Title: The Poems of John Donne, Volume 2 (of 2)

Author: John Donne

Editor: Sir Herbert John Clifford Grierson

Release date: April 24, 2015 [eBook #48772]

Most recently updated: June 25, 2020

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Jonathan Ingram, Lesley Halamek, Stephen Rowland,

E-text prepared by

Jonathan Ingram, Lesley Halamek, Stephen Rowland,

and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team

(http://www.pgdp.net)

This is the second Volume of two.

Volume I contains the Poems and Line Notes, showing textual and punctuaton differences between the various MSS. and Editons and the Index of First Lines. Volume II contains the Introduction and Commentary, Annotational Notes for the Poems of Vol. I, and the Index of First Lines for poems quoted in Vol. II. There are links between the Poems and the Commentary Notes, with various references back and forth. These links are designed to work when the books are read on line. For information on the downloading of both interlinked volumes so that the links work when the files are on your own computer, see the Transcriber's Note at the end of this book.

The rest of the Transcriber's Note is at the end of the book.

EDITED FROM THE OLD EDITIONS AND NUMEROUS MANUSCRIPTS,

WITH INTRODUCTIONS & COMMENTARY

BY

HERBERT J. C. GRIERSON M.A.

CHALMERS PROFESSOR OF ENGLISH LITERATURE

IN THE UNIVERSITY OF ABERDEEN

VOL. II

INTRODUCTION AND COMMENTARY

OXFORD

AT THE CLARENDON PRESS

1912

HENRY FROWDE, M.A.

PUBLISHER TO THE UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD

LONDON, EDINBURGH, NEW YORK

TORONTO AND MELBOURNE

| PAGE | ||

| INTRODUCTION | v | |

| I. | The Poetry of Donne | v |

| II. | The Text and Canon of Donne's Poems | lvi |

| COMMENTARY | 1 | |

| INDEX OF FIRST LINES | 276 | |

THE POETRY OF DONNE

Donne's position among English poets, regarded from the historical and what we like to call scientific point of view, has been defined with learning and discrimination by Mr. Courthope in his History of English Poetry. As a phenomenon of curious interest for the student of the history of thought and literary fashions, there it is. Mr. Courthope is far too well-informed and judicious a critic to explain Donne's subtle thought and erudite conceits by a reference to 'Marini and his followers'. Gongora and Du Bartas are alike passed over in silence. What we are shown is the connexion of 'metaphysical wit' with the complex and far-reaching changes in men's conception of Nature which make the seventeenth century perhaps the greatest epoch in human thought since human thinking began.

The only thing that such a criticism leaves unexplained and undefined is the interest which Donne's poetry still has for us, not as an historical phenomenon, but as poetry. Literary history has for the historian a quite distinct interest from that which it possesses for the student and lover of literature. For the historian it is a matter of positive interest to connect Donne's wit with the general disintegration of mediaeval thought, to recognize the influence on the Elizabethan drama of the doctrines of Machiavelli, or to find in Pope's achievement in poetry a counterpart to Walpole's in politics. For the lover of literature none of these facts has any positive interest whatsoever. Donne's wit attracts or repels him equally whatever be its source; Tamburlaine and Iago lose none of their interest for us though we know nothing of Machiavelli; [pg vi] Pope's poetry is not a whit more or less poetical by being a strange by-product of the Whig spirit in English life. For the lover of literature, literary history has an indirect value. He studies history that he may discount it. What he relishes in a poet of the past is exactly the same essential qualities as he enjoys in a poet of his own day—life and passion and art. But between us and every poet or thinker of the past hangs a thinner or thicker veil of outworn fashions and conventions. The same life has clothed itself in different garbs; the same passions have spoken in different images; the same art has adapted itself to different circumstances. To the historian these old clothes are in themselves a subject of interest. His enjoyment of Shakespeare is heightened by finding the explanation of Falstaff's hose, Pistol's hyperboles, and the poet's neglect of the Unities. To the lover of literature they are, until by understanding he can discount them, a disadvantage because they invest the work of the poet with an irrelevant air of strangeness. He studies them that he may grow familiar with them and forget them, that he may clear and intensify his sense of what alone has permanent value, the poet's individuality and the art in which it is expressed.

Donne's conceits, of which so much has been made and on whose historical significance Mr. Courthope has probably said the last word, are just like other examples of these old clothes. The question for literature is not whence they came, but how he used them. Is he a poet in virtue or in spite of them, or both? Are they fit only to be gathered into a museum of antiquated fashions such as Johnson prefixed to his study of the last poet who wore them in quite the old way (for Dryden, who pilfered more freely from Donne than from any of his predecessors, cut them to a new fashion), or are they the individual and still expressive dress of a true and great poet, commanding admiration in their own manner and degree as freshly and enduringly as the stiff and brocaded magnificence of Milton's no less individual, no less artificial style?

Donne's reputation as a poet has passed through many vicissitudes in the course of the last three centuries. With [pg vii] regard to his 'wit', its range and character, erudition and ingenuity, all generations of critics have been at one. It is as to the relation of this 'wit' to, and its effect on, his poetry that they have been at variance. To his contemporaries the 'wit' was identical with the poetry. Donne's 'wit' gave him the same supremacy among poets that learning and humour and art gave to Jonson among dramatists. To certain of his Dutch admirers the wit of The Flea seemed superhuman, and the epitaph with which Carew closes his Elegy expresses the almost universal English opinion of the seventeenth century:

Here lies a king that ruled as he thought fit

The universal monarchy of wit;

Here lies two flamens, and both those the best,

Apollo's first, at last the true God's priest.

It may be doubted if Milton shared this opinion. He never mentions Donne, but it was probably of him or his imitators he was thinking when in his verses at Cambridge he spoke of

those new-fangled toys and trimmings slight

Which take our late fantastics with delight.

Certainly the growing taste for 'correctness' led after the Restoration to a discrimination between Donne's wit and his poetry. 'The greatest wit,' Dryden calls him, 'though not the greatest poet of our nation.' What he wanted as a poet were just the two essentials of 'classical' poetry—smoothness of verse and dignity of expression. This point of view is stated with clearness and piquancy in the sentences of outrageous flattery which Dryden addressed to the Earl of Dorset in the opening paragraphs of his delightful Essay on Satire:

'There is more of salt in all your verses, than I have seen in any of the moderns, or even of the ancients; but you have been sparing of the gall, by which means you have pleased all readers, and offended none. Donne alone, of all our countrymen, had your talent; but was not happy enough to arrive at your versification; and were he translated into numbers, and English, he would yet be wanting in the dignity of expression. That which is the prime virtue, and chief ornament, of Virgil, which distinguishes him from the rest of writers, is so conspicuous [pg viii] in your verses, that it casts a shadow on all your contemporaries; we cannot be seen, or but obscurely, while you are present. You equal Donne in the variety, multiplicity, and choice of thoughts; you excel him in the manner and the words. I read you both with the same admiration, but not with the same delight.

He affects the metaphysics, not only in his satires, but in his amorous verses, where nature only should reign; and perplexes the minds of the fair sex with nice speculations of philosophy, when he should engage their hearts, and entertain them with the softnesses of love. In this (if I may be pardoned for so bold a truth) Mr. Cowley has copied him to a fault; so great a one, in my opinion, that it throws his Mistress infinitely below his Pindarics and his latter compositions, which are undoubtedly the best of his poems and the most correct.'

Dryden's estimate of Donne, as well as his application to his poetry of the epithet 'metaphysical', was transmitted through the eighteenth century. Johnson's famous paragraphs in the Life of Cowley do little more than echo and expand Dryden's pronouncement, with a rather vaguer use of the word 'metaphysical'. In Dryden's application it means correctly 'philosophical'; in Johnson's, no more than 'learned'. 'The metaphysical poets were men of learning, and to show their learning was their whole endeavour; but unluckily resolving to show it in rhyme, instead of writing poetry, they only wrote verses, and very often such verses as stood the trial of the fingers better than of the ear.' They 'drew their conceits from recesses of learning not very much frequented by common readers of poetry'. Waller is exempted from being a metaphysical poet because 'he seldom fetches an amorous sentiment from the depths of science; his thoughts are for the most part easily understood, and his images such as the superficies of nature readily supplies'.

Even to those critics with whom began a revived appreciation of Donne as a poet and preacher, his 'wit' still bulks largely. It is impossible to escape from it. 'Wonder-exciting vigour,' writes Coleridge, 'intenseness and peculiarity, using at will the almost boundless stores of a capacious memory, and exercised on subjects where we have no right [pg ix] to expect it—this is the wit of Donne.' And lastly De Quincey, who alone of these critics recognizes the essential quality which may, and in his best work does, make Donne's wit the instrument of a mind which is not only subtle and ingenious but profoundly poetical: 'Few writers have shown a more extraordinary compass of powers than Donne; for he combined what no other man has ever done—the last sublimation of dialectical subtlety and address with the most impassioned majesty. Massy diamonds compose the very substance of his poem on the Metempsychosis, thoughts and descriptions which have the fervent and gloomy sublimity of Ezekiel or Aeschylus, whilst a diamond dust of rhetorical brilliancies is strewed over the whole of his occasional verses and his prose.'

What is to-day the value and interest of this wit which has arrested the attention of so many generations? How far does it seem to us compatible with poetry in the full and generally accepted sense of the word, with poetry which quickens the imagination and touches the heart, which satisfies and delights, which is the verbal and rhythmical medium whereby a gifted soul communicates to those who have ears to hear the content of impassioned moments?

Before coming to close quarters with this difficult and debated question one may in the first place insist that there is in Donne's verse a great deal which, whether it be poetry in the full sense of the word or not, is arresting and of worth both historically and intrinsically. Whatever we may think of Donne's poetry, it is impossible not to recognize the extraordinary interest of his mind and character. In an age of great and fascinating men he is not the least so. The immortal and transcendent genius of Shakespeare leaves Donne, as every other contemporary, lost in the shadows and cross-lights of an age that is no longer ours, but from which Shakespeare emerges into the clear sunlight. Of Bacon's mind, 'deep and slow, exhausting thought,' and divining as none other the direction in which the road led through the débris of outworn learning to a renovated science and a new philosophy, [pg x] Donne could not boast. Alike in his poetry and in his soberest prose, treatise or sermon, Donne's mind seems to want the high seriousness which comes from a conviction that truth is, and is to be found. A spirit of scepticism and paradox plays through and disturbs almost everything he wrote, except at moments when an intense mood of feeling, whether love or devotion, begets faith, and silences the sceptical and destructive wit by the power of vision rather than of intellectual conviction. Poles apart as the two poets seem at a first glance to lie in feeling and in art, there is yet something of Tennyson in the conflict which wages perpetually in Donne's poetry between feeling and intellect.

But short of the highest gifts of serene imagination or serene wisdom Donne's mind has every power it well could, wit, insight, imagination; and these move in such a strange medium of feeling and learning, mediaeval, renaissance and modern, that every imprint becomes of interest. To do full justice to that interest one's study of Donne must include his prose as well as his verse, his paradoxical Pseudomartyr, and equally paradoxical, more strangely mooded Biathanatos, the intense and subtle eloquence of his sermons, the tormented passion and wit of his devotions, and the gaiety and melancholy, wit and wisdom, of his letters. But most of these qualities have left their mark on his poetry, and given it interests over and above its worth simply as poetry.

One quality of his verse, which has been somewhat overlooked by critics intent upon the definition and sources of metaphysical wit, is wit in our sense of the word, wit like the wit of Swift and Sheridan. The habit in which this wit masquerades is doubtless old-fashioned. It is not always the worse for that, for the wit of the Elizabethans is delightfully blended with fancy and feeling. There is a little of Jaques in all of them. But if fanciful and at times even boyish, Donne's wit is still amusing, the quickest and most fertile wit of the century till we come to the author of Hudibras.

It is not in the Satyres that this wit is to us most obvious. Nothing grows so soon out of date as contemporary satire. [pg xi] Even the brilliance and polish of Pope's satire—and Pope's art is nowhere more perfect than in The Dunciad and the Imitations of Horace—cannot interest us in Lord Hervey, Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, and the forgotten poets of an unpoetic age. How then should we be interested in Elizabeth's fantastic 'Presence', the streets of sixteenth-century London, and the knavery of pursuivants, presented with a satiric art which is wonderfully vivid and caustic but still tentative,—over-emphatic, rough in style and verse, though with a roughness which is obviously a studied and in a measure successful effect. The verses upon Coryats Crudities are in their way a masterpiece of insult veiled as compliment, but it is a rather boyish and barbarous way.

It is in the lighter of his love verses that Donne's laughable wit is most obvious and most agile. Whatever one may think of the choice of subject, and the flame of a young man's lust that burns undisguised in some of the Elegies, it is impossible to ignore the dazzling wit which neither flags nor falters from the first line to the last. And in the more graceful and fanciful, the less heated Songs and Sonets, the same wit, gay and insolent, disports itself in a philosophy of love which must not be taken altogether seriously. Donne at least, as we shall see, outgrew it. His attitude is very much that of Shakespeare in the early comedies. But the Petrarchian love, which Shakespeare treats with light and charming irony, the vows and tears of Romeo and Proteus, Donne openly scoffs. He is one of Shakespeare's young men as these were in the flesh and the Inns of Court, and he tells us frankly what in their youthful cynicism (which is often even more of a pose than their idealism) they think of love, and constancy, and women.

Of all miracles, Donne cries, a constant woman is the greatest, of all strange sights the strangest:

But is it true that we desire to find her? Donne's answer is Woman's Constancy:

Now thou hast lov'd me one whole day,

To-morrow when thou leav'st what wilt thou say?

She will, like Proteus in the Two Gentlemen of Verona, have no dearth of sophistries—but why elaborate them?

Vain lunatique, against these scapes I could

Dispute, and conquer, if I would,

Which I abstaine to doe,

For by to-morrow, I may think so too.

Why ask for constancy when change is the life and law of love?

I can love both fair and brown;

Her whom abundance melts, and her whom want betrays;

Her who loves loneness best, and her who masks and plays.

. . . . . . .

I can love her and her, and you and you,

I can love any so she be not true.

It is not often that the reckless and wilful gaiety of youth masking as cynicism has been expressed with such ebullient wit as in these and companion songs. And when he adopts for a time the pose of the faithful lover bewailing the cruelty of his mistress the sarcastic wit is no less fertile. It would be difficult to find in the language a more sustained succession of witty surprises than The Will. Others were to catch these notes from Donne, and Suckling later flutes them gaily in his lighter fashion, never with the same fullness of wit and fancy, never with the same ardour of passion divinable through the audacious extravagances.

But to amuse was by no means the sole aim of Donne's 'wit'; gay humour touched with fancy and feeling is not its only [pg xiii] quality. Donne's 'wit' has many strands, his humour many moods, and before considering how these are woven together into an effect that is entirely poetical, we may note one or two of the soberer strands which run through his Letters, Epicedes, and similar poems—descriptive, reflective, and complimentary.

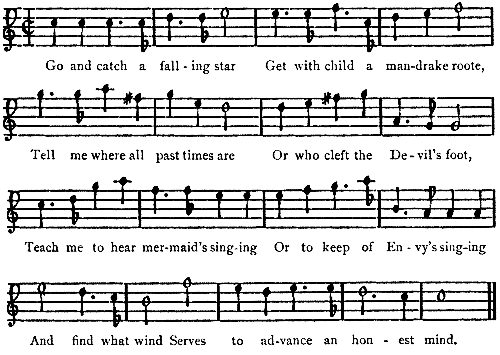

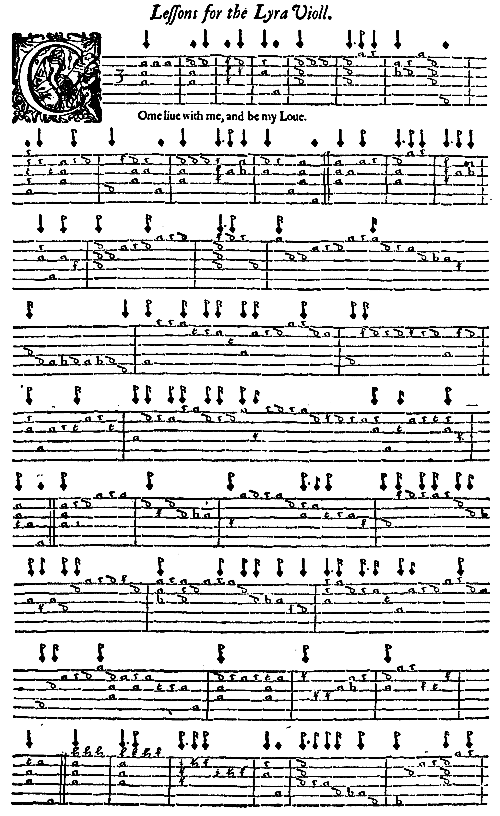

Not much of Donne's poetry is given to description. Of the feeling for nature of the Elizabethans, their pastoral and ideal pictures of meadow and wood and stream, which delighted the heart of Izaak Walton, there is nothing in Donne. A greater contrast than that between Marlowe's Come live with me and Donne's imitation The Baite it would be hard to conceive. But in The Storme and The Calme Donne used his wit to achieve an effect of realism which was something new in English poetry, and was not reproduced till Swift wrote The City Shower. From the first lines, which describe how

The South and West winds join'd, and as they blew,

Waves like a rolling trench before them threw,

to the close of The Storme the noise of the contending elements is deafening:

Thousands our noises were, yet we 'mongst all

Could none by his right name, but thunder call:

Lightning was all our light, and it rain'd more

Than if the Sunne had drunke the sea before.

. . . . . . . . .

Hearing hath deaf'd our sailors, and if they

Knew how to hear, there's none knowes what to say:

Compared to these stormes, death is but a qualme,

Hell somewhat lightsome, and the Bermuda calme.

The sense of tropical heat and calm in the companion poem is hardly less oppressive, and, if the whole is not quite so happy as the first, it contains two lines whose vivid and unexpected felicity is as delightful to-day as when Ben Jonson recited them to Drummond at Hawthornden:

No use of lanthorns; and in one place lay

Feathers and dust, to-day and yesterday.

Donne's letters generally fall into two groups. The first comprises those addressed to his fellow-students at Cambridge and the Inns of Court, the Woodwards, Brookes, and others, or to his maturer and more fashionable companions in the quest of favour and employment at Court, Wotton, and Goodyere, and Lord Herbert of Cherbury. To the other belong the complimentary and elegant epistles in which he delighted and perhaps bewildered his noble lady friends and patronesses with erudite and transcendental flattery.

In the first class, and the same is true of some of the Satyres, notably the third, and of the satirical Progresse of the Soule, especially at the beginning and the end, the reflective, moralizing strain predominates. Donne's 'wit' becomes the instrument of a criticism of life, grave or satiric, melancholy or stoical. Despite Matthew Arnold's definition, verse of this kind seldom is poetry in the full sense of the word; but, as Stevenson says in speaking of his own Scotch verses, talk not song. The first of English poets was a master of the art. Neither Horace nor Martial, whom Stevenson cites, is a more delightful talker in verse than Geoffrey Chaucer, and the archaism of his style seems only to lend the additional charm of a lisp to his babble. Since Donne's day English poetry has been rich in such verse talkers—Butler and Dryden, Pope and Swift, Cowper and Burns, Byron and Shelley, Browning and Landor. It did not come easy to the Elizabethans, whose natural accent was song. Donne's chief rivals were Daniel and Jonson, and I venture to think that he excels them both in the clear and pointed yet easy and conversational development of his thought, in the play of wit and wisdom, and, despite the pedantic cast of Elizabethan erudite moralizing, in the power to leave on the reader the impression of a potent and yet a winning personality. We seem to get nearer to the man himself in Donne's letters to Goodyere and Wotton than in Daniel's weighty, but also heavy, moralizing epistles to the Countess of Cumberland or Sir Thomas Egerton; and the personality whose voice sounds so distinct and human in our ear is a more attractive one than the harsh, censorious, burly [pg xv] but a little blustering Jonson of the epistles on country life and generous givers. Donne's style is less clumsy, his verse less stiff. His wit brings to a clear point whatever he has to say, while from his verse as from his prose letters there disengages itself a very distinct sense of what it was in the man, underlying his brilliant intellect, his almost superhuman cleverness, which won for him the devotion of friends like Wotton and Goodyere and Walton and King, the admiration of a stranger like Huyghens, who heard him talk as well as preach:—a serious and melancholy, a generous and chivalrous spirit.

However, keepe the lively tast you hold

Of God, love him as now, but feare him more,

And in your afternoones thinke what you told

And promis'd him, at morning prayer before.

Let falshood like a discord anger you,

Else be not froward. But why doe I touch

Things, of which none is in your practise new,

And Tables, or fruit-trenchers teach as much;

But thus I make you keepe your promise Sir,

Riding I had you, though you still staid there,

And in these thoughts, although you never stirre,

You came with mee to Micham, and are here.

So he writes to Goodyere, but the letter to Wotton going Ambassador to Venice is Donne's masterpiece in this simpler style, and it seems to me that neither Daniel nor Jonson nor Drayton ever catches this note at once sensitive and courtly. To find a like courtliness we must go to Wotton; witness the reply to Donne's earlier epistle which I have printed in the notes. But neither Wotton nor any other of the courtly poets in Hannah's collection adds to this dignity so poignant a personal accent.

This personal interest is very marked in the two satires which are connected by tone and temper with the letters, the third of the early, classical Satyres and the opening and closing stanzas of the Progresse of the Soule. Each is a vivid picture of the inner workings of Donne's soul at a critical period in his life. The first was doubtless written at the moment that he was passing from the Roman to the Anglican Church. It is one [pg xvi] of the earliest and most thoughtful appeals for toleration, for the candid scrutiny of religious differences, which was written perhaps in any country—one of the most striking symptoms of the new eddies produced in the stream of religious feeling by the meeting currents of the Reformation and the Counter-Reformation.

It was a difficult and dangerous process through which Donne was passing, this conversion from the Church of his fathers to conformity with the Church of England as by law established. It would be as absurd, in the face of a poem like this and of all that we know of Donne's subsequent life, to call it a conversion in the full sense of the term, a changed conviction, as to dub it an apostasy prompted by purely political considerations. Yet doubtless the latter predominated. The position of a Catholic in the reign of Elizabeth was that of a man cut off rigorously from the main life of the nation, with every avenue of honourable ambition closed to him. He had to live the starved, suspected life of a recusant or to seek service under a foreign power. Some of the most pathetic documents in Strype's Annals of the Reformation are those in which we hear the cry of young men of secure station and means driven by conscientious conviction to abandon home and country. It is possible that before 1592 Donne himself had been sent abroad by relatives with a view to his entering a seminary or the service of a foreign power. His mother spent a great part of her life abroad, and his own relatives were among those who suffered most severely under Walsingham's persecution. 'I had', Donne says, 'my first breeding and conversation with men of suppressed and afflicted Religion, accustomed to the despite of death, and hungry of an imagined Martyrdome.' To a young man of ambition, and as yet certainly with no bent to devotion or martyrdom, it was only common sense to conform if he might.

From this dilemma Donne escaped, not by any opportune change of conviction, or by any insincere profession, but by the way of intellectual emancipation. He looks round in this satire and sees that whichever be the true Church it is not by [pg xvii] any painful quest of truth, and through the attainment of conviction, that most people have accepted the Church to which they may belong. Circumstances and whim have had more to do with their choice than reason and serious conviction. Yet it is only by search that truth is to be found:

On a huge hill

Cragged, and steep, Truth stands, and hee that will

Reach her, about must, and about must goe;

And what the hills suddenes resists win so.

Yet strive so, that before age, deaths twilight,

Thy Soule rest, for none can work in that night.

It was not often in the sixteenth or seventeenth century that a completely emancipated and critical attitude on religious, not philosophical, questions was expressed with such entire frankness and seriousness. From this position, Walton would have us believe, Donne advanced through the study of Bellarmine and other controversialists to a convinced acceptance of Anglican doctrine. The evidence points to a rather different conclusion on Donne's part. He came to think that all the Churches were 'virtual beams of one sun', 'connatural pieces of one circle', a position from which the next step was to the conclusion that for an Englishman the Anglican Church was the right choice (Cujus regio, ejus religio); but Donne had not reached this conclusion when he wrote the Satyre, and doubtless did not till he had satisfied himself that the Church of England offered a reasonable via media. But changes of creed made on purely intellectual grounds, and prompted by practical motives, are not unattended with danger to a man's moral and spiritual life. Donne had doubtless outwardly conformed before he entered Egerton's service in 1598, but long afterwards, when he is already in Orders, he utters a cry which betrays how real the dilemma still was:

Show me, deare Christ, thy spouse, so bright and clear;

and the first result of his 'conversion' was apparently to deepen the sceptical vein in his mind.

Scepticism and melancholy, bitter and sardonic, are certainly [pg xviii] the dominant notes in the sombre fragment of satire The Progresse of the Soule, which he composed in 1601, when he was Sir Thomas Egerton's secretary, four months before his marriage and six months after the death of the Earl of Essex. There can be little doubt, as I have ventured to suggest elsewhere, that it was the latter event which provoked this strange and sombre explosion of spleen, a satire of the same order as the Tale of a Tub or the Vision of Judgment. The account of the poem which Jonson gave to Drummond does not seem to be quite accurate, though it was probably derived from Donne himself. It was, one suspects from several circumstances, a little Donne's way in later years to disguise the footprints of his earlier indiscretions. According to this tradition the final habitat of the soul which 'inanimated' the apple

Whose mortal taste

Brought death into the world and all our woe,

was to be John Calvin. The tradition is interesting as marking how far Donne was in 1601 from his later orthodox Protestantism, for Calvin is never mentioned but with respect in the Sermons. A few months later he wrote to Egerton disclaiming warmly all 'love of a corrupt religion'. But, though sceptical in tone, the poem is written from a Catholic standpoint; its theme is the progress of the soul of heresy. And, as the seventh stanza clearly indicates, the great heretic in whom the line closed was to be not Calvin but Queen Elizabeth:

the great soule which here among us now

Doth dwell, and moves that hand, and tongue, and brow

Which, as the Moone the sea, moves us.

Donne can hardly have thought of publishing such a poem, or circulating it in the Queen's lifetime. It was an expression of the mood which begot the 'black and envious slanders breath'd against Diana for her divine justice on Actaeon' to which Jonson refers in Cynthia's Revels the same year. That some copies were circulated in manuscript later is probably due to the reaction which brought into favour at James's [pg xix] Court the Earl of Southampton and the former adherents of Essex generally.

The tone, moreover, of the stanza quoted above suggests that it was no vulgar libel on Elizabeth which Donne contemplated. Elizabeth, the cruel persecutor of his Catholic kinsfolk, now stained with the blood of her favourite, appeared to him somewhat as she did to Pope Sixtus, a heretic but a great woman. He felt to her as Burke did to the 'whole race of Guises, Condés and Colignis'—'the hand that like a destroying angel smote the country communicated to it the force and energy under which it suffered.' In a mood of bitter admiration, of sceptical and sardonic wonder, he contemplates the great bad souls who had troubled the world and served it too, for the idea on which the poem was to rest is the disconcerting reflection that we owe many good things to heretics and bad men:

Who ere thou beest that read'st this sullen Writ,

Which just so much courts thee, as thou dost it,

Let me arrest thy thoughts; wonder with mee,

Why plowing, building, ruling and the rest,

Or most of those arts, whence our lives are blest,

By cursed Cains race invented be,

And blest Seth vext us with Astronomie.

Ther's nothing simply good, nor ill alone,

Of every quality comparison,

The onely measure is, and judge, opinion.

It would have been interesting to read Donne's history of the great souls that troubled and yet quickened the world from Cain to Arius and from Mahomet to Elizabeth, but unfortunately Donne never got beyond the introduction, a couple of cantos which describe the progress of the soul while it is still passing through the vegetable and animal planes, the motive of which, so far as it can be disentangled, is to describe the pre-human education of a woman's soul:

keeping some quality

Of every past shape, she knew treachery,

Rapine, deceit, and lust, and ills enow

To be a woman.

The fragment has some of the sombre power which De Quincey attributes to it, but on the whole one must confess it is a failure. The 'wit' of Donne did not apparently include invention, for many of the episodes seem pointless as well as disgusting, and indeed in no poem is the least attractive side of Donne's mind so clearly revealed, that aspect of his wit which to some readers is more repellent, more fatal to his claim to be a poet, than too subtle ingenuity or misplaced erudition—the vein of sheer ugliness which runs through his work, presenting details that seem merely and wantonly repulsive. The same vein is apparent in the work of Chapman, of Jonson, and even in places of Spenser, and the imagery of Hamlet and the tragedies owes some of its dramatic vividness and power to the same quality. The ugly has its place in art, and it would not be difficult to find it in every phase of Renaissance art, marked like the beautiful in that art by the same evidence of power. Decadence brought with it not ugliness but prettiness.

The reflective, philosophic, somewhat melancholy strain of the poems I have been touching on reappears in the letters addressed to noble ladies. Here, however, it is softened, less sardonic in tone, while it blends with or gives place to another strain, that of absurd and extravagant but fanciful and subtle compliment. Donne cannot write to a lady without his heart and fancy taking wing in their own passionate and erudite fashion. Scholastic theology is made the instrument of courtly compliment and pious flirtation. He blends in the same disturbing fashion as in some of the songs and elegies that depreciation of woman in general, which he owes less to classical poetry than to his over-acquaintance with the Fathers, with an adoration of her charms in the individual which passes into the transcendental. He tells the Countess of Huntingdon that active goodness in a woman is a miracle; but it is clear that she and the Countess of Bedford and Mrs. Herbert and Lady Carey and the Countess of Salisbury are all examples of such miracle—ladies whose beauty itself is virtue, while their virtues are a mystery revealable only to the initiated.

The highest place is held by Lady Bedford and Mrs. Herbert. [pg xxi] Nothing could surpass the strain of intellectual and etherealized compliment in which he addresses the Countess. If lines like the following are not pure poetry, they haunt some quaint borderland of poetry to which the polished felicities of Pope's compliments are a stranger. If not pure fancy, they are not mere ingenuity, being too intellectual and argumentative for the one, too winged and ardent for the other:

Should I say I liv'd darker then were true,

Your radiation can all clouds subdue;

But one, 'tis best light to contemplate you.

You, for whose body God made better clay,

Or tooke Soules stuffe such as shall late decay,

Or such as needs small change at the last day.

This, as an Amber drop enwraps a Bee,

Covering discovers your quicke Soule; that we

May in your through-shine front your hearts thoughts see.

You teach (though wee learne not) a thing unknowne

To our late times, the use of specular stone,

Through which all things within without were shown.

Of such were Temples; so and such you are;

Beeing and seeming is your equall care,

And vertues whole summe is but know and dare.

The long poem dedicated to the same lady's beauty,

You have refin'd me

is in a like dazzling and subtle vein. Those addressed to Mrs. Herbert, notably the letter

Mad paper stay,

and the beautiful Elegie

No Spring, nor Summer Beauty hath such grace

As I have seen in one Autumnall face,

are less transcendental in tone but bespeak an even warmer admiration. Indeed it is clear to any careful reader that in the poems addressed to both these ladies there is blended with the respectful flattery of the dependant not a little of the tone of warmer feeling permitted to the 'servant' by Troubadour [pg xxii] convention. And I suspect that some poems, the tone of which is still more frankly and ardently lover-like, were addressed to Lady Bedford and Mrs. Herbert, though they have come to us without positive indication.

The title of the subtle, passionate, sonorous lyric Twicknam Garden,

Blasted with sighs, and surrounded with teares,

points to the person addressed, for Twickenham Park was the residence of Lady Bedford from 1607 to 1618, and Donne's intimacy with her seems to have begun in or about 1608. There can, I think, be little doubt that it is to her, and neither to his wife nor the mistresses of his earlier, wandering fancy, that these lines, conventional in theme but given an amazing timbre by the impulse of Donne's subtle and passionate mind, were addressed. But if Twicknam Garden was written to Lady Bedford, so also, one is tempted to think, must have been A Nocturnall upon S. Lucies Day, for Lucy was the Countess's name, and the thought, feeling, and rhythm of the two poems are strikingly similar.

But the Nocturnall is a sincerer and profounder poem than Twicknam Garden, and it is more difficult to imagine it the expression of a conventional sentiment. Mr. Gosse, and there is no higher authority when it comes to the interpretation of Donne's character and mind, rightly, I think, suggests that the death of the lady addressed is assumed, not actual, but he connects the poem with Donne's earlier and troubled loves. 'So also in a most curious ode, the Nocturnal ..., amid fireworks of conceit, he calls his mistress dead and protests that his hatred has grown cold at last.' But I can find no note of bitterness, active or spent, in the song. It might have been written to Ann More. It is a highly metaphysical yet sombre and sincere description of the emptiness of life without love. The critics have, I think, failed somewhat to reckon with this stratum in Donne's songs, of poems Petrarchian in convention but with a Petrarchianism coloured by Donne's realistic temper and impatient wit. Any interpretation of so [pg xxiii] enigmatical a poem must be conjectural, but before one denied too positively that its subject was Lady Bedford—perhaps her illness in 1612—one would need to answer two questions, how far could a conventional passion inspire a strain so sincere, and what was Donne's feeling for Lady Bedford and hers for him?

Poetry is the language of passion, but the passion which moves the poet most constantly is the delight of making poetry, and very little is sufficient to quicken the imagination to its congenial task. Our soberer minds are apt to think that there must be an actual, particular experience behind every sincere poem. But history refutes the idea of such a simple relation between experience and art. No poet will sing of love convincingly who has never loved, but that experience will suffice him for many and diverse webs of song and drama. Without pursuing the theme, it is sufficient for the moment to recall that in the fashion of the day Spenser's sonnets were addressed to Lady Carey, not to his wife; that it was to Idea or to Anne Goodere that Drayton wrote so passionate a poem as

Since there's no help, come let us kiss and part;

and that we know very little of what really lies behind Shakespeare's profound and plangent sonnets, weave what web of fancy we will.

Of Lady Bedford's feeling for Donne we know only what his letters reveal, and that is no more than that she was his warm friend and generous patroness. It is clear, however, from their enduring friendship and from the tone of that correspondence that she found in him a friend of a rarer and finer calibre than in the other poets whom she patronized in turn, Daniel and Drayton and Jonson—some one whose sensitive, complex, fascinating personality could hardly fail to touch a woman's imagination and heart. Friendship between man and woman is love in some degree. There is no need to exaggerate the situation, or to reflect on either her loyalty or his to other claims, to recognize that their mutual feeling was of the kind for which the Petrarchian convention afforded a ready and recognized vehicle of expression.

And so it was, one fancies, with Mrs. Herbert. She too found in Donne a rare and comprehending spirit, and he in her a gracious and delicate friend. His relation to her, indeed, was probably simpler than to Lady Bedford, their friendship more equal. The letter and the elegy referred to already are instinct with affection and tender reverence. To her Donne sent some of his earliest religious sonnets, with a sonnet on her beautiful name. And to her also it would seem that at some period in the history of their friendship, the beginning of which is very difficult to date, he wrote songs in the tone of hopeless, impatient passion, of Petrarch writing to Laura, and others which celebrate their mutual affection as a love that rose superior to earthly and physical passion. The clue here is the title prefixed to that strange poem The Primrose, being at Montgomery Castle upon the hill on which it is situate. It is true that the title is found for the first time in the edition of 1635 and is in none of the manuscripts. But it is easier to explain the occasional suppression of a revealing title than to conceive a motive for inventing such a gloss. The poem is doubtless, as Mr. Gosse says, 'a mystical celebration of the beauty, dignity and intelligence of Magdalen Herbert'—a celebration, however, which takes the form (as it might with Petrarch) of a reproach, a reproach which Donne's passionate temper and caustic wit seem even to touch with scorn. He appears to hint to Mrs. Herbert that to wish to be more than a woman, to claim worship in place of love, is to be a worse monster than a coquette:

Since there must reside

Falshood in woman, I could more abide

She were by Art, than Nature falsifi'd.

Woman needs no advantages to arbitrate the fate of man.

In exactly the same mood as The Primrose is The Blossome, possibly written in the same place and on the same day, for the poet is preparing to return to London. The Dampe is in an even more scornful tone, and one hesitates to connect it with Mrs. Herbert. But all these poems recur so repeatedly together in the manuscripts as to suggest that they have a common origin. [pg xxv] And with them go the beautiful poems The Funerall and The Relique. In the former the cruelty of the lady has killed her lover, but in the second the tone changes entirely, the relation between Donne and Mrs. Herbert (note the lines

Thou shalt be a Mary Magdalen and I

A something else thereby)

has ceased to be Petrarchian and become Platonic, their love a thing pure and of the spirit, but none the less passionate for that:

First, we lov'd well and faithfully,

Yet knew not what wee lov'd, nor why,

Difference of sex no more wee knew,

Then our Guardian Angells doe;

Comming and going, wee

Perchance might kisse, but not between those meales;

Our hands ne'r toucht the seales,

Which nature, injur'd by late law, sets free:

These miracles wee did; but now alas,

All measure, and all language, I should passe,

Should I tell what a miracle shee was.

Such were the notes that a poet in the seventeenth century might still sing to a high-born lady his patroness and his friend. No one who knows the fashion of the day will read into them more than they were intended to convey. No one who knows human nature will read them as merely frigid and conventional compliments. Any uncertainty one may feel about the subject arises not from their being love-poems, but from the difficulty which Donne has in adjusting himself to the Petrarchian convention, the tendency of his passionate heart and satiric wit to break through the prescribed tone of worship and complaint.

Without some touch of passion, some vibration of the heart, Donne is only too apt to accumulate 'monstrous and disgusting hyperboles'. This is very obvious in the Epicedes—his complimentary laments for the young Lord Harington, Miss Boulstred, Lady Markham, Elizabeth Drury and the Marquis of Hamilton, poems in which it is difficult to find a line that moves. Indeed, seventeenth-century elegies are not as a rule [pg xxvi] pathetic. A poem in the simple, piercing strain and the Wordsworthian plainness of style of the Dutch poet Vondel's lament for his little daughter is hardly to be found in English. An occasional epitaph like Browne's

May! be thou never grac'd with birds that sing,

Nor Flora's pride!

In thee all flowers and roses spring,

Mine only died,

comes near it, but in general seventeenth-century elegy is apt to spend itself on three not easily reconcilable themes—extravagant eulogy of the dead, which is the characteristically Renaissance strain, the Mediaeval meditation on death and its horrors, the more simply Christian mood of hope rising at times to the rapt vision of a higher life. In the pastoral elegy, such as Lycidas, the poet was able to escape from a too literal treatment of the first into a sequence of charming conventions. The second was alien to Milton's thought, and with his genius for turning everything to beauty Milton extracts from the reference to the circumstances of King's death the only touch of pathos in the poem:

Ay me! whilst thee the shores and sounding Seas

Wash far away, where ere thy bones are hurld,

and some of his loveliest allusions:

Where the great vision of the guarded Mount

Looks towards Namancos and Bayona's hold;

Look homeward Angel now, and melt with ruth.

And, O ye Dolphins, waft the hapless youth.

In the metaphysical elegy as cultivated by Donne, Beaumont, and others there was no escape from extravagant eulogy and sorrow by way of pastoral convention and mythological embroidery, and this class of poetry includes some of the worst verses ever written. In Donne all three of the strains referred to are present, but only in the third does he achieve what can be truly called poetry. In the elegies on Lord Harington and Miss Boulstred and Lady Markham it is difficult to say which is more repellent—the images in which the poet [pg xxvii] sets forth the vanity of human life and the humiliations of death or the frigid and blasphemous hyperboles in which the virtues of the dead are eulogized.

Even the Second Anniversary, the greatest of Donne's epicedes, is marred throughout by these faults. There is no stranger poem in the English language in its combination of excellences and faults, splendid audacities and execrable extravagances. 'Fervour of inspiration, depth and force and glow of thought and emotion and expression'—it has something of all these high qualities which Swinburne claimed; but the fervour is in great part misdirected, the emotion only half sincere, the thought more subtle than profound, the expression heated indeed but with a heat which only in passages kindles to the glow of poetry.

Such are the passages in which the poet contemplates the joys of heaven. There is nothing more instinct with beautiful feeling in Lycidas than some of the lines of Apocalyptic imagery at the close:

There entertain him all the Saints above,

In solemn troops, and sweet Societies

That sing, and singing in their glory move,

And wipe the tears for ever from his eyes.

But in spiritual sense, in passionate awareness of the transcendent, there are lines in Donne's poem that seem to me superior to anything in Milton if not in purity of Christian feeling, yet in the passionate, mystical sense of the infinite as something other than the finite, something which no suggestion of illimitable extent and superhuman power can ever in any degree communicate.

Think then my soule that death is but a Groome,

Which brings a Taper to the outward roome,

Whence thou spiest first a little glimmering light,

And after brings it nearer to thy sight:

For such approaches does heaven make in death.

. . . . . . .

Up, up my drowsie Soule, where thy new eare

Shall in the Angels songs no discord heere, &c.

In passages like these there is an earnest of the highest note of [pg xxviii] spiritual eloquence that Donne was to attain to in his sermons and last hymns.

Another aspect of Donne's poetry in the Anniversaries, of his contemptus mundi and ecstatic vision, connects them more closely with Tennyson's In Memoriam than Milton's Lycidas. Like Tennyson, Donne is much concerned with the progress of science, the revolution which was going on in men's knowledge of the universe, and its disintegrating effect on accepted beliefs. To him the new astronomy is as bewildering in its displacement of the earth and disturbance of a concentric universe as the new geology was to be to Tennyson with the vistas which it opened into the infinities of time, the origin and the destiny of man:

The new philosophy calls all in doubt,

The Element of fire is quite put out;

The Sun is lost, and th' earth, and no mans wit

Can well direct him where to look for it.

And freely men confesse that this world's spent,

When in the Planets, and the Firmament

They seeke so many new; they see that this

Is crumbled out againe to his Atomies.

On Tennyson the effect of a similar dislocation of thought, the revelation of a Nature which seemed to bring to death and bring to life through endless ages, careless alike of individual and type, was religious doubt tending to despair:

O life as futile, then, as frail!

. . . . .

What hope of answer, or redress?

Behind the veil, behind the veil.

On Donne the effect was quite the opposite. It was not of religion he doubted but of science, of human knowledge with its uncertainties, its shifting theories, its concern about the unimportant:

Poore soule, in this thy flesh what dost thou know?

Thou know'st thy selfe so little, as thou know'st not,

How thou didst die, nor how thou wast begot.

. . . . . . . . .

Have not all soules thought

For many ages, that our body is wrought

[pg xxix]Of Ayre, and Fire, and other Elements?

And now they thinke of new ingredients;

And one Soule thinkes one, and another way

Another thinkes, and 'tis an even lay.

. . . . . . . . .

Wee see in Authors, too stiffe to recant,

A hundred controversies of an Ant;

And yet one watches, starves, freeses, and sweats,

To know but Catechismes and Alphabets

Of unconcerning things, matters of fact;

How others on our stage their parts did Act;

What Cæsar did, yea, and what Cicero said.

With this welter of shifting theories and worthless facts he contrasts the vision of which religious faith is the earnest here:

In this low forme, poore soule, what wilt thou doe?

When wilt thou shake off this Pedantery,

Of being taught by sense, and Fantasie?

Thou look'st through spectacles; small things seeme great

Below; But up unto the watch-towre get,

And see all things despoyl'd of fallacies:

Thou shalt not peepe through lattices of eyes,

Nor heare through Labyrinths of eares, nor learne

By circuit, or collections, to discerne.

In heaven thou straight know'st all concerning it,

And what concernes it not, shalt straight forget.

It will seem to some readers hardly fair to compare a poem like In Memoriam, which, if in places the staple of its feeling and thought wears a little thin, is entirely serious throughout, with poems which have so much the character of an intellectual tour de force as Donne's Anniversaries, but it is easy to be unjust to the sincerity of Donne in these poems. Their extravagant eulogy did not argue any insincerity to Sir Robert and Lady Drury. It was in the manner of the time, and doubtless seemed to them as natural an expression of grief as the elaborate marble and alabaster tomb which they erected to the memory of their daughter. The Second Anniversarie was written in France when Donne was resident there with the Drurys. And it was on this occasion that Donne had the vision of his absent wife which Walton has related so graphically. [pg xxx] The spiritual sense in Donne was as real a thing as the restless and unruly wit, or the sensual, passionate temperament. The main thesis of the poem, the comparative worthlessness of this life, the transcendence of the spiritual, was as sincere in Donne's case as was in Tennyson the conviction of the futility of life if death closes all. It was to be the theme of the finest passages in his eloquent sermons, the burden of all that is most truly religious in the verse and prose of a passionate, intellectual, self-tormenting soul to whom the pure ecstasy of love of a Vondel, the tender raptures of a Crashaw, the chastened piety of a Herbert, the mystical perceptions of a Vaughan could never be quite congenial.

I have dwelt at some length on those aspects of Donne's 'wit' which are of interest and value even to a reader who may feel doubtful as to the beauty and interest of his poetry as such, because they too have been obscured by the criticism which with Dr. Johnson and Mr. Courthope represents his wit as a monster of misapplied ingenuity, his interest as historical and historical only. Apart from poetry there is in Donne's 'wit' a great deal that is still fresh and vivid, wit as we understand wit; satire pungent and vivid; reflection on religion and on life, rugged at times in form but never really unmusical as Jonson's verse is unmusical, and, despite frequent carelessness, singularly lucid and felicitous in expression; elegant compliment, extravagant and grotesque at times but often subtle and piquant; and in the Anniversaries, amid much that is both puerile and extravagant, a loftier strain of impassioned reflection and vision. It is not of course that these things are not, or may not be constituents of poetry, made poetic by their handling. To me it seems that in Donne they generally are. It is the poet in Donne which flavours them all, touching his wit with fancy, his reflection with imagination, his vision with passion. But if we wish to estimate the poet simply in Donne, we must examine his love-poetry and his religious poetry. It is here that every one who cares for his unique and arresting genius will admit that he must stand or fall as a great poet.

For it is here that we find the full effect of what De Quincey points to as Donne's peculiarity, the combination of dialectical subtlety with weight and force of passion. Objections to admit the poetic worth and interest of Donne's love-poetry come from two sides—from those who are indisposed to admit that passion, and especially the passion of love, can ever speak so ingeniously (this was the eighteenth-century criticism); and from those, and these are his more modern critics, who deny that Donne is a great poet because with rare exceptions, exceptions rather of occasional lines and phrases than of whole poems, his songs and elegies lack beauty. Can poetry be at once passionate and ingenious, sincere in feeling and witty,—packed with thought, and that subtle and abstract thought, Scholastic dialectic? Can love-poetry speak a language which is impassioned and expressive but lacks beauty, is quite different from the language of Dante and Petrarch, the loveliest language that lovers ever spoke, or the picturesque hyperboles of Romeo and Juliet? Must not the imagery and the cadences of love poetry reflect 'l'infinita, ineffabile bellezza' which is its inspiration?

The first criticism is put very clearly by Steele, who goes so far as to exemplify what the style of love-poetry should be; and certainly it is something entirely different from that of The Extasie or the Nocturnall upon S. Lucies Day. Nothing could illustrate better the 'return to nature' of our Augustan literature than Steele's words:

'I will suppose an author to be really possessed with the passion which he writes upon and then we shall see how he would acquit himself. This I take to be the safest way to form a judgement upon him: since if he be not truly moved, he must at least work up his imagination as near as possible to resemble reality. I choose to instance in love, which is observed to have produced the most finished performances in this kind. A lover will be full of sincerity, that he may be believed by his mistress; he will therefore think simply; he will express himself perspicuously, that he may not perplex her; he will therefore write unaffectedly. Deep reflections are made by a head undisturbed; and points of wit and fancy are the [pg xxxii] work of a heart at ease; these two dangers then into which poets are apt to run, are effectually removed out of the lover's way. The selecting proper circumstances, and placing them in agreeable lights, are the finest secrets of all poetry; but the recollection of little circumstances is the lover's sole meditation, and relating them pleasantly, the business of his life. Accordingly we find that the most celebrated authors of this rank excel in love-verses. Out of ten thousand instances I shall name one which I think the most delicate and tender I ever saw.

To myself I sigh often, without knowing why;

And when absent from Phyllis methinks I could die.

A man who hath ever been in love will be touched by the reading of these lines; and everyone who now feels that passion, actually feels that they are true.'

It is not possible to find so distinct a statement of the other view to which I have referred, but I could imagine it coming from Mr. Robert Bridges, or (since I have no authority to quote Mr. Bridges in this connexion) from an admirer of his beautiful poetry. Mr. Bridges' love-poetry is far indeed from the vapid naturalness which Steele commended in The Guardian. It is as instinct with thought, and subtle thought, as Donne's own poetry; but the final effect of his poetry is beauty, emotion recollected in tranquillity, and recollected especially in order to fix its delicate beauty in appropriate and musical words:

Awake, my heart, to be loved, awake, awake!

The darkness silvers away, the morn doth break,

It leaps in the sky: unrisen lustres slake

The o'ertaken moon. Awake, O heart, awake!

She too that loveth awaketh and hopes for thee;

Her eyes already have sped the shades that flee,

Already they watch the path thy feet shall take:

Awake, O heart, to be loved, awake, awake!

And if thou tarry from her,—if this could be,—

She cometh herself, O heart, to be loved, to thee;

For thee would unashamed herself forsake:

Awake to be loved, my heart, awake, awake!

[pg xxxiii]Awake, the land is scattered with light, and see,

Uncanopied sleep is flying from field and tree:

And blossoming boughs of April in laughter shake;

Awake, O heart, to be loved, awake, awake!

Lo all things wake and tarry and look for thee:

She looketh and saith, 'O sun, now bring him to me.

Come more adored, O adored, for his coming's sake,

And awake my heart to be loved: awake, awake!'

Donne has written nothing at once so subtle and so pure and lovely as this, nothing the end and aim of which is so entirely to leave an untroubled impression of beauty.

But it is not true either that the thought and imagery of love-poetry must be of the simple, obvious kind which Steele supposes, that any display of dialectical subtlety, any scintillation of wit, must be fatal to the impression of sincerity and feeling, or on the other hand that love is always a beautiful emotion naturally expressing itself in delicate and beautiful language. To some natures love comes as above all things a force quickening the mind, intensifying its purely intellectual energy, opening new vistas of thought abstract and subtle, making the soul 'intensely, wondrously alive'. Of such were Donne and Browning. A love-poem like 'Come into the garden, Maud' suspends thought and fills the mind with a succession of picturesque and voluptuous images in harmony with the dominant mood. A poem such as The Anniversarie or The Extasie, The Last Ride Together or Too Late, is a record of intense, rapid thinking, expressed in the simplest, most appropriate language—and it is a no whit less natural utterance of passion. Even the abstractness of the thought, on which Mr. Courthope lays so much stress in speaking of Donne and the 'metaphysicals' generally, is no necessary implication of want of feeling. It has been said of St. Augustine 'that his most profound thoughts regarding the first and last things arose out of prayer ... concentration of his whole being in prayer led to the most abstract observation'. So it may be with love-poetry—so it was with Dante in the Vita Nuova, and so, on a lower scale, and allowing for the time that the passion [pg xxxiv] is a more earthly and sensual one, the thought more capricious and unruly, with Donne. The Nocturnall upon S. Lucies Day is not less passionate because that passion finds expression in abstract and subtle thought. Nor is it true that all love-poetry is beautiful. Of none of the four poems I have mentioned in the last paragraph is pure beauty, beauty such as is the note of Mr. Bridges' song, the distinctive quality. It is rather vivid realism:

And alive I shall keep and long, you will see!

I knew a man, was kicked like a dog

From gutter to cesspool; what cared he

So long as he picked from the filth his prog?

He saw youth, beauty and genius die,

And jollily lived to his hundredth year.

But I will live otherwise: none of such life!

At once I begin as I mean to end.

But this sacrifice of beauty to dramatic vividness is a characteristic of passionate poetry. Beauty is not precisely the quality we should predicate of the burning lines of Sappho translated by Catullus:

lingua sed torpet, tenuis sub artus

flamma demanat, sonitu suopte

tintinant aures geminae, teguntur

lumina nocte.

Beauty is the quality of poetry which records an ideal passion recollected in tranquillity, rather than of poetry either dramatic or lyric which utters the very movement and moment of passion itself.

Donne's love-poetry is a very complex phenomenon, but the two dominant strains in it are just these: the strain of dialectic, subtle play of argument and wit, erudite and fantastic; and the strain of vivid realism, the record of a passion which is not ideal nor conventional, neither recollected in tranquillity nor a pure product of literary fashion, but love as an actual, immediate experience in all its moods, gay and angry, scornful and rapturous with joy, touched with tenderness and darkened with sorrow—though these last two moods, the commonest in love-poetry, [pg xxxv] are with Donne the rarest. The first of these strains comes to Donne from the Middle Ages, the dialectic of the Schools, which passed into mediaeval love-poetry almost from its inception; the second is the expression of the new temper of the Renaissance as Donne had assimilated it in Latin countries. Donne uses the method, the dialectic of the mediaeval love-poets, the poets of the dolce stil nuovo, Guinicelli, Cavalcanti, Dante, and their successors, the intellectual, argumentative evolution of their canzoni, but he uses it to express a temper of mind and a conception of love which are at the opposite pole from their lofty idealism. The result, however, is not so entirely disintegrating as Mr. Courthope seems to think: 'This fine Platonic edifice is ruthlessly demolished in the poetry of Donne. To him love, in its infinite variety and inconsistency, represented the principle of perpetual flux in nature.'1 The truth is rather that, owing to the fullness of Donne's experience as a lover, the accident that made of the earlier libertine a devoted lover and husband, and from the play of his restless and subtle mind on the phenomenon of love conceived and realized in this less ideal fashion, there emerged in his poetry the suggestion of a new philosophy of love which, if less transcendental than that of Dante, rests on a juster, because a less dualistic and ascetic, conception of the nature of the love of man and woman.

The fundamental weakness of the mediaeval doctrine of love, despite its refining influence and its exaltation of woman, was that it proved unable to justify love ethically against the claims of the counter-ideal of asceticism. Taking its rise in a relationship which excluded the thought of marriage as the end and justification of love, which presumed in theory that the relation of the 'servant' to his lady must always be one of reverent and unrewarded service, this poetry found itself involved from the beginning in a dualism from which there was no escape. On the one hand the love of woman is the great ennobler of the [pg xxxvi] human heart, the influence which elicits its latent virtue as the sun converts clay to gold and precious stones. On the other hand, love is a passion which in the end is to be repented of in sackcloth and ashes. Lancelot is the knight whom love has made perfect in all the virtues of manhood and chivalry; but the vision of the Holy Grail is not for him, but for the virgin and stainless Sir Galahad.

In the high philosophy of the Tuscan poets of the 'sweet new style' that dualism was apparently transcended, but it was by making love identical with religion, by emptying it of earthly passion, making woman an Angel, a pure Intelligence, love of whom is the first awakening of the love of God. 'For Dante and the poets of the learned school love and virtue were one and the same thing; love was religion, the lady beloved the way to heaven, symbol of philosophy and finally of theology.'2 The culminating moment in Dante's love for Beatrice arrives when he has overcome even the desire that she should return his salutation and he finds his full beatitude in 'those words that do praise my lady'. The love that begins in the Vita Nuova is completed in the Paradiso.

The dualism thus in appearance transcended by Dante reappears sharply and distinctly in Petrarch. 'Petrarch', says Gaspary, 'adores not the idea but the person of his lady; he feels that in his affections there is an earthly element, he cannot separate it from the desire of the senses; this is the earthly tegument which draws us down. If not as, according to the ascetic doctrine, sin, if he could not be ashamed of his passion, yet he could repent of it as a vain and frivolous thing, regret his wasted hopes and griefs.'3 Laura is for Petrarch the flower of all perfection herself and the source of every virtue in her lover. Yet his love for Laura is a long and weary aberration of the soul from her true goal, which is the love of God. This is the contradiction from which flow some of the most lyrical [pg xxxvii] strains in Petrarch's poetry, as the fine canzone 'I'vo pensando', where he cries:

E sento ad ora ad or venirmi in core

Un leggiadro disdegno, aspro e severo,

Ch'ogni occulto pensero

Tira in mezzo la fronte, ov' altri 'l vede;

Che mortal cosa amar con tanta fede,

Quanta a Dio sol per debito convensi,

Più si disdice a chi più pregio brama.

Elizabethan love-poetry is descended from Petrarch by way of Cardinal Bembo and the French poets of the Pléiade, notably Ronsard and Desportes. Of all the Elizabethan sonneteers the most finely Petrarchian are Sidney and Spenser, especially the former. For Sidney, Stella is the school of virtue and nobility. He too writes at times in the impatient strain of Petrarch:

But ah! Desire still cries, give me some food.

And in the end both Sidney and Spenser turn from earthly to heavenly love:

Leave me, O love, which reachest but to dust,

And thou, my mind, aspire to higher things:

Grow rich in that which never taketh rust,

Whatever fades but fading pleasure brings.

And so Spenser:

Many lewd lays (Ah! woe is me the more)

In praise of that mad fit, which fools call love,

I have in the heat of youth made heretofore;

That in light wits affection loose did move,

But all these follies now I do reprove.

But two things had come over this idealist and courtly love-poetry by the end of the sixteenth century. It had become a literary artifice, a refining upon outworn and extravagant conceits, losing itself at times in the fantastic and absurd. A more important fact was that this poetry had begun to absorb a new warmth and spirit, not from Petrarch and mediaeval chivalry, but from classical love-poetry with its simpler, less metaphysical strain, its equally intense but more realistic [pg xxxviii] description of passion, its radically different conception of the relation between the lovers and of the influence of love in a man's life. The courtly, idealistic strain was crossed by an Epicurean and sensuous one that tends to treat with scorn the worship of woman, and echoes again and again the Pagan cry, never heard in Dante or Petrarch, of the fleetingness of beauty and love:

Vivamus, mea Lesbia, atque amemus!

Soles occidere et redire possunt:

Nobis quum semel occidit brevis lux

Nox est perpetua una dormienda.

Vivez si m'en croyez, n'attendez à demain;

Cueillez dès aujourd'hui les roses de la vie.

Since brass, nor stone, nor earth, nor boundless sea,

But sad mortality o'er-sways their power,

How with this rage shall beauty hold a plea

Whose action is no stronger than a flower?

Now if we turn from Elizabethan love-poetry to the Songs and Sonets and the Elegies of Donne, we find at once two distinguishing features. In the first place his poetry is in one respect less classical than theirs. There is far less in it of the superficial evidence of classical learning with which the poetry of the 'University Wits' abounds, pastoral and mythological imagery. The texture of his poetry is more mediaeval than theirs in as far as it is more dialectical, though a dialectical evolution is not infrequent in the Elizabethan sonnet, and the imagery is less picturesque, more scientific, philosophic, realistic, and homely. The place of the

goodly exiled train

Of gods and goddesses

is taken by images drawn from all the sciences of the day, from the definitions and distinctions of the Schoolmen, from the travels and speculations of the new age, and (as in Shakespeare's tragedies or Browning's poems) from the experiences of everyday life. Maps and sea discoveries, latitude and longitude, the phoenix and the mandrake's root, the Scholastic theories of Angelic bodies and Angelic knowledge, Alchemy [pg xxxix] and Astrology, legal contracts and non obstantes, 'late schoolboys and sour prentices,' 'the king's real and his stamped face'—these are the kind of images, erudite, fanciful, and homely, which give to Donne's poems a texture so different at a first glance from the florid and diffuse Elizabethan poetry, whether romantic epic, mythological idyll, sonnet, or song; while by their presence and their abundance they distinguish it equally (as Mr. Gosse has justly insisted) from the studiously moderate and plain style of 'well-languaged Daniel'.

But if the imagery of Donne's poetry be less classical than that of Marlowe or the younger Shakespeare there is no poet the spirit of whose love-poetry is so classical, so penetrated with the sensual, realistic, scornful tone of the Latin lyric and elegiac poets. If one reads rapidly through the three books of Ovid's Amores, and then in the same continuous rapid fashion the Songs and the Elegies of Donne, one will note striking differences of style and treatment. Ovid develops his theme simply and concretely, Donne dialectically and abstractly. There is little of the ease and grace of Ovid's verses in the rough and vehement lines of Donne's Elegies. Compare the song,

Busie old foole, unruly Sunne,

with the famous thirteenth Elegy of the first book,

Iam super oceanum venit a seniore marito,

Flava pruinoso quae vehit axe diem.

Ovid passes from one natural and simple thought to another, from one aspect of dawn to another equally objective. Donne just touches one or two of the same features, borrowing them doubtless from Ovid, but the greater part of the song is devoted to the subtle and extravagant, if you like, but not the less passionate development of the thought that for him the woman he loves is the whole world.

But if the difference between Donne's metaphysical conceits and Ovid's naturalness and simplicity is palpable it is not less clear that the emotions which they express, with some important [pg xl] exceptions to which I shall recur, are identical. The love which is the main burden of their song is something very different from the ideal passion of Dante or of Petrarch, of Sidney or Spenser. It is a more sensual passion. The same tone of witty depravity runs through the work of the two poets. There is in Donne a purer strain which, we shall see directly, is of the greatest importance, but such a rapid reader as I am contemplating might be forgiven if for the moment he overlooked it, and declared that the modern poet was as sensual and depraved as the ancient, that there was little to choose between the social morality reflected in the Elizabethan and in the Augustan poet.

And yet even in these more cynical and sensual poems a careful reader will soon detect a difference between Donne and Ovid. He will begin to suspect that the English poet is imitating the Roman, and that the depravity is in part a reflected depravity. In revolt from one convention the young poet is cultivating another, a cynicism and sensuality which is just as little to be taken au pied de la lettre as the idealizing worship, the anguish and adoration of the sonneteers. There is, as has been said already, a gaiety in the poems elaborating the thesis that love is a perpetual flux, fickleness the law of its being, which warns us against taking them too seriously; and even those Elegies which seem to our taste most reprehensible are aerated by a wit which makes us almost forget their indecency. In the last resort there is all the difference in the world between the untroubled, heartless sensuality of the Roman poet and the gay wit, the paradoxical and passionate audacities and sensualities of the young Elizabethan law-student impatient of an unreal convention, and eager to startle and delight his fellow students by the fertility and audacity of his wit.

It is not of course my intention to represent Donne's love-poetry as purely an 'evaporation' of wit, to suggest that there is in it no reflection either of his own life as a young man or the moral atmosphere of Elizabethan London. It would be a much less interesting poetry if this were so. Donne has pleaded guilty to a careless and passionate youth:

In mine Idolatry what showres of raine

Mine eyes did waste? what griefs my heart did rent?

That sufferance was my sinne; now I repent;

Cause I did suffer I must suffer pain.

From what we know of the lives of Essex, Raleigh, Southampton, Pembroke, and others it is probable that Donne's Elegies come quite as close to the truth of life as Sidney's Petrarchianism or Spenser's Platonism. The later cantos of The Faerie Queene reflect vividly the unchaste loves and troubled friendships of Elizabeth's Court. Whether we can accept in its entirety the history of Donne's early amours which Mr. Gosse has gathered from the poems or not, there can be no doubt that actual experiences do lie behind these poems as behind Shakespeare's sonnets. In the one case as in the other, to recognize a literary model is not to exclude the probability of a source in actual experience.

But however we may explain or palliate the tone of these poems it is impossible to deny their power, the vivid and packed force with which they portray a variously mooded passion working through a swift and subtle brain. If there is little of the elegant and accomplished art which Milton admired in the Latin Elegiasts while he 'deplored' their immorality, there is more strength and sincerity both of thought and imagination. The brutal cynicism of

Fond woman which would have thy husband die,

the witty anger of The Apparition, the mordant and paradoxical wit of The Perfume and The Bracelet, the passionate dignity and strength of His Picture,

My body a sack of bones broken within,

And powders blew stains scatter'd on my skin,

the passion that rises superior to sensuality and wit, and takes wing into a more spiritual and ideal atmosphere, of His parting from her,

I will not look upon the quick'ning Sun,

But straight her beauty to my sense shall run;

The ayre shall note her soft, the fire most pure;

Water suggest her clear, and the earth sure—

[pg xlii] compare these with Ovid and the difference is apparent between an artistic, witty voluptuary and a poet whose passionate force redeems many errors of taste and art. Compare them with the sonnets and mythological idylls and Heroicall Epistles of the Elizabethans and it is they, not Donne, who are revealed as witty and 'fantastic' poets content to adorn a conventional sentiment with mythological fancies and verbal conceits. Donne's interest is his theme, love and woman, and he uses words not for their own sake but to communicate his consciousness of these surprising phenomena in all their varying and conflicting aspects. The only contemporary poems that have the same dramatic quality are Shakespeare's sonnets and some of Drayton's later sonnets. In Shakespeare this dramatic intensity and variety is of course united with a rarer poetic charm. Charm is a quality which Donne's poetry possesses in a few single lines. But to the passion which animates these sensual, witty, troubled poems the closest parallel is to be sought in Shakespeare's sonnets to a dark lady and in some of the verses written by Catullus to or of Lesbia:

The expense of spirit in a waste of shame.