Title: The Boy Mechanic, Book 2: 1000 Things for Boys to Do

Editor: H. H. Windsor

Release date: January 4, 2014 [eBook #44585]

Most recently updated: September 18, 2025

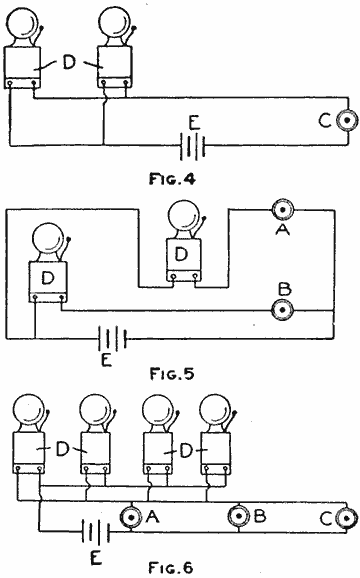

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Malcolm Farmer, tallforasmurf and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

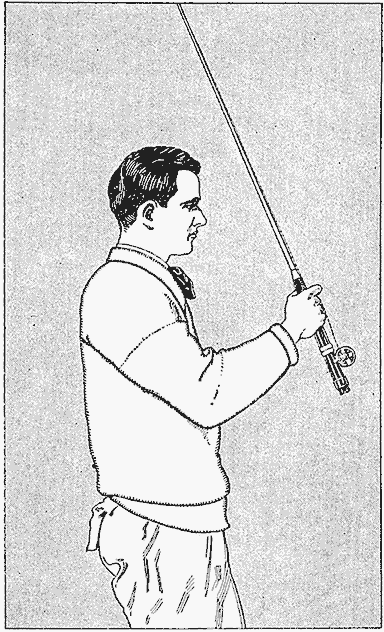

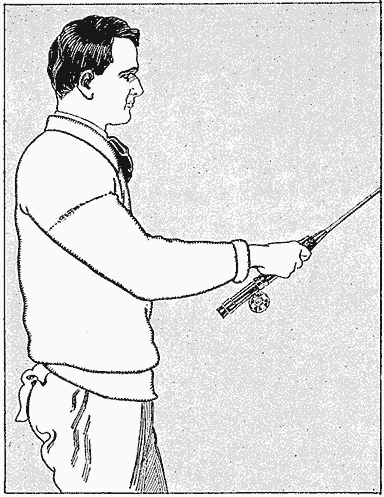

Two minor typographical errors were found and corrected. In the chapters on making fly-fishing rods (pages 59-71), two lists of materials that were printed as running text have been reformatted as unsigned lists for clarity. The text is unchanged.

The page numbers that appear in the right margin are links. To snap a page to the top of the window, click the page number. To obtain a link to a particular page, right-click on the page number and copy the link.

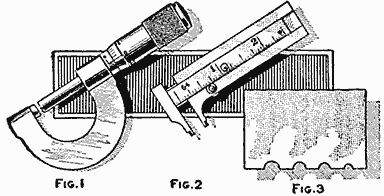

To speed loading, drawings in-line with the text are at most 512 pixels wide, often less. Drawings that have dimensions or other details that are important to properly executing a project (as well as some drawings that are simply charming to look at) are preserved as higher-resolution images linked to the embedded images. When an in-line image has a thin black border, you can click on it to open the larger version. These larger images are sized to print correctly at 150 px/in (60 px/cm).

COPYRIGHTED, 1915, BY H. H. WINDSOR

CHICAGO

POPULAR MECHANICS CO.

PUBLISHERS

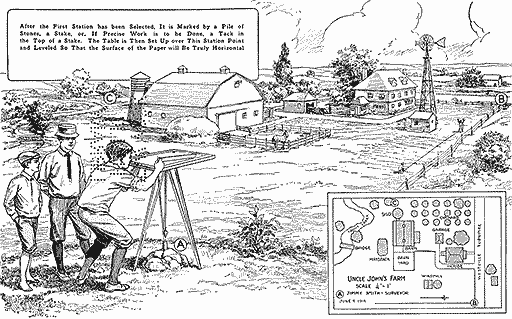

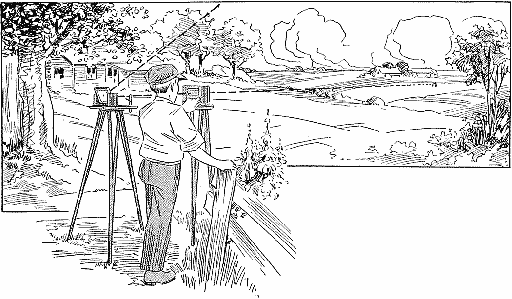

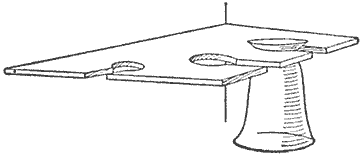

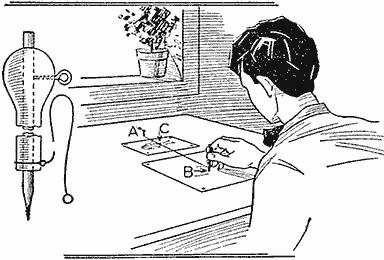

After the First Station has been Selected, It is Marked by a Pile of Stones, a Stake, or, If Precise Work is to be Done, a Tack in the Top of a Stake. The Table is Then Set Up over This Station Point and Leveled So That the Surface of the Paper will Be Truly Horizontal (Inset: UNCLE JOHN'S FARM Scale 1/16" = 1' Jimmy Smith—Surveyor)

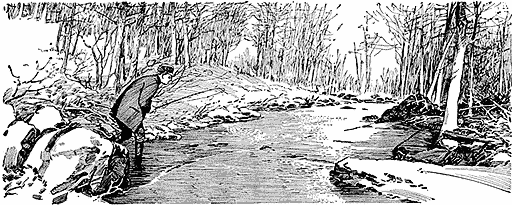

[In the training of a boy for a trade or profession there is none so profitable for outdoor work as that of a surveyor. This article sets forth how to accomplish surveying and the making of simple maps with the use of commonplace tools that any boy can make.—Editor.]

Surveying and map making have always been two of the most interesting things a civil engineer has had to do. And, like George Washington, many of the men we look up to today as successes in different lines worked as surveyors in their younger days. Surveying takes one out of doors, and is apt to lead him into the unknown and unexplored byways of the earth.

Though modern surveyors often use precise and expensive instruments, creditable surveys can be made with simple and inexpensive apparatus. Of such apparatus, two of the simplest are the plane table and the camera. Since one must know the principles of plane-table surveying before he can do camera surveying, this paper will describe the plane table alone, leaving the camera for another chapter.

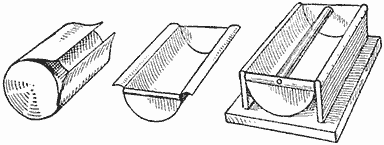

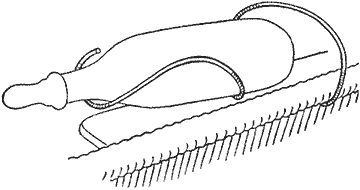

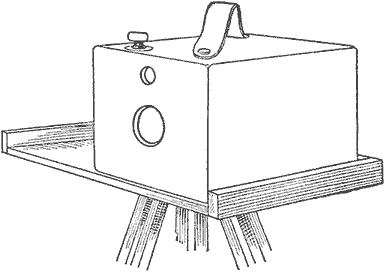

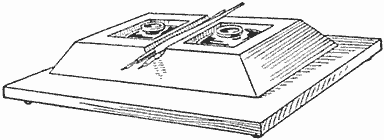

A plane table is simply a drawing board mounted on a tripod so that it can be set up and worked upon in the field. One kind of plane table, which is used in the army for reconnaissance, does not even have a tripod; it is simply strapped to the arm of the man who is using it.

Plane-table maps vary greatly in scale and the area they represent. Landscape artists' plans may show only single city lots, while some topographic maps cover hundreds of square miles on a single sheet. For maps of a small farm, a park, or a residence block in the city, a plane table is almost ideal, since plane-table maps are made with rather simple apparatus and do not require much actual measuring on the ground. Most objects are located without ever going to them, or even sending a rod-man to them.

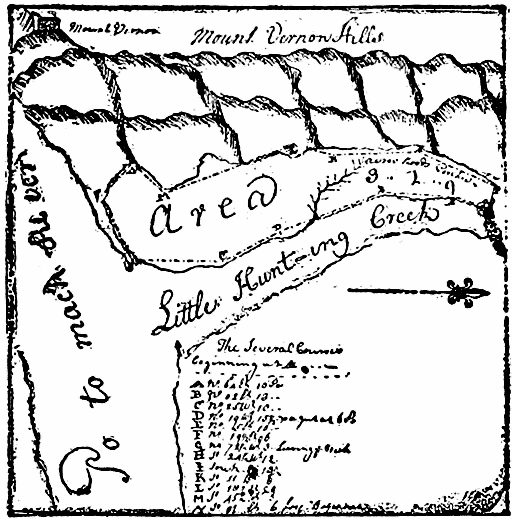

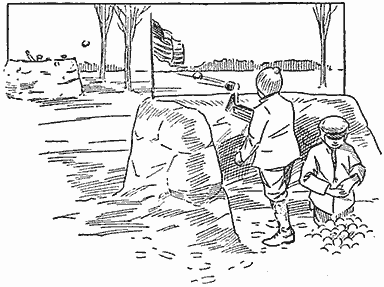

Just a Few Weeks After George Washington's Sixteenth Birthday, in 1748, Lord Fairfax, Owner of a Large Estate in Virginia, Took Him into His Employ as a Surveyor

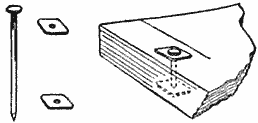

[2] Besides the plane table itself and a sheet of paper, only a small carpenter's level, a tape to measure a few distances with, and some spikes for markers, a hard lead pencil, a ruler, and a few needles are absolutely necessary for this sort of a map.

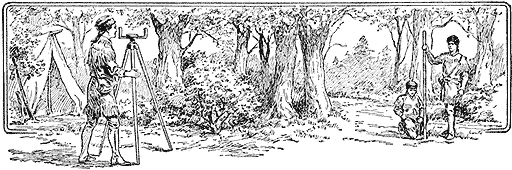

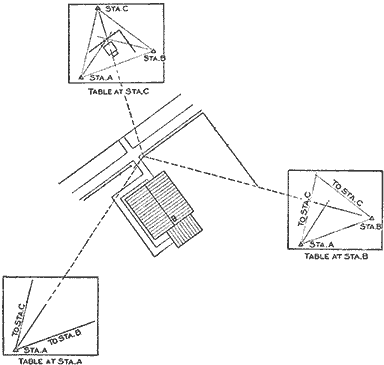

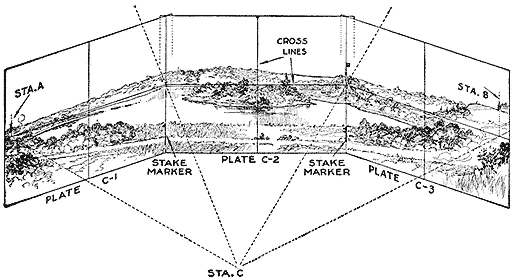

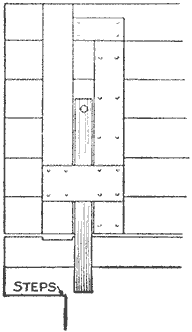

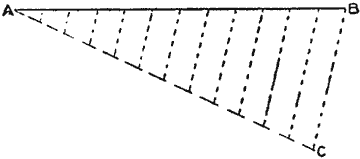

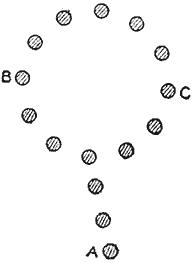

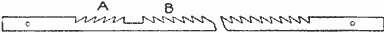

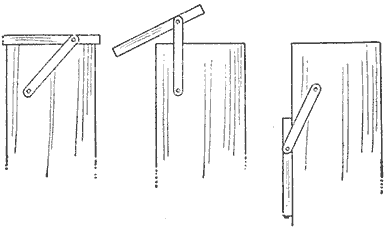

Three Stations are Used for Setting the Plane Table in Succession to Locate the Various Objects

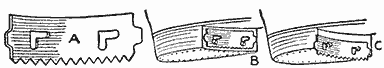

TABLE AT STA. A - TABLE AT STA. B - TABLE AT STA. C

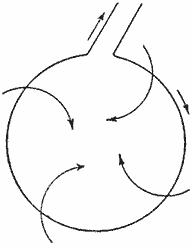

To start a plane-table map, a station must first be selected from which as many as possible of the objects to be located on the finished map can be seen. Ordinarily, the objects one would locate are corners of buildings, fence corners, intersections of roads, corners of lots, banks of streams, possibly trees, and section and quarter-section corners in the country. A railroad, a lake, a mountain, or anything which forms a noticeable landmark in any particular locality, ought to be on the map. In mapping a territory which has never been surveyed before, the first surveyor may name the hills and streams.

After the first station has been selected, it is marked by a pile of stones, a stake, or, if precise work is to be done, a tack in the top of a stake. The table is then set up over this station point and leveled so that the surface of the paper will be truly horizontal. Generally, too, the board is "oriented," that is, placed so that two of its edges point north and south and two east and west. It is then clamped so that it will not move while working on it.

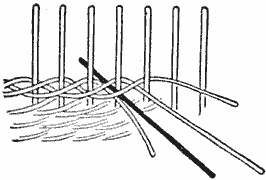

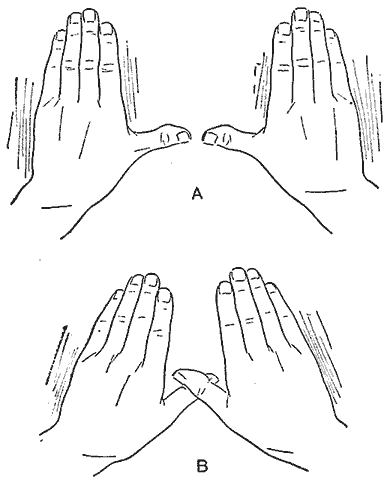

To begin the map, a point on the table is chosen to represent the station on the ground over which the table is set. This point is marked by sticking a fine needle into the paper, vertically. A small triangle should be drawn around the needle hole in the paper and labeled "Sta. A," so that it will not be lost in the maze of points which will soon cover the sheet. By sighting past this needle toward some object which is wanted on the map, like the corner of a house, its direction can be marked by setting another needle on the far side of the table, in line with the first and the given object. Then, if a ruler or straightedge be placed against these two needles and a fine line drawn connecting them, this line will show the exact direction of the object from Sta. A. All the other objects which are wanted on the finished map and can be seen from Sta. A are located by direction in the same way.

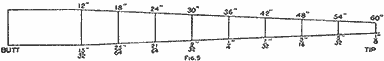

The first points to have their direction thus marked ought to be the next stations to be occupied. If all the objects to be located can be seen from three stations, or even two of three stations, three stations will be sufficient. The distance to one of them from Sta. A should be carefully measured and laid off to scale along its direction line on the map. Its place on the map should be marked exactly as the first station was, substituting B for A. It is wise, after every few sights at other objects, to take a sight along the line AB to make sure that the board has not turned. A good map is impossible if the board twists.

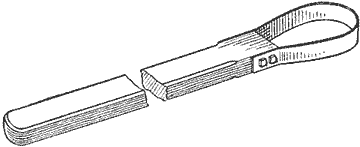

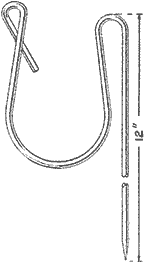

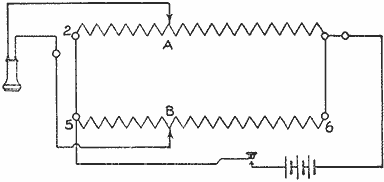

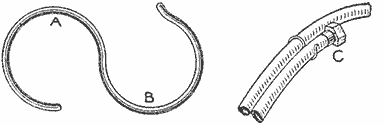

To measure the distance between [3] stations, a 50 or 100-ft. tape, or some accurate substitute, is necessary. An ordinary piece of iron telegraph wire, 105 ft. long, is a good substitute. A point, about 2-1/2 ft. from one end, is marked with a little lump of solder. A chisel dent in this solder will mark one end of the 100-ft. section. Then, with a borrowed tape or a good rule, measure off and mark every 10 ft., just as the first point was marked, until the entire 100 ft. have been laid off. The last 10 ft. should be divided into feet. In all this measuring and marking, the wire must be stretched out taut and straight. The extra 2-1/2 ft. at each end are used for making handles. By estimating the tenths of a foot, measurements can be made with such a tape, or "chain," as an old-time surveyor might call it, just as accurately as they can be laid off on the map.

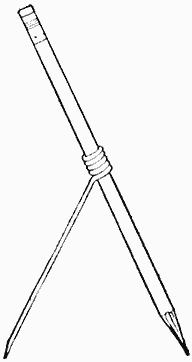

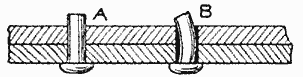

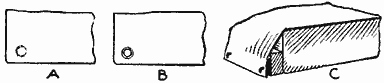

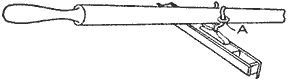

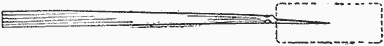

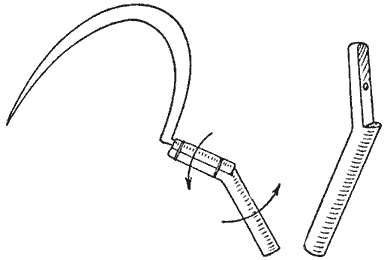

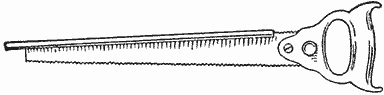

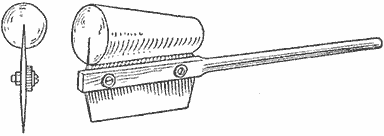

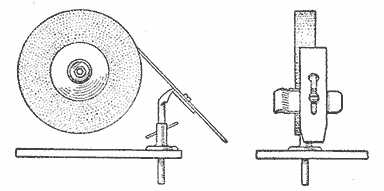

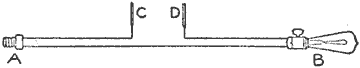

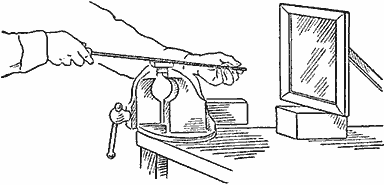

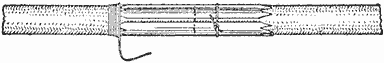

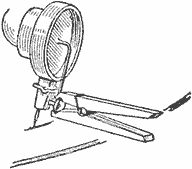

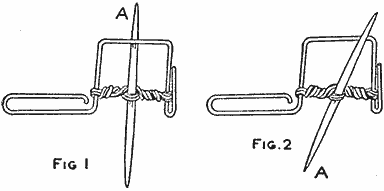

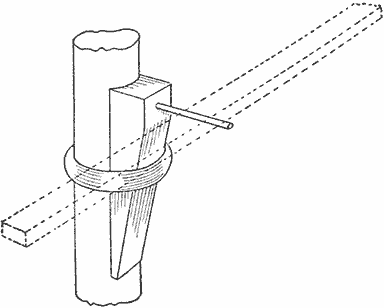

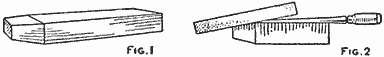

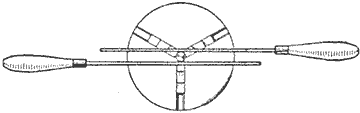

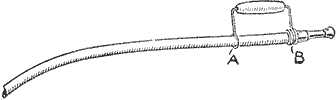

An Alidade, Consisting of Two Sights and a Straightedge, Takes the Place of the Two Needles

Two men are required for measuring, or "chaining," a head and a rear chainman. The rear chainman holds the 100-ft. end of the tape on the station point, while the head chainman takes his end forward toward the station to which they are measuring. When he has gone nearly the length of the tape, the rear chainman calls "halt." The head chainman stops and draws the tape up tight, while the rear chainman holds his division end on the starting point. Then the head chainman sticks a spike into the ground to mark the place where his division end comes, calls out "stuck," and starts on toward the object point.

Large spikes make good marking pins, especially if they have little red or white strips of cloth tied to them. Surveyors use 11 markers. One is stuck into the ground at the starting point and is carried forward by the rear chainman, who also picks up the markers at each 100-ft. point as soon as the head chainman calls "stuck." In this way, the number of markers which the rear chainman has in his hand is always the same as the number of hundreds of feet which the last set marker is from the starting point.

In measuring between two points, care must be taken to draw the tape out taut and straight, its two ends must be level with each other, and it must be exactly in line with the two points between which the measurement is being made. In measuring downhill, one end may have to be held up high, and the point on the ground where the end division would come, found by dropping a stone from the place where it is in the air and watching for the spot where the rock strikes the ground. A surer way to do this is to hold a plumb-bob string on the last division and carefully let the bob down until it touches the ground. A rod with a red or white flag on it ought to be placed at or just beyond the point to which the measurement is to be made so that the rear chainman can [4] easily line in the head chainman. The latter, before he places his marker, looks back to the rear chainman to be told whether or not he is "on line" with the object point. If he is not, and ought to go to the rear chainman's right to get "on," the latter holds out his right arm and the head chainman moves accordingly. When he reaches the right point, the rear chainman signals "all right" by holding out both of his arms and then dropping them to his side; the marker is stuck, and both move up a hundred feet and repeat the process.

After all the points possible have been located from Sta. A, and the direction lines labeled lightly in pencil so that they can be distinguished when the board has been removed from the station, the plane table is picked up and carried to Sta. B. Here it is again set up, leveled, and oriented by making the direction of the line AB on the paper exactly the same as that of the line from Sta. A to Sta. B on the ground. This is done by placing needles at points A and B on the table and then turning the board until the two needles and Sta. A are in line. Sights are taken on the same objects which were "shot" at Sta. A, and to objects which were not visible from Sta. A. The intersection of the lines of sight toward a given object from A and from B marks the location on the paper of that object. If the two ends of a straight fence have been located in this way, a straight line joining the points will show the location of the fence on the map. By exactly similar methods, every other object is located on the paper.

In order to avoid errors, it is an excellent scheme to locate three stations near the outside edges of the area to be mapped, and locate all objects possible by sights from each of the three stations. If, instead of all three crossing each other at a point, the lines of sight from the three stations form a triangle, something is wrong. If the triangle is very small, it may be safe to use its center as the correct point; if not, the work must be repeated and checked. Locating even a few points by this method may prevent some bad blunders. The three stations ought to form as nearly as possible, an equilateral triangle; and the distances between all of them should be measured and laid out accurately on the plane table.

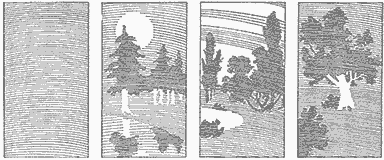

There are two ways in which the map may be finished, inked, or traced. By drawing in the "culture," that is, the things built by man, like the houses, the fences, the roads, and the railroads, in black ink; the topography, that is, the hills and valleys, in brown; the water, in blue, and then erasing all the construction lines, a very neat map can be made. Another way is to get some "onion-skin" paper, or some tracing cloth, tack it over the penciled map, and trace the lines right through, using black India ink. This tracing can be blueprinted, just as a photographic film. A plain, neat title, describing location of map; who made it and when; the scale used; why it was made, if it was made for a special [5] purpose, and the direction of the north point, ought to be on every map. The topographic sheets published by the United States Geological Survey are good samples to follow. They have been published for a great many places all over the country, and single copies can be obtained by sending 10 cents to the Director, United States Geological Survey, Washington, D. C.

From an Original Drawing of a Survey of Mount Vernon, Made by George Washington at the Age of 14

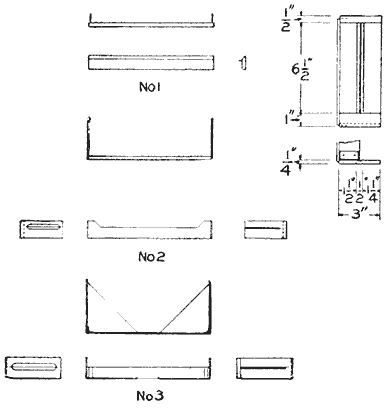

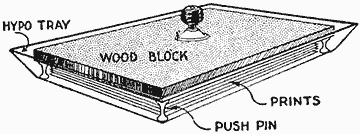

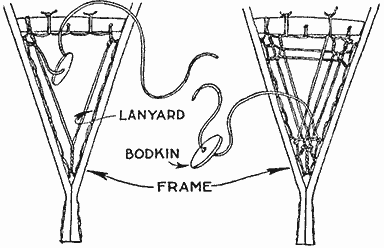

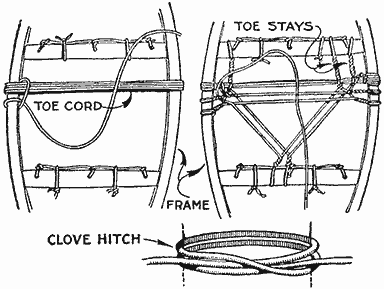

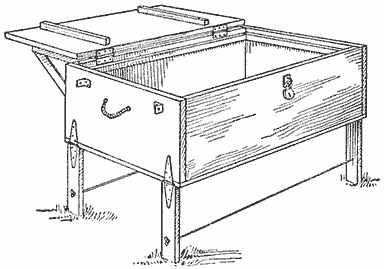

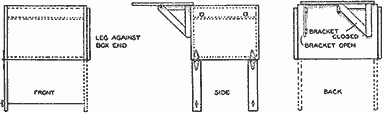

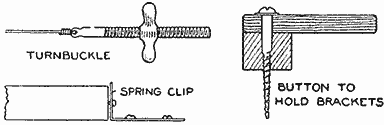

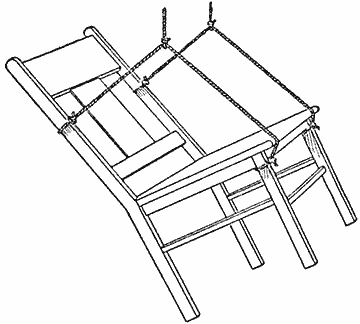

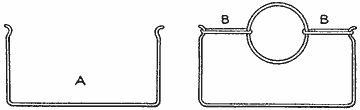

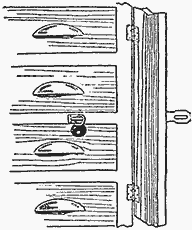

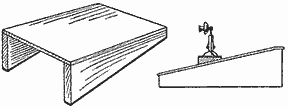

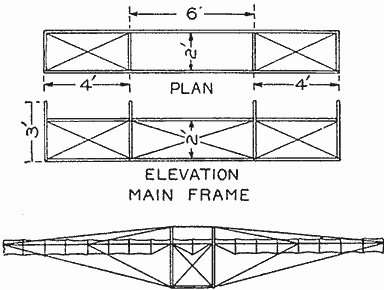

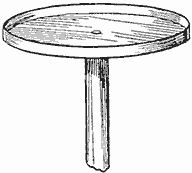

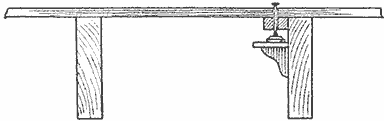

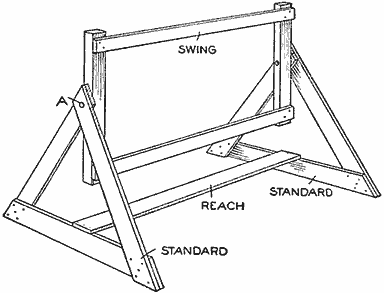

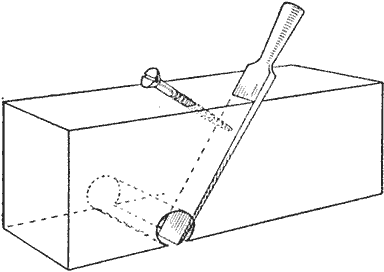

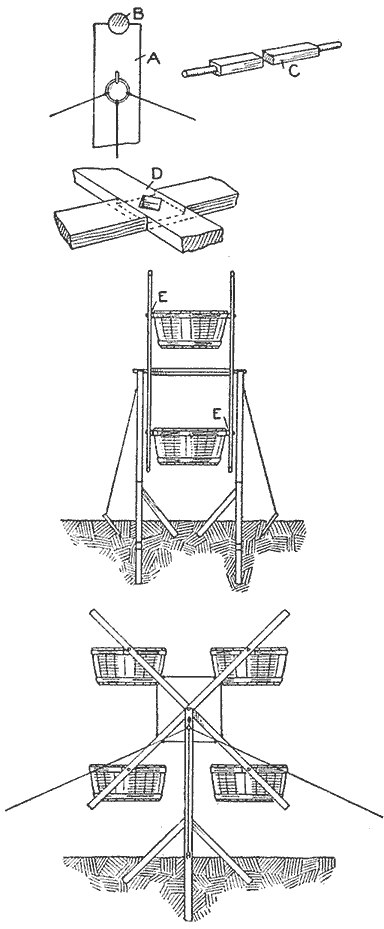

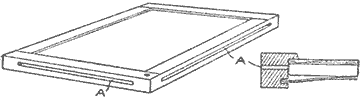

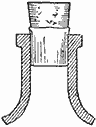

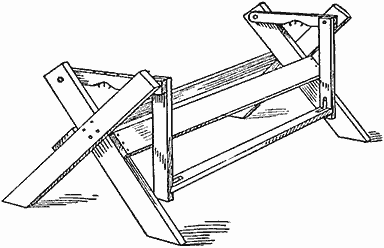

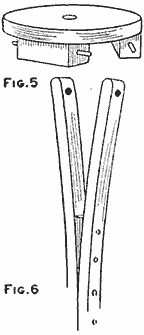

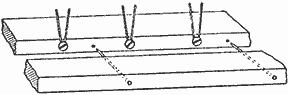

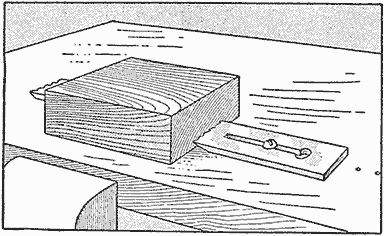

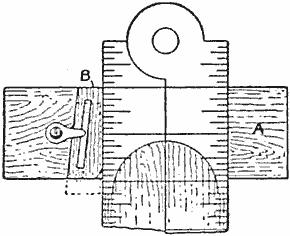

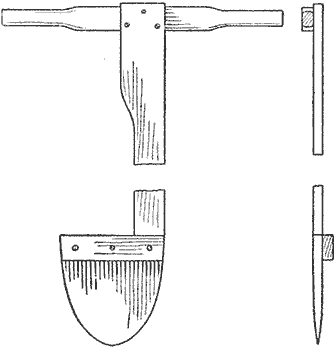

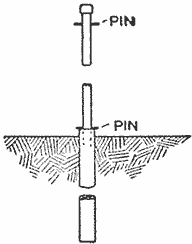

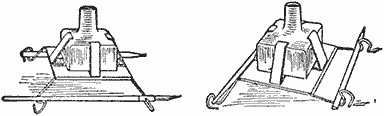

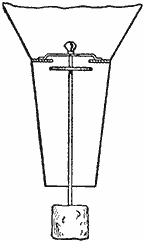

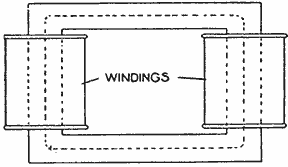

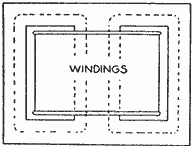

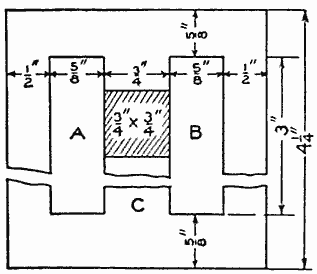

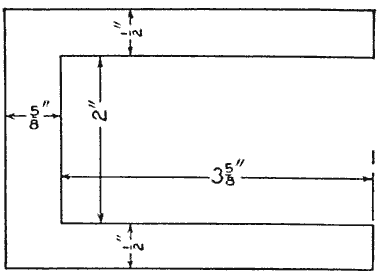

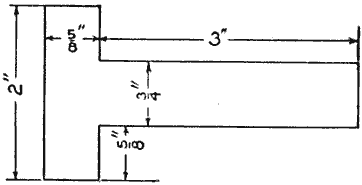

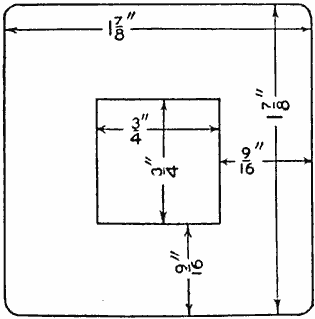

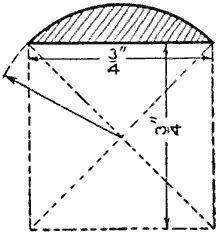

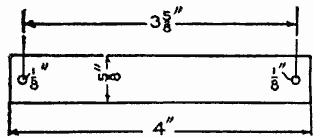

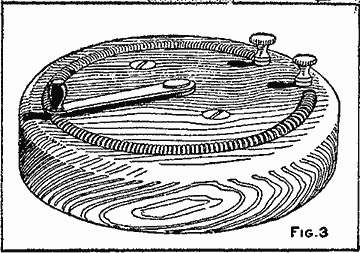

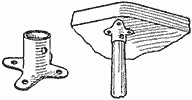

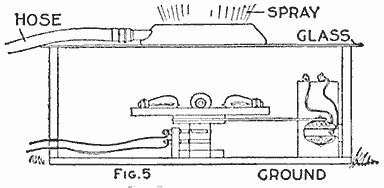

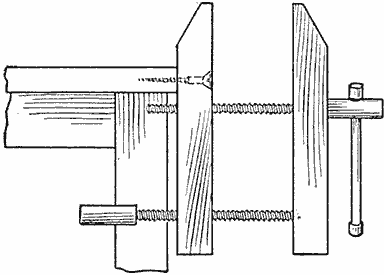

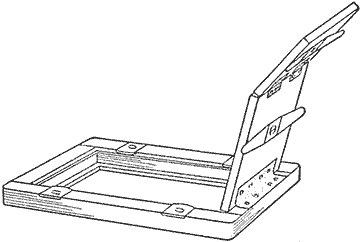

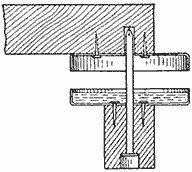

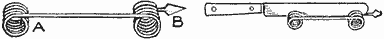

Plane tables are almost as easily made as they are bought. If there is no old drawing board around the house, a new bread board from the ten-cent store will serve. For ordinary work, a table which is 15 or 20 in. square will do very well. The board must be mounted on a tripod so that it will be rigid while it is being worked upon and yet can be unclamped and oriented. A brass plate, with a hole in it and a nut soldered over the hole, screwed to the bottom of the board will permit the board and tripod to be bolted together in good shape. Another method, which is not nearly as good, is to drill a hole clear through the board, countersink it on top for a bolt head, and bolt the board and tripod head directly together. With the brass plate and nut, the camera tripod can be pressed into service if a nut of the proper size has been used. The camera tripod is, however, apt to be wabbly with a drawing board on top; a much more satisfactory tripod can be built as shown in the accompanying drawings. Each leg is made of two strips of wood, 3/4 by 3/8 in. and 3 ft. long. These strips are screwed together at their lower ends, gripping a spike between them which will prevent the legs from slipping on the ground. The tops of the strips are spread apart and screwed to the opposite ends of an oak or maple cleat. This cleat is, in turn, screwed to the under side of the circular tripod head.

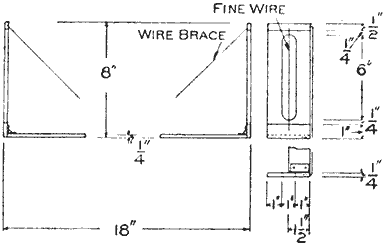

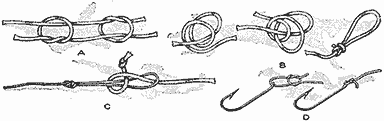

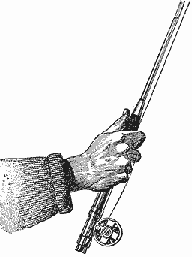

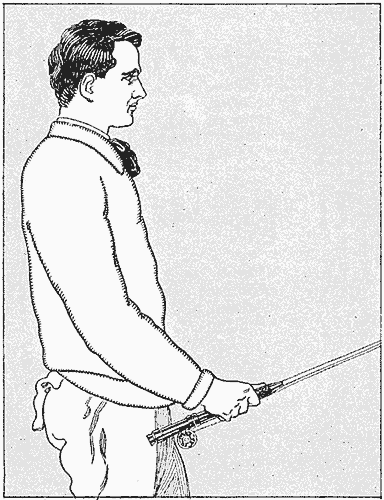

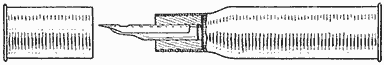

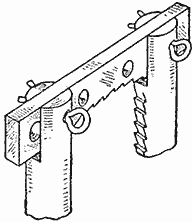

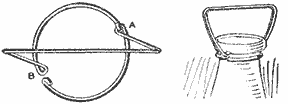

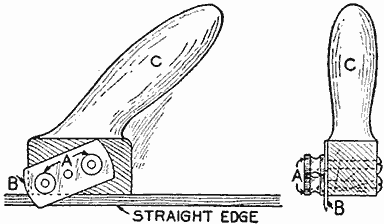

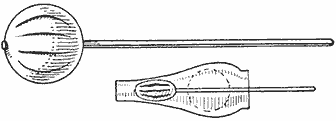

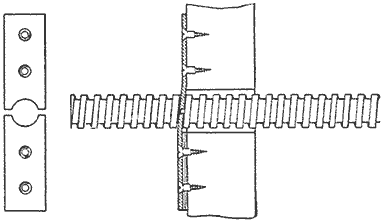

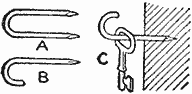

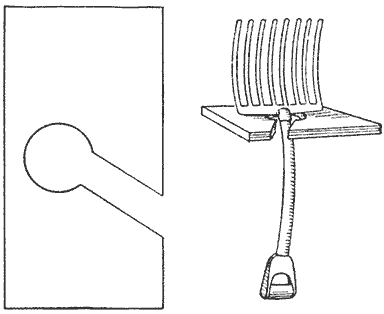

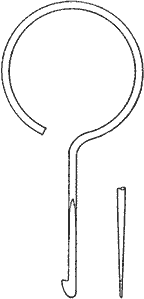

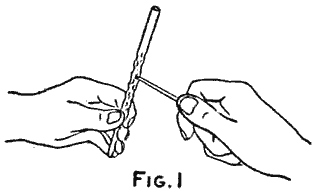

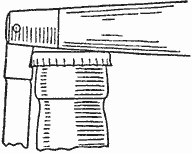

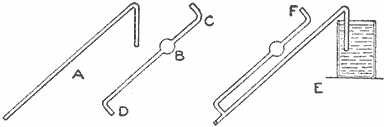

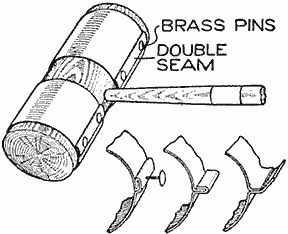

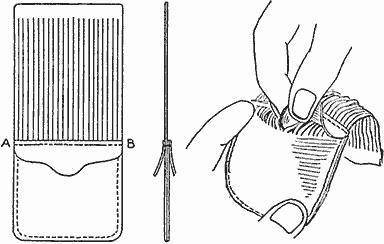

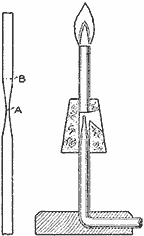

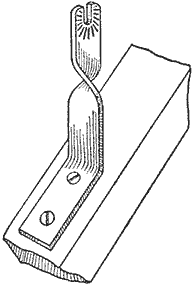

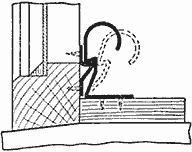

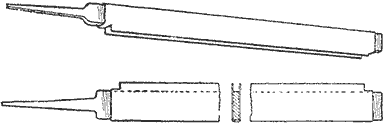

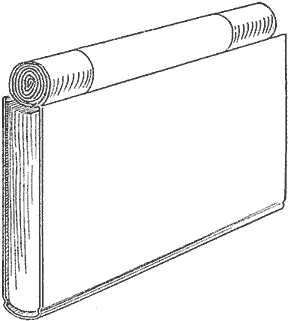

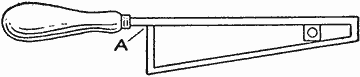

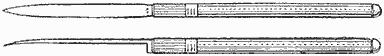

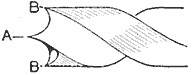

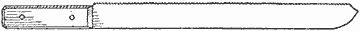

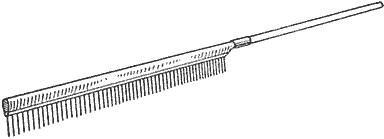

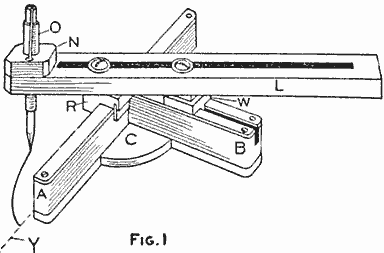

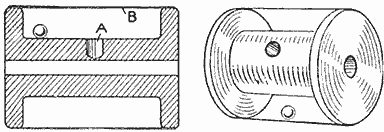

In place of the two needles and the ruler described for marking the line of sight, most plane-table men use an alidade, which is a combination of two sights and a straightedge. A very simple alidade may be made by mounting two needles on a ruler. The straight edge of the ruler is placed against the needle which marks the station at which the plane table is set up. Then, by swinging the ruler around this needle until its two sighting needles come in line with some object, the line of sight can be drawn directly on the paper along the edge of the ruler. A surveyor in India once made an alidade out of a piece of straightedge and two sights made of native coins hammered out by a native blacksmith. Two pieces of cigar box, one with a fine vertical saw slit in it, and the other with a vertical slot and a piece of fine wire or silk thread stretched down the center, glued to a well planed, straight, flat piece of wood, make a fine alidade. A careful worker may be able to put his sights on hinges so that they will fold down when not in use.

More than anything else, map making rewards care and accuracy, and shows up slipshod workmanship. If the pencils are sharp, the lines fine, and if the work is checked often, beautiful maps can be made with very simple apparatus.

White marks on waxed surfaces may be removed by rubbing lightly with a soft rag moistened in alcohol, after which rub with raw linseed oil.

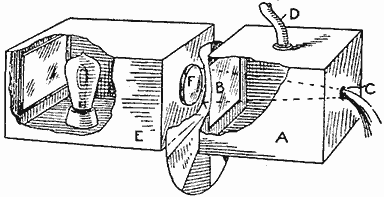

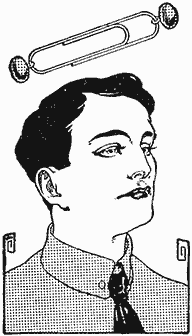

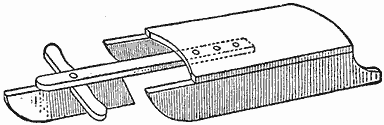

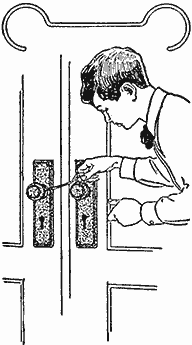

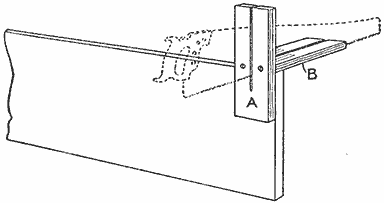

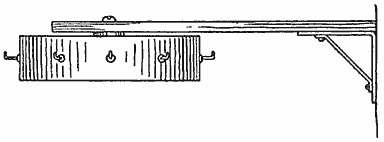

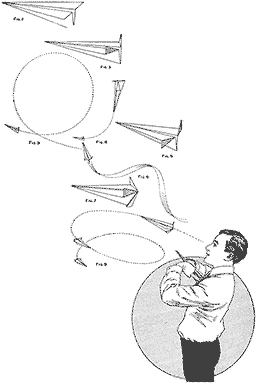

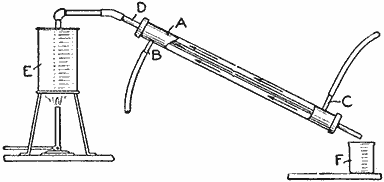

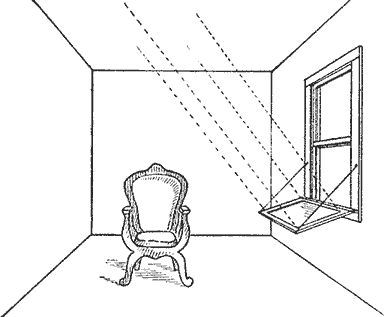

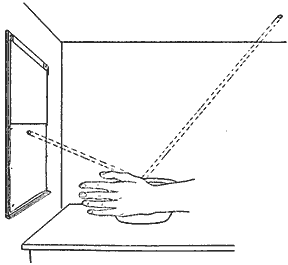

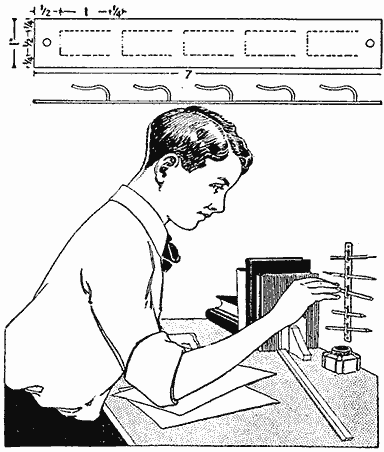

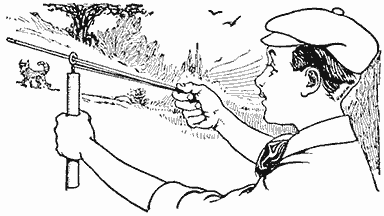

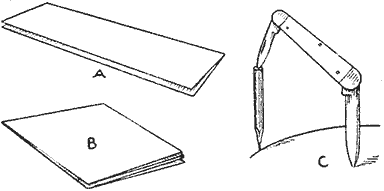

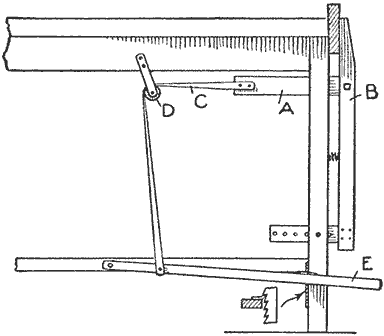

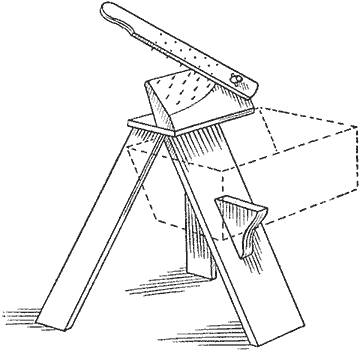

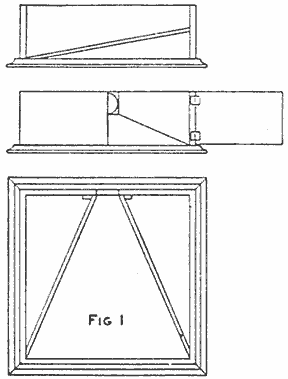

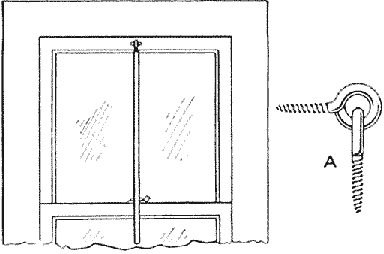

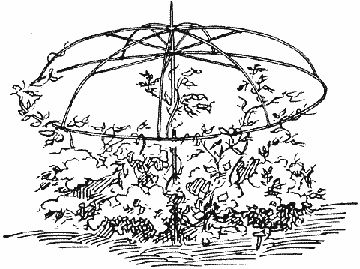

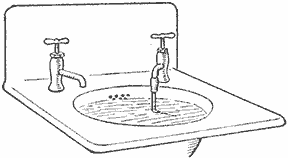

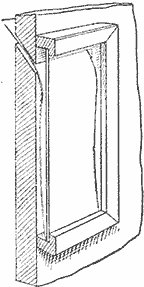

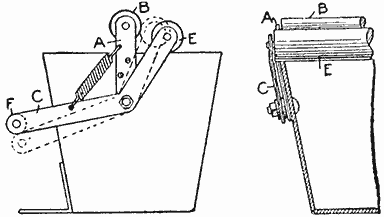

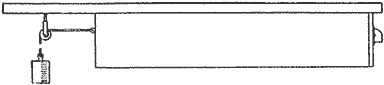

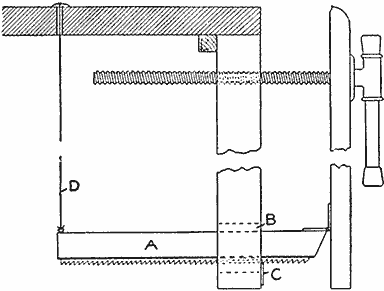

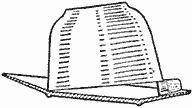

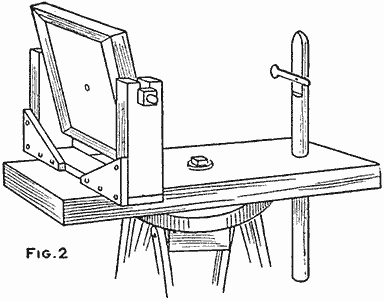

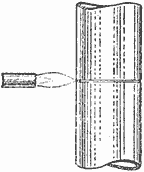

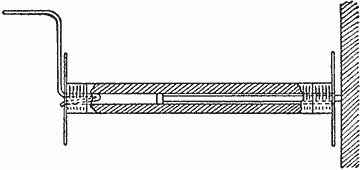

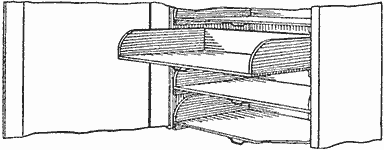

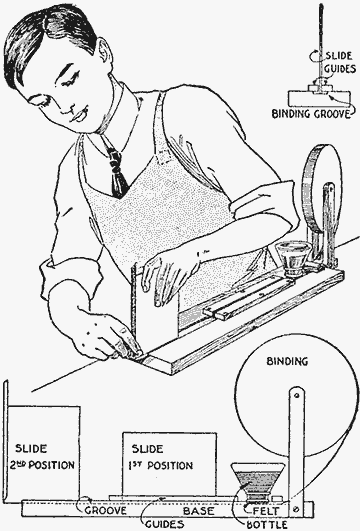

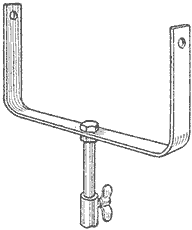

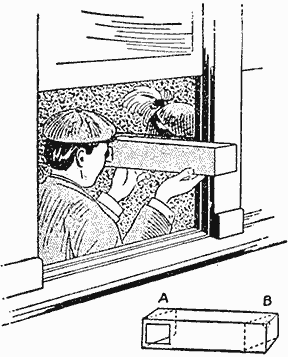

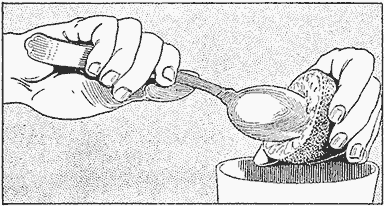

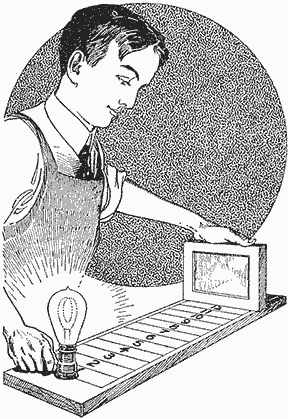

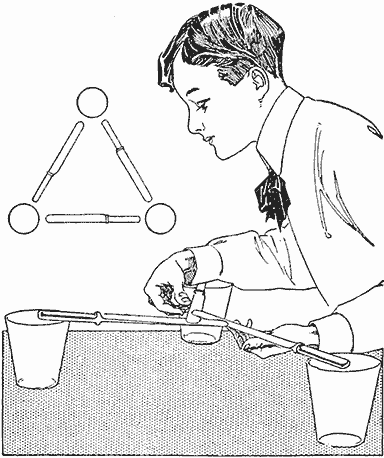

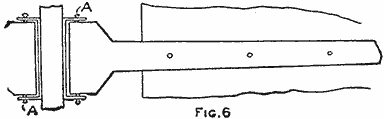

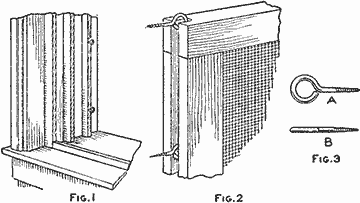

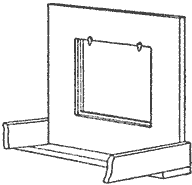

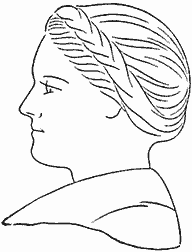

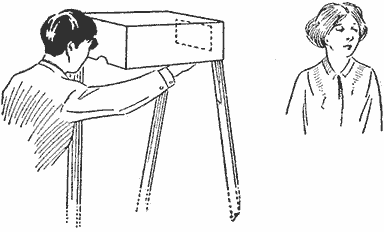

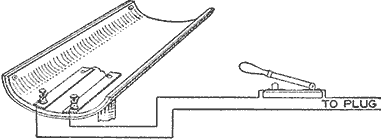

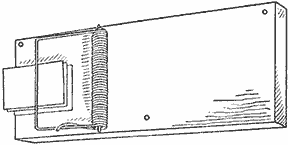

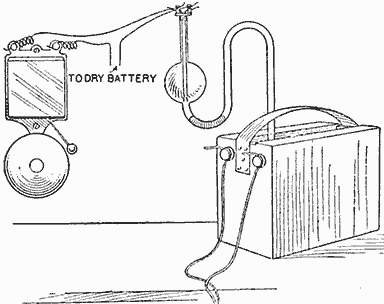

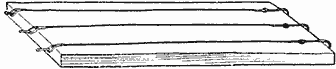

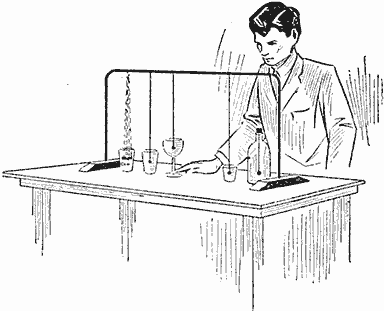

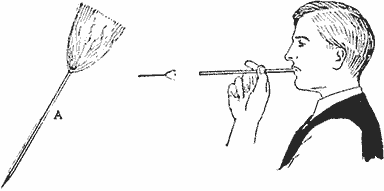

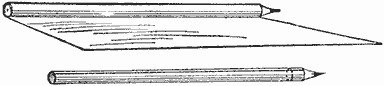

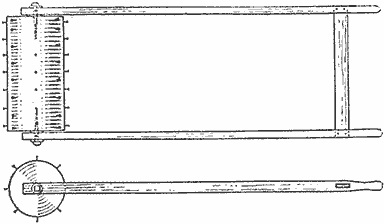

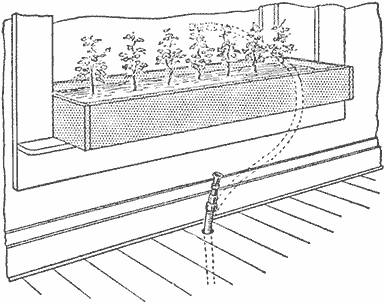

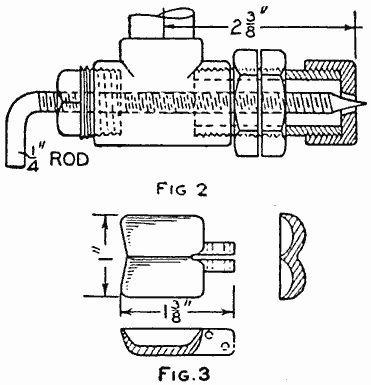

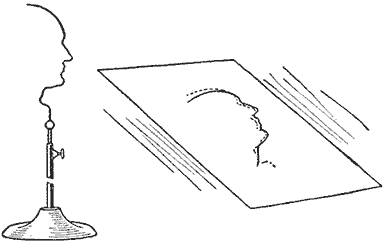

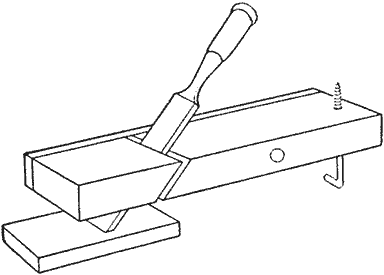

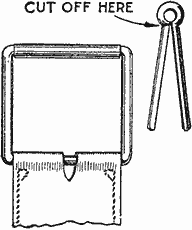

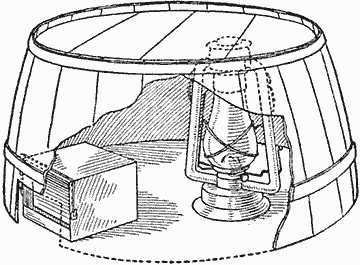

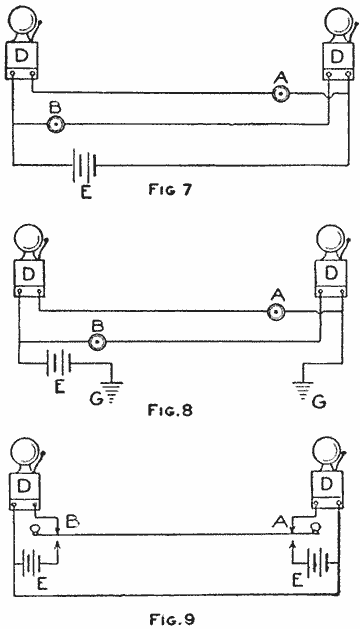

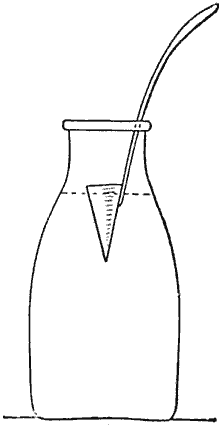

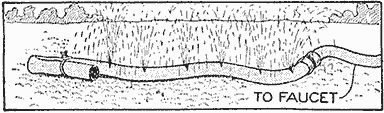

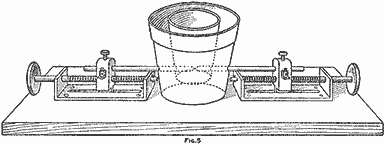

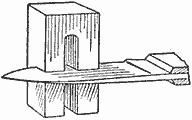

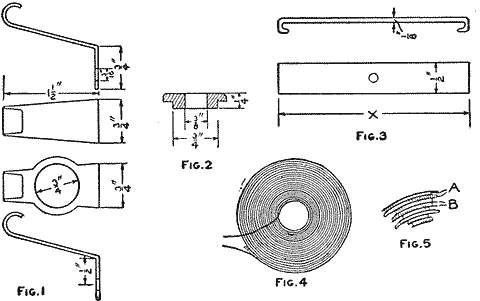

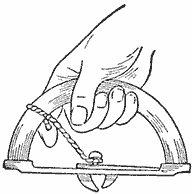

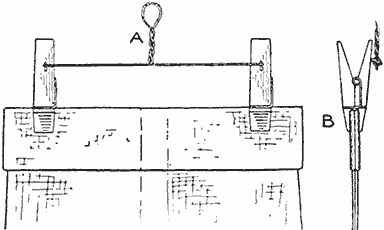

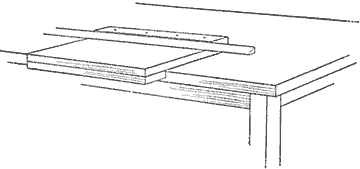

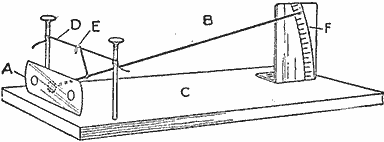

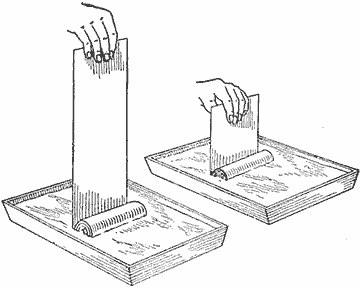

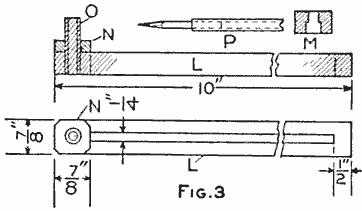

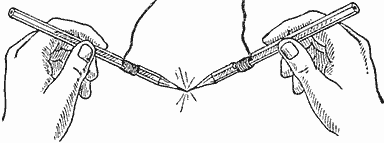

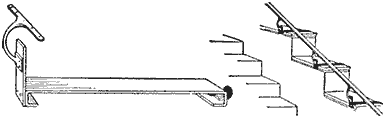

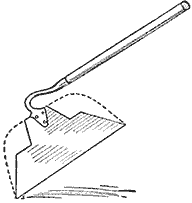

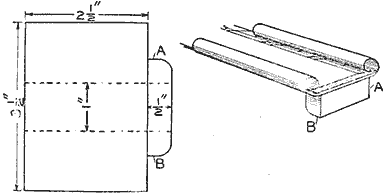

An ordinary drawing board, with the attachments shown, provides an easy way to sketch pictures, even if one is not proficient in this line of work. It is only necessary to look through the sight and move the pencil about so that the knot in the thread follows the outline of the landscape or object being drawn.

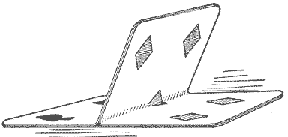

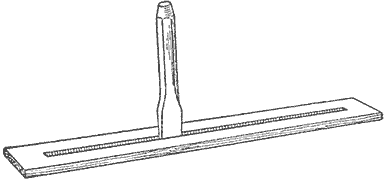

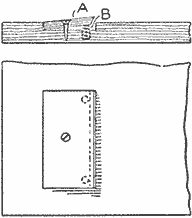

The size of the machine depends on the one building it, but a fair-sized drawing board is sufficient for the beginner. A strip of wood is fastened to the board, near one edge, which has a metal piece on each end, fastened to the under side and bent up over the end to form an extension for the rod to support the moving parts. The strip of wood should be 3/4 in. wide and 1/4 in. thick, and the sliding arm, holding the pencil, 1/2 in. wide and 1/4 in. thick. A like strip, but much shorter than the one fastened to the board, is also fitted with metal pieces in an inverted position so the projections will be downward. A 3/16-in. rod is run through holes in the metal pieces of the strips at both ends, and soldered to those on the strip fastened to the board. This will make a hinged joint, as well as one that will allow the upper strip to slide horizontally.

Centrally located on the upper strip are two more strips, fastened with screws at right angles to the former, with a space between them of 1/2 in. for the sliding center piece holding the pencil. These pieces are further braced with a wire at the back, and crosspieces are screwed both on top and under side, to make a rigid guide for the sliding pencil holder. An upright is fastened to the side of one of these pieces over the center of the upper horizontal sliding piece for a screw eye to hold the thread. Another screw eye is turned into the crosspiece just under the one on the support, so that the thread will run perpendicularly between them. Two more screw eyes are fastened, one into the upper surface of the rear crosspiece, and the other in the end of the pencil holder, near the pencil. By connecting these screw eyes, as shown, with a thread, having a rubber band fastened in the rear end and a knot tied in it near the screw eye in the upper end of the vertical stick, a means for following the outlines of the picture is provided.

A vertical stick is fastened to the front edge of the board by means of a notch and wedge. In the upper end of this stick a very small hole is bored for a sight, similar to a peep sight on a rifle.

To use the machine, set the board on a table, or tripod, and level it up in front of the object to be drawn. Look through the sight at the front of the board and move the pencil about to keep the knot of the thread on the outlines of the picture to be drawn.—Contributed by Wm. C. Coppess, Union City, Ind.

A walnut filler is made of 3 lb. burnt Turkey umber, 1 lb. of burnt Italian sienna, both ground in oil, then mixed to a paste with 1 qt. of turpentine and 1 pt. of japan drier.

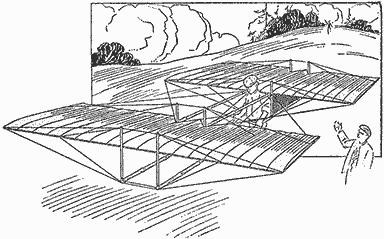

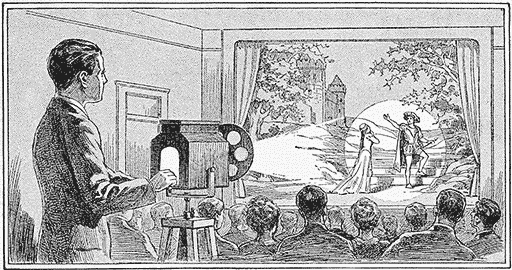

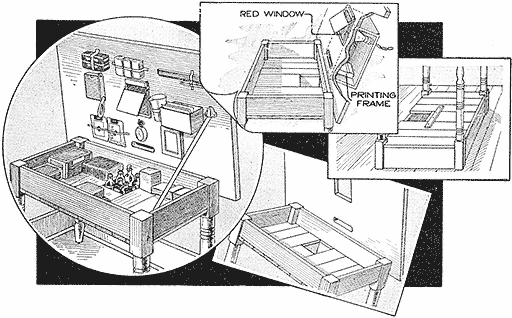

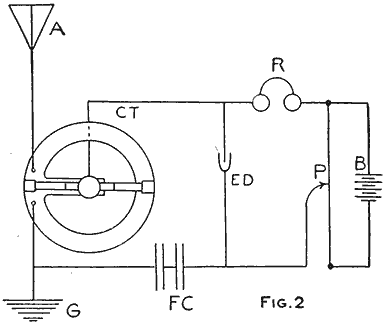

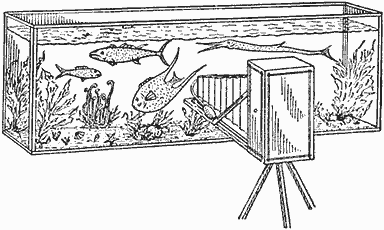

[This article explains the preparation of the camera for taking the pictures at each of the three stations, after which the plates are developed, printed and kept until a convenient time may be had for plotting the ground. The succeeding article will give in detail the making of the map from the photographs.—Editor.]

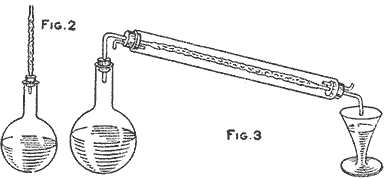

Camera surveying is simply plane-table surveying in which the landscape has been photographically picked up and carried indoors. It has the enormous advantage that one can obtain a record of the utmost fidelity in a small fraction of the time taken to do the field work of even a sketchy plane-table survey, and that plotting can be done in the comfort and with the conveniences of a drafting room. When the hours one can work are short or the periods of clear, dry weather are few and far between, a camera is an ideal surveying instrument. It sees and records with the click of the shutter.

Surveying by camera was proposed early in the infant days of photography; but not until the eighties were photographic surveys commenced in earnest. With the extensive surveys of the Canadian Rockies by the Canadian government within the past decade and the topographic surveys of the Alps, the camera has very recently indeed achieved the dignity of being known as a "sure-enough" surveying instrument. Even today, few surveyors have ever used photography for making surveys, even though for mountain topography or any survey which includes a large number of distinctive, inaccessible landmarks, the camera asks no odds of either the plane table or the stadia transit.

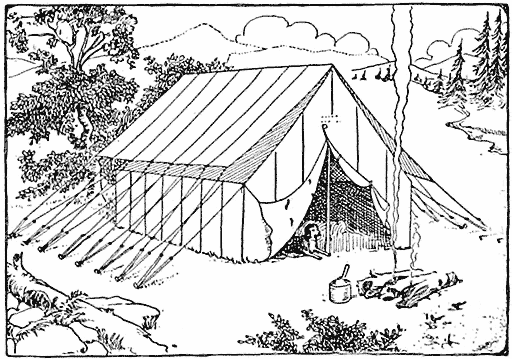

A camera survey taken of the summer cottage or the camping ground will be a source of great delight while it is being plotted up of winter evenings. There is something weird in watching each tent and dock slip into its place with naught but a pair of dividers and a few pictures to do the trick. And when the map is done, there are all the data to tell just where a tennis court can go or a walk ought to be built.

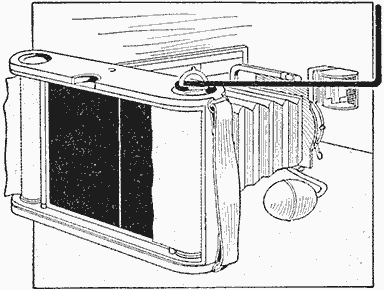

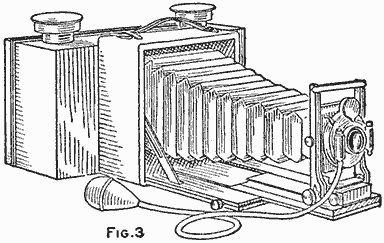

In making surveys, a plate camera will do more accurate work than will a film camera; and a fixed focus is a big help in plotting. In spite of the special and expensive instruments which have been designed solely for surveying work, a little ingenuity on the part of the owner of most any kind of a camera, be it big or little, film or plate, box or folding, will do wonders toward producing good results.

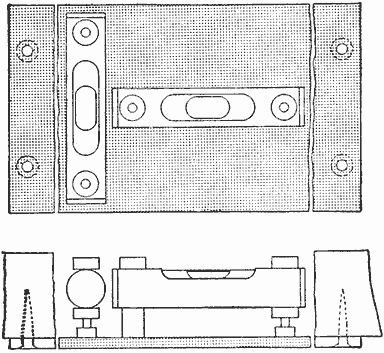

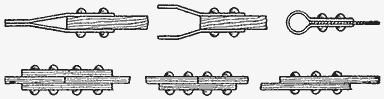

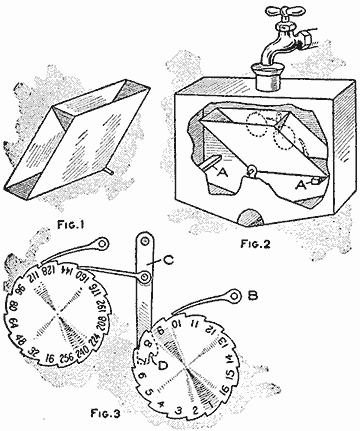

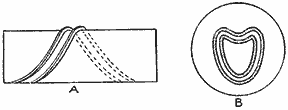

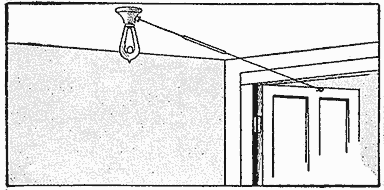

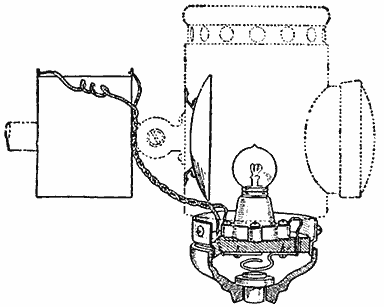

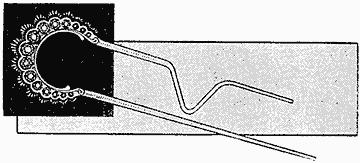

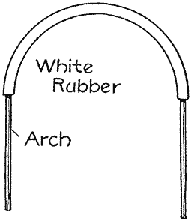

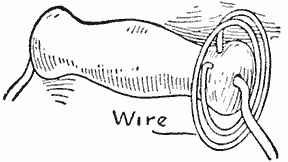

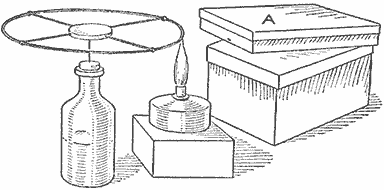

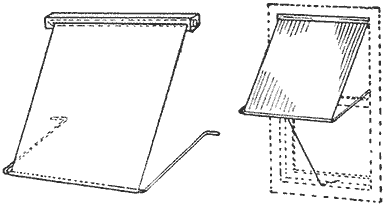

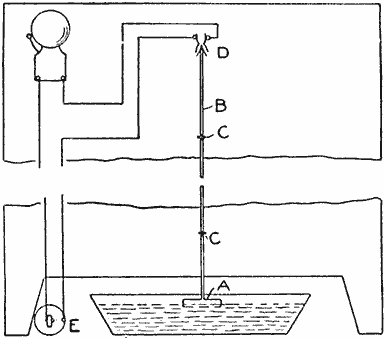

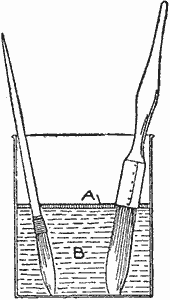

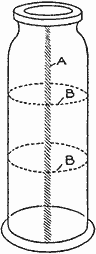

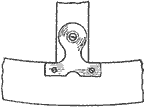

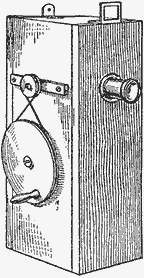

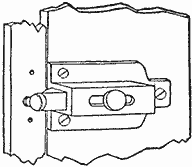

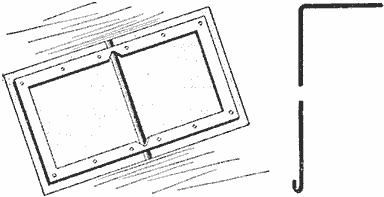

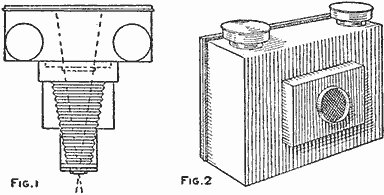

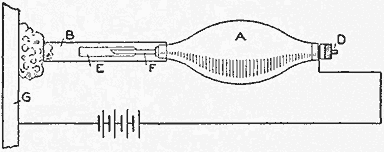

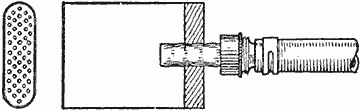

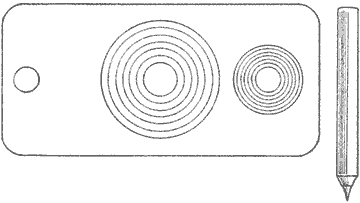

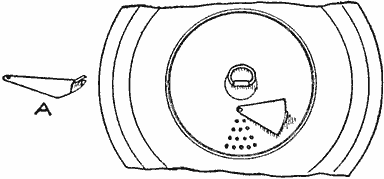

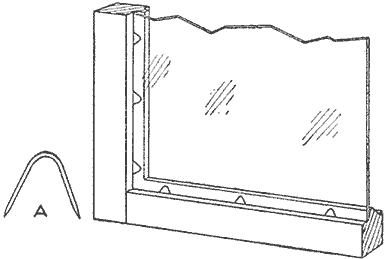

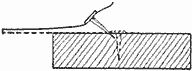

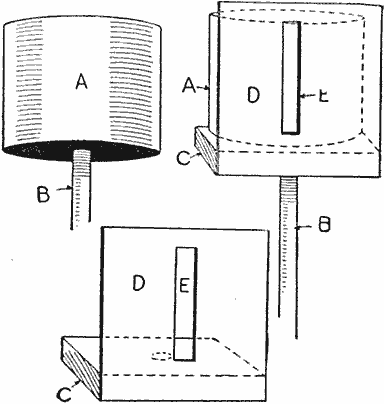

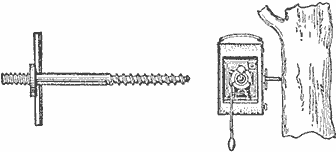

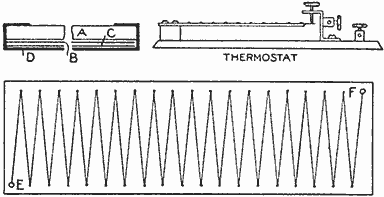

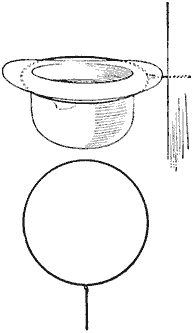

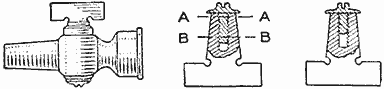

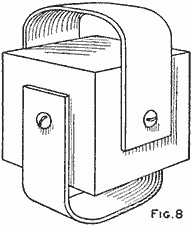

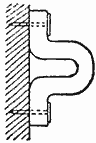

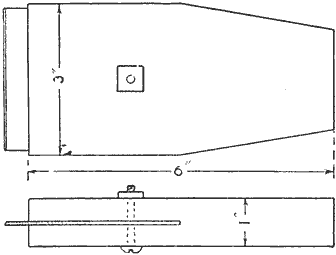

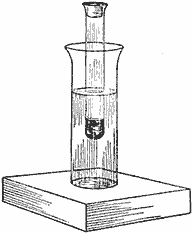

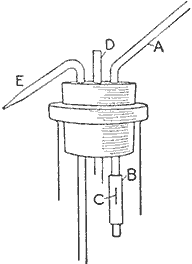

A T-Shaped Level with Adjusting Nuts is Located on the Camera Box, or on the Bed of the Folding Camera

To be used for surveying, a camera must be fitted with a spirit level and some arrangement for cross hairs. A T-shaped level on the bed or the box, carefully adjusted, will show when the [9] plate is vertical and when the perpendicular line from the center of the plate to the center of the lens is horizontal. Actual cross hairs in the camera are not as good as four tiny points of V's, one projecting from the middle of each side, top, and bottom of the camera box, just in front of the plate holder. How the level is to be adjusted so that a line between the upper and lower points will be truly vertical, and one through the die-side points truly horizontal and on a level with the center of the lens when the bubbles are in the center of the spirit level, will be described later.

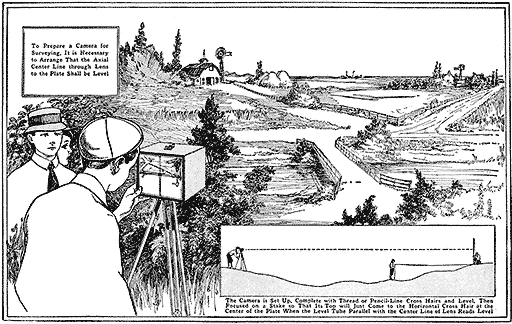

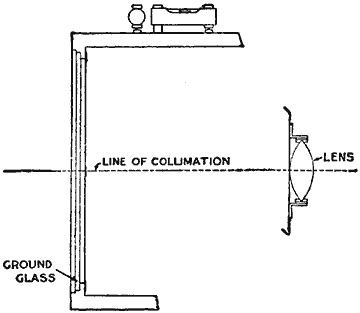

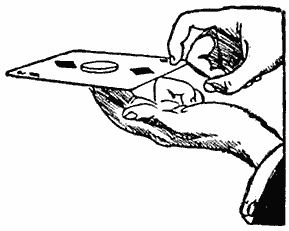

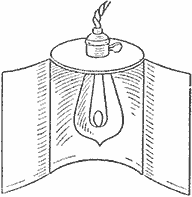

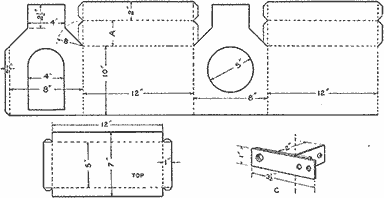

To Prepare a Camera for Surveying, It is Necessary to Arrange That the Axial Center Line through Lens to the Plate Shall be Level

(Inset: The Camera is Set Up, Complete with Thread or Pencil-Line Cross Hairs and Level, Then Focused on a Stake so That Its Top will Just Come to the Horizontal Cross Hair at the Center of the Plate When the Level Tube Parallel with the Center Line of Lens Reads Level)

To prepare a camera for surveying, it is necessary to arrange that the axial center line through the lens to the plate shall be level, and that the location of the horizontal and vertical center lines shall be indicated on the plate. A spirit level is the best solution of the first problem, and indicated center points of the second.

The spirit level preferably may be of the T-form, with two level tubes, or of the "universal" circular form, with which some hand cameras are equipped. However, ordinary hand-camera levels are generally too rough and difficult of adjustment to insure accurate work. On a view camera, the level may be conveniently located on the bed which carries the lens board. If it is screwed to the under side of the arms it will be convenient for use and out of the way. The bed is likewise a good location for the level on a folding hand camera, while the top of the box is about the only possible location with a box-type instrument.

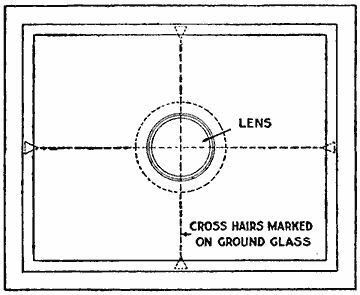

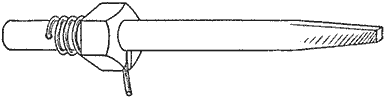

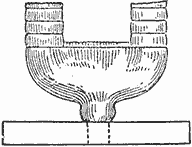

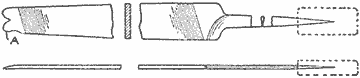

The cross hairs or center-line indicators should be placed on the back of the camera, just in front of the plate. If indicators are used, fine-thread cross hairs or pencil lines drawn on the ground glass must be used temporarily for making adjustments. Generally, the two cross hairs will divide the plate vertically and horizontally into four equal parts and the hairs or indicators will join the center point of the sides and top and bottom of the opening immediately in front of the plate. But it is essential that the cross hairs have their intersection in a line perpendicular to the plate and passing through the center of the lens. Thus in a camera in which the lens is not placed in the center of the plate, or in which the rising and sliding front has placed the lens off center, either or both of the cross hairs may be off center with regard to the plate.

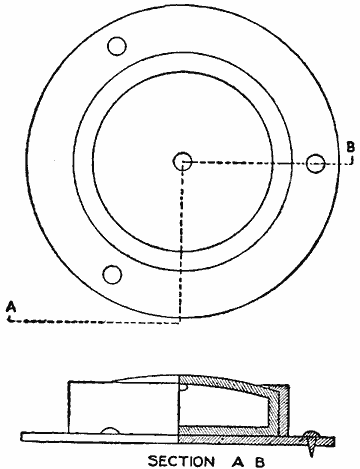

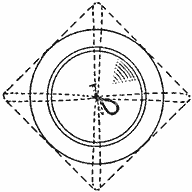

The Ordinary Round Level may be Used, but It Is Not so Good as the T-Level

After the cross-hair indicators and the level have been attached to the camera, adjustments are necessary. Surveyors distinguish between permanent and temporary adjustments, permanent adjustments being those for which the instrument maker is responsible, and temporary adjustments being those which can be and are made in the field. The principal permanent or maker's adjustments of the surveying camera are those which insure the center line through the lens, or axial center line, or line of collimation, being perpendicular to the plate, the intersection of the cross hairs being on this line, and that the cross hairs themselves are mutually perpendicular. Temporary or field adjustments must be so made that one tube of the spirit [10] level shall be parallel with the axial center line through the lens and the other parallel with the horizontal cross hair.

The Cross Hairs or Center-Line Indicators should be Placed on the Back of the Camera

The first field adjustment is made in the following manner. The camera is set up, complete with thread or pencil-line cross hairs and level, and focused on a stake whose top shall just come to the horizontal cross hair at the center of the plate, when the level tube parallel with the center line of the lens reads level. This stake may be driven to the required elevation or a rod may be held on it and the point where, in the image on the ground glass, it is intersected by the cross hair marked with pencil on the rod as it is held vertically on the stake. The distance to this stake is measured from the camera and another similar stake set at the same elevation by the same method, but in an opposite direction and at the same distance from the camera. The two stakes or the mark on the vertical rod which is held on these stakes in turn will be level with each other, though they may not be level with the camera. The camera is then moved to a point very much closer to one stake than to the other and again leveled. The vertical distance from one stake-top or mark on the rod is measured and the camera then focused on the second stake. If the level is actually in adjustment, the distance from the second stake top or mark will be exactly the same as it was on the first. If not, the difference, or "error," is found between the two vertical distances from the cross hair to the two stake tops. Half this error is corrected by raising or lowering one end of the level tube by means of the threaded nuts which are placed on it for the purpose. The whole process is then repeated until the vertical distances from the horizontal cross hair at the center to the two level stakes, one close to and one distant from the camera, are identical. The axial center line of the lens, or the line of collimation, is then in adjustment with the level. All that remains is to make the horizontal cross hair parallel with the cross level.

The Maker's Adjustments Should Insure the Line of Collimation being Perpendicular to the Plate

This is done by using one marked stake. The camera is leveled as far as the "fore-and-aft" level is concerned and the horizontal cross-hair point at the center marked on the stake. The camera is then swung round until the stake just shows on one edge of the ground glass, the fore-and-aft or longitudinal level being checked to make sure its bubble is still in the center. Then the bubble in the cross or transverse level tube is brought to the center by means of the threaded adjusting nuts, and the camera is thrown hard over so that the stake appears along the opposite edge of the plate. This time, the bubble of the longitudinal level being kept in the center, half the error introduced by turning from one edge to the other [11] is corrected. All of the adjustments are then rechecked, and if they are found correct the instrument is ready for use. If a circular level be used, the method of adjustment is exactly the same, the swing of the bubble along the axis of the camera and transverse to it being used to determine the longitudinal and transverse adjustments. Slips of paper may be used for lifting one side in place of the adjustment nuts of the T-level.

A leveling head or ball-and-socket joint on the top of the tripod will be found of material aid in leveling the instrument.

No great mechanical genius is necessary to prepare a camera for or to make a successful camera survey. But if a boy have not patience and an infinite desire for accuracy, camera surveying, or indeed any sort of surveying, will be a source of neither pleasure, satisfaction, nor profit.

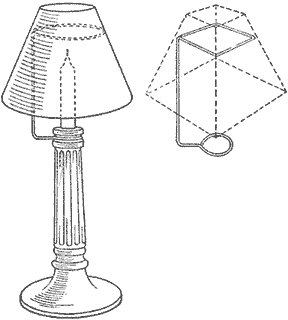

Transparent paper of parchmentlike appearance and strength, which can be dyed with almost all kinds of aniline dyes and assumes much more brilliant hues than ordinary colored glass, can be made in the following manner: Procure a white paper, made of cotton or linen rags, and put it to soak in a saturated solution of camphor in alcohol. When dry, the paper so treated can be cut up into any forms suitable for parts of lamp shades, etc.

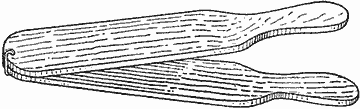

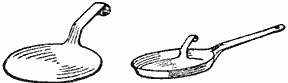

Having experienced some difficulty in obtaining good toast over a gas or open fire I tried the following plan with good results: An old tin pan was placed over the flame and the ordinary wire bread toaster clasping the slice of bread was held about 1/2 in. from the pan. In a few minutes the toast was crisp and ready to serve.—Contributed by Katy Doherty, New York City.

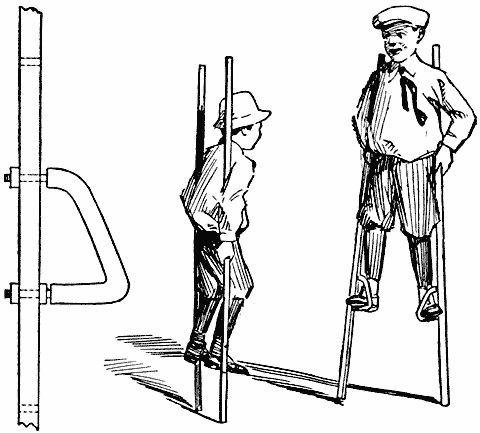

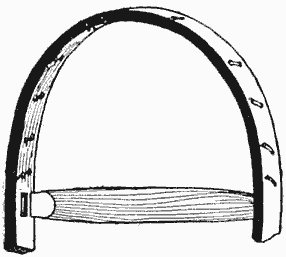

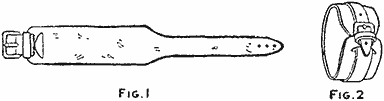

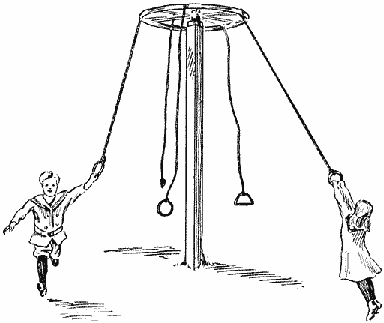

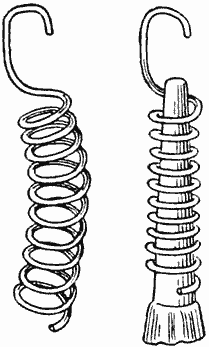

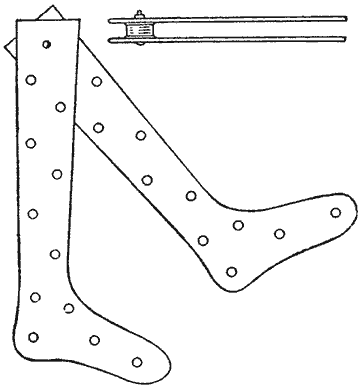

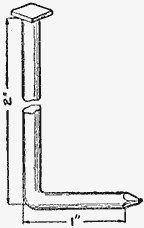

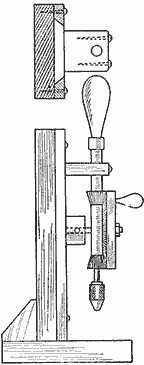

The beginner with stilts always selects short sticks so that he will not be very far from the ground, but as he becomes more experienced, the longer the sticks the better. Then, too, the small boy and the large boy require different lengths of sticks. The device shown makes a pair of sticks universal for use of beginners or a boy of any age or height.

Stilts Having Stirrups That can be Set at Any Desired Height

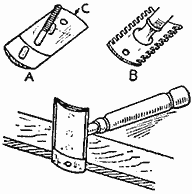

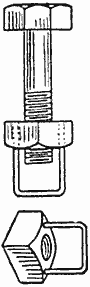

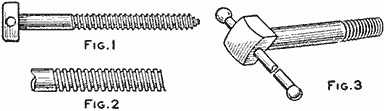

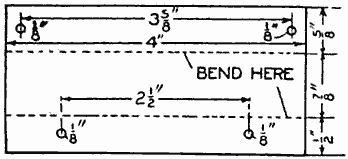

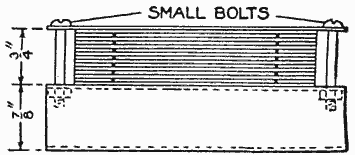

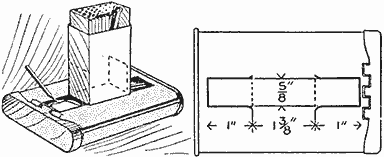

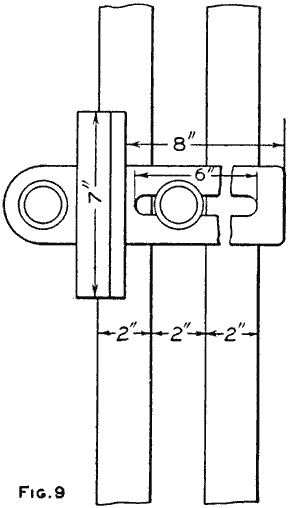

To make the stilts, procure two long sticks of even length, and smooth up the edges; then begin at a point 1 ft. from one end and bore 12 holes, 3/8 in. in diameter and 2 in. apart from center to center. If there is no diestock at hand, have a blacksmith, or mechanic, make a thread on both ends of a 3/8-in. rod, 12 in. long. Bend the rod in the shape shown, so that the two threaded ends will be just 2 in. apart from center to center. The thread on the straight horizontal end should be so long that a nut can be placed on both sides of the stick. A piece of a garden hose or small rubber hose, slipped on the rod, will keep the shoe sole from slipping. The steps can be set in any two adjacent holes to give the desired height.—Contributed by Walter Veene, San Diego, Cal.

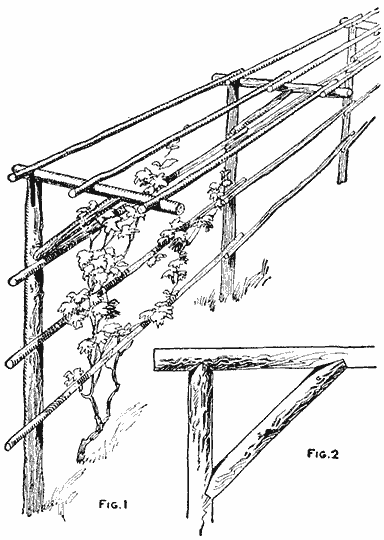

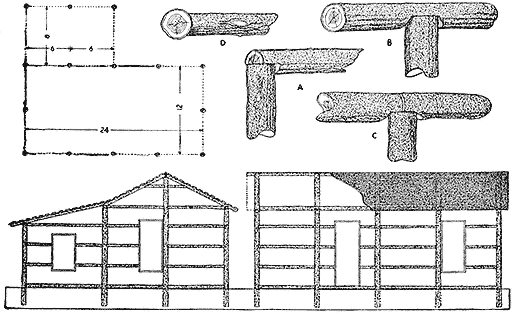

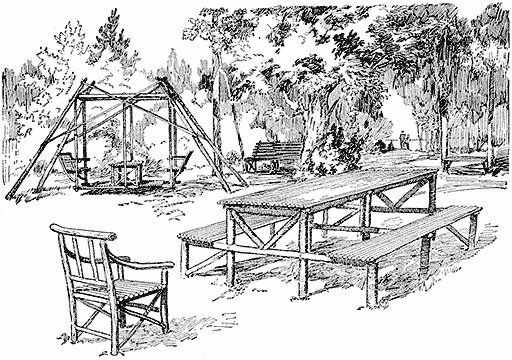

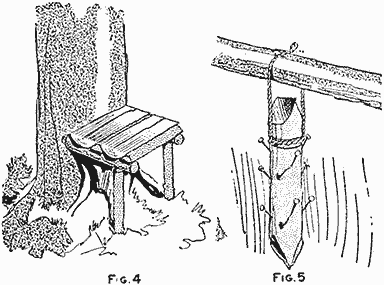

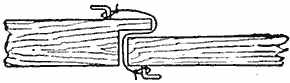

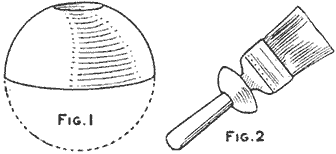

In building outdoor structures, such as grape arbors, pergolas, or arches, it is not necessary to use sawed lumber, as they can be built as substantial, and frequently more artistic and cheap, of poles. These are easily obtained, especially in the country or in the smaller cities where there usually are many trees and gardens.

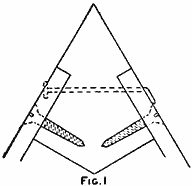

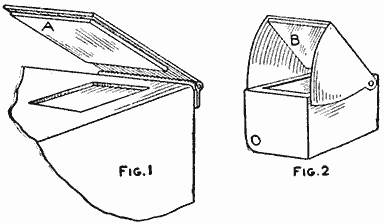

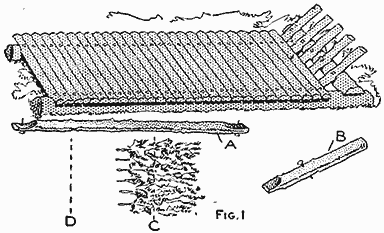

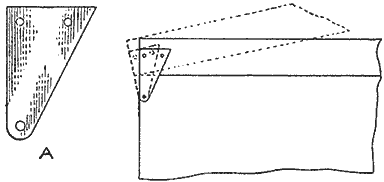

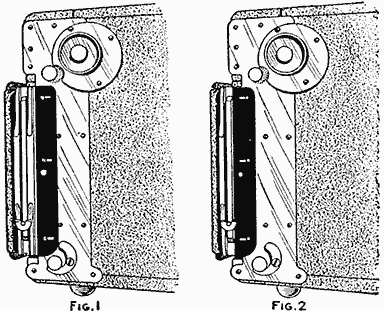

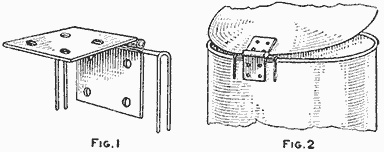

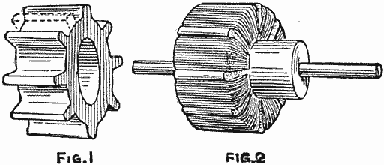

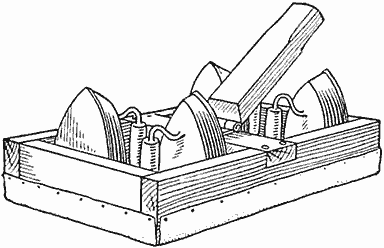

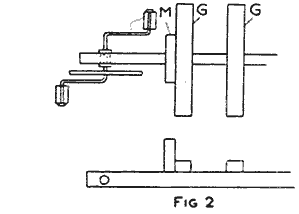

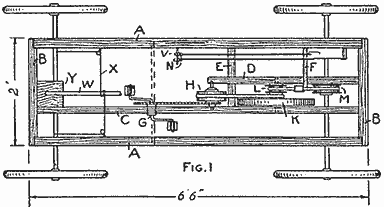

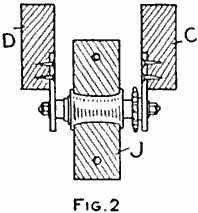

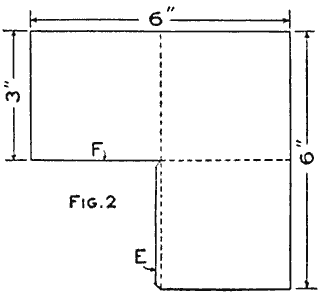

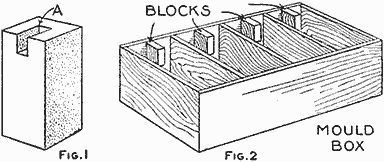

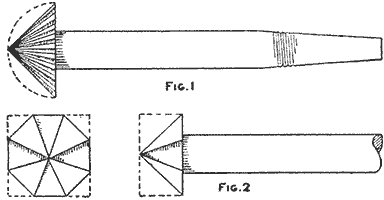

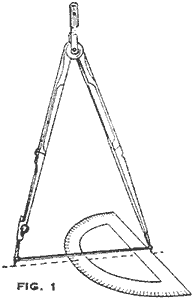

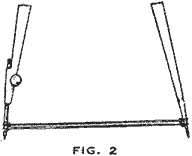

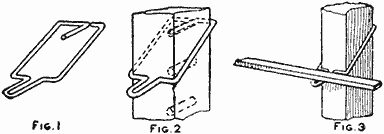

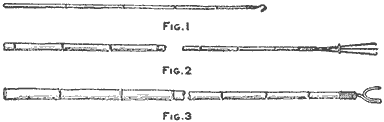

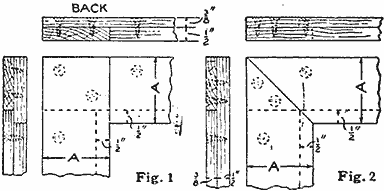

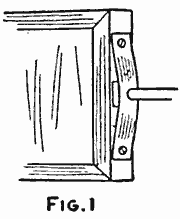

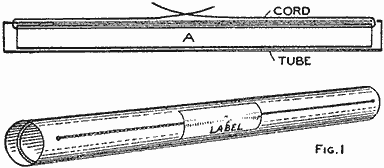

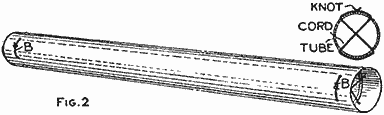

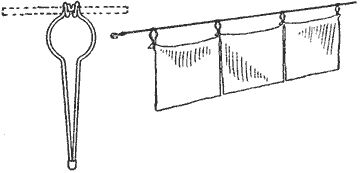

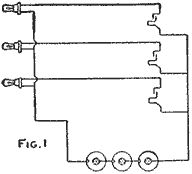

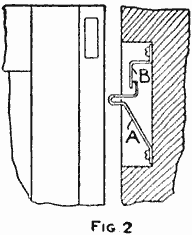

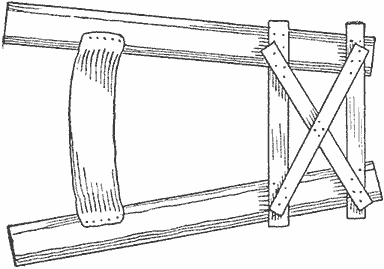

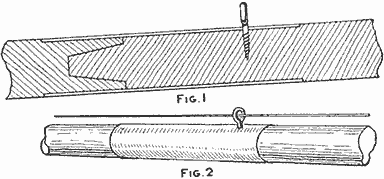

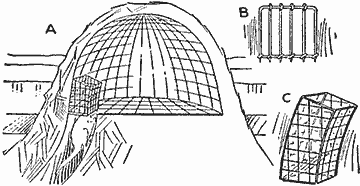

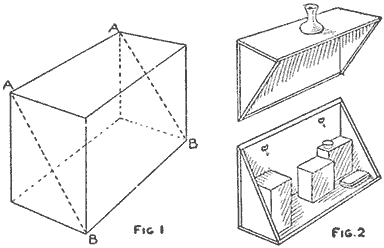

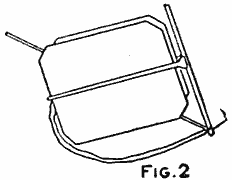

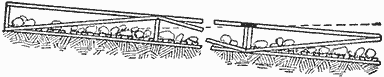

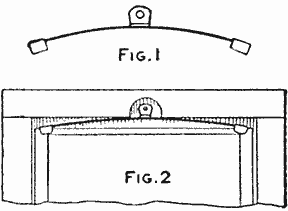

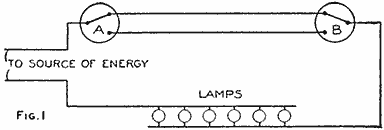

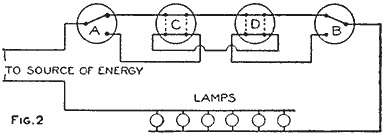

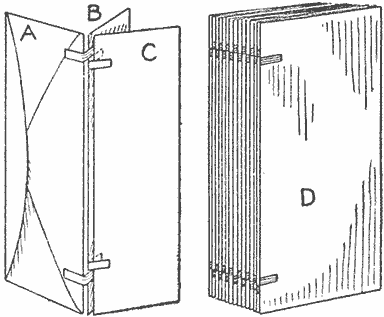

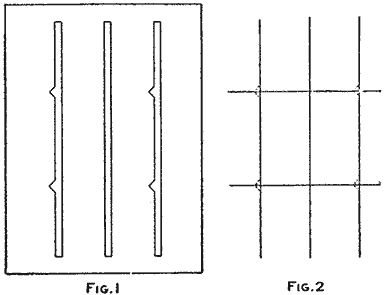

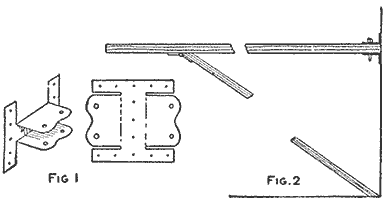

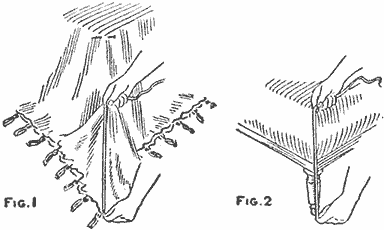

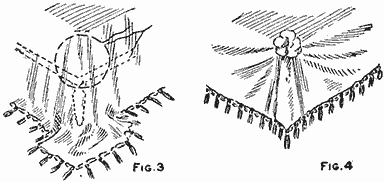

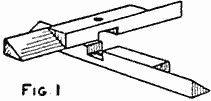

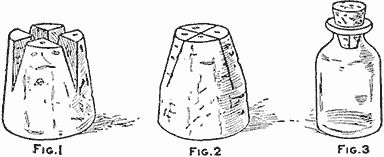

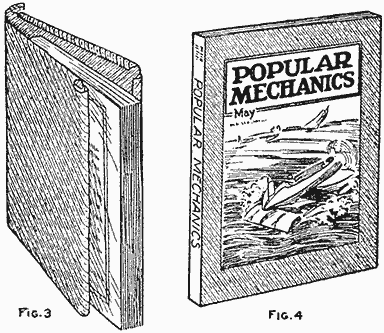

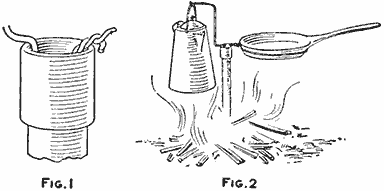

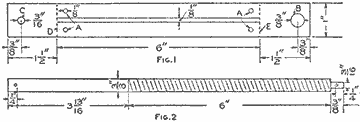

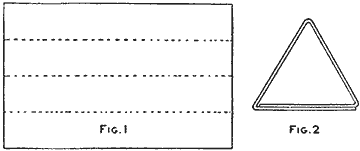

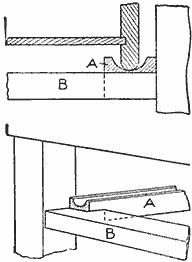

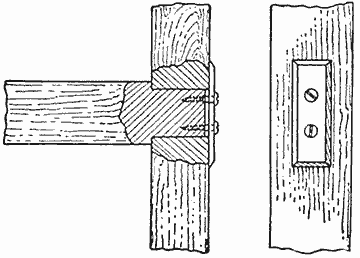

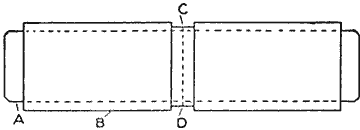

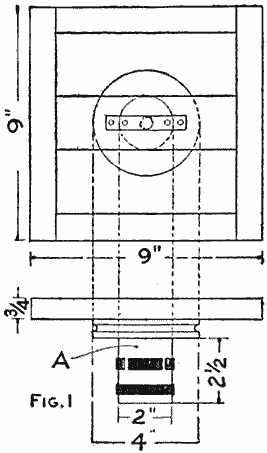

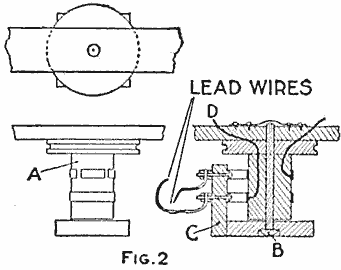

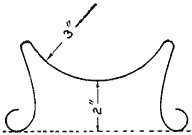

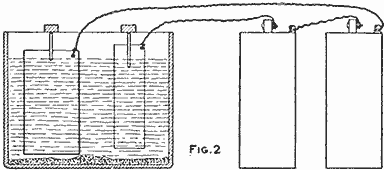

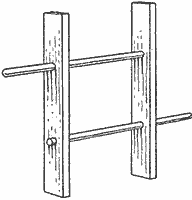

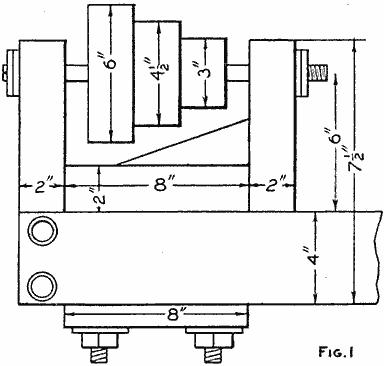

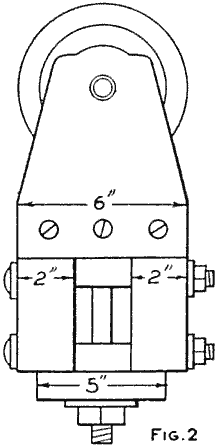

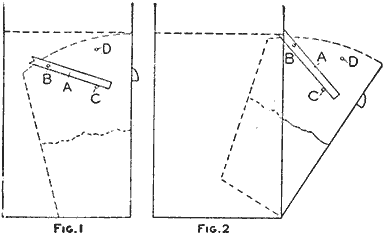

Arbor Made of Poles Which are Supported by One Row of Uprights (Fig. 1, Fig. 2)

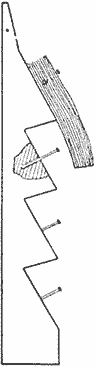

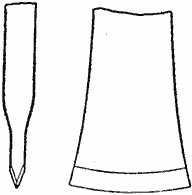

The illustrated grape arbor consists of but one row of uprights. Across the top of each is placed a horizontal support for the roof poles, as shown in Fig. 1, which is carried near its outer end by an inclined brace. The brace should be connected at each end with a toe joint, as shown in Fig. 2. The upper end of the upright is beveled off on both sides, to form a double-splayed joint with the crosspiece. In order to securely bind the roof of the arbor, the long poles, or roof beams, should be notched near each end to fit over the supports. Similar notches in the poles forming the side of the arbor are to fit the uprights, thereby binding them together and preventing toppling over. Each set of long poles connecting two uprights should have the end notches the same distance apart, one pole being used as a gauge. All the joints and notches may be cut with a sharp hatchet.

In setting the arbor, the uprights should first be assembled complete with braces and roof supports, and placed in the ground a distance apart corresponding to that of the notches on the long poles. The uprights being set, the long poles are placed and fastened with nails.—Contributed by W. E. Crane, Cleveland, Ohio.

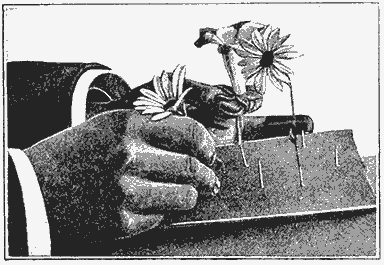

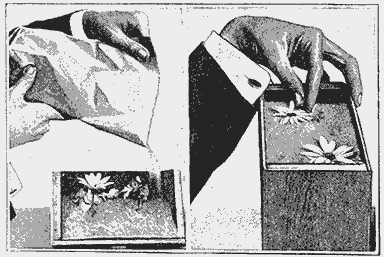

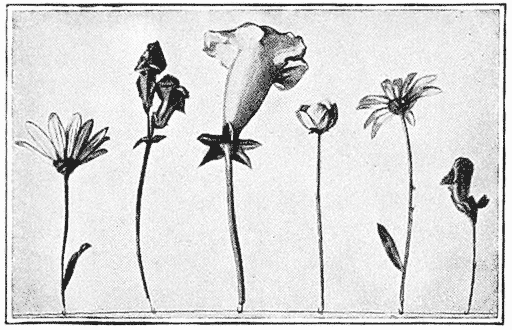

Twigs trimmed from the fruit trees rather late in the season had quite large buds on them, and we experimented with them in this way: A large box was filled with wet sand, and the twigs were stuck in it and the box set in the warmest corner of the yard. The buds soon swelled and burst into bloom. We then arranged a smaller box of sand and put the blooming twigs into it, and took it into the house where they remained fresh for several days.—Contributed by A. Louise Culver, Oakland, Cal.

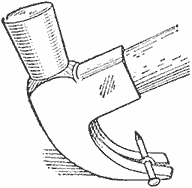

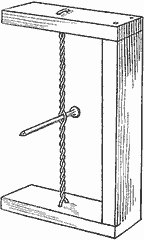

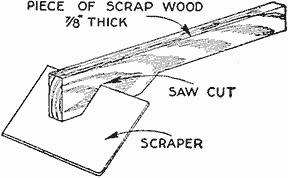

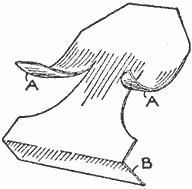

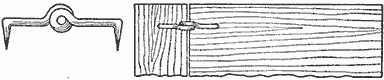

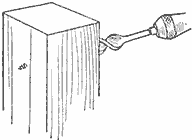

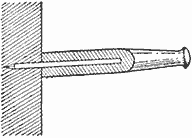

Dirt will accumulate and harden in the corners of a floor and the baseboard just because the end of the scrubbing brush will not enter them. The water gets in with the dirt and leaves a hard crust. This may be easily cleaned out if a metal point is attached to the end of the brush handle, as shown in the illustration. It is used as a scraper to break up the crust and clean it out where the bristles will not enter.—Contributed by L. E. Turner, New York City.

[The camera records pictures that can be taken in camp or on a vacation trip and kept until more leisure may be had in winter for plotting the ground.—Editor.]

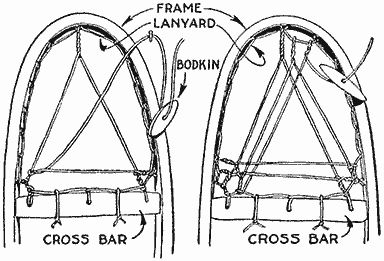

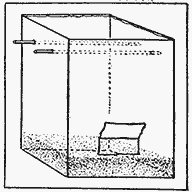

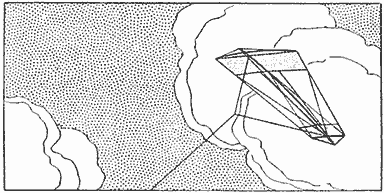

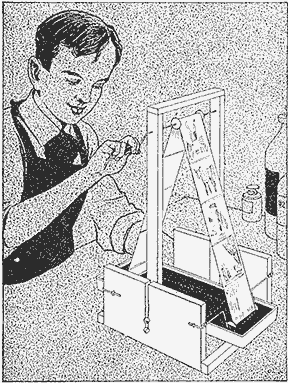

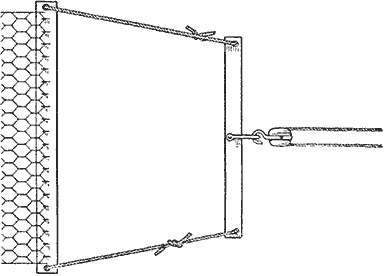

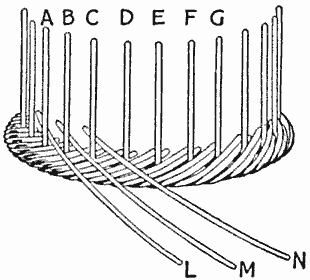

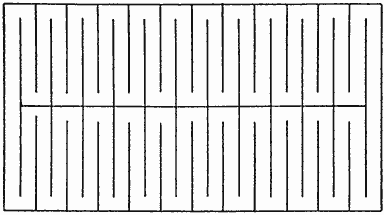

A previously measured base triangle with "stations" at each corner is necessary for making a camera survey, just as it is for the plane-table survey. It is preferable to have each of the three sides measured independently, though if one side has been accurately chained, the other two may be less satisfactorily determined by the use of the plane table. If the camera has a fixed focus, it is possible to make an entire survey from the two ends of a single base line; but this method has no check and should be used only when and where the triangle method is impossible. With an adjustable focus, it will rarely give good results.

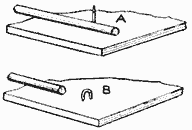

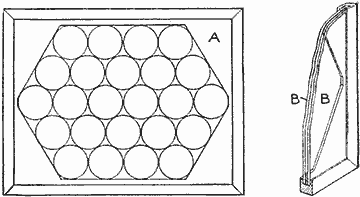

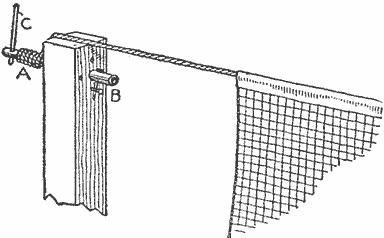

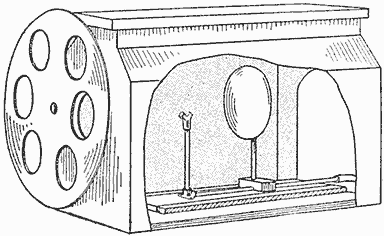

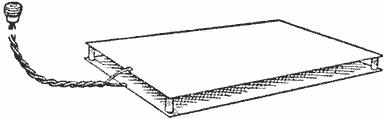

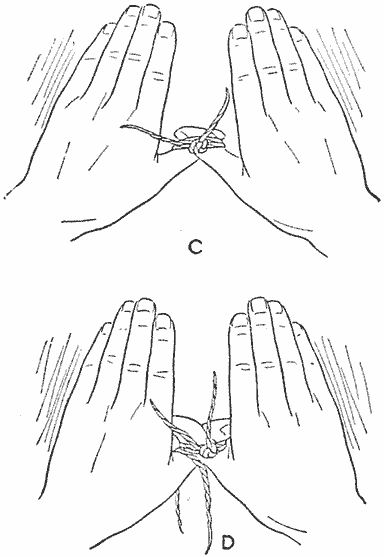

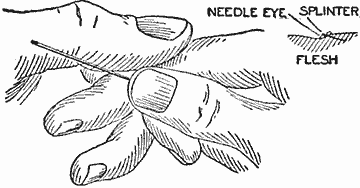

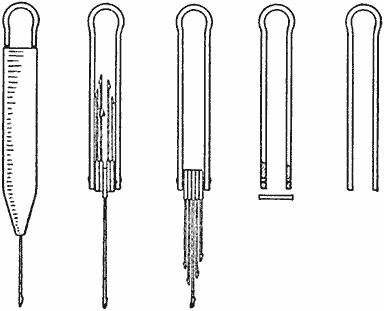

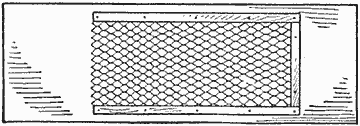

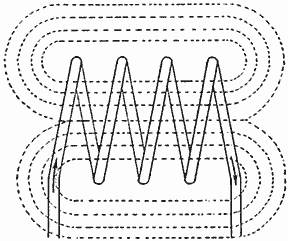

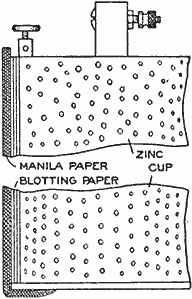

Two Fine Hair Lines must be Scratched on Each Plate Before It is Used to Plot From, or to Make Pictures from Which the Plotting is Done

Once the triangle has been laid out, the fieldwork is very simple. The camera is set up at one station, carefully leveled, and then a series of pictures is taken, each single plate overlapping the last so as to form a panorama of the area to be mapped. The focus of the lens must not be changed during a series, and plotting is facilitated by keeping the focus constant during all the exposures which make up a survey. To secure good depth of focus, a small stop is generally used, since it is necessary to use a tripod to keep the camera level. If contours are to be drawn, the height of the lens above the ground at the station should be measured and recorded. After a series has been taken at each station, the fieldwork is complete. It is an excellent plan to keep a record of the plate numbers, and the order in which and the station from which the exposures were made, so [15] that the 10 or 12 plates which a small survey will comprise may not get hopelessly mixed up. If the camera is turned each time to the right, clockwise, and the plates are numbered A-1, A-2, B-4, etc., indicating by A-1, for example, the leftmost plate taken at Sta. A; by A-2, the plate just to the right of A-1, just as II is to the right of I on the clock dial, and by B-4, the fourth to the right taken at Sta. B, there ought to be no difficulty in identifying the plates after the exact details of the ground are forgotten.

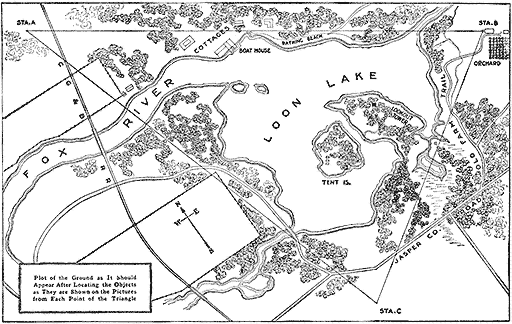

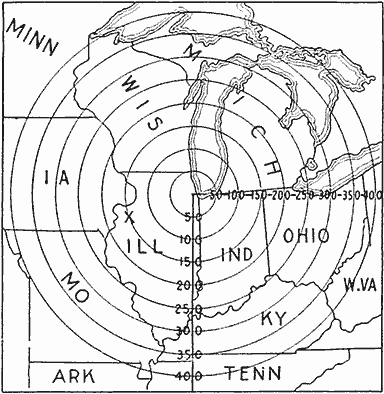

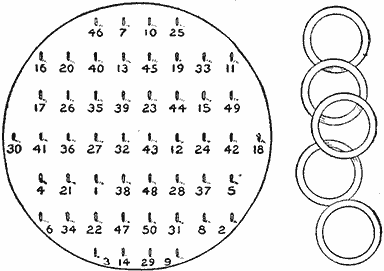

Plot of the Ground as It Should Appear After Locating the Objects as They are Shown on the Pictures from Each Point of the Triangle

While the pictures are being taken, "flags" of white wood or with white-cloth streamers tied to them must be stuck in the ground or held at the other stations in order that their exact location can be readily and certainly found on the plates. A few distinctive stakes, some with one and some with two or three strips of cloth tied to them, placed at important points on the ground will help immensely in the location of knolls and shore lines.

In plotting a camera survey, either the original plates, the prints, or enlargements may be used. The plates are the most accurate if a corrected lens has been used; and the enlargements made back through the lens will be best if the images on the plates are distorted. In any case, two fine hair lines must be scratched on each plate before it is used to plot from, or to make the prints from which the plotting is to be done. One of these lines should connect the points at the top and bottom of the plate, and the other, the points at the sides. The vertical line divides the objects which were on the right of the center of the camera from those that were on the left, and the horizontal line connecting the points on the sides separates the objects that were above the camera from those that were below.

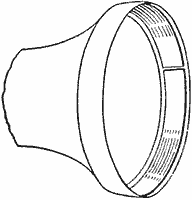

If the survey has been made with a lens that does not cover the plate fully or that has considerable uncorrected aberration, causing distorted shapes near the edges and corners of the picture, results can be materially improved by plotting from enlargements. In making the enlargements, the back of the camera should be removed and the light should be allowed to pass through the plate and the lens in the reverse order and direction of that in which it passed when the negative was made. In this way, the errors which were made by the lens originally will be straightened out, and the resulting enlargements will be free from distortion. To make successful enlargements for surveying work, the easel on which the bromide paper is tacked must be square with the camera, and the paper itself should be flat and smooth. It is just as necessary to keep the easel at a constant distance from the camera during the enlarging [16] as it was to keep the same focus while the original negatives were being made.

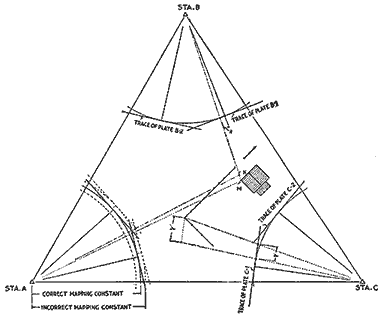

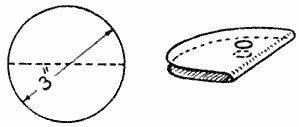

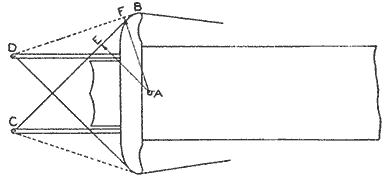

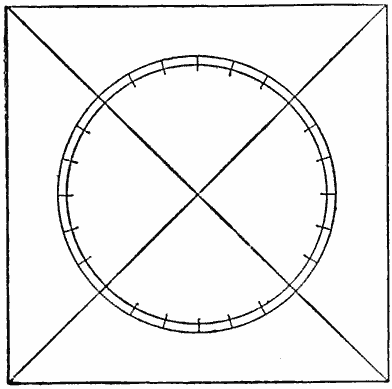

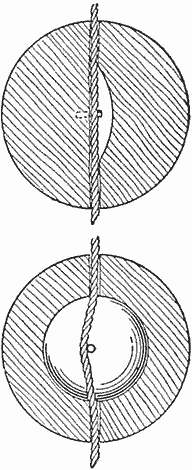

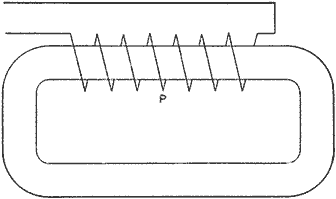

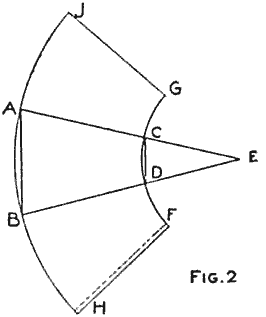

In Plotting a Camera Survey the Base Triangle is First Carefully Laid Out on the Paper to Such a Scale That the Map will be of Desirable Size

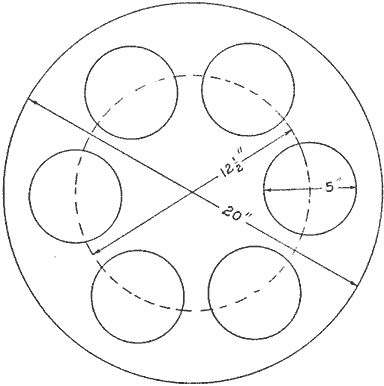

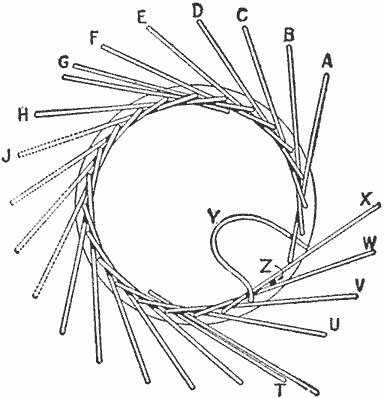

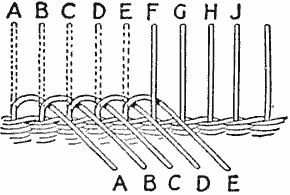

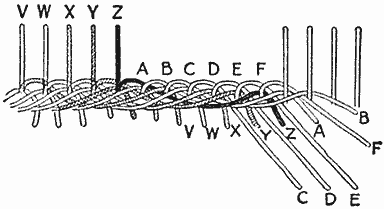

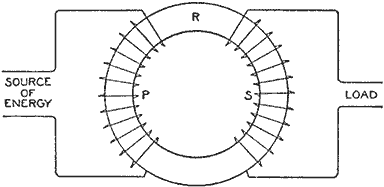

In plotting a camera survey the base triangle is first carefully laid out on the paper to such a scale that the map will be of a desirable size. With the apex of the triangle representing Sta. A, say, as a center, a circle is drawn with a radius as nearly equal as possible to the distance between the optical center of the lens and the plate when the picture was taken. Ordinarily this will be the focal length of the lens; but if the camera was not focused most sharply on an object a great distance off, the radius may be greater. This radius is called the "mapping constant." When an approximate distance for the mapping constant has been determined by measurements on the camera or by knowing the focal length of the lens, the circle, or rather the arc, FG between the two lines to stations B and C, is drawn. The plates taken at Sta. A, and ranged around this circle on the outside and just touching it, will show the landscape exactly as seen from A.

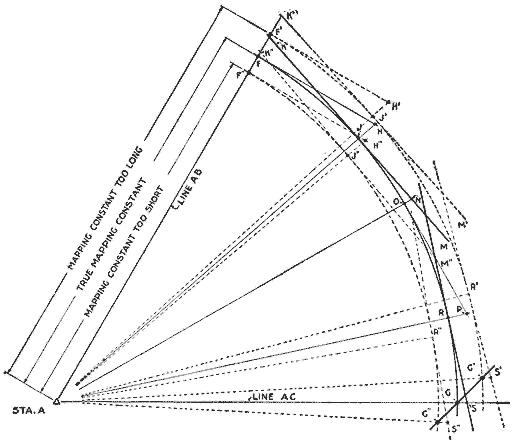

In the accompanying diagram showing the method of determining the mapping constant and of locating the traces of the plates, the letters F, G, H, J, P, R and S designate points referring to the true mapping constant, and the construction necessary to locate the traces of the plates. The primed letters F', F'', G', G'', etc., are used to show similar points where the trial mapping constant is either too long or too short. The following description refers equally to the construction necessary with true or trial-mapping constants.

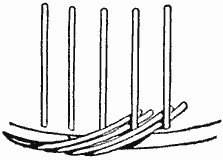

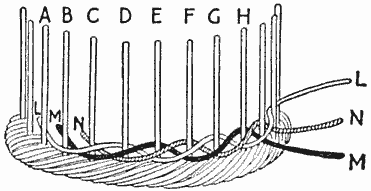

Next, a line FH is drawn perpendicular to the line AB of the triangle at the point F where the arc intersects it. On this line is laid off, in the proper direction, a distance equal to the distance on the plate or print from Sta. B to the center vertical line. From this point is drawn a light line, HJ, toward the center of the arc. Where this line crosses the arc, at J, a tangent, KJM, is drawn, which will show the location of the plate A-1 on the drawing. This line is called the trace of the plate. An object which appears both on plate A-1 and A-2 is next picked out and its location on the trace of plate A-1 determined by measuring the distance JN equal to the distance on the plate from the image of the object to the center vertical line. A light line, NO, joining this last-found point with Sta. A, is then drawn. Where this last line crosses the arc, at O, a tangent, OP, to the arc is drawn, and the trace of the plate A-2 is found with the aid of the point which appears on both plates just as plate A-1 was located from the picture of Sta. B. The traces of plates A-3 and A-4 are found in exactly the same way as was that of A-2. If the radius of the arc has been estimated correctly, Sta. C will be found to be exactly on the point where the trace of the plate showing the station crosses the line AC on the paper. If it does not fall on the line AC, which is generally the case, everything must be erased except the original triangle. First, however, a radial line S'G', or S''G'', is drawn from the location of Sta. C on the trace of the plate A-2, 3 or 4, as the case may be, to the arc, and the point of intersection of this line and the arc, G' or G'', is preserved. If this point, G' or G'', is outside the base triangle, the next trial arc should be drawn with a larger mapping constant as a radius, or vice versa. If the second mapping constant is off, find again the point of intersection of the radial line through the new location of Sta. C on the newly located trace of the last plate and the new arc. Join this point and the one found previously, in the same manner, with a straight line, G'G''. The point G where this last drawn line intersects the line AC of the base triangle, will be the point through which the arc, with the correct mapping constant as radius, ought to pass, provided the first two approximations were not too far in error. This third trial ought to make the location of the traces of the plates exactly correct. If, however, the focus of the camera was changed between [17] exposures at one station, the traces of the plates will not all be at an equal distance from the station point, and their location will be an almost impossible task. The traces of the plates taken at stations B and C are found in exactly the same manner as were those for Sta. A. After the traces have all been located, it is a good plan to ink them in lightly and erase the pencil construction lines which would otherwise form an impenetrable maze. The traces located, the difficult and tiresome part of the plotting is over; the landscape, brought indoors photographically, is located as with the plane table; all that remains to be done is to take the sights and find the points on the paper which show where the objects were on the ground.

From Each Station the Mapping Constant is Laid Out by the Focal Distance of the Camera or Distance of the Plate from the Lens, and the Location of Traces of the Plates Determined

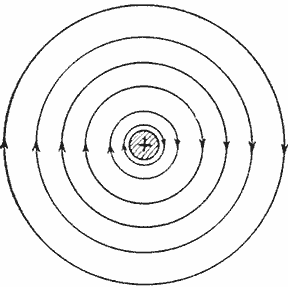

This taking the sights is a simple matter. With a pair of dividers, the distance from a given object from the center line of the plate is measured. This distance is laid off on the proper side of the point marking the center line of the trace of the same plate; a radial line is drawn through the trace at the given distance from the center-line point and the station at which the given plate is taken; this is one line of sight to the object. The same object is located from another station in the same way; as on the plane table, the intersection of the two lines to the same object marks the location of the point which represents the object on the map.

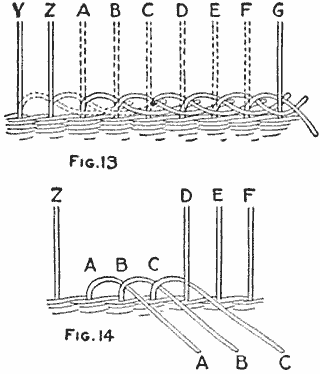

Obtaining elevations for the drawing of contours is a slightly longer process. Contours are lines joining points of equal elevation; they represent successive shore lines, if the area mapped were inundated and the water should rise slowly foot by foot. If the contours are close together, the ground represented has a steep slope, and vice versa. If, on a map, a number of points are of known elevation, it is simply a question of judgment and practice to tell where contour lines go.

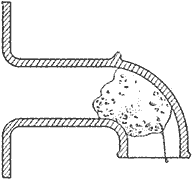

Before contours can be drawn the elevations of a considerable number of points must be known. If the elevation of any one of them is known and the difference between that one and any other can be found, determining the elevation of the second point is simply a problem in addition or subtraction. If it be desired to find, for [18] instance, the difference in elevation between Sta. C and the corner of the fence, as shown in the sketch, two solutions are possible, as follows:

First: Perpendicular to the line of sight from Sta. C to the fence corner, two lines are drawn, one at the intersection of the trace of the plate by the line of sight, and one at the point on the paper which shows the location of the fence corner. On the first of these two lines is laid off the distance Y', equal to the distance of the ground at the fence post above or below the horizontal center line on the plate. Through this point, on the first perpendicular on the line of sight, is drawn a line through the Sta. C and extended to an intersection with the second drawn perpendicular. The distance from the corner of the fence, on the paper, to this intersection is the distance Y, the difference in elevation from the center of the camera at Sta. C to the ground at the fence post. This solution is longer and less desirable than the second.

Second: In place of perpendicular lines to the line of sight, the trace of the plate, and a line, through the point representing the object, parallel with the trace, may be used.

A datum plane, or reference surface, from which all elevations are measured up to the ground surface must be assumed. The United States Geological Survey uses mean, or average, sea level for the datum in all its topographic sheets. Generally, unless there is a United States Geological Survey "bench mark," a monument of carefully determined elevation referred to sea level, within the limits of the survey, it is better to assume the elevation of some point, as Sta. C, at 100 ft., or greater if necessary to place the datum plane below the ground level at all points within the area to be mapped. Other elevations are figured from the assumed elevation of Sta. C. Allowance must be made for the height of the center of the camera above the ground at Sta. C in computing elevations above Sta. C. All elevations determined for the purpose of drawing contours are ground elevations and not the elevation of the top of objects located on the map. The topographic sheets of the Geological Survey are good examples to follow, in drawing contours. For many purposes, contours are not essential, and the refinements necessary for their drawing may be omitted.

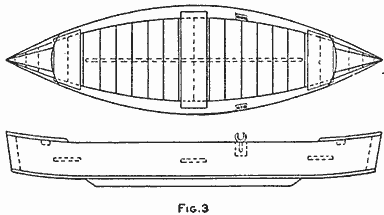

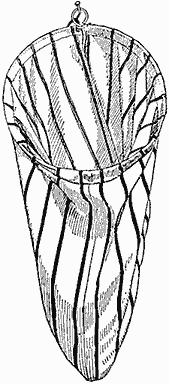

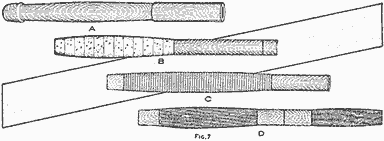

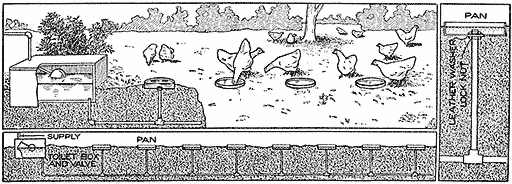

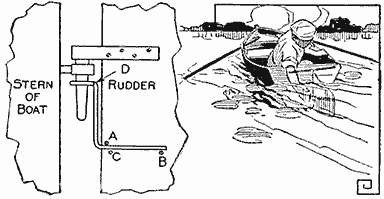

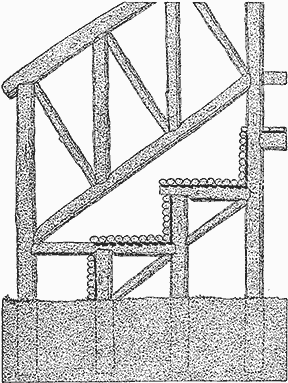

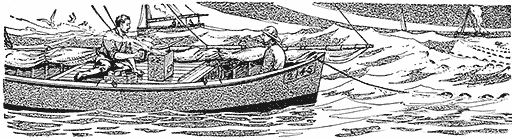

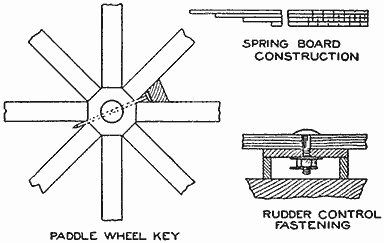

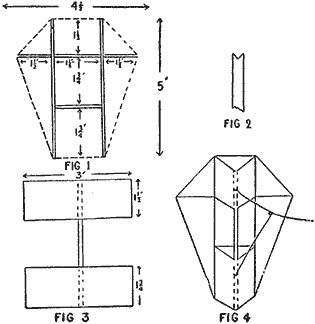

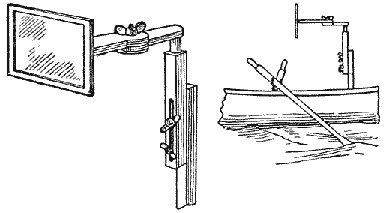

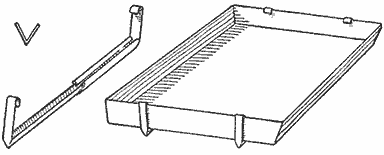

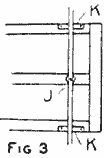

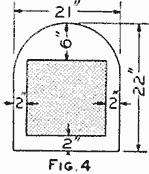

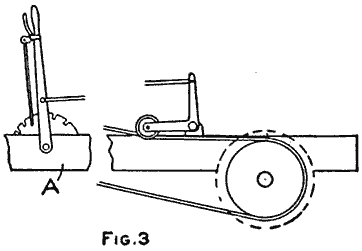

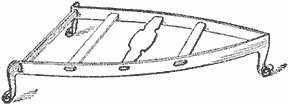

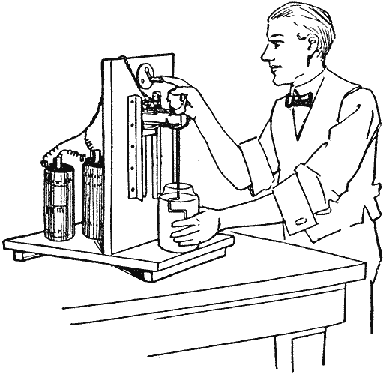

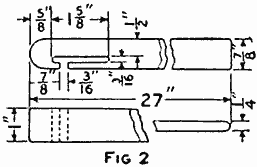

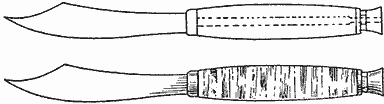

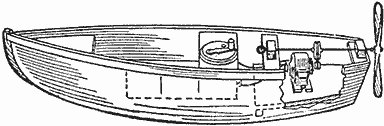

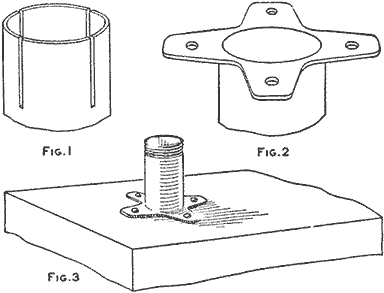

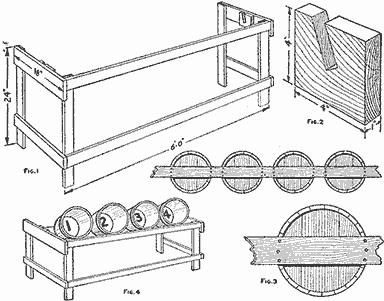

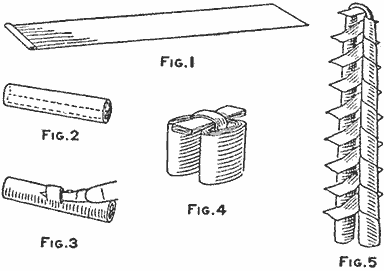

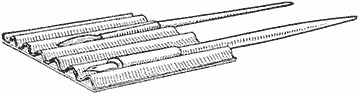

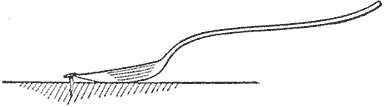

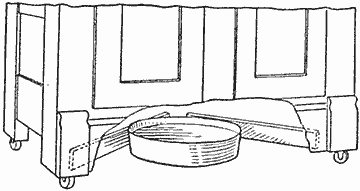

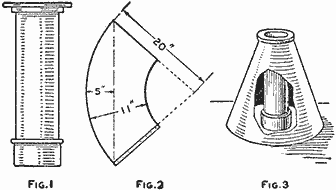

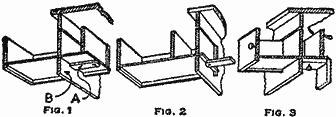

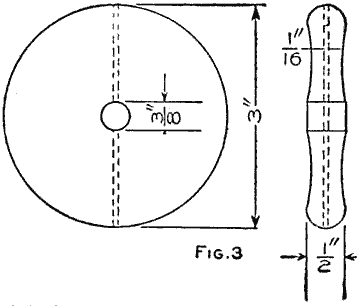

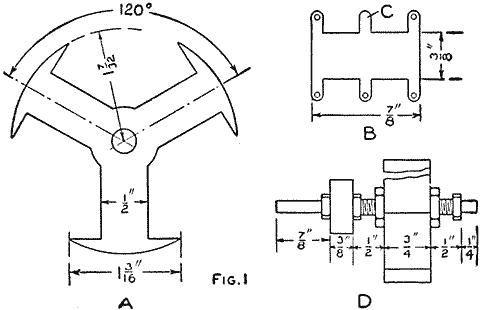

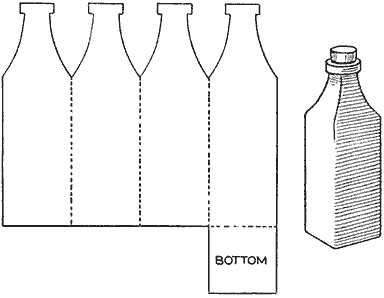

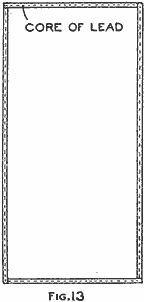

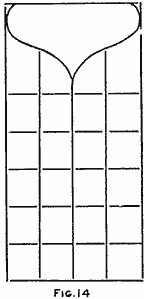

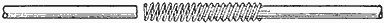

The following is a description of an easily constructed 12-ft. skiff, suitable for rowing and paddling. This is the type used by many duck hunters, as it may be easily pushed through marshes. It is constructed of 3/4-in. dressed pine, or cypress.

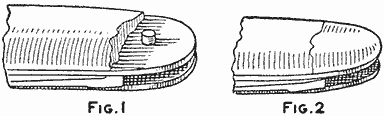

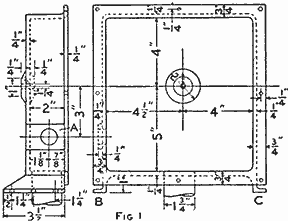

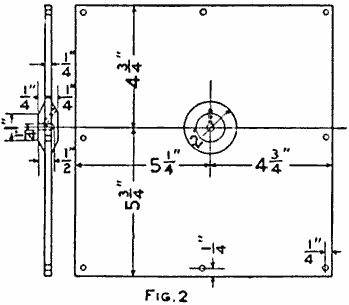

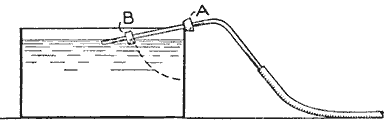

The Skiff is Especially Constructed for Use in Shallow Water and Marshes by Duck Hunters, but with the Addition of a Keel It Makes a Good Craft for Almost Any Water as a Rowboat (Fig. 1)

(Fig. 2)

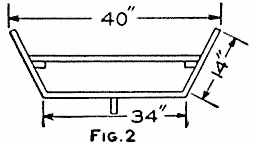

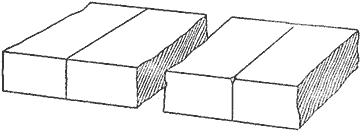

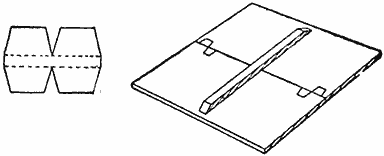

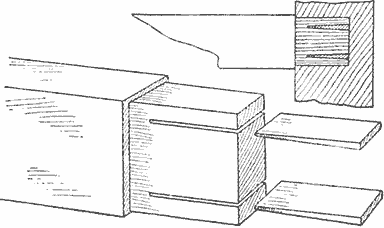

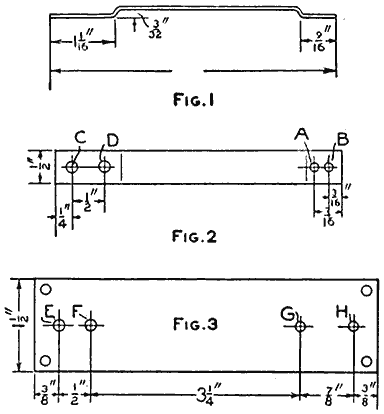

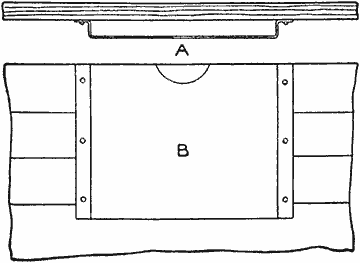

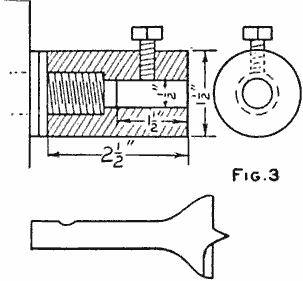

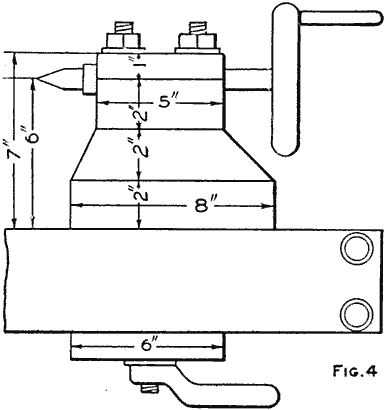

The sides consist of planks, 14 in. [19] wide, but 12-in. planks may be used, the length being 12 ft. 4 in. Two stem pieces are constructed as shown in Fig. 1, and the plank ends are fastened to them with screws. Nail a crosspiece on the plank edges in the exact center, so as to space the planks 34 in. apart, as shown in Fig. 2; then turn it over and nail another crosspiece in the center of the planks for width, and make the spacing of the other edges 40 in. Plane the lower edges so that, in placing a board across them, the surfaces will be level. The floor boards are 6 in. wide and fastened on crosswise, being careful to apply plenty of red lead between all joints and using galvanized nails, 2 in. long.

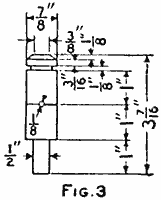

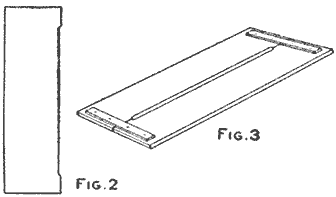

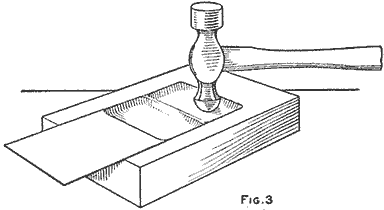

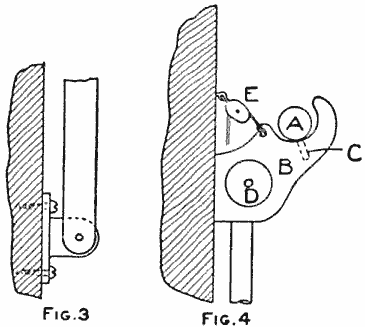

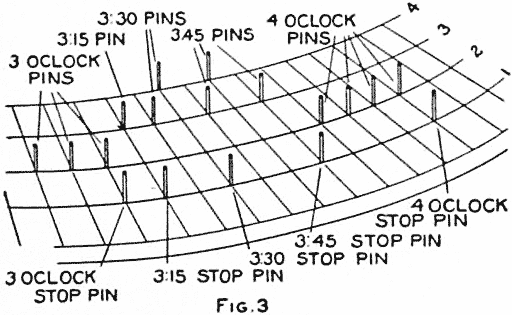

(Fig. 3)

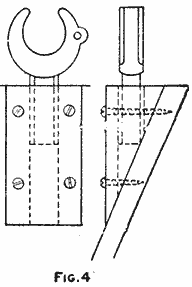

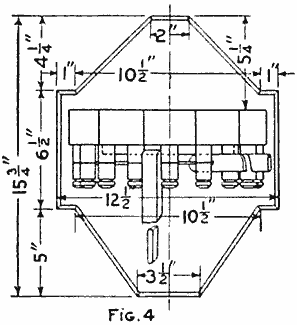

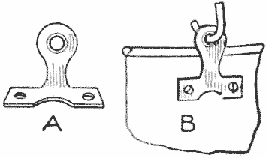

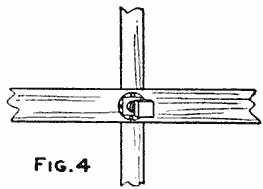

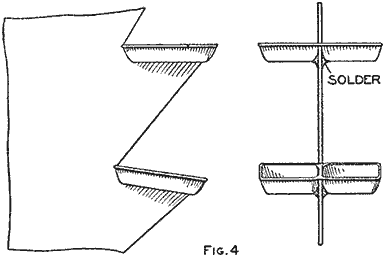

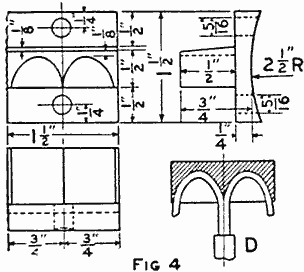

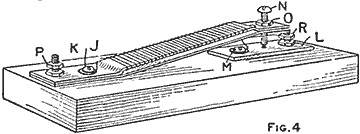

A deck, 18 in. long, is fastened on each end, as shown in Fig. 3. It is made of strips fastened to a crosspiece. The seats, or thwarts, consist of 10-in. boards, and are placed on short strips fastened to the side planks about 5 in. from the bottom. The oarlocks are held in a wedge-shaped piece of wood, having a piece of gas pipe in them for a bushing, the whole being fastened at the upper edge of the side planks with screws, as shown in Fig. 4. The location of these must be determined by the builder.

(Fig. 4)

Some calking may be required between the bottom, or floor, boards, if they are not nailed tightly against one another. The calking material may be loosely woven cotton cord, which is well forced into the seams. The first coat of paint should be of red lead mixed with raw linseed oil, and when dry any color may be applied for the second coat.

While, for use in shallow water, these boats are not built with a keel, one can be attached to prevent the boat from "sliding off" in a side wind or when turning around. When one is attached, it should be 3/4 in. thick, 3 in. wide, and about 8 ft. long.—Contributed by B. Francis Dashiell, Baltimore, Md.

An aniline color soluble in alcohol, by adding a little carbolic acid, will hold fast on celluloid.

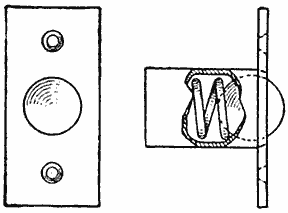

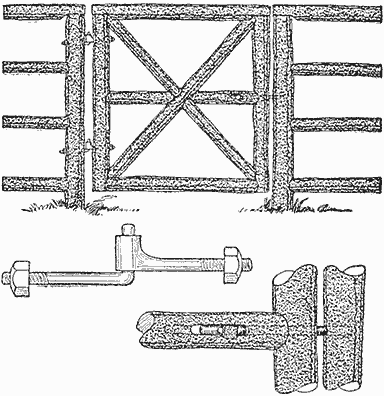

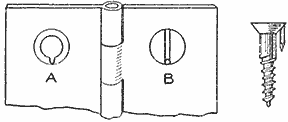

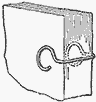

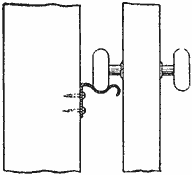

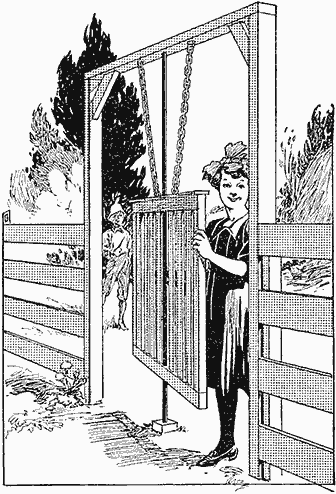

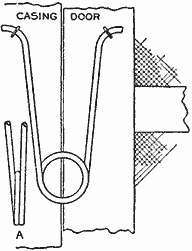

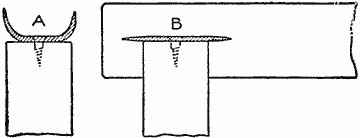

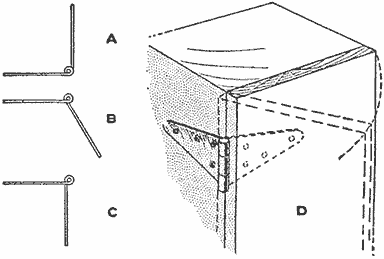

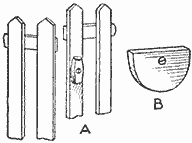

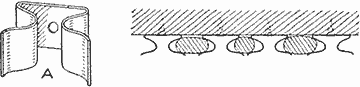

Ordinary hinges can be easily bent and so placed on posts that a gate can be swung in either direction. As shown in the illustration, hinges can be made to fit either round or square posts. The gate half of the hinge is fastened in the usual way. The post half is bent and so placed that the hinge pin will approximately be on a line between the centers of the posts. The gate and post should be beveled off to permit a full-open gateway.—Contributed by R. R. Schmitz, Birmingham, Ala.

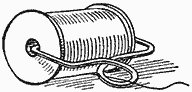

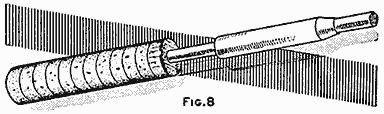

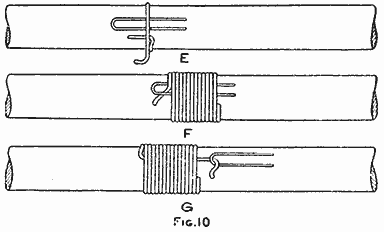

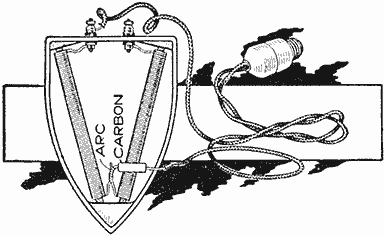

While winding an induction coil, I found it necessary to test the sections for continuity. Having no galvanometer, I connected a battery and low-resistance telephone receiver in series with the section and battery. The battery and telephone receiver may also be used for testing out the secondary of an induction coil, to determine if it is burnt out.—Contributed by John M. Wells, Moosomin, Can.

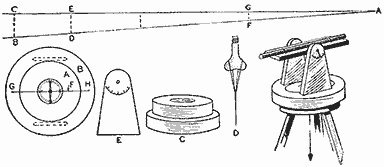

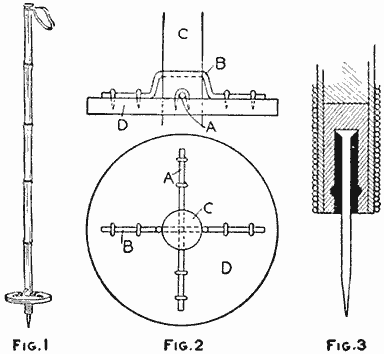

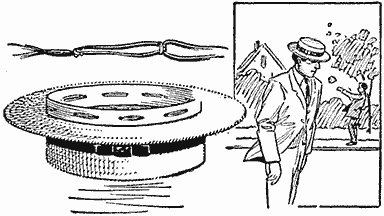

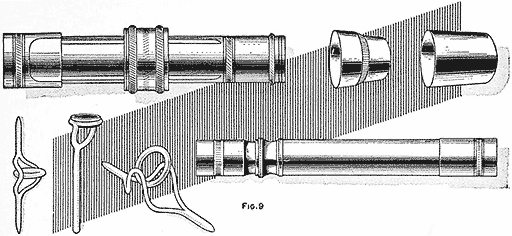

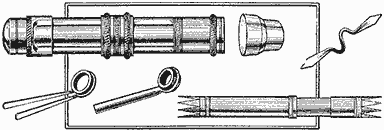

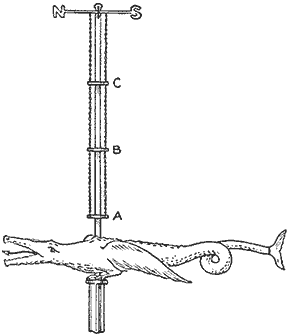

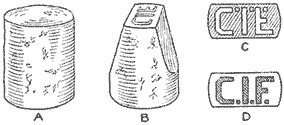

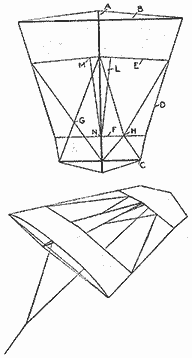

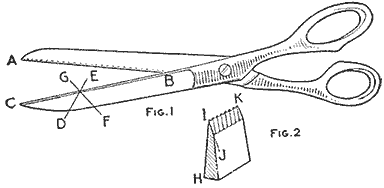

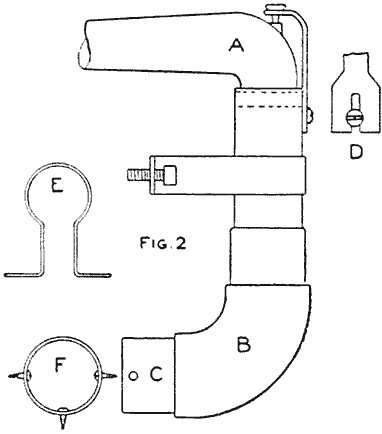

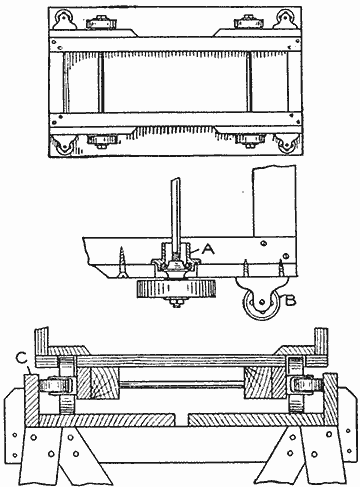

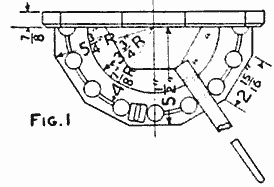

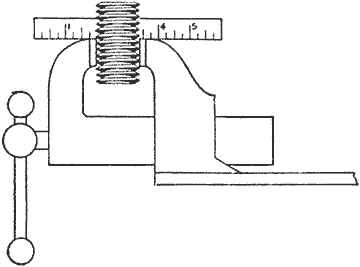

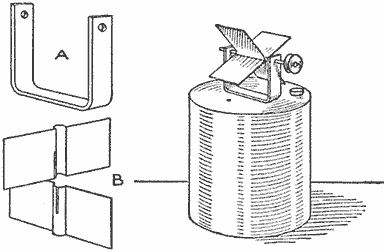

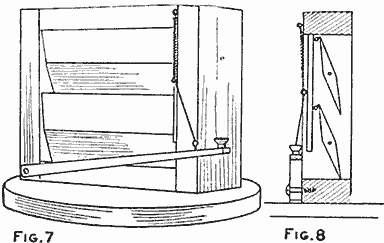

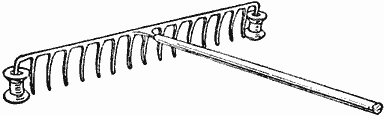

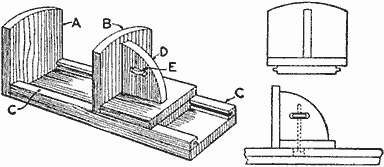

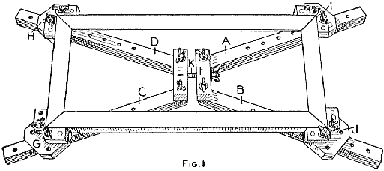

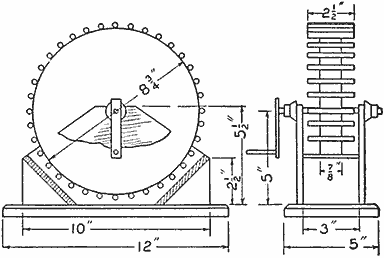

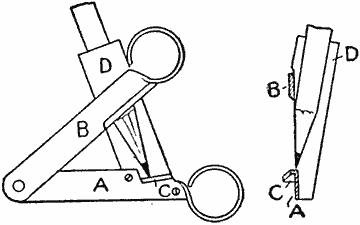

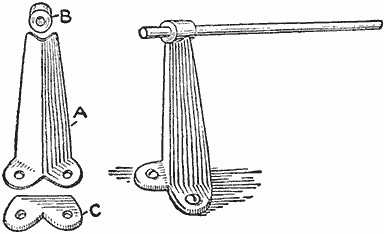

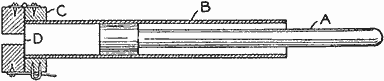

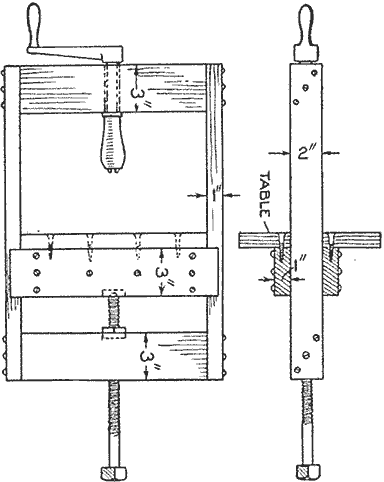

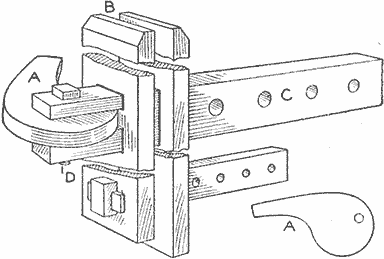

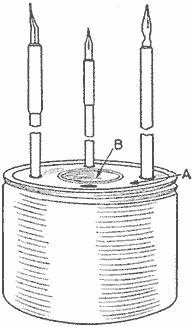

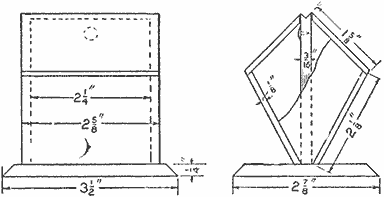

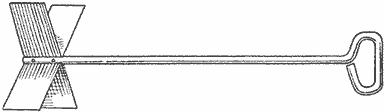

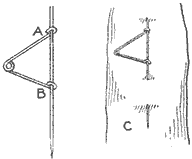

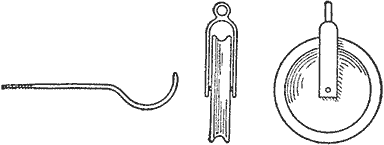

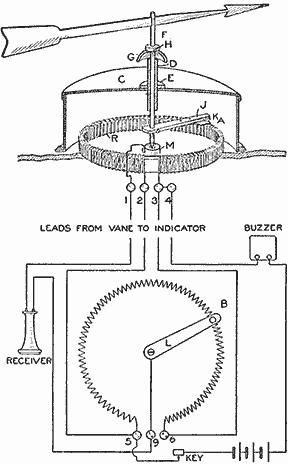

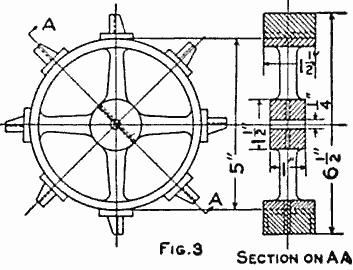

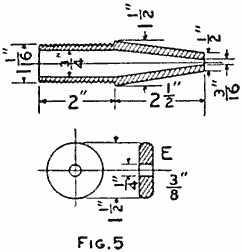

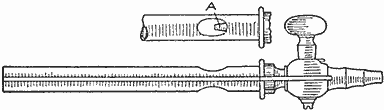

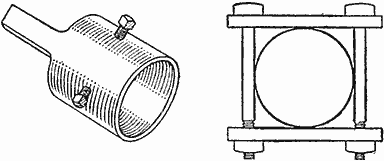

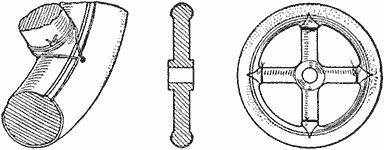

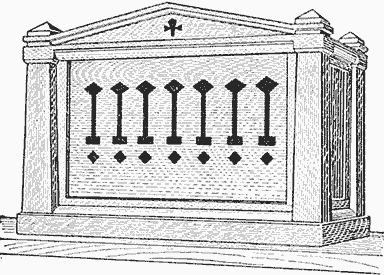

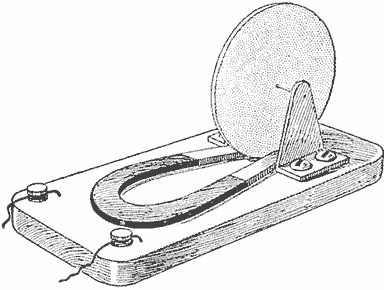

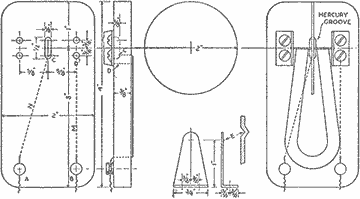

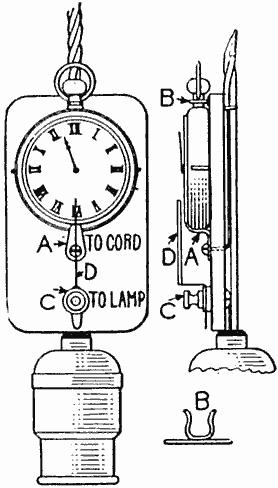

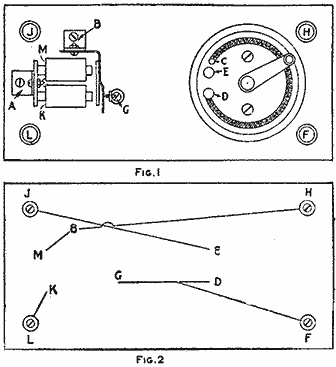

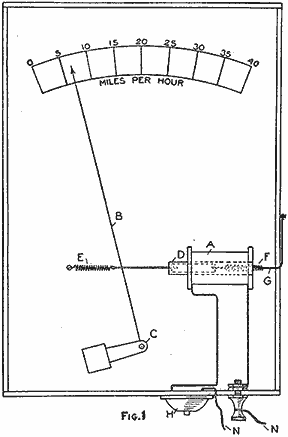

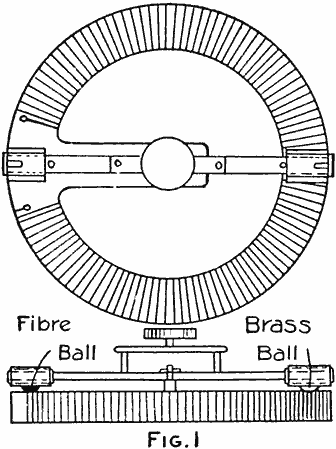

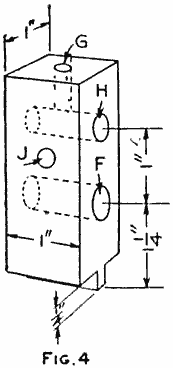

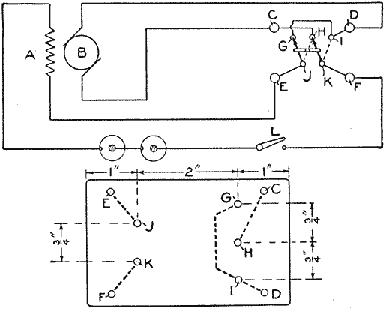

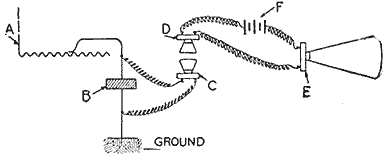

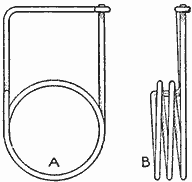

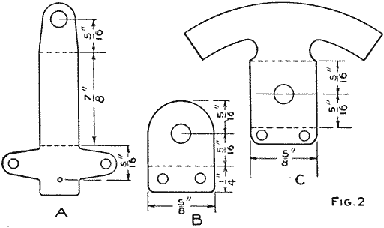

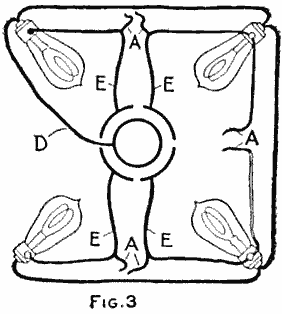

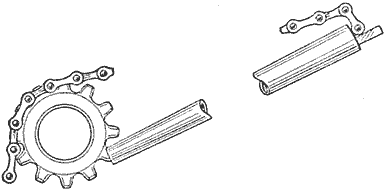

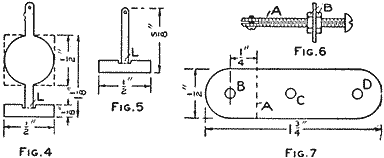

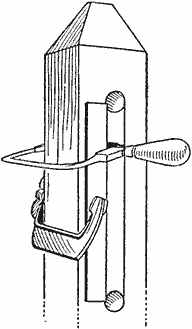

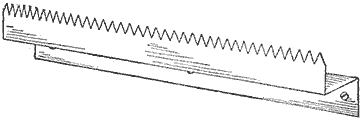

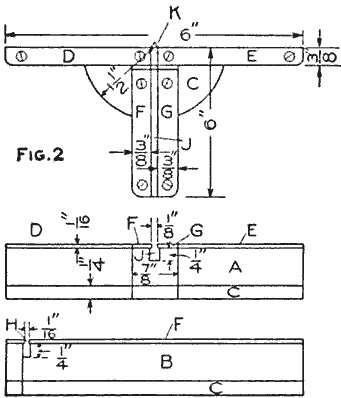

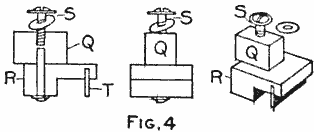

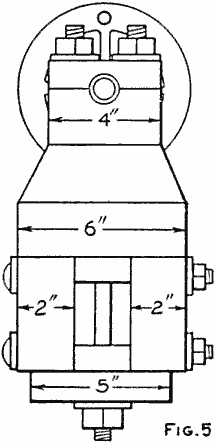

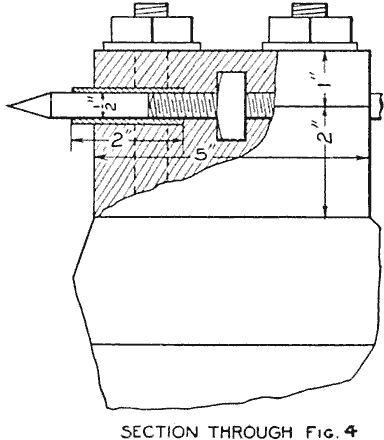

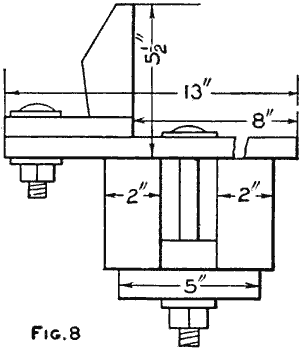

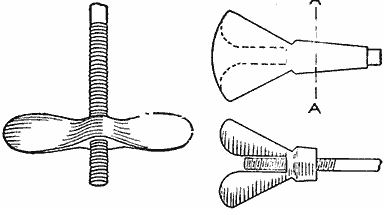

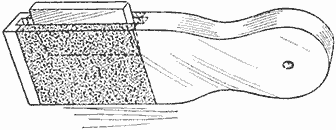

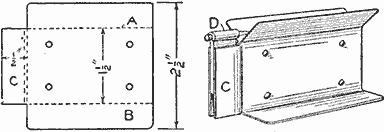

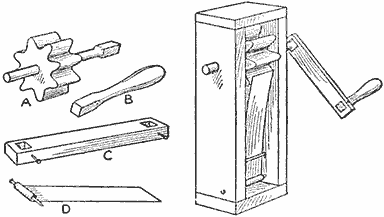

Detail of Parts for the Construction of a Transit Which can be Used, with Fairly Accurate Results, in Doing Amateur Surveying for Railroad Work, Town Sites and the Laying Out of Maps

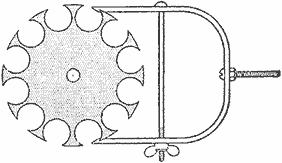

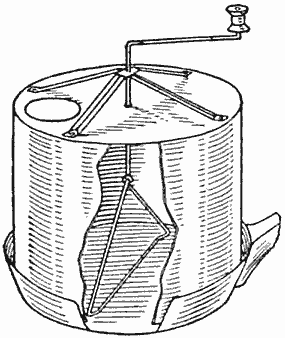

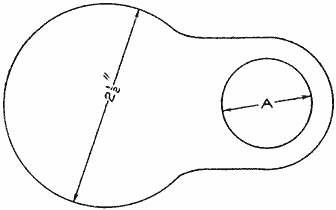

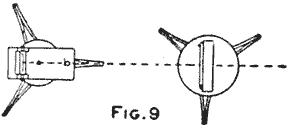

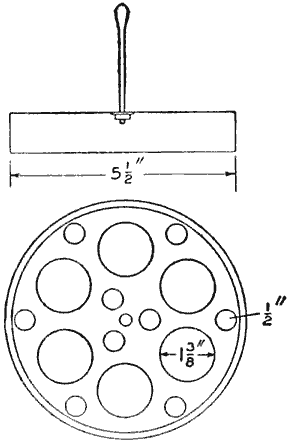

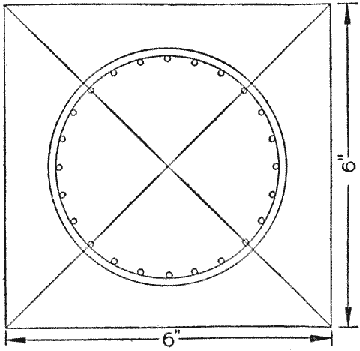

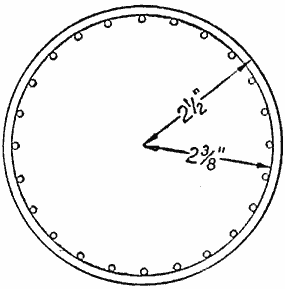

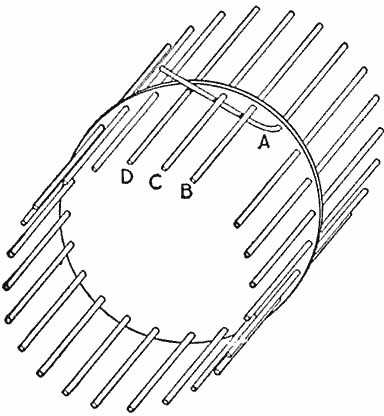

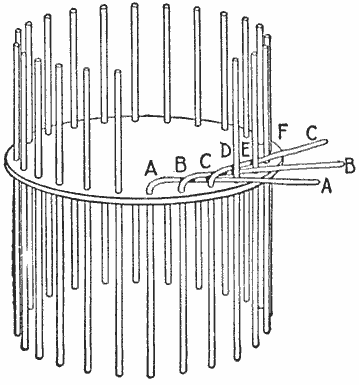

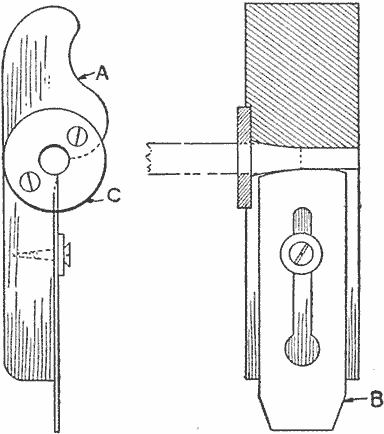

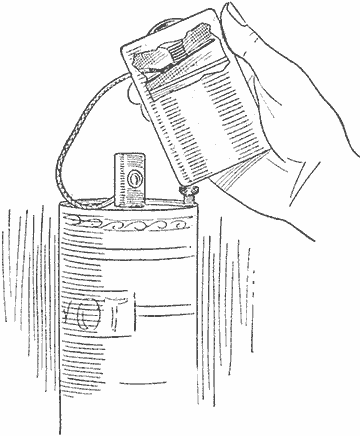

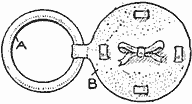

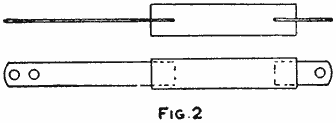

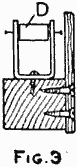

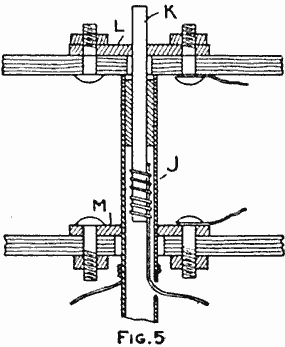

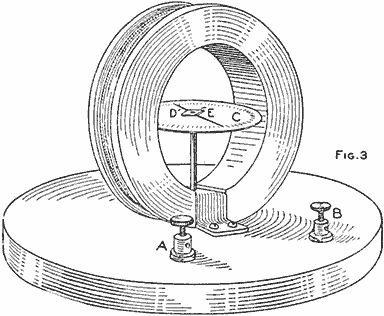

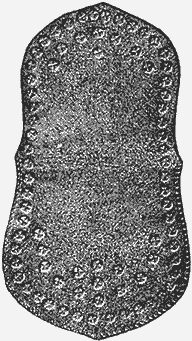

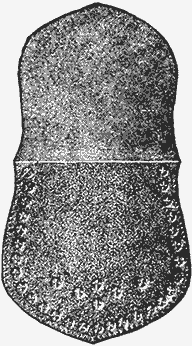

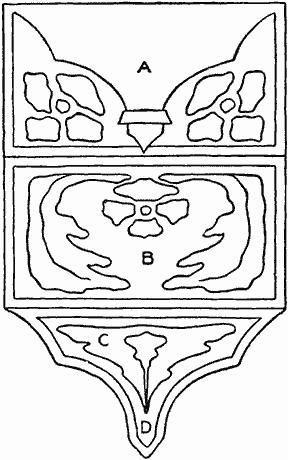

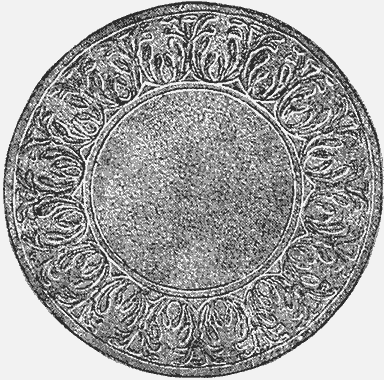

A boy who likes to do the things that "grown ups" do can derive considerable pleasure from the making of a transit, which will enable him to start in surveying railroads, laying off town sites, and doing lots of kindred work. It is necessary to have a compass, and one, 1-3/4 in. in diameter, can be purchased at a reasonable price. A hole is bored with an expansive bit into a board, 7/8 in. in thickness, just deep enough to admit the compass snugly, then a circle, A, 4-1/2 in. in diameter, is drawn, having the same center as the compass hole, and the disk is cut out with a compass or scroll saw. A ring, B, is cut in the same manner from the same material, its inside diameter being such that the ring just fits around the disk A, and the outside diameter, 6-3/4 in. Another block, 5-1/2 in. in diameter, is glued to the bottom of the small disk A. This will appear as shown at C. A small hole is bored in the center of the bottom block on the under side to receive the threaded end of the screw on a camera tripod. By careful adjustment the threads in the wood will hold the transit firmly. A plumb bob must be attached exactly in the center of the tripod head. This can be easily done if the head is wood, but in case the top is of metal, the line can be attached to the screw with a double loop, as shown at D, so that the bob will hang centrally. Two standards are made as shown at E, each about 5 in. high, and fastened to the ring B in the positions shown in the drawing of the complete instrument. An arc of a circle is marked on one of the standards, as shown, to designate angles, the markings being laid out with a bevel protractor. The pointer is a hand from an old alarm clock.

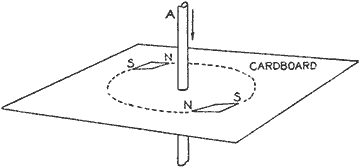

The telescope arrangement consists of a piece of pasteboard tubing, about 1-1/4 in. in diameter, one end being covered with a piece of black paper with a pinhole in the exact center, and the other equipped with "cross hairs." Four small notches are cut in the latter end of the tube, exactly quartering it, and two silk threads as fine as can be obtained, are stretched across in these notches. The tube is fastened to a block of wood, 5 in. wide and 7 in. long, with small tacks and two pieces of fine copper wire. This block is pinioned between the standards with two nails. The hand is secured to the nail in such a position that it will point straight down when the tube is level.

The instrument is adjusted in the following manner: It is set up where a lone tree can be seen, about one mile distant, and the center of the cross [21] hairs is carefully set on the tree. Then a very fine wire is stretched across the compass, as shown at F, and while keeping it directly over the center of the compass it is also placed on a direct line pointing to the tree. Very small brass nails, driven in at G and H, serve to fasten it in the position thus found. When this adjustment has been made the telescope can be turned to sight any object, after first placing the instrument so that the needle points to the N on the dial, and a glance at the wire will show the exact direction in which the object is located.

The instrument is then taken to a level stretch of road and set up, and a stick is placed on end and marked at the height of the telescope. The stick is taken along the road about 200 yd., the telescope sighted on it, and the hand set. This makes the instrument level enough for all practical purposes. The plumb bob is then dropped, a distance of 20 ft. measured from it on the road, and a mark made. The telescope is sighted on this mark, and a mark is made on the standard at the point of the arc, to which the hand points. Another 20 ft. is measured, or 40 ft. from the bob, and another mark made. The telescope is sighted on it, and the location of the hand again marked. This works well up to about 300 ft., then the marks begin to come very close together. This method is used for laying out town sites. The instrument is set up directly over a stake from which to work, and the telescope is turned down until the 20-ft. mark is indicated, when the operator looks through the telescope and tells his helper where to set the stake. Then another is driven at the next point, and so on, until the limit of the instrument is reached.

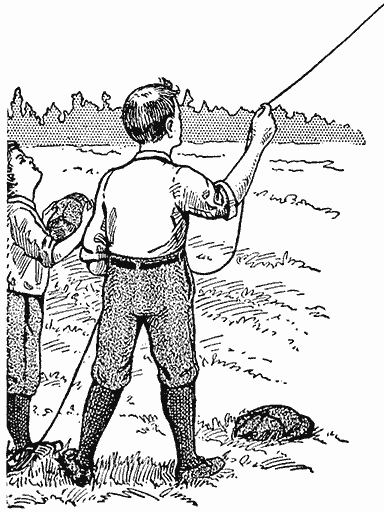

When doing railroad surveying several start out together, one with an ax to cut away brush; one to carry pegs; two to measure, or chain, the distance between stakes, and one to do the sighting. In this manner a line can be run that comes very near being perfectly straight for three miles.

A concrete example of how the transit was used to lay out a map of a ranch will now be given. The start was made on an east and west fence. The instrument was set 5 ft. from the fence at one point, and at the other end of the fence the stick was set at a point 5 ft. from the fence. When the stick was sighted, the wire cut the E and W on the compass, thus showing that the fence was set on a line, due east and west. The distance was measured from the fence to the house, which was 1/4 mile, and this was noted in a book. This operation was repeated on the rear, and the distance found to be 780 ft. while the compass showed the direction to be 4 deg. west of south. The next line ran 427 ft. and 1 deg. east of south. This was kept up all the way around. After these notes had been obtained, it was an easy matter to take a piece of plain paper and strike a line representing north and south and lay off the directions. A bevel protractor was used to find the degrees. The transit was set on the posts of the corrals and this saved the measuring out from the inclosure. The creek was surveyed in the same manner. So many feet south-west, so many feet west, so many feet 5 deg. south of west, and so on, until its length was run.

The transit can also be used for finding distances without measuring. A line from A to B is sighted, and F represents a point 1/2 mile distant, the line from F to G being 100 ft. A line is now sighted from A, through G to C. A person standing at D is directed to move toward the point E and he is stopped as soon as sighted in the telescope. He then measures the distance from D to E. Suppose this distance is 250 ft. As each 100 ft. means 1/2 mile, and the 50 ft., 1/4 mile, the point E is 1-1/4 miles from the transit. This method can be used quite extensively and distances obtained are fairly accurate.

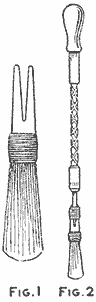

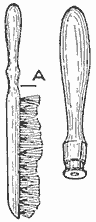

A small whisk broom makes a handy cleaner to brush the caked grease and lint from pulleys and gear wheels where waste and rags are useless.

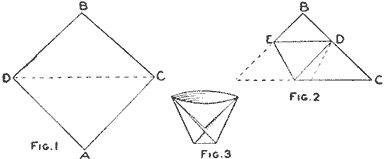

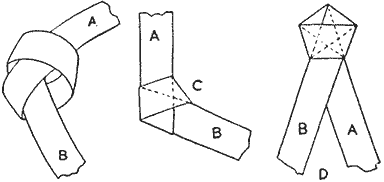

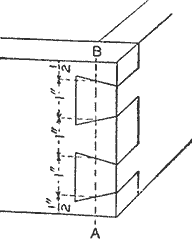

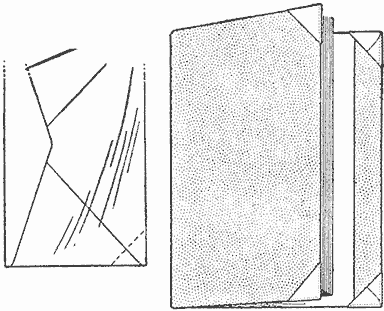

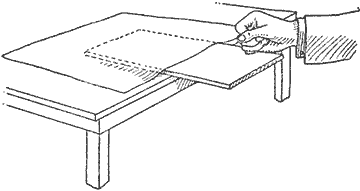

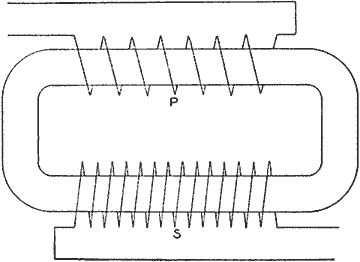

Sometimes it is necessary to enlarge or reduce a plot to a different scale. This can be easily and quickly accomplished without resorting to the slow process of protracting the angles and scaling the individual lines.

Take any point, P, and from it draw light pencil lines through each of the corners of the plot. On any one of these lines, as AP, lay off with dividers AC equal to CP. Place a triangle on the line AB and with a straightedge, or another triangle, laid on the line AP, slide the former to the point C, then draw line CD parallel with AB until it intersects the radial line PB. In the same manner draw line DE parallel with BF, and so on, all about the plot. A test of accuracy will be in striking the point C with the last line. If the original plot has a scale of 40 ft. to the inch the reduced plot would be 80 ft. to the inch. If it is required to enlarge the plot to 20 ft. to the inch, make AG equal to AP, and proceed as in the first case, using G as the starting point.

The location of the point P is arbitrary and may be outside of the boundary of the plot or figure to be enlarged or reduced, but should be so located, if possible, that the radial line to any corner does not parallel either of the plot lines to that corner. If the point cannot be so located for all the lines, it may be necessary to scale the lines. A little practice in picking out the best location for the point will give gratifying results.—Contributed by Junius D. McCabe, Pittsburgh, Pa.

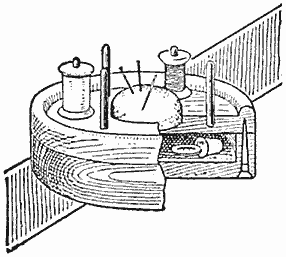

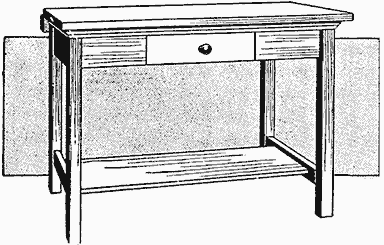

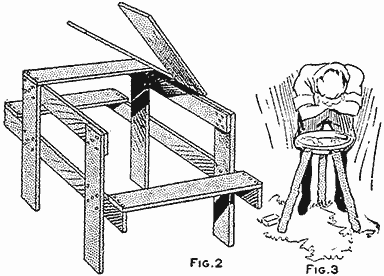

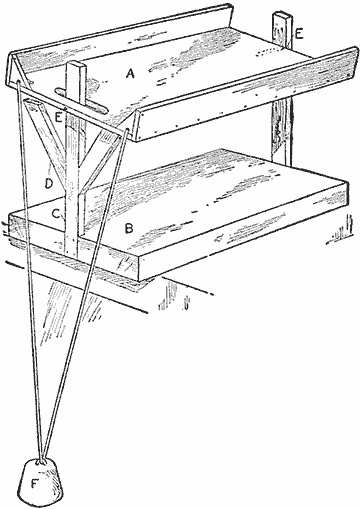

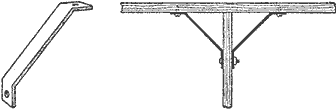

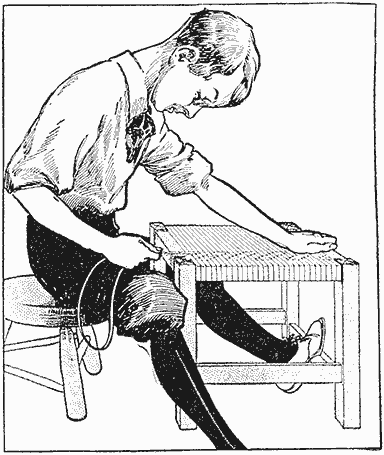

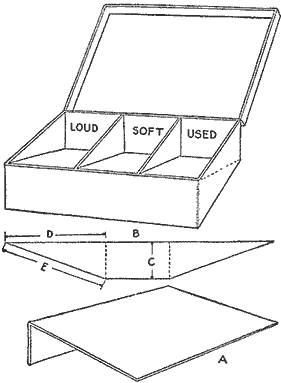

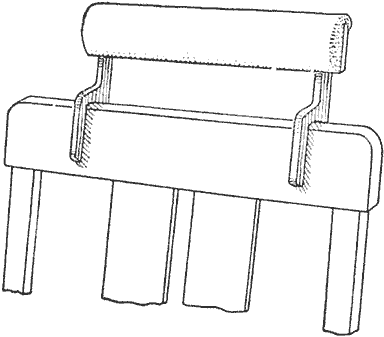

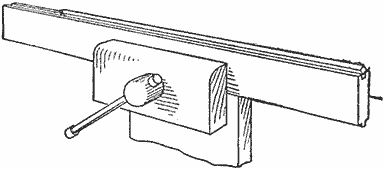

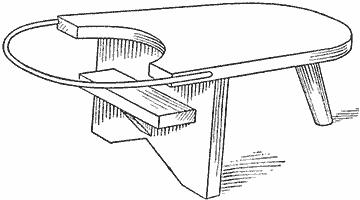

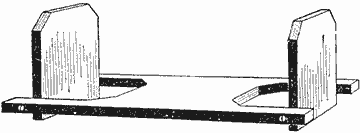

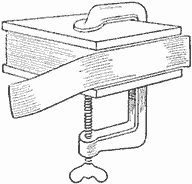

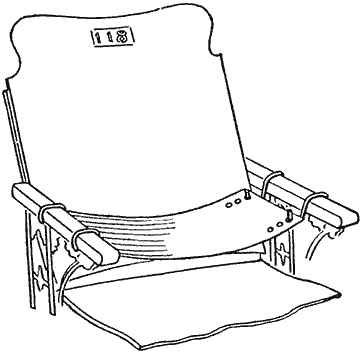

While working at a bench, or foot-power lathe, it is quite convenient to have some sort of a seat to sit on while at work, or between operations. In making such a seat, I used a board, 27 in. long and 12 in. wide, for the top, and two boards, 19 in. long and 12 in. wide, for the supports. These boards were 3/4 in. thick. The supports were squared at the ends and securely fastened to the top with nails, their positions being 3 in. in from the ends of the top board. These were well braced, as shown, and a cross board was placed between them, near the lower ends.

The projecting ends of the top were cut out, and a box, 5 in. deep, constructed against the supports. A [23] covering was made to fit in each of the openings in the top board and hinged to the outer edge of the box. The boxes made a convenient place for the tools used in the turning work.—Contributed by Harold R. Harvey, Buhl, Idaho.

In using the polishes now on the market for tan shoes, I found that the leather cracked in an unreasonably short time. The following was suggested and tried out with good results. Wash the shoes with castile soap and water by applying the mixture with a dauber. Work up a little lather and then rub dry with a cloth, without rinsing. The leather will be cleaned without becoming dark, and it will not crack. A higher polish may be obtained by using some paste polish in the usual manner.—Contributed by George Bliss, Washington, D. C.

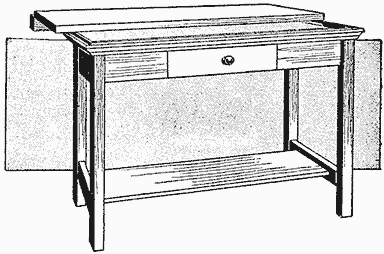

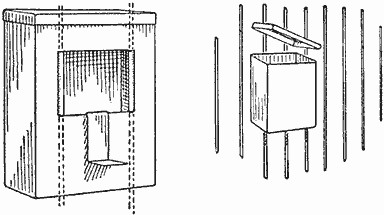

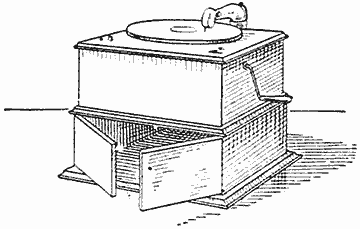

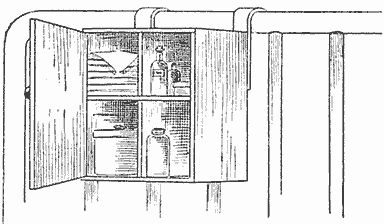

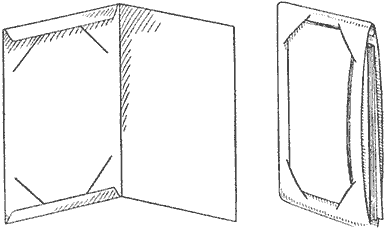

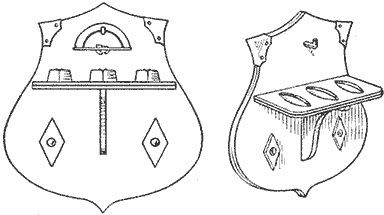

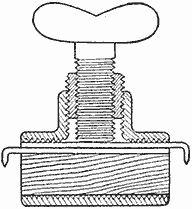

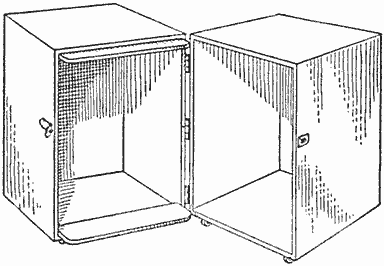

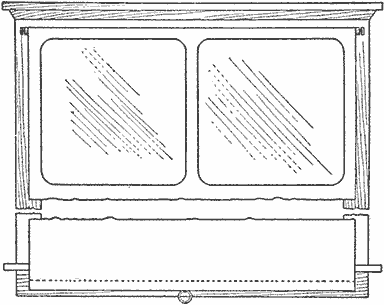

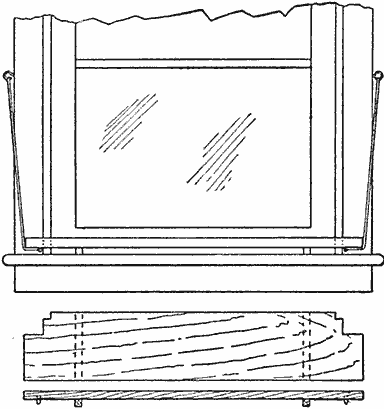

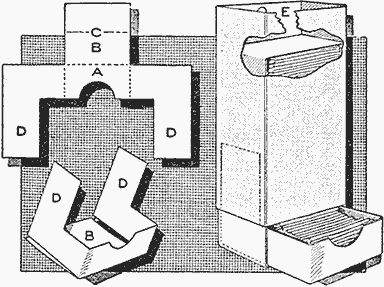

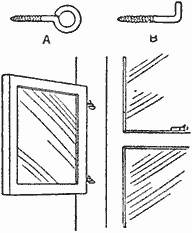

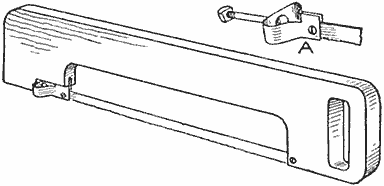

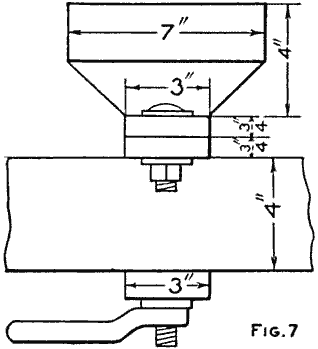

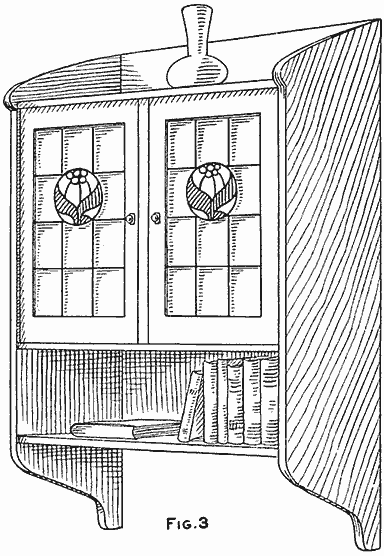

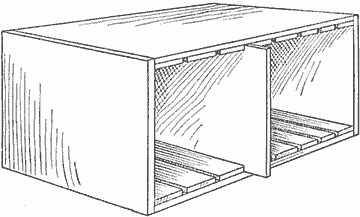

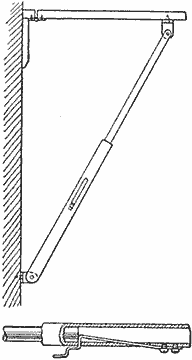

The illustration represents a shaving cabinet mounted on an adjustable pedestal, whose style and size are such that it may easily be moved about or set away without requiring much room. The material required for its construction is as follows:

| 1 | framed mirror, 8 by 10 in. |

| 1 | square-head bolt and wing nut, 1/2 by 4 in. |

| 2 | cabinet sides, 1/2 by 7 by 15 in. |

| 2 | partitions and shelf, 1/2 by 6 by 6 in. |

| 1 | cabinet top, 1/2 by 7 by 10-1/2 in. |

| 1 | cabinet bottom, 1/2 by 6 by 10-1/2 in. |

| 2 | cabinet backs and doors, 1/2 by 6-1/2 by 10-1/2 in. |

| 4 | cabinet moldings, 1 by 4 by 4 in. |

| 1 | cabinet support, 2 by 2 by 26 in. |

| 4 | pedestal moldings, 1 by 1 by 6 in. |

| 4 | pedestal frames, 1 by 3 by 36 in. |

| 1 | base, 2 by 12 by 12 in. |

| Screws, nails, and varnish. |

The sidepieces of the cabinet are extended at one corner, thereby forming the supports for the mirror. The door fits in between the sides and may be attached either by hinges or two wood screws, one on each side, holes being bored in the sides forming a loose fit for the screw so they can freely turn with the door. The pedestal consists of a 4-in. square box resting on the base block, and secured in place by means of molding strips. The sliding support for the cabinet consists of a 2-in. square piece secured to the bottom of the cabinet by means of molding, and provided with a slot so the support can freely slide over the clamp bolt, which fastens it in place by clamping it against the pedestal. If it is desired to conceal the head of the bolt, a recess should be made in the pedestal frame for it, as shown, so the support will freely slide over it. Before assembling the pedestal it will be necessary to drill a hole in the front side in line with the recess of the back side, and insert the bolt. If this precaution is not taken, it will not be possible to insert the bolt, unless a hole be made for the head either through the back side or front side.—Contributed by D. Toppan, Watervliet, N. Y.

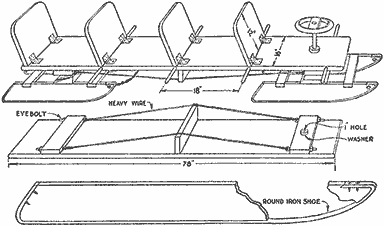

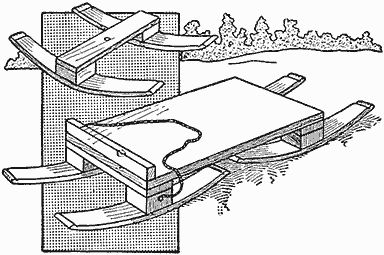

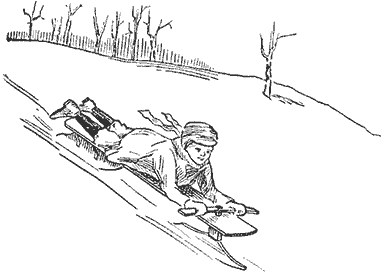

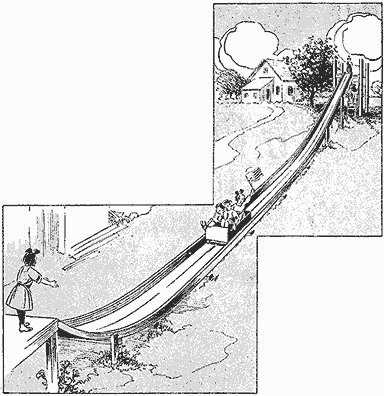

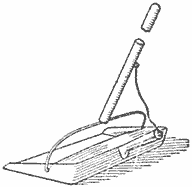

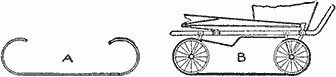

Coasting Is One of the Best Sports a Boy Enjoys during Winter, and a Sled of Luxury Is Something to Be Proud of among Others on a Hill or Toboggan Slide

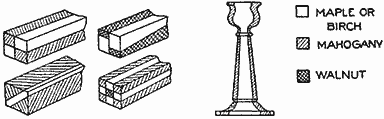

Coaster bobs usually have about the same form of construction, and only slight changes from the ordinary are made to satisfy the builder. The one shown has some distinctive features which make it a sled of luxury, and the builder will pride himself in the making. A list of the materials required is given on the opposite page. Any wood may be used for the sled, except for the runners, which should be made of ash.

Shape the runners all alike by cutting one out and using it as a pattern to make the others. After cutting them to the proper shape, a groove is formed on the under edge to admit the curve of a 5/8-in. round iron rod about 1/4 in. deep. The iron rods are then shaped to fit over the runner in the groove and extend up the back part of the runner and over the top at the front end. The extensions should be flattened so that two holes can be drilled in them for two wood screws at each end. If the builder does not have the necessary equipment for flattening these ends, a local blacksmith can do it at a nominal price. After the irons are fitted, they are fastened in place.

The top edges of the runners are notched for the crosspieces so that the top surfaces of these pieces will come flush with the upper edges of the runners. The location of these pieces is not essential, but should be near the ends of the runners, and the notches of each pair of runners should coincide. [25] When the notches are cut, fit in the pieces snugly, and fasten them with long, slim wood screws. Small metal braces are then fastened to the runners and crosspiece on the inside, to stiffen the joint.

As the rear sled must oscillate some, means must be provided for this tilting motion while at the same time preventing sidewise turning. The construction used for this purpose is a hinged joint. The heavy 2 by 5-in. crosspiece is cut sloping on the width so that it remains 2 in. thick at one edge and tapers down to a feather edge at the opposite side. This makes a wedge-shaped piece, to which surface the three large hinges are attached. The piece is then solidly fastened to the upper edges of the runners that are to be used for the rear sled, and so located that the center of the piece will be 8 in. from the front end of the runners.

The supporting crosspiece on the front sled is fastened on top of the runners, at a place where its center will be 11 in. from the front end of the runners.

The top board is prepared by making both ends rounding and planing the surfaces smooth. On the under side, the two crosspieces are placed, which should have two 1/2-in. holes bored through the width of each, near the ends, to receive the eyebolts. They are placed, one with its center 12 in. from the end to be used for the rear, and the other with its center 8 in. from the front end, and securely fastened with screws. The shore is placed in the center of the board, and wires are run over it connecting the eyebolts. The eyebolts are then drawn up tightly to make the wire taut over the shore. This will prevent the long board from sagging.

LIST OF MATERIALS

| 1 | top. 6-1/2 ft. long, 16 in. wide, and 1-1/4 in. thick. |

| 4 | runners. 22 in, long, 4 in. wide, and 1 in. thick. |

| 4 | crosspieces, 16 in. long, 3 in. wide, and 1 in. thick. |

| 3 | pieces, 16 in, long, 5 in. wide, and 2 in. thick. |

| 1 | piece, 16 in. long, 5 in. wide, and 1 in. thick. |

| 1 | shore, 16 in. long, 3 in. wide, and 1 in. thick. |

| 4 | seat backs. 12 in. long, 16 in. wide, and 1 in. thick. |

| 1 | dowel. 3 ft. long, and 1 in. in diameter. |

| 4 | rods. 5/8 in. in diameter, and 30 in. long. |

| 4 | eyebolts, 1/2 in. by 6 in. long. |

| 3 | hinges, 5-in. strap. |

| 8 | hinges, 3-in. strap. |

On the upper side of the board and [26] beginning at the rear end, the backs are fastened at intervals of 18 in. They are first prepared by rounding the corners on the ends used for the tops, and the opposite ends are cut slightly on an angle to give the back a slant. They are then fastened with the small hinges to the top board. On the edges of the top board, 1-in. holes are bored about 1 in. deep, and pins driven for foot rests. These are located 18 in. apart, beginning about 5 in. from the front end. The dowel is used for the pins, which are made 4 in. long.

The Top Board is Well Braced on the Under Side and Fitted with Four Backs on Top to Make It a Luxurious Riding Sled, and the Runners are Provided with Metal Shoes for Speed

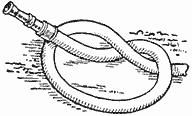

The steering device consists of a broom handle, cut to 18 in. in length, with one end fastened in a hole bored centrally in the 5-in. crosspiece of the front sled. A hole is bored in the top board through the center of the crosspiece fastened to the under side for the steering post. The broomstick is run through this hole after first placing two metal washers on it. After running the stick through, a collar is fastened to it just above the top board, so that the top cannot be raised away from the sled. At the upper end of the broomstick a steering wheel is attached, made from a nail-keg hoop. A piece of wood is fastened across its diameter, and the hoop is covered with a piece of garden hose and wrapped with twine. In the center of the crosspiece, a hole is bored to snugly fit on the broom handle, which is then fastened with screws.

The rear sled is fastened to the top board with screws through the extending wings of the hinges and into the crosspiece. Holes are bored in the front ends of all runners, and a chain or rope is attached in them, the loop end of the rear one being attached to the under side of the top board, and the one in the front used for drawing the sled.

The regular slope of a drill will cause the cutting edge to catch as it breaks through the metal on the opposite side of the piece being drilled. But if a twist drill is ground more flat like a flat drill, it will not "grab" into the metal as it passes through.—Contributed by James H. Beebee, Rochester, N. Y.

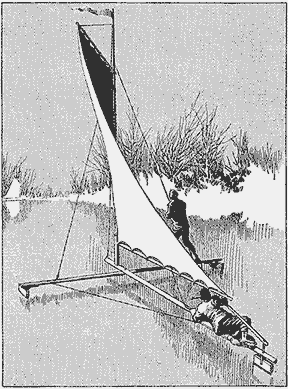

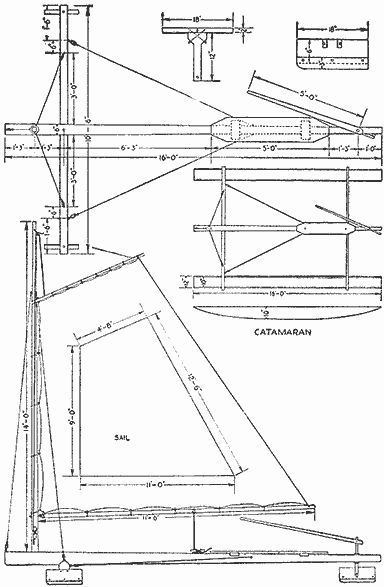

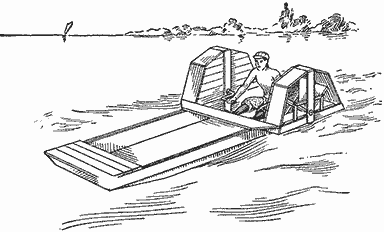

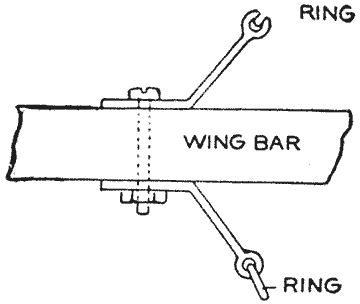

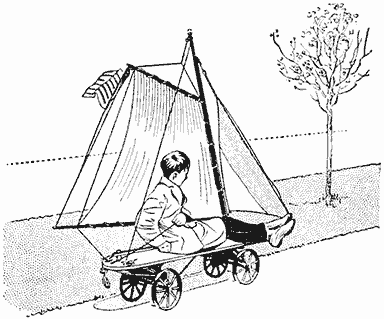

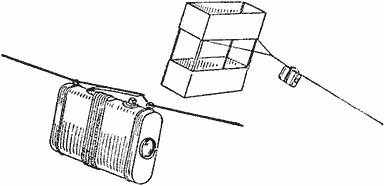

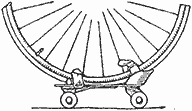

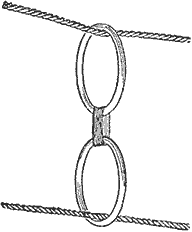

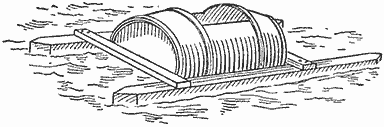

This combination is produced by using the regular type of ice boat and substituting boats for the runners, to make the catamaran.

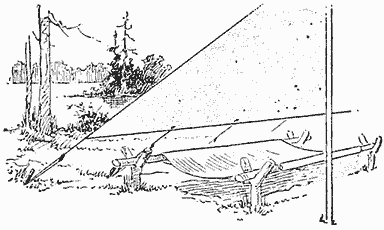

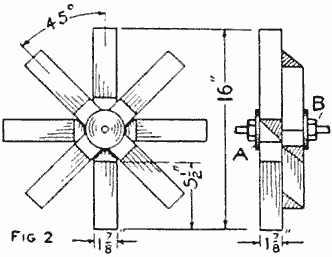

In constructing the ice boat, use two poles, or timbers, one 16 ft. and the other 10-1/2 ft. long, crossed at a point 2-1/2 ft. from one end of the longer timber. The crossed pieces are firmly braced with wires, as shown.

The mast, which should be about 12 ft. long, is set into a mortise cut in the long timber, 15 in. from the front end, and is further stabilized by wires, as shown. A jib boom, about 6 ft. long, as well as a main boom, which is 11-1/2 ft. long, are hung on the mast in the usual manner.

The Ice Boat Provides an Ideal Outing in Winter Where There Is a Body of Water Large Enough for Sailing

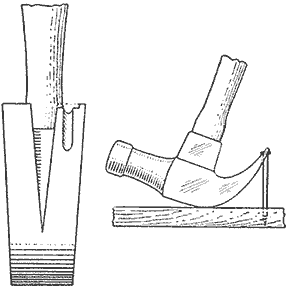

The front runners consist of band-iron strips, 18 in. long, 3 in. wide, and 1/8 in. thick, with one edge ground like the edge of a skate, and the ends rounding, which are fastened with bolts to the sides of wood pieces, 18 in. long, 6 in. wide, and 2 in. thick, allowing the ground edge to project about 1 inch.

When the ice-boat frame is made of poles, the runners are attached to a piece of wood, 12 in. long, shaped as shown and fastened at right angles with bolts running through the shouldered part diagonally. This makes a surface on which the pole end rests and where it is securely fastened with bolts. If squared timbers are used, the runners can be fastened directly to them. The rear, or guiding, runner is fastened between two pieces of wood, so that its edge projects; then it is clamped in a bicycle fork, which should be cut down so that about 3 in. of the forks remain. A hole is bored through the rear end of the long pole to receive the fork head, the upper end of which is supplied with a lever. The lever is attached to the fork head by [29] boring a hole through the lever end at a slight angle to fit the head, allowing sufficient end to be slotted, whereupon a hole is bored through the width of the handle, and a bolt inserted, to act as a clamp.

The Ice-Boat Details, Showing Construction with Straight Poles Having Detachable Runners So the Boats can be Supplied in Their Stead to Make a Sailing Catamaran for Use in Summer

A board is fastened on two crosspieces mortised in the upper part of the pole, for a place to sit on when driving the boat. The sail can be constructed of any good material to the dimensions given.

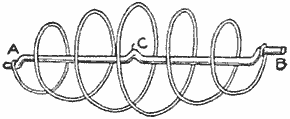

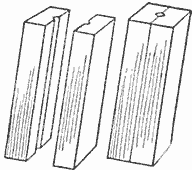

To rig up the ice boat for use as a catamaran, place a pole across the stern, the length of the pole being equal to the one used on the front part of the ice boat. Two water-tight boats are constructed, 16 ft. long, 12 in. wide, and 10 in. deep at the center. To make these two boats procure six boards, 16 ft. long, 10 in. wide, and 1 in. thick. Three boards are used to make each boat. Bend one board so that it will be in an arc of a circle, then nail on the two side boards, after which the edges of the sides are cut away to the shape of the bent board. The runners are removed from the ice boat, and the boats fastened to the pole ends. A rudder is attached in the place of the rear, or guiding, runner. The tops of the boats, or floats, can be covered and made water-tight.

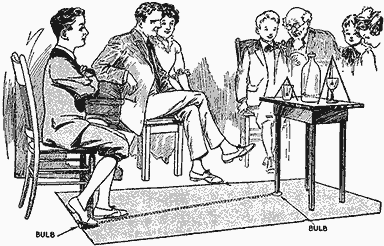

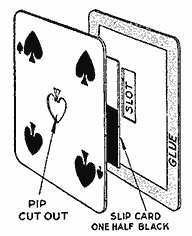

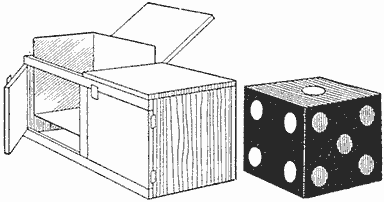

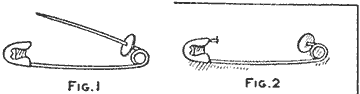

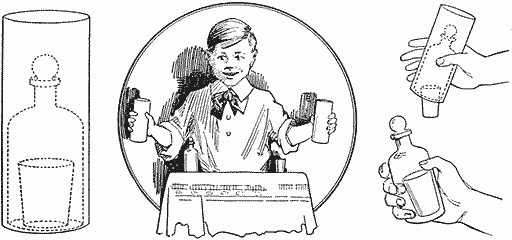

Five cards are shown, and some one person is asked to think of two cards in the lot, after which the performer places the cards behind his back and removes any two cards, then shows the remaining three and asks if the two cards in mind have been removed. The answer is always yes, as it cannot be otherwise.

To prepare the cards, take any 10 cards from the pack and paste the back of one card to another, making five double cards. Removing any two cards behind the performer's back reduces the number of cards to three, and when these are turned over they will not have the same faces so that the ones first seen cannot be shown the second time even though all five cards were turned over and shown.

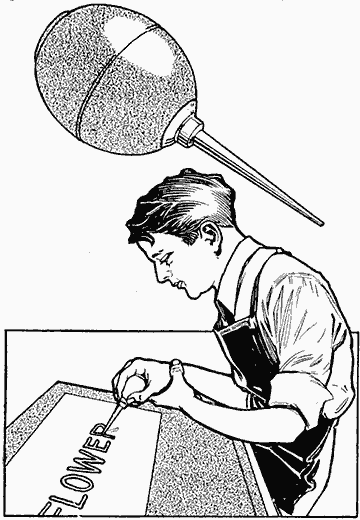

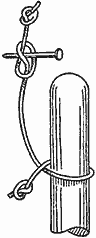

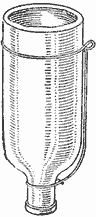

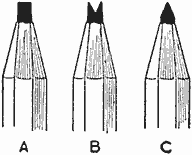

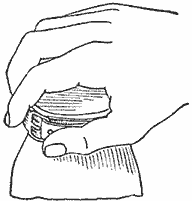

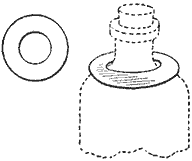

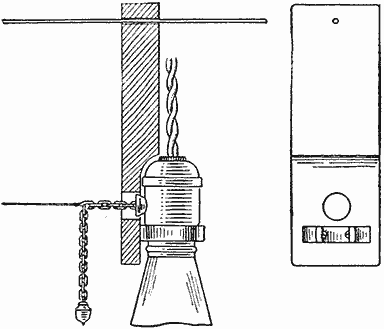

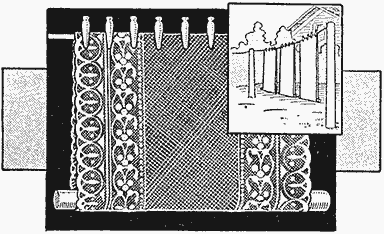

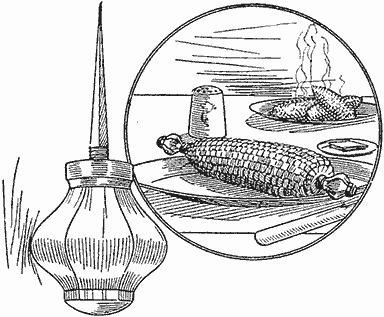

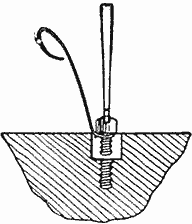

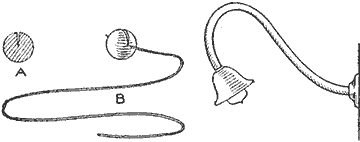

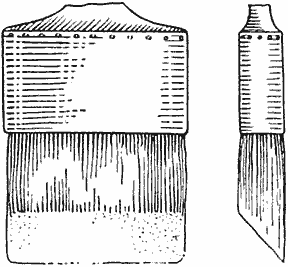

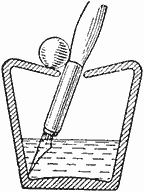

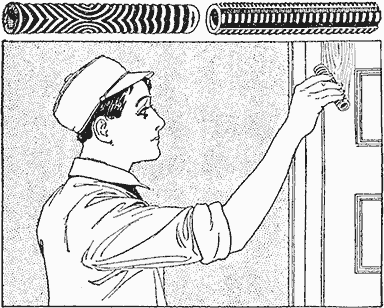

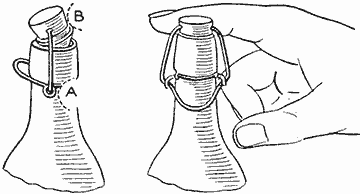

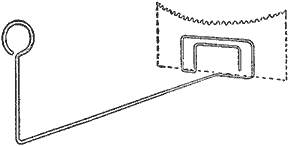

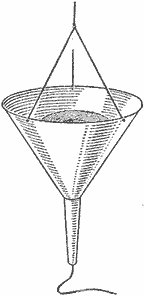

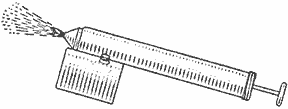

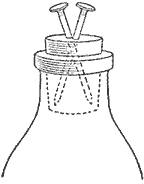

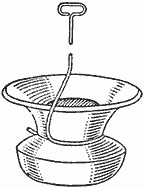

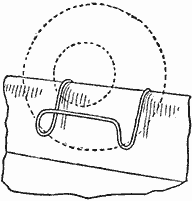

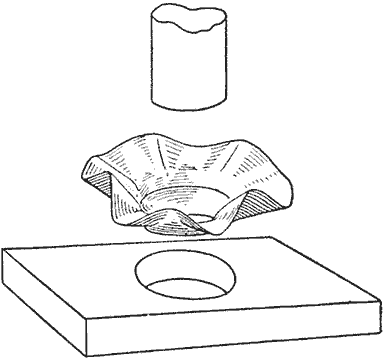

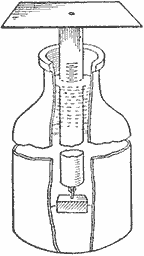

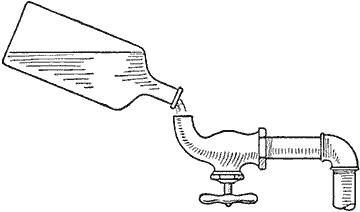

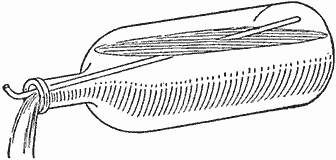

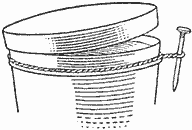

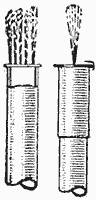

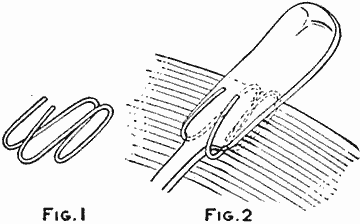

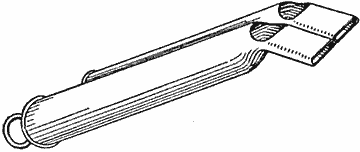

The device illustrated is for making embossed letters on show cards, signs, post cards, etc. A small bulb, such as used on cameras, is procured, also the spout from a small oilcan. The bulb is fastened to the spout as shown.

The material for use in the pencil is quick-drying mucilage thickened with flake white. If some special color is desired, tint the mixture with aniline. Fill the spout with the mixture and attach the bulb. Squeeze the bulb gently while forming the letters, then dust over with bronze, and allow to dry.

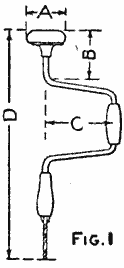

The Oilcan Spout Is the Reservoir to Hold the Paint, and the Bulb Produces the Air Pressure

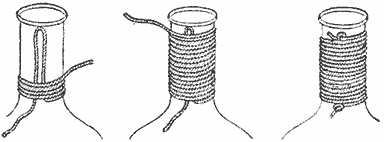

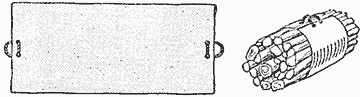

A good way to use up cord that collects about the house, is to make an endless dish or floor mop of it. Procure a thin board that will make a good length and wind the cord around it, then remove it from the board and tie the bunch together in the center.

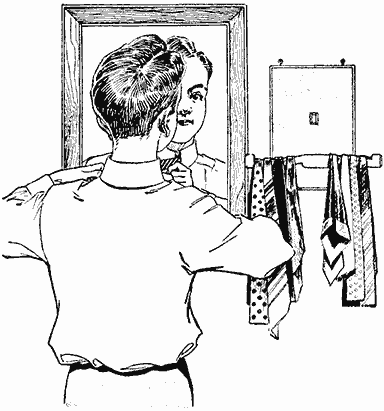

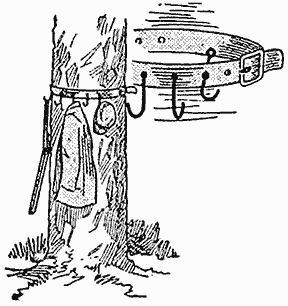

An unusual though simple tie rack can be made by supporting the tie bar in the center. By this arrangement the ties can be placed on it from either end, thus avoiding the tedious threading through, required on the ordinary rack supported at each end. Collars may be hung on a peg placed above the tie bar. The pieces can be glued together and a good finish given in the usual way. The rack can be hung up by two screw eyes. The material required consists of four pieces, dimensioned 5/8 by 5 by 8 in., 3/8 by 7/8 by 7-1/2 in., 3/8 by 5/8 by 3-1/8 in., and 7/8 by 7/8 by 2 in. respectively.—Contributed by Arthur C. Vener, Dallas, Texas.

Collar and Tie Rack with Open-End Hangers So That the Articles can be Slipped On Easily without being Passed behind a Bar as Is Usually the Case

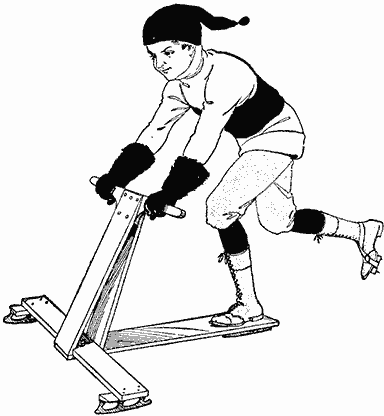

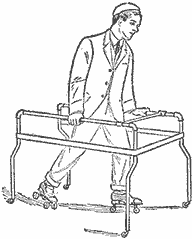

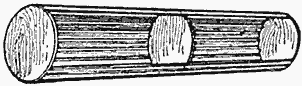

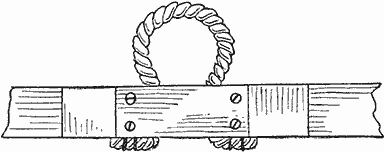

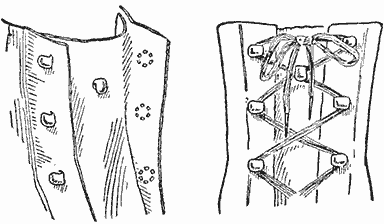

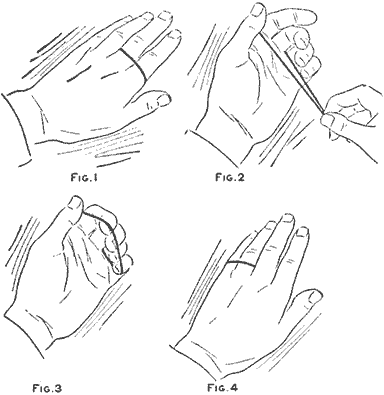

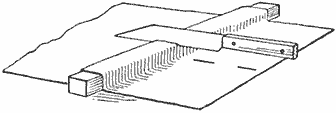

Skates that will take the place of the usual steel-runner kind and which will prevent spraining of the ankles, can be made of a few pieces of 1/2-in. boards.

Four runners are cut out, 2 in. wide at the back and 1-1/2 in. wide at the front, the length to be 2 in. longer than the shoe. The top edges of a pair of runners are then nailed to the under side of a board 4 in. wide, at its edges.

A piece of board, or block, 2 in. wide is fastened between the runners at the rear, and one 1 in. wide, in front. Two bolts are run through holes bored in the runners, one just back of the front board, or block, and the other in front of the rear one.

Four triangular pieces are fastened, one on each corner, so that the heel and toe of the shoe will fit between them, and, if desired, a crosspiece can be nailed in front of the heel. Straps are attached to the sides for attaching the skate to the shoe. Both skates are made alike.—Contributed by F. E. Kennar, Hennessey, Okla.

The best paint for paper roofing is asphaltum varnish.

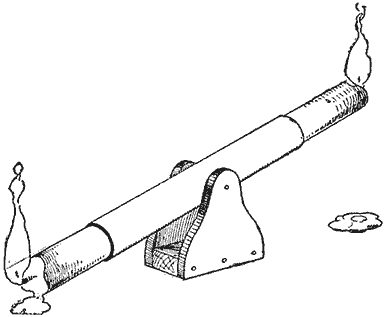

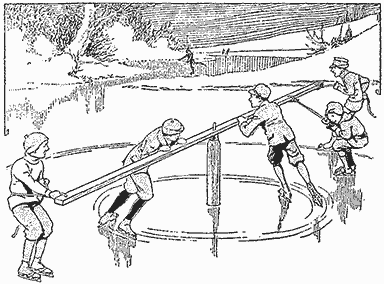

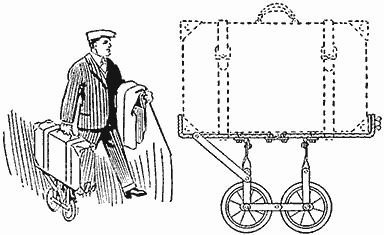

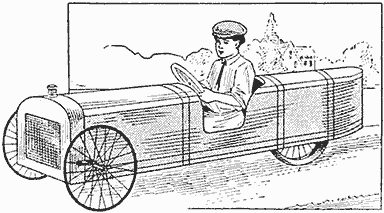

The enthusiastic pushmobilist need not put aside his hobby during the winter, as an amusement device for use on ice, which will surpass the very best pushmobile, can be easily made as shown in the illustration.

The Glider is Pushed over the Ice Similarly to a Pushmobile, and the Speed That can be Attained is Much Greater

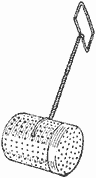

Similar to an ice yacht, only a great deal smaller, the ice glider will require three ordinary skates, two of which are fastened to the ends of the front crosspiece, so that their blades will stand at an angle of about 30 deg. with their edges outward. To get this angle, tapering blocks are fastened to the crosspiece ends, as shown. The skates are then fastened to these blocks.

The crosspiece is 30 in. long and about 8 in. wide. In the center of this piece an upright is constructed, 26 in. high. The edges of the front crosspiece are cut on a slant so that a piece nailed to its front and back edge will stand sloping toward the rear. A handle, 24 in. long, is fastened between the two uprights at the upper end. The rear part is made of a board, 8 in. wide and 40 in. long. The remaining skate is fastened in a perfectly straight position on the rear end. The skates may be attached with screws run through holes drilled in the top plates, or with straps. The front end of the rear board has a hole for a bolt to attach it to the center of the front crosspiece, so that the latter will turn to guide the glider.

A pusher is prepared from a block of wood, into which nails are driven with their ends projecting on the under side. The block is strapped to one shoe, as shown.

The glider is used in the same manner as a pushmobile.

The pusher can be made in another way by using sole leather instead of the block. Small slots are cut in the sides for the straps. Nails are driven [32] through the leather so that the points project. Either kind of pusher is especially adapted for the pushmobile to prevent wear on the shoe.

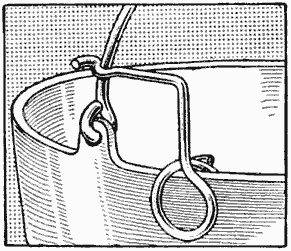

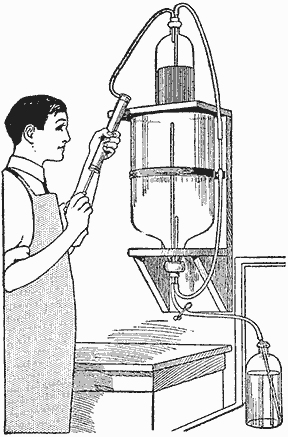

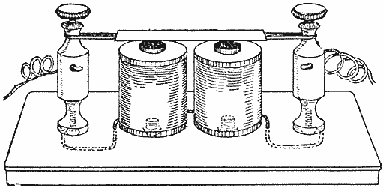

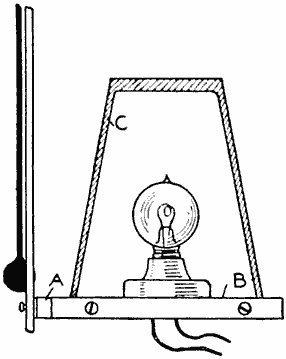

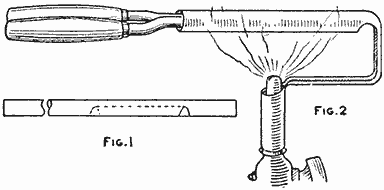

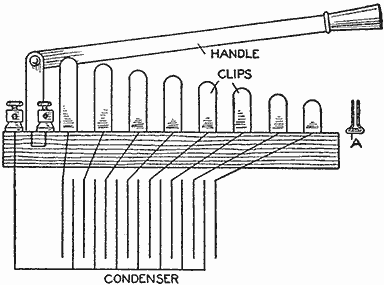

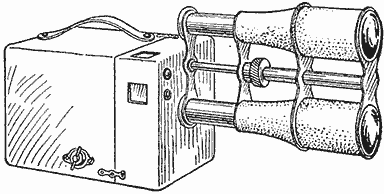

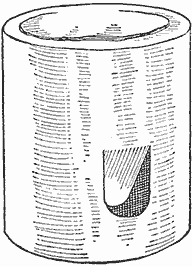

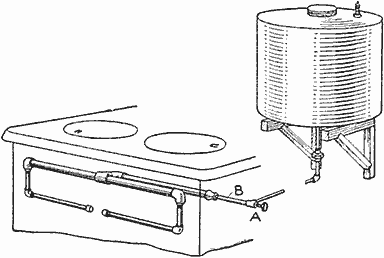

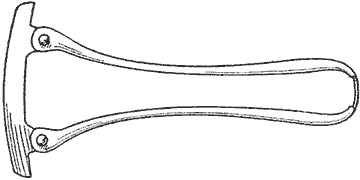

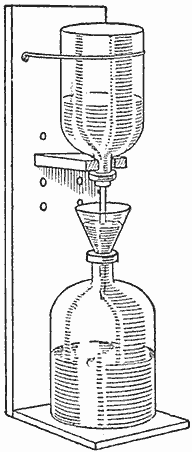

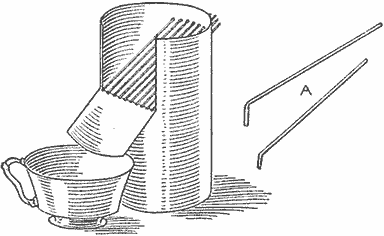

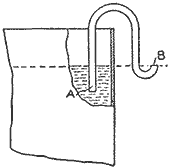

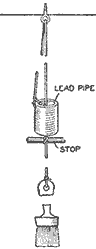

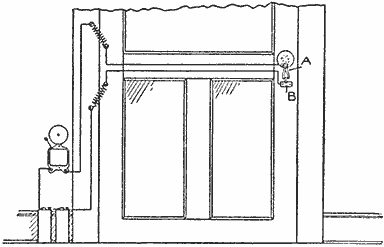

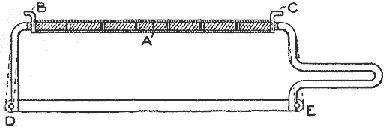

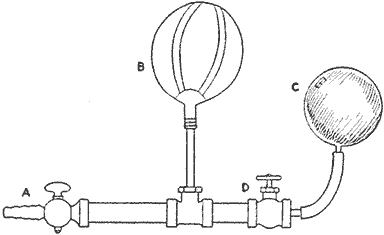

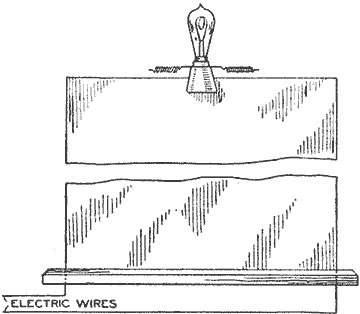

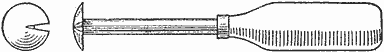

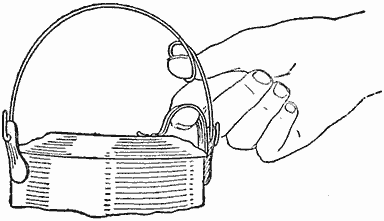

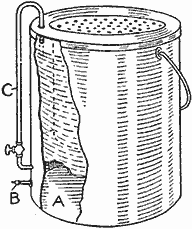

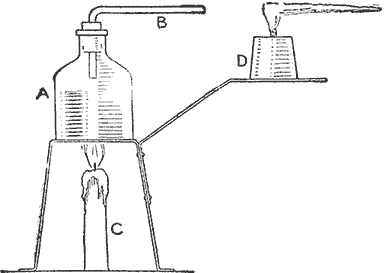

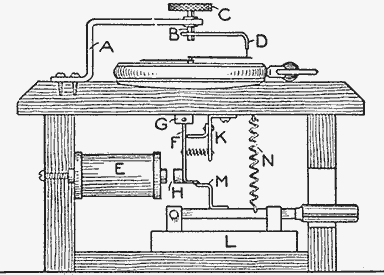

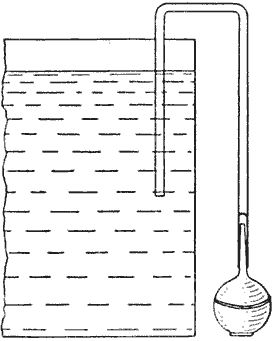

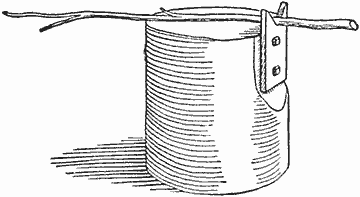

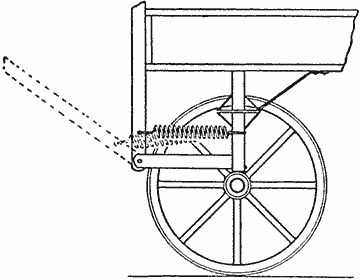

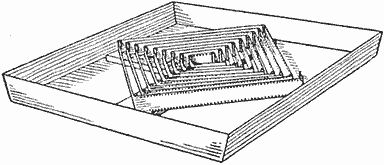

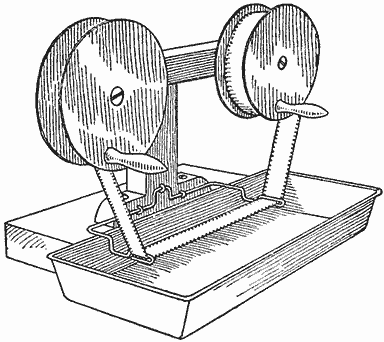

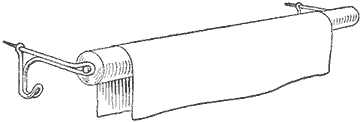

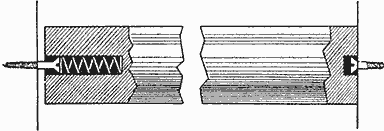

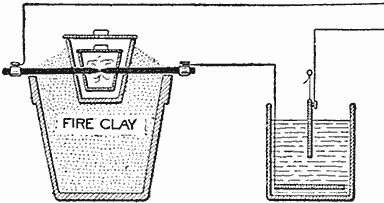

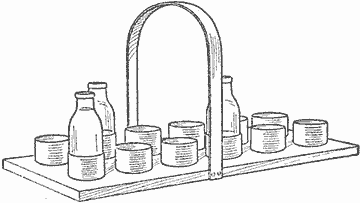

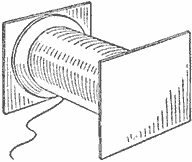

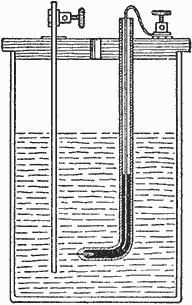

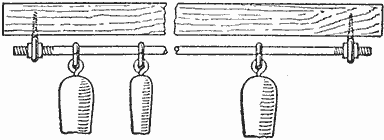

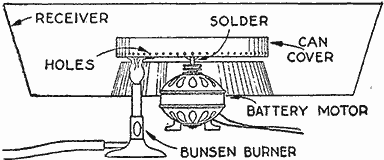

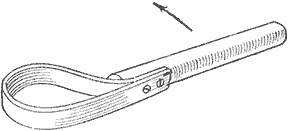

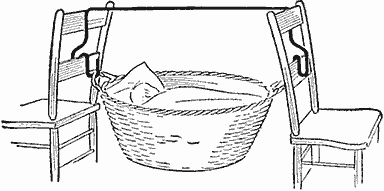

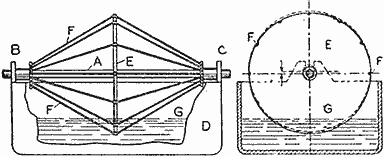

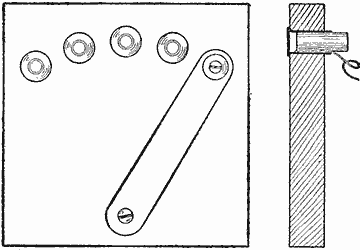

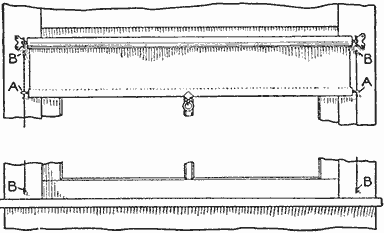

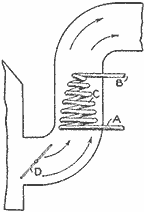

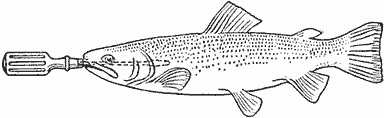

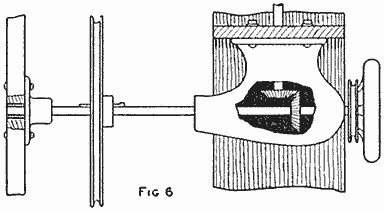

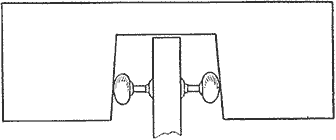

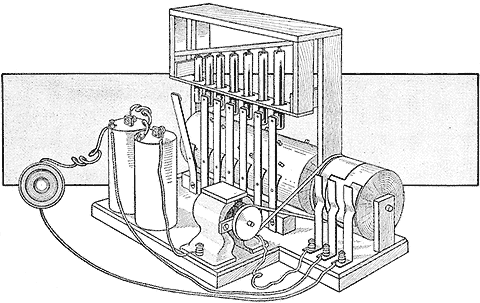

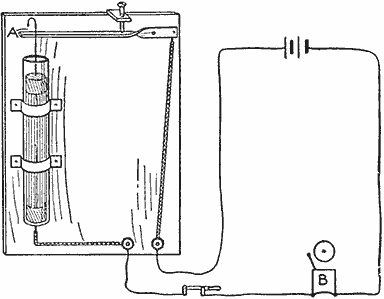

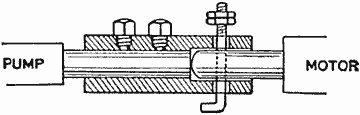

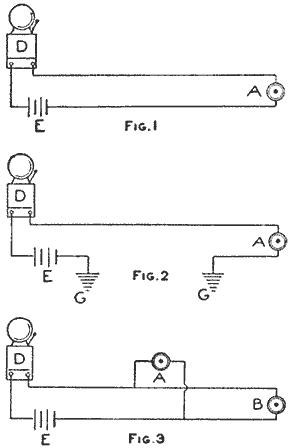

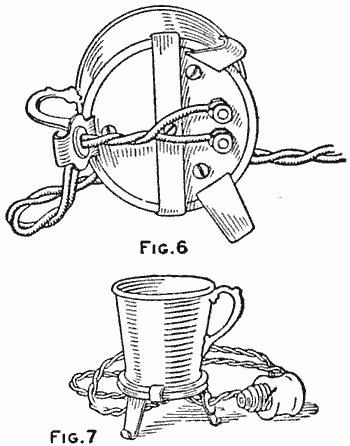

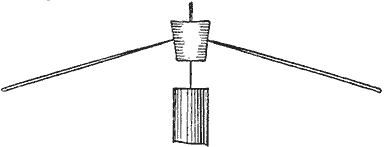

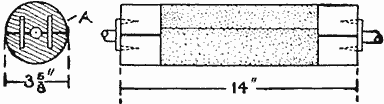

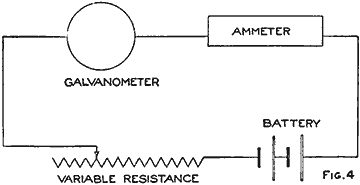

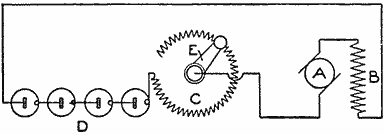

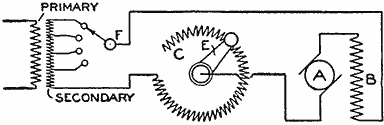

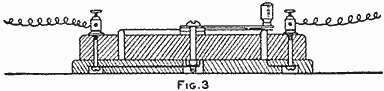

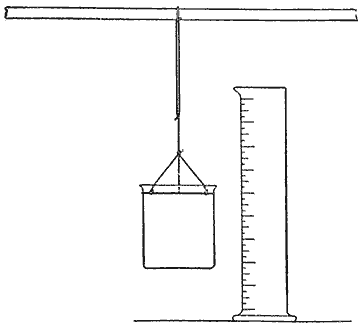

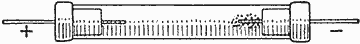

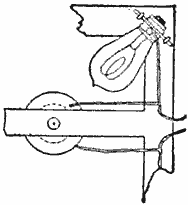

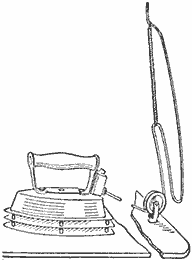

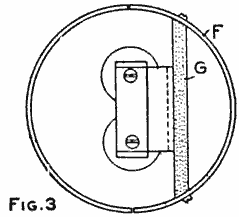

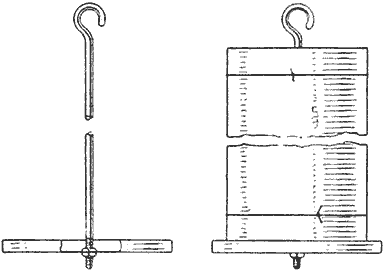

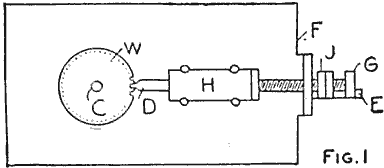

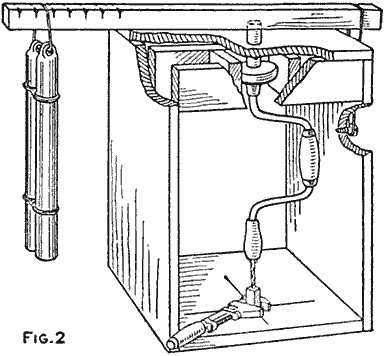

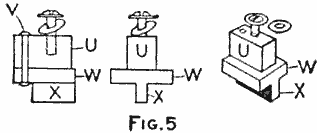

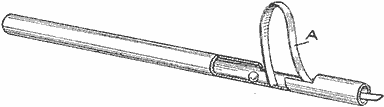

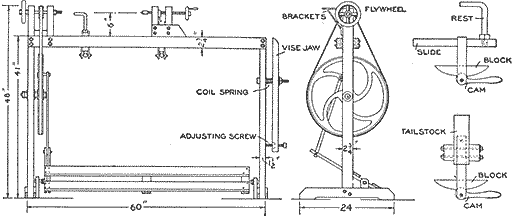

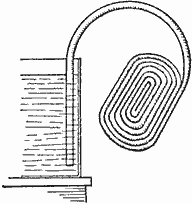

The ordinary prony brake is not, as a rule, sensitive enough to make an accurate test on small motors, such as those used in driving sewing machines, washing machines, vacuum cleaners, etc. The arrangement shown in the accompanying sketch has been used for this purpose with good results and was very accurate. The operation of the brake is exceedingly simple.

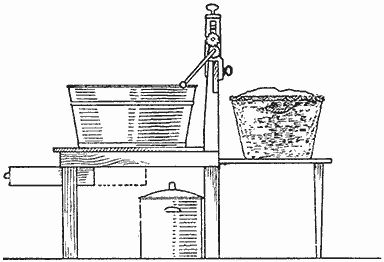

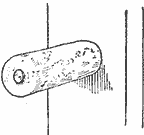

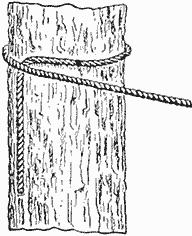

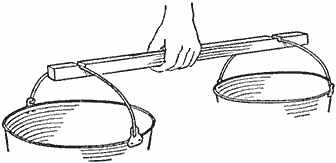

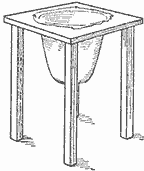

A pulley without a crown face is attached to the shaft of the motor, which is fastened to the top of a table or bench, and a balance mounted directly over the pulley. The support for the balance should be a narrow strip, which in turn is supported on two upright pieces, as shown. A light rope is put under the pulley, and the ends are looped over the platforms of the balance so that it does not interfere with the operation of the balance. The ends of the rope should be vertical and parallel. The piece upon which the balance rests is raised by inserting wedges, thus increasing the tension in the rope. The resulting friction of the rope on the pulley increases the load.

If the motor is running in the direction indicated by the arrow on the pulley, the tension in the left-hand end of the rope will be greater than in the right-hand end and a weight must be placed on the right-hand platform of the balance. When the weight W is adjusted so that the two pointers on the platforms are exactly opposite each other, the value of the weight W, in pounds, will represent the difference in pull, in pounds, between A and B. If the value of the weight W is known and also the speed of the machine when the weight was determined, the horsepower output can be computed by means of the following equation:

| 6.2832 × L × W × R.P.M. | |

| Hp. = | |

| 33,000 × 12 |

In this equation, L is the distance in inches from the center of the pulley to the center of the rope. Two ordinary spring balances may be substituted for the beam balance and the difference in their readings taken for the value W. For best results, the tension in the slack end of the rope should be as small as possible, and it may be necessary to wrap the rope one or more times completely around the pulley.