Title: The Story of Perugia

Author: Margaret Symonds

Lina Duff Gordon

Illustrator: Helen M. James

Release date: August 30, 2014 [eBook #46732]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chuck Greif and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images available at The Internet Archive)

|

Every attempt has been made to replicate the original as printed. Some typographical errors have been corrected; a list follows the text. In certain versions of this etext, in certain browsers,

clicking on this symbol

Contents (etext transcriber's note) |

The Story of Perugia

All rights reserved

First Edition, February 1898

Second Edition, December 1898

Third Edition, April 1900

Fourth Edition, May 1901

London:

J. M. Dent & Co.

Aldine House, 29 and 30 Bedford Street

Covent Garden W.C.

![]()

![]() 1901

1901

WHEN but a little while ago we undertook to write a “guide book” to one of the better known towns of Central Italy, we realised perhaps imperfectly how wide and full was the field of work which lay before us. The “story” of Perugia is, like the story of nearly all Italian towns, as full and varied as the story of a nation. Every side-light of history is cast upon it, and nearly every phase of man’s policy and art reflected on its monuments. To do justice to so grand a pageant in a narrow space of time and binding was, we may fairly plead, no easy task; and now that the work is done, and the proofs returned to the printer, we are left with an inevitable regret; for it has been impossible for us to retain in shortened sentences and cramped description the charm of all the tales and chronicles which we ourselves found necessary reading for a full knowledge of so wide a subject.

If this small book have any claim to merit it is greatly due to the faithful and ungrudging help rendered to its authors throughout their study, by one true guide; by many old friends; and by the inhabitants of the town whose name it bears for title. We can never adequately express our sense of gratitude to the people of Perugia, to whom we came as utter strangers, but who received us with such great courtesy and kindness as to make our stay and study in their midst a pleasure as well as an education.

Our book is intended for the general traveller rather{viii} than for the student. We have offered no criticism, and have quoted whenever we could from the pages of contemporary chronicles. We have dealt with Perugia as with the heroine of a novel, describing her particular progress, and not confounding it with that of neighbour towns, equally important in their way, and each struggling, as perhaps only the cities of Italy knew how to struggle, towards an individual supremacy in a state lacerated by foreign wars and policies.

In dealing with one of the most vivid points in the history of the town—the Rule of the Nobles—we have, with some diffidence, incorporated into our narrative the words of one who had already drawn his description of the subject straight from the original source, treating it with such a powerful sympathy as it would have been impossible for us to rival. For further knowledge of this terrible period we can but refer the student to the chronicle of Matarazzo. (Archivio Storico, vol. xvi. part 2.)

With the art of Umbria we have dealt only shortly, and from the point of view of sentiment rather than that of criticism. For a severe and thorough knowledge of the technique and use of colours employed by the men who lived through such scenes as we have described in chapters II. and III. we must refer the reader to the works of other authors. For our dates, and facts in reference to art, we have relied on Kugler, Crowe and Cavalcaselle, Rio, Vasari and the local writers, Mariotti, Lupatelli, Mezzanotte, etc.

It remains to give a list of the books which we have consulted for the history. Amongst these are the Perugian chronicles contained in the Archivio Storico d’Italia; Graziani, Matarazzo, Frolliere, and Bontempi; Fabretti’s chronicles of Perugia, and his “Vita dei Condottieri, etc.”; and the local histories of Ciatti, Pellini, Bartoli, Mariotti, and Bonazzi. Villani{ix} and Sismondi have been consulted; Creighton’s “History of the Papacy during the Reformation,” and von Ranke’s “History of the Popes.”

Of the purely local histories mentioned above Bonazzi’s is the most important. His two bulky volumes are excellent reading in spite of his sarcastic and often unjust bitterness against the clerical party. A number of local pamphlets, the names of whose authors we cannot here enumerate, have been used for various details, together with other books on a variety of subjects, such as Dennis’ “Etruria,” Broussole’s “Pélerinages Ombriens,” Hodgkin’s “Italy and her Invaders,” etc., etc.

When all is told, by far the most valuable and trustworthy authority on Perugian matters is Annibale Mariotti. A local gossip who combines with his gossiping qualities an exquisite sense of humour, and a real genius for investigation in matters relating to his native town, is the person of all others from whom to learn its actual life and history. Mariotti is an eminent specimen of this class of writers, and no one who is anxious to understand the spirit of Perugia should omit a careful study of his works on the Popes, the People, and the Painters of Perugia.

For personal help received we have the satisfaction of offering in this place our sincere thanks to Cav. Giuseppe Bellucci, professor at the University of Perugia, whose wise and kindly counsel has led us throughout to an understanding of countless points which must, without him, have remained unnoticed or obscure. Our notes on the museum are practically his own. We would mention also with grateful thanks Dr Marzio Romitelli, Arcidiacono of the cathedral of Perugia, who generously opened his library to us, and many of whose suggestions have been of service to us. To Count Vincenzo Ansidei, head of{x} the Perugian library, our sincere thanks are offered here.

We must further acknowledge the help of Signor Novelli of Perugia; of Mrs Ross, Mr Hayllar, and Cav. Bruschi, head of the Marucelliana Library at Florence. Lastly, of Mr Walter Leaf and Mr Sidney Colvin in the revision of proofs.

The comfort of our quarters in the Hotel Brufani needs no description to most Italian travellers, who are already familiar with that delightful house; but we are glad to mention here our appreciation of the care and thoughtful kindness shown to us by our English hostess in the Umbrian town. The courtesy received by us at headquarters from the Prefect of Umbria and Baroness Ferrari his wife, made our stay, from a purely social point of view, both easy and delightful.

To close these prefatory notes we can but say how sincerely we trust that the following pages may serve only as a preparation, in more capable hands, for further and far fuller records of a city whose history is as enthralling to the student of men as its pictures and position must ever be to the lover of what is beautiful in nature and in art.

August 21st, 1897.

Am Hof. Davos.

| CHAPTER I | |

|---|---|

| PAGE | |

The earliest Origins of Perugia and Growth of the City | 1 |

| CHAPTER II | |

The Condottieri and the Rise of the Nobles | 33 |

| CHAPTER III | |

The Baglioni. Paul III. and last years of the City | 58 |

| CHAPTER IV | |

The City of Perugia | 82 |

| CHAPTER V | |

Palazzo Pubblico, The Fountain and the Duomo | 109 |

| CHAPTER VI | |

Fortress of Paul III.—S. Ercolano—S. Domenico—S. Pietro—S. Costanzo{xii} | 151 |

| CHAPTER VII | |

Piazza del Papa, S. Severo, Porta Sole, S. Agostino and S. Francesco al Monte | 178 |

| CHAPTER VIII | |

Via dei Priori—Perugino’s House—Madonna della Luce, S. Bernardino and S. Francesco | 201 |

| CHAPTER IX | |

Pietro Perugino and the Cambio | 216 |

| CHAPTER X | |

The Pinacoteca | 230 |

| CHAPTER XI | |

The Museum and Tomb of the Volumnii | 267 |

| CHAPTER XII | |

In Umbria | 290 |

| PAGE | |

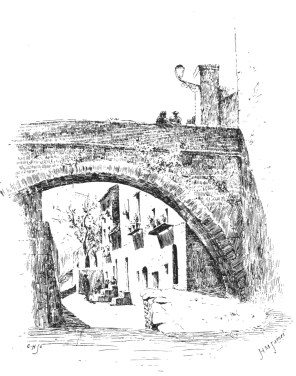

Via del Aquedotto, showing Tower of the Cathedral | 5 |

Lombard Arch on the Church of S. Agata | 14 |

Palazzo Baldeschi | 23 |

Arms of Perugia | 32 |

Via delle Stalle | 39 |

Niccolò Piccinino | 53 |

Palazzo Pubblico | 57 |

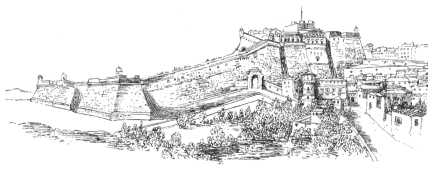

Fortress of Paul III., showing the Upper Part, now occupied by the Prefettura, etc., and the Lower Wing, which covered the site of the present Piazza D’Armi | 77 |

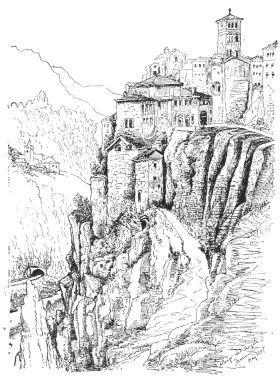

Perugia from the Road to the Campo Santo | 83 |

Etruscan Arch, Porta Eburnea | 87 |

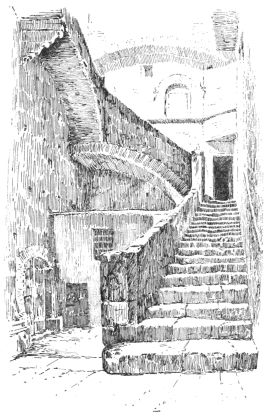

Mediæval Staircase in the Via Bartolo | 89 |

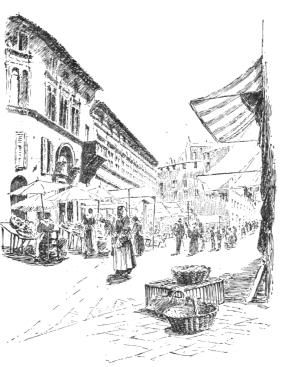

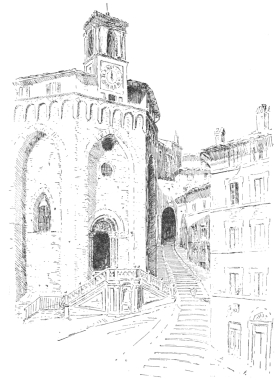

Piazza Sopramuro, showing the Palace of the Capitano del Popolo and the Buildings of the first University of Perugia | 101 |

Convent of Monte Luce | 107 |

Piazza di S. Lorenzo, seen from under the Arches of the Palazzo Pubblico{xiv} | 111 |

Remains of the First Palazzo dei Priori in the Via del Verzaro | 114 |

Oldest part of the Palazzo Pubblico | 121 |

The Reaper. Detail in a panel on the Fountain | 127 |

Geometry. Detail in a panel on the Fountain | 131 |

On the Steps of the Cathedral | 134 |

In the Cloisters of the Canonica (or Seminary) | 147 |

S. Francis | 150 |

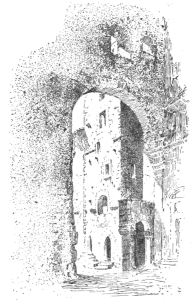

Porta Marzia | 155 |

Church of S. Ercolano and Archway in the Etruscan Wall | 157 |

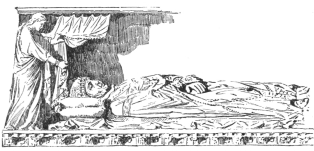

Detail of the Tomb of Pope Benedict XI. in the Church of S. Domenico | 166 |

House in the Via Pernice | 179 |

Arco d’Augusto | 189 |

S. Agostino and Porta Bulagajo | 191 |

Church of S. Angelo | 195 |

The Old Collegio dei Notari, said to be the studio of Perugino | 202 |

Torre degli Scirri | 203 |

Etruscan Arch of S. Luca | 205 |

Mercy. Detail on Façade of the Oratory of S. Bernardino | 209 |

Perugino: Madonna and Patron Saints of Perugia, painted for the Magistrates’ Chapel at Perugia, now in the Vatican at Rome | 221 |

First Translation of the Body of S. Ercolano (Fresco in the Pinacoteca of Perugia){xv} | 243 |

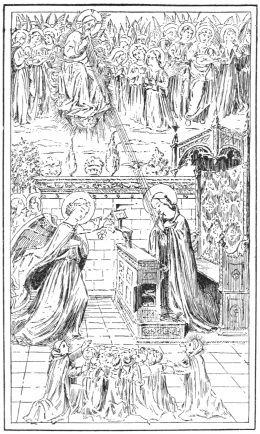

Gonfalone of the Annunciation attributed to Niccolò Alunno | 249 |

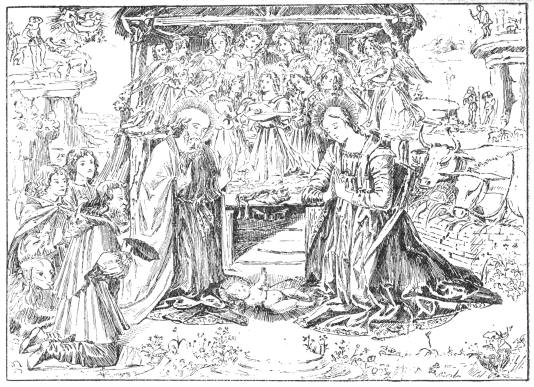

Adoration of the Shepherds. By Fiorenzo di Lorenzo | 253 |

Via Della Pera under the Aqueduct on the way to the University | 269 |

Etruscan Mirror in Guadabassi Collection | 280 |

Tomb of Aruns Volumnius | 287 |

The Temple of Clitumnus | 301 |

Narni (with Angelo Inn in foreground) | 307 |

| Plan of Perugia |

The Story of Perugia

SOMETIMES in a street or in a country road we meet an unknown person who seems to us wonderfully and inexplicably attractive. Perhaps we only catch a passing vision; the face, the figure passes us, oftener than not we never meet again, and even the memory of the vision which seemed so full of life, so strong, and so enduring, passes with the years, and we forget. But had we only tried a little, it would, in almost every instance, have been possible to follow the figure up, to learn what we wanted to know about it, to understand the reason why the face was full of meaning to us, and what it was which went before and gave the mouth its passion, the eyes their pain and sweetness. In nine cases out of ten we can, in this nineteenth century, discover the birth and parentage, the loves and hates, of any human being we may wish to know. But this is not the way with cities, and although they attract us in almost precisely the same fashion as people do, we cannot always trace their earliest origins. There are certain towns we come across in travel, of which we know very well that we want to know{2} more. Perugia is one of these. It at once catches hold of one’s imagination. No one can see it and forget it. A breath of the past is in it—of a past which we dimly feel to be prehistoric. Boldly we set to work to learn its history, and at first this seems an easy matter: the later centuries are a full and an enthralling study, for as long as men knew how to write they were certain to write about themselves, and the writers of Perugia had a wide dramatic field to work upon. But then come the records which are not written—which, in fact, are merely hearsay; and further even than hearsay is the period when we know that men existed, but which has no history at all beyond a few stone arrow heads, and bits of jade and flint. Yet, to be fair to a place of such extraordinary antiquity as this early city of the Etruscan league, one is unwilling to leave a single stone unturned, and in the following sketch we have gathered together, as closely as we could, the earliest facts about a city which attracts us, as those unknown people attract us whom we meet, admire, and lose again in the crowd.

“It seems,” says Bonazzi, the most modern historian of Perugia, “that in the earlier periods of the world all this land of ours (Umbria) was covered by the sea, and that only the highest tops of the Apennines rose here and there, as islands might, above the waves. Then other hills arose, a new soil was disclosed, and great and horrid animals, whose teeth were sometimes metres long, came forth and trod the terrible waste places. In the silence of these squalid solitudes, no voice of man had yet been heard, and the stars went on their way unnoticed, across the firmament of heaven....”

But Bonazzi’s science, though highly picturesque, was not entirely correct, and the following account, written by an inhabitant of Perugia who has studied the{3} history of his town and neighbourhood with faithful precision and from the darkest periods of their existence, may well be inserted here.

“The city of Perugia,” Prof. Bellucci writes, “is built upon a piece of land which was formed by a large delta of the primeval Tiber. In very early times (during the period known as pliocene) the Tiber, before running into the sea, formed in the central basin of Umbria an immense lake. The soil of which the actual plain of Umbria is now composed, and the numerous low hills which surround it, are made up either of river deposits such as sand and rubble left behind by the rush of waters, or else by clay deposits which slowly formed themselves in the quiet bosom of the lake. The date of these deposits is shown by the fossil remains which are found in them: elephants, rhinoceros, hippopotamus, stags, antelopes, hyenas, wild dogs, &c., all of which indicate a much warmer climate than that of the present day. In the period following on this, the great lake of Umbria began to empty itself; and as the soil washed gradually away, the waters forced a passage through the mountains below Todi, and from that time onward the Tiber gradually assumed its present course. The characteristic fauna of this second period distinguishes it from the first. Numerous remains found in the primitive gravel deposits of the Tiber prove the existence of man in our neighbourhood during both these periods (namely the paleolithic and neolithic). But the final drying up of the great lake basin or valley of Umbria was a very slow process, and even in Roman times the extent of these stagnant waters was so wide that the present town of Bastia on the road to Assisi was surrounded by them on every side and went by the name of Insula Romana. The final drainage of the lake was not completed till some time in 1400, when the river Chiagio burst through the rocky dykes under Torgiano and lowered the level of the water by four metres. Thus central Umbria at last assumed its present aspect. We stand upon the hill-top at Perugia where once thousands of years ago the turbid waters of the Tiber rushed along, and at our feet stretch the green and fertile fields of Umbria, all the fairer for the fertilising waters of that mighty lake which, in the dim and distant past, had covered them completely.”

We have no definite date or name for those first {4}men who came to live in this strange marshy wilderness. We have only the relics of their patient industry. An inexhaustible store of arrow-heads and other barbarous stone implements is found in all the hills around Perugia, and splendid hatchet heads of jade upon the shores of Trasimene. No doubt these men lived in holes and caves, perhaps at the foot of this hill where the present city of Perugia stands, or a little to the west of it, but their history is dark and very far away. Dark too and far away, as far as written facts remain, is the history of that almost more mysterious race of men which followed on the prehistoric one, namely, the Etruscans.

This is no place in which to discuss the origin of that extraordinary people whose language and parentage, though they lived and laboured side by side with the most cultivated and inquisitive of European nations, is practically dead to us. It is enough at this point of our history to note that the Etruscans were the first to seal their personality, with the seal of a visible and tangible intelligence, upon this corner of the world, and it is quite probable that they made one of their earliest colonies upon the jutting spur of a line of hills which would have attracted them upon arrival. It is certain that in course of time Perugia became one of the most powerful cities of the Etruscan league. Her museums are full of the pottery, tombs, inscriptions, toys, and coins of the mysterious nation (see Museum, chapter XI.).

Innumerable myths grew up around the foreign people, and individual historians described their advent in individual places and pretty much at random. The earliest chroniclers of Perugia, ignoring the men who had perhaps existed for centuries before this unknown nation landed,—ignoring too, the other settlers,—pounced upon a plum so precious and romantic to stick into the pie of legends that they were concocting; they{5}

![]()

VIA DEL AQUEDOTTO, SHOWING TOWER OF THE CATHEDRAL

peeled and stoned the plum to suit their fancy, and having done so, stuck it in with many others to swell the list of dubious tales in their long-winded manuscripts. As these chroniclers were nearly always monks, it was natural enough that they should form their shambling history on the one great history that{6} they possessed, i.e., the Bible. To them the Etruscans were easily and most satisfactorily explained: they descended from the first man, Adam, and they were the sons of Noah. Nay, the monks made an even happier hit, for they declared that Noah in person climbed the Apennines and pitched his tent upon the spur of hill where the present city stands! We can well imagine the old monk Ciatti, one of the earliest historians of Perugia, sitting before his wooden desk upon some dreamy night in May, his Bible propped before him, all Umbria asleep beneath the stars outside his window, and compiling the following entrancing legends concerning the Etruscans and their leader: “Serious writers hold Janus to be the same as Noah, who alone among men saw and knew all things during the space of six hundred years before the Deluge and three hundred years after the Deluge. The ancient medals which show the two faces of Janus are engraved with a ship, to denote that he was Noah, who, entering an ark in the form of a ship, was saved by divine decree from the universal Deluge.”[1] Ciatti next goes on to give a delightful description of the arrival of Noah and his sons; “they penetrated,” he says, “into Tuscany,[2] where, fascinated by the loveliness of the country, the agreeable qualities of the soil, the gentle air and the abundance of the earth, they determined to remain; but feeling uncertain where they should fix their dwelling, they were advised by certain augurs to build Perugia on the spot where it now stands.” Some say that the name Perugia comes from the Greek word for “abundance.” Certainly Ciatti was able to weave this fact into his legendary web: “Whilst, waiting{7} for the Augurs,” he writes, “two doves passed by them, flying to their nest, one carrying a branch loaded with olives and the other an ear of corn. Soon after there came a big wild boar carrying on his tusks a bunch of grapes. They took these signs to mean good omens, and they decided to build Perugia on the spot.”

Ciatti must have been an honest chronicler. Had we been given his early possibilities of making history in our own fashion, we must inevitably have told a credulous public that the ark itself rested upon the spurs of the Apennines and disgorged its contents on the hill where stands the present city of Perugia. But Ciatti withheld his hand from this, and we too must bare our heads before the fact of Ararat, and only hold to that of Noah, in his five-hundredth year or so, wandering unwearied forth to form a mighty nation on the coasts of Italy!

But before leaving Ciatti and his early myths, we must do him the justice to say that he was not utterly ignorant of a dim nation and of dimmer monsters living perhaps before the days of the Deluge. The old monk, like other wise historians, sets to work to hunt up the heraldry of his native city, and thus he explains the origin of the griffin on the city arms. The enthralling hunt described savours surely of something in an even earlier age?

“Now it so happened that, when the people of Perugia and of Narni were at the height of their prosperity, they became consumed by a very warlike spirit, and cultivated freely all military exercises, and on one occasion they challenged each other to a trial of prowess in a celebrated hunt. They agreed to meet in the mountains round about Perugia, which were then the haunt of fierce and terrifying wild beasts, and having come to that mountain which now takes its name from the event (Monte Griffone) they found there a griffin, which the Perugians captured and killed. After some dispute the monster was divided, the skin and claws being best worthy of preservation were taken by the Perugians, whilst the body{8} fell to the people of Narni. In memory of this occurrence the Perugians took for their arms a white griffin—white being the natural colour of that animal—while the people of Narni took a red griffin, corresponding to the part which had fallen to their share, on a white field.”[3]

But, to pass from the realms of myth to those of reality, it seems quite certain that the Etruscans—or Rasenae as they are sometimes called—spread themselves over a large part of Italy, building and fortifying their cities, making roads and laws and temples, and casting the light of an older art and civilisation upon the land to which they came as colonists. One of the chief of their cities was Perugia. Fragments of the old walls, built perhaps three thousand years ago, still stand in places, clean-cut, erect, and menacing, around the Umbrian city.

The lives of the Etruscans can only be studied through their art, and Perugia holds an ample store of this in her museums. There, in those rather dreary modern rooms, stone men and women smile upon their tombs, and the sides of these tombs bristle with long inscriptions written in an alphabet that we can partly read, but in a language that we cannot understand. Mirrors, and beautifully painted pots, children’s toys and ladies’ curling-tongs—the Etruscan dead have left no lack of records of their ways of living. But, strong as was their personality, another and a stronger force had struggled through the soil of Italy. Rome had arisen to shine upon the growing world. It remained for Rome to leave the stamp of veritable history upon the city of Perugia.{9}

Throughout the early history of Rome, we catch dim rumours of an occasional connection or warfare with this corner of Etruria. It is not till 309 B.C. that we have any distinct mention of Perugia in connection with Rome. In that year the Roman Consul, Fabius, fought a battle with the Etruscans under the walls of the town. The Etruscans lost the day, Perugia and other cities of the League sued for a truce with Rome which was granted to them. Fabius entered Perugia “and this was the first time,” says Bartoli, “that the banner of foreigners had waved across our city.” Perugia bitterly resented the rule of the foreign power, and, breaking her truce, she made several passionate efforts to regain her freedom. But in vain. Her blood, perhaps, was old, and grown corrupt, the blood of Rome was new and palpitating. She was again and again overcome by Fabius. In 206 B.C. we find her, not exactly submitting to Rome, but playing the part of a strong ally, and cutting down her woods to help in the building of a fleet for Scipio. Her history continues dark—overshadowed by that of Rome. We hear a faint rumble of the Roman battles. We catch dull echoes of Hannibal and Trasimene, for Trasimene is very near Perugia. Did some of her citizens creep down perhaps, and get a vision of the fight? Did any of those much-bewigged Etruscan ladies, who we know were very independent in their ways, tuck up their skirts and follow through the woods to have a look at the elephants and shudder at the swarthy African?

We cannot tell. The next clear point in her history is a terrible one for Perugia. She fell, but she fell by a mighty hand, by that of the emperor Augustus. In the year 40 B.C. the Roman Consul, Lucius Antoninus, who, it may be said, was defending the liberty of Rome whilst Mark Antony lay lost in a{10} love-dream upon the banks of Nile, took refuge within the walls of Perugia from the pursuit of Octavius (Augustus) who then laid siege to the town. For seven months the brave little city held out, but she was reduced to such a terrible distress of famine that Lucius at last gave way, and opened her gates to the conqueror. Octavius entered Perugia covered with laurels. The citizens prayed for mercy. He spared most of the men and women, but he excepted three hundred of the elders and saw them singly killed before his eyes. When they prayed for grace he merely tossed his head back and repeated: “They must die.” This ordeal over, Octavius decided to postpone the sack of the city until the following day. But one of its citizens, Caius Cestius Macedonicus, hot with all the shame of the thing, got up at night and made a funeral pyre of his house. He set fire to its walls, and as it burned he stabbed himself and died there. The flames spread through the city, and before the morning Perugia was burned to the ground. Nothing remained of all its buildings except the temple of Vulcan, and in memory of this fire the town was afterwards dedicated to Vulcan instead of to Juno to whom it had formerly belonged. Octavius returned to Rome bearing before him the image of Juno, which alone had been saved from the flames. Some years later he agreed to rebuild the city, and hence the letters Augusta Perusia over her gates.

* * * * * * * *

So laying aside for ever Perusia Etrusca, that city of strange beasts, strange people, and strange myths, we face Perusia Augusta, or the Perugia of Rome.

For some centuries, strange as it may appear, the powerful old Umbrian hill-town seems to have fallen contentedly asleep under the rule of her great protector.{11} It was, as we know, the policy of Rome to adopt the laws and customs of the people whom she conquered rather than to change them, and indeed the alteration seldom went further than in name. The Etruscan rulers therefore took the titles of Roman governors, they did not really alter, and it is probable that the laws of the very earliest settlement have never really become extinct. The Lucumo of the Etruscans was in all probability the descendant of the earliest prehistoric village chief, who developed into the Diumvir or representative of the Roman Consul pretty much as the present Sindaco succeeded to the position of the Podestà of the middle ages.

Rome had always loved and studied the religions of the older people, and Bonazzi infers that Rome “delighted in nursing on the breast of her republic those great masters of Divinity who could be made such powerful political instruments for her service.” The Romans must have intermarried freely with the Etruscans; the mixture of names and lettering upon their tombs points to this fact. But the strong fresh blood of the younger race seems to have overcome that of the more corrupt one. Other tribes and other tongues pressed in upon the first inhabitants and gradually the language, yes, and the memory of the strange and fascinating people, died.

Of the Roman occupation little trace can be found in the architecture of the city, beyond the walls and gates and the inscriptions over some of these, together with a sorry fragment of a Roman bath. It must be remembered that the entire city was burned to the ground after the siege—burned with all her wealth of monuments and temples—and it does not seem as though the Romans did much to beautify her with grand buildings. Having no old buildings to use as raw material, they were probably content at this period{12} to build strong walls and houses suitable for a fortified town, thus fostering the warlike character of her inhabitants which was to prove so great a point in following centuries.[4]

Roman rule was a very real piece of history, but it is not possible to say that the period of myth and darkness had wholly passed away. We possess a certain knowledge of the Roman government, but the shadow of the Gothic and Barbarian night closes in upon it like a heavy pall; and the next clear and startling point about Perugia is her recapture by Belisarius followed by the siege of Totila (or Baduila).

During those terrible centuries when Italy was being ravaged by perpetual invasions, her lands devastated by war and plagues and famine, and her cities, as one historian says, “no longer cities, but rather the corpses of cities,” we find scant mention of actual harm done to Perugia, for it was the north which suffered first. However, as the Goths pressed southward upon Rome, as Rome herself wavered and sank beneath the weight of the northern hordes, and of her own corruption, we gather that the Umbrian cities too became a prey to the barbarians, and that Perugia suffered the fate of all her neighbours. Her historians seek in vain for stated records of this time where all is darkness, but some dim facts shine out, among them the steady growth of Christianity within the city.

The first important date we find follows nearly six hundred years after her capture by Augustus. It was in 536 A.D., that Justinian, who had conceived the mighty plan of recovering Africa from the Vandals and Italy{13} from the Goths, sent one of his best generals, Constantine (under Belisarius), into Umbria to occupy the cities there. Constantine made Perugia his headquarters and for a while his possession of the town seems not to have been disputed by the Goths. Witigis left her on one side as he passed with his armies down to Rome, and it remained for the indomitable Totila to wrest her (in 545) from the power of the Byzantine Empire. Totila is a most prominent figure in the history of the city, and many are the myths which centre round him. He first attacked Assisi, and having conquered her, he turned his greedy gaze upon the fair hill city opposite and instantly desired to possess her also. But realising the strength of her position, which was largely increased by the occupation of a Byzantine general, he determined to get her by foul means rather than fair, and so he bribed one of her citizens to murder Cyprian, who was then the general in command. The citizens rose in eager revolt against this treachery, and Totila soon found that he had undertaken no light thing when he came to besiege the town. Indeed tradition says that the said siege lasted seven years, and however much this may have been exaggerated, it is certain that it was made a hard one for the Goth. Perugia was taken by storm, but after fearful fighting; she fell, but she was upheld to the last by a new power, namely that of her faith. The story of S. Ercolano, the faithful Bishop of the Perugians, is told in another place (see pp. 245-246). It has been admirably illustrated by Bonfigli, it has been described and hallowed in a hundred ways throughout the city’s chronicles, and it is vain for modern historians to tell us, as they are inclined to do, that Totila never set foot in Perugia. Bonfigli’s fresco is terribly convincing in itself, as are also the naïve and delightful records of Ciatti and Pellini. Among the people of the town Totila has become one{14} of its most important facts, and they declare that his wife lies buried close to the Ponte Felcino together with her husband’s hidden treasure.

![]()

LOMBARD ARCH ON THE CHURCH OF S. AGATA

Gothic rule was short. Infinite and hurried changes follow on this period. We next hear of the city in the hands of the Lombards. The Lombard occupation is almost as dark as the Gothic.[5] In 592, Perugia{15} became a Lombard Duchy ruled by the Duke Mauritius, who turned traitor to his trust and delivered the city to the Exarch of Ravenna. The news of the Duke’s treachery spread northward. Agilulf, King of the Lombards, came hastening down to recapture the city with a mighty army, and he made Mauritius pay for his treachery with his head. This was in 593. A few years later Perugia was restored to the Empire, but at the beginning of 700, she, like many other cities of Italy, attempted to shake herself free from Byzantine rule. It is probable that she did not really succeed in doing so, but this point is at any rate a great crisis in her history, for it is the first time that we find her at all tangibly connected with the Head of the Christian world—with that power of the Church which was to prove, throughout her future, alternately her safeguard and her scourge.

It was about 727 that Leo the Isaurian, Emperor of the East, terrified by certain evils in his kingdom which he took to be signs of Divine anger, made his famous decree against the worship of images. This proved of course a most unpopular edict in Italy, and the reigning Pope opposed it by every means in his power. Many of the most powerful cities joined him, amongst them Perugia, and Greek rule in Italy, already on the wane, was greatly weakened, but we do not hear of any settled breach with the Empire for many years to come. Perugia was, as we shall see, merely advancing towards her own liberation, but the acquired protection of the Popes proved useful to her in her next great crisis.

In 749 Ratchis, King of the Lombards, laid siege to the city, and her fall seemed inevitable. Then, in the moment of her great need, with the Lombard army beating in her very doors, the reigning Pope, S. Zacharias the Greek, accompanied by all his clergy, and{16} by many of the Roman nobles, arrived at her gates, and in words of extraordinary sweetness pleaded her cause with Ratchis. We do not hear what phrases the old man may have used to check a man on the verge of a great victory. We only hear that the Lombard king knelt down and kissed the feet of the Pope. “Thou hast conquered me,” he said, very simply, and then he withdrew from the battle, and S. Zacharias passed into the city, and was received with universal joy by her citizens. And not only did Ratchis abandon the siege of a town which he so greatly coveted, but, his whole soul being moved by this new power, he renounced his kingdom and his crown and retired to the monastery Monte Cassino, where he became a monk, living there until he died.

Thus closes another chapter of Perugian history. Within a space of three hundred years, roughly speaking, she had changed the nationality of her rulers four successive times, whilst she herself may be said never to have changed. Her internal history, her internal government, had all along continued pretty much on the first lines. Her entire future policy proves this. In all the small wars which follow, and which lead to her final supremacy over every other city in Umbria—cities which at the outset had been as strong as herself, and even stronger, we trace this masterful and incontestable personality—the personality of the griffin which the old Etruscan settlers captured thousands of years before upon the hill-tops and chose for their city arms.

* * * * * * * *

In all the intense complication of the times which follow it is almost impossible to unravel the exact position of individual towns. At one moment we find Perugia belonging apparently to the Duchy of Spoleto, at another joined to the Tuscan League, at another putting herself under the protection of the Pope,{17} whilst all the time nominally belonging to the Empire. Bonazzi remarks that one result of the perpetual conflict between Emperor and Pope was the liberty left to the citizens; in another place he says that in the scant documents which contain her early history, “Perugia is always mentioned alone, always managing her own affairs.” The said management dated back in all probability to that of the very earliest settlement, which was mainly agricultural, and managed by chiefs or a Village Council. As the town grew, so likewise did the numbers of its rulers. In Perugia, as in other places, the original Village Council, which was first held in the public square, was abandoned as politics grew complicated. The Consuls, ten in number, two to each Porta or gate, met in council on the steps of the first Cathedral. The finest architectural building in Perugia is notably the Palazzo Pubblico, but long before the construction of this palace there was another building which served the same purpose close to the Duomo in which the different protectors of the city met. We do not propose to trace the form of government here. Suffice it to say that, in Perugia as elsewhere, we find the usual titles of Consuli and Podestà, then of the Heads of City Guilds, the Priori (a very strong power in Perugia), Capitano del Popolo and Capitano della Parte Guelfa; all of whom recur again and again in her chronicles, playing important parts as peace-makers or as arbitrators in her turmoils and dissensions.

The historians of Perugia, naturally enough perhaps, tend to speak of her as of an independent Republic, but this she never was. She had her own rulers, she grew powerful and individual, she finally became a great capital, but she was never a free state like Florence or Rome. Something in her extraordinary position, something in the character of her people, warlike and tenacious from the first, proved her final force. Great{18} wandering hordes and armies thought twice before they attacked her walls. Thus she enjoyed long periods of ease, and in her stormy breast she nurtured the ferocious families which were to prove her strength, but equally her bane in later years.

Being utterly cut off from mercantile expansion or commerce of an ordinary sort, she used her concentrated force in subduing neighbouring towns, and thus extending her dominion over Umbria. Her power soon became recognised, and many little towns and hamlets sent envoys to present acts of submission to the growing power. When these were given freely she received them graciously, and when withheld she sometimes showed a power of rapacity and cruelty which is well nigh inconceivable.

Her history is full of wars against Siena, Gubbio, Arezzo, Città di Castello, Todi, Foligno, Spoleto and Assisi, all chronicled at great length by her proud historians. We have collected a few scattered facts relating to these, which cast some light upon the character of the Perugians, who, as their power strengthened, began to show, not only a tyrannous disposition, but an occasional spark of the grimmest humour. Leaving aside other events, such as the encroaching power of the Pope, we may now glance at some of these.

The first act of voluntary submission came from the island of Polvese in 1130, and was received with great solemnity in the Piazza di San Lorenzo and in the presence of all the inhabitants of the city. A little later more than nine hundred of the people of Castiglione del Lago came to place their land on the shores of Trasimene under the protection of Perugia. Città di Castello and Gubbio followed suit, and many of the smaller towns and hamlets. But, if submission was sweet, blows, one surmises, were well nigh sweeter to{19} the fierce and savage owners of Perugia, and horrid were the skirmishes—one can scarcely call them battles—which ensued from time to time when towns resisted or rebelled against them.

Assisi and Perugia were ever an eyesore to one another, and their inhabitants scoured the plain between them like packs of wolves. In one of these savage little contests tradition tells us that a certain Giovanni di Bernadone, a youth of only twenty summers, was taken prisoner by the Perugians and kept a year in the Campo di Battaglia. The Palace of the Capitano del Popolo in the Piazza Sopramuro now covers the place where the youth was chained, and we may look on it with veneration, for he was no other than that sweetest soul of mediæval history, St Francis of Assisi.

When Città della Pieve dared to rebel, the action of Perugia was prompt and effective. “Most gladly did the youth of Perugia—hot with the dignity of their city, and by no means disposed to forgive those who despised or disobeyed her—assemble in arms,” says Bartoli. The army thus assembled was instantly sent to the recalcitrant city, but the Pievese had scarcely caught sight of it hurrying towards their gates, than they sent their Procuratore, Peppone d’Alvato, to sue for peace and beg forgiveness for their misdeeds. This was kindly granted, but Peppone, accompanied by some hundred and thirty Pievese, was forced to come to Ripa di Grotto and there listen to the reproaches of the Podestà of Perugia, whilst the Bishops of Perugia and of Chiusi, the Provost of S. Mustiola, and the Arciprete of Perugia, sitting on high chairs, surrounded by various grandees, were in readiness to enjoy the spectacle. All were dressed in their finest, but we are told that the Arciprete of Corciano threw all his neighbours entirely into the shade by the splendour and the brilliancy of his many-coloured{20} garments.[6] Peppone kneeling at the Bishop’s feet with his hand on the gospels, swore faith and loyalty to the Perugians, and we hear that the Pievese returned home “rejoicing” at the pardon obtained in this most humiliating fashion. This last fact we may take the liberty to doubt, but it is certain that the Perugians enjoyed the whole episode immensely, neither did they consider the humiliation of their enemies complete. A further punishment had yet to be thought of, and at last a brilliant plan was resolved on. The Piazza of San Lorenzo needed paving, and the Pievese were told that they must provide all the necessary bricks for this purpose, and this “puerile waspishness,” as Bonazzi describes it, so delighted the hearts of the Perugians that, as we learn, not even the death of the great foe of the Guelph cause, Frederick II., “was able to give them a keener sense of joy.”

Perugia and Foligno had always regarded each other with undisguised dislike, skirmishing about and exchanging insults wherever they happened to meet. Once the people of Foligno had come bare-footed, and with a sword and knife hung round their necks, to implore pardon of Perugia, but they revolted again, and the Perugians continued to attack and to molest them. Three times in a single year (1282) their lands were devastated, and finally the town was taken, and the walls demolished, and imperative orders were issued absolutely forbidding these to be rebuilt on the western side. At last Pope Martin IV., amazed and disgusted by the behaviour of a people to whom he was honestly attached, interfered, but Perugia continued to molest her unhappy neighbour with a quite{21} peculiar animosity, whereupon the Pope, angered beyond measure by their disobedience, excommunicated them. “Into such a passion did the Pope fall with the people of Perugia,” says Mariotti, “that he issued a most severe excommunication against them.” It was just at the time of the Sicilian Vespers. The Perugians, irritated by their sentence of excommunication, determined to celebrate a kind of mock vespers on their own account. Gregorovius says that this is the first instance recorded in history of this strange form of popular demonstration. “They made a Pope and Cardinals of straw, and dragged them ignominiously through the city and up to a hill, where they burned the effigies in crimson robes, saying, as the flames leapt up, “That is such-and-such, a Cardinal; and this is such-and-such, another.”

A strange scene, truly, in a half-civilised city! But political and religious causes came between and put an end to these half childish squabbles. A little later the Pope forgave the Perugians, and they continued their evil ways, and persisted in destroying the peace of the Umbrian towns.

Arezzo had the satisfaction of a victory over Perugia in 1335, and in defiance and derision she hanged her Perugian prisoners with a tabby cat hung beside them, and a string of lasche dangling from their braces.[7] But pranks like these were not allowed to pass unnoticed, and Perugia did not fail to grasp her finest banner with the lion of the Guelph all rampant on a field of gules, and hurry out to subdue her insolent{22} neighbours. The people of Arezzo were humbled to the dust, but by means too barbaric to be here described.

Thus one by one the cities of Umbria became sufficiently impressed by this forcible fashion of dealing with insurrection, and they recognised that it would be wise, though it might not be pleasant, to swear allegiance to the imperious city. Gualdo next gave up her keys, together with Nocera, but the latter found it impossible to suppress a few oaths whilst signing the documents, and there was a loud wail over the laws imposed upon them.

says Dante, referring to the subject in the “Paradiso.”

Perugia’s culminating success seems to have been at Torrita in 1358, when the Sienese were defeated, and forty-nine banners brought back tied to the horses’ tails, and the chains of the Palace of Justice torn away and hung in triumph at the feet of the Perugian griffin. Even the powerful Florence accepted Perugia’s help in the Guelph cause, and so early as 1230 arbitrations had been exchanged for the purpose of settling all questions of commerce between the two cities.[8]

All these victories, these repeated successes, tended{23}

to increase Perugia’s independence of spirit, and she was very careful that no one, not even the Pope, should infringe on her rights, or dispute her authority. Her attitude towards the Church is somewhat difficult to understand. It seems to have mystified Clement IV., for he expresses his “dolorous wonder” that the Perugians, who were such devoted allies of the Holy See, could sometimes behave so wickedly towards the clergy. And, curiously enough, the Perugians, lovers{24} of processions, of patron-saints, miracles, and all the rest, could, and did, make laws to exclude all ecclesiastics from having anything to do with their charitable institutions or donations to Churches.[9]

We find them protesting both with menaces and oaths against any usurpation of the clergy, “In the names of Christ, the Virgin, S. Ercolano, and S. Costanzo.” Even the Pope was taught a lesson, for when John XXI. in 1277 asked for some lasche from the Lake of Trasimene, the Perugians called a general council in which it was resolved that the said lasche should be sent to His Holiness, but accompanied by the syndicate in order to show the Pope that the fish was the property of the city, and a gift from its citizens merely given to him for his Good Friday dinner!

These somewhat petty hostilities did not, however, materially affect the relations between the Papacy and the citizens of Perugia, and all through the twelfth and thirteenth centuries they remained on very friendly terms with one another.

We have thought it best to give a general sketch of the growth of the city, its customs and its wars, before touching on one of the chief characteristics of its history, namely, its close connection with the Papacy. It will, therefore, be necessary to glance back over some centuries, in order to follow the steps by which the power of the Popes arose in Perugia.

At first Papal authority was purely nominal. To the small towns of Italy, living each their concentrated and oftentimes tempestuous lives apart, the great Emperors who passed down to Rome in search of{25} crowns from the hands of Popes, must have appeared as ghosts, their documents as unsubstantial as themselves. The fact that one of these, Pepin, conceded large grants of land in Umbria, including Perugia, to a Pope who never came to look at them, must have seemed to the Perugians as little beyond a phantom transaction after all. We next hear of Charlemagne in 800 confirming an act by which Perugia, together with a number of other towns and territories, was placed under the alto dominio of the Holy See. In 962, Otto I. again confirmed the donation, but the iron hand of Papal power was not felt for many centuries in the rising town; and indeed, however deep the designs of the Church may have been from the very beginning, they were well concealed, and the first Popes who visited Perugia did so in the fashion of people starting on a summer excursion, and not at all in the character of conquerors. They would come to the city with all their suite of Cardinals and favourites, and take up their abode in the cool and spacious rooms of the Canonica, which, as Bonazzi with imperial pride declares, “became the Vatican of Perugia.”

Yet it is certain that the policy of the Holy See was deep, and that the growing capital of Umbria appeared no plaything in its eyes. The geographical position of the city—perched as it is on a hill which commands the Tiber and overlooks the two great highways from the Eternal City to the North and to the Eastern Sea—made it a most desirable possession for the Popes, and it was inevitable that Perugia should, sooner or later, submit to, or come into direct conflict with, the power of Papal rule. The open acknowledgment of such a situation was merely a question of time.

Innocent III., who has been called the founder of the States of the Church, was the first Pope who came{26} into direct personal contact with the Perugians. He accepted from them an offer to be their Padrone, and to exercise temporal power among them. Half playfully, though with what deep and powerful designs we may divine, he called the citizens his “vassals,” and to a certain extent they were willing to submit to his authority; but in so doing they were careful to wring from their “Padrone” a promise that their rights and privileges should be respected. Thus for the time they steered clear of the danger of subjection, continued to govern themselves, and preserved that free and independent spirit which hitherto, and in spite of every obstacle, had marked them as a race. Innocent was beloved by the citizens. He came amongst them at a time of much civil discord, when the nobles and the people were preparing for open strife. “He was a peace-maker,” says Bartoli, “and he kept his eye on all things; and on this city he looked with a peculiar partiality.” The Pope was anxious to promote the Crusades, and was on his way to Pisa to try to make a peace between the Genoese and the Venetians, whose quarrels interfered with his schemes, when he fell ill at Perugia, and died there in 1216.[10]

No sooner had he breathed his last than all his Cardinals hurried into the Canonica to elect his successor, and such was the impatience of the citizens that they even set a guard over these princes of the Church, and kept them short of food in order to hurry their decision. We are not therefore surprised to read that the Papal Throne remained vacant for the space of one day only, and that in consequence of this event the Perugians claim the privilege of having invented the Conclave.

Honorius III. succeeded Innocent, and he attempted, but without success, to heal the ever-widening breach between the nobles and the people. We have described{27} something of the wars outside, but Perugia herself within her walls was a veritable wasp’s nest during this period of her steady rise. Her inhabitants became more restless and unmanageable every year. In their perpetual broils the nobles fought beneath their emblem of the Falcon, and the popolo minuto (common folk), who sided with them, received the unamiable title of Beccherini.[11] The two extremes in the social scale joined hands in a perpetual opposition to the popolo grasso (well-to-do burghers), who were called Raspanti (raspare, to claw), a name probably suggested by their emblem of the Cat.

Honorius in his plan of dealing with the complicated situation can scarcely be described as disinterested; whilst apparently patching up peace, he really attempted to force an acknowledgment of papal power. His policy however, was fruitless, and the nobles resorted to the usual expedient of retiring to their country castles, for, as Bonazzi says, they “preferred to tyrannise alone in the silence of their isolated strongholds rather than to divide their forces in the capital of a powerful federation.” But the situation threatened to become intolerable, and we read that through the years from 1223 to 1228 a “perfect pandemonium reigned in and about the city.” Cardinal Colonna was sent to try and restore the balance between the rival factions, but, finally, Gregory IX. was forced to come in person, and through his influence the banished nobles were recalled from exile, and a certain degree of peace restored.

Gregory paid many visits to Perugia, much to the annoyance of the Romans, who expressed their wonder that the little hill-town with nothing but its brown walls,{28} towers, and landscape to recommend it, should be preferred by him to the plains and palaces of the Eternal City. This fact is recorded about the year 1228, when Gregory IX. was making an unusually long stay in his excellent and quiet quarters in the Canonica (at S. Lorenzo). The Romans were well aware, Bartoli says, that it was because of their ill-behaviour that he had retired into private life far away in the Umbrian city, and they even accepted as a judgment on their evil ways a certain most horrible inundation of the Tiber which befell them at that period. Deputies hurried across the land from Rome with supplications to the Pope to return to his people, and Gregory went, but he quickly returned to Perugia. The fame of S. Francis of Assisi was then at its height. Gregory felt inquisitive, but not altogether certain of the truth of the tales which were spread abroad concerning this wonderful man. He made numerous enquiries and sent his Cardinals to Assisi to gather all the information they were able to collect about the Saint. But the final manner of the doubting Pope’s conversion is described with such marvellous and touching piety in the “Fioretti” that we have inserted it at length in our description of the place where it occurred.[12] In the same year and place Gregory canonized S. Francis, “to the splendour of religion,” says one historian. He also canonized S. Dominic and Queen Elizabeth of Hungary, he sent missions into the land of the unfaithful, and gave indulgences of a year and forty days to all who would give money to the building of S. Domenico. So we may fairly say that he did not waste his time, but that he managed to get through a large amount of business during the time that he spent in Perugia.

* * * * * * * *

It is difficult to define the exact mutual relations of{29} Pope and city in any corner of Italy, but it is certain that Perugia found Papal power useful to her in many ways, and that on whatever side she happened to have a quarrel on hand, she always turned to the Papal See for help and arbitration. In spirit she was always Guelph, fighting under the emblem of the Guelph lion, and full of Guelph interests. Yet, although openly exercising self-government, almost in the manner of a free republic, under the protection and nominal rule of the popes, she was at the same time patronised by the emperors. In 1355 we read that her ancient privileges were confirmed and new ones granted by the Emperor Charles IV., who seems to have considered it worth his while to gain the friendship of her citizens.

Up to this period we have only had to deal with pleasant passing visits of the popes who sojourned in the city for a while. The time came, however, when the noose which Innocent had so lightly cast about their necks began to pull and tighten. The Perugians revolted hotly against the Popes of Avignon, who, incensed at their rebellion, attempted to check it by every means in their power. To understand the painful struggles which follow, it is necessary to remember that the end of the fourteenth and the whole of the fifteenth centuries were the most prosperous period in Perugia’s history. She had grown steadily and uninterruptedly both in power and riches, and in spite of terrible obstacles, ever since the day when the Romans rebuilt her walls more than fifteen hundred years before. In these two centuries she erected her public buildings, extended and settled her government, coined money, started her university, settled with her habitual promptitude all suspicion of rebellion, became one of the Tre Communi of Florence, Siena and Perugia, and whilst achieving all these things she continued to foster the passionate feuds and hopeless enmities between the different{30} factions which we have described above. Having grown strong and prosperous it was natural that she should resent any open attempt of a foreign power to subject her, and such an attempt came in the middle of the fourteenth century from the Papal See.

In 1367 the Spanish Cardinal Albornoz was busily employed in recovering the States of the Church. Perugia was at that time faithful to the Pope, and she received the Cardinal with due honours and gave him valuable help, especially in an expedition against Galeotto Malatesta of Rimini. Her goodwill however was of short duration, for the citizens saw themselves despoiled of Città di Castello and of Assisi during the Cardinal’s campaigns, and this they would not brook. They therefore sent a strong army at once towards Viterbo, but it was beaten back with heavy loss, and Urban V.’s authority was again firmly rooted at Perugia. He sent his brother, Cardinal Angelico, Bishop of Albano, as Vicar General to represent him in the city. Thus the authority of the popes crept in upon the town, and authority of some kind became every year more necessary as the voice of the people grew and strengthened and as the exiled nobles quarrelled outside the walls. Papal authority was finally represented in 1375 by an imperious French abbot, known in Perugian annals as Mommaggiore, whose doings and buildings have been described in another place. (See pp. 184-186.) The yoke that Mommaggiore—“that French Vandal, that most iniquitous Nero,” as the chroniclers call him,—put upon the neck of Perugia, proved unbearable to every party, and all the different factions for once joined together to break it. Florence and other cities, castles, and fortresses which had “unfurled the banner of liberty,” joined in the revolt, and in 1375 the abbot was driven in a very undignified fashion from the city. A republic was then declared{31} and the whole town rejoiced at having broken away from the thraldom of the Popes of Avignon. In vain did Gregory XI. call the people of Perugia “sons of iniquity”; in vain did he hurl the most terrible excommunications against them;[13] the feud between the city and the Pope was only laid to rest when the latter died. It had lasted long, and had produced something worse even than the struggle of two strong powers, for it had served to increase the terrible civil discord within the town. With the accession of Urban VI. a treaty was concluded, and Perugia acknowledged his right of dominion. In 1387 Urban arrived in the city, and as he entered the gates a white dove rested on his hat and refused to be removed by the servants who ran forward to deliver His Holiness from the unexpected visitor. It answered the Pope’s touch however, and was handed to his chaplain, and everyone accepted the event as an excellent omen. We will not linger to judge of its excellence, we can only say that the bird heralded an entirely new chapter in the history of the town, which hitherto had developed under general influences and many different hands. Her coming history is that of single influences, of personalities, or, in other words, of despots. The time had come when Perugia was to show the fruit of her stern ambitious character in the individual men whom she had reared. The names of Michelotti, Braccio Fortebraccio, Piccinino and of the noble families of Oddi and of Baglioni are familiar to all who have merely turned the pages of her history. Perugia, like other towns of Italy, had at the end of the fourteenth century reached a point of internal strife from which strong personalities could easily rise up to dispute or to control the existing{32} government. Why it was exactly that the Popes did not from the first forcibly interfere with the turbulent doings of these men, it is difficult to tell. They were constantly coming to the city, constantly appealed to by the citizens and nobles, for ever interfering both by menaces and arms, but it was not till more than a century of blood and tyranny had passed, not till the glory of the town was already on the wane, that the power of the Church came down to crush Perugia like a sledge-hammer.

Strangely enough it was a Pope who first gave the city away into the hands of a private person or Protector.

“The confusion, exhaustion, and demoralisation engendered by these conflicts determined the advent of Despots.... The Despot delivered the industrial classes from the tyranny and anarchy of faction, substituting a reign of personal terrorism that weighed more heavily upon the nobles than upon the artizans and peasants.... He accumulated in his despotic individuality the privileges previously acquired by centuries of consuls, podestàs, and captains of the people.”—See “Age of the Despots,” J. A. Symonds.

DEEP gloom closed in upon Perugia towards the end of the fourteenth century. The breach between the nobles and the people continued to widen. Sometimes one party was driven out of the city, sometimes another. Now and again both parties were recalled, and a compact of peace arranged by an arbitrary person from outside. But this last arrangement produced an even more terrible state of affairs, and crime and bloodshed were the inevitable result. We read of deaths by hundreds and not tens—cruel and indescribable deaths, which make one shudder—and already in the thick of the strife the names of Oddi and of Baglioni are stamped upon the records.

One of the strangest points in the history of the city at this time was the fashion in which these feuds between the rival factions were met by them. Whichever{34} party was weakest retired for the time to the country, leaving the city to their rival till time should favour their own cause.[14]

Bonazzi gives an almost extravagant account of the boorish manner of the exiled nobles’ lives. Down in the open country they hunted the abundant wild boar and devoured his flesh when they came home at night. They slept in dark and cavernous halls, and were out at dawn across the fields and forests, killing, hunting, fighting, according to the order of the day. Yet, although they were banished from the walls of their native town, they continued to molest and to disturb the citizens, and whenever the opportunity occurred, in they came again, sometimes openly, sometimes after the manner of thieves. We read of their entering the city at night across the roofs, robbing the cellars and granaries, and murdering such citizens as ventured to interfere.

Sometimes the order was reversed: the nobles got possession of the town, and the people were forced into the country. The terrible unrest of such a state of things may easily be imagined, and, added to these great evils, or, probably, produced by them, came the devastating plagues which ravaged the cities of Italy at the end of the fourteenth century, and the almost equal scourge of mercenary soldiers and private bands of foreign adventurers, who roamed through the rich, ill-governed towns and villages fighting for one family or{35} another, or else engaged in pillaging upon their own account.[15]

In all these quarrels, in all this turmoil and confusion, whichever party happened to be uppermost, the person to appeal to was the Pope, and endless were the messages sent down from Rome. At last, in 1392, both sides seemed to have wearied for the moment of the incessant strife (the nobles at this time were masters of the city, the Raspanti were away in exile), and when the Pope, Boniface IX., appeared in person, he was received with enthusiasm. We hear that the Priori and the treasurers of the city robed themselves in beautiful new scarlet mantles, the “companies” of the different gates danced through the streets with unmitigated joy, and the people went forth in crowds to meet him. But the breach between the factions was too wide, the situation too complicated for a Pope, who arrived merely in the character of a peacemaker, to grapple with successfully. The presence of Boniface brought no peace, and he retired into the monastery of S. Pietro, which he hastily converted into a fortress, demolishing its tower in his eagerness to secure his own personal safety; and there, as he nervously wondered what next he had better do, he heard the cries of “Down with the Raspanti!” answered by “Death to the nobles!” borne in upon the breeze.

Finally, in a manner peculiar to the Perugians, they met together in council to dictate the action of the person they had called in to act for them, and it was settled that the Pope should have full power as arbitrator of peace between themselves and the Raspanti. The Pope did exactly as he was asked. He recalled the Raspanti, and they entered the city on the 17th{36} October 1393, not merely as a body, but headed by a powerful personality—Biordo Michelotti, one of Perugia’s greatest citizens, and the first of the condottieri who ever got rule in the city.

Exiled in early youth from his native town, Biordo Michelotti had chosen the career of a condottiere, and roamed through the length and breadth of Italy, fighting the battles of different princes. Some say he had fought for the French king against the English. He was essentially a captain of adventure. His manner was kindly, he was brave, honest, frank, and popular among the people wherever he happened to go. Beloved all over Umbria, many of the towns which directly opposed Perugia’s tyrannical rule had submitted to that of Biordo. All these successes did not, however, satisfy the man in him, for the ruling ambition of his life was to get the dominion over his native city, and events were now combining to procure for him his heart’s desire. The Raspanti rallied round him in their exile, and he became their leader, and the champion of their liberty. The nobles, seeing the power of his popularity, offered him bribes to keep out of their way. But Biordo lay low in his fortress at Deruta, and when the Pope’s offers of peace arrived he hailed them with delight. A month later he entered Perugia at the head of about 2000 Raspanti, who had been exiled from their homes for years. They at once visited the Pope in token of homage and gratitude, and their new lease of power within the city was opened by the re-election of the priors, who were chosen half from the burgher faction and half from the nobility. By this means it was hoped that a lasting reconciliation might be made and an evenly balanced government established. Yet such seemed impossible. Peace endured for the space of one short month, and at the very first opportunity{37}—on the occasion of Biordo’s absence from the city—the smouldering fires of party feuds burst out in flames as rampant as before. One of the Raspanti was murdered by the nobles, and, just as the Podestà was preparing to pass sentence on the assassin, Pandolfo dei Baglioni, “that Perugian Satan,” as Bonazzi calls him, interfered on behalf of the criminal.[16] Whereupon the Raspanti vowed vengeance, assassinated Pandolfo and Pellini Baglioni on their own threshold, and murdered sixty of their clan. The Ranieri, another noble family, with their friends, took refuge in the strong Ranieri tower, where they were forced to go without food for three days. At last the people dragged them before the Podestà, but as he refused to execute them, the unhappy noblemen were conveyed back to their tower, where they were finally butchered, and their bodies thrown out of the windows.

Horrified by these fresh atrocities, and again in search of peace, the Pope loaded his mules and retired with his Cardinals to Assisi. The tumults were just subsiding when Biordo Michelotti returned, and this time he took absolute possession of the city. He met with no sort of opposition. The ring-leader of the nobles, Pandolfo Baglioni, was dead, and the Pope for the minute encouraged the attempt towards peace. Biordo used his power well, and every year his fame and honours increased. To the delight of the Perugians, he succeeded to the command of Sir John Hawkwood over the Florentine forces, and everywhere he pushed the interests of the town, wisely concluding a treaty with Gian Galeazzo Visconti, the powerful lord of Milan (1395).

The Pope, in the meantime, began to regret the encouragement he had given to this very popular hero.{38} His jealousy was roused, and he hired a condottiere for a month, in order to fight the Perugians. The hostilities, however, ended with the month, and nothing was accomplished beyond a demonstration of the Pontiff’s jealousy. But there was someone else beside the Pope who witnessed the honours paid to Biordo with a jealous hatred, and this was the Abbot of S. Pietro. “The wicked Abbot,” as the people called him, belonged to the noble family of the Guidalotti, and he probably felt that the power of his family was too much overshadowed by Michelotti. He had fresh cause to murmur, therefore, when Biordo married Bertolda Orsini of Rome, and the Lords of Urbino, Camerino, San Severo, Gubbio, and other towns came up to offer the happy pair rich presents, and to wish the bride-groom well. Biordo’s marriage was a splendid pageant. The city decked herself magnificently to do him honour, and all the people of the country round sent offerings of grain, and wine, and eggs, and cheese, everything which their small farms produced, to show their leader how they loved him.

The Abbot sat at his window, and with no kindly eye he watched the entry of the young bride, close by the monastery walls. Madonna Contessa Orsini came in escorted by the Florentine and Venetian ambassadors. Her dress was made of cloth of gold, she wore a garland of wild asparagus around her head, and jewels sparkled in her hair. The Abbot noted all these things, he saw the women of Perugia running out to meet her, he saw them throw flowers in her path, and then he returned to his cell to brood upon his horrid plans of vengeance. For he had determined to place the town once more beneath the sway of the Church, and in this way to gain for himself a Cardinal’s hat,{39} as it was probably the Pope himself who urged him to the deed.

On Sunday, in the month of March 1398, while the citizens were attending a sermon at S. Lorenzo, the Abbot arrived on horseback at the Guidalotti palace on Colle Landone, to collect his fellow-conspirators, and some twenty of them proceeded to Biordo’s house on Porta Sole. Word was sent up to Michelotti that there was important news for him, and he, suspecting nothing, hurried down to meet the Abbot with a courteous greeting. The Abbot stepped forward, took his hand, and kissed Biordo, at which sign the rest of the conspirators fell upon their victim and stabbed him with their poisoned daggers, hitting him such grievous blows that soon he lay weltering in a pool of blood. The conspirators had first intended openly to announce the deed in the piazza, but their courage failed them{40} and the Abbot merely muttered the news to the passers-by as he slunk away to S. Pietro with a few companions. Two of the braver of the assassins, however, stayed behind and, coming into the piazza, cried: “We have slain the tyrant.” The citizens, who were at mass, rose with one accord from their devotions, to avenge the death of their beloved leader, and leaving the preacher to continue his sermon to an empty church, they hurried to arms. The Abbot meanwhile hastened from his monastery at S. Pietro to a still safer refuge at Casalina. As he fled he looked back upon the city whose hero he had murdered, and he saw the flames and smoke break out from the palace of those same Guidalotti he had hoped to benefit, whilst the news of the death of his old father and many of his family in the carnage of that day was brought to him as a sorry consolation for his crime.

Biordo’s blood was gathered together by the citizens and put into a little silver basin, and above it they placed the banner of Perugia with the white griffin upon a crimson field; and as one chronicler informs us, a heart of stone must have melted at the sight of it.

Thus perished the first of that extraordinary series of men who took upon themselves the terrible task of governing single-handed the city of Perugia. Nearly all died by violence, but the violence done to Biordo was a cruel wrong. A short interval follows, and then the greatest name, perhaps, of all the city’s chronicles comes up upon the scene, namely, that of Braccio Fortebraccio di Montone.

The Perugians suspected the ungracious part that the Pope had played in the murder of their leader, and the suspicion made them restless and dissatisfied. It was probably owing to this that they fell a prey to the cunning wiles of the Duke of Milan.{41}

Gian Galeazzo had ingratiated himself with the citizens some time previously by giving them grain during a time of famine, and he now came forward to reap the benefit of his charity by getting himself accepted as Lord of Perugia, which would facilitate his designs on Tuscany. Perugia’s connection with Milan, however, only lasted four years. On Gian Galeazzo’s death, in 1402, the Duchess of Milan made peace with Boniface IX., and restored Bologna, Perugia, and Assisi to the Church. The Perugians submitted to the Pope (they seem not to have been consulted in the matter of the donation), but with the strict understanding that the exiled nobles should keep at least twenty miles distant from the city. Boniface agreed to this arrangement. Other popes before him had tried to patch up peace between the parties, but he had not the courage to attempt such difficult experiments. It remained for Braccio Fortebraccio to tear through the tangled network of Perugian politics, to unite within himself the powers of both parties, and as the city’s despot to raise it to “unprecedented glory.”

Braccio Fortebraccio was born at Montone in 1368. He was the son of Oddo Fortebraccio, Lord of Montone, and of Jacoma Montemelini, his wife, of a noble Perugian family. During his youth the Raspanti were dominant in the city, and the boy grew up as an exile. He had only his sword and an immense ambition with which to force his way to future power. It was at that time the fashion for young noblemen to win fame for themselves by the life or trade of the condottieri. Braccio therefore joined the famous Italian company of S. George, led by Alberigo di Barbiano, whose advent crushed the foreign captains of adventure whose lawless mercenaries had sent terror throughout the rich plains and villages of Italy during the fourteenth century.{42}

In the tents of Alberigo, Braccio di Montone and Sforza Attendolo[17] learned together the science of warfare. Thence they two went forth to fight the battles of princes, kings, and popes; to create two separate methods of combat, and to fill all Italy with tales of their great valour and their rivalry. Braccio’s ambition grew with his success, and he soon aspired to acquiring the whole of Italy. His first step towards this very large design was the capture of his native city of Perugia. But as he represented the party of the nobles, the Raspanti manfully resisted any efforts he made to approach them. “It is better even to submit to foreign rule than to make peace with the nobles,” they said; and thus it came about that they gave themselves over to Ladislaus, King of Naples, and remained for some six years in connection with the kingdom of Naples. When Ladislaus died in 1414, the Perugians were seized with terror, but the nobles saw their opportunity, and all things seemed to favour the scheme of Fortebraccio.

Braccio had joined the service of Pope John XXIII., and by him had been made governor of Bologna; but when the Pope was deposed by the Council of Constance, Braccio’s allegiance ended, and he at once sold the Bolognese their liberty, and with the 82,000 florins which he gained by this transaction he collected a strong army, the exiled nobles flocked to his standard, and they marched at once upon Perugia.

At the news of Braccio’s approach terror and consternation spread through the city. The gateways were built up, and the magistrates forbade anyone to leave the town. But the Perugians, “being the most warlike of the people of Italy,” as Sismondi says, could not resist so grand a chance of fighting, and seeing Braccio’s{43} men clustering around the city’s walls, they jumped down from the ramparts into their midst, and took the soldiers unawares by the suddenness of their attack. This was no real battle, but tumults of the sort were the order of the day. In the dead of night men would rush in panic into the piazza, not knowing what had brought them there, and only conscious of one fact: their desire to make a fierce stand for their liberty. Braccio made a fruitless effort to penetrate into the heart of the city, and was driven back ignominiously. The women threw down stones and boiling water on the assailants, whilst they goaded their own men to fight, crying aloud, “Now is your time to wound the enemy,—at him with your swords your teeth and nails!”