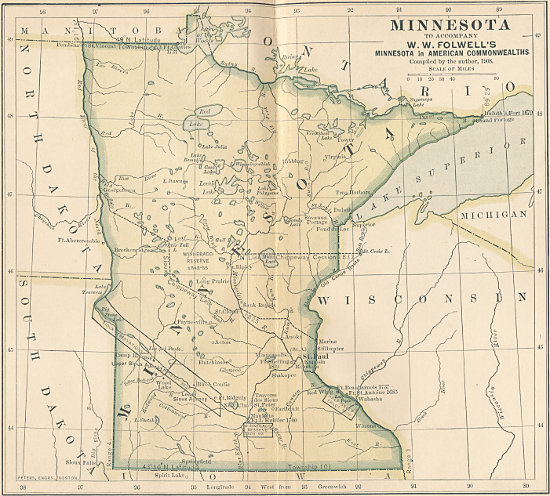

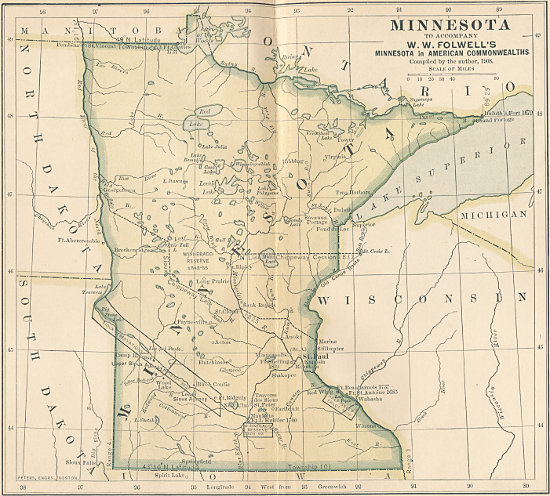

MINNESOTA

TO ACCOMPANY

W. W. FOLWELL’S

MINNESOTA in AMERICAN COMMONWEALTHS

Compiled by the author, 1908.

Title: Minnesota, the North Star State

Author: William Watts Folwell

Release date: December 20, 2014 [eBook #47725]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by K Nordquist and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This book was

produced from scanned images of public domain material

from the Google Print project.)

MINNESOTA

TO ACCOMPANY

W. W. FOLWELL’S

MINNESOTA in AMERICAN COMMONWEALTHS

Compiled by the author, 1908.

If this compend of Minnesota history shall be found a desirable addition to those already before the public, it will be due to the good fortune of the writer in reaching original sources of information not accessible to his predecessors.

The most important of them are: the papers of Governor Alexander Ramsey, in the possession of his daughter, Mrs. Marion R. Furness; the letter-books and papers of General H. H. Sibley, preserved in the library of the Minnesota Historical Society; some hundreds of letters saved by Colonel John H. Stevens, and deposited by him in the same library; the papers of Ignatius Donnelly, in the hands of his family; the great collection of Green Bay and Prairie du Chien papers belonging to the Wisconsin Historical Society; the remarkable group of early French documents owned by the Chicago Historical Society; and finally, the priceless collection of Minnesota newspapers preserved by the Minnesota Historical Society.

Grateful acknowledgments are offered to many citizens who have given information out of their own knowledge, or have directed the writer to other sources. Among “old Territorians” who have rendered invaluable aid must be named Simeon P. Folsom, John A. Ludden, Joseph W. Wheelock, Benjamin H. Randall, A. L. Larpenteur, A. W. Daniels, John Tapper, and William Pitt Murray. The last named has put me under the heaviest obligation.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | The French Period | 1 |

| II. | The English Dominion | 29 |

| III. | Minnesota West Annexed | 42 |

| IV. | Fort Snelling Established | 54 |

| V. | Explorations and Settlements | 70 |

| VI. | The Territory Organized | 86 |

| VII. | Territorial Development | 108 |

| VIII. | Transition to Statehood | 133 |

| IX. | The Struggle for Railroads | 159 |

| X. | Arming for the Civil War | 178 |

| XI. | The Outbreak of the Sioux | 190 |

| XII. | The Sioux War | 205 |

| XIII. | Sequel to the Indian War | 222 |

| XIV. | Honors of War | 240 |

| XV. | Revival | 254 |

| XVI. | Storm and Stress | 267 |

| XVII. | Clearing Up | 304 |

| XVIII. | Fair Weather | 333 |

| XIX. | A Chronicle of Recent Events | 340 |

| Index | 367 |

The word Minnesota was the Dakota name for that considerable tributary of the Mississippi which, issuing from Big Stone Lake, flows southeastward to Mankato, turns there at a right angle, and runs on to Fort Snelling, where it empties into the great river. It is a compound of “mini,” water, and “sota,” gray-blue or sky-colored. The name was given to the territory as established by act of Congress of March 3, 1849, and was retained by the state with her diminished area.

If one should travel in the extension of the jog in the north boundary, west of the Lake of the Woods, due south, he could hardly miss Lake Itasca. If then he should embark and follow the great river to the Iowa line, his course would have divided the state into two portions, not very unequal in extent. The political history of the two parts is sufficiently diverse to warrant a distinction between Minnesota East and Minnesota West. England never owned west of the river, Spain gained no foothold east of it. France, owning on both sides, yielded Minnesota East to England in 1763, and sold Minnesota West to the United States in 1803. Up to the former date, the whole area was part of New France and had no separate history.

Although the French dominion existed for more than two hundred years, it is not important for the present compendious work that an elaborate account be made of their explorations and commerce. They made no permanent settlement on Minnesota soil. No institution, nor monument, nor tradition, even, has survived to determine or affect the life of the commonwealth. It will be sufficient to summarize from an abounding literature the successive stages of the French advance from the Atlantic to the Mississippi, their late and brief efforts to establish trade and missions in the upper valley, and the circumstances which led to their expulsion from the American continent.

It is now well known that in the first decade of the sixteenth century Norman and Breton fishermen were taking cod in Newfoundland waters, and it is reasonably surmised that they had been so engaged before the Cabots, under English colors, had coasted from Labrador towards Cape Cod in 1497. The French authorities, occupied with wars, foreign and domestic, were unable to participate with Spain, England, and Portugal in pioneer explorations beyond seas. It was not till 1534 that Francis I, a brilliant and ambitious monarch, dispatched Jacques Cartier, a daring navigator, to explore lands and waters reported of by French fishermen, and, if possible, to discover the long-sought passage to Cathay. In the summer of that year Cartier made the circuit of the Gulf of St. Lawrence, and returned to France disappointed of his main purpose. His neglect to enter the great river flowing into the gulf is unexplained. At two convenient places he went ashore to set up ceremonial crosses and proclaim the dominion of his king. In the following year (1535), on a second expedition he ascended the St. Lawrence River to the Huron village Hochelaga, on or near the site of Montreal. He wintered in a fort built near Quebec, where one fourth of his crew died of scurvy. In May, 1536, after setting up another cross with a Latin inscription declaring the royal possession, he sailed away for home. Five years later (1541) Cartier participated in still another expedition, which, prosecuted into a third year, resulted disastrously. The king had spent much money, but the passage to China had not been found, no mines had been discovered, no colony had been planted, no heathen converted.

Throughout the remainder of the sixteenth century the French kings were too much engrossed in great religious wars, fierce and bloody beyond belief but for existing proofs, to give thought or effort to extending their dominion in the New World. The treaty of Vervins with Spain and the Edict of Nantes, both occurring in 1598, gave France an interval of peace within and without. Henry IV (“Henry of Navarre”) at once turned his eyes to the coasts of America, on which as yet no Europeans had made any permanent settlements. His activity took the form of patronizing a series of trading voyages. On one of these, which sailed in 1603, he sent Samuel Champlain, then about thirty-five years of age, a gallant soldier and an experienced navigator. He had already visited the West Indies and the Isthmus of Darien, and in his journal of the voyage had foreshadowed the Panama Canal. He was now particularly charged with reporting on explorations and discoveries. On this voyage Champlain ascended the St. Lawrence to Montreal and vainly attempted to surmount the Lachine Rapids. On the return of the expedition in September of the same year, Champlain laid before the king a report and map. They gave such satisfaction as to lead to a similar appointment on an expedition sent out the following year. For three years Champlain was occupied in exploring and charting the coasts of Nova Scotia and New England, a thousand miles or thereabout.

In 1608 he went out in the capacity of lieutenant-governor of New France, a post occupied for the remaining twenty-seven years of his life, with the exception of a brief interval. On July 3 he staked out the first plat of Quebec. His trifling official engagements left him ample leisure to prosecute those explorations on which his heart was set; chief of them the road to China.

In 1609, to gain assistance of the Indians in his neighborhood, he joined them in a war-party to the head of the lake to which he then gave his name. A single volley from the muskets of himself and two other Frenchmen put the Iroquois, as yet unprovided with firearms, to headlong rout. Six years later he led a large force of Hurons from their homes in upper Canada between Lake Simcoe and Georgian Bay, across Lake Ontario, to be defeated by the well-fortified Iroquois. The notes of his expedition added the Ottawa River, Lake Nipissing, the French River, Lake Huron, and Lake Ontario to his map. Could Champlain have foreseen the disasters to follow for New France and the Huron nation, he would not have made the Iroquois his and their implacable enemy. He made no further journeys westward in person, but adopted a plan of sending out young men, whom he had put to school among native tribes, to learn their languages and gather their traditions and surmises as to regions yet unvisited. One of them, Etienne Brulé, who had been his interpreter on the second expedition against the Iroquois, and detached before the battle on an embassy to an Indian tribe, did not return till after three years of extensive wanderings. He showed a chunk of copper which he declared he had brought from the shore of a great lake far to the west, nine days’ journey in length, which discharged over a waterfall into Lake Huron.

In 1634 another of Champlain’s apprentices, Jean Nicollet by name, passed through the Straits of Mackinaw and penetrated to the head of Green Bay and possibly farther. He may have been at the Sault Sainte Marie. So confident was he of reaching China that he took with him a gorgeous mandarin’s robe of damask to wear at his court reception. Attired in it he addressed the gaping Winnebagoes, putting a climax on his peroration by firing his pistols. Champlain’s map of 1632 showed his conjectured Lake Michigan north of Lake Huron. Nicollet gave it its proper location.

Champlain’s stormy career closed at Christmas, 1635. The honorable title of “Father of New France” rightly belongs to him, in spite of the fact that in none of his great plans had he achieved success. He had not found the road to the Indies, the savages remained in the power of the devil, and no self-supporting settlement had been planted. Quebec’s population did not exceed two hundred, soldiers, priests, fur-traders and their dependents. There was but one settler cultivating the soil.

Exploration languished after Champlain’s death, and for a generation was only incidentally prosecuted by missionaries and traders. In 1641 two Jesuit fathers, Jogues and Raymbault, traveled to the Sault Sainte Marie, and gave the first reliable account of the great lake.

From the earliest lodgments of white men on the St. Lawrence the fur-trade assumed an importance far greater than the primitive fisheries. In the seventeenth century the fashion of fur-wearing spread widely among the wealthier people of Europe. The beaver hat had superseded the Milan bonnet. No furs were in greater request than those gathered in the Canadian forests. A chief reason for the long delay of cultivation in the French settlements was the profit to be won by ranging for furs. Montreal, founded in 1642 as a mission station, not long after became, by reason of its location at the mouth of the Ottawa, the entrepôt of the western trade. The business took on a simple and effective organization. Responsible merchants provided the outfit, a canoe, guns, powder and lead, hulled corn and tallow for subsistence, and an assortment of cheap and tawdry merchandise. Late in the summer the “coureurs des bois” set out for the wilderness. Those bound for the west traveled by the Ottawa route in large companies, for better defense against skulking Iroquois. On reaching Lake Huron, they broke up, each crew departing to its favorite haunts.

The chances for large profits naturally attracted to this primitive commerce some men of talent and ambition. In 1656 two such came down to Montreal piloting a flotilla of fifty Ottawa canoes deeply laden with precious furs. They had been absent for two years, had traveled five hundred leagues from home, and had heard of various nations, among them the “Nadouesiouek.” The author of the Jesuit Relation for the year speaks of them as “two young Frenchmen, full of courage,” and as the “two young pilgrims,” but suppresses their names. Again, in 1660 two Frenchmen reach Montreal from the upper countries, with three hundred Algonquins in sixty canoes loaded with furs worth $40,000. The journal of the Jesuit fathers gives the name of one of them as of a person of consequence, Des Groseilliers; and says of him, “Des Grosillers wintered with the nation of the Ox ... they are sedentary Nadwesseronons.”

The two Frenchmen of 1660 are now believed to have been Medard Chouart, Sieur des Groseilliers, and Pierre d’Esprit, Sieur de Radisson, both best known by their titles. The latter was the younger man, and brother to Groseilliers’ second wife. In 1885 the Prince Society of Boston printed 250 copies of the “Voyages of Peter Esprit Radisson,” written by him in English. The manuscript had lain in the Bodleian Library of Oxford University for nearly two hundred years. No doubt has been raised as to its authenticity. While the accounts of the different voyages are not free from exaggerations, not to say outright fabrications, the reader will be satisfied that the writer in the main told a true story of the wanderings and transactions of himself and comrade. These two men a few years later went over to the English and became the promoters of the Hudson’s Bay Company.

If Radisson’s story be true, he and Groseilliers were the first white men to tread the soil of Minnesota. As he tells it, the two left Montreal in the month of August, 1658, and after much trouble with the “Iroquoits” along the Ottawa, reached the Sault Sainte Marie, where they “made good cheare” of whitefish. Embarking late in the same season, they went along “the most delightful and wonderous coasts” of Lake Superior, passed the Pictured Rocks, portaged over Keweenaw Point, and made their way to the head of Chequamegon Bay. Here they built a “fort” of stakes in two days, which was much admired by the wild men. Having cached a part of their goods, they proceeded inland to a Huron village on a lake believed to be Lake Courte Oreille, in Sawyer County, Wisconsin, where they were received with great ceremony. At the first snowfall the people departed for their winter hunt, and appointed a rendezvous after two months and a half. Before leaving the village the Frenchmen sent messengers “to all manner of persons and nations,” inviting them to a feast at which presents would be distributed. The best guess locates this rendezvous on or near Knife Lake, in Kanabec County, Minnesota. That was then Sioux country, and the people thereabout were long after known as Isantis or Knife Sioux, probably because they got their first steel knives from these Frenchmen. While at their rendezvous eight “ambassadors from the nation of the Beefe” (i. e. Buffalo, of course) came to give notice that a great number of their people would assemble for the coming feast. They brought a calumet “of red stone as big as a fist and as long as a hand.” Each ambassador was attended by two wives carrying wild rice and Indian corn as a present. For the feast a great concourse of Algonquin tribes gathered and prepared a “fort” six hundred paces square, obviously a mere corral of poles and brush. A “foreguard” of thirty young Sioux, “all proper men,” heralded the coming of the elders of their village, who arrived next day “with incredible pomp.” Grand councils were held, followed by feasting, dancing, mimic battles, and games of many sorts, including the greased pole. As described, this was no casual assemblage, but a great and extraordinary convocation. It lasted a fortnight.

The two Frenchmen now made seven small journeys “to return the visit of the Sioux, and found themselves in a town of great cabins covered with skins and mats, in a country without wood and where corn was grown.” The account of this six weeks’ trip is brief and indefinite. The conjecture that Groseilliers and Radisson traveled a hundred and fifty miles, more or less, into the prairie region west of the Mississippi, either by way of the Minnesota or the Crow Wing rivers, has slight support. The account may have been invented from information obtained of the Sioux at the convocation.

In the early spring of 1660 the two adventurers returned to Chequamegon Bay, whence they continued to Montreal without notable incident. In his narrative Radisson injects after the return from the nation of the Beefe a story of an excursion to Hudson’s Bay, occupying a year, which is probably fictitious. The time occupied by the whole journey is well known and could not have included a trip to the “Bay of the North.” Still, it is reasonably certain that Groseilliers and Radisson were in Minnesota twenty years before Duluth.

The reader will have already inquired whether the two young Frenchmen of 1654-56, unnamed, might not have been the same with these of 1658-60. This inquiry was frequently made before the discovery of Radisson’s narrative. The question was settled by that document. Radisson gives a separate and circumstantial account of a three years’ journey of trade and exploration to the west taken by himself and his brother-in-law in 1654. Leaving Montreal in the summer of that year, Groseilliers and Radisson, as the story runs, taking the usual Ottawa River route, reached the Straits of Mackinaw in the early fall. They passed the winter about Green Bay, Wisconsin. The following summer they coasted Lake Michigan and proceeded southward through a country “incomparable, though mighty hot,” to the shores of a great sea. They found “a barril broken, as they use in Spaine.” They passed the summer on “the shore of the Great sea.” Returning to the north, they spent a winter with the Ottawas on the upper Michigan peninsula. As the excursion to Hudson’s Bay already mentioned was a fiction, so is this to the Gulf of Mexico. The traders could not have been absent from the French settlement more than two years. It is in the early spring of 1655, therefore, that we find them setting out from their winter quarters to countries more remote. The essence of Radisson’s text is as follows: “We ... thwarted a land of allmost fifty leagues.... We arrived, some 150 of us men and women, to a river-side, where we stayed 3 weeks making boats.... We went up ye river 8 days till we came to a nation called ... the Scratchers. There we gott some Indian meale and corne ... which lasted us till we came to the first landing Isle. There we weare well received againe.”

Upon this indefinite passage has been put the following interpretation. The land journey of fifty leagues (about one hundred and forty miles) took the traders to the east bank of the Mississippi near the southeast corner of Minnesota, where they built boats; the nation who furnished provisions resided about the site of Winona, and the “first landing Isle” was Prairie Island, between Red Wing and Hastings. If this interpretation shall at length be confirmed, Groseilliers and Radisson were in Minnesota twenty-four years before Duluth. Subsequent passages of the narrative lend it some support.

These able and enterprising characters deserve, however, not the least degree of credit as explorers. If they saw the Mississippi and in the later voyage penetrated beyond the Big Woods, they studiously concealed their knowledge. They left no maps, and for no assignable reason suppressed a discovery which would have given them a world-wide fame.

When Cardinal Mazarin died, in 1661, Louis XIV, then twenty-two years of age, stepped on to the stage, “every inch a king.” He willingly listened to the suggestion of Colbert, his new minister, that it was time for France to follow English example and establish a colonial system for profit and glory. The Company of New France, promoted by Richelieu, which for nearly forty years had governed Canada, were quite content to surrender their franchises. In 1663 the colony was made a royal province. Associated with the governor a so-called “intendant of justice and finance” was provided in the new administration. The first incumbent was Jean Baptiste Talon, a man of brains, energy, and ambition. He was no sooner on the ground than he began to conceive great projects for extending the French dominion, expanding commerce, and fostering settlements. Colbert, although he sympathized, was obliged to restrain him and suggest that “the King would never depopulate France to people Canada.”

Rumors were multiplying of great openings for trade and missions along and beyond the great lakes. Talon was keen to follow up and verify them. In 1665 the Jesuit father Claude Allouez established a mission at La Pointe on Chequamegon Bay. Upon an excursion to the head of the lake (Superior) he saw some of the Nadouessiouek (Sioux) Indians, dwellers toward the great River Mississippi, in a country of prairies. They gave him some “marsh rye,” as he called their wild rice.

Four years later Father Jacques Marquette succeeded Allouez in that mission. He also heard stories of a great river flowing to a sea, on which canoes with wings might be seen. The Jesuit Relation of 1670-71 gives reports from Indians of a great river which “for more than three hundred leagues from its mouth is wider than the St. Lawrence at Quebec;” and people dwelling near its mouth “have houses on the water and cut down trees with large knives.” In the summer of 1669, Louis Joliet, whom Talon had sent to Lake Superior to search for copper, returned; and it was then, probably on his suggestion, that Talon resolved that it was time for the French to plant a military station at the Sault Sainte Marie, a point of notable strategic importance. He determined also to make an impression of French power on the Indians of the West. In the following year he dispatched Nicholas Perrot, of whom we are to hear later, to summon the Pottawattamies, the Winnebagoes, and other accessible nations to a grand convocation at the Sault Sainte Marie in the spring of 1671. To represent the government, Simon François Daumont, Sieur de St. Lusson, was commissioned and took his journey in October, 1670.

On the 14th of June, 1671, the appointed day, the council was held. Fourteen Indian nations were represented. Among the French present were Joliet, Father Allouez, and Perrot. The central act was the proclamation by St. Lusson of King Louis’s dominion over “lakes Huron and Superior, ... all countries, rivers, lakes and streams, contiguous and adjacent thereto, with those that have been discovered, and those which may be discovered hereafter, ... bounded by the seas of the north, west, and south.” This modest claim covered perhaps nine tenths of North America. As usual, a big wooden cross was erected and blest. A metallic plate bearing the king’s arms was nailed up, and a “procès-verbal” drawn and signed. In that day such a proclamation gave title to barbarian lands until annulled in battle by land or sea. Father Allouez made a speech, which has been preserved, describing the power and glory of the French king in extravagant terms.

Talon could not rest. He was on fire to unlock the secret of the great river and extend the French dominion to the unknown sea into which it might empty. In 1672, with the approval of Colbert, he planned an expedition to penetrate the region in which it was supposed to flow. Joliet was chosen to lead, and at the end of the year he was at Mackinaw. It was probably no accident that Père Marquette had just been transferred from La Pointe to that station. But the enthusiastic intendant was to close his Canadian career. In the very same year Count Frontenac, the greatest figure in Canadian history, came over to be governor. He was already past fifty, had seen many campaigns, and had wasted his fortune at court. He, too, had ideas, and an ambition to do great things for Canada and France. There was not room enough in the province for two such men as Talon and he. The intendant obtained his recall, and disappeared from the scene.

Frontenac at once adopted Talon’s scheme, and gave Joliet leave to go. Accompanied by Marquette he struck the great river at Prairie du Chien, June 17, 1673, and then followed its flow far enough to satisfy himself that it ran to the Mexican gulf. Joliet’s great map has a truly modern aspect. The importance of this discovery of the Mississippi for the present purpose is, that it was by way of the great river that the French, with a notable exception, pushed their way into Minnesota.

A company of Canadian merchants resolved to attempt an opening of trade about and beyond the head of Lake Superior, and selected as their agent Daniel Greyloson, the Sieur Duluth, a man of ability and enterprise. He evidently received some kind of public character from Frontenac, whose enemies insinuated that he was to be a sharer in profits. In the spring of 1679 Duluth penetrated to the shores of Mille Lacs, and in a great Sioux village which he understood to be called “Kathio,” on July 2 he planted the king’s arms and took possession in the royal name. Duluth, therefore, was the first white man in Minnesota not ashamed to report and record the fact. In the same season he retraced his steps to the head of the lake, and passed down the north shore to Pigeon River, which forms part of the Canadian boundary. There, on the left bank of that river, he built a trading post, on the site afterwards occupied by Fort William.

The next dash into the territory of the North Star State was directed by one who has been called the most picturesque figure in American history, Réné Robert Cavalier, Sieur de la Salle. At the age of twenty-three he broke away from the Jesuits with whom he was in training, and set sail for Canada with four hundred francs in his pocket, in the year 1663. When Frontenac came, nine years later, he found in young La Salle a man after his own heart, and sent him to France in 1674 to secure royal support for further explorations. Such support, then withheld, was vouchsafed four years later, when La Salle was again in Paris on the same errand. By a royal patent signed May 12, 1678, La Salle was authorized to extend the scope of Joliet’s exploration to the Gulf of Mexico and to pay his expenses by trade, provided he kept off the preserves of the Montreal traders.

With the king’s patent in hand, it was easy to attract capital and enlist volunteers. Early in the fall of the same year, La Salle was back in Canada with his men and outfit, and soon set out for the west. After battling with a series of delays and discouragements which need not be narrated, the undaunted leader established himself in a fort built on the east bank of the Illinois River, near Peoria, Illinois, in the winter of 1680. There is no record that La Salle had been authorized to explore the upper Mississippi, but he was not the man to lose a good opportunity for lack of technical instructions. To lead an exploring party up that stream he chose Michael Accault, an experienced voyageur, “prudent, brave, and cool,” and gave him two associates: Antoine Auguelle, called the Picard du Gay, was one; the other was the now famous Father Louis Hennepin, a Franciscan friar of the Recollet branch, who came over in the same ship with La Salle in 1678. He had wandered in many lands, knew some Indian dialects, and shared La Salle’s passion for adventure.

In a bark canoe laden with their arms, personal belongings, and some packs of merchandise which served for money between whites and Indians, the little party set out, after priestly benediction, on February 28, 1680. They dropped down the Illinois to its mouth, and took their toilsome way against the current of the Mississippi. On April 11, when near the southern line of Minnesota, they encountered a fleet of thirty-three canoes carrying a war-party intent on mischief to certain Illinois tribes. The savages frightened but did not harm the Frenchmen. Accault was able to inform them that the Illinois Indians had crossed the river to hunt. They therefore turned homewards, taking the explorers with them. At the end of the month the flotilla rounded up, as is believed, at the mouth of Phalen’s Creek, at St. Paul. Here they abandoned their canoes and set out overland by a trail which would naturally follow the divide between the waters of the Mississippi and the St. Croix, for their villages on Mille Lacs. On May 5 they arrived, and the Frenchmen, compelled to sell their effects to their captors, were sent to separate villages. The friar lost his portable altar and brocade vestments; otherwise they were not unkindly treated. Some weeks passed, when Hennepin and Auguelle were allowed to take a canoe and start for the mouth of the Wisconsin, where La Salle promised to send supplies. Accault preferred to join a great hunting party that was about setting out. Hennepin and his comrade left the hunters at the mouth of Rum River, and paddling with the current soon found themselves at the falls called by the Dakotas Mi-ni-i-ha-ha, the rushing water, then first seen by white men, to which he gave the name of his patron saint, Anthony of Padua. His description of the cataract and surroundings is reasonably accurate, although he greatly exaggerated its height. No rival has claimed the credit of their discovery. Passing on down the river, they met an Indian who informed them that the hunting party was not far away, on some tributary. They abandoned their lonesome journey and joined the hunters, who, the hunt over, were about returning to their villages.

We left Duluth in his fort at the mouth of Pigeon River in the fall of 1679. He wintered there, and, as he relates, dissatisfied with his discoveries of the previous summer, resolved on a new adventure. When the season of 1680 opened he set out with four Frenchmen and two Indian guides, ascended the Bois Brulé River, portaged over to the head of the St. Croix, and followed that down to Point Douglass, where he doubtless recognized the great river. Here he learned that but a short time before two Frenchmen had passed down in a canoe. He instantly followed, and after forty-eight hours of lively paddling met the Sioux hunters and with them Accault, Auguelle, and Hennepin. All the French now traveled with the Indians to their villages on Mille Lacs, this time up the Mississippi and Rum rivers. The season was now far advanced and Duluth was obliged to give up his project of a journey to “the ocean of the west,” which he believed to be not more than twenty days’ march distant. Furnished with a rude but truthful map sketched by one of the Sioux chiefs, and promising the Indians to return to trade, the eight white men took their departure for home by Prairie du Chien and Green Bay. Hennepin returned to France and in 1682 published his “Description of Louisiana.” He knew how to tell an interesting story, and stuck as close to the truth as most annalists of his day. He assumed to have been the leader of the exploring party. Fifteen years later there was published in Holland a book under the title of “A New Discovery of a Great Country.” It contained all the matter of Hennepin’s “Description,” and some one hundred and fifty pages more. These interpolated into the original story a journey of more than three thousand miles in thirty days, from the mouth of the Illinois to the Gulf of Mexico and back, before ascending the Mississippi. If Hennepin himself wrote the injected pages, he was the shameless liar which he has been frequently declared to be. There is room, however, for the suggestion that the added pages were the work of some literary hack employed by dishonest publishers to give the book the appearance of a new one; but a good degree of charity is necessary to entertain this theory, as there is no record of any disavowal by Hennepin. Granting Hennepin to have been the leader, it must be remembered he was an agent of La Salle. La Salle’s foresight and enterprise sent him to the land of the Dakotas and to the Falls of St. Anthony.

It was not till the winter of 1682 that La Salle was able to embark from his fort at Peoria. Sixty days of easy canoe navigation brought him to one of the islands at the mouth of the Mississippi. There in the month of April, under his royal patent, he set up a cross and proclaimed the sovereignty of Louis le Grand over the whole valley of the great river and all its tributaries. On the “procès-verbal” of that transaction rests every land title in Minnesota.

Duluth and La Salle by means of Accault’s reports revealed to Count Frontenac the magnificence of the upper Mississippi region, and Father Hennepin’s book, dedicated to the king, seems to have inspired Louis XIV with a desire to occupy and possess that goodly land. In 1686 the able and experienced Nicholas Perrot, who had been appointed commandant of the west with orders to make an establishment there, built a fort on the east bank of Lake Pepin, and called it Fort St. Antoine. The site has been clearly identified about two miles below the “Burlington” railroad station of Stockholm, Pepin County, Wisconsin. Summoned the following year to lead a contingent of voyageurs and savages in the campaign against the Iroquois in the Genesee valley of western New York, he did not return to Fort St. Antoine till late in 1688. To satisfy any lingering doubts about the legitimate sovereignty of those parts, he made formal proclamation of his king’s lordship over all the countries and rivers he had seen and would see. Perrot was too useful a man to be left in the wilderness, and was presently ordered on other service and his fort left empty.

Another attempt at settlement on the upper Mississippi was made by a Canadian, Pierre Le Sueur, an associate of Perrot, who in 1694 established a trading post on Prairie Island in the Mississippi, about nine miles below Hastings, the same on which Groseilliers and Radisson are imagined to have camped in 1655. Le Sueur stayed over one winter in the west, and returned to Montreal to discover to Frontenac a new project. He had located a copper mine. He hastened to Paris to obtain the king’s license, then necessary for mining operations. After a struggle of two years he got his permit and started for Canada. The English caught him and held him a prisoner for some months. Returning to France, he found his license canceled, because of a resolution of the government to abandon all trade west of Mackinaw. At length Le Sueur was excepted from the rule and his license renewed. In 1699 he sailed with the expedition of D’Iberville, which was to make and did make the first settlement out of which New Orleans grew.

In the midsummer following he made his way with a sailboat and two canoes up the Mississippi, reaching Fort Snelling September 19. He doubtless knew where he was going, for without delay he turned into the Minnesota River, which he followed to the mouth of the Mah-ka-to or Blue Earth. A short distance above, the latter stream receives the Le Sueur. At their junction he built a fort to which he gave the name of a treasury official of Paris who had supported him, “Fort L’Huillier.” The spot has been identified by a local archæologist. He was obliged to pacify with presents the Sioux who were displeased because he did not build at the mouth of the Minnesota. His company passed a comfortable winter, but before it was over they had to come down to buffalo beef without salt. Some of them could put away six pounds along with four bowls of broth daily. In the spring Le Sueur departed for Biloxi, with his shallop loaded with bluish green earth taken from a bluff near his fort. He never saw Minnesota again, and no later explorer has rediscovered his mine. The state geologist has not found the least trace of copper in the region.

The last decade of the seventeenth century was one of discouragement for old France and new. Louis XIV, decrepit and bankrupt, dominated by Madame Maintenon and a group of ecclesiastics, had, by revoking the Edict of Nantes in 1685, driven three hundred thousand and more of the most industrious and skillful artisans and tradesmen of France into exile. The dragonades, countenanced even by such men as Fénelon and Bossuet, had spread ruin throughout whole provinces. Foreign wars along with domestic convulsions had almost beggared the kingdom.

Frontenac had died in office in 1698, and Canadian affairs, fallen into less capable hands, were languishing. There was lack of men and money to protect the northwest trade. It needed protection. The English, holding the Iroquois in alliance, had pushed their trade into the Ohio valley and the lower peninsula of Michigan. The Sacs and Foxes of the Illinois country, old allies of the French, had broken away, and closed all the roads from the lakes to the Mississippi unless that of the St. Croix. For these reasons the Canadian government had in 1699 withdrawn the garrison from Mackinaw, abandoned all posts farther west, and ordered the concentration of Indian trade at Montreal. It was not till after the war of the Spanish Succession was closed by the treaty of Utrecht, in 1713, that any thought could be taken for the revival of trade and missions in the Mississippi valley. England might at that time have stripped France of all her transatlantic holdings, but contented herself with Newfoundland and the posts on Hudson’s Bay.

In 1714 the French garrison was reëstablished at Mackinaw, which remained the headquarters of trade with the Algonquins of the northwest till far into the nineteenth century. Three years later Duluth’s old fort on Pigeon River was reoccupied, to become a great entrepôt of trade with the inland natives; a year later still La Pointe received a small garrison.

Ten years passed before the effort to plant French trade and missions was renewed on the upper Mississippi. Charlevoix, the historian of New France, was over in 1720 and traveled by way of Mackinaw and Green Bay to New Orleans. By his advice the French government resolved to plant an establishment in the country of the Sioux, as a centre of trade and mission work, and as a point of departure for expeditions to gain the shores of the western sea. The hostile Sacs and Foxes having been placated, an expedition was planned with all the care which long experience could suggest. For leader was chosen Réné Boucher, Sieur de la Perrière, the same who in 1708 had headed the raiding party which descended on Haverhill, thirty-two miles north of Boston, where his Indians butchered thirty or forty of the English. Two Jesuit fathers, Guinas and De Gonor, attached themselves to the expedition, and asked for a supply of astronomical instruments. In June, 1727, the expedition set out from Montreal and took the then main traveled road by way of Mackinaw and Green Bay. A letter of De Gonor, which has been preserved, gives an interesting account of the journey.

On September 17, 1727, at noon, La Perrière beached his canoes on a low point of land on the west shore of Lake Pepin, near the steamboat landing at Frontenac. Putting his men to work with axes, he had them all comfortably housed by the end of October. There were three log buildings, each 16 feet wide; one 30, a second 38, and the third 25 feet long. Surrounding them was a stockade of tree-trunks 12 feet out of ground, 100 feet square, “with two good bastions.” The fort was named “Beauharnois” after the governor-general of Canada. To the first mission on Minnesota soil the priests gave the title, “Mission of St. Michael the Archangel.” On November 4 the company celebrated the birthday of the governor, but were obliged by the state of the weather to postpone to the night of the 14th the crowning event of their programme. They then set off “some very fine rockets.” When the visiting Indians saw the stars falling from heaven, the women and children took to the woods, while the men begged for an end of such marvelous medicine. The Sioux were not disposed to be hospitable, and the good behavior of the Sacs and Foxes could not be counted on. In the following season La Perrière departed with the Jesuits and eight other Frenchmen for Montreal. The post was held, and occupied off and on for twenty years or more. No settlement was made about it, no permanent mission work was established, and no expedition towards the Pacific was undertaken. The Indians were unreliable, the French had other interests to attend to, and, contrary to expectation, game was scarce in the region.

One of the successors of La Perrière in command of Fort Beauharnois was Captain Legardeur Saint Pierre, the same officer who in 1753 at his post on French Creek, not far from Pittsburg, was waited on by young Mr. Washington, bearing Governor Dinwiddie’s invitation to the French to get out of Virginian territory.

Another French adventure, although of slight import to Minnesota, deserves mention. The Sieur de la Verendrye, commanding the French post on Lake Nipigon, fell in with the Jesuit Guinas, who went out with La Perrière in 1727, and was inflamed by him with a desire to find the western ocean. At his own post he had found an Indian, Ochaga by name, who sketched for him an almost continuous water route thither; another offered to be his guide. He hastened to Montreal, secured the assent of the governor-general, Beauharnois, and in 1731 dispatched his advance party. It reached the foot of Rainy Lake that year, and there built a fort on the Canadian side. The next year the expedition made its way to the southwest margin of the Lake of the Woods and there built Fort Charles, giving it the Christian name of the governor-general. Whether this fort was on Minnesota soil is undecided.

So ardent was Verendrye’s passion for the glory of discovering the way to the western sea that, encouraged by the Canadian authorities, he kept up the quest for more than ten years longer. On January 12, 1743, the Chevalier Verendrye, as related, climbed one of the foothills of the Shining or Rocky Mountains, and gave it over. Sixty years later Lewis and Clark passed that barrier and won their way to the Pacific.

If the French failed to establish any permanent settlement in Minnesota, it was not wholly because their passion for trade discouraged home-building and cultivation; they had interests elsewhere in America more important than those of the northwest. La Salle’s proclamation of 1682 asserted dominion of the whole region drained by the Mississippi and its tributaries. For a time the Ohio was regarded as the main river and the upper Mississippi as an affluent. Before the close of the seventeenth century both French and English were awake to the beauty and richness of the Ohio valley and the Illinois country. The building of a fort by Cadillac at Detroit in 1701 revealed the firm purpose of the French to maintain their claim of sovereignty. In the treaty of Utrecht, 1713, the English, with a long look ahead, secured the concession that the Iroquois were the “subjects” of England. In a series of negotiations culminating in a treaty at Lancaster, Pa., the Iroquois ceded to the English all their lands west of the Alleghanies and south of the great lakes. On this cession the English put the liberal construction that the Iroquois were owners of all territory over which they had extended their victorious forays, and these they had good right to convey. In 1748 the Ohio Company, formed in Virginia, sent Christopher Gist to explore the Ohio valley. The next year a governor of Canada sent an expedition down the Ohio to conciliate the Indians and to bury leaden plates at chosen points, asserting the dominion of France. A line of fortified posts was stretched by the French from Quebec to Fort Charles below St. Louis, on the Mississippi.

When in 1754 a French battalion drove off the party of English backwoodsmen who had begun the erection of a fort at the forks of the Ohio, and proceeded to build Fort Duquesne, the French and Indian War began. The course of this struggle, exceeding by far in point of magnitude the war of the Revolution, cannot here be followed. At the close of the campaign of 1757 the French seemed triumphant. In the year following they lost Fort Duquesne, in 1759 Quebec, and in 1760 Montreal. The power of the French in North America was broken. Historians of Canada still name the epoch that of “the Conquest.”

The diplomatic settlement of this contest awaited the outcome of a great war raging in Europe, the so-called Seven Years’ War of Frederick the Great against Austria, Russia, and France. England was early drawn into the support of the Prussian monarch, and supplied his military chest and sent an army to the continent. France presumptuously aspired to wrest the empire of the seas from Britain, with the result that her navies were sunk or battered to useless wrecks. In a separate treaty signed at Paris, February 10, 1763, France surrendered to England all her possessions and claims east of the Mississippi except the city of New Orleans and the island embracing it. The British government, however, was none too desirous to accept this cession. It was a matter of lively debate in the ministry whether it would not be the better policy to leave Canada to the French and strip her of her West Indian possessions. That course might have been adopted, but for the influence exerted by Benjamin Franklin’s famous “Canada Pamphlet,” which is still “interesting reading.” Franklin was in England while the question was pending, and published his views in answer to “Remarks” ascribed to Edmund Burke.

It may be well to note here that in the year preceding the treaty of Paris (1762) France had taken the precaution to assign to Spain, by a secret treaty, all her North American possessions west of the Mississippi, in order to put them out of the reach of England.

It was the 8th of September, 1760, when the capitulation of Montreal was signed, turning all Canada over to the British. Five days later Amherst, the victorious commander, dispatched Major Robert Hayes with two hundred rangers to take possession of the western posts. Expected opposition at Detroit was not offered, and that important strategic point was occupied on November 29. The season was then too late for further movements, and more than a year passed before garrisons were established at Mackinaw and Green Bay. The British were none too welcome among the savages, long accustomed to French dealings and alliances. But French influence was not what it had formerly been. During the long struggle for the mastery of the continent the Indian trade had languished, and in remoter regions the savages had reverted to their ancient ways and standards of living. The trade revived, however, under British rule, which brought peace and protection. In 1762 the British commandant gave a permit to a Frenchman named Pinchon to trade on the Minnesota River, then in Spanish territory. Four years later the old post on Pigeon River was revived and trade was reopened in northern Minnesota. Prairie du Chien became in the course of a decade a village of some three hundred families, mostly French half-breeds, and remained a supply station for the Indian trade of southern and central Minnesota till far into the nineteenth century.

The British authorities in Canada indulged no romantic passion to discover the south or western sea, and were indifferent for a time to the development and protection of trade in the northwest. This fact lends brilliance to the adventures of a single American born subject who in 1766 set out alone for the wilderness, resolved to cross the Rocky Mountains, descend to the western ocean, and cross the Straits of Anion to Cathay. Such was the bold enterprise of Jonathan Carver of Canterbury, Connecticut, at thirty-four years of age. He was not unlettered, for he had studied medicine; and he was not inexperienced, for he had served with some distinction as a line officer in a colonial regiment in the French and Indian War. Departing from Boston in June (1766), he traveled the usual way by the lakes to Mackinaw, where he found that versatile Irish gentleman, Major Robert Rogers, his comrade in arms, in command. There is a tradition, needing confirmation, that this officer “grub-staked” Carver for trade with the Sioux and possible operations in land. However, he left Mackinaw in September supplied with credits on traders for the goods serving for money with Indians, and taking the Fox-Wisconsin route, found himself at the Falls of St. Anthony on the 17th of November. Although he estimated the descent of the cataract at thirty feet, it impressed him only as the striking feature of a beautiful landscape. “On the whole,” says he, “when the Falls are included, ... a more pleasing and picturesque view, I believe, cannot be found throughout the universe.” After a short excursion above the falls, Carver took his way up the Minnesota, as he estimated, two hundred miles. He passed the winter with a band of Sioux Indians which he fails to name, and in a place he does not describe, and in the spring came down to St. Paul with a party of three hundred, bringing the remains of their dead to be deposited in the well-known “Indian mounds” on Dayton’s Bluff. The cave in the white sand rock entered by him on his upward journey, and which bore his name till obliterated by railroad cuttings, was nearly beneath the Indian mounds. His report of a funeral oration delivered here by one of the chiefs so impressed the German poet Schiller that he wrote his “Song of the Nadowessee Chief,” which Goethe praised as one of his best. Two very distinguished Englishmen, Sir Edward Bulwer Lytton and Sir John Herschel, made metrical translations of this poem in the fashion of their time.

This journey was but a preliminary one to find and explore the Minnesota valley and acquaint Carver with the tribes dwelling there and their languages. He had conceived that a short march from the head of that river would take him to the Missouri. This he would ascend to its sources in the mountains, and crossing over these he would float down the Oregon to the ocean. Major Rogers, as he relates, had engaged to send him supplies to the Falls of St. Anthony. Receiving none, Carver hastened down to Prairie du Chien, to be again disappointed.

Resolved on prosecuting his great adventure, he decided to apply to the traders at Pigeon River for the necessary merchandise. Paddling back up the Mississippi, he took the St. Croix route to Lake Superior, and coasted along the north shore to that post, only to find, after many hundred miles of laborious travel, that the traders had no goods to spare him. He could do nothing but return to his home. In 1768 he went to England, hoping to interest the government in his project, and in the following year published his book of travels. It is now known that little if any of it was his own composition. His account of the customs of the Indians was pieced together from Charlevoix and Lahontan. But the work of his editor, a certain Dr. Littsom, was so well done that “Carver’s Travels” have been more widely read than the original works drawn upon.

There is very doubtful testimony to the effect that in 1774 the king made Carver a present of £1373 13s. 8d., and ordered the dispatch of a public vessel to carry him and a party of one hundred and fifty men by way of New Orleans to the upper Mississippi, to take possession of certain lands. The Revolutionary War breaking out, the expedition was abandoned.

Carver died in poverty in England in 1780, and might be dismissed but for a sequel which lingers in Minnesota to the present time. After his death there was brought to day a deed purporting to have been signed by two Indian chiefs, “at the great cave,” May 1, 1767, conveying to their “good brother Jonathan” a tract of land lying on the east side of the Mississippi one hundred miles wide, running from the Falls of St. Anthony down to the mouth of the Chippeway, embracing nearly two million acres. A married daughter, by his English wife, and her husband bargained their alleged interest to a London company for ten per cent. of the realized profits, but that company soon abandoned their venture. Carver left behind him an American family, a widow, two sons, and five daughters. In 1806 one Samuel Peters, an Episcopal clergyman of Vermont, represented in a petition to Congress that he had acquired the rights of these heirs to the Carver purchase, and prayed to have it confirmed to him. This Peters claim was kept before Congress for seventeen years. In 1822 the Mississippi Land Company was organized in New York to prosecute it. They seem to have been taken seriously, for in the next year a Senate committee, in a report of January 23, advised the rejection of the claim as utterly without merit. But it has been repeatedly renewed, and doubtless at the present time there are worthy people dreaming of pleasures and palaces when they come into their rights.

For the first three years following the Conquest all Canada remained under military rule. In 1763 George III by proclamation established four provinces with separate governments, but the great northwest region was included in none of these. That remained as crown land, reserved for the use of the Indians under royal protection. All squatters were ordered to depart and all persons were forbidden to attempt purchases of land from the Indians. This prohibition alone was fatal to Carver’s claim. The United States could not possibly confirm a purchase impossible under English law. It was the express design of the British government to prevent the thirteen colonies from gaining ground to the west, and “leave the savages to enjoy their deserts in quiet.”

In 1774, about the time when Parliament was extending its novel sway over the American colonies, the “Quebec act” was passed. This act extended the Province of Quebec to the Mississippi and gave to Minnesota East its first written constitution. This provided for a government by a governor and an appointed legislative council, but it was never actually effective west of Lake Michigan.

Under the definitive treaty of peace between Great Britain and the United States, the dominion of the former over Minnesota East ceased, but that of the United States government did not immediately supervene. Virginia under her charter of 1609 had claimed the whole Northwest, and her army, commanded by General George Rogers Clark, had in 1779 established her power in the Illinois country. Three years later the county of Illinois was created and an executive appointed by Governor Patrick Henry. The act of Congress of March 1, 1784, accepting the cession of her northwestern lands, amounting to a concession of colorable title, ended Virginia’s technical government in Minnesota East. From that date to the passage of the Ordinance of 1787 (July 13) this region remained unorganized Indian country. This great ordinance made it part of “the Northwest Territory” and gave it a written constitution. But this was nugatory for the reason that although Great Britain had in form surrendered the territory in the treaty of 1783, she continued her occupation for thirteen years longer. Her pretext for maintaining her garrisons at Detroit, Mackinaw, Green Bay, and elsewhere was the failure of the United States to prevent the states from confiscating the estates of loyalists and hindering English creditors from collecting their debts in full sterling value, as provided in the treaty. The actual reason was an expectation, or hope, that affairs would take such a turn that the whole or the greater part of the Ohio-Illinois country might revert to England. A new British fort was built on the Maumee River in northwestern Ohio in 1794. The surrender of this to General Anthony Wayne after the battle of Fallen Timbers, in August of that year, has been regarded as the last act in the war of the Revolution. By the Jay treaty it was agreed that the western posts should be given up to the United States, and on or about the 12th of July, 1796, the British commanders hauled down their flags and marched out their garrisons.

There was a powerful interest which had encouraged the British authorities to hold their grip on the Northwest. The revival of the fur-trade after the Conquest was tardy, but soon after Carver’s time a notable development took place. Another Connecticut Yankee, Peter Pond by name, in 1774 established a trading post at Traverse des Sioux on the Minnesota. On a map left by him it is marked “Fort Pond.” The trade west of the lakes, however, early fell into the hands of adventurous Scotchmen of Montreal, among whom competition became so sharp as to lead to what would have been called, a hundred years later, a “trust” or “combine.” An informal agreement between the principal traders at Montreal ripened, in 1787, into “The Northwest Company,” with headquarters in that city. This company promptly and effectually organized the northwestern fur-trade. It established a hierarchy of posts and stations, and introduced a quasi-military administration of the employees. It wisely took into its service the old French and half-breed “engagés and voyageurs,” and rewarded them so liberally as to win them from illicit traffic. For forty years the Northwest Company was the ruling power west of the lakes, although it had not, as had the Hudson’s Bay Company, its model, any authorized political functions. Its policy and discipline served in place of laws and police.

The greater distributing and collecting ports were Detroit, Mackinaw, and Fort William; and next in importance were such places as La Pointe, Fond du Lac, and Prairie du Chien, from which the trade of the upper Mississippi was managed. Fond du Lac, near the mouth of the St. Louis River, at the head of Lake Superior, was the gateway to an immense region abounding in the finest peltries and occupied by a large Chippeway population, eager to buy the white man’s guns and ammunition, knives, kettles, tobacco, and, most dearly prized of all, his deadly fire-water. From Fond du Lac there was a canoe route to the lakes which are the proximate sources of the great river. It led up the St. Louis River to the mouth of the East Savanna near the Floodwood railroad station. From the head of the East Savanna a short portage led to the West Savanna, an affluent of Prairie River which empties into Sandy Lake, near the southwest corner of Aitkin County. That water covers near half a township and discharges by a short outlet into the Mississippi, some twenty-five miles above the village and railroad station of Aitkin. Here in 1794 the Sandy Lake post of the Northwest Company was built. There was a stockade one hundred feet square, of hewn logs one foot square, and thirteen feet out of ground. Within were the necessary buildings, and without, fenced in, a considerable garden. From Sandy Lake radiated numerous “jackknife posts,” where the bushrangers wintered and swapped gewgaws for pelts. For many years Sandy Lake was the most important point in Minnesota, the chief factor there the big man of the Chippeway country.

The reader is asked to recall the cession by France, in 1762, of her American territory west of the Mississippi to Spain. The French population of Louisiana, resenting this arbitrary transfer, drove out the Spanish governor who came in 1766, and organized for a free state under French protection. In 1769 a Spanish fleet of twenty-four sail, bringing an army of twenty-six hundred men and fifty cannon, under the command of a forceful captain-general, securely established the power of Spain. The laws of Castile, derived from the civil code of Rome, were put in force, and they continue in force to the present day. By a line about on the latitude of Memphis a province of Upper Louisiana was set apart and placed under the control of a lieutenant-governor residing at St. Louis. Minnesota West was of course a part of this jurisdiction.

In the last years of the eighteenth century Napoleon Bonaparte was absolute in France, although not yet crowned emperor. Among the schemes with which his imagination was busied was one to establish another new France on the western continent. Louisiana had been a costly dependency for Spain, and it was only by a reluctant but timely concession of the right of navigation and deposit that an armed descent of Americans from the Ohio valley on New Orleans had been averted. That would have put an end to Spanish rule. Spain willingly retroceded to France for a nominal consideration, by the secret treaty of San Ildefonso, March 13, 1801. Already Napoleon had formed a definite plan and begun preparations to send 25,000 veteran soldiers to Louisiana, under convoy of a powerful fleet. His secret could not be kept, and England made ready to attack the expedition at sea. Napoleon had reason to expect that she would descend on New Orleans herself, and take possession of the province. While he was in this frame of mind the American minister, under instructions, expressed the desire of his government to buy the city and island of New Orleans and thus make the Mississippi the international boundary to its mouth. To his surprise Napoleon offered to sell the whole province, spite of his agreement with Spain never to cede to any other power. The Louisiana purchase was consummated by treaty April 30, 1803. Meantime the province had remained in the possession of Spain, and it was not till November 30 that she turned New Orleans over to the French. Twenty days later the United States came into possession. The upper province of Louisiana was held but one day by a French commissary, who on March 10, 1804, at St. Louis, conveyed it to the United States. The cost to the government was three and six tenths cents per acre.

The actual surrender of Upper Louisiana in 1804 added geographically Minnesota West, included in that province, to Minnesota East, then part of Crawford County, Indiana. The whole region was still occupied by aborigines, and a generation was to pass before any of it became white man’s country. Two great nations divided the territory: the Chippeways, of Algonquin stock, occupying the north and east; the Sioux or Dakotas the south and west. Both were immigrant from early eastern habitats, the Chippeways moving north of the lakes (Lake Superior split the stream), the Sioux south of the same. When first seen by white men, the latter held the country about the sources of the Mississippi, the head of Lake Superior, and to the St. Croix. The Chippeways were first to obtain guns from the white man, and began at once to push the Sioux before them. In Hennepin’s time (1680) the principal villages of the Sioux were in the Mille Lacs region. By the close of the Revolutionary War the Chippeways had driven them south of the Crow Wing and west of the Mississippi, leaving them only a precarious hold on the margin of their old hunting grounds. From their earliest encounters the two nations had been unremitting foes. But for occasional truces they were always at war; and this perennial feud did not cease till the government in 1863 moved the Sioux beyond the Missouri, out of the reach of the Chippeways. The two nations possessed in common the well-known characteristics of the red man, physical, mental, and social, but a difference of environment had established marked peculiarities. The Chippeways were men of the forest and stream; their women gathered wild rice, excellent for food. The Sioux, men of the prairie, were the taller and more agile, but the Chippeways outmatched them for strength and endurance.

Both peoples had already been profoundly affected by contact with white men. If the missionary had not broken the power of the medicine-man and converted them to the true faith, the trader had revolutionized their whole manner of life. He had given the Indian the gun for his bow and arrows, axes and knives of steel for those of stone, and the iron kettle for the earthen pot. The Mackinaw blanket and the trader’s strouds had replaced garments made from skins, and ornaments of shell and feathers had given way to those of metal and glass.

Before the trader the Indian had hunted for subsistence, content when he had supplied his family and dependents with food and clothing. The trader made him a pot-hunter, killing mostly for the skins alone. Game animals became scarce about the villages, and hunting expeditions had to be made to distant grounds, where the enemies’ parties would be met and fought. The Indian had become a vassal to the trader, who outfitted him for the hunt, and at its end took his furs in payment at rates little understood by the man who did not know that the white metal was worth more than the red. If anything remained from the Indian’s pack it was very likely to be forthwith spent for the highly diluted whiskey of the trader. The Indian’s fondness for spirits and their effects was at least equal to the white man’s, and he had not become immune from immemorial indulgence. The resulting crime and misery are beyond description,—conception, almost. And the trader’s excuse was that the Indians would not trade if whiskey was not furnished, and that it was absurd for one to refuse it when all the rest were selling. Along with the white man came his epidemic diseases. Smallpox and measles depopulated villages and almost extinguished tribes. A nameless contagion was only less deadly. Unbridled commerce with the women multiplied half-breeds, possessing frequently all of the vices and few of the virtues of both races. The half-breed was always a misfit, because he could assume by turns the character of white or red, according to convenience and profit.

All the Minnesota Indians were clients of the Northwest Company, unless where along the northern border the agents of the Hudson’s Bay Company were drawing off the trade by abundant whiskey. This competition at length brought the two companies to open war.

Long before he became president, Jefferson was curious to unlock the secret of the unknown west and learn the road to the Pacific. It was not till the early winter of 1803, however, that he was able to persuade Congress to make a small appropriation for a military expedition of discovery, and then under color of “extending the external commerce of the United States.” And more than a year passed before the expedition of Lewis and Clark set out from St. Louis May 4, 1804.

A similar expedition on a smaller scale left St. Louis in August, 1805, to discover the source of the Mississippi. It was led by First Lieutenant Zebulon Montgomery Pike of the First Infantry, a native of New Jersey, then twenty-six years of age. “He was five feet eight inches tall; eyes blue; hair light; abstemious, temperate, and unremitting in duty.” If there could have been doubt of his fitness for the enterprise, the sequel fully justified his selection. His instructions were carefully drawn to keep him and his errand within constitutional limits. The first entry of his journal reads, “Sailed from my encampment, near St. Louis, at 4 o’clock, P. M., on Friday the 9th of August, 1805: with one sergeant, two corporals, and seventeen privates, in a keel boat, 70 feet long, provisioned for four months.” On the 21st of September Pike reached the mouth of the Minnesota, and “encamped on the northeast point of the big island,” which still bears his name. The next day Little Crow, grandfather of the chief of the same name who led the outbreak of 1862, came with his band of one hundred and fifty warriors. On the third day a council was held under the shelter of the sails, on the beach. In his speech Pike let the Indians know that their Great Father no longer lived beyond the great salt water, and that the Canadian traders who tried to keep them in ignorance of American independence were “bad birds”; that traders were forbidden to sell rum, and the Indians ought to coöperate in preventing them; and that the Sioux and Chippeways ought to live in peace together. In particular he asked that they allow the United States to select two tracts of land, one at the mouth of the St. Croix, the other above the mouth of the Minnesota. On these the Great Father would establish military posts, and public trading factories, where Indians could get goods cheaper than from the traders.

The well-advised officer had already crossed the hands of the two head chiefs. He closed his speech with a reference to their “father’s tobacco and some other trifling things” as evidence of good will, and promised some liquor “to clear their throats.” The chiefs saw no need of their signing any paper, but did it to please the generous orator. The “treaty” is a curiosity in diplomacy. The first article grants, what the United States already possessed, “full sovereignty and power” over two tracts of land: one of nine miles square at the mouth of the St. Croix; the other “from below the confluence of the Mississippi and St. Peter’s (Minnesota) up the Mississippi to include the Falls of St. Anthony, extending nine miles on each side of the river.” Pike estimated the area of the latter grant to be about one hundred thousand acres and the value to be $200,000. The second article provides that “the United States shall pay ... dollars.” The final article permits the Sioux to retain the only right they could legally convey, that of occupancy for hunting and their other accustomed uses.

Five days were passed at the Falls of St. Anthony, partly because of the sickness of some of the men. Pike took measurements and made a map. He found the depth of the fall to be sixteen and a half feet. The portage on the east bank was two hundred and sixty rods. The navigation of the river above proved so difficult that it was not till the 16th of October that the party reached the mouth of the Swan River. It was the expectation of his general and of Pike himself that the march to the source of the Mississippi and back would certainly be finished before the close of the season. By the time he was ready to leave the falls, September 30, it was evident that the journey could not be accomplished in any such period. Resolved to prosecute it, and not go back defeated, he formed the plan to push on to the mouth of the Crow Wing, put his stores and part of his men under cover, and go forward on foot to his destination. On the way up river he had a foretaste of the hardships which awaited him. As he says, he “literally performed the duties of astronomer, surveyor, commanding officer, clerk, spy, and guide.” Finding it impossible to force his boats through the rapids below Little Falls, he selected a favorable site below the junction of the Swan with the Mississippi (the spot has been clearly identified), where he built, in the course of a week, two blockhouses, and in them bestowed his baggage and provisions. Here he remained till December 10, occupied with hunting, chopping out “peroques,” and building bob-sleds. It took thirty-four days to reach Sandy Lake, where the party met with generous hospitality at the post of the Northwest Company. A week was passed here in which the men replaced their sleds with the traineaux de glace, or toboggans, used by the voyageurs. On February 1 the leader, marching in advance, reached the establishment of the Northwest Company on the western margin of Leech Lake, and highly relished a “good dish of coffee, biscuit, butter, and cheese for supper.” Pike had now accomplished his voyage by reaching the main source of the Mississippi. Seventeen days were passed here, including three devoted to an excursion on snowshoes to Cass Lake, then known as Upper Red Cedar Lake. He now believed himself to have reached the “upper source of the Mississippi,” but wasted not a word of rhetoric on the achievement. While resting at Leech Lake Lieutenant Pike wrote out for the eye of Mr. Hugh McGillis, director of the Fond du Lac department of the Northwest Company, there present, a formal demand that he should smuggle no more British goods into the country, haul down the British flag at all his posts, give no more flags or medals to Indians, and hold no political intercourse with them. Mr. McGillis in a communication equally formal promised to do all those things. Pike estimated that the government was losing some $26,000 a year of unpaid customs. The two functionaries parted with mutual expressions of regard, and the genial lieutenant started off home with a cariole and dog team worth $200 presented by the gracious factor. Before his departure, however, he had his riflemen shoot down the English jack flying over the post. The return journey, ending April 30, 1806, cannot be followed. On the 10th of the month the expedition passed around the Falls of St. Anthony, and the journal records, “The appearance of the Falls was much more tremendous than when we ascended.” The ice was floating all day. The leader congratulated himself on having accomplished every wish, without the loss of a man. “Ours was the first canoe,” he says, “that ever crossed this portage.” In that belief he was content. Pike’s journal was not published till 1810, and it included his account of an expedition to the sources of the Arkansas, and an enforced tour in New Spain. It had but slight effect on the authorities at Washington, and still less on the public. The War of 1812 was brewing and there was little concern about this remote wilderness. The effect of Pike’s dramatic incursion, and his fine speeches to the Sioux and Chippeways soon wore off, the British flag went up over the old trading posts of Minnesota and Wisconsin, and the Northwest Company resumed its accustomed control over the Indians. It is not likely that many of their goods paid the duties at Mackinaw. When the war broke out the British-American authorities used all needful means in the way of presents and promises to hold the attachment of the nations. Some of the principal agents of the Northwest Company were actually commissioned in the British service and collected considerable bodies of Indians and half-breeds for the western operations. The news of the end of the war was slow in reaching these allies, and it was not till May 24, 1815, that the British captain commanding at Prairie du Chien, having received his orders, hauled down his flag and marched away with his garrison for Green Bay and Montreal. The treaty of Ghent had been concluded eight months and some days before. A serious proposition made by the British plenipotentiaries for negotiating that treaty proves that the British had cherished the hope that they might retain the great Northwest under their virtual dominion. The proposition was that the two powers should agree that the territory north and west of the “Greenville line of 1795,” roughly a zigzag from Cleveland to Cincinnati, should remain as a permanent barrier between their boundaries. Both parties were to be prohibited from buying land of the Indians, who were thus to be left in actual occupation. The British would continue to control their trade and hold their accustomed allegiance. The American commissioners refused of course to entertain the proposal.

Readers of Irving’s “Astoria” know how a young German, coming to America in the last year of the Revolution, by accident learned of the possible profits to be won in the fur-trade, and how he presently embarked in it. In the course of twenty-five years he made a million dollars, a colossal private fortune for that day. In 1809 he obtained from the New York legislature a charter, and organized the American Fur Company. The war suspended the development of its plans. In 1816 Mr. John Jacob Astor had little difficulty in securing an act of Congress restricting Indian trade to American citizens. This patriotic statute was intended to put the Northwest Company out of business on American territory. It did, and that company sold out to Mr. Astor all its posts and outfits south of the Canadian boundary at prices satisfactory to the purchaser. In 1821 the Northwest Company was merged into the Hudson’s Bay Company.

The American Fur Company adopted the policy of filling its leading positions with young Americans of good education and enterprise, and taking over the old engagés and voyageurs, inured to the service and useless for any other. These old campaigners easily won over the Indians to the new company and taught them to look to a Great Father at Washington. The chief western stations for the trade of the upper Mississippi were Mackinaw and Prairie du Chien. There was now an “interest” which desired the development of the upper country; and it lost no time in moving on the government. In the year last mentioned (1816) four companies of United States infantry were sent to Prairie du Chien, where they at once built Fort Crawford. In the next year, Pike’s reports having apparently been forgotten, Major Stephen H. Long of the Engineers traveled to Fort Snelling and in his report gave a conditional approval to Pike’s selection of a site for a fort; but it was not till the winter of 1819 that the government was moved to establish a military post at the junction of the St. Peter’s with the Mississippi. Lieutenant-Colonel Henry Leavenworth was ordered February 10 to proceed from Detroit, Michigan, to that point with a detachment of the Fifth Infantry.

Taking the Fox-Wisconsin route, his party of eighty-two persons reached Prairie du Chien July 1. “Scarcely an hour” after his arrival this number was increased by the birth of Charlotte Ouisconsin (Clarke) Van Cleve, long known to all Minnesotians, whose life was not ended till 1907.

The command arrived at Mendota August 24 and was at once put to building the log houses of a cantonment. The site was near the present ferry and the hamlet of Mendota, where a sharp eye may still note traces of foundations. In September a reinforcement of one hundred and twenty arrived. In the spring of 1820 the companies were put into camp above the fort, near the great spring known to all early settlers. It was named Camp Coldwater. In July the command passed to Colonel Joseph Snelling, who held it till near the time of his death in 1828. A daughter born in his family a short time after their arrival was the first white child born in Minnesota.

Colonel Snelling at once began the erection of a fort, which, however, was not ready for occupation till October, 1822. It was a wooden construction, for which the logs were cut on the Rum River. In 1821 a rude sawmill was built at “the Falls” which converted the logs into lumber. This was of course the first sawmill in Minnesota. Two years later a “run of buhrs” was put in, and a first flour mill established. Colonel Snelling named his work “Fort Saint Anthony,” but in 1824, upon recommendation of Major-General Winfield Scott, after a visit to the place, that name was changed to “Fort Snelling,” in recognition of the enterprise and efficiency of its builder.