Title: The Remarkable History of the Hudson's Bay Company

Author: George Bryce

Release date: November 30, 2013 [eBook #44312]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Melissa McDaniel, Christian Boissonnas and the

Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

INCLUDING THAT OF

The French Traders of

North-Western Canada

and of the North-West, X Y, and

Astor Fur Companies

BY

GEORGE BRYCE, M.A., LL.D.

PROFESSOR IN MANITOBA COLLEGE, WINNIPEG; DÉLÉGUÉ RÉGIONAL DE L'ALLIANCE SCIENTIFIQUE DE PARIS; MEMBER OF GENERAL COMMITTEE OF BRITISH ASSOCIATION; FELLOW OF AMERICAN ASSOCIATION FOR ADVANCEMENT OF SCIENCE; PRESIDENT ROYAL SOCIETY OF CANADA (1909); MEMBER OF THE COMMISSION ON CANADIAN RESOURCES (1909); MEMBER OF THE ROYAL COMMISSION ON TECHNICAL EDUCATION (1910); AUTHOR OF "MANITOBA" (1882); "SHORT HISTORY OF CANADIAN PEOPLE" (1887), MAKERS OF CANADA SERIES (MACKENZIE, SELKIRK AND SIMPSON); "ROMANTIC SETTLEMENT OF LORD SELKIRK'S COLONISTS" (1909); "CANADA" IN WINSOR'S NAR. AND CRIT. HIST. OF AMERICA, ETC., ETC.

THIRD EDITION

WITH NUMEROUS FULL-PAGE ILLUSTRATIONS AND MAPS

LONDON

SAMPSON LOW, MARSTON & CO.,

LTD.

Four Great Governors of the Hudson's Bay Company

The Hudson's Bay Company! What a record this name represents of British pluck and daring, of patient industry and hardy endurance, of wild adventure among savage Indian tribes, and of exposure to danger by mountain, precipice, and seething torrent and wintry plain!

In two full centuries the Hudson's Bay Company, under its original Charter, undertook financial enterprises of the greatest magnitude, promoted exploration and discovery, governed a vast domain in the northern part of the American Continent, and preserved to the British Empire the wide territory handed over to Canada in 1870. For nearly a generation since that time the veteran Company has carried on successful trade in competition with many rivals, and has shown the vigour of youth.

The present History includes not only the record of the remarkable exploits of this well-known Company, but also the accounts of the daring French soldiers and explorers who disputed the claim of the Company in the seventeenth century, and in the eighteenth century actually surpassed the English adventurers in penetrating the vast interior of Rupert's Land.

Special attention is given in this work to the picturesque history of what was the greatest rival of the Hudson's Bay Company, viz. the North-West Fur Company of Montreal, as well as to the extraordinary spirit of the X Y Company and the Astor Fur Company of New York.

A leading feature of this book is the adequate treatment for the first time of the history of the well-nigh eighty years just closing, from the union of all the fur traders of British North America under the name of the Hudson's Bay Company. This period, beginning with the career of the Emperor-Governor. Sir George Simpson (1821), and covering the life, adventure, conflicts, trade, and development of the vast region stretching from Labrador to Vancouver Island, and north to the Mackenzie River and the Yukon, down to the present year, is the most important part of the Company's history.

For the task thus undertaken the author is well fitted. He has had special opportunities for becoming acquainted with the history, position, and inner life of the Hudson's Bay Company. He has lived for nearly thirty years in Winnipeg, for the whole of that time in sight of Fort Garry, the fur traders' capital, or what remains of it; he has visited many of the Hudson's Bay Company's posts from Fort William to Victoria, in the Lake Superior and the Lake of the Woods region, in Manitoba, Assiniboia, Alberta, and British Columbia; in those districts he has run the rapids, crossed the portages, surveyed the ruins of old forts, and fixed the localities of long-forgotten posts; he is acquainted with a large number of the officers of the Company, has enjoyed their hospitality, read their journals, and listened with interest to their tales of adventure in many out-of-the-way posts; he is a lover of the romance, and story, and tradition of the fur traders' past.

The writer has had full means of examining documents, letters, journals, business records, heirlooms, and archives of the fur traders both in Great Britain and Canada. He returns thanks to the custodians of many valuable originals, which he has used, to the Governor of the Hudson's Bay Company in 1881, Right Hon. G. J. Goschen, who granted him the privilege of consulting all Hudson's Bay Company records up to the date of 1821, and he desires to still more warmly [Pg vii] acknowledge the permission given him by the distinguished patron of literature and education, the present Governor of the Hudson's Bay Company, Lord Strathcona and Mount Royal, to read any documents of public importance in the Hudson's Bay House in London. This unusual opportunity granted the author was largely used by him in 1896 and again in 1899.

Taking the advice of his publishers, the author, instead of publishing several volumes of annals of the Company, has condensed the important features of the history into one fair-sized volume, but has given in an Appendix references and authorities which may afford the reader, who desires more detailed information on special periods, the sources of knowledge for fuller research.

TO THE THIRD EDITION

The favor which has been shown to the "Remarkable History of the Hudson's Bay Company" has resulted in a large measure from its being written by a native-born Canadian, who is familiar with much of the ground over which the Company for two hundred years held sway.

A number of corrections have been made and the book has been brought up to date for this Edition.

It has been a pleasure to the Author, who has expressed himself without fear or favor regarding the Company men and their opponents, that he has received from the greater number of his readers commendations for his fairness and insight into the affairs of the Company and its wonderful history.

George Bryce.

Kilmadock, Winnipeg,

August 19, 1910.

| CHAPTER I. | |

| THE FIRST VOYAGE FOR TRADE. | Page |

| Famous Companies—"The old lady of Fenchurch Street"—The first voyage—Radisson and Groseilliers—Spurious claim of the French of having reached the Bay—"Journal published by Prince Society"—The claim invalid—Early voyages of Radisson—The Frenchmen go to Boston—Cross over to England—Help from Royalty—Fiery Rupert—The King a stockholder—Many hitherto unpublished facts—Capt. Zachariah Gillam—Charles Fort built on Rupert River—The founder's fame | 1 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| HUDSON'S BAY COMPANY FOUNDED. | |

| Royal charters—Good Queen Bess—"So miserable a wilderness"—Courtly stockholders—Correct spelling—"The nonsense of the Charters"—Mighty rivers—Lords of the territory—To execute justice—War on infidels—Power to seize—"Skin for skin"—Friends of the Red man | 12 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| METHODS OF TRADE. | |

| Rich Mr. Portman—Good ship Prince Rupert—The early adventurers—"Book of Common Prayer"—Five forts—Voting a funeral—Worth of a beaver—To Hudson Bay and back—Selling the pelts—Bottles of sack—Fat dividends—"Victorious as Cæsar"—"Golden Fruit" | 20 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| THREE GREAT GOVERNORS. | |

| Men of high station—Prince Rupert primus—Prince James, "nemine contradicente"—The hero of the hour—Churchill River named—Plate of solid gold—Off to the tower | 27 |

| [Pg xii] CHAPTER V. | |

| TWO ADROIT ADVENTURERS. | |

| Peter Radisson and "Mr. Gooseberry" again—Radisson v. Gillam—Back to France—A wife's influence—Paltry vessels—Radisson's diplomacy—Deserts to England—Shameful duplicity—"A hogshead of claret"—Adventurers appreciative—Twenty-five years of Radisson's life hitherto unknown—"In a low and mean condition"—The Company in Chancery—Lucky Radisson—A Company pensioner | 33 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| FRENCH RIVALRY. | |

| The golden lilies in danger—"To arrest Radisson"—The land called "Unknown"—A chain of claim—Imaginary pretensions—Chevalier de Troyes—The brave Lemoynes—Hudson Bay forts captured—A litigious governor—Laugh at treaties—The glory of France—Enormous claims—Consequential damages | 47 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| RYSWICK AND UTRECHT. | |

| The "Grand Monarque" humbled—Caught napping—The Company in peril—Glorious Utrecht—Forts restored—Damages to be considered—Commission useless | 56 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| DREAMS OF A NORTH-WEST PASSAGE. | |

| Stock rises—Jealousy aroused—Arthur Dobbs, Esq.—An ingenious attack—Appeal to the "Old Worthies"—Captain Christopher Middleton—Was the Company in earnest? The sloop Furnace—Dobbs' fierce attack—The great subscription—Independent expedition—"Henry Ellis, gentleman"—"Without success"—Dobbs' real purpose | 61 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| THE INTERESTING BLUE-BOOK OF 1749. | |

| "Le roi est mort"—Royalty unfavourable—Earl of Halifax—"Company asleep"—Petition to Parliament—Neglected discovery—Timidity or caution—Strong "Prince of Wales"—Increase of stock—A timid witness—Claims of discovery—To make Indians Christians—Charge of disloyalty—New Company promises largely—Result nil | 70 |

| [Pg xiii] CHAPTER X. | |

| FRENCH CANADIANS EXPLORE THE INTERIOR. | |

| The "Western Sea"—Ardent Duluth—"Kaministiquia"—Indian boasting—Père Charlevoix—Father Gonor—The man of the hour:—Verendrye—Indian map-maker—The North Shore—A line of forts—The Assiniboine country—A notable manuscript—A marvellous journey—Glory, but not wealth—Post of the Western Sea | 78 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| THE SCOTTISH MERCHANTS OF MONTREAL. | |

| Unyielding old Cadot—Competition—The enterprising Henry—Leads the way—Thomas Curry—The elder Finlay—Plundering Indians—Grand Portage—A famous mart—The plucky Frobishers—The Sleeping Giant aroused—Fort Cumberland—Churchill River—Indian rising—The deadly smallpox—The whites saved | 92 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| DISCOVERY OF THE COPPERMINE. | |

| Samuel Hearne—"The Mungo Park of Canada"—Perouse complains—The North-West Passage—Indian guides—Two failures—Third journey successful—Smokes the calumet—Discovers Arctic Ocean—Cruelty to the Eskimos—Error in latitude—Remarkable Indian woman—Capture of Prince of Wales Fort—Criticism by Umfreville | 100 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| FORTS ON HUDSON BAY LEFT BEHIND. | |

| Andrew Graham's "Memo."—Prince of Wales Fort—The garrison—Trade—York Factory—Furs—Albany—Subordinate forts—Moose—Moses Norton—Cumberland House—Upper Assiniboine—Rainy Lake—Brandon House—Red River—Conflict of the Companies | 109 |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| THE NORTH-WEST COMPANY FORMED. | |

| Hudson's Bay Company aggressive—The great McTavish—The Frobishers—Pond and Pangman dissatisfied—Gregory and McLeod—Strength of the North-West Company—Vessels to be built—New route from Lake Superior sought—Good will at times—Bloody Pond—Wider union, 1787—Fort Alexandria—Mouth of the Souris—Enormous fur trade—Wealthy Nor'-Westers—"The Haunted House | 116 |

| [Pg xiv] CHAPTER XV. | |

| VOYAGES OF SIR ALEXANDER MACKENZIE. | |

| A young Highlander—To rival Hearne—Fort Chipewyan built—French Canadian voyageurs—Trader Leroux—Perils of the route—Post erected on Arctic Coast—Return journey—Pond's miscalculations—Hudson Bay Turner—Roderick McKenzie's hospitality—Alexander Mackenzie—Astronomy and mathematics—Winters on Peace River—Terrific journey—The Pacific Slope—Dangerous Indians—Pacific Ocean, 1793—North-West Passage by land—Great achievement—A notable book | 124 |

| CHAPTER XVI. | |

| THE GREAT EXPLORATION. | |

| Grand Portage on American soil—Anxiety about the boundary—David Thompson, astronomer and surveyor—His instructions—By swift canoe—The land of beaver—A dash to the Mandans—Stone Indian House—Fixes the boundary at Pembina—Sources of the Mississippi—A marvellous explorer—Pacific Slope explored—Thompson down the Kootenay and Columbia—Fiery Simon Fraser in New Caledonia—Discovers Fraser River—Sturdy John Stuart—Thompson River—Bourgeois Quesnel—Transcontinental expeditions | 133 |

| CHAPTER XVII. | |

| THE X Y COMPANY. | |

| "Le Marquis" Simon McTavish unpopular—Alexander Mackenzie, his rival—Enormous activity of the "Potties"—Why called X Y—Five rival posts at Souris—Sir Alexander, the silent partner—Old Lion of Montreal roused—"Posts of the King"—Schooner sent to Hudson Bay—Nor'-Westers erect two posts on Hudson Bay—Supreme folly—Old and new Nor'-Westers unite—List of partners | 148 |

| CHAPTER XVIII. | |

| THE LORDS OF THE LAKES AND FORESTS.—I. | |

| New route to Kaministiquia—Vivid sketch of Fort William—"Cantine Salope"—Lively Christmas week—The feasting partners—Ex-Governor Masson's good work—Four great Mackenzies—A literary bourgeois—Three handsome demoiselles—"The man in the moon"—Story of "Bras Croche"—Around Cape Horn—Astoria taken over—A hot-headed trader—Sad case of "Little Labrie"—Punch on New Year's Day—The heart of a "vacher" | 155 |

| CHAPTER XIX. | |

| THE LORDS OF THE LAKES AND FORESTS.—II. | |

| Harmon and his book—An honest man—"Straight as an arrow"—New views—An uncouth giant—"Gaelic, English, French, [Pg xv]and Indian oaths"—McDonnell, "Le Prêtre"—St. Andrew's Day—"Fathoms of tobacco"—Down the Assiniboine—An entertaining journal—A good editor—A too frank trader—"Gun fire ten yards away"—Herds of buffalo—Packs and pemmican—"The fourth Gospel"—Drowning of Henry—"The weather cleared up"—Lost for forty days—"Cheepe," the corpse—Larocque and the Mandans—McKenzie and his half-breed children | 166 |

| CHAPTER XX. | |

| THE LORDS OF THE LAKES AND FORESTS.—III. | |

| Dashing French trader—"The country of fashion"—An air of great superiority—The road is that of heaven—Enough to intimidate a Cæsar—"The Bear" and the "Little Branch"—Yet more rum—A great Irishman—"In the wigwam of Wabogish dwelt his beautiful daughter"—Wedge of gold—Johnston and Henry Schoolcraft—Duncan Cameron on Lake Superior—His views of trade—Peter Grant, the ready writer—Paddling the canoe—Indian folk-lore—Chippewa burials—Remarkable men and great financiers, marvellous explorers, facile traders | 178 |

| CHAPTER XXI. | |

| THE IMPULSE OF UNION. | |

| North-West and X Y Companies unite—Recalls the Homeric period—Feuds forgotten—Men perform prodigies—The new fort re-christened—Vessel from Michilimackinac—The old canal—Wills builds Fort Gibraltar—A lordly sway—The "Beaver Club"—Sumptuous table—Exclusive society—"Fortitude in Distress"—Political leaders in Lower Canada | 189 |

| CHAPTER XXII. | |

| THE ASTOR FUR COMPANY. | |

| Old John Jacob Astor—American Fur Company—The Missouri Company—A line of posts—Approaches the Russians—Negotiates with Nor'-Westers—Fails—Four North-West officials join Astor—Songs of the voyageurs—True Britishers—Voyage of the Tonquin—Rollicking Nor'-Westers in Sandwich Islands—Astoria built—David Thompson appears—Terrible end of the Tonquin—Astor's overland expedition—Washington Irving's "Astoria, a romance"—The Beaver rounds the Cape—McDougall and his smallpox phial—The Beaver sails for Canton | 193 |

| CHAPTER XXIII. | |

| LORD SELKIRK'S COLONY. | |

| Alexander Mackenzie's book—Lord Selkirk interested—Emigration a boon—Writes to Imperial Government—In 1802 looks [Pg xvi]to Lake Winnipeg—Benevolent project of trade—Compelled to choose Prince Edward Island—Opinion as to Hudson's Bay Company Charter—Nor'-Westers alarmed—Hudson's Bay Company's Stock—Purchases Assiniboia—Advertises the new colony—Religion no disqualification—Sends first colony—Troubles of the project—Arrive at York Factory—The winter—The mutiny—"Essence of Malt"—Journey inland—A second party—Third party under Archibald Macdonald—From Helmsdale—The number of colonists | 203 |

| CHAPTER XXIV. | |

| TROUBLE BETWEEN THE COMPANIES. | |

| Nor'-Westers oppose the colony—Reason why—A considerable literature—Contentions of both parties—Both in fault—Miles Macdonell's mistake—Nor'-Wester arrogance—Duncan Cameron's ingenious plan—Stirring up the Chippewas—Nor'-Westers warn colonists to depart—McLeod's hitherto unpublished narrative—Vivid account of a brave defence—Chain shot from the blacksmith's smithy—Fort Douglas begun—Settlers driven out—Governor Semple arrives—Cameron last Governor of Fort Gibraltar—Cameron sent to Britain as a prisoner—Fort Gibraltar captured—Fort Gibraltar decreases, Fort Douglas increases—Free traders take to the plains—Indians favour the colonists | 215 |

| CHAPTER XXV. | |

| THE SKIRMISH OF SEVEN OAKS. | |

| Leader of the Bois Brûlés—A candid letter—Account of a prisoner—"Yellow Head"—Speech to the Indians—The chief knows nothing—On fleet Indian ponies—An eye-witness in Fort Douglas—A rash Governor—The massacre—"For God's sake save my life"—The Governor and twenty others slain—Colonists driven out—Eastern levy meets the settlers—Effects seized—Wild revelry—Chanson of Pierre Falcon | 229 |

| CHAPTER XXVI. | |

| LORD SELKIRK TO THE RESCUE. | |

| The Earl in Montreal—Alarming news—Engages a body of Swiss—The De Meurons—Embark for the North-West—Kawtawabetay's story—Hears of Seven Oaks—Lake Superior—Lord Selkirk—A doughty Douglas—Seizes Fort William—Canoes upset and Nor'-Westers drowned—"A banditti"—The Earl's blunder—A winter march —Fort Douglas recaptured—His Lordship soothes the settlers—An Indian treaty—"The Silver Chief"—The Earl's note-book | 238 |

| [Pg xvii] CHAPTER XXVII. | |

| THE BLUE-BOOK OF 1819 AND THE NORTH-WEST TRIALS. | |

| British law disgraced—Governor Sherbrooke's distress—A commission decided on—Few unbiassed Canadians—Colonel Coltman chosen—Over ice and snow—Alarming rumours—The Prince Regent's orders—Coltman at Red River—The Earl submissive—The Commissioner's report admirable—The celebrated Reinhart case—Disturbing lawsuits—Justice perverted—A store-house of facts—Sympathy of Sir Walter Scott—Lord Selkirk's death—Tomb at Orthes, in France | 252 |

| CHAPTER XXVIII. | |

| MEN WHO PLAYED A PART. | |

| The crisis reached—Consequences of Seven Oaks—The noble Earl—His generous spirit—His mistakes—Determined courage—Deserves the laurel crown—The first Governor—Macdonell's difficulties—His unwise step—A captain in red—Cameron's adroitness—A wearisome imprisonment—Last governor of Fort Gibraltar—The Metis chief—Half-breed son of old Cuthbert—A daring hunter—Warden of the plains—Lord Selkirk's agent—A Red River patriarch—A faithful witness—The French bard—Western war songs—Pierriche Falcon | 260 |

| CHAPTER XXIX. | |

| GOVERNOR SIMPSON UNITES ALL INTERESTS. | |

| Both Companies in danger—Edward Ellice, a mediator—George Simpson, the man of destiny—Old feuds buried—Gatherings at Norway House—Governor Simpson's skill—His marvellous energy—Reform in trade—Morality low—A famous canoe voyage—Salutes fired—Pompous ceremony at Norway House—Strains of the bagpipe—Across the Rocky Mountains—Fort Vancouver visited—Great executive ability—The governor knighted—Sir George goes round the world—Troubles of a book—Meets the Russians—Estimate of Sir George | 270 |

| CHAPTER XXX. | |

| THE LIFE OF THE TRADERS. | |

| Lonely trading posts—Skilful letter writers—Queer old Peter Fidler—Famous library—A remarkable will—A stubborn Highlander—Life at Red River—Badly-treated Pangman—Founding trading houses—Beating up recruits—Priest Provencher—A fur-trading mimic—Life far north—"Ruled with a rod of iron"—Seeking a fur country—Life in the canoe—A trusted trader—Sheaves of letters—A find in Edinburgh—Faithful correspondents—The Bishop's cask of wine—Red River, a "land of Canaan"—Governor Simpson's letters—The gigantic Archdeacon writes—"MacArgrave's" promotion—Kindly Sieveright—Traders and their books | 283 |

| [Pg xviii] CHAPTER XXXI. | |

| THE VOYAGEURS FROM MONTREAL. | |

| Lachine, the fur traders' Mecca—The departure—The flowing bowl—The canoe brigade—The voyageurs' song—"En roulant ma boule"—Village of St. Anne's—Legend of the church—The sailors' guardian—Origin of "Canadian Boat Song"—A loud invocation—"A la Claire Fontaine"—"Sing, nightingale"—At the rapids—The ominous crosses—"Lament of Cadieux"—A lonely maiden sits—The Wendigo—Home of the Ermatingers—A very old canal—The rugged coast—Fort William reached—A famous gathering—The joyous return | 304 |

| CHAPTER XXXII. | |

| EXPLORERS IN THE FAR NORTH. | |

| The North-West Passage again—Lieutenant John Franklin's land expedition—Two lonely winters—Hearne's mistake corrected—Franklin's second journey—Arctic sea coast explored—Franklin knighted—Captain John Ross by sea—Discovers magnetic pole—Magnetic needle nearly perpendicular—Back seeks for Ross—Dease and Simpson sent by Hudson's Bay Company to explore—Sir John in Erebus and Terror—The Paleocrystic Sea—Franklin never returns—Lady Franklin's devotion—The historic search—Dr. Rae secures relics—Captain McClintock finds the cairn and written record—Advantages of the search | 315 |

| CHAPTER XXXIII. | |

| EXPEDITIONS TO THE FRONTIER OF THE FUR COUNTRY. | |

| A disputed boundary—Sources of the Mississippi—The fur traders push southward—Expedition up the Missouri—Lewis and Clark meet Nor'-Westers—Claim of United States made—Sad death of Lewis—Lieutenant Pike's journey—Pike meets fur traders—Cautious Dakotas—Treaty with Chippewas—Violent death—Long and Keating fix 49 deg. N.—Visit Fort Garry—Follow old fur traders' route—An erratic Italian—Strange adventures—Almost finds source—Beltrami County—Cass and Schoolcraft fail—Schoolcraft afterwards succeeds—Lake Itasca—Curious origin of name—The source determined | 326 |

| CHAPTER XXXIV. | |

| FAMOUS JOURNEYS IN RUPERT'S LAND. | |

| Fascination of an unknown land—Adventure, science, or gain—Lieutenant Lefroy's magnetic survey—Hudson's Bay Company assists—Winters at Fort Chipewyan—First scientific visit to Peace River—Notes lost—Not "gratuitous canoe conveyance"—Captain Palliser and Lieutenant [Pg xix] Hector—Journey through Rupert's Land—Rocky Mountain passes—On to the coast—A successful expedition—Hind and Dawson—To spy out the land for Canada—The fertile belt—Hind's description good—Milton and Cheadle—Winter on the Saskatchewan—Reach Pacific Ocean in a pitiable condition—Captain Butler—The horse Blackie and dog "Cerf Vola"—Fleming and Grant—"Ocean to ocean"—"Land fitted for a healthy and hardy race"—Waggon road and railway | 337 |

| CHAPTER XXXV. | |

| RED RIVER SETTLEMENT. 1817-1846. |

|

| Chiefly Scottish and French settlers—Many hardships—Grasshoppers—Yellow Head—"Gouverneur Sauterelle"—Swiss settlers—Remarkable parchment—Captain Bulger, a military governor—Indian troubles—Donald McKenzie, a fur trader governor—Many projects fail—The flood—Plenty follows—Social condition—Lower Fort built—Upper Fort Garry—Council of Assiniboia—The settlement organized—Duncan Finlayson governor—English farmers—Governor Christie—Serious epidemic—A regiment of regulars—The unfortunate major—The people restless | 348 |

| CHAPTER XXXVI. | |

| THE PRAIRIES: SLEDGE, KEEL, WHEEL, CAYUSE, CHASE. | |

| A picturesque life—The prairie hunters and traders—Gaily-caparisoned dog trains—The great winter packets—Joy in the lonely forts—The summer trade—The York boat brigade—Expert voyageurs—The famous Red River cart—Shagganappe ponies—The screeching train—Tripping—The western cayuse—The great buffalo hunt—Warden of the plains—Pemmican and fat—The return in triumph | 360 |

| CHAPTER XXXVII. | |

| LIFE ON THE SHORES OF HUDSON BAY AND LABRADOR. | |

| The bleak shores unprogressive—Now as at the beginning—York Factory—Description of Ballantyne—The weather—Summer comes with a rush—Picking up subsistence—The Indian trade—Inhospitable Labrador—Establishment of Ungava Bay—McLean at Fort Chimo—Herds of cariboo—Eskimo rafts—"Shadowy Tartarus"—The king's domains—Mingan—Mackenzie—The gulf settlements—The Moravians—Their four missions—Rigolette, the chief trading post—A school for developing character—Chief Factor Donald A. Smith—Journeys along the coast—A barren shore | 376 |

| [Pg xx] CHAPTER XXXVIII. | |

| ATHABASCA, MACKENZIE RIVER, AND THE YUKON. | |

| Peter Pond reaches Athabasca River—Fort Chipewyan established—Starting point of Alexander Mackenzie—The Athabasca Library—The Hudson's Bay Company roused—Conflict at Fort Wedderburn—Suffering—The dash up the Peace River—Fort Dunvegan—Northern extension—Fort Resolution—Fort Providence—The great river occupied—Loss of life—Fort Simpson, the centre—Fort Reliance—Herds of cariboo—Fort Norman built—Fort Good Hope—The Northern Rockies—The Yukon reached and occupied—The fierce Liard River—Fort Halkett in the Mountains—Robert Campbell comes to the Stikine—Discovers the Upper Yukon—His great fame—The districts—Steamers on the water stretches | 386 |

| CHAPTER XXXIX. | |

| ON THE PACIFIC SLOPE. | |

| Extension of trade in New Caledonia—The Western Department—Fort Vancouver built—Governor's residence and Bachelors' Hall—Fort Colville—James Douglas, a man of note—A dignified official—An Indian rising—A brave woman—The fertile Columbia Valley—Finlayson, a man of action—Russian fur traders—Treaty of Alaska—Lease of Alaska to the Hudson's Bay Company—Fort Langley—The great farm—Black at Kamloops—Fur trader v. botanist—"No soul above a beaver's skin"—A tragic death—Chief Nicola's eloquence—A murderer's fate | 399 |

| CHAPTER XL. | |

| FROM OREGON TO VANCOUVER ISLAND. | |

| Fort Vancouver on American soil—Chief Factor Douglas chooses a new site—Young McLoughlin killed—Liquor selling prohibited—Dealing with the Songhies—A Jesuit father—Fort Victoria—Finlayson's skill—Chinook jargon—The brothers Ermatinger—A fur-trading Junius—"Fifty-four, forty, or fight"—Oregon Treaty—Hudson's Bay Company indemnified—The waggon road—A colony established—First governor—Gold fever—British Columbia—Fort Simpson—Hudson's Bay Company in the interior—The forts—A group of worthies—Service to Britain—The coast becomes Canadian | 408 |

| CHAPTER XLI. | |

| PRO GLORIA DEI. | |

| A vast region—First spiritual adviser—A locum tenens—Two French Canadian priests—St. Boniface founded—Missionary zeal in Mackenzie River district—Red River [Pg xxi] parishes—The great Archbishop Taché—John West—Archdeacon Cochrane, the founder—John McCallum—Bishop Anderson—English Missionary Societies—Archbishop Machray—Indian Missions—John Black, the Presbyterian apostle—Methodist Missions on Lake Winnipeg—The Cree syllabic—Chaplain Staines—Bishop Bridge—Missionary Duncan—Metlakahtla—Roman Catholic coast missions—Church of England bishop—Diocese of New Westminster—Dr. Evans—Robert Jamieson—Education | 420 |

| CHAPTER XLII. | |

| THE HUDSON'S BAY COMPANY AND THE INDIANS. | |

| Company's Indian policy—Character of officers—A race of hunters—Plan of advances—Charges against the Company—Liquor restriction—Capital punishment—Starving Indians—Diseased and helpless—Education and religion—The age of missions—Sturdy Saulteaux—The Muskegons—Wood Crees—Wandering Plain Crees—The Chipewyans—Wild Assiniboines—Blackfoot Indians—Polyglot coast tribes—Eskimos—No Indian war—No police—Pliable and docile—Success of the Company | 431 |

| CHAPTER XLIII. | |

| UNREST IN RUPERT'S LAND. 1844-1869. |

|

| Discontent on Red River—Queries to the Governor—A courageous Recorder—Free Trade in furs held illegal—Imprisonment—New land deed—Enormous freights—Petty revenge—Turbulent pensioners—Heart burnings—Heroic Isbister—Half-breed memorial—Mr. Beaver's letter—Hudson's Bay Company notified—Lord Elgin's reply—Voluminous correspondence—Company's full answer—Colonel Crofton's statement—Major Caldwell, a partisan—French petition—Nearly a thousand signatures—Love, a factor—The elder Riel—A court scene—Violence—"Vive la liberté!"—The Recorder checked—A new judge—Unruly Corbett—The prison broken—Another rescue—A valiant doctor—A Red River Nestor | 438 |

| CHAPTER XLIV. | |

| CANADA COVETS THE HUDSON'S BAY TERRITORY. | |

| Renewal of licence—Labouchere's letter—Canada claims to Pacific Ocean—Commissioner Chief-Justice Draper—Rests on Quebec Act, 1774—Quebec overlaps Indian territories—Company loses Vancouver Island—Cauchon's memorandum—Committee of 1857—Company on trial—A brilliant committee—Four hundred folios of evidence—To transfer Red [Pg xxii] River and Saskatchewan—Death of Sir George—Governor Dallas—A cunning scheme—Secret negotiations—The Watkin Company floated—Angry winterers—Dallas's soothing circular—The old order still—Ermatinger's letters—McDougall's resolutions—Cartier and McDougall as delegates—Company accepts the terms | 448 |

| CHAPTER XLV. | |

| TROUBLES OF THE TRANSFER OF RUPERT'S LAND. | |

| Transfer Act passed—A moribund Government—The Canadian surveying party—Causes of the rebellion—Turbulent Metis—American interference—Disloyal ecclesiastics—"Governor" McDougall—Riel and his rebel band—A blameworthy governor—The "blawsted fence"—Seizure of Fort Garry—Riel's ambitions—Loyal rising—Three wise men from the East—The New Nation—A winter meeting—Bill of Rights—A Canadian shot—The Wolseley expedition—Three renegades slink away—The end of Company rule—The new Province of Manitoba | 459 |

| CHAPTER XLVI. | |

| PRESENT STATUS OF THE COMPANY. | |

| A great land company—Fort Garry dismantled—The new buildings—New v. old—New life in the Company—Palmy days are recalled—Governors of ability—The present distinguished Governor—Vaster operations—Its eye not dimmed | 472 |

| CHAPTER XLVII. | |

| THE FUTURE OF THE CANADIAN WEST. | |

| The Greater Canada—Wide wheat fields—Vast pasture lands—Huronian mines—The Kootenay riches—Yukon nuggets—Forests—Iron and coal—Fisheries—Two great cities—Towns and villages—Anglo-Saxon institutions—The great outlook | 477 |

| APPENDIX. | |

| A.—Authorities and References | 483 |

| B.—Summary of Life of Pierre Esprit Radisson | 489 |

| C.—Company Posts in 1856, with Indians | 491 |

| D.—Chief Factors (1821-1896) | 493 |

| E.—Russian America (Alaska) | 495 |

| F.—The Cree Syllabic Character | 497 |

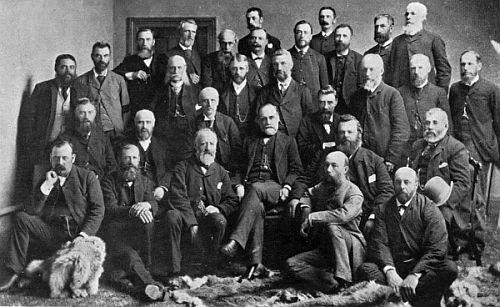

| G.—Names of H.B.Co. Officers in Plate opposite page 442 | 498 |

| Index | 499 |

THE FIRST VOYAGE FOR TRADE.

Charles Lamb—"delightful author"—opens his unique "Essays of Elia" with a picturesque description of the quaint "South Sea House." Threadneedle Street becomes a magnetic name as we wander along it toward Bishopsgate Street "from the Bank, thinking of the old house with the oaken wainscots hung with pictures of deceased governors and sub-governors of Queen Anne, and the first monarchs of the Brunswick dynasty—huge charts which subsequent discoveries have made antiquated—dusty maps, dim as dreams, and soundings of the Bay of Panama." But Lamb, after all, was only a short time in the South Sea House, while for more than thirty years he was a clerk in the India House, partaking of the genius of the place.

The India House was the abode of a Company far more famous than the South Sea Company, dating back more than a century before the "Bubble" Company, having been brought into existence on the last day of the sixteenth century by good Queen Bess herself. To a visitor, strolling down Leadenhall Street, it recalls the spirit of Lamb to turn into East India [Pg 2] Avenue, and the mind wanders back to Clive and Burke of Macaulay's brilliant essay, in which he impales, with balanced phrase and perfect impartiality, Philip Francis and Warren Hastings alike.

The London merchants were mighty men, men who could select their agents, and send their ships, and risk their money on every sea and on every shore. Nor was this only for gain, but for philanthropy as well. Across yonder is the abode of the New England Company, founded in 1649, and re-established by Charles II. in 1661—begun and still existing with its fixed income "for the propagation of the Gospel in New England and the adjoining parts of America," having had as its first president the Hon. Robert Boyle; and hard by are the offices of the Canada Company, now reaching its three-quarters of a century.

Not always, however, as Macaulay points out, did the trading Companies remember that the pressure on their agents abroad for increased returns meant the temptation to take doubtful or illicit methods to gain their ends. They would have recoiled from the charge of Lady Macbeth,—

Yet on the whole the Merchant Companies of London bear an honourable record, and have had a large share in laying the foundations of England's commercial greatness.

Wandering but a step further past East India Avenue, at the corner of Lime and Leadenhall Streets, we come to-day upon another building sitting somewhat sedately in the very heart of stirring and living commerce. This is the Hudson's Bay House, the successor of the old house on Fenchurch Street, the abode of another Company, whose history goes back for more than two centuries and a quarter, and which is to-day the most vigorous and vivacious of all the sisterhood of companies we have enumerated. While begun as a purely trading Company, it has shown in its remarkable history not only the shrewdness and business skill of the race, called by Napoleon a "nation of shopkeepers," but it has been the governing power over an empire compassing nearly one half [Pg 3] of North America, it has been the patron of science and exploration, the defender of the British flag and name, and the fosterer, to a certain extent, of education and religion.

Not only on the shores of Hudson Bay, but on the Pacific coast, in the prairies of Red River, and among the snows of the Arctic slope, on the rocky shores of Labrador and in the mountain fastnesses of the Yukon, in the posts of Fort William and Nepigon, on Lake Superior, and in far distant Athabasca, among the wild Crees, or greasy Eskimos, or treacherous Chinooks, it has floated the red cross standard, with the well-known letters H. B. C.—an "open sesame" to the resources of a wide extent of territory.

The founding of the Company has features of romance. These may well be detailed, and to do so leads us back several years before the incorporation of the Company by Charles II. in 1670. The story of the first voyage and how it came about is full of interest.

Two French Protestant adventurers—Medard Chouart and Pierre Esprit Radisson—the former born near Meaux, in France, and the other a resident of St. Malo, in Brittany—had gone to Canada about the middle of the seventeenth century. Full of energy and daring, they, some years afterwards, embarked in the fur trade, and had many adventures.

Radisson was first captured by the Iroquois, and adopted into one of their tribes. After two years he escaped, and having been taken to Europe, returned to Montreal. Shortly afterwards he took part in the wars between the Hurons and Iroquois. Chouart was for a time assistant in a Jesuit mission, but, like most young men of the time, yielded to the attractions of the fur trade. He had married first the daughter of Abraham Martin, the French settler, after whom the plains of Abraham at Quebec are named. On her death Chouart married the widowed sister of Radisson, and henceforth the fortunes of the two adventurers were closely bound up together. The marriage of Chouart brought him a certain amount of property, he purchased land out of the proceeds of his ventures, and assumed the title of Seignior, being known as "Sieur des Groseilliers." In the year 1658 Groseilliers and Radisson went on the third expedition to the west, and [Pg 4] returned after an absence of two years, having wintered at Lake Nepigon, which they called "Assiniboines." It is worthy of note that Radisson frankly states in the account of his third voyage that they had not been in the Bay of the North (Hudson Bay).

The fourth voyage of the two partners in 1661 was one of an eventful kind, and led to very important results. They had applied to the Governor for permission to trade in the interior, but this was refused, except on very severe conditions. Having had great success on their previous voyage, and with the spirit of adventure inflamed within them, the partners determined to throw off all authority, and at midnight departed without the Governor's leave, for the far west. During an absence of two years the adventurers turned their canoes northward, and explored the north shore of Lake Superior.

It is in connection with this fourth voyage (1661) that the question has been raised as to whether Radisson and his brother-in-law Groseilliers visited Hudson Bay by land. The conflicting claim to the territory about Hudson Bay by France and England gives interest to this question. Two French writers assert that the two explorers had visited Hudson Bay by land. These are, the one, M. Bacqueville de la Potherie, Paris; and the other, M. Jeremie, Governor of the French ports in Hudson Bay. Though both maintain that Hudson Bay was visited by the two Frenchmen, Radisson and Groseilliers, yet they differ entirely in details, Jeremie stating that they captured some Englishmen there, a plain impossibility.

Oldmixon, an English writer, in 1708, makes the following statement:—"Monsieur Radisson and Monsieur Gooselier, meeting with some savages in the Lake of the Assinipouals, in Canada, they learnt of them that they might go by land to the bottom of the bay, where the English had not yet been. Upon which they desired them to conduct them thither, and the savages accordingly did it." Oldmixon is, however, inaccurate in some other particulars, and probably had little authority for this statement.

THE CRITICAL PASSAGE.

The question arises in Radisson's Journals, which are published in the volume of the Prince Society.

For so great a discovery the passage strikes us as being very short and inadequate, and no other reference of the kind is made in the voyages. It is as follows, being taken from the fourth voyage, page 224:—

"We went away with all hast possible to arrive the sooner at ye great river. We came to the seaside, where we finde an old house all demolished and battered with boullets. We weare told yt those that came there were of two nations, one of the wolf, and the other of the long-horned beast. All those nations are distinguished by the representation of the beasts and animals. They tell us particularities of the Europians. We know ourselves, and what Europ is like, therefore in vaine they tell us as for that. We went from isle to isle all that summer. We pluckt abundance of ducks, as of other sort of fowles; we wanted not fish, nor fresh meat. We weare well beloved, and weare overjoyed that we promised them to come with such shipps as we invented. This place has a great store of cows. The wild men kill not except for necessary use. We went further in the bay to see the place that they weare to pass that summer. That river comes from the lake, and empties itself in ye river of Sagnes (Saguenay) called Tadousac, wch is a hundred leagues in the great river of Canada, as where we are in ye Bay of ye North. We left in this place our marks and rendezvous. The wild men yt brought us defended us above all things, if we would come quietly to them, that we should by no means land, & so goe to the river to the other side, that is to the North, towards the sea, telling us that those people weare very treacherous."

THE CLAIM INVALID.

We would remark as follows:—

1. The fourth voyage may be traced as a journey through Lake Superior, past the pictured rocks on its south side, beyond the copper deposits, westward to where there are prairie meadows, where the Indians grow Indian corn, and where elk and buffalo are found, in fact in the region toward the Mississippi River.

2. The country was toward that of the Nadoneseronons, i.e. the Nadouessi or Sioux; north-east of them were the [Pg 6] Christinos or Crees; so that the region must have been what we know at present as Northern Minnesota. They visited the country of the Sioux, the present States of Dakota, and promised to visit the Christinos on their side of the upper lake, evidently Lake of the Woods or Winnipeg.

3. In the passage before us they were fulfilling their promise. They came to the "seaside." This has given colour to the idea that Hudson Bay is meant. An examination of Radisson's writing shows us, however, that he uses the terms lake and sea interchangeably. For example, in page 155, he speaks of the "Christinos from the bay of the North Sea," which could only refer to the Lake of the Woods or Lake Winnipeg. Again, on page 134, Radisson speaks of the "Lake of the Hurrons which was upon the border of the sea," evidently meaning Lake Superior. On the same page, in the heading of the third voyage, he speaks of the "filthy Lake of the Hurrons, Upper Sea of the East, and Bay of the north," and yet no one has claimed that in this voyage he visited Hudson Bay. Again, elsewhere, Radisson uses the expression, "salted lake" for the Atlantic, which must be crossed to reach France.

4. Thus in the passage "the ruined house on the seaside" would seem to have been one of the lakes mentioned. The Christinos tell them of Europeans, whom they have met a few years before, perhaps an earlier French party on Lake Superior or at the Sault. The lake or sea abounded in islands. This would agree with the Lake of the Woods, where the Christinos lived, and not Hudson Bay. Whatever place it was it had a great store of cows or buffalo. Lake of the Woods is the eastern limit of the buffalo. They are not found on the shores of Hudson Bay.

5. It will be noticed also that he speaks of a river flowing from the lake, when he had gone further in the bay, evidently the extension of the lake, and this river empties itself into the Saguenay. This is plainly pure nonsense. It would be equally nonsensical to speak of it in connection with the Hudson Bay, as no river empties from it into the Saguenay.

Probably looking at the great River Winnipeg as it flows from Lake of the Woods, or Bay of Islands as it was early called, he sees it flowing north-easterly, and with the mistaken [Pg 7]views so common among early voyageurs, conjectures it to run toward the great Saguenay and to empty into it, thence into the St. Lawrence.

6. This passage shows the point reached, which some interpret as Hudson Bay or James Bay, could not have been so, for it speaks of a further point toward the north, toward the sea.

7. Closely interpreted, it is plain that Radisson [1] had not only not visited Hudson or James Bay, but that he had a wrong conception of it altogether. He is simply giving a vague story of the Christinos. [2]

On the return of Groseilliers and Radisson to Quebec, the former was made a prisoner by order of the Governor for illicit trading. The two partners were fined 4000l. for the purpose of erecting a fort at Three Rivers, and 6000l. to go to the general funds of New France.

A GREAT ENTERPRISE.

Filled with a sense of injustice at the amount of the fine placed upon them, the unfortunate traders crossed over to France and sought restitution. It was during their heroic efforts to secure a remission of the fine that the two partners urged the importance, both in Quebec and Paris, of an expedition being sent out to explore Hudson Bay, of which they had heard from the Indians. Their efforts in Paris were fruitless, and they came back to Quebec, burning for revenge upon the rapacious Governor.

Driven to desperation by what they considered a persecution, and no doubt influenced by their being Protestant in faith, the adventurers now turned their faces toward the English. In 1664 they went to Port Royal, in Acadia, and thence to New England. Boston was then the centre of English enterprise in America, and the French explorers brought their case before the merchants of that town. They asserted that having been on Lake Assiniboine, north of Lake Superior, they had there been assured by the Indians that Hudson Bay could be reached.

After much effort they succeeded in engaging a New England ship, which went as far as Lat. 61, to the entrance of Hudson Straits, but on account of the timidity of the master of the ship, the voyage was given up and the expedition was fruitless.

The two enterprising men were then promised by the ship-owners the use of two vessels to go on their search in 1665, but they were again discouraged by one of the vessels being sent on a trip to Sable Isle and the other to the fisheries in the Gulf of St. Lawrence. Groseilliers and Radisson, bitterly disappointed, sought to maintain their rights against the ship-owners in the Courts, and actually won their case, but they were still unable to organize an expedition.

At this juncture the almost discouraged Frenchmen met the two Royal Commissioners who were in America in behalf of Charles II. to settle a number of disputed questions in New England and New York. By one of these, Sir George Carteret, they were induced to visit England. Sir George was no other than the Vice-Chamberlain to the King and Treasurer of the Navy. He and our adventurers sailed for Europe, were captured by a Dutch ship, and after being landed on the coast of Spain, reached England.

Through the influence of Carteret they obtained an audience with King Charles on October 25th, 1666, and he promised that a ship should be supplied to them as soon as possible with which to proceed on their long-planned journey.

Even at this stage another influence came into view in the attempt of De Witt, the Dutch Ambassador, to induce the Frenchmen to desert England and go out under the auspices of Holland. Fortunately they refused these offers.

The war with the Dutch delayed the expedition for one year, and in the second year their vessel received orders too late to be fitted up for the voyage. The assistance of the English ambassador to France, Mr. Montague, was then invoked by Groseilliers and Radisson, now backed up by a number of merchant friends to prepare for the voyage.

Through this influence, an audience was obtained from Prince Rupert, the King's cousin, and his interest was awakened in the enterprise.

It was a remarkable thing that at this time the Royal House of England showed great interest in trade. A writer of a century ago has said, "Charles II., though addicted to pleasure, was capable of useful exertions, and he loved commerce. His brother, the Duke of York, though possessed of less ability, was endowed with greater perseverance, and by a peculiar felicity placed his chief amusement in commercial schemes whilst he possessed the whole influence of the State." "The Duke of York spent half his time in the business of commerce in the city, presiding frequently at meetings of courts of directors."

It will be seen that the circumstances were very favourable for the French enthusiasts who were to lead the way to Hudson Bay, and the royal personages who were anxious to engage in new and profitable schemes.

The first Stock Book (1667) is still in existence in the Hudson's Bay House, in London, and gives an account of the stock taken in the enterprise even before the Company was organized by charter. First on the list is the name of His Royal Highness the Duke of York, and, on the credit side of the account, "By a share presented to him in the stock and adventure by the Governor and Company, 300l."

The second stockholder on the list is the notable Prince Rupert, who took 300l. stock, and paid it up in the next two years, with the exception of 100l. which he transferred to Sir George Carteret, who evidently was the guiding mind in the beginning of the enterprise. Christopher, Duke of Albemarle—the son of the great General Monk, who had been so influential in the restoration of Charles II. to the throne of England, was a stockholder for 500l.

Then came as stockholders, and this before the Company had been formally organized, William, Earl of Craven, well known as a personal friend of Prince Rupert; Henry, Earl of Arlington, a member of the ruling cabal; while Anthony, Earl of Shaftesbury, the versatile minister of Charles, is down for 700l. Sir George Carteret is charged with between six and seven hundred pounds' worth of stock; Sir John Robinson, Sir Robert Vyner, Sir Peter Colleton and others with large sums.

As we have seen, in the year 1667 the project took shape, a [Pg 10] number of those mentioned being responsible for the ship, its cargo, and the expenses of the voyage. Among those who seem to have been most ready with their money were the Duke of Albemarle, Earl of Craven, Sir George Carteret, Sir John Robinson, and Sir Peter Colleton. An entry of great interest is made in connection with the last-named knight. He is credited with 96l. cash paid to the French explorers, who were the originators of the enterprise. It is amusing, however, to see Groseilliers spoken of as "Mr. Gooseberry"—a somewhat inaccurate translation of his name.

Two ships were secured by the merchant adventurers, the Eaglet, Captain Stannard, and the Nonsuch Ketch, Captain Zachariah Gillam. The former vessel has almost been forgotten, because after venturing on the journey, passing the Orkneys, crossing the Atlantic, and approaching Hudson Straits, the master thought the enterprise an impossible one, and returned to London.

Special interest attaches to the Nonsuch Ketch. It was the successful vessel, but another notable thing connected with it was that its New England captain, Zachariah Gillam, had led the expedition of 1664, though now the vessel under his command was one of the King's ships. [3]

It was in June, 1668, that the vessels sailed from Gravesend, on the Thames, and proceeded on their journey, Groseilliers being aboard the Nonsuch, and Radisson in the Eaglet. The Nonsuch found the Bay, discovered little more than half a century before by Hudson, and explored by Button, Fox, and James, the last-named less than forty years before. Captain Gillam is said to have sailed as far north as 75° N. in Baffin Bay, though this is disputed, and then to have returned into Hudson Bay, where, turning southward, he reached the bottom of the Bay on September 29th. Entering a stream, the Nemisco, on the south-east corner of the Bay—a point probably not less than 150 miles from the nearest French possessions in Canada—the party took possession of it, calling it, after the name of their distinguished patron, Prince Rupert's River.

Here, at their camping-place, they met the natives of the district, probably a branch of the Swampy Crees. With the Indians they held a parley, and came to an agreement by which they were allowed to occupy a certain portion of territory. With busy hands they went to work and built a stone fort, in Lat. 51° 20' N., Long. 78° W., which, in honour of their gracious sovereign, they called "Charles Fort."

Not far away from their fort lay Charlton Island, with its shores of white sand, and covered over with a growth of juniper and spruce. To this they crossed on the ice upon the freezing of the river on December 9th. Having made due preparations for the winter, they passed the long and dreary time, finding the cold excessive. As they looked out they saw "Nature looking like a carcase frozen to death."

In April, 1669, however, the cold was almost over, and they were surprised to see the bursting forth of the spring. Satisfied with their journey, they left the Bay in this year and sailed southward to Boston, from which port they crossed the ocean to London, and gave an account of their successful voyage.

The fame of the pioneer explorer is ever an enviable one. There can be but one Columbus, and so for all time this voyage of Zachariah Gillam, because it was the expedition which resulted in the founding of the first fort, and in the beginning of the great movement which has lasted for more than two centuries, will be memorable. It was not an event which made much stir in London at the time, but it was none the less the first of a long series of most important and far-reaching activities.

[2] Mr. Miller Christie, of London, and others are of opinion that Radisson visited Hudson Bay on this fourth voyage.

[3] A copy of the instructions given the captains may be found in State Papers, London, Charles II., 251, No. 180.

HUDSON'S BAY COMPANY FOUNDED.

The success of the first voyage made by the London merchants to Hudson Bay was so marked that the way was open for establishing the Company and carrying on a promising trade. The merchants who had given their names or credit for Gillam's expedition lost no time in applying, with their patron, Prince Rupert, at their head, to King Charles II. for a Charter to enable them more safely to carry out their plans. Their application was, after some delay, granted on May 2nd, 1670.

The modern method of obtaining privileges such as they sought would have been by an application to Parliament; but the seventeenth century was the era of Royal Charters. Much was said in England eighty years after the giving of this Charter, and again in Canada forty years ago, against the illegality and unwisdom of such Royal Charters as the one granted to the Hudson's Bay Company. These criticisms, while perhaps just, scarcely cover the ground in question.

As to the abstract point of the granting of Royal Charters, there would probably be no two opinions to-day, but it was conceded to be a royal prerogative two centuries ago, although the famous scene cannot be forgotten where Queen Elizabeth, in allowing many monopolies which she had granted to be repealed, said in answer to the Address from the House of Commons: "Never since I was a queen did I put my pen to any grant but upon pretext and semblance made to me that it [Pg 13] was both good and beneficial to the subject in general, though private profit to some of my ancient servants who had deserved well.... Never thought was cherished in my heart that tended not to my people's good."

The words, however, of the Imperial Attorney-General and Solicitor-General, Messrs. Bethel and Keating, of Lincoln's Inn, when appealed to by the British Parliament, are very wise: "The questions of the validity and construction of the Hudson's Bay Company Charter cannot be considered apart from the enjoyment that has been had under it during nearly two centuries, and the recognition made of the rights of the Company in various acts, both of the Government and Legislature."

The bestowal of such great privileges as those given to the Hudson's Bay Company are easily accounted for in the prevailing idea as to the royal prerogative, the strong influence at Court in favour of the applicants for the Charter, and, it may be said, in such opinions as that expressed forty years after by Oldmixon: "There being no towns or plantations in this country (Rupert's Land), but two or three forts to defend the factories, we thought we were at liberty to place it in our book where we pleased, and were loth to let our history open with the description of so wretched a Colony. For as rich as the trade to those parts has been or may be, the way of living is such that we cannot reckon any man happy whose lot is cast upon this Bay."

The Charter certainly opens with a breath of unrestrained heartiness on the part of the good-natured King Charles. First on the list of recipients is "our dear entirely beloved Prince Rupert, Count Palatine of the Rhine, Duke of Bavaria and Cumberland, etc," who seems to have taken the King captive, as if by one of his old charges when he gained the name of the fiery Rupert of Edgehill. Though the stock book of the Company has the entry made in favour of Christopher, Duke of Albemarle, yet the Charter contains that of the famous General Monk, who, as "Old George," stood his ground in London during the year of the plague and kept order in the terror-stricken city. The explanation of the occurrence of the two names is found in the fact that the father died in the year [Pg 14] of the granting of the Charter. The reason for the appearance of the name of Sir Philip Carteret in the Charter is not so evident, for not only was Sir George Carteret one of the promoters of the Company, but his name occurs as one of the Court of Adventurers in the year after the granting of the Charter. John Portman, citizen and goldsmith of London, is the only member named who is neither nobleman, knight, nor esquire, but he would seem to have been very useful to the Company as a man of means.

The Charter states that the eighteen incorporators named deserve the privileges granted because they "have at their own great cost and charges undertaken an expedition for Hudson Bay, in the north-west parts of America, for a discovery of a new passage into the South Sea, and for the finding of some trade for furs, minerals, and other considerable commodities, and by such their undertakings, have already made such discoveries as to encourage them to proceed farther in pursuance of their said design, by means whereof there may probably arise great advantage to Us and our kingdoms."

The full name of the Company given in the Charter is, "The Governor and Company of Adventurers of England, trading into Hudson Bay." They have usually been called "The Hudson's Bay Company," the form of the possessive case being kept in the name, though it is usual to speak of the bay itself as Hudson Bay. The adventurers are given the powers of possession, succession, and the legal rights and responsibilities usually bestowed in incorporation, with the power of adopting a seal or changing the same at their "will and pleasure"; and this is granted in the elaborate phraseology found in documents of that period. Full provision is made in the Charter for the election of Governor, Deputy-Governor, and the Managing Committee of seven. It is interesting to notice during the long career of the Company how the simple machinery thus provided was adapted, without amendment, in carrying out the immense projects of the Company during the two and a quarter centuries of its existence.

The grant was certainly sufficiently comprehensive. The opponents of the Company in later days mentioned that King Charles gave away in his sweeping phrase a vast territory of [Pg 15] which he had no conception, and that it was impossible to transfer property which could not be described. In the case of the English Colonies along the Atlantic coast it was held by the holders of the charters that the frontage of the seaboard carried with it the strip of land all the way across the continent. It will be remembered how, in the settlement with the Commissioners after the American Revolution, Lord Shelburne spoke of this theory as the "nonsense of the charters." The Hudson's Bay Company was always very successful in the maintenance of its claim to the full privileges of the Charter, and until the time of the surrender of its territory to Canada kept firm possession of the country from the shore of Hudson Bay even to the Rocky Mountains.

The generous monarch gave the Company "the whole trade of all those seas, streights, and bays, rivers, lakes, creeks, and sounds, in whatsoever latitude they shall be, that lie within the entrance of the streights commonly called Hudson's Streights, together with all the lands, countries, and territories upon the coasts and confines of the seas, streights, bays, lakes, rivers, creeks, and sounds aforesaid, which are not now actually possessed by any of our subjects, or by the subjects of any other Christian prince or State."

The wonderful water system by which this great claim was extended over so vast a portion of the American continent has been often described. The streams running from near the shore of Lake Superior find their way by Rainy Lake, Lake of the Woods, and Lake Winnipeg, then by the River Nelson, to Hudson Bay. Into Lake Winnipeg, which acts as a collecting basin for the interior, also run the Red River and mighty Saskatchewan, the latter in some ways rivalling the Mississippi, and springing from the very heart of the Rocky Mountains. The territory thus drained was all legitimately covered by the language of the Charter. The tenacious hold of its vast domain enabled the Company to secure in later years leases of territory lying beyond it on the Arctic and Pacific slopes. In the grant thus given perhaps the most troublesome feature was the exclusion, even from the territory granted, of the portion "possessed by the subjects of any other Christian prince or State." We shall see afterwards that within less than twenty [Pg 16] years claims were made by the French of a portion of the country on the south side of the Bay; and also a most strenuous contention was put forth at a later date for the French explorers, as having first entered in the territory lying in the basin of the Red and Saskatchewan Rivers. This claim, indeed, was advanced less than fifty years ago by Canada as the possessor of the rights once maintained by French Canada.

The grant in general included the trade of the country, but is made more specific in one of the articles of the Charter, in that "the fisheries within Hudson's Streights, the minerals, including gold, silver, gems, and precious stones, shall be possessed by the Company." It is interesting to note that the country thus vaguely described is recognized as one of the English "Plantations or Colonies in America," and is called, in compliment to the popular Prince, "Rupert's Land."

Perhaps the most astounding gift bestowed by the Charter is not that of the trade, or what might be called, in the phrase of the old Roman law, the "usufruct," but the transfer of the vast territory, possibly more than one quarter or a third of the whole of North America, to hold it "in free and common socage," i.e., as absolute proprietors. The value of this concession was tested in the early years of this century, when the Hudson's Bay Company sold to the Earl of Selkirk a portion of the territory greater in area than the whole of England and Scotland; and in this the Company was supported by the highest legal authorities in England.

To the minds of some, even more remarkable than the transfer of the ownership of so large a territory was the conferring upon the Company by the Crown of the power to make laws, not only for their own forts and plantations, with all their officers and servants, but having force over all persons upon the lands ceded to them so absolutely.

The authority to administer justice is also given in no uncertain terms. The officers of the Company "may have power to judge all persons belonging to the said Governor and Company, or that shall live under them, in all causes, whether civil or criminal, according to the laws of this kingdom, and execute justice accordingly." To this was also added the [Pg 17] power of sending those charged with offences to England to be tried and punished. The authorities, in the course of time, availed themselves of this right. We shall see in the history of the Red River Settlement, in the very heart of Rupert's Land, the spectacle of a community of several thousands of people within a circle having a radius of fifty miles ruled by Hudson's Bay Company authority, with the customs duties collected, certain municipal institutions established, and justice administered, and the people for two generations not possessed of representative institutions.

One of the powers most jealously guarded by all governments is the control of military expeditions. There is a settled unwillingness to allow private individuals to direct or influence them. No qualms of this sort seem to have been in the royal mind over this matter in connection with the Hudson's Bay Company. The Company is fully empowered in the Charter to send ships of war, men, or ammunition into their plantations, allowed to choose and appoint commanders and officers, and even to issue them their commissions.

There is a ludicrous ring about the words empowering the Company to make peace or war with any prince or people whatsoever that are not Christians, and to be permitted for this end to build all necessary castles and fortifications. It seems to have the spirit of the old formula leaving Jews, Turks, and Saracens to the uncovenanted mercies rather than to breathe the nobler principles of a Christian land. Surely, seldom before or since has a Company gone forth thus armed cap-à-pie to win glory and profit for their country.

An important proviso of the Charter, which was largely a logical sequence of the power given to possess the wide territory, was the grant of the "whole, entire, and only Liberty of Trade and Traffick." The claim of a complete monopoly of trade was held most strenuously by the Company from the very beginning. The early history of the Company abounds with accounts of the steps taken to prevent the incoming of interlopers. These were private traders, some from the English colonies in America, and others from England, who fitted out expeditions to trade upon the Bay. Full power was given by the Charter "to seize upon the persons of all such [Pg 18] English or any other subjects, which sail into Hudson's Bay or inhabit in any of the countries, islands, or territories granted to the said Governor and Company, without their leave and license in that behalf first had and obtained."

The abstract question of whether such monopoly may rightly be granted by a free government is a difficult one, and is variously decided by different authorities. The "free trader" was certainly a person greatly disliked in the early days of the Company. Frequent allusions are made in the minutes of the Company, during the first fifty years of its existence, to the arrest and punishment of servants or employés of the Company who secreted valuable furs on their homeward voyage for the purpose of disposing of them. As late as half a century ago, in the more settled parts of Rupert's Land, on the advice of a judge who had a high sense of its prerogative, an attempt was made by the Company to prevent private trading in furs. Very serious local disturbances took place in the Red River Settlement at that time, but wiser counsels prevailed, and in the later years of the Company's régime the imperative character of the right was largely relaxed.

The Charter fittingly closes with a commendation of the Company by the King to the good offices of all admirals, justices, mayors, sheriffs, and other officers of the Crown, enjoining them to give aid, favour, help, and assistance.

With such extensive powers, the wonder is that the Company bears, on the whole, after its long career over such an extended area of operations, and among savage and border people unaccustomed to the restraints of law, so honourable a record. Being governed by men of high standing, many of them closely associated with the operations of government at home, it is very easy to trace how, as "freedom broadened slowly down" from Charles II. to the present time, the method of dealing with subjects and subordinates became more and more gentle and considerate. As one reads the minutes of the Company in the Hudson's Bay House for the first quarter of a century of its history, the tyrannical spirit, even so far at the removal of troublesome or unpopular members of the Committee and the treatment of rivals, is very evident.

This intolerance was of the spirit of the age. In the Restora [Pg 19]tion, the Revolution, and the trials of prisoners after rebellion, men were accustomed to the exercise of the severest penalties for the crimes committed. As the spirit of more gentle administration of law found its way into more peaceful times the Company modified its policy.

The Hudson's Bay Company was, it is true, a keen trader, as the motto, "Pro Pelle Cutem"—"skin for skin"—clearly implies. With this no fault can be found, the more that its methods were nearly all honourable British methods. It never forgot the flag that floated over it. One of the greatest testimonies in its favour was that, when two centuries after its organization it gave up, except as a purely trading company, its power to Canada, yet its authority over the wide-spread Indian population of Rupert's Land was so great, that it was asked by the Canadian Government to retain one-twentieth of the land of that wide domain as a guarantee of its assistance in transferring power from the old to the new régime.

The Indian had in every part of Rupert's Land absolute trust in the good faith of the Company. To have been the possessor of such absolute powers as those given by the Charter; to have on the whole "borne their faculties so meek"; to have been able to carry on government and trade so long and so successfully, is not so much a commendation of the royal donor of the Charter as it is of the clemency and general fairness of the administration, which entitled it not only officially but also really, to the title "The Honourable Hudson's Bay Company."

METHODS OF TRADE.

Rich Mr. Portman—Good ship Prince Rupert—The early adventurers—"Book of Common Prayer"—Five forts—Voting a funeral—Worth of a beaver—To Hudson Bay and back—Selling the pelts—Bottles of sack—Fat dividends—"Victorious as Cæsar"—"Golden Fruit."

The generation that lived between the founding of the Company and the end of the century saw a great development in the trade of the infant enterprise. Meeting sometimes at the place of business of one of the Committee, and afterwards at hired premises, the energetic members of the sub-committee paid close attention to their work. Sir John Robinson, Sir John Kirke, and Mr. Portman acted as one such executive, and the monthly, and at times weekly meetings of the Court of Adventurers were held when they were needed. It brings the past very close to us as we read the minutes, still preserved in the Hudson's Bay House, Leadenhall Street, London, of a meeting at Whitehall in 1671, with His Highness Prince Rupert in the chair, and find the sub-committee appointed to carry on the business. Captain Gillam for a number of years remained in the service of the Company as a trusted captain, and commanded the ship Prince Rupert. Another vessel, the Windingoo, or Wyvenhoe Pinck, was soon added, also in time the Moosongee Dogger, then the Shaftsbury, the Albemarle, and the Craven Bark—the last three named from prominent members of the Company. Not more than three of these ships were in use at the same time.

The fitting out of these ships was a work needing much attention from the sub-committee. Year after year its members went down to Gravesend about the end of May, saw the goods which had been purchased placed aboard the ships, [Pg 21] paid the captain and men their wages, delivered the agents to be sent out their commissions, and exercised plenary power in regard to emergencies which arose. The articles selected indicate very clearly the kind of trade in which the Company engaged. The inventory of goods in 1672 shows how small an affair the trade at first was. "Two hundred fowling-pieces, and powder and shot; 200 brass kettles, size from five to sixteen gallons; twelve gross of knives; 900 or 1000 hatchets," is recorded as being the estimate of cargo for that year.

A few years, however, made a great change. Tobacco, glass beads, 6,000 flints, boxes of red lead, looking-glasses, netting for fishing, pewter dishes, and pewter plates were added to the consignments. That some attention was had by the Company to the morals of their employés is seen in that one ship's cargo was provided with "a book of common prayer, and a book of homilies."

About June 1st, the ship, or ships, sailed from the Thames, rounded the North of Scotland, and were not heard of till October, when they returned with their valuable cargoes. Year after year, as we read the records of the Company's history, we find the vessels sailing out and returning with the greatest regularity, and few losses took place from wind or weather during that time.

The agents of the Company on the Bay seem to have been well selected and generally reliable men. Certain French writers and also the English opponents of the Company have represented them as timid men, afraid to leave the coast and penetrate to the interior, and their conduct has been contrasted with that of the daring, if not reckless, French explorers. It is true that for about one hundred years the Hudson's Bay Company men did not leave the shores of Hudson Bay, but what was the need so long as the Indians came to the coast with their furs and afforded them profitable trade! By the orders of the Company they opened up trade at different places on the shores of the Bay, and we learn from Oldmixon that fifteen years after the founding of the Company there were forts established at (1) Albany River; (2) Hayes Island; (3) Rupert's River; (4) Port Nelson; (5) New Severn. According to another authority, Moose River takes the place of Hayes Island [Pg 22] in this list. These forts and factories, at first primitive and small, were gradually increased in size and comfort until they became, in some cases, quite extensive.

The plan of management was to have a governor appointed over each fort for a term of years, and a certain number of men placed under his direction. In the first year of the Hudson's Bay Company's operations as a corporate body, Governor Charles Bailey was sent out to take charge of Charles Fort at Rupert's River. With him was associated the French adventurer, Radisson, and his nephew, Jean Baptiste Groseilliers. Bailey seems to have been an efficient officer, though fault was found with him by the Company. Ten years after the founding of the Company he died in London, and was voted a funeral by the Company, which took place by twilight to St. Paul's, Covent Garden. The widow of the Governor maintained a contention against the Company for an allowance of 400l., which was given after three years' dispute. Another Governor was William Lydall, as also John Bridgar, Governor of the West Main; and again Henry Sargeant, Thomas Phipps, Governor of Fort Nelson, and John Knight, Governor of Albany, took an active part in the disputes of the Company with the French. Thus, with a considerable amount of friction, the affairs of the Company were conducted on the new and inhospitable coast of Hudson Bay.

To the forts from the vast interior of North America the various tribes of Indians, especially the Crees, Chipewyans, and Eskimos, brought their furs for barter. No doubt the prices were very much in favour of the traders at first, but during the first generation of traders the competition of French traders from the south for their share of the Indian trade tended to correct injustice and give the Indians better prices for their furs.

The following is the standard fixed at this time:—

| Guns | twelve winter beaver skins for largest, ten for medium, eight for smallest. |

| Powder | a beaver for ½ lb. |

| Shot | a beaver for 4 lbs. |

| Hatchets | a beaver for a great and little hatchet. |

| Knives | a beaver for eight great knives and eight jack knives. |

| Beads | a beaver for ½. of beads. |

| Laced coats | six beavers for one. |

| Plain coats | five beavers for one plain red coat. |

| Coats for women, laced, 2 yds. | six beavers. |

| Coats for women, plain | five beavers. |

| Tobacco | a beaver for 1 lb. |

| Powder-horn | a beaver for a large powder-horn and two small ones. |

| Kettles | a beaver for 1 lb. of kettle. |

| Looking-glass and comb | two skins. |

The trade conducted at the posts or factories along the shore was carried on by the local traders so soon as the rivers from the interior—the Nelson and the Churchill—were open, so that by the time the ship from London arrived, say in the end of July or beginning of August, the Indians were beginning to reach the coast. The month of August was a busy month, and by the close of it, or early in September, the ship was loaded and sent back on her journey.

By the end of October the ships arrived from Hudson Bay, and the anxiety of the Company to learn how the season's trade had succeeded was naturally very great. As soon as the vessels had arrived in the Downs or at Portsmouth, word was sent post haste to London, and the results were laid before a Committee of the Company. Much reference is made in the minutes to the difficulty of preventing the men employed in the ships from entering into illicit trade in furs. Strict orders were given to inspect the lockers for furs to prevent private trade. In due time the furs were unladen from the ships and put into the custody of the Company's secretary in the London warehouse.

The matter of selling the furs was one of very great importance. At times the Company found prices low, and deferred their sales until the outlook was more favourable. The method followed was to have an auction, and every precaution was taken to have the sales fair and aboveboard. Evidences are not wanting that at times it was difficult for the Court of Adventurers to secure this very desirable result.

The matter was not, however, one of dry routine, for the London merchants seem to have encouraged business with generous hospitality. On November 9th, 1681, the sale took place, and the following entry is found in the minutes: "A Committee was appointed to provide three dozen bottles of sack and three dozen bottles of claret, to be given to buyers at ye sale. Dinner was also bespoken at 'Ye Stillyard,' of a good dish of fish, a loyne of veal, two pullets, and four ducks."

As the years went on, the same variations in furs that we see in our day took place. New markets were then looked for and arrangements made for sending agents to Holland and finding the connections in Russia, that sales might be effected. In order to carry out the trade it was necessary to take large quantities of hemp from Holland in return for the furs sent. The employment of this article for cordage in the Navy led to the influence of important members of the Company being used with the Earl of Marlborough to secure a sale for this commodity. Pending the sales it was necessary for large sums of money to be advanced to carry on the business of the Company. This was generally accomplished by the liberality of members of the Company itself supplying the needed amounts.