| Spanish Explorations and Settlements In America FROM THE Fifteenth to the Seventeenth Century |

|

NARRATIVE AND CRITICAL

HISTORY OF AMERICA

EDITED

By JUSTIN WINSOR

LIBRARIAN OF HARVARD UNIVERSITY

CORRESPONDING SECRETARY MASSACHUSETTS HISTORICAL SOCIETY

VOL. II

BOSTON AND NEW YORK

HOUGHTON, MIFFLIN AND COMPANY

The Riverside Press, Cambridge

Copyright, 1886,

By HOUGHTON, MIFFLIN AND COMPANY.

All rights reserved.

CONTENTS AND ILLUSTRATIONS.

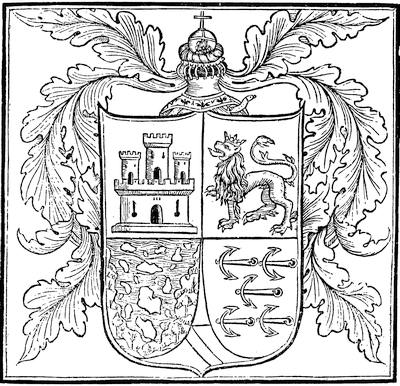

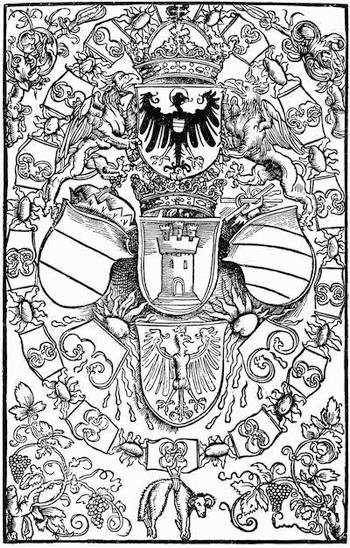

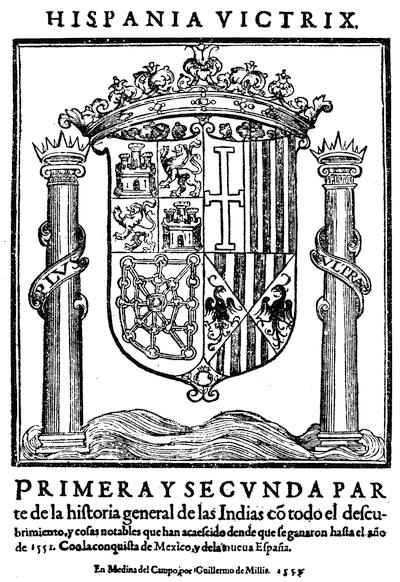

[The Spanish arms on the title are copied from the titlepage of Herrera.]

| INTRODUCTION. | |

| PAGE | |

| Documentary Sources of Early Spanish-American History. The Editor | i |

|

|

| CHAPTER I. | |

| Columbus and his Discoveries. The Editor | 1 |

| Illustrations: Columbus’ Armor, 4; Parting of Columbus with Ferdinand and Isabella, 6; Early Vessels, 7; Building a Ship, 8; Course of Columbus on his First Voyage, 9; Ship of Columbus’ Time, 10; Native House in Hispaniola, 11; Curing the Sick, 11; The Triumph of Columbus, 12; Columbus at Hispaniola, 13; Handwriting of Columbus, 14; Arms of Columbus, 15; Fruit-trees of Hispaniola, 16; Indian Club, 16; Indian Canoe, 17, 17; Columbus at Isla Margarita, 18; Early Americans, 19; House in which Columbus died, 23. | |

| Critical Essay | 24 |

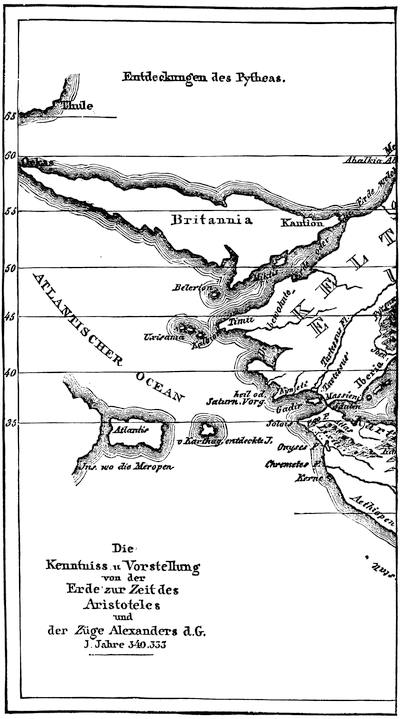

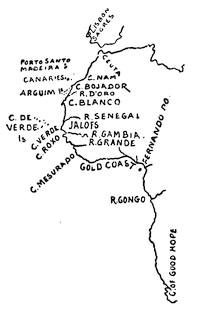

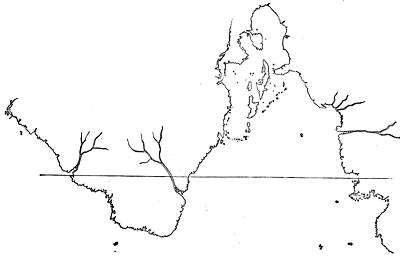

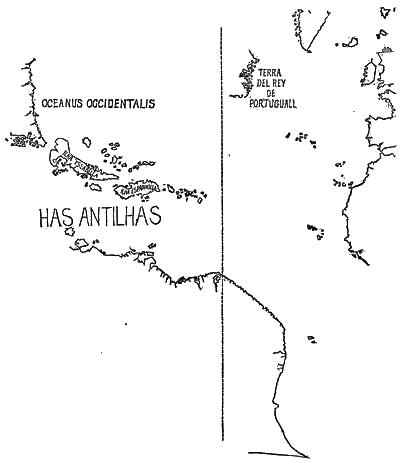

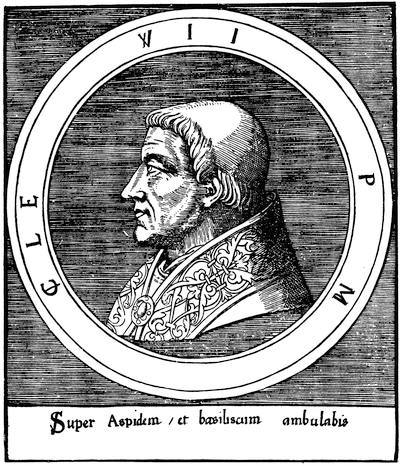

| Illustrations: Ptolemy, 26, 27; Albertus Magnus, 29; Marco Polo, 30; Columbus’ Annotations on the Imago Mundi, 31; on Æneas Sylvius, 32; the Atlantic of the Ancients, 37; Prince Henry the Navigator, 39; his Autograph, 39; Sketch-map of Portuguese Discoveries in Africa, 40; Portuguese Map of the Old World (1490), 41; Vasco da Gama and his Autograph, 42; Line of Demarcation (Map of 1527), 43; Pope Alexander VI., 44. | |

| Notes | 46 |

| A, First Voyage, 46; B, Landfall, 52; C, Effect of the Discovery in Europe, 56; D, Second Voyage, 57; E, Third Voyage, 58; F, Fourth Voyage, 59; G, Lives and Notices of Columbus, 62; H, Portraits of Columbus, 69; I, Burial and Remains of Columbus, 78; J, Birth of Columbus, and Accounts of his Family, 83. | |

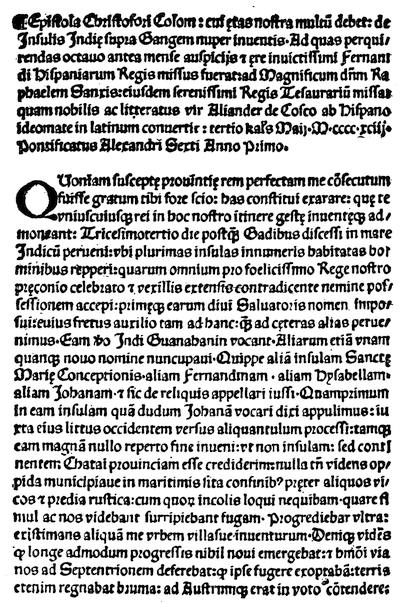

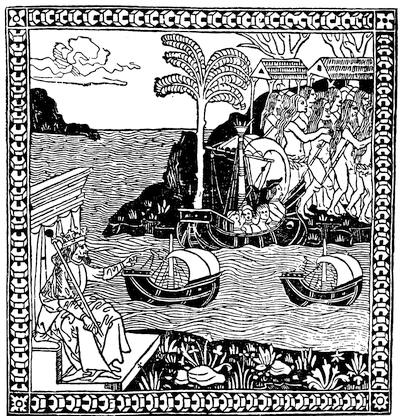

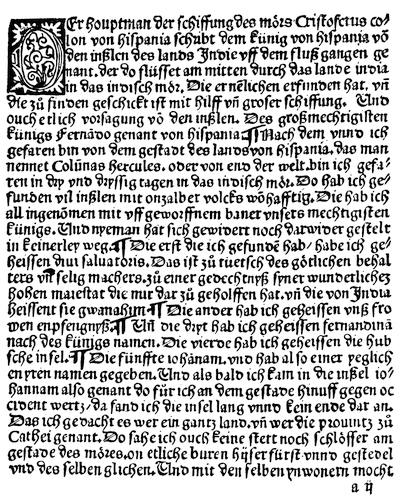

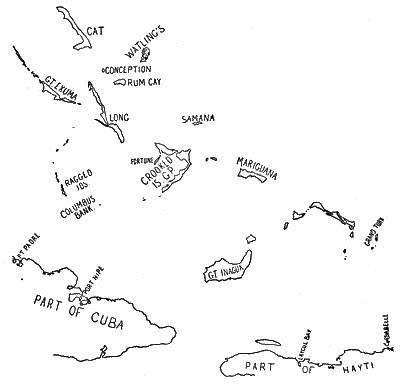

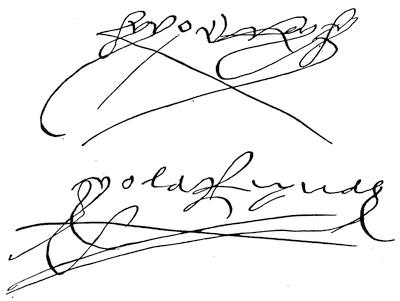

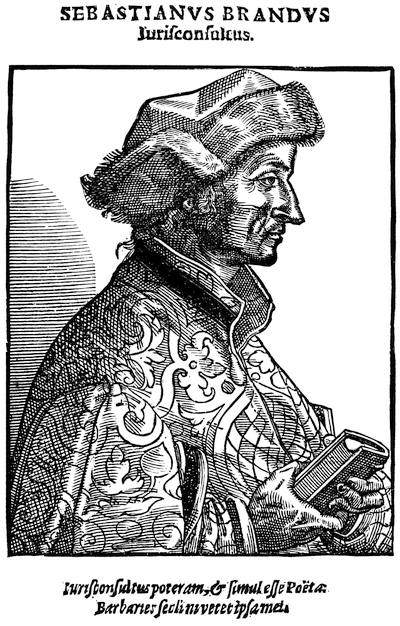

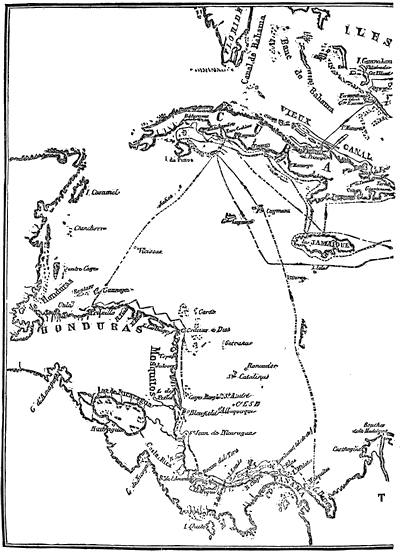

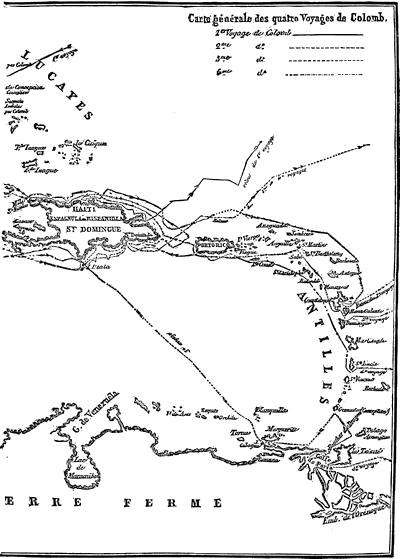

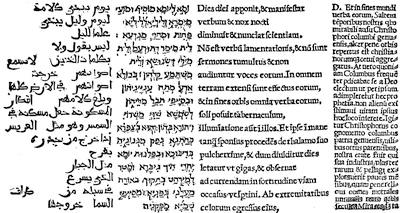

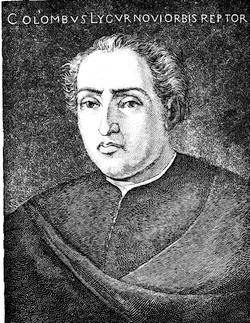

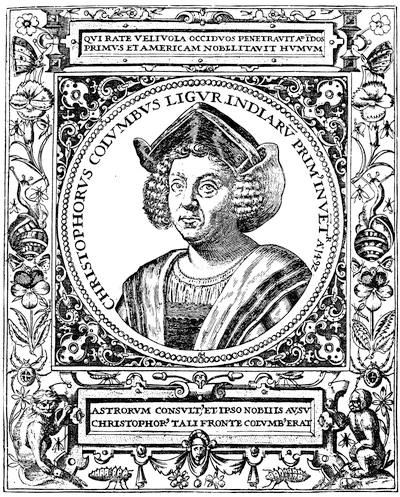

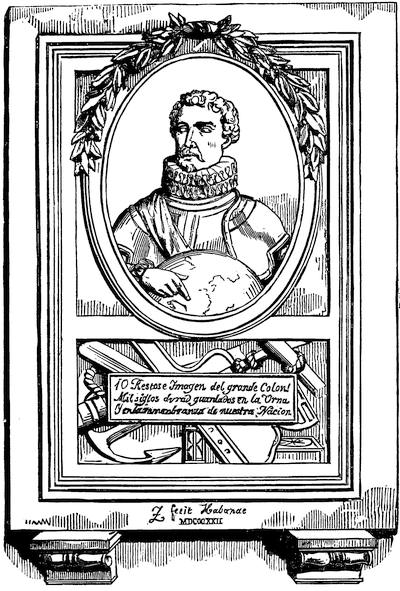

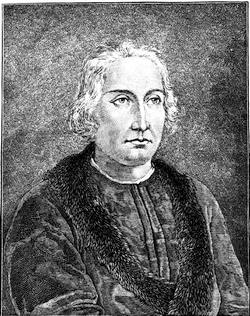

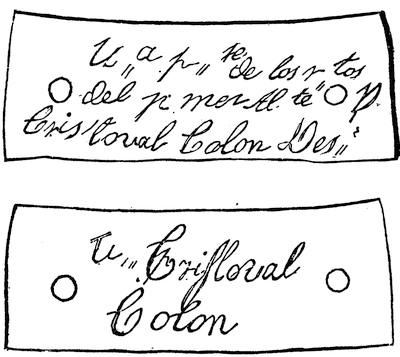

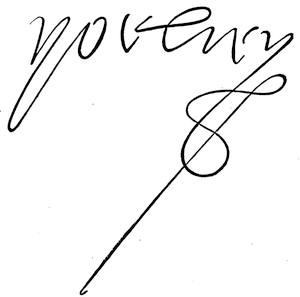

| [vi] Illustrations: Fac-simile of first page of Columbus’ Letter, No. III., 49; Cut on reverse of Title of Nos. V. and VI., 50; Title of No. VI., 51; The Landing of Columbus, 52; Cut in German Translation of the First Letter, 53; Text of the German Translation, 54; the Bahama Group (map), 55; Sign-manuals of Ferdinand and Isabella, 56; Sebastian Brant, 59; Map of Columbus’ Four Voyages, 60, 61; Fac-simile of page in the Glustiniani Psalter, 63; Ferdinand Columbus’ Register of Books, 65; Autograph of Humboldt, 68; Paulus Jovius, 70. Portraits of Columbus,—after Giovio, 71; the Yanez Portrait, 72; after Capriolo, 73; the Florence picture, 74; the De Bry Picture, 75; the Jomard Likeness, 76; the Havana Medallion, 77; Picture at Madrid, 78; after Montanus, 79; Coffer and Bones found in Santo Domingo, 80; Inscriptions on and in the Coffer, 81, 82; Portrait and Sign-manual of Ferdinand of Spain, 85; Bartholomew Columbus, 86. | |

| Postscript | 88 |

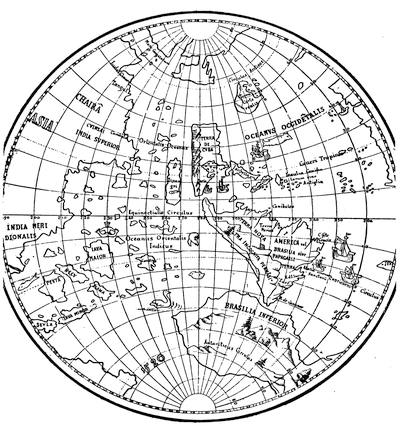

| THE EARLIEST MAPS OF THE SPANISH AND PORTUGUESE DISCOVERIES. The Editor | 93 |

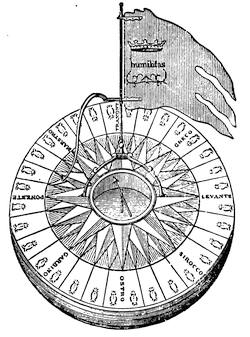

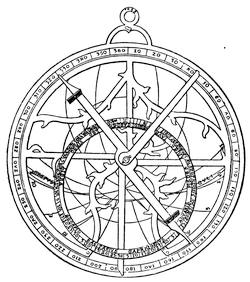

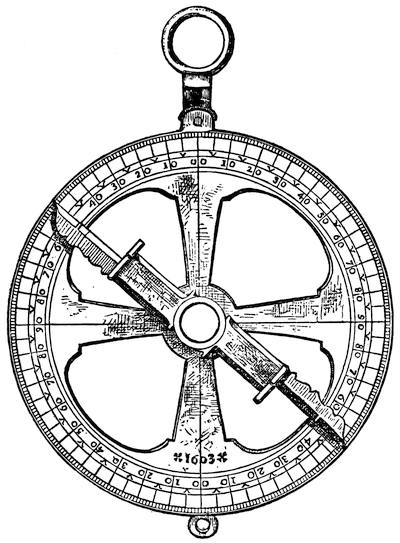

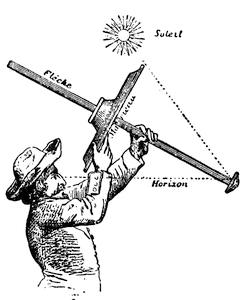

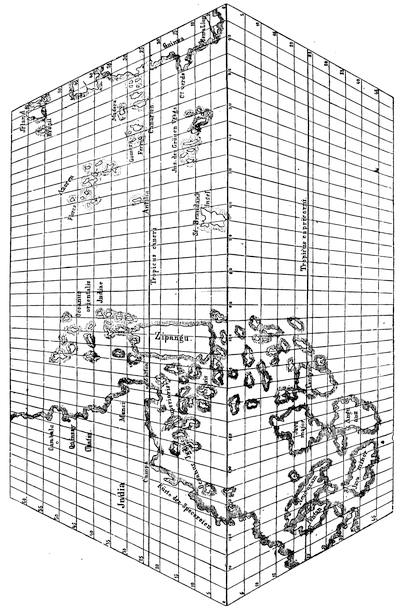

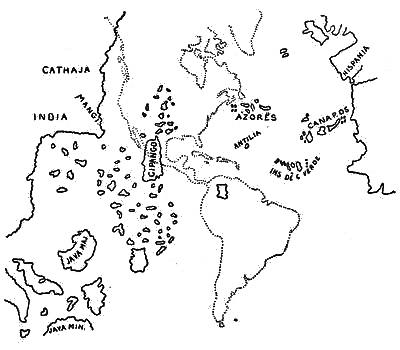

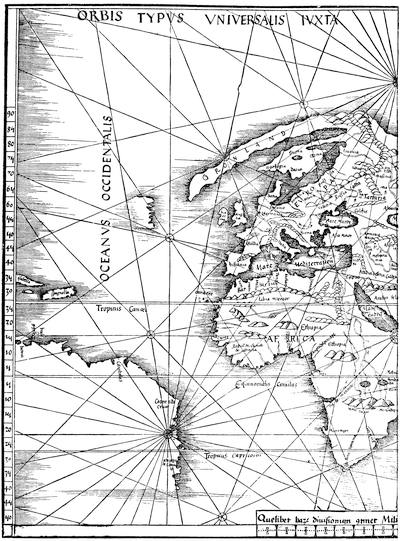

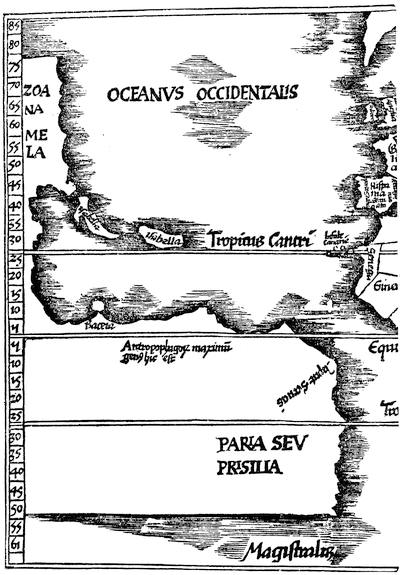

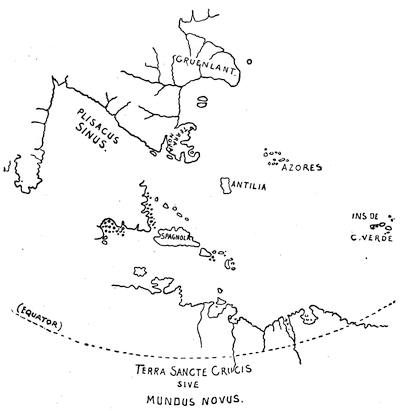

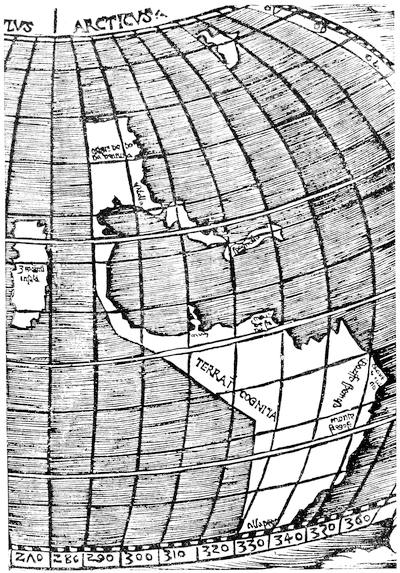

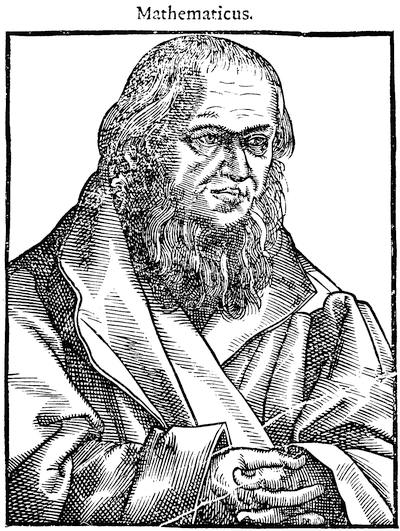

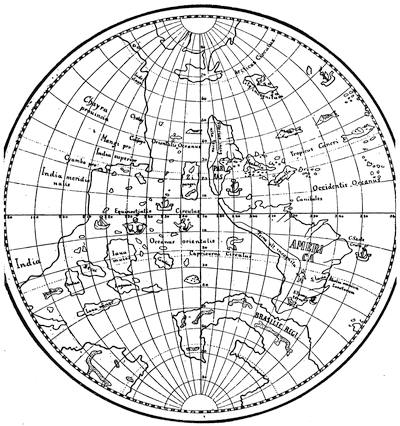

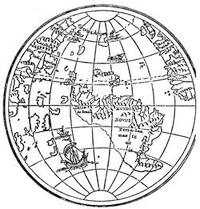

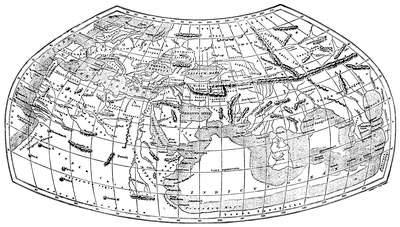

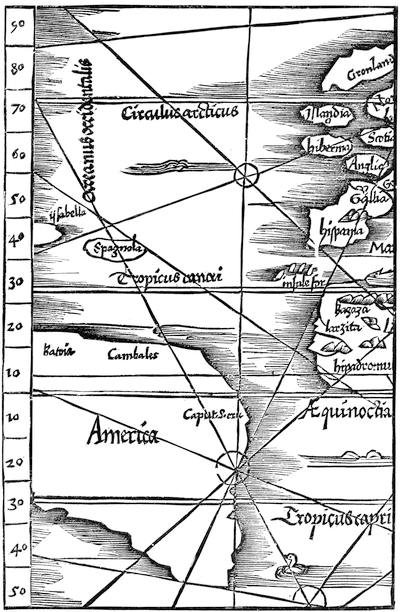

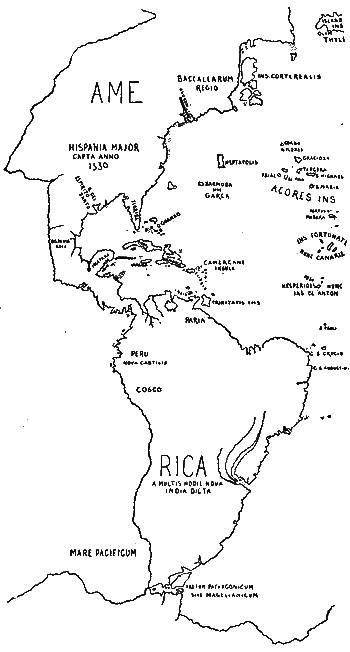

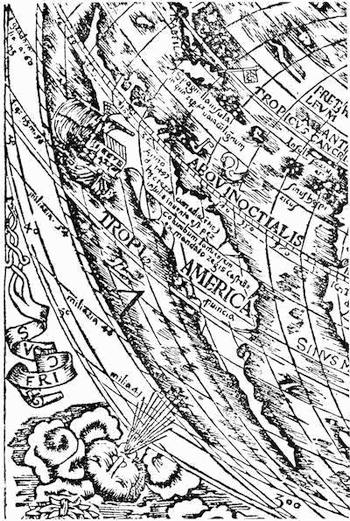

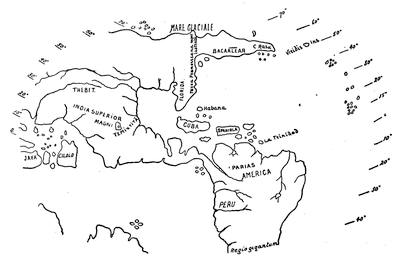

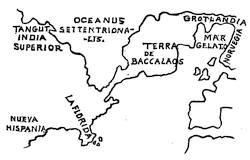

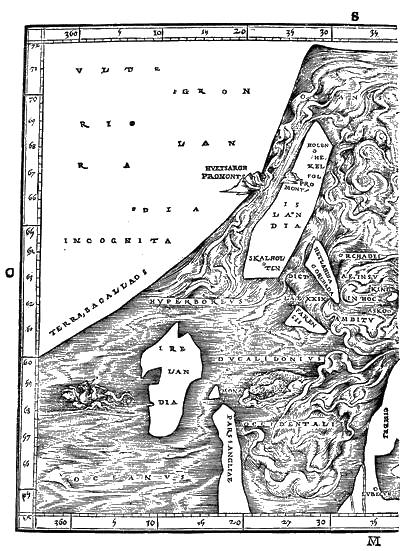

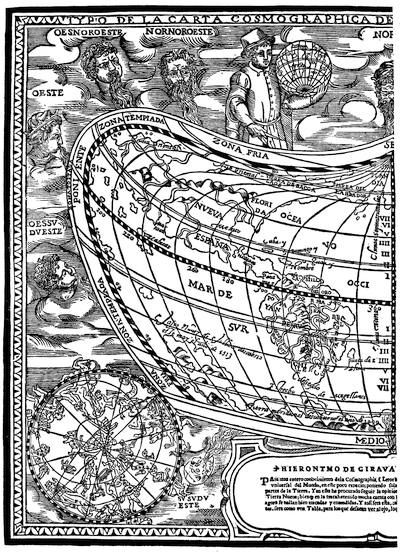

| Illustrations: Early Compass, 94; Astrolabe of Regiomontanus, 96; Later Astrolabe, 97; Jackstaff, 99; Backstaff, 100; Pirckeymerus, 102; Toscanelli’s Map, 103; Martin Behaim, 104; Extract from Behaim’s Globe, 105; Part of La Cosa’s Map, 106; of the Cantino Map, 108; Peter Martyr Map (1511), 110; Ptolemy Map (1513), 111; Admiral’s Map (1513), 112; Reisch’s Map (1515), 114; Ruysch’s Map (1508), 115; Stobnicza’s Map (1512), 116; Schöner, 117; Schöner’s Globe (1515), 118; (1520), 119; Tross Gores (1514-1519), 120; Münster’s Map (1532), 121; Sylvanus’ Map (1511), 122; Lenox Globe, 123; Da Vinci Sketch of Globe, 124, 125, 126; Carta Marina of Frisius (1525), 127; Coppo’s Map (1528), 127. | |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| Amerigo Vespucci. Sydney Howard Gay | 129 |

| Illustrations: Fac-simile of a Letter of Vespucci, 130; Autograph of Amerrigo Vespuche, 138; Portraits of Vespucci, 139, 140, 141. | |

| NOTES ON VESPUCIUS AND THE NAMING OF AMERICA. The Editor | 153 |

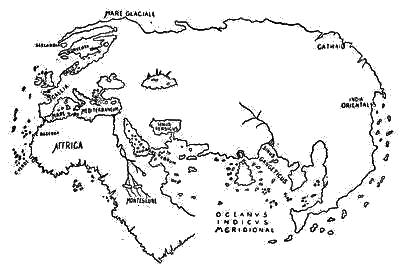

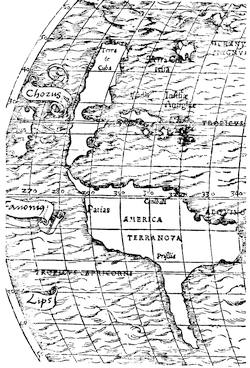

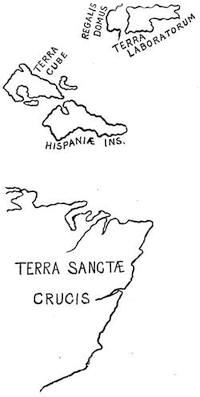

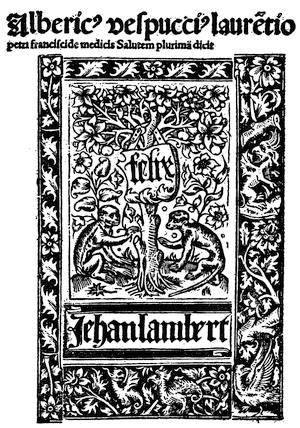

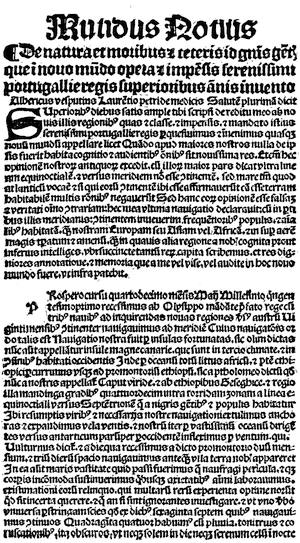

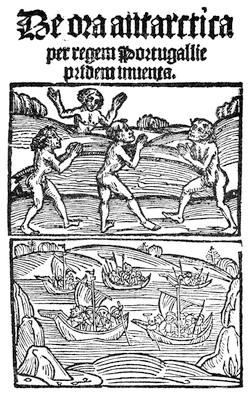

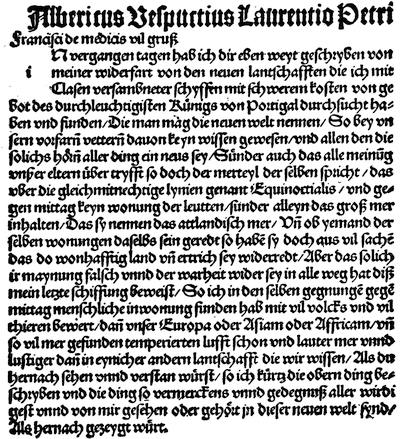

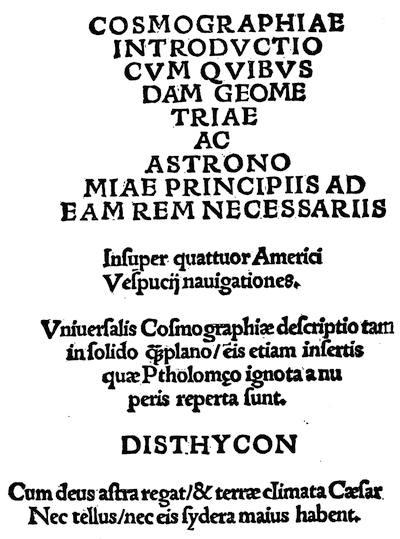

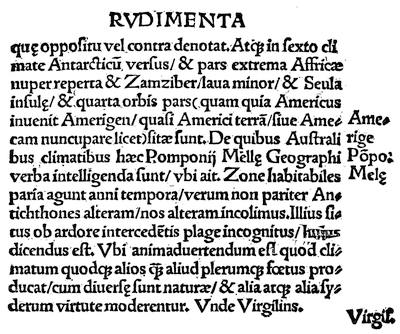

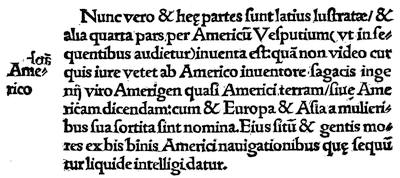

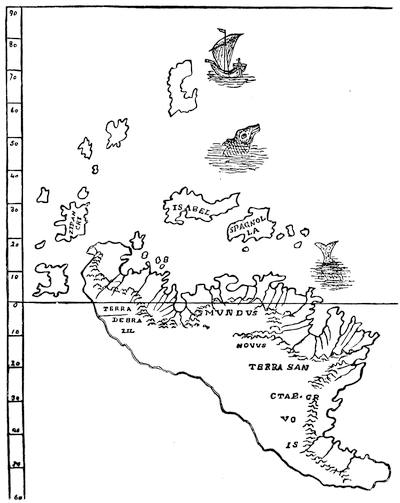

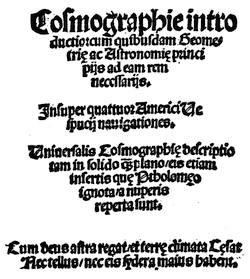

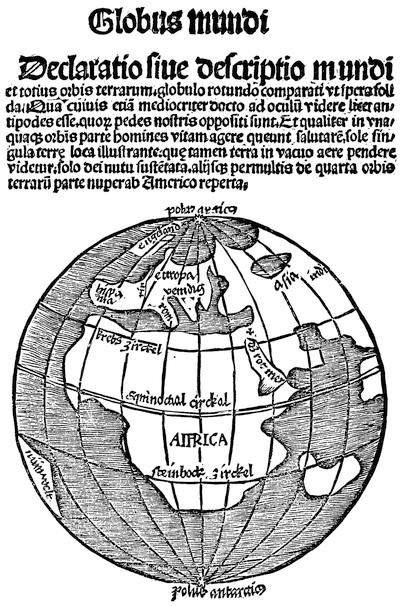

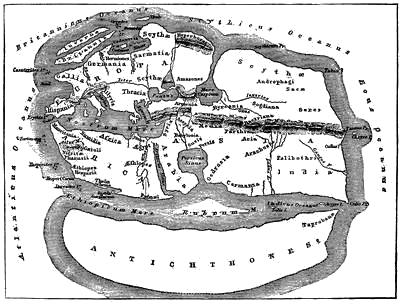

| Illustrations: Title of the Jehan Lambert edition of the Mundus Novus, 157; first page of Vorsterman’s Mundus Novus, 158; Title of De Ora Antarctica, 159; title of Von der neu gefunden Region, 160; Fac-simile of its first page, 161; Ptolemy’s World, 165; Title of the Cosmographiæ Introductio, 167; Fac-simile of its reference to the name of America, 168; the Lenox Globe (American parts), 170; Title of the 1509 edition of the Cosmographiæ Introductio, 171; title of the Globus Mundi, 172; Map of Laurentius Frisius in the Ptolemy of 1522, 175; American part of the Mercator Map of 1541, 177; Portrait of Apianus, 179. | |

| BIBLIOGRAPHY OF POMPONIUS MELA, SOLINUS, VADIANUS, AND APIANUS. The Editor | 180 |

| Illustrations: Pomponius Mela’s World, 180; Vadianus, 181; Part of Apianus’ Map (1520), 183; Apianus, 185. | |

| CHAPTER III.[vii] | |

| The Companions of Columbus. Edward Channing | 187 |

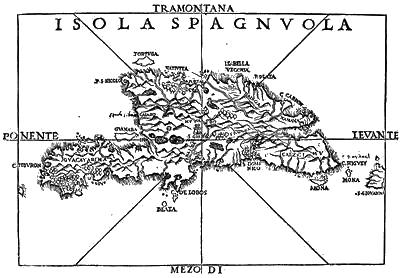

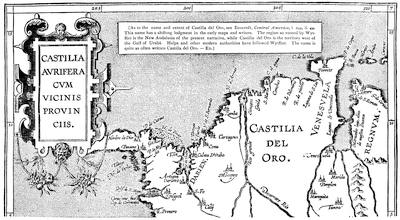

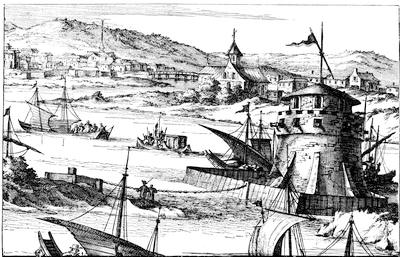

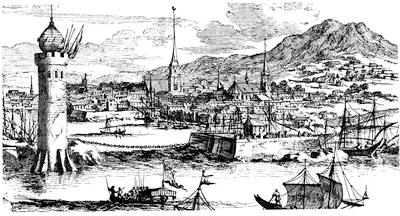

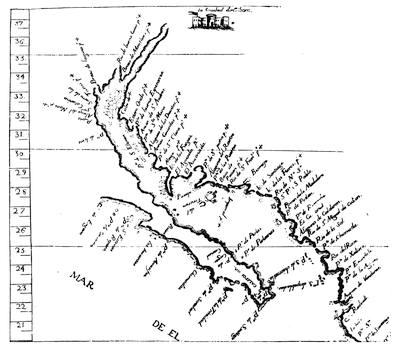

| Illustrations: Map of Hispaniola, 188; Castilia del Oro, 190; Cartagena, 192; Balbóa, 195; Havana, 202. | |

| Critical Essay | 204 |

| Illustration: Juan de Grijalva, 216. | |

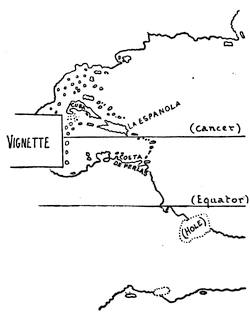

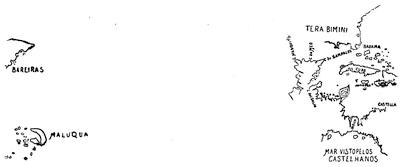

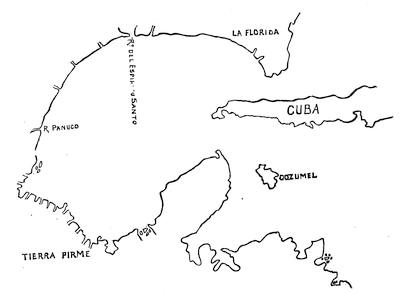

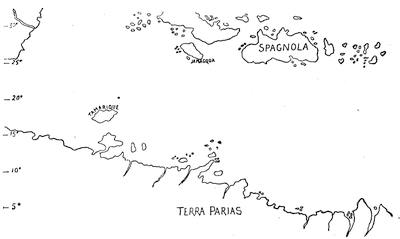

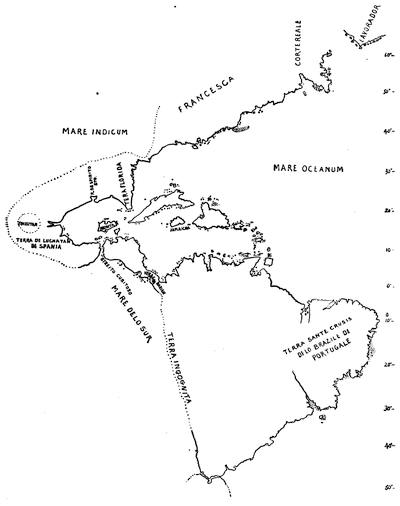

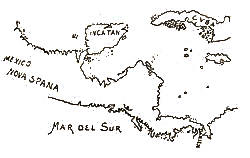

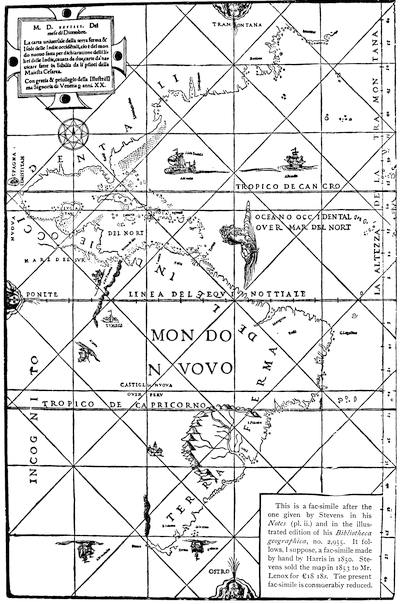

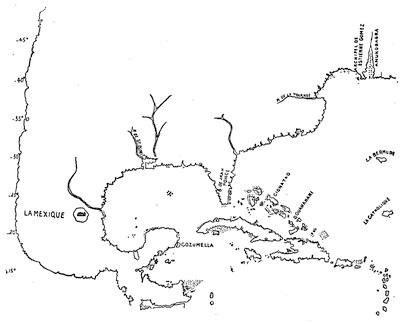

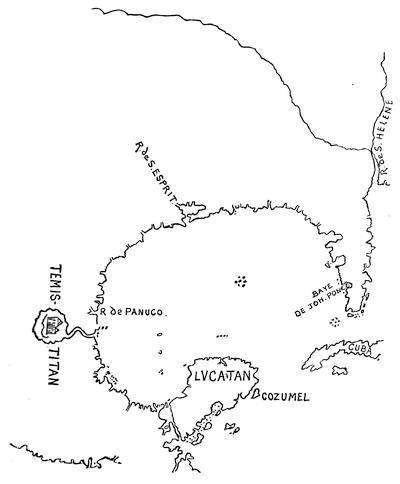

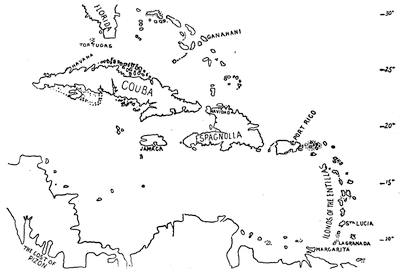

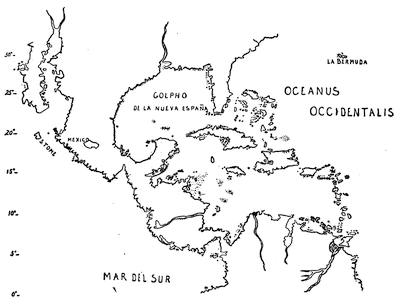

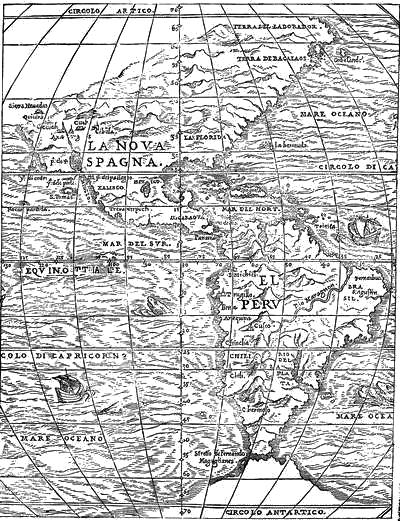

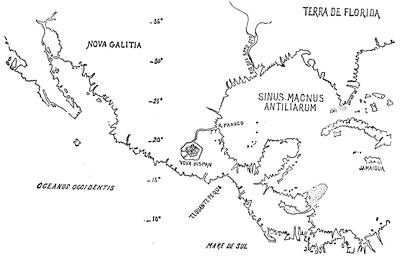

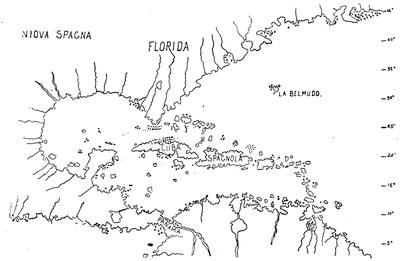

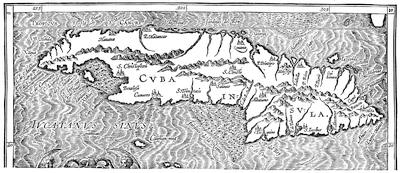

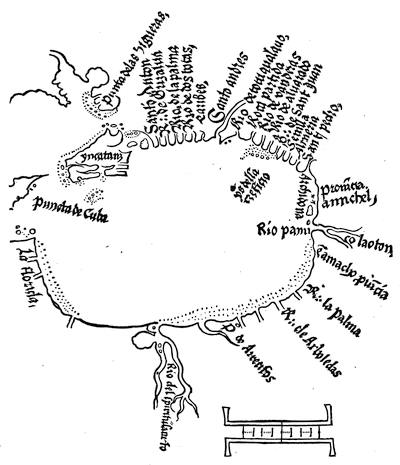

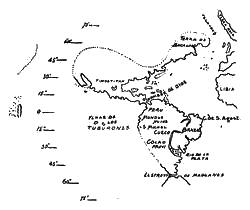

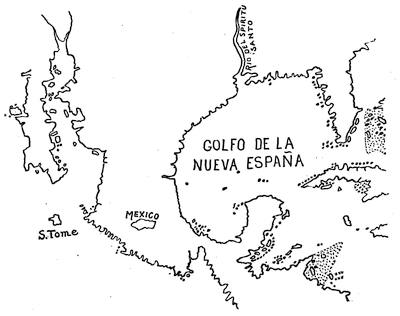

| THE EARLY CARTOGRAPHY OF THE GULF OF MEXICO AND ADJACENT PARTS. The Editor | 217 |

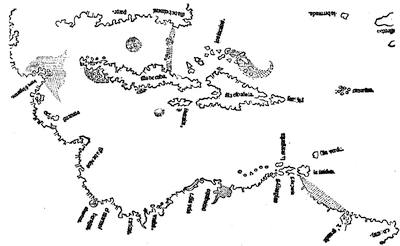

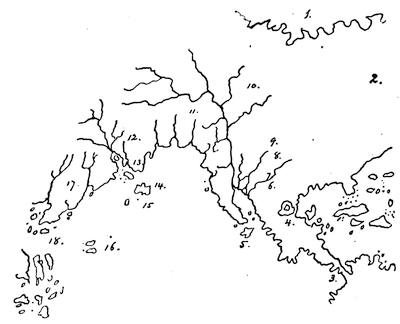

| Illustrations: Map of the Pacific (1518), 217; of the Gulf of Mexico (1520), 218; by Lorenz Friess (1522), 218; by Maiollo (1527), 219; by Nuño Garcia de Toreno (1527), 220; by Ribero (1529), 221; The so-called Lenox Woodcut (1534), 223; Early French Map, 224; Gulf of Mexico (1536), 225; by Rotz (1542), 226; by Cabot (1544), 227; in Ramusio (1556), 228; by Homem (1558), 229; by Martines (1578), 229; of Cuba, by Wytfliet (1597), 230. | |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

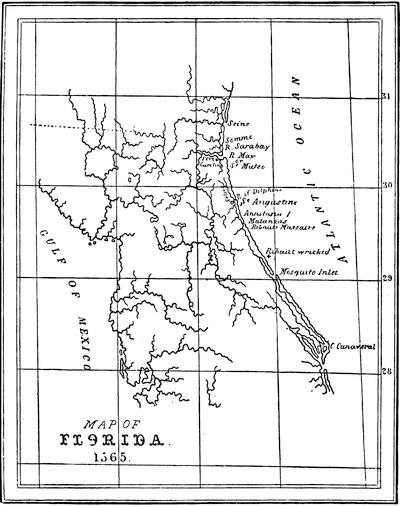

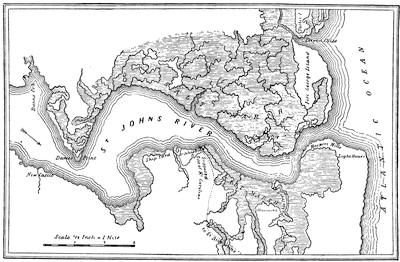

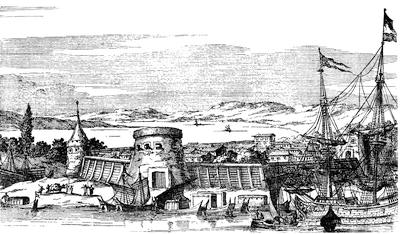

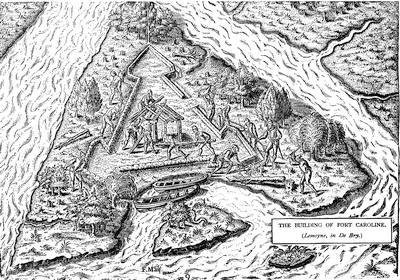

| Ancient Florida. John G. Shea | 231 |

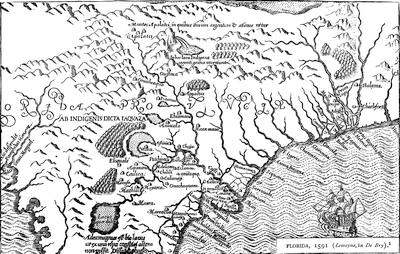

| Illustrations: Ponce de Leon, 235; Hernando de Soto, 252; Autograph of De Soto, 253; of Mendoza, 254; Map of Florida (1565), 264; Site of Fort Caroline, 265; View of St. Augustine, 266; Spanish Vessels, 267; Building of Fort Caroline, 268; Fort Caroline completed, 269; Map of Florida (1591), 274; Wytfliet’s Map (1597), 281. | |

| Critical Essay | 283 |

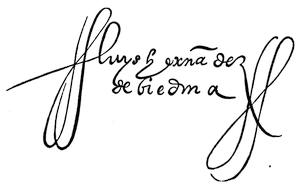

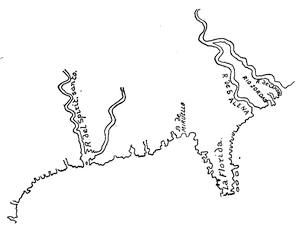

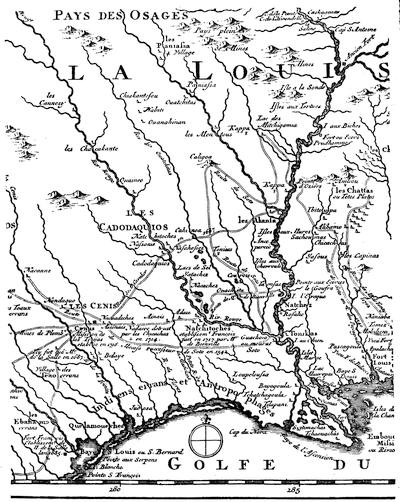

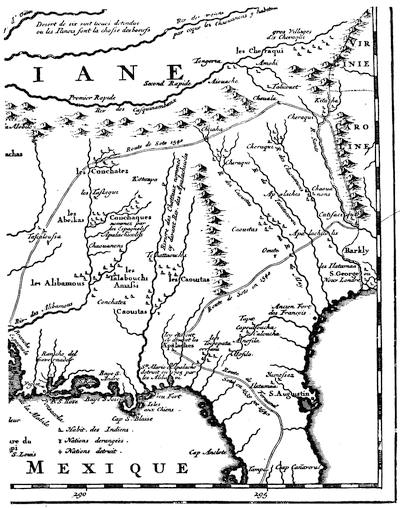

| Illustrations: Map of Ayllon’s Explorations, 285; Autograph of Narvaez, 286; of Cabeza de Vaca, 287; of Charles V., 289; of Biedma, 290; Map of the Mississippi (sixteenth century), 292; Delisle’s Map, with the Route of De Soto, 294, 295. | |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| Las Casas, and the Relations of the Spaniards to the Indians. George E. Ellis | 299 |

| Critical Essay | 331 |

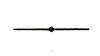

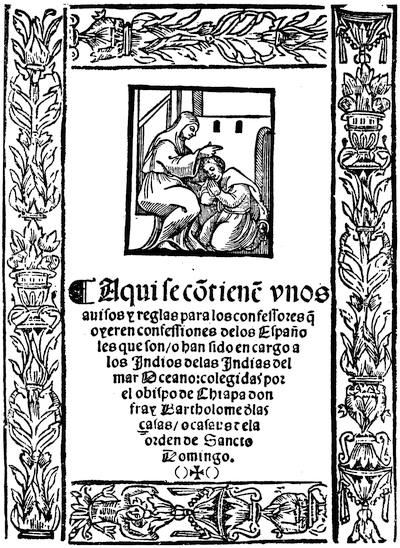

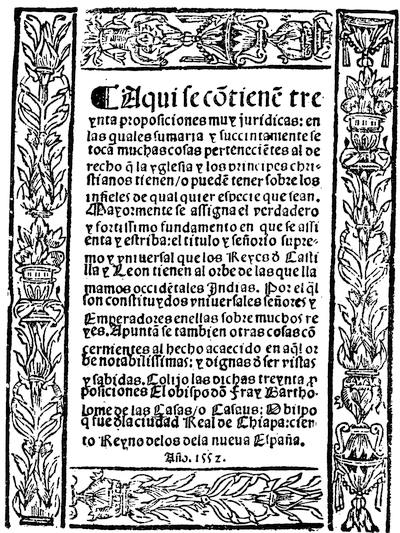

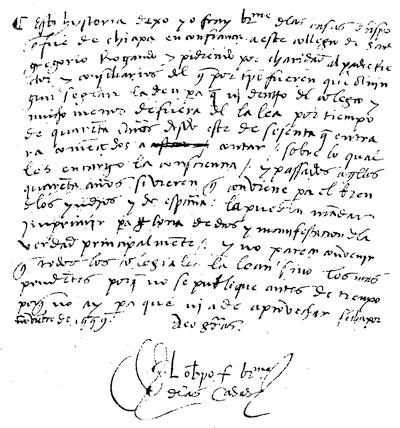

| Illustrations: Las Casas, 332; his Autograph, 333; Titlepages of his Tracts, 334, 336, 338; Fac-simile of his Handwriting, 339. | |

| Editorial Note | 343 |

| Illustrations: Autograph of Motolinia, 343; Title of Oviedo’s Natural Hystoria (1526), 344; Arms of Oviedo, 345; his Autograph, 346; Head of Benzoni, 347. | |

| CHAPTER VI.[viii] | |

| Cortés and his Companions. The Editor | 349 |

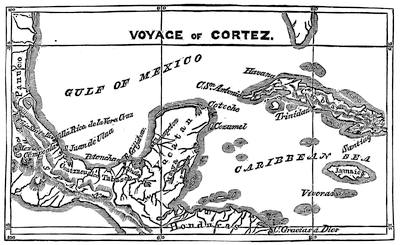

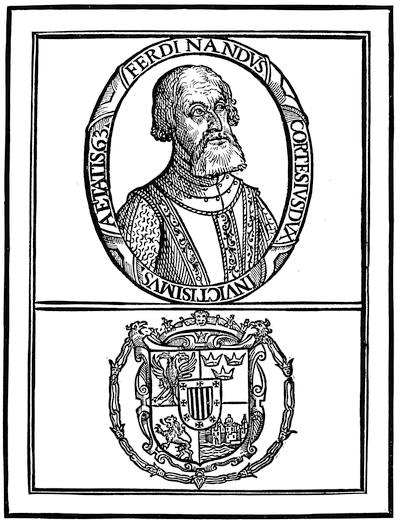

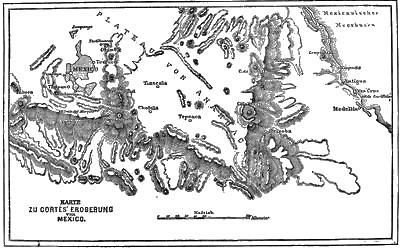

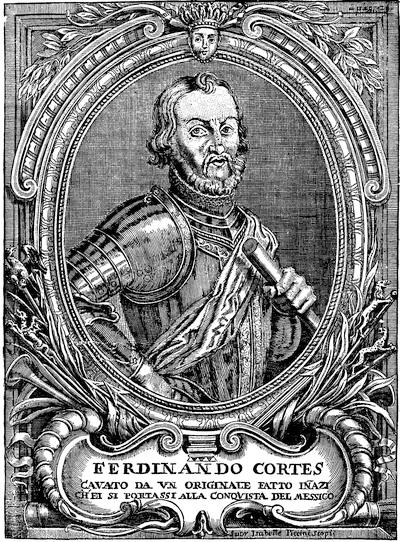

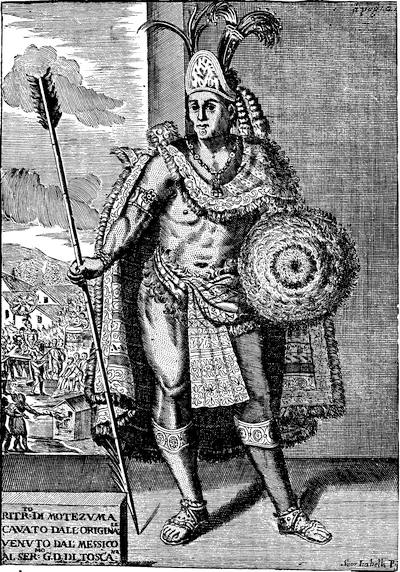

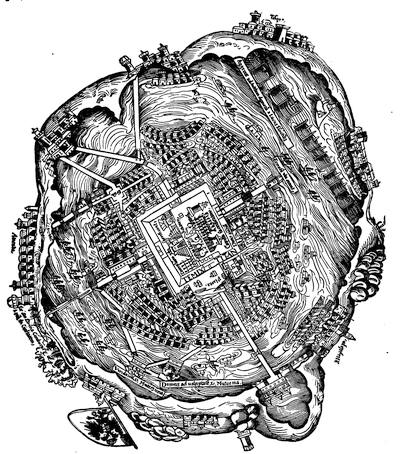

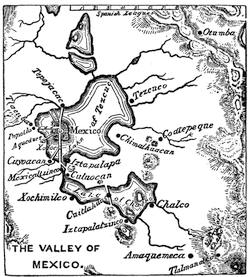

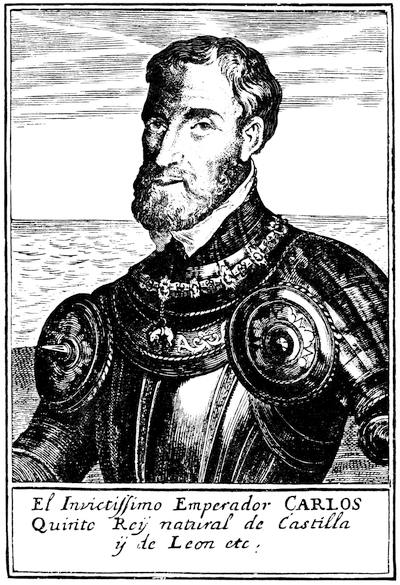

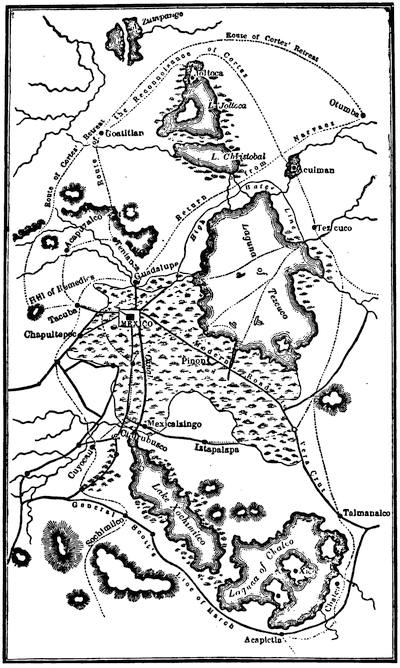

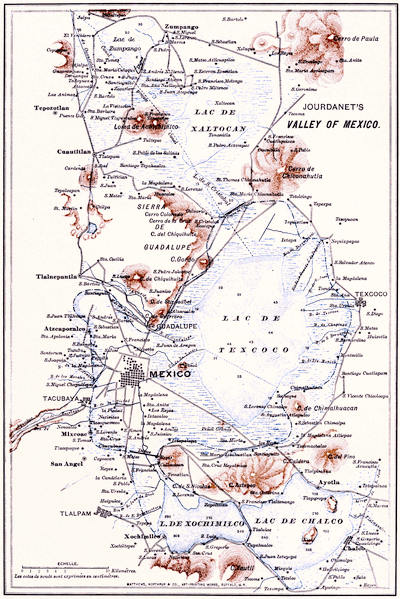

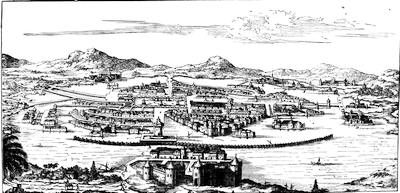

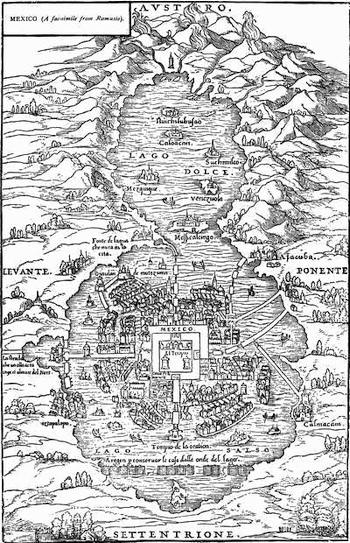

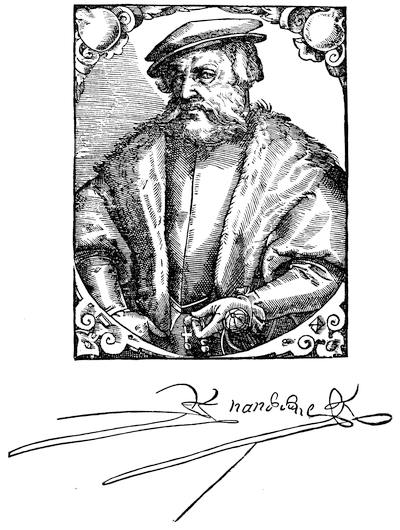

| Illustrations: Velasquez, 350; Cannon of Cortés’ time, 352; Helps’s Map of Cortés’ Voyage, 353; Cortés and his Arms, 354; Gabriel Lasso de la Vega, 355; Cortés, 357; Map of the March of Cortés, 358; Cortés, 360; Montezuma, 361, 363; Map of Mexico before the Conquest, 364; Pedro de Alvarado, 366; his Autograph, 367; Helps’s Map of the Mexican Valley, 369; Tree of Triste Noche, 370; Charles V., 371, 373; his Autograph, 372; Wilson’s Map of the Mexican Valley, 374; Jourdanet’s Map of the Valley, colored, 375; Mexico under the Conquerors, 377; Mexico according to Ramusio, 379; Cortés in Jovius, 381; his Autograph, 381; Map of Guatemala and Honduras, 384; Autograph of Sandoval, 387; his Portrait, 388; Cortés after Herrera, 389; his Armor, 390; Autograph of Fuenleal, 391; Map of Mexico after Herrera, 392; Acapulco, 394; Full-length Portrait of Cortés, 395; Likeness on a Medal, 396. | |

| Critical Essay | 397 |

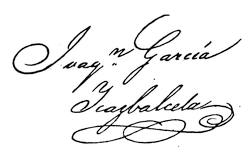

| Illustration: Autograph of Icazbalceta, 397. | |

| Notes | 402 |

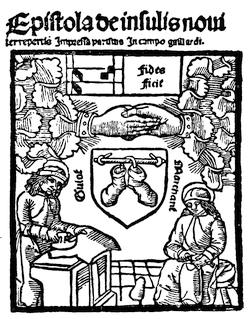

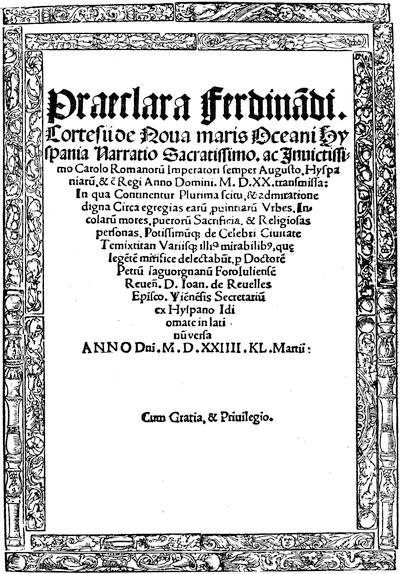

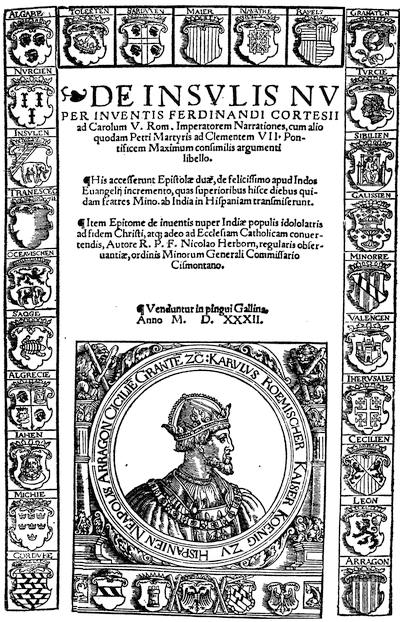

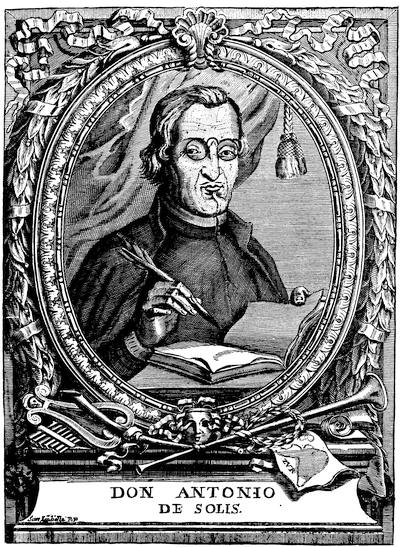

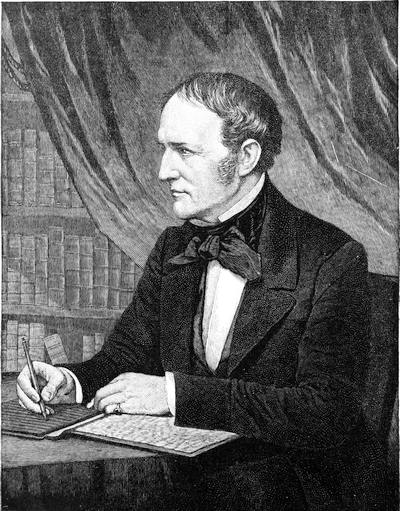

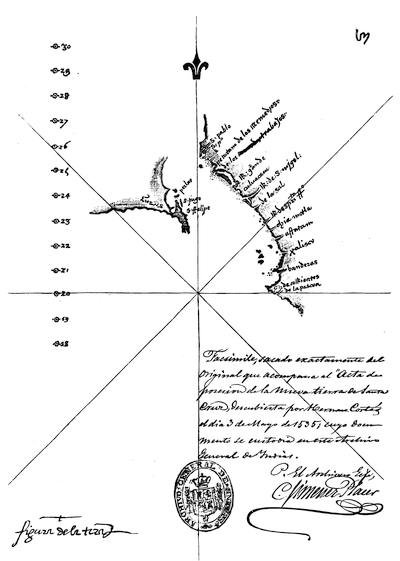

| Illustrations: Cortés before Charles V., 403; Cortés’ Map of the Gulf of Mexico, 404; Title of the Latin edition of his Letters (1524), 405; Reverse of its Title, 406; Portrait of Clement VII., 407; Autograph of Gayangos, 408; Lorenzana’s Map of Spain, 408; Title of De insulis nuper inventis, 409; Title of Gomara’s Historia (1553), 413; Autograph of Bernal Diaz, 414; of Sahagun, 416; Portrait of Solis, 423; Portrait of William H. Prescott, 426. | |

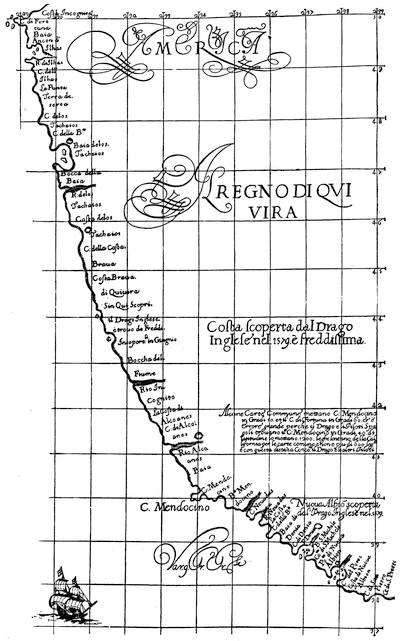

| DISCOVERIES ON THE PACIFIC COAST OF NORTH AMERICA. The Editor | 431 |

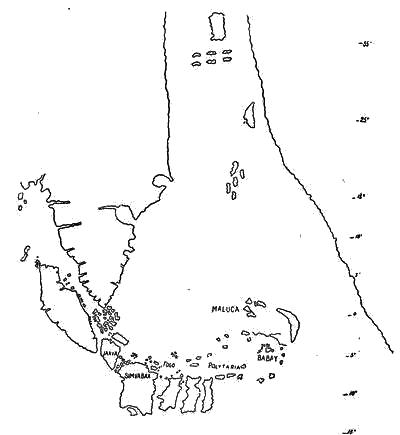

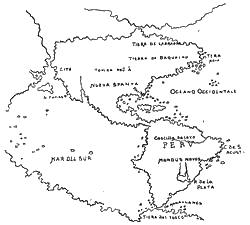

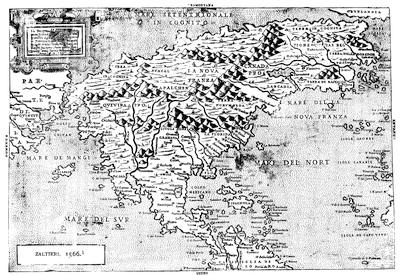

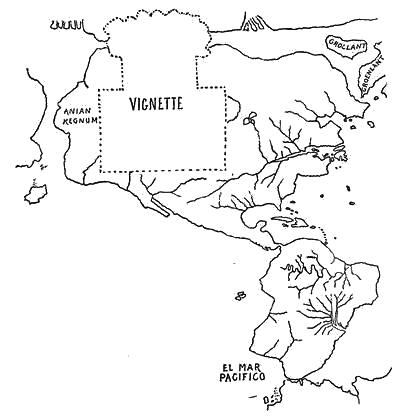

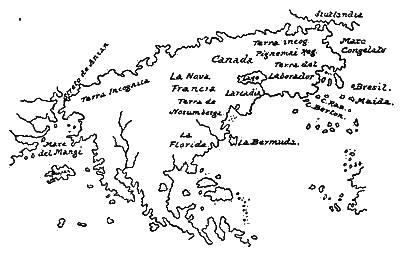

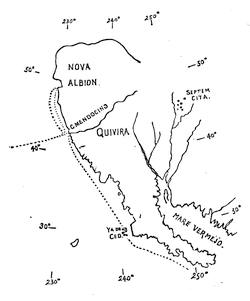

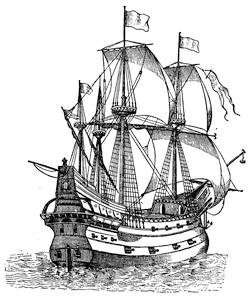

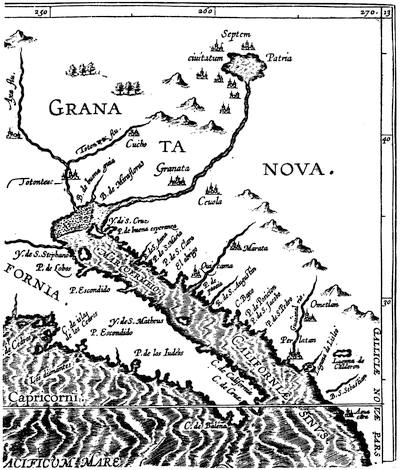

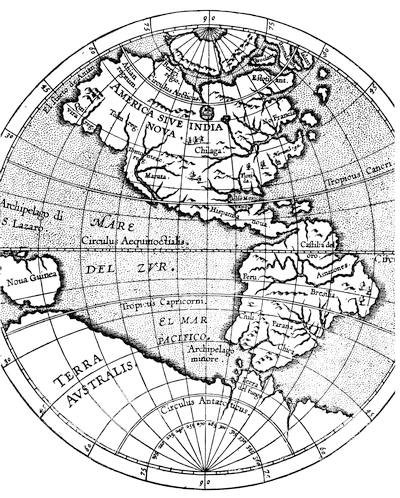

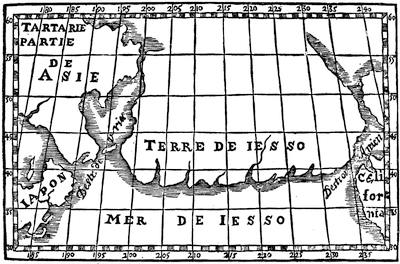

| Illustrations: Map from the Sloane Manuscripts (1530), 432; from Ruscelli (1544), 432; Nancy Globe, 433; from Ziegler’s Schondia (1532), 434; Carta Marina (1548), 435; Vopellio’s Map (1556), 436; Titlepage of Girava’s Cosmographia, 437; Furlani’s Map (1560), 438; Map of the Pacific (1513), 440; Cortés’ Map of the California Peninsula, 442; Castillo’s Map of the California Gulf (1541), 444; Map by Homem (1540), 446; by Cabot (1544), 447; by Freire (1546), 448; in Ptolemy (1548), 449; by Martines (155-?), 450; by Zaltieri (1566), 451; by Mercator (1569), 452; by Porcacchi (1572), 453; by Furlani (1574), 454; from Molineaux’ Globe (1592), 455; a Spanish Galleon, 456; Map of the Gulf of California by Wytfliet (1597), 458; of America by Wytfliet (1597), 459; of Terre de Iesso, 464; of the California Coast by Dudley (1646), 465; Diagram of Mercator’s Projection, 470. | |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

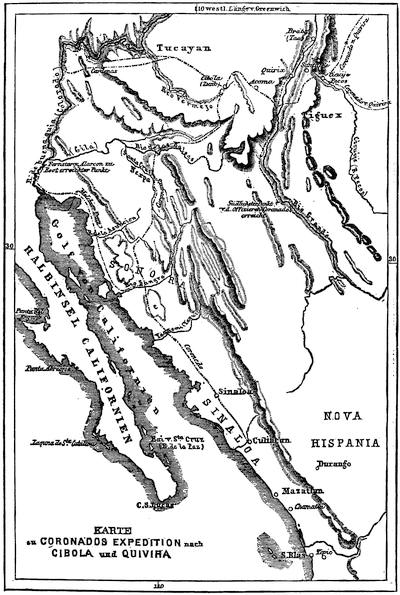

| Early Explorations of New Mexico. Henry W. Haynes | 473 |

| Illustrations: Autograph of Coronado, 481; Map of his Explorations, 485; Early Drawings of the Buffalo, 488, 489. | |

| Critical Essay[ix] | 498 |

| Editorial Note | 503 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| Pizarro, and the Conquest and Settlement of Peru and Chili. Clements R. Markham | 505 |

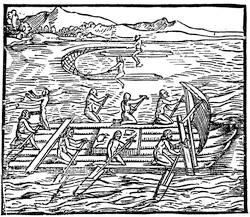

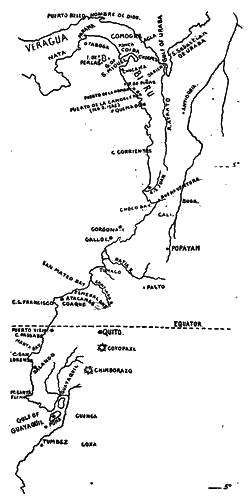

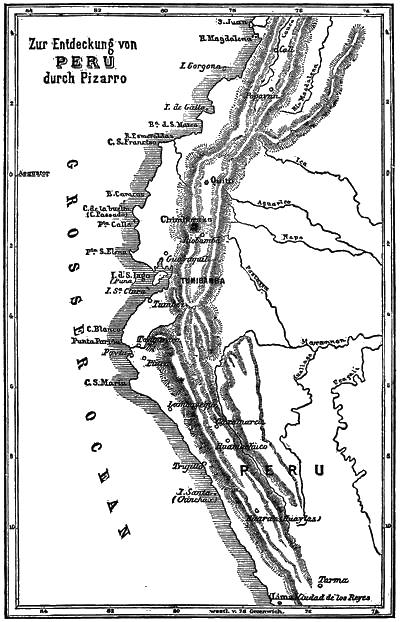

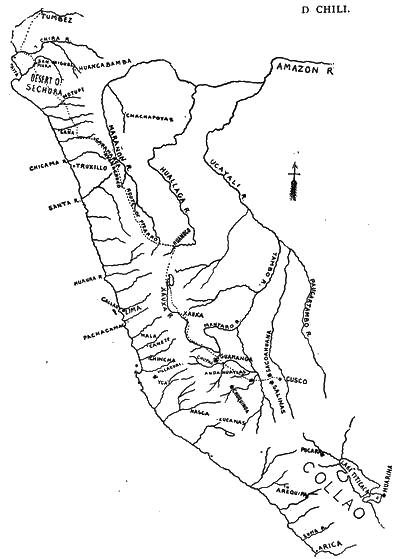

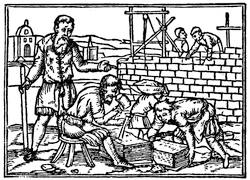

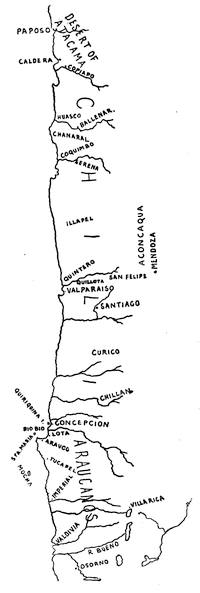

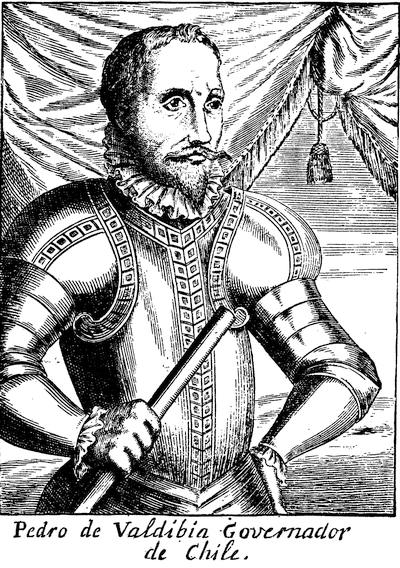

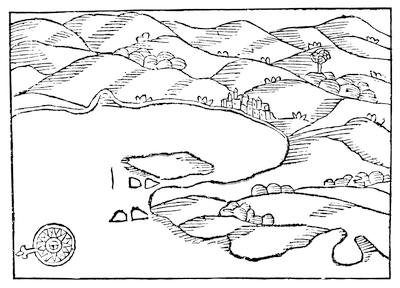

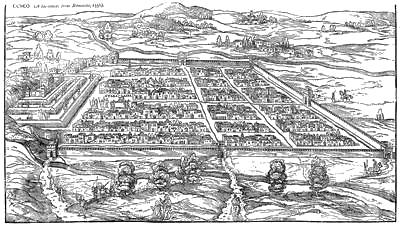

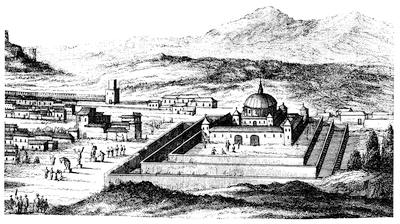

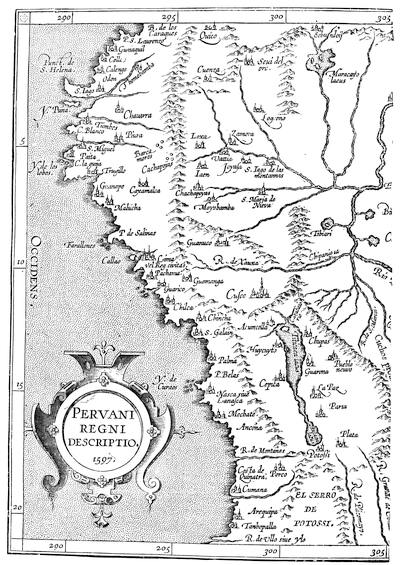

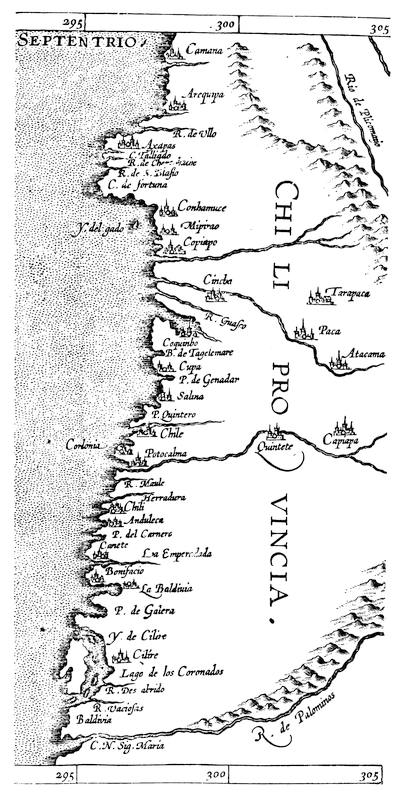

| Illustrations: Indian Rafts, 508; Sketch-maps of the Conquest of Peru, 509, 519; picture of Embarkation, 512; Ruge’s Map of Pizarro’s Discoveries, 513; Native Huts in Trees, 514; Atahualpa, 515, 516; Almagro, 518; Plan of Ynca Fortress near Cusco, 521; Building of a Town, 522; Gabriel de Rojas, 523; Sketch-map of the Conquest of Chili, 524; Pedro de Valdivia, 529, 530; Pastene, 531; Pizarro, 532, 533; Vaca de Castro, 535; Pedro de la Gasca, 539, 540; Alonzo de Alvarado, 544; Conception Bay, 548; Garcia Hurtado de Mendoza, 550; Peruvians worshipping the Sun, 551; Cusco, 554; Temple of Cusco, 555; Wytfliet’s Map of Peru, 558; of Chili, 559; Sotomayor, 562; Title of the 1535 Xeres, 565. | |

| Critical Essay | 563 |

| Illustration: Title of the 1535 Xeres, 565. | |

| Editorial Notes | 573 |

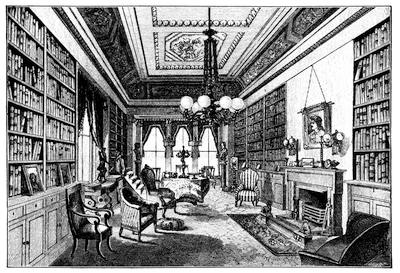

| Illustration: Prescott’s Library, 577. | |

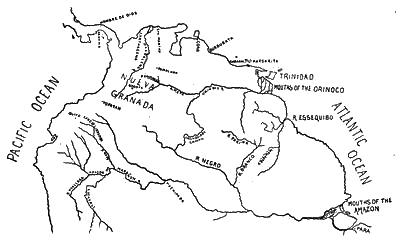

| THE AMAZON AND ELDORADO. The Editor | 579 |

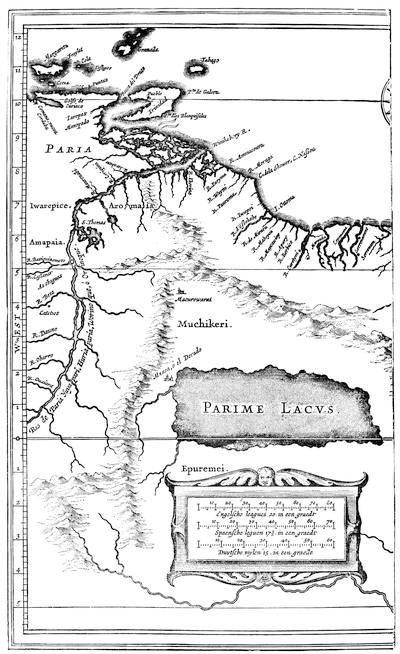

| Illustrations: Gonzalo Ximenes de Quesada, 580; Sketch-map, 581; Castellanos, 583; Map of the Mouths of the Orinoco, 586; De Laet’s Map of Parime Lacus, 588. | |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| Magellan’s Discovery. Edward E. Hale | 591 |

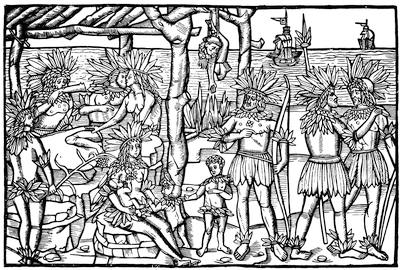

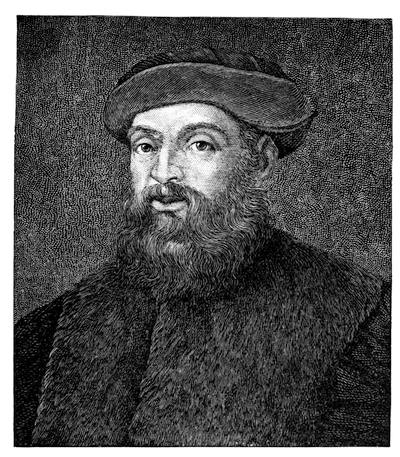

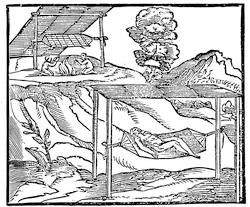

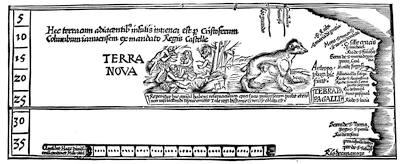

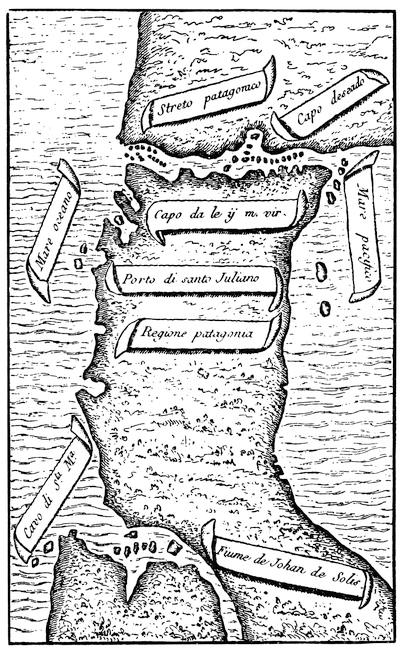

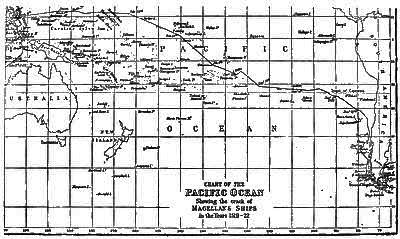

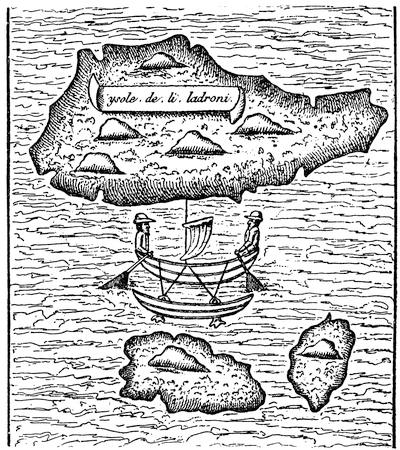

| Illustrations: Autograph of Magellan, 592; Portraits of Magellan, 593, 594, 595; Indian Beds, 597; South American Cannibals, 598; Giant’s Skeleton at Porto Desire, 602; Quoniambec, 603; Pigafetta’s Map of Magellan’s Straits, 605; Chart of the Pacific, showing Magellan’s Track, 610; Pigafetta’s Map of the Ladrones, 611. | |

| Critical Essay | 613 |

| INDEX | 619 |

INTRODUCTION.

BY THE EDITOR.

DOCUMENTARY SOURCES OF EARLY SPANISH-AMERICAN HISTORY.

THE earliest of the historians to use, to any extent, documentary proofs, was Herrera, in his Historia general, first published in 1601.[1] As the official historiographer of the Indies, he had the best of opportunities for access to the great wealth of documents which the Spanish archivists had preserved; but he never distinctly quotes them, or says where they are to be found.[2] It is through him that we are aware of some important manuscripts not now known to exist.[3]

The formation of the collections at Simancas, near Valladolid, dates back to an order of Charles the Fifth, Feb. 19, 1543. New accommodations were added from time to time, as documents were removed thither from the bureaus of the Crown Secretaries, and from those of the Councils of Seville and of the Indies. It was reorganized by Philip II., in 1567, on a larger basis, as a depository for historical research, when masses of manuscripts from other parts of Spain were transported thither;[4] but the comparatively small extent of the Simancas Collection does not indicate that the order was very extensively observed; though it must be remembered that Napoleon made havoc among these papers, and that in 1814 it was but a remnant which was rearranged.[5]

Dr. Robertson was the earliest of the English writers to make even scant use of the original manuscript sources of information; and such documents as he got from Spain were obtained through the solicitation and address of Lord Grantham, the English ambassador. Everything, however, was grudgingly given, after being first directly refused. It is well known that the Spanish Government considered even what he did obtain and make use of as unfit to be brought to the attention of their own public, and the authorities interposed to prevent the translation of Robertson’s history into Spanish.

In his preface Dr. Robertson speaks of the peculiar solicitude with which the Spanish archives were concealed from strangers in his time; and he tells how, to Spanish subjects even, those of Simancas were opened only upon a royal order. Papers notwithstanding such order, he says, could be copied only by payment of fees too exorbitant to favor research.[6] By order of Fernando VI., in the last century, a collection of selected copies of the most important documents in the various depositories of archives was made; and this was placed in the Biblioteca Nacional at Madrid.

In 1778 Charles III. ordered that the documents of the Indies in the Spanish offices and depositories should be brought together in one place. The movement did not receive form till 1785, when a commission was appointed; and not till 1788, did Simancas, and the other collections drawn upon, give up their treasures to be transported to Seville, where they were placed in the building provided for them.[7]

Muñoz, who was born in 1745, was commissioned in 1779 by the King with authority[8] to search archives, public and family, and to write and publish a Historia[iii] del nuevo mundo. Of this work only a single volume,[9] bringing the story down to 1500, was completed, and it was issued in 1793. Muñoz gave in its preface a critical review of the sources of his subject. In the prosecution of his labor he formed a collection of documents, which after his death was scattered; but parts of it were, in 1827, in the possession of Don Antonio de Uguina,[10] and later of Ternaux. The Spanish Government exerted itself to reassemble the fragments of this collection, which is now, in great part, in the Academy of History at Madrid,[11] where it has been increased by other manuscripts from the archives at Seville. Other portions are lodged, however, in ministerial offices, and the most interesting are noted by Harrisse in his Christophe Colomb.[12] A paper by Mr. J. Carson Brevoort on Muñoz and his manuscripts is in the American Bibliopolist (vol. viii. p. 21), February, 1876.[13] An English translation of Muñoz’s single volume appeared in 1797, with notes, mostly translated from the German version by Sprengel, published in 1795. Rich had a manuscript copy made of all that Muñoz wrote of his second volume (never printed), and this copy is noted in the Brinley Catalogue, no. 47.[14]

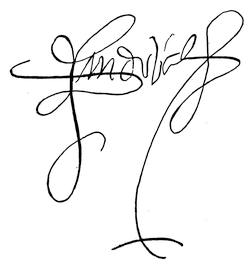

AUTOGRAPH OF MUÑOZ.

“In the days of Muñoz,” says Harrisse in his Notes on Columbus, p. 1, “the great repositories for original documents concerning Columbus and the early history of Spanish America were the Escurial, Simancas, the Convent of Monserrate, the colleges of St. Bartholomew and Cuenca at Salamanca, and St. Gregory at Valladolid, the Cathedral of Valencia, the Church of Sacro-Monte in Granada, the convents of St. Francis at Tolosa, St. Dominick at Malaga, St. Acacio, St. Joseph, and St. Isidro del Campo at Seville. There may be many valuable records still concealed in those churches and convents.”

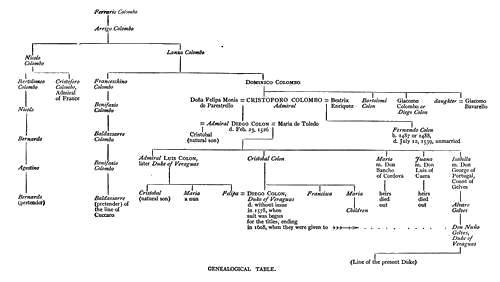

The originals of the letters-patent, and other evidences of privileges granted by the Spanish monarchs to Columbus, were preserved by him, and now constitute a part of the collection of the Duke of Veraguas, in Madrid. In 1502 Columbus caused several attested copies of them and of a few other documents to be made, raising the number of papers from thirty-six to forty-four. His care in causing these copies to be distributed among different custodians evinces the high importance which he held them to have, as testimonials to his fame and his prominence in the world’s history.[iv] One wishes he could have had a like solicitude for the exactness of his own statements. Before setting out on his fourth voyage, he intrusted one of these copies to Francesco di Rivarolo, for delivery to Nicoló Odérigo, the ambassador of Genoa, in Madrid. From Cadiz shortly afterwards he sent a second copy to the same Odérigo. In 1670 both of these copies were given, by a descendant of Odérigo, to the Republic of Genoa. They subsequently disappeared from the archives of the State, and Harrisse[15] has recently found one of them in the archives of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs at Paris. The other was bought in 1816 by the Sardinian Government, at a sale of the effects of Count Michael-Angelo Cambiasi. After a copy had been made and deposited in the archives at Turin, this second copy was deposited in a marble custodia, surmounted by a bust of Columbus, and placed in the palace of the Doges in Genoa.[16] These documents, with two of the letters addressed (March 21, 1502, and Dec. 27, 1504)[17] to Odérigo, were published in Genoa in 1823 in the Codice diplomatico Colombo-Americano, edited with a biographical introduction by Giovanni Battista Spotorno.[18] A third letter (April 2, 1502), addressed to the governors of the Bank of St. George, was not printed by Spotorno, but was given in English in 1851 in the Memorials of Columbus by Robert Dodge, published by the Maryland Historical Society.[19]

The State Archives of Genoa were transferred from the Ducal Palace, in 1817, to the Palazzetto, where they now are; and Harrisse’s account[20] of them tells us what they do not contain respecting Columbus, rather than what they do. We also learn from him something of the “Archives du Notariat Génois,” and of the collections formed by the Senator Federico Federici (d. 1647), by Gian Battista Richeri (circa 1724), and by others; but they seem to have afforded Harrisse little more than stray notices of early members of the Colombo family.

Washington Irving refers to the “self-sustained zeal of one of the last veterans of Spanish literature, who is almost alone, yet indefatigable, in his labors in a country where at present literary exertion meets with but little excitement or reward.” Such is his introduction of Martin Fernandez de Navarrete,[21] who was born in 1765,[v] and as a young man gave some active and meritorious service in the Spanish navy. In 1789 he was forced by ill-health to abandon the sea. He then accepted a commission from Charles IV. to examine all the depositories of documents in the kingdom, and arrange the material to be found in illustration of the history of the Spanish navy.[22] This work he continued, with interruptions, till 1825, when he began at Madrid the publication of his Coleccion de los viages y descubrimientos que hicieron por mar los Españoles desde fines del siglo XV.,[23] which reached an extent of five volumes, and was completed in 1837. It put in convenient printed form more than five hundred documents of great value, between the dates of 1393 and 1540. A sixth and seventh volume were left unfinished at his death, which occurred in 1844, at the age of seventy-eight.[24] His son afterward gathered some of his minor writings, including biographies of early navigators,[25] and printed (1848) them as a Coleccion de opúsculos; and in 1851 another of his works, Biblioteca maritima Española, was printed at Madrid in two volumes.[26]

The first two volumes of his collection (of which volumes there was a second edition in 1858) bore the distinctive title, Relaciones, cartas y otros documentos, concernientes á los cuatro viages que hizo el Almirante D. Cristóbal Colon para el descubrimiento de las Indias occidentales, and Documentos diplomáticos. Three years later (1828) a French version of these two volumes appeared at Paris, which Navarrete himself revised, and which is further enriched with notes by Humboldt, Jomard, Walckenaer, and others.[27] This French edition is entitled: Relation des quatres voyages entrepris par Ch. Colomb pour la découverte du Nouveau Monde de 1492 à 1504, traduite par Chalumeau de Vernéuil? et de la Roquette. It is in three volumes, and is worth about twenty francs. An Italian version, Narrazione dei quattro viaggi, etc., was made by F. Giuntini, and appeared in two volumes at Prato in 1840-1841.[28]

Navarrete’s literary labors did not prevent much conspicuous service on his part, both at sea and on land; and in 1823, not long before he published his great Collection, he became the head of the Spanish hydrographic bureau.[29] After his death the Spanish Academy printed (1846) his historical treatise on the Art of Navigation and kindred subjects (Disertacion sobre la historia de la náutica[30]), which was an enlargement of an earlier essay published in 1802.

While Navarrete’s great work was in progress at Madrid, Mr. Alexander H. Everett, the American Minister at that Court, urged upon Washington Irving, then at Bordeaux, the translation into English of the new material which Navarrete was preparing, together with his Commentary. Upon this incentive Irving went to Madrid and inspected the work, which was soon published. His sense of the popular demand easily convinced him that a continuous narrative, based upon Navarrete’s material,—but leaving himself free to use all other helps,—would afford him better opportunities to display his own graceful literary skill, and more readily to engage the favor of the general reader. Irving’s judgment was well founded; and Navarrete never quite forgave him for making a name more popularly associated with that of the great discoverer than his own.[31] Navarrete afforded Irving at this time much personal help and encouragement. Obadiah Rich, the American Consul at Valencia, under whose roof Irving lived, furnished him, however, his chief resource in a curious and extensive library. To the Royal Library, and to that of the Jesuit College of San Isidro, Irving also occasionally resorted. The Duke of Veraguas took pleasure in laying before him his own family archives.[32] The result was the Life and Voyages of Christopher Columbus; and in the Preface, dated at Madrid in 1827,[33] Irving made full acknowledgment of the services which had been rendered to him. This work was followed, not long after, by the Voyages and Discoveries of the Companions of Columbus; and ever since, in English and other languages, the two books have kept constant company.[34]

Irving proved an amiable hero-worshipper, and Columbus was pictured with few questionable traits. The writer’s literary canons did not call for the scrutiny which destroys a world’s exemplar. “One of the most salutary purposes of history,” he says, “is to furnish examples of what human genius and laudable enterprise may accomplish,”—and such brilliant examples must be rescued from the “pernicious erudition” of the investigator. Irving’s method at least had the effect to conciliate the upholders of the saintly character of the discoverer; and the modern school of the De Lorgues, who have been urging the canonization of Columbus, find Irving’s ideas of him higher and juster than those of Navarrete.

Henri Ternaux-Compans printed his Voyages, relations, et mémoires originaux pour servir à l’histoire de la dècouverte de l’Amérique, between 1837 and 1841.[35][vii] This collection included rare books and about seventy-five original documents, which it is suspected may have been obtained during the French occupation of Spain. Ternaux published his Archives des voyages, in two volumes, at Paris in 1840;[36] a minor part of it pertains to American affairs. Another volume, published at the same time, is often found with it,—Recueil de documents et mémoires originaux sur l’histoire des possessions Espagnoles dans l’Amérique, whose contents, it is said, were derived from the Muñoz Collection.

The Academy of History at Madrid began in 1842 a series of documentary illustrations which, though devoted to the history of Spain in general (Coleccion de documentos inéditos para la historia de España), contains much matter of the first importance in respect to the history of her colonies.[37] Navarrete was one of the original editors, but lived only to see five volumes published. Salvá, Baranda, and others have continued the publication since, which now amounts to eighty volumes, of which vols. 62, 63, and 64 are the famous history of Las Casas, then for the first time put in print.

In 1864 a new series was begun at Madrid,—Coleccion de documentos inéditos relativos al descubrimiento, conquista y colonizacion de las posesiones Españolas en América y Oceania, sacados, en su mayor parte, del Real Archivo de Indias. Nearly forty volumes have thus far been published, under the editing of Joaquin F. Pacheco, Francisco de Cárdenas, and Luis Torres de Mendoza at the start, but with changes later in the editorial staff.[38]

Mr. E. G. Squier edited at New York in 1860 a work called Collection of Rare and Original Documents and Relations concerning the Discovery and Conquest of America, chiefly from the Spanish Archives, in the original, with Translations, Notes, Maps, and Sketches. There was a small edition only,—one hundred copies on small paper, and ten on large paper.[39] This was but one of a large collection of manuscripts relative to Central America and Mexico which Mr. Squier had collected, partly during his term as chargé d’affaires in 1849. Out of these he intended a series of publications, which never went beyond this first number. The collection “consists,” says Bancroft,[40] “of extracts and copies of letters and reports of audiencias, governors, bishops, and various governmental officials, taken from the Spanish archives at Madrid and from the library of the Spanish Royal Academy of History, mostly under the direction of the indefatigable collector, Mr. Buckingham Smith.”

Early Spanish manuscripts on America in the British Museum are noted in its Index to Manuscripts, 1854-1875, p. 31; and Gayangos’ Catalogue of Spanish Manuscripts in the British Museum, vol. ii., has a section on America.[41]

Regarding the chances of further developments in depositories of manuscripts, Harrisse, in his Notes on Columbus,[42] says: “For the present the historian will find enough to gather from the Archivo General de Indias in the Lonja at Seville, which contains as many as forty-seven thousand huge packages, brought, within the last fifty years, from all parts of Spain. But the richest mine as yet unexplored we suppose to be the archives of the monastic orders in Italy; as all the expeditions to the New World were accompanied by Franciscan, Dominican, Benedictine, and other monks, who maintained an active correspondence with the heads of their respective congregations. The private archives of the Dukes of Veraguas, Medina-Sidonia, and Del Infantado, at Madrid, are very rich. There is scarce anything relating to that early period left in Simancas; but the original documents in the Torre do Tombo at Lisbon are all intact”[43]

Among the latest contributions to the documentary history of the Spanish colonization is a large folio, Cartas de Indias, publicalas por primera vez el ministerio de fomento, issued in Madrid in 1877 under the auspices of the Spanish Government. It contains one hundred and eight letters,[44] covering the period 1496 to 1586, the earliest date being a supposed one for a letter of Columbus which is without date.[ix] The late Mr. George Dexter,[45] who has printed[46] a translation of this letter (together with one of another letter, Feb. 6, 1502, and one of Vespucius, Dec. 9, 1508), gives his reasons for thinking the date should be between March 15 and Sept. 25, 1493.[47]

At Madrid and Paris was published, in 1883, a single octavo volume,—Costa-Rica, Nicaragua y Panamá en el siglo XVI., su historia y sus limítes segun los documentos del Archivo de Indias de Sevilla, del de Simancas, etc., recogidos y publicados con notas y aclaraciones históricas y geográficas, por D. Manuel M. de Peralta.

The more special and restricted documentary sources are examined in the successive chapters of the present volume.

NARRATIVE AND CRITICAL

HISTORY OF AMERICA.

CHAPTER I.

COLUMBUS AND HIS DISCOVERIES.

BY JUSTIN WINSOR,

The Editor.

BEYOND his birth, of poor and respectable parents, we know nothing positively about the earliest years of Columbus. His father was probably a wool-comber. The boy had the ordinary schooling of his time, and a touch of university life during a few months passed at Pavia; then at fourteen he chose to become a sailor. A seaman’s career in those days implied adventures more or less of a piratical kind. There are intimations, however, that in the intervals of this exciting life he followed the more humanizing occupation of selling books in Genoa, and perhaps got some employment in the making of charts, for he had a deft hand at design. We know his brother Bartholomew was earning his living in this way when Columbus joined him in Lisbon in 1470. Previous to this there seems to be some degree of certainty in connecting him with voyages made by a celebrated admiral of his time bearing the same family name, Colombo; he is also said to have joined the naval expedition of John of Anjou against Naples in 1459.[48] Again, he may have been the companion of another notorious corsair, a nephew of the one already mentioned, as is sometimes maintained; but this sea-rover’s proper name seems to have been more likely Caseneuve, though he was sometimes called Coulon or Colon.[49]

Columbus spent the years 1470-1484 in Portugal. It was a time when the air was filled with tales of discovery. The captains of Prince Henry of Portugal had been gradually pushing their ships down the African coast and in some of these voyages Columbus was a participant. To one of his navigators Prince Henry had given the governorship of the Island of Porto Santo, of the Madeira group. To the daughter of this man, Perestrello,[50] Columbus was married; and with his widow Columbus lived, and derived what advantage he could from the papers and charts of the old navigator. There was a tie between his own and his wife’s family in the fact that Perestrello was an Italian, and seems to have been of good family, but to have left little or no inheritance for his daughter beyond some property in Porto Santo, which Columbus went to enjoy. On this island Columbus’ son Diego was born in 1474.

It was in this same year (1474) that he had some correspondence with the Italian savant, Toscanelli, regarding the discovery of land westward. A belief in such discovery was a natural corollary of the object which Prince Henry had had in view,—by circumnavigating Africa to find a way to the countries of which Marco Polo had given golden accounts. It was to substitute for the tedious indirection of the African route a direct western passage,—a belief in the practicability of which was drawn from a confidence in the sphericity of the earth. Meanwhile, gathering what hope he could by reading the ancients, by conferring with wise men, and by questioning mariners returned from voyages which had borne them more or less westerly on the great ocean, Columbus suffered the thought to germinate as it would in his mind for several years. Even on the voyages which he made hither and thither for gain,—once far north, to Iceland even, or perhaps only to the Faröe Islands, as is inferred,—and in active participation in various warlike and marauding expeditions, like the attack on the Venetian galleys near Cape St. Vincent in 1485,[51] he constantly came in contact with those who could give him hints affecting his theory. Through all these years, however, we know not certainly what were the vicissitudes which fell to his lot.[52]

It seems possible, if not probable, that Columbus went to Genoa and Venice, and in the first instance presented his scheme of western exploration to the authorities of those cities.[53] He may, on the other hand; have tried earlier to get the approval of the King of Portugal. In this case the visit to Italy may have occurred in the year following his departure from Portugal, which is nearly a blank in the record of his life. De Lorgues[3] believes in the anterior Italian visit, when both Genoa and Venice rejected his plans; and then makes him live with his father at Savone, gaining a living by constructing charts, and by selling maps and books in Genoa.

It would appear that in 1484 Columbus had urged his views upon the Portuguese King, but with no further success than to induce the sovereign to despatch, on other pretences, a vessel to undertake the passage westerly in secrecy. Its return without accomplishing any discovery opened the eyes of Columbus to the deceit which that monarch would have put upon him, and he departed from the Portuguese dominions in not a little disgust.[54]

The death of his wife had severed another tie with Portugal; and taking with him his boy Diego, Columbus left, to go we scarcely know whither, so obscure is the record of his life for the next year. Muñoz claims for this period that he went to Italy. Sharon Turner has conjectured that he went to England; but there seems no ground to believe that he had any relations with the English Court except by deputy, for his brother Bartholomew was despatched to lay his schemes before Henry VII.[55] Whatever may have been the result of this application, no answer seems to have reached Columbus until he was committed to the service of Spain.

It was in 1485 or 1486—for authorities differ[56]—that a proposal was laid by Columbus before Ferdinand and Isabella; but the steps were slow by which he made even this progress. We know how, in the popular story, he presented himself at the Franciscan Convent of Santa María de la Rábida, asking for bread for himself and his boy. This convent stood on a steep promontory about half a league from Palos, and was then in charge of the Father Superior Juan Perez de Marchena.[57] The appearance of the stranger first, and his talk next, interested the Prior; and it was under his advice and support after a while—when Martin Alonzo Pinzon, of the neighboring town of Palos, had espoused the new theory—that Columbus was passed on to Cordova, with such claims to recognition as the Prior of Rabidá could bestow upon him.

It was perhaps while success did not seem likely here, in the midst of the preparations for a campaign against the Moorish kings, that his brother Bartholomew made his trip to England.[58] It was also in November, 1486, it[4] would seem, that Columbus formed his connection with Beatrix Enriquez, while he was waiting in Cordova for the attention of the monarch to be disengaged from this Moorish campaign.

COLUMBUS’ ARMOR.

This follows a cut in Ruge’s Geschichte des Zeitalters der Entdeckungen, p. 245. The armor is in the Collection in the Royal Palace at Madrid.

Among those at this time attached to the Court of Ferdinand and Isabella was Alexander Geraldinus, then about thirty years old. He was a traveller, a man of letters, and a mathematician; and it was afterward the boast of his kinsman, who edited his Itinerarium ad regiones sub æquinoctiali plaga constitutas[59] (Rome, 1631), that Geraldinus, in one way and another, aided Columbus in pressing his views upon their Majesties. It was through Geraldinus’ influence, or through that of others who had become impressed with his views, that Columbus finally got the ear of Pedro Gonzales de Mendoza, Archbishop of Toledo. The way was now surer. The King heeded the Archbishop’s advice, and a council of learned men was convened, by royal orders, at Salamanca, to judge Columbus and his theories. Here he was met by all that prejudice, content, and ignorance (as now understood, but wisdom then) could bring to bear, in the shape of Scriptural contradictions of his views, and the pseudo-scientific distrust of what were thought mere visionary aims. He met all to his own satisfaction, but not quite so successfully to the comprehension of his judges. He told them that he should find Asia that way; and that if he did not, there must be other lands westerly quite as desirable to discover. No conclusion had been reached when, in the spring of 1487, the Court departed from Cordova, and Columbus found himself left behind without encouragement, save in the support of a few whom he had convinced,—notably Diego de Deza, a friar destined to some ecclesiastical distinction as Archbishop of Seville.

During the next five years Columbus experienced every vexation attendant upon delay, varied by participancy in the wars which the Court urged against the Moors, and in which he sought to propitiate the royal powers by doing them good service in the field. At last, in 1491, wearied with excuses of pre-occupation and the ridicule of the King’s advisers, Columbus turned his back on the Court and left Seville,[60] to try his fortune with some of the Grandees. He still urged in vain, and sought again the Convent of Rabida. Here he made a renewed impression upon Marchena; so that finally, through the Prior’s interposition with Isabella, Columbus was summoned to Court. He arrived in time to witness the surrender of Granada, and to find the monarchs more at liberty to listen to his words. There seemed now a likelihood of reaching an end of his tribulations; when his demand of recognition as viceroy, and his claim to share one tenth of all income from the territories to be discovered, frightened as well as disgusted those appointed to negotiate with him, and all came once more to an end. Columbus mounted his mule and started for France. Two finance ministers of the Crown, Santangel for Arragon and Quintanilla for Castile, had been sufficiently impressed by the new theory to look with regret on what they thought might be a lost opportunity. Isabella was won; and a messenger was despatched to overtake Columbus.

The fugitive returned; and on April 17, 1492, at Santa Fé, an agreement was signed by Ferdinand and Isabella which gave Columbus the office of high-admiral and viceroy in parts to be discovered, and an income of one eighth of the profits, in consideration of his assuming one eighth of the costs. Castile bore the rest of the expense; but Arragon advanced the money,[61] and the Pinzons subscribed the eighth part for Columbus.

The happy man now solemnly vowed to use what profits should accrue in accomplishing the rescue of the Holy Sepulchre from the Moslems. Palos, owing some duty to the Crown, was ordered to furnish two armed caravels, and Columbus was empowered to fit out a third. On the 30th of April the letters-patent confirming his dignities were issued. His son Diego was made a page of the royal household. On May 12 he left the Court and hastened towards Palos. Here, upon showing his orders for the vessels, he found the town rebellious, with all the passion of a people who felt that some of their number were being simply doomed to destruction beyond that Sea of Darkness whose bounds they knew not. Affairs were in this unsatisfactory condition when the brothers Pinzon threw themselves and their own vessels into the cause; while a[6] third vessel, the “Pinta,” was impressed,—much to the alarm of its owners and crew.

PARTING OF COLUMBUS WITH FERDINAND AND ISABELLA.

Fac-simile of the engraving in Herrera. It originally appeared in De Bry, part iv.

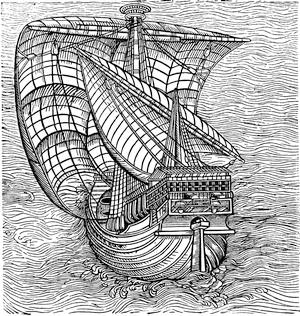

EARLY VESSELS.

This representation of the vessels of the early Spanish navigators is a fac-simile of a cut in Medina’s Arte de navegar, Valladolid, 1545, which was re-engraved in the Venice edition of 1555. Cf. Carter-Brown Catalogue, vol. i. nos. 137, 204; Ruge, Geschichte des Zeitalters der Entdeckungen, pp. 240, 241; Jurien de la Gravière’s Les marins du XVe et du XVIe siècle, vol. i. pp. 38, 151. In the variety of changes in methods of measurement it is not easy to find the equivalent in tonnage of the present day for the ships of Columbus’s time. Those constituting his little fleet seem to have been light and swift vessels of the class called caravels. One had a deck amidships, with high forecastle and poop, and two were without this deck, though high, and covered at the ends. Captain G. V. Fox has given what he supposes were the dimensions of the larger one,—a heavier craft and duller sailer than the others. He calculates for a hundred tons,—makes her sixty-three feet over all, fifty-one feet keel, twenty feet beam, and ten and a half feet draft of water. She carried the kind of gun termed lombards, and a crew of fifty men. U. S. Coast Survey Report, 1880, app. 18; Becher’s Landfall of Columbus; A. Jal’s Archéologie navale (Paris, 1840); Irving’s Columbus, app. xv.; H. H. Bancroft, Central America, i. 187; Das Ausland, 1867, p. 1. There are other views of the ships of Columbus’ time in the cuts in some of the early editions of his Letters on the discovery. See notes following this chapter.

And so, out of the harbor of Palos,[62] on the 3d of August, 1492, Columbus sailed with his three little vessels. The “Santa Maria,” which carried his flag, was the only one of the three which had a deck, while the other two, the “Niña” and the “Pinta,” were open caravels. The two Pinzons commanded these smaller ships,—Martin Alonzo the “Pinta”, and Vicente the “Niña.”

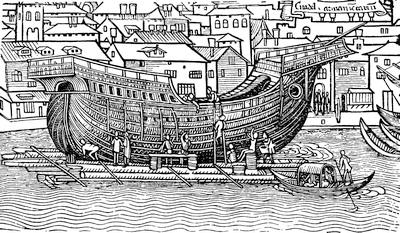

BUILDING A SHIP.

This follows a fac-simile, given in Ruge, Geschichte des Zeitalters der Entdeckungen p. 240, of a cut in Bernhardus de Breydenbach’s Peregrinationes, Mainz, 1486.

The voyage was uneventful, except that the expectancy of all quickened the eye, which sometimes saw over-much, and poised the mind, which was alert with hope and fear. It has been pointed out how a westerly course from Palos would have discouraged Columbus with head and variable winds. Running down to the Canaries (for Toscanelli put those islands in the latitude of Cipango), a westerly course thence would bring him within the continuous easterly trade-winds, whose favoring influence would inspirit his men,—as, indeed, was the case. Columbus, however, was very glad on the 22d of September to experience a west wind, just to convince his crew it was possible to have, now and then, the direction of it favorable to their return. He had proceeded, as he thought, some two hundred miles farther than the longitude in which he had conjectured Cipango to be, when the urging of Martin Alonzo Pinzon, and the flight of birds indicating land to be nearer in the southwest, induced him to change his course in that direction.[63]

COURSE OF COLUMBUS ON FIRST VOYAGE.

This follows a map given in Das Ausland, 1867, p. 4, in a paper on Columbus’ Journal, “Das Schiffsbuch des Entdeckers von Amerika.” The routes of Columbus’ four voyages are marked on the map accompanying the Studi biografici e bibliografici published by the Società Geografica Italiana in 1882. Cf. also the map in Charton’s Voyageurs, iii. 155, reproduced on a later page.

About midnight between the 11th and 12th of October, Columbus on the lookout thought he saw a light moving in the darkness. He called a companion, and the two in counsel agreed that it was so.[64] At about two o’clock, the moon then shining, a mariner on the “Pinta” discerned unmistakably a low sandy shore. In the morning a landing was made, and, with prayer[65] and ceremony,[10] possession was taken of the new-found island in the name of the Spanish sovereigns.

SHIP OF COLUMBUS’S TIME.

This follows a fac-simile, given in Ruge, Geschichte des Zeitalters der Entdeckungen, p. 241, of a cut in Bernhardus de Breydenbach’s Peregrinationes, Mainz, 1486.

On the third day (October 14) Columbus lifted anchor, and for ten days sailed among the minor islands of the archipelago; but struck the Cuban coast on the 28th.[66] Here the “Pinta,” without orders from the Admiral, went off to seek some gold-field, of which Martin Alonzo Pinzon, its commander, fancied he had got some intimation from the natives. Pinzon returned bootless; but Columbus was painfully conscious of the mutinous spirit of his lieutenant.[67] The little fleet next found Hayti (Hispaniæ insula,[68] as he called it), and on its northern side the Admiral’s ship was wrecked. Out of her timbers Columbus built a fort on the shore, called it “La Navidad,” and put into it a garrison under Diego de Arana.[69]

NATIVE HOUSE IN HISPANIOLA.

Fac-simile of a cut in Oviedo, edition of 1547, fol. lix. There is another engraving in Charton’s Voyageurs, iii. 124. Cf. also Ramusio, Nav. et Viaggi, iii.

With the rest of his company and in his two smaller vessels, on the 4th of January, 1493, Columbus started on his return to Spain. He ran northerly to the latitude of his destination, and then steered due east. He experienced severe weather, but reached the Azores safely; and then, passing on, entered the Tagus and had an interview with the Portuguese King. Leaving Lisbon on the 13th, he reached Palos on the 15th of March, after an absence of over seven months.

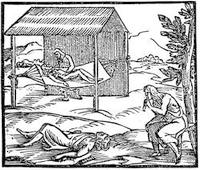

CURING THE SICK.

This is Benzoni’s sketch of the way in which the natives cure and tend their sick at Hispaniola. Edition of 1572, p. 56.

He was received by the people of the little seaport with acclamations and wonder; and, despatching a messenger to the Spanish Court at Barcelona, he proceeded to Seville to await the commands of the monarchs. He was soon bidden to hasten to them; and with the triumph of more than a conqueror, and preceded by the bedizened Indians whom he had brought with him, he entered the city and stood in the presence of the sovereigns. He was commanded to sit before them, and to tell the story of his discovery. This he did with conscious pride; and not forgetting the past,[12] he publicly renewed his previous vow to wrest the Holy Sepulchre from the Infidel.

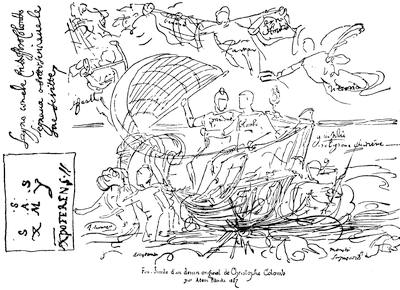

THE TRIUMPH OF COLUMBUS.

This is a reduction of a fac-simile by Pilinski, given in Margry’s Les Navigations Françaises, p. 360,—an earlier reproduction having been given by M. Jal in La France maritime. It is also figured in Charton’s Voyageurs, iii. 139. The original sketch, by Columbus himself, was sent by him from Seville in 1502, and is preserved in the city hall at Genoa. M. Jal gives a description of it in his De Paris à Naples, 1836, i. 257. The figure sitting beside Columbus is Providence; Envy and Ignorance are hinted at as monsters following in his wake; while Constancy, Tolerance, the Christian Religion, Victory, and Hope attend him. Above all is the floating figure of Fame blowing two trumpets, one marked “Genoa,” the other “Fama Columbi.” Harrisse (Notes on Columbus, p. 165) says that good judges assign this picture to Columbus’s own hand, though none of the drawings ascribed to him are authentic beyond doubt; while it is very true that he had the reputation of being a good draughtsman. Feuillet de Conches (Revue contemporaine, xxiv. 509) disbelieves in its authenticity. The usual signature of Columbus is in the lower left-hand corner of the above sketch, the initial letters in which have never been satisfactorily interpreted; but perhaps as reasonable a guess as any would make them stand for “Servus supplex Altissimi Salvatoris—Christus, Maria, Yoseph—Christo ferens.” Others read, “Servidor sus Altezas sacras, Christo, Maria, Ysabel [or Yoseph].” The “Christo ferens” is sometimes replaced by “El Almirante.” The essay on the autograph in the Cartas de Indias is translated in the Magazine of American History, Jan., 1883, p. 55. Cf. Irving, app. xxxv. Ruge, Geschichte des Zeitalters der Entdeckungen, p. 317; Massachusetts Historical Society Proceedings, xvi. 322, etc.

The expectation which had sustained Columbus in his voyage, and which he thought his discoveries had confirmed, was that he had reached[13] the western parts of India or Asia; and the new islands were accordingly everywhere spoken of as the West Indies, or the New World.

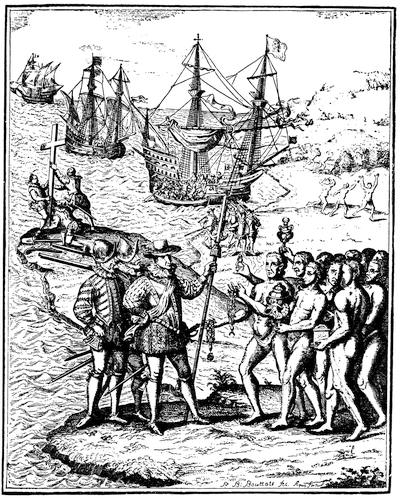

COLUMBUS AT HISPANIOLA.

Fac-simile of engraving in Herrera, who follows DeBry.

HANDWRITING OF COLUMBUS.

Last page of an autograph letter preserved in the Colombina Library at Seville, following a photograph in Harrisse’s Notes on Columbus, p. 218.

The ruling Pope, Alexander VI., was a native Valencian; and to him an appeal was now made for a Bull, confirming to Spain and Portugal respective[14] fields for discovery. This was issued May 4, 1493, fixing a line, on the thither side of which Spain was to be master; and on the hither side, Portugal. This was traced at a meridian one hundred leagues west of the Azores and Cape de Verde Islands, which were assumed to be in the same longitude practically. The thought of future complications from the running of this line to the antipodes does not seem to have alarmed either Pope or sovereigns; but troubles on the Atlantic side were soon to arise, to be promptly compounded by a convention at Tordesillas, which agreed (June 4, ratified June 7, 1494) to move the meridian line to a point three[15] hundred and seventy leagues west of the Cape de Verde Islands,—still without dream of the destined disputes respecting divisions on the other side of the globe.[70]

ARMS OF COLUMBUS.

As given in Oviedo’s Coronica, 1547, fol. x., from the Harvard College copy. There is no wholly satisfactory statement regarding the origin of these arms, or the Admiral’s right to bear them. It is the quartering of the royal lion and castle, for Arragon and Castile, with gold islands in azure waves. Five anchors and the motto,

“A [or POR] Castilla y a [or POR] Leon Nuevo Mundo dio [or HALLO] Colon,”

were later given or assumed. The crest varies in the Oviedo (i. cap. vii.) of 1535.

Thus everything favored Columbus in the preparations for a second voyage, which was to conduct a colony to the newly discovered lands. Twelve hundred souls were embarked on seventeen vessels, and among them persons of consideration and name in subsequent history,—Diego,[16] the Admiral’s brother, Bernal Diaz del Castillo, Ojeda, and La Cosa, with the Pope’s own vicar, a Benedictine named Buil, or Boil.

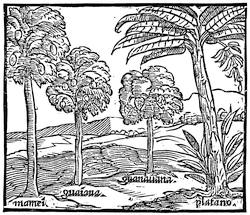

FRUIT-TREES OF HISPANIOLA.

This is Benzoni’s sketch, edition of 1572, p. 60.

Columbus and the destined colonists sailed from Cadiz on the 25th of September. The ships sighted an island on the 3d of November, and continuing their course among the Caribbee Islands, they finally reached La Navidad, and found it a waste. It was necessary, however, to make a beginning somewhere; and a little to the east of the ruined fort they landed their supplies and began the laying out of a city, which they called Isabella.[71] Expeditions were sent inland to find gold. The explorers reported success. Twelve of the ships were sent home with Indians who had been seized; and these ships were further laden with products of the soil which had been gathered. Columbus himself went with four hundred men to begin work at the interior mines; but the natives, upon whom he had counted for labor, had begun to fear enslavement for this purpose, and kept aloof. So mining did not flourish. Disease, too, was working evil. Columbus himself had been prostrated; but he was able to conduct three caravels westward, when he discovered Jamaica. On this expedition he made up his mind that Cuba was a part of the Asiatic main, and somewhat unadvisedly forced his men to sign a paper declaring their own belief to the same purport.[72]

INDIAN CLUB.

As given in Oviedo, edition of 1547, fol. lxi.

Returning to his colony, the Admiral found that all was not going well. He had not himself inspired confidence as a governor, and his fame as an explorer was fast being eclipsed by his misfortunes as a ruler. Some of his colonists, accompanied by the papal vicar, had seized ships and set sail[17] for home. The natives, emboldened by the cruelties practised upon them, were laying siege to his fortified posts. As an offset, however, his brother Bartholomew had arrived from Spain with three store-ships; and later came Antonio de Torres with four other ships, which in due time were sent back to carry some samples of gold and a cargo of natives to be sold as slaves. The vessels had brought tidings of the charges preferred at Court against the Admiral, and his brother Diego was sent back with the ships to answer these charges in the Admiral’s behalf. Unfortunately Diego was not a man of strong character, and his advocacy was not of the best.

INDIAN CANOE.

As depicted in Oviedo, edition of 1547, fol. lxi. There is another engraving in Charton’s Voyageurs, iii. 106, called “Pirogue Indienne.”

INDIAN CANOE.

Benzoni gives this drawing of the canoes of the coast of the Gulf of Paria and thereabout. Edition of 1572, p. 5.

In March (1495) Columbus conducted an expedition into the interior to subdue and hold tributary the native population. It was cruelly done, as the world looks upon such transactions to-day.

Meanwhile in Spain reiteration of charges was beginning to shake the confidence of his sovereigns; and Juan Aguado, a friend of Columbus, was sent to investigate. He reached[18] Isabella in October,—Diego, the Admiral’s brother, accompanying him. Aguado did not find affairs reassuring; and when he returned to Spain with his report in March (1496), Columbus thought it best to go too, and to make his excuses or explanations in person. They reached Cadiz in June, just as Niño was sailing with three caravels to the new colony.

COLUMBUS AT ISLA MARGARITA.

Fac-simile of engraving in Herrera.

Ferdinand and Isabella received him kindly, gave him new honors, and promised him other outfits. Enthusiasm, however, had died out, and delays took place. The reports of the returning ships did not correspond with the pictures of Marco Polo, and the new-found world was thought to be a very poor India after all. Most people were of this mind; though Columbus was not disheartened, and the public treasury was readily opened for a third voyage.

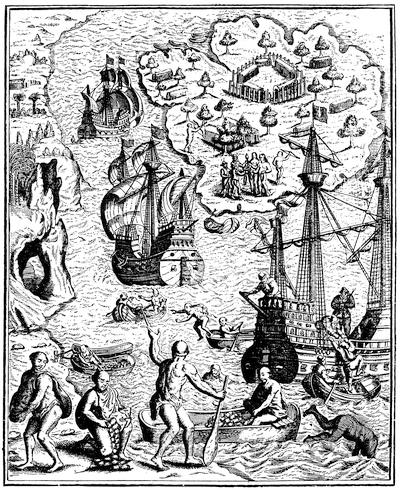

AMERICANS.

This is the earliest representation which we have of the natives of the New World, showing such as were found by the Portuguese on the north coast of South America. It has been supposed that it was issued in Augsburg somewhere between 1497 and 1504, for it is not dated. The only copy ever known to bibliographers is not now to be traced. Stevens, Recoll. of James Lenox, p. 174. It measures 13½ × 8½ inches, with a German title and inscription, to be translated as follows:—

“This figure represents to us the people and island which have been discovered by the Christian King of Portugal, or his subjects. The people are thus naked, handsome, brown, well-shaped in body; their heads, necks, arms, private parts, feet of men and women, are a little covered with feathers. The men also have many precious stones on their faces and breasts. No one else has anything, but all things are in common. And the men have as wives those who please them, be they mothers, sisters, or friends; therein make they no distinction. They also fight with each other; they also eat each other, even those who are slain, and hang the flesh of them in the smoke. They become a hundred and fifty years of age, and have no government.”

The present engraving follows the fac-simile given in Stevens’s American Bibliographer, pp. 7, 8. Cf. Sabin, vol. i. no. 1,031; vol. v. no. 20,257; Harrisse, Bibl. Amer. Vet., no. 20.

Coronel sailed early in 1498 with two ships, and Columbus followed with six, embarking at San Lucar on the 30th of May. He now discovered[20] Trinidad (July 31), which he named either from its three peaks, or from the Holy Trinity; struck the northern coast of South America,[73] and skirted what was later known as the Pearl coast, going as far as the Island of Margarita. He wondered at the roaring fresh waters which the Orinoco pours into the Gulf of Pearls, as he called it, and he half believed that its exuberant tide came from the terrestrial paradise.[74] He touched the southern coast of Hayti on the 30th of August. Here already his colonists had established a fortified post, and founded the town of Santo Domingo. His brother Bartholomew had ruled energetically during the Admiral’s absence, but he had not prevented a revolt, which was headed by Roldan. Columbus on his arrival found the insurgents still defiant, but was able after a while to reconcile them, and he even succeeded in attaching Roldan warmly to his interests.

Columbus’ absence from Spain, however, left his good name without sponsors; and to satisfy detractors, a new commissioner was sent over with enlarged powers, even with authority to supersede Columbus in general command, if necessary. This emissary was Francisco de Bobadilla, who arrived at Santo Domingo with two caravels on the 23d of August, 1500, finding Diego in command, his brother the Admiral being absent. An issue was at once made. Diego refused to accede to the commissioner’s orders till Columbus returned to judge the case himself; so Bobadilla assumed charge of the Crown property violently, took possession of the Admiral’s house, and when Columbus returned, he with his brother was arrested and put in irons. In this condition the prisoners were placed on shipboard, and sailed for Spain. The captain of the ship offered to remove the manacles; but Columbus would not permit it, being determined to land in Spain bound as he was; and so he did. The effect of his degradation was to his advantage; sovereigns and people were shocked at the sight; and Ferdinand and Isabella hastened to make amends by receiving him with renewed favor. It was soon apparent that everything reasonable would be granted him by the monarchs, and that he could have all he might wish, short of receiving a new lease of power in the islands, which the sovereigns were determined to see pacified at least before Columbus should again assume government of them. The Admiral had not forgotten his vow to wrest the Holy Sepulchre from the Infidel; but the monarchs did not accede to his wish to undertake it. Disappointed in this, he proposed a new voyage; and getting the royal countenance for this scheme, he was supplied with four vessels of from fifty to seventy tons each,—the “Capitana,” the “Santiago de Palos,” the “Gallego,” and the “Vizcaino.” He[21] sailed from Cadiz May 9, 1502, accompanied by his brother Bartholomew and his son Fernando. The vessels reached San Domingo June 29.

Bobadilla, whose rule of a year and a half had been an unhappy one, had given place to Nicholás de Ovando; and the fleet which brought the new governor,—with Maldonado, Las Casas, and others,—now lay in the harbor waiting to receive Bobadilla for the return voyage. Columbus had been instructed to avoid Hispaniola; but now that one of his vessels leaked, and he needed to make repairs, he sent a boat ashore, asking permission to enter the harbor. He was refused, though a storm was impending. He sheltered his vessels as best he could, and rode out the gale. The fleet which had on board Bobadilla and Roldan, with their ill-gotten gains, was wrecked, and these enemies of Columbus were drowned. The Admiral found a small harbor where he could make his repairs; and then, July 14, sailed westward to find, as he supposed, the richer portions of India in exchange for the barbarous outlying districts which others had appropriated to themselves. He went on through calm and storm, giving names to islands,—which later explorers re-named, and spread thereby confusion on the early maps. He began to find more intelligence in the natives of these islands than those of Cuba had betrayed, and got intimations of lands still farther west, where copper and gold were in abundance. An old Indian made them a rough map of the main shore. Columbus took him on board, and proceeding onward a landing was made on the coast of Honduras August 14. Three days later the explorers landed again fifteen leagues farther east, and took possession of the country for Spain. Still east they went; and, in gratitude for safety after a long storm, they named a cape which they rounded Gracias á Dios,—a name still preserved at the point where the coast of Honduras begins to trend southward. Columbus was now lying ill on his bed, placed on deck, and was half the time in revery. Still the vessels coasted south. They lost a boat’s crew in getting water at one place; and tarrying near the mouth of the Rio San Juan, they thought they got from the signs of the natives intelligence of a rich and populous country over the mountains inland, where the men wore clothes and bore weapons of steel, and the women were decked with corals and pearls. These stories were reassuring; but the exorcising incantations of the natives were quite otherwise for the superstitious among the Spaniards.

They were now on the shores of Costa Rica, where the coast trends southeast; and both the rich foliage and the gold plate on the necks of the savages enchanted the explorers. They went on towards the source of this wealth, as they fancied. The natives began to show some signs of repulsion; but a few hawk’s-bells beguiled them, and gold plates were received in exchange for the trinkets. The vessels were now within the southernmost loop of the shore, and a bit of stone wall seemed to the Spaniards a token of civilization. The natives called a town hereabouts Veragua,—whence, years after, the descendants of Columbus borrowed the[22] ducal title of his line. In this region Columbus dallied, not suspecting how thin the strip of country was which separated him from the great ocean whose farther waves washed his desired India. Then, still pursuing the coast, which now turned to the northeast, he reached Porto Bello, as we call it, where he found houses and orchards. Tracking the Gulf side of the Panama isthmus, he encountered storms that forced him into harbors, which continued to disclose the richness of the country.[75]

It became now apparent that they had reached the farthest spot of Bastidas’ exploring, who had, in 1501, sailed westward along the northern coast of South America. Amid something like mutinous cries from the sailors, Columbus was fain to turn back to the neighborhood of Veragua, where the gold was; but on arriving there, the seas, lately so fair, were tumultuous, and the Spaniards were obliged to repeat the gospel of Saint John to keep a water-spout, which they saw, from coming their way,—so Fernando says in his Life of the Admiral. They finally made a harbor at the mouth of the River Belen, and began to traffic with the natives, who proved very cautious and evasive when inquiries were made respecting gold-mines. Bartholomew explored the neighboring Veragua River in armed boats, and met the chief of the region, with retainers, in a fleet of canoes. Gold and trinkets were exchanged, as usual, both here and later on the Admiral’s deck. Again Bartholomew led another expedition, and getting the direction—a purposely false one, as it proved—from the chief in his own village, he went to a mountain, near the abode of an enemy of the chief, and found gold,—scant, however, in quantity compared with that of the crafty chief’s own fields. The inducements were sufficient, however, as Columbus thought, to found a colony; but before he got ready to leave it, he suspected the neighboring chief was planning offensive operations. An expedition was accordingly sent to seize the chief, and he was captured in his own village; and so suddenly that his own people could not protect him. The craft of the savage, however, stood him in good stead; and while one of the Spaniards was conveying him down the river in a boat, he jumped overboard and disappeared, only to reappear, a few days later, in leading an attack on the Spanish camp. In this the Indians were repulsed; but it was the beginning of a kind of lurking warfare that disheartened the Spaniards. Meanwhile Columbus, with the ship, was outside the harbor’s bar buffeting the gales. The rest of the prisoners who had been taken with the chief were confined in his forecastle. By concerted action some of them got out and jumped overboard, while those not so fortunate killed themselves. As soon as the storm was over, Columbus withdrew the colonists and sailed away. He abandoned one worm-eaten caravel at Porto Bello, and, reaching Jamaica, beached two others.

A year of disappointment, grief, and want followed. Columbus clung to his wrecked vessels. His crew alternately mutinied at his side, and roved[23] about the island. Ovando, at Hispaniola, heard of his straits, but only tardily and scantily relieved him. The discontented were finally humbled; and some ships, despatched by the Admiral’s agent in Santo Domingo, at last reached him, and brought him and his companions to that place, where Ovando received him with ostentatious kindness, lodging him in his house till Columbus departed for Spain, Sept. 12, 1504.

On the 7th of November the Admiral reached the harbor of San Lucar. Weakness and disease later kept him in bed in Seville, and to his letters of appeal the King paid little attention. He finally recovered sufficiently to go to the Court at Segovia, in May, 1505; but Ferdinand—Isabella had died Nov. 26, 1504—gave him scant courtesy. With a fatalistic iteration, which had been his error in life, Columbus insisted still on the rights which a better skill in governing might have saved for him; and Ferdinand, with a dread of continued maladministration, as constantly evaded the issue. While still hope was deferred, the infirmities of age and a life of hardships brought Columbus to his end; and on Ascension Day, the 20th of May, 1506, he died, with his son Diego and a few devoted friends by his bedside.

HOUSE IN WHICH COLUMBUS DIED.

This follows an engraving in Ruge, Geschichte des Zeitalters der Entdeckungen, p. 313, taken from a photograph. The house is in Valladolid.

The character of Columbus is not difficult to discern. If his mental and moral equipoise had been as true, and his judgment as clear, as his spirit was lofty and impressive, he could have controlled the actions of men as readily as he subjected their imaginations to his will, and more than one brilliant opportunity for a record befitting a ruler of men would not have been lost. The world always admires constancy and zeal; but when it is fed, not by well-rounded performance, but by self-satisfaction and self-interest, and tarnished by deceit, we lament where we would approve. Columbus’ imagination was eager, and unfortunately ungovernable. It led him to a great discovery, which he was not seeking for; and he was far enough right to make his error more emphatic. He is certainly not alone among the great men of the world’s regard who have some of the attributes of the small and mean.

CRITICAL ESSAY ON THE SOURCES OF INFORMATION.

It would appear, from documents printed by Navarrete, that in 1470 Columbus was brooding on the idea of land to the west. It is not at all probable that he would himself have been able to trace from germ to flower the conception which finally possessed his mind.[76] The age was ripened for it; and the finding of Brazil in 1500 by Cabral showed how by an accident the theory might have become a practical result at any time after the sailors of Europe had dared to take long ocean voyages. Columbus grew to imagine that he had been independent of the influences of his time; and in a manuscript in his own hand, preserved in the Colombina Library at Seville, he shows the weak, almost irresponsible, side of his mind, and flouts at the grounds of reasonable progress which many others besides himself had been making to a belief in the feasibility of a western passage. In this unfortunate writing he declares that under inspiration he simply accomplished the prophecy of Isaiah.[77] This assertion has not prevented saner and later writers[78] from surveying the evidences of the growth of the belief in the mind, not of Columbus only, but of others whom he may have impressed, and by whom he may have been influenced. The new intuition was but the result of intellectual reciprocity. It needed a daring exponent, and found one.

The geographical ideas which bear on this question depend, of course, upon the sphericity of the earth.[79] This was entertained by the leading cosmographical thinkers of that age,—who were far however from being in accord in respect to the size of the globe. Going back to antiquity, Aristotle and Strabo had both taught in their respective times the spherical theory; but they too were widely divergent upon the question of size,—Aristotle’s ball being but mean in comparison with that of Strabo, who was not far wrong when he contended that the world then known was something more than one third of the actual circumference of the whole, or one hundred and twenty-nine degrees, as he put it; while Marinus, the Tyrian, of the opposing school, and the most eminent geographer before Ptolemy, held that the extent of the then known world spanned as much as two hundred and twenty-five degrees, or about one hundred degrees too much.[80] Columbus’ calculations were all on the side of this insufficient size.[81] He wrote to Queen Isabella in 1503 that “the earth is smaller than people suppose.” He thought but one seventh of it was water. In sailing a direct western course his expectation was to reach Cipango after having gone[25] about three thousand miles. This would actually have brought him within a hundred miles or so of Cape Henlopen, or the neighboring coast; while if no land had intervened he would have gone nine thousand eight hundred miles to reach Japan, the modern Cipango.[82] Thus Columbus’ earth was something like two thirds of the actual magnitude.[83] It can readily be understood how the lesser distance was helpful in inducing a crew to accompany Columbus, and in strengthening his own determination.

Whatever the size of the earth, there was far less palpable reason to determine it than to settle the question of its sphericity. The phenomena which convince the ordinary mind to-day, weighed with Columbus as they had weighed in earlier ages. These were the hulling down of ships at sea, and the curved shadow of the earth on the moon in an eclipse. The law of gravity was not yet proclaimed, indeed; but it had been observed that the men on two ships, however far apart, stood perpendicular to their decks at rest.

Columbus was also certainly aware of some of the views and allusions to be found in the ancient writers, indicating a belief in lands lying beyond the Pillars of Hercules.[84] He enumerates some of them in the letter which he wrote about his third voyage, and which is printed in Navarrete. The Colombina Library contains two interesting memorials of his[26] connection with this belief. One is a treatise in his own hand, giving his correspondence with Father Gorricio, who gathered the ancient views and prophecies;[85] and the other is a copy of Gaietanus’ edition of Seneca’s tragedies, published indeed after Columbus’ death, in which the passage of the Medea, known to have been much in Columbus’ mind, is scored with the marginal comment of Ferdinand, his son, “Hæc prophetia expleta ē per patrē meus cristoforū colō almirātē anno 1492.”[86] Columbus, further, could not have been unaware of the opposing theories of Ptolemy and Pomponius Mela as to the course in which the further extension of the known world should be pursued. Ptolemy held to the east and west theory, and Mela to the northern and southern view.

PTOLEMY.

Fac-simile of a cut in Icones sive imagines vivæ literis cl. virorum ... cum elogiis variis per Nicolaum Reusnerum. Basiliæ, CIƆ IƆ XIC, Sig. A. 4.

The Angelo Latin translation of Ptolemy’s Greek Geographia had served to disseminate the Alexandrian geographer’s views through almost the whole of the fifteenth century,[27] for that version had been first made in 1409. In 1475 it had been printed, and it had helped strengthen the arguments of those who favored a belief in the position of India as lying over against Spain. Several other editions were yet to be printed in the new typographical centres of Europe, all exerting more or less influence in support of the new views advocated by Columbus.[87] Five of these editions of Ptolemy appeared during the interval[28] from 1475 to 1492. Of Pomponius Mela, advocating the views of which the Portuguese were at this time proving the truth, the earliest printed edition had appeared in 1471. Mela’s treatise, De situ orbis, had been produced in the first century, while Ptolemy had made his views known in the second; and the age of Vasco da Gama, Columbus, and Magellan were to prove the complemental relations of their respective theories.

PTOLEMY.

Fac-simile of cut in Icones sive imagines virorum literis illustrium ... ex secunda recognitione Nicolai Reusneri. Argentorati, CIƆ IƆ XC, p. 1. The first edition appeared in 1587. Brunet, vol. iv., col. 1255, calls the editions of 1590 and Frankfort, 1620, inferior.

ALBERTUS MAGNUS.

Fac-simile of cut in Reusner’s Icones, Strasburg, 1590, p. 4. There is another cut in Paulus Jovius’s Elogia virorum litteris illustrium, Basle, 1575, p. 7 (copy in Harvard College Library).

MARCO POLO.

This follows an engraving in Ruge’s Geschichte des Zeitalters der Entdeckungen, p. 53. The original is at Rome. There is a copy of an old print in Jules Verne’s Découverte de la Terre.

It has been said that Macrobius, a Roman of the fifth century, in a commentary on the Dream of Scipio, had maintained a division of the globe into four continents, of which two were then unknown. In the twelfth century this idea had been revived by Guillaume de Conches (who died about 1150) in his Philosophia Minor, lib. iv. cap. 3. It was again later further promulgated in the writings of Bede and Honoré d’Autun, and in the Microcosmos of Geoffroy de Saint-Victor,—a manuscript of the thirteenth century still preserved.[88] It is not known that this theory was familiar to Columbus. The chief directors of his thoughts among anterior writers appear to have been, directly or indirectly, Albertus Magnus, Roger Bacon, and Vincenzius of Beauvais;[89] and first among them, for importance, we must place the Opus Majus Of Roger Bacon, completed in 1267. It was from Bacon that Petrus de Aliaco, Or Pierre d’Ailly (b. 1340; d. 1416 or 1425), in his Ymago mundi, borrowed the passage which, in this French imitator’s language, so impressed Columbus.[90]

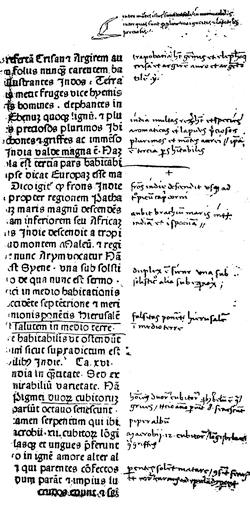

ANNOTATIONS BY COLUMBUS.

On a copy of Pierre d’Ailly’s Imago mundi, preserved in the Colombina Library at Seville, following a photograph in Harrisse’s Notes on Columbus, p. 84.

An important element in the problem was the statements of Marco Polo regarding a large island, which he called Cipango, and which he represented as lying in the ocean off the eastern coast of Asia. This carried the eastern verge of the Asiatic world farther than the ancients had known; and, on the spherical theory, brought land nearer westward from[30] Europe than could earlier have been supposed. It is a question, however, if Columbus had any knowledge of the Latin or Italian manuscripts of Marco Polo,—the only form in which anybody could have studied his narrative before the printing of it at Nuremberg in 1477, in German, a language which Columbus is not likely to have known. Humboldt has pointed out that neither Columbus nor his son Ferdinand mentions Marco Polo; still we know that he had read his book. Columbus further knew, it would seem, what Æneas Sylvius had written on Asia. Toscanelli had also imparted to him what he knew. A second German edition of Marco Polo appeared at Augsburg in 1481. In 1485, with the Itinerarius of Mandeville,[91] published at Zwolle, the account—“De regionibus orientalibus”—of Marco Polo first appeared in Latin, translated from the original French, in which it had been dictated. It was probably in this form that Columbus first saw it.[92] There was a separate Latin edition in 1490.[93]

The most definite confirmation and encouragement which Columbus received in his views would seem to have come from Toscanelli, in 1474. This eminent Italian astronomer, who was now about seventy-eight years old, and was to die, in 1482, before Columbus and Da Gama had consummated their discoveries, had reached a conclusion in his own mind that only about fifty-two degrees of longitude separated Europe westerly from Asia, making the earth much smaller even than Columbus’ inadequate views had fashioned it; for Columbus had[31] satisfied himself that one hundred and twenty degrees of the entire three hundred and sixty was only as yet unknown.[94] With such views of the inferiority of the earth, Toscanelli had addressed a letter to Martinez, a prebendary of Lisbon, accompanied by a map professedly based on information derived from the book of Marco Polo.[95] When Toscanelli received a letter of inquiry from Columbus, he replied by sending a copy of this letter and the map. As the testimony to a western passage from a man of Toscanelli’s eminence, it was of marked importance in the conversion of others to similar views.[96]

It has always been a question how far the practical evidence of chance phenomena, and the absolute knowledge, derived from other explorers, bearing upon the views advocated by Columbus, may have instigated or confirmed him in his belief. There is just enough plausibility in some of the stories which are cited to make them fall easily into the pleas of detraction to which Columbus has been subjected.

ANNOTATIONS BY COLUMBUS.

On a copy of the Historia rerum ubique gestarum of Æneas Sylvius, preserved in the Colombina Library at Seville, following a photograph in Harrisse’s Notes on Columbus, appendix.