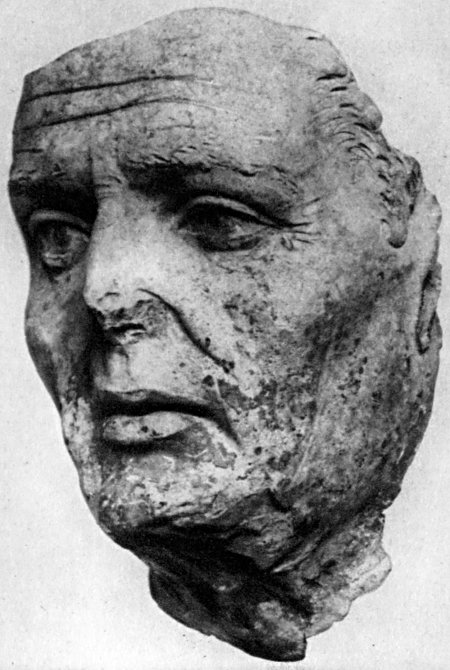

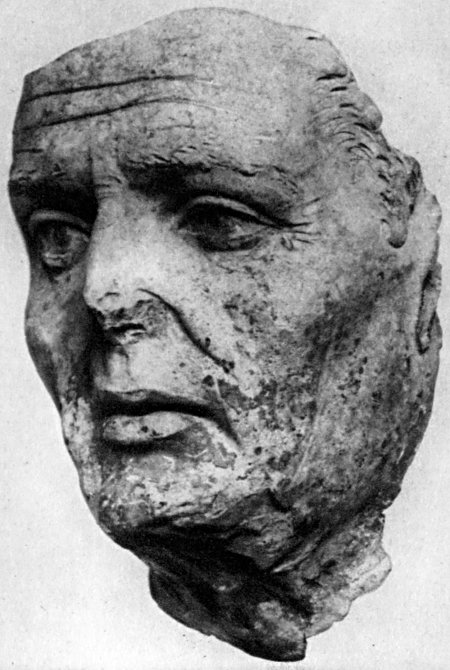

M. TULLIUS CICERO.

M. TULLIUS CICERO.FROM THE JAMES LOEB COLLECTION.

Title: De Officiis

Author: Marcus Tullius Cicero

Translator: Walter Miller

Release date: September 29, 2014 [eBook #47001]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English, Latin

Credits: Ted Garvin and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team

TRANSCRIBER'S NOTE:

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

Inconsistencies in hyphenation have not been corrected, punctuation has been silently corrected. A list of corrections to the text can be found at the end of the document.

M. TULLIUS CICERO.

M. TULLIUS CICERO.CICERO

WITH AN ENGLISH TRANSLATION BY

WALTER MILLER

LONDON: WILLIAM HEINEMANN

NEW YORK: THE MACMILLAN CO.

MCMXIII

In the de Officiis we have, save for the latter Philippics, the great orator's last contribution to literature. The last, sad, troubled years of his busy life could not be given to his profession; and he turned his never-resting thoughts to the second love of his student days and made Greek philosophy a possibility for Roman readers. The senate had been abolished; the courts had been closed. His occupation was gone; but Cicero could not surrender himself to idleness. In those days of distraction (46-43 b.c.) he produced for publication almost as much as in all his years of active life.

The liberators had been able to remove the tyrant, but they could not restore the republic. Cicero's own life was in danger from the fury of mad Antony and he left Rome about the end of March, 44 b.c. He dared not even stop permanently in any one of his various country estates, but, wretched, wandered from one of his villas to another nearly all the summer and autumn through. He would not suffer himself to become a prey to his overwhelming sorrow at the death of the republic and the final crushing of the hopes that had risen with Caesar's downfall, but worked at the highest tension on his philosophical studies.

The Romans were not philosophical. In 161 b.c. the senate passed a decree excluding all philosophers and teachers of rhetoric from the city. They had no taste for philosophical speculation, in which the Greeks were the world's masters. They were intensely, narrowly practical. And Cicero was thoroughly [x] Roman. As a student in a Greek university he had had to study philosophy. His mind was broad enough and his soul great enough to give him a joy in following after the mighty masters, Socrates, Plato, Zeno, Cleanthes, Aristotle, Theophrastus, and the rest. But he pursued his study of it, like a Roman, from a "practical" motive—to promote thereby his power as an orator and to augment his success and happiness in life. To him the goal of philosophy was not primarily to know but to do. Its end was to point out the course of conduct that would lead to success and happiness. The only side of philosophy, therefore, that could make much appeal to the Roman mind was ethics; pure science could have little meaning for the practical Roman; metaphysics might supplement ethics and religion, without which true happiness was felt to be impossible.

Philosophical study had its place, therefore, and the most important department of philosophy was ethics. The treatise on Moral Duties has the very practical purpose of giving a practical discussion of the basic principles of Moral Duty and practical rules for personal conduct.

As a philosopher, if we may so stretch the term as to include him, Cicero avows himself an adherent of the New Academy and a disciple of Carneades. He had tried Epicureanism under Phaedrus and Zeno, Stoicism under Diodotus and Posidonius; but Philo of Larissa converted him to the New Academy.

Scepticism declared the attainment of absolute knowledge impossible. But there is the easily obtainable golden mean of the probable; and that appealed to the practical Roman. It appealed especially to Cicero; and the same indecision that had been his [xi] bane in political life naturally led him first to scepticism, then to eclecticism, where his choice is dictated by his bias for the practical and his scepticism itself disappears from view. And while Antiochus, the eclectic Academician of Athens, and Posidonius, the eclectic Stoic of Rhodes, seem to have had the strongest influence upon him, he draws at his own discretion from the founts of Stoics, Peripatetics, and Academicians alike; he has only contempt for the Epicureans, Cynics, and Cyrenaics. But the more he studied and lived, the more of a Stoic in ethics he became.

The cap-sheaf of Cicero's ethical studies is the treatise on the Moral Duties. It takes the form of a letter addressed to his son Marcus (see Index), at this time a youth of twenty-one, pursuing his university studies in the Peripatetic school of Cratippus in Athens, and sowing for what promised to be an abundant crop of wild oats. This situation gives force and definiteness to the practical tendencies of the father's ethical teachings. And yet, be it observed, that same father is not without censure for contributing to his son's extravagant and riotous living by giving him an allowance of nearly £870 a year.

Our Roman makes no pretensions to originality in philosophic thinking. He is a follower—an expositor—of the Greeks. As the basis of his discussion of the Moral Duties he takes the Stoic Panaetius of Rhodes (see Index), Περὶ Καθήκοντος, drawing also from many other sources, but following him more or less closely in Books I and II; Book III is more independent and much inferior. He is usually superficial and not always clear. He translates and [xii] paraphrases Greek philosophy, weaving in illustrations from Roman history and suggestions of Roman mould in a form intended to make it, if not popular, at least comprehensible, to the Roman mind. How well he succeeded is evidenced by the comparative receptivity of Roman soil prepared by Stoic doctrine for the teachings of Christianity. Indeed, Anthony Trollope labels our author the "Pagan Christian." "You would fancy sometimes," says Petrarch, "it is not a Pagan philosopher but a Christian apostle who is speaking." No less an authority than Frederick the Great has called our book "the best work on morals that has been or can be written." Cicero himself looked upon it as his masterpiece.

It has its strength and its weakness—its sane common sense and noble patriotism, its self-conceit and partisan politics; it has the master's brilliant style, but it is full of repetitions and rhetorical flourishes, and it fails often in logical order and power; it rings true in its moral tone, but it shows in what haste and distraction it was composed; for it was not written as a contribution to close scientific thinking; it was written as a means of occupation and diversion.

The following works are quoted in the critical notes:—

| MSS. A = | codex Ambrosianus. Milan. 10th century. | ||

| B = | codex Bambergensis. Hamburg. 10th century. | ||

| H = | codex Herbipolitanus. Würzburg. 10th century. | ||

| L = | codex Harleianus. London. 9th century. | ||

| a b = | codices Bernenses. Bern. 10th century. | ||

| c = | codex Bernensis. Bern. 13th century. | ||

| p = | codex Palatinus. Rome. 12th century. | ||

| Editio Princeps: | The first edition of the de Officiis was from the press of Sweynheim and Pannartz at the Monastery of Subiaco; possibly the edition published by Fust and Schöffer at Mainz is a little older. Both appeared in 1465. The latter was the first to print the Greek words in Greek type. The de Officiis is, therefore, the first classical book to be issued from a printing press, with the possible exception of Lactantius and Cicero's de Oratore which bear the more exact date of October 30, 1465, and were likewise issued from the Monastery press at Subiaco. | ||

| Baiter & Kayser: | M. Tullii Ciceronis opera quae supersunt omnia. Lipsiae, 1860-69. | ||

| Beier: | M. Tullii Ciceronis de Officiis libri tres ... cum commentariis editi a Carolo Beiero. Lipsiae, 1820. | ||

| Erasmus: | – | M. Tullii Ciceronis Officia, diligenter restituta. Ejusdem de Amicitia et [xiv] Senectute dialogi...: cum annotationibus Erasmi et P. Melanchthonis. Parisiis, 1533. | |

| Melanchthon: | |||

| Ed.: | M. Tullii Ciceronis Scripta quae manserunt omnia recognovit C. F. W. Müller. Teubner: Lipsiae, 1879. This edition is the basis of the text of the present volume. | ||

| Ernesti: | M. Tullii Ciceronis opera ex recensione novissima. J. A. Ernesti; cum eiusdem notis, et clave Ciceroniana. Editio prima Americana. Bostoniae, 1815-16. | ||

| Facciolati: | M. Tullii Ciceronis de Officiis libri tres, de Senectute, de Amicitia, de Somnio Scipionis, et Paradoxa. Accedit Q. fratris commentariolum petitionis. Ex recensione J. Facciolati. Venetiis, 1747. | ||

| Fleckeisen, Alf.: | Kritische Miscellen. Dresden, 1864. | ||

| Gernhard: | M. Tullii Ciceronis de Officiis libri tres. Rec. et scholiis Iac. Facciolati suisque animadversionibus instruxit Aug. G. Gernhard. Lipsiae, 1811. | ||

| Graevius: | M. Tullii Ciceronis de Officiis libri tres; ... de Senectute; ... de Amicitia; Paradoxa; Somnium Scipionis; ex recensione J. G. Graevii. Amstelodami, 1689. | ||

| Gulielmus: | – | M. Tullii Ciceronis opera omnia quae extant ... emendata studio ... J. Gulielmi et J. Gruteri. Hamburgi, 1618-19. | |

| Gruter: | |||

| Heine, Otto: | M. Tullii Ciceronis de Officiis ad Marcum Filium Libri tres. 6te Aufl. Berlin, 1885. | ||

| Heusinger: | M. Tullii Ciceronis de Officiis libri tres ... recensuit adjectisque J. M. Heusingeri e suis annotationibus ... editurus erat J. F. Heusinger. (Edited by C. Heusinger.) Brunsvigae, 1783. | ||

| [xv] Holden: | M. Tullii Ciceronis de Officiis libri tres, with Introduction, Analysis and Commentary by Herbert Ashton Holden. 7th Edition. Cambridge, 1891. To his full notes the translator is indebted for many a word and phrase. | ||

| Klotz: | M. Tullii Ciceronis Scripta quae manserunt omnia. Recognovit Reinholdus Klotz. Lipsiae, 1850-57, 1869-74. | ||

| Lambinus: | M. Tullii Ciceronis opera omnia quae extant, a D. Lambino ... ex codicibus manuscriptis emendata et aucta ... Lutetiae, 1566-84. | ||

| Lange: | M. Tullii Ciceronis de Officiis lib. III. Cato Major vel de Senectute ... Laelius vel de Amicitia ... Paradoxa Stoicorum sex, Somnium Scipionis ... opera C. Langii recogniti ... ejusdem in hosce ... libros annotationes. Cum annotationibus P. Manutii, etc. Antverpiae, 1568. | ||

| Lund: | De emendandis Ciceronis libris de Officiis observationes criticae. Scripsit G. F. G. Lund. Kopenhagen, 1848. | ||

| Manutius: | M. Tullii Ciceronis Officiorum libri tres: Cato Maior, vel de Senectute: Laelius, vel de Amicitia: Paradoxa Stoicorum sex ... additae sunt ... variae lectiones. (Edited by P. Manuzio.) P. Manutius: Venetiis, 1541. | ||

| Müller, C. F. W.: | M. Tullii Ciceronis de Officiis libri III. Für den Schulgebrauch erklärt. Leipzig, 1882. | ||

| Muretus: | M. Antoni Mureti Scholia in Cic. officia. Mureti opera ed. Ruhnken. Lugd. Bat., 1879. | ||

| Orelli: | – | M. Tullii Ciceronis opera quae supersunt omnia, ac deperditorum fragmenta ... Edidit J. C. Orellius (M. Tullii Ciceronis [xvi] Scholiastae. C. M. Victorinus, Rufinus, C. Julius Victor, Boethius, Favonius Eulogius, Asconius Pedianus, Scholia Bobiensia, Scholiasta Gronovianus, Ediderunt J. C. Orellius et J. G. Baiter. Turici, 1826-38). Ed. 2. Opus morte Orellii interruptum contin. J. G. Baiterus et C. Halmius, 1845-62. | |

| Baiter: | |||

| Halm: | |||

| Pearce: | M. Ciceronis de Officiis ad Marcum filium libri tres. Notis illustravit et ... emendavit Z. Pearce. Londini, 1745. | ||

| Stuerenburg: | M. Tullii Ciceronis de Officiis libri III. Recensuit R. Stuerenburg. Accedit Commentarius. Lipsiae, 1843. | ||

| Unger: | M. Tullii Ciceronis de Officiis libri III. Erklärt v. G. F. Unger. Leipzig, 1852. | ||

| Victorius, P.: | M. Tullii Ciceronis opera, omnium quae hactenus excusa sunt castigatissima, nunc primum in lucem edita. 4 tom. Venetiis, 1532-34-36. | ||

| Zumpt: | M. Tullii Ciceronis de Officiis libri tres cum selectis J. M. et J. F. Heusingerorum suisque notis. Scholarum in usum iterum edidit Car. Tim. Zumptius. Brunsvigae, 1849. | ||

CICERO DE OFFICIIS

LIBER PRIMUS

1 I. Quamquam te, Marce fili, annum iam audientem Cratippum, idque Athenis, abundare oportet praeceptis institutisque philosophiae propter summam et doctoris auctoritatem et urbis, quorum alter te scientia augere potest, altera exemplis, tamen, ut ipse ad meam utilitatem semper cum Graecis Latina coniunxi neque id in philosophia solum, sed etiam in dicendi exercitatione feci, idem tibi censeo faciendum, ut par sis in utriusque orationis facultate. Quam quidem ad rem nos, ut videmur, magnum attulimus adiumentum hominibus nostris, ut non modo Graecarum litterarum rudes, sed etiam docti aliquantum se arbitrentur adeptos et ad dicendum[1] et ad iudicandum.

2 Quam ob rem disces tu quidem a principe huius aetatis philosophorum, et disces, quam diu voles; tam diu autem velle debebis, quoad te, quantum proficias, non paenitebit; sed tamen nostra legens non multum a Peripateticis dissidentia, quoniam utrique Socratici et Platonici volumus esse, de rebus ipsis utere tuo iudicio (nihil enim impedio), orationem autem Latinam efficies profecto legendis nostris pleniorem. Nec vero hoc arroganter dictum existimari velim. Nam philosophandi scientiam concedens multis, quod est oratoris proprium, apte, distincte, ornate dicere, quoniam in eo studio aetatem consumpsi, si id mihi assumo, videor id meo iure quodam modo vindicare.

3 Quam ob rem magnopere te hortor, mi Cicero, ut non solum orationes meas, sed hos etiam de philosophia libros, qui iam illis fere se[2] aequarunt, studiose legas; vis enim maior in illis dicendi, sed hoc quoque colendum est aequabile et temperatum orationis genus. Et id quidem nemini video Graecorum adhuc contigisse, ut idem utroque in genere elaboraret[3] sequereturque et illud forense dicendi et hoc quietum disputandi genus, nisi forte Demetrius Phalereus in hoc numero haberi potest, disputator subtilis, orator parum vehemens, dulcis tamen, ut Theophrasti discipulum possis agnoscere. Nos autem quantum in utroque profecerimus, aliorum sit iudicium, utrumque certe secuti sumus.

4 Equidem et Platonem existimo, si genus forense dicendi tractare voluisset, gravissime et copiosissime potuisse dicere, et Demosthenem, si illa, quae a Platone didicerat, tenuisset et pronuntiare voluisset, ornate splendideque facere potuisse; eodemque modo de Aristotele et Isocrate iudico, quorum uterque suo studio delectatus contempsit alterum.

BOOK I

1 I. My dear son Marcus, you have now been studying a full year under Cratippus, and that too in Athens, and you should be fully equipped with the practical precepts and the principles of philosophy; so much at least one might expect from the pre-eminence not only of your teacher but also of the city; the former is able to enrich you with learning, the latter to supply you with models. Nevertheless, just as I for my own improvement have always combined Greek and Latin studies—and I have done this not only in the study of philosophy but also in the practice of oratory—so I recommend that you should do the same, so that you may have equal command of both languages. And it is in this very direction that I have, if I mistake not, rendered a great service to our countrymen, so that not only those who are unacquainted with Greek literature but even the cultured consider that they have gained much both in oratorical power and in mental training.

2 You will, therefore, learn from the foremost of present-day philosophers, and you will go on learning as long as you wish; and your wish ought to continue as long as you are not dissatisfied with the progress you are making. For all that, if you will read my philosophical books, you will be helped; my philosophy is not very different from that of the Peripatetics (for both they and I claim to be followers of Socrates and Plato). As to the conclusions you may reach, I leave that to your own judgment (for I would put no hindrance in your way), but by reading my philosophical [5] writings you will be sure to render your mastery of the Latin language more complete. But I would by no means have you think that this is said boastfully. For there are many to whom I yield precedence in knowledge of philosophy; but if I lay claim to the orator's peculiar ability to speak with propriety, clearness, elegance, I think my claim is in a measure justified, for I have spent my life in that profession.

3 And therefore, my dear Cicero, I cordially recommend you to read carefully not only my orations but also these[A] books of mine on philosophy, which are now about as extensive. For while the orations exhibit a more vigorous style, yet the unimpassioned, restrained style of my philosophical productions is also worth cultivating. Moreover, for the same man to succeed in both departments, both in the forensic style and in that of calm philosophic discussion has not, I observe, been the good fortune of any one of the Greeks so far, unless, perhaps, Demetrius of Phalerum can be reckoned in that number—a clever reasoner, indeed, and, though rather a spiritless orator, he is yet charming, so that you can recognize in him the disciple of Theophrastus. But let others judge how much I have accomplished in each pursuit; I have at least attempted both.

4 I believe, of course, that if Plato had been willing to devote himself to forensic oratory, he could have spoken with the greatest eloquence and power; and that if Demosthenes had continued the studies he pursued with Plato and had wished to expound his views, he could have done so with elegance and brilliancy. I feel the same way about Aristotle and Isocrates, each of whom, engrossed in his own profession, undervalued that of the other.

II. Sed cum statuissem scribere ad te aliquid hoc tempore, multa posthac, ab eo ordiri maxime volui, quod et aetati tuae esset aptissimum et auctoritati meae. Nam cum multa sint in philosophia et gravia et utilia accurate copioseque a philosophis disputata, latissime patere videntur ea, quae de officiis tradita ab illis et praecepta sunt. Nulla enim vitae pars neque publicis neque privatis neque forensibus neque domesticis in rebus, neque si tecum agas quid, neque si cum altero contrahas, vacare officio potest, in eoque et colendo sita vitae est honestas omnis et neglegendo[4] turpitudo.

5 Atque haec quidem quaestio communis est omnium philosophorum; quis est enim, qui nullis officii praeceptis tradendis philosophum se audeat dicere? Sed sunt non nullae disciplinae, quae propositis bonorum et malorum finibus officium omne pervertant. Nam qui summum bonum sic instituit, ut nihil habeat cum virtute coniunctum, idque suis commodis, non honestate metitur, hic, si sibi ipse consentiat et non interdum naturae bonitate vincatur neque amicitiam colere possit nec iustitiam nec liberalitatem; fortis vero dolorem summum malum iudicans aut temperans voluptatem summum bonum statuens esse certe nullo modo potest.

6 Quae quamquam ita sunt in promptu, ut res disputatione non egeat, tamen sunt a nobis alio loco disputata. Hae disciplinae igitur si sibi consentaneae velint esse, de officio nihil queant dicere, neque ulla officii praecepta firma, stabilia, coniuncta naturae tradi possunt nisi aut ab iis, qui solam, aut ab iis, qui maxime honestatem propter se dicant expetendam. Ita propria est ea praeceptio Stoicorum, Academicorum, Peripateticorum, quoniam Aristonis, Pyrrhonis, Erilli iam pridem explosa sententia est; qui tamen haberent ius suum disputandi de officio, si rerum aliquem dilectum[5] reliquissent, ut ad officii inventionem aditus esset. Sequemur[6] igitur hoc quidem tempore et hac in quaestione potissimum Stoicos non ut interpretes, sed, ut solemus, e fontibus eorum iudicio arbitrioque nostro, quantum quoque modo videbitur, hauriemus.

7 Placet igitur, quoniam omnis disputatio de officio futura est, ante definire, quid sit officium; quod a Panaetio praetermissum esse miror. Omnis enim, quae [a] ratione[7] suscipitur de aliqua re institutio, debet a definitione proficisci, ut intellegatur, quid sit id, de quo disputetur....[8]

[7] II. But since I have decided to write you a little now (and a great deal by and by), I wish, if possible, to begin with a matter most suited at once to your years and to my position. Although philosophy offers many problems, both important and useful, that have been fully and carefully discussed by philosophers, those teachings which have been handed down on the subject of moral duties seem to have the widest practical application. For no phase of life, whether public or private, whether in business or in the home, whether one is working on what concerns oneself alone or dealing with another, can be without its moral duty; on the discharge of such duties depends all that is morally right, and on their neglect all that is morally wrong in life.

5 Moreover, the subject of this inquiry is the common property of all philosophers; for who would presume to call himself a philosopher, if he did not inculcate any lessons of duty? But there are some schools that distort all notions of duty by the theories they propose touching the supreme good and the supreme evil. For he who posits the supreme good as having no connection with virtue and measures it not by a moral standard but by his own interests—if he should be consistent and not rather at times over-ruled by his better nature, he could value neither friendship nor justice nor generosity; and brave he surely cannot possibly be that counts pain the supreme evil, nor temperate he that holds pleasure to be the supreme good.

6 Although these truths are so self-evident that the subject does not call for discussion, still I have discussed it in another connection. If, therefore, these [9] schools should claim to be consistent, they could not say anything about duty; and no fixed, invariable, natural rules of duty can be posited except by those who say that moral goodness is worth seeking solely or chiefly for its own sake. Accordingly, the teaching of ethics is the peculiar right of the Stoics, the Academicians, and the Peripatetics; for the theories of Aristo, Pyrrho, and Erillus have been long since rejected; and yet they would have the right to discuss duty if they had left us any power of choosing between things, so that there might be a way of finding out what duty is. I shall, therefore, at this time and in this investigation follow chiefly the Stoics, not as a translator, but, as is my custom, I shall at my own option and discretion draw from those sources in such measure and in such manner as shall suit my purpose.

7 Since, therefore, the whole discussion is to be on the subject of duty, I should like at the outset to define what duty is, as, to my surprise, Panaetius has failed to do. For every systematic development of any subject ought to begin with a definition, so that every one may understand what the discussion is about.

III. Omnis de officio duplex est quaestio: unum genus est, quod pertinet ad finem bonorum, alterum, quod positum est in praeceptis, quibus in omnis partis usus vitae conformari[9] possit. Superioris generis huius modi sunt exempla: omniane officia perfecta sint, num quod officium aliud alio maius sit, et quae sunt generis eiusdem. Quorum autem officiorum praecepta traduntur, ea quamquam pertinent ad finem bonorum, tamen minus id apparet, quia magis ad institutionem vitae communis spectare videntur; de quibus est nobis his libris explicandum. Atque etiam alia divisio est officii.

8 Nam et medium quoddam officium dicitur et perfectum. Perfectum officium rectum, opinor, vocemus, quoniam Graeci κατόρθωμα, hoc autem commune officium καθῆκον vocant.[10] Atque ea sic definiunt, ut, rectum quod sit, id officium perfectum esse definiant; medium autem officium id esse dicunt, quod cur factum sit, ratio probabilis reddi possit.

9 Triplex igitur est, ut Panaetio videtur, consilii capiendi deliberatio. Nam aut honestumne factu sit an turpe dubitant id, quod in deliberationem cadit; in quo considerando saepe animi in contrarias sententias distrahuntur. Tum autem aut anquirunt[11] aut consultant, ad vitae commoditatem iucunditatemque, ad facultates rerum atque copias, ad opes, ad potentiam, quibus et se possint iuvare et suos, conducat id necne, de quo deliberant; quae deliberatio omnis in rationem utilitatis cadit. Tertium dubitandi genus est, cum pugnare videtur cum honesto id, quod videtur esse utile; cum enim utilitas ad se rapere, honestas contra revocare ad se videtur, fit ut distrahatur in deliberando animus afferatque ancipitem curam cogitandi.

10 Hac divisione, cum praeterire aliquid maximum vitium in dividendo sit, duo praetermissa sunt; nec enim solum utrum honestum an turpe sit, deliberari solet, sed etiam duobus propositis honestis utrum honestius, itemque duobus propositis utilibus utrum utilius. Ita, quam ille triplicem putavit esse rationem, in quinque partes distribui debere reperitur. Primum igitur est de honesto, sed dupliciter, tum pari ratione de utili, post de comparatione eorum disserendum.

III. Every treatise on duty has two parts: one, dealing with the doctrine of the supreme good; the other, with the practical rules by which daily life in all its bearings may be regulated. The following questions are illustrative of the first part: whether all duties are absolute; whether one duty is more important than another; and so on. But as regards special duties for which positive rules are laid down, though they are affected by the doctrine of the supreme good, still the fact is not so obvious, because they seem rather to look to the regulation of every-day [11] life; and it is these special duties that I propose to treat at length in the following books.

8 And yet there is still another classification of duties: we distinguish between "mean"[B] duty, so-called, and "absolute" duty. Absolute duty we may, I presume, call "right," for the Greeks call it κατόρθωμα, while the ordinary duty they call καθῆκον. And the meaning of those terms they fix thus: whatever is right they define as absolute duty, but "mean" duty, they say, is duty for the performance of which an adequate reason may be rendered.

9 The consideration necessary to determine conduct is, therefore, as Panaetius thinks, a threefold one: first, people question whether the contemplated act is morally right or morally wrong; and in such deliberation their minds are often led to widely divergent conclusions. And then they examine and consider the question whether the action contemplated is or is not conducive to comfort and happiness in life, to the command of means and wealth, to influence, and to power, by which they may be able to help themselves and their friends; this whole matter turns upon a question of expediency. The third type of question arises when that which seems to be expedient seems to conflict with that which is morally right; for when expediency seems to be pulling one way, while moral right seems to be calling back in the opposite direction, the result is that the mind is distracted in its inquiry and brings to it the irresolution that is born of deliberation.

10 Although omission is a most serious defect in classification, two points have been overlooked in [13] the foregoing:[C] for we usually consider not only whether an action is morally right or morally wrong, but also, when a choice of two morally right courses is offered, which one is morally better; and likewise, when a choice of two expedients is offered, which one is more expedient. Thus the question which Panaetius thought threefold ought, we find, to be divided into five parts. First, therefore, we must discuss the moral—and that, under two sub-heads; secondly, in the same manner, the expedient; and finally, the cases where they must be weighed against each other.

11 IV. Principio generi animantium omni est a natura tributum, ut se, vitam corpusque tueatur, declinet ea, quae nocitura videantur, omniaque, quae sint ad vivendum necessaria, anquirat et paret, ut pastum, ut latibula, ut alia generis eiusdem. Commune item[12] animantium omnium est coniunctionis adpetitus procreandi causa et cura quaedam eorum, quae procreata sint[13]; sed inter hominem et beluam hoc maxime interest, quod haec tantum, quantum sensu movetur, ad id solum, quod adest quodque praesens est, se accommodat paulum admodum sentiens praeteritum aut futurum; homo autem, quod rationis est particeps, per quam consequentia cernit, causas rerum videt earumque praegressus[14] et quasi antecessiones non ignorat, similitudines comparat rebusque praesentibus adiungit atque annectit futuras, facile totius vitae cursum videt ad eamque degendam praeparat res necessarias.

12 Eademque natura vi rationis hominem conciliat homini et ad orationis et ad vitae societatem ingeneratque in primis praecipuum quendam amorem in eos, qui procreati sunt, impellitque, ut hominum coetus et celebrationes et esse et a se obiri velit ob easque causas studeat parare ea, quae suppeditent ad cultum et ad victum, nec sibi soli, sed coniugi, liberis ceterisque, quos caros habeat tuerique debeat; quae cura exsuscitat etiam animos et maiores ad rem gerendam facit.

13 In primisque hominis est propria veri inquisitio atque investigatio. Itaque cum sumus necessariis negotiis curisque vacui, tum avemus aliquid videre, audire, addiscere cognitionemque rerum aut occultarum aut admirabilium ad beate vivendum necessariam ducimus. Ex quo intellegitur, quod verum, simplex sincerumque sit, id esse naturae hominis aptissimum. Huic veri videndi cupiditati adiuncta est appetitio quaedam principatus, ut nemini parere animus bene informatus a natura velit nisi praecipienti aut docenti aut utilitatis causa iuste et legitime imperanti; ex quo magnitudo animi existit humanarumque rerum contemptio.

14 Nec vero illa parva vis naturae est rationisque, quod unum hoc animal sentit, quid sit ordo, quid sit, quod deceat, in factis dictisque qui modus. Itaque eorum ipsorum, quae aspectu sentiuntur, nullum aliud animal pulchritudinem, venustatem, convenientiam partium sentit; quam similitudinem natura ratioque ab oculis ad animum transferens multo etiam magis pulchritudinem, constantiam, ordinem in consiliis factisque conservandam[15] putat cavetque, ne quid indecore effeminateve faciat, tum in omnibus et opinionibus et factis ne quid libidinose aut faciat aut cogitet.

Quibus ex rebus conflatur et efficitur id, quod quaerimus, honestum, quod etiamsi nobilitatum non sit, tamen honestum sit, quodque vere dicimus, etiamsi a nullo laudetur, natura esse laudabile.

11 IV. First of all, Nature has endowed every species of living creature with the instinct of self-preservation, of avoiding what seems likely to cause injury to life or limb, and of procuring and providing everything needful for life—food, shelter, and the like. A common property of all creatures is also the reproductive instinct (the purpose of which is the propagation of the species) and also a certain amount of concern for their offspring. |Instinct and Reason.| But the most marked difference between man and beast is this: the beast, just as far as it is moved by the senses and with very little perception of past or future, adapts itself to that alone which is present at the moment; while man—because he is endowed with reason, by which he comprehends the chain of consequences, perceives the causes of things, understands the relation of cause to effect and of effect to cause, draws analogies, and connects and associates the present and the future—easily surveys the course of his whole life and makes the necessary preparations for its conduct.

12 Nature likewise by the power of reason associates man with man in the common bonds of speech and life; she implants in him above all, I may say, a [15] strangely tender love for his offspring. She also prompts men to meet in companies, to form public assemblies and to take part in them themselves; and she further dictates, as a consequence of this, the effort on man's part to provide a store of things that minister to his comforts and wants—and not for himself alone, but for his wife and children and the others whom he holds dear and for whom he ought to provide; and this responsibility also stimulates his courage and makes it stronger for the active duties of life.

13 Above all, the search after truth and its eager pursuit are peculiar to man. And so, when we have leisure from the demands of business cares, we are eager to see, to hear, to learn something new, and we esteem a desire to know the secrets or wonders of creation as indispensable to a happy life. Thus we come to understand that what is true, simple, and genuine appeals most strongly to a man's nature. To this passion for discovering truth there is added a hungering, as it were, for independence, so that a mind well-moulded by Nature is unwilling to be subject to anybody save one who gives rules of conduct or is a teacher of truth or who, for the general good, rules according to justice and law. From this attitude come greatness of soul and a sense of superiority to worldly conditions.

14 And it is no mean manifestation of Nature and Reason that man is the only animal that has a feeling for order, for propriety, for moderation in word and deed. And so no other animal has a sense of beauty, loveliness, harmony in the visible world; and Nature and Reason, extending the analogy of this from the world of sense to the world of spirit, find that beauty, [17] consistency, order are far more to be maintained in thought and deed, and the same Nature and Reason are careful to do nothing in an improper or unmanly fashion, and in every thought and deed to do or think nothing capriciously.

It is from these elements that is forged and fashioned that moral goodness which is the subject of this inquiry—something that, even though it be not generally ennobled, is still worthy of all honour[D]; and by its own nature, we correctly maintain, it merits praise, even though it be praised by none.

15 V. Formam quidem ipsam, Marce fili, et tamquam faciem honesti vides, "quae si oculis cerneretur, mirabiles amores," ut ait Plato, "excitaret sapientiae." Sed omne, quod est honestum, id quattuor partium oritur ex aliqua: aut enim in perspicientia veri sollertiaque versatur aut in hominum societate tuenda tribuendoque suum cuique et rerum contractarum fide aut in animi excelsi atque invicti magnitudine ac robore aut in omnium, quae fiunt quaeque dicuntur, ordine et modo, in quo inest modestia et temperantia.

(15) Quae quattuor quamquam inter se colligata atque implicata sunt, tamen ex singulis certa officiorum genera nascuntur, velut ex ea parte, quae prima discripta[16] est, in qua sapientiam et prudentiam ponimus, inest indagatio atque inventio veri, eiusque virtutis hoc munus est proprium. 16 Ut enim quisque maxime perspicit, quid in re quaque verissimum sit, quique acutissime et celerrime potest et videre et explicare rationem, is prudentissimus et sapientissimus rite haberi solet. Quocirca huic quasi materia, quam tractet et in qua versetur, subiecta est veritas.

17 Reliquis autem tribus virtutibus necessitates propositae sunt ad eas res parandas tuendasque, quibus actio vitae continetur, ut et societas hominum coniunctioque servetur et animi excellentia magnitudoque cum in augendis opibus utilitatibusque et sibi et suis comparandis, tum multo magis in his ipsis despiciendis eluceat. Ordo autem[17] et constantia et moderatio et ea, quae sunt his similia, versantur in eo genere, ad quod est adhibenda actio quaedam, non solum mentis agitatio. Iis enim rebus, quae tractantur in vita, modum quendam et ordinem adhibentes honestatem et decus conservabimus.

15 V. You see here, Marcus, my son, the very form and as it were the face of Moral Goodness; "and if," as Plato says, "it could be seen with the physical eye, it would awaken a marvellous love of wisdom." |The four Cardinal Virtues.| But all that is morally right rises from some one of four sources: it is concerned either (1) with the full perception and intelligent development of the true; or (2) with the conservation of organized society, with rendering to every man his due, and with the faithful discharge of obligations assumed; or (3) with the greatness and strength of a noble and invincible spirit; or (4) with the orderliness and moderation of everything that is said and done, wherein consist temperance and self-control.

(15) Although these four are connected and interwoven, still it is in each one considered singly that certain definite kinds of moral duties have their origin: in that category, for instance, which was designated first in our division and in which we place wisdom and prudence, belong the search after truth and its discovery; and this is the peculiar province of that virtue. 16 For the more clearly anyone observes the most essential truth in any given [19] case and the more quickly and accurately he can see and explain the reasons for it, the more understanding and wise he is generally esteemed, and justly so. So, then, it is truth that is, as it were, the stuff with which this virtue has to deal and on which it employs itself.

17 Before the three remaining virtues, on the other hand, is set the task of providing and maintaining those things on which the practical business of life depends, so that the relations of man to man in human society may be conserved, and that largeness and nobility of soul may be revealed not only in increasing one's resources and acquiring advantages for one's self and one's family but far more in rising superior to these very things. But orderly behaviour and consistency of demeanour and self-control and the like have their sphere in that department of things in which a certain amount of physical exertion, and not mental activity merely, is required. For if we bring a certain amount of propriety and order into the transactions of daily life, we shall be conserving moral rectitude and moral dignity.

18 VI. Ex quattuor autem locis, in quos honesti naturam vimque divisimus, primus ille, qui in veri cognitione consistit, maxime naturam attingit humanam. Omnes enim trahimur et ducimur ad cognitionis et scientiae cupiditatem, in qua excellere pulchrum putamus, labi autem, errare, nescire, decipi et malum et turpe ducimus.[18] In hoc genere et naturali et honesto duo vitia vitanda sunt, unum, ne incognita pro cognitis habeamus iisque temere assentiamur; quod vitium effugere qui volet (omnes autem velle debent), adhibebit ad considerandas res et tempus et diligentiam. 19 Alterum est vitium, quod quidam nimis magnum studium multamque operam in res obscuras atque difficiles conferunt easdemque non necessarias.

Quibus vitiis declinatis quod in rebus honestis et cognitione dignis operae curaeque ponetur, id iure laudabitur, ut in astrologia C. Sulpicium audivimus, in geometria Sex. Pompeium ipsi cognovimus, multos in dialecticis, plures in iure civili, quae omnes artes in veri investigatione versantur; cuius studio a rebus gerendis abduci contra officium est. Virtutis enim laus omnis in actione consistit; a qua tamen fit intermissio saepe multique dantur ad studia reditus; tum agitatio mentis, quae numquam acquiescit, potest nos in studiis cognitionis[19] etiam sine opera nostra continere. Omnis autem cogitatio motusque animi aut in consiliis capiendis de rebus honestis et pertinentibus ad bene beateque vivendum aut in studiis scientiae cognitionisque versabitur.

Ac de primo quidem officii fonte diximus.

18 VI. Now, of the four divisions which we have made of the essential idea of moral goodness, the first, consisting in the knowledge of truth, touches human nature most closely. For we are all attracted and drawn to a zeal for learning and knowing; and we think it glorious to excel therein, while we count it base and immoral to fall into error, to wander from the truth, to be ignorant, to be led astray. In this pursuit, which is both natural and morally right, two errors are to be avoided: first, we must not treat the unknown as known and too readily accept it; and he who wishes to avoid this error (as [21] all should do) will devote both time and attention to the weighing of evidence. 19 The other error is that some people devote too much industry and too deep study to matters that are obscure and difficult and useless as well.

If these errors are successfully avoided, all the labour and pains expended upon problems that are morally right and worth the solving will be fully rewarded. Such a worker in the field of astronomy, for example, was Gaius Sulpicius, of whom we have heard; in mathematics, Sextus Pompey, whom I have known personally; in dialectics, many; in civil law, still more. All these professions are occupied with the search after truth; but to be drawn by study away from active life is contrary to moral duty. For the whole glory of virtue is in activity; activity, however, may often be interrupted, and many opportunities for returning to study are opened. Besides, the working of the mind, which is never at rest, can keep us busy in the pursuit of knowledge even without conscious effort on our part. Moreover, all our thought and mental activity will be devoted either to planning for things that are morally right and that conduce to a good and happy life, or to the pursuits of science and learning.

With this we close the discussion of the first source of duty.

20 VII. De tribus autem reliquis latissime patet ea ratio, qua societas hominum inter ipsos et vitae quasi communitas continetur; cuius partes duae,[20] iustitia, in qua virtutis est splendor maximus, ex qua viri boni nominantur, et huic coniuncta beneficentia, quam eandem vel benignitatem vel liberalitatem appellari licet.

Sed iustitiae primum munus est, ut ne cui quis noceat nisi lacessitus iniuria, deinde ut communibus pro communibus utatur, privatis ut suis.

21 Sunt autem privata nulla natura, sed aut vetere occupatione, ut qui quondam in vacua venerunt, aut victoria, ut qui bello potiti sunt, aut lege, pactione, condicione, sorte; ex quo fit, ut ager Arpinas Arpinatium dicatur, Tusculanus Tusculanorum; similisque est privatarum possessionum discriptio.[21] Ex quo, quia suum cuiusque fit eorum, quae natura fuerant communia, quod cuique obtigit, id quisque teneat; e quo[22] si quis sibi appetet, violabit ius humanae societatis.

22 Sed quoniam, ut praeclare scriptum est a Platone, non nobis solum nati sumus ortusque nostri partem patria vindicat, partem amici, atque, ut placet Stoicis, quae in terris gignantur, ad usum hominum omnia creari, homines autem hominum causa esse generatos, ut ipsi inter se aliis alii prodesse possent, in hoc naturam debemus ducem sequi, communes utilitates in medium afferre mutatione officiorum, dando accipiendo, tum artibus, tum opera, tum facultatibus devincire hominum inter homines societatem.

23 Fundamentum autem est iustitiae fides, id est dictorum conventorumque constantia et veritas. Ex quo, quamquam hoc videbitur fortasse cuipiam durius, tamen audeamus imitari Stoicos, qui studiose exquirunt, unde verba sint ducta, credamusque, quia fiat, quod dictum est, appellatam fidem.

Sed iniustitiae genera duo sunt, unum eorum, qui inferunt, alterum eorum, qui ab iis, quibus infertur, si possunt, non propulsant iniuriam. Nam qui iniuste impetum in quempiam facit aut ira aut aliqua perturbatione incitatus, is quasi manus afferre videtur socio; qui autem non defendit nec obsistit, si potest, iniuriae, tam est in vitio, quam si parentes aut amicos aut patriam deserat. 24 Atque illae quidem iniuriae, quae nocendi causa de industria inferuntur, saepe a metu proficiscuntur, cum is, qui nocere alteri cogitat, timet ne, nisi id fecerit, ipse aliquo afficiatur incommodo. Maximam autem partem ad iniuriam faciendam aggrediuntur, ut adipiscantur ea, quae concupiverunt; in quo vitio latissime patet avaritia.

20 VII. Of the three remaining divisions, the most extensive in its application is the principle by which society and what we may call its "common bonds" are maintained. Of this again there are two divisions—justice, in which is the crowning glory of the virtues and on the basis of which men are called "good men"; and, close akin to justice, [23] charity, which may also be called kindness or generosity.

The first office of justice is to keep one man from doing harm to another, unless provoked by wrong; and the next is to lead men to use common possessions for the common interests, private property for their own.

21 There is, however, no such thing as private ownership established by nature, but property becomes private either through long occupancy (as in the case of those who long ago settled in unoccupied territory) or through conquest (as in the case of those who took it in war) or by due process of law, bargain, or purchase, or by allotment. On this principle the lands of Arpinum are said to belong to the Arpinates, the Tusculan lands to the Tusculans; and similar is the assignment of private property. Therefore, inasmuch as in each case some of those things which by nature had been common property became the property of individuals, each one should retain possession of that which has fallen to his lot; and if anyone appropriates to himself anything beyond that, he will be violating the laws of human society.

22 But since, as Plato has admirably expressed it, we are not born for ourselves alone, but our country claims a share of our being, and our friends a share; and since, as the Stoics hold, everything that the earth produces is created for man's use; and as men, too, are born for the sake of men, that they may be able mutually to help one another; in this direction we ought to follow Nature as our guide, to contribute to the general good by an interchange of acts of kindness, by giving and receiving, and thus by [25] our skill, our industry, and our talents to cement human society more closely together, man to man.

23 The foundation of justice, moreover, is good faith—that is, truth and fidelity to promises and agreements. And therefore we may follow the Stoics, who diligently investigate the etymology of words; and we may accept their statement that "good faith" is so called because what is promised is "made good," although some may find this derivation[E] rather far-fetched.

There are, on the other hand, two kinds of injustice—the one, on the part of those who inflict wrong, the other on the part of those who, when they can, do not shield from wrong those upon whom it is being inflicted. For he who, under the influence of anger or some other passion, wrongfully assaults another seems, as it were, to be laying violent hands upon a comrade; but he who does not prevent or oppose wrong, if he can, is just as guilty of wrong as if he deserted his parents or his friends or his country. 24 Then, too, those very wrongs which people try to inflict on purpose to injure are often the result of fear: that is, he who premeditates injuring another is afraid that, if he does not do so, he may himself be made to suffer some hurt. But for the most part, people are led to wrong-doing in order to secure some personal end; in this vice, avarice is generally the controlling motive.

25 VIII. Expetuntur autem divitiae cum ad usus vitae necessarios, tum ad perfruendas voluptates. In quibus autem maior est animus, in iis pecuniae cupiditas spectat ad opes et ad gratificandi facultatem, ut nuper M. Crassus negabat ullam satis magnam pecuniam esse ei, qui in re publica princeps vellet esse, cuius fructibus exercitum alere non posset. Delectant etiam magnifici apparatus vitaeque cultus cum elegantia et copia; quibus rebus effectum est, ut infinita pecuniae cupiditas esset. Nec vero rei familiaris amplificatio nemini nocens vituperanda est, sed fugienda semper iniuria est.

26 Maxime autem adducuntur plerique, ut eos iustitiae capiat oblivio, cum in imperiorum, honorum, gloriae cupiditatem inciderunt.[23] Quod enim est apud Ennium:

id latius patet. Nam quicquid eius modi est, in quo non possint plures excellere, in eo fit plerumque tanta contentio, ut difficillimum sit servare "sanctam societatem." Declaravit id modo temeritas C. Caesaris, qui omnia iura divina et humana pervertit propter eum, quem sibi ipse opinionis errore finxerat, principatum. Est autem in hoc genere molestum, quod in maximis animis splendidissimisque ingeniis plerumque exsistunt honoris, imperii, potentiae, gloriae cupiditates. Quo magis cavendum est, ne quid in eo genere peccetur.

27 Sed in omni iniustitia permultum interest, utrum perturbatione aliqua animi, quae plerumque brevis est et ad tempus, an consulto et cogitata[24] fiat iniuria. Leviora enim sunt ea, quae repentino aliquo motu accidunt, quam ea, quae meditata et praeparata inferuntur.

Ac de inferenda quidem iniuria satis dictum est.

25 VIII. Again, men seek riches partly to supply the needs of life, partly to secure the enjoyment of pleasure. |The dangers of ambition.| With those who cherish higher ambitions, the desire for wealth is entertained with a view to power and influence and the means of bestowing favours; Marcus Crassus, for example, not long since [27] declared that no amount of wealth was enough for the man who aspired to be the foremost citizen of the state, unless with the income from it he could maintain an army. Fine establishments and the comforts of life in elegance and abundance also afford pleasure, and the desire to secure it gives rise to the insatiable thirst for wealth. Still, I do not mean to find fault with the accumulation of property, provided it hurts nobody, but unjust acquisition of it is always to be avoided.

26 The great majority of people, however, when they fall a prey to ambition for either military or civil authority, are carried away by it so completely that they quite lose sight of the claims of justice. For Ennius says:

and the truth of his words has an uncommonly wide application. For whenever a situation is of such a nature that not more than one can hold pre-eminence in it, competition for it usually becomes so keen that it is an extremely difficult matter to maintain a "fellowship inviolate." |Caesar.| We saw this proved but now in the effrontery of Gaius Caesar, who, to gain that sovereign power which by a depraved imagination he had conceived in his fancy, trod underfoot all laws of gods and men. But the trouble about this matter is that it is in the greatest souls and in the most brilliant geniuses that we usually find ambitions for civil and military authority, for power, and for glory, springing up; and therefore we must be the more heedful not to go wrong in that direction.

27 But in any case of injustice it makes a vast deal [29]of difference whether the wrong is done as a result of some impulse of passion, which is usually brief and transient, or whether it is committed wilfully and with premeditation; for offences that come through some sudden impulse are less culpable than those committed designedly and with malice aforethought.

But enough has been said on the subject of inflicting injury.

28 IX. Praetermittendae autem defensionis deserendique officii plures solent esse causae; nam aut inimicitias aut laborem aut sumptus suscipere nolunt aut etiam neglegentia, pigritia, inertia aut suis studiis quibusdam occupationibusve sic impediuntur, ut eos, quos tutari debeant, desertos esse patiantur. |Rep. VI, 485 ff. VII, 520 D| Itaque videndum est, ne non satis sit id, quod apud Platonem est in philosophos dictum, quod in veri investigatione versentur quodque ea, quae plerique vehementer expetant,[25] de quibus inter se digladiari soleant, contemnant et pro nihilo putent, propterea iustos esse. Nam alterum [iustitiae genus] assequuntur,[26] ut[27] inferenda ne cui noceant iniuria, in alterum incidunt[28]; discendi enim studio impediti, quos tueri debent, deserunt. |Rep. I, 347 C| Itaque eos ne ad rem publicam quidem accessuros putat nisi coactos. Aequius autem erat id voluntate fieri; nam hoc ipsum ita iustum est, quod recte fit, si est voluntarium.

29 Sunt etiam, qui aut studio rei familiaris tuendae aut odio quodam hominum suum se negotium agere dicant nec facere cuiquam videantur iniuriam. Qui altero genere iniustitiae vacant, in alterum incurrunt; deserunt enim vitae societatem, quia nihil conferunt in eam studii, nihil operae, nihil facultatum.

Quando igitur duobus generibus iniustitiae propositis adiunximus causas utriusque generis easque res ante constituimus, quibus iustitia contineretur, facile, quod cuiusque temporis officium sit, poterimus, nisi nosmet ipsos valde amabimus, iudicare; 30 est enim difficilis cura rerum alienarum. |Heaut. Tim. 77| Quamquam Terentianus ille Chremes "humani nihil a se alienum putat"; sed tamen, quia magis ea percipimus atque sentimus, quae nobis ipsis aut prospera aut adversa eveniunt, quam illa, quae ceteris, quae quasi longo intervallo interiecto videmus, aliter de illis ac de nobis iudicamus. Quocirca bene praecipiunt, qui vetant quicquam agere, quod dubites aequum sit an iniquum. Aequitas enim lucet ipsa per se, dubitatio cogitationem significat iniuriae.

28 IX. The motives for failure to prevent injury and so for slighting duty are likely to be various: people either are reluctant to incur enmity or trouble or expense; |a. Preoccupation.| or through indifference, indolence, or incompetence, or through some preoccupation or self-interest they are so absorbed that they suffer those to be neglected whom it is their duty to protect. And so there is reason to fear that what Plato declares of the philosophers may be inadequate, when he says that they are just because they are busied with the pursuit of truth and because they despise and count as naught that which most men eagerly seek and for which they are prone to do battle against each other to the death. For they secure one sort of justice, to be sure, in that they do no positive wrong to anyone, but they fall into the opposite injustice; for hampered by their pursuit of learning they leave to their fate those whom they ought to defend. And so, Plato thinks, they will not even assume their civic duties except under compulsion. But in fact it were better that they should assume them of their own accord; for an action intrinsically right is just only on condition that it is voluntary.

29 There are some also who, either from zeal in attending to their own business or through some [31] sort of aversion to their fellow-men, claim that they are occupied solely with their own affairs, without seeming to themselves to be doing anyone any injury. But while they steer clear of the one kind of injustice, they fall into the other: they are traitors to social life, for they contribute to it none of their interest, none of their effort, none of their means.

Now since we have set forth the two kinds of injustice and assigned the motives that lead to each, and since we have previously established the principles by which justice is constituted, we shall be in a position easily to decide what our duty on each occasion is, unless we are extremely self-centred; 30 for indeed it is not an easy matter to be really concerned with other people's affairs; and yet in Terence's play, we know, Chremes "thinks that nothing that concerns man is foreign to him." Nevertheless, when things turn out for our own good or ill, we realize it more fully and feel it more deeply than when the same things happen to others and we see them only, as it were, in the far distance; and for this reason we judge their case differently from our own. It is, therefore, an excellent rule that they give who bid us not to do a thing, when there is a doubt whether it be right or wrong; for righteousness shines with a brilliance of its own, but doubt is a sign that we are thinking of a possible wrong.

31 X. Sed incidunt saepe tempora, cum ea, quae maxime videntur digna esse iusto homine eoque, quem virum bonum dicimus, commutantur fiuntque contraria, ut reddere depositum, facere promissum; quaeque pertinent ad veritatem et ad fidem, ea migrare interdum et non servare fit iustum. |Ch. VII| Referri enim decet ad ea, quae posui principio, fundamenta iustitiae, primum ut ne cui noceatur, deinde ut communi utilitati serviatur. Ea cum tempore commutantur, commutatur officium et non semper est idem. 32 Potest enim accidere promissum aliquod et conventum, ut id effici sit inutile vel ei, cui promissum sit, vel ei, qui promiserit. |e.g. Eur. Hipp. 1315-1319| Nam si, ut in fabulis est, Neptunus, quod Theseo promiserat, non fecisset, Theseus Hippolyto filio non esset orbatus; ex tribus enim optatis, ut scribitur, hoc erat tertium, quod de Hippolyti interitu iratus optavit; quo impetrato in maximos luctus incidit. Nec promissa igitur servanda sunt ea, quae sint iis, quibus promiseris, inutilia, nec, si plus tibi ea noceant quam illi prosint, cui[29] promiseris, contra officium est maius anteponi minori; ut, si constitueris cuipiam te advocatum in rem praesentem esse venturum atque interim graviter aegrotare filius coeperit, non sit contra officium non facere, quod dixeris, magisque ille, cui promissum sit, ab officio discedat, si se destitutum queratur. Iam illis promissis standum non esse quis non videt, quae coactus quis metu, quae deceptus dolo promiserit? quae quidem pleraque iure praetorio liberantur, non nulla legibus.

33 Exsistunt etiam saepe iniuriae calumnia quadam et nimis callida, sed malitiosa iuris interpretatione. Ex quo illud "Summum ius summa iniuria" factum est iam tritum sermone proverbium. Quo in genere etiam in re publica multa peccantur, ut ille, qui, cum triginta dierum essent cum hoste indutiae factae, noctu populabatur agros, quod dierum essent pactae, non noctium indutiae. Ne noster quidem probandus, si verum est Q. Fabium Labeonem seu quem alium (nihil enim habeo praeter auditum) arbitrum Nolanis et Neapolitanis de finibus a senatu datum, cum ad locum venisset, cum utrisque separatim locutum, ne cupide quid agerent, ne appetenter, atque ut regredi quam progredi mallent. Id cum utrique fecissent, aliquantum agri in medio relictum est. Itaque illorum finis sic, ut ipsi dixerant, terminavit; in medio relictum quod erat, populo Romano adiudicavit. Decipere hoc quidem est, non iudicare. Quocirca in omni est re fugienda talis sollertia.

31 X. But occasions often arise, when those duties which seem most becoming to the just man and to the "good man," as we call him, undergo a change and take on a contrary aspect. It may, for example, not be a duty to restore a trust or to fulfil a promise, and it may become right and proper sometimes to evade and not to observe what truth and honour [33] would usually demand. For we may well be guided by those fundamental principles of justice which I laid down at the outset: first, that no harm be done to anyone; second, that the common interests be conserved. When these are modified under changed circumstances, moral duty also undergoes a change, and it does not always remain the same. 32 |Non-fulfilment of promises.| For a given promise or agreement may turn out in such a way that its performance will prove detrimental either to the one to whom the promise has been made or to the one who has made it. If, for example, Neptune, in the drama, had not carried out his promise to Theseus, Theseus would not have lost his son Hippolytus; for, as the story runs, of the three wishes[F] that Neptune had promised to grant him the third was this: in a fit of anger he prayed for the death of Hippolytus, and the granting of this prayer plunged him into unspeakable grief. Promises are, therefore, not to be kept, if the keeping of them is to prove harmful to those to whom you have made them; and, if the fulfilment of a promise should do more harm to you than good to him to whom you have made it, it is no violation of moral duty to give the greater good precedence over the lesser good. For example, if you have made an appointment with anyone to appear as his advocate in court, and if in the meantime your son should fall dangerously ill, it would be no breach of your moral duty to fail in what you agreed to do; nay, rather, he to whom your promise was given would have a false conception of duty, if he should complain that he had been deserted in his time of need. Further than this, who fails to see that those promises are not binding which are extorted by intimidation or which we make when [35] misled by false pretences? Such obligations are annulled in most cases by the praetor's edict in equity,[G] in some cases by the laws.

33 Injustice often arises also through chicanery, that is, through an over-subtle and even fraudulent construction of the law. This it is that gave rise to the now familiar saw, "More law, less justice." Through such interpretation also a great deal of wrong is committed in transactions between state and state; thus, when a truce had been made with the enemy for thirty days, a famous general[H] went to ravaging their fields by night, because, he said, the truce stipulated "days," not nights. Not even our own countryman's action is to be commended, if what is told of Quintus Fabius Labeo is true—or whoever it was (for I have no authority but hearsay): appointed by the Senate to arbitrate a boundary dispute between Nola and Naples, he took up the case and interviewed both parties separately, asking them not to proceed in a covetous or grasping spirit, but to make some concession rather than claim some accession. When each party had agreed to this, there was a considerable strip of territory left between them. And so he set the boundary of each city as each had severally agreed; and the tract in between he awarded to the Roman People. Now that is swindling, not arbitration. And therefore such sharp practice is under all circumstances to be avoided.

XI. Sunt autem quaedam officia etiam adversus eos servanda, a quibus iniuriam acceperis. Est enim ulciscendi et puniendi modus; atque haud scio an satis sit eum, qui lacessierit, iniuriae suae paenitere, ut et ipse ne quid tale posthac et ceteri sint ad iniuriam tardiores.

34 Atque in re publica maxime conservanda sunt iura belli. Nam cum sint duo genera decertandi, unum per disceptationem, alterum per vim, cumque illud proprium sit hominis, hoc beluarum, confugiendum est ad posterius, si uti non licet superiore. 35 Quare suscipienda quidem bella sunt ob eam causam, ut sine iniuria in pace vivatur, parta autem victoria conservandi ii, qui non crudeles in bello, non immanes fuerunt, ut maiores nostri Tusculanos, Aequos, Volscos, Sabinos, Hernicos in civitatem etiam acceperunt, at Carthaginem et Numantiam funditus sustulerunt; nollem Corinthum, sed credo aliquid secutos, opportunitatem loci maxime, ne posset aliquando ad bellum faciendum locus ipse adhortari. Mea quidem sententia paci, quae nihil habitura sit insidiarum, semper est consulendum. In quo si mihi esset optemperatum, si non optimam, at aliquam rem publicam, quae nunc nulla est, haberemus.

Et cum iis, quos vi deviceris, consulendum est, tum ii, qui armis positis ad imperatorum fidem confugient, quamvis murum aries percusserit, recipiendi. In quo tantopere apud nostros iustitia culta est, ut ii, qui civitates aut nationes devictas bello in fidem recepissent, earum patroni essent more maiorum.

36 Ac belli quidem aequitas sanctissime fetiali populi Romani iure perscripta est. Ex quo intellegi potest nullum bellum esse iustum, nisi quod aut rebus repetitis geratur aut denuntiatum ante sit et indictum. [Popilius imperator tenebat provinciam, in cuius exercitu Catonis filius tiro militabat. Cum autem Popilio videretur unam dimittere legionem, Catonis quoque filium, qui in eadem legione militabat, dimisit. Sed cum amore pugnandi in exercitu remansisset, Cato ad Popilium scripsit, ut, si eum patitur[30] in exercitu remanere, secundo eum obliget militiae sacramento, quia priore amisso iure cum hostibus pugnare non poterat. 37 Adeo summa erat observatio in bello movendo.][31] M. quidem Catonis senis est epistula ad M. filium, in qua scribit se audisse eum missum factum esse a consule, cum in Macedonia bello Persico miles esset. Monet igitur, ut caveat, ne proelium ineat; negat enim ius esse, qui miles non sit, cum hoste pugnare.

XI. Again, there are certain duties that we owe even to those who have wronged us. For there is a limit to retribution and to punishment; or rather, I am inclined to think, it is sufficient that the aggressor should be brought to repent of his wrong-doing, in [37] order that he may not repeat the offence and that others may be deterred from doing wrong.

34 Then, too, in the case of a state in its external relations, the rights of war must be strictly observed. For since there are two ways of settling a dispute: first, by discussion; second, by physical force; and since the former is characteristic of man, the latter of the brute, we must resort to force only in case we may not avail ourselves of discussion. 35 |Excuse for war.| The only excuse, therefore, for going to war is that we may live in peace unharmed; and when the victory is won, we should spare those who have not been blood-thirsty and barbarous in their warfare. |Justice toward the vanquished.| For instance, our forefathers actually admitted to full rights of citizenship the Tusculans, Aequians, Volscians, Sabines, and Hernicians, but they razed Carthage and Numantia to the ground. I wish they had not destroyed Corinth; but I believe they had some special reason for what they did—its convenient situation, probably—and feared that its very location might some day furnish a temptation to renew the war. In my opinion, at least, we should always strive to secure a peace that shall not admit of guile. And if my advice had been heeded on this point, we should still have at least some sort of constitutional government, if not the best in the world, whereas, as it is, we have none at all.

Not only must we show consideration for those whom we have conquered by force of arms but we must also ensure protection to those who lay down their arms and throw themselves upon the mercy of our generals, even though the battering-ram has hammered at their walls. And among our countrymen justice has been observed so conscientiously in [39] this direction, that those who have given promise of protection to states or nations subdued in war become, after the custom of our forefathers, the patrons of those states.

36 As for war, humane laws touching it are drawn up in the fetial code of the Roman People under all the guarantees of religion; and from this it may be gathered that no war is just, unless it is entered upon after an official demand for satisfaction has been submitted or warning has been given and a formal declaration made. Popilius was general in command of a province. In his army Cato's son was serving on his first campaign. When Popilius decided to disband one of his legions, he discharged also young Cato who was serving in that same legion. But when the young man out of love for the service stayed on in the field, his father wrote to Popilius to say that if he let him stay in the army, he should swear him into service with a new oath of allegiance, for in view of the voidance of his former oath he could not legally fight the foe. So extremely scrupulous was the observance of the laws in regard to the conduct of war. 37 There is extant, too, a letter of the elder Marcus Cato to his son Marcus, in which he writes that he has heard that the youth has been discharged by the consul,[I] when he was serving in Macedonia in the war with Perseus. He warns him, therefore, to be careful not to go into battle; for, he says, the man who is not legally a soldier has no right to be fighting the foe.

XII. Equidem etiam illud animadverto, quod, qui proprio nomine perduellis esset, is hostis vocaretur, lenitate verbi rei tristitiam mitigatam. Hostis enim apud maiores nostros is dicebatur, quem nunc peregrinum dicimus. Indicant duodecim tabulae: aut status dies cum hoste, itemque: adversus hostem aeterna auctoritas. Quid ad hanc mansuetudinem addi potest, eum, quicum bellum geras, tam molli nomine appellare? Quamquam id nomen durius effecit[32] iam vetustas; a peregrino enim recessit et proprie in eo, qui arma contra ferret, remansit.

38 Cum vero de imperio decertatur belloque quaeritur gloria, causas omnino subesse tamen oportet easdem, quas dixi paulo ante iustas causas esse bellorum. Sed ea bella, quibus imperii proposita gloria est, minus acerbe gerenda sunt. Ut enim cum civi aliter contendimus, si[33] est inimicus, aliter, si competitor (cum altero certamen honoris et dignitatis est, cum altero capitis et famae), sic cum Celtiberis, cum Cimbris bellum ut cum inimicis gerebatur, uter esset, non uter imperaret, cum Latinis, Sabinis, Samnitibus, Poenis, Pyrrho de imperio dimicabatur. Poeni foedifragi, crudelis Hannibal, reliqui iustiores. Pyrrhi quidem de captivis reddendis illa praeclara:

Regalis sane et digna Aeacidarum genere sententia.

XII. This also I observe—that he who would properly have been called "a fighting enemy" (perduellis) was called "a guest" (hostis), thus relieving the ugliness of the fact by a softened expression; for "enemy" (hostis) meant to our ancestors [41] what we now call "stranger" (peregrinus). This is proved by the usage in the Twelve Tables: "Or a day fixed for trial with a stranger" (hostis). And again: "Right of ownership is inalienable for ever in dealings with a stranger" (hostis). What can exceed such charity, when he with whom one is at war is called by so gentle a name? And yet long lapse of time has given that word a harsher meaning: for it has lost its signification of "stranger" and has taken on the technical connotation of "an enemy under arms."

38 But when a war is fought out for supremacy and when glory is the object of war, it must still not fail to start from the same motives which I said a moment ago were the only righteous grounds for going to war. But those wars which have glory for their end must be carried on with less bitterness. For we contend, for example, with a fellow-citizen in one way, if he is a personal enemy, in another, if he is a rival: with the rival it is a struggle for office and position, with the enemy for life and honour. So with the Celtiberians and the Cimbrians we fought as with deadly enemies, not to determine which should be supreme, but which should survive; but with the Latins, Sabines, Samnites, Carthaginians, and Pyrrhus we fought for supremacy. The Carthaginians violated treaties; Hannibal was cruel; the others were more merciful. From Pyrrhus we have this famous speech on the exchange of prisoners:

A right kingly sentiment this and worthy a scion of the Aeacidae.

39 XIII. Atque etiam si quid singuli temporibus adducti hosti promiserunt, est in eo ipso fides conservanda, ut primo Punico bello Regulus captus a Poenis cum de captivis commutandis Romam missus esset iurassetque se rediturum, primum, ut venit, captivos reddendos in senatu non censuit, deinde, cum retineretur a propinquis et ab amicis, ad supplicium redire maluit quam fidem hosti datam fallere.

40 [Secundo autem Punico bello post Cannensem pugnam quos decem Hannibal Romam astrictos misit iure iurando se redituros esse, nisi de redimendis iis, qui capti erant, impetrassent, eos omnes censores, quoad quisque eorum vixit, qui peierassent, in aerariis reliquerunt nec minus illum, qui iuris iurandi fraude culpam invenerat. Cum enim Hannibalis permissu exisset de castris, rediit paulo post, quod se oblitum nescio quid diceret; deinde egressus e castris iure iurando se solutum putabat, et erat verbis, re non erat. Semper autem in fide quid senseris, non quid dixeris, cogitandum.

Maximum autem exemplum est iustitiae in hostem a maioribus nostris constitutum, cum a Pyrrho perfuga senatui est pollicitus se venenum regi daturum et eum necaturum, senatus et C. Fabricius perfugam Pyrrho dedidit. Ita ne hostis quidem et potentis et bellum ultro inferentis interitum cum scelere approbavit.][36]

41 Ac de bellicis quidem officiis satis dictum est.

Meminerimus autem etiam adversus infimos iustitiam esse servandam. Est autem infima condicio et fortuna servorum, quibus non male praecipiunt qui ita iubent uti, ut mercennariis: operam exigendam, iusta praebenda.

Cum autem duobus modis, id est aut vi aut fraude, fiat iniuria, fraus quasi vulpeculae, vis leonis videtur; utrumque homine alienissimum, sed fraus odio digna maiore. Totius autem iniustitiae nulla capitalior quam eorum, qui tum, cum maxime fallunt, id agunt, ut viri boni esse videantur.

De iustitia satis dictum.

39 XIII. Again, if under stress of circumstances individuals have made any promise to the enemy, they are bound to keep their word even then. |(1) Regulus.| For instance, in the First Punic War, when Regulus was taken prisoner by the Carthaginians, he was sent to Rome on parole to negotiate an exchange of prisoners; he came and, in the first place, it was he that made the motion in the senate that the prisoners should not be restored; and in the second place, when his relatives and friends would have kept him back, he chose to return to a death by torture rather than prove false to his promise, though given to an enemy.

40 And again in the Second Punic War, after the Battle of Cannae, Hannibal sent to Rome ten Roman captives bound by an oath to return to him, if they did not succeed in ransoming his prisoners; and as long as any one of them lived, the censors kept them all degraded and disfranchised, because they were [45] guilty of perjury in not returning. And they punished in like manner the one who had incurred guilt by an evasion of his oath: with Hannibal's permission this man left the camp and returned a little later on the pretext that he had forgotten something or other; and then, when he left the camp the second time, he claimed that he was released from the obligation of his oath; and so he was, according to the letter of it, but not according to the spirit. In the matter of a promise one must always consider the meaning and not the mere words.

Our forefathers have given us another striking example of justice toward an enemy: when a deserter from Pyrrhus promised the senate to administer poison to the king and thus work his death, the senate and Gaius Fabricius delivered the deserter up to Pyrrhus. Thus they stamped with their disapproval the treacherous murder even of an enemy who was at once powerful, unprovoked, aggressive, and successful.

41 With this I will close my discussion of the duties connected with war.

But let us remember that we must have regard for justice even towards the humblest. Now the humblest station and the poorest fortune are those of slaves; and they give us no bad rule who bid us treat our slaves as we should our employees: they must be required to work; they must be given their dues.

While wrong may be done, then, in either of two ways, that is, by force or by fraud, both are bestial: fraud seems to belong to the cunning fox, force to the lion; both are wholly unworthy of man, but fraud is the more contemptible. But of all forms of [47] injustice, none is more flagrant than that of the hypocrite who, at the very moment when he is most false, makes it his business to appear virtuous.

This must conclude our discussion of justice.

42 XIV. Deinceps, ut erat propositum, de beneficentia ac de liberalitate dicatur, qua quidem nihil est naturae hominis accommodatius, sed habet multas cautiones. Videndum est enim, primum ne obsit benignitas et iis ipsis, quibus benigne videbitur fieri, et ceteris, deinde ne maior benignitas sit quam facultates, tum ut pro dignitate cuique tribuatur; id enim est iustitiae fundamentum, ad quam haec referenda sunt omnia. Nam et qui gratificantur cuipiam, quod obsit illi, cui prodesse velle videantur, non benefici neque liberales, sed perniciosi assentatores iudicandi sunt, et qui aliis nocent, ut in alios liberales sint, in eadem sunt iniustitia, ut si in suam rem aliena convertant.

43 Sunt autem multi, et quidem cupidi splendoris et gloriae, qui eripiunt aliis, quod aliis largiantur, iique arbitrantur se beneficos in suos amicos visum iri, si locupletent eos quacumque ratione. Id autem tantum abest ab[37] officio, ut nihil magis officio possit esse contrarium. Videndum est igitur, ut ea liberalitate utamur, quae prosit amicis, noceat nemini. Quare L. Sullae, C. Caesaris pecuniarum translatio a iustis dominis ad alienos non debet liberalis videri; nihil est enim liberale, quod non idem iustum.

44 Alter locus erat cautionis, ne benignitas maior esset quam facultates, quod, qui benigniores volunt esse, quam res patitur, primum in eo peccant, quod iniuriosi sunt in proximos; quas enim copias his[38] et suppeditari aequius est et relinqui, eas transferunt ad alienos. Inest autem in tali liberalitate cupiditas plerumque rapiendi et auferendi per iniuriam, ut ad largiendum suppetant copiae. Videre etiam licet plerosque non tam natura liberales quam quadam gloria ductos, ut benefici videantur, facere multa, quae proficisci ab ostentatione magis quam a voluntate videantur. Talis autem simulatio vanitati est coniunctior quam aut liberalitati aut honestati.

45 Tertium est propositum, ut in beneficentia dilectus esset dignitatis; in quo et mores eius erunt spectandi in quem beneficium conferetur, et animus erga nos et communitas ac societas vitae et ad nostras utilitates officia ante collata; quae ut concurrant omnia, optabile est; si minus, plures causae maioresque ponderis plus habebunt.

42 XIV. Next in order, as outlined above, let us speak of kindness and generosity. Nothing appeals more to the best in human nature than this, but it calls for the exercise of caution in many particulars: we must, in the first place, see to it that our act of kindness shall not prove an injury either to the object of our beneficence or to others; in the second place, that it shall not be beyond our means; and finally, that it shall be proportioned to the worthiness of the recipient; for this is the corner-stone of justice; and by the standard of justice all acts of kindness must be measured. For those who confer a harmful favour upon some one whom they seemingly wish to help are to be accounted not generous benefactors but dangerous sycophants; and likewise those who injure one man, in order to be generous to another, are guilty of the same injustice as if they diverted to their own accounts the property of their neighbours.