Title: East-West Trade Trends

Author: United States. Foreign Operations Administration

Author of introduction, etc.: Harold E. Stassen

Release date: November 23, 2014 [eBook #47437]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Juliet Sutherland, Ralph Carmichael and the

Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

MUTUAL DEFENSE ASSISTANCE

CONTROL ACT OF 1951

(the Battle Act)

* * *

FOURTH REPORT TO CONGRESS

Second Half of 1953

To the Congress of the United States:

I have the honor to submit herewith the fourth semiannual report on operations under the Mutual Defense Assistance Control Act of 1951 (Battle Act), the administration of which is a part of my responsibilities.

The period covered is July through December 1953.

A large part of this report is an examination of what the Soviet Union has been doing in its trade relations with the free world. In order to put the Russian activities of the last half of 1953 in a more understandable framework we have ranged back over the last 30 years to show how foreign trade fits into their economy and serves their purposes. To study Soviet trends and tactics is obviously important to the economic defense of the free world. To make a report to the Congress and the public on these matters should also be useful. There has been much public interest in the subject.

The selection of this theme, however, does not mean that Soviet trade activities are the only important consideration to be taken into account in the formulation of U. S. economic defense policy. They are not. Many other factors enter in, as told in Chapter V.

In preparing the report my staff has drawn heavily upon the expert knowledge of the Department of State and other agencies. But of course the responsibility for the report is ours.

In my last Battle Act report I said that the strategic trade control program had been hampered by lack of public knowledge. This is still true, but to a less extent, it seems to me. There is a better understanding of the Government’s policies, a greater realization that the soundness of East-West trade policy is to be judged not primarily on the amount of trade, but more on what kind of goods move back and forth, and on what terms they move.

Harold E. Stassen,

Director, Foreign Operations Administration.

May 17, 1954.

| CONTENTS | ||

| INTRODUCTION: | Page | |

| Note on “Strategic” and “Nonstrategic” | 1 | |

| CHAPTERS: | ||

| I. | Stalin’s Lopsided Economy | 3 |

| Emphasis on Heavy Industry | ||

| How Forced Industrialization Affects Trade | ||

| How the Kremlin Controls Trade | ||

| West Has Never Barred Peaceful Exports | ||

| Stalin’s Last Gospel | ||

| II. | The New Regime and the Consumer | 11 |

| Letting Off Pressure | ||

| The “New Economic Courses” | ||

| Malenkov’s Big Announcement | ||

| Khrushchev and the Livestock Lag | ||

| Mikoyan Advertises the Program | ||

| Has Stalin Been Overruled? | ||

| III. | The Kremlin’s Recent Trading Activities | 19 |

| The New Trade Agreements | ||

| More Consumer Goods Ordered | ||

| A Shopping Spree for Ships | ||

| Most of All, They Want Hard Goods | ||

| Something Different in Soviet Exports | ||

| They Have Dug Up Manganese | ||

| The Emergence of Russian Oil | ||

| Gold Sales Expanded | ||

| Reaching Outside Europe | ||

| IV. | What’s Behind It All | 35 |

| The Kremlin and Peace | ||

| A Mixture of Motives | ||

| Their Objectives Haven’t Changed | ||

| Their Practices Haven’t Changed | ||

| The Challenge | ||

| V. | U. S. Policy on Strategic Trade Controls | 43 |

| The Background | ||

| Basic Policy Reaffirmed | ||

| The New Direction of Policy | ||

| Reviewing the Control Lists | ||

| East-West Trade: Road to Peace | ||

| Trade Within the Free World | ||

| The China Trade Falls Off | ||

| They Play by Their Own Rules | ||

| United States Policy on the China Trade | ||

| VI. | The Battle Act and Economic Defense | 55 |

| Battle Act Functions | ||

| The Money and the Manpower | ||

| Meshing the Gears | ||

| Improving the Machinery | ||

| The Termination-of-Aid Provision | ||

| Miscellaneous Activities | ||

| Summary of the Report | ||

| APPENDICES | ||

| A. | Trade Controls of Free World Countries | 65 |

| B. | Statistical Tables | 89 |

| C. | Text of Battle Act | 99 |

| CHARTS | ||

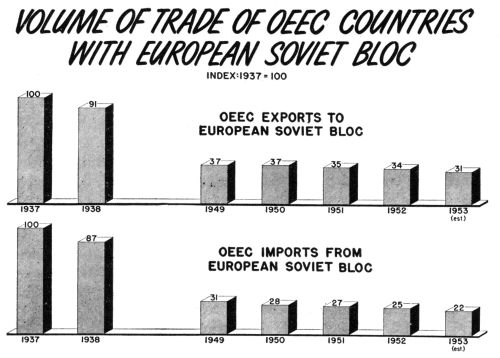

| 1. | Volume of Trade of OEEC Countries With European Soviet Bloc | 6 |

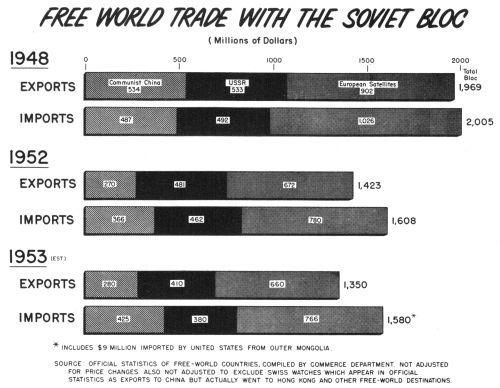

| 2. | Free World Trade With the Soviet Bloc | 21 |

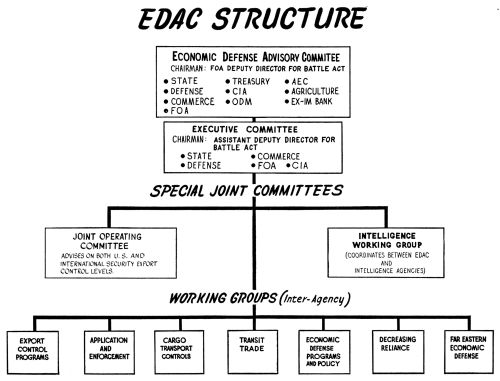

| 3. | EDAC Structure | 57 |

Note on “Strategic” and “Nonstrategic”

To help protect the security of the free world, the United States and certain other countries have been working together for more than four years to withhold strategic goods from the Soviet bloc.

But how can you tell strategic goods from nonstrategic goods? A good many people have asked that question. It is a reasonable question and it deserves a nontechnical answer.

The answer is that strategic goods, as understood in the day-to-day operations of the program, are those goods which would make a significant contribution to the warmaking power of the Soviet bloc.

This is a practical guide to action. There is no rigid definition that holds good for all times, places, and circumstances. All strategic goods don’t have the same degree of strategicness. The free countries have embargoed some, merely limited others in quantity, and kept still other items under surveillance so that controls could be imposed if necessary. Even the same item may vary in strategic importance, depending on the destination, the changing supply situation behind the Iron Curtain, and other circumstances which may change from time to time. Whether an item includes advanced technology is an important consideration. In specific cases, two experts of equal competence may disagree on these things. Two agencies of government, differing in function, may bring different points of view to a given problem. The same is true of governments.

Since there is no distinctly visible boundary between “strategic” and “nonstrategic,” some people insist there is no such thing as a nonstrategic item at all. It is true that even bicycles, typewriters, or ordinary hardware may help the other fellow by strengthening his general economy. And these people argue that anything that contributes to the general economy helps in a military way, too.

That is a correct concept in actual warfare but it is not an acceptable concept of “strategic” in the present situation, for trade on certain terms can help the free nations too. They carry on two-way trade with the Soviet bloc for concrete commercial benefits. The problem is to gain those benefits without permitting the Kremlin to accelerate the growth of military power or to divide the free world.

In rating items as strategic or nonstrategic, it is clear that there are innumerable commodities, used entirely or mainly for civilian[Pg 2] purposes, which would not make a clearly significant contribution to war potential. No one would have trouble drawing a line between a jet plane and a suit of clothing, to take an extreme example. Few would have difficulty putting cobalt on one side of the line and butter on the other. As for the border area where it is less clear what contribution an item would make, the allied governments put their heads together, pool their facts, and try to arrive at mutually acceptable judgments.

As President Eisenhower has said, “Unity among free nations is our only hope for survival in the face of the worldwide Soviet conspiracy backed by the weight of Soviet military power.”

Stalin’s Lopsided Economy

The weakest link of the socialist chain is merchandising and distribution; if this can be strengthened, present difficulties will be overcome. Upon it the Kremlin has wisely concentrated attention. The Kremlin’s immediate objective, as recently announced by the resolutions voted at the plenary session of Bolshevik leaders, is to increase the supply of foodstuffs and consumers’ goods and stimulate their mutual exchange.

That quotation is from a Moscow dispatch to the New York Times. The dispatch was written by Walter Duranty and printed on November 6, 1932.

As long ago as that, and even before, the Russian people were wondering when something was going to be done about the supply of food and other things they needed, and the dictatorship was making motions—but not very helpful—in that direction. Goals were set and decrees were issued. But the results were disappointing, and the standards of living of the Russian people stayed low.

Stalin’s First Five-Year Plan called for a 50 percent rise in gross farm production during 1928-32 inclusive. But by 1932, farm production had declined by 20 percent. The difficulties have continued ever since. For example, the Third Five-Year Plan, beginning with 1938, was scheduled to bring a large increase in consumer goods—larger than the increase being promised nowadays—but instead the supply of consumer goods actually decreased, even in the three prewar years of the period. Per capita consumption in the Soviet Union is lower now than it was in the 1920’s, before the 5-year plans commenced.

The basic cause of these continual disappointments now is widely understood: The Communist elite, while preaching continually about the “uneven development of capitalism” and the “ever-increasing decomposition of the world economic system of capitalism,” created a remarkably lopsided economy of their own, in comparison with which the free economies of the West look very well-balanced indeed.

Beginning in the 1920’s the Bolsheviks deliberately concentrated on building a base of heavy industry. In their 5-year plans, pig iron, steel, coal, oil, electric power, factories, heavy machinery, armaments have always been given the right of way over the needs of the people for meat, fish, vegetables, vegetable oils, milk, butter, chairs, tables, beds, bicycles, watches and clocks, radio sets, decent homes, boots and shoes, fabrics of cotton, wool, and silk—and so on through the myriads of consumer items that are commonplace in most Western countries.

Impressive advances have been made in heavy industry. But this was done at a staggering cost to the inhabitants. It was accomplished through a vast use of forced labor and police discipline, and through the neglect of the manufacturing of consumer articles, the growing of foodstuffs and textile fibers, and the building of homes and retail stores.

The Kremlin made strenuous efforts to maintain the flow of farm products to the cities, even while drawing labor away from the farms. But heavy metalworking industry was always considered more important than food and clothing. And more important, too, was the long, bitter and as yet unsuccessful attempt to cram collectivism down the throat of the Russian farmer. Stalin considered this struggle ideologically essential. Moreover, it was the means of forcing the peasants to supply food and raw materials to the growing industrial complex without receiving consumer goods in return. All in all, the failure of Soviet farm policy was one of the most resounding failures in the brief history of the U.S.S.R.—and it still is. Bread and potatoes are the principal diet of the masses, and even the grain and potato crops are unsatisfactory.

During the years of Hitler’s devastating invasion, the Kremlin had to dedicate the energies of Soviet Russia to a fight for survival. But when the Grand Alliance crushed Hitler, and the western nations, hoping for a peaceful world under the United Nations, practically dismantled their military establishments and fell back into their normal roles as consumption economies, the Kremlin did not alter the lopsided war economy of the Soviet setup. The Stalin regime inaugurated a new phase of hostility toward the West. The grim drive to build up an industrial-military foundation continued. Consumer goods were still given a low priority in the scheme of things. And all this was discouraging not only to prospects of world peace but also to the prospects of happiness and dignity for the weary and heroic Soviet peoples.

Moscow laid the same pattern upon the European satellite countries and cut them to fit the pattern. Heavy industrialization was[Pg 5] imposed on them regardless of their desires and the needs of the people. This forced industrialization absorbed large amounts of commodities that were formerly available for export to the free world. At the same time the collectivization of agriculture was imposed on the satellites, and this aggravated the difficulties of keeping pace in farm output.

While these policies were reducing the total amounts of goods the satellites had available for export to the West, the U.S.S.R. was siphoning off great trainloads of what remained. The ability of these countries to trade with the West was further reduced as they were pushed into granting priorities to one another on the exchange of items they could have more profitably sold to the free world.

Moscow also forced upon the satellites the characteristic Soviet trading goal of reducing and eventually eliminating all dependence on the free world. Lenin himself had emphasized that the first goal of the Soviet Union in its economic relations with the outside world was to gain “economic independence from the capitalist countries.” A prominent Soviet economist, Mishustin, in a book published in 1941, spelled out this principle in greater detail:

The main goal of the Soviet import (policy) is to utilize foreign products, and above all, foreign machinery ... for the technical and economic independence of the U.S.S.R.... The import (policy) of the U.S.S.R. is so organized that it aids the speediest liberation from the need to import.

In 1946 the leading Soviet economist, Vosnosensky, restated the objective in the Government periodical, Planned Economy:

The U.S.S.R. will continue in the future to maintain economic ties with foreign countries in accordance with the tested line of the Soviet government directed towards the attainment of the technical-economic independence of the Soviet Union.

The Kremlin’s new Eastern European empire included vast natural resources and sizeable labor reserves. Nevertheless it was—and still is—a long way from being self-sufficient, in the sense of being able to match the production levels of the free world, or even in the sense of fulfilling its own ambitious production plans, without trade with the West. Imposing an ultimate goal of self-sufficiency thus could not eliminate the Soviet bloc’s dependence on the free world. Communist trade planners still found it advantageous to import from the free world many things the bloc countries needed. The new goal did, however, affect the composition of the satellites’ trade. The planners placed much greater emphasis on the importation of industrial raw materials and equipment that would, in the long run, reduce the need to import.

In the U.S.S.R. itself, the Government had always been disinclined to offer exports in order to import consumer goods, like meat, butter, textiles, and appliances. Now the same policy was clamped on the[Pg 6] satellites. So the bulk of Soviet-bloc imports from the West consisted of goods that did not enter the homes of the people.

The result of all this was a big decline in trade between Western and Eastern Europe, as compared with prewar years. Before the war, countries which now make up the Soviet bloc in Europe carried on less than 10 percent of their foreign trade with one another; now this has risen to more than 75 percent.

All foreign trade of the countries of the enlarged Soviet empire was placed under absolute state control. For both the U.S.S.R. and the satellites, international trade is now not only a 100-percent monopoly of the state, but also an in*tegral part of the planned economy, officially proclaimed as such. Each country, as a part of its general economic plan, estimates its import requirements and then develops a program of exports to pay for the imports. These country plans are coordinated by Moscow. Part of the machinery of all this economic planning and trade coordination is an organization, with headquarters in Moscow, called the Council of Mutual Economic Assistance.

This totalitarian trading system insures that foreign trade serves the purposes of the state.

Top priority in trade planning is given to the requirements of the U.S.S.R. Bloc countries are required to give one another preferential treatment in trade. With this system the export of any items to the West is easily restricted as it suits government purposes—whether or not the items could be considered as “strategic.”

A vast amount of commercial information is obtained by bloc governments through their dealings with free-world traders and through their intelligence services. This provides Moscow with a comprehensive picture of the bargaining strengths and weaknesses of free-world traders.

Moreover the Soviet-bloc governments, as large buyers and sellers controlling the production and trade of a whole country, indeed a group of countries, enjoy certain bargaining advantages in dealing with the many smaller competing buyers and sellers in the marketplaces of the free world. Since losses on individual transactions can be absorbed in longer-term government gains on other deals, the unit profit need not be the factor that determines the advantage of a deal, as it generally does for the free-world trader. Soviet-bloc governments can—and not infrequently do—set their prices at levels which discriminate among the various buyers and sellers with whom they deal. They exercise monopoly control not only in selling their own goods abroad but also in disposing of imported goods at home. The Soviet-bloc governments get bargaining advantages from such practices, made possible by their totalitarian trading system—practices which the West would not wish to imitate but which it might as well squarely face.

Foreign trade is a political as well as an economic weapon in the hands of the Soviet Communist state. By way of illustration, in 1948 it was possible for the Kremlin first to reduce and then to cut off all trade between Eastern Europe and Yugoslavia as a part of the attempt to bring Marshal Tito to his knees. The attempt failed, but the Yugoslavs suffered serious economic difficulties before they could readjust. Even earlier, the world had seen how the Kremlin refused to allow the Eastern European countries to benefit from the flow of Western goods that could have been theirs under the Marshall plan—another evidence of how the state’s objectives took precedence over the people’s needs.

The Kremlin in its propaganda made much of Western trade restrictions. But the West’s limited controls over the shipment of[Pg 8] strategic goods did not come into existence until long after the Kremlin had begun using trade as a cold-war weapon. Even then these Western controls, far from being aggressive actions against peaceful trade or against the welfare of populations, were common-sense measures of economic defense, designed only to foster Western security by withholding from aggression-minded governments the important war-building materials that would make aggression easier.

On the other hand, the Kremlin’s long-term objectives in its economic relations with the free world are far more than defensive. They have a dual character: strengthening the bloc and weakening the free-world powers. These objectives can be summarized as follows:

The Kremlin, while coldly managing the East-West trade of its domain in the manner described, always had its propagandists and fellow travelers out beating the drums and making a continual outcry against the security trade controls of the West. The main line of the propaganda was that trade was equivalent to peace and prosperity, and that the Soviet bloc always stood ready for unlimited trade, but that the Western “economic blockade” barred the way. In each country the businessmen were constantly handed the false but inflammatory story that they were being shamefully discriminated against by their government and that the businessmen of neighboring countries were less subject to restrictions. Western Europe as a whole was treated to an alluring picture of a vast prospect of East-West trade, beyond all factual probability in view of Soviet policies.

This propaganda cannot be separated from the Soviet trading objectives. It is merely one of the instruments used in trying to achieve those objectives. It was used lavishly at a Moscow Economic Conference in April 1952, but although some Western businessmen who attended that meeting were impressed, the chief result was not an expansion of trade or elimination of Soviet discriminatory practices, but only the formation of new propaganda councils. And one of the significant facts of the present situation is that, although some new economic factors have arisen, the main propaganda line stays the same.[Pg 9] At the Berlin four-power conference in late January 1954, Molotov used it again.

The truth is that Western controls, which did not become effective until the 1950’s, have never been an “economic blockade.” The controls apply to a small percentage of the types of goods which made up East-West trade in the prewar years or in 1948. They leave room for the expansion of trade in many items. There are even many kinds of industrial raw materials and products which have never been embargoed by the Western Governments. Western security controls were not primarily responsible for the low levels of East-West trade.

The main causes were Soviet policies, which wrenched the customary trade of the satellites away from Western Europe, tying it to the U.S.S.R., and which forced industrialization upon the whole European bloc in a manner which reduced its ability to trade with the West. In addition to these basic causes, the bloc countries were unsatisfactory trading partners in many ways. The prices were often higher than the world market; the deliveries were uncertain and sometimes deliberately withheld; the quality of their goods was often inferior; and some of the countries had a regrettable—and perhaps intentional—tendency to go into debt to the West.

Stalin himself, in the year before he died, made some illuminating statements about the reorientation of the trade of Eastern Europe. He wrote an article, The Economic Problems of Socialism in the U.S.S.R., which was published in October 1952, though it had been written earlier in the year. In this article Stalin said that the most important economic consequence of World War II was “the disintegration of the single, all-embracing world market.” Actually there was scarcely a single world market before the war, but Stalin obviously was talking about the change in the trade of those countries that fell into the Soviet orbit during the war or shortly thereafter. He said that “now we have parallel world markets,” confronting one another. He then made the customary charge that the Western countries, through an “economic blockade,” had tried to “strangle” the Eastern European countries. He said the West had thereby unintentionally contributed to the formation of the new parallel world market. On this occasion, however, Stalin went on to say that “the fundamental thing, of course,” is not the Western economic blockade, but the fact that since the war the Eastern European countries “have joined together economically and established economic cooperation and mutual assistance.”

He made it perfectly plain that, in Kremlin thinking, the breakdown of the “one world market” and the establishment of two rival markets was a tremendous boon to the Communist cause, because it shrank the markets available to the “capitalist countries” and intensified a struggle which the Communists always see as going on among those countries. And this, Stalin said, rendered more acute what he called the “general crisis of capitalism.”

To picture the free world as in or near a general economic crisis is of course familiar Communist mythology. But Stalin’s discussion did reveal clearly the Communist indifference to the mutually fruitful and expanding international trade that the West desires. It was an admission of Communist responsibility for—or at least satisfaction with—a divided trade world.

So much for Stalin’s last economic gospel. Stalin’s death was announced on March 5, 1953. Now let us examine what has been going on in his absence.

The New Regime and the Consumer

After Stalin, the Soviet leadership was taken up by a group of top party officials. Georgi M. Malenkov was the Premier and the most influential, but apparently several other men held important shares of the responsibility and the power. This elite group included, with varying degrees of personal influence, Beria (temporarily), Molotov, Khrushchev, Voroshilov, Bulganin, Kaganovich, and Mikoyan. None of this new group was new to Soviet leadership. All had been close lieutenants of Stalin. All are known to have had important roles in previous policy formulation, and in directing key operations.

The system that this group took over in the U. S. S. R. was their own as well as Stalin’s creation. Under this system, the economy is organized along authoritarian lines and characterized by state ownership of the means of production and state planning of practically all economic activity. It is the Central Committee of the Communist party which lays down the economic and social policies which the state production plans are desired to implement. The new regime modified this system in no essential respect.

In addition to inheriting the system, Malenkov and his associates inherited economic policies and economic conditions which they themselves had helped to create.

In the U.S.S.R., as we have seen, Soviet economic policy had long been to force industrialization by every means. And this objective required such a concentration of capital investment—both civilian and military—as to deprive the growing population of advances in living standards commensurate with the overall expansion of the Soviet economy. That is another way of saying they took it out of the people’s hides.

Each of the European satellites, too, had undertaken, under Soviet direction, to develop an economic structure similar to that of the Soviet Union. By 1953 all foreign trade, nearly all industry, and a very substantial portion of domestic trade had been nationalized in those countries. Where collectivization of agriculture was not completed, the Government controlled agriculture by means of centralized planning and a system of compulsory deliveries. Each satellite government[Pg 12] had drawn up a long-term comprehensive economic plan which, like that of the U.S.S.R., emphasized rapid industrialization.

These developments brought the Communist leaders many serious problems—and the people many deprivations. Before the war, as independent states, most of these satellite countries had devoted a much higher percentage of resources to the consumer sectors of their economies than was customary for the U.S.S.R. When the Communists took control, belts were tightened. The standards of living of the satellite peoples began to decline toward the low levels long prevalent in the U.S.S.R. But denying the satellite peoples the fruits of their labors, in imitation of Moscow patterns, still did not bring the overambitious war-economy plans to success. Agriculture and industry both had difficulty in keeping pace. The world has heard how the transformation of satellite agriculture into the Soviet pattern was impeded by the opposition of the rural populations to collectivization and by the difficulties of mechanizing farm output; how shortages of raw materials slowed the textile program in Czechoslovakia and the electric power industry in Hungary; how the mining and metallurgical industries lagged in some areas; how the rights of labor were obliterated in the attempt to shift manpower into heavy industry; how purges furnished scapegoats for Communist failures.

In the summer of 1953 came the electrifying news of rioting in East Germany.

Also in the summer of 1953, new economic targets were announced in the U.S.S.R. and some of the satellites. These new targets—which will be discussed further in a moment—were said to be a means of improving the lot of consumers.

Some observers in the West assumed that economic difficulties in the bloc were erupting with such force that they threatened to topple the Malenkov regime. This interpretation is understandable—any democratic nation would have long since replaced a regime that in peacetime so subjugated the needs of the people—but such an interpretation of the Soviet scene must be viewed with great skepticism. At this writing there was some evidence that the problems faced by the Kremlin may in some respects have become more difficult since Stalin’s death, but one could not infer that the chronic economic difficulties of the Soviet bloc were especially different in nature from previous post-war years, nor that the Communist governments with their inhuman police control were about to collapse.

What the Communist rulers were facing was their perennial problem of developing lopsided economies without letting the lopsidedness become so repressive on the people as to upset the plans and[Pg 13] timetables. Even in police states there are physical and psychological limits beyond which human beings cannot be driven without lowering their incentives, their energy, their morale to the degree that production is severely hampered. The Soviet leaders have always recognized this. At three different periods in the thirty-odd years of their control of the U.S.S.R. they have shown themselves adept at opening the valves enough to relieve accumulating pressures and then shutting them again—always without swerving very far in the basic drive to build the industrial-military machine.

Many observers believe that even prior to Stalin’s death the time was ripe for a slight relaxation in the postwar consumption squeeze. The Kremlin faced multiple problems in consolidating its new empire. External foreign developments had been adding to the difficulties of achieving the overambitious industrial and military goals. Western export controls on the shipment of strategic goods into the bloc had been impeding the planned development of the military sectors of the economies.

In any event, a close examination of the new actions proposed by the Malenkov regime to improve the consumer’s lot, insofar as they have been revealed, indicate that plans for heavy industry and for military preparation will not be materially affected.

During the summer and fall of 1953, Communist governments all over Eastern Europe announced in turn so-called “new economic courses.” East Germany announced its “new economic course” on June 11, just before the East Berlin riots of June 17. Then came Hungary (July 4), the U.S.S.R. (August 8), Rumania (August 22), Bulgaria (September 8) and Czechoslovakia (September 15). Smaller adjustments were announced earlier for Albania, and later for Poland.

The announced programs differed according to local problems, but almost everywhere the solution of agricultural troubles was a key objective. Better collection and distribution facilities for farm products were demanded. This theme was almost invariably played to the popular tune of helping the consumer—especially in the U.S.S.R. Deplorable housing conditions came in for a share of the attention.

In the satellites the programs reflected openly the inability to meet many of the exacting goals that had been set. In some countries, the emphasis was on bigger industrial investments in scarce basic materials. In others, concessions to the peasants were paramount. The initial implementation, as well as some of the program announcements, was confusing and sometimes contradictory.

The new economic course for the U.S.S.R. itself was unfolded in three major speeches during the second half of 1953—by Malenkov in August, Khrushchev in September, and Mikoyan in October—and in a series of decrees and lesser pronouncements.

Premier Malenkov, addressing the Supreme Soviet on August 8, made repeated claims of Soviet strength and progress. For example, he said the United States had no monopoly on the hydrogen bomb and added that such facts “are shattering the wagging of tongues about the weakness of the Soviet Union.” But in the section on consumer goods he gave a revealing picture of weakness.

He spoke at great length about lags and failures in agriculture and in the manufacture of consumer articles. He severely criticized the poor quality and appearance of goods, the “serious shortcomings” in the organization of domestic trade, the “unsatisfactory leadership of enterprises,” the “high production costs” and high prices of coal and timber, the “neglected state” of agriculture in many districts, the “serious lagging” in livestock, potatoes, and vegetables. He said the Government considered it “essential to increase considerably” the investment in consumer industries.

The urgent task [Malenkov said] lies in raising sharply in 2 or 3 years the population’s supply of foodstuffs and manufactured goods, meat and meat produce, fish and fish produce, butter, sugar, confectionery, textiles, garments, footwear, crockery, furniture and other cultural and household goods; in raising considerably the supply to the population of all kinds of consumer goods.

The program was to be accomplished in “2 or 3 years,” and this was later repeated in other official statements. In other words it was to be a relatively short-term program of expansion, hardly long enough to make a major shift in industrial emphasis—nor did Malenkov claim such a shift. He said, “We shall continue to develop, by all possible means, heavy industry and transport.... We must always remember that heavy industry constitutes the basic foundation of our socialist economy, because without its development, it is impossible to insure further growth of light industry, increase productivity of agriculture, and the strengthening of the defensive power of our country.” Taking up this theme, the Communist propagandists in the U.S.S.R. and the satellites have constantly assured the people that they should not interpret the “present tasks of the economic policy as a retreat from the Marxist-Leninist principles of building up socialism.” The continued growth of basic industries was declared to be essential.

The assertion was made, not that the consumer program would displace basic industrialization, but that both could progress simultaneously.[Pg 15] Malenkov said that heavy industry had risen from 34 percent of the total industrial output in 1924-25 to 70 percent in 1953. And while that was going on, he said, the U.S.S.R. was unable to develop light industry (textiles, garments, shoes) and the food industry at the same rate as heavy industry. But now, he said, the Nation was at last able to develop those industries rapidly.

This “now-we-are-strong-enough” theme runs all through the Communist propaganda on the subject. But it doesn’t harmonize with existing facts and figures.

In the first place, though the Soviet Union has made large industrial gains, it has not built its industrial base anywhere near the long-term goals that Stalin set in 1946 for the ensuing 15 years or so—goals which, even if attained, would not bring the U.S.S.R. in most respects to the production levels which the United States has already reached.

In the second place, the “now-we-are-strong” theme seems to leave out of account the truly deplorable condition of Soviet agriculture. Malenkov himself said a drastic increase in consumer goods could not be achieved without “further development and upsurge” of agriculture, because agriculture “supplies the population with food and light industry with raw materials.”

On the condition of agriculture, Nikita S. Khrushchev had a great deal to say at a session of the Communist Party’s Central Committee on September 7. Khrushchev is the First Secretary of the Party. His speech was an even more dismal confession of the “serious lag” than Malenkov’s. He revealed that the Soviet Union had 10 million fewer cattle at the beginning of 1953 than in 1928, and that the number fell by 2,200,000 during 1952 alone, instead of increasing by that same number as planned. In biting words he described the sharp decline in pork production and in wool, the unsatisfactory fodder situation, the deficiencies in potatoes and vegetables. His speech showed beyond doubt that even the production of grain, traditionally the Soviet Union’s No. 1 food staple and No. 1 export commodity, was in bad shape and that a far greater acreage needed to be devoted to feed grains in order to bolster the faltering livestock industry.

Khrushchev listed a number of measures to raise production. They included higher farm prices for livestock, milk, butter, and vegetables; the reduction of obligatory deliveries from the small private plots still held by collective farm members; the assignment of more tractors and more skilled workers to the collective farms; and the tightening of Communist Party control over agriculture. The decisions to place greater reliance on material incentives and to give slightly more recognition[Pg 16] to what remains of private enterprise were intriguing, but the collective farm system itself remained basically unchanged.

Students of the Soviet economy, surveying previous efforts to stimulate agriculture and especially mindful of the biological limitations on the reproduction of livestock, were doubtful that the new measures could bring anything like the planned increase in 1954 or 1955.

Anastas I. Mikoyan, the Soviet Minister of Domestic Trade, then made a speech October 17 before the All-Union Conference of Trade Workers.

Mikoyan, as the man in charge of large segments of the consumer goods program, enthusiastically described the program as “gigantic”. In the manner of Malenkov and Khrushchev, he also enthusiastically flayed an astonishing number of deficiencies in the production, packaging, distribution, and marketing of consumer goods. He even condemned dull advertising slogans and inconsiderate retail clerks, and said there were some things about capitalist business methods that were worthy of emulating.

He stated, too, that not only the Ministry of Consumer Goods Industry but other ministries—including aircraft and defense—were getting assignments to produce such things as refrigerators, washing machines, metal beds, bicycles, and radio and television sets. Actually, small quantities of durable consumer goods have always been produced by heavy industry ministries. Mikoyan’s statement was, no doubt, intended to sound as if these ministries were being transformed, but there is no evidence that the U.S.S.R. actually planned to reduce its production of aircraft and armaments to make way for household appliances. If such evidence shows up, the free world will welcome it.

Mikoyan gave a few figures on the production of household appliances. They revealed plans for large percentage increases, but even if achieved, these increases would still leave the consumer many years behind. For example, he said the output of refrigerators would rise from 62,000 in 1953 to 330,000 in 1955 (for a population of more than 200 million). This, even if achieved, would still be tiny by Western standards.

In August, Premier Malenkov had spoken cordially of the expansion of trade of the U.S.S.R. with Western countries but he had avoided connecting this with consumer goods. Now, however, the following brief passage appeared in the middle of Mikoyan’s long and rambling speech:

A few words must be said about the import of consumer goods. During recent years we have been making use of this additional source of supply for the population. Having become better off we can now allow ourselves[Pg 17] to import such foodstuffs as rice, citrus fruits, bananas, pineapples, herrings, and such manufactured goods as high standard woolens and silk fabrics, furniture, and certain other goods supplementing our range. These goods are in demand by the population.

Although we are buying 4 billion rubles’ worth of consumer goods from abroad this year, two-thirds of this sum will be spent on goods from the People’s Democracies. In turn, we are exporting certain consumer goods of which we have a sufficiency, and are helping the People’s Democracies with certain commodities.

Mikoyan, revising his figures in December, estimated the Soviet Union’s imports of consumer goods from non-Communist countries in 1953 at 1 billion rubles. Rubles are not used in foreign trade and translation into dollar values may be misleading, but at the official (although artificial) rate, 1 billion rubles would be 250 million dollars. This is a slender figure in relation to the annual consumption needs of more than 200 million persons. Even so, the amount that was actually imported during the year did not equal the $250 million estimate.

There is, however, some connection between the new regime’s promises of more consumer goods and the recent activities of the Soviet Union in the field of East-West trade. We shall be examining those activities in the next chapter.

In early 1954 the situation could be summarized something like this:

The Soviet-bloc rulers have put on a more affable diplomatic face and made a number of conciliatory gestures to the Western world without altering their fundamental hostile objectives, and they have made a great fanfare about supplying more consumer goods to their people without basically changing their war-oriented economy.

The conciliatory diplomatic tactics of Stalin’s successors have sometimes been called a “peace offensive,” but the term is hardly justified. Since last June the peaceful sounds have alternated curiously with renewals of the old name-calling and intransigeance. And behind their Curtain the Communists never stopped teaching their students that capitalistic society must be overthrown. The North Atlantic Council could not avoid the conclusion at Paris on December 16 “that there had been no evidence of any change in ultimate Soviet objectives and that it remained a principal Soviet aim to bring about the disintegration of the Atlantic alliance.”

The evidence indicated that the Communist rulers, while making gestures to their multitudes, were trying not to interfere with industrial-military development.

The evidence included the Soviet Union’s own budget figures, which indicated that the state investment (there is no private investment) in consumer goods ministries is still extremely small; that the extremely[Pg 18] large specific allocations to the military in the 1953 budget were no lower than actual expenditures in 1952; and that the budget’s “unexplained” category, which almost certainly includes “sensitive” military projects, greatly increased.

It seemed most unlikely that increases in domestic output of consumer goods, even supplemented by increased imports, could be large enough to make a substantial improvement in the traditionally low living standards in the Soviet Union.

We must suppose that the intent of any steps to improve the lot of the Soviet-bloc consumer is to improve it just enough to rescue his productivity in the interest of the state, but not enough to give him such a taste of better living as would lead to a wider and wider opening of the valves and hinder the buildup of the totalitarian war economy.

If that is a correct assumption, the world, yearning for assurance of peace, is entitled to wish that the Kremlin’s calculations might be upset and the consumer might get enough to whet his appetite in a big way.

The Kremlin’s Recent Trading Activities

In midsummer of 1953, at about the time of the Korean armistice of July 27 and just before Malenkov’s major speech of August 8, the Soviet Union attracted world attention by a flurry of new trade agreements with non-Communist countries. There was another flurry around the end of the year.

During the last 9 months of 1953 and the early part of 1954, the representatives of U.S.S.R. adopted a somewhat more polite and businesslike manner in their commercial dealings with the free world. They not only said they wanted more trade (they had never stopped saying it) but they took more steps to bring it about. Besides trade agreements, they signed more contracts with private firms. In Moscow they warmly entertained traveling salesmen from the West. In Western capitals they staged a few cocktail parties and press conferences. They poured more funds into eye-catching exhibits at “trade fairs” from Copenhagen to Bangkok. They made grandiose offers to buy, and gave them great publicity. Some offers to buy, sell, or barter they made quietly through commercial channels. They showed signs of wanting the nonindustrial portions of the world to regard them as a helpful “big brother” bringing both trade and aid.

These activities, which many writers have called a “trade offensive,” carried with them important meanings for the free world. In this chapter we shall examine the activities and probe for the meanings.

In a period of about 3 weeks, in late July and early August, the U.S.S.R. concluded trade agreements with France, Greece, Argentina, Denmark, and Iceland. These were not mere renewals of expiring agreements. The U.S.S.R. had never before had trade agreements with France, Greece, or Argentina (or any other Latin American country). Its last trade agreement with Denmark had expired in 1950, and with Iceland in 1947. Its trade with three of the countries, Greece, Iceland, and Argentina, had been almost nonexistent in recent years. Considerable trade, however, had been carried on with France and Denmark without benefit of trade agreements.

The U.S.S.R. also renewed existing trade agreements with Iran and Afghanistan and signed a “payments agreement” with Egypt. Most of these trade agreements signed during the summer of 1953 became effective as of July 1.

The second group of trade agreements, clustered shortly before or after January 1, 1954, and mainly effective as of that date, was with India, Belgium, Norway, Sweden, and Finland. It was the first time the U.S.S.R. had ever had a trade agreement with India. There had not been one with Belgium since 1951. The others were renewals. Barter deals were also made with some of the countries already mentioned, and with Israel and Japan.

Not since 1948, when the U.S.S.R. had entered into annual or long-term trade agreements with eight countries of Western Europe, had there been a period of Soviet trade-agreement activity that could compare with the paper blitzkriegs just described. And the result was that in the early part of 1954 the U.S.S.R. had trade agreements with more free-world countries than at any other time in the postwar period.

This fact and the hefty amounts of trade which were called for in some of the agreements have given many people the impression that a historic increase in the size of East-West trade was taking place. The impression seems hardly justified.

In the first place, trade agreements are usually only hunting licenses. They merely authorize—but do not guarantee—the exchange of goods. The governments agree to permit the export and import of the types listed—if contracts can be arrived at between Soviet monopolies and Western business. If the goods turn out to be unavailable, or if the demand is not forthcoming, or if the price is too high or the quality too low, the publicized amounts of the trade agreements do not materialize in the export-import statistics. And this fact rarely receives as much public attention as the original announcement. To illustrate, a spokesman for the Greek Foreign Ministry told the press on January 19 that the U.S.S.R. had lagged far behind in shipments under the 1-year trade agreement of July 1953. That agreement had been publicized as calling for trade of $10 million each way, but the Greek official said few Russian deliveries had been made and “it will be a miracle” if these deliveries reached $3 million.

In the second place, even a big percentage of fulfillment would not necessarily increase trade between the U.S.S.R. and the free world to the high points of 1948 and 1952. The 1948 turnover—that is, the sum of exports and imports—had been about $1 billion. It declined to $545 million in 1950. By 1952 it was back up to $943 million. The preliminary estimate for 1953 is $790 million. Thus the year which saw the Kremlin’s new trading tactics was also the year that saw a slump of about 16 percent in the dollar value of its trade with the free world. The trade was rising moderately in the last part of 1953 and a further moderate rise in 1954 would not be surprising.

But there is still another reason why the new Soviet trade arrangements will not necessarily mean a historic upsweep in East-West trade: The satellite countries have not been behaving in quite the same way.

The U.S.S.R. is only one part of the Soviet bloc, albeit the center of power. The U.S.S.R. accounts for about 30 percent of the trade which the European Soviet bloc carries on with the free world. (The percentage would be still less if Communist China were included, but Communist China will be discussed in another chapter.) In other words, Czechoslovakia, Poland, Hungary, the Soviet zone of Germany, Rumania, Bulgaria, and Albania, despite the long, steady decline of their trade with the free world ever since “sovietization” took hold in about 1948, still exchange about twice as much merchandise with free-world countries as does the U.S.S.R. These satellites, or some of them, have long had trade agreements with countries in Western Europe. During the last year or so they have renewed about 45 of those. In addition they renewed about a dozen agreements with non-European countries.

The brand-new agreements which the satellites concluded in Europe were mainly with France and Greece, thus conforming to the Soviet pattern of increased attention to those two countries. But in other respects the satellite trade pattern was different from that of the U.S.S.R., for while recent U.S.S.R. commitments, if fulfilled, seem to indicate increased trade, there was no evidence of a reversal in the long slide of the East-West trade of the satellites. Therefore one could not ignore the possibility that the U.S.S.R., with a flourishing of fountain pens and a blare of trumpets, was merely shifting to itself a bigger percentage of all bloc trade with the rest of the world.

Now let’s see what kinds of goods are involved in the new trade agreements and other commitments that the U.S.S.R. has been making.

Consumer goods, the items about which Malenkov, Khrushchev, and Mikoyan made such a fanfare in announcing the new course for the Soviet domestic economy, make up one class of commodities, though not the most important, that the U.S.S.R. has been ordering from the Western world. It appears that the U.S.S.R. has committed itself to buy consumer goods at a somewhat brisker rate than in recent years.

Most of these consumer goods were food items. During the last 6 months of 1953 and the first month of 1954, the known Soviet arrangements to buy food from the free world amounted to about $90 million. Some of the deliveries were scheduled in 1953, some in 1954.

Butter was the biggest item. In trade agreements and contracts, butter quotas amounted to 37,500 tons, with an estimated value of $40 million. Denmark was to provide about $18.6 million of this. The second most important source of butter was to be the Netherlands, with $13.7 million. Lesser amounts were to come from New Zealand, Australia, Sweden, and Uruguay.

Meat quotas came to about $22 million, with Denmark and Argentina the leading suppliers. Smaller amounts were to come from the Netherlands, Uruguay, and other countries.

Fish quotas amounted to $15 million. Nearly all of this was herring. The leading suppliers were to be Iceland and Norway, and others were the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, and Denmark.

The U.S.S.R. during the 7-month period also arranged to buy $7 million worth of citrus fruits from Italy, Japan, and Israel (and apparently made a whopping profit selling oranges to the Russian people); $4 million worth of cheese from Argentina and the Netherlands; $2.4 million worth of lard from Denmark and Argentina; and $1.4 million worth of sugar from the United Kingdom and Cuba.

Besides food, the most important consumer item ordered from the West was textiles. The amount is harder to estimate, but it was somewhat larger than the Soviet textile imports of any recent year. The principal suppliers were to be Belgium, France, the Netherlands, Italy, and the United Kingdom.

In addition to contracts already made, the Soviet officials were still putting out feelers for consumer goods. Some of them reached across the Atlantic. In January much publicity was given to the efforts of an American firm to buy a large quantity of Government-owned surplus butter and sell it abroad—ultimate destination Russia.

Secretary of Commerce Sinclair Weeks announced on January 15 that he would not approve any application “which would permit an exporter to buy butter at considerably lower prices than those paid by the American housewife and then send that butter into Russia.” On February 10 he announced that it had been “decided as a matter of policy to deny commercial export license applications for the export for cash of United States Government-owned surplus agricultural or vegetable fiber products to Russia or her satellites.” He pointed out, however, that this ban “does not preclude study of export license applications for these nonstrategic products to the Soviet bloc if acquired by exporters in the open market and not from the Commodity Credit Corporation surplus stocks.”

It is difficult at this writing to compare the Soviet Union’s new commitments to buy consumer goods with the actual imports of previous years. Total free-world exports to the U.S.S.R. in 1953 are estimated at $410 million (compared with $481 million in 1952) but how much of this $410 million was consumer goods is not yet determined. The 1954 figure can only be speculated upon. But certain generalizations about consumer goods are possible.

As evident in chapter 1, the U.S.S.R. was never very much interested in importing consumer goods from the West. The items it did import for the consumer were not the household appliances and luxury items we sometimes think of as consumer goods—but were usually food. These imports have been higher at times than others: for example they were relatively high in the late 1930’s and again in 1948. Since 1950 they have been rising again, but by 1953 they were still breaking no records. They have always represented a relatively small percentage of total Soviet imports. At the same time, during the postwar years Soviet policies were forcing the consumer-goods imports of the European satellites steadily downward.

These contrasting trends of rising Soviet imports and sinking satellite imports seemed likely to continue in 1954. This probability, plus Mikoyan’s statement in his October speech that “we are helping the People’s Democracies with certain commodities,” made one wonder how much of the new Soviet imports of butter and other food were being reshipped to Eastern Germany and other satellites to alleviate the unrest there.

The U.S.S.R., while ordering more consumer goods, seemed even more anxious to buy ships.

Every trade agreement which the U.S.S.R. has signed with a shipbuilding nation of Western Europe since mid-1953—that is, with Finland, Italy, Belgium, the Netherlands, Denmark, France and Sweden—has included a sizeable quota for ship purchases, particularly fishing vessels and refrigerator ships. Contracts for fishing vessels were also made with firms in the United Kingdom and Western Germany.

It was safe to say that Soviet activity with respect to Western European shipyards since mid-1953 surpassed the biggest previous shopping expedition for ships, which came around 1949. And it was clear that by early 1954 the U.S.S.R. had greater commitments on the books to buy ships from the West than at any other time in its history. This was true in tonnage, value, and number of vessels.

Probably not all the trade agreement commitments will result in[Pg 25] actual deliveries; on the other hand, the shopping spree is still going on and further commitments are likely.

Because of Western restrictions on the export of certain types of ships, the new vessels destined for the Soviet Union were mainly of smaller types. A large number were fishing vessels, such as trawlers, fish processing craft, and refrigerator ships. Others were cargo ships, tugs and barges.

The buying of fishing vessels accords with the shortage of food in the Soviet bloc. Mikoyan in his October speech admitted there had been many complaints about the fish supply and that the Soviet fishing goals had not been met. But the Soviet search for ships could not be viewed entirely in the light of a desire to produce more consumer goods. The U.S.S.R. was seeking cargo ships in addition to fishing boats, ordering other marine equipment such as component parts and floating cranes and trying to arrange for more ship repairs in free-world ports. Western shipbuilders were inclined to be receptive to orders for vessels at a time when ship orders from Western countries were declining. At the same time it was impossible to ignore the fact that Soviet-bloc orders in the West can have the effect of freeing Soviet-bloc shipyards for the building of naval vessels. The campaign to buy ships thus presented the free world not only with more orders but also with a security problem.

The development of a Soviet merchant fleet is relatively recent. In 1939 the U.S.S.R. had seagoing merchant vessels totaling only 1,135,000 gross tons. It emerged from World War II with more than twice this tonnage. The main sources of the increase were lend-lease ships from the United States and war reparations. The United States in its lend-lease program leased to the U.S.S.R. 121 merchant vessels with gross tonnage of some 750,000 tons. Of these, 30 were returned to the United States and 4 were lost. The U.S.S.R. kept the others, and long exhaustive negotiations since 1946 have failed to settle this and other lend-lease claims. Through war reparations the U.S.S.R. acquired 170 more ships with gross tonnage just over one-half million tons. By 1953 the Soviet bloc—the U.S.S.R. and Poland for the most part—had a seagoing merchant fleet with a gross tonnage of 2-1/2 million tons, compared with free-world fleets totaling about 21 million tons.

The new Soviet purchases of butter, meat, and other consumer items have sometimes obscured the continuing heavy demand for equipment and raw materials needed for industrialization. There has been no appreciable decline in the Soviet interest in buying industrial commodities.[Pg 26] Such goods still dominate Soviet imports and new agreements to import—and that goes for the European satellites, too.

The Soviet bloc has shifted some of its priorities. The Soviet eagerness to buy ships is an example of a raised priority. The sharp drop in Soviet buying of Malayan rubber from the United Kingdom in 1953 was an example of a lowered priority. There are some other changes, but no change in the emphasis on industrial goods in general.

All the trade agreements concluded between countries of Eastern and Western Europe since mid-1953 have included quantities of such items—limited, of course, by the West’s security controls which provide for the embargo of some items and quantitative restrictions on others. In the trade agreements of Czechoslovakia and Poland, we find quotas for deliveries from the free world of electrical equipment, ball bearings, steel products, pyrites, lead, zinc, aluminum, and many others. Bulgaria also has shopped for capital equipment. In exchange for their grain, vegetables, fruits, tobacco, and a small amount of manganese and chrome, the Bulgarians made trade-agreement commitments to get important amounts of cables, rods, bars, plate steel, railroad equipment, floating cranes, electrical machines and installations, mining equipment, and miscellaneous machinery. The U.S.S.R., besides its procurement program for ships, has written into its trade agreements certain kinds of machine tools, various kinds of steel, equipment for electric power plants, construction equipment, chemical products, textile machinery and machinery for the timber and food-processing industries. An analysis of one recent trade agreement showed that three-quarters of the value of the Soviet imports consisted of products of the metal working industries. Businessmen in the United Kingdom, which has concluded no recent trade agreement with the U.S.S.R., have reported that the Soviet bloc’s real interest in buying British goods was confined mainly to items for production.

The attempts to purchase items like those named in the foregoing paragraph are nothing new. The point is, these efforts are continuing.

Many of these items have been under quantitative controls by the major free-world countries—that is, exported to the bloc in limited quantities only. Some of the most highly strategic items, such as the types of machine tools and bearings that are essential to war production, have been under embargo, and when that was true, the free countries that participate in the international control program have generally shipped them only to fulfill commitments made before controls went into effect, or in special cases where the countries felt strongly that the shipment was justified in view of the benefits to the free world that resulted from the two-way trade made possible by the shipment. In 1952 and 1953, for example, all nations receiving aid from the United States permitted the shipment to the Soviet bloc[Pg 27] of roughly $15 million in items that were listed for embargo under the Battle Act (Mutual Defense Assistance Control Act of 1951), as compared with total free-world shipments to the bloc of about $2.7 billion in the same 2 years.

These highly strategic items, of course, are the ones which the countries of the Soviet empire have wanted most of all. And when not able to get them legally, they have continued their efforts to get them illegally. The third semiannual Battle Act report, World-Wide Enforcement of Strategic Trade Controls, contained a detailed account of the underground trade that violates Western regulations. Since all foreign trade of a Soviet-bloc country is a state monopoly, it follows that the state is an active participant in this underground traffic. With the bloc, circumvention is an official policy.

The Soviet Union, despite its publicized buying of consumer goods—which have never been restricted by the free world—has definitely not slackened its efforts to obtain industrial goods whether strategic or nonstrategic in nature.

As told in chapter I of this report, the economic planners of the Soviet empire first figure out their import requirements and then decide what they want to export in order to pay for the imports. They look upon exports primarily as a means of obtaining goods which are more advantageous to import than to produce, or which they cannot produce.

In the present chapter, we have seen what sort of items they are currently interested in importing. Now we turn the coin over and look at the export side.

The most noticeable feature is that the U.S.S.R. in the last half of 1953 and the early part of 1954 introduced into free-world markets a number of mineral products which they had not sold in such quantities for some years.

These commodities included manganese, petroleum, and gold. All of them at one time or another have been among the major Soviet exports. Together with grain, timber, and furs, they make up the principal means that the U.S.S.R. possesses to procure the imports they want.

Why have the mineral exports been revived at this time? This leads us to the grain situation.

Grain has long been the Soviet Union’s No. 1 export commodity, and still is. But Soviet grain shipments declined precipitately in 1953. The United Kingdom, usually the main Western customer for this commodity, stopped buying grain on a government-to-government basis and turned the purchasing over to private firms. At the[Pg 28] same time the U.S.S.R. apparently decided to keep more of its grain stores at home. The efforts to furnish more fodder to livestock, together with below-average crops and collective-farm headaches in the U.S.S.R. and satellites, suggest the motivation for this. At any rate the private British firms were unenthusiastic about signing large contracts at the high prices set by the U.S.S.R., and grain shipments to the United Kingdom skidded from $101 million in 1952 to only $10.1 million in 1953.

Although grain was far from disappearing as a Soviet export to the West, it became less potent—for the time being, at least—as a means of acquiring foreign exchange to pay for imports. This loss was only partially offset by a moderate increase in sales of Soviet timber to Britain and a big drop in the amount of Malayan rubber that the U.S.S.R. bought from the British. Meanwhile war reparations from Finland had ended in 1952, and deliveries of Swedish goods under a long-term credit agreement ended the same year. The Finnish and Swedish developments meant that about $80 million worth of goods which the U.S.S.R. had received from those countries in 1952 could not be duplicated in 1953 unless some other means of payment were created. All these events contributed to the reviving of some other export commodities.

How far the shift is going and how long it will continue cannot be predicted. Abrupt alteration in Soviet exports is hardly a novel development. For a time, around 1930, when forced collectivization of agriculture and forced exports of grain had induced famine in some areas of the U.S.S.R., the Kremlin opened the pressure valves a mite, heavily slashed the exportation of grain, and even bought some grain on the Baltimore exchange. That was a breathing spell in the midst of the first big Soviet push toward rapid industrialization. During the same general period, the U.S.S.R. found it expedient to force more production and more exports of furs, coal, and some of the same commodities now receiving special attention—petroleum and metallic ores—in order to get imports of capital goods needed in the ambitious industrial program.

Manganese is a silvery-white metal used in the making of hard steels. The U.S.S.R. is one of the world’s major sources of manganese. It can produce a large amount each year, depending on how much manpower it decides to throw into the effort. It consumes a lot in its own steel industry, even using manganese as a substitute for scarcer alloys like nickel and molybdenum. In addition, its plans usually provide for certain quantities of manganese ore to sell abroad.

These exports have continually fluctuated. Before the war they[Pg 29] ranged from about 400,000 metric tons a year to about 1 million. The United States, which produces very little manganese, was a major customer. In the 1930’s we got about 40 percent of our manganese imports from the U.S.S.R. Other important customers were France, Germany, Belgium, and Japan.

During the war, Soviet manganese vanished from world markets. The United States and other customers turned to sources in Africa, Latin America, and India.

In March 1945, Soviet manganese ore reemerged. The United States was the principal buyer, receiving 1,168,000 tons in about 4 years. In February 1947 the Soviet Foreign Trade Journal pointed out the importance of the United States to future Soviet plans for the export of manganese. But late in 1948 the Kremlin suddenly reduced its shipments to the United States almost to the point of embargo. A few shipments trickled in during the next 2 years and stopped entirely in 1951. Meanwhile deliveries to Western Europe did not undergo a compensating rise; they were little more than 100,000 tons a year.

Came the season of the last half of 1953 and the early part of 1954. The Kremlin’s zeal for exporting manganese bloomed again. Commitments to ship over 300,000 tons of the ore were written into trade agreements with Western European countries. Offers of manganese reached the United States through various channels.

Chrome is usually part of the package when manganese is sold. As could be expected, Soviet chrome commitments also climbed in late 1953.

There was also a revival of activity in the export of silver, platinum, and palladium.

But a more interesting commodity which the U.S.S.R. has begun to put on the market in bigger quantities was oil.

In approximately the last half of 1953 the U.S.S.R. made agreements to ship to free-world countries about 3.5 million metric tons of crude petroleum, kerosene, diesel fuel, and other petroleum products. The countries due to receive the largest amounts—if delivered—were Finland, France, and Argentina. Other customers were Greece, Italy, Iceland, Denmark, Sweden, Israel, and the Netherlands. Some deliveries were made in 1953; more would be made in 1954; there was no certainty that all the commitments would be fulfilled. But even a two-thirds fulfillment apparently would be enough to hoist petroleum ahead of lumber and furs and place it second only to grain among Soviet exports to the free world.

What would this mean to the free world? What problems would[Pg 30] it raise? Again we can find clues in the past. The present situation is not the first time that the U.S.S.R. has created a stir by abruptly entering oil markets. This also happened in the late 1920’s, when the U.S.S.R. began exporting large amounts of oil as a means of obtaining industrial imports. These exports grew each year and were 6.1 million metric tons in 1932. This was around 10 percent of the world’s oil exports, and was almost 30 percent of Soviet oil production at the time. The United Kingdom and Italy were the major customers for this oil, but there were many others. The marketing was done through various channels. The Soviet monopoly that controlled all oil exports set up a network of sales offices abroad. Long-term contracts were made in Spain, Italy, France, Belgium, and the Netherlands.

The expansion of Soviet oil sales gave rise to bitter price wars with established oil groups. The bitterness was made more intense by the fact that the Bolsheviks had neglected to settle for the foreign oil properties that they had seized after the revolution. As in all exports, the U.S.S.R. was more interested in total receipts of foreign exchange than in making high per-unit profits; so it could and did use price cutting as a means of achieving a foothold. Subsidiaries of some of the world oil trusts then tried to drive the Soviet oil back home by underselling the Soviet monopoly. But the attempts failed, and Soviet oil won an important place in world markets.

In the late 1930’s, the oil was withdrawn. Soviet exports dropped back to 1.4 million tons in 1938, and kept fading. After the war, they came back only in a trickle—for example, 100,000 metric tons in 1951 and 250,000 in 1952, then rising to 450,000 in 1953 as some of the new commitments of 3.5 million tons began to be fulfilled.

Meanwhile the war had swept additional oil into the Kremlin’s hands, including the oil wells of Rumania and those which were taken over as “German assets” in the Soviet zone of Austria. And the oil exported to the West from these new Eastern European acquisitions greatly exceeded the exports of the U.S.S.R. itself, amounting to 1.2 million metric tons in 1951, 1.7 million in 1952, and 2.3 million in 1953. In recent months, while the U.S.S.R. was making agreements to ship 3.5 million tons, the new export commitments of these other properties in Eastern Europe became known only in part, at least at this writing.

The Soviet bloc, though still short of certain specialized refined products, probably has the oil capacity to make considerable exports for at least some years, if the Kremlin so decides. Whether the bloc will indeed step into the world markets in an important way, as the U.S.S.R. did in the twenties, is of course not known. The West is watching closely to see whether the Kremlin will again use its[Pg 31] monopoly control to undertake a major campaign of underselling other suppliers in world markets.

It was natural for oil-importing countries in the free world to be interested in new supplies from the Soviet bloc, especially if the price was attractive or if the transaction also enabled a free country to market its own products in the East. But the West could not forget past patterns, nor ignore the problems brought by new Soviet sales.

When the Russians abruptly disappear from markets, free-world importers turn to free-world sources to make up the difference. And if the importers later jump whenever the Soviet Government decides to stage another of their dramatic entrances, the free-world sources whose production has been stimulated will be the losers. And who can predict when the dictates of the Kremlin—economic or political—will override the dictates of the market place, and the oil, manganese, chrome, or whatever it may be, will suddenly be whisked out of reach?

Down through the centuries, the word gold has exerted a powerful effect upon the imaginations of mankind. And last December, when the news came out that airplanes laden with gold bullion were flying from Moscow to London, there was a great buzz of interest. What were the Russians up to now?

The export of Russian gold was not new. The Soviet Union had been selling a sizeable amount each year in the free world. But in the last few months of 1953 a larger amount of Russian gold came out into the free world than had emerged in any recent year. Most of it, instead of entering the free market, went to the Bank of England. The total amount exported to England, Switzerland, and other countries during 1953 was not announced, but it was somewhere between $100 and $200 million.

There has been much speculation on the reasons for an increase in gold sales. The best explanation seemed to be that the Kremlin, hard pressed for adequate exports, decided—as in the case of manganese and oil—to use a fraction of its gold hoard so that it could continue to import the things it wanted from the free world. It has done the same thing on past occasions. For example, in 1928 the U.S.S.R. exported $167 million worth of gold and in 1937, $212 million worth.

Whether still larger amounts of Russian gold would be exported in the future was of course unknown. Concerning the size of the Soviet gold stock many guesses have been made, most of them ranging from $3 billion to $6 billion. The Soviet Union attaches great importance to its gold reserve. It has been willing to part with gold only in limited amounts or for special purposes. In any event, the gold[Pg 32] hoard would not be big enough to use as a base for a large-scale, long-term trade relationship. Nevertheless, over the short run, and for limited purposes, the U.S.S.R. could, if it desired, export a lot more gold than it has to date. Gold therefore is an intriguing question mark of East-West trade.

Moscow, while shopping for more ships, peddling more gold, and making other moves in the industrial countries of Western Europe, also reached outside Europe and tried to fasten closer economic ties with Asia and Latin America. The trade of the Soviet Union with the non-Communist areas of Asia, and with Latin America, has never amounted to more than driblets. That of Czechoslovakia and Poland has been a little bigger. The U.S.S.R. entered this field in 1953 with a good deal of propaganda effect. The effect in delivery of goods was still to be seen.

The Soviet trade bosses used a number of devices.

One device was to offer loans and technical assistance. Some of the loans were connected with trade. Others, related to construction activities within free-world countries, were more suggestive of investments and provided opportunity for increased Soviet or Communist Party economic penetration. There was a marked interest in assisting in the establishment of storage and supply facilities. So far, few Soviet offers have been accepted. Possibly this is because they are disturbingly reminiscent of the penetration techniques that were used to gain economic leverage inside the Eastern European countries and China prior to Soviet political domination of these regions. Or it may be that skepticism has been aroused by the experience with Communist Party use of commercial enterprises in some Western European countries to finance the local party and the Kremlin’s activities.

Another device has been to build lavish exhibits at “trade fairs.” This activity, though carried on in Western Europe too, was especially marked in South Asia. On an increasing scale, since 1951, the Soviet Union and its satellites have been using trade fairs for a double purpose—to promote the kind of trade the bloc desires and to propagate Communist ideas.

By elaborate and costly displays the Soviet-bloc governments seek to dominate the fairs; to overshadow the exhibits of the United States and other free-world countries; and to create the illusion of an industrial and commercial superiority over the Western nations, especially the United States. The U.S.S.R. makes a concerted and determined effort to discredit and minimize the industrial and technological achievements of the United States by contrasting the great size of the Communist nations’ participation with the usually modest[Pg 33] representation by United States firms. An important distinction between Soviet and U.S. exhibits is that the former are developed as a state trade promotion and propaganda undertaking, and involve the building of special pavilions, whereas U.S. participation amounts to the sum total of exhibits of individual U.S. industrial and commercial companies assembled for the single purpose of promoting the sale of individual products.