THE

CHRONICLES

OF

ENGUERRAND DE MONSTRELET.

THE

CHRONICLES

OF

ENGUERRAND DE MONSTRELET;

CONTAINING

AN ACCOUNT OF THE CRUEL CIVIL WARS BETWEEN THE HOUSES OF

ORLEANS AND BURGUNDY;

OF THE POSSESSION OF

PARIS AND NORMANDY BY THE ENGLISH;

THEIR EXPULSION THENCE;

AND OF OTHER

MEMORABLE EVENTS THAT HAPPENED IN THE KINGDOM OF FRANCE,

AS WELL AS IN OTHER COUNTRIES.

A HISTORY OF FAIR EXAMPLE, AND OF GREAT PROFIT TO THE

FRENCH,

Beginning at the Year MCCCC. where that of Sir JOHN FROISSART finishes, and ending

at the Year MCCCCLXVII. and continued by others to the Year MDXVI.

TRANSLATED

BY THOMAS JOHNES, ESQ.

IN THIRTEEN VOLUMES ... VOL. I.

LONDON:

PRINTED FOR LONGMAN, HURST, REES, ORME, AND BROWN, PATERNOSTER-ROW;

AND J. WHITE AND CO. FLEET-STREET.

1810.

TO

HIS GRACE

JOHN DUKE OF BEDFORD,

&c. &c. &c.

MY LORD,

I am happy in this opportunity of dedicating

the Chronicles of Monstrelet

to your grace, to show my high respect for

your many virtues, public and private, and

the value I set on the honour of your

grace’s friendship.

One of Monstrelet’s principal characters

was John duke of Bedford, regent

of France; and your grace has fully

displayed your abilities, as regent, to be at

least equal to those of your namesake, in

the milder and more valuable virtues.

Those of a hero may dazzle in this life;

but the others are, I trust, recorded in a

better place; and your late wise, although,

unfortunately, short government of Ireland

will be long and thankfully remembered

by a gallant and warm-hearted people.

I have the honour to remain,

Your grace’s much obliged,

Humble servant and friend,

CASTLE-HILL,

March 13, 1808.

CONTENTS

OF

THE FIRST VOLUME.

|

PAGE |

| |

| The prologue |

1 |

| |

| CHAP. I. |

| |

| How Charles the well-beloved reigned in France, after he had been crowned at Rheims, in the year thirteen hundred and eighty |

7 |

| |

| CHAP. II. |

| |

| An esquire of Arragon, named Michel d’Orris, sends challenges to England. The answer he receives from a knight of that country |

13 |

| |

| CHAP. III. |

| |

| Great pardons granted at Rome |

38 |

| |

| CHAP. IV. |

| |

| John of Montfort, duke of Brittany, dies. The emperor departs from Paris. Isabella queen of England returns to France |

39 |

| |

| CHAP. V. |

| |

| The duke of Burgundy, by orders from the king of France, goes into Brittany, and the duke of Orleans to Luxembourg. A quarrel ensues between them |

42 |

| |

| CHAP. VI. |

| |

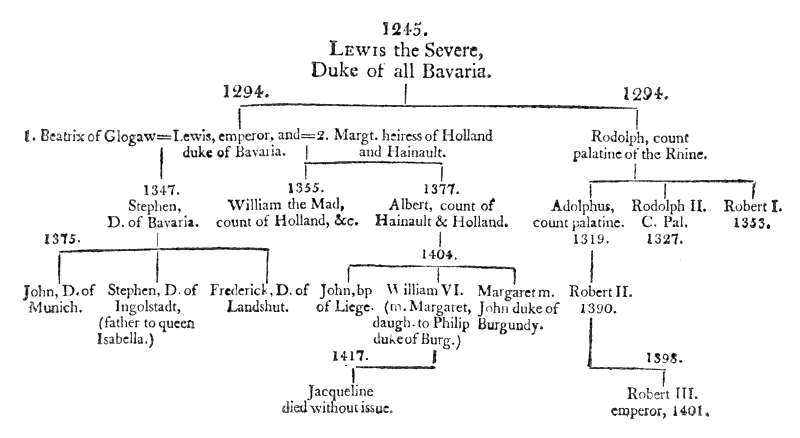

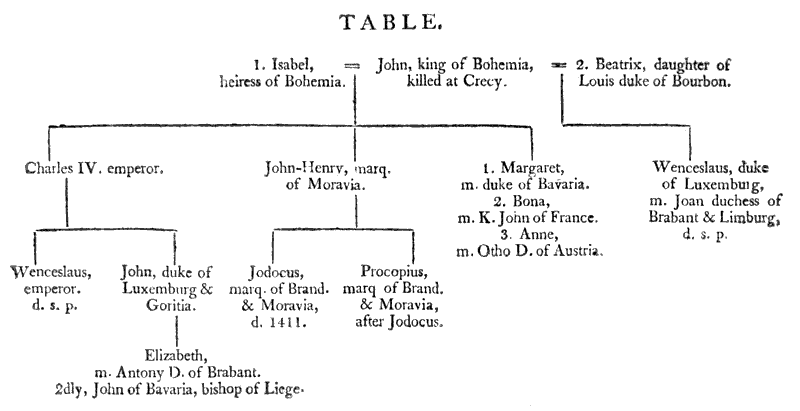

| Clement duke of Bavaria is elected emperor of Germany, and afterward conducted with a numerous retinue to Frankfort |

45 |

| |

| CHAP. VII. |

| |

| Henry of Lancaster, king of England, combats the Percies and Welshmen, who had invaded his kingdom, and defeats them |

47 |

| |

| CHAP. VIII. |

| |

| John de Verchin, a knight of great renown, and seneschal of Hainault, sends, by his herald, a challenge into divers countries, proposing a deed of arms |

49 |

| |

| CHAP. IX. |

| |

| The duke of Orleans, brother to the king of France, sends a challenge to the king of England. The answer he receives |

55 |

| |

| CHAP. X. |

| |

| Waleran count de Saint Pol sends a challenge to the king of England |

84 |

| |

| CHAP. XI. |

| |

| Concerning the sending of sir James de Bourbon, count de la Marche, and his two brothers, by orders from the king of France, to the assistance of the Welsh, and other matters |

87 |

| |

| CHAP. XII. |

| |

| The admiral of Brittany, with other lords, fights the English at sea. Gilbert de Fretun makes war against king Henry |

89 |

| |

| CHAP. XIII. |

| |

| The university of Paris quarrels with sir Charles de Savoisy and with the provost of Paris |

91 |

| |

| CHAP. XIV. |

| |

| The seneschal of Hainault performs a deed of arms with three others, in the presence of the king of Arragon. The admiral of Brittany undertakes an expedition against England |

95 |

| |

| CHAP. XV. |

| |

| The marshal of France and the master of the cross-bows, by orders from the king of France, go to England, to the assistance of the prince of Wales |

103 |

| |

| CHAP. XVI. |

| |

| A powerful infidel, called Tamerlane, invades the kingdom of the king Bajazet, who marches against and fights with him |

106 |

| |

| CHAP. XVII. |

| |

| Charles king of Navarre negotiates with the king of France, and obtains the duchy of Nemours. Duke Philip of Burgundy makes a journey to Bar-le-Duc and to Brussels |

108 |

| |

| CHAP. XVIII. |

| |

| The duke of Burgundy dies in the town of Halle, in Hainault. His body is carried to the Carthusian convent at Dijon, in Burgundy |

110 |

| |

| CHAP. XIX. |

| |

| Waleran count de St Pol lands a large force on the Isle of Wight, to make war against England, but returns without having performed any great deeds |

114 |

| |

| CHAP. XX. |

| |

| Louis duke of Orleans is sent by the king to the pope at Marseilles. The duke of Bourbon is ordered into Languedoc, and the constable into Acquitaine |

116 |

| |

| CHAP. XXI. |

| |

| The death of duke Albert, count of Hainault, and of Margaret duchess of Burgundy, daughter to Louis earl of Flanders |

120 |

| |

| CHAP. XXII. |

| |

| John duke of Burgundy, after the death of the duchess Margaret, is received by the principal towns in Flanders as their lord |

122 |

| |

| CHAP. XXIII. |

| |

| Duke William count of Hainault presides at a combat for life or death, in his town of Quesnoy, in which one of the champions is slain |

124 |

| |

| CHAP. XXIV. |

| |

| The count de St Pol marches an army before the castle of Mercq, where the English from Calais meet and discomfit him |

126 |

| |

| CHAP. XXV. |

| |

| John duke of Burgundy goes to Paris, and causes the dauphin and queen to return thither, whom the duke of Orleans was carrying off, with other matters |

136 |

| |

| CHAP. XXVI. |

| |

| Duke John of Burgundy obtains from the king of France the government of Picardy. An embassy from England to France. An account of Clugnet de Brabant, knight |

157 |

| |

| CHAP. XXVII. |

| |

| The war is renewed between the dukes of Bar and Lorraine. Marriages concluded at Compiegne. An alliance between the dukes of Orleans and Burgundy |

161 |

| |

| CHAP. XXVIII. |

| |

| The duke of Orleans, by the king’s orders, marches a powerful army to Acquitaine, and besieges Blay and le Bourg |

167 |

| |

| CHAP. XXIX. |

| |

| The duke of Burgundy prevails on the king of France and his council, that he may have permission to assemble men at arms to besiege Calais |

169 |

| |

| CHAP. XXX. |

| |

| The prelates and clergy of France are summoned to attend the king at Paris, on the subject of an union of the church |

174 |

| |

| CHAP. XXXI. |

| |

| The Liegeois eject their bishop, John of Bavaria, for refusing to be consecrated as a churchman, according to his promise |

176 |

| |

| CHAP. XXXII. |

| |

| Anthony duke of Limbourg takes possession of that duchy, and afterward of the town of Maestricht, to the great displeasure of the Liegeois |

179 |

| |

| CHAP. XXXIII. |

| |

| Ambassadors from pope Gregory arrive at Paris, with bulls from the pope to the king and university of Paris |

182 |

| |

| CHAP. XXXIV. |

| |

| The duke of Orleans receives the duchy of Acquitaine, as a present, from the king of France. A truce concluded between England and France |

188 |

| |

| CHAP. XXXV. |

| |

| The prince of Wales, accompanied by his two uncles, marches a considerable force to wage war against the Scots |

189 |

| |

| CHAP. XXXVI. |

| |

| The duke of Orleans, only brother to Charles VI. the well beloved, king of France, is inhumanly assassinated in the town of Paris |

191 |

| |

| CHAP. XXXVII. |

| |

| The duchess of Orleans with her youngest son wait on the king in Paris, to make complaint of the cruel murder of the late duke her husband |

206 |

| |

| CHAP. XXXVIII. |

| |

| The duke of Burgundy assembles a number of his dependants, at Lille in Flanders, to a council, respecting the death of the duke of Orleans. He goes to Amiens, and thence to Paris |

211 |

| |

| CHAP. XXXIX. |

| |

| The duke of Burgundy offers his justification, for having caused the death of the duke of Orleans, in the presence of the king and his great council |

220 |

| |

| CHAP. XL. |

| |

| The king of France sends a solemn embassy to the pope. The answer they receive. The pope excommunicates the king and his adherents |

302 |

| |

| CHAP. XLI. |

| |

| The university of Paris declares against the pope della Luna, in the presence of the king of France. King Louis of Sicily leaves Paris. Of the borgne de la Heuse |

315 |

| |

| CHAP. XLII. |

| |

| The duke of Burgundy departs from Paris, on account of the affairs of Liege. The king of Spain combats the saracen fleet. The king of Hungary writes to the university of Paris |

320 |

| |

| CHAP. XLIII. |

| |

| How all the prelates and clergy of France were summoned to Paris. The arrival of the queen and of the duchess of Orleans |

325 |

| |

| CHAP. XLIV. |

| |

| The duchess-dowager of Orleans and her son cause a public answer to be made, at Paris, to the charges of the duke of Burgundy against the late duke of Orleans, and challenge the duke of Burgundy for his murder |

331 |

THE

LIFE OF MONSTRELET.

Materials for the biography of Monstrelet

are still more scanty than for that of

Froissart. The most satisfactory account,

both of his life and of the continuators of

his history, is contained in the Memoires de

l’Académie de Belles Lettres, vol. XLIII.

p. 535. by M. Dacier.

‘We are ignorant of the birthplace of

Enguerrand de Monstrelet, and of the period

when he was born, as well as of the

names of his parents. All we know is,

that he sprang from a noble family,—which

he takes care to tell us himself, in

his introduction to the first volume of the

chronicles; and his testimony is confirmed

by a variety of original deeds, in which his

name is always accompanied with the distinction

of ‘noble man,’ or ‘esquire.[1]’

‘According to the historian of the Cambresis,

Monstrelet was descended from a

noble family settled in Ponthieu from the

beginning of the twelfth century, where

one of his ancestors, named Enguerrand,

possessed the estate of Monstrelet in the

year 1125,—but Carpentier does not name

his authority for this. A contemporary historian

(Matthieu de Couci, of whom I shall

have occasion to speak in the course of this

essay,) who lived at Peronne, and who

seems to have been personally acquainted

with Monstrelet, positively asserts that this

historian was a native of the county of the

Boulonnois, without precisely mentioning

the place of his birth. This authority ought

to weigh much: besides, Ponthieu and the

Boulonnois are so near to each other that

a mistake on this point might easily have

happened. It results, from what these two

writers say, that we may fix his birthplace

in Picardy.

‘M. l’abbé Carlier, however, in his

history of the duchy of Valois, claims this

honour for his province, wherein he has

discovered an ancient family of the same

name,—a branch of which, he pretends,

settled in the Cambresis, and he believes

that from this branch sprung Enguerrand

de Monstrelet. This opinion is advanced

without proof, and the work of Monstrelet

itself is sufficient to destroy it. He shows

so great an affection for Picardy, in divers

parts of his chronicle, that we cannot doubt

of his being strongly attached to it: he is

better acquainted with it than with any

other parts of the realm: he enters into

the fullest details concerning it: he frequently

gives the names of such picard gentlemen,

whether knights or esquires, as had

been engaged in any battle, which he

omits to do in regard to the nobility of

other countries,—in the latter case, naming

only the chief commanders. It is almost

always from the bailiff of Amiens that he

reports the royal edicts, letters missive, and

ordinances, &c. which abound in the two

first volumes. In short, he speaks of the

Picards with so much interest, and relates

their gallant actions with such pleasure,

that it clearly appears that he treats them

like countrymen.

‘Monstrelet was a nobleman then, and

a nobleman of Picardy; but we have good

reason to suspect that his birth was not spotless.

John le Robert, abbot of St Aubert

in Cambray from the year 1432 to that of

1469, and author of an exact journal of

every thing that passed during his time in

the town of Cambray and its environs, under

the title of ‘Memoriaux,’[2] says plainly,

‘qu’il fut né de bas,’—which term, according

to the glossary of du Cange, and in the

opinion of learned genealogists, constantly

means a natural son; for at this period,

bastards were acknowledged according to

the rank of their fathers. Monstrelet, therefore,

was not the less noble; and the same

John le Robert qualifies him, two lines

higher, with the titles of ‘noble man’ and

‘esquire,’ to which he adds an eulogium,

which I shall hereafter mention,—because,

at the same time that it does honour to Monstrelet,

it confirms the opinion I had formed

of his character when attentively reading

his work.

‘My researches to discover the precise

year of his birth have been fruitless. I

believe, however, it may be safely placed

prior to the close of the fourteenth century;

for, besides speaking of events at the beginning

of the fifteenth as having happened in

his time, he states positively, in his introduction,

that he had been told of the early

events in his book (namely, from the year

1400,) by persons worthy of credit, who

had been eye-witnesses of them. To this

proof, or to this deduction, I shall add,

that under the year 1415, he says, that he

heard (at the time) of the anger of the

count de Charolois, afterwards Philippe le

bon duke of Burgundy, because his governors

would not permit him to take part in

the battle of Azincourt. I shall also add,

that under the year 1420, he speaks of the

homage which John duke of Burgundy

paid the king of the Romans for the counties

of Burgundy and of Alost. It cannot

be supposed that he would have inquired

into such particulars, or that any one would

have taken the trouble to inform him of

them if he had not been of a certain age,

such as twenty or twenty-five years old,

which would fix the date of his birth about

1390 or 1395.

‘No particulars of his early years are

known, except that he evinced, when

young, a love for application, and a dislike

to indolence. The quotations from Sallust,

Livy, Vegetius, and other ancient authors,

that occur in his chronicles, show

that he must have made some progress in

latin literature. Whether his love for study

was superior to his desire of military glory,

or whether a weakly constitution or some

other reason, prevented him from following

the profession of arms, I do not find that

he yielded to the reigning passion of his

age, when the names of gentleman and of

soldier were almost synonimous.

‘The wish to avoid indolence by collecting

the events of his time, which he

testifies in the introduction to his chronicles,

proves, I think, that he was but a tranquil

spectator of them. Had he been an Armagnac

or a Burgundian, he would not

have had occasion to seek for solitary occupations;

but what proves more strongly

that Monstrelet was not of either faction is

the care he takes to inform his readers of

the rank, quality, and often of the names

of the persons from whose report he writes,

without ever boasting of his own testimony.

In his whole work, he speaks but once from

his own knowledge, when he relates the

manner in which the Pucelle d’Orléans was

made prisoner before Compiégne; but he

does not say, that he was present at the

skirmish when this unfortunate heroine was

taken: he gives us to understand the contrary,

and that he was only present at the

conversation of the prisoner with the duke

of Burgundy,—for he had accompanied

Philip on this expedition, perhaps in quality

of historian. And why may not we

presume that he may have done so on other

occasions, to be nearer at hand to collect

the real state of facts which he intended

to relate?

‘However this may be, it is certain

that he was resident in Cambray, when he

composed his history, and passed there the

remainder of his life. He was indeed fixed

there, as I shall hereafter state, by different

important employments, each of which required

the residence of him who enjoyed

them. From his living in Cambray, La

Croix du Maine has concluded, without

further examination, that he was born there,

and this mistake has been copied by other

writers.

‘Monstrelet was married to Jeanne de

Valbuon, or Valhuon, and had several children

by her, although only two of them

were known,—a daughter called Bona,

married to Martin de Beulaincourt, a gentleman

of that country, surnamed the Bold,

and a son of the name of Pierre. It is

probable, that Bona was married, or of age,

prior to the year 1438,—for in the register

of the officiality of Cambray, towards the

end of that year, is an entry, that Enguerrand

de Monstrelet was appointed guardian

to his young son Pierre, without any

mention of his daughter Bona. It follows,

therefore, that Monstrelet was a widower

at that period.

‘In the year 1436, Monstrelet was nominated

to the office of Lieutenant du

Gavènier of the Cambresis, conjointly with

Le Bon de Saveuses, master of the horse

to the duke of Burgundy, as appears from

the letters patent to this effect, addressed

by the duke to his nephew the count

d’Estampes, of the date of the 13th May

in this year, and which are preserved in the

chartulary of the church of Cambray.

‘It is even supposed that Monstrelet

had for some time enjoyed this office,—for

it is therein declared, that he shall continue

in the receipt of the Gavène, as he has

heretofore done, until this present time.

‘Gave,’ or ‘Gavène,’ (I speak from the

papers I have just quoted,) signifies in

Flemish, a gift, or a present. It was an

annual due payable to the duke of Burgundy,

by the subjects of the churches in

the Cambresis, for his protection of them

as earl of Flanders. From the name of the

tribute was formed that of Gavènier, which

was often given to the duke of Burgundy,

and the nobleman he appointed his deputy

was styled Lieutenant du Gavènier. I have

said ‘the nobleman whom he appointed,’

because in the list of those lieutenants,

which the historian of Cambray has published,

there is not one who has not shown

sufficient proofs of nobility. Such was,

therefore, the employment with which Monstrelet

was invested; and shortly after, another

office was added to it, that of Bailiff

to the chapter of Cambray, for which he

took the oaths on the 20th of June, 1436,

and entered that day on its duties. He

kept this place until the beginning of January,

in the year 1440, when another was

appointed.

‘I have mentioned Pierre de Monstrelet,

his son; and it is probable that he is

the person who was made a knight of St

John of Jerusalem in the month of July,

in 1444, although the acts of the chapter

of Cambray do not confirm this opinion,

nor specify the Christian name of the new

knight by that of Pierre. It is only declared

in the register, that the canons, as

an especial favour, on the 6th of July, permitted

Enguerrand de Monstrelet, esquire,

to have his son invested with the order of

St John of Jerusalem, on Sunday the 19th

of the same month, in the choir of their

church.

‘The respect and consideration which

he had now acquired, gained him the dignity

of governor of Cambray, for which

he took the usual oath on the 9th of November;

and on the 12th of March, in the

following year, he was nominated bailiff of

Wallaincourt. He retained both of these

places until his death, which happened

about the middle of July, in the year 1453.

This date cannot be disputed: it was discovered

in the 17th century by John le

Carpentier, who has inserted it in his history

of the Cambresis. But in consequence

of little attention being paid to this work,

or because the common opinion has been

blindly followed, that Monstrelet had continued

his history to the death of the duke

of Burgundy in 1467, this date was not considered

as true until the publication of an

extract from the register of the Cordeliers

in Cambray, where he was buried.[3] Although

this extract fully establishes the year

and month when Monstrelet died, I shall

insert here what relates to it from the ‘Memoriaux’

of John le Robert, before mentioned,

because they contain some circumstances

that are not to be found in the register

of the Cordeliers. When several

years of his history are to be retrenched

from an historian of such credit, authorities

for so doing cannot be too much multiplied.

This is the text of the abbot of St Aubert,

and I have put in italics the words that are

not in the register:

“The 20th day of July, in the year

1453, that honourable and noble man Enguerrand

de Monstrelet, esquire, governor

of Cambray, and bailiff of Wallaincourt,

departed this life, and was buried at the Cordeliers

of Cambray, according to his desire.

He was carried thither on a bier covered

with a mat, clothed in the frock of a

cordelier friar, his face uncovered: six

flambeaux and three chirons, each weighing

three quarters of a pound, were around the

bier, whereon was a sheet thrown over the

cordelier frock. Il fut nez de bas, and was

a very honourable and peaceable man. He

chronicled the wars which took place in his

time in France, Artois, Picardy, England,

Flanders, and those of the Gantois against

their lord duke Philip. He died fifteen or

sixteen days before peace was concluded,

which took place toward the end of July,

in the year 1453.”

‘I shall observe, by the way, that the

person who drew up this register assigns two

different dates for the death of Monstrelet,

and in this he has been followed by John

le Robert. Both of them say, that Monstrelet

died on the 20th of July,—and, a

few lines farther, add, that he died about

sixteen days before peace was concluded

between duke Philip and Ghent, which

was signed about the end of the month:

it was, in fact, concluded on the 31st: now,

from twenty to thirty-one, we can only

reckon eleven days,—and I therefore think,

that one of these dates must mean the day

of his death, and the other that of his

funeral,—namely, that Monstrelet died on

the 15th and was buried on the 20th. The

precise date of his death is, however, of

little importance: it is enough for us to be

assured, that it took place in the month of

July, in 1453, and consequently that the

thirteen last years of his history, printed

under his name, cannot have been written

by him. I shall examine this first continuation

of his history, and endeavour to ascertain

the time when Monstrelet ceased to

write,—and likewise attempt to discover

whether, during the years immediately preceding

his death, some things have not been

inserted that do not belong to him.

‘Before I enter upon this discussion

of his work, I shall conclude what I have

to say of him personally, according to what

the writer of the register of the Cordeliers

and the abbot of St Aubert testify of him.

He was, says each of them, ‘a very honourable

and peaceable man;’ expressions

that appear simple at first sight, but which

contain a real eulogium, if we consider the

troublesome times in which Monstrelet lived,

the places he held, the interest he must

have had sometimes to betray the truth in

favour of one of the factions which then

divided France, and caused the revolutions

the history of which he has published during

the life of the principal actors. I have

had more than one occasion to ascertain

that the two above-mentioned writers, in

thus painting his character, have not flattered

him.

‘The Chronicles of Monstrelet commence

on Easter-day,[4] in the year 1400,

when those of Froissart end, and extend to

the death of the duke of Burgundy in the

year 1467. I have before stated, that the

thirteen last years of his chronicle were

written by an unknown author,—and this

matter I shall discuss at the end of this essay.

In the printed as well as in the manuscript

copies, the chronicle is divided into

three volumes, and each volume into

chapters. The first of these divisions is

evidently by the author: his prologues at

the head of the first and second volumes,

in which he marks the extent of each conformable

to the number of years therein

contained, leave no room to doubt of it.

‘His work is called Chronicles; but

we must not, however, consider this title in

the sense commonly attached to it, which

merely conveys the idea of simple annals.

The chronicles of Monstrelet are real history,

wherein, notwithstanding its imperfections

and omissions, are found all the

characteristics of historical writing. He

traces events to their source, developes the

causes, and traces them with the minutest

details; and what renders these chronicles

infinitely precious is, his never-failing attention

to report all edicts, declarations,

summonses, letters, negotiations, treaties,

&c. as justificatory proofs of the truth of

the facts he relates.

‘After the example of Froissart, he

does not confine himself to events that

passed in France: he embraces, with almost

equal detail, the most remarkable circumstances

which happened during his time in

Flanders, England, Scotland and Ireland.

He relates, but more succinctly, whatsoever

he had been informed of as having passed

in Germany, Italy, Hungary, Poland: in

short, in the different european states. Some

events, particularly the war of the Saracens

against the king of Cyprus, are treated at

greater length than could have been expected

in a general history.

‘Although it appears that the principal

object of Monstrelet in writing this history

was to preserve the memory of those

wars which in his time, desolated France

and the adjoining countries, to bring into

public notice such personages as distinguished

themselves by actions of valour in

battles, assaults, skirmishes, duels and tournaments,—and

to show to posterity that his

age had produced as many heroes as any

of the preceding ones. He does not fail

to give an account of such great political

or ecclesiastical events as took place during

the period of which he seemed only inclined

to write the military history. He

relates many important details respecting

the councils of Pisa, Constance, and of

Basil, of which the authors who have

written the history of these councils ought

to have availed themselves, to compare

them with the other materials of which

they made use.

‘There is no historian who does not

seek to gain the confidence of his readers,

by first explaining in a preface all that he

has done to acquire the fullest information

respecting the events he is about to relate.

All protest that they have not omitted any

possible means to ascertain the truth of facts,

and that they have spared neither time nor

trouble to collect the minutest details concerning

them. Without doubt, great deductions

must be made from such protestations:

those of Monstrelet, however, are

accompanied with circumstances which convince

us that a dependance may be placed

on them. Would he have dared to tell

his contemporaries, who could instantly

have detected a falsehood had he imposed

on them, that he had been careful to consult

on military affairs those who, from their

employments, must have been eye-witnesses

of the actions that he describes? that on other

matters he had consulted such as, from their

situations, must have been among the principal

actors, and the great lords of both

parties, whom he had often to address, to

engage in conversation on these events, at

divers times, to confront them, as it were,

with themselves? On objects of less importance,

such as feasts, justs, tournaments,

he had made his inquiries from heralds, poursuivants,

and kings at arms, who, from their

office, must have been appointed judges of

the lists, or assistants, at such entertainments

and pastimes. For greater security, it was

always more than a year after any event

had happened, before he began to arrange

his materials and insert them in his chronicle.

He waited until time should have destroyed

what may have been exaggerated in

the accounts of such events, or should have

confirmed their truth.

‘An infinite number of traits throughout

his work proves the fidelity of his narration.

He marks the difference between

facts of which he is perfectly sure and those

of which he is doubtful: if he cannot produce

his proof, he says so, and does not

advance more. When he thinks that he

has omitted some details which he ought to

have known, he frankly owns that he has

forgotten them. For instance, when speaking

of the conversation between the duke

of Burgundy and the Pucelle d’Orléans, at

which he was present, he recollects that

some circumstances have escaped his memory,

and avows that he does not remember them.

‘When after having related any event,

he gains further knowledge concerning it,

he immediately informs his readers of it,

and either adds to or retrenches from his

former narration, conformably to the last

information he had received. Froissart acted

in a similar manner; and Montaigne

praises him for it. ‘The good Froissart,’

says he, ‘proceeds in his undertaking with

such frank simplicity that having committed

a mistake he is no way afraid of owning it,

and of correcting it at the moment he is

sensible of it.’[5] We ought certainly to

feel ourselves obliged to these two writers

for their attention in returning back to correct

any mistakes; but we should have been

more thankful to them if they had been

pleased to add their corrections to the articles

which had been mistated, instead of

scattering their amendments at hazard, as it

were, and leaving the readers to connect

and compare them with the original article

as well as they can.

‘This is not the only defect common

to both these historians. The greater part

of the chronological mistakes, which have

been so ably corrected by M. de Sainte

Palaye in Froissart, are to be found in Monstrelet;

and what deserves particularly to

be noticed, to avoid falling into errors, is,

that each of them, when passing from the

history of one country to another, introduces

events of an earlier date, without

ever mentioning it, and intermix them in

the same chapter, as if they had taken

place in the same period,—but Monstrelet

has the advantage of Froissart in the correctness

of counting the years, which he

invariably begins on Easter-day and closes

them on Easter-eve.

‘To chronological mistakes must be

added the frequent disfiguring of proper

names,—more especially foreign ones, which

are often so mangled that it is impossible to

decipher them. M. du Cange has corrected

from one thousand to eleven hundred on

the margin of his copy of the edition of

1572, which is now in the imperial library

at Paris, and would be of great assistance,

should another edition of Monstrelet be

called for.[6] Names of places are not more

clearly written, excepting those in Flanders

and Picardy, with which, of course, he was

well acquainted. We know not whether

it be through affectation or ignorance that

he calls many towns by their latin names,

frenchifying the termination: for instance,

Aix-la-Chapelle, Aquisgranie; Oxford, Oxonie,—and

several others in the like manner.

‘These defects are far from being repaid,

as they are in Froissart, by the agreeableness

of the narration: that of Monstrelet

is heavy, monotonous, weak and diffuse.

Sometimes a whole page is barely

sufficient for him to relate what would have

been better told in six lines; and it is commonly

on the least important facts that he

labours the most.

‘The second chapter of the first volume,

consisting of thirteen pages, contains

only a challenge from a spanish esquire,

accepted by an esquire of England, which,

after four years of letters and messages,

ends in nothing. The ridiculousness of so

pompous a narration had struck Rabelais,

who says, at page 158 of his third volume,—‘In

reading this tedious detail, (which he

calls a little before le tant long, curieux et

fâcheux conte) we should imagine that it was

the beginning, or occasion, of some severe

war, or of a great revolution of kingdoms;

but at the end of the tale we laugh at the

stupid champion, the Englishman, and Enguerrand

their scribe, plus baveux qu’un pot

à moutarde.’[7]

‘Monstrelet employs many pages to

report the challenges sent by the duke of

Orleans, brother to king Charles VI., to

Henry IV. king of England,—challenges

which are equally ridiculous with the former,

and which had a similar termination.

When he meets with any event that particularly

regards Flanders or Picardy, he does

not omit the smallest circumstance: the

most minute and most useless seem to him

worth preserving,—and this same man, so

prolix when it were to be wished he was

concise, omits, for the sake of brevity, as

he says, the most interesting details. This

excuse he repeats more than once, for neglecting

to enlarge on facts far more interesting

than the quarrels of the Flemings and

Picards. When speaking of those towns

in Champagne and Brie which surrendered

to Charles VII. immediately after his coronation,

he says, ‘As for these surrenders,

I omit the particular detail of each for the

sake of brevity.’ In another place, he says,

‘Of these reparations, for brevity sake, I

shall not make mention.’ These reparations

were the articles of the treaty of peace concluded

in 1437, between the duke of Burgundy

and the townsmen of Bruges.

‘I have observed an omission of another

sort, but which must be attributed

solely to the copyists,—for I suspect them

of having lost a considerable part of a chapter

in the second volume. The head of

this chapter is, ‘The duke of Orleans returns

to the duke of Burgundy,’—and the

beginning of it describes the meeting of the

two princes in the town of Hêdin in 1441

(1442). They there determine to meet

again almost immediately in the town of

Nevers, ‘with many others of the great

princes and lords of the kingdom of France,’

and at the end of eight days they separate;

the one taking the road through Paris for

Blois, and the other going into Burgundy.

‘This recital consists of about twenty

lines, and then we read, ‘Here follows a

copy of the declaration sent to king Charles

of France by the lords assembled at Nevers,

with the answers returned thereto by the

members of the great council, and certain

requests made by them.’ This title is followed

by the declaration he has mentioned,

and the answer the king made to the ambassadors

who had presented it to him.—Now,

can it be conceived that Monstrelet

would have been silent as to the object of

the assembly of nobles? or not have named

some of those who had been present? and

that, after having mentioned Nevers as the

place of meeting, he should have passed

over every circumstance respecting it, to the

declarations and resolutions that had there

been determined upon? There are two reasons

for concluding that part of this chapter

must be wanting: first, when Monstrelet

returns to his narration, after having related

the king’s answer to the assembled lords, he

speaks as having before mentioned them,

‘the aforesaid lords,’ and I have just noticed

that he names none of them; secondly,

when in the next chapter he relates

the expedition to Tartas, which was to decide

on the fate of Guienne, as having

before mentioned it, ‘of which notice has

been taken in another place,’ it must have

been in the preceding chapter,—but it is not

there spoken of, nor in any other place.

‘If the numerous imperfections of Monstrelet

are not made amends for, as I have

said, by the beauty of his style, we must

allow that they are compensated by advantages

of another kind. His narration is diffuse,

but clear,—and his style heavy, but

always equal. He rarely offers any reflections,—and

they are always short and judicious.

The temper of his mind is particularly

manifested by the circumstance that

we do not find in his work any ridiculous

stories of sorcery, magic, astrology, or any

of those absurd prodigies which disgrace

the greater part of the historians of his

time. The goodness of his heart also displays

itself in the traits of sensibility which

he discovers in his recitals of battles, sieges,

and of towns won by storm: he seems then

to rise superior to himself,—and his style

acquires strength and warmth. When he

relates the preparations for, and the commencement

of, a war, his first sentiment is

to deplore the evils by which he foresees

that the poorer ranks will soon be overwhelmed.

Whilst he paints the despair of

the wretched inhabitants of the country, pillaged

and massacred by both sides, we perceive

that he is really affected by his subject,

and writes from his feelings. The

writer of the cordelier register and the abbot

of St Aubert, have not, therefore, said

too much, when they called him, ‘a very

honest and peaceable man.’ It appears, in

fact, that benevolence was the marked feature

of his character, to which I am not

afraid to add the love of truth.

‘I know that in respect to this last

virtue, his reputation is not spotless, and

that he has been commonly charged with

partiality for the house of Burgundy, and

for that faction. Lancelot Voesin de la

Popeliniere is, I believe, the first who

brought this accusation against him. ‘Monstrelet,’

says he, ‘has scarcely shown himself

a better narrator than Froissart,—but

a little more attached to truth, and less of

a party man.’ Denis Godefroy denies this

small advantage over Froissart which had

been conceded to him by La Popeliniere.

‘Both of them,’ he says, ‘incline toward

the Burgundians.’

‘Le Gendre in his critical examination

of the french historians, repeats the same

thing, but in more words. ‘Monstrelet,’

he writes, ‘too plainly discovers his intentions

of favouring, when he can, the dukes

of Burgundy and their friends.’ Many authors

have adopted some of these opinions,

more or less disadvantageous to Monstrelet;

hence has been formed an almost universal

prejudice, that he has, in his work, often

disfigured the truth in favour of the dukes

of Burgundy.

‘I am persuaded that these different

opinions, advanced without proof, are void

of foundation; and I have noticed facts,

which having happened during the years of

which Monstrelet writes the history, may,

from the manner in which he narrates them,

enable us to judge whether he was capable

of sacrificing truth to his attachment to the

house of Burgundy.

‘In 1407, doctor John Petit, having

undertaken to justify the assassination of

the duke of Orleans by orders from the duke

of Burgundy, sought to diminish the horror

of such a deed, by tarnishing the memory

of the murdered prince with the blackest

imputations. Monstrelet, however, does

not hesitate to say, that many persons

thought these imputations false and indecent.

He reports, in the same chapter, the

divers opinions to which this unfortunate

event gave rise, and does not omit to say,

that ‘many great lords, and other wise

men, were much astonished that the king

should pardon the burgundian prince, considering

that the crime was committed on

the person of the duke of Orleans.’ We

perceive, in reading this passage, that Monstrelet

was of the same opinion with the

‘other wise men.’

‘In 1408, Charles VI. having insisted

that the children of the late duke of Orleans

should be reconciled to the duke of

Burgundy, they were forced to consent.—‘Sire,

since you are pleased to command

us, we grant his request;’ and Monstrelet

lets it appear that he considers their compliance

as a weakness, which he excuses on

account of their youth, and the state of

neglect they were in after the death of

their mother the duchess of Orleans, who

had sunk under her grief on not being

able to avenge the murder of her husband.

‘To say the truth, in consequence of the

death of their father, and also from the loss

of their mother, they were greatly wanting

in advice and support.’ He likewise relates,

at the same time, the conversations held by

different great lords on this occasion, in

whom sentiments of humanity and respect

for the blood-royal were not totally extinguished.

‘That henceforward it would be

no great offence to murder a prince of the

blood, since those who had done so were

so easily acquitted, without making any

reparation, or even begging pardon.’ A

determined partisan of the house of Burgundy

would have abstained from transmitting

such a reflection to posterity.

‘I shall mention another fact, which

will be fully sufficient for the justification

of the historian. None of the writers of his

time have spoken with such minuteness of

the most abominable of the actions of the

duke of Burgundy: I mean that horrid

conspiracy which he had planned in 1415,

by sending his emissaries to Paris to intrigue

and bring it to maturity, and the object of

which was nothing less than to seize and

confine the king, and to put him to death,

with the queen, the chancellor of France,

the queen of Sicily, and numberless others.

Monstrelet lays open, without reserve, all

the circumstances of the conspiracy: he

tells us by whom it was discovered: he

names the principal conspirators, some of

whom were beheaded, others drowned.—He

adds, ‘However, those nobles whom

the duke of Burgundy had sent to Paris

returned as secretly and as quietly as they

could without being arrested or stopped.’

‘An historian devoted to the duke of

Burgundy would have treated this affair

more tenderly, and would not have failed

to throw the whole blame of the plot on

the wicked partisans of the duke, without

saying expressly that they had acted under

his directions and by his orders contained

‘in credential letters signed with his hand.’

It is rather singular, that Juvénal des Ursins,

who cannot be suspected of being a

Burgundian, should, in his history of Charles

VI. have merely related this event, and

that very summarily, without attributing

any part of it to the duke of Burgundy,

whom he does not even name.

‘The impartiality of Monstrelet is not

less clear in the manner in which he speaks

of the leaders of the two factions, Burgundians

or Armagnacs, who are praised or

blamed without exception of persons, according

to the merit of their actions. The

excesses which both parties indulged in are

described with the same strength of style,

and in the same tone of indignation. In

1411, when Charles VI. in league with the

duke of Burgundy, ordered, by an express

edict, that all of the Orleans party should

be attacked as enemies throughout the kingdom,

‘it was a pitiful thing,’ says the historian,

‘to hear daily miserable complaints

of the persecutions and sufferings of individuals.’

He is no way sparing of his expressions

in this instance, and they are still

stronger in the recital which immediately

follows: ‘Three thousand combatants

marched to Bicêtre, a very handsome house

belonging to the duke of Berry (who was

of the Orleans party),—and from hatred to

the said duke, they destroyed and villainously

demolished the whole, excepting the

walls.’

‘The interest which Monstrelet here

displays for the duke of Berry, agrees perfectly

with that which he elsewhere shows

for Charles VI. He must have had a heart

truly French to have painted in the manner

he has done the state of debasement and

neglect to which the court of France was

reduced in 1420, compared with the pompous

state of the king of England: he is

affected with the humiliation of the one,

and hurt at the magnificence of the other,

which formed so great a contrast. ‘The

king of France was meanly and poorly

served, and was scarcely visited on this day

by any but some old courtiers and persons

of low degree, which must have wounded

all true french hearts.’ And a few lines

farther, he says, ‘With regard to the state

of the king of England, it is impossible to

recount its great magnificence and pomp,

or to describe the grand entertainments and

attendance in his palace.’

‘This idea had made such an impression

on him that he returns again to it on

occasion of the solemn feast of Whitsuntide,

which the king and queen of England

came to celebrate in Paris, in 1422. ‘On

this day, the king and queen of England

held a numerous and magnificent court,—but

king Charles remained with his queen

at the palace of St Pol, neglected by all,

which caused great grief to numbers of

loyal Frenchmen, and not without cause.’

‘These different traits, thus united,

form a strong conclusion, or I am deceived,

that Monstrelet has been too lightly charged

with partiality for the house of Burgundy,

and with disaffection to the crown of France.

‘I have hitherto only spoken of the

two first volumes of the chronicles of Monstrelet;

the third, which commences in

April 1444, I think should be treated of

separately, because I scarcely see any thing

in it that may be attributed to him. In the

first place, the thirteen last years, from his

death in 1453 to that of the duke of Burgundy

in 1467, which form the contents of

the greater part of this volume, cannot have

been written by him. Secondly, the nine

preceding years, of which Monstrelet, who

was then living, may have been the author,

seem to me to be written by another hand.

We do not find in this part either his style

or manner of writing: instead of that prolixity

which has been so justly found fault

with, the whole is treated with the dryness

of the poorest chronicle: it is an abridged

journal of what passed worthy of remembrance

in Europe, but more particularly in

France, from 1444 to 1453,—in which the

events are arranged methodically, according

to the days on which they happened,

without other connexion than that of the

dates.

‘Each of the two first volumes is preceded

by a prologue, which serves as an introduction

to the history of the events that

follow: the third has neither prologue nor

preface. In short, with the exception of

the sentence passed on the duke of Alençon,

there are not, in this volume, any justificatory

pieces, negotiations, letters, treaties,

ordinances, which constitute the principal

merit of the two preceding ones. It would,

however, have been very easy for the compiler

to have imitated Monstrelet in this

point, for the greater part of these pieces

are reported by the chronicler of St Denis,

whom he often quotes in his first fifty pages.

I am confirmed in this idea by having examined

into the truth of different events,

when I found that the compiler had scarcely

done more than copy, word for word,—sometimes

from the Grandes Chroniques of

France,—at others, though rarely, from the

history of Charles VII. by Jean Chartier,

and, still more rarely, from the chronicler

of Arras, of whom he borrows some facts

relative to the history of Flanders.[8]

‘To explain this resemblance, it cannot

be said that the editors of the Grandes

Chroniques have copied Monstrelet, for the

Grandes Chroniques are often quoted in

this third volume, which consequently must

have been written posterior to them. There

would be as little foundation to suppose that

Monstrelet had copied them himself, and

inserted only such facts as more particularly

belonged to the history of the dukes of Burgundy.

The difference of the plan and

execution of the two first volumes and of

this evidently points out another author.

But should any doubt remain, it will soon

be removed by the evidence of a contemporary

writer, who precisely fixes on the

year 1444 as the conclusion of the labours

of Monstrelet.

‘Matthieu d’Escouchy, or de Couci,

author of a history published by Denis

Godefroy, at the end of that of Charles VII.

by Chartier, thus expresses himself in the

prologue at the beginning of his work: ‘I

shall commence my said history from the

20th day of May, in the year 1444, when

the last book, which that noble and valiant

man Enguerrand de Monstrelet chronicled

in his time, concludes. He was a native

of the county of the Boulonnois, and at

the time of his death was governor and

citizen of Cambray, whose works will be

in renown long after his decease. It is my

intention to take up the history where the

late Enguerrand left it,—namely, at the

truces which were made and concluded at

Tours, in Touraine, in the month of May,

on the day and year before mentioned, between

the most excellent, most powerful,

Charles, the well-served king of France,

of most noble memory, seventh of the

name, and Henry king of England his

nephew.’

‘These truces conclude the last chapter

of the second volume of Monstrelet:

it is there where the real chronicles end;

and he has improperly been hitherto considered

as the author of the history of the

nine years that preceded his death, for I

cannot suppose that the evidence of Matthieu

de Coucy will be disputed. He was

born at Quesnoy, in Hainault, and living

at Peronne while Monstrelet resided at

Cambray. The proximity of the places

must have enabled him to be fully informed

of every thing that concerned the historian

and his work.

‘If we take from Monstrelet what has

been improperly attributed to him, it is but

just to restore that which legally belongs to

him. According to the register of the Cordeliers

of Cambray, and the Memoriaux of

Jean le Robert, he had written the history

of the war of the Ghent-men against the

duke of Burgundy. Now the events of

this war, which began in the month of

April 1452, and was not terminated before

the end of July in the following year, are

related with much minuteness in the third

volume.[9] After the authorities above quoted,

we cannot doubt that Monstrelet was

the author, if not of the whole account, at

least of the greater part of it: I say ‘part

of it,’ for he could not have narrated the

end of this war, since peace between the

Ghent-men and their prince was not concluded

until the 31st July, and Monstrelet

was buried on the 20th. It is not even

probable that he would have had time to

collect the events that happened at the beginning

of the month, unless we suppose

that he died suddenly; whence I think it

may be conjectured, that Monstrelet ceased

to write towards the end of June, when the

castle of Helsebecque was taken by the

duke of Burgundy, and that the history

of the war was written by another hand,

who may have arranged the materials which

Monstrelet had collected, but had not reduced

to order.

‘There seems here to arise a sort of contradiction

between Matthieu de Coucy, who

fixes, as I have said, the conclusion of Monstrelet’s

writing at the year 1444, and the

register of the Cordeliers, which agrees

with the Memoriaux of Jean le Robert;

but this contradiction will vanish, if we reflect

that the history of the revolt of Ghent,

in 1453, is an insulated matter, having no

connexion with the history of the reign of

Charles VII. and that it cannot be considered

as forming part of the two first volumes,

from which it is detached by a space

of eight years. Matthieu de Coucy, therefore,

who may not, perhaps, have known

of this historical fragment, was entitled to

say, that the chronicles written by Monstrelet

ended at the year 1444.

‘The continuator of these chronicles

having reported the conclusion of the war

between the Ghent-men and their prince, then

copies indiscriminately from the Grandes

Chroniques, or from Jean Chartier, with

more or less exactness, as may readily be

discovered on collating them, as I have

done. He only adds some facts relative

to the history of Burgundy, and carries

the history to the death of Charles VII.

This part, which is more interesting than

the former, because the writer has added

to the chronicles facts in which they were

deficient, is more defective in the arrangement.

Several events that relate to the

general history of the realm are told twice

over, and in succession,—first in an abridged

state, and then more minutely,—and sometimes

with differences so great that it seems

impossible that both should have been written

by the same person.[10]

‘This defect, however, we cannot without

injustice attribute to the continuator of

Monstrelet,—for it is clearly perceptible that

he only treats of the general history of

France in as far as it is connected with that

of Burgundy, and we cannot suppose that

he would repeat twice events foreign to the

principal object of his work. It is much

more natural to believe that the abridged

accounts are his, and that the first copiers,

thinking they were too short, have added

the whole detail of these articles from the

Grandes Chroniques or from Jean Chartier,

whence he had been satisfied with merely

making extracts.

‘From the death of Charles VII. in

1461, to that of Philip duke of Burgundy,

we meet with no more of these repetitions.

The historian (for he then deserves the

name) leaves off copying the Chronicles,

and advances without a guide: consequently,

he is very frequently bewildered. I

shall not attempt to notice his faults, which

are the same with those of Monstrelet, and

I could but repeat what I have said before.

There is, however, one which is peculiar to

him, and which pervades the whole work:

it is an outrageous partiality for the house

of Burgundy.

‘We may excuse him for having written,

under the title of a General History

of France, the particular history of Burgundy,

and for having only treated of that

of France incidentally, in as far as it interested

the burgundian princes. We may,

indeed, more readily pardon him for having

painted Charles VII. as a voluptuous

monarch, and Louis XI. sometimes as a

tyrant, at others as a deep and ferocious

politician, holding in contempt the most

sacred engagements. But the fidelity of

history required that he should not have

been silent as to the vices of the duke of

Burgundy and his son, who plunged France

into an abyss of calamities, and that his

predilection for these two princes should

not burst forth in every page.

‘The person who continued this first

part of the chronicles of Monstrelet has

been hitherto unknown, but I believe a

lucky accident has enabled me to discover

him. Dom Berthod, a learned benedictine

monk of the congregation of St Vanne,

having employed himself for these many

years in searching the libraries and ancient

rolls in Flanders for facts relative to our

history, has made a report with extracts

from numerous manuscripts, of which we

had only vague ideas. He has had the

goodness to communicate some of them to

me, and among others the chronicle of

Jacques du Clercq,[11] which begins at 1448,

and ends, like the continuator of Monstrelet,

at the death of the duke of Burgundy

in 1467. In order to give a general idea of

the contents of the work, D. Berthod has

copied, with the utmost exactness, the table

of chapters composed by Jacques du Clercq

himself, as he tells us in his prologue. I

have compared this table and the extracts

with the continuation of Monstrelet, and

have observed such a similarity, particularly

from the year 1453 to 1467, that I

think it impossible for any two writers to

be so exactly the same unless one had copied

after the other.

‘As we do not possess the whole of

this chronicle, I can but offer this as a very

probable conjecture, which will be corroborated,

when it is considered that Jacques du

Clercq and the continuator of Monstrelet

lived in the same country. The first resided

in Arras; and by the minute details the

second enters into concerning Flanders, we

may judge that he was an inhabitant of

that country. Some villages burnt, or events

still less interesting, and unknown beyond

the places where they happened, are introduced

into his history. In like manner,

we should discover without difficulty (if it

were otherwise unknown), that the editor

of the Grandes Chroniques was a monk of

the abbey of St Denis, when he gravely

relates, as an important event, that on such

a day the scullion of the abbey was found

dead in his bed,—and that a peasant of

Clignancourt beat his wife until she died.

‘To these divers relations between the

two writers, we must add the period when

they wrote. We see by the preface of

Jacques du Clercq, that he composed his

history shortly after the death of Philip

duke of Burgundy in 1467; and the continuator

of Monstrelet, when speaking of

the arrest of the bastard de Rubempré in

Holland, whither he had been sent by

Louis XI. says, that the bastard was a prisoner

at the time he was writing, ‘at the

end of February 1468, before Easter;’ that

is to say, that he was at work on his history

in the month of February 1469, according

to our mode of beginning the year.

‘Whether this continuation be an

abridgment of the chronicle of Jacques du

Clercq or an original chronicle, it seems

very clear that Monstrelet has been tried

by the merits of this third volume, and

that his reputation of being a party-writer

has been grounded on the false opinion that

he was the author of it.

‘I cannot close this essay without expressing

my surprise that no one, before

the publication of the article respecting

Monstrelet in the register of the Cordeliers,

had suspected that part, at least, of this

third volume, which has been attributed

to him, could not have come from his hand.

Any attentive reader must have been struck

with the passage where the continuator relates

the death of Charles duke of Orleans,

when, after recapitulating in a few words

the misfortunes which the murder of his

father had caused to France, he refers the

reader for more ample details to the history

‘of Monstrelet:’ as ‘may be seen,’ says

he, ‘in the Chronicles of Enguerrand de

Monstrelet.’

‘I shall not notice the other continuations,

which carry the history to the reign

of Francis I.; for this article has been discussed

by M. de Foncemagne, in an essay

read before the Academy in 1742;[12] nor

the different editions of Monstrelet. M. le

Duchat, in his ‘Remarques sur divers Sujets

de Littérature,’ and the editor of ‘La

nouvelle Bibliothéque des Historiens de

France,’ have left nothing more to be said

on the subject.’

OBSERVATIONS

ON THE CHRONICLE OF ENGUERRAND DE

MONSTRELET, BY M. DE FONCEMAGNE,

MENTIONED IN THE PRECEDING PAGE,

TRANSLATED FROM THE XVITH VOLUME

OF THE ‘MEMOIRES DE L’ACADÉMIE DE

BELLES LETTRES,’ &c.

The Chronicle of Enguerrand de Monstrelet,

governor of Cambray, commences

at the year 1400, where that of Froissart

ends, and terminates at 1467; but different

editors have successively added several continuations,

which bring it down to the year

1516.

The critics have before remarked, that

the first of these additions was nothing more

than a chronicle of Louis XI. known under

the name of the ‘Chronique Scandaleuse,’

and attributed to John de Troyes,

registrar of the hôtel de ville of Paris.

Those who have made this remark should

have added, that the beginning of the two

works is different, and that they only become

uniform at the description of the great

floods of the Seine and Marne, which happened

in 1460, for the author takes up the

history at that year. This event will be

found at the ninth page of the Chronique

Scandaleuse (in the second volume of the

Brussels-edition of Comines), and at the

third leaf of the last volume of Monstrelet

(second order of ciphers) edition of 1603.

The second continuation includes the

whole of the reign of Charles VIII. It is

written by Pierre Desrey, who styles himself

in the title, ‘simple orateur de Troyes

en Champagne.’ The greater part of this

addition, more especially what respects the

invasion of Italy, is again to be met with

at the end of the translation of Gaguin’s

chronicle made by this same Desrey,—at

the conclusion of ‘La Chronique de Bretagne,’

by Alain Bouchard,—and in the

history of Charles VIII. by M. Godefroi,

page 190, where it is called ‘a relation of

the expedition of Charles VIII.’

M. de Foncemagne says nothing more

of the other continuations, which he had

not occasion to examine with the same

care; but he thinks they may have been

taken from those which Desrey has added

to his translation of Gaguin, as far as the

year 1538. This notice may be useful to

those who shall study the history of Louis

XI. and of Charles VIII. inasmuch as it

will spare them the trouble and disgust of

reading several times the same things, which

they could have no reason to suspect had

been copied from each other.

We should be under great obligations

to the authors of rules for reading, if in

pointing out what on each subject ought

to be read, they would, at the same time,

inform us what ought not to be read. This

information is particularly necessary in regard

to old chronicles, or what are called

in France Recueils de Pieces. The greater

part of the chroniclers have copied each

other, at least for the years that have preceded

their own writings: in like manner,

an infinite number of detached pieces have

been published by different editors. Thus

books multiply, volumes thicken, and the

only result to men of letters is an increase

of obstacles in their progress.

The learned Benedictine, who is labouring

at the collection of french historians,

has wisely avoided this inconvenience

in regard to the chronicles.[13] A society of

learned men announced in 1734 an alphabetical

library, or a general index of ancient

pieces scattered in those compilations

known under the names of Spicilegia, Analecta,

Anecdota, by which would be seen

at a glance in how many places the same

piece could be found. This project, on its

appearance, gave rise to a literary warfare,

the only fruit of which was to cool the zeal

of the illustrious authors who had conceived

it, and to prevent the execution of

a work which would have been of infinite

utility to the republic of letters.[14]

THE

PROLOGUE.

As Sallust says, at the commencement of

his Bellum Catalinarium, wherein he relates

many extraordinary deeds of arms done by

the Romans and their adversaries, that every

man ought to avoid idleness, and exercise

himself in good works, to the end that he

may not resemble beasts, who are only useful

to themselves unless otherwise instructed,—and

as there cannot be any more suitable or

worthy occupation than handing down to

posterity the grand and magnanimous feats

of arms, and the inestimable subtleties of war

which by valiant men have been performed,

as well those descended from noble families as

others of low degree, in the most Christian

kingdom of France, and in many other

countries of Christendom under different

laws, for the instruction and information of

those who in a just cause may be desirous of

honourably exercising their prowess in arms;

and also to celebrate the glory and renown of

those who by strength of courage and bodily

vigour have gallantly distinguished themselves,

as well in sudden rencounters as in pitched

battles, armies against armies, or in single

combats, like as valiant men ought to do,

who, reading or hearing these accounts, should

attentively consider them, in order to bring to

remembrance the above deeds of arms and

other matters worthy of record, and especially

particular acts of prowess that have happened

within the period of this history, as well as the

discords, wars and quarrels that have arisen

between princes and great lords of the kingdom

of France, also between those of the adjoining

countries, that have been continued for a long

time, specifying the causes whence these wars

have had their origin.

I Enguerrand de Monstrelet, descended

from a noble family, and residing, at the time

of composing this present book, in the noble

city of Cambray, a town belonging to the

empire of Germany, employed myself in

writing a history in prose, although the matter

required a genius superior to mine, from the

great weight of many of the events relative to

the royal majesty of princes, and grand deeds

of arms that will enter into its composition.

It requires also great subtlety of knowledge to

describe the causes of many of the events,

seeing that several of them have been very

diversely related. I have frequently marvelled

within myself how this could have happened,

and whether the diversity of these accounts of

the same event could have any other foundation

than in party-prejudice; and perhaps it may

have been the case, that those who have been

engaged in battles or skirmishes have paid so

much attention to conduct themselves with

honour that they have been unable to notice

particularly what was passing in other parts of

the field of battle.

Nevertheless, as I was from my youth

fond of hearing such histories, I took pains,

according to the extent of my understanding

until of mature age, to make every diligent

inquiry as to the truth of different events, and

questioned such persons as from their rank

and birth would disdain to relate a falsehood,

and others known for their love of truth in the

different and opposing parties, on every point

in these chronicles from the first book to the

last; and particularly, I made inquiries from

kings at arms, heralds, poursuivants, and lords

resident on their estates, respecting the wars of

France, who, from their offices or situations,

ought to be well informed of facts, and relaters

of the truth concerning them.

On their informations often repeated, and

throwing aside every thing I thought doubtful

or false, or not proved by the continuation of

their accounts, and having maturely considered

their relations, at the end of a year I had them

fairly written down, and not sooner. I then

determined to pursue my work to a conclusion,

without leaning or showing favour to any party,

but simply to give to every one his due share of

honour, according to the best of my abilities;

for to do otherwise would be to detract from

the honour and prowess which valiant and

prudent men have acquired at the risk of

their lives, whose glory and renown should be

exalted in recompense for their noble deeds.

And inasmuch as this is a difficult

undertaking, and cannot be pleasing to all

parties,—some of whom may maintain, that

what I have related of particular events is not

the truth,—I therefore entreat and request all

noble persons who may read this book to excuse

me, if they find in it some things that may not

be perfectly agreeable to them; for I declare

I have written nothing but what has been

asserted to me as fact, and told to me as such,

and, should it not prove so, on those who have

been my informants must the blame be laid.

If, on the contrary, they find any virtuous

actions worthy of preservation, and that may

with delight be proposed as proper examples

to be followed, let the honour and praise be

bestowed on those who performed them, and

not on me, who am simply the narrator.

This present Chronicle will commence

on Easter-day, in the year of Grace 1400, at

which time was concluded the last volume of

the Chronicles of sir John Froissart, native of

Valenciennes in Hainault, whose renown on

account of his excellent work will be of long

duration. The first book of this work concludes

with the death of Charles VI. the most Christian

and most worthy king of France, surnamed

‘the well beloved,’ who deceased at his hôtel

of St Pol at Paris, near the Celestins, the 22d

day of October 1422. But that the causes of

these divisions and discords which arose in

that most renowned and excellent kingdom of

France may be known, discords which caused

such desolation and misery to that realm as is

pitiful to relate, I shall touch a little at the

commencement of my history on the state,

government, manners and conduct of the

aforesaid king Charles during his youth.

THE

FIRST VOLUME

OF THE

CHRONICLES

OF

ENGUERRAND DE MONSTRELET.

CHAP. I.

HOW CHARLES THE WELL-BELOVED REIGNED

IN FRANCE, AFTER HE HAD BEEN CROWNED

AT RHEIMS, IN THE YEAR THIRTEEN

HUNDRED AND EIGHTY.

In conformity to what I said in my prologue,

that I would speak of the state and government

of king Charles VI. of France, surnamed the

well-beloved, in order to explain the causes of

the divisions and quarrels of the princes of the

blood royal during his reign and afterward, I

shall devote this first chapter to that purpose.

True it is, that the above-mentioned king

Charles the well-beloved, son to king Charles V.

began to reign and was crowned at Rheims the

Sunday before All-saints-day, in the year of

Grace one thousand three hundred and eighty,

as is fully described in the Chronicles of sir John

Froissart. He was then but fourteen years old,

and thenceforward for some time governed his

kingdom right well. By following prudent

advice at the commencement of his reign,

he undertook several expeditions, in which,

considering his youth, he conducted himself

soberly and valiantly, as well in Flanders,

where he gained the battle of Rosebeque and

reduced the Flemings to his obedience, as

afterward in the valley of Cassel and on that

frontier against the duke of Gueldres. He then

made preparations at Sluys for an invasion of

England. All which enterprises made him

redoubted in every part of the world that

heard of him.

But Fortune, who frequently turns her

wheel against those of high rank as well as

against those of low degree, began to play

him her tricks[15]; for, in the year one thousand

three hundred and ninety-two, the king had

resolved in his council to march a powerful

army to the town of Mans, and thence invade

Brittany, to subjugate and bring under his

obedience the duke of Brittany, for having

received and supported the lord Peter de

Craon, who had beaten and insulted in Paris,