Title: Moni the Goat Boy, and Other Stories

Author: Johanna Spyri

Translator: Edith F. Kunz

Release date: February 14, 2015 [eBook #48254]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by David Edwards, Haragos Pál, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team (http://www.pgdp.net) from page images generously made available by Internet Archive (https://archive.org)

The Project Gutenberg eBook, Moni the Goat Boy and Other Stories, by Johanna Spyri, Translated by Edith F. Kunz

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See https://archive.org/details/monigoatboyother00spyr |

|

Translated from the German of

Johanna Spyri, author of "Heidi" BY EDITH F. KUNZ GINN & COMPANY BOSTON · NEW YORK · CHICAGO · LONDON |

|

Copyright, 1906

By EDITH F. KUNZ

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

614.3

The Athenæum Press

GINN & COMPANY · PROPRIETORS ·

BOSTON · U.S.A.

Outside of the province of the Märchen, which constitutes so rich a field in German literature, there is no writer better known or better loved in the young German-speaking world than Johanna Spyri. Her stories, written "for children and those who love children," are read and reread as something that never grows old. The secret of this charm lies, above all, in the author's genuine love of children, as shown in her sympathetic insight into the joys, the hopes, and the longings of childhood, and in her skillful selection of characteristic details, which creates an atmosphere of reality that is rare in books written for children.

Johanna Heusser Spyri was born in the little Swiss town of Hirzel, canton of Zürich, in 1827, and died in Zürich in 1901. She wrote especially for young people, her writings dealing mostly with Swiss mountain life and portraying the thrifty, industrious nature of the people. The stories are sometimes sad,—for the peasant's life is full of hardships,—but through them all a fresh mountain breeze is blowing and a play of sunlight illumines the high Alps.

| MONI THE GOAT BOY | ||

| Chapter | Page | |

|---|---|---|

| I. | Moni is Happy | 3 |

| II. | Moni's Life on the Mountain | 10 |

| III. | A Visit | 21 |

| IV. | Moni Cannot Sing | 31 |

| V. | Moni Sings Once More | 41 |

| WITHOUT A FRIEND | ||

| I. | He is Good for Nothing | 49 |

| II. | In the Upper Pasture | 61 |

| III. | A Ministering Angel | 75 |

| IV. | As the Mother Wishes It | 85 |

| THE LITTLE RUNAWAY | ||

| I. | Under the Alders | 103 |

| II. | The Two Farms | 119 |

| III. | Going Astray | 139 |

| IV. | What Gretchen learned at Sunday | 159 |

| V. | How Renti Learns a Motto | 175 |

| VI. | All Buschweil is Amazed | 186 |

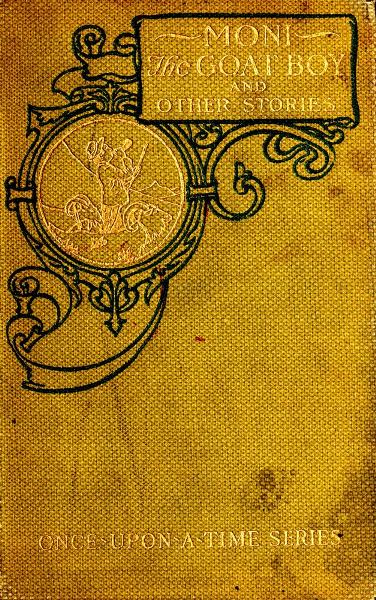

| Running along in their midst came the goat boy | Frontispiece |

| Page | |

|---|---|

| "Hold fast, Meggy!... I'm coming down to get you" | 17 |

| He drew her close to him and held her fast | 25 |

| He thought over what he had promised Jordie | 33 |

| With happy song and yodel Moni returned in the evening | 45 |

| He would hunt up a hedge or a bush and hide behind it | 57 |

| "Come out, child! You need not be afraid" | 69 |

| He greedily drank the cool water | 83 |

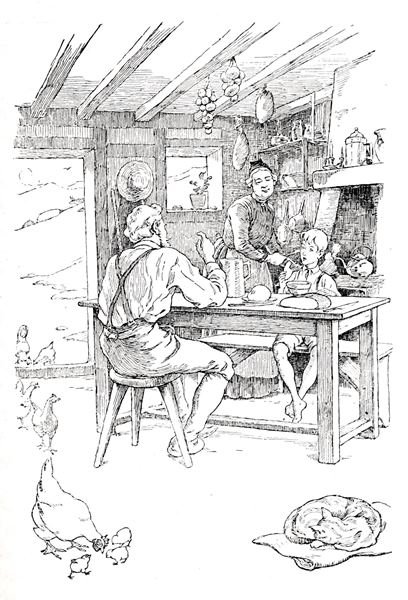

| Never in his life had Rudi seen so many good things together on a table | 97 |

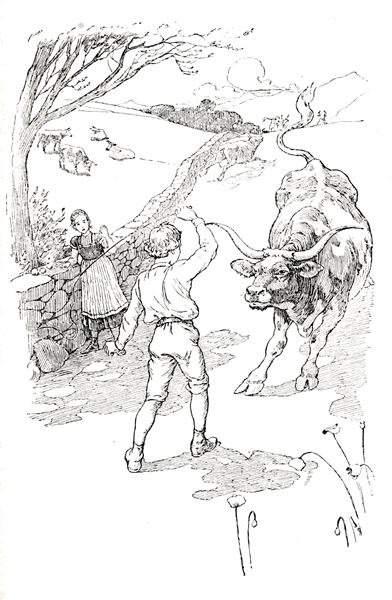

| He charged down upon the steer | 109 |

| There he stayed for hours without stirring | 136 |

| "Why are you standing out here?... And why are you crying?" | 150 |

| "I'd like to chop down all his trees!" | 168 |

| "The dog will understand instantly, you may depend upon it" | 179 |

| "Brindle, dear Brindle, do you know me?" | 203 |

MONI THE GOAT BOY

The baths of Fideris lie halfway up the mountain side, overlooking the long valley of the Prättigau. After you leave the highway and climb a long, steep ascent, you come first upon the village of Fideris, with its pleasant green slopes. Then, ascending still higher into the mountains, you at length come upon the lonely hotel building in the midst of rocky cliffs and fir trees. Here the region would indeed be rather dreary looking were it not for the bright little mountain flowers that shine forth everywhere from the low grass.

One pleasant summer evening two ladies stepped out from the hotel and ascended the narrow footpath [Pg 4]that runs up steeply from the house to the rugged cliffs above. On reaching the first peak the visitors stopped and looked about, for they had but recently come to the resort.

"Not very cheerful up here, is it, auntie?" said the younger of the two, as she surveyed the scene. "Nothing but rocks and fir trees, and beyond, more rocks and firs. If we are to spend six weeks here, I wish we might have some pleasanter prospect."

"I'm afraid it would not add to your cheerfulness, Paula, if you should lose your diamond pendant up here," replied her aunt, as she fastened Paula's velvet neck ribbon from which the sparkling cross hung. "This is the third time I have tied it since we came. I don't know whether the fault is in yourself or in the ribbon, but I do know that you would be sorry to lose it."

"No, no," cried Paula; "I must not lose the cross! No, indeed! It is from grandmamma and is my dearest treasure."

She added two or three knots to the ribbon herself to make it secure. Suddenly she raised her head attentively and exclaimed: "Listen, listen, auntie! that sounds like something really jolly."

From far above came the notes of a merry song; occasionally there was heard a long, echoing yodel, then more singing. The ladies looked up, but no[Pg 5] living creature was to be seen. The winding path, turning in great curves between rocks and bushes, was visible only in patches. But presently it seemed all alive,—above, below, wherever parts of it could be seen,—and louder and nearer came the singing.

"Look, look, auntie! There, there! see!" cried Paula in great delight, as three, four, five goats came bounding down, and behind them others and still others, each one wearing a little tinkling bell. Running along in their midst came the goat boy, singing the last lines of his song:

With an echoing yodel the boy finished his song, and skipping along meanwhile in his bare feet as nimbly as his goats, he presently reached the side of the ladies.

"Good evening to you," he said, looking up at them with dancing eyes, and was about to go on. But they liked this goat boy with the bright eyes.

"Wait a moment," said Paula. "Are you the goat boy of Fideris? And are these the goats from the village?"

"To be sure they are," he answered.

"And do you take them up every day?"

"Yes, of course."

"Indeed? And what is your name?"

"I am called Moni."

"Will you sing me the song you were just singing? We heard only a few lines of it."

"It is too long," said Moni. "The goats shouldn't be kept out so late; they must go home." Setting his weathered little hat to rights, he flourished his switch at the browsing goats and called, "Home, home!"

"Then you will sing it for me some other time, won't you, Moni?" cried Paula after him.

"Yes, yes; good night!" he called back and started on a trot with his goats. In a few moments the whole flock had arrived at the outbuildings of the hotel, where Moni had to leave the landlord's goats, the pretty white one and the black one with the dainty little kid. This little one Moni cared for very tenderly, for it was a delicate little creature and his favorite of them all. Little Meggy, in turn, showed her affection for the boy by keeping very close to him all day long. In the stable he put her gently in her place, saying: "There, sleep well, little Meggy; you must be tired. It's a long trip for a little goat like you. But here is your nice clean bed."

After laying her down in the fresh straw he started with his herd down the highway toward the village. Presently he lifted his little horn to his lips and blew a blast that resounded far down the valley. At that the village children came tumbling from their homes on all sides. Each one recognizing his own goat made a rush for it and took it home, while women, too, came out of the near-by houses and led away their goats by neck ropes or by the horns. In a few moments the whole herd was dispersed and each goat was stabled in its proper place. Moni was left with his own goat, Brownie, and the two started off toward the little house on the hillside, where grandmother was waiting for them in the door.

"Has everything gone well, Moni?" she asked in friendly tones, while she led Brownie into the stable and began milking her. The old grandmother was still a strong, vigorous woman, herself performing all the duties of house and stable and preserving the best of order everywhere. Moni stood in the stable door and watched her. When she had finished milking she went into the house saying, "Come Moni; you must be hungry."

Everything was ready and Moni sat down to eat; she sat beside him, and though the meal consisted of but a simple dish of porridge stewed in [Pg 8]goat's milk, it was a feast for the hungry boy. Meanwhile he told grandmother what had happened during the day; then, as soon as he had finished his supper, he slipped off to bed, for at early dawn he was to start out again with his flock.

In this way Moni had now spent two summers and had grown so accustomed to this life and to the companionship of his goats that he could hardly think of any other existence for himself. He had lived with his grandmother ever since he could remember. His mother had died when he was a tiny baby; his father had soon after left him to go into military service in Naples. The grandmother was herself poor, but she immediately took the forsaken little boy, Solomon, into her own home and shared with him whatever she had of food and other goods. And, indeed, a blessing seemed to rest upon the house from that day, for never since had she suffered want.

Honest old Elsbeth was much respected in the village, and when there had been a call two years before for a new goat boy the choice fell unanimously upon Moni, for every one was glad to help the good woman along in this way. Not a single morning had the God-fearing grandmother started the boy off without reminding him: "Moni, do not forget how close you are to God up there in the[Pg 9] mountains; how he sees and hears everything and how you can hide nothing from his eyes. But remember, too, that he is always near to help you, so you need not fear; and if there is no one at hand to help you in time of need, call upon God, and his hand will not fail you."

So Moni had always gone forth trustfully to his mountain heights, and on the loneliest peaks he knew no fear, for he always thought, "The higher up I go, the nearer I am to the good God and therefore the safer in everything that may happen to me." So, free from care, he could enjoy everything about him from morning to night. No wonder, then, that he sang and whistled and yodeled all day long, for he must express his happiness somehow.

Next morning Paula awakened unusually early; a lusty singing had roused her from sleep. "It must be the goat boy," she said, jumping up and running to the window.

Sure enough, there he stood with bright, shining face; he had just taken the old goat and the little kid out of the stable. Now he flourished his switch, the goats skipped and ran about him, and the whole procession started on. Presently Moni's voice was again heard echoing from the hills:

"This evening he must sing me the whole song," said Paula; for Moni had now disappeared and his distant song could no longer be heard.

Red morning clouds still hung in the sky and a fresh mountain breeze was rustling about Moni's ears as he climbed up the mountain. It was just what he liked. He stopped on the first peak, and for sheer happiness yodeled forth so lustily into the valley that many a sleeper in the hotel opened his eyes in surprise, but quickly closed them again, for he recognized the voice and so knew that he might have another hour's nap, as the goat boy always came very early. Meanwhile Moni continued climbing for an hour, higher and higher, up to the rocky ledges.

The view grew wider and more beautiful the higher he climbed. Occasionally he would stop to look about him, across at the mountains and up to the bright sky that was growing bluer and bluer, and then he would sing out in a strong, happy voice:

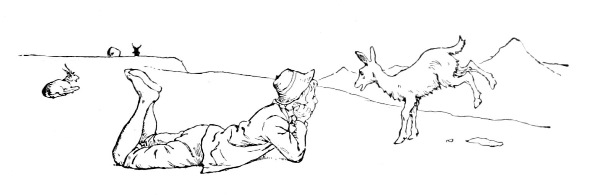

Now he had reached the spot where he usually stayed and where he meant to rest for a while to-day. It was a little green plateau standing out from the mountain side, so that one might look out from it in all directions and far down into the valley. This projection was called the "Pulpit." Here Moni would often sit for hours, looking out over the surrounding country, whistling to himself, while his goats were contentedly gathering herbs.

As soon as Moni had reached this spot he unstrapped his lunch box from his back, laid it in a little hollow which he had dug for it in the earth, and then went out on the Pulpit, where he stretched[Pg 13] out on the ground and gave himself up to the full enjoyment of the hour. The sky was now dark blue; on the opposite mountains ice fields and sharp peaks had come to view, and far below the green valley lay sparkling in the morning light. Moni lay there, looking about him, singing and whistling. The wind cooled his hot face, and when his own notes ceased for a moment the birds overhead whistled all the more merrily as they mounted into the blue sky. Moni felt indescribably happy. Now and then little Meggy would come to him and rub her head against his shoulder in her affectionate way, bleat tenderly, and then go to the other side and rub against his other shoulder. The old ones, too, would come up now and then and show their friendship in their own particular fashion.

Brownie, his own goat, had a way of coming up to him quite anxiously and looking him over very carefully to see whether he was all right. She would stand before him, waiting, until he said: "Yes, yes, Brownie; it's all right. Go back to your grazing now." Swallow, the slender, lively little creature that darted to and fro like a swallow in and out of its nest, always came up with the young white one. The two would charge down upon Moni with a force that would have overthrown him had he not already been stretched flat[Pg 14] on the ground. After a brief visit they would dart off again as quickly as they had come.

The shiny black one, little Meggy's mother, who belonged to the hotel, was rather proud. She would stand off several feet from the boy, look at him with a lofty air, as if afraid of seeming too familiar, and then pass on her way. Sultan, the big leader of the flock, in the one daily visit that he paid would rudely push aside any other goat that might be near, give several significant bleats,—probably meant for reports on the condition of his family,—and then turn away.

Little Meggy alone refused to be pushed away from her protector. When Sultan came and tried to thrust her aside, she would slip down as far as she could under Moni's arm, and thus protected she had no fear of the big buck, who was otherwise so formidable to her.

Thus the sunshiny morning passed. Moni had finished his noon lunch and was leaning meditatively on the long cane which he always kept at hand for difficult places. He was thinking about a new ascent, for he meant to go up higher with the goats this afternoon. The question was, which side should he take, right or left? He chose the left, for there he would come to the three "Dragon Rocks," about which the tenderest, most luscious herbage grew.

The path was steep and there were dangerous places along a precipitous wall, but he knew a good road and the goats were sensible creatures and would not easily run astray. He started and the goats ran merrily along, now before him, now behind, little Meggy always very close to him; sometimes he picked her up and carried her over the worst places. But all went well and they reached the desired spot safely. The goats made a rush for the green bushes, remembering the juicy shoots they had enjoyed there before.

"Gently, gently!" Moni warned them. "Don't butt one another along the steep places. You might easily slide off and have your legs broken. Swallow, Swallow, what are you about?" he called out excitedly to the cliff above. The nimble goat had scrambled over the high Dragon Rock and was now standing on the outer edge of the cliff, looking down saucily upon him. He hastily scrambled up the cliff, meanwhile keeping an anxious eye upon the goat, for a single misstep would have landed her in the abyss below. Moni was agile and in a few moments he had climbed the rock and, with a quick movement, had grasped Swallow by the leg and pulled her back. "You come with me now, you foolish little beast," he said as he drew her down to where the others were feeding. He held her[Pg 16] for a while, until she was contentedly nibbling at a tender shrub and had no more thoughts of running away.

Suddenly Moni cried out, "Where is little Meggy?" He saw the black mother standing alone by a steep wall; she was not eating, but was looking all about her and pointing her ears in a strange manner. The little kid was always either beside Moni or running after its mother.

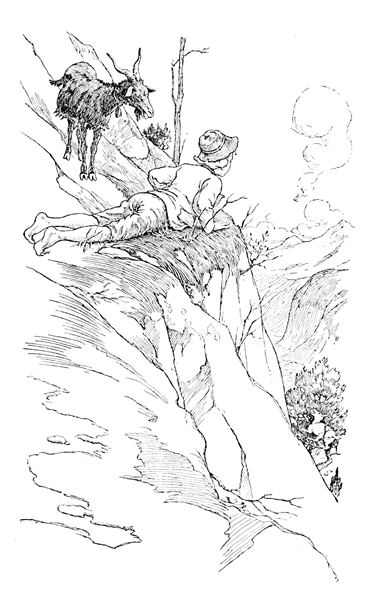

"Where is your little one, Blackie?" he said, standing close beside her and looking up and down. Then he heard a faint, wailing bleat. It was Meggy's voice and came from far below, piteous, entreating. Moni got down on the ground and leaned forward. Below him something seemed to be moving; now he saw it plainly,—it was Meggy hanging in the branches of a tree that grew out of the rocks. She was wailing pitifully.

Luckily the branch had caught her, else she would have fallen into the abyss and been dashed to death. If she should even now lose her hold, she must plunge instantly into the depths below. In terror he called to her: "Hold fast, Meggy! hold fast to the tree! I'm coming down to get you."

But how was he to get there? The rocks were so steep at this point that he could not possibly get down. But he reflected that he must be somewhere near the "Rain Rock," that overhanging [Pg 18]cliff under which the goat boys had for generations found shelter. From there, thought Moni, he might climb across the rocks and so get back with the kid. He quickly called the goats together and took them to the entrance of the Rain Rock. There he left them to graze and went out toward the cliff. Some distance above him he saw the tree with Meggy clinging to it.

He realized that it would be no easy matter to climb up the cliff and then down again with Meggy on his back, but there was no other way of rescuing her. And then, too, he felt sure the dear God would help him, so that he could not fall. He folded his hands, looked up into heaven, and prayed, "Dear God, please help me to save little Meggy."

Then he felt confident that all would go well and he climbed bravely up the cliff until he reached the tree. Here he held himself tight with both feet, lifted the trembling, whining little creature to his shoulders, and then worked his way down very cautiously. When they had the solid ground once more underfoot and he saw that the frightened little goat was safe, he felt so glad that he had to speak his thanks aloud, and he called up to heaven: "Dear God, I thank you a thousand, thousand times for helping us back safely. We are both so very, very glad."

He sat down on the ground for a while to caress and quiet the little creature, that was still trembling in every limb, until it had somewhat recovered from its terrible experience.

When it was time, soon afterward, for breaking up, Moni again lifted the kid to his shoulders, saying solicitously: "Come, my poor little Meggy; you are still trembling; you cannot walk home to-day; I must carry you." And so he carried her, cuddled close in his arm, all the way home.

Paula was standing on the ledge near the hotel, waiting for the boy to pass. Her aunt was with her. When Moni came along with his burden, Paula wanted to know whether the little goat was sick. She seemed so interested that Moni sat down on the ground before her and told the whole story about Meggy.

The young Fräulein showed great sympathy and stooped to caress the little creature, that was now lying quietly on Moni's knees, looking very pretty with its little white feet and smooth black coat, and evidently enjoying the girl's attention.

"Now sing me your song while you are resting here so comfortably," said Paula.

Moni was so happy that he gladly complied with her request, and sang the song through to a lusty close.

Paula was delighted with it and said he must sing it for her often. Then the whole company went on down to the hotel. There the little kid was put to bed. Moni took his leave. Paula went to her room and talked for a long time about the goat boy, about his happy nature, his lonely life on the mountain, and the joys and privations of such a life. In this far-off, strange hotel there was little diversion for the girl, and she was already looking forward to the boy's happy morning song as one of the pleasures of the morrow.

Thus several days passed, each one as sunny and bright as the one before it; for it was an unusually fine summer, and from morning to night the sky was blue and cloudless.

Every morning at early dawn the goat boy had passed the hotel singing his merry song, and had come back still singing at evening; and all the guests were so accustomed to the cheerful sound that they would have been sorry not to hear it.

But Paula, most of all, enjoyed Moni's happiness, and went to meet him every evening, that she might have a little talk with him.

One sunshiny morning Moni had again reached the Pulpit and was just about to settle down upon the ground when he reflected: "No, we'll go on farther to-day. The last time we had to leave all the good, juicy food because we went after little Meggy. Now we'll go up again and you can finish grazing."

Joyously the goats ran after him, for they understood that they were being led to the fine feeding on Dragon Rock. But this time Moni was careful to hold little Meggy close in his arm all the way. He picked the tenderest leaves and fed them to her, and the little kid showed her appreciation by rubbing her head against his arm and bleating contentedly from time to time. So the morning passed until Moni presently realized from his hunger that it had grown surprisingly late. But his lunch was in the little cave by the Pulpit, for he had intended to be back there by noon.

"Now you have had many a good mouthful and I have had nothing," he said to his goats. "It is time I had something, too. Come, we'll go down; there is enough left for you on the lower slope."

With that he whistled shrilly, and the whole flock started downward, the liveliest ones in the van; Swallow, the light-footed one,—for whom there were unexpected things in store that day,—in advance of them all. She jumped from rock to rock and over many a chasm; but suddenly she could go no farther, for directly in front of her stood a chamois, looking her saucily in the face. Swallow had never had such an experience before. She stood still and looked questioningly at the stranger, waiting for him to step aside and allow her to make[Pg 23] the fine jump she had in mind to the opposite rock. But the chamois never moved, and stood staring boldly into Swallow's face. So they faced each other, getting more and more obstinate every moment; they would probably be standing there to this day had not Sultan come up at this point. Taking in the situation, he carefully moved past Swallow and pushed the stranger so forcibly to one side that he had to make a quick jump to escape sliding off the cliff. Then Swallow passed triumphantly on her way and Sultan marched proudly behind her, feeling himself to be the mighty protector of the herd.

Meanwhile another meeting was taking place. Moni, coming from above, and another goat boy from below, had met face to face and were looking at each other in astonishment. But they were old acquaintances and, after their first surprise, greeted each other heartily. The newcomer was Jordie from Kueblis. He had been looking for Moni half the morning, and now found him where he least expected.

"I did not think you went up so high with the goats," said Jordie.

"To be sure I do," answered Moni, "but not always. I am generally somewhere near the Pulpit. But why are you up here?"

"I wanted to see you; I have lots to tell you. And these two goats here I am taking to the hotel[Pg 24] keeper; he wants to buy one,—so I thought I'd visit you on the way."

"Are they your goats?" asked Moni.

"Of course they are. I don't herd other people's goats any longer. I'm not goat boy now."

Moni was surprised at this, for Jordie had started out as goat boy of Kueblis at the same time that he had been chosen from Fideris. He could not understand how that could all be ended without a sign of regret on Jordie's part.

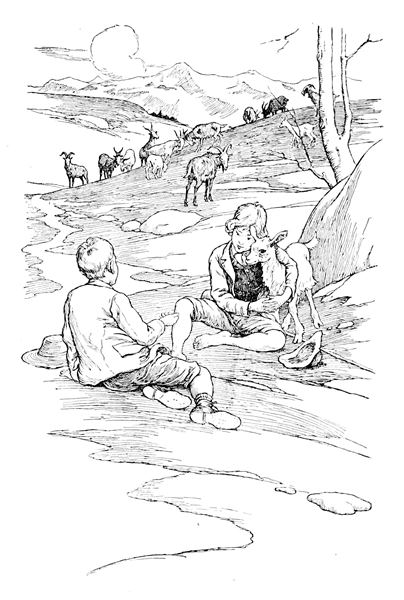

But the boys had by this time reached the Pulpit. Here Moni brought out his bread and dried meat and invited Jordie to lunch. They sat out on the Pulpit and ate their lunch with a relish, for it had grown late and both were hungry. When they had eaten everything and finished off with a drink of goat's milk, Jordie stretched out full length on the ground and leaned his head on his arms; but Moni preferred to sit up and look out over the great valley.

"But if you are no longer goat boy, Jordie, what are you?" Moni began. "You must be something."

"Of course I am something,—something worth while, you may believe," answered Jordie. "I am egg boy. I go to the hotels with eggs every day. I go up to the baths, too. Was there yesterday."

Moni shook his head. "That wouldn't do for me,—to be egg boy. No, I'd rather be goat boy, a thousand times rather. That is much better."

"And why, I'd like to know?"

"Eggs aren't alive. You can't talk with them, and they won't follow you like goats, and be glad when you come, and love you, and understand every word you say to them. You can't possibly enjoy your eggs as I do my goats."

"Yes; great enjoyment you must have up here!" said Jordie scornfully. "What pleasures do you have? Since we've been sitting here you've had to jump up six times to run after that silly little goat, to keep her from falling over the rock. Is that any pleasure?"

"Yes, I like it. You know that, Meggy, don't you? Careful, careful!" he called, jumping up and running after her, for in her joy she was capering about most recklessly.

When he came back Jordie said, "Don't you know that there is another way of keeping young goats from falling over the cliffs, that will save your running after them every few minutes?"

"How is that?" asked Moni.

"Drive a stake into the ground and tie the goat to it by one leg; she will struggle desperately, but she can't get away."

"You don't really think that I would do such a thing to little Meggy!" cried Moni indignantly, while he drew her close to him and held her fast, as though to defend her from such treatment.

"This little one, of course, won't bother you much longer," Jordie went on. "There won't be many more times for it to come up."

"What? what? What did you say, Jordie?"

"Pshaw! Don't you know that the landlord doesn't mean to raise it? It is too weak; he thinks it will never grow to be a strong goat. He wanted to sell it to my father, but father did not want it. So now he is going to kill it, and then he will buy our Spottie."

Moni had grown white with horror. For a moment he could not speak; then he broke forth in a loud wail over the little goat: "No, no! they shan't do it, my little Meggy; they shan't kill you. I won't have it; I'd rather die with you! No, no! I can't let them; I can't let them."

"Don't carry on so!" said Jordie, annoyed; and he pulled Moni up from the ground, where he had thrown himself, face downward, in his grief. "Come, get up. You know the kid belongs to the landlord and he can do with it as he pleases. Don't think about it any more. Here, I have something else. Look! look here!" and Jordie held out[Pg 28] one hand toward Moni, while with the other he almost covered something that he was offering for Moni's admiration. It flashed out most wonderfully from between his hands as the sun shone upon it.

"What is it?" asked Moni, seeing it sparkle.

"Guess!"

"A ring?"

"No; but something of the sort."

"Who gave it to you?"

"Gave it? Nobody. I found it."

"Then it doesn't belong to you, Jordie."

"Why not? I didn't steal it. I almost stepped on it; then it would have been crushed anyway. So I might as well have it."

"Where did you find it?"

"Down by the hotel last night."

"Then somebody in the house lost it; you must tell the landlord. If you don't, I'll tell him this evening."

"No, no! you mustn't do that," cried Jordie. "Look! I'll let you see it. I'm going to sell it to a chambermaid in one of the hotels; but she must give me at least four francs, and I will give you one, or perhaps two, and no one shall know anything about it."

"I don't want it! I don't want it!" Moni interrupted angrily; "and God has heard every word you said."

Jordie looked up to heaven. "Too far away," he said doubtfully, but he took care to lower his voice.

"He'll hear you, anyway," said Moni with assurance.

Jordie began to feel uncomfortable. He must get Moni over to his side or he would spoil the whole game. Jordie thought and thought.

"Moni," he said suddenly, "I will promise you something that will please you, if you won't tell any one about what I found. And you needn't take any of the money; then you won't have anything to do with it. If you'll promise, then I will persuade father to buy little Meggy, so that she won't be killed. Will you?"

That started a hard struggle in Moni. It would be sinful to conceal the finding of the treasure. Jordie had opened his hand; there lay a cross set with many jewels that sparkled with all colors. Moni saw that it was no trifling thing that would not be searched after. He felt that if he did not tell it would be the same as though he himself were keeping something that did not belong to him. But, on the other hand, there was dear little Meggy; she would be killed—horribly butchered with a knife, and he could prevent it if he kept silent. The little kid was at that moment lying trustfully [Pg 30]beside him, as though she knew that he would always protect her. No, he must not let such a thing happen; he must do something to save her.

"Then I will, Jordie," he said, but without any enthusiasm.

"Your hand on it!" and Jordie held out his own hand, for thus a promise was made inviolable.

Jordie was very glad that he was now safe with his treasure; but as Moni had grown so quiet, and as he had a longer way home than Moni, he thought it best to start on. He took leave of Moni and whistled to his two goats, which had meanwhile joined Moni's grazing flock,—not without various buttings and other doubtful encounters, however; for the goats of Fideris had never heard that one must be polite to company, and the goats of Kueblis did not know that when one is on a visit it is not proper to pick out the best feeding for oneself and push every one else away from it. When Jordie was halfway down the mountain Moni, too, set out with his flock, but he was very quiet and gave forth not a note of song or whistle all the way home.

The next morning Moni came to the hotel as quiet and downcast as he had been the evening before. He came silently, took away the landlord's goats, and then started on his upward journey, without ever opening his lips for a song or a yodel; he hung his head and looked as though he were afraid of something. Now and then he cast a furtive glance around to see if some one was not following him.

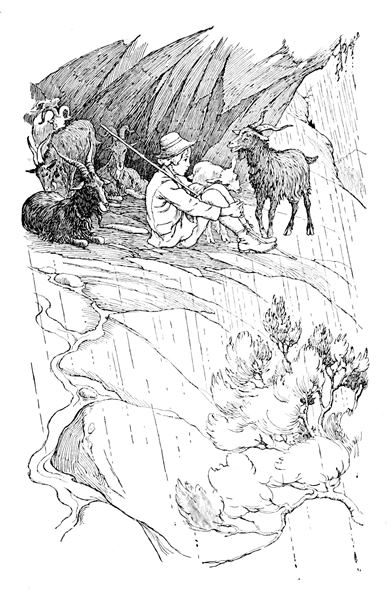

Moni could not be happy any more; he could hardly tell why. He felt that he ought to be glad because he had saved little Meggy, and he tried to sing, but he could not. The sun happened to be clouded that day; he thought that when the sky cleared he would feel quite different, and would be happy again. When he got up on the mountain it began to rain hard. Soon the rain came down in torrents and he took refuge under the Rain Rock.

The goats, too, came and stood under the rock. The proud black one, careful of her fine glossy coat, had crept in even before Moni. She now lay behind him, looking out contentedly from her comfortable corner into the streaming rain. Meggy stood in front of her protector and rubbed her head affectionately against his knee, then looked up astonished to find that he did not say a word to her, for that was most extraordinary. His own brown goat, too, pawed at his feet and bleated, for he had not spoken to her all the morning. He sat there, leaning thoughtfully on his cane, which he carried in rainy weather to keep him from slipping on the rocks, for on such days he wore shoes. To-day, as he sat for hours under the rock, he had plenty of time for reflection.

He thought over what he had promised Jordie. It seemed as though Jordie had stolen something and he had done the same; for was not Jordie going to give him something for it? He had at any rate done what was wrong, and God was displeased with him,—he felt that in his heart. He was glad that it was dark and rainy, and that he was hidden under the rock, for he would not dare look up into the blue sky as he had formerly. He was afraid now of the dear God.

Other things, too, came into his mind. What if Meggy should fall over a steep place again, and he [Pg 34]should try to save her, and God would no longer help him? What if he could never pray to him any more, or have any hope of help from him? And what if his feet should slip? Then he and Meggy would fall down on the jagged rocks and lie there all torn and mangled.

"Oh, no!" he cried in his troubled heart; "this cannot be." He must make his peace with the dear God, so that he could pray once more and go to him with all his troubles; then he could be happy again. He would throw off the weight that was upon him; he would go and tell the landlord everything. But then? Then Jordie would not persuade his father, and the landlord would have little Meggy butchered. Oh, no, no, no! he could not endure that; and he said: "No, I will not. I will say nothing." But that did not relieve him; the weight on his heart grew heavier and heavier.

So the whole day passed. He came home at night as silent as he had gone forth in the morning; and when Paula, waiting at the hotel, eagerly ran out to him and asked sympathetically: "Moni, what is the matter? Why don't you sing?" he turned away embarrassed, saying, "Can't," and went away as quickly as possible.

In their room upstairs Paula said to her aunt: "If I only knew what is wrong with the goat boy![Pg 35] He is so changed I hardly know him. If he would only sing again!"

"This wretched weather probably spoils the boy's humor," said her aunt.

"Everything seems to be going wrong. Let us go home, auntie," begged Paula. "Our good times are over. First I lose my beautiful cross and there is no trace of it anywhere; then this endless rain sets in; and now there is not even the jolly goat boy to listen to. Let us go home."

"But we must finish the treatment here. There is no way out of it," said her aunt.

The next morning was again dark and cloudy and the rain poured down without intermission. Moni spent the day as he had the one before. He sat under the rocks, his thoughts going round and round in the same circle. Whenever he reached the resolution, "Now I will go and confess the wrong, so that I can look up to God once more," he saw the little goat under the butcher's knife, and the whole struggle began again from the beginning; so that he was quite worn out when evening came, and went crawling home through the drenching rain as though he hardly noticed it.

As he passed the hotel the landlord called to him: "Can't you get along a little faster? Look how wet they are. What's come over you, anyway, lately?"

Such cross words had never been addressed to him before by the landlord. On the contrary, the latter had always shown special friendliness to the boy; but now he was irritated by Moni's altered manner, and was in bad humor otherwise, for Paula had told him about her missing jewel, which she declared could have been lost only within the hotel or directly before the door, for she had left the house on that day only to listen to the goat boy's song. To have it said that so valuable an article could be lost in his house, and not be returned, annoyed the landlord extremely. On the previous day he had summoned the whole staff of servants, had examined them, threatened them, and had finally offered a reward to the finder. The whole establishment was upset by the occurrence.

When Moni passed the front of the hotel Paula was there waiting for him, wondering why he had not yet found his song.

"Moni, Moni!" she called; "are you really the same boy who used to come by here singing from morning to night,—

Moni heard the words and they made a deep impression on him, but he gave no answer. He[Pg 37] felt that it had indeed been different when he went about singing all day, with a spirit as happy as his song. Would such days ever come again?

The next morning he climbed the mountain sad and silent as the day before. The rain had stopped, but a heavy mist hung over the mountains, and the sky was covered with dark clouds. Moni sat under the rocks, tortured with distressing thoughts. Toward noon the sky began to clear. It grew brighter and brighter, and Moni came out of the cave and looked about. The goats were gayly skipping about once more, the little kid wantonly capering in the sunshine.

Moni stood out on the Pulpit watching the sky and the mountains as they came out brighter and brighter. When the clouds parted and the blue heavens shone forth, it seemed to Moni as though the dear God were looking down on him from heaven. Suddenly things within him seemed to grow very clear, and he knew what he must do. He could not carry the wrong about in his heart any longer; he felt that he must cast it off. Then he seized the frolicsome little kid, took it in his arms, and said tenderly: "O my Meggy, my poor little Meggy! I have surely done what I could; but it was sinful and bad. Now you must die. Oh, oh! how can I endure it!" And he began to cry so bitterly that he could say no more.

The little kid uttered a sad cry and crept as far under his arm as she could, as though to hide and be safe with him. He lifted her to his shoulders.

"Come, Meggy," he said; "I'll carry you home once more. Perhaps soon I shall not have you to carry."

When the company reached the hotel Paula was again waiting. Moni left the little kid and the old black mother in the stable. Then, instead of going on down, he came to the house and was about to go in, when the Fräulein stopped him.

"Haven't you found your song yet, Moni? Where are you going with that look of woe?"

"I have something to report," answered Moni, without raising his eyes.

"To report? What is it? Won't you tell me?"

"I must see the landlord. Something was found."

"Found? What? I lost something,—a beautiful cross."

"That is it."

"What did you say?" cried Paula, in greatest astonishment. "A cross with sparkling stones?"

"Yes, exactly."

"Where is it, Moni? Give it to me. Did you find it?"

"No; Jordie of Kueblis did."

Paula wanted to know who Jordie was and where he lived, and was about to send some one down to Kueblis right away to get the cross.

"I will go; and if he still has the cross, I will bring it," said Moni.

"If he still has it!" cried Paula. "Why should he not have it? and how do you know all about this, Moni? When did he find it, and how did you hear about it?"

Moni stared at the ground; he dared not tell how it had all happened and how he had helped to hide the discovery until he had been forced to speak.

But Paula was very kind to him. She led him aside, sat down on a tree stump with him, and said reassuringly: "Come, tell me how it happened, Moni. I want you to tell me all about it."

So Moni took courage and began. He told the whole story,—all about his struggles for Meggy's sake; how he had grown so miserable through it all and dared not look up to God; and how he had not been able to endure it longer and had resolved to tell.

Then Paula gave him friendly advice and said he ought to have come at once and reported, but it was right that he had now told her everything so frankly, and he would not regret it. She said[Pg 40] he might promise Jordie ten francs as soon as she had the cross in her possession once more.

"Ten francs!" repeated Moni in surprise, remembering how Jordie had wanted to sell it. Then he rose. He would go back to Kueblis that very night, and if he got the cross, bring it back to-morrow morning. Then he ran away, realizing as he went that he could skip and jump once more, and that the heavy burden was no longer on his heart.

On reaching home he merely told his grandmother that he had an errand in Kueblis, and at once started off. He found Jordie at home and told him what he had done. Jordie was quite angry with him for a moment, but when he reflected that further concealment was now impossible he brought out the cross, asking, "What is she going to give me for it?"

Moni was ready with his answer: "Ten francs. You see honest dealing would have paid you best, for with your dishonesty you expected to get only four francs; but you will get your money."

Jordie was surprised, and regretted that he had not gone to the hotel at once with the cross, and so come off with a clear conscience, which he certainly had not now. Things might have been quite different, but it was too late. He gave the cross to Moni, who hurried home, as it had grown quite dark.

Paula had left orders that she was to be called early in the morning. She wanted to be on hand when the goat boy came, and settle with him herself. The previous evening she had had a long interview with the landlord, coming away from his room with a look of satisfaction, as though she had made some pleasant arrangement with him.

When Moni came up with his herd in the morning Paula called to him, "Moni, can't you sing even now?"

He shook his head. "I can't. I keep thinking of poor little Meggy and how many days longer she will be with me. I'll never sing again as long as I live; but here is the cross." With that he gave her the parcel, which his grandmother had carefully done up for him in many wrappings.

Paula took the jewel from its coverings and examined it closely; it was really her precious cross of sparkling stones, perfectly unharmed.

"Well, Moni, you have made me very happy. Without you I should probably never have seen my cross again. So I want to make you happy, too. Go and get little Meggy; she belongs to you now."

Moni stared at the Fräulein as though he could not comprehend her words. At length he stammered, "But how—how can Meggy belong to me?"

"How?" said Paula, smiling. "Last night I bought her from the landlord, and to-day I give her to you. Can you sing now?"

"Oh! oh! oh!" cried Moni, running to the stable like mad. He took the little goat and held her close in his arms. Then he came running back and held out his hand to the Fräulein, saying over and over again, "I thank you a thousand, thousand times! God reward you for it! If I could only do something for you!"

"Then sing your song and let us hear whether it has the old ring," said Paula.

So Moni lifted up his voice, and as he climbed the mountain his joyous notes rang out so clearly through the valley that every one in the hotel noticed it, and many a sleeper turned on his pillow, saying, "Good! the goat boy has sunshine once more."

They were all glad to hear him sing again, for they liked the early notes, which were to some[Pg 43] a sign for rising, to others leave for another nap. When Moni looked down from the first ledge and saw the Fräulein still standing before the hotel, he stepped forward and sang as loudly as he could:

Nothing but sounds of joy came from his lips all day, and the goats, too, seemed to feel that it was a day of gladness, and skipped and capered about as never before. The sun was so bright, the sky so blue, and after the heavy rains the grasses so green and the flowers so gay, that Moni thought he had never seen the world so beautiful. He kept his little kid beside him all day, plucked the best herbs for it, and fed it from his hand, saying again and again: "Meggy, dear little Meggy, you are not going to be killed. You are mine now, and will come up the mountain with me as long as we both live."

With happy song and yodel Moni returned in the evening, and after he had led the black goat to her stable he took the little one on his arm; she was henceforth to go home with him. Meggy seemed very well satisfied, and cuddled up to him as though she felt herself in the best of care; for he had always treated her more tenderly than her own mother had.

When Moni came home with the little one on his shoulder his grandmother hardly knew what to make of him. His calling out, "It is mine, grandmother; it is mine!" explained nothing to her. But Moni could not stop to explain until he had run to the stable and made a good bed for Meggy close beside their own goat, so that the little one would not be lonely.

"There, Meggy; now sleep well in your new home. You shall always have a good bed. I will make it fresh for you every day."

Then Moni ran in to the wondering grandmother, and while they sat at supper he told her the whole story,—of his three sad, troubled days and the happy ending of it all. His grandmother listened attentively, and when he had finished she said earnestly: "Moni, this experience you must always remember. Had you done right in the first place, trusting in the good God, then everything would have gone well. Now God has helped you so much more than you deserve that you must not forget it as long as you live." And Moni was very sure that he would not forget.

Before he went to sleep he had to go to the stable once more to make sure that the little kid really belonged to him and was there in its bed.

Jordie got his ten francs, as promised, but that did not end the matter for him. When he went to [Pg 46]the hotel he was taken before the landlord, who gave him a severe lecture. But the worst of it all was that whenever anything was missed after that, it was Jordie who was immediately suspected of having stolen it. He had no more peace, for he was continually in dread of being punished for something that he had never done.

Moni's little goat throve and grew strong, and the boy continued to sing all summer. But often when he was comfortably stretched out on the Pulpit, he thought of the troubled days under the Rain Rock, and he said to himself, "It must never happen so again."

But when he was too long absorbed in such reflections one or another of the goats would come and rouse him with a questioning bleat.

WITHOUT A FRIEND

The traveler who ascends Mt. Seelis from the rear will presently find himself coming out upon a spot where a green meadow, fresh and vivid, is spread out upon the mountain side. The place is so inviting that one feels tempted to join the peacefully grazing cows and fall to eating the soft green grass with them. The clean, well-fed cattle wander about with pleasant musical accompaniment; for each cow wears a bell, so that one may tell by the sound whether any of them are straying too far out toward the edge, where the precipice is hidden by bushes and where a single misstep would be fatal. There is a company of boys, to be sure, to watch the cows, but the bells are also necessary, and their tinkling is so pleasant to hear that it would be a pity not to have them.

Little wooden houses dot the mountain side, and here and there a turbulent stream comes tumbling down the slope. Not one of the cottages stands on level ground; it seems as though they had somehow been thrown against the mountain and had stuck there, for it would be hard to conceive of their being built on this steep slope. From the highway below you might think them all equally neat and cheery, with their open galleries and little wooden stairways, but when you came nearer to them you would notice that they differed very much in character.

The two first ones were not at all alike. The distance between them was not very great, yet they stood quite apart, for the largest stream of the neighborhood, Clear Brook, as it is called, rushed down between them. In the first cottage all the little windows were kept tightly closed even through the finest summer days, and no fresh air was ever let in except through the broken windowpanes, and that was little enough, for the holes had been pasted over with paper to keep out the winter's cold. The steps of the outside stairway were in many places broken away, and the gallery was in such a ruinous state that it seemed as though the many little children crawling and stumbling about on it must surely break their arms or legs. But[Pg 51] they all were sound enough in body though very dirty; their faces were covered with grime and their hair had never been touched by a comb. Four of these little urchins scrambled about here through the day, and at evening they were joined by four older ones,—three sturdy boys and a girl,—who were at work during the day. These, too, were none too clean, but they looked a little better than the younger ones, for they could at least wash themselves.

The little house across the stream had quite a different air. Even before you reached the steps, everything looked so clean and tidy that you thought the very ground must be different from that across the stream. The steps always looked as though they had just been scrubbed, and on the gallery there were three pots of blooming pinks that wafted fragrance through the windows all summer long. One of the bright little windows stood open to let in the fresh mountain air, and within the room a woman might be seen, still strong and active in spite of the snowy white hair under her neat black cap. She was often at work mending a man's shirt, that was stout and coarse in material but was always washed with great care.

The woman herself looked so trim and neat in her simple dress that one fancied she had never[Pg 52] in her life touched anything unclean. It was Frau Vincenze, mother of the young herdsman Franz Martin, he of the smiling face and strong arm. Franz Martin lived in his little hut on the mountain all summer making cheese, and returned to his mother's cottage only in the late fall, to spend the winter with her and make butter in the lower dairy hut near by.

As there was no bridge across the wild stream, the two cottages were quite separated, and there were other people much farther away whom Frau Vincenze knew better than these neighbors right across the brook; for she seldom looked over at them,—the sight was not agreeable to her. She would shake her head disapprovingly when she saw the black faces and dirty rags on the children, while the stream of fresh, clean water ran so near their door. She preferred, when the twilight rest hour came, to enjoy her red carnations on the gallery, or to look down over the green slope that stretched from her cottage to the valley below.

The neglected children across the stream belonged to "Poor Grass Joe," as he was called, who was usually employed away from home in haying, or chopping wood, or carrying burdens up the mountain. The wife had much to do at home, to be sure, but she seemed to take it for granted that[Pg 53] so many children could not possibly be kept in order, and that in time, when the children grew older, things would mend of their own accord. So she let everything go as it would, and in the fresh, pure air the children remained healthy and were happy enough scrambling around on the steps and on the ground.

In the summer time the four older ones were out all day herding cows; for here in the lower pasture the whole herd of cows was not left to graze under one or two boys, as on the high Alps, but each farmer had to hire his own herd boy to look after his cows. This made jolly times for the boys and girls, who spent the long days together playing pranks and making merry in the broad green fields. Sometimes Joe's children were hired for potato weeding farther down the valley, or for other light field work. Thus they earned their living through the summer and brought home many a penny besides, which their mother could turn to good account; for there were always the four little mouths to be fed and clothes to be got for all the children. However simple these clothes might be, each child must have at least a little shirt, and the older ones one other garment besides. The family was too poor to possess even a cow, though there was scarcely a farmer in the neighborhood[Pg 54] who did not own one, however small his piece of land might be.

Poor Grass Joe had got his name from the fact that the spears of grass on his land were so scarce that they would not support so much as a cow. He had only a goat and a potato field. With these small resources the wife had to struggle through the summer and provide for the four little ones, and sometimes, when work was scarce, for one or two of the older ones also. The father occasionally came home in the winter, but he brought very little to his family, for his house and land were so heavily mortgaged that he was never out of debt throughout the whole year. Whenever he had earned a little money, some one whom he owed would come and take it all away.

So the wife had a hard time to get along,—all the more so because she had no order in her house-keeping and was not skillful in any kind of work. She would often go out and stand on the tumbledown gallery, where the boards were lying loose and ready to drop off, and instead of taking a hammer and fastening them down would look across the stream at the neat little cottage with the bright windows, and would say fretfully, "Yes, it's all very well for her to clean and scrub,—she has nothing else to do; but with me it's quite different."

Then she would turn back angrily into the close, dingy room and vent her anger on the first person who crossed her path. This usually happened to be a boy of ten or eleven years, who was not her own child, but who had lived in her house ever since he was a baby. This little fellow, known only by the name of "Stupid Rudi," was so lean and gaunt looking that one would have taken him to be scarcely eight years old. His timid, shrinking manner made it difficult to tell what kind of a looking boy he really was, for he never took his eyes from the ground when any one spoke to him.

Rudi had never known a mother; she had died when he was hardly two years old, and shortly afterward his father had met with an accident when returning from the mountain one evening. He had been wild haying, and, seeking to reach home by a short cut, had lost his footing and fallen over a precipice. The fall lamed him, and after that he was not fit for any other work but braiding mats, which he sold in the big hotel on Mt. Seelis. Little Rudi never saw his father otherwise than sitting on a low stool with a straw mat on his knees. "Lame Rudolph" was the name the man went by. Now he had been dead six years. After his wife's death he had rented a little corner in Joe's house for himself and boy to sleep in, and the little fellow[Pg 56] had remained there ever since. The few pennies paid by the community for Rudi's support were very acceptable to Joe's wife, and the extra space in his bedroom, after the father's death, was eagerly seized for two of her own boys, who had scarcely had sleeping room for some time.

Rudi had been by nature a shy, quiet little fellow. The father, after the loss of his wife and the added misfortune of being crippled, lost all spirit; little as he had been given to talking before his misfortune, he was even more silent afterward.

So little Rudi would sit beside his father for whole days without hearing a word spoken, and did not himself learn to speak for a long time. After his father died and he belonged altogether to Joe's household, he hardly ever spoke at all. He was scolded and pushed about by everybody, but he never thought of resisting; it was not in his nature to fight. The children did what they pleased to him, and besides their abuse he had to bear the woman's scoldings, especially when she was in a bad temper about the neat little house across the stream. But Rudi did not rebel, for he had the feeling that the whole world was against him, so what good would it do? With all this the boy in time grew so shy that it seemed as though he hardly noticed what was going on about him, [Pg 58]and he usually gave no answer when any one spoke to him. He seemed, in fact, to be always looking for some hole that he might crawl into, where he would never be found again.

So it had come about that the older children, Jopp, Hans, Uli, and the girl Lisi, often said to him, "What a stupid Rudi you are!" and the four little ones began saying it as soon as they could talk. As Rudi never tried to deny it, all the people in time assumed that it must be so, and he was known throughout the neighborhood simply as "Stupid Rudi." And it really seemed as though the boy could not attend to anything properly as the other children did. If he was sent along with the other boys to herd cows, he would immediately hunt up a hedge or a bush and hide behind it. There he would sit trembling with fear, for he could hear the other boys hunting him and calling to him to come and join their game. The games always ended with a great deal of thumping and thrashing, of which Rudi invariably got the worst, because he would not defend himself, and, in fact, could not defend himself against the many stronger boys. So he crept away and hid as quickly as he could; meanwhile his cows wandered where they pleased and grazed on the neighbors' fields. This was sure to make trouble, and all agreed that Rudi was too[Pg 59] stupid even to herd cows, and no one would engage him any more. In the field work there was the same trouble. When the boys were hired to weed potatoes they thought it great fun to pelt each other with bunches of potato blossoms,—it made the time pass more quickly,—and of course each one paid back generously what he got. Rudi alone gave back nothing, but looked about anxiously in all directions to see who had hit him. That was exactly what amused the other boys; and so, amid shouts and laughter, he was pelted from all sides,—on his head, his back, or wherever the balls might strike. But while the others had time to work in the intervals, Rudi did nothing but dodge and hide behind the potato bushes. So at this work he was a failure, too, and young and old agreed that Rudi was too stupid for any kind of work, and that Rudi would never amount to anything. As he could earn nothing and would never amount to anything, he was treated accordingly by Joe's wife. Her own four little ones had hardly enough to eat, and so it usually happened that for Rudi there was nothing at all and he was told, "You can find something; you are old enough."

How he really existed no one knew, not even Joe's wife; yet he had always managed somehow. He never begged; he would not do that; but many[Pg 60] a good woman would hand out a piece of bread or a potato to the poor, starved little fellow as he went stealing by her door, not venturing to look up, much less to ask for anything. He had never in his life had enough to eat, but still that was not so hard for him as the persecution and derision he had to take from the other boys. As he grew older he became more and more sensitive to their ridicule, and his main thought at all times was to escape notice as much as possible. As he was never seen to take any part with the other children in work or play, people took it for granted that he was incapable of doing what the others did, and they declared that he was growing more stupid from day to day.

On a pleasant summer afternoon when the flies were dancing gayly in the sun, all the boys and girls of the Hillside were running about so excitedly that it was evident there was something particular on hand for that day. Jopp, the oldest one of them all, was leader of the assembly, and when all the company had come together he announced that they would now go to the dairy hut in the upper pasture, for this was the day for a "cheese party." But first of all they must decide who was to stay below and watch the cows while the others went to the party. That was, of course, a difficult question, for no one was inclined to sacrifice himself for the sake of the others and stay behind. Uli suggested that they might for once make Rudi take care of the cows, and in order to keep him mindful of his duties[Pg 62] they had best thrash him beforehand. His suggestion met with approval, and some of the leaders were already starting off to find the victim, when Lisi's voice was heard shrilly screaming above the others: "I think Uli's notion is a very stupid one, for we'll all have to pay for it when we come home and find the cows strayed off. You don't suppose that if Rudi is too stupid to watch two cows he would suddenly be smart enough to take care of twenty! We must draw lots and three of us must stay here with the cows. That's the only way."

Lisi's argument was convincing. The company took her advice, and three of the number were sentenced to stay behind, Uli himself being one of those upon whom the unhappy lot fell. Mumbling and grumbling he turned his back upon the exultant throng and sat down upon the ground,—the other two beside him,—while the rest, with shouts and laughter, went scampering up the mountain, wild with expectation.

The boys were always notified by Franz Martin of the coming of cheese day, and they, in turn, never failed to remind him if they thought he might forget, for it was a gala occasion to them. It was the day when Franz Martin trimmed his fresh cheeses, after these had been pressed, a soft mass, into the round wooden forms. When the weight[Pg 63] was laid upon it some of the cheesy mass would be pressed out from the edge of the mold in the form of a long, snow-white sausage. This was trimmed off, broken into pieces, and distributed among the children by the good-natured dairyman. The festival of cheese distribution occurred every two weeks throughout the summer and was hailed each time with loud expressions of joy.

While the children were settling their plans Rudi had been hiding behind a big thistle bush. He kept very quiet and did not move until he heard the whole company racing up the mountain; then he looked out very cautiously. The three who had been blackballed sat sulking on the ground with their backs toward him. The others were some distance up the mountain; their shouting and yodeling rang out merrily from above. Rudi, hearing their shouts, was suddenly seized with an overwhelming desire to join the cheese party. He stole out from behind the bush, cast a swift glance over toward the three grumblers, and then, softly and lightly as a weasel, slipped up the mountain side.

After scrambling up the last steep ascent he came upon a little fresh green plateau, and there stood the dairy hut; close beside it Clear Brook went tumbling down the slope. In the door of his hut stood Franz Martin with round, smiling face,[Pg 64] laughing at the strange capers that the boys and girls were making in their efforts to get to the feast. They had all reached the hut and were pushing one another forward in order to be as close as possible when the distribution should begin.

"Gently, gently," laughed Franz Martin; "if you all crowd into the hut, I shall have no room to cut the cheese, and that will be your loss."

Then he took a stout knife and went to the great round cheese that he had ready on the table. He trimmed it off quickly and came out with a long, snow-white roll, and, breaking off pieces from it, passed them about here and there, sometimes over the heads of the taller ones to the little fellows who could not push forward,—for Franz Martin wanted to be just and fair in his distribution.

Rudi had been standing in the outermost row, and when he tried to push forward he got a thump now on one side and now on the other. So he ran from side to side; but Franz Martin did not see him at all, because some bigger, stouter boy always crowded in ahead of him. Finally he got such a fierce blow from big, burly Jopp that he was flung far off to one side, almost turning a somersault before he got his footing. He saw that the distribution was almost at an end and that he was not to[Pg 65] get even a tiny bit of cheese roll, so he did not propose to get any more thumps. He went off by himself down the slope, where some young fir trees stood, and sat down under them. On the tallest of these trees a little bird was whistling forth gayly into the bright heavens, as though there were nothing else in the world but blue skies and sunshine.

Rudi, listening to the glad song, almost forgot his troubles of a moment ago; but he could not help looking over occasionally to the hut, where the shouting and laughter continued as the children chased each other about, trying to snatch pieces of cheese from each other. When Rudi saw them biting off delicious mouthfuls of the snowy mass, he would sigh and say to himself, "Oh, if I could only have a little taste!" for he had never had a single bite of cheese roll; never before had he even ventured so far as to join a party. But it availed him nothing, even if he summoned forth all his courage, as he had to-day, and so he came to the melancholy conclusion that he would never in his life get a taste of cheese roll. The thought was so disheartening to him that he no longer heard the song of the little bird, but sat under the bushes quite hopeless.

Now the feast at the hut was ended and the revelers came down the slope with a rush, each[Pg 66] one trying to get ahead of the others, their eagerness leading to many a roll and tumble down the steep places. As Hans went shouting past the group of fir trees he discovered Rudi half hidden under them.

"Come out of there, old mole! You must play with us!" he shouted; and Rudi understood what he was expected to "play" with them.

He was to stand as block, so that the others might jump over him. He was usually knocked over at every jump, and he would much rather have stayed in his little retreat; but he knew what was in store for him if he did not follow their commands, so he came out obediently.

"How much cheese roll did you get?" Hans yelled at him.

"None," answered Rudi.

"What a simpleton!" yelled Hans still louder. "He comes up here expressly to get cheese roll, and then he goes away without any!"

"You stupid Rudi!" they shouted at him from all sides, and the big boys began jumping over him, so that he had hard work getting on his feet as fast as they knocked him over. Sometimes he would roll down the hill with a whole clump of them, and they would all continue rolling until some chance obstacle brought them to their feet once more.[Pg 67] After their boisterous descent they all ran in different directions, each one to seek his own cows. Rudi ran off by himself, far away from them all, for now he expected even worse treatment from the three unfortunates, because he had deserted them. He slipped down the hill to the swamp hole, and crouched down so that he could not be seen from above or below.

The swamp hole was a hollow where water gathered in spring and fall and made the ground swampy. Now it was quite dry,—a pleasant spot, where fine, dark red strawberries ripened in the warm sun that beat against the side of the hollow. But Rudi trembled as long as he was in the neighborhood of houses and herd boys, for the latter might discover him at any moment and renew their persecutions. He sat there trembling at every sound, for he kept thinking, "Now they are coming after me." Suddenly he was filled with a delightful memory of the little nook under the fir trees and of the whistling bird overhead. He felt irresistibly drawn to it; he must go back to that spot.

He ran with all his might up the mountain, never stopping once until he had reached the group of trees and had slipped in under them. The only opening in this retreat was on the outer side, toward the valley, so he felt safely hidden. All around him[Pg 68] was great silence; no sound came up from below; only the little bird was still whistling its merry tune. The sun was setting; the high snow peaks began to glimmer and to glow, and over the whole green alp lay the golden evening light. Rudi looked about him in silent wonder; an unknown feeling of security and comfort came over him. Here he was safe; there was no one to be seen or heard in any direction.

He sat there a long time and would have liked never to go away again, for he had never felt so happy in his life. But he heard heavy steps coming from the hut behind him. It was the herdsman; he was coming along carrying a small bucket; he was probably going to the stream to fetch water. Rudi tried to be as quiet as a mouse, for he was so used to having every one scold and ridicule him that he thought the herdsman would do the same, or at least would drive him away. He huddled down under the bushes; but the branches crackled. Franz Martin listened, then came over and looked under the fir trees.

"What are you doing in there, half buried in the ground?" asked the herdsman with smiling face.

"Nothing," answered Rudi in a faint voice that trembled with fear.

"Come out, child! You need not be afraid, if you have done nothing wrong. Why are you [Pg 70]hiding? Did you creep in here with your cheese roll so that you could eat it in peace?"

"No; I had no cheese roll," said Rudi, still trembling.

"You didn't? and why not?" asked the herdsman in a tone of voice that no one had ever used toward Rudi before, arousing an altogether new feeling in him,—trust in a human being.

"They pushed me away," he answered, as he arose from his hiding place.

"There, now," continued the friendly herdsman; "I can at least see you. Come a little nearer. And why don't you defend yourself when they push you away? They all push each other, but every one manages to get a turn, and why not you?"

"They are stronger," said Rudi, so convincingly that Franz Martin could offer no further argument in the matter. He now got a good look at the boy, who stood before the stalwart herdsman like a little stick before a great pine tree. The strong man looked down pityingly at the meager little figure, that seemed actually mere skin and bones; out of the pale, pinched face two big eyes looked up timidly.

"Whose boy are you?" asked the herdsman.

"Nobody's," was the answer.

"But you must have a home somewhere. Where do you live?"

"With Poor Grass Joe."

Franz Martin began to understand. "Ah! so you are that one," he said, as if remembering something; for he had often heard of Stupid Rudi, who was of no use to anybody, and was too dull even to herd a cow.

"Come along with me," he said sympathetically; "if you live with Joe, no wonder you look like a little spear of grass yourself. Come! the cheese roll is all gone, but we'll find something else."

Rudi hardly knew what was happening to him. He followed after Franz Martin because he had been told to, but it seemed as though he were going to some pleasure, and that was something altogether new to him. Franz Martin went into the hut, and taking down a round loaf of bread from an upper shelf, he cut a big slice across the whole loaf. Then he went to the huge ball of butter, shining like a lump of gold in the corner, and hacked off a generous piece. This he spread over the bread and then handed the thickly buttered slice to Rudi. Never in all his life had the boy had anything like it. He looked at it as though it could not possibly belong to him.

"Come outside and eat it; I must go for water," said Franz Martin, while he watched with twinkling eyes the expression of joy and amazement[Pg 72] on the child's face. Rudi obeyed. Outside he sat down on the ground, and while the herdsman went over to Clear Brook he took a big bite into his bread, and then another and another, and could not understand how there could be anything in the world so delicious, and how he could have it, and how there could still be some of it left,—for it was a huge piece. The evening breeze played softly about his head and swayed the young fir trees to and fro, where the little bird was still sitting on its topmost branch and singing forth into the golden evening sky. Rudi's heart swelled with unknown happiness and he felt like singing with the little bird.

Franz Martin had meanwhile gone back and forth several times with his little pail. Each time he had stood awhile by the stream and looked about him. The mountains no longer glowed with the evening light, but now the moon rose full and golden from behind the white peaks. The herdsman came back to the hut and stood beside Rudi, who was still sitting quietly in the same spot.

"You like it here, do you?" he asked with a smile. "You have finished your supper, I see. What do you say to going home? See how the moon has come to light your way."

Rudi had really had no thought of leaving, but now he realized that it would probably be necessary.[Pg 73] He arose, thanked Franz Martin once more, and started off. But he got no farther than the little fir trees; something held him back. He looked around once more, and finding that the herdsman had gone into the cottage and could not see him, he slipped in quickly under the shadowy bushes. Franz Martin was the only person in all the world who had ever been kind or sympathetic toward him. This had so touched the boy that he could not go away; he felt he must stay near this good man. Hidden by the branches, Rudi peeped through an opening to see if he might not get another glimpse of his friend.

After a little while Franz Martin did come out again. He stood before the door of his hut and with folded arms looked out over the silent mountain world as it lay before him in the soft moonlight. The face of the herdsman, too, was illumined by the gentle light. Any one seeing the face at that moment, with its expression of peaceful happiness, would have been the better for it. The man folded his hands; he seemed to be saying a silent evening prayer. Suddenly he said in a loud voice, "God give you good night," and went into his hut and closed the door. The good-night message must have been for his old friends the mountains, and the people whom he held in his heart, though he[Pg 74] could not see them. Rudi had been looking on with silent awe. If Franz Martin attracted every one who ever knew him by his serene, pleasant ways, what love and admiration must he have aroused in the heart of little Rudi, whose only friend and benefactor he was!

When all was dark and quiet in the hut, Rudi rose and ran down the mountain as fast as he could.

It was late, and there was no light to be seen in the cottage; but he did not mind, for he knew the door was never locked. He went quietly into the house and crept into his bed, which he shared with Uli. The latter was now sleeping heavily, after having expressed his satisfaction at Rudi's absence by exclaiming, "How lucky that Rudi is getting too stupid even to find his bed! I have room to sleep in comfort for once."

Rudi lay down quietly, and until his eyes closed he still saw Franz Martin before him, standing in the moonlight with folded hands. For the first time in his life Rudi fell asleep with a happy heart.

The following day was Sunday. The community of the Hillside belonged to the Beckenried church in the valley. It was a long walk to church, but the children were obliged to go to Sunday school regularly, for the pastor was stern in insisting that the children must be properly brought up. So on that day the whole troop wended its way as usual down the hill, and soon they were all sitting as quietly as possible on the long wooden benches in church. Other groups had assembled; the pastor got them all settled, and then began. He said that he had told them the last time about the life hereafter, and as his glance fell on Rudi, he continued: "Now, Rudi, I will ask you something that you can surely answer, even if we cannot expect much of you. Where will all good Christians—even the poorest and lowliest of us, if we have led good lives—finally be so happy as to know no more sorrow?"

"In the hut of the high pasture," Rudi replied without hesitating.

But he heard snickering all about him and looked around timidly. Mocking faces met him on every side and the children all seemed bursting with suppressed laughter. Rudi bent down his head as though he wished to crawl into the floor. Of the pastor's previous lesson he had heard nothing, because he had been engaged the whole hour in dodging sly attacks from the rear. Now he had answered the question entirely from his own experience.

The pastor looked at him steadily; but when he saw that Rudi had no thought of laughing, but was sitting there in fear and mortification, he shook his head doubtfully and said, "There is nothing to be done with him."

When the lesson was over the whole crowd came running after Rudi, laughing noisily and shouting, "Rudi, were you dreaming of the cheese party in Sunday school?" and "Rudi, why didn't you tell about cheese rolls?"

The boy ran away like a hunted rabbit, trying to escape from his noisy tormentors. He ran up the hill, where he knew the others would not pursue him, for they meant to pass the pleasant summer afternoon down in the village.

He ran farther and farther up the mountain. For all his trials he had now a solace: he could fly to the upper pasture and console himself with the[Pg 77] sight of Franz Martin's friendly face. There he could sit very quietly in his little retreat and be safe from pursuit. As he sat there to-day under the fir trees, the little bird was again singing overhead. The snow peaks glistened in the sun, and here and there a clear mountain stream made its way between green slopes of verdure.