Title: Lion and Dragon in Northern China

Author: Sir Reginald Fleming Johnston

Release date: April 24, 2015 [eBook #48782]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chris Curnow, Moti Ben-Ari and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

LION AND DRAGON IN NORTHERN CHINA

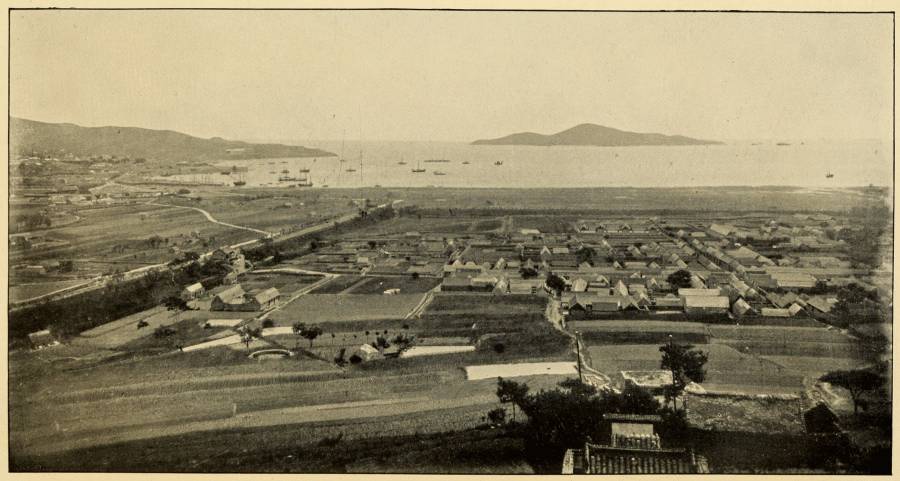

VIEW FROM THE HUAN-TS'UI-LOU ON THE CITY WALL OF WEIHAIWEI.

(Showing the interior of the walled city, the island of Liukung and the Harbour, and the European settlement of Port Edward).

BY R. F. JOHNSTON, M.A. (Oxon.), F.R.G.S.

DISTRICT OFFICER AND MAGISTRATE, WEIHAIWEI

FORMERLY PRIVATE SECRETARY TO THE GOVERNOR OF HONGKONG, ETC.

AUTHOR OF "FROM PEKING TO MANDALAY"

WITH MAP AND ILLUSTRATIONS

NEW YORK

E. P. DUTTON AND COMPANY

1910

The meeting-place of the British Lion and the Chinese Dragon in northern China consists of the port and Territory of Weihaiwei. It is therefore with this district, and the history, folk-lore, religious practices and social customs of its people, that the following pages are largely occupied. But Weihaiwei is in many respects a true miniature of China, and a careful study of native life and character, as they are exhibited in this small district, may perhaps give us a clearer and truer insight into the life and character of the Chinese race than we should gain from any superficial survey of China as a whole. Its present status under the British Crown supplies European observers with a unique opportunity for the close study of sociological and other conditions in rural China. If several chapters of this book seem to be but slightly concerned with the special subject of Weihaiwei, it is because the chief interest of the place to the student lies in the fact that it is an epitomised China, and because if we wish fully to understand even this small fragment of the Empire we must make many long excursions through the wider fields[viii] of Chinese history, sociology and religion. The photographs (with certain exceptions noted in each case) have been taken by the author during his residence at Weihaiwei. From Sir James H. Stewart Lockhart, K.C.M.G., Commissioner of Weihaiwei, he has received much kind encouragement which he is glad to take this opportunity of acknowledging; and he is indebted to Captain A. Hilton-Johnson for certain information regarding the personnel of the late Chinese Regiment. His thanks are more especially due to his old friend Mr. D. P. Heatley, Lecturer in History at the University of Edinburgh, for his generous assistance in superintending the publication of the book.

Wên-ch'üan-t'ang,

Weihaiwei,

May 1, 1910.

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

| I. | INTRODUCTION | 1 |

| II. | WEIHAIWEI AND THE SHANTUNG PROMONTORY | 12 |

| III. | HISTORY AND LEGEND | 34 |

| IV. | CHINESE CHRONICLES AND LOCAL CELEBRITIES | 57 |

| V. | BRITISH RULE | 77 |

| VI. | LITIGATION | 102 |

| VII. | VILLAGE LIFE AND LAND TENURE | 127 |

| VIII. | VILLAGE CUSTOMS, FESTIVALS AND FOLK-LORE | 155 |

| IX. | THE WOMEN OF WEIHAIWEI | 195 |

| X. | WIDOWS AND CHILDREN | 217 |

| XI. | FAMILY GRAVEYARDS | 254 |

| XII. | DEAD MEN AND GHOST-LORE | 276 |

| XIII. | CONFUCIANISM—I[x] | 300 |

| XIV. | CONFUCIANISM—II | 328 |

| XV. | TAOISM, LOCAL DEITIES, TREE-WORSHIP | 351 |

| XVI. | THE DRAGON, MOUNTAIN-WORSHIP, BUDDHISM | 385 |

| XVII. | RELIGION AND SUPERSTITION IN EAST AND WEST | 408 |

| XVIII. | THE FUTURE | 426 |

| INDEX | 451 |

| VIEW FROM THE HUAN-TS'UI-LOU ON THE CITY WALL OF WEIHAIWEI | Frontispiece |

| FACING PAGE | |

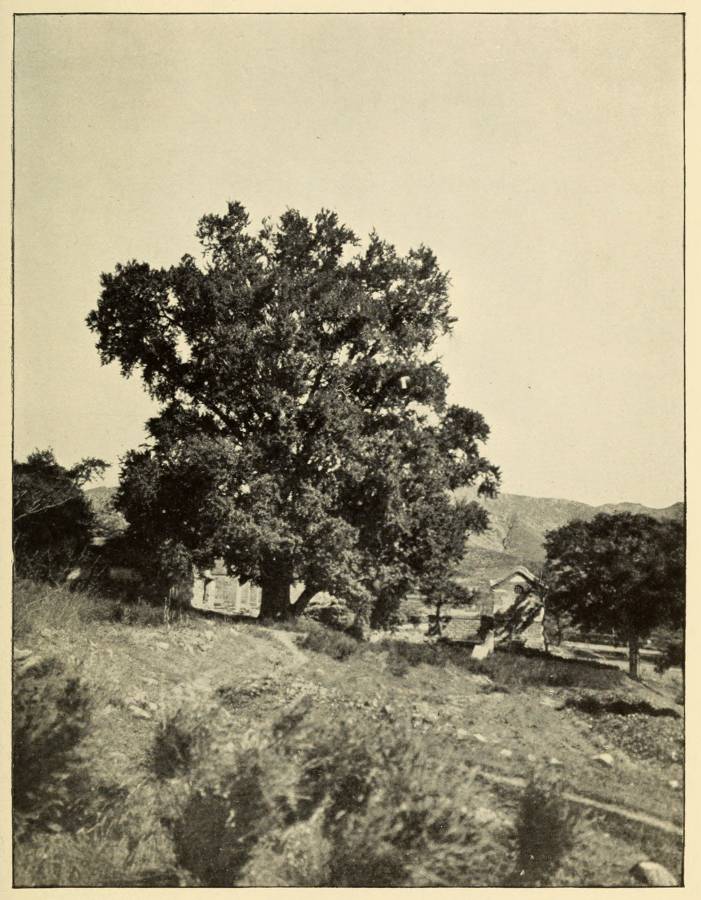

| THE MANG-TAO TREE | 18 |

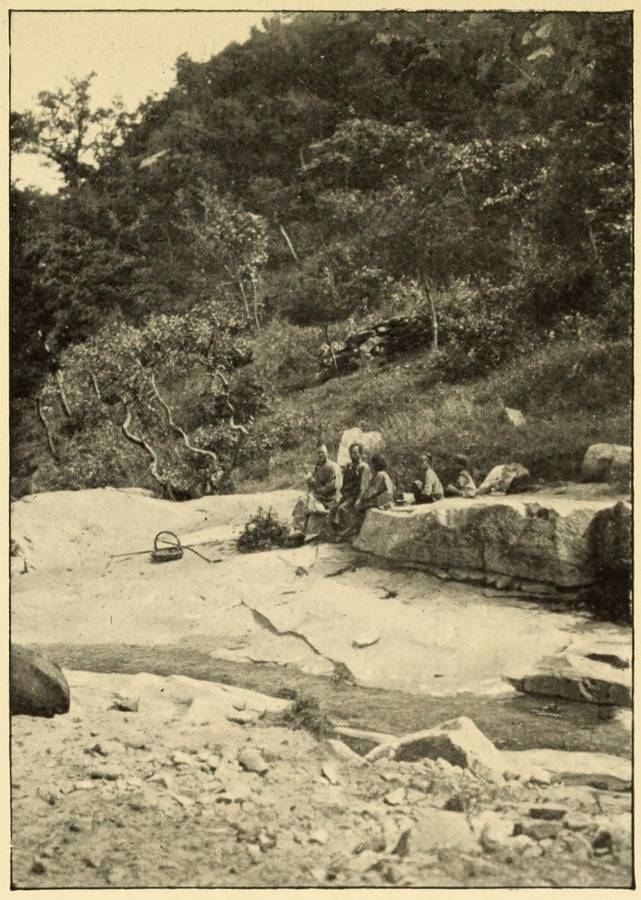

| A HALT IN YÜ-CHIA-K'UANG DEFILE | 18 |

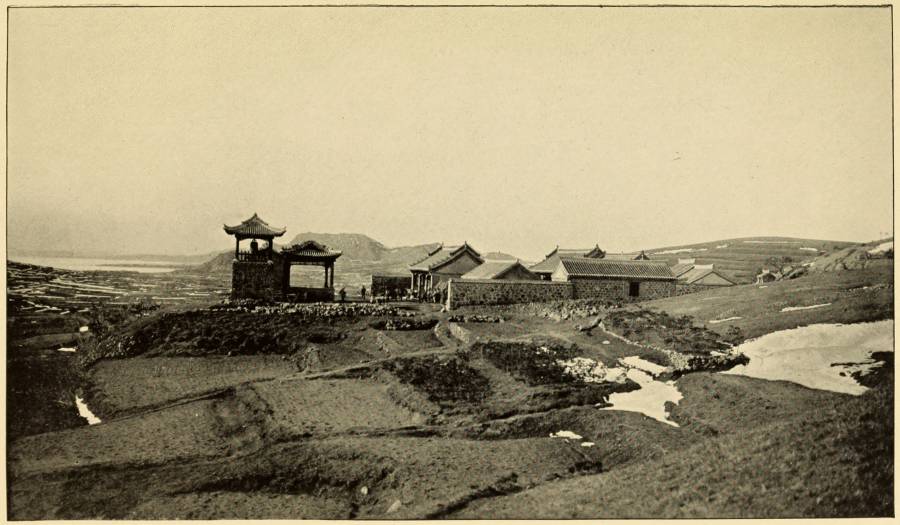

| THE TEMPLE AT THE SHANTUNG PROMONTORY | 22 |

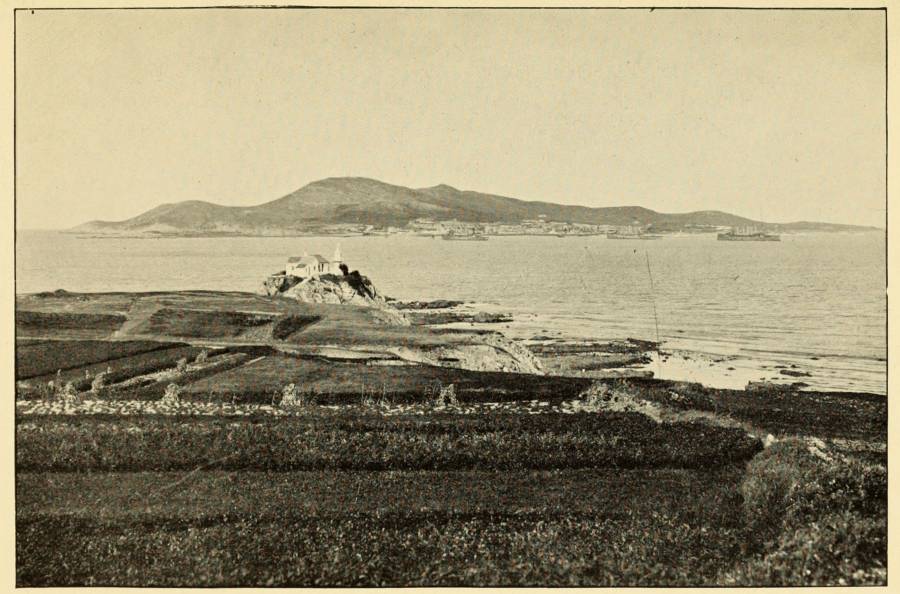

| WEIHAIWEI HARBOUR, LIUKUNGTAO AND CHU-TAO LIGHTHOUSE | 26 |

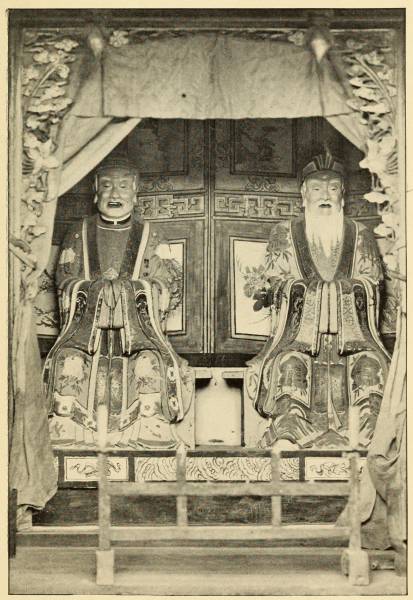

| IMAGES OF "MR. AND MRS. LIU" | 28 |

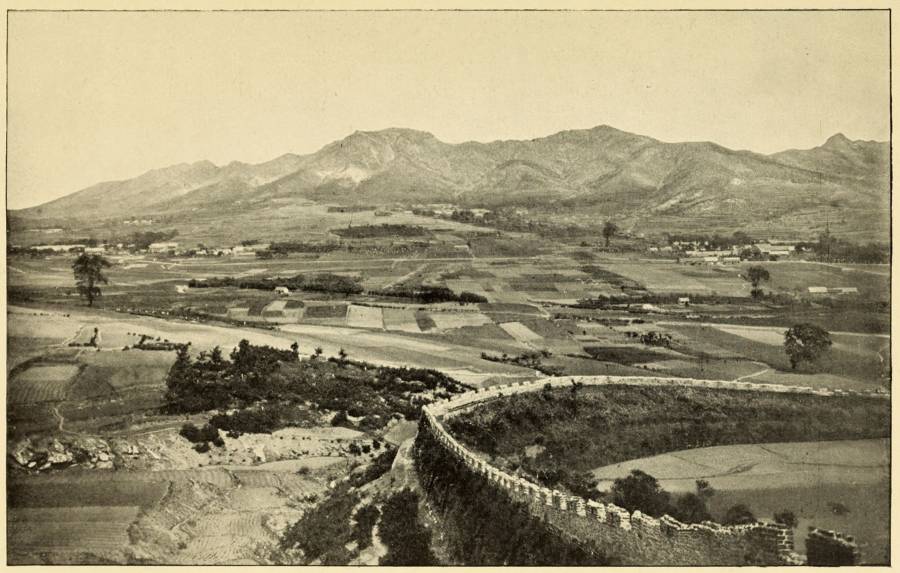

| A VIEW FROM THE WALL OF WEIHAIWEI CITY | 30 |

| PART OF WEIHAIWEI CITY WALL | 46 |

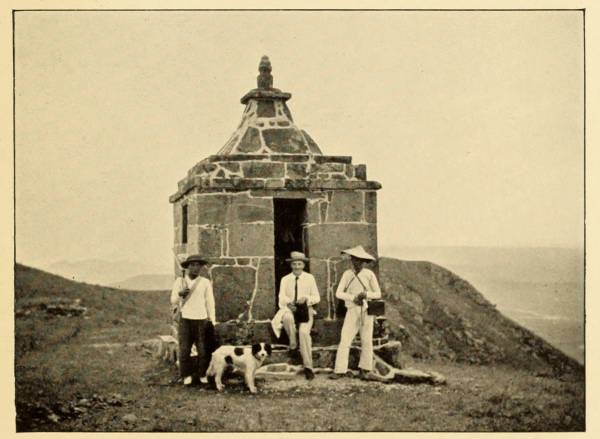

| THE AUTHOR AND TOMMIE ON THE QUORK'S PEAK | 46 |

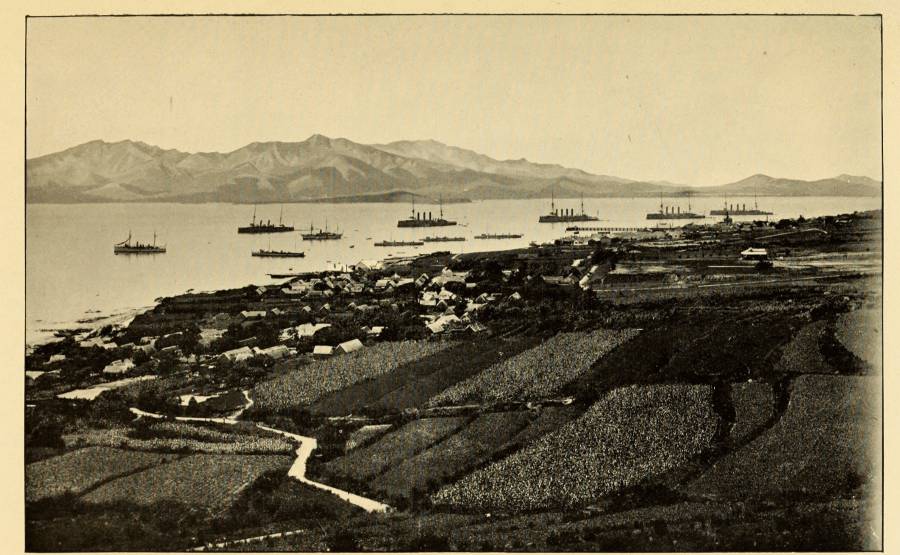

| THE HARBOUR WITH BRITISH WARSHIPS, FROM LIUKUNGTAO | 80 |

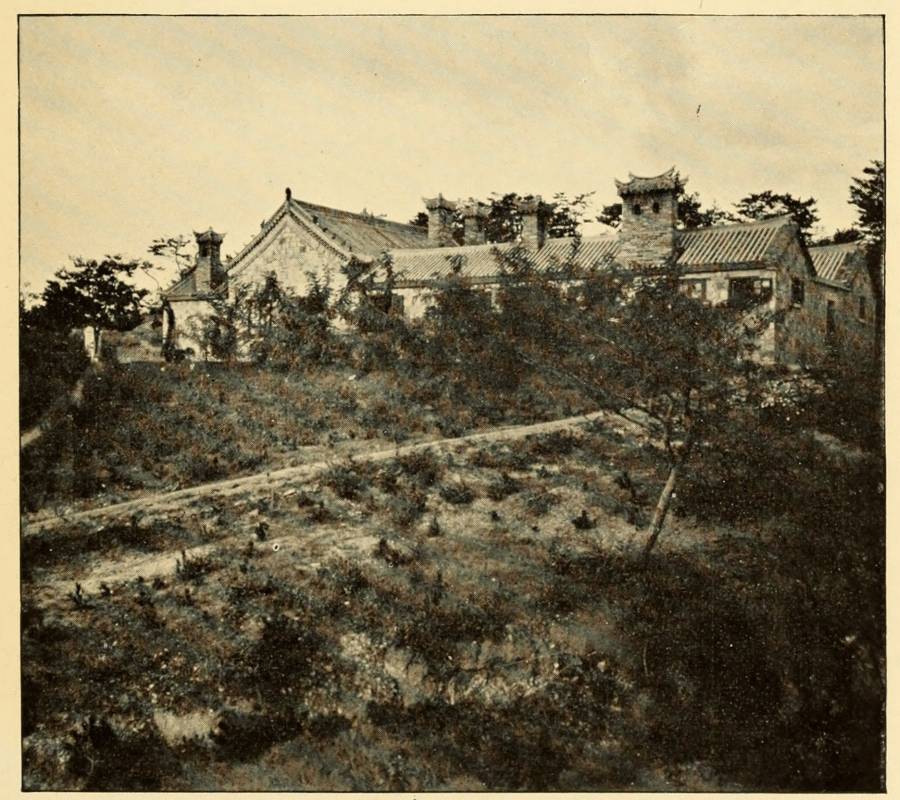

| DISTRICT OFFICER'S QUARTERS | 100 |

| THE COURT-HOUSE, WÊN-CH'ÜAN-T'ANG | 100 |

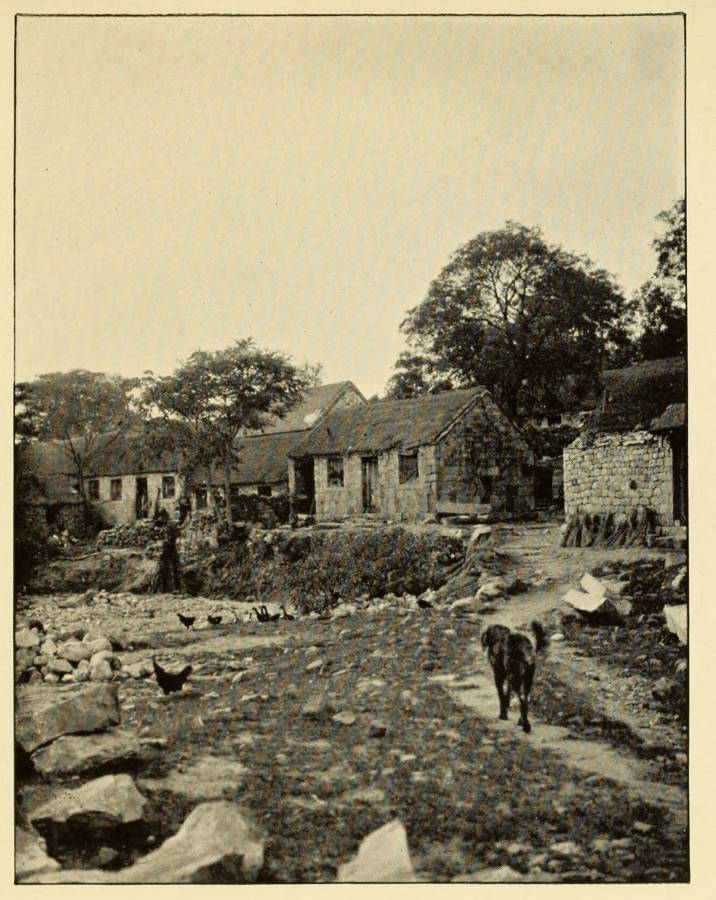

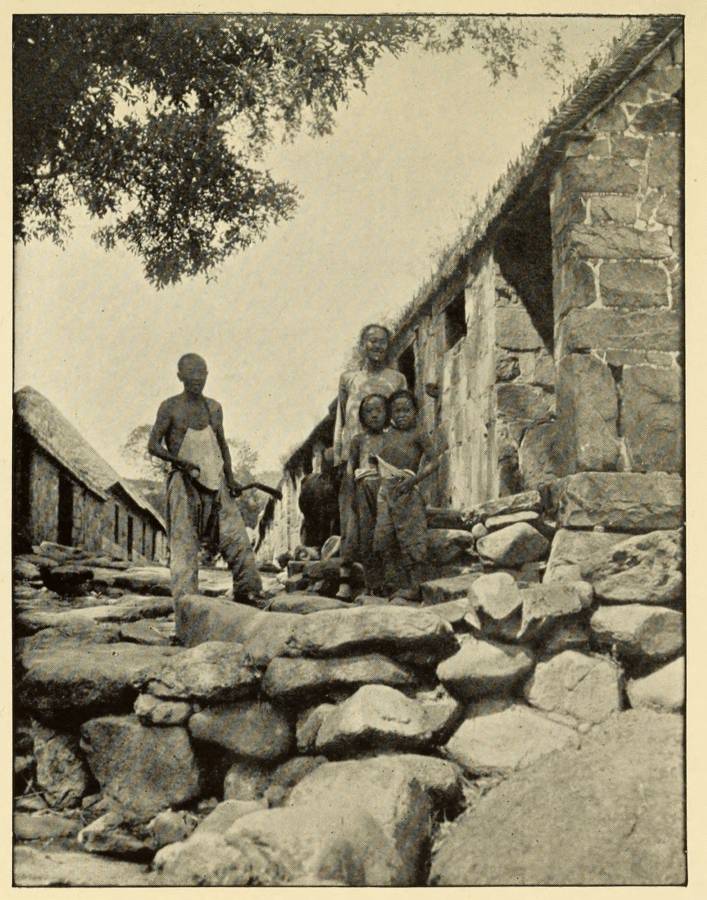

| "WE ARE THREE"[xii] | 128 |

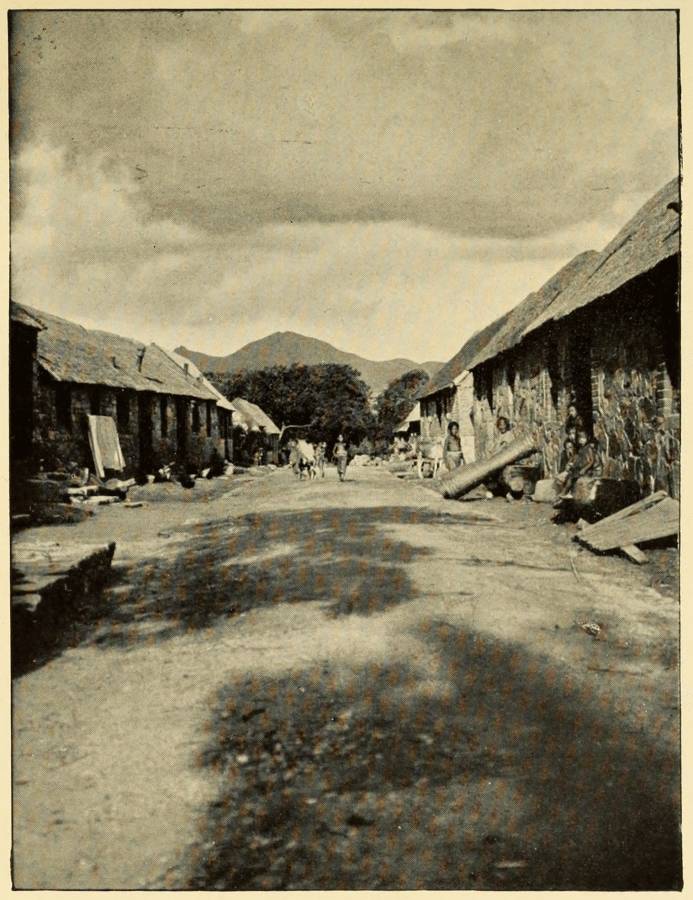

| VILLAGE OF T'ANG HO-HSI | 128 |

| A TYPICAL THEATRICAL STAGE BELONGING TO A TEMPLE | 130 |

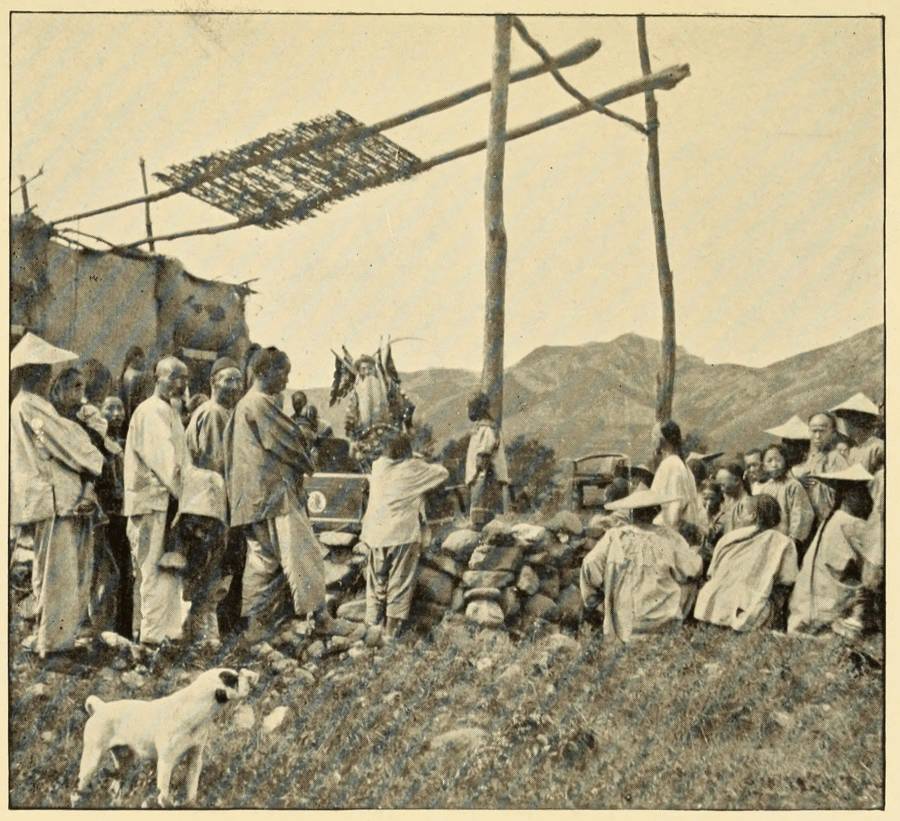

| VILLAGE THEATRICALS | 130 |

| A DISTRICT HEADMAN AND HIS COMPLIMENTARY TABLET | 158 |

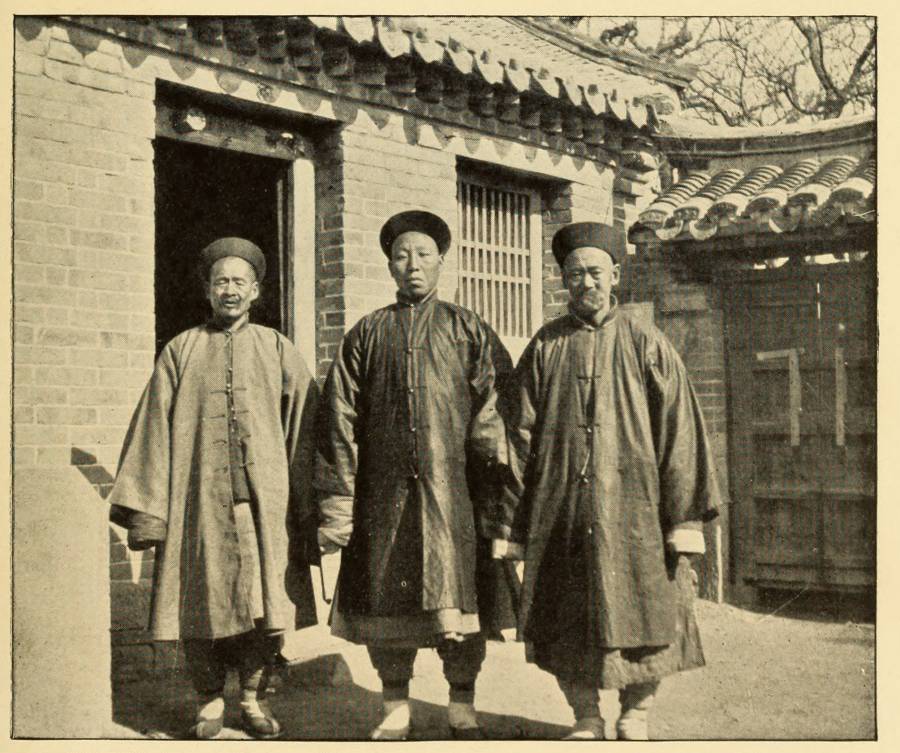

| THREE VILLAGE HEADMEN | 158 |

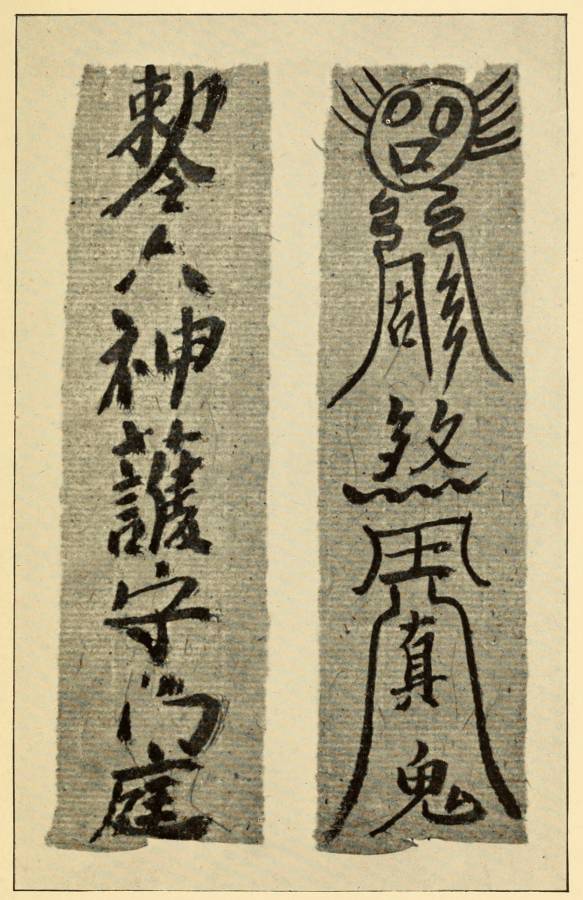

| PROTECTIVE CHARMS USED IN WEIHAIWEI | 174 |

| FIRST-FULL-MOON STILT-WALKERS | 182 |

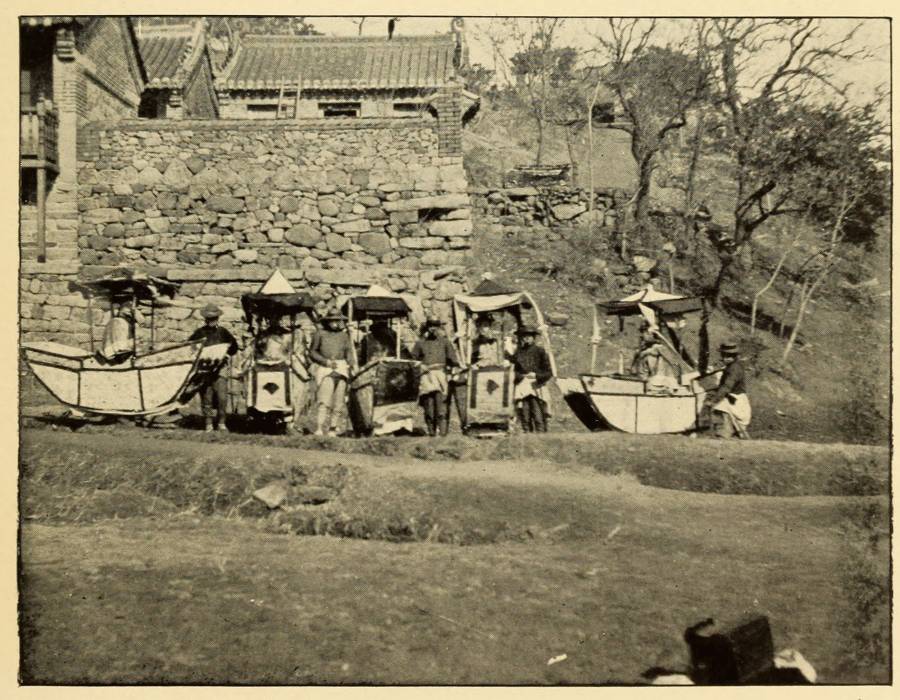

| "WALKING BOATS" AT THE FIRST-FULL-MOON FESTIVAL | 182 |

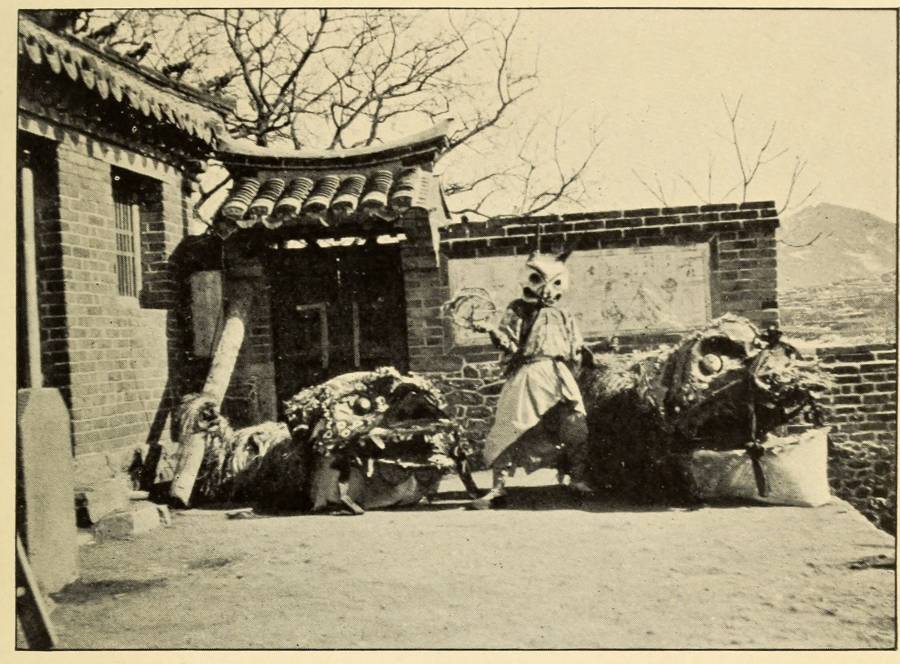

| MASQUERADERS AT FESTIVAL OF FIRST FULL MOON | 184 |

| GROUP OF VILLAGERS WATCHING FIRST-FULL-MOON MASQUERADERS | 184 |

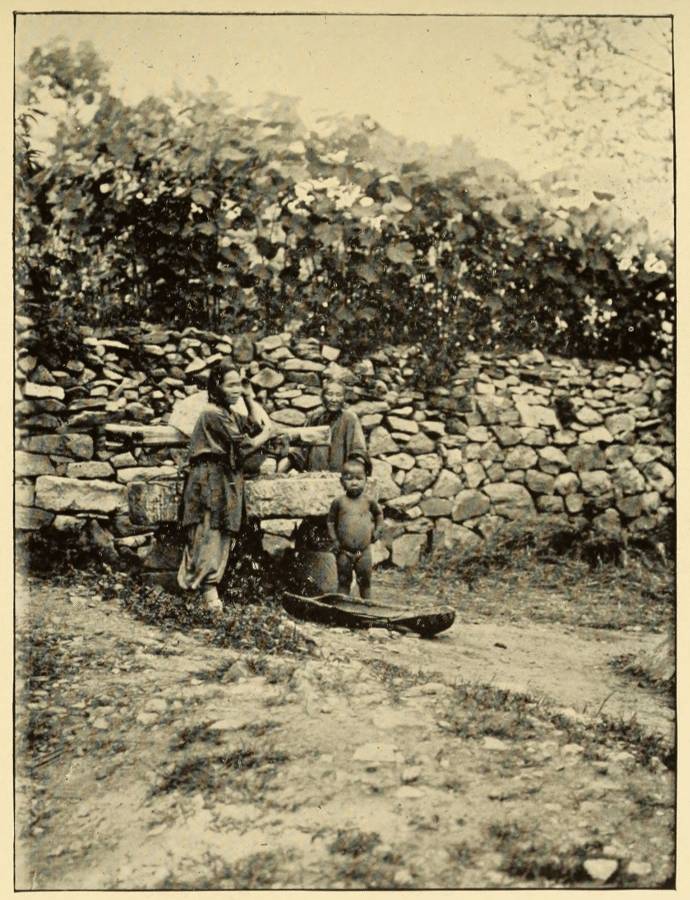

| THREE WOMEN AND A HAYRICK | 206 |

| THREE GENERATIONS—AT THE VILLAGE GRINDSTONE | 206 |

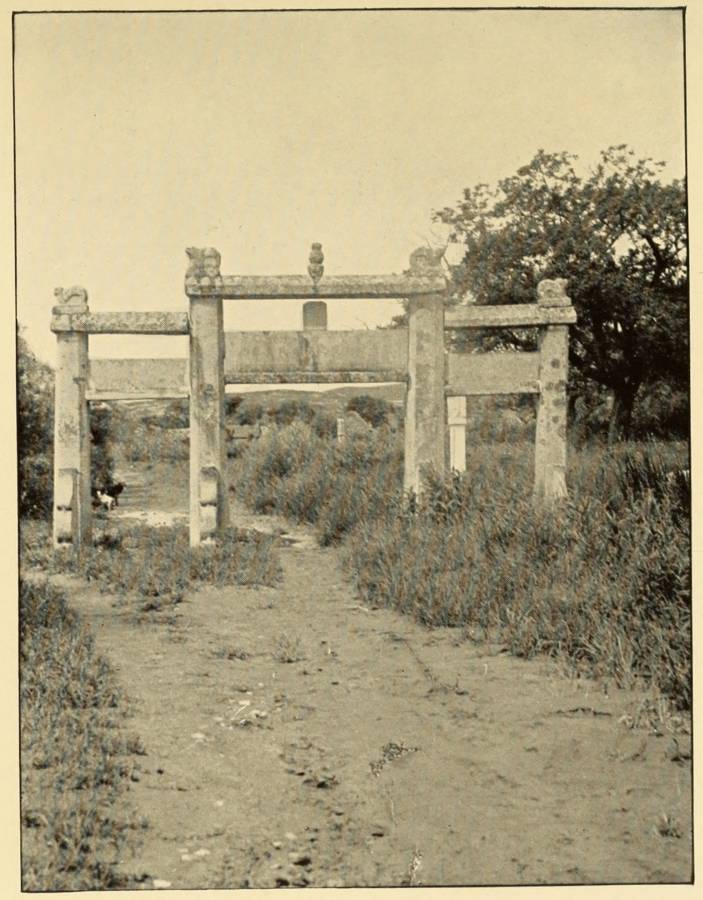

| VILLAGE OF KU-SHAN-HOU, SHOWING HONORARY POLES IN | |

| FRONT OF THE ANCESTRAL TEMPLE | 224 |

| MONUMENT TO FAITHFUL WIDOW, KU-SHAN-HOU | 224 |

| AN AFTERNOON SIESTA | 252 |

| WASHING CLOTHES | 252 |

| THE ANCESTRAL GRAVEYARD OF THE CHOU FAMILY | 256 |

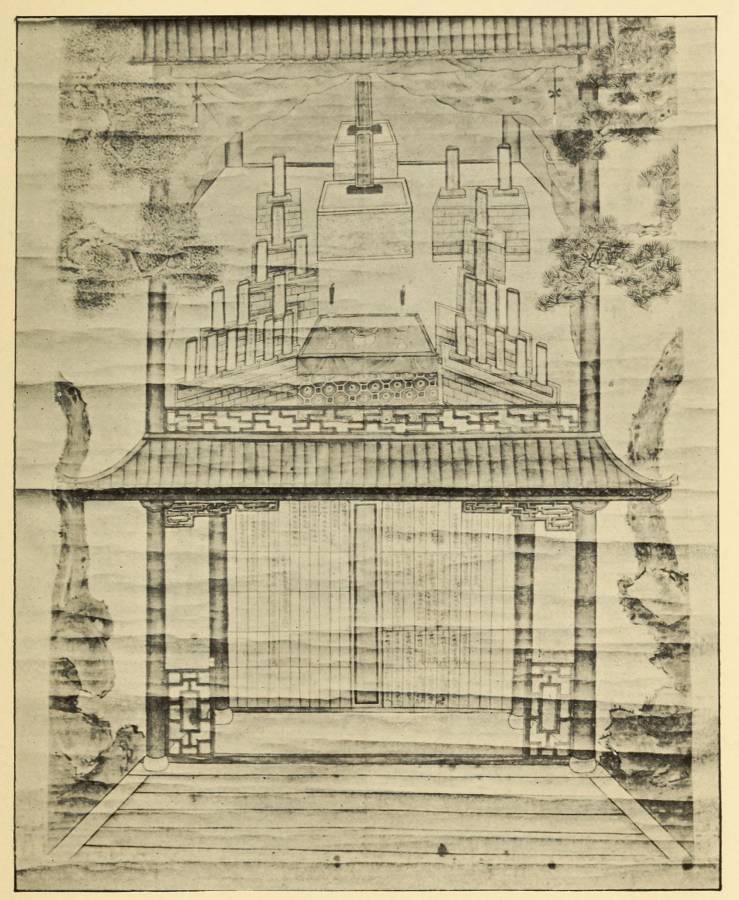

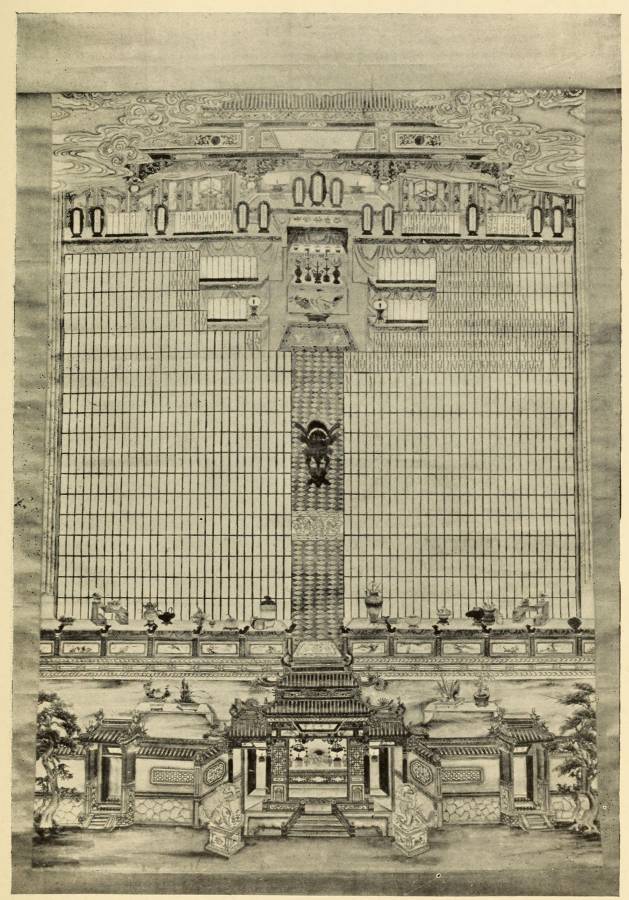

| A PEDIGREE-SCROLL (CHIA P'U) | 264 |

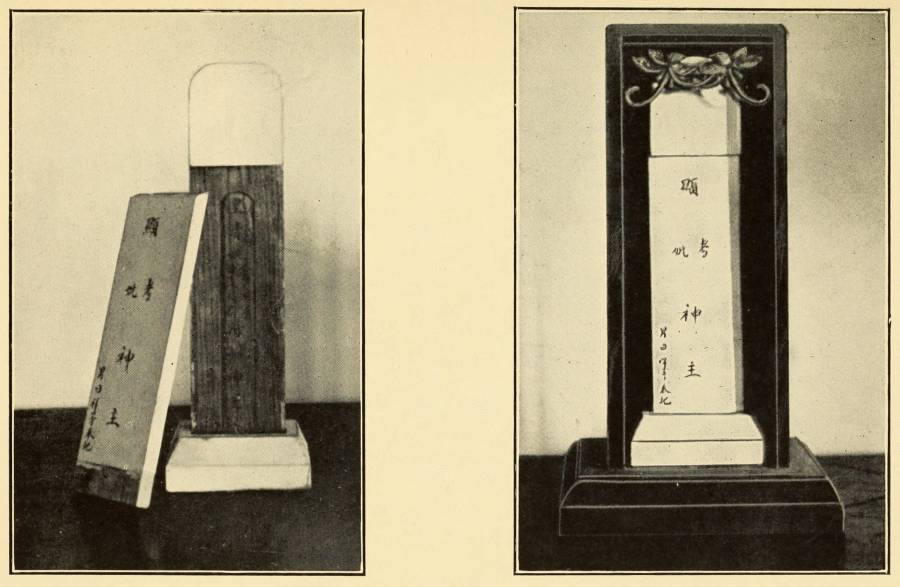

| SPIRIT-TABLETS[xiii] | 278 |

| A PEDIGREE SCROLL (CHIA P'U) | 280 |

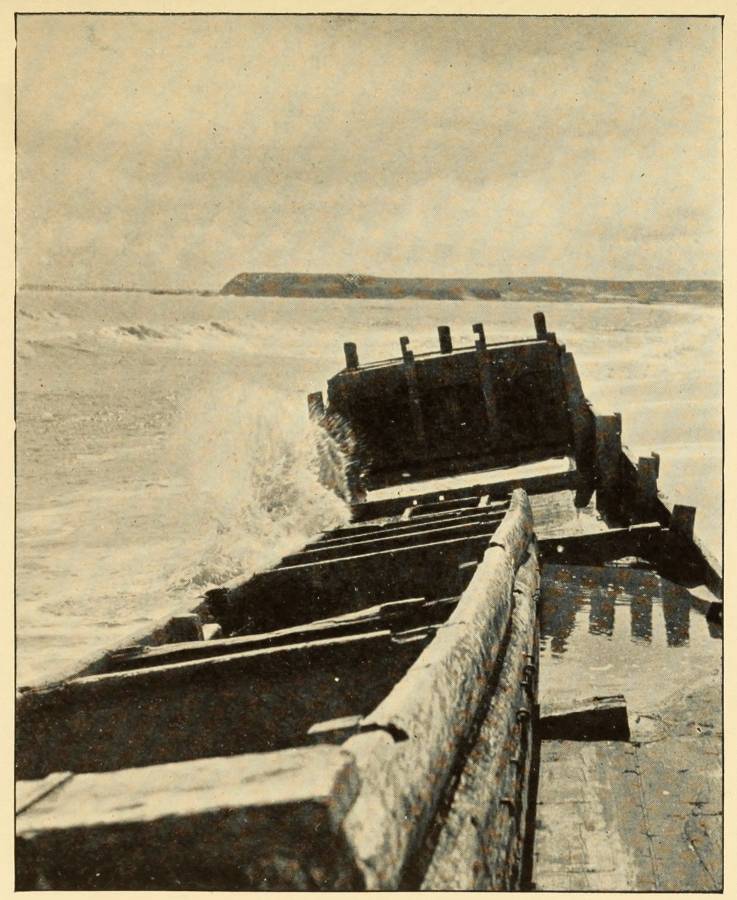

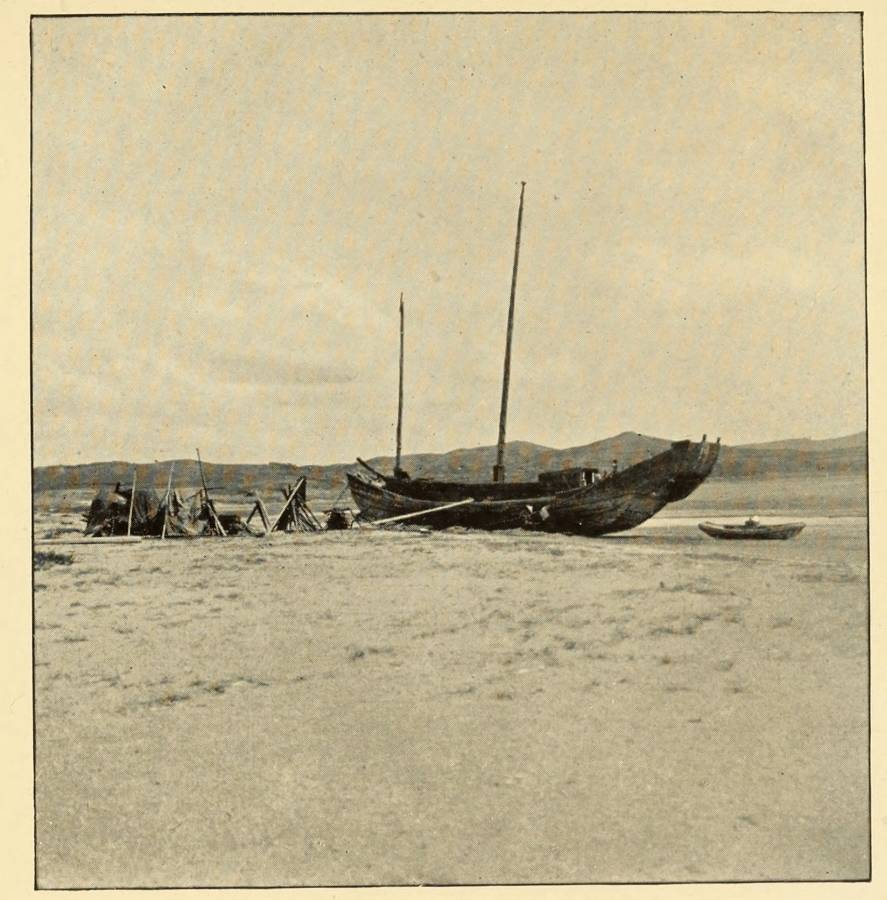

| A WRECKED JUNK | 288 |

| A JUNK ASHORE | 288 |

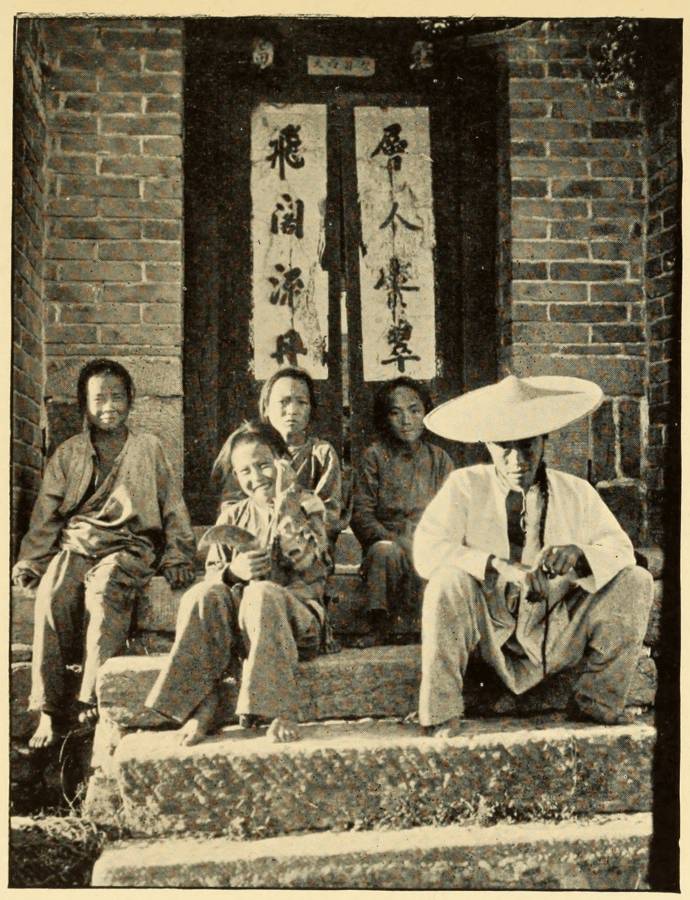

| WEIHAIWEI VILLAGERS | 314 |

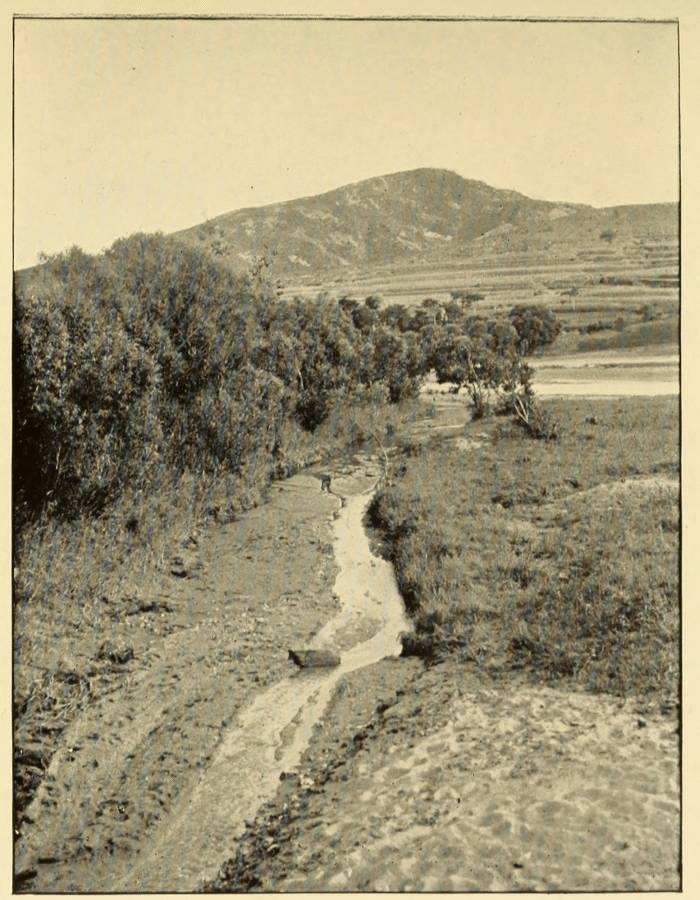

| SHEN-TZŬ (MULE-LITTER) FORDING A STREAM | 314 |

| HILLS NEAR AI-SHAN | 330 |

| HILL, WOOD AND STREAM | 330 |

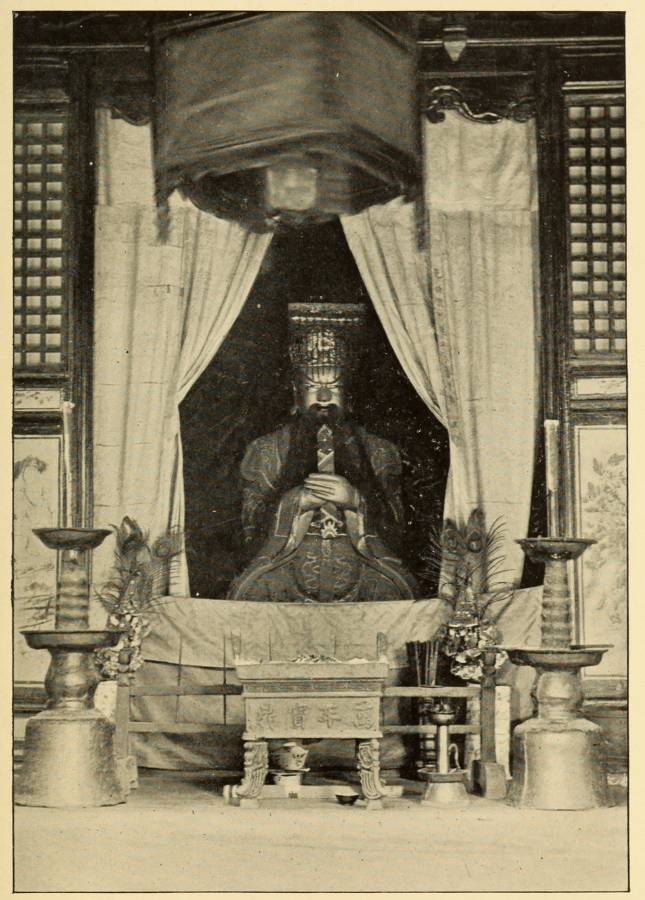

| IMAGE OF KUAN TI, WEIHAIWEI | 362 |

| THE BUDDHA OF KU SHAN TEMPLE | 368 |

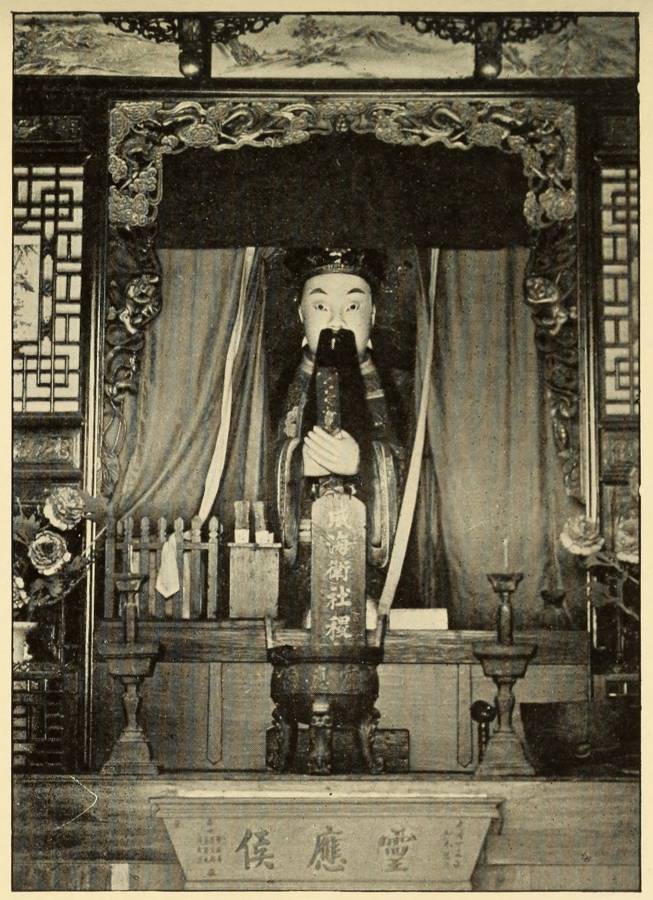

| THE CITY-GOD OF WEIHAIWEI | 368 |

| SHRINE TO THE GOD OF LITERATURE | 372 |

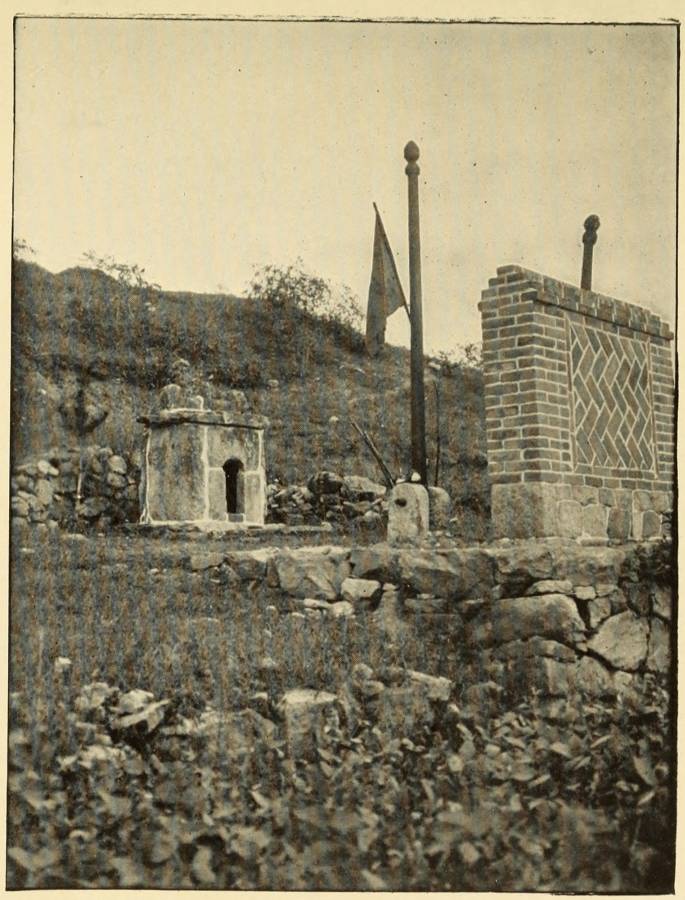

| A T'U TI SHRINE | 372 |

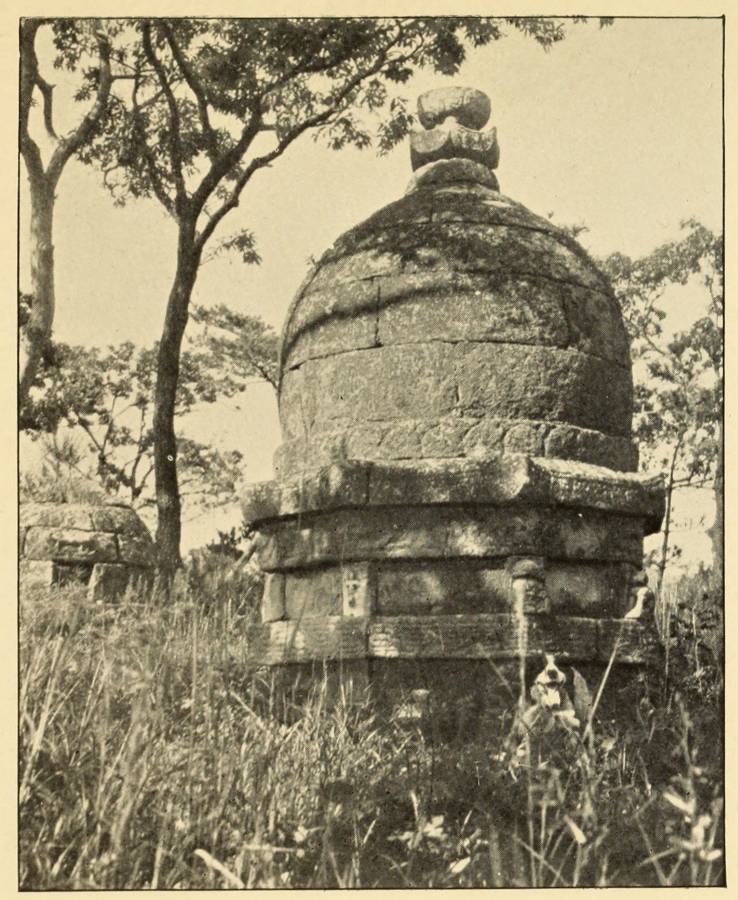

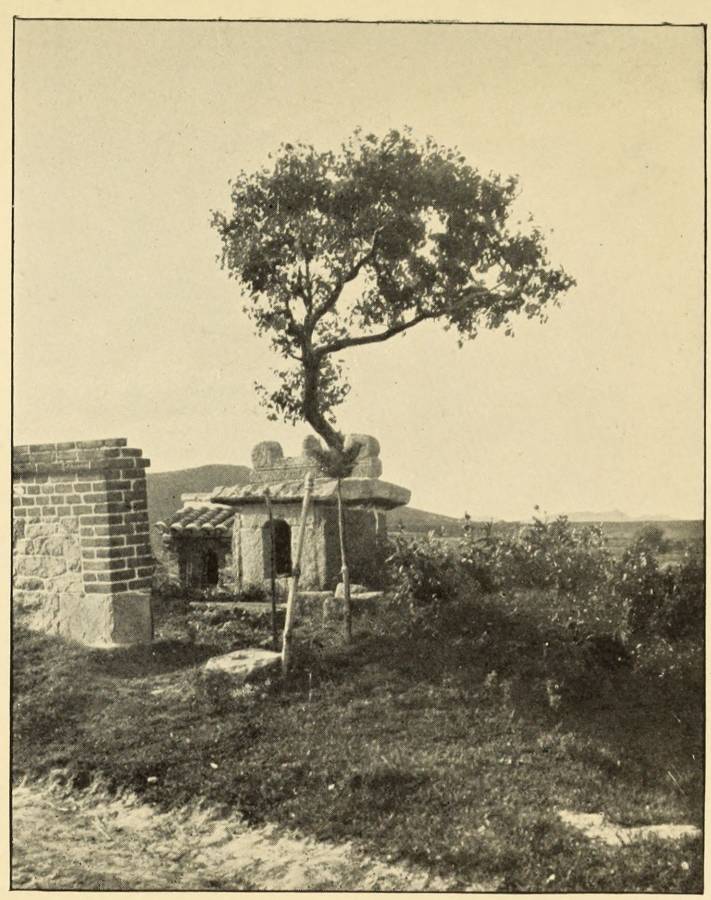

| YÜAN DYNASTY GRAVES | 376 |

| A T'U TI SHRINE, SHOWING RAG-POLES AND TREE | 376 |

| THE HAUNTED TREE OF LIN-CHIA-YÜAN | 380 |

| A VILLAGE | 382 |

| AT CHANG-CHIA-SHAN | 382 |

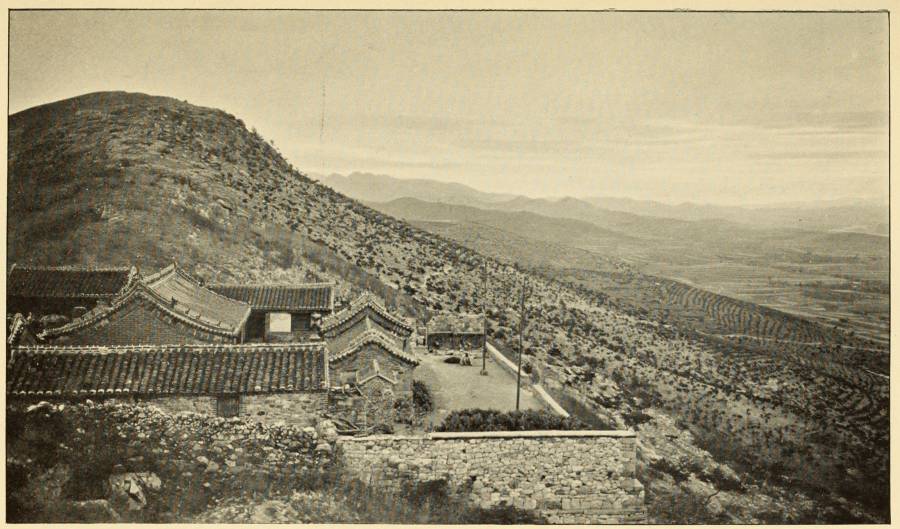

| AI-SHAN PASS AND TEMPLE | 386 |

| SHRINES TO THE MOUNTAIN-SPIRIT AND LUNG WANG[xiv] | 396 |

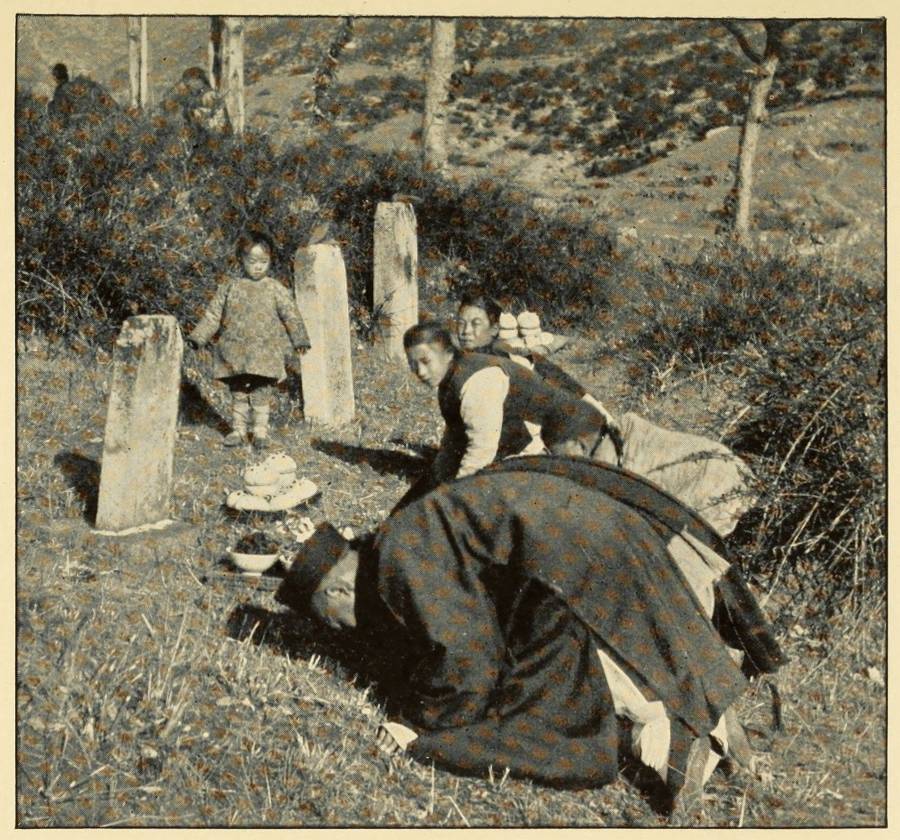

| WORSHIP AT THE ANCESTRAL TOMBS | 396 |

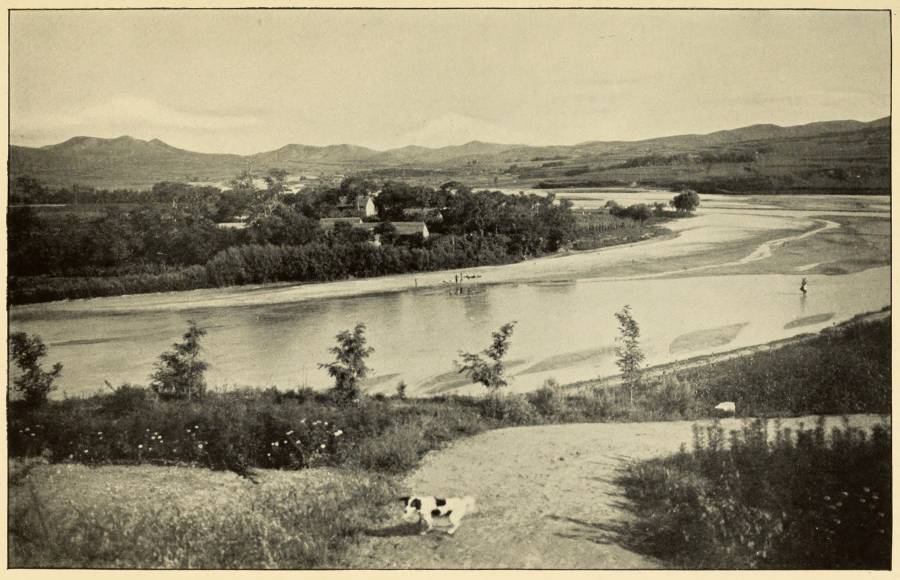

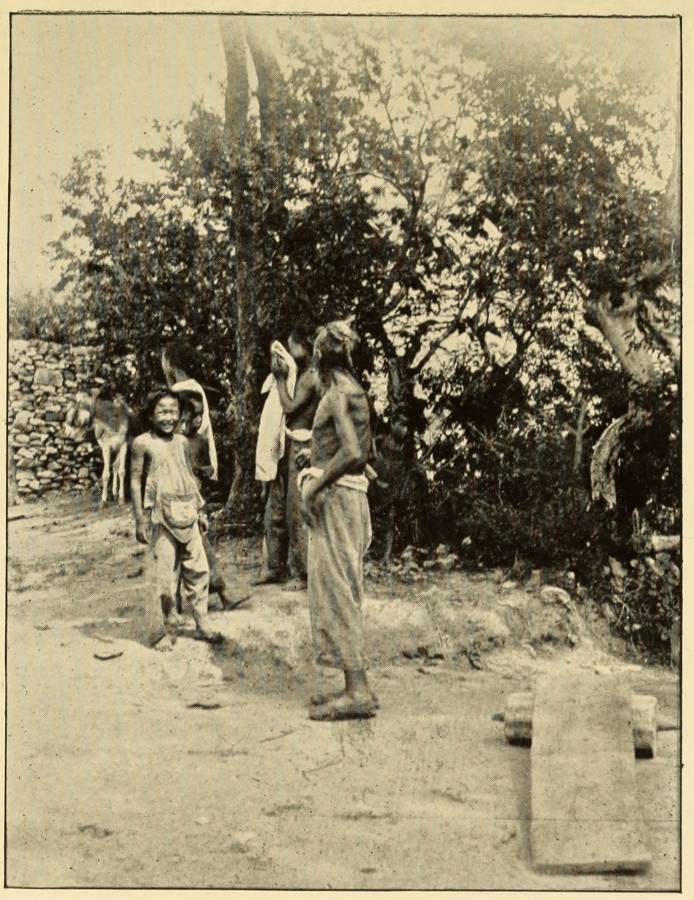

| AT THE VILLAGE OF YÜ-CHIA-K'UANG | 398 |

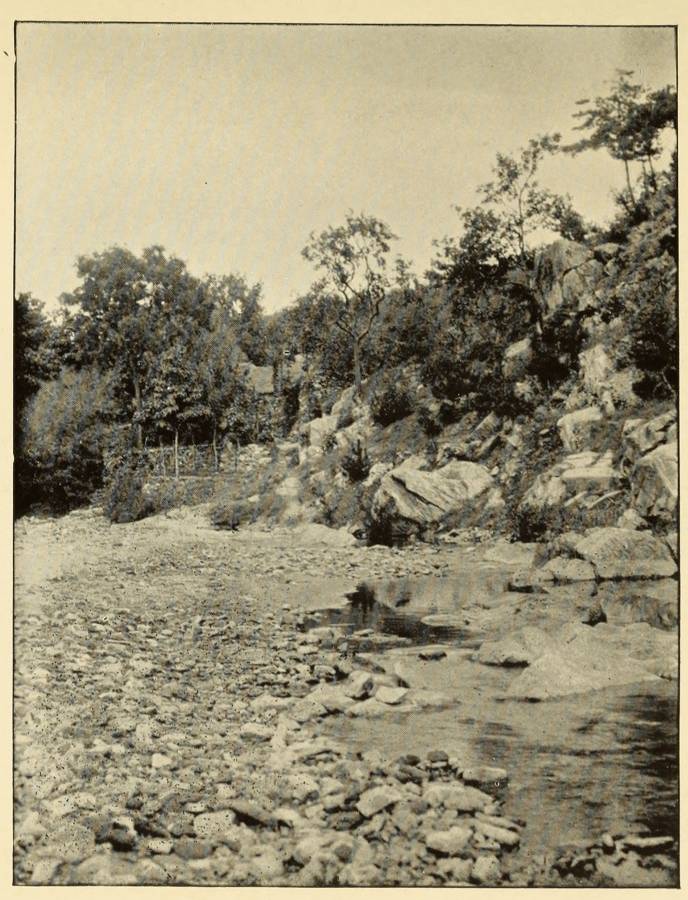

| A MOUNTAIN STREAM AND HAMLET | 398 |

| WÊN-CH'ÜAN-T'ANG | 400 |

| SHRINE ON SUMMIT OF KU SHAN | 414 |

| VILLAGERS AT A TEMPLE DOORWAY | 414 |

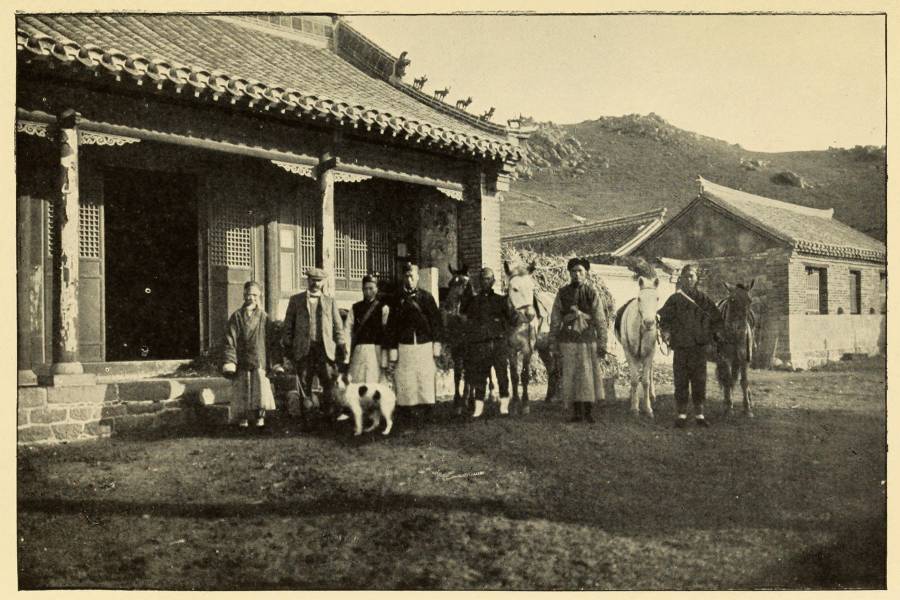

| TWO BRITISH RULERS ON THE MARCH, WITH MULE-LITTER AND HORSE | 434 |

| A ROADSIDE SCENE | 434 |

| THE COMMISSIONER OF WEIHAIWEI (SIR J. H. STEWART | |

| LOCKHART, K.C.M.G.), WITH PRIEST AND ATTENDANTS | |

| AT THE TEMPLE OF CH'ÊNG SHAN | 440 |

| MAP | |

| WEIHAIWEI | at the end |

Less than a dozen years have passed since the guns of British warships first saluted the flag of their country at the Chinese port of Weihaiwei, yet it is nearly a century since the white ensign was seen there for the first time. In the summer of 1816 His Britannic Majesty's frigate Alceste, accompanied by the sloop Lyra, bound for the still mysterious and unsurveyed coasts of Korea and the Luchu Islands, sailed eastwards from the mouth of the Pei-ho along the northern coast of the province of Shantung, and on the 27th August of that year cast anchor in the harbour of "Oie-hai-oie." Had the gallant officers of the Alceste and Lyra been inspired with knowledge of future political developments, they would doubtless have handed down to us an interesting account of the place and its inhabitants. All we learn from Captain Basil Hall's delightful chronicle of the voyage of the two ships consists of a few details—in the truest sense ephemeral—as to wind and weather, and a statement that the rocks of the mainland consist of "yellowish felspar, white quartz, and black mica." The rest is silence.

From that time until the outbreak of the Sino-Japanese[2] War in 1894 the British public heard little or nothing of Weihaiwei. After the fall of Port Arthur, during that war, it was China's only remaining naval base. The struggle that ensued in January 1895, when, with vastly superior force, the Japanese attacked it by land and sea, forms one of the few episodes of that war upon which the Chinese can look back without overwhelming shame. Victory, however, went to those who had the strongest battalions and the stoutest hearts. The three-weeks siege ended in the suicide of the brave Chinese Commander-in-Chief, Admiral Ting, and in the loss to China of her last coast-fortress and the whole of her fleet. Finally, as a result of the seizure of Port Arthur by Russia and a subsequent three-cornered agreement between Japan, China and England, Weihaiwei was leased to Great Britain under the terms of a Convention signed at Peking in July 1898.

The British robe of empire is a very splendid and wonderfully variegated garment. It bears the gorgeous scarlets and purples of the Indies, it shimmers with the diamonds of Africa, it is lustrous with the whiteness of our Lady of Snows, it is scented with the spices of Ceylon, it is decked with the pearls and soft fleeces of Australia. But there is also—pinned to the edge of this magnificent robe—a little drab-coloured ribbon that is in constant danger of being dragged in the mud or trodden underfoot, and is frequently the object of disrespectful gibes. This is Weihaiwei.

Whether the imperial robe would not look more imposing without this nondescript appendage is a question which may be left to the student of political fashion-plates: it will concern us hardly at all in the pages of this book. An English newspaper published in China has dubbed Weihaiwei the Cinderella of the British Empire, and speculates vaguely as to where her Fairy Prince is to come from. Alas, the Fairy Godmother must first do her share in making poor[3] Cinderella beautiful and presentable before any Fairy Prince can be expected to find in her the lady of his dreams: and the Godmother has certainly not yet made her appearance, unless, indeed, the British Colonial Office is presumptuous enough to put forward a claim (totally unjustifiable) to that position. By no means do I, in the absence of the Fairy Prince, propose to ride knight-like into the lists of political controversy wearing the gage of so forlorn a damsel-in-distress as Weihaiwei. Let me explain, dropping metaphor, that the following pages will contain but slender contribution to the vexed questions of the strategic importance of the port or of its potential value as a depôt of commerce. Are not such things set down in the books of the official scribes? Nor will they constitute a guide-book that might help exiled Europeans to decide upon the merits of Weihaiwei as a resort for white-cheeked children from Shanghai and Hongkong, or as affording a dumping-ground for brass-bands and bathing-machines. On these matters, too, information is not lacking. As for the position of Weihaiwei on the playground of international politics, it may be that Foreign Ministers have not yet ceased to regard it as an interesting toy to be played with when sterner excitements are lacking. But it will be the aim of these pages to avoid as far as possible any incursion into the realm of politics: for it is not with Weihaiwei as a diplomatic shuttlecock that they profess to deal, but with Weihaiwei as the ancestral home of many thousands of Chinese peasants, who present a stolid and almost changeless front to all the storms and fluctuations of politics and war.

Books on China have appeared in large numbers during the past few years, and the production of another seems to demand some kind of apology. Yet it cannot be said that as a field for the ethnologist, the historian, the student of comparative religion and of folk-lore, the sociologist or the moral philosopher,[4] China has been worked out. The demand for books that profess to deal in a broad and general way with China and its people as a whole has probably, indeed, been fully satisfied: but China is too vast a country to be adequately described by any one writer or group of writers, and the more we know about China and its people the more strongly we shall feel that future workers must confine themselves to less ambitious objects of study than the whole Empire. The pioneer who with his prismatic compass passes rapidly over half a continent has nearly finished all he can be expected to do; he must soon give place to the surveyor who with plane-table and theodolite will content himself with mapping a section of a single province.

It is a mistake to suppose that any class of European residents in or visitors to the Far East possesses the means of acquiring sound knowledge of China and the Chinese. Government officials—whether Colonial or Consular—are sometimes rather apt to assume that what they do not know about China is not worth knowing; missionaries show a similar tendency to believe that an adequate knowledge of the life and "soul" of the Chinese people is attainable only by themselves; while journalists and travellers, believing that officials and missionaries are necessarily one-sided or bigoted, profess to speak with the authority that comes of breezy open-mindedness and impartiality. The tendency in future will be for each writer to confine himself to that aspect of Chinese life with which he is personally familiar, or that small portion of the Empire that comes within the radius of his personal experience. If he is a keen observer he will find no lack of material ready to his hand. Perhaps the richer and more luxuriant fields of inquiry may be occupied by other zealous workers: then let him steal quietly into some thorny and stony corner which they have neglected, some wilderness that no one else cares about, and set to[5] work with spade and hoe to prepare a little garden for himself. Perhaps if he is industrious the results may be not wholly disappointing; and the passer-by who peeps over his hedge to jeer at his folly and simplicity in cultivating a barren moor may be astonished to find that the stony soil has after all produced good fruit and beautiful flowers. In attempting a description of the people of Weihaiwei, their customs and manners, their religion and superstitions, their folk-lore, their personal characteristics, their village homes, I have endeavoured to justify my choice of a field of investigation that has so far been neglected by serious students of things Chinese. It may be foolish to hope that this little wilderness will prove to be of the kind that blossoms like a rose, yet at least I shall escape the charge of having staked out a valley and a hill and labelled it "China."

Hitherto Weihaiwei has been left in placid enjoyment of its bucolic repose. The lords of commerce despise it, the traveller dismisses it in a line, the sinologue knows it not, the ethnologist ignores it, the historian omits to recognise its existence before the fateful year 1895, while the local British official, contenting himself with issuing tiny Blue-book reports which nobody reads, dexterously strives to convince himself and others that its administrative problems are sufficiently weighty to justify his existence and his salary. And yet a few years of residence in this unpampered little patch of territory—years spent to a great extent without European companionship, when one must either come to know something of the inhabitants and their ways or live like a mole—have convinced one observer, and would doubtless convince many others, that to the people of Weihaiwei life is as momentous and vivid, as full of joyous and tragic interest, as it is to the proud people of the West, and that mankind here is no less worthy the pains of study than mankind elsewhere.

There is an interesting discovery to be made almost[6] as soon as one has dipped below the surface of the daily life of the Weihaiwei villagers, and it affords perhaps ample compensation and consolation for the apparent narrowness of our field of inquiry. In spite of their position at one of the extremities of the empire, a position which would seemingly render them peculiarly receptive to alien ideas from foreign lands, the people of Weihaiwei remain on the whole steadfastly loyal to the views of life and conduct which are, or were till recently, recognised as typically Chinese. Indeed, not only do we find here most of the religious ideas, superstitious notions and social practices which are still a living force in more centrally-situated parts of the Empire, but we may also discover strange instances of the survival of immemorial rites and quasi-religious usages which are known to have flourished dim ages ago throughout China, but which in less conservative districts than Weihaiwei have been gradually eliminated and forgotten. One example of this is the queer practice of celebrating marriages between the dead. The reasons for this strange custom must be dealt with later;[1] here it is only desirable to mention the fact that in many other parts of China it appears to have been long extinct. The greatest authority on the religious systems of China, Dr. De Groot, whose erudite volumes should be in the hands of every serious student of Chinese rites and ceremonies, came across no case of "dead-marriage" during his residence in China, and he expressed uncertainty as to whether this custom was still practised.[2] Another religious rite which has died out in many other places and yet survives in Weihaiwei, is that of burying the soul of a dead man (or perhaps it would be more correct to say one of his souls) without his body.[3] Of such burials, which must also be dealt with later on, Dr. De Groot, in spite of all his researches, seems to have come across no instance, though he confidently expressed the correct belief that somewhere or other they still took place.[4]

As the people of Weihaiwei are so tenacious of old customs and traditions, the reader may ask with what feelings they regard the small foreign community which for the last decade and more has been dwelling in their midst. Is British authority merely regarded as an unavoidable evil, something like a drought or bad harvest? Does British influence have no effect whatever on the evolution of the native character and modes of thought? The last chapter of this book will be found to contain some observations on these matters: but in a general way it may be said that the great mass of the Chinese population of Weihaiwei has been only very slightly, and perhaps transiently, affected by foreign influences. The British community is very small, consisting of a few officials, merchants, and missionaries. With two or three exceptions all the Europeans reside on the island of Liukung and in the small British settlement of Port Edward, where the native population (especially on the island) is to a great extent drawn from the south-eastern provinces of China and from Japan. The European residents—other than officials and missionaries—have few or no dealings with the people except through the medium of their native clerks and servants. The missionaries, it need hardly be said, do not interfere, and of course in no circumstances would be permitted to interfere, with the cherished customs of the people, even those which are branded as the idolatrous rites of "paganism."

Apart from the missionaries, the officials are the only Europeans who come in direct contact with the people, and it is, and always has been, the settled policy of the local Government not only to leave the people to lead their own lives in their own way, but, when disputes arise between natives, to adjudicate[8] between them in strict conformity with their own ancestral usages. In this the local Government is only acting in obedience to the Order-in-Council under which British rule in Weihaiwei was inaugurated. "In civil cases between natives," says the Order, "the Court shall be guided by Chinese or other native law and custom, so far as any such law or custom is not repugnant to justice and morality." The treatment accorded to the people of Weihaiwei in this respect is, indeed, no different from that accorded to other subject races of the Empire; but whereas, in other colonies and protectorates, commercial or economic interests or political considerations have generally made it necessary to introduce a body of English-made law which to a great extent annuls or transforms the native traditions and customary law, the circumstances of Weihaiwei have not yet made it necessary to introduce more than a very slender body of legislative enactments, hardly any of which run counter to or modify Chinese theory or local practice.

From the point of view of the European student of Chinese life and manners the conditions thus existing in Weihaiwei are highly advantageous. Nowhere else can "Old China" be studied in pleasanter or more suitable surroundings than here. The theories of "Young China," which are destined to improve so much of the bad and to spoil so much of the good elements in the political and social systems of the Empire, have not yet had any deeply-marked influence on the minds of this industrious population of simple-minded farmers. The Government official in Weihaiwei, whose duties throw him into immediate contact with the natives, and who in a combined magisterial and executive capacity is obliged to acquaint himself with the multitudinous details of their daily life, has a unique opportunity for acquiring an insight into the actual working of the social machine and the complexities of Chinese character.

This satisfactory state of things cannot be regarded as permanent, even if the foreigner himself does not soon become a mere memory. If Weihaiwei were to undergo development as a commercial or industrial centre, present conditions would be greatly modified. Not only would the people themselves pass through a startling change in manners and disposition—a change more or less rapid and fundamental according to the manner in which the new conditions affected the ordinary life of the villagers—but their foreign rulers would, in a great measure, lose the opportunities which they now possess of acquiring first-hand knowledge of the people and their ancestral customs. Government departments and officials would be multiplied in order to cope with the necessary increase of routine work, the executive and judicial functions would be carefully separated, and the individual civil servant would become a mere member or mouthpiece of a single department, instead of uniting in his own person—as he does at present—half a dozen different executive functions and wide discretionary powers with regard to general administration. Losing thereby a great part of his personal influence and prestige, he would tend to be regarded more and more as the salaried servant of the public, less and less as a recognisable representative of the fu-mu-kuan (the "father-and-mother official") of the time-honoured administrative system of China. That these results would assuredly be brought about by any great change in the economic position of Weihaiwei cannot be doubted, since similar causes have produced such results in nearly all the foreign and especially the Asiatic possessions of the British Crown.

But there are other forces at work besides those that may come from foreign commercial or industrial enterprise, whereby Weihaiwei may become a far less desirable school than it is at present for the student of the Chinese social organism. Hitherto Weihaiwei has with considerable success protected[10] itself behind walls of conservatism and obedience to tradition against the onslaughts of what a Confucian archbishop, if such a dignitary existed, might denounce as "Modernism." But those walls, however substantial they may appear to the casual eye, are beginning to show signs of decay. There is indeed no part of China, or perhaps it would be truer to say no section of the Chinese people, that is totally unaffected at the present day by the modern spirit of change and reform. It is naturally the most highly educated of the people who are the most quickly influenced and roused to action, and the people of Weihaiwei, as it happens, are, with comparatively few exceptions, almost illiterate. But the spirit of change is "in the air," and reveals itself in cottage-homes as well as in books and newspapers and the marketplaces of great cities. Let us hope, for the good of China, that the stout walls of conservatism both in Weihaiwei and elsewhere will not be battered down too soon or too suddenly.

One of the gravest dangers overhanging China at the present day is the threatened triumph of mere theory over the results of accumulated experience. Multitudes of the ardent young reformers of to-day—not unlike some of the early dreamers of the French Revolution—are aiming at the destruction of all the doctrines that have guided the political and social life of their country for three thousand years, and hope to build up a strong and progressive China on a foundation of abstract principles. With the hot-headed enthusiasm of youth they speak lightly of the impending overthrow, not only of the decaying forces of Buddhism and Taoism, but also of the great politico-social structure of Confucianism, heedless of the possibility that these may drag with them to destruction all that is good and sound in Chinese life and thought. Buddhism (in its present Chinese form) might, indeed, be extinguished without much loss to the people; Taoism (such as it is nowadays)[11] might vanish absolutely and for ever, leaving perhaps no greater sense of loss than was left by the decay of a belief in witchcraft and alchemy among ourselves; but Confucianism (or rather the principles and doctrines which Confucianism connotes, for the system dates from an age long anterior to that of Confucius) cannot be annihilated without perhaps irreparable injury to the body-social and body-politic of China. The collapse of Confucianism would undoubtedly involve, for example, the partial or total ruin of the Chinese family system and the cult of ancestors.

With the exception of Roman Catholics and the older generation of Protestant missionaries with a good many of their successors, who condemn all Chinese religion as false or "idolatrous," few, if any, European students of China will be heard to disapprove—whether on ethical or religious grounds—of that keystone of the Chinese social edifice known to Europeans as ancestor-worship. To the revolutionary doctrines of the extreme reformers Weihaiwei and other "backward" and conservative parts of China are—half unconsciously—opposing a salutary bulwark. They cannot hope to keep change and reform altogether at a distance, nor is it at all desirable that they should do so; indeed, as we have seen, their walls of conservatism are already beginning to crumble. But if they only succeed in keeping the old flag flying until the attacking party has been sobered down by time and experience and has become less anxious to sweep away all the time-honoured bases of morality and social government, these old centres of conservatism will have deserved the gratitude of their country. What indeed could be more fitting than that the Confucian system should find its strongest support, and perhaps make its last fight for life, in the very province in which the national sage lived and taught, and where his body has lain buried for twenty-five centuries?

As applied to the territory leased by China to Great Britain the word Weihaiwei is in certain respects a misnomer. The European reader should understand that the name is composed of three separate Chinese characters, each of which has a meaning of its own.[5] The first of the three characters (transliterated Wei in Roman letters) is not the same as the third: the pronunciation is the same but the "tone" is different, and the Chinese symbols for the two words are quite distinct. The first Wei is a word meaning Terrible, Majestic, or Imposing, according to its context or combinations. The word hai means the Sea. The combined words Weihai Ch'êng or Weihai City, which is the real name of the little town that stands on the mainland opposite the island of Liukung, might be roughly explained as meaning "City of the August Ocean," but in the case of Chinese place-names, as of personal names, translations are always unnecessary and often meaningless. The third character, Wei, signifies a Guard or Protection; but in a technical sense, as applied to the names of places, it denotes a certain kind of garrisoned and fortified post partially exempted from civil jurisdiction and established for the protection of the coast from piratical raids, or for guarding the highways along which tribute-grain and public funds are carried through the provinces to the capital.

A Wei is more than a mere fort or even a fortified town. It often implies the existence of a military colony and lands held by military tenure, and may embrace an area of some scores of square miles. Perhaps the best translation of the term would be "Military District." The Wei of Weihai was only one of several Wei established along the coast of Shantung, and like them it owed its creation chiefly to the piratical attacks of the Japanese. More remains to be said on this point in the next chapter; here it will be enough to say that the Military District of Weihai was established in 1398 and was abolished in 1735. From that time up to the date of the Japanese occupation in 1895 it formed part of the magisterial (civil) district of Wên-têng, though this does not mean that the forts were dismantled or the place left without troops. In strictness, therefore, we should speak not of Weihaiwei but of Weihai, which would have the advantage of brevity: though as the old name is used quite as much by the Chinese as by ourselves there is no urgent necessity for a change. But in yet another respect the name is erroneous, for the territory leased to Great Britain, though much larger than that assigned to the ancient Wei, does not include the walled city which gives its name to the whole. The Territory, however, embraces not only all that the Wei included except the city, but also a considerable slice of the districts of Wên-têng and Jung-ch'êng. It should therefore be understood that the Weihaiwei with which these pages deal is not merely the small area comprised in the old Chinese Wei, but the three hundred square miles (nearly) of territory ruled since 1898 by Great Britain. We shall have cause also to make an occasional excursion into the much larger area (comprising perhaps a thousand square miles) over which Great Britain has certain[14] vague military rights but within which she has no civil jurisdiction.

A glance at a map of eastern Shantung will show the position of the Weihaiwei Territory (for such is its official designation under the British administration) with regard to the cities of Wên-têng (south), Jung-ch'êng (east), and Ning-hai (west). Starting from the most easterly point in the Province, the Shantung Promontory, and proceeding westwards towards Weihaiwei, we find that the Jung-ch'êng district embraces all the country lying eastward of the Territory; under the Chinese régime it also included all that portion of what is at present British territory which lies east of a line drawn from the sea near the village of Shêng-tzŭ to the British frontier south of the village of Ch'iao-t'ou. All the rest of the Territory falls within the Chinese district of which Wên-têng is the capital. Jung-ch'êng city is situated five miles from the eastern British frontier, Wên-têng city about six miles from the southern. The magisterial district of Ning-hai has its headquarters in a city that lies over thirty miles west of the British western boundary. The official Chinese distances from Weihaiwei city to the principal places of importance in the neighbourhood are these: to Ning-hai, 120 li; to Wên-têng, 100 li; to Jung-ch'êng, 110 li. A li is somewhat variable, but is generally regarded as equivalent to about a third of an English mile. The distance to Chinan, the capital of the Shantung Province, is reckoned at 1,350 li, and to Peking (by road) 2,300 li.[6]

The mention of magisterial districts makes it desirable to explain, for the benefit of readers whose knowledge of China is limited, that every Province (there are at present eighteen Provinces in China excluding Chinese Turkestan and the Manchurian Provinces) is subdivided for administrative purposes into Fu and Hsien, words generally translated by the terms Prefecture and District-Magistracy. The prefects and magistrates are the fu-mu-kuan or father-and-mother officials; that is, it is they who are the direct rulers of the people, are supposed to know their wants, to be always ready to listen to their complaints and relieve their necessities, and to love them as if the relationship were in reality that of parent and children. That a Chinese magistrate has often very queer ways of showing his paternal affection is a matter which need not concern us here. In the eyes of the people the fu-mu-kuan is the living embodiment of imperial as well as merely patriarchal authority, and in the eyes of the higher rulers of the Province he is the official representative of the thousands of families over whom his jurisdiction extends. The father-and-mother official is in short looked up to by the people as representing the Emperor, the august Head of all the heads of families, the Universal Patriarch; he is looked down to by his superiors as representing all the families to whom he stands in loco parentis.[7] A district magistrate is subordinate to a prefect, for there are several magistracies in each prefecture, but both are addressed as Ta lao-yeh. This term—a very appropriate one for an official who represents the patriarchal idea—may be literally rendered Great Old Parent or Grandfather; whereas the more exalted provincial officials, who are regarded less as parents of the people than as Servants of the Emperor, are known as Ta-jên: a term which, literally meaning Great Man, is often but not always appropriately regarded as equivalent to "Excellency."

All the district-magistracies mentioned in connexion with Weihaiwei are subordinate to a single prefecture. The headquarters of the prefect, who presides over a tract of country several thousand square miles in extent, are at the city of Têng-chou, situated on the north coast of Shantung 330 li or about 110 miles by road west of Weihaiwei. The total number of prefectures (fu) in Shantung is ten, of magistracies one hundred and seven. As Shantung itself is estimated to contain 56,000 square miles of territory,[8] the average size of each of the Shantung prefectures may be put down at 5,600 and that of each of the magistracies at about 520 square miles. The British territory of Weihaiwei being rather less than 300 square miles in extent is equivalent in area to a small-sized district-magistracy. The functions of a Chinese district magistrate have been described by some Europeans as somewhat analogous to those of an English mayor, but the analogy is very misleading. Not only has the district magistrate greater powers and responsibilities than the average mayor, but he presides over a far larger area. He is chief civil officer not only within the walls of the district capital but also throughout an extensive tract of country that is often rich and populous and full of towns and villages.

The eastern part of the Shantung Peninsula, in which Weihaiwei and the neighbouring districts of Jung-ch'êng, Wên-têng and Ning-hai are situated, is neither rich nor populous as compared with the south-western parts of the Province. The land is not unfertile, but the agricultural area is somewhat small, for the country is very hilly. Like the greater part of north China, Shantung is liable to floods and droughts, and local famines are not uncommon. The unequal distribution of the rainfall is no doubt partly the result of the almost total absence of forest. Forestation is and always has been a totally neglected art in China, and the wanton manner in which timber has been wasted and destroyed without any serious attempt at replacement is one of the most serious blots on Chinese administration, as well as one of the chief causes of the poverty of the people.[9] If north China is to be saved from becoming a desert (for the arable land in certain districts is undoubtedly diminishing in quantity year by year) it will become urgently necessary for the Government to undertake forestation on a large scale and to spend money liberally in protecting the young forests from the cupidity of the ignorant peasants. The German Government in Kiaochou is doing most valuable work in the reforestation of the hills that lie within its jurisdiction, and to a very modest extent Weihaiwei is acting similarly. Perhaps the most encouraging sign is the genuine interest that the Chinese are beginning to take in these experiments, though it is difficult to make them realise the enormous economic and climatic advantages which forestation on a large scale would bring to their country.

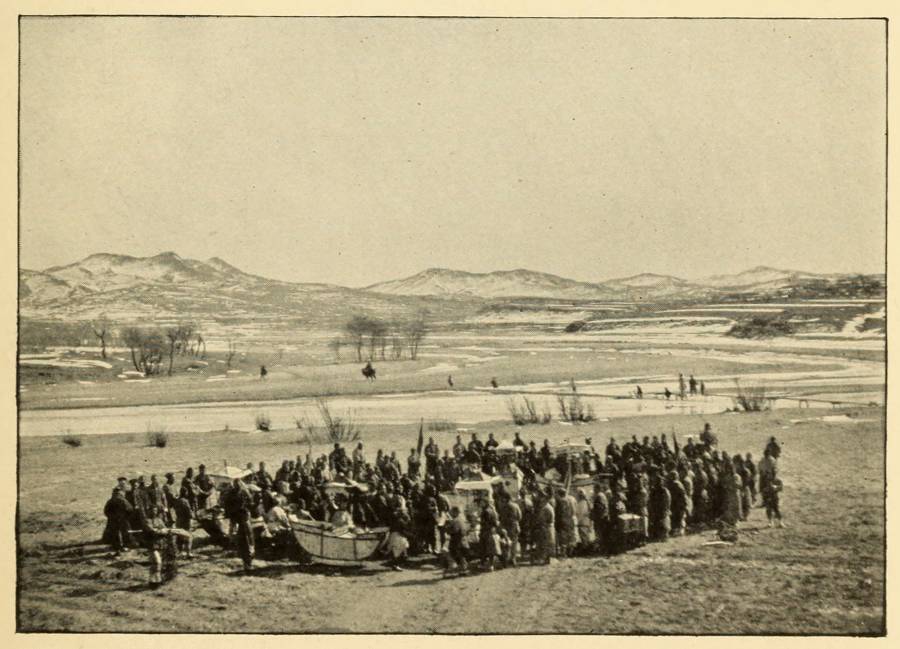

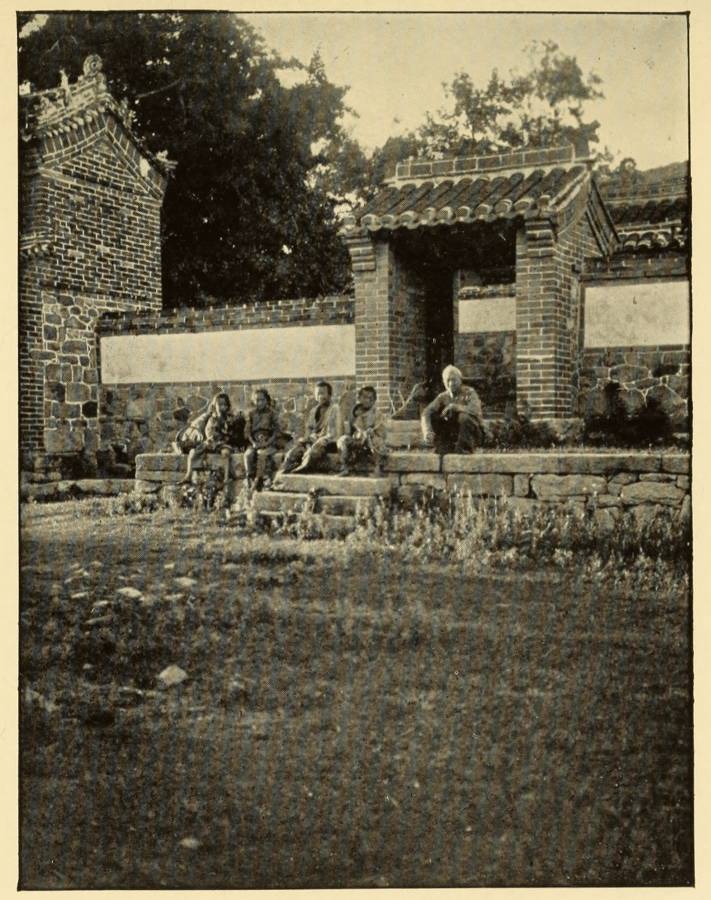

A HALT IN YÜ-CHIA-K'UANG DEFILE (see p. 18).

It must have been the treelessness of the district and the waterless condition of the mountains as viewed from the harbour and the sea-coast that prompted the remark made in an official report some years ago that Weihaiwei is "a colder Aden"; and indeed if we contemplate the coast-line from the deck of a steamer the description seems apt enough. A ramble through the Territory among the valleys and glens that penetrate the interior in every direction is bound to modify one's first cheerless impressions very considerably. Trees, it is true, are abundant only in the immediate neighbourhood of villages and in the numerous family burial-grounds; but the streams are often lined with graceful willows, and large areas on the mountain-slopes are covered with green vegetation in the shape of scrub-oak. At certain seasons of the year the want of trees is from an æsthetic point of view partly atoned for by the blended tints of the growing crops; and certainly to the average English eye the waving wheat-fields and the harvesters moving sickle in hand through the yellow grain offer a fairer and more home-like spectacle than is afforded by the marshy rice-lands of the southern provinces. On the whole, indeed, the scenery of Weihaiwei is picturesque and in some places beautiful.[10] The chief drawback next to lack of forest is the want of running water. The streams are only brooks that can be crossed by stepping-stones. In July and August, when the rainfall is greatest, they become enormously swollen for a few days, but their courses are short and the flood-waters are soon carried down to the sea. In winter and spring some of the streams wholly disappear, and the greatest of them becomes the merest rivulet.

The traveller who approaches Weihaiwei by sea from the east or south makes his first acquaintance with the Shantung coast at a point about thirty miles (by sea) east of the Weihaiwei harbour. This is the Shantung Promontory, the Chinese name of which is Ch'êng Shan Tsui or Ch'êng Shan T'ou. Ch'êng Shan is the name of the hill which forms the Promontory, while Tsui and T'ou (literally Mouth and Head) mean Cape or Headland. Before the Jung-ch'êng magistracy was founded (in 1735) this extreme eastern region was a military district like Weihaiwei. Taking its name from the Promontory, it was known as Ch'êng-shan-wei.

Ch'êng Shan, with all the rest of the present Jun-ch'êng district, is within the British "sphere of influence"; that is to say, Great Britain has the right to erect fortifications there and to station troops: rights which, it may be mentioned, have never been exercised.

The Shantung Promontory has been the scene of innumerable shipwrecks, for the sea there is apt to be rough, fogs are not uncommon, and there are many dangerous rocks. The first lighthouse—a primitive affair—is said to have been erected in 1821 by a pious person named Hsü Fu-ch'ang; but long before that a guild of merchants used to light a great beacon fire every night on a conspicuous part of the hill. A large bell was struck, so the records state, when the weather was foggy. The present lighthouse is a modern structure under the charge of the Chinese Imperial Customs authorities. Behind the Promontory—that is, to the west (landward) side—there is a wide stretch of comparatively flat land which extends across the peninsula. It may be worth noting that an official of the Ming dynasty named T'ien Shih-lung actually recommended in a state paper that a canal should be cut through this neck of land so as to enable junks to escape the perils of the rock-bound Promontory. He pointed out that the land was level and sandy and that several ponds already existed which could be utilised in the construction of the canal. Thus, he said, could be avoided the great dangers of the rocks known as Shih Huang Ch'iao and Wo Lung Shih. The advice of the amateur engineer was not acted upon, but his memorial (perhaps on account of its literary style) was carefully preserved and has been printed in the Chinese annals of the Jung-ch'êng district.

These annals contain an interesting reference to one of the two groups of rocks just named. Wo Lung Shih means "Sleeping dragon rocks," and no particular legend appears to be attached to them, though it[20] would have been easy to invent one. But the Shih Huang Ch'iao, or Bridge of the First Emperor, is regarded by the people as a permanent memorial of that distinguished monarch who in the third century B.C. seized the tottering throne of the classic Chou dynasty and established himself as the First Emperor (for such is the title he gave himself) of a united China. Most Europeans know nothing of this remarkable man except that he built the Great Wall of China and rendered his reign infamous by the Burning of the Books and the slaughter of the scholars. Whether his main object in the latter proceeding was to stamp out all memory of the acts of former dynasties so that to succeeding ages he might indeed be the First of the historical Emperors, or whether it was not rather an act of savagery such as might have been expected of one who was not "born in the purple" and who derived his notions of civilisation from the semi-barbarous far-western state of Ch'in, is perhaps an impossible question to decide: and indeed the hatred of the Chinese literati for a sovereign who despised literature and art may possibly have led them to be guilty of some exaggeration in the accounts they have given us of his acts of vandalism and murder.

During his short reign as Emperor, Ch'in Shih Huang-ti (who died in 210 B.C.) is said to have travelled through the Empire to an extent that was only surpassed by the shadowy Emperor Yü who lived in the third millennium B.C. Yü was, according to tradition, the prince of engineers. He it was who "drained the Empire" and led the rivers into their proper and appropriate channels. The First Emperor might be said, had he not affected contempt for all who went before him, to have taken the great Yü as his model, for he too left a reputation of an ambitious if not altogether successful engineer. The story goes that he travelled all the way to the easternmost point of Shantung, and having arrived at the Promontory, decided to build a bridge from there to Korea, or to[21] the mysterious islands of P'êng-lai where the herb of immortality grew, or to the equally marvellous region of Fu-sang.

The case of the First Emperor affords a good example of how wild myths can be built up on a slender substratum of fact. Had he lived a few centuries earlier instead of in historic times, his name doubtless would have come down the ages as that of a demi-god; even as things are, the legends that sprang up about him in various parts of northern China might well be connected with the name of some prehistoric hero. The Chinese of eastern Shantung have less to say of him as a monarch than as a mighty magician. In order to have continuous daylight for building the Great Wall, he is said to have been inspired with the happy device of transfixing the sun with a needle, thus preventing it from moving. His idea of bridge-building had the simplicity of genius: it was simply to pick up the neighbouring mountains and throw them into the sea. He was not without valuable assistance from persons who possessed powers even more remarkable than his own. A certain spirit helped him by summoning a number of hills to contribute their building-stone. At the spirit's summons, so the story goes, thirteen hills obediently sent their stones rolling down eastwards towards the sea. On came the boulders, big and little, one after another, just as if they were so many live things walking. When they went too slowly or showed signs of laziness the spirit flogged them with a whip until the blood came.

The truth of this story, in the opinion of the people, is sufficiently attested by the facts that one of the mountains is still known as Chao-shih-shan or "Summon-the-rocks hill," and that many of the stones on its slopes and at its base are reddish in hue.[11] The Emperor was also helped by certain Spirits of the Ocean (hai-shên), who did useful work in establishing the piers of his bridge in deep water.[12] The Emperor, according to the story, was deeply grateful to these Ocean Spirits for their assistance, and begged for a personal interview with them so that he might express his thanks in proper form. "We are horribly ugly," replied the modest Spirits, "and you must not pay us a visit unless you will promise not to draw pictures of us." The Emperor promised, and rode along the bridge to pay his visit. When he had gone a distance of forty li he was met by the Spirits, who received him with due ceremony. During the interview, the Emperor, who like Odysseus was a man of many wiles, furtively drew his hosts' portraits on the ground with his foot. As luck would have it the Spirits discovered what he was doing, and naturally became highly indignant. "Your Majesty has broken faith with us," they said. "Begone!" The Emperor mounted his horse and tried to ride back the way he had come, but lo! the animal remained rigid and immovable, for the Spirits had bewitched it and turned it into a rock; and his Majesty had to go all the way back to the shore on foot.[13]

THE TEMPLE AT THE SHANTUNG PROMONTORY (see p. 23).

This regrettable incident did not cause the cessation of work on the bridge, though the Emperor presumably received no more help from the Spirits of the Ocean. But on one unlucky day the Emperor's wife presumed without invitation to pay her industrious husband a visit, and brought with her such savoury dishes as she thought would tempt the imperial appetite. Now the presence of women, say the Chinese, is utterly destructive of all magical influences. The alchemists, for example, cannot compound the elixir of life in the presence of women, chickens, or cats. The lady had no sooner made her appearance at Ch'êng Shan than the bridge, which was all but finished, instantaneously crumbled to pieces. So furious was her imperial spouse at the ruin of his work that he immediately tore the unhappy dame to pieces and scattered her limbs over the sea-shore, where they can be seen in rock-form to this day. The treacherous rocks that stretch out seawards in a line from the Promontory are the ruins of the famous bridge, and still bear the name of the imperial magician.

Legends say that a successor of the First Emperor, namely Han Wu Ti (140-87 B.C.), who also made a journey to eastern Shantung, was ill-advised enough to make an attempt to continue the construction of the mythical bridge; but he only went so far as to set up two great pillars. These are still to be seen at ebb-tide, though the uninitiated would take them to be mere shapeless rocks. Han Wu Ti's exploits were but a faint copy of those of the First Emperor. Ch'êng Shan Tsui has for many centuries been dedicated to that ruler's memory, and on its slopes his temple may still be visited. The original temple, we are told, was built out of part of the ruins of the great bridge. In 1512 it was destroyed by fire and rebuilt on a smaller scale. Since then it has been restored more than once, and the present building is comparatively new.

There is no legend, apparently, which associates the First Emperor with the territory at present directly administered by Great Britain, but there is a foolish story that connects him with Wên-têng Shan, a hill from which the Wên-têng district takes its name. It is said that having arrived at this hill the Emperor summoned his civil officials (wên) to ascend (têng) the hill in question and there proclaim to a marvelling world his own great exploits and virtues; but this story is evidently a late invention to account for the name Wên-têng. Among other localities associated with this Emperor may be mentioned a terrace, which he visited for the sake of a sea-view, and a pond[24] (near Jung-ch'êng city) at which His Majesty's horses were watered: hence the name Yin-ma-ch'ih (Drink-horse-pool). But the Chinese are always ready to invent stories to suit place-names, and seeing that every Chinese syllable (whether part of a name or not) has several meanings, the strain on the imaginative faculties is not severe.

The feat performed by the Emperor close to the modern treaty-port of Chefoo—only a couple of hours' steaming from Weihaiwei—may be slightly more worthy of record than the Wên-têng legend. His first visit to Chih-fu (Chefoo) Hill—by which is meant one of the islands off the coast—is said to have taken place in 218 B.C., when he left a record of himself in a rock-inscription which—if it ever existed—has doubtless long ago disappeared. In 210, the last year of his busy life, he sent a certain Hsü Fu to gather medicinal herbs (or rather the herbs out of which the drug of immortality was made) at the Chefoo Hill. In his journeys across the waters to and from the hill Hsü Fu was much harassed by the attacks of a mighty fish, and gave his imperial master a full account of the perils which constantly menaced him owing to this monster's disagreeable attentions. The Emperor, always ready for an adventure, immediately started for Chefoo, climbed the hill, caught sight of the great fish wallowing in the waters, and promptly shot it dead with his bow and arrow.

It is natural that the Shantung Promontory and the eastern peninsula in general should have become the centre of legend and myth. We know from classical tradition that to the people of Europe the western ocean—the Atlantic—was a region of marvel. There—beyond the ken of ships made or manned by ordinary mortals—lay the Fortunate Islands, the Isles of the Blest. The Chinese have similar legends, but their Fairy Isles—P'êng-lai and Fu-sang—lay, as a matter of course, somewhere in the undiscovered east, about the shimmering region of the rising sun. Many and[25] many are the Chinese dreamers and poets who have yearned for those islands, and have longed to pluck the wondrous fruit that ripened only once in three thousand years and then imparted a golden lustre to him who tasted of it. The Shantung Promontory became a region of marvel because it formed the borderland between the known and the unknown, the stepping-stone from the realm of prosaic fact to that of fancy and romance.

The coast-line from the Promontory to Weihaiwei possesses no features of outstanding interest. It consists of long sandy beaches broken by occasional rocks and cliffs. The villages are small and, from the sea, almost invisible. Undulating hills, seldom rising above a thousand feet in height, but sometimes bold and rugged in outline, form a pleasant background. There are a few islets, of which one of the most conspicuous is Chi-ming-tao—"Cock-crow Island"—lying ten miles from the most easterly point of the Weihaiwei harbour. All the mainland from here onwards lies within the territory directly ruled by Great Britain. On the port side of the steamer as she enters the harbour will be seen a line of low cliffs crowned by a lighthouse; on the starboard side lies Liukungtao, the island of Liukung.

As in the case of Hongkong, it is the island that creates the harbour; and, similarly, the position of the island provides two entrances available at all times for the largest ships. The island is two and a quarter miles long and has a maximum breadth of seven-eighths of a mile and a circumference of five and a half miles. The eastern harbour entrance is two miles broad, the western entrance only three-quarters of a mile. The total superficial area of the harbour is estimated at eleven square miles. Under the lee of the island, which might be described as a miniature Hongkong, is the deep-water anchorage for warships, and it is here that the British China Squadron lies when it pays its[26] annual summer visit to north China. On the island are situated the headquarters of the permanent naval establishment, the naval canteen (formerly a picturesque Chinese official yamên), a United Services club, a few bungalows for summer visitors, an hotel, the offices of a few shipping firms, and several streets of shops kept chiefly by natives of south China and by Japanese. There are also the usual recreation-grounds, tennis-courts, and golf-links, without which no British colony would be able to exist. The whole island practically consists of one hill, which rises to a point (the Signal Station) 498 feet above sea-level. On the seaward side it ends precipitously in a fringe of broken cliffs, while on the landward side its gentle slopes are covered with streets and houses and open spaces.

Photo by Ah Fong.

WEIHAIWEI HARBOUR, LIUKUNGTAO AND CHU-TAO LIGHTHOUSE.

The name Liukungtao means the Island of Mr. Liu, and the records refer to it variously as Liu-chia-tao (the Island of the Liu family), as Liutao (Liu Island), and as Liukungtao. Who Mr. Liu was and when he lived is a matter of uncertainty, upon which the local Chinese chronicles have very little to tell us. "Tradition says," so writes the chronicler, "that the original Mr. Liu lived a very long time ago, but no one knows when." The principal habitation of the family is said to have been not on the island but at a village called Shih-lo-ts'un on the mainland. This village was situated somewhere to the south of the walled city. The family must have been a wealthy one, for it appears to have owned the island and made of it a summer residence or "retreat." It was while residing at Shih-lo-ts'un that one of the Liu family made a very remarkable discovery. On the sea-shore he came across a gigantic decayed fish with a bone measuring one hundred chang in length. According to English measurement this monstrous creature must have been no less than three hundred and ninety yards long. Liu had the mighty fishbone carried to a temple in the neighbouring walled city, and there it was reverently presented to the presiding deity. The only way to get the bone into the temple was to cut it up into shorter lengths. This was done, and the various pieces were utilised as subsidiary rafters for portions of the temple roof. They are still in existence, as any inquirer may see for himself by visiting the Kuan Ti temple in Weihaiwei city. Perhaps if Europeans insist upon depriving China of the honour of having invented the mariner's compass they may be willing to leave her the distinction of having discovered the first sea-serpent.[14]

From time immemorial there existed on the island a temple which contained two images representing an elderly gentleman and his wife. These were Liu Kung and Liu Mu—Father and Mother Liu. They afford a good example of how quite undistinguished men and women can in favourable circumstances attain the position of local deities or saints: for the persons represented by these two images have been regularly worshipped—especially by sailors—for several centuries. The curious thing is that the deification of the old couple has taken place without any apparent justification from legend or myth. Perhaps they were a benevolent pair who were in the habit of ministering to the wants of shipwrecked sailors; but if so there is no testimony to that effect. When the British Government acquired the island and began to make preparations for the construction of naval works and forts, which were never completed, the Chinese decided to remove the venerated images of Father and Mother Liu to the mainland. They are now handsomely housed in a new temple that stands between the walled city and the European settlement of Port Edward, and it is still the custom for many of the local junkmen to come here and make their pious offerings of money and incense, believing that in return for these gifts old Liu and his wife will[28] graciously grant them good fortune at sea and freedom from storm and shipwreck.

IMAGES OF "MR. AND MRS. LIU" (see p. 27).

It is on the island that the majority of the British residents dwell, but Liukungtao does not occupy with respect to the mainland the same all-important and dominating position that Hongkong occupies (or did till recently occupy) with regard to the Kowloon peninsula and the New Territory. The seat of the British Government of Weihaiwei is on the mainland, and the small group of civil officers are far more busily employed in connexion with the administration of that part of the Territory and its 150,000 villagers than with the little island and its few British residents and native shopkeepers. The British administrative centre, then, is the village of Ma-t'ou, which before the arrival of the British was the port of the walled city of Weihaiwei, but is gradually becoming more and more European in appearance and has been appropriately re-named Port Edward. It lies snugly on the south-west side of the harbour and is well sheltered from storms; the water in the vicinity of Port Edward is, however, too shallow for vessels larger than sea-going junks and small coasting-steamers. Ferry-launches run several times daily between the island and the mainland, the distance between the two piers being two and a half miles. Government House, the residence of the British Commissioner, is situated on a slight eminence overlooking the village, and not far off are situated the Government Offices and the buildings occupied, until 1906, by the officers and men of the 1st Chinese Regiment of Infantry. At the northern end of the village, well situated on a bluff overlooking the sea, is a large hotel: far from beautiful in outward appearance, but comfortable and well managed. A little further off stands the Weihaiwei School for European boys. It would be difficult anywhere in Asia to find a healthier place for a school, and certainly on the coast of China the site is peerless.

Elsewhere in the neighbourhood of Port Edward there are well-situated bungalows for European summer visitors, natural sulphur baths well managed by Japanese, and a small golf course. Other attractions for Europeans are not wanting, but as these pages are not written for the purpose either of eulogising British enterprise or of attracting British visitors, detailed reference to them is unnecessary.

It may be mentioned, however, that from the European point of view, the most pleasing feature of Port Edward and its neighbourhood is the absence of any large and congested centre of Chinese population. The city of Weihaiwei is indeed close by—only half a mile from the main street of Port Edward. But it is a city only in name, for though it possesses a battlemented wall and imposing gates, it contains only a few quiet streets, three or four temples, an official yamên, wide open spaces which are a favourite resort of snipe, and a population of about two thousand.

The reader may remember that when the New Territory was added to the Colony of Hongkong in 1898 a clause in the treaty provided that the walled city of Kowloon, though completely surrounded by British territory, should be left under Chinese rule. This arrangement was due merely to the strong sentimental objection of the Chinese to surrendering a walled city. In the case of Kowloon, as it happened, circumstances soon made it necessary for this part of the treaty to be annulled, and very soon after the New Territory had passed into British hands the Union Jack was hoisted also on the walls of Kowloon. When the territory of Weihaiwei was "leased" to Great Britain in the same eventful year (1898) a somewhat similar agreement was made "that within the walled city of Weihaiwei Chinese officials shall continue to exercise jurisdiction, except so far as may be inconsistent with naval and military requirements for the defence of the territory leased." So correct has been the attitude of the Chinese officials since the[30] Weihaiwei Convention was signed that it has never been found necessary to raise any question as to the status of the little walled town.

A VIEW FROM THE WALL OF WEIHAIWEI CITY (see p. 31).

Nominally it is ruled by the Wên-têng magistrate, whose resident delegate is a hsün-chien or sub-district deputy magistrate;[15] but as the hsün-chien has no authority an inch beyond the city walls, and in practice is perfectly ready to acknowledge British authority in such matters as sanitation (towards the expenses of which he receives a small subsidy from the British Government), it may be easily understood why this imperium in imperio has not hitherto led to friction or unpleasantness.

A walk round the well-preserved walls of Weihaiwei city affords a good view of the surroundings of Port Edward and the contour of the sea-coast bordering on the harbour. At the highest point of the city wall stands a little tower called the Huan-ts'ui-lou, the view from which has for centuries past been much praised by the local bards. It was built in the Ming dynasty by a military official named Wang, as a spot from which he might observe the sunrise and enjoy the sea view. From here can be seen, at favourable times, a locally-celebrated mirage (called by the Chinese a "market in the ocean") over and beyond the little islet of Jih-tao or Sun Island, which lies between Liukungtao and the mainland. The view from this tower is very pleasing, though one need not be prepared to endorse the ecstatic words of a sentimental captain from the Wên-têng camp, who closed a little poem of his own with the words "How entrancing is this fair landscape: this must indeed be Fairyland!"

Many of the most conspicuous hills in the northern portion of the Territory can be seen to advantage from the Huan-ts'ui-lou. The small hill immediately behind the city wall and the tower is the Nai-ku-shan.[16]

Like many other hills in the neighbourhood and along the coast, it possesses the remains of a stone-built beacon-tumulus (fêng tun), on which signal fires were lighted in the old days of warfare. To the northward lie Ku-mo Shan, the hill of Yao-yao, and Tiao-wo Shan, all included in the range that bears in the British map the name of Admiral Fitzgerald.

The highest point of the range is described in the local chronicle as "a solitary peak, seldom visited by human foot," though it is nowadays a common objective for European pedestrians, and also, indeed, for active Chinese children. The height is barely one thousand feet above sea-level. Tiao-we Shan and a neighbouring peak called Sung Ting Shan were resorted to by hundreds of the inhabitants of Weihaiwei as a place of refuge from the bands of robbers and disorganised soldiers who pillaged the homes and fields of the people during the commotions which marked the last year of the Ming dynasty (1643). To the northward of the Huan-ts'ui-lou may be seen a little hill—not far from the European bungalows at Narcissus Bay—crowned with a small stone obelisk of a kind often seen in China and known to foreigners as a Confucian Pencil. This was put up by a graduate of the present dynasty named Hsia Shih-yen and others, as a means of bringing good luck to the neighbourhood, and also, perhaps, as a memorial of their own literary abilities and successes. It bears no inscription.

A loftier hill is Lao-ya Shan, which is or used to be the principal resort of the local officials and people when offering up public supplications for rain. Its name (which means the Hill of the Crows) is derived from the black clouds which as they cluster round the summit are supposed to resemble the gathering of crows. An alternative name is Hsi-yü-ting—the Happy Rain Peak. The highest point in this section of the Territory lies among the imposing range of mountains to the south of Weihaiwei city, and is[32] known to the Chinese as Fo-erh-ting—"Buddha's Head"—the height of which is about 1,350 feet. This range of hills has been named by the British after Admiral Sir Edward Seymour.

The enumeration of all the hills of so mountainous a district as the Weihaiwei Territory would be useless and of little interest. Some of them, distinguished by miniature temples dedicated to the Shan-shên (Spirit of the Hill) and to the Supreme God of Taoism, will be referred to later on.[17] The loftiest hill in the Territory—about 1,700 feet—lies fourteen miles south of Port Edward, and is known to Europeans as Mount Macdonald, and to the Chinese as Chêng-ch'i Shan or Cho-ch'i Shan.[18] The Chinese name is derived from a stone chessboard said to have been carved out of a rock by a hsien-jên, a kind of wizard or mountain recluse who lived there in bygone ages. Most of the more remarkable or conspicuous hills in China are believed by the people to have been the abode of weird old men who never came to an end like ordinary people, but went on living with absurdly long beards and a profound knowledge of nature's secrets. There are endless legends about these mysterious beings, many of whom were in fact hermits with a distaste for the commonplace joys of life and a passion for mountain scenery.[19]

On the rocky summit of the Li-k'ou hill (situated in the range of which Fo-erh-ting is the highest point) there is a large stone which is symmetrical in shape and differs in appearance from the surrounding boulders. Legend says that a hermit who cultivated the occult arts brewed for himself on the top of the hill the elixir of life. An ox that was employed in grinding wheat at the foot of the hill sniffed the fragrant brew and broke away from his tether. Rushing up the hill in hot haste, he dragged after him the great grindstone. Arriving at the summit, he butted against the cauldron in which the hermit had cooked the soup of immortality, and eagerly lapped[33] up the liquid as it trickled down the side. The hermit, emulating an ancient worthy called Kou Shan-chih who was charioted on the wings of a crane, jumped on the ox's back, and thereupon the two immortal beings, leaving the grindstone behind them as a memorial, passed away to heaven and were seen no more. This is only one of many quaint stories told by the old folks of Weihaiwei to explain the peculiar formation of a rock, the existence of a cave in a cliff, or the sanctity of some nameless mountain-shrine. Thus even the hills of Weihaiwei, bare of forests as they are and devoid of mystery as they would seem to be, have yet their gleam of human interest, their little store of romance, their bond of kinship with the creative mind of man.

[5] The three characters in question are depicted on the binding of this book.

[6] The following list of distances by sea to the principal neighbouring ports may be of interest. The distance is in each case reckoned from the Weihaiwei harbour. Shantung Promontory, 30 miles; Chefoo, 42 miles; Port Arthur, 89 miles; Dalny, 91 miles; Chemulpo, 232 miles; Taku, 234 miles; Shanghai 452 miles; Kiaochou, 194 miles; Nagasaki, 510 miles.

[7] "The magistrate is the unit of government; he is the backbone of the whole official system; and to ninety per cent. of the population he is the Government."—Byron Brenan's Office of District Magistrate in China.

[8] England and Wales contain 58,000 square miles, with a population perhaps slightly less than that of Shantung.

[9] As early as the seventh century B.C. deforestation had become a recognised evil in the State of Ch'i (part of the modern Shantung), chiefly owing to the lavish use of timber for coffins and grave-vaults. (See De Groot's Religious System of China, vol. ii. pp. 660-1.)

[10] Especially some of the sea-beaches, the defiles that lie between Yü-chia-k'uang and Shang Chuang, and the valleys in which are situated Ch'i-k'uang, Wang-chia-k'uang, Pei k'ou, Chang-chia-shan, and Ch'ien Li-k'ou.

[11] The story is quoted in the T'ai P'ing Huan Yü Chi (chüan 20).

[12] With regard to this assistance from spirits, cf. the Jewish legend that King Solomon by the aid of a magic ring controlled the demons and compelled them to give their help in the building of the great Temple.

[13] See T'ai P'ing Huan Yü Chi, loc. cit.

[14] For accounts of other appearances of the "sea-serpent" in Chinese waters, see Dennys's Folk-lore of China, pp. 109, 113-4.

[16] Shan is the Chinese word for "Hill."

Though Chinese historians have never set themselves to solve that modern European problem as to whether history is or is not a science, they have always—or at least since the days of Confucius—had a strong sense of its philosophical significance and its didactic value. Of the writings with which the name of Confucius is connected, that known as the Ch'un Ch'iu or "Spring and Autumn Annals" is the one that he himself considered his greatest achievement, and Mencius assures us that when the Master had written this historical work, "rebellious ministers and bad sons were struck with terror." The modern reader is perhaps apt to wonder what there was in the jerky, disconnected statements of the Ch'un Ch'iu to terrify any one, however conscience-stricken; but Mencius's remark shows that history was already regarded as a serious employment, well fitted to engage the attention of philosophers and teachers of the people.

For a long time, indeed, practice lagged a long way behind theory. There is some reason to suppose that Confucius himself was not above adapting facts to suit his political opinions, which shows that history had not yet secured for itself a position of great dignity. The oldest historical work in the language is the Shu Ching, which is believed to have been edited by Confucius. Certainly the sage's study of[35] this work does not seem to have inspired him with any lofty theories as to how history ought to be treated, for his own work is considerably balder and less interesting than the old one. The Confucian who wrote the historical commentary known as the Tso-chuan improved upon his master's methods very greatly, and his work can be read with pleasure at the present day; but the first great Chinese historian did not appear till the second century B.C. in the person of Ssŭ-ma Ch'ien. For several reasons it would be incorrect to style him the Herodotus of China, but he may at least be regarded as the father of the modern art of historical writing in that country.[20]

Yet his example did not bring about the abolition of the old methods of the dry-bones annalists; for while the writers of the great Dynastic Histories have been careful to imitate and if possible improve upon his advanced style and method, and have thus produced historical works which for fidelity to truth, comprehensiveness, and literary workmanship will often bear comparison with similar productions in Europe, the compilers of the innumerable local histories have almost invariably contented themselves with legends, fairy-tales, and the merest chronicle of notable events arranged under the heads of successive years. The enormous quantity of these local histories may be realised from the fact that each province, prefecture and district, as well as each famous lake and each celebrated mountain, has one of its own.

These works are often very voluminous: an account of a single famous mountain, with its monasteries, sometimes extends over a dozen separate books; and the account of Ssŭch'uan, a single province, is not far short of two hundred volumes in length. These productions are not, indeed, only of an historical and legendary nature: they include full topographical information, elaborate descriptions of cities, temples, and physical features, separate chapters on local customs, natural productions and distinguished men and women, and anthologies of the best poems and essays descriptive of special features of interest or inspired by the local scenery.

On legends and folk-lore and anything that seems in any way marvellous or miraculous, the compiler lingers long and lovingly; but when he comes to the narrative of definite historical facts he is apparently anxious to get over that dry but necessary part of his labours as rapidly as possible, and so gives us but a bare enumeration of the events in the order of their occurrence, and in the briefest and most direct manner possible.

As a rule, his succinctly-stated matters of fact may be regarded as thoroughly reliable. When a Chinese annalist states that in the year 990 there was a serious famine at Weihaiwei, the reader may take it for granted that the famine undoubtedly occurred, however uninstructive the fact may be in the opinion of those who live nearly a thousand years later. What is apt to strike one as inexplicable is the occasional appearance, in a list of prosaic details which may be accepted as generally reliable, of some statement which suggests that the compiler must have suddenly lost control of his senses. For instance, we read in the Wên-têng Chih or Annals of the district in which the greater part of Weihaiwei is situated, that in the year which corresponds with 1539 there were disastrous floods, and that in the autumn a large dragon suddenly made its appearance in a private dwelling. "It burst the walls of the house," says the chronicler, "and so got away; and then there was a terrific[37] hailstorm." Why such startling absurdities are introduced into a narrative that is generally devoid of the least imaginative sparkle, may be easily understood when we remember that such animals as dragons, phœnixes and unicorns and many other strange creatures were believed in (or at least their existence was not questioned) by educated Chinese up to a quite recent date; and the writer of the Wên-têng Chih, when noting down remarkable occurrences as they were brought to his notice, saw no reason whatever why he should doubt the appearance of the dragon any more than he should doubt the reality of the floods or the hailstorm. That the dragon episode could not have happened because dragons did not exist was no more likely to occur to the honest Chinese chronicler than a doubt about the real existence of a personal Devil and a fiery Hell was likely to beset a pious Scottish Presbyterian of the eighteenth century, or than a disbelief in the creation of the world in six days in the year 4004 B.C. was likely to disturb the minds of the pupils of Archbishop Ussher.

The Chinese chronicles from which we derive our knowledge of the past history of Weihaiwei and the adjacent country are those of Wên-têng in four volumes, Jung-ch'êng in four, Ning-hai in six and Weihaiwei (that is, the Wei of Weihai) in two. The first three are printed from wooden blocks in the usual old-fashioned Chinese style, and this means that recently-printed copies are far less clear and legible than the first impressions, which are unfortunately difficult to obtain; the last (that of Weihaiwei) seems to exist in manuscript only, and is consequently very rare. It is from these four works chiefly, though not solely, that the information given in the rest of this chapter, as in many other parts of the book, has been culled; and while endeavouring to include only such details as are likely to be of some interest to the European reader, I trust there will be enough to[38] give him an accurate idea not only of the history of Weihaiwei but also of that prodigious branch of Chinese literature of which these works are typical.

The traditions of Weihaiwei and its neighbourhood take us back to the days of myth. The position of this region at the end of a peninsula which formed, so far as China knew, the eastern limit of the civilised world, made it, as we have seen, the fitting birthplace of legend and marvel. Not content with taking us back to the earliest days of eastern Shantung as a habitable region, the legends assure us of a time when it was completely covered by the ocean. Thousands of years ago, it is said, a Chinese princess was drowned there.[21] She was then miraculously turned into a bird called a ching wei, and devoted herself in her new state of existence to wreaking vengeance on the cruel sea for having cut short her human life. This she did by flying to and fro between land and sea carrying stones in her beak and dropping them into the water one by one until, by degrees, they emerged above the surface and formed dry land. Thus her revenge for the drowning incident was complete: she punished the sea by annihilating it.

For many centuries—and in this matter history and legend coincide—the peninsular district of Shantung, including Weihaiwei, was inhabited by a non-Chinese race of barbarians. Not improbably they were among the aboriginal inhabitants of the central plains of China, who were driven west, south and east before the steady march of the invading Chinese, or—if we prefer to believe that the latter were an autochthonous race—by the irresistible pressure of Chinese expansion. The eastward-driven section of the aborigines, having been pressed into far-distant Shantung, perhaps discovered that unless they made a stand there they would be driven into the sea and exterminated; so they held their ground and adapted themselves to the new conditions like the Celts in Wales and Strathclyde, while the Chinese, observing that the country was hilly, forest-clad, and not very fertile, swept away to the richer and more tempting plains of the south-west.