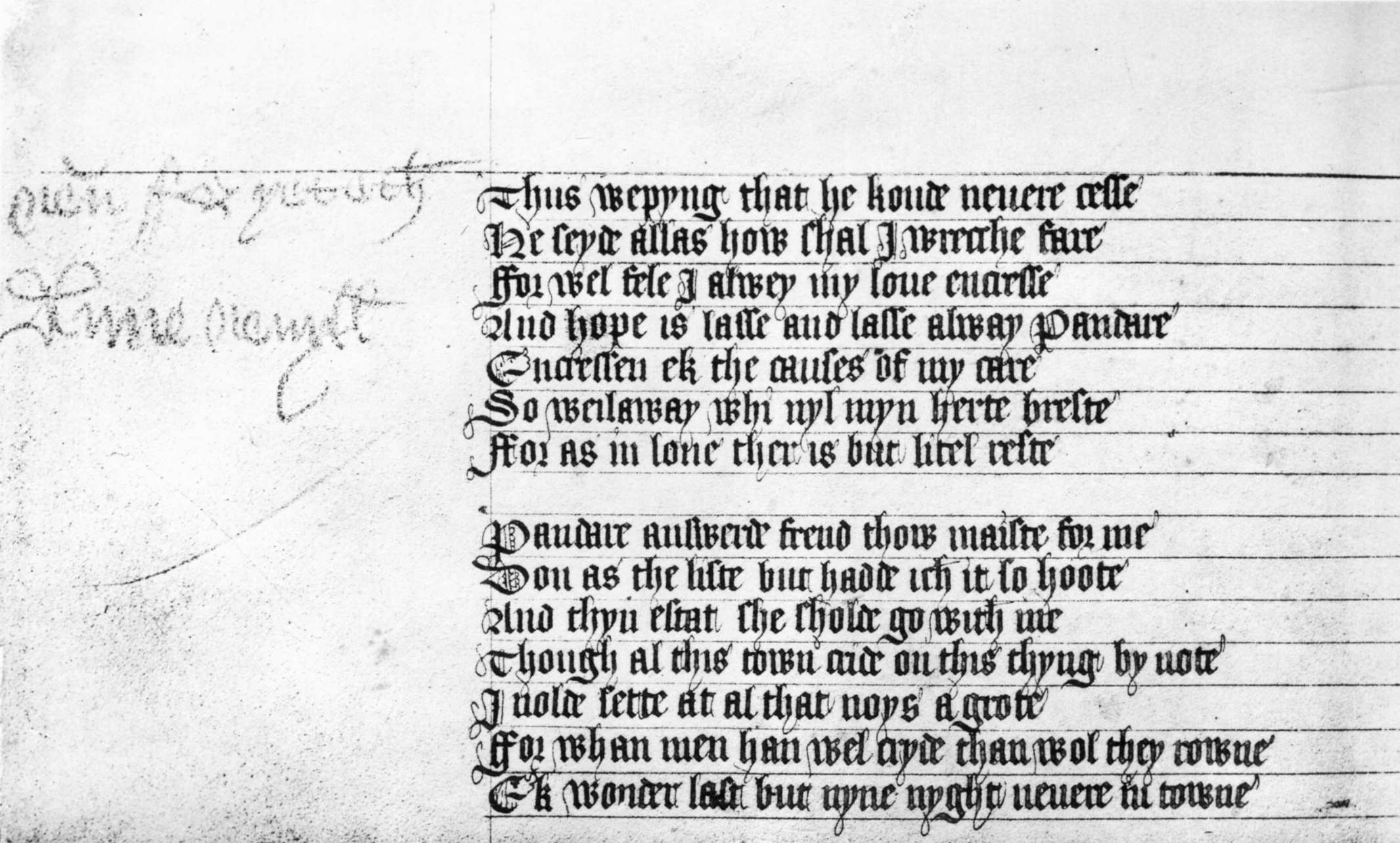

MS. Corp. Chr. Coll., Cambridge. Troil. iv. 575-588

Frontispiece**

Title: Chaucer's Works, Volume 2 — Boethius and Troilus

Author: Geoffrey Chaucer

Editor: Walter W. Skeat

Release date: February 5, 2014 [eBook #44833]

Most recently updated: October 24, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Jonathan Ingram, Keith Edkins and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

| Transcriber's note: | A Glossary including words from the two texts in this volume is included in Skeat's Volume VI, available from Project Gutenberg here. |

THE COMPLETE WORKS

OF

GEOFFREY CHAUCER

EDITED, FROM NUMEROUS MANUSCRIPTS

BY THE

Rev. WALTER W. SKEAT, M.A.

Litt.D., LL.D., D.C.L., Ph.D.

ELRINGTON AND BOSWORTH

PROFESSOR OF ANGLO-SAXON

AND FELLOW OF CHRIST'S COLLEGE, CAMBRIDGE

* *

BOETHIUS AND TROILUS

'Adam scriveyn, if ever it thee befalle

Boece or Troilus to wryten newe,

Under thy lokkes thou most have the scalle,

But after my making thou wryte trewe.'

Chaucers Wordes unto Adam.

SECOND EDITION

Oxford

AT THE CLARENDON PRESS

M DCCCC

Oxford

PRINTED AT THE CLARENDON PRESS

BY HORACE HART, M.A.

PRINTER TO THE UNIVERSITY

| PAGE | |

| Introduction to Boethius.—§ 1. Date of the Work. § 2. Boethius. § 3. The Consolation of Philosophy; and fate of its author. § 4. Jean de Meun. § 5. References by Boethius to current events. § 6. Cassiodorus. § 7. Form of the Treatise. § 8. Brief sketch of its general contents. § 9. Early translations. § 10. Translation by Ælfred. § 11. MS. copy, with A.S. glosses. § 12. Chaucer's translation mentioned. § 13. Walton's verse translation. § 14. Specimen of the same. § 15. His translation of Book ii. met. 5. § 16. M. E. prose translation; and others. § 17. Chaucer's translation and le Roman de la Rose. § 18. Chaucer's scholarship. § 19. Chaucer's prose. § 20. Some of his mistakes. § 21. Other variations considered. § 22. Imitations of Boethius in Chaucer's works. § 23. Comparison with 'Boece' of other works by Chaucer. § 24. Chronology of Chaucer's works, as illustrated by 'Boece.' § 25. The Manuscripts. § 26. The Printed Editions. § 27. The Present Edition | vii |

| Introduction to Troilus.—§ 1. Date of the Work. § 2. Sources of the Work; Boccaccio's Filostrato. §§ 3, 4. Other sources. § 5. Chaucer's share in it. § 6. Vagueness of reference to sources. § 7. Medieval note-books. § 8. Lollius. § 9. Guido delle Colonne. § 10. 'Trophee.' §§ 11, 12. The same continued. §§ 13-17. Passages from Guido. §§ 18, 19. Dares, Dictys, and Benôit de Ste-More. § 20. The names; Troilus, &c. § 21. Roman de la Rose. § 22. Gest Historiale. § 23. Lydgate's Siege of Troye. § 24. Henrysoun's Testament of Criseyde. § 25. The MSS. § 26. The Editions. § 27. The Present Edition. § 28. Deficient lines. § 29. Proverbs. § 30. Kinaston's Latin translation. § 31. Sidnam's translation | xlix |

| Boethius de Consolatione Philosophie | 1 |

| Book I. | 1 |

| Book II. | 23 |

| Book III. | 51 |

| Book IV. | 92 |

| Book V. | 126 |

| {vi}

Troilus and Criseyde |

153 |

| Book I. | 153 |

| Book II. | 189 |

| Book III. | 244 |

| Book IV. | 302 |

| Book V. | 357 |

| Notes to Boethius | 419 |

| Notes to Troilus | 461 |

In my introductory remarks to the Legend of Good Women, I refer to the close connection that is easily seen to subsist between Chaucer's translation of Boethius and his Troilus and Criseyde. All critics seem now to agree in placing these two works in close conjunction, and in making the prose work somewhat the earlier of the two; though it is not at all unlikely that, for a short time, both works were in hand together. It is also clear that they were completed before the author commenced the House of Fame, the date of which is, almost certainly, about 1383-4. Dr. Koch, in his Essay on the Chronology of Chaucer's Writings, proposes to date 'Boethius' about 1377-8, and 'Troilus' about 1380-1. It is sufficient to be able to infer, as we can with tolerable certainty, that these two works belong to the period between 1377 and 1383. And we may also feel sure that the well-known lines to Adam, beginning—

'Adam scriveyn, if ever it thee befalle

Boece or Troilus to wryten newe'—

were composed at the time when the fair copy of Troilus had just been finished, and may be dated, without fear of mistake, in 1381-3. It is not likely that we shall be able to determine these dates within closer limits; nor is it at all necessary that we should be able to do so. A few further remarks upon this subject are given below.

Before proceeding to remark upon Chaucer's translation of Boethius, or (as he calls him) Boece, it is necessary to say a few words as to the original work, and its author.

Anicius Manlius Torquatus Severinus Boethius, the most {viii}learned philosopher of his time, was born at Rome about A. D. 480, and was put to death A. D. 524. In his youth, he had the advantage of a liberal training, and enjoyed the rare privilege of being able to read the Greek philosophers in their own tongue. In the particular treatise which here most concerns us, his Greek quotations are mostly taken from Plato, and there are a few references to Aristotle, Homer, and to the Andromache of Euripides. His extant works shew that he was well acquainted with geometry, mechanics, astronomy, and music, as well as with logic and theology; and it is an interesting fact that an illustration of the way in which waves of sound are propagated through the air, introduced by Chaucer into his House of Fame, ll. 788-822, is almost certainly derived from the treatise of Boethius De Musica, as pointed out in the note upon that passage. At any rate, there is an unequivocal reference to 'the felinge' of Boece 'in musik' in the Nonnes Preestes Tale, B 4484.

§ 3. The most important part of his political life was passed in the service of the celebrated Theodoric the Goth, who, after the defeat and death of Odoacer, A. D. 493, had made himself undisputed master of Italy, and had fixed the seat of his government in Ravenna. The usual account, that Boethius was twice married, is now discredited, there being no clear evidence with respect to Elpis, the name assigned to his supposed first wife; but it is certain that he married Rusticiana, the daughter of the patrician Symmachus, a man of great influence and probity, and much respected, who had been consul under Odoacer in 485. Boethius had the singular felicity of seeing his two sons, Boethius and Symmachus, raised to the consular dignity on the same day, in 522. After many years spent in indefatigable study and great public usefulness, he fell under the suspicion of Theodoric; and, notwithstanding an indignant denial of his supposed crimes, was hurried away to Pavia, where he was imprisoned in a tower, and denied the means of justifying his conduct. The rest must be told in the eloquent words of Gibbon[1].

'While Boethius, oppressed with fetters, expected each moment the sentence or the stroke of death, he composed in the tower of Pavia the "Consolation of Philosophy"; a golden volume, not unworthy of the leisure of Plato or Tully, but which claims {ix}incomparable merit from the barbarism of the times and the situation of the author. The celestial guide[2], whom he had so long invoked at Rome and at Athens, now condescended to illumine his dungeon, to revive his courage, and to pour into his wounds her salutary balm. She taught him to compare his long prosperity and his recent distress, and to conceive new hopes from the inconstancy of fortune[3]. Reason had informed him of the precarious condition of her gifts; experience had satisfied him of their real value[4]; he had enjoyed them without guilt; he might resign them without a sigh, and calmly disdain the impotent malice of his enemies, who had left him happiness, since they had left him virtue[5]. From the earth, Boethius ascended to heaven in search of the SUPREME GOOD[6], explored the metaphysical labyrinth of chance and destiny[7], of prescience and freewill, of time and eternity, and generously attempted to reconcile the perfect attributes of the Deity with the apparent disorders of his moral and physical government[8]. Such topics of consolation, so obvious, so vague, or so abstruse, are ineffectual to subdue the feelings of human nature. Yet the sense of misfortune may be diverted by the labour of thought; and the sage who could artfully combine, in the same work, the various riches of philosophy, poetry, and eloquence, must already have possessed the intrepid calmness which he affected to seek. Suspense, the worst of evils, was at length determined by the ministers of death, who executed, and perhaps exceeded, the inhuman mandate of Theodoric. A strong cord was fastened round the head of Boethius, and forcibly tightened till his eyes almost started from their sockets; and some mercy may be discovered in the milder torture of beating him with clubs till he expired. But his genius survived to diffuse a ray of knowledge over the darkest ages of the Latin world; the writings of the philosopher were translated by the most glorious of the English Kings, and the third emperor of the name of Otho removed to a more honourable tomb the bones of a catholic saint, who, from his Arian persecutors, had acquired the honours of martyrdom and the fame of miracles. In the last hours of Boethius, he derived some comfort from the {x}safety of his two sons, of his wife, and of his father-in-law, the venerable Symmachus. But the grief of Symmachus was indiscreet, and perhaps disrespectful; he had presumed to lament, he might dare to revenge, the death of an injured friend. He was dragged in chains from Rome to the palace of Ravenna; and the suspicions of Theodoric could only be appeased by the blood of an innocent and aged senator.'

This deed of injustice brought small profit to its perpetrator; for we read that Theodoric's own death took place shortly afterwards; and that, on his death-bed, 'he expressed in broken murmurs to his physician Elpidius, his deep repentance for the murders of Boethius and Symmachus.'

§ 4. For further details, I beg leave to refer the reader to the essay on 'Boethius' by H. F. Stewart, published by W. Blackwood and Sons, Edinburgh and London, in 1891. We are chiefly concerned here with the 'Consolation of Philosophy,' a work which enjoyed great popularity in the middle ages, and first influenced Chaucer indirectly, through the use of it made by Jean de Meun in the poem entitled Le Roman de la Rose, as well as directly, at a later period, through his own translation of it. Indeed, I have little doubt that Chaucer's attention was drawn to it when, somewhat early in life, he first perused with diligence that remarkable poem; and that it was from the following passage that he probably drew the inference that it might be well for him to translate the whole work:—

'Ce puet l'en bien des clers enquerre

Qui Boëce de Confort lisent,

Et les sentences qui là gisent,

Dont grans biens as gens laiz feroit

Qui bien le lor translateroit' (ll. 5052-6).

I.e. in modern English:—'This can be easily ascertained from the learned men who read Boece on the Consolation of Philosophy, and the opinions which are found therein; as to which, any one who would well translate it for them would confer much benefit on the unlearned folk':—a pretty strong hint[9]!

§ 5. The chief events in the life of Boethius which are referred to in the present treatise are duly pointed out in the notes; and it may be well to bear in mind that, as to some of these, nothing further is known beyond what the author himself tells us. Most of the personal references occur in Book i. Prose 4, Book ii. Prose 3, and in Book iii. Prose 4. In the first of these passages, Boethius recalls the manner in which he withstood one Conigastus, because he oppressed the poor (l. 40); and how he defeated the iniquities of Triguilla, 'provost' (præpositus) of the royal household (l. 43). He takes credit for defending the people of Campania against a particularly obnoxious fiscal measure instituted by Theodoric, which was called 'coemption' (coemptio); (l. 59.) This Mr. Stewart describes as 'a fiscal measure which allowed the state to buy provisions for the army at something under market-price—which threatened to ruin the province.' He tells us that he rescued Decius Paulinus, who had been consul in 498, from the rapacity of the officers of the royal palace (l. 68); and that, in order to save Decius Albinus, who had been consul in 493, from wrongful punishment, he ran the risk of incurring the hate of the informer Cyprian (l. 75). In these ways, he had rendered himself odious to the court-party, whom he had declined to bribe (l. 79). His accusers were Basilius, who had been expelled from the king's service, and was impelled to accuse him by pressure of debt (l. 81); and Opilio and Gaudentius, who had been sentenced to exile by royal decree for their numberless frauds and crimes, but had escaped the sentence by taking sanctuary. 'And when,' as he tells us, 'the king discovered this evasion, he gave orders that, unless they quitted Ravenna by a given day, they should be branded on the forehead with a hot iron and driven out of the city. Nevertheless on that very day the information laid against me by these men was admitted' (ll. 89-94). He next alludes to some forged letters (l. 123), by means of which he had been accused of 'hoping for the freedom of Rome,' (which was of course interpreted to mean that he wished to deliver Rome from the tyranny of Theodoric). He then boldly declares that if he had had the opportunity of confronting his accusers, he would have answered in the words of Canius, when accused by Caligula of having been privy to a conspiracy against him—'If I had known it, thou shouldst never have known it' (ll. 126-135). This, by the way, was rather an {xii}imprudent expression, and probably told against him when his case was considered by Theodoric.

He further refers to an incident that took place at Verona (l. 153), when the king, eager for a general slaughter of his enemies, endeavoured to extend to the whole body of the senate the charge of treason, of which Albinus had been accused; on which occasion, at great personal risk, Boethius had defended the senate against so sweeping an accusation.

In Book ii. Prose 3, he refers to his former state of happiness and good fortune (l. 26), when he was blessed with rich and influential parents-in-law, with a beloved wife, and with two noble sons; in particular (l. 35), he speaks with justifiable pride of the day when his sons were both elected consuls together, and when, sitting in the Circus between them, he won general praise for his wit and eloquence.

In Book iii. Prose 4, he declaims against Decoratus, with whom he refused to be associated in office, on account of his infamous character.

§ 6. The chief source of further information about these circumstances is a collection of letters (Variæ Epistolæ) by Cassiodorus, a statesman who enjoyed the full confidence of Theodoric, and collected various state-papers under his direction. These tell us, in some measure, what can be said on the other side. Here Cyprian and his brother Opilio are spoken of with respect and honour; and the only Decoratus whose name appears is spoken of as a young man of great promise, who had won the king's sincere esteem. But when all has been said, the reader will most likely be inclined to think that, in cases of conflicting evidence, he would rather take the word of the noble Boethius than that of any of his opponents.

§ 7. The treatise 'De Consolatione Philosophiæ' is written in the form of a discourse between himself and the personification of Philosophy, who appears to him in his prison, and endeavours to soothe and console him in his time of trial. It is divided (as in this volume) into five Books; and each Book is subdivided into chapters, entitled Metres and Proses, because, in the original, the alternate chapters are written in a metrical form, the metres employed being of various kinds. Thus Metre 1 of Book I is written in alternate hexameters and pentameters; while Metre 7 consists of very short lines, each consisting of a single dactyl and {xiii}spondee. The Proses contain the main arguments; the Metres serve for embellishment and recreation.

In some MSS. of Chaucer's translation, a few words of the original are quoted at the beginning of each Prose and Metre, and are duly printed in this edition, in a corrected form.

§ 8. A very brief sketch of the general contents of the volume may be of some service.

Book I. Boethius deplores his misfortunes (met. 1). Philosophy appears to him in a female form (pr. 2), and condoles with him in song (met. 2); after which she addresses him, telling him that she is willing to share his misfortunes (pr. 3). Boethius pours out his complaints, and vindicates his past conduct (pr. 4). Philosophy reminds him that he seeks a heavenly country (pr. 5). The world is not governed by chance (pr. 6). The book concludes with a lay of hope (met. 7).

Book II. Philosophy enlarges on the wiles of Fortune (pr. 1), and addresses him in Fortune's name, asserting that her mutability is natural and to be expected (pr. 2). Adversity is transient (pr. 3), and Boethius has still much to be thankful for (pr. 4). Riches only bring anxieties, and cannot confer happiness (pr. 5); they were unknown in the Golden Age (met. 5). Neither does happiness consist in honours and power (pr. 6). The power of Nero only taught him cruelty (met. 6). Fame is but vanity (pr. 7), and is ended by death (met. 7). Adversity is beneficial (pr. 8). All things are bound together by the chain of Love (met. 8).

Book III. Boethius begins to receive comfort (pr. 1). Philosophy discourses on the search for the Supreme Good (summum bonum; pr. 2). The laws of nature are immutable (met. 2). All men are engaged in the pursuit of happiness (pr. 3). Dignities properly appertain to virtue (pr. 4). Power cannot drive away care (pr. 5). Glory is deceptive, and the only true nobility is that of character (pr. 6). Happiness does not consist in corporeal pleasures (pr. 7); nor in bodily strength or beauty (pr. 8). Worldly bliss is insufficient and false; and in seeking true felicity, we must invoke God's aid (pr. 9). Boethius sings a hymn to the Creator (met. 9); and acknowledges that God alone is the Supreme Good (p. 10). The unity of soul and body is necessary to existence, and the love of life is instinctive (pr. 11). Error is dispersed by the light of Truth (met. 11). God governs the world, and is all-sufficient, whilst evil has no true existence (pr. 12). The book ends with the story of Orpheus (met. 12).

Book IV. This book opens with a discussion of the existence of evil, and the system of rewards and punishments (pr. 1). Boethius describes the flight of Imagination through the planetary spheres till it reaches heaven itself (met. 1). The good are strong, but the wicked are powerless, having no real existence (pr. 2). Tyrants are chastised by their own passions (met. 2). Virtue secures reward; but the wicked lose even their human nature, and become as mere beasts (pr. 3). Consider the enchantments of Circe, though these merely affected the outward form (met. 4). The wicked are thrice wretched; they will to do evil, they can do evil, and they actually do it. Virtue is its own reward; so that the wicked should excite our pity (pr. 4). Here follows {xiv}a poem on the folly of war (met. 4). Boethius inquires why the good suffer (pr. 5). Philosophy reminds him that the motions of the stars are inexplicable to one who does not understand astronomy (met. 5). She explains the difference between Providence and Destiny (pr. 6). In all nature we see concord, due to controlling Love (met. 6). All fortune is good; for punishment is beneficial (pr. 7). The labours of Hercules afford us an example of endurance (met. 7).

Book V. Boethius asks questions concerning Chance (pr. 1). An example from the courses of the rivers Tigris and Euphrates (met. 1). Boethius asks questions concerning Free-will (pr. 2). God, who sees all things, is the true Sun (met. 2). Boethius is puzzled by the consideration of God's Predestination and man's Free-will (pr. 3). Men are too eager to inquire into the unknown (met. 3). Philosophy replies to Boethius on the subjects of Predestination, Necessity, and the nature of true Knowledge (pr. 4); on the impressions received by the mind (met. 4); and on the powers of Sense and Imagination (pr. 5). Beasts look downward to the earth, but man is upright, and looks up to heaven (met. 5). This world is not eternal, but only God is such; whose prescience is not subject to necessity, nor altered by human intentions. He upholds the good, and condemns the wicked; therefore be constant in eschewing vice, and devote all thy powers to the love of virtue (pr. 6).

§ 9. It is unnecessary to enlarge here upon the importance of this treatise, and its influence upon medieval literature. Mr. Stewart, in the work already referred to, has an excellent chapter 'On Some Ancient Translations' of it. The number of translations that still exist, in various languages, sufficiently testify to its extraordinary popularity in the middle ages. Copies of it are found, for example, in Old High German by Notker, and in later German by Peter of Kastl; in Anglo-French by Simun de Fraisne; in continental French by Jean de Meun[10], Pierre de Paris, Jehan de Cis, Frere Renaut de Louhans, and by two anonymous authors; in Italian, by Alberto della Piagentina and several others; in Greek, by Maximus Planudes; and in Spanish, by Fra Antonio Ginebreda; besides various versions in later times. But the most interesting, to us, are those in English, which are somewhat numerous, and are worthy of some special notice. I shall here dismiss, as improbable and unnecessary, a suggestion sometimes made, that Chaucer may have consulted some French version in the hope of obtaining assistance from it; there is no sure trace of anything of the kind, and the internal evidence is, in my opinion, decisively against it.

§ 10. The earliest English translation is that by king Ælfred, which is particularly interesting from the fact that the royal author {xv}frequently deviates from his original, and introduces various notes, explanations, and allusions of his own. The opening chapter, for example, is really a preface, giving a brief account of Theodoric and of the circumstances which led to the imprisonment of Boethius. This work exists only in two MSS., neither being of early date, viz. MS. Cotton, Otho A VI, and MS. Bodley NE. C. 3. 11. It has been thrice edited; by Rawlinson, in 1698; by J. S. Cardale, in 1829; and by S. Fox, in 1864. The last of these includes a modern English translation, and forms one of the volumes of Bohn's Antiquarian Library; so that it is a cheap and accessible work. Moreover, it contains an alliterative verse translation of most of the Metres contained in Boethius (excluding the Proses), which is also attributed to Ælfred in a brief metrical preface; but whether this ascription is to be relied upon, or not, is a difficult question, which has hardly as yet been decided. A summary of the arguments, for and against Ælfred's authorship, will be found in Wülker's Grundriss zur Geschichte der angelsächsischen Litteratur, pp. 421-435.

§ 11. I may here mention that there is a manuscript copy of this work by Boethius, in the original Latin, in Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, No. 214, which contains a considerable number of Anglo-Saxon glosses. A description of this MS., by Prof. J. W. Bright and myself, is printed in the American Journal of Philology, vol. v, no. 4.

§ 12. The next English translation, in point of date, is Chaucer's; concerning which I have more to say below.

§ 13. In the year 1410, we meet with a verse translation of the whole treatise, ascribed by Warton (Hist. E. Poetry, § 20, ed. 1871, iii. 39) to John Walton, Capellanus, or John the Chaplain, a canon of Oseney. 'In the British Museum,' says Warton, 'there is a correct MS. on parchment[11] of Walton's translation of Boethius; and the margin is filled throughout with the Latin text, written by Chaundler above mentioned [i. e. Thomas Chaundler, among other preferments dean of the king's chapel and of Hereford Cathedral, chancellor of Wells, and successively warden of Wykeham's two colleges at Winchester and Oxford.] There is another less elegant MS. in the same collection[12]. But at the end is this {xvi}note:—'Explicit liber Boecij de Consolatione Philosophie de Latino in Anglicum translatus A.D. 1410, per Capellanum Ioannem. This is the beginning of the prologue:—"In suffisaunce of cunnyng and witte[13]." And of the translation:—"Alas, I wrecch, that whilom was in welth." I have seen a third copy in the library of Lincoln cathedral[14], and a fourth in Baliol college[15]. This is the translation of Boethius printed in the monastery of Tavistock in 1525[16], and in octave stanzas. This translation was made at the request of Elizabeth Berkeley.'

Todd, in his Illustrations of Gower and Chaucer, p. xxxi, mentions another MS. 'in the possession of Mr. G. Nicol, his Majesty's bookseller,' in which the above translation is differently attributed in the colophon, which ends thus: 'translatus anno domini millesimo ccccxo. per Capellanum Iohannem Tebaud, alius Watyrbeche.' This can hardly be correct[17].

I may here note that this verse translation has two separate Prologues. One Prologue gives a short account of Boethius and his times, and is extant in MS. Gg. iv. 18 in the Cambridge University Library. An extract from the other is quoted below. MS. E Museo 53, in the Bodleian Library, contains both of them.

§ 14. As to the work itself, Metre 1 of Book i. and Metre 5 of the same are printed entire in Wülker's Altenglisches Lesebuch, ii. 56-9. In one of the metrical prologues to the whole work the following passage occurs, which I copy from MS. Royal 18 A xiii:—

'I have herd spek and sumwhat haue y-seyne,

Of diuerse men[18], that wounder subtyllye,

{xvii}In metir sum, and sum in prosë pleyne,

This book translated haue[19] suffishantlye

In-to[20] Englissh tongë, word for word, wel nye[21];

Bot I most vse the wittes that I haue;

Thogh I may noght do so, yit noght-for-thye,

With helpe of god, the sentence schall I saue.

To Chaucer, that is floure of rethoryk

In Englisshe tong, and excellent poete,

This wot I wel, no-thing may I do lyk,

Thogh so that I of makynge entyrmete:

And Gower, that so craftily doth trete,

As in his book, of moralitee,

Thogh I to theym in makyng am vnmete,

Ȝit most I schewe it forth, that is in me.'

This is an early tribute to the excellence of Chaucer and Gower as poets.

§ 15. When we examine Walton's translation a little more closely, it soon becomes apparent that he has largely availed himself of Chaucer's prose translation, which he evidently kept before him as a model of language. For example, in Bk. ii. met. 5, l. 16, Chaucer has the expression:—'tho weren the cruel clariouns ful hust and ful stille.' This reappears in one of Walton's lines in the form:—'Tho was ful huscht the cruel clarioun.' This is poetry made easy, no doubt.

In order to exhibit this a little more fully, I here transcribe the whole of Walton's translation of this metre, which may be compared with Chaucer's rendering at pp. 40, 41 below. I print in italics all the words which are common to the two versions, so as to shew this curious result, viz. that Walton was here more indebted to Chaucer, than Chaucer, when writing his poem of 'The Former Age,' was to himself. The MS. followed is the Royal MS. mentioned above (p. xvi).

Boethius: Book II: Meter V.

A verse translation by John Walton.

Full wonder blisseful was that rather age,

When mortal men couthe holde hem-selven[22] payed

{xviii}To fede hem-selve[23] with-oute suche outerage,

With mete that trewe feeldes[24] have arrayed;

With acorne[s] thaire hunger was alayed,

And so thei couthe sese thaire talent;

Thei had[den] yit no queynt[e] craft assayed,

As clarry for to make ne pyment[25].

To de[y]en purpure couthe thei noght be-thynke,

The white flees, with venym Tyryen;

The rennyng ryver yaf hem lusty drynke,

And holsom sleep the[y] took vpon the grene.

The pynes, that so full of braunches been,

That was thaire hous, to kepe[n] vnder schade.

The see[26] to kerve no schippes were there seen;

Ther was no man that marchaundise made.

They liked not to sailen vp and doun,

But kepe hem-selven[27] where thei weren bred;

Tho was ful huscht the cruel clarioun,

For eger hate ther was no blood I-sched,

Ne therwith was non armour yet be-bled;

For in that tyme who durst have be so wood

Suche bitter woundes that he nold have dred,

With-outen réward, for to lese his blood.

I wold oure tyme myght turne certanly,

And wise[28] maneres alwey with vs dwelle;

But love of hauyng brenneth feruently,

More fersere than the verray fuyre of helle.

Allas! who was that man that wold him melle

With[29] gold and gemmes that were kevered thus[30],

That first began to myne; I can not telle,

But that he fond a perel[31] precious.

§ 16. MS. Auct. F. 3. 5, in the Bodleian Library, contains a prose translation, different from Chaucer's. After this, the next translation seems to be one by George Colvile; the title is thus given by Lowndes: 'Boetius de Consolatione Philosophiæ, translated by George Coluile, alias Coldewel. London: by John Cawoode; 1556. 4to.' This work was dedicated to Queen Mary, and reprinted in 1561; and again, without date.

There is an unprinted translation, in hexameters and other metres, in the British Museum (MS. Addit. 11401), by Bracegirdle, temp. Elizabeth. See Warton, ed. Hazlitt, iii. 39, note 6.

Lowndes next mentions a translation by J. T., printed at London in 1609, 12mo.

A translation 'Anglo-Latine expressus per S. E. M.' was printed at London in quarto, in 1654, according to Hazlitt's Hand-book to Popular Literature.

Next, a translation into English verse by H. Conningesbye, in 1664, 12mo.

The next is thus described: 'Of the Consolation of Philosophy, made English and illustrated with Notes by the Right Hon. Richard (Graham) Lord Viscount Preston. London; 1695, 8vo. Second edition, corrected; London; 1712, 8vo.'

A translation by W. Causton was printed in London in 1730; 8vo.

A translation by the Rev. Philip Ridpath, printed in London in 1785, 8vo., is described by Lowndes as 'an excellent translation with very useful notes, and a life of Boethius, drawn up with great accuracy and fidelity.'

A translation by R. Duncan was printed at Edinburgh in 1789, 8vo.; and an anonymous translation, described by Lowndes as 'a pitiful performance,' was printed in London in 1792, 8vo.

In a list of works which the Early English Text Society proposes shortly to print, we are told that 'Miss Pemberton has sent to press her edition of the fragments of Queen Elizabeth's Englishings (in the Record Office) from Boethius, Plutarch, &c.'

§ 17. I now return to the consideration of Chaucer's translation, as printed in the present volume.

I do not think the question as to the probable date of its composition need detain us long. It is so obviously connected with 'Troilus' and the 'House of Fame,' which it probably did not long precede, that we can hardly be wrong in dating it, as said above, about 1377-1380; or, in round numbers, about 1380 or a little earlier. I quite agree with Mr. Stewart (Essay, p. 226), that, 'it is surely most reasonable to connect its composition with those poems which contain the greatest number of recollections and imitations of his original;' and I see no reason for ascribing it, with Professor Morley (English Writers, v. 144), to Chaucer's {xx}youth. Even Mr. Stewart is so incautious as to suggest that Chaucer's 'acquaintance with the works of the Roman philosopher ... would seem to date from about the year 1369, when he wrote the Deth of Blaunche.' When we ask for some tangible evidence of this statement, we are simply referred to the following passages in that poem, viz. the mention of 'Tityus (588); of Fortune the debonaire (623); Fortune the monster (627); Fortune's capriciousness and her rolling wheel (634, 642); Tantalus (708); the mind compared to a clean parchment (778); and Alcibiades (1055-6);' see Essay, p. 267. In every one of these instances, I believe the inference to be fallacious, and that Chaucer got all these illustrations, at second hand, from Le Roman de la Rose. As a matter of fact, they are all to be found there; and I find, on reference, that I have, in most instances, already given the parallel passages in my notes. However, to make the matter clearer, I repeat them here.

Book Duch. 588. Cf. Comment li juisier Ticius

Book Duch. 588. Cf. S'efforcent ostoir de mangier;

Book Duch. 588. Cf. Rom. Rom. Rose, 19506.

Book Duch. 588. Cf. Si cum tu fez, las Sisifus, &c.;

Book Duch. 588. Cf. Rom. R. R. 19499.

Book Duch. 623. The dispitouse debonaire,

Book Duch. 623. That scorneth many a creature.

I cannot give the exact reference, because Jean de Meun's description of the various moods of Fortune extends to a portentous length. Chaucer reproduces the general impression which a perusal of the poem leaves on the mind. However, take ll. 4860-62 of Le Roman:—

Que miex vaut asses et profite

Fortune perverse et contraire

Que la mole et la debonnaire.

Surely 'debonaire' in Chaucer is rather French than Latin. And see debonaire in the E. version of the Romaunt, l. 5412.

Book Duch. 627. She is the monstres heed y-wryen,

Book Duch. 627. As filth over y-strawed with floures.

Book Duch. 627. Si di, par ma parole ovrir,

Book Duch. 627. Qui vodroit un femier covrir

Book Duch. 627. De dras de soie ou de floretes; R. R. 8995.

As the second of the above lines from the Book of the Duchesse is obviously taken from Le Roman, it is probable that the first is {xxi}also; but it is a hard task to discover the particular word monstre in this vast poem. However, I find it, in l. 4917, with reference to Fortune; and her wheel is not far off, six lines above.

B. D. 634, 642. Fortune's capriciousness is treated of by Jean de Meun at intolerable length, ll. 4863-8492; and elsewhere. As to her wheel, it is continually rolling through his verses; see ll. 4911, 5366, 5870, 5925, 6172, 6434, 6648, 6880, &c.

B. D. 708. Cf. Et de fain avec Tentalus; R. R. 19482.

B. D. 778. Not from Le Roman, nor from Boethius, but from Machault's Remède de Fortune, as pointed out by M. Sandras long ago; see my note.

B. D. 1055-6. Cf. Car le cors Alcipiades

B. D. 1055-6. Cf. Qui de biauté avoit adés ...

B. D. 1055-6. Cf. Ainsinc le raconte Boece; R. R. 8981.

See my note on the line; and note the spelling of Alcipiades with a p, as in the English MSS.

We thus see that all these passages (except l. 778) are really taken from Le Roman, not to mention many more, already pointed out by Dr. Köppel (Anglia, xiv. 238). And, this being so, we may safely conclude that they were not taken from Boethius directly. Hence we may further infer that, in all probability, Chaucer, in 1369, was not very familiar with Boethius in the Latin original. And this accounts at once for the fact that he seldom quotes Boethius at first hand, perhaps not at all, in any of his earlier poems, such as the Complaint unto Pite, the Complaint of Mars, or Anelida and Arcite, or the Lyf of St. Cecilie. I see no reason for supposing that he had closely studied Boethius before (let us say) 1375; though it is extremely probable, as was said above, that Jean de Meun inspired him with the idea of reading it, to see whether it was really worth translating, as the French poet said it was.

§ 18. When we come to consider the style and manner in which Chaucer has executed his self-imposed task, we must first of all make some allowance for the difference between the scholarship of his age and of our own. One great difference is obvious, though constantly lost sight of, viz. that the teaching in those days was almost entirely oral, and that the student had to depend upon his {xxii}memory to an extent which would now be regarded by many as extremely inconvenient. Suppose that, in reading Boethius, Chaucer comes across the phrase 'ueluti quidam clauus atque gubernaculum' (Bk. iii. pr. 12, note to l. 55), and does not remember the sense of clauus; what is to be done? It is quite certain, though this again is frequently lost sight of, that he had no access to a convenient and well-arranged Latin Dictionary, but only to such imperfect glossaries as were then in use. Almost the only resource, unless he had at hand a friend more learned than himself, was to guess. He guesses accordingly; and, taking clauus to mean much the same thing as clauis, puts down in his translation: 'and he is as a keye and a stere.' Some mistakes of this character were almost inevitable; and it must not greatly surprise us to be told, that the 'inaccuracy and infelicity' of Chaucer's translation 'is not that of an inexperienced Latin scholar, but rather of one who was no Latin scholar at all,' as Mr. Stewart says in his Essay, p. 226. It is useful to bear this in mind, because a similar lack of accuracy is characteristic of Chaucer's other works also; and we must not always infer that emendation is necessary, when we find in his text some curious error.

§ 19. The next passage in Mr. Stewart's Essay so well expresses the state of the case, that I do not hesitate to quote it at length. 'Given (he says) a man who is sufficiently conversant with a language to read it fluently without paying too much heed to the precise value of participle and preposition, who has the wit and the sagacity to grasp the meaning of his author, but not the intimate knowledge of his style and manner necessary to a right appreciation of either, and—especially if he set himself to write in an uncongenial and unfamiliar form—he will assuredly produce just such a result as Chaucer has done.

'We must now glance (he adds) at the literary style of the translation. As Ten Brink has observed, we can here see as clearly as in any work of the middle ages what a high cultivation is requisite for the production of a good prose. Verse, and not prose, is the natural vehicle for the expression of every language in its infancy, and it is certainly not in prose that Chaucer's genius shews to best advantage. The restrictions of metre were indeed to him as silken fetters, while the freedom of prose only served to embarrass him; just as a bird that has been born and bred in captivity, whose traditions are all domestic, finds itself at a sad loss when it escapes {xxiii}from its cage and has to fall back on its own resources for sustenance. In reading "Boece," we have often as it were to pause and look on while Chaucer has a desperate wrestle with a tough sentence; but though now he may appear to be down, with a victorious knee upon him, next moment he is on his feet again, disclaiming defeat in a gloss which makes us doubt whether his adversary had so much the best of it after all. But such strenuous endeavour, even when it is crowned with success, is strange in a writer one of whose chief charms is the delightful ease, the complete absence of effort, with which he says his best things. It is only necessary to compare the passages in Boethius in the prose version with the same when they reappear in the poems, to realise how much better they look in their verse dress. Let the reader take Troilus' soliloquy on Freewill and Predestination (Bk. iv. ll. 958-1078), and read it side by side with the corresponding passage in "Boece" (Bk. v. proses 2 and 3), and he cannot fail to feel the superiority of the former to the latter. With what clearness and precision does the argument unfold itself, how close is the reasoning, how vigorous and yet graceful is the language! It is to be regretted that Chaucer did not do for all the Metra of the "Consolation" what he did for the fifth of the second book. A solitary gem like "The Former Age" makes us long for a whole set[32]. Sometimes, whether unconsciously or of set purpose, it is difficult to decide, his prose slips into verse:—

It lyketh me to shewe, by subtil song,

With slakke and délitáble soun of strenges (Bk. iii. met. 2. 1).

Whan Fortune, with a proud right hand (Bk. ii. met. 1. 1)[33].'

The reader should also consult Ten Brink's History of English Literature, Book iv. sect. 7. I here give a useful extract.

'This version is complete, and faithful in all essential points. Chaucer had no other purpose than to disclose, if possible wholly, the meaning of this famous work to his contemporaries; and notwithstanding many errors in single points, he has fairly well succeeded in reproducing the sense of the original. He often employs for this purpose periphrastic turns, and for the explanation of difficult passages, poetical figures, mythological and historical allusions; and he even incorporates a number of notes in his text. His version thus becomes somewhat diffuse, and, in the undeveloped state of prose composition so characteristic of that age, often quite unwieldy. But there is no lack of warmth, and even of a certain colouring....

'The language of the translation shews many a peculiarity; viz. numerous Latinisms, and even Roman idioms in synthesis, inflexion, or syntax, which are either wholly absent or at least found very rarely in Chaucer's poems. The labour of this translation proved a school for the poet, from which his powers of speech came forth not only more elevated but more self-reliant; and above all, with a greater aptitude to express thoughts of a deeper nature.'

§ 20. Most of the instances in which Chaucer's rendering is inaccurate, unhappy, or insufficient are pointed out in the notes. I here collect some examples, many of which have already been remarked upon by Dr. Morris and Mr. Stewart.

i. met. 1. 3. rendinge Muses: 'lacerae Camenae.'

i. "et. 1. 20. unagreable dwellinges[34]: 'ingratas moras.'

i. pr. 1. 49. til it be at the laste: 'usque in exitium;' (but see the note).

i. pr. 3. 2. I took hevene: 'hausi caelum.'

i. met. 4. 5. hete: 'aestum;' (see the note). So again, in met. 7. 3.

i. pr. 4. 83. for nede of foreine moneye: 'alienae aeris necessitate.'

i. pr. 4. 93. lykned: 'astrui;' (see the note).

i. met. 5. 9. cometh eft ayein hir used cours: 'Solitas iterum mutet habenas;' (see the note).

ii. pr. 1. 22. entree: 'adyto;' (see the note).

ii. pr. 1. 45. use hir maneres: 'utere moribus.'

ii. pr. 5. 10. to hem that despenden it: 'effundendo.'

ii. "r. 5. 11. to thilke folk that mokeren it: 'coaceruando.'

ii. "r. 5. 90. subgit: 'sepositis;' (see the note).

ii. met. 6. 21. the gloss is wrong; (see the note).

ii. met. 7. 20. cruel day: 'sera dies;' (see the note).

iii. pr. 2. 57. birefte awey: 'adferre.' Here MS. C. has afferre, and Chaucer seems to have resolved this into ab-ferre.

iii. pr. 3. 48. foreyne: 'forenses.'

iii. pr. 4. 42. many maner dignitees of consules: 'multiplici consulatu.'

iii. pr. 4. 64. of usaunces: 'utentium.'

iii. pr. 8. 11. anoyously: 'obnoxius;' (see the note).

iii. "r. 8. 29. of a beest that highte lynx: 'Lynceis;' (see the note).

iii. pr. 9. 16. Wenest thou that he, that hath nede of power, that him ne lakketh no-thing? 'An tu arbitraris quod nihilo indigeat egere potentia?' On this Mr. Stewart remarks that 'it is easy to see that indigeat and egere have changed places.' To me, it is not quite easy; for the senses of the M.E. nede and lakken are very slippery. Suppose we make them change places, and read:—'Wenest thou that he, that hath lak of power, that him ne nedeth no-thing?' This may be better, but it is not wholly satisfactory.

iii. pr.9. 39-41. that he ... yif him nedeth = whether he needeth. A very clumsy passage; see the Latin quoted in the note.

iii. pr. 10. 165. the soverein fyn and the cause: 'summa, cardo, atque caussa.'

iii. pr. 12. 55, 67. a keye: 'clauus;' and again, 'clauo.'

iii. p". 12. 55, 74. a yok of misdrawinges: 'detrectantium iugum.'

iii. p". 12. 55, 75. the savinge of obedient thinges: 'obtemperantium salus.'

iii. pr. 12. 136. the whiche proeves drawen to hem-self hir feith and hir acord, everich of hem of other: 'altero ex altero fidem trahente ... probationibus.' (Not well expressed.)

iii. met. 12. 5. the wodes, moveable, to rennen; and had maked the riveres, &c.: 'Siluas currere, mobiles Amnes,' &c.

iii. met. 17-19. Obscure and involved.

iv. pr. 1. 22. of wikkede felounes: 'facinorum.'

iv. pr. 2. 97. Iugement: 'indicium' (misread as iudicium).

iv. met. 7. 15. empty: 'immani;' (misread as inani).

v. pr. 1. 3. ful digne by auctoritee: 'auctoritate dignissima.'

v. p". 1. 34. prince: 'principio.'

v. p". 1. 57. the abregginge of fortuit hap: 'fortuiti caussae compendii.'

v. pr. 4. 30. by grace of position (or possessioun): 'positionis gratia.'

v. pr. 4. 56. right as we trowen: 'quasi uero credamus.'

v. met. 5. 6. by moist fleeinge: 'liquido uolatu.'

§ 21. In the case of a few supposed errors, as pointed out by Mr. Stewart, there remains something to be said on the other side. I note the following instances.

i. pr. 6. 28. Lat. 'uelut hiante ualli robore.' Here Mr. Stewart quotes the reading of MS. A., viz. 'so as the strengthe of the paleys schynyng is open.' But the English text in that MS. is corrupt. The correct reading is 'palis chyning;' where palis means palisade, and translates ualli; and chyning is open means is gaping open, and translates hiante.

ii. pr. 5. 16. Lat. 'largiendi usu.' The translation has: 'by usage of large yevinge of him that hath yeven it.' I fail to see much amiss; for the usual sense of large in M. E. is liberal, bounteous, lavish. Of course we must not substitute the modern sense without justification.

ii. pr. 5. 35. 'of the laste beautee' translates Lat. 'postremae pulcritudinis.' For this, see my note on p. 431.

ii. pr. 7. 38. Lat. 'tum commercii insolentia.' Chaucer has: 'what for defaute of unusage and entrecomuninge of marchaundise.' There is not much amiss; but MS. A. omits the word and after unusage, which of course makes nonsense of the passage.

ii. met. 8. 6. Lat. 'Ut fluctus auidum mare Certo fine coerceat.' Chaucer has: 'that the see, greedy to flowen, constreyned with a certein ende hise floodes.' Mr. Stewart understands 'greedy to flowen' to refer to 'fluctus auidum.' It seems to me that this was merely Chaucer's first idea of the passage, and that he afterwards meant 'hise floodes' to translate 'fluctus,' but forgot to strike out 'to flowen.' I do not defend the translation.

iii. pr. 11. 86. Lat. 'sede;' Eng. 'sete.' This is quite right. Mr. Stewart quotes the Eng. version as having 'feete,' but this is only a corrupt reading, though found in the best MS. Any one {xxvii}who is acquainted with M. E. MSS. will easily guess that 'feete' is merely mis-copied from 'ſeete,' with a long s; and, indeed, sete is the reading of the black-letter editions. There is a blunder here, certainly; only it is not the author's, but due to the scribes.

iv. pr. 6. 176. Lat. 'quidam me quoque excellentior:' Eng. 'a philosophre, the more excellent by me.' The M. E. use of by is ambiguous; it frequently means 'in comparison with.'

v. met. 5. 14. Lat. 'male dissipis:' Eng. 'wexest yvel out of thy wit.' In this case, wexest out of thy wit translates dissipis; and yvel, which is here an adverb, translates male.

Of course we must also make allowances for the variations in Chaucer's Latin MS. from the usually received text. Here we are much assisted by MS. C., which, as explained below, appears to contain a copy of the very text which he consulted, and helps to settle several doubtful points. To take two examples. In Book ii. met. 5. 17, Chaucer has 'ne hadde nat deyed yit armures,' where the usual Lat. text has 'tinxerat arua.' But many MSS. have arma; and, of these, MS. C. is one.

Once more, in Book ii. met. 2. 11, Chaucer has 'sheweth other gapinges,' where the usual Lat. text has 'Altos pandit hiatus.' But some MSS. have Alios; and, of these, MS. C. is one.

§ 22. After all, the chief point of interest about Chaucer's translation of Boethius is the influence that this labour exercised upon his later work, owing to the close familiarity with the text which he thus acquired. I have shewn that we must not expect to find such influence upon his earliest writings; and that, in the case of the Book of the Duchesse, it affected him at second hand, through Jean de Meun. But in other poems, viz. Troilus, the House of Fame, The Legend of Good Women, some of the Balades, and in the Canterbury Tales, the influence of Boethius is frequently observable; and we may usually suppose such influence to have been direct and immediate; nevertheless, we should always keep an eye on Le Roman de la Rose, for Jean de Meun was, in like manner, influenced in no slight degree by the same work. I have often taken an opportunity of pointing out, in my Notes to Chaucer, passages of this character; and I find that Mr. Stewart, with praiseworthy diligence, has endeavoured to give (in Appendix B, following his Essay, at p. 260) 'An Index of Passages in Chaucer which seem to have been {xxviii}suggested by the De Consolatione Philosophiae.' Very useful, in connection with this subject, is the list of passages in which Chaucer seems to have been indebted to Le Roman de la Rose, as given by Dr. E. Köppel in Anglia, vol. xiv. 238-265. Another most useful help is the comparison between Troilus and Boccaccio's Filostrato, by Mr. W. M. Rossetti; which sometimes proves, beyond all doubt, that a passage which may seem to be due to Boethius, is really taken from the Italian poet. As this seems to be the right place for exhibiting the results thus obtained, I proceed to give them, and gladly express my thanks to the above-named authors for the opportunity thus afforded.

§ 23. Comparison with 'Boece' of other works by Chaucer.

Troilus and Criseyde: Book I.

365.[35] a mirour.—Cf. B. v. met. 4. 8.

638. sweetnesse, &c.—B. iii. met. 1. 4.

730. What? slombrestow as in a lytargye?—See B. i. pr. 2. 14.

731. an asse to the harpe.—B. i. pr. 4. 2.

786. Ticius.—B. iii. met. 12. 29.

837. Fortune is my fo.—B. i. pr. 4. 8.

838-9. May of hir cruel wheel the harm withstonde.—B. ii. pr. 1. 80-82.

840. she pleyeth.—B. ii. met. 1. 10; pr. 2. 36.

841. than blamestow Fortune.—B. ii. pr. 2. 14.

846-7. That, as hir Ioyes moten overgoon,

846-7. So mote hir sorwes passen everichoon.—B. ii. pr. 3.

52-4.

848-9. For if hir wheel stinte any-thing to torne,

848-9. Than cessed she Fortune anoon to be.

B. ii. pr. 1. 82-4.

850. Now, sith hir wheel by no wey may soiorne, &c.—B. ii. pr. 2. 59.

857. For who-so list have helping of his leche.—B. i. pr. 4. 3.

1065-71. For every wight that hath an hous to founde.—B. iv. pr. 6. 57-60.

Troilus: Book II.

*42.[36] Forthy men seyn, ech contree hath his lawes.—B. ii. pr. 7. 49-51. (This case is doubtful. Chaucer's phrase—men seyn—shews that he is quoting a common proverb. 'Ase fele thedes, as fele thewes, quoth Hendyng.' 'Tant de gens, tant de guises.'—Ray. So many countries, so many customs.—Hazlitt).

526. O god, that at thy disposicioun

526. Ledest the fyn, by Iuste purveyaunce,

526. Of every wight. B.

iv. pr. 6. 149-151.

766-7. And that a cloud is put with wind to flighte

766-7. Which over-sprat the sonne as for a space.

B. i. met. 3. 8-10.

Troilus: Book III.

617.[37] But O, Fortune, executrice of

wierdes,

617. O influences of thise hevenes hye!

617. Soth is, that, under god, ye ben our hierdes.

B. iv. pr. 6. 60-71.

624. The bente mone with hir hornes pale.—B. i. met. 5. 6.

813. O god—quod she—so worldly selinesse ...

813. Y-medled is with many a bitternesse.—B. ii. pr. 4. 86, 87.

816. Ful anguisshous than is, god woot—quod she—

816. Condicioun of veyn prosperitee.

B. ii. pr. 4. 56.

820-833.—B. ii. pr. 4. 109-117.

*836. Ther is no verray wele in this world here.

B. ii. pr. 4. 130.

1219. And now swetnesse semeth more swete.—B. iii. met. 1. 4.

1261. Benigne Love, thou holy bond of thinges.—B. ii. met. 8. 9-11.

1625-8. For of Fortunes sharp adversitee, &c.—B. ii. pr. 4. 4-7.

1691-2. Feicitee.—B. iii. pr. 2. 55.

1744-68. Love, that of erthe and see hath governaunce, &c.

B. ii. met. 8. 9-11; 15, 16; 3-8; 11-14; 17,

18.

Troilus: Book IV.

*1-7. (Fortune's changes, her wheel, and her scorn).—B. ii. pr. 1. 12; met. 1. 1, 5-10; pr. ii. 37. (But note, that ll. 1-3 are really due to the Filostrato, Bk. iii. st. 94; and ll. 6, 7 are copied from Le Roman de la Rose, 8076-9).

200. cloud of errour.—B. iii. met. 11. 7.

391. Ne trust no wight to finden in Fortune

391. Ay propretee; hir yeftes ben comune.

B. ii. pr. 2. 7-9; 61-2.

*481-2. (Repeated from Book III. 1625-8. But, this time, it is copied from the Filostrato, Bk. iv. st. 56).

503. For sely is that deeth, soth for to seyne,

503. That, oft y-cleped, comth and endeth peyne.

B. i. met. 1. 12-14.

*835. And alle worldly blisse, as thinketh me,

*835. The ende of blisse ay sorwe it occupyeth.

B. ii. pr. 4. 90.

(A very doubtful instance; for l. 836 is precisely the same as Prov. xiv. 13. The word occupyeth is decisive; see my note to Cant. Ta. B 421).

958; 963-6. (Predestination).—B. v. pr. 2. 30-34.

974-1078. (Necessity and Free Will).—B. v. pr. 3. 7-19; 21-71.

*1587. ... thenk that lord is he

*1587. Of Fortune ay, that nought wol of hir recche;

*1587. And she ne daunteth no wight but a wrecche.

B. ii. pr. 4. 98-101.

(But note that l. 1589 really translates two lines in the Filostrato, Bk. iv. st. 154).

Troilus: Book V.

278. And Phebus with his rosy carte.—B. ii. met. 3. 1, 2.

763. Felicitee clepe I my suffisaunce.—B. iii. pr. 2. 6-8.

*1541-4. Fortune, whiche that permutacioun

*1541-4. Of thinges hath, as it is hir committed

*1541-4. Through purveyaunce and disposicioun

*1541-4. Of heighe Iove. B. iv. pr. 6. 75-77.

*1809. (The allusion here to the 'seventh spere' has but a remote reference to Boethius (iv. met. 1. 16-19); for this stanza 259 is translated from Boccaccio's Teseide, Bk. xi. st. 1).

It thus appears that, for this poem, Chaucer made use of B. i. met. 1, pr. 2, met. 3, pr. 4, met. 5; ii. pr. 1, met. 1, pr. 2, pr. 3, met. 3, pr. 4, pr. 7, met. 8; iii. met. 1, pr. 2, met. 2, pr. 3, met. 11, 12; iv. pr. 6; v. pr. 2, pr. 3.

The House of Fame.

*535 (Book ii. 27). Foudre. (This allusion to the thunderbolt is copied from Machault, as shewn in my note; but Machault probably took it from Boeth. i. met. 4. 8; and it is curious that Chaucer has tour, not toun).

730-746 (Book ii. 222-238).—Compare B. iii. pr. 11; esp. 98-111. (Also Le Roman de la Rose, 16957-69; Dante, Purg. xviii. 28).

972-8 (Book ii. 464-70).—B. iv. met. 1. 1-5.

1368-1375 (Book iii. 278-285).—Compare B. i. pr. 1. 8-12.

*1545-8 (Book iii. 455-8).—Compare B. i. pr. 5. 43, 44. (The likeness is very slight).

1920 (Book iii. 830). An hous, that domus Dedali, That Laborintus cleped is.—B. iii. pr. 12. 118.

Legend of Good Women.

195 (p. 78). tonne.—B. ii. pr. 2. 53-5.

*2228-30. (Philomela, 1-3).—B. iii. met. 9. 8-10. (Doubtful; for the same is in Le Roman de la Rose, 16931-6, which is taken from Boethius. And Köppel remarks that the word Eternally answers to nothing in the Latin text, whilst it corresponds to the French Tous jors en pardurableté).

MINOR POEMS.

III. Book of the Duchesse.

The quotations from Boethius are all taken at second-hand. See above, pp. xx, xxi.

V. Parlement of Foules.

*380. That hoot, cold, hevy, light, [and] moist and dreye, &c.—B. iii. pr. 11. 98-103.

(Practically, a chance resemblance; these lines are really from Alanus, De Planctu Naturæ; see the note).

599. ... as oules doon by

light;

599. The day hem blent, ful wel they see by night.

B. iv. pr. 4. 132-3.

IX. The Former Age.

Partly from B. ii. met. 5; see the notes.

X. Fortune.

1-4. Compare B. ii. met. 1. 5-7.

10-12. Compare B. ii. pr. 8. 22-25.

13. Compare B. ii. pr. 4. 98-101.

*17. Socrates.—B. i. pr. 3. 20. (But really from Le Roman de la Rose, 5871-4).

25. No man is wrecched, but himself it wene.—B. ii. pr. 4. 79, 80; cf. pr. 2. 1-10.

29-30. Cf. B. ii. pr. 2. 17, 18.

31. Cf. B. ii. pr. 2. 59, 60.

33, 34. Cf. B. ii. pr. 8. 25-28.

38. Yit halt thyn ancre.—B. ii. pr. 4. 40.

43, 44. Cf. B. ii. pr. 1. 69-72, and 78-80.

45, 46. Cf. B. ii. pr. 2. 60-62; and 37.

50-52. Cf. B. ii. pr. 8. 25-28.

57-64. Cf. B. ii. pr. 2. 11-18.

65-68. Cf. B. iv. pr. 6. 42-46.

68. Ye blinde bestes.—B. iii. pr. 3. 1.

71. Thy laste day.—B. ii. pr. 3. 60, 61.

XIII. Truth.

2. Cf. B. ii. pr. 5. 56, 57.

3. For hord hath hate.—B. ii. pr. 5. 11.

3. and climbing tikelnesse.—B. iii. pr. 8. 10, 11.

7. And trouthe shal delivere. Cf. B. iii. met. 11. 7-9; 15-20.

8. Tempest thee noght.—B. ii. pr. 4. 50.

9. hir that turneth as a bal.—B. ii. pr. 2. 37.

15. That thee is sent, receyve in buxumnesse.—B. ii. pr. 1. 66-68.

17, 19. Her nis non hoom. Cf. B. i. pr. 5. 11-15.

18. Forth, beste.—B. iii. pr. 3. 1.

19. Know thy contree, lok up.—B. v. met. 5. 14, 15.

XIV. Gentilesse.

For the general idea, see B. iii. pr. 6. 24-38; met. 6. 2, and 6-10. With l. 5 compare B. iii. pr. 4. 25.

XV. Lak of Stedfastnesse.

For the general idea, cf. B. ii. met. 8.

Canterbury Tales: Group A.

Prologue. 337-8. Pleyn delyt, &c.—B. iii. pr. 2. 55.

741-2. The wordes mote be cosin to the dede.—B. iii. pr. 12. 152.

Knightes Tale. 925. Thanked be Fortune, and hir false wheel.—B. ii. pr. 2. 37-39.

1164. Who shal yeve a lover any lawe?—B. iii, met. 12. 37.

*1251-4. Cf. B. iv. pr. 6. 147-151.

1255, 1256. Cf. B. iii. pr. 2. 19; ii. pr. 5. 122.

1262. A dronke man, &c.—B. iii. pr. 2. 61.

1266. We seke faste after felicitee,

1266. But we goon wrong ful often, trewely.

B. iii. pr. 2. 59, 60; met. 8. 1.

1303-12. O cruel goddes, that governe, &c.—B. i. met. 5. 22-26; iv. pr. 1. 19-26.

*1946. The riche Cresus. Cf. B. ii. pr. 2. 44. (But cf. Monkes Ta. B. 3917, and notes.)

2987-2993[38]. The firste moevere, &c.—B. ii. met. 8. 6-11. (But see also the Teseide, Bk. ix. st. 51.)

2994-9, 3003-4.—B. iv. pr. 6. 29-35.

3005-3010.—B. iii. pr. 10. 18-22.

3011-5.—B. iv. pr. 6.

Group B.

Man of Lawes Tale. 295-299. O firste moeving cruel firmament. Cf. B. i. met. 5. 1-3; iii. pr. 8. 22; pr. 12. 145-147; iv. met. 1. 6.

481-3. Doth thing for certein ende that ful derk is.—B. iv. pr. 6. 114-117, and 152-154.

813-6. O mighty god, if that it be thy wille.—B. i. met. 5. 22-30; iv. pr. 1. 19-26.

N.B. The stanzas 421-7, and 925-931, are not from Boethius, but from Pope Innocent; see notes.

The Tale of Melibeus. The suggested parallels between this {xxxiv}Tale and Boece are only three; the first is marked by Mr. Stewart as doubtful, the third follows Albertano of Brescia word for word; and the second is too general a statement. It is best to say that no certain instance can be given[39].

The Monk's Prologue. 3163. Tragedie.—B. ii. pr. 2. 51.

The Monkes Tale: Hercules. 3285-3300.—B. iv. met. 7. 20-42. (But see Sources of the Tales, § 48; vol. iii. p. 430.)

*3329. Ful wys is he that can him-selven knowe. Cf. B. ii. pr. 4. 98-101.

3434. For what man that hath freendes thurgh fortune,

3434. Mishap wol make hem enemys, I gesse.

B. iii. pr. 5. 48-50.

3537. But ay fortune hath in hir hony galle.—B. ii. pr. 4. 86-7.

3587. Thus can fortune hir wheel governe and gye.—B. ii. pr. 2. 37-39.

*3636. Thy false wheel my wo al may I wyte.—B. ii. pr. 1. 7-10.

3653. Nero. See B. ii. met. 6; esp. 5-16.

3914. Julius Cesar. No man ne truste upon hir favour longe. B. ii. pr. 1. 48-53.

3921. Cresus.—B. ii. pr. 2. 44-46.

3951. Tragedie.—B. ii. pr. 2. 51-2. (See 3163 above.)

3956. And covere hir brighte face with a cloude.—B. ii. pr. 1. 42.

Nonne Preestes Tale. 4190. That us governeth alle as in comune.—B. ii. pr. 2. 61.

4424. But what that god forwoot mot nedes be.—B. v. pr. 3. 7-10.

4433. Whether that godes worthy forwiting, &c.—B. v. pr. 3. 5-15; 27-39; pr. 4. 25-34; &c.

Group D.

*100. Wyf of Bath. He hath not every vessel al of gold.—B. iv. pr. 1. 30-33. (But cf. 2 Tim. ii. 20.)

170. Another tonne.—B. ii. pr. 2. 53.

1109-1116. 'Gentilesse.'—B. iii. pr. 6. 24-38; met. 6. 6, 7.

1140. Caucasus.—B. ii. pr. 7. 43.

1142. Yit wol the fyr as faire lye and brenne.—B. iii. pr. 4. 47.

1170. That he is gentil that doth gentil dedis.—B. iii. met. 6. 7-10.

1187. He that coveyteth is a povre wight.—B. iii. pr. 5. 20-32.

1203. Povert a spectacle is, as thinketh me.—B. ii. pr. 8. 23-25, 31-33.

The Freres Tale. 1483. For som-tyme we ben goddes instruments.—B. iv. pr. 6. 62-71.

The Somnours Tale. 1968. Lo, ech thing that is oned in him-selve, &c.—B. iii. pr. 11. 37-40.

Group E.

The Clerkes Tale. Mr. Stewart refers ll. 810-2 to Boethius, but these lines translate Petrarch's sentence—'Nulla homini perpetua sors est.' Also ll. 1155-1158, 1161; but these lines translate Petrarch's sentence—'Probat tamen et sæpe nos, multis ac grauibus flagellis exerceri sinit, non ut animum nostrum sciat, quem sciuit antequam crearemur ... abundè ergo constantibus uiris ascripserim, quisquis is fuerit, qui pro Deo suo sine murmure patiatur.' I find no hint that Chaucer was directly influenced by Boethius, while writing this Tale.

The Marchantes Tale. Mr. Stewart refers ll. 1311-4 to Boethius, but they are more likely from Albertanus Brixiensis, Liber de Amore dei, fol. 30 a (as shewn by Dr. Köppel):—'Et merito uxor est diligenda, qui donum est Dei,' followed by a quotation from Prov. xix. 14.

1582. a mirour—B. v. met. 4. 8.

1784. O famulier foo.—B. iii. pr. 5. 50.

1849. The slakke skin.—B. i. met. 1. 12.

1967-9. Were it by destinee or aventure, &c.—B. iv. pr. 6. 62-71.

2021. felicitee Stant in delyt.—B. iii. pr. 2. 55.

2062. O monstre, &c.—B. ii. pr. 1. 10-14.

Group F.

The Squieres Tale. *258. As sore wondren somme on cause of thonder. Cf. B. iv. met. 5. 6. (Somewhat doubtful.)

608. Alle thing, repeiring to his kinde.—B. iii. met. 2. 27-29.

611. As briddes doon that men in cages fede.—B. iii. met. 2. 15-22.

The Frankeleins Tale. 865. Eterne god, that thurgh thy purveyaunce, &c.—B. i. met. 5. 22, 23; iii. met. 9. 1; cf. iii. pr. 9. 147, 148.

879. Which mankinde is so fair part of thy werk.—B. i. met. 5. 38.

886. Al is for the beste.—B. iv. pr. 6. 194-196.

1031. God and governour, &c.—B. i. met. 6. 10-14.

Group G.

The Seconde Nonnes Tale. I think it certain that this early Tale is quite independent of Boethius. L. 114, instanced by Mr. Stewart, is from 'Ysidorus'; see my note.

The Canouns Yemannes Tale. *958. We fayle of that which that we wolden have.—B. iii. pr. 9. 89-91. (Very doubtful.)

Group H.

The Maunciples Tale. 160.

ther may no man embrace

As to destreyne a thing, which that nature

Hath naturelly set in a creature.—B. iii. met. 2. 1-5.

163. Tak any brid, &c.—B. iii. met. 2. 15-22.

Group I.

The Persones Tale. *212. A shadwe hath the lyknesse of the thing of which it is shadwe, but shadwe is nat the same thing of which it is shadwe.—B. v. pr. 4. 45, 46. (Doubtful.)

*471. Who-so prydeth him in the goodes of fortune, he is a ful greet fool; for som-tyme is a man a greet lord by the morwe, that is a caitif and a wrecche er it be night.—B. ii. met. 3. 16-18. (I think this is doubtful, and mark it as such.)

472. Som-tyme the delyces of a man is cause of the grevous maladye thurgh which he dyeth.—B. iii. pr. 7. 3-5.

§ 24. It is worth while to see what light is thrown upon the chronology of the Canterbury Tales by comparison with Boethius.

In the first place, we may remark that, of the Tales mentioned above, there is nothing to shew that The Seconde Nonnes Tale, the Clerkes Tale, or even the Tale of Melibeus, really refer to {xxxvii}any passages in Boethius. They may, in fact, have been written before that translation was made. In the instance of the Second Nonnes Tale, this was certainly the case; and it is not unlikely that the same is true with respect to the others.

But the following Tales (as revised) seem to be later than 'Boece,' viz. The Knightes Tale, The Man of Lawes Tale, and The Monkes Tale; whilst it is quite certain that the following Tales were amongst the latest written, viz. the Nonne Preestes Tale, the three tales in Group D (Wyf, Frere, Somnour), the Marchantes Tale, the Squieres Tale, the Frankeleins Tale, the Canouns Yemannes Tale, and the Maunciples Tale; all of which are in the heroic couplet, and later than 1385.

The case of the Knightes Tale is especially interesting; for the numerous references in it to Boece, and the verbal resemblances between it and Troilus shew that either the original Palamoun and Arcite was written just after those works, or else (which is more likely) it was revised, and became the Knight's Tale, nearly at that time. The connection between Palamon and Arcite, Anelida, and the Parlement of Foules, and the introduction of three stanzas from the Teseide near the end of Troilus, render the former supposition unlikely; whilst at the same time we are confirmed in the impression that the (revised) Knightes Tale succeeded Boece and Troilus at no long interval, and was, in fact, the first of the Canterbury Tales that was written expressly for the purpose of being inserted in that collection, viz. about 1385-6.

I have now to explain the sources of the present edition.

1. MS. C. = MS. Camb. Ii. 3. 21. This MS., in the Cambridge University Library, is certainly the best; and has therefore been taken as the basis of the text. The English portion of it was printed by Dr. Furnivall for the Chaucer Society in 1886; and I have usually relied upon this very useful edition[40]. It is a fine folio MS., wholly occupied with Boethius (De Consolatione Philosophiae), and comments upon it.

It is divided into two distinct parts, which have been bound up together. The latter portion consists of a lengthy commentary upon Boethius, at the end of which we find the title, viz.—'Exposicio preclara quam Iohannes Theutonicus prescripsit et finiuit Anno domini MoCCCvj viij ydus Iunii;' i.e. An Excellent Commentary, written by Johannes Teutonicus, and finished June 6, 1306. This vast commentary occupies 118 folios, in double columns.

The former part of the volume concerns us more nearly. I take it to be, for all practical purposes, the authentic copy. For it presents the following peculiarities. It contains the whole of the Latin text, as well as Chaucer's English version; and it is surprising to find that these are written in alternate chapters. Thus the volume begins with the Latin text of Metre 1, at the close of which there follows immediately, on the same page, Chaucer's translation of Metre 1. Next comes Prose 1 in Latin, followed by Prose 1 in English; and so throughout.

Again, if we examine the Latin text, there seems reason to suppose that it fairly represents the very recension which Chaucer used. It abounds with side-notes and glosses, all in Latin; and the glosses correspond to those in Chaucer's version. Thus, to take an example, the following lines occur near the end of Bk. iii. met. 11:—

'Nam cur rogati sponte recte[41] censetis

Ni mersus alto uiueret fomes corde.'

Over rogati is written the gloss i. interrogato.

Over censetis is written i. iudicatis.

Over Ni is i. nisi; over mersus alto is i. latenter conditos; over uiueret is i. vigeret; and over fomes is i. radix veritatis.

Besides these glosses, there is here the following side-note:—'Nisi radix veritatis latenter conditus vigeret in abscondito mentis, homo non iudicaret recta quacunque ordinata interrogata.'

When we turn to Chaucer's version, we find that he first gives a translation of the two verses, thus:—

'For wherefor elles demen ye of your owne wil the rightes, whan ye ben axed, but-yif so were that the norisshinge of resoun ne livede y-plounged in the depthe of your herte?'

After this he adds, by way of comment:—'This is to seyn, how sholden men demen the sooth of anything that were axed, yif ther nere a rote of soothfastnesse that were y-plounged and hid in naturel principles, the whiche soothfastnesse lived with-in the deepnesse of the thought.'

It is obvious that he has here reproduced the general sense of the Latin side-note above quoted. The chief thing which is missing in the Latin is the expression 'in naturel principles.' But we have only to look to a passage a little higher up, and we find the line—

'Suis retrusum possidere thesauris.'

Over the word retrusum is written i. absconditum; and over thesauris is i. naturalibus policiis et principiis naturaliter inditis. Out of these we have only to pick the words absconditum naturalibus ... principiis, and we at once obtain the missing phrase—'hid in naturel principles.'

Or, to take another striking example. Bk. iv. met. 7 begins, in the MS., with the lines:

'Bella bis quinis operatus annis

Vltor attrides frigie ruinis,

Fratris amissos thalamos piauit.'

At the beginning, just above these, is written a note: 'Istud metrum est de tribus exemplis: de agamenone (sic); secundum de vlixe; tertium, de hercule.'

The glosses are these; over quinis is i. decim; over attrides is agamenon (sic); over Fratris is s. menelai; and over piauit is i. vlcissendo (sic) purgauit: troia enim erat metropolis Frigie.

If we turn to Chaucer's version, in which I print the additions to the text in italics, we find that it runs thus:—

'The wreker Attrides, that is to seyn, Agamenon, that wroughte and continuede the batailes by ten yeer, recovered and purgede in wrekinge, by the destruccioun of Troye, the loste chaumbres of {xl}mariage of his brother; this is to seyn, that he, Agamenon, wan ayein Eleyne, that was Menelaus wyf his brother.'

We see how this was made up. Not a little curious are the spellings Attrides and Agamenon[42], as occurring both in the Latin part of this MS. and in Chaucer's version. Again, Chaucer has ten, corresponding to the gloss decim, not to the textual phrase bis quinis. His explanation of piauit by recovered and purgede in wrekinge is clearly due to the gloss ulciscendo purgauit. His substitution of Troye for Frigie is due to the gloss: troia enim erat metropolis Frigie. And even the name Menelaus his brother answers to Fratris, s. menelai. And all that is left, as being absolutely his own, are the words and continuede, recovered, and wan ayein Eleyne. We soon discover that, in a hundred instances, he renders a single Latin verb or substantive by two English verbs or substantives, by way of making the sense clearer; which accounts for his introduction of the verbs continuede and recovered; and this consideration reduces Chaucer's additional contribution to a mention of the name of Eleyne, which was of course extremely familiar to him.

Similarly, we find in this MS. the original of the gloss explaining coempcioun (p. 11); of the 'Glose' on p. 15; of the 'Glosa' on p. 26; and of most of the notes which, at first sight, look like additions by Chaucer himself[43].

The result is that, in all difficulties, the first authority to be consulted is the Latin text in this particular MS.; for we are easily led to conclude that it was intentionally designed to preserve both Chaucer's translation and the original text. It does not follow that it is always perfect; for it can only be a copy of the Latin, and the scribe may err. In writing recte for recta (see note on p. xxxviii), he has certainly committed an error by a slip of the pen. The same mistake has been observed to occur in another MS., viz. Codex Gothanus I.

The only drawback is this. The MS. is so crowded with glosses and side-notes, many of them closely written in small characters, that it is almost impossible to consult them all. I have therefore contented myself with resorting to them for information in difficult passages only. For further remarks on this subject, I must refer the reader to the Notes.

Lastly, I may observe that the design of preserving in this MS. all the apparatus referring to Chaucer's Boethius, is made the more apparent by the curious fact that, in this MS. only, the two poems by Chaucer that are closely related to Boethius, viz. The Former Age, and Fortune, are actually inserted into the very body of it, immediately after Bk. ii. met. 5. This place was of course chosen because The Former Age is, to some extent, a verse translation of that metre; and Fortune was added because, being founded upon scraps from several chapters, it had no definite claim to any specific place of its own.

In this MS., the English text, like the Latin one, has a few imperfections. One imperfection appears in certain peculiarities of spelling. The scribe seems to have had some habits of pronunciation that betoken a greater familiarity with Anglo-French than with English. The awkward position of the guttural sound of gh in neighebour seems to have been too much for him; hence he substituted ssh (= sh-sh) for gh, and gives us the spelling neysshebour (Bk. ii. pr. 3. 24, foot-note; pr. 7. 57, foot-note.) Nevertheless, it is the best MS. and has most authority. For further remarks, see the account of the present edition, on pp. xlvi-xlviii.

2. MS. Camb. Ii. 1. 38. This MS. also belongs to the Cambridge University Library, and was written early in the fifteenth century. It contains 8 complete quires of 8 leaves, and 1 incomplete quire of 6 leaves, making 70 leaves in all. The English version appears alone, and occupies 68 leaves, and part of leaf 69 recto; leaf 69, verso, and leaf 70, are blank. The last words are:—'þe eyen of þe Iuge þat seeth and demeth alle thinges. Explicit liber boecij, &c.' Other treatises, in Latin, are bound up with it, but are unrelated. The readings of this MS. agree very closely with those of Ii. 3. 21, and of our text. Thus, in Met. i. l. 9, it has the reading wyerdes, with the gloss s. fata, as in Ii. 3. 21. (The scribe at first wrote wyerldes, but the l is marked for expunction.) In l. 12, it has emptid, whereas the Addit. MS. has emty; and in l. 16 it has nayteth, whereas the Addit. MS. wrongly {xlii}has naieth. On account of its close agreement with the text, I have made but little use of it.

It is worth notice that this MS. (like Harl. 2421) frequently has correct readings in cases where even the MS. above described exhibits some blunder. A few such instances are given in the notes. For example, it has the reading wrythith in Bk. i. met. 4. 7, where MS. C. has the absurd word writith, and MS. A. has wircheth. In the very next line, it has thonder-leit, and it is highly probable that leit is the real word, and light an ignorant substitution; for leit (answering to A.S. lēget, līget) is the right M.E. word for 'lightning'; see the examples in Stratmann. So again, in Bk. ii. met. 3. 13, it reads ouer-whelueth, like the black-letter editions; whilst MS. C. turns whelueth into welueeth, and MS. A. gives the spelling whelweth. In Bk. ii. pr. 6. 63, it correctly retains I after may, though MSS. C. and A. both omit it. In Bk. ii. pr. 8. 17, it has wyndy, not wyndynge; and I shew (in the note at p. 434) that windy is, after all, the correct reading, since the Lat. text has uentosam. In Bk. iii. met. 3. 1, it resembles the printed editions in the insertion of the words or a goter after river. In Bk. iv. pr. 3. 47, 48, it preserves the missing words: peyne, he ne douteth nat þat he nys entecchid and defouled with. In Bk. iv. met. 6. 24, it has the right reading, viz. brethith. Finally, it usually retains the word whylom in places where the MS. next described substitutes the word somtyme. If any difficulty in the text raises future discussion, it is clear that this MS. should be consulted.

3. MS. A. = MS. Addit. 10340, in the British Museum. This is the MS. printed at length by Dr. Morris for the Early English Text Society, and denoted by the letter 'A.' in my foot-notes. As it is so accessible, I need say but little. It is less correct than MS. Ii. 3. 21 in many readings, and the spelling, on the whole, is not so good. The omissions in it are also more numerous, but it occasionally preserves a passage which the Cambridge MS. omits. It is also imperfect, as it omits Prose 8 and Metre 8 of Bk. ii., and Prose 1 of Bk. iii. It has been collated throughout, though I have usually refrained from quoting such readings from it as are evidently inferior or wrong. I notice one peculiarity in particular, viz. that it almost invariably substitutes the word somtyme for the whylom found in other copies; and whylom, in this treatise, is a rather common word. Dr. Morris's account of the MS. is here copied.

'The Additional MS. is written by a scribe who was unacquainted with the force of the final -e. Thus he adds it to the preterites of strong verbs, which do not require it; he omits it in the preterites of weak verbs where it is wanted, and attaches it to passive participles of weak verbs, where it is superfluous. The scribe of the Cambridge MS. is careful to preserve the final -e where it is a sign (1) of the definite declension of the adjective; (2) of the plural adjective; (3) of the infinitive mood; (4) of the preterite of weak verbs; (5) of present participles; (6) of the 2nd pers. pret. indic. of strong verbs; (7) of adverbs; (8) of an older vowel-ending.

'The Addit. MS. has frequently thilk (singular and plural) and -nes (in wrechednes, &c.), when the Camb. MS. has thilke (as usual in the Canterbury Tales) and -nesse.'