Title: Points of Humour, Part 2 (of 2)

Illustrator: George Cruikshank

Release date: December 26, 2013 [eBook #44518]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by David Widger from images provided by the Internet Archive

" Let me play the fool: With mirth and laughter let old wrinkles come; And let my liver rather heat with wine, Than my heart cool with mortifying groans. Why should a man, whose blood is warm within, Sit like his grandsire, cut in alabaster? Sleep when he wakes? and creep into the jaundice By being peevish?" Shakspeare

CONTENTS

POINT I. THE THREE HUNCHBACKS.

POINT II. A RELISH BEFORE DINNER.

POINT III. THE HAUNTED PHYSICIANS.

POINT IV. THE FOUR BLIND BEGGARS.

POINT IX. A NEW WAY TO PAY OLD DEBTS,

The best preface to this set of the Points of Humour is the former set, which, we are credibly informed, has favorably disposed the muscles of our readers for repeating a certain cackling sound, which is heart-food to our friend George Cruikshank.

One individual, for certain, has laughed over these Points, and he is a very worthy gentleman, who may be, discerned wedging his way through sundry piles of books in a remarkable part of Newgate-street, being opposite to the huge prison of that name. No one ever asked him after the sale of this little work, without observing an instantaneous distension of that feature of the face which is used for more purposes than merely grinning. It is to be devoutly hoped that this second set will not spoil his merriment, and that, as rather a coarse saying goes, "he will not be made to sing to another tune."

The author, collector, compiler, editor, writer, or whatever name the daily or weekly critics may give him, for they have given him all these, will, undoubtedly, be heartily sorry should this change take place, for he avows that since the publication of the Points, the face of the worthy gentleman alluded to has been illuminated by one unclouded sunshine, so much so, indeed, that to enter his shop has been a constant resource against melancholy during this gloomy weather. A face lighted up with good humour in a dark shop, is like a blaze of light in the middle of one of Rembrandt's murky pictures.

It will be seen that the compiler has taken a hint, or rather followed a hint of one of the critics upon this little book. He has resorted for part of his materials, to the author, who is the richest of all in the humour of situation. Fielding has been suggested; but though some things, excellent in their kind, might be found in him, yet it will be observed, on a more accurate consideration, that this admirable author is infinitely less adapted to the pencil of Cruikshank, than his successor in the walk of humour. Fielding is a master in the power of laying open all the springs which regulate the motion of that curious piece of mechanism, the human heart. He wrote with the inspiration of genius, and is true to nature in her minutest circumstances. He involuntarily and unconsciously catches the look, the word, the gesture, which would undoubtedly have manifested itself, and which is in itself a strong gleam of light upon the whole character. His dramatis personae are not, generally, very extraordinary people.—He dealt in that which is common to all. While, on the contrary, Smollett is rich in that which is uncommon and eccentric. His field is among oddities, hobby-horses, foibles, and singularities of all kinds, which he groups in the most extraordinary manner, and colours for the most striking effect. We read Fielding with a satisfied smile, but it is over the page of Smollett that the loud laugh is heard to break forth.—How much at home our artist is in the conception of Smollett may be seen in the following, plates.

It has been said that it is a pity Mr. Cruikshank should waste his talents upon ephemeral anecdotes, and not hand down his name by illustrating the works of our great Novelists. As well might it have been said to these great Novelists, "confine yourselves to commenting upon, or translating Cervantes or Le Sage." Genius consecrates and immortalizes all it touches.—If the tales or anecdotes be ephemeral, the plates will stamp them for a good old age. Hogarth did not paint his Rake's Progress in illustration of any immortal work, nor does it require a set of octavo volumes to remind posterity of his existence.

A similar excuse may apply to Cruikshank, who, generally, would chuse rather to exalt the humble, than endow the rich.

We have an observation to make respecting one of the plates, the last in the order. It will be seen that the costume of the characters there pourtrayed, is essentially different from that adopted by every illustrator of Shakspeare. This has not been done unadvisedly. The proper authorities have been in this, as in other cases, diligently consulted, and it has appeared that these artists, in their endeayour to discover the dress of our ancestors, have stopped short at the reign of Charles II., instead of penetrating to that of Henry V.

March, 1824.

At a short distance from Douai, there stood a castle on the bank of a river near a bridge. The master of this castle was hunchbacked. Nature had exhausted her ingenuity in the formation of his whimsical figure. In place of understanding, she had given him an immense head, which nevertheless was lost between his two shoulders: he had thick hair, a short neck, and a horrible visage.

Spite of his deformity, this bugbear bethought himself of falling in love with a beautiful young woman, the daughter of a poor but respectable burgess of Douai. He sought her in marriage, and as he was the richest person in the district, the poor girl was delivered up to him. After the nuptials he was as much an object of pity as she, for, being devoured by jealousy, he had no tranquillity night nor day, but went prying and rambling every where, and suffered no stranger to enter the castle.

One day during the Christmas festival, while standing sentinel at his gate, he was accosted by three humpbacked minstrels. They saluted him as a brother, as such asked him for refreshments, and at the same time, to establish the fraternity, they ostentatiously shouldered their humps at him. Contrary to expectation, he conducted them to his kitchen, gave them a capon with peas, and to each a piece of money over and above. Before their departure, however, he warned them never to return on pain of being thrown into the river. At this threat of the Chatelain the minstrels laughed heartily and took the road to the town, singing in full chorus, and dancing in a grotesque manner, in derision of their brother-hump of the castle. He, on his part, without paying farther attention, went to walk in the fields.

The lady, who saw her husband cross the bridge, and had heard the minstrels, called them back to amuse her. They had not been long returned to the castle, when her husband knocked at the gate, by which she and the minstrels were equally alarmed. Fortunately, the lady perceived in a neighbouring room three empty coffers. Into each of these she stuffed a minstrel, shut the covers, and then opened the gate to her husband. He had only come back to espy the conduct of his wife as usual, and, after a short stay, went out anew, at which you may believe his wife was not dissatisfied. She instantly ran to the coffers to release her prisoners, for night was approaching and her husband would not probably be long absent. But what was her dismay, when she found them all three suffocated!

Lamentation, however, was useless. The main object now was to get rid of the dead bodies, and she had not a moment to lose. She ran then to the gate, and seeing a peasant go by, she offered him a reward of thirty livres, and leading him into the castle, she took him to one of the coffers, and shewing him its contents, told him he must throw the dead body into the river: he asked for a sack, put the carcase into it, pitched it over the bridge, and then returned quite out of breath to claim the promised reward.

"I certainly intended to satisfy you," said the lady, "but you ought first to fulfil the condition of the bargain—you have agreed to rid me of the dead body, have you not? There, however, it is still." Saying this, she showed him the other coffer in which, the second humpbacked minstrel had expired. At this sight the clown was perfectly confounded—"how the devil! come back! a sorcerer!"—he then stuffed the body into the sack and threw it, like the other, over the bridge, taking care to put the head down and to observe that it sank.

Meanwhile the lady had again changed the position of the coffers, so that the third was now in the place which had been successively occupied by the two others. When the peasant returned, she shewed him the remaining dead body—"you are right, friend," said she, "he must be a magician, for there he is again." The rustic gnashed his teeth with rage. "What the devil! am I to do nothing but carry about this humpback?" He then lifted him up, with dreadful imprecations, and having tied a stone round the neck, threw him into the middle of the current, threatening, if he came out a third time, to despatch him with a cudgel.

The first object that presented itself to the clown, on his way back for his reward, was the hunchbacked master of the castle returning from his evening walk, and making towards the gate. At this sight the peasant could no longer restrain his fury. "Dog of a humpback, are you there again?" So saying, he sprung on the Chatelain, threw him over his shoulders, and hurled him headlong into the river after the minstrels.

"I'll venture a wager you have not seen him this last time," said the peasant, entering the room where the lady was seated. She answered, she had not. "You were not far from it," replied he: "the sorcerer was already at the gate, but I have taken care of him—be at your ease—he will not come back now."

The lady instantly comprehended what had occurred, and recompensed the peasant with much satisfaction.

When Charles Gustavus, King of Sweden, was besieging Prague, a boor, of a most extraordinary visage, desired admittance to his tent; and being allowed to enter, he offered, by way of amusement, to devour a large hog in his presence. The old general Konigsmark, who stood by the king's side, notwithstanding his bravery, had not got rid of the prejudices of his childhood, and hinted to his royal master, that the peasant ought to be burnt as a sorcerer. "Sir," said the fellow, irritated at the remark, "if your majesty will but make that old gentleman take off his sword and spurs, I will eat him before I begin the pig." General Konigsmark, who had, at the head of a body of Swedes, performed wonders against the Austrians, could not stand this proposal, especially as it was accompanied by a most hideous expansion of the jaws and mouth. Without uttering a word, the veteran turned pale and suddenly ran out of the tent, and did not think himself safe till he arrived at his quarters, where he remained above twenty-four hours, locked securely, before he got rid of the panic which had so strongly seized him.

A lover, whose mistress was dangerously ill, sought every where for a skilful physician in whom he could place confidence, and to whose care he might confide a life so dear to him. In the course of his search he met with a talisman, by the aid of which spirits might be rendered visible. The young man exchanged, for this talisman, half his possessions, and having secured his treasure, ran with it to the house of a famous physician. Flocking round the door he beheld a crowd of shades, the ghosts of those persons whom this physician had killed. Some old, some young; some the skeletons of fat old men; some gigantic frames of gaunt fellows; some little puling infants and squalling women; all joined in menaces and threats against the house of the physician—the den of their destroyer—who however peacefully marched through them with his cane to his chin, and a grave and solemn air.

The same vision presented itself, more or less, at the house of every physician of eminence. One at length was pointed out to him in a distant quarter of the city, at whose door he only perceived two little ghosts. "Behold," exclaimed he, with a joyful cry, "the good physician of whom I have been so long in search!" The doctor, astonished, asked him how he had been able to discover this? "Pardon me," said the afflicted lover complacently, "your ability and your reputation are well known to me."

"My reputation!" said the physician, "why I have been in Paris but eight days, and in that time I have had but two patients."

"Good God!" involuntarily exclaimed the young man, "and there they are!"

There was a man, whose name was Backbac; he was blind, and his evil destiny reduced him to beg from door to door. He had been so long accustomed to walk through the streets alone, that he wanted none to lead him: he had a custom to knock at people's doors, and not answer till they opened to him. One day he knocked thus, and the master of the house, who was alone, cried, "who is there?" Backbac made no answer, and knocked a second time: the master of the house asked again and again, "who is there?" but to no purpose, no one answered; upon which he came down, opened the door, and asked the man what he wanted? "Give me something, for Heaven's sake," said Backbac; "you seem to be blind," replied the master of the house; "yes, to my sorrow," answered Backbac. "Give me your hand," resumed the master of the house; he did so, thinking he was going to give him alms; but he only took him by the hand to lead him up to his chamber. Backbac thought he had been carrying him to dine with him, as many people had done. When they reached the chamber, the man let go his hand, and sitting down, asked him again what he wanted? "I have already told you," said Backbac, "that I want something for God's sake."

"Good blind man," replied the master of the house, "all that I can do for you is to wish that God may restore your sight."

"You might have told me that at the door," replied Backbac, "and not have given me the trouble to come up stairs."

"And why, fool," said the man of the house, "do not you answer at first, when people ask you who is there? why do you give any body the trouble to come and open the door when they speak to you?"—"What will you do with me then?" asked Backbac; "I tell you again," said the man of the house, "I have nothing to give you."

"Help me down the stairs then, as you brought me up."—"The stairs are before you," said the man of the house, "and you may go down by yourself if you will." The blind man attempted to descend, but missing a step, about the middle of the stairs, fell to the bottom and hurt his head and his back: he got up again with much difficulty, and went out, cursing the master of the house, who laughed at his fall.

As Backbac went out of the house, three blind men, his companions, were going by, knew him by his voice, and asked him what was the matter? He told them what had happened; and afterwards said, "I have eaten nothing to day; I conjure you to go along with me to my house, that I may take some of this money that we four have in common, to buy me something for supper." The blind men agreed, and they went home with him.

You must know that the master of the house where Backbac was so ill used, was a robber, and of a cunning and malicious disposition; he overheard from his window what Backbac had said to his companions, and came down and followed them to Backbac's house. The blind men being seated, Backbac said to them, "brothers, we must shut the door, and take care there be no stranger with us." At this the robber was much perplexed; but perceiving a rope hanging down from a beam, he caught hold of it, and hung by it while the blind men shut the door, and felt about the room with their sticks. When they had done, and had sat down again in their places, the robber left his rope, and seated himself softly by Backbac: who, thinking himself alone with his blind comrades, said to them, "brothers, since you have trusted me with the money, which we have been a long time gathering, I will shew you that I am not unworthy of the confidence you repose in me. The last time we reckoned, you know that we had ten thousand dirhems, and that we put them into ten bags: I will shew you that I have not touched one of them;" having so said, he put his hand among some old clothes, and taking out the bags one after another, gave them to his comrades, saying, "there they are: you may judge by their weight that they are whole, or you may tell them if you please." His comrades answered, "there was no need, they did not mistrust him;" so he opened one of the bags, and took out ten dirhems, and each of the other blind men did the like.

Backbac put the bags into their place again; after which, one of the blind men said to him, "there is no need to lay out any thing for supper, for I have collected as much victuals from good people as will serve us all;" at the same time he took out of his bag bread and cheese, and some fruit, and putting all upon the table, they began to eat. The robber, who sat at Backbac's right hand, picked out the best, and eat with them; but, whatever care he took to make no noise, Backbac heard his chaps going, and cried out immediately, "We are undone, there is a stranger among us!" Having so said, he stretched out his hand, and caught hold of the robber by the arm, cried out "thieves!" fell upon him, and struck him. The other blind men fell upon him in like manner; the robber defended himself as well as he could, and being young and vigorous, besides having the advantage of his eyes, he swung by the hanging rope, and gave furious kicks, sometimes to one, sometimes to another, and cried out "thieves!" louder than they did.

The neighbours came running at the noise, broke open the door, and had much ado to separate the combatants; but having at last succeeded, they asked the cause of their quarrel. Backbac, who still had hold of the robber, cried out, "gentlemen, this man I have hold of is a thief, and stole in with us on purpose to rob us of the little money we have." The thief, who shut his eyes as soon as the neighbours came, feigned himself blind, and exclaimed, "gentlemen, he is a liar. I swear to you by heavens, and by the life of the caliph, that I am their companion, and they, refuse to give me my just share. They have all four fallen upon me, and I demand justice." The neighbours would not interfere in their quarrel, but carried them all before the judge. When they came before the magistrate, the robber, without staying to be examined, cried out, still feigning to be blind, "sir, since you are deputed to administer justice by the caliph, whom God prosper, I declare to you that we are equally criminal, my four comrades and I; but we have all engaged, upon oath, to confess nothing except we be bastinadoed; so that if you would know our crime, you need only order us to be bastinadoed, and begin with me." Backbac would have spoken, but was not allowed to do so, and the robber was put under the bastinado.

The robber, being under the bastinado, had the courage to bear twenty or thirty blows: when, pretending to be overcome with pain, he first opened one eye, and then the other, and crying out for mercy, begged the judge would put a stop to the blows. The judge, perceiving that he looked upon him with his eyes open, was much surprised, and said to him, "rogue, what is the meaning of this miracle?"

"Sir," replied the robber, "I will discover to you an important secret, if you will pardon me, and give me, as a pledge that you will keep your word, the seal-ring which you have on your finger." The judge consented, gave him his ring, and promised him pardon. "Under this promise," continued the robber, "I must confess to you, sir, that I and my four comrades do all see very well. We feigned ourselves to be blind, that we might freely enter people's houses, and women's apartments, where we abuse their weakness. I must farther confess to you, that by this trick we have gained together ten thousand dirhems: this day I demanded of my partners two thousand that belonged to my share, but they refused, because I told them I would leave them, and they were afraid I should accuse them. Upon my pressing still to have my share, they fell upon me; for which I appeal to those people who brought us before you. I expect from your justice, sir, that you will make them deliver me the two thousand dirhems which are my due; and if you have a mind that my comrades should confess the truth, you must order them three times as many blows as I have had, and you will find they will open their eyes as well as I have done." Backbac, and the other three blind men, would have cleared themselves of this horrid charge, but the judge would not hear them; "villains," said he, "do you feign yourselves blind then, and, under that pretext of moving their compassion, cheat people, and commit such crimes?"

"He is an impostor," cried Backbac, "and we take God to witness that none of us can see." All that Backbac could say was in vain, his comrades and he received each of them two hundred blows. The judge expected them to open their eyes, and ascribed to their obstinacy what really they could not do; all the while the robber said to the blind men, "Poor fools that you are, open your eyes, and do not suffer yourselves to be beaten to death." Then addressing himself to the judge, said, "I perceive, sir, that they will be maliciously obstinate to the last, and will never open their eyes. They wish certainly to avoid the shame of reading their own condemnation in the face of every one that looks upon them; it were better, if you think fit, to pardon them, and to send some person along with me for the ten thousand dirhems they have hidden."

The judge consented to give the robber two thousand dirhems, and kept the rest himself; and as for Backbac and his three companions, he thought he shewed them pity by sentencing them only to be banished.

Among those who frequented the pump-room at Bath, was an old officer, whose temper, naturally impatient, was, by repeated attacks of the gout, which had almost deprived him of the use of his limbs, sublimated into a remarkable degree of virulence and perverseness: he imputed the inveteracy of his distemper to the mal-practice of a surgeon who had administered to him, while he laboured under the consequences of an unfortunate amour; and this supposition had inspired him with an insurmountable antipathy to all the professors of the medical art, which was more and more confirmed by the information of a friend at London, who had told him, that it was a common practice among the physicians at Bath to dissuade their patients from drinking the water, that the cure, and in consequence their attendance, might be longer protracted.

Thus prepossessed, he had come to Bath, and, conformable to a few general instructions he had received, used the waters without any farther direction, taking all occasions of manifesting his hatred and contempt of the sons of Æsculapius, both by speech and gesticulations, and even by pursuing a regimen quite contrary to that which he knew they prescribed to others who seemed to be exactly in his condition. But he did not find his account in this method, how successful soever it may have been in other cases. His complaints, instead of vanishing, were every day more and more enraged; and at length he was confined to his bed, where he lay blaspheming from morn to night, and from night to morn, though still more determined than ever to adhere to his former maxims.

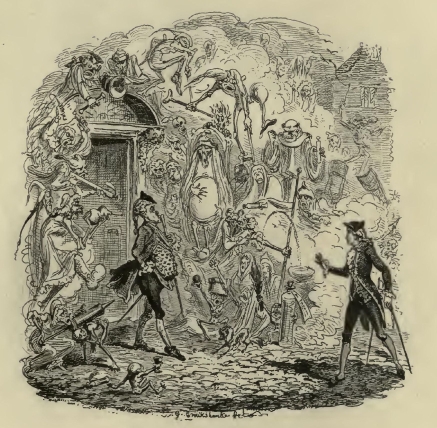

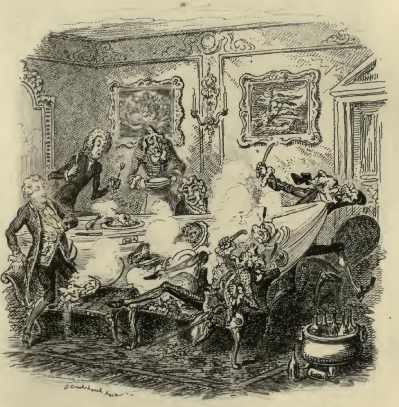

In the midst of his torture, which was become the common joke of the town, being circulated through the industry of the physicians, who triumphed in his disaster, Peregrine, by means of Mr. Pipes, employed a country fellow, who had come to market, to run with great haste, early one morning, to the lodgings of all the doctors in town, and desire them to attend the colonel with all imaginable despatch. In consequence of this summons, the whole faculty put themselves in motion; and three of the foremost arriving at the same instant of time, far from complimenting one another with the door, each separately essayed to enter, and the whole triumvirate stuck in the passage; while they remained thus wedged together, they descried two of their brethren posting towards the same goal, with all the speed that God had enabled them to exert; upon which they came to a parley, and agreed to stand by one another. This covenant being made, they disentangled themselves, and, inquiring about the patient, were told by the servant that he had just fallen asleep.

Having received this intelligence, they took possession of his antichamber, and shut the door, while the rest of the tribe posted themselves on the outside as they arrived; so that the whole passage was filled, from the top of the stair-case to the street-door; and the people of the house, together with the colonel's servant, struck dumb with astonishment. The three leaders of this learned gang had no sooner made their lodgement good, than they began to consult about the patient's malady, which every one of them pretended to have considered with great care and assiduity. The first who gave his opinion said, the distemper was an obstinate arthritis; the second affirmed, that it was no other than a confirmed lues; and the third swore it was an inveterate scurvy. This diversity of opinions was supported by a variety of quotations from medical authors, ancient as well as modern; but these were not of sufficient authority, or at least not explicit enough, to decide the dispute; for there are many schisms in medicine, as well as in religion, and each set can quote the fathers in support of the tenets they profess. In short, the contention rose to such a pitch of clamour, as not only alarmed the brethren on the stair, but also awaked the patient from the first nap he had enjoyed in the space of ten whole days. Had it been simply waking, he would have been obliged to them for the noise that disturbed him; for, in that case, he would have been relieved from the tortures of hell fire, to which, in his dream, he fancied himself exposed: but this dreadful vision had been the result of that impression which was made upon his brain by the intolerable anguish of his joints; so that when he waked, the pain, instead of being allayed, was rather aggravated, by a great acuteness of sensation; and the confused vociferation in the next room invading his ears at the same time, he began to think his dream was realized, and, in the pangs of despair, applied himself to a bell that stood by his bedside, which he rung with great violence and perseverance.

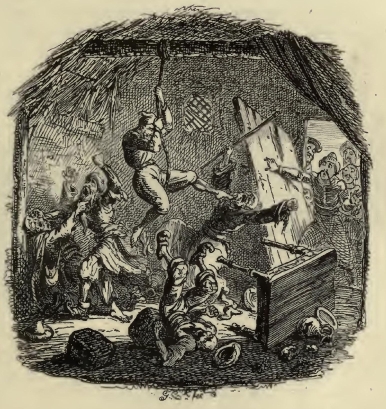

This alarm put an immediate stop to the disputation of the three doctors, who, upon this notice of his being awake, rushed into his chamber without ceremony; and two of them seizing his arms, the third made the like application to one of his temples. Before the patient could recollect himself from the amazement which had laid hold on him at this unexpected irruption, the room was filled by the rest of the faculty, who followed the servant that entered in obedience to his master's call; and the bed was in a moment surrounded by these gaunt ministers of death. The colonel seeing himself beset with such an assemblage of solemn visages and figures, which he had always considered with the utmost detestation and abhorrence, was incensed to a most inexpressible degree of indignation; and so inspirited by his rage, that, though his tongue denied its office, his other limbs performed their functions: he disengaged himself from the triumvirate, who had taken possession of his body, sprung out of bed with incredible agility, and, seizing one of his crutches, applied it so effectually to one of the three, just as he stooped to examine the patient's water, that his tye-periwig dropped into the pot, while he himself fell motionless on the floor.

This significant explanation disconcerted the whole fraternity; every man turned his face, as if it were by instinct, towards the door; and the retreat of the community being obstructed by the efforts of individuals, confusion and tumultuous uproar ensued: for the colonel, far from limiting his prowess to the first exploit, handled his weapon with astonishing vigour and dexterity, without respect of persons; so that few or none of them had escaped without marks of his displeasure, when his spirits failed, and he sunk down again quite exhausted on his bed.

Favoured by this respite, the discomfited faculty collected their hats and wigs, which had fallen off in the fray; and perceiving the assailant too much enfeebled to renew the attack, set up their throats altogether, and loudly threatened to prosecute him severely for such an outrageous assault.

By this time the landlord had interposed; and inquiring into the cause of the disturbance, was informed of what had happened by the complainants, who, at the same time, giving him to understand that they had been severally summoned to attend the colonel that morning, he assured them, that they had been imposed upon by some wag, for his lodger had never dreamed of consulting any one of their profession.

Thunderstruck at this declaration, the general clamour instantaneously ceased; and each, in particular, at once comprehending the nature of the joke, they sneaked silently off with the loss they had sustained, in unutterable shame and mortification, while Peregrine and his friend, who took care to be passing that way by accident, made a full stop at sight of such an extraordinary efflux, and enjoyed the countenance and condition of every one as he appeared; nay, even made up to some of those who seemed most affected with their situation, and mischievously tormented them with questions touching this unusual congregation; then, in consequence of the information they received from the landlord and the colonel's valet, subjected the sufferers to the ridicule of all the company in town.

As it would have been impossible for the authors of the farce to keep themselves concealed from the indefatigable inquiries of the physicians, they made no secret of their having directed the whole; though they took care to own it in such an ambiguous manner as afforded no handle of prosecution.

Peregrine, by his insinuating behaviour, acquired the full confidence of the doctor, who invited him to an entertainment, which he intended to prepare in the manner of the ancients. Pickle, struck with this idea, eagerly embraced the proposal, which he honoured with many encomiums, as a plan in all respects worthy of his genius and apprehension; and the day was appointed at some distance of time, that the treater might have leisure to compose certain pickles and confections, which were not to be found among the culinary preparations of these degenerate days.

With a view of rendering the physician's taste more conspicuous, and extracting from it more diversion, Peregrine proposed that some foreigners should partake of the banquet; and the task being left to his care and discretion, he actually bespoke the company of a French marquis, an Italian count, and a German baron, whom he knew to be most egregious coxcombs, and therefore more likely to enhance the joy of the entertainment.

Accordingly, the hour being arrived, he conducted them to the hotel where the physician lodged, after having regaled their expectations with an elegant meal in the genuine old Roman taste; and they were received by Mr. Pallet, who did the honours of the house, while his friend superintended the cook below. By this communicative painter, the guests understood that the doctor had met with numerous difficulties in the execution of his design; that no fewer than five cooks had been dismissed, because they could not prevail upon their own consciences to obey his directions in things that were contrary to the present practice of their art; and that although he had at last engaged a person, by an extraordinary premium, to comply with his orders, the fellow was so astonished, mortified, and incensed, at the commands he had received, that his hair stood on end, and he begged on his knees to be released from the agreement he had made; but finding that his employer insisted upon the performance of his contract, and threatened to introduce him to the commissaire, if he should flinch from the bargain, he had, in the discharge of his office, wept, sung, cursed, and capered, for two hours without intermission.

While the company listened to this odd information, by which they were prepossessed with strange notions of the dinner, their ears were invaded by a piteous voice, that exclaimed in French, "For the love of God! dear sir! for the passion of Jesus Christ! spare me the mortification of the honey and oil!" Their ears still vibrated with the sound, when the doctor entering, was by Peregrine made acquainted with the strangers, to whom he, in the transports of his wrath, could not help complaining of the want of complaisance he had found in the Parisian vulgar, by which his plan had been almost entirely ruined and set aside. The French marquis, who thought the honour of his nation was concerned at this declaration, professed his sorrow for what had happened, so contrary to the established character of the people, and undertook to see the delinquents severely punished, provided he could be informed of their names or places of abode. The mutual compliments that passed on this occasion were scarce finished, when a servant coming into the room, announced dinner; and the entertainer led the way into another apartment, where they found a long table, or rather two boards joined together, and furnished with a variety of dishes, the steams of which had such evident effect upon the nerves of the company, that the marquis made frightful grimaces, under pretence of taking snuff; the Italian's eyes watered, the German's visage underwent several distortions of feature; our hero found means to exclude the odour from his sense of smelling, by breathing only through his mouth; and the poor painter, running into another room, plugged his nostrils with, tobacco. The doctor himself, who was the only person then present whose organs were not discomposed, pointing to a couple of couches placed on each side of the table, told his guests that he was sorry he could not procure the exact triclinia of the ancients, which were somewhat different from these conveniences, and desired they would have the goodness to repose themselves without ceremony, each in his respective couchette, while he and his friend Mr. Pallet would place themselves upright at the ends, that they might have the pleasure of serving those that lay along. This disposition, of which the strangers had no previous idea, disconcerted and perplexed them in a most ridiculous manner; the marquis and baron stood bowing to each other, on pretence of disputing the lower seat, but, in reality, with a view of profiting by the example of each other: for neither of them understood the manner in which they were to loll; and Peregrine, who enjoyed their confusion, handed the count to the other side, where, with the most mischievous politeness, he insisted upon his taking possession of the upper place.

In this disagreeable and ludicrous suspense, they continued acting a pantomime of gesticulations, until the doctor earnestly entreated them to wave all compliment and form, lest the dinner should be spoiled before the ceremonial could be adjusted. Thus conjured, Peregrine took the lower couch on the left-hand side, laying himself gently down, with his face towards the table. The marquis, in imitation of this pattern, (though he would have much rather fasted three days than run the risk of discomposing his dress by such an attitude,) stretched himself, upon the opposite place, reclining upon his elbow in a most painful and awkward situation, with his head raised above the end of the couch, that the economy of his hair might not suffer by the projection of his body. The Italian, being a thin limber creature, planted himself next to Pickle, without sustaining any misfortune, but that of his stocking being tom by a ragged nail of the seat, as he raised his legs on a level with the rest of his limbs. But the baron, who was neither so wieldy nor supple in his joints as his companions, flounced himself down with such precipitation, that his feet, suddenly tilting up, came in furious contact with the head of the marquis, and demolished every curl in a twinkling, while his own skull, at the same instant, descended upon the side of his couch with such violence, that his periwig was struck off, and the whole room filled with pulvilio.

The drollery of distress that attended this disaster entirely vanquished the affected gravity of our young gentleman, who was obliged to suppress his laughter by cramming his handkerchief into his mouth; for the bareheaded German asked pardon with such ridiculous confusion, and the marquis admitted his apology with such rueful complaisance, as were sufficient to awaken the mirth of a quietist.

This misfortune being repaired, as well as the circumstances of the occasion would permit, and every one settled according to the arrangement already described, the doctor graciously undertook to give some account of the dishes as they occurred, that the company might be directed in their choice; and, with an air of infinite satisfaction, thus began:—"This here, gentlemen, is a boiled goose, served up in a sauce composed of pepper, lovage, coriander, mint, rue, anchovies, and oil. I wish for your sakes, gentlemen, it was one of the geese of Ferrara, so much celebrated among the ancients for the magnitude of their livers, one of which is said to have weighed upwards of two pounds; with this food, exquisite as it was, did the tyrant Heliogabalus regale his hounds. But I beg pardon, I had almost forgot the soup, which I hear is so necessary an article at all tables in France. At each end there are dishes of the salacacabia of the Romans; one is made of parsley, pennyroyal, cheese, pine-tops, honey, vinegar, brine, eggs, cucumbers, onions, and hen livers; the other is much the same as the soup-maigre of this country. Then there is a loin of boiled veal with fennel and carraway seed, on a pottage composed of pickle, oil, honey, and flour, and a curious hashis of the lights, liver, and blood of a hare, together with a dish of roasted pigeons. Monsieur le Baron, shall I help you to a plate of this soup?" The German, who did not at all disapprove of the ingredients, assented to the proposal, and seemed to relish the composition; while the marquis, being asked by the painter which of the sillykickabys he chose, was, in consequence of his desire, accommodated with a portion of the soup-maigre; and the count, in lieu of spoon meat, of which he said he was no great admirer, supplied himself with a pigeon, therein conforming to the choice of our young gentleman, whose example he determined to follow through the whole course of the entertainment.

The Frenchman, having swallowed the first spoonful, made a full pause, his throat swelled as if an egg had stuck in his gullet, his eyes rolled, and his mouth underwent a series of involuntary contractions and dilations. Pallet, who looked steadfastly at this connoisseur, with a view of consulting his taste, before he himself would venture upon the soup, began to be disturbed at these emotions, and observed, with some concern, that the poor gentleman seemed to be going into a fit; when Peregrine assured him, that these were symptoms of ecstacy, and, for further confirmation, asked the marquis how he found the soup. It was with infinite difficulty that his complaisance could so far master his disgust, as to enable him to answer, "altogether excellent, upon my honour!" and the painter, being certified of his approbation, lifted the spoon to his mouth without scruple; but far from justifying the eulogium of his taster, when this precious composition diffused itself upon his palate; he seemed to be deprived of all sense and motion, and sat like the leaden statue of some river god, with the liquor flowing out at both sides of his mouth.

The doctor, alarmed at this indecent phenomenon, earnestly inquired into the cause of it; and when Pallet recovered his recollection, and swore that he would rather swallow porridge made of burning brimstone than such an infernal mess as that which he had tasted, the physician, in his own vindication, assured the company, that, except the usual ingredients, he had mixed nothing in the soup but some sal ammoniac, instead of the ancient nitrum, which could not now be procured; and appealed to the marquis, whether such a succedaneum was not an improvement on the whole. The unfortunate petit maître, driven to the extremity of his condescension, acknowledged it to be a masterly refinement; and deeming himself obliged, in point of honour, to evince his sentiments by his practice, forced a few more mouthfuls of this disagreeable potion down his throat, till his stomach was so much offended, that he was compelled to start up of a sudden; and, in the hurry of his elevation, overturned his plate into the bosom of the baron. The emergency of his occasions would not permit him to stay and make apologies for this abrupt behaviour; so that he flew into another apartment, where Pickle found him puking, and crossing himself with great devotion; and a chair, at his desire, being brought to the door, he slipped into it more dead than alive, conjuring his friend Pickle to make his peace with the company, and in particular excuse him to the baron, on account of the violent fit of illness with which he had been seized. It was not without reason that he employed a mediator; for when our hero returned to the dining-room, the German had got up, and was under the hands of his own lacquey, who wiped the grease from a rich embroidered waistcoat, while he, almost frantic with his misfortune, stamped upon the ground, and in High Dutch cursed the unlucky banquet, and the impertinent entertainer, who all this time, with great deliberation, consoled him for the disaster, by assuring him, that the damage might be repaired with some oil of turpentine and a hot iron. Peregrine, who could scarce refrain from laughing in his face, appeased his indignation, by telling him how much the whole company, and especially the marquis, was mortified at the accident; and the unhappy salacacabia being removed, the places were filled with two pyes, one of dormice, liquored with syrup of white poppies, which the doctor had substituted in the room of roasted poppy-seed, formerly eaten with honey, as a dessert; and the other composed of a hock of pork baked in honey.

Pallet, hearing the first of these dishes described, lifted up his hands and eyes, and, with signs of loathing and amazement, pronounced, "A pye made of dormice and syrup of poppies! Lord in heaven! what beastly fellows those Romans were!" His friend checked him for his irreverent exclamation with a severe look, and recommended the veal, of which he himself cheerfully ate, with such encomiums to the company, that the baron resolved to imitate his example, after having called for abumper of Burgundy, which the physician, for his sake, wished to have been the true wine of Falernum. The painter, seeing nothing else upon the table which he would venture to touch, made a merit of necessity, and had recourse to the veal also; although he could not help saying, that he would not give one slice of the roast beef of Old England for all the dainties of a Roman emperor's table. But all the doctor's invitations and assurances could not prevail upon his guests to honour the hashis and the goose; and that course was succeeded by another, in which he told them there were divers of those dishes, which, among the ancients, had obtained the appellation of politeles, or magnificent. "That which smokes in the middle," said he, "is a sow's stomach, filled with a composition of minced pork, hog's brains, eggs, pepper, cloves, garlic, aniseed, rue, ginger, oil, wine, and pickle. On the right-hand side are the teats and belly of a sow, just farrowed, fried with sweet wine, oil, flour, lovage, and pepper. On the left is a fricassee of snails, fed, or rather purged, with milk. At that end next Mr. Pallet, are fritters of pompions, lovage, origanum, and oil; and here are a couple of pullets. roasted and stuffed in the manner of Apicius."

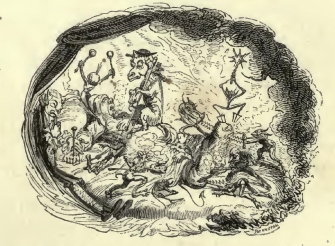

The painter, who had by wry faces testified his abhorrence of the sow's stomach, which he compared to a bagpipe, and the snails which had undergone purgation, no sooner heard him mention the roasted pullets, than he eagerly solicited a wing of the fowl; upon which the doctor desired he would take the trouble of cutting them up, and accordingly sent them round, while Mr. Pallet tucked the table-cloth under his chin, and brandished his knife, and, fork with singular address; but scarce were they set down before him, when the tears ran down his cheeks, and he called aloud, in manifest disorder,—"Zounds! this is the essence, of a whole bed of garlic!" That he might not, however, disappoint or disgrace the entertainer, he applied his instruments to one of the birds; and, when he opened up the cavity, was assaulted by such an irruption of intolerable smells, that, without staying to disengage himself from the cloth, he sprung away, with an exclamation of "Lord Jesus!" and involved the whole table in havoc, ruin, and confusion.

Before Pickle could accomplish his escape, he was sauced with a syrup of the dormice pye, which went to-pieces in the general wreck: and as for the Italian count, he was overwhelmed by the sow's stomach, which, bursting in the fall, discharged its contents upon his leg and thigh, and scalded him so miserably, that he shrieked with anguish, and grinned with a most ghastly and horrible aspect.

The baron, who sat secure without the vortex of this tumult, was not at all displeased at seeing his companions involved in such a calamity as that which he had already shared; but the doctor was confounded with shame and vexation. After having prescribed an application of oil to the count's leg, he expressed his sorrow for the misadventure, which he openly ascribed to want of taste and prudence in the painter, who did not think proper to return, and make an apology in person; and protested that there was nothing in the fowls which could give offence to a sensible nose, the stuffing being a mixture of pepper, loyage, and assafotida, and the sauce consisting of wine and herring-pickle, which he had used instead of the celebrated garum of the Romans; that famous pickle having been prepared sometimes of the scombri, which were a sort of tunny fish, and sometimes of the silurus, or shad fish; nay, he observed, that there was a third kind called garum homation, made of the guts, gills, and blood of the thynnus.

The physician, finding it would be impracticable to re-establish the order of the banquet, by presenting again the dishes which had been discomposed, ordered every thing to be removed, a clean cloth to be laid, and the dessert to be brought in.

Meanwhile, he regretted his incapacity to give them a specimen of the alieus, or fish-meals of the ancients, such as the jus diabaton, the conger-eel, which, in Galen's opinion, is hard of digestion; the cornuta, or gurnard, described by Pliny in his Natural History, who says, the horns of many were a foot and a half in length; the mullet and lamprey, that were in the highest estimation of old, of which last Julius Cæsar borrowed six thousand for one triumphal supper. He observed, that the manner of dressing them was described by Horace, in the account he gives of the entertainment to which Maecenas was invited by the epicure Nasiedenus,

Affertur squillas inter muraena natantes, &c.

and told them, that they were commonly eaten with the thus Syriacum, a certain anodyne and astringent seed, which qualified the purgative nature of the fish. Finally, this learned physician gave them to understand, that, though this was reckoned a luxurious dish in the zenith of the Roman taste, it was by no means comparable, in point of expense, to some preparations in vogue about the time of that absurd voluptuary Heliogabalus, who ordered the brains of six hundred ostriches to be compounded in one mess.

By this time the dessert appeared, and the company were not a little rejoiced to see plain olives in salt and water: but what the master of the feast valued himself upon was a sort of jelly, which he affirmed to be preferable to the hypotrimma of Hesychius, being a mixture of vinegar, pickle, and honey, boiled to a proper consistence, and candied assafotida, which he asserted, in contradiction to Aumelbergius and Lister, was no other than the laser Syriacum, so precious as to be sold among the ancients to the weight of a silver penny. The gentlemen took his word for the excellency of this gum, but contented themselves with the olives, which gave such an agreeable relish to the wine, that they seemed very well disposed to console themselves for the disgraces they had endured; and Pickle, unwilling to lose the least circumstance of entertainment that could be enjoyed in their company, went in quest of the painter, who remained in his penitentials in another apartment, and could not be persuaded to re-enter the banqueting-room, until Peregrine undertook to procure his pardon from those whom he had injured. Having assured him of this indulgence, our young gentleman led him in like a criminal, bowing on all hands with an air of humility and contrition; and particularly addressing himself to the count, to whom he swore in English, as God was his Saviour, he had no intent to affront man, woman, or child; but was fain to make the best of his way, that he might not give the honourable company cause of offence, by obeying the dictates of nature in their presence.

When Pickle interpreted this apology to the Italian, Pallet was forgiven in very polite terms, and even received into favour by his friend the doctor, in consequence of our hero's intercession; so that all the guests forgot their chagrin, and paid their respects so piously to the bottle, that, in a short time, the champaign produced very evident effects in the behaviour of all present.

The painter betook himself to the house of the Flemish Raphael, and the rest of the company went back to their lodgings; where Peregrine, taking the advantage of being alone with the physician, recapitulated all the affronts he had sustained from the painter's petulance, aggravating every circumstance of the disgrace, and advising him, in the capacity of a friend, to take care of his honour, which could not fail to suffer in the opinion of the world, if he allowed himself to be insulted with impunity by one so much his inferior in every degree of consideration.

The physician assured him, that Pallet had hitherto escaped chastisement, by being deemed an object unworthy his resentment, and in consideration of the wretch's family, for which his compassion was interested; but that repeated injuries would inflame the most benevolent disposition; and although he could find no precedent of duelling among the Greeks and Romans, whom he considered as the patterns of demeanour, Pallet should no longer avail himself of his veneration for the ancients, but be punished for the very, next offence he should commit.

Having thus spirited up the doctor to a resolution from which he could not decently swerve, our adventurer acted the incendiary with the other party also; giving him to understand, that the physician treated his character with such contempt, and behaved to him with such insolence, as no gentleman ought to bear: that, for his own part, he was every day put out of countenance by their mutual animosity, which appeared in nothing but vulgar expressions, more becoming shoe-boys and oyster-women than men of honour and education; and therefore he should be obliged, contrary to his inclination, to break off all correspondence with them both, if they would not fall upon some method to retrieve the dignity of their characters.

These representations would have had little effect upon the timidity of the painter, who was likewise too much of a Grecian to approve of single combat, in any other way than that of boxing, an exercise in which he was well skilled, had they not been accompanied with an insinuation, that his antagonist was no Hector, and that he might humble him into any concession, without running the least personal risk. Animated by this assurance, our second Rubens set the trumpet of defiance to his mouth, swore he valued not his life a rush, when his honour was concerned, and entreated Mr. Pickle to be the bearer of a challenge, which he would instantly commit to writing.

The mischievous fomenter highly applauded this manifestation of courage, by which he was at liberty to cultivate his friendship and society, but declined the office of carrying the billet, that his tenderness of Pallet's reputation might not be misinterpreted into an officious desire of promoting quarrels. At the same time he recommended Tom Pipes, not only as a very proper messenger on this occasion, but also as a trusty second in the field. The magnanimous painter took his advice, and, retiring to his chamber, penned a challenge in these terms,—

Sir,—When I am heartily provoked, I fear not the devil himself; much less——I will not call you a pedantic coxcomb, nor an unmannerly fellow, because these are the hippythets of the wulgar: but, remember, such as you are, I nyther love you nor fear you; but, on the contrary, expect satisfaction for your audacious behaviour to me on divers occasions; and will, this evening, in the twilight, meet you on the ramparts with sword and pistol, where the Lord have mercy on the soul of one of us, for your body shall find no favour with your incensed defier, till death. 'Layman Pallet'

This resolute defiance, after having been submitted to the perusal, and honoured with the approbation of our youth, was committed to the charge of Pipes, who, according to his orders, delivered it in the afternoon; and brought for answer, that the physician would attend him at the appointed time and place. The challenger was evidently discomposed at the unexpected news of this acceptance, and ran about the house in great disorder, in quest of Peregrine, to beg his further advice and assistance: but understanding that the youth was engaged in private with his adversary, he began to suspect some collusion, and cursed himself for his folly and precipitation. He even entertained some thoughts of retracting his invitation, and submitting to the triumph of his antagonist: but before he would stoop to this opprobrious condescension, he resolved to try another expedient, which might be the means of saving both his character and person. In this hope he visited Mr. Jolter, and very gravely desired he would be so good as to undertake the office of his second in a duel which he was to fight that evening with the physician.

The governor, instead of answering his expectation, in expressing fear and concern, and breaking forth into exclamations of, 'Good God! gentlemen! what d'ye mean? You shall not murder one another while it is in my power to prevent your purpose.' I will go directly to the governor of the place, who shall interpose his authority,' I say, instead of these and other friendly menaces of prevention, Jolter heard the proposal with the most phlegmatic tranquillity, and excused himself from accepting the honour intended for him, on account of his character and situation, which would not permit him to be concerned in any such rencounters. Indeed this mortifying reception was owing to a previous hint from Peregrine, who, dreading some sort of interruption from his governor, had made him acquainted with his design, and assured him, that the affair should not be brought to any dangerous issue.

Thus disappointed, the dejected challenger was overwhelmed with perplexity and dismay; and, in the terrors of death or mutilation, resolved to deprecate the wrath of his enemy, and conform to any submission he should propose, when he was accidentally encountered by our adventurer, who, with demonstrations of infinite satisfaction, told him, in confidence, that his billet had thrown the doctor into an agony of consternation; that his acceptance of his challenge was a mere effort of despair, calculated, to confound the ferocity of the sender, and dispose him to listen to terms of accommodation; that he had imparted the letter to him, with fear and trembling, on pretence of engaging him as a second, but, in reality, with a view of obtaining his good offices in promoting a reconciliation; but perceiving the situation of his mind,' added our hero, 'I thought it would be more for your honour to baffle his expectation, and therefore I readily undertook the task of attending him to the field, in full assurance that he will there humble himself before you, even to prostration. In this security you may go and prepare your arms, and bespeak the assistance of Pipes, who will squire you to the field, while I keep myself up, that our correspondence may not be suspected by the physician.' Pallet's spirits, that were sunk to dejection; rose at this encouragement to all the insolence of triumph; he again declared his contempt of danger; and his pistols being loaded and accommodated with new flints, by his trusty armour-bearer, he waited, without flinching, for the hour of battle.

On the first approach of twilight, somebody knocked at his door, and Pipes having opened it at his desire, he heard the voice of his antagonist pronounce,—'Tell Mr. Pallet, that I am going to the place of appointment.' The painter was not a little surprised at this anticipation, which, so ill agreed with the information he had received from Pickle; and his concern beginning to recur, he fortified himself with a large bumper of brandy, which, however, did not overcome the anxiety of his thoughts. Nevertheless, he set out on the expedition with his second, betwixt whom and himself the following dialogue passed, in their way to the ramparts.—

'Mr. Pipes,' said the painter, with disordered accent, 'methinks the doctor was in a pestilent hurry with that message of his.'—'Ey, ey,' answered Tom, 'I do suppose he longs to be foul of you.' 'What!' replied the other, 'd'ye think he thirsts after my blood?' 'To be sure a does,' (said Pipes, thrusting a large quid of tobacco into his cheek with great deliberation). 'If that be the case,' cried Pallet, beginning to shake, 'he is no better than a cannibal, and no Christian ought to fight him on equal footing.' Tom observing his emotion, eyed him with a frown of indignation, saying,

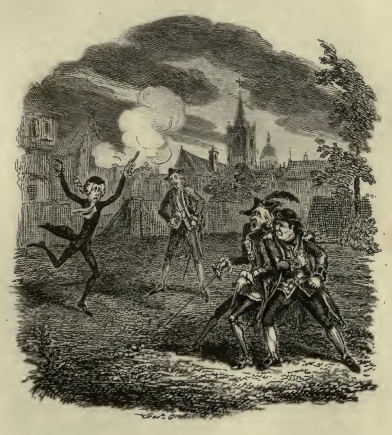

'You an't afraid, are you?' 'God forbid!' replied the challenger, stammering with fear, 'what should I be afraid of? the worst he can do is to 'take my life, and then he'll be answerable both to God and man for the murder: don't you think he will?'—'I think no such matter,' answered the second: 'if so be as how he puts a brace of bullets through your bows, and kills you fairly, it is no more murder than if I was to bring down a noddy from the main-top-sail-yard.' By this time Pallet's teeth chattered with such violence, that he could scarce pronounce this reply.—'Mr. Thomas, you seem to make very light of a man's life; but I trust in the Almighty I shall not be so easily brought down. Sure many a man has fought a duel without losing his life. Do you imagine that I run such a hazard of falling by the hand of my adversary?' 'You may or you may not,' said the unconcerned Pipes, 'just as it happens. What then! death is a debt that every man owes, according to the song; and if you set foot to foot, I think one of you must go to pot,' 'Foot to foot!' exclaimed the terrified painter, 'that's downright butchery; and I'll be damned before I fight any man on earth in such a barbarous way. What! d'ye take me to be a savage beast?' This declaration he made while they ascended the ramparts. His attendant, perceiving the physician and his second at the distance of an hundred paces before them, gave him notice of their appearance, and advised him to make ready, and behave like a man. Pallet in vain endeavoured to conceal his panic, which discovered itself in an universal trepidation of body, and the lamentable tone in which he answered this exhortation of Pipes, saying,—'I do behave like a man; but you would have me act the part of a brute.—Are they coming this way?' When Tom told him that they had faced about, and admonished him to advance, the nerves of his arm refused, their office, he could not hold out his pistol, and instead of going forward, retreated with an insensibility of motion; till Pipes, placing himself in the rear, set his own back to that of his principal, and swore he should not budge an inch farther in that direction.

While the valet thus tutored the painter, his master enjoyed the terrors of the physician, which were more ridiculous than those of Pallet, because he was more intent upon disguising them. His declaration to Pickle in the morning would not suffer him to start any objections when he received the challenge; and finding that the young gentleman made no offer of mediating the affair, but rather congratulated him on the occasion, when he communicated the painter's billet, all his efforts consisted in oblique hints, and general reflexions, upon the absurdity of duelling, which was first introduced among civilized nations by the barbarous Huns and Longobards. He likewise pretended to ridicule the use of fire-arms, which confounded all the distinctions of skill and address, and deprived a combatant of the opportunity of signalizing his personal prowess.

Pickle assented to the justness of his observations; but, at the same time, represented the necessity of complying with the customs of this world (ridiculous as they were), on which a man's honour and reputation depend. So that, seeing no hopes of profiting by that artifice, the republican's agitation became more and more remarkable; and he proposed, in plain terms, that they should contend in armour, like the combatants of ancient days; for it was but reasonable, that they should practise the manner of fighting, since they adopted the disposition of those iron times.

Nothing could have afforded more diversion to our hero than the sight of two such duellists cased in iron; and he wished that he had promoted the quarrel in Brussels, where he could have hired the armour of Charles the Fifth, and the valiant Duke of Parma, for their accommodation; but as there was no possibility of furnishing them cap-à-pee at Antwerp, he persuaded him to conform to the modern use of the sword, and meet the painter on his own terms; and suspecting that his fear would supply him with other excuses for declining, the combat, he comforted him with some distant insinuations, to the prejudice of his adversary's courage, which would, in all probability, evaporate before any mischief could happen.

Notwithstanding this encouragement, he could not suppress the reluctance with which he went to the field, and cast many a wishful look over his left shoulder, to see whether or not his adversary was at his heels. When, by the advice of his second, he took possession of the ground, and turned about with his face to the enemy, it was not so dark, but that Peregrine could perceive the unusual paleness of his countenance, and the sweat standing in large drops upon his forehead; nay, there was a manifest disorder in his speech, when he regretted his want of the pila and parma, with which he would have made a rattling noise, to astonish his foe, in springing forward, and singing the hymn to battle, in the manner of the ancients.

In the mean time, observing the hesitation of his antagonist, who, far from advancing, seemed to recoil, and even struggle with his second, he guessed the situation of the painter's thoughts, and collecting all the manhood that he possessed, seized the opportunity of profiting by his enemy's consternation. Striking his sword and pistol together, he advanced in a sort of a trot, raising a loud howl, in which he repeated, in lieu of the Spartan song, part of the strophe from one of Pindar's Pythia, beginning with ek theon gar mekanai pasai Broteais aretais, &c. This imitation of the Greeks had all the desired effect upon the painter, who seeing the physician running towards him like a fury, with a pistol in his right hand, which was extended, and hearing the dreadful yell he uttered, and the outlandish words he produced, was seized with an universal palsy of his limbs. He would have dropped down upon the ground, had not Pipes supported and encouraged him to stand upon his defence. The doctor, contrary to his expectation, finding that he had not flinched from the spot, though he had now performed one half of his career, put in practice the last effort, by firing his pistol, the noise of which no sooner reached the ears of the affrighted painter, than he recommended his soul to God, and roared for mercy with great vociferation.

The republican, overjoyed at this exclamation, commanded him to yield, and surrender his arms, on pain of immediate death; upon which he threw away his pistols and sword, in spite of all the admonitions and even threats of his second, who left him to his fate, and went up to his master, stopping his nose with signs of loathing and abhorrence.

The victor, having won the spolia opima, granted him his life, on condition that he would on his knees supplicate his pardon, acknowledging him inferior to his conqueror in every virtue and qualification, and promise for the future to merit his favour by submission and respect. These insolent terms were readily embraced by the unfortunate challenger, who fairly owned, that he was not at all calculated for the purposes of war, and that henceforth he would contend with no weapon but his pencil. He begged, with great humility, that Mr. Pickle would not think the worse of his morals for this defect of courage, which was a natural infirmity inherited from his father, and suspend his opinion of his talents, until he should have an opportunity of contemplating the charms of his Cleopatra, which would be finished in less than three months.

Our hero observed, with an affected air of displeasure, that no man could be justly condemned for being subject to the impressions of fear; and therefore his cowardice might easily be forgiven: but there was something so presumptuous, dishonest, and disingenuous, in arrogating a quality to which he knew he had not the smallest pretension, that he could not forget his misbehaviour all at once, though he would condescend to communicate with him as formerly, in hopes of seeing a reformation in his conduct. Pallet protested that there was no dissimulation in the case: for he was ignorant of his own weakness, until his resolution was put to the trial: he faithfully promised to demean himself, during the remaining part of the tour, with that conscious modesty and penitence which became a person in his condition: and, for the present, implored the assistance of Mr. Pipes, in disembarrassing him from the disagreeable consequence of his fear.

The town of Ashbourn, being a great thoroughfare to Buxton Wells, to the High-peak, and many parts of the North; and being inhabited by many substantial people concerned in the mines, and having also three or four of the greatest horse-fairs in that part of England, every year; is a very populous town.

There appeared at Ashbourn, for some market-days, a very extraordinary person, in a character, and with an equipage, somewhat singular and paradoxical: this was one Dr. Stubbs, a physician of the itinerant kind. The doctor came to town on horseback, yet dressed in a plaid night gown and red velvet cap. He had a small reading-desk fixed upon the pummel of his saddle, that supported a large folio, in which, by the help of a monstrous pair of spectacles, the doctor seemed to read, as the horse moved slowly on, with a profound attention. A portmanteau behind him contained his cargo of sovereign medicines, which, as brick-dust was probably the principal ingredient, must have been no small burden to his lean steed.

The 'squire, or assistant, led the doctor's horse slowly along, in a dress less solemn, but not less remarkable, than that of his master.

The doctor, from his Rozinante, attended by his merry-andrew (mounted on a horse-block before the principal inn), had just begun to harangue the multitude, and the speech with which he introduced himself each market-day was to this effect—

"My friends and countrymen! you have frequently been imposed upon, no doubt, by, quacks and ignorant pretenders to the noble art of physic; who, in order to gain your attention, have boasted of their many years' travels into foreign parts, and even the most remote regions of the habitable globe. One has been physician to the Sophi of Persia, to the Great Mogul, or the Empress of Russia; and displayed his skill at Moscow, Constantinople, Delhi, or Ispahan. Another, perhaps, has been tooth-drawer to the king of Morocco, or corn-cutter to the sultan of Egypt, or to the grand Turk; or has administered a clyster to the queen of Trebisond, or to Prester John, or the Lord, knows who—as if the wandering about from place to place (supposing it to be true) could make a man a jot the wiser. No, gentlemen, don't be imposed upon by pompous words and magnificent pretensions. He that goes abroad a fool will come home a coxcomb.

"Gentlemen! I am no High German or unborn doctor—But here I am—your own countryman—your fellow subject—your neighbour, as I may say. Why, gentlemen, eminent as I am now become, I was born but at Coventry, where my mother now lives—Mary Stubbs by name.

"One thing, indeed, I must boast of, without which I would not presume to practise the sublime art and mystery of physic. I am the seventh son of a seventh, son. Seven days was I before I sucked the breast. Seven months before I was seen to laugh or cry. Seven years before I was heard to utter seven words; and twice seven years have I studied, night and day, for the benefit of you, my friends and countrymen: and now here I am, ready to assist the afflicted, and to cure all manner of diseases, past, present, and to come; and that out of pure love to my country and fellow creatures, without fee or reward—except a trifling gratuity, the prime cost of my medicines; or what you may choose voluntarily to contribute hereafter, out of gratitude for the great benefit, which, I am convinced, you will receive from the use of them.

"But come, gentlemen, here is my famous, * Antifebrifuge Tincture; that cures all internal disorders whatsoever; the whole bottle for one poor shilling.

* A celebrated quack made this blunder; that is, in plain English, a tincture that will bring on a fever.

"Here's my Cataplasma Diabolicum, or my Diabolical Cataplasm; that will cure all external disorders, cuts, bruises, contusions, excoriations, and dislocations; and all for sixpence.

"But here, gentlemen, here's my famous Balsamum Stubbianum, or Dr. Stubbs's Sovereign Balsam; renowned over the whole Christian world, as an universal remedy, which no family ought to be without: it will keep seven years, and—be as good as it is now. Here's this large bottle, gentlemen, for the trifling sum of eighteen-pence.

"I am aware that your physical gentlemen here have called me quack, and ignorant pretender, and the like. But here I am.—Let Dr. Pestle or Dr. Clyster come forth. I challenge the whole faculty of the town of Ashbourn, to appear before this good company, and dispute with me in seven languages, ancient or modern; in Latin, Greek, or Hebrew—in High-Dutch, French, Italian, or Portuguese. Let them ask me any question in Hebrew or Arabic, and then it will appear who are men of solid learning, and who are quacks and ignorant pretenders.

"You see, gentlemen, I challenge them to a fair trial of skill, but not one of them dares show his face; they confess their ignorance by their silence.

"But come, gentlemen, who buys my elixir Cephalicum, Asthmaticum, Arthriticum, Diureticum, Emeticum, Diaphoriticum, Nephriticum, Catharticum.—Come, gentlemen, seize the golden opportunity, whilst health is so cheaply to be purchased."

After having disposed of a few packets, the doctor told the company, that as this was the last time of his appearing at Ashbourn (other parts of the kingdom claiming a part in his patriotic labours), he was determined to make a present to all those who had been his patients, of a shilling a-piece. He therefore called upon all those who could produce any one of Dr. Stubbs's bottles, pill-boxes, plaisters, or even his hand-bills, to make their appearance, and partake of his generosity. This produced no small degree of expectation amongst those that had been the doctor's customers, who gathered round him, with their hands stretched out, and with wishful looks. "Here, gentlemen," says the doctor, "stand forth! hold up your hands. I promised to give you a shilling a-piece. I will immediately per-; form my promise. Here's my Balsamum Stubbianum; which I have hitherto sold at eighteen-pence the bottle, you shall now have it for sixpence."

"Come! gemmen," says the merry-andrew, "where are you? Be quick! Don't stand in your own light. You'll never have such another opportunity—as long as you live."

The people looked upon each other with an air of disappointment. Some shook their heads, some grinned at the conceit, and others uttered their execrations—some few, however, who had been unwilling to throw away eighteen-pence upon the experiment, ventured to give a single sixpence; and the doctor picked up eight or nine shillings more by this stratagem, which was more than the intrinsic value of his horse-load of medicines.

This egregious quack conceiving that he had now squeezed the last farthing out of his audience, commenced his retreat from the crowd with his usual solemnity of deportment, and mock-heroic dignity; when a sly countryman, who had stood near him for some time, and had listened with a less than ordinary portion of credulity, nay, who had, indeed, more than once lifted up his eyes in token of disbelief, and curved his mouth into an arch of humourous contempt—raised a pitchfork which he had been leaning upon, and urged it into the posterior of the poor beast, who was condemned to crawl underneath the Doctor and his baggage.—This Rozinante no sooner felt the insidious prick, than; bent on revenge, she raised her heels with deadly intent; but in order to raise her heels, the old creature found it necessary to lower her head, when the Doctor took that opportunity, which to say the truth, he could not avoid, of toppling over her shoulders. While the medical gentleman was performing his somerset in the air, amidst a shower of his own bottles, to the manifest delight of the multitude, who shouted and screamed with joy, and pelted him with stones, and mud, and filth—purely out of the extacy of their gratification, another well disposed patient taking advantage of the moment, presented a besom to the Merry Andrew, and fairly swept him from the horse-block, on which he was capering, among his master's bottles, gallipots, and nostrums, which now bestrewed the pavement.—After a few minutes floundering, the faithful pair regained their legs, and gathering up the remnants of their trade, retreated to their inn with all convenient speed, amidst the huzzas and laughter of the mob.

One evening that those heroes, the Baron of Felsheim and Brandt, were reclined on their beds, beginning to drink freely, relating their high feats, and, with becoming modesty, comparing themselves to nothing less than an Eugene or a Marlborough, Brandt was on a sudden struck with a sort of inspiration.—"We are very comfortable here," said he to the Baron.—"Very well indeed," replied Ferdinand XV. with a slight symptom of ebriety.—"No more guard at night."—"No longer compelled to drink water."—"No more black bread, Colonel."—"No more Frenchmen, Brandt, though we beat them sometimes, eh?"—"Aye, but with the loss of an eye." —"And my poor arm, you have not forgot that?"—"No more than I have your leg."—"My leg, my leg, ah! that was a sad affair."—"Your health, Colonel."

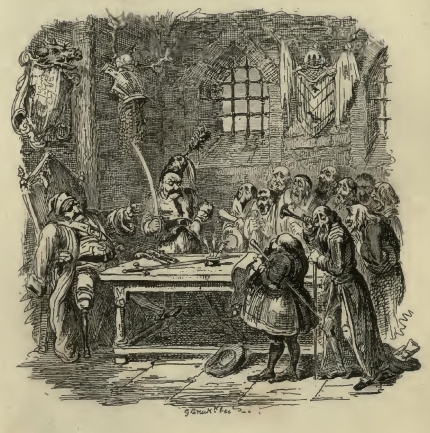

"Your's, Brandt."—"I foresee but one little accident, my Lord, that can disturb our present felicity."—"What's that?"—"O nothing, a mere trifle.—I was thinking that the good Jews of Franckfort may, if they please, turn the Baron of Felsheim out of his own castle."—"Faith! I had forgot those scoundrels," answered the Baron, drinking a bumper; "however, you shall go to Franckfort to-morrow morning, collect the rabble together, and bring them here. I will receive them in that famous tower, where Witikind, with only thirty Saxons, stopped, for three days, an army of one hundred thousand men, led by Charlemagne in person. The place will inspire them with that veneration for my person which its shattered state no longer enforces."—"I will go, Colonel."—"If they are reasonable—we will pay them."—"If they are not—we must sabre them."—"That is well said, Brandt,—bravo!"—"Let us drink, Colonel."—"With all my heart."

The next morning, at break of day, Brandt saddled his horse, gallopped towards Franckfort, assembled the Israelites, imparted to them the good intentions of his master, appointed a day the Colonel would be ready to receive them, and then returned to the castle.

The punctuality of a good soldier to be at his post in the hour of battle, of a lover in keeping the first appointment of his mistress, or of a courtier at the levee, is not to be compared with the precision of a Jew, who has money to receive. Those of Franckfort arrived on the appointed day, at the appointed hour, and long before the Baron had slept himself sober. Brandt went to inform him of the arrival of his creditors, assisted him in putting on a dressing-gown of blue velvet lined with green stuff, which descended from Ferdinand XIII. and which Ferdinand XIV. had never worn but to give his public audiences; tied his sabre over the said gown, placed his double-barrelled pistols in his belt, combed his whiskers, and put a white cap over that of dirty brown, which he commonly wore. The Baron, thus accoutred, came forth from his bed-chamber, leaning on his Squire's shoulder; walked majestically through two rows, formed by his creditors, and was followed by them to the tower of Witikind.

After depositing, on a worm-eaten table, his naked sword and his pistols, the Baron seated himself in an immense arm-chair, stroked his whiskers, and spoke in the following terms:—