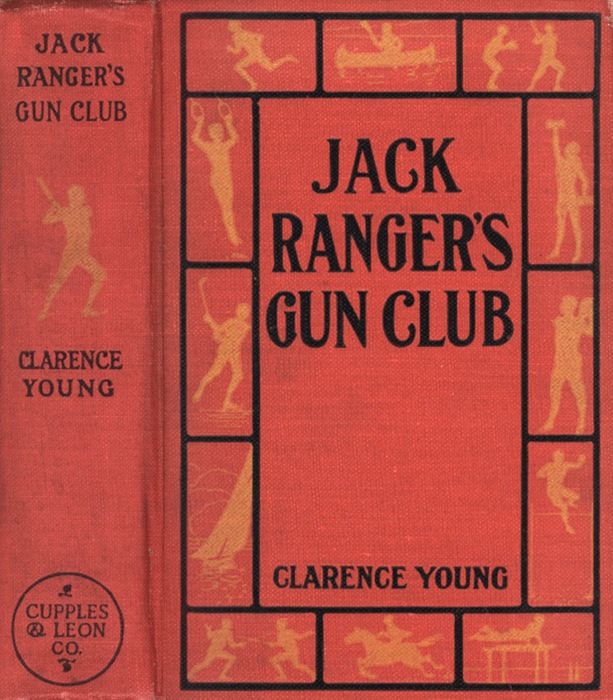

Title: Jack Ranger's Gun Club; Or, From Schoolroom to Camp and Trail

Author: Clarence Young

Illustrator: Charles Nuttall

Release date: May 4, 2014 [eBook #45582]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Juliet Sutherland, Sean Bartell and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

BY

CLARENCE YOUNG

AUTHOR OF “JACK RANGER’S SCHOOLDAYS,”

“JACK RANGER’S WESTERN TRIP,”

“JACK RANGER’S OCEAN CRUISE,” “THE MOTOR BOYS,”

“THE MOTOR BOYS IN THE CLOUDS,” ETC.

ILLUSTRATED

NEW YORK

CUPPLES & LEON COMPANY

BOOKS BY CLARENCE YOUNG

THE JACK RANGER SERIES

12mo. Finely Illustrated

THE MOTOR BOYS SERIES

(Trade Mark, Reg. U. S. Pat. Of.)

12mo. Illustrated

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

|---|---|---|

| I | Jack Wins a Race | 1 |

| II | The New Boy | 12 |

| III | A Curious Lad | 22 |

| IV | Bully Snaith | 30 |

| V | A German-French Alliance | 36 |

| VI | A | 46 |

| VII | A Strange Confession | 55 |

| VIII | The Midnight Feast | 64 |

| IX | An Alarm of Fire | 71 |

| X | Saving the Flags | 78 |

| XI | The Gun Club | 85 |

| XII | Will Runs Away | 93 |

| XIII | Off on the Trip | 101 |

| XIV | The Broken Train | 108 |

| XV | Jack Meets a Girl | 117 |

| XVI | A Dangerous Descent | 125 |

| XVII | Thirsty on the Desert | 133 |

| XVIII | Lost in the Bad Lands | 146 |

| XIX | A Perilous Slide | 155 |

| XX | Long Gun Is Afraid | 162 |

| XXI | The Deadly Gas | 171 |

| XXII | An Unexpected Encounter | 178 |

| XXIII | Another Night Scare | 184 |

| XXIV | Jack Gets a Bear | 191 |

| XXV | Some Peculiar Marks | 199 |

| XXVI | The Spring Trap | 206 |

| XXVII | Ordered Back | 212 |

| XXVIII | Will Saves Jack’s Life | 223 |

| XXIX | The Blizzard | 231 |

| XXX | Jack’s Hazardous Plan | 238 |

| XXXI | A Perilous Ride | 245 |

| XXXII | Into a Strange Camp | 254 |

| XXXIII | Held Captives | 262 |

| XXXIV | The Mystery Explained | 272 |

| XXXV | Jack Meets Mabel—Conclusion. | 283 |

“Now, then, are you all ready?”

“I’m as ready as I ever shall be,” answered Jack Ranger, in reply to the question from Sam Chalmers. “Let her go!”

“Wait a minute,” cried Dock Snaith. “I want to put a little more oil on my oarlocks.”

“Oh, you’re always fussing about something, Dock,” said Sam. “It looks as if you didn’t want to go into this race after all your boasting.”

“That’s what it does,” came from Nat Anderson.

“Hu! Think I can’t beat Jack Ranger?” replied Dock with a sneer as he began putting more oil on the oarlock sockets. “I could beat him rowing with one hand.”

“Get out!” cried Sam. “You’ve got a swelled head, Dock.”

“I have, eh?”

“Now are you ready?” asked Sam again, as he stepped forward and raised the pistol, ready to fire the starting shot in a small race between Jack Ranger, one of the best-liked students at Washington Hall, and Dock Snaith, a bullying sort of chap, but who, in spite of his rather mean ways, had some friends.

“I guess I’m all ready now,” replied Dock, as he got on the center of the seat and adjusted the oars.

“Better send for your secretary to make sure,” said Nat Anderson, and at this there was a laugh from the students who had gathered to see the contest. “Rusticating rowlocks, but you’re slow!”

“You mind your own business, Anderson,” came from the bully, “or I’ll make you.”

“It’ll take more than you to make me,” responded Nat boldly, for more than once he had come into conflict with Snaith and did not fear him.

“It will, eh? Well, if I can get out of this boat——”

“Aw, go on! Row if you’re going to!” exclaimed Sam. “Think I haven’t anything to do except stay here and start this race? You challenged Jack, now go ahead and beat him—if you can.”

“Yes, come on,” added Jack, a tall, good-looking, bronzed youth, who sat on the seat in the small boat, impatiently moving the oars slowly to and fro.

“Oh, I’ll beat you,” said the bully confidently. “You can give the word whenever you’re ready, Chalmers.”

“Ah! that’s awfully kind of you, really it is,” said Jack in a high, falsetto voice, which produced another laugh.

Dock Snaith scowled at Jack, but said nothing. There was a moment’s delay, while Sam looked down the course to see if all was clear on Rudmore Lake, where the contest was taking place.

“I’m going to fire!” cried Sam.

The two contestants gripped their oars a little more firmly, they leaned forward, ready to plunge them into the water and pull a heavy stroke at the sound of the pistol. Their eyes were bright with anticipation, and their muscles tense.

Crack! There was a puff of white smoke, a

little sliver of flame, hardly noticeable in the bright

October sunlight; then samecame a splash in the water as the broad blades

were dipped in, and the race was on.

“Jack’s got the lead! Jack’s ahead!” cried the friends of our hero, as they ran along the shore of the lake.

“Dock is only tiring him out,” added the adherents of the school bully. “He’ll come in strong at the finish.”

“He will if he doesn’t tire out,” was Nat Anderson’s opinion. “Dock smokes too many cigarettes to be a good oarsman.”

“I suppose you think Ranger will have it all his own way?” spoke Pud Armstrong, a crony of Snaith.

“Not necessarily,” was Nat’s answer as he jogged along. “But I think he’s the better rower.”

“We’ll see,” sneered Pud.

“Yes, we’ll see,” admitted Nat.

The two contestants were now rowing steadily.

They had a little over a mile to go to reach the

Point, as istit was called; that

being the usual limit of impromptu racing events.

The contest between Jack Ranger and Dock Snaith was the result of an argument on oarsmanship, which had taken place in the school gym the night before. It was shortly after the opening of the term at Washington Hall, and in addition to football, which would soon be in full sway, there was rowing to occupy the attention of the students, for the lake, on the shores of which the academy was situated, was well adapted for aquatic sports.

The talk had turned on who were the best individual oarsmen in the school, and Jack Ranger’s friends lost no time in mentioning him as the champion, for more than once he had demonstrated that in a single shell, or a large, eight-oared one, he could pull a winning stroke.

Dock Snaith’s admirers were not slow in advocating his powers, and the bully, not at all backward to boast of his own abilities, had challenged Jack to a small race the next day. Jack had consented, and the contest was now under way.

“Jack’s going to walk right away from him,” said Dick Balmore, otherwise known as “Bony,” from the manner in which his inner skeleton was visible through his skin, and from a habit he had of cracking his knuckles.

“Don’t be too sure,” cautioned Sam. “Snaith has lots of muscle. Our only hope is that he won’t last. His wind isn’t very good, and Jack has set him a fast clip.”

“Go on, Dock,” cried Pud Armstrong. “Go on! You can do him easy!”

Dock nodded, the boats both being so close to shore that ordinary conversation could easily be heard.

“That’s the stuff, Jack!” cried Nat Anderson. “Keep it up!”

Jack had increased his stroke two or three more per minute, and Dock found it necessary to do likewise, in order not to get too far behind. He was letting his rival set the pace, and so far had been content merely to trail along, with the sharp bow of his frail craft lapping the stern of Jack’s a few feet.

“Dock’s holding back for the finish,” remarked Pud as he raced along, and in passing Nat he dug his elbow into the side of Jack’s chum.

“Well, if he is, that’s no reason why you should try to puncture my inner tubes,” expostulated Nat. “I’ll pitch you into the lake if you do that again.”

“Aw, you’re getting mad ’cause Jack’s going to lose,” sneered Pud.

“That’s what he is,” added Glen Forker, another crony of the bully.

“Am I? Just wait,” was all Nat answered as he rubbed his ribs. “Slithering side saddles! but you gave me a dig!”

The contestants were now rowing more rapidly, and the students on shore, who were following the race, had to increase their pace to keep up to them.

“Hit it up a little, Jack!” called Sam. “You’ve got him breathing hard.”

“He has—not! I’m—I’m all right,” answered Dock from his boat, and very foolishly, too, for he was getting winded, and he needed to save all his breath, and not waste it in talking. Besides, the halting manner in which he answered showed his condition. Sam noticed it at once.

“You’ve got him! You’ve got him, Jack!” he cried exultantly. “Go on! Row hard!”

“Say, that ain’t fair!” cried Pud Armstrong.

“What isn’t?” asked Sam.

“Telling Jack like that. Let him find out about Dock.”

“I guess I know what’s fair,” replied Sam with a withering look. “I’ll call all I want to, and don’t you interfere with me, or it won’t be healthy for you.”

Pud subsided. Sam Chalmers was the foremost authority, among the students, on everything connected with games and sports, for he played on the football eleven, on the nine, and was a general leader.

“You’d better hit it up a bit, Dock,” was Glen Forker’s advice to his crony, as he saw Jack’s lead increasing. “Beat him good and proper.”

“He’ll have to get up earlier in the morning if he wants to do that,” commented Bony Balmore, as he cracked his big knuckles in his excitement.

And it was high time for Dock to do some rowing. Jack had not been unaware of his rival’s difficulty, and deciding that the best way to win the race would be to make a spurt and tire him out before the finish, he “hit up a faster clip,” the broad blades of the oars dipping into the water, coming out and going in again with scarcely a ripple.

“There he goes! There he goes!” cried Sam. “That’s the ticket, Jack!”

“Go on! Go on!” yelled Nat.

“Get right after him, Dock,” advised Pud.

“You can beat him! Do it!” cried Glen.

But it was easier said than done. Jack was rowing his best, and when our hero did that it was “going some,” as Sam used to say. He had opened up quite a stretch of water between his boat and Dock’s, and the bully, with a quick glance over his shoulder, seeing this, resolved to close it up and then pass his rival. There was less than a quarter of a mile to the finish, and he must needs row hard if he was to win.

Dock bent to the task. He was a powerfully built lad, and had he been in good condition there is no question but what he could have beaten Jack. But cigarette-smoking, an occasional bottle of beer, late hours and too much rich food had made him fat, and anything but an ideal athlete.

Still he had plenty of “row” left in him yet, as he demonstrated a few seconds later, when by increasing not only the number of his strokes per minute, but also putting more power into them, he crept up on Jack, until he was even with him.

Jack rowed the same rate he had settled on to pull until he was within a short distance of the finish. He was saving himself for a spurt.

Suddenly Dock’s boat crept a little past Jack’s.

“There he goes! There he goes!” cried Pud, capering about on the bank in delight. “What did I tell you?”

“He’ll win easy,” was Glen’s opinion.

“It isn’t over yet,” remarked Nat quietly, but he glanced anxiously at Sam, who shook his head in a reassuring manner.

Dock began to increase his lead. Jack looked over his shoulder for one glance at his rival’s boat. The two were now rowing well and swiftly.

“Go on, Jack! Go on! Go on!” begged Bony, cracking his eight fingers and two thumbs in rapid succession, like a battery of popguns. “Don’t let him beat you!”

Dock was now a boat’s length ahead, and rowing well, but a critical observer could notice that his breathing distressed him.

“Now’s your chance, Jack!” yelled Sam.

But Jack did not need any one to tell him. Another glance over his shoulder at his rival showed him that the time had come to make the spurt. He leaned forward, took a firmer grip on the ash handles, and then gave such an exhibition of rowing as was seldom seen at Washington Hall.

Dock saw his enemy coming, and tried to stave off defeat, but it was no use. He was completely fagged out. Jack went right past him, “as if Dock was standing still,” was the way Sam expressed it.

“Go on! Go on!” screamed Pud. “You’ve got to row, Dock!”

But Dock could not imitate the pace that Jack had set. He tried, but the effort was saddening. He splashed, and the oars all but slipped from his hands. His heart was fluttering like that of a wounded bird.

“You’ve got him! You’ve got him, Jack!” yelled Nat; and, sure enough, Jack Ranger had.

On and on he rowed, increasing every second the open water between his boat and his rival’s, until he shot past the Point, a winner by several lengths.

“That’s the way to do it!”

“I knew he’d win!”

“Three cheers for Jack Ranger!”

These, and other cries of victory, greeted our hero’s ears as he allowed his oars to rest on the water flat, while he recovered his wind after the heart-breaking finish.

“Well, Dock could beat him if he was in training,” said Pud doggedly.

“That’s what he could,” echoed Glen.

“Not in a thousand years!” was Nat’s positive assertion.

The boys crowded to the float that marked the finish of the course. Jack reached it first, and stepped out of his shell, being greeted by his friends. Then Dock rowed slowly up. His distress showed plainly in his puffy, white face.

He got out clumsily, and staggered as he clambered upon the float.

“Hard luck, old man,” said Jack good-humoredly.

“I don’t want your sympathy!” snapped Dock. “I’ll row you again, and I’ll beat you!”

Jack had held out his hand, but the bully ignored it. He turned aside, and whether the float tilted, or whether Snaith tottered because of a cramp in his leg, was never known, but he staggered for a moment, tried unsuccessfully to recover his balance, and then plunged into the lake at one of the deepest spots, right off the float.

“There goes Dock!”

“Pull him out!”

“Yes, before he gets under the float!”

“He can’t swim! He’s too exhausted!”

These were some of the expressions the excited lads shouted as they surged forward to look at the spot where Dock had disappeared. A string of bubbles and some swirling eddies were all that marked the place.

The float began to tilt with the weight of so many boys on one edge.

“Stand back!” cried Jack Ranger. “Stand back, or we’ll all be in the lake!”

They heeded his words, and moved toward the middle of the platform.

“Some one ought to go in after him,” said Pud Armstrong, his teeth fairly chattering from fright and nervousness. “I—I can’t swim.”

“Look out!” cried Jack. “I’m going in!”

He began pulling off the sweater which some of the lads had helped put on him, when he stepped from the shell all perspiration.

He poised for an instant on the edge of the float, looking down into the dark waters, beneath which Dock had disappeared, and then dived in.

“Get one of the boats out. Maybe he won’t come

up near the float,” orderordered Sam

Chalmers, and several lads hurriedly shoved out into the lake a broad barge,

which could safely be used by Jack in getting Dock out of the water, if he was

fortunate enough to find the youth.

“Queer he doesn’t come up,” spoke Glen in a whisper.

“Who—Dock or Jack?” asked Bony, cracking his finger knuckles in double relays.

“Dock.”

“He’s too exhausted,” replied Bony. “Can’t swim. But Jack’ll get him.”

How long it seemed since Jack had dived down! The swirl he made had subsided, and the water was almost calm again. Anxiously the lads on the float and shore watched to see him reappear. Would he come up alone, or would he bring Dock with him?

“Maybe Jack hit his head on something,” suggested Nat.

“Jack knows how to dive, and it’s deep here,” said Sam. “I guess he’ll come up all right, but——”

He did not finish the sentence. At that moment there was a disturbance beneath the surface of the lake. A head bobbed up.

“There’s Jack!” cried Bony delightedly.

A white arm shot up and began sweeping the water.

“He’s got him!” yelled Nat. “He’s got Dock!”

Sure enough, Jack had come to the surface, encircling in his left arm the unconscious form of Dock Snaith, while with his sturdy right he was swimming slowly toward the float.

“The boat! the boat! It’s nearer!” cried Sam, for Jack had come up at some distance from the little pier and closer to the rowboat which had put out from shore.

Jack heard and understood. Turning, he began swimming toward the craft, and the lads in it rowed toward him. A few seconds later Jack had clutched the gunwale, holding Dock’s head out of water.

Several eager hands reached down to grasp our hero.

“Take—take him first,” he said pantingly. “I’m—I’m all right.”

Dock was hauled into the boat.

“Now row ashore. I’ll swim it,” went on Jack. “Get the water out of him as soon as you can. He—he was right on the bottom. Struck—struck on the—on the float, I guess.”

“We’ll take you in,” cried Bob Movel.

“Sure! There’s lots of room,” added Fred Kaler.

“No. Get Dock on shore,” ordered Jack, and they obeyed.

Relieved of his burden, and having recovered his wind, Jack swam slowly to the float. The boat reached it some time ahead of him, and Dock was lifted out, while, under the direction of Sam Chalmers, the students administered first aid to the drowned.

Dock was turned over on his face, a roll of coats having been placed under his stomach to aid in forcing the water out of him. There was no need to remove his clothing, as he and Jack were clad only in rowing trunks and light shirts.

“Now turn him over on his back and hold out his tongue, fellows,” directed Sam, and this was done, the tongue being held by Nat Anderson, who used his handkerchief to prevent it slipping away. This was done so that it might not fall back into the throat and prevent Dock from breathing.

“Now work his arms! Over his head! Press up his diaphragm and start artificial respiration,” went on Sam, and under the ministrations of the lads, Dock soon began to breathe again.

He sighed, took in a long breath naturally, opened his eyes, and gasped feebly.

“He’s all right now,” said Sam in a relieved tone. “How do you feel, Dock?”

“All—right—I—guess. My head——”

He closed his eyes again. Sam passed his hand over the prostrate lad’s skull.

“He’s got a nasty cut there,” he said, as he felt of a big lump, “but I guess it’s not serious. We must get him up to the school.”

“Come on, let’s carry him,” suggested Nat.

“Never mind—here comes Hexter!” cried Bony.

As he spoke the chug-chugging of an automobile was heard, and a touring car came along the road down to the float. It was a machine kept at Washington Hall, and used by the teachers, and, occasionally, when Hexter, the chauffeur, would allow it, by the students.

“Dr. Mead sent me down to see what the matter was,” said Hexter as he stopped the car. “He saw a crowd on the float and thought something might have happened.”

“There has,” replied Sam. “Here, Hexter, help us get Dock into the car, and then throw on all the speed you’ve got, if you have to blow out a spark-plug.”

“Is he—is he dead?” asked Hexter quickly.

“No; only stunned. Lively, now!”

Hexter aided the boys in lifting Dock into the machine, and then he made speed to the school, where the injured lad was cared for by Dr. Henry Mead, the master of Washington Hall.

“Well, that was an exciting finish to the race,” remarked Jack as he walked up from the float to the shore, surrounded by some of his chums, after Dock had been taken away.

“He oughtn’t to try to row,” said Fred Kaler. “He hasn’t got the staying powers.”

“Well, he didn’t have to-day,” observed Jack; “but if he would only train, he’d make a good oarsman. He’s got lots of muscle. I hope he isn’t hurt much.”

“He’ll be all right in a few days,” was Nat’s opinion. “Say, Jack, but you’re shivering.”

“Yes, that water’s a little cooler than it was Fourth of July.”

“Here, put a couple of sweaters on,” went on Nat, and soon Jack was warmly wrapped up.

“Now run up and change your duds,” advised Bony, and Jack broke into a dog-trot, his friends trailing along behind him and discussing the race and the accident.

While they are thus engaged I will take the opportunity to tell you a little something about Jack Ranger and his friends, so that you who have not previously read of him may feel better acquainted with our hero.

The first volume of this series was called “Jack Ranger’s Schooldays,” and in it there was related some of the fun Jack and his special friend, Nat Anderson, had in their native town of Denton. So exciting were some of their escapades that it was decided to send them off to boarding-school, and Washington Hall, sometimes called Lakeside Academy, from the fact that it was located on the shore of Lake Rudmore, was selected. There Jack made friends with most of the students, including some who have already been mentioned in this present tale. He incurred the enmity of a bully, Jerry Chowden, who, however, was not now at the academy, as you will presently learn.

Jack’s home was with three maiden aunts, the Misses Angelina, Josephine and Mary Stebbins, who took good care of him. In the first volume there was related something of a certain mystery concerning Jack’s father, Robert Ranger, and how he had to go into hiding in the West because of complications over a land deal.

In the second volume of the series, “Jack Ranger’s Western Trip,” was related what happened to Jack, Nat Anderson, and a half-breed Indian, John Smith, whose acquaintance Jack had made at Washington Hall, when they went West in search of Mr. Ranger.

They journeyed to a ranch, owned by Nat’s uncle, and they had many exciting times, not a few of which were caused by a certain faker, whose real name was Hemp Smith, but who assumed the title Marinello Booghoobally, and various other appellations as suited his fancy.

Mr. Ranger was located, but only after the boys had suffered many hardships and gone through not a few perils, and Jack was happy to be able to bring his father back East, there being no longer any reason for Mr. Ranger remaining in exile.

“Jack Ranger’s School Victories,” was the title of the third volume, and in that was told of Jack’s successes on track, gridiron and diamond. Hemp Smith and Jerry Chowden made trouble for him, but he bested them. He had plenty of fun, for which two teachers at the school, Professor Socrat, an instructor in French, and Professor Garlach, a German authority, furnished an excuse.

But Jack’s activities did not all center about the school. There was told in the fourth volume, “Jack Ranger’s Ocean Cruise,” what happened to him and his chums when they went camping one summer. Jack, Nat Anderson, Sam Chalmers, Bony Balmore, and an odd character, Budge Rankin, who chewed gum and ran his words together, went off to live in the woods, near the seacoast, for a few weeks.

There they fell in with a scoundrel named Jonas Lavine, who was aided in his plots by Jerry Chowden and Hemp Smith.

Jack and his chums stumbled upon a printing plant, maintained in a cave by Lavine and his confederates, where bogus bonds were made. Before they had time to inform the authorities Jack and Nat were captured by Lavine and sent to sea in a ship in charge of Captain Reeger, a tool of Lavine.

Jack learned that Captain Reeger wanted to be freed from the toils of Lavine, and our hero agreed to assist him, in return for which the captain said he would aid Jack.

Jack and Nat managed to get out of the cabin in which they were confined. As they were about to escape from the Polly Ann a terrible storm came up, and the ship was wrecked. But not before Jerry Chowden had boarded her, to help in keeping Jack and Nat captives.

They had many hardships, afloat on a raft in a fog, and saved Jerry Chowden from drowning. Finally they were rescued, and Lavine and his confederates were arrested, Captain Reeger being exonerated. Jerry Chowden fled to the West, fearing arrest should he remain in the East. Jack and his chums were reunited, and they again enjoyed life under the canvas, until it was time to resume their studies at Washington Hall, where the opening of this story finds them.

As Jack and his chums walked up the gravel path to the dormitories, where our hero intended to get into dry clothes, the group of youths chatting eagerly of the events which had just taken place passed a lad standing beneath a clump of trees. The latter, instead of coming to join the throng, turned away.

“Who’s that?” asked Jack of Bony Balmore. “I don’t remember to have seen him before.”

“He’s a new boy,” replied Bony, cracking three finger knuckles in his absent-minded way.

“What’s his name?”

“Will Williams.”

“Looks like a nice sort of chap,” added Nat.

“But his face is sad,” said Jack slowly. “I wonder why he should be sad when he’s at such a jolly place as Washington Hall?”

“Maybe he’s lonesome,” suggested Fred Kaler.

“Give him a tune on your mouth-organ, and he’ll be more so,” spoke Bob Movel, but he took good care to get beyond the reach of Fred’s fist, at this insult to his musical abilities.

“Let’s make friends with him,” went on Jack. “Hey, Williams, come on over and get acquainted,” he called.

But the new boy, instead of answering, or turning to join the happy crowd of students, kept on walking away.

“That’s funny,” said Jack, with a puzzled look at his chums. “Fellows, there’s something wrong about that boy. I can tell by his face, and I’m going to find out what it is.”

“You’d better get dry first,” suggested Nat.

“I will, but later I’m going to make that lad’s acquaintance. He looks as if he needed a friend.”

“There’s Hexter!” exclaimed Jack as he saw the chauffeur slowly running the automobile to the garage. “Hello, Hexter, is Snaith all right?”

“I think so,” replied the automobilist. “Dr. Mead says the hurt on his head doesn’t amount to much, and that he is suffering mostly from shock. He’ll be all right in a day or so.”

“That’s good,” said Jack. “I don’t want him to be laid up right after I won the race from him.”

The students began to disperse, Jack to remove his wet clothes, and the others to retire to their rooms to get ready for the summons to supper, which would soon sound.

“Why, Mr. Ranger!” exclaimed Socker, the janitor at Washington Hall, as he saw Jack entering the gymnasium, “you’re all wet.”

“Yes, it’s a trifle difficult to fall in the lake and keep dry, especially at this time of year,” went on Jack. “But I say, Socker, get me a couple of good, dry, heavy towels, will you? I want to take a rub-down.”

“I certainly will, Mr. Ranger. So you fell in the lake, eh?”

“No, I jumped in.”

“Jumped in? Why, that reminds me of what happened when I was fighting in the Battle of the Wilderness, in the Civil War. We were on the march, and we came to a little stream. The captain called for us to jump over, but——”

“Say, Socker, if it’s all the same to you will you chop that off there, and make it continued in our next? I’m cold, and I want to rub-down. Get me the towels, and then I’ll listen to that yarn. If there’s one kind of a story I like above all others, it’s about war. I want to hear what happened, but not now.”

“Do you really? Then I’ll tell you after you’ve rubbed down,” and Socker hurried off after the towels. He was always telling of what he called his war experiences, though there was very much doubt that he had ever been farther than a temporary camp. He repeated the same stories so often that the boys had become tired of them, and lost no chance to escape from his narratives.

“There you are, Mr. Ranger,” went on the janitor as he came back with the towels. “Now, as soon as you’re dry I’ll tell you that story about the Battle of the Wilderness.”

“You’ll not if I know it,” said Jack to himself, as he went in the room where the shower-baths were, to take a warm one. “I’ll sneak out the back way.”

Which he did, after his rub-down, leaving Socker sitting in the main room of the gym, waiting for him, and wondering why the lad did not come out to hear the war story.

Jack reached his room, little the worse for his experience at the lake. He possessed a fine appetite, which he was soon appeasing by vigorous attacks on the food in the dining-room.

“I say, Jack,” called Nat, “have you heard the latest?”

“What’s that? Has the clock struck?” inquired Jack, ready to have some joke sprung on him.

“No, but Fred Kaler has composed a song about the race and your rescue. He’s going to play it on the mouth-organ, and sing it at the same time to-night.”

“I am not, you big duffer!” cried Fred, throwing a generous crust of bread at Nat, but first taking good care to see that Martin, the monitor, was not looking.

“Sure he is,” insisted Nat.

“Tell him how it goes,” suggested Bony.

“It’s to the tune of ‘Who Put Tacks in Willie’s Shoes?’” went on Nat, “and the first verse is something like this——”

“Aw, cheese it, will you?” pleaded Fred, blushing, but Nat went on:

“How’s that?” asked Nat, amid laughter.

“Punk!” cried one student.

“Put it on ice!” added another.

“Can it!”

“Cage it!”

“Put salt on its tail! It’s wild!”

“Put a new record in; that one scratches.”

These were some of the calls that greeted Nat’s rendition of what he said was Fred’s song.

“I never made that up!” cried the musical student. “I can make better verse than that.”

“Go on, give us the tune,” shouted Sam.

“That’s right—make him play,” came a score of calls.

“Order, young gentlemen, order!” suddenly interrupted the harsh voice of Martin, the monitor. “I shall be obliged to report you to Dr. Mead unless you are more quiet.”

“Send in Professors Socrat and Garlach,” advisdadvised Jack. “They

can keep order.”

“That’s it, and we’ll get them to sing Fred’s song,” added Sam Chalmers.

“Ranger—Chalmers—silence!” ordered Martin, and not wishing to be sent to Dr. Mead’s office the two lively students, as well as their no less fun-loving companions, subsided.

Quiet finally reigned in the regions of Washington Hall, for the students had to retire to their rooms to study. There were mysterious whisperings here and there, however, and occasionally shadowy forms moved about the corridors, for, in spite of rules against it, the lads would visit each other in their rooms after hours. Several called on Jack to see how he felt after his experience. They found him and Nat Anderson busy looking over some gun catalogues.

“Going in for hunting?” asked Sam.

“Maybe,” replied Jack. “Say, there are some dandy rifles in this book, and they’re cheap, too. I’d like to get one.”

“So would I,” added Sam.

“And go hunting,” put in Bony, cracking his finger knuckles, as if firing off an air-rifle.

“It would be sport to organize a gun club, and do some hunting,” went on Jack. “Only I’d like to shoot bigger game than there is around here. Maybe we can——”

“Hark, some one’s coming! It’s Martin,” said Fred Kaler in a whisper.

Jack’s hand shot out and quickly turned down the light. Then he bounded into bed, dressed as he was. Nat followed his example. It was well that they did so, for a moment later there came a knock on their door, and the voice of Martin, the monitor, asked:

“Ranger, are you in bed?”

“Yes,” replied our hero.

“Anderson, are you in bed?”

“Yes, Martin.”

“Humph! I thought I heard voices in your room.”

Jack replied with a snore, and the monitor passed on.

“You fellows had better take a sneak,” whispered Jack, when Martin’s footsteps had died away. “He’s watching this room, and he may catch you.”

The outsiders thought this was good advice, and soon Nat and Jack were left alone.

“Did you mean that about a gun club?” asked Nat.

“Sure,” replied his chum, “but we’ll talk about it to-morrow. Better go to sleep. Martin will be sneaking around.”

Jack was up early the next morning, and went down to the lake for a row before breakfast. As he approached the float, where he kept his boat, he saw a student standing there.

“That looks like the new chap—Will Williams,” he mused. “I’ll ask him to go for a row.”

He approached the new lad, and was again struck by a peculiar look of sadness on his face.

“Good-morning,” said Jack pleasantly. “My name is Ranger. Wouldn’t you like to go for a row?”

Will Williams turned and looked at Jack for several seconds without speaking. He did not seem to have heard what was said.

“Perhaps he’s a trifle deaf,” thought Jack, and he asked again more loudly:

“Wouldn’t you like to go for a row?”

“I don’t row,” was the answer, rather snappily given.

“Well, I guess I can manage to row both of us,” was our hero’s reply.

“No, I’m not fond of the water.”

“Perhaps you like football or baseball better,” went on Jack, a little puzzled. “We have a good eleven.”

“I’m not allowed to play football.”

“Maybe you’d like to go for a walk,” persisted Jack, who had the kindest heart in the world, and who felt sorry for the lonely new boy. “I’ll show you around. I understand you just came.”

“Yes; I arrived yesterday morning.”

“Would you like to take a walk? I don’t know but what I’d just as soon do that as row.”

“No, I—I don’t care for walking.”

The lad turned aside and started away from the lake, without even so much as thanking Jack for his effort to make friends with him.

“Humph!” mused Jack as he got into his boat. “You certainly are a queer customer. Just like a snail, you go in your house and walk off with it. There’s something wrong about you, and I’m going to find out what it is. Don’t like rowing, don’t like walking, afraid of the water—you certainly are queer.”

“Hello, Dock, I’m glad to see you out of the hospital,” remarked Jack one morning about a week later, when his boating rival was walking down the campus. “You had quite a time of it.”

“Yes,” admitted Snaith, “I got a nasty bump on the head. Say, Ranger, I haven’t had a chance to thank you for pulling me out. I’m much obliged to you.”

“Oh, that’s all right. Don’t mention it,” answered Jack. “If I hadn’t done it, some one else would.”

“Well, I’m glad you did. But say, I still think I can beat you rowing. Want to try it again?”

“I won’t mind, when you think you’re well enough.”

“Oh, I’ll be all right in a day or so.”

“Be careful. You don’t want to overdo yourself.”

“Oh, I’ll beat you next time. But I want to race for money. What do you say to twenty-five dollars as a side bet?”

“No, thanks, I don’t bet,” replied Jack quietly.

“Hu! Afraid of losing the money, I s’pose,” sneered Dock.

“No, but I don’t believe in betting on amateur sport.”

“Well, if you think you can beat me, why don’t you bet? It’s a chance to make twenty-five.”

“Because I don’t particularly need the money; and when I race I like to do it just for the fun that’s in it.”

“Aw, you’re no sport,” growled Snaith as he turned aside. “I thought you had some spunk.”

“So I have, but I don’t bet,” replied Jack quickly. He felt angry at the bully, but did not want to get into a dispute with him.

“Hello, Dock,” called Pud Armstrong, as, walking along with Glen Forker, he caught sight of his crony. “How you feeling?”

“Fine, but I’d feel better if there weren’t so many Sunday-school kids at this institution. I thought this was a swell place, but it’s a regular kindergarten,” and he looked meaningly at Jack.

“What’s up?” asked Pud.

“Why, I wanted to make a little wager with Ranger about rowing him again, but he’s afraid.”

“It isn’t that, and you know it,” retorted our hero quickly, for he overheard what Snaith said. “And I don’t want you to go about circulating such a report, either, Dock Snaith.”

With flashing eyes and clenched fists Jack took a step toward the bully.

“Oh, well, I didn’t mean anything,” stammered Snaith. “You needn’t be so all-fired touchy!”

“I’m not, but I won’t stand for having that said about me. I’ll race you for fun, and you know it. Say the word.”

“Well—some other time, maybe,” muttered Snaith, as he strolled off with his two cronies.

It was that afternoon when Jack, with Nat Anderson, walking down a path that led to the lake, came upon a scene that made them stop, and which, later, was productive of unexpected results.

The two friends saw Dock Snaith, together with Pud Armstrong and Glen Forker, facing the new boy, Will Williams. They had him in a corner of a fence, near the lake, and from the high words that came to Jack and Nat, it indicated that a quarrel was in progress.

“What’s up?” asked Nat.

“Oh, it’s that bully, Snaith, making trouble for the freshman,” replied Jack. “Isn’t it queer he can’t live one day without being mean? Snaith, I’m speaking of. He’s a worthy successor to Jerry Chowden.”

“Well, you polished off Chowden; maybe you can do the same to Snaith.”

“There’s no question but what I can do it, if I get the chance. He’s just like Jerry was—always picking on the new boys, or some one smaller than he is.”

“Come on, let’s see what’s up.”

They did not have to go much closer to overhear what was being said by Snaith and his cronies on one side, and Will on the other.

“I say, you new kid, what’s your name?” asked the bully.

“Yes, speak up, and don’t mumble,” added Pud.

“My name is Williams,” replied the new lad. “I wish you would let me go.”

“Can’t just yet, sonny,” said Glen. “We are just making your acquaintance,” and he punched Will in the stomach, making him double up.

“Hold on, there,” cried Snaith. “I didn’t ask you to make a bow. Wait until you’re told,” and he shoved the lad’s head back.

“Now you stop that!” exclaimed Will with considerable spirit.

“What’s that! Hark to him talking back to us!” exclaimed Pud. “Now you’ll have to bow again,” and once more he punched the new boy.

“Please let me alone!” cried Will. “I haven’t done anything to you.”

“No, but you might,” spoke Snaith. “Have you been hazed yet?”

“Of course he hasn’t,” added Glen. “He came in late, and he hasn’t been initiated. I guess it’s time to do it.”

“Sure it is,” agreed the bully with a grin. “Let’s see—we’ll give him the water cure.”

“That’s it! Toss him in the lake and watch him swim out!” added Pud. “Come on, Glen, catch hold!”

“Oh, no! Please don’t!” begged Will.

“Aw, dry up! What you howling about?” asked Pud. “Every new boy has to be hazed, and you’re getting off easy. A bath will do you good. Let’s take him down to the float. It’s real deep there.”

“Oh, no! No! Please don’t! Anything but that!” begged Will. “I—I can’t swim.”

“Then it’s time you learned,” said Snaith with a brutal laugh. “Catch hold of his other leg, Pud.”

They quickly made a grab for the unfortunate lad, and, despite his struggles, carried him toward the lake. It was not an uncommon form of hazing, but it was usually done when a crowd was present, and the hazing committee always took care to find out that the candidates could swim. In addition, there were always lads ready to go to the rescue in case of accident. But this was entirely different.

“Oh, don’t! Please don’t!” begged Will. “I—I don’t want to go in the water. Do anything but that.”

“Listen to him cry!” mocked Glen. “Hasn’t he got a sweet voice?”

Nearer to the lake approached the three bullies and their victim, who was struggling to escape. He was pleading piteously.

“I can’t stand this,” murmured Jack. “Williams is afraid of water. He told me so. It’s probably a nervous dread, and if they throw him in he may go into a spasm and drown. They should do something else if they want to haze him.”

“What are you going to do?” asked Nat. He and his chum were hidden from the others by a clump of trees.

“I’m going to make Snaith stop!” said Jack determinedly as he strode forward with flashing eyes. “You wait here, Nat.”

“Oh, fellows, please let go! Don’t throw me in the lake! I—I can’t swim!”

It was Will’s final appeal.

“Well, it’s time you learned,” exclaimed Snaith with a laugh. “Come on now, boys, take it on the run!”

But at that moment Jack Ranger fairly leaped from behind the clump of trees where he and Nat Anderson stood, and running after the three mean lads who were carrying the struggling Will, our hero planted himself in front of them.

“Here—drop him!” he cried, barring their way.

Surprise at Jack’s sudden appearance, no less than at his words and bearing, brought the hazers to a stop.

“What—what’s that you said?” asked Snaith, as if disbelieving the evidence of his ears.

“I said to drop this, and let Williams go.”

“What for?” demanded Pud.

“For several reasons. He can’t swim, and he has a nervous dread of the water, as I happen to know. Besides, it’s too chilly to throw any one in the lake now.”

“Are those all your reasons?” asked Snaith with a sneer.

“No!” cried Jack. “If you want another, it’s because I tell you to stop!”

“S’posing we don’t?”

“Then I’ll make you.”

“Oh, you will, eh? Well, I guess we three can take care of you, all right, even if you are Jack Ranger.”

Snaith had a tight hold on Will’s arm. The timid lad had been set down by his captors, but they still had hold of him.

“Please let me go,” pleaded Williams.

“We will—after you’ve had your dip in the lake,” said Glen.

“Yes, come on,” added Snaith. “Get out of the way, Ranger, if you don’t want to get bumped.”

“You let Williams go!” demanded Jack, still barring the way.

“We’ll not! Stand aside or I’ll hit you!” snapped Snaith.

He and his cronies again picked Williams up, and were advancing with him toward the lake. Snaith had one hand free, and as he approached Jack, who had not moved, the bully struck out at him. The blow landed lightly on Jack’s chest, but the next instant his fist shot out, catching Snaith under the ear, and the bully suddenly toppled over backward, measuring his length on the ground.

He was up again in a second, however, and spluttered out:

“Wha—what do you mean? I’ll fix you for this! I’ll make you pay for that, Jack Ranger!”

“Whenever you like,” replied Jack coolly, as he stood waiting the attack.

“Come on, fellows, let’s do him up!” cried Pud. “We’re three to one, and I owe him something on my own account.”

“Shall we let the freshman go?” asked Glen.

“Sure!” exclaimed Snaith. “We can catch him again. We’ll do up Ranger now!”

The bully and his cronies advanced toward Jack. Will, hardly understanding that he was released, stood still, though Jack called to him:

“Better run, youngster. I can look out for myself.”

“Oh, you can, eh?” sneered Snaith. “Well, I guess you’ll have your hands full. Come on, now, fellows! Give it to him!”

The three advanced with the intention of administering a sound drubbing to our hero, and it is more than likely that they would have succeeded, for Jack could not tackle three at once very well. But something happened.

This “something” was a lad who came bounding up from the rear, with a roar like a small, maddened bull, and then with a cry Nat Anderson flung himself on the back of Pud Armstrong.

“Flabgastered punching-bags!” he cried. “Three to one, eh? Well, I guess not! Acrimonious Abercrombie! But I’ll take a hand in this game!”

“Here! Quit that! Let me go! Stop! That’s no way to fight! Get off my back!” yelled the startled Pud.

“I’m not fighting yet,” said Nat coolly, as he skillfully locked his legs in those of Pud and sent him to the ground with a wrestler’s trick. “I’m only getting ready to wallop you!”

Snaith, who had rushed at Jack with raised fists, was met by another left-hander that again sent him to the ground. And then, to the surprise of the rescuers, no less than that of the would-be hazers, Will, who had seemed so timid in the hands of his captors, rushed at Glen Forker, and before that bully could get out of the way, had dealt him a blow on the chest.

“There!” cried Will. “I guess we’re three to three now!”

“Good for you, youngster!” cried Jack heartily. “You’ve got more spunk than I gave you credit for. Hit him again!”

“Now, Pud, if you’ll get up, you and I will have our innings,” announced Nat to the lad he had thrown. “Suffering snufflebugs! but I guess the game isn’t so one-sided now.”

But, though Pud got up, he evinced no desire to come to close quarters with Nat. Instead, he sneaked to one side, muttering:

“You wait—that’s all! You just wait!”

“Well, I’m a pretty good waiter. I used to work in a hash foundry and a beanery,” said Nat with a smile.

Snaith, too, seemed to have had enough, for he sat on the ground rubbing a lump on his head, while as for Glen, he was in full retreat.

“I hope I didn’t hurt you, Snaith,” said Jack politely.

“Don’t you speak to me!” snarled the bully.

“All right,” said Jack. “I’ll not.”

“I’ll get square with you for this,” went on Snaith as he arose and began to retreat, followed by Pud. “You wait!”

“That’s what Pud said,” interjected Nat. “It’s getting tiresome.”

The two bullies hurried off in the direction taken by Glen, leaving Jack, Nat and Will masters of the field.

“I—I’m ever so much obliged to you,” said Will to Jack after a pause.

“That’s all right. Glad I happened along.”

“I—I don’t mind being hazed,” went on the timid lad. “I expected it, but I have a weak heart, and the doctor said a sudden shock would be bad for me. I’m very much afraid of water, and I can’t swim, or I wouldn’t have minded being thrown into the lake. I—I hope you don’t think I’m a coward.”

“Not a bit of it.”

“And I—I hope the fellows won’t make fun of me.”

“They won’t,” said Jack very positively, for, somehow, his heart went out to the queer lad. “If they do, just send them to me. As for Snaith and his crowd, I guess they won’t bother you after this. Say, but you went right up to Glen, all right.”

“I took boxing lessons—once,” went on Will timidly. “I’m not afraid in a fair fight.”

“Glad to hear it, but I fancy they’ll not bother you any more. Do you know Nat Anderson?” and Jack nodded at his chum.

“I’m glad to meet you,” spoke Will, holding out his hand.

“Same here,” responded Nat. “Unified uppercuts! but you went at Glen good and proper!”

“You mustn’t mind Nat’s queer expressions,” said Jack with a smile, as he saw Will looking in rather a puzzled way at Nat. “They were vaccinated in him, and he can’t get rid of them.”

“You get out!” exclaimed Jack’s chum.

“Going anywhere in particular?” asked Jack of Will, as he straightened out a cuff that had become disarranged in the scrimmage.

“No, I guess not.”

“Then come on and take a walk with us.”

The lad appeared to hesitate. Then he said slowly.

“No—no, thank you. I—I don’t believe I will. I think I’ll go back to my room.”

He turned aside and walked away.

Jack and Nat stared after him in silence.

“Well, he certainly is a queer case,” remarked Nat in a low voice. “I don’t know what to make of him.”

“I, either,” admitted Jack. “He showed some spunk when he went at Glen, but now it appears to have oozed away.”

The two chums continued their walk, discussing the recent happening.

“Do you know, I think something is about due to happen, fellows,” announced Fred Kaler that night, when he and some of Jack’s and Nat’s chums were in the latters’ room.

“Why, what’s up, you animated jewsharp?” asked Nat.

“I don’t know, but it’s been so quiet in the sacred precincts of our school lately that it’s about time for something to arrive. Do you know that Socrat and Garlach haven’t spoken to each other this term yet?”

“What’s the trouble now?” asked Jack, for the French and German teachers, with the characteristics of their race, were generally at swords’ points for some reason or other.

“Why, you know their classrooms are next to each other, and one day, the first week of the term, Professor Socrat, in giving the French lesson, touched on history, and gave an instance of where frog-eaters with a small army had downed the troops from der Vaterland. He spoke so loud that Professor Garlach heard him, his German blood boiled over, and since then neither has spoken to the other.”

“Well, that often happens,” remarked Nat.

“Sure,” added Bony Balmore, cracking his finger knuckles by way of practice.

“Yes,” admitted Fred, as he took out his mouth-organ, preparatory to rendering a tune, “but this time it has lasted longer than usual, and it’s about time something was done about it.”

Fred began softly to play “On the Banks of the Wabash Far Away.”

“Cheese it,” advised Nat. “Martin will hear.”

“He’s gone to the village on an errand for the doctor,” said Fred as he continued to play. Then he stopped long enough to remark: “I’d like to hear from our fellow member, Jack Ranger.”

“That’s it,” exclaimed Sam Chalmers. “I wonder Jack hasn’t suggested something before this.”

“Say!” exclaimed Jack, “have I got to do everything around this school? Why don’t some of the rest of you think up something? I haven’t any monopoly.”

“No, but you’ve got the nerve,” said Bony. “Say, Jack, can’t you think of some scheme for getting Garlach and Socrat to speak? Once they are on talking terms we can have some fun.”

Jack seemed lost in thought. Then he began to pace the room.

“Our noble leader has his thinking apparatus in working order,” announced Nat.

“Hum!” mused Jack. “You say the trouble occurred over something in history, eh?”

“Sure,” replied Fred.

“Then I guess I’ve got it!” cried Jack. “Wait a minute, now, until I work out all the details.”

He sat down to the table, took out pencil and paper, and began to write. The others watched him interestedly.

“Here we are!” Jack cried at length. “Now to carry out the scheme and bring about a German-French alliance!”

“What are you going to do?” asked Nat.

“Here are two notes,” said Jack, holding aloft two envelopes.

“We’ll take your word for it,” remarked Bob Movel.

“One is addressed to Professor Garlach,” went on Jack, “and in it he is advised that if he proceeds in the proper manner he can obtain information of a certain incident in history, not generally known, but in which is related how Frederic II, with a small squad of Germans, put a whole army of French to flight. It is even more wonderful than the incident which Professor Socrat related to his class, and if he speaks loudly enough in the classroom, Professor Socrat can’t help but hear it.”

“What are you going to do with the note?” asked Fred.

“Send it to Garlach.”

“And then?”

“Ah, yes—then,” said Jack. “Well, what will happen next will surprise some folks, I think. The information which Garlach will be sure to want to obtain can only be had by going to a certain hollow tree, on the shore of the lake, and he must go there just at midnight.”

“Well?” asked Dick Balmore as Jack paused, while the silence in the room was broken by Bony’s performance on his finger battery.

“Well,” repeated Jack, “what happens then will be continued in our next, as the novelists say. Now come on and help me fix it up,” and he motioned for his chums to draw more closely around the table, while he imparted something to them in guarded whispers.

Professor Garlach received the next day a neatly-written note. It was thrust under the door of his private apartment, just as he was getting ready to go to breakfast.

“Ach! Dis is a letter,” he said, carefully looking at the envelope, as if there was some doubt of it. “I vunder who can haf sent it to me?”

He turned it over several times, but seeing no way of learning what he wished to know save by opening the epistle, he did so.

“Vot is dis?” he murmured as he read. “Ha! dot is der best news vot I haf heard in a long time. Ach! now I gets me efen mid dot wienerwurst of a Socrat! I vill vanquishes him!”

This is what the German professor read:

“I am a lover of the Fatherland, and I understand that an insult has been offered her glory by a Frenchman who is a professor in the same school where you teach. I understand that he said a small body of the despised French beat a large army of Germans. This is not true, but I am in a position to prove the contrary, namely, that in the Hanoverian or Seven Years’ War, in 1756, a small troop of Germans, under Frederic II, defeated a large army of the French. The incident is little known in history, but I have all the facts at hand, and I will give them to you.

“The information is secret, and I cannot reveal to you my name, or I might get into trouble with the German war authorities, so I will have to ask you to proceed cautiously. I will deposit the proofs of what I say in the hollow of the old oak tree that stands near the shore of the lake, not far from the school. If you will go there at midnight to-night, you may take the papers away and demonstrate to your classes that the Germans are always the superiors of the French in war. I must beg of you to say nothing about this to any one. Proceed in secret, and you will be able to refute the base charges made against our countrymen by a base Frenchman. Do not fail. Be at the old tree at midnight. For obvious reasons I sign myself only

“Bismark.”

“Ha!” exclaimed Professor Garlach. “I vill do as you direct. T’anks, mine unknown frient! T’anks! Now vill I make to der utmost confusionability dot frog-eater of a Socrat! Ha! ve shall see. I vill be on der spot at midnight!”

All that day there might have been noticed that there was a subdued excitement hovering about Professor Garlach. Jack and his chums observing it, smiled.

“He’s taken the bait, hook and sinker,” said Jack.

When the class in history was called before him to recite, Professor Garlach remarked:

“Young gentlemens, I shall have some surprising informations to impart by you to-morrow. I am about to come into possession of some remarkable facts, but I cannot reveal dem to you now. But I vill say dot dey vill simply astonishment to you make alretty yet. You are dismissed.”

He had spoken quite loudly, and Professor Socrat, in the next room, hearing him, smiled.

“Ah,” murmured the Frenchman, “so my unknown friend, who was so kind as to write zis note, did not deceive me. Sacre! But I will bring his plans to nottingness! Ah, beware, Professor Garlach—pig-dog zat you are! I will foil you. But let me read ze note once more.”

Alone in the classroom, he took from his pocket a letter. It looked just like the one professor Garlach had received that morning.

“Ha, yes. I am not mistake! I will be at ze old oak tree on ze shore of ze lake at midnight by ze clock. And I will catch in ze act Professor Garlach when he make ze attempt to blow up zat sacred tree. Zat tree under which La Fayette once slept. Queer zat I did not know it before. Ha! I will drape ze flag of France on ze beloved branches. Ah! my beloved country!”

For this is the note which Professor Socrat received:

“Dear Professor: This is written by a true friend of France, who is not at liberty to reveal his name. I have information to the effect that the old oak tree which stands on the shore of the lake is a landmark in history. Under it, during the American war of independence, the immortal Washington and La Fayette once slept before a great battle, when their tents had not arrived. The tree should be honored by all Frenchmen, as well as by all Americans.

“But, though it is not generally known that La Fayette slept under the tree, Professor Garlach has learned of it in some way. Such is his hatred of all things French, as you well know, that he has planned to destroy the tree. At midnight to-night he is going to put a dynamite bomb in the tree, and blow it to atoms. He hopes the plot will be laid to the students. If you wish to foil him be at the tree at midnight. I will sign myself only

“Napoleon.”

“Ha! destroy zat sacred tree by dynamite!” murmured Professor Socrat. “I will be zere! I will be zere!”

It lacked some time before twelve o’clock that night, when several figures stole out of a dormitory of Washington Hall.

“Have you got everything, Jack?” asked a voice.

“Yes; but for cats’ sake, keep quiet,” was the rejoinder. “Come on now. Lucky Martin didn’t spot us.”

“That’s what,” added Nat Anderson. “Scouring sky-rockets, but there’ll be some fun!”

“Easy!” cautioned Jack as he led a band of fellow conspirators toward the lake.

They reached the old, hollow oak tree, of which Jack had spoken in his two letters to the professors, and which he had made the rendezvous for his joke. Into the hollow he thrust a bundle of papers. Then, some distance away from the tree, he stuck something else upright in the ground, and trailing off from it were what seemed to be twisted strings.

“Lucky it’s a dark night,” whispered Bony. “They won’t see each other until they get right here. What time is it now?”

“Lacks a quarter of twelve,” replied Jack, striking a match and shielding it from observation under the flap of his coat as he looked at his watch.

The boys crouched down in the bushes and waited. It was not long before they heard some one approaching in the darkness.

“That’s Garlach by the way he walks,” whispered Bob Movel.

“Yes,” assented Jack. “I hope Socrat is on time.”

The German professor approached the tree, anxious to take from it the papers that were to prove the valor of German soldiers. A moment later another figure loomed up in the darkness on the other side of the big trunk.

“There’s Socrat,” whispered Nat. “But what is he carrying?”

“Blessed if I know,” answered Jack; “but we’ll soon see.”

He struck a match and touched it to the end of the twisted strings. There was a splutter of flame, and some sparks ran along the ground. A moment later the scene was lighted up by glaring red fire, the fuse of which Jack had touched off. By the illumination the boys hidden in the bushes could see Professor Garlach, with his hand and arm down the hollow of the old oak tree. At the same time Professor Socrat rushed forward, and what he had in his hand was a pail of water.

“So!” cried the Frenchman. “I have caught you in ze act! I will foil you!”

“Don’t bodder me!” cried the German. “Ach! You would steal der evidence of your countrymen’s cowardice, vould you? But you shall not! I vill haf my revenge!”

“Stop! stop!” cried Professor Socrat. “You shall not destroy ze tree under which ze immortal Washington and La Fayette slept! You shall not! I, Professor Socrat, say it! Ha! you have already lighted ze dynamite fuse! But I will destroy it!”

Professor Garlach drew from the tree the bundle of papers. No sooner had he done so than Professor Socrat dashed the pail of water over him, drenching him from head to foot.

“Du meine zeit! Himmel! Hund vot you are! I am drowning!” cried the German, choking.

“Ha! ha! I have put out ze fuse! I have quenched ze dynamite cartridge! Ze tree shall not be blown to atoms! I will drape it wiz my country’s flag.”

From his coat the French professor drew the tri-colored flag, which he draped over the lowest branches of the old tree. Then, as the red fire died out, the boys saw the German make a spring for his enemy.

“Come on, fellows!” softly called Jack. “We’d better skip while they’re at one another.”

They glided from the bushes, while at the foot of the tree, in the dying glow from the red fire, could be seen two shapes struggling desperately together. From the midst came such alternate expressions as:

“Ach! Pig-dog! Frog-eater! Sauerkraut! Maccaroni! Himmel! Sacre! La Fayette!”

“Oh, but aren’t they having a grand time!” said Nat as he hurried along at Jack’s side. “It worked like a charm. But who would have thought that Socrat would have brought along a pail of water?”

“Couldn’t have been better,” admitted Jack, “if I do say it myself.”

“But won’t they find out who did it?” asked Bony.

“They may suspect, but they’ll never know for sure,” said the perpetrator of the trick.

“How about the bundle of papers you left in the tree?”

“Nothing but newspapers, and they can’t talk. But I guess we’ve livened things up some. Anyhow, they’ve spoken to each other.”

“They sure have,” admitted Sam, as from the darkness, at the foot of the tree, came the sounds of voices in high dispute.

The next day Professor Socrat passed Professor Garlach without so much as a look in the direction of the German, but when he got past he muttered:

“Ze La Fayette tree still stands.”

And Professor Garlach replied:

“Pig-dog vot you are! To destroy dot secret of history!”

Jack and his chums awaited rather anxiously the calling of the French and German classes that day, but neither professor made any reference to the happenings of the night previous. All there was to remind a passer-by of it were some shreds of a French flag hanging to the limbs of the tree.

“They must have ripped the flag apart in their struggle with each other,” said Sam as he and Jack passed the place.

Matters at Washington Hall went on the even tenor of their ways for about two weeks. The boys buckled down to study, though there was plenty of time for sport, and the football eleven, of which Jack was a member, played several games.

The weather was getting cold and snappy, and there were signs of an early and severe winter. These signs were borne out one morning when Jack crawled out of bed.

“Whew! but it’s cold!” he said as he pulled aside the window curtains and looked out. Then he uttered an exclamation. “Say, Nat, it’s snowing to beat the band!”

“Snowing?”

“Sure, and I’ve got to go to the village this afternoon. Look!”

Nat crawled out, shivering, and stood beside Jack.

“Why, it is quite a storm,” he admitted. “B-r-r-r-r! I’m going to get my flannels out!”

“No football game to-morrow,” said Jack. “I guess winter’s come to stay.”

“Say, Jack,” began Nat at breakfast a little later, “what are you going to the village for?”

“Got to get something Aunt Angelina sent me,” replied our hero. “I got a letter saying she had forwarded me a package by express. It’s got some heavy underwear in it for one thing, but I know enough of my aunt to know that’s not all that’s in it.”

“What else?”

“Well, I shouldn’t be surprised if there were some pies and doughnuts and cakes and——”

“Quit!” begged Bony, who sat on the other side of Jack. “You make me hungry.”

“What’s the matter with this grub?” inquired Jack.

“Oh, it’s all right as far as it goes——”

“Smithering slaboleens!” exclaimed Nat. “Doesn’t it go far enough in you, Bony?” and he looked at his tall chum. “Do you want it to go all the way to your toes?”

“No; but when I hear Jack speak of pies and doughnuts——”

“You’ll do more than hear me speak of them if they come, Bony,” went on Jack. “We’ll have a little feast in my room to-night, when Martin, the monitor, is gone to bed.”

“When are you going?” asked Nat.

“Right after dinner. Want to come along? I guess you can get permission. I did.”

“Nope. I’ve got to stay here and bone up on geometry. I flunked twice this week, and Doc. Mead says I’ve got to do better. Take Bony.”

“Not for mine,” said Bony, shivering as he looked out of the window and saw the snow still coming down. “I’m going to stay in.”

“Then I’ll go alone,” decided Jack, and he started off soon after the midday meal. The storm was not a severe one, though it was cold and the snow was quite heavy. It was a good three-mile walk to the village, but Jack had often taken it.

He was about a mile from the school, and was swinging along the country road, thinking of many things, when, through the white blanket of snowflakes, he saw a figure just ahead of him on the highway.

“That looks familiar,” he said to himself. “That’s Will Williams. Wonder what he can be doing out here? Guess he’s going to town also. I’ll catch up with him. I wish I could get better acquainted with him, but he goes in his shell as soon as I try to make friends.”

He hastened his pace, but it was slow going on account of the snow. When Jack was about a hundred yards behind Will he was surprised to see the odd student suddenly turn off the main road and make toward a chain of small hills that bordered it on the right.

“That’s queer,” murmured Jack. “I wonder what he’s doing that for?”

He stood still a moment, looking at Will. The new boy kept on, plodding through the snow, which lay in heavy drifts over the unbroken path he was taking.

“Why, he’s heading for the ravine,” said Jack to himself. “He’ll be lost if he goes there in this storm, and it’s dangerous. He may fall down the chasm and break an arm or a leg.”

The ravine he referred to was a deep gully in

the hills, a wild, desolate sort of place, seldom

visited. It was in the midst of thick woods, and

more than once solitary travelers had lost their

way there, while one or two, unfamiliar with the

suddenesssuddenness

with which the chasm dipped down, had

fallen and been severely hurt.

“What in the world can he want out there?” went on Jack. “I’d better hail him. Guess he doesn’t know the danger, especially in a storm like this, when bad holes are likely to be hidden from sight.”

He hurried forward, and then, making a sort of megaphone of his hands, called out:

“Williams! I say, Williams, where are you going?”

The new boy turned quickly, looked back at Jack, and then continued his journey.

“Hey! Come back!” yelled our hero. “You’ll be lost if you go up in those hills. It’s dangerous! Come on back!”

Williams stopped again, and turned half around.

“Guess he didn’t hear me plainly,” thought Jack. “I’ll catch up to him. Wait a minute,” he called again, and he hastened forward, Will waiting for him.

“Where are you going?” asked Jack, when he had caught up to him.

“I don’t know,” was the answer, and Jack was struck by the lad’s despondent tone.

“Don’t you know there’s a dangerous ravine just ahead here?” went on Jack. “You might tumble in and lose your life.”

“I don’t care if I do lose my life,” was the unexpected rejoinder.

“You don’t care?” repeated Jack, much surprised.

“No.”

“Do you realize what you’re saying?” asked Jack sternly.

“Yes, I do. I don’t care! I want to be lost! I never want to see any one again! I came out here—I don’t care what becomes of me—I’d like to fall down under the snow and—and die—that would end it all!”

Then, to Jack’s astonishment, Will burst into tears, though he bravely tried to stifle them.

“Well—of all the——” began Jack, and words failed him. Clearly he had a most peculiar case to deal with. He took a step nearer, and put his arm affectionately around Will’s shoulder. Then he patted him on the back, and his own voice was a trifle husky as he said:

“Say, old man, what’s the matter? Own up, now, you’re in trouble. Maybe I can help you. It doesn’t take half an eye to see that’s something’s wrong. The idea of a chap like you wanting to die! It’s nonsense. You must be sick. Brace up, now! Tell me all about it. Maybe I can help you.”

There was silence, broken only by Will’s half-choked sobs.

“Go ahead, tell me,” urged Jack. “I’ll keep your secret, and help you if I can. Tell me what the trouble is.”

“I will!” exclaimed the new boy with sudden determination. “I will tell you, Jack Ranger, but I don’t think you can help me. I’m the most miserable lad at Washington Hall.”

“You only think so,” rejoined Jack brightly. “Go ahead. I’ll wager we can make you feel better. You want some friends, that’s what you want.”

“Yes,” said Will slowly, “I do. I need friends, for I don’t believe I’ve got a single one in the world.”

“Well, you’ve got one, and that’s me,” went on Jack. “Go ahead, now, let’s hear your story.”

And then, standing in the midst of the storm, Will told his pitiful tale.

“My father and mother have been dead for some time,” he said, “and for several years I lived with my uncle, Andrew Swaim, my mother’s brother. He was good to me, but he had to go out West on business, and he left me in charge of a man named Lewis Gabel, who was appointed my guardian.

“This Gabel treated me pretty good at first, for my uncle sent money regularly for my board. Then, for some reason, the money stopped coming, and Mr. Gabel turned mean. He hardly gave me enough to eat, and I had to work like a horse on his farm. I wrote to my uncle, but I never got an answer.

“Then, all at once, my uncle began sending money again, but he didn’t state where he was. After that I had it a little easier, until some one stole quite a sum from Mr. Gabel. He’s a regular miser, and he loves money more than anything else. He accused me of robbing him, and declared he wouldn’t have me around his house any longer.

“So he sent me off to this school, but he doesn’t give me a cent of spending money, and pays all the bills himself. He still thinks I stole his money, and he says he will hold back my spending cash, which my uncle forwards, until he has made up the amount that was stolen.

“I tried to prove to him that I was innocent, but he won’t believe me. He is always writing me mean letters, reminding me that I am a thief, and not fit for decent people to associate with. I’m miserable, and I wish I was dead. I got a mean, accusing letter from him to-day, and it made me feel so bad that I didn’t care what became of me. I wandered off, and I thought if I fell down and died under the snow it would be a good thing.”

“Say, you certainly are up against it,” murmured Jack. “I’d like to get hold of that rascally guardian of yours. But why don’t you tell your uncle?”

“I can’t, for I don’t know his address.”

“But he sends money for your schooling and board to Mr. Gabel, doesn’t he?”

“Yes, but he sends cash in a letter, and he doesn’t even register it. I wrote to the postal authorities of the Western city where his letters were mailed, but they said they could give me no information.”

“What is your uncle doing in the West?”

“He is engaged in some secret mission. I never could find out what it is, and I don’t believe Mr. Gabel knows, either. Oh, but Gabel is a mean man! He seems to take delight in making me miserable. Now you know why I act so queerly. I like a good time, and I like to be with the fellows, but I haven’t a cent to spend to treat them with, and I’m not going to accept favors that I can’t return. Why, I haven’t had a cent to spend for myself in six months!”

Jack whistled.

“That’s tough,” he said. “But say, Will, you’re mistaken if you think our crowd cares anything for money. Why didn’t you say something about this before?”

“I—I was ashamed to.”

“Why, we thought you didn’t like us,” went on Jack. “Now I see that we were mistaken. I wish we had Mr. Gabel here. We’d haze him first, and throw him into the lake afterward. Now, Will, I’ll tell you what you’re going to do?”

“What?” asked the lad, who seemed much better in spirits, now that he had made a confession.

“In the first place, you’re coming to the village with me,” said Jack. “Then you’re going to forget all about your troubles and about dying under the snow. Then, when I get a bundle from home, you’re coming back with me, and——”

“Home!” exclaimed Will with a catch in his voice. “How good that word sounds! I—I haven’t had a home in so long that—that I don’t know what it seems like.”

“Well, we’re going to make you right at home here,” went on Jack. “I’m expecting a bundle of good things from my aunt, and when it comes, why, you and me and Nat and Sam and Bony and Fred and Bob, and some other choice spirits, are going to gather in my room to-night, and we’re going to have the finest spread you ever saw. I’ll make you acquainted with the boys, and then we’ll see what happens. No spending money? As if we cared for that! Now, come on, old chap, we’ll leg it to the village, for it’s cold standing here,” and clapping Will on the back, Jack linked his arm in that of the new boy and led him back to the road.

“Well, fellows, are we all here?” asked Jack Ranger later that night, as he gazed around on a crowd in his room.

“If there were any more we couldn’t breathe,” replied Bony Balmore, and the cracking of his finger knuckles punctuated his remark.

“When does the fun begin?” asked Bob Movel.

“Soon,” answered Jack.

“We ought to have some music. Tune up, Fred,” said Sam.

“Not here,” interposed Jack quickly. “Wait a bit and we can make all the noise we want to.”

“How’s that?” inquired Bony. “Have you hypnotized Dr. Mead and put wax in Martin’s ears so he can’t hear us?”

“No, but it’s something just as good. This afternoon I sat and listened while Socker, the janitor, told me one of his war stories.”

“You must have had patience,” interrupted Nat Anderson. “Bob cats and bombshells, but Socker is tiresome!”

“Well, I had an object in it,” explained Jack. “I wanted him to do me a favor, and he did it—after I’d let him tell me how, single-handed, he captured a lot of Confederates. I told him about this spread to-night, and was lamenting the fact that my room was so small, and that we couldn’t make any noise, or have any lights. And you know how awkward it is to eat in the dark.”

“Sure,” admitted Bony. “You can’t always find your mouth.”

“And if there’s anything I dislike,” added Nat, “it’s putting pie in my ear.”

“Easy!” cautioned Jack at the laugh which followed. “Wait a few minutes and we can make all the noise we want to.”

“How?” asked Bony.

“Because, as I’m trying to tell you, Socker did me a favor. He’s going to let us in the storeroom, back of where the boiler is, in the basement. It’ll be nice and warm there, and we can have our midnight feast in comfort, and make all the row we like, for Martin can’t hear us there.”

“Good for you, Jack!” cried Nat.

“That’s all to the horse radish!” observed Sam.

Jack’s trip to town that afternoon had been most successful. He had found at the express office a big package from home, and from the note that accompanied it he knew it contained good things to eat, made by his loving aunts. But, desiring to give an unusually fine spread to celebrate the occasion of having made the acquaintance of Will Williams, Jack purchased some other good things at the village stores.

He and Will carried them back to school, and managed to smuggle them in. It was a new experience for Will to have a friend like Jack Ranger, and to be taking part in this daring but harmless breach of the school rules. Under this stimulus Will was fast losing his melancholy mood, and he responded brightly to Jack’s jokes.

“Now you stay in your room until I call for you,” our hero had said to Will on parting after supper that night. Jack wanted to spring a sort of surprise on his chums, and introduce Will to them at the feast. In accordance with his instructions the lads had gathered in his room about ten o’clock that night, stealing softly in after Martin, the monitor, had made his last round to see that lights were out. Then Jack had announced his plan of having the feast in the basement.

“Grab up the grub and come on,” said the leader a little later. “Softly now—no noise until we’re downstairs.”

“Will Socker keep mum?” asked Bony.

“As an oyster in a church sociable stew,” replied Jack. “I’ve promised to listen to another of his war tales.”

“Jack’s getting to be a regular martyr,” observed Sam.

“Silence in the ranks!” commanded Captain Jack.

The lads stole softly along the corridors. Just as they got opposite the door of Martin’s room, there was a dull thud.

“What’s that?” whispered Jack softly.

“I—I dropped one of the pies,” replied Bony, cracking his knuckles at the double-quick in his excitement.

“Scoop it up and come on. You’ll have to eat it,” said Jack.

In fear and trembling they went on. Fortunately, Martin did not hear the noise, and the lads got safely past.

Jack, who was in the rear, paused at a door at the end of the hall, and knocked softly.

“Yes,” answered a voice from within.

“Come on,” commanded Jack, and he was joined by a dark figure.

They reached the basement safely, no one having disputed their night march. Socker, the janitor, met them at the door of the boiler-room.

“Here we are,” said Jack.

“So I see, Mr. Ranger. Why, it reminds me of the time when Captain Crawford and me took a forced night march of ten miles to get some rations. We were with Sherman, on his trip to the sea, and——”

“You must be sure to tell me that story,” interrupted Jack. “But not now. Is everything all right?”

“Yes, Mr. Ranger. But I depend on you not to say anything about this to Dr. Mead in case——”

“Oh, you can depend on us,” Jack assured him.

“I thought I could. It reminds me of the time when we were before Petersburgh, and a comrade and I went to——”

“You must not forget to tell me that story,” interrupted Jack. “I particularly want to hear it, Socker.”

“I will,” said the janitor, delighted that he had at last found an earnest listener.

“But not now,” said Jack. “We must get to work. Do you like pie, Socker?”

“Do I, Mr. Ranger? Well, I guess I do. I remember once when we were at Gettysburg——”

“Bony, where’s that extra choice pie you had?” asked Jack with a wink at his chum. “Give it to Mr. Socker here,” and Bony passed over the bit of pastry that had met with the accident in the hall.

“That will keep him quiet for a while,” said Jack in a whisper.