Title: Original Photographs Taken on the Battlefields during the Civil War of the United States

Compiler: Edward Bailey Eaton

Author: Francis Trevelyan Miller

Photographer: Mathew B. Brady

Alexander Gardner

Release date: October 10, 2013 [eBook #43922]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by David Edwards, Ernest Schaal, and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

Original Photographs

Taken on the

BATTLEFIELDS

During the

Civil War of the United States

By Mathew B. Brady and Alexander Gardner

Who operated under the Authority of the War Department and the Protection of the Secret Service

Rare Reproductions from Photographs Selected from Seven Thousand

Original Negatives Taken under Most Hazardous Conditions in the

Midst of One of the Most Terrific Conflicts of Men that the

World Has Ever Known, and in the Earliest Days of

Photography—These Negatives Have Been in

Storage Vaults for More than Forty

Years and are now the

Private Collection of Edward Bailey Eaton

Valued at $150,000

FIRST PRESENTATION FROM THIS HISTORIC COLLECTION

MADE OFFICIALLY AND EXCLUSIVELY

BY THE OWNER

Hartford, Connecticut

1907

COPYRIGHT 1907 BY E. B. EATON

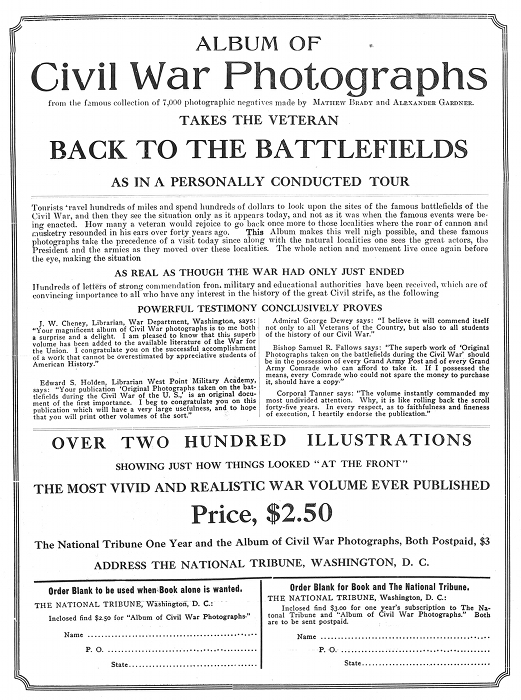

COPIES OF THIS ALBUM MAY BE OBTAINED

BY A REMITTANCE OF THREE DOLLARS TO

EDWARD B. EATON

HARTFORD, CONNECTICUT

PUBLISHER

Martyrs on Altar of Civilization

by

FRANCIS TREVELYAN MILLER

Editor of the Journal of American History

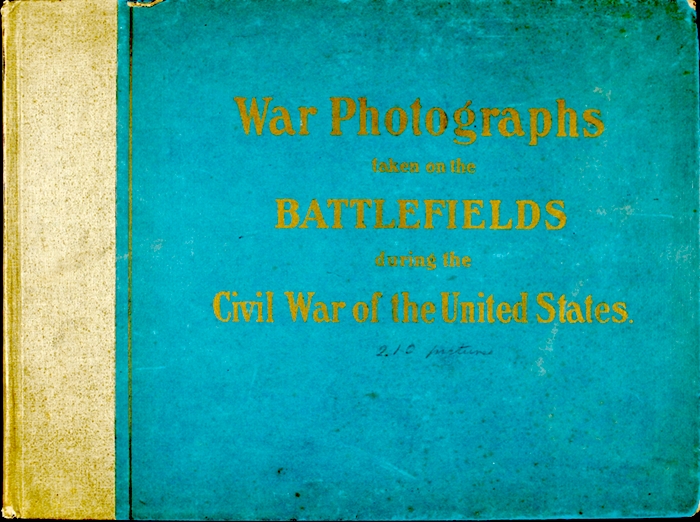

MATHEW BRADY, FIRST WAR PHOTOGRAPHER IN AMERICA

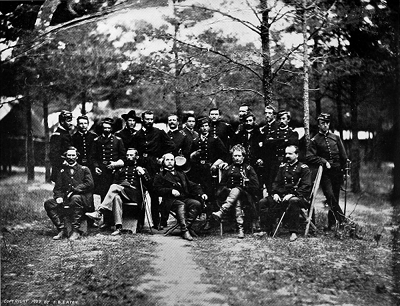

He followed the Armies during the Civil War and secured these remarkable Negatives—In conference with Major-General Burnside at the Headquarters of the Army of the Potomac near Richmond, Virginia—Brady occupies the chair directly in front of the tree while General Burnside is reading a newspaper—This picture was found amoSng his negatives

THIS is undoubtedly the most valuable collection of historic photographs in America. It is believed to be the first time that the camera was used so extensively and practically on the battle-field. It is the first known collection of its size on the Western Continent and it is the only witness of the scenes enacted during the greatest crisis in the annals of the American nation. As a contribution to history it occupies a position that the higher art of painting, or scholarly research and literal description, can never usurp. It records a tragedy that neither the imagination of the painter nor the skill of the historian can so dramatically relate.

The existence of this collection is unknown by the public at large. Even while this book has been in preparation eminent photographers have pronounced it impossible, declaring that photography was not sufficiently advanced at that period to prove of such practical use in War. Distinguished veterans of the Civil War have informed me that they knew positively that there were no cameras in the wake of the army. This incredulity of men in a position to know the truth enhances the value of the collection inasmuch that its genuineness is officially proven by the testimony of those who saw the pictures taken, by the personal statement of the man who took them, and by the Government Records. For forty-two years the original negatives have been in storage, secreted from public view, except as an occasional proof is drawn for some special use. How these negatives came to be taken under most hazardous conditions in the storm and stress of a War that threatened to change the entire history of the world is itself an interesting historical incident. Moreover, it is one of the tragedies of genius.

While the clouds were gathering, which finally broke into the Civil War in the United States, there died in London one named Scott-Archer, a man who had found one of the great factors in civilization, but died poor and before his time because he had overstrained his powers in the cause of science. It was necessary to raise a subscription for his widow, and the government settled upon the children a pension of fifty pounds per annum on the ground that their father was "the discoverer of a scientific process of great value to the nation, from which the inventor had reaped little or no benefit."

This was in 1857, and four years later, when the American Republic became rent by a conflict of brother against brother, Mathew B. Brady of Washington and New York, asked the permission of the Government and the protection of the Secret Service to demonstrate the practicability of Scott-Archer's discovery in the severest test that the invention had ever been given. Brady was an artist by temperament and gained his technical knowledge of portraiture in the rendezvous of Paris. He had been interested in the discoveries of Niepce and Daguerre and Fox-Talbot along the crude lines of photography but with the introduction of the collodion process of Scott-Archer he accepted the science as a profession and, during twenty-five years of labor as a pioneer photographer, took the likenesses of the political celebrities of the epoch and of eminent men and women throughout the country.

Brady's request was granted and he invested heavily in cameras which were made specially for the hard usage of warfare. These cameras were cumbersome and were operated by what is known as the old wet-plate process, requiring a dark room which was carried with them onto the battle-fields. The experimental operations under Brady proved so successful that they attracted the immediate attention of President Lincoln, General Grant and Allan Pinkerton, known as Major Allen and chief of the Secret Service. Equipments were hurried to all divisions of the great army and some of them found their way into the Confederate ranks.

"THE black art," by which Brady secured these photographs, was as mystifying as the work of a magician. It required a knowledge of chemistry and, considering the difficulties, one wonders how Brady had courage to undertake it on the battle-field. He first immersed eighty grains of cotton-wool in a mixture of one ounce each of nitric and sulphuric acids for fifteen seconds, washing them in running water. The pyroxylin was dissolved in a mixture of equal parts of sulphuric ether and absolute alcohol. This solution gave him the ordinary collodion to which he added iodide of potassium and a little potassium bromide. He then poured the iodized collodion on a clean piece of sheet glass and allowed two or three minutes for the film to set. The coated plate was taken into a "dark room," which Brady carried with him, and immersed for about a minute in a bath of thirty grains of silver nitrate to every ounce of water. The plate was now sensitive to white light and must be placed immediately in the camera and exposed and developed within five minutes to get good results, especially in the South during the summer months. It was returned to the dark room at once and developed by pouring over it a mixture of water, one ounce; acetic acid, one dram; pyrogallic acid, three grains, and "fixed" by soaking in a strong solution of hyposulphite of soda or cyanide of potassium. This photograph shows Brady's "dark room" in the Confederate lines southeast of Atlanta, Georgia, shortly before the battle of July 22, 1864. It is a fine example of wet-plate photography.

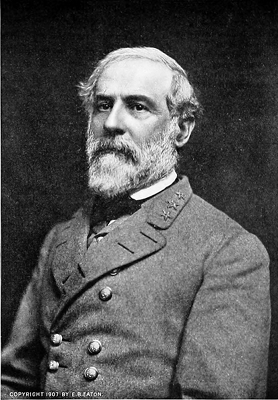

THE secret never has been divulged. How Mr. Brady gained the confidence of such men as Jefferson Davis and General Robert E. Lee, and was passed through the Confederate lines, may never be known. It is certain that he never betrayed the confidence reposed in him and that the negatives were not used for secret service information, and this despite the fact, that Allan Pinkerton and the Artist Brady were intimate. Neither of these men had any idea of the years which the conflict was to rage and Mr. Brady expended all his available funds upon paraphernalia. The government was strained to its utmost resources in keeping its defenders in food and ammunition. It was not concerned in the development of a new science nor the preservation of historical record. It faced a mighty foe of its own blood. It must either fall or rise in a decisive blow.

It was indeed a sorry time for an aesthete. Mr. Brady was unable to secure money. His only recourse was credit. This he secured from Anthony, who was importing photographic materials into America and was a founder of the trade on this continent. The next obstacle was the securing of men competent to operate a camera. Nearly every able-bodied man was engaged in warfare. The science was new and required a knowledge of chemistry. Brady was a man of speculative disposition and plunged into the apparently impossible undertaking of preserving on glass the scenes of action during one of the most tremendous conflicts that the world has known. Pressing toward the firing-line, planting his camera on the field almost before the smoke of artillery and musket had cleared, he came out of the War with his thousands of negatives, perpetuating scenes that human eyes never expected to look upon again. There can be but very few important movements that failed to become imprinted on these glass records.

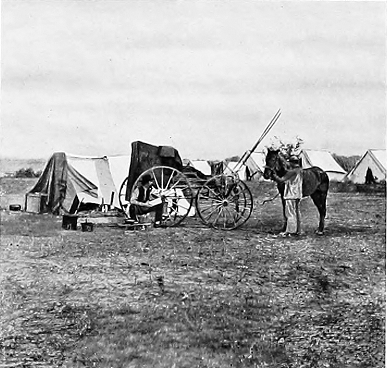

FIRST CAMERAS EVER USED ON THE BATTLEFIELD

One of Brady's Photograph Wagons in the wake of the Army at Manassas on the Fourth of July, in 1862—These mysterious canvas-covered wagons, traveling under the protection of the Secret Service, aroused the curiosity of the soldiers whose frequent queries "What is it?" soon earned for them the epithet of the "What is it?" wagon—Found among Brady's negatives

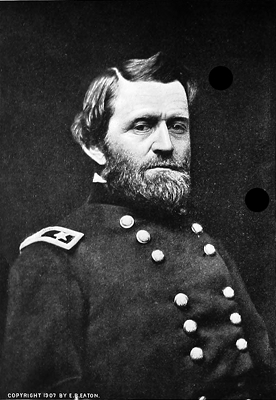

With the close of the War, Brady was in the direst financial straits. He had spent every dollar of the money accumulated in early portraiture and was heavily in debt. Seven thousand of his negatives were sent to New York as security for Anthony, his largest creditor. The remaining six thousand negatives were placed in a warehouse in Washington. Brady then began negotiations for replenishing his funds by disposing of the property. He exhibited proofs of his negatives in galleries of the New York Historical Society the year following the cessation of the conflict. On the twenty-ninth of January of that same year, 1866, the Council of the National Academy of Design adopted a resolution in which it acknowledged the value of the Brady collection as a reliable authority for art and an important contribution to American history. It indorsed the proposal to place the collection permanently with the New York Historical Society. General Ulysses S. Grant had been much interested in the work of Brady on the battlefield, and in a letter written on February third, 1866, spoke of it as "a collection of photographic views of battlefields taken on the spot, while the occurrences represented were taking place." General Grant added: "I knew when many of these representations were being taken and I can say that the scenes are not only spirited and correct, but also well-chosen. The collection will be valuable to the student and artist of the present generation, but how much more valuable it will be to future generations?"

These were days of reconstruction. It was almost impossible to interest men in matters not pertaining to the re-establishment of Commerce and Trade. Brady had spent twenty-five years in collecting the portraits of distinguished personages and endeavored to dispose of these to the Government. The joint committee on libraries, on March third, 1871, recommended the purchase of some two thousand portraits which they called: "A National Collection of Portraits of Eminent Americans." The congressmen, however, faced problems too great to allow them to give attention to pictorial art and took no final action on the subject. In the meantime Brady was unable to meet the bill for storage and the negatives in Washington were offered at auction. William W. Belknap, the Secretary of War, was advised of the conditions and in July, 1874, he paid the storage bill and the negatives fell into possession of the Government. The purchase was made at a public auction and the Government bid was $2840 from money accumulated by Provost Marshals and turned in to the Adjutant-General at the close of the Civil War. The Government Records fail to give a list of the negatives made either at the time of the purchase or for many subsequent years. The original voucher dated July 31st, 1874, is silent as to the number of negatives received by the Government.

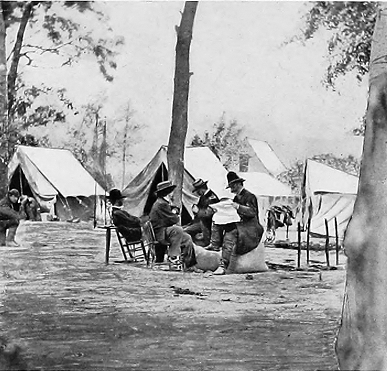

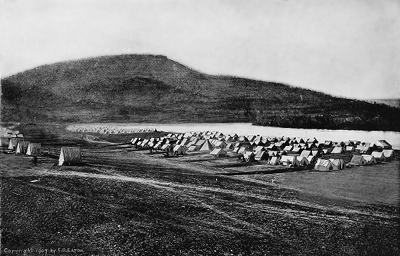

THIS photograph is selected from the seven thousand negatives left by Mathew B. Brady, the celebrated government photographer, as one of the most valuable in existence. It seems to be the first instance on the Western Continent, and possibly in the world, in which a camera successfully imprinted on glass the actual vision of a great army in camp. While scenes such as this are engraved on the memories of the venerable warriors who participated in the terrific struggle this remarkable negative preserves for all ages the magnificent pageant of men, who have offered their lives in defense of their country, waiting for the call to the battle-line. The photograph was taken on a day in the middle of May in 1862 when the Army of the Potomac was encamped at Cumberland Landing on the Pamunky River. A hundred thousand men rested in this city of tents, in the seclusion of the hills, eager to strike a blow for the flag they loved, yet such was the tragic stillness that one who recalls it says that absolute quiet reigned throughout the vast concourse like the peace of the Sabbath-day. On every side were immense fields of wheat, promising an abundant harvest, but trammeled under the feet of the encroaching armies. Occasionally the silence was broken by the strains of a national song that swept from tent to tent as the men smoked and drowsed, fearless of the morrow. The encampment covered many square miles and this picture represents but one brigade on the old Custis place, near White House, which became the estate of General Fitzhugh Lee, the indomitable cavalry leader of the Confederacy and an American patriot during the later war with Spain. The original negative, although now forty-five years old, has required but slight retouching in the background.

GENERAL JAMES A. GARFIELD was fully acquainted with the conditions under which the negatives were taken and the subsequent impoverishment of Mathew Brady. He insisted that something should be done for the man who risked all he had in the world and through misfortune lost the results of his labors. General Benjamin Butler, Congressman from Massachusetts, also felt the injustice, and on his motion a paragraph was inserted in the Sundry Civil Appropriation Bill for $25,000 "to enable the Secretary of War to acquire a full and perfect title to the Brady collection of photographs of the War." The business element in Congress was inclined to question the material value of the negatives. They were but little concerned with the art value and the discussion became a matter of business inventory. Generals Garfield and Butler in reply to the economists declared: "The commercial value of the entire collection is at least $150,000." Ten years after the War, but too late to save him a vestige of business credit, the Government came to Brady's relief and on April 15, 1875, the sum of $25,000 was paid to him. During these years of waiting, Brady had been unable to satisfy the demands of his creditors and an attachment was placed on the negatives in storage in New York. Judgment was rendered to his creditor, Anthony, and the negatives became his property.

Army officers who knew of the existence of the negatives urged the Government to publish them as a part of the Official Records of the War. The Government stated in reply: "The photographic views of the War showing the battlefields, military divisions, fortifications, etc., are among the most authentic and valuable records of the Rebellion. The preservation of these interesting records of the War is too important to be intrusted in glass plates so easily destroyed by accident or design and no more effective means than printing can be devised to save them from destruction." While a few proofs were taken for the purpose of official records, the public still remained unacquainted with the scenes so graphically preserved. One who is acquainted with the conditions says: "From different sources verbal and unofficial, it was learned that quite a number of the negatives were broken through careless handling by the employees of the War Department." The negatives were transferred to the War Records Office and placed under the careful supervision of Colonel R. N. Scott.

BRADY'S "WHAT IS IT?" IN THE CIVIL WAR

The Photographer's Headquarters at Cold Harbor, Virginia, in 1862, where he had taken refuge to prepare his paraphernalia for a long and hazardous journey—It was with much difficulty that the delicate glass negatives were protected from breakage on these daring rides through forests and fields and proofs were taken at the first opportunity that offered

Twenty-five years ago, in 1882, Bierstadt, a chemist, informed the Government: "The breakableness of the glass and the fugitive character of photograph chemicals will in short time obliterate all traces of the scenes these represent. Unless they are reproduced in some permanent form they will soon be lost." Fifty-two negatives were sent to him and he reproduced six of these by a photographic mechanical process. The Government, however, decided that the cost was prohibitive, the expense of making the prints was seventy-five dollars a thousand and would not allow any general circulation.

Honorable John C. Taylor, of Hartford, Connecticut, a veteran of the Civil War, believed that the heroes of the conflict should be allowed to look upon the scenes in which they participated, and made a thorough investigation. Mr. Taylor is now Secretary of the Connecticut Prison Association and Past Commander of Post No. 50, Grand Army of the Republic. In relating his experiences to me a few days ago he said; "I found the seven thousand negatives in New York stored in an old garret. Anthony, the creditor, had drawn prints from some of them and I purchased all that were in his possession. I also made a deal with him to allow me to use the prints exclusively. General Albert Ordway of the Loyal Legion became acquainted with the conditions and, with Colonel Rand of Boston, he purchased the negatives from Anthony who had a clear title through court procedure. I met these gentlemen and contracted to continue my arrangement with them for the exclusive use of the prints. I finally purchased the Brady negatives from General Ordway and Colonel Rand with the intention of bringing them before the eyes of all the old soldiers so that they might see that the lens had forever perpetuated their struggle for the Union. The Government collection had for nine years remained comparatively neglected but through ordinary breakage, lax supervision, and disregard of orders, nearly three hundred of their negatives were broken or lost. To assist them in securing the prints for Government Records I loaned my seven thousand negatives to the Navy Department and shipped them to Washington where they were placed in a fireproof warehouse at 920 E Street, North West. I did all that was possible to facilitate the important work."

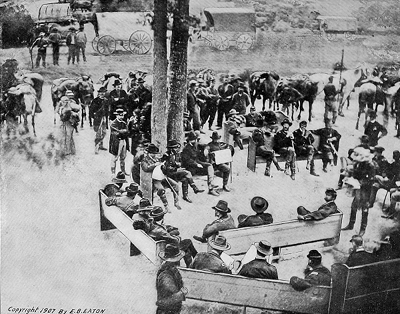

THE lens here perpetuates the interesting spectacle of an army wagon train being "parked" and guarded from a raid by the enemy's cavalry. With a million of the nation's strongest men abandoning production to wage devastation and destruction the problem of providing them with food barely sufficient to sustain life was an almost incalculable enigma. The able-bodied men of the North and the South had turned from the fields and factories to maintain what both conscientiously believed to be their rights. Harvests were left to the elements and the wheels of industry fell into silence. The good women and children at home, aided by men willing but unable to meet the hardships and exposures of warfare, worked heroically to hold their families together and to send to their dear ones at the battle-front whatever comforts came within their humble power. The supply trains of the great armies numbered thousands of six-mule teams and when on the march they would stretch out for many miles. It was in May, in 1863, that one of these wagon trains safely reached Brandy Station, Virginia. Its journey had been one of imminent danger as both armies were in dire need of provisions and the capture of a wagon train was as good fortune as victory in a skirmish. To protect this train from a desperate dash of the Confederate cavalry it was "parked" on the outskirts of a forest that protected it from envious eyes and guarded by the Union lines. One of Mr. Brady's cameras took this photograph during this critical moment. It shows but one division of one corps. As there were three divisions in each corps, and there were many corps in the army, some idea of the immense size of the trains may be gained by this view. The train succeeded in reaching its destination at a time of much need.

ENDEAVORS to reveal these negatives have been futile as far as rank and file of the army and the public at large are concerned. The Government, as the years passed, became impressed with the value of this wonderful record, but has now officially stated with positive finality: "It is evident that these invaluable negatives are rapidly disappearing and in order to insure their preservation it is ordered that hereafter negatives shall not be loaned to private parties for exploitation or to subserve private interest in any manner."

The genius Brady, in possession of $25,000, which, came from the Government too late to save his property, entirely lost track of his collection. Misfortune seemed to follow him and his Government money was soon exhausted. In speaking of him a few days ago, John N. Stewart, Past Vice Commander of the Department of Illinois, Grand Army of the Republic, told me: "I was with the Army of the Potomac as telegraph operator. I knew that views of battlefields were taken by men with a cumbersome outfit as compared with the modern field photographer. I have often wondered what became of their product. I saw Mr. Brady in Washington, shortly before his death, and I made inquiry of him as to the whereabouts of his war scenes. I asked him if the negatives were still in existence and where proofs could be procured. He replied: 'I do not know!' The vast collection must possess great value and be of remarkable historical interest at this late date."

BRADY ON THE BATTLEFIELD OF GETTYSBURG IN JULY 1863—The smoke of the terrific conflict had hardly cleared away when Brady's "What is it" wagon rolled onto the bloody "wheat field"—This picture shows Brady looking toward McPherson's woods on the left of the Chambersburg Pike at the point near which the Battle of Gettysburg began

In talking with Mr. Taylor, in his office at the State Capitol at Hartford, Connecticut, recently he recalled his acquaintance with Brady, and said: "I met him frequently. He was a man of artistic appearance and of very slight physique. I should judge that he was about five feet, six inches tall. He generally wore a broad-brimmed hat similar to those worn by the art students in Paris. His hair was long and bushy. The last time I met him was about twenty-five years after the War and he appeared to be a man of about sixty-five years of age. Despite his financial reverses he was still true to his love for art. I told him that I owned seven thousand of his negatives and he seemed to be pleased. He became reminiscent and among the things that he told me I especially remember these words: 'No one will ever know what I went through in securing those negatives. The world can never appreciate it. It changed the whole course of my life. By persistence and all the political influence that I could control I finally secured permission from Stanton, the Secretary of War, to go onto the battlefields with my cameras. Some of those negatives nearly cost me my life.'" Mr. Brady told Mr. Taylor of his difficulty in finding men to operate his cameras.

"PINKERTON" is a name associated with the discovery of crime the world over. It is a word shrouded in mystery and through it works one of the most subtle forces on the face of the earth to-day. Sixty-five years ago an unassuming man fled from Scotland to America. It was charged against him that he was a chartist. Eight years later he was in Chicago established in the detection of crime. While the distant rumbles of a Civil War were warning the nation, he went to Washington and became closely attached to President Lincoln. When a plot was organized to assassinate Lincoln in his first days of the presidency, this strange man discovered the murderous compact. It was he who, in 1861, hurriedly organized the Secret Service of the National Army and forestalled conspiracies that threatened to overthrow the Republic. In speaking of himself he once said: "Now that it is all over I am tempted to reveal the secret. I have had many intimate friends in the army and in the government. They all know Major E. J. Allen, but many of them will never know that their friend, Major Allen and Allan Pinkerton, are one and the same person." To those who knew Major Allen this picture is dedicated. It reveals Allan Pinkerton divested of all mystery, father of the great system that has literally drawn a net around the world into which all fugitive wrongdoers must eventually fall. Under the guise of Major Allen, chief of the Secret Service in the Civil War, he was passing through the camp at Antietam one September day in 1862. He was riding his favorite horse and carelessly smoking a cigar when one of Mr. Brady's men called to him to halt a moment while he took this picture.

BRADY said he always made two exposures of the same scene, sometimes with a shift of the camera which gave a slight change in the same general view. He related several interesting incidents of his early experiences in photography in America. It is generally conceded that Mr. Brady should be recognized as one of the great figures of the epoch in which he worked.

It is here my duty to record an unfortunate incident that is not unusual in the annals of art and literature. Brady's life, which seems to have been burdened with more ill luck than the ordinary lot of man, found little relief in its venerable years. Misfortune followed him to the very threshold of his last hour. He died about eight years ago in New York, with a few staunch friends, but without money, and without public recognition for his services to mankind. Since Brady's death some of those who knew and esteemed him have been interested in making a last endeavor to bring his work before the world. Mr. Taylor has worked unceasingly to accomplish this result. The late Daniel S. Lamont, Secretary of War in President Cleveland's Cabinet, was much interested. Brigadier-General A. W. Greeley, in supervisory charge of the Government collection, said: "This collection cost the United States originally the sum of $27,840, and it is a matter of general regret that these invaluable reproductions of scenes and faces connected with the late civil conflict should remain inaccessible to the general public. The features of most of the permanent actors connected with the War for the Union have been preserved in these negatives, where also are portrayed certain physical aspects of the War that are of interest and of historic value ... graphic representations of the greatest of American, if not of all, wars."

SECRET SERVICE GUIDE DIRECTING BRADY TO SCENE OF ACTION—Pointing toward the edge of the woods where General Reynolds was killed at Gettysburg in July, 1863—Brady carried his cameras onto this field

The Government, however, has stated positively that their negatives must not be exploited for commercial purposes. They are the historic treasures of the whole people and the Government has justly refused to establish a dangerous system of "special privilege" by granting permission for publication to individuals. As the property of the people the Government negatives are held in sacred trust.

Mr. Edward B. Eaton, the first president of the Connecticut Magazine, one of the leading historical publications in this country, became interested in the historical significance of the Brady collection and conferred with the War Department at Washington about the Brady negatives. He found that the only possible way to bring the scenes before the public was through the private collection which not only includes practically all of the six thousand Government negatives but is supplemented by a thousand negatives not in the Government collection.

Mr. Johann Olsen of Hartford, who was one of the first operators of the old wet-plate process used by Brady, personally examined many of the negatives in storage in Washington and stated that some action should be taken immediately. He says: "Many of the negatives are undergoing chemical action which will soon destroy them. Others are in a remarkable state of preservation. I have found among them some of the finest specimens of photography that this country has ever seen. The modern development of the art is placed at a disadvantage when compared with some of these wonderful negatives. I do not believe that General Garfield overestimated their value when he said they were worth $150,000. I do not believe that their value to American History can be estimated in dollars. I was personally acquainted with one of Brady's men at the time these pictures were taken and I know something of the tremendous difficulties in securing them." A few months ago Mr. Eaton secured a clear title to the seven thousand Brady negatives owned by Mr. Taylor with a full understanding that he would immediately place the scenes before the public. The delicate glass plates were fully protected and removed from Washington to Hartford, where they are today in storage in a fire-proof vault.

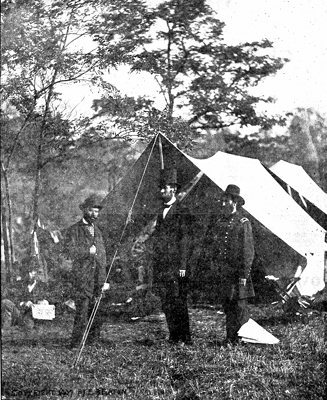

THIS is conceded to be the most characteristic photograph of Lincoln ever taken. It shows him on the battle-field, towering head and shoulders above his army officers. It is said that Lincoln once sent for this photograph and after looking at it for several minutes he remarked that it was the best full-length picture that the camera had ever "perpetrated." The original negative is in a good state of preservation. The greater significance of this picture, however, is the incident which it perpetuates. There had been unfortunate differences between the government and the Army of the Potomac. The future of the Union cause looked dark. A critical state of the disorder had been reached; collapse seemed imminent. On the first day of October, in 1862, President Lincoln went to the headquarters of the Army of the Potomac and traversed the scenes of action, walking over the battlefields of South Mountain, Crampton's Gap, and Antietam with General McClellan. As Lincoln was bidding good-bye to McClellan and a group of officers at Antietam on October 4, 1862, this photograph was taken. Two days later Lincoln ordered McClellan to cross the Potomac and give battle to the enemy. Misunderstandings followed, and on the fifth of November, President Lincoln, with his own hand, wrote the historic order that deposed the beloved commander of the Potomac, and started controversies which are still renewed and vigorously argued by army officers and historians. It is one of the sad incidents of the passing of a hero, who had endeared himself to his men as have few generals in the annals of war.

MODERN photographers have experienced some difficulty in securing proofs from the collodion negatives, due both to the years that the negatives have been neglected and their inexperience with the peculiar wet-plate process. Mr. Olsen is still working over them and has succeeded in stopping the chemical action that threatened to destroy many of them. Six thousand of the negatives are pronounced to be in as good condition today as on the day they were taken, nearly a half-century ago. Accompanying the collection is found an occasional negative that seems to have been made by Alexander Gardner or Samuel Cooley. Gardner was one of the photographers employed by Brady, but he later left him and entered into competition. Cooley was an early photographer who conceived a plan similar to Brady's, but operated on a very limited scale. Most of his negatives were taken in South Carolina.

From this remarkable collection, witnessing the darkest days on the American continent and the first days of modern American photography, the prints are selected for these pages and are here dedicated to the American People. Until recent years there has been no mechanical process by which these negatives could be reproduced for general observation. The negatives are here accurately presented from the originals, by the modern half-tone process with only the slightest retouching where chemical action has made it absolutely necessary.

In selecting these prints it has been the desire of the editor to present, as nearly as possible, a chronological pictorial record of the Civil War in the United States. At strategic points where the large cameras could not be drawn into the conflict, Brady used a smaller and lighter camera that allowed him to get very close to the field of action. Many of the most critical moments in the long siege are embodied in these small negatives. They link the larger pictures into one strong chain of indisputable evidence. It would require forty volumes to present the entire collection. This book can be but a kaleidoscopic vision of the great conflict. Thousands of remarkable scenes must for the present, at least remain unveiled. That the public may know just what these negatives conceal, a partial record has been compiled in the closing pages of this volume.

It has been estimated that since the beginning of authentic history war has destroyed fifteen billions of human lives. I have seen the estimate put at twice that number. The estimated loss of life by war in the past century is fourteen millions. Napoleon's campaigns of twenty years cost Europe six millions of lives.

| The Crimean War | 1854 | 750,000 |

| The Italian War | 1859 | 63,000 |

| Our Civil War, North and South | (killed and died in other ways) | 1,000,000 |

| The Prussian-Austrian War | 1866 | 45,000 |

| The expeditions to Mexico, China, Morocco, etc | 65,000 | |

| The Franco-German War | 1870 | 250,000 |

| The Russo-Turkish War | 1877 | 225,000 |

| The Zulu and Afghan Wars | 1879 | 40,000 |

| The Chinese-Japanese War | 1894 | 10,000 |

| The Spanish-American War | 5,000 | |

| The Philippine War | 1899 | { Americans 5,000 { Filipinos 1,000,000 |

| The Boer War | (killed and wounded) | { Boers 25,000 { British 100,000 |

| The Russo-Japanese War | 450,500 |

These are probably all under the actual facts.

The drama here revealed by the lens is one of intense realism. In it one can almost hear the beat of the drum and the call of the bugle. It throbs with all the passions known to humanity. It brings one face to face with the madness of battle, the thrill of victory, the broken heart of defeat. There is in it the loyalty of comradeship, the tenderness of brotherhood, the pathos of the soldier's last hour; the willingness to sacrifice, the fidelity to principle, the love of country.

Far be it from the power of these old negatives to bring back the memory of forgotten dissensions or long-gone contentions. Whatever may have been the differences that threw a million of America's strongest manhood into bloody combat, each one offered his life for what he believed to be the right. The American People today are more strongly united then ever before—North, South, East and West, all are working for the moral, the intellectual, the industrial and political upbuilding of Our Beloved Land.

The path of Progress has been blazed by fire. Strong men with strong purposes have thrown their lives on the altar of civilization that their children and their children's children might live and work in the light of a new epoch that found its birth in the agonizing throes of human sacrifice. From the beginning of all ages the soldier has been, and always must be, a mighty man.

He who will step deliberately into the demon's jaws to defend a principle or to save his country must be among the greatest of men. His is the heroic heart to whom the world must look for the dawn of the Age of Universal Peace. It is his courageous arm that must force the world to halt. The citizenship of the future must be moulded and dominated by the men with the willingness to sacrifice for the sake of Justice and such men are soldiers, whether it be in War or Peace.

There is a longing in the hearts of men, and especially those who have felt the ravages of battle, for the day when there shall be no more War; when Force will be dethroned and Reason will rule triumphant. The Great Washington, who led the conflict for our National Independence, longed for the epoch of Peace. "My first wish," he exclaimed, "is to see this plague to mankind banished from the earth."

The mission of these pages is one of Peace—that all may look upon the horrors of War and pledge their manhood to "Peace on Earth, Good Will toward Men!"

"WAR is hell!" The daring Sherman's familiar truth is here witnessed with all its horrors. War is hell, and this is war! If it were not for the service that this negative should do for the great cause of the world's Peace, this picture, which has lain in a vault in Washington for an epoch, would never be exposed to public view. Its very gruesomeness is a plea to men to lay down arms. Its ghastliness is an admonition to the coming generations. It is a silent prayer for universal brotherhood. The negative was taken after the third day's battle at Gettysburg. The din of the batteries had died away. The clash of arms had ceased. The tumult of men was hushed. The clouds of smoke had lifted and the morning sun engraved on the glass plate this mute witness of the tragedy that had made history. It was the nation's holiday—the Fourth of July in 1863. The camera was taken into the wheat-field near the extreme left of the Union line. The heroes had been dead about nineteen hours. It will be observed that their bodies are already much bloated by exposure to the sun. These men were killed on July 3, 1863, by one discharge of "canister" from a Confederate cannon which they were attempting to capture. Tin cans were filled with small balls about the size of marbles and when the cannon was fired the force of the discharge burst open the can, and the shower of canister balls swept everything before it. When this photograph was taken a detail had already passed over the field, and gathered the guns and accoutrements of the dead and wounded. Shoes, cartridge belts and canteens have been removed from these dead heroes as it was frequently necessary to appropriate them to relieve the needs of the living soldiers. From diamond at extreme right of picture these men are identified as belonging to the second division of third army corps.

IN the conflicts within the lifetime of men now living, more than three billions of dollars sterling have been thrown into the cannon's mouth, and nearly five millions of human lives have fallen martyrs to the battlefield. In the United States of America, a government founded on the Brotherhood of Man, the greatest expenditure since the beginning of the Republic has been for bloodshed, over six billions for War, nearly two billions for navy, and about three and one-half billions for pensions—more than eleven billions out of a total of something over nineteen billions of dollars. In the last half century the population of the world has doubled; its indebtedness, chiefly for war purposes, has quadrupled. It was but eight billions fifty years ago; it is thirty-two billions today.

America has never been a war-seeking nation. Its one desire has been to "live and let live." When once aroused, however, it is the greatest fighting force on the face of the globe. It is in this peace-loving land that civilization witnessed the most terrible and heart-rending struggle that ever befell men of the same blood. "Men speaking the same language, living for eighty-four years under the same flag, stood as enemies in deadly combat. Brother fighting against brother; father against son; mothers praying for their boys—one in the uniform of blue, and the other wearing the gray; and churches of the same faith appealing to God, each for the other's overthrow."

There were 2,841,906 men and boys sworn into the defence of their country during the Civil War in the United States. The extreme youth of these patriots is one of the most remarkable records in the annals of the world's warfare. The average age of the soldier in the army and navy was about nineteen years. Some of them followed the marching armies on the impulse of the moment; most of them were enlisted with the consent of their parents or guardians. Thousands of them never returned home; thousands more came back to the pursuits of Peace and have contributed for nearly a half century to the Good Citizenship of the Republic. Today they are gray-haired patriarchs. One by one they are stepping from the ranks to answer the call to the Greater Army from which no soldier has ever returned. This record has been compiled for this volume from an authoritative source. The men who re-enlisted are counted twice as there is no practical way to estimate the number of individual persons:

When the Great Struggle began, the United States was the home of less than thirty-two millions of people. Today it has passed eighty millions and the peoples from all the nations of the earth are flooding into our open gates to the extent of more than a million a year. A new community of more than three thousand inhabitants could be founded every day from the men, women and children who disembark from the sea of ships charted to the American shores. There are among us today more than forty-eight millions who have been born here or immigrated into this country since the beginning of the Civil War. These people have no personal knowledge of it and their information is gathered from the narrations of others. These Brady negatives will come as a revelation to them and give a truer understanding of the meaning of it all. The good service they may do for the nation in this one respect cannot be overestimated.

With thirty-two millions of people aroused by an overpowering impulse that dared them to follow the dictates of conscience by pledging their loyalty to the states they loved—whether it be under Southern suns or Northern snows—it is almost beyond comprehension that Brady came out of the chaos with even one photographic record. While his extensive operations could not begin until system and organization were accomplished, he did secure many negatives in 1861.

Hardly had the news of the first gun passed around the globe when a half million men were offering their services to their country. Loyal Massachusetts was the first to march her strong and willing sons to the protection of the Government. The shrill notes of the fife sounded throughout the land and battle-scarred old Europe beheld in amazement the marshalling of great armies from a nation of volunteer patriots wholly inexperienced in military discipline—a miracle in the eyes of older civilization that had been drenched in the blood of centuries.

It was the simultaneous uprising of a Great People. The first shot from South Carolina transformed Virginia, the beloved mother of presidents, into a battleground. The streets of Baltimore became a scene of riot. The guns of the navy boomed on the North Carolina coast. The men of the West moved on through Missouri, blazing their way with shot and shell. Through Kentucky and Tennessee the reign of fire swept on until it re-echoed from Florida on the gulf to the wilderness of New Mexico and the borderline of Texas.

The American Republic was in the clutches of terrific conflict and in the first twelve months nearly a million and a quarter of its manhood was fighting for the National Flag. There was no turning from the struggle. It must be waged to its deadliest end. From this moment, for four dreadful years, fighting was taking place somewhere along the line every day and more than seven thousand battles and skirmishes were fought on land and sea.

Nearly three-fourths of the men who stood in the Union ranks in the Civil War were native-born Americans. The others were the best and bravest blood of fellow-nations.

"THEY have fired on Fort Sumter!" These are the words that rang across the continent on the morning of the twelfth of April, in 1861, and the echo was heard around the world. The shot that began one of the fiercest conflicts that civilization has ever seen was fired just before sunrise at four in the morning. Special editions of newspapers heralded the tidings through the land. Thousands of excited men crowded the streets. Trade was suspended. Night and day the people thronged the thoroughfares, eager to hear the latest word from the scene of action. Friday and Saturday were the most anxious days that the American people have ever experienced. When the news came on Sunday morning that Major Robert Anderson had evacuated the fort with flags flying and drums beating "Yankee Doodle," the North was electrified with patriotism. The stars and stripes were thrown to the breeze from spires of churches, windows of residences, railway stations and public buildings. The fife and drum were heard in the streets. Recruiting offices were opened on public squares. Men left their business and stepped into the ranks. A few days later, when the brave defenders of Fort Sumter reached New York, the air was alive with floating banners. Flowers, fruits and delicacies were showered upon the one hundred and twenty-nine courageous men who had so gallantly withstood the onslaught of six thousand. Crowds seized the heroes and carried them through the streets on their shoulders. The South was mad with victory. It was believed that its independence had been already gained. Several days after the bombardment this picture was secured of the historic fort in South Carolina, about which centered the beginning of a great war. It was taken in four sections and this is a panoramic view of them all. The photograph did not fall into the possession of the Government, but was held for many years by a Confederate naval officer, Daniel Ellis, commander of the twenty-gun ram "Chicora" and at one time in command of Fort Sumter. It is now in possession of James W. Eldridge of Hartford. It corrects the erroneous impression that the fort was demolished in 1861. It stood the bombardment with but slight damage, other than a few holes knocked in the masonry as this picture testifies. In saluting the American flag before the evacuation on April 15, Private Daniel Hough was killed and three men wounded by the premature explosion of one of their own guns.

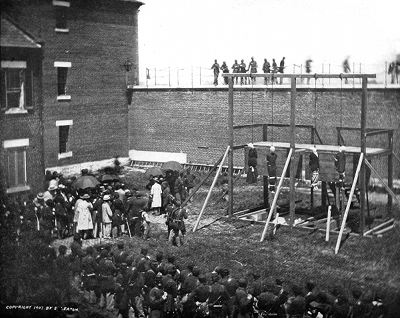

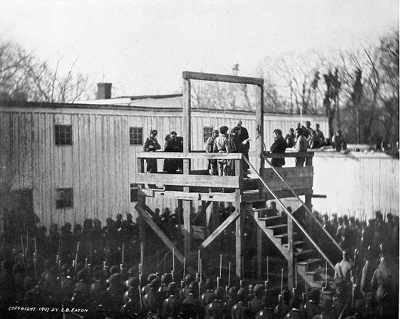

"JOHN BROWN'S body lies a-mouldering in the grave; his soul is marching on!" In every public meeting, through village and town, along the lines of recruits marching to the front, around the army campfires, this song became the battle-cry. It had been but three years since John Brown, with seventeen whites and five negroes, seized the United States Arsenal at Harper's Ferry, Virginia, and began the freeing of slaves. It required eighteen hours and 1,500 militia and marines to subdue the ardent abolitionist. He took refuge in the armory engine house. The doors were battered down. Eight of the insurgents were killed. Brown, with three whites and a half dozen negroes, was captured and hanged. The Confederates planned its capture, but upon their approach on the eighteenth of April, in 1861, three days after the firing on Fort Sumter, they found only the burning arsenal. They held the coveted position with 6,500 men, but fearing the attack of 20,000 Unionists, deserted it. It was held by the Union troops until 1862, when, on the fifteenth of September, Stonewall Jackson bombarded the town and forced its surrender. The Union loss was 80 killed, 120 wounded, 11,583 captured. The Confederate loss was 500. In this engagement were the brave boys of the 12th New York State Militia; 39th, 111th, 115th, 125th and 126th New York; 32nd, 60th and 87th Ohio; 9th Vermont; 65th Illinois; 1st and 3rd Maryland "Home Brigade;" 15th Indiana Volunteers; Phillips' Battery; 5th New York; Graham's, Pott's and Rigby's Batteries; 8th New York; 12th Illinois, and 1st Maryland Cavalry. It was during these days that the Army of the Potomac engaged the Confederate forces in bloody conflict at Turner's and Crampton's Gap, South Mountain, Maryland, leaving Harper's Ferry again in the hands of the Union.

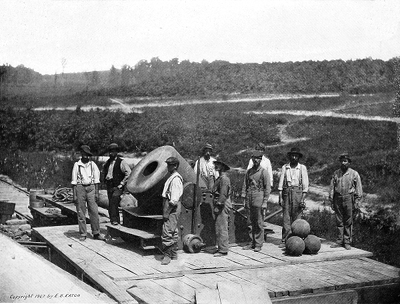

THERE is not a fleet on the seas that can withstand a modern battery if kept under fire by proper obstructions. Modern sea-coast artillery can destroy a vessel at a single shot. The watchdog that guarded the waterway to the National Capital in the Civil War was Fortress Monroe. The old stone fort, partially protected by masses of earth that sheltered it from the view and fire of the assailant, challenged the ugliest iron-clads to pass through Hampton Roads. Fortress Monroe early became the base of operations and under its protection volunteer regiments were mobilized. When the 2nd New York Volunteers reached the fort, about six weeks after the firing on Fort Sumter, the 4th Massachusetts Volunteers had come to the assistance of the regular garrison of four companies of artillery on duty day and night over their guns. Something of the conditions may be understood by the statement of an officer who says that his men had to appear on parade with blankets wrapped about them to conceal a lack of proper garments, and sometimes stood sentinel with naked feet and almost naked bodies. The volunteers arrived faster than provisions could be furnished and there was a scarcity of food. So great was the difficulty in procuring small arms that some of the soldiers were not really fitted for war during the year of 1861. The Government operations were centered around Fortress Monroe and President Lincoln personally visited the headquarters to ascertain the actual conditions. Brady was admitted behind the parapets with his camera and secured this photograph of one of the heaviest guns in the great fortification.

TO feed the millions of fighting men in both armies during the years 1861 to 1865, was an enigma equalled only by the problem of ammunition. After the diets of hardtack on the long marches there is no memory dearer to the heart of the old veteran than a good, old-fashioned "square meal" from the log-cabin kitchen in the camp. This is a typical scene of one of these winter camps. They were substantially built of logs, chinked in with mud and provided on one end with a generous mud chimney and fireplace. The most "palatial" afforded a door and a window. Roaring fires burned on the hearths. With the arrival of the soldiers, knapsacks and traps were unpacked. The canteen was hung on its proper peg. The musket found its place on the wall. The old frying pan and tin cup were hung near the fire. There was to be a real "old home feast." The soldiers crowded around the sutler's tent dickering over canned goods and other luxuries which cost perhaps a half-month's pay. The log settlement was all astir. Smoke issued from the mud chimneys. Crackling fires and savory odors lightened the hearts of the warriors and the community of huts rang with jovialty, laughter and song. Stories of the conflict were told as the soldiers revelled over the hot and hearty meal and not until the late hours did the tired comrades wrap themselves in their blankets and fall onto their beds of pine needles or hard board bunks.

THE charge of the cavalry is an intense moment on the battlefield. At the time of the Civil War nothing was known of the snap-shot process in photography and Brady tried frequently throughout the four years to secure negatives of the cavalry. It seems to have been an impossibility under the long "time exposure process." He did, however, succeed in securing negatives of horses. Frequent opportunity to try to secure a photograph of the cavalry, is proven by the fact that there were 3,266 troops, or more than 272 regiments, in defense of the Government. This picture is found in Brady's collection and shows the cavalry depot at Giesboro Point, Maryland, just outside of Washington. At the beginning of the war the mounted men were used as scouts, orderlies, and in outpost duty. General "Joe" Hooker finally turned a multitude of detachments into a compact army corps of 12,000 horsemen. The gallant horseman, "Phil" Sheridan, under instructions from General Grant, organized three divisions of 5,000 mounted men, each armed with repeating carbines and sabers. It was with this force that Sheridan met the Confederate cavalry at Yellow Tavern, near Richmond, and demonstrated the importance of mounted troops by great military powers. One of the most magnificent scenes in the war was when 10,000 horsemen moved out on the Telegraph Road leading from Fredericksburg to Richmond, and the column, as it stood in "fours," well closed up, was thirteen miles long and required four hours to pass a given point.

"CAPTURE the National Capital, throw the city into confusion and terror by conflagration, seize the President and his Cabinet, and secure control of the Government." This was the first cry of the Confederacy. Thousands of volunteers were moving toward the city in answer to the call for men to save the Nation. Orders were issued to hold back the enemy from crossing the bridges that entered Washington. Two batteries were thrown up at the east end of the Upper, or Chain Bridge, and a heavy two-leaved gate covered with iron plates pierced for musketry, was constructed at the center of the bridge. Blockhouses at Arlington Heights and the battery at Georgetown Heights, guarded the Aqueduct Bridge. The largest approach to Washington was the famous Long Bridge, a mile in length, and connecting the National Capital with Alexandria, Virginia, the gateway to the Confederacy. Three earthen forts commanded its entrance. All soldiers of the Army of the Potomac remember Long Bridge. It was over this structure that a hundred thousand men passed in defense of their country, many of them never to recross it. This was one of the strategic points in the first days of the war and consequently one of the first pictures taken by Brady, with its sentinel on duty and the sergeant of the guard ready to examine the pass. No man ever crossed Long Bridge without this written oath: "It is understood that the within named and subscriber accepts this pass on his word of honor that he is and will be ever loyal to the United States; and if hereafter found in arms against the Union, or in any way aiding her enemies, the penalty will be death."

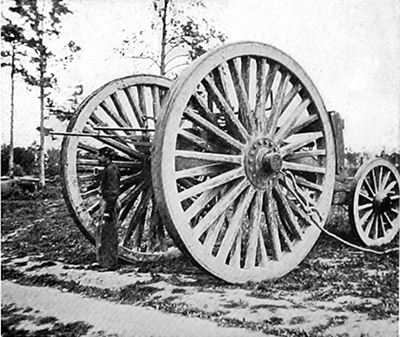

THERE is nothing impossible to any army in time of war. Bridges are thrown across rivers in a night; roads are constructed as the line advances; telegraph wires are uncoiled in the wake of the moving regiments. To protect from a delay that might mean defeat, the army frequently carried its own "bridges" with it. These army or pontoon bridges consisted of boats over which planks were thrown to span the waterways. This view shows two of the boat's wheels ready for the march. Each pontoon wagon is drawn by six mules. These pontoons were always getting stuck in the mud, and the soldiers, struggling along under their own burdens, were obliged to haul on the drag ropes, and raise the blockade. Probably no soldier will see this picture without being reminded of the time when he helped to pull these pontoons out of the mud, and comforted himself by shouting at the mules. A view is also shown of a pontoon bridge across the James River ready for the approach of the army. It was often necessary to establish an immediate telegraph service between different points in the lines. This photograph shows one of the characteristic field telegraph stations. An old piece of canvas stretched over some rails forms the telegrapher's office, and a "hardtack" box is his telegraph table; but from such a rude station messages were often sent which involved the lives of hundreds and thousands of soldiers. The building of corduroy roads to allow ammunition and provision trains to pass on their journeys was of utmost importance. An hour's delay might throw them into the hands of the enemy. Many disasters were averted by the ingenuity of the engineers' corps.

"IF any one attempts to haul down the American flag, shoot him on the spot!" The order rang from town to town. Old Glory waved in the breeze defiantly. "The flag of the Confederacy will be hoisted over Washington within sixty days," came the retort from the far South. "Only over our dead bodies," replied the men of the North. The National Government discovered that a conspiracy had been in operation to denude its armories and weaken its defenses. Political influences had secretly disarmed the incoming administration, scattering the regular army in helpless and hopeless positions far from the seat of the Government and beyond its call in an emergency. Northern forts had been dismantled and the munitions from Northern arsenals had been dispatched to Southern vantage grounds to be used in case of necessity. The treasury had been depleted and the Government was on the verge of bankruptcy. Eleven of the historic old states of the Union had withdrawn and formed a new republic, the "Confederate States of America." These were the conditions that confronted Lincoln in his first days of the Presidency. Plots were rampant to take his life. His steps were shadowed by Secret Service detectives to safeguard him against assassins, and he was practically held a prisoner in the White House. In further protection the defenses around the city were strengthened. From every hillside grim guns turned their deep mouths into the valleys until a chain of fortifications made the city impregnable. Brady secured permission to take his cameras into these fortifications. This is the best negative which he secured. It is taken behind the breastworks at Fort Lincoln, near Washington.

THE first serious collision of the two great armies of divided Americans took place at Bull Run, in Virginia, on the twenty-first of July, in 1861. The Government had confined its operations almost wholly to the protection of Washington, and the public demand for more aggressive action was loud and alarming. The Confederate pickets had become so confident that they advanced within sight of the National Capital. Accusations were strong against the seeming desire of the Government to evade the enemy. Charges of deliberate delay and cowardice came from the North. "On to Richmond," the stronghold of the Confederacy, was the demand. So great became the public clamor that, despite the judgment of military authorities, 29,000 Federals under McDowell advanced against the 32,000 Confederates under Beauregard, driving them back only to be repulsed, after one of the hardest and strangest combats that military history has ever recorded. The Union ranks were so demoralized that they retreated without orders and straggled back to Washington, although a strong stand might have turned the tide of battle. The Union loss was 481 killed; 2,471 wounded and missing, besides 27 cannon and 4,000 muskets. The Confederate loss was 378 killed; 1,489 wounded and missing. Brady's cameras were soon on the field. He did not reach it in time, however, to secure pictures of the fighting armies. One of his negatives shows the historic stream of Bull Run along which the battle occurred. Another negative shows the field over which the hardest fighting took place. A third negative is that of Sudley Church, which was the main hospital after the conflict. It was here that, after a long detour, the Union forces found a vulnerable point and crossed to meet the enemy. Brady also secured a negative of Fairfax Court House, one of the outposts of the Confederacy, in this campaign.

THE man behind the gun risks his life on his faith in the ammunition train to keep him supplied with powder and shell. An old warrior estimates that an army of 60,000 men, comprising a fair average of infantry, cavalry, artillery and engineers must be provided with no less than 18,000,000 ball cartridges for small arms, rifles, muskets, carbines and pistols for six months' operation. In the field an infantry soldier usually carries about sixty rounds. The lives of the men depend upon the promptness of the ammunition trains. To supply these 60,000 men requires one thousand ammunition wagons and 3,600 horses. The wagon constructed for this service will carry 20,000 rounds of small-arm munition. The cartridges are packed in boxes and the wagon is generally drawn by four to six horses or mules. Several wagons are organized into an "equipment," moving under the charge of an artillery, and there are several such "equipments" for an army of this magnitude, one for each division of infantry, a small portion for the cavalry, and the rest in reserve. Early in the Civil War a chemist suggested to General McClellan that he could throw shells from a mortar that would discharge streams of fire "most fearfully in all directions." McClellan replied: "Such means of destruction are hardly within the category of civilized warfare. I could not recommend their employment until we have exhausted the ordinary means of warfare." The Government preferred to depend largely upon these silent, ghost-like wagons, with their deadly loads of millions of cartridges, pressing toward the battle lines throughout the conflict. This picture shows an ammunition train of the Third Division Cavalry Corps in motion with the army encamped on the distant hills. It is one of Brady's best negatives.

SLAVE pens were common institutions in the days of negro bondage in America. The system had developed from the early days of colonization and was for many generations a legitimate occupation throughout the country. So many rumors, false and true, were told of the "pens" that Brady schemed to secure photographs of some of them. Early in 1861 he succeeded in gaining entrance to one of the typical institutions in Alexandria, Virginia. The results are here shown. The cell rooms with their iron-barred doors and small cage windows relate their own story. While they were installed by the larger slave traders they were wholly unknown on most of the old Southern plantations. A picture is also here shown of the exterior of the "slave pen" kept at Alexandria with the inscription over the door, "Price, Birch & Co., Dealers in Slaves." This shows the proportions to which the system had grown in the greatest republic in the world. Enormous fortunes were being accumulated by some dealers who had thrown aside sentiment and humanity and were herding black men for the market. With the outbreak of the war many of the slaves sought the protection of the Union Army, while others, who had kind masters, were willing to remain on the plantations. Mr. Brady secured several photographs of these typical slave groups. The one here shown is a party of "contrabands" that had fled to the Union lines. Another familiar scene in 1861 was the pilgrimage of poor whites to the Union ranks. When the troops passed through many of the mountain villages, these frightened white sympathizers would hastily gather their scanty belongings, pile them onto an old wagon, desert their homes and follow the army, to be passed on from line to line until they reached the North.

ONE of the greatest secret forces in the Civil War was the electric telegraph. Wires were uncoiled as the army moved on its march toward the enemy and over them passed the hurried words that frequently saved hundreds and thousands of lives. While England was the first to experiment with the new science on the battlefield, the war in America demonstrated its permanent importance in the maneuvers of armies. Brady was much interested in the development of telegraphy as a factor in war and never missed any opportunity to take a photograph of the field telegraph corps as they passed him on marches. This picture shows one of the construction corps in operation. The wires were laid as each column advanced, keeping the General in command fully informed of every movement and enabling him to communicate from his headquarters in the rear of the army with his officers in charge of the wings. The military construction corps laid and took up these wires as fast as an infantry regiment marches. An instant's intelligence may cause a charge, a flank or a retreat. By connecting with the semi-permanent lines strung through woods and fields, into which the enemy would have little reason to venture unless aroused by suspicion, the commander on the field is kept informed of the transportation of troops and supplies and the approach of reinforcements. It was also the duty of the military construction corps to seize all wires discovered by them and to utilize them for their own army or tear them down. Constant watch is kept for these secret lines. Great care must also be taken that false messages do not pass over them. Their destruction is generally left to the cavalry. The heavy construction wagons, carrying many miles of telegraph wire in coils, were drawn by four horses.

TELEGRAPH stations in wagons were not uncommon sights to the soldiers between the years of 1861 to 1865. Great responsibility rested upon the operators who halted alongside the road to send a message back to headquarters that might change the whole course of events and defeat into victory. The operators in the Civil War stood by their posts like sentinels. The confidential communications of commanders and the movements of the morrow were intrusted with them, but not in a single instance is one known to have proven false to that trust. It was part of the duty of the telegraph service to take messages from the scouts sent out to ascertain the resources of the country, the advantages of certain routes, and the general lay of the land. Every click of the instrument transmitted secrets upon which might depend the rise or fall of the nation. These field telegraph wagons, drawn by horses, carried the instruments and batteries which had but recently been invented by an American scientist, and by which an electric spark shot messages through wire in the fraction of a second's time. The War of 1861 proved for all time the advantages of this new science. It left the signal corps to attend to only short-range communications and lightened the duties of mounted orderlies, conveying messages in a flash of electricity that had hitherto taken a day's reckless riding on horseback. While it saved the orderlies from many hazardous journeys there were many more where the telegraph wires did not penetrate and dependence was still placed on the dashing mounted messenger. The chief service of the electric telegraph was to maintain communication between corps and divisions and headquarters. It was also utilized in some of the brilliant strokes of the Secret Service in forestalling deep-laid plots.

THE downfall of Washington in the first days of the war would have meant the downfall of the Republic. What changes this would have wrought in the history of the Western Continent can never be known. Its probabilities were such that the Treasury Building was guarded by howitzers, the Halls of Congress were occupied by soldiers, the Capitol building became a garrisoned citadel. Lincoln was virtually imprisoned by guards in the White House, and the streets were patrolled by armed men. Troops were quartered in the Patent Building. The basement galleries of the Capitol were converted into store-rooms for barrels of pork, beef and rations for a long siege. The vaults under the broad terrace on the western front were turned into bakeries where sixteen thousand loaves of bread were baked every day. The chimneys of the ovens pierced the terrace and smoke poured out in dense black clouds like a smoldering volcano. Ammunition and artillery were held in readiness to answer a moment's call. So intense was the excitement that one of the generals in command at the Government arsenal exclaimed: "We are now in such a state that a dog-fight might cause the gutters of the Capital to run with blood." There was the clank of cavalry on the pavements, the tramp, tramp of regiments of men whose polished muskets flashed in the sunlight as they moved over Long Bridge. Cavalcades of teams and white-topped army wagons carrying provisions, munitions of war and baggage followed in weird procession. Brady was then in Washington negotiating with the Government and the Secret Service for permission to follow the armies with his cameras. This is one of the pictures that he took at that time, showing the artillery and cannon-balls parked at the National Capital.

NO one, except the men who did it, can ever know the tremendous difficulties overcome in preparing an army for warfare. The transformation of a nation of peaceful home-lovers to a battle-thirsty, fighting populace is almost beyond human understanding. To arm them instantly with the implements of war is a problem hardly conceivable. When the first guns of the Civil War were belching their death-fire, all the man-killing weapons known to civilization were being hurried to the front. There were flint and percussion and long-range muskets and rifles; bayonets and cavalry sabers; field and siege cannon; mortars and sea-coast howitzers; projectiles, shot, shell, grape and canister; powder, balls, strap and buckshot; minie balls and percussion caps; fuses, wads and grenades; columbiads and navy carronades; lances, pistols and revolvers; heavy ordnance and carriages. Europe was called upon to send its explosives across the sea. Caves were opened for the mining of nitre, lead and sulphur. Factories were run day and night for the manufacture of saltpeter. On land and sea the greatest activity prevailed. This photograph was taken on the twenty-sixth day of August in 1861, when the ammunition schooners, accompanying the fleet from Fortress Monroe on the expedition to Fort Hatteras, N. C., were passing through Hampton Roads. The fleet, sailing under sealed orders, in command of Flag Officer Silas H. Stringham, arrived before sunset. Two days later, in conjunction with the troops of the 9th, 20th, and 99th New York Volunteers, under General Benjamin F. Butler, it forced the surrender of Fort Hatteras without the loss of a man and took seven hundred prisoners. The Confederates lost about fifty killed and wounded.

SPIES lived in the White House according to the rumors in 1861, and every council of the Administration was reported to the enemy. Whether this is true or not has never been verified, but by some mysterious channel the Administration's plans invariably fell into the hands of the Confederates. One of the first instances of this is the expedition to Port Royal on the South Carolina coast. This was one of the finest harbors along the South Atlantic and it was planned to take it from the Confederates and use it as a base for future Union operations. The most careful preparations were laid for two months. On the twenty-ninth of October, in 1861, fifty vessels under sealed orders with secret destination sailed from Hampton Roads. The fleet had hardly left the range of Fortress Monroe when the full details of its sealed orders reached the Confederates at Port Royal. Off Cape Hatteras it ran into a severe gale; one transport was completely wrecked, with a loss of seven lives; another transport threw over her cargo; a storeship went down in the storm, and a gunboat was saved only by throwing her broadside battery into the sea. The fleet was so scattered that when the storm cleared there was only a single gunboat in sight of the flagship. Undismayed by the misfortune, within a few hours the vessels that had withstood the tremendous gale were moving on to Port Royal. Several frigates that had been blockading Charleston Harbor joined them and on the morning of the seventh of November the attack was made on Fort Walker at Hilton Head and Fort Beauregard on St. Helena Island. The guns of the fleet wrought dreadful havoc. The stream of fire was more than the entrenched men had expected or could endure. The troops fled across Hilton Head in panic from Fort Walker. When the commander at Fort Beauregard looked upon the fleeing soldiers he abandoned his position and joined the retreat. A flag of truce was sent ashore but there was no one to receive it, and soon after two o'clock the National colors were floating over the first permanent foothold of the Government in South Carolina, a Confederate stronghold.

THE AMERICAN PEOPLE, in their one hundred and twenty years of "Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of Happiness," have had but three wars with the outside world. They have enjoyed a greater immunity from armed encounter than any of their neighbors. Other than the grievous struggle which we have had with our own people, it may be fairly said that we have been blessed by Peace.

As if by magic the hundreds of thousands of volunteers were armed with the munitions of War and marched to the battle-front. The great Lincoln, under the constitutional provisions, was commander-in-chief of the citizen armies, and worked in conjunction with his War Department at Washington. The military genius of a trained fighter was needed and from the outbreak of the War until November 6, 1861, Brevet-Lieutenant Winfield Scott was in command; then came Major-General George B. McClellan, a man of great caution, until March 11, 1862. From that time until July 12, 1862, the Government was without a general commander until Major-General Henry W. Halleck took control and continued till March 12, 1864. It was then that Lieutenant-General Ulysses S. Grant was called upon to end the struggle. Under these military leaders the great fighting force of volunteers was organized into armies. The first of these patriot legions was the Army of the Potomac.

Army of the Potomac was called into existence in July, 1861, and was organized by Major-General George B. McClellan, its first commander; November 5, 1862, Major-General A. E. Burnside took command of it; January 25, 1863, Major-General Joe Hooker was placed in command, and June 27, 1863, Major-General George G. Meade succeeded him.

Army of Virginia was organized August 12, 1862. The forces under Major-Generals Fremont, Banks, and McDowell, including the troops then under Brigadier-General Sturgis at Washington, were consolidated under the command of Major-General John Pope; and in the first part of September, 1862, the troops forming this army were transferred to other organizations, and the army as such discontinued.

Army of the Ohio became a power, November 9, 1861. General Don Carlos Buell assumed command of the Department of the Ohio. The troops serving in this department were organized by him as the Army of the Ohio, General Buell remaining in command until October 30, 1862, when he was succeeded by General W. S. Rosecranz. This Army of the Ohio became, at the same time, the Army of the Cumberland. A new Department of the Ohio having been created, Major-General H. G. Wright was assigned to the command thereof; he was succeeded by Major-General Burnside, who was relieved by Major-General J. G. Foster of the command of the Department and Army. Major-General J. M. Schofield took command January 28, 1864, and January 17, 1865, the Department was merged into the Department of the Cumberland.

Army of the Cumberland developed from the Army of the Ohio, commanded by General Don Carlos Buell, October 24, 1862, and was placed under the command of Major-General W. S. Rosecranz; it was also organized at the same time as the Fourteenth Corps. In January, 1863, it was divided into three corps, the Fourteenth, Twentieth and Twenty-first; in September, 1863, the Twentieth and Twenty-first Corps were consolidated into the Fourth Corps. October, 1863, General George H. Thomas took command of the army, and the Eleventh and Twelfth Corps were added to it. In January, 1864, the Eleventh and Twelfth Corps were consolidated and known as the Twentieth Corps.

Army of the Tennessee was originally the Army of the District of Western Tennessee, fighting as such at Shiloh, Tennessee. It became the Army of the Tennessee upon the concentration of troops at Pittsburg Landing, under General Halleck; and when the Department of the Tennessee was formed, October 16, 1862, the troops serving therein were placed under the command of Major-General U. S. Grant. October 24, 1862, the troops in this Department were organized as the Thirteenth Corps; December 18, 1862, they were divided into the Thirteenth, Fifteenth, Sixteenth and Seventeenth Corps. October 27, 1863, Major-General William T. Sherman was appointed to the command of this army; March 12, 1864, Major-General J. B. McPherson succeeded him; July 30, 1864, McPherson having been killed, Major-General O. O. Howard was placed in command, and May 19, 1865, Major-General John A. Logan succeeded him.

Army of the Mississippi began operations on the Mississippi River in Spring, 1862; before Corinth, Mississippi, in May, 1862; Iuka and Corinth, Mississippi, in September and October, 1862.

Army of the Gulf operated at Siege of Port Hudson, Louisiana, May, June, and July, 1863.

Army of the James consisted of the Tenth and Eighteenth Corps and Cavalry, Major-General Butler commanding and operating in conjunction with Army of the Potomac.

Army of West Virginia was active at Cloyd's Mountain, May 9 and 10, 1864.

Army of the Middle Military Division operated at Opepuan and Cedar Creek, September and October, 1864.

During the year 1862, Brady's men followed these legions. Both armies were maneuvering to strike a decisive blow at the National Capital of either foe—one aiming at Washington and the other at Richmond. The scenes enacted in these campaigns are remarkable in military strategy, and Brady's men succeeded in perpetuating nearly every important event.

Cameras were also hurried to the far South and West where great leaders with great soldiers were doing great things. Several of these cameras arrived in time to bear witness to the bravery of the men of the Mississippi, who were waging battle along the greatest waterway in North America—the stronghold of the Confederacy and the control of the inland commerce of the Continent.