Title: Radioisotopes in Medicine

Author: Earl W. Phelan

Release date: July 6, 2015 [eBook #49377]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Stephen Hutcheson, Dave Morgan and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

The Understanding the Atom Series

Nuclear energy is playing a vital role in the life of every man, woman, and child in the United States today. In the years ahead it will affect increasingly all the peoples of the earth. It is essential that all Americans gain an understanding of this vital force if they are to discharge thoughtfully their responsibilities as citizens and if they are to realize fully the myriad benefits that nuclear energy offers them.

The United States Atomic Energy Commission provides this booklet to help you achieve such understanding.

Edward J. Brunenkant, Director Division of Technical Information

UNITED STATES ATOMIC ENERGY COMMISSION

by Earl W. Phelan

United States Atomic Energy Commission

Division of Technical Information

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 66-62749

1966

THE COVER

This multi-detector positron scanner is used to locate tumors. A radioisotope-labeled substance is injected into the body and subsequently concentrates in the tumor tissue. The radioisotope emits positrons that immediately decay and produce two gamma rays that travel in opposite directions. These rays are detected simultaneously on a pair of opposing detection crystals and a line is established along which the tumor is located. This method is one of many ways doctors use radioisotopes to combat disease. In this, as in many other procedures described in this booklet, the patient remains comfortable at all times.

THE AUTHOR

Earl W. Phelan is Professor of Chemistry at Tusculum College, Greeneville, Tennessee. From 1952 to 1965, he served as Staff Assistant in the Laboratory Director’s Office at Argonne National Laboratory, where his duties included editing the Argonne Reviews and supplying information to students. For 22 years prior to moving to Argonne he served as Head of the Chemistry Department of the Valdosta State College In Georgia. He received his B.S. and Ph.D. degrees from Cornell University.

By EARL W. PHELAN

The history of the use of radioisotopes for medical purposes is filled with names of Nobel Prize winners. It is inspiring to read how great minds attacked puzzling phenomena, worked out the theoretical and practical implications of what they observed, and were rewarded by the highest honor in science.

For example, in 1895 a German physicist, Wilhelm Konrad Roentgen, noticed that certain crystals became luminescent when they were in the vicinity of a highly evacuated electric-discharge tube. Objects placed between the tube and the crystals screened out some of the invisible radiation that caused this effect, and he observed that the greater the density of the object so placed, the greater the screening effect. He called this new radiation X rays, because x was the standard algebraic symbol for an unknown quantity. His discovery won him the first Nobel Prize in physics in 1901.

Wilhelm Roentgen

A French physicist, Antoine Henri Becquerel, newly appointed to the chair of physics at the Ecole Polytechnique in Paris, saw that this discovery opened up a new field for research and set to work on some of its ramifications. One of the evident features of the production of X rays was the fact that while they were being created, the glass of the vacuum tube gave off a greenish phosphorescent glow. This suggested to several physicists that substances which become phosphorescent upon exposure to visible light might give off X rays along with the phosphorescence.

Becquerel experimented with this by exposing various crystals to sunlight and then placing each of them on a black paper envelope enclosing an unexposed photographic plate. If any X rays were thus produced, he reasoned, they would penetrate the wrapping and create a developable spot of exposure on the plate. To his delight, he indeed observed just this effect when he used a phosphorescent material, uranium potassium sulfate. Then he made a confusing discovery. For several days there was no sunshine, so he could not expose the phosphorescent material. For no particular reason (other than that there was nothing else to do) Becquerel developed a plate that had been in contact with uranium material in a dark drawer, even though there had been no phosphorescence. The telltale black spot marking the position of the mineral nevertheless appeared on the developed plate! His conclusion was that uranium in its normal state gave off X rays or something similar.

Henri Becquerel

At this point, Pierre Curie, a friend of Becquerel and also a professor of physics in Paris, suggested to one of his graduate students, his young bride, Marie, that she study this new phenomenon. She found that both uranium and thorium possessed this property of radioactivity, but also, surprisingly, that some uranium minerals were more radioactive than uranium itself. Through a tedious series of chemical separations, she obtained from pitchblende (a uranium ore) small amounts of two new elements, polonium 3 and radium, and showed that they possessed far greater radioactivity than uranium itself. For this work Becquerel and the two Curies were jointly awarded the Nobel Prize in physics in 1903.

Pierre and Marie Curie

At the outset, Roentgen had noticed that although X rays passed through human tissue without causing any immediate sensation, they definitely affected the skin and underlying cells. Soon after exposure, it was evident that X rays could cause redness of the skin, blistering, and even ulceration, either in single doses or in repeated smaller doses. In spite of the hazards[1] involved, early experimenters determined that X rays could destroy cancer tissues more rapidly than they affected healthy organs, so a basis was established quite soon for one of Medicine’s few methods of curing or at least restraining cancer.

The work of the Curies in turn stimulated many studies of the effect of radioactivity. It was not long before experimenters learned that naturally radioactive elements—like radium—were also useful in cancer therapy. These elements emitted gamma rays,[2] which are like X rays but usually are even more penetrating, and their application often could be controlled better than X rays. Slowly, over the years, reliable methods were developed for treatment with these radioactive sources, and instruments were designed for measuring the quantity of radiation received by the patient.

Frederic and Irene Joliot-Curie

The next momentous advance was made by Frederic Joliot, a French chemist who married Irene Curie, daughter of Pierre and Marie Curie. He discovered in 1934 that when aluminum was bombarded with alpha particles[3] from a radioactive source, emission of positrons (positive electrons) was induced. Moreover, the emission continued long after the alpha source was removed. This was the first example of artificially induced radioactivity, and it stimulated a new flood of discoveries. Frederic and Irene Joliot-Curie won the Nobel Prize in chemistry in 1935 for this work.

Others who followed this discovery with the development of additional ways to create artificial radioactivity were two Americans, H. Richard Crane and C. C. Lauritsen, the British scientists, John Cockcroft and E. T. S. Walton, and an American, Robert J. Van de Graaff. Ernest O. Lawrence, an American physicist, invented the cyclotron (or “atom smasher”), a powerful source of high-energy particles that induced radioactivity in whatever target materials they impinged upon. Enrico Fermi, an Italian physicist, seized upon the idea of using the newly discovered neutron (an electrically neutral particle) and showed that bombardment with neutrons also could induce radioactivity in a target substance. Cockcroft and Walton, Lawrence, and Fermi all won Nobel Prizes for their work.

Patient application of these new sources of bombarding particles resulted in the creation of small quantities of hundreds of radioactive isotopic species, each with distinctive characteristics. In turn, as we shall see, many ways to use radioisotopes have been developed in medical therapy, diagnosis, and research. By now, more than 3000 hospitals hold licenses from the Atomic Energy Commission to use radioisotopes. In addition, many thousands of doctors, dentists, and hospitals have X-ray machines that they use for some of the same broad purposes. One of the results of all this is that every month new uses of radioisotopes are developed.

More persons are trained every year in methods of radioisotope use and more manufacturers are producing and packaging radioactive materials. This booklet tells some of the successes achieved with these materials for medical purposes.

Radiation is the propagation of radiant energy in the form of waves or particles. It includes electromagnetic radiation ranging from radio waves, infrared heat waves, visible light, ultraviolet light, and X rays to gamma rays. It may also include beams of particles of which electrons, positrons, neutrons, protons, deuterons, and alpha particles are the best known.[4]

It took several years following the basic discovery by Becquerel, and the work of many investigators, to systematize the information about this phenomenon. Radioactivity is defined as the property, possessed by some materials, of spontaneously emitting alpha or beta particles or gamma rays as the unstable (or radioactive) nuclei of their atoms disintegrate.

Frederick Soddy

In the 19th Century an Englishman, John Dalton, put forth his atomic theory, which stated that all atoms of the same element were exactly alike. This remained unchallenged for 100 years, until experiments by the British chemist, Frederick Soddy, proved conclusively that the element neon consisted of two different kinds of atoms. All were alike in chemical behavior but some had an atomic weight (their mass relative to other atoms) of 20 and some a weight of 22. He coined the word isotope to describe one of two or more atoms having the same atomic number but different atomic weights.[5]

Radioisotopes are isotopes that are unstable, or radioactive, and give off radiation spontaneously. Many radioisotopes are produced by bombarding suitable targets with neutrons now readily available inside atomic reactors. Some of them, however, are more satisfactorily created by the action of protons, deuterons, or other subatomic particles that have been given high velocities in a cyclotron or similar accelerator.

Radioactivity is a process that is practically uninfluenced by any of the factors, such as temperature and pressure, that are used to control the rate of chemical reactions. The rate of radioactive decay appears to be affected only by the structure of the unstable (decaying) nucleus. Each radioisotope has its own half-life, which is the time it takes for one half the number of atoms present to decay. These half-lives vary from fractions of a second to millions of years, depending only upon the atom. We shall see that the half-life is one factor considered in choosing a particular isotope for certain uses.

HALF-LIFE PATTERN OF STRONTIUM-90

Most artificially made radioisotopes have relatively short half-lives. This makes them useful in two ways. First, it means that very little material is needed to obtain a significant number of disintegrations. It should be evident that, with any given number of radioactive atoms, the number of disintegrations per second will be inversely proportional to the half-life. Second, by the time 10 half-lives have elapsed, the number of disintegrations per second will have dwindled to ¹/₁₀₂₄ the original number, and the amount of radioactive material is so small it is usually no longer significant. (Note the decrease in the figure above.)

A radioisotope may be used either as a source of radiation energy (energy is always released during decay), or as a tracer: an identifying and readily detectable marker material. The location of this material during a given treatment can be determined with a suitable instrument even though an unweighably small amount of it is present in a mixture with other materials. On the following pages we will discuss medical uses of individual radioisotopes—first those used as tracers and then those used for their energy. In general, tracers are used for analysis and 8 diagnosis, and radiant-energy emitters are used for treatment (therapy).

Radioisotopes offer two advantages. First, they can be used in extremely small amounts. As little as one-billionth of a gram can be measured with suitable apparatus. Secondly, they can be directed to various definitely known parts of the body. For example, radioactive sodium iodide behaves in the body just the same as normal sodium iodide found in the iodized salt used in many homes. The iodine concentrates in the thyroid gland where it is converted to the hormone thyroxin. Other radioactive, or “tagged”, atoms can be routed to bone marrow, red blood cells, the liver, the kidneys, or made to remain in the blood stream, where they are measured using suitable instruments.[6]

Of the three types of radiation, alpha particles (helium nuclei) are of such low penetrating power that they cannot be used for measurement from outside the body. Beta particles (electrons) have a moderate penetrating power, therefore they produce useful therapeutic results in the vicinity of their release, and they can be detected by sensitive counting devices. Gamma rays are highly energetic, and they can be readily detected by counters—radiation measurement devices—used outside the body.

Relative penetration of alpha, beta, and gamma radiation.

For comparison, a sheet of paper stops alpha particles, a block of wood stops beta particles, and a thick concrete wall stops gamma rays.

In one way or another, the key to the usefulness of radioisotopes lies in the energy of the radiation. When radiation is used for treatment, the energy absorbed by the body is used either to destroy tissue, particularly cancer, or to suppress some function of the body. Properly calculated and applied doses of radiation can be used to produce the desired effect with minimum side reactions. Expressed in terms of the usual work or heat units, ergs or calories, the amount of energy associated with a radiation dose is small. The significance lies in the fact that this energy is released in such a way as to produce important changes in the molecular composition of individual cells within the body.

When a radioisotope is used as a tracer, the energy of the radiation triggers the counting device, and the exact amount of energy from each disintegrating atom is measured. This differentiates the substance being traced from other materials naturally present.

This is the first photoscanner, which was developed in 1954 at the University of Pennsylvania and was retired from service in 1963. When gamma rays emitted by a tracer isotope in the patient’s body struck the scanner, a flashing light produced a dot on photographic film. The intensity of the light varied with the counting rate and thus diseased tissues that differed little from normal tissue except in their uptake of an isotope could be discerned.

With one conspicuous exception, it is impossible for a chemist to distinguish any one atom of an element from another. Once ordinary salt gets into the blood stream, for example, it normally has no characteristic by which anyone can decide what its source was, or which sodium atoms were added to the blood and which were already present. The exception to this is the case in which some of the atoms are “tagged” by being made radioactive. Then the radioactive atoms are readily identified and their quantity can be measured with a counting device.

A radioactive tracer, it is apparent, corresponds in chemical nature and behavior to the thing it traces. It is a true part of it, and the body treats the tagged and untagged material in the same way. A molecule of hemoglobin carrying a radioactive iron atom is still hemoglobin, and the body processes affect it just as they do an untagged hemoglobin molecule. The difference is that a scientist can use counting devices to follow the tracer molecules wherever they go.

One of the first scans made by a photoscanner. The photorecording (dark bands), superimposed on an X-ray picture for orientation, shows radioactivity in a cancer in the patient’s neck.

It should be evident that tracers used in diagnosis—to identify disease or improper body function—are present in such small quantities that they are relatively harmless. 11 Their effects are analogous to those from the radiation that every one of us continually receives from natural sources within and without the body. Therapeutic doses—those given for medical treatment—by contrast, are given to patients with a disease that is in need of control, that is, the physician desires to destroy selectively cells or tissues that are abnormal. In these cases, therefore, the skill and experience of the attending physician must be applied to limit the effects to the desired benefits, without damage to healthy organs.

This booklet is devoted to these two functions of radioisotopes, diagnosis and therapy; the field of medical research using radioactive tools is so large that it requires separate coverage.[7]

Mr. Peters, 35-year-old father of four and a resident of Chicago’s northwest side, went to a Chicago hospital one winter day after persistent headaches had made his life miserable. Routine examinations showed nothing amiss and his doctor ordered a “brain scan” in the hospital’s department of nuclear medicine.

Thirty minutes before “scan time”, Mr. Peters was given, by intravenous injection, a minute amount of radioactive technetium. This radiochemical had been structured so that, if there were a tumor in his cranium, the radioisotopes would be attracted to it. Then he was positioned so an instrument called a scanner could pass close to his head.

As the motor-driven scanner passed back and forth, it picked up the gamma rays being emitted by the radioactive technetium, much as a Geiger counter detects other radiation. These rays were recorded as black blocks on sensitized film inside the scanner. The result was a piece of exposed film that, when developed, bore an architectural likeness or image of Mr. Peters’ cranium.

The inset picture shows a brain scan made with a positron scintillation camera. A tumor is indicated by light area above ear. (Light area in facial region is caused by uptake in bone and extracellular space.) The photograph shows a patient, completely comfortable, receiving a brain scan on one of the three rectilinear scanning devices in the nuclear medicine laboratory of a hospital.

Mr. Peters, who admitted to no pain or other adverse reaction from the scanning, was photographed by the scanner from the front and both sides. The procedure took less than an hour. The developed film showed that the technetium had concentrated in one spot, indicating definitely that a tumor was present. Comparison of front and side views made it possible to pinpoint the location exactly.

Surgery followed to remove the tumor. Today, thanks to sound and early diagnosis, Mr. Peters is well and back on the job. His case is an example of how radioisotopes are used in hospitals and medical centers for diagnosis.

The first whole body scanner, which was developed at the Donner Laboratory in 1952 and is still being used. The lead collimator contains 10 scintillation counters and moves across the subject. The bed is moved and serial scans are made and then joined together to form a head-to-toe picture of the subject.

The diagram shows a scan and the parts of a scanner. (Also see page 21.)

In one representative hospital, 17 different kinds of radioisotope measurements are available to aid physicians in making their diagnoses. All the methods use tracer quantities of materials. Other hospitals may use only a few of them, some may use even more. In any case they are merely tools to augment the doctors’ skill. Examples of measurements that can be made include blood volume, blood circulation rate, red blood cell turnover, glandular activity, location of cancerous tissue, and rates of formation of bone tissue or blood cells.

Of the more than 100 different radioisotopes that have been used by doctors during the past 30 years, five have received by far the greatest attention. These are iodine-131, phosphorus-32, gold-198, chromium-51, and iron-59. Some others have important uses, too, but have been less widely employed than these five. The use of individual radioisotopes in making important diagnostic tests makes a fascinating story. Typical instances will be described in the following pages.

A differential multi-detector developed at Brookhaven National Laboratory locates brain tumors with positron-emitting isotopes. By using many pairs of detection crystals, the device shortens the scanning time and increases accuracy. (See cover for another type of positron scanner.)

Brain tumors tend to concentrate certain ions (charged atoms or molecules). When these ions are gamma-ray emitters, it is possible to take advantage of the penetrating power of their gamma rays to locate the tumor with a scanning device located outside the skull.

Arsenic-74 and copper-64 are isotopes emitting positrons,[8] which have one peculiar property. Immediately after a positron is emitted from a nucleus it decays, producing two gamma rays that travel in exactly opposite directions. The scanning device has two detectors called 15 scintillation counters, one mounted on each side of the patient’s head.

The electrical circuitry in the scanner is such that only those gamma rays are counted that impinge simultaneously on both counters. This procedure eliminates most of the “noise”, or scattered and background radiation.

Because chromium, in the molecule sodium chromate, attaches itself to red blood cells, it is useful in several kinds of tests. The procedures are slightly complicated, but yield useful information. In one, a sample of the patient’s blood is withdrawn, stabilized with heparin (to prevent clotting) and incubated with a tracer of radioactive sodium chromate. Excess chromate that is not taken up by the cells is reduced and washed away. Then the radioactivity of the cells is measured, just before injection into the patient. After a suitable time to permit thorough mixing of the added material throughout the blood stream, a new blood sample is taken and its radioactivity is measured. The total volume of red blood cells then can be calculated by dividing the total radioactivity of the injected sample by the activity per milliliter of the second sample.

Spleen scans made with red blood cells, which had been altered by heat treatment and tagged with chromium-51. Such damaged cells are selectively removed by the spleen. A is a normal spleen. B shows an abscess in the spleen. Note dark ring of radioactivity surrounding the lighter area of decreased activity at the central portion of spleen.

In certain types of anemia the patient’s red blood cells die before completing the usual red-cell lifetime of about 120 days. To diagnose this, red cells are tagged with chromium-51 (⁵¹Cr) in the manner just described. Then 16 some of them are injected back into the patient and an identical sample is injected into a compatible normal individual. If the tracer shows that the cells’ survival time is too short in both recipients to the same degree, the conclusion is that the red cells themselves must be abnormal. On the other hand, if the cell-survival time is normal in the normal individual and too short in the patient, the diagnosis is that the patient’s blood contains some substance that destroys the red cells.

When chromium trichloride, CrCl₃, is used as the tagging agent, the chromium is bound almost exclusively to plasma proteins, rather than the red cells. Chromium-51 may thus be used for estimating the volume of plasma circulating in the heart and blood vessels. The same type of computation is carried on for red cells (after correction for a small amount of chromium taken up by the red blood cells). This procedure is easy to carry out because the radioactive chromium chloride is injected directly into a vein.

An ingenious automatic device has been devised for computing a patient’s total blood volume using the ⁵¹Cr measurement of the red blood cell volume as its basis. This determination of total blood volume is of course necessary in deciding whether blood or plasma transfusions are needed in cases involving bleeding, burns, or surgical shock. This ⁵¹Cr procedure was used during the Korean War to determine how much blood had been lost by wounded patients, and helped to save many, many lives.

For several years, iodine-131 has been used as a tracer in determining cardiac output, which is the rate of blood flow from the heart. It has appeared recently that red blood cells tagged with ⁵¹Cr are more satisfactory for this measurement than iodine-labeled albumin in the blood serum. It is obvious that the blood-flow rate is an extremely important physiological quantity, and a doctor must know it to treat either heart ailments or circulatory disturbances.

In contrast to the iodine-131 procedure, which requires that an artery be punctured and blood samples be removed regularly for measurement, chromium labeling merely 17 requires that a radiation counter be mounted on the outside of the chest over the aorta (main artery leaving the heart). A sample of labeled red blood cells is introduced into a vein, and the recording device counts the radioactivity appearing in the aorta as a function of time. Eventually, of course, the counting rate (the number of radioactive disintegrations per second) levels off when the indicator sample has become mixed uniformly in the blood stream. From the shape of the curve on which the data are recorded during the measurements taken before that time, the operator calculates the heart output per second.

In this cardiac output study a probe is positioned over the heart and the passage of iodine-131 labeled human serum albumin through this area is recorded.

Obstetricians caring for expectant mothers use red cells tagged with ⁵¹Cr to find the exact location of the placenta. For example, in the condition known as placenta previa, the placenta—the organ within the uterus by which nourishment is transferred from the mother’s blood to that of the unborn child—may be placed in such a position that fatal bleeding can occur. A radiation-counting instrument placed over the lower abdomen gives information about the exact location of the placenta. If an abnormal situation exists, the attending physician is then alert and ready to cope with it. The advantages of chromium over iodine-131, which has also been used, are that smaller doses are required, and that there is no transfer of radioactivity to the fetal circulation.

Still another common measurement using ⁵¹Cr-labeled red blood cells is the determination of the amount and location of bleeding from the gastrointestinal tract (the stomach and bowels). The amount is found by simple measurement of chromium in the blood that appears in the stools. To find the location is slightly more complicated. The intestinal contents are sampled at different levels through an inserted tube, and the radiation of the samples determined separately.

Finally, gastrointestinal loss of protein can be measured with the aid of ⁵¹Cr-labeled blood serum. The serum is treated with CrCl₃ and then injected into a vein. In several very serious ailments there is serious loss of blood protein through the intestines. In these conditions the ⁵¹Cr level in the intestinal excretions is high, and this alerts the doctor to apply remedial measures.

Vitamin B₁₂ is a cobalt compound. Normally the few milligrams of B₁₂ in the body are stored in the liver and released to the blood stream as needed. In pernicious anemia, a potentially fatal but curable disease, the B₁₂ content of the blood falls from the usual level of 300-900 micromicrograms per milliliter (ml) to 0 to 100 micromicrograms per ml. The administration of massive doses of B₁₂ is the only known remedy for this condition.

If the B₁₂ is labeled with radioactive cobalt, its passage into the blood stream may be observed by several different methods. The simplest is to give the B₁₂ by mouth, and after about 8 hours study the level of cobalt radioactivity in the blood. Cobalt-60 has been used for several years, but recently cobalt-58 has been found more satisfactory. It has a half-life of 72 days while ⁶⁰Co has a 5.3-year half-life. This reduces greatly the amount of radiation to the patient’s liver by the retained radioactivity.

Like chromium-51, iodine is a versatile tracer element. It is used to determine blood volume, cardiac output, plasma volume, liver activity, fat metabolism, thyroid 19 cancer metastases, brain tumors, and the size, shape, and activity of the thyroid gland.

A linear photoscanner produced these pictures of (A) a normal thyroid, (B) an enlarged thyroid, and (C) a cancerous thyroid.

Because of its unique connection with the thyroid gland, iodine-131 is most valuable in measurements connected with that organ. Thyroxin, an iodine compound, is manufactured in the thyroid gland, and transferred by the blood stream to the body tissues. The thyroxin helps to govern the oxygen consumption of the body and therefore helps control its metabolism. Proper production of thyroxin is essential to the proper utilization of nutrients. Lowered metabolism means increased body weight. Lowered thyroid activity may mean expansion of the gland, causing one form of goiter.

Iodine-131 behaves in the body just as the natural non-radioactive isotope, iodine-127, does, but the radioactivity permits observation from outside the body with some form of radiation counter. Iodine can exist in the body in many different chemical compounds, and the counter can tell where it is but not in what form. Hence chemical manipulation is necessary in applying this technique to different diagnostic procedures.

The thyroid gland, which is located at the base of the neck, is very efficient in trapping inorganic iodide from the blood stream, concentrating and storing the iodine-containing material and gradually releasing it to the blood stream in the form of protein-bound iodine (PBI).

One of the common diagnostic procedures for determining thyroid function, therefore, is to measure the percentage of an administered dose of ¹³¹I that is taken up by the gland. Usually the patient is given a very small dose of radioactive sodium iodide solution to drink, and two hours later the amount of iodine in the gland is determined by measuring the radiation coming from the neck area. In 20 hyperthyroidism, or high thyroid gland activity, the gland removes iodide ions from the blood stream more rapidly than normal.

Screening test for Hyperthyroidism

It is especially important in isotope studies on infants and small children that the radiation exposure be low. By carrying out studies in the whole body counter room, the administered dose can be greatly reduced. The photographs illustrate a technique of measuring radioiodine uptake in the thyroid gland with extremely small amounts of a mixture of iodine-131 and iodine-125. A shows a small television set that is mounted above the crystal in such a way that good viewing requires that the head be kept in the desired position. This helps solve the problem of keeping small children still during a 15-minute counting period. B shows a child in position for a thyroid uptake study.

This simple procedure has been used widely. One difficulty in using it is that its success is dependent upon the time interval between injection and measurement. An overactive gland both concentrates iodine rapidly and also 21 discharges it back to the blood stream as PBI more rapidly than normal. Modifications of the test have been made to compare the amount of iodine-131 that was administered with the amount circulating in the blood as PBI. The system acquires chemical separation of the two forms of iodine from a sample of blood removed from a vein, followed by separate counting. This computation of the “conversion ratio” of radioactive plasma PBI to plasma-total ¹³¹I gives results that are less subject to misinterpretation.

To determine local activity in small portions of the thyroid, an automatic scanner is used. A collimator[9] shields the detector (a Geiger-Müller tube or scintillating crystal) so that only those impulses originating within a very small area are accepted by the instrument. The detector is then moved back and forth slowly over the entire area and the radiation is automatically recorded at definite intervals, creating a “map” of the active area. In cases where lumps, or nodules, have been discovered in the thyroid, the map is quite helpful in distinguishing between cancerous and benign nodules. The former are almost always less radioactive than surrounding tissues.

Seven serial scans made with the whole body scanner were put together to provide a whole body scan of this patient with thyroid cancer that had spread to the lung. One millicurie of iodine-131 was administered and the scan made 72 hours later. Note the uptake in the lung. This patient was successfully treated with large doses of iodine-131.

Fragments of cancerous thyroid tissue may migrate to other parts of the body and grow there. These new cancers are known as metastatic cancers and are a signal of an advanced state of disease. In such a situation even complete surgical removal of the original cancer may not save the patient. If these metastases are capable of concentrating iodine (less than 10% of them are), they can be located by scanning the whole body in the manner that was just described. When a thyroid cancer is discovered, therefore, a doctor may look for metastases before deciding to operate.

Human blood serum albumin labeled with ¹³¹I is used for measurement of the volume of circulating plasma. The procedure is quite similar to that used with radioactive chromium. Iodinated human serum albumin labeled with ¹³¹I is injected into a vein. Then, after allowing time for complete mixing of the sample with the blood, a second sample is counted using a scintillation counter.

Time-lapse motion pictures of the liver of a 3-year-old girl were made with the scintillation camera 1 hour after injection of 50 microcuries of iodine-131-labeled rose bengal dye. This child was born without a bile-duct system and an artificial bile duct had been created surgically. She developed symptoms that caused concern that the duct had closed. These scans show the mass of material containing the radioactive material (small light area) moving downward and to the right, indicating that the duct was still open.

For many years, a dye known as rose bengal has been used in testing liver function. About 10 years ago this procedure was improved by labeling the dye with ¹³¹I. When this dye is injected into a vein it goes to the liver, which removes it from the blood stream and transfers it to the intestines to be excreted. The rate of disappearance of the dye from the blood stream is therefore a measure of the liver activity. Immediately after administration of the radioactive dye, counts are recorded, preferably continuously from several sites with shielded, collimated detectors. One counter is placed over the side of the head or the thigh to record the clearance of the dye from the blood stream. A second is placed over the liver, and a third over the abdomen to record the passage of the dye into the small intestine.

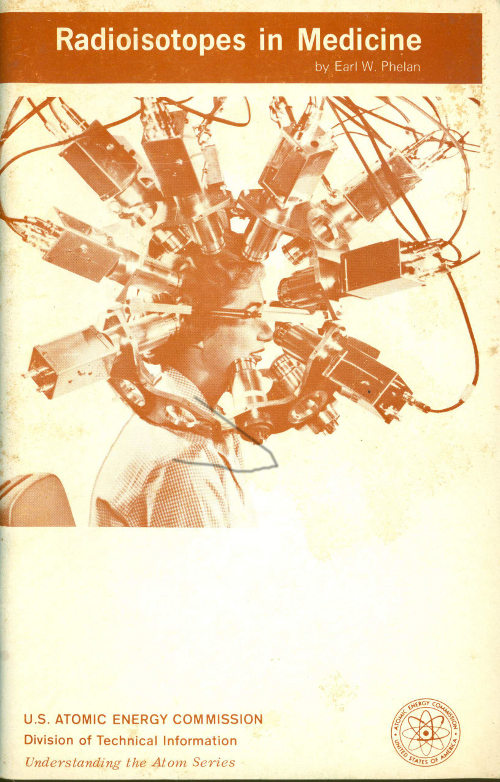

Human serum albumin labeled with ¹³¹I is sometimes used for location of brain tumors. It appears that tumors 23 alter a normal “barrier” between the brain and blood in such a manner that the labeled albumin can penetrate tumorous tissues although it would be excluded from healthy brain tissue.

The brain behaves almost uniquely among body tissues in that a “blood-brain barrier” exists, so that substances injected into the blood stream will not pass into brain cells although they will pass readily into muscular tissue. This blood-brain barrier does not exist in brain tumors. A systematic scanning of the skull then permits location of these cancerous “hot spots”.

Iron is a necessary constituent of red blood cells, so its radioactive form, ⁵⁹Fe, has been used frequently in measurement of the rate of formation of red cells, the lifetime of red cells, and red cell volumes. The labeling is more difficult than labeling with chromium for the same purposes, so this procedure no longer has the importance it once had.

On the other hand, direct measurement of absorption of iron by the digestive tract can be accomplished only by using ⁵⁹Fe. In achlorhydria the gastric juice in the stomach is deficient in hydrochloric acid, and this condition has been shown to lower the iron absorption. A normal diet contains much more iron than the body needs, but in special 24 cases, sometimes called “tired blood” in advertising for medicines, iron compounds are prescribed for the patient. If ⁵⁹Fe is included, its appearance in the blood stream can be monitored and the effectiveness of the medication noted.

This multiple-port scintillation counter is used for iron-kinetic studies. The tracer dose of iron-59 is administered into the arm vein and then the activities in the bone marrow, liver, and spleen are recorded simultaneously with counters positioned over these areas, and show distribution of iron-59 as a function of time. When the data are analyzed in conjunction with iron-59 content in blood, information can be obtained about sites of red blood cell production and destruction.

The phosphate ion is a normal constituent of the blood. In many kinds of tumors, phosphates seem to be present in the cancerous tissue in a concentration several times that of the surrounding healthy tissue. This offers a way of using phosphorus-32 to distinguish between cancer cells and their neighbors. Due to the fact that ³²P gives off beta rays but no gammas, the counter must be placed very close to the suspected tissue, since beta particles have very 25 little penetrating power. This fact limits the use of the test to skin cancers or to cancers exposed by surgery.

Some kinds of brain tumors, for instance, are difficult to distinguish visually from the healthy brain tissue. In such cases, the patient may be given ³²P labeled phosphate intravenously some hours before surgery. A tiny beta-sensitive probe counter then can be moved about within the operative site to indicate to the surgeon the limits of the cancerous area.

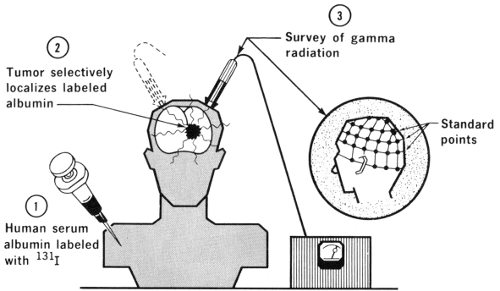

Normal blood is about 1% sodium chloride or ordinary salt. This fact makes possible the use of ²⁴Na in some measurements of the blood and other fluids. The figure illustrates this technique. A sample of ²⁴NaCl solution is injected into a vein in an arm or leg. The time the radioisotope arrives at another part of the body is detected with a shielded radiation counter. The elapsed time is a good indication of the presence or absence of constrictions or obstructions in the circulatory system.

The passage of blood through the heart may also be measured with the aid of sodium-24. Since this isotope emits gamma rays, measurement is done using counters on the outside of the body, placed at appropriate locations above the different sections of the heart.

Because of its short half-life of six hours, technetium-99m[10] is coming into use for diagnosis using scanning devices, particularly for brain tumors. It lasts such a short time it obviously cannot be kept in stock, so it is prepared by the beta decay of molybdenum-99.[11] A stock of molybdenum is kept in a shielded container in which it undergoes radioactive decay yielding technetium. Every morning, as the technetium is needed, it is extracted from its parent by a brine solution. This general procedure of extracting a short-lived isotope from its parent is also used in other cases. We shall see later that radon gas is obtained by an analogous method from its parent, radium.

Using a “nuclear cow” to get technetium from its parent isotope. The “cow” is being fed saltwater through a tube. The saltwater drains through a high-radiation (hot) isotope. The resultant drip-off is a daughter such as technetium-99m. This new, mild isotope can be mixed with other elements and these become the day’s supply of radioisotopes for other scans. Technetium-99m decays in 6 hours. Thus greater amounts, with less possibility of injury, can be administered and a better picture results.

For years it has been recognized that there would be many uses for a truly portable device for taking X-ray pictures—one that could be carried by the doctor to the bedside or to the scene of an accident. Conventional X-ray equipment has been in use by doctors for many years, and highly efficient apparatus has become indispensable, especially in treating bone conditions. There is, however, a need for a means of examining patients who cannot be moved to a hospital X-ray room, and are located where electric current sources are not available.

A few years ago, a unit was devised that weighed only a few pounds, and could take “X-ray pictures” (actually gamma radiographs) using the gamma rays from the radioisotope thulium-170. The thulium source is kept inside a lead shield, but a photographic shutter-release cable can be pressed to move it momentarily over an open port in the shielding. The picture is taken with an exposure of a few seconds. A somewhat similar device uses strontium-90 as the source of beta radiation that in turn stimulates the emission of gamma rays from a target within the instrument.

A technician holds an inexpensive portable X-ray unit that was developed by the Argonne National Laboratory. Compare its size with the standard X-ray machine shown at left and above.

Still more recently, ¹²⁵I has been used very successfully in a portable device as a low-energy gamma source for radiography. The gamma rays from this source are sufficiently penetrating for photographing the arms and legs, and the necessary shielding is easily supplied to protect the operator. By contrast with larger devices, the gamma-ray source can be as small as one-tenth millimeter in diameter, virtually a point source; this makes possible maximum sharpness of image. The latest device, using up to one curie[12] of ¹²⁵I, weighs 2 pounds, yet has adequate shielding for the operator. It is truly portable.

If this X-ray source is combined with a rapid developing photographic film, a physician can be completely freed from dependence upon the hospital laboratory for emergency X rays. A finished print can be ready for inspection in 10 seconds. The doctor thus can decide quickly whether it is safe to move an accident victim, for instance. In military operations, similarly, it becomes a simple matter to examine wounded soldiers in the field where conventional equipment is not available.

More than 30 years ago, when deuterium (heavy hydrogen) was first discovered, heavy water (D₂O) was used for the 29 determination of total body water. A small sample of heavy water was given either intravenously or orally, and time was allowed for it to mix uniformly with all the water in the body (about 4 to 6 hours). A sample was then obtained of the mixed water and analyzed for its heavy water content. This procedure was useful but it was hard to make an accurate analysis of low concentrations of heavy water.

More recently, however, tritium (³H) (radioactive hydrogen) has been produced in abundance. Its oxide, tritiated water (³H₂O), is chemically almost the same as ordinary water, but physically it may be distinguished by the beta rays given off by the tritium. This very soft (low-energy) beta ray requires the use of special counting equipment, either a windowless flow-gas counter or a liquid scintillator, but with the proper techniques accurate measurement is possible. The total body water can then be computed by the general isotope dilution formula used for measuring blood plasma volume.

The total body water is determined by the dilution method using tritiated water. This technician is purifying a urine sample so that the tritium content can be determined and the total body water calculated.

Another booklet in this series, Neutron Activation Analysis, discusses a new process by which microscopic quantities of many different materials may be analyzed accurately. Neutron irradiation of these samples changes some of their atoms to radioactive isotopes. A multichannel analyzer instrument gives a record of the concentration of any of about 50 of the known elements.

One use of this technique involved the analysis of a hair from Napoleon’s head. More than 100 years after his death it was shown that the French Emperor had been given arsenic in large quantities and that this possibly caused his death.

The ways in which activation analysis can be applied to medical diagnosis are at present largely limited to toxicology, the study of poisons, but the future may bring new possibilities.

Knowledge is still being sought, for example, about the physiological role played by minute quantities of some of the elements found in the body. The ability to determine accurately a few parts per million of “trace elements” in the various tissues and body fluids is expected to provide much useful information as to the functions of these materials.

A large number of different radioisotopes have been used for measurement of disease conditions in the human body. They may measure liquid volumes, rates of flow or rates of transfer through organs or membranes; they may show the behavior of internal organs; they may differentiate between normal and malignant tissues. Hundreds of hospitals are now making thousands of these tests annually.

This does not mean that all the diagnostic problems have been solved. Much of the work is on an experimental rather than a routine basis. Improvements in techniques are still being made. As quantities of radioisotopes available for these purposes grow, and as the cost continues to drop, it is expected there will be still more applications. Finally, this does not mean we no longer need the doctor’s diagnostic 31 skill. All radioisotope procedures are merely tools to aid the skilled physician. As the practice of medicine has changed from an art to a science, radioisotopes have played a useful part.

A doctor recently told this story about a cancer patient who was cured by irradiation with cobalt-60.

“A 75-year-old white male patient, who had been hoarse for one month, was treated unsuccessfully with the usual medications given for a bad cold. Finally, examination of his larynx revealed an ulcerated swelling on the right vocal cord. A biopsy (microscopic examination of a tissue sample) was made, and it was found the swelling was a squamous-cell cancer.

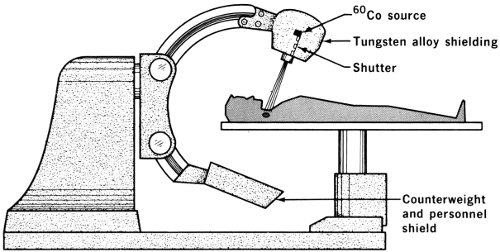

“Daily radiation treatment using a cobalt-60 device was started and continued for 31 days. This was in September 1959. The cobalt-60 unit is one that can be operated by remote control. It positions radioactive cobalt over a collimator, which determines the size of the radiation beam reaching the patient. The machine may be made to rotate around the patient or can be used at any desired angle or position.

“When the treatment series was in progress, the patient’s voice was temporarily made worse, but it returned to normal within two months after the treatment ended. The radiation destroyed the cancerous growth, and frequent examinations over 6 years since have failed to reveal any regrowth.

“The treatment spared the patient’s vocal cords, and his voice, airway, and food passage were preserved.”

This dramatic tale with a happy ending is a good one with which to start a discussion of how doctors use radioisotopes for treatment of disease.

Radioisotopes have an important role in the treatment of disease, particularly cancer. It is still believed that cancer is not one but several diseases with possible multiple causes. Great progress is being made in development of chemicals for relief of cancer. Nevertheless, radiation and surgery are still the main methods for treating cancer, and there are many conditions in which relief can be obtained through use of radiation. Moreover, the imaginative use of radioisotopes gives much greater flexibility in radiation therapy. This is expected to be true for some years to come even as progress continues.

Radioisotopes serve as concentrated sources of radiation and frequently are localized within the diseased cells or organs. The dose can be computed to yield the maximum therapeutic effect without harming adjacent healthy tissues. Let us see some of the ways in which this is done.

Iodine, as was mentioned earlier, concentrates in the thyroid gland, and is converted there to protein-bound iodine that is slowly released to the blood stream. Iodine-131, in concentrations much higher than those used in diagnostic tests, will irradiate thyroid cells, thereby damage them, and reduce the activity of an overactive thyroid (hyperthyroidism). The energy is released within the affected gland, and much of it is absorbed there. Iodine-131 has a half-life of 8.1 days. In contrast, ¹³²I has 33 a half-life of only 2.33 hours. What this means is that the same weight of radioactive ¹³²I will give a greater radiation dose than ¹³¹I would, and lose its activity rapidly enough to present much less hazard by the time the iodine is released to the blood stream. Iodine-132 is therefore often preferred for treatment of this sort.

Boron-10 has been used experimentally in the treatment of inoperable brain tumors. Glioblastoma multiforme, a particularly malignant form of cancer, is an invariably fatal disease in which the patient has a probable life expectancy of only 1 year. The tumor extends roots into normal tissues to such an extent that it is virtually impossible for the surgeon to remove all malignant tissue even if he removes enough normal brain to affect the functioning of the patient seriously. With or without operation the patient dies within months. This is therefore a case in which any improvement at all is significantly helpful.

The blood-brain barrier that was mentioned earlier minimizes the passages of many materials into normal brain tissues. But when some organic or inorganic compounds, such as the boron compounds, are injected into the blood stream, they will pass readily into brain tumors and not move into normal brain cells.

Boron-10 absorbs slow neutrons readily, and becomes boron-11, which disintegrates almost immediately into alpha particles and a lithium isotope. Alpha particles, remember, have very little penetrating power, so all the energy of the alpha radioactivity is expended within the individual tumor cells. This is an ideal situation, for it makes possible destruction of tumor cells with virtually no harm to normal cells, even when the two kinds are closely intermingled.

Slow neutrons pass through the human body with very little damage, so a fairly strong dose of them can be safely applied to the head. Many of them will be absorbed by the boron-10, and maximum destruction of the cancer will occur, along with minimum hazard to the patient. This treatment is accomplished by placing the head of the patient in a beam of slow neutrons emerging from a nuclear reactor a few minutes after the boron-10 compound has been injected into a vein.

SEQUENCE OF EVENTS IN NEUTRON CAPTURE THERAPY USING BORON-10

Neutron capture treatment of a brain tumor, using the Brookhaven National Laboratory research reactor (center).

(1) A lead shutter shields the patient from reactor neutrons.

(2) A compound containing the stable element boron is injected into the bloodstream; the tumor absorbs most of the boron.

(3) After 8 minutes, when the tumor is saturated, the shutter is removed and neutrons bombard the brain, splitting boron atoms so that fragments destroy tumor tissue.

(4) Twenty minutes later the shutter is closed and the treatment ends.

The difficulty is that most boron compounds themselves are poisonous to human tissues, and only small concentrations can be tolerated in the blood. Efforts have been made, with some success, to synthesize new boron compounds that have the greatest possible degree of selective absorption by the tumors. Both organic and inorganic compounds have been tried, and the degree of selectivity has been shown to be much greater for some than for others. So far it is too early to say that any cures have been brought about, but results have been very encouraging. The ideal drug, one which will make possible complete destruction of the cancer without harming the patient, is probably still to be devised.

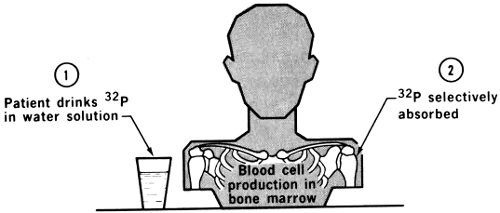

Another disease which is peculiarly open to attack by radioisotopes is polycythemia vera. This is an insidious ailment of a chronic, slowly progressive nature, characterized by an abnormal increase in the number of red blood cells, an increase in total blood volume, enlargement of the spleen, and a tendency for bleeding to occur. There is some indication that it may be related to leukemia.

Until recent years there was no very satisfactory treatment of this malady. The ancient practice of bleeding was as useful as anything, giving temporary relief but not striking at the underlying cause. There is still no true cure, but the use of phosphorus-32 has been very effective in causing disappearance of symptoms for periods from months to years, lengthening the patient’s life considerably. The purpose of the ³²P treatment (using a sodium-radiophosphate solution) is not to destroy the excess of red cells, as had been tried with some drugs, but rather to slow down their formation and thereby get at the basic cause.

Phosphorus-32 emits pure beta rays having an average path in tissue only 2 millimeters long. Its half-life is 14.3 days. When it is given intravenously it mixes rapidly with the circulating blood and slowly accumulates in tissues that utilize phosphates in their metabolism. This brings 36 appreciable concentration in the blood-forming tissues (about twice as much in blood cells as in general body cells).

Survival of polycythemia vera patients after ³²P therapy.

One other pertinent fact is that these rapidly dividing hematopoietic cells are extremely sensitive to radiation. (Hematopoietic cells are those that are actively forming blood cells and are therefore those that should be attacked selectively.) The dose required is of course many times that needed for diagnostic studies, and careful observation of the results is necessary to determine that exactly the desired effect has been obtained.

There exists some controversy over this course of treatment. No one denies that the lives of patients have been lengthened notably. Nevertheless since the purpose of the procedure is to reduce red cell formation, there exists the hazard of too great a reduction, and the possibility of causing leukemia (a disease of too few red cells). There 37 may be a small increase in the number of cases of leukemia among those treated with ³²P compared with the general population. The controversy arises over whether the ³²P treatment caused the leukemia, or whether it merely prolonged the lives of the patients until leukemia appeared as it would have in these persons even without treatment. This is probably quibbling, and many doctors believe that the slight unproven risk is worth taking to produce the admitted lengthy freedom from symptoms.

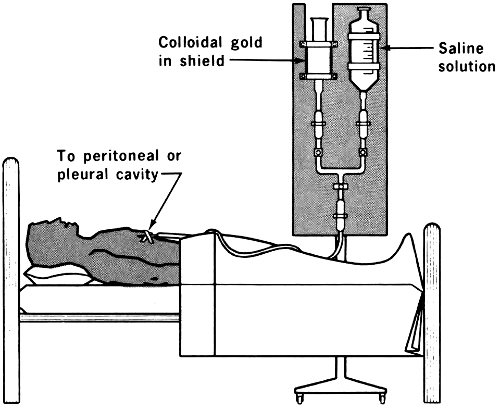

The last ailment we shall discuss in this section is the accumulation of large quantities of excess fluid in the chest and abdominal cavities from their linings, as a consequence of the growth of certain types of malignant tumors.

Frequent surgical drainage was at one time the only very useful treatment, and of course this was both uncomfortable and dangerous. The use of radioactive colloidal suspensions, primarily colloidal gold-198, has been quite successful in palliative treatment: It does not cure, but it does give marked relief.

Radioactive colloids (a colloid is a suspension of one very finely divided substance in some other medium) can be introduced into the abdominal cavity, where they may 38 remain suspended or settle out upon the lining. In either case, since they are not dissolved, they do not pass through the membranes or cell walls but remain within the cavity. Through its destructive and retarding effect on the cancer cells the radiation inhibits the oozing of fluids.

Gold-198 offers several advantages in such cases. It has a short half-life (2.7 days); it is chemically inert and therefore nontoxic; and it emits beta and gamma radiation that is almost entirely absorbed by the tissues in its immediate neighborhood.

The results have been very encouraging. There is admittedly no evidence of any cures, or even lengthening of life, but there has been marked reduction of discomfort and control of the oozing in over two-thirds of the cases treated.

Radium salts were the first materials to be used for radiation treatment of cancer. Being both very expensive and very long-lived, they could not be injected but were used in temporary implants. Radium salts in powder form were packed into tiny hollow needles about 1 centimeter long, which were then sealed tightly to prevent the escape of radon gas. As radium decays (half-life 1620 years) it becomes gaseous radon. The latter is also radioactive, so it must be prevented from escaping. These gold needles could be inserted into tumors and left there until the desired dosage had been administered. One difficulty in radium treatment was that the needles were so tiny that on numerous occasions they were lost, having been thrown out with the dressings. Then, both because of their value and their hazard, a frantic search ensued when this happened, not always ending successfully.

The needle used for implantation of yttrium-90 pellets into the pituitary gland is shown in the top photograph. In the center X ray the needle is in place and the pellets have just been passed through it into the bone area surrounding the pituitary gland. The bottom X ray shows the needle withdrawn and the pellets within the bone.

The fact that radon, the daughter of radium, is constantly produced from its parent, helped to eliminate some of this difficulty. Radium could be kept in solution, decaying constantly to yield radon. The latter, with a half-life of 4 days, could be sealed into gold seeds 3 by 0.5 millimeters and left in the patient without much risk, even if he failed to return for its removal at exactly the appointed time. The cost was low even if the seeds were lost.

During the last 20 years, other highly radioactive sources have been developed that have been used successfully. Cobalt-60 is one popular material. Cobalt-59 can be neutron-irradiated in a reactor to yield cobalt-60 with such a high specific activity that a small cylinder of it is more radioactive than the entire world’s supply of radium. Cobalt-60 has been encapsulated in gold or silver needles, sometimes of special shapes for adaptation to specific tumors such as carcinoma of the cervix. Sometimes needles have been spaced at intervals on plastic ribbon that adapts itself readily to the shape of the organ treated.

Gold-198 is also an interesting isotope. Since it is chemically inert in the body, it needs no protective coating, and as is the case with radon, its short half-life makes its use simpler in that the time of removal is not of critical importance.

Ceramic beads made of yttrium-90 oxide are a moderately new development. One very successful application of this material has been for the destruction of the pituitary gland.

Cancer may be described as the runaway growth of cells. The secretions of the pituitary gland serve to stimulate cell reproduction, so it was reasoned that destruction of this gland might well slow down growth of a tumor elsewhere in the body. The trouble was that the pituitary is small and located at the base of the brain. Surgical removal had brought dramatic relief (not cure) to many patients, but the surgery itself was difficult and hazardous. Tiny yttrium-90 oxide beads, glasslike in nature, can be implanted directly in the gland with much less difficulty and risk, and do the work of destroying the gland with little damage to its surroundings. The key to the success of yttrium-90 is the fact that it is a beta-emitter, and beta rays have so little penetrating power that their effect is limited to the immediate area of the implant.

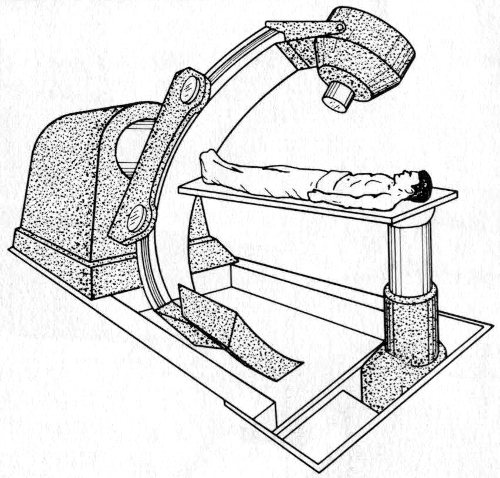

Over 200 teletherapy units are now in use in the United States for treatment of patients by using very high intensity sources of cobalt-60 (usually) or cesium-137. Units carrying sources with intensities of more than a thousand curies are common.

The cobalt-60 unit at the M. D. Anderson Hospital and Tumor Institute in Houston, Texas, employs a 3000-curie source. This unit has a mechanism that allows for rotation therapy about a stationary patient. Many different treatment positions are possible. This patient, shown in position for therapy, has above her chest an auxiliary diaphragm that consists of an expanded metal tray on which blocks of either tungsten or lead are placed to absorb gamma rays and thus shape the field of treatment. In this case they allow for irradiation of the portions of the neck and chest delineated by the lines visible on the patient.

Since a curie is the amount of radioactivity in a gram of radium that is in equilibrium with its decay products, a 1000-curie source is comparable to 2 pounds of pure radium. Neglecting for the moment the scarcity and enormous cost of that much radium (millions of dollars), we 42 have to consider that it would be large in volume and consequently difficult to apply. Radiation from such a quantity cannot be focussed; consequently, either much of it will fall upon healthy tissue surrounding the cancer or much of it will be wasted if a narrow passage through the shield is aimed at the tumor. In contrast, a tiny cobalt source provides just as much radiation and more if it can be brought to bear upon the exact spot to be treated.

Most interesting of all is the principle by which internal cancers can be treated with a minimum of damage to the skin. Deep x-irradiation has always been the approved treatment for deep-lying cancers, but until recently this required very cumbersome units. With the modern rotational device shown in the diagram, a very narrow beam is aimed at the patient while the source is mounted upon a carrier that revolves completely around him. The patient is positioned carefully so that the lesion to be treated is exactly at the center of the circular path of the carrier. The result is that the beam strikes its internal target during the entire circular orbit, but the same amount of radiation is spread out over a belt of skin and tissue all the way around the patient. The damage to any one skin cell is minimized. The advantage of this device over an earlier device, in which the patient was revolved in a stationary beam, is that the mechanical equipment is much simpler.

In summary, then, we may say that radioisotopes play an important role in medicine. For the diagnostician, small harmless quantities of many isotopes serve as tools to aid him in gaining information about normal and abnormal life processes. The usefulness of this information depends upon his ingenuity in devising questions to be answered, apparatus to measure the results, and explanations for the results.

For therapeutic uses, on the other hand, the important thing to remember is that radiation damages many kinds of cells, especially while they are in the process of division (reproduction).[13] Cancer cells are self-reproducing cells, but do so in an uncontrolled manner. Hence cancer cells are particularly vulnerable to radiation. This treatment requires potent sources and correspondingly increases the hazards of use.

In all cases, the use of these potentially hazardous materials belongs under the supervision of the U. S. Atomic Energy Commission.[14] Licenses are issued by the Commission after investigation of the training, ability, and facilities possessed by prospective users of dangerous quantities. At regular intervals courses are given to train individuals in the techniques necessary for safe handling, and graduates of these courses are now located in laboratories all over the country.

The future of this field cannot be predicted with certainty. Research in hundreds of laboratories is continuing to add to our knowledge, through new apparatus, new techniques, and new experiments. Necessarily the number of totally new fields is becoming smaller, but most certainly the number of cases using procedures already established is bound to increase. We foresee steady improvement and growth in all uses of radioisotopes in medicine.

The measurement of radioactivity must be accomplished indirectly, so use is made of the physical, chemical, and electrical effects of radiation on materials. One commonly used effect is that of ionization. Alpha and beta particles ionize gases through which they pass, thereby making the gases electrically conductive. A family of counters uses this principle: the ionization chamber, the proportional counter, and the Geiger-Müller counter.

Certain crystals, sodium iodide being an excellent example, emit flashes of visible light when struck by ionizing radiation. These crystals are used in scintillation counters.

One of a pair of electrodes is a wire located centrally within a cylinder. The other electrode is the wall of the chamber. Radiation ionizes the gas within the chamber, permitting the passage of current between the electrodes. The thickness of a window in the chamber wall determines the type of radiation it can measure. Only gamma rays will pass through a heavy metal wall, glass windows will admit all gammas and most betas, and plastic (Mylar) windows are necessary to admit alpha particles. Counters of this type, when properly calibrated, will measure the total amount of radiation received by the body of the wearer.

This is a type of ionization chamber in which the intensity of the electrical pulse it produces is proportional to the energy of the incoming particle. This makes it possible to record alpha particles and discriminate against gamma rays.

These have been widely used and are versatile in their applications. The potential difference between the electrodes in the Geiger-Müller tube (similar to an ionization chamber) is high. A single alpha or beta particle ionizes some of the gas within the chamber. In turn these ions strike other gas molecules producing secondary ionization. The result is an “avalanche” or high-intensity pulse of electricity passing between the electrodes. These pulses can be counted electrically and recorded on a meter at rates up to several thousand per minute.

Since the development of the photoelectric tube and the photomultiplier tube (a combination of photoelectric cell and amplifier), the scintillation counter has become the most popular instrument for most purposes described in this booklet. The flash of light produced when an individual ionizing particle or ray strikes a sodium-iodide crystal is noted by a photoelectric cell. The intensity of the flash is a measure of the energy of the radiation, so the voltage of the output of the photomultiplier tube is a measure of the wavelength of the original gamma ray. The scintillation counter can observe up to a million counts per minute and discriminate sharply between gamma rays of different energies. With proper windows it can be used for alpha or beta counts as well.

The latest development is a tiny silicon (transistor-type) diode detector that can be made as small as a grain of sand and placed within the body with very little discomfort.

Many of the applications described in this booklet require accurate knowledge of the exact location of the radioactive source within the body. Commonly a detecting tube is used having a collimating shield so that it accepts only that radiation that strikes it head-on. A motor-driven carrier 46 moves the counter linearly at a slow rate. Radiation is counted and whenever the count reaches the predetermined amount—from one count to many—an electric impulse causes a synchronously moving pen to make a dot on a chart. The scanner, upon reaching the end of a line moves down to the next line and starts over, eventually producing a complete record of the radiation sources it has passed over.

Radioactive Isotopes in Medicine and Biology, Solomon Silver, Lea & Febiger, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19106, 1962, 347 pp., $8.00.

Atomic Medicine, Charles F. Behrens and E. Richard King (Eds.), The Williams & Wilkins Company, Baltimore, Maryland 21202, 1964, 766 pp., $18.00.

The Practice of Nuclear Medicine, William H. Blahd, Franz K. Bauer, and Benedict Cassen, Charles C. Thomas, Publisher, Springfield, Illinois 62703, 1958, 432 pp., $12.50.

Progress in Atomic Medicine, John H. Lawrence (Ed.), Grune & Stratton, Inc., New York 10016, 1965, volume 1, 240 pp., $9.75.

Radiation Biology and Medicine, Walter D. Claus (Ed.), Addison-Wesley Publishing Company, Reading, Massachusetts 01867, 1958, 944 pp., $17.50. Part 7, Medical Uses of Atomic Radiation, pp. 471-589.

Radioisotopes and Radiation, John H. Lawrence, Bernard Manowitz, and Benjamin S. Loeb, McGraw-Hill Book Company, New York 10036, 1964, 131 pp., $18.00. Chapter 1, Medical Diagnosis and Research, pp. 5-45; Chapter 2, Medical Therapy, pp. 49-62.

Atoms Today and Tomorrow (revised edition), Margaret O. Hyde, McGraw-Hill Book Company, Inc., New York 10036, 1966, 160 pp., $3.25. Chapter 9, The Doctor and the Atom, pp. 79-101.

Atomic Energy in Medicine, K. E. Halnan, Philosophical Library, Inc., New York 10016, 1958, 157 pp., $6.00. (Out of print but available through libraries.)

Teach Yourself Atomic Physics, James M. Valentine, The Macmillan Company, New York 10011, 1961, 192 pp., $1.95. (Out of print but available through libraries.) Chapter X, Medical and Biological Uses of Radioactive Isotopes, pp. 173-184.

Atoms for Peace, David O. Woodbury, Dodd, Mead & Company, New York 10016, 1965, 259 pp., $4.50. Pp. 174-191.

The Atom at Work, Jacob Sacks, The Ronald Press Company, New York 10010, 1956, 341 pp., $5.50. Chapter 13, Radioactive Isotopes in Hospital and Clinic, pp. 244-264.

Ionizing Radiation and Medicine, S. Warren, Scientific American, 201: 164 (September 1959).

Nuclear Nurses Learn to Tame the Atom, W. McGaffin, Today’s Health, 37: 62 (December 1959).

How Isotopes Aid Medicine in Tracking Down Your Ailments, J. Foster, Today’s Health, 42: 40 (May 1964).

Nuclear Energy as a Medical Tool, G. W. Tressel, Today’s Health, 43: 50 (May 1965).

Radioisotopes in Medicine (SRIA-13), Stanford Research Institute, Clearinghouse for Federal Scientific and Technical Information, 5285 Port Royal Road, Springfield, Virginia 22151, 1959, 180 pp., $3.00.

The following reports are available from the Superintendent of Documents, U. S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D. C. 20402.

Isotopes and Radiation Technology (Fall 1963), P. S. Baker, A. F. Rupp, and Associates, Oak Ridge National Laboratory, U. S. Atomic Energy Commission, 123 pp., $0.70.

Radioisotopes in Medicine (ORO-125), Gould A. Andrews, Marshall Brucer, and Elizabeth B. Anderson, 1956, 817 pp., $6.00.

Applications of Radioisotopes and Radiation in the Life Sciences, Hearings before the Subcommittee on Research, Development, and Radiation of the Joint Committee on Atomic Energy, 87th Congress, 1st Session, 1961, 513 pp., $1.50; Summary Analysis of the Hearings, 23 pp., $0.15.

Available for loan without charge from the AEC Headquarters Film Library, Division of Public Information, U. S. Atomic Energy Commission, Washington, D. C. 20545 and from other AEC film libraries.

Radioisotope Applications in Medicine, 26 minutes, black and white, sound, 1964. Produced by the Educational Broadcasting Corporation under the joint direction of the U. S. Atomic Energy Commission’s Divisions of Isotopes Development and Nuclear Education and Training, and the Oak Ridge Institute of Nuclear Studies. This film traces the development of the use of radioisotopes and radiation in the field of medicine from the early work of Hevesy to the present. Descriptions of the following are given: study of cholesterol and arteriosclerosis; cobalt labeled vitamin B₁₂ used to study pernicious anemia; history of iodine radioisotopes and the thyroid; brain tumor localization; determination of body fluid volumes; red cell lifetime; and use of radioisotopes for the treatment of various diseases.

Medicine, 20 minutes, sound, color, 1957. Produced by the U. S. Information Agency. Four illustrations of the use of radioactive materials in diagnosis and therapy are given: exact preoperative location of brain tumor; scanning and charting of thyroids; cancer therapy research; and the study of blood diseases and hardening of the arteries.

Radiation Protection in Nuclear Medicine, 45 minutes, sound, color, 1962. Produced by the Fordel Films for the Bureau of Medicine and Surgery of the U. S. Navy. This semitechnical film demonstrates the procedures devised for naval hospitals to protect against the gamma radiation emitted from materials used in radiation therapy.

The following films in the Magic of the Atom Series were produced by the Handel Film Corporation. They are each 12½ minutes long, have sound, and are in black and white.

The Atom and the Doctor (1954) shows three applications of radioisotopes in medicine: testing for leukemia and other blood disorders with radioiron; diagnosis of thyroid conditions with radioiodine; and cancer research and therapy with radiogallium.

The Atom in the Hospital (1961) (available in color and black and white) illustrates the following facilities at the City of Hope Medical Center in Los Angeles: the stationary cobalt source that is used to treat various forms of malignancies; a rotational therapy unit called the “cesium ring”, which revolves around the patient and focuses its beam on the diseased area; and the total-body irradiation chamber for studying the effects of radiation on living things. Research with these facilities is explained.

Atomic Biology for Medicine (1956) explains experiments performed to discover effects of radiation on mammals.

Atoms for Health (1956) outlines two methods of diagnosis and treatment possible with radiation: a diagnostic test of the liver, and cancer therapy with a radioactive cobalt device. Case histories are presented step-by-step.

Radiation: Silent Servant of Mankind (1956) depicts four uses of controlled radiation that can benefit mankind: bombardment of plants from a radioactive cobalt source to induce genetic changes for study and crop improvement; irradiation of deep-seated tumors with a beam from a particle accelerator; therapy of thyroid cancer with radioactive iodine; and possibilities for treating brain tumors.

Cover Courtesy Brookhaven National Laboratory

| Page | |

| 1 | General Electric Company |

| 2, 3, & 4 | Discovery of the Elements. Mary Elvira Weeks, Journal of Chemical Education |

| 6 | Nobel Institute |

| 12 | Chicago Wesley Memorial Hospital (main photo) |

| 13 | Lawrence Radiation Laboratory (LRL) |

| 14 | Brookhaven National Laboratory |

| 17 | LRL |

| 21 | LRL |

| 22 | Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory |

| 24 | LRL |

| 28 | Argonne National Laboratory |

| 39 | Paul V. Harper, M. D. |

| 41 | University of Texas, M. D. Anderson Hospital and Tumor Institute |

This booklet is one of the “Understanding the Atom” Series. Comments are invited on this booklet and others in the series; please send them to the Division of Technical Information, U. S. Atomic Energy Commission, Washington, D. C. 20545.

Published as part of the AEC’s educational assistance program, the series includes these titles:

A single copy of any one booklet, or of no more than three different booklets, may be obtained free by writing to:

USAEC, P. O. BOX 62, OAK RIDGE, TENNESSEE 37830

Complete sets of the series are available to school and public librarians, and to teachers who can make them available for reference or for use by groups. Requests should be made on school or library letterheads and indicate the proposed use.

Students and teachers who need other material on specific aspects of nuclear science, or references to other reading material, may also write to the Oak Ridge address. Requests should state the topic of interest exactly, and the use intended.

In all requests, include “Zip Code” in return address.

Printed in the United States of America

USAEC Division of Technical Information Extension, Oak Ridge, Tennessee