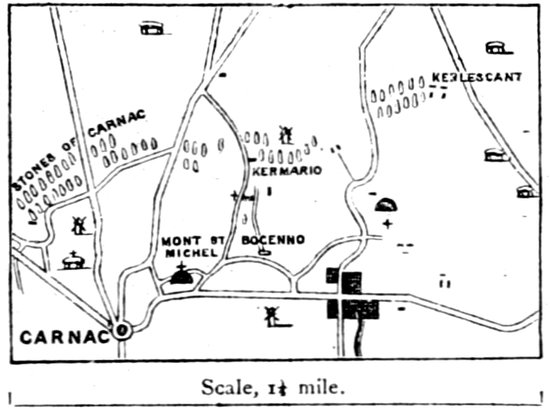

| Map of Carnac | 182 | |

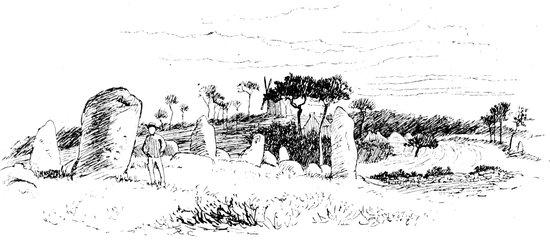

| Sketch on the Fields of Carnac | 183 | |

| In the Kitchen of the Hôtel des Voyageurs at Carnac | 185 | |

| On the Road | 186 | |

| In the Wind | 187 | |

| The Great Menhir | 188 | |

| Scavengers | 189 | |

| xiiCHAPTER XIII. | ||

| Caps of Morbihan | 190 | |

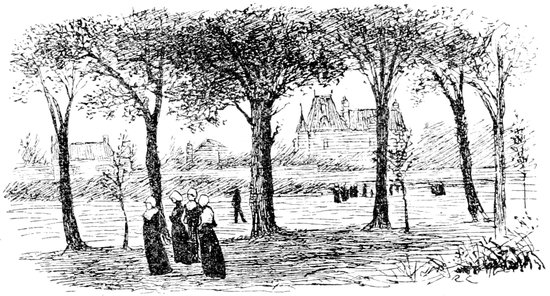

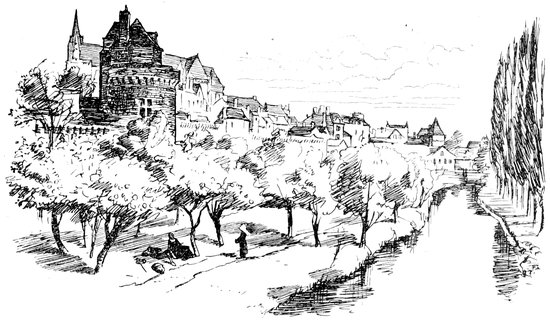

| Vannes from the River | face | 190 |

| An Old Inn | 192 | |

| In a Café | 193 | |

| Three Hot Men of Vannes | 194 | |

| Side-spring Boots | 195 | |

| Some Inhabitants | 198 | |

| A Chase | 200 | |

In an old-fashioned country-house there is often to be found a room built out from the rest of the structure, forming, as it were, the extreme western wing. It has windows looking to the west, its door of communication with the great house, and, in summer-time, a southern exterior wall laden with fruit and fragrant with clematis, honeysuckle, or jasmine. The interior differs from the rest of the mansion both in 2its furnishing and in the habits of its occupants. It is a room in which there is an absence of bright colours, where everything is quiet in tone and more or less harmonious in aspect; where solid woodwork takes the place of gilding, where furniture is made simply and solidly for use and ease, where decoration is the work of the hand—holding a needle, a chisel, or a hammer. The prevailing colours in this quaint old room, which give a sense of repose on coming from more highly decorated saloons, are blue, grey, and green—the blue of old china, the grey of a landscape by Millet or Corot, the green that we may see sometimes in the works of Paul Veronese.

This “western wing” is haunted, and full of mysteries and legends; its furniture is antique, and has seldom been dusted or put in order. Nearly every object is a curiosity in some way, and was designed in a past age; on the high wooden shelves over the open fireplace there are objects in wrought metal work, antique-shaped pots and jars. About the room are fragments of Druidical monuments, menhirs and dolmens of almost fabulous antiquity, ancient stone crosses, calvaries, and carvings, piled together in disorderly fashion, with odd-shaped pipes, snuffboxes, fishing-rods, guns, and the like; on the walls are small, elaborate, paintings of mediæval saints in roughly carved gilt frames, and a few low-toned landscapes by painters of France; on shelves and in niches are large brown volumes with antique clasps, and perhaps a model in clay of an old woman in a high cap, a priest, or a child in sabots.

The room is a snuggery, well furnished with pipes and tobacco, and hitherto evidently not much visited by ladies; but the door is open wide to the rest of the mansion, through which the strains of Meyerbeer’s opera of Dinorah may sometimes be heard. The lady visitor is welcome to this out-of-the-way corner, but she must not be surprised to find herself greeted on entering in a language which, with all her knowledge of French, she can scarcely understand; to be asked, perhaps, to take a pinch of snuff, and to conform in other homely ways to the habits of the inhabitants.

Such a quiet, unobtrusive corner—pleasant with its open windows to the summer air, but much blown and rained upon by winter storms—is 3Brittany, the “western wing” of France, holding much the same position geographically and socially to the rest of the country, as the room we have pictured in the great house, to the rest of the mansion.

The Brittany described in these pages is comprised principally of the three departments of Côtes-du-Nord, Finistère, and Morbihan, the inhabitants of these districts standing apart, as it were, from the rest of France, preserving their own customs and traditions, speaking their own language, singing their own songs, and dancing their own dances in the streets in 1879. In these three departments is comprehended nearly all that is most characteristic of the Bretons, and the district forms itself naturally into a convenient summer tour of three or four weeks.

Brittany is essentially the land of the painter. It would be strange indeed if a country sprinkled with white caps, and set thickly in summer with the brightest blossoms of the fields, should not attract artists in search of picturesque costume and scenes of pastoral life. Rougher and wilder than Normandy, more thinly populated, and less visited by the tourists, Brittany offers better opportunities for outdoor study, and more suggestive scenes for the painter. Nowhere in France are there finer peasantry; nowhere do we see more dignity of aspect in field labour, more nobility of feature amongst men and women; nowhere more picturesque ruins; nowhere such primitive habitations and, it must be added, such dirt. Brittany is still behindhand in civilisation, the land is only half cultivated and divided into small holdings, and the fields are strewn with Druidical stones. From the dark recesses of the Montagnes Noires the streams come down between deep ravines as wild and bare of cultivation as the moors of Scotland, but the hillsides are clothed thickly in summer with ferns, broom, and heather. Follow one of these streams in its windings towards the sea, where the troubled waters rest in the shade of overhanging trees, by pastures and cultivated lands, and we may see the Breton peasants at their “gathering-in,” reaping and carrying their small harvest of corn and rye, oats and buckwheat; the women with white caps and wide collars, short dark skirts, and heavy wooden sabots, the men in white woollen jackets, breeks (bragous bras), and black gaiters, 4broad-brimmed hats and long hair streaming in the wind—leading oxen yoked to heavy carts painted blue. Here we are reminded at once of the French painters of pastoral life, of Jules Breton, Millet, Troyon, and Rosa Bonheur; and as we see the dark brown harvest fields, with the white clouds lying low on the horizon, and the strong, erect figures and grand faces of the peasants lighted by the evening sun, we understand why Brittany is a chosen land for the painter of paysages. Low in tone as the landscape is, sombre as are the costumes of the people, cloudy and fitful in light and shade as is all this wind-blown land, there is yet a clearness in the atmosphere which brings out the features of the country with great distinctness, and impresses them upon the mind.

To the antiquary who knows the country, and is perchance on the track of a newly discovered menhir, long buried in the sands; to the poet who would seek out and see that mystic island of Avilion,

to the historian who would add yet other links in the chain of facts in the strange eventful history of Brittany; to the resident Englishman and sportsman, who knows the corners of the trout streams and the best covers for game, scanty though they be, the tour suggested in these pages will have little interest; but to the English traveller who would see what is most characteristic and beautiful in Brittany in a short time, we should say—

Enter by the port of St. Malo from Southampton (or by Dol, if coming from France), and take the following route, diverging from it into the country districts as time and opportunity will permit. From St. Malo to Dinan by water; from Dinan to Lamballe by diligence (or railway), thence to St. Brieuc, Guingamp, Lannion, Morlaix, Brest, Quimper, Quimperlé, Hennebont, Auray, Vannes, and Rennes.

Thus, then, having set the modern tourist on his way, and provided for the exigencies of rapid holiday-making, let us recommend him to diverge from the beaten track as much as possible, striking out in every direction from the main line of route, both inland and to the coast, 5travelling by road as much as possible, and seeing the people, as they are only to be seen, “off the line.”

In Breton Folk the reader will be troubled little with the history of Brittany, with the wars of the Plantagenets, or with the merits of various styles of architecture, but some general impression of the country may be gathered from its pages, and especially of the people as they are to be seen to-day.

On a bright summer’s morning in July the ballon captif, which we may use in imagination in these pages—our French friends having taught us its use in peace as well as in war—floats over the blue water-gate of Brittany like a golden ball. The sun is high, and the tide is flowing fast round the dark rock islands that lie at our feet, pouring into the harbour of St. Malo, floating the vessels and fishing-boats innumerable that line the quays inside the narrow neck of land called Le Sillon, which connects the city with the mainland, and driving gay parties of bathers up the sands of the beautiful Baie d’Écluse at Dinard.

On the map on the opposite page, we see the relative positions of St. Malo, St. Servan, and Dinard, also the mouth of the river Rance, which flows southward, wide and strong, into innumerable bays, until it winds under the walls and towers of Dinan. Looking down upon the city, now alive with the life which the rising tide gives to every sea-port; seeing the strength of its position seaward, and the protection from without to the little forests of masts, whose leaves are the bright trade banners of many nations, it is easy to understand how centuries ago St. Malo and St. Servan were chosen as military strongholds,[1] and 7how in these later times St. Malo has a maritime importance apparently out of proportion to its trade, and to its population of not more than 14,000 inhabitants.

1. St. Servan is built on the site of Aleth, one of the six capitals of ancient Armorica; there was a monastery here in the sixth century.

From a bird’s-eye point of view we may obtain a clearer idea of St. Malo and its neighbourhood than many who have actually visited these places, and can judge for ourselves of its probable attractions for a summer visit. It seems unusually bright and pleasant this morning, for the light west wind has cleared the air, and carried the odours of St. Malo landward. There is to be a regatta in the afternoon, the principal course being across, and across, the mouth of the Rance, between St. Malo and Dinard, and already little white sails may be seen spread in various directions, darting in and out between the rock islands outside the bay. On one of these islands, Grand Bé, marked with a cross on the map, is the tomb of the illustrious Châteaubriand, a plain granite slab, surmounted by a cross, and railed in with a very ordinary-looking iron railing. This gravestone, which stands upon an eminence, and is conspicuous rather than solitary, is described by a French writer as a romantic resting-place for the departed diplomatist, characteristic and sublime—“ni arbres, ni fleurs, ni inscription—le roc, la mer et l’immensité”; but as a matter of fact it is anything but solitary in summer-time, and it is more visited by tourists than sea-gulls. The waves are beating round it now, but at low water there will be a line of pedestrians crossing the sands; some to bathe and some to place immortelles on the tomb.

The sands of Le Sillon are covered with bathers and holiday crowds in dazzling costumes, the rising tide driving them up closer to the rocks every minute. Everywhere there is life and movement; the narrow, winding streets of St. Malo pour out their contents on the seashore; little steamers pass to and from Dinard continually, fishing and pilot 8boats come and go, and yachts are fluttering their white sails far out at sea. Everything looks gay, for the sun is bright, and it is the day of the regatta.

Looking landward, the eye ranges over a district of flat, marshy land, that once was sea, and we may discern in the direction of Dol an island rock in the midst of a marshy plain, at least three miles from the sea. On the summit of this rock is a chapel to Notre Dame de l’Espérance, and near it, standing alone on the plain, is a column of grey granite nearly thirty feet high, one of the “menhirs” or “Druid stones” that we shall see often in Brittany. Eastward there is the beautiful bay of Cancale, famous for its oyster-fisheries; the village built on the heights is glistening in the sunlight, and the blue bay stretches away east and north as far as Granville. Cancale is also crowded this morning, for it is the fashion to come from St. Malo on fête days, to eat oysters, and to pay for them. A summer correspondent, who followed the fashion, writes: “The people of Cancale are amongst the most able and industrious fishermen in Brittany, and the oysters from the parcs of Cancale are famous even in the Parisian restaurants; but in the cabarets of Cancale the charges resemble those of Paris.” We mention this by the way because travellers who have taken up their quarters at the principal hotels at St. Malo, finding the charges higher than they expected, might, without a caution, take wing to Cancale. They may be attracted thither, for the day at least, to see the fishing operations, to study costume, to explore the coast by boat, or to visit the island monastery of St. Michel. The water is smooth in the shallow bay of Cancale, and the view extending over miles of blue sea to the green hills beyond Avranches makes a charming picture.

The aspect of St. Malo from the sea is that of a crowd of grey houses with high-pitched roofs, surrounded with stone walls and sixteenth-century towers, and with one church spire conspicuous in the centre. At high-water the waves beat up against the granite rocks and battlements, and St. Malo seems an island; at low water it stands high on a pediment of granite, surrounded by little island rocks and wide plains of sand; the spring tides rising nearly forty feet above low-water mark.

9But the chief interest of St. Malo is undoubtedly outside of it. In the narrow, tortuous streets, shut in by high walls, we experience something of the sensation of dwellers in modern Gothic villas; we have insufficient light and air, we are cramped for space, but we know at the same time that, outwardly, we are extremely picturesque. “Rien de triste et de provinciale comme la ville de Saint-Malo, où tout le monde est couché à 9 h. du soir; rues noires et tortueuses; pas de soleil, ni de mouvement; enfin une ville morte.” Such is the popular French view of it in the height of the season, when prices at the hotels are nearly as high as in Paris.

The fortifications and towers of St. Malo are interesting as examples of military architecture of the sixteenth century; the castle with its four round towers was erected, it is said, by Queen-Duchess Anne to assert her power over the bishops of St. Malo, who had held it from the time when it was an island monastery. From the ramparts and quays we can best see many of the old houses and residences of the wealthy traders of the last century, now dilapidated or turned into barracks or public offices; and we may also note here and there, in narrow streets, remnants of carved timber beams and wooden pillars which formed the frontage of some of the oldest houses. We can walk upon the ramparts all round the town, from which there are extensive views over sea and land; and we can inhale, on the western side, the fresh breezes of the sea, and, on the other, the odours rising from innumerable unwashed streets and alleys. The church, the spire of which was completed by order of Napoléon III., has little architectural interest. The structure dates from the twelfth century, but its present aspect is modern and tawdry, with a huge high-altar, candlesticks, gilt furniture, relics, and artificial flowers. The most noteworthy objects are some carved woodwork in the chancel, and a stained-glass window.

The principal streets of St. Malo are modernised, and the shops are full of wares from Paris and Rennes. The appearance and manners of the people are French rather than Breton, and—although the strange patterns of the white caps worn by the peasants and fisherwomen, and the curiously uncouth intonation of voices which already 10greets our ears, remind us that we are very far from the capital of France—there is little here of distinctive Breton costume.

St. Malo from its position is an important maritime station. It is busy, and busier every year, with shipbuilding, for it has a large fishing population and an export trade with all parts of the world. Brittany is a food-producing land, and St. Malo is its principal northern port; but its manufactures are comparatively unimportant, and its retail trade is largely dependent on the influx of visitors.

In the suburb of St. Servan, where a few English people live quietly, there is less appearance of commercial activity than in St. Malo. It is in fact a faubourg, comparatively unprotected by walls, and undisturbed by much traffic. Its population of 12,000 have their principal business in St. Malo, and there is a constant stream of pedestrians passing to and fro, crossing on a movable bridge worked by steam, the supports of which are on rails under water. The principal street of St. Servan is wider than Wardour Street in London, but it resembles it somewhat in dinginess, and in the fact that its shops are full of tempting baits for the bric-à-brac hunter; old wood carvings, pots, and stones, which should be purchased with caution.

The Bretons, both in St. Malo and St. Servan, are a little demoralised in summer, and wish to be “fine.” To-day being a fête day, they are en grande toilette, and the wonderful white caps worn by some of the women are trimmed with real old lace. In the shops and on the promenades the majority of women are dressed as in Paris, and they wear kid gloves “like their betters”; the country people and the fishing and poorer class of Malouins, only, wearing any distinctive costume. The fishermen of Cancale make money and save it, and send their children to school by train to Rennes, and the fisherman’s daughter comes back in a costume that makes her neighbours envious. Every year more white caps are thrown aside, for Mathilde will not be outdone by Louise; and so the change goes on, and each year the markets of St. Malo and St. Servan have less individuality of costume.

Nevertheless, groups such as are sketched are to be seen to-day in St. Malo, St. Servan, and Dinard: the women in white caps, dark 11stuff gowns, and neatly made shoes; the men in blue serge and sabots. The women’s caps vary in pattern according to their district. They generally wear a close-fitting under cap, with a small high-crimped crown, and a wide lappet pinned on the top of the head. In St. Malo we may see Normandy as well as Brittany caps, and it is not until we get farther into the interior that the costume of the district is strongly marked.[2]

2. The caps peculiar to different parts of Brittany are indicated at the head of each chapter.

12Dinard—once a little fishing-village, now a fashionable watering-place—the position of which we see on the map on page 7, is a delightful residence in summer, and nearly as dear as Trouville, in Normandy; but the air is bracing and exceptionally good, the walks in the neighbourhood shady and delightful, and the bathing in the sheltered Baie d’Écluse as good as any in France. In Dinard there are about 800 houses and villas in pleasant gardens, most of which are let for a short summer season of three months. There is a well managed “Établissement des Bains” and casino, and several good hotels. Dinard is the starting-point to reach Dinan by road; also for the little fishing-villages of St. Briac and St. Jacut, on the coast, westward. At St. Briac the visitor who does not care to be fashionable will find an inn, good bathing, and summer quarters of a rougher kind than at Dinard; and at St. Jacut there is a convent standing almost out at sea, where the nuns take boarders in summer for a very small sum. At Dinard you play at croquet on the sands; at St. Briac you scramble over granite rocks, and fish in the pools under their shadows; at St. Jacut you wander over the sands with a shrimp-net, and in the evening help the nuns to draw water from the convent well.

But we have come to Brittany to sketch and to note what is most characteristic and picturesque. So far, on the threshold as it were, what have we seen? Coming from England, and sailing southward into its blue bay on a summer morning, there was an impression of brightness and colour unusual on our own shores. In St. Malo itself three pictures remain upon the memory. The first is the sunset between the islands and across the sands, near the bathing-place of Le Sillon; the second the moonlight view of its cathedral tower at the end of a narrow street, filling it and towering above it with a grandeur of effect almost equal to that of St. Stephen’s at Vienna; the third picture is in the small courtyard of the Hôtel de France. This house, or part of it, belonged to the family of the Vicomte de Châteaubriand, and it was here, in a room facing the sea, that the celebrated author and diplomatist was born. In the hotel the family arms (the peacock’s plume) are emblazoned, and just outside its gates, in the little dusty square called 13“La Place de Châteaubriand,” a new bronze statue, bright and shining, has lately been erected to his memory. Travellers imprisoned between the narrow streets and dingy walls of St. Malo, fortified and barricaded against the fresh breezes of the sea, may perchance seek the cool courtyard of the Hôtel de France as a place of refuge during the heat of the day, and, if not quite tired of hearing of Châteaubriand, may dwell in imagination upon the historic associations of this house. In a corner of the courtyard, now used as a café, there is an old stone staircase leading to the first étage, such as we may see in the courtyard of many a French château, and upon it there lingers this afternoon an English girl in the costume most affected by society in 1878. She wears a rich, dark, close-fitting dress in simple folds, spreading where it trails upon the rough granite steps with the stealthy grandeur of a peacock’s tail upon a ruined wall. As she turns her head and leans over between the pillars of the covered balcony, her “Rubens hat” and fair hair are framed in antique carved stone. The effect is accidental, but the harmonious combination of costume and architecture brings out suddenly the beauties of each, and gives us a glimpse, not to be forgotten, of the graces of a past age.

The tide is now flowing fast up the Rance, filling its numerous bays and inlets, floating odd-shaped little boats and rafts that are moored off the villages on its banks, running up here and there inland between rocks and trees and forming miniature lakes, which will disappear as the tide goes down. The little steamer for Dinan starts from the Quai Napoléon, and goes up on the flood in about three hours, having just time to reach Dinan and return to St. Malo before the water has subsided. The foredeck is crowded with market-women and small merchandise, and on the afterdeck, which is but a few yards square, there are some French and English tourists under a canvas awning, which is useful alike for shelter from sun, rain, or cinders. Steering south-east by south, we steam gently up the Rance, getting a fine 14view of St. Servan in passing (a view which we should have missed altogether by the land route to Dinan); a river that, near its mouth, seems to have no boundaries or banks, that flows in and out amongst cultivated fields, then suddenly through narrow defiles of rocks and under the shadow of forest trees that might be Switzerland. Once or twice we sail, as it were, in an inland lake, or, as the French call it, “une petite Mediterranée”; we can neither see where we entered nor any outlet on our route. There are fishing and market boats, lying in quiet corners, and one or two pleasure yachts with flags flying, moored in the prettiest spots near modern summer châlets, the slate roofs of which appear above the trees. We pass one considerable village, St. Suliac, on the east bank, behind which is the ancient fort of Châteauneuf; and, on the west, the grey walls of more than one old château are visible. The water is blue and tidal until we arrive at a lock a few miles from Dinan, when the little steamer ploughs through a narrow canal-like stream, and sends the water flowing over the banks, washing the stems of the poplar trees.

Fruit Stall at Dinan.

We are entering Brittany now, and are far out of hearing of the waves that beat upon St. Malo, and of the band of the casino on its sands. On either side the valleys are rich with verdure and with orchards of fruit. There are farmhouses and villas dotted about, and peasants at work in the fields. We pass close to the banks during the last mile, and are shut in by rocks and trees; but all at once the view enlarges, and there rises before us a scene so grand and, at the same time, so familiar that we feel delighted and rewarded at having approached Dinan by water. The prevailing tone of landscape during the last few miles has been sombre, and the valleys in shadow with their dark granite rocks and gloom of firs have contrasted picturesquely with the sunshine on distant fields. As we reach Dinan in the afternoon, the valley of the Rance is in shadow, whilst above and before us, crowning a hill, are the old roofs, towers, and spires of Dinan shining in the sun. The sides of the valley here are almost precipitous, and across it, high above our heads, is a plain modern viaduct, reaching to the suburb of Lanvallay. Dinan is on the west or left bank of the Rance; and near the bridge where we land the steep streets of the old town reach to the water’s edge. Above our heads are feudal towers, and parts of old walls, and the grey roofs of houses between the trees, and away southward the valley of the Rance winding out of sight. We said it was a familiar picture, for the approach to Dinan by water and the view from the hills on the opposite bank of the Rance, seen under summer suns, have been perpetuated in brightness by many an English artist. It is well to see Dinan thus, en couleur de rose, and to remember it in its most bright and attractive aspect, for on a nearer and longer acquaintance 16our impressions may change. Dinan—situated on the summit and slopes of wooded hills, their dark granite sides appearing here and there through the trees, its mediæval towers and terraces, and its old grey houses with pointed roofs, and its handsome white modern houses—forms a good background to the market-women, with their stalls of fruit and vegetables, peasants in blue blouses, and the usual summer crowd of tourists, including Parisians in suits of white, with broad straw hats and blue umbrellas, thronging on the quay waiting for our little steamer. There are several hundred English residents in Dinan, and the voices in the streets have a familiar sound, neither French nor Breton. But the population, including English, scarcely exceeds 10,000 even in summer; and the inhabitants, who are not given up to trading with visitors, are principally occupied in agriculture, or working in their dark dwellings at hand looms.

As we climb up a steep, dirty street, leading from the quay, called the Rue de Jersual, and under a Gothic gateway—past old houses, with high-pitched roofs and leaning timbers, rising one above another in irregular steps—we hear the sound of the loom in the darkness on either side, and the inhabitants come out to stare as usual; shining red faces, under white caps, lean out from little latticed windows and from doorways, and in the gutters many a little pair of sabots stuffed with hay is rattling on the stones. It is a ladder of cobblestones and dirt, cool and slippery, sheltered by projecting eaves from the afternoon sun; the principal approach from the river a century ago, up which a stream of pilgrims files into the upper town. They pause to take breath at the top, and then disperse on the Place, where, in front of dusty rows of trees, the omnibuses and carts, which have come round by the broad, circuitous road, are setting down travellers. The entrance to the inn is blocked by a loaded hay cart, stuck fast in the archway of the house, as in the sketch. We have ascended at least 17300 feet to the Place, and take up our quarters in one of the hotels in the wide open square, looking as dusty and uncared for as usual in French provincial towns, and commanding, as usual also, no view of the country round.

In a few minutes the bustle caused by the arrival of travellers has ceased, and the principal square of Dinan resumes its ordinary aspect on a summer’s day. Nurses, in white caps, sit knitting under the shadows of stunted trees, while the children play in the dust; cavalry officers of all grades play at cards and drink absinthe at little tables half hidden by trees planted in boxes at the hotel doors; ladies and children, a priest, a workman in blue blouse dragging a load of stones, a woman coming from market, and an Englishman or two, on pleasure intent, with draggled beard and grey knickerbockers, as is the fashion of the time. Above the trees, the houses across the square rise in irregular lines, their steep roofs, old and sun-stained, are full of variety and colour; behind them tree tops wave, and great masses of white clouds drive northward to the sea.

Dinan is full of interest both for the artist and the antiquary. The cathedral of St. Sauveur, with its fine carved doorway and Romanesque architecture, the old clock-tower in the Rue de l’Horloge, the mediæval gateways, and the old houses in the narrow streets, form a succession of pictures worthy of study. It is well to examine the castle, once occupied by the Queen-Duchess Anne and now a prison, and to ascend the tower, from which there is a magnificent view. In the museum at the Mairie there are several interesting monuments and ecclesiastical relics. And yet perhaps the chief interest of Dinan is in the variety and beauty of its environs; on every side will be found charming wooded walks and valleys, from which we can see its position, set high on green hills, the sky-line a fringe of trees and towers. The walks on the ramparts, with their lines of poplars and the views across the deep fosse below will give an idea of the military architecture of the middle ages, and especially of the natural strength and importance of Dinan as a fortified city when besieged by the Duke of Lancaster in 1359 and defended by the brave Du Guesclin. In St. Malo, Châteaubriand was 19the hero; in Dinan it is Du Guesclin, constable of France in the fourteenth century. In the cathedral of St. Sauveur they have burned candles before the jewelled casket containing his heart, for centuries, and on the Place there is a poor statue of him in plaster; but the more lasting monuments are the records of his deeds and the songs of the people, which we shall hear often on our travels.

Whichever way we turn in Dinan, we find some new view and point of interest, and the inhabitants are so accustomed to the incursion of strangers, and reap so many benefits by their coming, that we are allowed to sketch almost undisturbed. There is an old woman with deformed hands and feet, who sits knitting on the Place, whose familiar figure will be recalled by the sketch on page 21.

The ramparts are comparatively deserted by day, and form a promenade by moonlight worth coming far to see. If ever there was a spot on earth prepared for lovers, it is surely the broad walk on the southern ramparts of Dinan, where the moon shines upon the path between tall waving poplars and silvers the distant trees, where there is scarcely a sound to break the stillness, where there is room for every Romeo out of hearing of his neighbour, and where the sounds of the city are hushed behind granite walls. It is naturally romantic and beautiful, and, with the associations which cling around its towers, has a charm which is almost unique; but we must tell the truth. There are clusters of white roses clinging to the old masonry above, which have scattered their full-blown leaves at our feet, and below, in the deep dell which formed the ancient fosse, there is honeysuckle in the straggling garden; but the odours that rise on the evening air are not of roses nor of honeysuckle, nor from the broad champaign around. There surely was never a beautiful spot so defiled. As a picture, the general aspect of Dinan will remain in memory—a picture not to be effaced by the erection of large new barracks, or by the railway now constructing in the valley—stately Dinan with its ancient groves and terraces, its hanging gardens, and sylvan views.

We must not linger in such a well-known part of Brittany, or we would take the reader in imagination to one or two of the old houses in the neighbourhood, like the one sketched below; also, a little way up the river, to the picturesque ruins of the abbey of Lehon. This last is a spot especially to be visited, and where, if we are wise and have time, we should take apartments for a week in summer. Another favourite walk is on the opposite side of Dinan, leaving the town by the ramparts towards the north. Here in the midst of a tangle of briars and bushes, hemmed in on every side, run over with ivy and every variety of creeper, shut off entirely from some points of view by an orchard laden to the ground with fruit and by a garden of flowers, is the one tower left of the famous château of La Garaye The grey octagonal turret, with its crumbling Renaissance ornament, stands high above the surrounding trees, and catches the evening sunlight long after the avenue of beeches by which it is approached is in gloom. The place is as solemn and quiet, at the end of a long avenue, as any poet could desire; but as we approach the gates of the château of “the lady with the liberal hand,” whom Mrs. Norton has immortalised in her poem, there are the usual signs of demoralisation. There are pigs about, and tourists; and the show is charged for in the usual way. We pay our money and take away some souvenir of the place. Americans who have read (and recited often in their own homes) 21“The Lady of La Garaye” sometimes make Dinan the extreme western point of their tour in Europe, and have trodden the ground into a deep track to the château with their pilgrim feet; but the position is inconvenient for tourists who have much to see, and so, it is understood, they are going to buy the turret and take it home. The idea is not as absurd as it may sound; it is a very pretty ruin as it stands, but it will fall soon if not cared for, and the low wall on either side of the turret will disappear behind the fruitful orchard. The old hospital is now used as a farm-shed, but wants repairing to be habitable; and the ancient cider-press, with its massive wooden beams, lies rotting in the sun. The farm children are gathering blackberries from the bushes which grow between the hearthstones of the old banquet-hall, poultry swarm in my lady’s boudoir, and there is a hum of bees and insects about the ruin.

22We have said nothing of the English colony and church at Dinan, of the convent of the Ursulines and their good works, or of the people to be seen on market-days, because Dinan is well known to travellers, and there is very little to distinguish it from other French towns. To see the people, and sketch the Bretons in their most picturesque aspects, we must go farther afield.

As we leave Dinan by diligence with much cracking of whips and jingling of bells, through the wide square tenanted as usual by white-capped nurses and idlers; rolling in the high banquette down past the old gateways, out into the country road towards the west, we see the last of Dinan and its towers. Whether in its autumn beauty with rich surrounding woods, or with its winter curtain folded softly, with tassels and fringes of frost, Dinan leaves a brilliant impression upon the mind. We forget the modern incursion of tourists, and the demoralisation amongst the poorer inhabitants caused by the scattering of sous, we forgive its dingy, neglected streets, its ill-kept boulevards and squares, and its slow, unenterprising ways; we remember only its grandeur and picturesqueness.

As we pass out by the Porte de Brest, we meet a Breton propriétaire and his wife in a cart, whom we must not take for peasants because of the black stuff gown and white cap of the bright-faced woman, and the broad-brimmed hat and blouse of the man.

We drive through a straggling suburb of houses, where the peasants stare at us from their dark dwellings; we stop at wayside inns—unnecessarily, it would seem—and are surrounded by beggars of all ages and sizes. Here is one who comes suddenly to earth at the sound 23of wheels, and peers from the darkness of her home underground with the brightness and vivacity of a weasel; her black eyes glisten with astonishment and with the instinct of animal nature scenting food; she transforms herself in an instant from the buoyant youth and almost cherub-like beauty in the sketch to a cringing, whining mendicant. “Quelque chose, quelque chose pour l’amour de Dieu,” in good, clear French, nearly all the words that her parents would have her learn, in the intervals of playing and road-scraping—the latter her only serious business in life. But the schoolmaster is abroad in Brittany; the edict has gone forth that every child of France shall henceforth learn the French tongue; and this little creature will be caught and tamed, and civilised into ways that her parents never knew.

One more picture on the road, an incident common enough, but characteristic and worth recording. It is a sultry afternoon, with a deep blue sky and a burning sun. So fierce is the heat that it has silenced for a time the barking of dogs and the arguments of some of our passengers. Just outside a village the straight road, unsheltered even by poplars, is fringed with low brushwood and long grasses withering under a curtain of dust. There is nothing stirring but a little yellowhammer and a magpie on the road, a cantonnière in wide straw hat, chipping at a heap of stones, and the lumbering diligence in which we travel; no shelter but in a wood hard by.

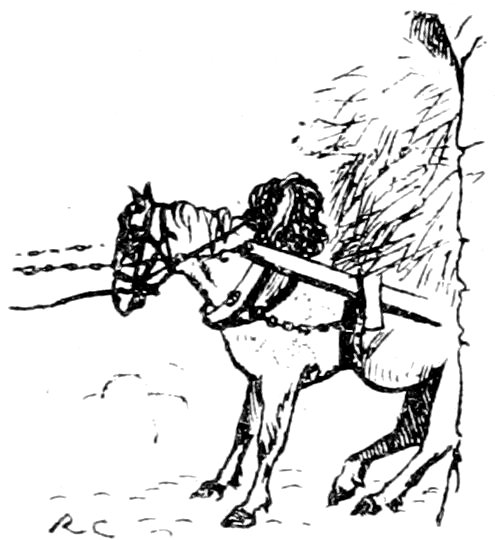

Presently we come to a halt in a narrow part of the road, for M. Achille Dufaure’s cart of charcoal stops the way. It is a suggestive picture, which we may call “The Hour of Repose.” In the foreground, in the burning road, is a tall white charger, encumbered, now in his old age, with a great wooden collar and clumsy harness, 24chained to a dark blue cart with dirt-encrusted wheels, half smothered on this summer’s day with a blue woolsack over his shoulders, foaming at the mouth, and streaming with the wounds of flies and other injuries, but pricking his ears as of old at the sound of approaching wheels. In the background, but a few yards off, is a cool wood of beech and elm, dark in its shadows, green in its depth with ivy and fern, and fringed against the sky with tops of waving poplars. This broad mass of green, which comes between the brightness of sky and the burning road, with its foreground of dry grasses, is relieved on one spot by a cool ripple of blue—it is Achille lying on his face asleep, his blouse just lifted by a breeze; he will repose for two or three hours, whilst his horse stands in the sun, and the hot shadows lengthen from his heels. No amount of shouting on the part of our driver will waken the sleeper; blessings and curses, cracking of whips and blowing of horns, are all tried in vain, and the monotony of our journey is relieved by the diligence being dragged, as it might have been at first, over the field at the roadside, and we resume our way.

As we travel westward, the aspect of the land becomes suddenly changed; it is clouded over and rained upon, and is a sombre 25contrast to the former brightness. After the glare of the sun the senses are grateful for quiet tones; but the sight is strange, almost mournful. The district is only a few miles from busy towns and sea-ports, and on the main line of railway from Paris to Brest, but it is out of the world, and seems, under its cloudy aspect, farther than ever removed from civilisation; we pass substantial-looking farmhouses, but the dwellings of the peasants are generally hovels, with tumble-down mud walls and immovable windows; in their gardens are dungheaps and stagnant pools of water. We see women at work in the fields, girls tending cattle, and the men, generally, looking on.

The distance from Dinan to Lamballe by road is twenty-five miles, a slow and sleepy journey of about five hours by the direct route; a journey seldom taken by travellers since the completion of the railway westward. Everything we pass on the road looks comparatively untidy, rough, and poor, with the poverty of ignorance and neglect rather than 26of means, for the soil, as we approach Lamballe, is rich, and yields well. The country is really fruitful, but an acre of land is often divided into twenty different lots, in each of which there are separate crops of hemp, buckwheat, or potatoes, or they are filled with gorse for winter fodder for cattle. The hedges are made of mud-banks, gorse, and ferns, and the gates between them are formed of felled trees, the stem forming the upper bar, the roots being left as a counterpoise to lift the gate on its rough, wooden latch.

The rain ceases as we approach Lamballe; the air is fresh with the wind coming from the bay of St. Brieuc, and as the sky clears, we obtain, at intervals on the undulating road, views over finely wooded valleys, with high hedgerows, banked up and planted with elms and oaks. The chestnut trees, wet with the rain, are rich in colour, and the fields of buckwheat lighten the landscape again. Another turn in the road, and we are in evening light, there is open pasture land, and the cattle are winding home; at another, a farmer is meditating on his stock in the corner of a field. Thus we pass from one picture to another, quaint and idyllic, the last reminding us more of Troyon than of Rosa Bonheur.

It is half past five o’clock on a summer’s morning at Lamballe, and the deep-toned bell of Notre Dame resounds through the valley of The Gouessan. The sun is up, and gleams upon the roof tops, and upon the heads of the old women who are sitting thus early in the market-place, surrounded with flowers, taking their morning meal of potage. It is market morning, and the open square in the centre of the town is filling fast with arrivals from the country. Everything is fresh from the late rains, and the air is laden with the scent of flowers, butter, and milk. On every side carts are unloading, and itinerant vendors are fitting up stalls for the sale of provisions and goods. There are rows of stalls for the sale of cloth stuffs, shoes, and wooden sabots, for pots and pans, and for innumerable trinkets of small value to tempt the peasantry. The shops are opening one by one, displaying less fashionable, if more useful, wares than we have seen at St. Malo and Dinan; agricultural implements, and all articles for the use and temptation of the country people who come from far to make purchases, bargaining in a rather uncouth tongue, but with a certain dignity and determination of manner which we shall find peculiar to the Bretons. Both buyers and sellers speak in a language apparently half French and half Welsh, and the majority dress in plain, 28dark, home-spun stuffs, the men with their blouses, the women with their caps, all put on clean for the day. This market-place at Lamballe is a sight, if only to see the fowls and the flowers. It is full of the killed and wounded, bright plumage and delicate leaves; beauty led captive by vigorous hands, hustled out of the market-place by rosy, unsentimental housekeepers; carried heads downwards, both fowls and flowers!

The noise and chattering of a market morning have begun in earnest, but the great bell of Notre Dame resounds above all; two other churches soon join in the concert, and the clatter of sabots over the rough cobblestones up to the church doors adds to the clamour. It is time to follow the people up the streets, almost too steep for wheels, which lead to the great church of Notre Dame, built oh the site of the ancient castle of the counts of Penthièvre.

Travellers, especially summer tourists coming from Dinan or Rennes, on their way westward by railway, seeing the beautiful position of this town, with its church above the valley, pause sometimes to consider “whether Lamballe is worth stopping at for a night.” As we are writing for all, we may tell them, as we pause to take breath on the ladder of stones which leads to Notre Dame, that the Gothic pile which crowns the hill before them, whose granite walls almost overhang a precipice, and from the rocks of which its pillars and arches seem to spring, is not only full of historic interest, but has a grandeur of effect in the interior which we shall seldom find equalled in Brittany. The original structure was a castle chapel, built early in the sixteenth century, but the present building does not present many special architectural features of interest, excepting the remains of an ancient rood-loft and some stained glass. The building has undergone several periods of restoration down to the present time, when workmen are busy repairing its outer walls. But the interior, on Sundays and fête days, is a picture to be remembered, and is especially full of human interest. The nave is less obstructed with modern ornaments than usual, and there is a quietness about the services which we do not find in larger towns. There are the usual wooden cabinets set against 29the side wall with green curtains in place of doors; in the centre compartment there is a dark object concealed, and on one side the skirt of a woman’s dress peeps from under the curtain; it is only Marie in a new gown telling some of her sins. There are several women kneeling on chairs, dressed in dark green or brown shawls, stuff dresses, and neat strong shoes; all heads turn one way as we enter, the old women, especially, scanning us from head to foot and mentally taking our measure as they pray. Here, on this summer morning, crowded with men, women, and children on their knees, their figures just distinguishable in the subdued light, the proportions of the lancet arches supported by clustering pillars, and the stained-glass windows, have a fine effect.

Before leaving Lamballe, a sketch should be made, from the valley, of the church of Notre Dame, with its surrounding houses, walls and rocks in evening light. The drawing, if accurate, will be considered exaggerated, on account of the extraordinarily picturesque and commanding site. The views from the terraces and old ramparts of Lamballe form an almost complete panorama of the country round. It is a view of rich cultivated land, covered with crops of cereals, and cattle grazing in the valleys. Over all this land the great bell of Lamballe makes itself heard in company with the whistle of the locomotive which hurries travellers on to St. Brieuc, a distance of twelve miles westward.

In St. Brieuc we find ourselves in a busy city of 15,000 inhabitants, apparently too much occupied with trade and agriculture to think about beautifying their houses and streets. There are many narrow, irregular streets, in which the old houses have been replaced by others generally modern and mean; “une vraie ville de rentiers qui aurait besoin d’être ‘hausmannisée.’” There is a large square Place for the military, and a market-place near the cathedral, where the old women congregate. St. Brieuc, as will be seen on the map, is the principal town in the department; it carries on a large export trade in the produce of the country, especially in butter and vegetables, for the English and European markets. Cattle are exported largely from Légué, the actual port, about two miles off, in the centre of the bay of Brieuc, hidden from the town by intervening hills.

In the country round and on the hills overlooking the sea, there are men and women at work in the fields, girls carrying milk on their heads from the neighbouring farms, and others busy in the farmyards. The buckwheat harvest has commenced, and the fields are being robbed of their rich colour; but the scene is bright with fresh green and yellow mustard, and rich here and there with clover. The sombre figures are the peasantry with their dark costumes. Here we feel inclined, for the first time, to stay and sketch, wandering along the coast to the fishing villages on the western shore of the wide-spreading bay of St. Brieuc, visiting the farms and homesteads, and making studies of the interiors of dwellings. The 31rough, wasteful method of husbandry, the old farmhouses with their one living-room with massive furniture and mud floors, and the simple manners of the peasants, remind us irresistibly of Ireland, whilst the names of people and places and the intonation of voices are altogether Welsh.

Everyone is at work near St. Brieuc in the summer months, every man, woman, and child, in the fields, on the roads, or on the shore; a bright, quick-witted population, accustomed to the inroads of strangers. The inhabitants are superintended in their occupations by some officers of the line, whose regiments are quartered near the town. The soldiers are sprinkled over the streets, and dot the hillsides with colour. The rattle of drums and the smoke of innumerable bad cigars make a lasting impression in this city.

St. Brieuc, or St. Brioc, is the site of a very ancient bishopric, whose chapter was loyal and powerful to the last. Its history is told best in the strength of its cathedral walls, and especially in the ruins of the tower of Cesson, a castle once commanding the entrance to the bay and the approach to St. Brieuc from the sea. There is 32little that is remarkable in the churches, and, unless it be some old overhanging houses near the cathedral, little to sketch in the town that we shall not find of a better type elsewhere. The business of nearly everyone at St. Brieuc is to prepare ox hides, tallow, hemp, and flax, to sell stores for the ships that fit out here for the Newfoundland cod-fisheries, and generally to provide the agricultural population with the necessaries of civilisation. The town is as noisy as any French market-town where soldiers are quartered. In the evening come the carts from the country, and the clatter of sabots over the stones; at sundown the regimental drums, at midnight the evacuation of the cafés, and the songs of warriors going to their rest; at dawn a market generally begins under our windows. When do these people find rest? The answer comes laconically from the femme de chambre at our inn. “There is the winter for rest”; and there is the French saying, applicable enough in this land of noises, that we have “l’éternité pour nous reposer.”

In the neighbourhood of St. Brieuc is a picturesque château, part of which is shown in the sketch; on the sky-line fringing the roof are metal figures of horses, men, and dogs, typical of the chase.

33There are modern innovations of high white houses, factories, steam ploughs, plate-glass windows, and smooth pavements to walk on, and the majority of people one meets in St. Brieuc are dressed in modern fashion, but there are odd corners, and very odd old men and women in the by-streets. There is an old woman who sits in the market-place surrounded by earthenware pots, rather disconsolately, for trade is bad; but who, facing the last rays of the setting sun, unconsciously makes a picture which for colour is a delight to the eye; a comfortable old woman in dark blue dress, with dazzling white cap, bronzed hands and wrinkled face, all aglow under its snowy awning; a background of brown and blue earthenware piled in straw, a distance of dark shadows, and half defined leaning eaves.

St. Brieuc is much visited in the summer for sea bathing. The large buildings near the sea, surrounded by high walls and gardens, are convents or seminaries, where several hundred children are boarded and educated for about £20 a year. In the summer the children give place to adult pensionnaires, who come from all parts of France for the bathing season, and the convents are turned into lodging-houses, reaping a good harvest in spite of the apparently moderate terms of five or six francs a day. These pensionnaires spread over the cliffs and sands like summer flies, to be discerned sometimes in the distance as in the sketch.

Winnowing near St. Brieuc.

35It is at a village on the cliff near Fort Rosalier that we first see men and women winnowing, their arms extended in the breeze, a bright and characteristic scene recorded exactly in the sketch; a picture soon to vanish before patent winnowing-machines and other improvements. Mathurine, one of the party—who has pinned a clean white band of linen over her flowing hair and under-cap, and put on a dark brown embroidered shawl—takes the opportunity, during the midday meal of potage, to stand for her portrait.

About midway between St. Brieuc and Guingamp, on the north side of the railway, is the quiet little town of Châtelaudren. It is washed and watered by the Leff, the “river of tears,” which, coming from the mountains that we see to the south, winds its way through rich valleys, seaward. In its course, and in its time, the Leff has done much havoc in this peaceful valley, inundating and destroying Châtelaudren in 1773, and still occasionally overflowing its banks. To-day it is to the angler a capital trout stream, if he will follow its course southward to the mountains; to the artistic eye it is a sparkling river of light, set in a landscape of green and grey. In the town of Châtelaudren, with its one wide and rather dreary-looking street, there is not much to detain the visitor, but it is a good starting-point from which to explore the country and the Montagnes Noires. The land is thickly cultivated, and well grown with crops almost down to the sea; and on every side in this autumn time 36there are signs of industry. From the fields we hear voices of women at work; in the farmyards there is the dull thud of the flail and the burr of the winnowing-machine. Across the sloping fields from the sea come sounds of singing and laughter, disconnected and weird sometimes, from being caught up by the wind, then dropped and taken up again.

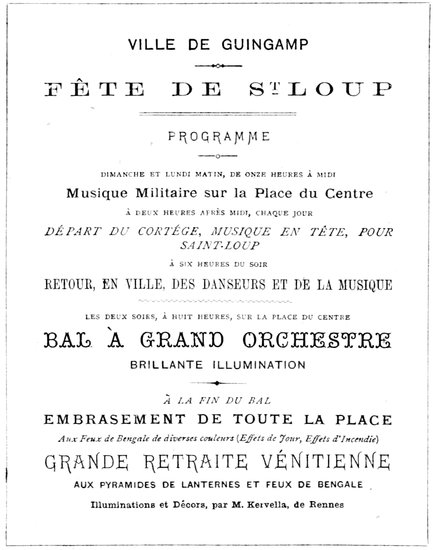

Eight miles from Châtelaudren, in a green valley watered by the river Trieux, is the quiet old town of Guingamp. Its past history, like that of nearly every town in Brittany, has been so eventful that its present normal state may well be calm; but once a year its inhabitants neither work nor repose. In the month of September they hold their annual Fête de St. Loup, and pilgrims come from all parts of Brittany by excursion trains to the famous “Pardon” of Guingamp.

These religious festivals which are held once a year in nearly every town in Brittany, and are generally combined with dancing, fireworks, and other festivities, are the occasion of a great gathering of the people from remote parts of the country; excursion trains bring tourists and pilgrims from all parts of France, and during the week of the fête it is difficult to find a resting-place in Guingamp. The three principal Pardons are generally held at Ste. Anne d’Auray in Morbihan, in July, at Ste. Anne de la Palue in Finistère, in August, and at Guingamp, in September. The Pardon at Guingamp is held on Sunday and Monday, when processions are formed to the shrine of a saint a mile and a half outside the town, indulgences are granted, relics and crosses are distributed, trinkets are blessed, and sermons preached by the bishop of the diocese to the people assembled in the open air. After the services there is a fête in the town, of which the programme on the next page will give the best idea.

38The religious aspect of these Pardons, and the gathering of the pilgrims, is sketched in Chapter XII.; we will therefore speak of Guingamp as it is seen every day. Whether it be from the interest attaching to the great annual fête, or from reports of the miraculous cures that have been effected by the patron saint, Guingamp has always attracted travellers, and has been written of in terms of rapture which may astonish a visitor when he sees it for the first time. It is a town of not more than 8000 inhabitants, with one principal street, which winds irregularly down like a stream, spreading and overflowing its banks at one point, in triangular fashion, in what is called the market-place, then narrowing again, and working its way through a suburb of small houses into the great high-road to Morlaix. It has two monuments—the church of Notre Dame, and a bronze fountain in the market-place. The timbered houses are old, and many of their gables lean; the cobblestones in the streets are rough, and the public square of dust, with withering trees, built on the old ramparts, looks as dreary as any we shall see on our travels. But it is surrounded by green landscape, and the view from the walks on the ramparts, seen through the tops of poplars, is of a green valley with trees and grey roof-tops, between which winds the river Trieux, slowly turning water-wheels.

The church was built between the fourteenth and sixteenth centuries, and represents several styles of architecture—Romanesque, Gothic, and Renaissance. It was originally founded as a castle chapel, and part of the structure is as early as the thirteenth century. It has three towers, the centre one having a spire. The interior is impressive, on account of the simplicity of arrangement for services and the comparatively uninterrupted view of the nave and aisles; an effect more like that on entering a cathedral in Spain than in France.

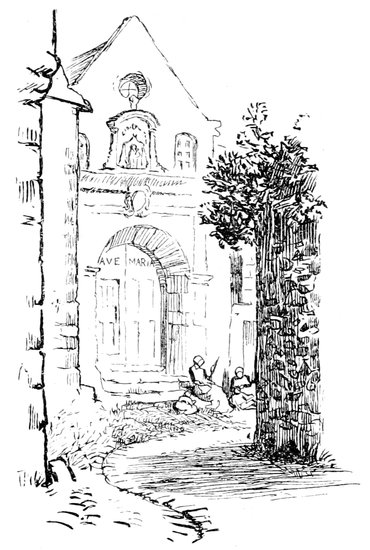

Brittany is a land of lasting monuments; and of its buildings it has been well said, “ce que la Normandie modelait dans le tuf, la Basse-Bretagne le ciselait en granit”; but remembering the magnificent churches we have seen in Normandy, we need not detain the reader long in Notre Dame de Guingamp. If we were asked by tourists if the church of Notre Dame at Guingamp was worth going very far to see, we should answer, No. It is only as a picture that it attracts us much. We shall see finer buildings in other parts of Brittany, but nowhere a more characteristic assembly. The most curious feature is a chapel forming the north porch, which is open and close to the street, lighted at night for services, and separated only from the road by a grille. This portail, as it is called, forms the chapel of Notre Dame de Halgoet, and is the sacred shrine to which all come at the fête of Guingamp. It is ornamented by rich stone carving and grotesque gurgoyles. The people of Guingamp love the chapel of Notre Dame de Halgoet; it is a retreat for them by day and by night, a place of meeting for old and young, with a perpetual beggars’ mart at the door. This north porch with its open grille is a house of call for rich and poor of both sexes, and placed as it is in the centre of the town, abutting upon the principal street, it forms part of their everyday life to go in and out as they pass by. It is one of the many welcome retreats in France; in a land of perpetual noises and glare, of shrill, uncouth voices and latch-less doors, it is the church that gives us peace and shade.

In the centre of Guingamp is its market-place, and in the centre of the market-place is a fountain, consisting of a circular granite basin with a wrought-iron railing. There is a second basin of bronze, supported by four sea-horses with conventional wings, and a third by four naiads; the central figure is the Virgin, her feet resting on a crescent. This fountain was constructed by an Italian artist, and its waters played for the first time on the night of the annual Pardon, in 1745. The history of Guingamp is not complete without recounting the story of the 41construction of this fountain; but regarded from a picturesque point of view, the smooth green bronze with its Renaissance ornamentation harmonises neither with the surrounding houses, with their high-pitched roofs and pointed turrets, nor with the towers of Notre Dame. We are more interested with the living groups which furnish the wide market-place in the morning sun.

A few yards from the cathedral, on the opposite side of the street, is the old Hôtel de l’Ouest, where travellers are entertained in rather rough but bountiful fashion.

“Take a little trout or salmon, caught this morning in the Trieux, a little beef, a little mutton, a little veal, some tongue, some omelettes, some pheasant, some fish salad, some sweets, some coffee, and then—stir gently,” is the prescription for travellers who stay at the Hôtel de l’Ouest. As this is an average hotel, it may be worth while to state that the bill presented (by the young lady in the sketch) to three English travellers, who spent a night and part of a day there, was 12 fr. 80 c.

Excepting at the time of fêtes, Guingamp is almost as quiet and primitive in its ways as in the days of the Black Prince. Our notes of days spent in this city in different years are the most uneventful in our records. On one summer’s morning we hear an unusual sound from the great bell of Notre Dame, and find a procession of priests and choristers winding up the principal street, followed by hundreds of the inhabitants. What is the occasion? “The mother of the Maire is dead; she was a bountiful lady, beloved by all, and we are to bury her this morning.” And so the inhabitants turn out en masse, and march with slow steps, for about half a mile, to the cemetery. It is a dark, silent stream of people, filling the street, and carrying everything slowly before it; the only sounds being the chanting of the choir, and the repetition of prayers. We 42follow to the cemetery, which is crowded with graves, each headed by little iron or wooden crosses, hung with immortelles. The procession divides and disperses down the narrow paths, a few only of the friends of the deceased standing near the grave.

At one corner of the cemetery is a shabby little wooden building, like a gardener’s tool-house, which seems to excite much interest. A girl, with shining bronzed face, in a snow-white cap, holding a little child by the hand, is coming out of the door; we venture to ask the reason of her visit. “Just to see my father for a minute,” is the ready answer.

In a little wooden box, about the size of a small dog kennel, is her father’s skull or chef, as it is called; he is tumbling over with his friends in other boxes exactly as in the sketch, which, rough as it is, has the grim merit of accuracy. The sight is a common one in Brittany, but it is startling and takes us by surprise at first, to see at least fifty of these shabby boxes, some on shelves in rows, but generally piled up in disorder and neglect. The lady who is being buried so solemnly this morning will some day be unearthed, and her chef, in a box duly labelled and decorated with immortelles, will take its place in the ossuary of Guingamp.

From the high ground near the cemetery, and especially from a hill a little farther from the town in a north-easterly direction, we obtain a good view of Guingamp and of the country round. There is a mound, covered with smooth grass, clumps of gorse, and tall fir trees, through which the wind moans on the calmest day; a spot 43much favoured on summer evenings by the youth of Guingamp. Looking round over the thickly wooded but rather sombre landscape, and on the old grey roofs of the town, one is a little at a loss to account for the rapturous descriptions which nearly all travellers give of Guingamp. On a fine summer’s morning the landscape is seen to perfection; but to tell the truth about it, the scene is not very striking either for beauty or for colour. Guingamp has been described as “a diamond set in emeralds,” and we read of its landscape “riant,” and so on. “Guingamp m’a pris le cœur,” says another traveller; but their interest is in the past, they people it with memories, and with the events of past years.

Our business is with the present aspect of Brittany, and we are bound to record that Guingamp, excepting at the time of the Pardon, is a very ordinary place indeed. The artist and the angler may linger in its valleys, and make it headquarters for many an excursion. If we might suggest one walk to them, we should say—

Go out of the town in a south-easterly direction, following the course of the river Trieux on its right bank for half an hour, and you will come to a suburban village, with a rough wooden cross (like the one sketched on page 89) raised aloft in the centre of the street, and the bright and trim new stone spire of a chapel conspicuous amongst its irregular roof-tops.

Turn round to the right hand, just by the cross, and enter a large farmyard; the women are busy winnowing, not with hands upraised in the wind, as we have seen them at St. Brieuc, but twirling by hand a new patent blue-painted rotatory winnowing-machine with a burring sound, in a cloud of choking dust. They are storing their harvest in a large barn, the remains of an ancient Gothic church, the abbey of Ste. Croix, with its choir window piled up with straw. Immediately in front are the farm buildings, part of a round tower and a corner turret standing, and much of the old woodwork and massive interior fittings is still preserved. The garden reaches to the river, where ancient and historic trout disregard the angler of to-day. The farm and its surroundings are as picturesque as any painter could desire.

44The inhabitants of this suburb have a real grievance; they had lived for generations in familiar sight and sound of the cathedral of Guingamp; they saw its spire and towers at evening, standing out sharp and clear against the western sky, and were in feeling living almost in the town itself, when suddenly the engineers of the “Chemin de Fer de l’Ouest” threw up a mountain of earth in their midst, and shut out the town and the sunset light from them, and from their children, for evermore.

Twelve miles north-east of Guingamp is Lanleff—“the land of tears,” celebrated for one of the most curious architectural monuments in Brittany, the circular temple of Lanleff. Leaving Guingamp, we pass through a solitary wooded country, the undulating road soon rising high above the valley of the Trieux. The air is fresh and invigorating, and the views from the summits of the hills extend over a wide range of land. At Gommenech we enter the valley of the Leff that we passed at Châtelaudren. There is no prettier river, or one that should more truly delight an artist’s eye, than the Leff in its long, winding journey from the mountains to the sea.

Sheltered by woods, shut in here and there by granite walls, with ruins crowning the heights, between green banks and through sloping fields, it is one of those picturesque rivers which are peculiar to Brittany of which we seldom hear mention, but which many an English angler knows well. The view of Gommenech is to be remembered as we cross the valley on our way to the temple of Lanleff; the temple is in ruins, and partially unroofed, but enough remains of the original nave supported by pillars, and its outer circle of aisles, to give us a perfect idea of the structure, which resembles closely and has, doubtless, the same origin as the round churches in England built by the Crusaders on their return from the Holy Land. The diameter of the 46church to the walls of the outer aisles is not more than 20 feet; in the inner circle, or nave, the twelve arches are round and Romanesque in style, with rude carvings on the capitals. A chancel was afterwards built into the original structure, so that the unroofed walls of the temple formed, as it were, a vestibule to the parish church, and in this circular open porch, under the shadow of a yew-tree, the congregations used to kneel. But the people now assemble in the new parish church on the hillside, and the temple is kept for show. The “holy well with its blood-stained stone” is pointed out to visitors; the pieces of oolite, that encircle the well, show shining red spots when wetted, to mark the place where, according to tradition, “an avaricious priest received money from a father who sold his child to the Evil One.”

We listen to the story gravely, and certainly no sign of doubt, or of levity, passes over the grave face of the Breton woman who tells it; we are in a land of historic monuments and traditions of the past, and the people who live at Lanleff are too wise even to smile at the interest travellers take in these things. The story has been handed down from father to son, from mother to daughter, and is now passed on to tourists who can master a little of the Breton tongue.

Continuing our journey northward, we soon arrive at the summit of a hill overlooking the bay of Paimpol and the thickly wooded country round; we have passed good country-houses on the route, with flower-gardens skirted by hanging woods; and as we approach Paimpol, there are houses scattered in sheltered bays, with fishing and pleasure boats aground; an old church surrounded closely by houses, a little Place, a custom house, a quay, boatmen, and fisherwomen; but—where is the water? It has retreated for more than a mile, and the long bay or estuary and the port of Paimpol are a desolate waste of mud. Paimpol is a small but busy fishing village, much frequented in summer by the French for bathing. It is not fashionable, but the inns are comfortable, and the country is full of attractions for the summer visitor. The houses on the Place and in the narrow streets are old and weather-worn; some 47are dark and mysterious-looking, and have that peculiar smuggling aspect with which we soon become familiar on this coast.

In a corner of the quiet churchyard of Paimpol there reposes at full length, in stone, “L’Abbé Jean Vincent Moy,” many years curé of this place and honorary canon of St. Brieuc; and round about him, placed thickly in rows, the former inhabitants of Paimpol rest under black wooden crosses. The curé is carved in dark green stone, from which time has taken the sharpness of the chiselling; but the expression is life-like, representing him in the popular act of blessing. There is a cup of holy water at his feet, supplied by an old woman who kneels before the tomb on the damp ground. It is her pious office to guard the tomb of her pastor, and brush off the leaves which fall thickly from the grove of elms overhead. They move slowly and die leisurely at Paimpol; this old woman’s time is not yet, for she “has only eighty years.” In four newly made graves there repose Eugénie, Marie, Mathilde, and Hortense, and their respective ages are eighty-two, eighty-four, eighty-eight, and eighty-nine!