Title: Twenty-Five Ghost Stories

Editor: W. Bob Holland

Release date: October 31, 2016 [eBook #53419]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by David Edwards, Chuck Greif and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

book was produced from scanned images of public domain

material from the Google Books project.)

COMPILED AND EDITED

BY

W. BOB HOLLAND.

————————

Copyright, 1904, by

J. S. Ogilvie Publishing Company.

————————

New York:

J. S. OGILVIE PUBLISHING COMPANY,

57 Rose Street.

This collection of ghost stories owes its publication to an interest that I have long felt in the supernatural and in works of the imagination. As a child I was deeply concerned in tales of spooks, haunted houses, wraiths and specters and stories of weird experiences, clanking chains, ghostly sights and gruesome sounds always held me spellbound and breathless.

Experiences in editorial offices taught me that I was not alone in liking stories of mystery. The desire to know something of that existence that is veiled by Death is equally potent in old age and in youth, and men, women and children like to be thrilled and to have a “creepy” feeling along the spinal column as the result of reading of a visitor from beyond the grave.

This volume contains the most famous of the weird stories of Edgar Allan Poe, that master of this form of literature. “The Black Cat” contains all the needed element of mystery and supernatural, and yet the feline acts in a natural manner all of the time, and the story is quite possibly true. It is only in the manner of its{6} telling that the tale becomes one that fittingly finds its place in this collection.

Guy de Maupassant, the clever Frenchman, is also represented by two effective bits of work, and other less widely known writers have also contributed stories that are worth reading, and when once read will be remembered. There is not a story among the twenty-five that is not worthy of close reading.

There has recently been a revival in interest in ghost stories. Many of the high-class magazines have within a few months printed stories with supernatural incidents, and writers whose names are known to all who read have turned their attention to this form of literature.

Whether or not the reader believe in ghosts, he cannot fail to be interested in this little book. Without venturing to express a positive opinion either way, I will only say with Hamlet: “There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio, than are dreamt of in your philosophy.”

W. Bob Holland.

For the most wild, yet most homely narrative which I am about to pen, I neither expect nor solicit belief. Mad indeed would I be to expect it, in a case where my very senses reject their own evidence. Yet, mad am I not—and very surely do I not dream. But to-morrow I die, and to-day I would unburden my soul. My immediate purpose is to place before the world, plainly, succinctly and without comment a series of mere household events. In their consequences, these events have terrified—have tortured—have destroyed me. Yet I will not attempt to expound them. To me they have presented little but horror, to many they will seem less terrible than baroques. Hereafter, perhaps, some intellect may be found which will reduce my phantasm to the commonplace—some intellect more{8} calm, more logical, and far less excitable than my own, which will perceive in the circumstances I detail with awe nothing more than an ordinary succession of very natural causes and effects.

From my infancy I was noted for the docility and humanity of my disposition. My tenderness of heart was even so conspicuous as to make me the jest of my companions. I was especially fond of animals, and was indulged by my parents with a great variety of pets. With these I spent most of my time, and never was so happy as when feeding and caressing them. This peculiarity of character grew with my growth, and in my manhood I derived from it one of my principal sources of pleasure. To those who have cherished an affection for a faithful and sagacious dog, I need hardly be at the trouble of explaining the nature or the intensity of the gratification thus derivable. There is something in the unselfish and self-sacrificing love of a brute, which goes directly to the heart of him who has had frequent occasion to test the paltry friendship and gossamer fidelity of mere Man.

I married early, and was happy to find in my wife a disposition not uncongenial with my own. Observing my partiality for domestic pets she lost no opportunity of procuring those of the most agreeable kind. We had birds, goldfish, a fine dog, rabbits, a small monkey and a cat.{9}

This latter was a remarkably large and beautiful animal, entirely black, and sagacious to an astonishing degree. In speaking of his intelligence, my wife, who at heart was not a little tinctured with superstition, made frequent allusion to the ancient popular notion, which regarded all black cats as witches in disguise. Not that she was ever serious upon this point—and I mention the matter at all for no better reason than that it happens, just now, to be remembered.

Pluto—this was the cat’s name—was my favorite pet and playmate. I alone fed him, and he attended me wherever I went about the house. It was even with difficulty that I could prevent him from following me through the streets.

Our friendship lasted, in this manner, for several years, during which my general temperament and character—through the instrumentality of the fiend Intemperance—had (I blush to confess it) experienced a radical alteration for the worse. I grew, day by day, more moody, more irritable, more regardless of the feelings of others. I suffered myself to use intemperate language to my wife. At length I even offered her personal violence. My pets, of course, were made to feel the change in my disposition. I not only neglected them, but ill-used them. For Pluto, however, I still retained sufficient regard to restrain me from maltreating him, as I made no scruple of maltreating the rabbits, the monkey{10} or even the dog, when by accident or through affection they came in my way. But my disease grew upon me—for what disease is like alcohol! And at length even Pluto, who was now becoming old, and consequently somewhat peevish—even Pluto began to experience the effects of my ill-temper.

One night, returning home much intoxicated from one of my haunts about town, I fancied that the cat avoided my presence. I seized him, when, in his fright at my violence, he inflicted a slight wound upon my hand with his teeth. The fury of a demon instantly possessed me. I knew myself no longer. My original soul seemed, at once, to take its flight from my body; and a more than fiendish malevolence, gin-nurtured, thrilled every fiber of my frame. I took from my waistcoat pocket a penknife, opened it, grasped the poor beast by the throat, and deliberately cut one of its eyes from the socket! I blush, I burn, I shudder while I pen the damnable atrocity.

When reason returned with the morning—when I had slept off the fumes of the night’s debauch—I experienced a sentiment half of horror, half of remorse, for the crime of which I had been guilty; but it was, at best, a feeble and equivocal feeling, and the soul remained untouched. I again plunged into excess, and soon drowned in wine all memory of the deed.

In the meantime the cat slowly recovered.{11}

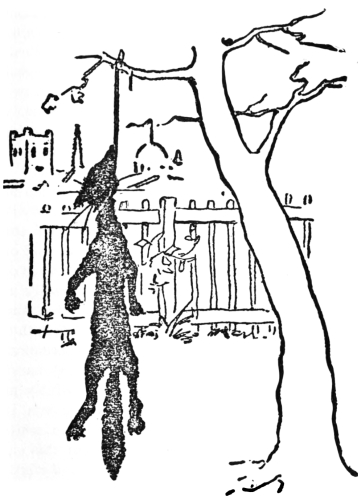

The socket of the lost eye presented, it is true, a frightful appearance, but he no longer appeared to suffer any pain. He went about the house as usual, but, as might be expected, fled in extreme terror at my approach. I had so much of my old heart left as to be at first grieved by this evident dislike on the part of a creature which had once so loved me. But this feeling soon gave place to irritation. And then came, as if to my final and irrevocable overthrow, the spirit of perverseness. Of this spirit philosophy takes no account. Yet I am not more sure that my soul lives than I am that perverseness is one of the primitive impulses of the human heart—one of the indivisible primary faculties or sentiments which give direction to the character of man. Who has not, hundreds of times, found himself committing a vile or silly action, for no other reason than because he knows he should not? Have we not a perpetual inclination, in the teeth of our best judgment, to violate that which is Law, merely because we understand it to be such? This spirit of perverseness, I say, came to my final overthrow. It was this unfathomable longing of the soul to vex itself—to offer violence to its own nature—to do wrong for the wrong’s sake only—that urged me to continue and finally to consummate the injury I had inflicted upon the unoffending brute. One morning, in cold blood, I slipped a noose about its neck, and hung it to{13} the limb of a tree; hung it with the tears streaming from my eyes and the bitterest remorse at my heart; hung it because I knew that it had loved me, and because I felt it had given me no offense; hung it because I knew that in so doing I was committing a sin—a deadly sin that would so jeopardize my immortal soul as to place it, if such a thing were possible—even beyond the reach of the infinite mercy of the most merciful and most terrible God.

On the night of the day on which this cruel deed was done, I was aroused from sleep by the cry of “fire!” The curtains of my bed were in flames. The whole house was blazing. It was with great difficulty that my wife, a servant and myself made our escape from the conflagration. The destruction was complete. My entire worldly wealth was swallowed up, and I resigned myself thenceforward to despair.

I am above the weakness of seeking to establish a sequence of cause and effect between the disaster and the atrocity. But I am detailing a chain of facts, and wish not to leave even a possible link imperfect. On the day succeeding the fire I visited the ruins. The walls, with one exception, had fallen in. This exception was found in a compartment wall, not very thick, which stood about the middle of the house, and against which had rested the head of my bed. The plastering had here, in great measure, resisted the{14} action of the fire—a fact which I attributed to its having been recently spread. About this wall a dense crowd were collected, and many persons seemed to be examining a particular portion of it with very minute and eager attention. The words “strange!” “singular!” and other similar expressions excited my curiosity. I approached and saw, as if graven in bas-relief upon the white surface, the figure of a gigantic cat. The impression was given with an accuracy truly marvelous. There was a rope about the animal’s neck.

When I first beheld this apparition—for I could scarcely regard it as less—my wonder and my terror were extreme. But at length reflection came to my aid. The cat, I remembered, had been hung in a garden adjacent to the house. Upon the alarm of fire this garden had been immediately filled by the crowd—by some one of whom the animal must have been cut from the tree and thrown through an open window into my chamber. This had probably been done with the view of arousing me from sleep. The falling of other walls had compressed the victim of my cruelty into the substance of the freshly spread plaster, the lime of which with the flames, and the ammonia from the carcass, had then accomplished the portraiture as I saw it.

Although I thus readily accounted to my reason, if not altogether to my conscience, for the{15}

startling fact just detailed, it did not the less fail to make a deep impression upon my fancy. For months I could not rid myself of the phantasm of the cat; and, during this period, there came back into my spirit a half sentiment that seemed, but was not, remorse. I went so far as to regret the loss of the animal, and to look about me, among the vile haunts which I now habitually frequented, for another pet of the same species and of somewhat similar appearance, with which to supply its place.

One night as I sat, half stupefied, in a den of more than infamy, my attention was suddenly drawn to some black object, reposing upon the head of one of the immense hogsheads of gin, or of rum, which constituted the chief furniture of the apartment. I had been looking steadily at the top of this hogshead for some minutes, and what now caused me surprise was the fact that I had not sooner perceived the object thereupon. I approached it and touched it with my hand. It was a black cat—a very large one—fully as large as Pluto, and closely resembling him in every respect, but only Pluto had not a white hair upon any portion of his body; but this cat had a large, although indefinite, splotch of white, covering nearly the whole region of the breast.

Upon my touching him he immediately arose, purred loudly, rubbed against my hand, and appeared delighted with my notice. This,{17} then, was the very creature of which I was in search. I at once offered to purchase it of the landlord; but this person made no claim to it—knew nothing of it—had never seen it before.

I continued my caresses, and when I prepared to go home the animal evinced a disposition to accompany me. I permitted it to do so, occasionally stooping and patting it as I proceeded. When it reached the house it domesticated itself at once, and became immediately a great favorite with my wife.

For my own part, I soon found a dislike to it arising within me. This was just the reverse of what I had anticipated; but—I know not how or why it was—its evident fondness for myself rather disgusted and annoyed me. By slow degrees these feelings of disgust and annoyance rose into the bitterness of hatred. I avoided the creature; a certain sense of shame, and the remembrance of my former deed of cruelty, preventing me from physically abusing it. I did not, for some weeks, strike, or otherwise violently ill use it; but gradually—very gradually—I came to look upon it with unutterable loathing, and to flee silently from its odious presence, as from the breath of a pestilence.

What added, no doubt, to my hatred of the beast, was the discovery, on the morning after I brought it home, that, like Pluto, it also had been deprived of one of its eyes. This circumstance,{18} however, only endeared it to my wife, who, as I have already said, possessed, in a high degree, that humanity of feeling which had once been my distinguishing trait, and the source of many of my simplest and purest pleasures.

With my aversion to this cat, however, its partiality for myself seemed to increase. It followed my footsteps with a pertinacity which it would be difficult to make the reader comprehend. Whenever I sat it would crouch beneath my chair or spring upon my knees, covering me with its loathsome caresses. If I arose to walk it would get between my feet, and thus nearly throw me down, or, fastening its long and sharp claws in my dress, clamber, in this manner, to my breast. At such times, although I longed to destroy it with a blow, I was yet withheld from so doing, partly by a memory of my former crime, but chiefly—let me confess it at once—by absolute dread of the beast.

This dread was not exactly a dread of physical evil—and yet I should be at a loss how otherwise to define it. I am almost ashamed to own—yes, even in this felon’s cell, I am almost ashamed to own—that the terror and horror with which the animal inspired me had been heightened by one of the merest chimeras it would be possible to conceive. My wife had called my attention more than once, to the character of the mark of white hair, of which I have spoken, and which{19}

constituted the sole visible difference between the strange beast and the one I had destroyed. The reader will remember that this mark, although large, had been originally very indefinite; but, by slow degrees—degrees nearly imperceptible, and which for a long time my reason struggled to reject as fanciful—it had, at length, assumed a rigorous distinctness of outline. It was now the representation of an object that I shudder to name—and for this, above all, I loathed and dreaded, and would have rid myself of the monster had I dared—it was now I say the image of a hideous, of a ghastly thing—of the gallows! Oh, mournful and terrible engine of horror and of crime—of agony and of death!

And now was I indeed wretched beyond the wretchedness of mere humanity. And a brute beast, whose fellow I had contemptuously destroyed—a brute beast to work out for me—for me, a man, fashioned in the image of the High God—so much of insufferable woe. Alas! neither by day nor night knew I the blessing of rest any more. During the former the creature left me no moment alone, and in the latter I started hourly from dreams of unutterable fear, to find the hot breath of the thing upon my face, and its vast weight—an incarnate nightmare that I had no power to shake off—incumbent eternally upon my heart.

Beneath the pressure of torments such as these{21} the feeble remnants of the good within me succumbed. Evil thoughts became my sole intimates—the darkest and most evil of thoughts. The moodiness of my usual temper increased to hatred of all things and of all mankind; while, from the sudden, frequent and ungovernable outbursts of a fury to which I now blindly abandoned myself, my uncomplaining wife, alas! was the most usual and the most patient of sufferers.

One day she accompanied me upon some household errand into the cellar of the old building, which our poverty compelled us to inhabit. The cat followed me down the steep stairs, and, nearly throwing me headlong, exasperated me to madness. Uplifting an axe, and forgetting, in my wrath, the childish dread which had hitherto stayed my hand, I aimed a blow at the animal which, of course, would have proved instantly fatal had it descended as I wished. But this blow was arrested by the hand of my wife. Goaded, by the interference, into a rage more than demoniacal, I withdrew my arm from her grasp, and buried the ax in her brain. She fell dead upon the spot, without a groan.

This hideous murder accomplished, I set myself forthwith, and with entire deliberation, to the task of concealing the body. I knew that I could not remove it from the house, either by day or by night, without the risk of being observed by the neighbors. Many projects entered my mind. At{22} one period I thought of cutting the corpse into minute fragments and destroying them by fire. At another I resolved to dig a grave for it in the floor of the cellar. Again, I deliberated about casting it into the well in the yard—about packing it in a box, as if merchandise, with the usual arrangements, and so getting a porter to take it from the house. Finally I hit upon what I considered a far better expedient than either of these. I determined to wall it up in the cellar—as the monks of the middle ages are recorded to have walled up their victims.

For a purpose such as this the cellar was well adapted. Its walls were loosely constructed, and had lately been plastered throughout with a rough plaster, which the dampness of the atmosphere had prevented from hardening. Moreover, in one of the walls was a projection, caused by a false chimney, or fireplace, that had been filled up, and made to resemble the rest of the cellar. I made no doubt that I could readily displace the bricks at this point, insert the corpse, and wall the whole up as before, so that no eye could detect anything suspicious.

And in this calculation I was not deceived. By means of a crowbar I easily dislodged the bricks, and, having carefully deposited the body against the inner wall, I propped it in that position, while, with little trouble, I relaid the whole structure as it originally stood. Having{23}

procured mortar, sand and hair with every possible precaution, I prepared a plaster which could not be distinguished from the old, and with this I very carefully went over the new brickwork. When I had finished I felt satisfied that all was right. The wall did not present the slightest appearance of having been disturbed. The rubbish on the floor was picked up with the minutest care. I looked around triumphantly and said to myself, “Here, at least, then, my labor has not been in vain.”

My next step was to look for the beast which had been the cause of so much wretchedness, for I had at length firmly resolved to put it to death. Had I been able to meet with it at the moment there could have been no doubt of its fate; but it appeared that the crafty animal had been alarmed at the violence of my previous anger and forebore to present itself in my present mood. It is impossible to describe or to imagine the deep, the blissful sense of relief which the absence of the detested creature occasioned in my bosom. It did not make its appearance during the night—and thus, for one night at least since its introduction into the house, I soundly and tranquilly slept—aye, slept, even with the burden of murder upon my soul!

The second and the third day passed, and still my tormentor came not. Once again I breathed as a free man. The monster, in terror, had fled{25} the premises forever! I should behold it no more! My happiness was supreme! The guilt of my dark deed disturbed me but little. Some few inquiries had been made, but these had been readily answered. Even a search had been instituted—but, of course, nothing was to be discovered. I looked upon my future felicity as secured.

Upon the fourth day of the assassination a party of the police came very unexpectedly into the house and proceeded again to make a rigorous investigation of the premises. Secure, however, in the inscrutability of my place of concealment, I felt no embarrassment whatever. The officers bade me accompany them in their search. They left no nook or corner unexplored. At length, for the third or fourth time, they descended into the cellar. I quivered not in a muscle. My heart beat as calmly as that of one who slumbers in innocence. I walked the cellar from end to end. I folded my arms upon my bosom and roamed easily to and fro. The police were thoroughly satisfied and prepared to depart. The glee at my heart was too strong to be restrained. I burned to say but one word, by way of triumph, and to render doubly sure their assurance of my guiltlessness.

“Gentlemen,” I said at last, as the party ascended the steps, “I delight to have allayed your suspicions. I wish you all health and a little{26} more courtesy. By the by, gentlemen, this—this is a very well constructed house.” (In the rabid desire to say something easily I scarcely knew what I uttered at all.) “I may say an excellently well constructed house. These walls—are you going, gentlemen?—these walls are solidly put together;” and here, through the mere frenzy of bravado, I rapped heavily, with a cane which I held in my hand, upon that very portion of the brickwork behind which stood the corpse of the wife of my bosom.

But may God shield and deliver me from the fangs of the Arch Fiend! No sooner had the reverberation of my blows sunk into silence than I was answered by a voice from within the tomb!—by a cry, at first muffled and broken, like the sobbing of a child, and then quickly swelling into one long, loud and continuous scream, utterly anomalous and inhuman—a howl!—a wailing shriek, half of horror and half of triumph, such as might have arisen only out of hell, conjointly from the throats of the damned in their agony and of the demons that exult in the damnation.

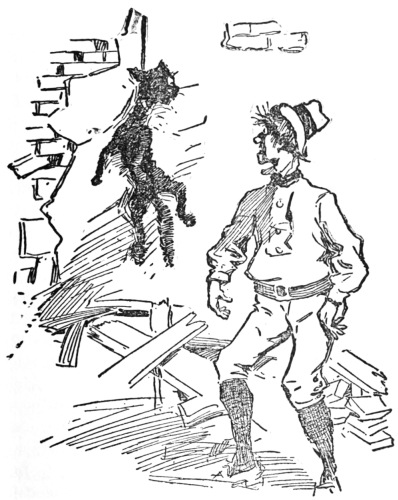

Of my own thoughts it is folly to speak. Swooning, I staggered to the opposite wall. For an instant the party upon the stairs remained motionless, through extremity of terror and of awe. In the next a dozen stout arms were toiling at the wall. It fell bodily. The corpse, already getting decayed and clotted with gore, stood{27} erect before the eyes of the spectators. Upon its head, with red, extended mouth and solitary eye of fire, sat the hideous beast whose craft had seduced me into murder, and whose informing voice had consigned me to the hangman. I had walled the monster up within the tomb!{28}

One evening about eight months ago I met with some college comrades at the lodgings of our friend Louis R. We drank punch and smoked, talked of literature and art, and made jokes like any other company of young men. Suddenly the door flew open, and one who had been my friend since boyhood burst in like a hurricane.

“Guess where I come from?” he cried.

“I bet on the Mabille,” responded one. “No,” said another, “you are too gay; you come from borrowing money, from burying a rich uncle, or from pawning your watch.” “You are getting sober,” cried a third, “and, as you scented the punch in Louis’ room, you came up here to get drunk again.”

“You are all wrong,” he replied. “I come from P., in Normandy, where I have spent eight days, and whence I have brought one of my friends, a great criminal, whom I ask permission to present to you.”

With these words he drew from his pocket a{29} long, black hand, from which the skin had been stripped. It had been severed at the wrist. Its dry and shriveled shape, and the narrow, yellowed nails still clinging to the fingers, made it frightful to look upon. The muscles, which showed that its first owner had been possessed of great strength, were bound in place by a strip of parchment-like skin.

“Just fancy,” said my friend, “the other day they sold the effects of an old sorcerer, recently deceased, well known in all the country. Every Saturday night he used to go to witch gatherings on a broomstick; he practised the white magic and the black, gave blue milk to the cows, and made them wear tails like that of the companion of Saint Anthony. The old scoundrel always had a deep affection for this hand, which, he said, was that of a celebrated criminal, executed in 1736 for having thrown his lawful wife head first into a well—for which I do not blame him—and then hanging in the belfry the priest who had married him. After this double exploit he went away, and, during his subsequent career, which was brief but exciting, he robbed twelve travelers, smoked a score of monks in their monastery, and made a seraglio of a convent.”

“But what are you going to do with this horror?” we cried.

“Eh! parbleu! I will make it the handle to my door-bell and frighten my creditors.”{30}

“My friend,” said Henry Smith, a big, phlegmatic Englishman, “I believe that this hand is only a kind of Indian meat, preserved by a new process; I advise you to make bouillon of it.”

“Rail not, messieurs,” said, with the utmost sang froid, a medical student who was three-quarters drunk, “but if you follow my advice, Pierre, you will give this piece of human debris Christian burial, for fear lest its owner should come to demand it. Then, too, this hand has acquired some bad habits, for you know the proverb, ‘Who has killed will kill.’”

“And who has drank will drink,” replied the host as he poured out a big glass of punch for the student, who emptied it at a draught and slid dead drunk under the table. His sudden dropping out of the company was greeted with a burst of laughter, and Pierre, raising his glass and saluting the hand, cried:

“I drink to the next visit of thy master.”

Then the conversation turned upon other subjects, and shortly afterward each returned to his lodgings.

* * * * *

About two o’clock the next day, as I was passing Pierre’s door, I entered and found him reading and smoking.

“Well, how goes it?” said I. “Very well,” he responded. “And your hand?” “My hand? Did you not see it on the bell-pull? I put it there{31} when I returned home last night. But, apropos of this, what do you think? Some idiot, doubtless to play a stupid joke on me, came ringing at my door towards midnight. I demanded who was there, but as no one replied, I went back to bed again, and to sleep.”

At this moment the door opened and the landlord, a fat and extremely impertinent person, entered without saluting us.

“Sir,” said he, “I pray you to take away immediately that carrion which you have hung to your bell-pull. Unless you do this I shall be compelled to ask you to leave.”

“Sir,” responded Pierre, with much gravity, “you insult a hand which does not merit it. Know you that it belonged to a man of high breeding?”

The landlord turned on his heel and made his exit, without speaking. Pierre followed him, detached the hand and affixed it to the bell-cord hanging in his alcove.

“That is better,” he said. “This hand, like the ‘Brother, all must die,’ of the Trappists, will give my thoughts a serious turn every night before I sleep.”

At the end of an hour I left him and returned to my own apartment.

I slept badly the following night, was nervous and agitated, and several times awoke with a start. Once I imagined, even, that a man had{32} broken into my room, and I sprang up and searched the closets and under the bed. Towards six o’clock in the morning I was commencing to doze at last, when a loud knocking at my door made me jump from my couch. It was my friend Pierre’s servant, half dressed, pale and trembling.

“Ah, sir!” cried he, sobbing, “my poor master. Someone has murdered him.”

I dressed myself hastily and ran to Pierre’s lodgings. The house was full of people disputing together, and everything was in a commotion. Everyone was talking at the same time, recounting and commenting on the occurrence in all sorts of ways. With great difficulty I reached the bedroom, made myself known to those guarding the door and was permitted to enter. Four agents of police were standing in the middle of the apartment, pencils in hand, examining every detail, conferring in low voices and writing from time to time in their note-books. Two doctors were in consultation by the bed on which lay the unconscious form of Pierre. He was not dead, but his face was fixed in an expression of the most awful terror. His eyes were open their widest, and the dilated pupils seemed to regard fixedly, with unspeakable horror, something unknown and frightful. His hands were clinched. I raised the quilt, which covered his body from the chin downward, and saw on his neck, deeply{33} sunk in the flesh, the marks of fingers. Some drops of blood spotted his shirt. At that moment one thing struck me. I chanced to notice that the shriveled hand was no longer attached to the bell-cord. The doctors had doubtless removed it to avoid the comments of those entering the chamber where the wounded man lay, because the appearance of this hand was indeed frightful. I did not inquire what had become of it.

I now clip from a newspaper of the next day the story of the crime with all the details that the police were able to procure:

“A frightful attempt was made yesterday on the life of young M. Pierre B., student, who belongs to one of the best families in Normandy. He returned home about ten o’clock in the evening, and excused his valet, Bouvin, from further attendance upon him, saying that he felt fatigued and was going to bed. Towards midnight Bouvin was suddenly awakened by the furious ringing of his master’s bell. He was afraid, and lighted a lamp and waited. The bell was silent about a minute, then rang again with such vehemence that the domestic, mad with fright, flew from his room to awaken the concierge, who ran to summon the police, and, at the end of about fifteen minutes, two policemen forced open the door. A horrible sight met their eyes. The furniture was overturned, giving evidence of a fearful{34} struggle between the victim and his assailant. In the middle of the room, upon his back, his body rigid, with livid face and frightfully dilated eyes, lay, motionless, young Pierre B., bearing upon his neck the deep imprints of five fingers. Dr. Bourdean was called immediately, and his report says that the aggressor must have been possessed of prodigious strength and have had an extraordinarily thin and sinewy hand, because the fingers left in the flesh of the victim five holes like those from a pistol ball, and had penetrated until they almost met. There is no clue to the motive of the crime or to its perpetrator. The police are making a thorough investigation.”

The following appeared in the same newspaper next day:

“M. Pierre B., the victim of the frightful assault of which we published an account yesterday, has regained consciousness after two hours of the most assiduous care by Dr. Bourdean. His life is not in danger, but it is strongly feared that he has lost his reason. No trace has been found of his assailant.”

My poor friend was indeed insane. For seven months I visited him daily at the hospital where we had placed him, but he did not recover the light of reason. In his delirium strange words escaped him, and, like all madmen, he had one fixed idea: he believed himself continually pursued by a specter. One day they came for me in{35} haste, saying he was worse, and when I arrived I found him dying. For two hours he remained very calm, then, suddenly, rising from his bed in spite of our efforts, he cried, waving his arms as if a prey to the most awful terror: “Take it away! Take it away! It strangles me! Help! Help!” Twice he made the circuit of the room, uttering horrible screams, then fell face downward, dead.

* * * * *

As he was an orphan I was charged to take his body to the little village of P., in Normandy, where his parents were buried. It was the place from which he had arrived the evening he found us drinking punch in Louis R.’s room, when he had presented to us the flayed hand. His body was inclosed in a leaden coffin, and four days afterwards I walked sadly beside the old cure, who had given him his first lessons, to the little cemetery where they dug his grave. It was a beautiful day, and sunshine from a cloudless sky flooded the earth. Birds sang from the blackberry bushes where many a time when we were children we had stolen to eat the fruit. Again I saw Pierre and myself creeping along behind the hedge and slipping through the gap that we knew so well, down at the end of the little plot where they bury the poor. Again we would return to the house with cheeks and lips black with the juice of the berries we had eaten. I looked at{36} the bushes; they were covered with fruit; mechanically I picked some and bore it to my mouth. The cure had opened his breviary, and was muttering his prayers in a low voice. I heard at the end of the walk the spades of the grave-diggers who were opening the tomb. Suddenly they called out, the cure closed his book, and we went to see what they wished of us. They had found a coffin; in digging a stroke of the pickaxe had started the cover, and we perceived within a skeleton of unusual stature, lying on its back, its hollow eyes seeming yet to menace and defy us. I was troubled, I know not why, and almost afraid.

“Hold!” cried one of the men, “look there! One of the rascal’s hands has been severed at the wrist. Ah, here it is!” and he picked up from beside the body a huge withered hand, and held it out to us.

“See,” cried the other, laughing, “see how he glares at you, as if he would spring at your throat to make you give him back his hand.”

“Go,” said the cure, “leave the dead in peace, and close the coffin. We will make poor Pierre’s grave elsewhere.”

The next day all was finished, and I returned to Paris, after having left fifty francs with the old cure for masses to be said for the repose of the soul of him whose sepulchre we had troubled.{37}

Through the windows of Jim Daly’s saloon, in the little town of C——, the setting sun streamed in yellow patches, lighting up the glasses scattered on the tables and the faces of several men who were gathered near the bar. Farmers mostly they were, with a sprinkling of shopkeepers, while prominent among them was the village editor, and all were discussing a startling piece of news that had spread through the town and its surroundings. The tidings that Walter Stedman, a laborer on Albert Kelsey’s ranch, had assaulted and murdered his employer’s daughter, had reached them, and had spread universal horror among the people.

A farmer declared that he had seen the deed committed as he walked through a neighboring lane, and, having always been noted for his cowardice, instead of running to the girl’s aid, had hailed a party of miners who were returning from their mid-day meal through a field near by.{38} When they reached the spot, however, where Stedman (as they supposed) had done his black deed, only the girl lay there, in the stillness of death. Her murderer had taken the opportunity to fly. The party had searched the woods of the Kelsey estate, and just as they were nearing the house itself the appearance of Walter Stedman, walking in a strangely unsteady manner toward it, made them quicken their pace.

He was soon in custody, although he had protested his innocence of the crime. He said that he had just seen the body himself on his way to the station, and that when they had found him he was going to the house for help. But they had laughed at his story and had flung him into the tiny, stifling calaboose of the town.

What were their proofs? Walter Stedman, a young fellow of about twenty-six, had come from the city to their quiet town, just when times were at their hardest, in search of work. The most of the men living in the town were honest fellows, doing their work faithfully, when they could get it, and when they had socially asked Stedman to have a drink with them, he had refused in rather a scornful manner. “That infernal city chap,” he was called, and their hate and envy increased in strength when Albert Kelsey had employed him in preference to any of themselves. As time went on, the story of Stedman’s admiration for Margaret Kelsey had gone afloat, with the added{39} information that his employer’s daughter had repulsed him, saying that she would not marry a common laborer. So Stedman, when this news reached his employer’s ears, was discharged, and this, then, was his revenge! For them, these proofs were sufficient to pronounce him guilty.

Yet that afternoon, as Stedman, crouched on the floor of the calaboose, grew hopeless in the knowledge that no one would believe his story, and that his undeserved punishment would be swift and sure, a tramp, boarding a freight car several miles from the town, sped away from the spot where his crime had been committed, and knew that forever its shadow would follow him.

From the tiny window of his prison Walter Stedman could see the red glow of the heavens that betokened the setting of the sun. So the red sun of his life was soon to set, a life that had been innocent of all crime, and that now was to be ended for a deed that he had never committed. Most prominent of all the visions that swept through his mind was that of Margaret Kelsey, lying as he had first found her, fresh from the hands of her murderer. But there was another of a more tender nature. How long he and Margaret had tried to keep their secret, until Walter could be promoted to a higher position, so that he could ask for her hand with no fear of the father’s antagonism! Then came the remembrance of an afternoon meeting between the two{40} in the woods of the Kelsey estate—how, just as they were parting, Walter had heard footsteps near them, and, glancing sharply around, saw an evil, scowling, murderous face peering through the brush. He had started toward it, but the owner of the countenance had taken himself hurriedly off.

The gossiping townspeople had misconstrued this romance, and when Albert Kelsey had heard of this clandestine meeting from the man who was later on to appear as a leader of the mob, and that he had discharged Stedman, they had believed that the young man had formally proposed and had been rejected. But justice had gone wrong, as it had done innumerable times before, and will again. An innocent man was to be hanged, even without the comfort of a trial, while the man who was guilty was free to wander where he would.

That autumn night the darkness came quickly, and only the stars did their best to light the scene. A body of men, all masked, and having as a leader one who had ever since Stedman’s arrival in town, cherished a secret hatred of the young man, dragged Stedman from the calaboose and tramped through the town, defying all, defying even God himself. Along the highway, and into Farmer Brown’s “cross cut,” they went, vigilantly guarding their prisoner, who, with the lanterns lighting up his haggard face, walked{41} among them with the lagging step of utter hopelessness.

“That’s a good tree,” their leader said, presently, stopping and pointing out a spreading oak; when the slipknot was adjusted and Stedman had stepped on the box, he added: “If you’ve got anything to say, you’d better say it now.”

“I am innocent, I swear before God,” the doomed man answered; “I never took the life of Margaret Kelsey.”

“Give us your proof,” jeered the leader, and when Stedman kept a despairing silence, he laughed shortly.

“Ready, men!” he gave the order. The box was kicked aside, and then—only a writhing body swung to and fro in the gloom.

In front of the men stood their leader, watching the contortions of the body with silent glee. “I’ll tell you a secret, boys,” he said suddenly. “I was after that poor murdered girl myself. A d—— little chance I had; but, by ——, he had just as little!”

A pause—then: “He’s shunted this earth. Cut him down, you fellows!”

* * * * *

“It’s no use, son. I’ll give up the blasted thing as a bad job. There’s something queer about that there tree. Do you see how its branches balance it? We have cut the trunk nearly in two, but it won’t come down. There’s{42} plenty of others around; we’ll take one of them. If I’d a long rope with me I’d get that tree down, and yet the way the thing stands it would be risking a fellow’s life to climb it. It’s got the devil in it, sure.”

So old Farmer Brown shouldered his axe and made for another tree, his son following. They had sawed and chopped and chopped and sawed, and yet the tall white oak, with its branches jutting out almost as regularly as if done by the work of a machine, stood straight and firm.

Farmer Brown, well known for his weak, cowardly spirit, who in beholding the murder of Albert Kelsey’s daughter, had in his fright mistaken the criminal, now in his superstition let the oak stand, because its well-balanced position saved it from falling, when other trees would have been down. And so this tree, the same one to which an innocent man had been hanged, was left—for other work.

It was a bleak, rainy night—such a night as can be found only in central California. The wind howled like a thousand demons, and lashed the trees together in wild embraces. Now and then the weird “hoot, hoot!” of an owl came softly from the distance in the lulls of the storm, while the barking of coyotes woke the echoes of the hills into sounds like fiendish laughter.

In the wind and rain a man fought his path through the bush and into Farmer Brown’s{43} “cross cut,” as the shortest way home. Suddenly he stopped, trembling, as if held by some unseen impulse. Before him rose the white oak, wavering and swaying in the storm.

“Good God! it’s the tree I swung Stedman from!” he cried, and a strange fear thrilled him.

His eyes were fixed on it, held by some undefinable fascination. Yes, there on one of the longest branches a small piece of rope still dangled. And then, to the murderer’s excited vision, this rope seemed to lengthen, to form at the end into a slipknot, a knot that encircled a purple neck, while below it writhed and swayed the body of a man!

“Damn him!” he muttered, starting toward the hanging form, as if about to help the rope in its work of strangulation; “will he forever follow me? And yet he deserved it, the black-hearted villain! He took her life——”

He never finished the sentence. The white oak, towering above him in its strength, seemed to grow like a frenzied, living creature. There was a sudden splitting sound, then came a crash, and under the fallen tree lay Stedman’s murderer, crushed and mangled.

From between the broken trunk and the stump that was left, a gray, dim shape sprang out, and sped past the man’s still form, away into the wild blackness of the night.{44}

All draped with blue denim—the seaside cottage of my friend, Sara Pyne. She asked me to go there with her when she opened it to have it set in order for the summer. She confessed that she felt a trifle nervous at the idea of entering it alone. And I am always ready for an excursion. So much blue denim rather surprised me, because blue is not complimentary to Sara’s complexion—she always wears some shade of red, by preference. She perceived my wonder; she is very near-sighted, and therefore sees everything by some sort of sixth sense.

“You do not like my portieres and curtains and table-covers,” said she. “Neither do I. But I did it to accommodate. And now he rests well in his grave, I hope.”

“Whose grave, for pity’s sake?”

“Mr. J. Billington Price’s.”

“And who is he? He doesn’t sound interesting.”

“Then I will tell you about him,” said Sara, taking a seat directly in front of one of those curtains. “Last autumn I was leaving this place for New York, traveling on the fast express train{45} known as the Flying Yankee. Of course, I thought of the Flying Dutchman and Wagner’s musical setting of the uncanny legend, and how different things are in these days of steam, etc. Then I looked out of the window at the landscape, the horizon that seemed to wheel in a great curve as the train sped on. Every now and then I had an impression at the ‘tail of the eye’ that a man was sitting in a chair three or four numbers in front of me on the opposite side of the car. Each time that I saw this shape I looked at the chair and ascertained that it was unoccupied. But it was an odd trick of vision. I raised my lorgnette, and the chair showed emptier than before. There was nobody in it, certainly. But the more I knew that it was vacant the more plainly I saw the man. Always with the corner of my eye. It made me nervous. When passengers entered the car I dreaded lest they might take that seat. What would happen if they should? A bag was put in the chair—that made me uncomfortable. The bag was removed at the next station. Then a baby was placed in the seat. It began to laugh as though someone had gently tickled it. There was something odd about that chair—thirteen was its number. When I looked away from it the impression was strong upon me that some person sitting there was watching me.

“Really, it would not do to humor such fancies. So I touched the electric button, asked the porter{46} to bring me a table, and taking from my bag a pack of cards, proceeded to divert myself with a game of patience. I was puzzling where to put a seven of spades. ‘Where can it go?’ I murmured to myself. A voice behind me prompted: ‘Play the four of diamonds on the five, and you can do it.’ I started. The only occupants of the car, besides me, were a bridal couple, a mother with three little children, and a typical preacher of one of the straitest sects. Who had spoken? ‘Play up the four, madam,’ repeated this voice.

“I looked fearfully over my shoulder. At first I saw a bluish cloud, like cigar smoke, but inodorous. Then the vision cleared, and I saw a young man whom I knew by a subtle intuition to be the occupant, seen and not seen, of chair number thirteen. Evidently he was a traveling salesman—and a ghost. Of course, a drummer’s ghost sounds ridiculous—they’re so extremely alive! Or else you would expect a dead drummer to be particularly dead and not ‘walk.’ This was a most commonplace-looking ghost, cordial, pushing, businesslike. At the same time, his face had an expression of utter despair and horror which made him still more preposterous. Of course it is not nice to let a stranger speak to one, even on so impersonal a topic as a four of diamonds. But a ghost—there can’t be any rule of etiquette about talking with a ghost! My dear, it was dreadful! That forward creature showed{47} me how to play all the cards, and then begged me to lay them out again, in order that he might give me some clever points. I was too much amazed and disturbed to speak. I could only place the cards at his suggestion. This I did so as not to appear to be listening to the empty air, and be supposed to be a crazy woman. Presently the ghost spoke again, and told me his story.

“‘Madam,’ he said, ‘I have been riding back and forth on this car ever since February 22, 189—. Seven months and eleven days. All this time I have not exchanged a word with anyone. For a drummer, that is pretty hard, you may believe! You know the story of the Flying Dutchman? Well, that is very nearly my case. A curse is upon me and will not be removed until some kind soul——. But I’m getting ahead of my text. That day there were four of us, traveling for different houses. One of the boys was in wool, one in baking powder, one in boots and shoes, and myself in cotton goods. We met on the road, took seats together and fell into talking shop.

“‘Those fellows told big lies about their sales, Washington’s Birthday though it was. The baking powder man raised the amount of the bills of goods which he had sold better than a whole can of his stuff could have done. I admitted the straight truth, that I had not yet been able to make a sale. And then I swore—not in a light-minded,{48} chipper style of verbal trimmings, but a great, round, heaven-defying oath—that I would sell a case of blue denims on that trip if it took me forever. We became dry with talk, and when the train stopped at Rivermouth, we went out to have some beer. It is good there, you know—pardon me, I forgot that I was speaking to a lady. Well, we had to run to get aboard. I missed my footing, fell under the wheels, and the next thing that I knew they were holding an inquest over my remains; while I, disemboweled, was sitting on a corner of the undertaker’s table, wondering which of the coroner’s jury was likely to want a case of blue denims.

“‘Then I remembered my wicked oath, and understood that I was a soul doomed to wander until I could succeed in selling that bill of goods. I spoke once or twice, offering the denims under value, but nobody noticed me. Verdict: accidental death; negligence of deceased; railroad corporation not to blame; deceased got out for beer at his own risk. The other drummers took charge of the remains, and wrote a beautiful letter to my relatives about my social qualities and my impressive conversation. I wish it had been less impressive that time! I might have lied about my sales, or I might have said that I hoped for better luck. But after that oath there was nothing for it. Back and forth, back and forth, on this road, in chair number{49} thirteen, to all eternity. Nobody suspects my presence. They sit on my knees—I’m playing in luck when it is a nice baby as it was this afternoon! They pile wraps, bags, even railway literature on me. They play cards under my nose—and what duffers some of them are! You, madam, are the first person who has perceived me; and therefore I ventured to speak to you, meaning no offense. I can see that you are sorry for me. Now, if you recall the story of the Flying Dutchman, he was saved by the charity of a good woman. In fact, Senta married him. Now I’m not asking anything of that size. I see that you wear a wedding ring, and no doubt you make some man’s happiness. I wasn’t a marrying man myself, and, naturally, am not a marrying ghost. And that has nothing to do with the matter anyway. But if you could—I don’t suppose you would have any use for them—but if you were disposed to do a turn of good, solid, Christian charity—I should be everlastingly grateful, and you may have that case of denims at $72.50. And that quality is quoted to-day at $80. Does it go, madam?’

“The speech of the poor ghost was not very eloquent, but his eyes had an intense, eager glare, which was terrible. Something—pity, fear, I do not know what—compelled me. I decided to do without that white and gold evening cloak. Instead, I gave $72.50 to the ghost and took from{50} him a receipt for the sum, signed J. Billington Price. Then he smiled contentedly, thanked me with emotion, and returned to chair number thirteen. Several times on the journey, although I did not perceive him again, I felt dazed. When the train arrived at New York, and I, with the other passengers, dismounted, it seemed to me that a strong hand passed under my elbow, steadying me down the steps. As I walked the length of the station my bag—not heavy at any time—appeared to become weightless. I believe that the parlor-car ghost walked beside me, carrying the bag, whose handle still remained in my other hand. Indeed, once or twice I thought I felt the touch of cold fingers against mine. Since then I have no reason to suppose that the poor ghost is not at rest. I hope he is.

“But I never expected nor wished for the blue denims. The next day, however, a dray belonging to a great wholesale house backed up to our door and delivered a case of denims, with a receipted bill for the same. What was I to do? I could not go about selling blue denims; I could not give them away without exciting comment. So I furnished the cottage with them—and you know the effect on my complexion. Pity me, dear! And credit me, frivolous woman as I am, with having saved a soul at the expense of my own vanity. My story is told. What do you think about it?”{51}

Several travel-worn drummers sat in the lobby exchanging yarns. It was Rodney Green’s turn, and he looked wise and began his tale.

“I don’t claim, by any means, that the belief in ghosts is a general thing in Arkansas, but I do say that I had an experience out there a few years ago.

“It was late in the fall, and I happened to be in the village of Buckstown, which desecrates a very limited portion of the State. The town is about as small and dirty a place as ever I saw, and the Buckstown Inn is not much above the general character of the place. The region is inhabited by natives who still cling to all sorts of foolish superstitions. The inn, in the ante-bellum days, was kept by one who was said to be the meanest and most crabbed of mortals. The old demon was as miserly as he was mean, and all his narrow life he hoarded his filthy lucre with fiendish greed. Report had it also that he had even murdered his patrons in their beds for their{52} money. What the facts actually were I don’t know, but even to this day the old inn is held in suspicion. A lingering effect of former horrors still clouds its memory.

“The present proprietor, Bunk Watson—his real name is Bunker, I believe—is an altogether different sort of chap—a Southern type, in fact—one of those shiftless, heedless, happy-go-lucky mortals who loves strong whiskey and who chews an enormous quid of black tobacco and smokes a corncob pipe at the same time.

“When the former keeper ‘shuffled off,’ his property fell to a distant relative, the present keeper, who, with his family, immediately moved in from a neighboring hamlet and took possession. It was well known that the old proprietor had accumulated considerable wealth during his sojourn among the living, but all efforts to discover any treasure upon the premises had failed, and now the idea of ever finding it was practically given up. As far as Bunk was concerned, the matter troubled him little. He had a hard-working wife who ran things the best she could under the circumstances, and saw that his meals were forthcoming at their respective intervals. What more could he wish? Why should he care if there was a treasure buried upon his place? Indeed, it would have been a sore puzzle for him to know what to do with a fortune unless perhaps his wife came to his aid.{53}

“Among the stories that hovered in the history of the Buckstown Inn was one which involved a ghost. In the room where the former keeper had died peculiar noises were heard at unearthly hours: sighing, moaning, and, in fact, all the other indications which point to the existence of ghosts, were said to be present. On account of this the chamber had long since been abandoned.

“I listened with keen interest to the wonderful tales about the haunted room, and then suddenly resolved to investigate—to sleep in that chamber that very night and see for myself all that was to be seen. I told Buck of my purpose. He shook his head, shrugged his shoulders, but instead of warning me and offering a flood of protests, as I expected, he merely took his pipe from his mouth, let fly a quart or so of yellowish juice from between a pair of brown-stained lips, and, opening one corner of his wide mouth, lazily called out: ‘Jane.’ His wife appeared, and he intimated that I should settle the matter with the ‘old woman.’ The prospect of a fee persuaded the wife, and off she went to arrange for my bed in that ill-fated room.

“At nine o’clock that evening I bid the family good-night, took my candle, ascended the rickety stairs and entered the chamber of horrors. The atmosphere was heavy and had a peculiar odor that was not at all pleasing. However, I latched the door and was soon in bed. Having propped{54} myself up with pillows, I was prepared to await the coming of the ghost.

“Overhead the dusty rafters, which once had experienced the sensation of being whitewashed, but which were now a dirty, yellowish color, were hung with a fantastic array of cobwebs. The flickering light of the candle reflected upon the walls and against the ceiling a pyramid of grotesque shapes, and with this effect being continually disturbed by the swaying cobwebs, the whole caused the room to appear rather ghostly after all, and especially so to an imaginative mind.

“I waited and waited for hours, it seemed, but still no ghost. Perhaps it was afraid of my candle light, so I blew it out. No sooner had I done this and settled back in bed again than a white hand appeared through the door, then a whole figure—at last the ghost had come, a white and sheeted ghost!

“It had come right through the door, although it was locked, and now it advanced toward the bed. Raising its long, white arm, it pointed a bony finger at me, and then commanded: ‘Come with me!’ Thereupon it turned to the door, while instantly I jumped out of bed to follow. Some unseen power compelled me to obey. The door flew open and the ghost led me down the stairs, through long halls into the cellar, through mysterious underground corridors, upstairs{55} again, in and out rooms which I never dreamed were to be found in that old rambling inn. Finally, through a small door in the rear, we left the house. I was in my sleeping garments, but no matter, I had to follow.

“The white form, with a slow and measured tread and as silent as death, led the way into the orchard. There, under a tree at the farther end, it pointed to the ground, and in the same ghostly tones before used, said:

“‘Here you will find a great treasure buried.’

“The ghost then disappeared, and I saw it no more. I stood dazed and trembling. Upon recovering my wits I started to dig, but the chill of the night air and the scantiness of my night robes made such labor impracticable. So I decided to leave some mark to identify the place and come around again at daybreak. I reached up and broke off a limb. Overcome with my night’s exertions I slept the next morning until a loud rapping on my door and a croaking voice warned me that it was noon.

“I had intended to leave Buckstown Inn that day, but, prompted by curiosity and anxious to investigate, I unpacked my gripsack for a comfortable stay.

“You must understand that this was my first experience with a ghost, and I feared I might never see another.

“At breakfast my landlady waited on me in{56} silence, though once I detected her eyes following me with a peculiar expression. She wanted to ask me how I enjoyed the night, but I would not gratify her by volunteering a word.

“My host was more outspoken.

“‘Reckon ye didn’t get much sleep,’ said he, with a queer smile.

“‘Did you hear anything?’ I asked.

“‘Well, I did—ye-es,’ he said, with a drawl. ‘But ye didn’t disturb me any. I knew ye’d hev trouble when ye went in thet room ter sleep.’

“That afternoon I slipped out to the tree. But to my amazement I found that the twig I had broken from the branches was gone. Finally I found under the lower trunk of an apple tree an open place from which a small branch had evidently been wrested. But on looking further, I discovered that every apple tree in the orchard had been similarly disfigured.

“‘More mysterious than ever,’ I said; ‘but to-night shall decide.’

“That night I pleaded weariness, which no one seemed inclined to question, and sought my couch earlier.

“‘Goin’ ter try it again?’ asked my host.

“‘Yes; and I’ll stay all winter but what I’ll get even with that ghost,’ I said.

“That night I kept the candle burning until midnight, when I blew it out.

“Instantly the room was flooded with a soft{57} light, and at the foot of the bed stood my ghost, the identical ghost of last night.

“Again the bony finger beckoned and a sepulchral voice whispered, ‘Follow me!’ I sprang from the bed, but the figure darted ahead of me. It flew through the doorway and down the stairs, and I after it. At the foot of the staircase an unseen hand reached forward and caught my foot and I fell sprawling headlong.

“But in a second I was on my feet and pursuing the ghost. It had gained on me a few yards, but I was quicker, and just as we reached the outside door I nearly touched its robes. They sent a chill through my frame, and I nearly gave up the pursuit.

“As it passed through the doorway it turned and gave me one look, and I caught the same malignant light in its eyes that I remembered from the night before.

“In the open orchard I felt sure I could catch it.

“But my ghost had no intention of allowing me any such opportunity. To my disgust, it darted backward and into the house, slamming the door in my face.

“In my frenzy of fear and chagrin I threw myself against the oaken door with such force that its rusty old hinges yielded and I landed in the big front room of the inn just in time to see the white skirts of the ghost flit up the stairs.{58}

“Upstairs I flew after it, and into an old chamber. There, huddled in a corner, I saw it. In the minute’s delay it had secured a lighted candle and, as I entered, it advanced to daunt me with bony arm upraised to a great height.

“‘Caught!’ I cried, throwing my arms around the figure. And I had made the acquaintance of a real live ghost.

“The white robes fell, and I saw revealed my hostess of Buckstown Inn.

“Next morning, when I threatened to call the police, she confessed to me that she masqueraded as a ghost to draw visitors to the out-of-the-way old place, and that she found its tale of being haunted highly profitable to her.”{59}

I am not an imaginative man, and no one who knows me can say that I have ever indulged in sentimental ideas upon any subject. I am rather predisposed, in fact, to look at everything from a purely practical standpoint, and this quality has been further developed in me by the fact that for twenty years I have been an active member of the detective police force at Westford, a large town in one of our most important manufacturing districts. A policeman, as most people will readily believe, has to deal with so much practical life that he has small opportunity for developing other than practical qualities, and he is more apt to believe in tangible things than in ideas of a somewhat superstitious nature. However, I was once under the firm conviction that I had been largely helped up the ladder of life by the ghost of a once well-known burglar. I have told the story to many, and have heard it commented upon in various fashions. Whether the comments were satirical or practical, it made no difference to me; I had a firm faith at that time in the truth of my tale.{60}

Eighteen years ago I was a plain clothes officer at Westford. I was then twenty-three years of age, and very anxious about two matters. First and foremost I desired promotion; second, I wished to be married. Of course I was more eager about the second than the first, because my sweetheart, Alice Moore, was one of the prettiest and cleverest girls in the town; but I put promotion first for the simple reason that with me promotion must come before marriage. Knowing this, I was always on the lookout for a chance of distinguishing myself, and I paid such attention to my duties that my superiors began to notice me, and foretold a successful career for me in the future.

One evening in the last week of September, 1873, I was sitting in my lodgings wondering what I could do to earn the promotion which I so earnestly wished for. Things were quiet just then in Westford, and I am afraid I half wished that something dreadful might occur if I only could have a share in it. I was pursuing this train of thought when I suddenly heard a voice say, “Good evening, officer.”

I turned sharply around. It was almost dusk and my lamp was not lighted. For all that, I could see clearly enough a man who was sitting by a chest of drawers that stood between the door and the window. His chair stood between the drawers and the door, and I concluded that he{61} had quietly entered my room and seated himself before addressing me.

“Good evening!” I replied. “I didn’t hear you come in.”

He laughed when I said that—a low, chuckling, rather sly laugh. “No,” he said, “I dessay not, officer. I’m a very quiet sort of person. You might say, in fact, noiseless. Just so.”

I looked at him narrowly, feeling considerably surprised and astonished at his presence. He was a thickly built man, with a square face and heavy chin. His nose was small, but aggressive; his eyes were little and overshadowed by heavy eyebrows; I could see them twinkle when he spoke. As for his dress, it was in keeping with his face.

He wore a rough suit of woolen or frieze; a thick, gayly colored Belcher neckerchief encircled his bull-like throat, and in his big hands he continually twirled and twisted a fur cap, made apparently out of the skin of some favorite dog. As he sat there smiling at me and saying nothing, it made me feel uncomfortable.

“What do you want with me?” I asked.

“Just a little matter o’ business,” he answered.

“You should have gone to the office,” I said. “We’re not supposed to do business at home.”

“Right you are, guv’nor,” he replied; “but I wanted to see you. It’s you that’s got to do my job. If I’d ha’ seen the superintendent he might{62} ha’ put somebody else on to it. That wouldn’t ha’ suited me. You see, officer, you’re young, and nat’rally eager-like for promotion. Eh?”

“What is it you want?” I inquired again.

“Ain’t you eager to be promoted?” he reiterated. “Ain’t you now, officer?”

I saw no reason why I should conceal the fact, even from this strange visitor. I admitted that I was eager for promotion.

“Ah!” he said, with a satisfied smile; “I’m glad o’ that. It’ll make you all the keener. Now, officer, you listen to me. I’m a-goin’ to put you on to a nice little job. Ah! I dessay you’ll be a sergeant before long, you will. You’ll be complimented and praised for your clever conduck in this ’ere affair. Mark my words if you ain’t.”

“Out with it,” I said, fancying I saw through the man’s meaning. “You’re going to split on some of your pals, I suppose, and you’ll want a reward.”

He shook his head. “A reward,” he said, “wouldn’t be no use to me at all—no, not if it was a thousand pounds. No, it ain’t nothing to do with reward. But now, officer, did you ever hear of Light Toed Jim?”

Light Toed Jim! I should have been a poor detective if I had not. Why, the man known under that sobriquet was one of the cleverest burglars and thieves in England, and had enjoyed such a famous career that his name was a household{63} word. At that moment there was an additional interest attached to him. He had been convicted of burglary at the Northminster assizes in 1871, and sentenced to ten years’ penal servitude. After serving nearly two years of his time he had escaped from Portland, getting away in such clever fashion that he had never been heard of since. Where he was no one could say; but lately there had been a strong suspicion among the police that Light Toed Jim was at his old tricks again.

“Light Toed Jim!” I repeated. “I should think so. Why, what do you know about him?”

He smiled and nodded his head. “Light Toed Jim,” said he, “is in Westford at this ’ere hidentical moment. Listen to me, officer. Light Toed Jim is a-goin’ to crack a crib to-night. Said crib is the mansion of Miss Singleton, that ’ere rich old lady as lives out on the Mapleton Road. You know her—awfully rich, with naught but women servants and animals about the place. There’s some very valyable plate there. That’s what Light Toed Jim’s after. He’ll get in through the scullery window about 1 a. m., then he’ll pass through the back and front kitchens and into the butler’s pantry—only it’s a butleress, ’cos there ain’t no men at all—and there he’ll set to work on the safe. Some of his late pals in Portland give him the tip about this ’ere job.”

“How did you come to hear of it?” I asked.{64}

“Never mind, guv’nor. You wouldn’t understand. Now, I wants you to be up there to-night and to nab Light Toed Jim red-handed, so to speak. It’ll mean promotion for you, and it’ll suit me down to the ground. You wants to be about and to watch him enter. Then follow him and dog him. And be armed, officer, for Jim’ll fight like a tiger if you don’t draw his teeth first.”

“Now, look here, my man,” said I, “this is all very well, but it’s all irregular. You must just tell me who you are and how you come to be in Light Toed Jim’s secrets, and I’ll put it down in black and white.”

I turned away from him to get my writing materials. I was not half a minute with my back to him, but when I turned round he was gone. The door was shut, but I had heard no sound from it either opening or shutting. Quick as thought I darted to it, tore it wide open, and looked down the narrow staircase. There was no one there. I ran hastily downstairs into the passage, and found my landlady, Mrs. Marriner, standing at the open door with a female friend. “Mrs. Marriner,” I said, breaking in upon their conversation, “which way did that man go who came downstairs just now?”

Mrs. Marriner looked at me strangely. “There ain’t been no man come downstairs, Mr. Parker,” said she; “leastways, not this good three-quarters of an hour, which me and Missis Higgins ’ere, as{65} ’ave come out to take an airing, her having been ironin’ all this blessed day, has been standin’ ’ere all the time and ain’t never seen a soul.”

“Nonsense,” I said. “A man came down from my room just now—the man you sent up twenty minutes since.”

Mrs. Marriner looked at me with an expression betokening the most profound astonishment. Mrs. Higgins sighed deeply.

“Mr. Parker,” said Mrs. Marriner, “sorry am I to say it, sir, but you’re either intoxicated or else you’re a-sickening for brain fever, sir. There ain’t no person entered this door, in or out, for nigh onto an hour, as me and Missis Higgins ’ere will take our Bible oaths on.”

I went upstairs and looked in the rooms on either side of mine. The man was not there. I looked under my bed, and of course he was not there. He must have gone downstairs. But then the women must have seen him. There was only one door to the house. I gave it up in despair and began to smoke my pipe. By the time I had drawn the last whiff I decided that if anyone was “intoxicated,” it was probably Mrs. Marriner and Mrs. Higgins, and that my strange visitor had departed by the door. I was not going to believe that he had anything supernatural about him.

I had no duty that night, and as the hours wore on I found myself stern in my resolve to go{66} up to Miss Singleton’s house and see what I could make out of my informant’s story. It was my opinion that my late visitor was a whilom “pal” of Light Toed Jim, and that having become aware of the latter’s plot, he had, for some reason of his own, decided to split on his old chum. Thieves’ disagreement is an honest man’s opportunity, and I determined to solve the truth of the story told me. Lest it should come to nothing, I decided not to report the matter to my chief. If I could really capture Light Toed Jim, my success would be all the more brilliant by being suddenly sprung upon the authorities.

I made my plan of action rapidly. I took a revolver with me and went up to Miss Singleton’s house. Fortunately, I knew the housekeeper there—a middle-aged, strong-minded woman, not easily frightened, which was a good thing. To her I communicated such information as I considered necessary. She consented to conceal me in the room where the safe stood. There was a cupboard close by the safe from which I could command a full view of the burglar’s operations and pounce upon him at the right moment. If only my information was to be relied upon, there was every chance of my capturing the famous burglar.

Soon after midnight, when the house was all quiet, I went to the pantry and got into the cupboard, locking myself in. There were two openings{67} in the panel, through either of which I was able to command a full view of the room. My position was somewhat cramped, but the time soon passed away. My mind was principally occupied in wondering if I was really about to have a chance of distinguishing myself. Somehow, there was an air of unreality about the events of the evening which puzzled me.

Suddenly I heard a sound which put me on the alert at once. It was nothing more than the creaking of a board or opening of a door would make in a quiet house; but it sounded intensified to my expectant ears. I drew myself up against the door of the cupboard and placed my eye to the opening in the panel. I had oiled the key of the door, and kept my fingers upon it in readiness to spring upon the burglar at the proper moment. After what seemed some time I saw the gleam of light through the keyhole of the door opening into the pantry. Then it opened, and a man carrying a small lantern came gently into the room. At first I could see nothing of his face; but when my eyes grew accustomed to the hazy light I saw that I had been rightly informed, and that the burglar was indeed no other than the famous Light Toed Jim.

As I stood there watching him I could not help admiring the cool fashion in which he went to work. He went over to the window and examined it. He tried the door of the cupboard{68} in which I stood concealed. Then he locked the door of the pantry and turned his attention to the safe. He set his lamp on a chair before the lock and took from his pocket as neat and pretty a collection of tools as ever I saw. With these he went quietly and swiftly to work.

Light Toed Jim was a somewhat slimly built fellow, with little muscular development about him, while I am a big man with plenty of bone and sinew. If matters had come to a fight between us I could have done what I pleased with him; but I knew that Jim would not chance a fight. Somewhere about him I felt sure there was a revolver, which he would use on the least provocation. My plan, therefore, was to wait until his back was bent over the lock of the safe, then to open the cupboard door noiselessly and fall bodily upon him, pinning him to the ground beneath me.

Before long the moment came. He was working steadily away at the lock, his whole attention concentrated on the job. The slight noise of his drill was sufficient to drown the faint click of the key in the cupboard door. I turned it quickly and tumbled right upon him, driving the tool out of his hands and tumbling him into a heap at the foot of the safe. He uttered an exclamation of rage and astonishment as he went down, and immediately began to wriggle under me like an eel. As I kept him down with one hand I tried to pull{69} out the handcuffs with the other. This somewhat embarrassed me, and the burglar profited by it to pull out a sharp knife. He had worked himself round on his back, and before I realized what he was after he was hacking furiously at me with his keen, dagger-like blade. Then I realized that we were going to have a fight for it, and prepared myself. He tried to run the knife into my side. I warded it off, but the blade caught the fleshy part of my left arm and I felt a warm stream of blood spurt out.

That maddened me, and I seized one of the steel drills lying near at hand, and hit my man such a blow over the temple that he collapsed at once, and lay as if dead. I put the handcuffs on him instantly, and, to make matters still more certain, I secured his ankles. Then I rose and looked at my arm. The knife had made a nasty gash, and the blood was flowing freely, but it was not serious; and when the housekeeper, who had just then appeared on the scene, had bandaged it, I went out and secured the help of the first policeman I met in conveying Light Toed Jim to the office.

I felt a proud man when I made my report to the inspector.

“Light Toed Jim?” said he. “What, James Bland? Nonsense, Parker.” But I took him to the cells where Jim was being attended to by the doctor.{70}

“You’re right, Parker,” he said. “That’s the man. Well, this will be a fine thing for you.”

After a time, feeling a little exhausted, I went home to try and get some sleep. The surgeon had attended to my arm, and told me it was but a superficial wound. It felt sore enough in spite of that.

I had no sooner reached my lodgings than I saw sitting in my easy-chair the strange man who had called upon me earlier in the evening. He rose to his feet when I entered. I stared at him in utter astonishment.

“Well, guv’nor,” said he, “I see you’ve done it. You’ve got him square and fair, I reckon?”

“Yes,” I said.

“Ah!” he said, with a sigh of complete satisfaction. “Then I’m satisfied. Yes, I don’t know as how there’s aught more I could say. I reckon as how Light Toed Jim an’ me is quits.”

I was determined to find out who this man was this time. “Sit down,” I said. “There’s a question or two I must ask you. Just let me get my coat off and I’ll talk to you.” I took my coat off and went over to the bed to lay it down. “Now then,” I began, and looked around at him. I said no more, being literally struck dumb. The man was gone!

I began to feel uncomfortable. I ran hastily downstairs, only to find the outer door locked and bolted, as I had left it a few minutes before.{71} I went back, utterly nonplussed. For an hour I pondered the matter over, but could neither make head nor tail of it.