Maria Montessori

Title: Pedagogical Anthropology

Author: Maria Montessori

Translator: Frederic Taber Cooper

Release date: August 21, 2014 [eBook #46643]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Richard Tonsing, Alicia Williams, Brenda Lewis

and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

http://www.pgdp.net (This book was produced from scanned

images of public domain material from the Google Print

project.)

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

PEDAGOGICAL ANTHROPOLOGY

Maria Montessori

BY

MARIA MONTESSORI

Author of "The Montessori Method"

TRANSLATED FROM THE ITALIAN BY

FREDERIC TABER COOPER

WITH 163 ILLUSTRATIONS AND DIAGRAMS

NEW YORK

FREDERICK A. STOKES COMPANY

MCMXIII

Copyright, 1913, by

Frederick A. Stokes Company

All rights reserved, including that of translation into foreign languages, including the Scandinavian

July, 1913

THE·MAPLE·PRESS·YORK·PA·

TO MY MOTHER RENILDE STOPPANI AND MY FATHER ALESSANDRO MONTESSORI ON THE OCCASION OF THE FORTY-FIFTH ANNIVERSARY OF THEIR UNCLOUDED UNION, I DEDICATE THIS BOOK, FRUIT OF THE SPIRIT OF LOVE AND CONTENTMENT WITH WHICH THEY HAVE INSPIRED ME

For some time past much has been said in Italy regarding Pedagogical Anthropology; but I do not think that until now any attempt has been made to define a science corresponding to such a title; that is to say, a method that systematises the positive study of the pupil for pedagogic purposes and with a view to establishing philosophic principles of education.

As soon as anthropology annexes the adjective, "pedagogical," it should base its scope upon the fundamental conception of a possible amelioration of man, founded upon the positive knowledge of the laws of human life. In contrast to general anthropology which, starting from a basis of positive data founded on observation, mounts toward philosophic problems regarding the origin of man, pedagogic anthropology, starting from an analogous basis of observation and research, must rise to philosophic conceptions regarding the future destiny of man from the biological point of view. The study of congenital anomalies and of their biological and social origin, must undoubtedly form a part of pedagogical anthropology, in order to afford a positive basis for a universal human hygiene, whose sole field of action must be the school; but an even greater importance is assumed by the study of defects of growth in the normal man; because the battle against these evidently constitutes the practical avenue for a wide regeneration of mankind.

If in the future a scientific pedagogy is destined to rise, it will devote itself to the education of men already rendered physically better through the agency of the allied positive sciences, among which pedagogic anthropology holds first place.

The present-day importance assumed by all the sciences calculated to regenerate education and its environment, the school, has profound social roots and is forced upon us as the necessary path toward further progress; in fact the transformation of the outer environment through the mighty development of experimen[Pg viii]tal sciences during the past century, must result in a correspondingly transformed man; or else civilisation must come to a halt before the obstacle offered by a human race lacking in organic strength and character.

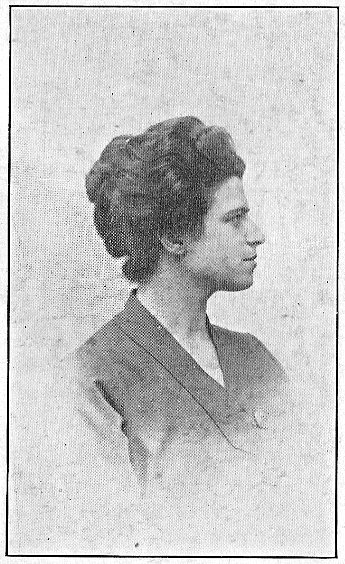

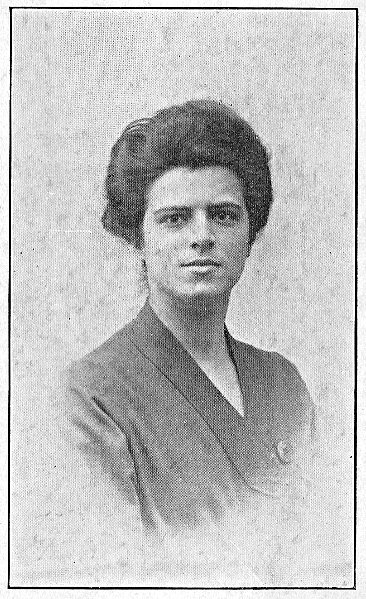

The present volume comprises the lectures given by me in the University of Rome, during a period of four years, all of which were diligently preserved by one of my students, Signor Franceschetti. My thanks are due to my master, Professor Giuseppe Sergi who, after having urged me to turn my anthropological studies in the direction of the school, recommended me as a specialist in the subject; and my free university course for students in the Faculty of Natural Sciences and Medicine was established, in pursuance of his advice, by the Pedagogic School of the University of Rome. The volume also contains the pictures used in the form of lantern slides to illustrate the lectures, pictures taken in part from various works of research mentioned in this volume. Acknowledgment is gratefully made to the scientists and scholars whose work is thus referred to.

I have divided my subject into ten chapters, according to a special system: namely, that each chapter is complete in itself—for example, the first chapter, which is very long, contains an outline of general biology, and at the same time biological and social generalisations concerning man considered from our point of view as educators, and thus furnishes a complete organic conception which the remainder of the book proceeds to analyse, one part at a time; the chapter on the pelvis, on the other hand, is exceedingly short, but it completely covers the principles relating to this particular part, because they lend themselves to such condensed treatment.

Far from assuming that I have written a definitive work, it is only at the request of my students and publisher that I have consented to the publication of these lectures, which represent a modest effort to justify the faith of the master who urged me to devote my services as a teacher to the advancement of the school.

Maria Montessori.

The figures in parenthesis refer to the number of the page)

INTRODUCTION

MODERN TENDENCIES OF ANTHROPOLOGY AND THEIR RELATION TO PEDAGOGY

The Old Anthropology(1)—Modern Anthropology(4)—De Giovanni and Physiological Anthropology(11)—Sergi and Pedagogic Anthropology(14)—Morselli and Scientific Philosophy(21)—Importance of Method in Experimental Sciences(23)—Objective Collecting of Single Facts(24)—Passage from Analysis to Synthesis (26)—Method to be followed in the present Course of Lectures(30)—Limits of Pedagogical Anthropology(34). The School as a Field of Research(37).

CHAPTER I

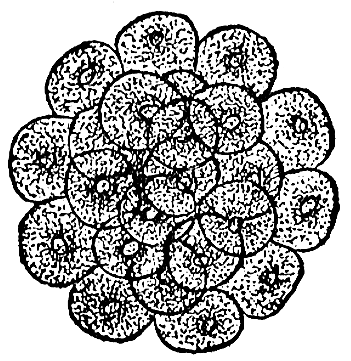

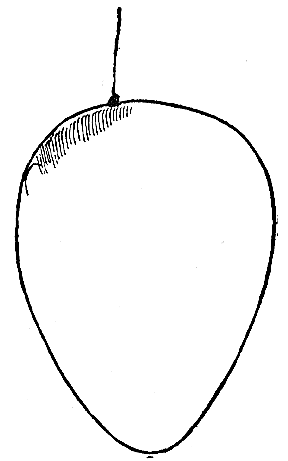

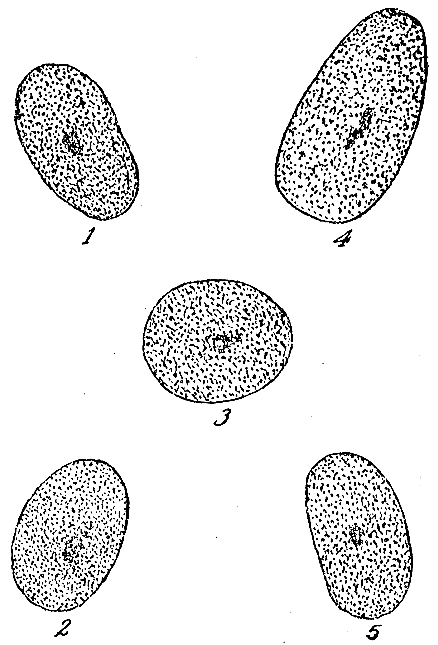

CERTAIN PRINCIPLES OF GENERAL BIOLOGY

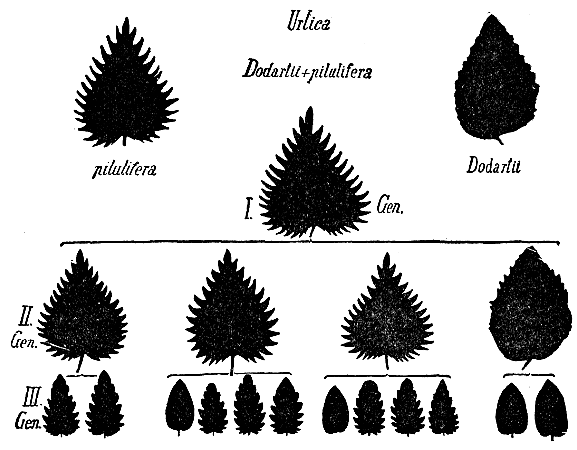

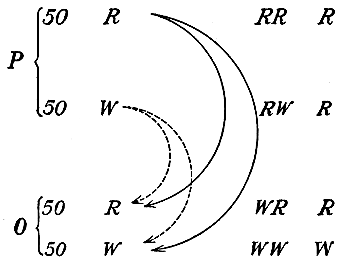

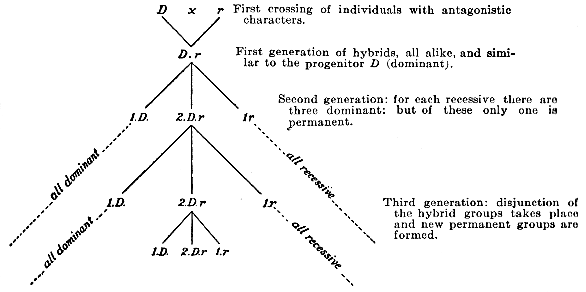

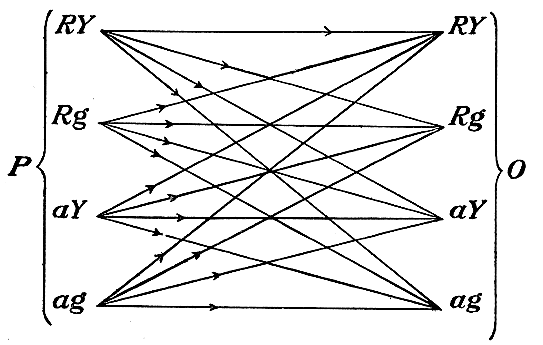

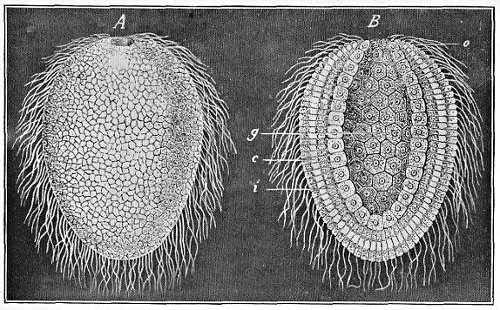

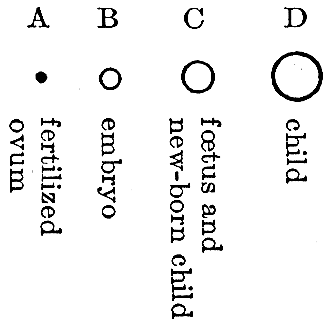

The Material Substratum of Life(38)—Synthetic Concept of the Individual in Biology(38)—Formation of Multicellular Organisms(42)—Theories of Evolution(46)—Phenomena of Heredity(50)—Phenomena of Hybridism(51)—Mendel's Laws(51).

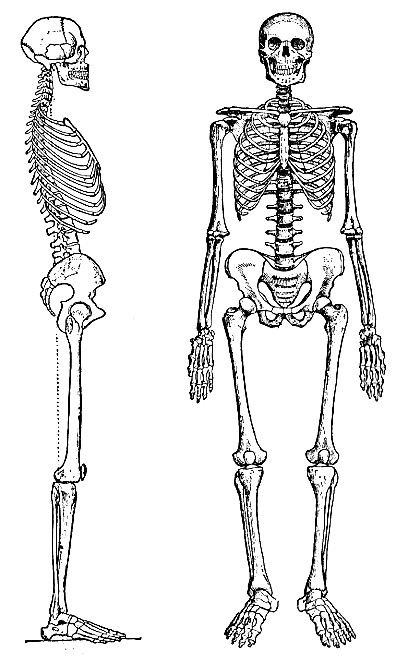

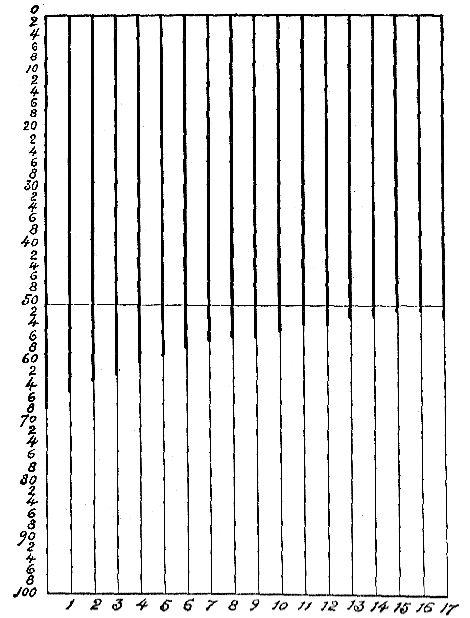

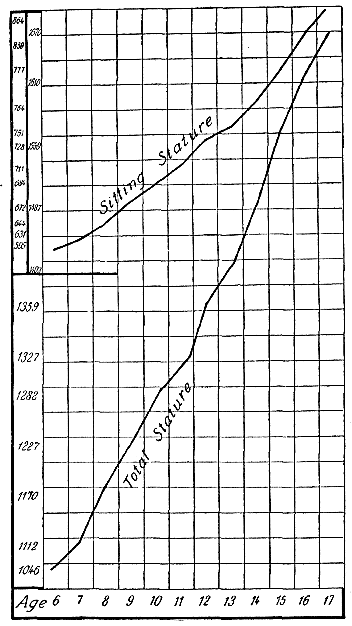

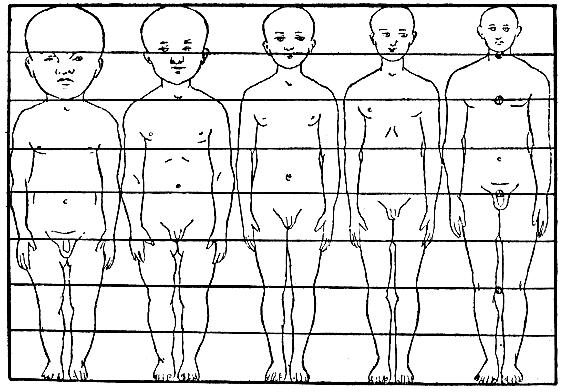

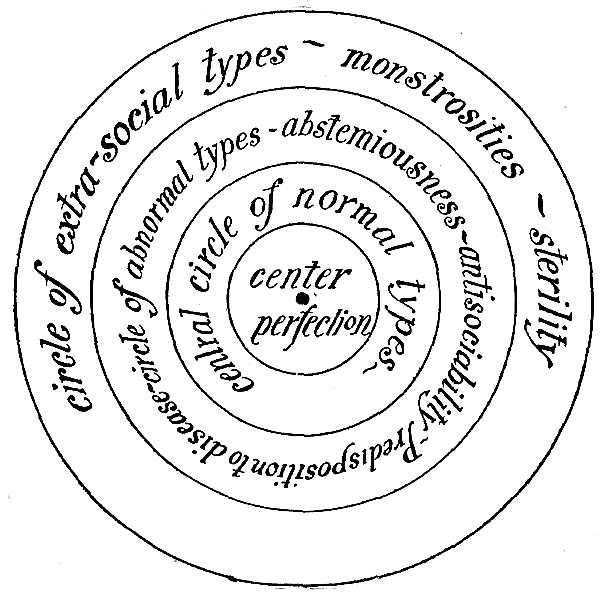

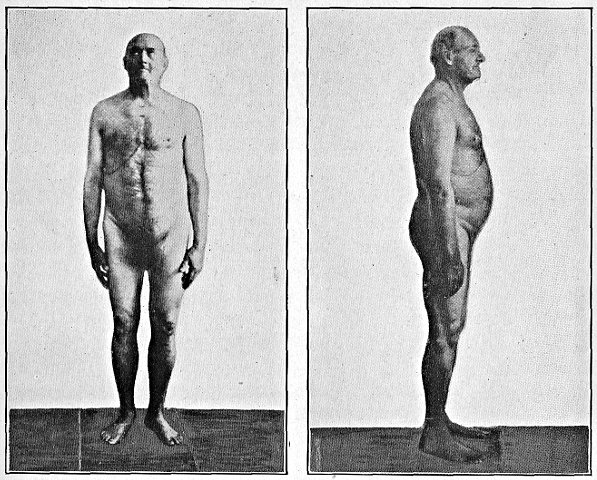

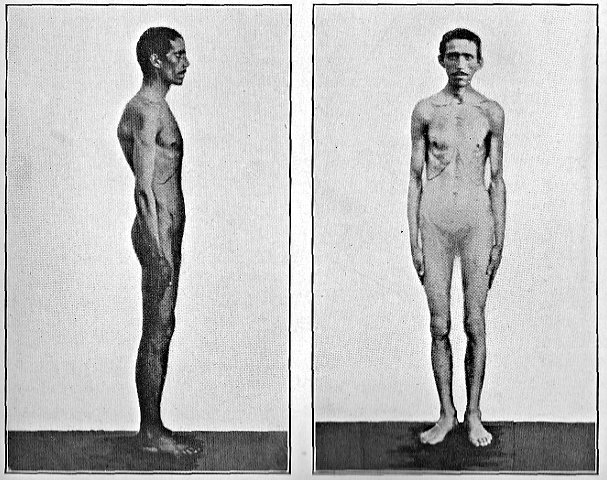

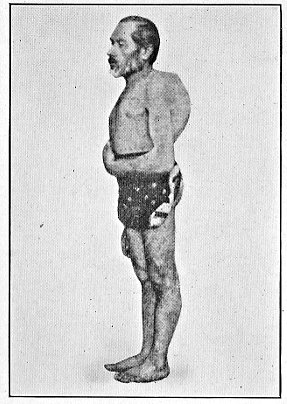

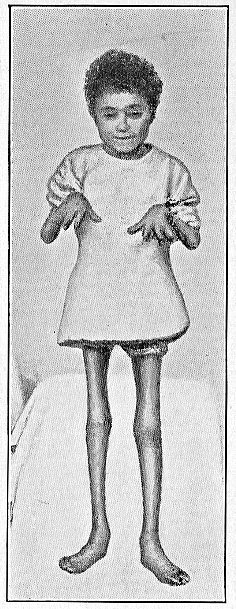

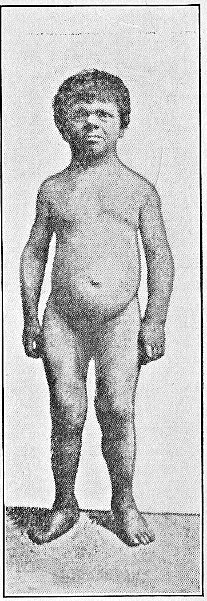

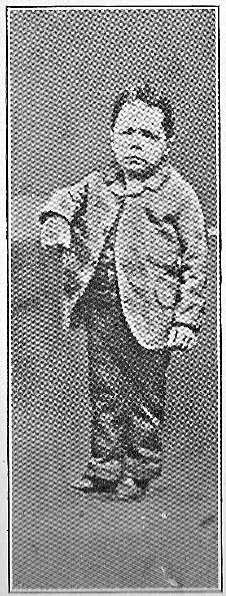

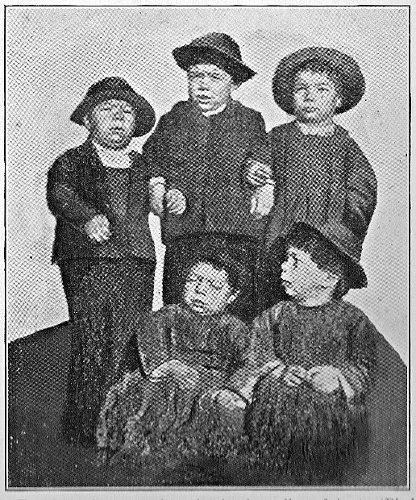

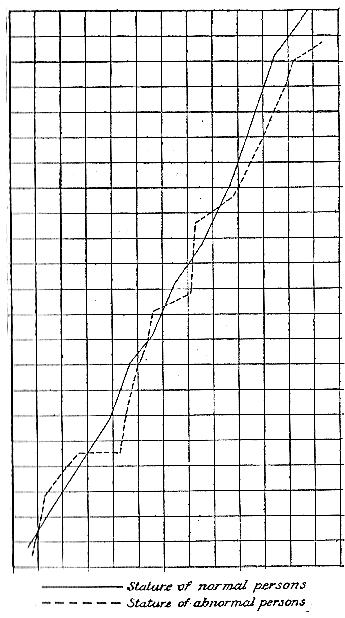

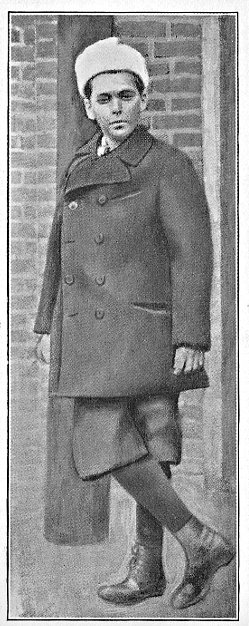

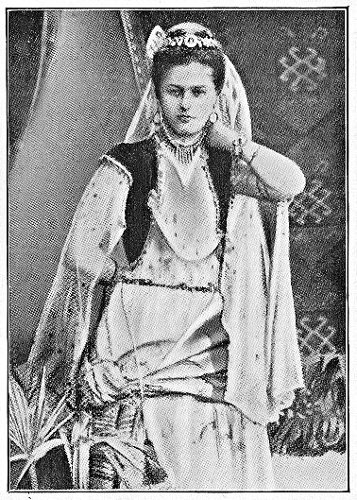

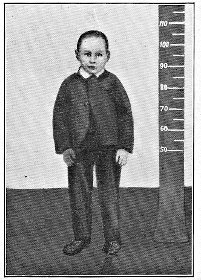

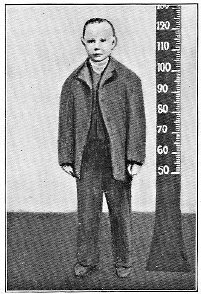

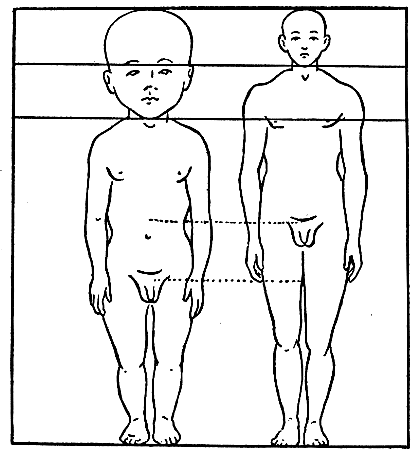

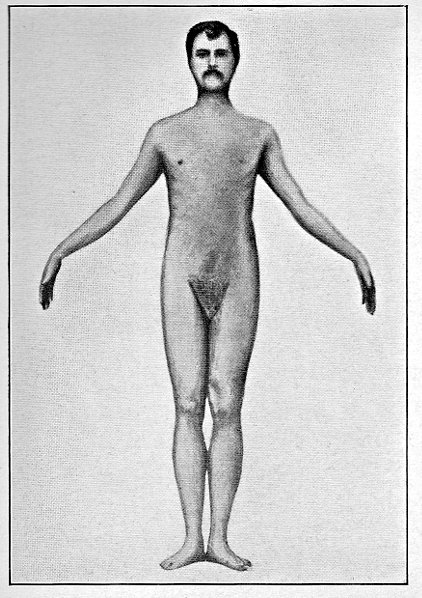

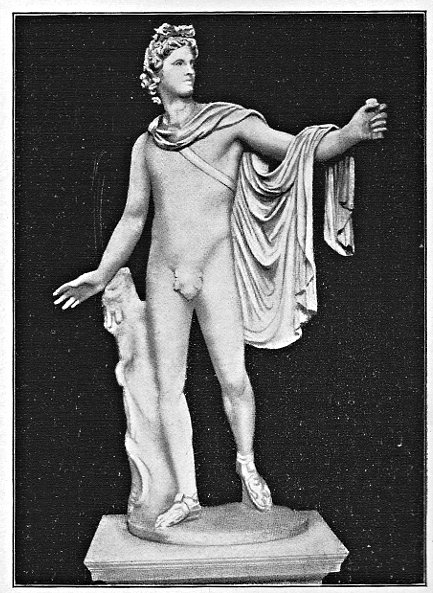

THE FORM AND TYPES OF STATURE

The Form(67)—Fundamental Canons regarding the Form(74)—Types of Stature, Macroscelia and Brachyscelia; their Physiological Significance(75)—Types of Stature in relation to Race(77), Sex(80), and Age(81)—Pedagogic Considerations(88)—Abnormal Types of Stature in their relation to Moral Training(91)—Macroscelia and Brachyscelia in Pathological Individuals (De Giovanni's Hyposthenic and Hypersthenic Types)(95)—Types of Stature in Emotional Criminals and in Parasites(101)—Extreme types of Stature among the Extra-social: Nanism and Gigantism(103)—Summary of Types of Stature(105).

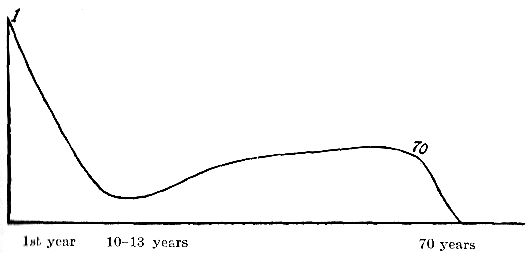

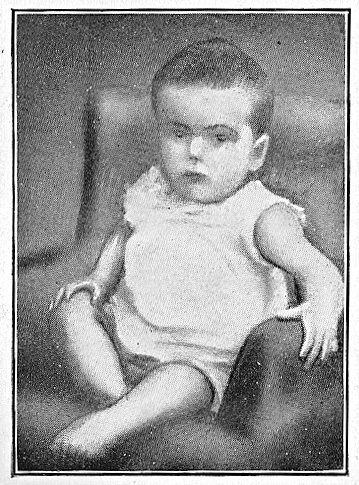

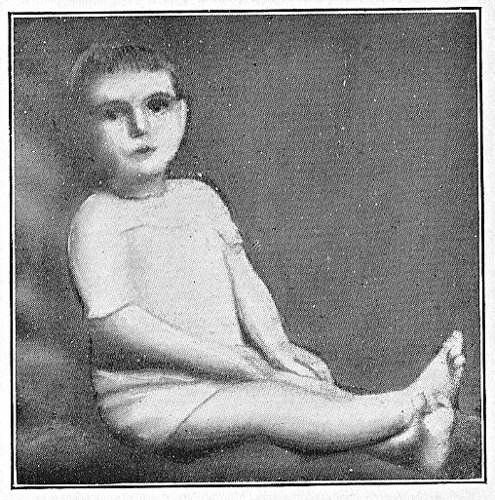

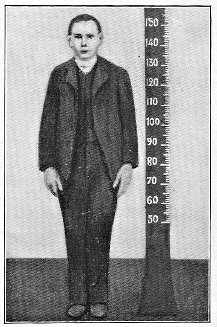

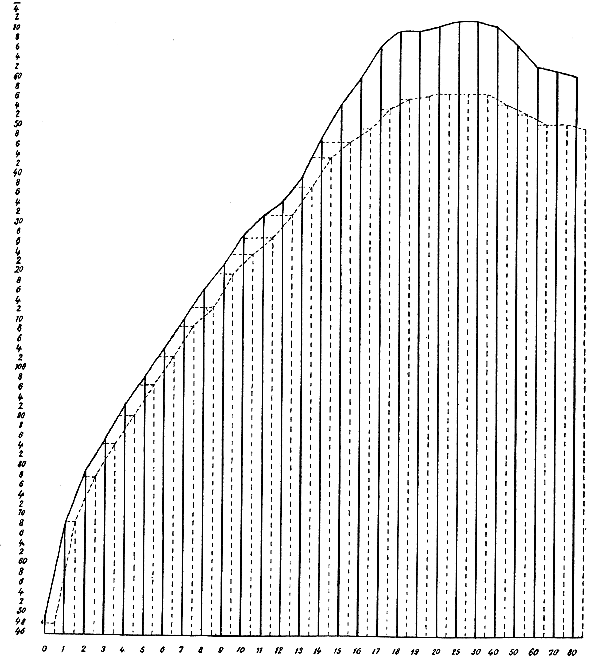

THE STATURE

The Stature as a Linear Index(106)—Limits of Stature according to Race(108)—Stature in relation to Sex(111)—Variations in Stature with Age, according to Sex(118)—Variations due to Mechanical Causes(119)—Variations due to Adaptation in connection with various Causes, Social, Physical, Psychic, Pathological, etc. (124)—Effect of Light, Heat, Electricity(132)—Variations in Growth according to the Season(138)—Pathogenesis of Infantilism(151)—Stature affected by Syphilis (157), Tuberculosis(158), Malaria(160), Pellagra(161), Rickets(164)—Moral and Pedagogical Considerations(168)—Summary of Stature(170).

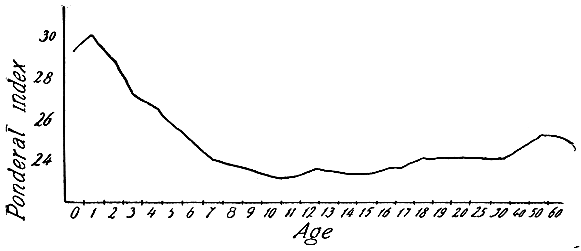

THE WEIGHT

The Weight considered as Total Measure of Mass(172)—Weight of Child at Birth (173)—Loss of Weight(176)—Specific Gravity of Body(178)—Index of Weight(181).

CHAPTER II

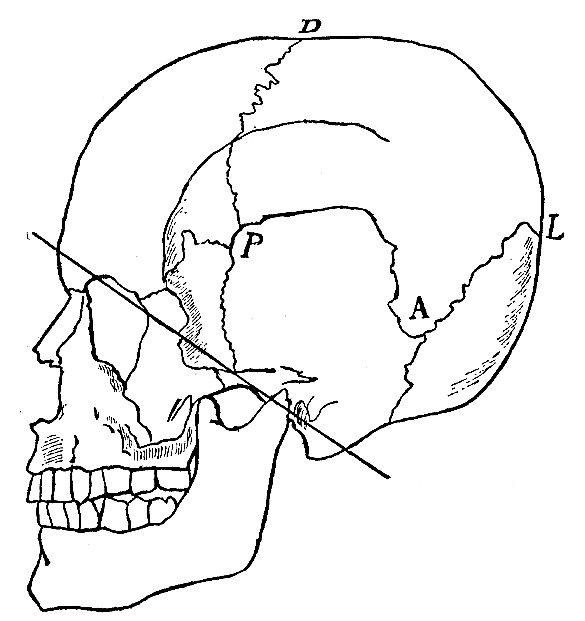

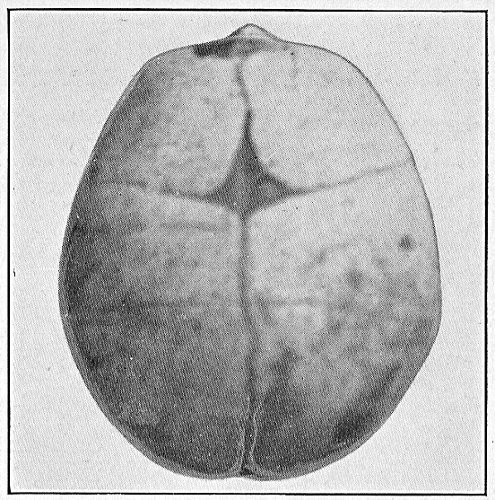

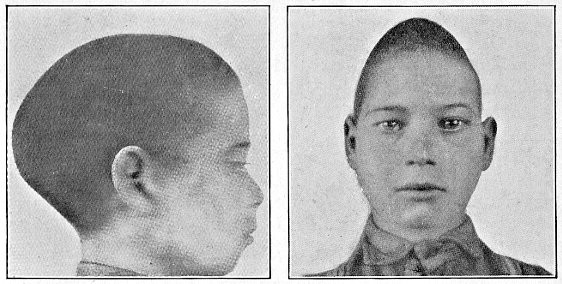

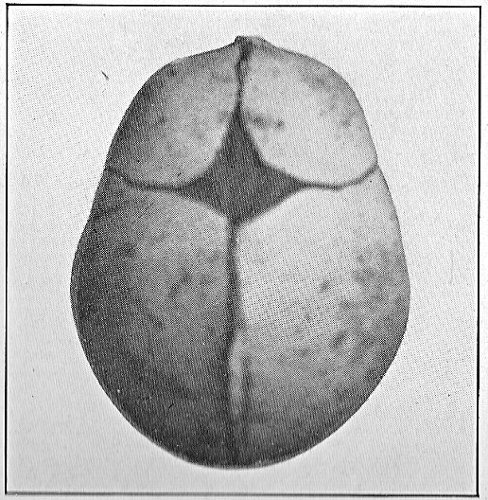

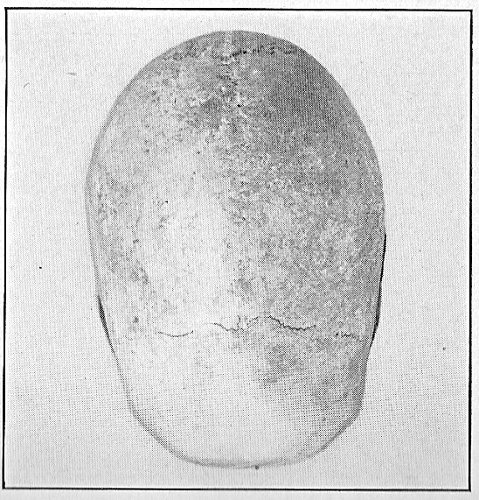

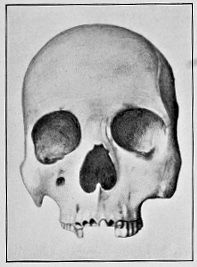

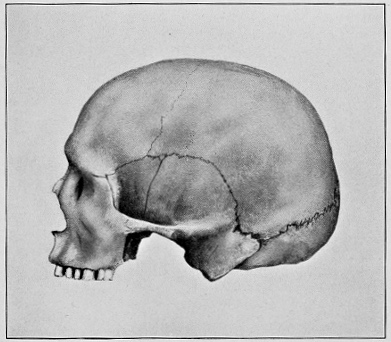

CRANIOLOGY

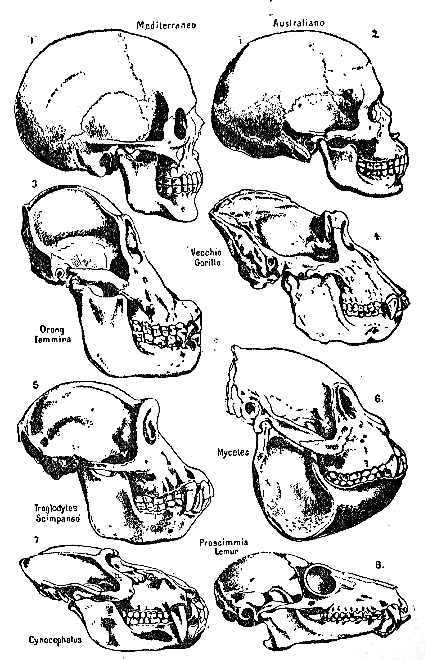

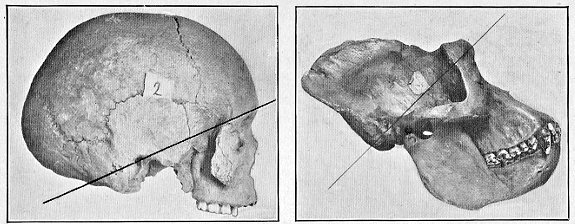

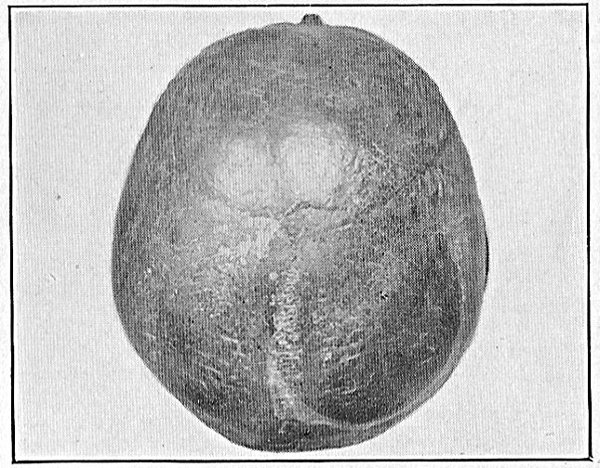

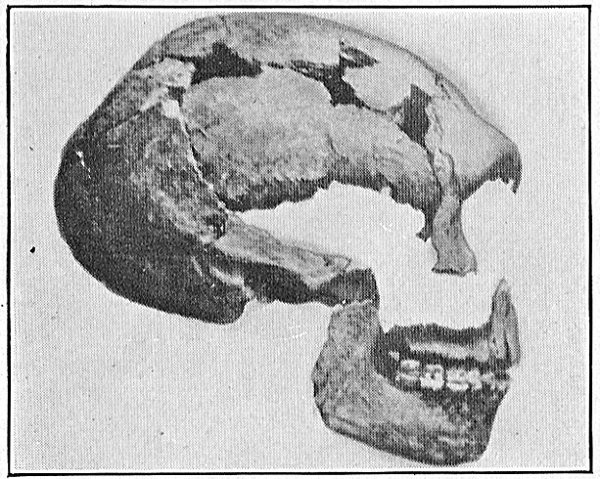

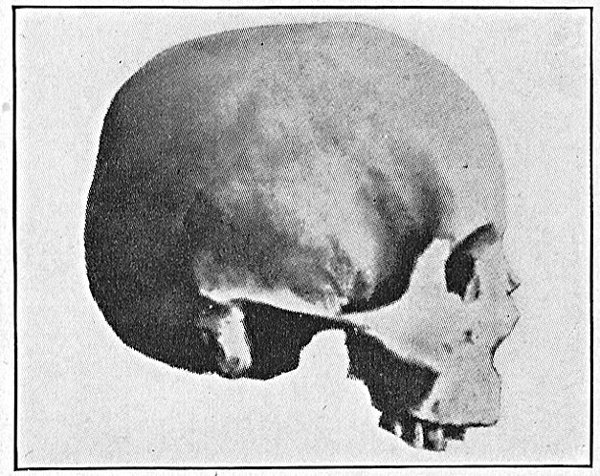

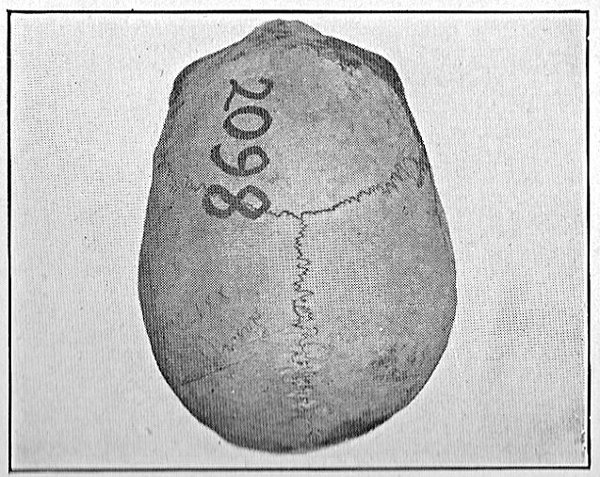

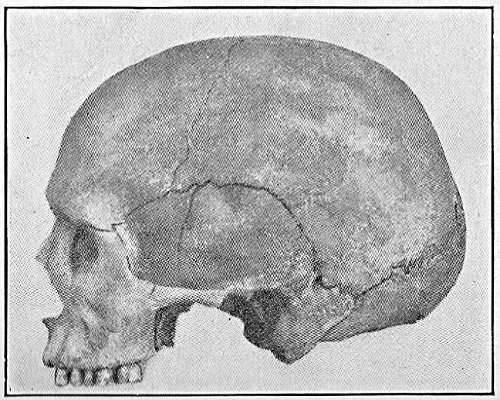

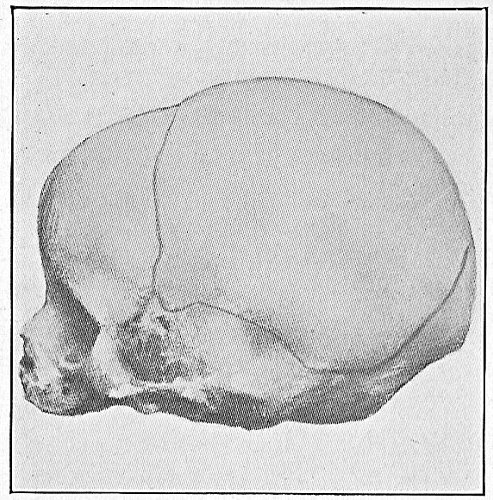

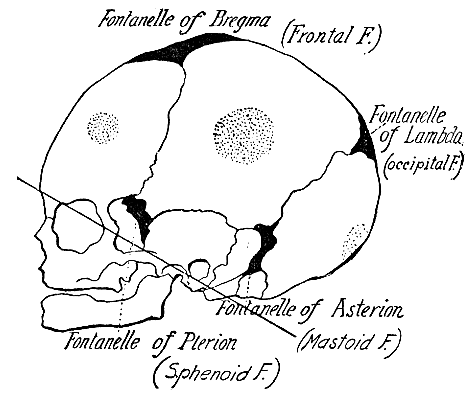

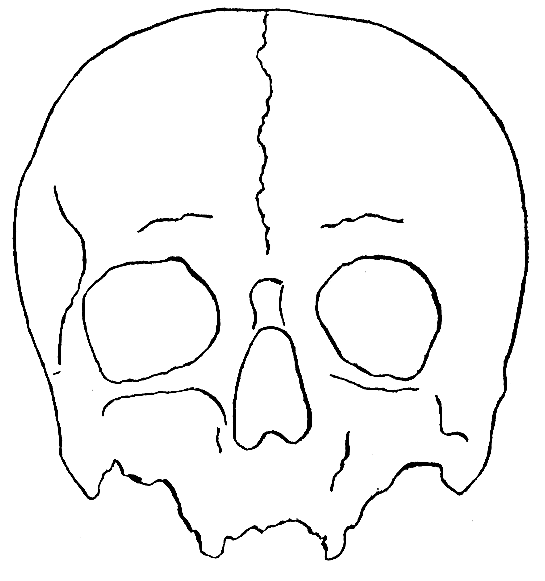

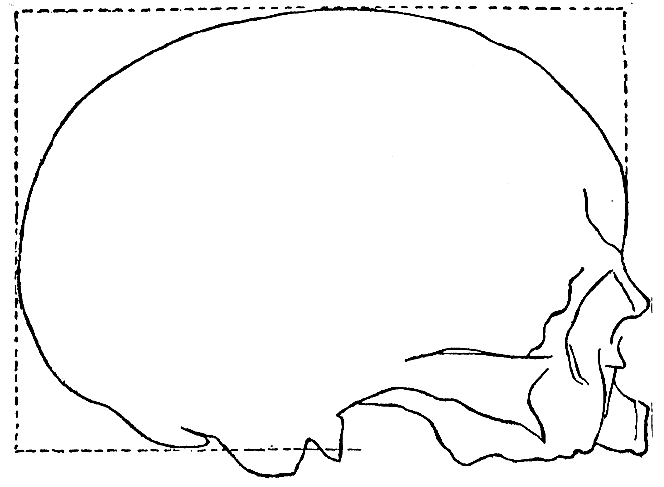

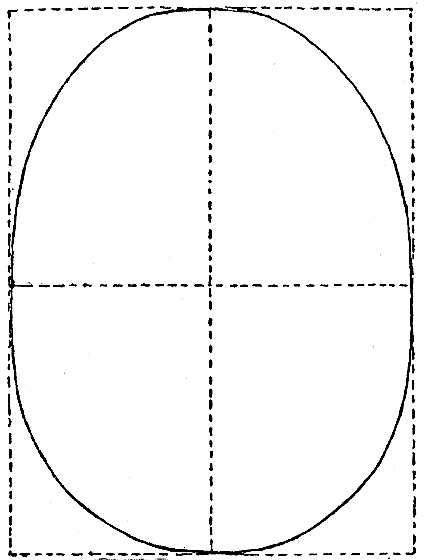

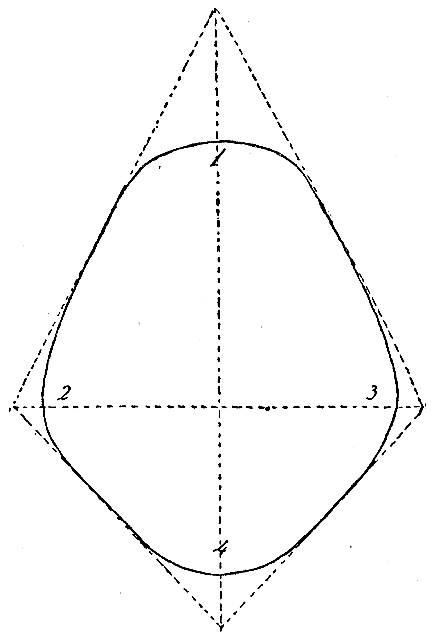

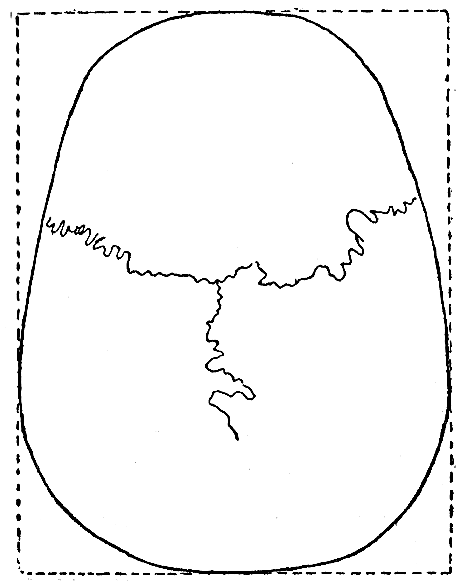

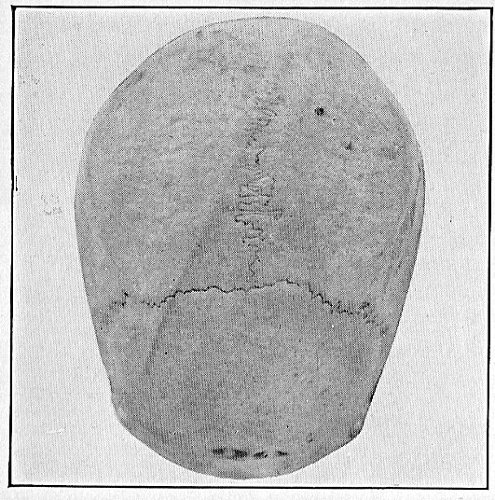

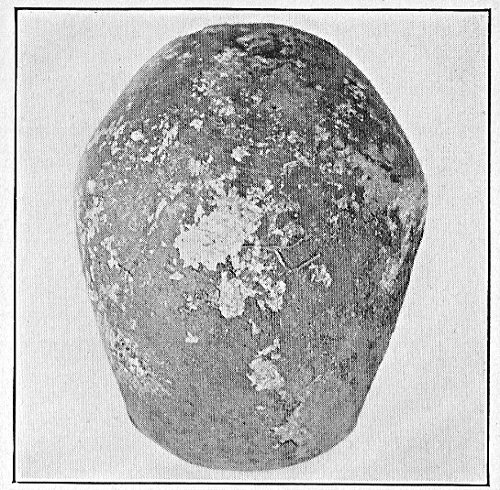

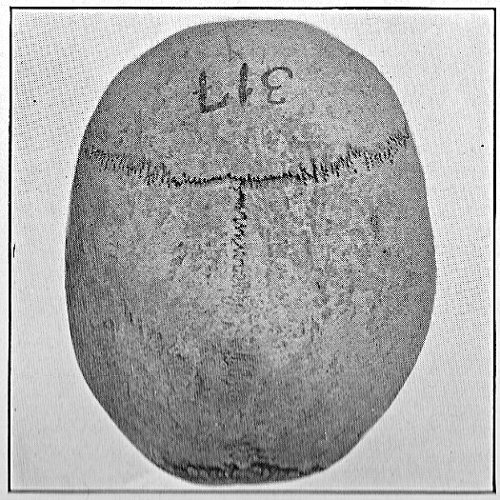

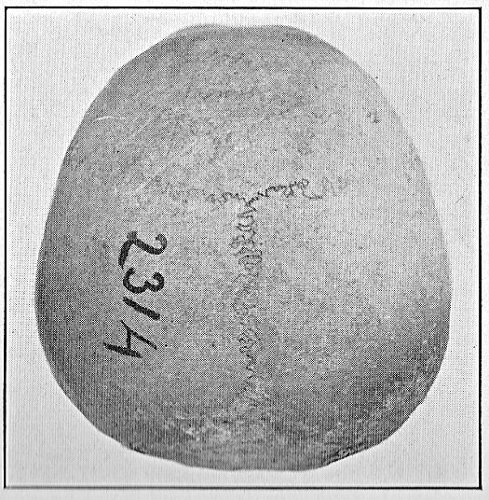

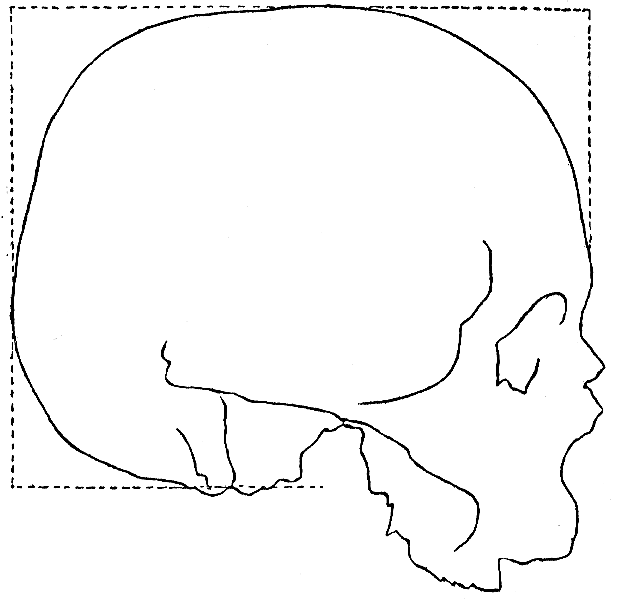

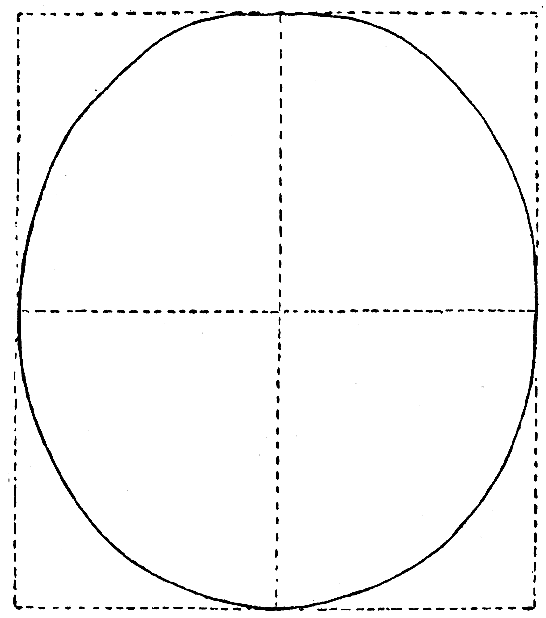

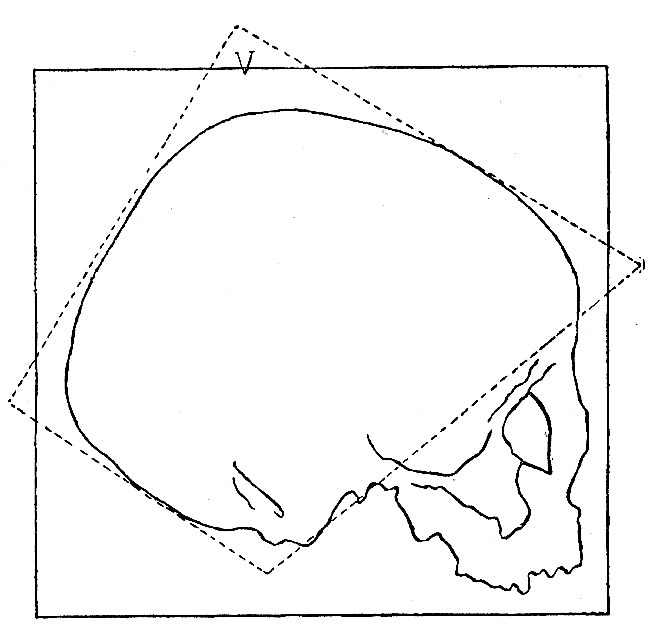

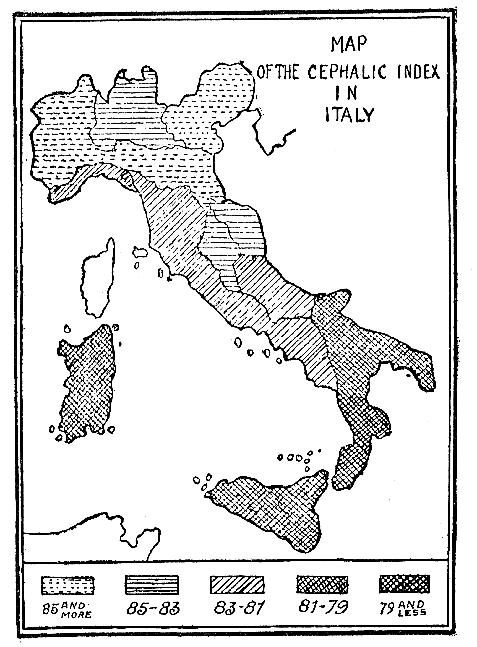

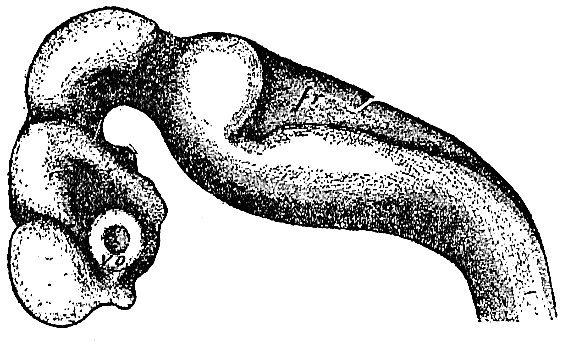

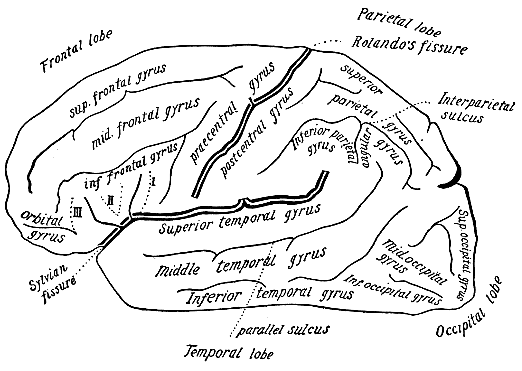

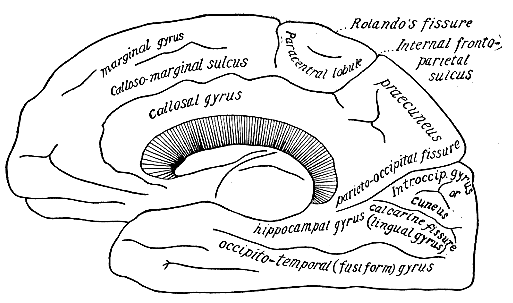

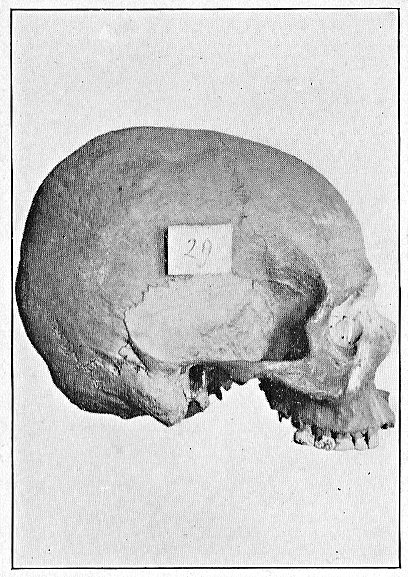

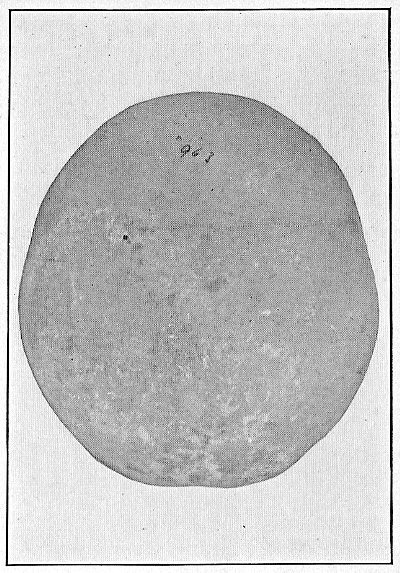

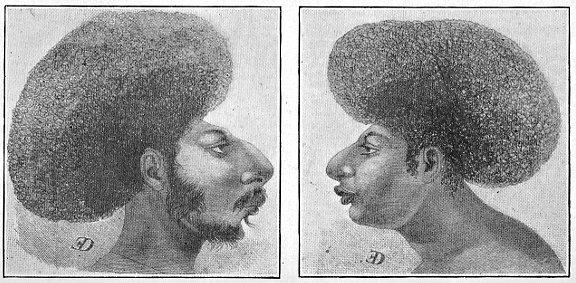

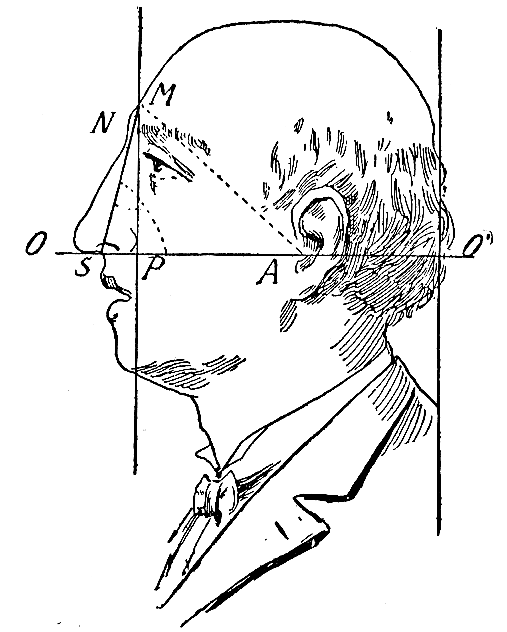

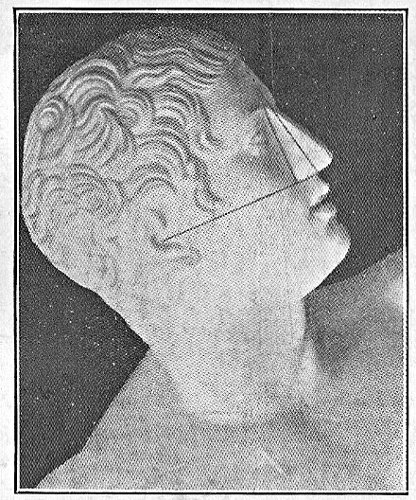

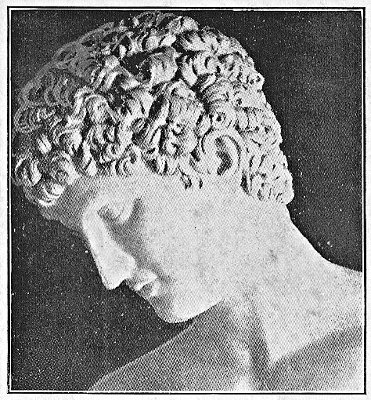

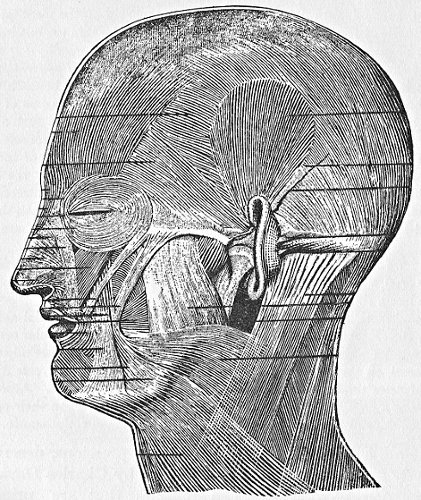

The Head and Cranium(187)—The Face(188)—Characteristics of the Human Cranium(191)—Evolution of the Forehead; Inferior Skull Caps; the Pithecanthropus; the Neanderthal Man(192)—Morphological Evolution of the Cranium through different Periods of Life(197)—Normal Forms of Cranium(202)—the Cephalic Index(207)—Volume of Cranium(220)—Development of Brain(220)—Extreme Variations in Volume of Brain(229)—Nomenclature of Cranial Capacity(242)—Chemistry of the Brain(247)—Human Intelligence(252)—Influence of Mental Exercise(254)—Pretended Cerebral Inferiority of Woman(256)—Limits of the Face(259)—Human Character of the Face(260)—Normal Visage(262)—Prognathism(268)—Evolution of the Face(272)—Facial Expression(276)—the Neck(282).

CHAPTER III

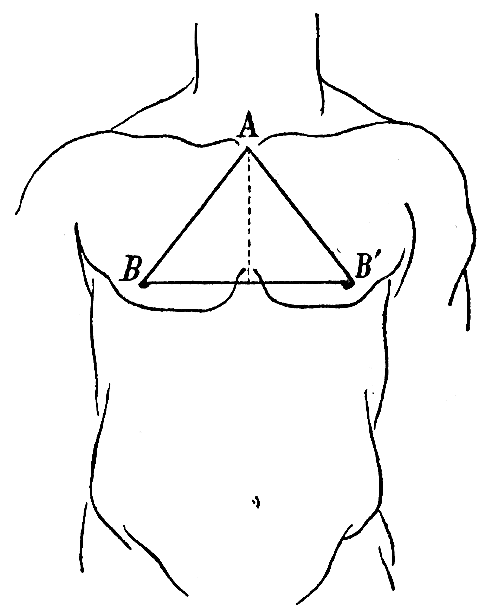

THE THORAX

Anatomical Parts of the Thorax(281)—Physiological and Hygienic Aspect of Thorax (286)—Spirometry(288)—Growth of Thorax(294)—Dimensions of Thorax in relation to Stature(295)—Thoracic Index(297)—Shape of Thorax(299)—Anomalies of Shape(301)—Pedagogical Considerations: the Evil of School Benches(302).

CHAPTER IV

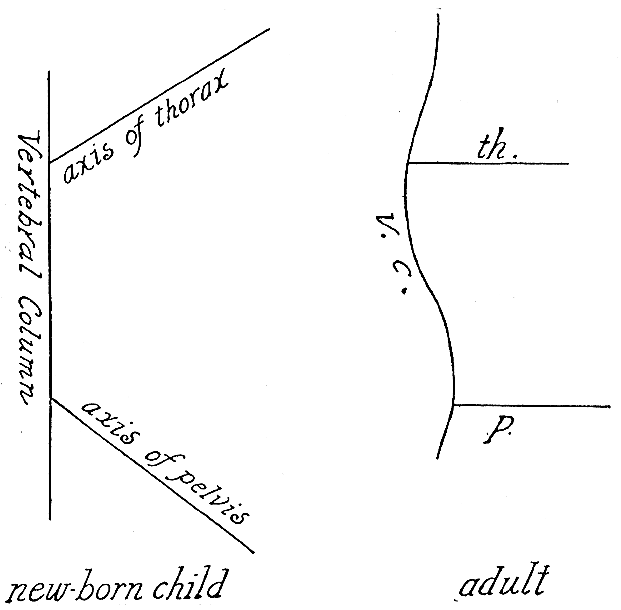

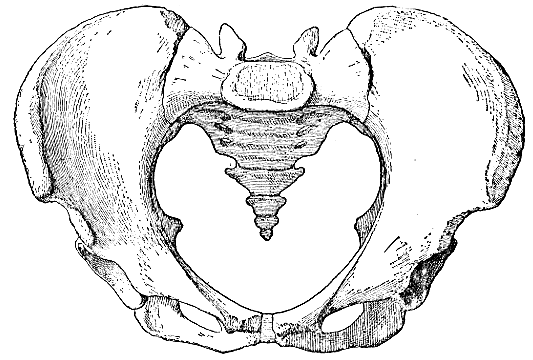

THE PELVIS

Anatomical Parts of the Pelvis(304)—Growth of Pelvis(306)—Shape of Pelvis in relation to Childbirth(307).

CHAPTER V

THE LIMBS

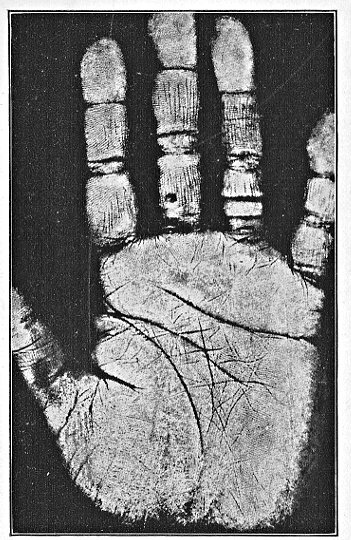

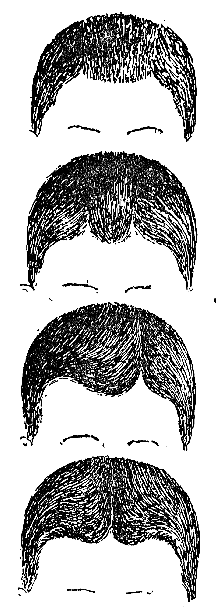

Anatomy of the Limbs(308)—Growth of Limbs(309)—Malformations: Flat-foot, Opposable Big Toe(311), Curvature of Leg, Club-foot(312)—The Hand(312)—Chiromancy and Physiognomy; the Hand in Figurative Speech; High and Low Types of Hand(312)—Dimensions of Hand(315)—Proportions of Fingers(316)—the Nails(317)—Anomalies of the Hand(317)—Lines of the Palm(318)—Papillary Lines(319).

CHAPTER VI

THE SKIN AND PIGMENTS

Pigmentation and Cutaneous Apparatus(320)—Pigmentation of the Hair(323)—of the Skin(325)—of the Iris(325)—Form of the Hair(327)—Anomalies of Pigment: Icthyosis, Birth-marks, Freckles, etc.(329)—Anomalies of Hair(330).

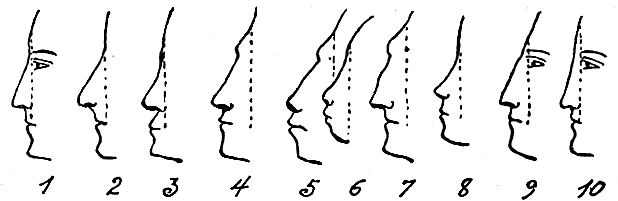

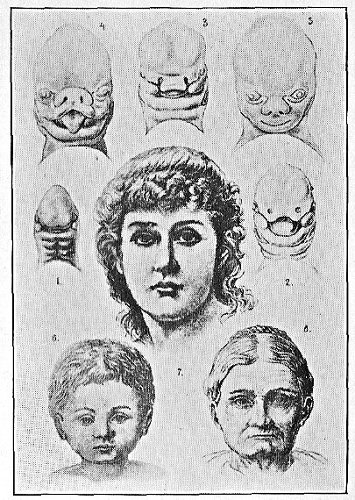

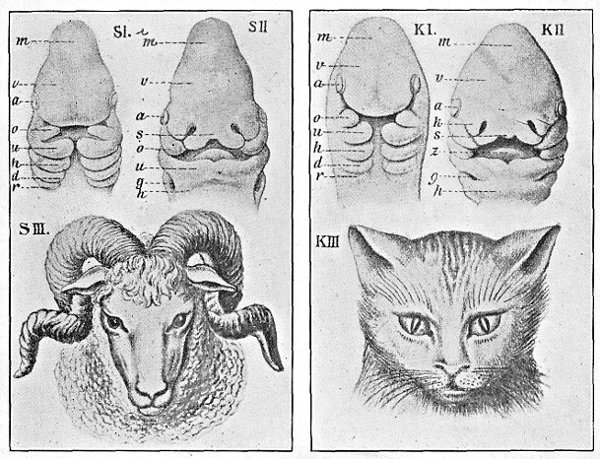

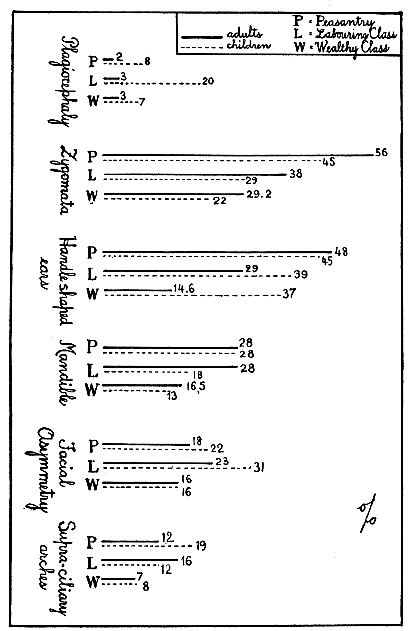

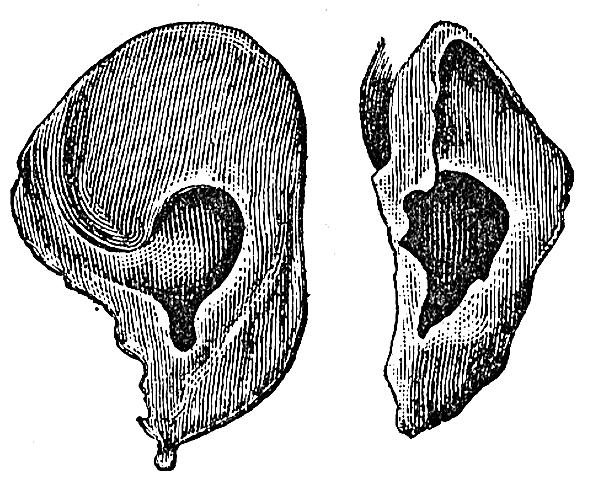

MORPHOLOGICAL ANALYSIS OF CERTAIN ORGANS (STIGMATA)

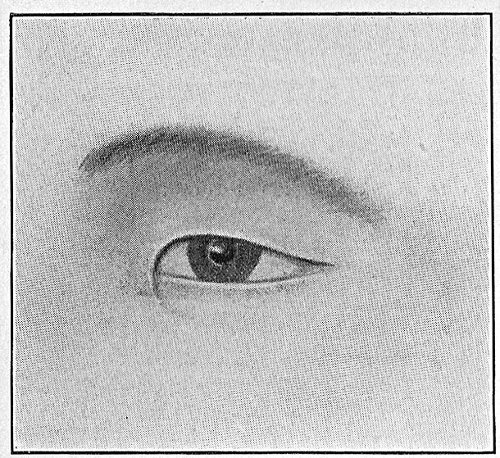

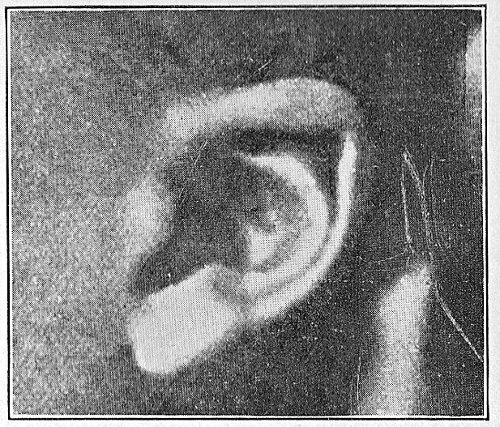

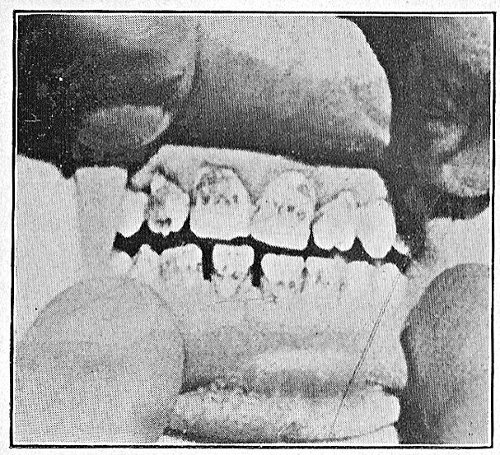

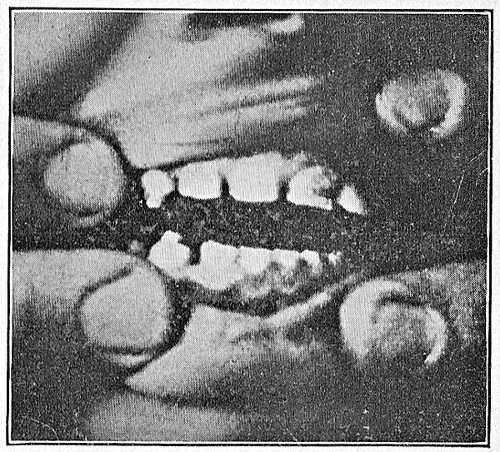

Synoptic Chart of Stigmata(332)—Anomalies of the Eye(333)—of the Ear(334)—of the Nose(335)—of the Teeth(336)—Importance of the Study of Morphology(338)—Significance of the Stigmata of Degeneration(342)—Distribution of Malformations(344)—Individual Number of Malformations(347)—Origin of Malformations(355)—Humanity's Dependence upon Woman(357)—Moral and Pedagogical Problems within the School(358).

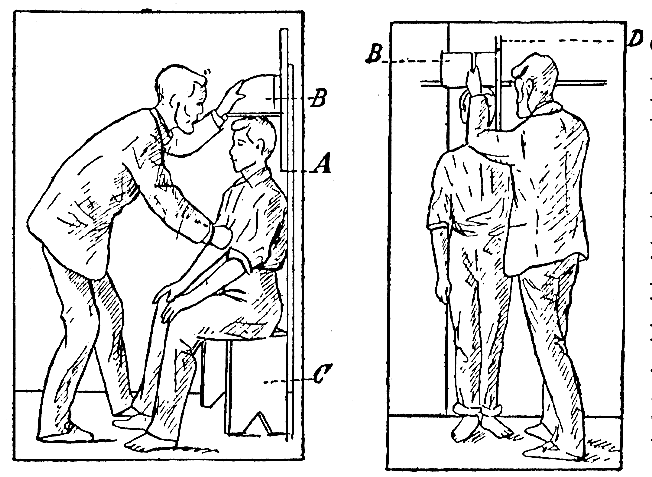

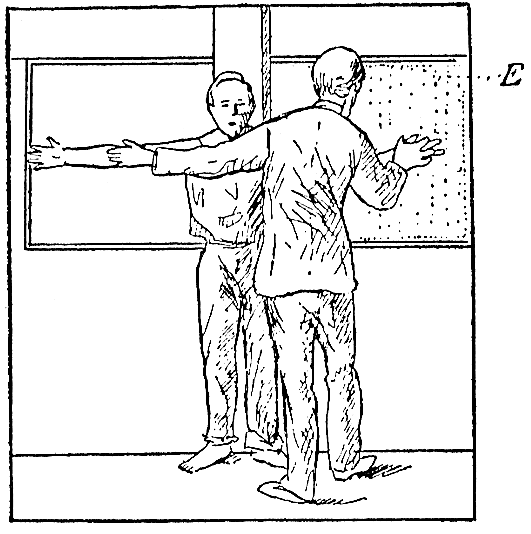

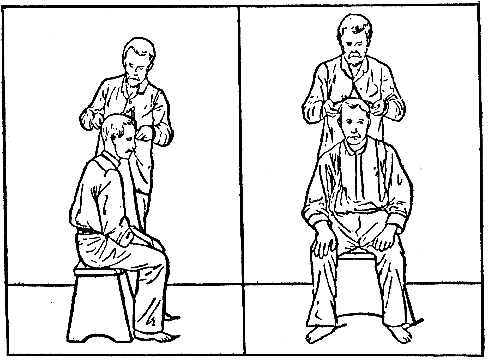

CHAPTER VII

TECHNICAL PART

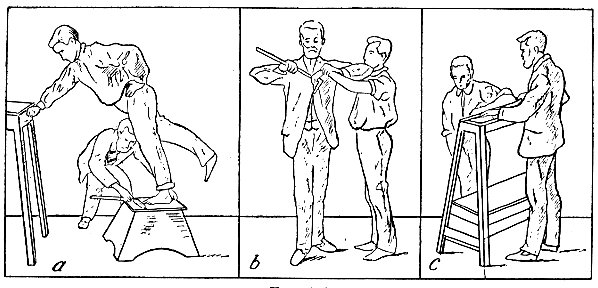

The Form(361)—Measurement of Stature(362)—the Anthropometer(363)—the Sitting Stature(365)—Total Spread of Arms(367)—Thoracic Perimeter(368)—Weight(368)—Ponderal Index(368)—Head and Cranium(369)—Cranioscopy (370)—Craniometry(373)—Cephalic Index(376)—Measurements of Thorax(385)—of Abdomen (386).

THE PERSONAL ERROR

Need of Practical Experience in Anthropology(387)—Average Personal Error(388)—Susceptibility to Suggestion(389).

CHAPTER VIII

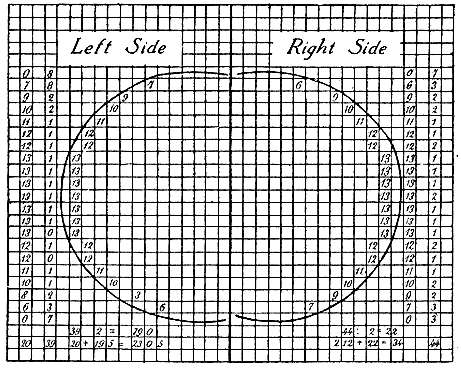

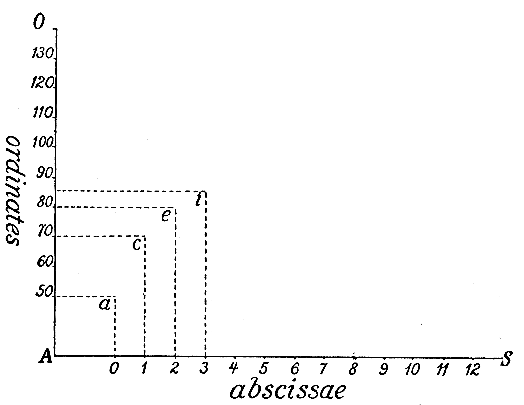

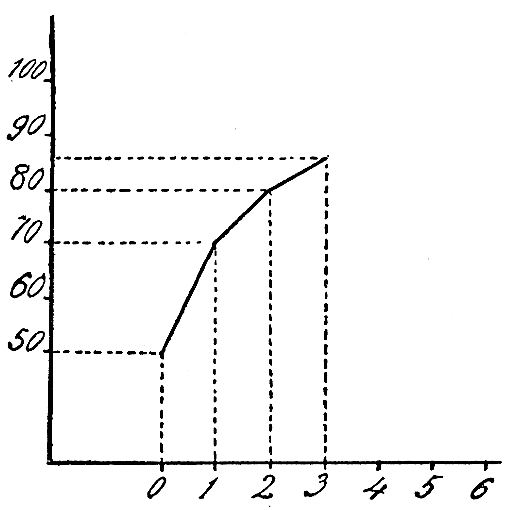

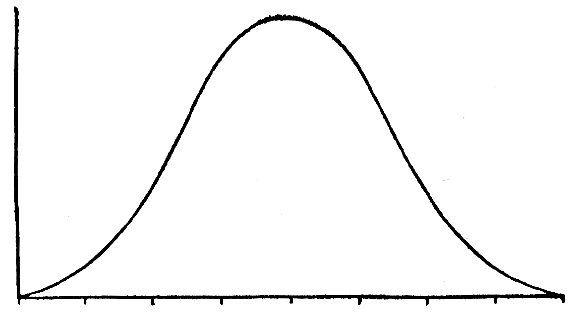

STATISTICAL METHODOLOGY

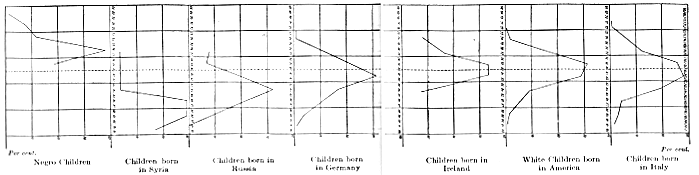

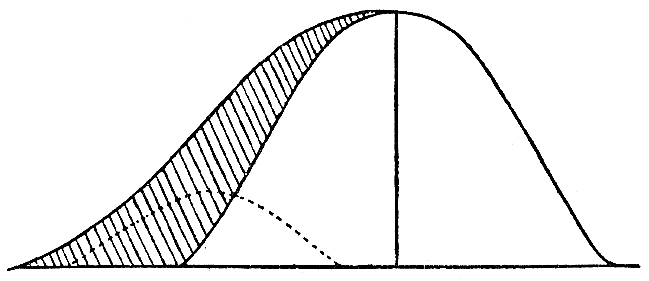

Mean Averages(391)—Seriation(396)—Quétélet's Binomial Curve(398).

CHAPTER IX

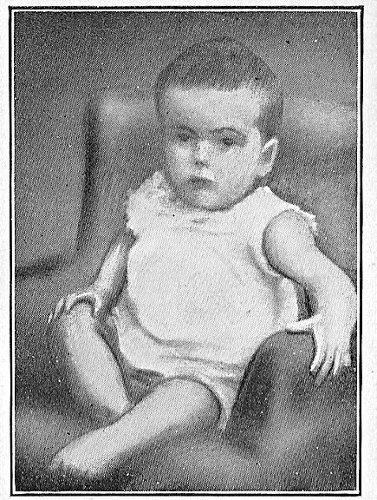

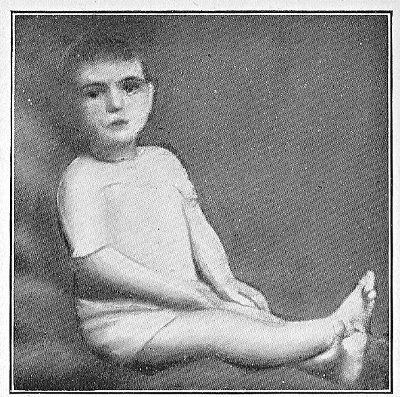

THE BIOGRAPHIC HISTORY OF THE PUPIL AND HIS ANTECEDENTS

Biographic Histories(404)—Remote Antecedents(406)—Near Biopathological Antecedents(407)—Sociological Antecedents(411)—School Records(411)—Biographic Charts(422)—Psychic Tests(425)—Typical Biographic History of an Idiot Boy(434)—Proper Treatment of Defective Pupils(446)—Rational Medico-pedagogical Method(448).

CHAPTER X

THE APPLICATION OF BIOMETRY TO ANTHROPOLOGY FOR THE PURPOSE OF DETERMINING THE MEDIAL MAN

Theory of the Medial Man(454)—Importance of Seriation(455)—De Helguero's Curves(460)—Viola's Medial Man(463)—Human Hybridism(466)—the Medial Intellectual and Moral Man(469)—Sexual Morality(473)—Sacredness of Maternity(474)—Biological Liberty and the New Pedagogy(477).

Table of Mean Proportions of the Body According to Age(480).

Tables for Calculating the Cephalic Index(485).

Tables for Calculating the Ponderal Index(491).

General Index:

A. Index of Names(501).

B. Index of Subjects(503).

The Old Anthropology.—Anthropology was defined by Broca as "the natural history of man," and was intended to be the application of the "zoological method" to the study of the human species.

As a matter of fact, as with all positive sciences, the essential characteristic of Anthropology is its "method." We could not say, if we wished to speak quite accurately, that "Anthropology is the study of man"; because the greater part of acquirable knowledge has for its subject the human race or the individual human being; philosophy studies his origin, his essential nature, his characteristics; linguistics, history and representative art investigate the collective phenomena of physiological and social orders, or determine the morphological characteristics of the idealised human body.

Accordingly, what characterises Anthropology is not its subject: man; but rather the method by which it proposes to study him.

The selfsame procedure which zoology, a branch of the natural sciences, applies to the study of animals, anthropology must apply to the study of man; and by doing so it enrolls itself as a science in the field of nature.

Zoology has a well-defined point of departure, that clearly distinguishes it from the other allied sciences: it studies the living animal. Consequently, it is an eminently synthetic science, because it cannot proceed apart from the individual, which represents in itself a sum of complex morphological and psychic characteristics, associated with the species; and which furthermore, during life, exhibits certain special distinguishing traits resulting from instincts, habits, migration and geographical distribution.

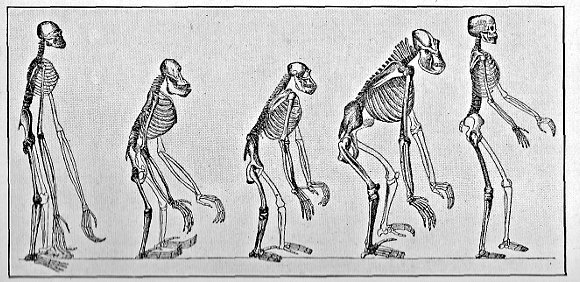

Zoology consequently includes a vast but well-defined field. Fundamentally, it is a descriptive science, and when the general character of the individual living creatures has been determined, it proceeds to draw comparisons between them, distinguishing genus and species, and thus working toward a classification. Down to the time of Linnaeus, these were its limits; but since the studies of Lamarck and Charles Darwin, it has gone a step further, and has proceeded to investigate the origin of species, an example that was destined to be followed by botany and biology as a whole, which is the study of living things.

When anthropology attained, under Broca, the dignity of a branch of the natural sciences, the evolutionary theory already held the field, and man had begun to be studied as an animal in his relation to species of the lower orders. But, just as in zoology, the fundamental part of anthropology was descriptive; and the description of the morphology of the body was divided, according to the method followed, into anthropology, or the method of inspection, and anthropometry, or the method of measurements.

By these means, many problems important to the biological side of the subject were solved—such, for instance, as racial characteristics—and a classification of "the human races" was achieved through the evidences afforded by comparative studies.

But the descriptive part of anthropology is not limited to the inspection and measurement of the body; on the contrary, just as in zoology, it is extended to include the habits of the individual living being; that is to say, in the case of man, the language, the manners and customs (data that determine the level of civilisation), emigration and the consequent intermixture of races in the original formation of nations, thus constituting a special branch of science properly known by the name of ethnology.

In this manner, while still adhering rigorously to zoological methods, anthropology found itself compelled to throw out numerous collateral branches into widely different fields, such as those of linguistics and archæology; because man is a speaking animal and a social animal.

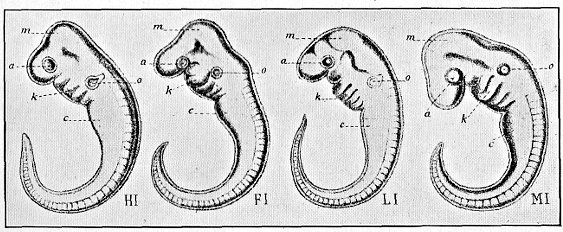

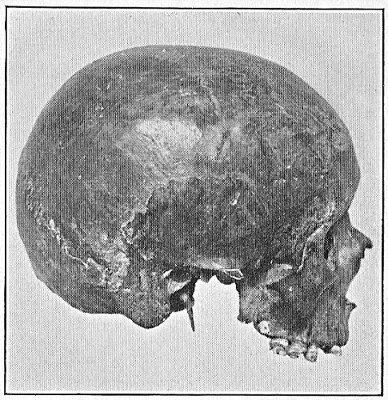

One strictly anthropological problem is that of the origin of man, and its ultimate analogy with that of the other animal species. Hence the comparative studies between man and the anthropoid apes; while palæontological discoveries of pre-human forms, such as the pithecanthropus, were just so many arguments[Pg 3] calculated to bring the human species within the scheme of a biological philosophy, based upon evolution, which held its own, for nearly half a century, on the battle-ground of natural sciences, under the glorious leadership of Darwin.

Yet, notwithstanding that it offered studies and problems of direct interest to man, anthropology failed to achieve popularity. During that half century (the second half of the Nineteenth), which beheld the scientific branches of biology multiply throughout the entire field of analytical research, from histology to biochemistry, and succeeded especially in making a practical application of them in medicine, Anthropology failed to raise itself from the status of a pure and aristocratic, in other words, a superfluous science, a status that prevented it from ranking among the sciences of primary importance. As a matter of fact, while zoology is a required study in the universities, Anthropology still remains an elective study, which in Italy is relegated to three or four universities at most. The epoch of materialistic philosophy and analytical investigation could naturally hardly be expected to prove a field of victory for man, the intelligent animal, and nature's most splendid achievement in construction.

The impressive magnificence of this thought, that bursts like pent-up waters from the results of positive research into man considered as a living individual, was forced to await the patient preparation of material on which to build, such as the gathering of partial and disorganised facts, which were accumulated through rigorous and minute analyses, conducted under the guidance of the experimental sciences. It was in this manner that anthropology slowly evolved a method and, by doing so, raised itself to the rank of a science, without ever once being utilised for practical purposes or recognised as necessary as a supplemental or integral element of other sciences.

One branch of learning which might have utilised the important scientific discoveries regarding the antiquity of man, his nature considered as an animal, his first efforts as a labourer and a member of society, is pedagogy.

What could be more truly instructive and educative than to describe to children that first heroic Robinson Crusoe, primitive man, cast away on this vast island, the earth, lost in the midst of the universe? Mankind, weak and naked, without iron, because it still remained mysteriously hidden in the bowels of the earth, without fire because they had not yet discovered the means of procuring it; stones were their only weapons of defense against the ferocious and gigantic beasts that roared on all sides of them in the forests. The rude, splin[Pg 4]tered stone, the first handiwork of intelligent man, his first instrument and his first weapon, could be prepared solely from one kind of mineral, of which the local deposit began to fail—a state of things which, let us suppose, occurred on some ocean island. Thereupon the men constructed a small boat from the bark of trees, and sped over the waters, in search of the needed stone, passing from island to island, with scanty nourishment, without lights in the night-time, and without a guide.

These marvelous accounts ought to be easily understood by children, and to awaken in them an admiration for their own kinship with humanity, and a profound sense of indebtedness to the mighty power of labour, which to-day is rendered so productive and so easy by our advanced civilisation, in which the environment, thanks to the works of man, has done so much to make our lives enjoyable.

But pedagogy, no less than the other branches of learning, has disdained to accept any contribution from anthropology; it has failed to see man as the mighty wrestler, at close grips with environment, man the toiler and transmuter, man the hero of creation. Of the history of human evolution, not a single ray sheds light upon the child and adolescent, the coming generation. The schools teach the history of wars—the history of disasters and crimes—which were painful necessities in the successive passages through civilisations created by the labour and slow perfectioning of humanity; but civilisation itself, which abides in the evolution of labour and of thought, remains hidden from our children in the darkness of silence.

Let us compare the appearance of man upon the earth to the discovery of the motive power of steam and to the subsequent appearance of railways as a factor in our social life. The railway has no limits of space, it overruns the world, unresting and unconscious, and by doing so promotes the brotherhood of men, of nations, of business interests. Let us suppose that we should choose to remain silent about the work performed by our railways and their social significance in the world to-day, and should teach our children only about the accidents, after the fashion of the newspapers, and keep their sensitive minds lingering in the presence of shattered and motionless heaps of carriages, amid the cries of anguish and the bleeding limbs of the victims.

The children would certainly ask themselves what possible connection there could be between such a disaster and the progress of civilisation. Well, this is precisely what we do when, from all the prehistoric and historic ages of humanity, we teach the children nothing but a series of wars, oppressions, tyrannies and betrayals; and, equipped with such knowledge, we push them out, in all their ignorance, into the century of the redemption of labour and the triumph of universal peace, telling them that "history is the teacher of life."

Modern Anthropology: Cesare Lombroso and Criminal Anthropology. The Anthropological Principles of Moral Hygiene.—The credit rests with Italy for having rescued Anthropology from a sort of scientific Olympus, and led it by new paths to the performance of an eminent and practical service.

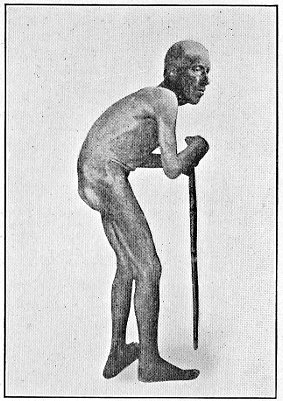

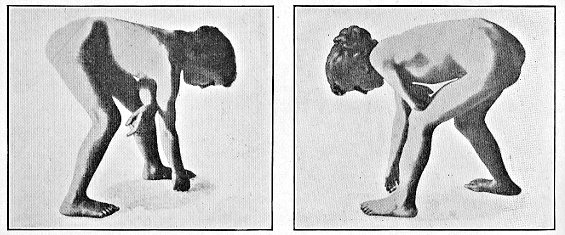

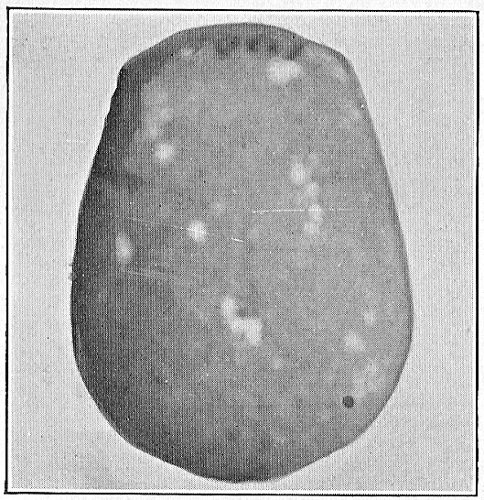

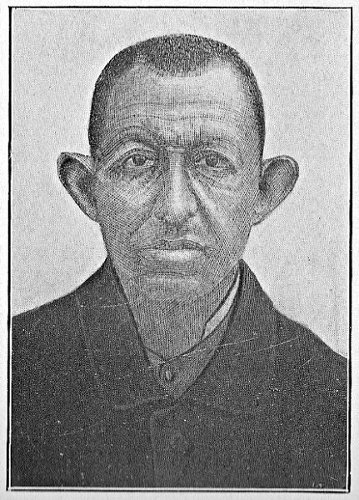

It was about the year 1855 that Cesare Lombroso applied the[Pg 5] anthropological method first to the study of the insane, and then to that of criminals, having perceived a similarity or relationship between these two categories of abnormal individuals. The observation and measurement of clinical subjects, studied especially in regard to the cranium by anthropometric methods, led the young innovator to discover that the mental derangements of the insane were accompanied by morphological and physical abnormalities that bore witness to a profound and congenital alteration of the entire personality. Accordingly, for the purposes of diagnosis, Lombroso came to adopt a somatic basis. And his anthropological studies of criminals led him to analogous results.

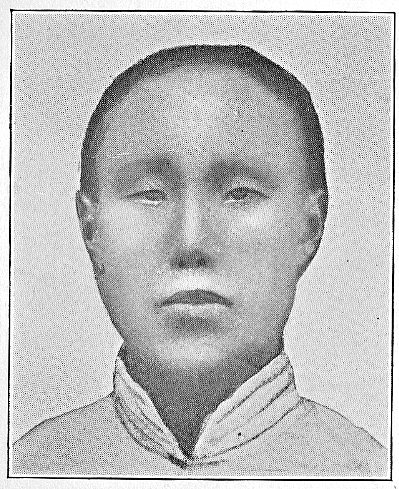

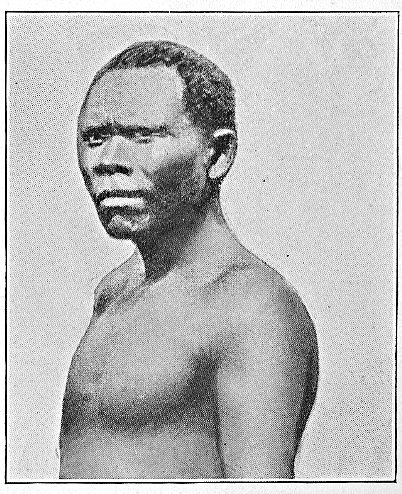

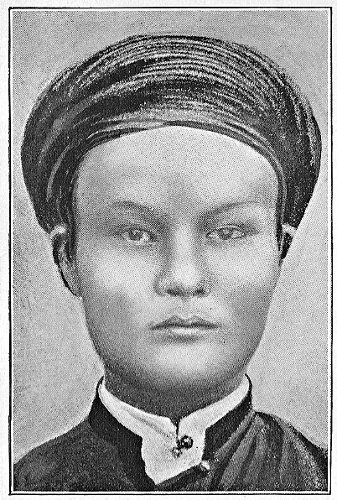

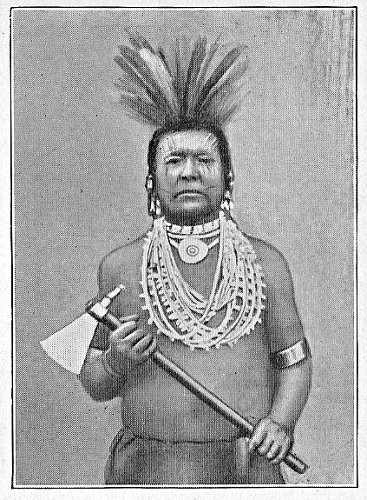

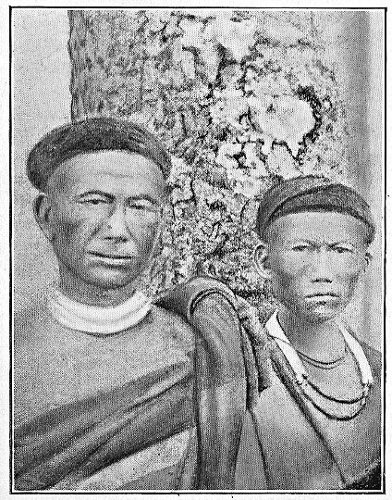

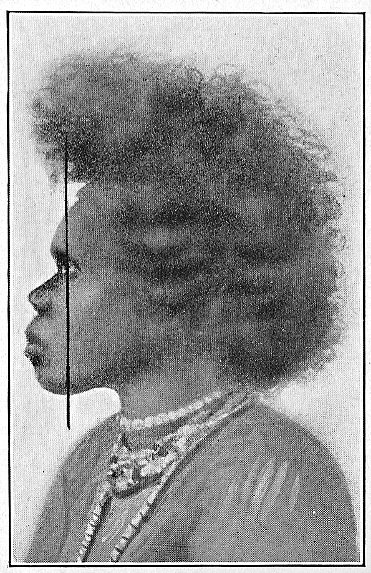

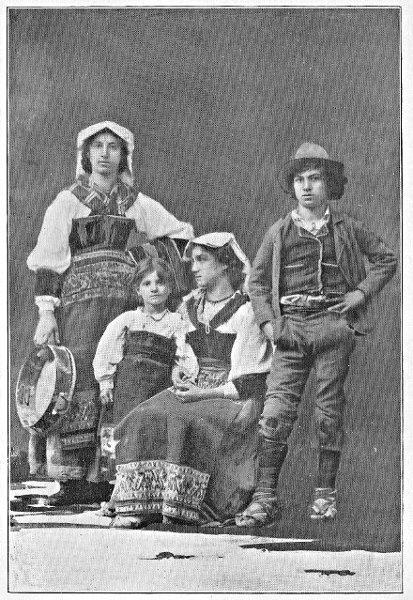

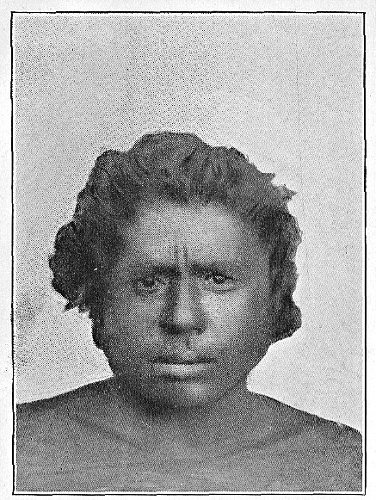

The method employed was in all respects similar to the naturalistic method which anthropology had taken over from zoology; that is to say, the description of the individual subject considered chiefly in his somatic or corporeal personality, but also in his physiological and mental aspect; the study of his responsiveness to his environment, and of his habits (manners and customs); the grouping of subjects under types according to their dominant characteristic (classification); and finally, the study of their origin, which, in this case, meant a sociological investigation into the genesis of degenerate and abnormal types. Thus, since the principles of the Lombrosian doctrine spread with a precocious rapidity, it is a matter of common knowledge that criminals present anomalies of form, or rather morphological deviations associated with degeneration and known under the name of stigmata (now called malformations), which, when they occur together in one and the same subject, confer upon him a wellnigh characteristic aspect, notably different from that of the normal individual; in other words, they stamp him as belonging to an inferior type, which, according to Lombroso's earlier interpretation, is a reversion toward the lower orders of the human race (negroid and mongoloid types), as evidenced by anomalies of the vital organs, or internal animal-like characteristics (pithecoids); and that such stigmata were often accompanied by a predisposition to maladies tending to shorten life. Side by side with his somatic chart, Lombroso painstakingly prepared a physio-pathological chart of criminal subjects, based upon a study of their sensibility, their grasp of ideas, their social and ethical standards, their thieves' jargon and tattoo-marks, their handwriting and literary productions.

And, by deducing certain common characteristics from these[Pg 6] complex charts, he distinguished, in his classic work, Delinquent Man, a variety of types, such as the morally insane, the epileptic delinquent, the delinquent from impulse or passion (irresistible impulsion), the insane delinquent, and the occasional delinquent.

In this way, he succeeded in classifying a series of types—what we might call sub-species—diverging from the somatic and psycho-moral charts of normal men. But the common biopathological foundation of such types (with the exception of the last) was degeneration. We may well agree with Morselli that, in many parts of his treatise, Lombroso completed and amplified Morel, whose classic work, A Study of the Degeneration of the Human Species, was published in France at a time when Lombroso had hardly started upon his anthropological researches.

Both of these great teachers based their doctrine upon a naturalistic concept of man, and then proceeded to consider him, through all his anomalies and perversions, in relation to that extraneous factor, his environment. Morel, indeed, considers the social causes of degeneration, that is to say, of progressive organic impoverishment, as more important than the individual phenomena; they act upon posterity and tend to create a human variety deviating from the normal type. Such causes may be summed up as including whatever tends to the organic detriment of civilised man: such (in the first rank) as alcoholism, poisoning associated with professional industries (metallic poisons), or with lack of nutriment (pellagra), conditions endemic in certain localities (goitre), infective maladies (malaria, tuberculosis), denutrition (surménage). It may be said that whatever produces prolonged suffering, or whatever we class under the term vices, or even the neglect of our duties, chief among which is that of working (parasitism of the rich), or any of the causes which exhaust, or paralyse, or perturb our normal functions, are causes of degeneration, of impoverishment of the species.

Such is the doctrine which underlies the etiological concept of abnormal personality in psychiatry as well as in criminology, or points the way to its bio-social sources.

Accordingly, just as general Anthropology sought to investigate the origins of races or that of the human species in the very roots of life, so criminal Anthropology searches the origins of defective personality in its social surroundings.

The ethical problems which are raised by such a doctrine[Pg 7] cannot fail to be of interest to us. The Lombrosian theories, by raising these problems, have not only shaken the foundations of penal law, but have even brought about a moral renovation of conscience. We will leave to the jurists the great civic labor resulting from having brought the individual as well as the crime under consideration, in relation to the social phenomenon of delinquency—in other words, of having substituted an anthropological for a speculative attitude. Whether the delinquent should be cured, or simply isolated, or even subjected to punishment; whether the prison should be transformed into an asylum for the criminal insane; whether the penal laws should be reformed on principles of a higher order of civil morality: these are problems which interest us only secondarily.

What does interest us directly as educators is the necessity of laying our course in accordance with the standard of social morality which such a doctrine reveals and imposes upon us: since it is our duty to prepare the conscience of the rising generation. And, furthermore, to consider whether the organisation of our schools and of their methods is in conformity with such social progress.

If we cast a general glance at social ethics, from the primitive beginnings of human intercourse, we witness the evolution of the vendetta. There was, first, the individual vendetta. It was a form of primordial justice, with which were associated the sentiments of dignity, honour and solidarity; the injured party avenged himself by slaying; and the family of the slain retaliated by a new vendetta against the family of the slayer; and thus from generation to generation the tragic heritage continued to be handed down. Even now, in certain districts of civilised countries there exist survivals of these primitive forms of justice. In such cases, the slayer is held to be, not only honourable but virtuous. Analogously, in course of time, the individual vendetta, regulated by special formalities, developed into the duel for a point of honour.

At a more advanced period, in the course of the organisation of society, the task of vengeance was taken away from the individual, and the social administration of justice was established. Thereafter, the act of an offender was punished by the people collectively, and the victims of the act had no other recompense from society than that of a sense of satisfied hatred.

But throughout all civil progress, from the most primitive forms of society down to our own times, there persisted, as a[Pg 8] fundamental principle, the concept of vengeance, coupled with the two great moral principles, individually and collectively, of human society: honour and justice. The naturalistic concept introduced by the Lombrosian doctrine, namely, living man entering as a concrete reality into the midst of abstract moral principles, shatters this association of ideas, and by so doing prepares the way for a new order of things—which is not a process of evolution, but the beginning of an epoch. Vengeance disappears in the new conception of the defense of society and of an active campaign for the progress of humanity; and it ushers in an epoch of redemption and of solidarity, in which all limitations of human brotherhood are swept away.

The theories of Morel and Lombroso have resulted in calling the attention of civilised man to all the types of the physiologically inferior; the mentally deficient, epileptics, delinquents; shedding light upon their pathological personality, and transforming into interest and pity the contempt and neglect that were formerly the portion of such creatures. In this way science has accomplished in their behalf a work analogous to that of certain saints on behalf of lepers and sufferers from cancer in the middle ages. At that epoch, and even down to the beginning of modern times, the sick were abandoned to themselves and languished, covered with sores, in the midst of the horrors of infection; lepers were universally shunned, and their bodies decomposed without succor. It was only when these miserable beings began to awaken pity, in the place of loathing and repulsion, and to attract the charity of saints, instead of spreading panic among egoists and cowards, that the care of the sick began upon a vast scale, with the foundation of hospitals, the progress of medicine, and later of hygiene.

To-day those purulent plague-spots of the middle ages no longer exist; and infection is being combated with progressive success, in the triumph of physical health.

Yet, we are standing to-day on the selfsame level as the middle ages, in respect to moral plague-spots and infections; the phenomenon of criminality spreads without check or succor, and up to yesterday it aroused in us nothing but repulsion and loathing. But now that science has laid its finger upon this moral fester, it demands the cooperation of all mankind to combat it.

Accordingly we find ourselves in the epoch of hospitals for the morally diseased, the century of their treatment and cure; we have[Pg 9] initiated a social movement toward the triumph of morality. We educators must not forget that we have inaugurated the epoch of spiritual health; because I believe that it is we who are destined to be the true physicians and nurses of this new cure. From the middle ages until now, the science of medicine has slowly been evolving for us the principles required to guarantee our bodily health; but we know very well that while cleanliness and hygiene are signs of civilisation, it is its moral standard that establishes its level.

This moral solidarity is something which it is our duty to understand thoroughly, if we wish to undertake the noble task of educators in the Twentieth Century, which was prepared in advance by the intensive intellectual activity of the century of science.

Granting the social phenomenon of crime, we ought to ask ourselves: where does the fault lie? If we are to acquit the individual criminal of responsibility, it falls back necessarily upon the social community through which the causes of degeneration and disease have filtered. Accordingly, it is we, every one of us, who are at fault: or rather, we are beginning to awaken to a consciousness that it is a sin to foster or to tolerate such social conditions as make possible the suffering, the vices, the errors that lead to physiological pauperism, to pathology, to the degeneration of posterity. The idea is not a new one: all great truths were perceived in every age by the elect few; the fundamental principles of the doctrine of Lombroso are to be already found in Greek philosophy and in that of Christ; Aristotle, in his belief that there is some one particular organism corresponding to each separate manifestation of nature, foreshadows the concept of the correspondence between the morphological and psychic personality; and St. John Chrisostom expounds the principle of moral solidarity in the collective responsibility of society, when he says: "you will render account, not only of your own salvation, but of that of all mankind; whoever prays ought to feel himself burdened with the interests of the entire human race."

Now, if it is not yet in our power to achieve a social reform based on the eradication of degenerative causes—since society can be perfected only gradually—it is nevertheless within our power to prepare the conscience for acceptance of the new morality, and by educational means to help along the civil progress which science has revealed to us. The honest man, the worthy man, the[Pg 10] man of honour, is not he who avenges himself; but he who works for something outside himself, for the sake of society at large, in order to purify it of its evils and its sins, and advance it on its path of future progress. In this way, even though we fail to prepare the material environment, we shall have prepared efficient men.

In addition to this momentous principle of social ethics, the Lombrosian doctrines confront us squarely with the philosophic question of liberty of action, the controverted question of Stuart Mill, namely that of "free will." The libertarians admit the freedom of the will as one of the noblest of human prerogatives, on which the responsibility for our acts depends; the determinists recognise that the act of volition obeys certain predetermined causes. Now the Lombrosian theories find these causes, not after the fashion of the Pythagoreans, in cosmic laws or astrology, but in the constitution of the organism, thus serving as a powerful illustration of that physiological determinism, under whose guidance modern positive philosophy draws its inspiration.[1]

In the case of criminality, the actions of the degenerate delinquent are dependent upon a multiplicity of internal factors, that are almost necessarily governed by special predispositions. But, also in accordance with the Lombrosian doctrine, there are external factors which concur in determining acts of volition, factors relating to the environment, studied in accordance with rather vast conceptions: the actions of the individual are determined in advance by that social intercourse in which the great phenomena of any given civilisation have their necessary origin—phenomena such as crime, prostitution, the grade of culture accessible to the majority, the character of industrial products, the limits of general mortality. Now, just as there are necessary fluctuations in the tables of mortality, so also there are fluctuations in the quantity and quality of those individual phenomena that are looked upon as crimes: and in the one case no less than in the other, those who are predisposed are the ones in whom occurs the necessary outbreak of phenomena having their origin in society.

This constitutes in criminology, as well as in psychiatry, the resultant of all etiological concepts, pertaining to the interpretation of individual phenomena. It is precisely the same concept as that so exhaustively demonstrated by Quétélet, with the aid of European statistics, in his Social Physics, and it has come to represent in [Pg 11]modern science that fundamental concept which was to be found in all the great religions, of the dependence of the individual upon a governing force that is superior to him. This interpretation of individual phenomena cannot be ignored in the great problems of education; because the more literally we interpret the doctrine here set forth, just so much the less trust must be placed in the efficacy of education as a modifying influence upon personality, while it will acquire new importance as a co-worker in the interpretation of social epochs and individual activities, over which it should exercise a watchful guidance.

But meanwhile it is of interest to us to note how the anthropological movement, introduced with great simplicity of method, without any scientific or philosophical preconceptions, has led the investigations of psychiatry into vast and unsuspected fields of social ethics, bringing into practice fundamental reforms, analogous to those relating to penal law.

Achille De Giovanni and Physiological Anthropology; Anthropological Principles of Physical Hygiene.—Another practical development of anthropology is that instituted by Professor De Giovanni, who has introduced into his medical clinic at Padua the anthropological method in the clinical examination of patients. He applies the well-known naturalistic procedure, namely, the description of individuals, their classification into types, according to common fundamental characteristics, and the etiological study of their personality. But while Lombroso took note of malformations solely in relation to other symptoms of degeneration, De Giovanni has established a strictly physiological basis for his investigations. Accordingly, he considers the human individual in his entirety, as a functionating organism, and he regards all inharmonious bodily proportions as signifying a necessary predisposition to certain determined forms of illness. With this end in view, he does not concern himself about single malformations, such for example as prognathism, the frontal angle, etc., but rather with the general relations of development between the bust which contains the organs essential to vegetative life, and the limbs; and from the external morphology of the bust, determined by measurements, he seeks to establish the reciprocal relations in development within the visceral cavities: "the proportions of the human body depend upon the development of its organs; and equally with its proportions, the whole physiological strength of the body depends[Pg 12] upon its organs taken collectively." Whoever has a defective chest capacity not only possesses a smaller allowance of organs fitted for respiration and circulation of the blood, but as a result of such anomaly of development he is also predisposed to attacks of special maladies, such for example as chronic catarrh of the bronchial tubes or pulmonary tuberculosis. Whoever, on the contrary, is overdeveloped in abdominal dimensions, will be subject to disturbances of the digestive system and of the liver. In his classic work, Morphology of the Human Body, De Giovanni proceeds to elaborate a doctrine of temperaments, and of their several predispositions to disease, the tendency of which is to transfer the basis of medicine from a study of diseases to that of the individual patients, and to revive in modern days the ancient concepts of the Greek school of medicine, which from the time of Hippocrates and Galen drew up admirable charts of the fundamental physical types. In place of the ancient classification of temperaments into nervous, sanguine, bilious and lymphatic, we have to-day as substitutes, according to the school of De Giovanni, morphological types that are very nearly equivalent, and in which the predominant disorders are respectively diseases of the heart, the nervous system, the liver and the lungs.

In short, the result of this theory has been to establish an internal factor of predisposition to disease, analogous to that established by Lombroso as a predisposition to the phenomena of crime. And even here the mesogenic factors, that is, the influence of environment, must be taken into consideration: but environment acts equally upon all individuals: nearly everyone encounters, in his surroundings, that nerve-strain which leads to cardiac disorders and to neurasthenia; almost everyone encounters the bacilli of tuberculosis; the causes of general mortality are dictated by the very conditions of civilisation. But among the vast majority who pass unharmed along the insidious paths of adaptation, only a few fall victims to the particular disease to which some special anomaly of their organism predisposes them. In this way we can understand how it happens that certain ones have reason to dread a cold that will develop into bronchitis, and others on the contrary must guard themselves from errors in diet which will lead to intestinal disorders.

The part of De Giovanni's theory which is of special interest is that which leads to a consideration of the [Pg 13]ontogenetic development in relation to the anomalies of the physio-morphological personality: "At every epoch of life this principle is applicable: Namely, that the reason for a special predisposition to disease is to be found in a special organic morphology. The individual is in a ceaseless state of transformation, and consequently at different periods of his life he may show a susceptibility to different diseases." A person who is predisposed to suffer continually from some complaint during his adult years, was usually unwell during the greater part of his childhood, although from some other disease; and with this as a basis, a scientific system of observation could speak prophetically regarding the physio-pathological destiny of a child. It is known, for example, that children subject to scrofula are predisposed to arrive at maturity with an undeveloped chest and a tendency to pulmonary tuberculosis.

From our point of view as educators, the doctrine of temperaments, and of their respective predispositions to disease, offers a deep interest, the nature of which is made evident by the author of the theory himself: for he points out that the period of childhood is the one best fitted in which to combat the abnormal predispositions of the organism, wisely guiding its development, to the final end of achieving an ideal of health, which depends upon the harmony of form and consequently of functions, in other words, upon the full attainment of physical beauty.

Here also, as in the Lombrosian doctrines, etiology fulfils the lofty task of throwing light upon the causal links between the biosociologic causes and the congenital anomalies of the physiological personality. The hereditary tendencies to disease, the errors of sexual hygiene, especially those regarding maternity, reveal to us the principal causes of that accumulation of imperfections that oppress and deform the average normal human being. It is because of such errors and such ignorance that hardly any of us attain that harmonic beauty that would render us immune to the treacheries of environment, and enable us to achieve, in the triumphant security of good health, our normal biological development.

It is not too much to say, that it is etiology which, applied to the Lombrosian doctrines, reveals the faults of society, the sins of the world, and, applied to the theories of De Giovanni, reveals its errors; and that from the two together there results a sort of ethical guide leading toward the supreme ideal of the[Pg 14] purification of the world and the perfectionment of the human species. These are ideals which were in part cherished by the Greeks, who made their system of education the basis of their physical development. Such physiological doctrines are precisely what we also need to round out our plan for a moral education.

Giuseppe Sergi and Pedagogic Anthropology: Anthropological Bases of Human Hygiene.—It is also an Italian to whom we owe that practical extension of anthropology that leads us straight into the field of pedagogy. It was my former teacher, Giuseppe Sergi, who, as early as 1886, defended with the ardor of a prophet the new scientific principle of studying the pupils in our schools by methods prescribed by anthropology. Like the scientists who preceded him, he was thus led to substitute (in the field of pedagogy) the human individual taken from actual life, in place of general principles or abstract philosophical ideas.

As a matter of fact, while the doctrines of Lombroso and De Giovanni are profoundly reformatory, they nevertheless offer us nothing more substantial than certain new ideals of morality and social improvement. But the really practical field in which these ideals might in a large measure be realised is the school.

What progress would result for humanity if, on the basis of these new ethical principles, we contented ourselves with transforming our prisons into insane asylums? Such scanty fruit might well be compared to the mercy of that mediæval lordling who, out of consideration for a gentleman, commuted his sentence from hanging to decapitation. And scanty fruit would also be reaped by the science of medicine if, in its new anthropological development, it should content itself merely with diagnosing the personality of the patient, in addition to the disease; that is to say, for example, if, instead of telling a patient that his attack of bronchitis would be cured within twenty days, it should go on to predict, on the basis of the morphology of his body, that he would infallibly fall ill every year, until such time as pulmonary tuberculosis should put a fatal ending to his days.

On the contrary, behind the light of ideality that shimmers through and across these doctrines, we perceive our plain duty to trace out a path that will lead to a regeneration of humanity. If some practical line of action is to result, it will undoubtedly have to be exerted upon humanity in the course of development, in other words, at that period of life when the organism, being still in the[Pg 15] course of formation, may be effectively directed and consequently corrected in its mode of growth.

Accordingly, the possible solution of the most momentous social problems, such as those of criminality, predisposition to disease, and degeneration, may be hoped for only within the limits of that space which society sets aside for guiding the new generations in their development.

In the school, we have hitherto retained, almost as a principle of justice, a leveling uniformity among the pupils: an abstract equality which seeks to guide all these separate childish individualities toward a single type which cannot be called an idealised type, because it does not represent a standard of perfection, but is on the contrary a non-existent philosophical abstraction: the Child. Educators are prepared for their practical services to childhood, by studies based upon this abstract infantile personality; and they enter upon their active work in school with the preconception that they must discover in every pupil a more or less faithful incarnation of the said type; and thus, year after year, they delude themselves with the idea that they have understood and educated the child. Now, this supposed uniformity cannot exist in the children of a human race so varied that it can produce, at the selfsame time, a Musolino[A] and a Luccheni,[2] a Guglielmo Marconi and a Giosue Carducci. All the different social types of men who labor with their hands and with their brains, the transformers of their environment, the producers of wealth, the directors of governments, equally with the undistinguished crowd of parasites, the enemies of society, all lived together in childhood, sitting side by side, upon the same school benches.

It was in 1898 that the first Italian Pedagogical Congress was held in Turin, and was attended by about three thousand educators. Under the spur of a new passion, that made me foresee the future mission and transformation of a chosen social class, setting forth upon a glorious task of redemption—the class of educators—I attended the Congress. I was at that time an interloper, because the subsequent felicitous union between medicine and pedagogy still remained a thing undreamed of, in the thoughts of that period. We had reached the third day of our sessions, and were all awaiting with interest an address by Professor Ildebrando Bencivenni, who was announced to speak upon the theme of "The School that [Pg 16]Educates." The discussion of this subject was expected to constitute the substantial work of the Congress, which seemed to have been called together chiefly in order to solve the problem of the greatest pedagogic importance: how to give a moral education. It was that very morning, just as the session was opening, that the frightful news burst upon us like a thunderbolt, that the Empress, Elizabeth of Austria, had been assassinated, and that once again an Italian had struck the blow! The third regicide in Europe within a brief time, that was due to an Italian hand!

The entire public press was unanimously stirred to indignation against the educators of the people; and as a demonstration of hostility, they all absented themselves that day from participating in the Congress.

There was something approaching a tumult in the ranks of teachers; inasmuch as they felt themselves innocent, they protested against the calumny of the newspapers in thus unjustly holding them responsible.

Amid the intense silence of the assembly, Bencivenni delivered a splendid discourse regarding the reform of educative methods in the school. Next in order, I took the platform and, speaking as a physician, I said: It will be all in vain for you to reform the methods of moral education in our schools, if you do not bear in mind that certain individuals exist, who are the very ones capable of committing such unspeakable deeds, and who pass through school without ever once being influenced in any manner by education. There exist various categories of abnormal children, who will fruitlessly go through the same grade over and over again, disturbing the routine and discipline of the class: and in spite of punishments and reprimands, they will end by being expelled without having learned anything at all, without having been modified in any manner. What becomes of these individuals who, even in childhood, reveal themselves as the future rebels and enemies of society? Yet we leave such a dangerous class in the most complete abandonment. Now, it is useless to reform the school and its methods, if the reformed school and the reformed methods are still going to fail to reach the very children who, for the protection of society, are most in need of being reached! Any method whatever suffices to fit a sane and normal child for a useful and moral life. The reform that is demanded in school and in pedagogy is one that will lead to the protection of all children[Pg 17] during their years of development, including those who have shown themselves refractory to the environment of social life.

Thus I laid the first stone toward the education of mentally deficient children and the foundation of special schools for them. The work which followed forms, I think, the first historic page of a great regeneration in the whole class of teachers and of a profound reform in the school; a question so momentous that it spread rapidly throughout all Italy and was followed by the establishment of institutes and classes designed expressly for the deficient; and, most important of all, by the universal conviction which it carried, it also constituted the first page of pedagogy reformed upon an anthropological basis.

This is precisely the new development of pedagogy that goes under the name of scientific: in order to educate, it is essential to know those who are to be educated. "Taking measurements of the head, the stature, etc." (in other words, applying the anthropological method), "is, to be sure, not in itself the practice of pedagogy," says Sergi, in speaking of what the biological sciences have contributed to this branch of learning during the nineteenth century, "But it does mean that we are following the path that leads to pedagogy, because we cannot educate anyone until we know him thoroughly."

Here again, in the field of pedagogy, the naturalistic method must lead us to the study of the separate subjects, to a description of them as individuals, and their classification on a basis of characteristics in common; and since the child must be studied not by himself alone, but also in relation to the factors of his origin and his individual evolution—since every one of us represents the effect of multifold causes—it follows that the etiological side of the pedagogical branch of modern anthropology, like all its other branches, necessarily invades the field of biology and at the same time of sociology.

Among the types which it will be of pedagogic interest to trace in school-children, we must undoubtedly find those that correspond to the childhood of those abnormal individuals already studied in Lombroso's Criminal Anthropology, and in De Giovanni's Clinical Morphology.

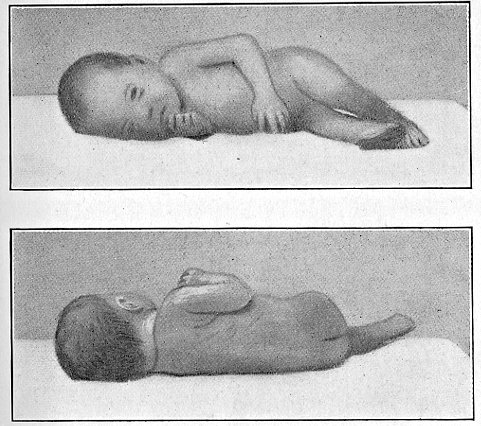

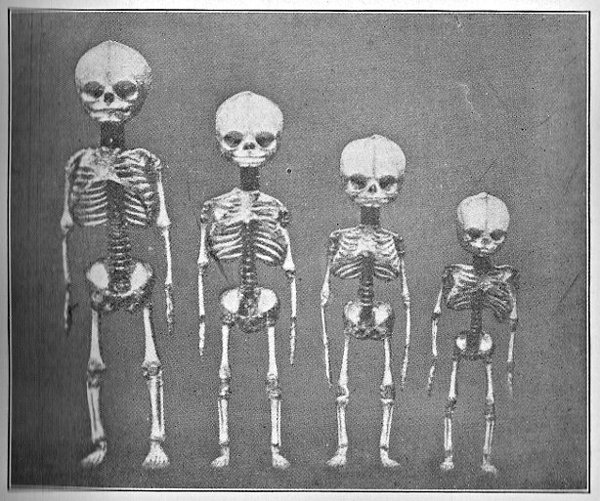

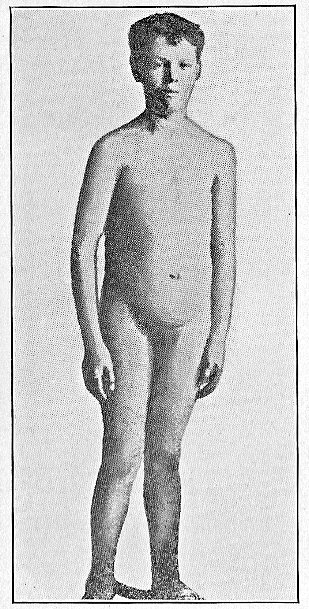

Nevertheless, it is a new study, because the characteristics of the child are not those of the adult reduced to a diminutive scale, but they constitute childhood characteristics. Man changes as he[Pg 18] grows; the body itself not only undergoes an increase in volume, but a profound evolution in the harmony of its parts and the composition of its tissues; in the same way, the psychic personality of the man does not grow, but evolves; like the predisposition to disease which varies at different ages in each individual considered pathologically. For all those anomalous types which to-day are included under the popular term of deficients, for the pathological weaklings who reveal symptoms of scrofula or rickets, there is no doubt that special schools and methods of education are essential. We teachers would like, through educative means, to counteract the ultimate consequences of degeneration and predisposition to disease: if criminal anthropology has been able to revolutionise the penalty in modern civilisation, it is our duty to undertake, in the school of the future, to revolutionise the individual. And by achieving this ideal, pedagogic anthropology will to a large extent have taken the place of criminal anthropology, just as schools for the abnormal and feeble, multiplied and perfected under the protection of an advanced civilisation, will in a large measure have replaced the prisons and the hospitals.

We owe to the intuitive genius of Giuseppe Sergi the conception of a form of pedagogic anthropology far more exact in its methods of investigation than anything which had hitherto been foreshadowed. This master takes the ground that a study of abnormal and weakly children is a task of absolutely secondary importance. What is imperative for us to know, he claims, is normal humanity, if we are to guide it intelligently toward that biological and moral perfection, on which the progress of humanity must depend. If general pedagogy is destined to be transformed under a naturalistic impulse, this will be effected only when anthropology turns its investigations to the normal human being.

Educators are still very far from having a real knowledge of that collective body of school-children, on whom a uniformity of method, of encouragement and punishment is blindly inflicted; if, instead of this, the child could be brought before the teacher's eyes as a living individuality, he would be forced to adopt very different standards of judgment, and would be shaken to the very depths of his conscience by the revelation of a responsibility hitherto unsuspected.

Let us take one or two examples; let us consider, among the pupils, one child who is very poor.

Studied by the anthropological method, he is revealed, in every personal physiological detail, as an inferior type. The child of poverty, as Niceforo has well shown, is an inferior in stature, in cranium, in weight, in muscular and intellectual strength; and the malformations, resulting from defects of growth, condemn him to an æsthetic inferiority; in other words, environment, mode of living, and nutrition may result in modifying even the relative beauty of the individual. The normal man may bear within him a germ of physical beauty inherited from parents who begot him normally, and yet this germ may not be able to develop, because impeded by environment. Accordingly, physical beauty constitutes in itself a class privilege. This child, weak in mind and in muscular force, when compared with the child of wealth, grown up in a favorable environment, shows less attractive manners, because he has been reared in an atmosphere of social inferiority, and in school is classed as a pariah. Less good looking and less refined, he fails to enlist the sympathy which the teacher so readily concedes to the courteous manners of more fortunate children; less intelligent himself, and unable to look for help from parents who, more than likely, are illiterate, he fails to obtain the encouragement of praise and high credit marks that are lavished upon stronger children, who have no need of being encouraged. Thus it happens that the down-trodden of society are also the down-trodden in the school. And we call this justice; and we say that demerit is punished and merit is rewarded; but in this way we make ourselves the sycophants of nature and of social error, and not the administrators of justice in education!

On the other hand, let us examine another child, living in an agreeable environment, in the higher social circles; he possesses all the physical attraction and grace that render childhood charming. He is intelligent, smiling, gentle-mannered; at the cost of small effort he gives his teacher ample satisfaction by his progress, and even if the teacher's method of instruction happens to be somewhat faulty, the child's family hasten privately to make up for the deficiency. This child is destined to reap a harvest of praise and rewards; the teacher, egotistically complacent over the abundant fruit gathered with so little effort, and the moral and æsthetic satisfaction derived from the fortunate pupil, gives him unmeasured affection and smooths his whole course through school. But if we study the rich, intelligent, prize-winning child carefully, we[Pg 20] find that he, too, is not perfect in his anthropological development; he is too narrow-chested. This is the penalty of the rich and the studious; every privilege brings its own peril; every benefit contains a snare; every one of us to-day, without the light of science, runs the risk of diminishing our physiological equilibrium, by living in an environment that contains so many defects. The child of luxury, living continually indoors, diligently studying in his well-warmed home, under his mother's vigilant eye, is impeding the development of his own chest; and when he has completed his growth and his education, will find himself with insufficient lungs; his physical personality will have been permanently thrown out of equilibrium by a defective environment. This highly cultured man may some day find himself urged on to big endeavour; his intelligence will create vast ideals, but he will not have at his disposal the physical force that is so strictly associated with the power to draw from the surrounding air a sufficient quantity of oxygen by means of respiration. The spirit is ready, but the flesh is weary; and all his ambitious hopes may be shattered in the very flower of life by pulmonary tuberculosis, to which he has himself created an artificial predisposition.

It is our duty to understand the individual, in order to avoid these fatal errors; and to arise to higher standards of justice, founded upon the real exigencies of life—guided by that spirit of love which is essential to the teacher, in order to render him truly an educator of humanity.

Love is the essential spirit of fecundity whose one purpose is to beget life. And in the teacher, love of humanity must find expression through his work, because the very purpose of love is to create something. Accordingly, this spirit of fecundity ought to produce the teacher's mission, which to-day is the mission of reforming the school and accepting the proud duty of universal motherhood, destined to protect all mankind, the normal and abnormal alike. This is a reform, not only of the school, but of society as a whole, because through the redeeming and protective labours of pedagogy, the lowest human manifestations of degeneration and disease will disappear; and, more important still, it will make it henceforth impossible for normal human beings, conceived from germs that promise strength and beauty, little by little to lose that beauty and strength along the rough paths of life, through which no one has hitherto had the knowledge to guide them.[Pg 21] "In the social life of to-day an urgent need has arisen," says our common master, Giuseppi Sergi, "a renovation of our methods of education and instruction; and whoever enrolls himself under this standard, is fighting for the regeneration of man."

Enrico Morselli and Scientific Philosophy.—Among the names of Italian scientists that must be called to mind, in discussing the modern developments of anthropology, a special lustre attaches to that of Enrico Morselli, who has earned the right to call himself the critic, or rather, the philosopher of anthropology. Notwithstanding that he has made his name famous in the vast field of psychiatry, this distinguished Genoese practitioner has found time to assimilate the most diverse branches of science and the most widely separated avenues of thought, qualifying himself as a critic, and systematising experimental science on the lines of scientific philosophy.

His great work, General Anthropology, is developed on synthetic lines, embracing in a single scientific system all the acquired knowledge of the past two centuries, and may rightfully be called the first treatise on philosophic anthropology. While the experimental sciences, by collecting and recording separate phenomena, were gradually preparing, throughout the nineteenth century, a great mass of analytical material, chosen blindly and without form, they apparently engendered a new trend of thought positively hostile to philosophy: the odium antiphilosophicum, as Morselli calls it. And conversely, the speculative positivism of Ardigo remained throughout its development a stranger to the immediate sources of experimental research, and adhered strictly to the field of pure philosophy. It remained for Morselli to perceive that the scientific material prepared by experimental science was in reality philosophical material, for which it was only necessary to prepare instruments and means in order to systematise it and lead it into the proper channels for the construction of a scientific philosophy.

Throughout the whole period of his intellectual activity, Morselli sought to unite experimental science and philosophy, by taking his content from the former and his form from the latter. To gather and catalogue bare facts could not be the scope of science; such labour could result only in sterilising the mind. "The human mind," says Morselli, "does not stop at the objective study of a phenomenon and its laws; it wants also to fathom their[Pg 22] nature; the how does not content it, but it must also have the wherefore." It must mount from facts to synthesis, constantly achieving a new and fuller understanding. But what determines the content of philosophy is not speculative thought, but facts that have been collected objectively. Such is the view of Enrico Morselli, expressed in the introduction to his Review of Scientific Philosophy: "We think the moment has come for professional philosophers to allow themselves to be convinced that the progress of physical and biological sciences has profoundly changed the tendencies of philosophy; so that it is no longer an assemblage of speculative systems, but rather the synthesis of partial scientific doctrines, the expression of the highest general truths, derived solely and immediately from the study of facts. On the other hand, we hope also that in every student of the separate sciences, whether pure or applied, the intimate conviction will take root that no science which applies the method of observation and experiment to the particular class of phenomena which form its subject, can call itself fully developed so long as it is limited to the collection and classification of facts. Scientific dilettantism of this sort must end by sterilising the human mind, whose natural tendency is to advance from observed phenomena by successive stages to the investigation of their partial laws, and from these to the research of more and more general truths. But philosophy, thus understood, can never confine itself within the dogmatism of a system, but rather will leave the individual mind free to make constant new concessions, in the pursuit of the truth.

"The human mind is condemned to search forever, and perhaps never to find, the ultimate solution to the eternal problem which it offers to itself; accordingly, let it keep itself at liberty to accept to-day as probable, a solution which further researches or newly discovered facts will compel it to reject to-morrow in favor of another. We must admit that in philosophic concepts there is a constant evolution, or rather natural selection, thanks to which the strongest concepts, those best constituted, those that are fitted to make use of scientific discoveries with the broadest liberality, are predisposed to prove victorious or at least to hold their own for a long time in the struggle."[3]

It is this liberty that makes it possible for us to pursue experimental [Pg 23]investigations, without fear that our brains may become sterile. And by liberty we mean the readiness to accept new concepts whenever experience proves to us that they are better and closer to the truth which we are seeking. Even though the absolute truth were never reached, the experimental method is the path most likely to lead us toward it step by step.

Accordingly, what we should demand of investigators is not a creed, a philosophic system, but "the objective method in their researches and in the sources of their inductions." For this is the way to train the workers and philosophers of experimental science.

And the same lines must serve us for building up a philosophy capable of shaping a regenerated method of pedagogy.

The determining factor in anthropology is the same that determines all experimental science: the method. A well-defined method in natural science applied to the study of living man offers us the scientific content, which we are in the course of seeking.

The content bursts upon us as a surprise, as the result of applying the method, by means of which we make advances in the investigation of truth.

Whenever a science prescribes for itself, not a content but a method of experimenting, it is for that reason called an experimental science.

It is not easy for those who come fresh from the pursuit of philosophic studies to adapt themselves to this order of ideas. The philosopher, the historian, the man of letters prepare themselves by assimilating the content of one particular branch of learning; and thereby they define the boundaries of their individual knowledge and close the circle of their individual thought, however vast that circle may be.

Indeed, the elaboration of human thought, the series of historic deeds, the accumulated mass of literature, may offer immense fields; but after the student has little by little assimilated them, he cannot do otherwise than contain them within him precisely as they are. Their extent is limited by the centuries that cover the history of civilised man, and it is invariable, since it exists as a work accomplished by man.

Experimental science is of an entirely different sort. We must look upon it as a means of investigation into the field of the infinite and the unknown. If we wish to compare it to some branch of learning that is universally familiar, we may say that an experimental science is similar to learning to read. When as children we learn to read, we may, to be sure, estimate the effort that it costs us to master a mechanical device; but such a mechanical device is a means, it is a magic key that will unlock the secrets of wisdom, multiply our power to share the thoughts of our contemporaries, and render us dexterous in despatching the practical affairs of life.

Thus considered, reading is a branch of learning that has no prescribed limits.

It is our duty to learn to read the truth, in the book of nature; I. by collecting separate facts, according to the objective method; II. by proceeding methodically from analysis to synthesis. The subject of our research is the individual human being.

1. The Objective Collecting of Single Facts.—In the gathering of data, our science makes use of two means of investigation, as we have already seen: observation or anthroposcopy; and measurement or anthropometry. In order to take measurements, we must know the special anthropometric instruments and how to use them; and in making observations, we must treat ourselves as instruments, that is, we must divest ourselves of our own personality, of every preconception, in order to become capable of recording the real facts objectively. For since our purpose is to gather our facts from nature and await her revelations, if we allowed ourselves to have scientific preconceptions, we might distort the truth. Here is the point which distinguishes experimental science from a speculative science; in the former, we must banish thought, in the latter we must build by means of thought. Accordingly at the moment when we are collecting our data, we must possess no other capacity than that of knowing how to collect them with extreme exactness and objectivity.

Accordingly we need a method and a mental preparation, that is, a training which will accustom us to divest ourselves of our own personalities, in order to become simple instruments of investigation. For instance, if it were a question of measuring the heads of illiterate children and of other children of the same age, who are attending school, in order to learn whether the heads of[Pg 25] educated children show greater development, we need not only to know how to use the millimetric scale and the cranial calipers which are the instruments adapted to this purpose; we need not only to know the anatomical points at which the instruments must be applied in the manner established by the accepted method; but we need in addition to be unaware, while taking the measurements, whether the child before us at a given moment is educated or illiterate because the preconception might work upon us by suggestion and thus alter the result. Or again, to take what in a certain sense is an opposite case, and nevertheless analogous, we may undertake a research into some absolutely unknown question, as for instance, what are the psychic characteristics of children whose development has kept fairly close to the normal average, and of those whose anthropological measurements diverge notably from the average: in such a case we ought to measure all the children, make the required psychological tests separately, and then compare the results of the two investigations.

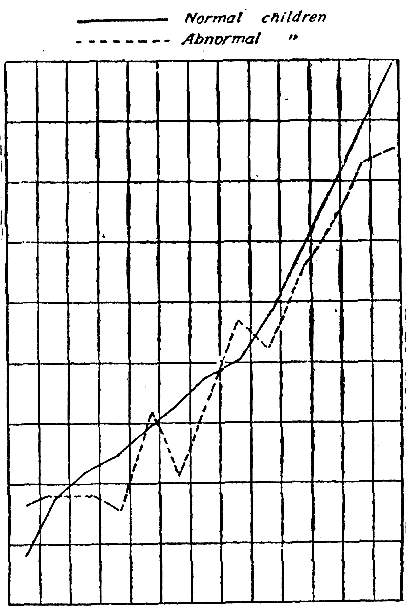

A woman student in my course, last year, undertook precisely this sort of investigation, namely, to find out what was the standing in school of children who represent the normal average anthropological type, that is to say, those whose physical development had been all that was to be desired: and she found that normal children are vivacious (happy), very intelligent, but negligent; and consequently their number never includes the heads of the classes, the winners of prizes.

In addition to gathering anthropological data, which requires a special technique of research, we need to know how to proceed to interpret them.

We are no longer at the outset of our observations. No sooner was the method established, than there were a multitude of students in all parts of the world capable of objective research, that is to say, of anthropological investigations. The sum total of all these researches forms a scientific patrimony, which needs to be known to us, in order that our own conclusions may serve to complete those of other investigators, who have preceded us, and thus form a contribution to science.

In other words, there have already been certain principles established and certain laws discovered, on an experimental basis; and all this forms a true and fitting content of our science. It will serve to guide us in our researches, and to furnish us with a [Pg 26]standard of comparison for our own conclusions. Thus, for example, when we have measured the stature of a boy of ten, we have undoubtedly gathered an individual anthropological fact; but in order to interpret it, we must know what is the average stature of boys of ten; and the average will be found established by previous investigators, who have obtained it from actuality, by applying the well-known method of measuring the stature, to a great number of individuals of a specified race, sex, and age, and by obtaining an average on the basis of such research.

Accordingly, we ought to profit from the researches of others, whenever they have been received, as noteworthy, into the literature of science. Nevertheless, the patrimony which science places at our disposition must never be considered as anything more than a guide, an expression of universal collaboration, in accordance with a uniform method. We must never jurare in verba magistri, never accept any master as infallible: we are always at liberty to repeat any research already made, in order to verify it; and this form of investigation is part of the established method of experimental science. One fundamental principle must be clearly understood; that we can never become anthropologists merely by reading all the existing literature of anthropology, including the voluminous works on kindred studies and the innumerable periodicals; we shall become anthropologists only at the moment when, having mastered the method, we become investigators of living human individuals.

We must, in short, be producers, or nothing at all; assimilation is useless. For example, let us suppose that a certain teacher has studied anthropology in books: if, after that, he is incapable of making practical observations upon his own pupils, to what end does his theoretical knowledge serve him? It is evident that theoretic study can have no other purpose than to guide us in the interpretation of data gathered directly from nature.

Our only book should be the living individual; all the rest taken together form only the necessary means for reading it.

2. The Passage from Analysis to Synthesis.—Assuming that we have learned how to gather anthropological data with a rigorously exact technique, and that we possess a theoretic knowledge and tables of comparative data: all this together does not suffice to qualify us as interpreters of nature. The marvellous reading of this amazing book demands on our part still other forms of prepara[Pg 27]tion. In gathering the separate data, it may be said that we have learned how to spell, but not yet how to read and interpret the sense. The reading must be accomplished with broad, sweeping glances, and must enable us to penetrate in thought into the very synthesis of life. And it is the simple truth that life manifests itself through the living individual, and in no other way. But through these means it reveals certain general properties, certain laws that will guide us in grouping the living individuals according to their common properties; it is necessary to know them, in order to interpret individual differences dependent upon race, age, and sex, and upon variations due to the effort of adaptation to environment, or to pathological or degenerative causes. That is to say, certain general principles exist, which serve to make us interpreters of the meaning, when we read in the book of life.

This is the loftiest part of our work, carrying us above and beyond the individual, and bringing us in contact with the very fountain-heads of life, almost as though it were granted us to materialise the unknowable. In this way we may rise from the arid and fatiguing gathering of analytical data, toward conceptions of noble grandeur, toward a positive philosophy of life; and unveil certain secrets of existence, that will teach us the moral norms of life.

Because, unquestionably, we are immoral, when we disobey the laws of life; for the triumphant rule of life throughout the universe is what constitutes our conception of beauty and goodness and truth—in short, of divinity.

The technical method of proceeding toward synthesis, we may find well defined in biology: the data gathered by measurement can be grouped according to the statistical method, be represented graphically and calculated by the application of mathematics to biology: to-day, indeed, biometry and biostatistics tend to assume so vast a development as to give promise of forming independent sciences.

The method in biology, considered as a whole, may be compared to the microscope and telescope, which are instruments, and yet enable us to rise above and beyond our own natural powers and come into contact with the two extremes of infinity; the infinitely little and the infinitely large.

Objections and Defences.—One of the objections made to pedagogical anthropology is that it has not yet a completely defined con[Pg 28]tent, on which to base an organic system of instruction and reliable general rules.

It is the method alone that enables us to be eloquent in defence of pedagogic anthropology, against such an accusation. For the accusation itself is the embodiment of a conception of a method differing widely from our own: it is the accusation made by speculative science, which, resting on the basis of a content, refuses to acknowledge a science that is still lacking and incomplete in its content, because it is unable to conceive that a science may be essentially summed up in its method, which makes it a means of revelation.